If your best employee can’t hit the protocol, your farm has a six‑figure problem — not a training issue.

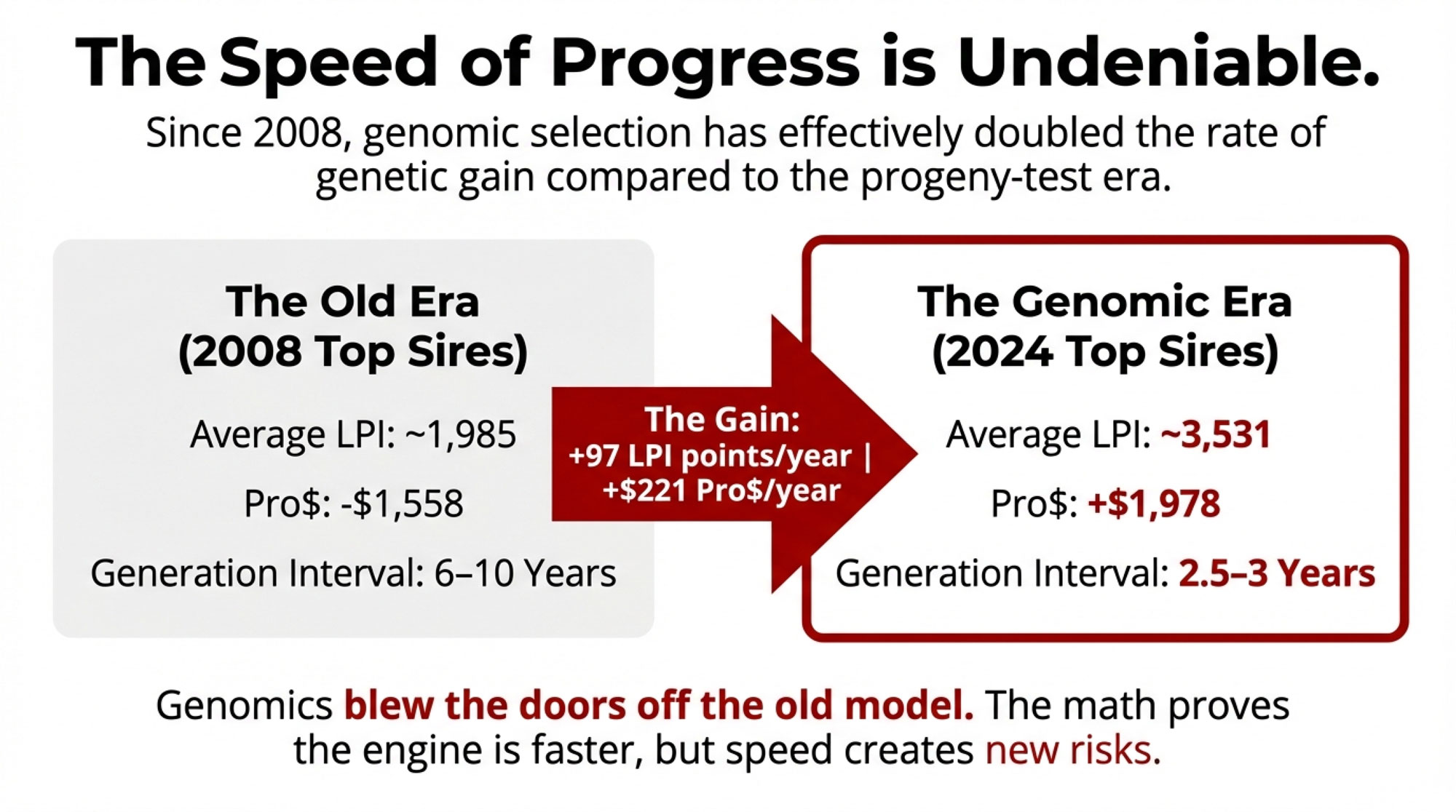

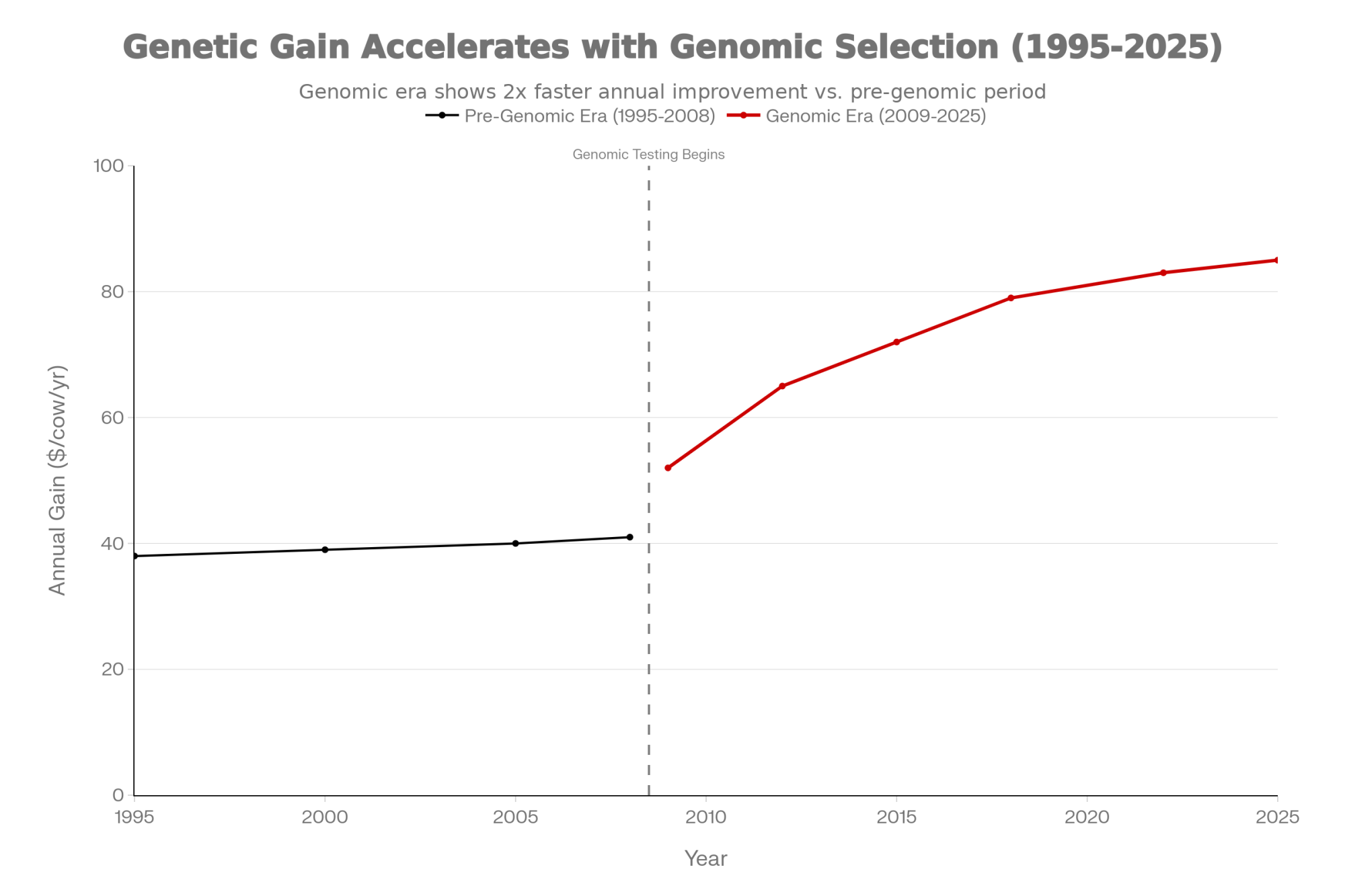

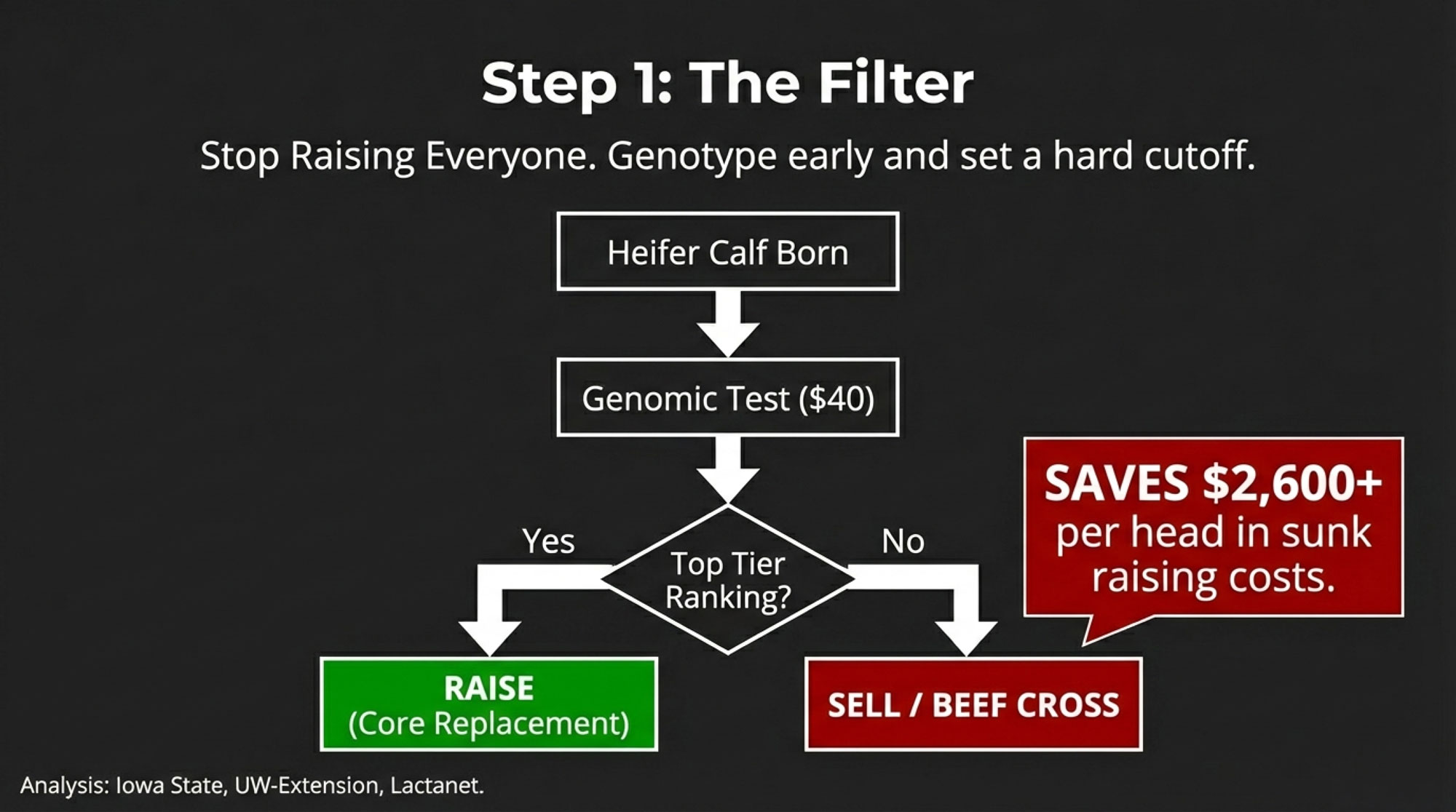

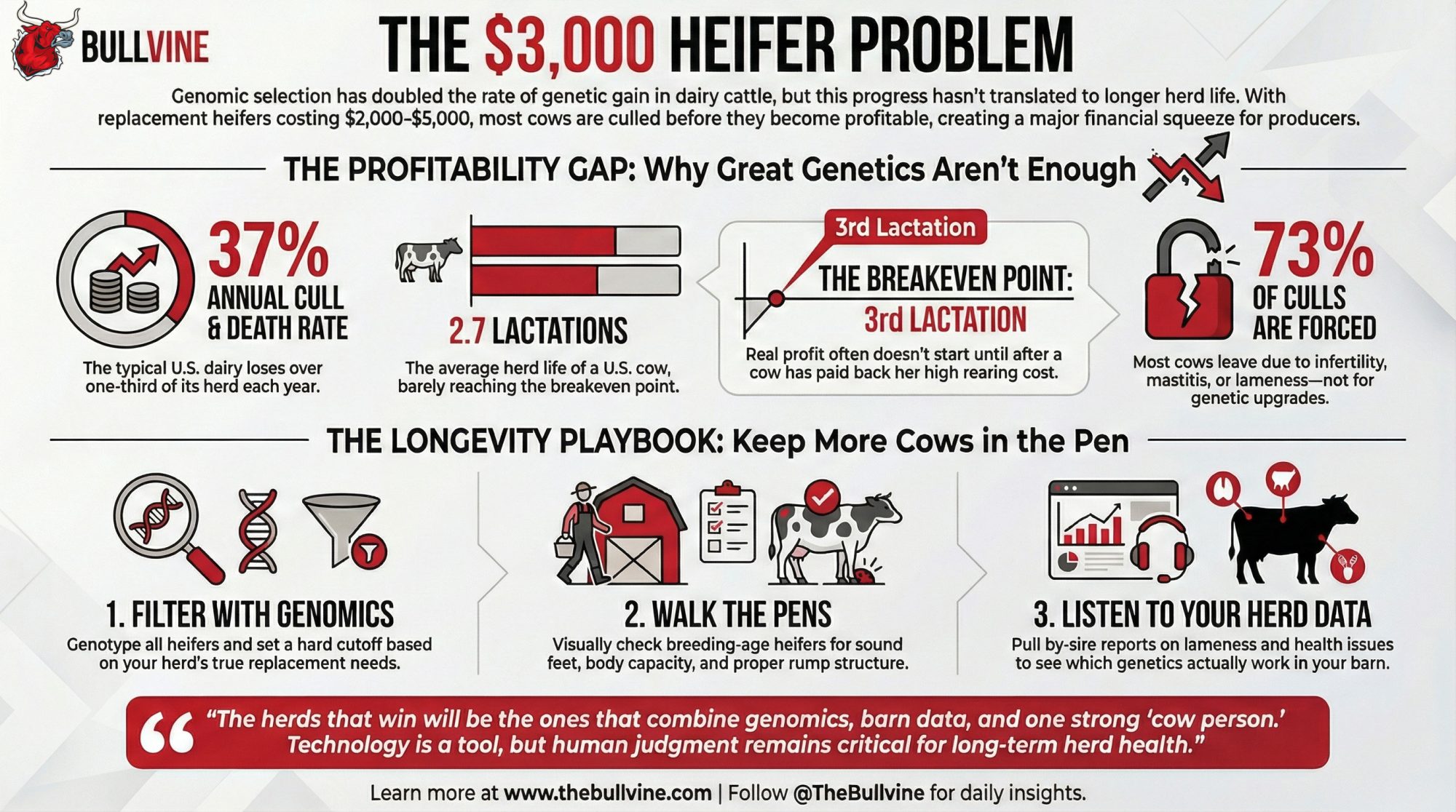

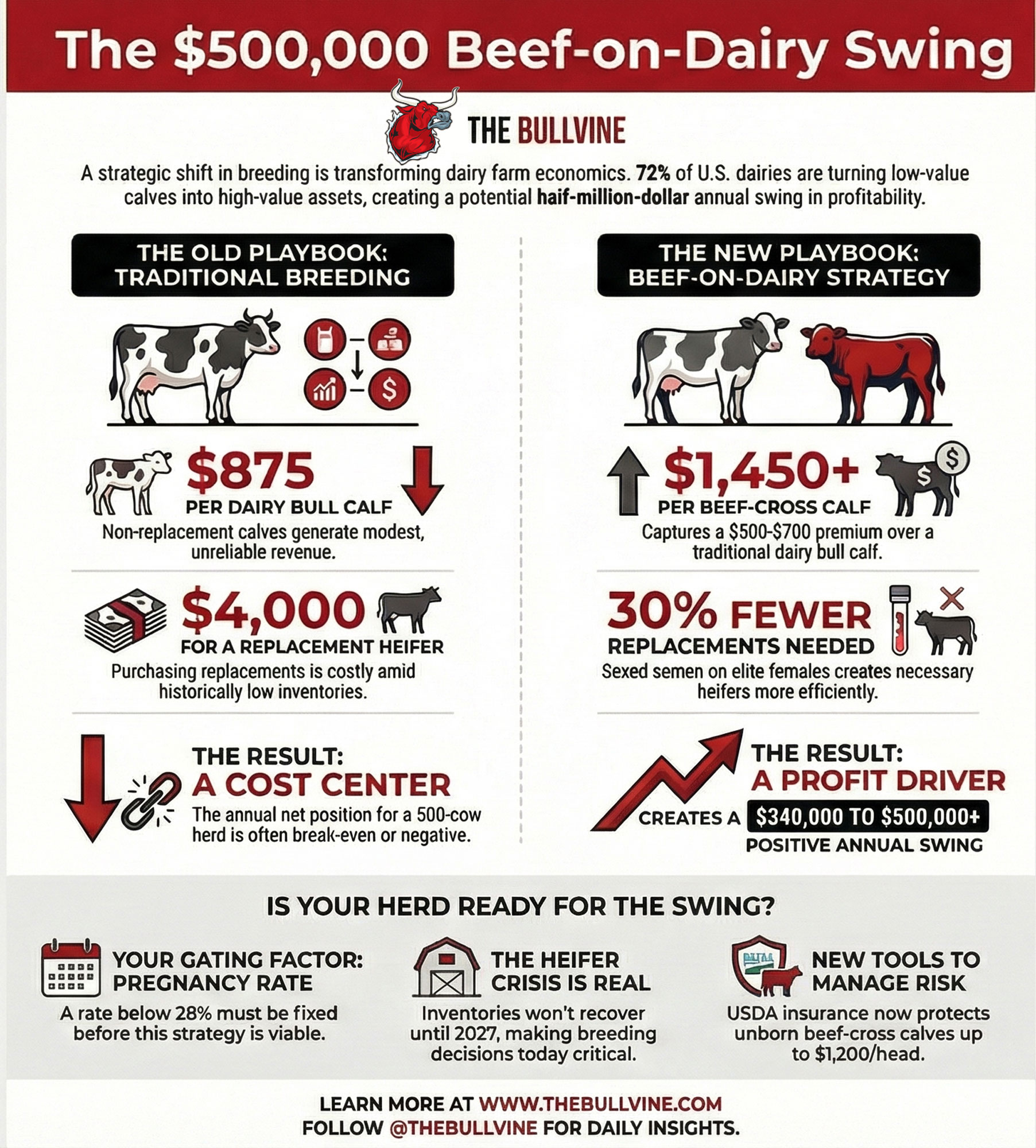

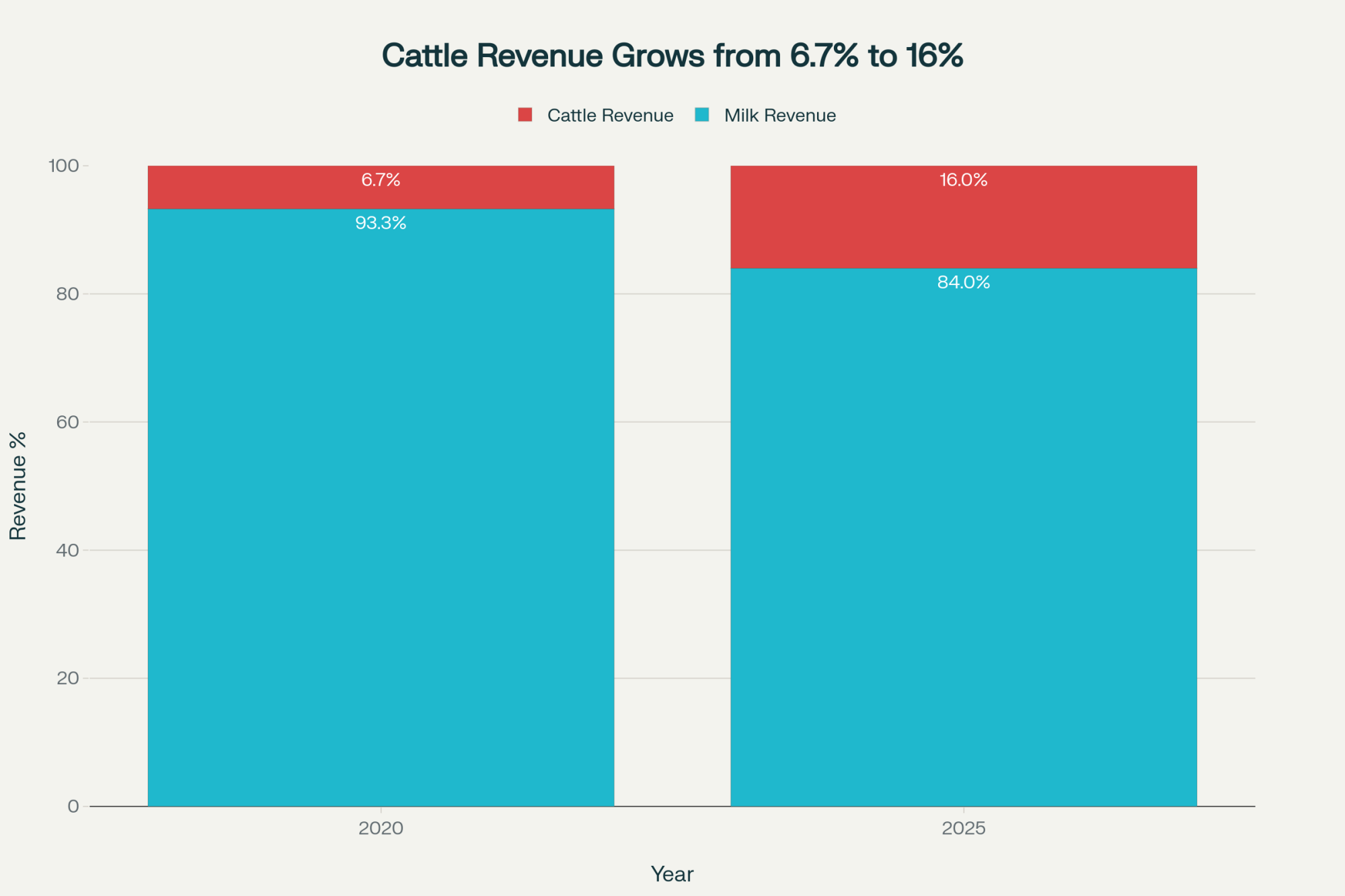

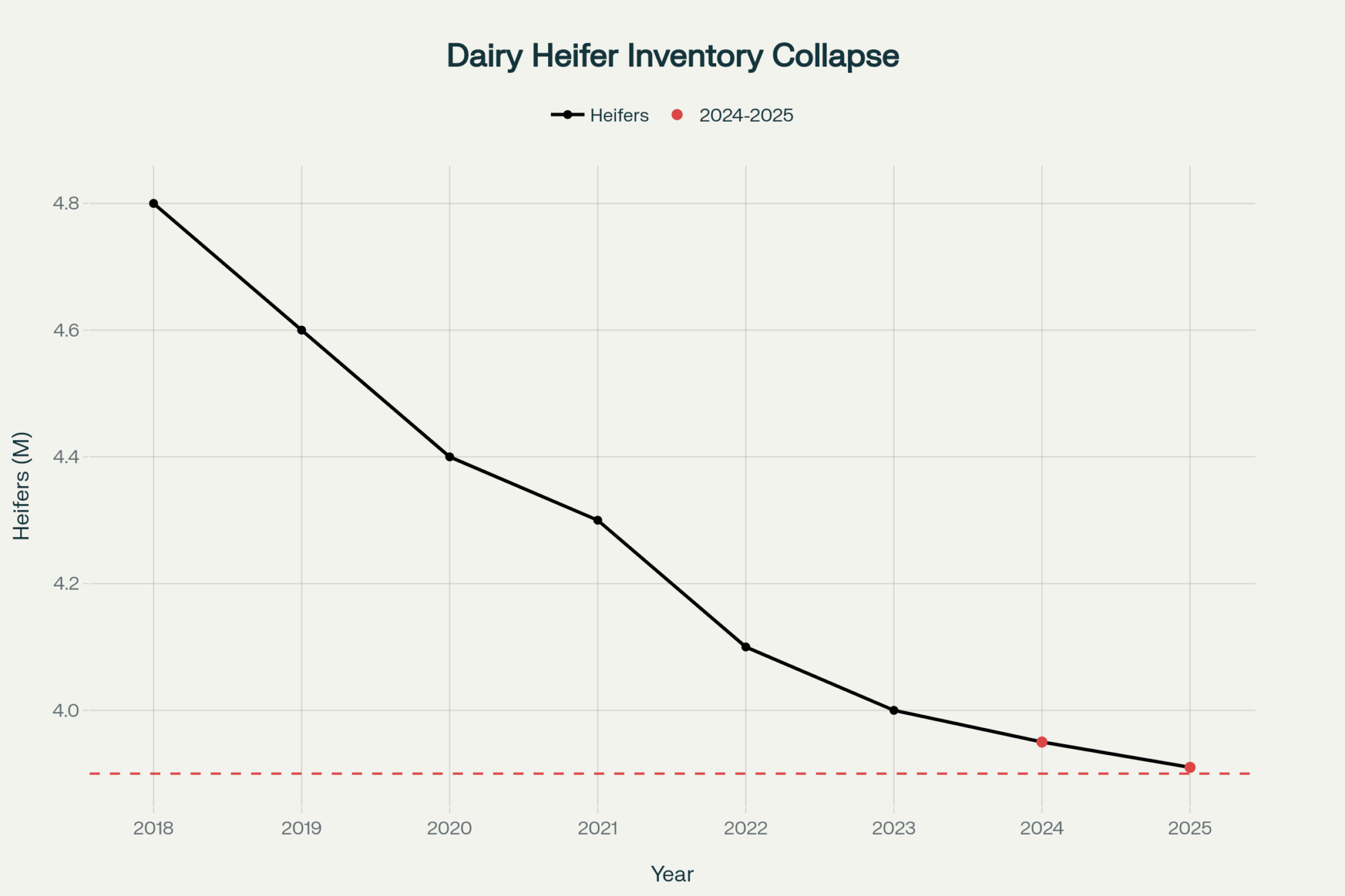

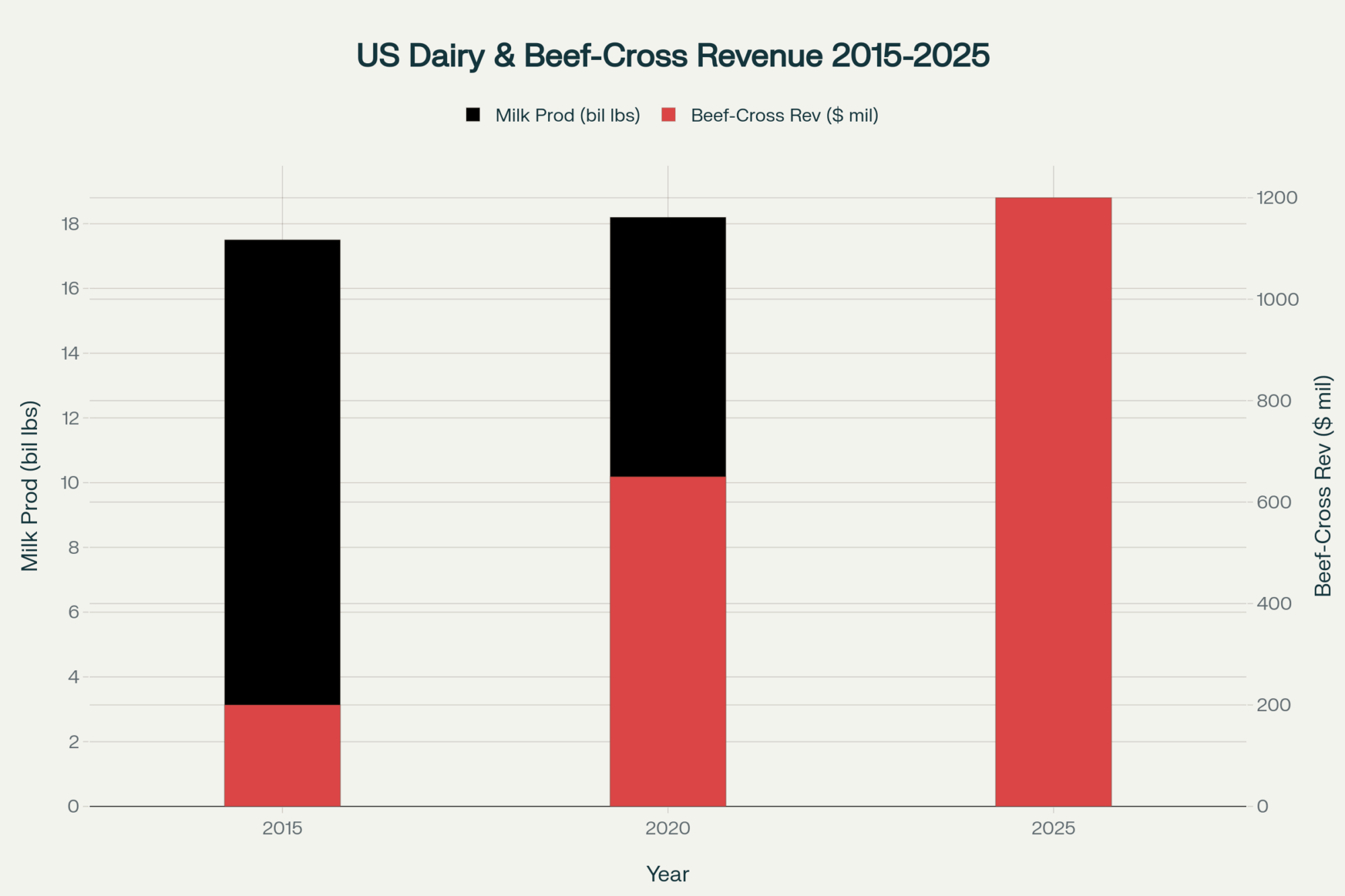

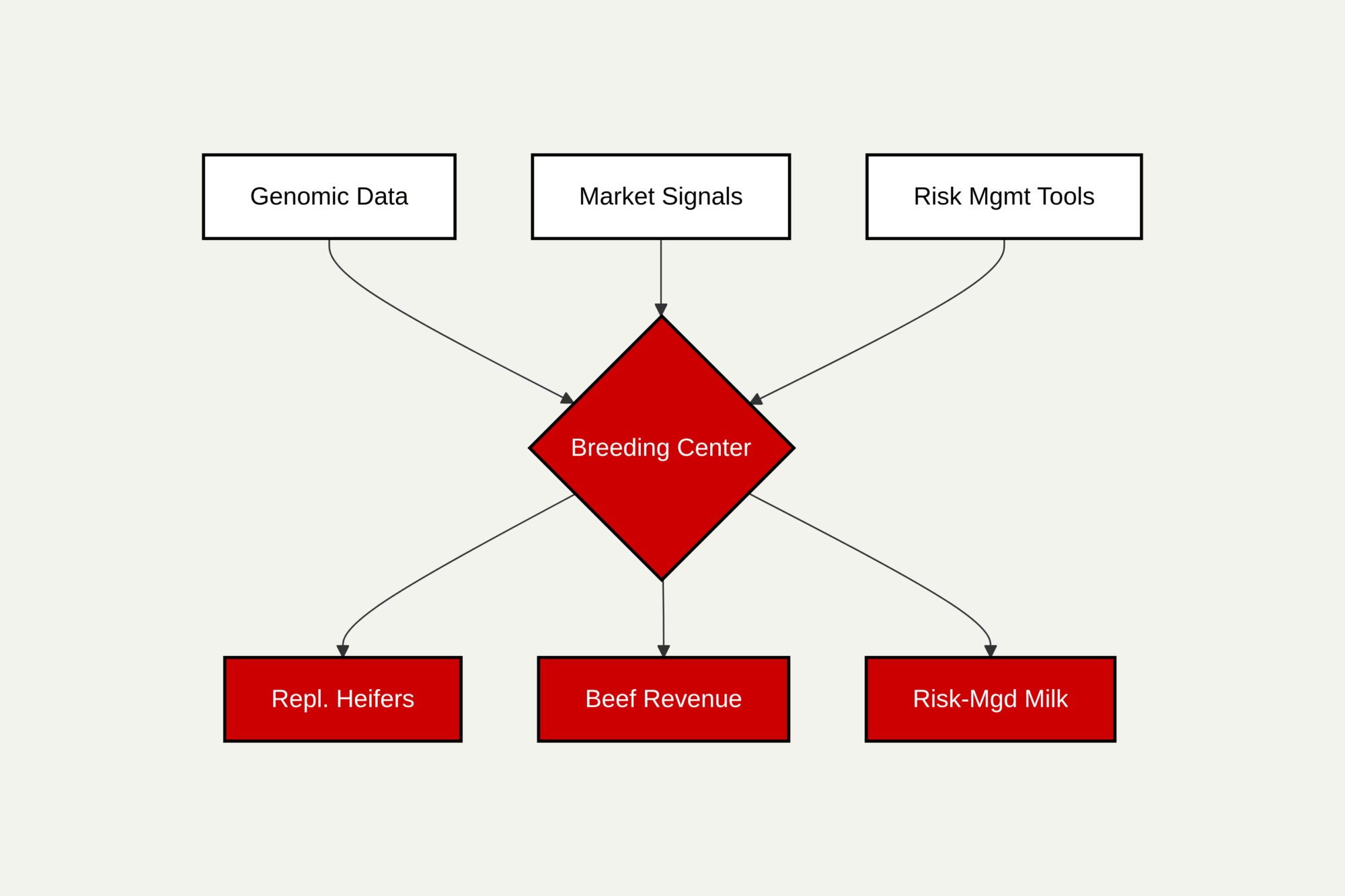

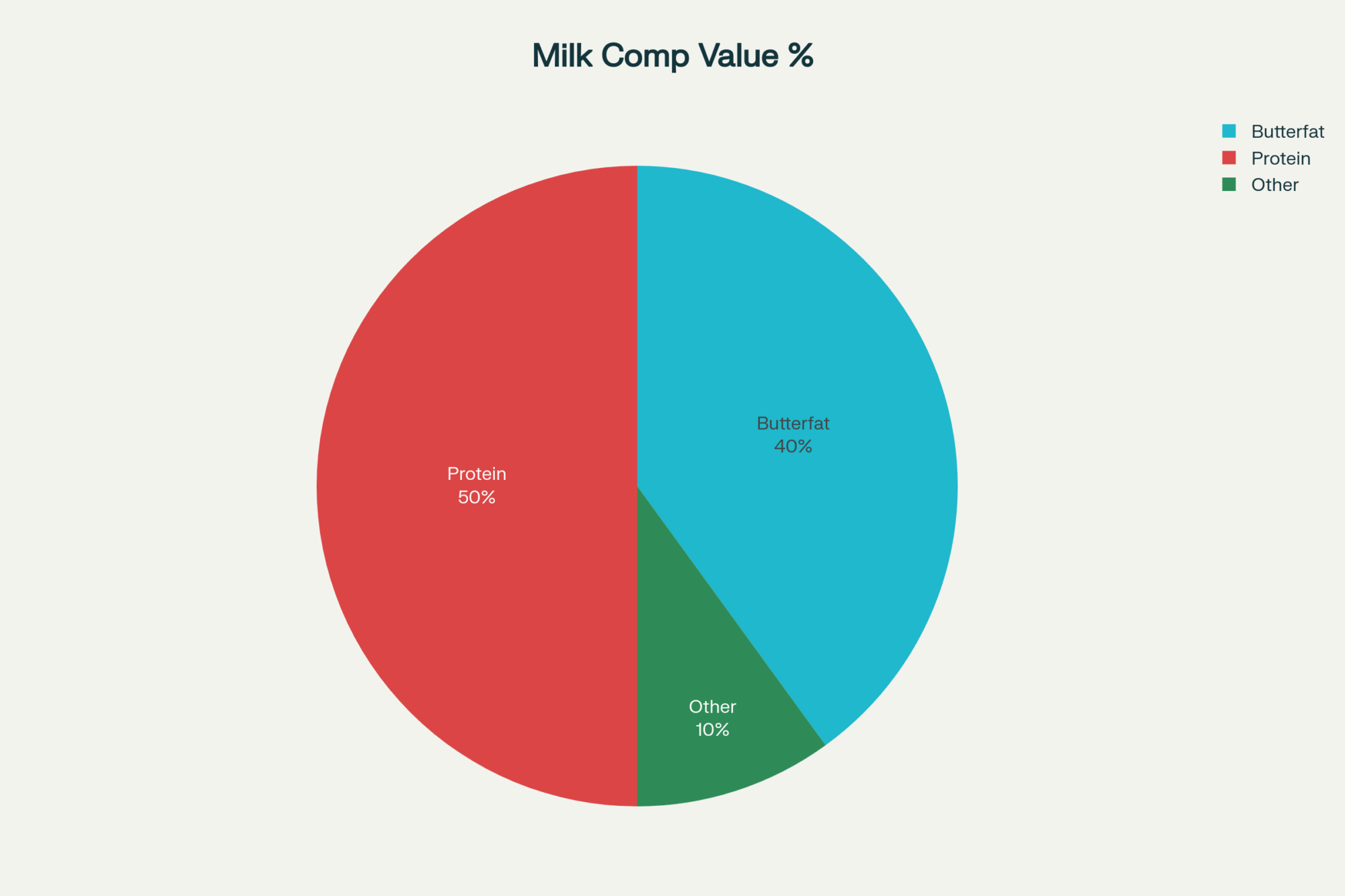

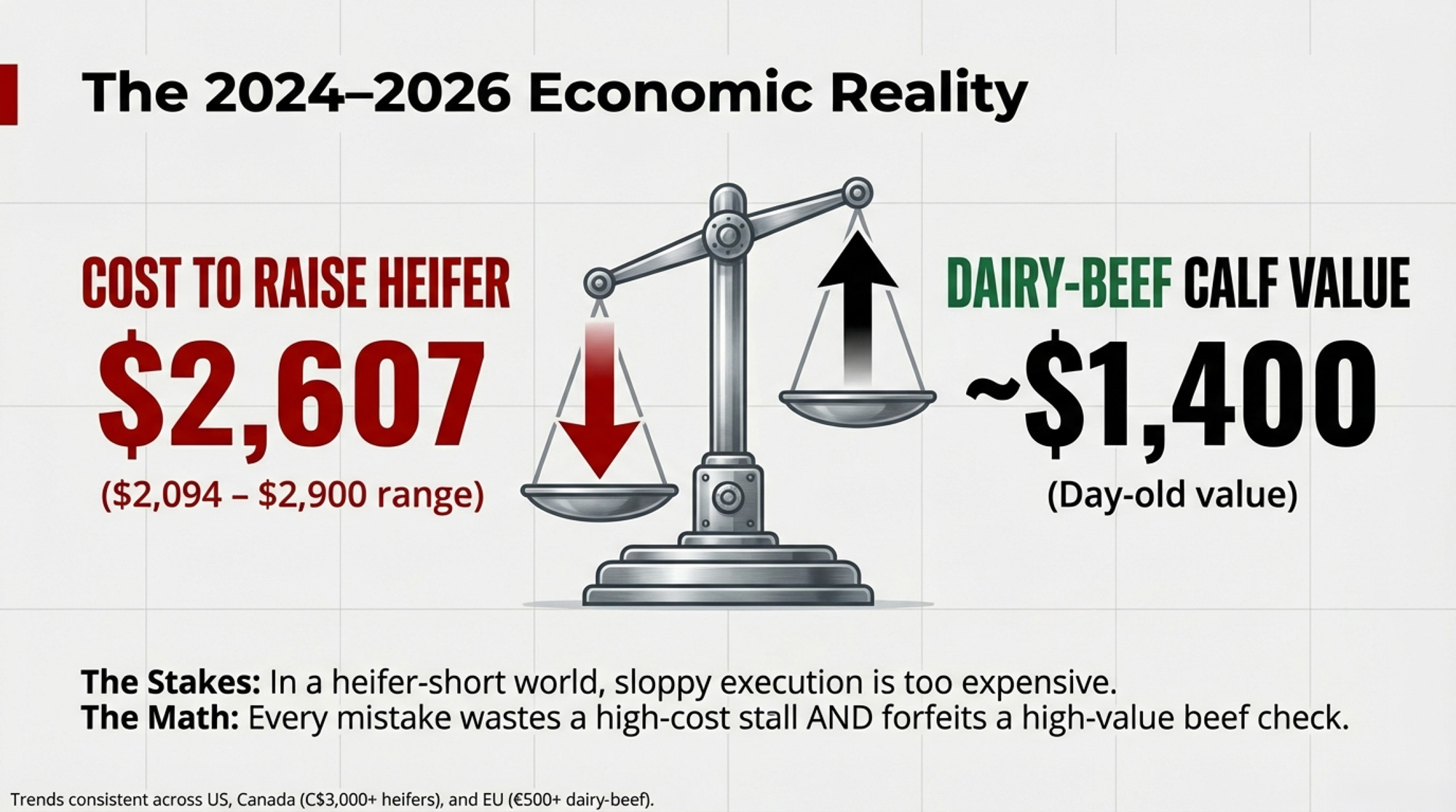

Executive Summary: In a heifer‑short, dairy‑beef market where it costs US$2,094–2,607 to raise a replacement, and day‑old beef‑on‑dairy calves can bring about US$1,400, sloppy execution has turned into a six‑figure problem for many dairies. This article uses McCarty Family Farm’s “top half only” genomic rule to show what happens when breeding, colostrum, and culling decisions actually match the math instead of the emotion. Data from MSU, Taiwanese sire‑checks, and large‑herd audits make the leak obvious: only 36% of farms hit FTPI targets, 27.78% of recorded sires are wrong, and even small timing errors in Double‑Ovsynch leave roughly a quarter of cows off‑protocol. From there, you get four concrete paths — harder genomic cutoffs with heifer‑inventory guardrails, redesigning impossible protocols instead of retraining, tracking results by person, and treating consistency as infrastructure — plus the trade‑offs on each. The summary farm‑level math on RPO, stall value, STP, and calf checks gives you simple “run your own numbers” thresholds so you can decide when to breed dairy, breed beef, or ship a cow based on what that stall can really earn over the next 12–24 months.

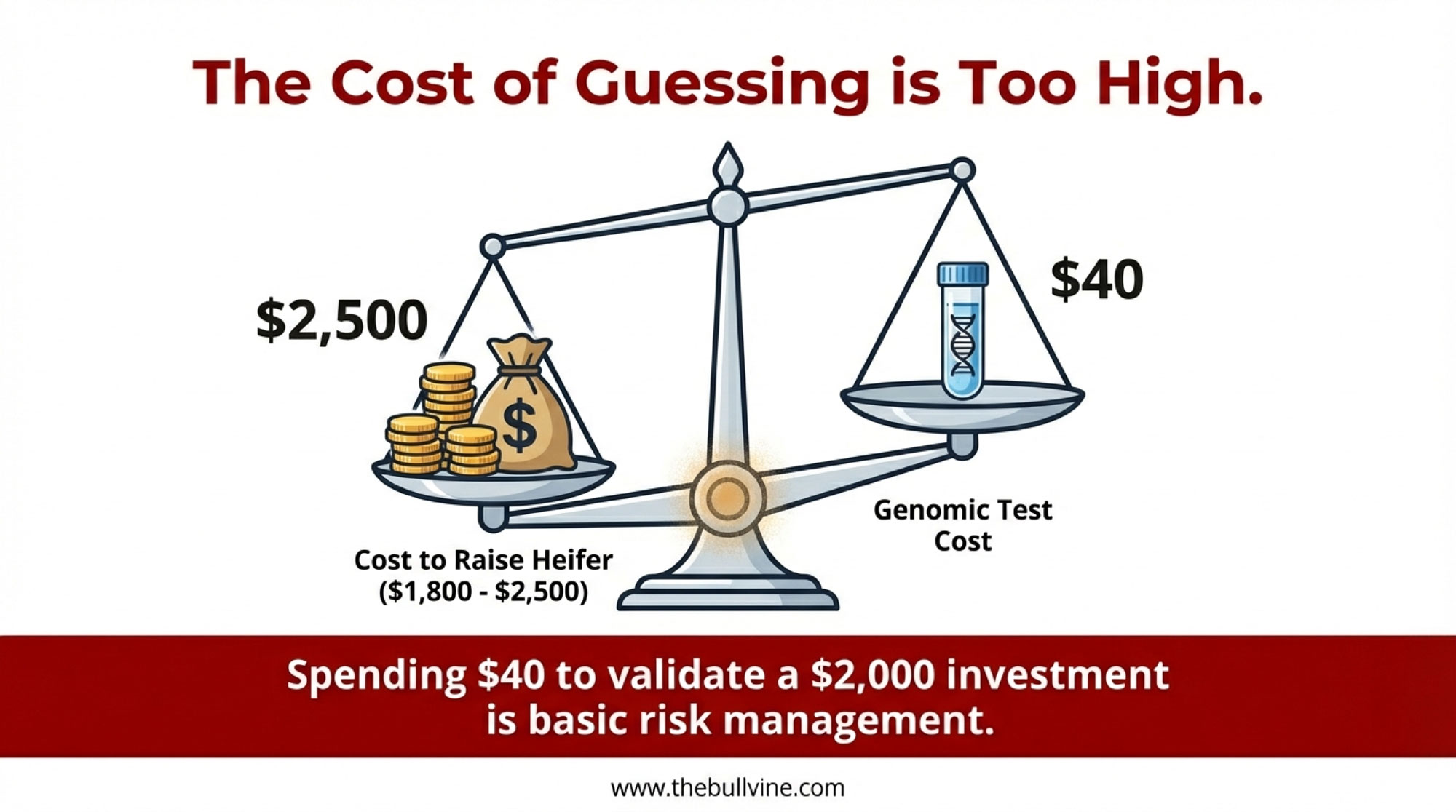

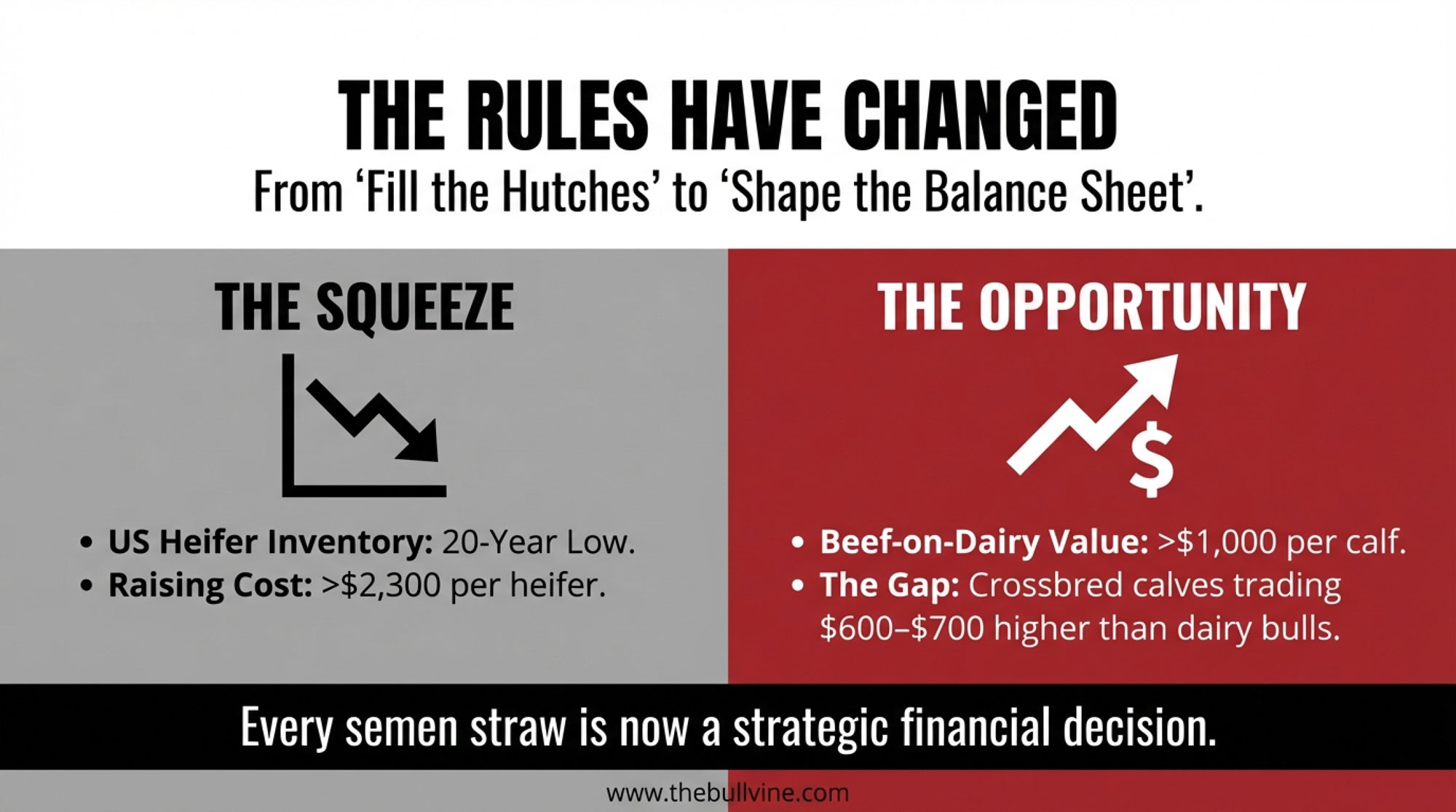

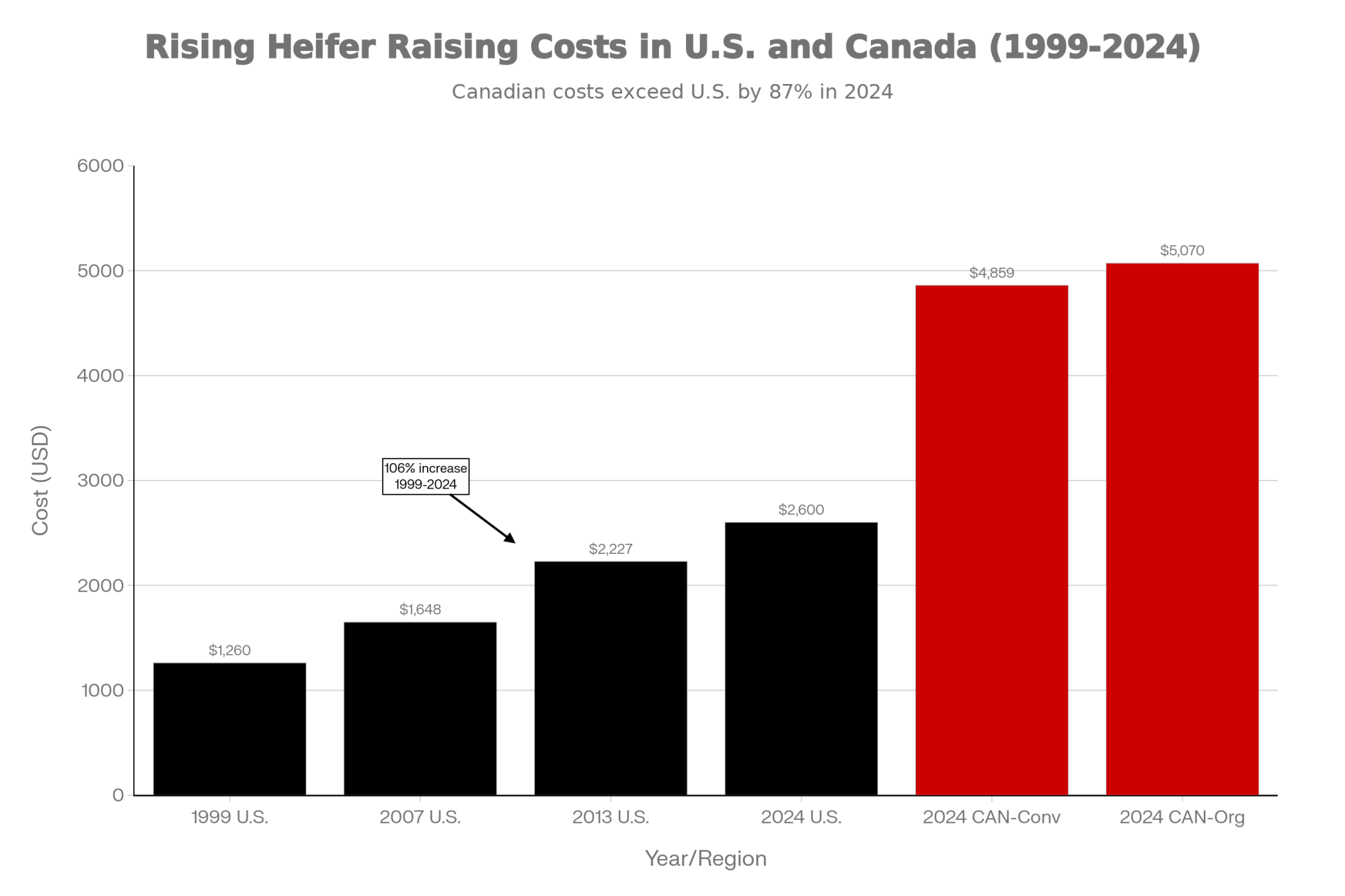

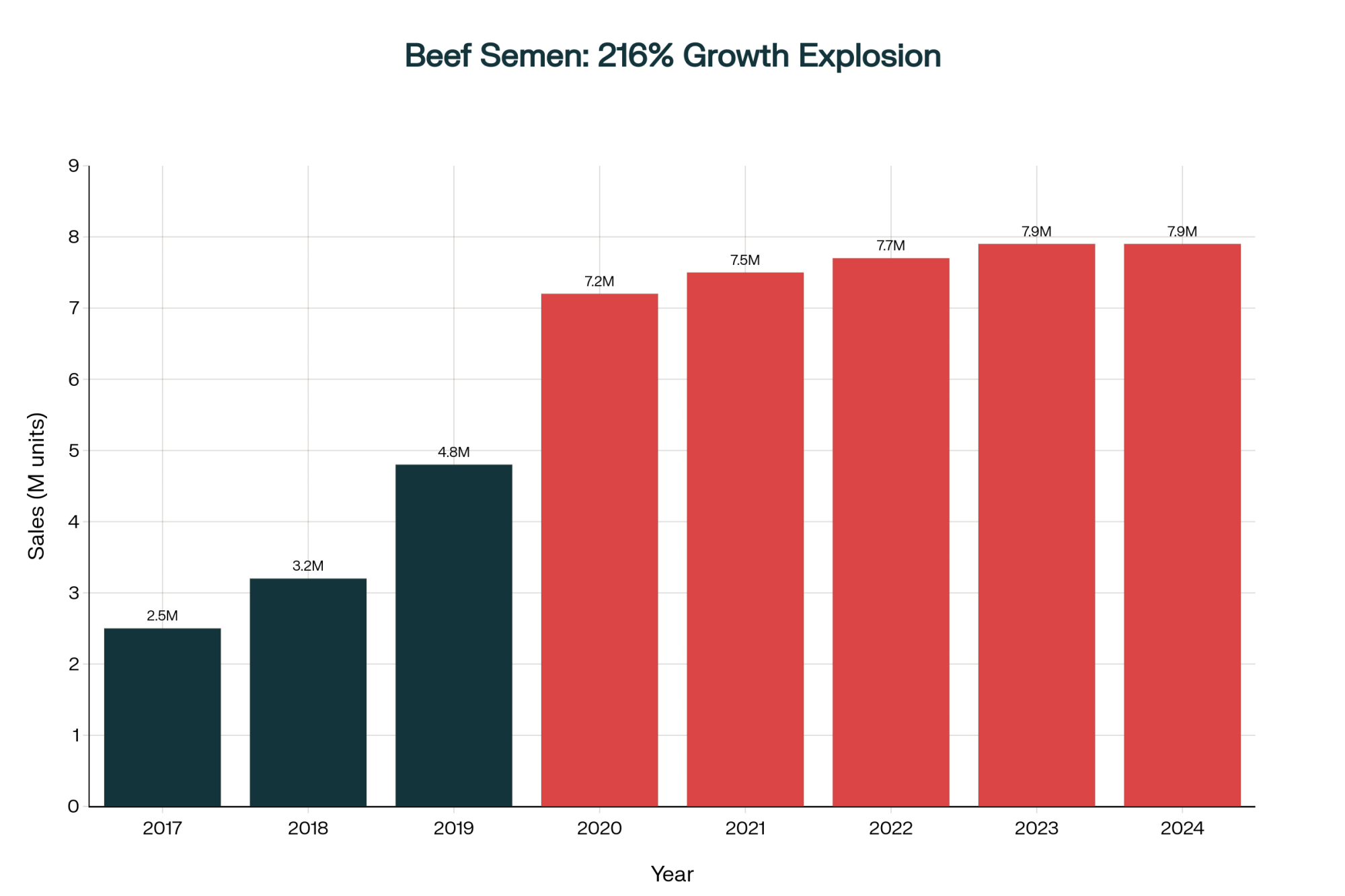

The most expensive execution gap on your dairy isn’t your semen bill, your ration, or even the latest heifer price spike. It’s the distance between what your protocols say and what actually happens when someone is standing in front of a cow with the wrong straw in his hand. In a heifer‑short, dairy‑beef world where total raising cost runs US$2,094–US$2,607 per heifer on many U.S. farms and can approach US$2,900 in higher‑cost systems, while top dairy‑beef calves in strong programs are bringing around US$1,400 per head, that gap adds up fast.

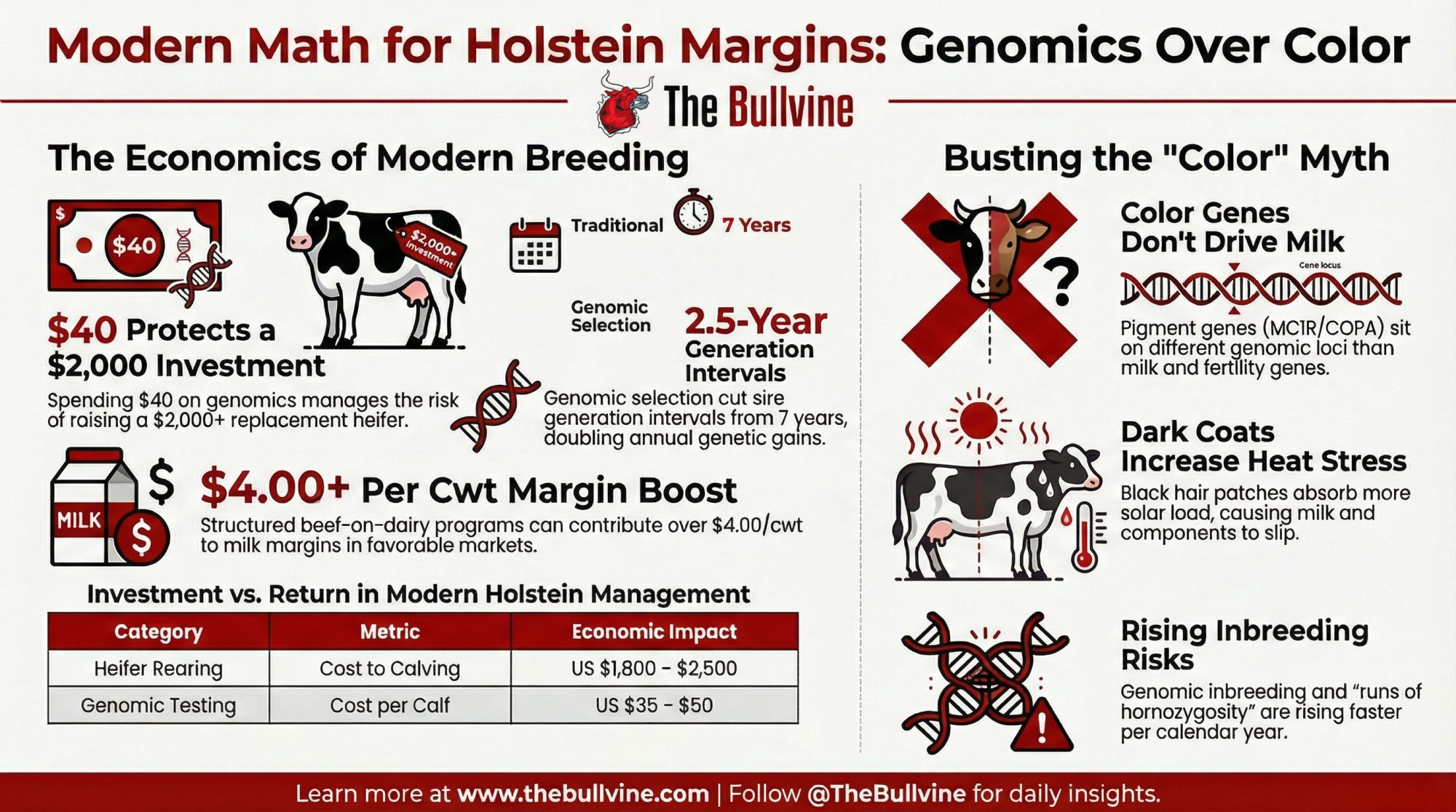

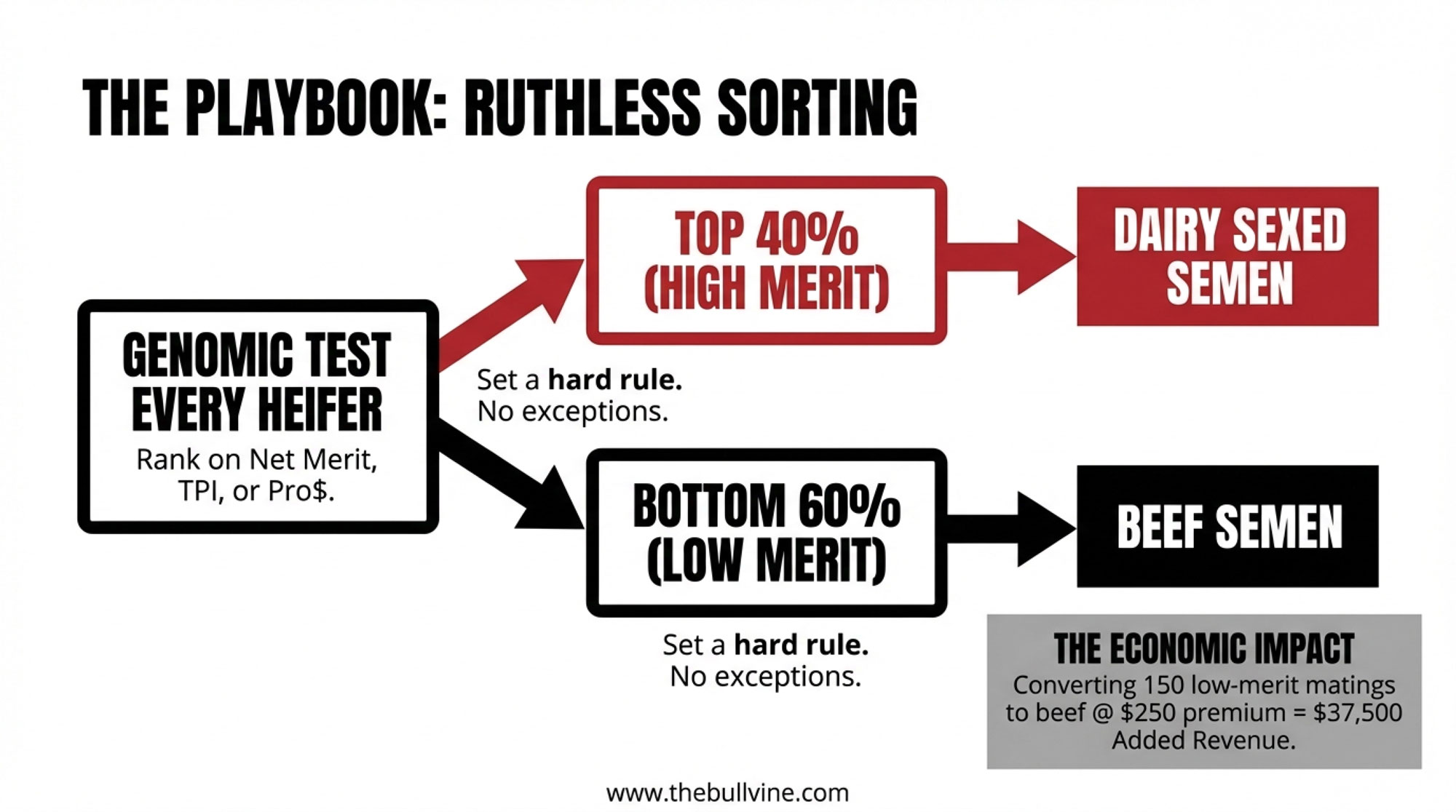

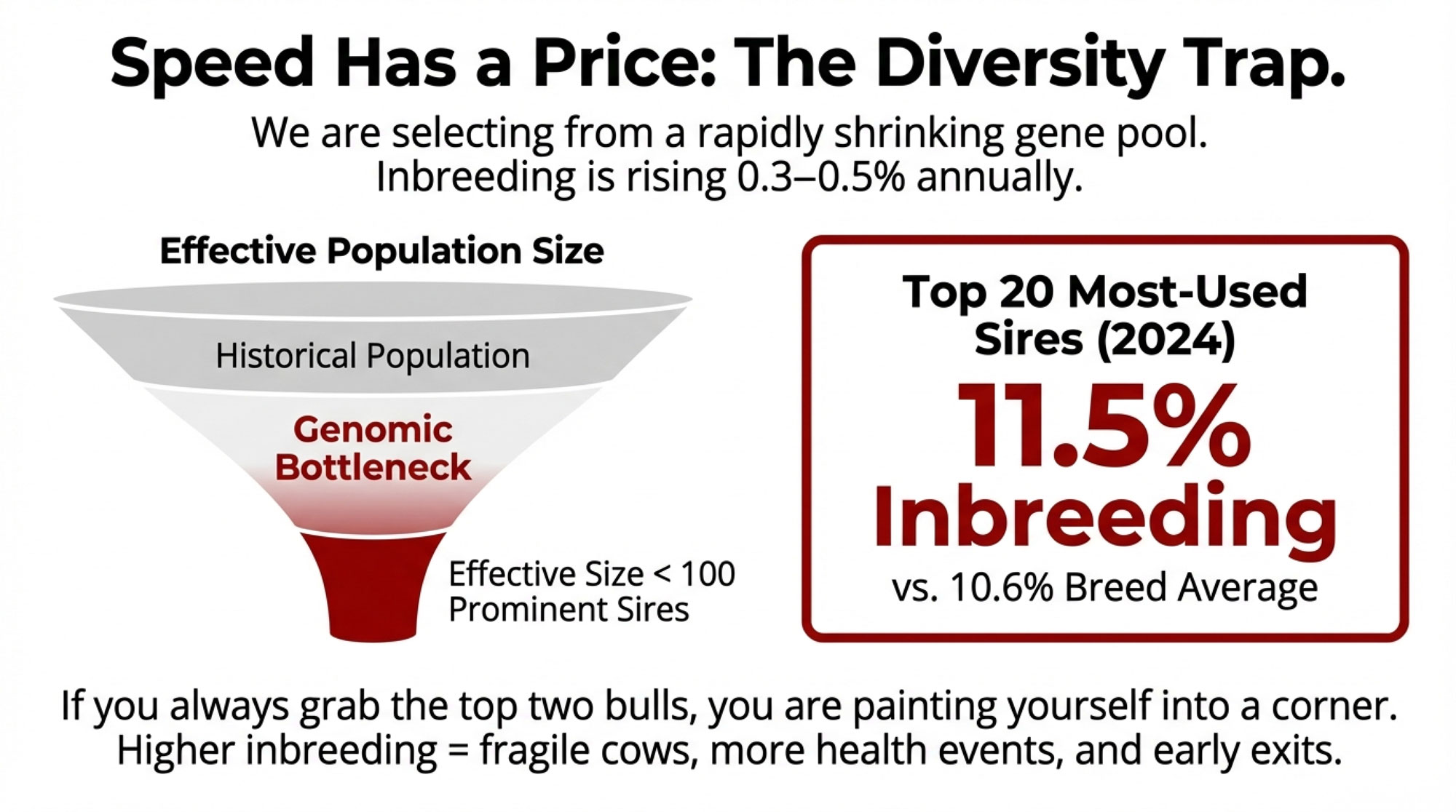

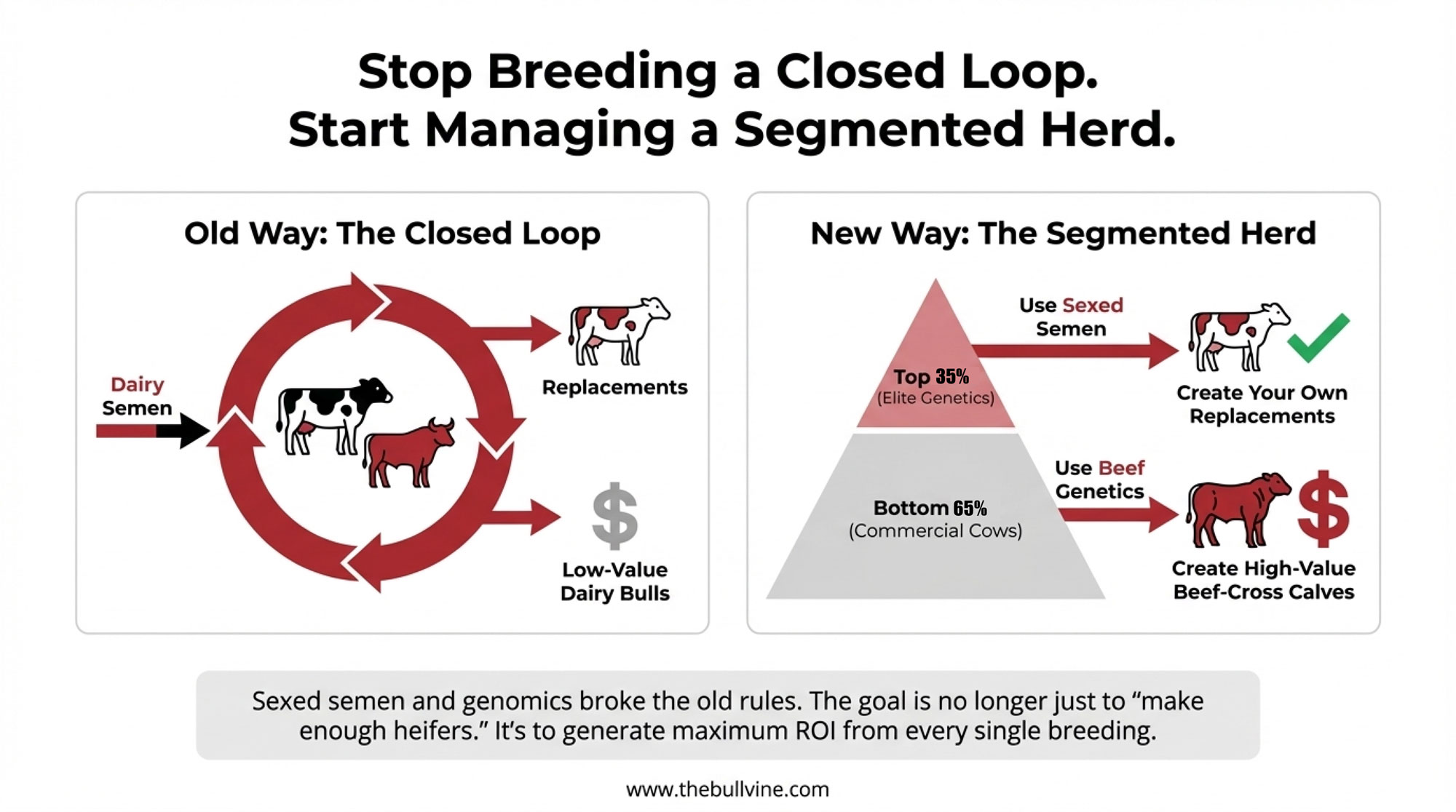

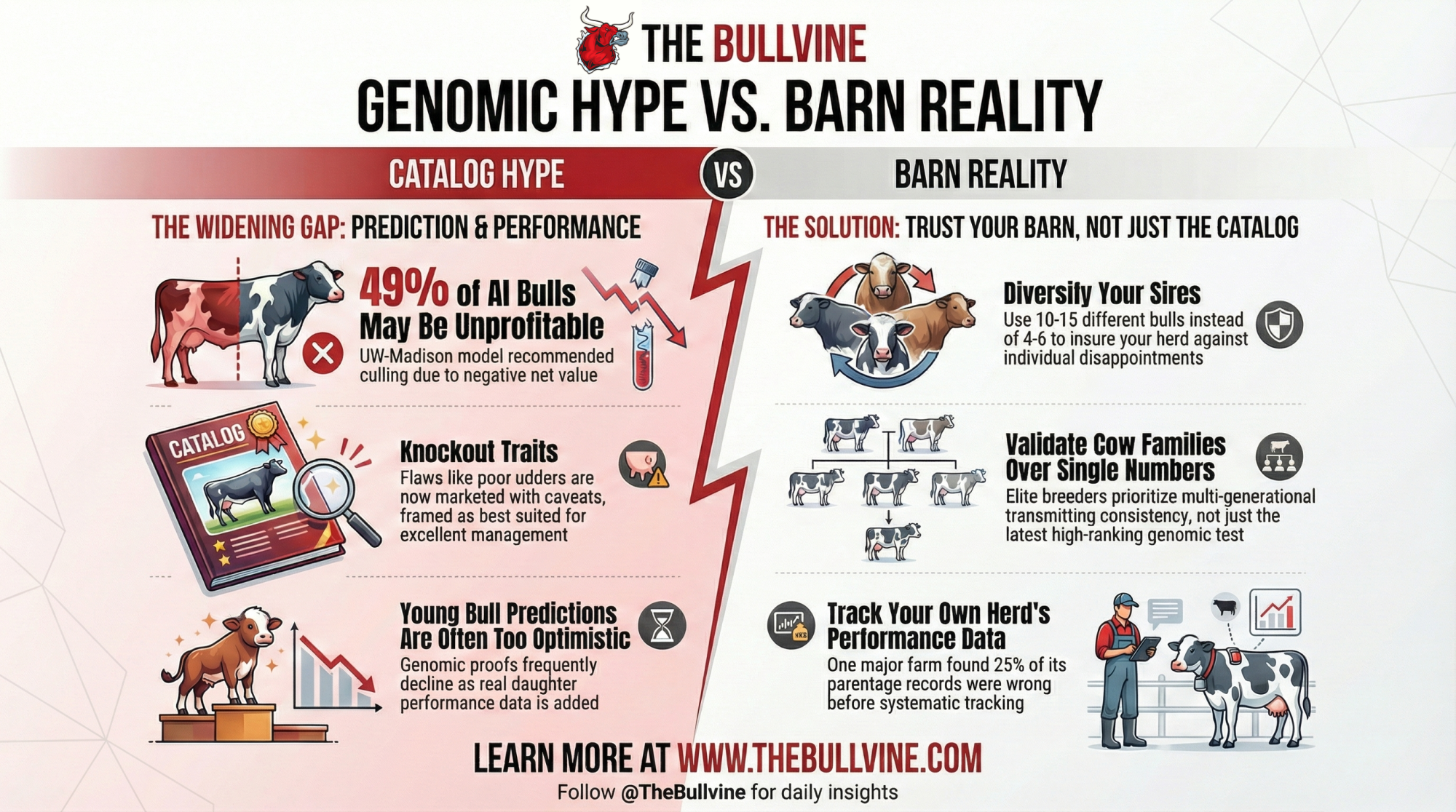

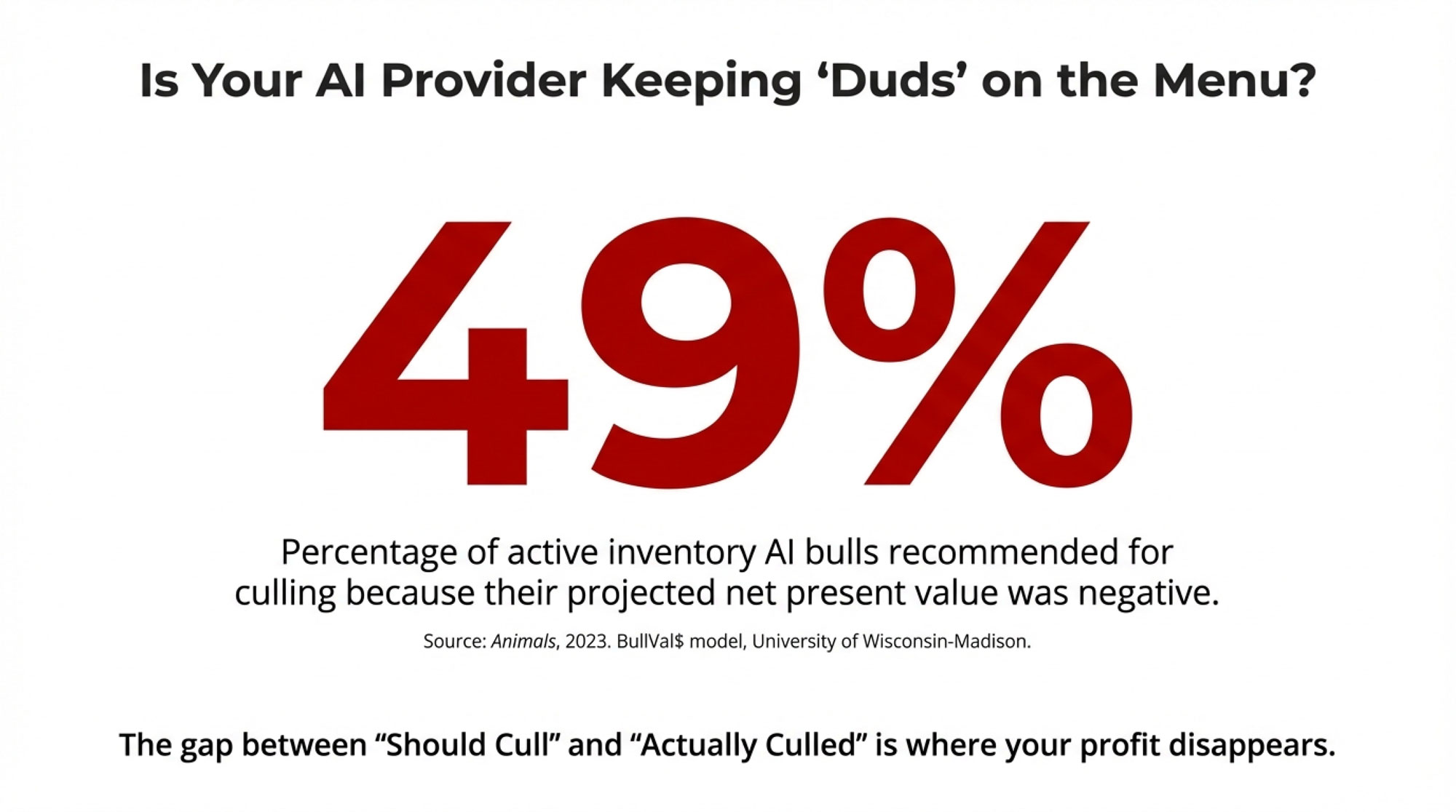

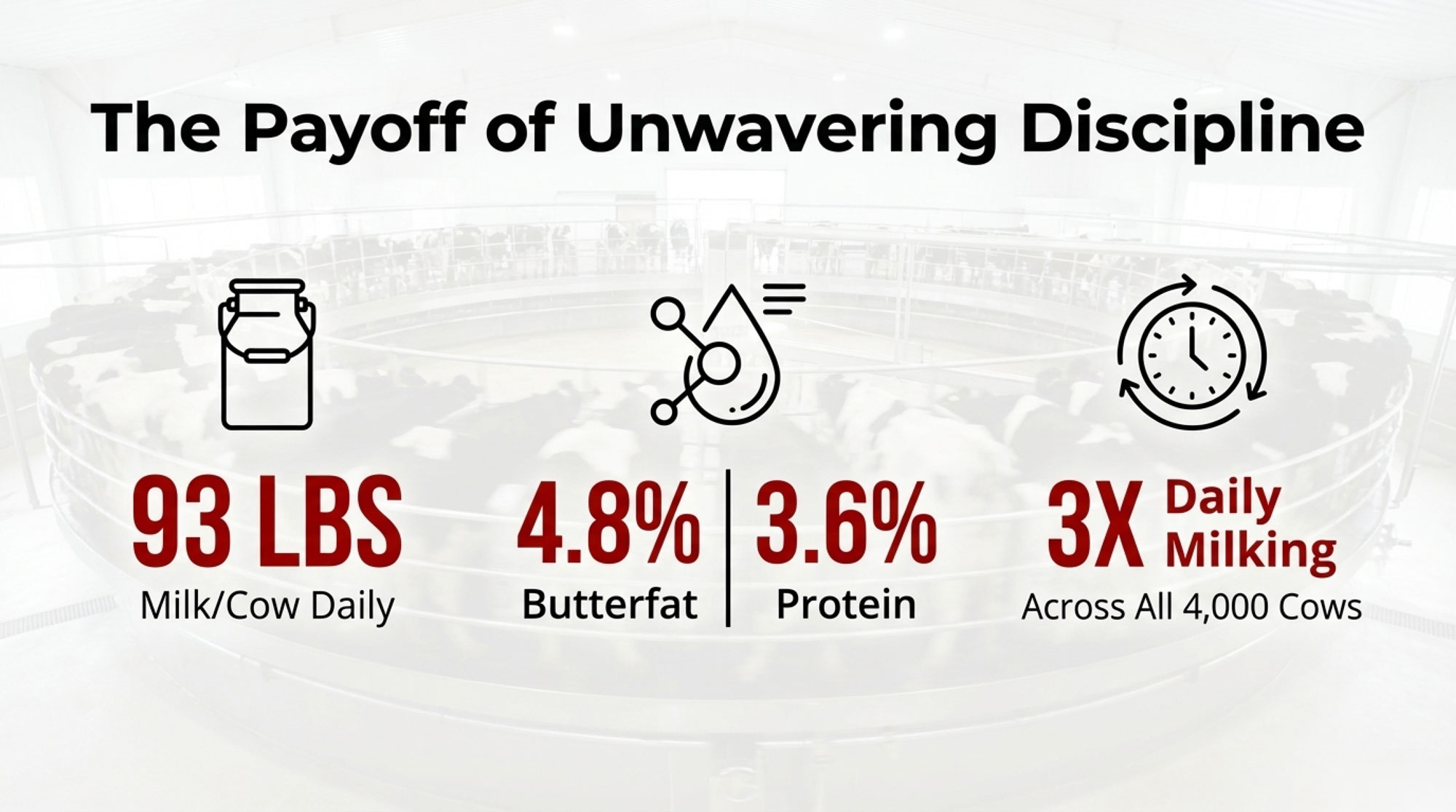

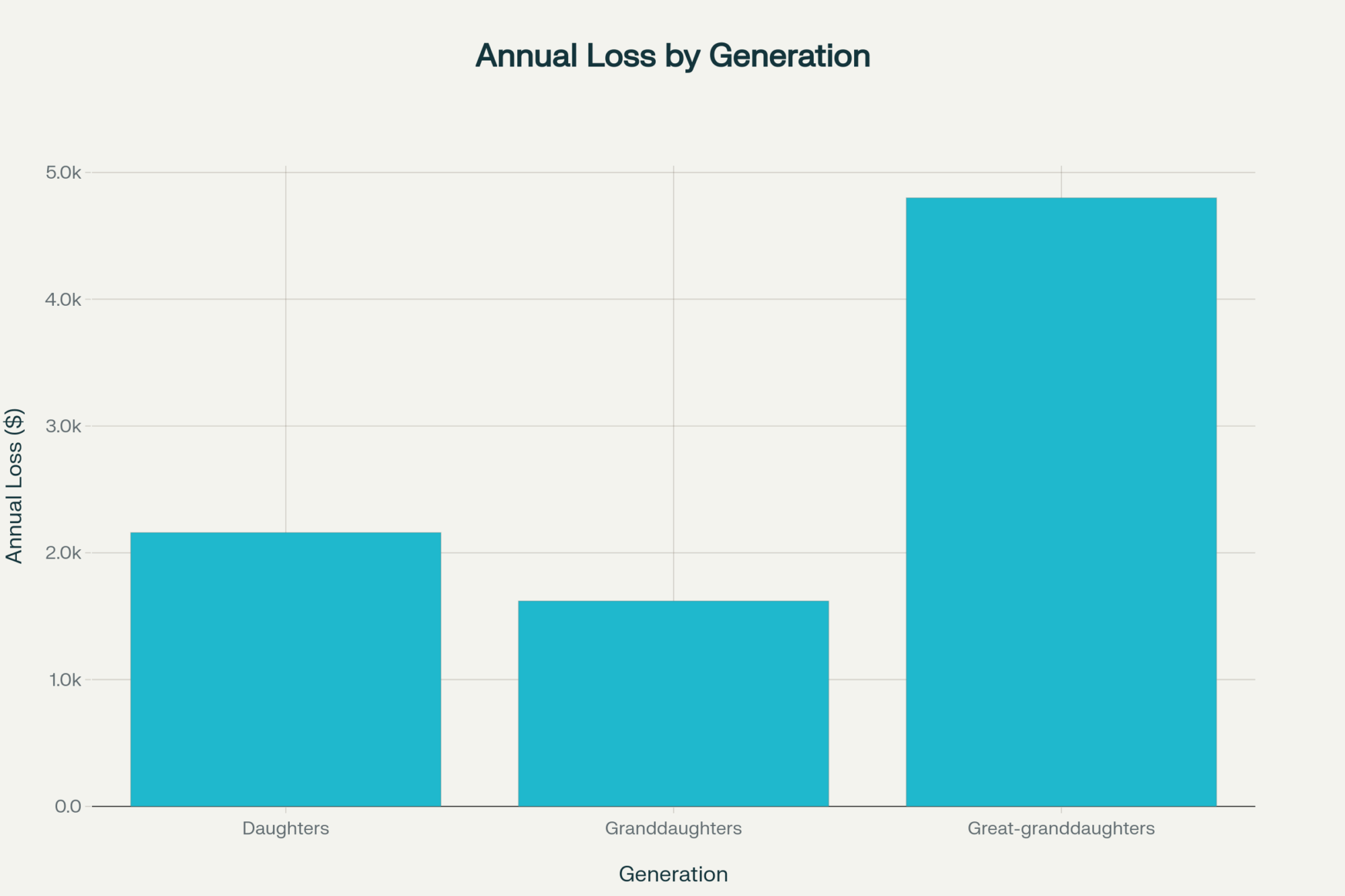

McCarty Family Farm in Kansas reports, based on its own records, that it has genomically tested more than 75,000 females since 2018. Their rule is brutally simple: the top half of the breeding herd creates the next generation, the bottom half goes to beef — regardless of age or stage. Applied consistently across breeding, colostrum, and culling, that kind of discipline can drive a six‑figure annual swing in profitability for larger herds compared to “raise every heifer” systems once you factor in stall value, heifer cost, and dairy‑beef calf prices.

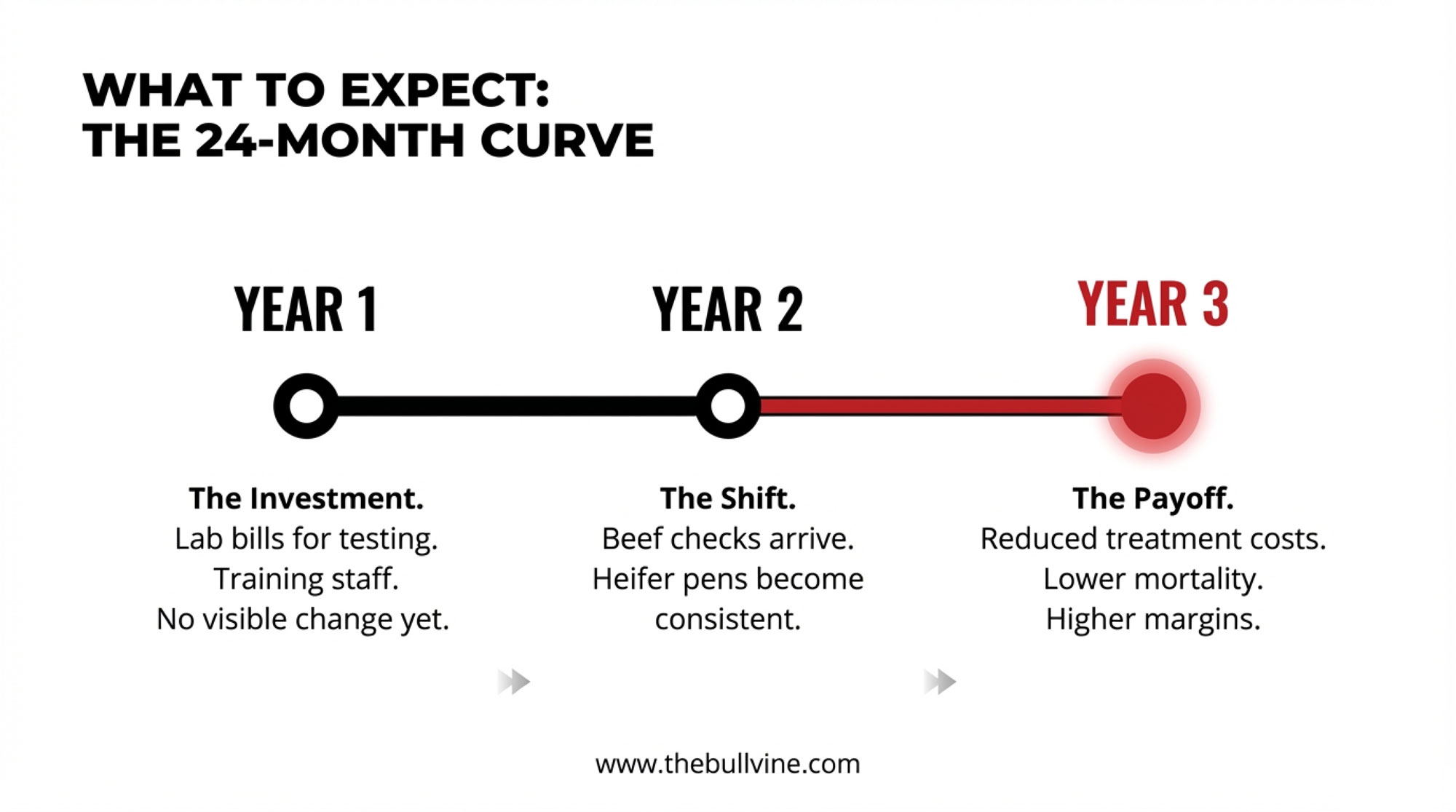

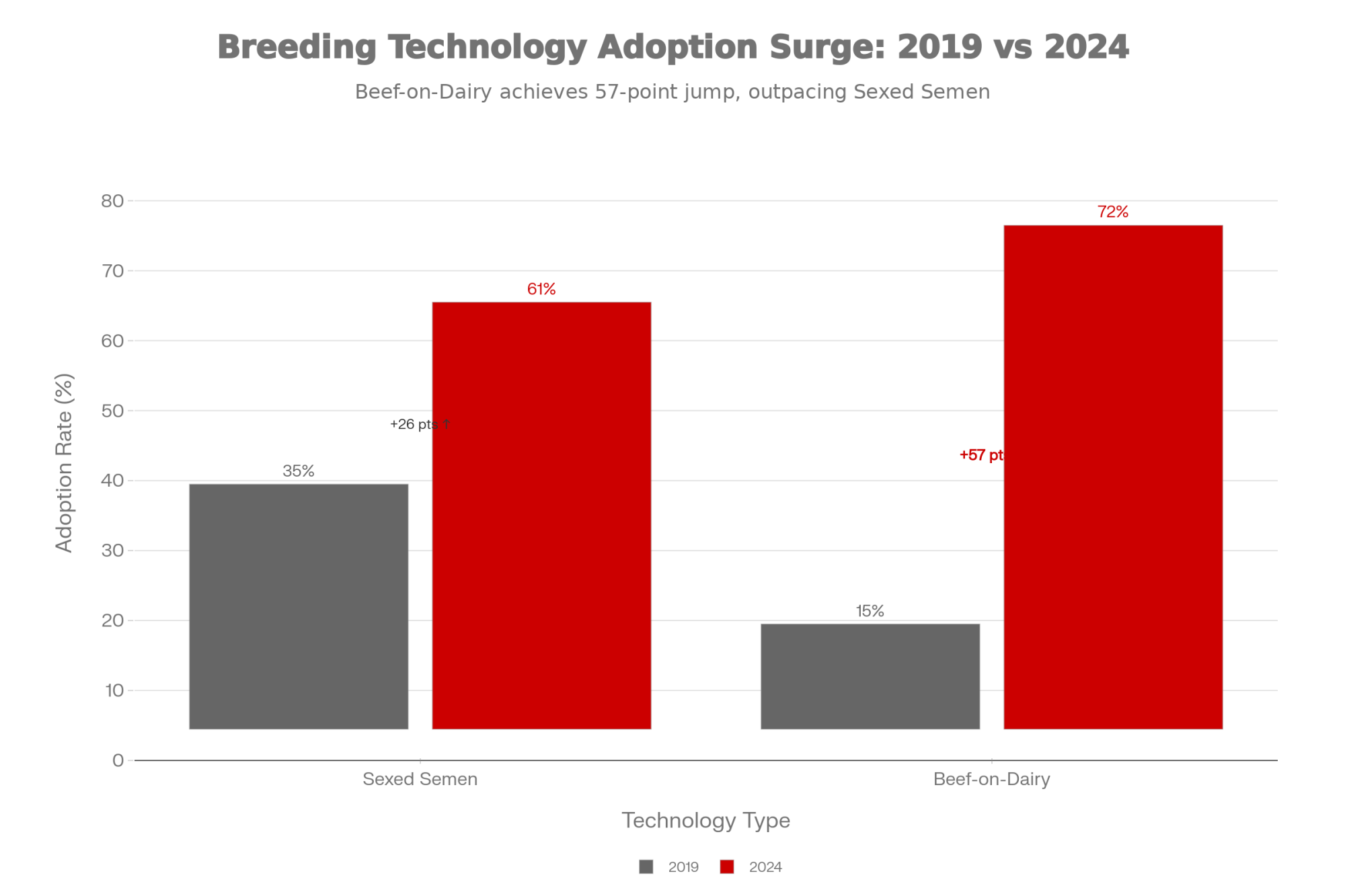

If you’re running genomics, dairy‑beef, or both, this isn’t theory. This is your milk cheque, your replacement pipeline, and your risk exposure for 2024–2026.

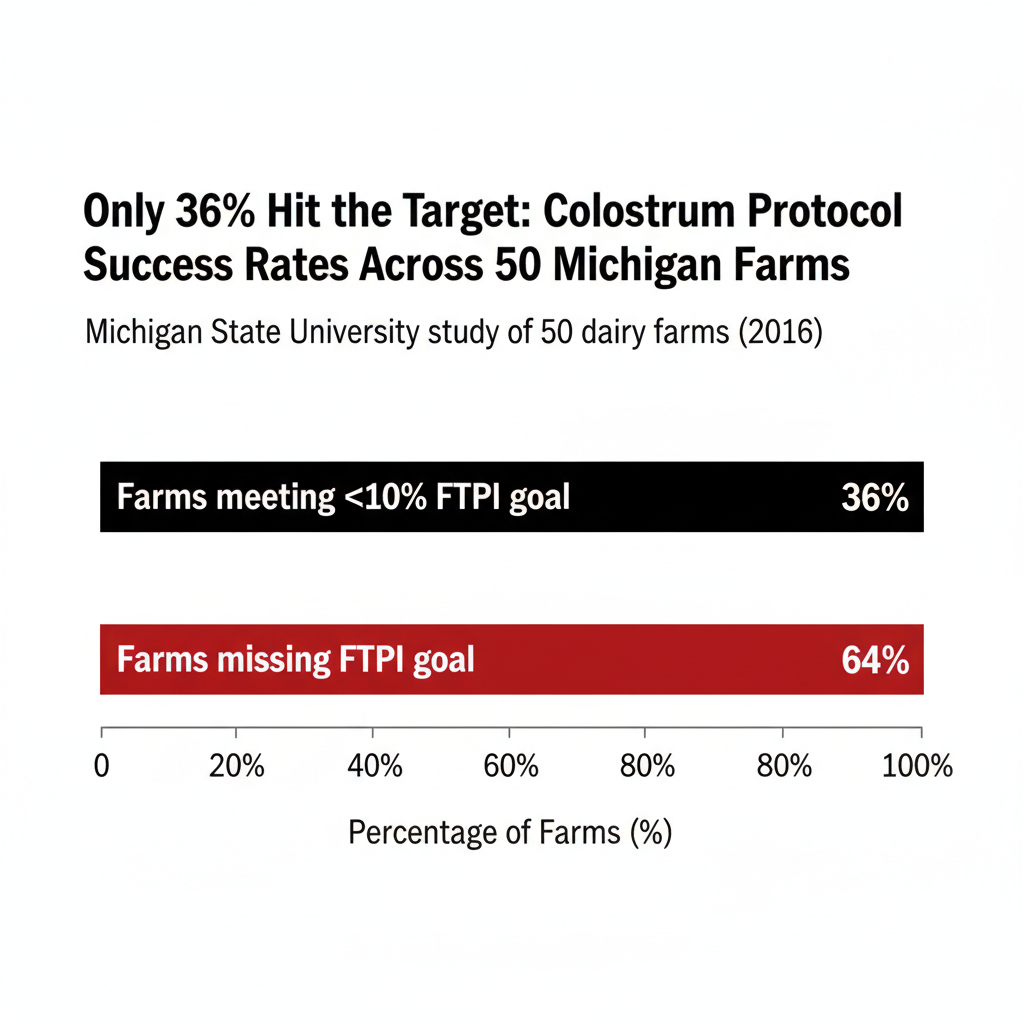

Only 36% of Farms Hit Their Colostrum Targets

Back in 2016, Michigan State University Extension and collaborators looked at the failure of passive transfer (FTPI) and colostrum management on 50 Michigan dairy farms. Only 18 of those 50 farms (36%) hit the industry goal of less than 10% FTPI, meaning at least 90% of calves achieved successful passive transfer. That left 32 farms missing the target, and on six of those herds, half or more of the calves failed. These weren’t wrecks. They were farms that thought their colostrum program worked.

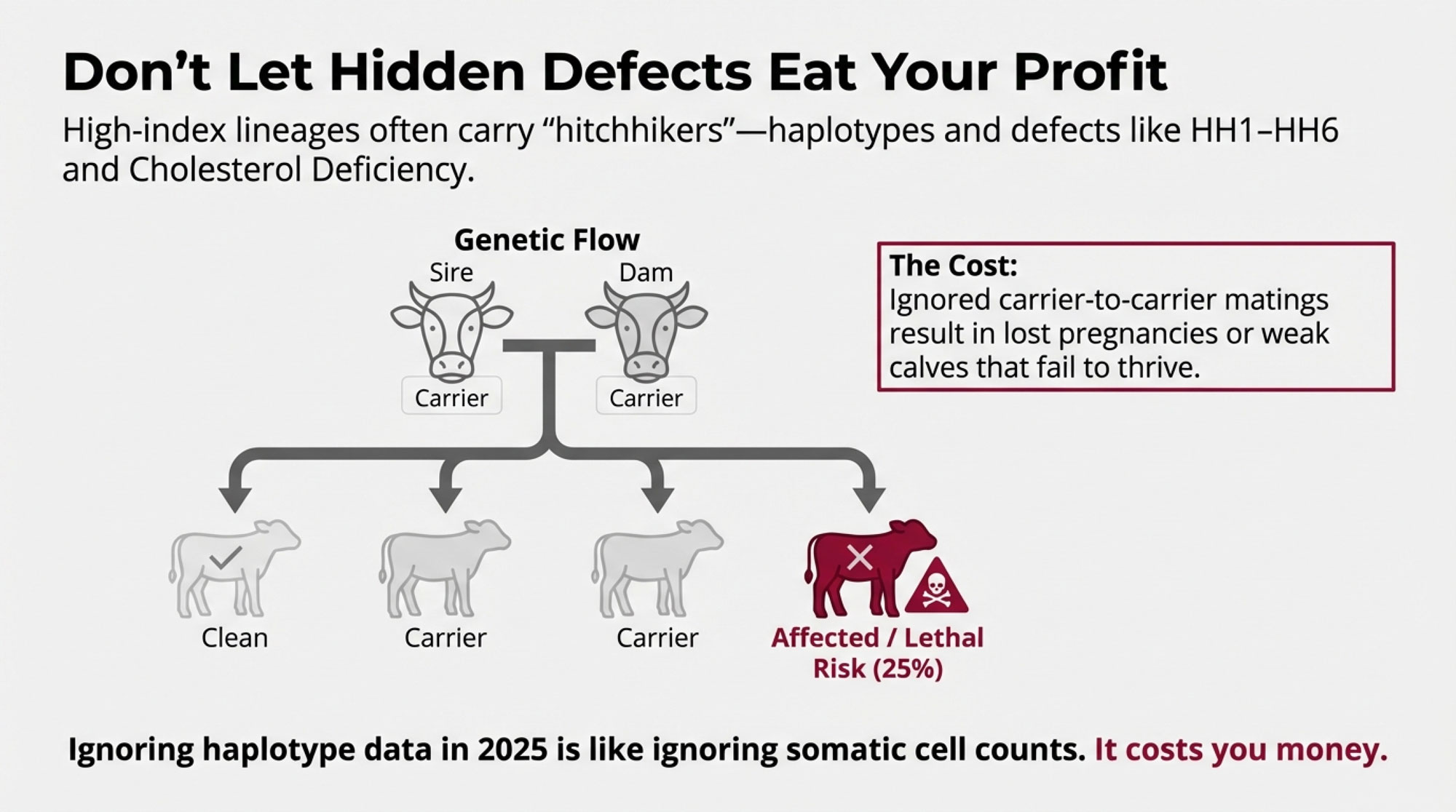

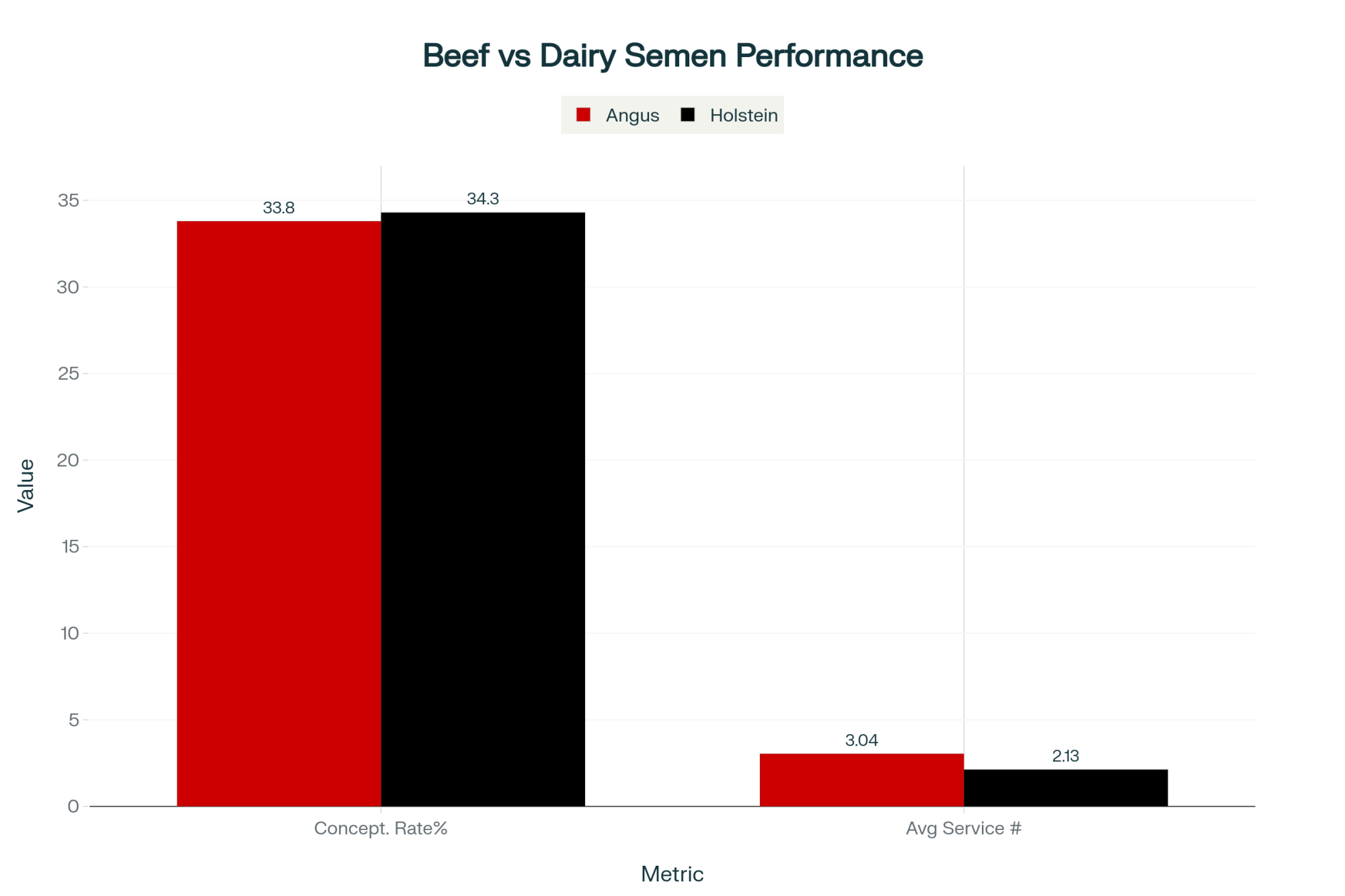

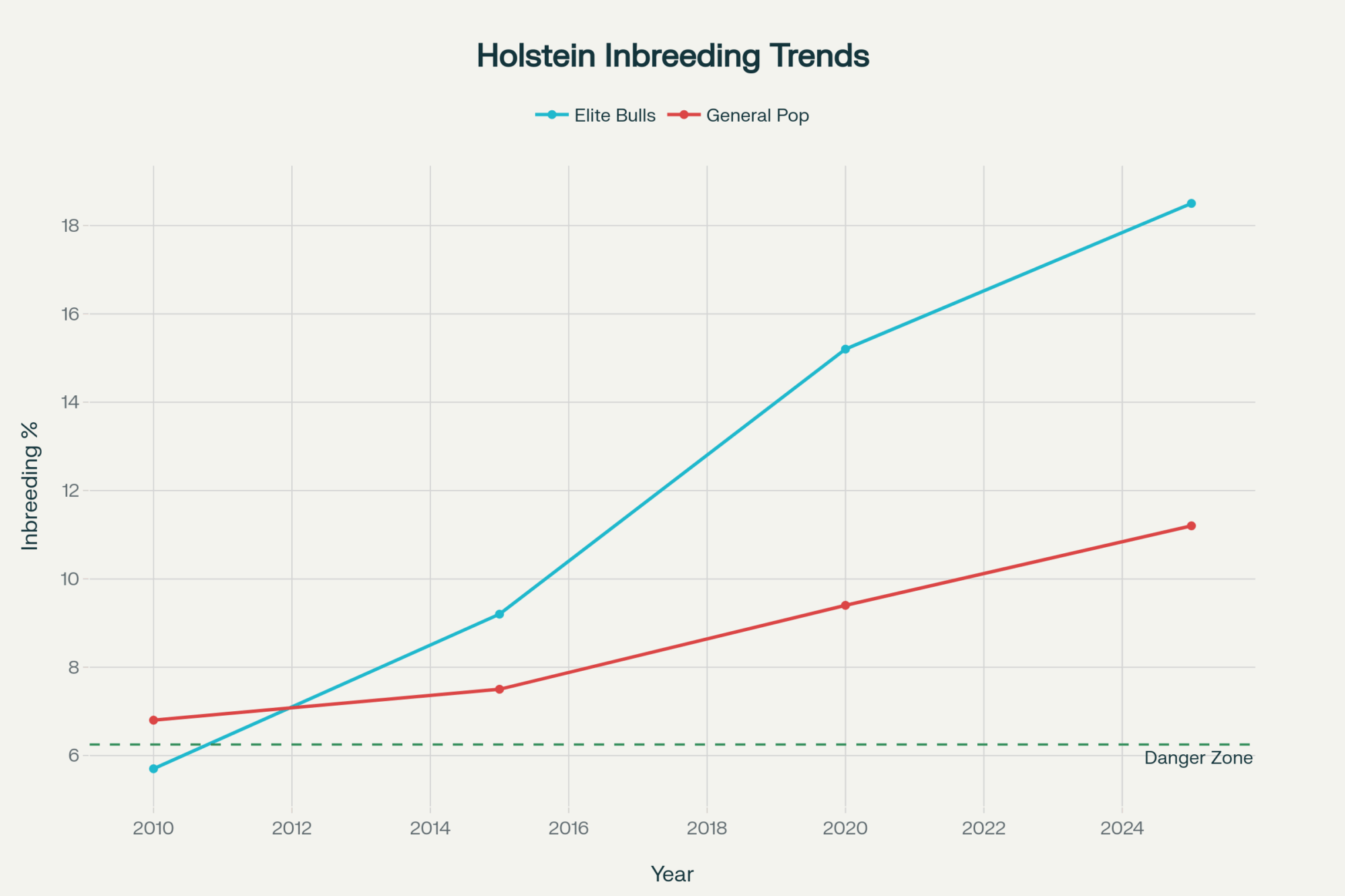

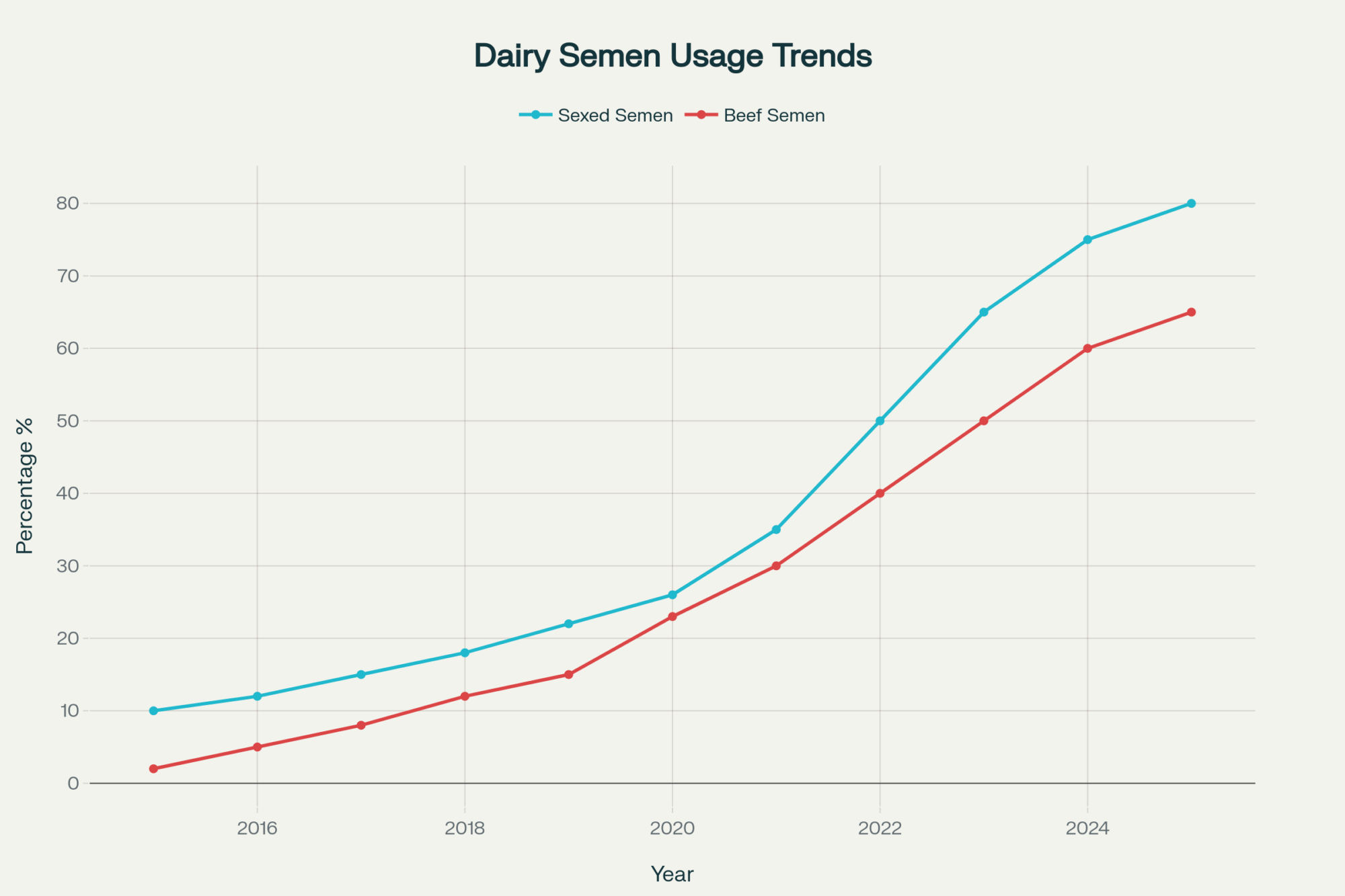

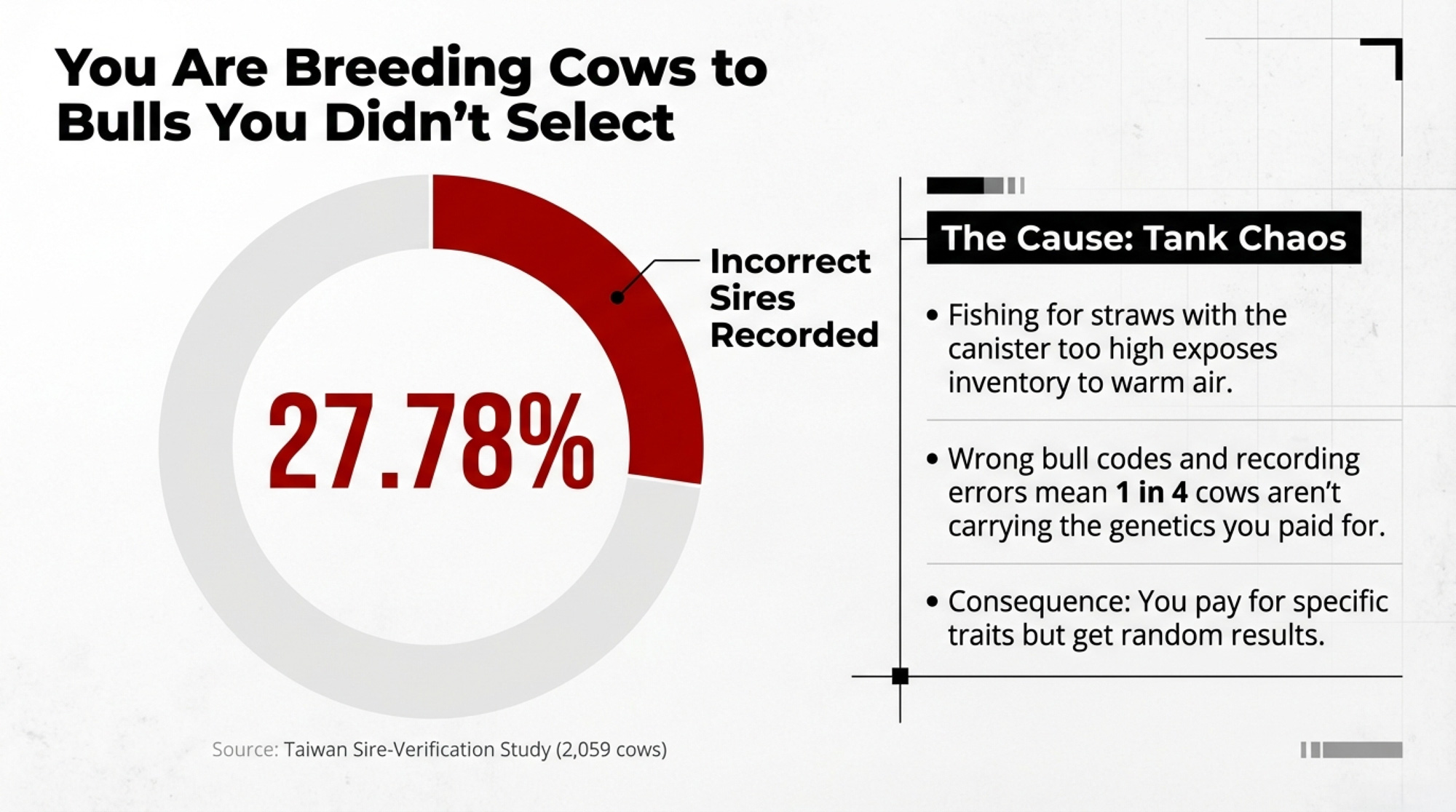

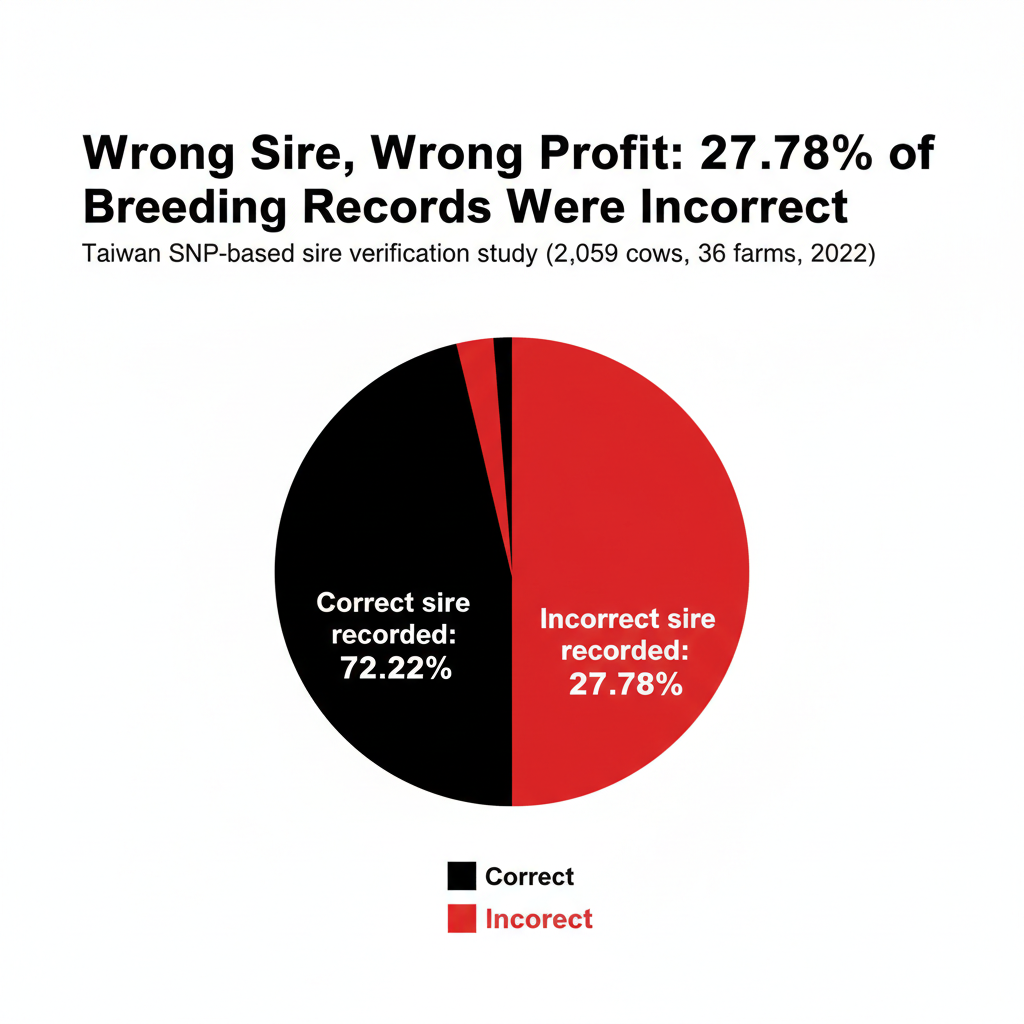

You see the same pattern in breeding records. A 2022 SNP‑based sire‑verification study from Taiwan checked 2,059 cows on 36 dairy farms and found that 27.78% of recorded sires were incorrect — wrong bull codes, wrong storage location, or recording errors. In other words, more than one in four matings went to a different bull than the records claimed.

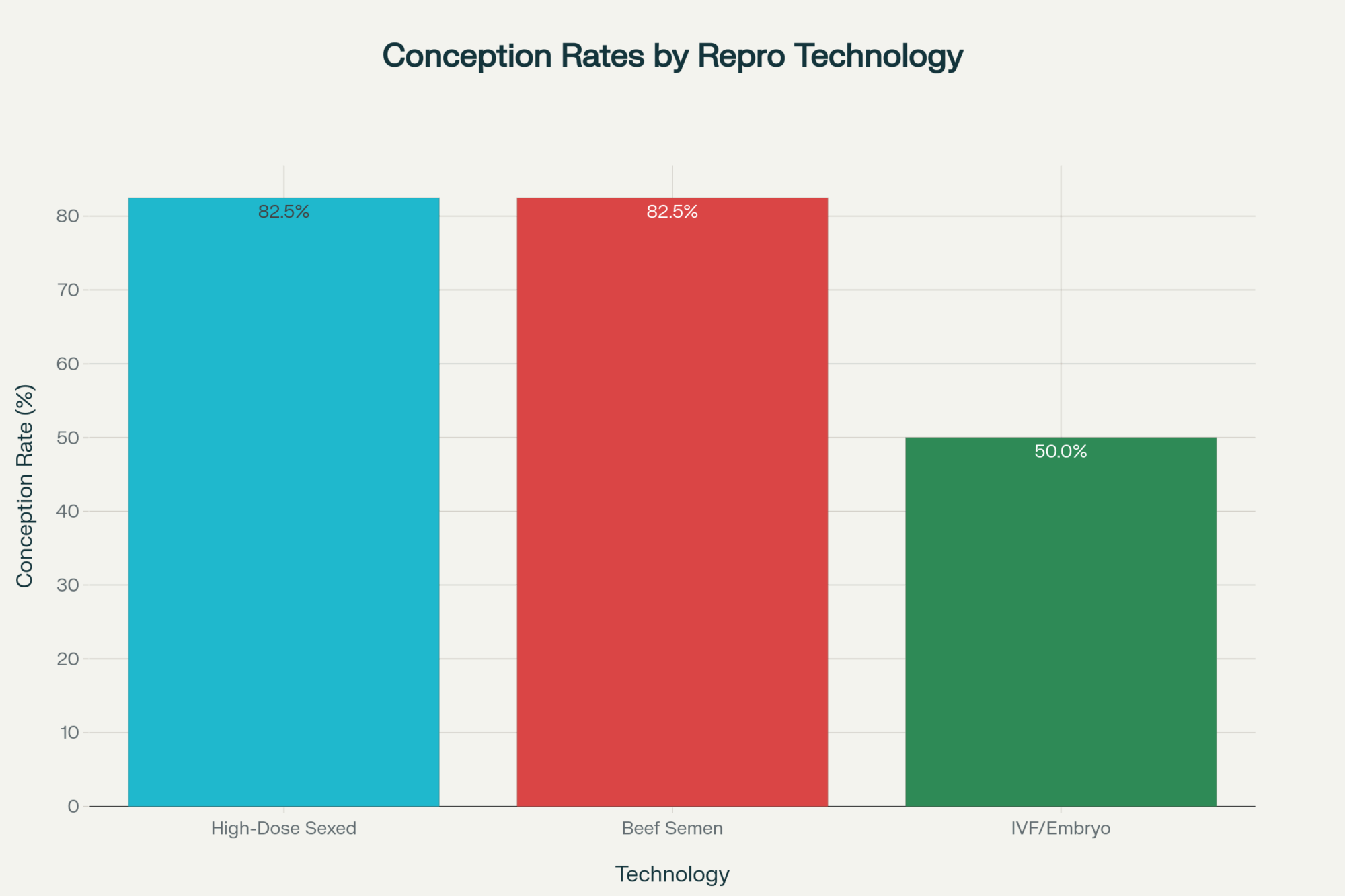

Semen handling has its own quiet leak. Extension and A.I. handling guidelines generally recommend that sexed semen be deposited within about 10 minutes of thawing to protect fertility. On a busy timed‑AI morning with 40–80 cows, that window gets stretched more often than anyone likes to admit.

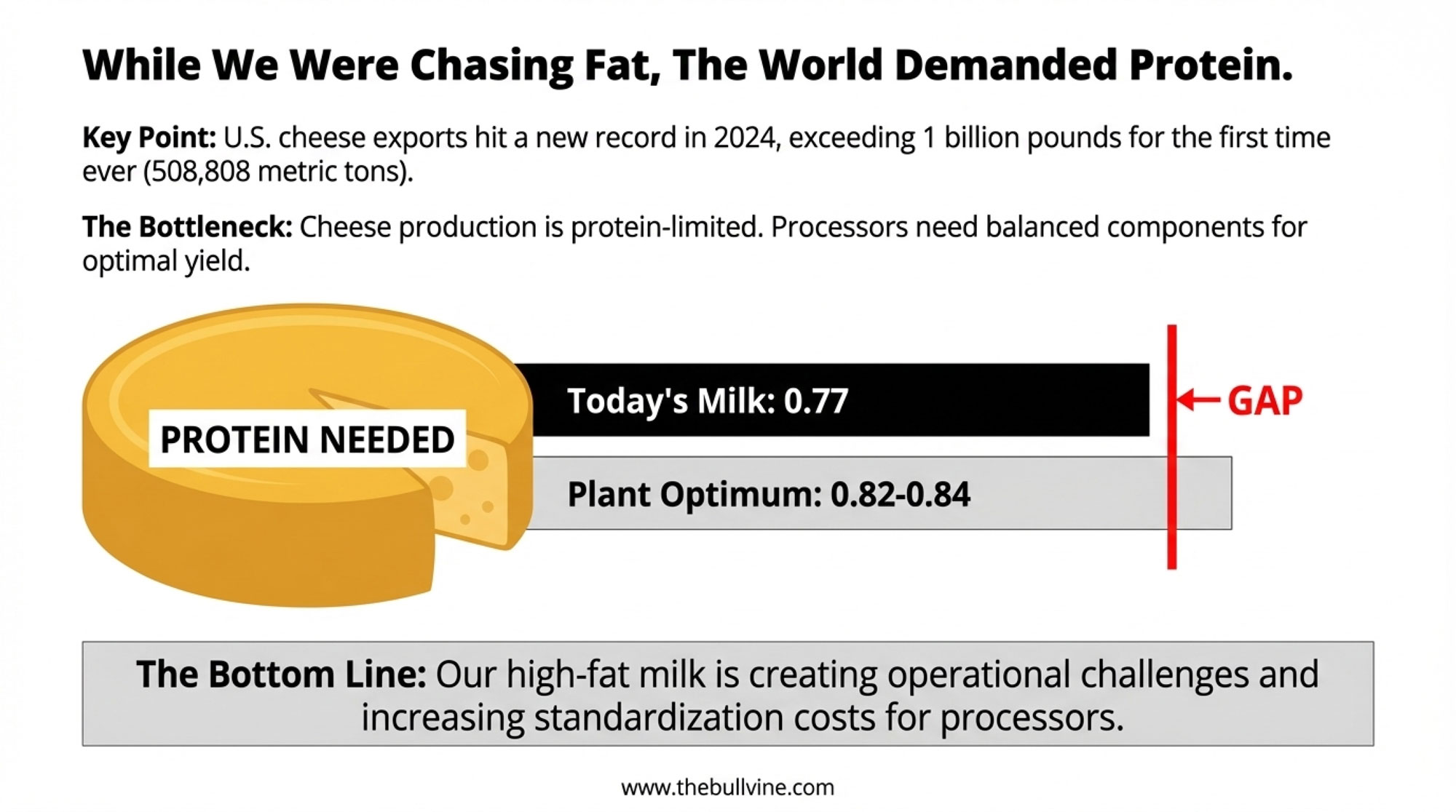

Feed isn’t immune. Nutritionists will tell you there are three rations on every dairy: the ration on paper, the ration delivered, and the ration cows actually consume. Forage dry matter swings, over‑mixing that chews up effective fiber, and real intakes drifting several percentage points from the estimate are common. A lot of the math you use on feed cost and income over feed cost still assumes a ration that your cows never really eat.

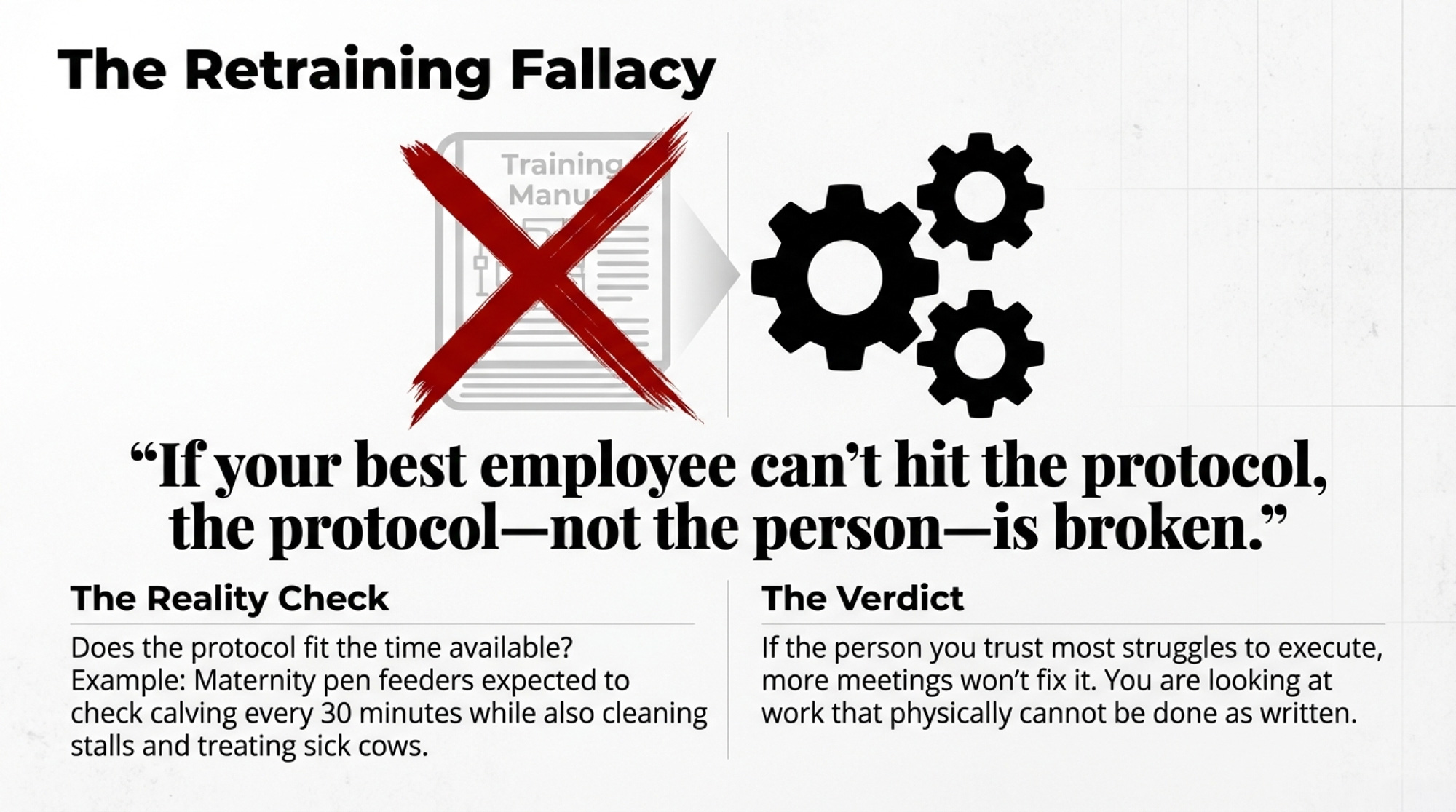

This isn’t a “people don’t care” problem. It’s a “protocols don’t fit reality” problem.

The Retraining Fallacy

Here’s the default move that quietly costs you: a protocol misses its target, so you schedule more training. Another meeting. Another sign.

But when the same protocol keeps failing after you’ve retrained more than twice, you’re almost never looking at a knowledge problem. You’re looking at work that simply can’t be done the way it’s written.

MSU’s colostrum work shares a good example from the maternity pen. Feeders in one herd were expected to check calving progress every 30 minutes, in addition to cleaning stalls, processing newborns, and treating sick cows. On paper, that looks like “best practice.” On a rough day, it’s physically impossible.

There’s a sharper question than “Who screwed up?” Ask this instead: Does your best employee also struggle with this protocol? If the person you trust most can’t hit it consistently, the protocol is broken—not them. At that point, more training isn’t a solution. It’s self‑deception.

And if you’ve watched a good A.I. tech or feeder drowning in a pile of “must‑do” tasks, you’ve seen exactly how that plays out.

“If your best employee can’t hit the protocol, the protocol — not the person — is broken.”

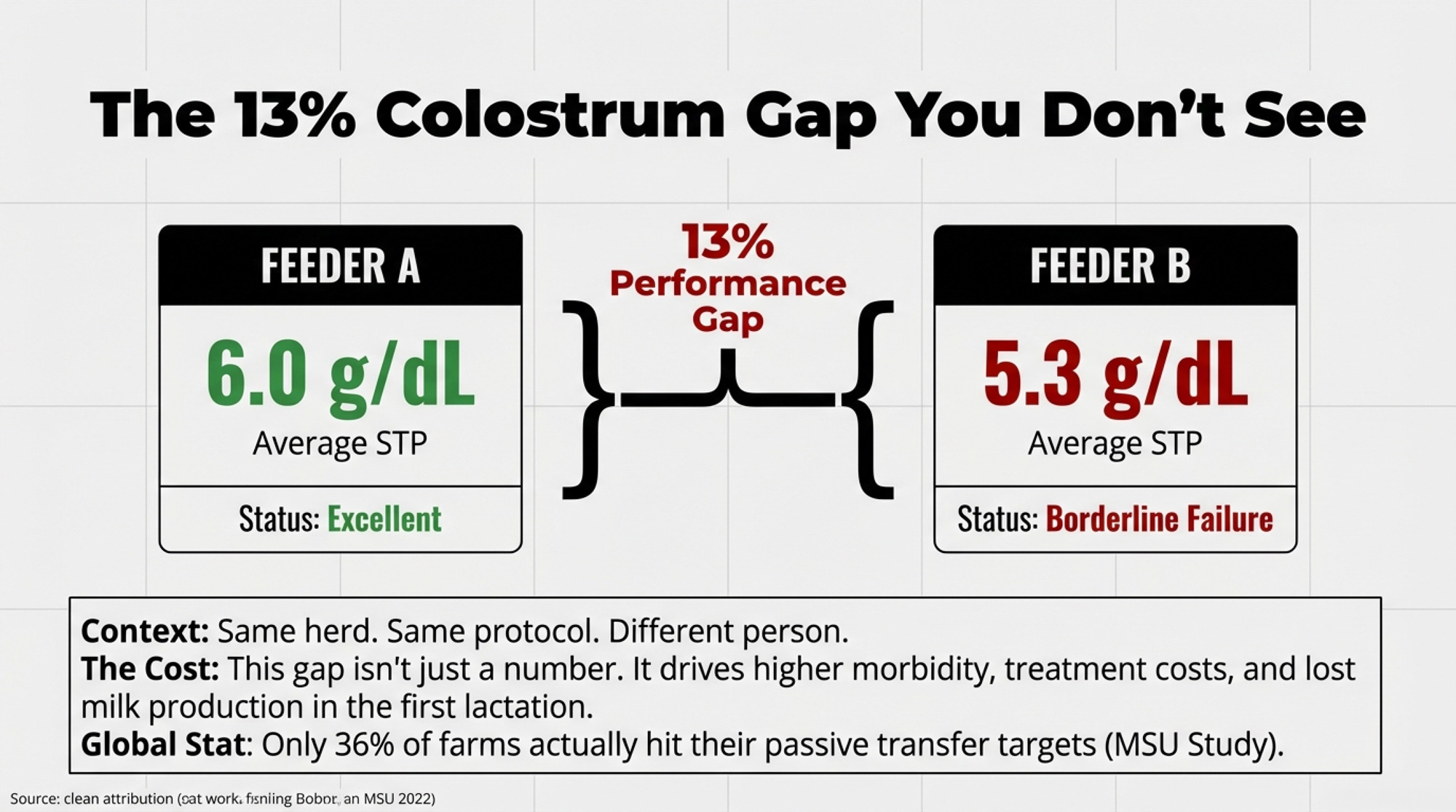

The 13% Colostrum Gap You Don’t See Until You Measure It

At one large U.S. dairy, a retrospective review of colostrum results showed that an employee measured serum total protein (STP) using a simple refractometer. Same herd, same colostrum, same written protocol — just different people doing the work.

- One feeder averaged 6.0 g/dL STP.

- Another averaged 5.3 g/dL STP.

On that farm, that’s roughly a 13% performance gap between 6.0 g/dL “excellent” results and 5.3 g/dL borderline passive transfer. The only real difference was who mixed and fed the colostrum.

Economically, FTPI is a slow bleed. Calves with FTPI have higher morbidity and mortality, weaker pre‑weaning growth, and higher treatment costs. Some never reach first calving. Others enter the milking string and never deliver the production their genetics suggest they can. Spread that 13% gap over a few hundred calves, and you’re looking at a five‑figure cost that never shows up as a separate line on the milk cheque.

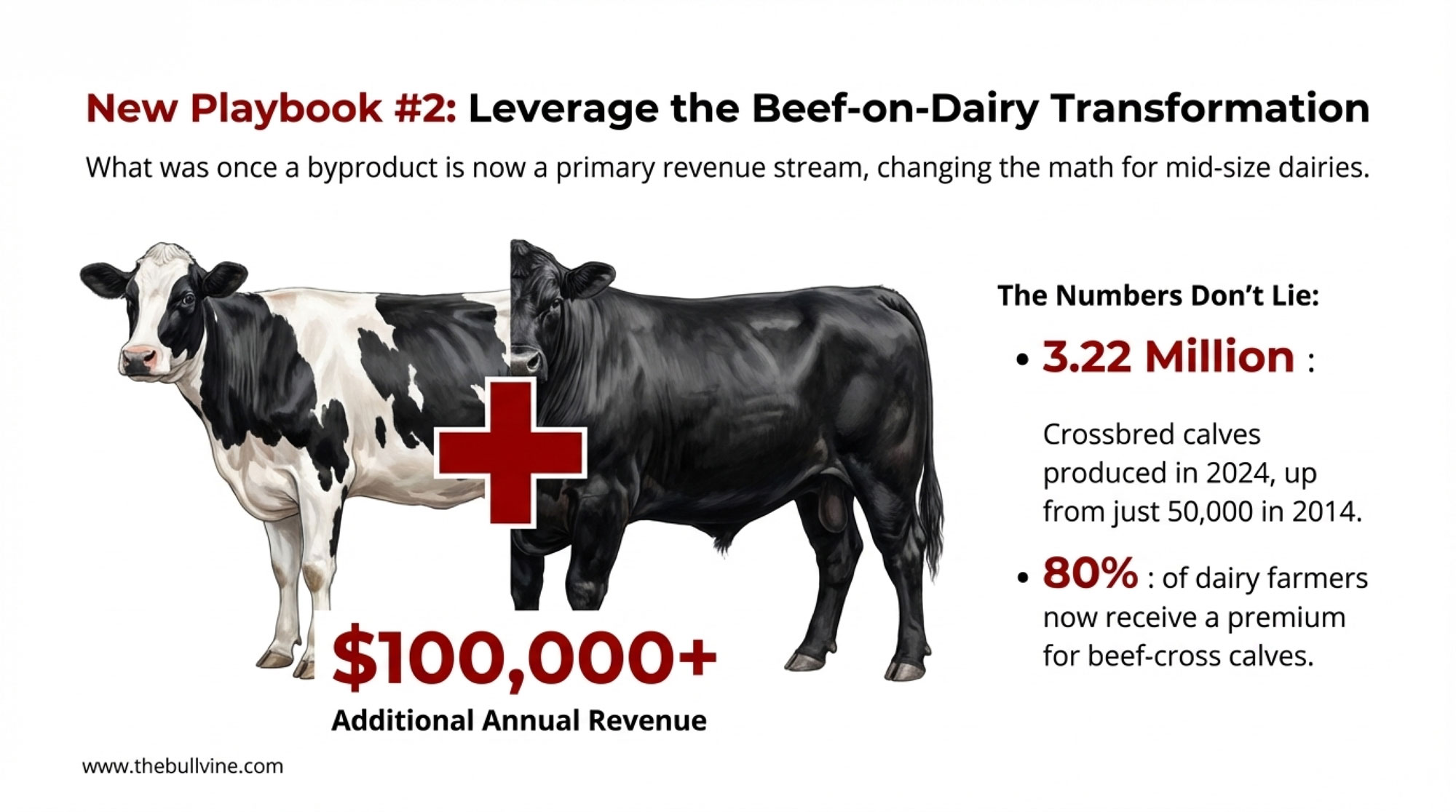

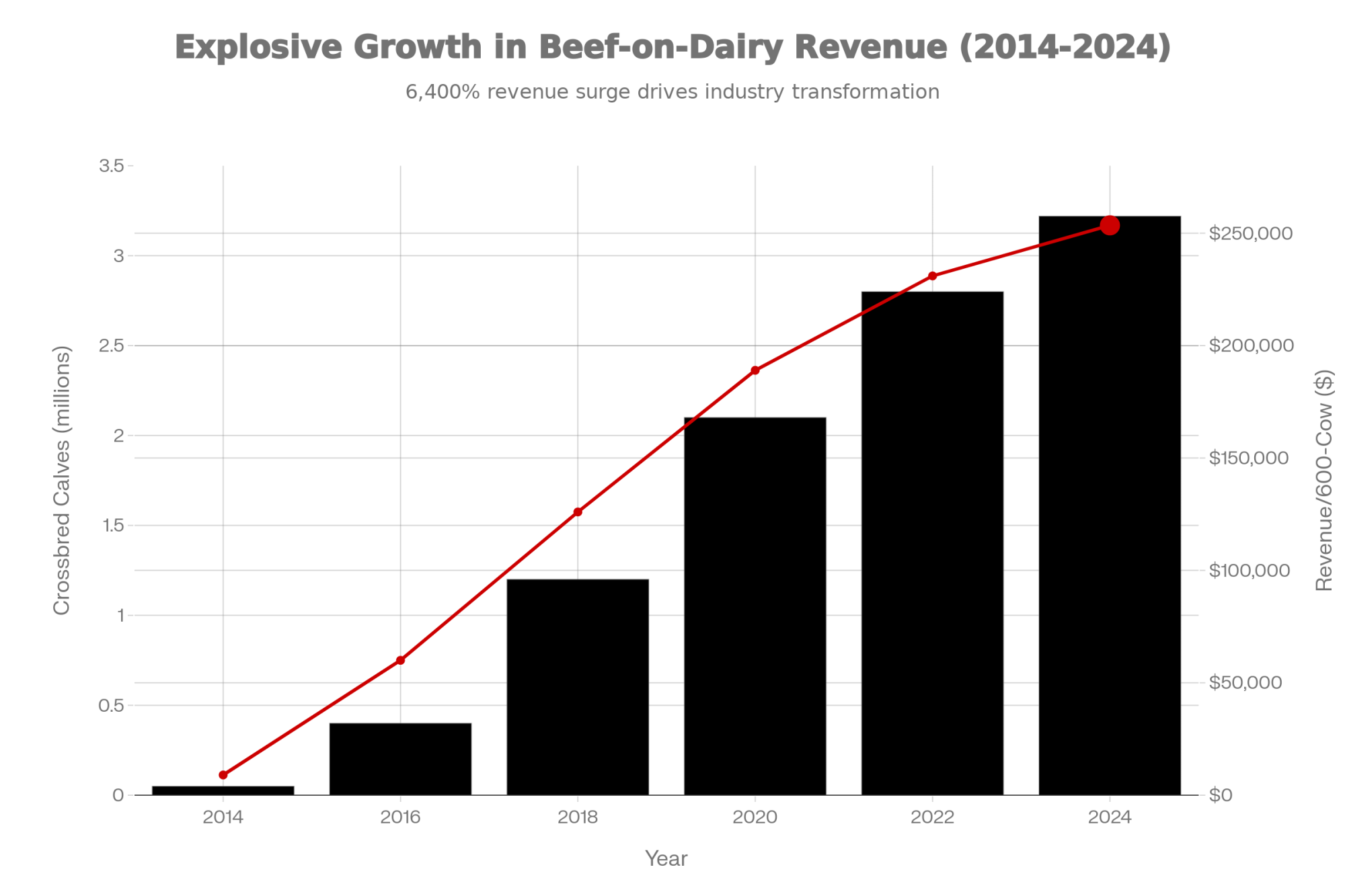

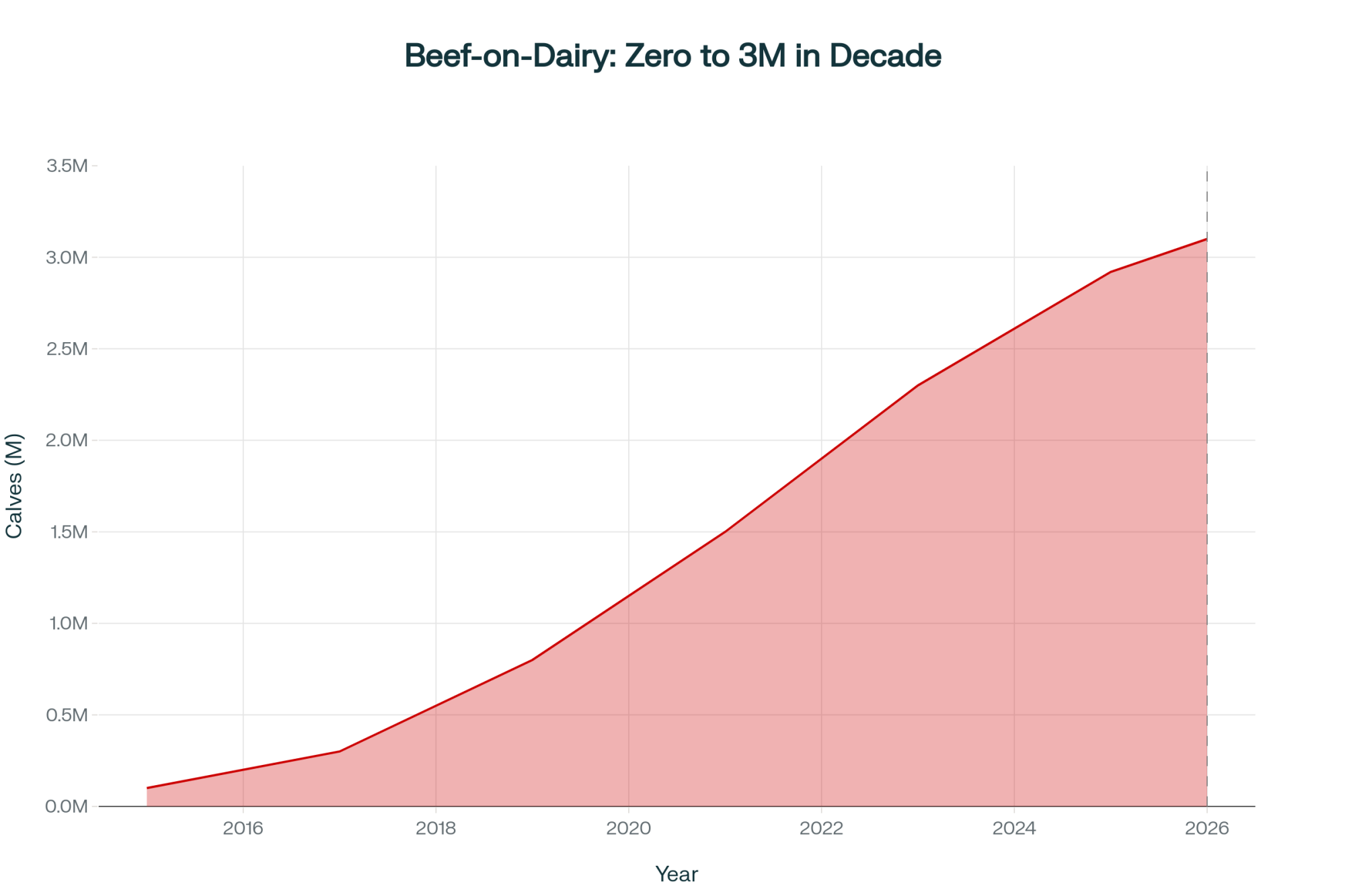

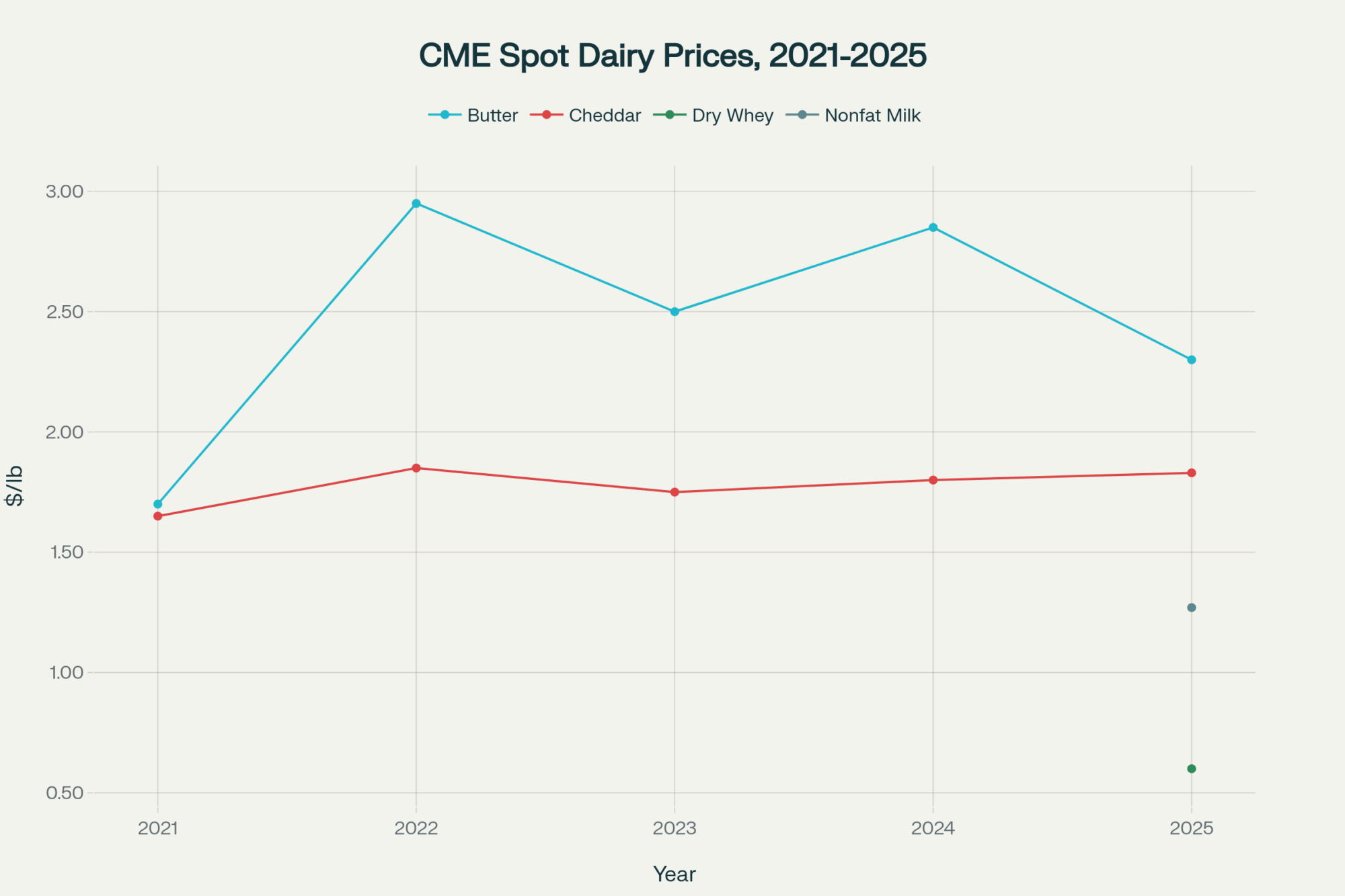

Now layer in dairy‑beef. A 2025 Purina/CattleFax analysis put average day‑old dairy‑beef calves around US$1,400, up from roughly US$650 three years earlier — more than double in a short window. Hoard’s Dairyman has been blunt that dairy‑beef calf prices are “breaking records” at many U.S. sales. A calf that ships at three days old with poor passive transfer is more likely to get sick, die, or need heavy treatment, and those problems pull down the prices buyers are willing to pay.

Colostrum research from MSU, Wisconsin, and others all point the same way: what you did with colostrum this morning is one of the main predictors of that heifer’s health and productivity down the road. If you haven’t pulled STP by employee lately, you’re relying on a farm average that might be hiding your weakest link.

Where Good Breeding Programs Quietly Go Sideways

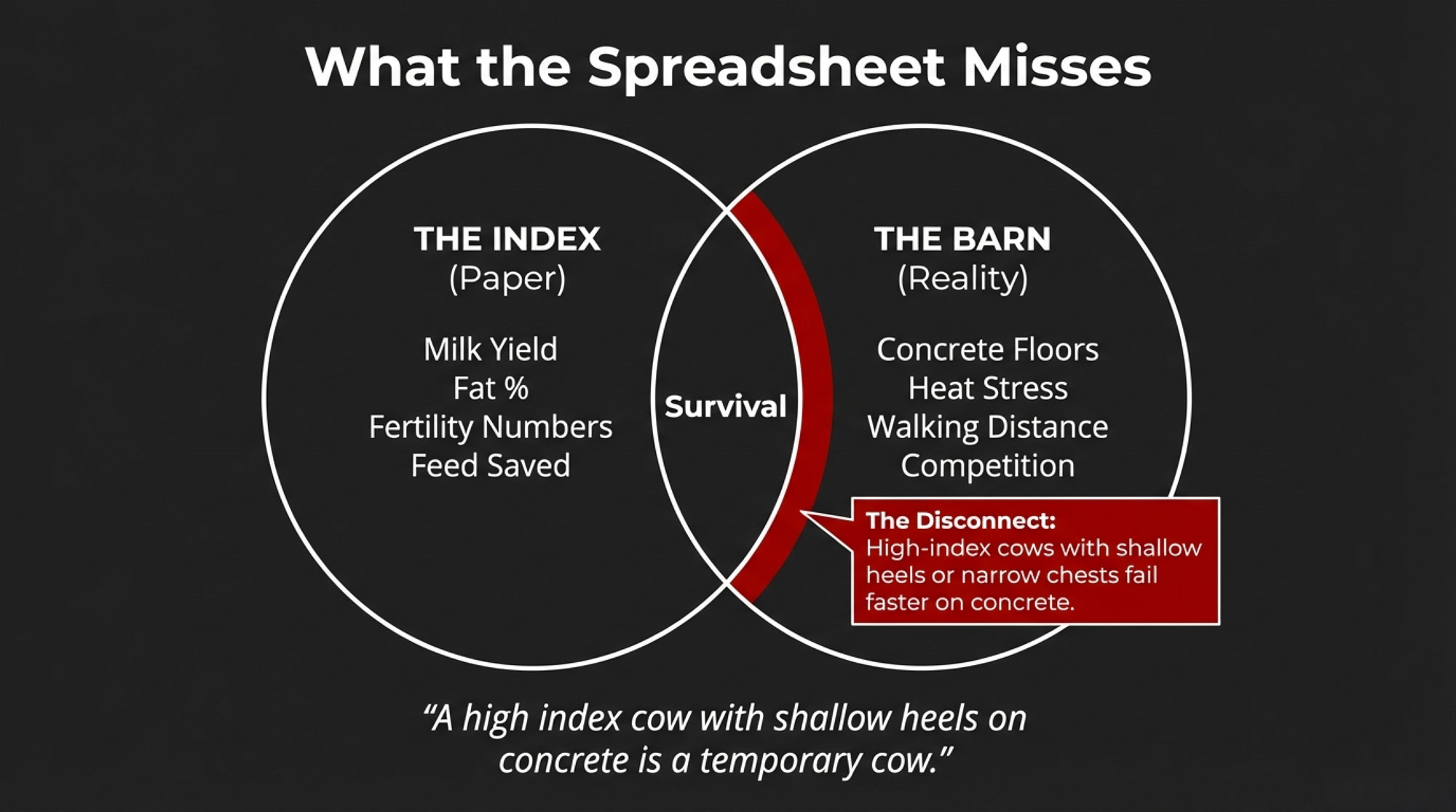

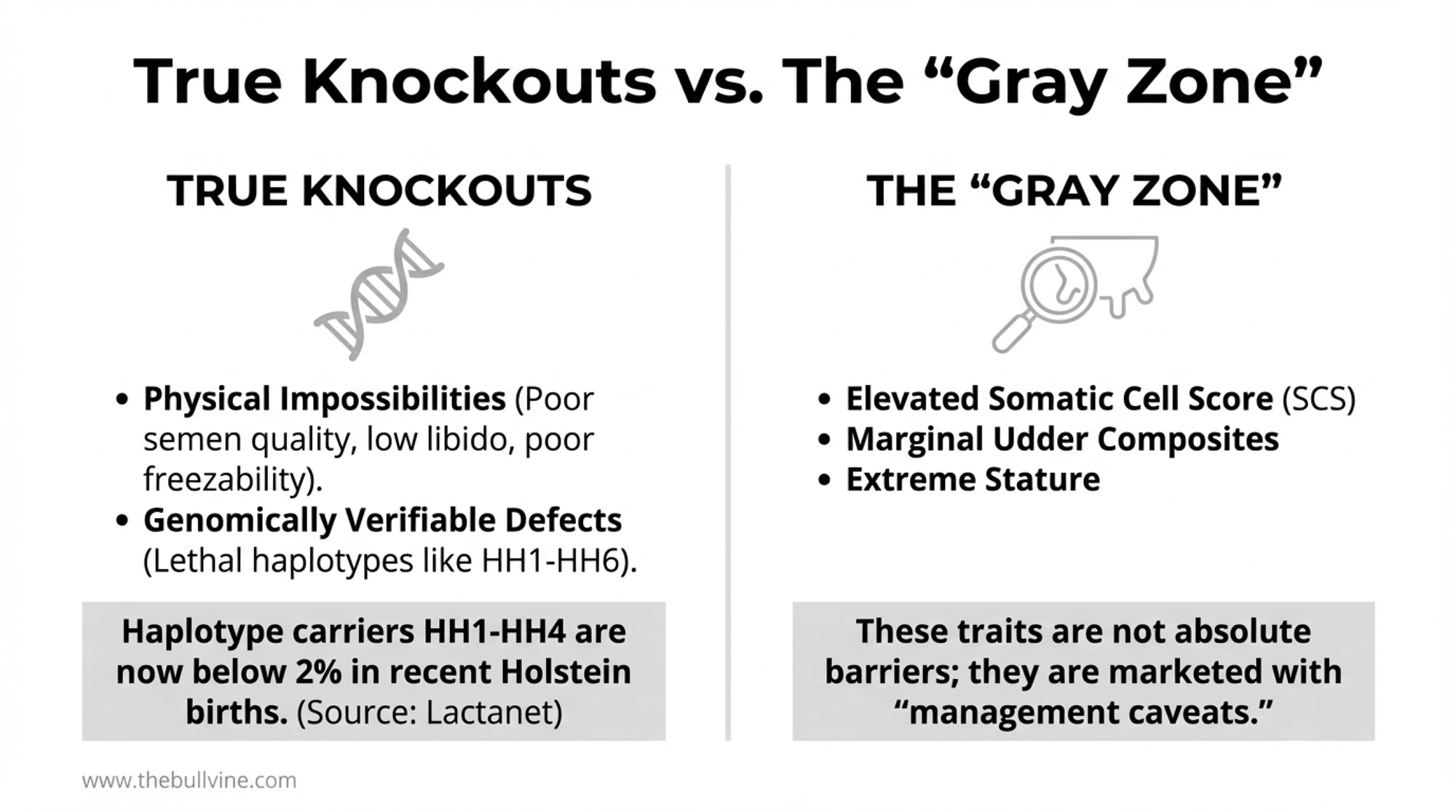

On paper, your breeding plan might be elite. Genomics. Customized matings. Sexed semen on your best heifers. Beef semen on the bottom half.

But if the wrong semen ends up in the cow, or the right straw gets mishandled, the whole thing quietly falls apart.

The Taiwanese SNP‑based sire‑verification study puts hard numbers to that risk: 27.78% of recorded sires were wrong across 36 herds and 2,059 cows. That’s not a rounding error. That’s more than one in four cows with a different sire than your records say.

Here’s where the leaks show up on‑farm:

- Tank chaos. Straws from multiple bulls share a goblet. The breeder fishes for the right code with the canister too high in the neck, exposing every straw they aren’t using to warm air. Semen‑handling guides warn that when liquid nitrogen depth drops below about 6 inches, the temperature in the neck can rise sharply; straws left above the frost line quickly take damage. Late nights, cramped spaces, and tanks tucked into corners all make it easier to stay above the frost line longer than you should.

- Service‑number blind spots. Your plan says: sexed dairy for first and second service, beef from third service on. But if service numbers aren’t updated promptly, the person with the gun can’t follow the plan, no matter how good the spreadsheet looks.

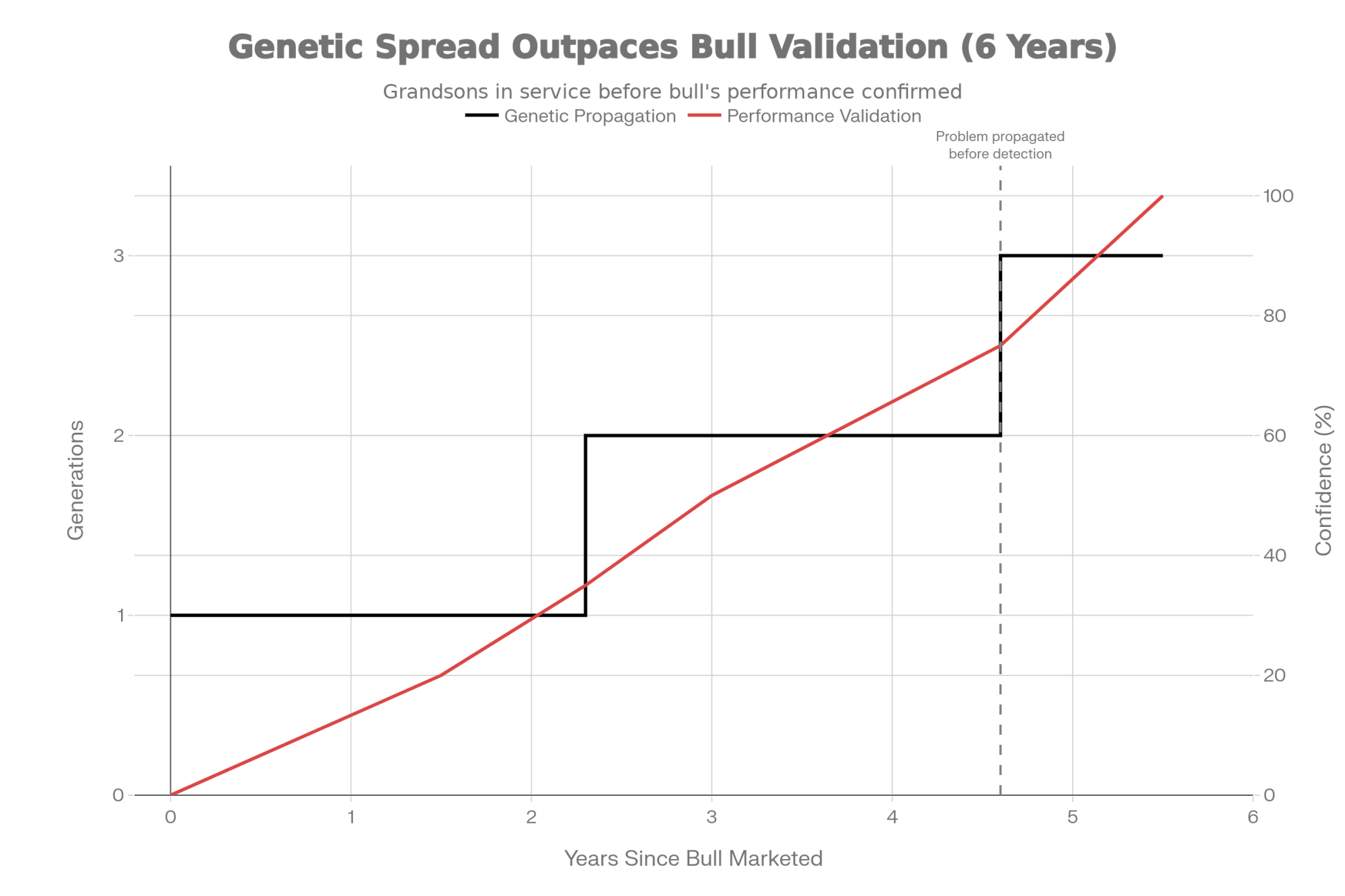

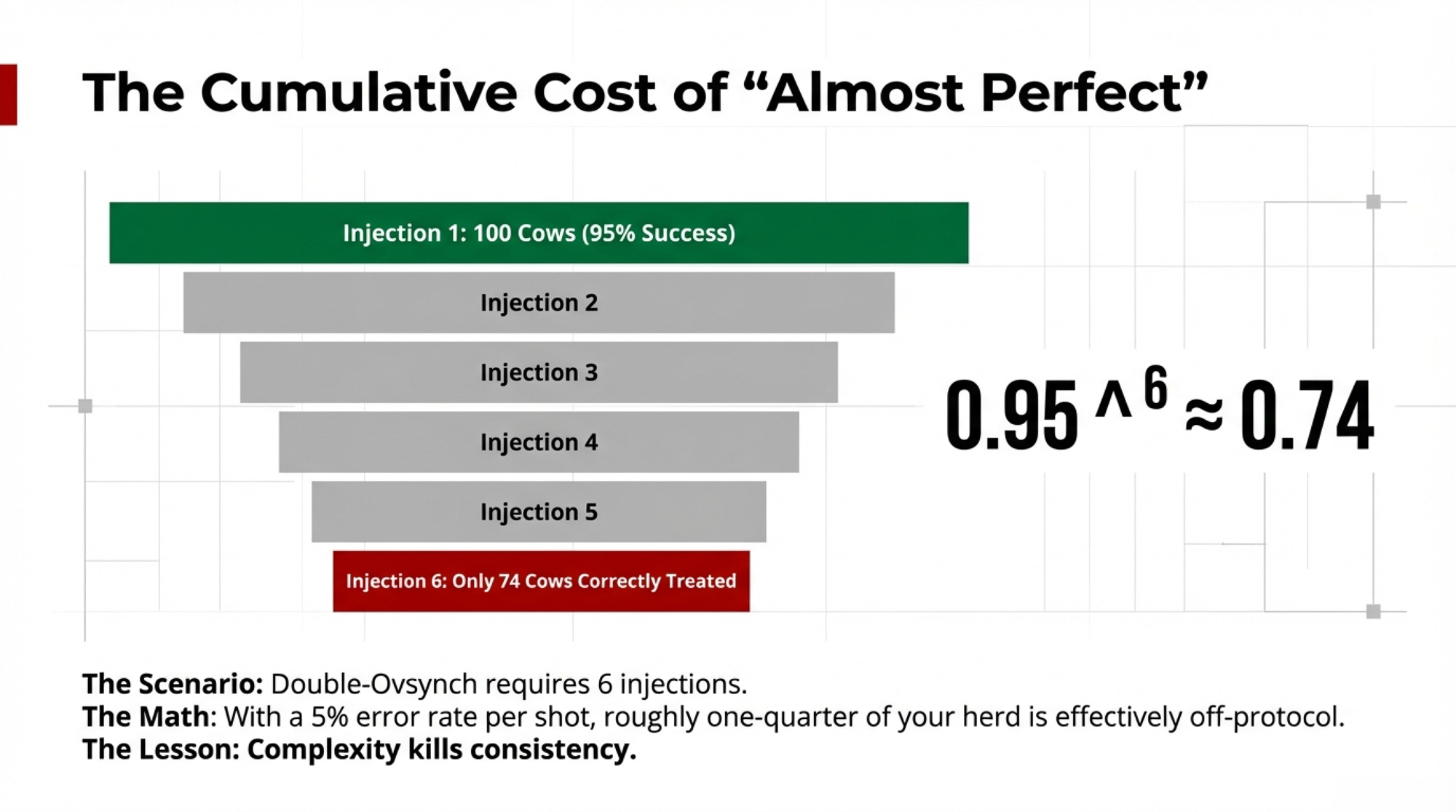

- Synchronization drift. Double‑Ovsynch is powerful — six injections, tight timing, strong conception when done right. Do the math: at just a 5% error rate per shot, the chance of a cow receiving all six injections correctly is about 74%, because 0.95 6 ≈ 0.735. That means roughly a quarter of your herd is on some other version of the protocol than you think.

The herds that consistently post top‑end reproduction numbers almost always share one habit: the same person both breeds and records, backed by a setup that makes the right straw easy and the wrong straw hard. Every handoff — between people, between shifts, between paper and software — is another leak you have to pay for.

Why That 95‑Pound Cow Is Still Standing in Your Barn

McCarty’s “top half only” rule sounds ruthless until you stand in front of a cow who’s right on the bubble.

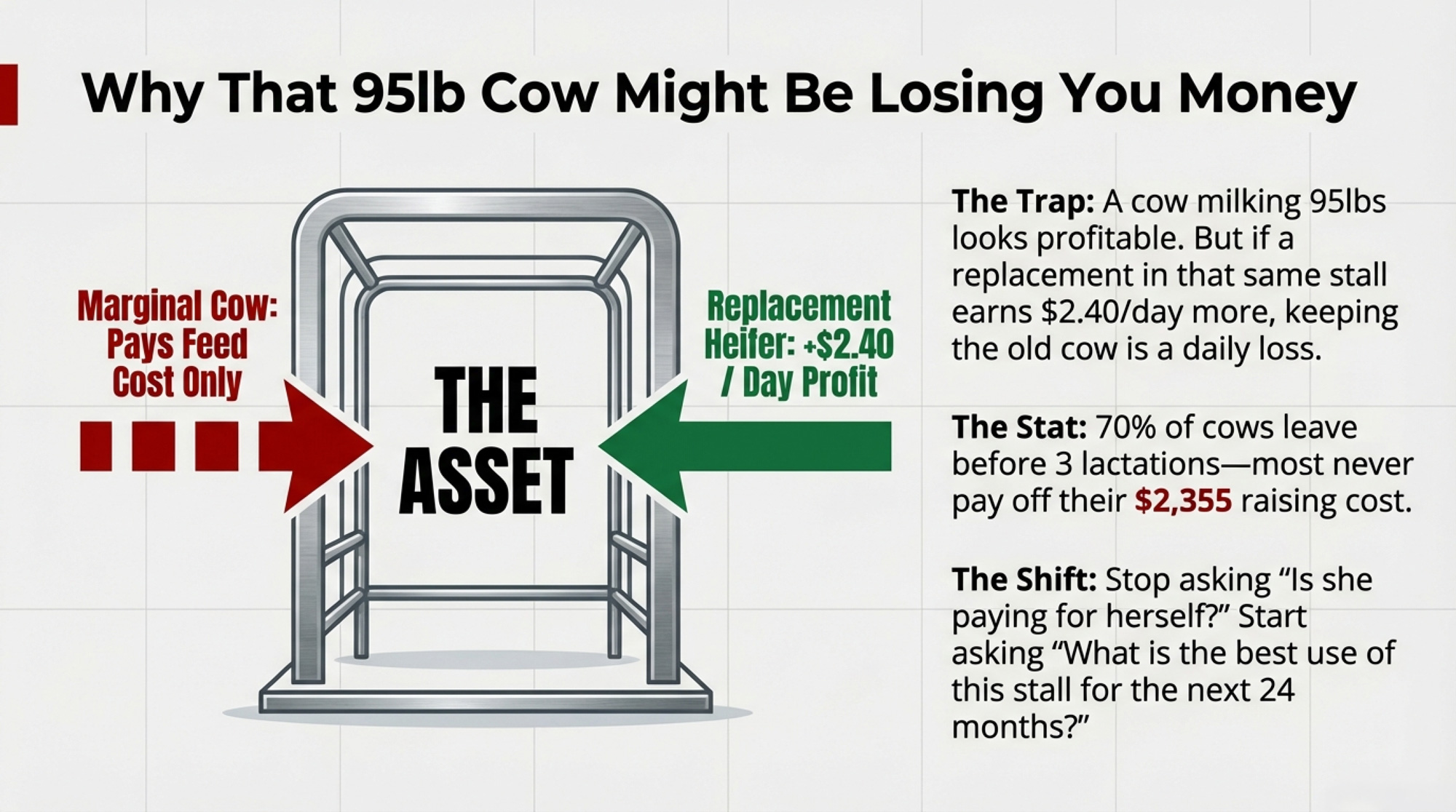

Picture a second‑lactation cow giving 95 pounds, sitting in your bottom‑third genomically. On your genetic ranking, she’s an easy cull. In the parlor, she looks like money. Human brains are wired to value today’s visible rewards — that full unit of milk — more than abstract, future gains like a higher‑merit daughter calving in three years.

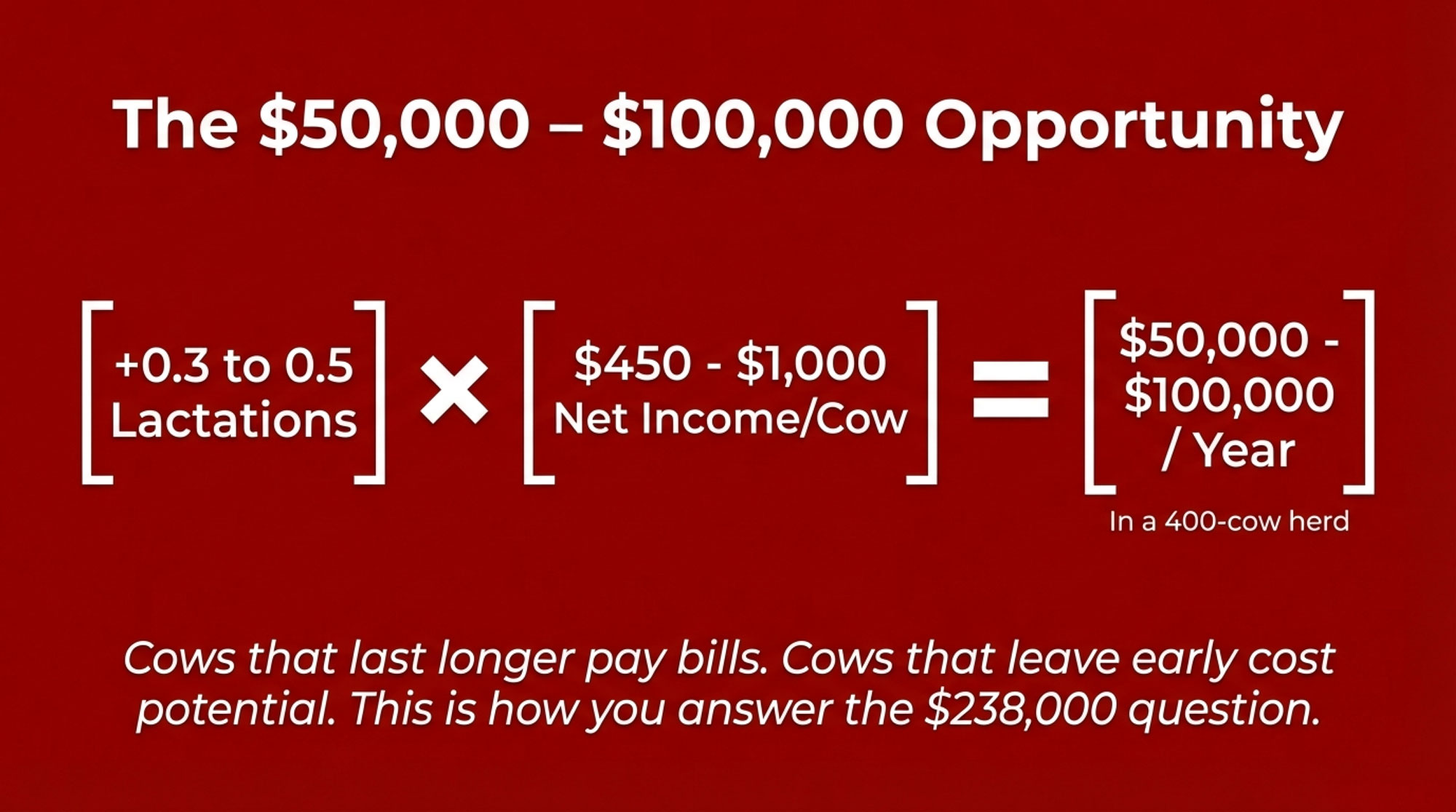

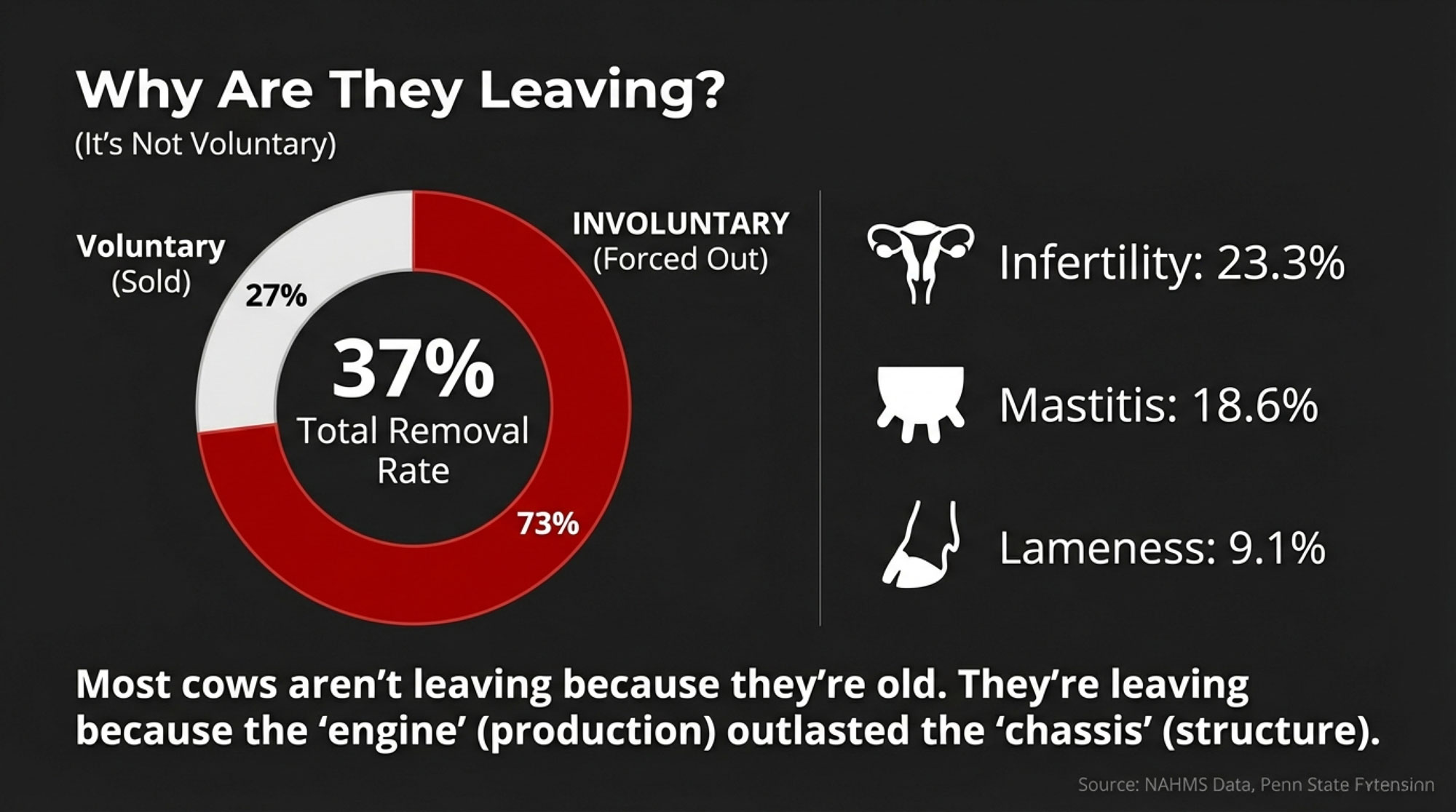

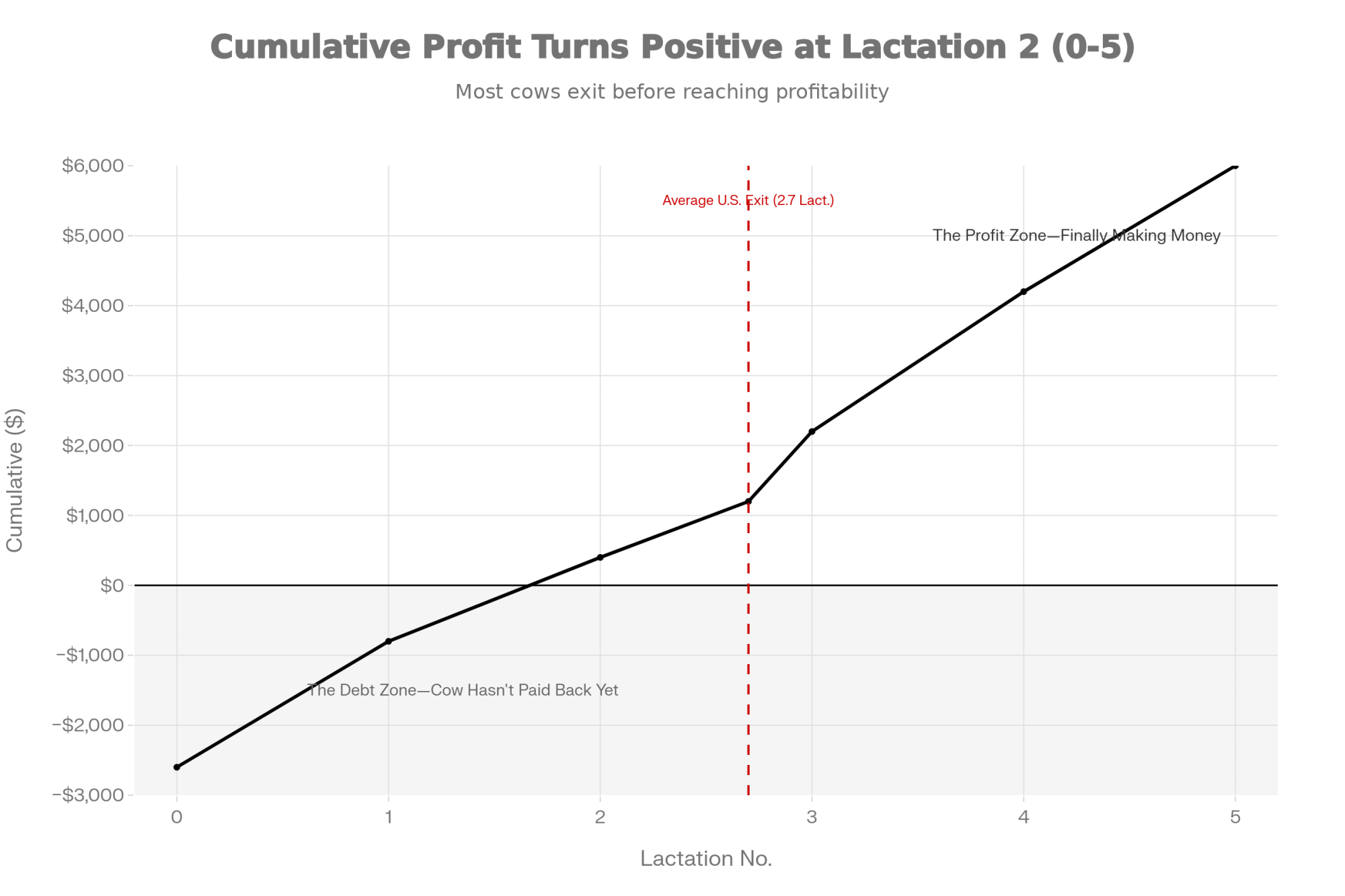

Culling work backs this up. Dairy Herd Management’s 2024 review of USDA/NAHMS data shows that about 70% of cows leave the herd within their first three lactations, and the average productive life is just 2.7 lactations. That same piece notes it takes more than three lactations to recoup roughly US$2,000 in raising cost. In other words, the “she hasn’t paid herself off yet” argument doesn’t hold up for most cows — they’re likely to leave before that point anyway.

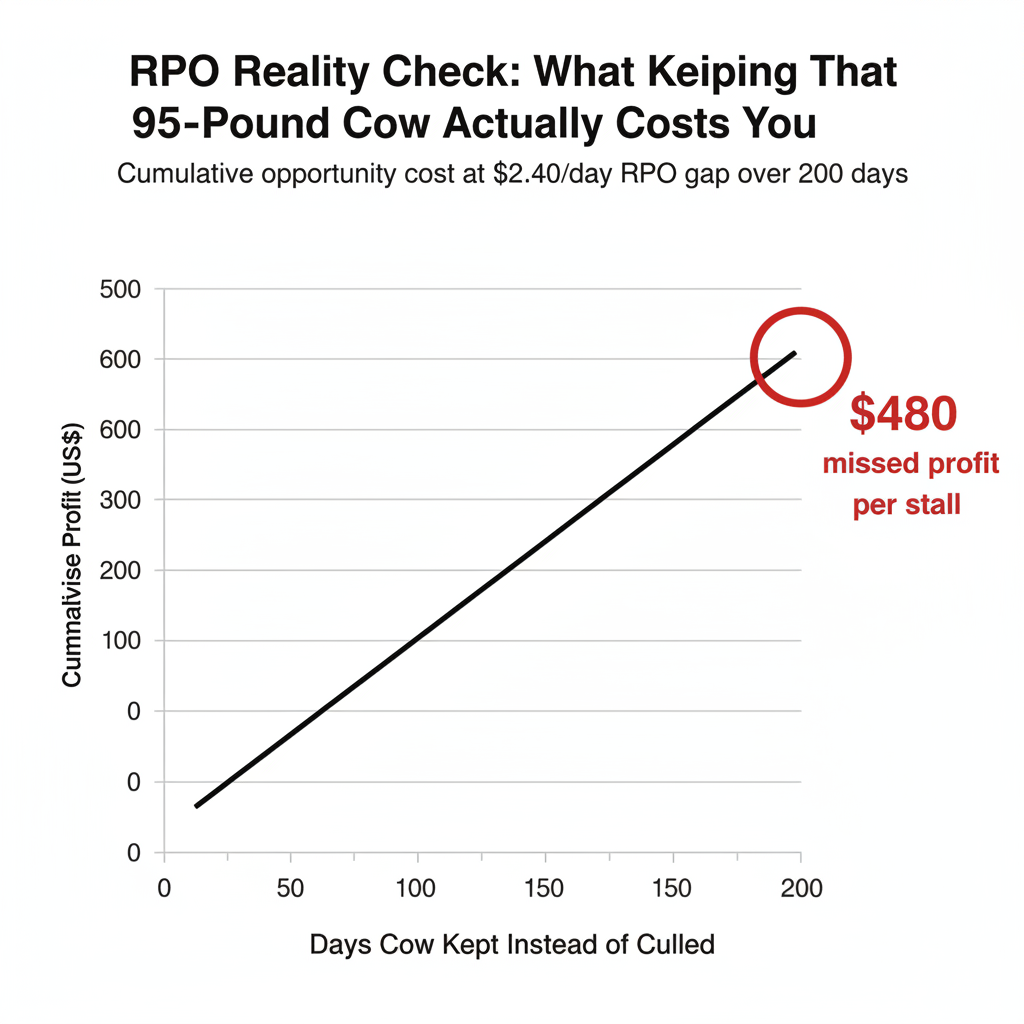

This is where Retention Pay‑Off (RPO) earns its keep. RPO is the expected profit difference between keeping a cow versus replacing her in that stall. That 95‑pound cow might be cash‑positive day to day. But if a replacement would generate US$2.40/day more in the same stall, you’re effectively giving up US$2.40/day by keeping her. Over 200 days, that’s US$480 in missed profit per stall. The cow isn’t necessarily losing money — she’s just blocking a more profitable animal from using that space.

Recent reports show that average U.S. raising cost at US$2,355 per head, with most farms between US$2,094 and US$2,607. Other cost‑of‑raising work shows some systems pushing near US$2,900 per heifer. With those numbers and a 2.7‑lactation average productive life, hanging onto every decent cow just because she’s milking OK is usually the more expensive choice, not the safer one.

So the real money question isn’t “Is she still paying for herself?” It’s: “What’s the best use of this stall over the next 12–24 months?”

Four Practical Paths to Close the Execution Gap — and Protect Profit

You don’t close this gap with a nicer poster or one more meeting. You close it by picking an approach that fits your people and facilities, then building systems that still hold together on the worst days.

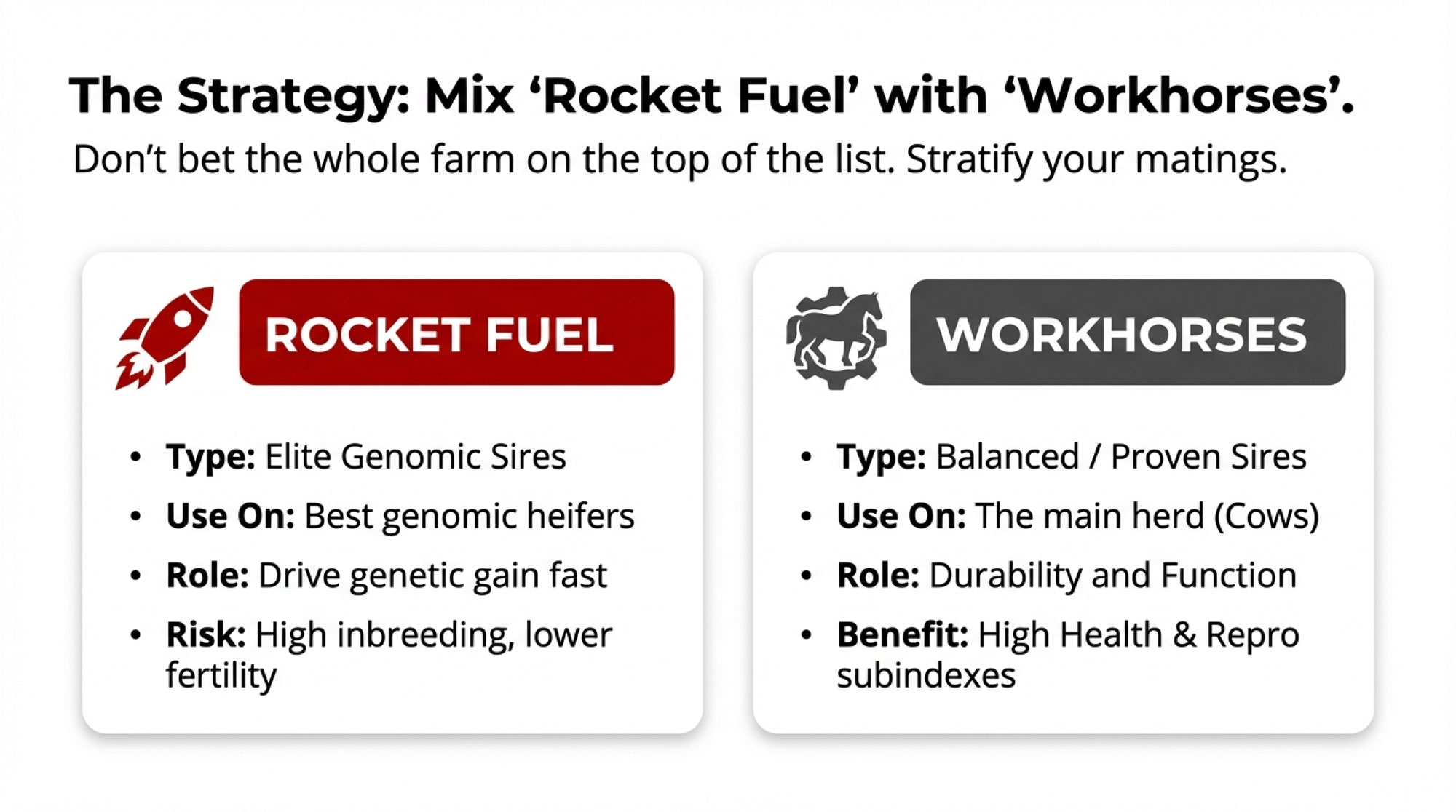

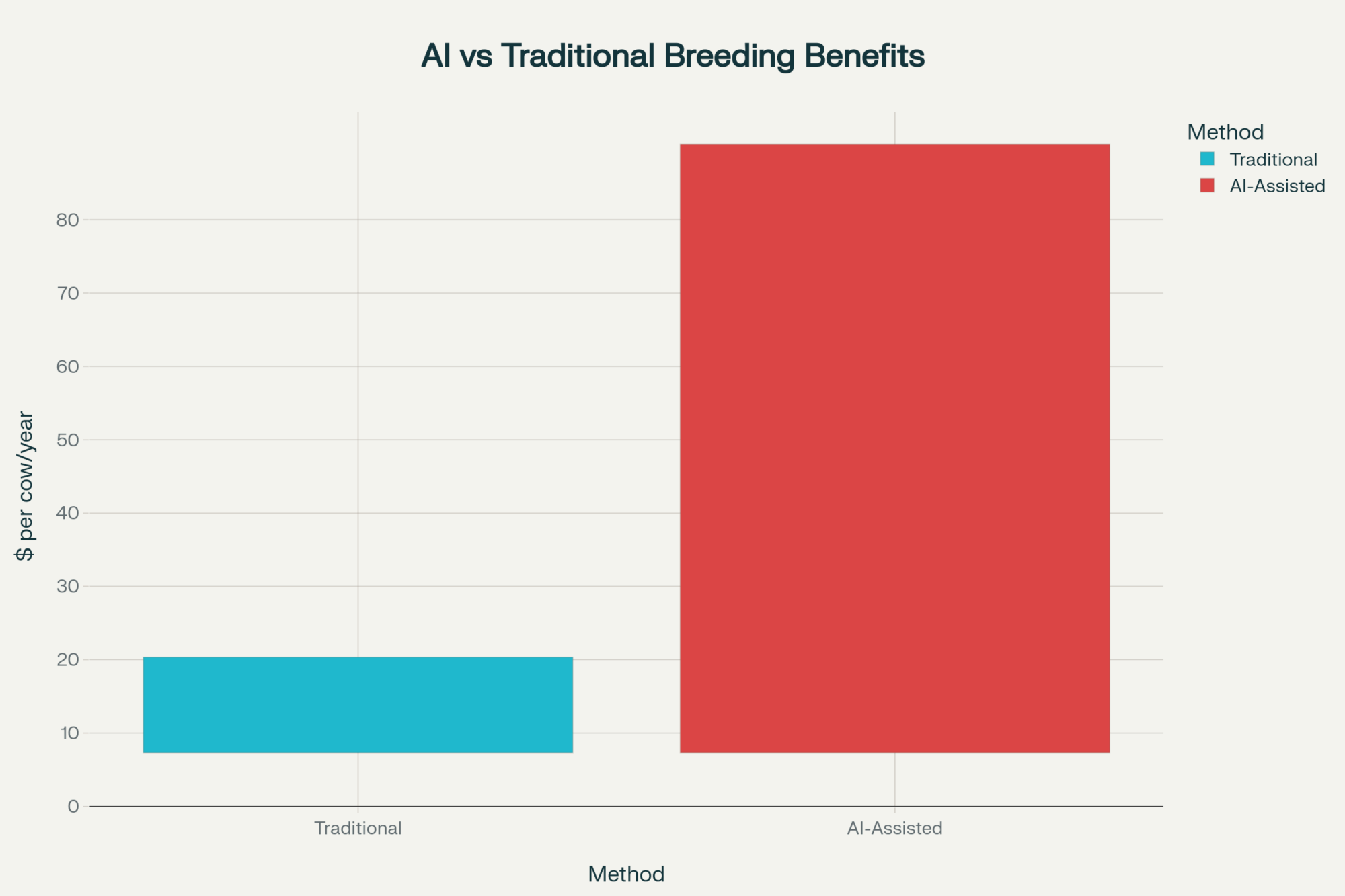

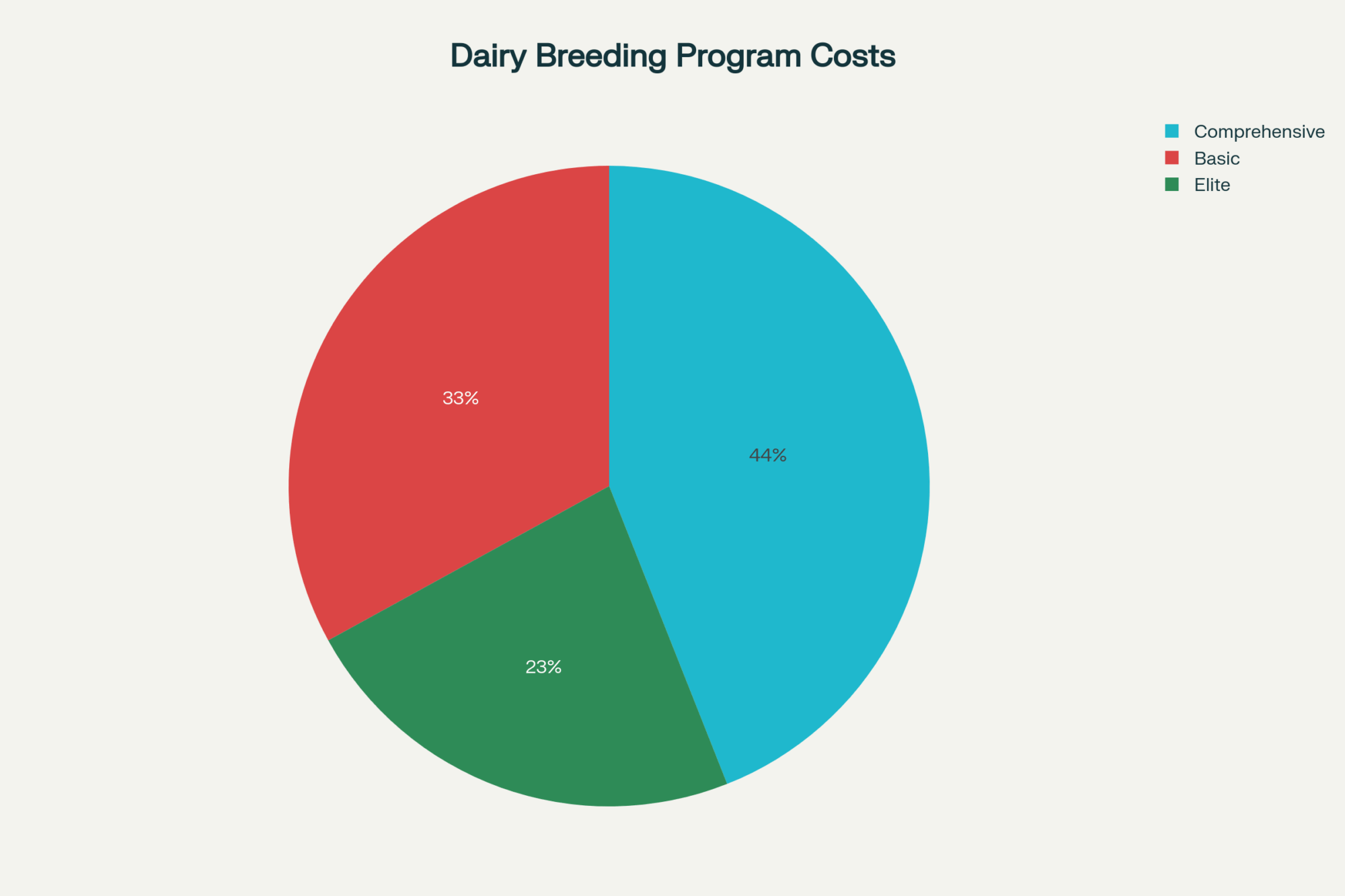

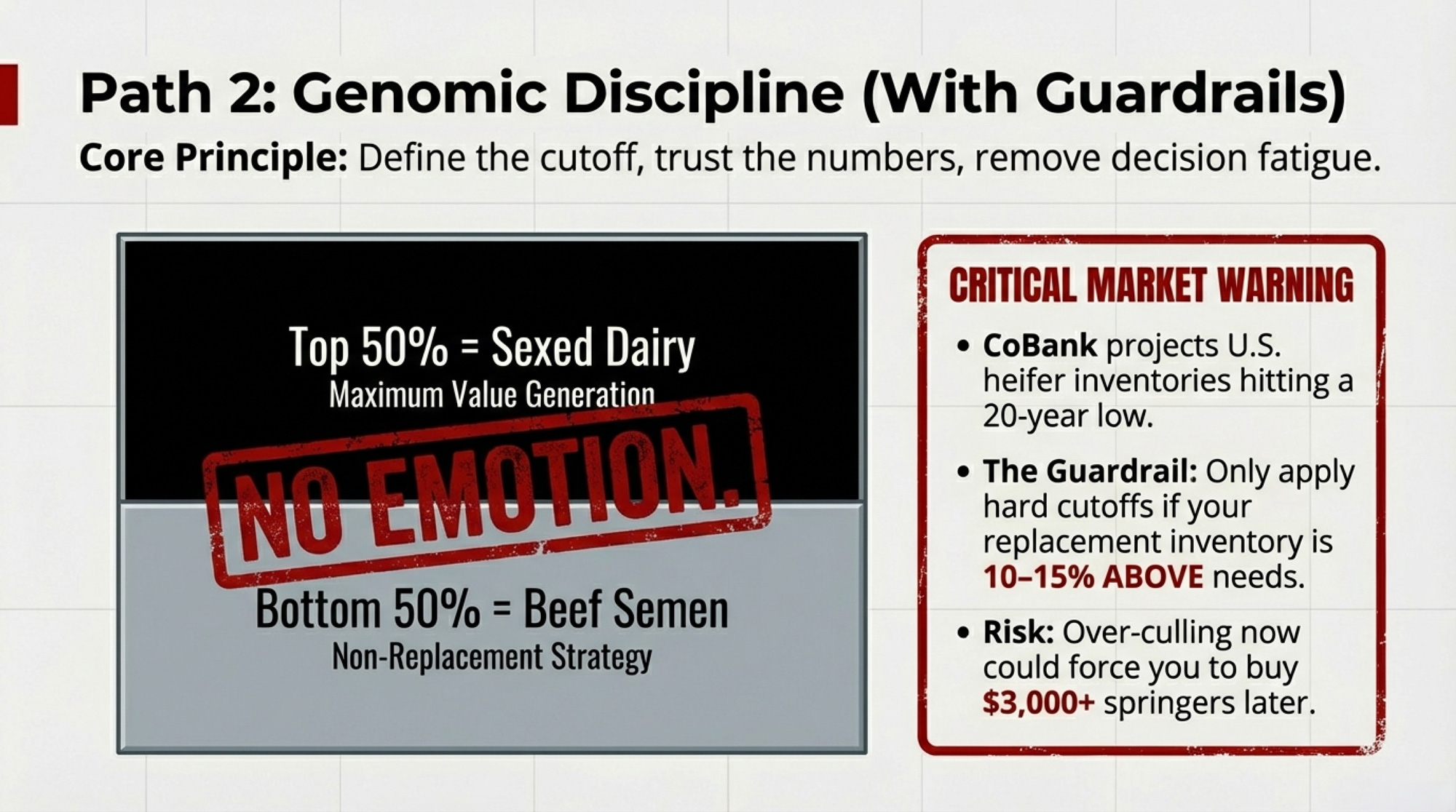

Path 1: Genomic Ranking With Hard Cutoffs

When it fits.

You’re already genomic‑testing, you’ve got more heifers than you absolutely need, and you’re willing to let numbers overrule emotion when it comes to who gets dairy semen versus beef.

What it takes.

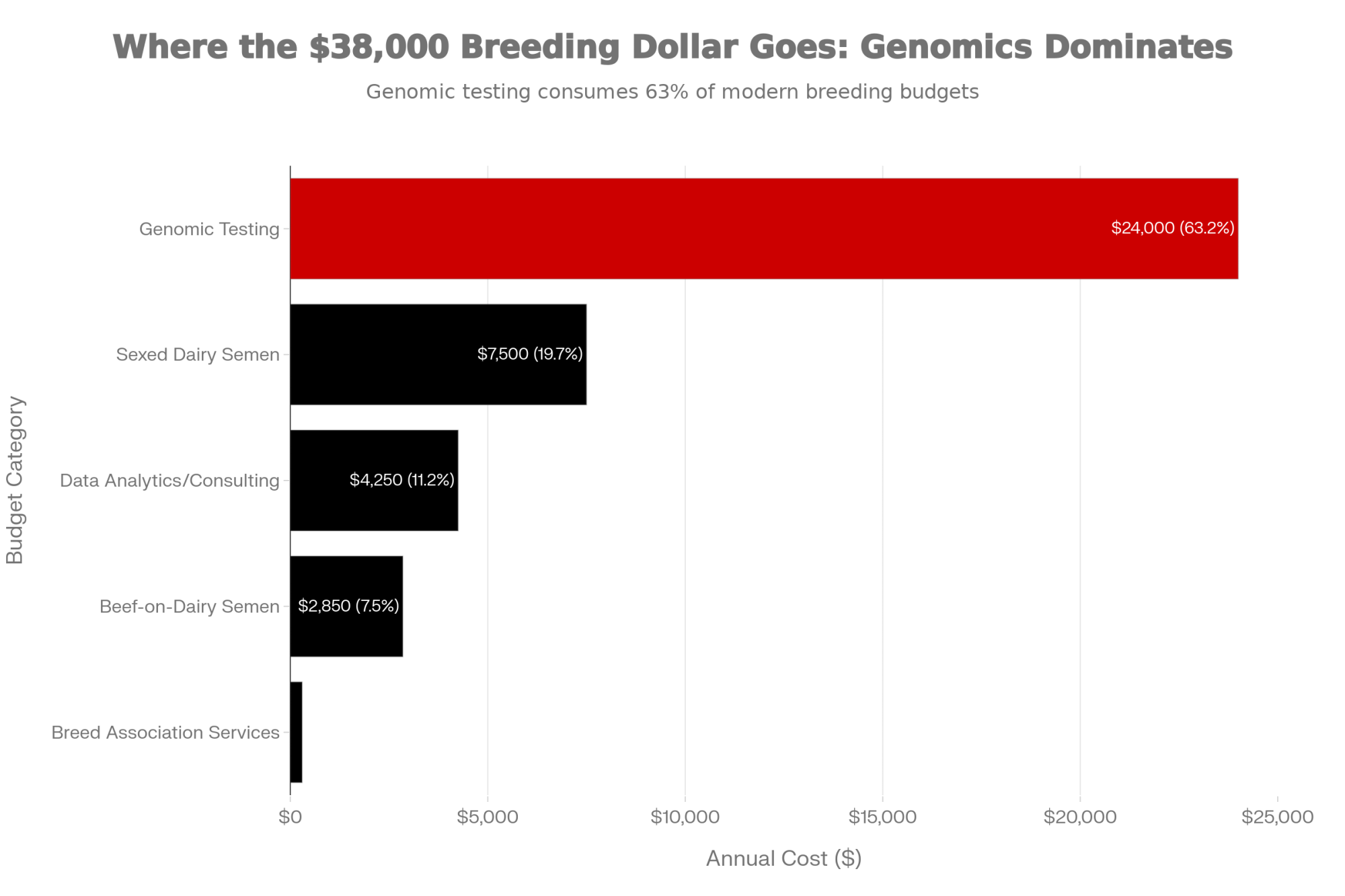

- Genomic tests running roughly US$40–US$50 per head in many programs.

- Software and discipline to rank animals, keep that list current, and get it in front of whoever is breeding.

- A clear rule: top 40–60% by index get dairy semen, the rest get beef. No exceptions.

Where it bites back.

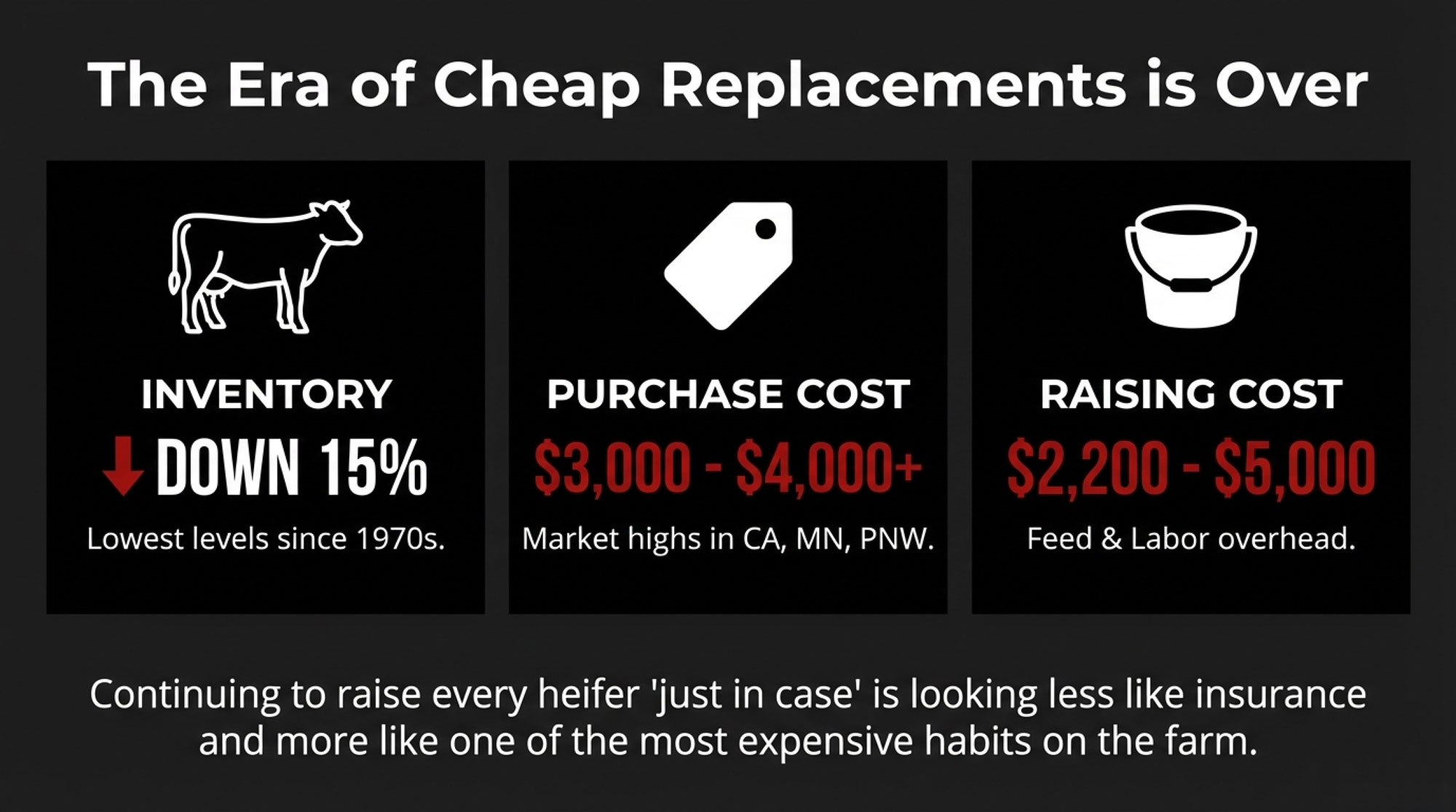

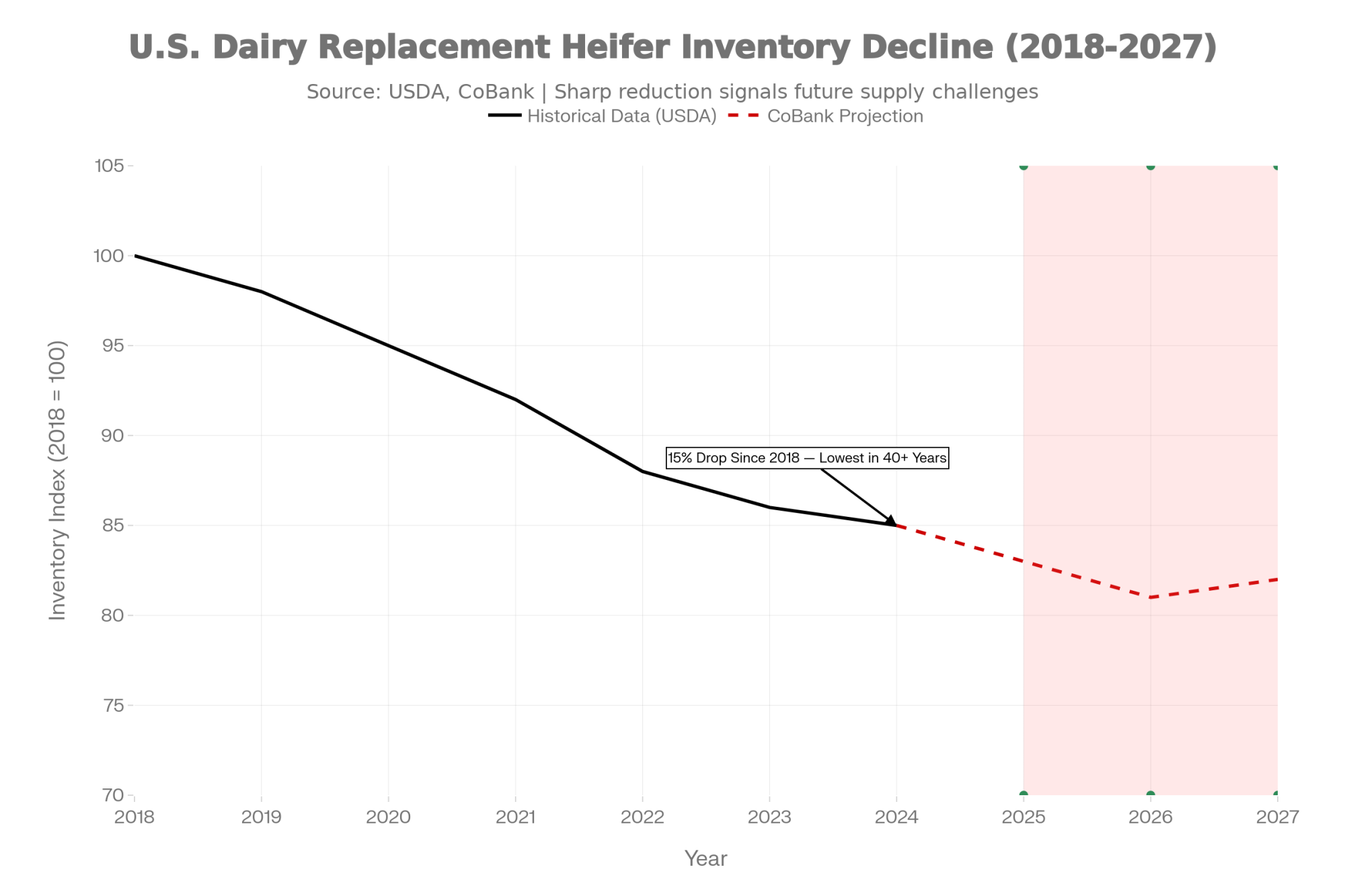

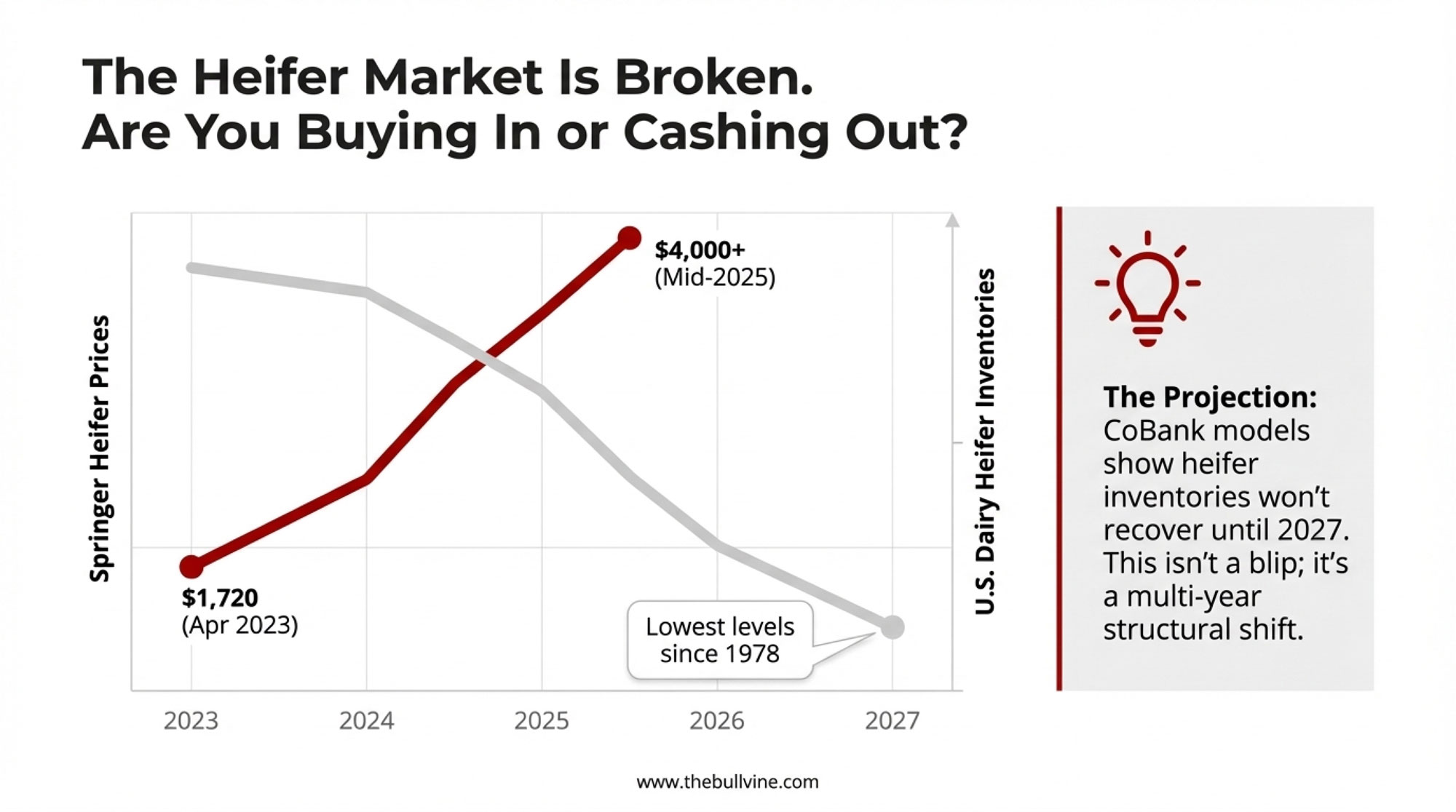

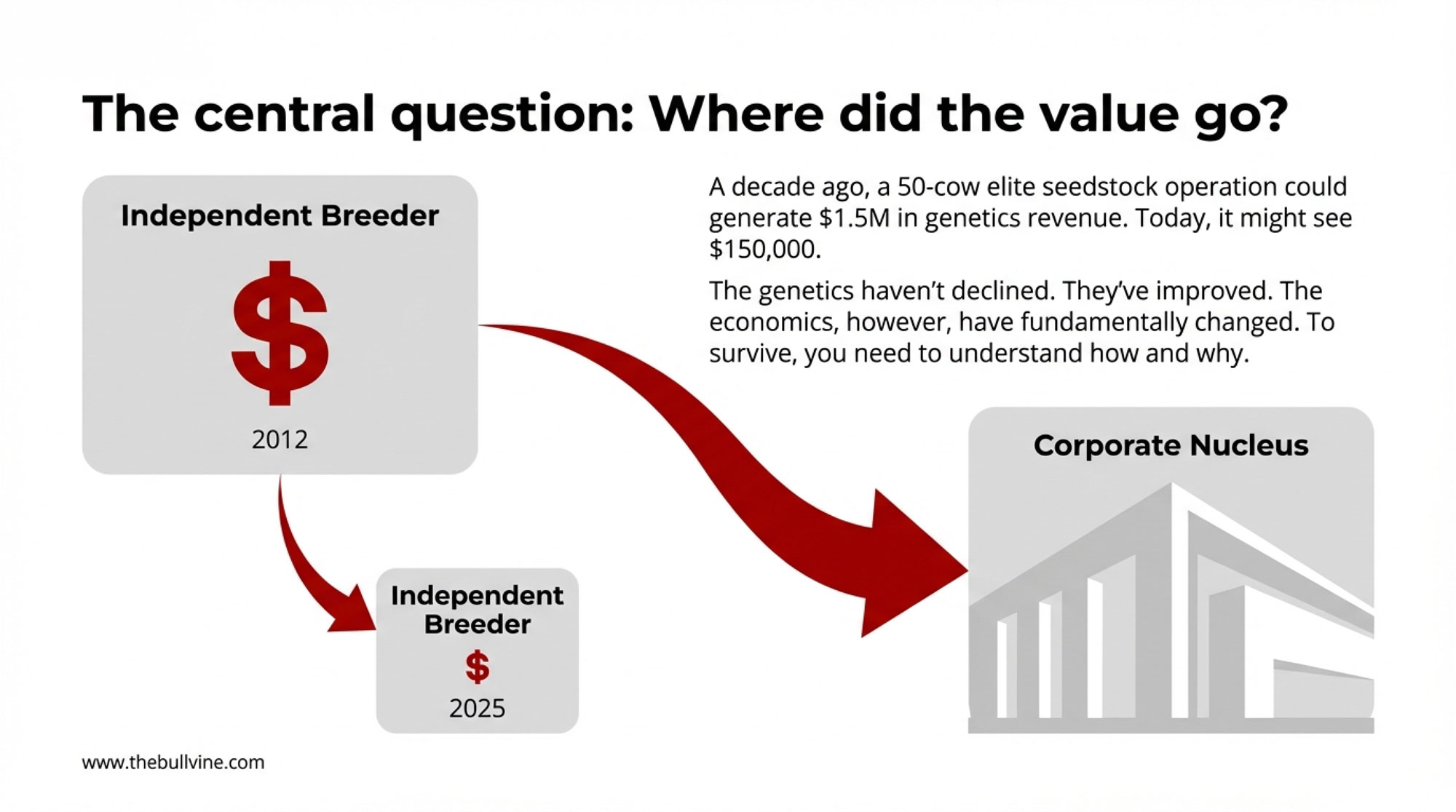

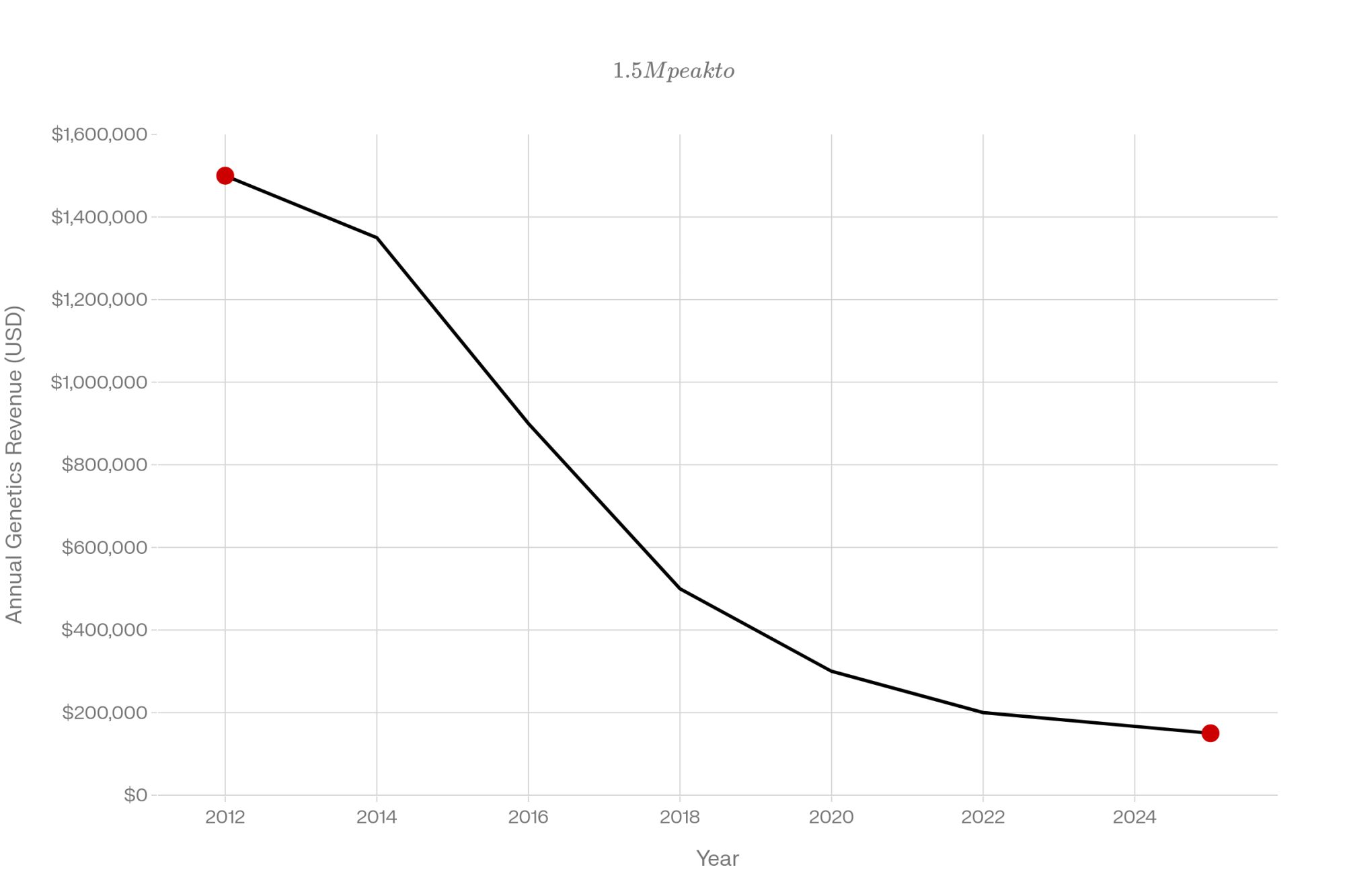

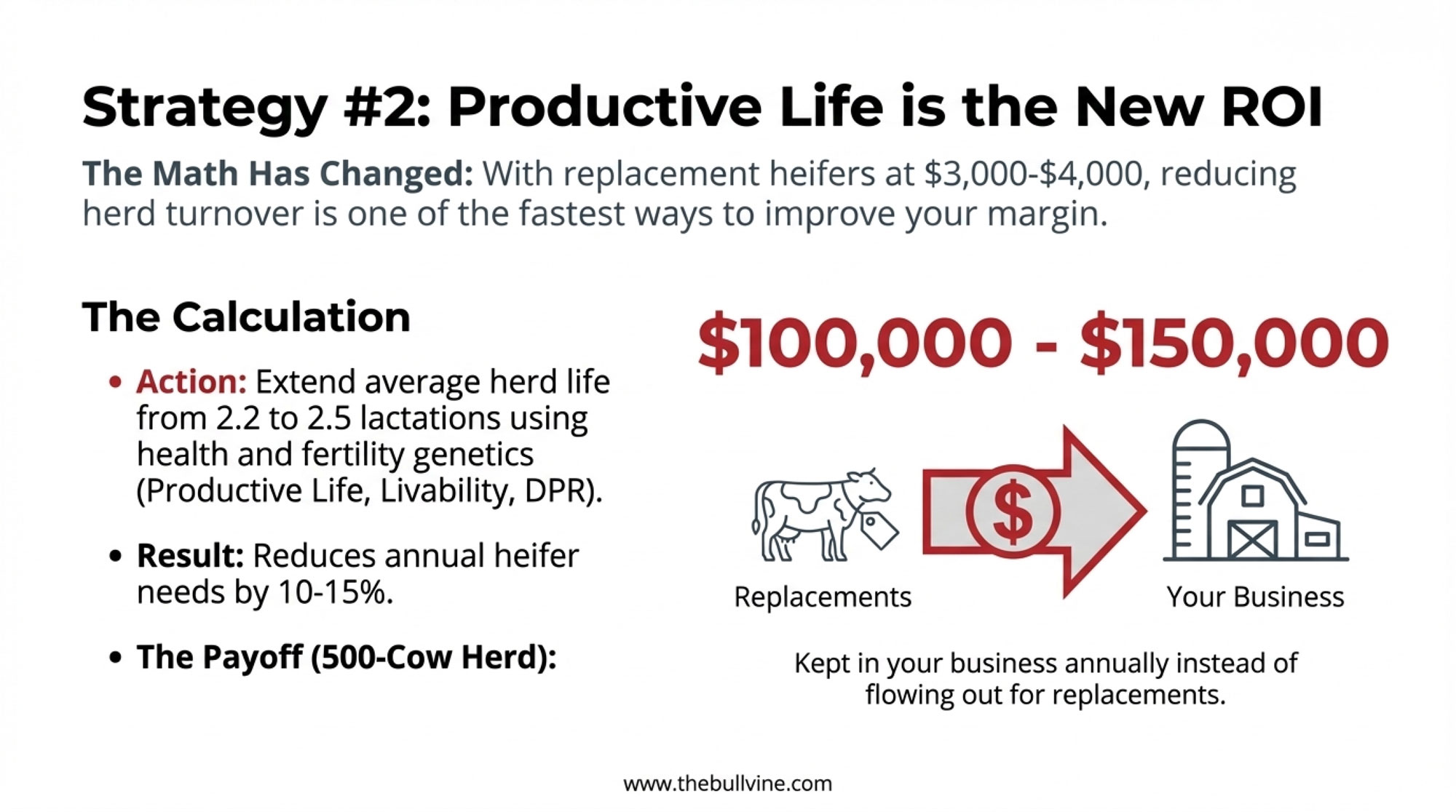

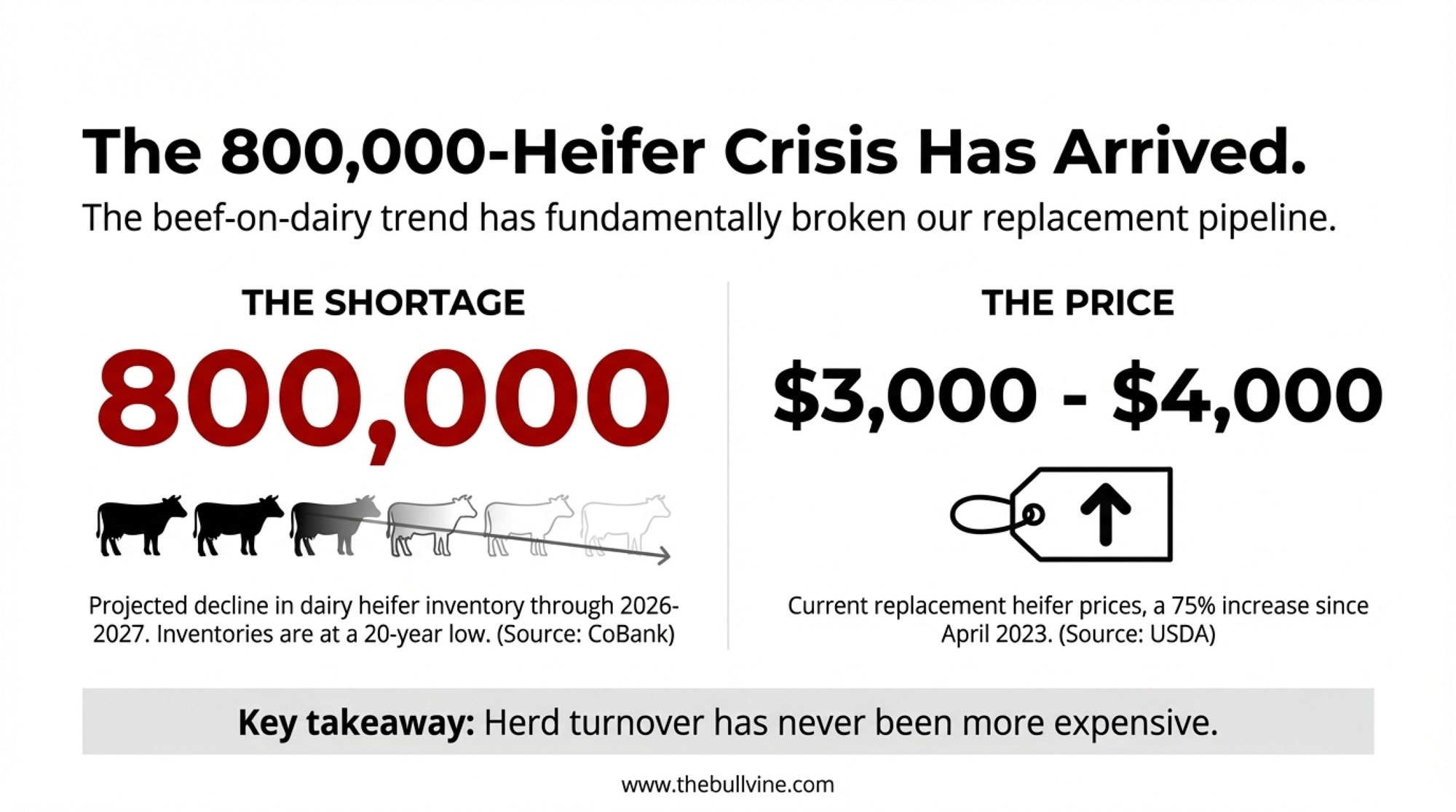

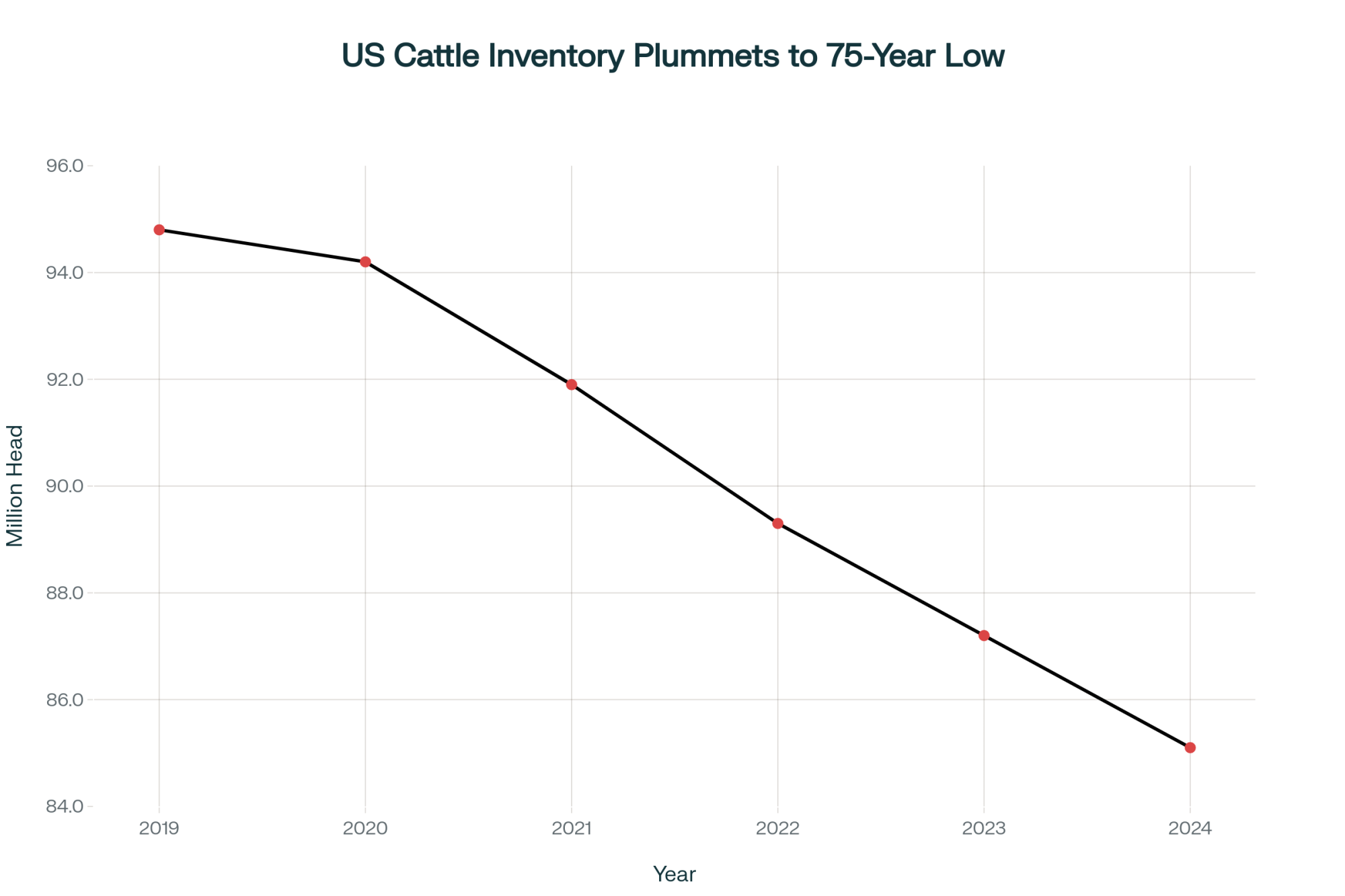

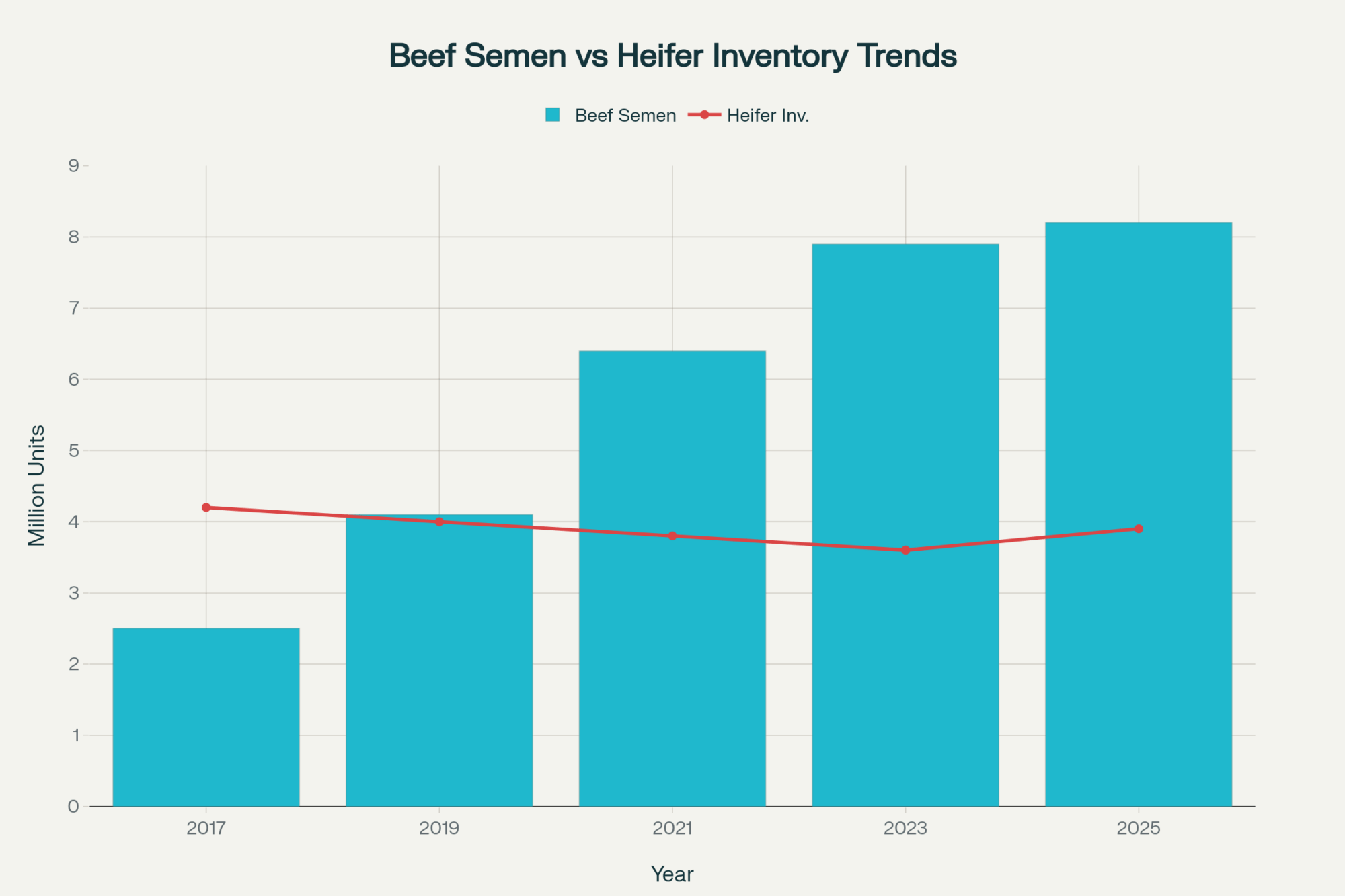

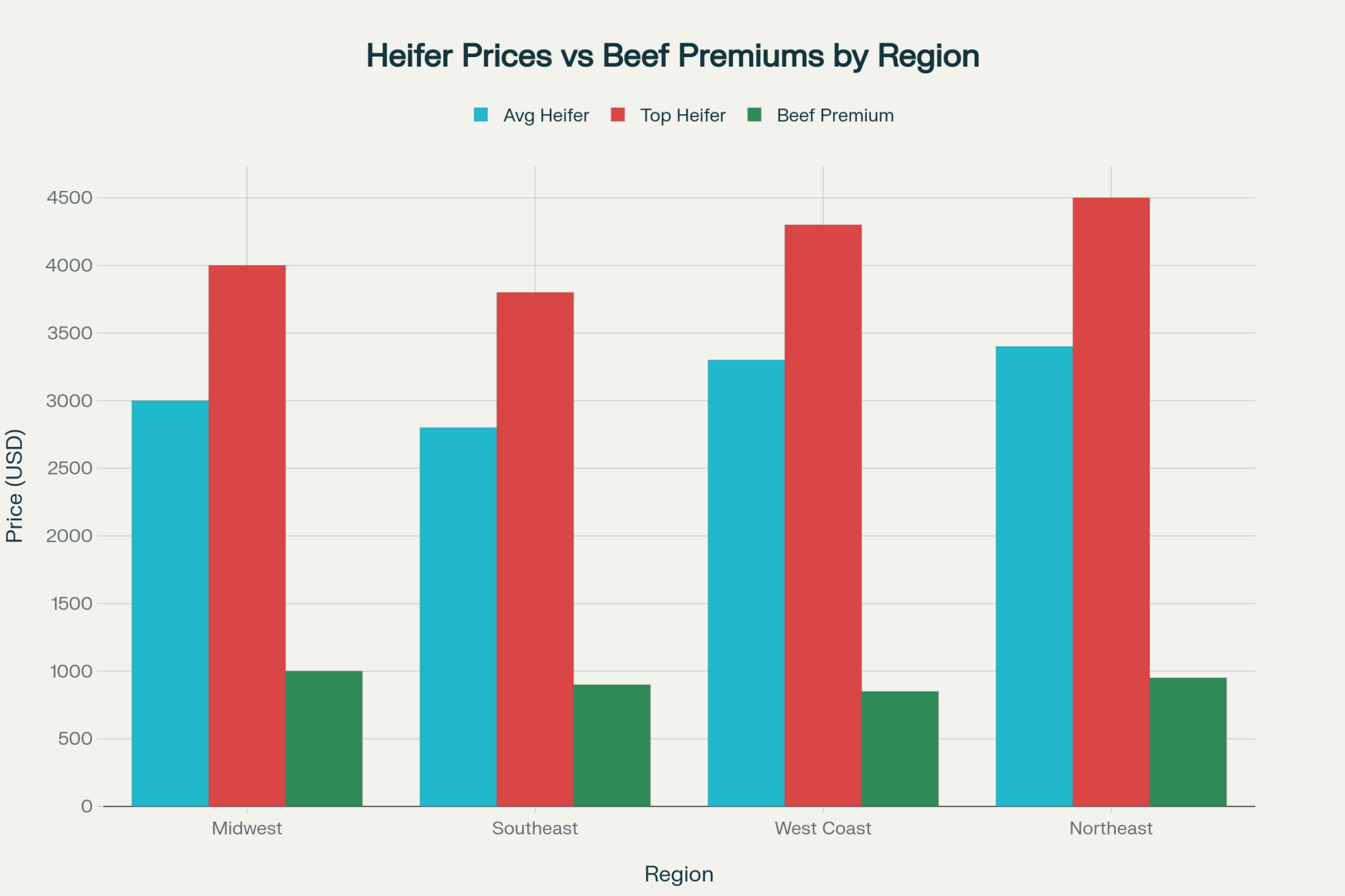

CoBank’s August 2025 analysis — echoed by Hoard’s Dairyman and other outlets — projects U.S. replacement heifer inventories hitting a 20‑year low, dropping by roughly 800,000 head before they start rebounding in 2027. Fresh heifer prices “vaulted far into record territory” in spring 2025, with baseline pregnant heifers averaging about US$2,870 and premium groups fetching “upward of US$4,000” per head. Over‑culling in that environment can easily push you into US$3,000–US$4,000 heifer purchases just to refill stalls. If your replacement inventory isn’t at least 10–15% aboveminimum needs, going full “top half only” overnight is asking for trouble.

Phone‑friendly takeaway: Use genomics to steer dairy vs. beef, but only go harsh on the bottom half if you’ve clearly got a 10–15% replacement surplus and you’re truly comfortable buying heifers at US$3,000+ if you mis‑judge it.

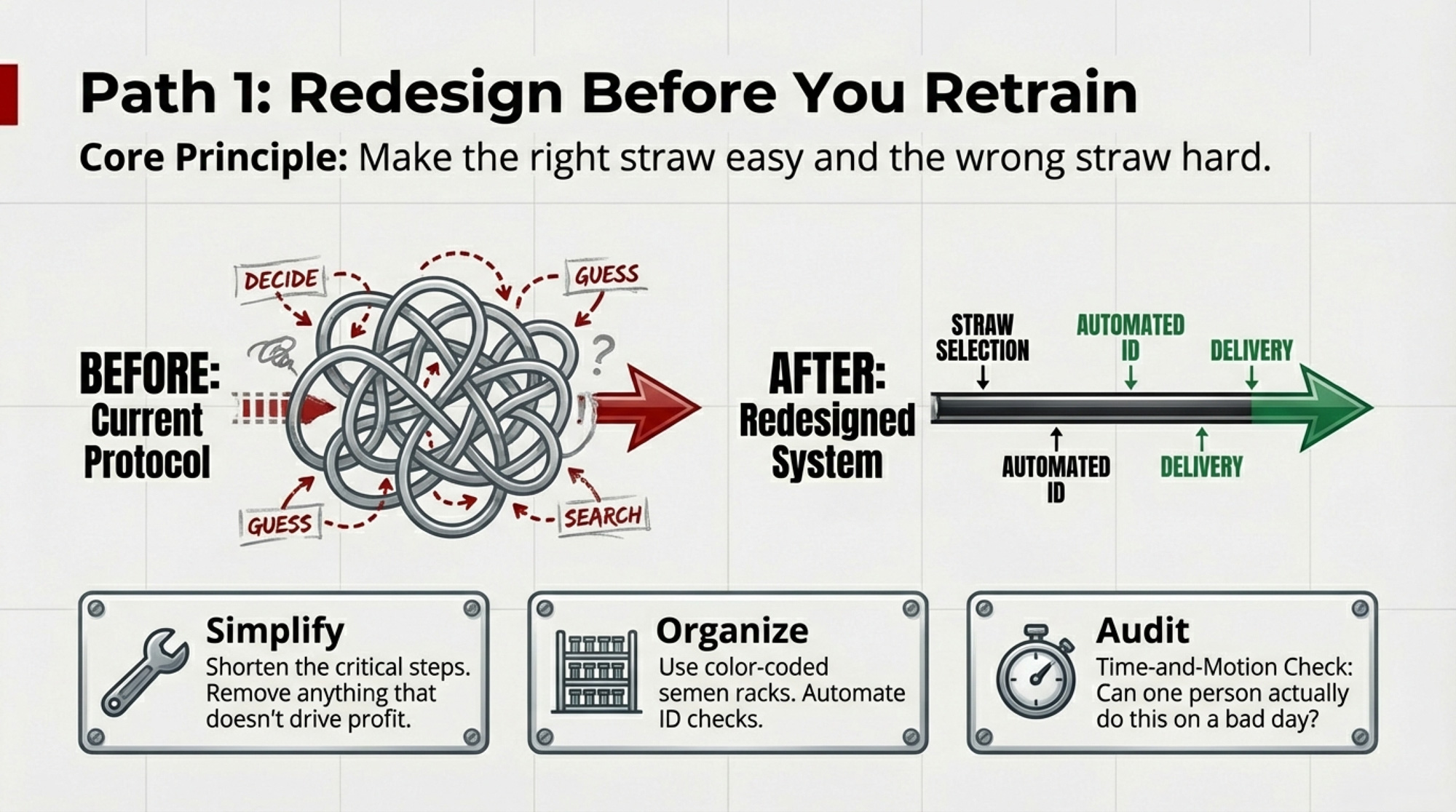

Path 2: Redesign the System Before You Rewrite the Protocol

When it fits.

You’ve already retrained a protocol two or three times, and you’re still not seeing the results move. Your best employees are missing steps or improvising on the fly.

What it takes.

- A blunt look at time and motion: can one person actually do what you’re asking on a bad day?

- A shorter list of critical steps that really move the needle (for colostrum, that usually means timing, volume, and quality at the first and second feeds).

- Tools that remove choices: organized semen racks, simple color‑coding, auto‑ID checks, and checklists that must be signed off.

Where it bites back.

You can absolutely overcorrect and strip out tasks that genuinely pay — like a documented second colostrum feeding — in the name of simplicity. The sweet spot is the simplest protocol that still pays, given your milk price, calf value, and labor cost.

Phone‑friendly takeaway: If your best person can’t hit the protocol, shorten it until they can. Then, only add back steps that clearly improve profit.

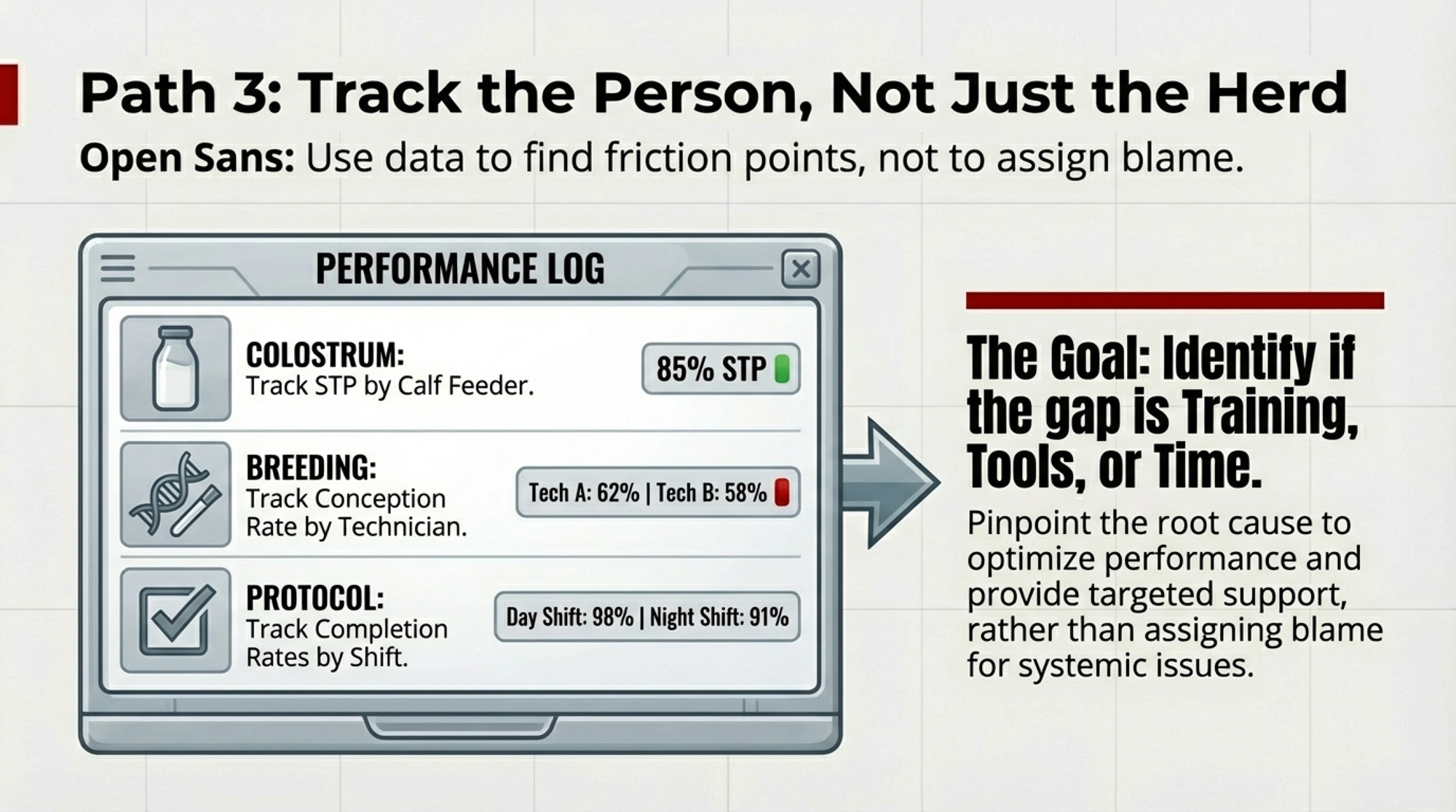

Path 3: Track Results by Person, Not Just Herd

When it fits.

You know there are good days and bad days, but you’re not sure where the swings are coming from.

What it takes.

- STP by calf feeder for the next 30–60 days.

- Conception rate and pregnancy risk by A.I. technician and by protocol (e.g., Double‑Ovsynch vs. natural heats).

- Protocol completion rates by shift for things like second colostrum feeds, vaccines, and synchronization shots.

The Michigan colostrum work and that large‑herd STP example both show it: the gap between “excellent” and “fair” passive transfer can sit almost entirely in who mixes and feeds colostrum.

Where it bites back.

If you jump straight from data to blame, you’ll destroy trust. The order has to be:

- Check whether they had the time, tools, and information.

- Fix those gaps.

- Then, coach, reassign, or change staffing if you still see the same pattern.

Phone‑friendly takeaway: Use the numbers to identify friction points and training needs—not to pin everything on one person.

Path 4: Treat Consistency as Infrastructure

When it fits.

Every operation, regardless of size or system.

What it takes.

- Written, non‑negotiable checklists for key jobs (colostrum, transition cows, breeding, semen tank handling).

- Documented second colostrum feeding where your disease risk and calf value justify the extra pass.

- Scheduled mixer‑wagon calibrations and forage dry‑matter checks so your ration on paper stays close to the ration in the bunk.

- Feeding times that stay within a tight window day after day to smooth out intakes.

Where it bites back.

Consistency without review can lock you into executing a plan that no longer fits 2024–2026 economics. Feed prices, calf values, and heifer costs have all moved since 2020. Consistency has to be paired with regular “does this still make money?” checks.

Phone‑friendly takeaway: Lock in consistency for the handful of jobs that really drive calf health, conception, and stall value — then put a date on the calendar to re‑run the math.

Running the Numbers: Dairy‑Beef Calves vs. Raising Replacements

| Scenario | Raise as Dairy Replacement | Sell as Dairy‑Beef Calf |

| Raising cost | US$2,094–US$2,607 per heifer on typical U.S. farms; some systems near US$2,900 | ≈US$50–US$75 in first‑week costs |

| Forgone dairy‑beef sale | ≈US$1,400/calf (recent U.S. average in strong programs) | N/A |

| Total exposure per head | Roughly US$3,250–US$4,350 (raising cost + forgone calf sale) | ≈US$75 |

| Return | Depends on genetics, health, and reaching 3+ lactations; average life ≈2.7 lactations | ≈US$1,400 day‑old income in active programs |

| Break‑even requires | More than 3 lactations to recoup the raising cost | Essentially week one |

Exact numbers depend on your region and marketing channel. Recent U.S. commentary shows day‑old dairy‑beef calves averaging around US$1,400, with some lots higher and some lower, while straight Holstein bull calves still trail by several hundred dollars.

This isn’t a blanket order to stop raising heifers. It’s a reminder that every “just in case” heifer carries a real opportunity cost in a heifer‑short, dairy‑beef world.

Regional Sidebar: Calf and Heifer Prices Outside the U.S.

If you’re reading this from outside the U.S., the exact dollar or euro values look different. But the pattern is starting to feel very familiar.

- Canada.

Manitoba and national beef‑market reviews for 2024–2025 point to stronger calf prices lifted by tighter beef cow inventories. At the dairy end, Ontario auction reports show fresh milk cows and bred heifers trading in the C$3,000–C$4,400 range at selected sales, with individual top cows over C$5,000 and quality springers frequently around C$3,000–C$3,800, while open heifers often fall in the C$1,500–C$2,250 band. That’s not a national average, but it’s a clear signal that replacements aren’t cheap. - European Union (example: Ireland and Denmark).

In June 2025, the Irish Farmers Journal reported that Friesian bull calf averages jumped to €209, nearly three times the roughly €67 average a year earlier, while Angus and Hereford dairy‑beef calves were regularly trading in the mid‑€200s to mid‑€300s. Teagasc’s mid‑2025 update noted that €500–€700 for very strong dairy‑beef calves had become “the new normal” for the top of the trade in some rings. In Denmark, there is a national calf‑pricing scheme where a 60 kg Holstein x beef calf earns about €100, plus bonuses that can add another €100 for the best male calves.

The exact dollar or euro values are different, but the pattern is similar: stronger beef prices and constrained replacement supplies are lifting both dairy‑beef calf values and in‑calf heifer prices in Canada and parts of Europe. The stall‑value and opportunity‑cost questions in this article still apply — you just need to plug in your local calf and heifer prices.

The Execution Cost in One Table

| Leak Point | Statistical Frequency | Economic Impact (per event) |

| Incorrect sire recording | 27.78% of cows had a wrong recorded sire in one Taiwanese dataset | Loss of expected genetic gain; weaker matings; less reliable proofs |

| Colostrum execution (STP) | 13% performance gap between 6.0 g/dL and 5.3 g/dL by an employee on one large herd | Higher morbidity and mortality, more treatments, and lost milk in the first lactation |

| Timed‑AI protocol errors | 5% error per shot ≈ , 26% of cows missing at least one of six Double‑Ovsynch injections | More open cows, longer calving intervals, fewer high‑value dairy pregnancies |

| Culling delay (RPO) | N/A (herd‑specific) | Example: ≈US$480 missed profit per stall over 200 days at US$2.40/day lost opportunity |

Signals to Watch Over the Next 24–36 Months

Your own execution data.

If you want to know where your biggest leaks are:

- Pull STP distributions by feeder for the next 30–60 days.

- Track conception and pregnancy risk by technician and by protocol type.

- Audit how many cows actually complete full synchronization protocols and second colostrum feeds.

Until you see those numbers by person and protocol, you’re guessing where your execution gap really sits.

Replacement pipeline stress.

CoBank’s August 2025 report predicts that: U.S. replacement heifers are expected to hit a 20‑year low, with an ~800,000‑head reduction before inventories start to rebuild in 2027. Heifer prices have already “vaulted far into record territory,” with baseline bred heifers near US$2,870 and premium groups “upward of US$4,000.” Any aggressive culling or dairy‑beef plan has to start with an honest count of how many replacements you have and how many you really need.

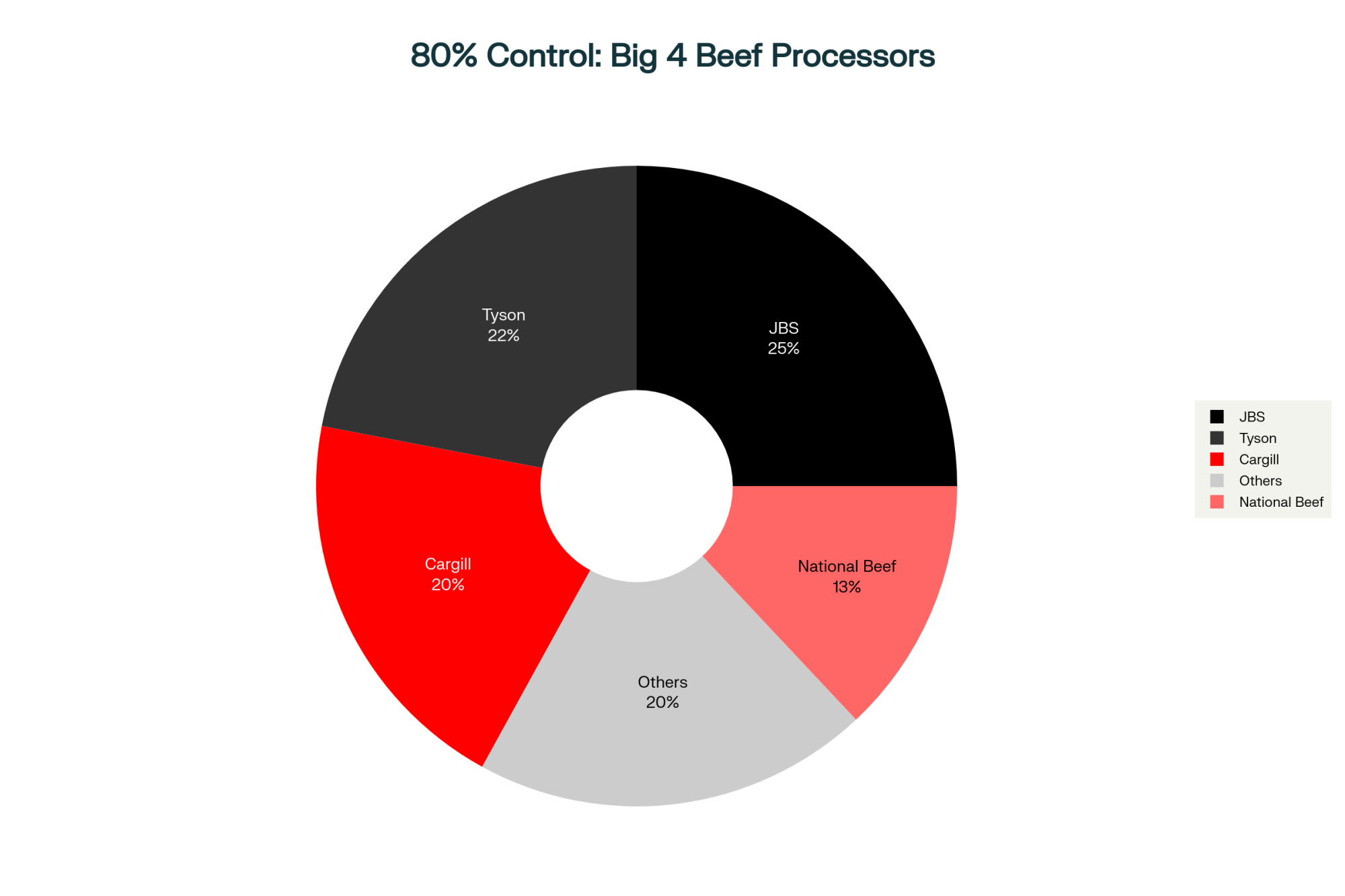

Dairy‑beef premium durability.

Dairy‑beef calves are benefiting from tight beef supplies and expanded fed‑beef capacity. CoBank’s outlook suggests 2027 as a likely turning point in the heifer cycle, and broader beef‑market work points to eventual easing of the tightest supply conditions. That doesn’t mean the bottom falls out, but it does mean the easiest premiums can narrow. Herds with consistently low FTPI and strong calf health should stay at the top of the dairy‑beef market even when everyone else starts catching up.

What This Means for Your Operation

- If your best person can’t hit a protocol, stop retraining and start redesigning. Before the next “training session,” audit the time, tools, and information they actually have. If the protocol doesn’t fit reality, fix the protocol—not the person.

- Audit colostrum by person, not just herd average. If STP by employee shows a spread of 0.5–1.0 g/dL, you’ve got an execution gap that will come back at you in treatment costs, death loss, and weak first‑lactation cows.

- Run RPO, not emotions, on your bottom third. When a cow’s projected daily profit is clearly below what a replacement could do in that stall — and your heifer inventory is solid — it’s time to let her go, even if her current milk looks good.

- Use genomic ranks to control who gets dairy semen, but only as aggressive as your replacement math allows. If your replacement count isn’t at least 10–15% above minimum needs, phase in hard cutoffs instead of flipping the switch to “top half only” overnight.

- Treat dairy‑beef as a serious margin tool, not a fad. It only really pays if your colostrum and calf care are strong enough to deliver high‑value calves consistently. If FTPI is shaky, fix that first before you chase top‑tier calf checks.

- Spend time in the parlor and by the tank. Watch how IDs are read, how long the canister stays in the neck, and how often people hunt for the right straw above the frost line. The cheapest fixes usually hide in daily habits, not in new technology.

Key Takeaways

- Execution gaps — not genetics or feed alone — may be one of the biggest hidden costs on modern dairies, once you line up the FTPI data, sire‑error rates, and heifer economics against what you thought your protocols were delivering.

- Only 36% of the 50 Michigan farms in a major colostrum project actually met passive transfer goals, even though most believed their routines were solid. Until you track STP by person, you honestly don’t know where your farm sits.

- When you’ve retrained a protocol twice, and results haven’t moved, the problem is almost always the system — not the people. Redesign the work, remove failure points, and then retrain with a protocol that fits real‑world conditions.

- Retention Pay‑Off and stall opportunity cost matter more than whether a cow is “still paying for herself” on paper, especially when 70% of cows leave before three lactations and the average heifer raising cost sits around US$2,355 per head.

- Tight heifer inventories and record dairy‑beef calf values make poor execution more expensive than ever.In 2024–2026, every protocol miss has the potential to waste a historically valuable calf and a historically valuable stall.

The Bottom Line

The herds that win over the next few years won’t be the ones with the fanciest protocols in a binder. They’ll be the ones that build simple, durable systems their people can hit on the worst days, not just the best.

If you pulled your numbers tomorrow, which protocol would look the worst — and what’s your plan to rebuild it before it costs you another year?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

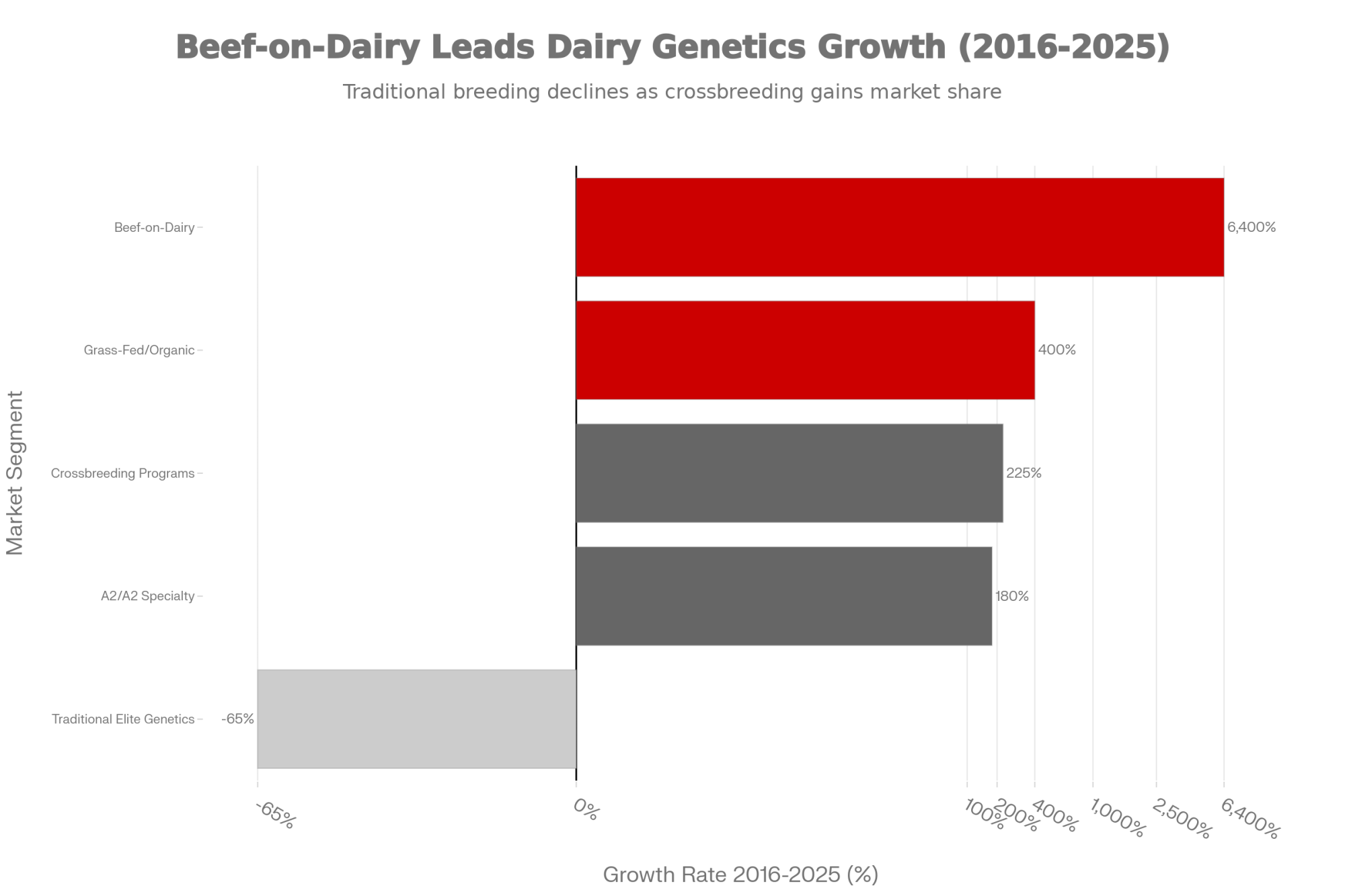

- Beef-on-Dairy’s $6,215 Secret: Why 72% of Herds Are Playing It Wrong – Arms you with the reproductive benchmarks and genomic multipliers needed to separate elite operators from the 72% currently leaking cash. You’ll gain a direct method for identifying high-value pregnancies that turn standard heifers into six-figure margin drivers.

- 438,000 Missing Heifers. $4,100 Price Tags. Beef-on-Dairy’s Reckoning Has Arrived. – Exposes the structural $4,100 heifer shortage and delivers a long-term roadmap for surviving the “missing heifer” era. This analysis positions your operation for 2027 by breaking down how to balance immediate beef-check revenue against future milk-string stability.

- CDCB’s December ‘Housekeeping’ Is Actually Preparing Dairy Breeding for an AI Revolution – Reveals the digital infrastructure being built for the 2028 AI transition and arms you with the data-quality steps needed today. This guide ensures your breeding program stays competitive as machine learning replaces traditional evaluations to maximize genetic accuracy.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!