“Reminder: every extra pound of pre‑weaning gain can mean 1,000+ lbs more milk later. Are your calves leaving money on the table?

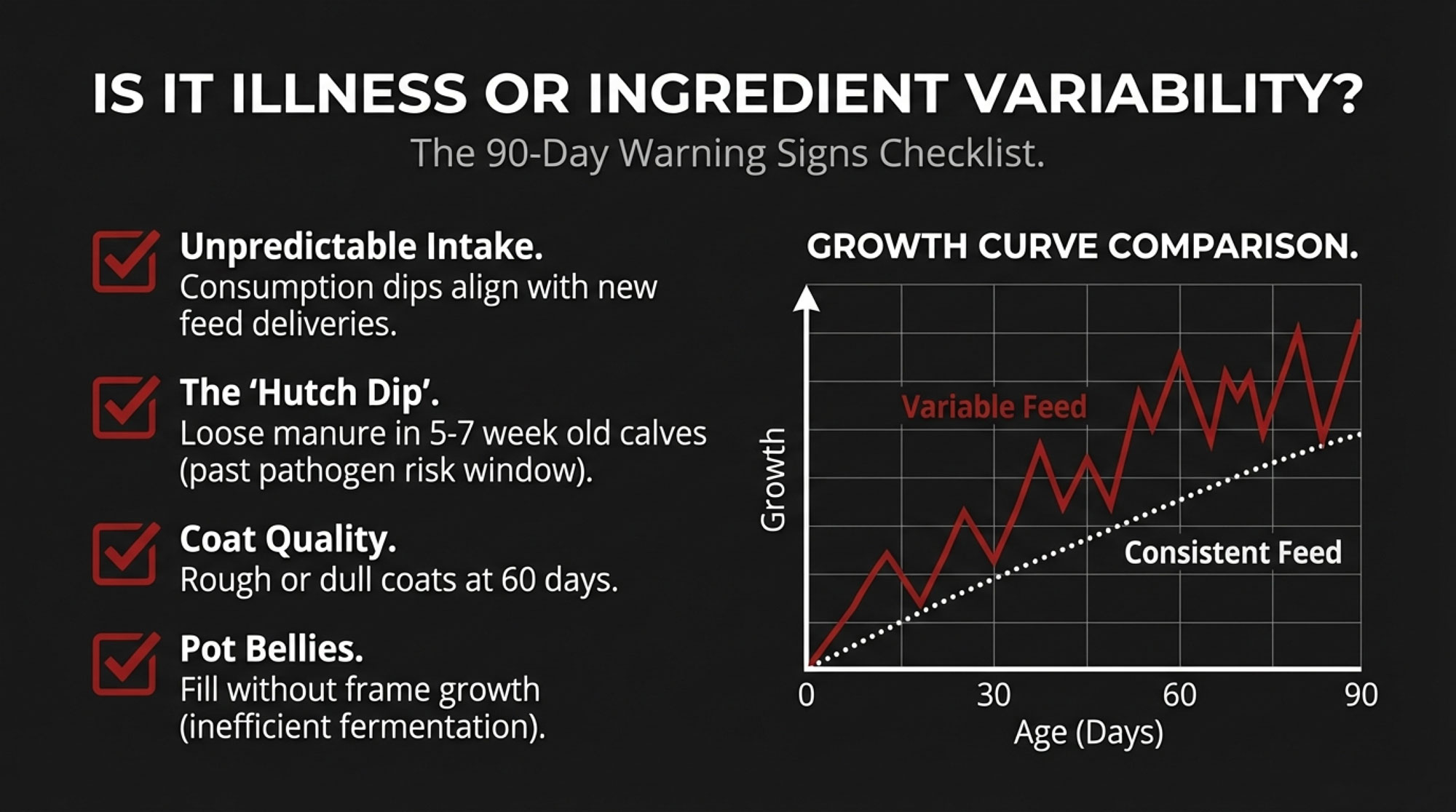

You know that frustration when calves look fine one week and then crash the next? Weaning dip stretches into three weeks of depressed intake, respiratory disease clusters right around that vulnerable transition window, and it happens no matter what you try. Most of us have been there—whether you’re running 200 cows in Vermont or 2,000 in the Central Valley. It’s one of those persistent challengesc in calf nutrition and heifer development that never quite seems to get solved.

For decades, we’ve treated this as just the cost of doing business. Calves are fragile. Weaning is stressful. Budget for the treatments and move on.

But here’s what’s interesting—a growing body of research and a smaller group of producers willing to rethink their protocols suggest something different. The weaning dip may be less about inevitable stress and more about accumulated decisions made weeks earlier. And the solutions aren’t necessarily expensive or complicated. They’re just… different from how most of us learned to do things.

I want to walk through what the research actually shows, what some operations are finding when they apply it, and—just as importantly—why this approach doesn’t work for everyone.

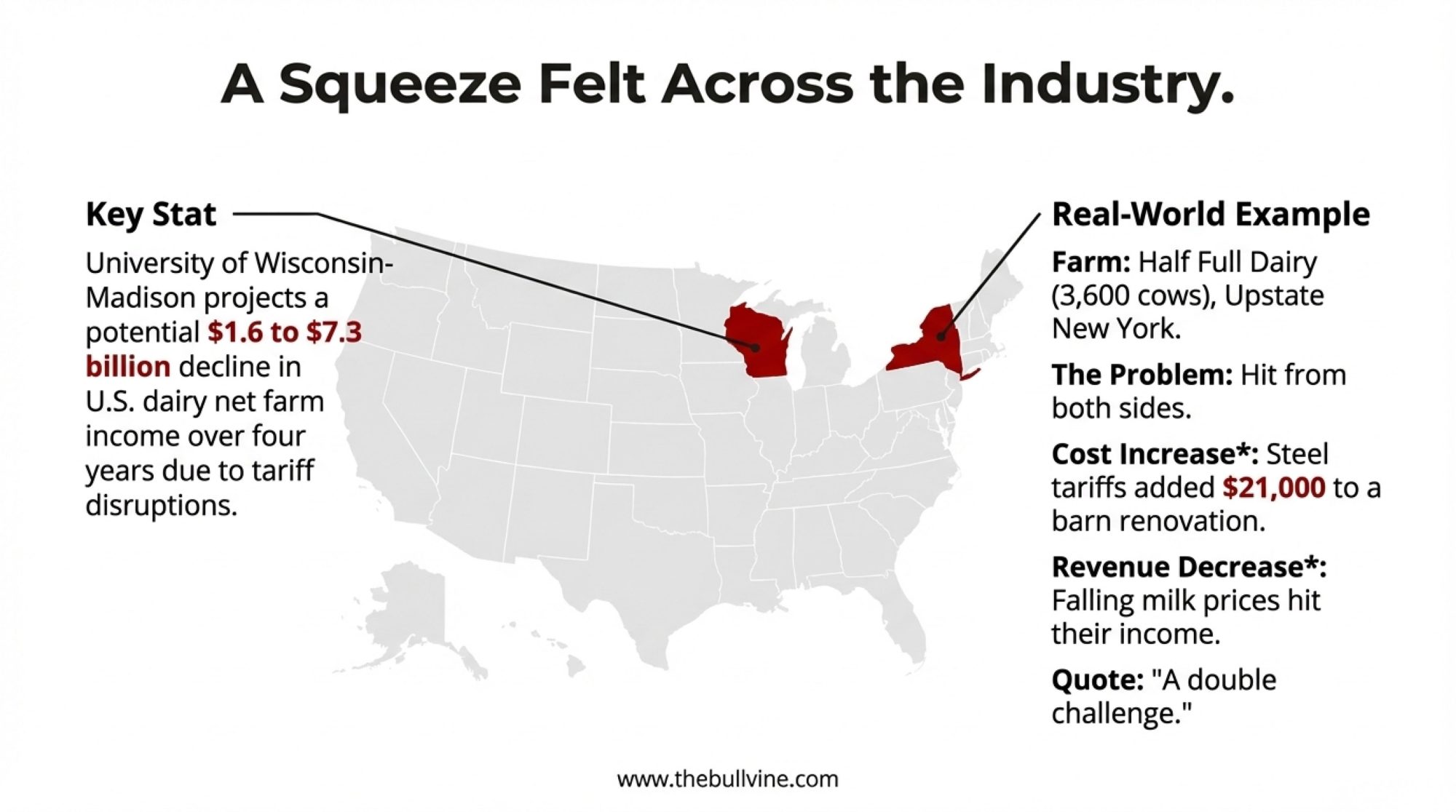

The Economics Nobody Wants to Talk About

Let’s start with the numbers, because that’s ultimately what drives decisions.

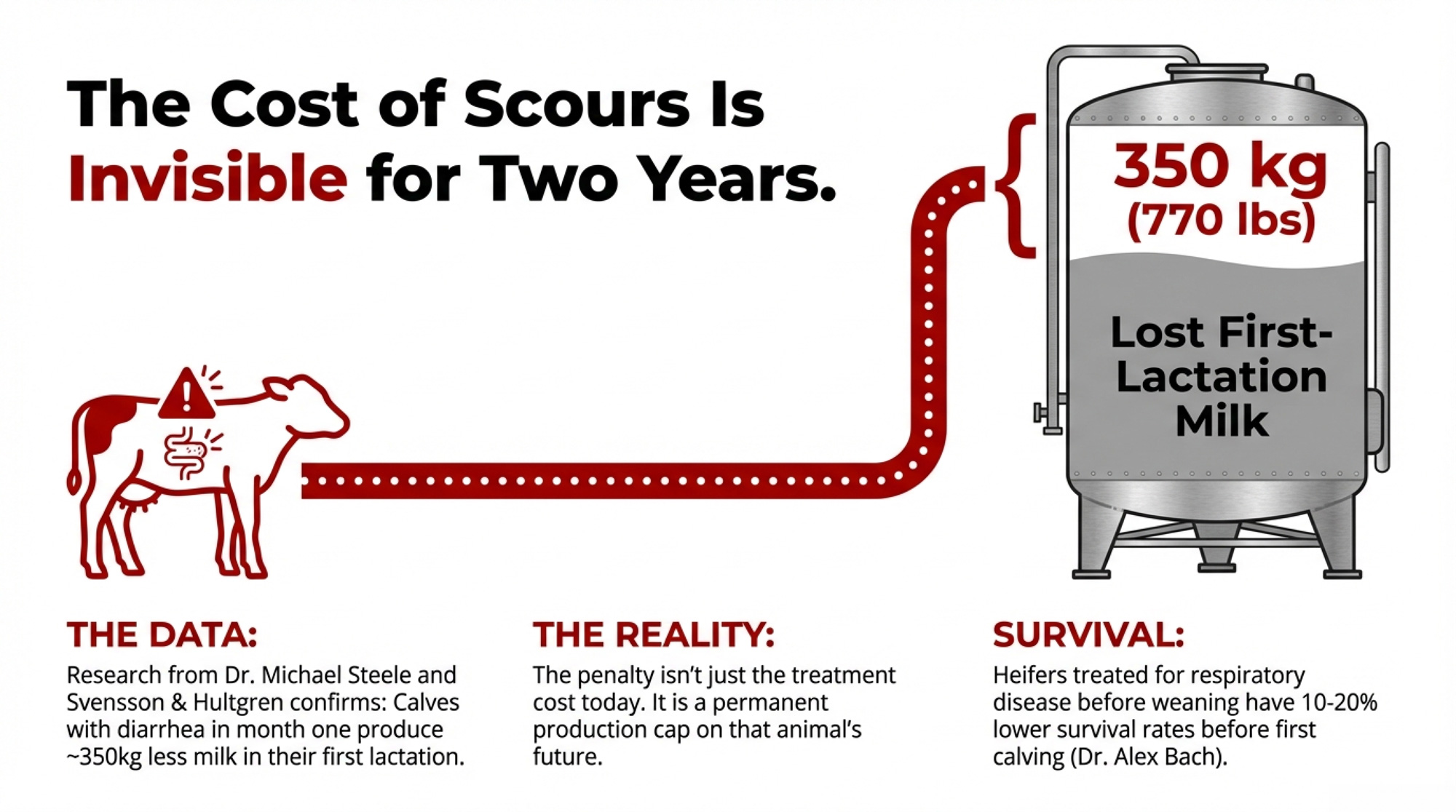

Dr. Michael Steele’s research group at the University of Guelph has been tracking the long-term consequences of early-life calf health for years. Their work, combined with Swedish research by Svensson and Hultgren, which has been widely cited in the Journal of Dairy Science, documents something that should give us pause: calves experiencing diarrhea in their first month of life produce roughly 340-350 kg (748 – 770 lbs) less milk in their first lactation than healthy calves.

That’s not a typo. We’re talking about nearly 350 kg (770 lbs) of milk—gone—because of a bout of scours in week two.

Dr. Alex Bach, an ICREA research professor working with IRTA in Spain, has been equally direct about respiratory disease. His research shows that heifers treated for bovine respiratory disease before weaning have significantly higher odds of dying or being culled before first calving—with survival rates often running 10-20 percentage points lower than healthy cohorts. The immune insult doesn’t resolve simply because the calf clinically recovers. It reverberates through her productive life.

This connection between early-life health and lifetime performance continues to be reinforced by ongoing research. A 2025 study by Leal and colleagues in the Journal of Dairy Science demonstrated that suboptimal preweaning nutrition creates measurable metabolic differences that persist through first lactation—effects visible in glucose metabolism and overall metabolic profiles well into the heifer’s productive life.

Now, here’s where I think our industry gets stuck. These are long-term consequences. The treatment costs are visible today—you see them on this month’s vet bill. The first-lactation milk penalty won’t appear for 2 years. Most operations—understandably—optimize for what they can see and measure right now.

The challenge, as multiple dairy economists have noted, is convincing producers to invest today for returns they won’t see until that heifer’s second lactation. It’s fundamentally different from evaluating the price of a bag of milk replacer.

And it’s worth sitting with that tension for a moment, because it explains why adoption of these practices has been slower than the research might predict.

What’s Actually Happening in the Calf’s Gut

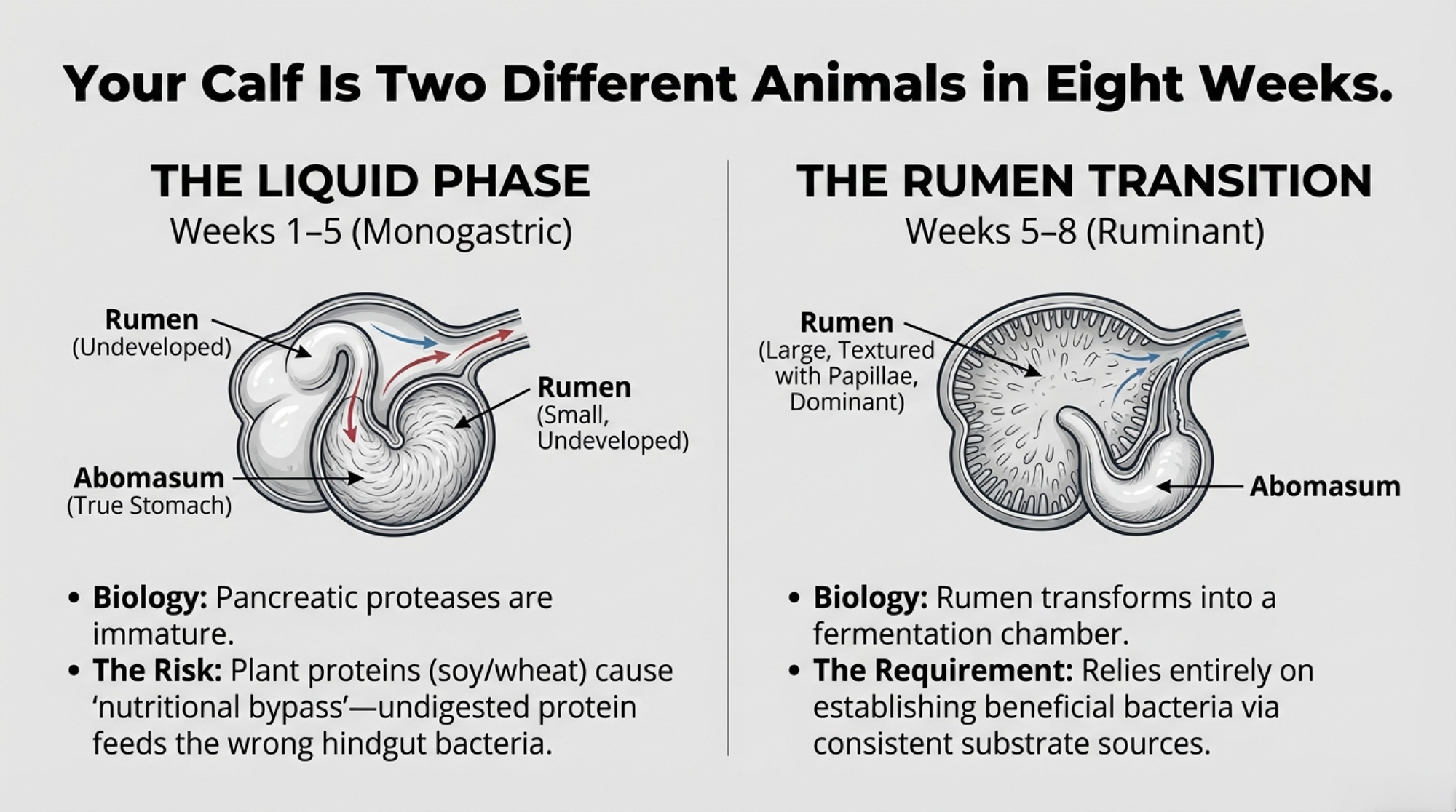

To understand why certain interventions work, you need to understand what’s developing inside the calf during those first critical weeks. The science here has advanced dramatically in the past decade—and it’s reshaping how progressive operations think about their calf programs.

The Small Intestine Window

Before the rumen becomes functional—roughly weeks one through five—the calf is essentially a monogastric animal. The small intestine handles the heavy lifting for nutrient absorption, and it’s susceptible to early nutrition choices.

Research published in peer-reviewed nutrition journals has mapped digestive enzyme development in young calves, and what these studies have found matters for anyone making decisions about milk replacer formulation: pancreatic proteases operate at only a fraction of adult capacity at birth, gradually maturing over the first three to four weeks.

Why does this matter practically? The calf’s enzyme systems evolved to digest milk proteins, including casein and whey. When you substitute milk proteins by plant proteins like soybean meal or wheat gluten (often done to reduce costs), you’re asking an immature digestive system to handle substrates it’s not fully equipped to handle.

Work published in the Journal of Dairy Science by Ansia and colleagues compared nitrogen digestibility between all-milk protein replacers and those supplemented with enzyme-treated soybean meal. The pattern was clear: all-milk formulas showed notably better digestibility by week three compared to plant-supplemented formulas. That gap represents protein that isn’t nourishing the calf—it’s passing through to the hindgut, where it can feed the wrong bacteria.

Research presented at the 2024 Healthy Calf Conference in Ontario reinforced this point: early-life nutrition—specifically the first 60 days—affects digestive function throughout the animal’s productive life. That framing helps explain why the details matter so much during this critical window.

The Rumen Transition

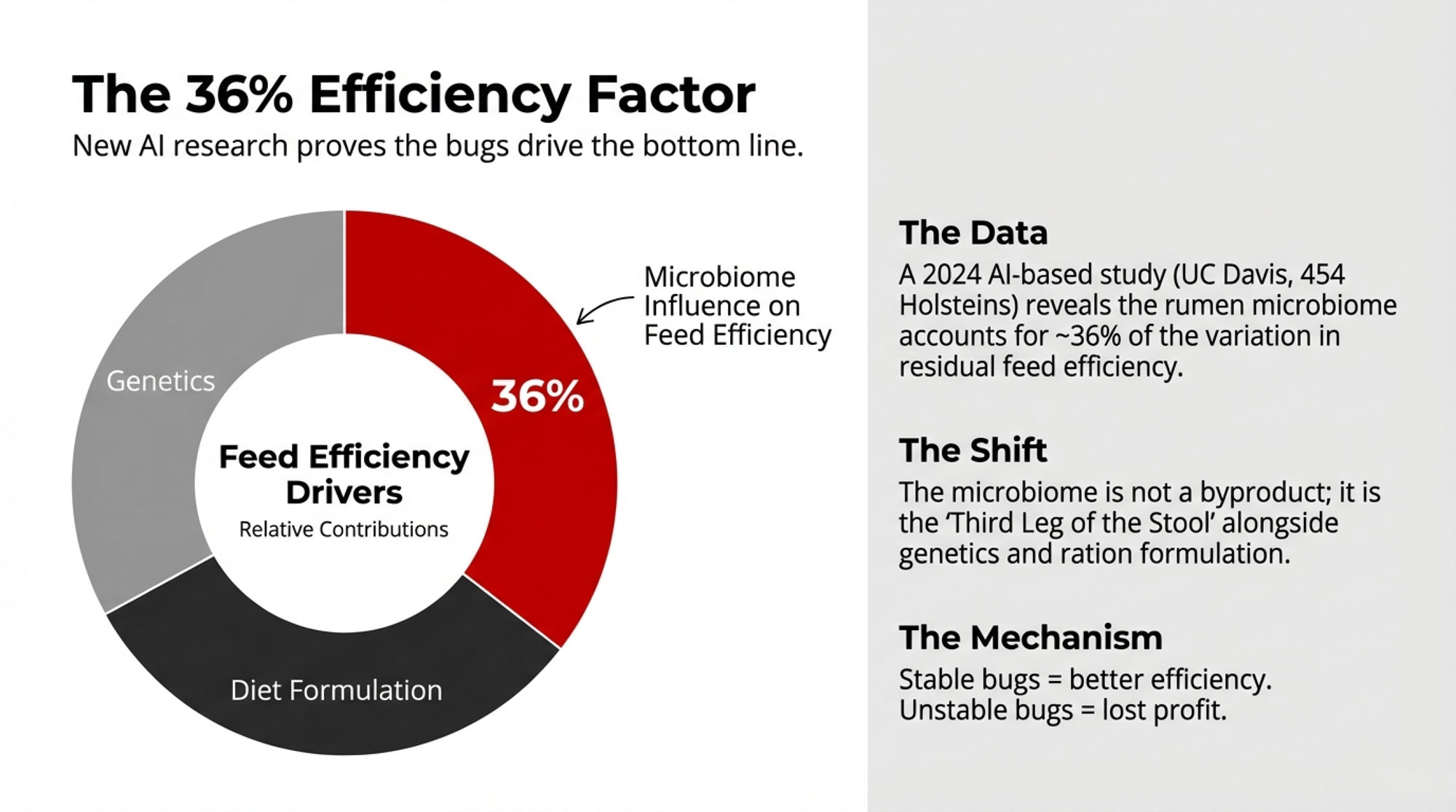

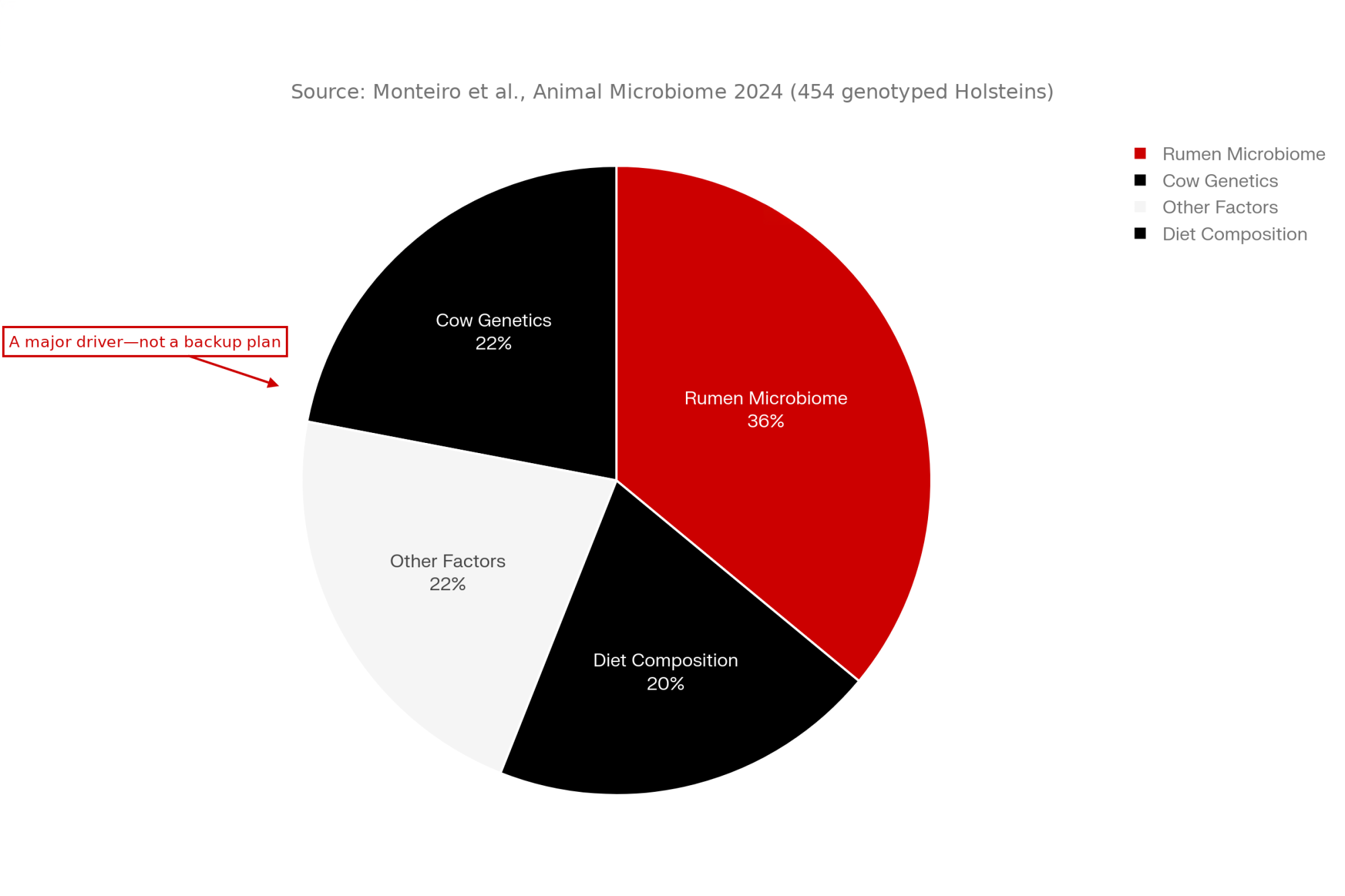

As starter intake increases around weeks five through eight, something remarkable happens. The rumen transforms from a collapsed, non-functional organ into the calf’s primary fermentation chamber. This transition depends entirely on establishing stable populations of beneficial bacteria—and this is where substrate consistency becomes critical.

Dr. Phil Cardoso’s lab at the University of Illinois has done elegant work tracking how rumen microbial communities develop. Here’s the part that surprised me when I first dug into this literature: rumen bacteria are extraordinarily substrate-specific.

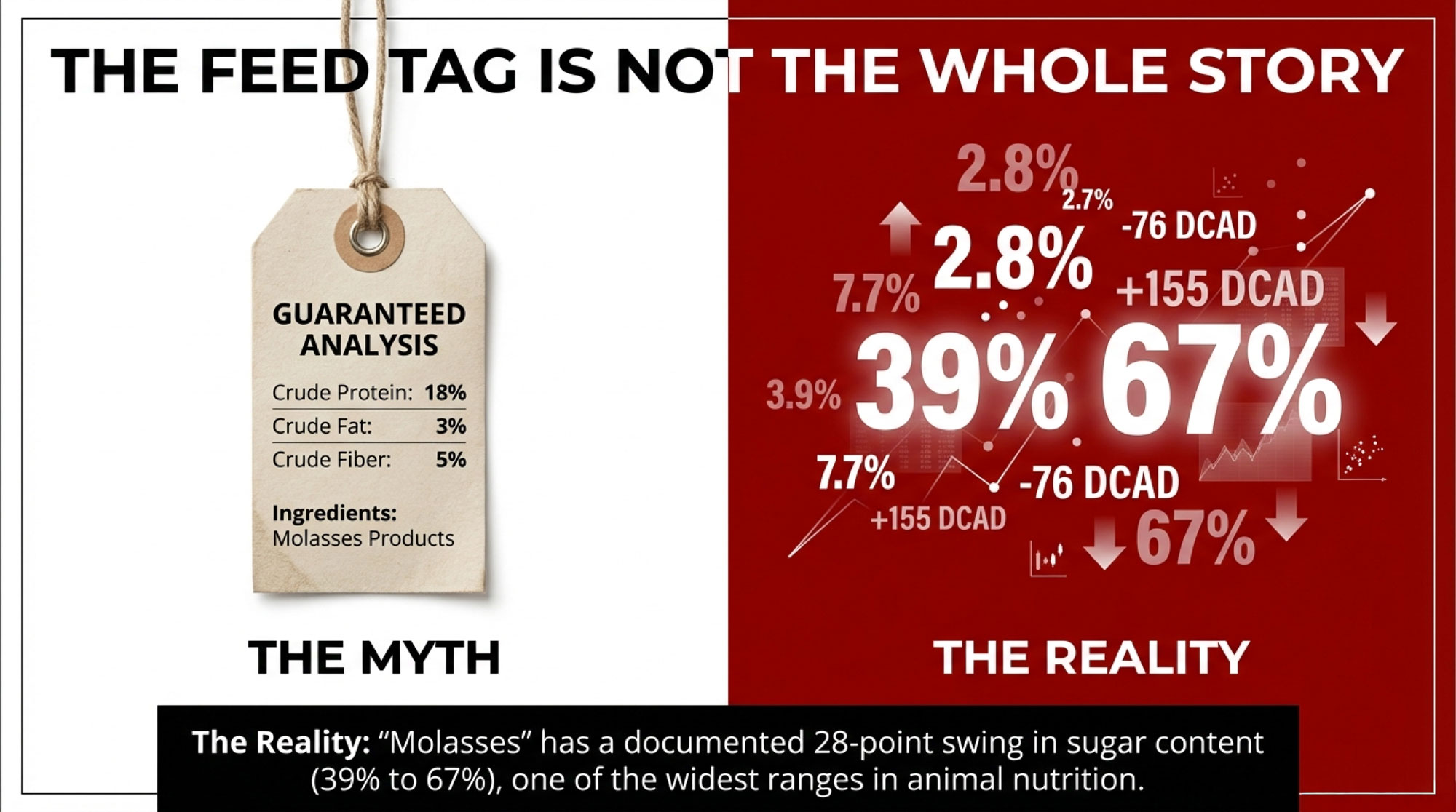

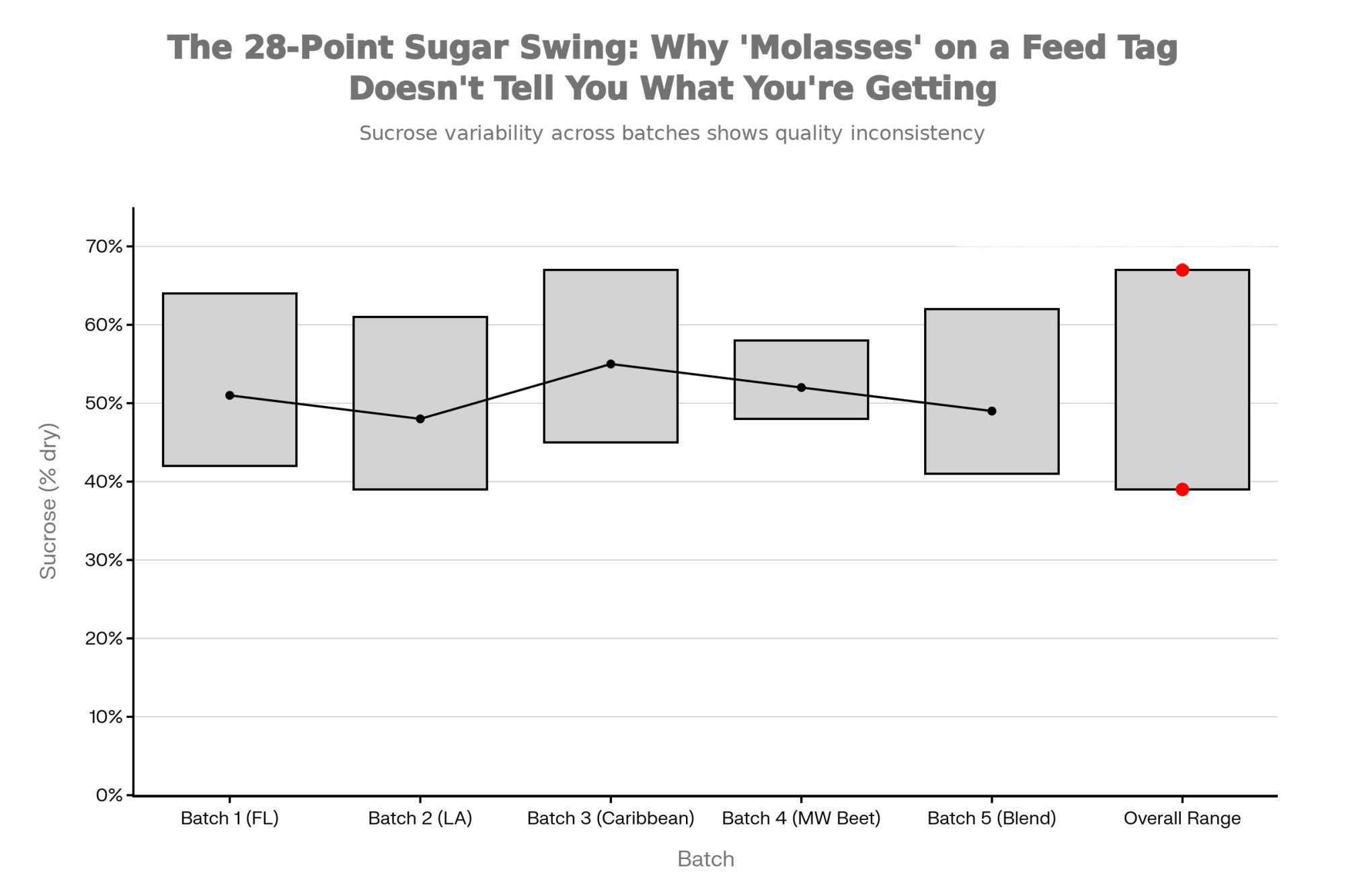

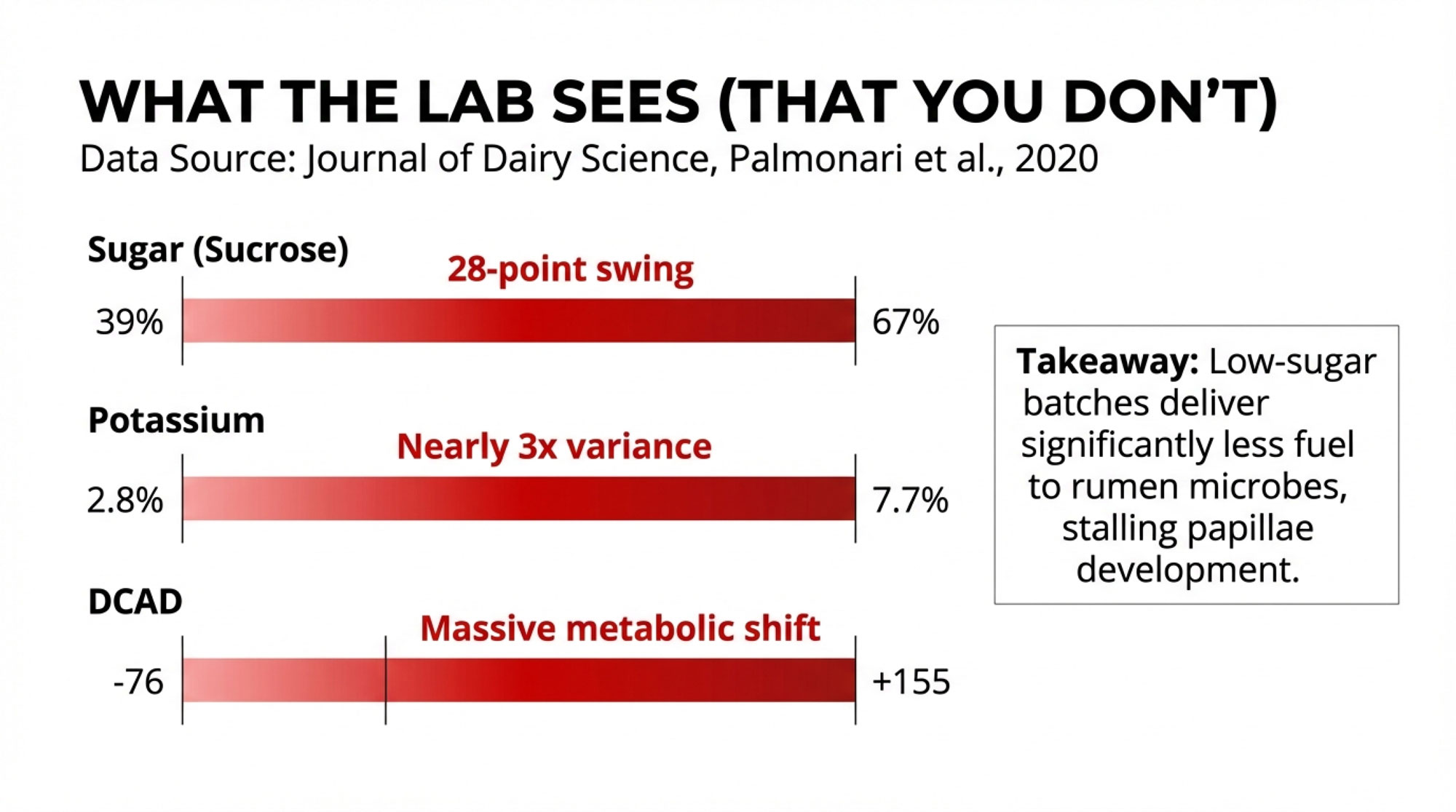

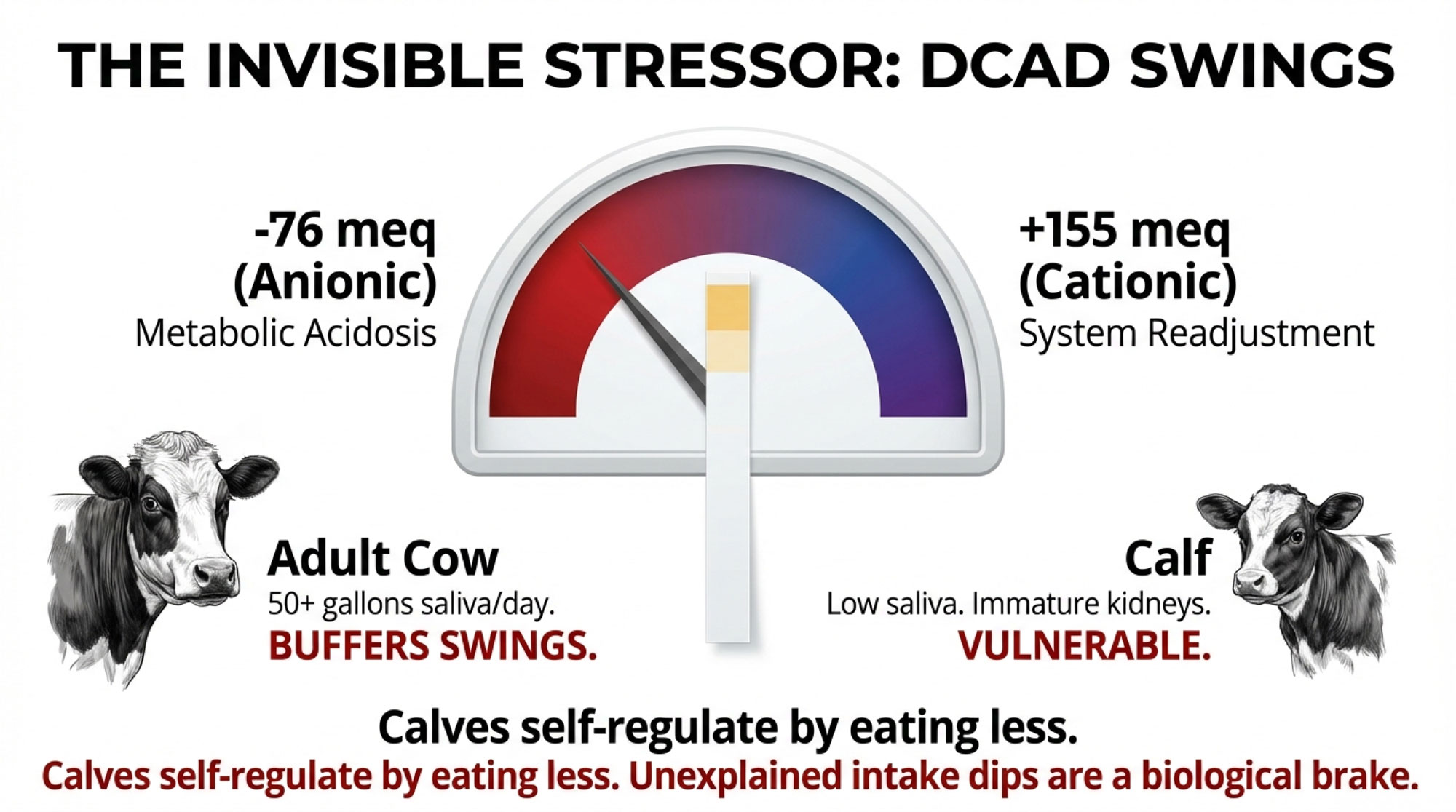

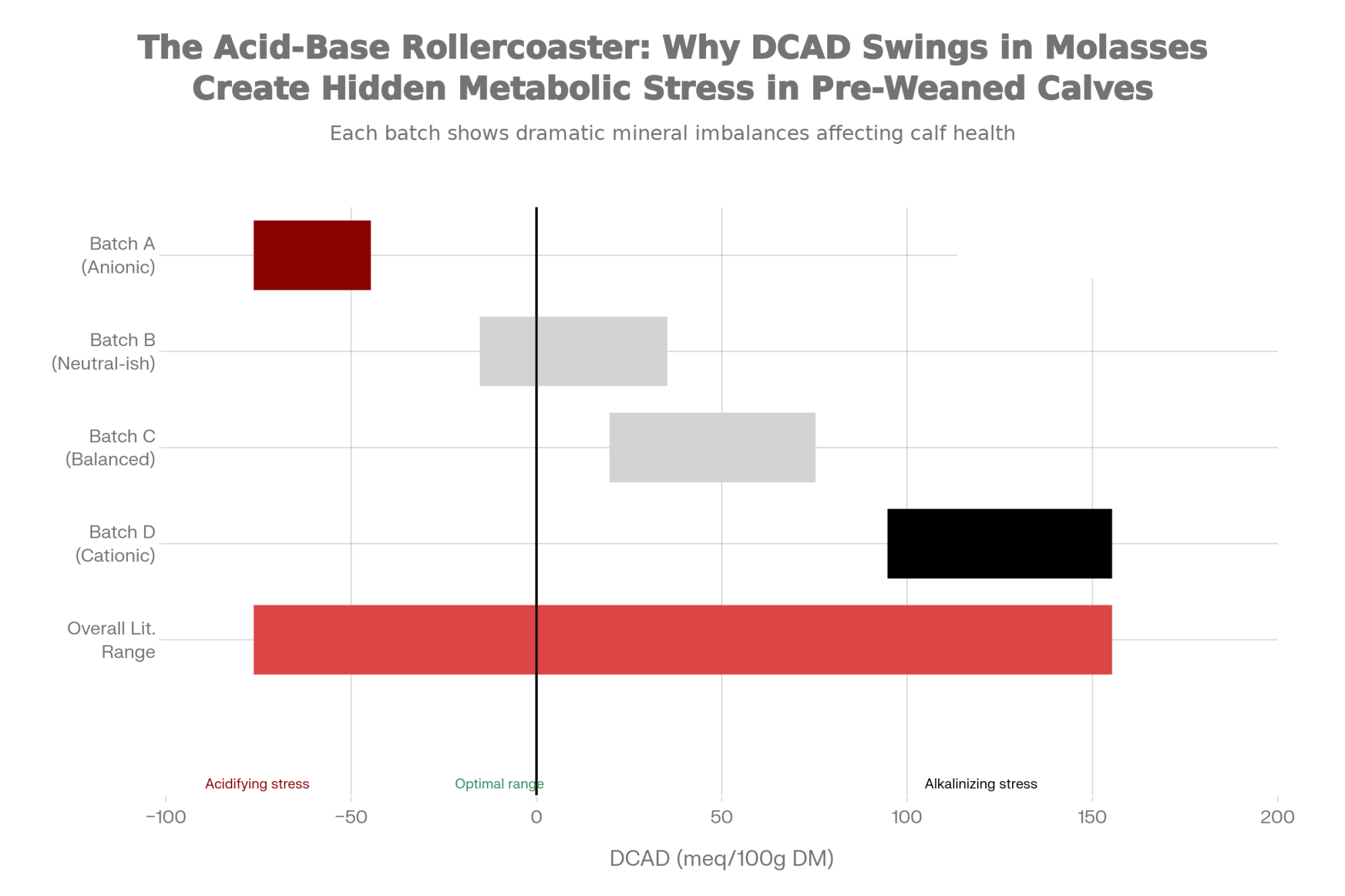

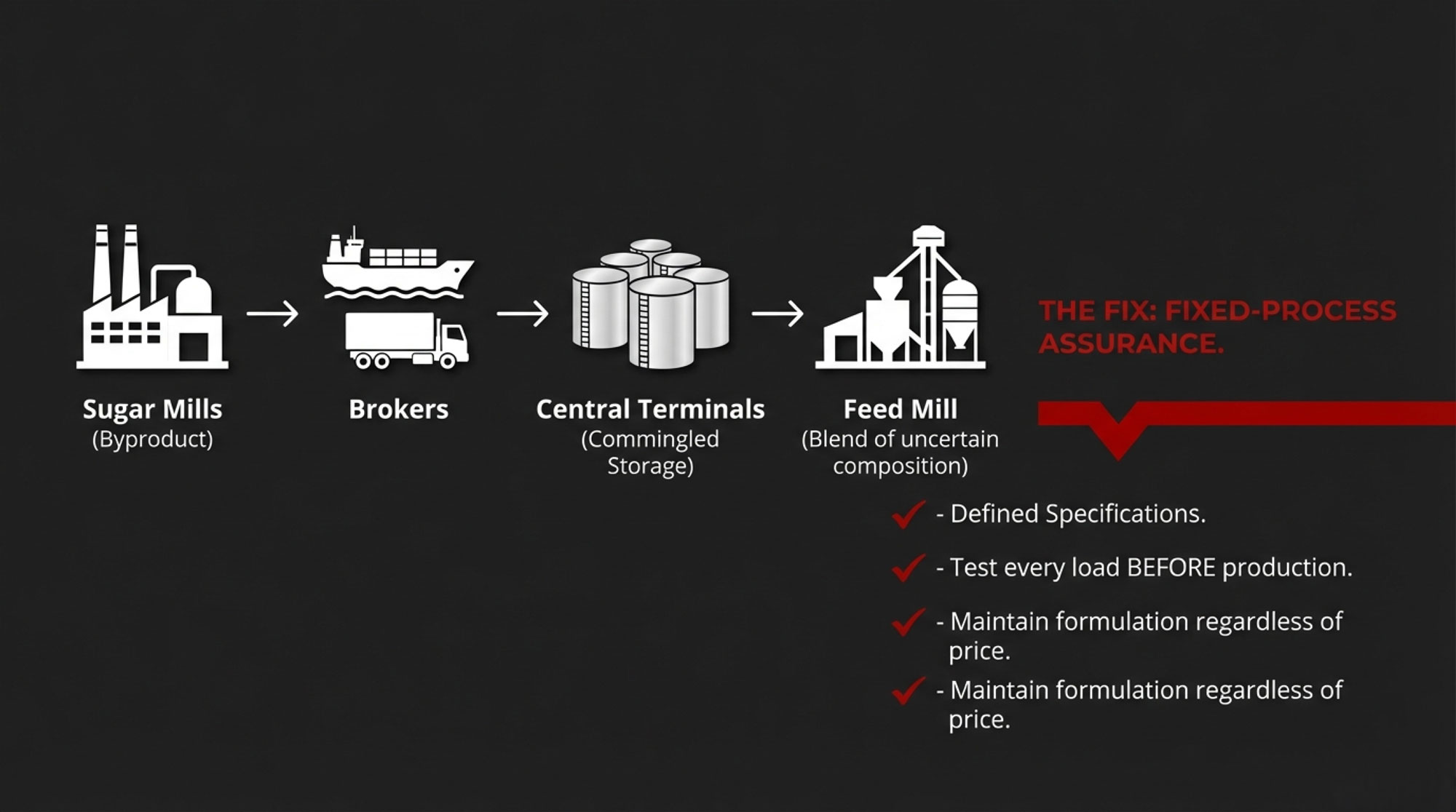

Different bacterial species have evolved enzymatic machinery optimized for specific fermentation substrates. When feed composition shifts—different molasses sources, varying grain suppliers, new protein ingredients—the microbial community has to reorganize around the new substrate profile.

A 2024 study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, which tracked fecal microbiota development in Holstein and Jersey heifer calves, found that the gut microbiome changes rapidly during early life. Instability during colonization leaves the microbial community vulnerable to dysbiosis, where pathogenic species can outcompete beneficial microbes, leading to suppressed immune function and inflammation.

The time required for microbial reorganization varies considerably depending on what you’re measuring and how dramatic the diet change is. Some studies suggest bacterial communities can shift within a week or two. Others indicate that full functional stabilization can take considerably longer, sometimes several weeks or more.

The practical takeaway? During that reorganization period, volatile fatty acid production becomes erratic. And VFAs—particularly butyrate—are what drive rumen papillae development. Inconsistent VFA production means inconsistent rumen development.

Sponsored Post

The Substrate Consistency Question

This is where things get practical, and also where opinions start to diverge among nutritionists.

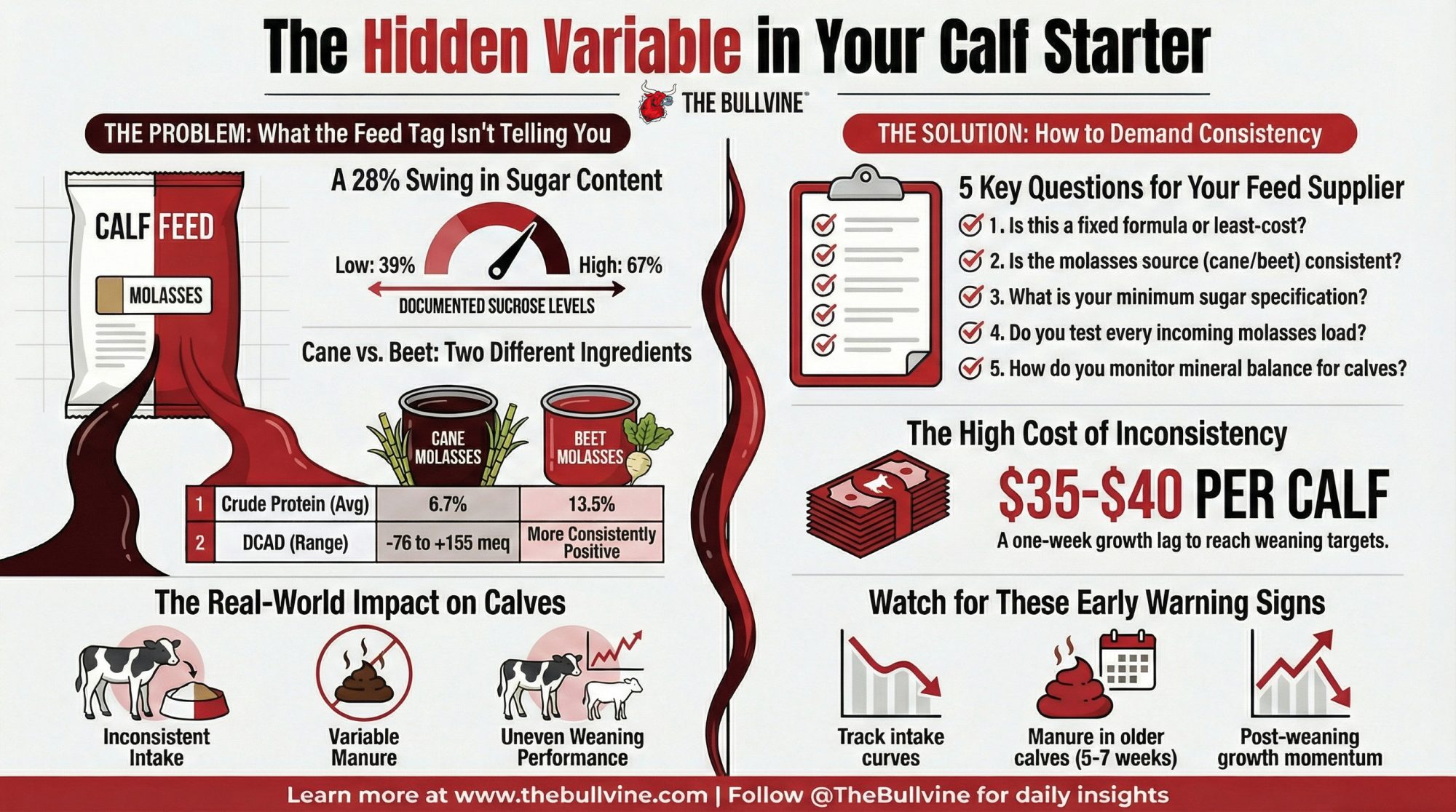

Several nutritionists I’ve spoken with point to ingredient consistency as the single most overlooked variable in calf programs. The logic is straightforward: if rumen bacteria need stable substrates to establish and function, then constantly changing feed ingredients creates perpetual instability.

Research from the University of Minnesota and other institutions has documented this pattern: calves on fixed formulations show much more consistent day-to-day starter consumption than calves on least-cost programs where ingredients shift with commodity prices. The intake variability isn’t dramatic on any given day, but it compounds over the critical period of rumen development.

Industry estimates suggest the cost premium for specification-guaranteed, consistent-source ingredients is approximately 2-4%—typically $8-12 per calf over a 12-week rearing period. That number varies by region and current commodity markets, but it gives you a ballpark for planning purposes.

The Other Perspective

Now, I want to be fair here, because this isn’t settled science. Not every nutritionist is convinced that ingredient consistency matters as much as some of the research suggests.

“Look, rumen bacteria are adaptable,” argues one dairy nutritionist who asked not to be named because he works with several least-cost formulation systems. “They’ve evolved to handle dietary variation. A healthy calf can adjust to different molasses sources reasonably quickly.”

He has a point about adaptability—cattle wouldn’t have survived as a species without metabolic flexibility. And the research on substrate consistency, specifically in pre-weaned calves (as opposed to mature cattle), is still developing. Most of the microbial stabilization studies were conducted in older animals.

What we can say with confidence is that operations running fixed formulations generally report lower variability in calf performance. Whether that’s causation or correlation with other management factors—like the kind of attention to detail that leads someone to specify ingredients in the first place—is harder to untangle.

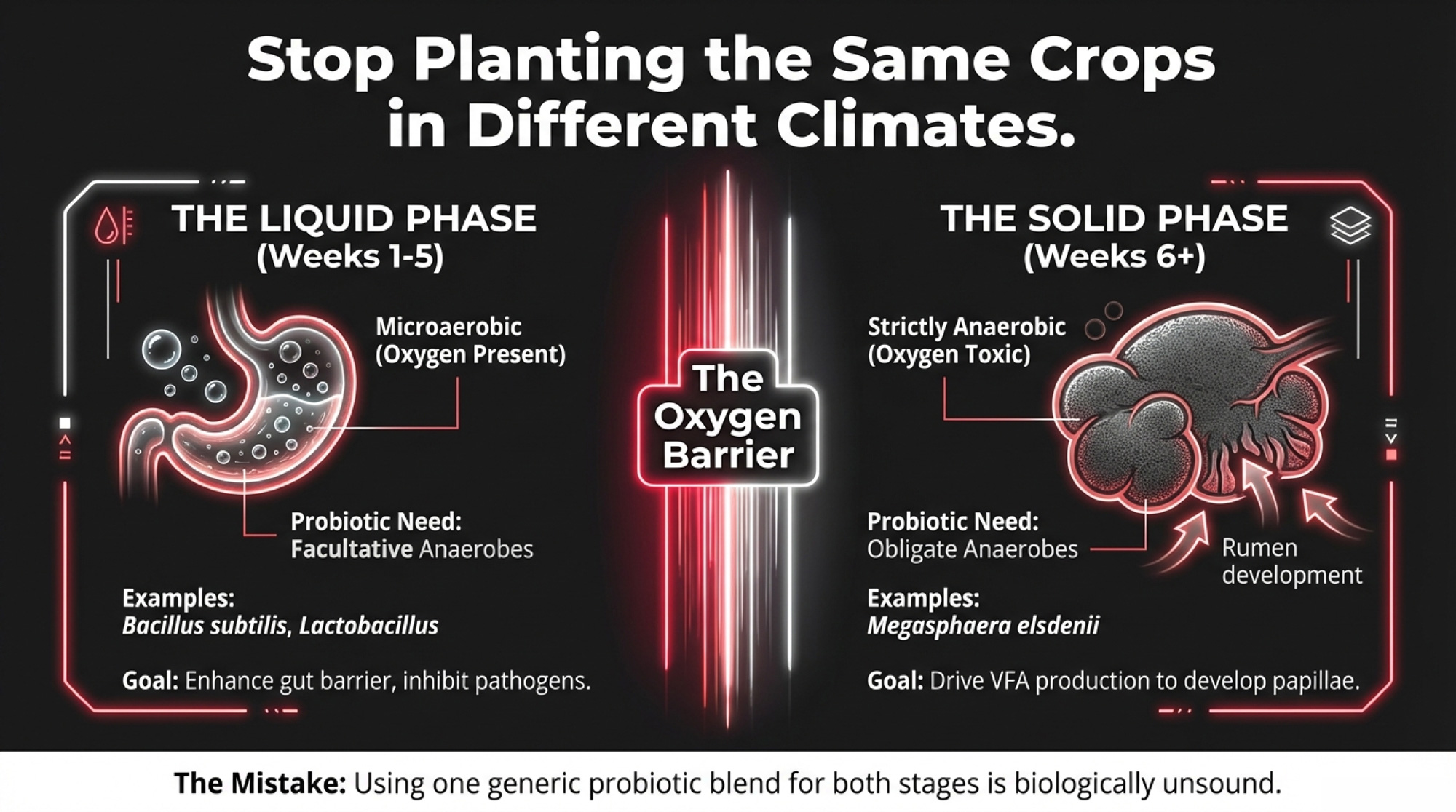

Stage-Matched Microbial Support

The growing interest in probiotic supplementation for calves has created what I’d call an implementation gap. Most operations using probiotics deploy the same blend in both milk replacer and starter feed, assuming gut health support works the same way throughout development.

The research suggests otherwise—and this is where things get interesting.

Different Ecosystems, Different Needs

The small intestine during liquid feeding operates in a microaerobic environment—there’s oxygen present. Effective probiotics for this phase include facultative anaerobes like Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium species that can survive stomach acid and establish quickly.

A 2024 study in ASM Spectrum demonstrated that compound probiotics containing multiple Lactobacillus and Bacillusstrains accelerated both immune function development and the establishment of a healthy gut microbiome in newborn Holstein calves—reducing the abundance of harmful bacteria while promoting beneficial populations.

Research published in Scientific Reports and the Journal of Animal Science has shown how certain Bacillus species secrete compounds that promote intestinal epithelial cell differentiation and help inhibit pathogenic biofilm formation. There’s good evidence for measurable improvements in gut barrier function when appropriate strains are delivered during the liquid feeding phase.

The developing rumen is a completely different environment—strictly anaerobic. Oxygen is toxic to the bacteria that should dominate there. Effective rumen probiotics include obligate anaerobes such as Megasphaera elsdenii and Butyrivibrio species, which would die immediately if exposed to the oxygen-rich environment of the small intestine.

“Using the same probiotic blend in milk and starter is like planting the same crops in two completely different climates,” explains Dr. Mike Flythe, a microbiologist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Lexington, Kentucky. “You might get something to grow, but you’re not optimizing for either environment.”

| Gut Environment | Oxygen Level | Effective Probiotic Species | Primary Mechanism | What Happens If Mismatched |

| Small Intestine (liquid feeding phase) | Microaerobic (oxygen present) | Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Epithelial cell differentiation; pathogen inhibition; gut barrier function | Anaerobic rumen species die immediately upon exposure |

| Developing Rumen (starter feeding phase) | Strictly anaerobic (no oxygen) | Megasphaera elsdenii, Butyrivibrio species | VFA production optimization; pH stabilization; fiber digestion | Oxygen toxic to obligate anaerobes |

| Industry Standard (single-blend approach) | Both environments, same formulation | Mixed facultative species | Compromise formulation attempting dual-use | Suboptimal colonization in both environments |

| Stage-Matched Approach | Environment-specific formulations | Oxygen-matched species for each developmental phase | Optimized for gut compartment and maturity stage | Maximizes colonization success and functional support |

That analogy stuck with me—it’s a useful way to think about what we’re trying to accomplish.

What the Market Offers

Several feed companies have developed stage-matched probiotic programs. Kalmbach Feeds’ LifeGuard and Opti-Ferm XL technologies represent one approach—different formulations designed for the liquid and solid feeding phases, respectively. Other companies offer similar stage-specific options, and the market continues to evolve as the research develops.

Stage-matched programs do represent a greater investment than basic single-probiotic approaches, though the actual cost differential varies considerably by program design, feeding rates, and supplier. For operations weighing this decision, it’s worth getting specific quotes based on your calf numbers and current protocols—the investment can range from modest to meaningful depending on how programs are structured.

Whether that investment makes sense depends heavily on your baseline performance. Operations already running tight calf programs with low disease incidence will see smaller marginal returns than operations struggling with persistent scours or respiratory challenges. This isn’t a universal solution—it’s a tool that works better in some contexts than others.

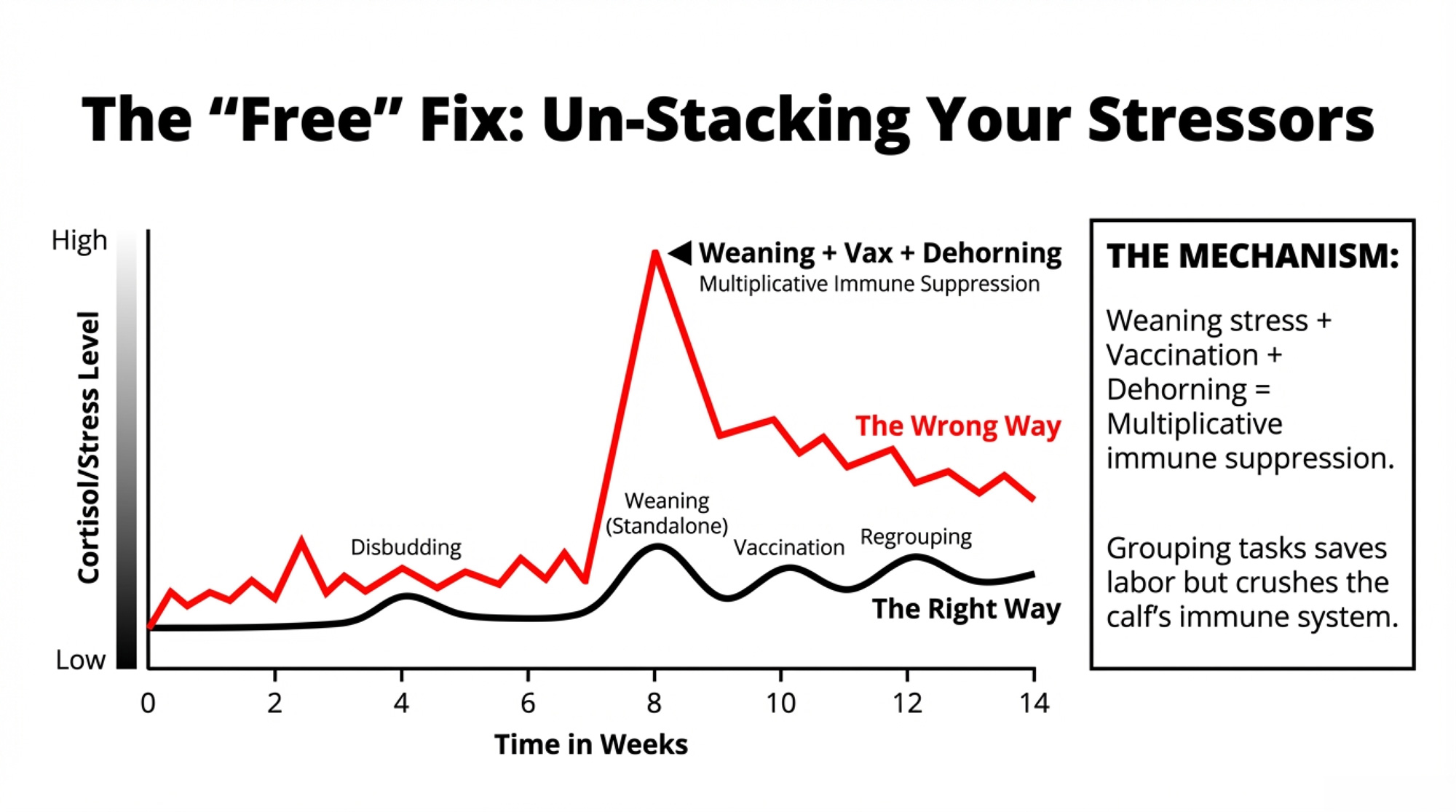

The Stress Calendar: Potentially Free Improvement

Here’s something that costs nothing but requires real management discipline—and it might be the most overlooked opportunity in calf management.

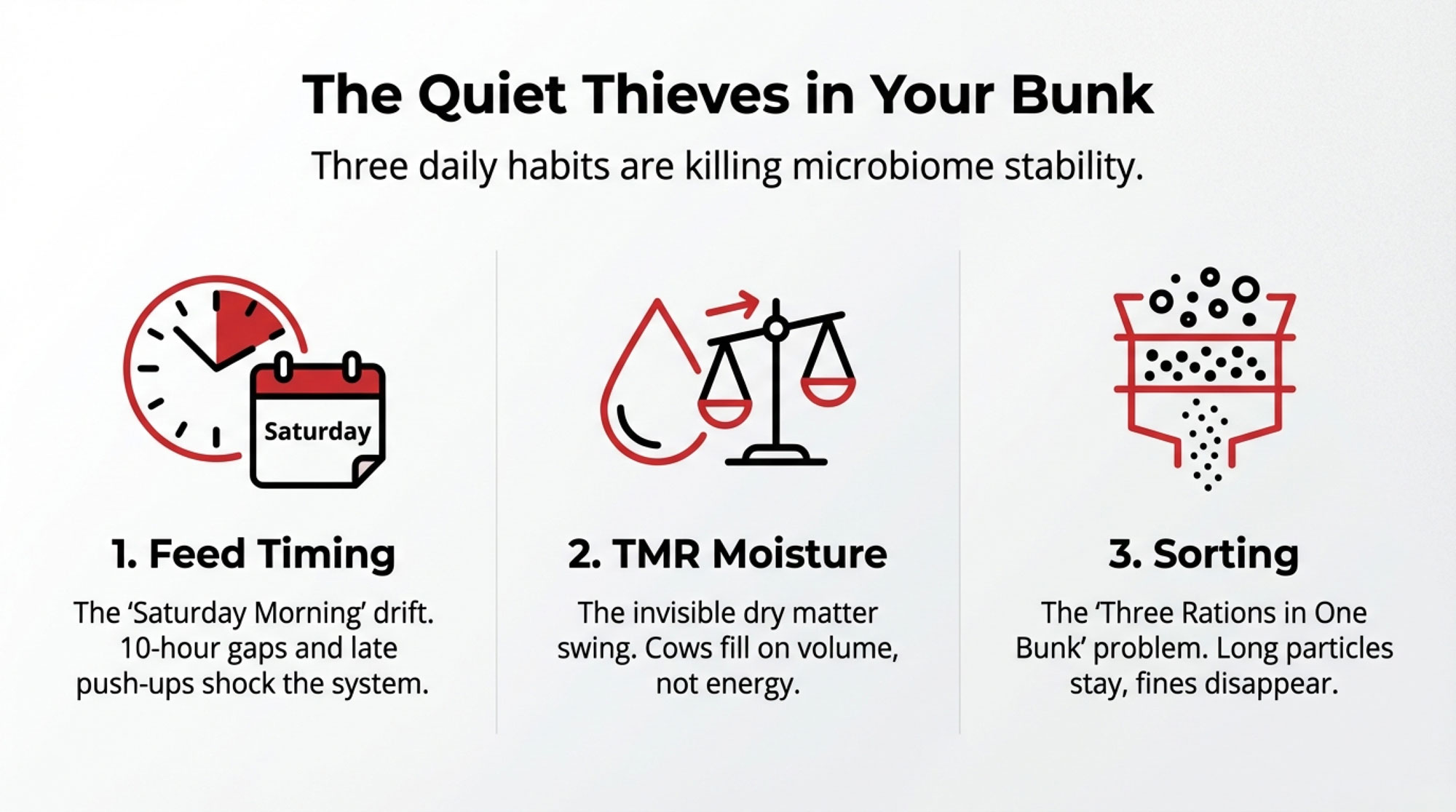

Research on weaning stress—particularly work from Dr. Jeff Carroll and colleagues at the USDA-ARS Livestock Issues Research Unit—shows that cortisol elevation from weaning alone is acute but manageable. Elevated for 3-5 days, then returning toward baseline as the calf adapts.

But when weaning coincides with vaccination, dehorning, regrouping, or housing changes, cortisol can remain elevated for 2 weeks or longer, resulting in sustained immune suppression. The calf never gets a chance to recover before the next challenge hits.

The mechanism isn’t additive—it’s multiplicative. Each stressor independently activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. When stressors overlap, you’re compounding the immune suppression rather than just extending it.

What this means practically: the common approach of “we have the crew here anyway, let’s do everything at once” may be one of the most costly management decisions we make. It’s efficient from a labor standpoint. It’s terrible from a calf physiology standpoint.

Building a Stress Calendar

Operations that separate stressors generally report meaningful improvements. The specific timing depends on your operation, but here’s a general framework:

- Disbudding/dehorning: Position 4-5 weeks before weaning, allowing full recovery before weaning stress begins

- Weaning: Gradual over 5-7 days (the most recommended weaning is step down process for 10 – 14 days, even if it is not the most used), treated as a standalone event with no concurrent stressors

- Vaccination: 7-14 days post-weaning, after acute stress resolves

- Regrouping/housing changes: 2+ weeks post-weaning when possible

Research presented at the 2024 Healthy Calf Conference emphasized that gradual weaning has become non-negotiable for operations feeding today’s higher milk volumes. When calves consume eight to twelve liters of milk per day, abrupt weaning creates severe physiological stress. Comparing five-day versus ten-day weaning programs, longer-weaned calves performed better in both gain and grain intake, with fewer health issues during the transition.

I’ve spoken with producers in Wisconsin and across the Upper Midwest who’ve tried separating procedures, and the feedback has been generally positive—many report noticeable reductions in post-weaning respiratory cases. A producer in central Minnesota told me his post-weaning BRD treatments dropped by about a third after implementing a stress calendar. That’s anecdotal, but it’s consistent with the research’s predictions.

That said, I’ve also heard from smaller operations—particularly in the Northeast, where labor is especially tight—where this approach is genuinely impractical. The separated stress calendar requires scheduling flexibility that not every operation has.

And that’s okay. Not every intervention works for every farm.

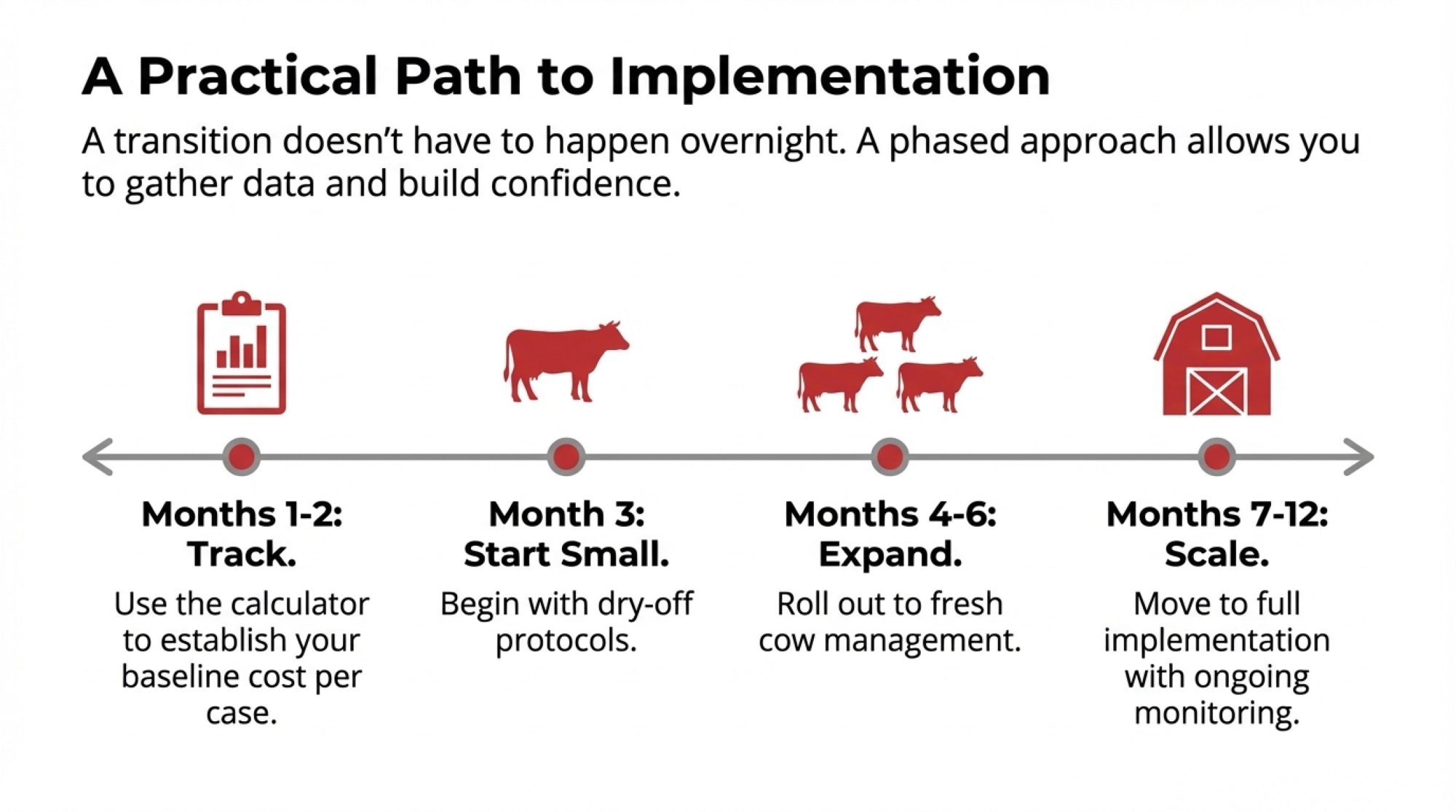

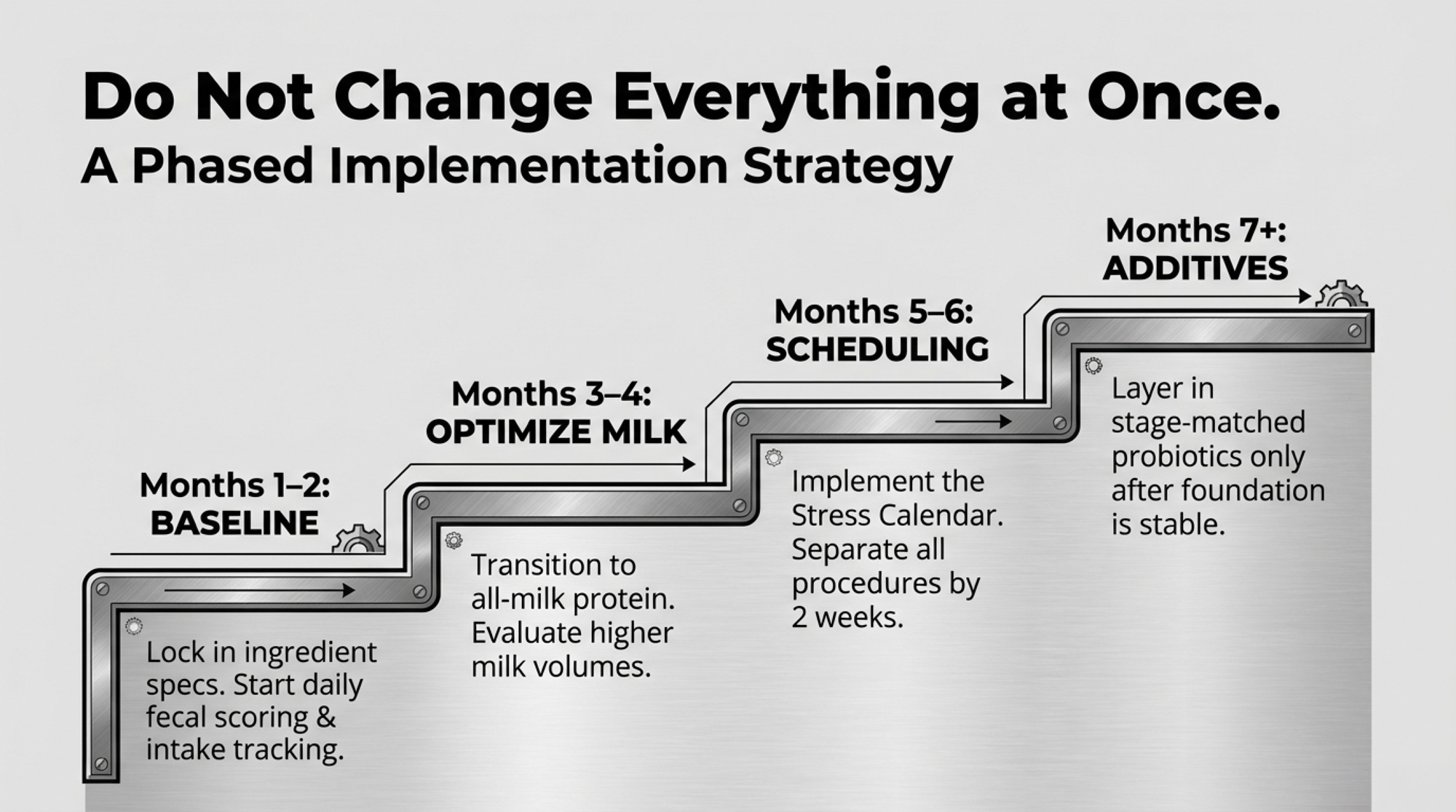

What Implementation Actually Looks Like

The operations I’ve spoken with that have successfully adopted systems-based approaches share a common thread: they didn’t try to change everything at once. That seems to be the critical success factor.

A Phased Approach

Months 1-2: Establish measurement baseline and address substrate

- Lock in ingredient specifications with your feed supplier

- Begin rigorous daily measurement—fecal scores, intake tracking, treatment records

- Expected outcome: Modest improvement in consistency; proof of concept that builds confidence for next steps

Months 3-4: Optimize milk program

- Transition to all-milk protein if appropriate for your operation and budget

- Evaluate milk allowance; the research increasingly favors higher volumes in early life

- Expected outcome: Improved pre-weaning growth and intake stability

Months 5-6: Implement stress calendar

- Separate management procedures where labor and facilities allow

- This is the “free” intervention—no additional cost, just scheduling discipline

- Expected outcome: Reduced weaning dip severity and faster recovery

Months 7+: Layer in stage-matched probiotics

- Add appropriate formulations to milk replacer and starter

- Expected outcome: Further optimization of gut development and immune function

Research consistently shows that sequencing matters when implementing these changes. Layering probiotics onto an unstable nutritional foundation often produces disappointing results. The operations seeing the best outcomes start by stabilizing their feed program, then build additional interventions on that foundation.

That’s advice worth taking seriously. The producers who struggle with this approach are usually the ones who tried to implement everything simultaneously and couldn’t tell what was working.

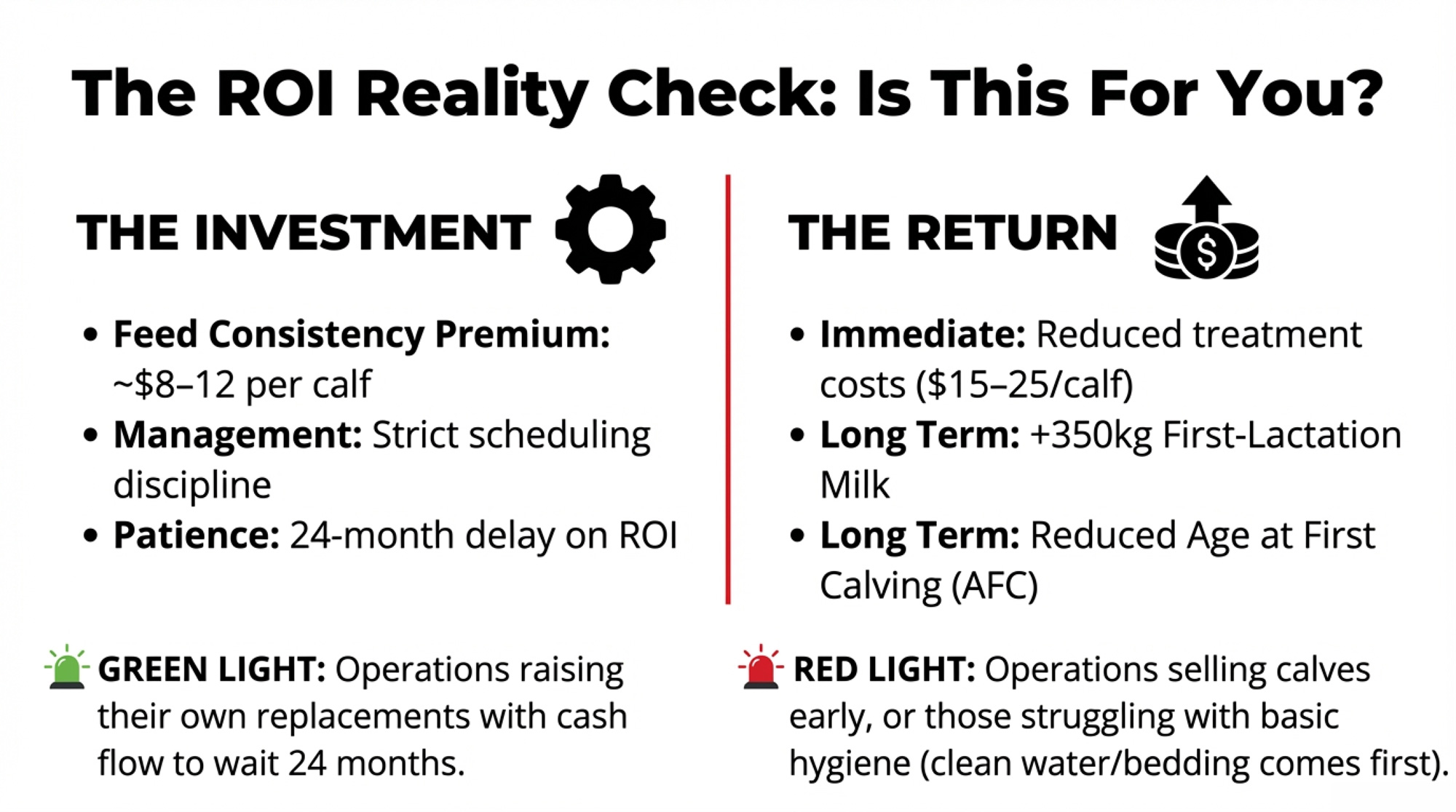

Honest Talk About Economics

Let me lay out the math as clearly as I can, with the caveat that these figures will vary based on your specific situation, region, and current market conditions.

Investment Breakdown (Per Calf Estimates)

| Component | Estimated Range | Notes |

| Substrate consistency premium (Calf Starter with fixed formulation) | $8-12 | Quality-controlled, specification-guaranteed ingredients |

| Milk program optimization | $5-12 | All-milk protein and/or increased volume |

| Stage-matched probiotics | Varies by program | Intestine-phase and rumen-phase formulations; get specific quotes based on your feeding rates |

| Stress calendar implementation | $0 | Labor reallocation only |

| Total Investment | Varies | Depends on baseline program and scope of changes |

| Potential Long-term Return | +350 kg first-lactation milk | Per heifer kept healthy through weaning (Svensson & Hultgren research) |

What the Research Suggests You Might Get Back

- Reduced treatment costs: Often in the $15-25 per calf for operations with high baseline disease incidence

- Labor savings from fewer sick calves: Variable but meaningful for operations currently spending significant time on treatments

- Improved growth trajectory affecting age at first calving (AFC): This is the big variable, and honestly, the hardest to pin down precisely

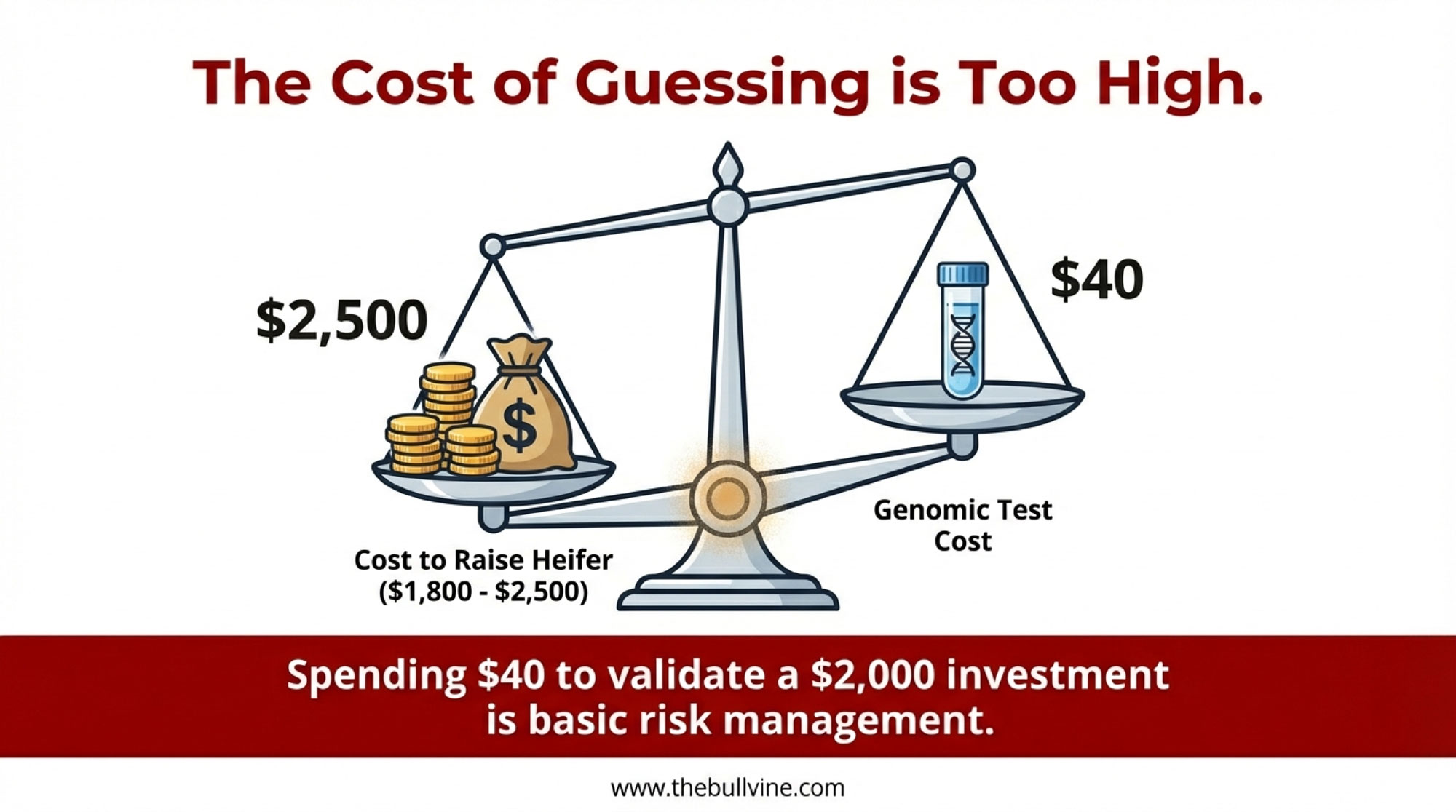

The age-at-first-calving benefit is where the math gets compelling—or speculative, depending on your perspective. If improved early-life health allows you to gain 30 -60 days on AFC and you’re spending $2.50-3.00 per day to raise a heifer (a reasonable estimate for many operations), you’re looking at meaningful savings per animal.

The timing challenge: You invest in month one. You might see reduced treatments by month two. But the AFC benefit doesn’t materialize for 18-24 months. That requires patience and cash flow that not every operation has, especially in tight milk price environments.

As dairy economists frequently point out, the ROI is real, but the payback period tests most producers’ patience and cash flow.

Who This Works For—And Who It Doesn’t

Let me be direct about something the advocates for systems-based calf programs don’t always acknowledge: this approach isn’t right for every operation. Understanding that might save you time and money.

It likely makes sense if:

- You’re experiencing persistent calf health challenges—say, diarrhea incidence above 25% or respiratory disease above 15%

- You have the management bandwidth for more rigorous protocols and measurement

- Your cash flow can absorb increased upfront costs for 6-12 months without strain

- You’re tracking lifetime performance and can actually measure long-term returns

- You’re raising your own replacements and capturing the downstream value

It may not make sense if:

- Your current calf program is already performing reasonably well (if it ain’t broke…)

- Labor constraints make separated stress events genuinely impractical

- You’re operating on thin margins that can’t absorb any additional costs right now

- You’re selling calves rather than raising replacements—someone else captures the long-term value

Paul Rapnicki, DVM, who has extensive experience consulting with dairies across the Midwest, puts it this way: “I’ve seen operations transform their calf programs with this approach. I’ve also seen operations spend money on premium ingredients and probiotics while ignoring basic management—clean water, dry bedding, adequate ventilation. The fancy stuff doesn’t fix the fundamentals.”

That’s worth remembering. Before you invest in stage-matched probiotics and specification-guaranteed molasses, make sure your calves have clean, dry housing and fresh water available at all times. Get the basics right first.

Practical Takeaways

For producers considering a more systematic approach to calf gut health, here’s what seems to matter most:

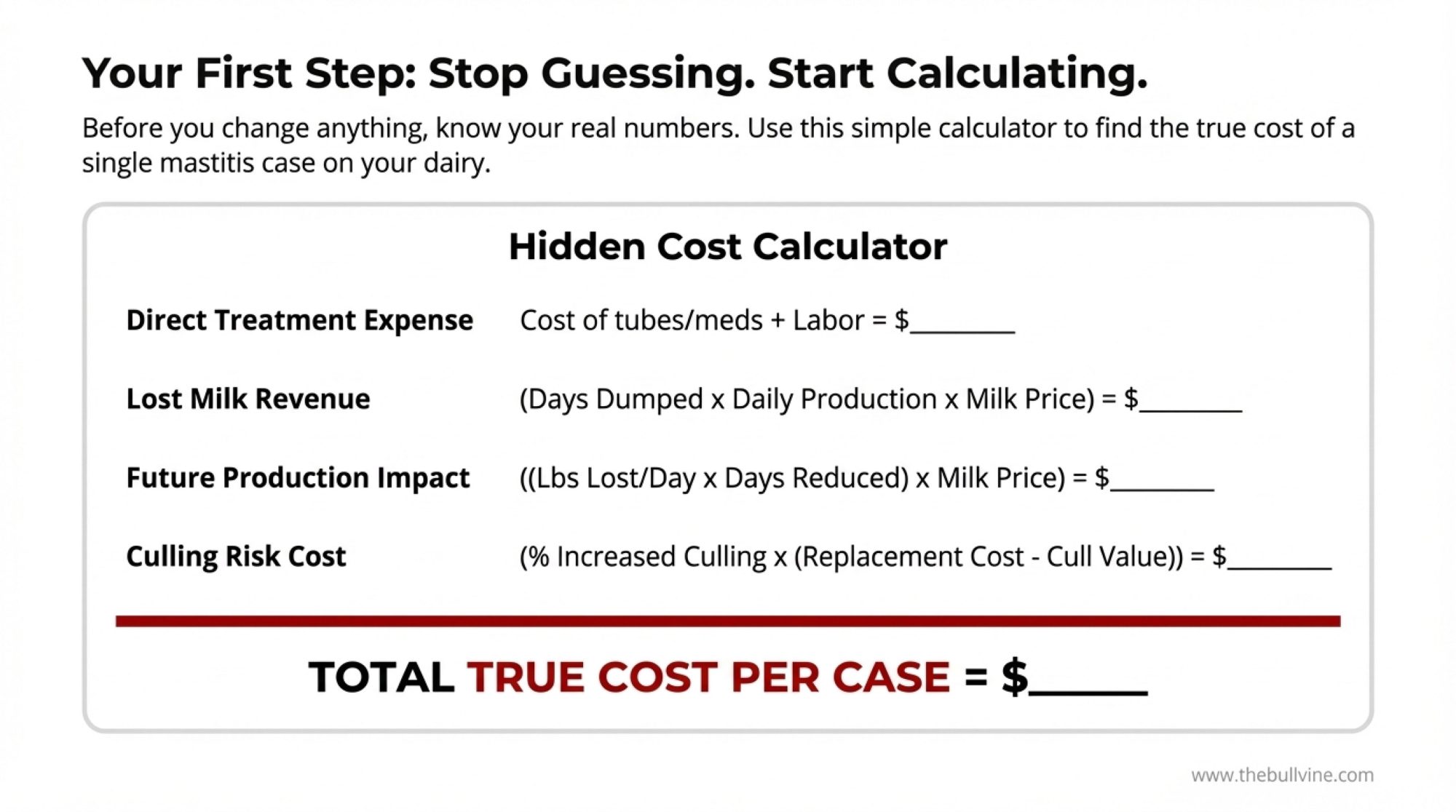

Start with measurement. You can’t improve what you don’t track. Daily fecal scoring, intake monitoring, and treatment records create the baseline you need to evaluate any intervention. Without data, you’re just guessing—and guessing gets expensive.

Fix one thing at a time. The phased implementation approach isn’t just about budget management—it lets you identify what’s actually working. Change everything at once, and you’ll never know what made the difference. You’ll also have nowhere to go if something doesn’t work.

Respect the stress calendar. Of all the interventions discussed here, separating management stressors has clear research support and zero additional cost. If you do nothing else, consider this. It’s the closest thing to a free lunch in calf management.

Be realistic about timelines. The full benefit of optimized early-life nutrition takes 18-24 months to materialize. Plan accordingly and ensure your operation can sustain the approach long enough to see results. Starting and stopping is worse than not starting at all.

Talk to your nutritionist. The research on substrate consistency and stage-matched probiotics is interesting, but the application depends on your specific operation. A good nutritionist can help evaluate whether changes make sense for your situation—and which changes to prioritize given your current performance and constraints.

The Bottom Line

Your calves don’t care about tradition, and they don’t care about how busy you are. They only reflect the system you build for them.

Stop treating the weaning dip as a mystery and start treating it as a management decision. The research is clear: early-life gut health programs and lifetime performance. The tools exist. The question is whether you’re willing to invest in month one for returns that show up in year two.

For some operations, the answer is yes—and they’re seeing the results. For others, the timing isn’t right, and that’s a legitimate business decision too.

But don’t let inertia make the choice for you. Run the numbers for your operation. Talk to your nutritionist. Look at your treatment records from last year.

Then decide deliberately.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- One week of scours = 350 kg less milk in first lactation — The cost is invisible for two years, but the research is clear: early-life gut health programs lifetime productivity

- The weaning dip is a management decision, not inevitable — Outcomes trace back to nutrition and timing choices made weeks before weaning begins

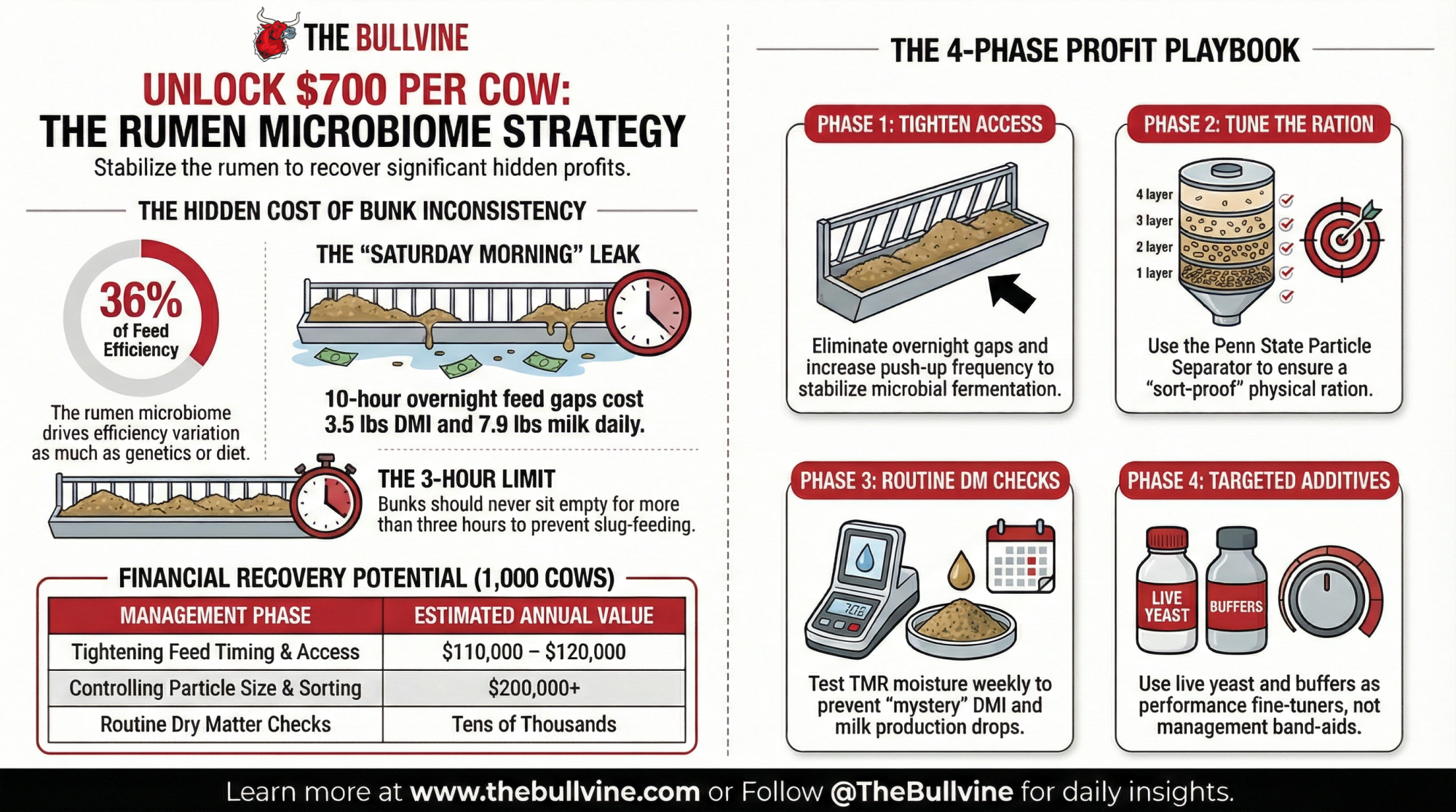

- Ingredient consistency may matter more than ingredient cost — Rumen bacteria are substrate-specific; least-cost formulations that shift with commodity markets create ongoing microbial disruption

- Separate your stressors—it’s free — Spacing dehorning, weaning, and vaccination prevents compounding immune suppression; it’s the closest thing to a free lunch in calf management

- This approach isn’t right for every operation — If your current program performs well or you’re selling calves rather than raising replacements, the investment may not pay back for your situation

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The weaning dip isn’t bad luck—it’s a management decision. Research confirms that calves experiencing diarrhea or respiratory disease in their first month lose 340-350 kg of milk production in the first lactation, a penalty that stays hidden for two years but compounds across your herd. This feature examines why some operations are rethinking calf nutrition entirely: stabilizing feed ingredients to support rumen microbial development, matching probiotic strategies to different gut environments, and separating management stressors from weaning. One intervention—the stress calendar—costs nothing beyond scheduling discipline, and producers report meaningful reductions in post-weaning respiratory disease. The full approach requires patience; ROI takes 18-24 months to materialize and depends on your baseline performance. For operations already running successful calf programs, the investment may not pencil out. But for those watching the same health patterns repeat season after season, this research offers something more valuable than another treatment protocol: a different set of decisions to make.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- 17-26x ROI: Why Top Dairies Stopped Saving Calves and Started Preventing Loss – Arms you with the hard numbers on the “prevention vs. treatment” debate. It breaks down how a simple Brix refractometer delivers massive returns, allowing you to stop bleeding capital on sick calves and capture $800 in added lifetime value.

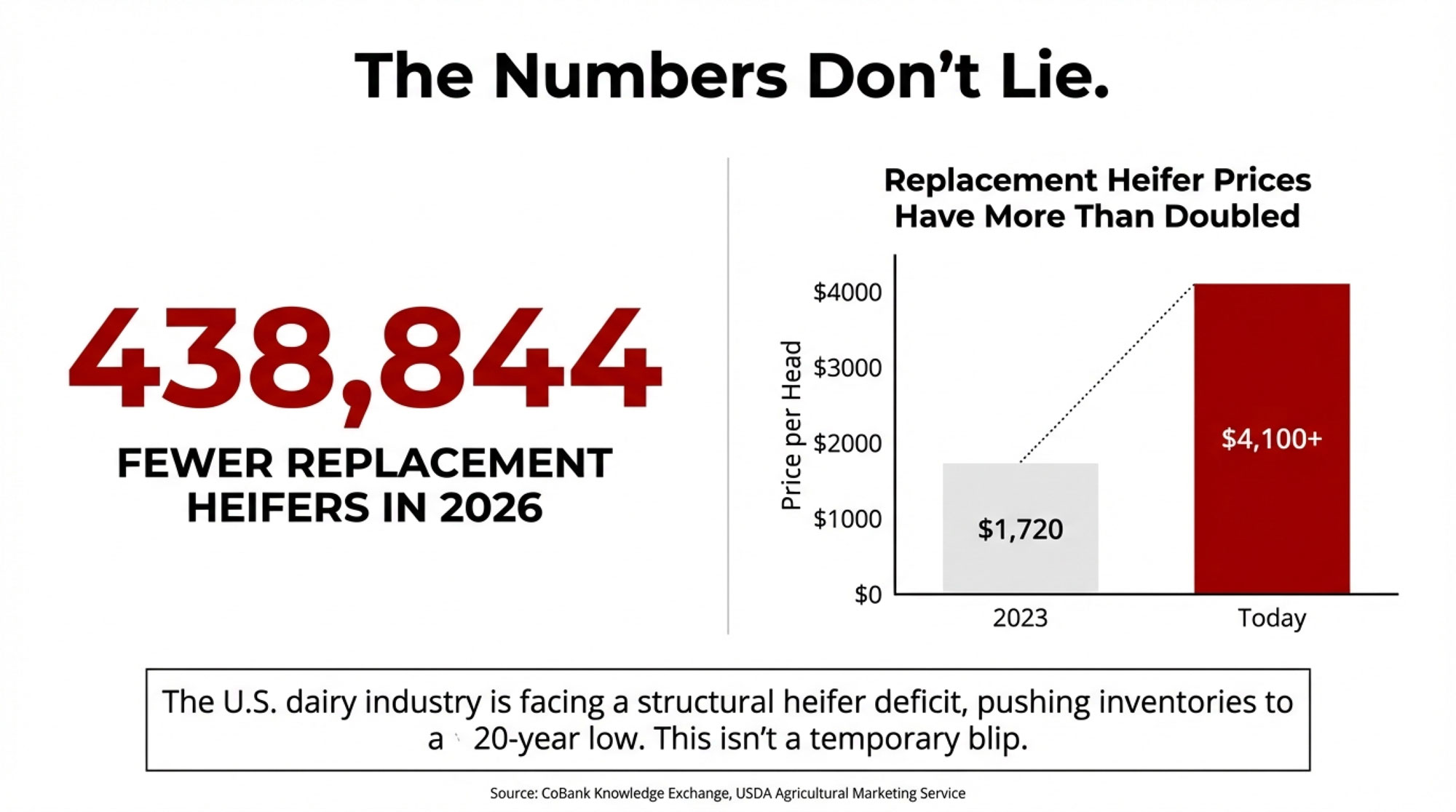

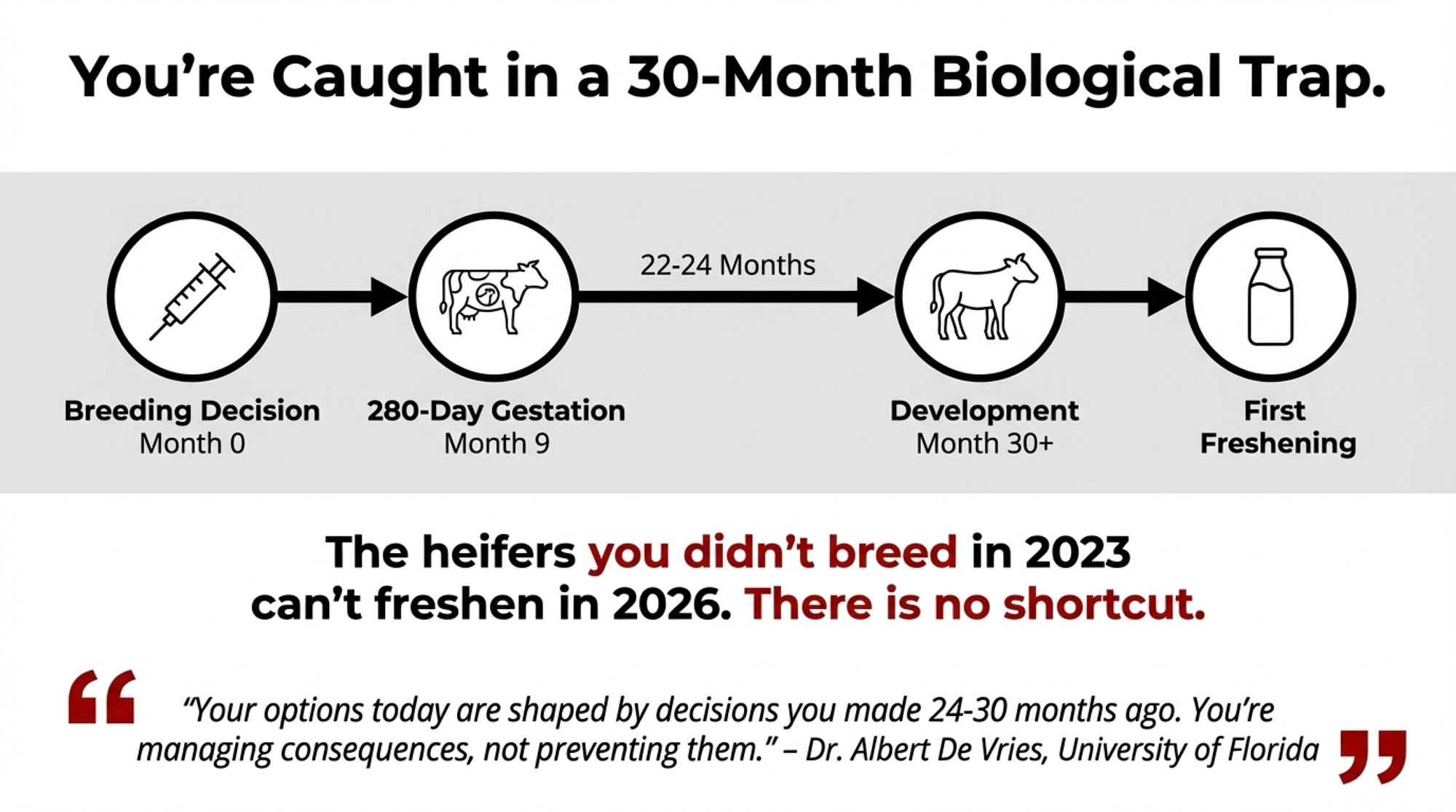

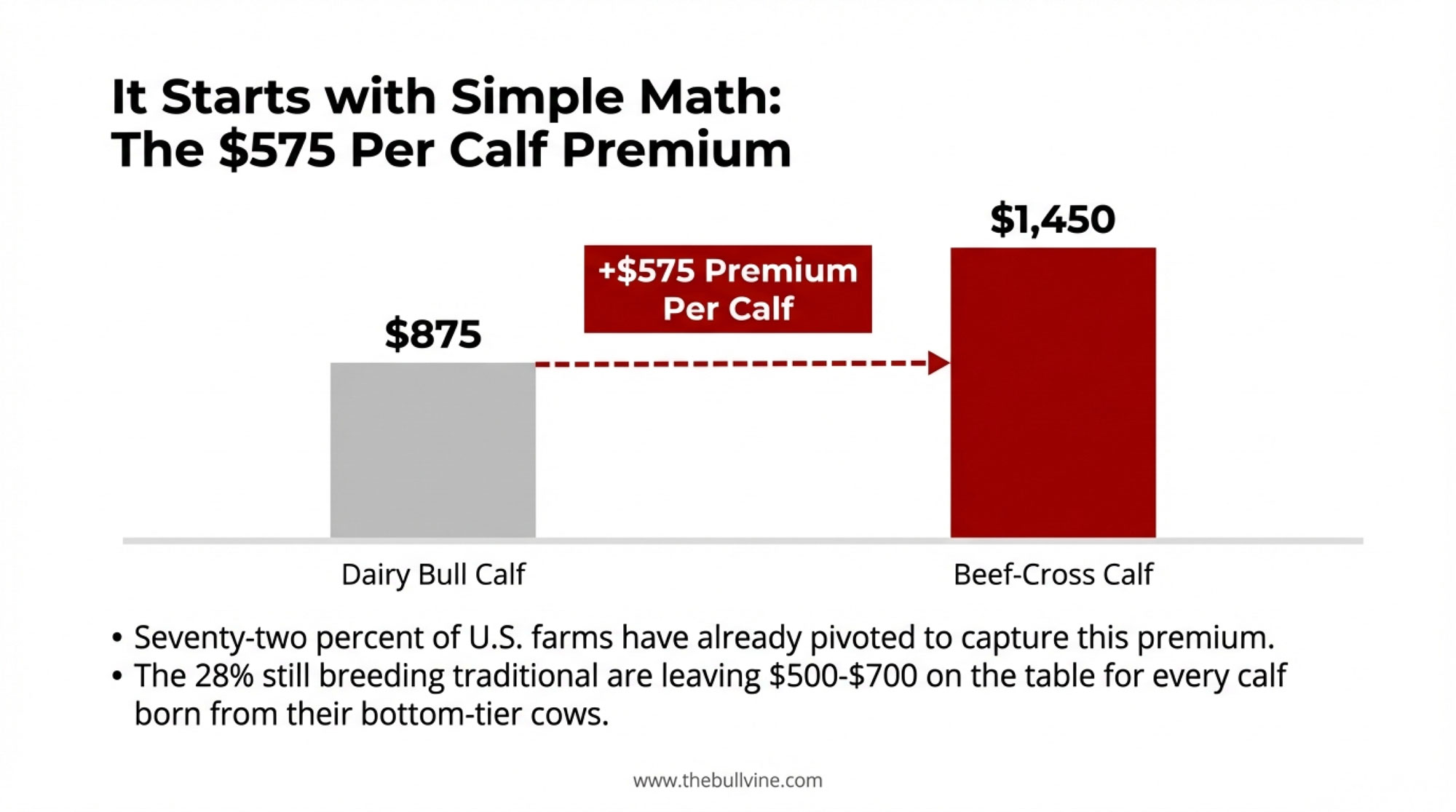

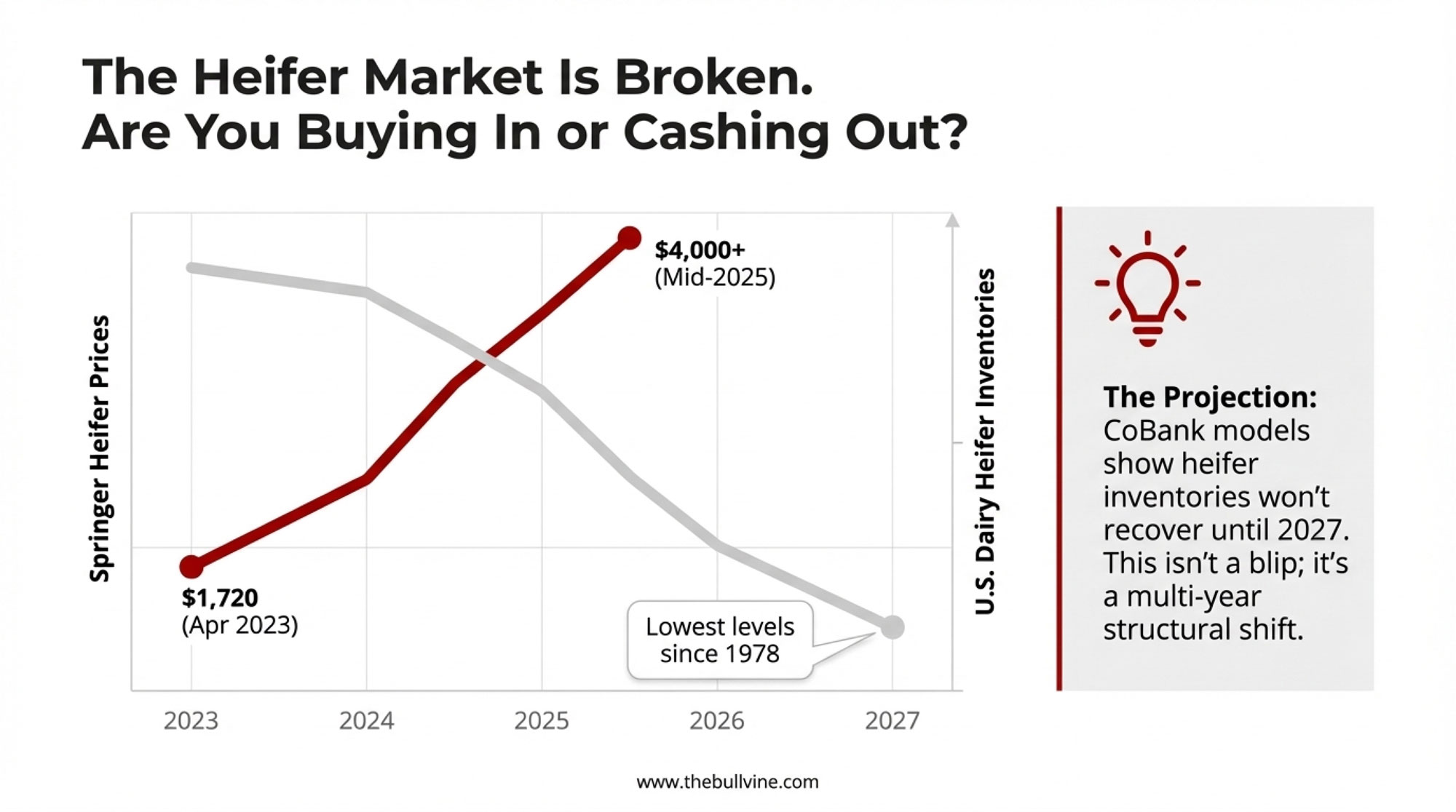

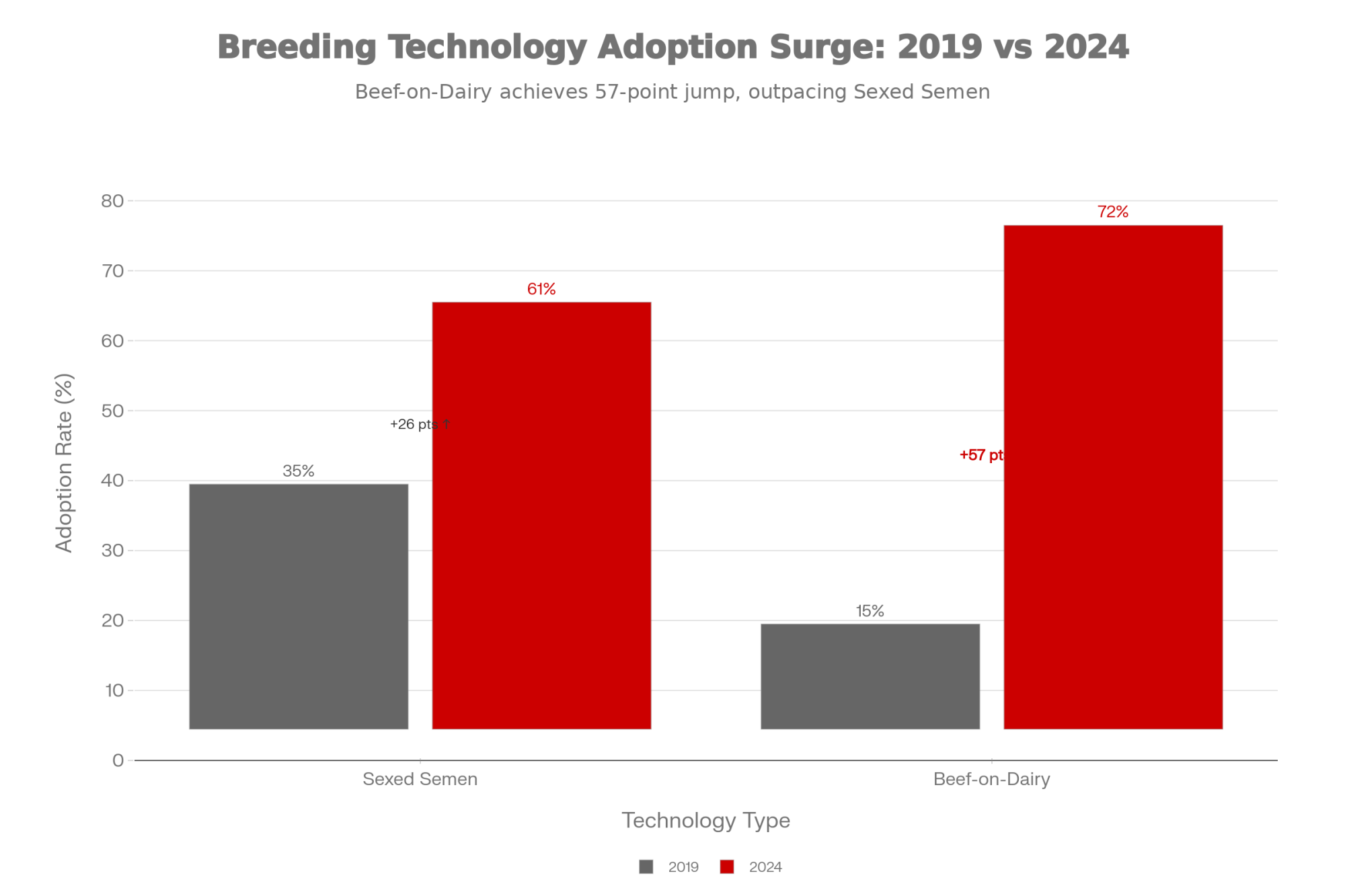

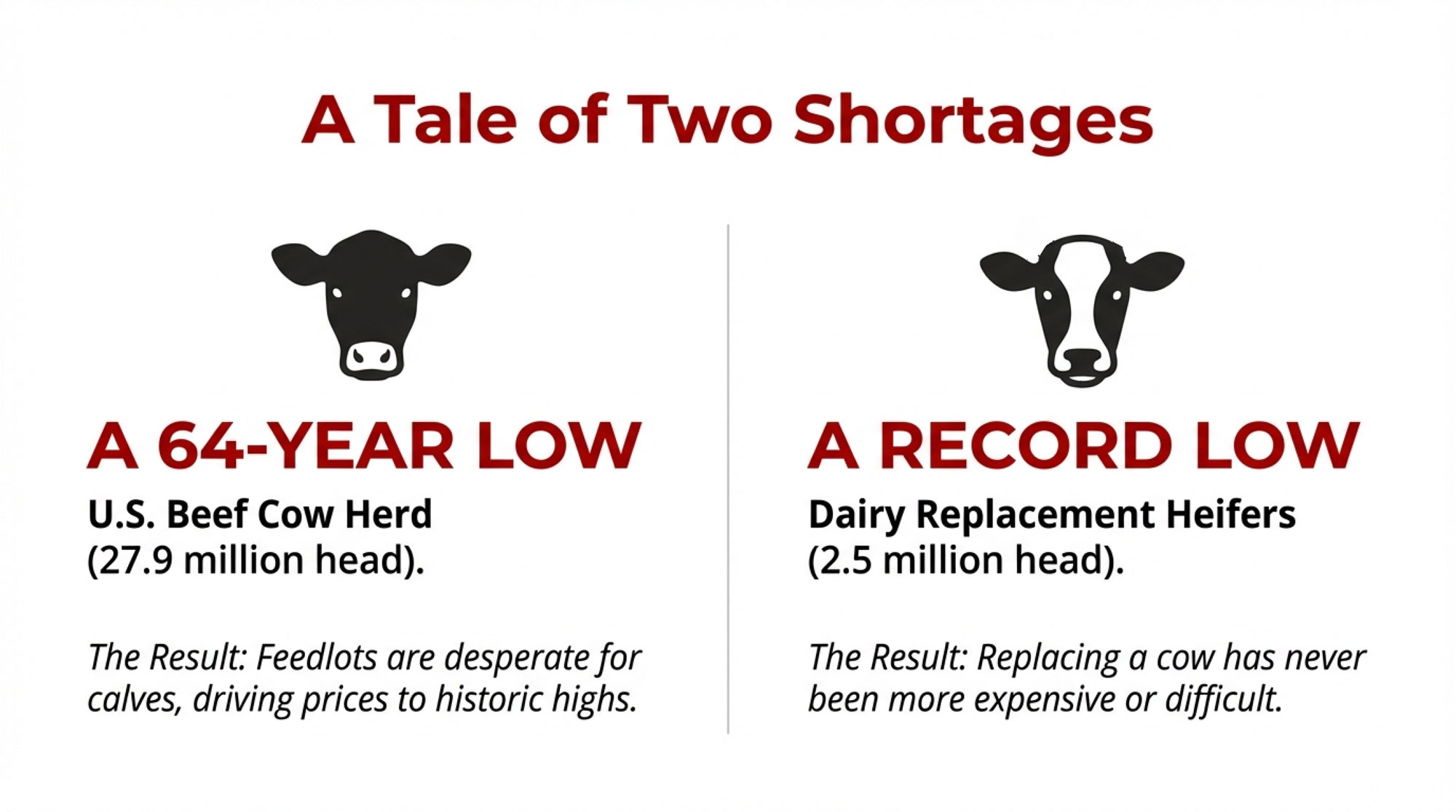

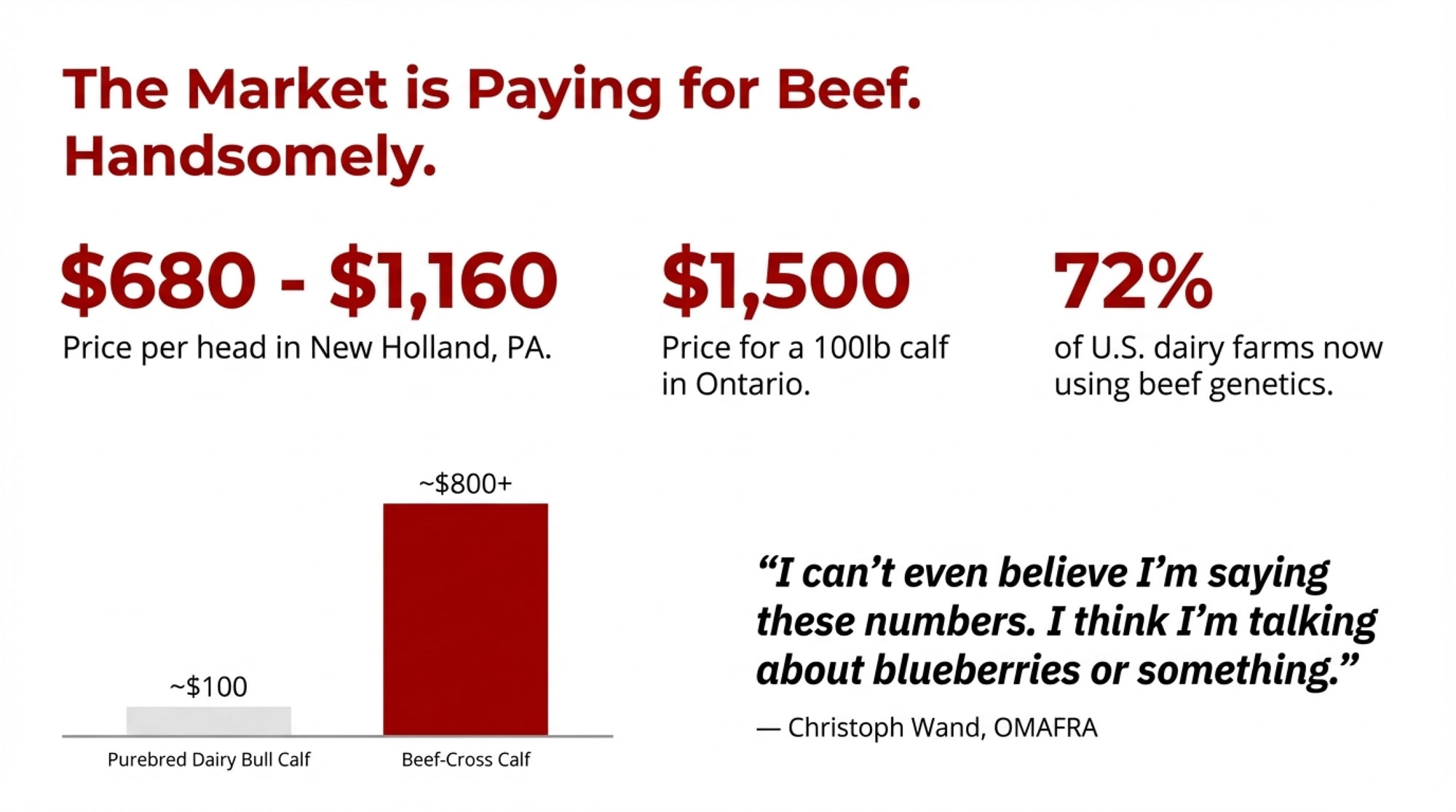

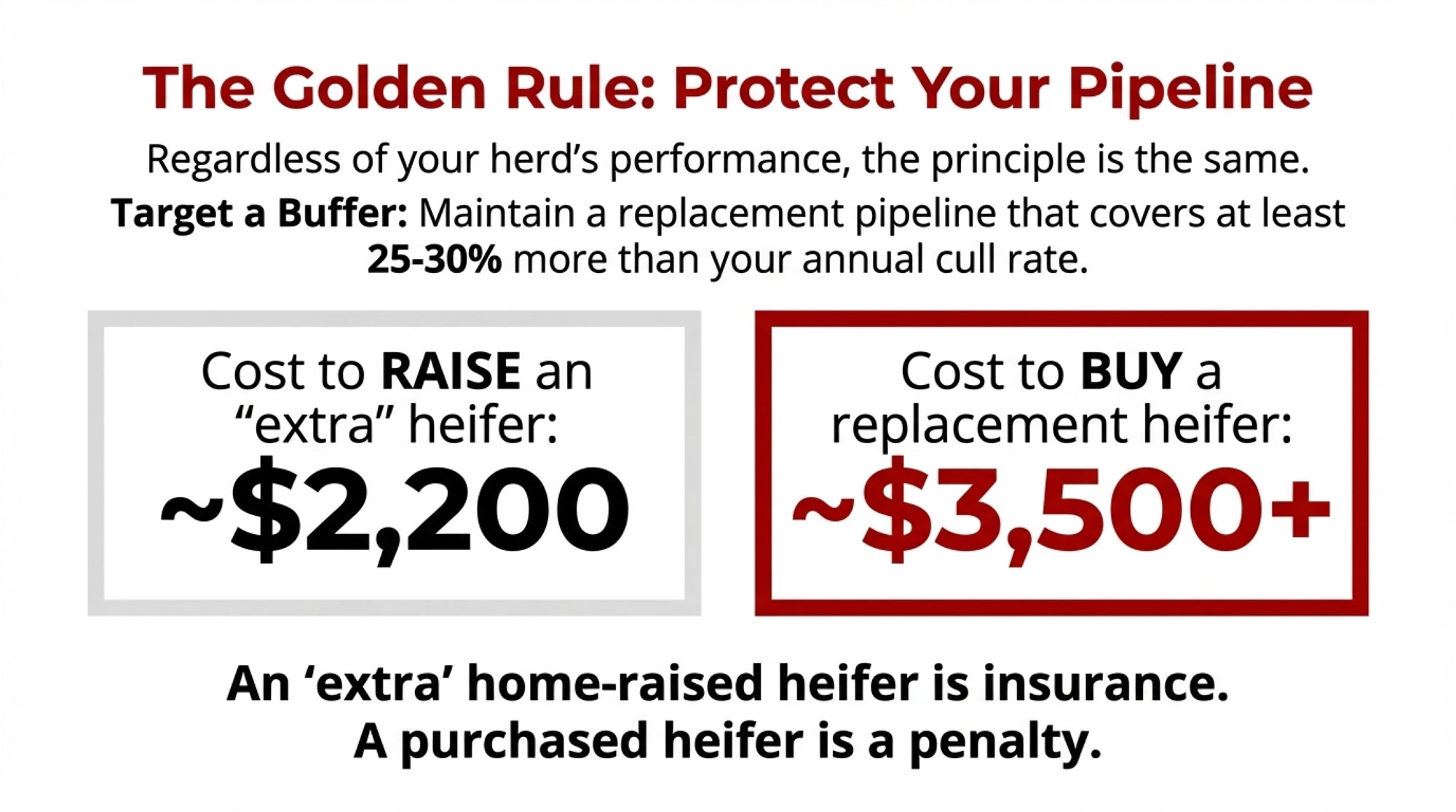

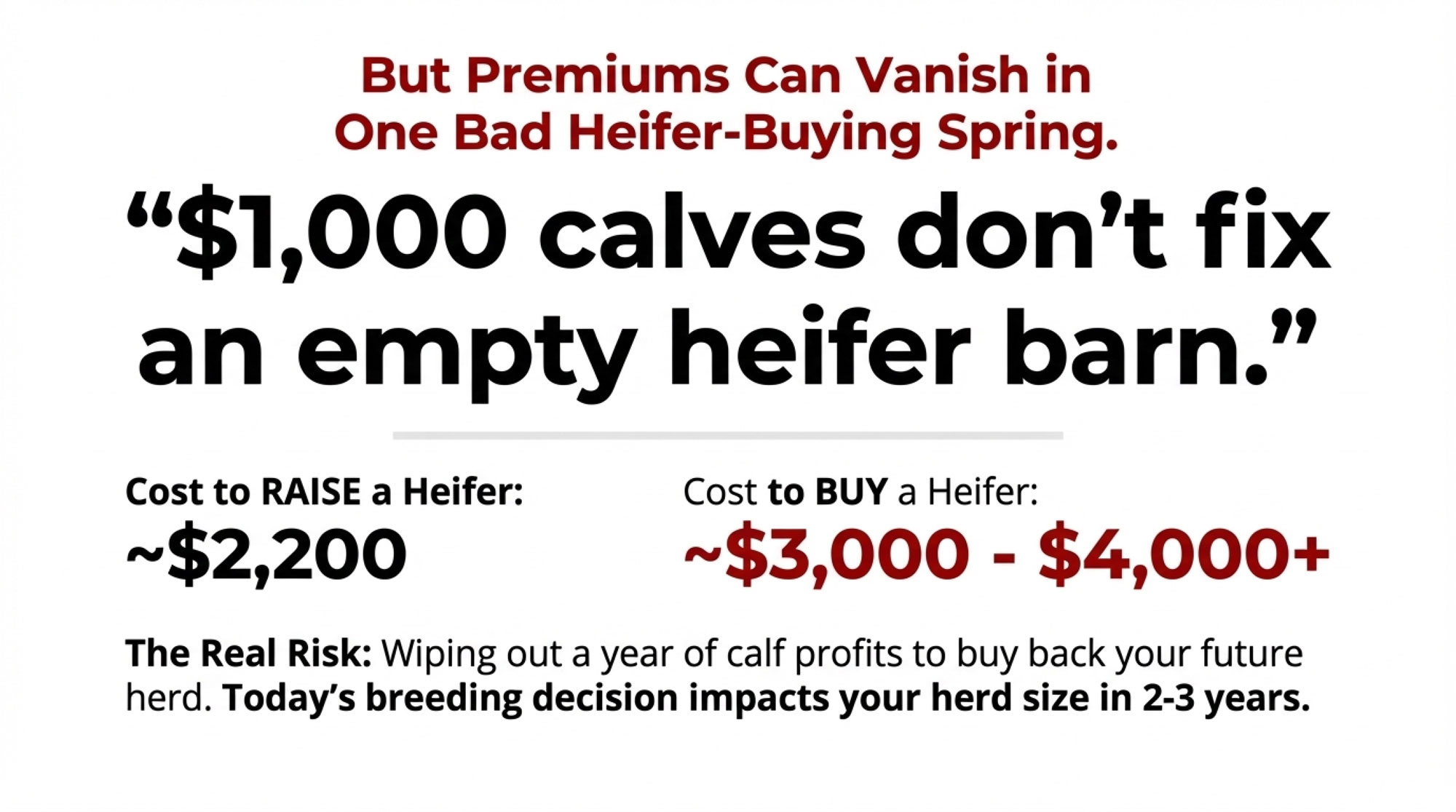

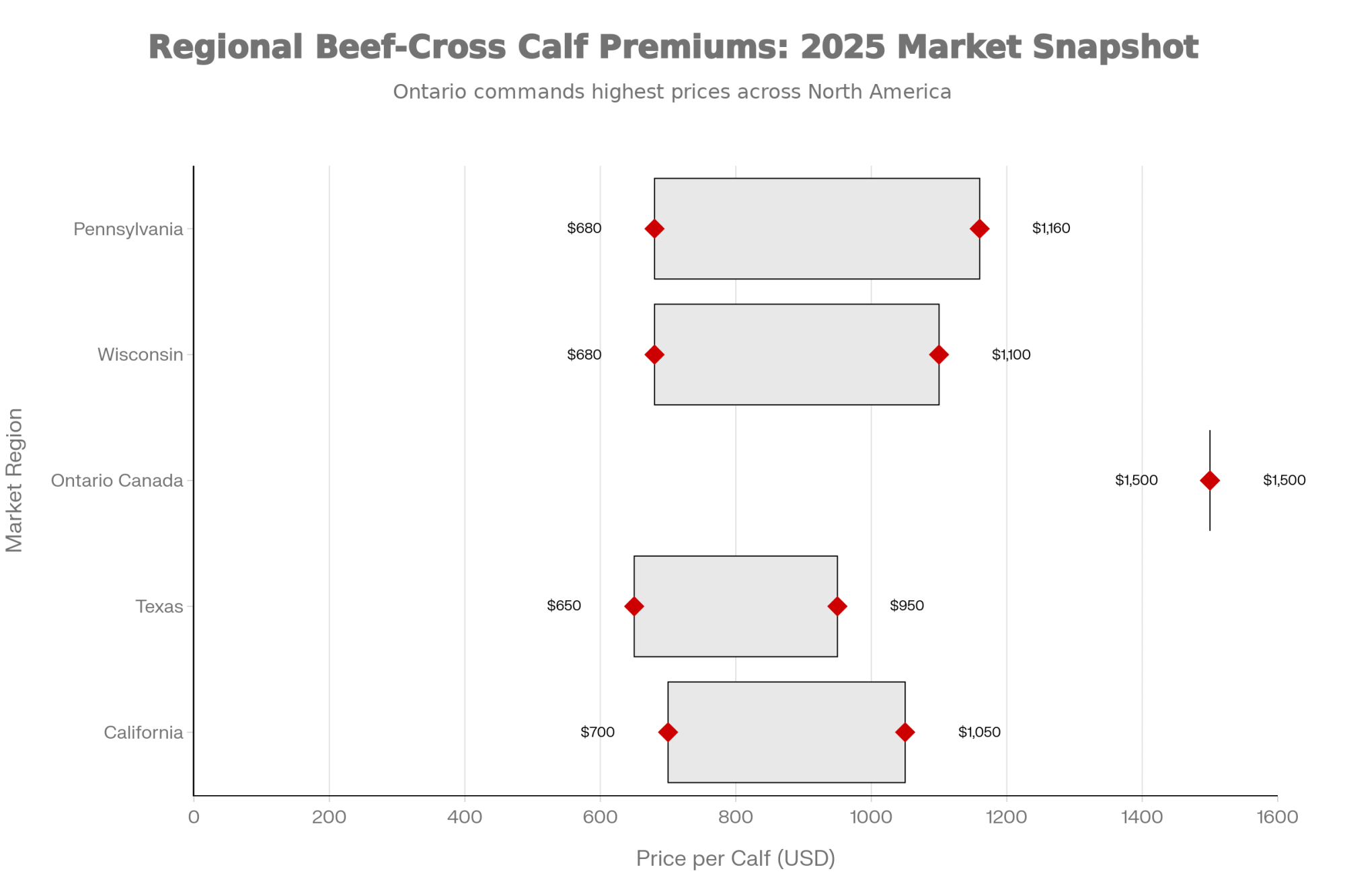

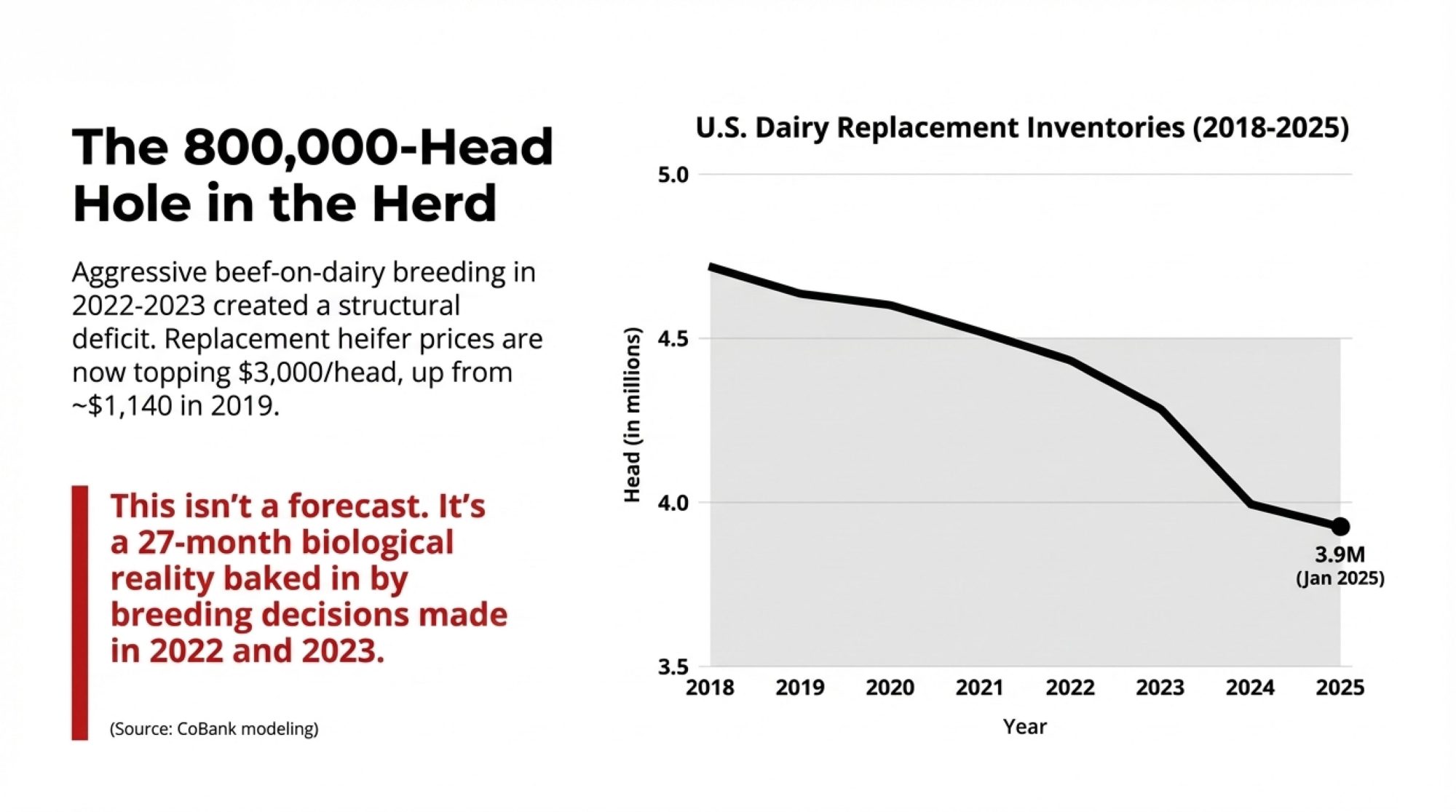

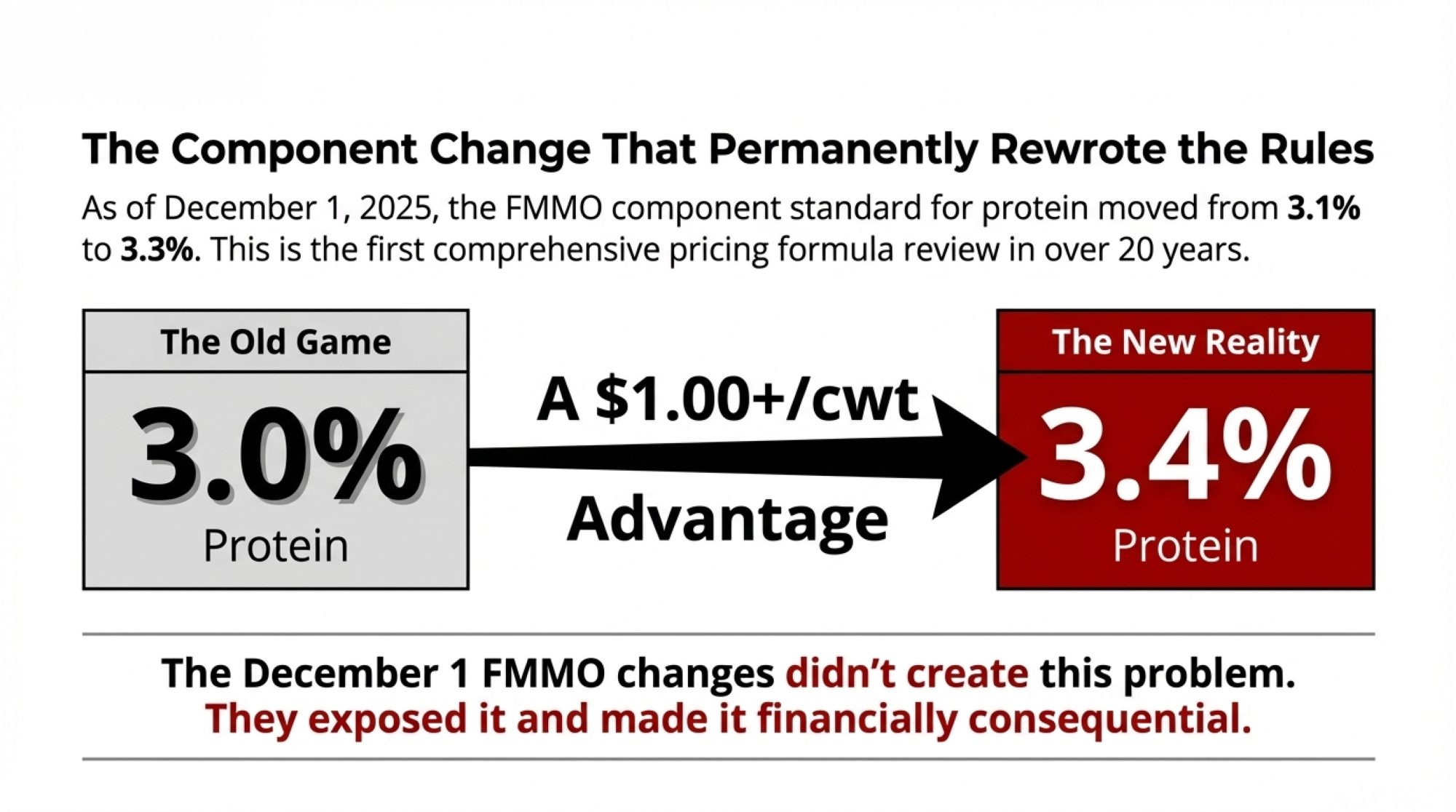

- When Your Calves Outearn Your Cows: The 357,000-Heifer Shortage and the $200K Math Reshaping Dairy Survival – Exposes the strategic “biological trap” of the current national heifer shortage. It delivers a 2026 roadmap for balancing replacement needs against $1,400 beef-on-dairy windfalls, ensuring your operation remains stocked for a high-value future despite tight margins.

- Revolutionizing Calf Rearing: 5 Game-Changing Nutrition Strategies That Deliver $4.20 ROI for Every Dollar Invested – Breaks down five unconventional tactics, including pair housing and strategic hay introduction, that return over four dollars for every one spent. It delivers a proven method for boosting the social development and rumen capacity that traditional systems often miss.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!