Explore how transitioning from linear selection to genetic indexes can transform your dairy breeding approach. Are you prepared to maximize your herd’s capabilities?

For decades, dairy breeders have relied heavily on linear selection, prioritizing traits such as “taller,” “stronger,” and “wider.” While linear selection provided a straightforward blueprint, modern dairy operations showcase shortcomings. The key to success lies in accurate information. As genetic herd audits and sophisticated indexes become commonplace, the emphasis shifts toward traits like health, fertility, and lifetime productivity. The industry has been conditioned to believe that bulls with negative linear traits would sire inferior progeny. However, this concept is becoming increasingly outdated. Understanding the limitations of linear selection is essential as the industry evolves. This isn’t just theoretical—it’s about providing dairy breeders with the tools they need to thrive in an ever-changing agricultural landscape.

Accurate Information: The Cornerstone of Modern Dairy Management

Accurate information is not just important; it’s paramount in dairy management. It’s the bedrock for productive and profitable decisions. As the dairy industry evolves, the reliance on precise data becomes even more critical. Outdated methods and obsolete data can significantly misguide breeding choices, resulting in unfavorable outcomes. The role of accurate information in dairy management cannot be overstated, as it underlines the importance of data-driven decisions and the potential risks of relying on outdated methods.

For example, continuing to use linear selection as the sole criterion despite its directional simplicity can lead to the accidental selection of traits that do not align with contemporary herd needs. When the industry previously emphasized parameters like height and strength, it inadvertently cultivated cows with extreme stature, resulting in too tall and frail animals for optimal health and productivity. Such misguided selection pressures are evident in traits like rear teat placement, which suffered due to linear selection focused on front teat placement.

In contrast, indexes offer a more holistic approach, integrating multiple traits and their relative importance tailored to specific herd environments. They enable producers to weigh diverse factors such as health, fertility, and lifespan, resulting in more accurate breeding decisions that align with the desired outcomes. By employing up-to-date and comprehensive genetic audits, dairy managers can avoid the pitfalls of outdated methodologies, ensuring that their decisions are grounded in the most current and relevant information available.

Ultimately, the shift from traditional linear selection to more nuanced approaches underscores the critical role of accurate information. It empowers dairy producers to navigate the complexities of modern herd management effectively, allowing them to cultivate genetically superior cows that meet the industry’s evolving demands.

Enter the Genetic Index: A Holistic Approach to Herd Management

Enter the genetic index—a tool that presents a more stable and comprehensive selection method than the often rigid linear selection. Genetic indexes aggregate various trait data into a weighted value that better represents an animal’s overall genetic potential. This method effectively transcends the restrictive and sometimes misleading binary of linear selection.

Unlike the linear approach that prioritizes specific traits in isolation, genetic indexes consider a spectrum of factors influencing health, fertility, and productivity. For instance, an index can balance the importance of traits such as mastitis resistance, milk yield, and udder conformation, providing a holistic view of an animal’s genetic worth. This balance ensures that no single trait is disproportionately emphasized to the detriment of overall functionality and longevity.

Moreover, genetic indexes introduce flexibility into breeding decisions, allowing dairy producers to tailor selection criteria based on their herd’s unique challenges and goals. Genetic indexes support more precise and effective selection strategies by weighting traits according to their relevance to a dairy operation’s specific environmental and management conditions. This not only optimizes the genetic development of the herd but also enhances the adaptability and resilience of the cattle population, providing a sense of reassurance and security in the face of changing conditions.

The Limitations of Linear Selection in Modern Dairy Breeding

Linear selection, by its very nature, is limited in scope due to its two-dimensional approach. This method tends to focus on individual traits in isolation, often ignoring the broader genetic interconnections and environmental factors that also play crucial roles in a cow’s productivity and overall health. By simplifying selection to terms like “taller” or “stronger,” breeders are led to prioritize specific physical characteristics without fully understanding their implications on other vital aspects such as fertility, longevity, and disease resistance.

Moreover, the reliance on isolated traits can lead to unintended consequences. For instance, selecting taller cows might inadvertently result in too frail animals, as the emphasis on height could overshadow the need for robust body structure. Similarly, the traditional approach of choosing bulls based on their linear traits might not account for the holistic needs of a modern dairy operation. It creates a scenario where the ideal cow for a particular environment is overlooked instead of one that fits a historical and now possibly outdated, linear profile.

Such an approach also fails to account for the dynamic nature of genetic progress. While linear selection might have worked under past environmental and market conditions, today’s dairy industry demands a more nuanced and comprehensive strategy. The ever-changing landscapes of health challenges, market preferences, and production environments necessitate a departure from the rigid, two-dimensional framework that linear selection represents.

The Evolution of Linear Selection: A Historical Perspective on Dairy Breeding

Understanding the evolution of linear selection in dairy breeding requires a historical lens through which we observe genetic trends and the shifting paradigms that have guided these trends. Over the past five decades, one prominent example is the selection for stature in U.S. Holsteins. Initially intended to produce taller cows, this linear selection was driven by the belief that larger animals would be more productive. From a base stature of 52 inches (132 centimeters) in the early 1970s, selective breeding practices have seen this trait rise by an average of 5.5 inches (14 centimeters). Today, the daughters of Holstein bulls with an STA of 0.00 for stature typically measure around 57.5 inches (160 centimeters).

However, as cows grew taller, unintended consequences emerged. Larger cows often experienced greater strain on their skeletal structures and faced increased incidences of lameness. Additionally, the shift toward extreme measurements, such as overly tall and frail cows, suggested that these changes might have overshot the ideal productive physique for dairy cows. The selection pressure inadvertently guided breeding decisions to focus on traits that, although historically perceived as desirable, began to conflict with emerging dairy production environments and herd health priorities.

These changes also had profound implications for other linear traits. For instance, as the focus shifted towards enhancing front teat placement, little attention was paid to rear teat placement, creating new challenges for dairy breeders. This historical perspective underscores the adaptability required in breeding practices. It suggests the necessity for a more balanced, holistic approach moving forward—a lesson clearly illustrated by the evolution of indices in modern selective breeding. The need for a more balanced, holistic approach in breeding practices is a crucial takeaway from past experiences, highlighting the industry’s adaptability.

Refining Genetic Evaluations: Understanding Standard Transmitting Abilities (STAs)

Standard Transmitting Abilities (STAs) is a refined way of expressing genetic evaluations for linear-type traits, offering a clearer and standardized metric for comparison. Calculating STAs involves transforming Predicted Transmitting Abilities (PTAs) into a common scale, making disparate traits easily comparable.

To calculate STAs, PTAs are first derived using advanced genetic models that consider various data points, including parent averages, progeny records, and contemporary group adjustments. These PTAs are then converted into STAs, standardized values representing animals’ genetic merit relative to a modern population base. The practical range of STAs spans from -3.0 to +3.0, with most bulls and cows falling within -2.0 to +2.0, ensuring a bell-curve distribution that simplifies interpretation.

Understanding STAs involves recognizing their role in evaluating linear-type traits with precision. For instance, an STA of 0.00 indicates an animal is average for the trait in the current population, while positive or negative values denote deviations above or below this average. This standardization allows producers to make informed breeding decisions by identifying superior genetics that align with specific breeding goals. By focusing on STAs, breeders can strategically select traits that enhance overall herd performance, ensuring that each generation successfully builds on the genetic progress of the previous one.

The Case of Stature: Unintended Consequences of Generational Linear Selection

The case of stature vividly illustrates the unintended consequences of linear selection over generations. Initially, breeders prioritized increasing the height of cows, associating taller stature with improved dairy production and greater robustness. However, this singular focus on height overlooked other crucial traits, including udder health and reproductive efficiency. As a result, while stature improved dramatically—rising by an average of 5.5 inches (14 centimeters) over the past five decades—dairy cows’ overall performance and longevity faced unforeseen challenges.

Consider the comparative example of Holstein cows. A bull with a Standard Transmitting Ability (STA) of 0.00 today would sire daughters averaging 57.5 inches (160 centimeters) in height—significantly taller than the 52-inch (132 centimeters) cows at the same STA level five decades ago. If breeders were to select bulls with a -3.00 STA for stature now, their daughters would still be 56.5 inches (143.5 centimeters) tall, which reveals the lasting impact of generational selection for height.

This relentless push for increased height did not occur in isolation. Physical attributes and health traits were often compromised to achieve a taller stature. Breeders globally started observing cows “too tall, too frail,” with structural deficiencies such as “short teats and rear teats being too close together.” These physical alterations posed significant management issues—cows with excessively tall stature frequently experienced increased stress on their skeletal systems and a higher propensity for lameness, negatively affecting their productivity and well-being.

Consequently, this relentless focus on linear selection for stature resulted in a breed that, while visually impressive, often struggled with underlying health and productivity challenges. This is a stark reminder that breeding programs must consider a holistic approach, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of genetic traits, to develop a well-rounded, high-performing herd suited for sustainable dairy farming.

The Overlooked Consequence: Rear Teat Placement and the Pitfalls of Linear Selection

The issue of rear teat placement offers a stark example of the unintended consequences that can arise from linear selection focused predominantly on front teat traits. Historically, the selection protocols that emphasized front teat placement, aiming for a “Plus” positioning, did not account for the correlated effects on the rear teats. As a result, we observed rear teats becoming too close together, an outcome that was neither anticipated nor desired. This misalignment can compromise udder health and milking efficiency, leading to increased mastitis and difficulties in machine milking. The focus on improving one set of traits—front teat placement—without considering the holistic impact on the overall udder structure underscores the pitfalls of a unidimensional approach to selection. By shifting towards more integrated evaluation methods, like indexes that incorporate multiple relevant traits, we can better address such complex genetic interrelations and enhance the overall functionality and health of the herd.

Redefining Priorities: From Linear Extremes to Balanced Herd Management

Linear selection has driven the dairy industry’s breeding decisions to a point where the traits we once sought to enhance have become liabilities. The focus on extremes—stature, strength, or teat placement—has created cows that are often too tall, frail, or have inefficient udder configurations. These unintended consequences affect the cows’ health and productivity and create additional management challenges, thereby impacting the overall efficiency of dairy operations.

A paradigm shift is necessary, moving from the myopic focus on linear traits to a more balanced and holistic breeding approach. The comprehensive indexes available today offer a more nuanced and multi-dimensional framework. Unlike linear selection, which tends to prioritize singular traits often to the detriment of others, indexes provide a weighted consideration of a range of characteristics that directly impact a cow’s longevity, health, and productivity. This method aligns with the practical realities of modern dairy farming and supports the creation of robust, well-rounded cows capable of thriving in diverse environments.

Relying solely on linear selection is an outdated practice in a time of paramount precision and efficiency. The industry’s future is leveraging complex genetic evaluations and indexes incorporating various health, productivity, and fertility traits. Such a move will ensure the creation of an optimal herd that meets both contemporary market demands and the rigorous demands of modern dairy farming.

Embracing Indexes: A Paradigm Shift from Linear Composites

Indexes represent a modern and holistic approach to genetic selection that contrasts significantly with traditional composites. While composites aggregate linear values into a single selection metric, they often fail to account for the nuances needed for specific herd environments. On the other hand, Indexes maintain each trait’s integrity by assigning a weighted value to it based on its relevance to the optimal cow profile for a given environment. This method ensures that traits essential to the animal’s health, productivity, and longevity are prioritized according to their real-world importance. For instance, if mastitis is prevalent in a particular region, the index would appropriately weigh this health trait to screen for less-prone genetics. By doing so, indexes facilitate a targeted and balanced breeding strategy, allowing producers to cultivate not only productive but also well-suited cows to thrive in their specific operational conditions.

Indexes: A Multifaceted Approach Beyond Linear Selection

Indexes offer a multifaceted approach to dairy breeding, transcending the limitations of linear selection. One of the primary advantages of using indexes is their capacity to integrate a wide array of traits, including those related to health and overall performance. Indexes provide a more comprehensive assessment of genetic potential by weighting each trait according to its relevance and impact on the ideal cow for a specific environment.

This holistic approach ensures that essential health traits, such as mastitis resistance and fertility, are factored into breeding decisions. By incorporating these traits, indexes help identify cows that are not only high performers but also robust and resilient, enhancing their longevity within the herd. The ability to screen for low-heritability traits, which might otherwise be overlooked in linear selection, further refines the selection process, aiding in avoiding genetic extremes that could compromise herd health and productivity.

Moreover, indexes facilitate more accurate and adaptable breeding strategies that align with a given dairy operation’s specific challenges and goals. Whether the focus is on increasing milk yield, improving udder health, or selecting moderate frame sizes, the weighted values in an index can be tailored to match the unique conditions of the herd’s environment.

In essence, indexes empower dairy producers to make informed decisions that balance productivity with sustainability, ultimately leading to the development of cows that excel in performance and longevity. This strategic approach not only optimizes genetic gains but also promotes the welfare and durability of the herd, ensuring a more stable and prosperous future for dairy operations.

Navigating Genetic Index Selection: Tailoring Traits to Your Herd’s Needs

Choosing the right genetic index for your dairy cows involves understanding and prioritizing the traits that align with your herd’s needs and environmental conditions. Here are essential steps to guide you:

- Identify Herd Goals: Define what you want to achieve with your herd. Are you focusing on milk production, fertility, health, or longevity? Your goals will determine the traits you must prioritize in your genetic index.

- Analyze Current Herd Performance: Use data from sources like the DHI-202 Herd Summary Report to evaluate your herd’s strengths and weaknesses. This helps identify traits that require improvement.

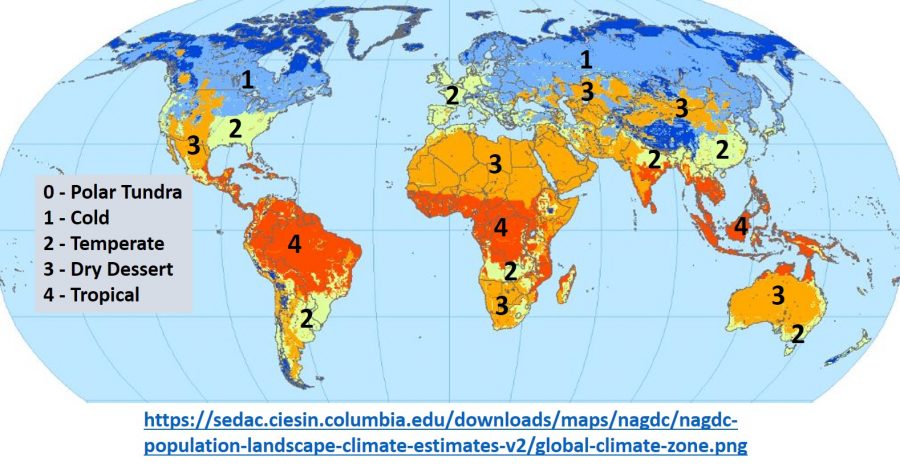

- Consider Environmental Factors: Consider the environmental conditions your cows face. Weather, feed quality, and herd health can influence which traits are most beneficial to focus on for optimal performance.

- Review Trait Heritability and Economic Impact: Not all traits are equally heritable, and some have a more significant economic impact than others. To maximize genetic progress, focus on traits with higher heritability and substantial financial benefits.

- Weight Traits Appropriately: Use the relative importance of each trait in your selected index. Traits that significantly impact your herd’s productivity and profitability should have higher weightings in the index.

- Utilize Comprehensive Genetic Audits: Engage in periodic genetic audits to track the progress and effectiveness of your breeding decisions. This ensures your genetic selection continues to align with your evolving herd goals.

- Consult Industry Experts: Work with genetic consultants or utilize industry tools and resources to refine your genetic indexes. Expert advice can provide valuable insights and help tailor indexes to your herd’s unique needs.

By thoughtfully choosing and applying the proper genetic indexes, dairy producers can enhance the overall genetic quality of their herd, achieving a balance between high productivity and sustainable herd health.

The Bottom Line

As we navigate dairy breeding, shifting from linear selection to genetic indexes is revolutionary. Indexes align breeding strategies with modern needs, ensuring cows are robust, fertile, and productive over their lifetimes. While linear selection once worked, it shows limitations like increased stature and flawed teat placement. In contrast, genetic indexes consider health, fertility, and productivity dynamically. Indexes breed cows that are better suited to their roles by weighting traits for specific environments.

Adopting genetic indexes has profound implications. Herds become more resilient, operations more sustainable, and the genetic health of dairy populations improves. This approach reduces breeding extremes, fostering balanced herd management that adapts to varying challenges and environments. Embracing genetic indexes addresses past shortcomings and shapes the future of dairy breeding.

Key Takeaways:

- Shifting from linear selection to genetic indexes can provide more stability and adaptability in herd management.

- Linear selection has historically led to unintended consequences, such as overly tall cows and poorly placed rear teats.

- Genetic indexes offer a holistic approach by weighting traits based on their importance to the specific herd environment.

- Utilizing indexes enables producers to make more informed decisions, balancing traits like health, fertility, and productivity.

- Transitioning to genetic indexes requires understanding and interpreting Standard Transmitting Abilities (STAs) for accurate selection.

- Indexes can integrate lower heritability traits, including health factors like mastitis resistance, enhancing overall herd performance.

- Adopting index-based selection helps mitigate the risk of extreme genetic profiles and promotes balanced genetic improvements.

Summary:

The dairy industry has traditionally used linear selection, prioritizing traits like “taller,” “stronger,” and “wider,” but this approach has shown shortcomings in modern operations. Accurate information is crucial in dairy management, and outdated methods can lead to accidental selection of traits that do not align with contemporary herd needs. Genetic indexes offer a more holistic approach, integrating multiple traits and their relative importance tailored to specific herd environments. Genetic indexes aggregate various trait data into a weighted value, better representing an animal’s overall genetic potential. This method transcends the restrictive binary of linear selection, considering factors influencing health, fertility, and productivity. Linear selection is limited in scope due to its two-dimensional approach, ignoring broader genetic interconnections and environmental factors. Standard Transmitting Abilities (STAs) offer a refined way of expressing genetic evaluations for linear-type traits, allowing breeders to strategically select traits that enhance overall herd performance and build on the genetic progress of the previous generation.

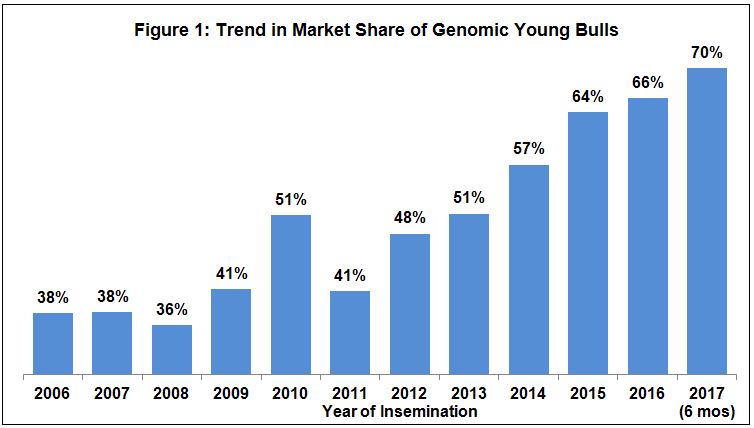

Dairy products are a key source of valuable proteins and fats for many millions of people worldwide. Dairy cattle are highly susceptible to heat-stress induced decline in milk production, and as the frequency and duration of heat-stress events increases, the long term security of nutrition from dairy products is threatened. Identification of dairy cattle more tolerant of heat stress conditions would be an important progression towards breeding better adapted dairy herds to future climates. Breeding for heat tolerance could be accelerated with genomic selection, using genome wide DNA markers that predict tolerance to heat stress. Here we demonstrate the value of genomic predictions for heat tolerance in cohorts of Holstein cows predicted to be heat tolerant and heat susceptible using controlled-climate chambers simulating a moderate heatwave event. Not only was the heat challenge stimulated decline in milk production less in cows genomically predicted to be heat-tolerant, physiological indicators such as rectal and intra-vaginal temperatures had reduced increases over the 4 day heat challenge. This demonstrates that genomic selection for heat tolerance in dairy cattle is a step towards securing a valuable source of nutrition and improving animal welfare facing a future with predicted increases in heat stress events. (

Dairy products are a key source of valuable proteins and fats for many millions of people worldwide. Dairy cattle are highly susceptible to heat-stress induced decline in milk production, and as the frequency and duration of heat-stress events increases, the long term security of nutrition from dairy products is threatened. Identification of dairy cattle more tolerant of heat stress conditions would be an important progression towards breeding better adapted dairy herds to future climates. Breeding for heat tolerance could be accelerated with genomic selection, using genome wide DNA markers that predict tolerance to heat stress. Here we demonstrate the value of genomic predictions for heat tolerance in cohorts of Holstein cows predicted to be heat tolerant and heat susceptible using controlled-climate chambers simulating a moderate heatwave event. Not only was the heat challenge stimulated decline in milk production less in cows genomically predicted to be heat-tolerant, physiological indicators such as rectal and intra-vaginal temperatures had reduced increases over the 4 day heat challenge. This demonstrates that genomic selection for heat tolerance in dairy cattle is a step towards securing a valuable source of nutrition and improving animal welfare facing a future with predicted increases in heat stress events. (