A Gunny Sack, a Christmas Calf, and the Brood Cow Behind Bootmaker’s 100 Gold Medal Dams

Act I – The Old Friend in the Dry Cow Class

The barn at Waterloo had that sound to it—the low hum that means the good cows are already clipped and bedded, and everyone’s just waiting to see if the judge agrees with what they saw in the tie‑ups. Colored shavings, steel rafters, the smell of iodine and lineament hanging over the ring. Out they came, the Dry Aged Cows, and near the end of the string was one that, by all rights, should’ve been home on a straw pack by then.

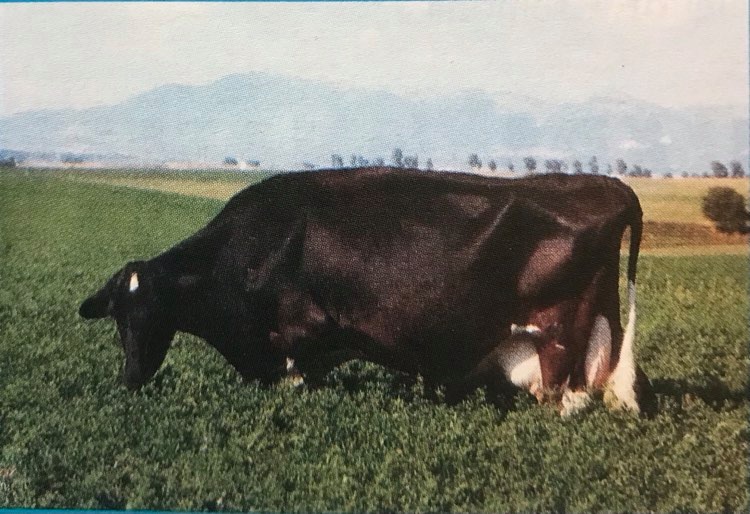

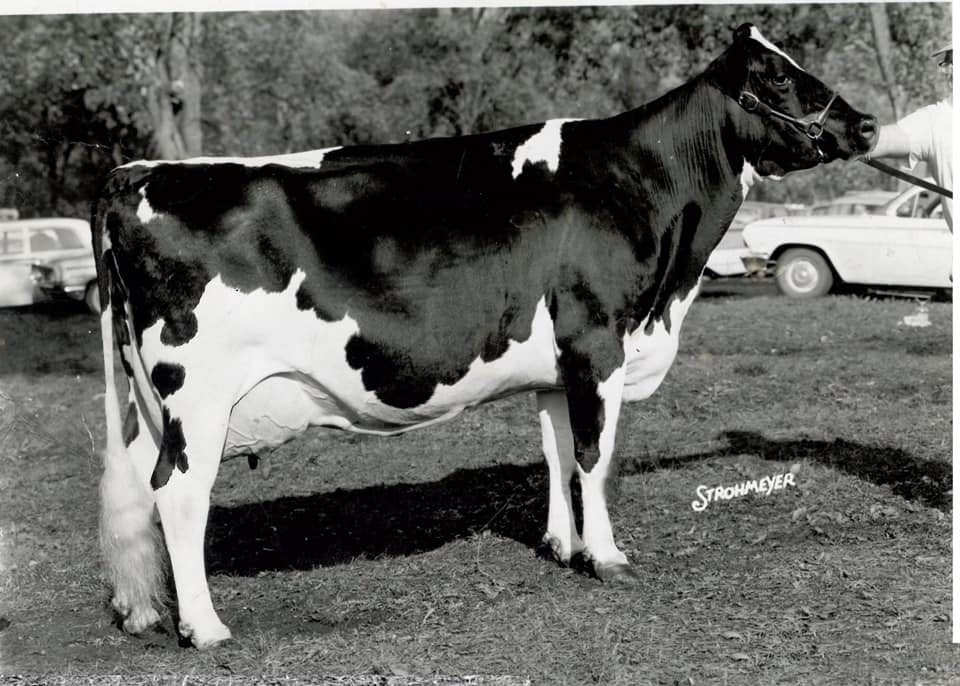

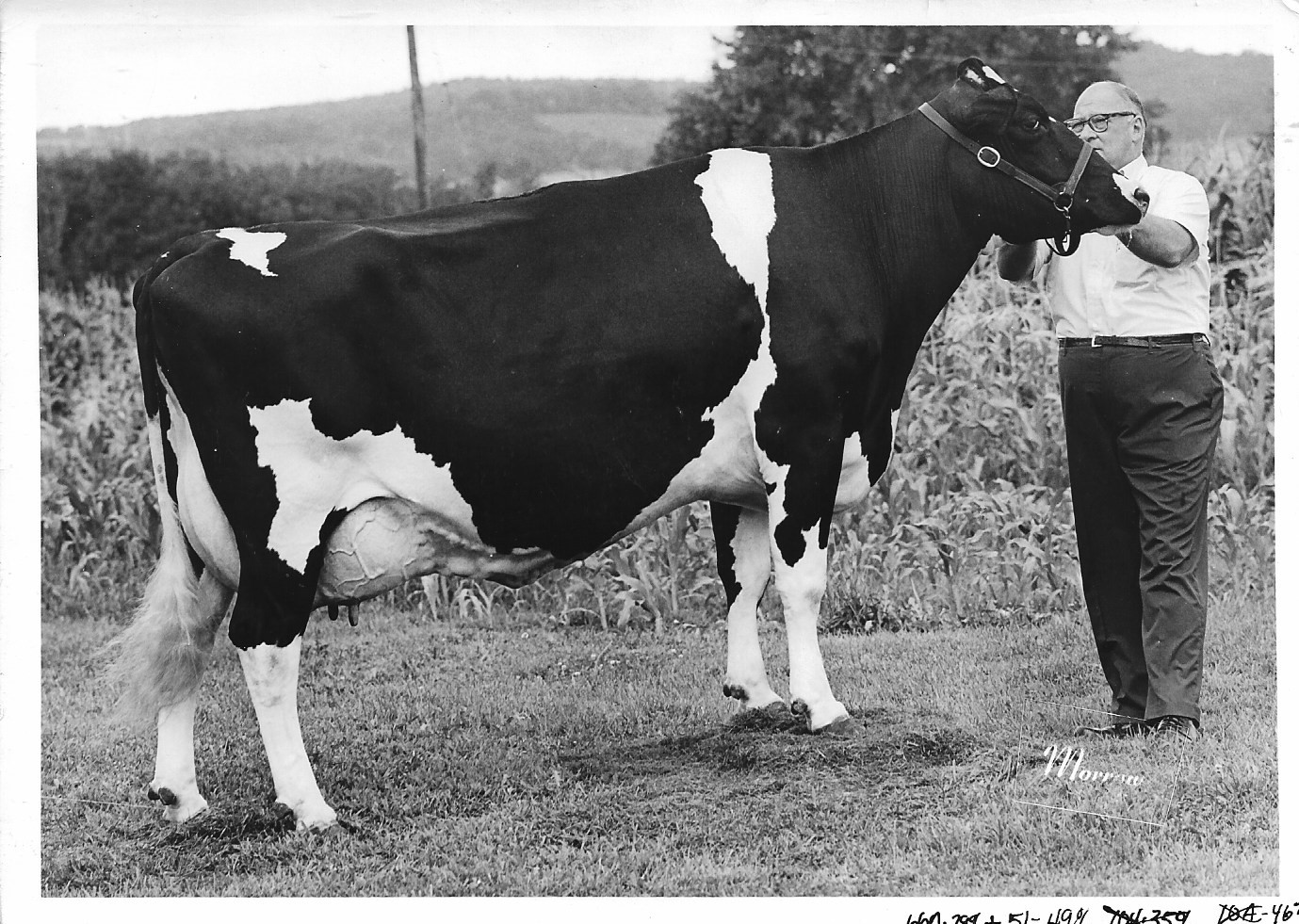

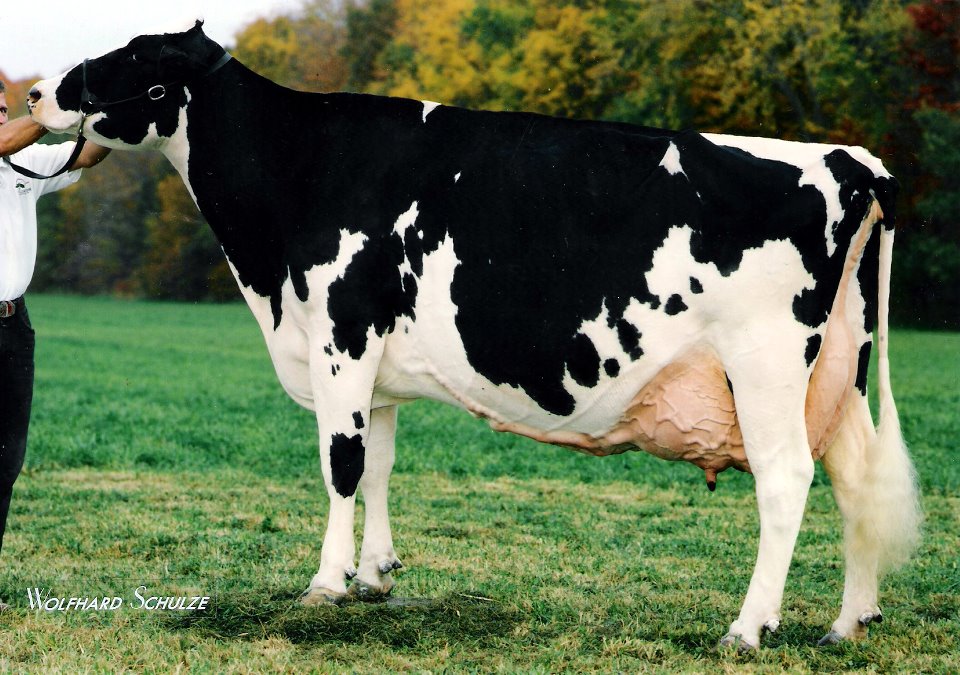

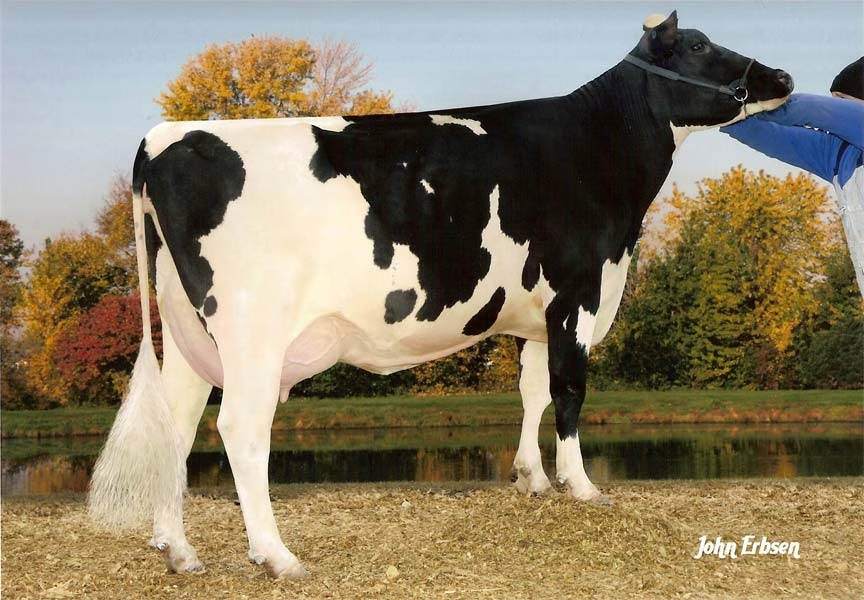

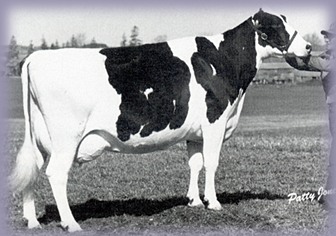

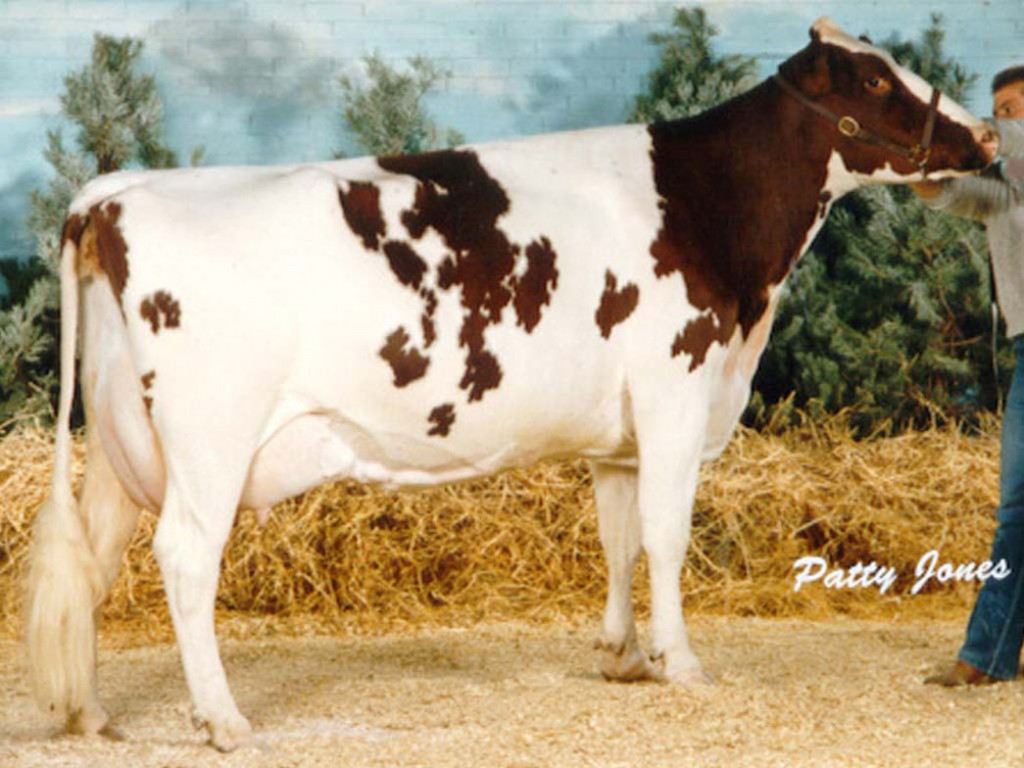

Nearly twelve years old. Dry. Heavy in calf with her eleventh. That was Snowboots Wis Milky Way. When Allen Hetts walked the line that day at the National Dairy Cattle Congress and pulled her to the top of the class, the Holstein World called her “an old friend” who “almost seems to get better as she goes along,” and said her “great quality, strength and substance stand out in every line.” Think about that for a second. In a dry cow class. At almost twelve. She wasn’t just hanging on—she was still the one they wanted to see.

Now, the thing about that era. late ’50s into the ’60s, is that “Excellent” really meant something. You didn’t have TMR audits on your phone or a genomic index to hide behind. You had a classifier with a clipboard, a state Black & White show, and maybe, if things went very right, a trip to Waterloo, the Nebraska State Fair, Mid‑America at Topeka, or the International in Chicago. EX‑95 was rare air. EX‑97? That bordered on myth. And shows like the National Dairy Cattle Congress were where the breed went to sort out who deserved to be talked about all winter.

Snowboots belonged to that world. But she didn’t start out there. She started on a wheat farm.

Out near Abilene, Kansas, a man who was “not a dairyman, but a wheat farmer” kept a small registered Holstein herd on the side. His son’s 4‑H project was a Meierkord Netherland Triune daughter—EX‑92, by the most popular bull in the KABSU stud at the time. She had a good udder, nice teat placement. Just one big headache: her teats were so short that when she calved with her first heifer on Christmas Day, she had to be milked by hand, every milking.

That Christmas calf—the one they almost kept for another 4‑H project—would change everything.

Here’s what made her different. Jack Sexton of Ja‑Sal Farm, one of Ed Reed’s closest friends and cow‑trip partners, heard that the cow and calf might be for sale. Jack went over to look. The young cow was tagged at $250, and he liked her. But what really caught him was the little two‑month‑old heifer at her side: long‑necked, full of Triune breeding, the kind of calf you notice without quite knowing why.

The calf “was not for sale”—likely because the boy had her earmarked as his next 4‑H project. So Jack did what a practical cattleman does. He pointed right at the problem.

He told them, essentially, “You probably ought to sell her. She’ll probably grow up to have short teats like her dam.” That hit home. A deal got struck: $325 for the pair—$250 for the cow, $75 for the calf. The boy had one condition: name the calf “Snowboots.”

So she was Snowboots from that day on. Jack stuffed her into a gunny sack, set her in the back seat of his car, and hauled her home to Ja‑Sal Farm. No fanfare. Just a little heifer in a sack on a Kansas back road.

Looking back, the signs were there. At the time, she was just a Christmas calf with a pedigree that said “Triune” and a future that could’ve gone quietly nowhere.

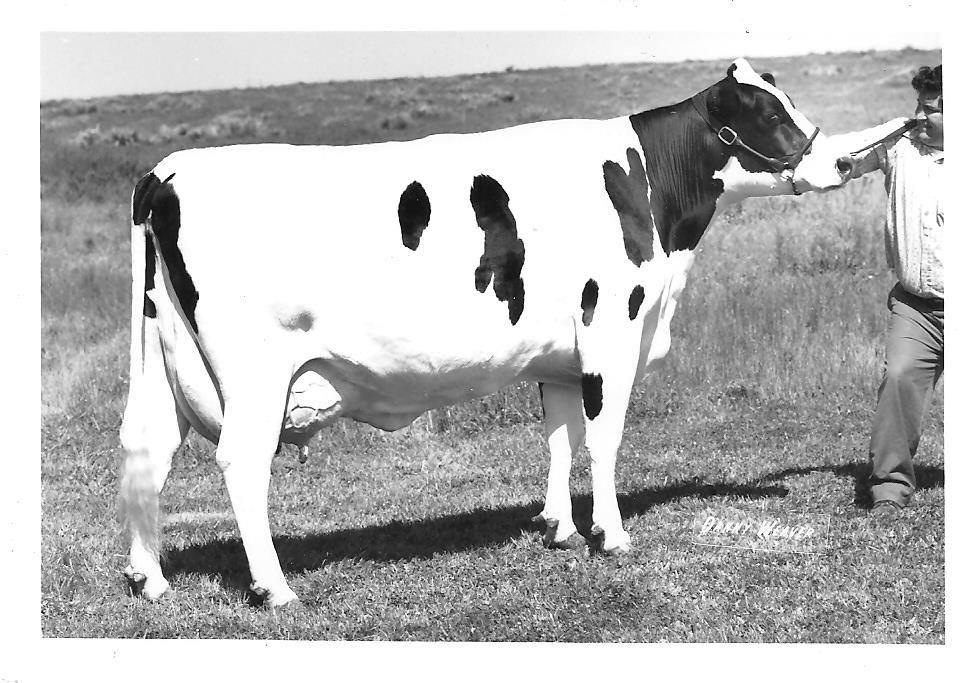

At Ja‑Sal, Snowboots did what good cows do: she calved, she bred back, she raised useful offspring. Her first calf, Ja‑Sal Whirlwind Princess, became an EX‑93 cow with records over 1,000 pounds of fat and ended up in the Paclamar herd. A Wis Trademark son turned into the main herd sire at Ja‑Sal for several years, pulling the herd average from 79 points to 84, according to Jack. Another son by Gray View Skyliner went on to Paclamar and Gray View Farm in Wisconsin.

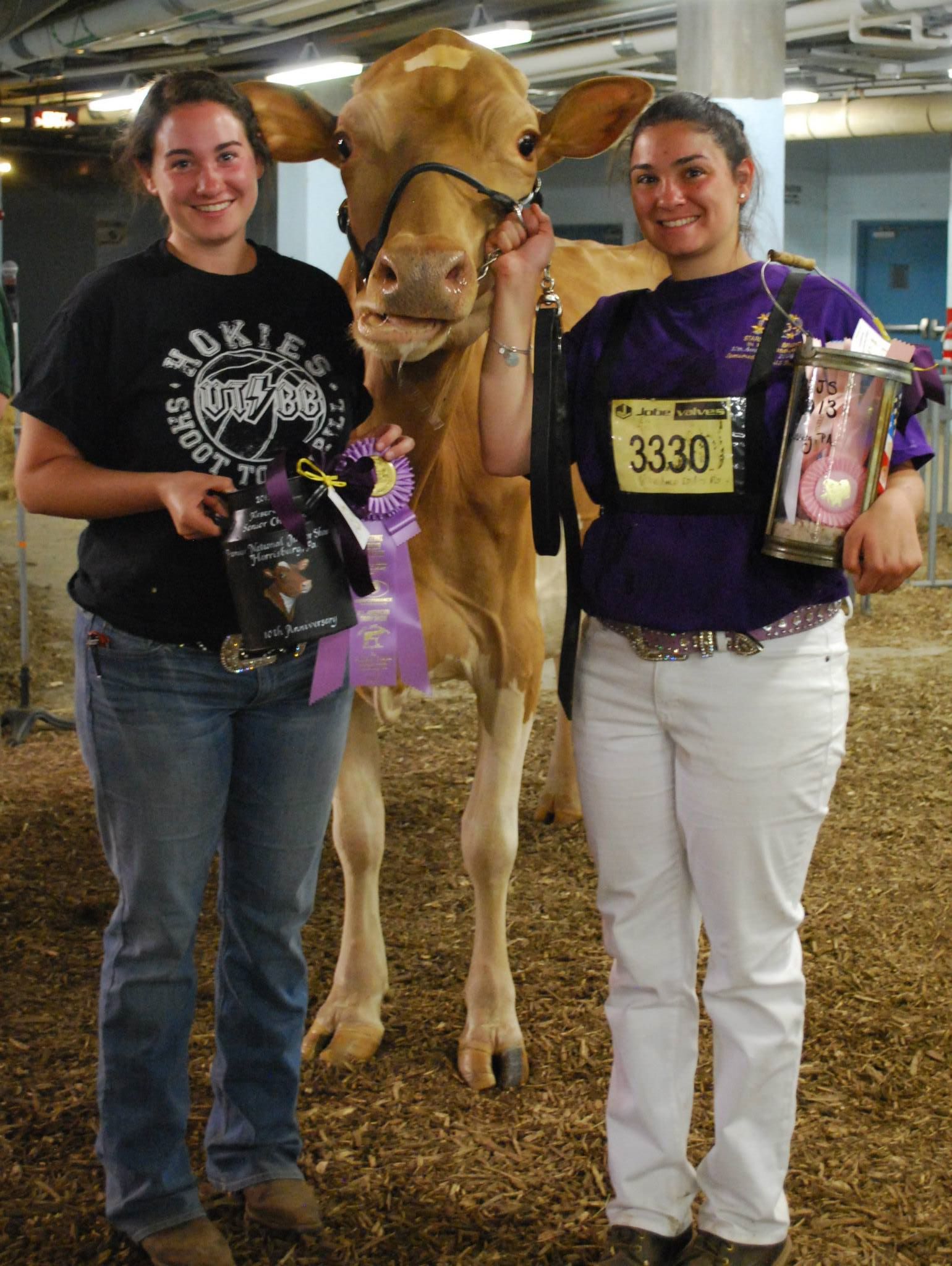

She wasn’t a natural show star. “The first time Jack ever showed ‘Snowboots’ it was at the local district show, and she placed 21st in a class of 22!” Reed remembered. Years later, when she was Grand Champion at Waterloo in 1962 and 1963, “you’ve come a long way, baby” seemed about right.

For seven and a half years, she quietly built a cow family at Ja‑Sal. Then, one day in 1961, at a regional show in Abilene, another breeder came along who saw something more.

Act II – Two Great Cows, One Big Gamble

The thing about those old‑time breeders like Dick Brooks—they carried a lot of history in their head before they ever walked down a show aisle. Brooks had grown up in Ohio, in a family that made its living trading draft horses and milking cows. He’d studied animal husbandry at Ohio State, left when the Depression dragged him home, and built a herd that twice won the National Dairy Efficiency Production Award by the mid‑1950s.

When his son Philip’s health pushed the family west to Colorado, Brooks went from successful dairy farmer to milkman, then to feed salesman, then to commercial heifer grower. Somewhere in there, he signed an oil lease with a Texan named Howard Sluyter—”in the ahl bidness”—for $1,000 down. They hit it off. Four years later, that handshake turned into Paclamar Farm.

Paclamar was built big from the start. Seventeen steel‑frame buildings with blue vinyl panels on about 1,240 acres at Louisville, Colorado. They milked in an eight‑stall parlor, piped warm milk into a 500‑gallon insulated tank on a VW truck, and fed 70 or more drop calves at a time with a quart‑at‑a‑pull metering device. All the machinery—tractors, bunk feeders—was leased from Allis‑Chalmers, and six men, including Brooks, ran the whole show.

But here’s what set Brooks apart—he wasn’t just buying cows; he was building a herd around a philosophy. He liked Ormsby blood—the Winterthur and Maytag branches in particular. He believed in cow families, pedigrees, and in a Kansas foundation sire named Fredmar Sir Fobes Triune, whose influence ran deep through herds like Thonyma, Meierkord, and Skyway.

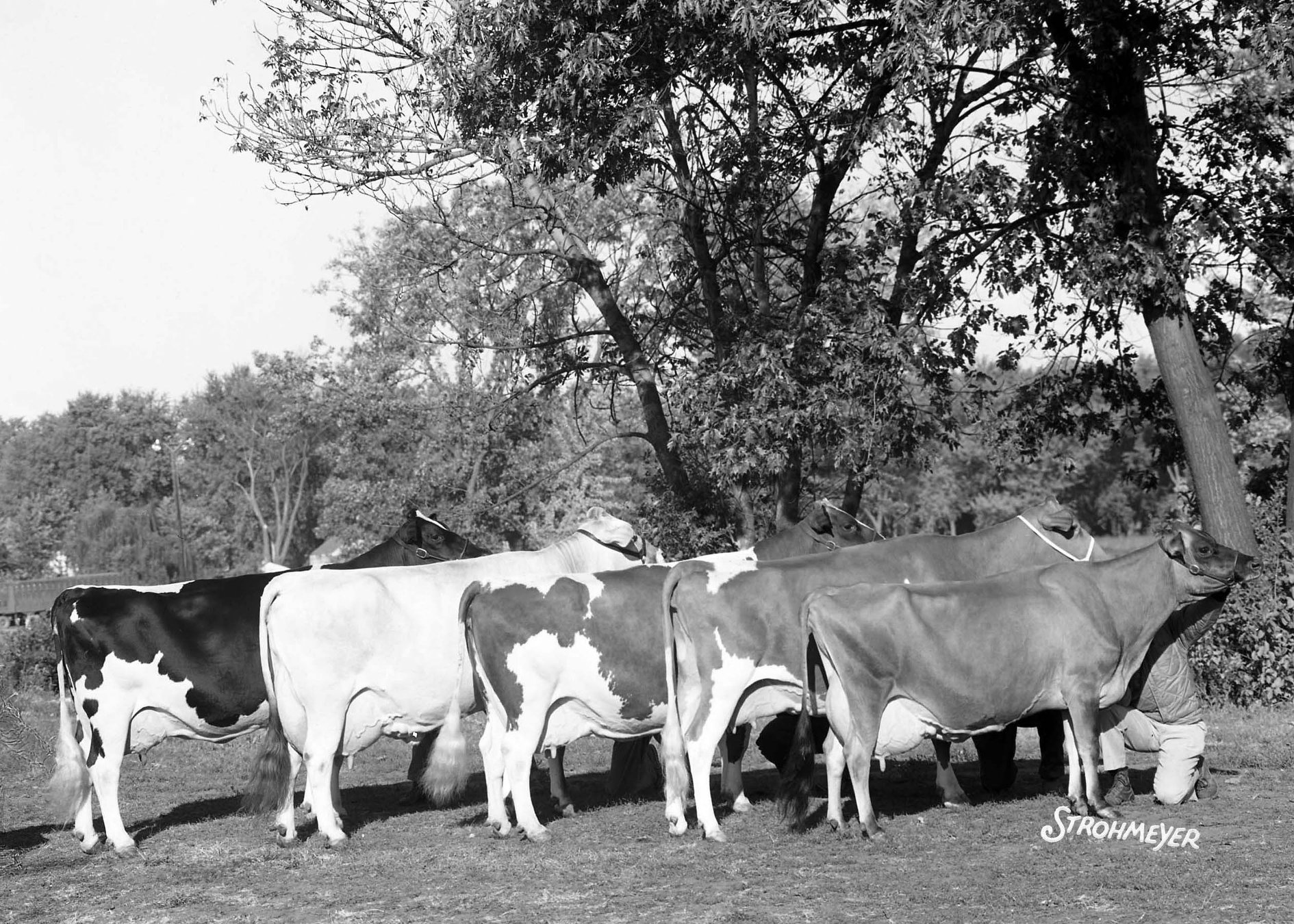

He bought 18 head at Hilltop, including five Osborndale Ivanhoe daughters. He bought from Harris Wilcox’s Canandaigua Classic, the National Convention Sale at Syracuse, and the Sunny Vale dispersal. He bought the Vista Peaks herd and its Thonyma‑bred Ormsby blood. And he bought deep into the Thonyma herd itself—79 head over two trips—including the Senatora family.

Then came Kansas and Snowboots.

“In 1961 at a regional show in Abilene, Kansas,” Brooks later wrote, “even though no one can be sure how great a young cow can turn out to be, I was really excited about her potential. Jack had used the cow extensively in his program, and I really liked what I saw.” He offered Jack $2,500 for the cow plus one of Paclamar’s best young bulls as a future herd sire.

Jack’s widow told Reed that he lay awake all night, trying to talk himself into letting Dick have the cow. One can imagine him thinking about that first local show—21st of 22—and about the calves she’d already given him. Then picturing what she might do in a big, well‑funded program with a national show schedule and access to bulls he’d only ever seen in catalog photos.

“Finally,” Reed wrote, “reasoning that Paclamar could give the cow an opportunity that he could not, he let her go.” In November 1961, Snowboots left Ja‑Sal and headed for Colorado.

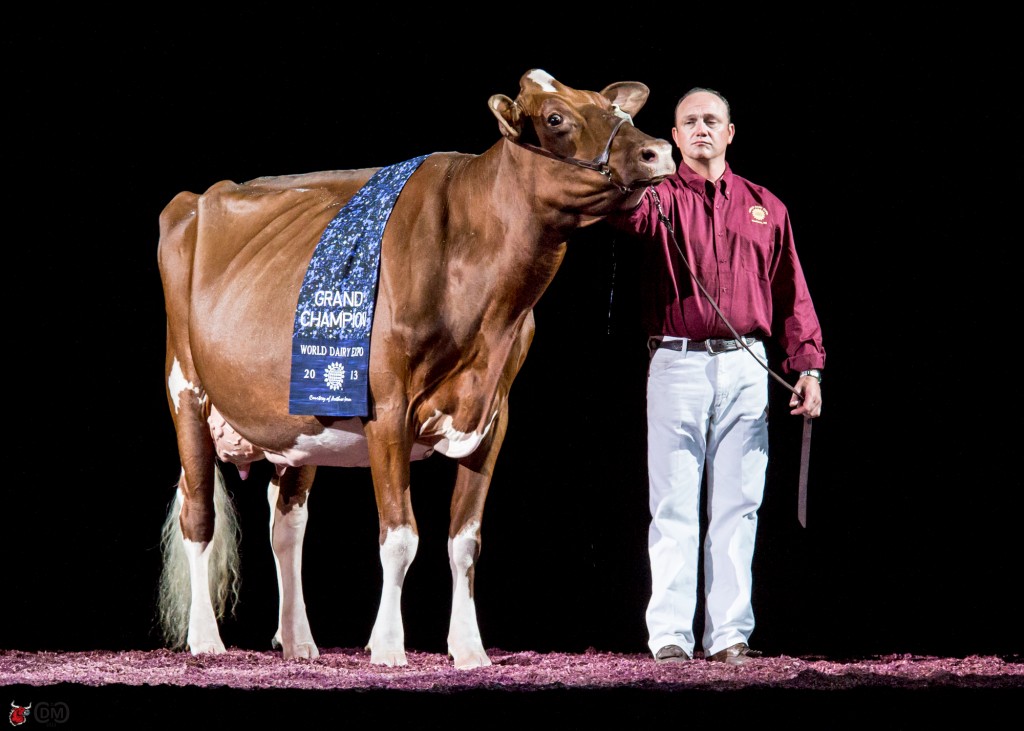

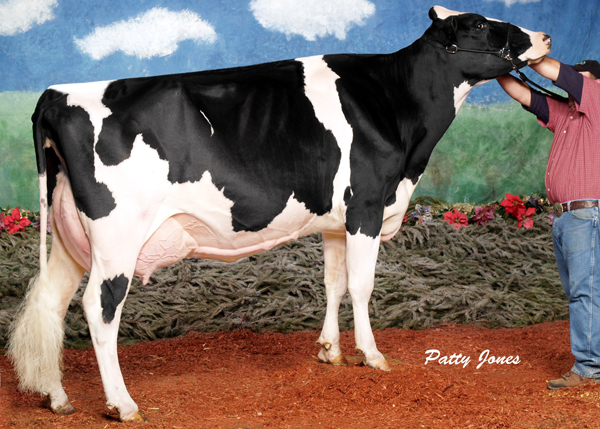

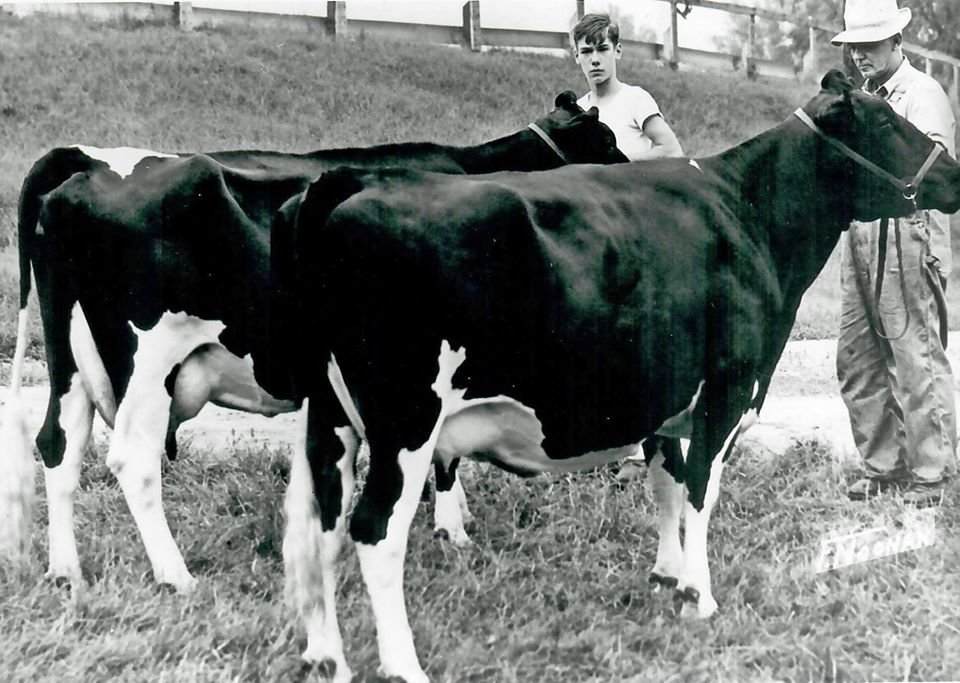

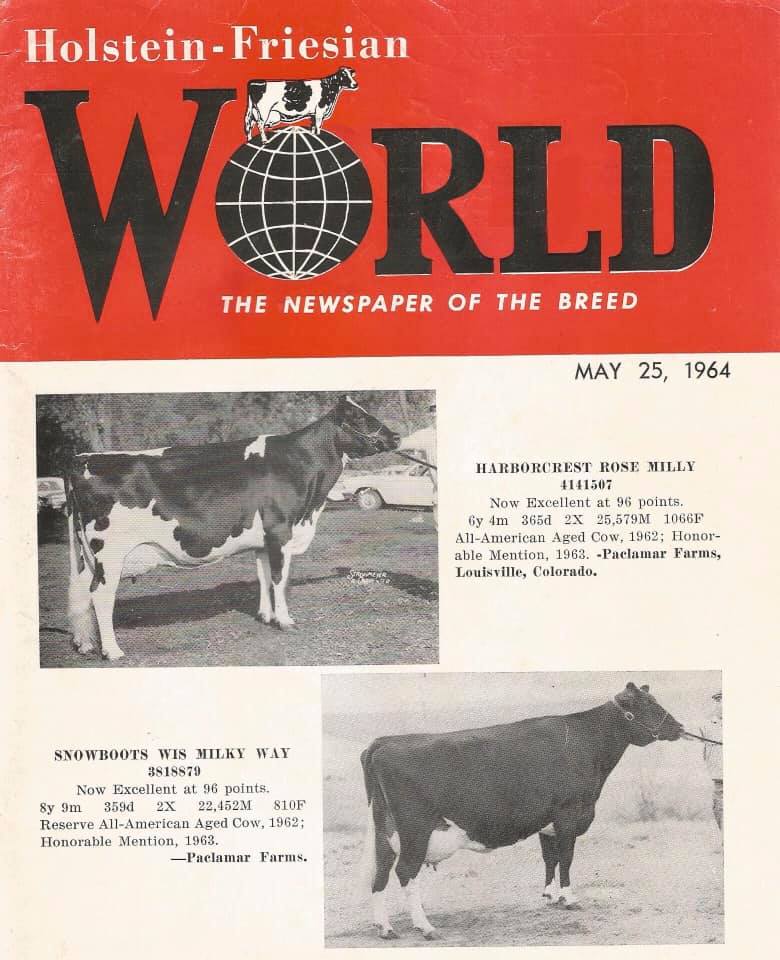

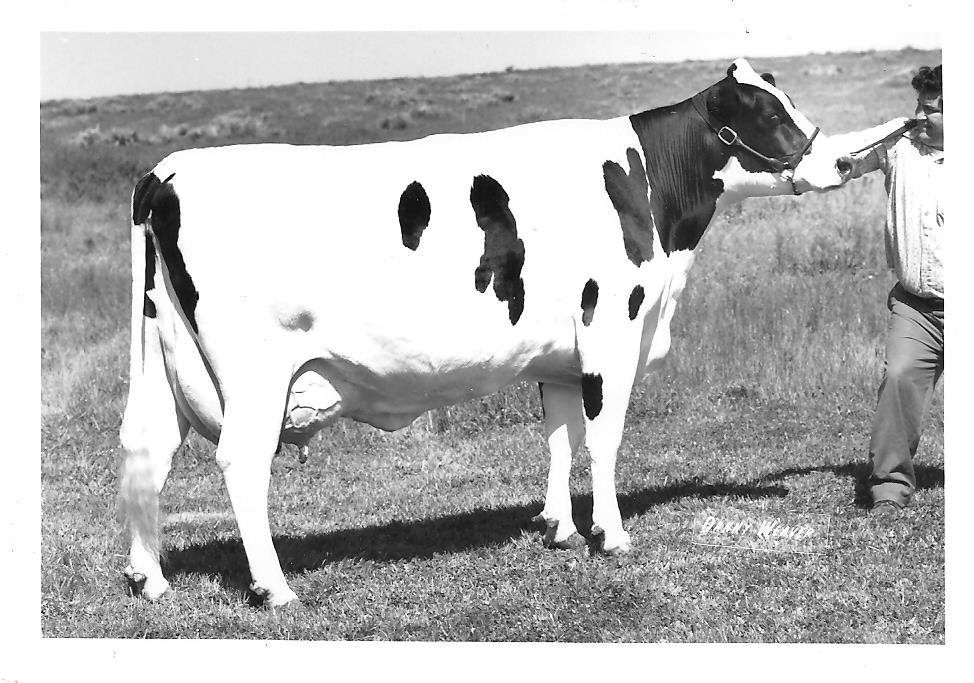

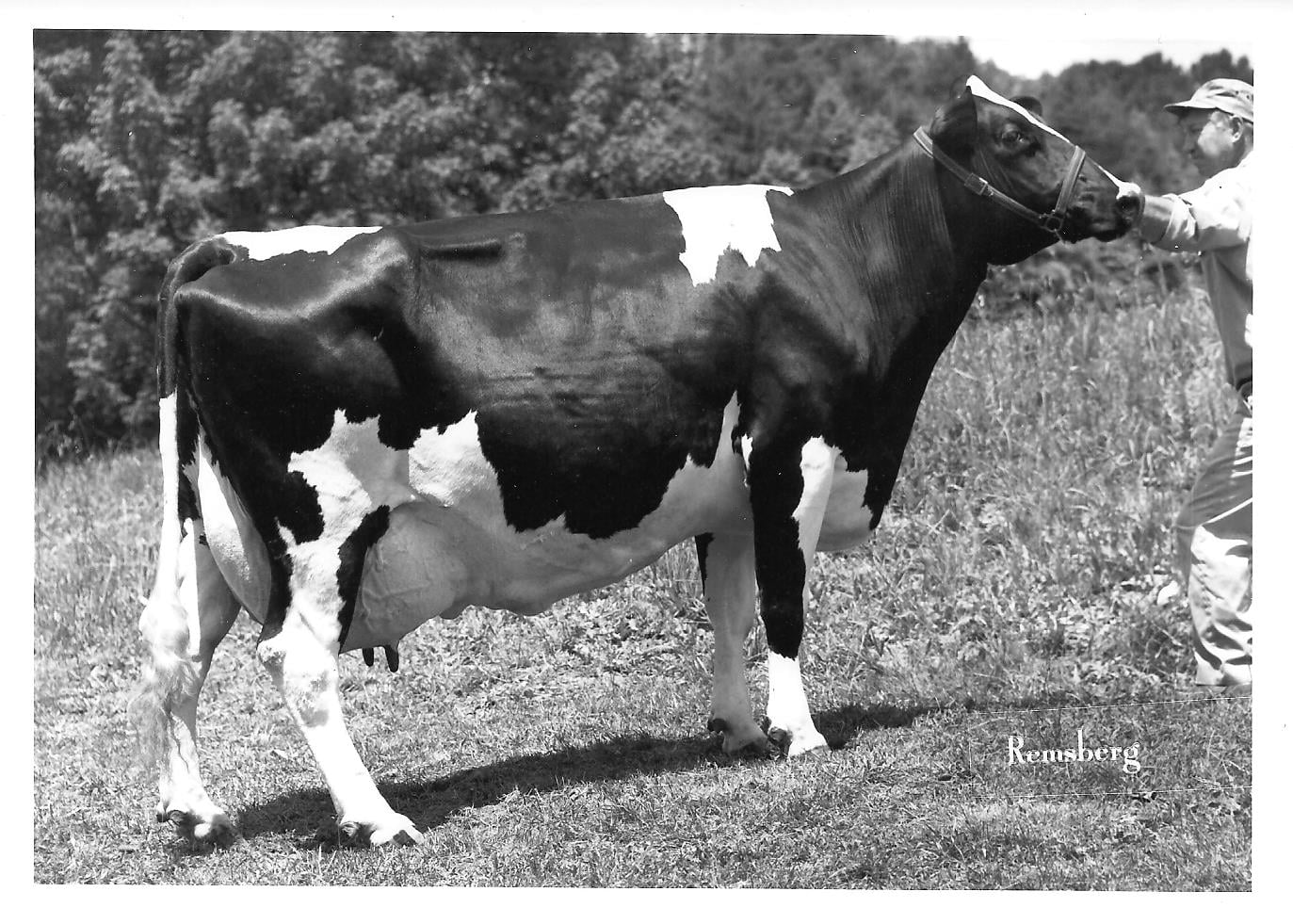

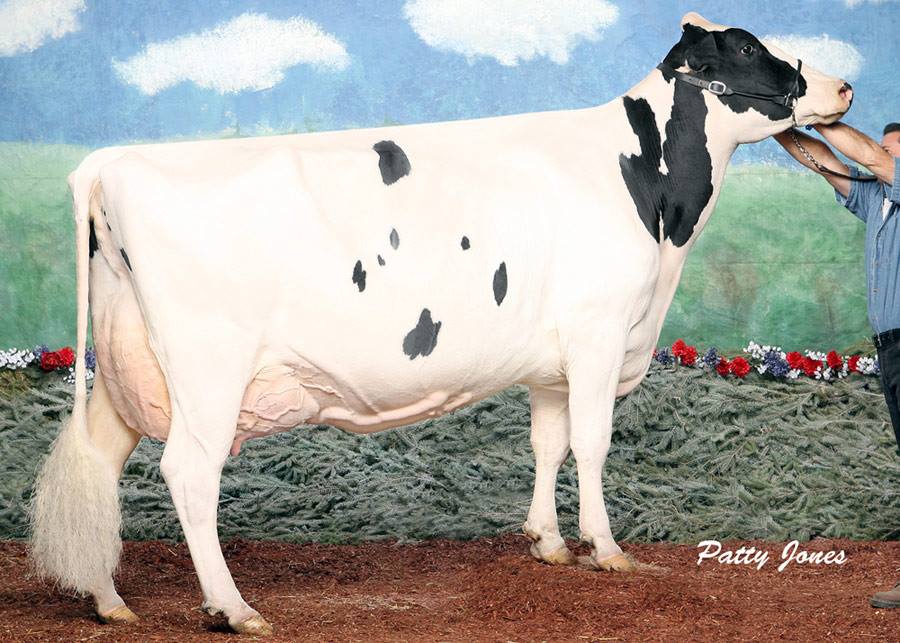

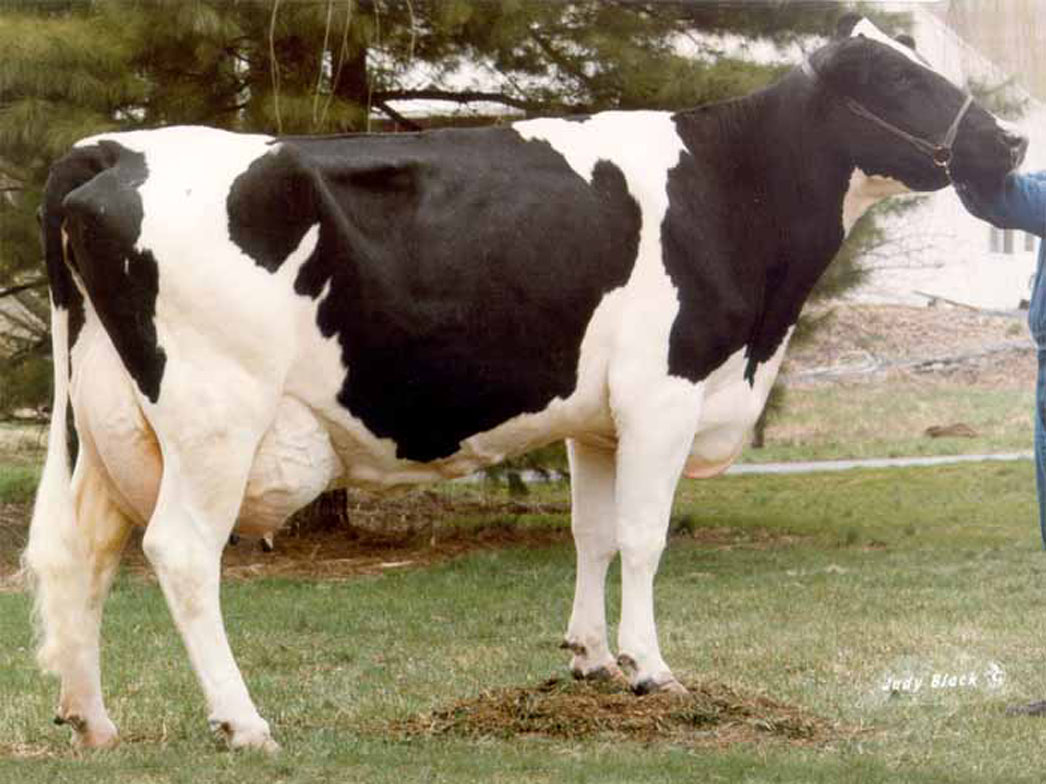

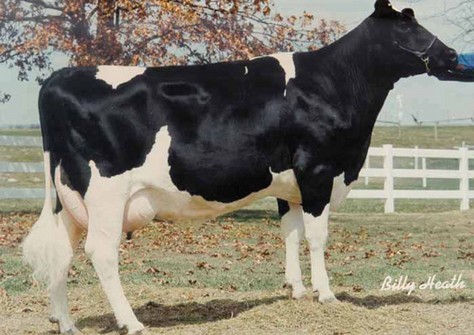

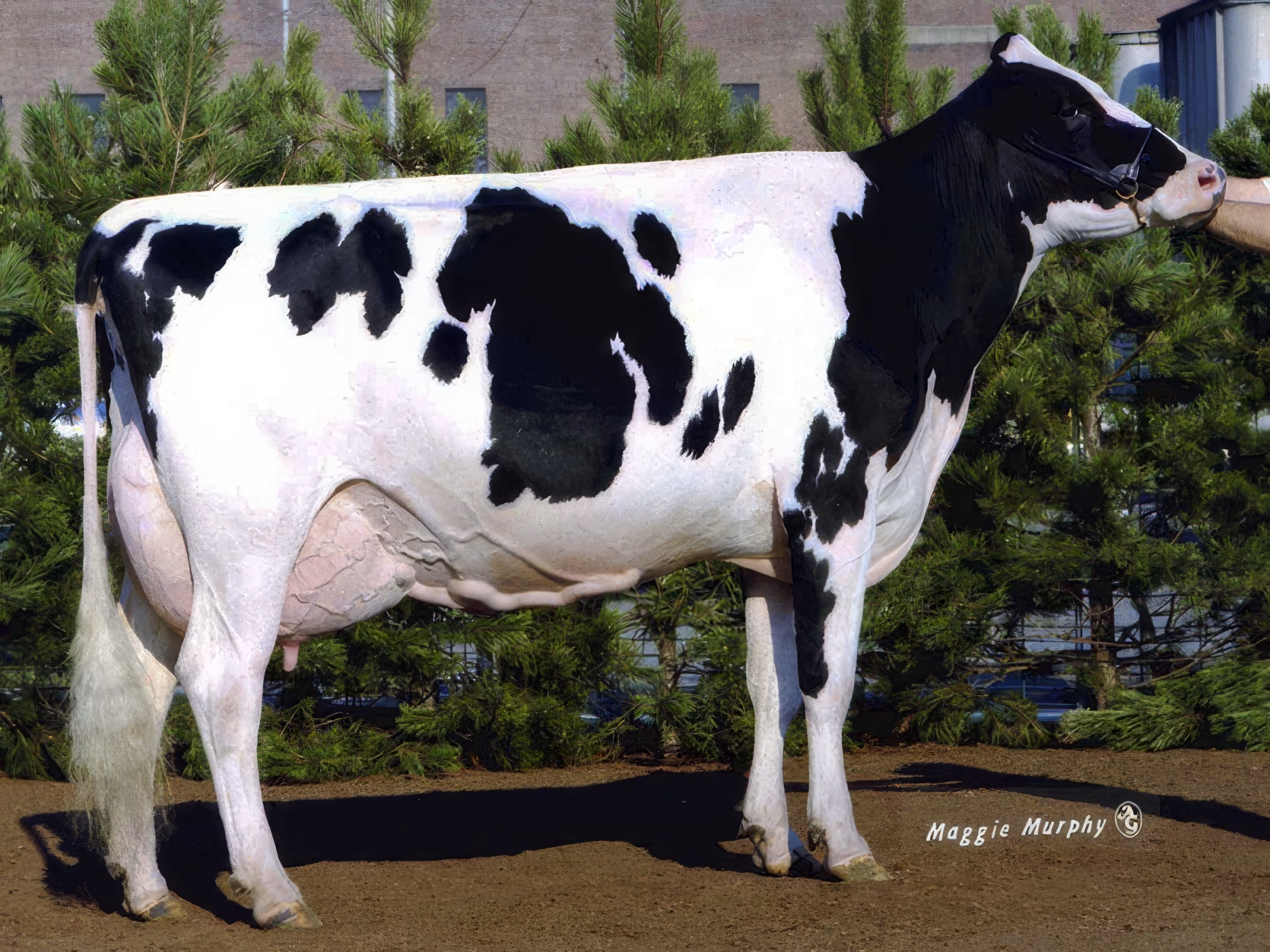

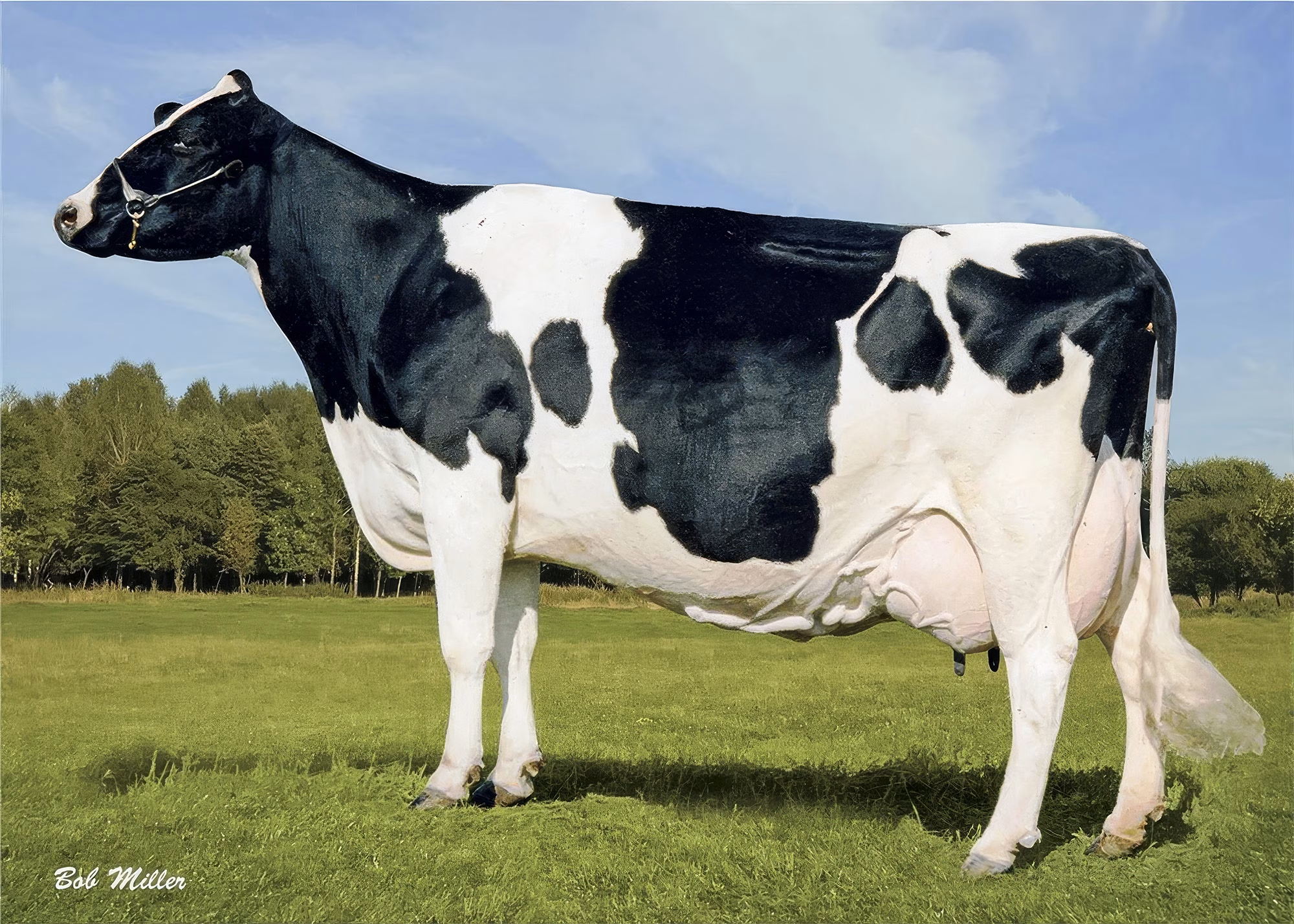

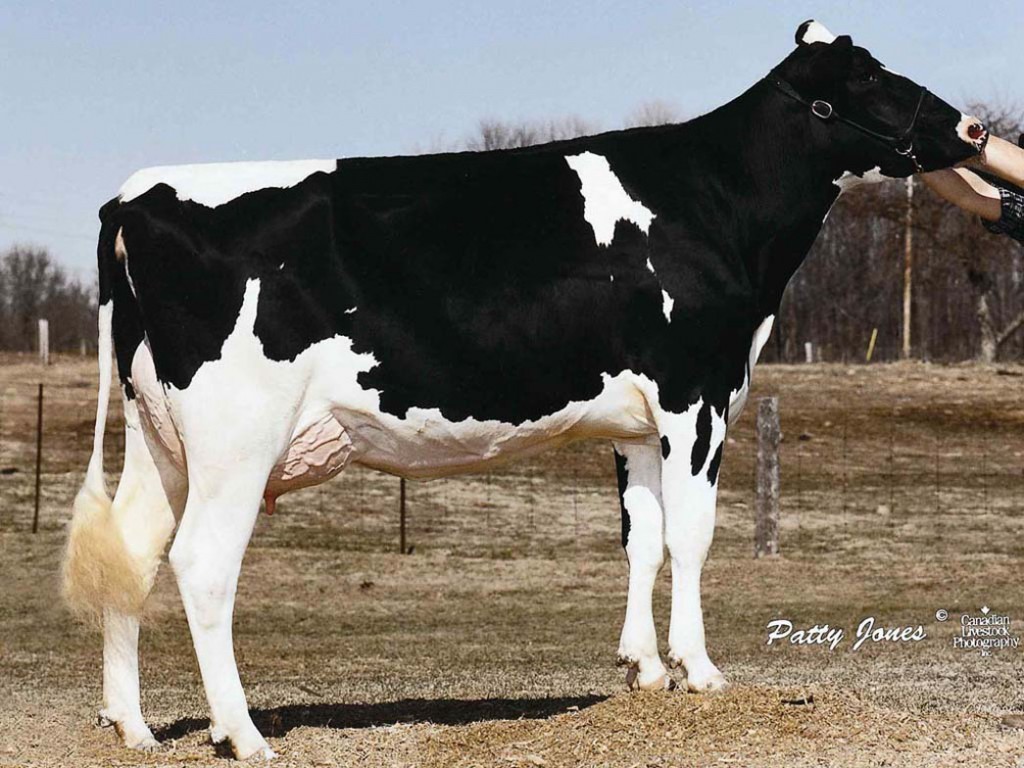

At Paclamar, she walked into a barn that already housed Harborcrest Rose Milly, a show cow from Ohio who would go on to be All‑American Aged Cow in 1962, 1964, and 1965. Reed later said there was only one time in his memory when one farm owned the two most outstanding cows of the breed at the same time—and that was when Paclamar had Milly and Snowboots side by side. Milly was the flashy one, “unbeatable in the show ring when in bloom.” Snowboots was the one the crew liked to look at day after day—a big cow, but never coarse, with a long, clean neck and that sweep of rib that made her look right from every angle. She quickly became the favorite cow of those at Paclamar.

Now, what most people don’t realize is that Snowboots did her best work on two fronts at once.

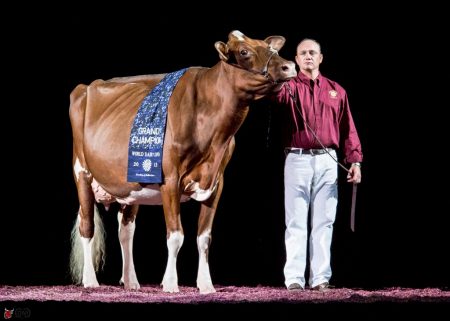

On the show side, she and Milly went toe‑to‑toe in the early ’60s. Between 1953 and 1967, Snowboots was a four‑time class winner and twice Grand Champion at Waterloo, and Grand Champion at the Nebraska State Fair. In that odd 1962 season, she was Grand at Waterloo and Nebraska, but Reserve Grand to Milly at Mid‑America Topeka and the Colorado State Fair. When All‑American ballots were counted, Milly took All‑American Aged Cow with 18 first‑place votes and 133 points; Snowboots got 2 firsts and 38 points as Reserve All‑American Aged Cow. She’d be Reserve again in 1965.

On the milk side, she was building a lifetime that would make even modern producers nod. Over 3,551 days of twice‑a‑day milking, she made 201,187 pounds of milk at 3.8% and 7,729 pounds of fat. Her best record came at 11 years 11 months—24,006 pounds of milk at 4.1% and 995 pounds of fat in 365 days. In that era, with state averages far lower and no fancy supplements, that’s the kind of record that gets read out loud around the kitchen table.

And classification? She climbed the ladder to EX‑97‑3E‑GMD. There’s no write‑up of the moment the score was announced, but one can picture a classifier straightening up, reading “97,” and the barn going quiet for half a breath. In those days, EX‑97 wasn’t just rare—it was almost a rumor come to life.

All that set the stage for one October day that still stands as Paclamar’s best.

The Day Paclamar Owned the Ring

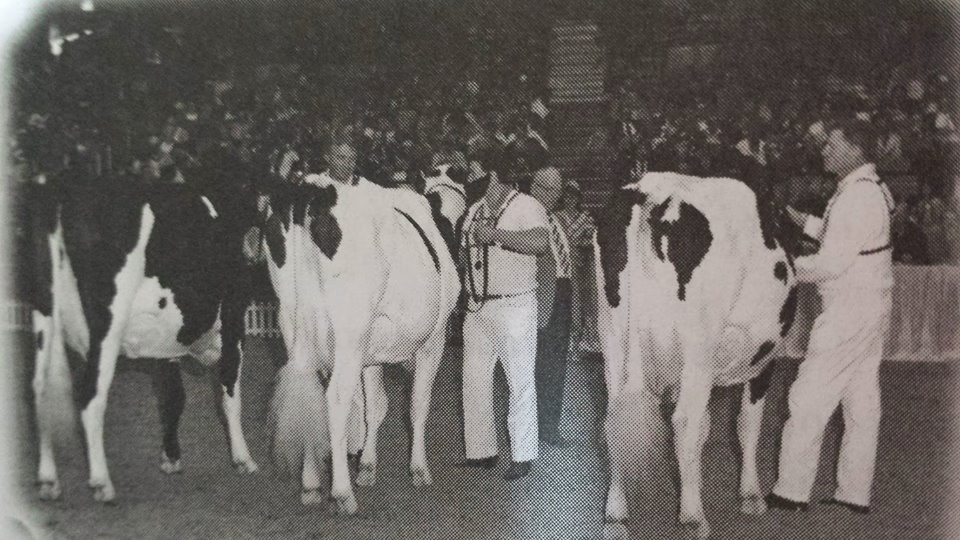

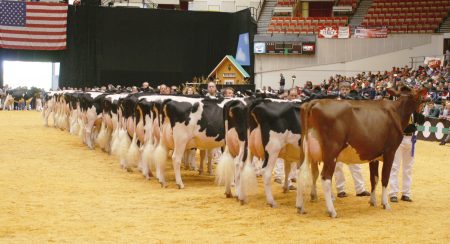

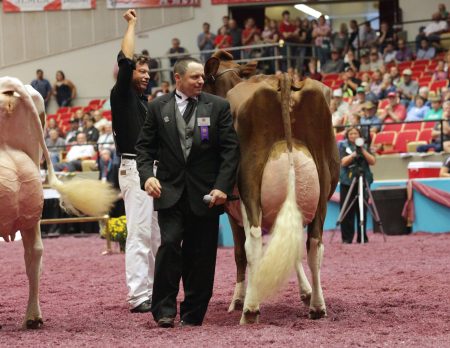

On October 5, 1962, Paclamar brought Milly and Snowboots to Waterloo. In the Aged Cow class, Snowboots stood first, Milly second under Jack Fraser. Then they came back for the championship.

The Holstein‑Friesian World had to go back through the books. Their report read:

“Paclamar Farms, Louisville, Colo., made history for our national show by winning both the Grand Champion and Reserve Grand Champion awards of the female section with the first and second prize aged cows. We are unable to find any previous instance since the Reserve championships were inaugurated at the National in 1935, where one exhibitor has taken both the Grand and Reserve Grand female honors.”

The banners went to Harborcrest Rose Milly and Snowboots Wis Milky Way. One farm. One manager. Two aged cows. Grand and Reserve at the National Dairy Cattle Congress on their first big crack at the national spotlight.

That’s the peak. That’s the moment everything that came before—the wheat farm, the gunny sack, the 21st‑of‑22 district placing, Jack’s sleepless night, the move to Colorado—comes together in one ring.

And still, for Brooks, the real work with Snowboots wasn’t just in winning banners. It was in what he could put behind a young bull code.

Bottling Kansas in One Black Calf

This is where the story shifts from colored shavings to cow families and calculated risk.

By 1962, Brooks had decided that Snowboots’ next mating should “hopefully produce a son that would develop into the main herdsire at Paclamar.” Reed, who knew him as well as anyone, said he’d never seen Brooks spend more time on a breeding decision.

The checklist was tight: no obvious weaknesses introduced; a bull that would sire flat bone and high, wide rear udders; and a pedigree loaded with crosses to Fredmar Sir Fobes Triune, the Kansas foundation sire Brooks loved.

Snowboots already had Triune bred into her. Her dam, Milkyway Judy Triune GP‑83, was by Meierkord Netherland Triune, the best of Old Triune’s sons. Her third dam was also a direct descendant of Triune.

The trouble was that by 1962, almost all the proven Triune‑bred bulls were gone. A few had been heavily used in early AI, but that was before frozen semen; when those bulls died, their influence stopped with them.

So Brooks did something that, in hindsight, took more nerve than people sometimes appreciate. He looked to an unproven bull.

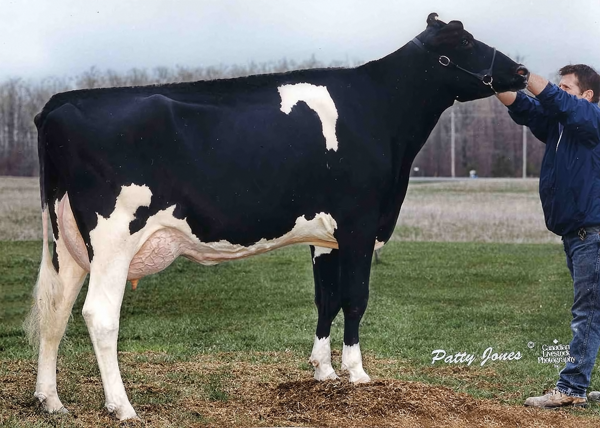

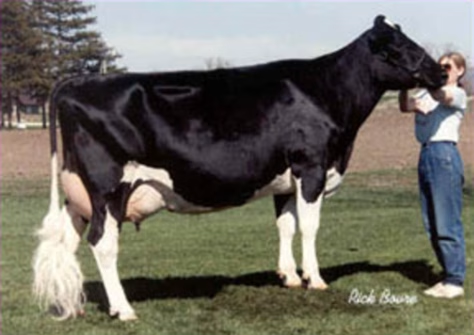

His friend Bill Weeks up in Vermont had spent years building a Holstein family known as the Skyways—tall in front, long wide rumps, flat bone, high wide udders. Weeks had bought a calf named Valla Vista Polkadot Ike off a big white cow, Valla Vista Flicka Mercury EX, in the Phillips Brothers show string at Kingman, Kansas, after seeing her on classification duty. Ike daughters did well at Skyway, and even better at Bristol Farm in Wisconsin, where nine of his best daughters averaged 88.4 points and formed an Honorable Mention All‑American Get of Sire in 1962.

One of those daughters, Skyway Valla Vista Hopeful EX‑92, dropped a bull calf by Skyway Esteem Sam, himself from the Ike line. That calf was Skyway Valla Vista Double. Double was linebred Ike—his dam and paternal granddam both Ike daughters—and carried multiple crosses to Fredmar Sir Fobes Triune plus one to Prince Triune Supreme. Bristol’s Ike daughters were the kind that stopped you in the aisle—flat‑boned, wide‑rumped, rear udders snug right up under the pin bones.

Pedigree‑wise, Double “filled the bill.” He came from the kind of cows Brooks liked to look at and from a breeder he trusted. There was just one problem: Double was two years and one month old, and his sire was still unproven.

One can imagine Brooks in his office, pedigrees spread out, asking himself if he really wanted to risk one of the two best cows on earth on a young bull with zero daughters in milk. He did it anyway.

He bred Snowboots Wis Milky Way to Skyway Valla Vista Double.

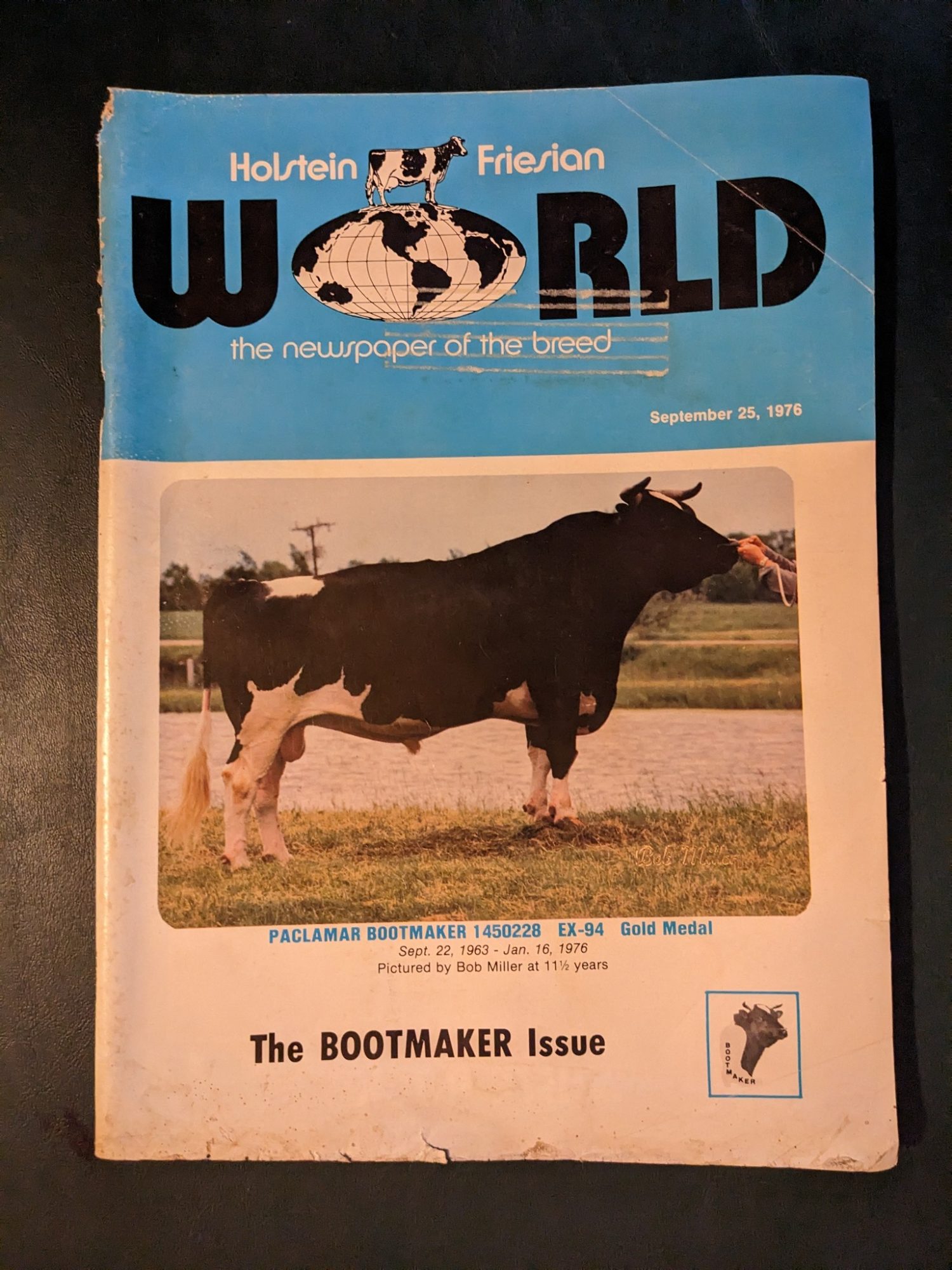

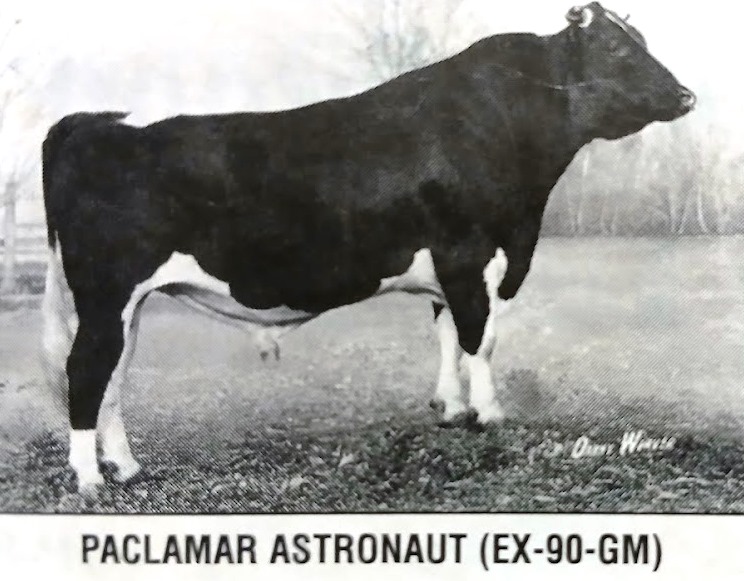

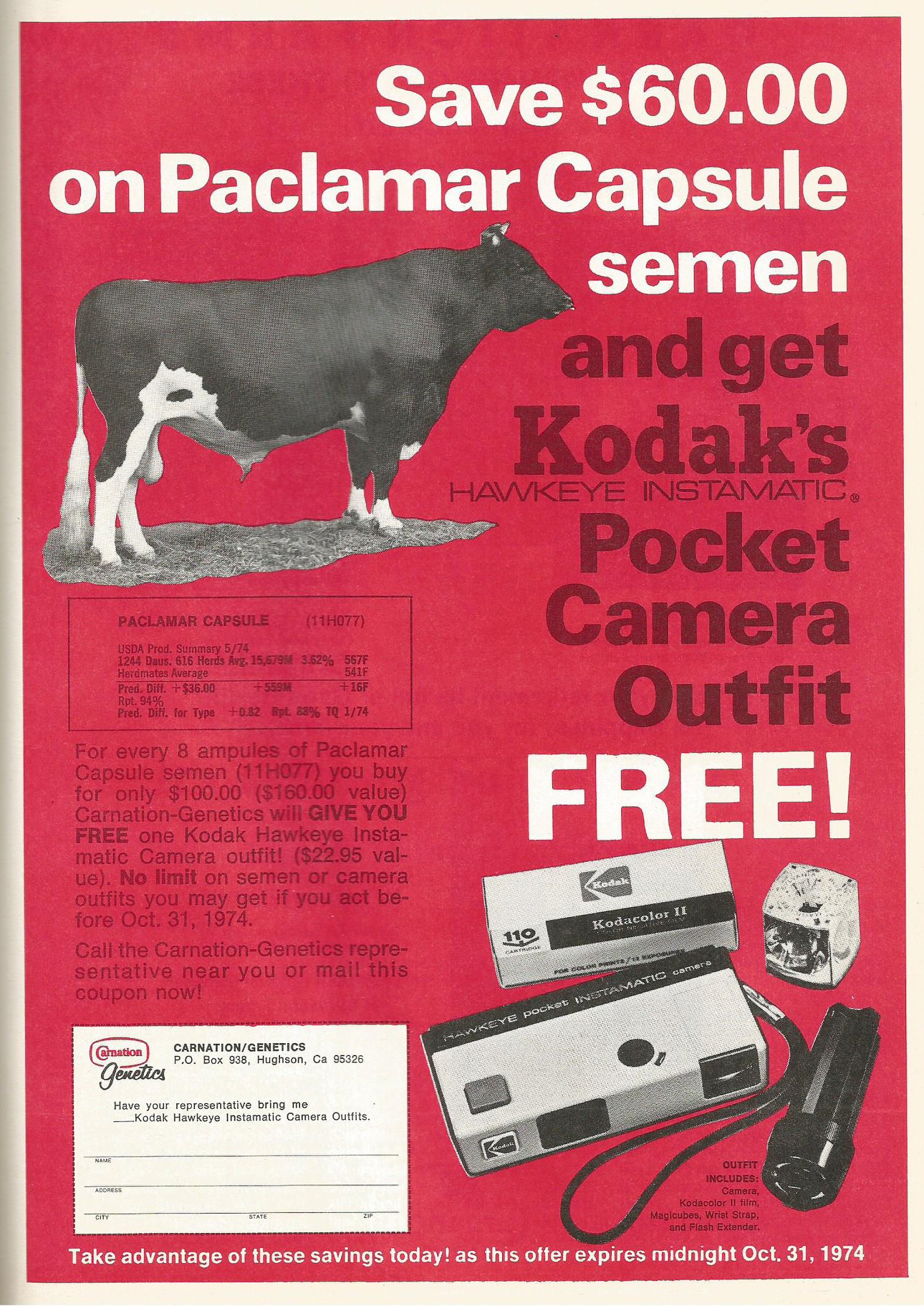

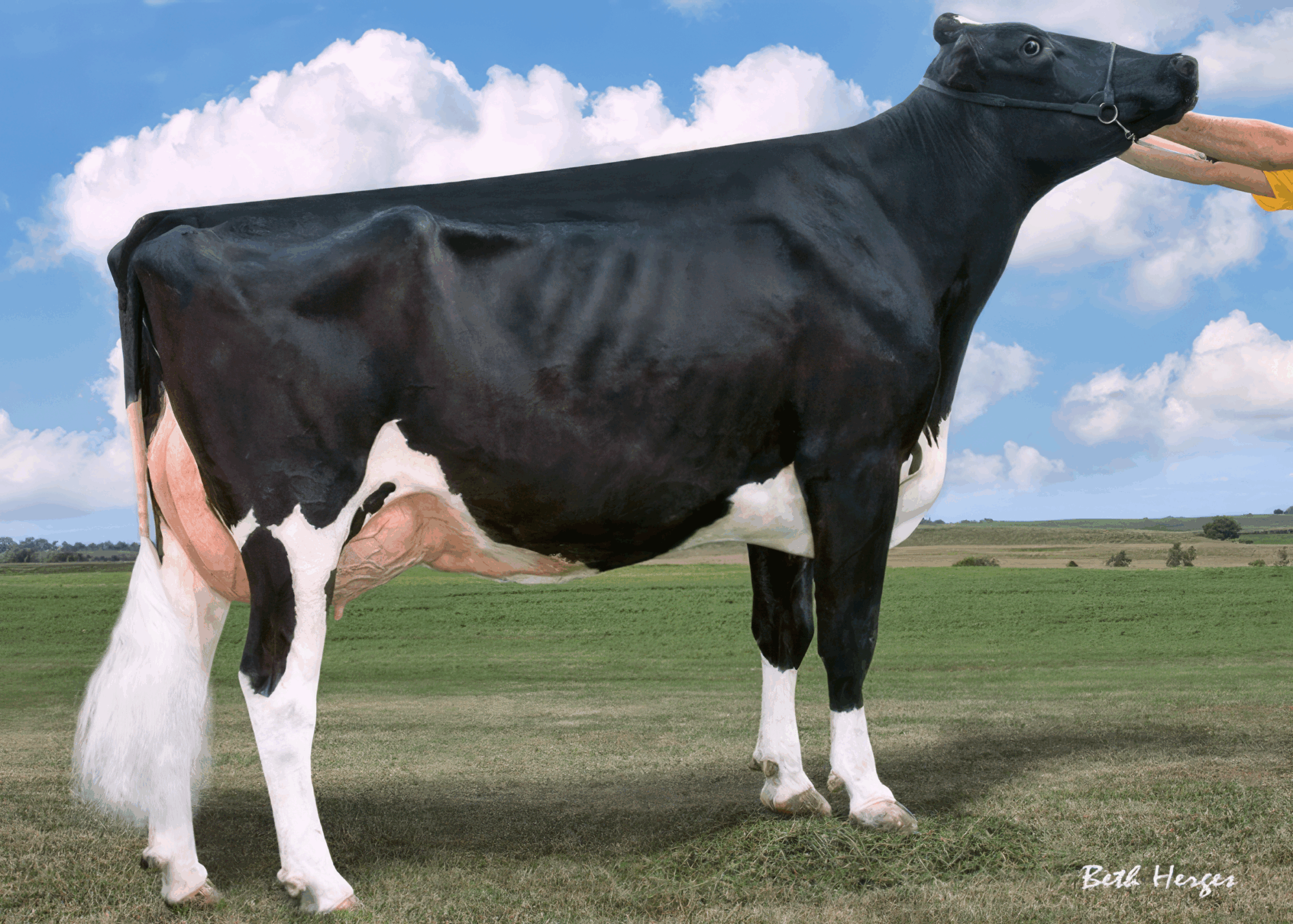

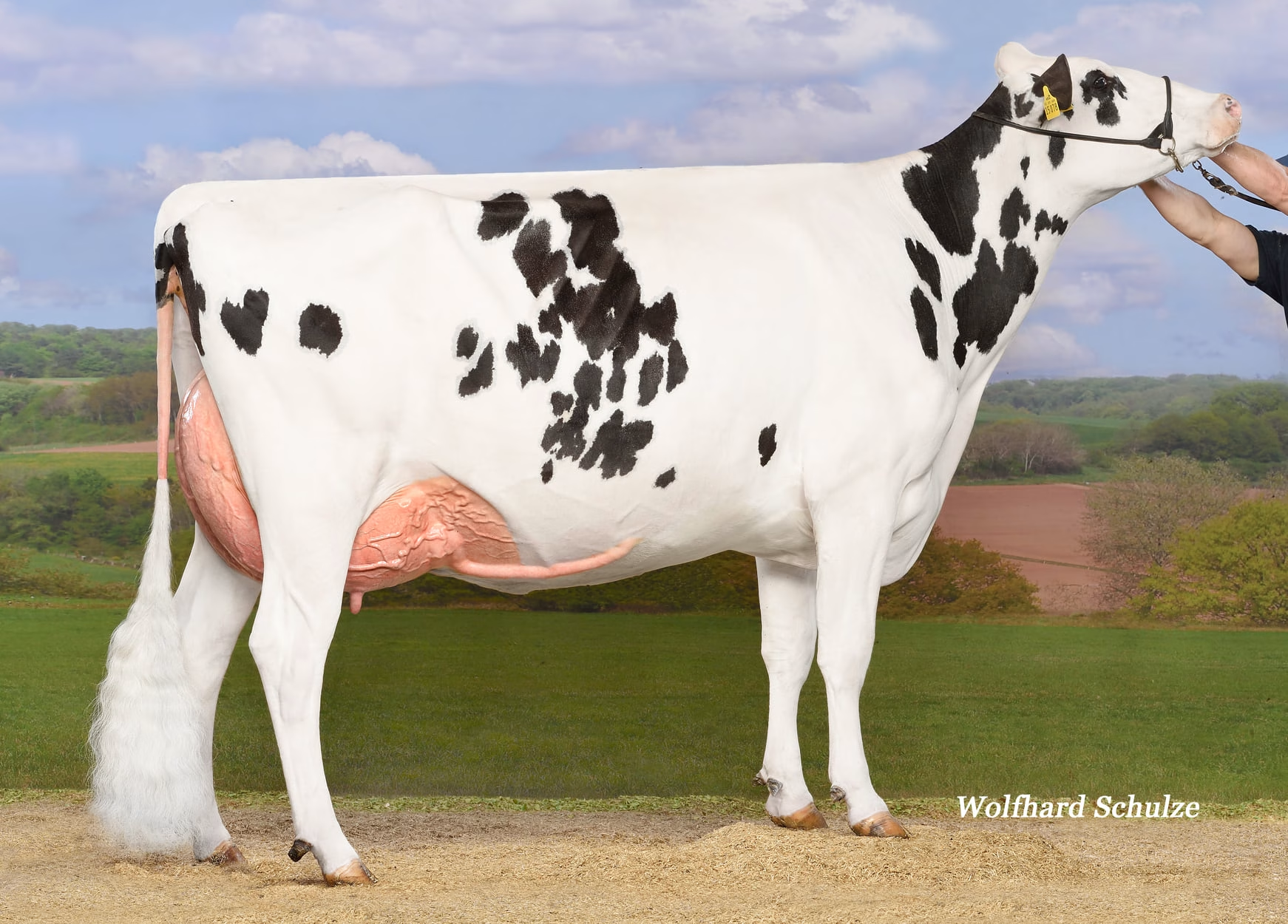

On September 22, 1963, she dropped a black bull calf. They named him Paclamar Bootmaker.

In that one calf, Brooks pulled together a dam who would stand Grand at Waterloo, score EX‑97‑3E‑GMD, and make over 200,000 pounds of milk in 3,551 days of 2x milking; six direct crosses to Fredmar Sir Fobes Triune and two to his brother Fredmar Prince Triune Supreme; and Skyway/Ike type for wide rumps and high udders.

At the time, Bootmaker was just another September calf on straw, nosing for milk. No one in that barn knew he’d end up with 27,252 production‑tested daughters in 8,006 U.S. herds. Or that he’d become the first bull ever to sire 100 Gold Medal Dams.

And before any of that could happen, there was one more gamble to play.

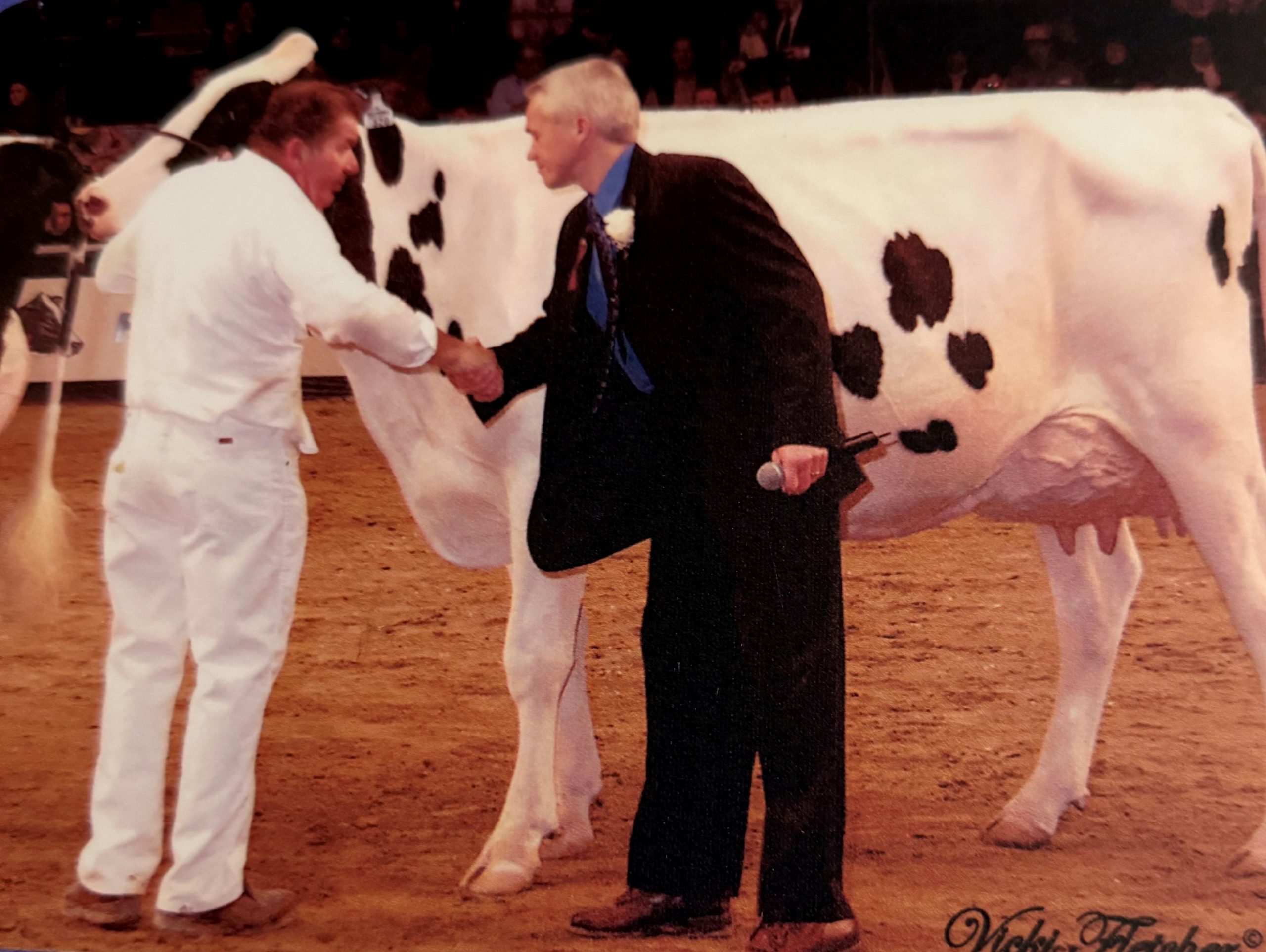

The $80,000 Pair and a Shaky First Look

Fast‑forward to November 10, 1967. Paclamar’s first dispersal. The herd numbered 425 head; 200 would sell, along with 50 pairs where the buyer would pick one, and the other would go back to Paclamar. The average on 249 head was $1,692, with cattle going to 38 states and five foreign countries.

Snowboots was gone by then, but her presence was still in the barn in the form of Ja‑Sal Whirlwind Princess EX‑93, and, of course, in Bootmaker. Brooks wanted both Princess and Milly for the “new” Paclamar.

Months before the sale, Reed had told him there was no way he could save both cows unless he paired them with bulls buyers would be more interested in than the females. So Brooks rolled the dice again.

He paired Milly with Bootmaker. He paired Princess with Paclamar Double Triune, a Bootmaker son out of Skyway Esteem, full sister to Double’s dam. When the Milly–Bootmaker pair came into the ring, the bidding climbed all the way to $80,000. The Bootmaker Syndicate took the pair. Eugene Vesely of E‑L‑V Ranch in Michigan was the under‑bidder at $77,000; he later said he’d have taken Milly if he’d won, which is exactly what Brooks had hoped.

The syndicate chose Bootmaker. Paclamar kept Milly. Same story with Princess and Double Triune—the buyers picked the bulls, Brooks kept the cows. Reed recalled that Brooks saved about 80% of the cows he most wanted that day.

From the sale ring, Bootmaker looked every bit the star: $80,000 price tag, Milly beside him, Snowboots behind him, Triune blood all through him. Down in the cattle rows, the mood was more cautious.

“At the sale,” Reed wrote, “the first three or four ‘Bootmaker’ daughters had just calved. They were not very impressive. True.” He had his two best cows bred to Bootmaker at that time and admitted he “was less than happy with what I saw.” Stud interest wasn’t exactly stampeding either.

What no one saw coming, standing in that barn with those first plain daughters, was what would happen once enough Bootmaker heifers freshened in good herds.

Almost all of the Paclamar‑bred Bootmaker daughters that sold in that first dispersal developed into very good cows, some outstanding. Reed’s two Bootmaker heifers out of his best cows both grew into Excellent Gold Medal Dams. As more daughters went on test and classification, American Breeders Service stepped in and leased Bootmaker.

By 1999, Bootmaker had sired 27,252 production‑tested daughters in 8,006 herds and 14,307 classified daughters averaging 82.66. He was the number‑two Honor List sire in 1976, behind Paclamar Astronaut and ahead of Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief and Round Oak Rag Apple Elevation. He never rivaled Chief or Elevation for great sons, but he made his mark where his mother had—through the female side.

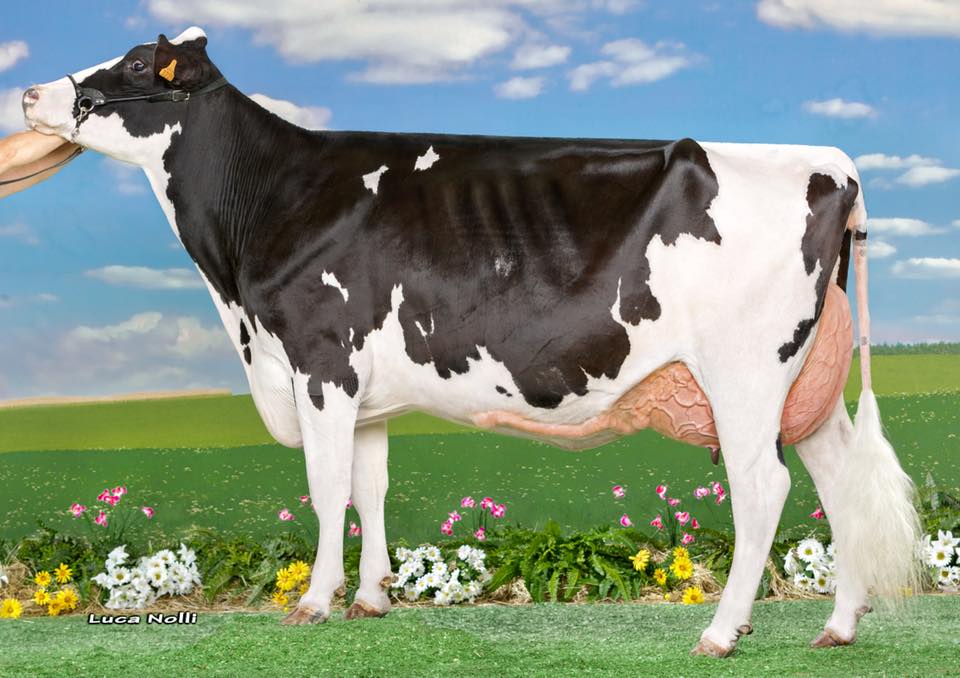

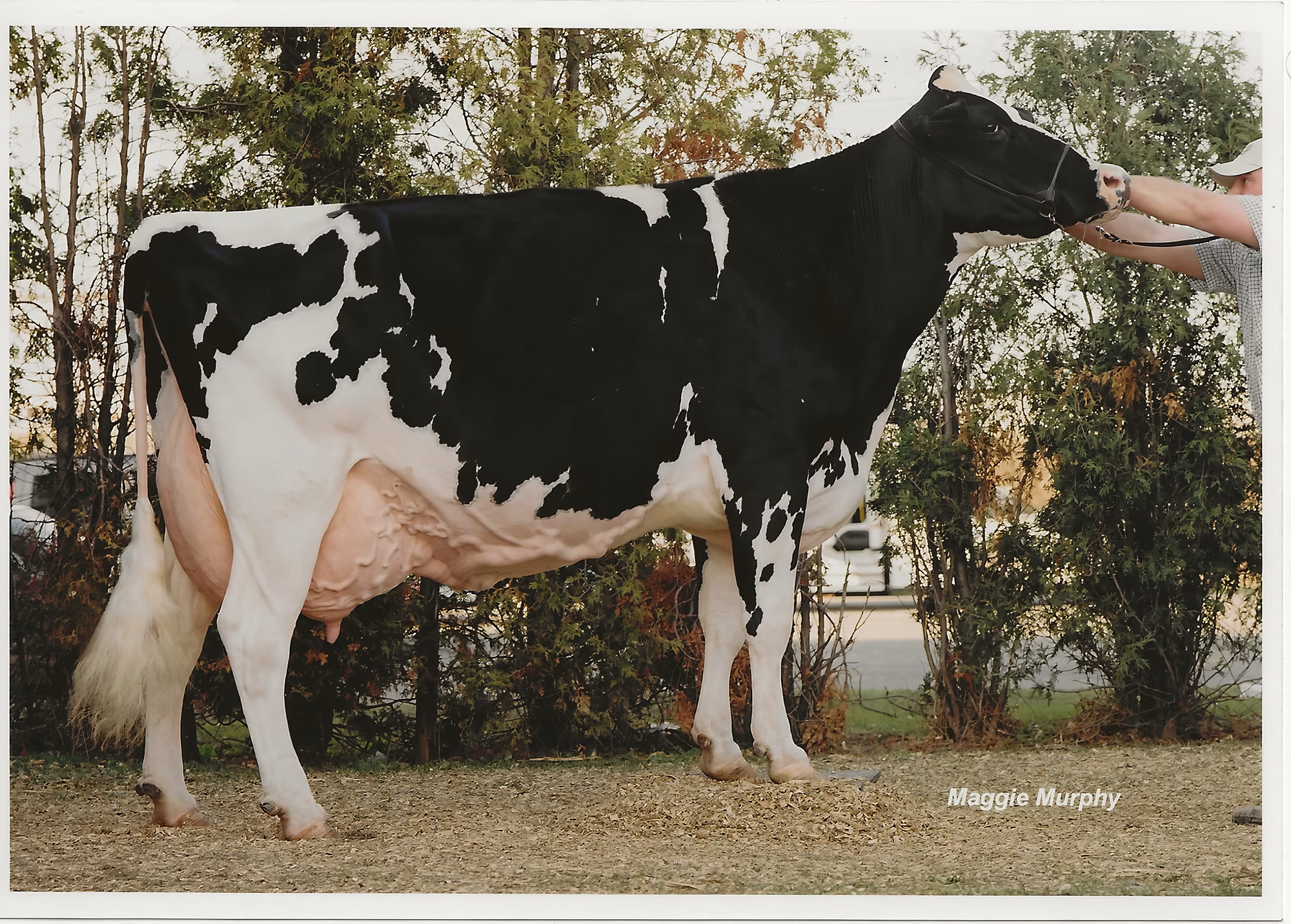

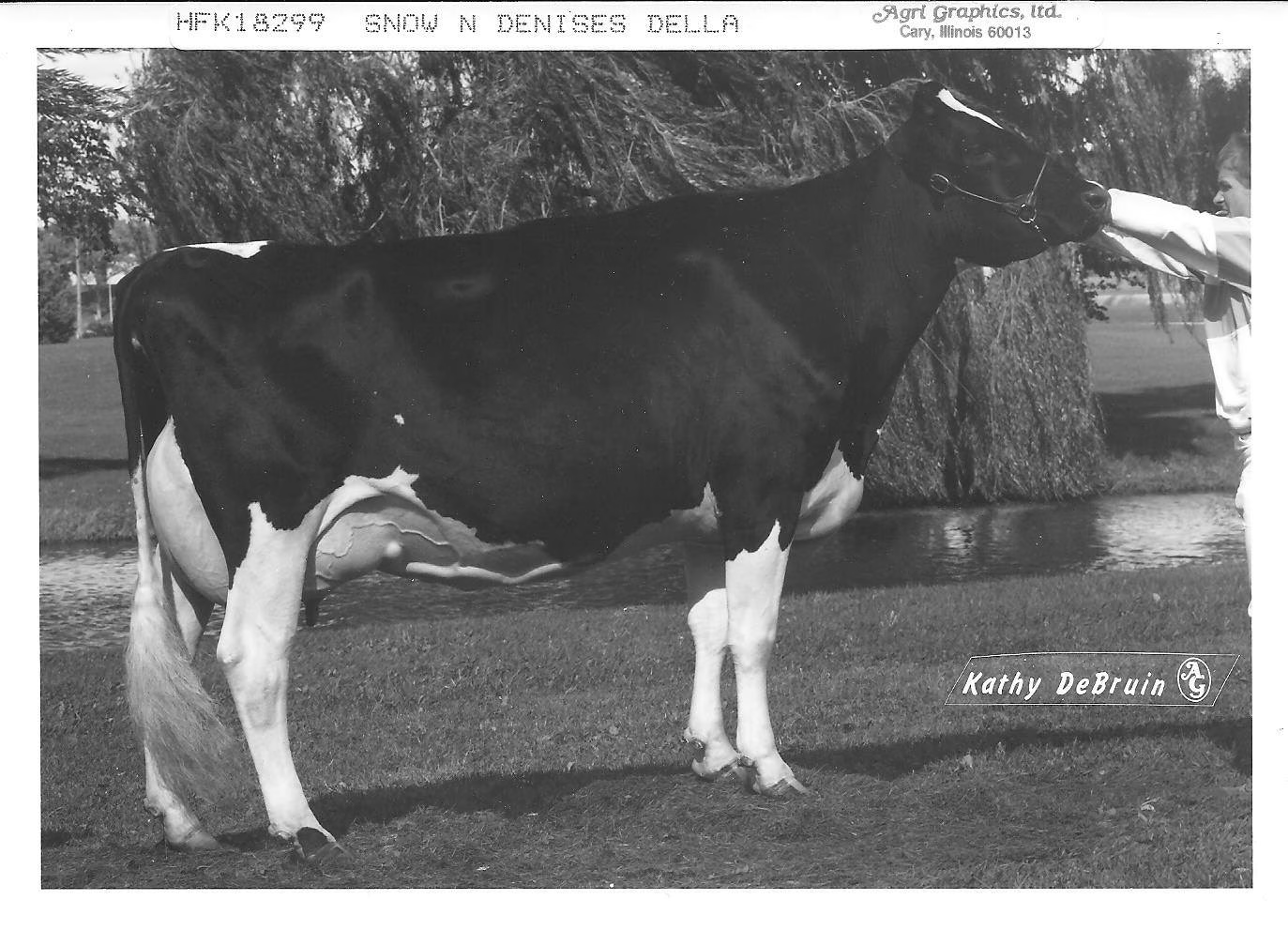

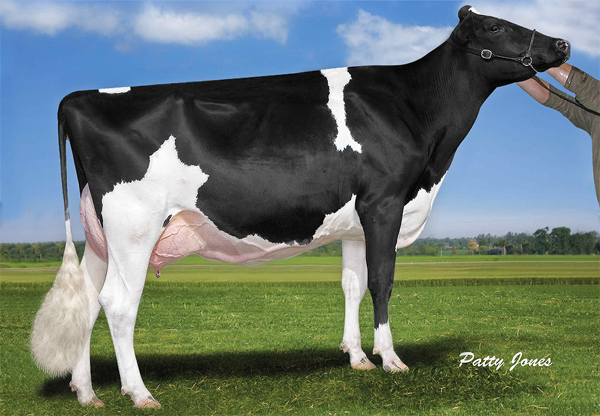

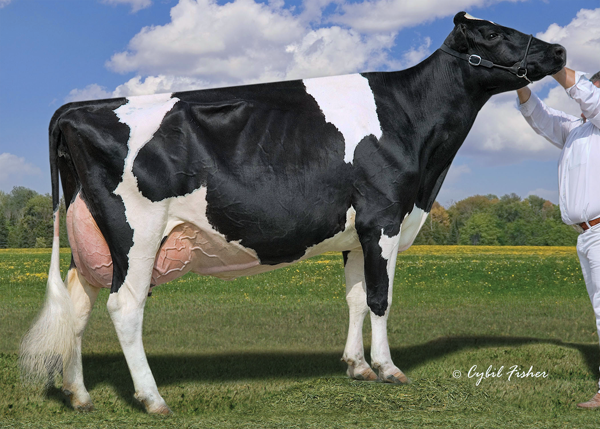

Bootmaker became the first bull ever to sire 100 Gold Medal Dams. Those included cows like Wapa Bootmaker Mandy EX‑96‑GMD, Fleetridge Bootmaker Dixie EX‑2E‑GMD, Gor‑Wood‑D Bootmaker Jennifer EX‑92‑GMD, Holtex Triune S Peggy EX‑91‑GMD, Holtex Triune Fond Fay EX‑94‑3E‑GMD, Burley Bootmaker Valid EX‑93‑4E, Pinehurst Pleasure EX‑93‑4E‑GMD, and Sully Fobes Bootmaker Dot EX‑97‑3E‑GMD—the kind of cows you’d walk back to see twice in a show barn. They were the kind of daughters you built herds and cow families around.

Put simply: Bootmaker did in the AI era what his dam had done in Kansas and Colorado. He made the kind you kept.

Act III – Quiet Passing, Loud Echo

The years between the 1967 sale and Snowboots’ death weren’t long, but they mattered. She’d delivered her last calf at Paclamar—a Rosafe Citation R daughter with black markings down to the foot, disqualifying her from registry under the color rules of the time—and that heifer went to Larry Moore’s Red Holstein herd for $5,000. Darrell Pidgeon later said she looked like she’d have gone Excellent.

Then, one night, it just ended.

Lowell Nelson, herdsman at Paclamar, remembered it this way:

“Each night I went to the barn to check the cows before I went to bed. One particular night, ‘Snowboots’ was lying in her box stall, due to freshen in a month to ‘Fury.’ When I walked by, she was resting with her head back on her side. The next morning, when we got to the barn, she was still lying there, her head on one side, dead. Without a struggle, she had passed away from an apparent heart attack. It was truly a sad day at Paclamar. She was buried there on the farm.”

No thrashing, no long illness. Just a nearly 14‑year‑old cow, carrying her eleventh calf, gone quietly in the night. For a farm that had built so much of its identity around a handful of truly great cows, that had to hurt.

Brooks summed her up in a way only a man who’d handled thousands of cattle could:

“Few cows, if any, had ever contributed as much to the genetic advancement of the breed. She was a cow you could breed once and get a conception. She was a cow that could be bred to more kinds of bulls and still have a good offspring than any cow that I ever worked with. She was a cow that had the greatest disposition of them all, and everyone loved to work with her.”

Back in Kansas, Reed said they still refer to her as “everyone’s favorite brood cow.” That’s not a title the breed hands out lightly.

Now, what most people don’t realize when they look at modern pedigrees is just how much of Snowboots’ world they’re still living in.

On the bull side, the Paclamar story is better known. Astronaut, Milly’s son by Thonyma Ormsby Senator, sold for $9,000 at the 1964 National Convention Sale and went on to sire nearly 60,000 production‑tested daughters. Through Hanoverhill Starbuck—out of an Astronaut daughter—and Startmore Rudolph—by Aerostar, a Starbuck son, with an Astronaut third dam—Astronaut sits right in the backbone of the modern Holstein genotype. When people talk about the “Starbuck look” and about bulls like Rudolph reshaping both type and production worldwide, Astronaut is sitting there in the pedigree every time.

On the cow‑family side, Bootmaker and Snowboots have been doing the same kind of work, just more quietly. Bootmaker’s 100 Gold Medal Dams anchored herds from Pinehurst to Wapa and beyond, and their descendants show up again and again in cow families that lasted—families with multiple generations of high classification and strong production. Many of those daughters carried “Triune” in their name, a nod to the Kansas bull Brooks and Reed both believed in so strongly.

Every time a modern breeder says, “She’s a brood cow—you can breed her to just about anything and get something useful,” they’re talking about the same kind of cow Brooks described when he talked about Snowboots. Every time a salesperson pulls up a pedigree and points to Bootmaker a couple of generations back on the maternal side, they’re looking at her influence coming through in practical ways—conception, udder, attitude.

And it’s not just paper. In today’s barns, heifer calves are expensive. A week‑old dairy‑beef cross can bring four figures; replacement heifers can cost more than a decent used truck. Research on lightly selected “control line” cows versus intensely selected modern lines suggests what a lot of old‑timers already knew in their bones: cows bred too hard for peak yield can sacrifice fertility and survivability, while the “old‑fashioned” kind hangs around and raises more calves.

Snowboots was that “old‑fashioned” kind—except she did it with numbers that still stack up: 3,551 days, 201,187 pounds of milk, 7,729 pounds of fat, calving in September six years in a row, and in calf with number eleven when she died. She proved you could have both: production and longevity. In an era when we talk a lot about lifetime milk per stall and cows that “pay for their replacements,” her life reads like a case study.

So what would the Holstein breed look like if she’d stayed a 4‑H project on that wheat farm, or if Jack had gone home without that $325 pair? Paclamar doesn’t have Snowboots to stand beside Milly in 1962, and that “Grand and Reserve from one farm” headline never gets written. Brooks doesn’t have the dam he needs for Bootmaker—no black September calf with six crosses to Triune and 27,000 daughters to spread that influence around. Those 100 Gold Medal Dams with “Bootmaker” in their name belong to other bulls, or don’t exist at all. And the maternal backbone in a lot of modern pedigrees looks just a little less sturdy.

The records tell us one thing: show wins, scores, production totals, sale prices. The people who were there fill in the rest. Reed remembering her as “everyone’s favorite brood cow.” Nelson seeing her every night at barn check. Brooks saying she “could be bred to more kinds of bulls and still have a good offspring” than any cow he ever worked with.

If you’ve ever stood in your own barn after evening milking, watching an old cow chew her cud and thinking, “If I had ten more just like her, I’d sleep a lot better at night,” you already understand Snowboots Wis Milky Way. She was that cow for three different men, in two different states, and then for a breed that spread her influence around the world.

From a short‑teated Christmas dam on a Kansas wheat farm, to 21st in a local show, to leading the string when Paclamar took both Grand and Reserve at Waterloo, to EX‑97‑3E‑GMD and the dam of an $80,000 bull who filled barns from Colorado to Canada—that’s the arc we’re talking about.

In a Holstein world where it’s easy to get dazzled by the names on semen tanks and the lights on the colored shavings, Snowboots Wis Milky Way pulls us back to where it all really starts: the brood cow in the box stall. The cow who breeds back. The cow who raises daughters and sons that other people want. The cow whose family keeps turning up in your best group long after she’s gone.

For a calf that left her first home in a gunny sack for $75 of that $325 deal, that’s quite a life. And for everyone who loves this breed—for everyone who cares about cows that last and families that matter—Snowboots has earned her place as the brood cow they’ll still be talking about when our grandchildren are arguing pedigrees on the rail at World Dairy Expo.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- A $75 gunny‑sack calf became the dam of 100 Gold Medal Dams. Snowboots Wis Milky Way went from nearly staying a 4‑H project to scoring EX‑97 and producing Paclamar Bootmaker—proof that the next great brood cow might be the one nobody else sees yet.

- Brood cows outlast show cows. Milly took the All‑American banners; Snowboots raised the kind you built herds around. She bred back every time, held together structurally, and produced good offspring no matter the sire—exactly what Dick Brooks meant when he called her the best cow he ever worked with.

- 201,187 lbs milk · 11 calves · 3,551 days on 2x milking. When heifers cost $4,000 and average cows leave before their fourth lactation, Snowboots’ career is the financial case for breeding cows that last.

- Betting on pedigree over proof built a maternal dynasty. Brooks mated one of the two best cows in the breed to an unproven two‑year‑old because the Kansas Triune crosses fit his vision. The result—Bootmaker and his 27,252 daughters—anchored cow families for generations.

- The female side carries the long game. Bootmaker never rivaled Chief or Elevation for famous sons, but his Gold Medal Dams quietly stacked maternal value into pedigrees that are still paying dividends today.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

This is the story of a $75 Christmas calf that left her first home in a gunny sack and ended up as Snowboots Wis Milky Way—EX‑97‑3E‑GMD, and the brood cow Paclamar herdsmen simply called “everyone’s favorite.” She went from 21st out of 22 at a Kansas district show to standing at the head of the aged cow class when Paclamar made history at Waterloo, taking both Grand and Reserve with Milly and Snowboots on the same day. Her Double‑sired son, Paclamar Bootmaker, turned that type and durability into numbers: 27,252 production‑tested daughters, 14,307 classified at 82.66, and a breed‑first 100 Gold Medal Dams. Behind those stats was a cow that bred back easily, held together structurally, and made 201,187 pounds of milk in 3,551 days of 2x milking—calving in September six years in a row and carrying her eleventh calf when she died quietly in her box stall. In a 2026 dairy world where heifers are expensive, cows leave too early, and genotypes change every proof run, Snowboots’ life is a reminder that long‑lived, fertile brood cows aren’t “old‑fashioned”—they’re the genetic insurance policy your future herd depends on.

Continue the Story

- From a $50 Calf to Dairy Royalty: The Peace & Plenty Legacy That Built a Holstein Empire – While Snowboots began in a gunny sack, Joe Schwartzbeck started his empire with a $50 teen gamble. This profile follows another breeder who ignored the experts to build a legacy of 181 Excellents from humble beginnings.

- Trembling Hands, A Decade of Faith, 200 Fewer Cows: Three Paths to the Same Truth – Michael Lovich’s blunt focus on cow families over screens helps us understand the world Snowboots navigated. This piece proves the point that trusting your eyes and breeding for the barn, not the index, still conquers the world.

- Larcrest Cosmopolitan: How a Spotted Minnesota Cow Built a Dynasty – If you’ve seen how Snowboots’ influence carries forward, you’ll recognize the same magic in Cosmopolitan. This profile examines how one “spotted Minnesota cow” transformed global AI, proving that elite maternal lines are the breed’s ultimate insurance policy.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

David Brown, like all of us, had his flaws. Endowed with remarkable skills as a breeder, showman, and promoter, he was often hailed as the finest cattleman of his era. Growing up on Browndale Farms in Paris, Ontario, he had towering expectations to meet. His father, R.F. Brown, was a luminary in the dairy world, winning the esteemed Curtis Clark Achievement Award in 1988 and the Klussendorf Trophy at the 1993 World Dairy Expo. As one of Canada’s most successful breeders, R.F. clinched Premier Breeder and Exhibitor honors at the World Dairy Expo and the Royal Winter Fair. His accolades included five Grand Champions at the Royal Winter Fair: Green Elms Echo Christina (1972 and dam of Browndale Commissioner), Vanlea Nugget Joyce (1974), Marfield Marquis Molly (1978), and Du-Ma-Ti Valiant Boots Jewel (1988). David certainly had big shoes to fill. And fill them he did. His list of accomplishments was extensive: He led Ontario’s top herd in production in 1991, bred two All-Canadian Breeder’s Herd groups, and produced the All-American Best Three Females in 1998. He was twice crowned Premier Breeder at the International Holstein Show and accumulated 92 awards in All-Canadian and All-American contests from 1986 through 2004. Yet, despite two auction sales in 1991 and 1996 aimed at reducing his debts, financial relief was elusive. Over time, his wife left him, his children moved away, and his prized cattle were sold off. Eventually, David relocated to Colombia, where he passed away. Views on Brown are mixed—some saw him as a charming inspiration, while others regarded him as a rule-bending showman or an irresponsible debtor. Nonetheless, his rapid ascent and remarkable achievements in his lifetime are indisputable. Many wealthy individuals have invested vast sums of money into the cattle industry, chasing the same recognition, only to leave empty-handed. What distinguished David Brown was his nearly mystical talent for preparing animals for the show ring and transforming them into champions.

David Brown, like all of us, had his flaws. Endowed with remarkable skills as a breeder, showman, and promoter, he was often hailed as the finest cattleman of his era. Growing up on Browndale Farms in Paris, Ontario, he had towering expectations to meet. His father, R.F. Brown, was a luminary in the dairy world, winning the esteemed Curtis Clark Achievement Award in 1988 and the Klussendorf Trophy at the 1993 World Dairy Expo. As one of Canada’s most successful breeders, R.F. clinched Premier Breeder and Exhibitor honors at the World Dairy Expo and the Royal Winter Fair. His accolades included five Grand Champions at the Royal Winter Fair: Green Elms Echo Christina (1972 and dam of Browndale Commissioner), Vanlea Nugget Joyce (1974), Marfield Marquis Molly (1978), and Du-Ma-Ti Valiant Boots Jewel (1988). David certainly had big shoes to fill. And fill them he did. His list of accomplishments was extensive: He led Ontario’s top herd in production in 1991, bred two All-Canadian Breeder’s Herd groups, and produced the All-American Best Three Females in 1998. He was twice crowned Premier Breeder at the International Holstein Show and accumulated 92 awards in All-Canadian and All-American contests from 1986 through 2004. Yet, despite two auction sales in 1991 and 1996 aimed at reducing his debts, financial relief was elusive. Over time, his wife left him, his children moved away, and his prized cattle were sold off. Eventually, David relocated to Colombia, where he passed away. Views on Brown are mixed—some saw him as a charming inspiration, while others regarded him as a rule-bending showman or an irresponsible debtor. Nonetheless, his rapid ascent and remarkable achievements in his lifetime are indisputable. Many wealthy individuals have invested vast sums of money into the cattle industry, chasing the same recognition, only to leave empty-handed. What distinguished David Brown was his nearly mystical talent for preparing animals for the show ring and transforming them into champions. Edward Young Morwick, a distinguished author, cattle breeder, and lawyer, was born in 1945 on the Holstein dairy farm owned by his father, Hugh G. Morwick. His early memories of his mother carrying him through the cow aisles profoundly shaped his trajectory. Although Edward pursued a career in law, excelling immediately by finishing second out of 306 in his first year, he harbored a deep-seated passion for journalism. This led to his later work chronicling Holstein’s cow history. His seminal work, “The Chosen Breed and The Holstein History,” stands as a cornerstone for those delving into the evolution of the North American Holstein breed. In it, he compellingly argues that the most influential bulls were those of the early historical period. (Read more:

Edward Young Morwick, a distinguished author, cattle breeder, and lawyer, was born in 1945 on the Holstein dairy farm owned by his father, Hugh G. Morwick. His early memories of his mother carrying him through the cow aisles profoundly shaped his trajectory. Although Edward pursued a career in law, excelling immediately by finishing second out of 306 in his first year, he harbored a deep-seated passion for journalism. This led to his later work chronicling Holstein’s cow history. His seminal work, “The Chosen Breed and The Holstein History,” stands as a cornerstone for those delving into the evolution of the North American Holstein breed. In it, he compellingly argues that the most influential bulls were those of the early historical period. (Read more:

”SHAKIRA STOOD OUT FROM THE REST FROM THE BEGINNING”

”SHAKIRA STOOD OUT FROM THE REST FROM THE BEGINNING”

“SHAKIRA’S STAR TREK”

“SHAKIRA’S STAR TREK”

![ho000008724158[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ho0000087241581-1024x768.jpg)

![54993[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/549931.jpg)

Holstein Association USA is pleased to announce Bur-Wall Buckeye Gigi and Idee Shottle Lalia as 2013 Star of the Breed recipients.

Holstein Association USA is pleased to announce Bur-Wall Buckeye Gigi and Idee Shottle Lalia as 2013 Star of the Breed recipients.

![841[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/8411-1024x731.jpg)

![328477_242047159196902_1437414927_o[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/328477_242047159196902_1437414927_o1-1024x731.jpg)

![014ho06429p-cookiecutter-mom-halo-et[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/014ho06429p-cookiecutter-mom-halo-et1-1024x729.jpg)