Record butterfat. Shrinking checks. The industry’s 25-year breeding strategy just ate itself.

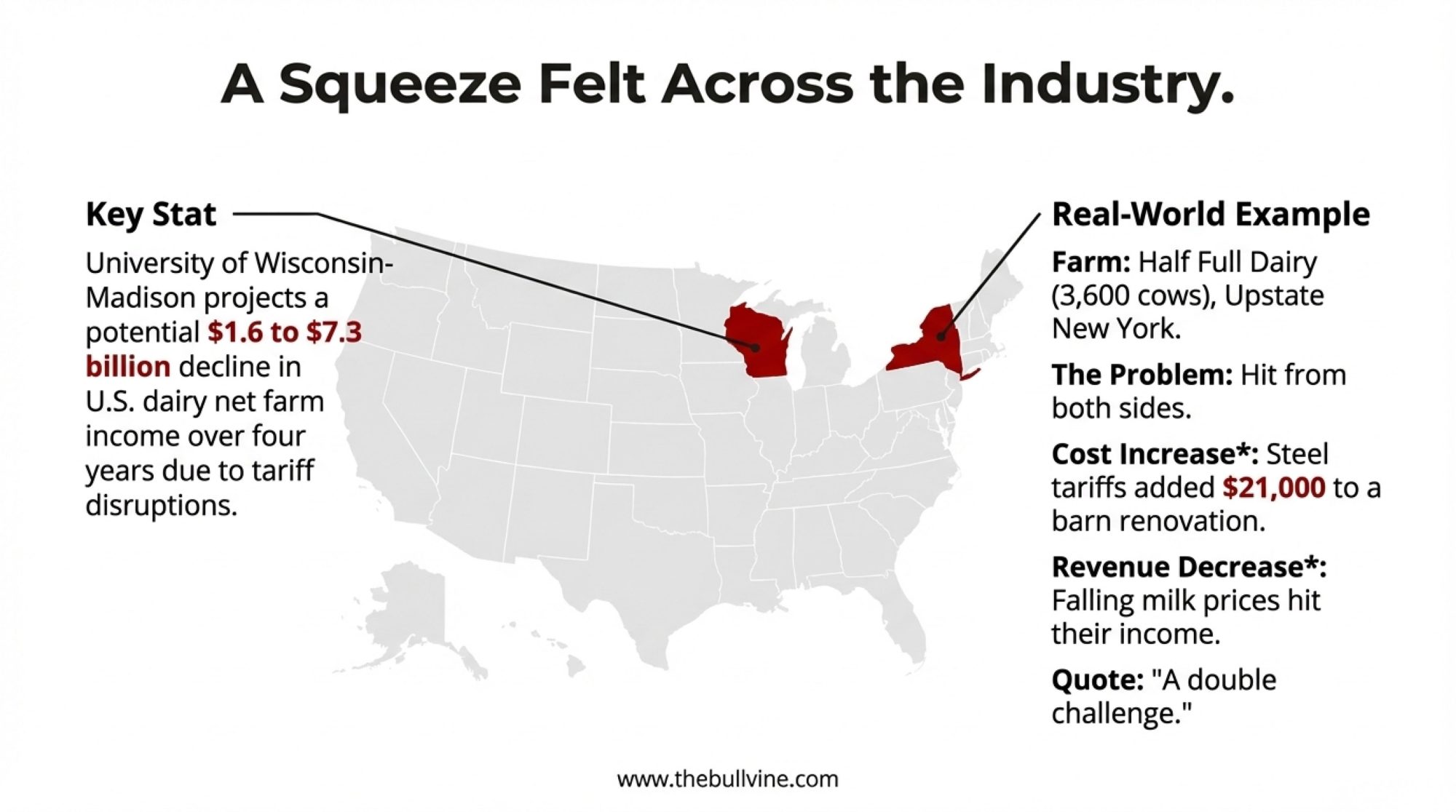

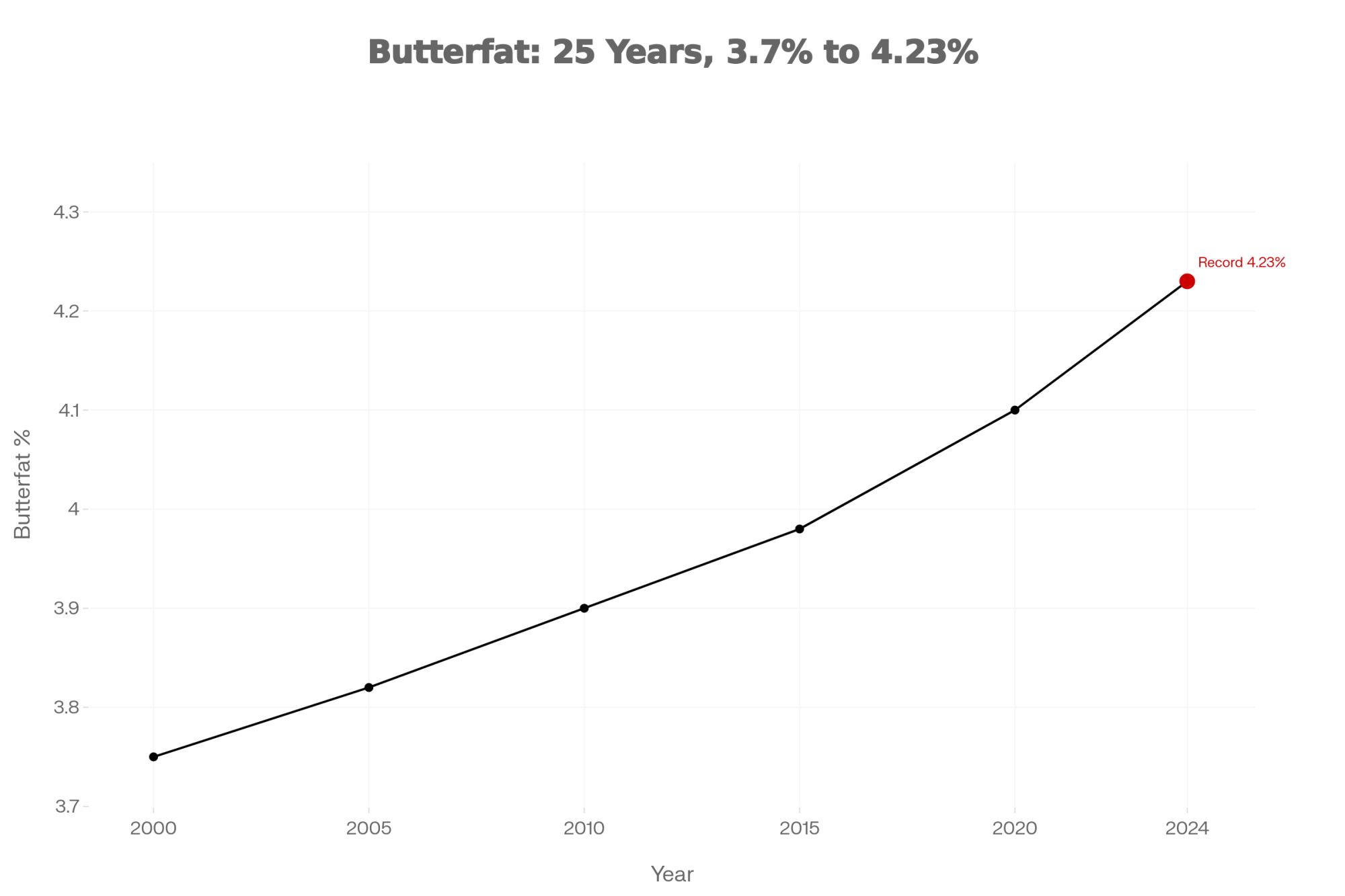

Executive Summary: Here’s the paradox: U.S. dairy herds are testing 4.23% butterfat—an all-time record—yet milk checks are running $3-5/cwt below last year. The genetic industry’s 25-year push for components worked perfectly, and now everyone’s drowning in the success. Butter stocks are up 14%, Class IV prices hit $13.89/cwt in November (lowest since 2020), and the traditional cull-and-restock response is off the table with springers at $3,000+ and heifer inventory at a 47-year low. For operations in the 500-1,500 cow range carrying moderate debt, the next 90 days are decisive—DMC enrollment closes in February, DRP in March, and the choices made before spring will separate farms that reposition from those that get squeezed. Three viable paths exist: optimize for efficiency, transition to premium markets, or exit strategically while equity remains. Standing still isn’t on the list.

I’ve been talking with farmers across the Midwest and Northeast over the past few weeks, and there’s a common thread running through those conversations. A producer will mention their herd’s butterfat at 4.3%—exactly what they spent a decade breeding for—and then pause. Because that same milk is now flowing into a market where the cream premiums just don’t look like they used to.

It’s a strange place to be. You made sound breeding decisions. The genetics are performing. The components are there. And yet the check doesn’t quite reflect it.

So what’s actually going on here? And more importantly, what can we realistically do about it in the next 90 days?

[Image: Side-by-side comparison of a milk check from 2023 vs. 2025 showing component premiums shrinking despite higher butterfat test]

After reviewing the latest market data and speaking with lender advisors, farm management consultants, and producers who’ve been through similar cycles, a clearer picture emerges. This isn’t simply a temporary dip that’ll correct by spring flush. It’s a structural shift that’s been building for years—and the farms that come through it successfully will be those that understand both what’s driving it and which decisions actually move the needle.

The Component Trap: How 25 Years of Smart Breeding Created Today’s Problem

Here’s something that needs to be said plainly, even if it’s uncomfortable: the genetic industry—breeders, AI companies, genomic providers—collectively steered the entire U.S. dairy herd in one direction, and now we’re all standing here wondering what comes next.

That’s not an accusation. Everyone was following the economic signals. But the result is undeniable.

You probably know the broad outlines already, but it’s worth walking through the numbers because they’re pretty striking when you see them together. None of this happened by accident. It’s the result of pricing signals that consistently rewarded butterfat production across two and a half decades.

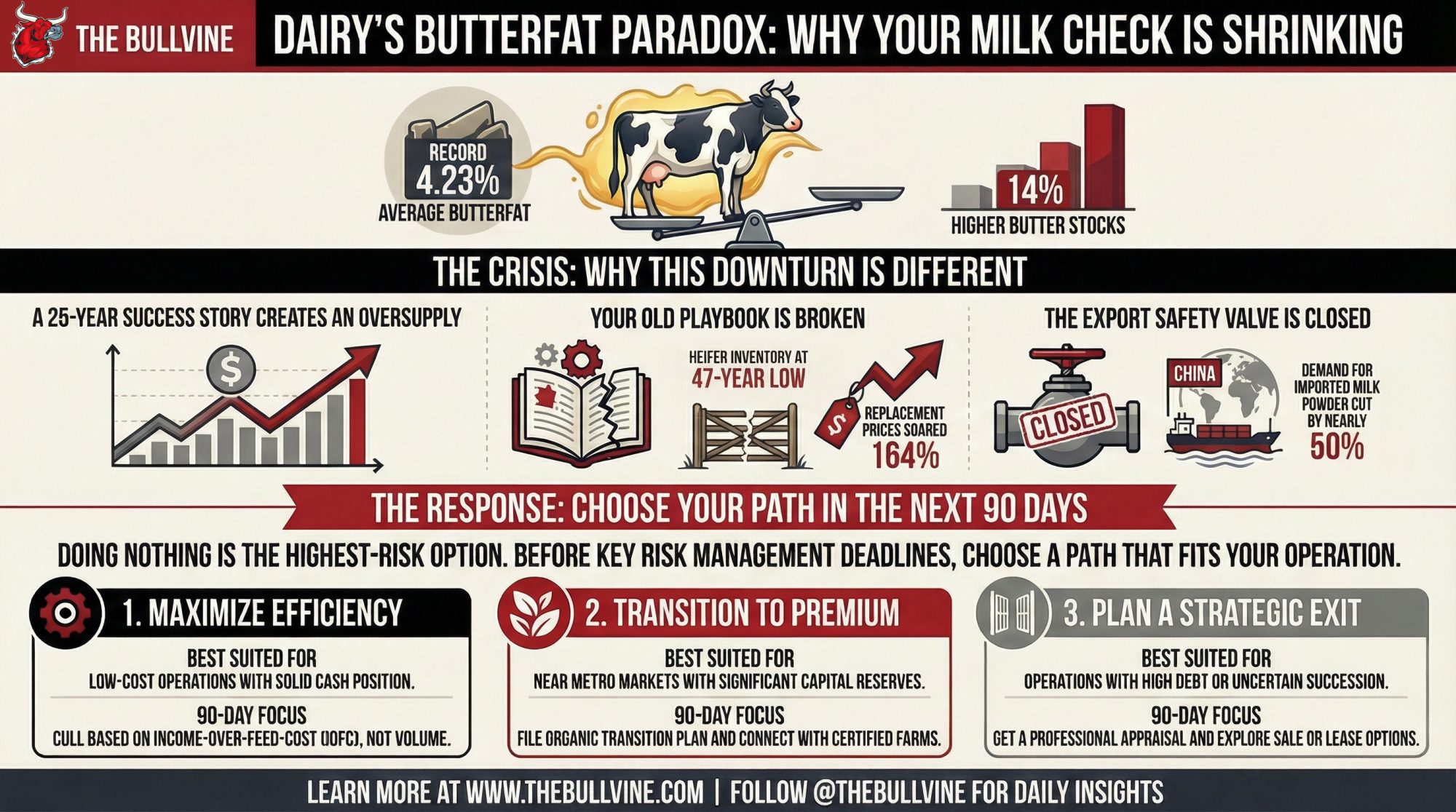

Consider the trajectory. The average Holstein was testing around 3.7-3.8% butterfat back in 2000, according to Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding historical data. By 2024, that figure had climbed to a record 4.23%—a substantial jump in component concentration. CoBank’s lead dairy economist, Corey Geiger, noted in his analysis last year that milkfat, on both a percentage and per-pound basis, reached an all-time high. In high-genetics herds, 4.3-4.5% is now pretty common.

This wasn’t a failure of individual breeding decisions. It was a success—of everyone doing the exact same thing at the exact same time.

[Image: Line graph showing U.S. average butterfat percentage climbing from 3.7% in 2000 to 4.23% in 2024]

Federal Milk Marketing Order formulas rewarded butterfat with premium pricing, and the industry responded accordingly. Then, genomic selection tools, which really gained traction around 2009, accelerated genetic progress dramatically. What once took 15-20 years of conventional breeding can now be achieved in roughly half that time. The April 2025 CDCB genetic base reset tells the story—it rolled back butterfat by 45 pounds for Holsteins, nearly double any previous adjustment. That’s how much progress has accumulated in the genetic pipeline.

The economics seemed compelling at the time. A farm producing 4.2% butterfat milk versus 3.8% butterfat earned roughly $0.80-1.20/cwt more on the same volume, based on component pricing formulas. For a 1,000-cow herd producing 25,000 lbs/cow annually, that translated to $200,000-300,000 in additional annual revenue. The incentives pointed clearly in one direction.

And here’s where it gets tricky.

When an entire industry simultaneously optimizes for the same trait, supply eventually outpaces demand. U.S. butter production has grown substantially over the past decade, according to USDA Agricultural Marketing Service data. Cold storage butter inventories showed elevated stocks throughout late 2024, with USDA Cold Storage data reporting September levels at approximately 303 million pounds—up about 14% from year-earlier figures.

Class IV milk futures, which price butter and powder, have reflected this pressure. USDA announced the November 2025 Class IV price at $13.89/cwt—levels we haven’t seen since 2020.

The question nobody in the genetic industry is asking publicly: Should we have seen this coming? And what does it mean for how we select sires going forward?

The Heifer Crisis: Why Your Normal Playbook Won’t Work This Time

What makes this particular cycle tricky is that some of the standard farm-level responses to low prices just aren’t available anymore. I’ve watched this play out in conversations with producers who are working through every option—and finding that familiar levers don’t pull the way they expect.

[Image: Infographic showing dairy heifer inventory decline from 4.5 million in 2018 to 3.914 million in 2025]

The Numbers That Should Keep You Up at Night

The logical response to component oversupply would be culling toward different genetics and restocking. But there’s a significant constraint worth understanding.

Replacement heifers simply aren’t available in the numbers many operations need—and the available ones have gotten expensive. The widespread adoption of beef-on-dairy breeding, which made excellent economic sense when beef prices surged, has reduced dairy heifer inventories to approximately 3.914 million head according to the January 2025 USDA cattle inventory report. That’s the lowest level since 1978.

Here’s where the math gets painful. CoBank reported these figures in their August 2025 analysis:

- National average springer price (July 2025): $3,010 per head

- Wisconsin average: $3,290 per head

- California/Minnesota top auction prices: $4,000+ per head

- April 2019 low point: $1,140 per head

- Price increase since then: 164%

Let that sink in. If you want to cull your bottom 50 cows and replace them, you’re looking at $150,000-$225,000 just in replacement costs—before you account for the production lag while those heifers freshen and ramp up.

This creates real tension. Operations that would like to cull more aggressively face either limited availability or elevated replacement costs. It’s a completely different calculation than we’ve seen in past downturns.

There’s also a timing consideration that’s easy to overlook. The replacement heifers entering milking strings in 2025-2026 were born and selected 2-3 years ago, when butterfat premiums were still paying handsomely. That genetic pipeline takes time to shift—meaningful changes in herd composition typically require 5-7 years, even with aggressive selection, according to dairy geneticists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension.

The practical takeaway: Even if you start selecting differently today, you won’t see the results in your tank until 2030.

The Ration Workaround That Doesn’t Actually Work

Some producers have explored nutritional adjustments to modify butterfat percentage. I’ve heard this come up in several conversations, and it’s worth addressing directly.

Here’s the challenge—the rumen chemistry driving fat synthesis is interconnected with overall milk production in ways that make targeted adjustments difficult. Dairy nutritionists at Penn State and other land-grant universities have studied this extensively: adjustments that reduce butterfat typically also reduce total milk yield by 3-8%. The feed cost savings, maybe $0.30-0.50/cow/day depending on your ration costs, are often outweighed by lost milk revenue of $1.00-2.00/cow/day at current prices.

In most scenarios, ration manipulation doesn’t improve the overall financial picture. Counterintuitive, but the numbers generally bear it out.

The China Factor: The Export Valve That Closed

One element that’s amplified the current situation—and this deserves more attention in domestic discussions—is the shift in Chinese dairy import patterns.

[Image: Bar chart comparing China whole milk powder imports: approximately 800,000-850,000 MT peak around 2021 vs. approximately 430,000 MT in 2024]

For roughly two decades, China served as a significant outlet for global dairy surplus. When exporting regions overproduced, Chinese buyers absorbed much of the excess. That dynamic has evolved considerably.

China’s domestic milk production has grown substantially over the past several years, reaching over 41 million tonnesaccording to USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data. Self-sufficiency has risen from roughly 70% to around 85%, thereby reducing import demand.

The import trends tell the story clearly. Whole milk powder imports peaked at approximately 800,000-850,000 metric tonnes around 2021, according to Chinese customs data compiled by Rabobank. By 2024, that figure had declined to around 430,000 metric tonnes—a reduction of roughly 50%.

Here’s what that means at the farm level: when 400,000 metric tonnes of powder that used to go to Shanghai starts competing for space in domestic and alternative export markets, that’s pressure that eventually shows up in your component check. Global dairy markets are interconnected in ways that weren’t true 20 years ago.

Rabobank senior dairy analyst Michael Harvey noted in their Q4 2024 Global Dairy Quarterly that Chinese imports could surprise to the upside if domestic production disappoints and consumer confidence improves. That’s a reasonable alternative scenario to consider.

Honestly? Nobody knows exactly where China goes from here. But planning as if that export outlet will suddenly reopen at 2021 levels seems optimistic at this point.

The Consolidation Accelerator

Dairy farming has been consolidating for decades—that’s well understood by anyone who’s watched their neighbor’s barn go quiet. What’s different about this period is the potential for that trend to accelerate under sustained margin pressure.

According to U.S. Courts data reported by Farm Policy News, 361 Chapter 12 farm bankruptcy filings occurred in the first half of 2025—a 13% increase over the same period last year.

Here’s an important nuance, though: milk production isn’t expected to decline in proportion to the number of farms. The operations most likely to exit tend to be smaller ones that represent a modest share of total volume. USDA projects national milk output at 231.3 billion pounds in 2026—essentially flat—even as the number of operations continues to decrease.

What this means for price recovery: Supply adjustments through consolidation happen more gradually than we might hope.

Three Directions for the Coming Months

For farmers operating in that 500-1,500 cow range—moderate scale, moderate debt, positioned to continue but facing real pressure—the next 90 days present some important decisions.

What’s been striking in conversations with experienced advisors is how consistently they point to the same priorities. The focus isn’t on finding some novel solution. It’s about executing fundamentals with careful attention during a demanding period.

[Image: Calendar graphic highlighting key deadlines: February 2026 (DMC), March 15 (DRP), March 31 (SARE grants)]

Key Dates Worth Tracking

- December 31, 2025: Target for completing financial position analysis

- February 2026: DMC enrollment deadline (confirm with your FSA office)

- March 15, 2026: DRP enrollment deadline for Q2 coverage

- March 31, 2026: SARE grant application deadline for organic transition support

- Q2 2026: Period when margin pressure may be most pronounced

Priority 1: Knowing Exactly Where You Stand (Weeks 1-2)

Here’s what farm management consultants consistently emphasize: many operations lack precise clarity about their actual cost of production by component. They know their budgeted figures, but actual costs in the current environment often run $2-4/cwt higher than estimates suggest.

Consider a professional cost analysis through your lender or an independent agricultural accountant. Costs typically run $1,500-3,000, depending on scope and region—but the analysis frequently reveals $50,000-100,000 in costs that weren’t clearly showing up in standard bookkeeping. Your actual investment depends on your operation’s complexity.

Model three price scenarios for 2026:

| Scenario | Class III | Class IV |

| Base Case | $17/cwt | $14/cwt |

| Stressed | $15/cwt | $12/cwt |

| Severe | $13/cwt | — |

The key benchmark: if your debt service coverage ratio falls below 1.25x in the base case, you’re facing primarily a financing challenge rather than a production management challenge. That distinction shapes everything that follows.

Priority 2: Securing Protection Before Deadlines (Weeks 2-3)

DMC triggered payouts in August-September 2025 when milk margins compressed below coverage thresholds, according to USDA Farm Service Agency payment data. For operations that had enrolled, those payments provided meaningful cash flow support. For those that hadn’t… well, that opportunity has passed.

For a 700-cow operation, margin protection typically costs $35,000-40,000 in premiums based on standard coverage levels—though actual costs vary by operation size and coverage choices. What matters is the asymmetric protection: coverage that could preserve $200,000-300,000 in margin under severe scenarios.

[Related: Understanding DMC Enrollment for 2026 — A step-by-step walkthrough of coverage options and deadlines]

Priority 3: Choosing a Direction (Weeks 3-4)

| Efficiency Focus | Premium Markets | Strategic Transition | |

| Best suited for | Sub-$15/cwt cost structure, solid cash position | Within 50 miles of metro market, $300K+ reserve | Age 55+, elevated debt, uncertain direction |

| 90-day focus | IOFC-based culling, Feed Saved genetics | File organic transition, apply for SARE grants | Professional appraisal, explore sale/lease |

| Timeline | 12-18 months | 36-48 months | 6-12 months |

| Capital required | Low to moderate | $200K-400K | Low (advisory fees) |

[Image: Decision tree flowchart helping farmers identify which of the three paths fits their situation]

Path A: Efficiency Focus

The core approach remains culling the bottom 15-20% of cows ranked by income-over-feed-cost, not by volume alone. Your 50 lowest-margin cows likely cost $300-400/month more than your top 50 to produce milk. Addressing that can improve annual cash flow by $180,000-240,000.

What I keep hearing from producers who went through aggressive IOFC-based culling during 2015-2016 is pretty consistent: it felt counterintuitive at first. Some of those cows were producing 90 pounds a day. But when they ran the actual economics, those high-volume cows were undermining their cost structure. Taking them out changed everything. Many came out of that period in better shape than they went in.

Producers running large dry lot operations in the West report similar experiences. The temptation is always to keep milking cows. But when you run the numbers, the bottom 10-15% of the herd is often break-even in a good month and loses money in a bad one. Letting them go without immediately restocking—just accepting a smaller herd—can actually improve your average component check per cow. Sometimes, smaller really is more profitable.

On the genetics side, it’s worth looking at “Feed Saved” as a selection trait. CDCB introduced this in December 2020, specifically to identify animals that are more efficient at converting feed to milk. The trait’s weight in Net Merit increased to 17.8% in the 2025 update, which tells you how seriously the industry is taking feed efficiency now. The potential savings vary by herd, but for operations where feed accounts for 50-60% of costs, even modest efficiency gains can translate into meaningful dollars. Talk to your AI rep about what realistic expectations might look like for your specific situation.

Path B: Premium Market Transition

For operations within a reasonable distance of major metro markets and with capital reserves to absorb transition costs, organic conversion or specialty milk contracts offer an alternative direction.

This path involves more complexity than it might initially appear. Organic transition typically means 3-year yield reductions of 10-15% according to data from the Organic Dairy Research Institute, followed by meaningful price premiums once certified. The economics can work—eventually—but the transition period requires substantial financial runway.

What I hear consistently from producers who’ve made this transition: the middle years are harder than expected. You’re essentially getting conventional prices while operating organically. But once you reach certification, the price difference is real. NODPA and USDA Organic Dairy Market News report certified operations receiving farmgate prices ranging from the mid-$20s to $30s per cwt for conventional organic, with grass-fed premiums often running significantly higher—sometimes into the $40s or above depending on your processor and region.

If this direction fits your situation, the 90-day priorities include:

Connect with certified organic dairies in your region through your state organic association—NOFA chapters in the Northeast, MOSA in the Upper Midwest, or similar organizations in your area. Request 2-3 farm visits to understand actual transition costs and challenges. The real-world experience matters more than marketing materials.

Explore SARE grants before the March 31, 2026, deadline. These grants may provide significant cost-sharing support for organic transition—contact your regional SARE coordinator for current funding levels and application requirements, since program specifics change annually.

If you’re committed, file your transition plan with your certifier by March 1, 2026, to start the 3-year clock. Earlier starts mean earlier access to premium pricing.

[Related: Organic Transition Economics: What the Numbers Actually Look Like — Real producer case studies and financial breakdowns]

Important consideration: This path makes most sense if you have substantial equity reserves and you’re genuinely within reach of organic market demand. Not every region has processors paying meaningful organic premiums. Market research should come before commitment—talk to Organic Valley, HP Hood, or whoever handles organic milk in your region about their current intake and premium structure.

Path C: Strategic Transition

This is the path that’s hardest to discuss, but for operators over 55, carrying elevated debt, or genuinely uncertain about long-term direction, a strategic exit while equity remains may represent sound financial planning.

Here’s what farm transition specialists consistently emphasize: a farm with a 45% debt-to-asset ratio that transitions strategically today typically retains significantly more family wealth than the same farm forced to exit in 2027-2028 after extended margin erosion. The difference can easily be $300,000-500,000, depending on circumstances.

That’s not failure. That’s recognizing circumstances and making a thoughtful decision.

University of Wisconsin Extension farm transition advisors make this point regularly in producer workshops: the families who come through in the best financial shape are almost always the ones who made the call themselves, not the ones who waited until circumstances forced their hand. There’s real value in choosing your path.

The 90-day approach for this path:

Obtain a professional appraisal ($2,500-4,000 depending on operation complexity) covering real estate, equipment, herd genetics, and any production contracts.

Explore multiple options—they’re not mutually exclusive:

- Direct sale to a larger operation (typically a 12-18 month process)

- Lease arrangement retaining land equity

- Solar lease opportunities—rates vary significantly by region, but can provide meaningful annual income on 20-30+ acres depending on your location and utility contracts

- Custom heifer rearing using your existing facilities—particularly relevant given the shortage we discussed earlier

Consult with a farm transition tax advisor. How you structure an exit matters enormously for what you ultimately retain—installment sales versus lump sum, 1031 exchanges, charitable remainder trusts, and other tools can make six-figure differences in after-tax proceeds.

Regional Realities: One Market, Many Situations

One pattern that emerges from these conversations is how differently the same market dynamics play out depending on where you’re farming. The fundamentals we’ve discussed apply broadly, but the specific numbers vary considerably by region.

In Idaho and the Southwest, large-scale operations with export-oriented processing face one set of calculations. These are often dry lot systems with 3,000+ cows, lower land costs, and direct relationships with major cheese manufacturers. When Glanbia or Leprino adjusts their intake, the regional implications differ from what you’d see in Wisconsin. The scale efficiencies are real, but so is the commodity price exposure. Producers in the Magic Valley are watching Class III futures more closely than component premiums—their economics are tied to cheese demand in ways that Upper Midwest producers selling to smaller plants simply aren’t.

In Wisconsin and the Upper Midwest, you’re more likely to encounter diversified operations—500-1,200 cows, often family-owned across generations, with a mix of cheese plant contracts and cooperative relationships. The smaller average herd size means fixed costs per hundredweight run higher, but there’s also more flexibility to adapt. I’ve talked with Wisconsin producers seriously exploring farmstead cheese or agritourism as margin supplements—approaches that wouldn’t make sense at 5,000 cows but can work at 400.

In the Northeast, higher land costs and proximity to population centers create yet another calculation. Fluid milk markets still matter more here than in most regions, even as fluid consumption continues its long decline. The premium path—organic, grass-fed, local branding—tends to be more viable in Vermont or upstate New York than in the Texas Panhandle simply because the customer base is closer and the logistics work better.

Here’s the bottom line on regional differences: Conversations with farmers and advisors who know your specific market really matter. Your cooperative field staff, extension dairy specialist, or lender can help translate these broader trends into your local context. The three-path framework applies everywhere, but the details of execution—which processors are actively buying, what premiums are realistically available, how constrained the local heifer market is—vary enough to influence decisions.

The Bottom Line

The farms that navigate this period most successfully won’t be those that discovered some novel solution—there isn’t one waiting to be found. They’ll be operations that understood the dynamics early, made honest assessments of their own position, and moved decisively while flexibility remained.

The window for making these decisions is now.

For additional resources on margin protection enrollment and strategic planning, contact your local FSA office, cooperative field representative, agricultural lender, or university extension dairy specialist.

Editor’s Note: Production cost data comes from the USDA Economic Research Service 2024 reports. Heifer pricing reflects USDA NASS data through July 2025. Bankruptcy statistics are from U.S. Courts data reported by Farm Policy News. Genetic progress figures reference the CDCB April 2025 genetic base reset. Cold storage and production data are from the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. International trade figures come from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and Rabobank Global Dairy Quarterly. National and regional averages may not reflect your specific operation, market access, or management system. We welcome producer feedback for future reporting.

Key Takeaways:

- Record butterfat, weaker checks: U.S. herds are averaging 4.23% butterfat, but Class IV has slipped to $13.89/cwt, and butter stocks are up 14%, so the component bonuses many bred for are no longer rescuing the milk check.

- Heifer math has flipped: Dairy heifer inventory is at a 47-year low (3.914 million head), and quality springers are $3,000+ per head, which means the traditional “cull hard and restock” playbook often destroys equity instead of saving it.

- This is a structural shift, not a blip: Twenty-five years of selecting for butterfat, China’s reduced powder imports, and slow-moving U.S. consolidation are combining into a multi-year margin squeeze, not just another bad winter of prices.

- Your next 90 days are critical: Before DMC and DRP deadlines hit in February and March, farms in the 500–1,500 cow range need a clear cost-of-production picture, stress-tested cash-flow scenarios, and margin protection in place.

- You have three realistic paths: Use this window to either tighten efficiency and genetics around IOFC and Feed Saved, transition into premium/organic markets where they truly exist, or plan a strategic exit while there’s still equity to protect—doing nothing is the highest‑risk option.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Is Beef-on-Dairy Causing America’s Heifer Shortage? – Reveals the structural mechanics behind today’s replacement crisis, detailing how the aggressive industry-wide shift to beef genetics created the specific inventory gap that is now driving heifer prices to record highs.

- Cracking the Code: Behavioral Traits and Feed Efficiency – Provides the tactical “how-to” for the Efficiency Focus path, explaining how wearable sensors and behavioral data (rumination/lying time) can identify the most feed-efficient cows to retain when you can’t afford to restock.

- How Rising Interest Rates Are Shaking Up Dairy Farm Finances – Delivers critical financial context for the Strategic Transition path, analyzing how the increased cost of capital is compressing margins and why debt servicing capacity—not just milk price—must drive your 2026 decision-making.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!