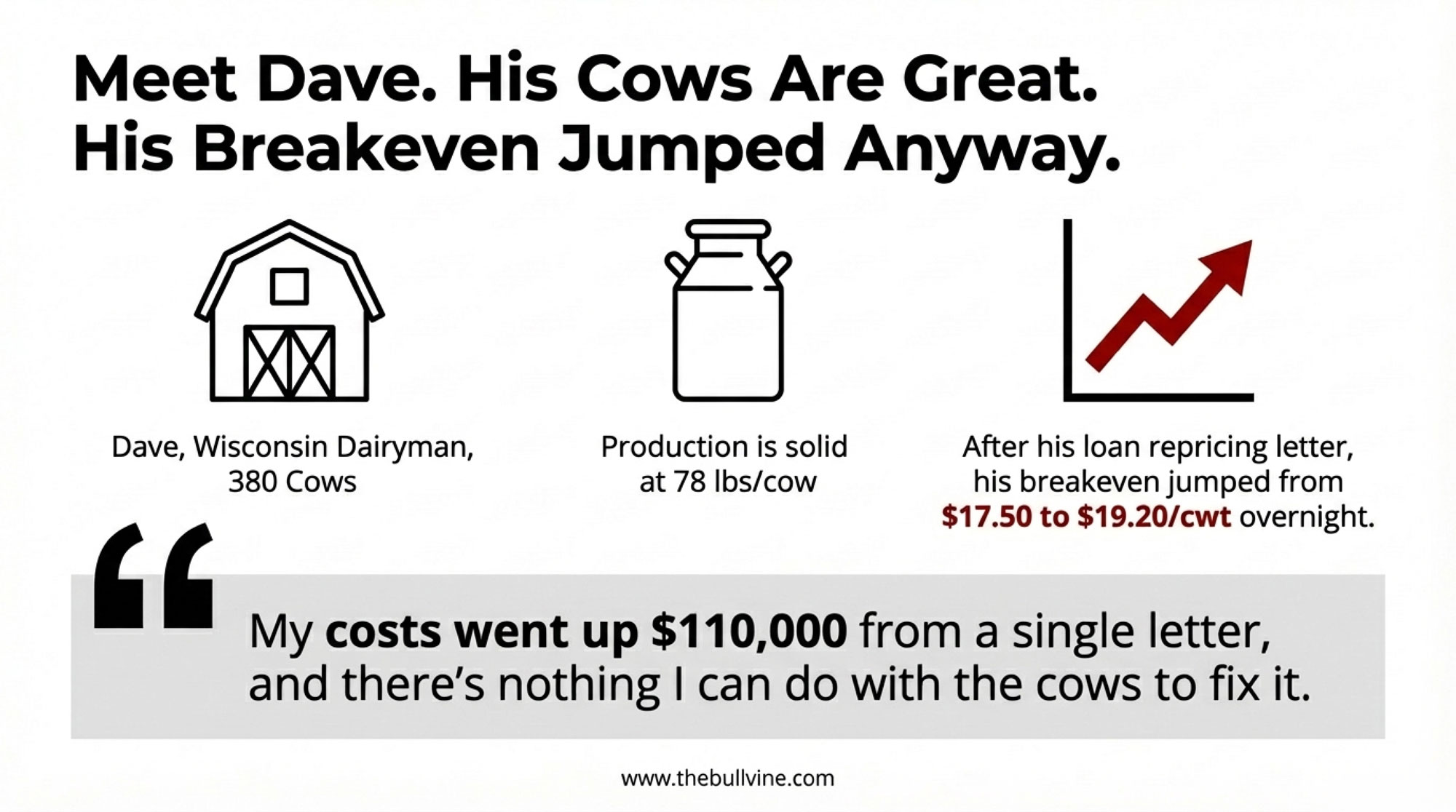

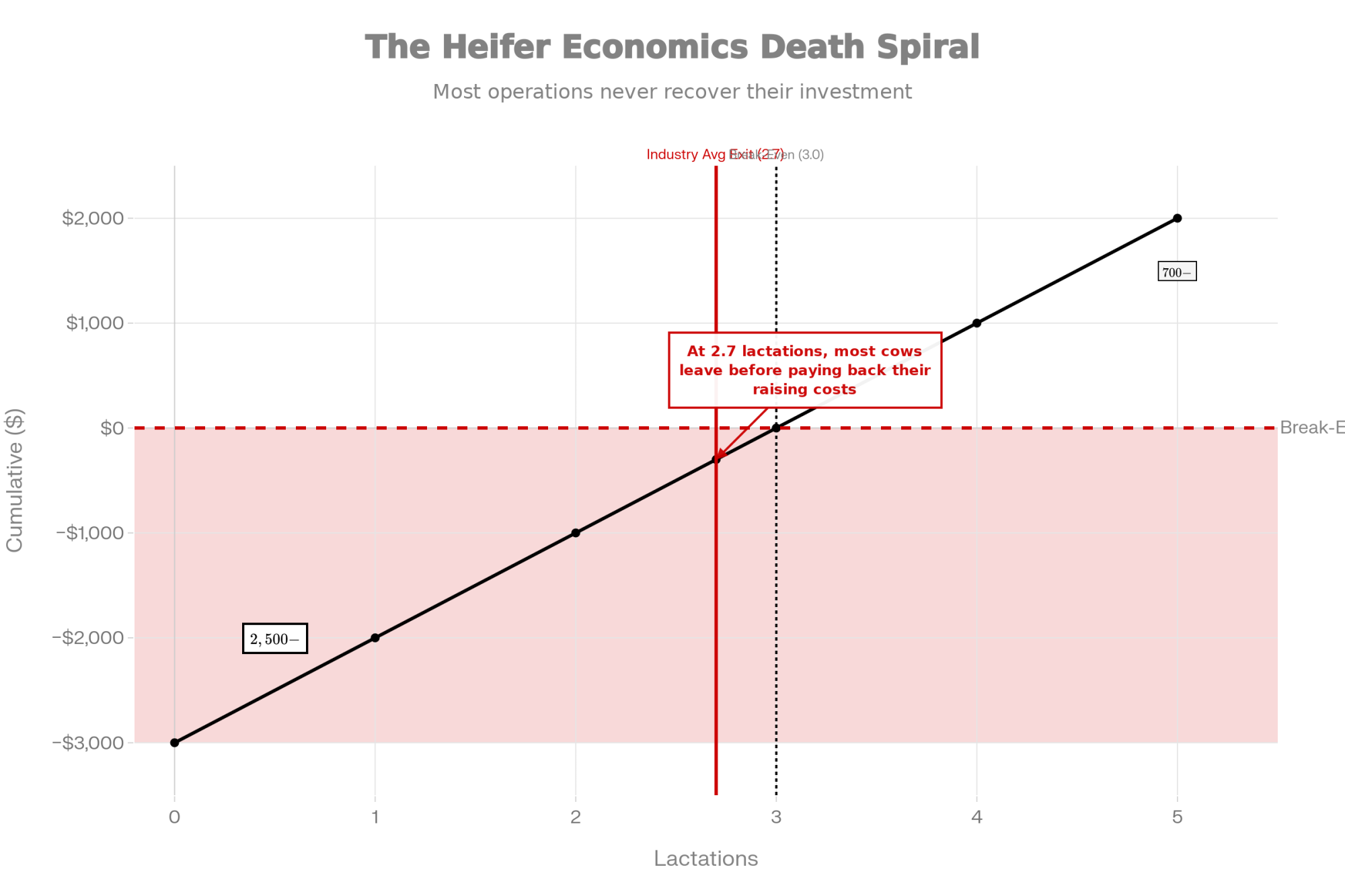

A 55-year-old expands with $3M debt. He’s 70 before it’s manageable—exactly when the transition should happen. That’s the trap nobody talks about.

I’ve been thinking about this for quite a while now. When we looked back at the profiles that resonated most with Bullvine readers this year—from Juan Moreno’s long game at STgenetics to the sobering collapse of Jack Stookey’s tax-shelter empire back in the 1980s—something clicked that I hadn’t expected.

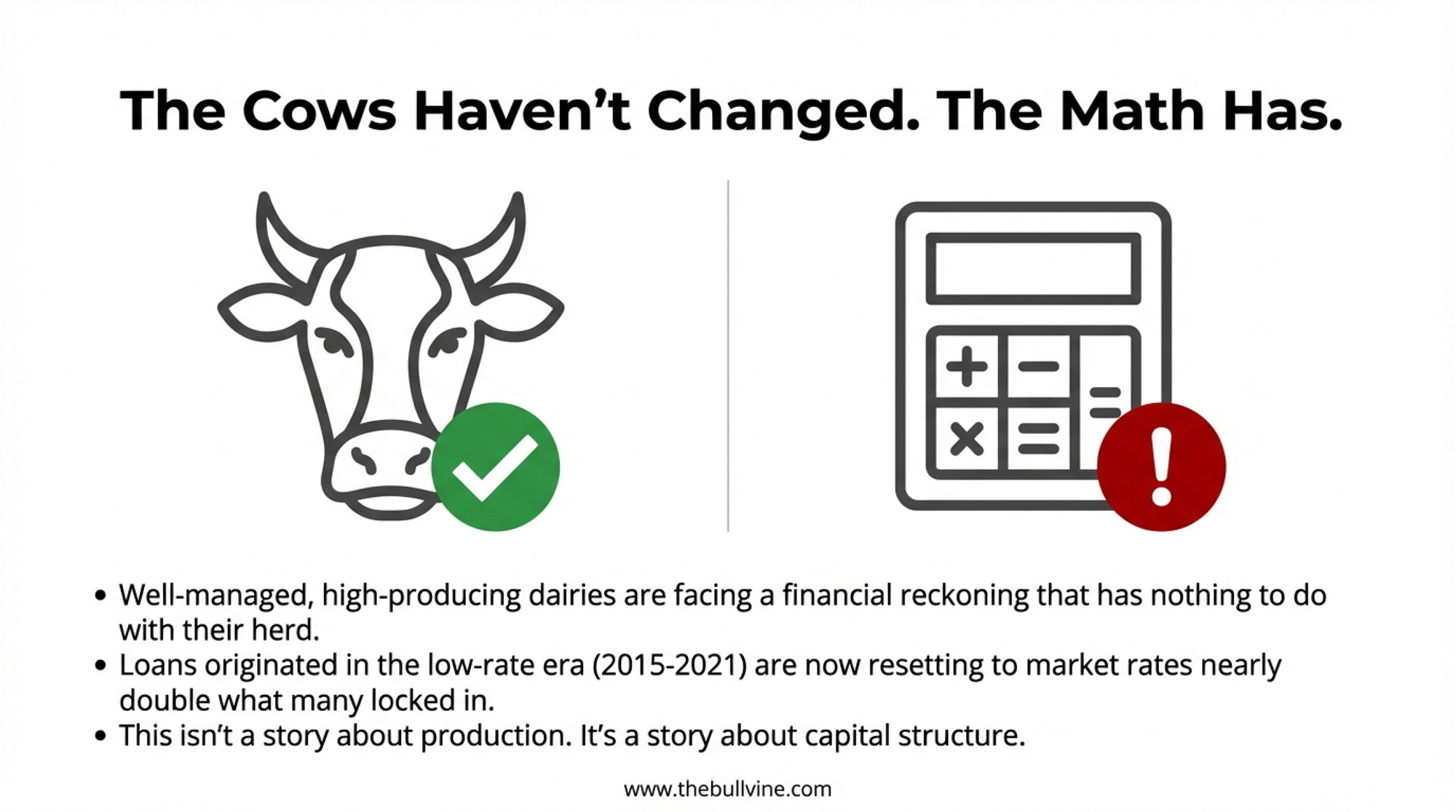

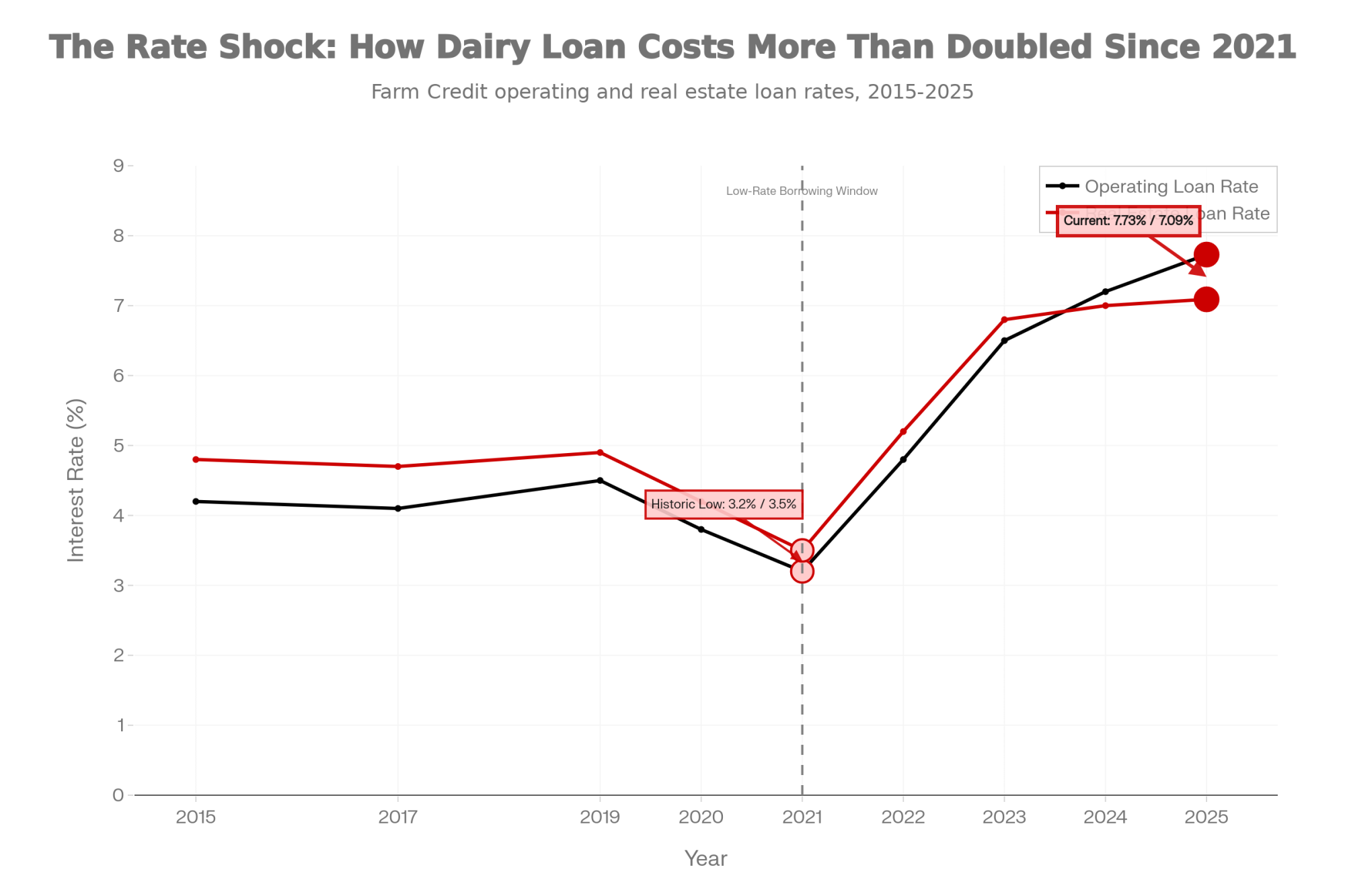

The operators who built lasting enterprises didn’t necessarily make smarter bets. What they did was structure their risks so they could survive being wrong.

And the ones who struggled? Many were equally talented, equally hardworking. But they built business models that needed favorable conditions to keep working. When conditions shifted, everything came undone.

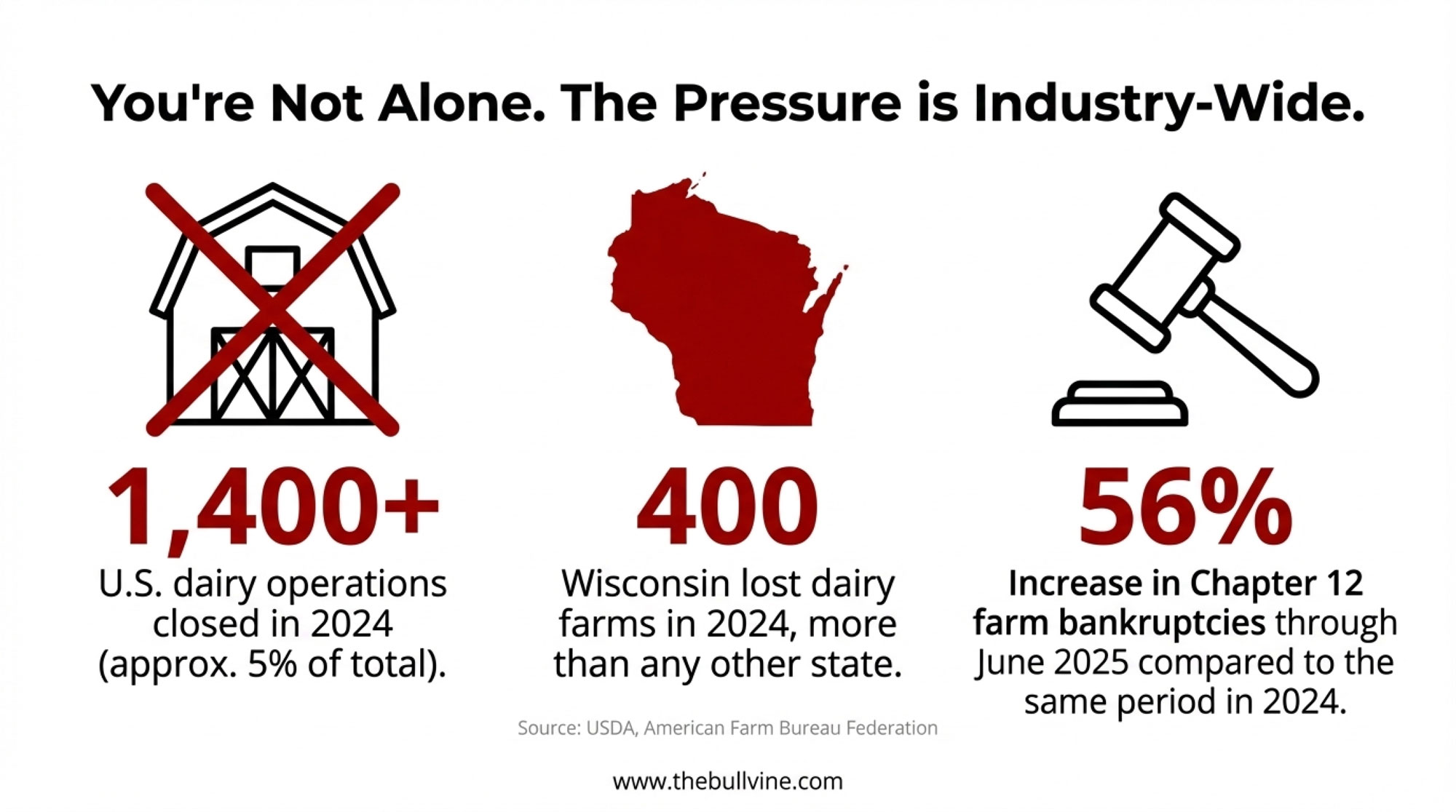

If current trends continue, we’re likely to see thousands more exits over the next decade. So, understanding what actually separates the winners from everyone else? That’s not academic anymore. It’s something we need to think carefully about.

The Disruptors Who Actually Delivered

Juan Moreno and the Infrastructure Play

Here’s what’s interesting about Juan Moreno’s trajectory at STgenetics. He didn’t just build a company with 1,800 employees across 16 countries. He fundamentally changed how genetics move from bull to barn.

STgenetics estimates that around 30% of dairy semen sold worldwide now uses sex-sorted technology—much of it processed using systems they pioneered. That’s not market share in the traditional sense. That’s infrastructure. When your technology becomes the standard methodology for an entire industry, you’ve built something more durable than a competitive advantage.

What I find instructive is the discipline behind it. Sex-sorted semen had terrible conception rates in the early years—and if you were breeding fresh cows during that era, you remember the frustration. Early flow-sorting systems required specialized equipment costing several hundred thousand dollars, and the sorting process discarded a substantial share of sperm cells during processing. Any purely rational investor looking at those economics might have walked away.

Moreno kept investing anyway. The payoff came between 2013, with the SexedULTRA launch, and 2017 with SexedULTRA 4M, when conception rates finally approached conventional semen levels.

When World Dairy Expo named him 2025 International Person of the Year this past October, the recognition committee specifically cited his “commercial innovation that delivers practical value to producers worldwide.” That phrase stuck with me—practical value to producers. Not laboratory curiosities.

In interviews during his World Dairy Expo recognition, Moreno offered a window into his philosophy when asked about genetic modification: “If they don’t want to go any further with genetic modification, why on earth would we get involved with it as an industry? We’re playing with fire by doing that.”

That restraint—knowing when not to push—tells you something about how infrastructure builders think differently than pure innovators.

“The operators who built lasting enterprises didn’t necessarily make smarter bets. They structured their risks so they could survive being wrong.”

Read more: Bull in a China Shop: How Juan Moreno Turned the Dairy World Upside Down

The McCarty Family: When Vertical Integration Works

The McCarty Family earned World Dairy Expo’s 2025 Dairy Producer of the Year recognition for reasons that illuminate where parts of this industry are heading.

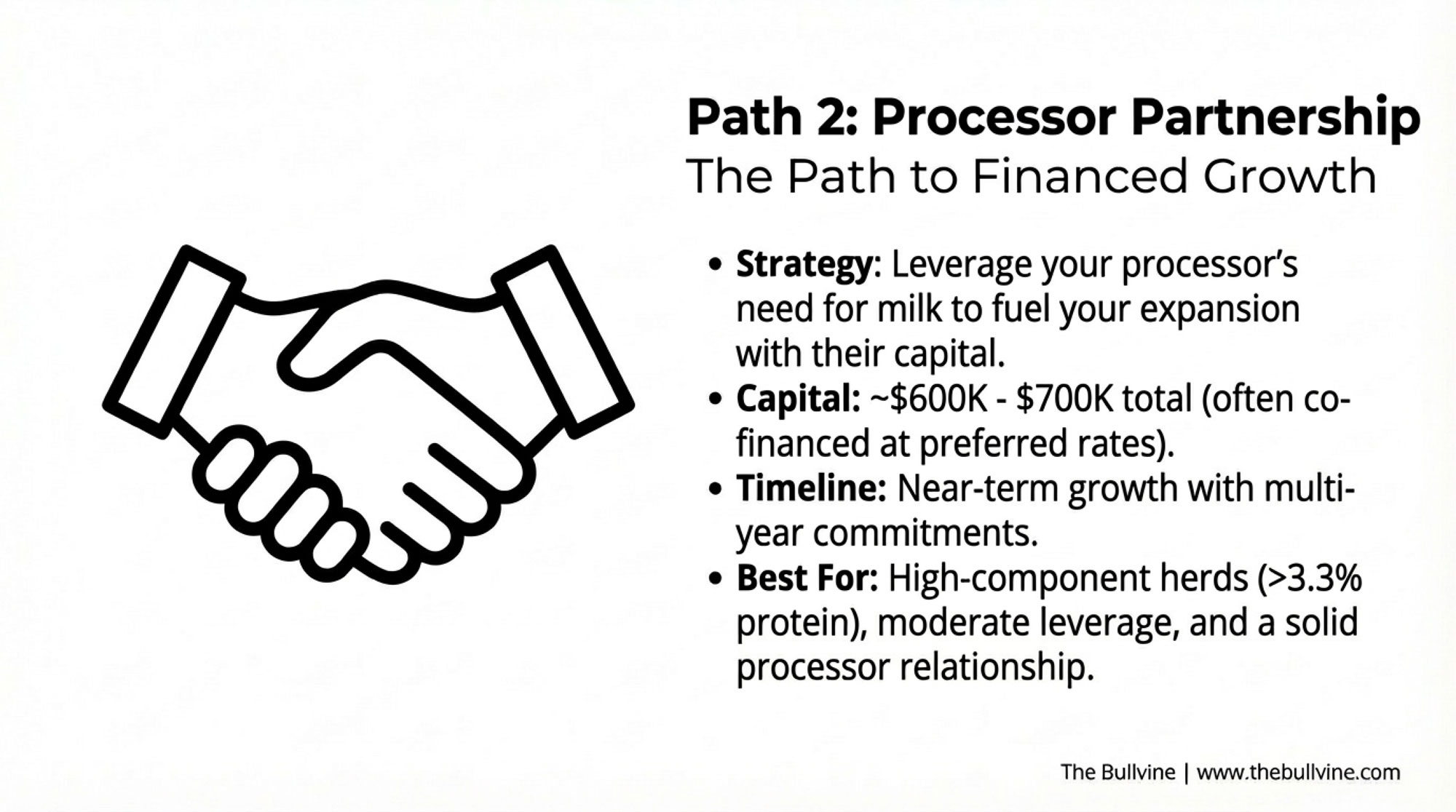

McCarty Family Farms and MVP Dairy together milk roughly 18,000 to 20,000 cows across Kansas and Ohio, according to coverage in Dairy Star and the Kansas State University alumni magazine K-Stater. That makes them one of the largest registered Holstein operations in North America. Their processing partnership with Danone means they don’t just produce milk; they control what happens to it afterward. Ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis technology. B Corporation certification. A fully integrated supply chain that gives them options most producers simply don’t have.

Now, what farmers considering similar approaches need to understand: this model required Danone’s partnership, Danone’s distribution network, and access to processing infrastructure investment that most operations can’t realistically replicate. I’m not knocking it—just providing context for what made it possible.

I talked with a 400-cow operator in Wisconsin last month who asked me point-blank: “Should I be trying to do what McCarty did?”

My honest answer: probably not, at least not in that exact form. The lesson from McCarty isn’t “build processing infrastructure.” It’s “understand what advantages you actually have access to before choosing your strategy.”

The McCarty approach works brilliantly at their scale, given their capital access and specific processor relationship. That doesn’t mean it translates to a 300-cow operation in Vermont or a 600-cow dairy in California’s Central Valley. Different operations need different playbooks.

Read more: The McCarty Magic: How a Family Farm Became the Dairy Industry’s Brightest Star

GenoSource: What Collaboration Actually Looks Like

In 2014, eight Iowa farming families—Carroll, Simon, Rauen, and Demmer among them—pooled resources and created something I still find remarkable. Not a loose alliance where everyone keeps doing their own thing. A unified partnership operating one farm with centralized decision-making.

The result was GenoSource Captain, who has ranked among the very top genomic Holstein sires across multiple proof runs. After the April 2025 base change, Captain maintained his #1 position with an impressive 3441 TPI according to CDCB evaluations—and he’s remained near the top of industry rankings since. That kind of sustained elite performance is genuinely rare in the genomic era, where new bulls constantly shuffle the leaderboard. (Read more: CAPTAIN: The Bull That Rewrote the Rules for Modern Breeding)

GenoSource has developed into a high-output embryo and bull-testing program, supplying significant numbers of embryos and young sires into AI platforms each year. Leadership from Tim Rauen, handling genetics and risk management; Kyle Demmer, running operations; and Matt Simon, overseeing finance and technology, drives consistent execution.

Why does this matter for mid-sized operations? Because it demonstrates that collective investment can produce results that neither individual operations nor corporate genetics companies can achieve alone. In an era of consolidation, when most breeders feel squeezed, this represents a genuine countermodel worth studying.

But—and this context matters—farmers considering similar approaches should note that GenoSource benefited from specific advantages that don’t automatically transfer. They were founded during the 2014 post-crisis recovery when capital was available, and milk prices were stabilizing. They had exceptional talent concentration in their leadership team. And when a derecho destroyed half their facilities in August 2020, they had enough equity to rebuild with state-of-the-art infrastructure rather than being forced into liquidation.

What’s replicable: genomic testing discipline, component-focused genetics, cooperative purchasing arrangements. Regional farm groups can absolutely implement these elements.

What’s harder to replicate: the timing, the specific talent mix, the capital depth from eight committed families working together over a decade.

Read more: From Pasture to Powerhouse: The GenoSource Story

When Expansion Actually Works

I want to be careful here not to paint all expansion as inherently risky. Because that’s not what the data shows, and it wouldn’t be fair to the operators who’ve grown successfully.

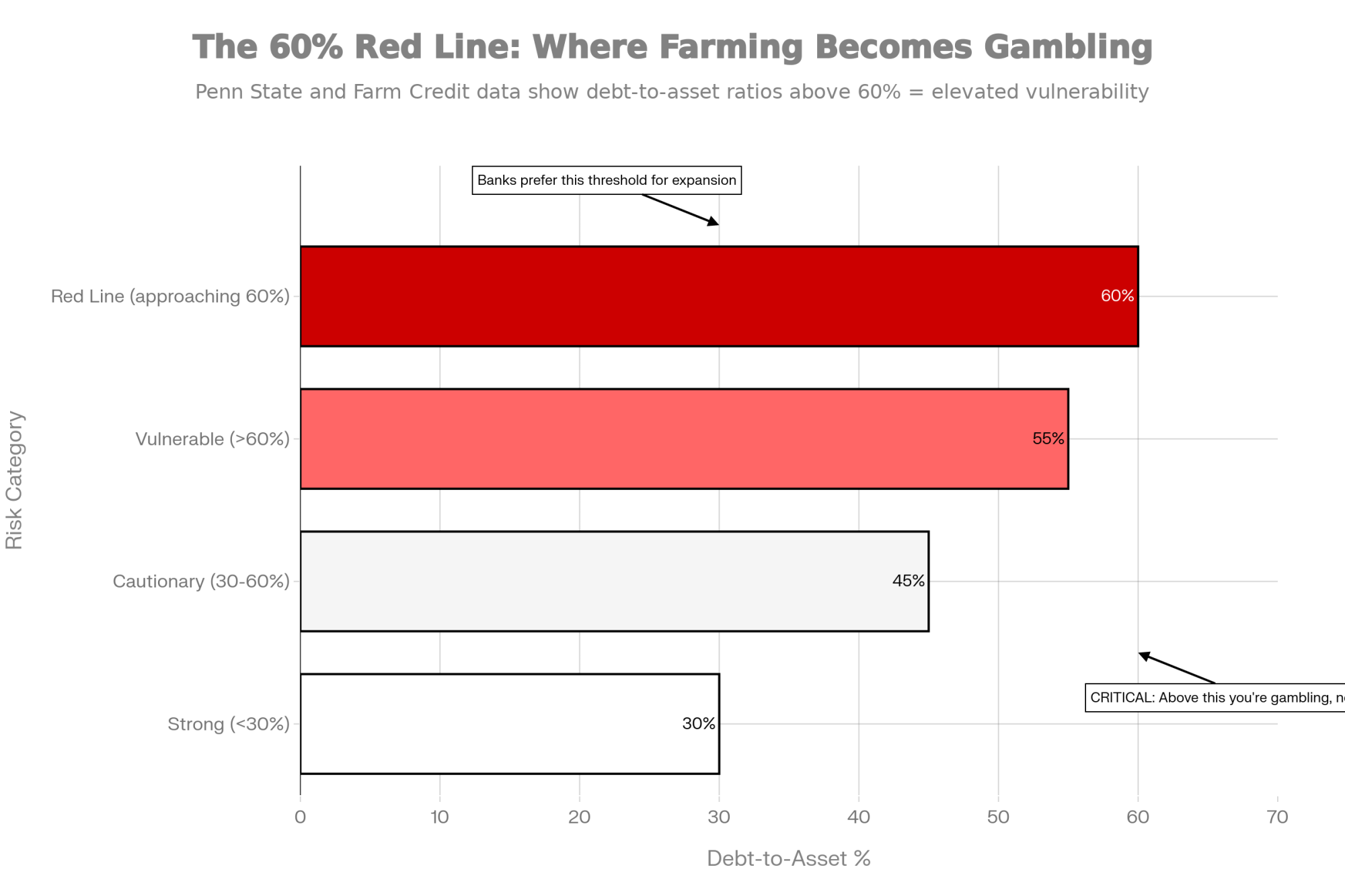

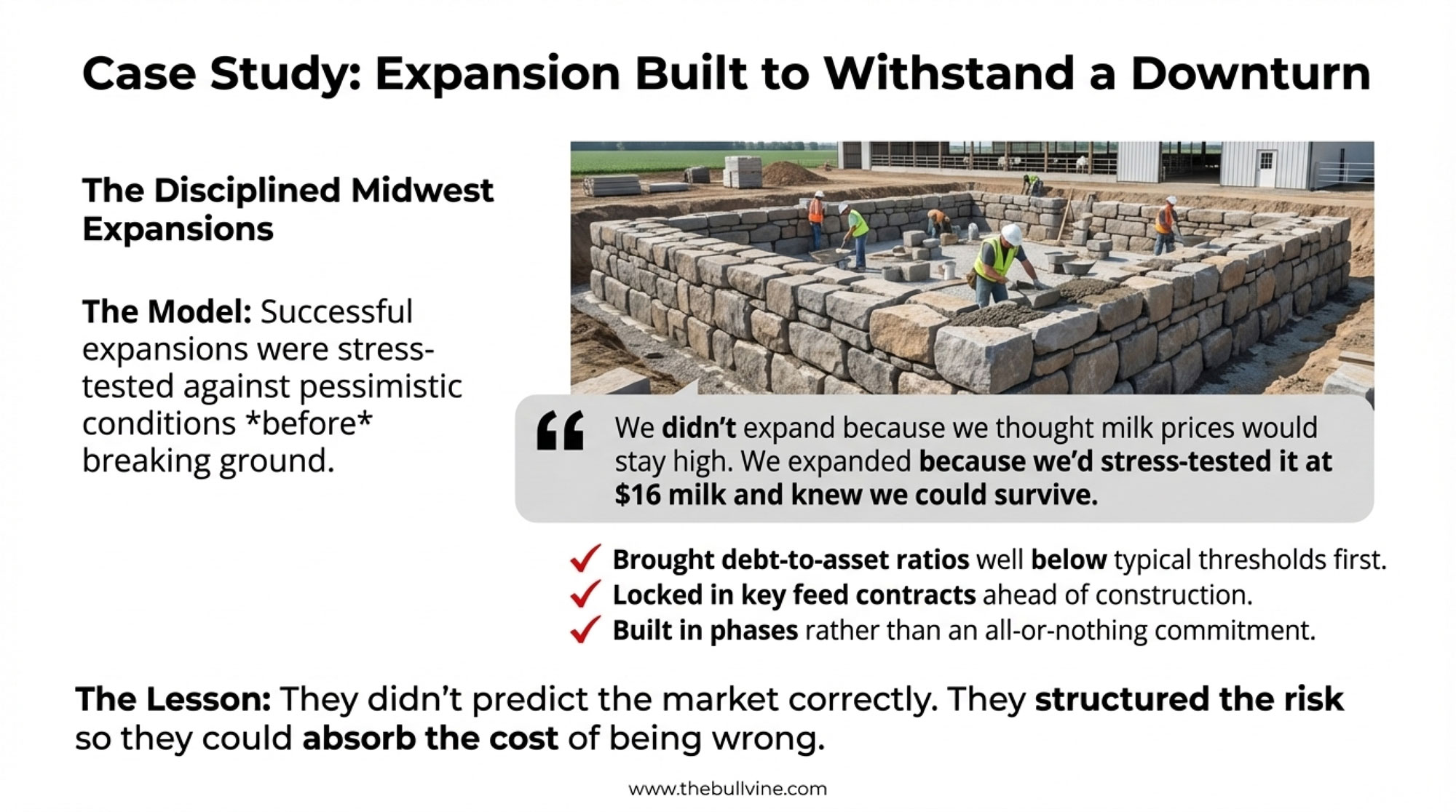

Extension economists across the Midwest have highlighted herds that successfully expanded by bringing their debt-to-asset ratios well below typical thresholds before breaking ground, stress-testing projections at pessimistic milk prices like $16/cwt, and locking in key feed contracts ahead of construction. Farms in those examples were built in phases rather than all at once—moves that helped them absorb the shocks of 2020-2022 when feed costs spiked, and markets got volatile.

One producer’s comment from those discussions stuck with me: “We didn’t expand because we thought milk prices would stay high. We expanded because we’d stress-tested it at $16 milk and knew we could survive.”

That’s the framework in action. These operators didn’t predict the market correctly—nobody predicted 2022’s feed costs. But they’d structured the risk so they could absorb the cost of being wrong. That’s a meaningful distinction.

If you’re considering expansion and want to run similar stress tests, your state extension dairy specialist can help you build scenarios, and the USDA’s Farm Service Agency offers financial planning tools through their farm loan programs. Taking time with these resources before committing capital is almost always worthwhile.

Not every expansion is speculation. The difference is whether the structure survives unfavorable conditions.

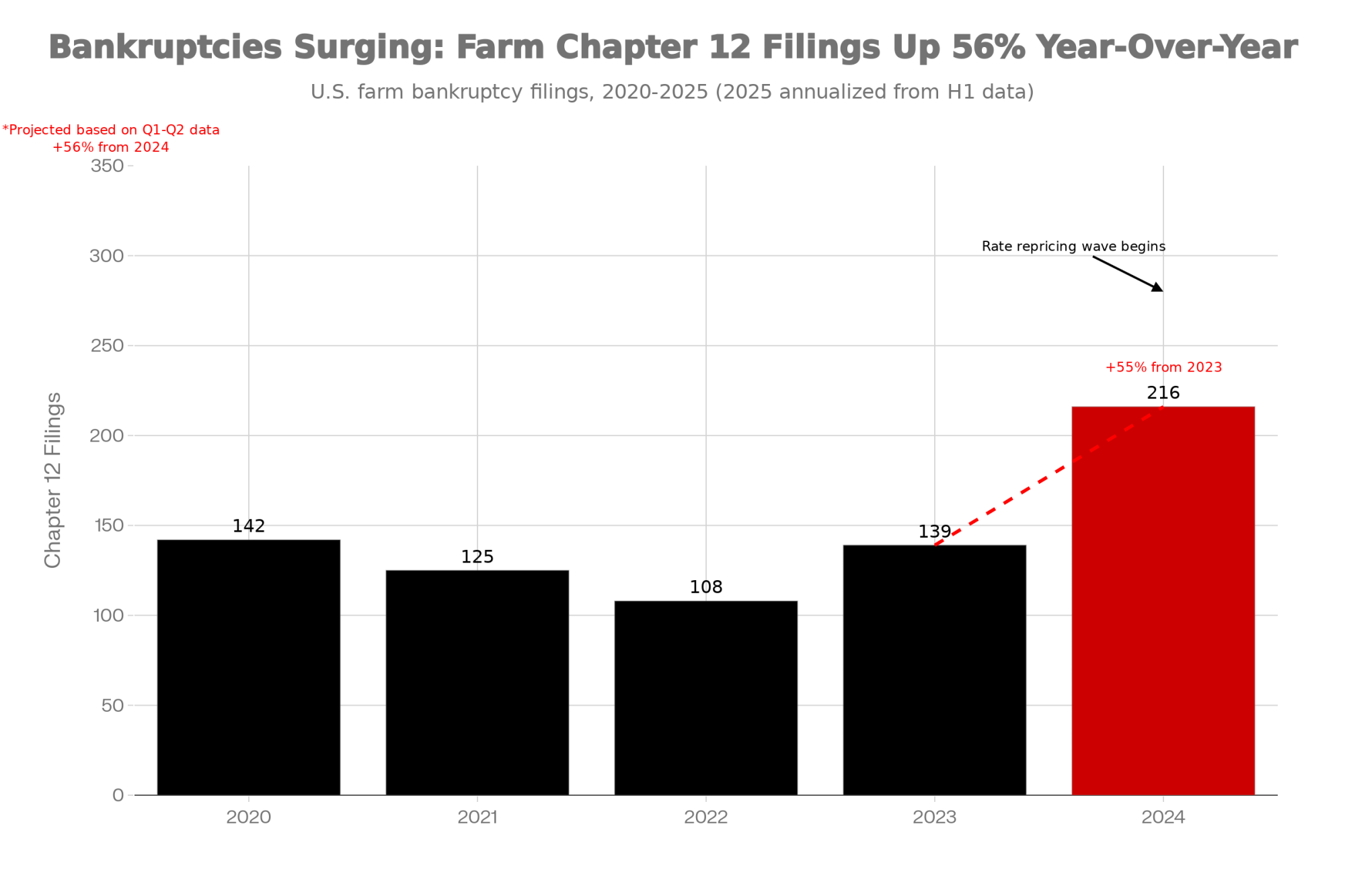

When Strategy Becomes Speculation

The expansion examples above show growth done right. But our historical profiles this year also surfaced a very different pattern—what happens when business models depend on conditions that can disappear overnight.

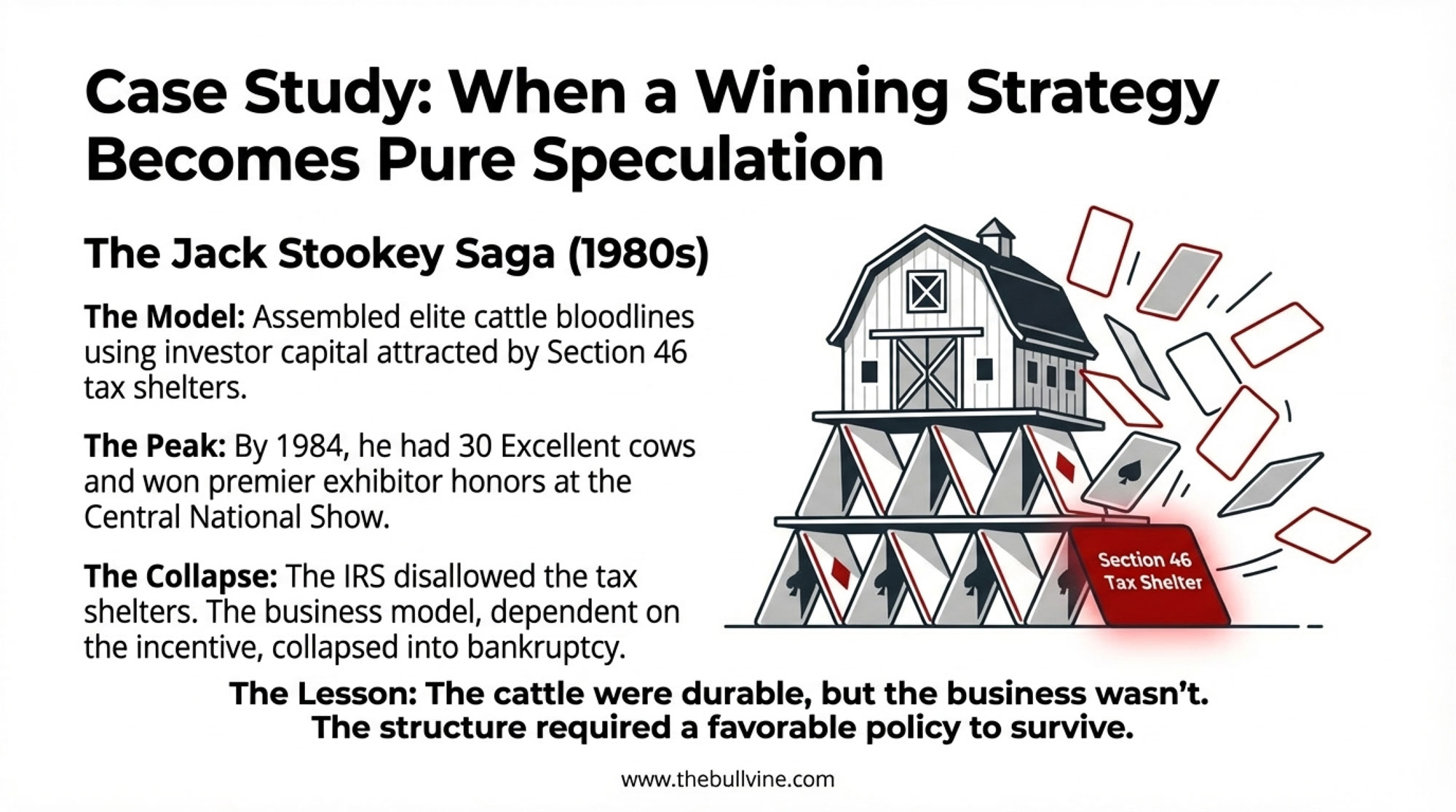

The Jack Stookey saga from the 1980s resonated with readers because it shows how speculation can undermine even genuine talent.

For context: in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Section 46 tax shelters allowed investors to claim accelerated depreciation on livestock. Stookey assembled elite bloodlines—genuinely excellent cattle by any measure—using investor capital attracted by tax benefits rather than production economics.

By 1983-1984, according to show records from that era, his operation peaked with 30 Excellent cows and 33 Very Good cows on a 1,500-acre showcase facility. He won premier exhibitor honors at the Central National Show. By the standards of the day, he’d built something impressive.

Then the IRS disallowed the tax shelters. They demanded six figures in back taxes—a pattern that played out across multiple investor-backed operations during that period, as we documented in The Bullvine’s September 2024 feature on the Section 46 era. Stookey filed for bankruptcy.

The instructive detail—and I think about this often—is that the Stookey Elm Park Blackrose cow family survived the bankruptcy and went on to produce modern genetics stars. The cattle Stookey assembled proved durable. But Stookey himself didn’t survive because his business model depended on the tax incentive.

Remove the incentive, and everything collapsed.

The contrast with the disciplined Midwest expansions is striking. Both took on significant risk. But one group structured theirs to survive stress. Stookey’s structure required a favorable policy to continue. That’s the difference between calculated risk and speculation.

“The farms thriving in 2035 won’t necessarily be the ones who expanded. They’ll be the ones who built operations that work whether conditions cooperate or not.”

Read more: The Notorious Jack Stookey, When Financial Disaster Breeds Genetic Gold: The Blackrose Story That Changed Everything and The Investor Era: How Section 46 Revolutionized Dairy Cattle Breeding)

The Five-Question Framework

Looking at these profiles together—Moreno, McCarty, GenoSource, the disciplined expanders, Stookey—a pattern emerges that I think you can actually use when evaluating major capital decisions on your own operation.

A calculated risk survives the removal of what initially made it attractive.

Moreno’s sex-sorted semen investment assumed technology would eventually improve enough to stand on production economics alone. When early adoption incentives disappeared, the technology kept improving until farmers chose it because it worked, not because it was novel.

The disciplined expansions assumed operators could survive $16 milk. When conditions got worse than expected, they had a margin to absorb it.

Stookey’s tax-shelter cattle couldn’t survive the removal of Section 46 credits. The economics required the subsidy to function.

Here are five questions worth working through with your advisors before any major expansion or investment decision:

- What has to remain true for this to work? If the answer involves external policy, market sentiment, or continued access to cheap capital that you can’t control—that’s worth pausing on.

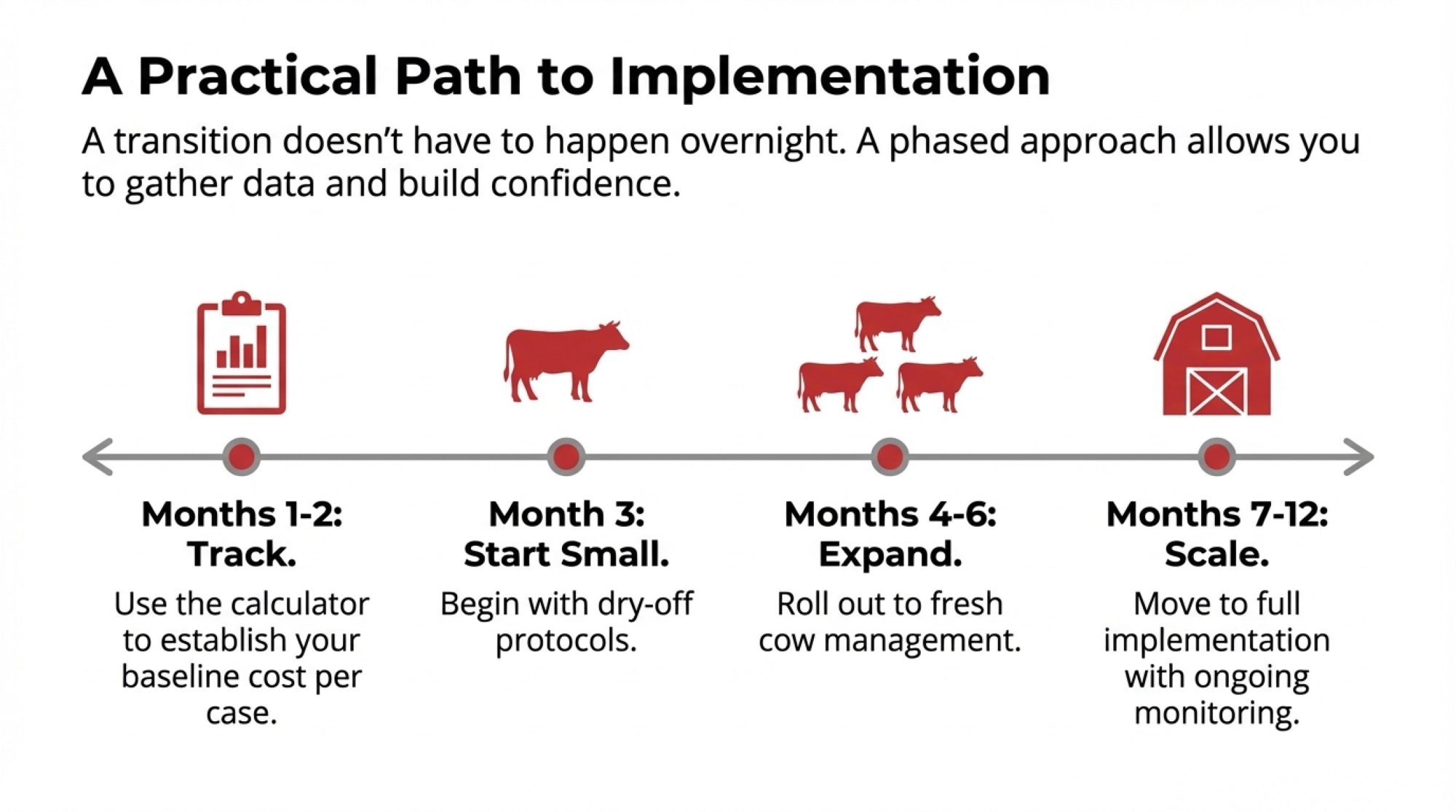

- Can you test the thesis incrementally? Deploying capital in stages where you learn along the way is fundamentally different from an all-or-nothing commitment. The two-phase approach that many successful expanders used did exactly this.

- What do you actually control? Success dependent on internal execution (herd health improvements, customer relationships, operational discipline) differs from success dependent on things outside your control (policy changes, market bubbles, other actors’ decisions).

- Does the economics work without the incentive, making it attractive right now? Remove the tax benefit, the cheap credit line, the currently high milk price—does the fundamental transaction still make sense?

- What does failure look like, and can you survive it? Losing some capital while the operation continues is categorically different from failure, meaning bankruptcy. Know which scenario you’re facing.

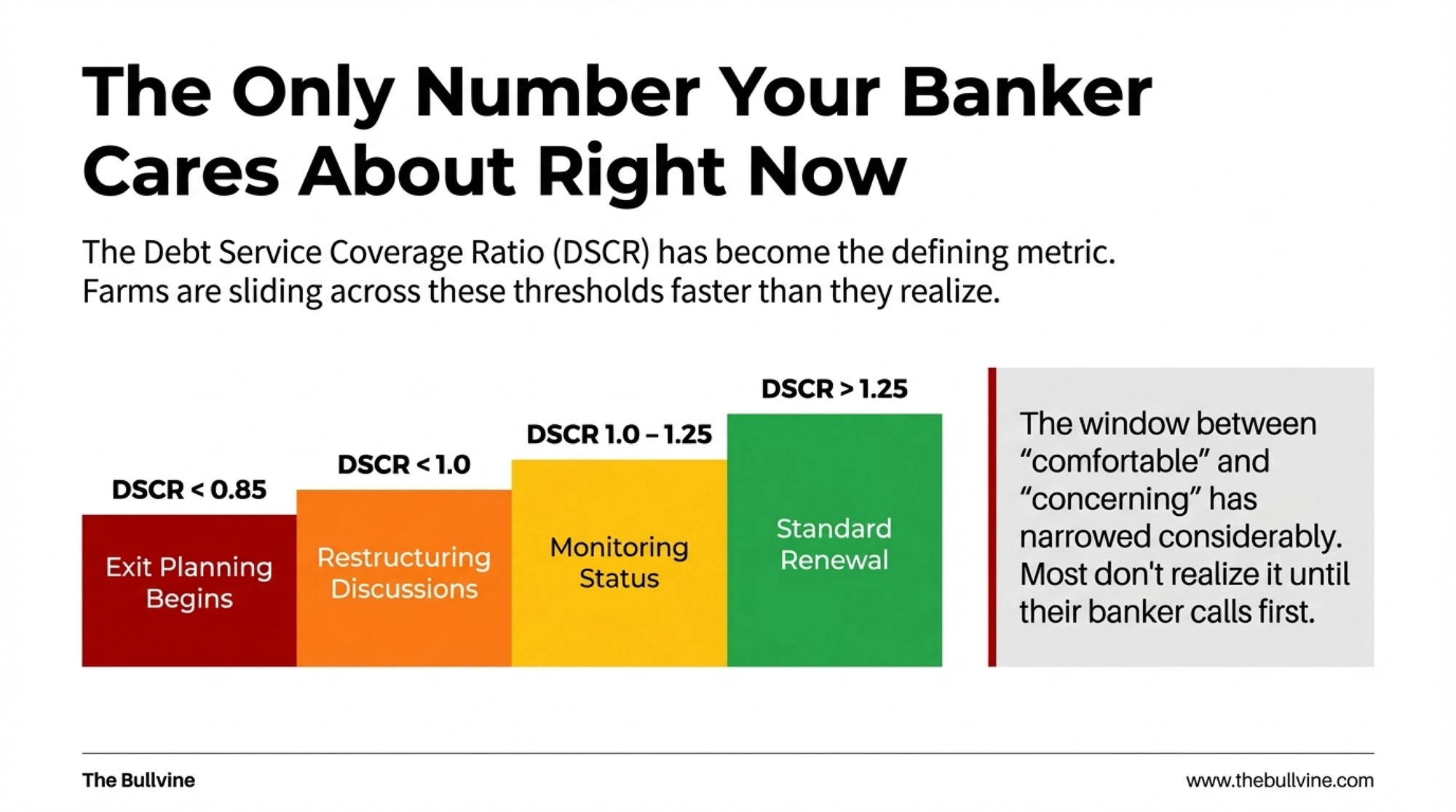

A lender in Minnesota, who asked to remain anonymous given his institution’s policies, shared an observation that stuck with me: “I’ve approved expansion loans where I knew the borrower understood these questions, and I’ve approved loans where I could tell they just wanted to hear yes. Five years later, the first group is still farming. The second group mostly isn’t.”

Understanding Different Advisor Perspectives

Something I’ve noticed farmers finding helpful: understanding how different advisors naturally approach expansion conversations. This isn’t about good advisors versus bad ones—it’s about recognizing different incentive structures.

Advisors with transaction-based compensation—lenders earning origination fees, equipment dealers earning sales commissions, consultants paid by project scope—naturally focus on opportunities that generate transactions. That’s not dishonest. It’s how their business models work. A commercial lender I interviewed for this piece explained it this way: “My job is to find creditworthy borrowers and structure loans that work. If someone qualifies and the project pencils out, I’m going to recommend moving forward. That’s what I’m here for.”

Fair enough. But you probably know this already—these advisors generally aren’t structured to recommend “stay at current size and optimize.”

Advisors with relationship-based compensation—veterinarians earning service revenue, accountants earning retainer fees, cooperative extension agents on fixed salaries—often provide different perspectives. A large-animal vet in Pennsylvania told me: “I’ve watched clients expand into financial difficulty more times than I want to count. When someone asks me if they should add 200 cows, my first question is always about their current cows. How’s reproduction? How’s fresh cow health? If those metrics aren’t where they should be, adding cows just multiplies the problems.”

The most valuable approach seems to be assembling multiple perspectives rather than relying on any single source. Running financial stress tests with an accountant before accepting expansion recommendations can reveal whether a proposed expansion survives unfavorable conditions—or whether it only works when everything goes right. Both viewpoints have value.

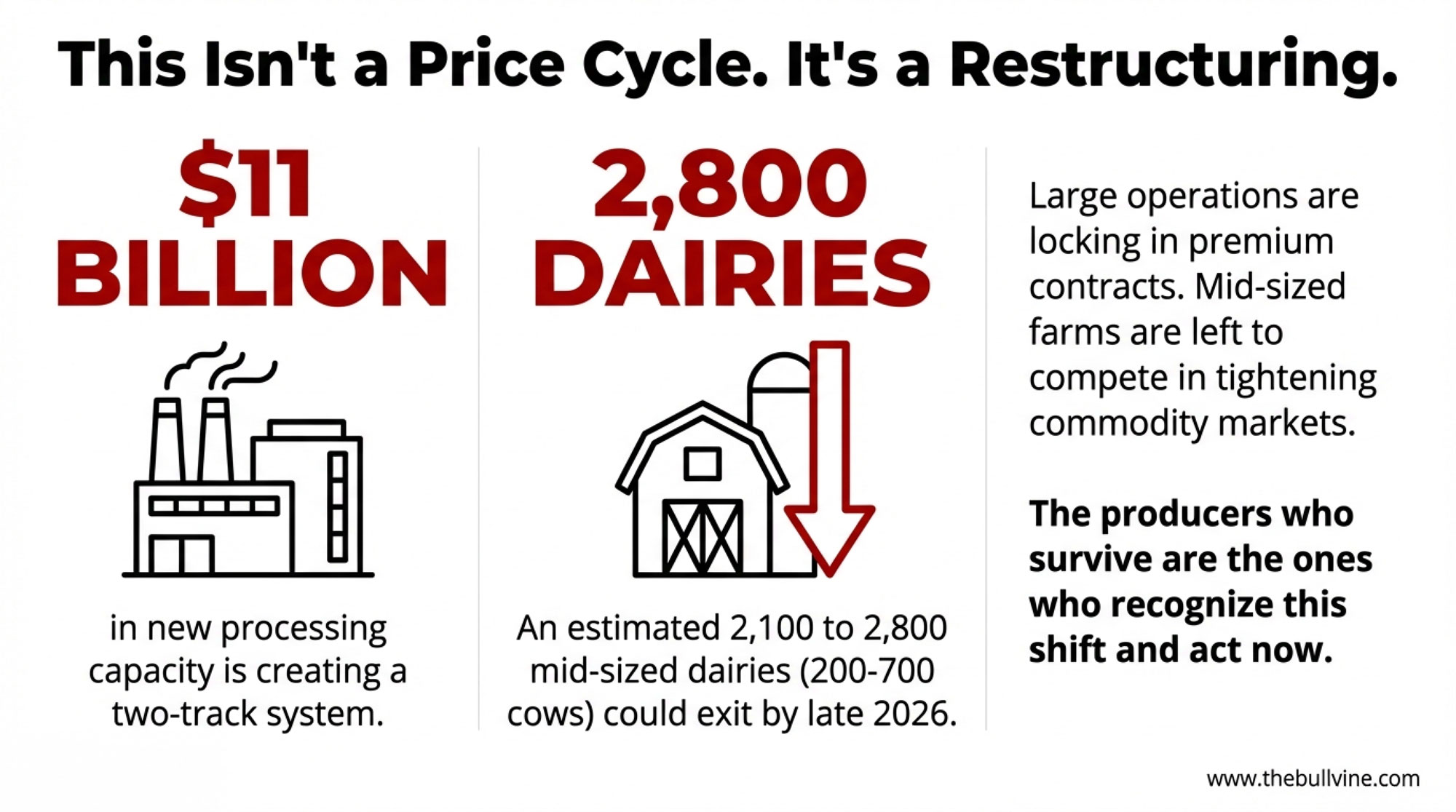

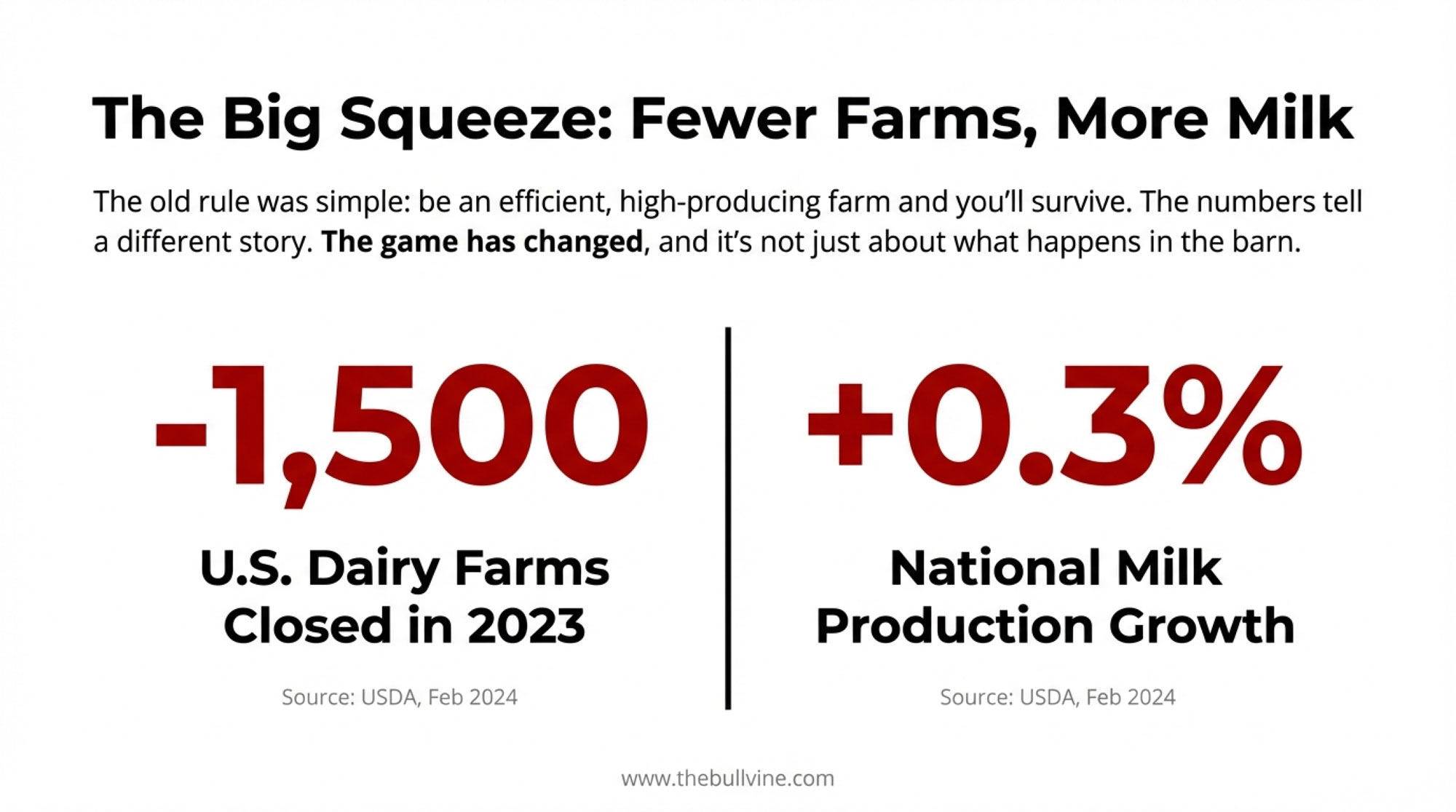

What the Consolidation Data Actually Shows

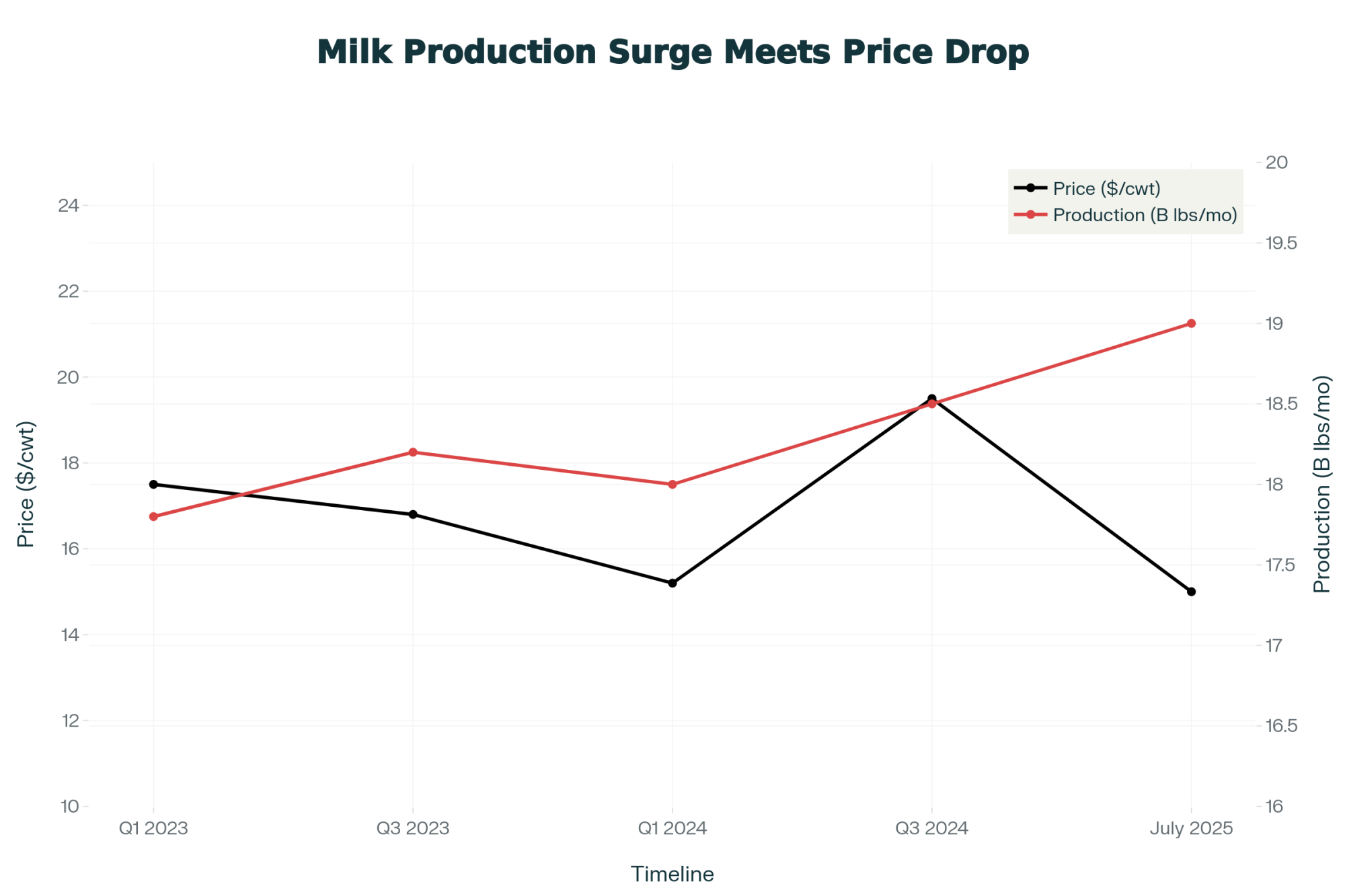

Let’s talk about where this industry is heading, because the 2022 Census numbers are worth understanding.

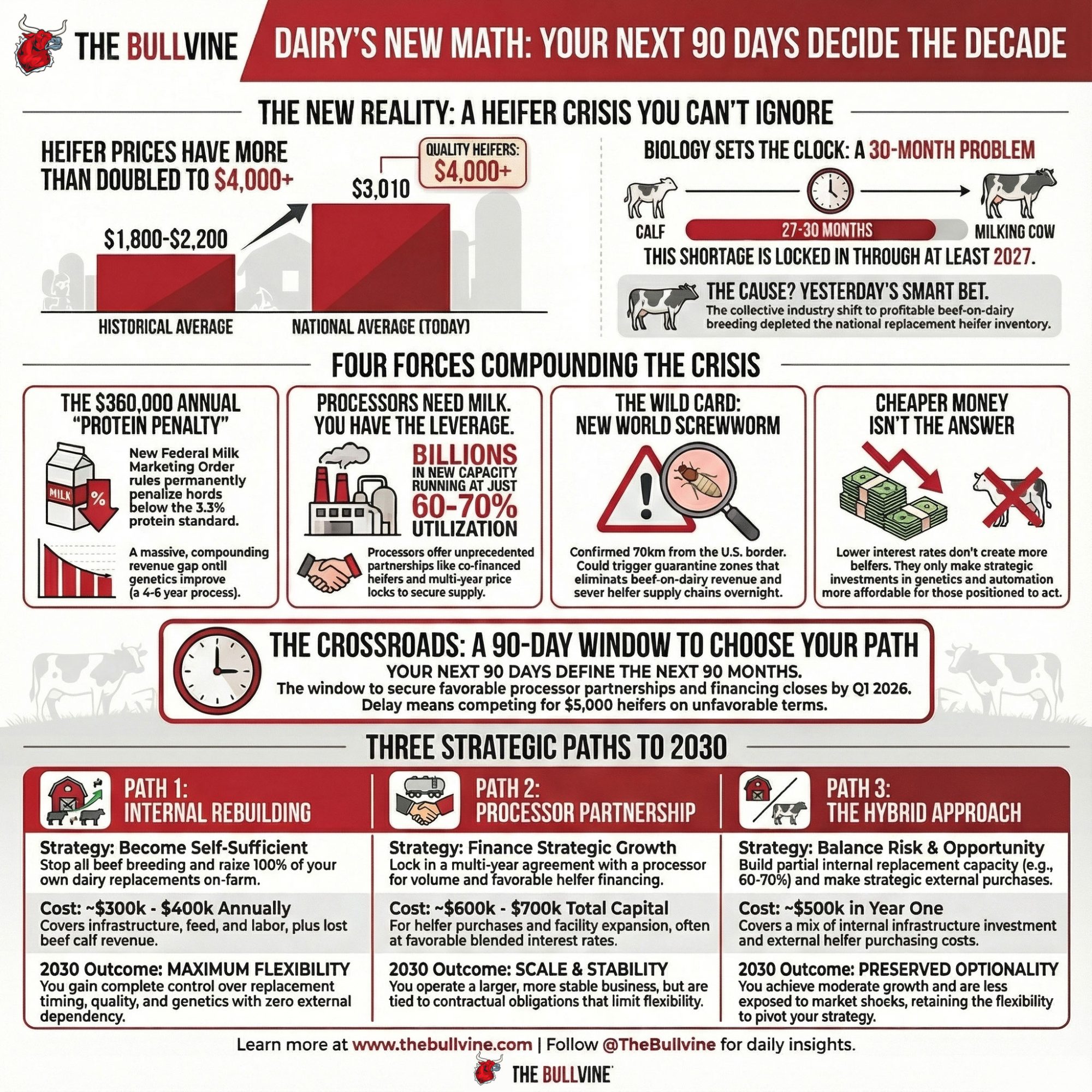

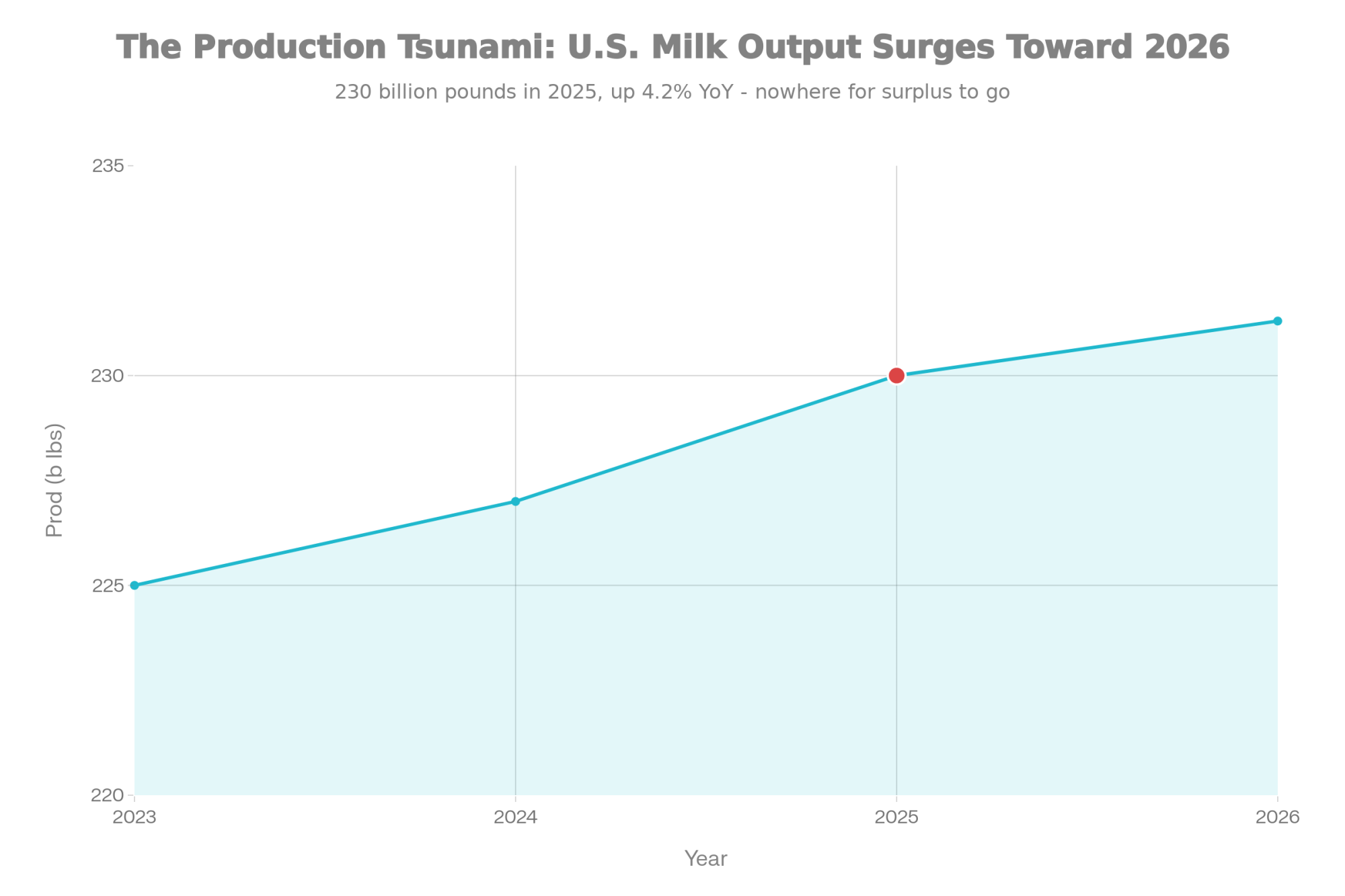

USDA long-term projections indicate modest growth in national milk production through 2030, with total output rising while cow numbers remain roughly stable around 9 to 9.5 million head. Fewer farms. More milk. The math tells you who’s growing and who’s leaving.

Here’s what the Census specifically shows: operations with 2,500 or more cows grew from 714 to 834 between 2017 and 2022, according to Farmdoc Daily analysis. These very large herds account for a rising share of national milk output.

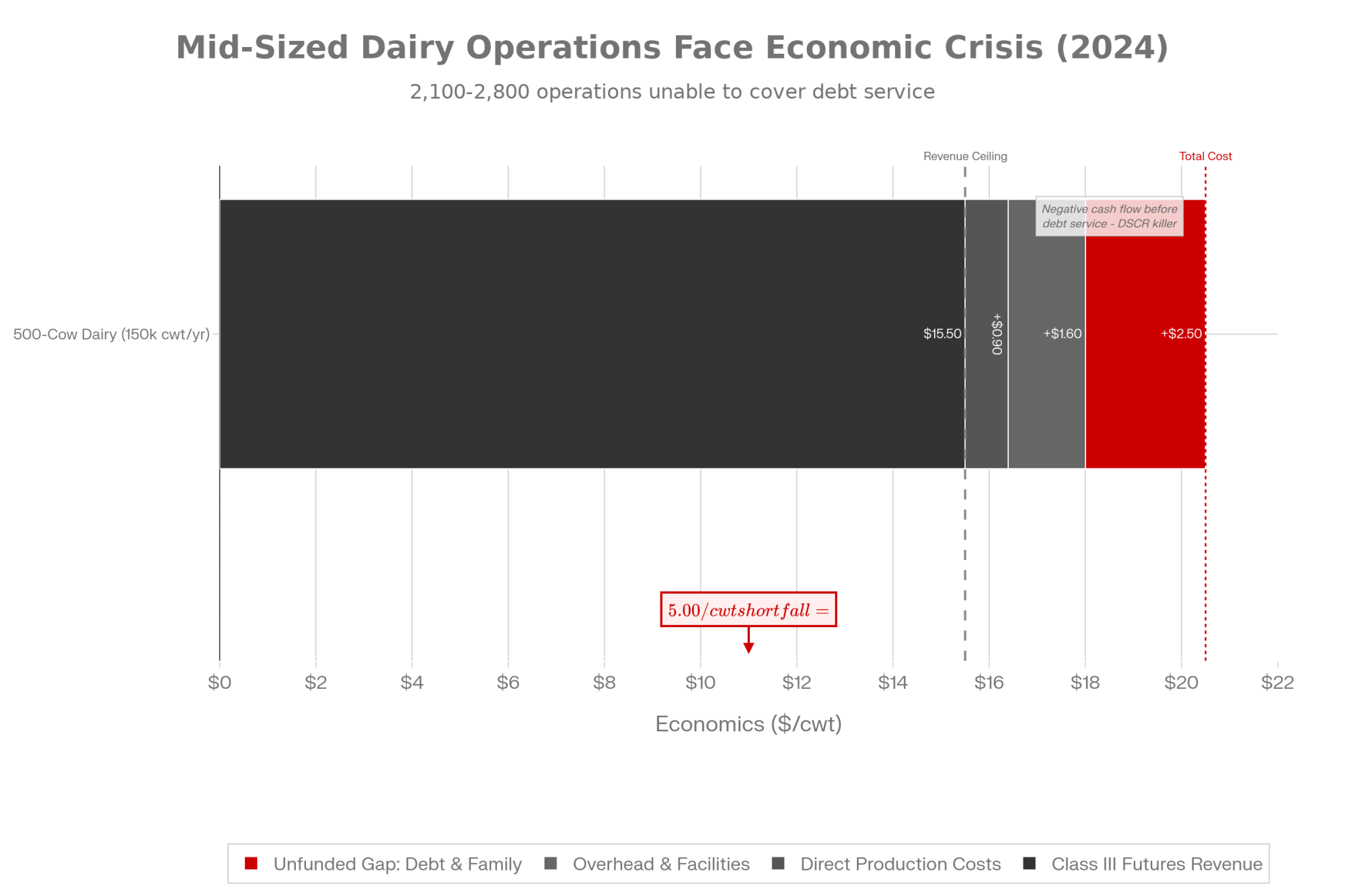

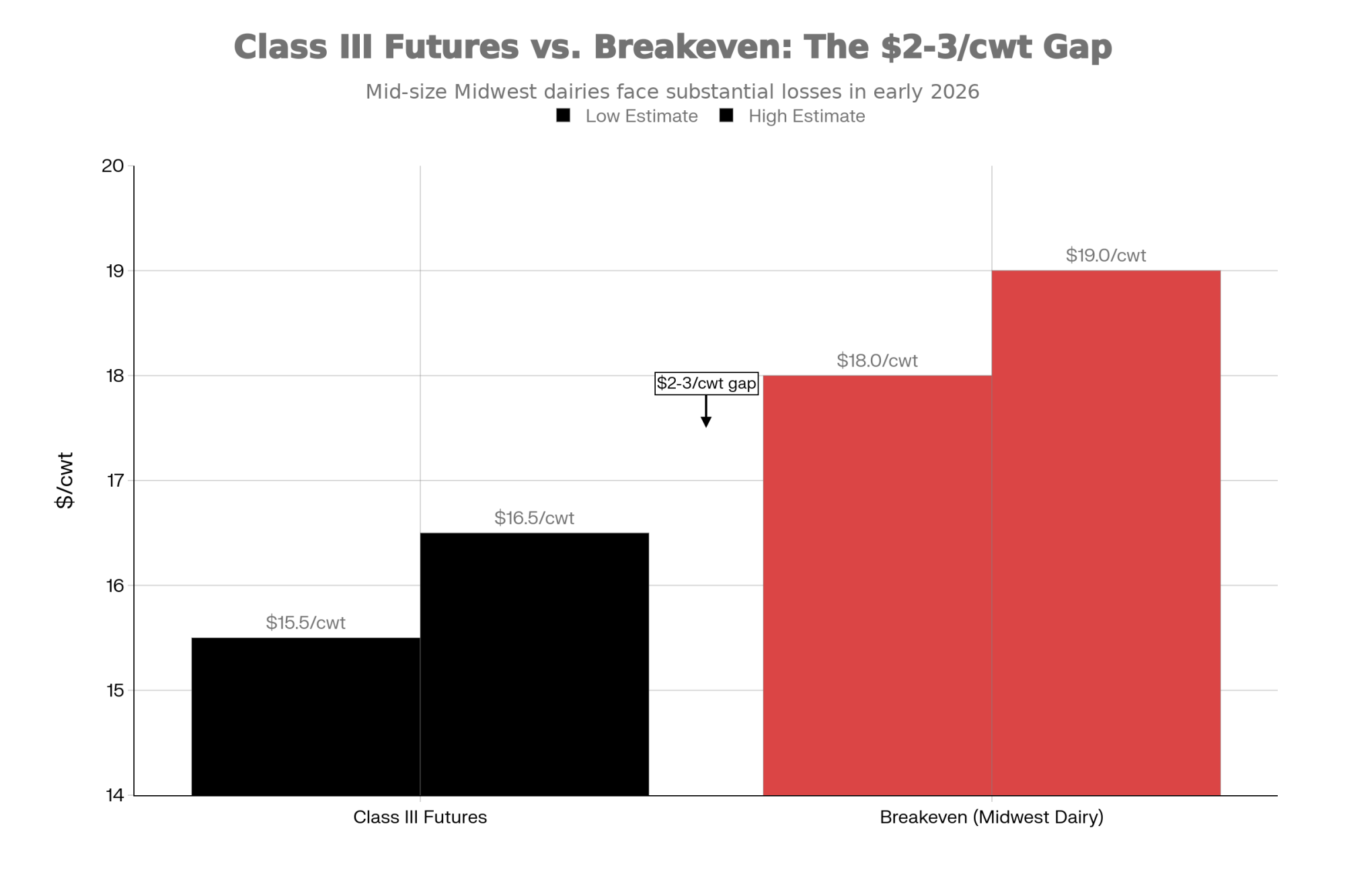

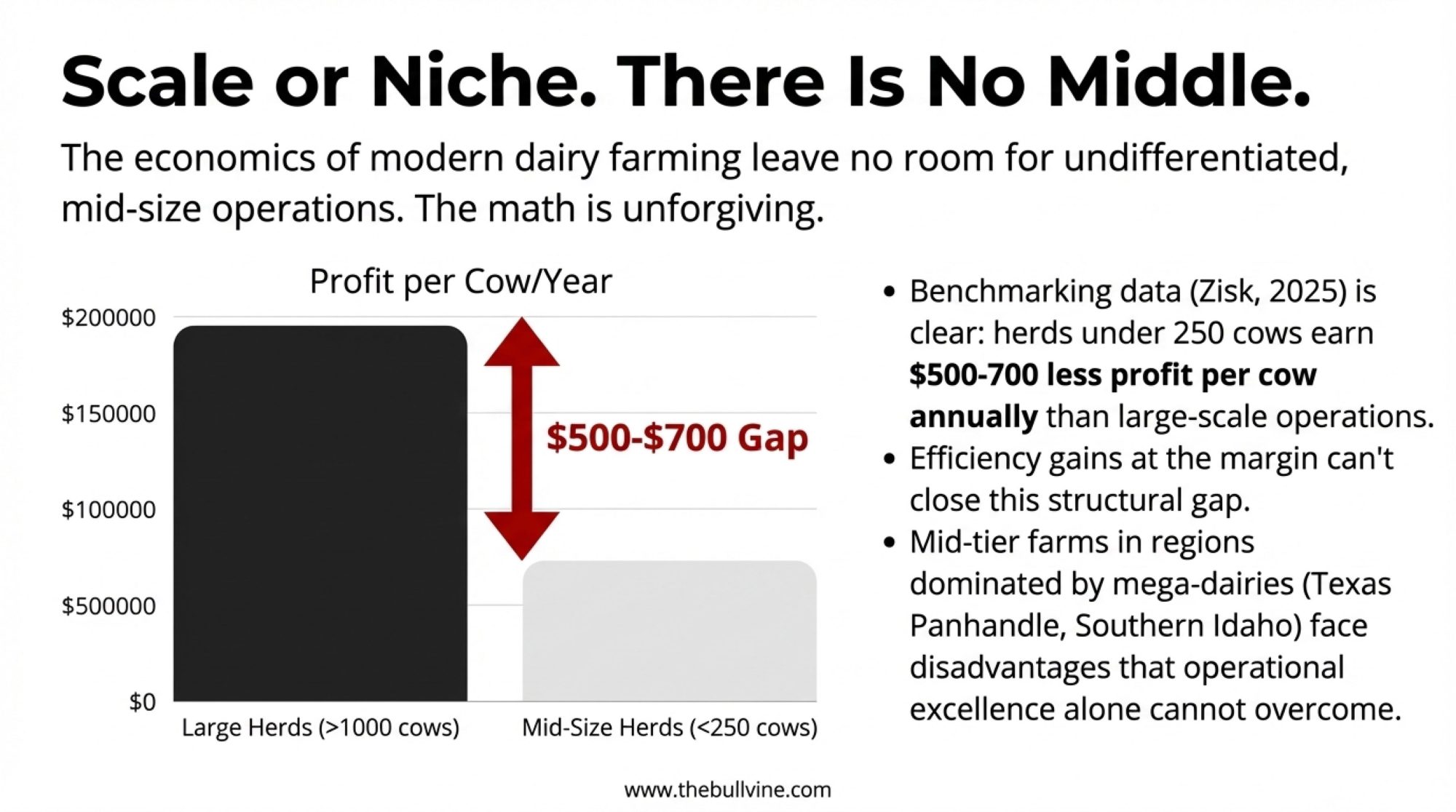

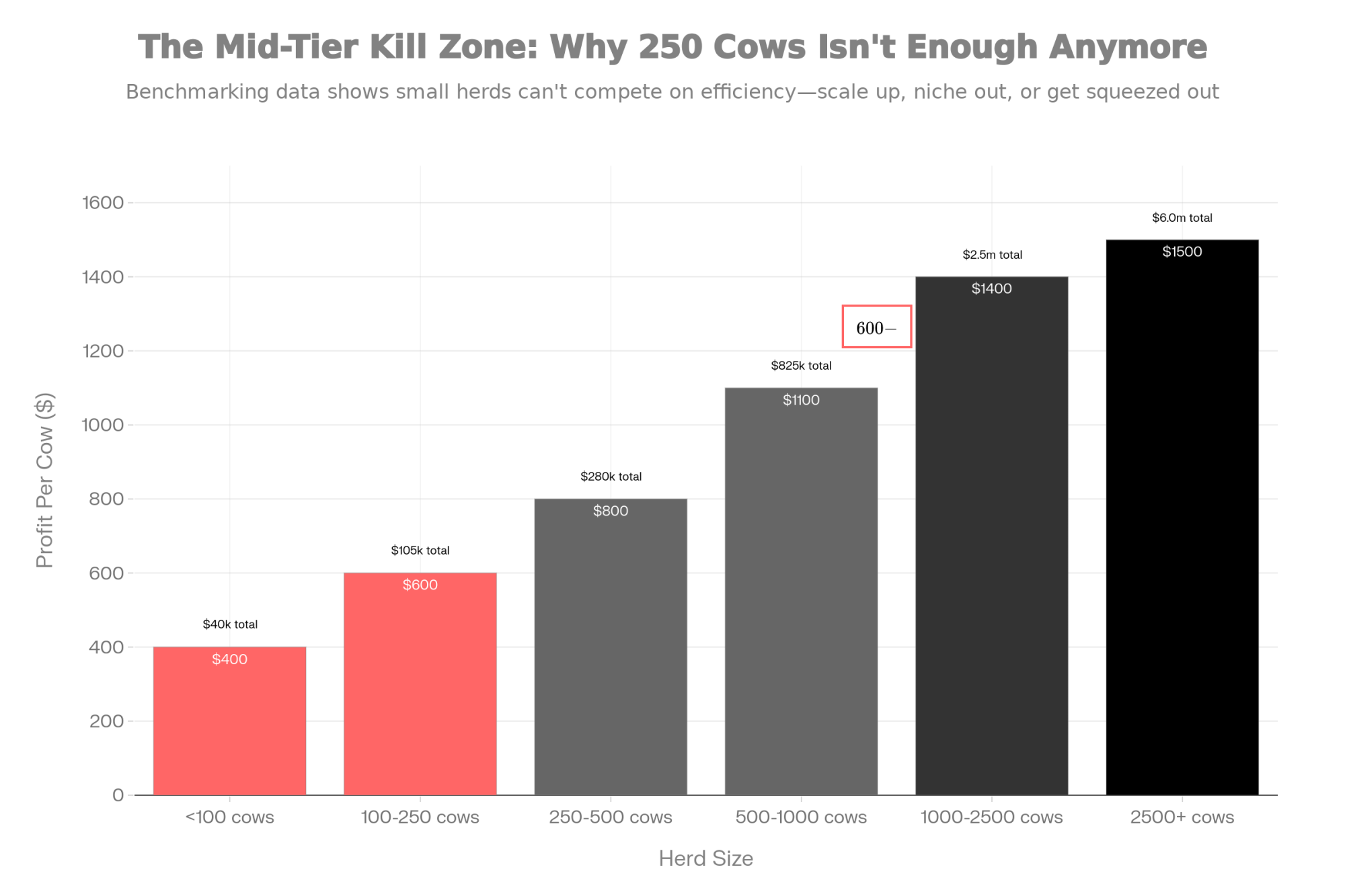

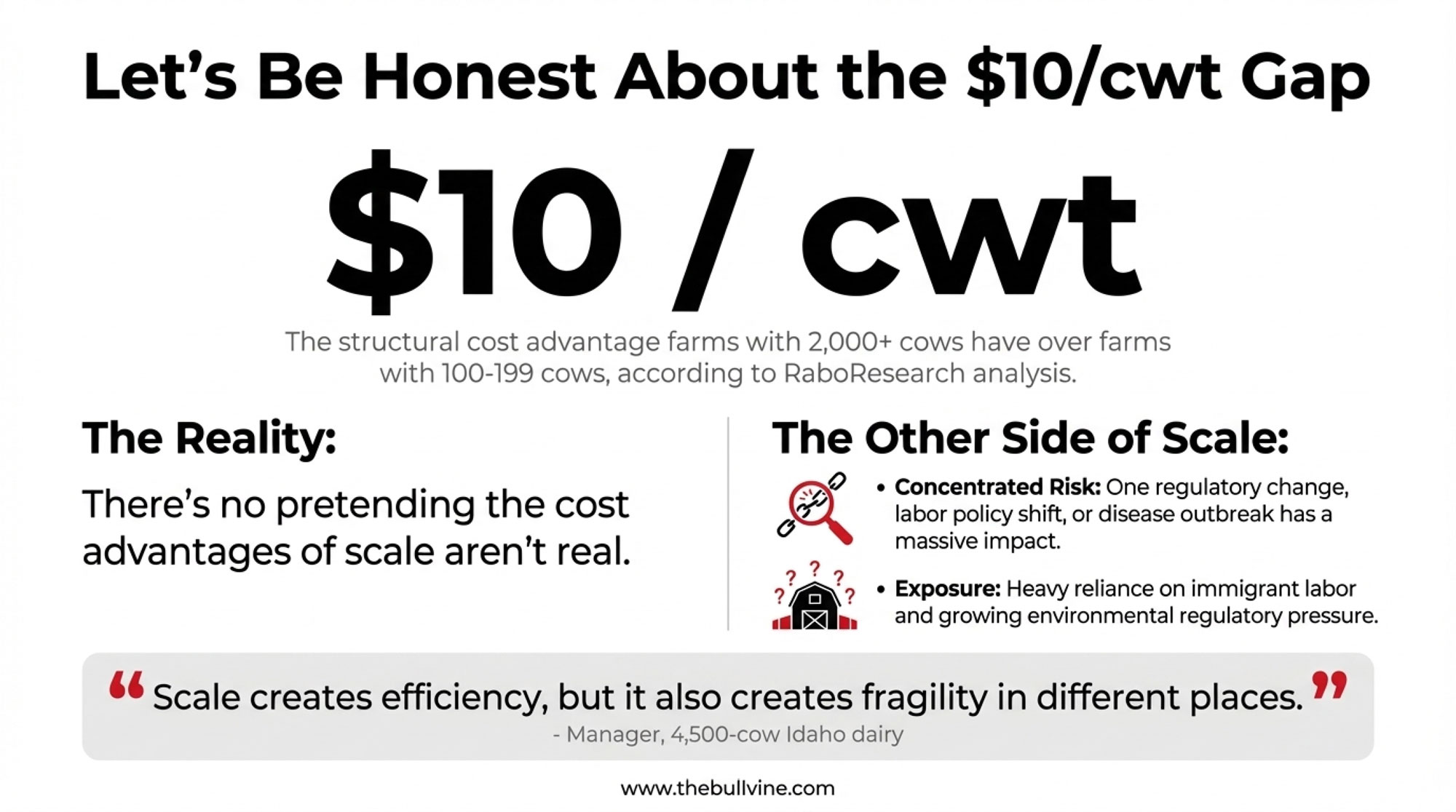

And the cost advantages are real—there’s no point pretending otherwise. RaboResearch analysis found that farms milking more than 2,000 cows can operate about $10 less per hundredweight than farms with 100-199 cows, as senior analyst Lucas Fuess noted in Brownfield Ag News coverage. That’s a substantial structural gap.

| Cost Category | 100-199 Cows | 500-999 Cows | 2,000+ Cows | Gap (Small vs Large) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Cost | $9.50 | $8.80 | $7.90 | -$1.60 |

| Labor Cost | $6.20 | $5.10 | $4.30 | -$1.90 |

| Operating Overhead | $4.80 | $3.90 | $3.20 | -$1.60 |

| Capital/Depreciation | $3.40 | $2.80 | $2.10 | -$1.30 |

| Other Costs | $4.10 | $3.60 | $2.50 | -$1.60 |

| Interest Expense | $2.00 | $1.80 | $1.00 | -$1.00 |

| TOTAL | $30.00 | $26.00 | $21.00 | -$9.00 |

A manager at a 4,500-cow operation in Idaho, who spoke on background, offered important nuance: “People see our cost advantages and think we have it easy. But our exposure is different, not smaller. One regulatory change, one labor policy shift, one disease outbreak—and our risk is concentrated in ways a 300-cow dairy never faces. Scale creates efficiency, but it also creates fragility in different places.”

Regional snapshot:

- Wisconsin: Continues gaining cows as consolidation concentrates there

- Idaho, Texas, New Mexico: Receiving ongoing capital investment

- California: Facing projected losses due to CEQA requirements and SGMA groundwater mandates, adding compliance costs

- Northeast: Slower decline but continued exits amid urban pressure and processing distance

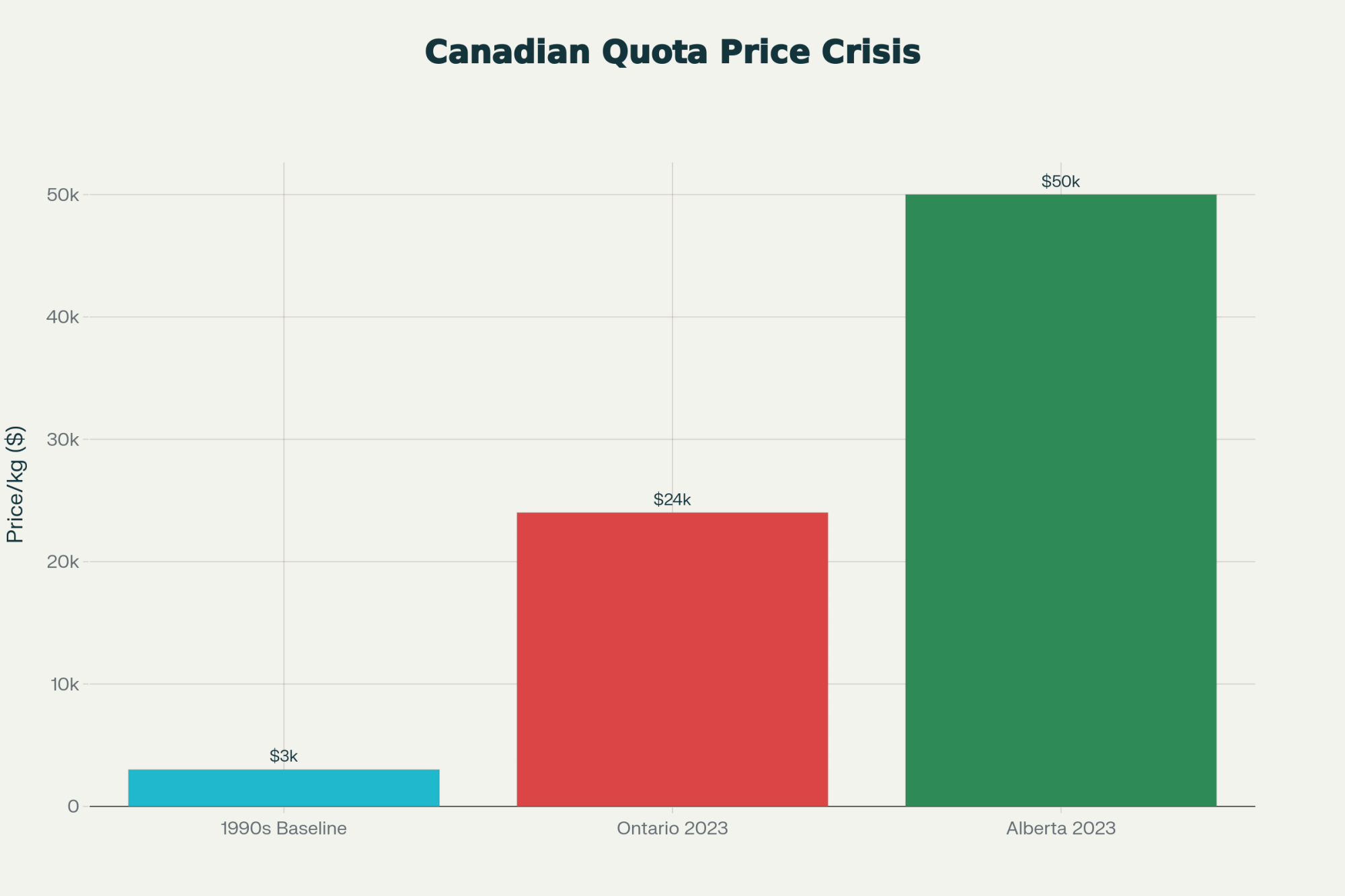

- Canada: BC Milk Marketing Board announced November 2025 phased grass-fed premiums reaching $0.16/liter by February 2027; Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta are seeing consolidation pressures within the quota framework

| Region | 2022 Farm Count | 2030 Projected | Change (%) | Key Pressure Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin | 6,450 | 5,200 | -19% | Consolidation within state |

| California | 1,150 | 850 | -26% | SGMA groundwater + CEQA regs |

| Idaho | 450 | 520 | +16% | Continued capital investment |

| Texas | 380 | 450 | +18% | Low regulatory burden |

| New York | 3,200 | 2,600 | -19% | Urban pressure + processing distance |

| Pennsylvania | 4,950 | 4,100 | -17% | Mid-size squeeze |

| Ontario | 3,380 | 3,100 | -8% | Quota system slows but doesn’t stop exits |

| New Mexico | 140 | 155 | +11% | Favorable climate + infrastructure |

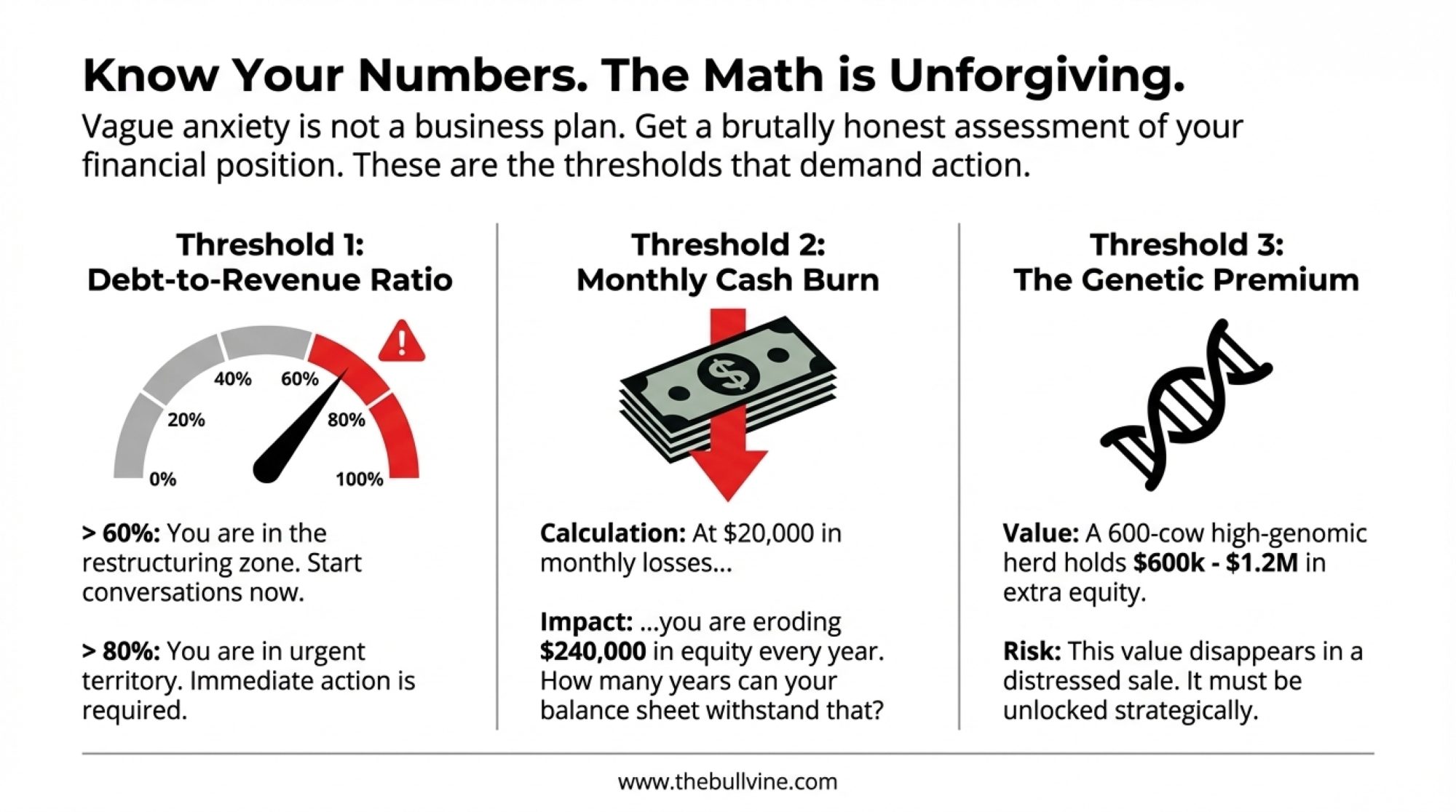

What this means for the traditional 300-700 cow single-family dairy: real structural challenges. These operations are simultaneously too large for efficient direct marketing and too small for commodity-scale economics. That’s simply the competitive reality right now.

Large-scale dairies carry their own vulnerabilities, too. Several national surveys suggest that well over half of hired dairy workers are immigrants, particularly on larger operations—leaving those herds exposed to changes in immigration policy. Environmental regulatory exposure is growing. Capital concentration creates risks during credit contractions. The large-dairy model has structural weaknesses; they’re just different weaknesses.

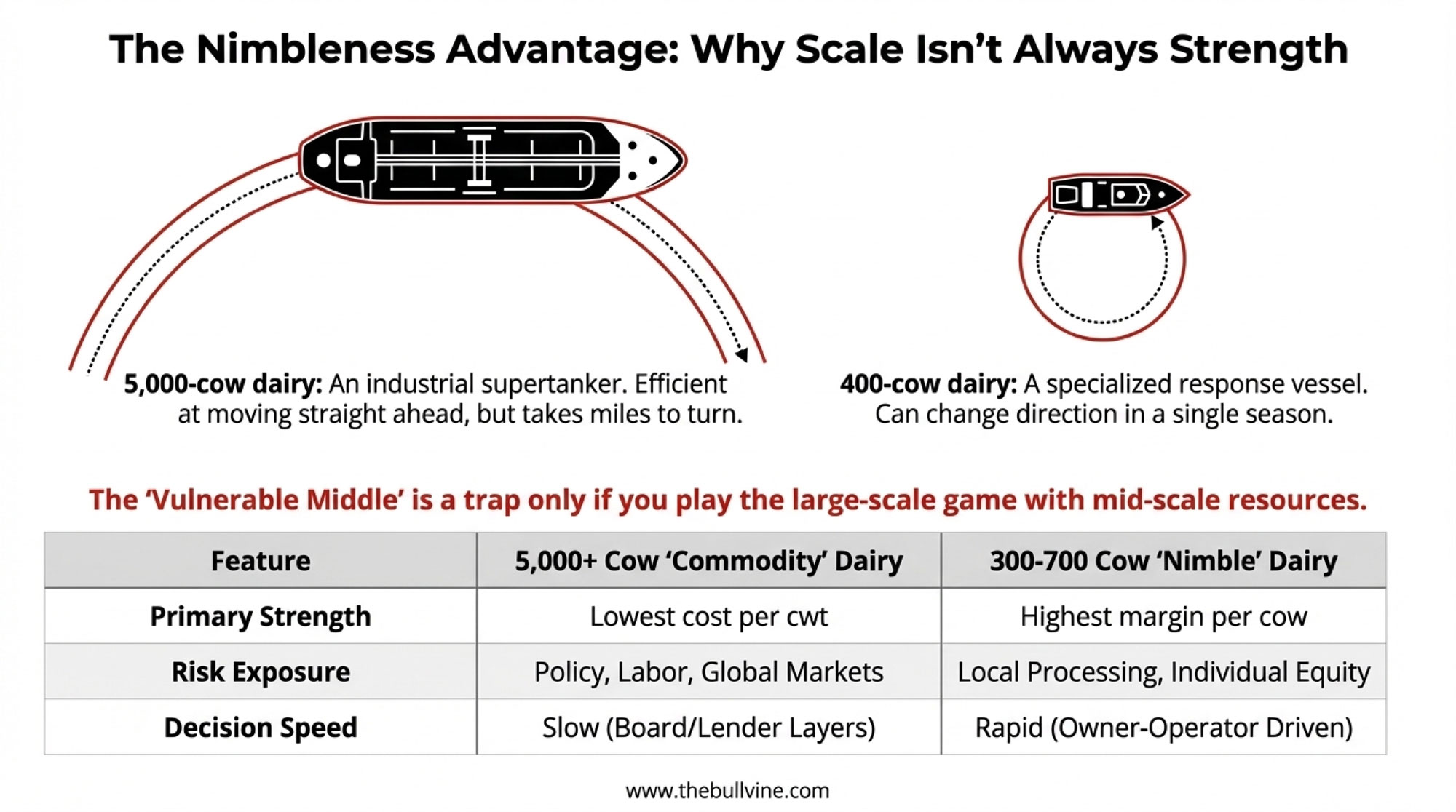

The “Nimbleness” Advantage: Why Scale Isn’t Always Strength

If the consolidation data makes the 300–700 cow operation look like an endangered species, it’s because we are looking at the industry through a single lens: commodity efficiency.

But efficiency is not the same thing as resilience.

A 5,000-cow dairy is an industrial supertanker. It is incredibly efficient at moving straight ahead in deep water, but it requires miles of clearance to turn. A 400-cow dairy is a specialized response vessel. It can change direction in a single season. This nimbleness is a competitive advantage that ultra-large dairies lose the moment they reach 2,000 cows.

The Nimbleness Gap

When we look at the survivors in the “vulnerable middle,” they aren’t trying to out-commodity the big players. They are using their size to exploit three specific gaps:

- Genetic Agility: A 400-cow herd can transition its entire genetic profile—shifting to 100% A2/A2 or high-component Jersey crosses—in a few years. For a 5,000-cow operation, that same transition is a decade-long logistical nightmare.

- Labor Intimacy: In a mid-sized operation, the owner often identifies a sick cow or a broken gate before it becomes a line-item loss. Large-scale management relies on “lagging indicators” (data reports) rather than “leading indicators” (physical observation).

- Market Pivot Capability: If a local processor offers a premium for grass-fed or specific protein thresholds, a mid-sized farm can adjust its ration and grazing plan almost immediately. The supertanker is usually “locked-in” to massive, standardized contracts.

| Feature | 5,000+ Cow “Commodity” Dairy | 300-700 Cow “Nimble” Dairy |

| Primary Strength | Lowest cost per hundredweight | Highest margin per cow |

| Risk Exposure | Policy, Labor, & Global Markets | Local Processing & Individual Equity |

| Decision Speed | Slow (requires board/lender layers) | Rapid (owner-operator driven) |

| Market Role | Price Taker | Potential Price Maker |

The “vulnerable middle” only becomes a trap when you try to play the large-scale game with mid-scale resources. The survivors are those who recognize that being smaller allows them to be “heavier”—increasing the value of every pound of milk and every animal on the trailer.

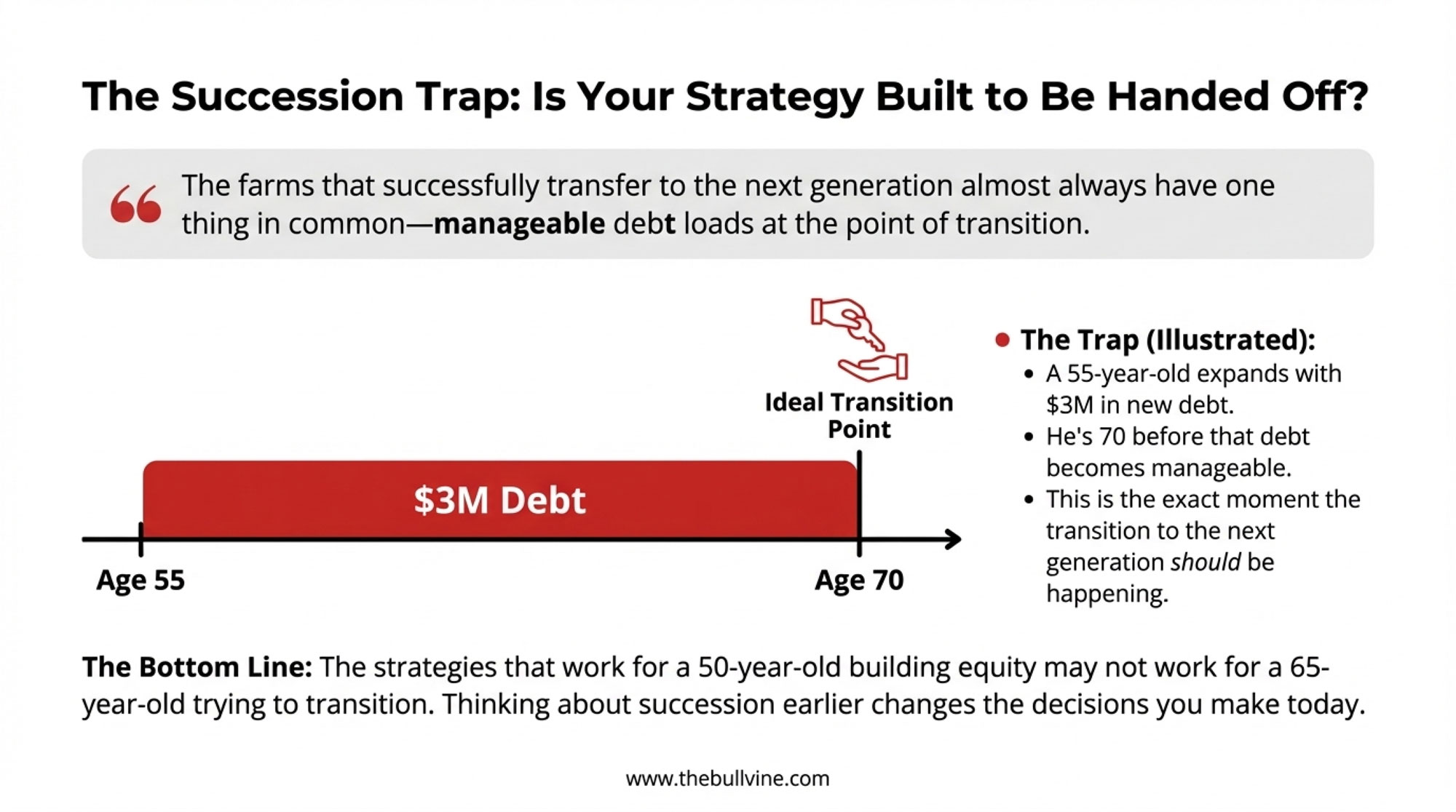

The Succession Question Worth Asking Earlier

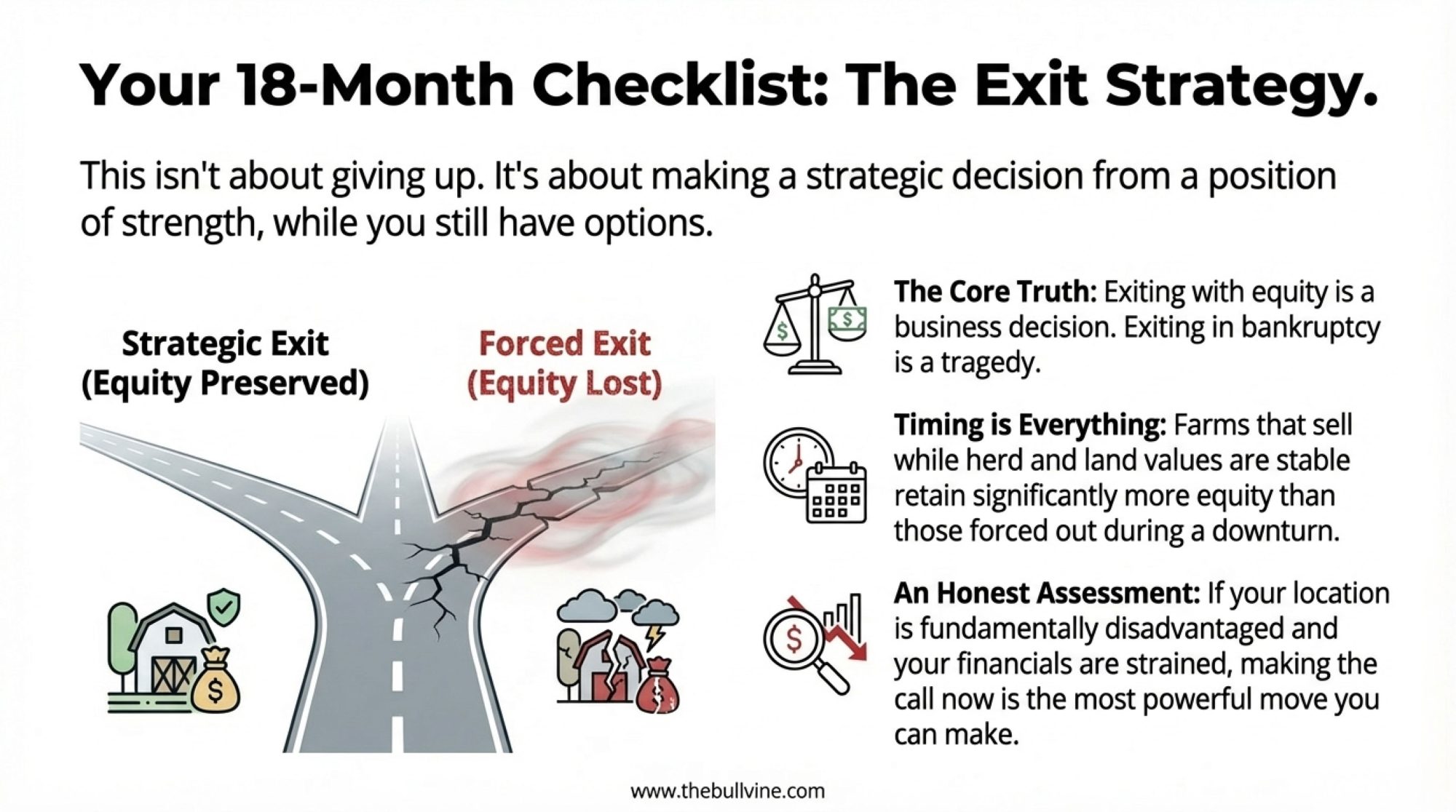

Here’s something that kept coming up in conversations this year: how do different strategies affect your ability to hand the operation to the next generation?

An extension economist who’s been tracking farm transitions shared this observation: “The farms that successfully transfer to the next generation almost always have one thing in common—manageable debt loads at the point of transition. It’s not about being the biggest or most efficient. It’s about whether the next generation can afford to take it over.”

Think about what that means for strategy selection.

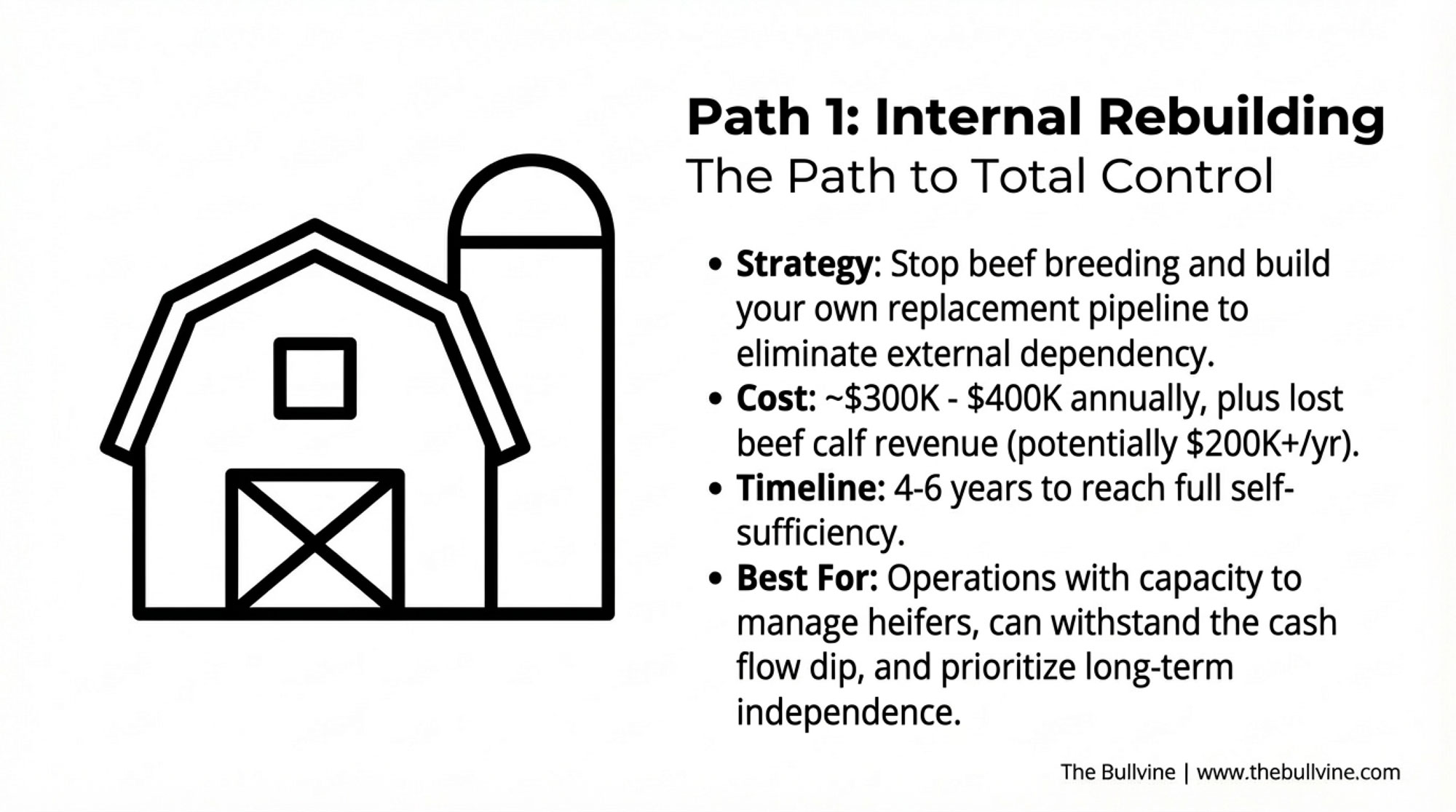

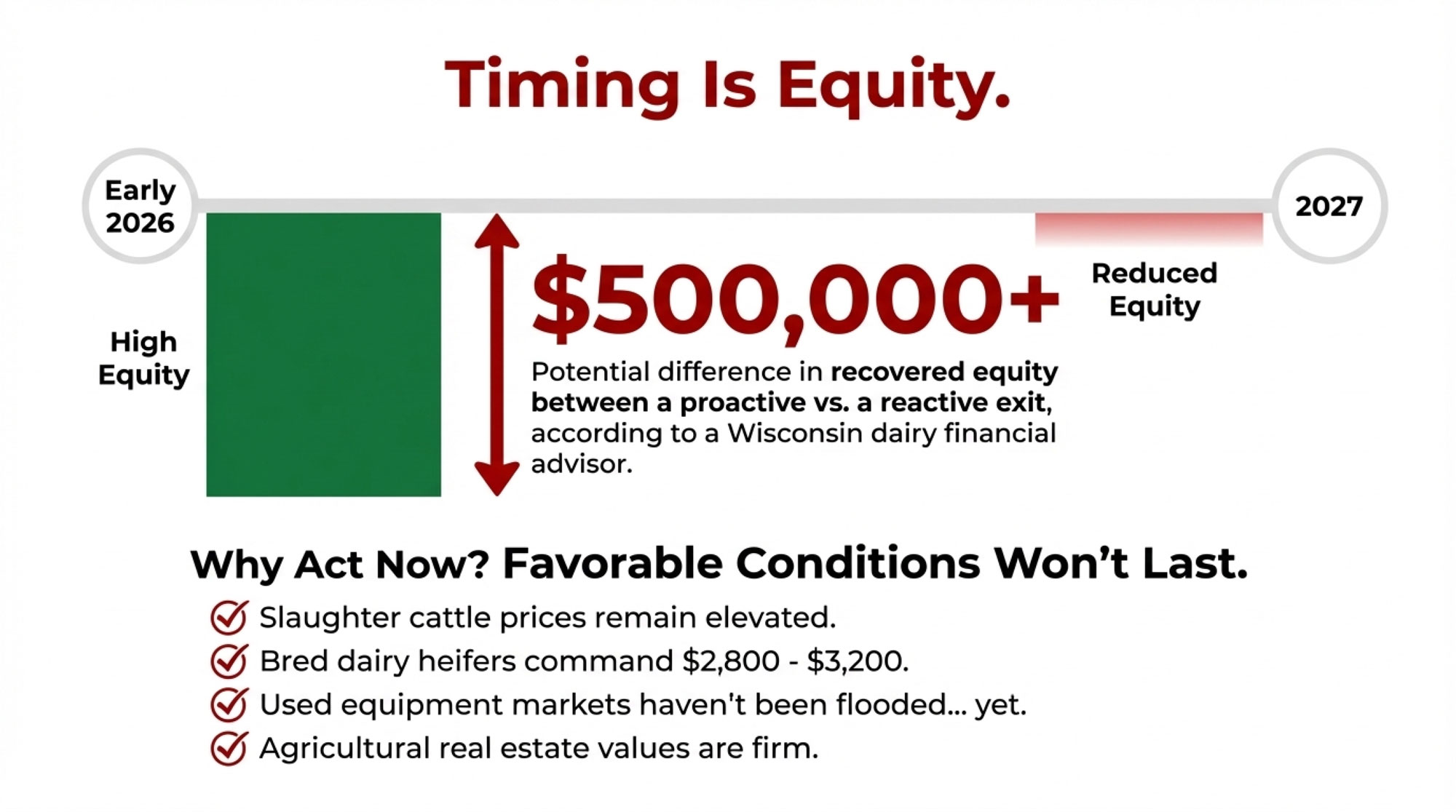

- Expansion-based strategies often leave operations with significant debt, just as the founding generation wants to step back. A 55-year-old who takes on several million in new debt may be 70 before that debt becomes manageable—exactly when the transition should be happening.

- Niche and diversification strategies typically carry lower debt but require management capabilities that the next generation may or may not have. Running a farm store or agritourism operation requires skills different from those of commodity milk production.

- Partnership models like GenoSource can actually ease succession because multiple families share the transition risk. When one family’s next generation isn’t interested, others can absorb their share without collapsing the whole operation.

I’ve noticed that operators who think explicitly about succession tend to make different strategic choices than those focused purely on next-quarter economics. Neither approach is wrong—but they lead to different places.

“The farms that successfully transfer to the next generation almost always have one thing in common—manageable debt loads at the point of transition.”

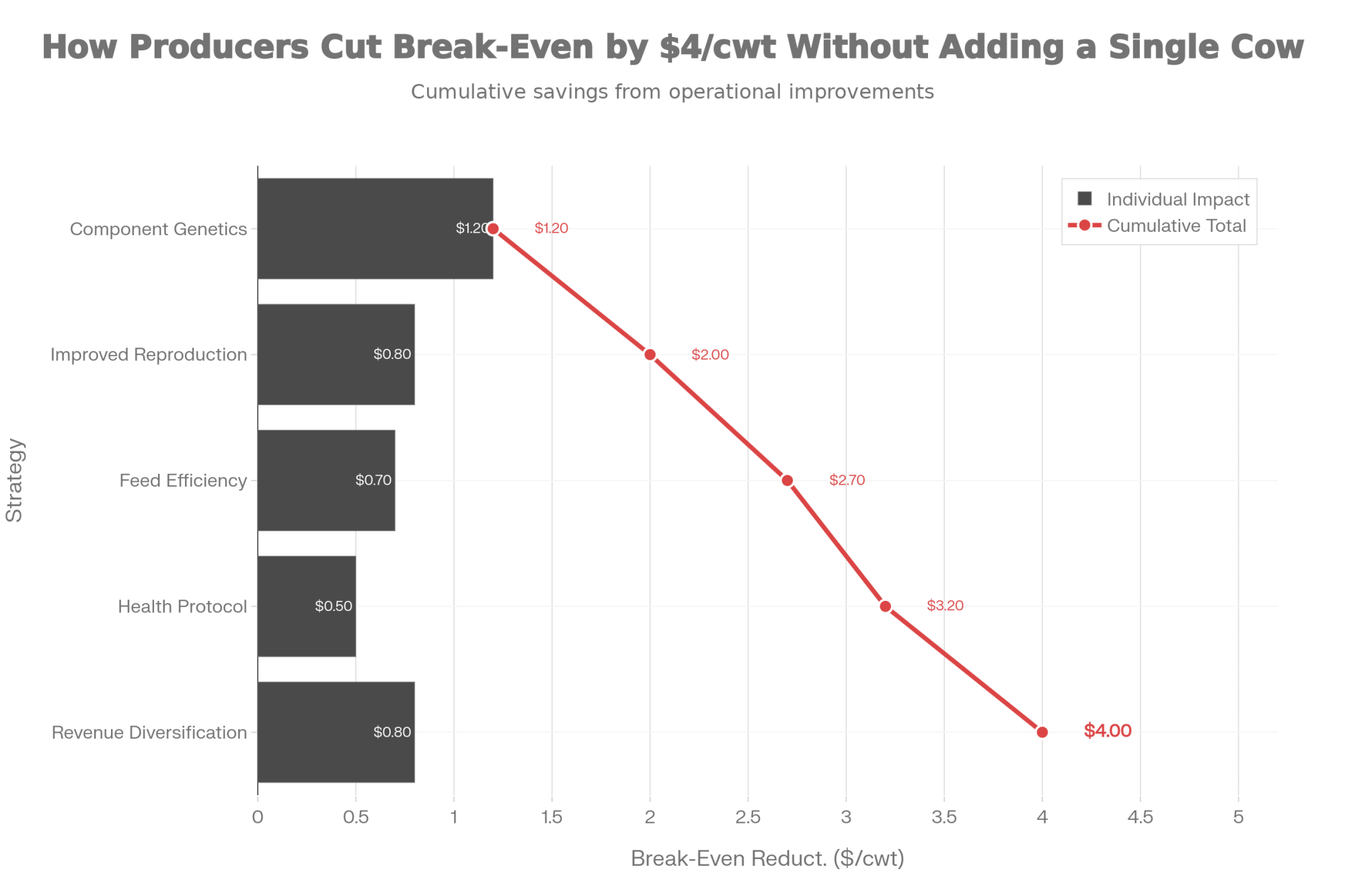

Practical Strategies for Mid-Sized Operations

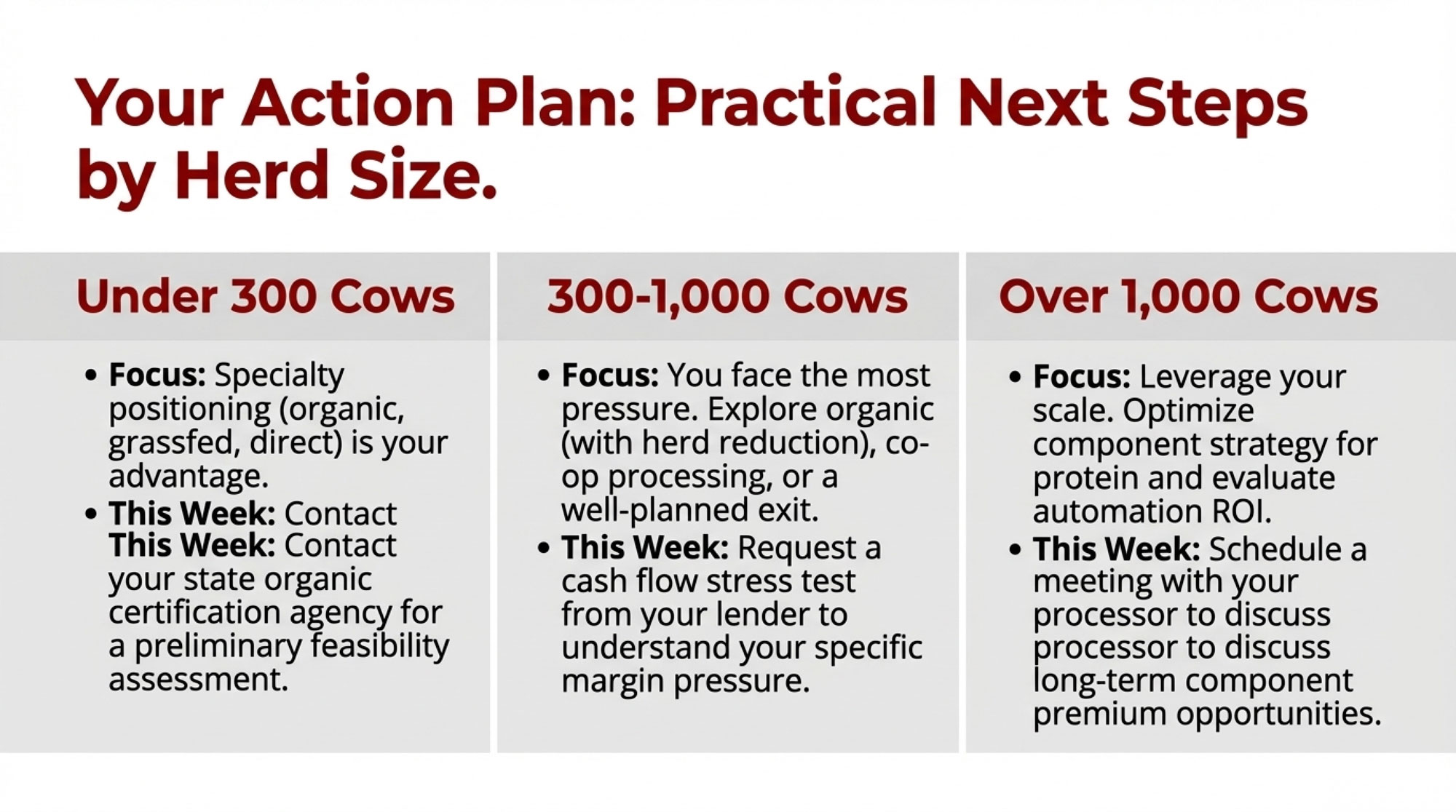

For operators running 300-500 cows who are evaluating their options, several approaches are showing promise. None is a silver bullet, but they’re worth examining based on your specific circumstances.

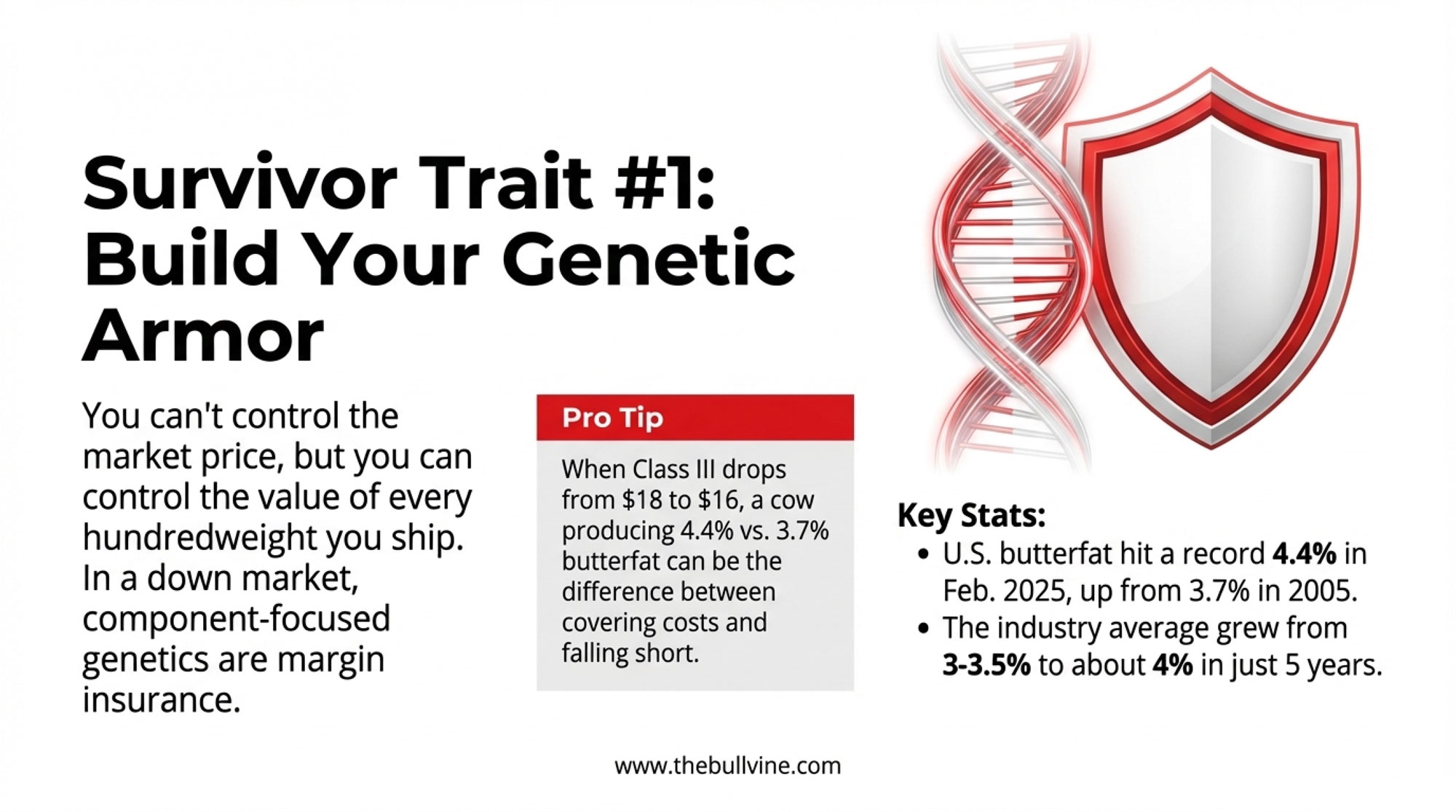

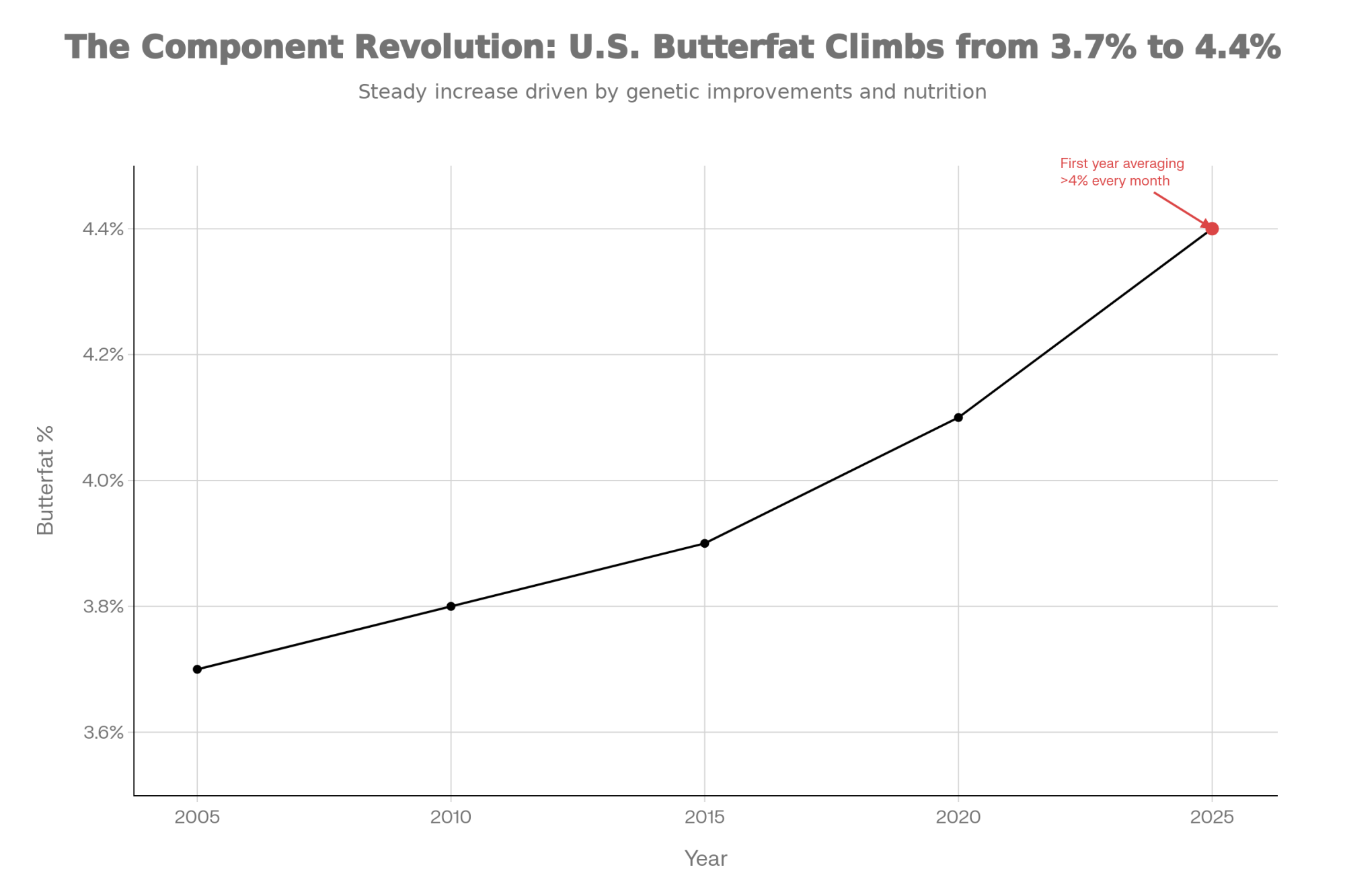

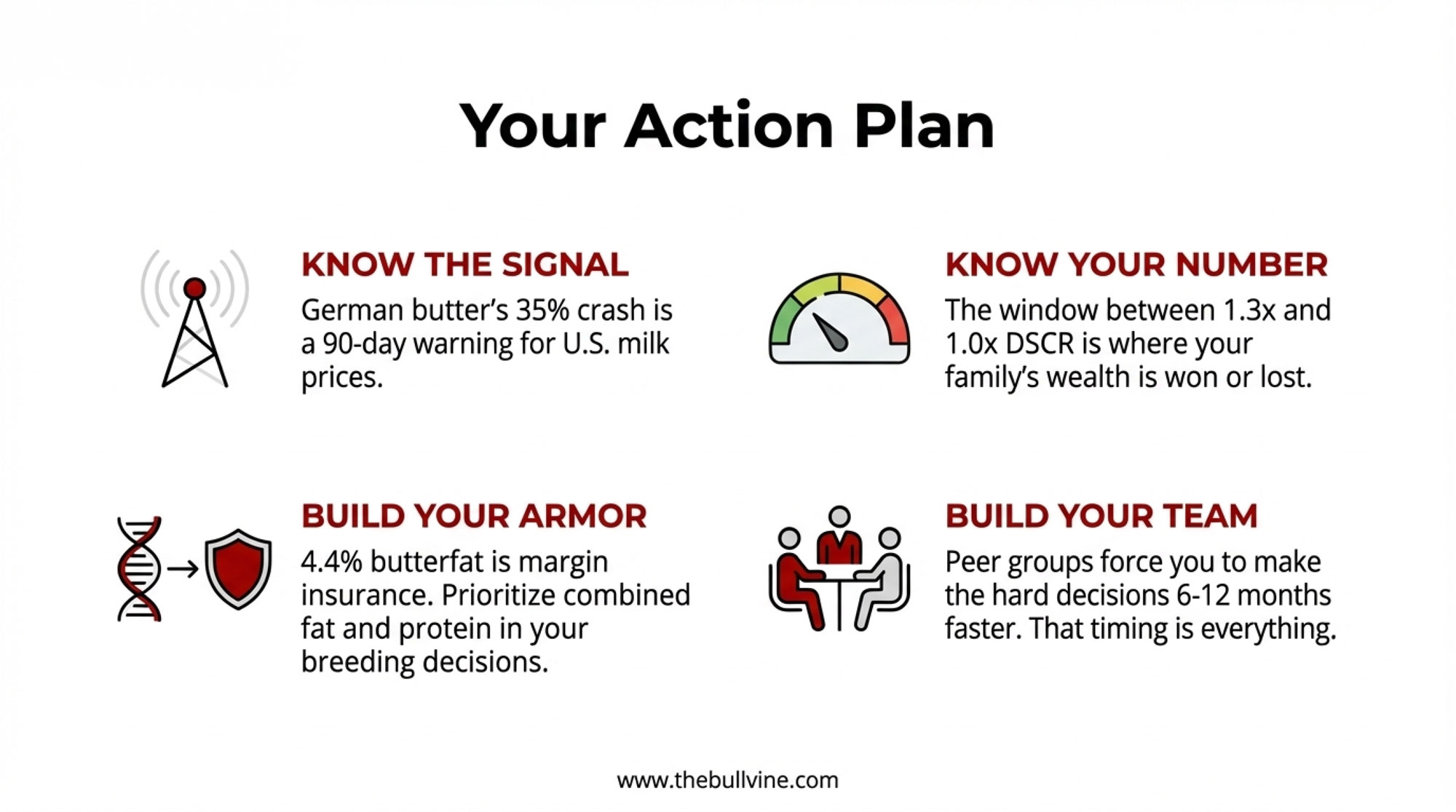

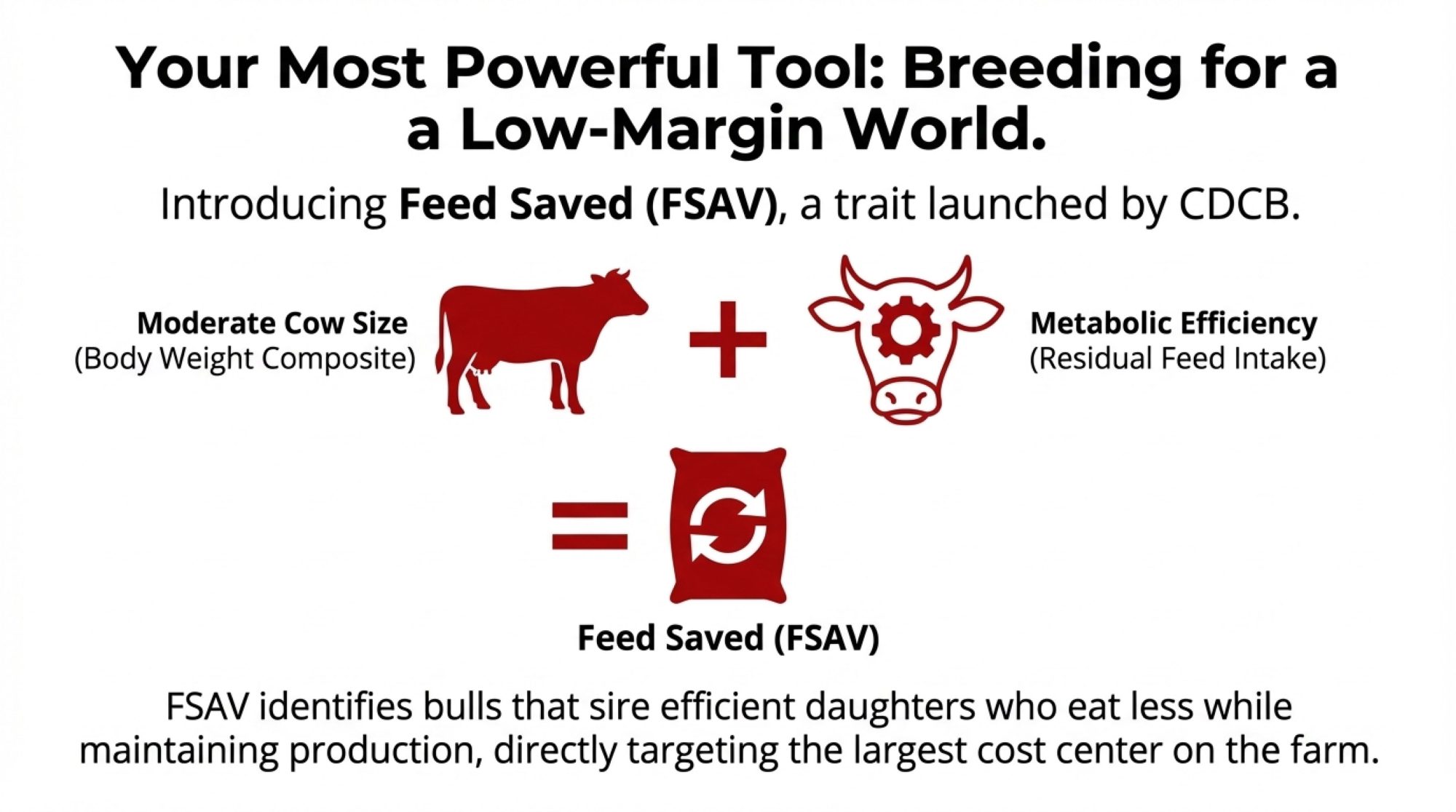

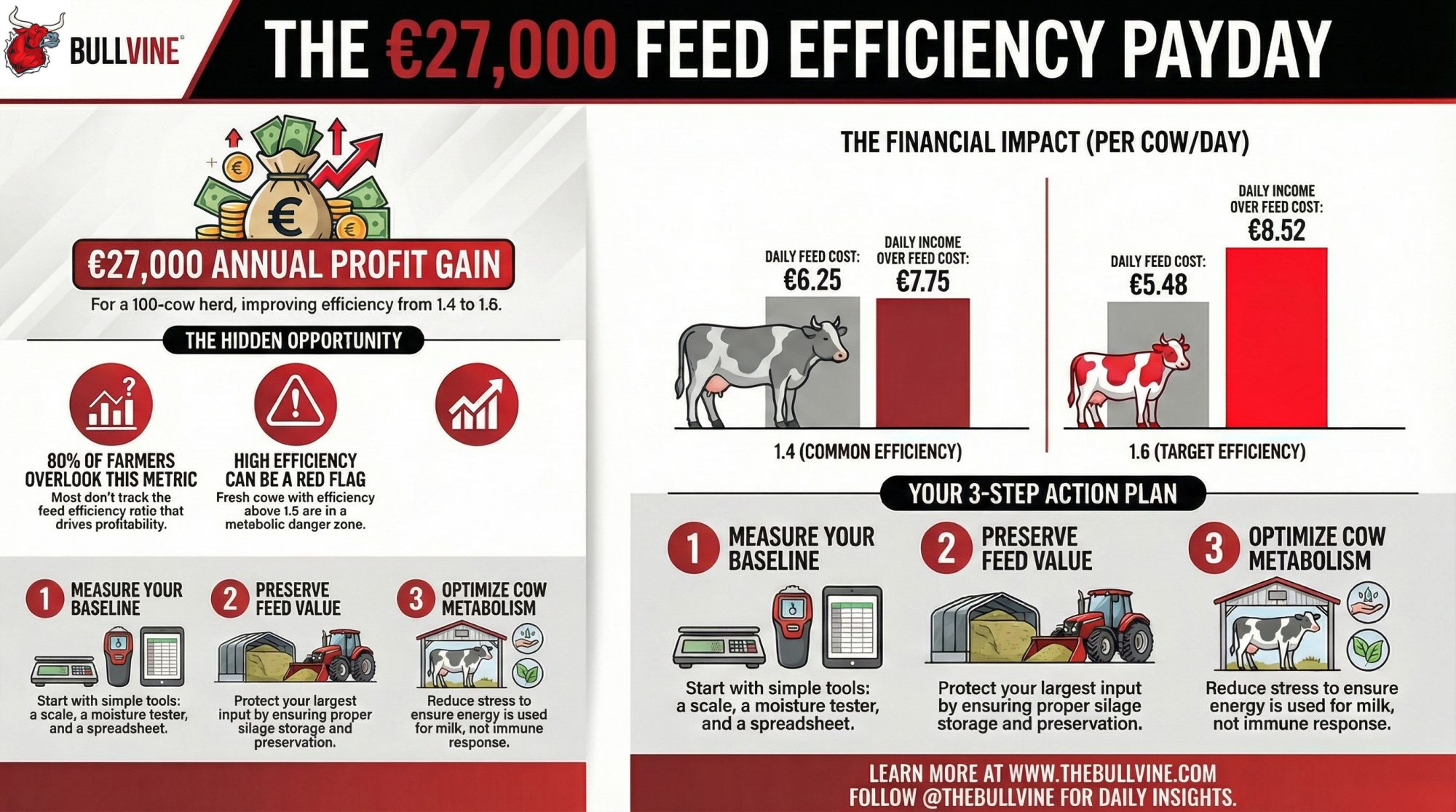

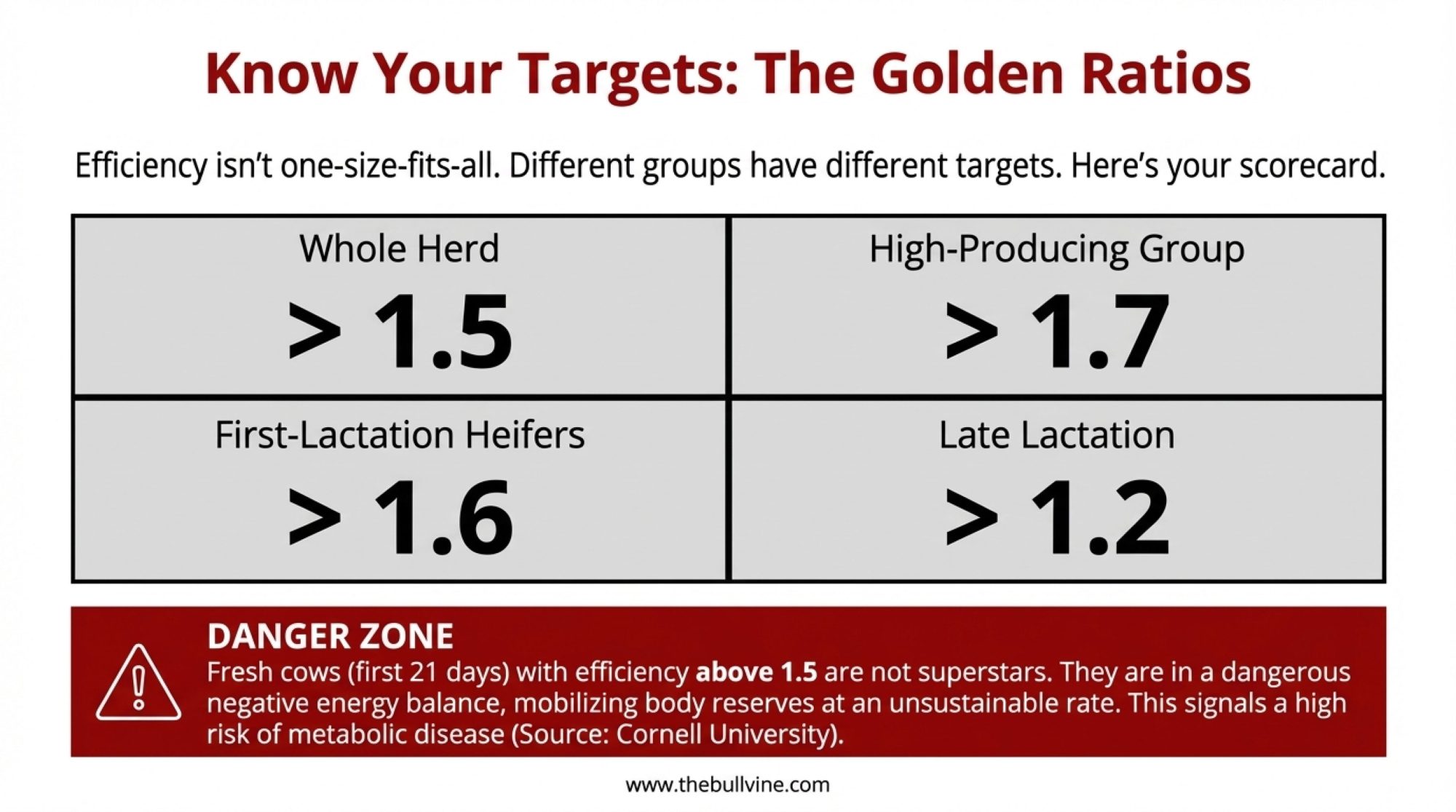

Component-Focused Genetics

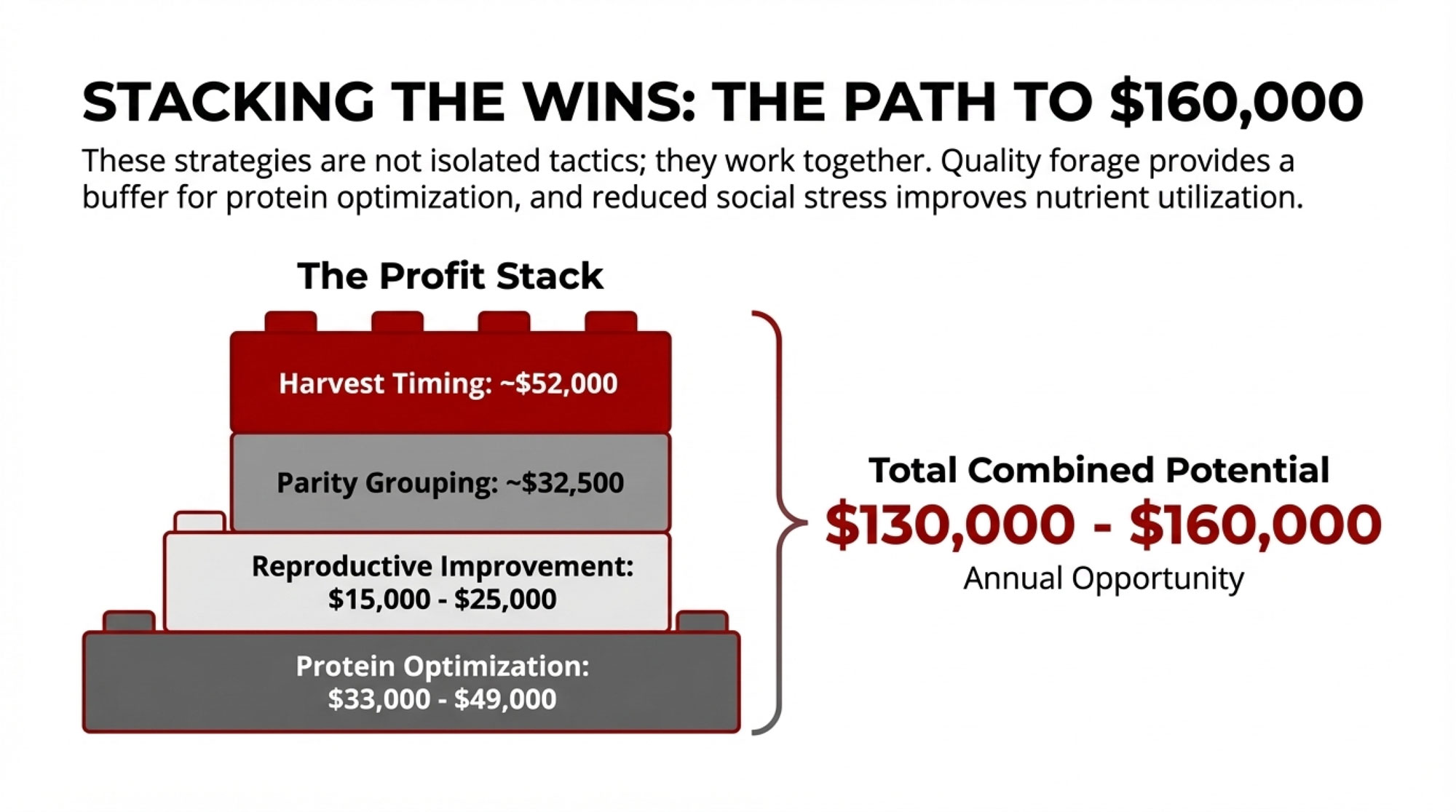

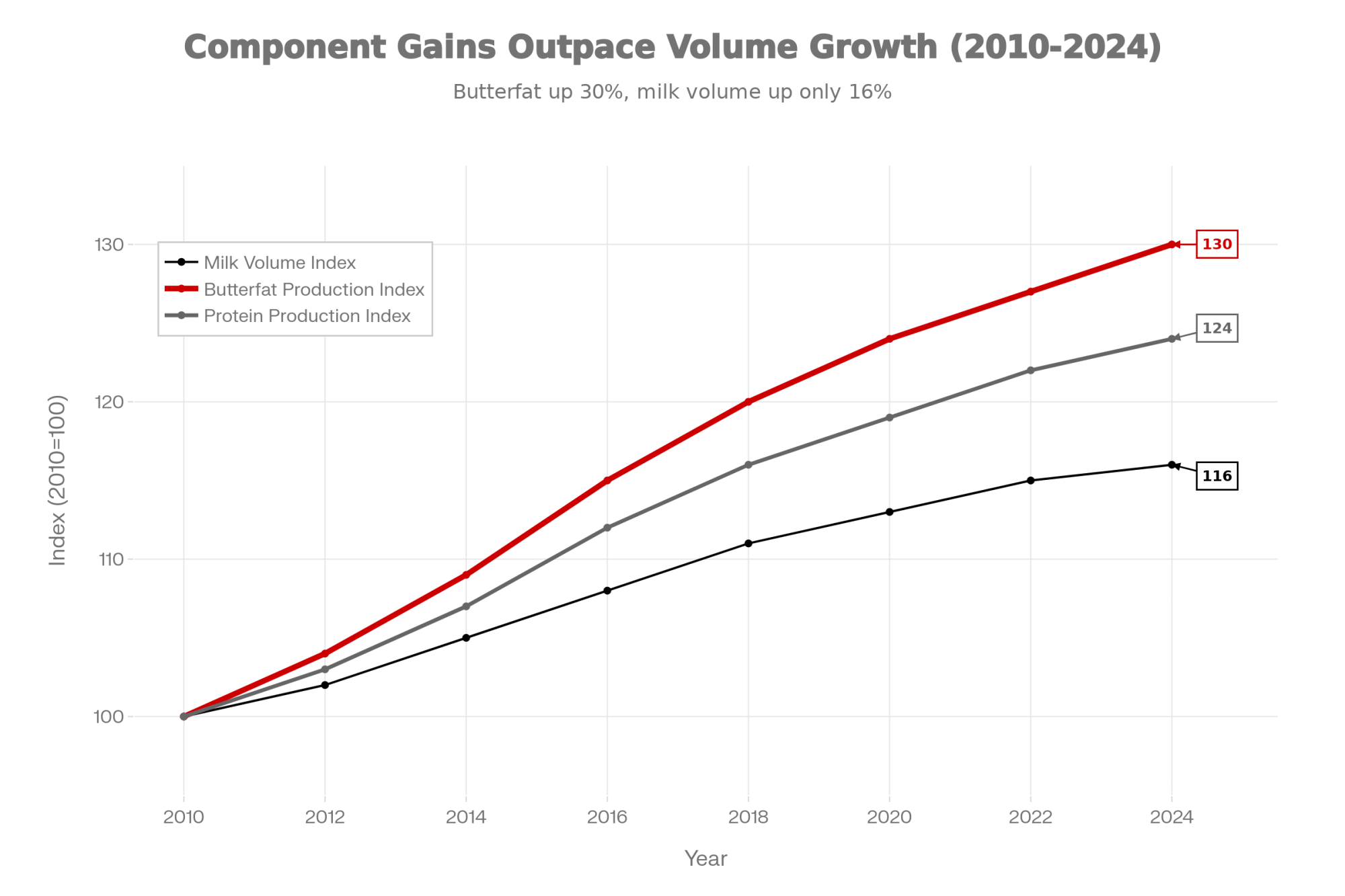

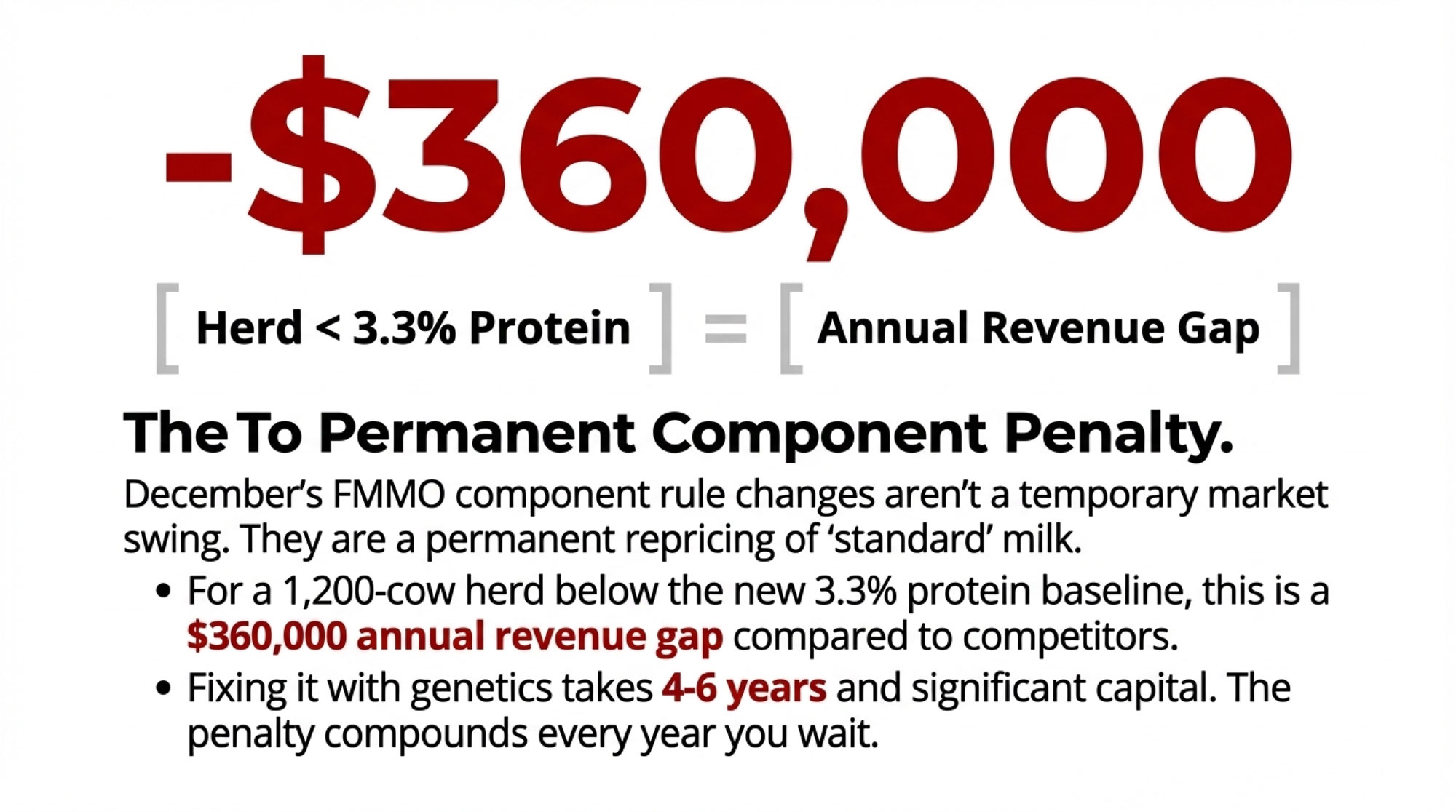

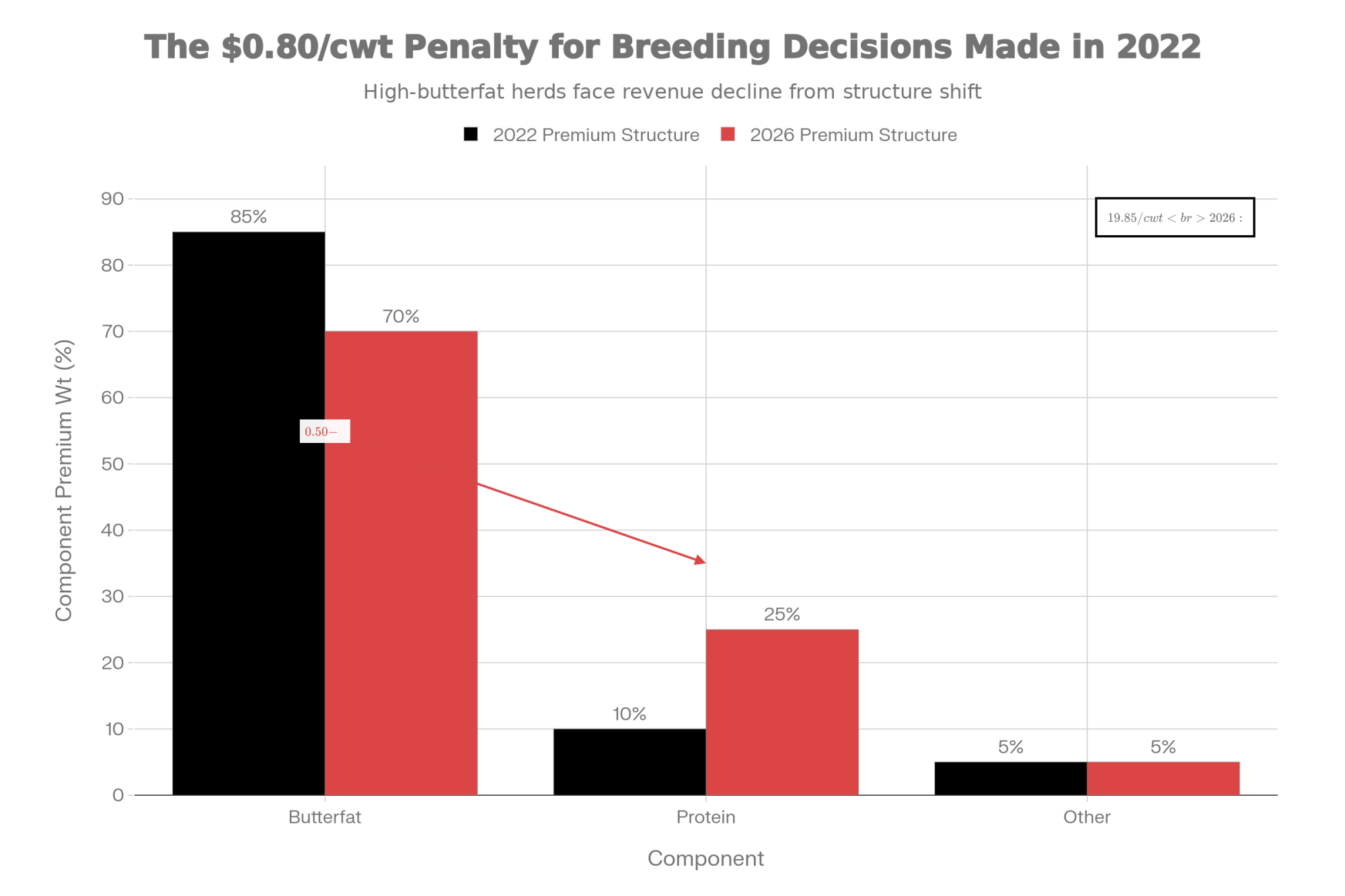

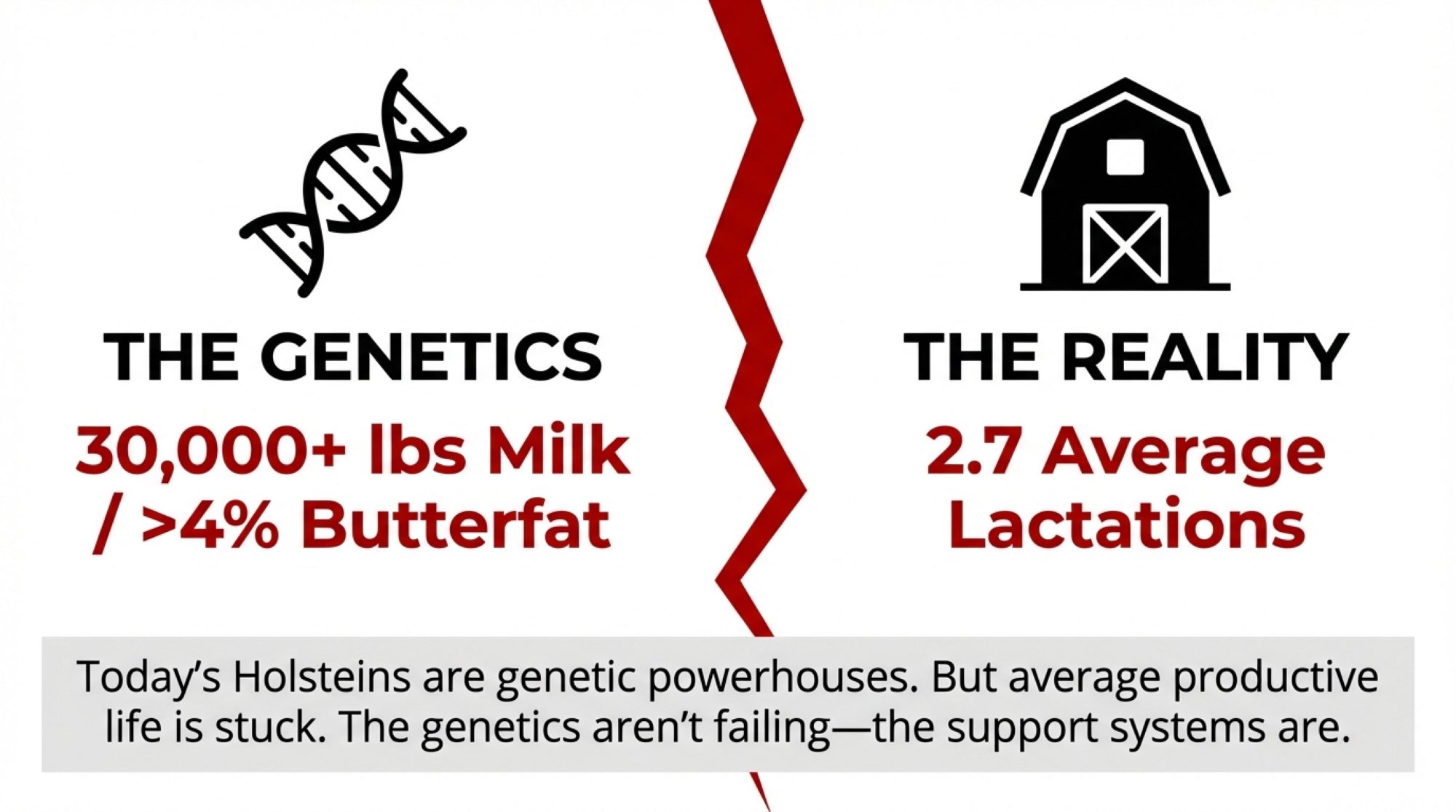

Shifting breeding selection from volume to margins can improve economics without expansion. In most Federal Milk Marketing Orders, the majority of the milk check now comes from butterfat and protein values rather than fluid volume—which is why so many herds are focusing on component yields.

Farms achieving 4.5%+ butterfat and 3.4%+ protein create differentiated products that can command premiums. Implementation requires genomic testing at $35-55 per animal according to CDCB fee schedules, plus discipline in sire selection.

Timeline: Expect 18-24 months for measurable herd-wide improvement. Full genetic transition takes 4-6 years as replacement heifers enter the milking string.

Niche Market Positioning

Operators with geographic advantages—primarily proximity to population centers—are capturing premiums through grass-fed positioning, A2/A2 genetics, organic certification (a 3-year transition is required), and local direct marketing. On-farm store operations often report retail pricing several times commodity equivalent—a pattern documented across university extension programs.

The practical insight: Pick one positioning and execute it well. Farms that attempt multiple niches simultaneously typically struggle to excel in any of them.

Diversified Income Streams

Revenue diversification reduces milk price dependence:

- Custom heifer raising: $3-5/day per heifer according to University of Wisconsin Extension surveys

- Educational farm programs: Can generate $25,000+ annually with modest infrastructure

- On-farm dairy retail: 3-4x commodity margins; requires $30,000-50,000 infrastructure investment

- Agritourism: The 2022 Census reported $1.26 billion in national agritourism revenue, according to the USDA Economic Research Service analysis

A producer in Vermont, who asked to remain anonymous given ongoing business negotiations, has combined component-focused genetics with a small on-farm store and summer farm tours. “None of it alone would save us,” she said. “But together, we’ve reduced our break-even milk price by almost $4/cwt. That’s the difference between surviving a bad year and not.”

Where This Leaves Us

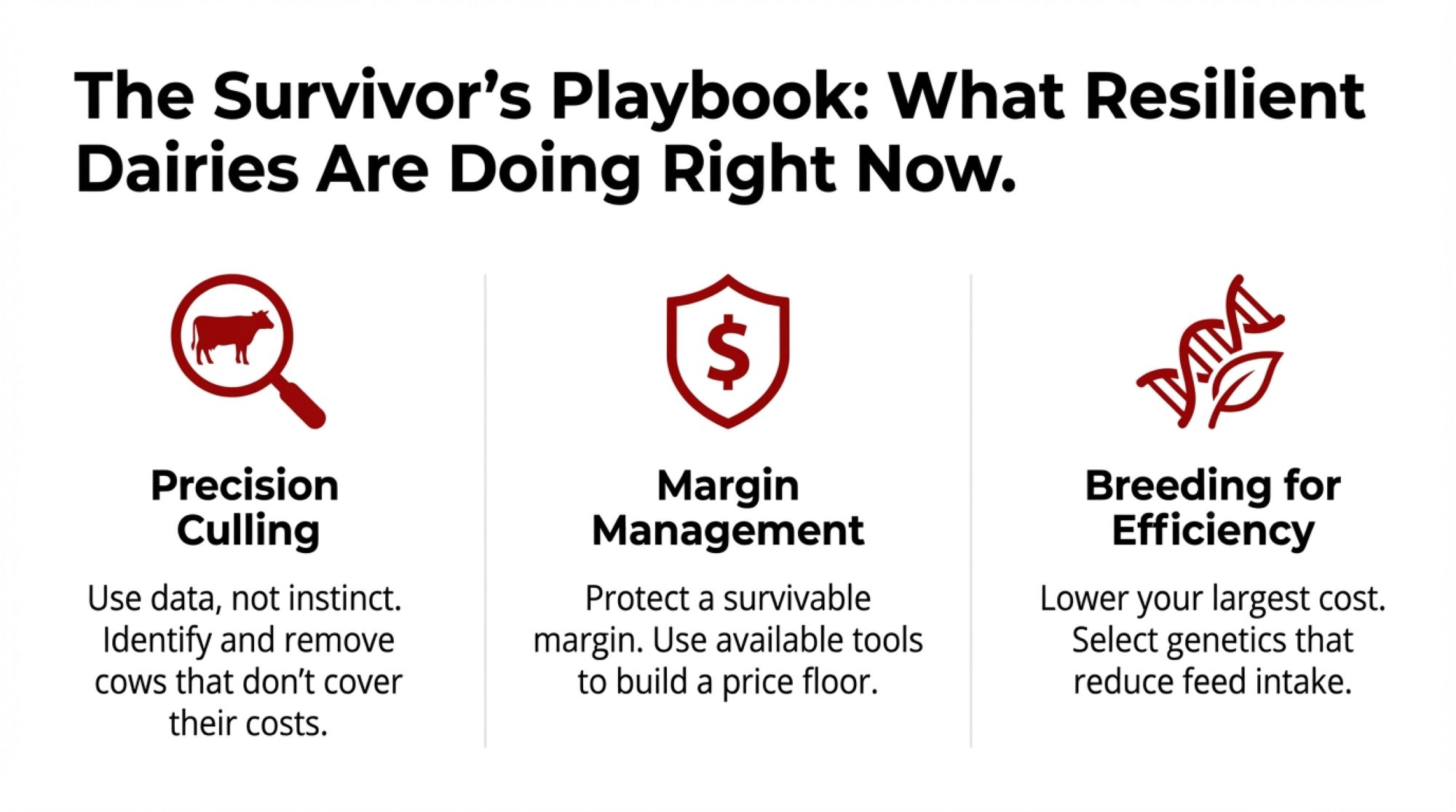

After spending months with these profiles and the data behind them, a few things have become clearer.

- Structure matters more than strategy. The difference between Moreno and Stookey wasn’t intelligence or effort—it was that Moreno’s approach could withstand technological disappointments, while Stookey’s couldn’t withstand policy change.

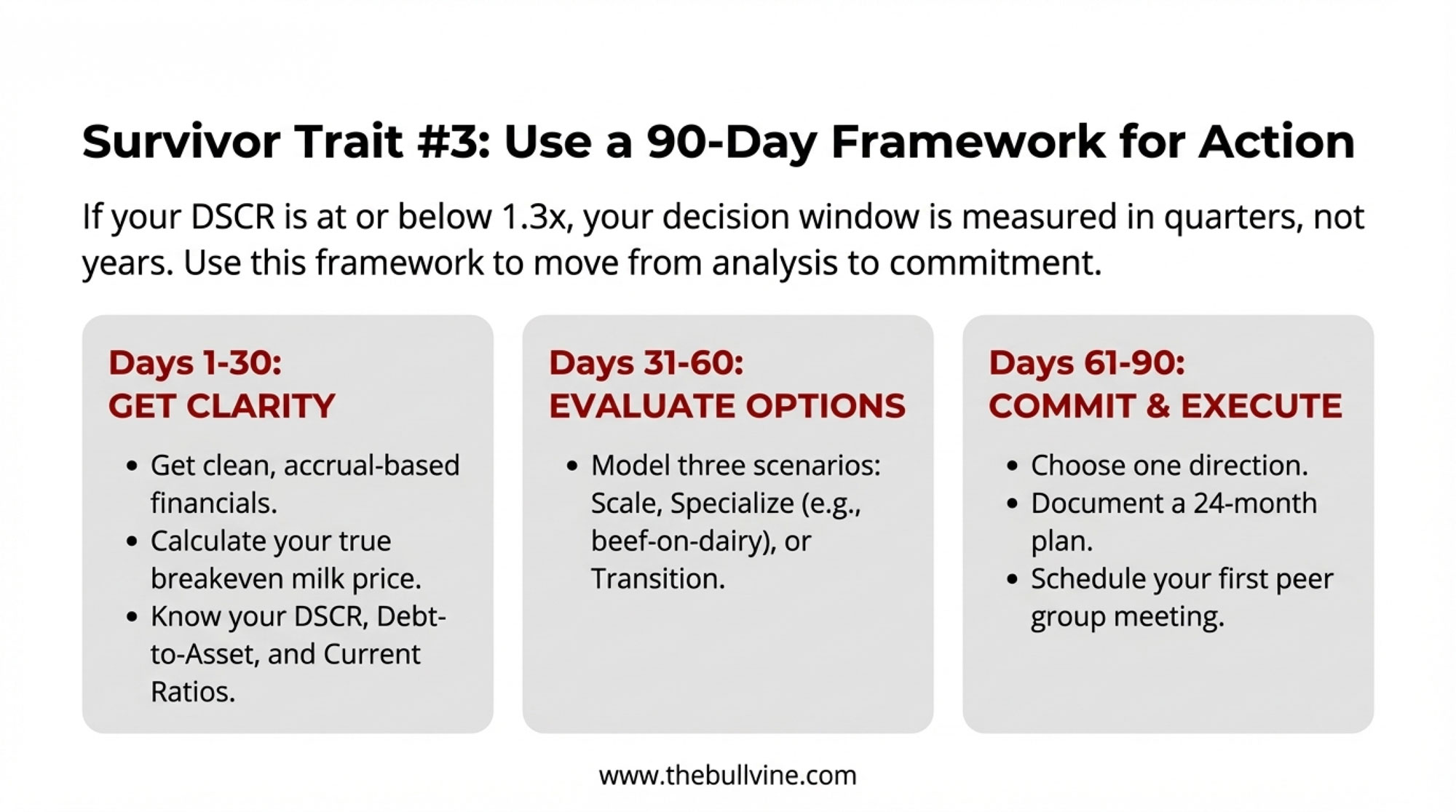

- Test expansion decisions against unfavorable conditions. What happens if milk drops to $16/cwt, feed costs spike 30%, and rates stay elevated? If the expansion fails that test, it’s speculation regardless of how the pro forma looks.

- Assemble multiple advisor perspectives. Transaction-based and relationship-based advisors see different things. Both perspectives have value; neither alone is complete.

- Recognize survivorship bias. The expansion success stories you hear come from operators who structured their risk with enough cushion to survive. The ones who didn’t aren’t around to share their experience.

- Consider whether you’re playing the right game. Mid-sized operations generally can’t win commodity volume competition against the largest dairies. But margin-per-cow, customer relationships, and operational flexibility favor smaller, more nimble operations.

- Think about succession earlier than it feels necessary. The strategies that work for a 50-year-old building equity may not work for a 65-year-old trying to transition.

The Bottom Line

The profiles that resonated with Bullvine readers this year weren’t just about genetics, equipment, or scale. They were about strategic judgment—understanding which game you’re actually playing, what advantages you genuinely have access to, and whether your business model survives when you turn out to be wrong about something.

The operators who will still be thriving in 2035 aren’t necessarily the ones making smarter predictions about milk prices or feed costs. They’re the ones building operations that work, whether their predictions turn out to be right or wrong.

Whether you’re evaluating an expansion, choosing advisors, or planning succession, the five questions in this piece are worth working through before your next major decision.

That’s what these architects understood. And it’s worth taking into 2026.

For questions about this analysis or to share your operation’s experience navigating these decisions, contact The Bullvine editorial team. We’re always interested in hearing how these trends are playing out in different regions.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- 16,000 farms gone in 5 years. Thousands more are projected this decade. Consolidation isn’t slowing—operations with 2,500+ cows grew from 714 to 834 between 2017-2022.

- Survivors didn’t predict markets better. They structured risk to survive being wrong. The test: does your operation work if the incentive that made it attractive disappears?

- Run the 5-question framework before any major investment. It separates calculated risk from speculation—and a Minnesota lender says it predicts who will still be farming five years later.

- Mid-sized dairies face a $10/cwt structural gap. Large dairies face different fragility. Scale brings labor exposure, regulatory concentration, and capital risk during downturns. Neither model is safe—they’re vulnerable in different places.

- Succession is a strategy, not an afterthought. Expand at 55 with $3M debt? You’re 70 before it’s manageable—exactly when transition should happen. The farms that transfer successfully have one thing in common: manageable debt at the time of transition.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

16,000 dairy farms gone between 2017 and 2022. A 40% decline—with thousands more exits projected this decade. After analyzing the profiles that resonated most with Bullvine readers this year, from Juan Moreno’s STgenetics infrastructure play to Jack Stookey’s 1980s tax-shelter collapse, one pattern emerged: survivors didn’t predict markets better. They structured risk so they could survive being wrong. Inside: a five-question framework to stress-test any major investment, the $10/cwt cost gap facing mid-sized operations, and practical strategies from producers who’ve cut break-even by $4/cwt. The core test for any expansion: does your operation survive if the thing that made it attractive disappears?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

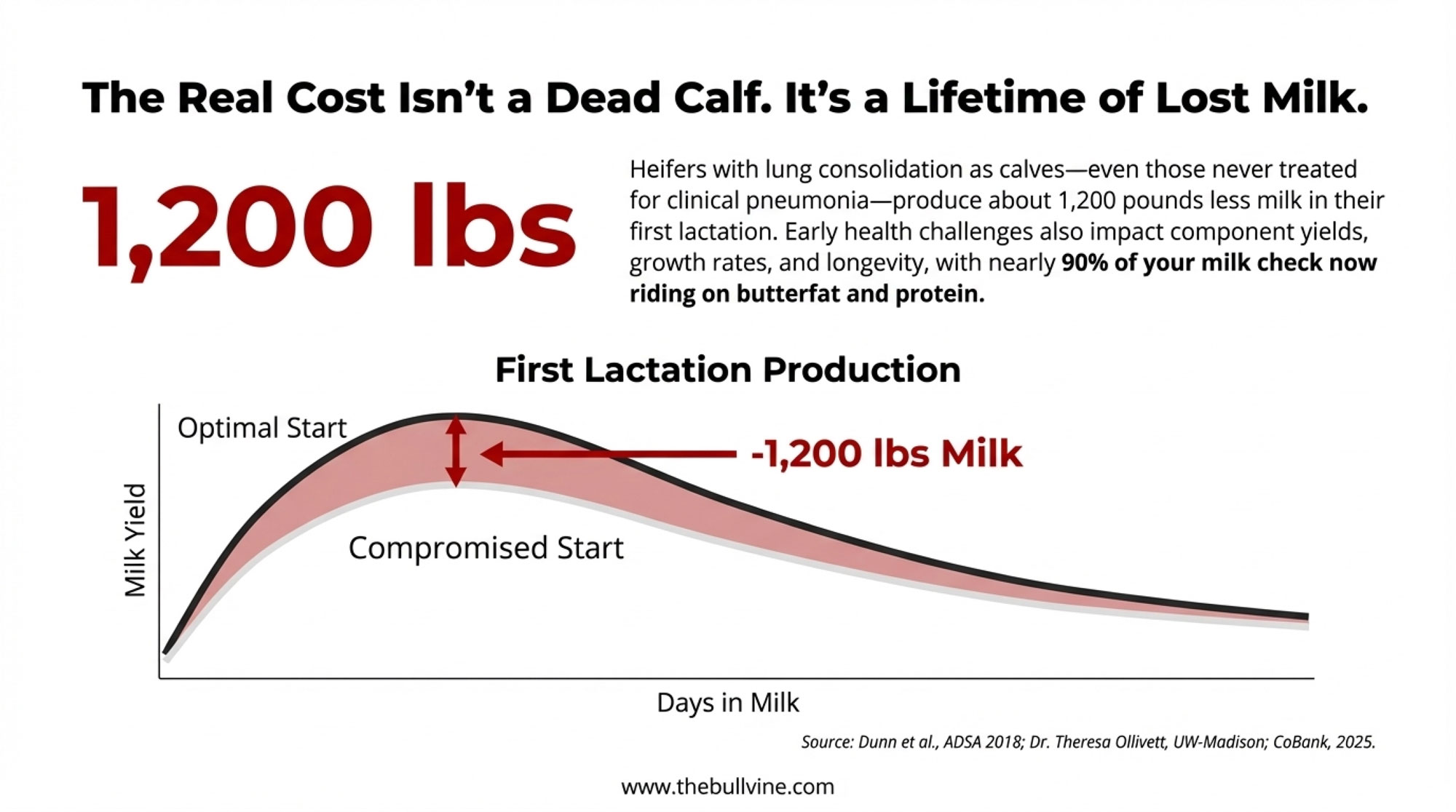

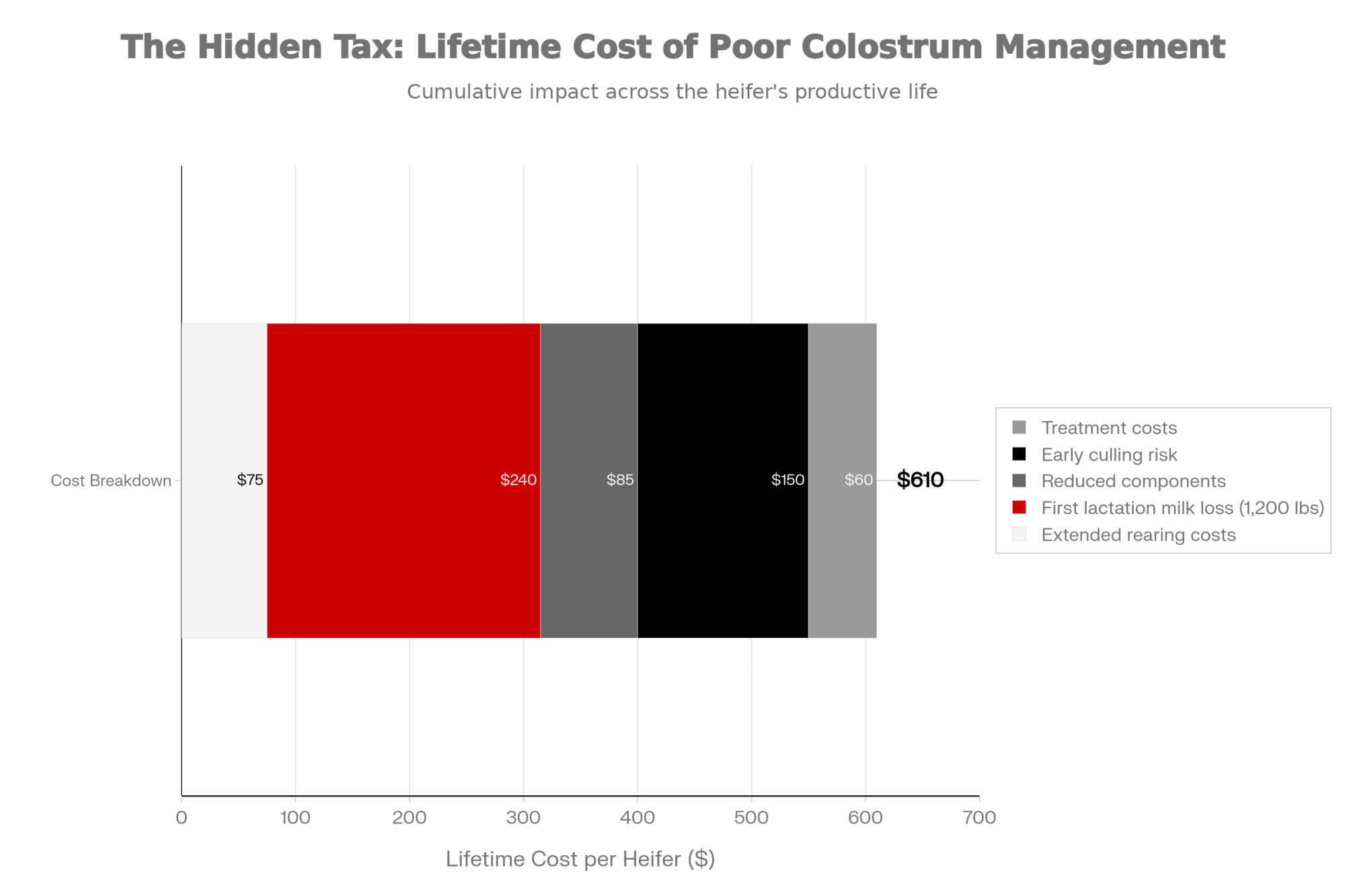

- 17-26x ROI: Why Top Dairies Stopped Saving Calves and Started Preventing Loss – Exposes the staggering 17-26x ROI hidden in your heifer pens by shifting from treating sickness to precision prevention. You’ll arm your operation with a specific protocol overhaul to secure first-lactation milk and slash culling risk immediately.

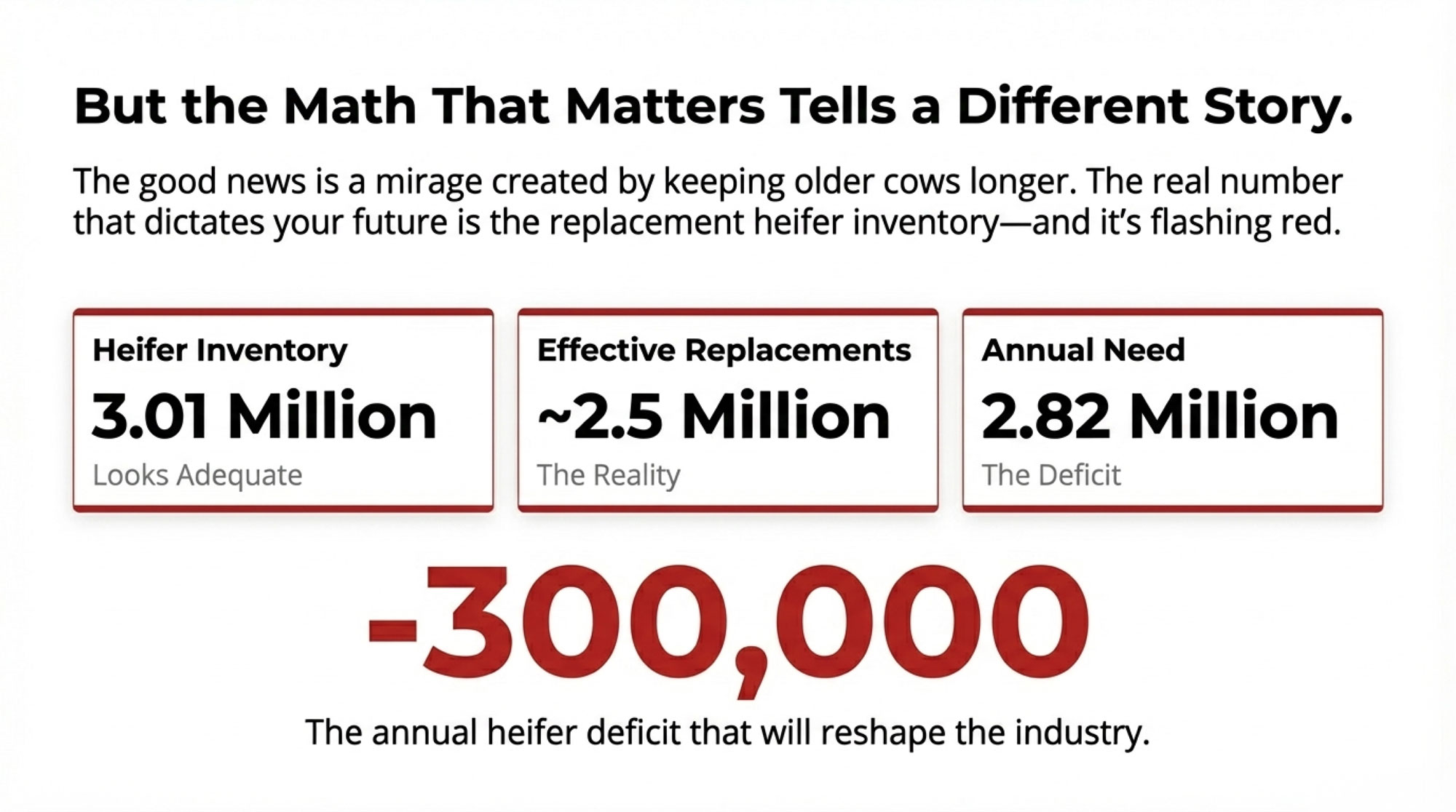

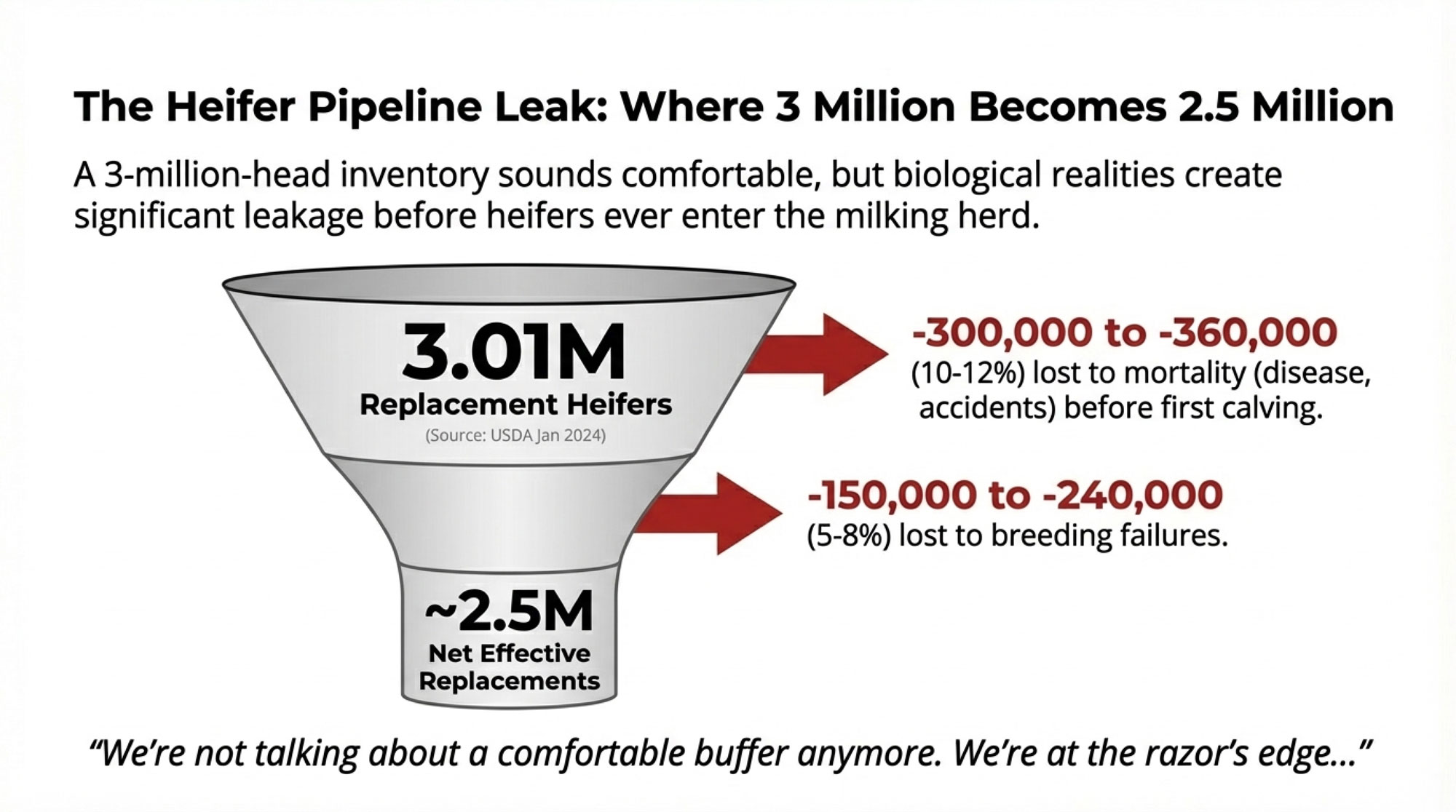

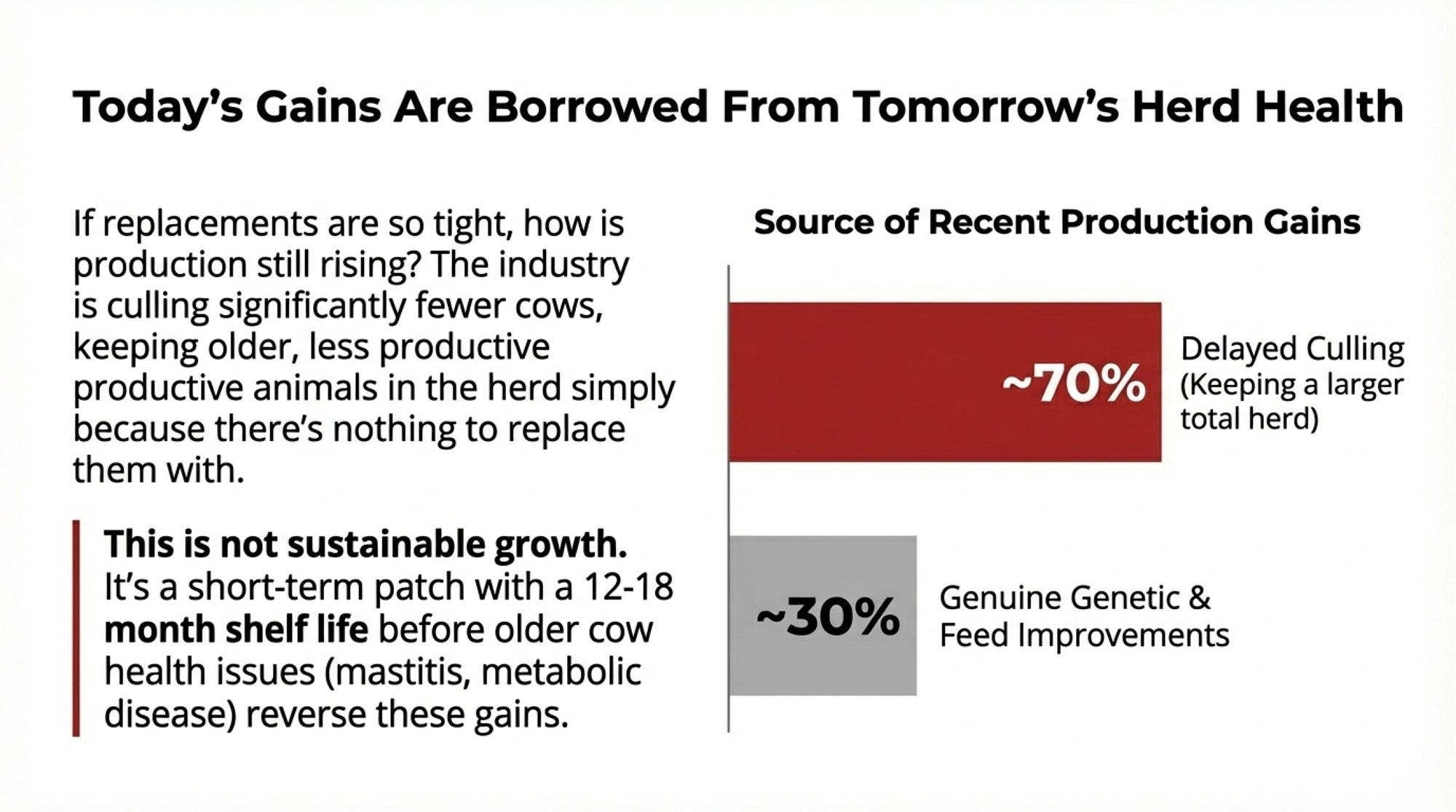

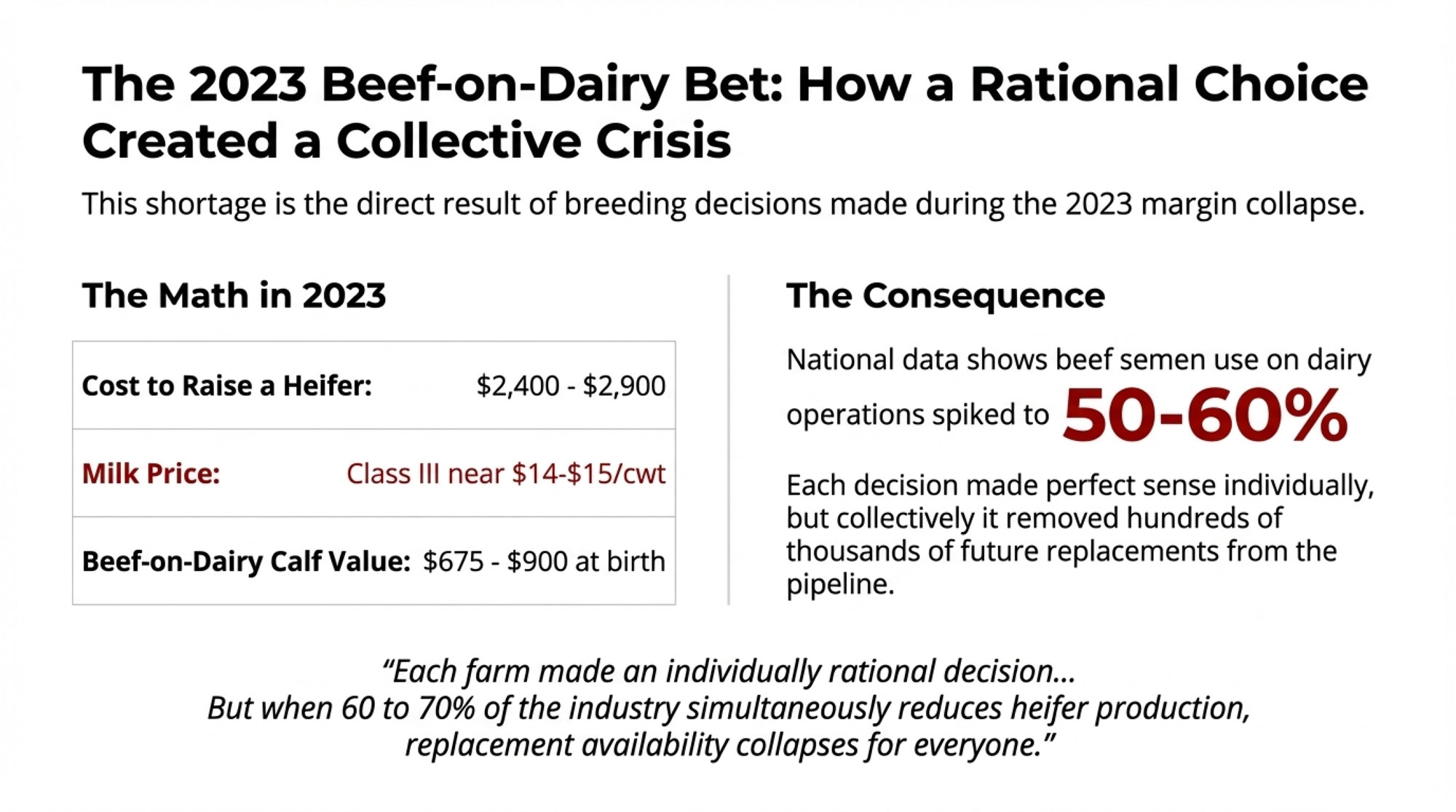

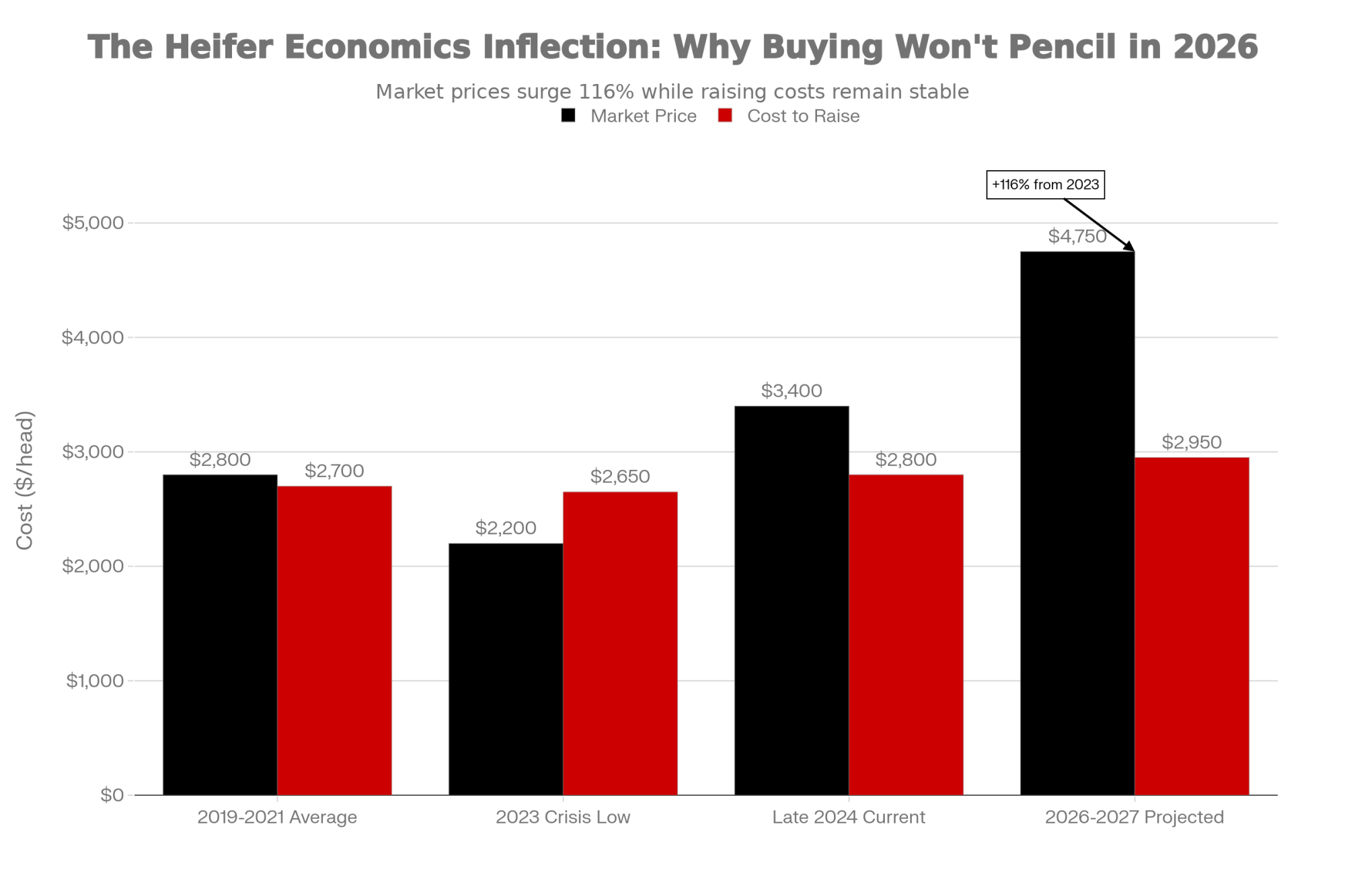

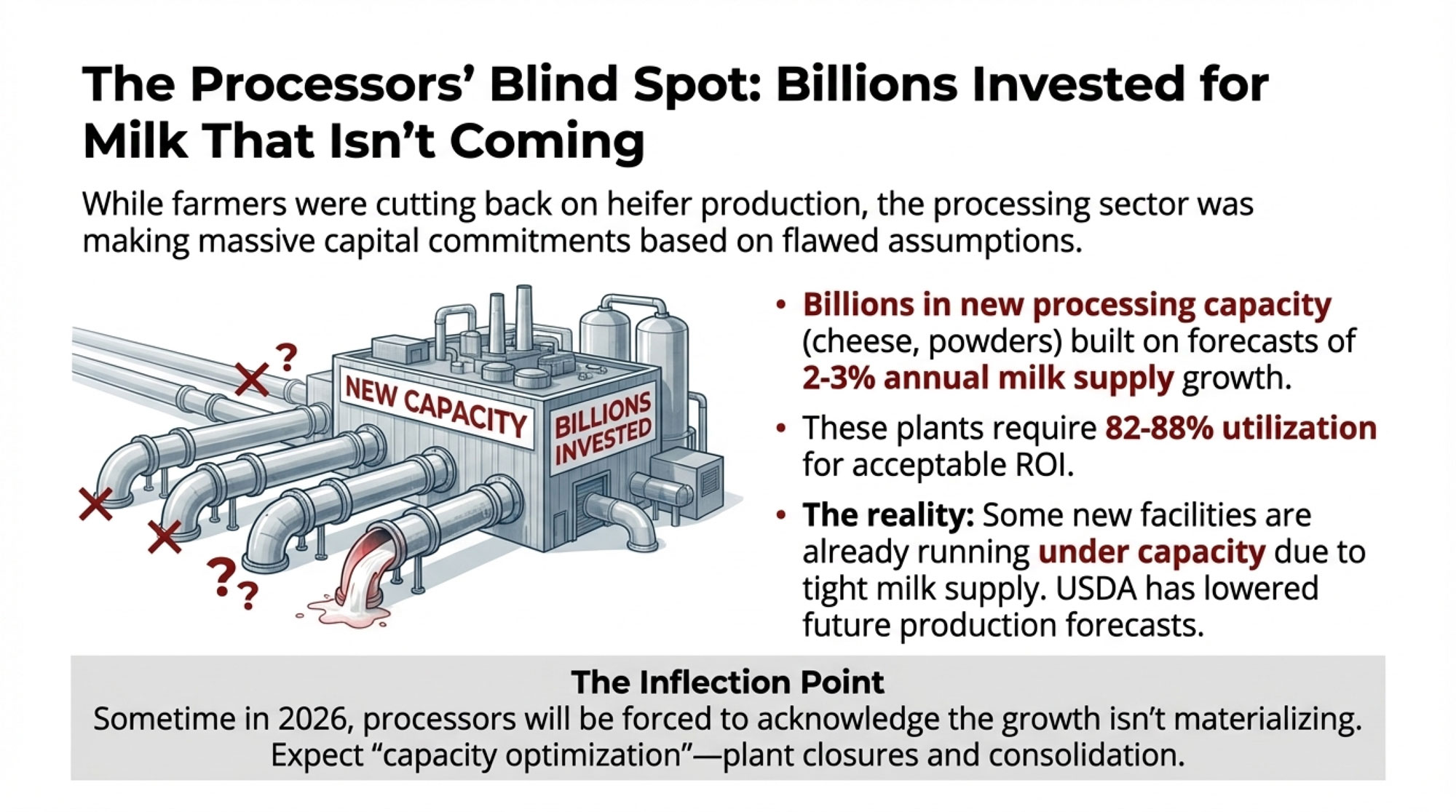

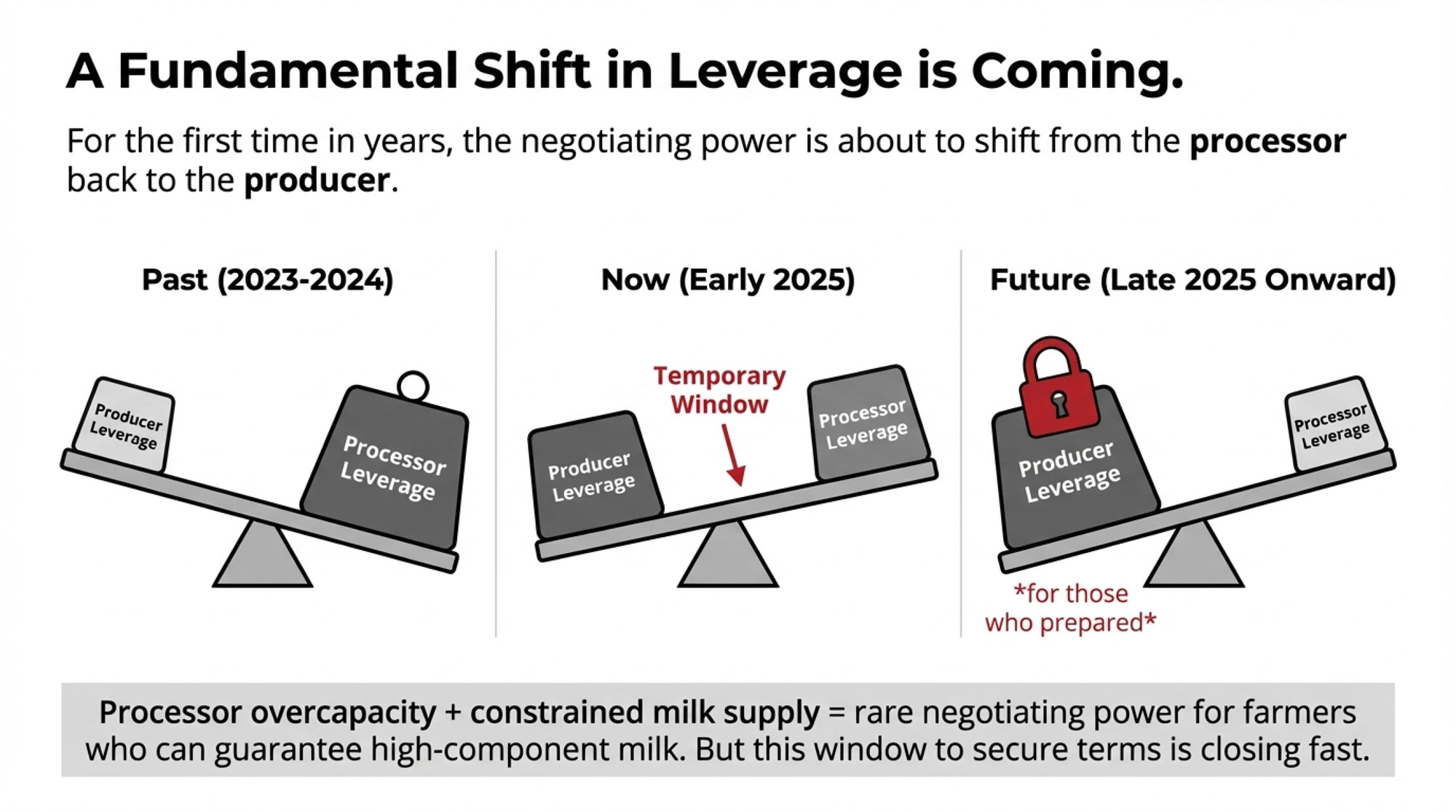

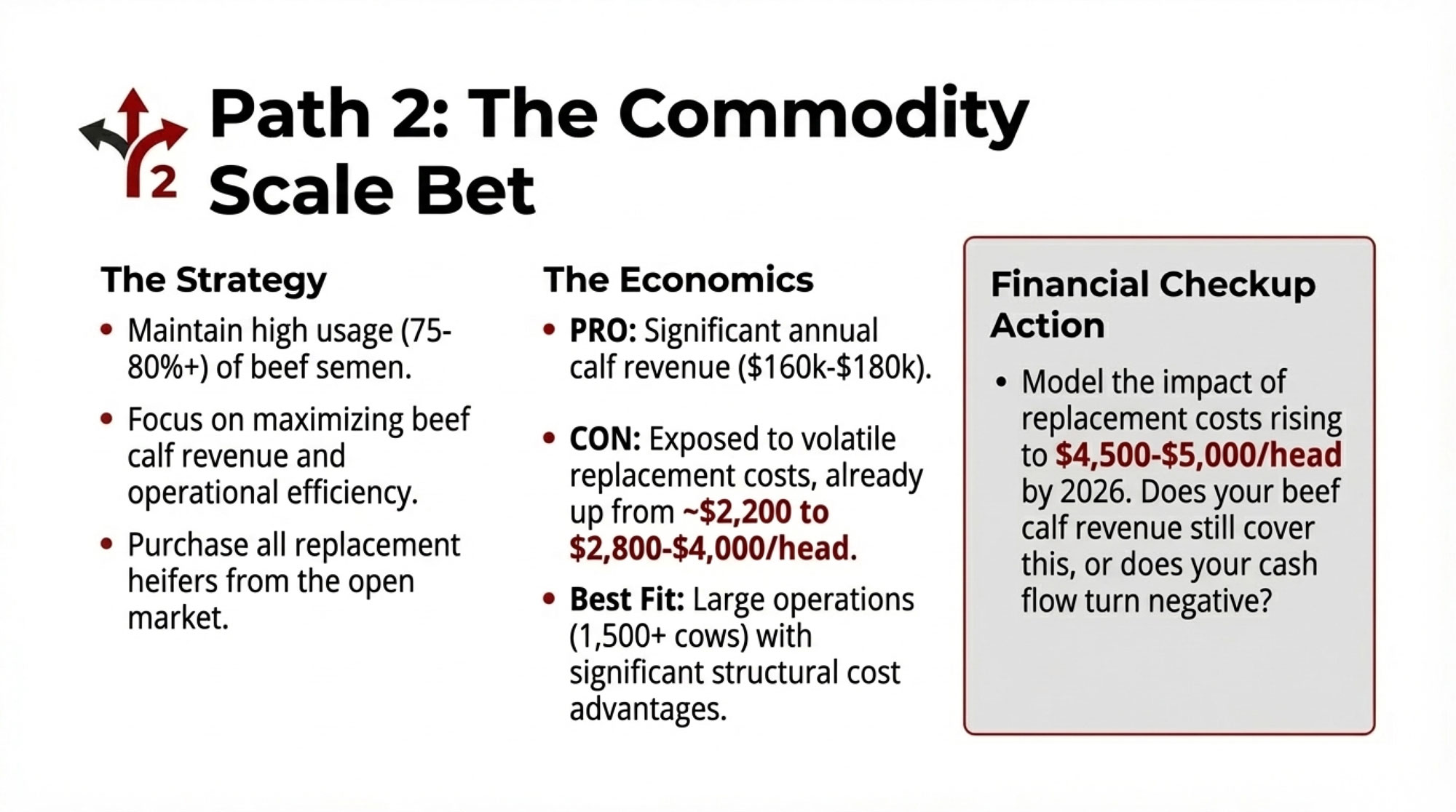

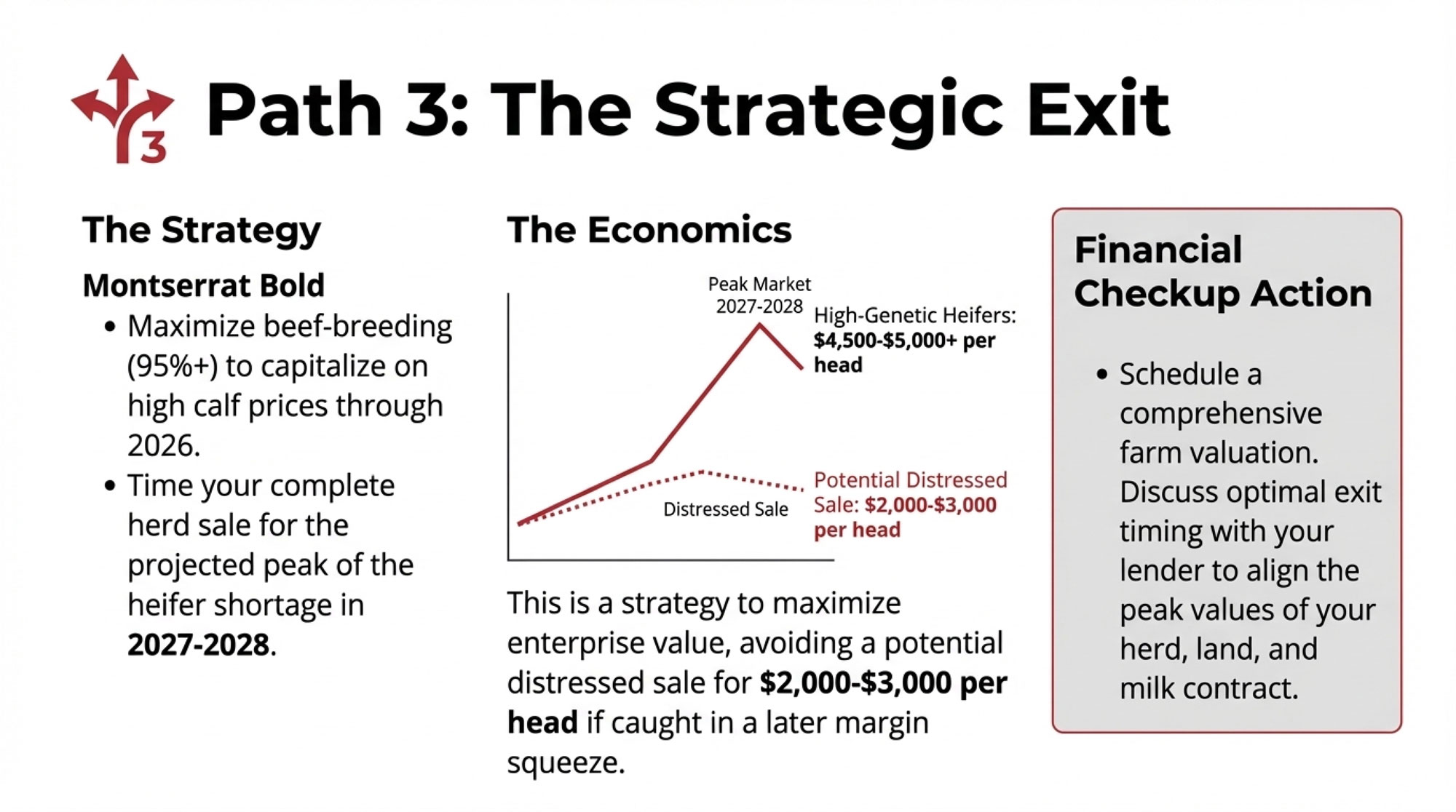

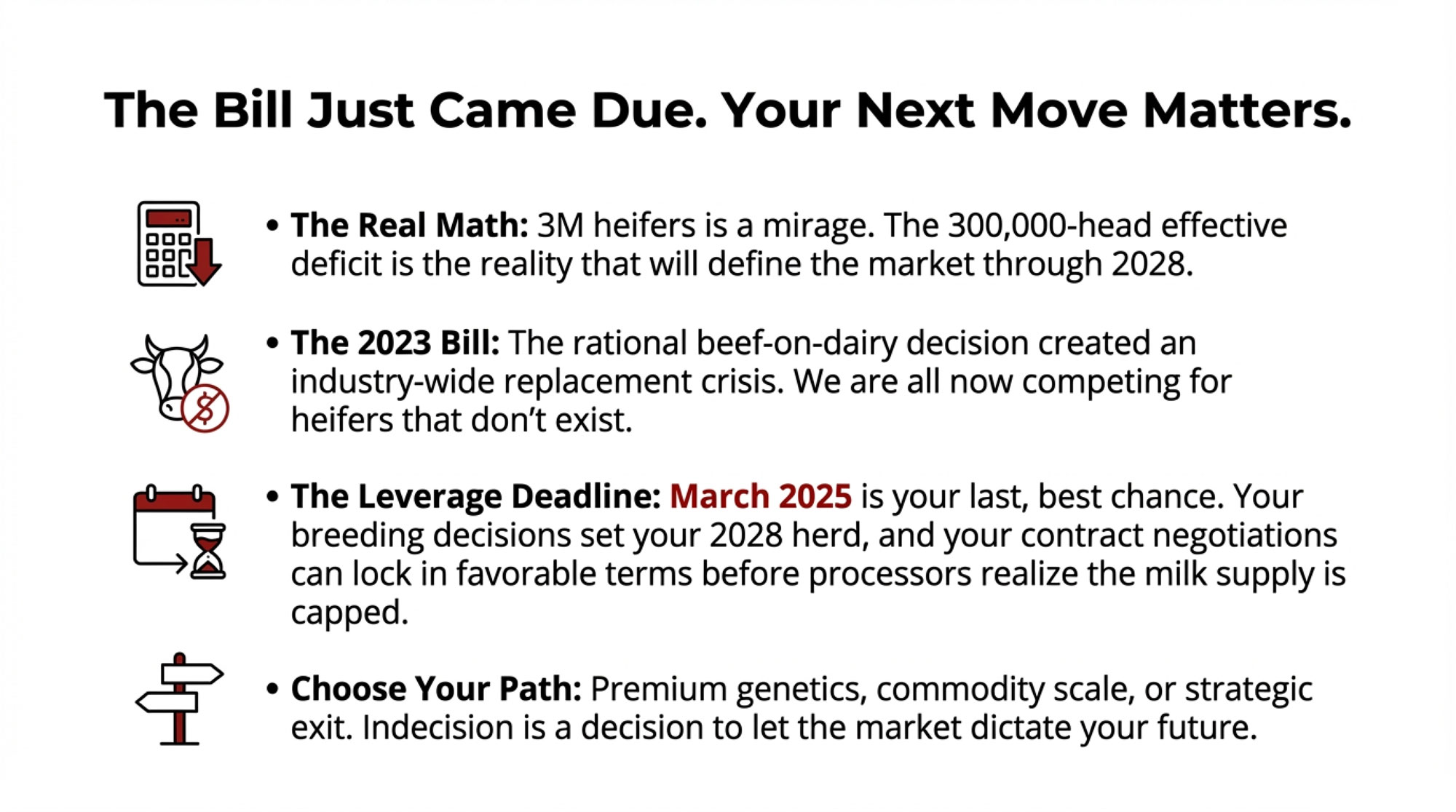

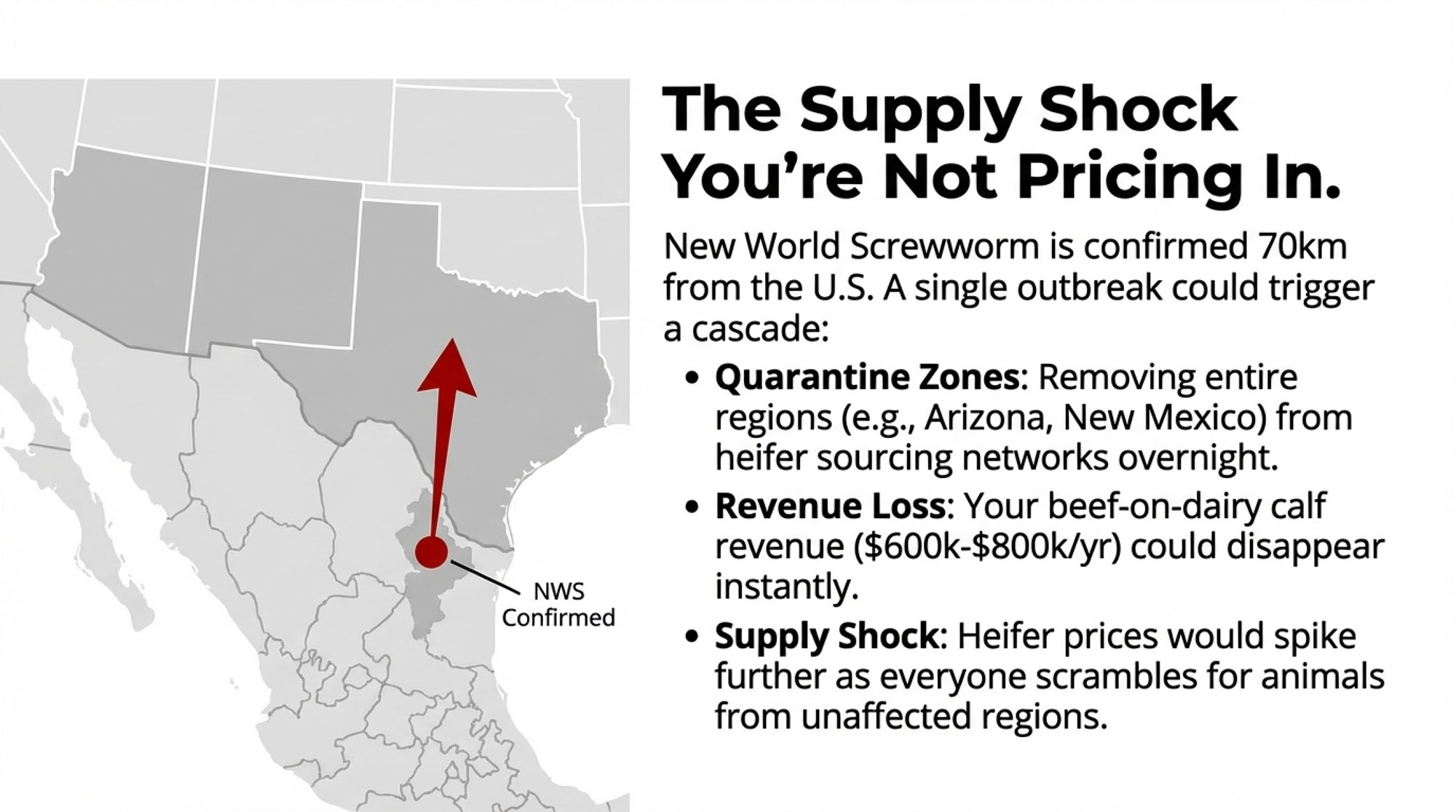

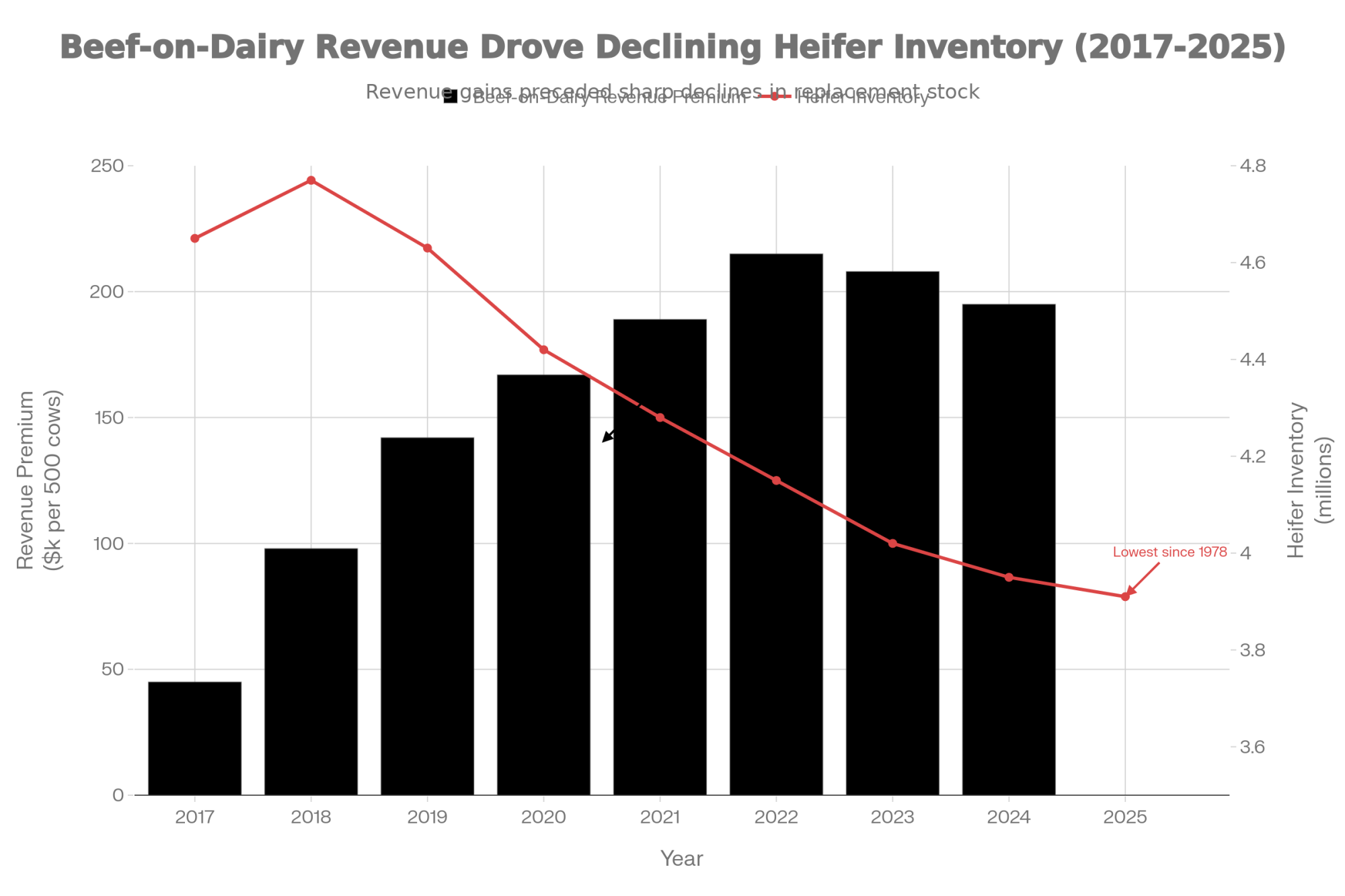

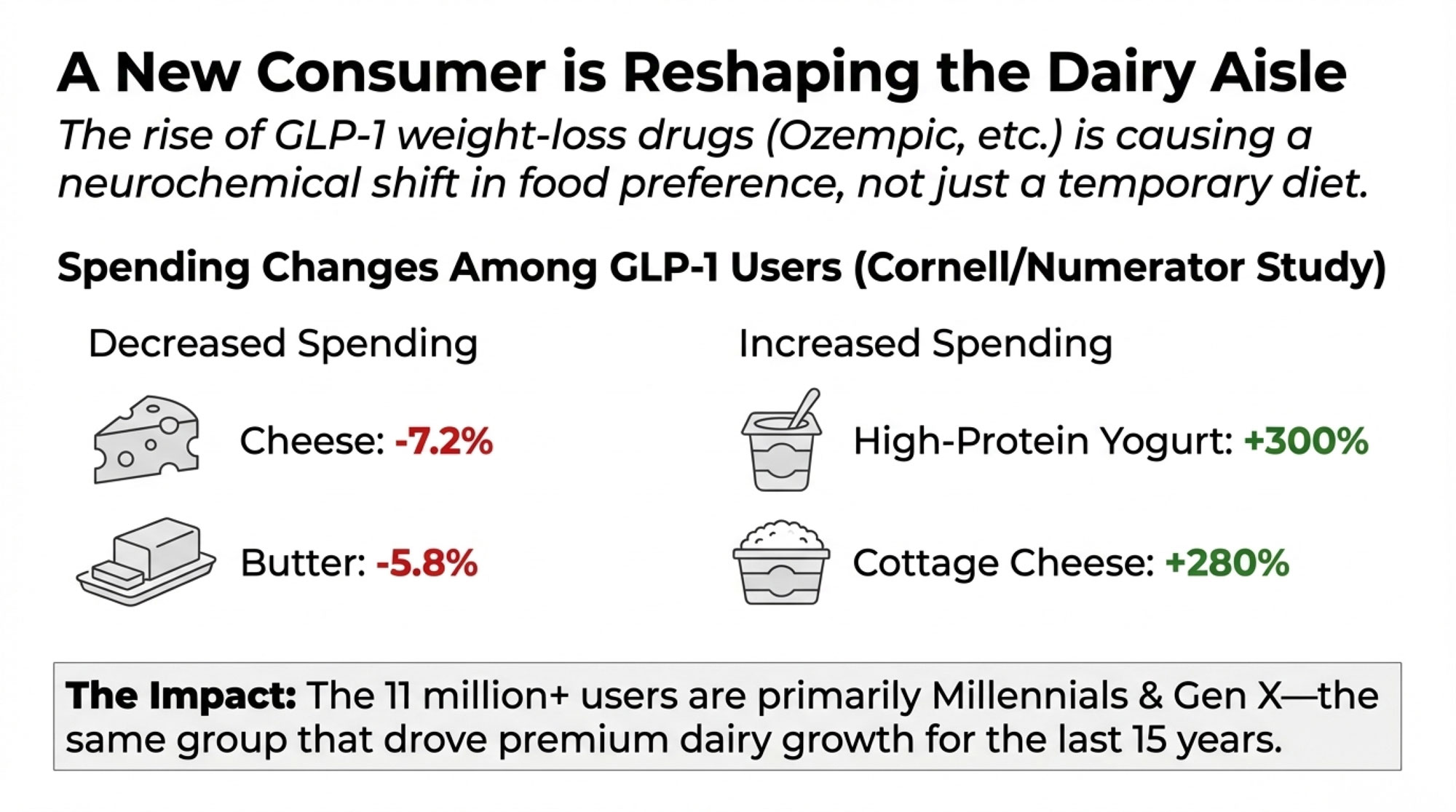

- The Triple Cushion Trap: Why 2025’s Strong Margins Won’t Save You in 2026 – Reveals the three temporary forces—beef-on-dairy, cheap feed, and margin coverage—masking structural fragility today. It delivers a hard-hitting 18-month roadmap to restructure your debt and herd before these market cushions deflate in late 2026.

- New Sensor-Based Milking Speed Trait from CDCB Debuts August 2025 – Breaks down the revolutionary sensor-based Milking Speed trait debuting in late 2025 to slash parlor labor hours without new capital. By selecting for precision flow-rate data, you gain a massive competitive advantage in throughput and efficiency.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!