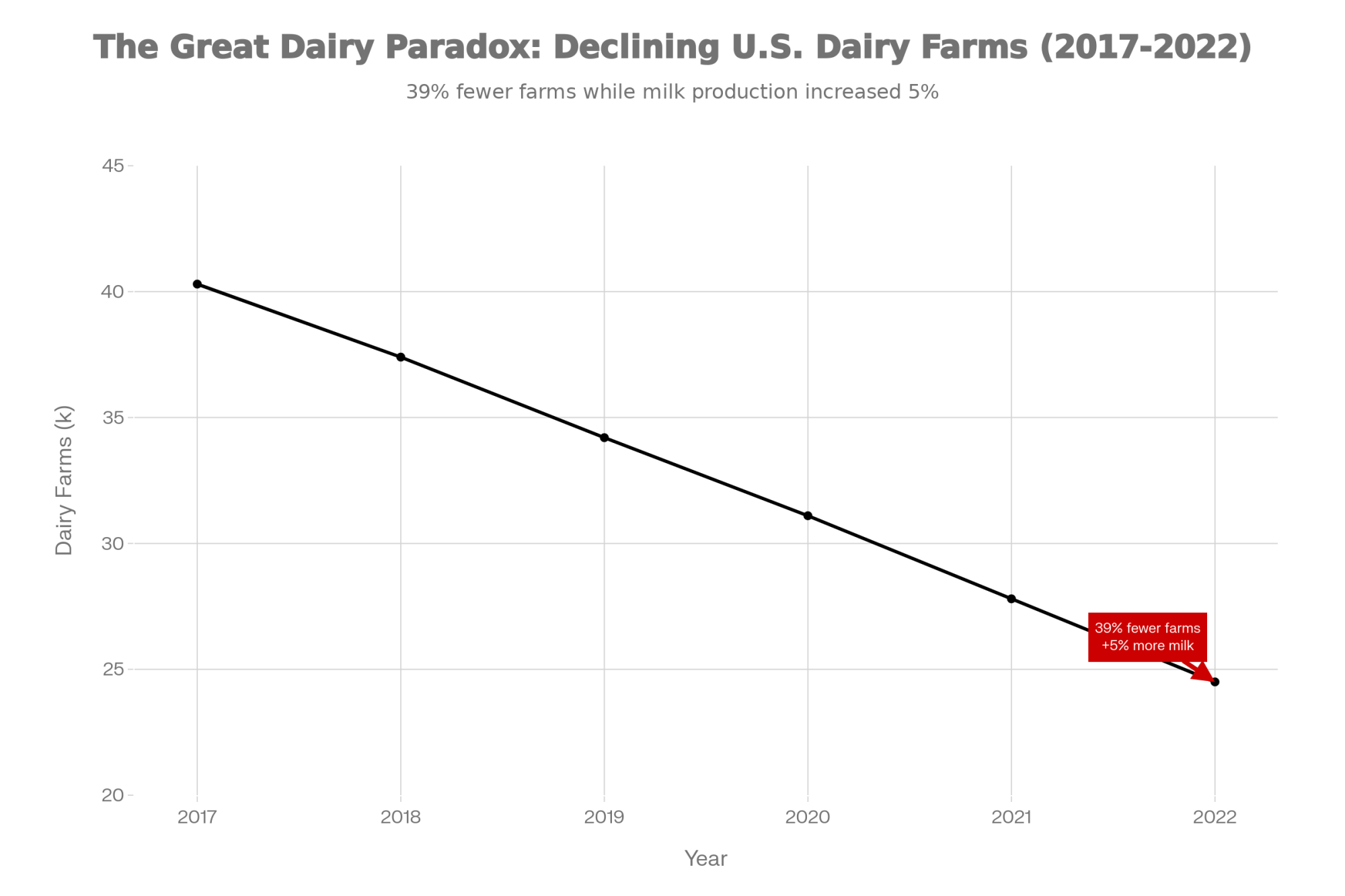

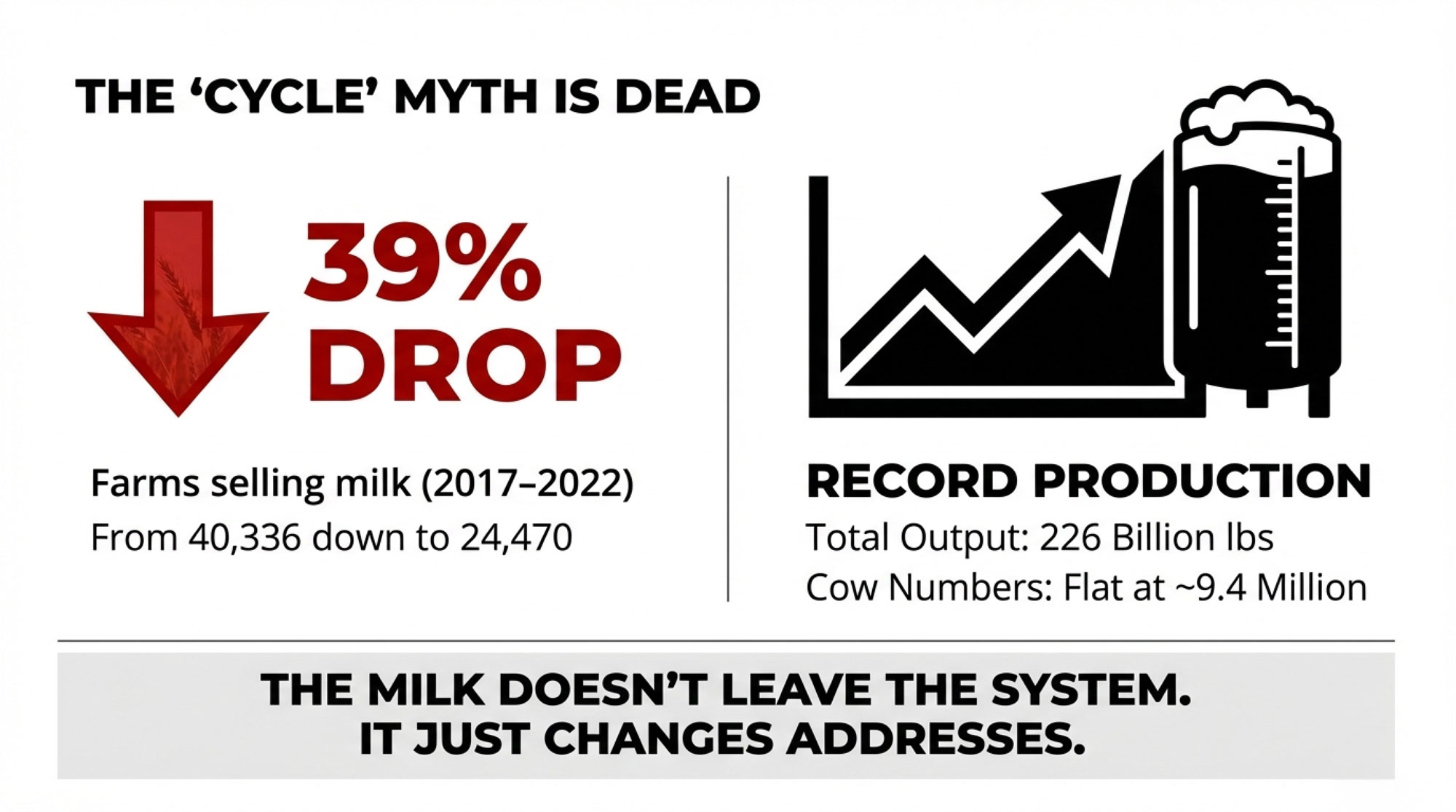

US$8B in whey plants is coming online. Will any of that protein cash ever reach your milk cheque?

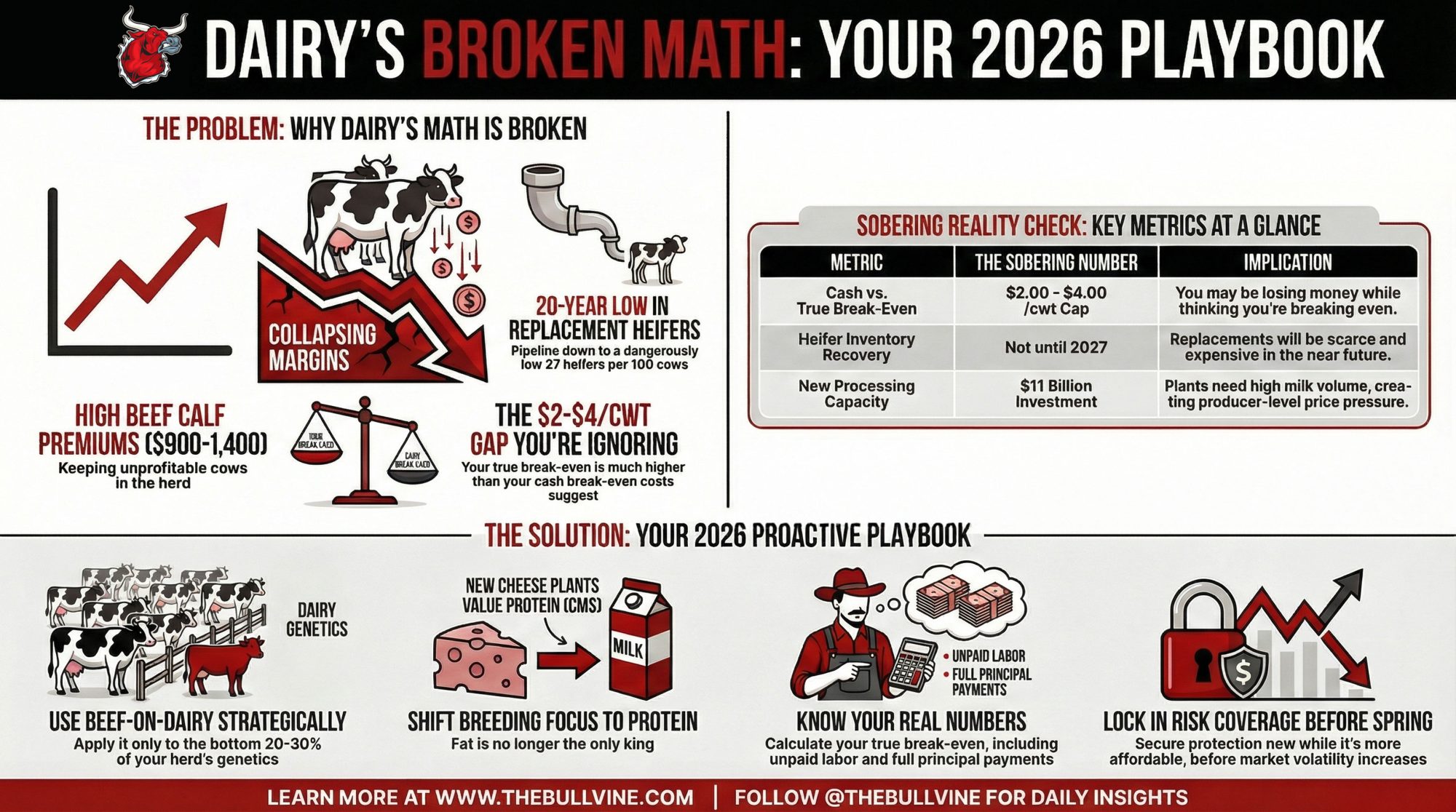

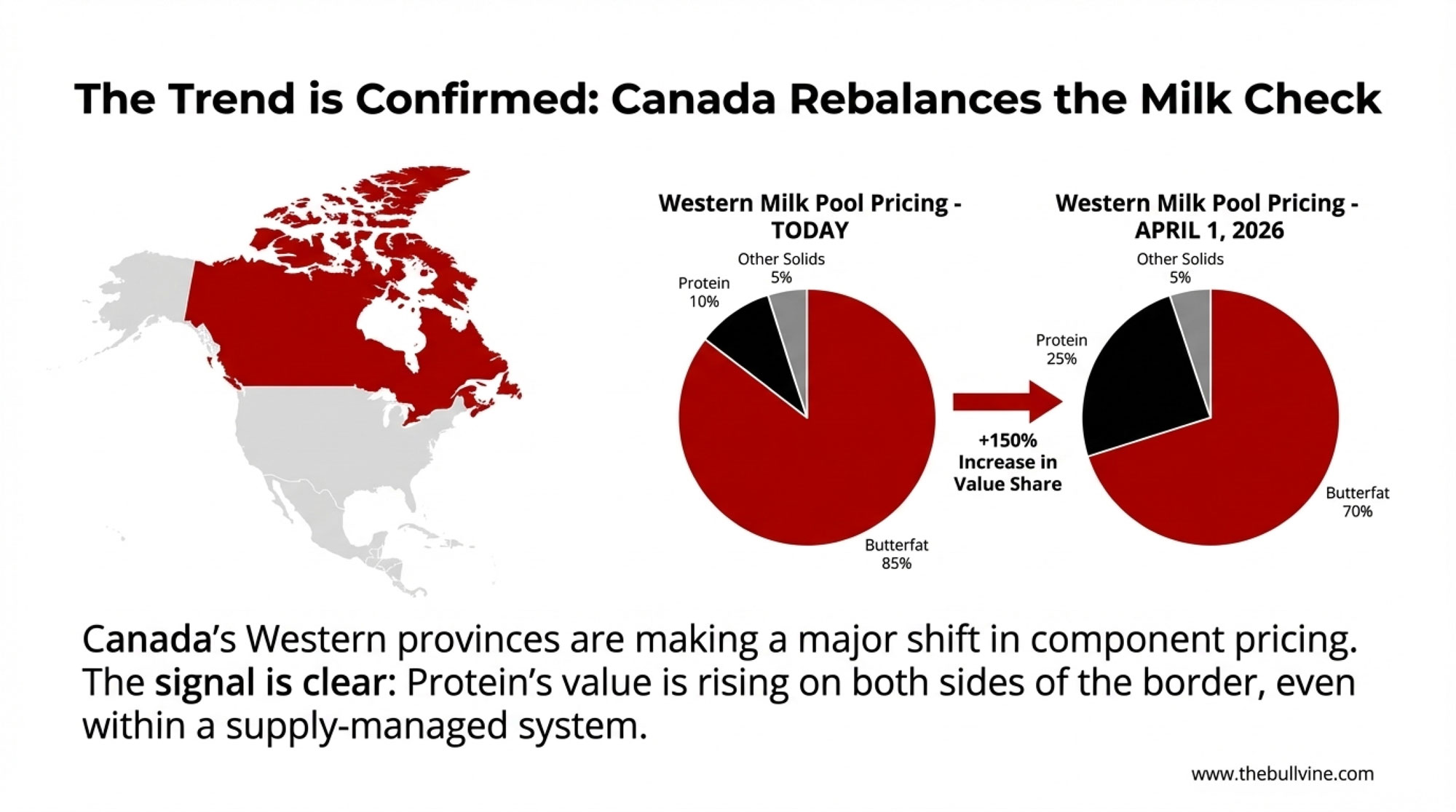

Executive Summary: Processors are spending about US$8 billion on new cheese and whey plants because GLP‑1 drugs and protein‑driven diets are pushing global whey demand to record levels. Yet most milk cheques still key off commodity dry whey prices, while the real “protein money” sits in higher‑value ingredients like WPC‑80 and WPI, inside co‑op balance sheets and patronage systems. This article shows, in plain language, how that gap forms—and then uses simple math (like turning a 30¢/cwt whey margin into roughly US$40 per cow per year) to show what it could mean on your farm. From there, it gives you a clear playbook: how to read your equity statement, how to benchmark your all‑in price, and the three questions to ask at your next co‑op meeting about project financing, whey division reporting, and cash vs retained patronage. It also compares what this whey boom means if you ship to an ingredient‑heavy plant in the Texas Panhandle or Upper Midwest, a more commodity‑focused co‑op in the East, or a quota system in Canada. In short, it’s a guide to turning the whey boom from a stainless‑steel story into a milk‑cheque strategy.

You know how every winter meeting seems to have the same slide deck these days? Somebody from a processor or a bank stands up, talks about protein, GLP‑1 weight‑loss drugs, and this “massive opportunity in whey,” and then you’re driving home thinking, “OK, but where does that show up in my milk cheque?”

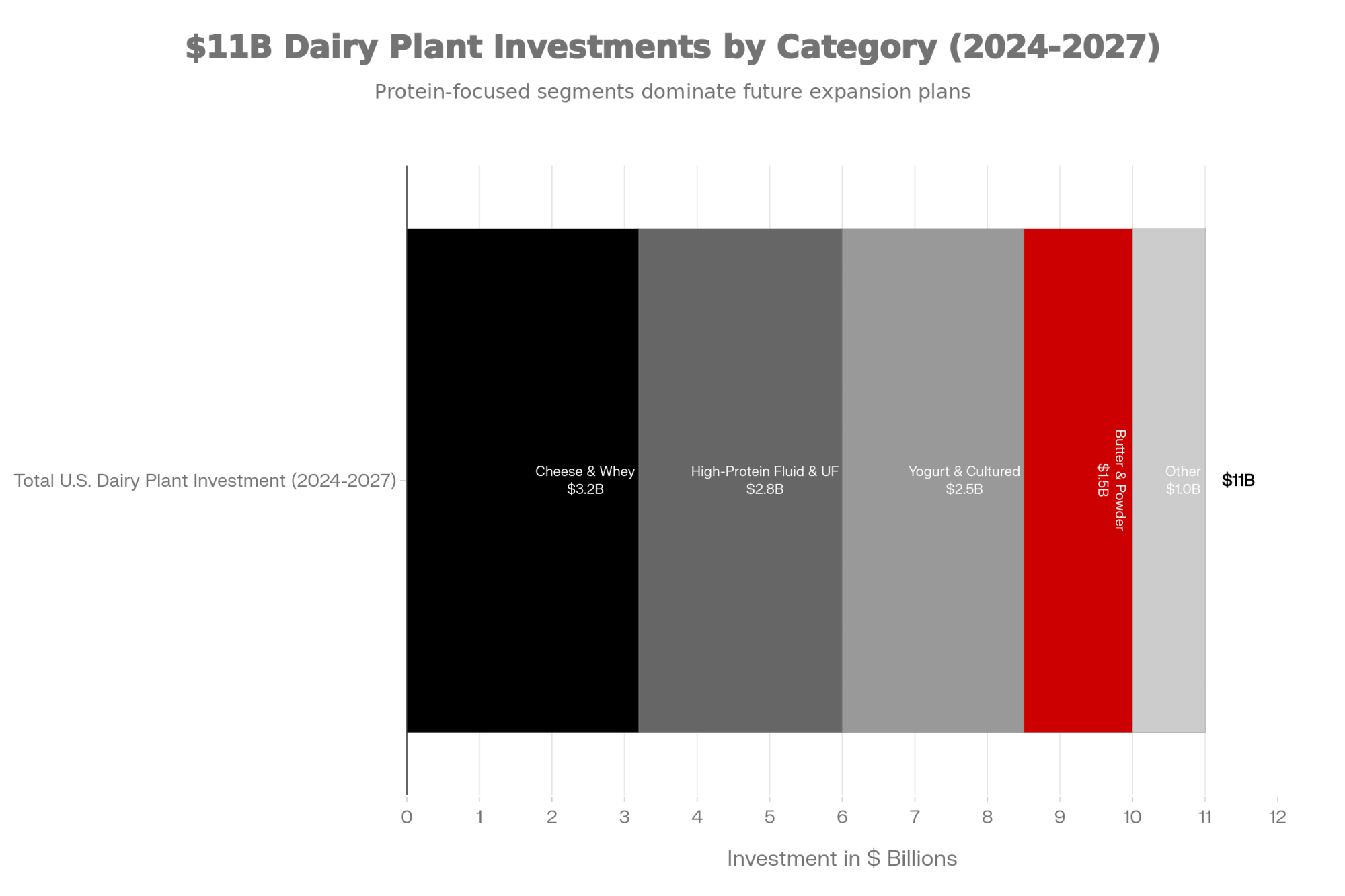

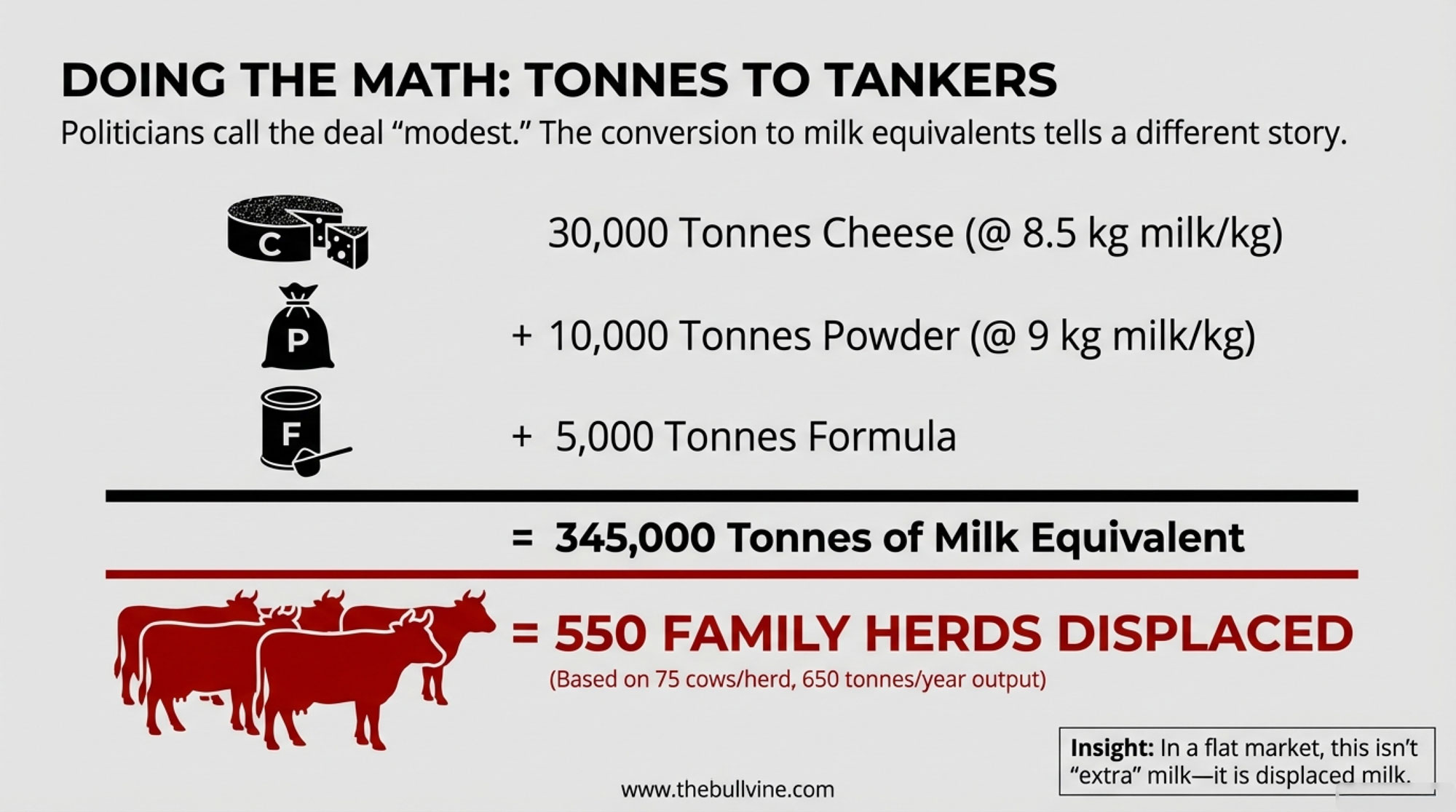

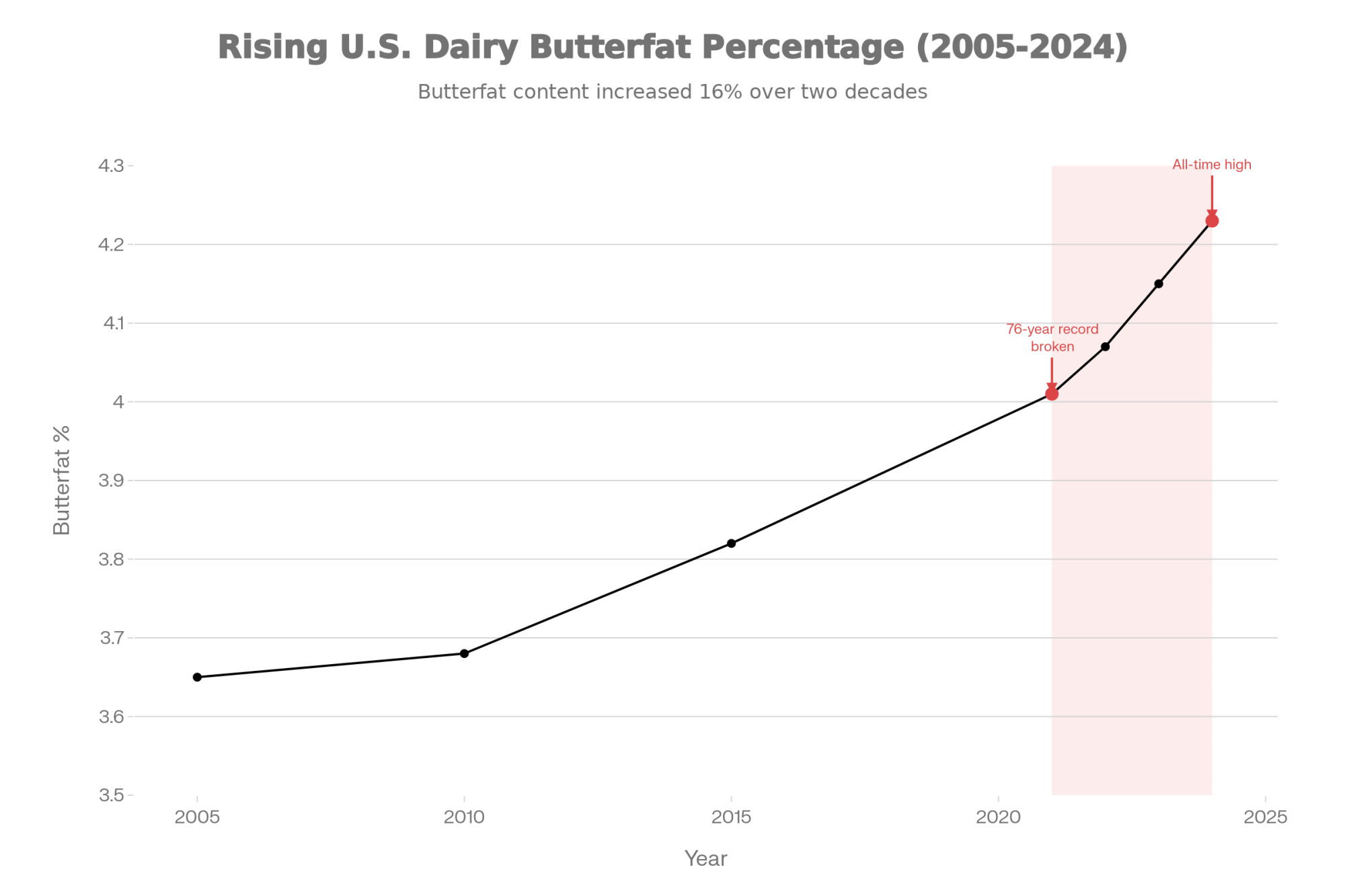

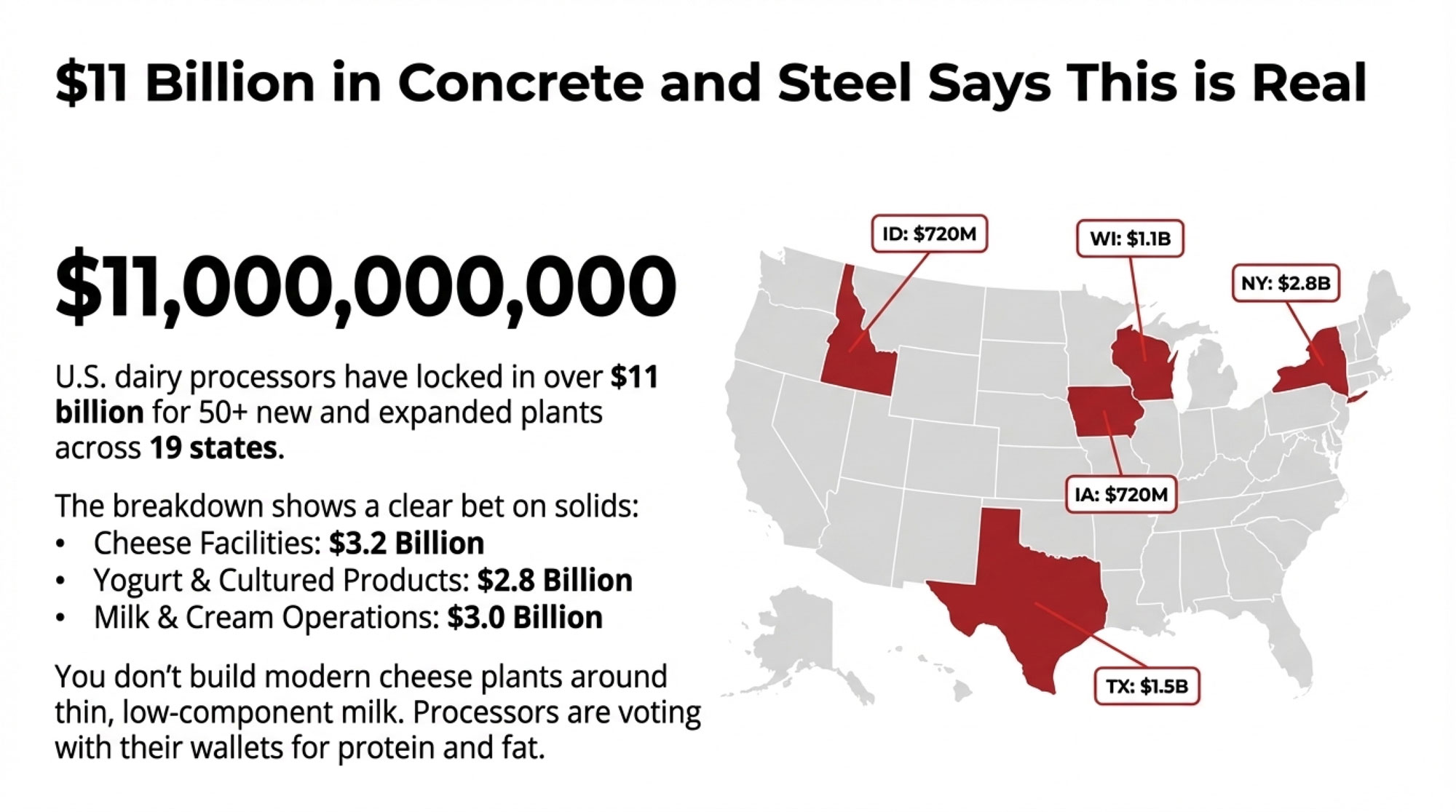

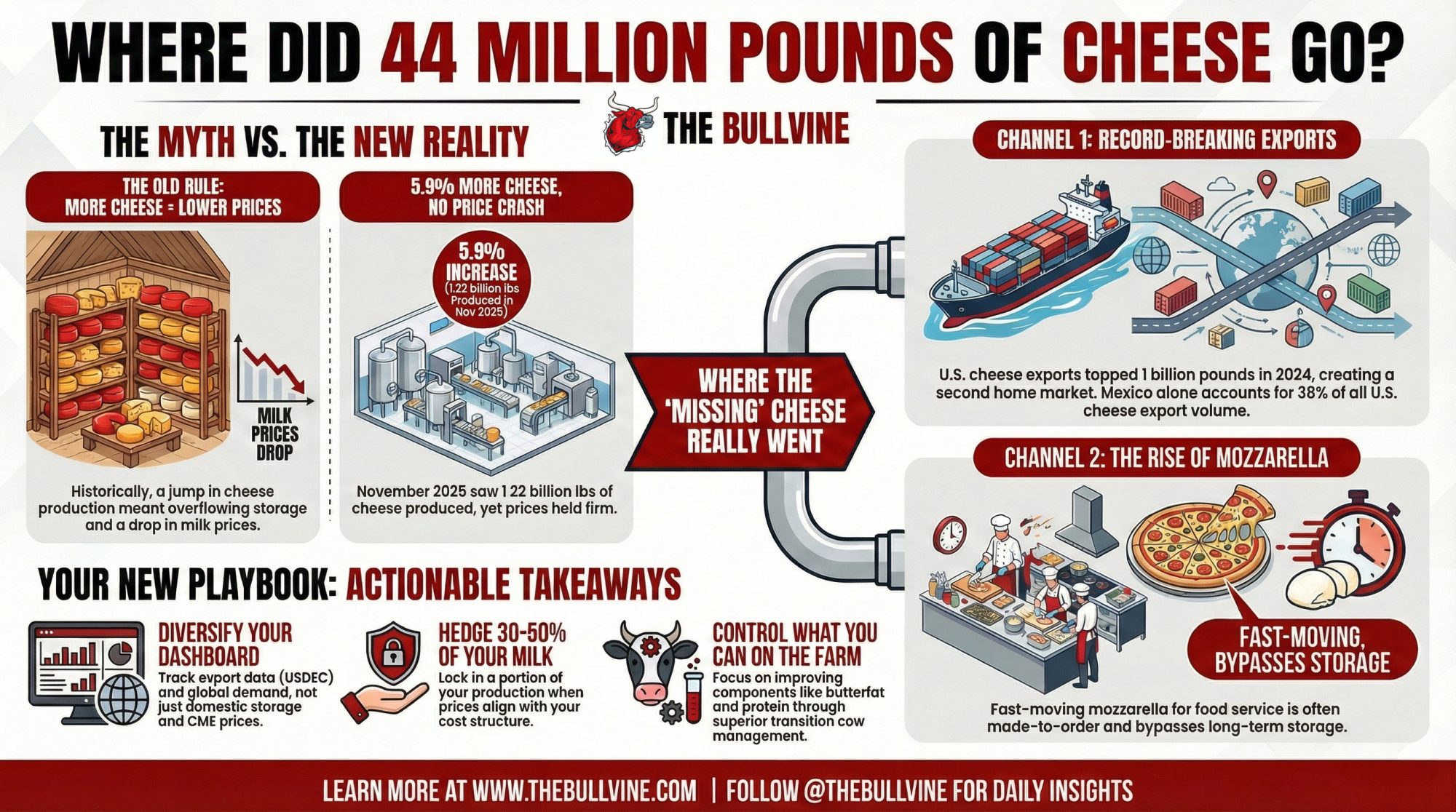

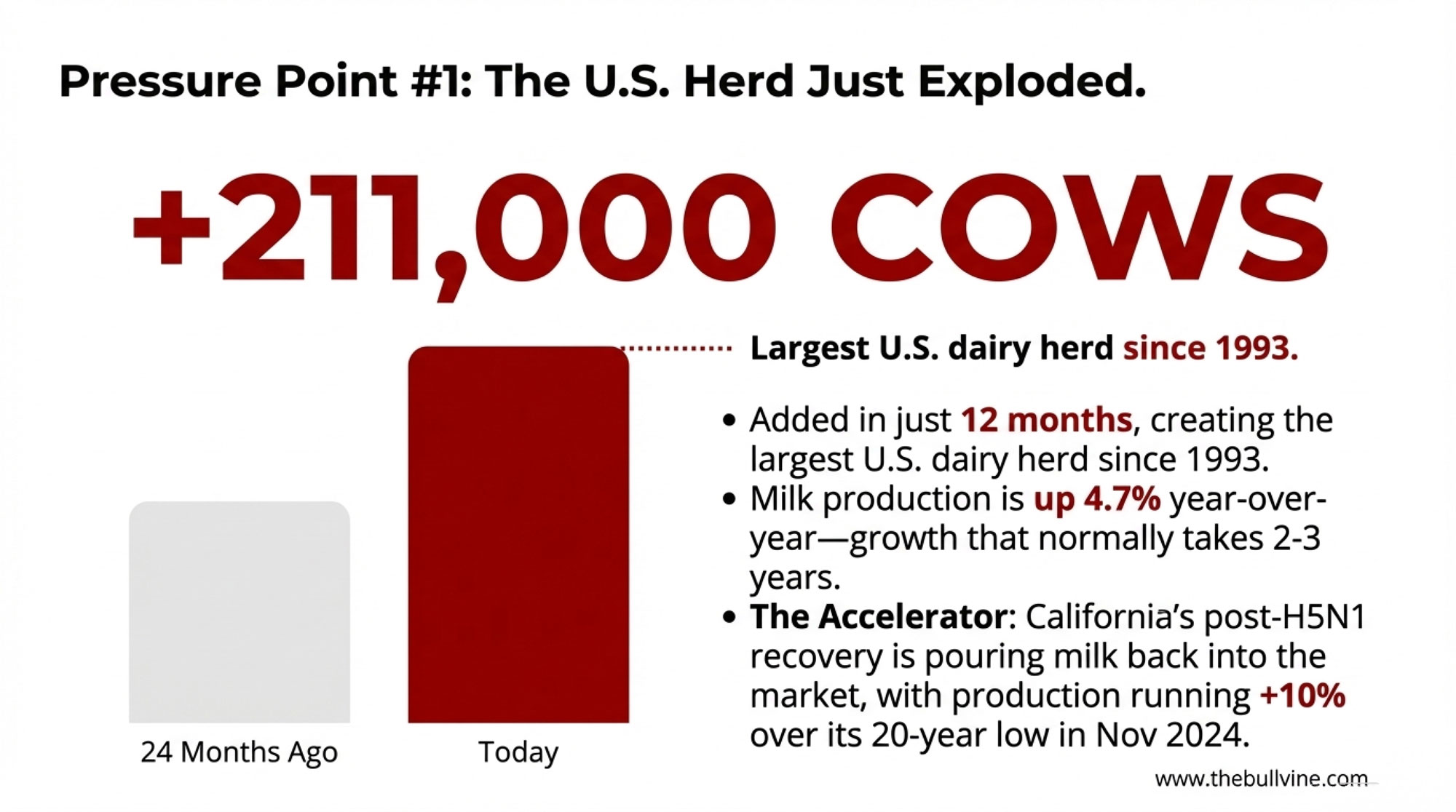

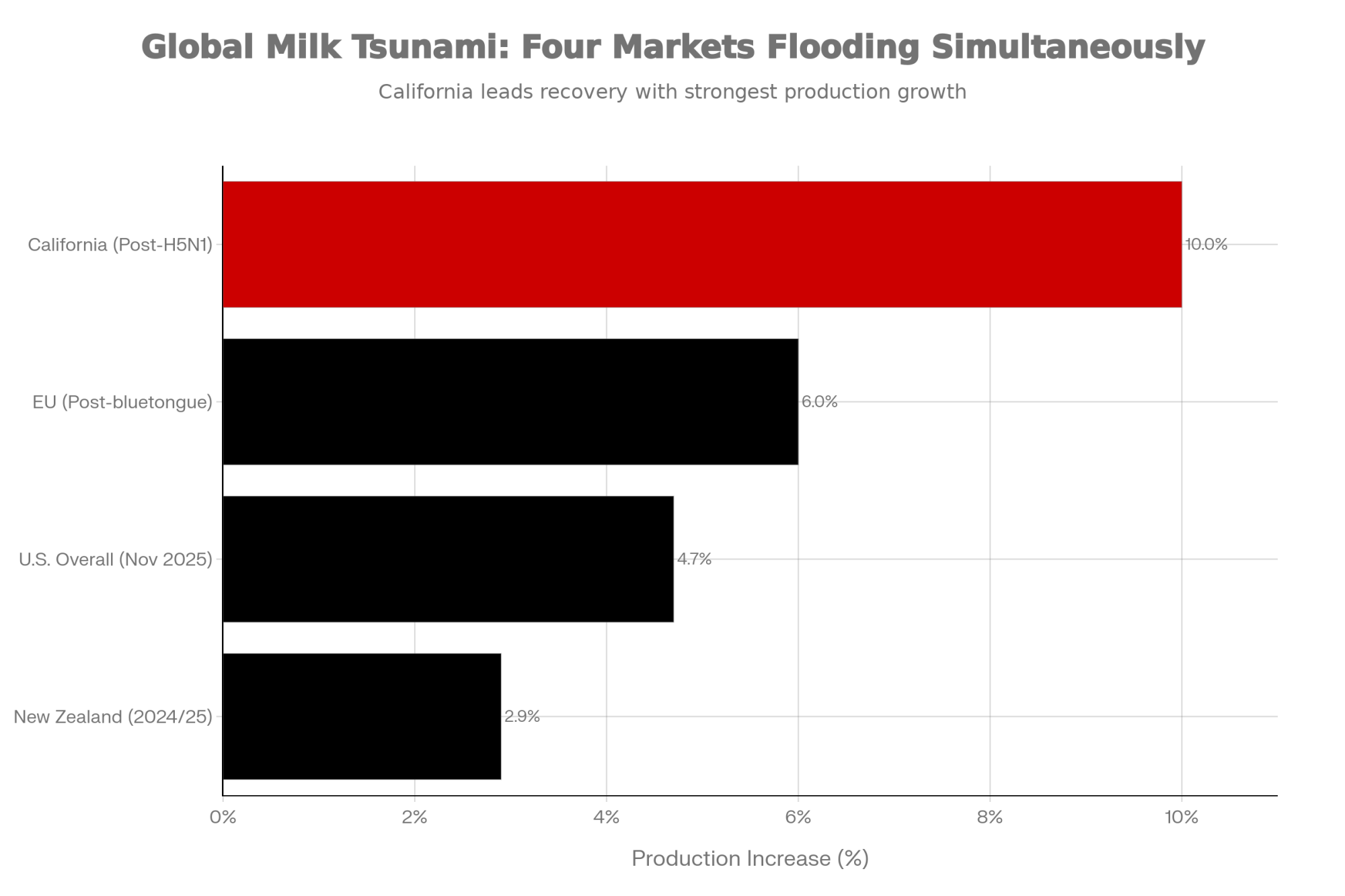

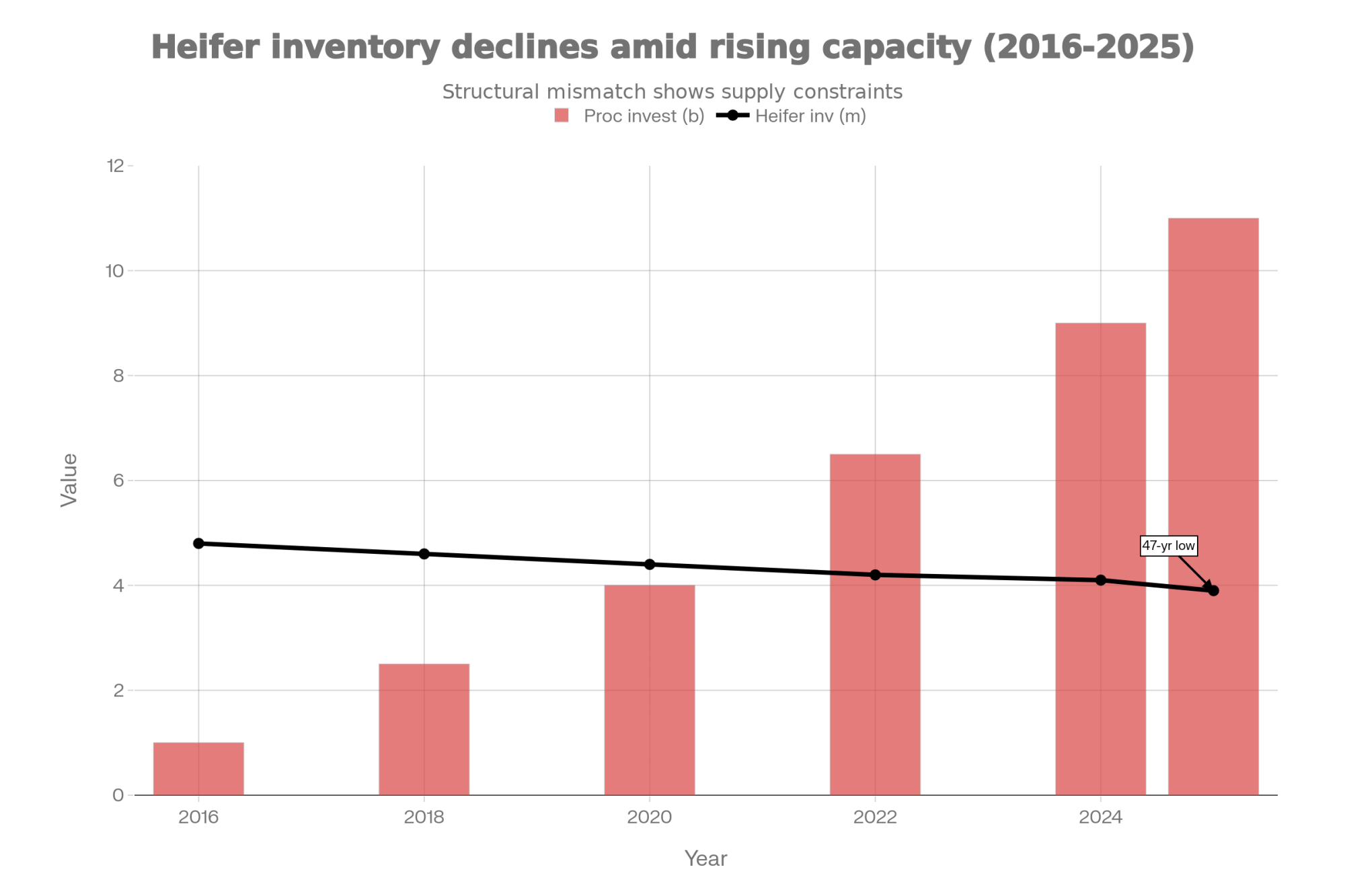

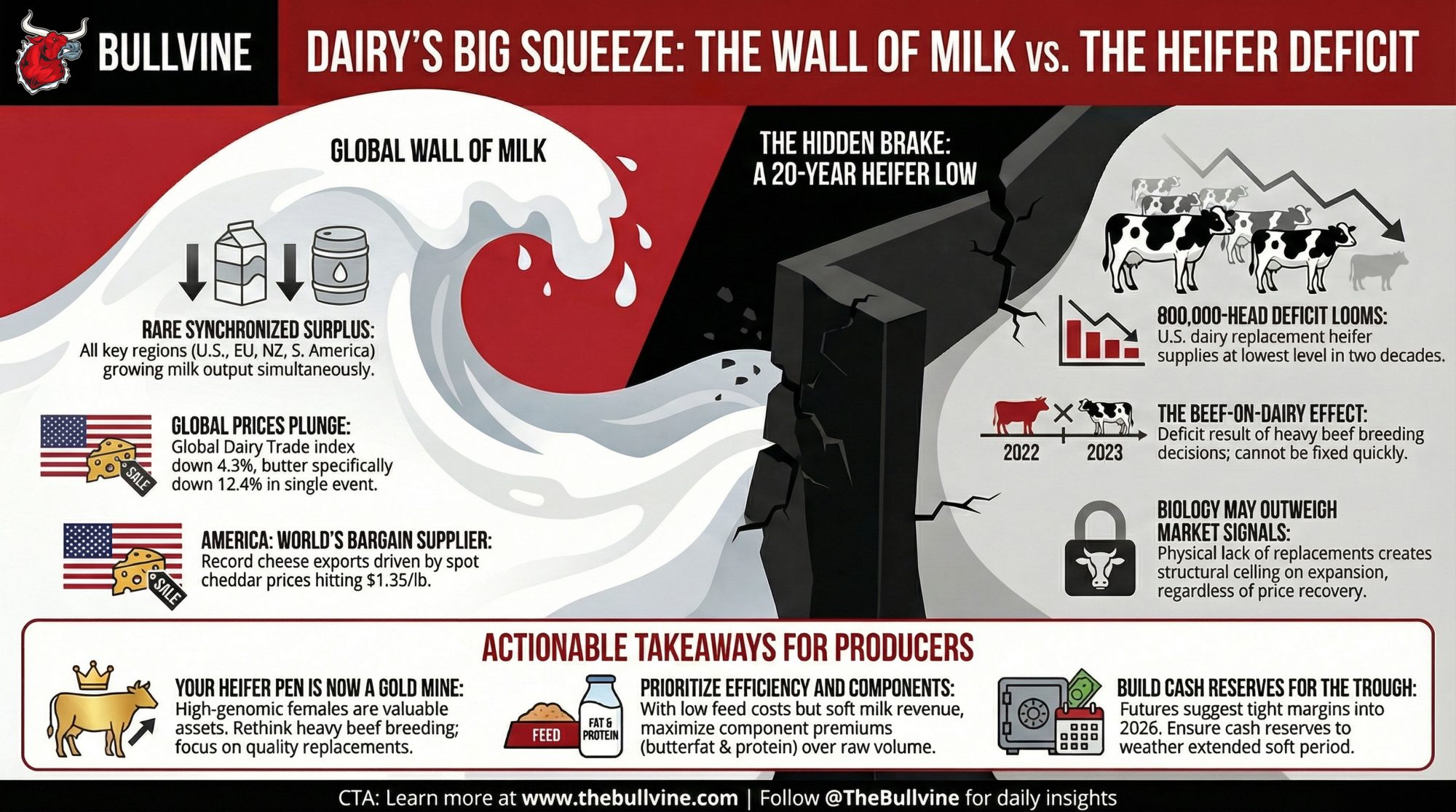

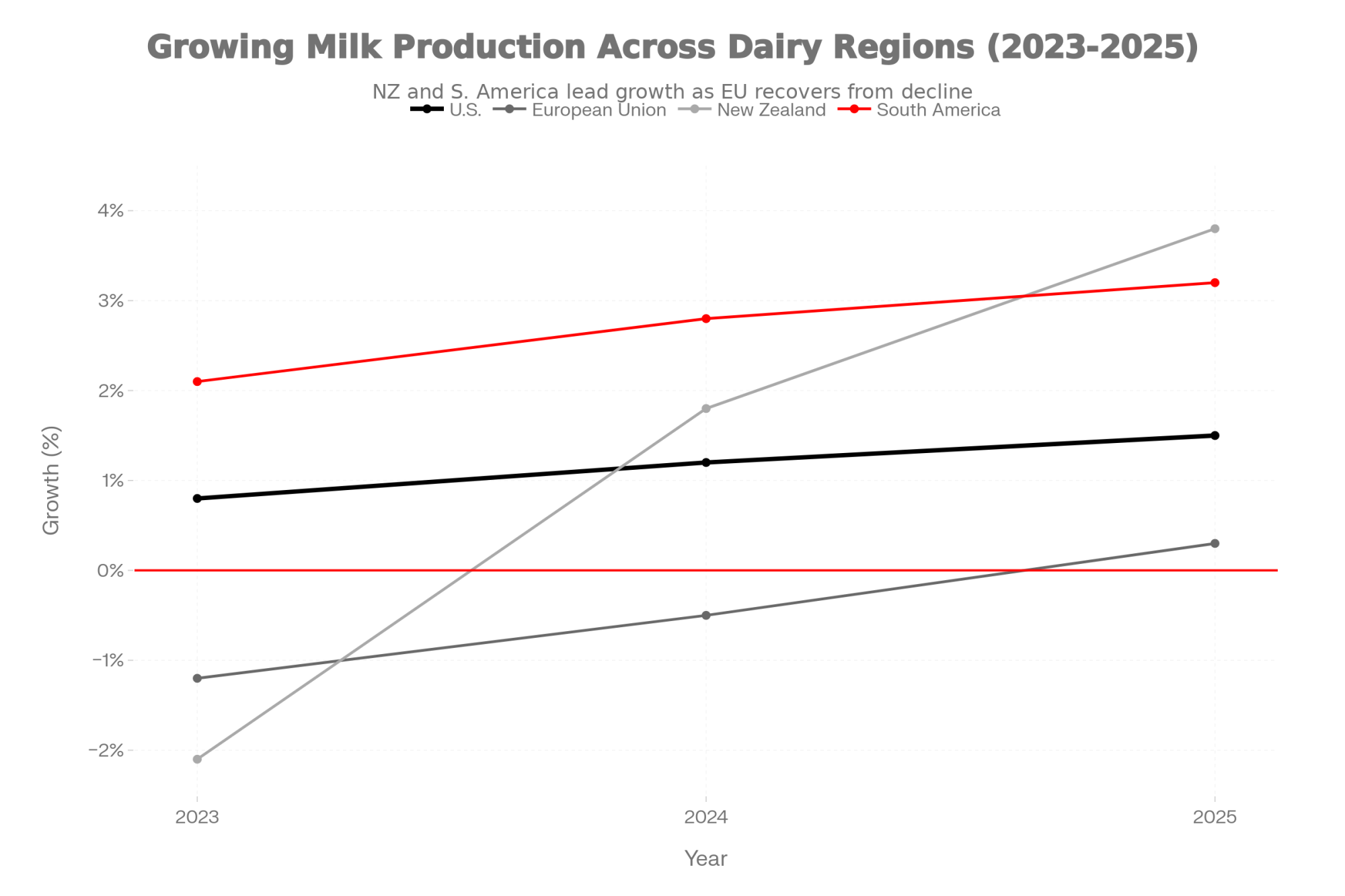

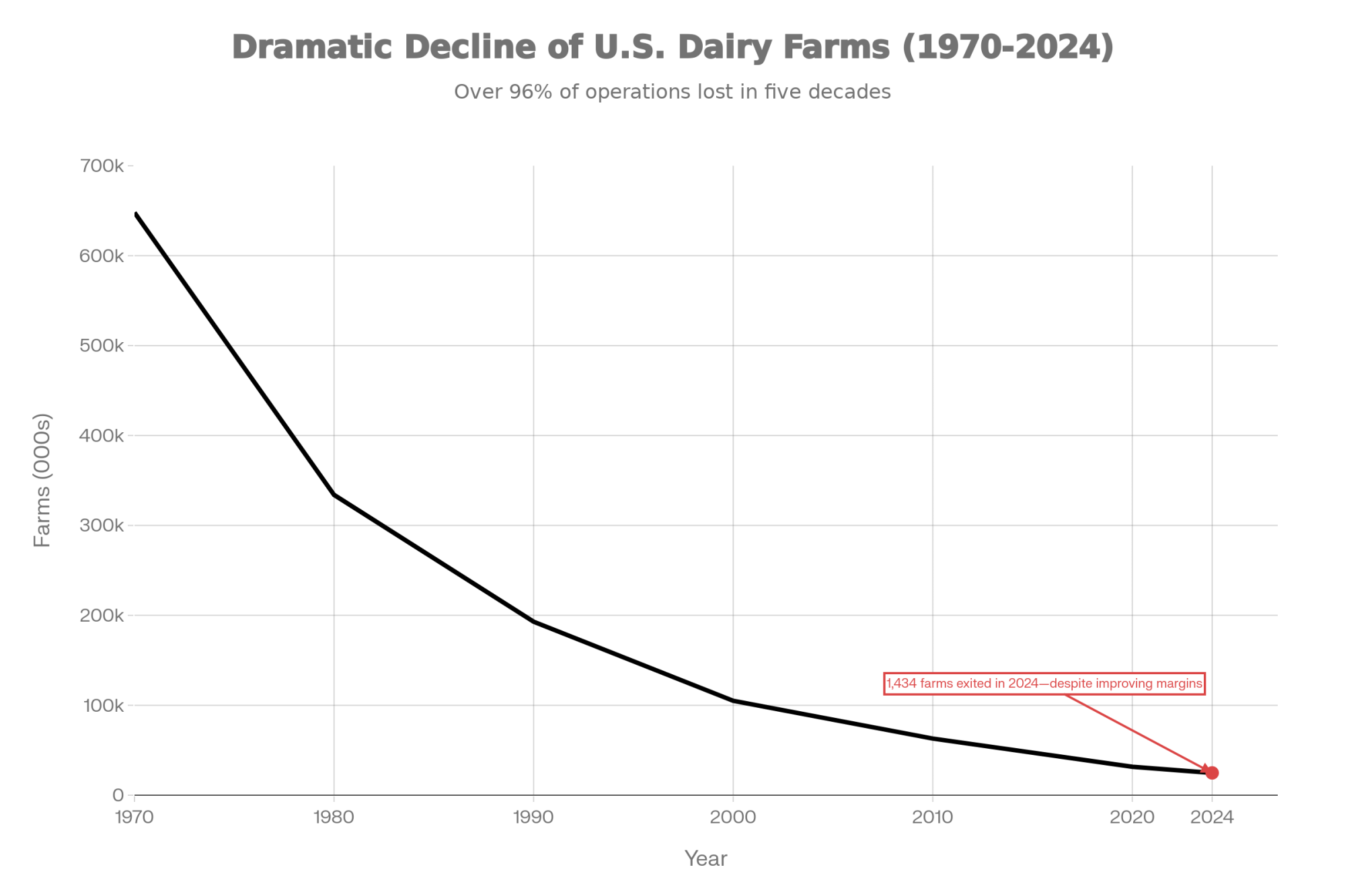

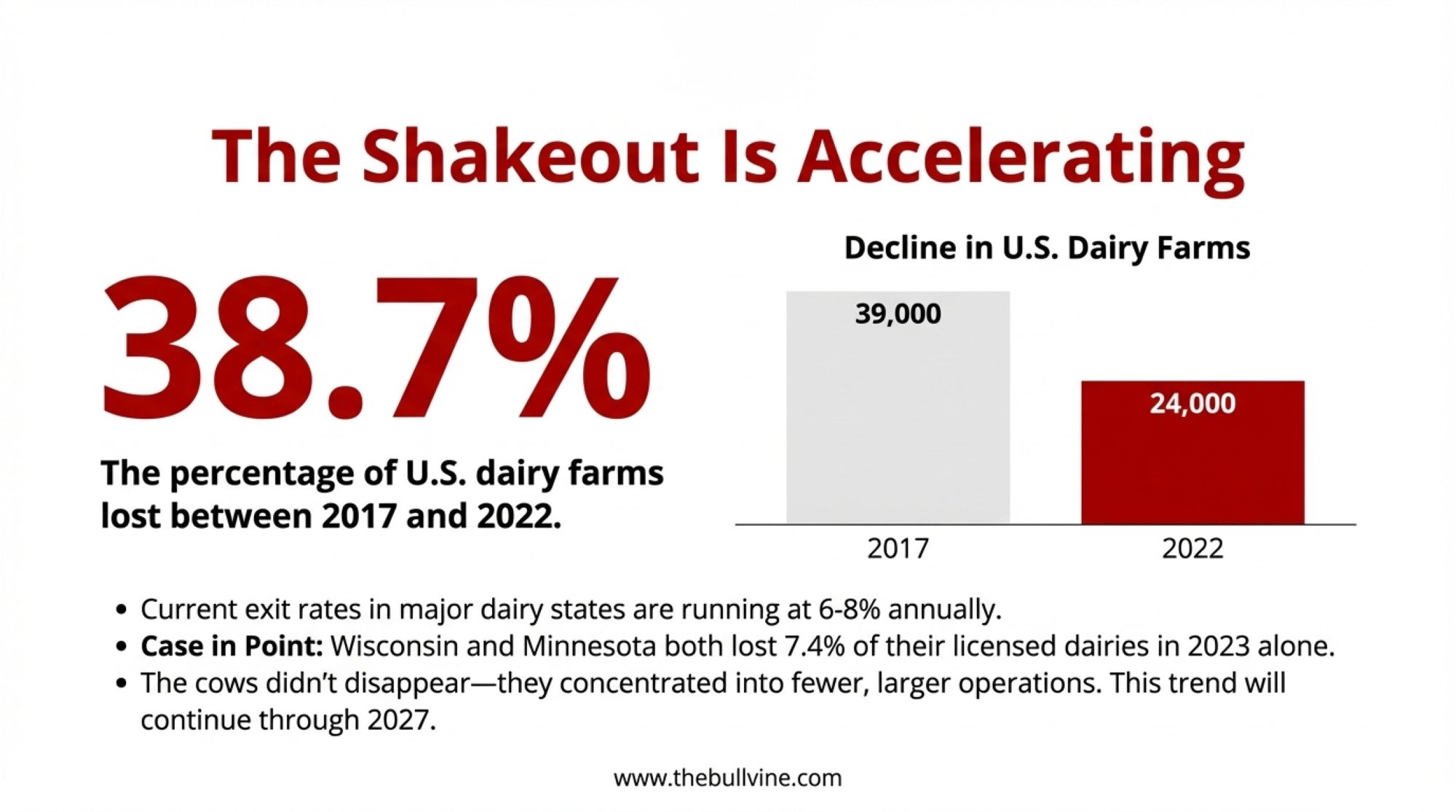

What’s interesting here is that this time, the stainless is real. University of Wisconsin–Madison Extension dairy economist Leonard Polzin told Brownfield Ag News that more than eight billion dollars’ worth of stainless steel is being invested in new and expanded dairy processing in various parts of the U.S., with a few plants starting in February and more coming online “in 2025 and in future years,” across a range of products from cheese to fluid and other dairy categories. About US$8billion in new U.S. dairy processing investment through 2026, with a big share of that going into cheese and whey capacity.

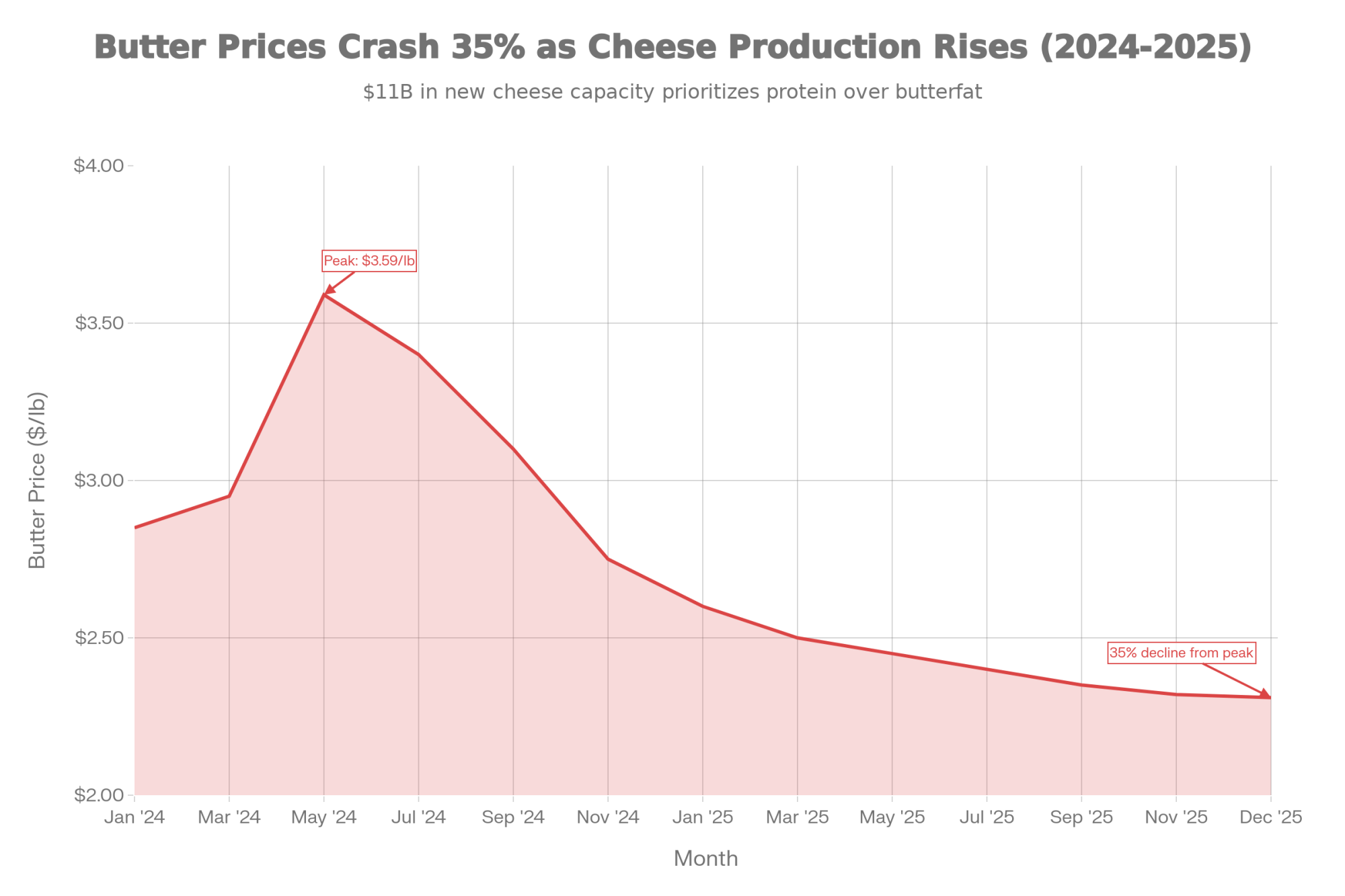

And this isn’t just a Wisconsin or South Dakota story anymore. New cheese plants in Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Texas are expected to add roughly 360 million pounds of cheese annually by the end of 2025, and industry coverage points to big new facilities in the Texas Panhandle and eastern New Mexico, designed specifically to turn High Plains milk into cheese and high‑value whey ingredients. So while the Upper Midwest still matters, a lot of the newest “stainless” is actually being welded out West.

| Region | Estimated New Capacity (2024–2026) | Primary Product Focus | Key New Facilities | Co-op / Processor Type | Whey Ingredient Emphasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Midwest (WI, MI, MN) | ~$2.5–3.0B | Cheese + Whey | Established complexes + expansions | Ingredient-heavy co-ops (e.g., AMPI) | High (WPC-80, WPI, export) |

| Upper Plains (SD, ND) | ~$1.5–2.0B | Cheese + Whey | Regional & private plants | Mixed (co-op + private) | Medium–High |

| Texas Panhandle + E. New Mexico | ~$2.0–2.5B | Cheese + Whey | New-build, High Plains focused | Private processors + regional co-ops | High (WPC-80, sports nutrition) |

| Idaho + Pacific NW | ~$1.0–1.5B | Cheese + Whey + Specialty | Existing + niche biorefinery | Ingredient specialists (co-op + private) | Very High (niche isolates, clinical) |

| Northeast + Southeast | ~$0.5–1.0B | Fluid + Cheese (commodity focus) | Limited new builds | Commodity-focused regional co-ops | Low–Medium |

| Western Canada (QC, ON under quota) | ~$0.5B (capacity additions under supply management) | Cheese + Specialty Whey | Quebec + Ontario expansions | Processor cooperatives | Medium (regulated pricing) |

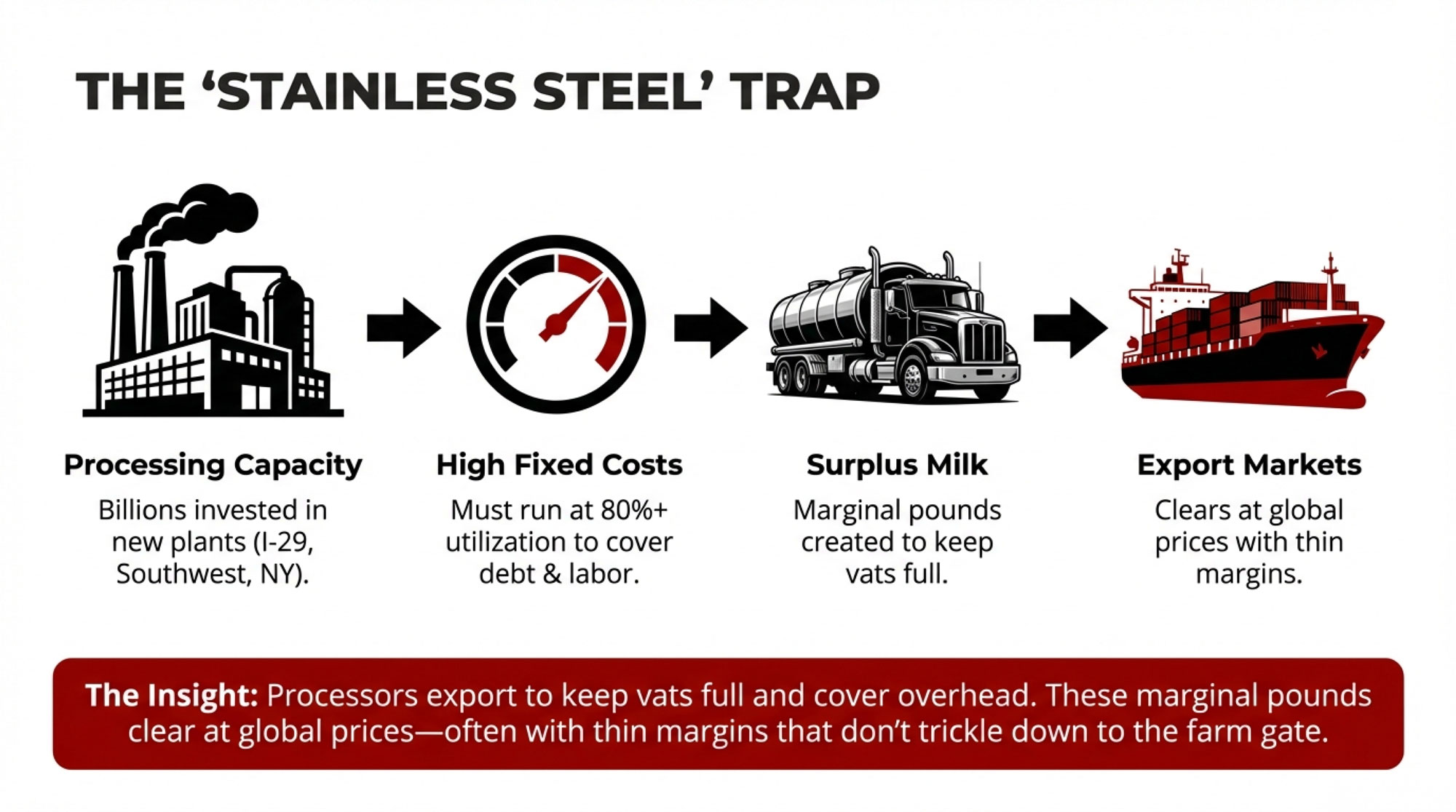

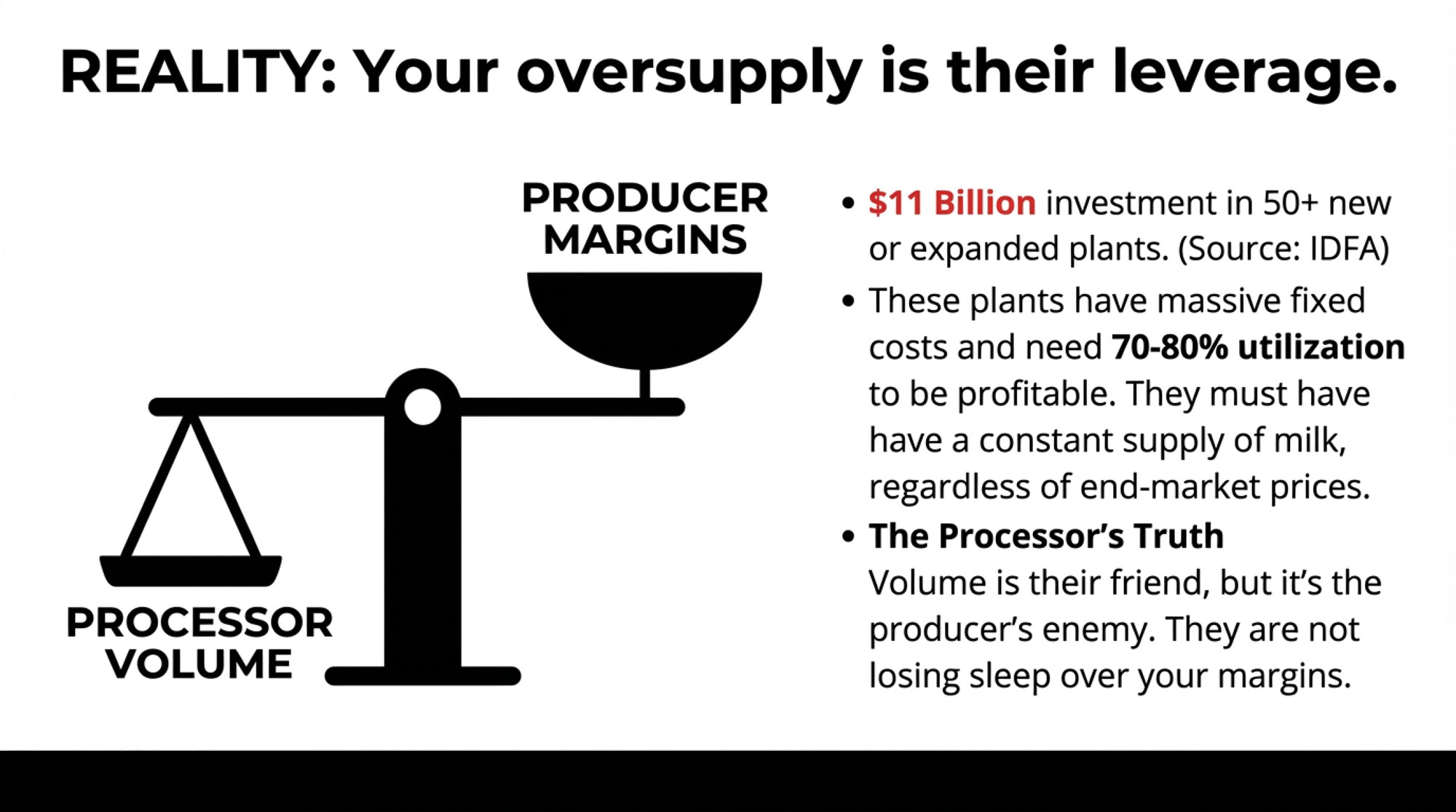

So here’s the real question many of us are asking: with all that stainless going into cheese and whey, how much of that value actually flows back to your farm—and how much stays inside the plant and on the co‑op balance sheet?

Let’s walk through that together, like we would over coffee.

Looking at This Trend: Why Whey Is Suddenly Center Stage

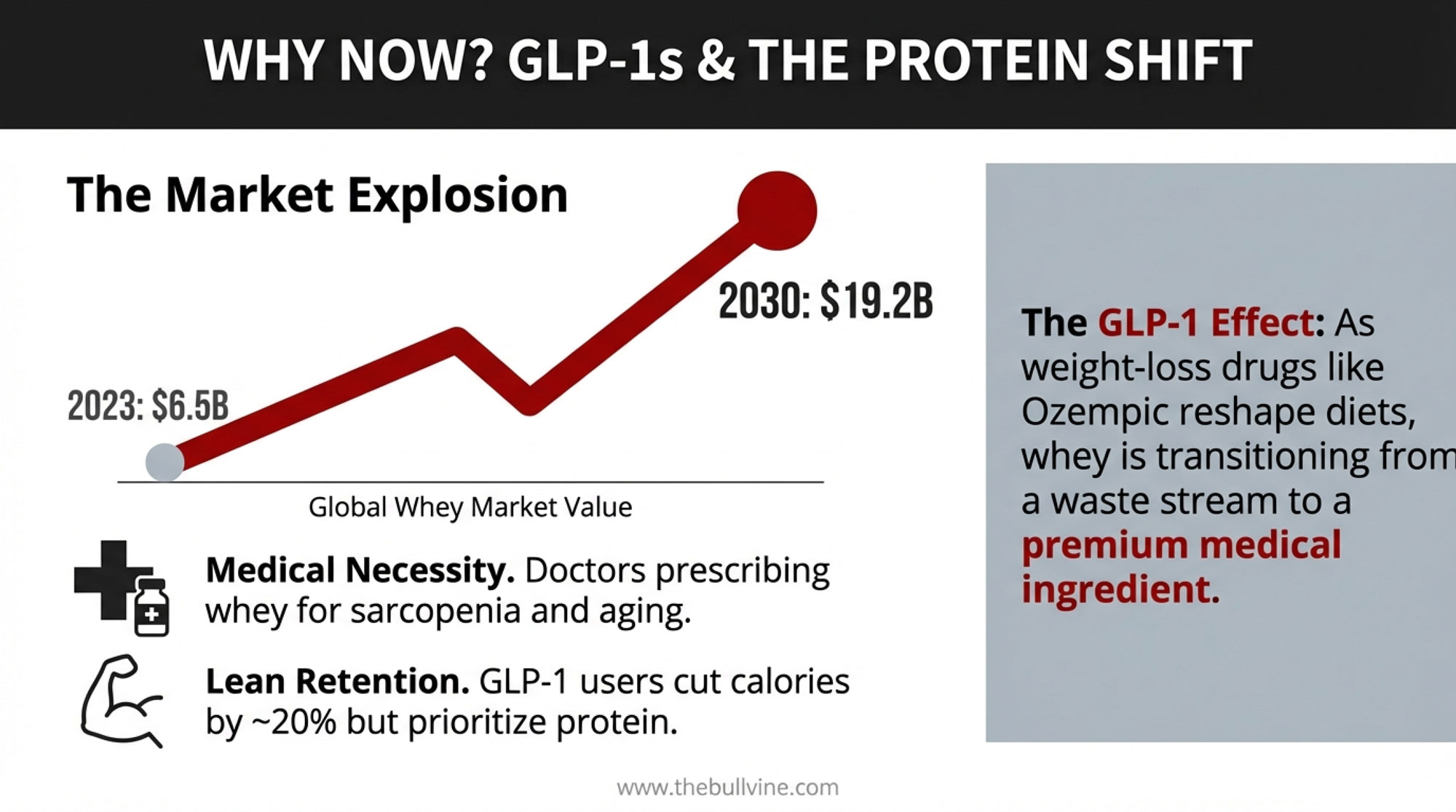

Looking at this trend from a distance, three big forces are pushing whey into the spotlight:

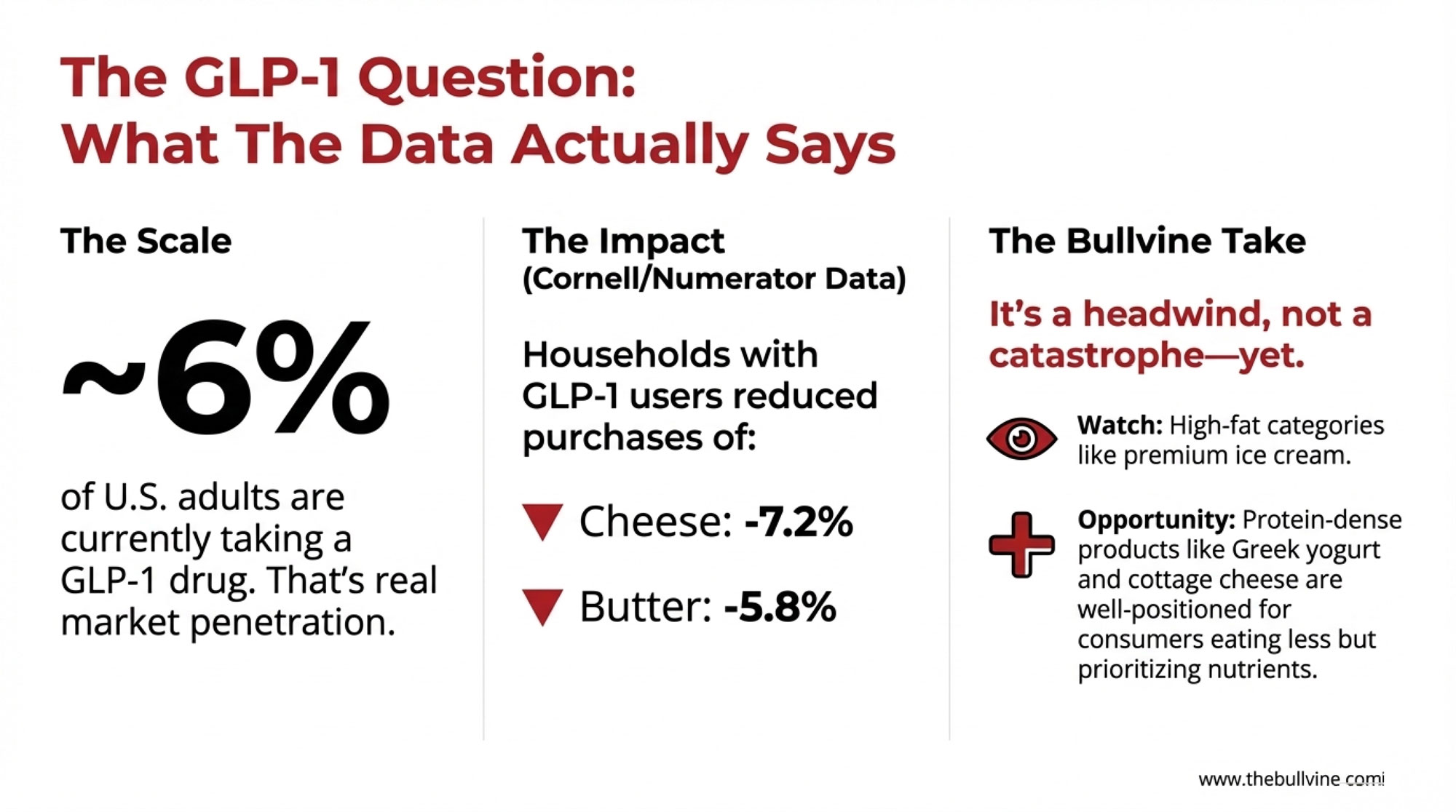

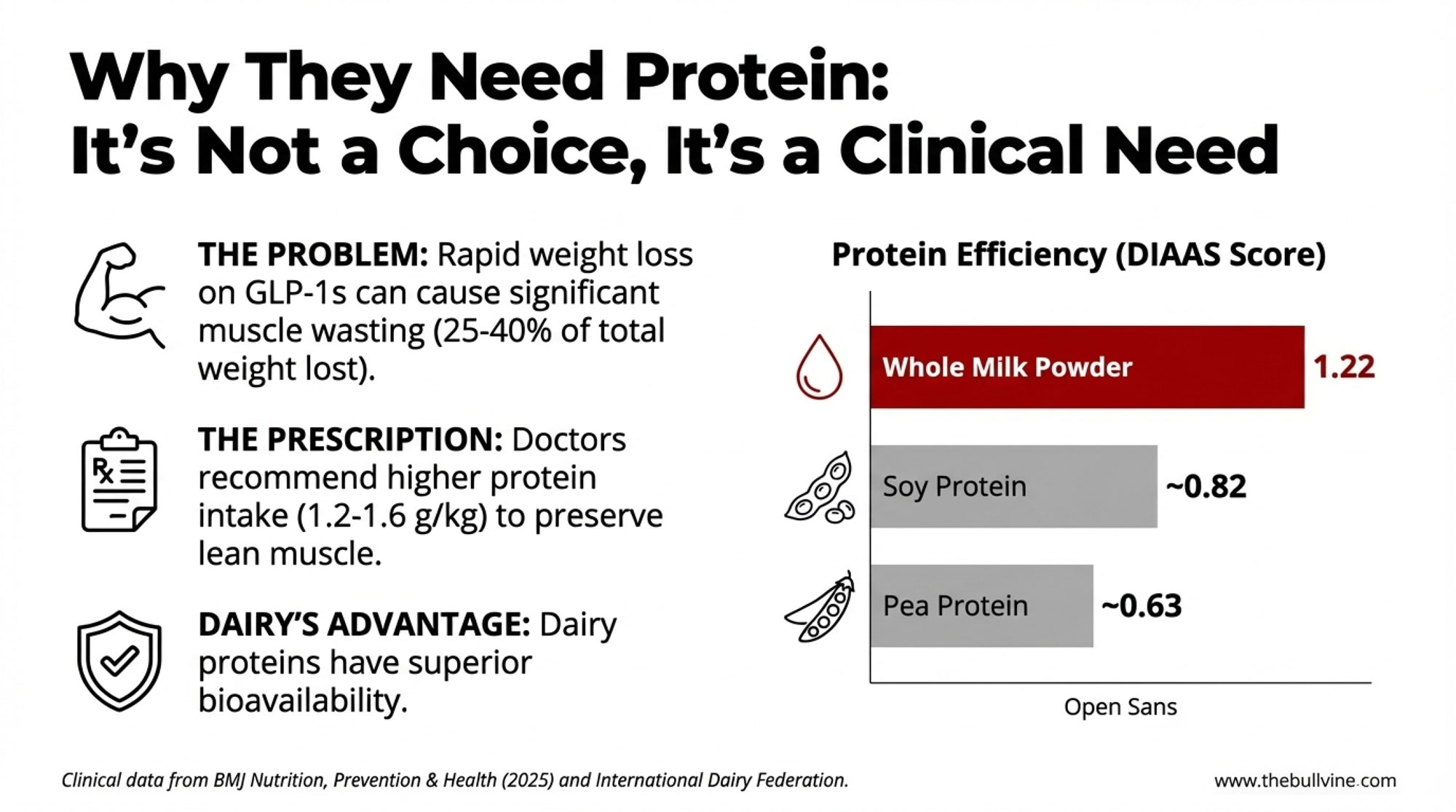

- GLP‑1 weight‑loss drugs are changing how some people eat.

- A long boom in sports and active nutrition.

- A serious build‑out of processing capacity tied to cheese and whey.

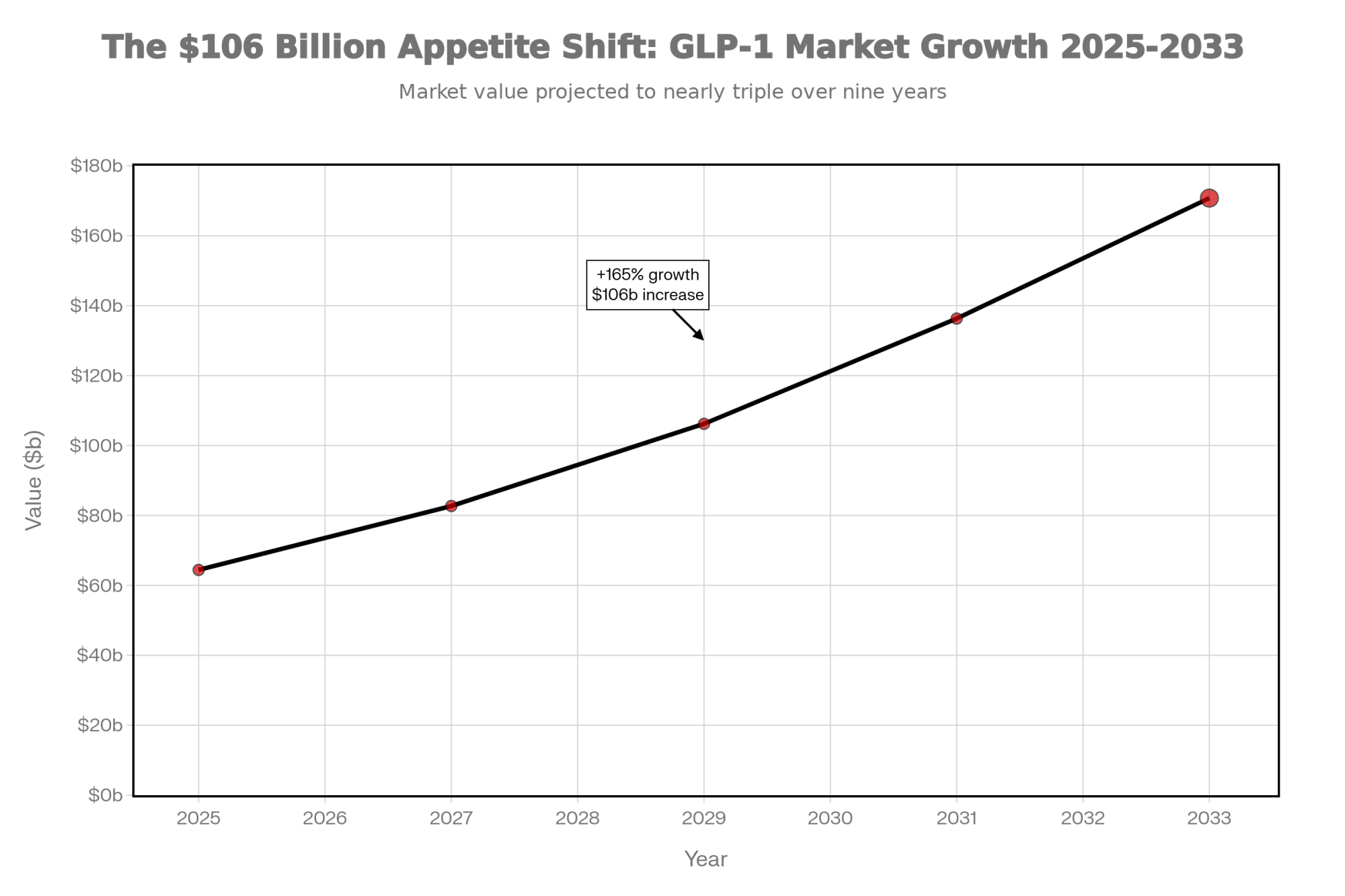

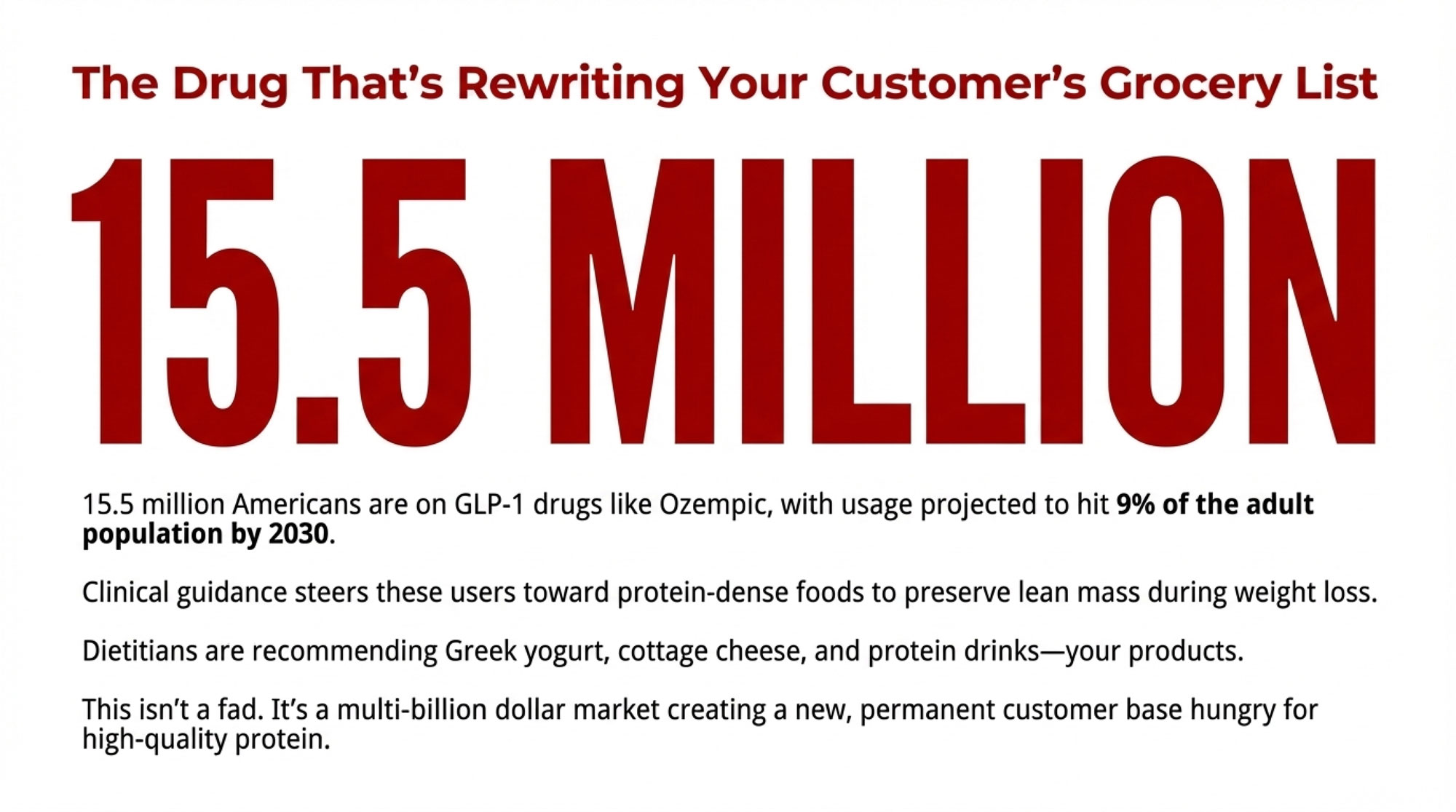

GLP‑1 drugs are changing what some customers put in their carts

You’ve probably heard about Ozempic, Wegovy, and other GLP‑1 medications from TV ads or from your doctor. They started as diabetes drugs, but they’ve quickly turned into a major weight‑management tool. An economic evaluation in JAMA Network Open found that U.S. spending on GLP‑1 receptor agonists among adults jumped from about 13.7 billion dollars in 2018 to 71.7 billion dollars in 2023, more than a five‑fold increase in five years. That tells you right away this isn’t a niche anymore.

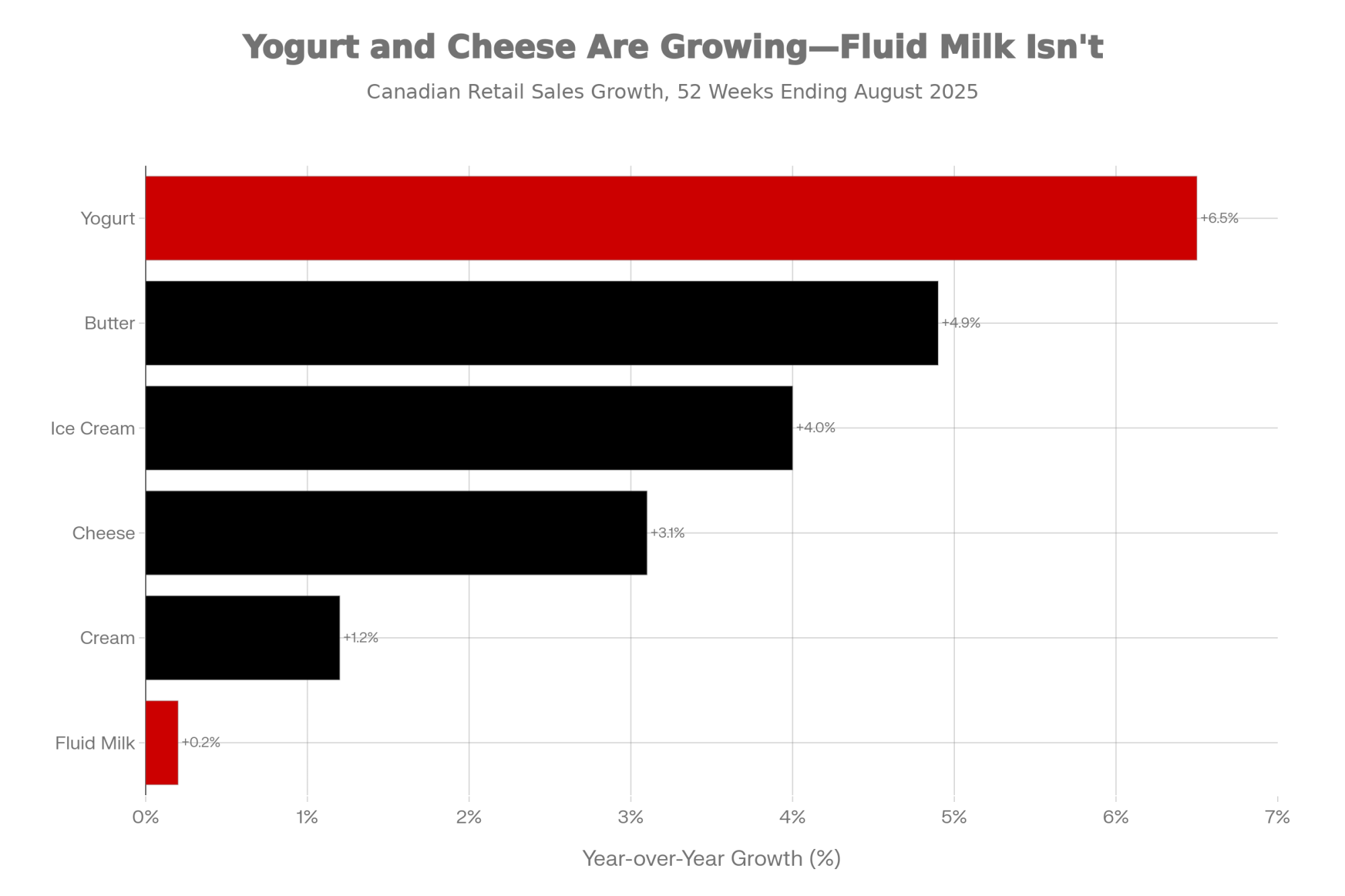

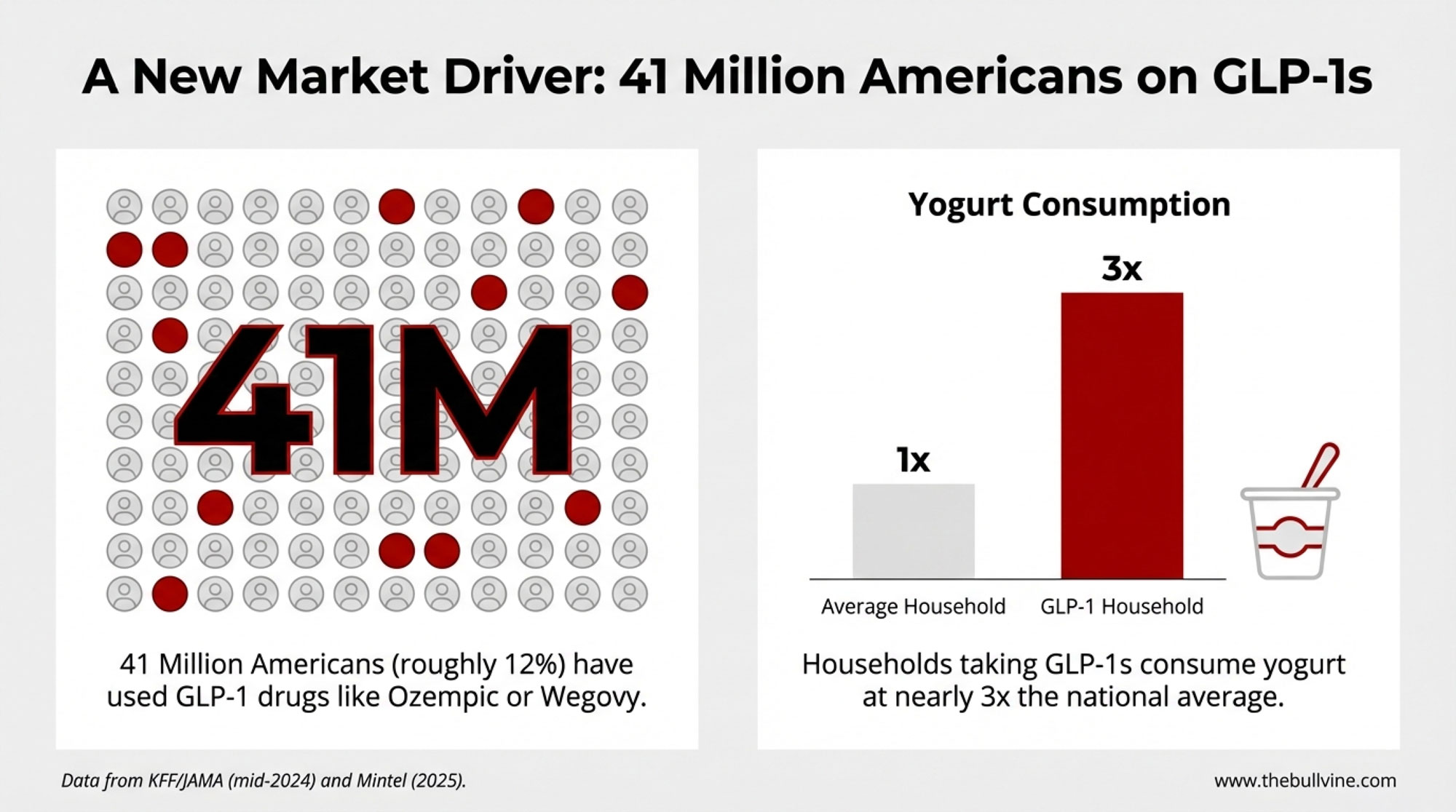

Retail analytics firm Circana has been digging into what that means at the grocery store. Their 2025 work, covered by food‑industry media, shows that households with at least one GLP‑1 user already make up around 23% of U.S. households and are projected to account for about 35% of all food and beverage sales by 2030. Those households don’t just buy less food; they tend to shift toward more nutrient‑dense, higher‑protein items.

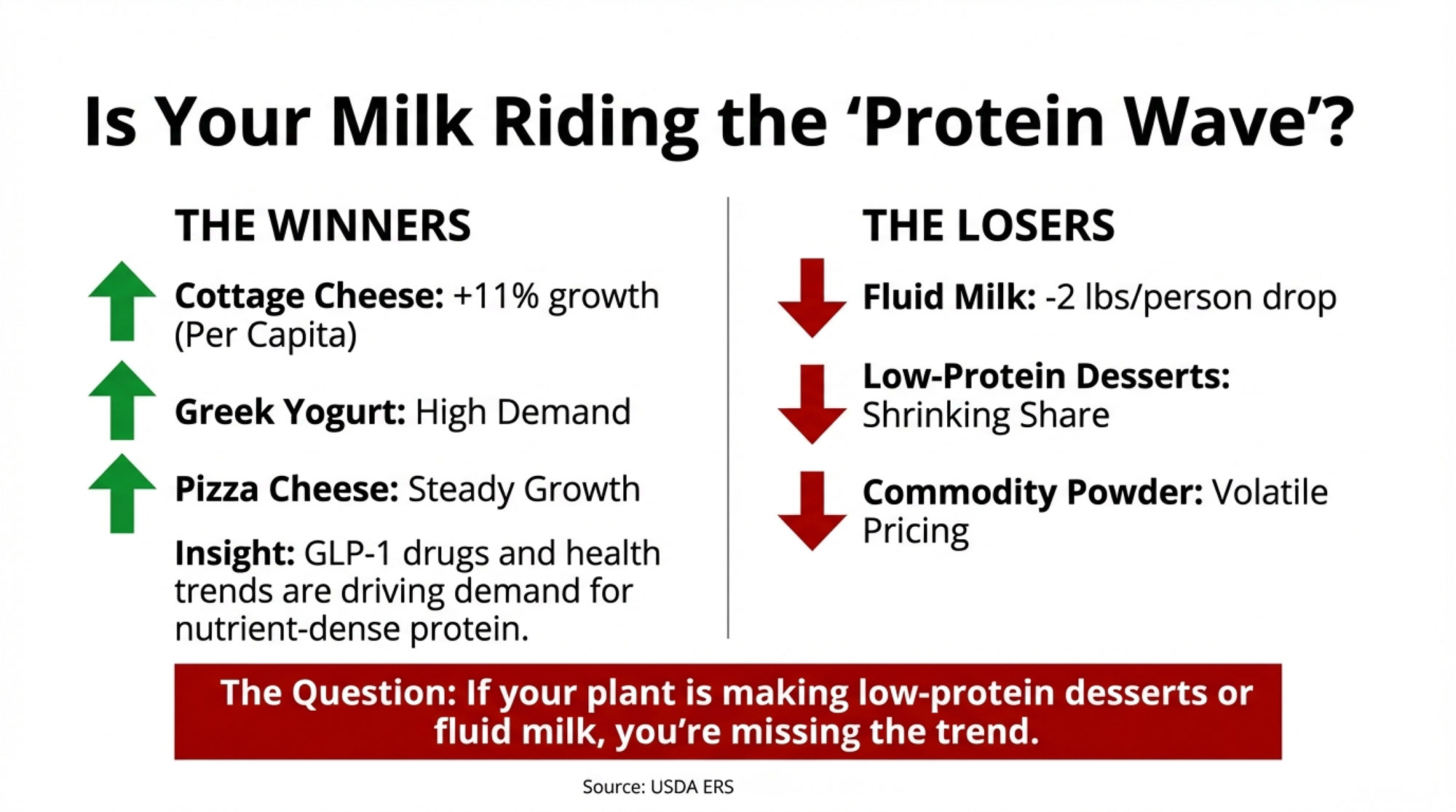

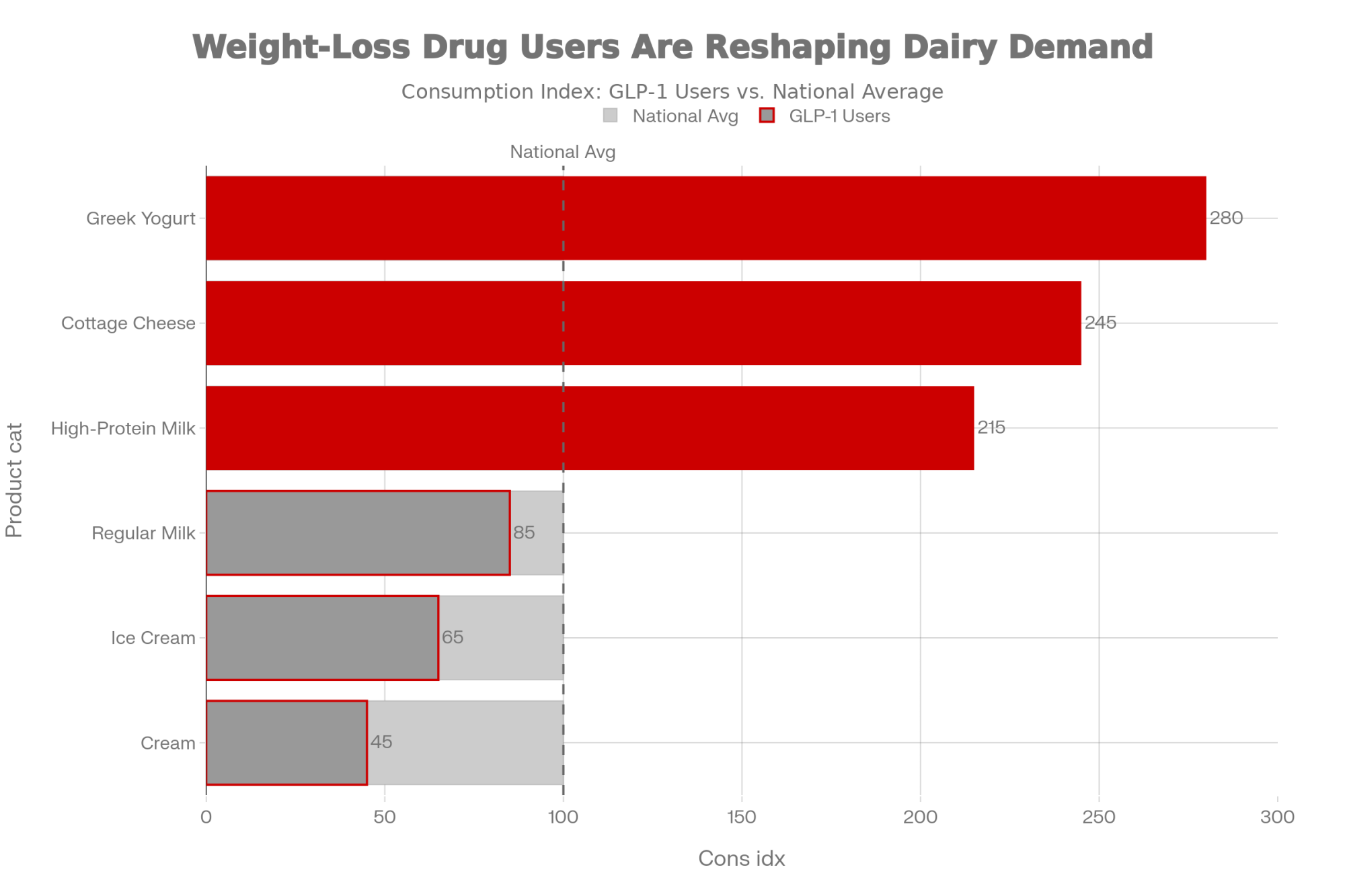

In a 2025 industry report on GLP‑1 and dairy, they reported on a poll of GLP‑1 users showing that people in that sample cut their daily calorie intake by roughly 20%—about 800 kilocalories—and favoured lean proteins over fatty, salty, sugary, or highly processed foods. For our sector, they described a clear divide: pure proteins like skim milk and whey have “immense potential,” while more indulgent, high‑fat, high‑sugar dairy products such as certain cheese dips and frozen desserts face more headwinds.

Nutrition guidelines back this up. Clinical nutrition and obesity guidelines generally stress that when calories go down, protein and micronutrient density must increase, especially in older adults and people with chronic conditions. Dietitians and GLP‑1 programs are steered towards lean meats, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, and protein shakes as tools to help keep weight off.

You can see where whey fits in that pattern: very concentrated, highly digestible protein in a small serving.

Sports and active nutrition aren’t niche anymore

On top of the GLP‑1 story, sports and active‑nutrition products have moved from the specialty aisle right into the heart of the store.

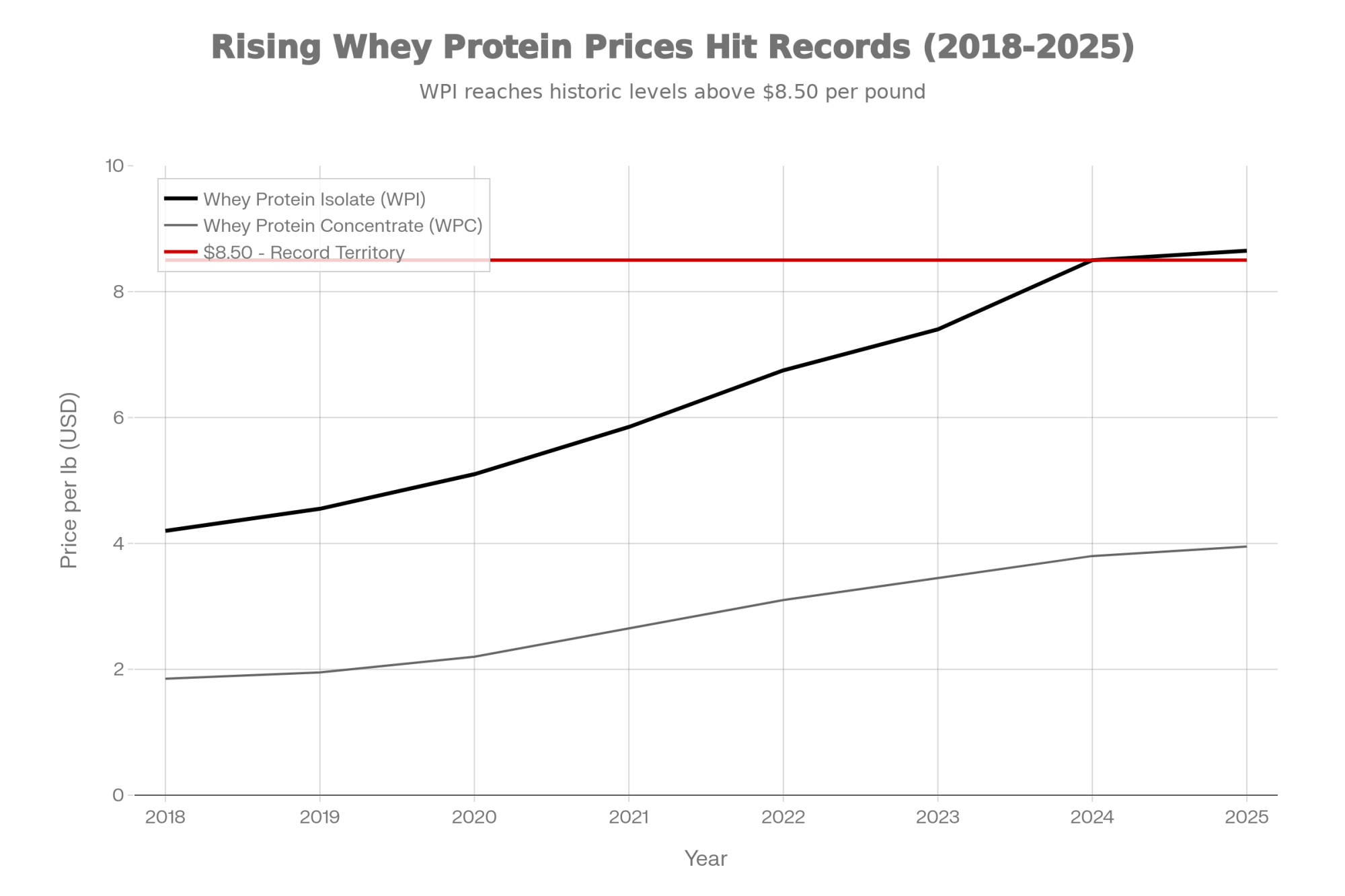

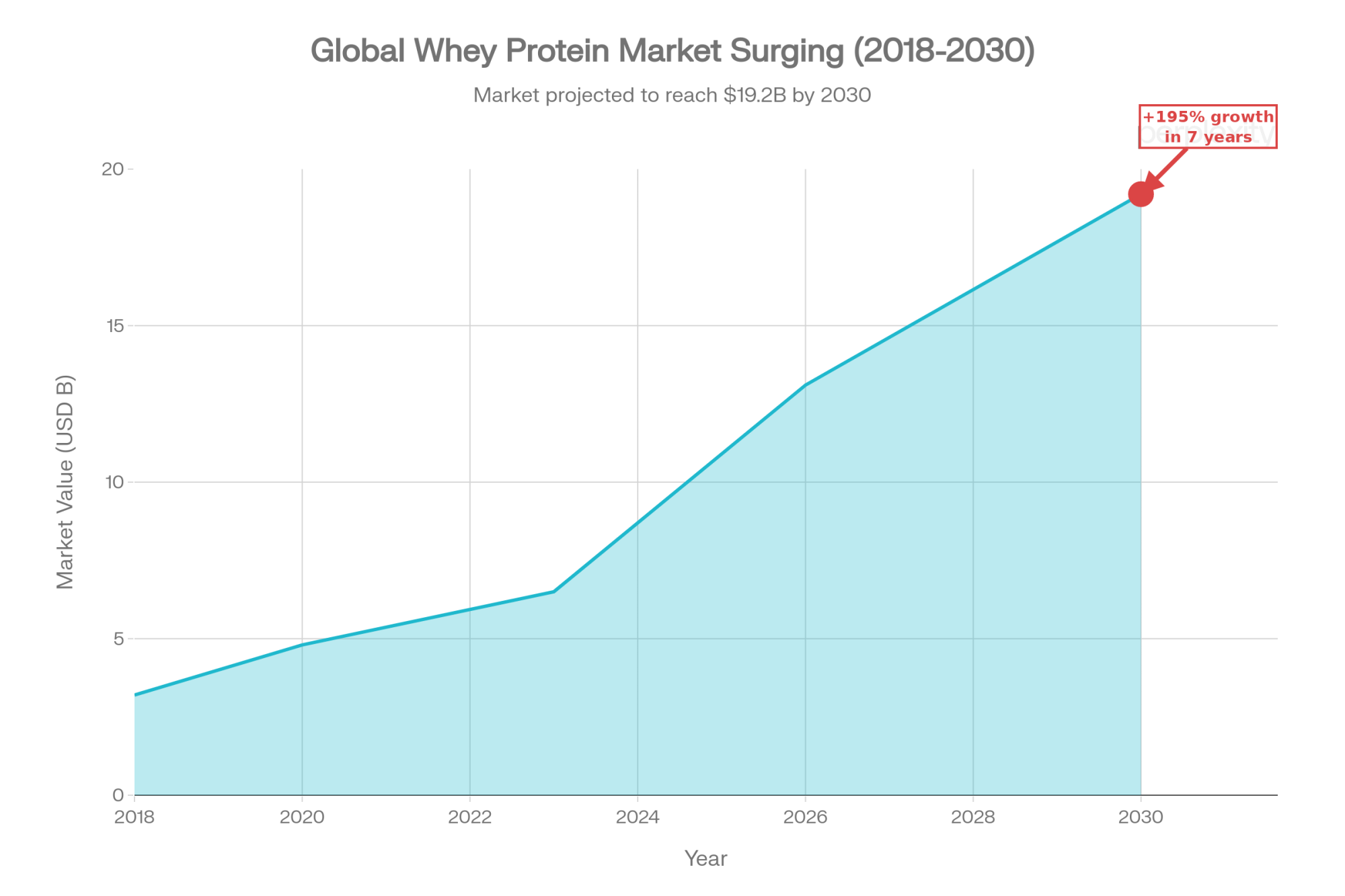

Market research from MarkNtel Advisors estimates that the global whey protein market was worth about 6.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2023 and is projected to reach roughly 19.2 billion dollars by 2030, growing at around 9% per year from 2024 through 2030. That’s a big leap for something that used to be a byproduct we hauled away or spread on fields.

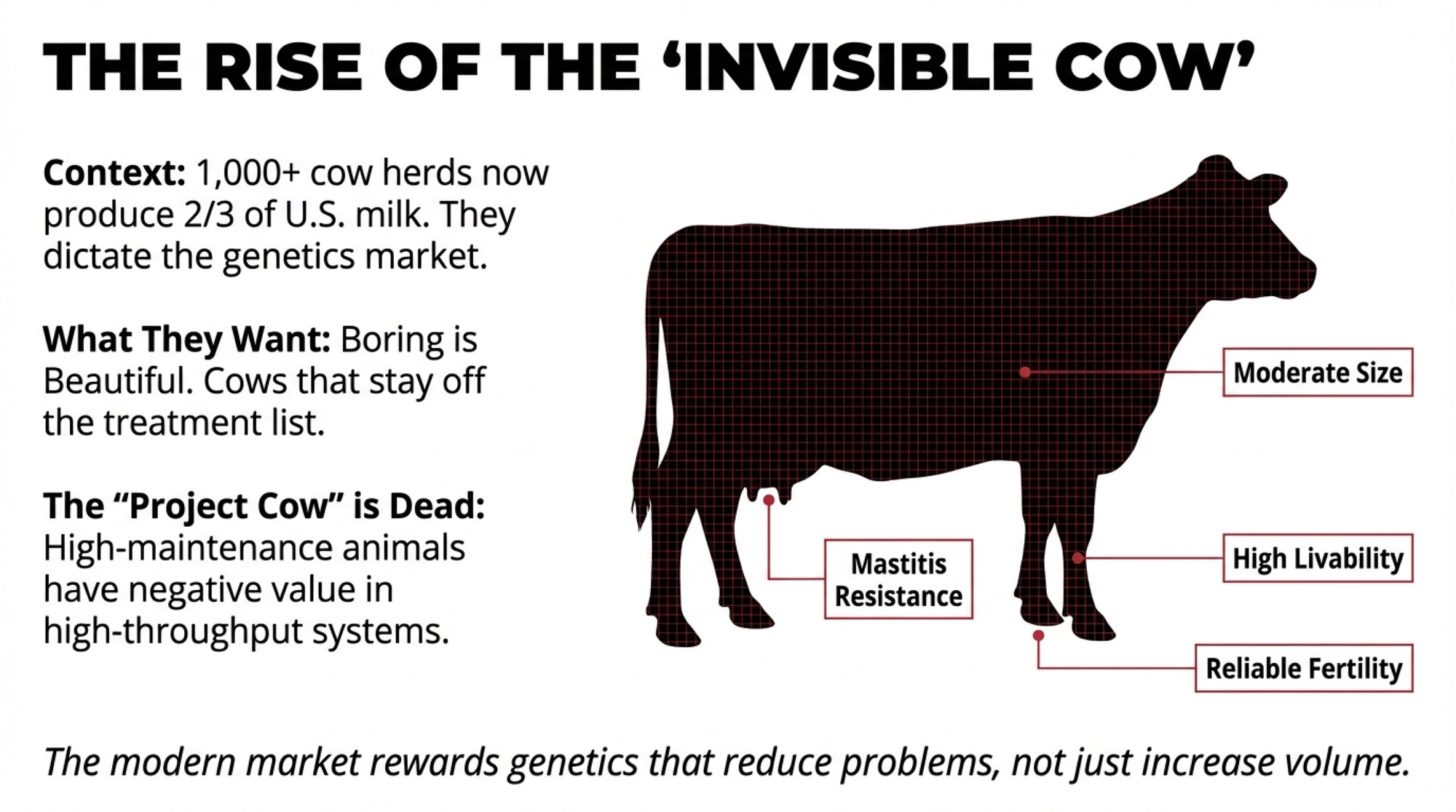

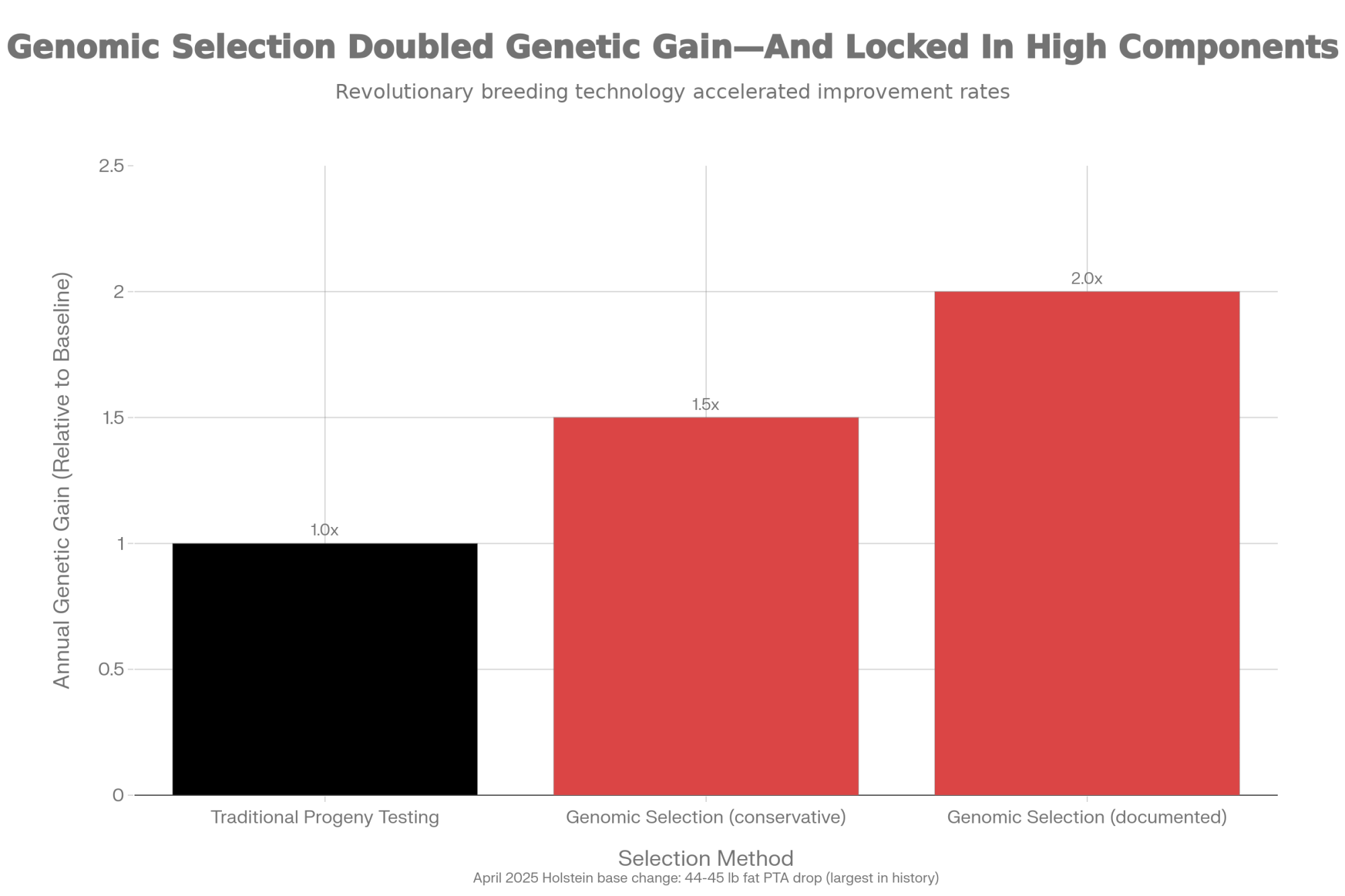

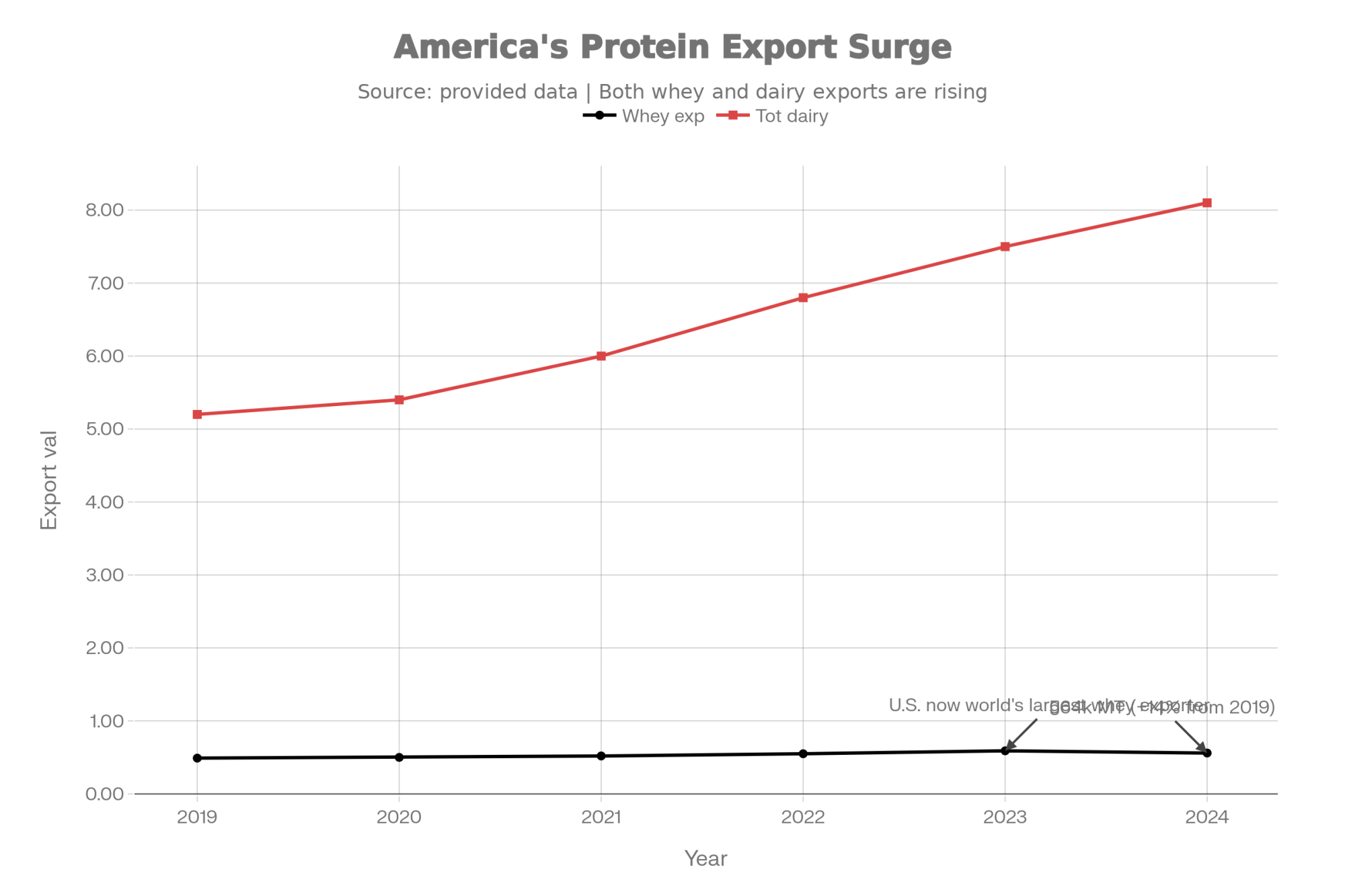

Tanner Ehmke, lead dairy economist with CoBank, has explained in reports that whey used to be dumped or land‑spread, but by 2021 had reached almost 5 billion dollars in global market value, and that demand for whey protein concentrate has been growing for more than 25 years, driven mainly by export demand. He also notes that U.S. cheese production capacity is expected to expand by about 10% over a five‑year window, and that processors need state‑of‑the‑art technology to meet global whey needs, especially in Asia.

On the shelf, many of us have noticed the same thing: more ready‑to‑drink protein shakes, high‑protein yogurts, and fortified bars in Costco, farm stores, and even truck stops. The International Dairy Foods Association’s president, Michael Dykes, a veterinarian by training and long‑time dairy policy leader, told Dairy Forum attendees that most of the “protein‑added” products consumers see today are still built on dairy‑derived proteins, especially whey from cheese plants.

There’s growing clinical evidence backing whey’s role in health, too. A 2024 meta‑analysis in Clinical Nutrition ESPEN looked at randomized trials in older adults with sarcopenia (age‑related muscle loss) and found that whey protein supplementation, especially when combined with resistance training, improved lean mass and functional performance compared with control groups. Industry reports have summarized research on inflammatory bowel disease, showing that participants receiving whey‑based nutrition supplements alongside exercise gained more muscle mass and strength than those who exercised without whey. That kind of evidence gives doctors and dietitians a reason to keep whey‑based products in their toolbox.

So when you put all of that together—GLP‑1 users cutting calories but chasing protein, mainstream shoppers grabbing RTD protein drinks, and clinicians using whey to help protect muscle—it makes sense that whey demand looks strong.

And the stainless is really going into cheese and whey

Now, back to that eight‑billion‑dollar pile of stainless.

In a interview, Leonard Polzin lays out that more than eight billion dollars’ worth of stainless steel is being installed in new and expanded dairy processing plants across the U.S., with some plants starting in early 2025 and others coming online over the following years, covering cheese, fluid, soft, and hard dairy products.

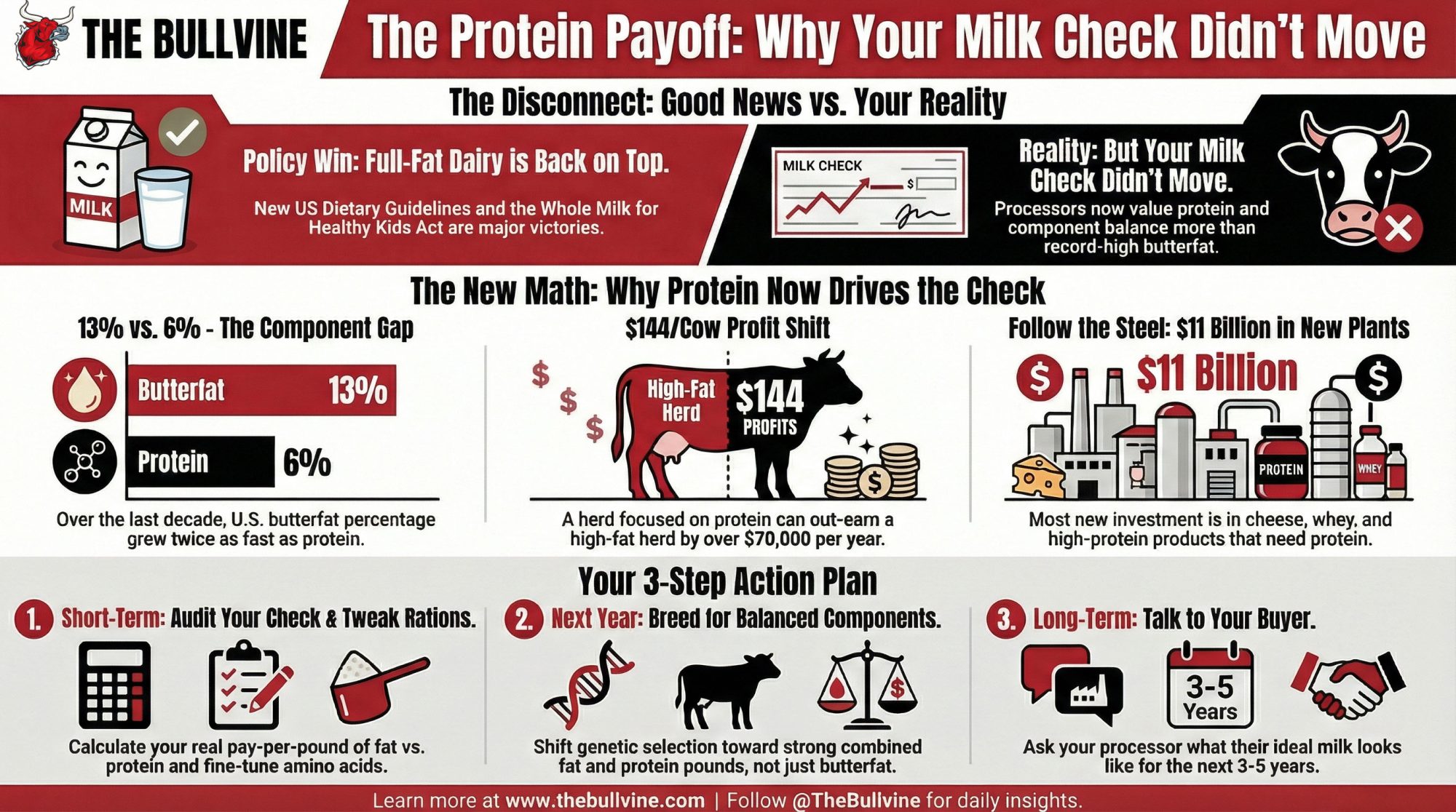

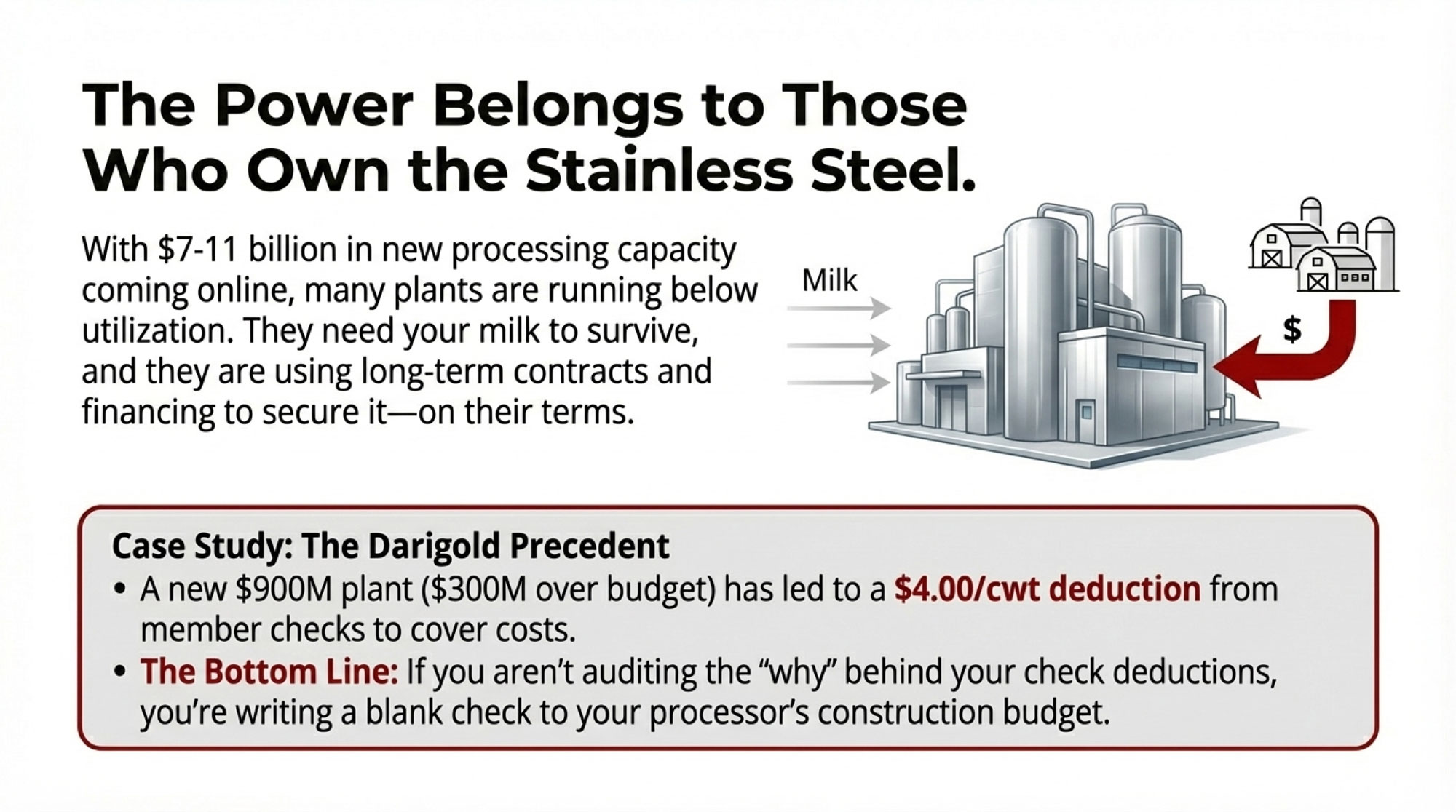

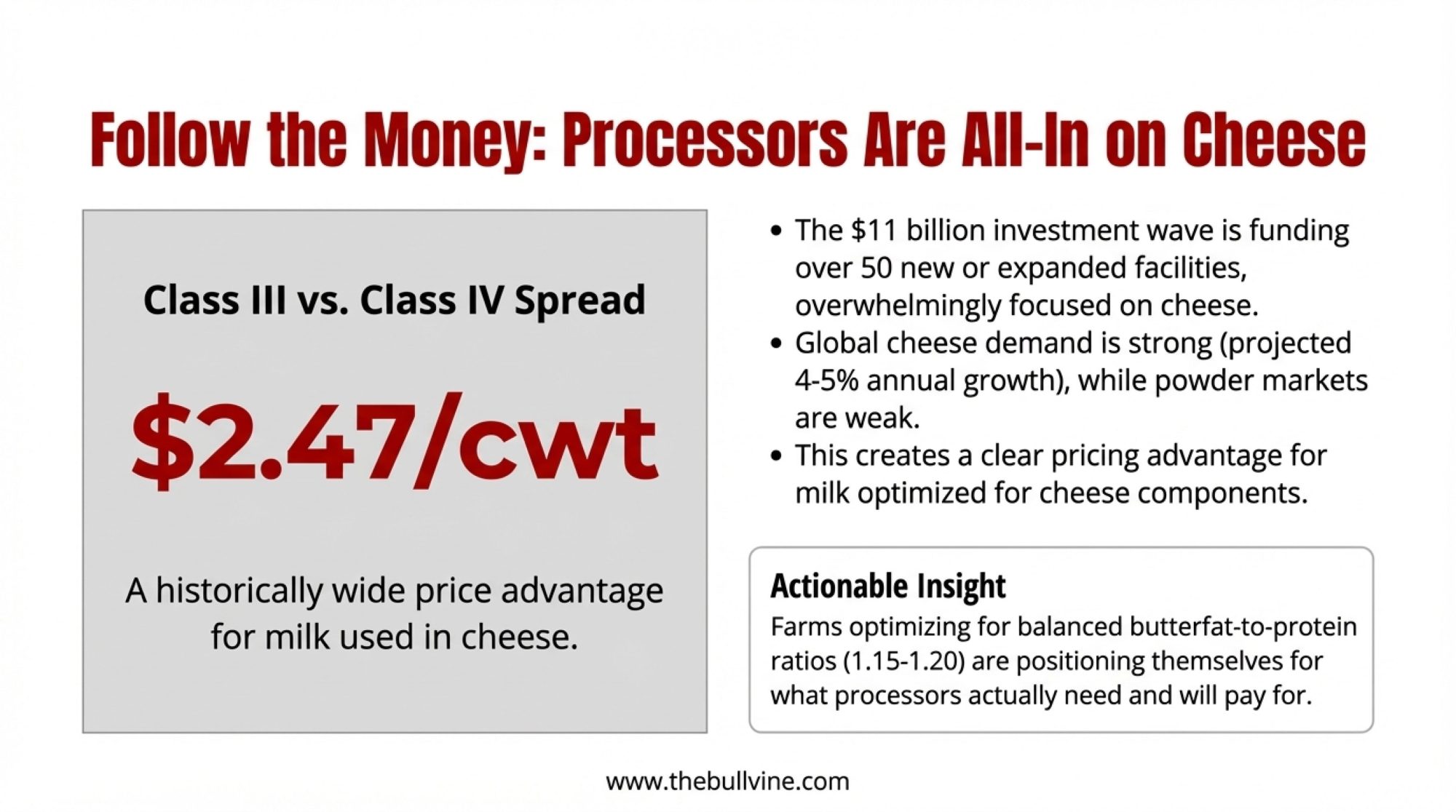

Corey Geiger’s view from CoBank is that about eight billion dollars in new U.S. dairy processing investment is expected through 2026, and industry reports indicate that a large share of that is going into cheese and whey capacity. Dykes told Dairy Forum in 2024 that more than $7 billion in dairy processing expansions were underway, and later coverage has raised that figure to over $11 billion when you extend the horizon a few more years and count additional projects. He links that investment directly to the protein opportunity.

What I’ve found is that when you step back, you see three layers stacking:

- Demand: GLP‑1 and protein‑focused diets plus sports and clinical nutrition.

- Processing: a wave of new cheese and whey plants and expansions worth roughly eight billion dollars in this cycle.

- Ingredients: continued shift from whey as a waste stream to whey as a core protein ingredient.

That’s a pretty big structural shift. The question is how much of it was built with your equity, and how much of it comes back as farm‑level pay price.

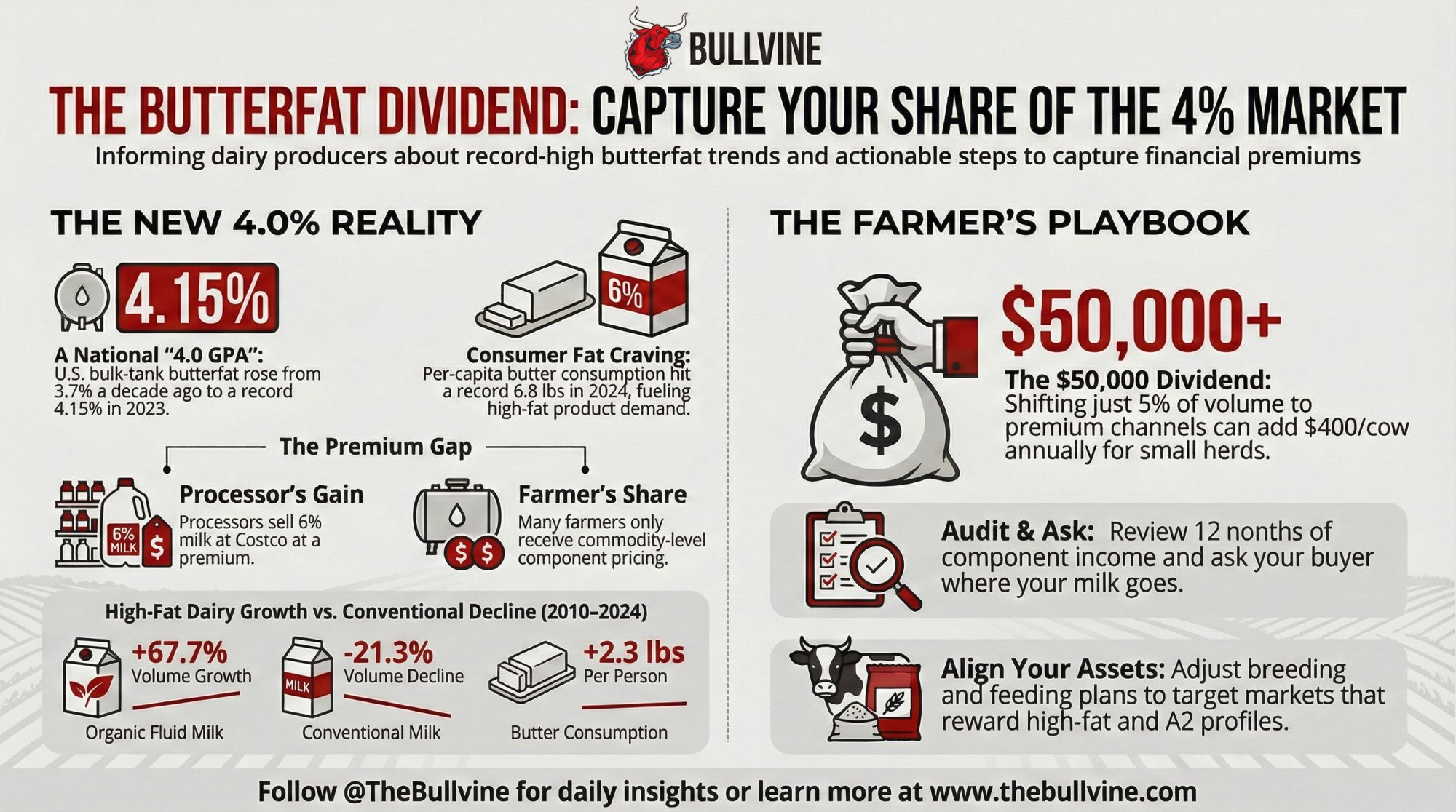

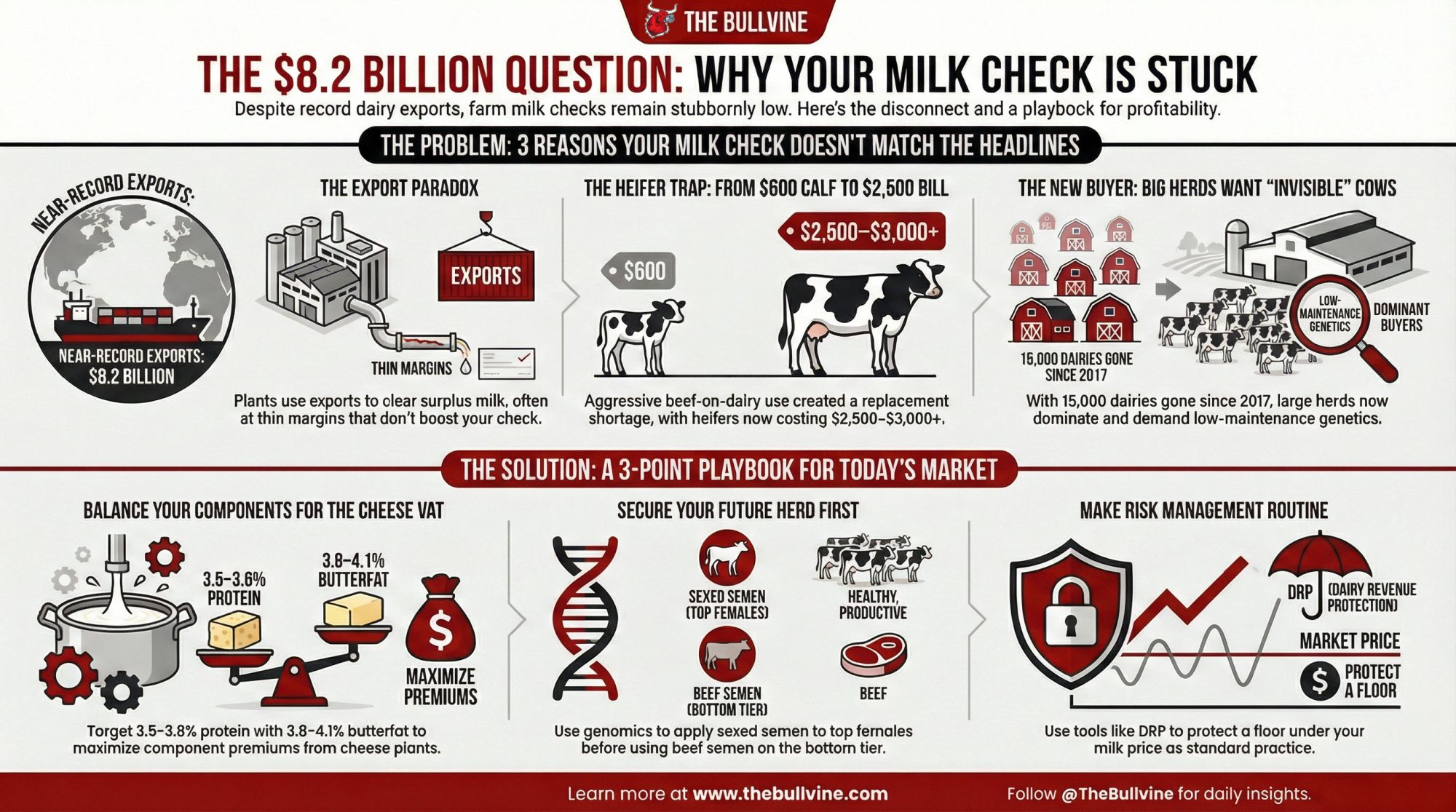

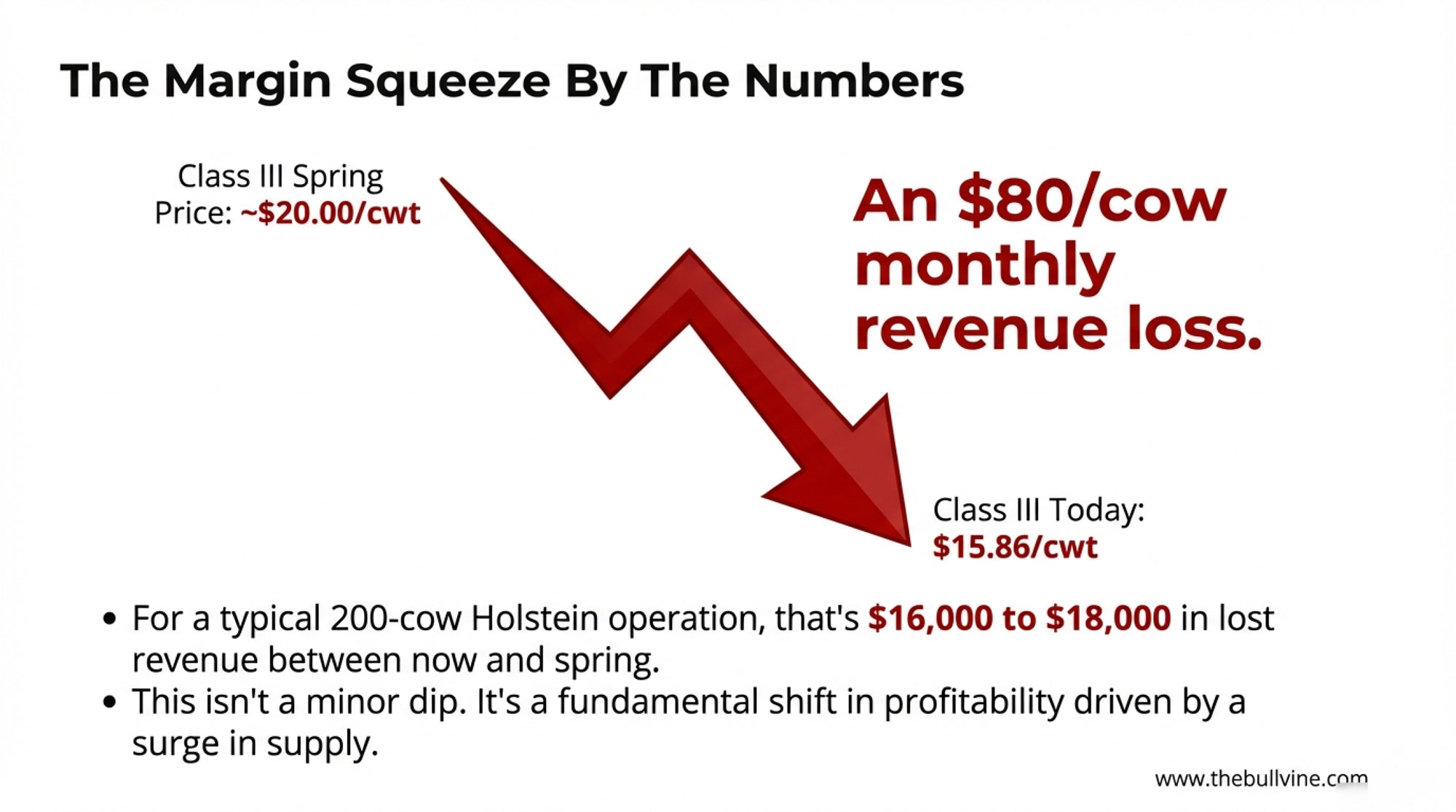

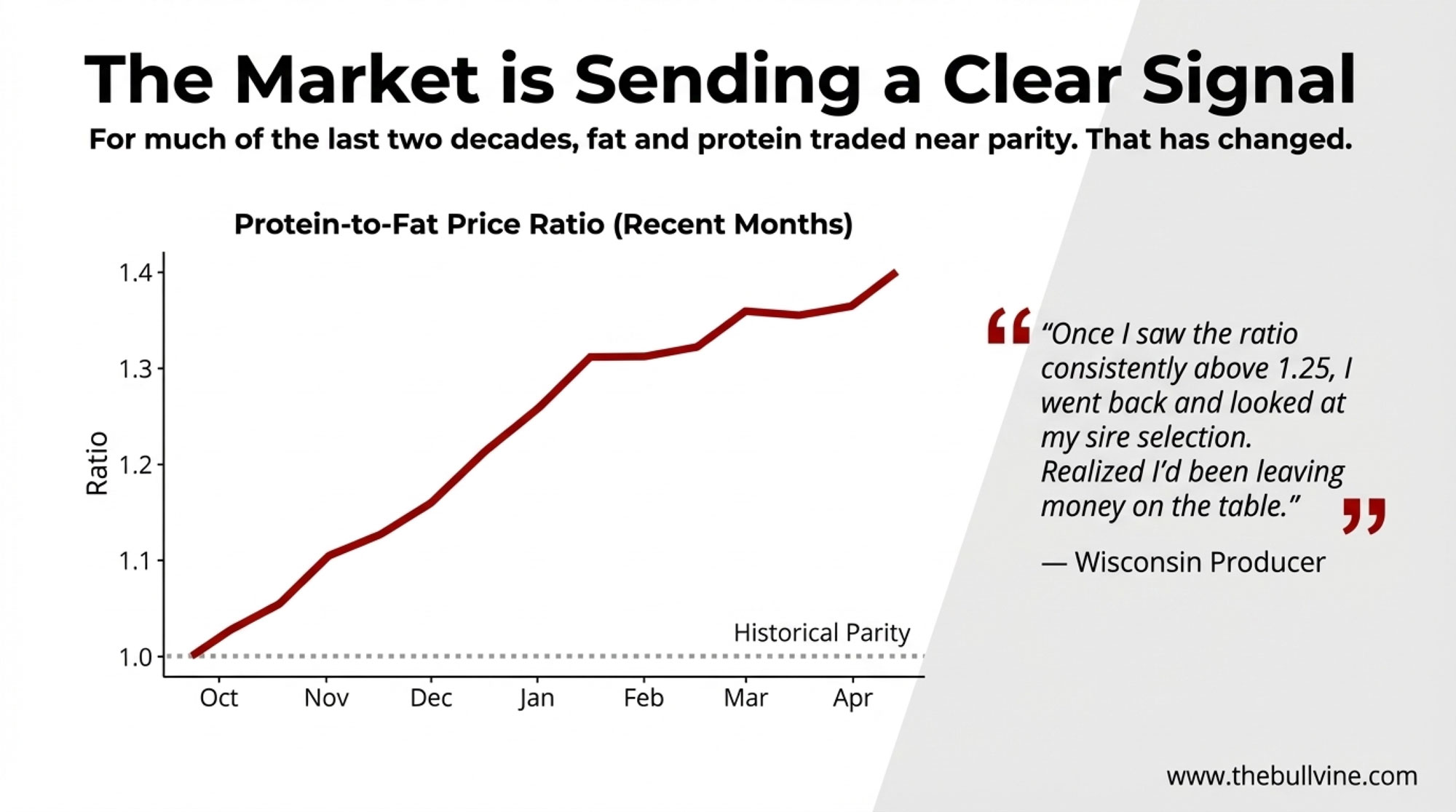

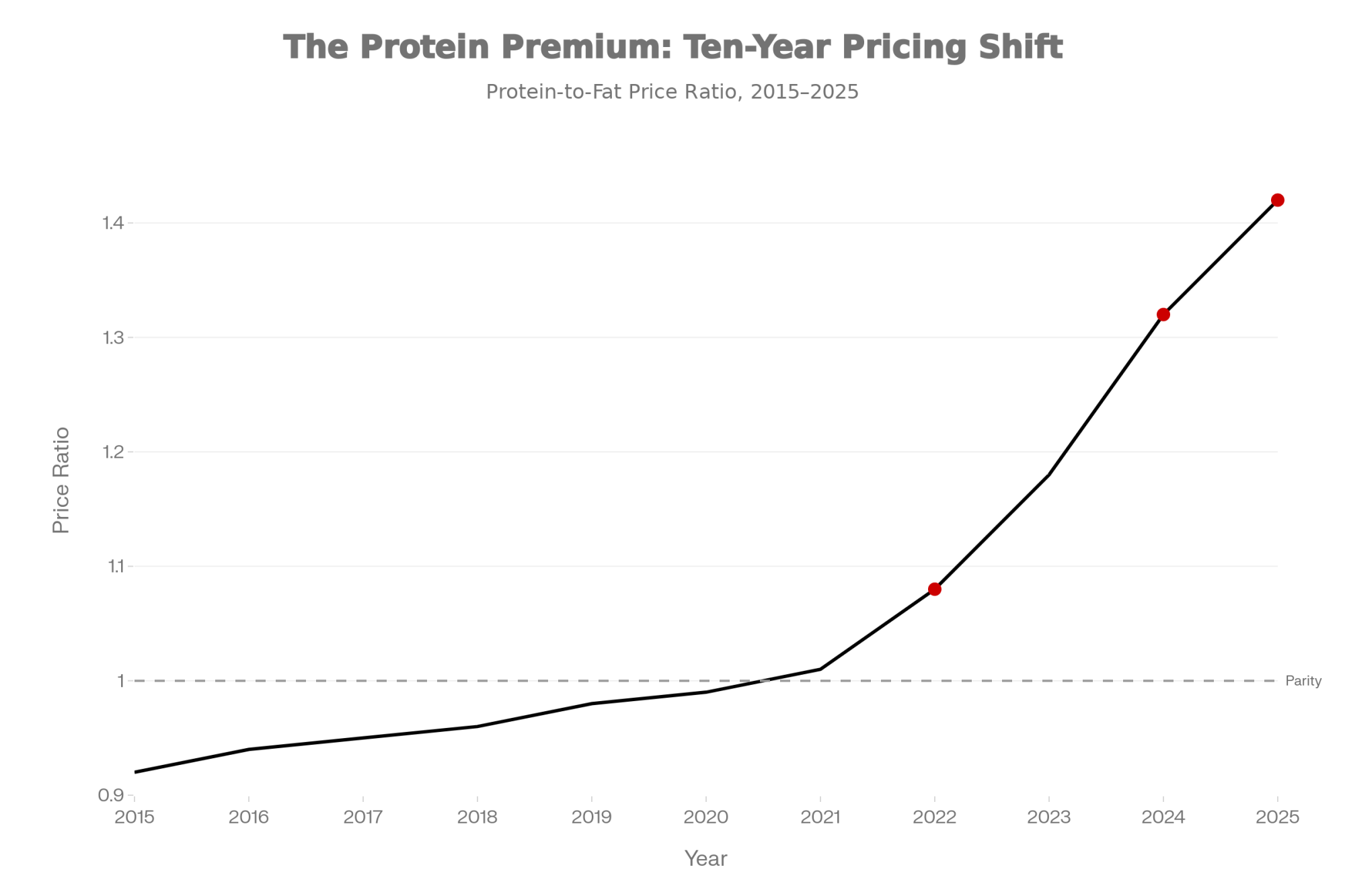

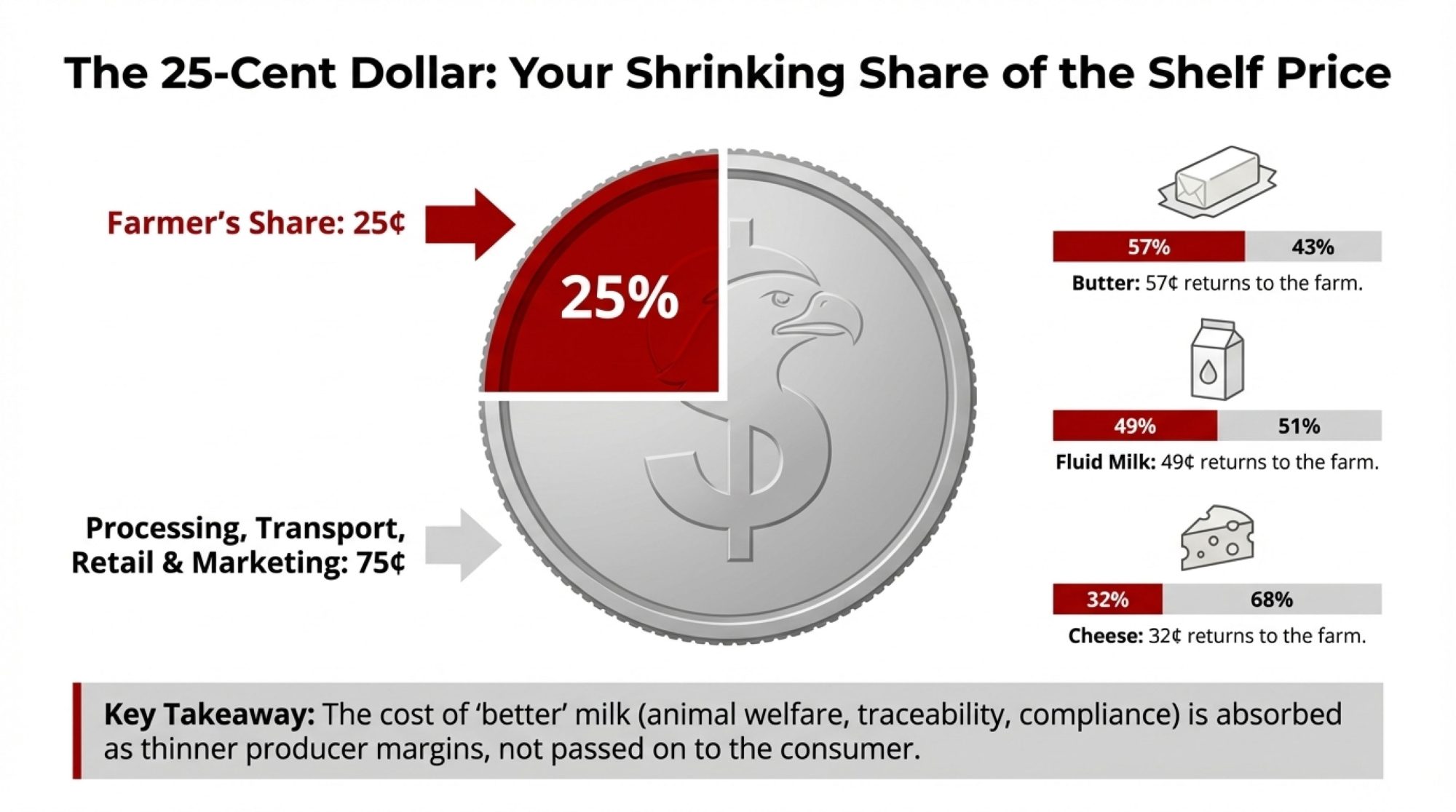

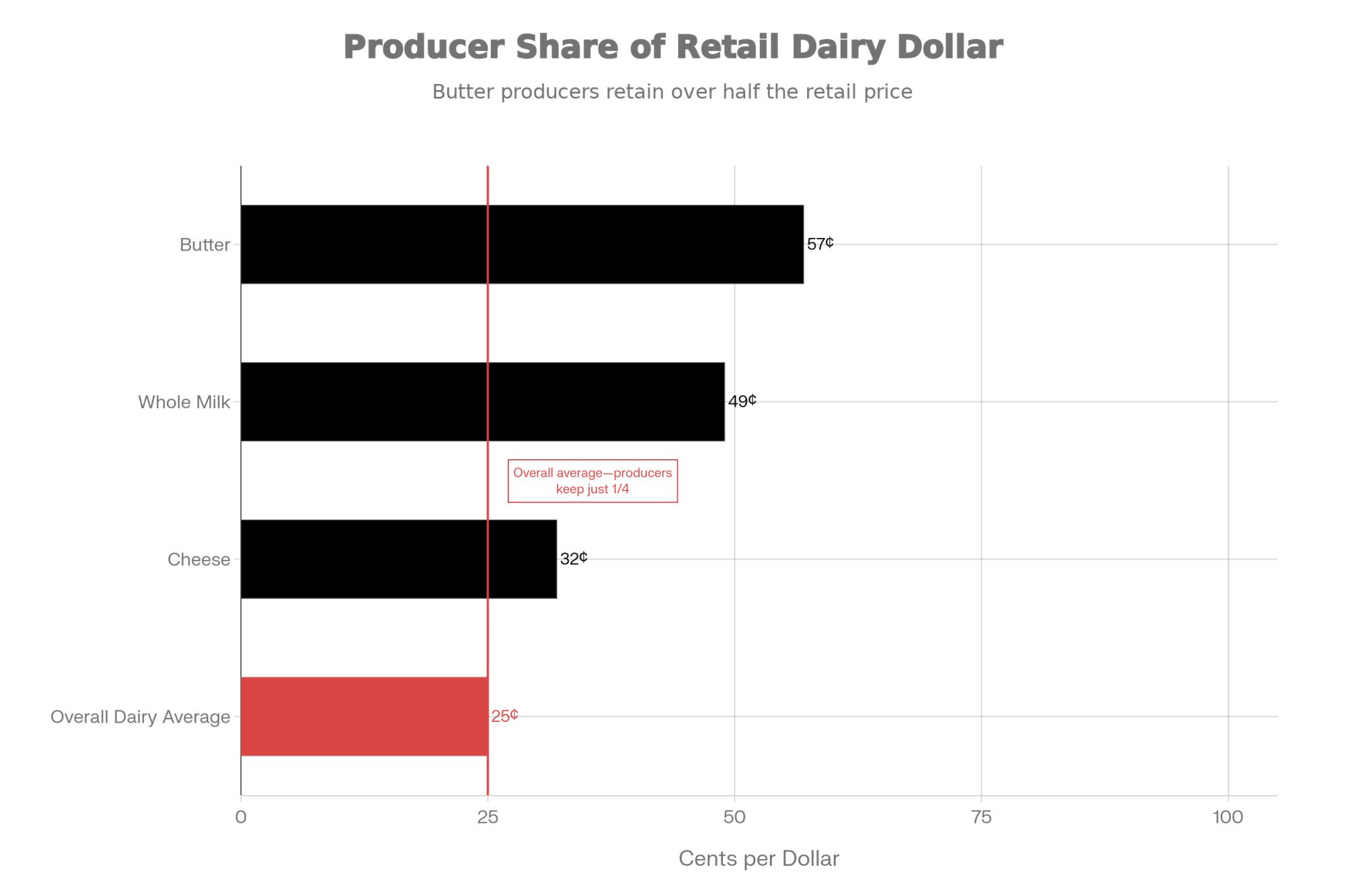

The Big Disconnect in the Milk Check

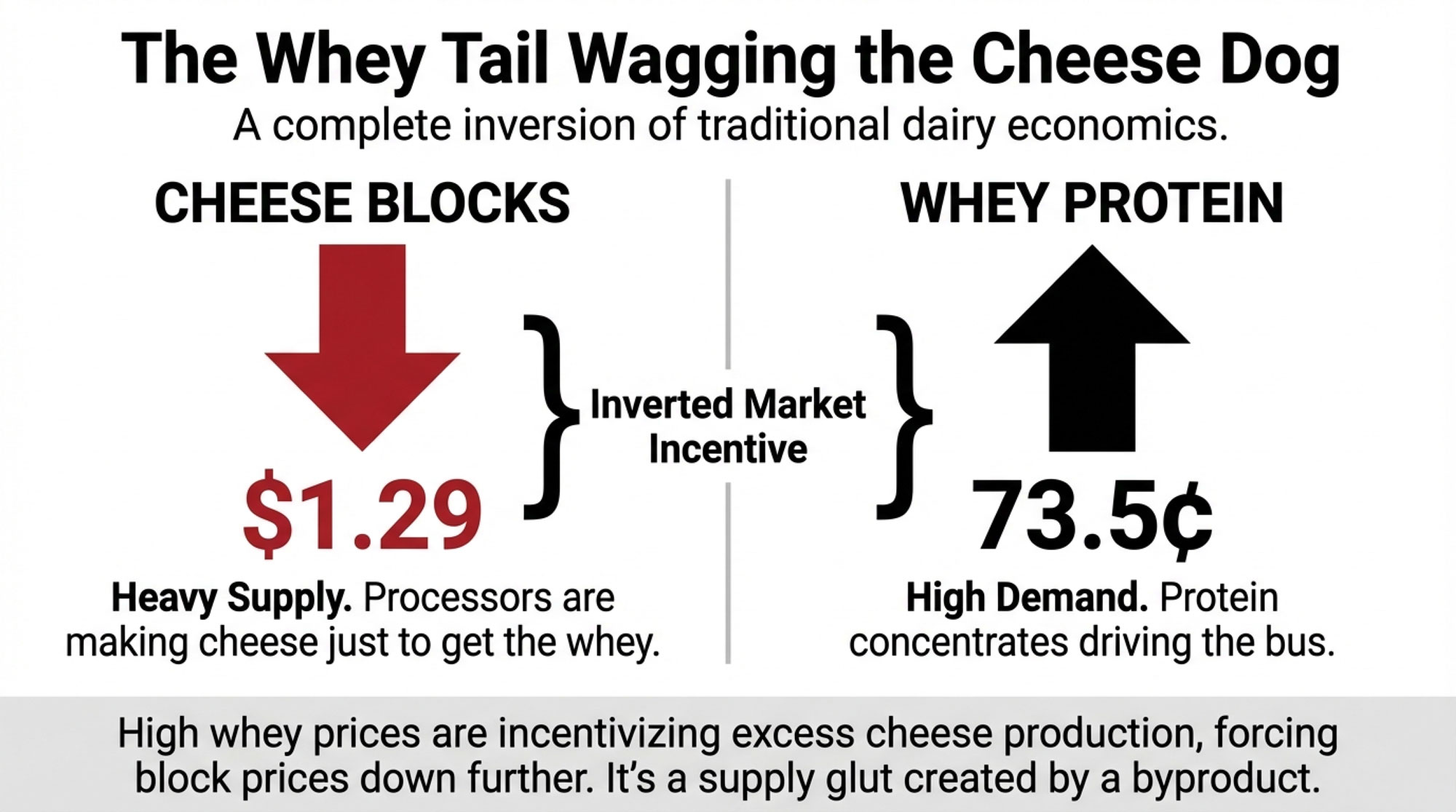

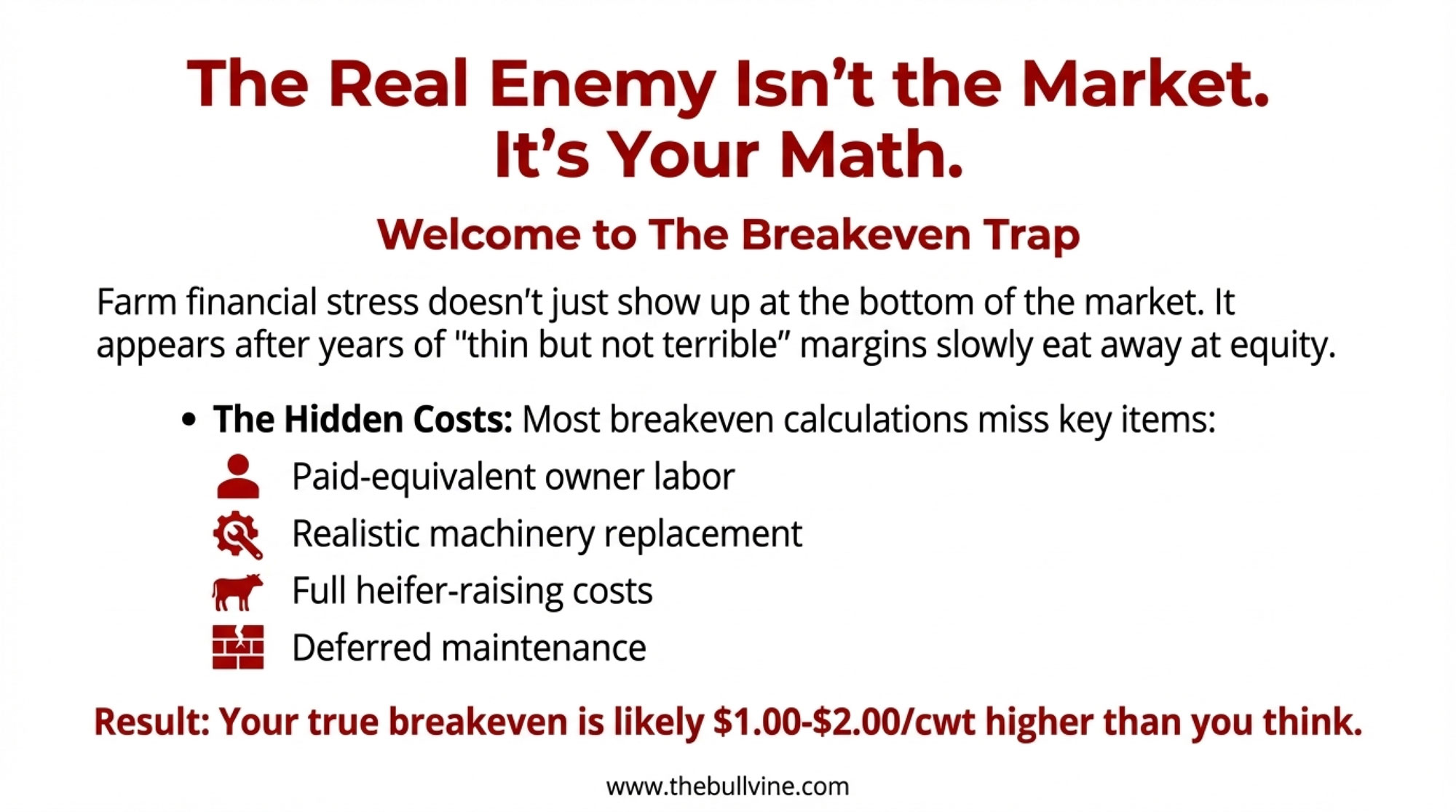

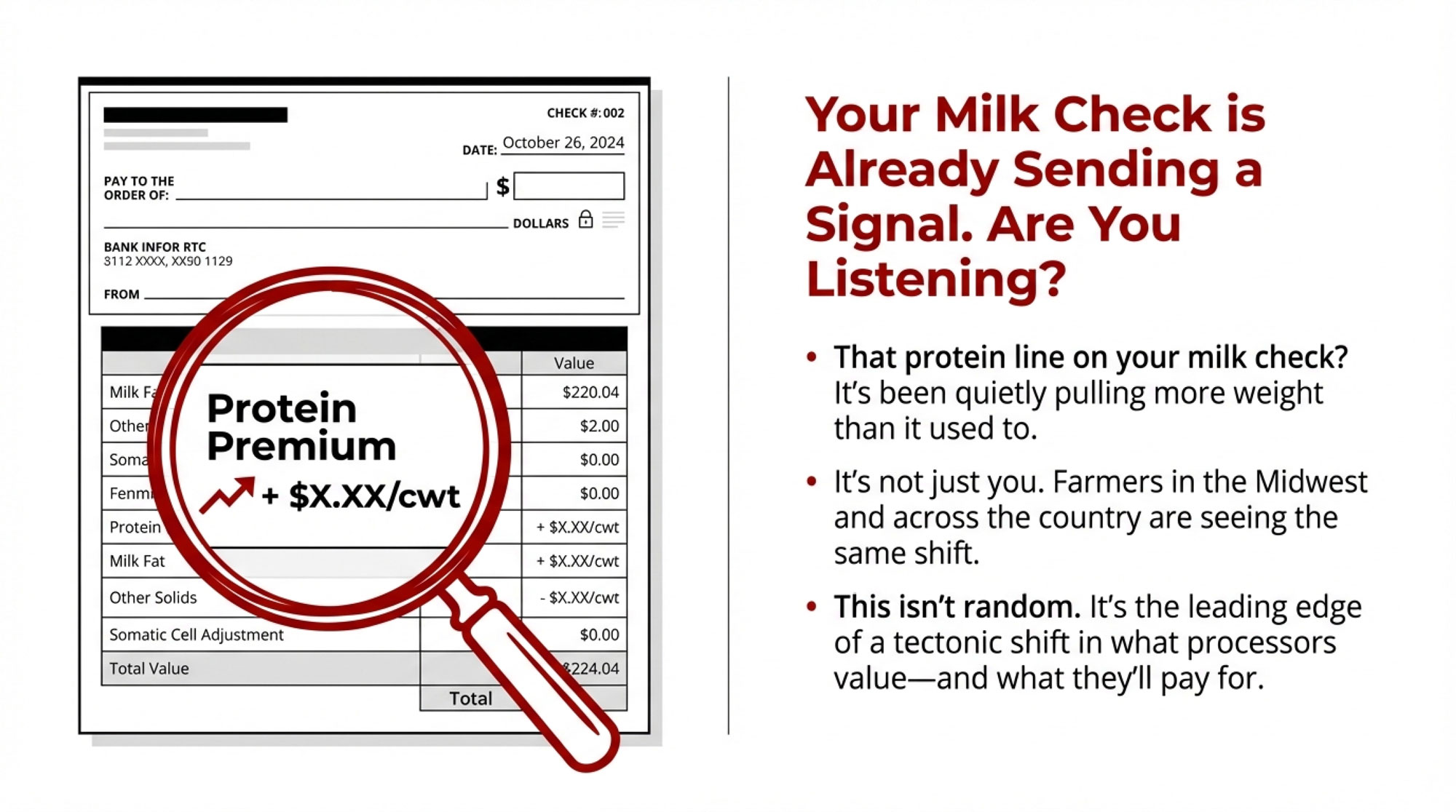

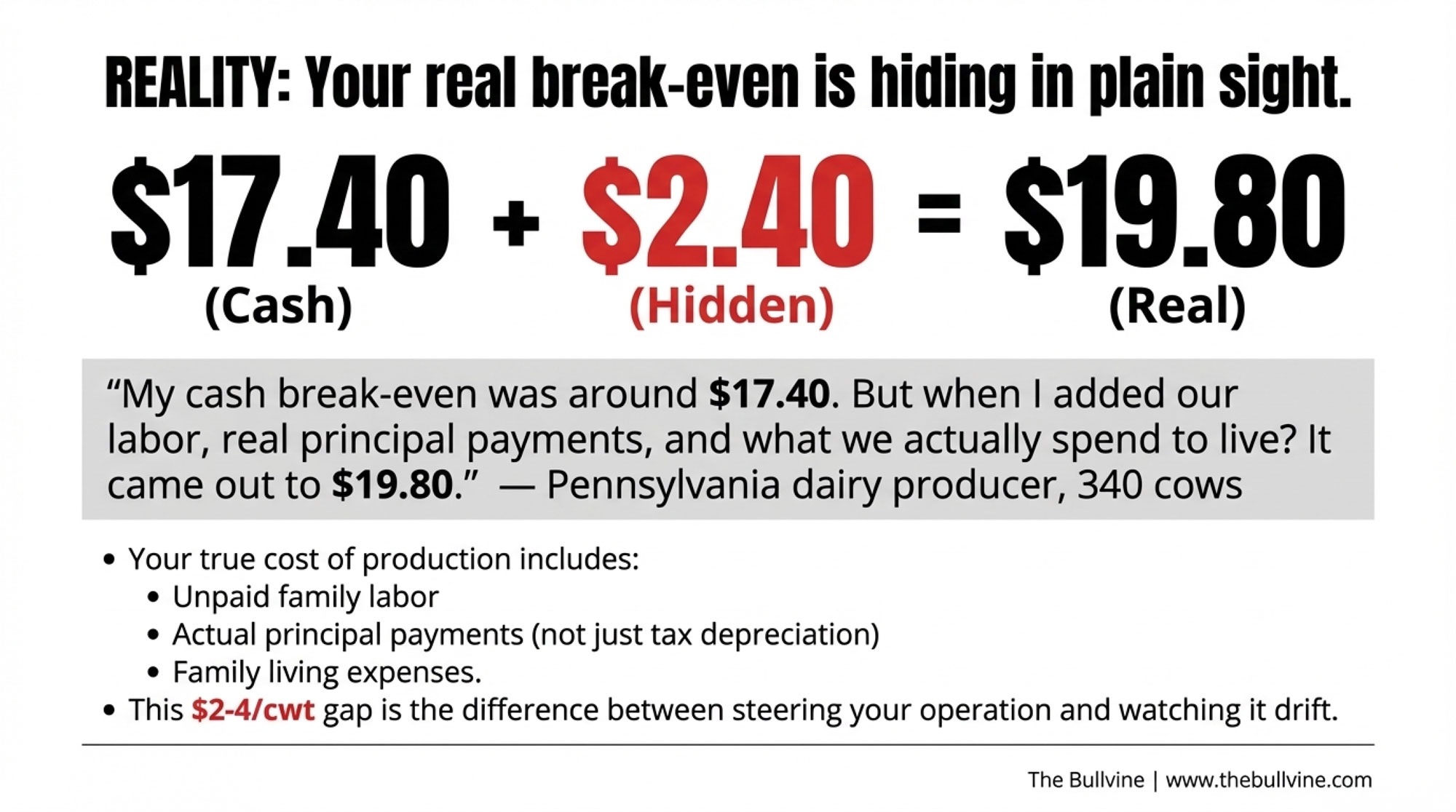

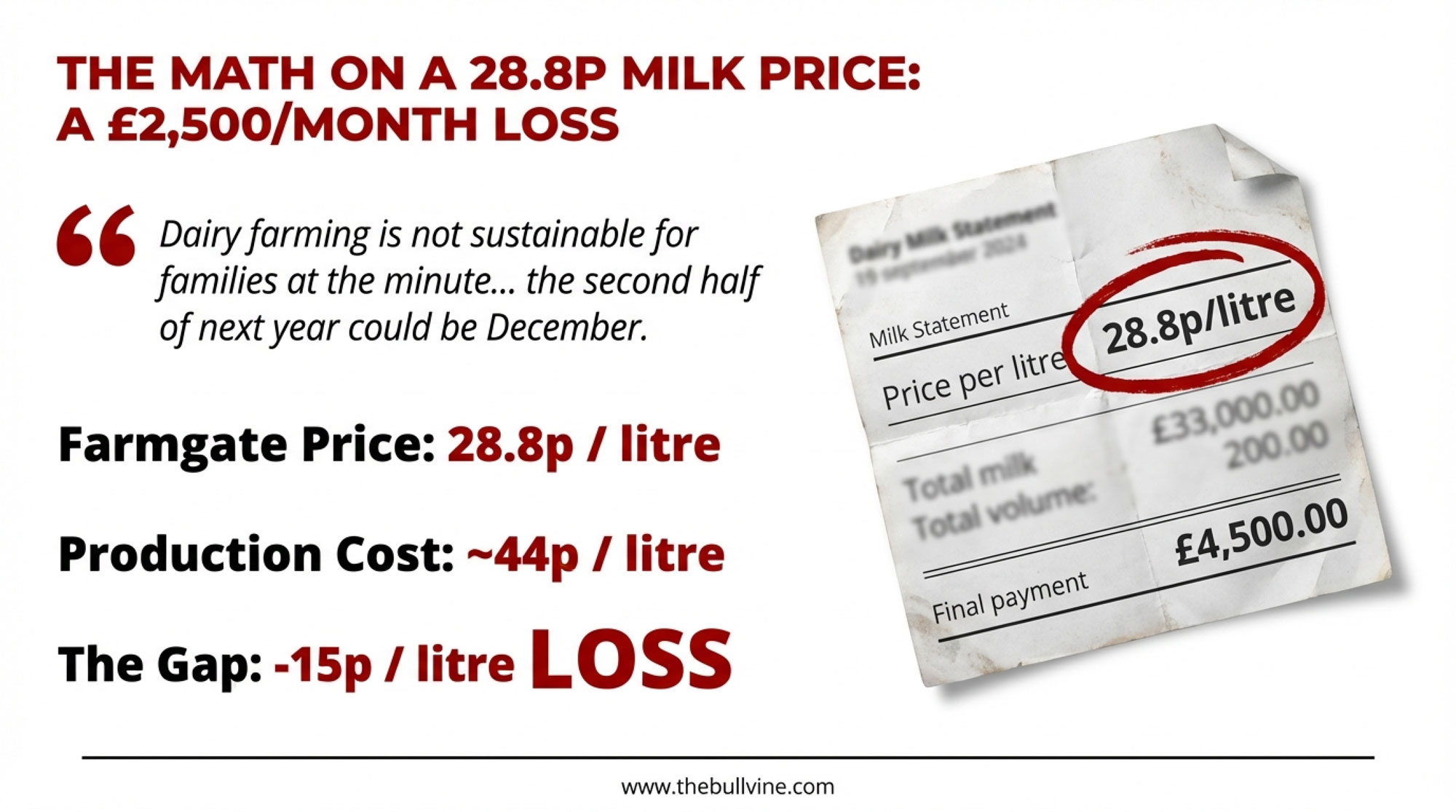

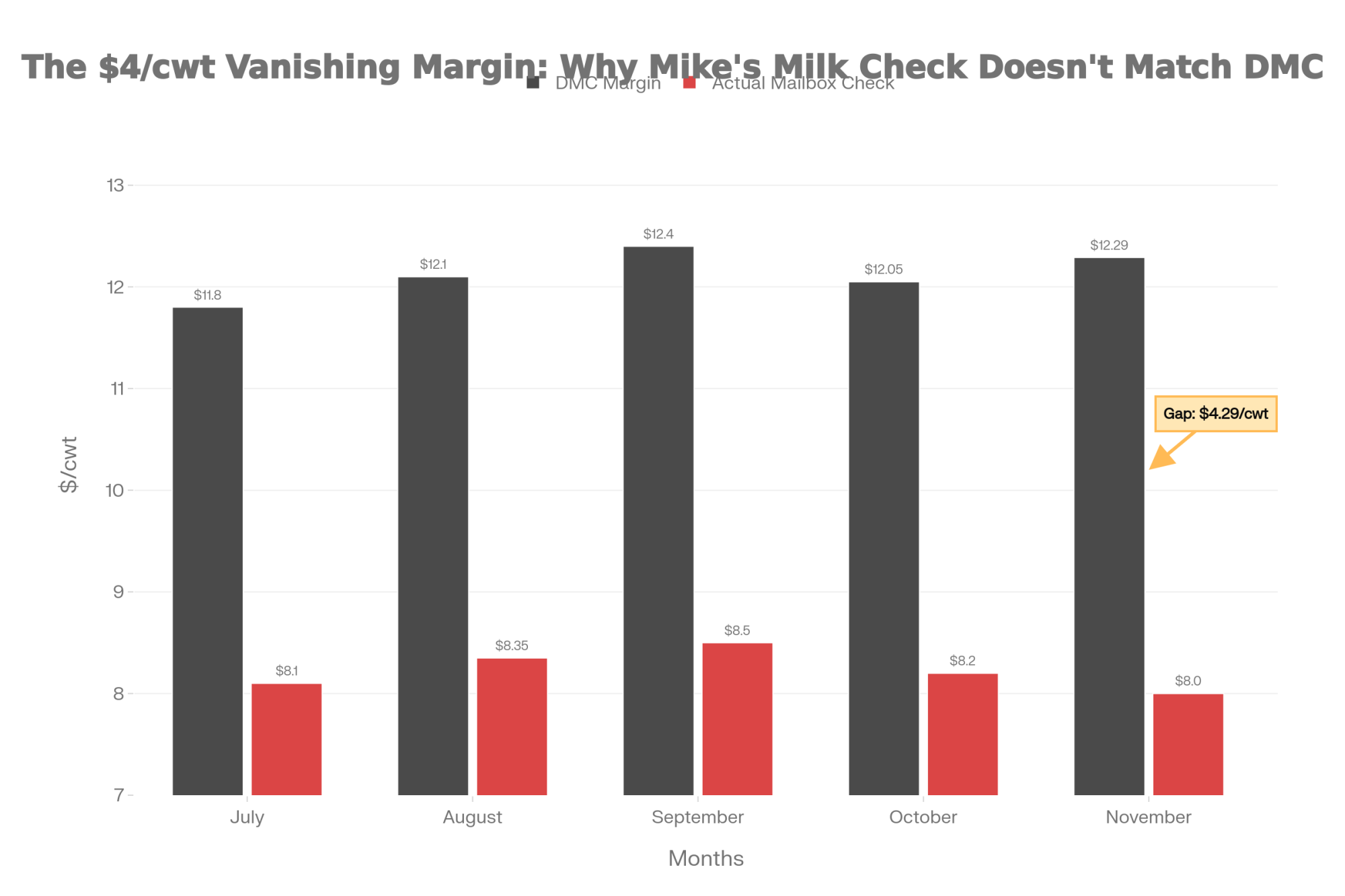

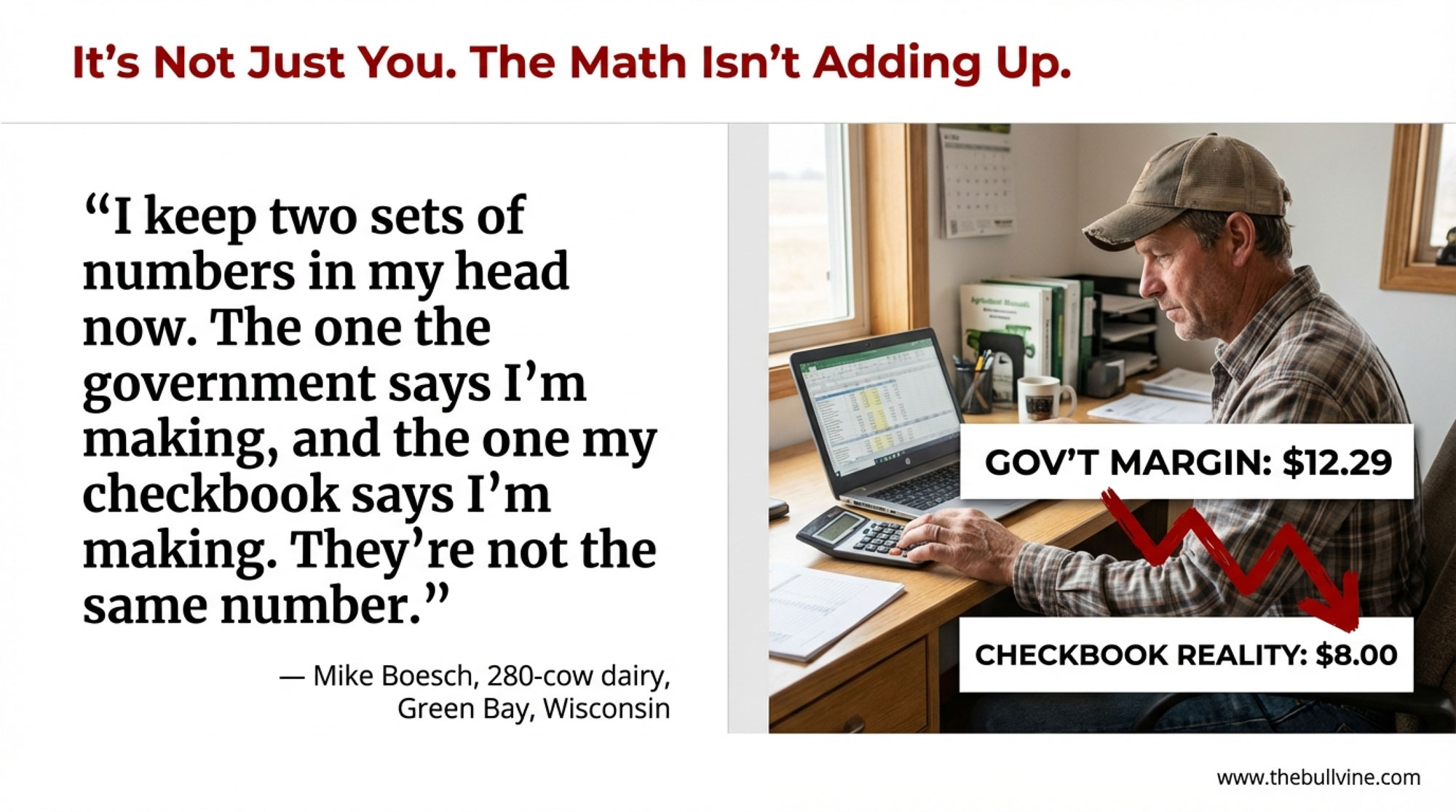

This is usually where the meeting room goes quiet: the space between whey’s ingredient value and what shows up in your milk cheque.

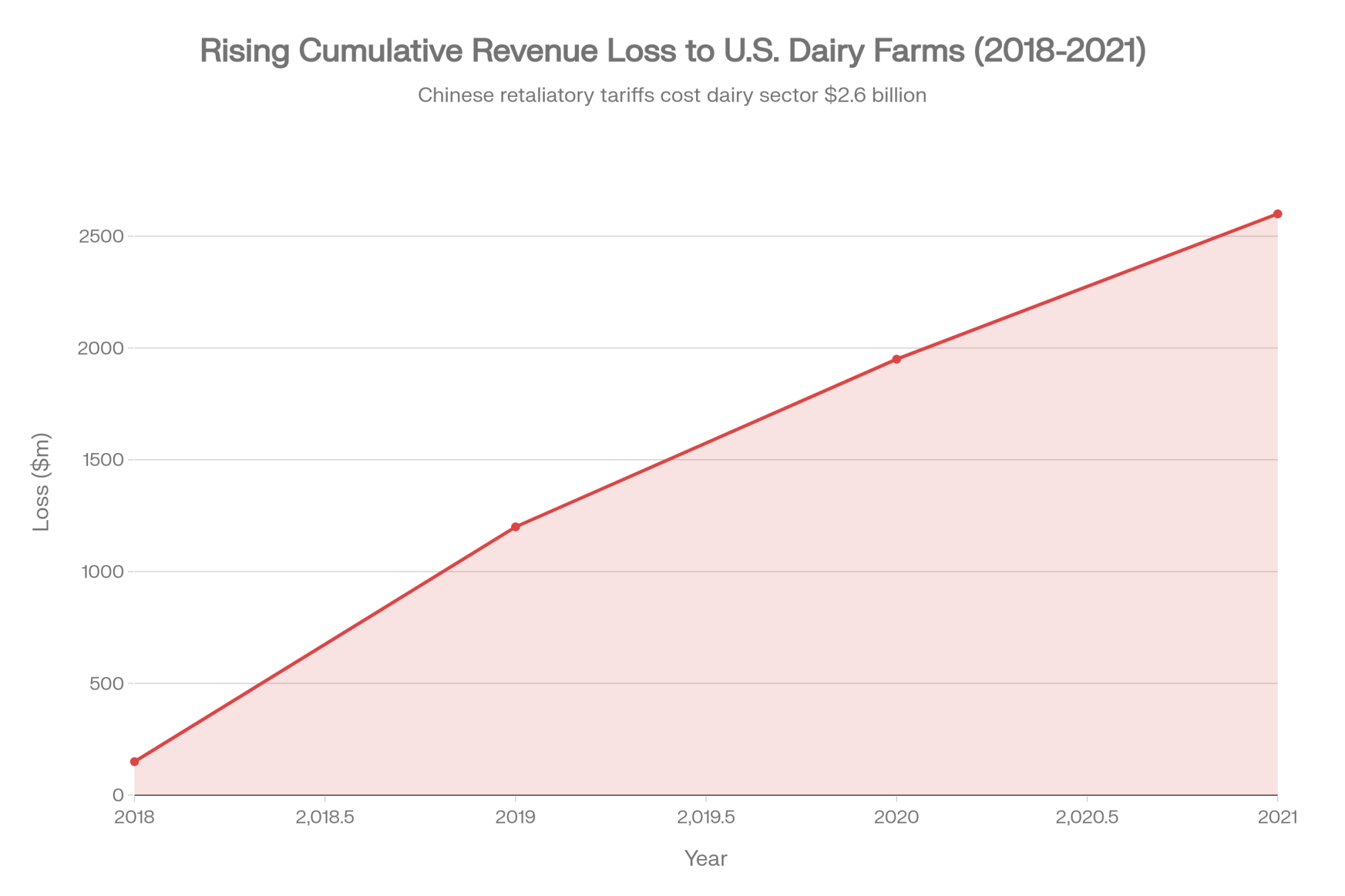

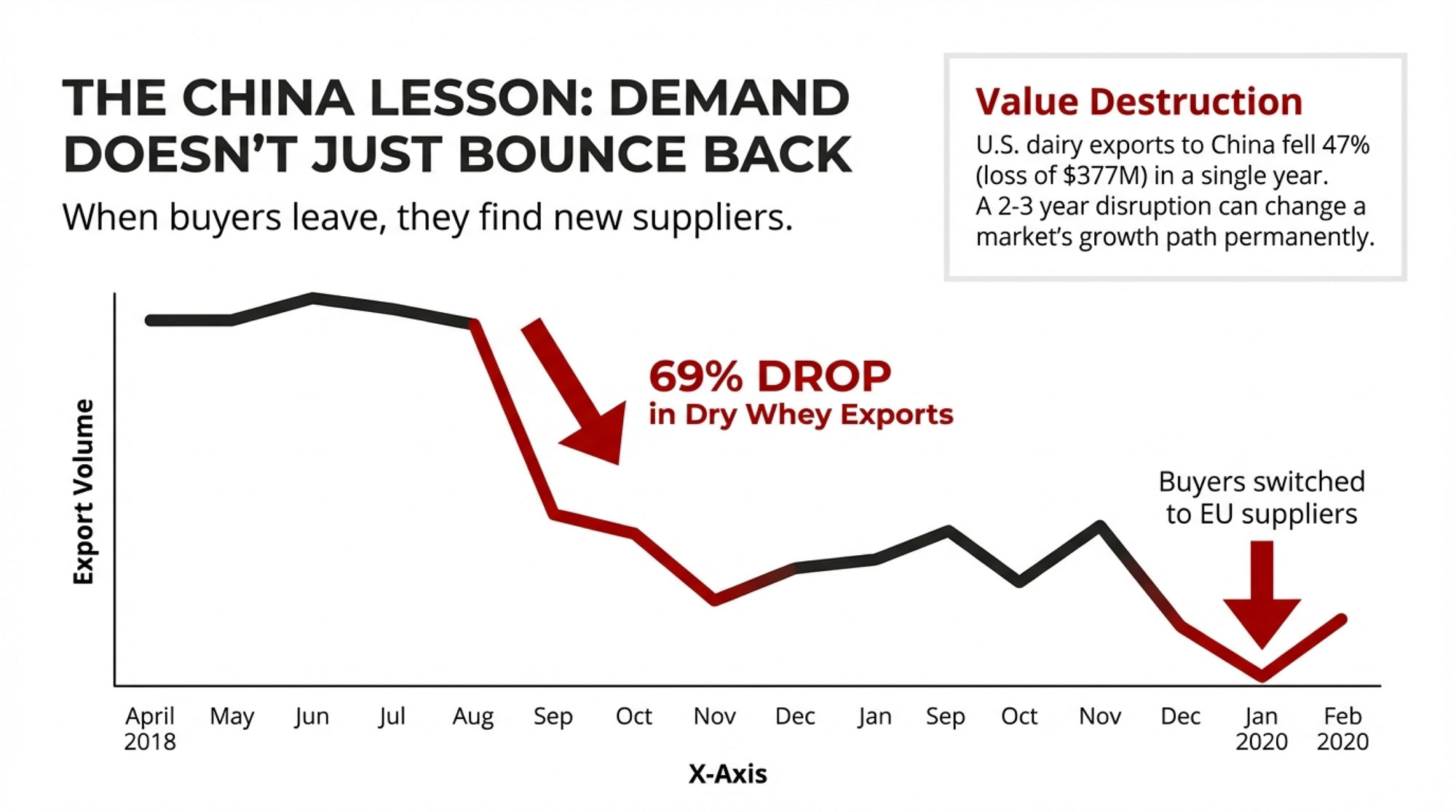

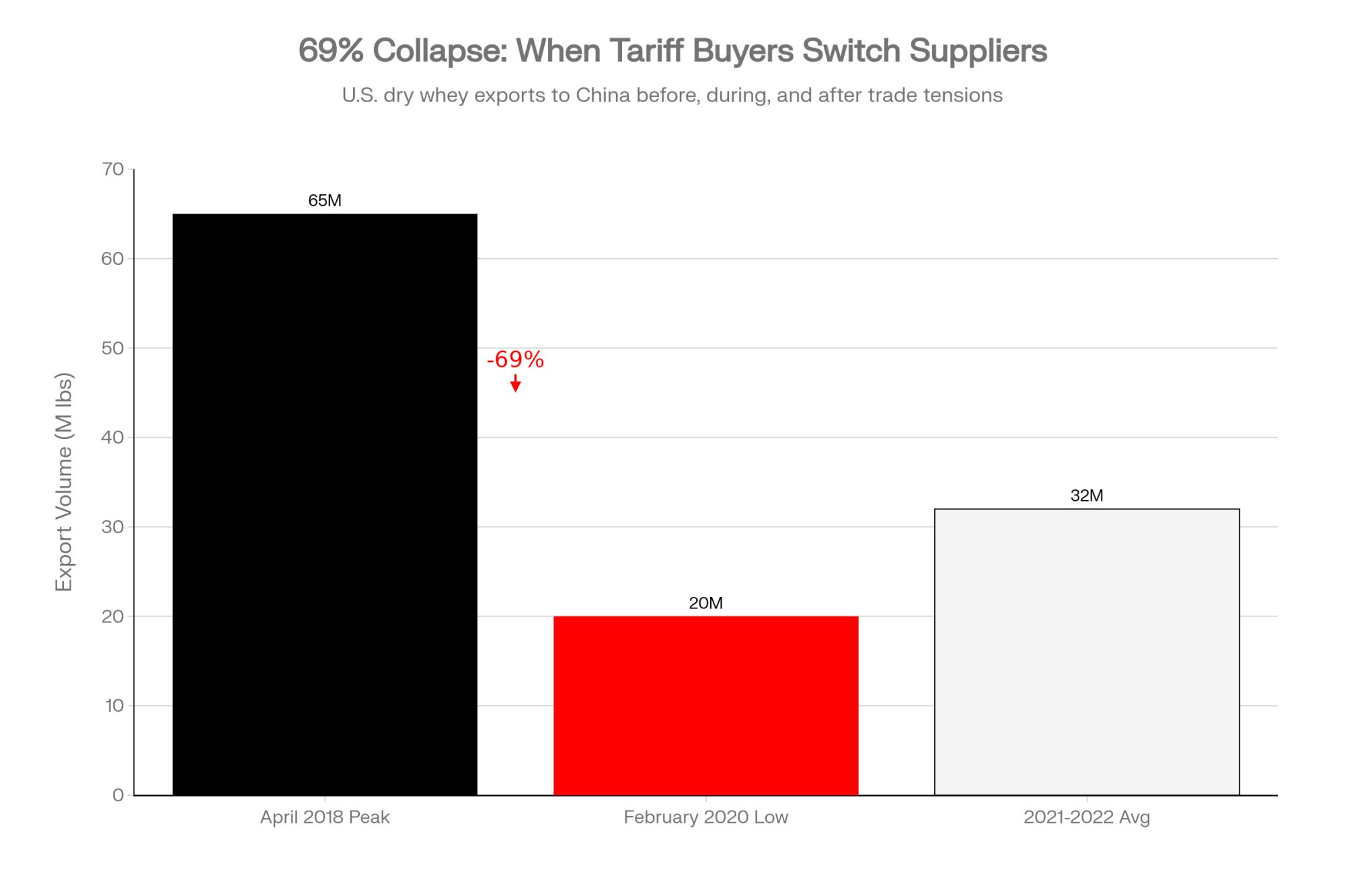

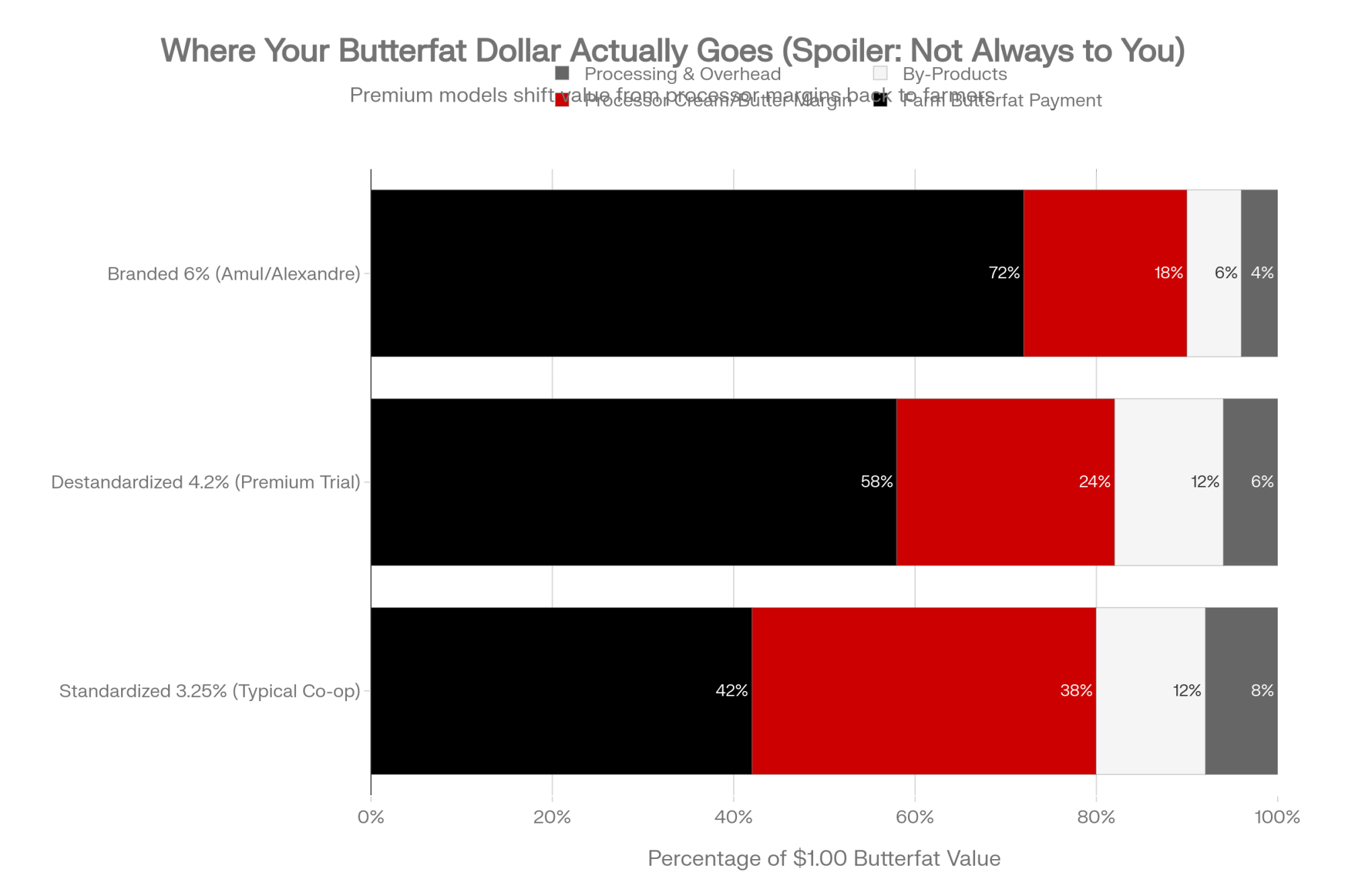

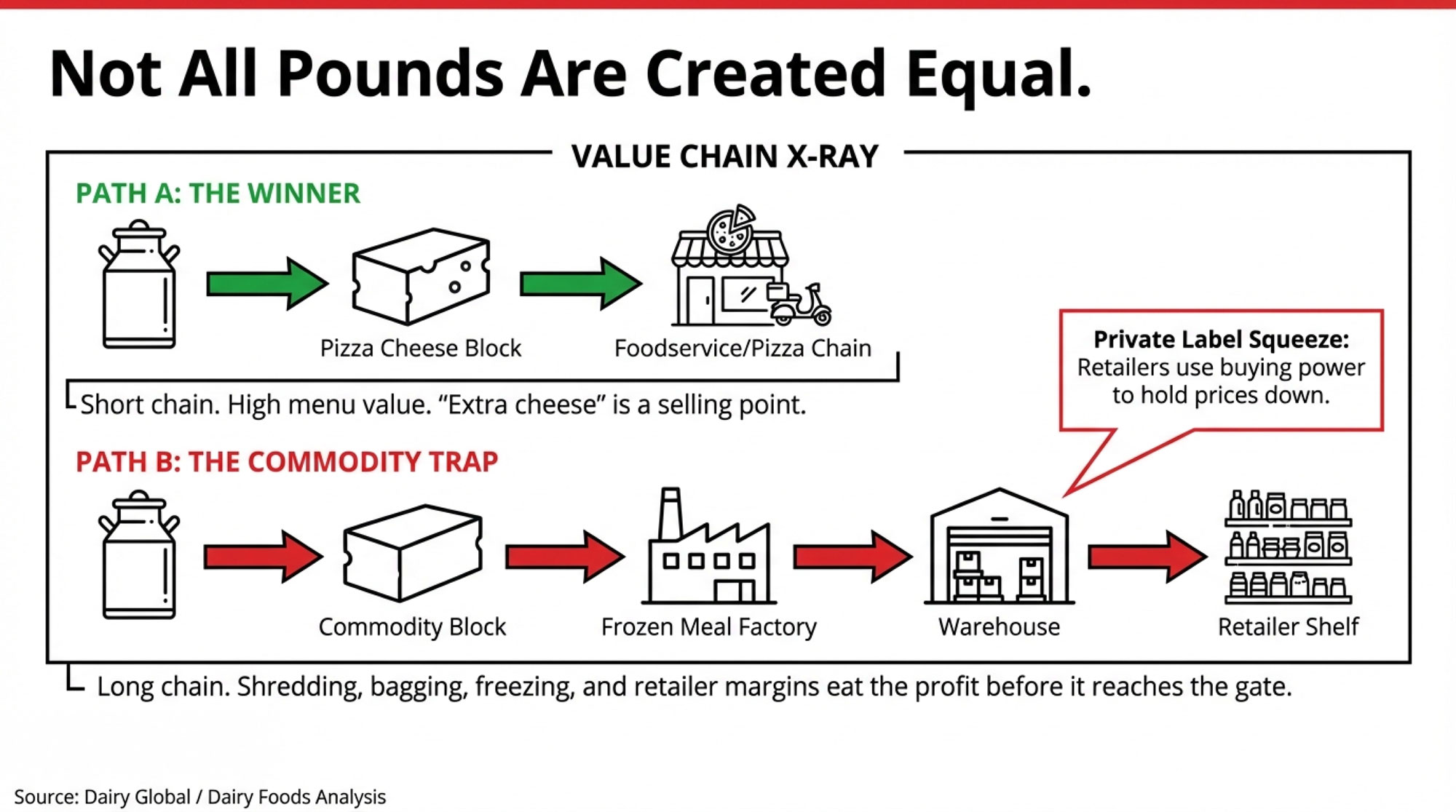

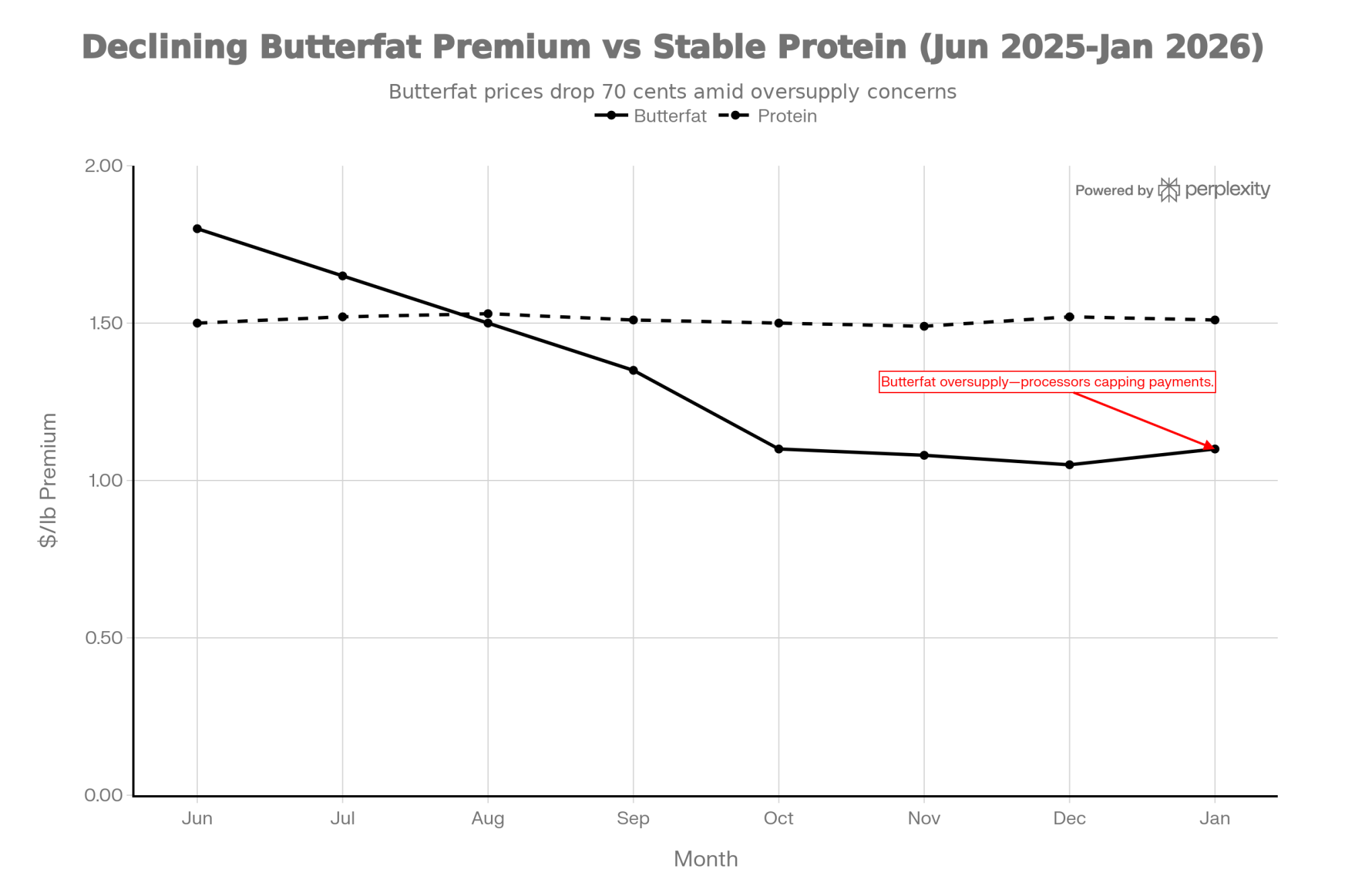

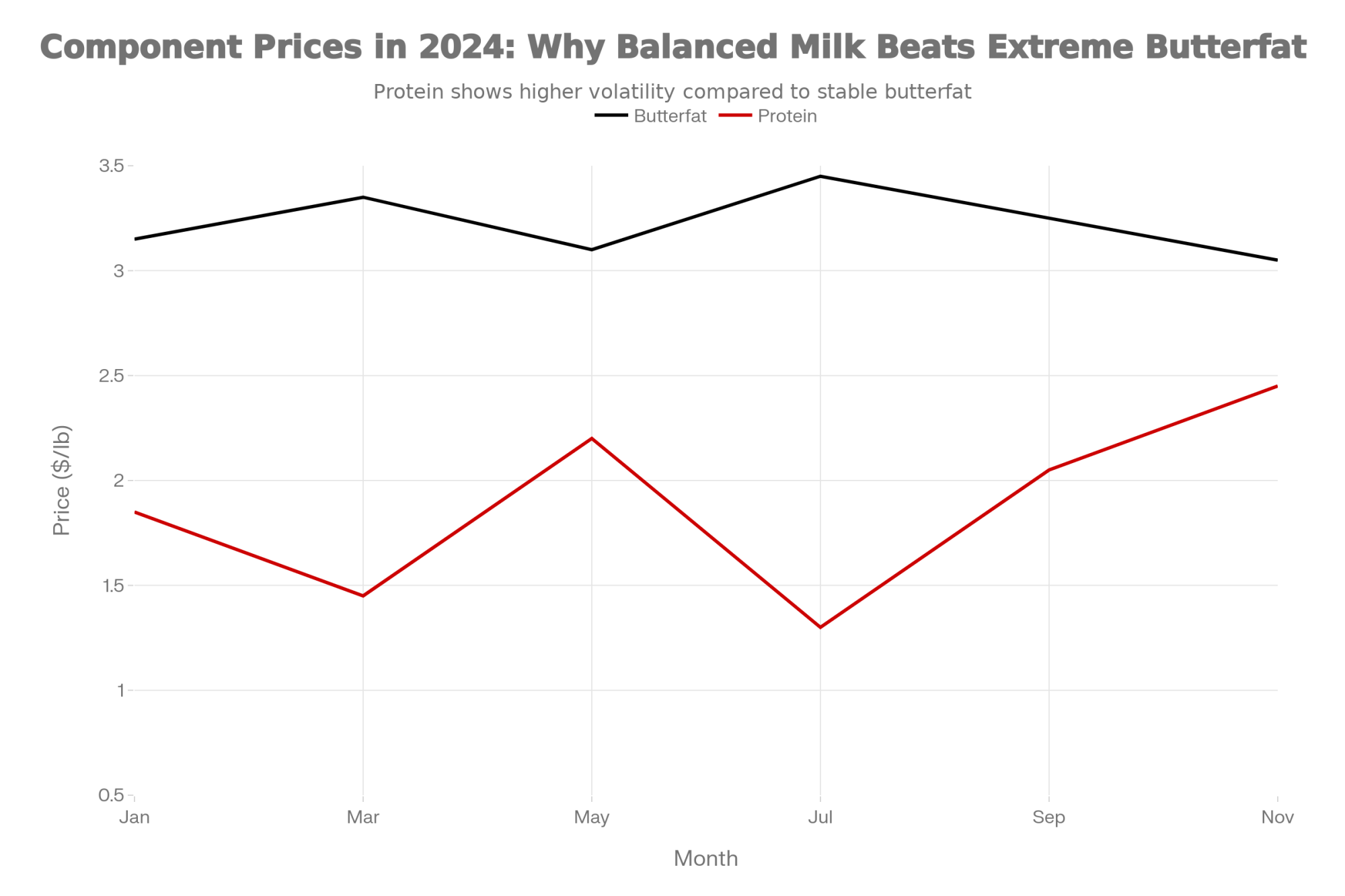

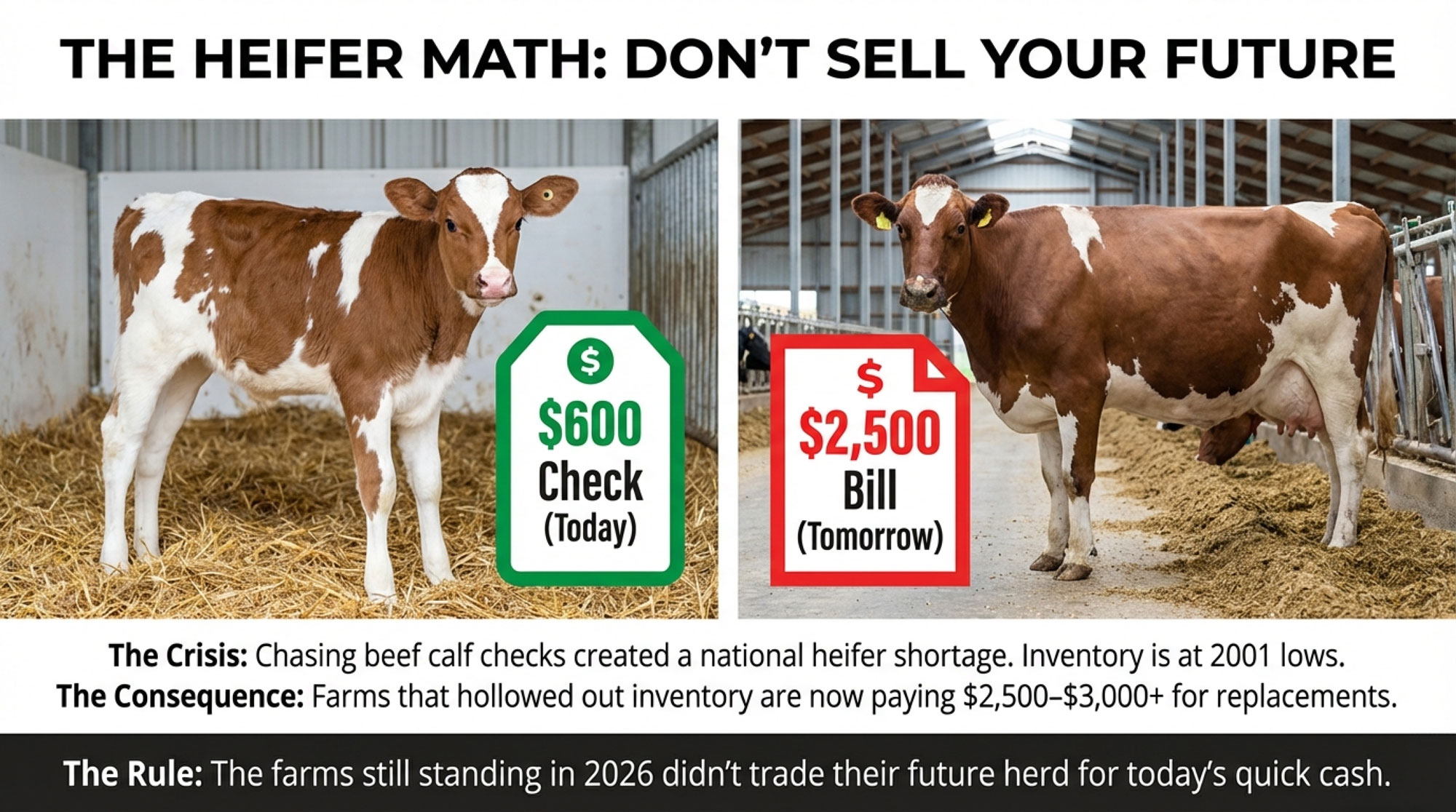

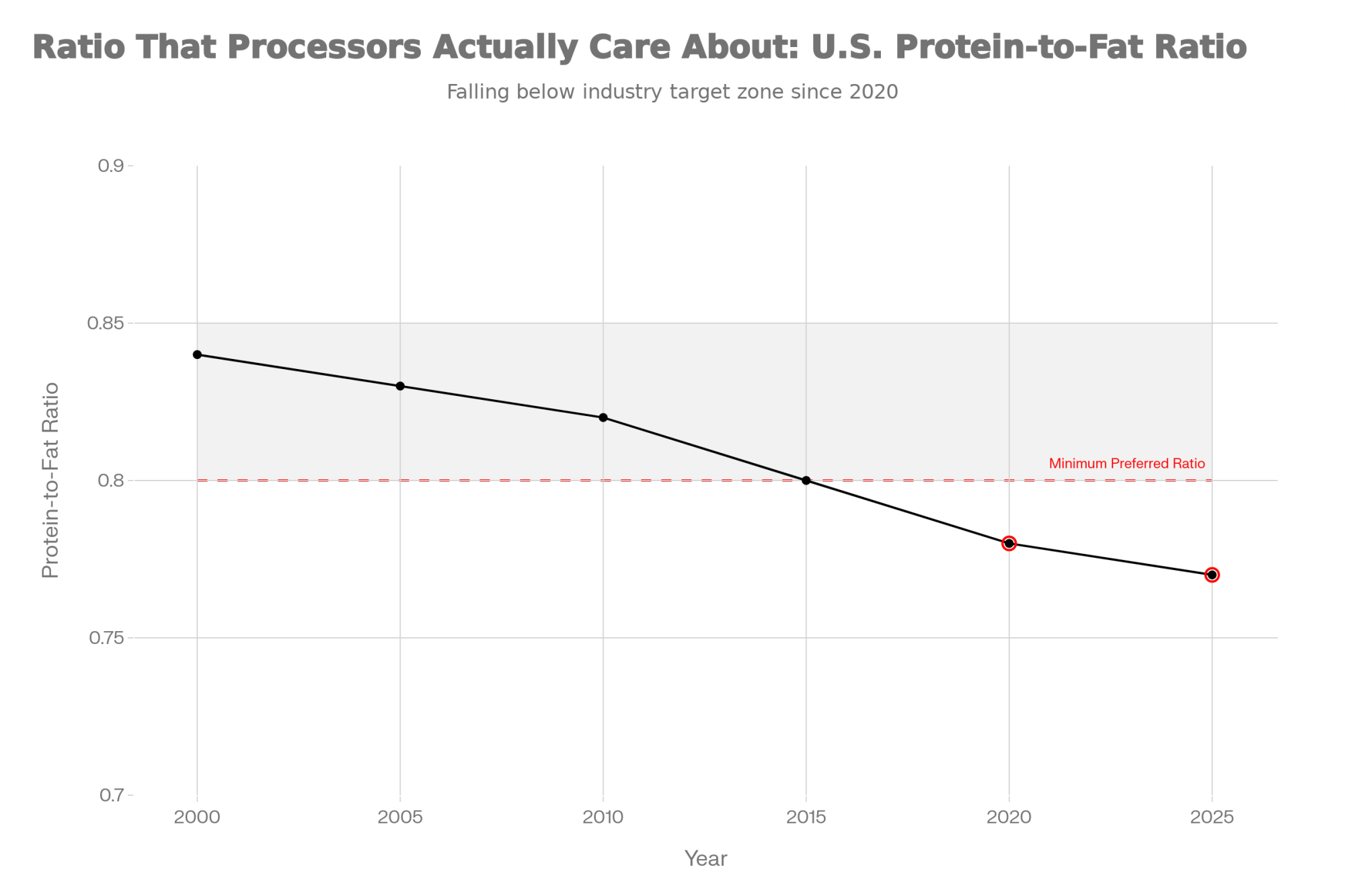

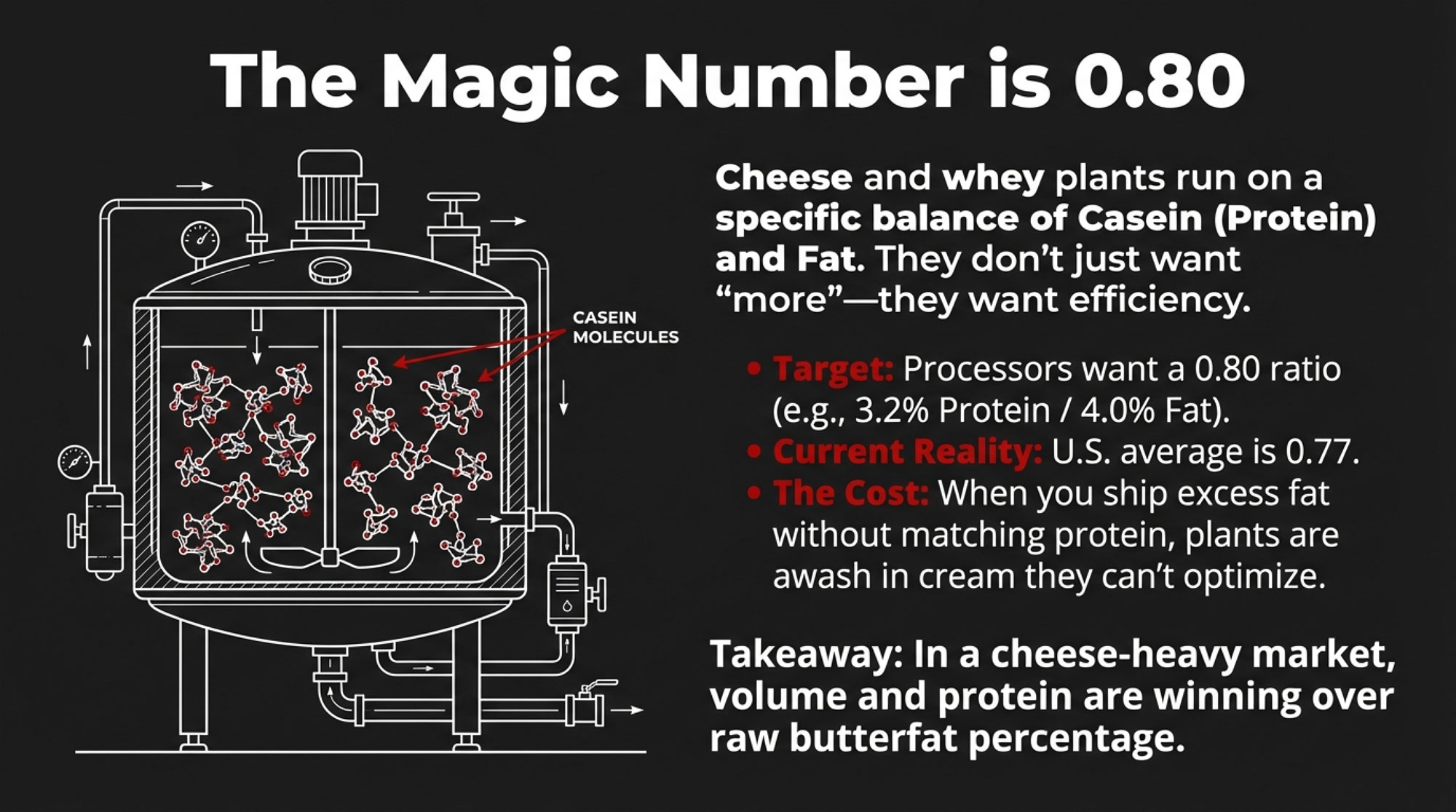

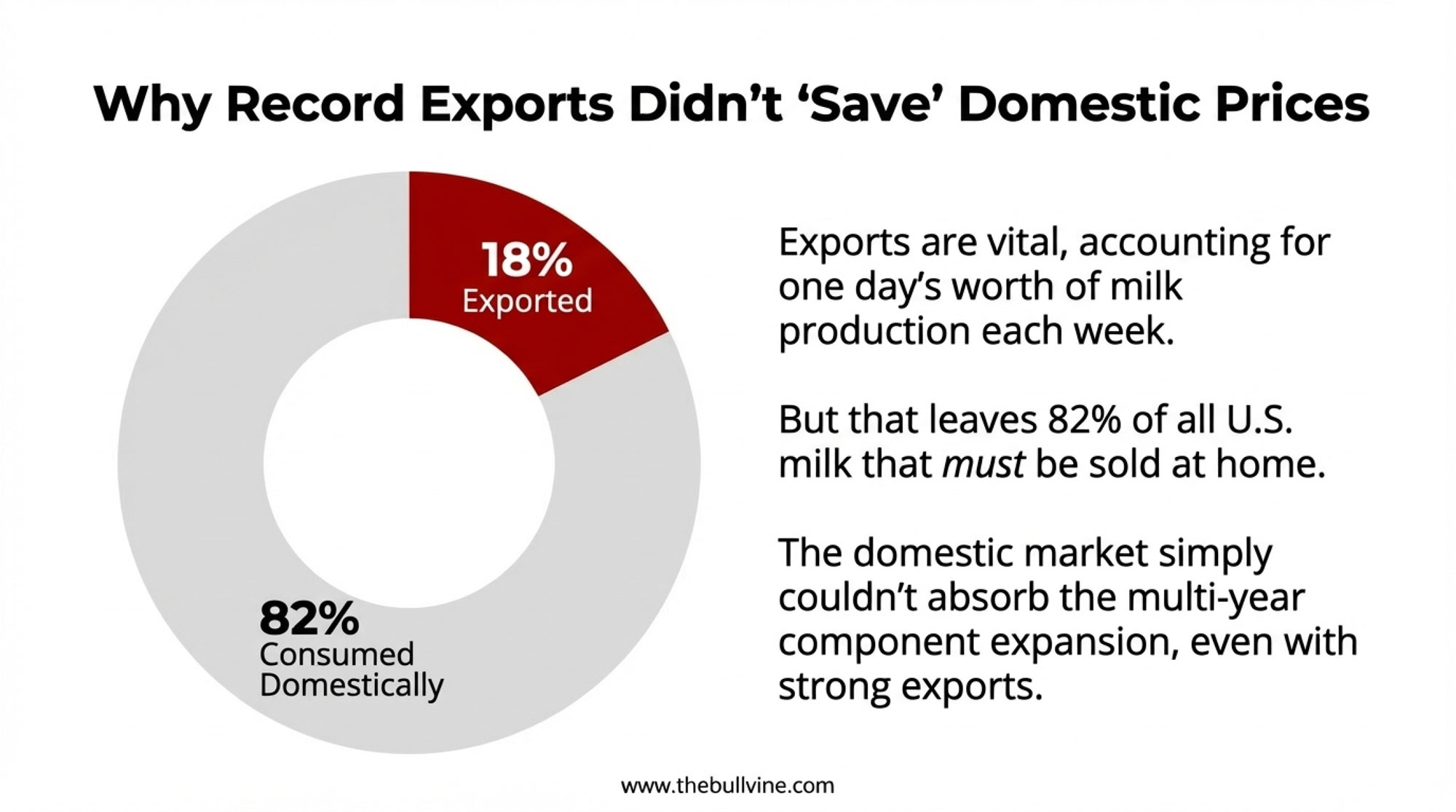

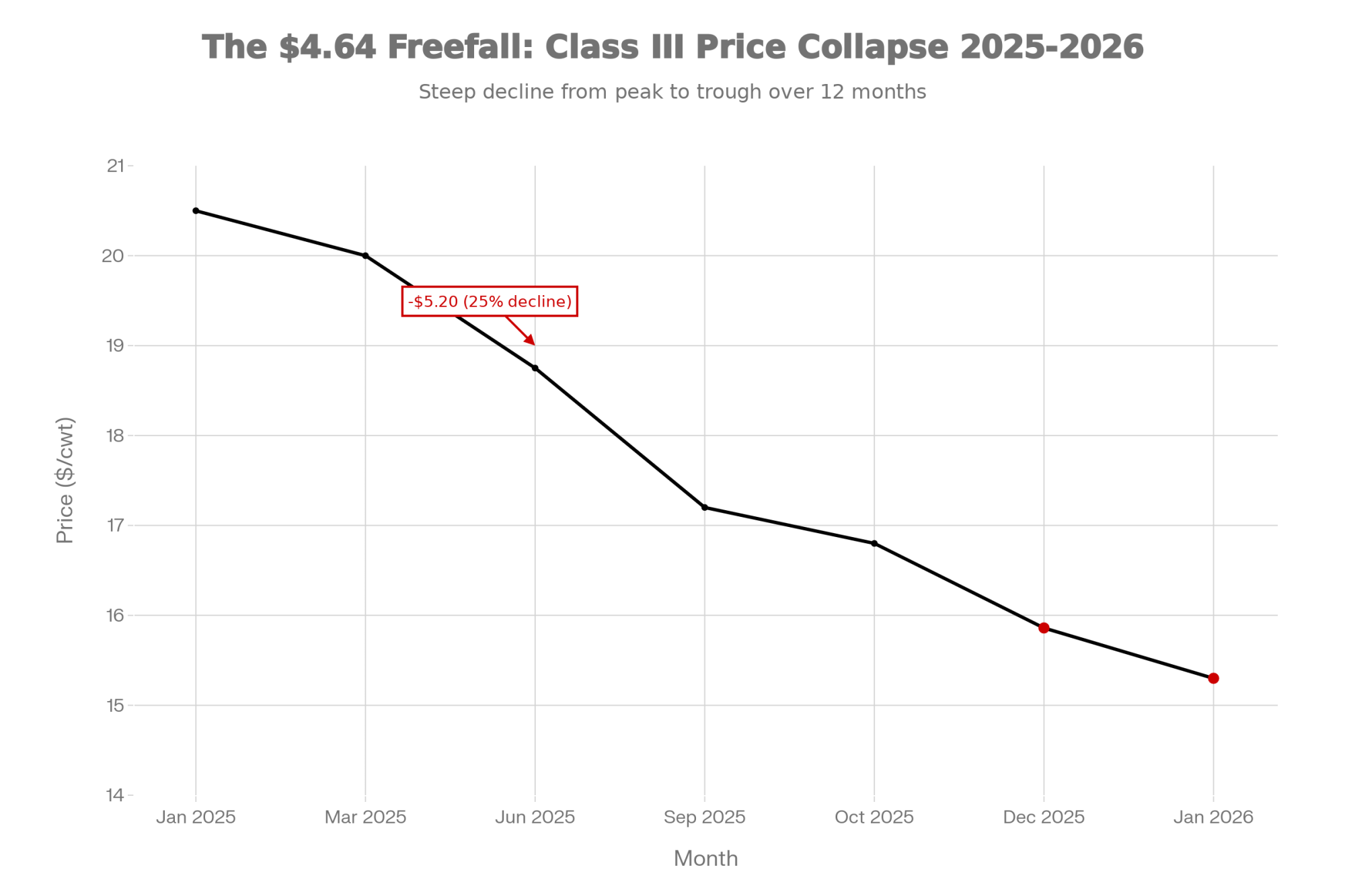

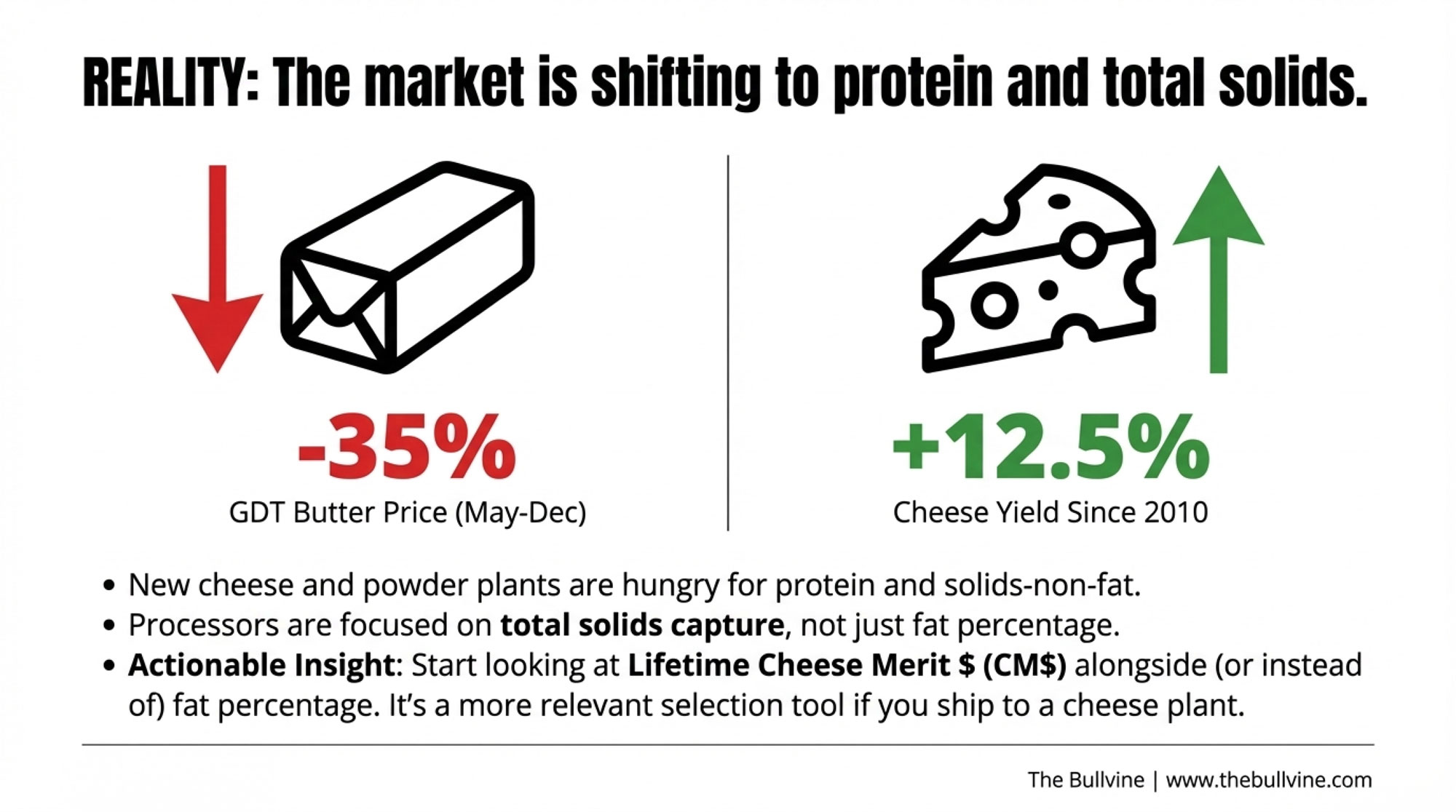

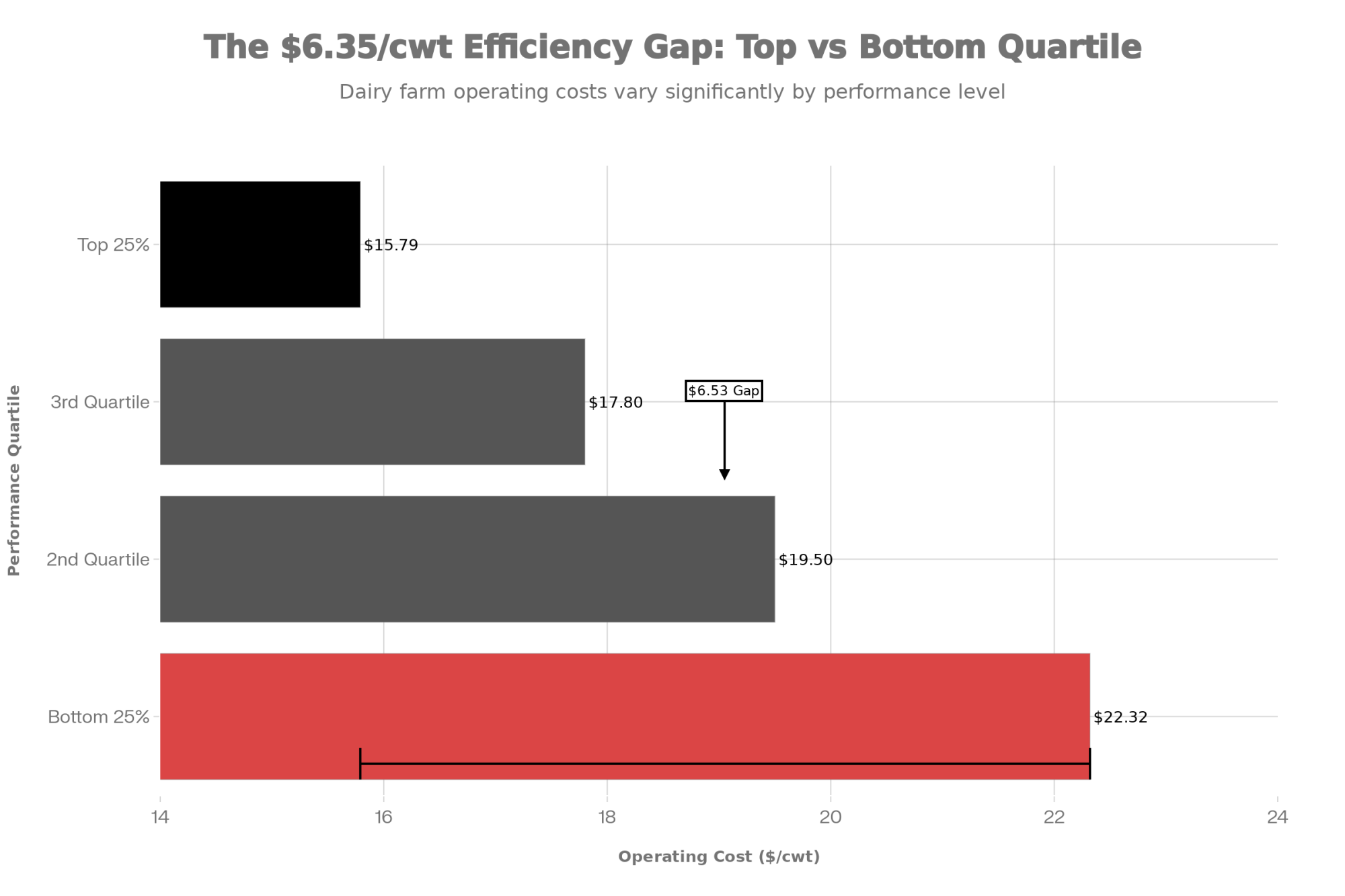

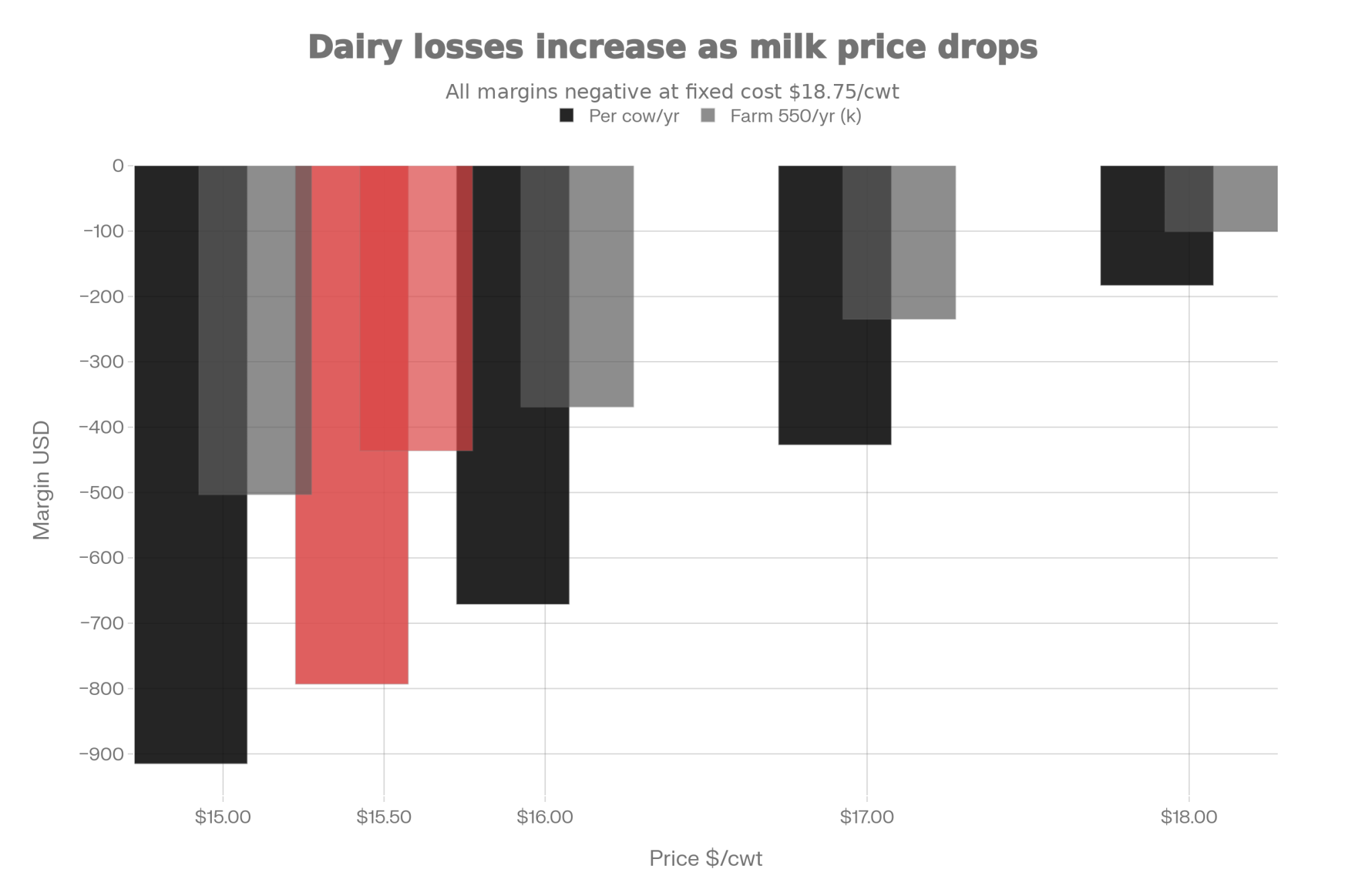

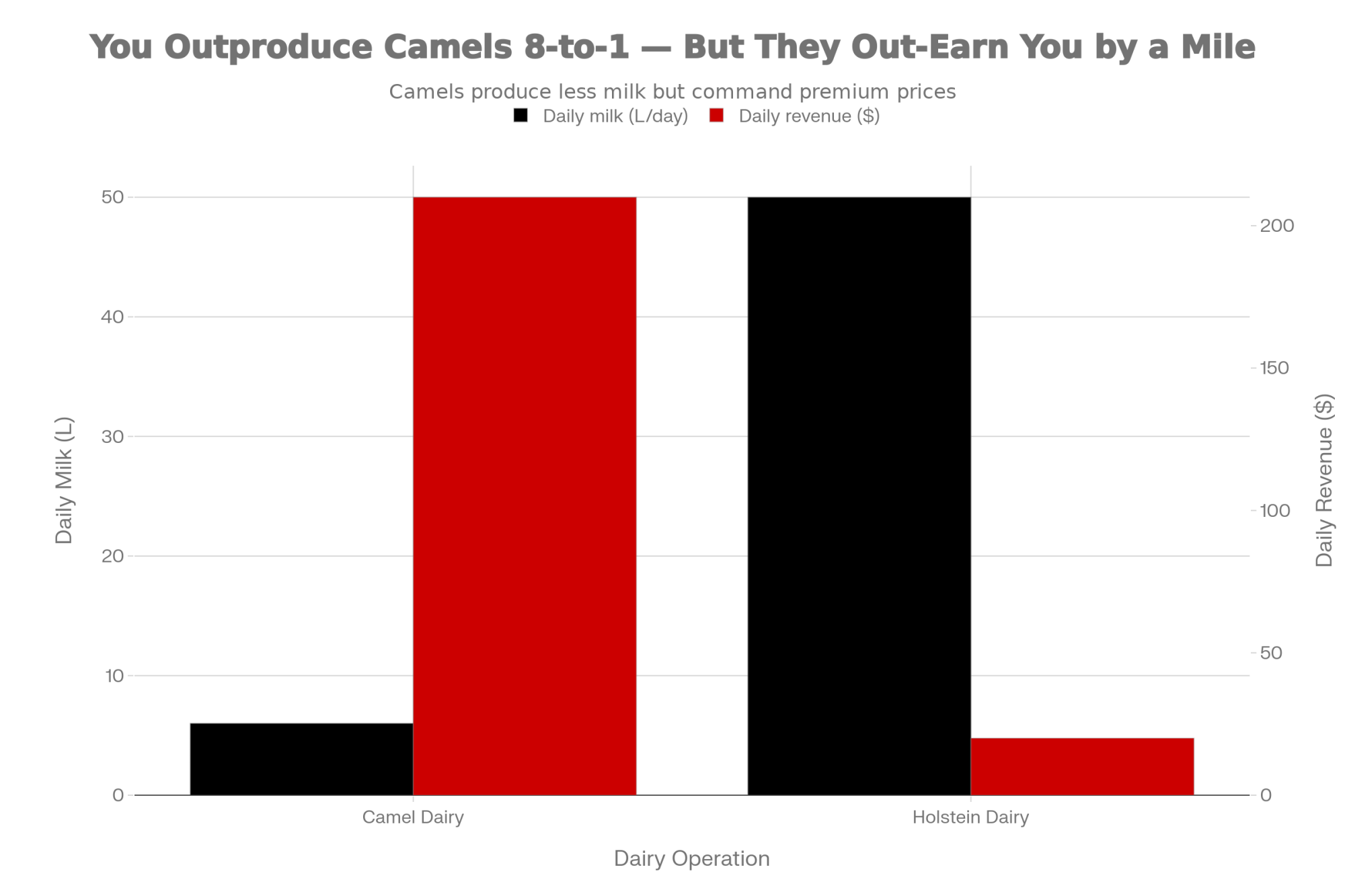

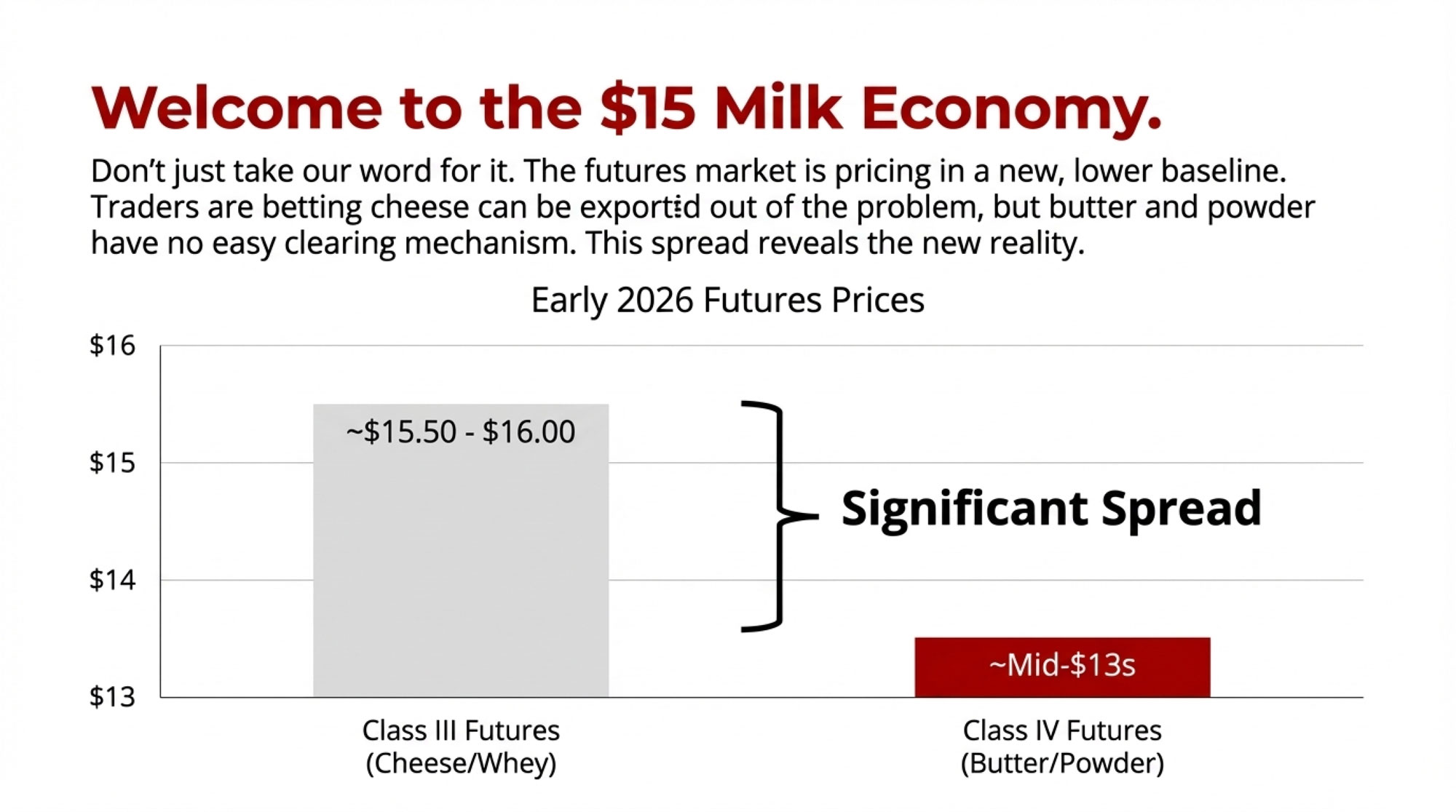

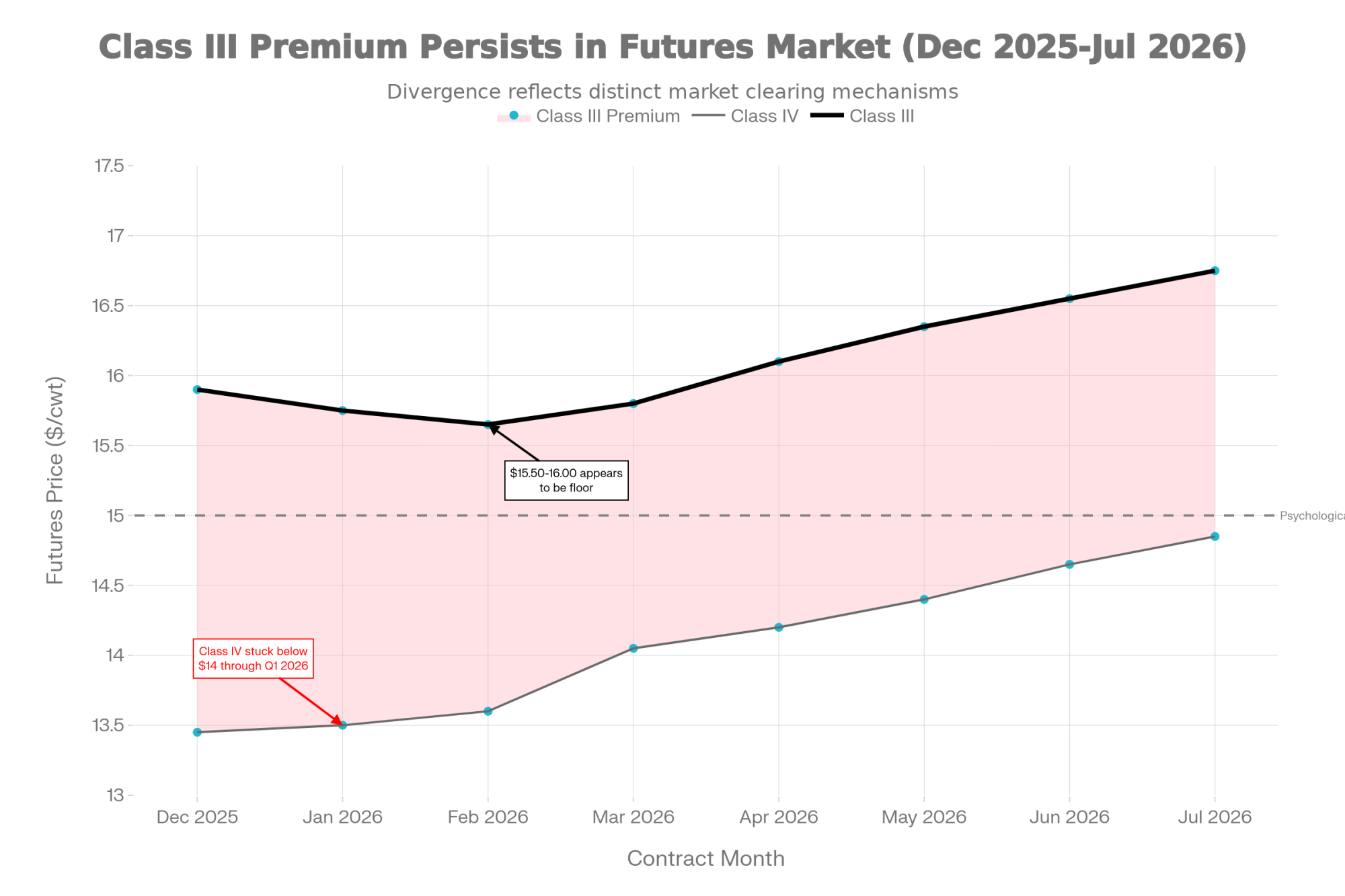

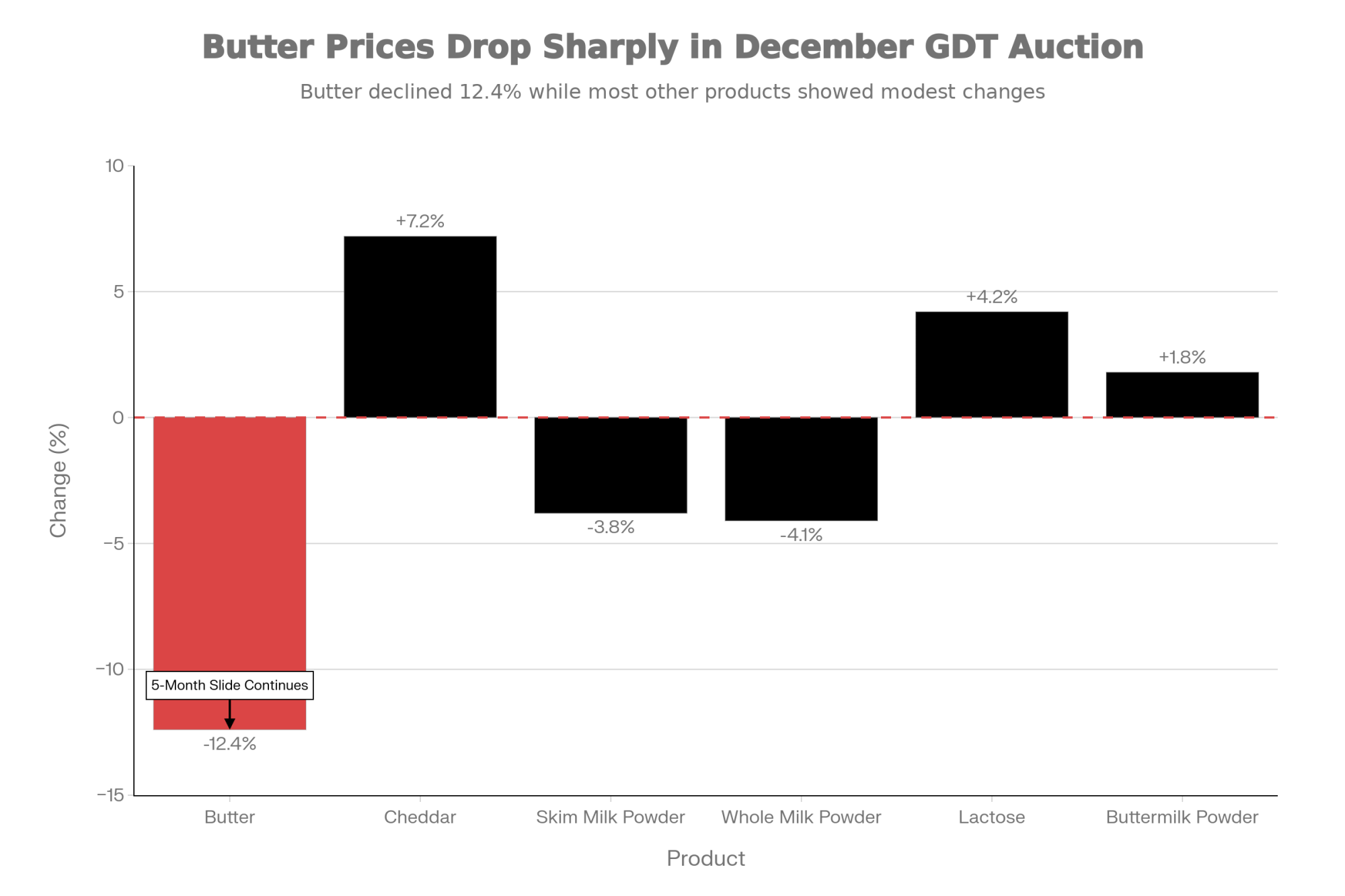

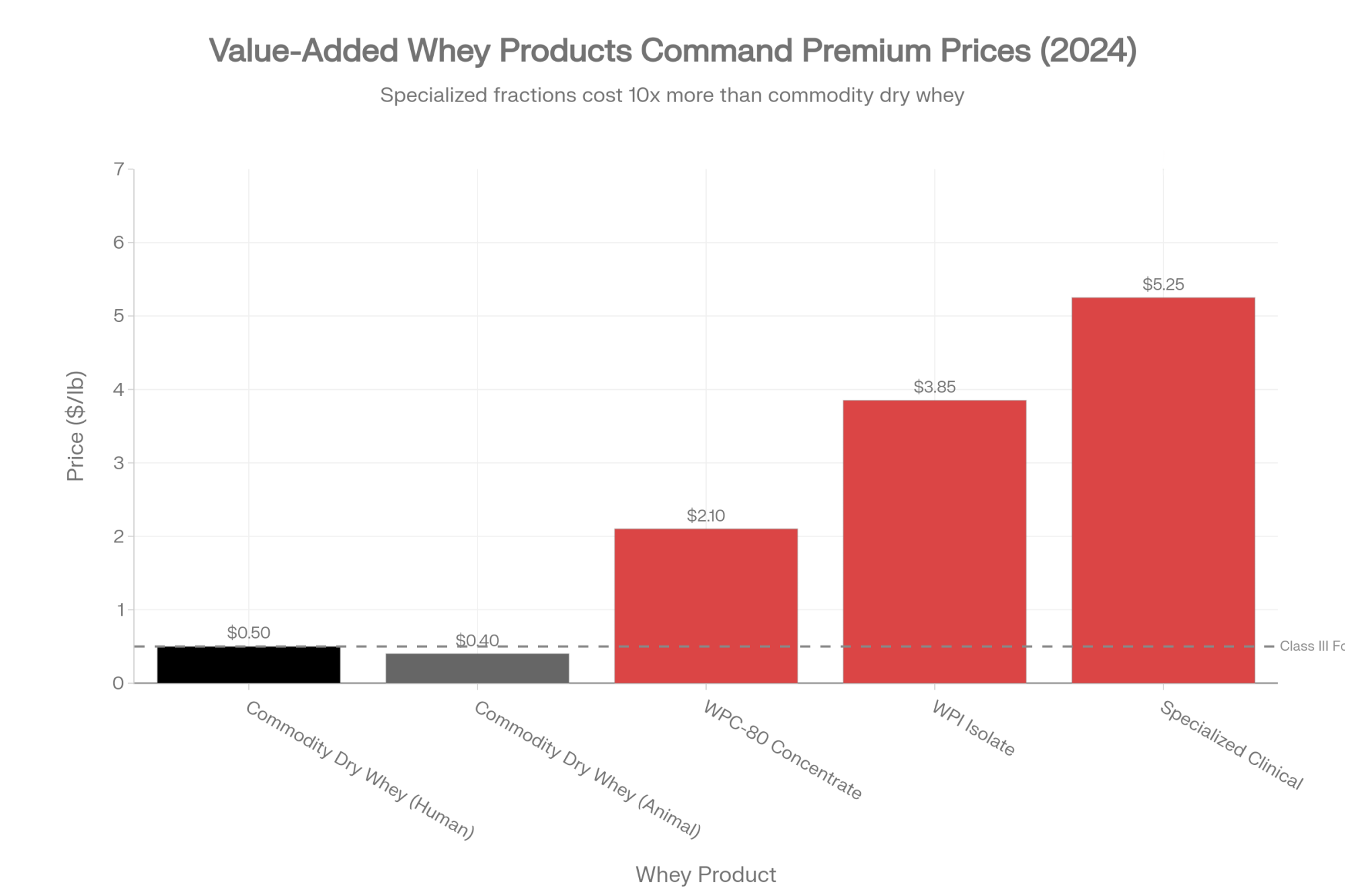

Most of the tools that touch your pay price—Class III formulas, many component programs, and a lot of co‑op base prices—are still built around commodity dry whey. USDA’s Dairy Market News for the Central region shows that through 2024, dry whey for human food often traded within a band from about 40 to 60 cents per pound, with “mostly” values often in the mid‑50s at times. Dry whey for animal feed typically sat lower, often in the high‑30s to low‑40s per pound.

Those dry whey numbers feed directly into the Class III formula. That’s the part your milk cheque “sees.”

But in a lot of bigger cheese and whey plants—especially in those new Western facilities and in long‑standing ingredient complexes in Idaho and the Upper Midwest—the whey stream doesn’t stop at dry powder. Potable whey is being:

- Concentrated into whey protein concentrates (like WPC‑80),

- Further refined into whey protein isolates (WPI),

- Sometimes split into more specialized fractions for infant formula, sports, and medical nutrition.

| Ingredient / Form | Typical Price Range (2024) | What’s Included in Your Class III Formula? | Market Margin vs. Commodity Dry Whey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity Dry Whey (Human Food) | $0.45–$0.60/lb | ✓ Yes—directly | Baseline (this is the “standard”) |

| Commodity Dry Whey (Animal Feed) | $0.38–$0.42/lb | Limited | −12 to −18¢/lb vs. human food |

| Whey Protein Concentrate (WPC-80) | $1.80–$2.40/lb | ✗ No—stays internal | +$1.20–$1.80/lb over commodity dry |

| Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) | $3.20–$4.50/lb | ✗ No—stays internal | +$2.60–$3.90/lb over commodity dry |

| Specialized Fractions (infant formula, clinical) | $4.00–$6.50/lb | ✗ No—not in formula | +$3.40–$5.90/lb over commodity dry |

Those ingredients sell at much higher per‑pound prices than bulk dry whey. Market research from MarkNtel and ingredient trade coverage show that high‑grade whey proteins typically command a multiple of whey powder prices, especially when export and sports demand are strong.

Obviously, there are extra costs—membranes, energy, drying, quality systems, and marketing. But even after that, the margin between the dry whey value that goes into your formula and the finished ingredient values can be significant.

So the real question isn’t whether whey has value. It’s this:

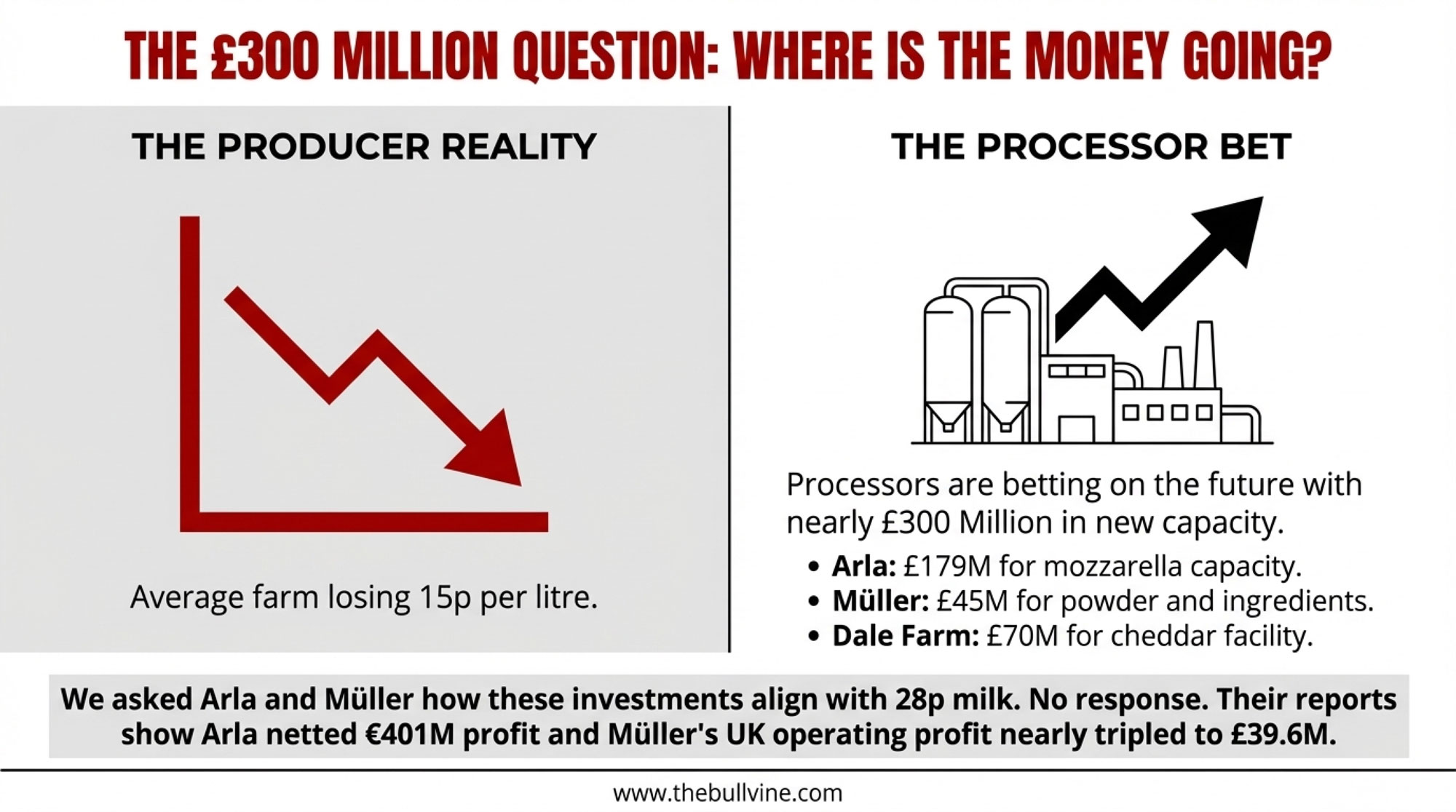

- When your co‑op or processor turns your whey into higher‑value ingredients, how much of that extra value comes back to you—and how much stays inside the plant and on the balance sheet?

That’s where co‑op finance and governance make all the difference.

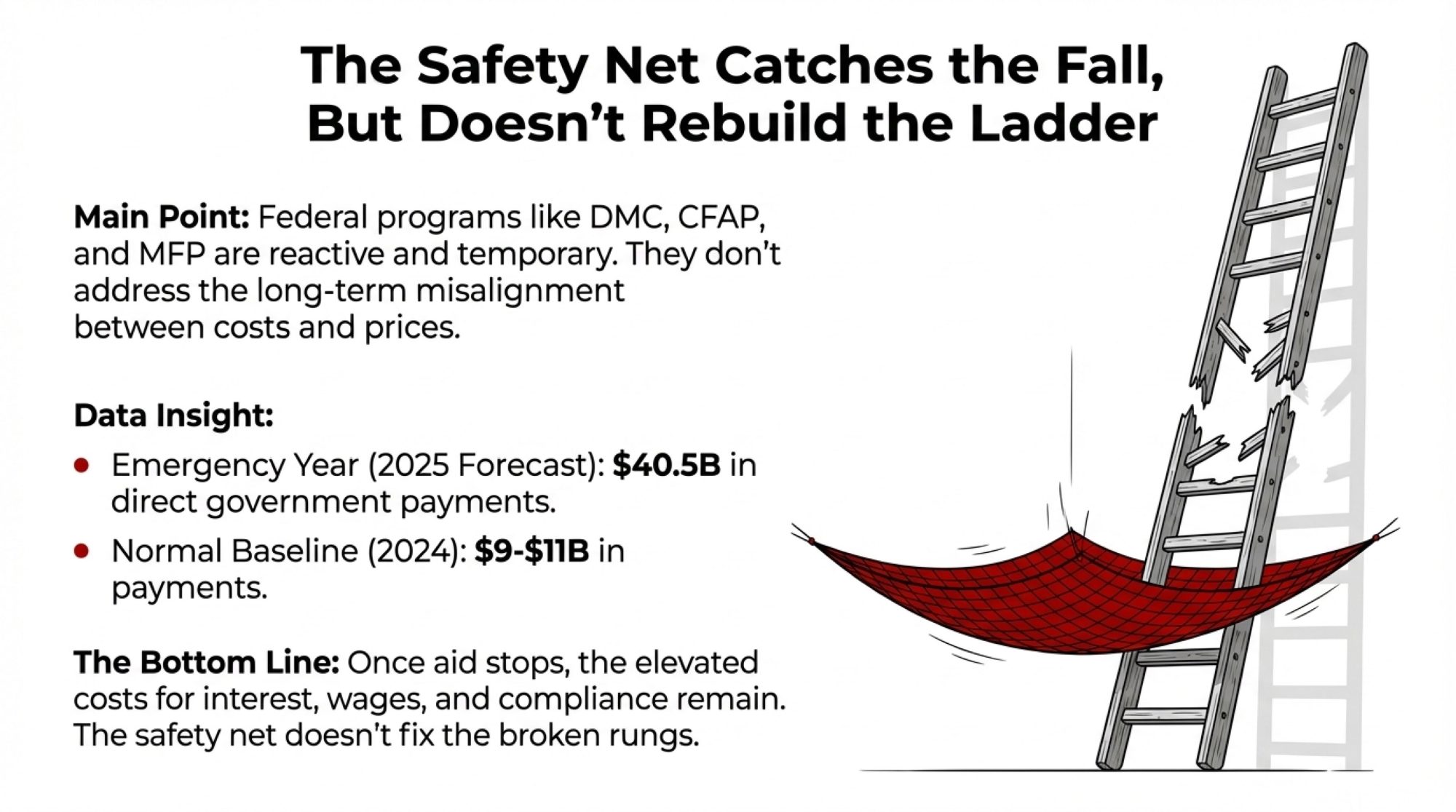

How Co‑op Finance Shapes Who Wins in the Whey Boom

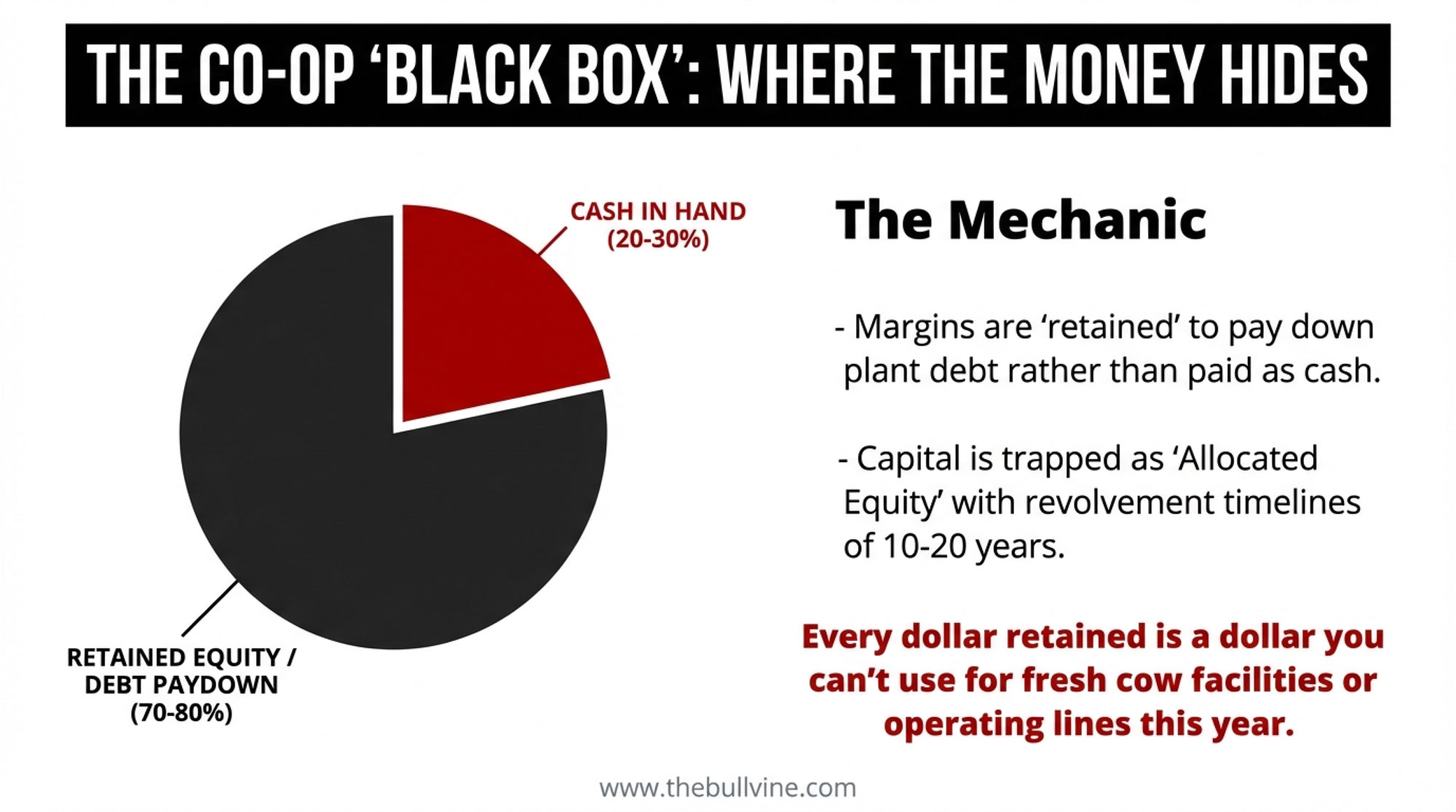

In many dairy co‑ops, the year‑end pattern looks something like this:

- The co‑op calculates its earnings and declares patronage refunds based on the volume or value of milk you delivered.

- A portion of those refunds is paid out in cash.

- The rest is retained as allocated member equity in your capital account.

Oklahoma State University Extension’s bulletin “Valuing the Cooperative Firm” lays this out neatly. In their sample, cash patronage ranged from about 21% to 70% of total patronage, with the rest retained as equity, and at least one co‑op paid as little as 15% in cash and 85% in equity. In dairy, because plants are so capital‑intensive, it’s common—and OSU’s data supports this pattern—to see something in the ballpark of 20–30% of patronage paid as cash and 70–80% retained in some co‑ops, but there is no single standard. Policies vary widely by co‑op and over time.

On top of that, most co‑ops use revolving equity. That means your retained patronage from a given year is supposed to be redeemed at some point in the future—either on a revolving schedule (oldest years first), at retirement, or a combination of both. USDA and extension guides emphasize that revolving timelines can range from a few years to decades, depending on each co‑op’s rules, performance, and board decisions.

So when a board approves a major whey or cheese expansion, the financing stack often looks like this:

- A chunk of debt from banks or bond markets.

- A big share of retained member equity that’s already on the books.

- Sometimes, new per‑unit retains or special capital assessments on current milk.

From a board’s perspective, this can be perfectly rational. They’re trying to keep the co‑op’s equity‑to‑debt ratio strong enough to make lenders comfortable, while leaving room for future projects.

From your perspective, sitting at the kitchen table with your lender, a few fair questions pop up:

- If my retained equity helped build this plant, when does that investment realistically come back to my farm as cash?

- When the whey and ingredients division has a strong year, does that show up as better cash patronage or faster equity redemption, or mostly as accelerated debt pay‑down and a stronger co‑op balance sheet?

- Can I actually see how the whey and ingredients business is performing as its own line, or is it lumped into one big profit number?

It’s worth noting something simple that often gets glossed over: every dollar the co‑op retains is a dollar you can’t use this year to pay down your operating line, improve fresh cow facilities, or tweak ventilation and cow flow to protect butterfat performance in summer.

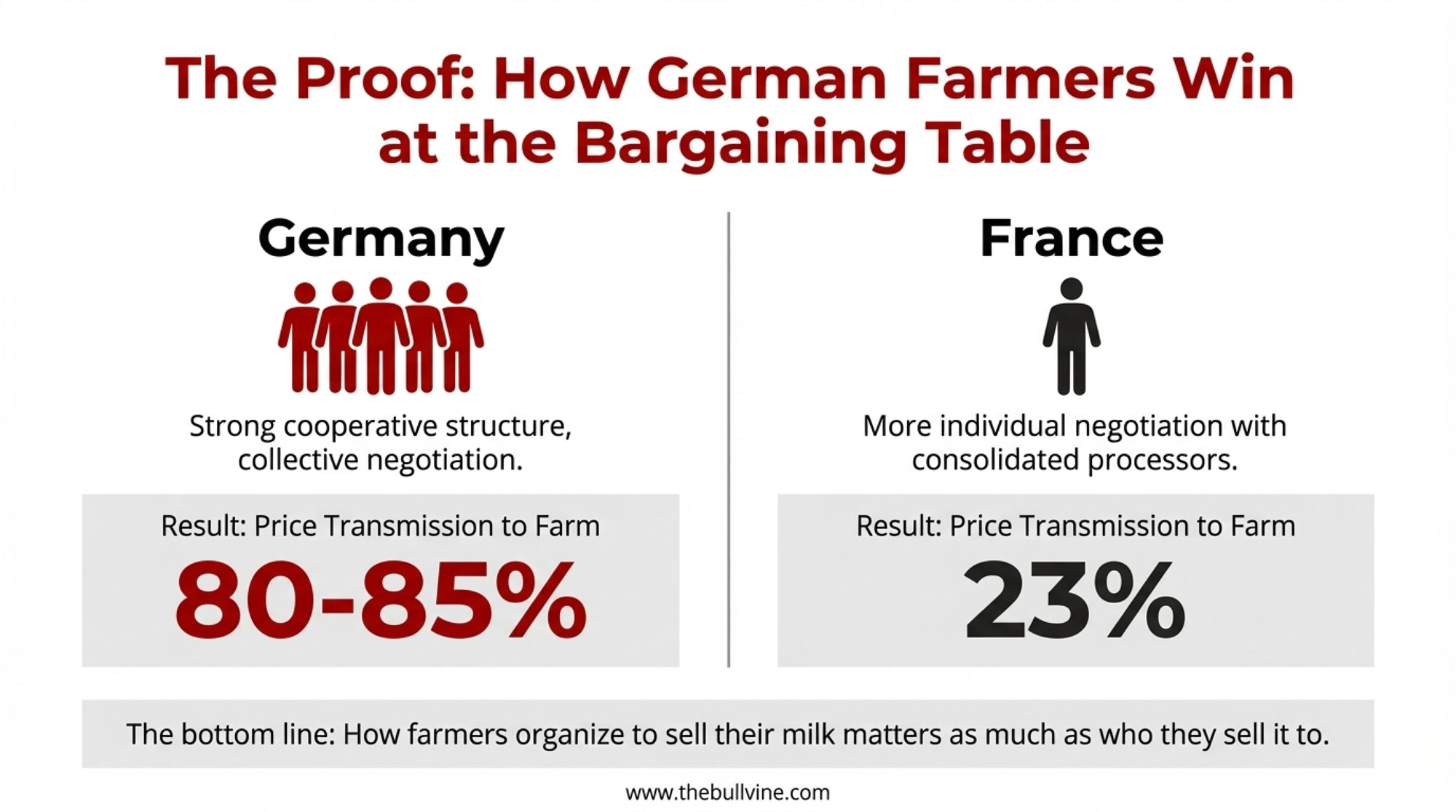

Research on European dairy co‑ops in specialty cheese and ingredient markets, summarized in global dairy sector reviews, has found that co‑ops with clear segment reporting and active member participation tend to maintain member trust and perform more steadily across market cycles than those with opaque structures. Members in those systems may not love every decision, but they can see whether the whey or ingredients division is doing what it was supposed to do and how that performance connects to patronage and equity.

Key takeaway for co‑op finance:

If whey and ingredient projects are funded heavily with member equity and the performance of those divisions isn’t clearly reported or tied to cash patronage and equity redemption, it’s very easy for ingredient value to get “stuck” at the co‑op level instead of showing up in your milk cheque.

That’s why transparency and structure matter just as much as stainless steel and membranes.

Whey Investments Can Pay Off—But Not Automatically

A fair question at this point is, “Do these whey investments actually pay back fast, or is that just a nice line in a PowerPoint?”

Several techno‑economic and “dairy biorefinery” studies have worked through the numbers on whey valorization—turning whey into higher‑value products instead of low‑value powder or waste. Reviews in journals like Foods and Journal of Environmental Management have concluded that whey is a promising feedstock for higher‑value ingredients and bioproducts and that, under favorable conditions—strong demand, good utilization, reasonable energy costs—those projects can deliver relatively fast payback compared with some other dairy investments.

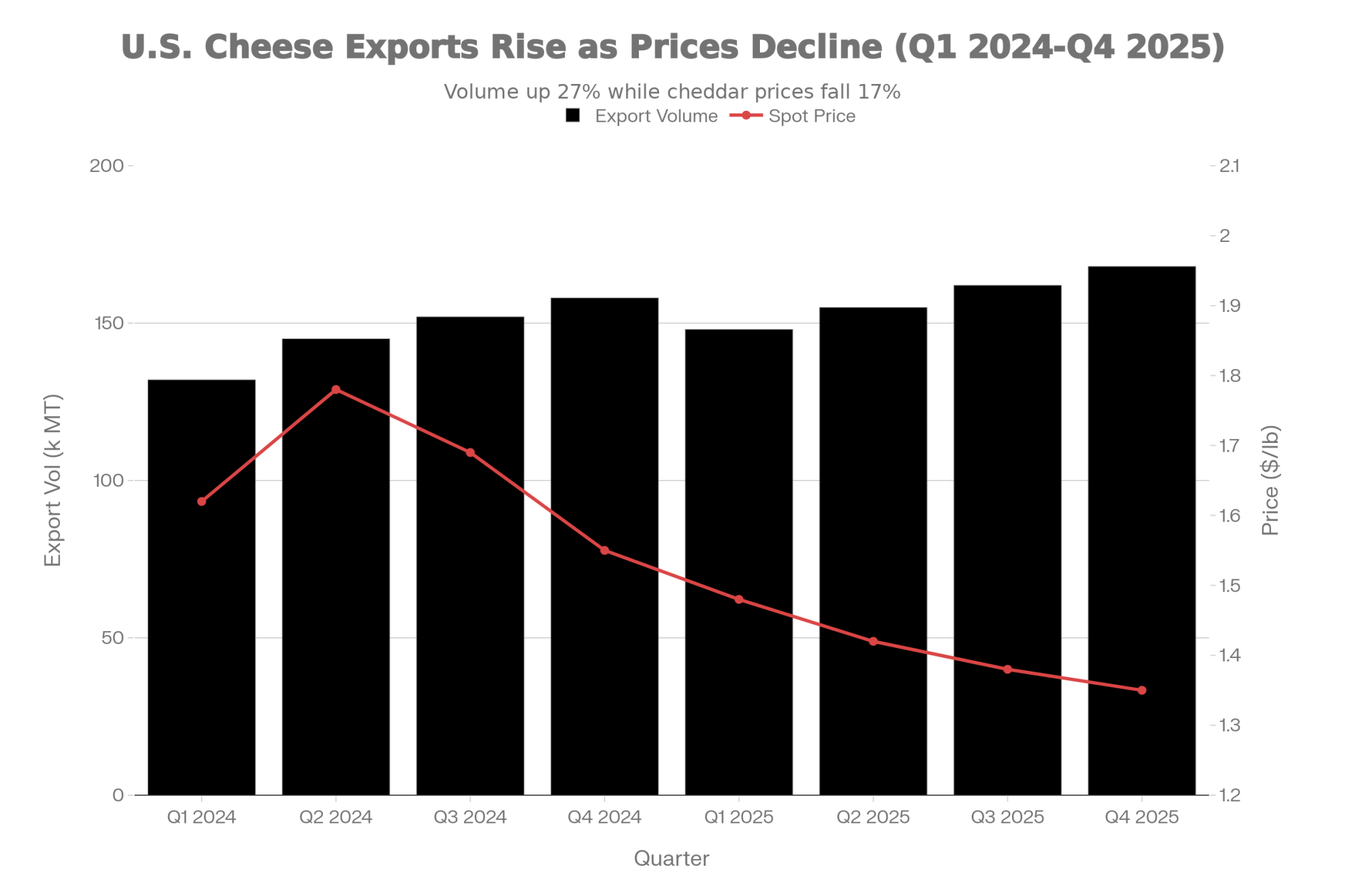

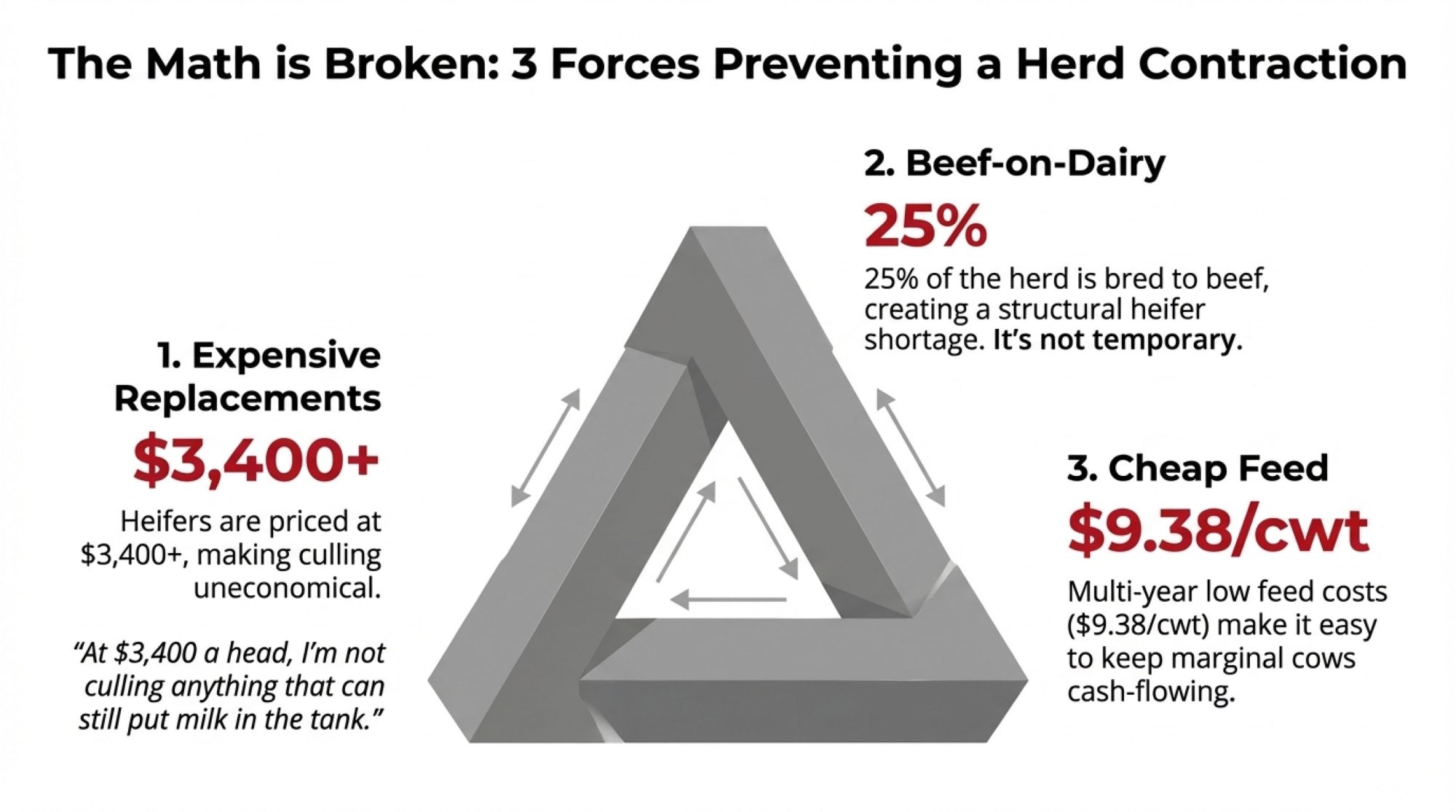

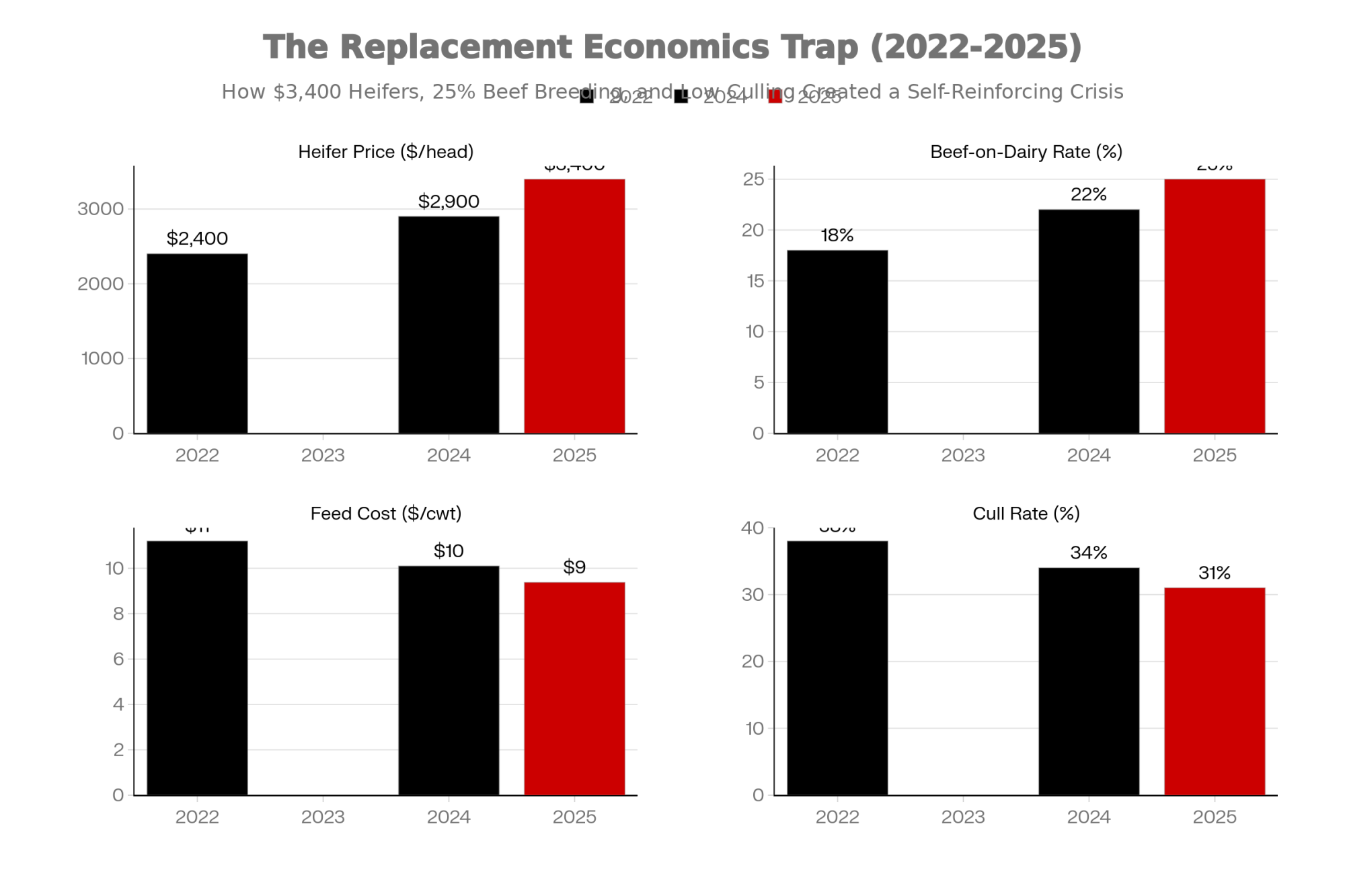

On the ground, I’ve noticed a pattern that fits that. Plants that bolt modern whey lines onto existing cheese operations often go through a bumpy “transition period”—membrane fouling, staffing issues, quality glitches. But once they settle in and run near design capacity, that whey-and-ingredients side often becomes one of the more attractive contributors to plant margins, especially when WPC‑80 and WPI exports are strong.

But there are some real “ifs” here:

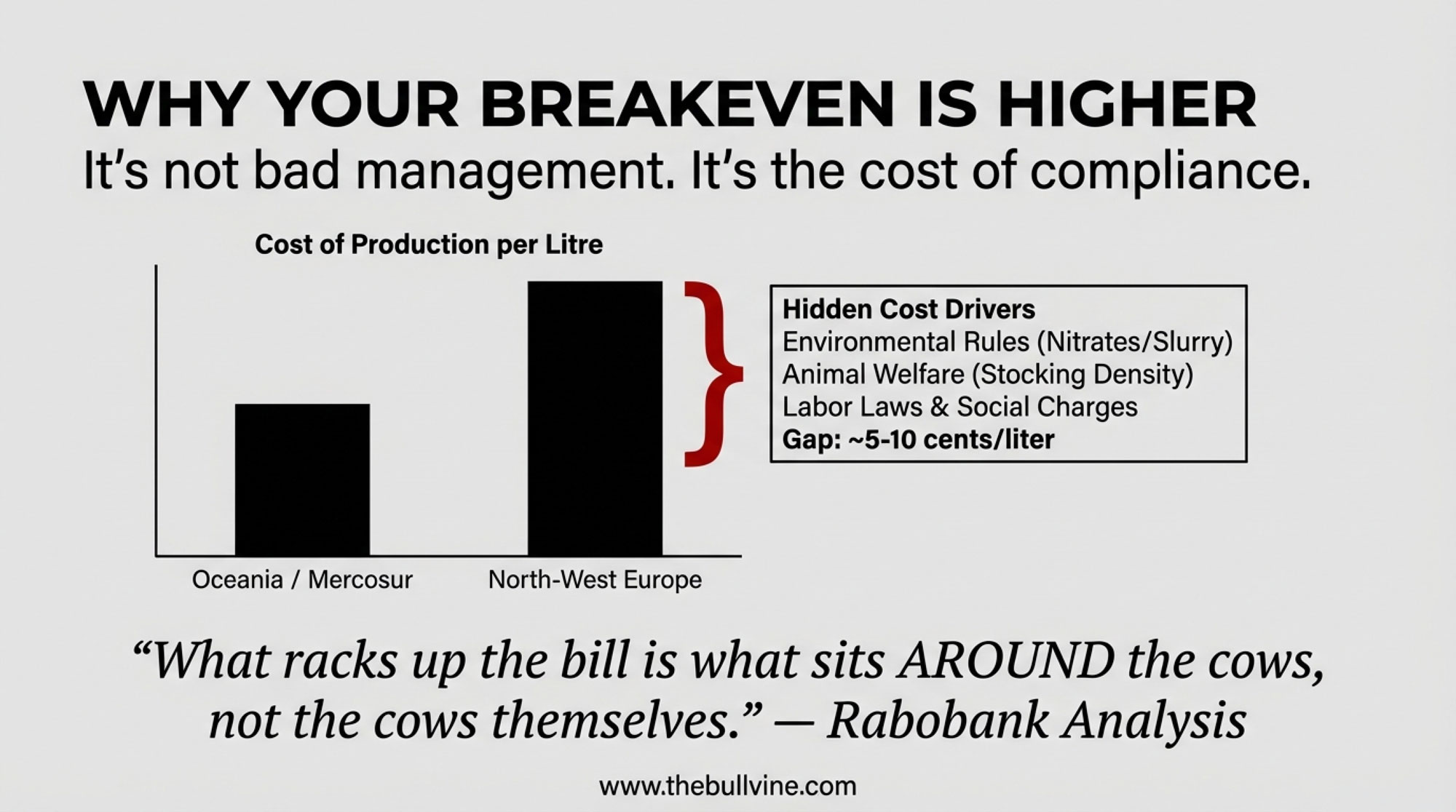

- If energy is expensive in your region, it can eat into those margins fast.

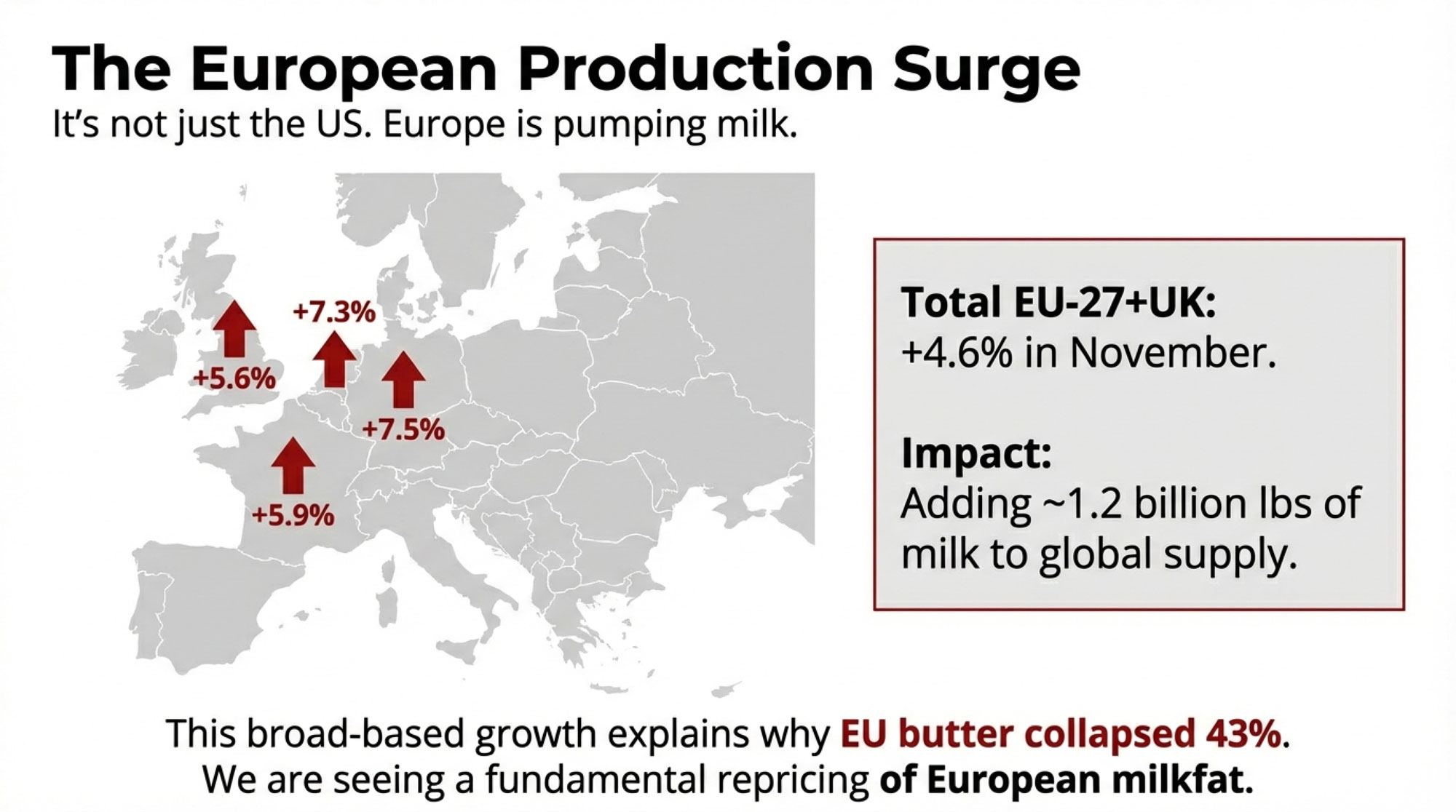

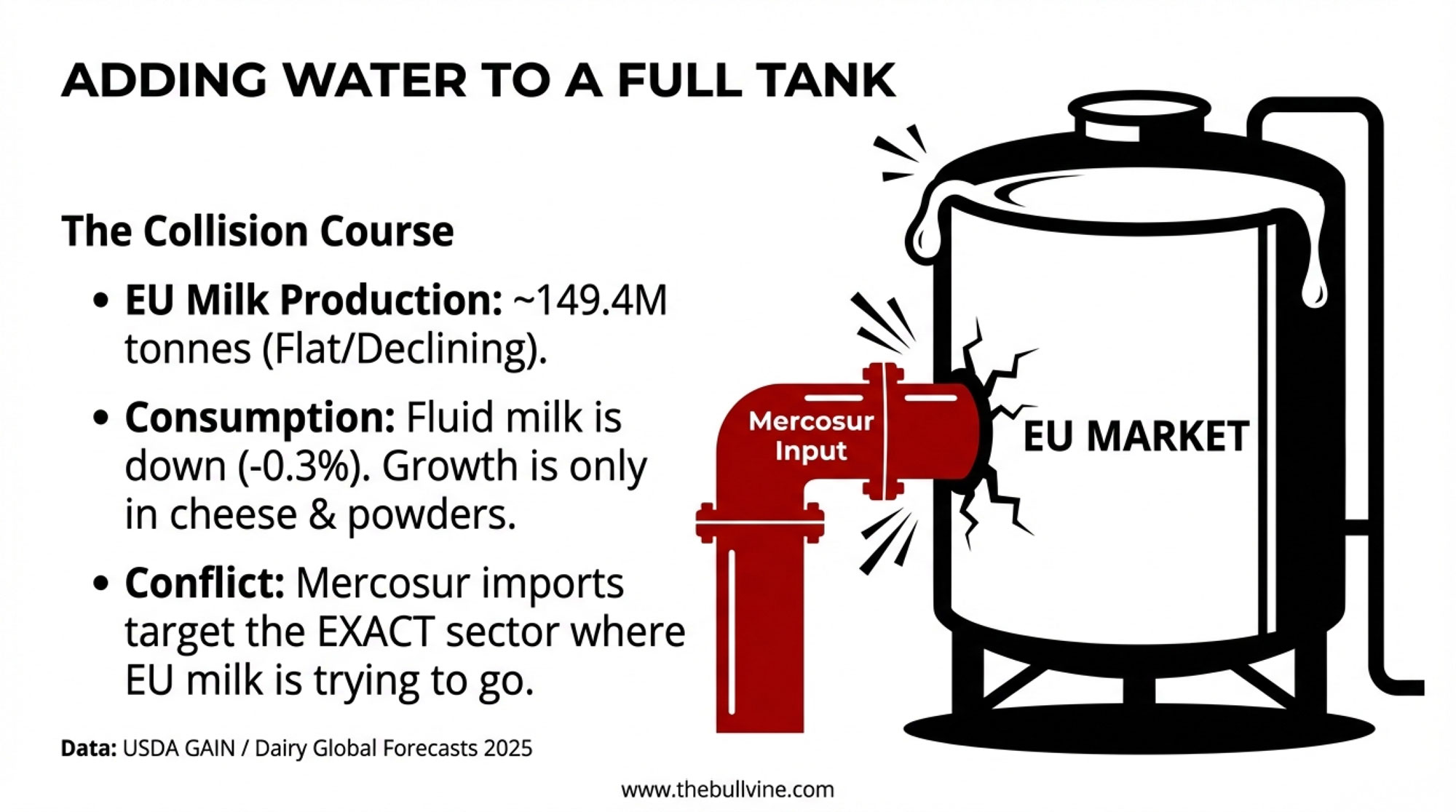

- If multiple plants in a region all add similar whey capacity at the same time, ingredient prices can soften just as everyone’s ramping up.

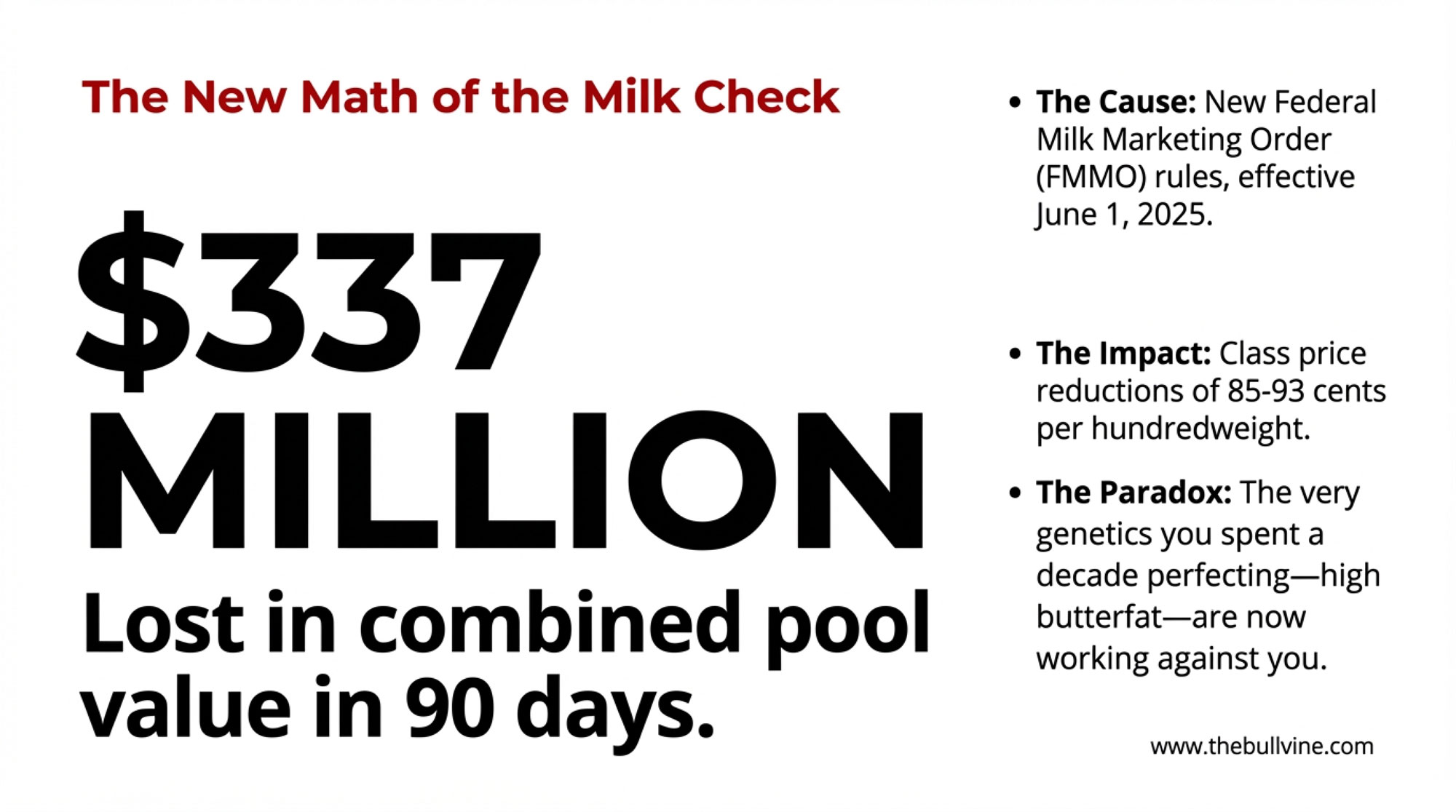

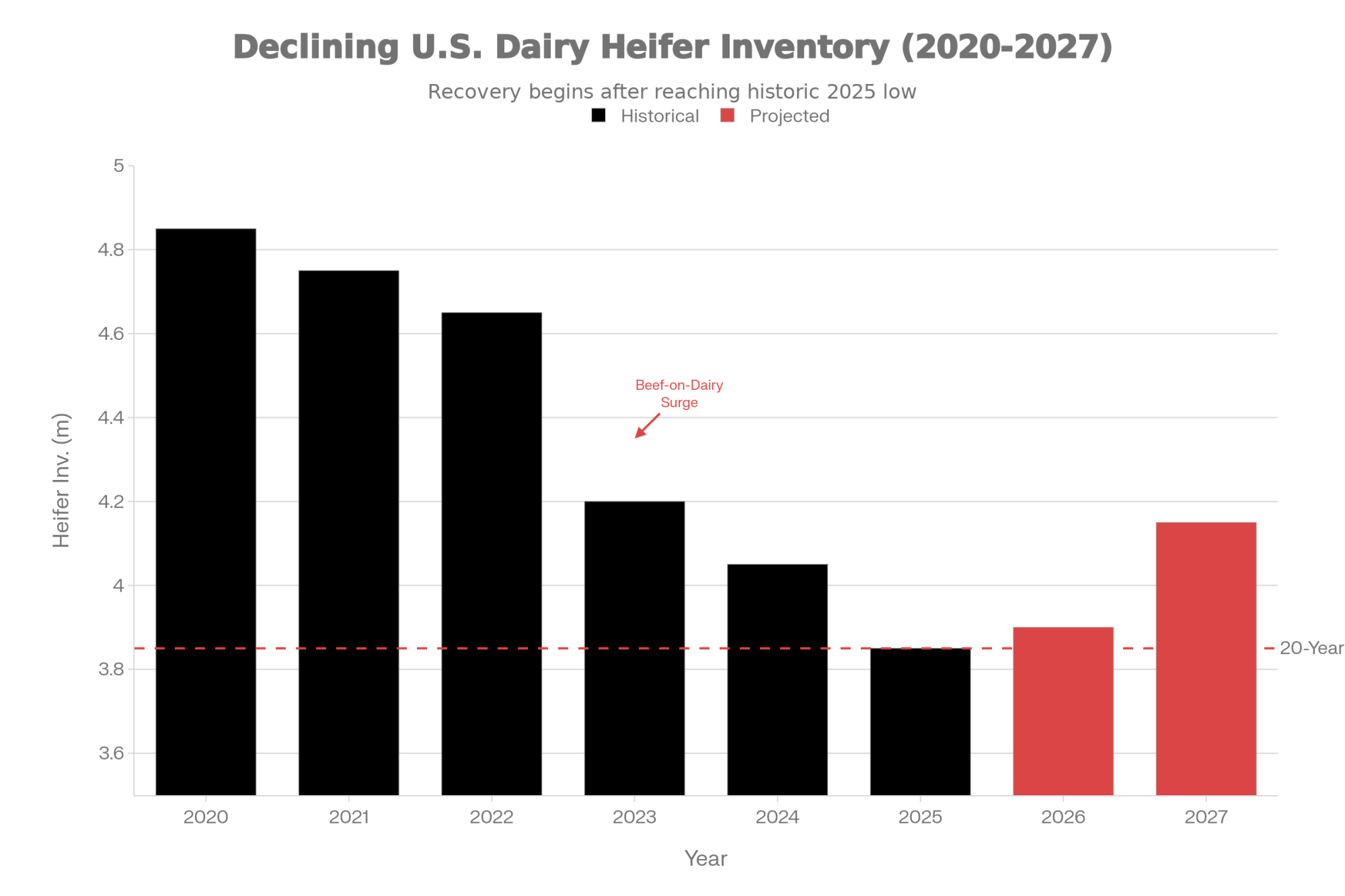

- If milk supply is flat or constrained by environmental rules, permits, or cow numbers, it’s harder to hit the utilization rates the original models assumed.

So yes, whey projects can pay back relatively quickly when they’re sized well, run well, and markets cooperate. But they’re not automatic winners. And even when they do pay off at the plant level, it’s still an open question how that success is shared between the co‑op’s books and your farm’s balance sheet.

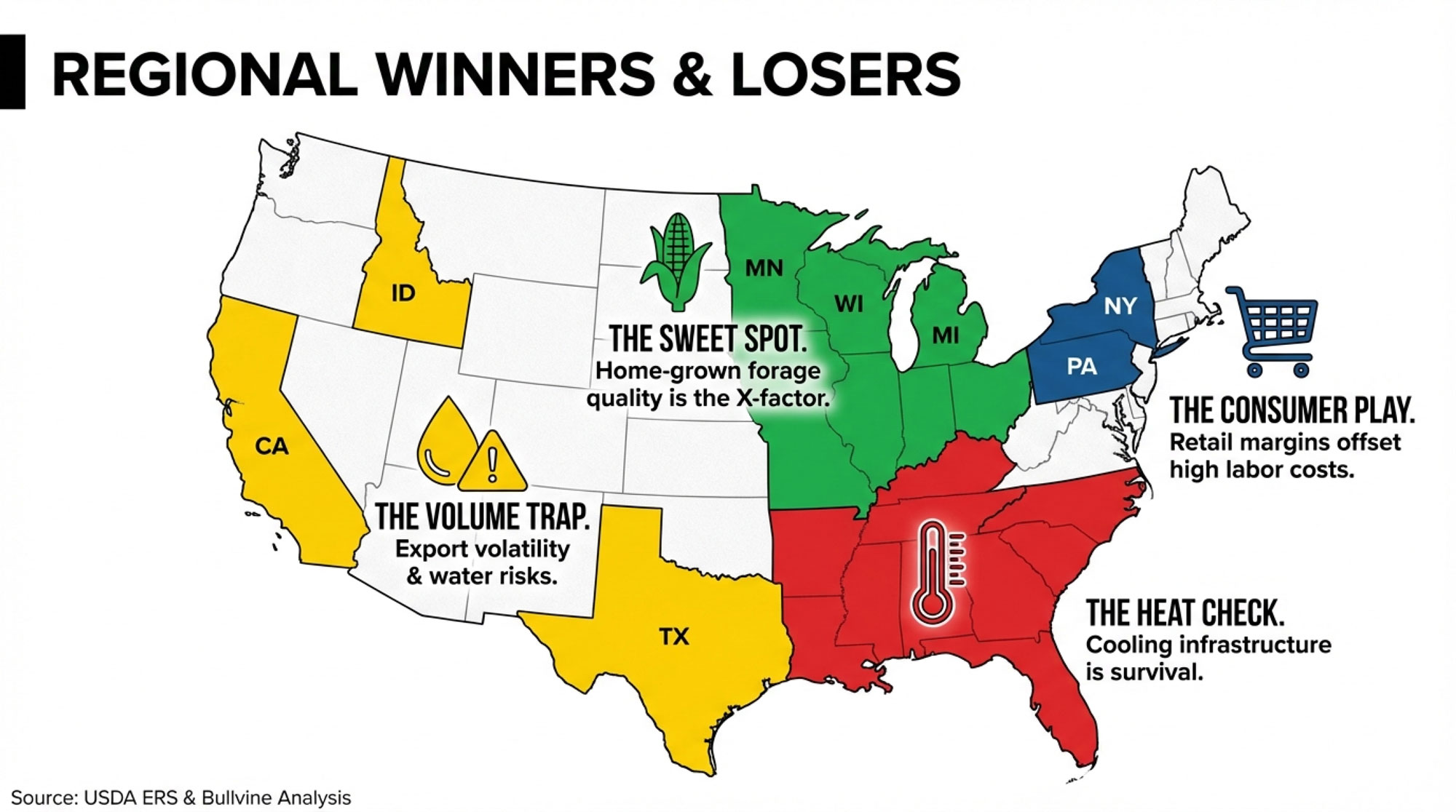

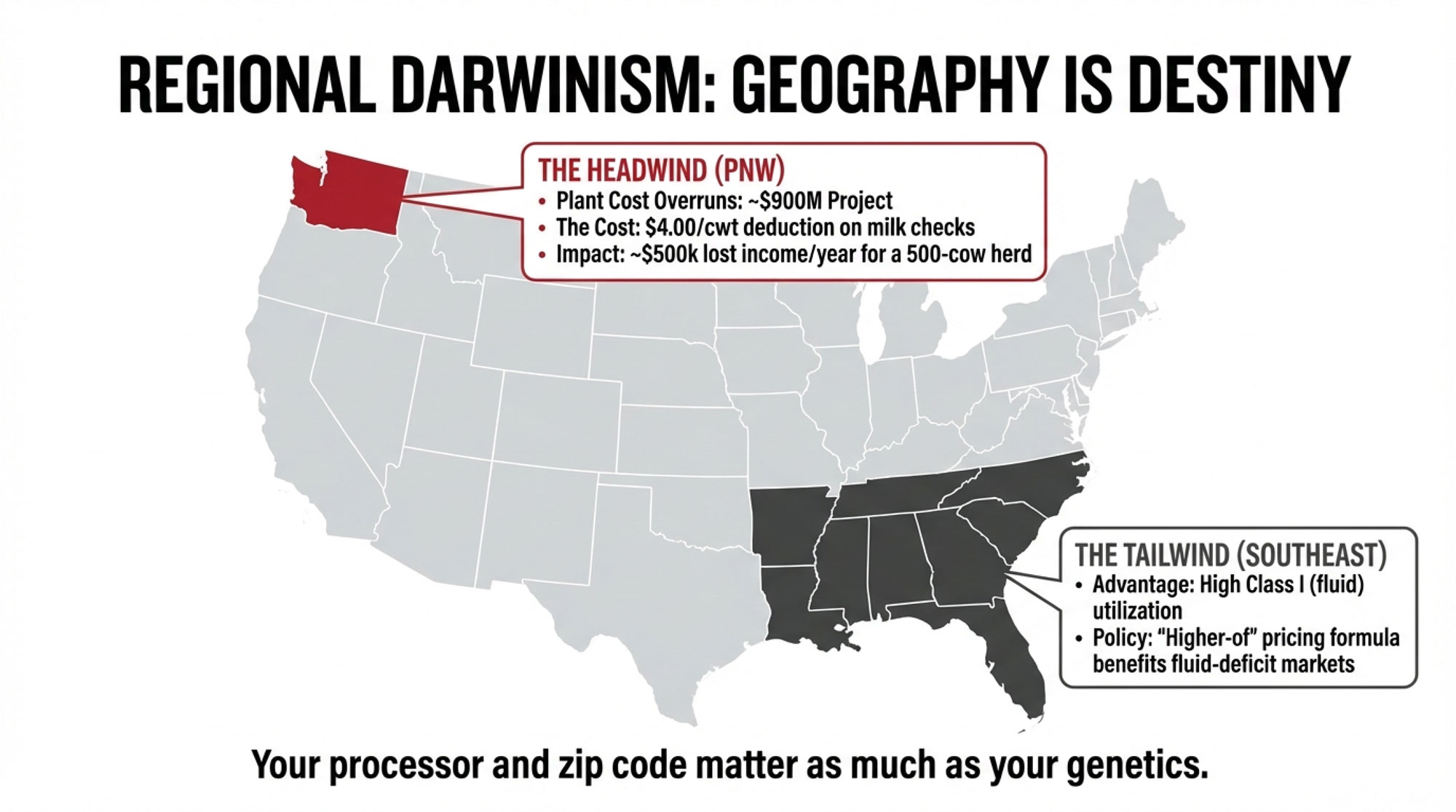

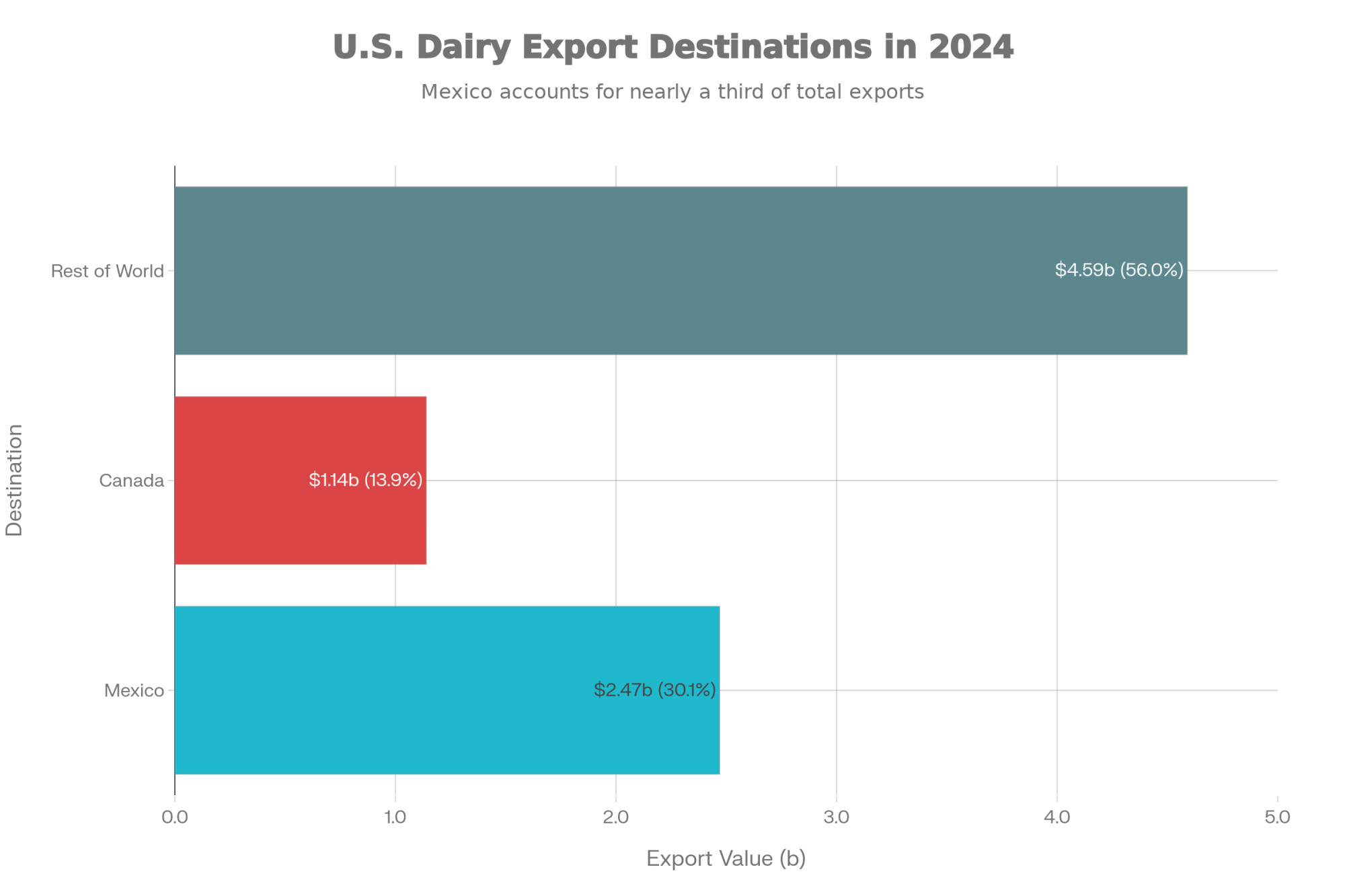

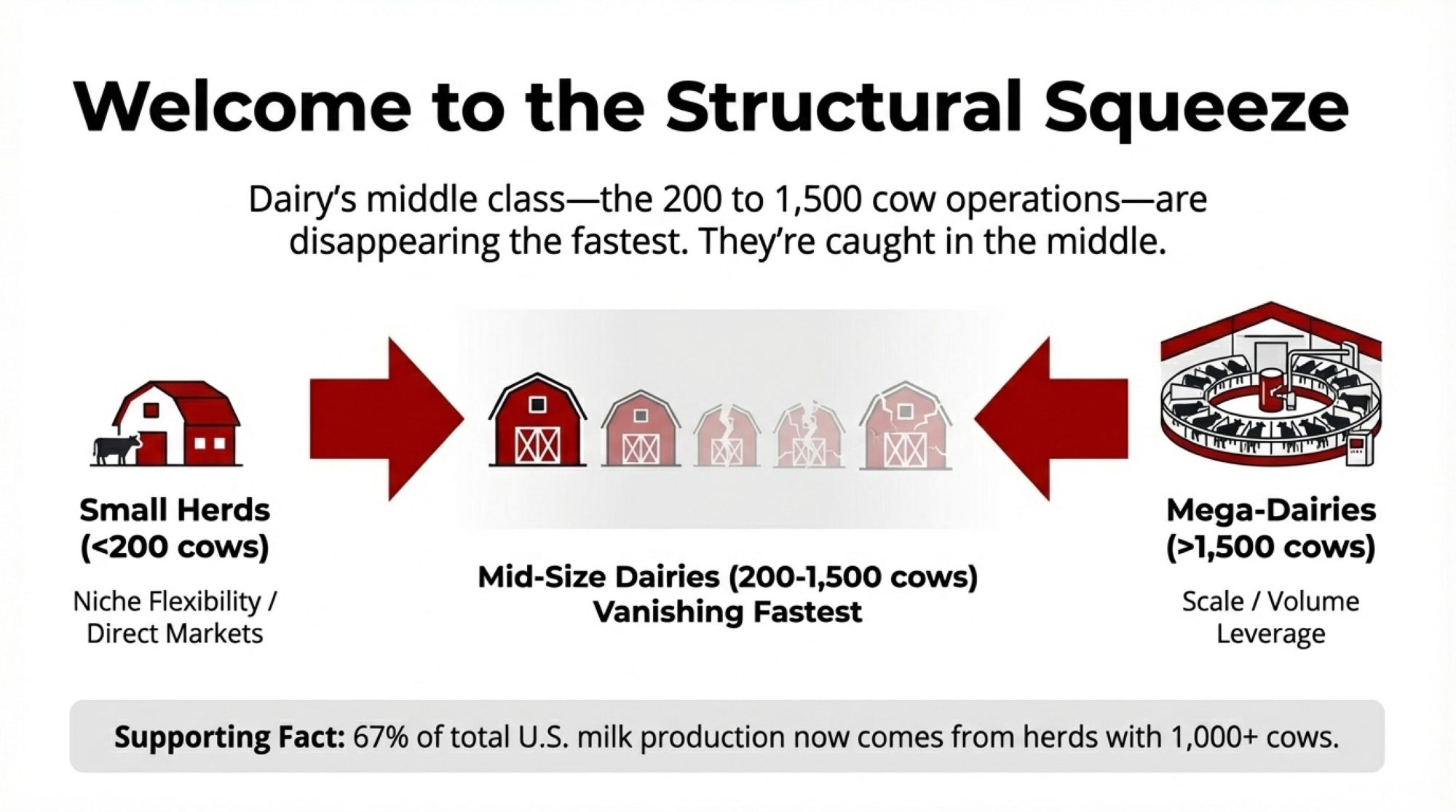

Where You Sit Depends on Who You Ship To

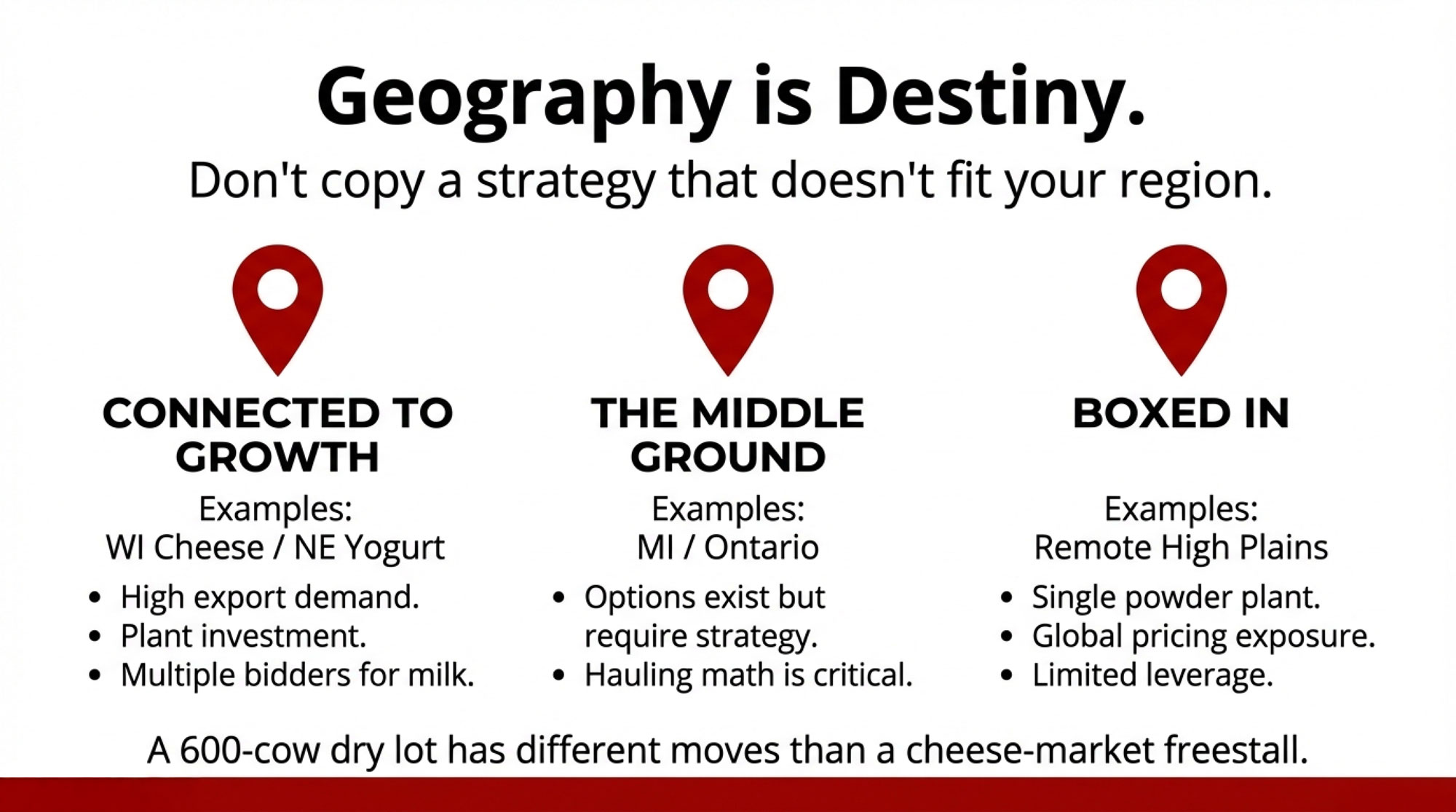

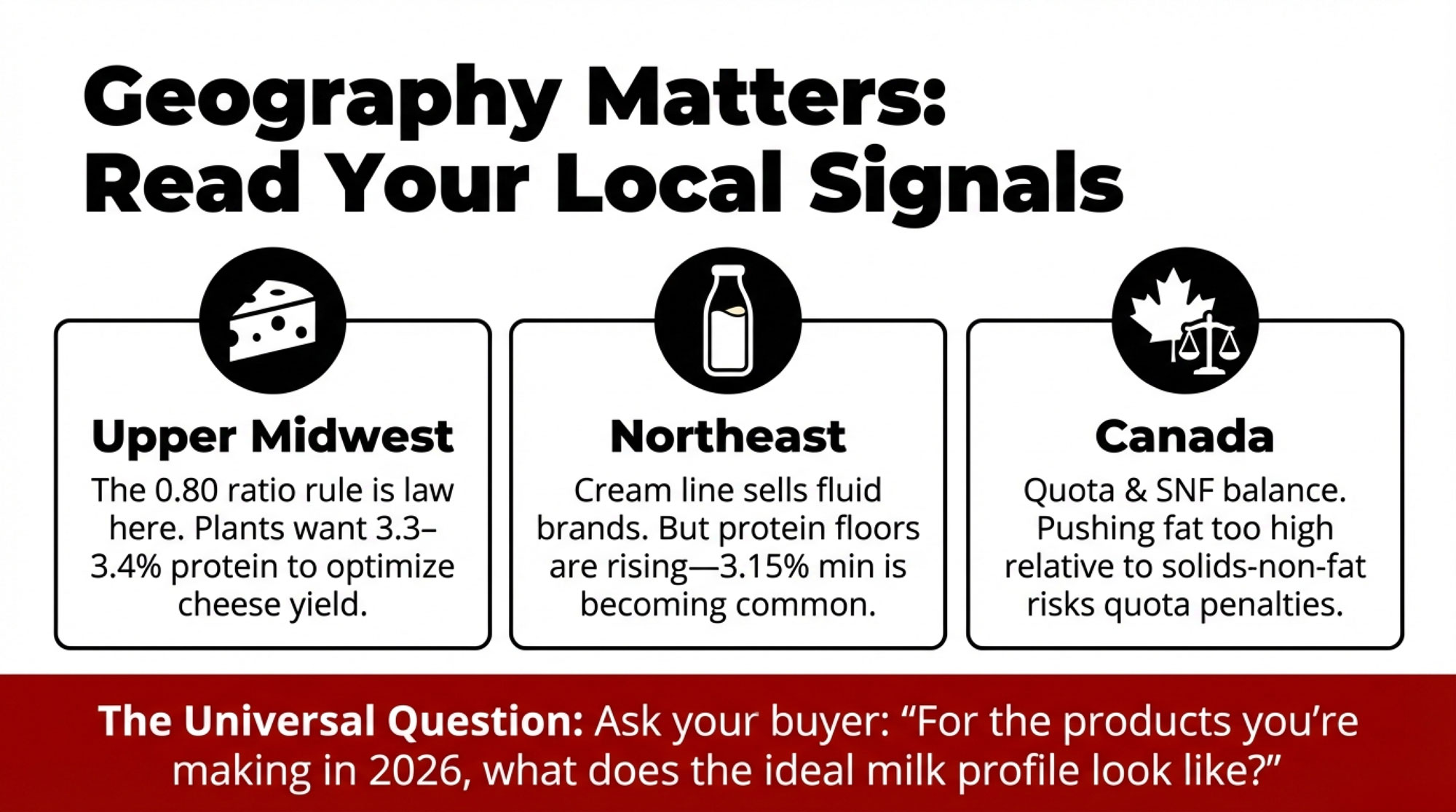

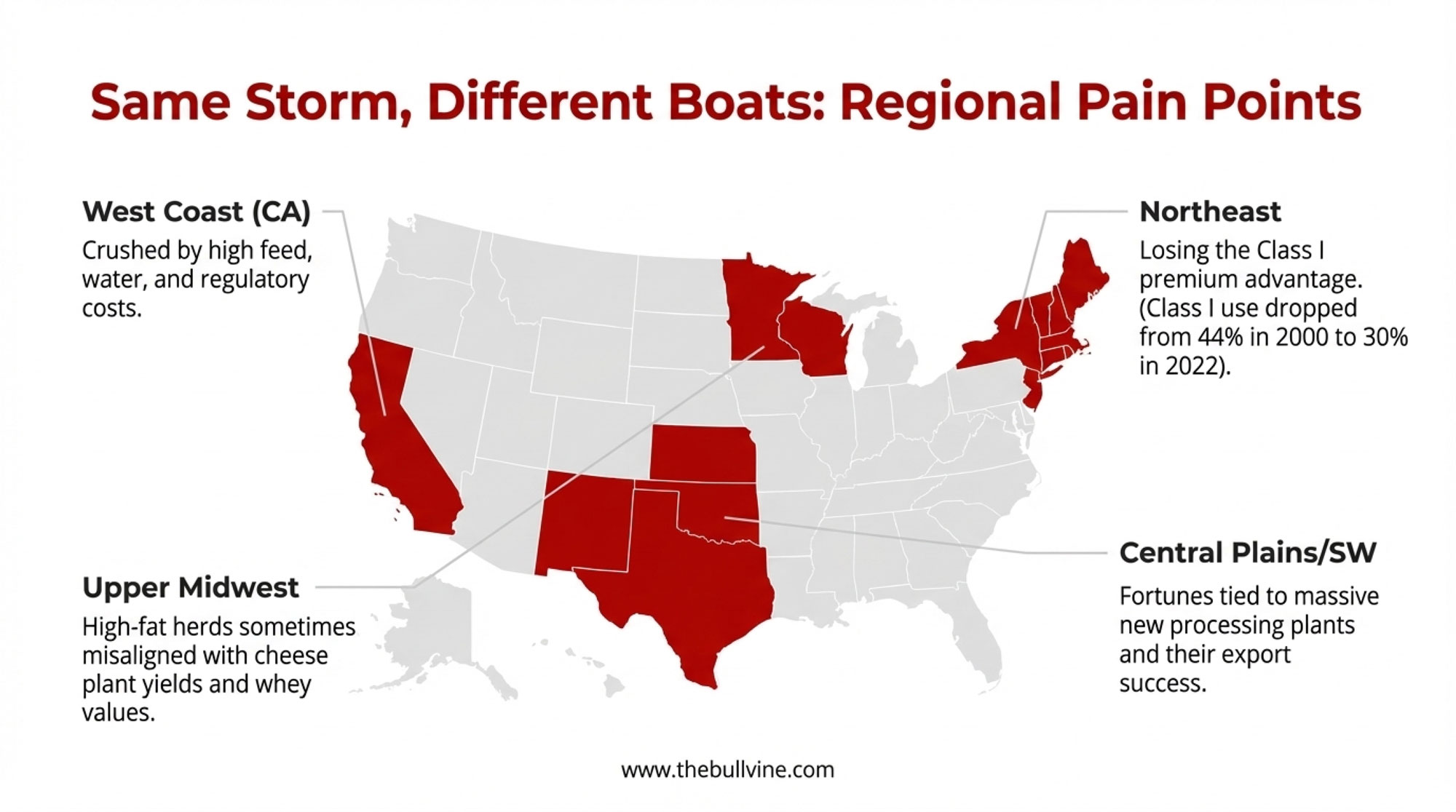

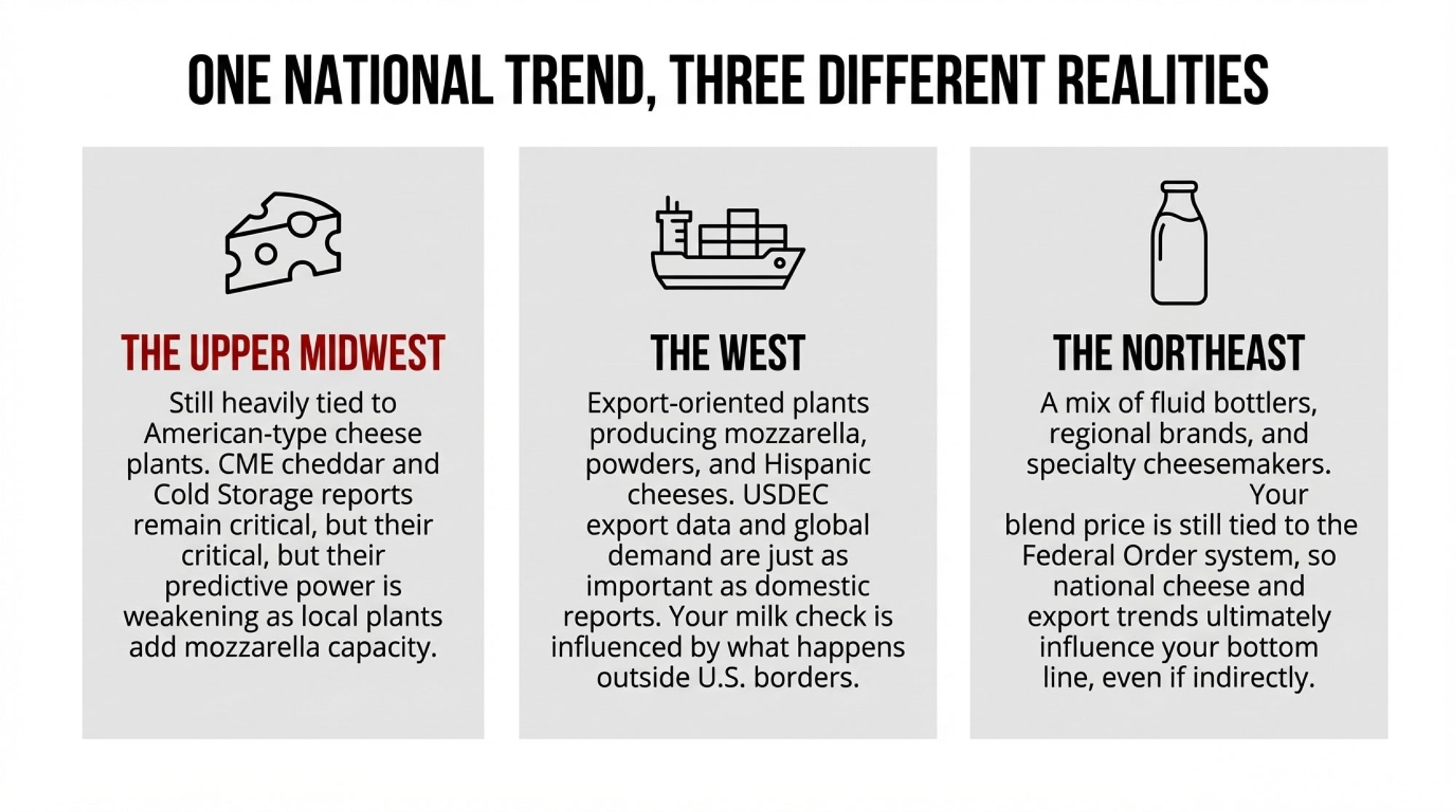

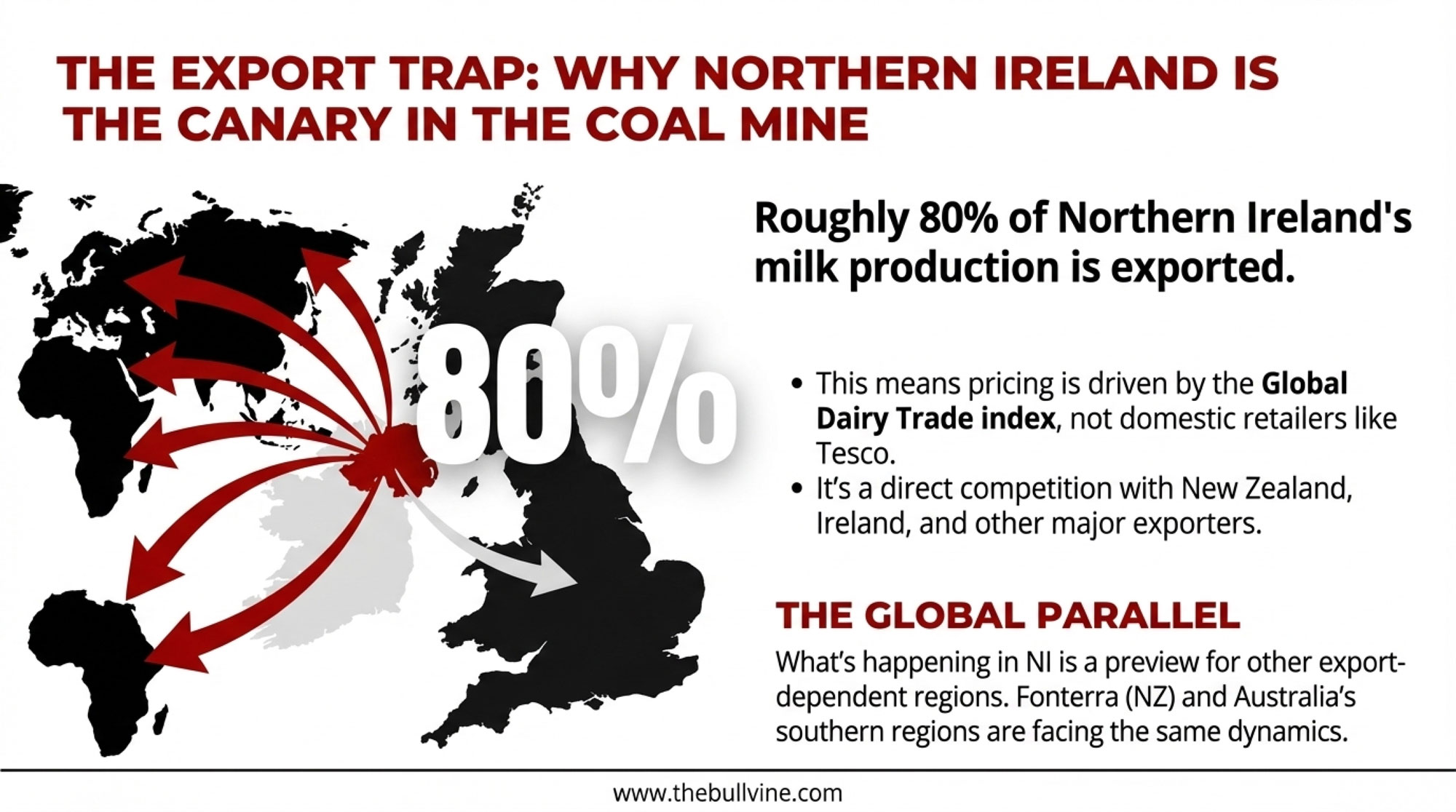

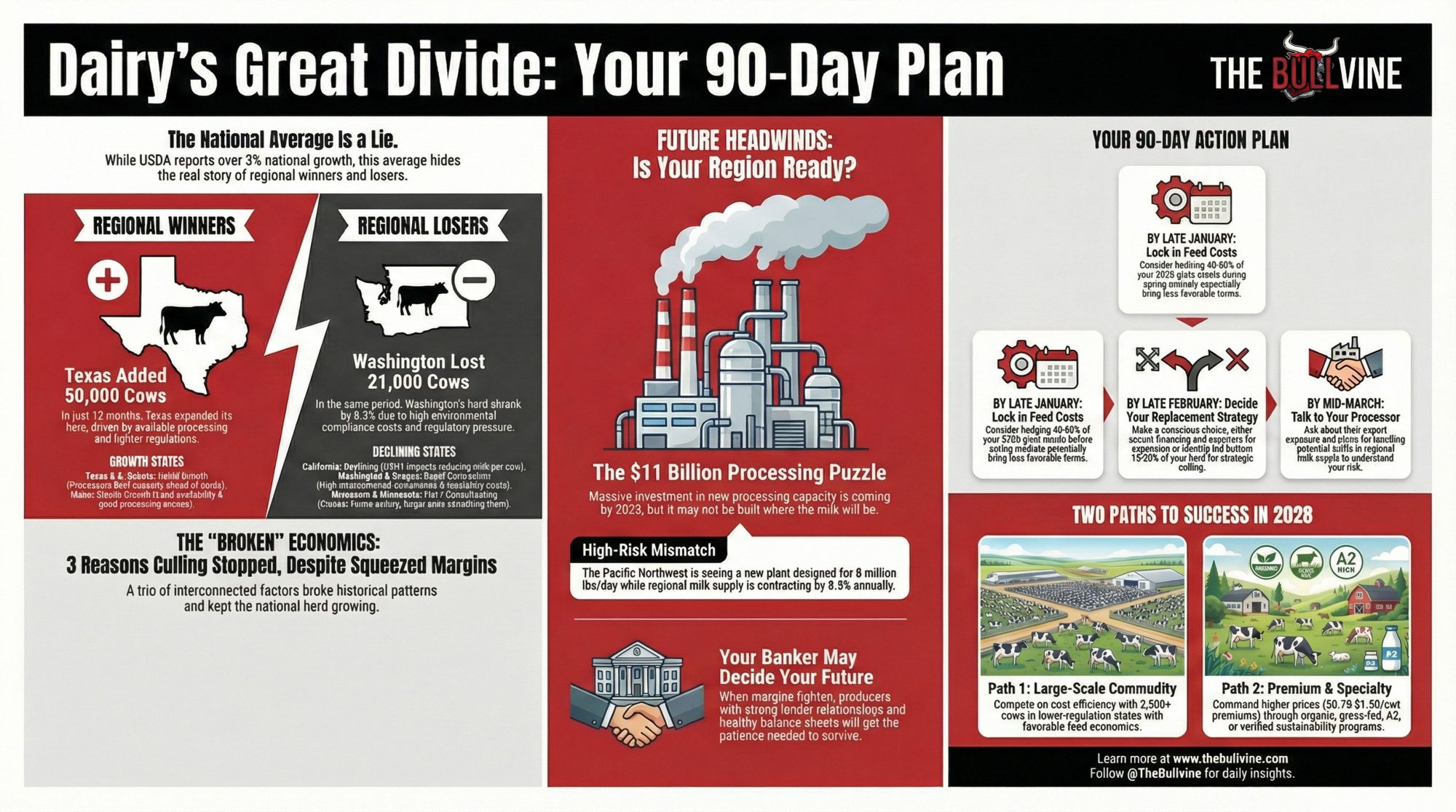

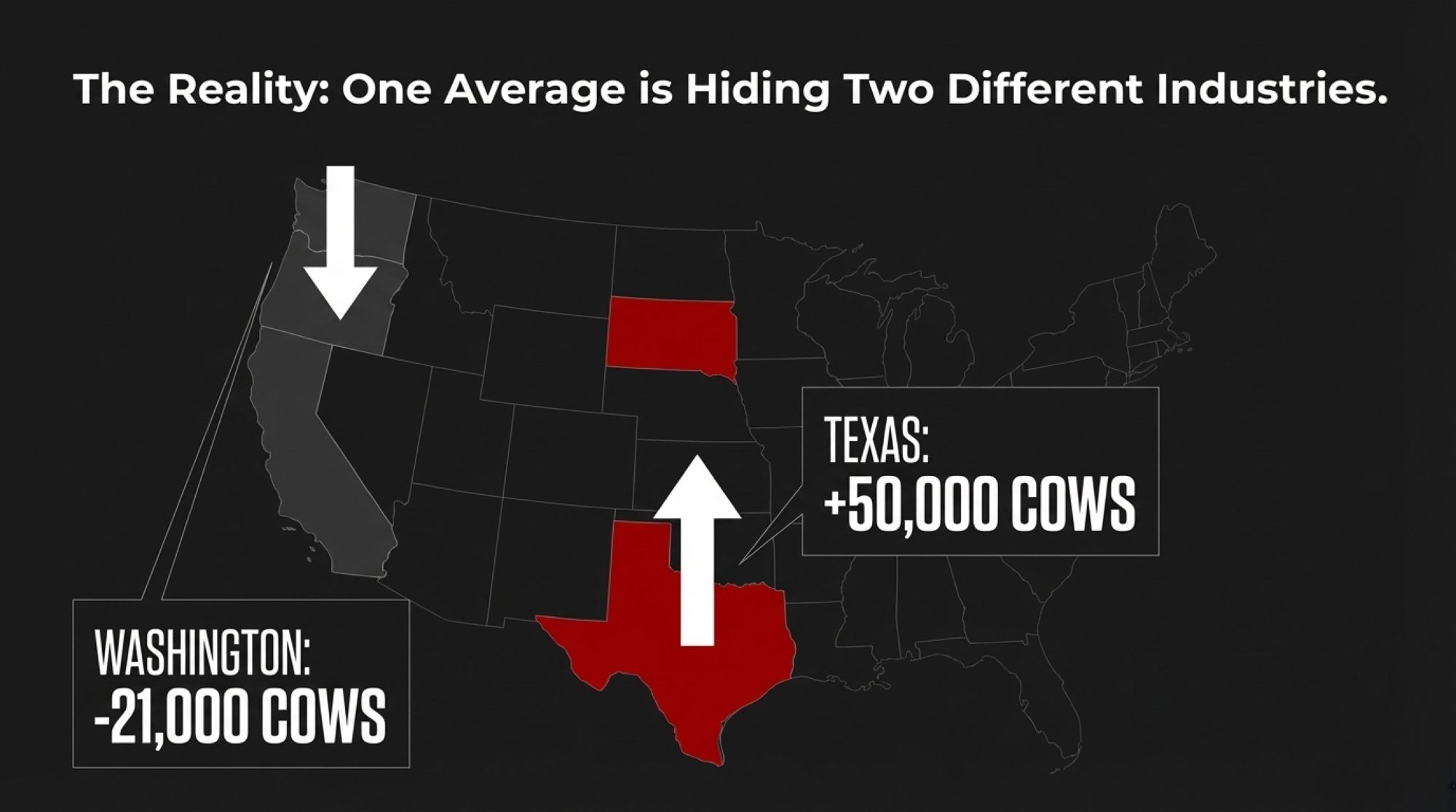

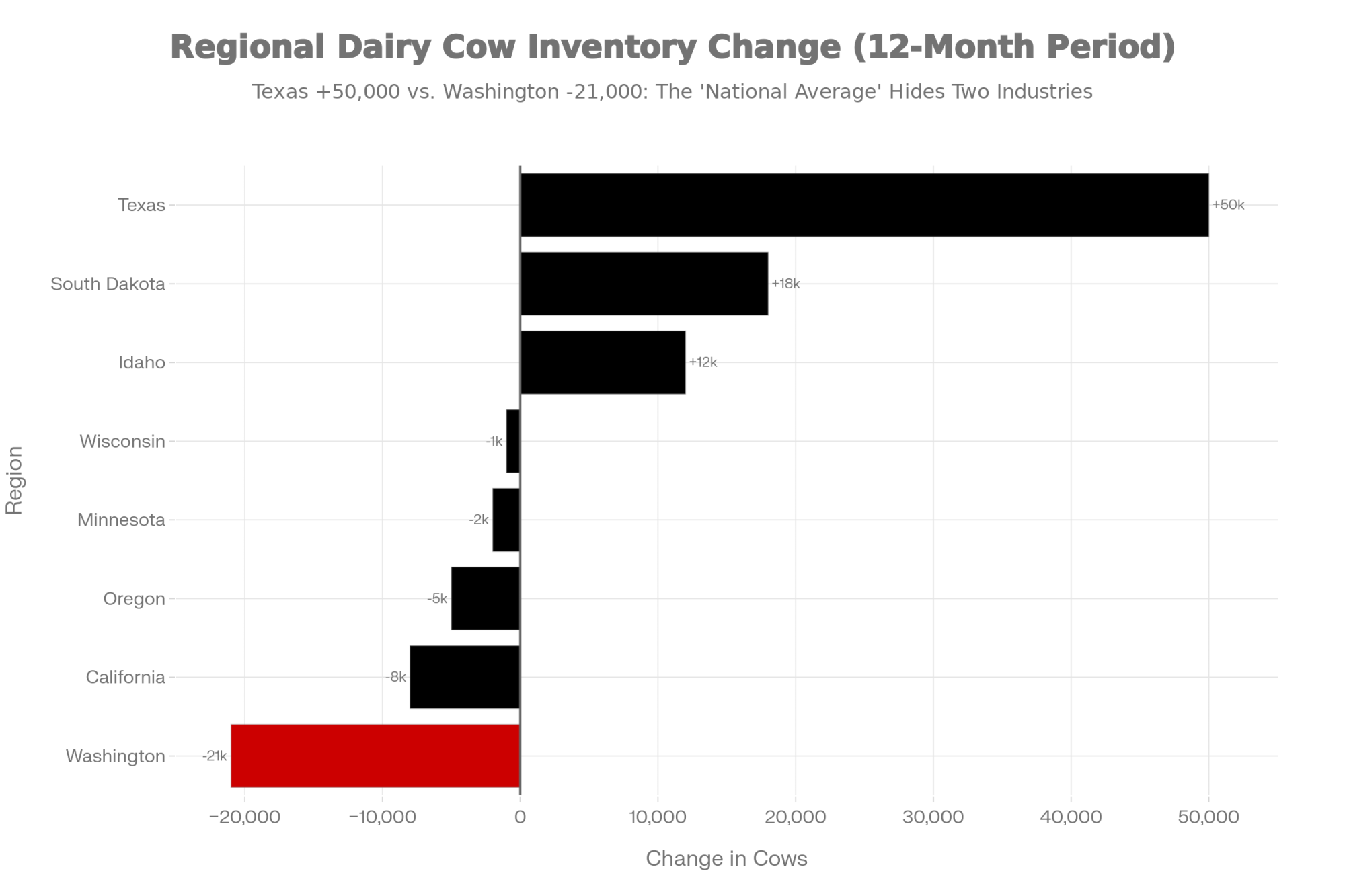

What farmers are finding is that their place in this whey story depends a lot on who they ship to and which region they’re in.

Ingredient‑heavy co‑ops and processors

In Wisconsin, Idaho, parts of Michigan and South Dakota, and now in the Texas Panhandle and eastern New Mexico, quite a few producers ship to co‑ops and private processors running big cheese and whey complexes. Those plants:

- Turn a lot of milk into cheese.

- Run modern whey lines making WPC‑80, WPI, and sometimes more specialized ingredients.

- Sell into sports, clinical, and active‑nutrition markets that are still growing.

CoBank’s outlook suggests U.S. cheese capacity will grow by around 10% over a five‑year period, with whey processing expanding alongside it. That means farms shipping into these systems—from the Upper Midwest to the High Plains—are sitting right on top of where much of the new ingredient value is being created.

In those regions, the coffee‑shop conversation often sounds like, “I’m glad our co‑op is serious about ingredients and not stuck in 1985. I just wish I could see where that whey plant shows up in my patronage and equity.”

If that’s you, some smart questions include:

- Does our co‑op report whey and ingredients as their own division with at least basic volume, revenue, and margin information?

- In strong whey years, do we actually see that reflected in cash patronage or faster equity revolvement, or does most of the gain show up as lower debt and a stronger balance sheet?

- Once the project has essentially hit the payback window we were shown, is there a plan to adjust patronage or redemption policies so more of the ongoing margin flows back to members?

More commodity‑ and fluid‑focused systems

In parts of the Northeast and Southeast, and in some smaller regional co‑ops, the product line is still heavily weighted toward fluid milk, butter, and nonfat dry milk. Whey may be in the mix as a commodity powder, but it’s not a big branded-ingredient business.

For those farms, the whey story sounds different:

- Some co‑ops simply don’t have the scale or balance sheet to build and run their own WPC/WPI plants.

- They may sell whey as basic dry whey, or explore joint ventures and toll-processing arrangements with ingredient specialists.

- The strategic question becomes: do we move up the whey value chain, or do we double down on being a lean, low‑cost commodity producer?

In those systems, it’s worth watching:

- Whether your co‑op is actively exploring partnerships that let members participate in some ingredient value without carrying all the risk.

- Whether being a “commodity‑lean” co‑op is a conscious strategy with clear economics, or just the default because big ingredient projects feel too risky.

Quota systems, like in Canada

Under Canada’s supply‑managed system, milk is produced under quota, and national and provincial boards determine farm‑gate prices. That changes how the whey value shows up.

Canadian processors still capture value from cheese and whey ingredients, especially in export and specialty product niches. But farm revenue is much less tied to spot commodity swings and much more to regulated prices and pooled returns. In that context, whey value tends to affect processor health, competition, and long‑term investment capacity more than you see in day‑to‑day cheques.

So for many Canadian producers, the whey question sounds more like:

- Are processors capturing enough ingredient value to stay financially healthy and keep investing in plants and products?

- Is competition between processors strong enough to reward farms that invest in components, cow comfort, and better housing—whether that’s freestalls, tie‑stalls, or dry lot systems?

In places like New Zealand and parts of Europe, the picture is further shaped by emissions rules, subsidy structures, and trade agreements. But the core issue is the same: who gets the whey margin, and does the farm see enough of it to justify continuing to invest?

Questions That Actually Move the Needle in Co‑op Meetings

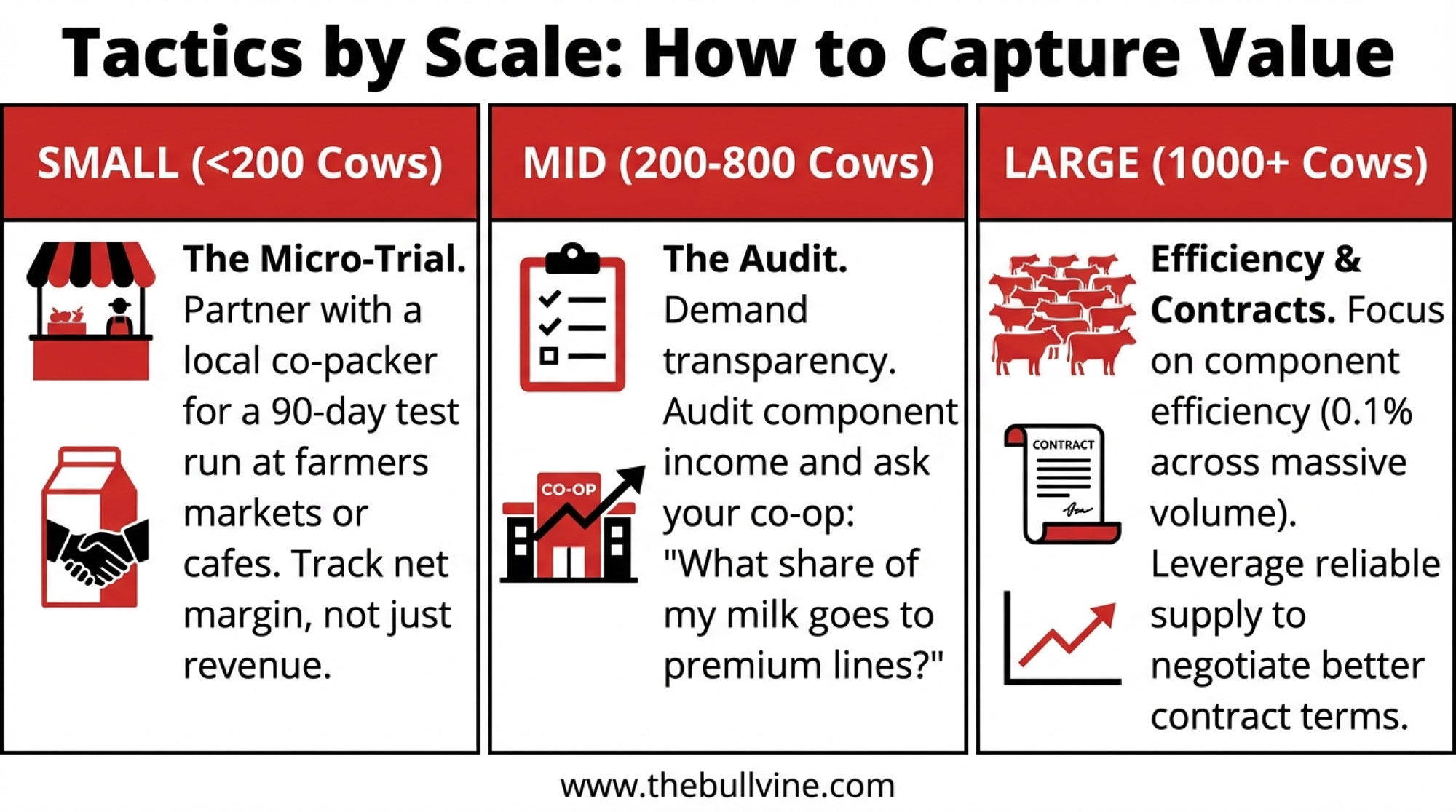

So what do you do with all this when you’re one member in a district meeting, trying to decide whether to stand up?

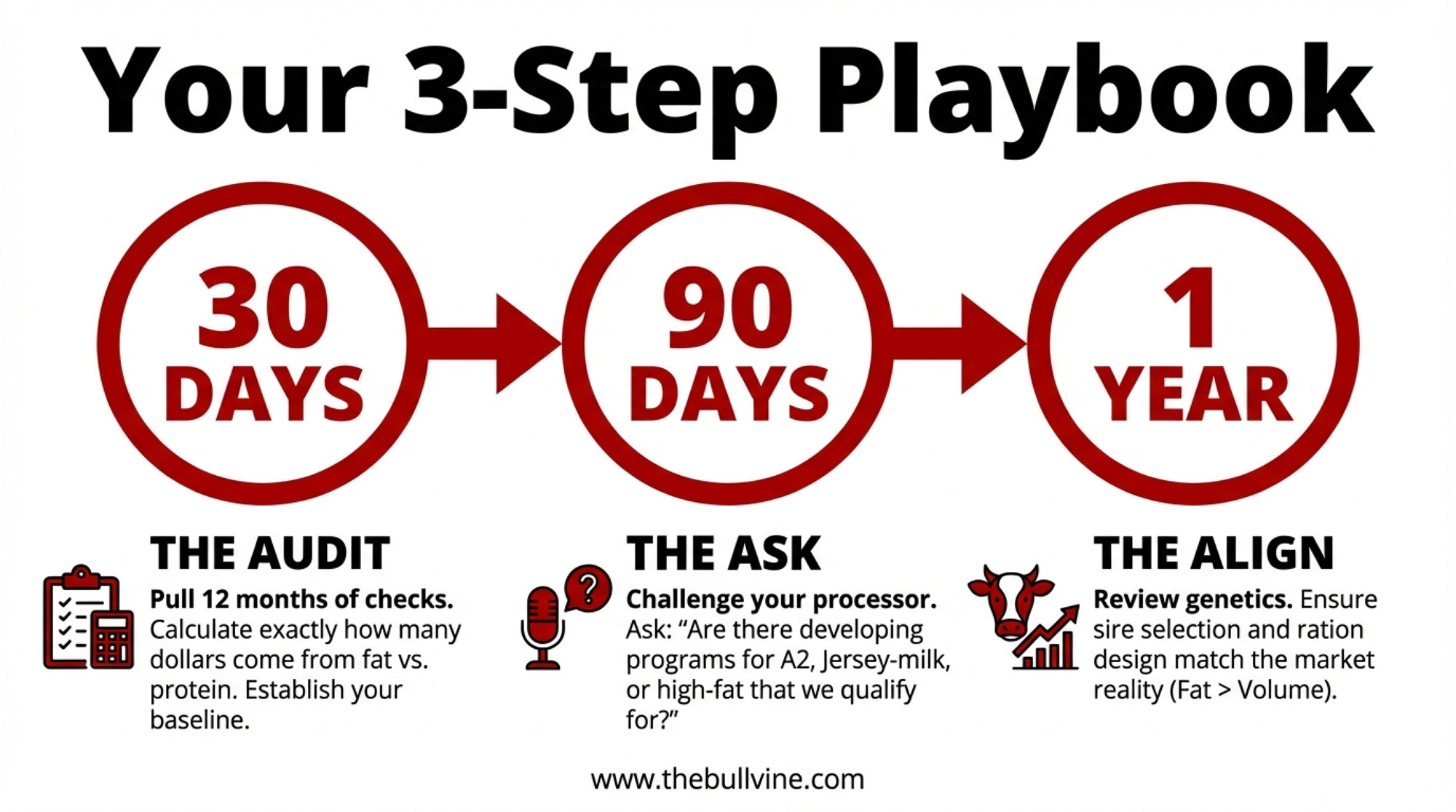

What I’ve found is that one or two well‑aimed, respectful questions will do more than a long speech. Here are three that line up well with what co‑op finance specialists and extension folks suggest.

| Question to Ask | What It Reveals | Weak Answer (Red Flag) | Strong Answer (Green Light) | Your Follow-Up Move |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “How is this whey project being financed?” | Mix of debt vs. member equity; equity leverage risk | “We’re financing it the normal way” or vague numbers | “60% bank debt, 40% member equity retained over 3 years; target debt-to-equity 50:50 post-payback” | Ask: “When equity is fully retired, does the patronage policy change?” |

| “Will whey and ingredients be reported as their own division?” | Transparency; whether co-op sees whey as core profit driver or afterthought | “It’s in the consolidated number” or “We don’t break that out” | “Yes—volume in tonnes, revenue, EBITDA margin, and narrative explaining performance vs. plan, starting next annual report” | Follow-up: “What was last year’s volume and margin?” (tests if they have real data) |

| “What’s our patronage approach for higher-margin businesses?” | Whether co-op evolves policies as projects mature; whether members benefit from success | “We have a standard patronage policy; everybody gets the same” | “We’re targeting 30% cash payout on whey division within 2 years of payback; board will revisit if equity targets are hit” | Challenge: “Show me in writing how that ties to whey margin, not just total co-op earnings” |

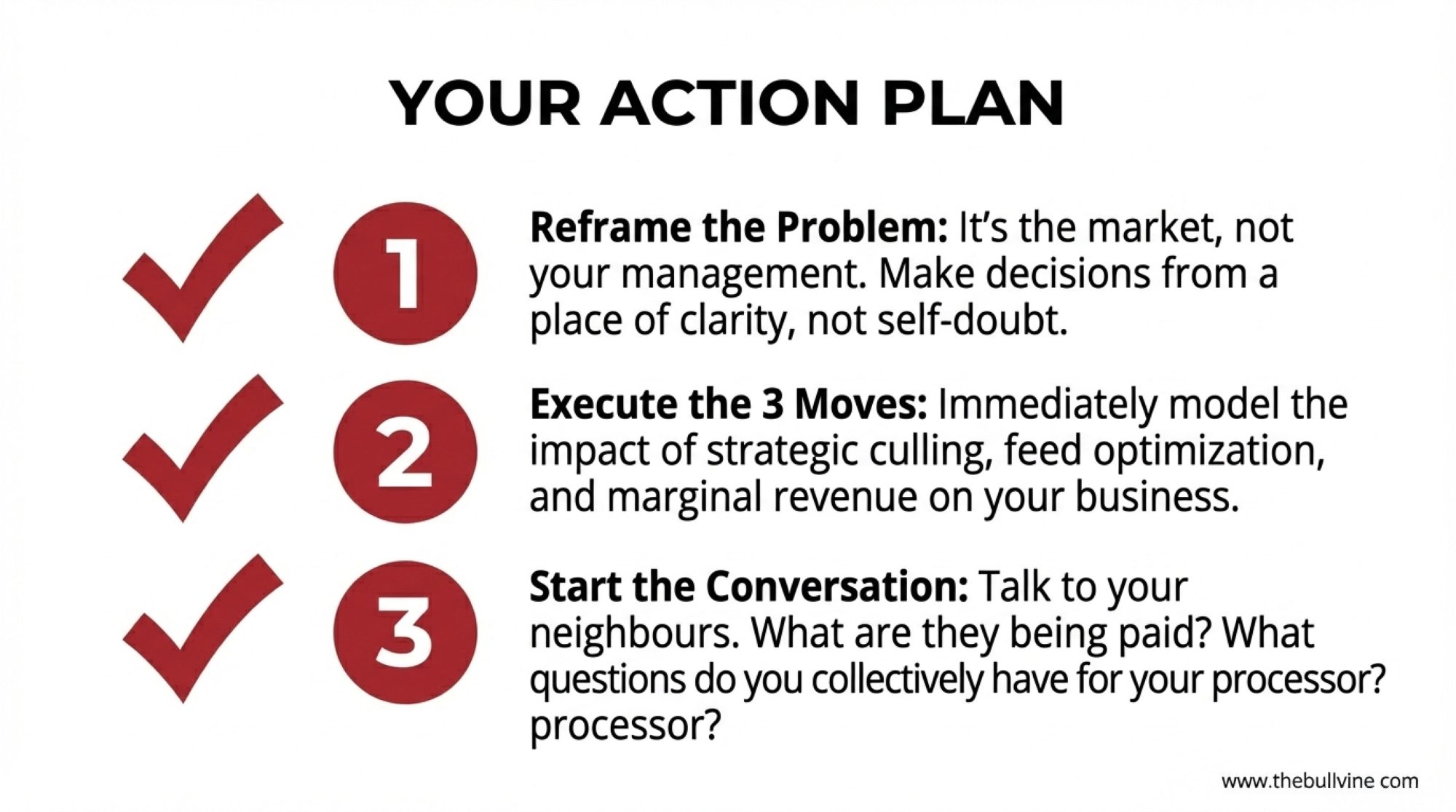

1. “How is this whey project being financed?”

Instead of “this feels risky,” you might ask:

- Roughly what share of the capital is funded with debt from banks or bond investors?

- How much is coming from retained member equity that’s already on the books?

- Are there any new per‑unit retains or special capital assessments tied specifically to this project?

- Once the plant is online, what equity‑to‑debt ratio is the board aiming for?

OSU Extension’s co‑op work stresses that you can’t really understand risk and return without knowing how much is coming from lenders versus members. If a project leans heavily on member equity, it’s natural to ask what the plan is for that equity to work back in your favour over time.

2. “Will whey and ingredients be reported as their own business?”

More producers are starting to ask for segment reporting, not just a single, blended profit number.

That might look like:

- A line in the annual report for “whey and proteins” or “ingredients.”

- Simple, high‑level metrics: tonnes sold (or equivalent), revenue, and a margin range.

- A short narrative each year explaining whether that division performed above or below expectations and why.

Studies of European dairy co‑ops suggest that groups with clearer divisional reporting and stronger member engagement tend to maintain trust and ride out downturns more smoothly. When whey is clearly reported, members can see whether the business is working as promised.

And I’ll say this as gently as possible: if your co‑op consistently refuses to share even basic performance information about a big new division like whey and ingredients, that’s telling you something about how it views member‑owners.

3. “What’s our patronage approach for higher‑margin businesses like whey?”

Lots of co‑op patronage policies were written in a world dominated by commodity milk, butter, and powder. Higher‑margin, capital‑intensive businesses like whey can behave very differently.

Good questions here include:

- In years when whey and ingredients do especially well, is there room—within our financial targets—to increase the cash portion of patronage tied to that division?

- Once the project has effectively paid for itself, has the board considered accelerating equity revolvement or increasing the cash share from that business, as long as equity and debt ratios stay healthy?

- Could the board walk through a simple, realistic example of how a strong whey year would show up for a 200‑cow or 400‑cow member, both in cash and in equity?

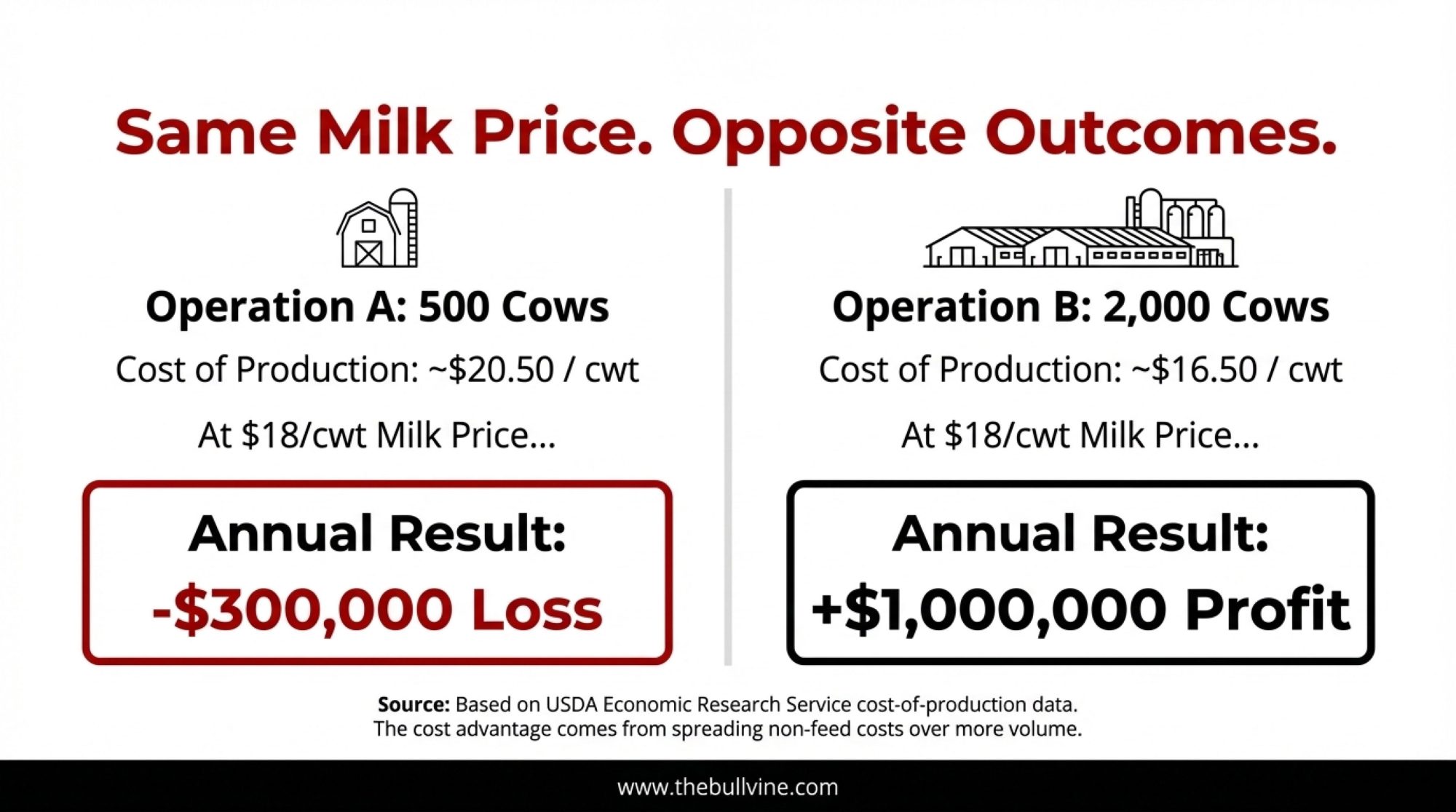

| Farm Size | Annual Milk Volume | Scenario A: Co-op Retains 100% (Zero Cash) | Scenario B: Co-op Shares 50% of Whey Margin as Cash Patronage (+15¢/cwt) | Scenario B Impact: Dollars Per Cow Per Year | Farm-Level Decision Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-Cow Herd | 27,000 cwt/yr | $0 additional cash | +$4,050 annual cash | +$40.50/cow | Worth 3–4 parlour upgrades or a genetics consultant annual fee |

| 250-Cow Herd | 67,500 cwt/yr | $0 additional cash | +$10,125 annual cash | +$40.50/cow | Worth deferring a major repair vs. doing it now; offsets half a veterinary rotation |

| 500-Cow Herd | 135,000 cwt/yr | $0 additional cash | +$20,250 annual cash | +$40.50/cow | Worth a part-time employee’s wages for one season; meaningful debt service relief |

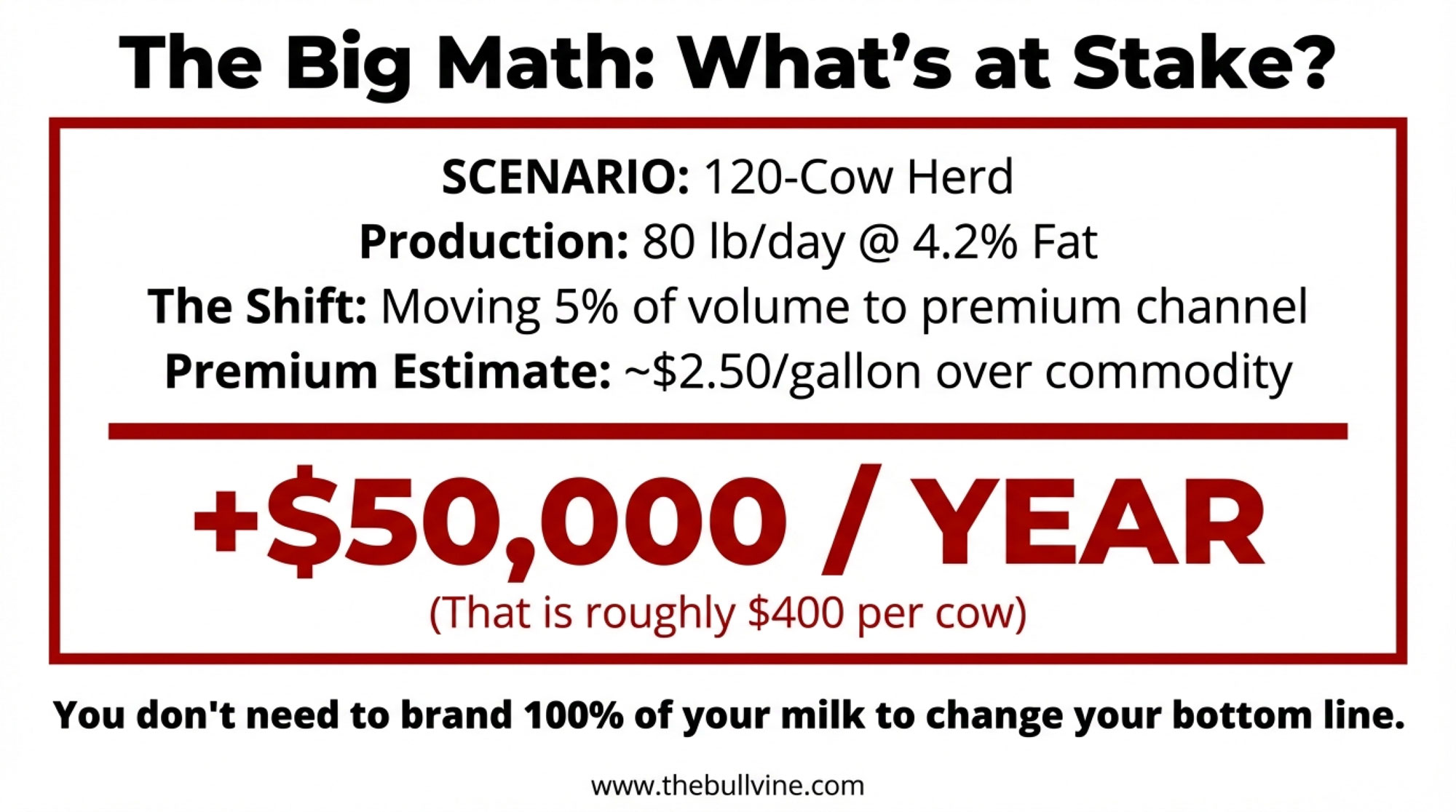

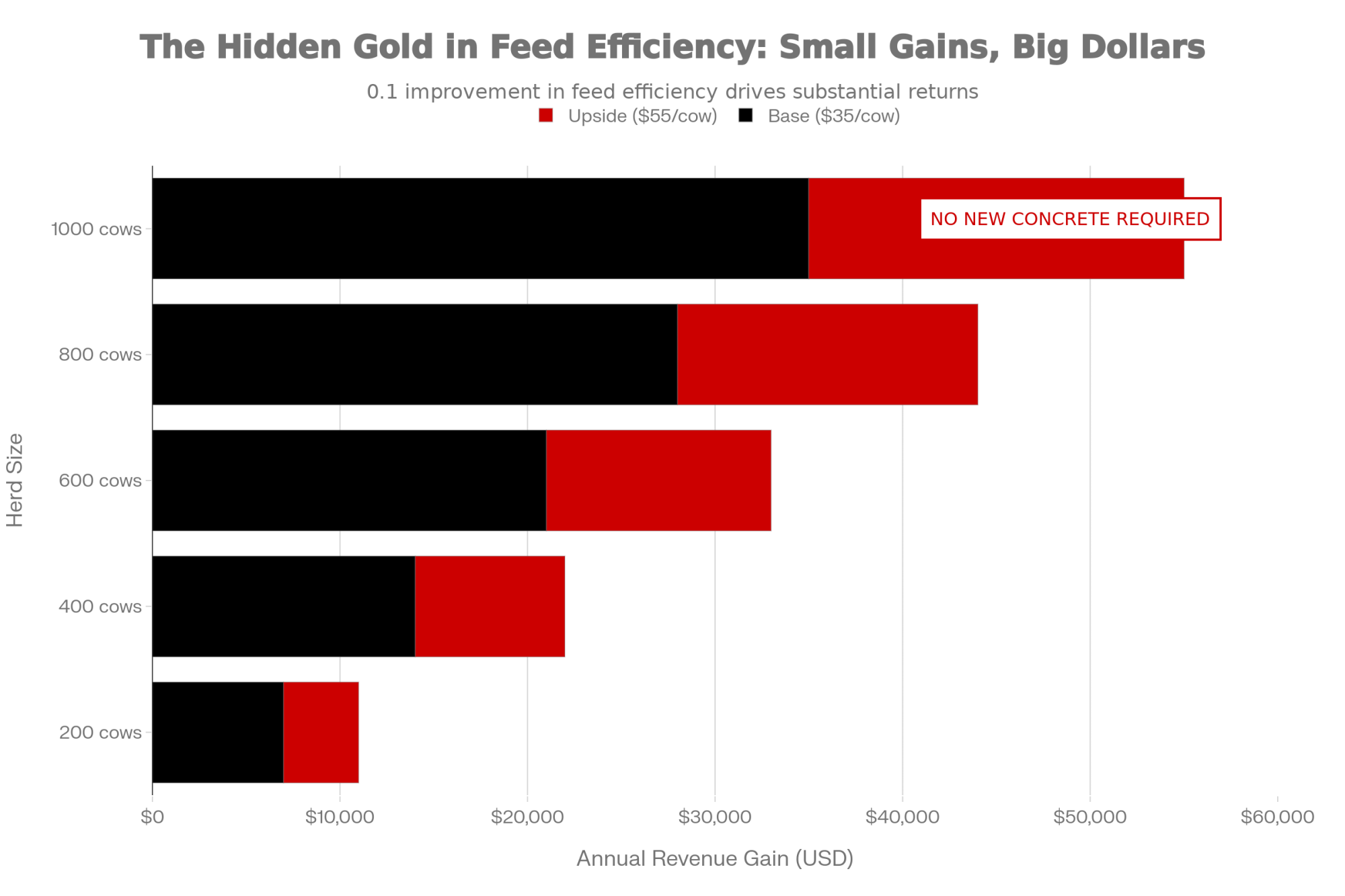

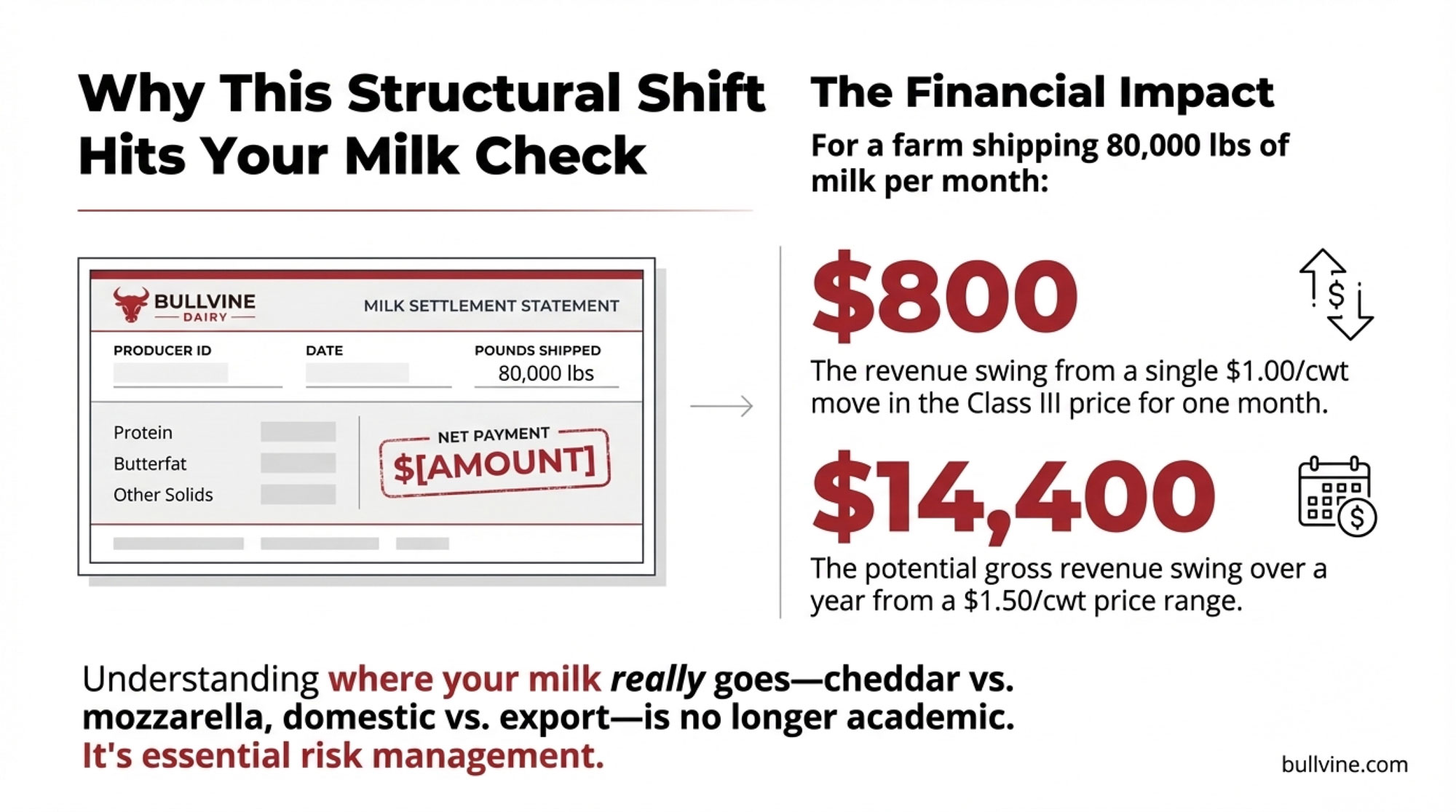

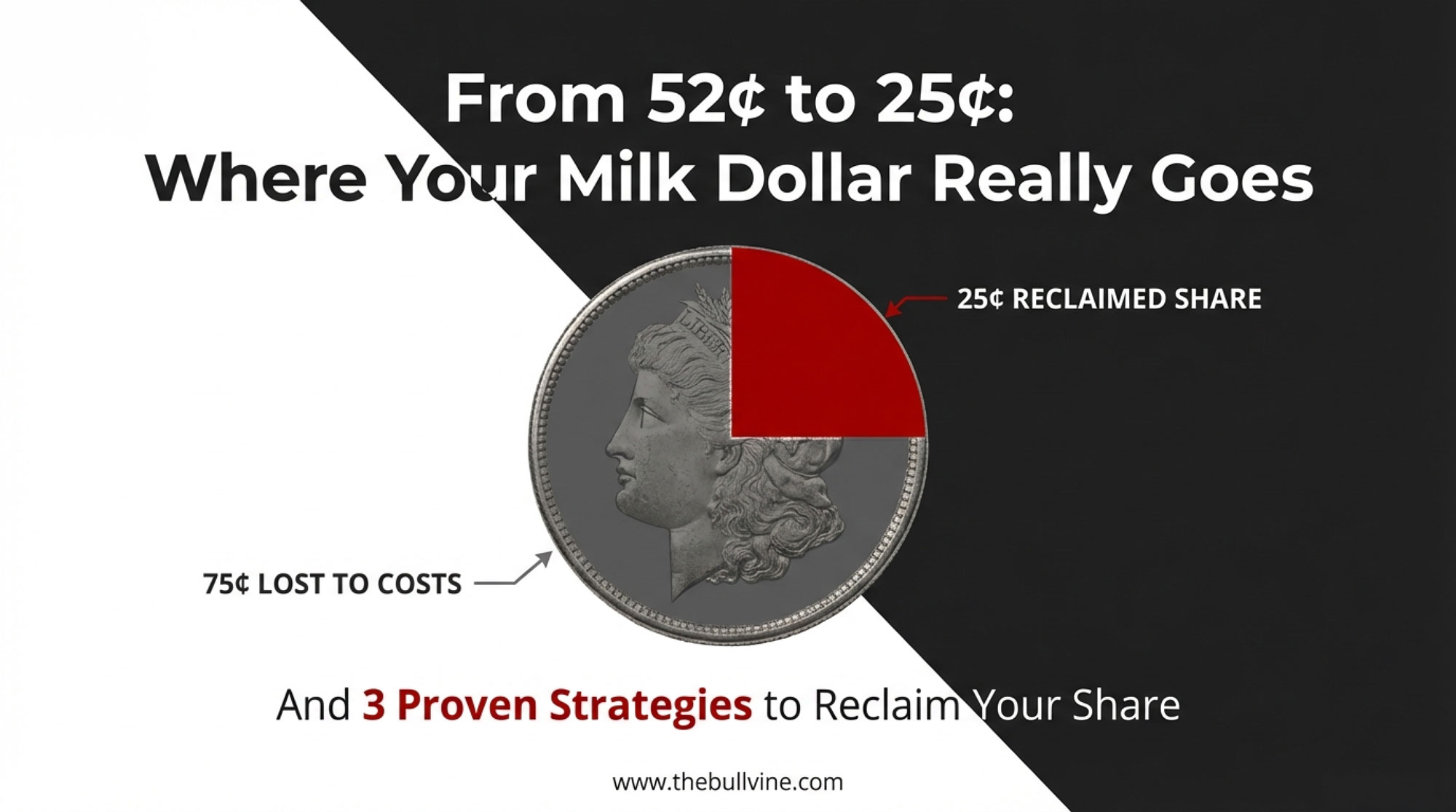

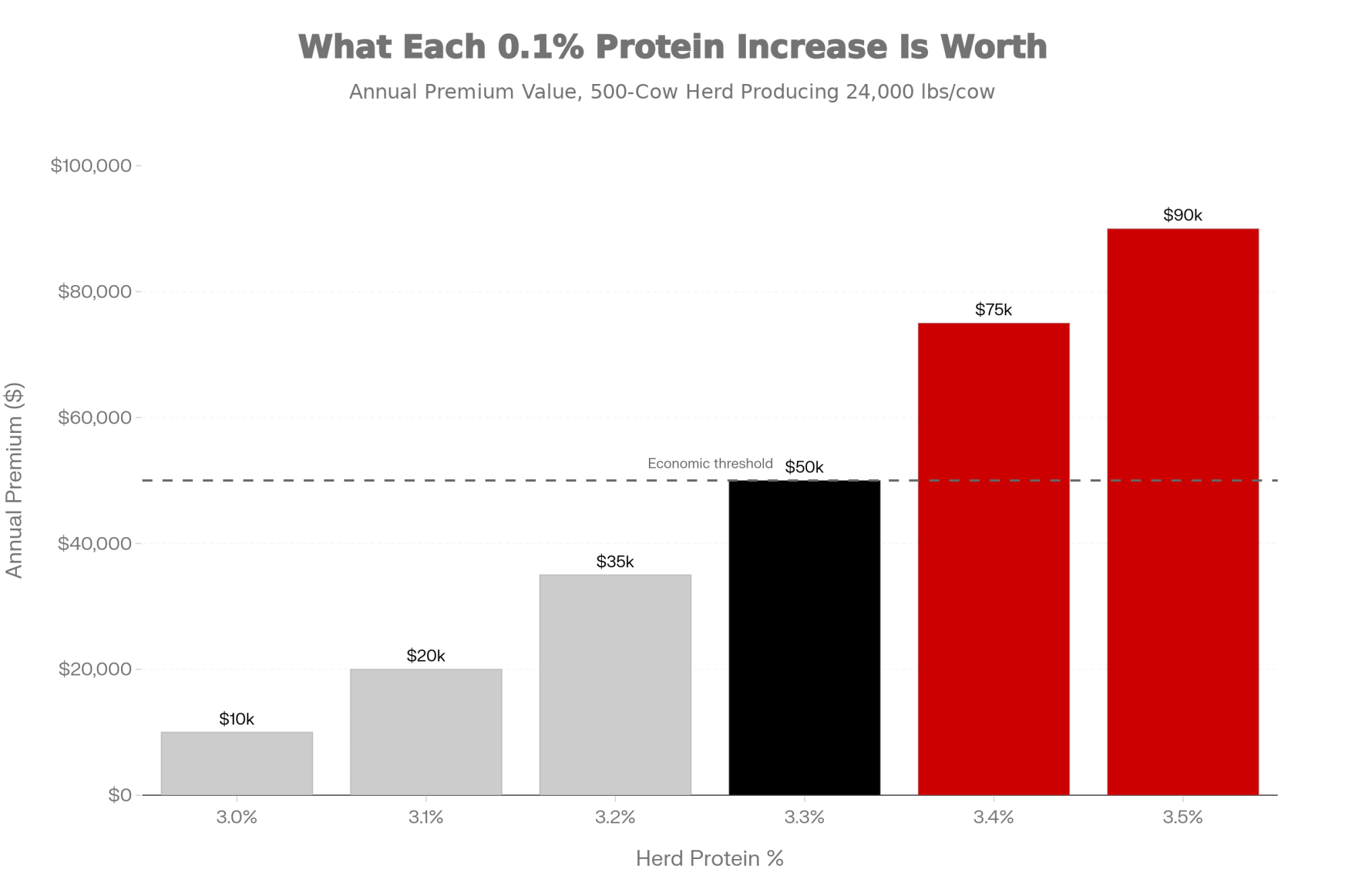

To give that some scale, here’s an example you can scribble in your notebook:

- Suppose the whey and ingredients division lifts overall co‑op margins by 30 cents per hundredweight in a given year.

- If the board decides to pass half of that—15 cents per cwt—through as extra cash patronage:

- A farm shipping 10,000 cwt/year would see about 1,500 dollars in additional cash.

- A farm shipping 20,000 cwt/year would see about 3,000 dollars in additional cash.

- At around 270 cwt per cow per year (about 27,000 pounds), that 15¢/cwt adds up to roughly 40 dollars per cow per year. On a 250‑cow herd, that’s in the neighborhood of 10,000 dollars.

That’s not going to buy a whole new parlour, but it might be the difference between putting off a key repair and finally doing it—or between feeling forced to stretch your line of credit and sleeping a little better.

Seeing It from the Board’s Side Too

To keep this fair, it helps to slide into the board chair for a minute and think about what directors and managers are juggling.

They’re dealing with:

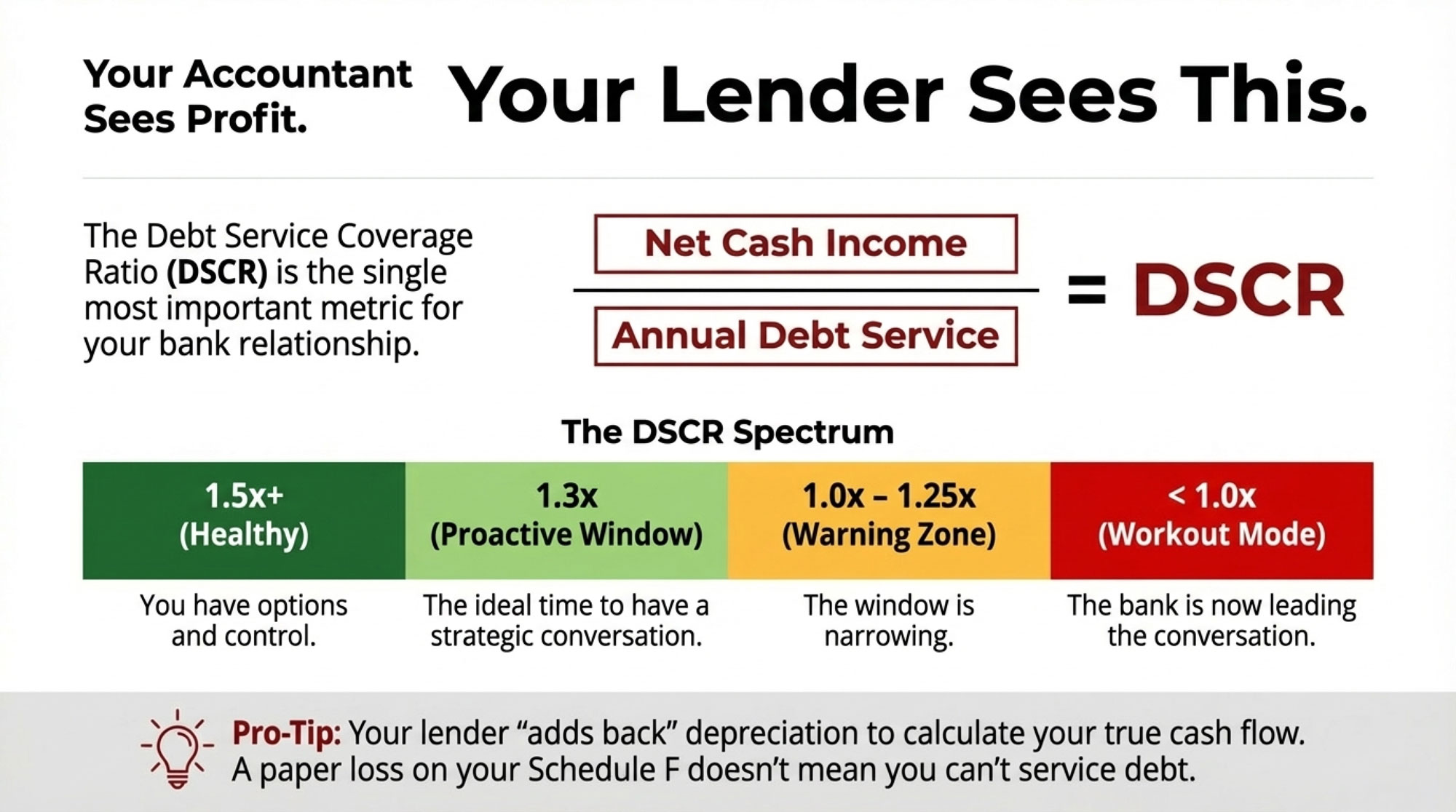

- Lender expectations. Co‑op lenders want to see strong equity and comfortable coverage ratios, especially when whey, cheese, and powder prices are volatile.

- Price and demand swings. CoBank’s work on whey markets has highlighted that strong demand periods can be followed by softer prices, especially when new capacity floods the market.

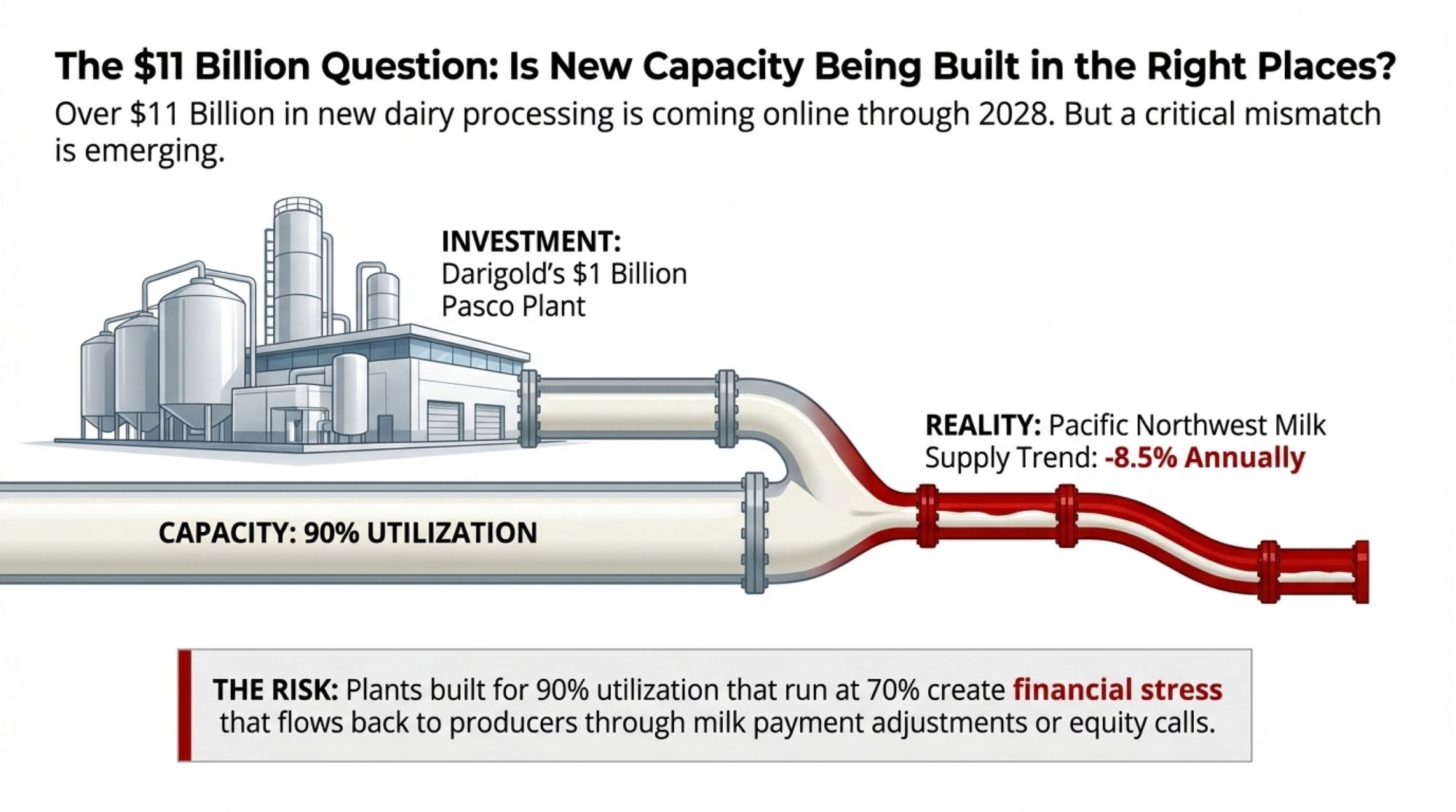

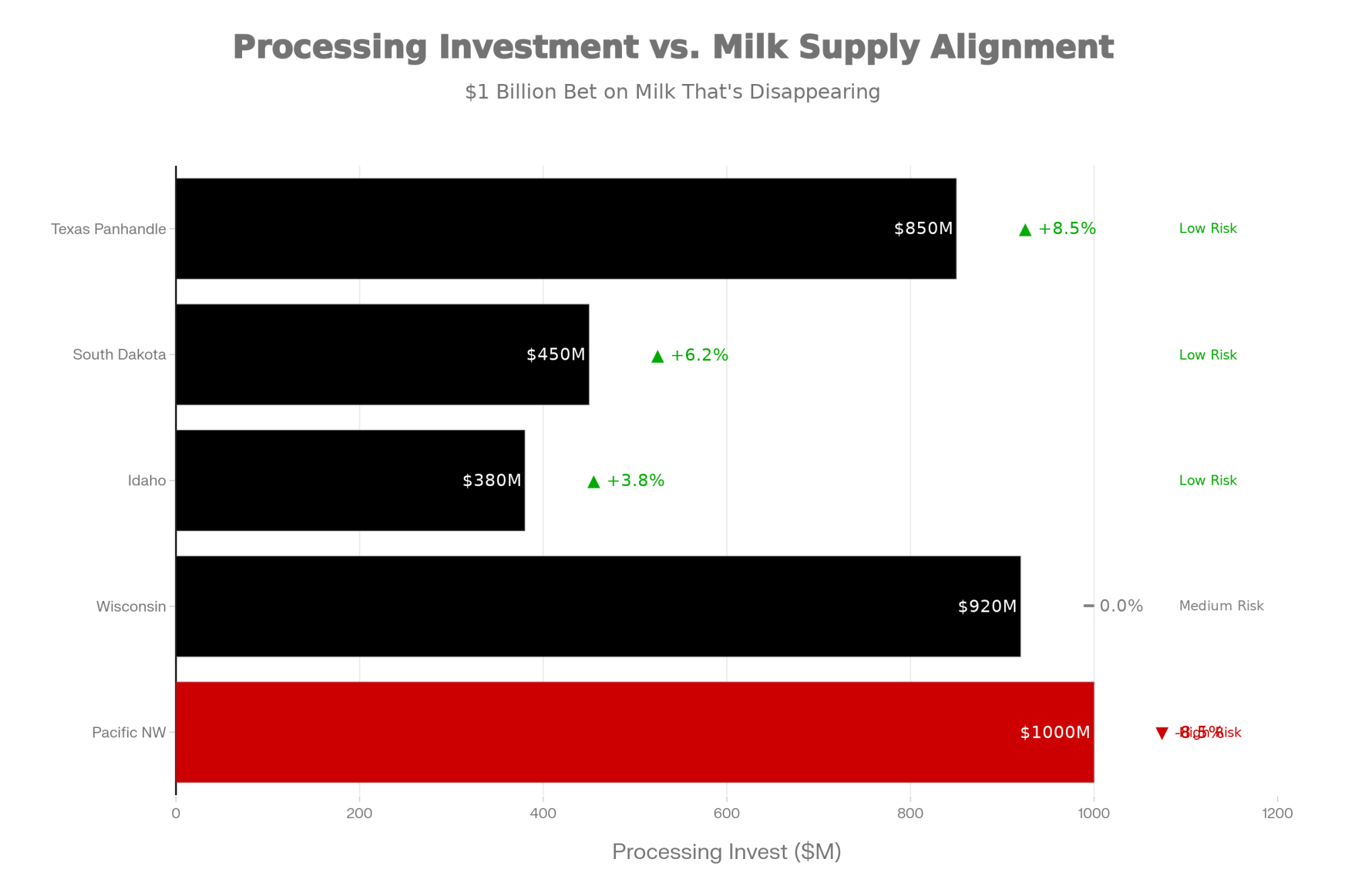

- Utilization risk. A plant designed for 90% utilization looks fantastic on the spreadsheet; at 65–70%, especially in regions where cow numbers are flat or environmental rules are tight, the economics change quickly.

- Future capital needs. Even if this whey project goes well, there are always other needs coming—dryer upgrades, cheese‑line modernization, wastewater and energy projects.

So when boards decide to retain a larger share of patronage during the early years of a big whey project, they’re often trying to keep the co‑op solid and bankable, not trying to short‑change members.

The tension comes when:

- Retention policies don’t seem to evolve even after a plant appears to be past its payback window, or

- Members don’t get enough information to judge whether their equity is being used well.

That’s why those three questions—about financing mix, segment reporting, and patronage for higher‑margin businesses—are so important. They help shift the conversation from frustration to shared problem‑solving.

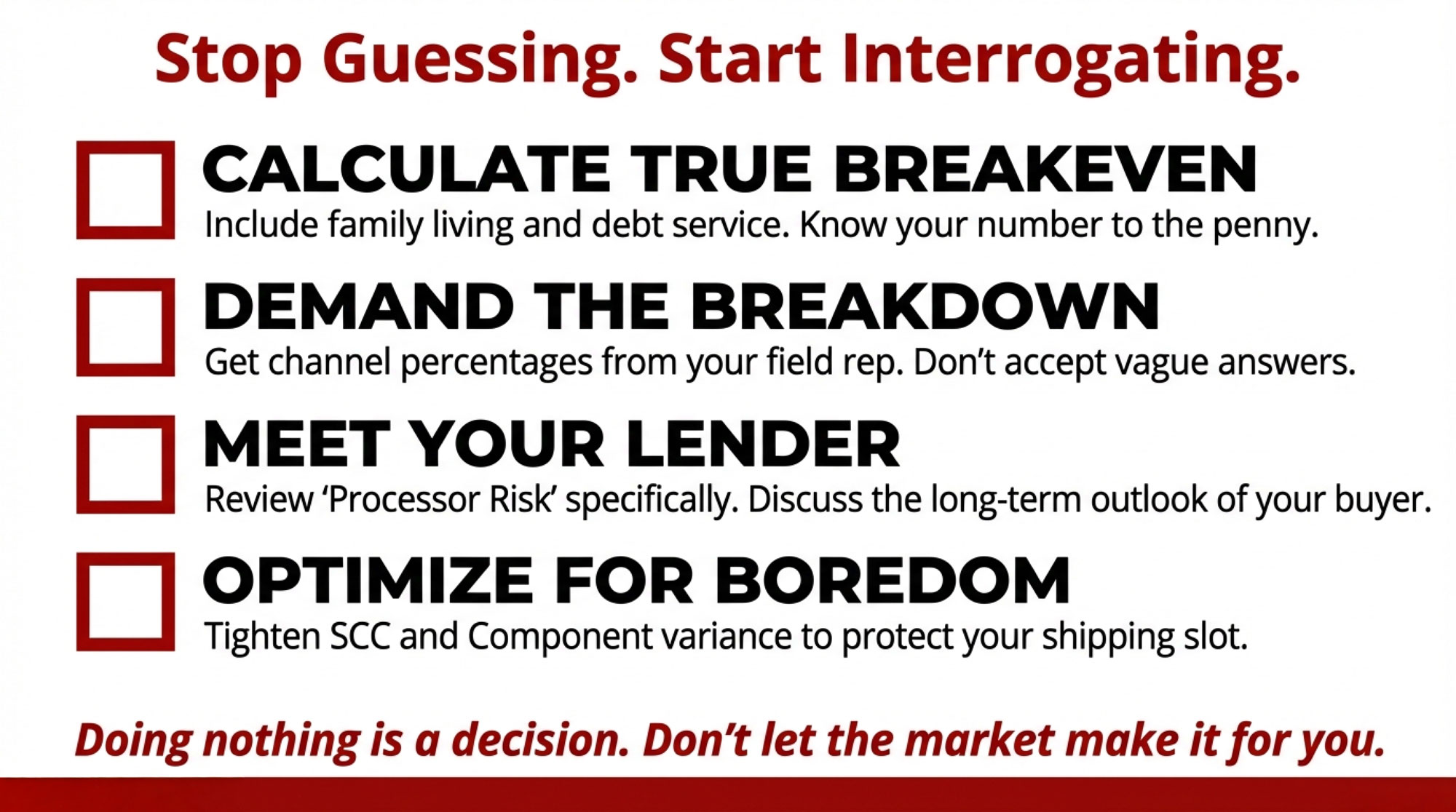

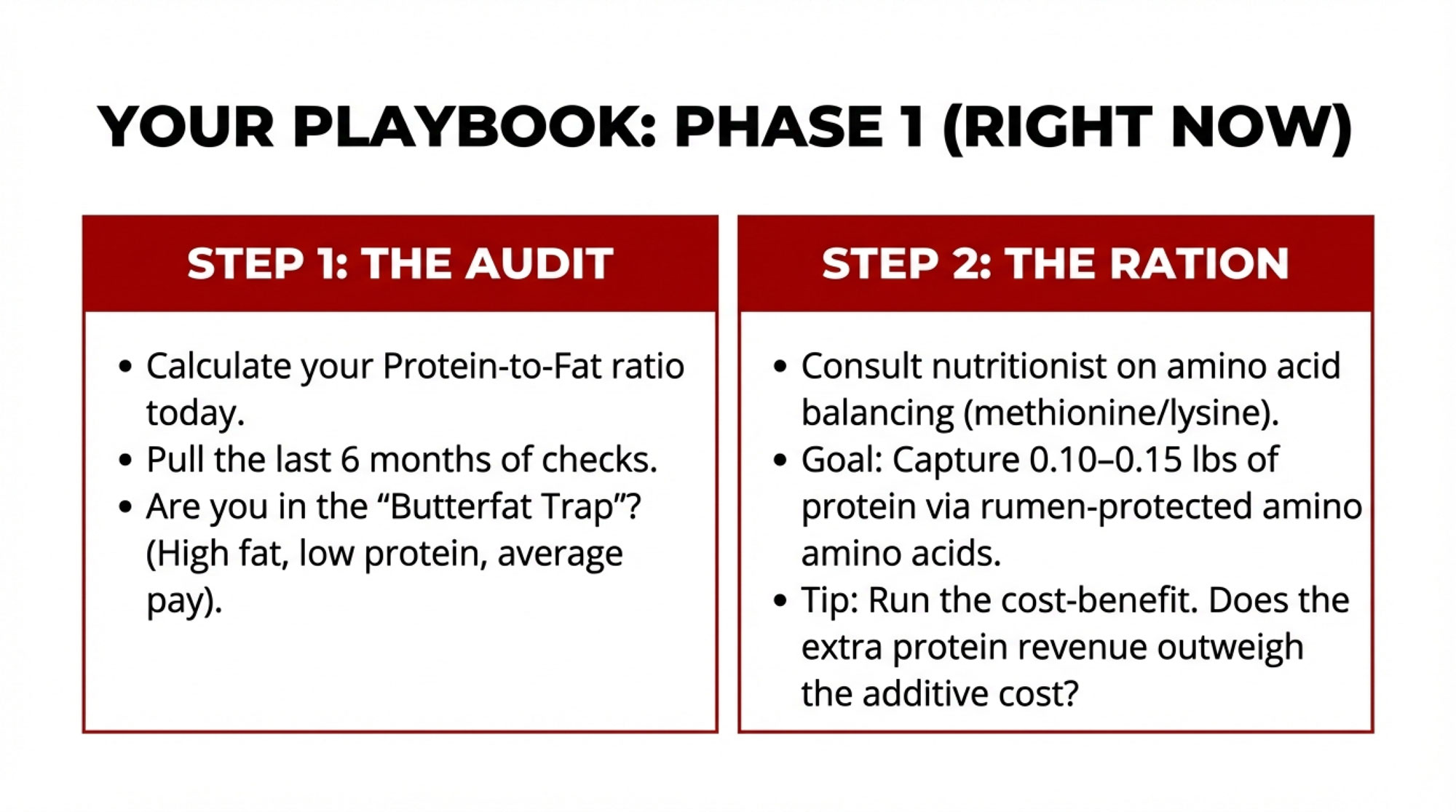

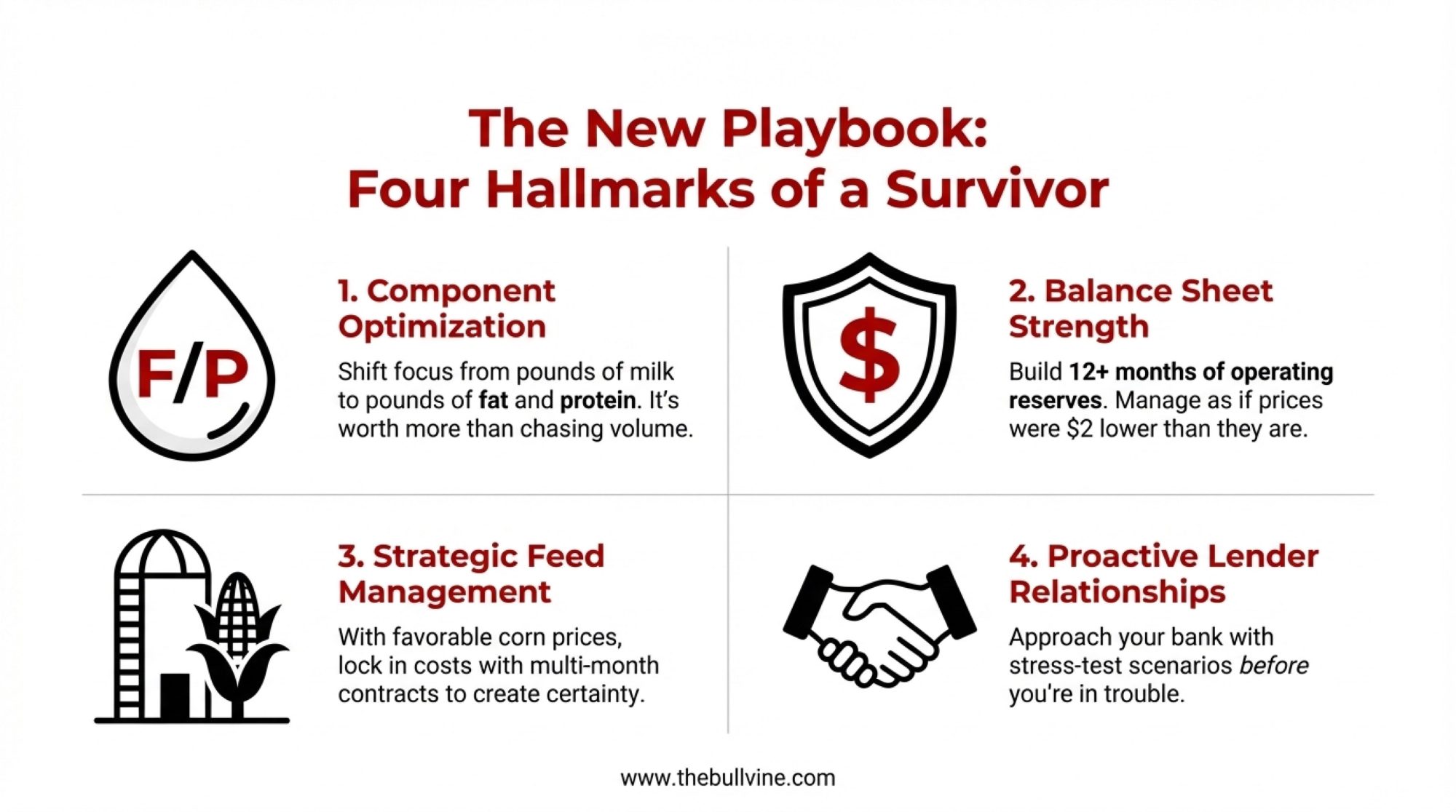

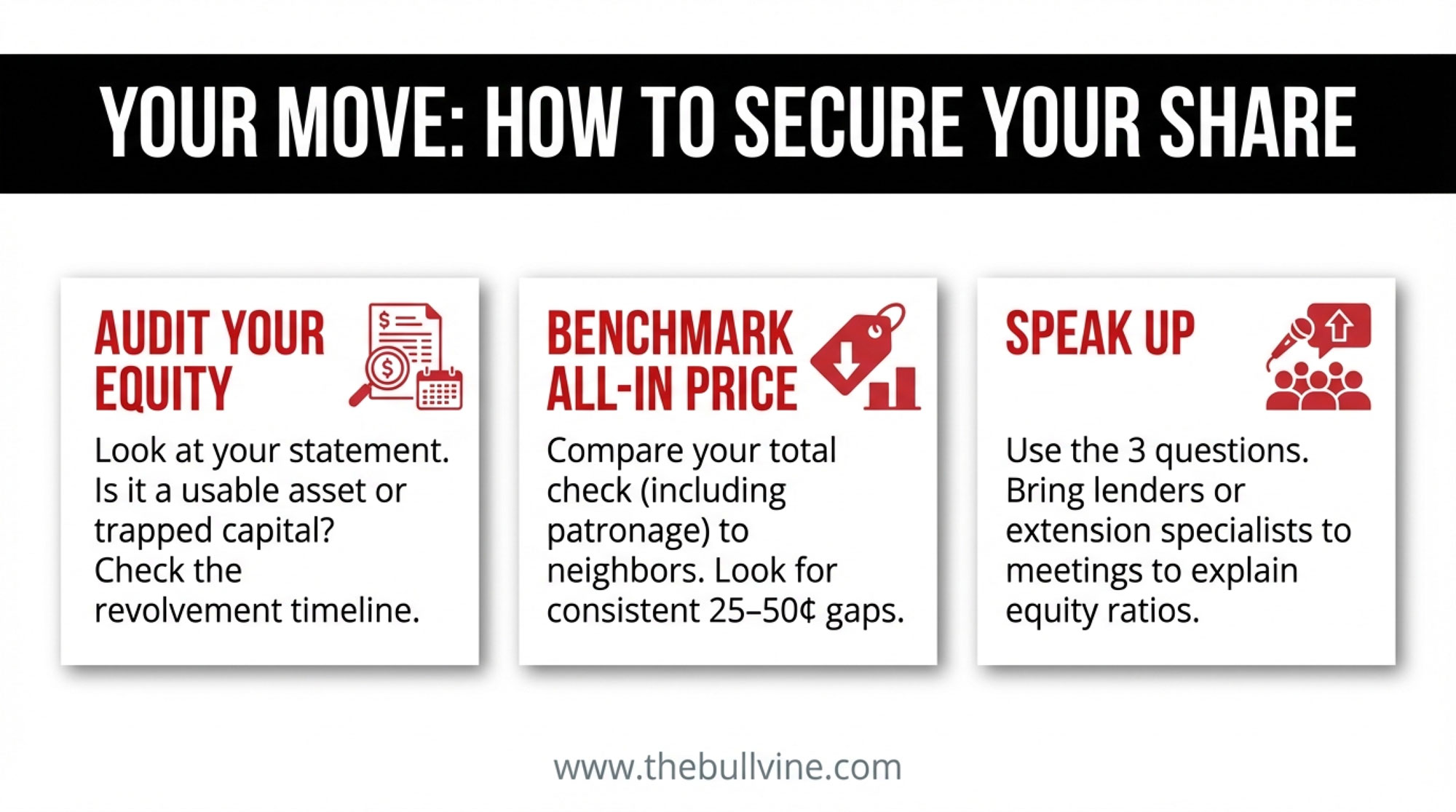

Practical Moves for Your Farm Before the Next Wave of Stainless

With everything else on your plate—fresh cow management, labour, feed, keeping barns or dry lot systems in shape—it’s easy to shrug and say, “That’s co‑op stuff. I don’t have time for it.” But there are a few manageable steps that can put you in a much better spot without turning you into a full‑time analyst.

1. Really look at your co‑op equity statement

Start by grabbing your latest capital account statement:

- How much total retained equity do you have?

- How much of that has built up over roughly the last decade, during this wave of processing expansion?

- Which patronage years are being revolved now, and what does the stated policy say about future revolvement?

Then sit down with your lender or adviser and look at that equity alongside your debt, age, and plans. OSU’s co‑op work points out that the value of co‑op equity depends heavily on your time horizon and the co‑op’s actual redemption practices. For a 35‑year‑old with 400 cows, a strong equity balance with predictable revolvementcan look like an asset. For a 60‑year‑old with 100 cows, a big equity number with no clear path to redemption may feel more like trapped capital.

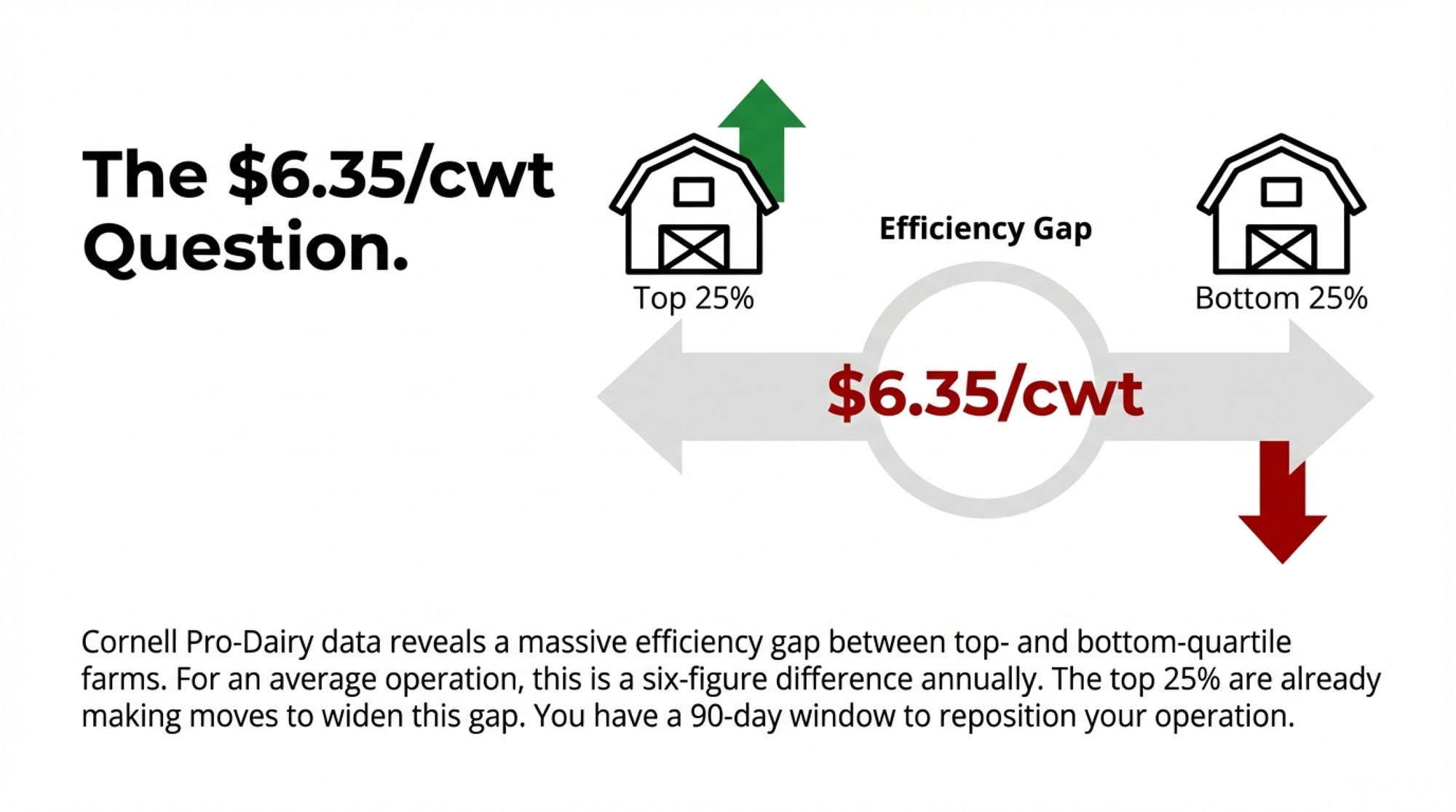

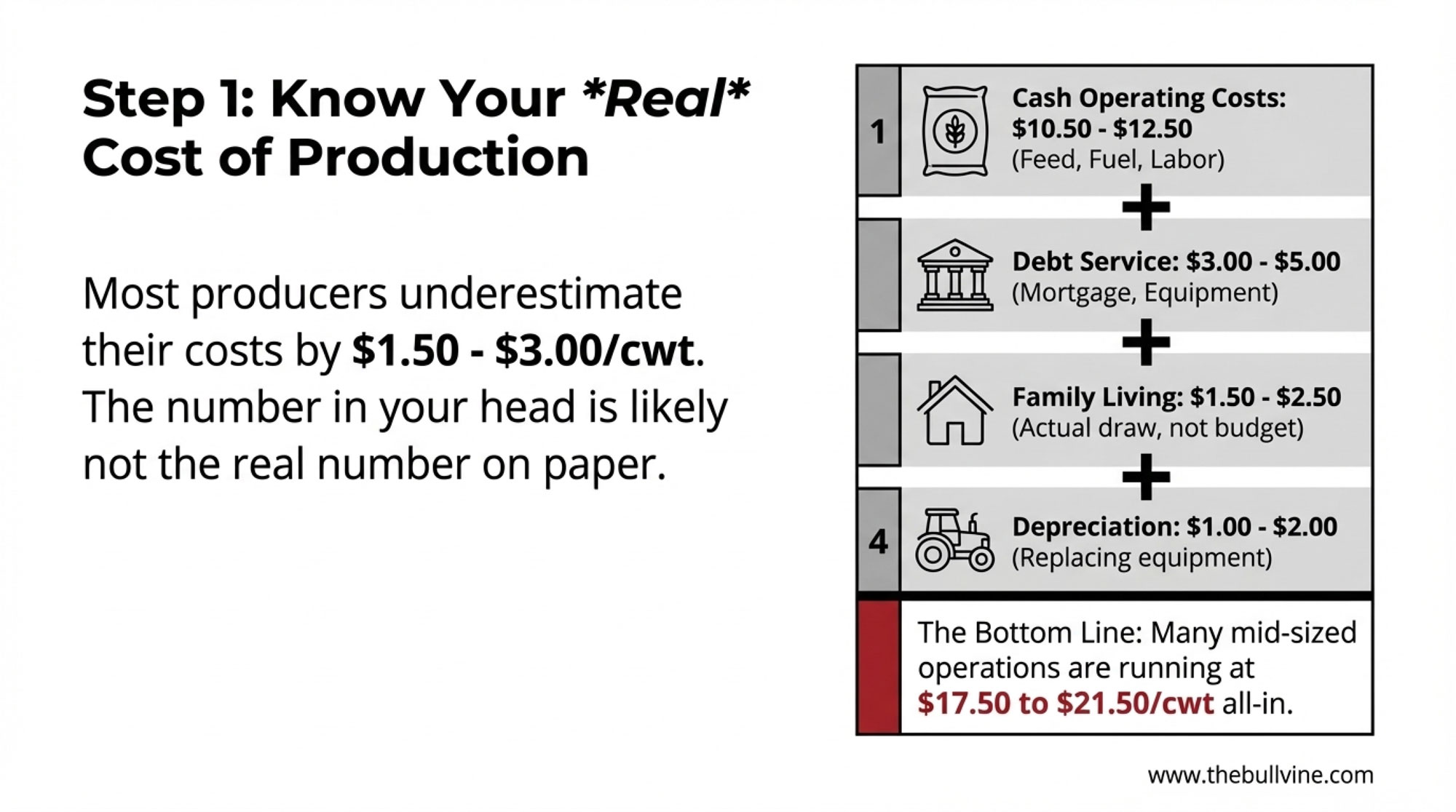

2. Benchmark your all‑in price

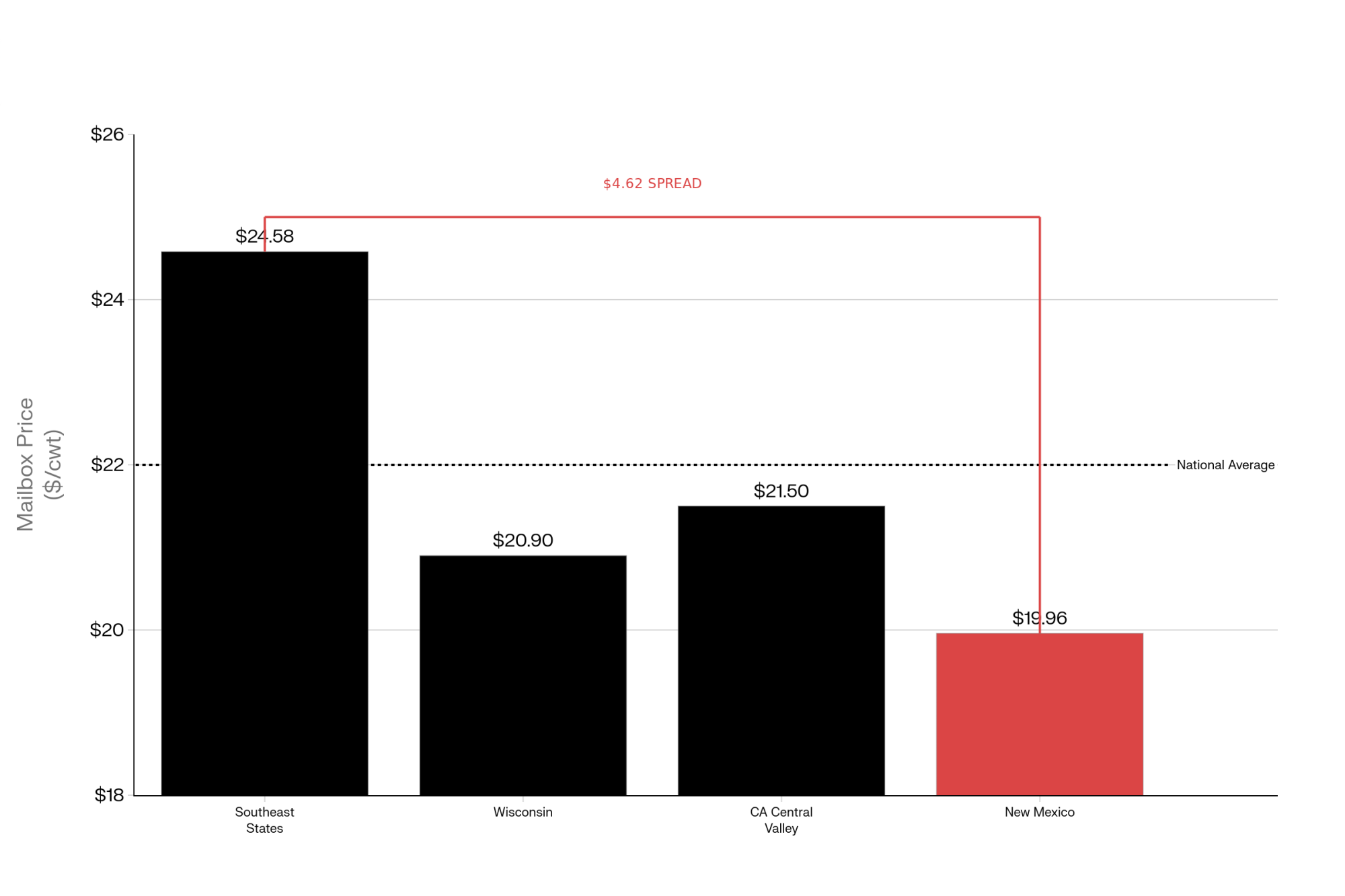

Every year or so, it’s worth asking, “How do we actually compare?”

- Calculate your average pay price per cwt (or per 100 litres) over the last 12–24 months, including both the cheque and any cash patronage you actually received.

- Compare that with USDA mailbox prices or provincial benchmarks for your region.

- Quietly compare notes with one or two trusted neighbours who ship to other buyers, adjusting for components, quality, and hauling.

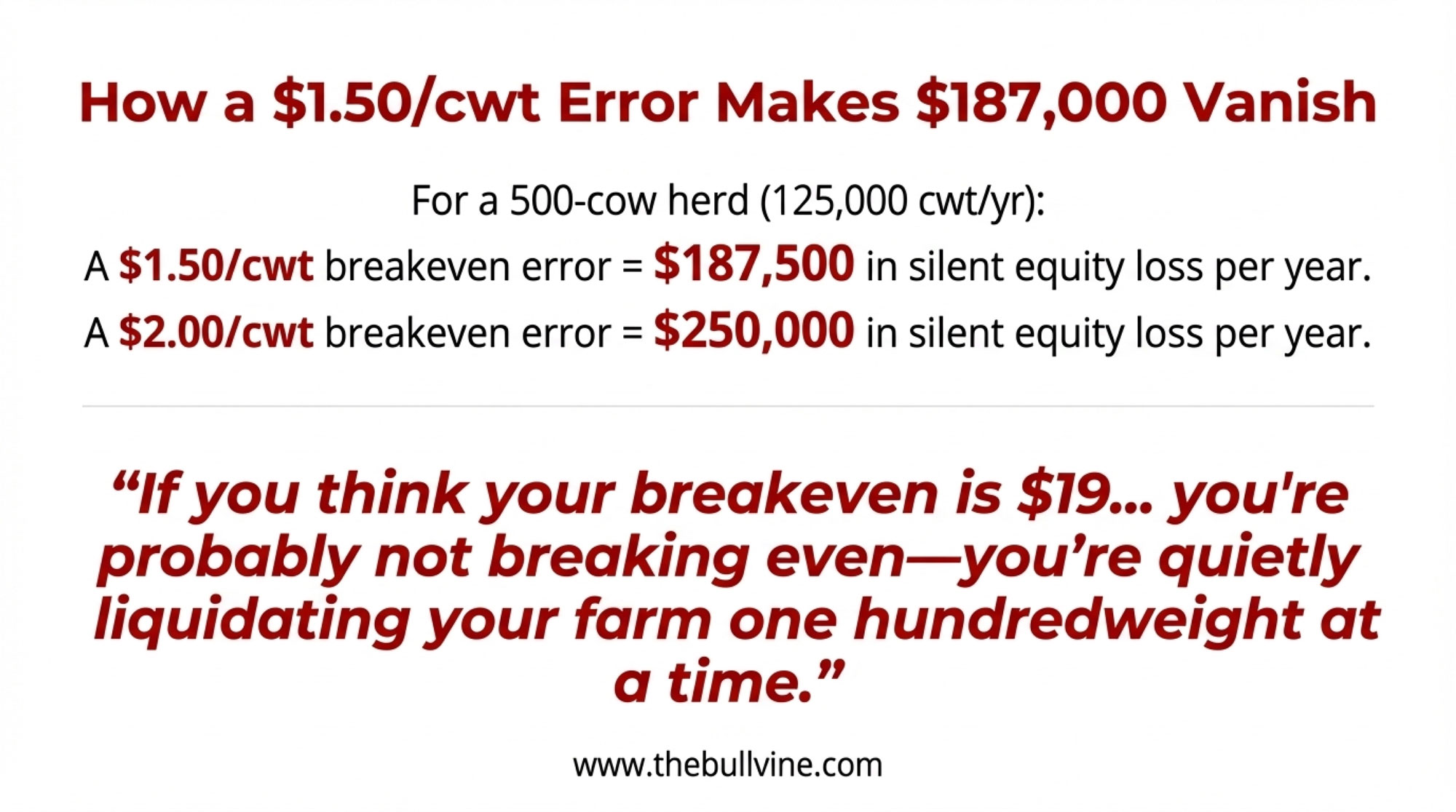

You’re not reacting to every ten‑cent blip. You’re looking for patterns. If, over time, your all‑in price is consistently 25–50¢/cwt behind similar herds, that’s 2,500–5,000 dollars on 10,000 cwt and 5,000–10,000 dollars on 20,000 cwt.That’s enough to matter when you’re trying to catch up on deferred maintenance or manage your operating line.

3. Take one or two good questions into your next meeting

You don’t have to take over the microphone. One or two clear questions can change the tone of a district meeting:

- “Could the board give a simple overview of how our whey or ingredients division performed last year—rough volume, revenue, and whether it was on track with what we were told when we approved the project?”

- “When we first discussed this whey plant, what kind of payback window were we shown, and based on what you’re seeing now, are we roughly in that range?”

- “As this project matures and we hit the equity and debt ratios we’ve targeted, has the board discussed changing the cash portion of patronage tied to that division?”

Those are owner‑level questions. They show you’re engaged and thinking like an investor, not just a supplier.

4. Use the experts who already work for dairy farmers

There’s a lot of good help already in the system:

- Ask your university or provincial extension folks if they’ll run a winter session on whey markets, co‑op financials, and how processing investments connect to milk pricing.

- Encourage your co‑op to invite its primary lender or a co‑op finance specialist to member meetings to explain how they look at equity, debt, and project risk around cheese and whey plants.

- If your region has a co‑op development center or a similar organization, consider bringing together a small group of members to sit down with them and discuss governance tools and best practices.

These people see multiple co‑ops and processors. They know what “normal” looks like and where the outliers are, and they can help translate that into plain language.

The Bottom Line

So why spend this much energy thinking about whey when you’ve got cows to breed, feed to buy, and a to‑do list that never seems to shrink?

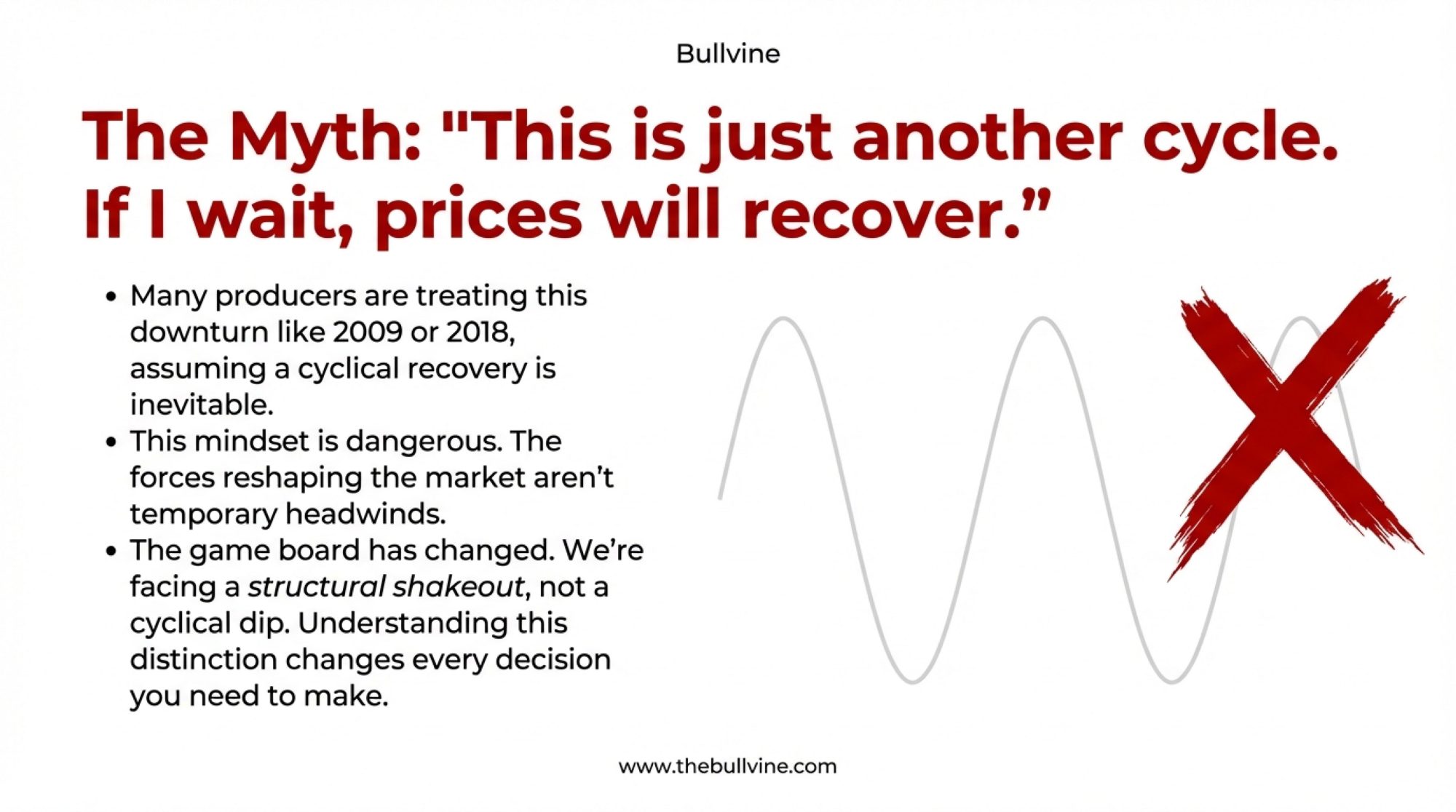

Because this isn’t just another short‑term price swing. The combination of:

- GLP‑1 weight‑loss drugs are pushing a significant share of consumers toward fewer calories but more protein‑dense foods,

- Strong, still‑growing global demand for whey protein, with the market projected to nearly triple from 6.5 billion dollars in 2023 to 19.2 billion by 2030,

- And solid clinical evidence that whey helps older and medically vulnerable people maintain muscle and function,

…all point toward durable demand for high‑quality dairy protein.

At the same time:

- The spread between commodity dry whey and higher‑value whey proteins is large enough to change plant economics materially.

- More than eight billion dollars in new processing capacity—a big chunk of it in cheese and whey, including major builds in the Texas–New Mexico corridor and the Upper Midwest—is being built or expanded in this cycle.

- And both techno‑economic research and real plant experience suggest that, when they’re sized and run well, whey investments can be among the quicker‑paying projects in a processor’s portfolio.

Those are the big structural forces. What’s still very much in our hands, as producers and co‑op members, is how those whey projects are financed, how their performance is reported, how patronage is structured, and how actively we choose to engage in those decisions.

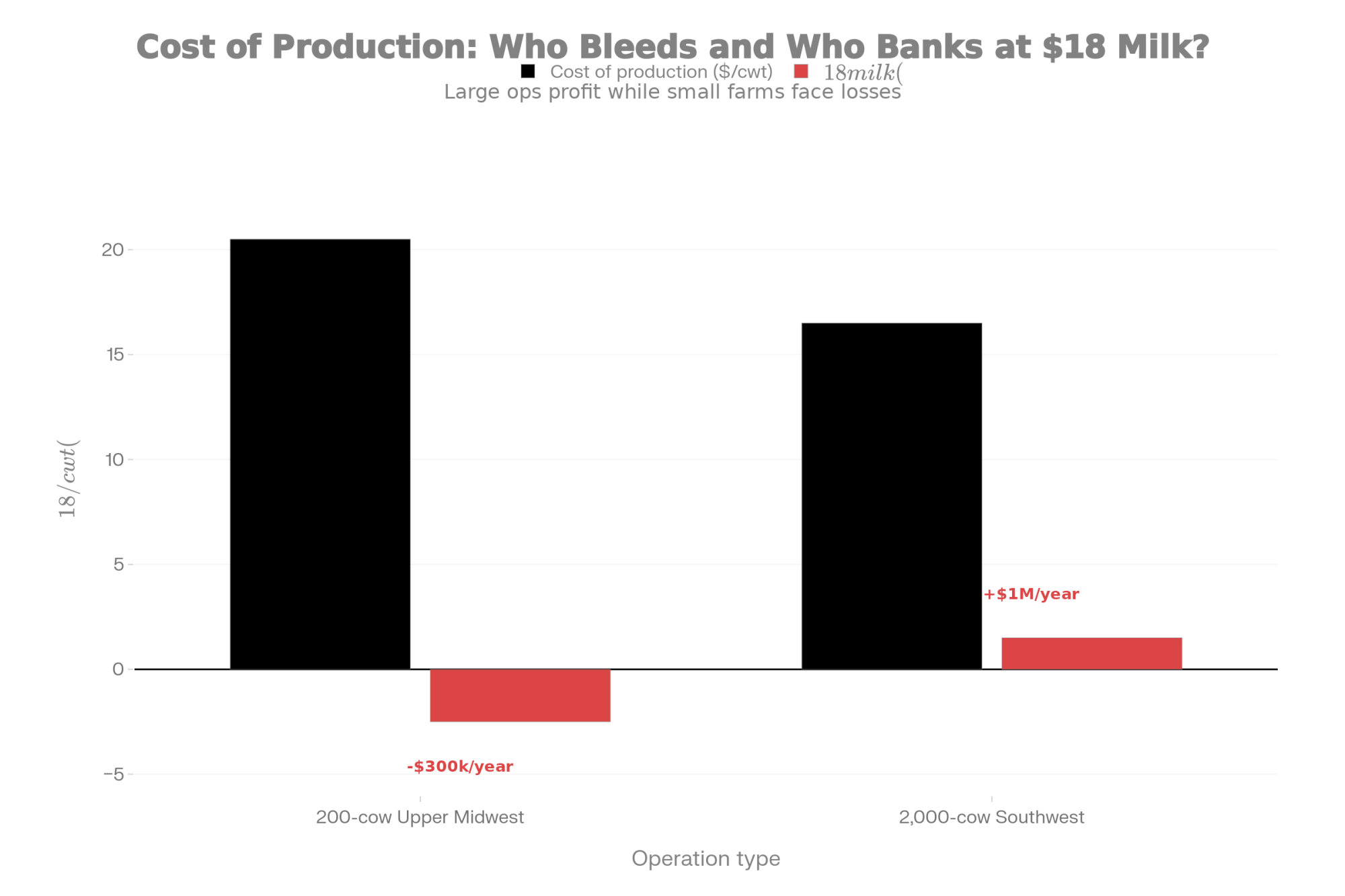

There’s no one right answer. A 2,000‑cow dry lot in the Texas Panhandle, a 600‑cow freestall in Ontario, and a 120‑cow tie‑stall in Vermont are going to make different calls on risk, equity, and time horizon. But producers who:

- Understand their co‑op’s equity structure,

- Know where their all‑in price sits relative to neighbours and benchmarks,

- And are willing to ask a few focused questions in the right rooms,

They are in a much stronger position to decide what this whey boom means for their own operation.

What’s encouraging is that we’re not starting from scratch. We’ve got solid data, extension specialists who understand both cows and co‑ops, lenders who will explain their thinking if we ask, and real‑world examples—here and overseas—of co‑ops and processors that have handled big investments in ways that kept both plants and farms healthy.

The opportunity now is to bring that same level of clarity and shared purpose to this “whey moment,” so that ten years from now we’re not just proud of the shiny stainless on plant tours—we’re also standing in barns and dry lot systems we’re proud to hand on to the next generation.

Key Takeaways:

- US$8B in stainless, coming fast: New cheese and whey plants from Wisconsin to the Texas Panhandle are adding ~360 million pounds of cheese capacity by the end of 2025—with whey protein lines riding alongside.

- Whey demand is structural, not hype: GLP-1 drugs and protein-obsessed consumers are pushing the global whey market from US$6.5B (2023) toward US$19.2B by 2030—a near tripling in seven years.

- Your formula doesn’t capture the real value: Class III still prices whey at commodity dry whey levels (40–60¢/lb), while WPC-80 and WPI sell at multiples of that.

- Co-op structure determines whether you ever see that margin: cash patronage splits range from 15–70%; equity can take years or decades to turn. If whey isn’t reported or tied to patronage, the value often stays parked on the co-op balance sheet.

- Bring three questions to your next meeting: (1) How is this project financed—debt vs. member equity? (2) Will whey be reported as its own division? (3) When whey margins are strong, does cash patronage or redemption actually improve?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

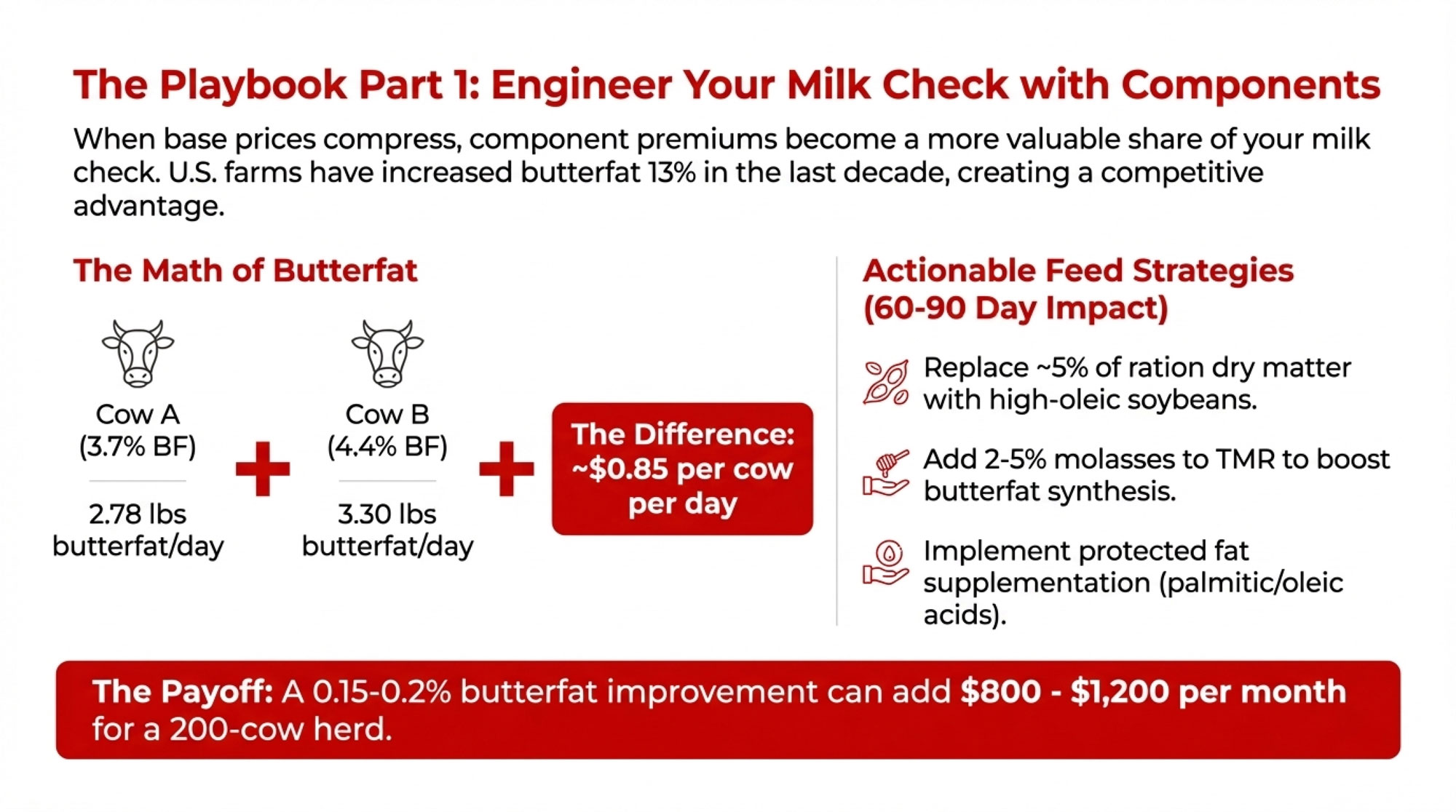

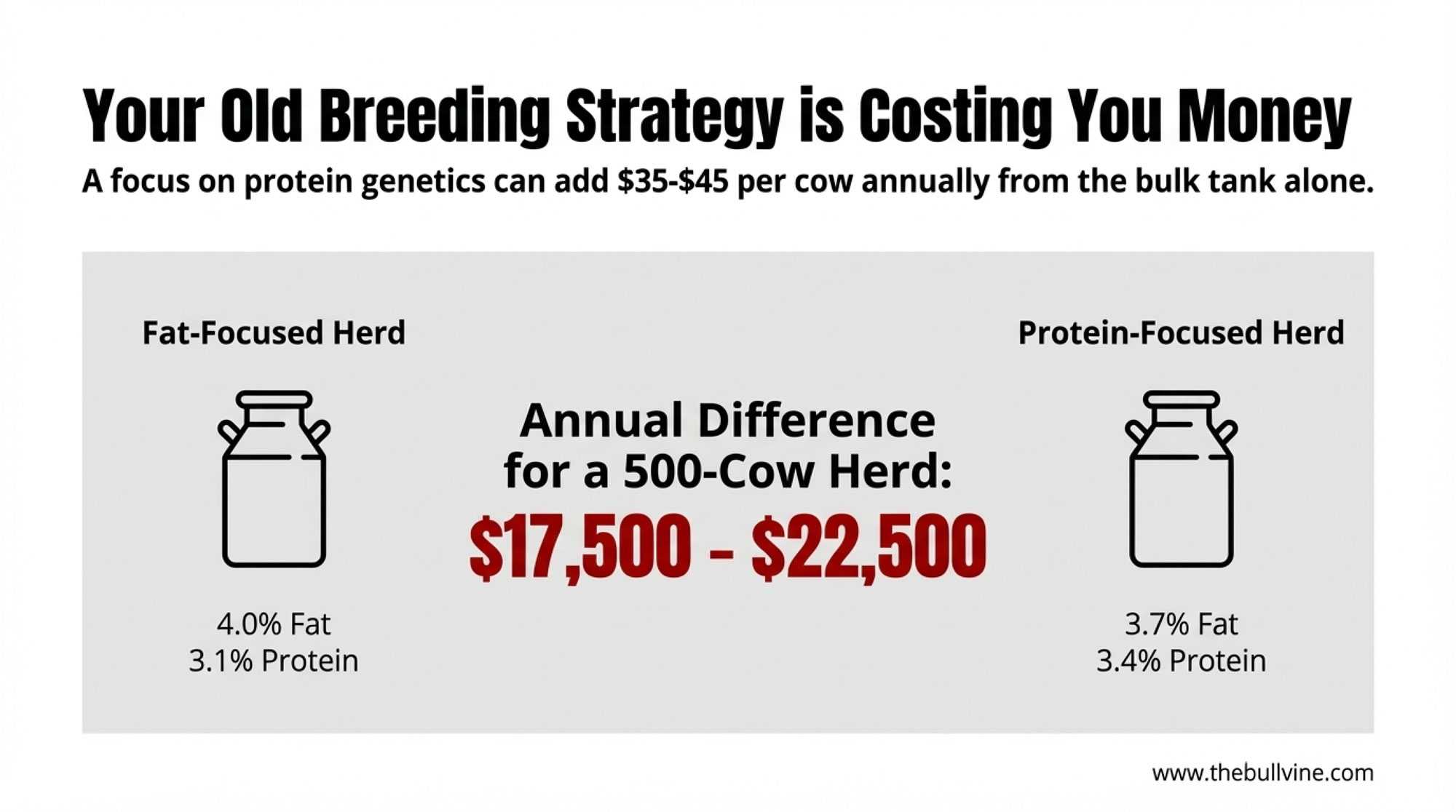

- Why Milk Components Are Your Best Friend Now (and Why Chasing Volume is Yesterday’s News) – Delivers the exact ROI math behind boosting components by a tenth of a percent, arming you with a $66,000-per-month revenue strategy that shifts your focus from outdated volume goals to high-value solids production.

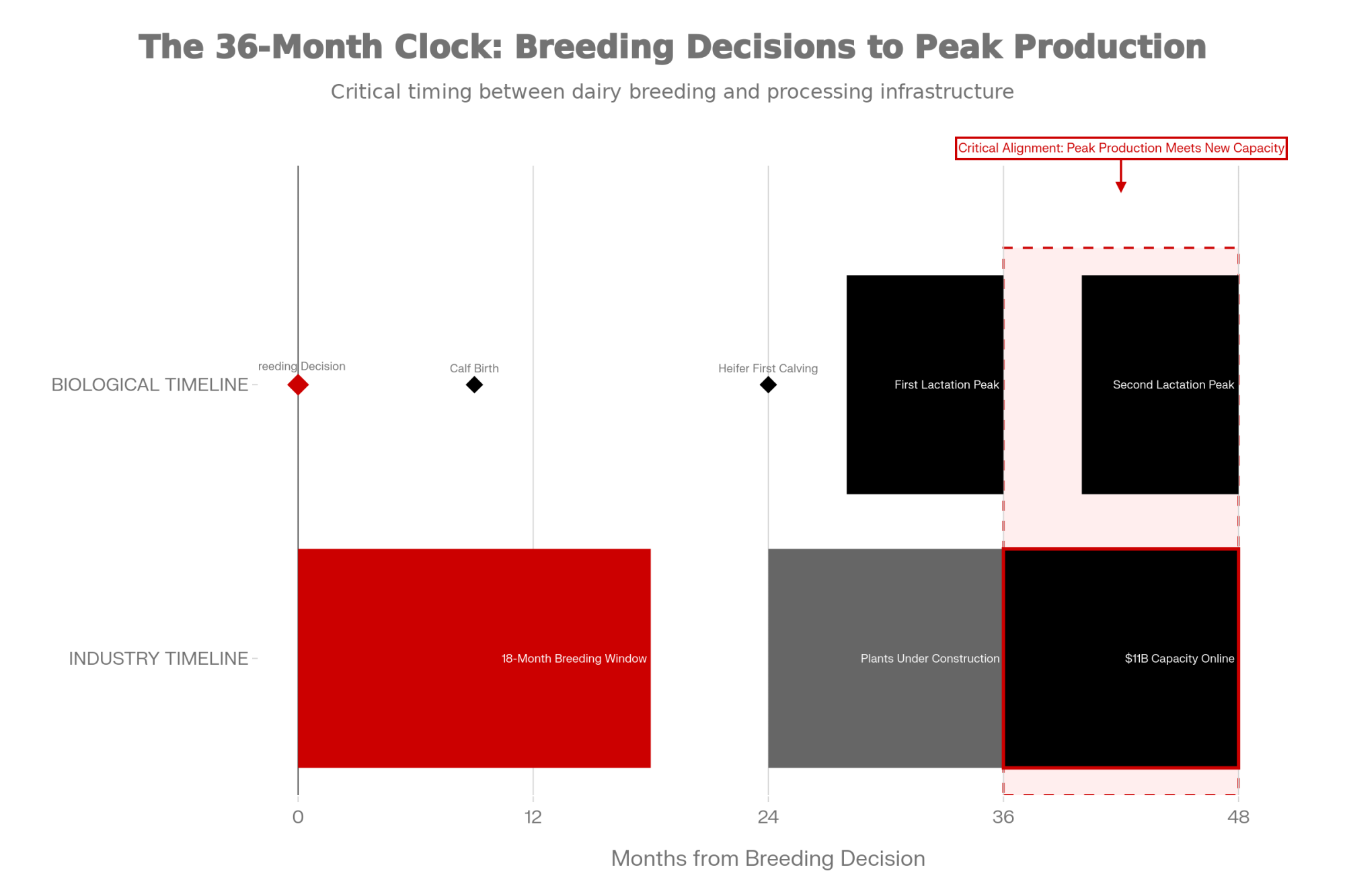

- The 18-Month Protein Window: $11 Billion in New Plants Signals It’s Time to Rethink Your Sire Lineup – Delivers a strategic blueprint for aligning your current breeding decisions with the $11 billion processing wave, revealing how to secure your spot as a preferred supplier for the high-protein plants coming online through 2028.

- Genetic Correlations Upended: Why Sticking with Old Breeding Indices Could Cost Your Dairy $486 Per Cow – And What the Data Really Proves – Exposes the $486-per-cow profit opportunity hidden in the 2025 genetic base reset, breaking down how switching from volume-heavy indices to the new Net Merit benchmarks converts feed efficiency into a permanent competitive advantage.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

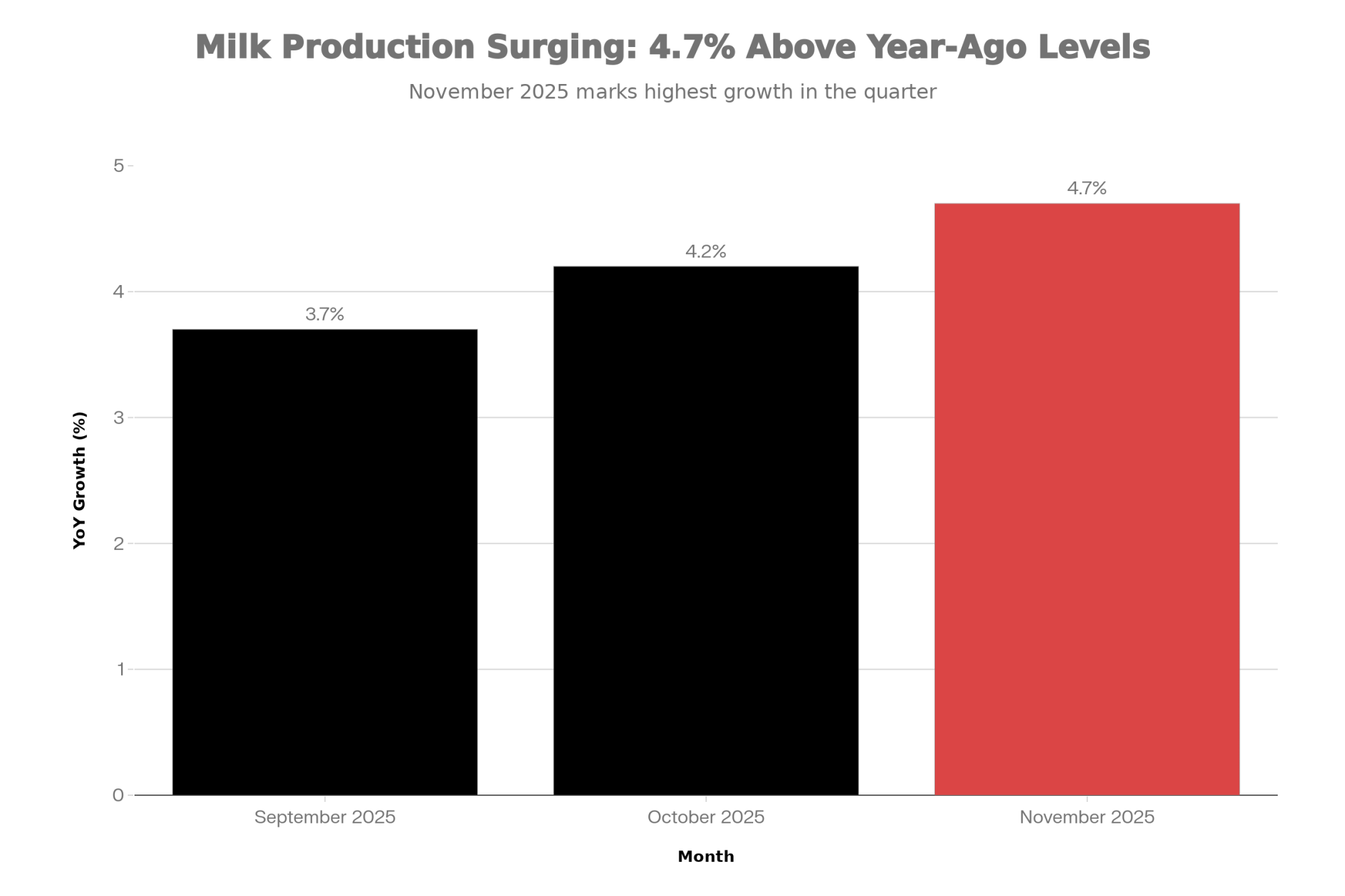

Join the Revolution!