You don’t need a new barn to find $300,000. A stopwatch and the 3.5‑hour cow rule might be the cheapest margin boost on your farm.

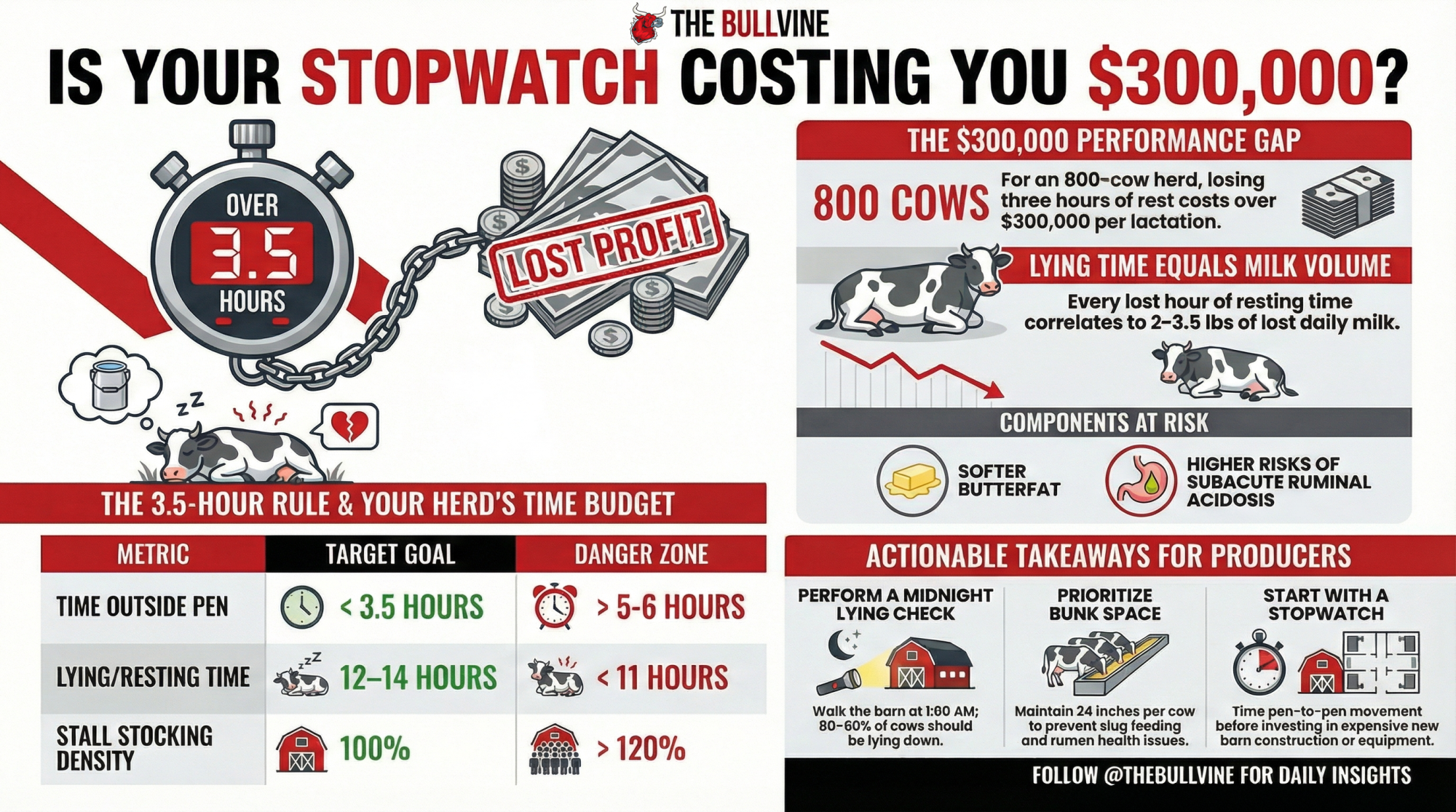

Executive Summary: Most producers assume their cows are out of the pen ‘a couple hours a day’—but when you time it, you often find five or six. That’s a six-figure problem: cows need roughly 21 hours per day for eating, lying, and ruminating, leaving only 3–3.5 hours for milking and handling before they cut into rest or meals. Miner Institute research ties each lost hour of lying time to 2–3.5 pounds of lost milk per cow per day, along with softer butterfat and increased lameness. For an 800-cow herd, that gap can quietly strip over $300,000 from your milk cheque each lactation. The diagnostic takes no capital—just a stopwatch, a stocking count, and one midnight lying check. In a tight-margin 2025, time budgets may be the cheapest performance lever you haven’t measured yet.

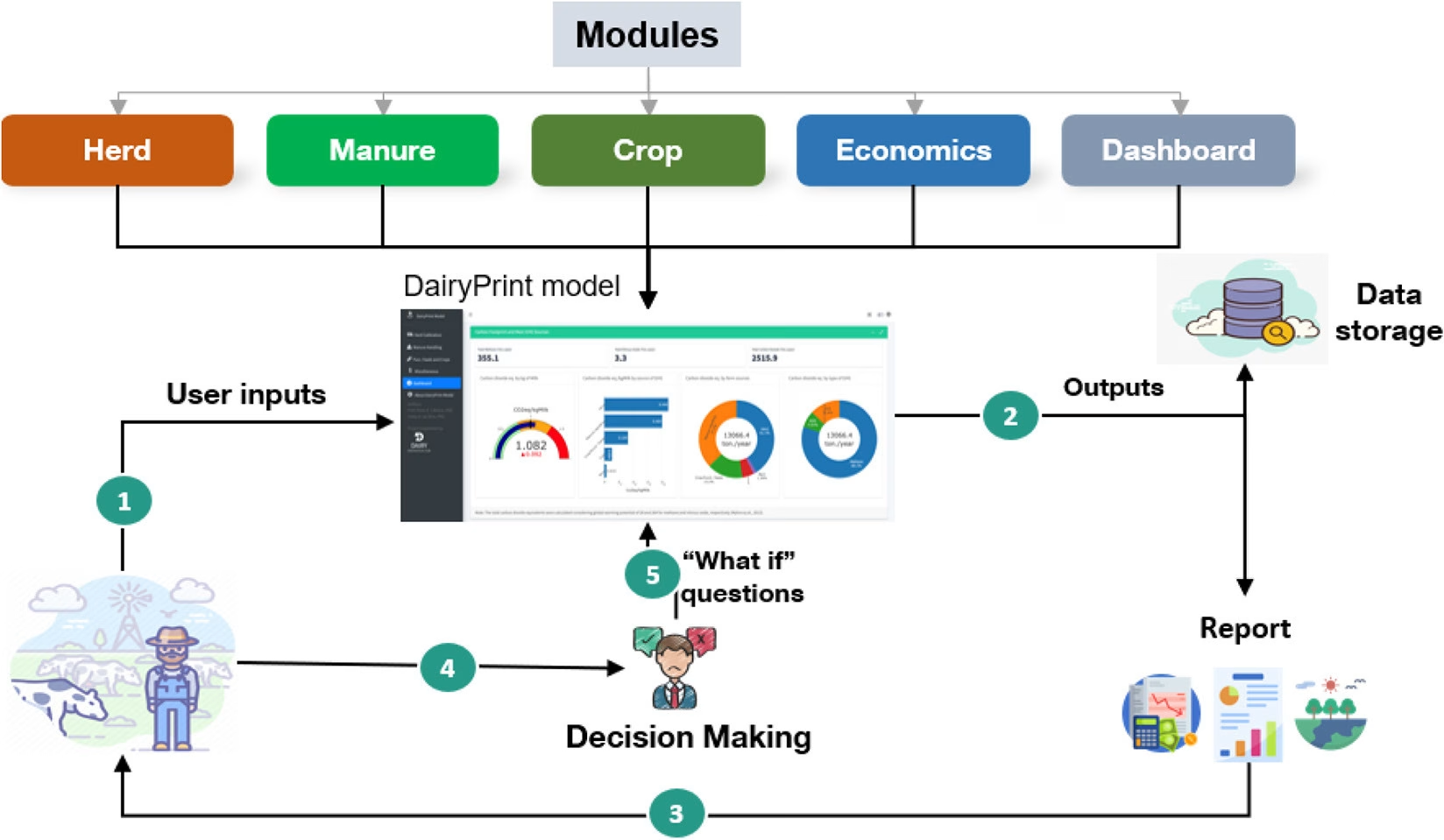

If you sit down with dairy folks at a winter meeting in Wisconsin or around a kitchen table in Ontario, the talk usually kicks off with rations, genetics, and parlors. But what’s interesting these days is how often it drifts back to a deceptively simple question: how much time do our cows actually get to do what cows need to do in a 24‑hour day? Michigan State University Extension has been hammering on this idea of cow “time budgets,” building on work from researchers like Dr. Rick Grant, long‑time president of the William H. Miner Agricultural Research Institute, who helped turn barn‑floor observations into hard numbers on how cows use their day.

What I’ve noticed—looking at those MSU guidelines, Grant’s stocking‑density work, and newer sensor‑based studies from commercial herds—is that the gap between “we’re doing alright” and an extra 5–8 pounds of milk per cow per day often comes down to how close you keep cows to roughly three to three‑and‑a‑half hours per day away from their pen for milking and handling. In a world where interest rates and building costs are higher than they used to be, labor’s tight, and component prices move enough to make budgeting feel like a moving target, that little block of time might be one of the cheapest and most overlooked levers you’ve got to protect both cow welfare and profitability.

Looking at This Trend Through the Cow’s Day

Looking at this trend, the place to start really isn’t the ration sheet or the parlor report. It’s the cow’s day.

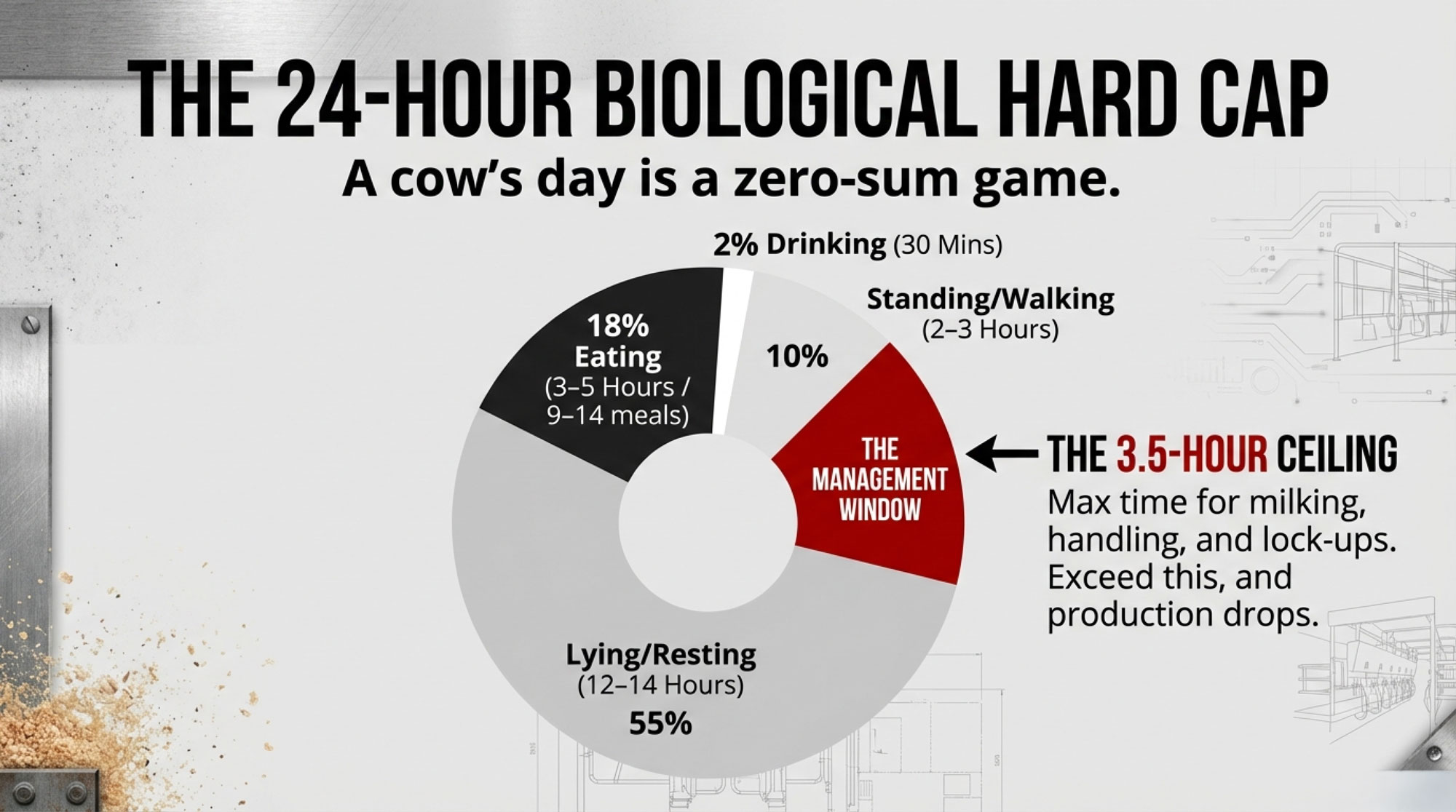

Michigan State’s “Time management for dairy cows” article pulls together behavior research, including Grant’s work, to lay out a typical 24‑hour time budget for a lactating cow in a freestall barn. In a well‑run system, they describe cows generally spending:

- About 3 to 5 hours per day eating, eating across roughly 9 to 14 meals.

- Around 12 to 14 hours lying and resting.

- Roughly 2 to 3 hours standing and walking in alleys.

- About 30 minutes of drinking.

Rumination sits on top of this. MSU and follow‑up work from other groups describe cows typically ruminating 7–10 hours per day, mostly while lying or quietly standing, with clear 24‑hour patterns: more eating and walking during the day, more lying and ruminating at night. A 2022 sensor‑based study from commercial Dutch herds, for example, showed that cows on both conventional and automatic milking systems followed that pattern fairly consistently, with differences by parity and system, but the same basic rhythm.

Here’s what’s important for management. When you plug the mid‑range of MSU’s time‑budget numbers into their table, you end up with 20.5 to 21.5 hours per day already spoken for by basic cow behaviors: eating, lying, walking, drinking, and chewing cud. If you accept that as the “absolute time requirement” for a cow—which is exactly how Grant frames it in his Western Dairy Management Conference work and later extension pieces—then you’re left with only about 2.5 to 3.5 hours in a day to spend on the things we add: walking to and from the parlor, standing in the holding pen, lockup for fresh cow management and herd checks, breeding work, hoof trimming, you name it.

And here’s the kicker MSU and Grant both emphasize: if we routinely keep cows out of their pens and away from their stalls, feed, and water for more than about 3.5 hours per day, they can’t stretch the day—they have to cut time from somewhere else, and it’s usually resting or eating.

If you’ve ever walked the barn at one in the morning on a cold January night with a flashlight and counted how many cows are lying versus standing, you’ve already been doing a simple version of a time‑budget check. The research just gives you some numbers and targets to go with what your gut already tells you when you see too many cows on their feet at that hour.

What You See When You Actually Put a Watch on It

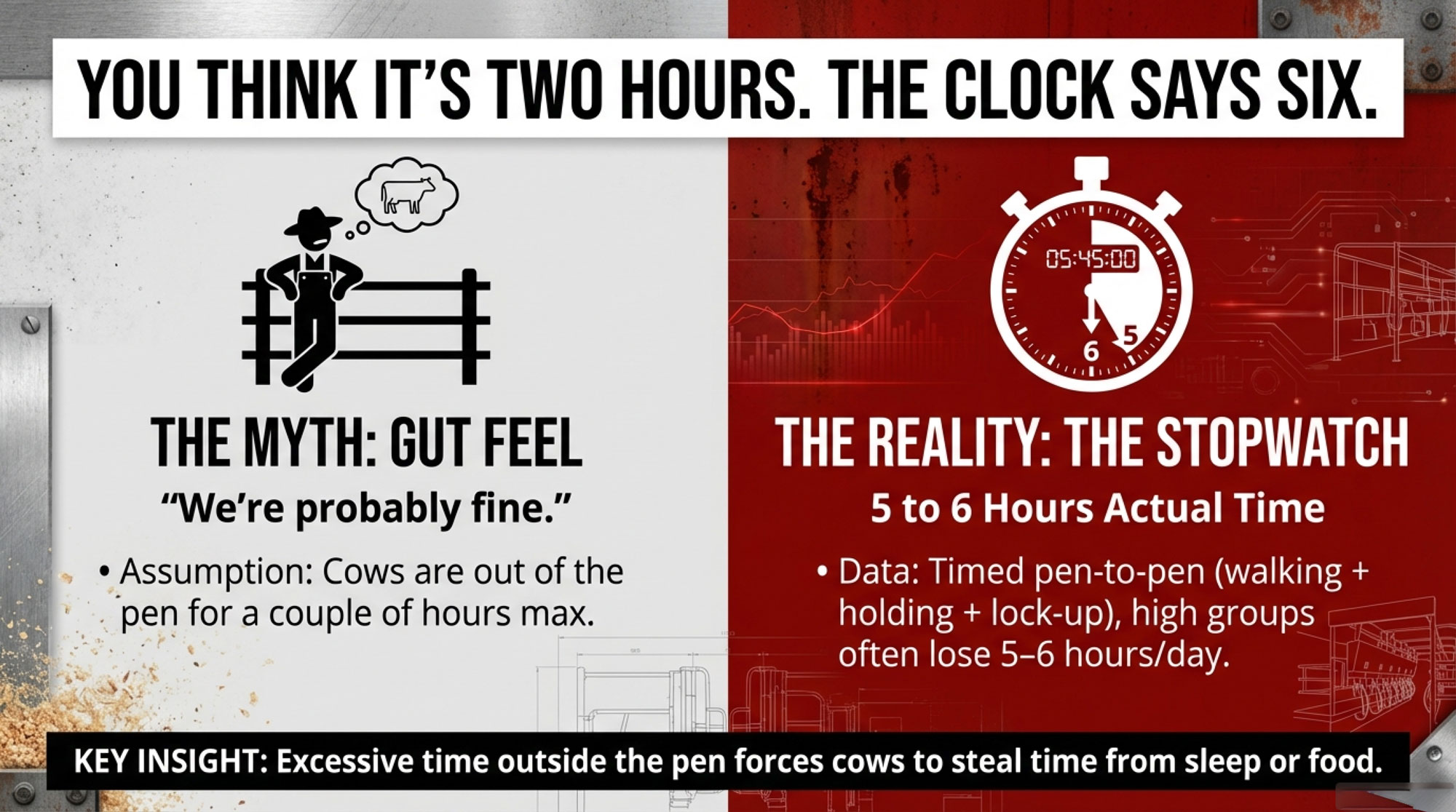

What farmers are finding is that once they get past “we’re probably fine” and actually time cows from pen to pen, the picture usually changes.

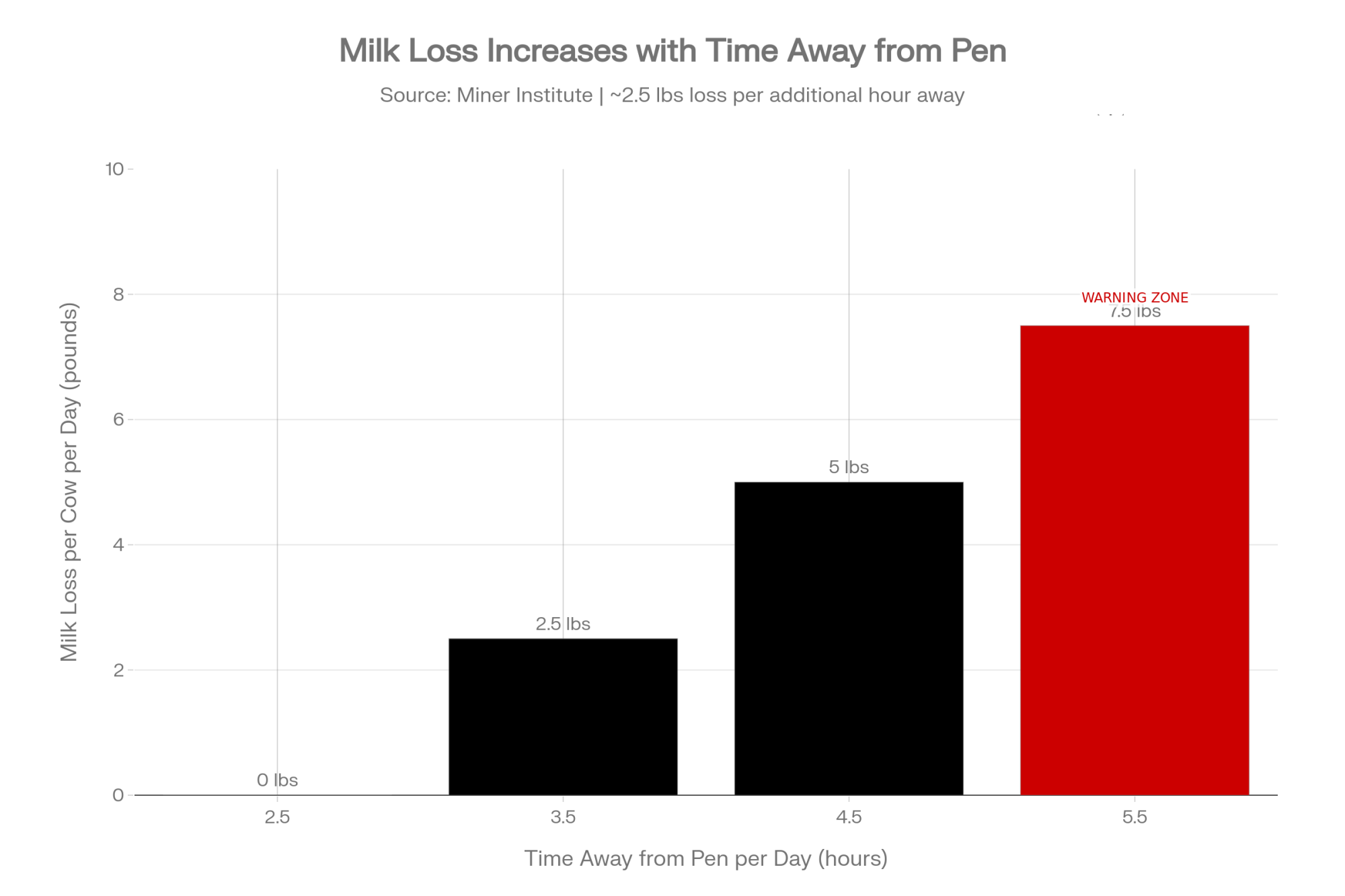

On a lot of Midwest freestall operations I’ve been on, people will say, “Our cows are only out of the pen a couple of hours a day.” And sometimes they are. But when we pull out a notebook and start timing groups from first cow leaving the pen to last cow returning—including the walk, holding‑pen waiting, and lockup tied directly to milking or fresh cow checks—we often find totals closer to five or even six hours per day outside the pen for some high groups. That’s exactly the kind of pattern MSU’s time‑management piece warns about when they highlight “excessive time outside of the pen” and “prolonged times for milking and in lock‑ups” as key risks for reduced resting and eating time.

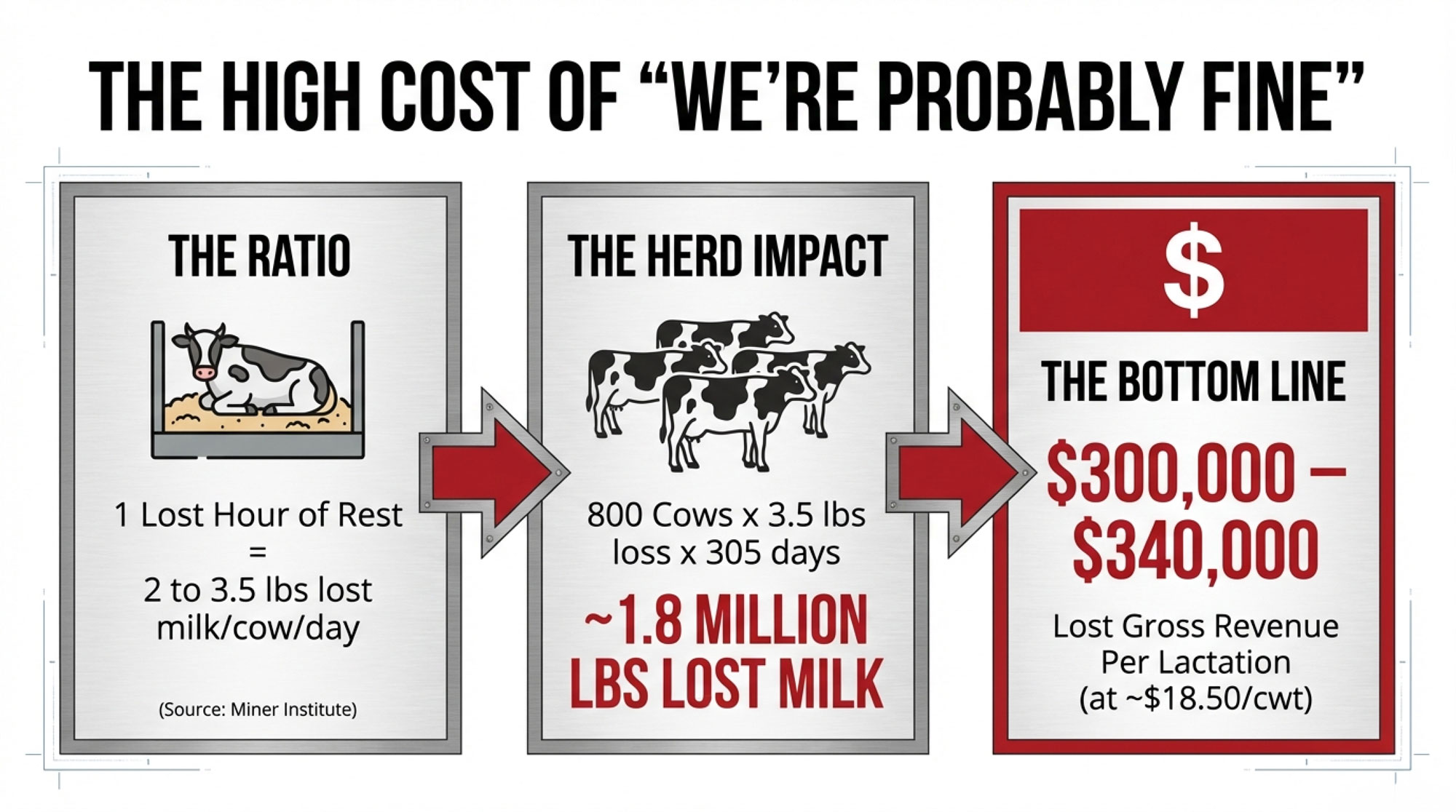

Grant’s work at Miner Institute helps put that into the context of the bulk tank. In a stocking‑density trial there, his team increased stall stocking density from 100% to 145% while holding alley space constant. Lying time dropped by 1.1 hours per cow per day, and average milk yield fell from 94.6 pounds to 91.3 pounds per cow per day—a 3.3‑pound drop. In his conference paper, Grant noted that this fit well with a larger Miner data set, in which each one‑hour change in resting time was associated with a 3.5‑pound change in daily milk yield.

Now, that doesn’t mean every herd will see exactly 3.5 pounds of milk response for every extra hour of rest. Genetics, ration, health, and management all play a role. That’s why many extension educators and industry advisors talk about a band—roughly 2 to 3.5 pounds of milk per cow per day for each additional hour of lying time in high‑producing herds—rather than a single magic number. The lower end reflects other comfort and stocking‑density studies and field experience; the upper end is anchored in Grant’s Miner data.

If you take a conservative mid‑point in that band—say 2.5 pounds per cow per day per extra hour of lying, and you look at a group that’s slipped from about 13 hours of rest down to 10, you’re staring at a three‑hour gap. On that mid‑point assumption, that’s roughly 7.5 pounds of potential milk per cow per day tied to rest and comfort, before you touch the ration. It’s a scenario, not a promise, but it’s grounded in relationships we’ve seen again and again in both research and field work.

Now lay that scenario over an 800‑cow milking group. Seven‑and‑a‑half pounds per cow per day works out to about 6,000 pounds of milk per day. Over a 305‑day lactation, that’s roughly 1.8 million pounds of milk. At $18.50 per hundredweight, that kind of response would be worth somewhere in the neighborhood of $330,000–$340,000 in gross revenue for that group. If you prefer to think per cow, you’re looking at roughly $400–$425 per cow in that group on those assumptions. The exact number on your farm will depend on how your cows respond, but it gives you a sense of just how expensive “we’re probably fine” can be when time away from pens quietly creeps up.

Comparison Table – 800-Cow Herd Economic Impact

| Metric | Well-Managed (3.5 hrs away) | Typical Overrun (5.5 hrs away) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time away from pen (hrs/day) | 3.5 | 5.5 | +2.0 hrs |

| Lying time per cow (hrs/day) | 13.0 | 10.0 | −3.0 hrs |

| Milk per cow per day (lbs) | 77.5 | 70.0 | −7.5 lbs |

| Total daily milk (800 cows, lbs) | 62,000 | 56,000 | −6,000 lbs |

| Butterfat % | 3.85 | 3.62 | −0.23 pp |

| Estimated milk price ($/cwt) | $18.50 | $18.50 | — |

| Daily milk revenue | $11,455 | $10,360 | −$1,095 |

| Annual milk revenue (305-day lactation) | $3,494,075 | $3,159,800 | −$334,275 |

| Estimated vet & culling cost increase (annual) | $8,000 | $24,000 | +$16,000 |

| Total estimated annual gap per herd | — | — | −$350,275 |

Notes:

- Milk price based on 2024–2025 North American averages; butterfat premium not included in base calculation.

- Vet & culling costs estimated from lameness, reproductive, and mortality increases reported in comfort trials.

- Assumes 3.5-hour baseline; gap widens if your herd currently exceeds 5.5 hours away.

And remember—that’s just the production side. The same shift that cuts lying time and milk also pushes cows to spend more time on their feet on concrete, which is tied to more claw lesions, hock injuries, and lameness. Reviews of lying behavior and productive efficiency indicate that when cows lose resting time, they don’t just give up milk; they develop more leg problems and often leave the herd sooner. That doesn’t show up in tomorrow’s bulk tank, but it absolutely shows up in culling and vet bills over the next few years.

What’s encouraging is that when herds work with their veterinarians and nutritionists to tighten up milking routines, trim unnecessary lockup, and improve cow flow—without changing barns—they often see lying time go up and milk follow. Extension case material and advisor reports consistently show more resting time, calmer cows, and better production when time outside the pen is brought back inside that three-to-three-and-a-half-hour window. For many of us, that’s low‑hanging fruit.

Why Lying Time Has Turned Into a Performance Metric

Looking at this trend, one thing that jumps out is how lying time has shifted from being a “comfort” topic to a performance metric.

A 2024 practical overview on lying behavior and productive efficiency in dairy cattle pulled together several studies and concluded that cows are motivated to rest roughly 10–12 hours per day, and that comfortable, well‑bedded freestalls often see lying times closer to 12–14 hours. Dr. Peter Krawczel’s review on lying time, from the University of Tennessee, echoes that: he highlights that lying is a high‑priority behavior, that cows will often sacrifice some feeding time before they give up rest, and that overstocking and poor stall design consistently reduce lying time and alter feeding and rumination patterns.

That’s why more welfare assessment systems and practical farm protocols now treat lying time as a core measure. A 2022 pasture‑based welfare assessment protocol, for instance, used late‑night lying percentages in the 80–90% range as a practical threshold for good welfare on grazing dairy farms. Extension advisors have taken that idea into freestall barns as a realistic, boots‑on‑the‑ground check: if you walk the barn between midnight and three in the morning and see far fewer than 80% of cows lying in a freestall group, something’s crowding resting time.

On the performance side, Grant’s work and related cow‑comfort research have tied rest to milk production with much greater confidence. That Miner trial we talked about—where a 1.1‑hour drop in lying time came with a 3.3‑pound drop in milk—wasn’t a one‑off. When Grant compared the results to a larger data set from Miner, the pattern of about 3.5 pounds of milk per cow per day for each hour of resting time. Other work on stall comfort and stocking has documented smaller gains, which is why it’s more honest to talk about a range than a single number.

Biologically, it adds up. When cows lie down, blood flow through the udder increases, supporting milk secretion. When they spend less time standing on concrete, they reduce constant load on claws and joints, which reduces lameness risk and lameness‑related milk and reproduction losses. And when they ruminate while lying, they produce large volumes of saliva rich in bicarbonate and phosphate that help buffer rumen pH on high‑energy diets.

What I’ve noticed is that once producers start thinking of lying time not just as “comfort,” but as “milk time” and “soundness time,” their perspective on stocking density, holding‑pen design, and headlock duration shifts. It stops being a welfare box you check for someone else and becomes a performance indicator right alongside butterfat performance and fresh cow management in the transition period.

Rumination While Lying: The Quiet Edge Behind Strong Butterfat and Protein

As more herds add rumination and activity collars, you can do more than just look at total minutes ruminated per day. That’s helpful, but where and how that rumination happens adds another layer.

A 2021 study led by Caitlin McWilliams and Dr. Trevor DeVries at the University of Guelph looked at this in a free‑traffic automatic milking system. They introduced a measure they called the “probability of ruminating while lying down” (RwL probability) and then examined how that related to total rumination time, lying time, dry matter intake, and milk production outcomes.

Here’s what their data showed: cows with a higher RwL probability spent more time ruminating and more time lying. Those same cows tended to have higher dry matter intake. They also produced milk with higher protein content, which and often had higher fat content, even though there wasn’t a clear association between RwL and milk yield in a particular herd.

This development suggests something quite practical. Encouraging rumination while lying may not automatically add litres, but it does appear connected with better component performance and intake. That matches what many of us see: in herds where cows spend plenty of time lying quietly and chewing their cud, butterfat performance and protein levels tend to look more stable, even if their total volume isn’t wildly high.

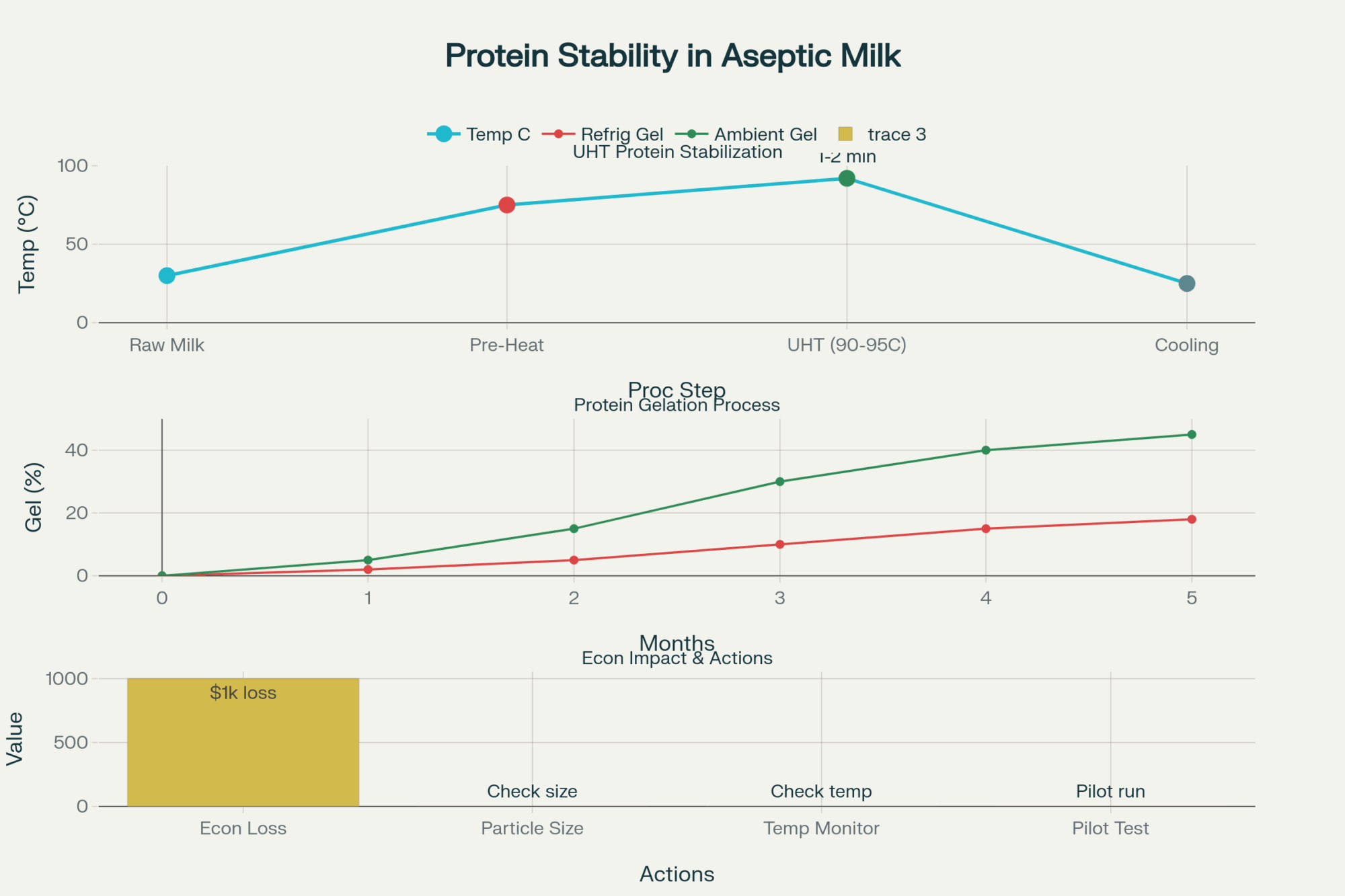

From a rumen perspective, that fits. Reviews on SARA and feeding behavior point out that high‑producing cows can generate more than 100 liters of saliva per day, much of it during rumination. That saliva is loaded with bicarbonate and phosphate, which help maintain a healthier rumen pH on high‑energy diets. When rumination happens while cows are lying comfortably, rumen contractions tend to be more regular, gas escapes better, and the fiber mat stays more stable. In simple terms, the time budget and stall comfort you invest in turn into more effective rumen function—and better butterfat and protein cheques—rather than just “happy cows” for their own sake.

How Overstocking, Bunk Space, and SARA Tie Together

Looking at this trend inside the barn, the time‑budget conversation really comes to a head when you look at how hard you’re pushing stocking density and bunk space.

Comparison Table – Stocking Density, Bunk Space & Farm Outcomes

| Stall Stocking Density | Bunk Space per Cow | Lying Time (hrs/day) | Feeding Behavior | Primary Health Risk |

| 100% (1 stall per cow) | 24″–30″ | 13–14 hrs | 9–14 meals/day, steady intake | Low—Baseline |

| 110% (1.1 cows per stall) | 22″–24″ | 12–13 hrs | 8–10 meals/day, slight acceleration | Mild increase in standing; early hock wear |

| 120% (1.2 cows per stall) | 20″–22″ | 10–12 hrs (−12% to −27% vs. 100%) | 6–8 meals/day, +20% eating speed, competition | SARA risk, lameness, softer butterfat |

| 130%+ (1.3+ cows per stall) | <20″ | <10 hrs (−27%+ vs. 100%) | 4–6 meals/day, slug feeding, intense competition | High SARA, severe lameness, milk drop (>3 lbs/cow/day), early culling |

Notes:

- Thresholds based on MSU Extension, Miner Institute, and KSU stocking-density trials.

- Eating speed increase (~20%) from competition studies on commercial farms.

- Rumination drop: ~25% decrease when stocking goes from 100% to 130%.

- Milk yield loss: ~0.5 lbs per 10% increase in stocking density; butterfat often softer by 0.15–0.25 percentage points.

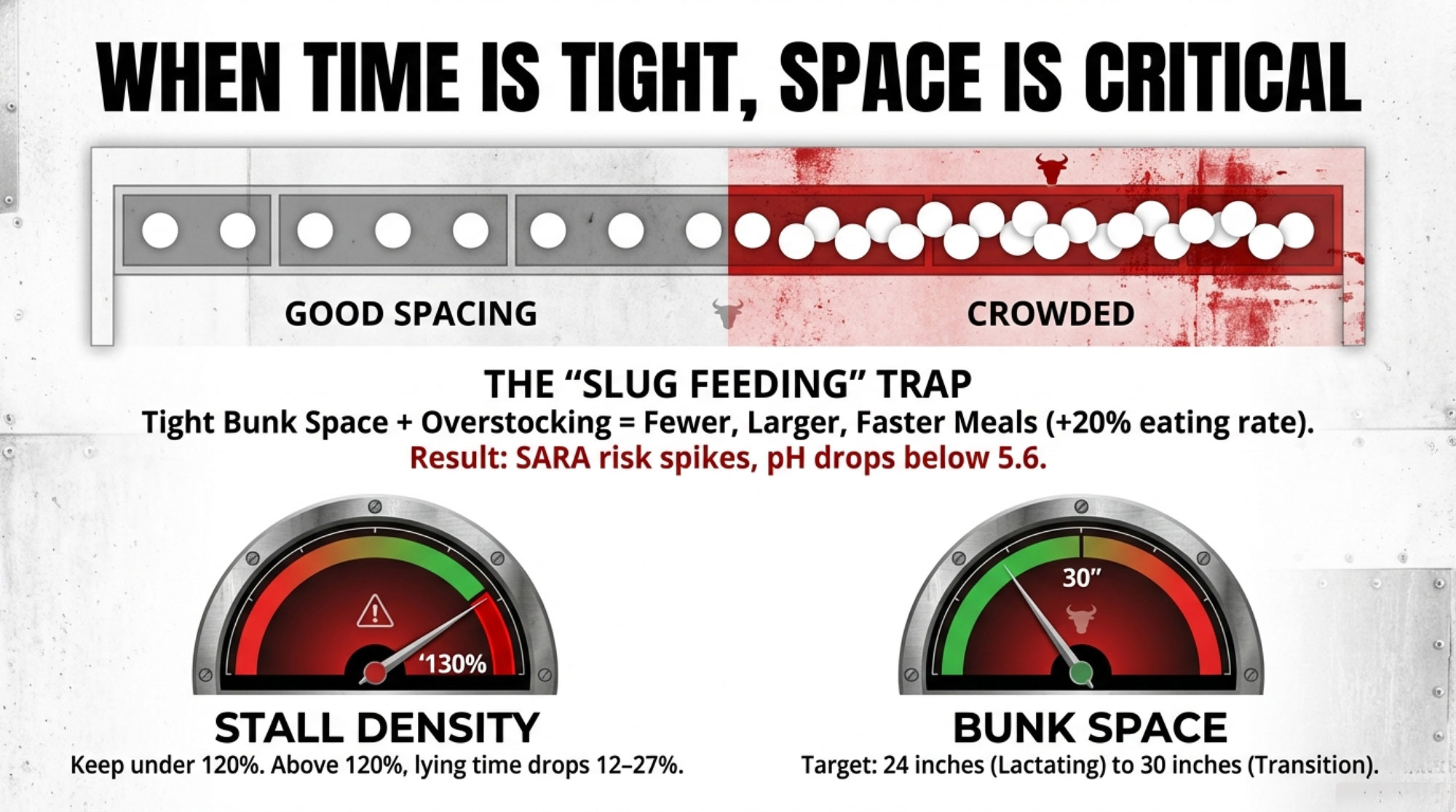

MSU’s time‑management guidelines pull together several studies and note that when stall stocking density is pushed to around 120% and higher, resting time typically drops 12–27% compared with 100% stocking, and cows spend more time standing, often waiting for a stall. Grant’s Western Dairy Management Conference paper on stocking density and time budgets reports that increasing stall stocking from 100% to 145% cut lying time by 1.1 hours and reduced milk yield by 3.3 pounds per cow per day, and he cites other work showing that rumination can drop by about 25% when stocking density goes from 100% to 130%.

At the bunk, MSU and other extension sources recommend at least 24 inches of bunk space per cow for most lactating groups, and around 30 inches or more for transition and fresh pens. When bunk space gets tight—especially when combined with overstocking—cows don’t just spread out their meals and share nicely. Research on commercial farms shows that they shift to fewer meals per day, eat larger meals, and eat faster, with the eating rate increasing by roughly 20% or more in some comparisons.

That’s exactly the sort of slug feeding pattern that sets the stage for subacute ruminal acidosis. Reviews of SARA describe it as rumen pH dropping below about 5.6 for several hours per day in a significant portion of the herd, particularly when diets are rich in fermentable carbohydrates and marginal in physically effective fiber. On the ground, it doesn’t show up as one big crash so much as a pattern: lower or more volatile butterfat, on‑again/off‑again intakes, more laminitis and sole ulcers, and poorer feed efficiency.

In practical terms, when you overstock pens and tighten the bunk, you usually see the same cluster of problems:

- Less lying time and more standing and waiting.

- Fewer, larger, faster meals.

- More pressure on rumen pH and higher SARA risk.

- More hoof problems and softer butterfat performance.

To put it in barn language, when you combine too many cows, too few stalls, tight bunk space, and long parlor or lockup times, you’re taking time and space away from lying and from steady, comfortable eating. The costs show up as lost milk, weaker butterfat performance, more hoof problems, and cows that don’t last as long in the herd—all things most of us would rather avoid.

Why the Economics Make This Worth Another Look in 2026

So why push on this now?

In 2026, many of you are looking at expansion, remodeling, or equipment upgrades with a different lens than you would have a decade ago. Interest rates have been higher than we were used to for much of the previous decade, construction costs are elevated, and labor remains a constant constraint. At the same time, milk and component prices have enough volatility baked in that locking into large capital projects can feel risky.

In Canada, quota limits how much you can ship, so the question is often “How do I get more from the litres I’m already allowed to send?” rather than “How do I add cows?” In parts of Europe and New Zealand, climate and stocking regulations under frameworks such as the EU Green Deal and national emissions policies are pushing producers to get more from fewer cows, not just to increase herd size.

That’s where time budgets become a pretty attractive lever. They’re one of the few big knobs you can turn that doesn’t automatically involve concrete and steel. Tightening up how long cows spend away from pens and how crowded those pens are is about measurement, schedule, and flow. You can use the resting‑time–milk relationships as rough guides—knowing that extra rest has been associated with better milk and health—to get a sense of what you might be leaving on the table.

On top of that, component prices matter. If you look at 2024–2025 pay schedules and convert them, butterfat often clears the equivalent of more than $2.50 per kilogram, and protein frequently carries an even higher per‑kilogram value in some markets. That means better butterfat performance and more stable protein—tied to better time budgets and rumen function—can be worth as much as, or more than, an extra pound or two of volume on a mid‑sized herd. In other words, a more relaxed cow with plenty of lying and rumination time may not just give more milk; she may give more valuable milk.

What Farmers Are Finding When They Start Measuring

What farmers are finding, once they get serious about it, is that timing cows and counting resources changes the conversation fast. If you haven’t timed cows from pen to pen in the last year, you’re managing time budgets based on gut feel.

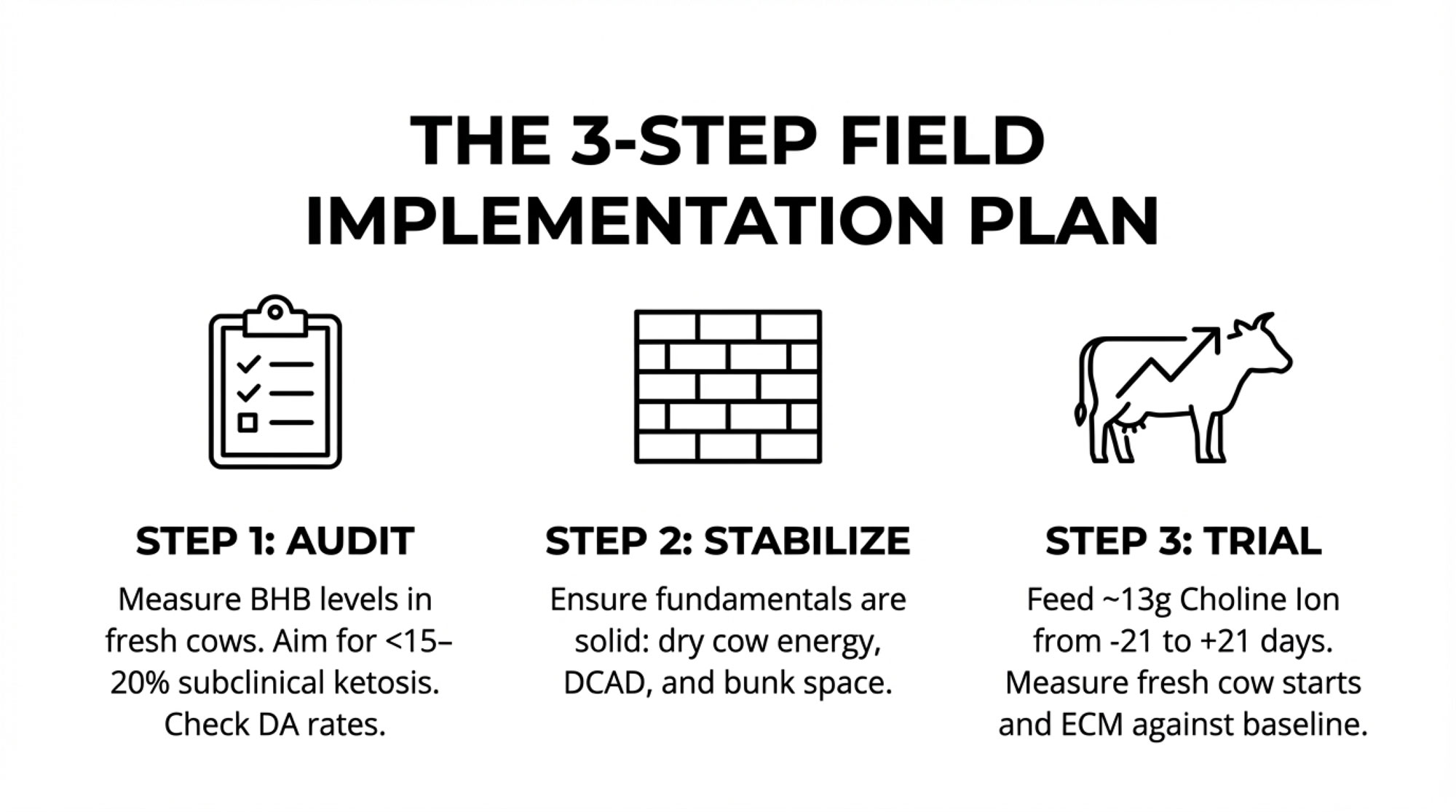

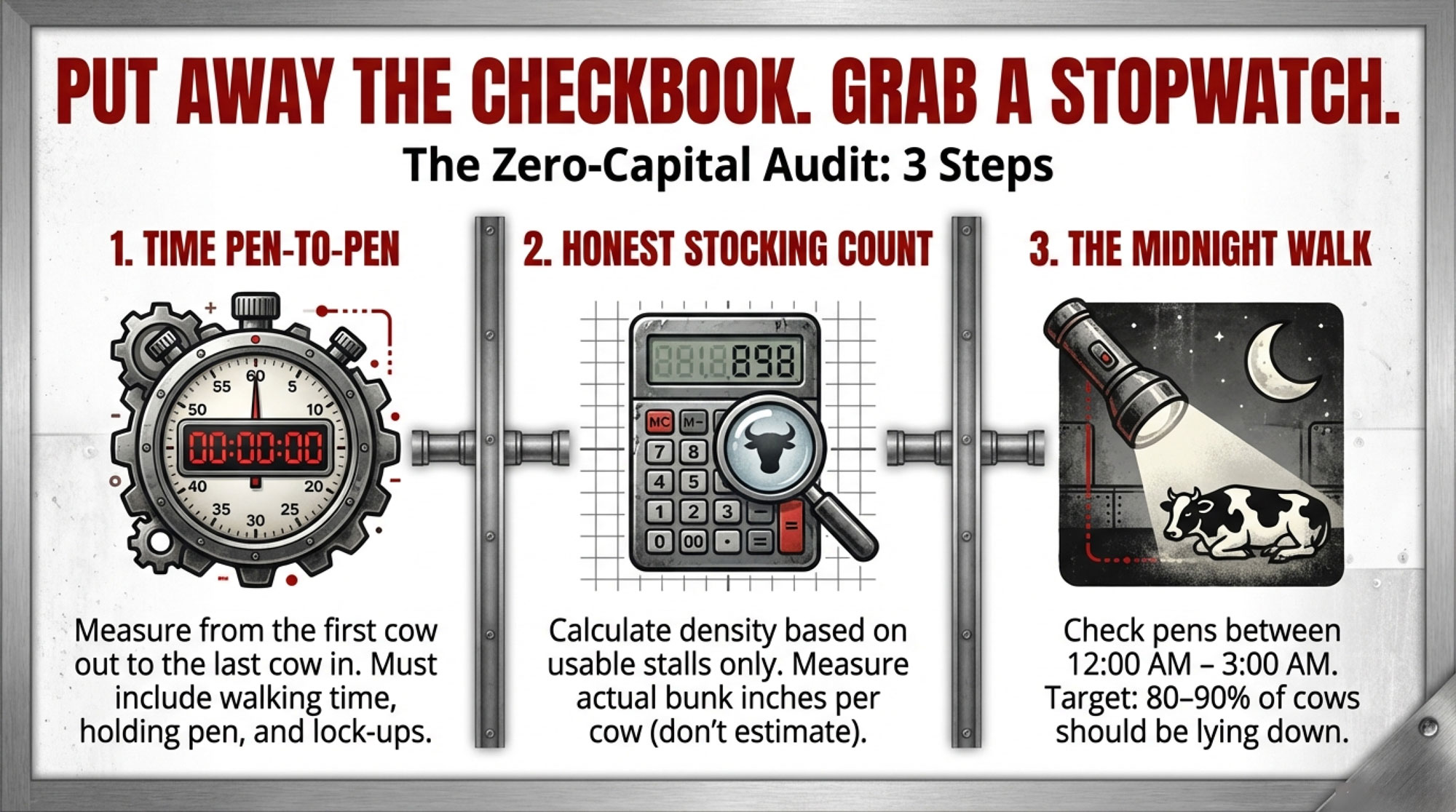

Most herds that take a real look at this follow a similar three‑step path.

Step 1: Time cows from pen to pen.

For each group, write down when the first cow leaves the pen and when the last cow returns after each milking for several days. Include walking time, holding‑pen staging, and lockup directly tied to milking or fresh cow work. In pasture‑based systems—like many in New Zealand—researchers have used leg sensors to track walking distance and time away from paddocks. In one 2021 study, when time away from pasture for milking and travel increased to around four hours per day, cows spent less time lying, and in at least one once‑a‑day herd, milk yield declined as time away increased—even though grazing and rumination time were fairly stable.

Step 2: Check stocking density and bunk space honestly.

Count the number of usable stalls and cows in each group to calculate stall stocking density. Measure total feed‑rail length and divide by cow numbers to get true bunk space per head. MSU and other extension resources encourage aiming for around 100% stall stocking or less in most lactating pens, and roughly 80–100% in close‑up and fresh pens. On the feed line, that means about 24 inches of bunk space per cow in most lactating groups and about 30 inches or more per cow in transition and fresh pens. When you grab the tape and the notebook, it’s not uncommon to find that some key pens—often the fresh and high groups—are tighter than anyone realized.

Step 3: Do a late‑night lying check.

Sometime between midnight and three in the morning, walk through each pen quietly and estimate what percentage of cows are lying down. Welfare assessment work and practical protocols often use a range of 80–90% lying at that time of night as a realistic target in well‑managed freestall groups. If your numbers come in much lower than that—or you see a lot of cows standing half‑in, half‑out of stalls—that’s a strong signal that either time away from pens, stocking, or stall comfort is getting in the way of rest.

If you do nothing else this month but time your high group’s trips to and from the parlor, count stalls and bunk space, and walk pens once late at night, you’ll at least know whether time and space are more friend or foe in your setup.

Case Snapshots Across Different Systems

Looking at this trend across different systems, the specific bottlenecks change, but the underlying biology doesn’t.

- Pasture‑based herds in New Zealand.

In New Zealand, where cows spend most of their time grazing, researchers have used sensors to track grazing, rumination, and idling across full lactations. One 2023 paper reported that cows spent most of their 24‑hour day grazing, followed by ruminating and then idling, with season and supplementary feeding affecting the distribution of those behaviors. In the related time‑away work, when cows spent more time off pasture for milking and travel—up toward four hours a day—lying time dropped, and in at least one once‑a‑day herd, milk yield decreased as time away increased. It’s essentially the grazing version of long milking and holding‑pen times in a freestall system. - Tie‑stall herds in Quebec and the Northeast.

In regions like Quebec and parts of the northeastern U.S., where tie‑stall barns are still common, studies comparing tie‑stall and freestall housing show that stall design and bedding depth seriously affect lying time and leg health in both systems. Narrow stalls, poor neck‑rail placement, or thin bedding cut lying time and increase hock and knee injuries; better stall dimensions and deeper bedding do the opposite. Extension work in those regions shows that when producers deepen bedding, adjust stall hardware, and reorganize herd‑health and vet visits so cows aren’t tied up long beyond milking, follow‑up assessments tend to show more lying between milkings, fewer injuries, and steadier production. - Dry lot systems in the West and Southwest.

In large dry lot systems in California and the Southwest, the story’s usually about heat and distance. Heat‑stress research from Israel and western U.S. dairies consistently shows that shade and cooling around parlors and resting areas help maintain milk yield and fertility in hot conditions. When high‑producing cows have to walk long distances in the heat and stand in unshaded, crowded holding pens for long periods, their lying time and rumination suffer, and heat load climbs. When farms add shade and cooling near parlors and change milking schedules to avoid peak afternoon heat, behavior and production data both show that cows spend more time lying and hold milk and repro performance better.

Across all these systems—freestall, tie‑stall, pasture, dry lot—the same basic needs show up. Cows need enough time to eat, lie, walk, drink, and ruminate. The details of how time gets stolen differ, but the cost tends to fall into the same areas: milk, butterfat performance, hoof health, and longevity.

Quick Reference: Time‑Budget Targets at a Glance

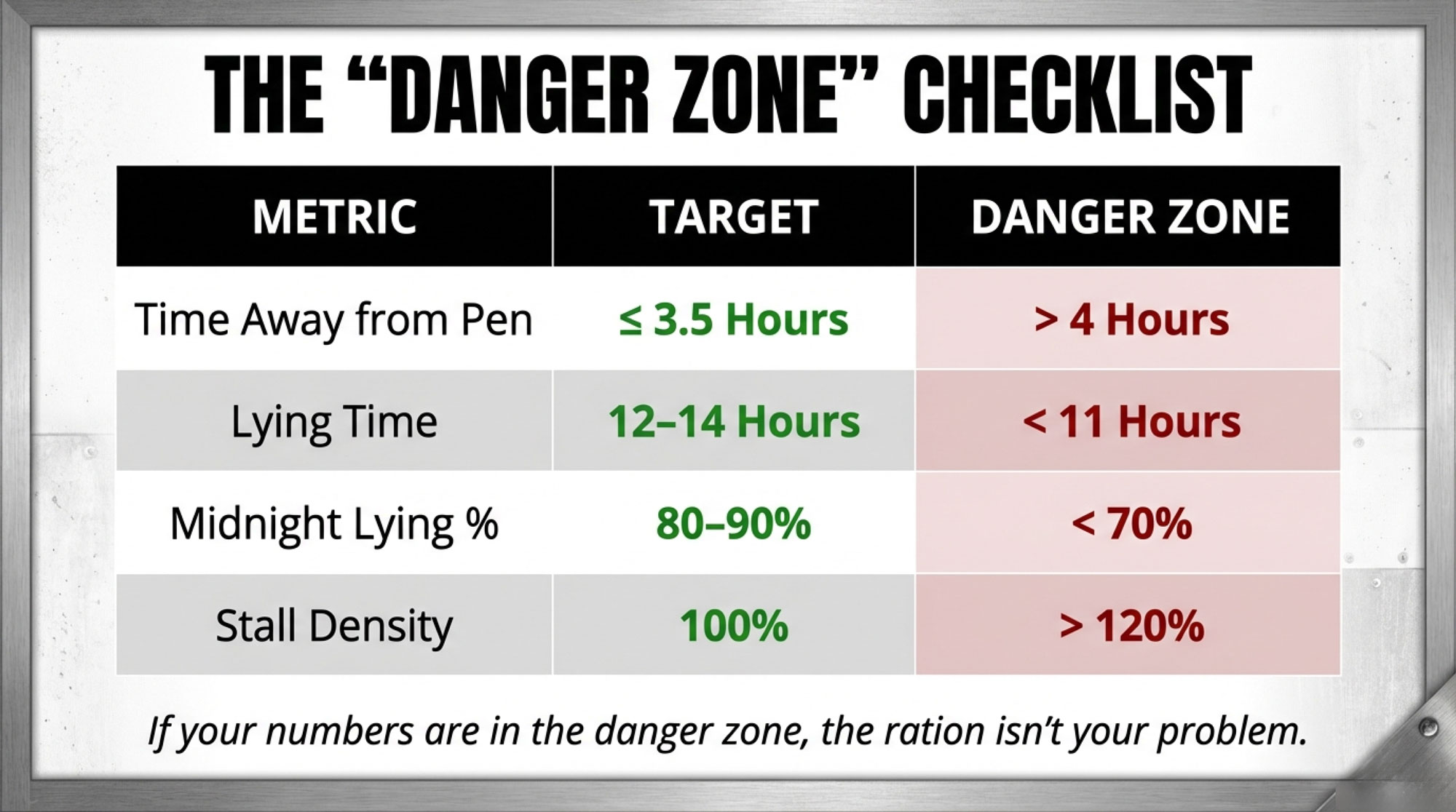

If you’re reading this on your phone between milkings, here’s a quick snapshot of the key targets from the research and extension work we’ve been discussing.

| Time‑Budget Target | Recommended Range | Why It Matters |

| Total time for core behaviors (eat, lie, walk, drink, ruminate) | ~20.5–21.5 hours/day | Leaves only 2.5–3.5 hours for milking and handling; beyond that, cows must give up lying or eating. |

| Time away from pen (milking + handling) | Aim for ≤ 3–3.5 hours/day | Longer times are associated with reduced lying and eating and, in some grazing herds, lower milk yield. |

| Lying time | At least 12 hours/day; often 13–14 in comfortable freestalls | Shorter lying times are associated with lower milk production, more lameness, and higher stress. |

| Late‑night lying percentage (midnight–3am) | Roughly 80–90% of cows lying | Practical on‑farm indicator that groups are meeting resting needs. |

| Bunk space | ~24″ per cow in most lactating pens; ~30″+ in transition/fresh pens | Tight bunk space and overstocking push slug feeding, competition, and SARA risk. |

| Stall stocking density | Around 100% in most lactating pens; 80–100% in transition/fresh; issues grow above ~120% | Over‑stocking reduces lying time by 12–27%, increases standing, and reduces rumination. |

If your numbers are far outside those ranges, it’s a strong signal that time and space deserve a closer look before you assume the ration is the whole story.

Bringing It Back to Nutrition, Fresh Cow Management, and the Big Picture

Looking at this trend, one thing that often gets missed is that time budgets and nutrition aren’t separate projects. They’re deeply linked.

Over the last decade, many herds in North America and Europe have done impressive work on nutrition and transition: improving forage quality, dialing in chop length and physically effective fiber, tightening TMR mixing and delivery, refining transition‑period diets, and experimenting with different calving intervals and extended lactations. At the same time, many operations have invested heavily in cow comfort—better freestall design, deeper bedding, improved ventilation and cooling, and more thoughtful fresh cow management protocols.

What the time‑budget and welfare work add is a reminder that all those investments only deliver full value if cows have enough usable hours in the day to eat and rest on the facilities you’ve provided. A fresh cow on a top‑notch transition ration can still struggle if she’s spending a big chunk of her day standing in a crowded holding pen or stuck in a headlock and not enough time lying and ruminating on the comfortable stall you’ve paid for.

So a fair question to ask yourself is: are we giving our cows enough time to actually use the feed and facilities we’ve invested in? If your time‑budget numbers say yes—that you’re within that three to three‑and‑a‑half‑hour window for milking and handling, that stocking and bunk space are in line with the targets, and that most cows are lying at night—then you’re probably right to keep your main focus on forage, ration structure, fresh cow management, breeding, and repro. If the numbers say you’re outside those windows—or you simply don’t know yet—then a month of timing and some targeted adjustments might be one of the best returns you can get this year without signing a construction contract.

Five Things to Take Back to the Barn

If we were sitting at your kitchen table right now, coffee mugs between us and a notepad on the table, and you asked, “Alright, what do I actually do with this?”, here are the five points I’d want you to carry back out to the barn.

- Cows don’t have much spare time.

When you add up the behavior research and extension guidelines, cows need roughly 20.5–21.5 hours a day for eating, lying, walking, drinking, and ruminating. That leaves only about 2.5–3.5 hours for milking and handling before they’re forced to cut into rest or eating. Before you change anything else, it’s worth timing your groups and seeing whether your management fits inside that window. - Lying time really is milk time—and soundness time.

Field data from Miner Institute and other cow‑comfort work show that more resting time is associated with higher milk yield and better hoof health, while less rest and more standing go hand‑in‑hand with lower production and more leg problems. If your high group is averaging under about 12 hours of lying time, that’s a strong hint that improving rest might give you a better return than one more ration tweak. - How cows ruminate matters as much as how much.

The robot‑herd study from Guelph showed that cows with a higher probability of ruminating while lying spent more total time ruminating and lying, tended to eat more, and produced milk with higher protein and better fat, even though they didn’t necessarily produce more volume. Getting cows out of holding pens, lockups, and hot alleys and back onto comfortable beds is part of protecting rumen function and component performance. - Overstocking and tight bunks have a real biological ceiling.

Once stall stocking pushes past about 120% and bunk space falls below roughly 24 inches in lactating pens and 30 inches in transition pens, research consistently shows shorter resting time, more competition, faster eating, and a higher risk of SARA and lameness. If your butterfat performance is jumpy, hoof issues are creeping up, and pens are crowded, time budgets and space are almost certainly part of the picture. - Start with a stopwatch, not a checkbook.

Before you dive into new barns or major parlor work, it’s worth spending a few weeks timing cows from pen to pen, counting stalls and bunk space, and doing at least one late‑night lying check. Those simple steps can show you whether time and space are really the bottlenecks—and they often point you toward schedule and flow fixes you can make long before you need to pour concrete.

If you run these numbers and find something surprising—or make changes and see results—I’d be genuinely interested in what you see in your own barns. In a year when interest is high, margins are tight, and big capital projects are harder to justify, taking a fresh, honest look at that 3.5‑hour window and the full 24‑hour time budget may be one of the most practical ways left to find the next few pounds of milk, steadier butterfat performance, and a calmer, more resilient herd.

Diagnostic Checklist Table – 3-Step On-Farm Audit

| Measurement | Target Range | Red Flag | Action If Red Flag |

| Time Away from Pen (group average, hrs/day) | ≤ 3.0–3.5 hrs | > 4.5 hrs | ⚠ Review milking schedule. Reduce holding-pen time. Stagger milking groups if possible. Audit parlor efficiency. Expected gain: 2–4 lbs milk/cow/day. |

| Stall Stocking Density | 100% (or <110% in fresh/close-up pens) | > 120% | ⚠ Reduce cow numbers in pen or add stalls. Overstocking cuts lying time by 12–27%. Contributes to SARA, lameness, reduced butterfat. Expect 2–3 hour lying-time loss per 20% overstocking. |

| Bunk Space per Cow | 24″ (lactating); 30″+ (transition/fresh) | < 22″ in lactating; < 28″ in transition | ⚠ Extend feed rail, reduce cow numbers per pen, or add feeders. Tight bunk = slug feeding, higher SARA risk, softer butterfat. |

| Late-Night Lying % (midnight–3 AM walking count) | 80–90% of cows lying | < 75% cows lying | ⚠ Multiple causes likely: check time away, stocking, stall comfort (bedding, neck-rail position), heat stress. Start with time-away and stocking audits. Expect lying time to improve 1–2 hours within 2–3 weeks if time/space issues fixed. |

How to Use This Table:

- Pick one group (usually high group or fresh pen) and one measurement.

- Time, count, or walk as described.

- Check your number against the target and red-flag ranges.

- If you’re in the red flag zone, follow the action steps.

- Repeat after 2–4 weeks to track improvement.

Notes:

- Timing cows: Write down first cow leaving pen and last cow returning (include walk, holding, lockup). Do this 3–5 days in a row to get a true average.

- Stall count: Usable stalls only (exclude broken, blocked, or poorly positioned stalls).

- Bunk measure: Total feed-rail length (both sides if applicable) divided by number of cows in pen.

- Walking count: Do this in the dark with a headlamp or flashlight; cows are more likely to be in a natural resting posture if they don’t see you.

Key Takeaways

- Your cows only have ~3 hours of “spare” time per day. After eating, lying, ruminating, and drinking, just 2.5–3.5 hours remain for milking and handling—exceed that, and cows sacrifice rest or meals.

- Lost lying time costs real milk and real component dollars. Miner Institute data link each lost hour of rest to 2–3.5 lb of milk per cow per day, along with softer butterfat and a higher lameness risk.

- For an 800-cow herd, that gap can quietly strip $300,000+ from your milk cheque each lactation—and most producers don’t know their actual numbers until they measure.

- Overstocking past ~120% and tight bunk space compound the damage. Lying time drops, slug feeding spikes, and SARA and hoof problems follow.

- Start with a stopwatch, not a checkbook. Time cows pen-to-pen, count stalls and bunk space, and walk pens at midnight—before you approve any new concrete.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Vermont Drought Forces Dairy Farms Into Costly Survival Mode – Arms you with battle-tested survival strategies managers used to navigate the 2025 drought. Reveals exactly how to pivot forage and water management to stop a climate crisis from tanking your 2026 milk checks.

- World Dairy Expo’s Coliseum Is Finally Getting the Overhaul It Deserves – Exposes the long-term impact of the Expo’s major structural overhaul on the global show circuit. Position your operation to capitalize on the modernized facilities that will drive genetics marketing and industry prestige for the next decade.

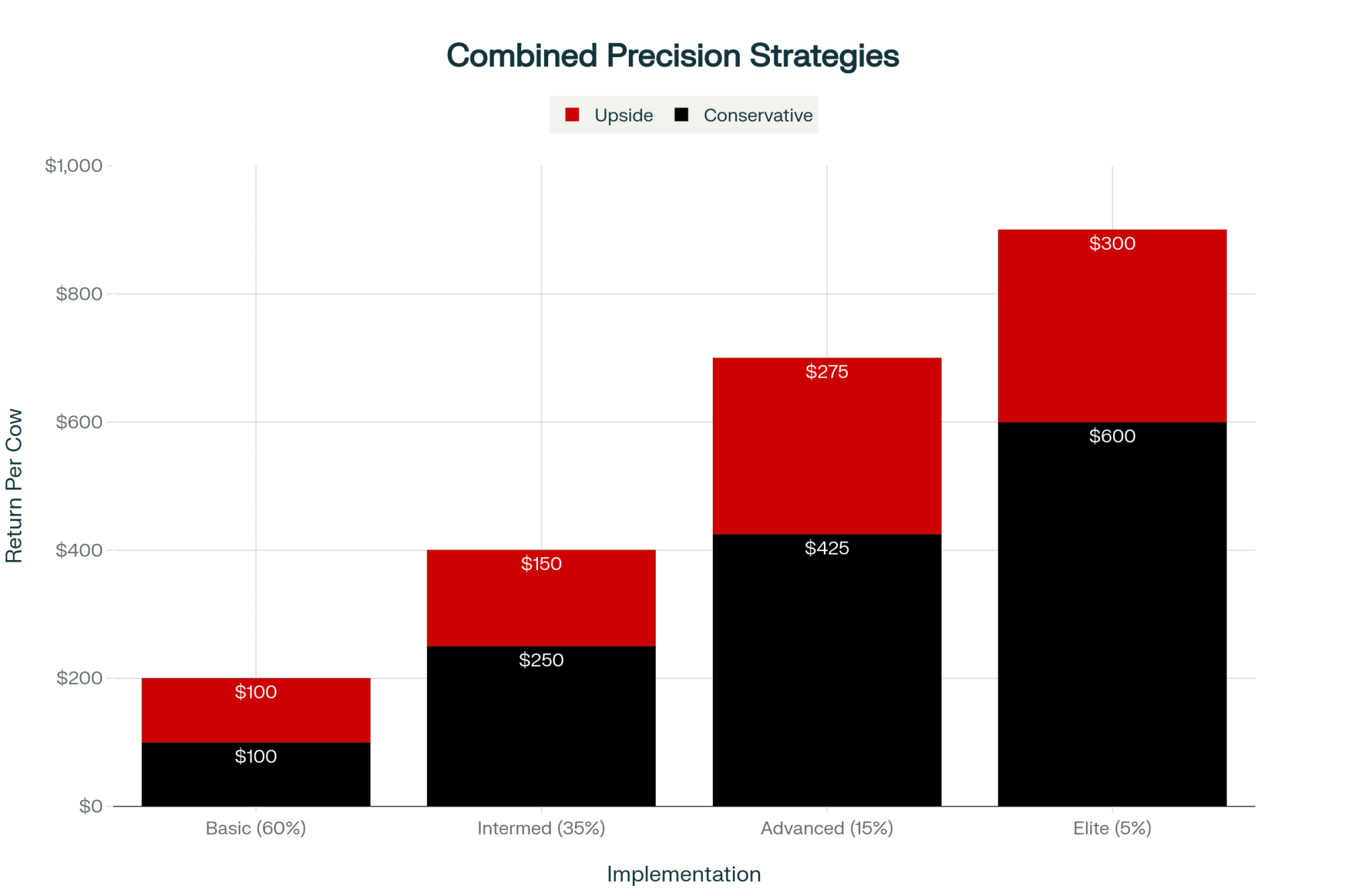

- Precision Management: Translating Cow Behavior into Bulk Tank Dollars – Delivers a focused method for turning wearable sensor data into targeted barn-floor wins. Stop drowning in “data noise” and start leveraging specific rumination and activity metrics to boost individual cow profitability and reduce silent metabolic losses.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!