Super Bowl LX will burn $8M a spot. Your sire picks can swing $869 per cow. Still letting someone else call the breeding plays?

Executive Summary: Top‑quartile genetics are already worth $869 more lifetime profit per cow, according to a nine‑year Zoetis study on 12,952 Holsteins across 11 US dairies. This article shows how that gap has widened with the 2025 NM$ revision, where a higher weight on Feed Saved and longevity – and a 11% hit on cow size – quietly killed the idea that a show‑ring cow is also the most profitable commercial cow. Framed against Super Bowl LX’s $8 million ad slots, it argues your sire choices deserve the same level of strategy, because they move far more money across a 200‑cow herd than any 30‑second commercial. You’ll get a concrete “game plan”: a four‑slot sire roster with named December 2025 bulls, a one‑page scorecard to run every bull through, and a simple starting plan for genomic testing on your next 20 heifers. Stories from Simon Vander Woude in California, the Baileys at Moorhouse Hall Farm in the UK, and DataGene focus farms in Australia show what happens when producers stop delegating sire selection and let the numbers challenge old habits. The core message is direct: over the next five years, genetics is shifting from “nice‑to‑optimize” to a structural survival factor for any dairy paid on components.

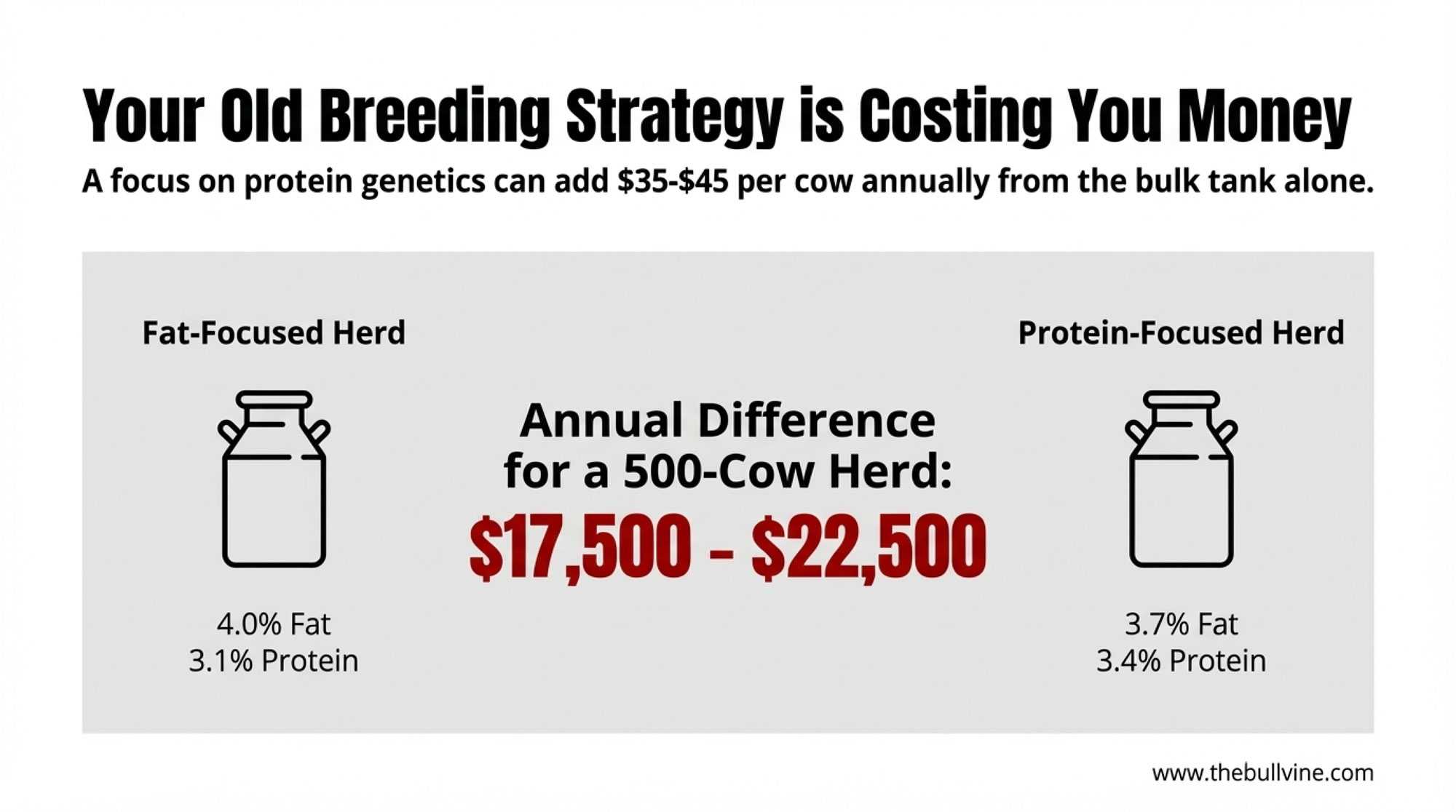

A nine-year Zoetis study tracking 12,952 Holsteins across 11 US dairies found that cows in the top 25% of genetic profitability generated $869 more in lifetime profit than cows in the bottom 25% (Zoetis, August 2022, ranked by Dairy Wellness Profit Index). On a 200-cow herd, that gap adds up to $173,800 per cow generation. On a 100-cow herd, $86,900. That’s not a model. It’s observed data from real operations over nearly a decade.

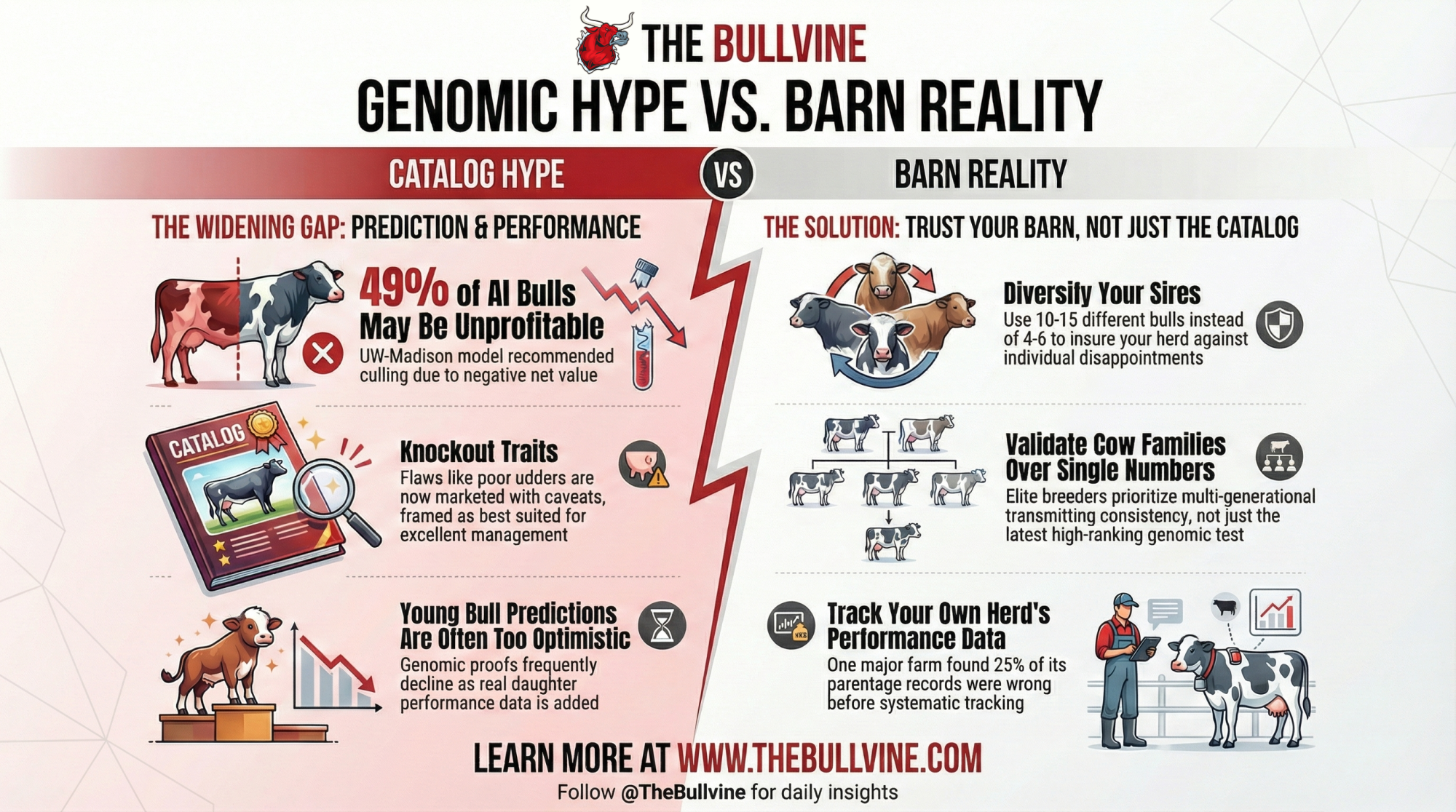

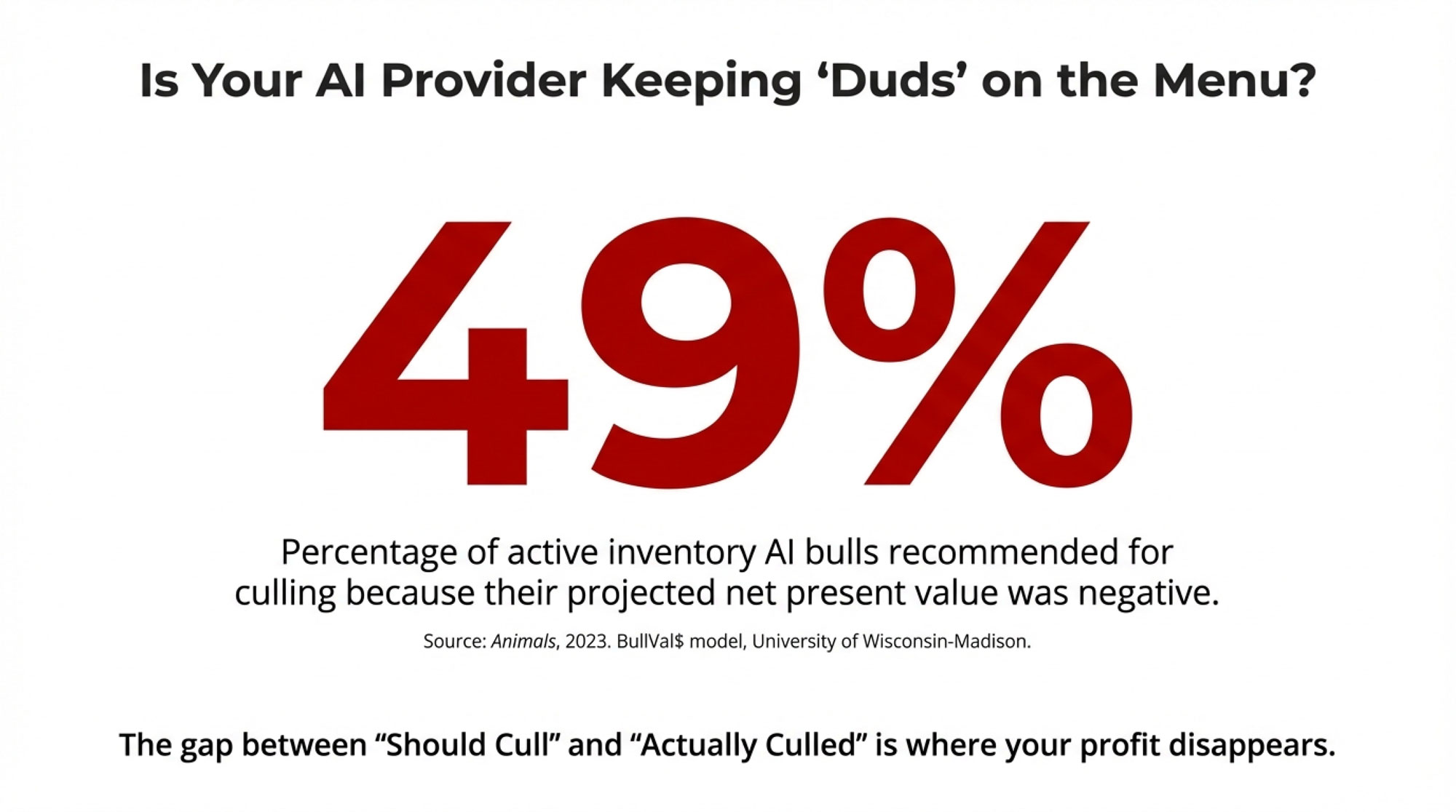

Tonight, brands paying $8 million for 30 seconds of Super Bowl LX airtime at Levi’s Stadium have stress-tested their campaigns for months — audience-segmented, ROI-modeled, every frame data-validated. Meanwhile, a 2010 reader survey found that 46% of producers simply use whatever mating program their A.I. company provides, and only 11% match sire traits to individual cow weaknesses. That survey is 16 years old now — and given the complexity genomics has added, the delegation rate may well be higher today.

Your sire selection deserves the same analytical rigor that advertisers bring to a 30-second spot.

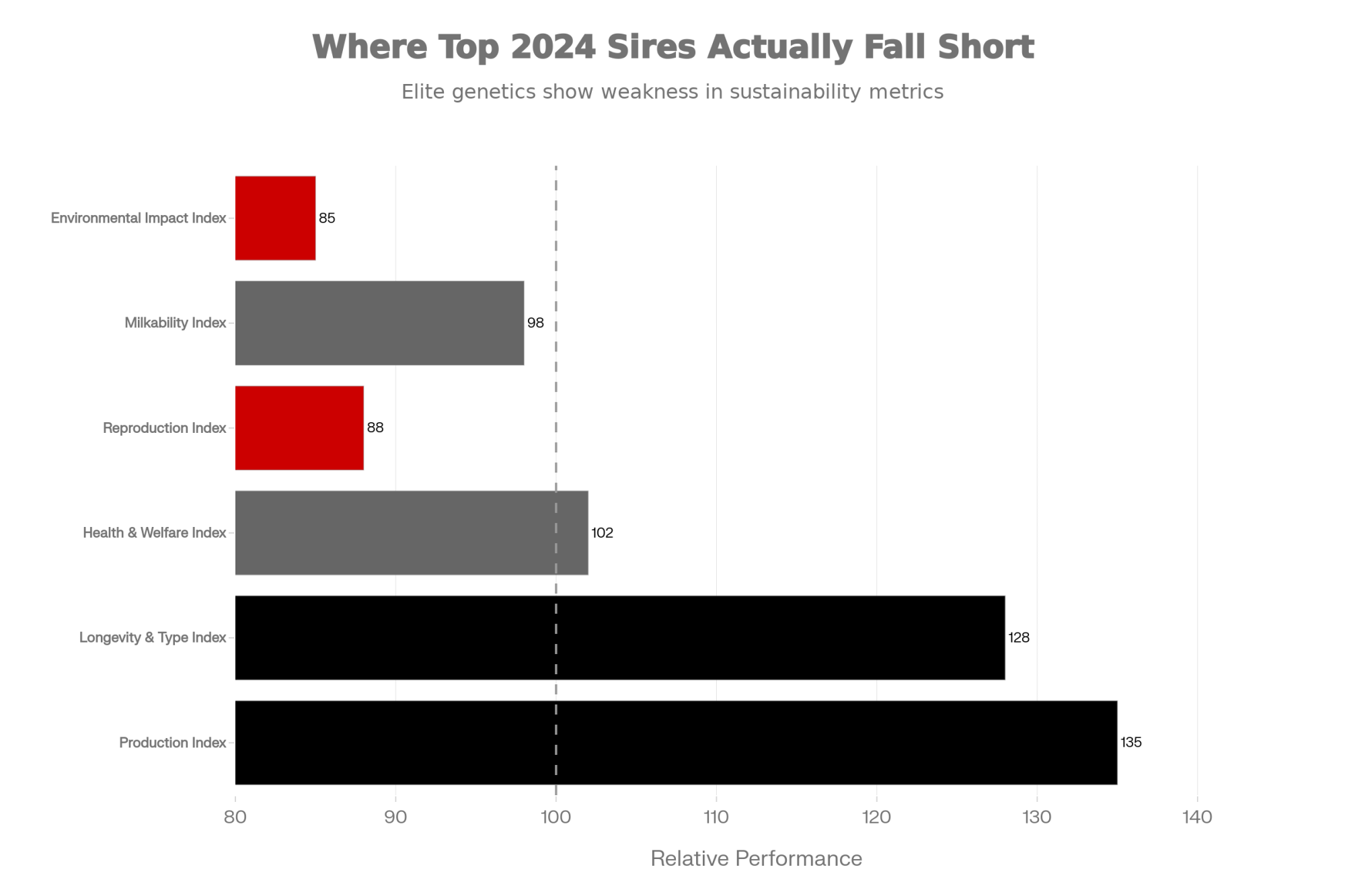

The Widening Genetic Gap

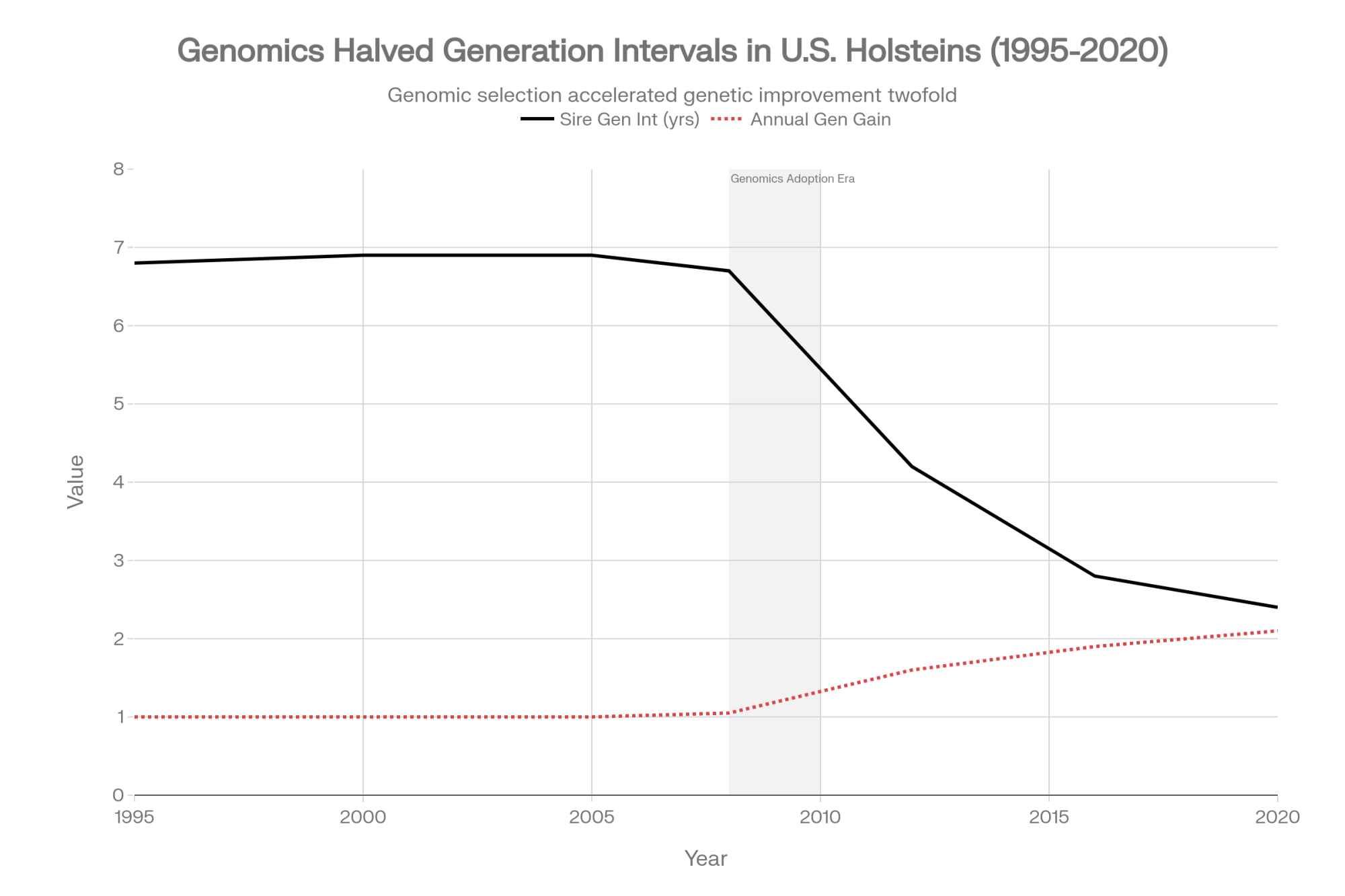

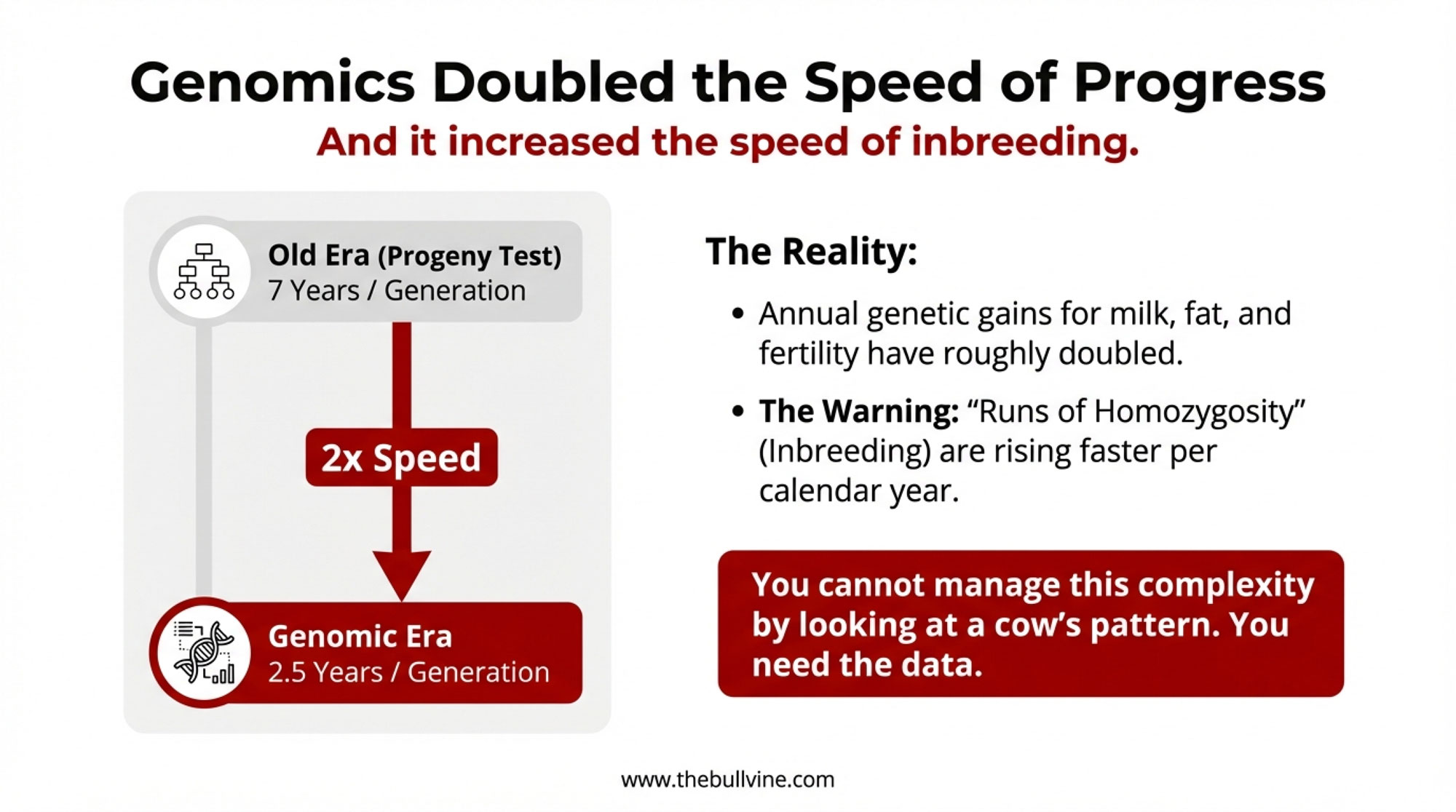

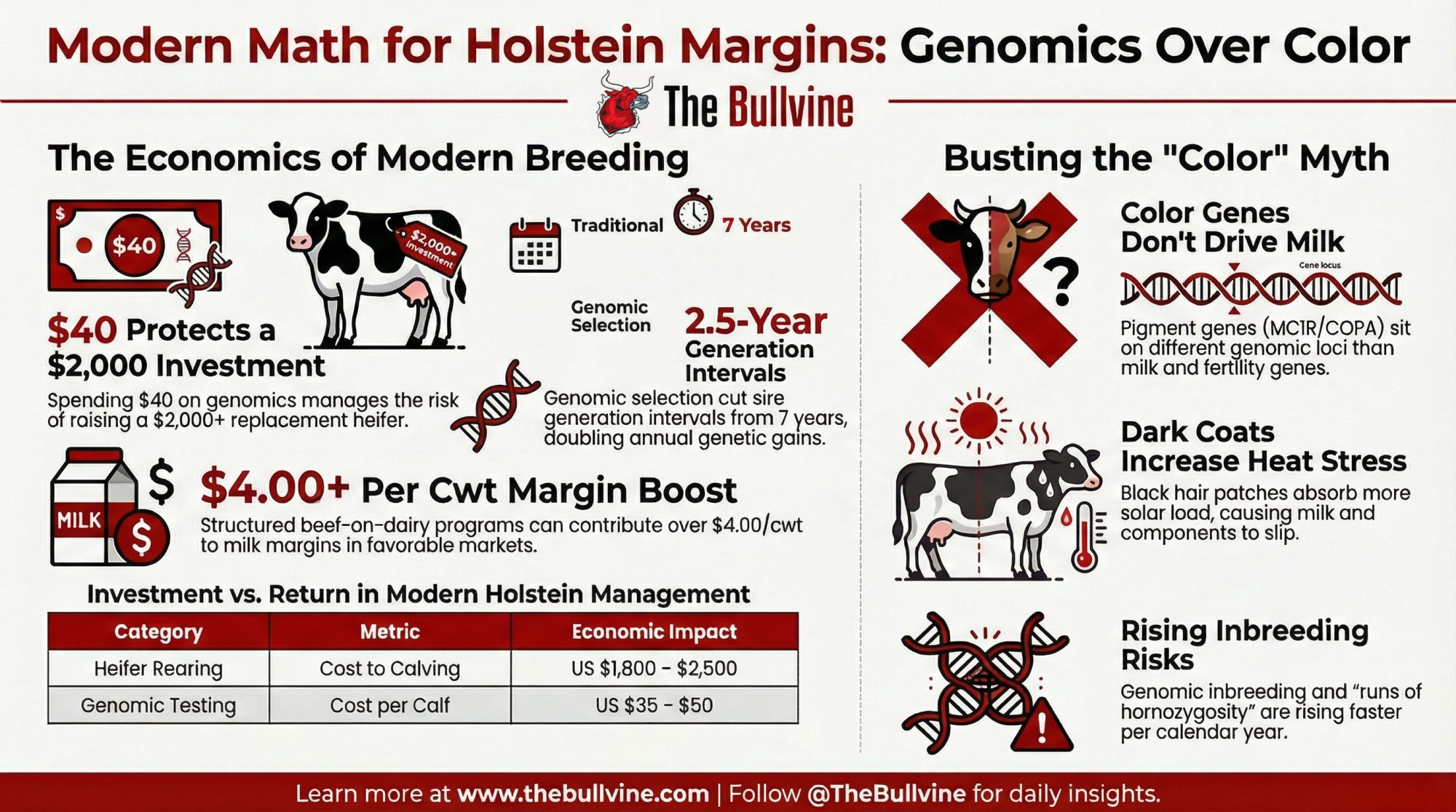

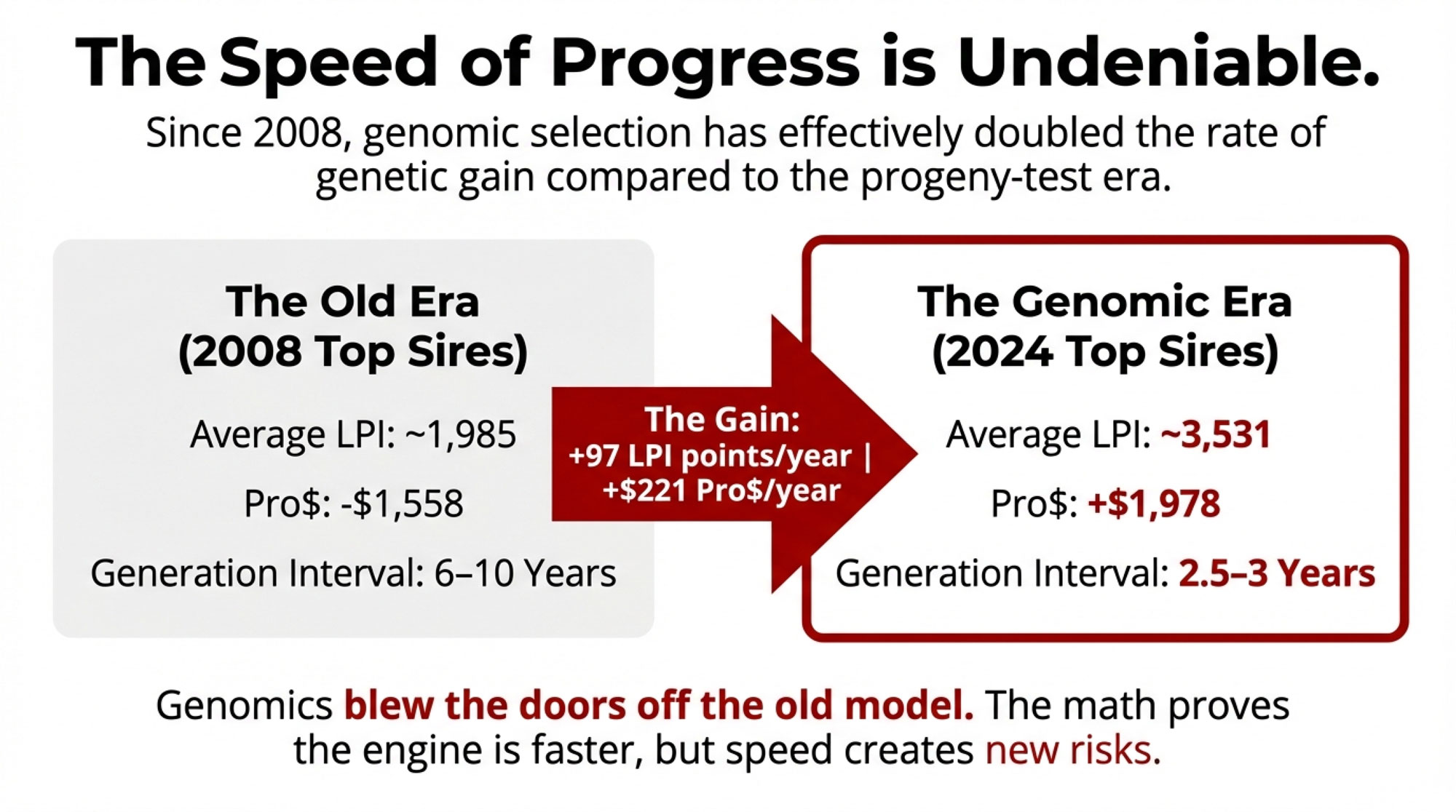

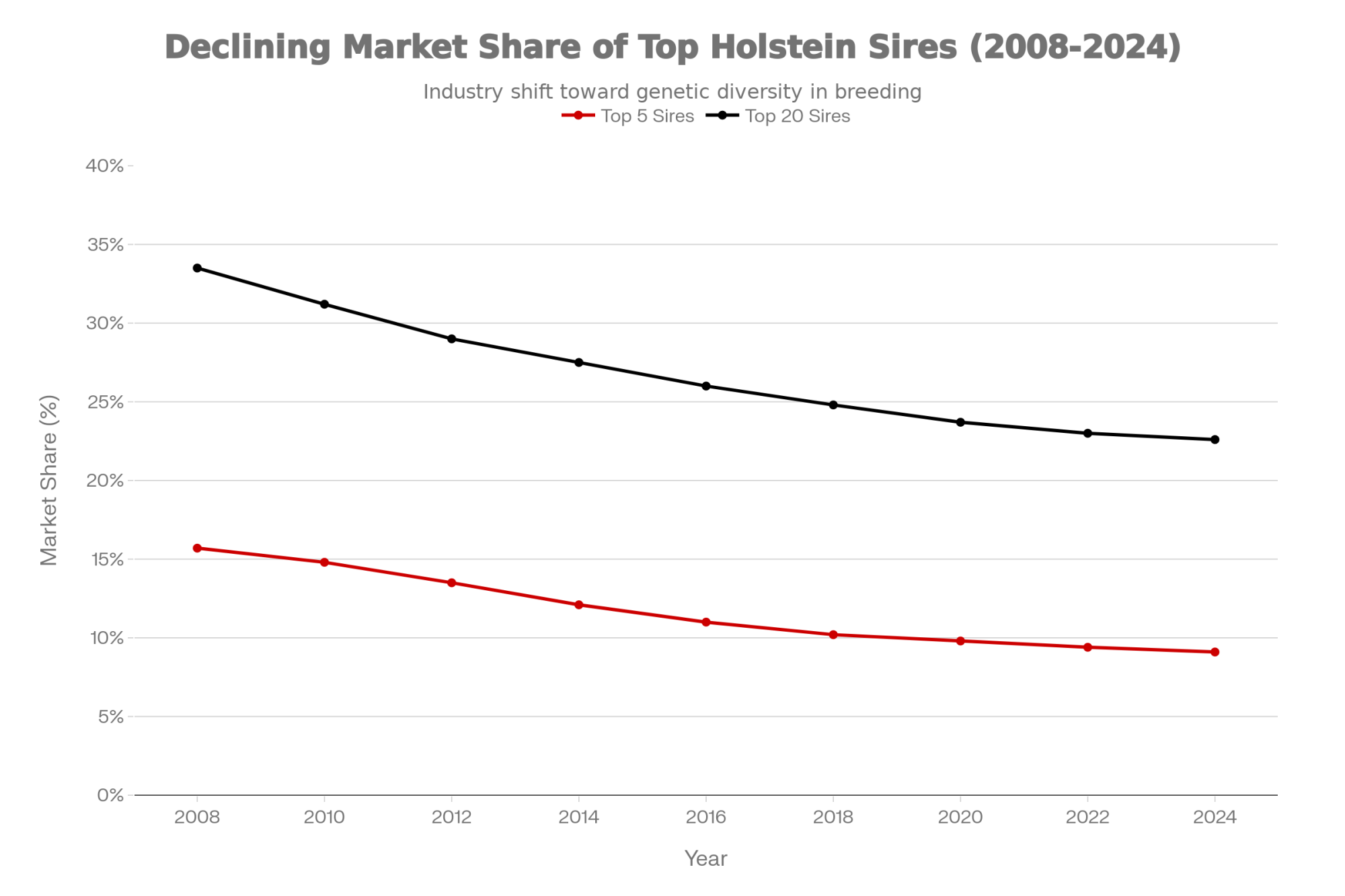

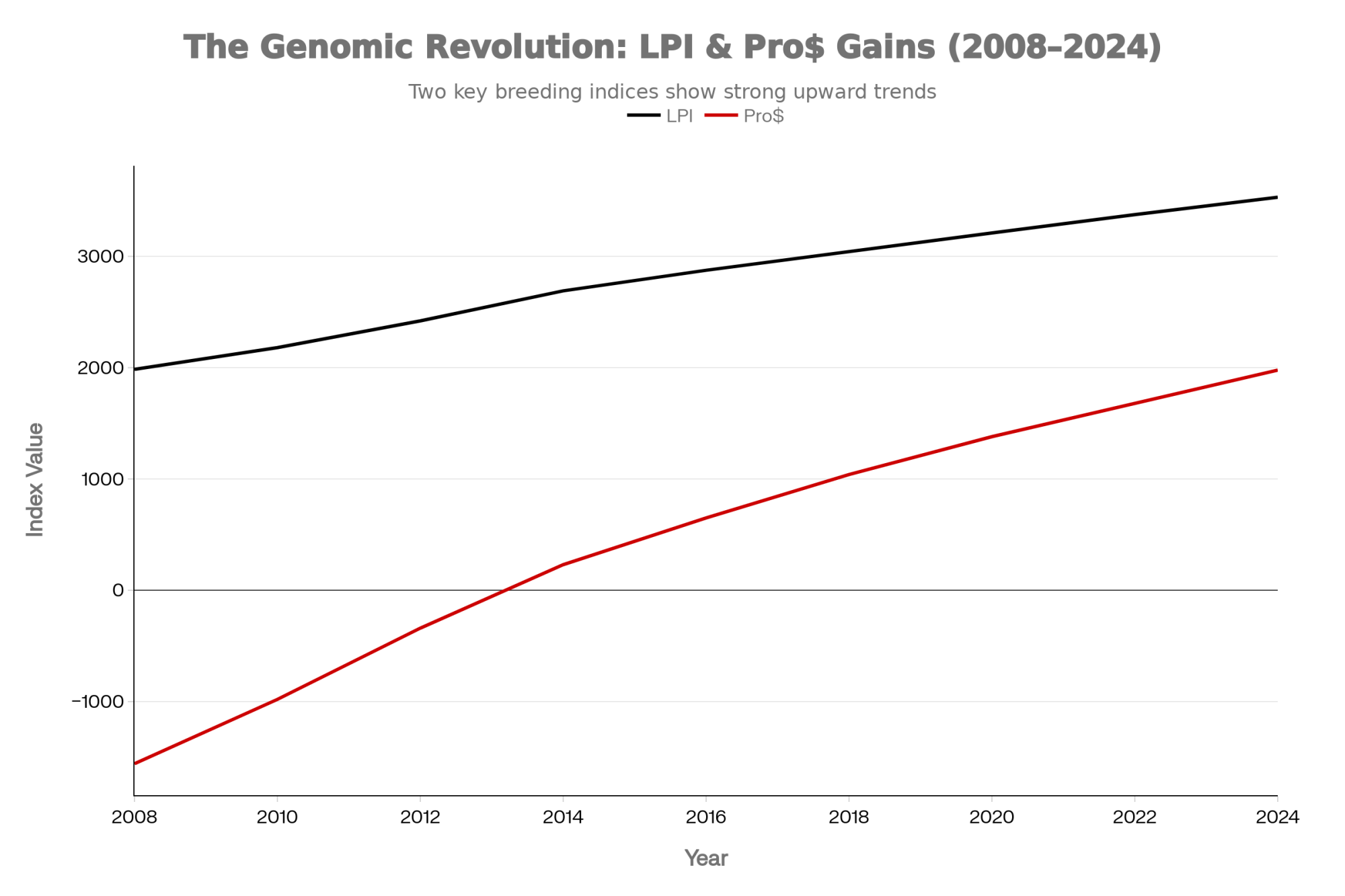

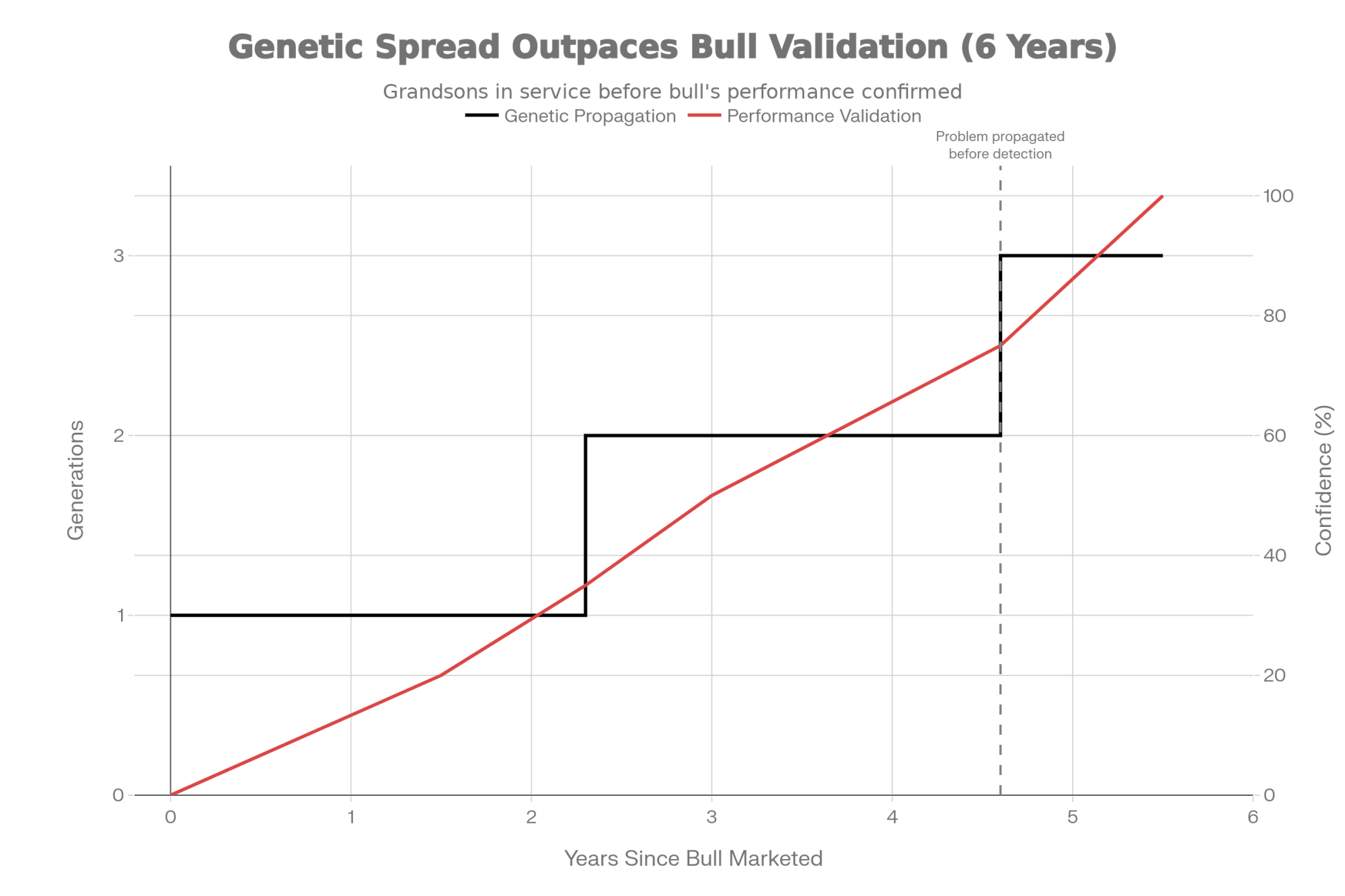

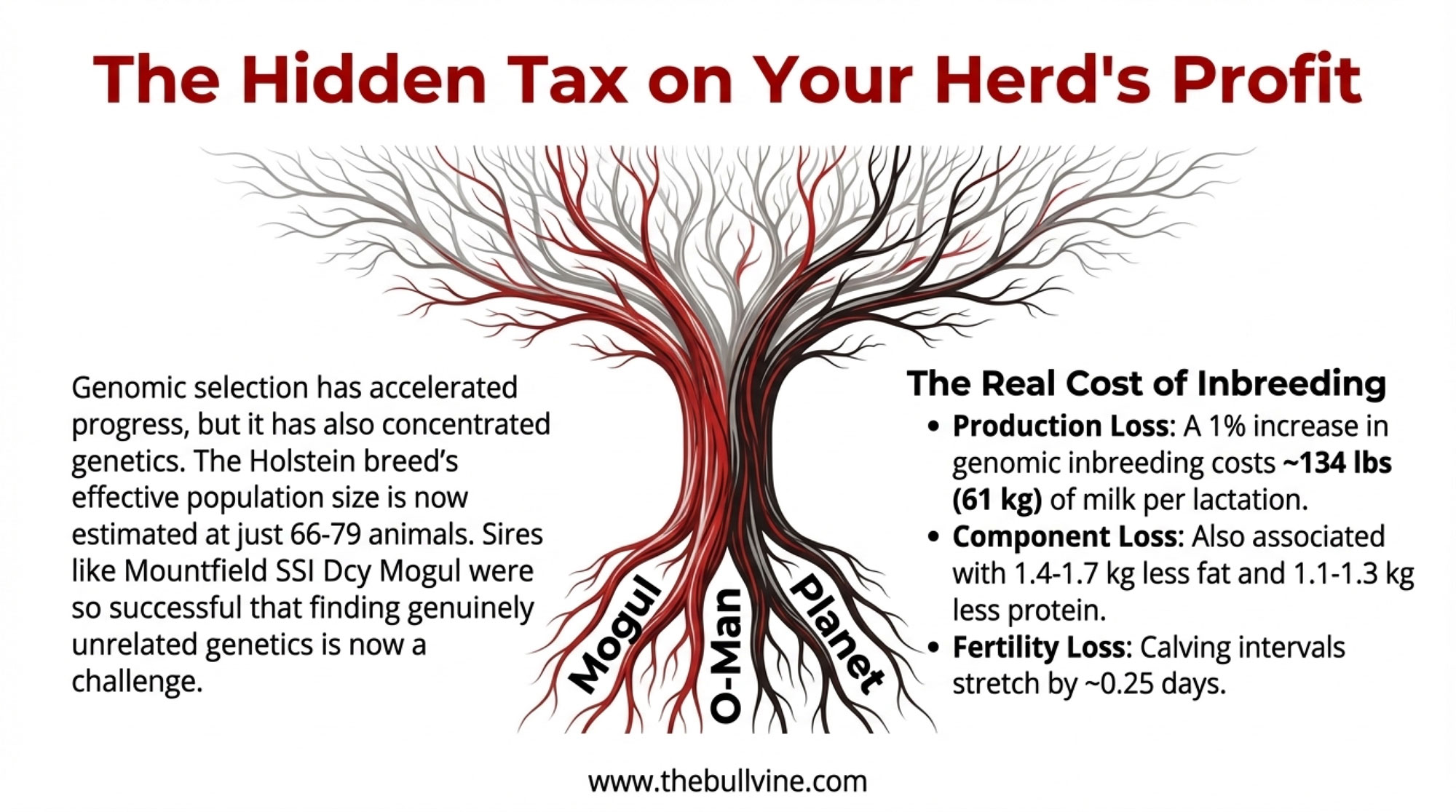

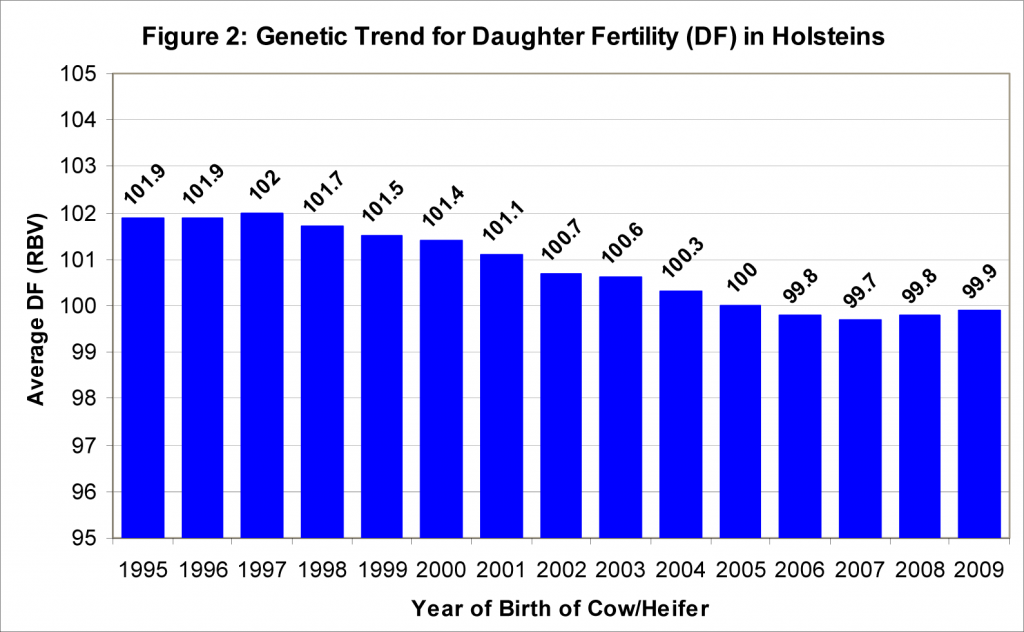

Genomic selection has fundamentally accelerated genetic progress in US Holsteins. Before genomics took hold, from 2005 through 2009, the average Net Merit gain for marketed Holstein bulls was roughly $40 per year. Since 2011, that rate has more than doubled. Wiggans and Carrillo documented the acceleration in a 2022 review published in Frontiers in Genetics. CDCB’s own genomic impact data tells a similar story — $40.33 per year from 2005–2010, jumping to $79.20 per year from 2016–2020. The distance between elite and middle-of-the-pack genetics grows larger with each proof round, and if you’re not actively capturing that progress, you fall further behind every cycle.

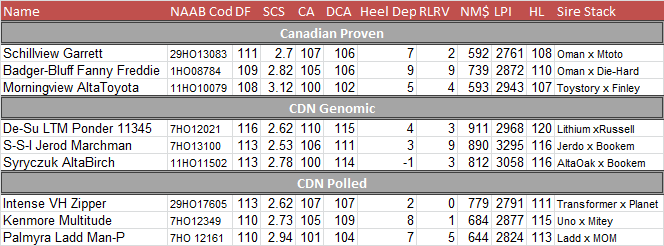

The December 2025 US Holstein genetic evaluations made the concentration at the top impossible to ignore. Genosource now holds 22 of the top 30 NM$ positions — 73% of the industry’s elite profitability bracket. The number-one bull, GENOSOURCE RETROSPECT-ET, sits at +1,296 NM$. The NM$ true transmitting ability standard deviation is $228 (VanRaden et al., NM$, January 2025), which means a single standard deviation of difference between your sire battery and the industry average shows up as real dollars at the bulk tank. Every month. For years.

Mid-size operations — 100 to 500 cows — feel this most acutely. You’re large enough that genetic differences compound into serious money, but you probably don’t have a dedicated genetics manager parsing proof sheets three times a year.

What Producers Discovered When They Stopped Delegating

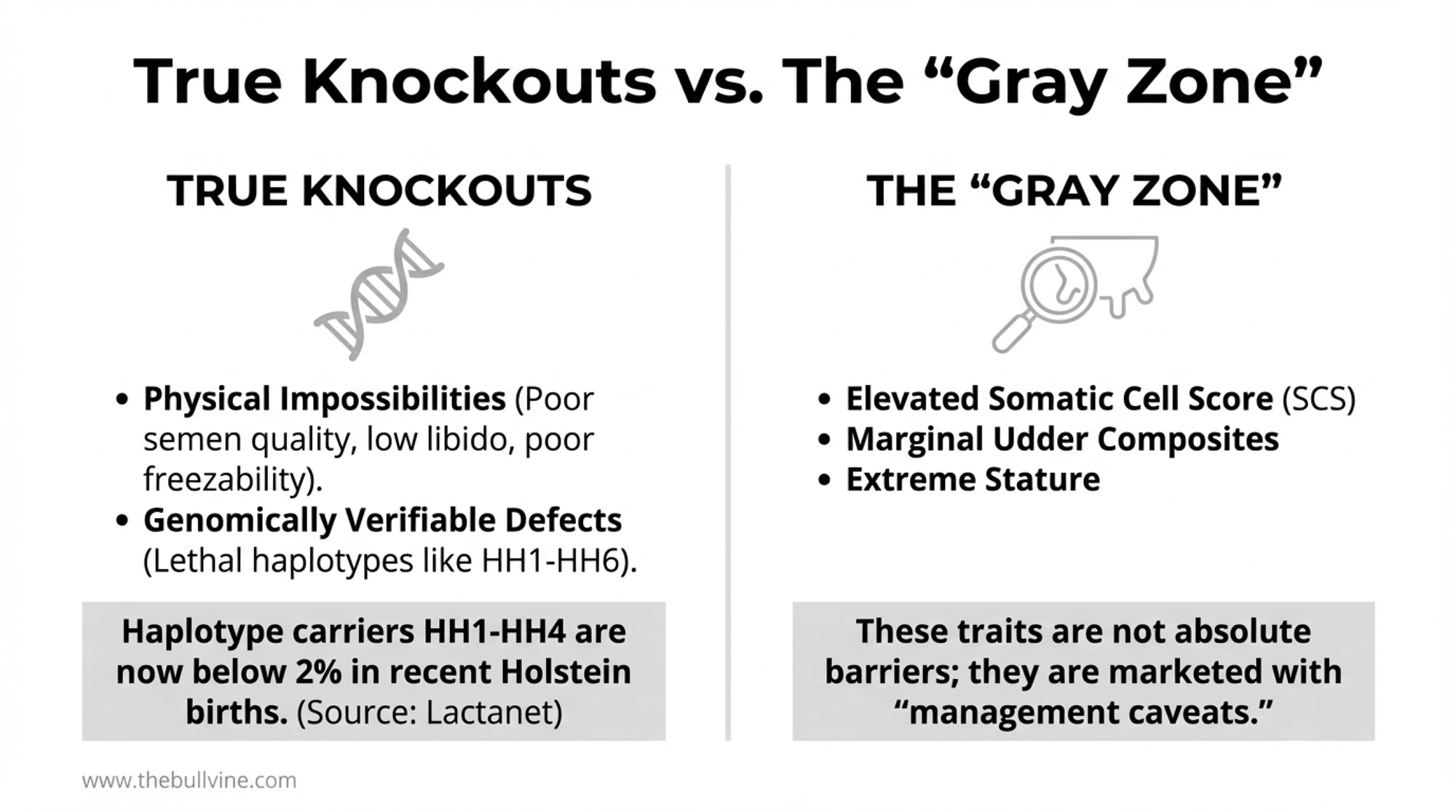

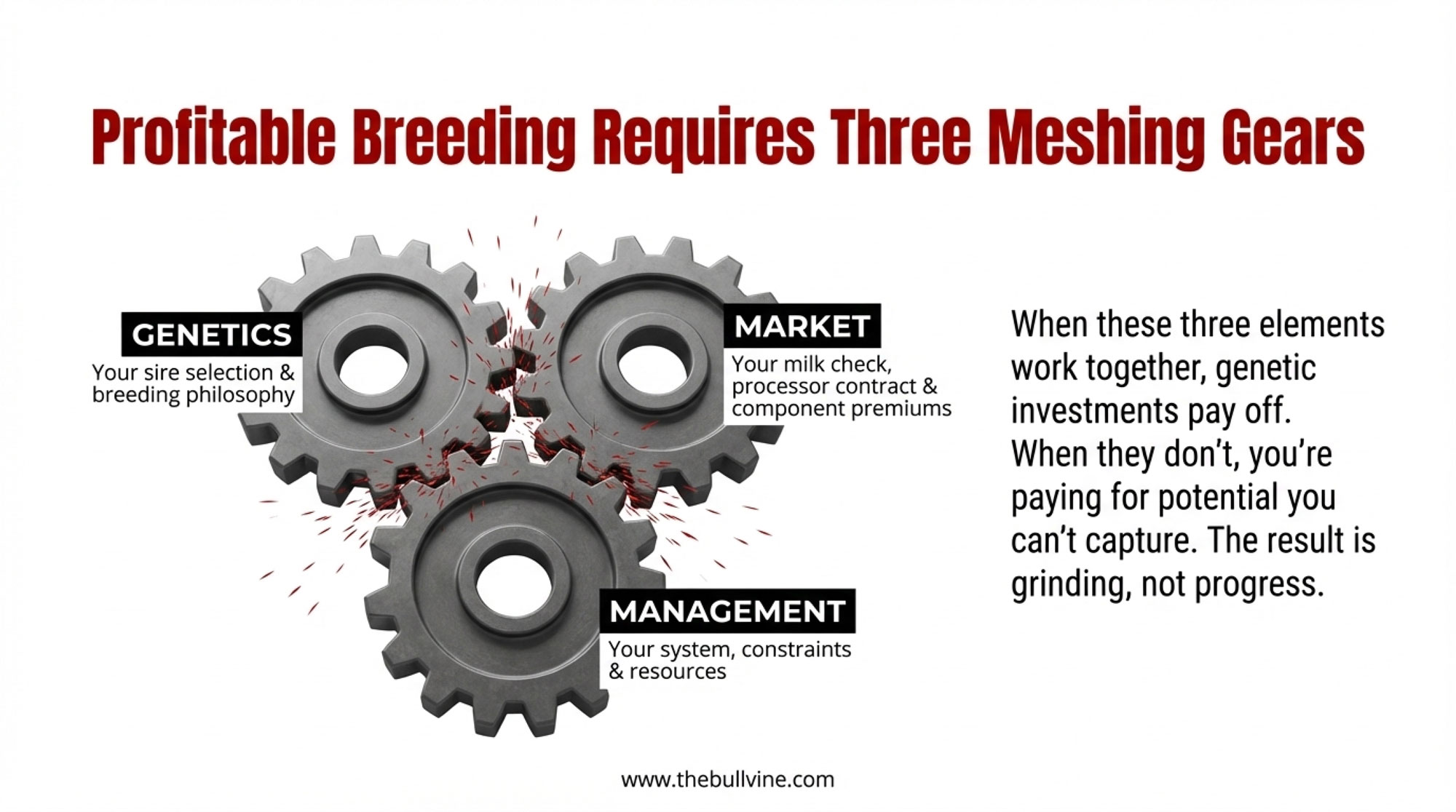

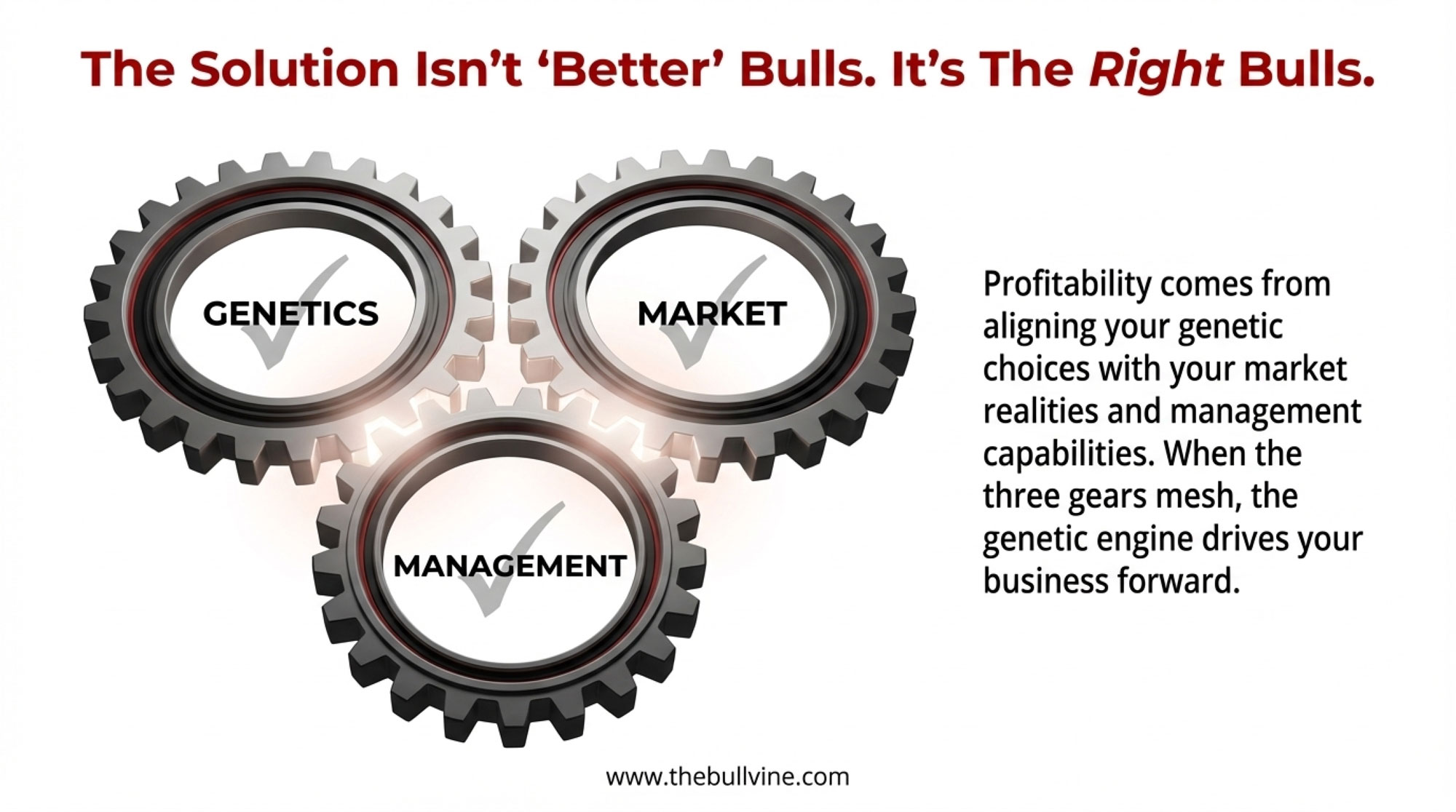

Alta Genetics has built its entire product philosophy around what they call the 4-EVENT COW — a cow whose card reads FRESH, BRED, PREGNANT, DRY, and nothing else. No treatments, no repros, no vet calls between those four entries. Their Alta CONCEPT PLUS sire fertility evaluation, built on real pregnancy check data from progressive dairies across North America since 2001, identifies bulls that create more pregnancies faster — CONCEPT PLUS DxD sires deliver a 2–5% conception rate advantage over the average conventional sire on cows, and CONCEPT PLUS 511 sires add 3–7% when using sexed semen on heifers (Alta Genetics, 2025). A mating program adjusts the consistency of type traits within your herd. Sire selection determines the genetic level of the herd itself. Delegate the selection, and no mating optimization closes the gap.

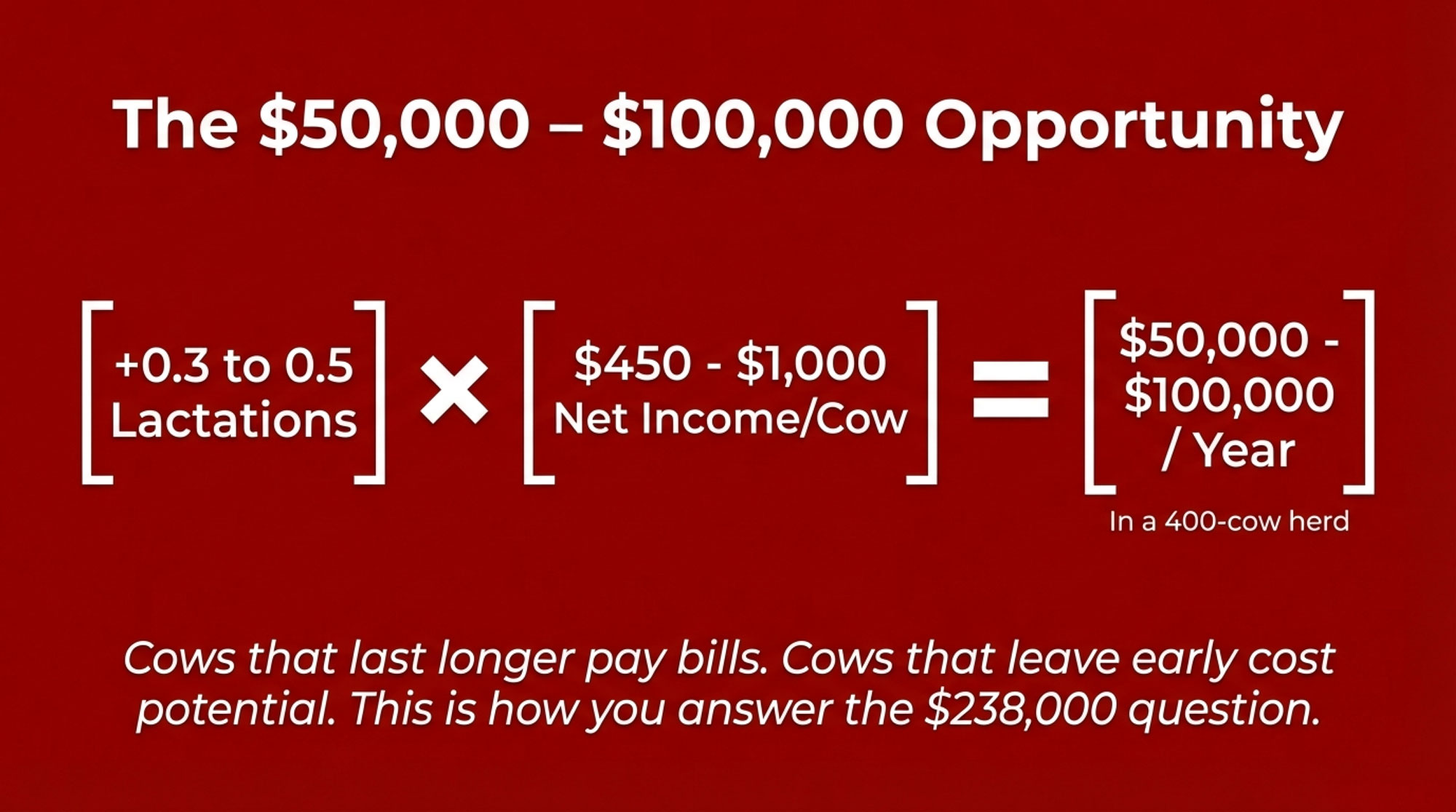

The Zoetis study made this concrete. The difference between top-quartile and bottom-quartile genetics wasn’t just dollars — it was 35% more milk, 44% fewer antibiotic treatments over their lifetimes, 5% less feed for maintenance, and an estimated 10% less enteric methane. And that gap held regardless of management quality across all 11 herds studied. That’s why the conversation has shifted from “genetics is about production” to “genetics is about total cost structure.”

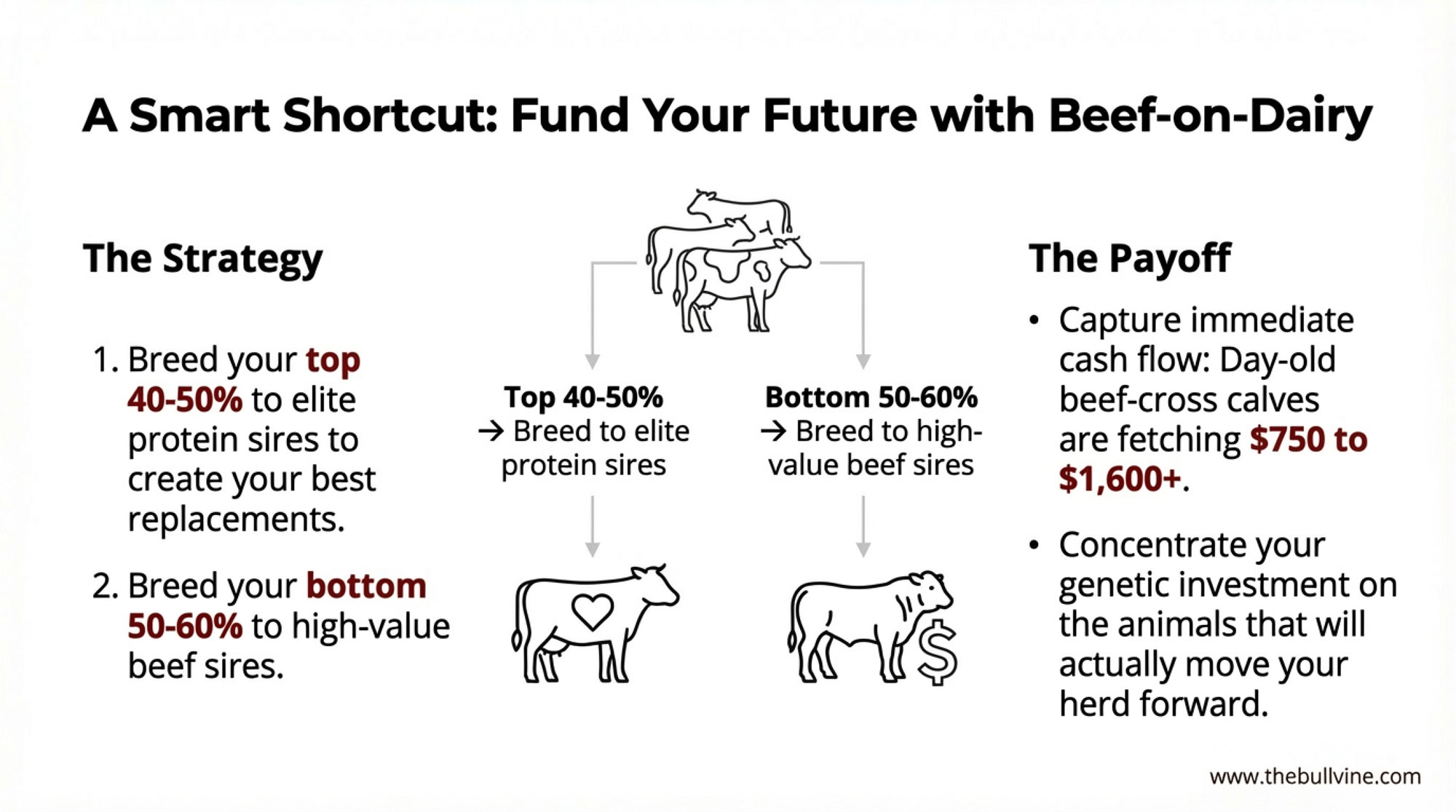

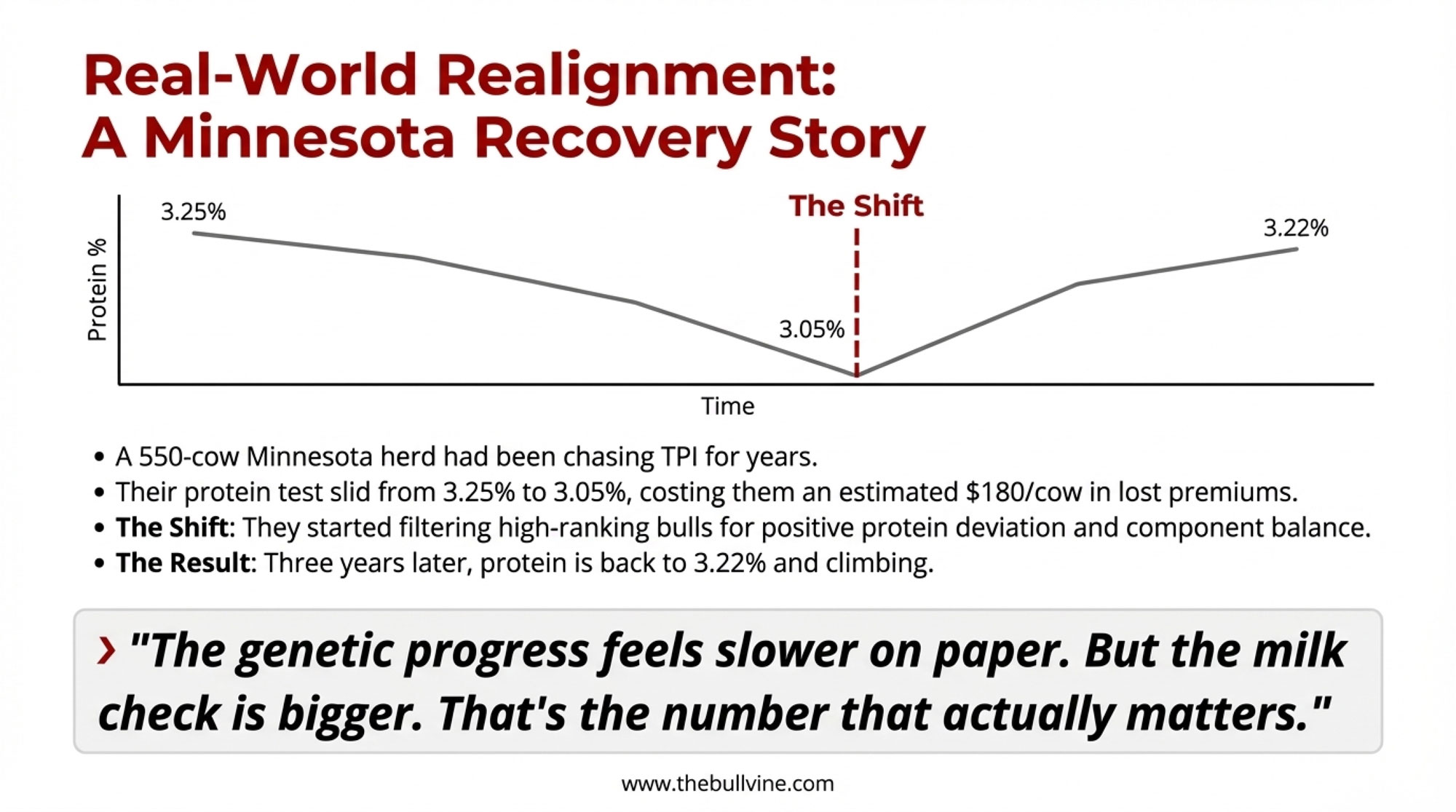

Simon Vander Woude’s operation illustrates how the shift actually happens on a working farm. Vander Woude owns and operates three dairies totaling 6,000 cows near Merced, California, and has run over 10,000 genomic tests with Zoetis CLARIFIDE Plus. His team started genomic testing simply to identify bottom-end heifers to sell off and get heifer inventory in line with cow numbers. But the test results revealed something uncomfortable: they’d been chasing Daughter Pregnancy Rate as a standalone trait without evaluating how it connected to the rest of the animal. “We focused on DPR pretty heavily and kind of forgot about milk for a while,” Vander Woude shared in 2022. “We’ve stubbed our toes plenty along this path.” That honest reassessment reshaped their entire program. Today, they run IVF on top genomic females — 40 to 60 embryo calves born per month — sexed Holstein semen on the next tier, and Angus on everything else. A tiered system that didn’t exist before they let the data challenge their assumptions.

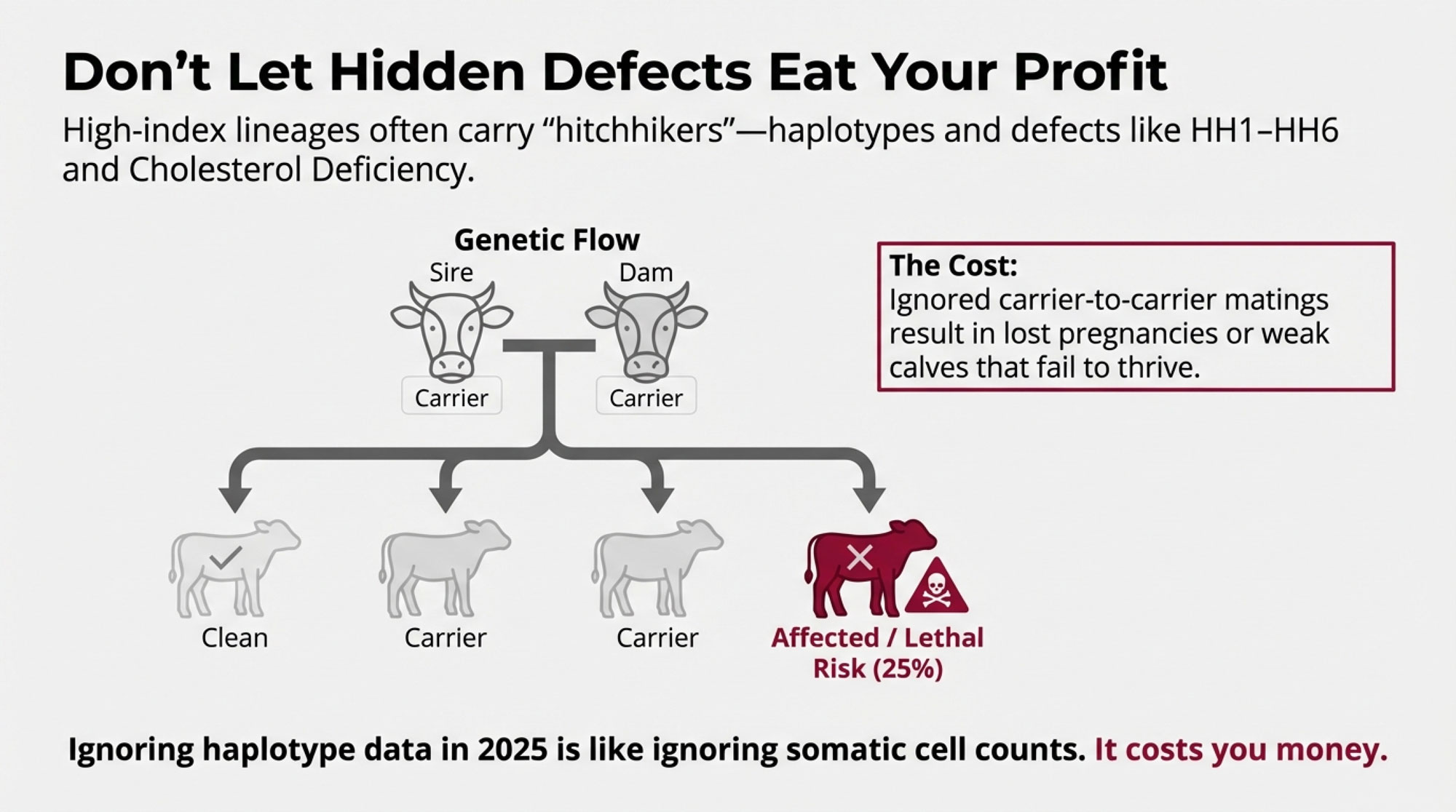

The Bailey family at Moorhouse Hall Farm in Cumbria, England, had a different trigger entirely. John, Kate, and their son Chris — a full-time vet — started genomic testing their heifers after hearing Nuffield Scholar Neil Easter describe how he’d built a herd with youngstock in the top 1% for Profitable Lifetime Index. As they tested, AHDB’s broader UK analysis revealed a startling finding: around 17% of calves had their recorded sires updated when genotypes were analysed — 7% because the wrong sire was recorded, another 10% because no sire was recorded at all (AHDB, 2024). The Baileys now genomic test every heifer, breed their top-performing animals to dairy sires and the bottom 10–20% to beef, and sit just shy of the top 1% nationally for £PLI in their youngstock. “We used to always find an excuse for why a certain cow should be bred,” John Bailey told AHDB. “But now with genomics, the data gives us much more confidence in identifying the bottom performers.”

The 2025 NM$ Revision: Why USDA Rewrote the Formula

Here’s where a lot of conventional wisdom about cow size and type starts to break down.

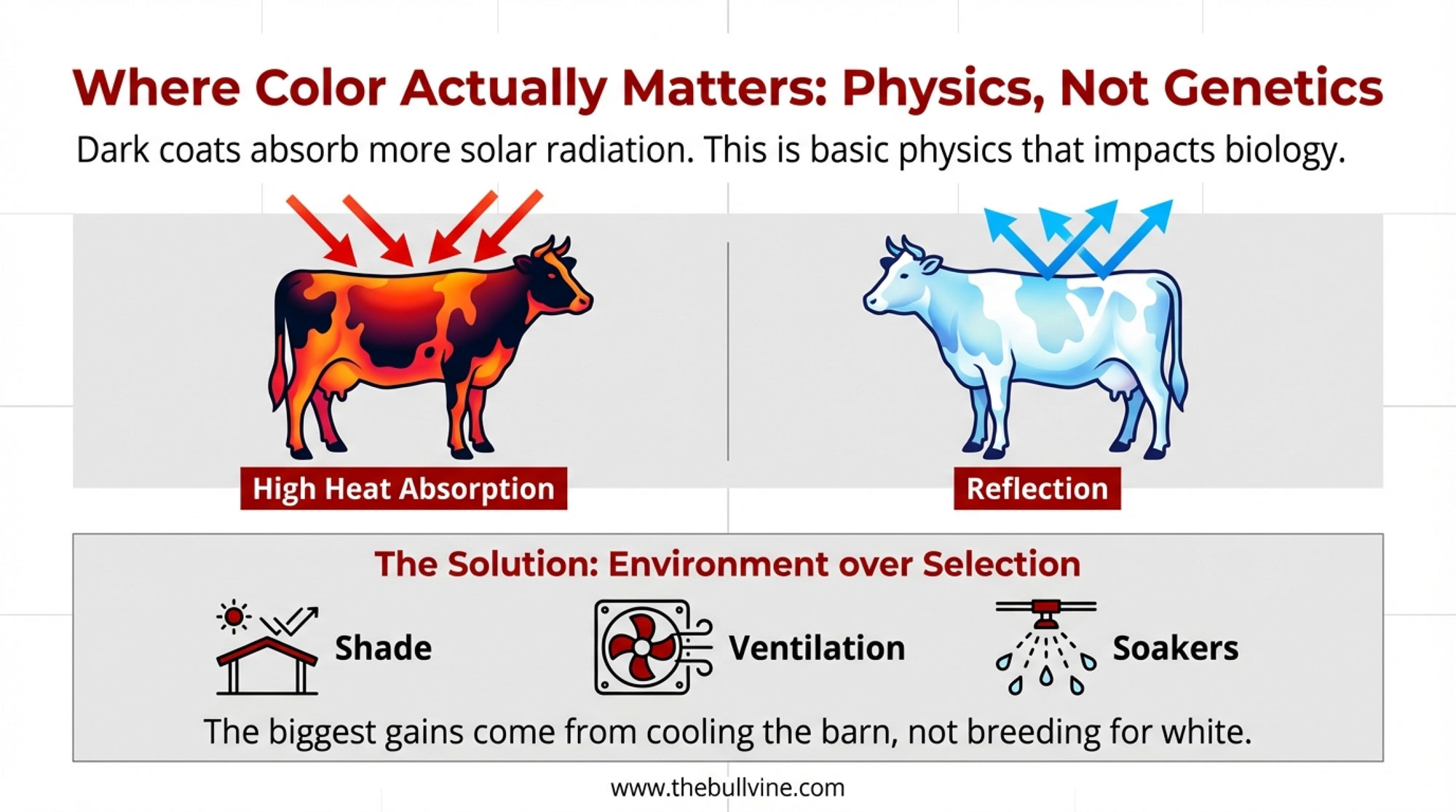

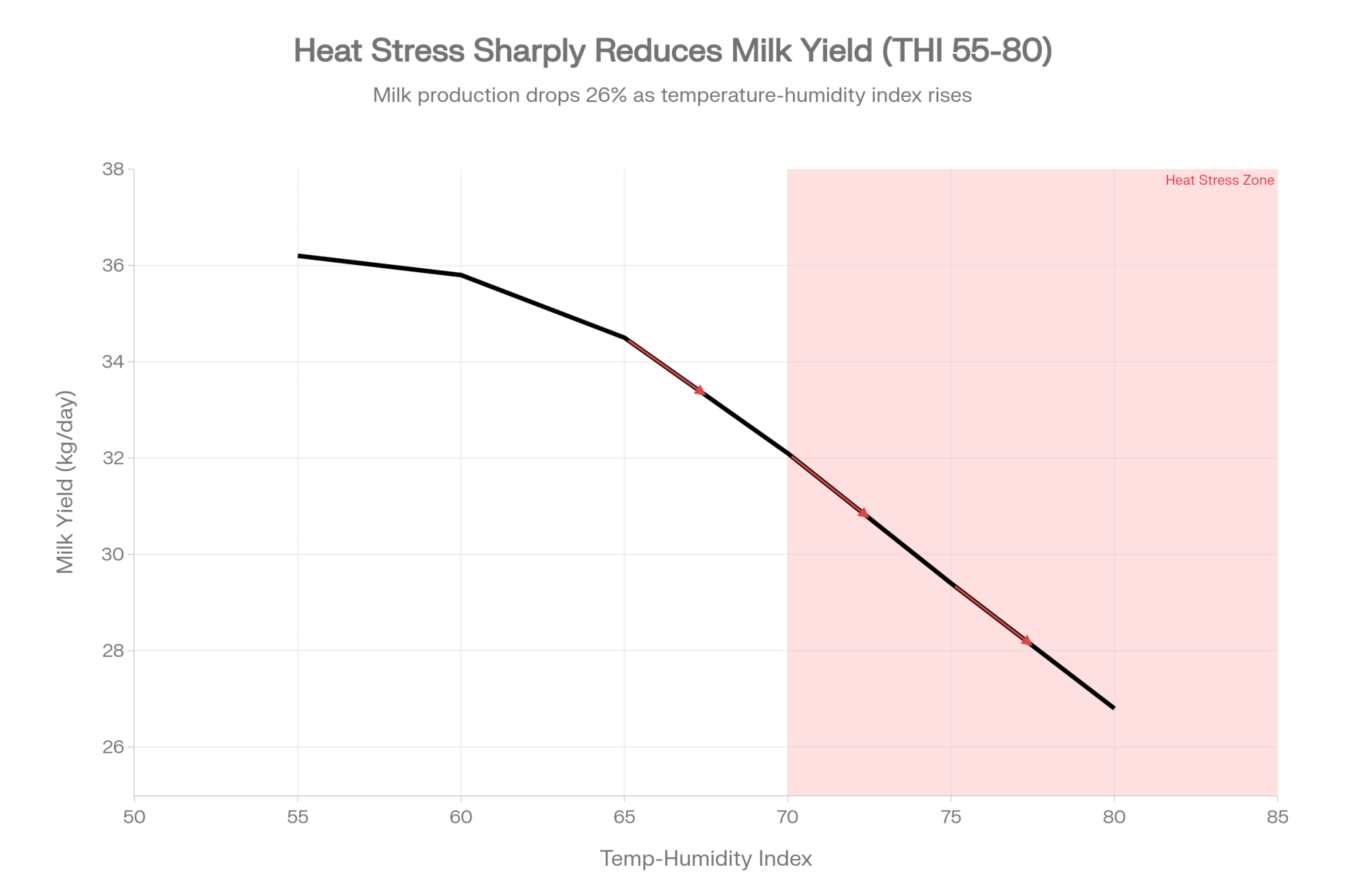

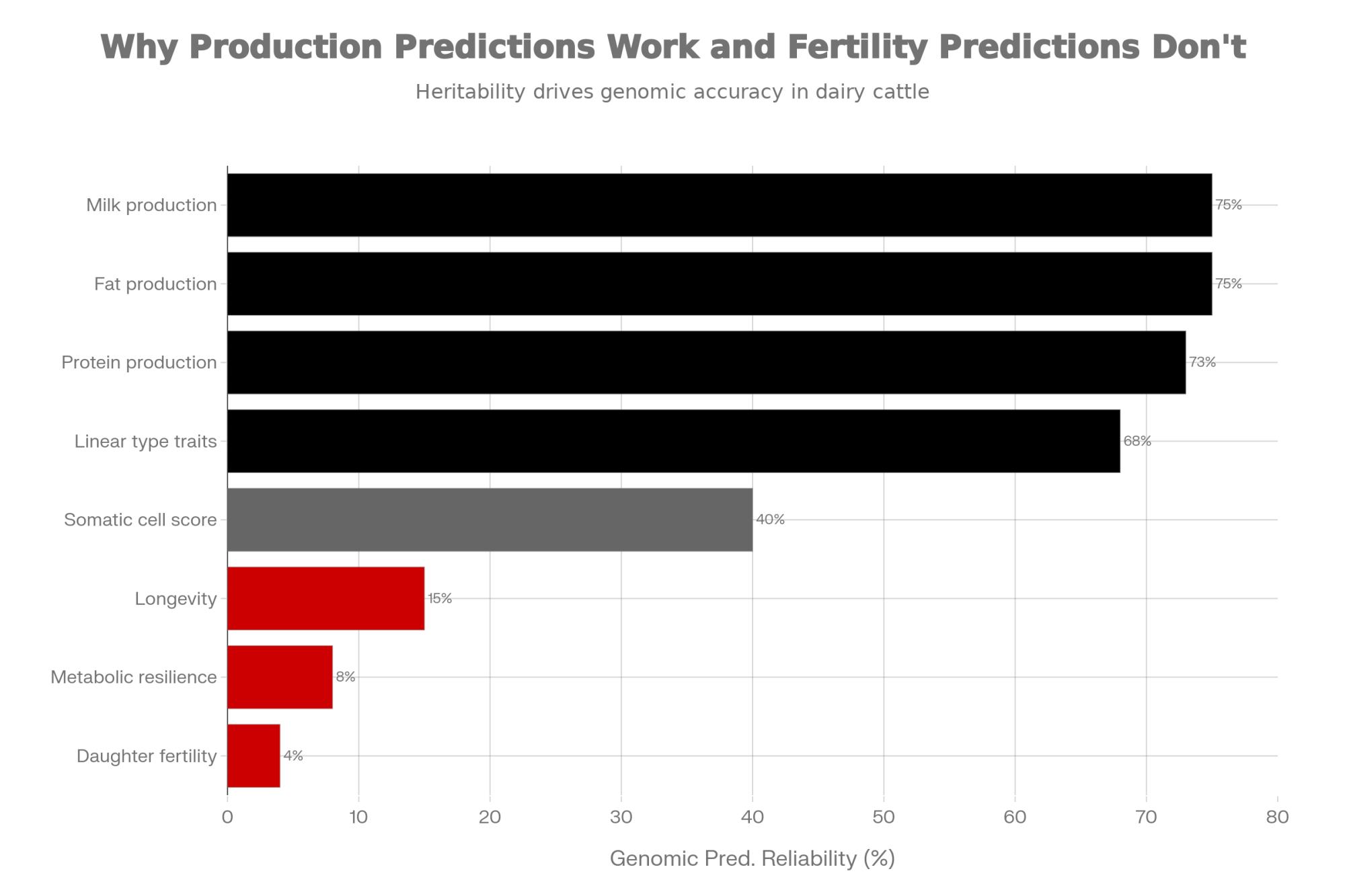

When USDA researchers ran genomic regressions on actual feed intake data from over 8,500 lactations of more than 6,600 dairy cows in US and Canadian research herds, the number that came back caught everyone off guard: real maintenance costs were 5.5 pounds of dry matter intake 1,000 per pound of body weight per lactation. That’s roughly twice the previously used phenotypic regression estimates. Every producer who’d been selecting for bigger, taller cows had been unknowingly selecting for higher maintenance costs than anyone calculated.

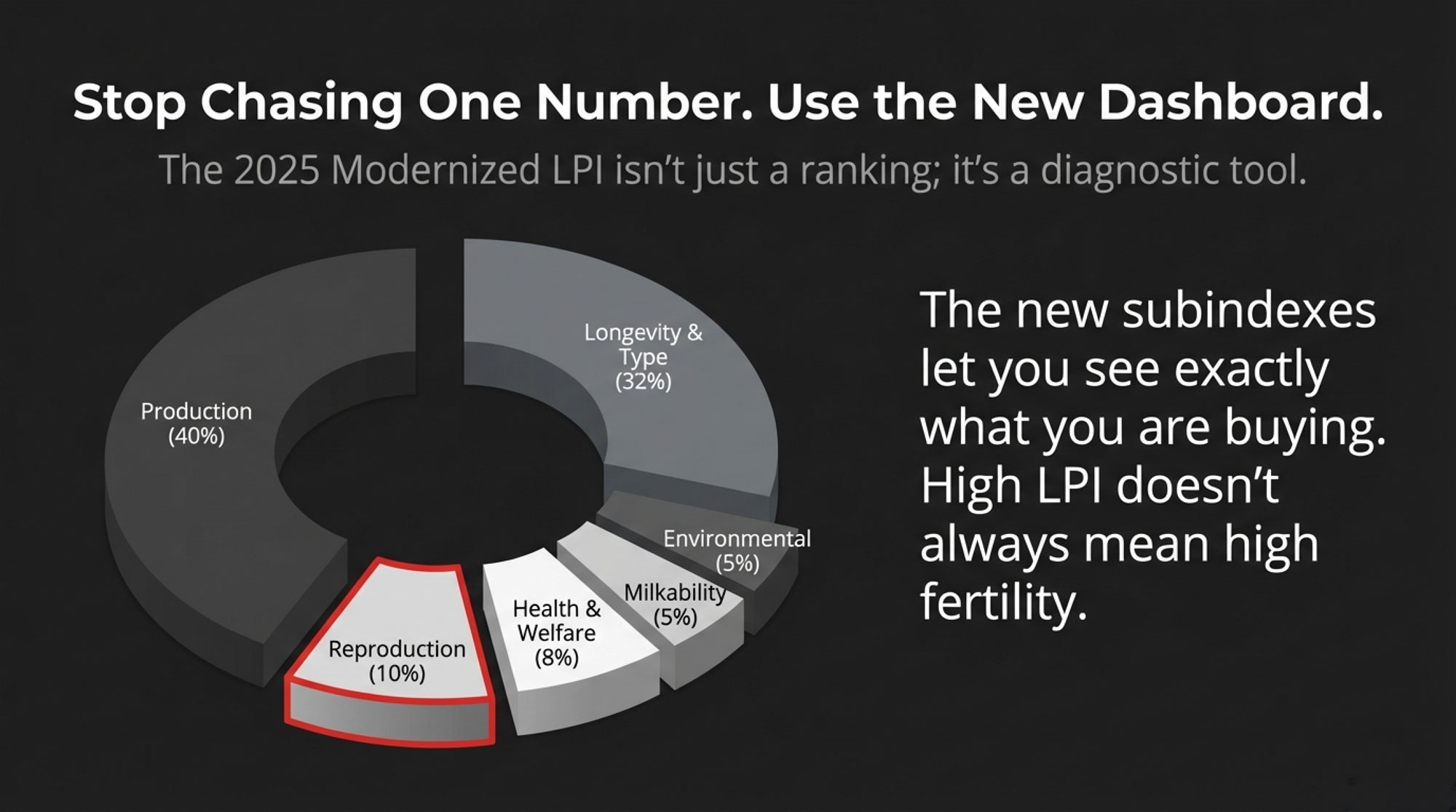

So USDA rebuilt the formula. Here’s what changed (VanRaden et al., NM$, January 2025):

Feed Saved now commands 17.8% combined emphasis — 11% from body weight composite and 6.8% from residual feed intake. Productive Life carries 13% emphasis at $30 per month, and when you add Cow Livability’s 5.9%, the durability complex totals 18.9% — making longevity the largest non-yield trait group in the index. The lifetime economic values driving NM$ are $5.01 per pound of fat PTA and $3.32 per pound of protein PTA, calculated across 2.70 average lifetime lactation equivalents for Holsteins.

And the traditional type-trait weightings? They dropped hard enough to change the conversation:

| Trait Category | NM$ Emphasis | Direction | What Changed | Why It Matters for Your Herd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Saved | +17.8% | ↑ | Real maintenance costs were 2× previous estimates; emphasis jumped from ~9% to 17.8% | Bigger cows now cost you more than the old formula calculated—select for efficiency, not size |

| Productive Life + Cow Livability | +18.9% | ↑ | PL at 13% ($30/month), Livability 5.9%—longevity is now the largest non-yield trait group | Cows that last five lactations beat cows that peak high and break down by lactation three |

| Udder Composite | 1.3% | ↓ | Dropped from ~5%; two decades of selection finished the job | Further emphasis yields diminishing returns on work already done—udders are largely fixed |

| Feet & Legs Composite | 0.4% | ↓ | Classifier scores correlated poorly with actual lameness and hoof health | Direct health traits predict lameness better than visual scores ever did |

| Body Weight Composite | −11.0% | ↓↓ | Active penalty—NM$ now selects against excess cow size | Every extra pound of body weight costs you 5.5 lbs DMI per lactation; the show-ring cow is now a commercial liability |

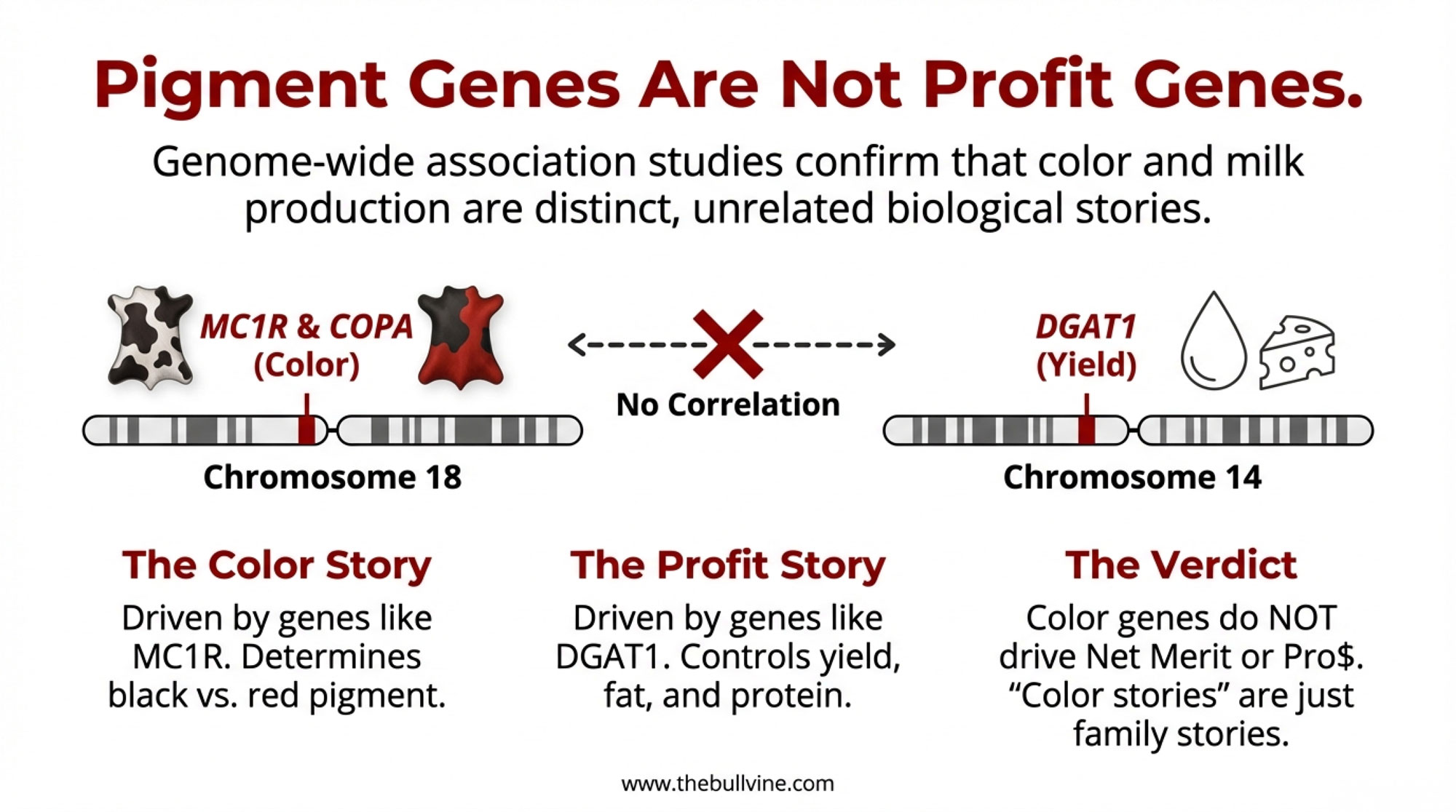

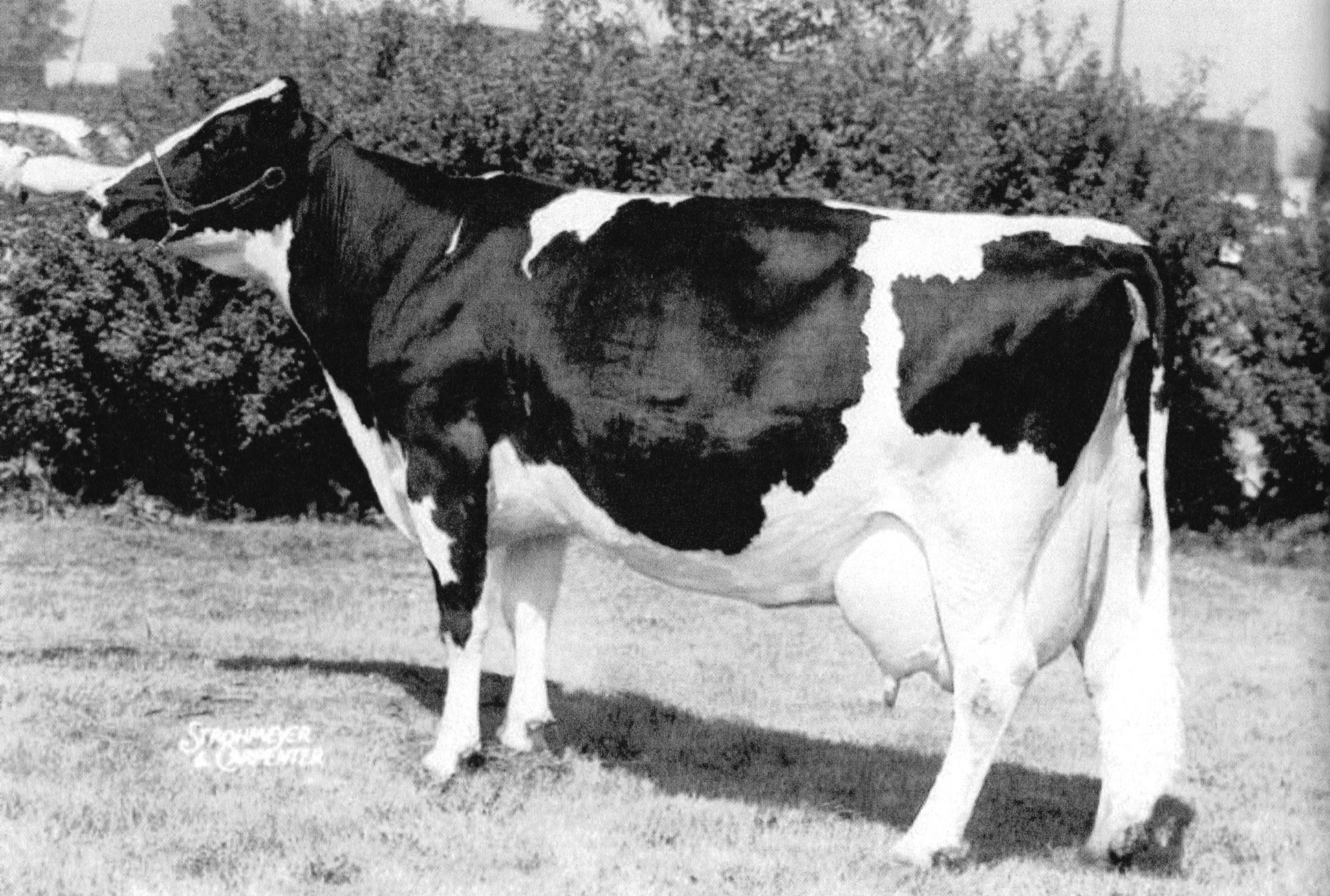

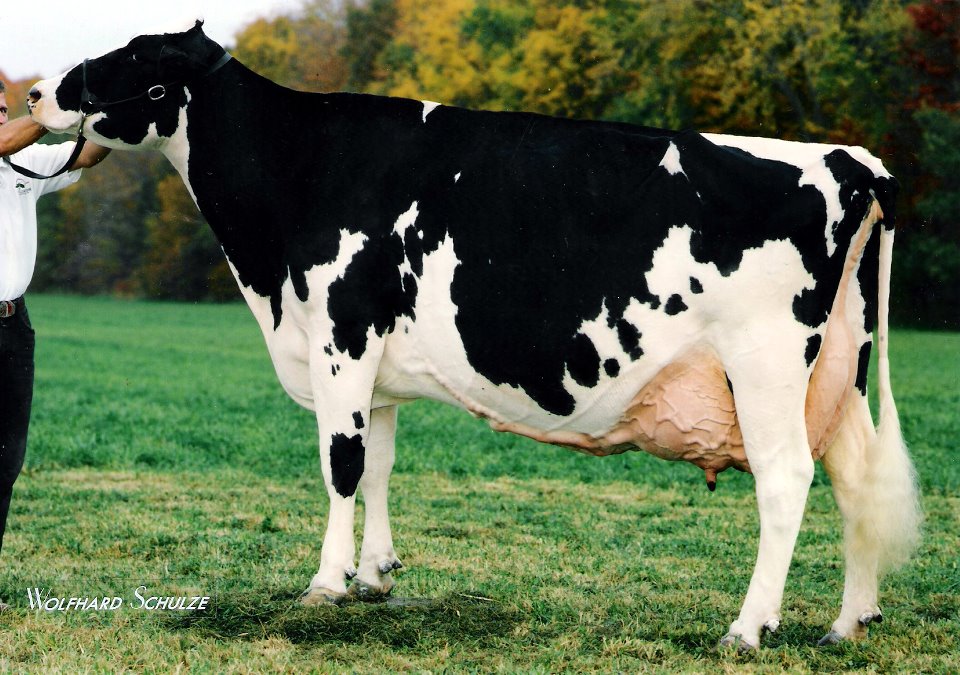

The math is hard to argue with: NM$ has driven a permanent wedge between the show ring cow and the commercially profitable cow. For two decades, the industry could pretend the gap wasn’t that wide. With Udder Composite at 1.3%, Feet and Legs at 0.4%, and body weight penalized at −11%, that pretense is over. You can still breed show cattle. You can still win banners. But the economics now say, clearly and quantifiably, that the traits rewarded in the ring and the traits rewarded at the bulk tank have parted ways.

The type-to-health connection runs deeper than index weightings. Dechow et al. (2003, Journal of Dairy Science) documented a −0.73 genetic correlation between Body Condition Score and Dairy Form in first-lactation Holsteins — meaning cows that score high for angular dairy character are genetically predisposed to thin body condition at calving. That predisposition elevates ketosis risk.

The traits that actually drive longevity are functional: rear udder height, teat placement, and udder depth. Not the visual sharpness that wins ribbons.

One caveat worth stating plainly: if you market breeding stock, embryos, or show cattle, you may rationally weight type traits higher than a commercial herd optimizing for tank revenue. The NM$ recalibration reflects commercial profitability priorities. Seedstock economics are different — that’s a legitimate strategic choice, not a mistake. But don’t confuse the two. And don’t let anyone tell you that a cow that scores EX-95 is automatically more profitable than a VG-86 daughter who freshens easy, breeds back fast, and milks hard for five lactations. The numbers no longer support that story.

Your Game Plan: Three Strategies Producers Are Using Right Now

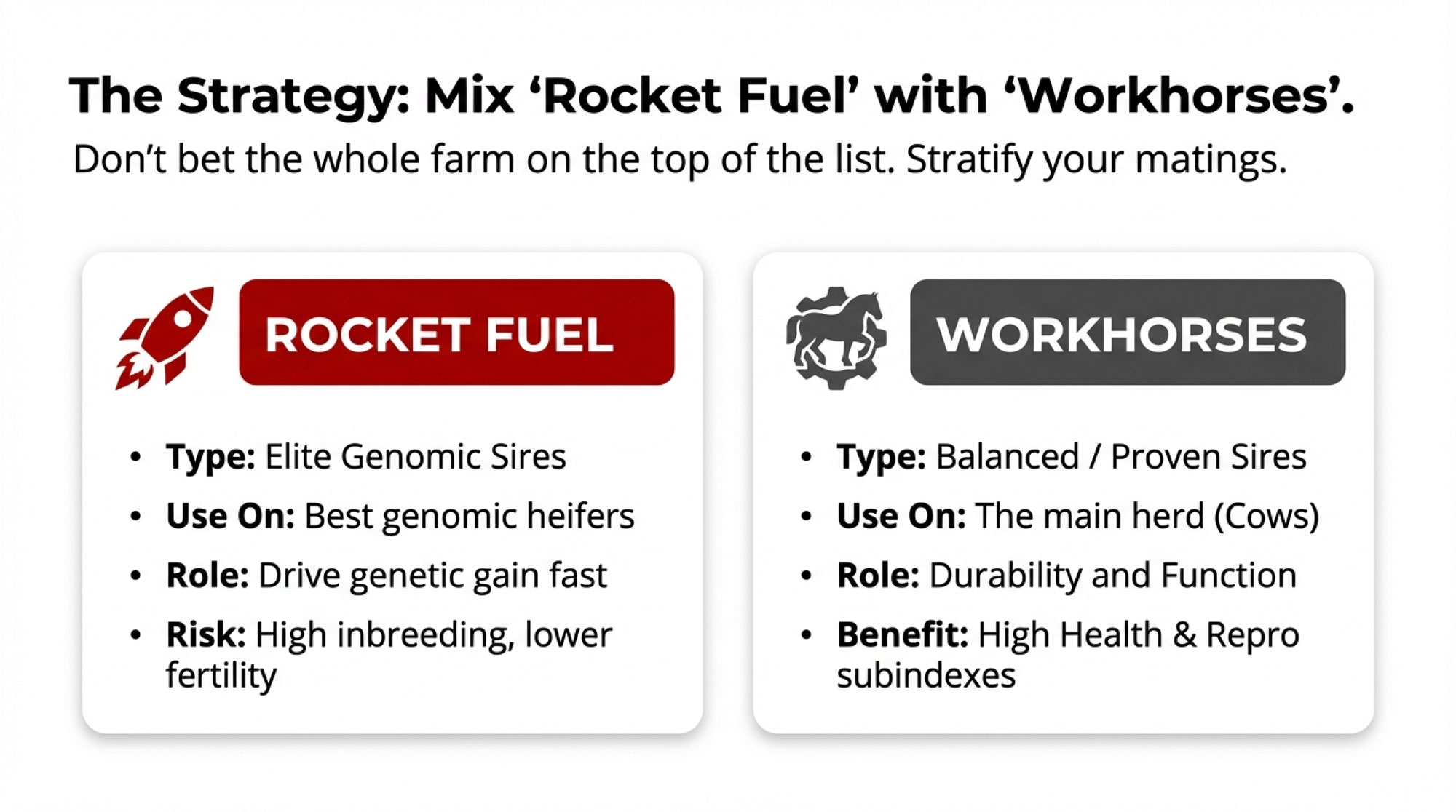

Build a Complementary Sire Roster — Not a Ranked List

Think of it like building a Super Bowl roster. You don’t field a team of four quarterbacks. You need depth at every position, and each player fills a specific role. Same with your sire lineup.

The instinct is to line up your top four NM$ bulls and start breeding. But a ranked list isn’t a roster. Four bulls who share the same weaknesses leave your herd exposed in exactly the same spots.

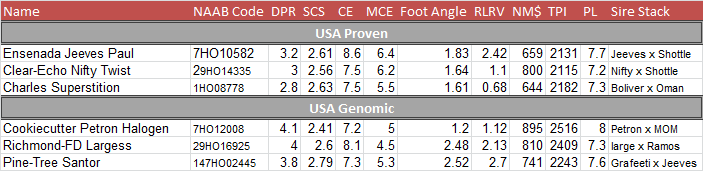

A complementary depth chart assigns each sire a defined role:

| Roster Position | % of Matings | Strategic Role | December 2025 Example | Key Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franchise | ≈35% | High NM$, balanced, no catastrophic weakness | STGEN STUART-ET (NM$ not specified, 1,666 Milk, 145 Fat, 71 Protein) | Overall profitability, proven reliability, well-rounded trait profile |

| Component Specialist | ≈25% | Maximize fat + protein revenue | GENOSOURCE BENCHMARK-ET (228 CFP, highest among top NM$ sires) | Elite Combined Fat + Protein, strong production firepower |

| Longevity/Fertility Fixer | ≈25% | Address durability and reproduction gaps | FB 8084 ADEBAYO-P-ET (PL +5.3, LIV +4.5, FI +2.5, SCS 2.78, BWC −0.39, polled) | High Productive Life, fertility traits, moderate body weight, functional focus |

| Outcross/Inbreeding Hedge | ≈15% | Distinct sire line and maternal grandsire | Prioritize different sire lines and MGS not in your other three slots | Pedigree diversity, Expected Future Inbreeding <7%, distinct lineage |

Adebayo-P is a functional specialist, not a production leader (56M, 54F, 33P per Holstein Association August 2025 TPI list)—that’s precisely why he fills a role your franchise and component bulls can’t. All rankings may shift at the April 2026 proof run.

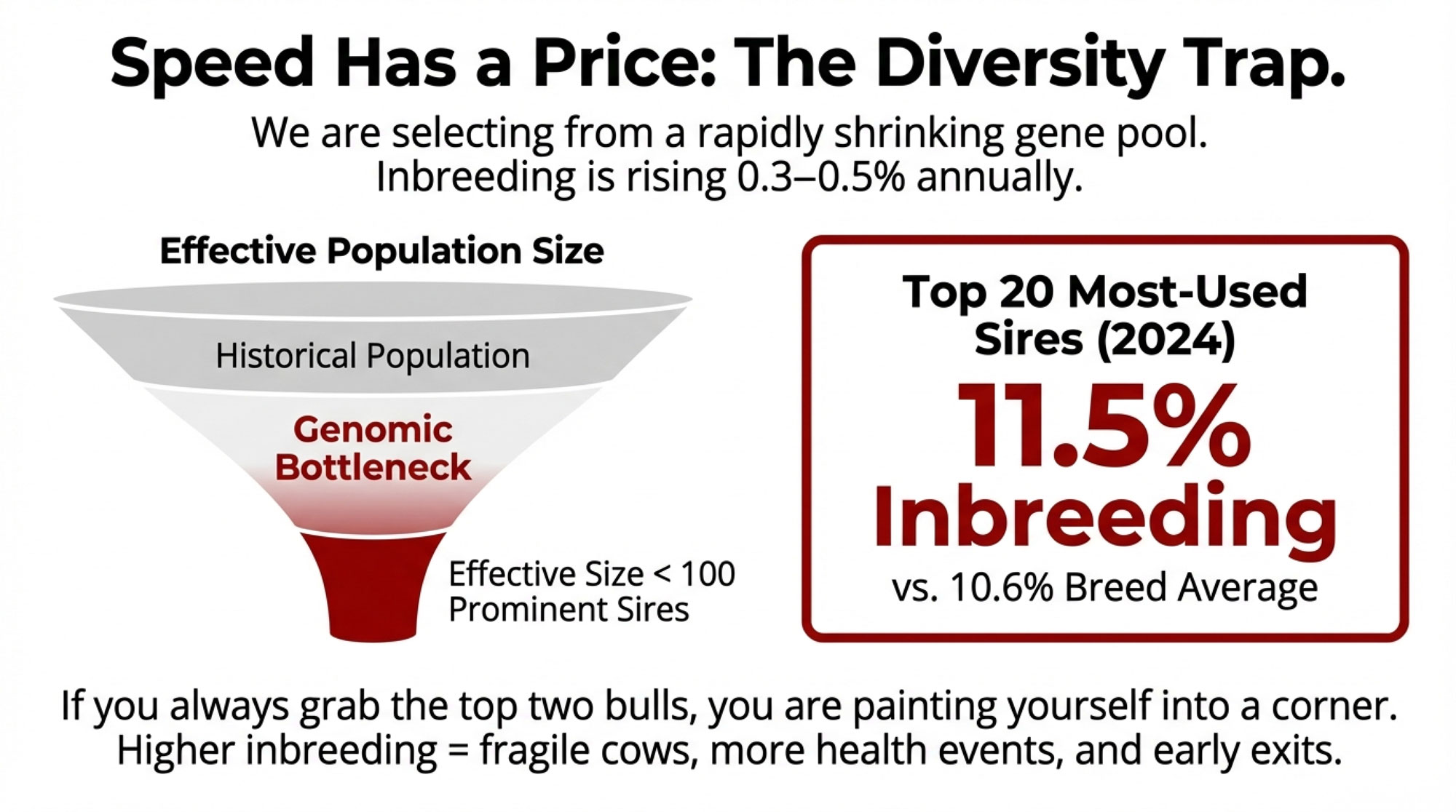

Verrier et al. (1993, Journal of Dairy Science) showed that factorial mating designs — where dams see several different sires — produced significantly lower inbreeding rates relative to genetic gain than single-sire approaches. And the December 2025 rankings saw considerable reshuffling, including BEYOND SHPSTR GOLLEY-ET vaulting to #2 GTPI at 3,605. A diversified roster absorbs that kind of volatility. A single-sire strategy doesn’t.

Where this can fall short: It takes more time and familiarity with trait profiles than picking one bull. If reading sire summaries feels overwhelming, you can capture roughly 80% of the benefit by setting an NM$ floor and using three bulls from different sire lines — even without position-specific assignments. For more on building genetic selection resources, start with the evaluation archives.

Genomic young sires carry reliability of roughly 70–75%, compared to 95%+ for daughter-proven bulls. Using three or four sires instead of one hedges that reliability gap — another reason the roster approach outperforms going all-in.

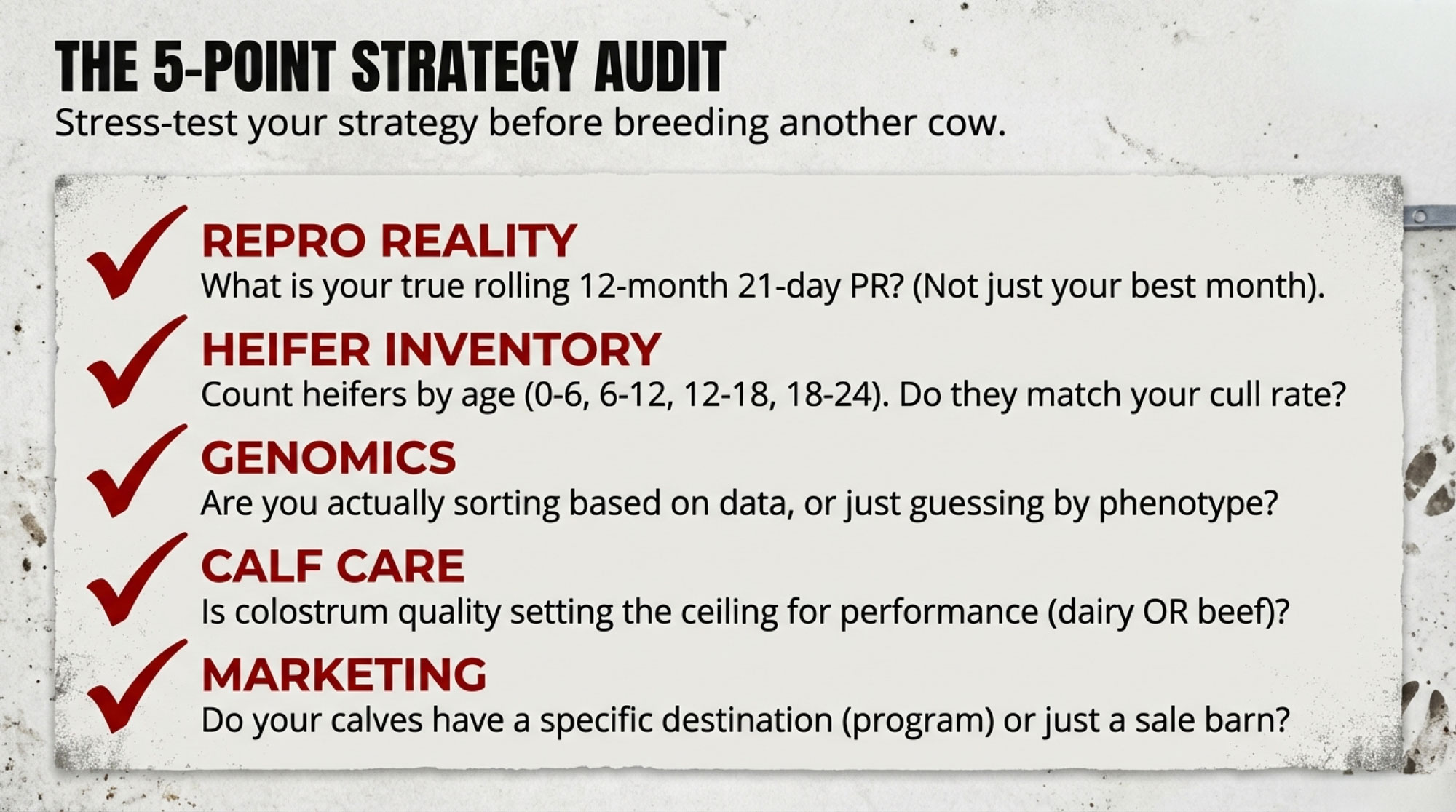

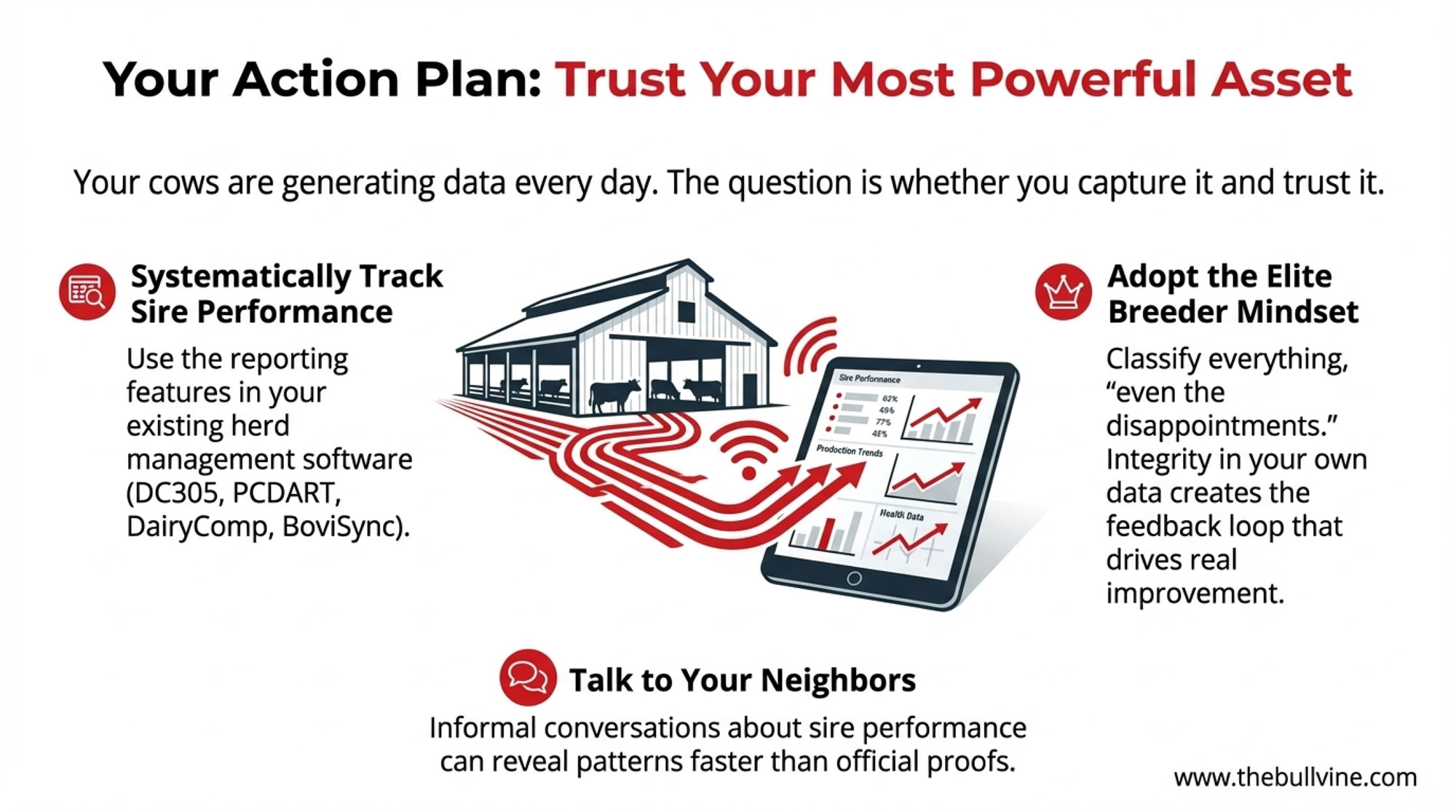

Your Halftime Adjustments: The One-Page Sire Scorecard

Every team makes adjustments at the half based on what the first two quarters showed them. Your sire scorecard works the same way — it forces you to look at what your herd actually needs before your next breeding play.

Before you open a catalog or take a call from your rep, answer these questions and write down actual numbers:

- What are your current fat and protein pounds per cow? Pull your last three DHIA milk recording reports.

- What are your top three cull reasons over the past 12 months? Most DHI software generates this in minutes.

- What’s your NM$ floor? With December 2025 bulls clearing $1,200+, there’s little reason to go below $900 on any roster sire.

- What’s your maximum Expected Future Inbreeding? Most geneticists suggest keeping genomic inbreeding below 7–8%.

- What functional traits does your facility specifically demand? Robotic milking needs teat placement and milking speed. Grazing operations weight feet-and-legs and body weight differently than freestalls.

Tape that sheet to the wall. Next time anyone recommends a bull — your rep, a catalog, a neighbor — run him through the scorecard first.

This doesn’t replace your A.I. rep. It redirects the relationship. You direct the strategy. They source bulls that fit your framework. That’s a fundamentally different conversation than “send me what you think is good.”

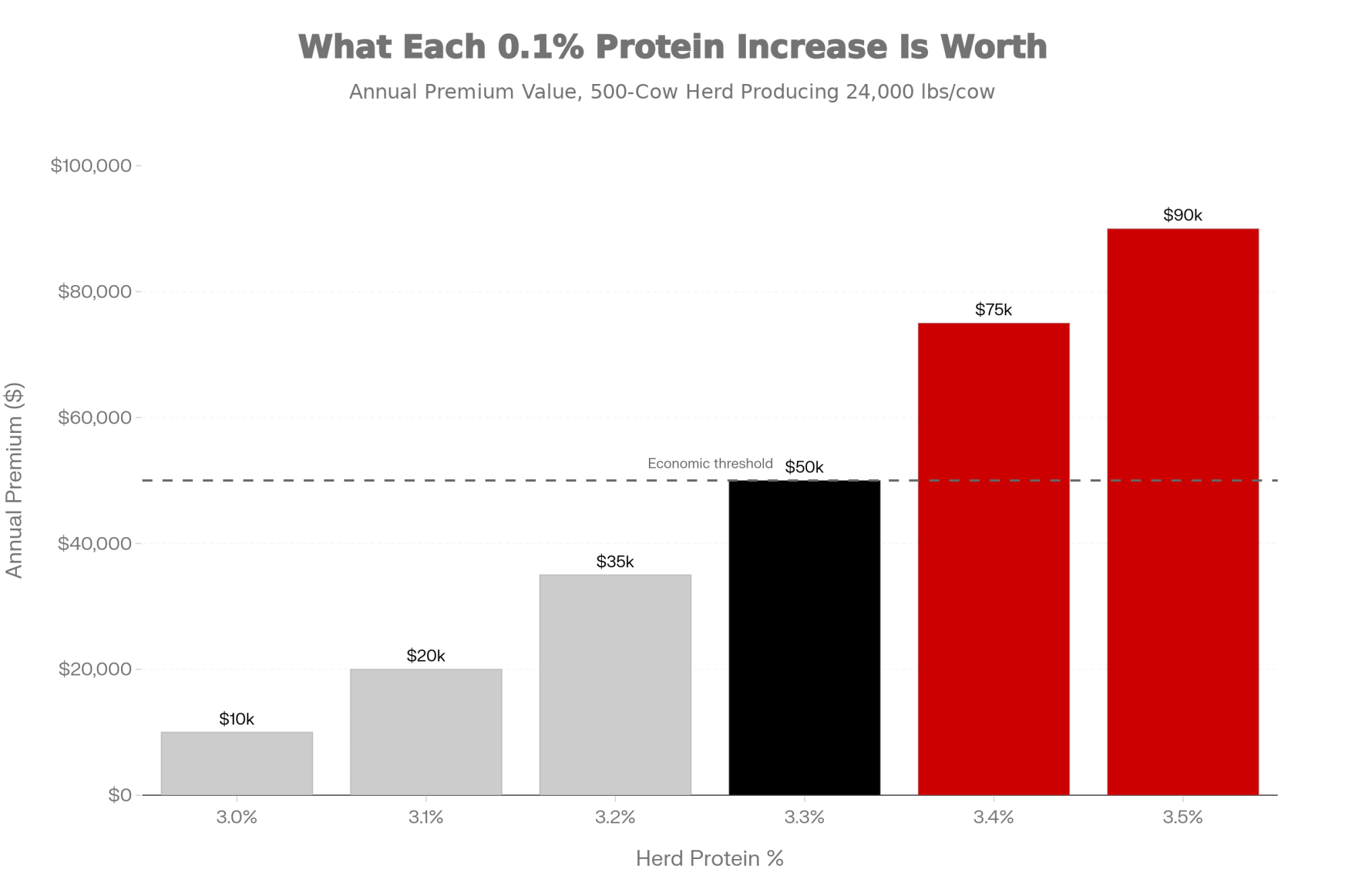

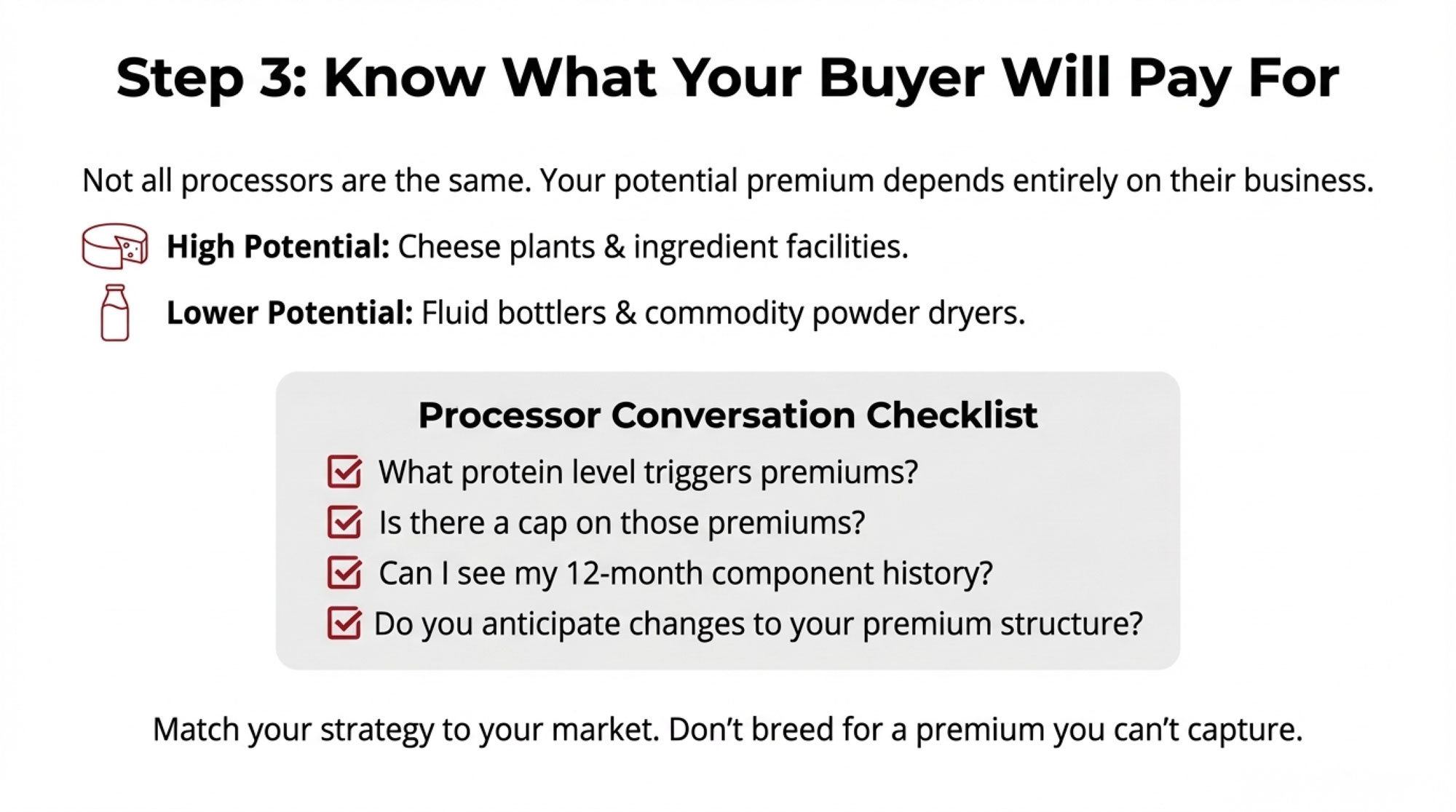

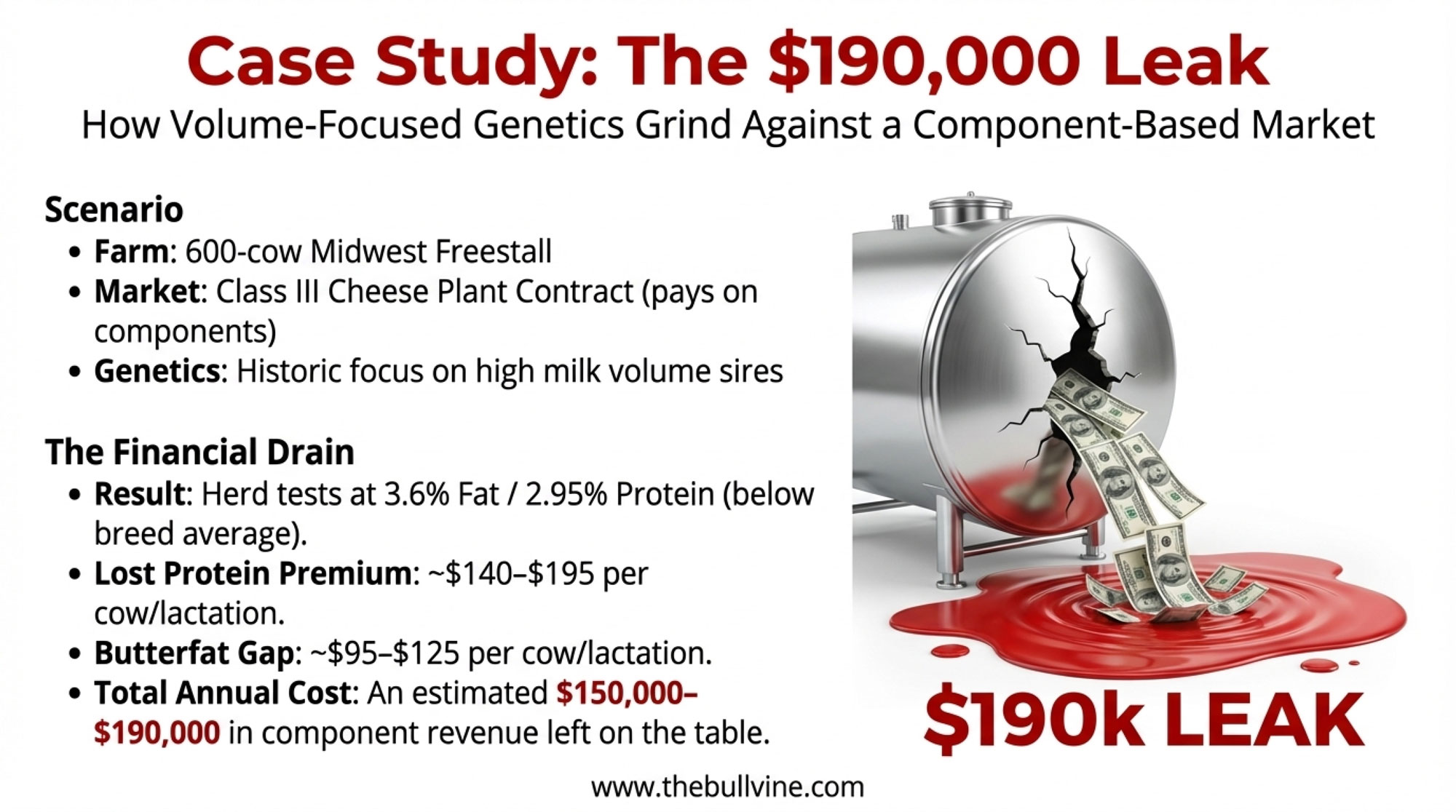

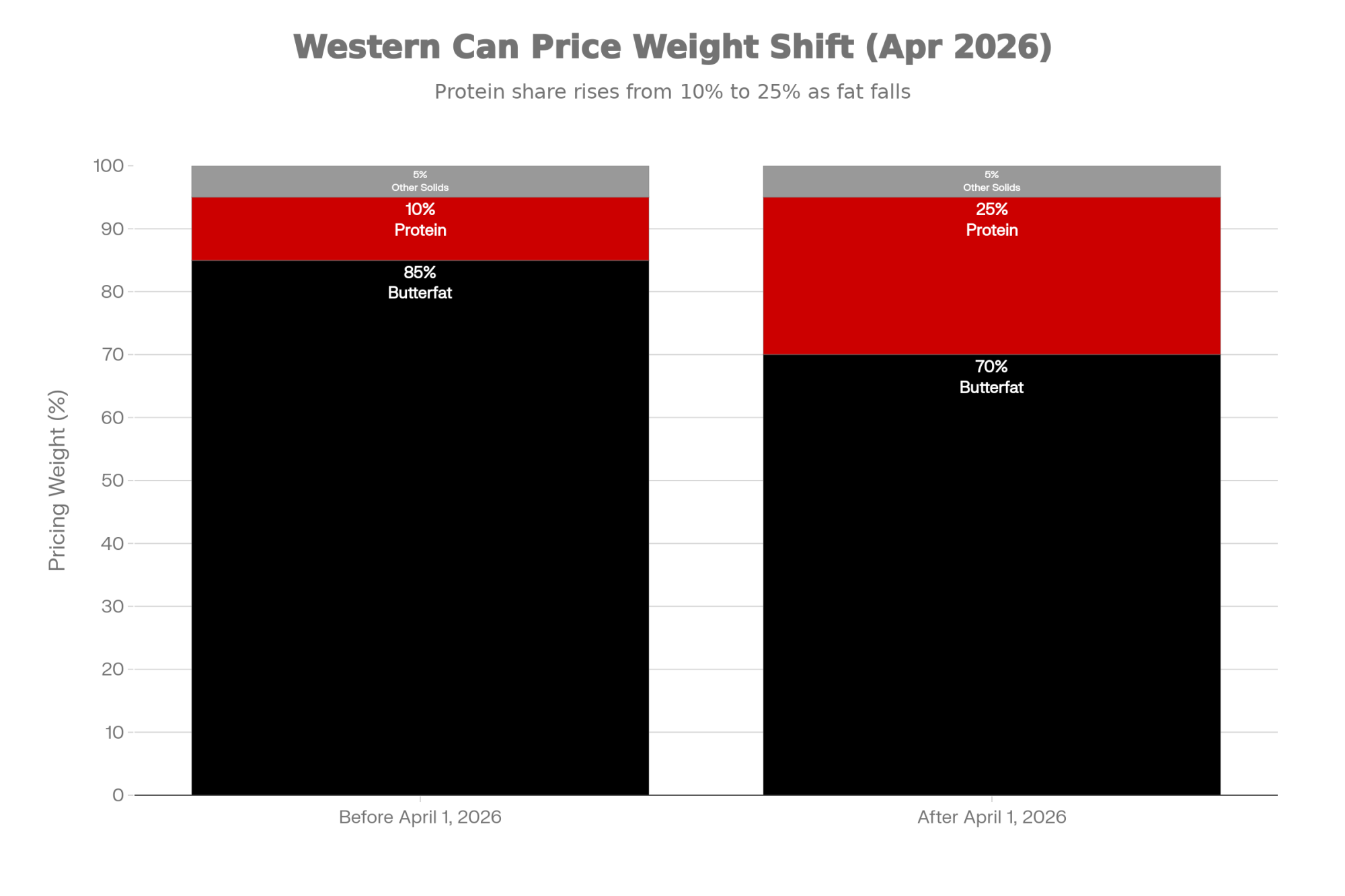

One index note: If your plant pays a cheese yield premium, consider weighting CM$ alongside NM$. Under CM$, protein carries $4.73/lb emphasis versus $3.32 in NM$ (VanRaden et al., NM$, 2025). If you’re on a Class I fluid contract, FM$ may be your better primary index. Know your market before you choose your yardstick.

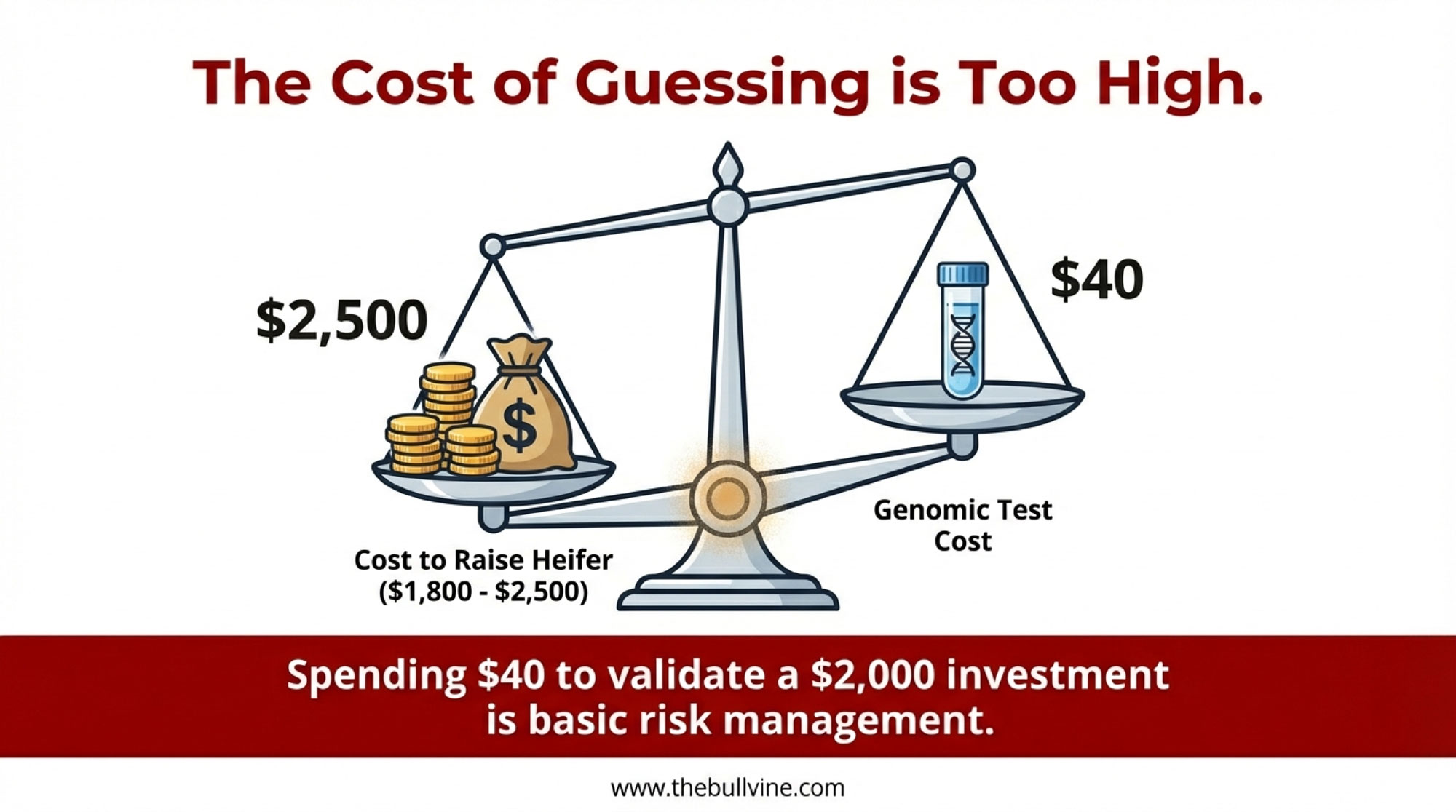

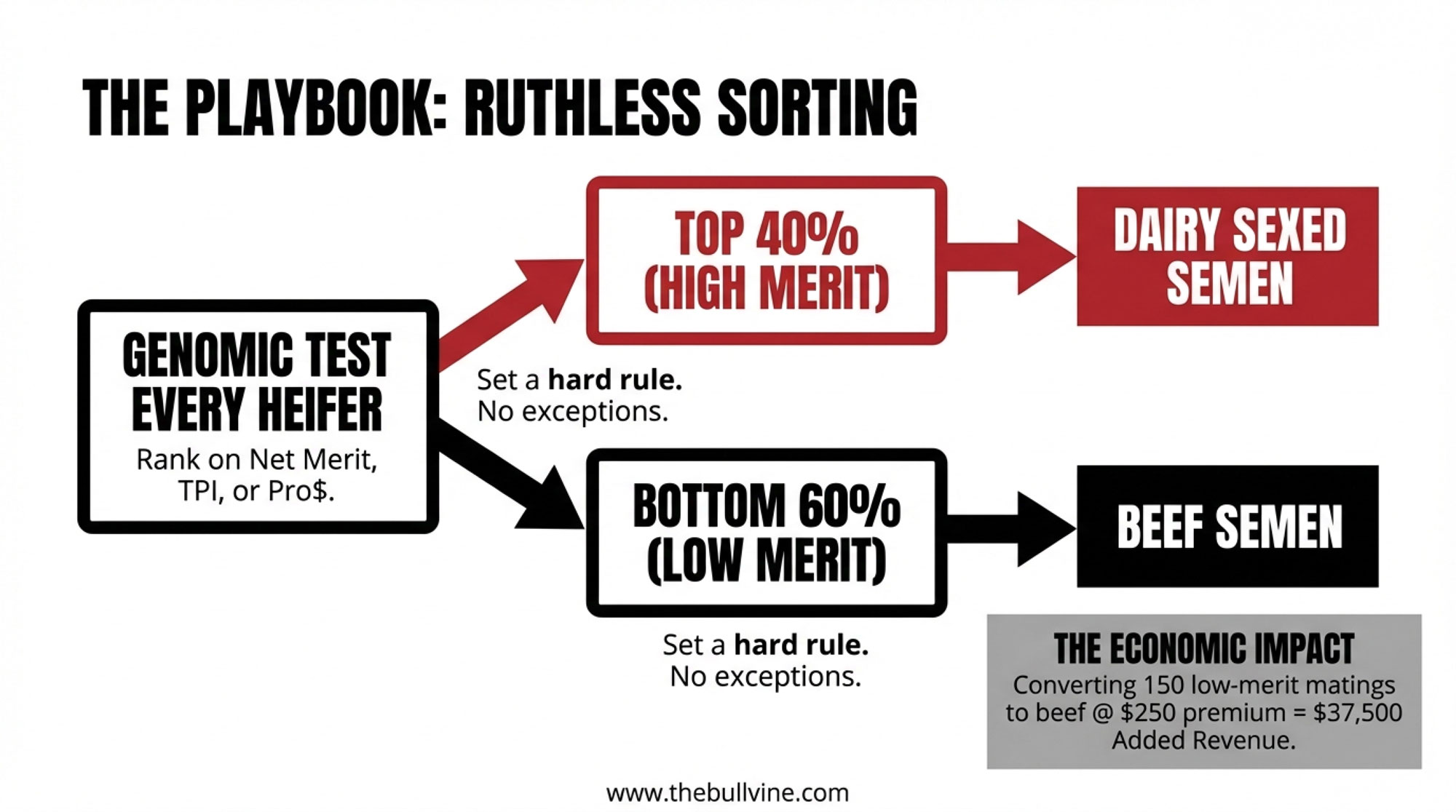

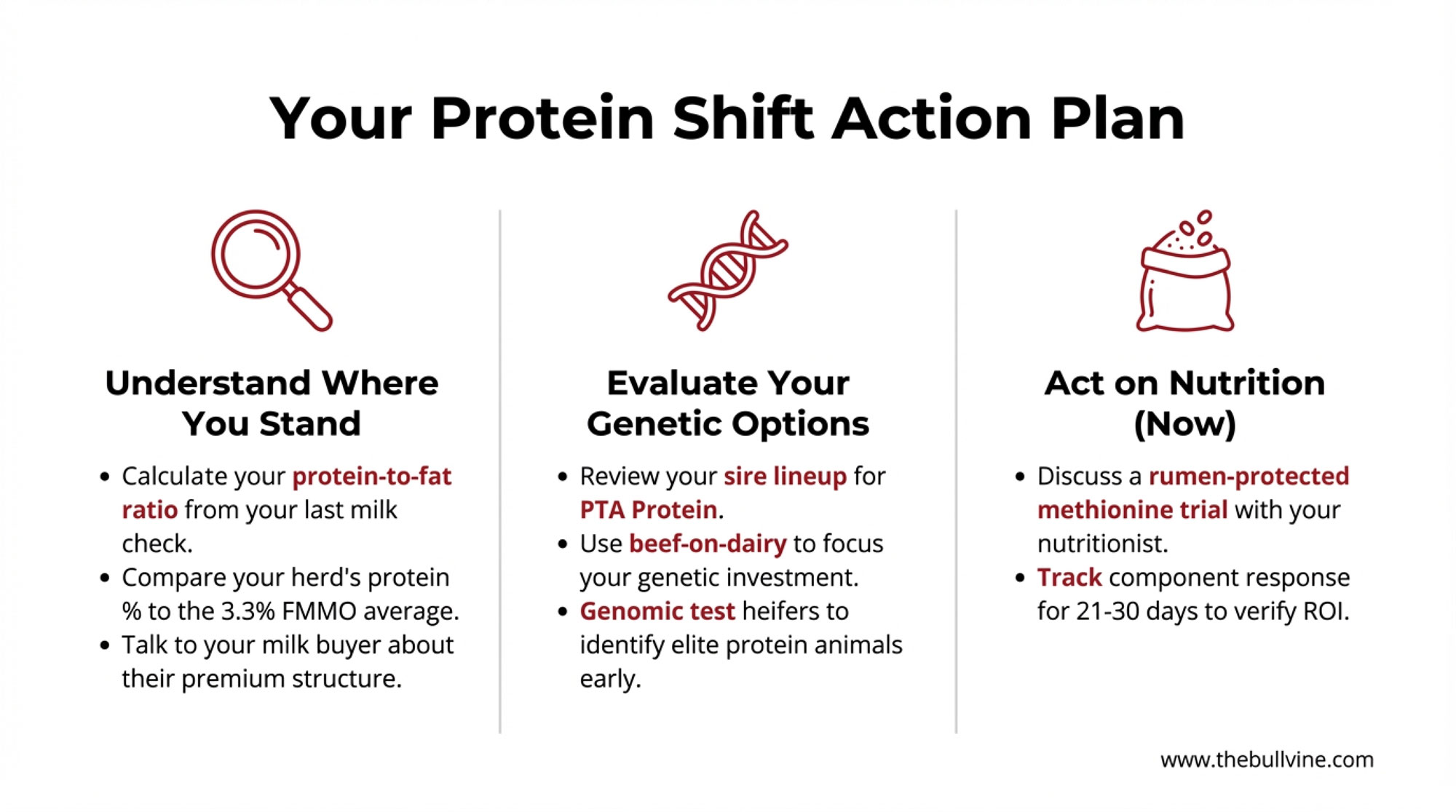

Genomic Test Your Next 20 Replacement Heifers

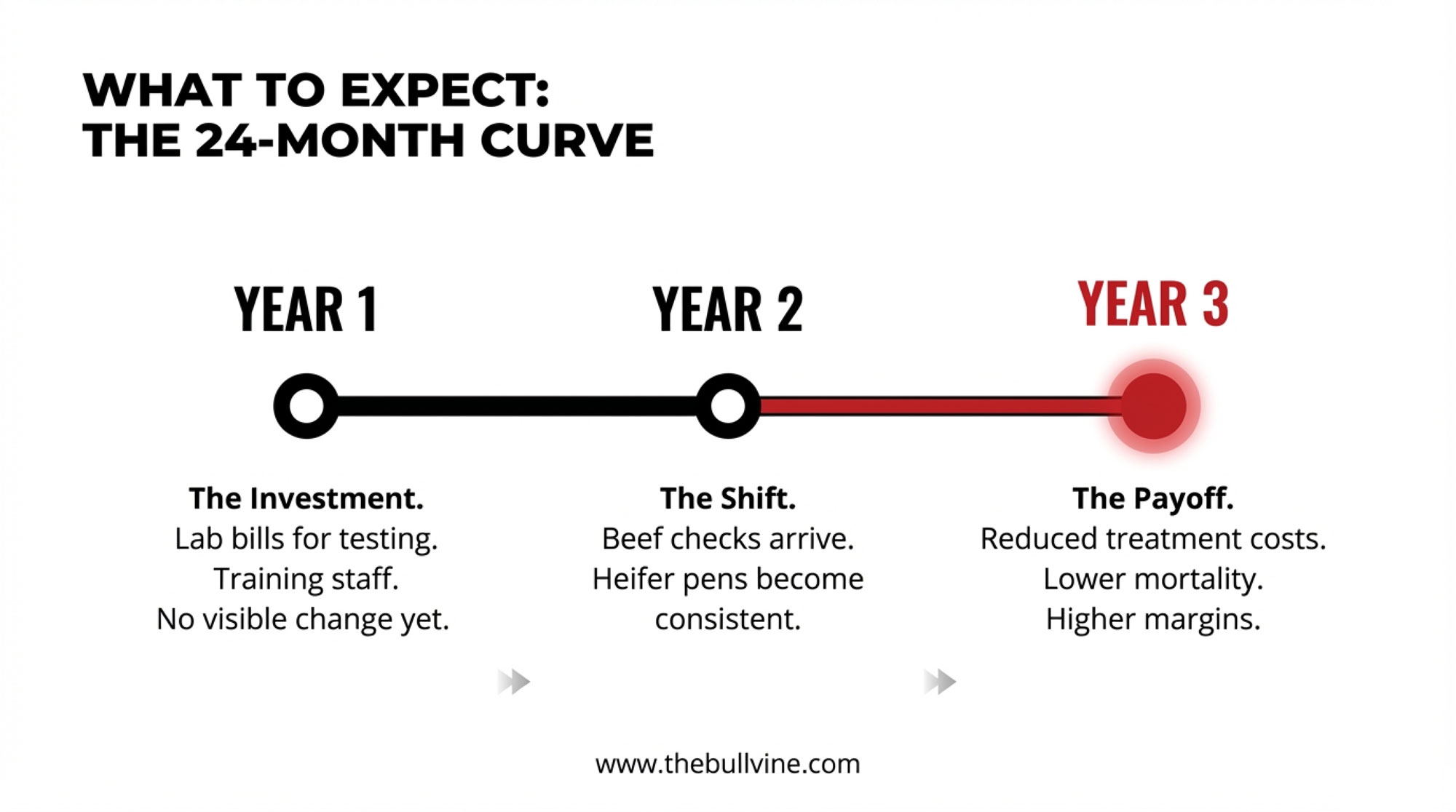

You don’t have to test every animal tomorrow. Start with the next group approaching breeding age. UK data from the AHDB showed that herds genotyping 75–100% of their heifers had an average Profitable Lifetime Index of £430 per animal in their 2023 calf crop, compared to £237 for herds testing 0–25% of heifers. That £193 gap translates to roughly £19,300 in theoretical profit potential for a typical 175-head herd — but AHDB’s analysis of actual farm business accounts revealed the real advantage at that genetic difference to be over £50,000. Those aren’t projections. They’re margins from real accounts.

| Genomic Testing Rate | Avg £PLI Per Animal | Theoretical Profit Potential (175-head herd) | Actual Profit Advantage (Farm Accounts) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–25% Testing | £237 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 75–100% Testing | £430 | +£19,300 | +£50,000+ |

| The Gap | +£193 per animal | — | Real margins from UK farm business accounts, not projections |

Dave Erf, dairy technical services geneticist with Zoetis, offers three ground rules for getting started: have a plan for how you’ll use the results before you test, lay out a herd roadmap of where you’re strong and where you need to improve, and test all your heifers — not just the ones you think are best. “If you just test your best ones, you can’t make a culling decision, because you don’t know,” Erf shared.

The trade-off is real, though. Testing creates a two-tier system — dairy sires on your top genomic females, beef sires on the bottom. If you test but don’t actually follow through on that split, you’ve spent the money without capturing the value. And on very small herds under 50 cows with limited replacement needs, the per-head cost may not generate enough selection differential to justify universal testing. Start with 20 and scale from there.

The Five-Year Outlook: Marginal Edge or Structural Separation

Five years out, is disciplined sire selection a nice-to-have or a survival factor?

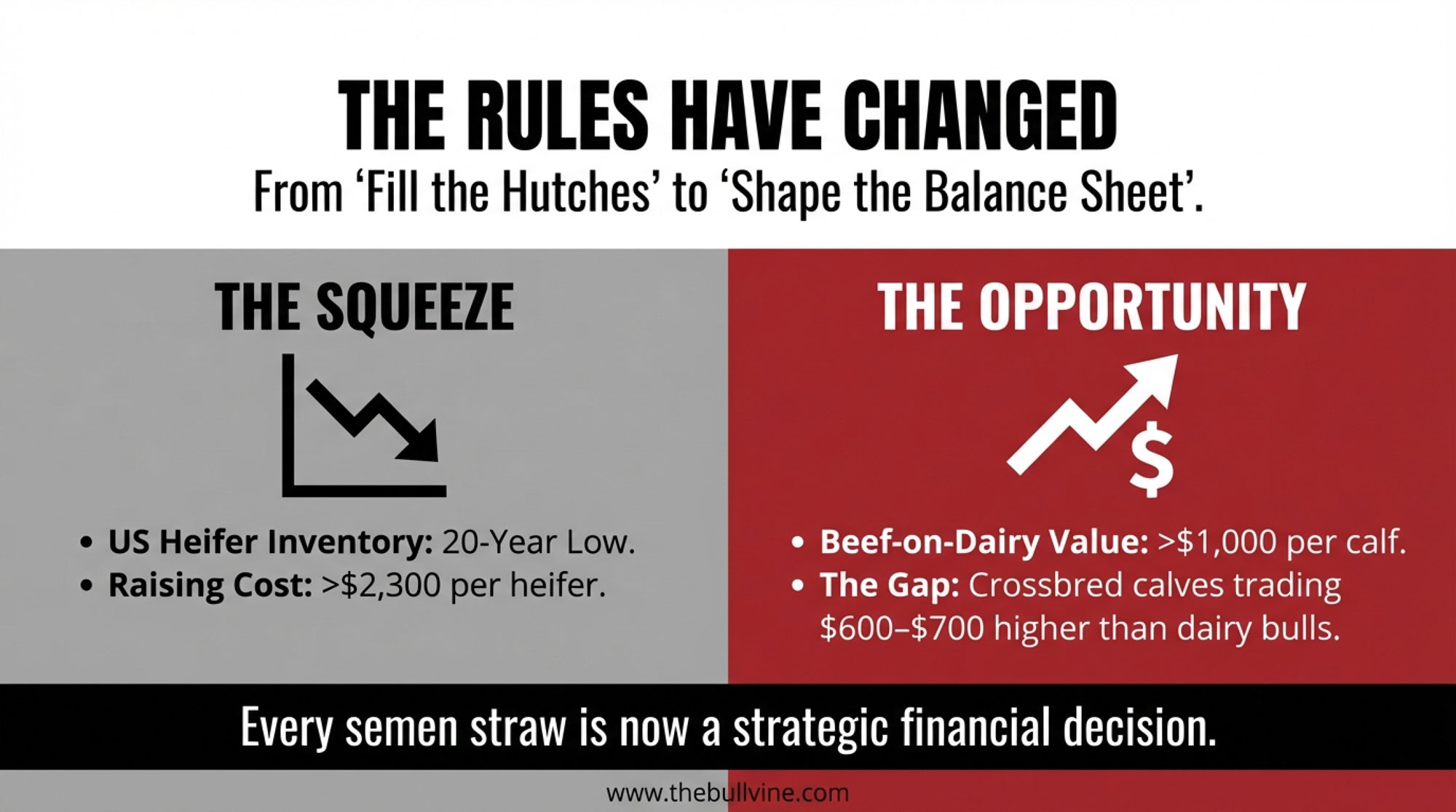

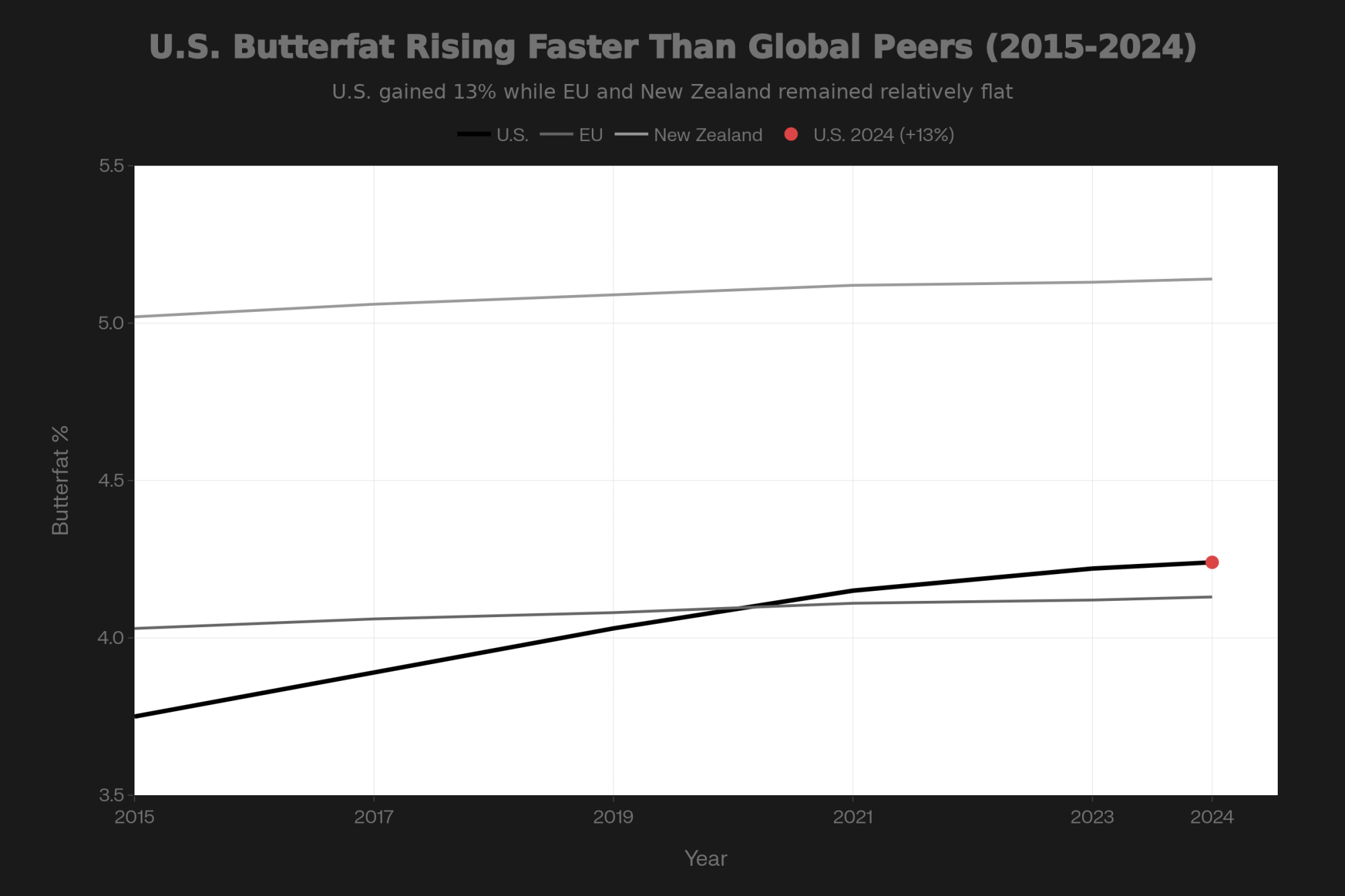

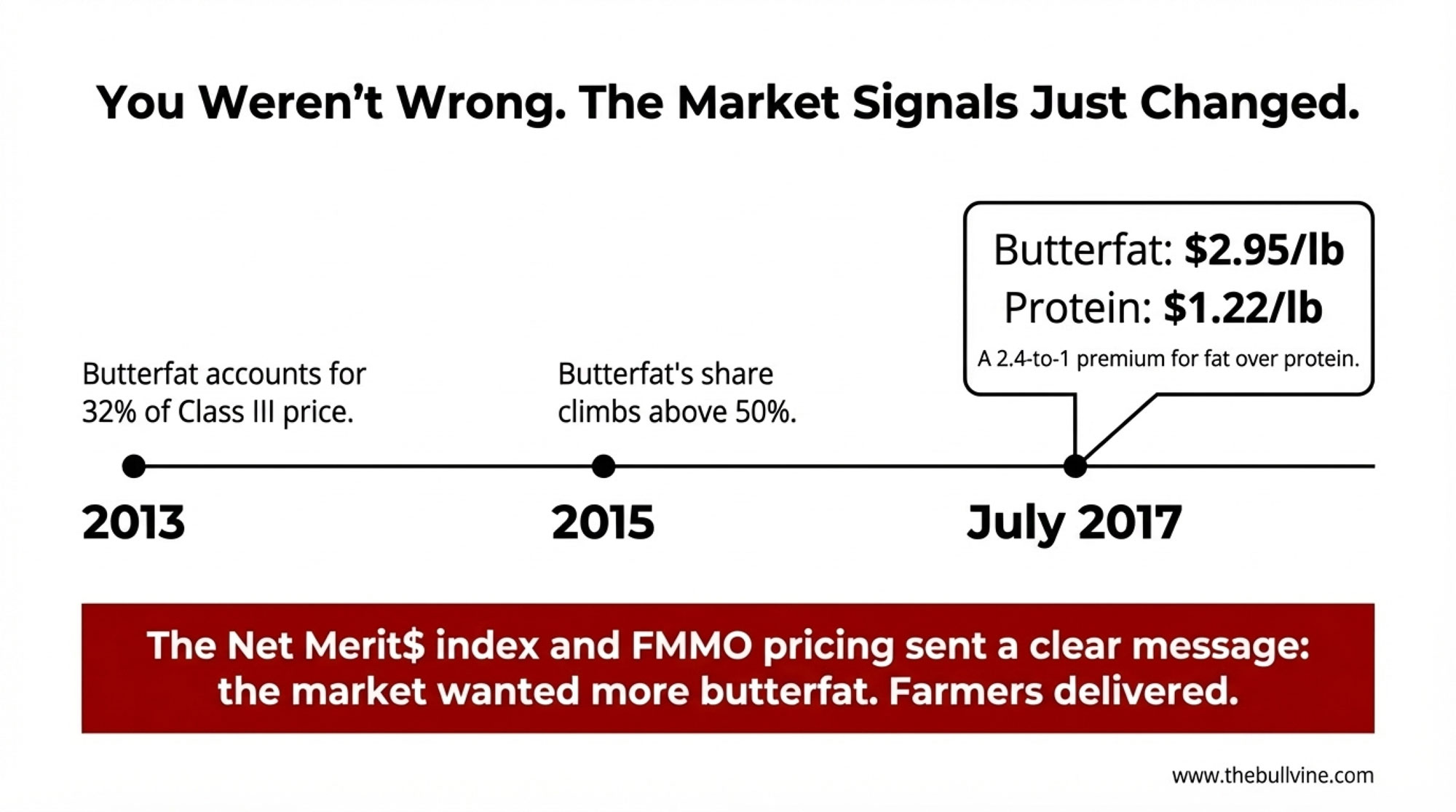

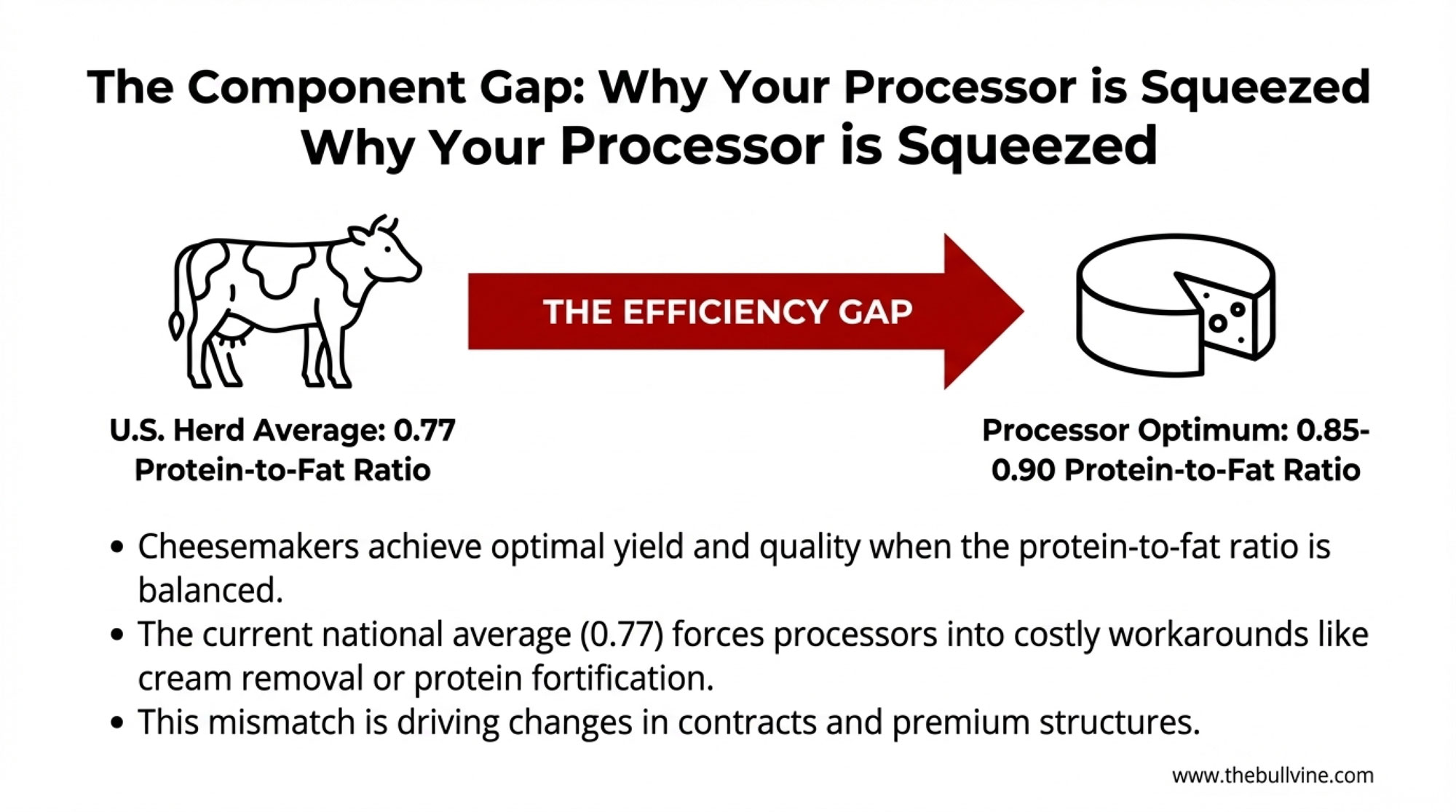

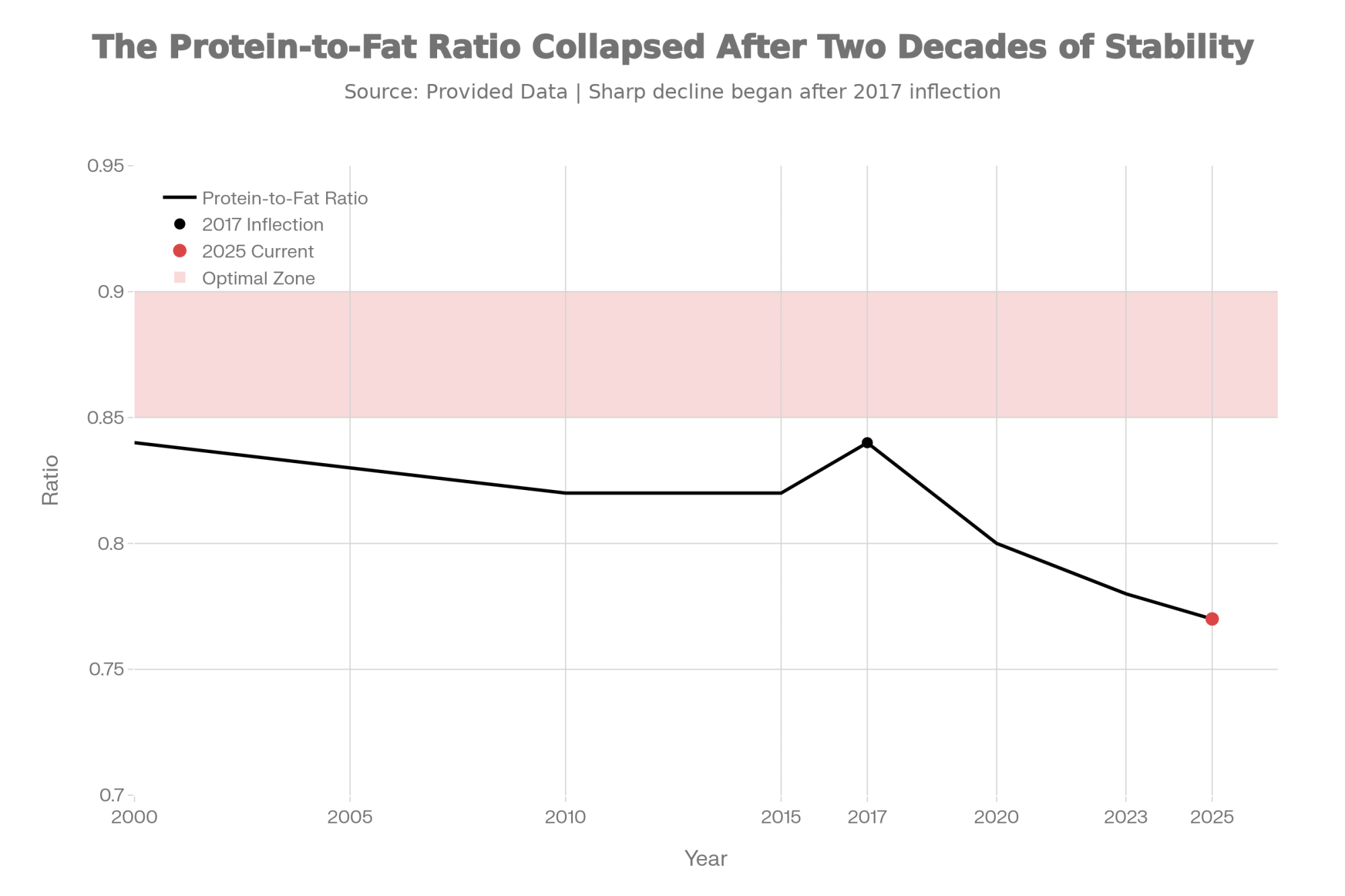

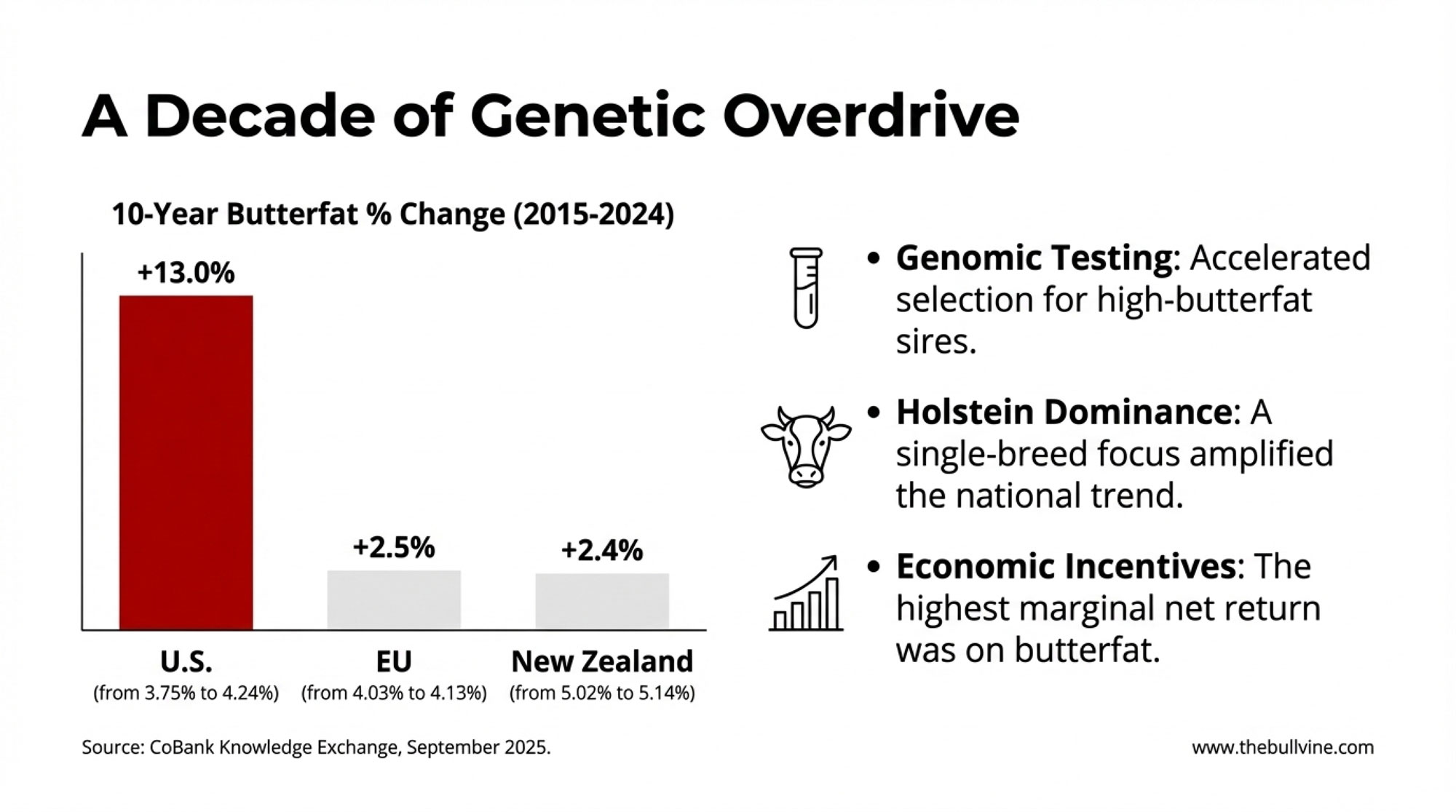

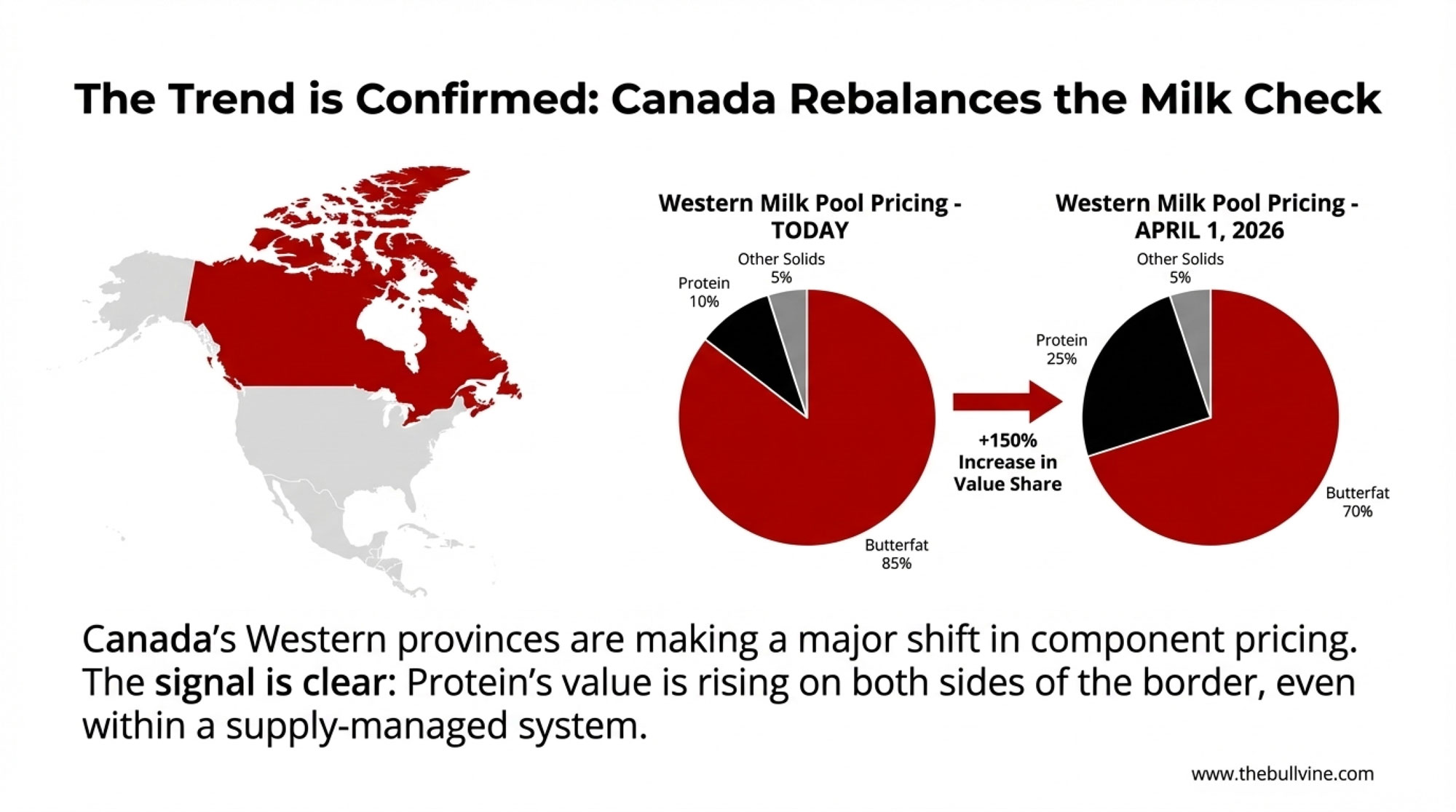

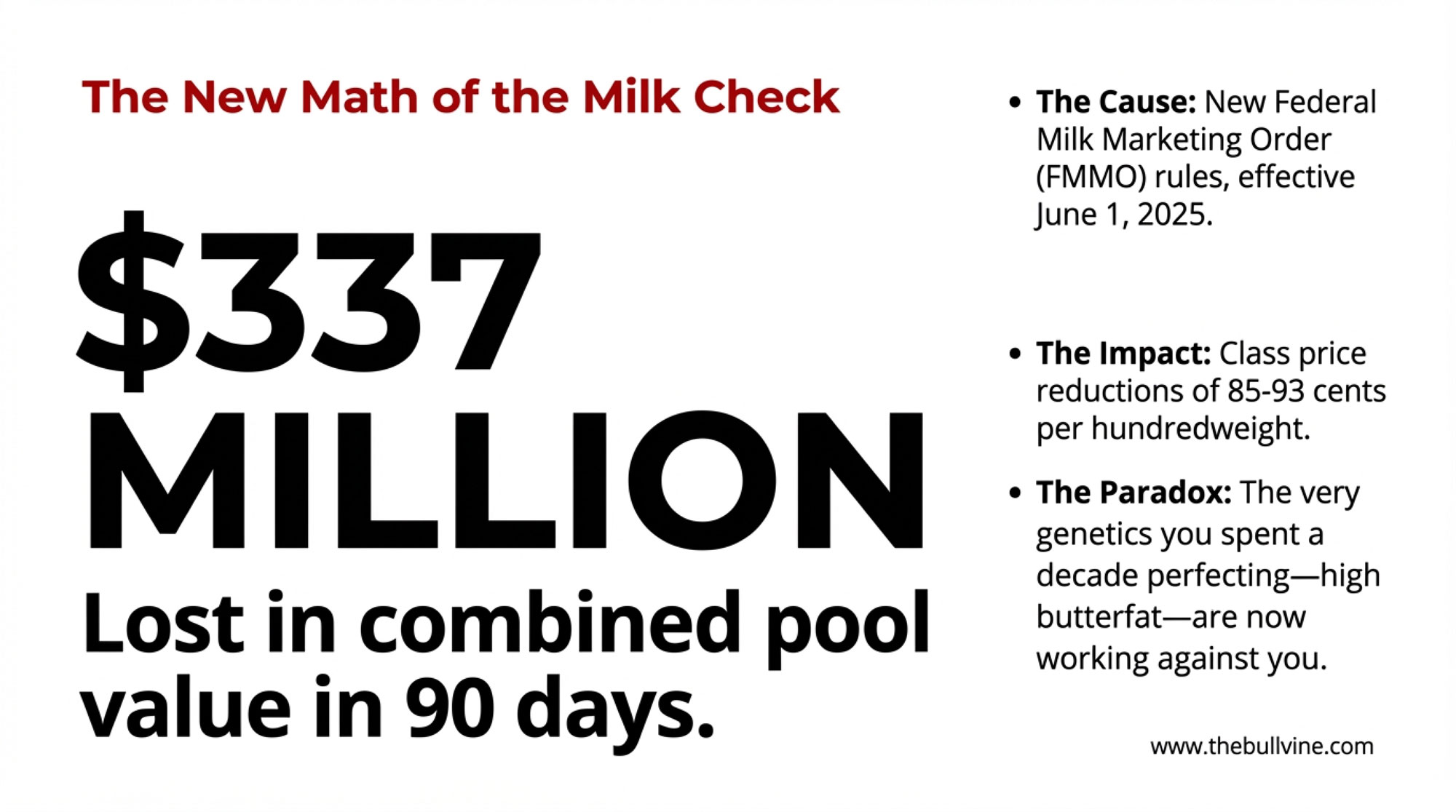

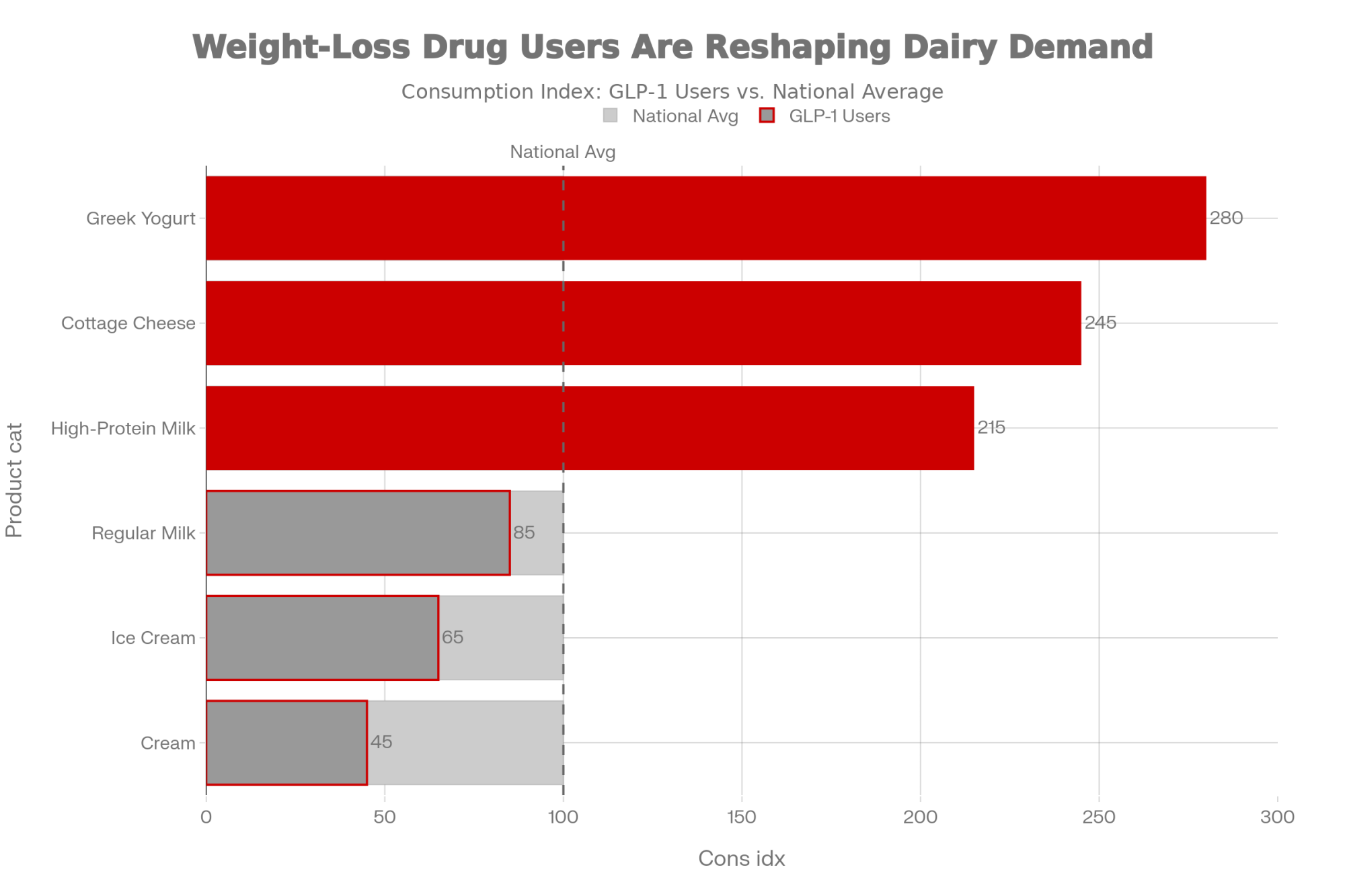

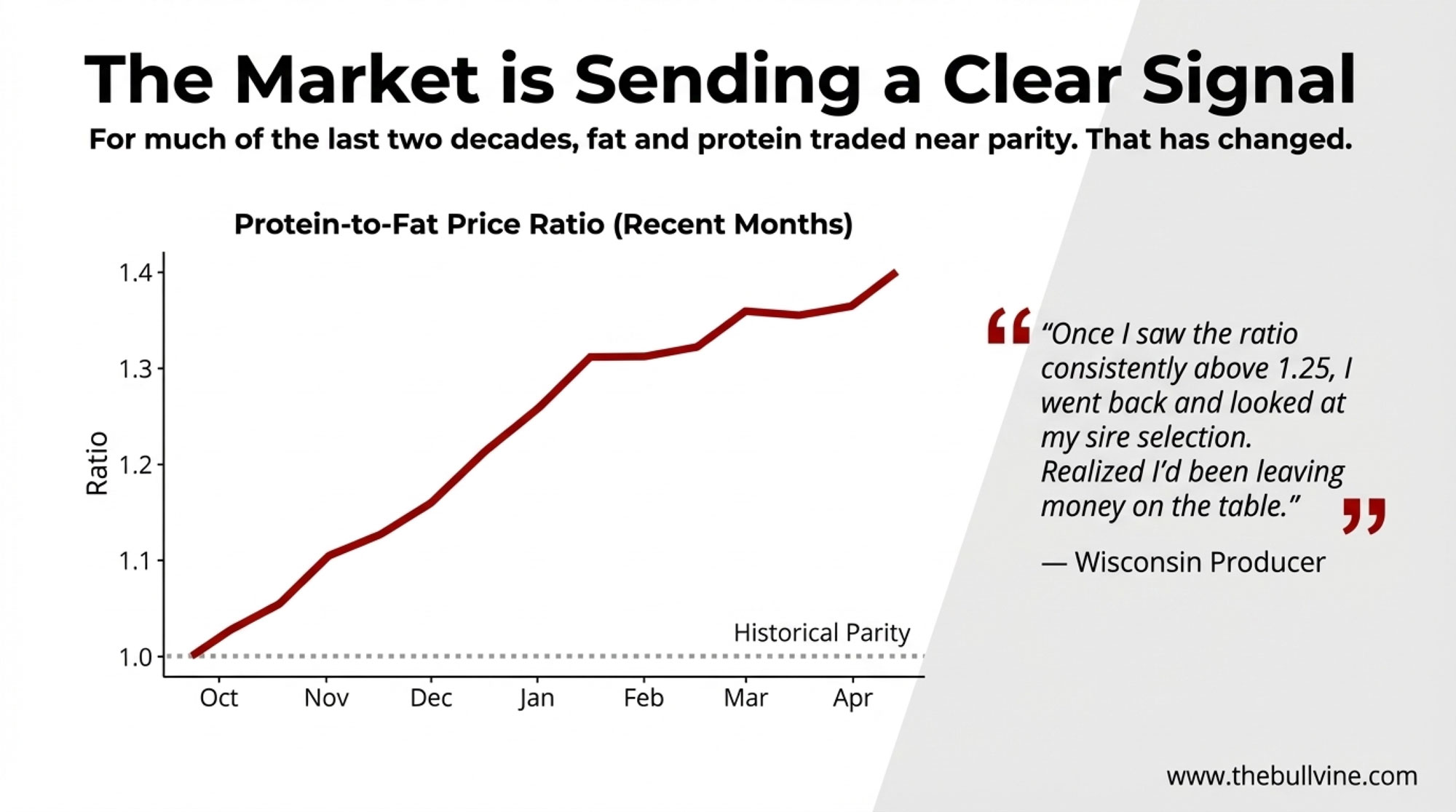

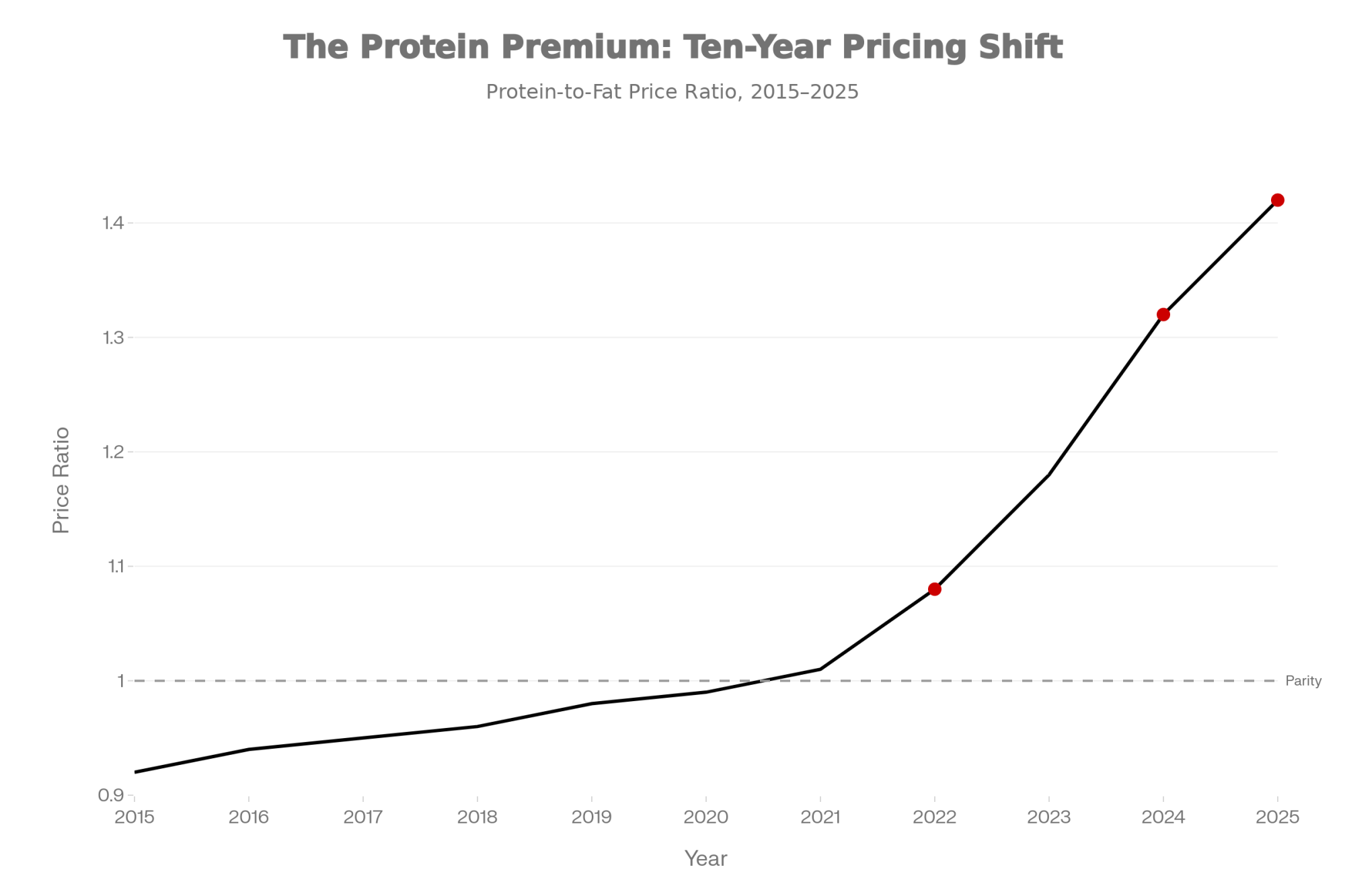

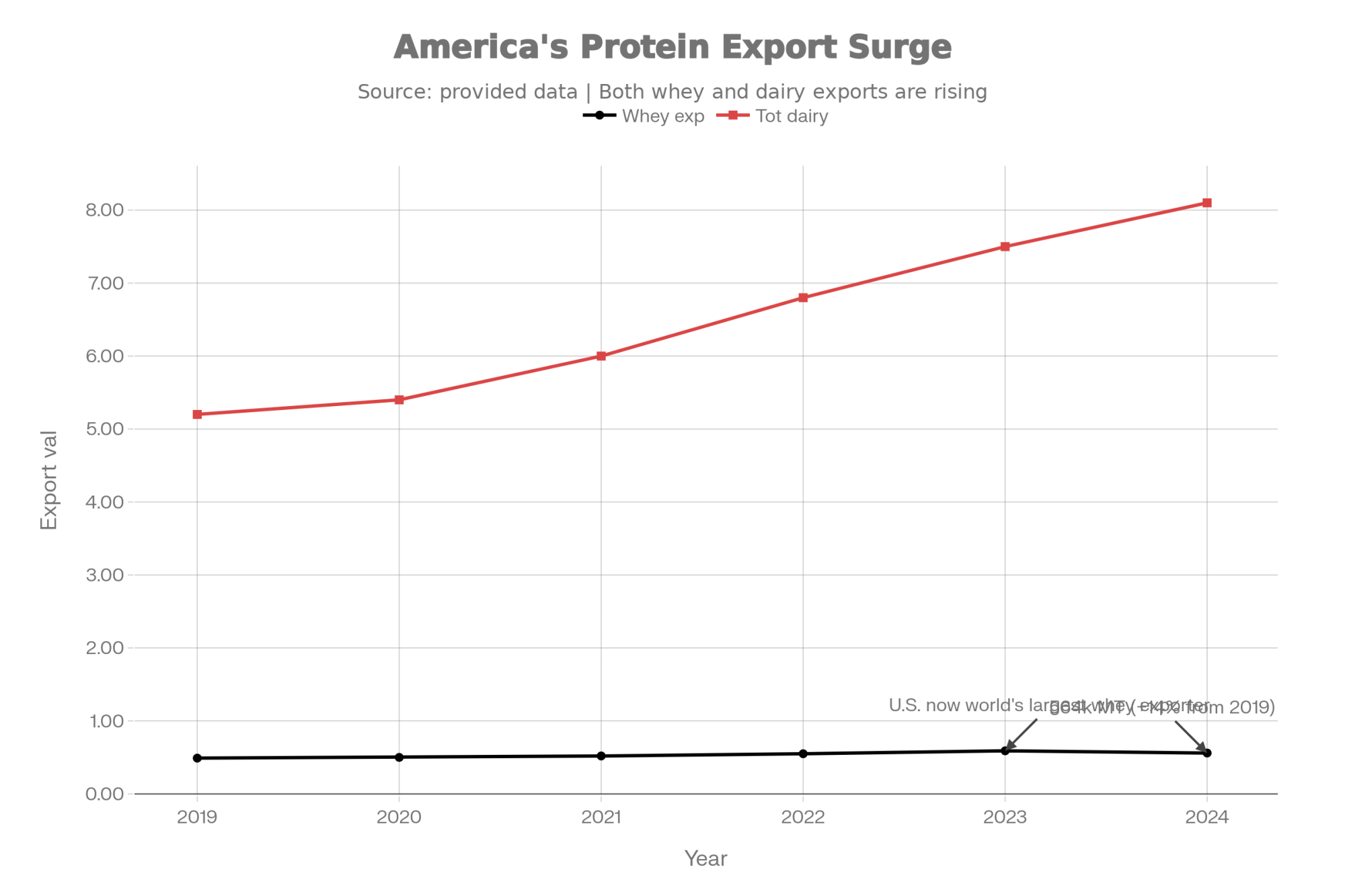

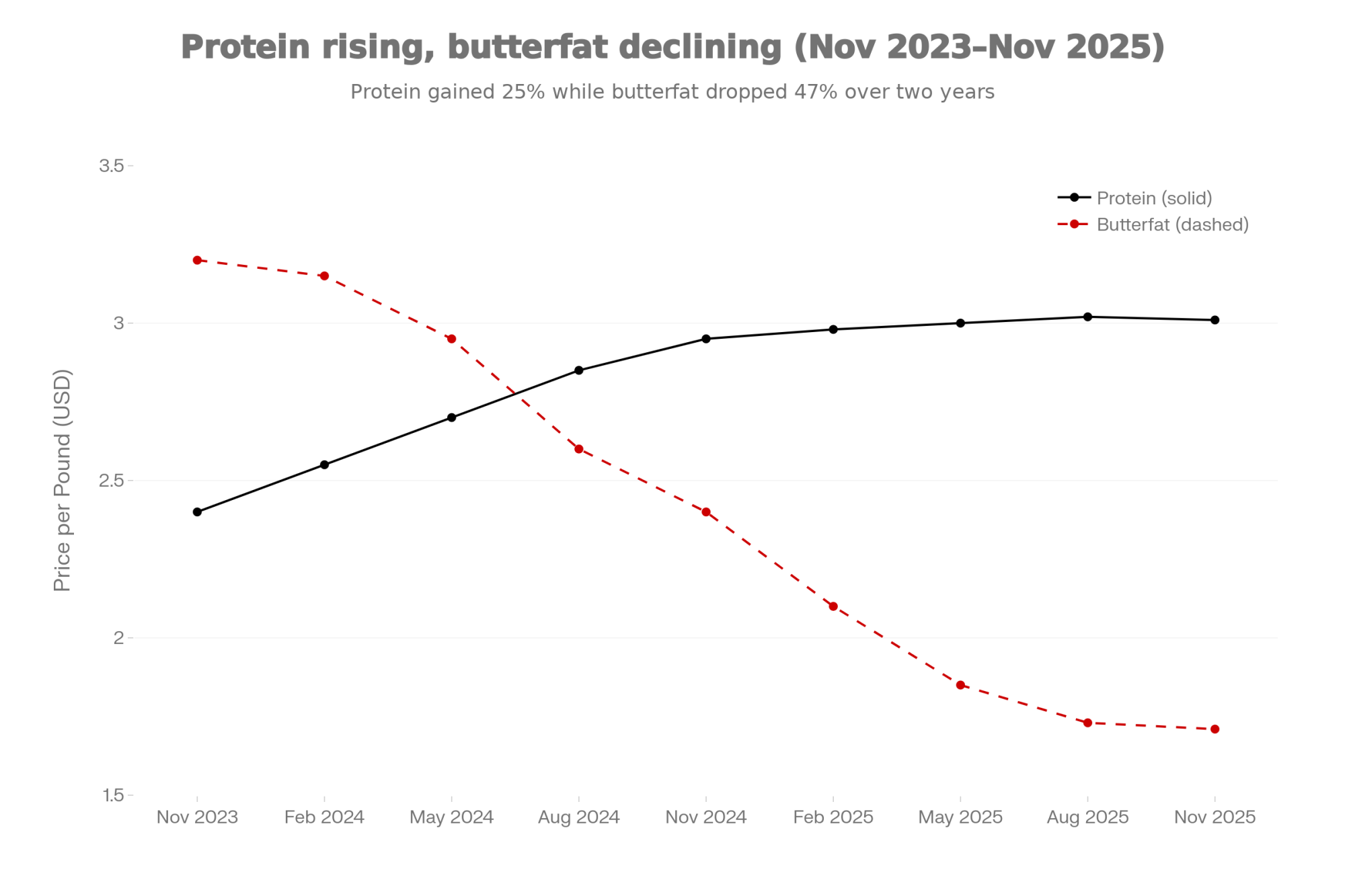

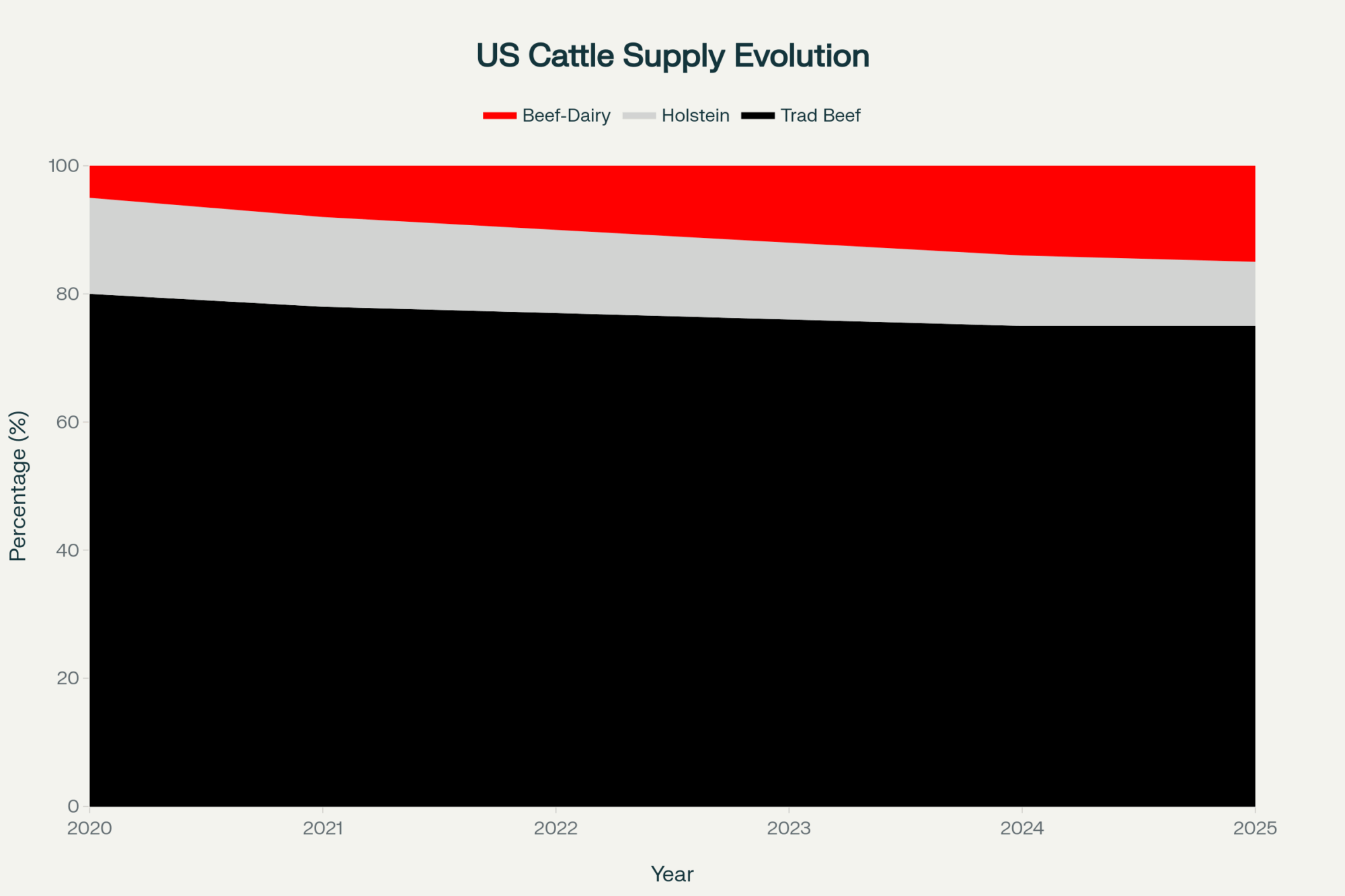

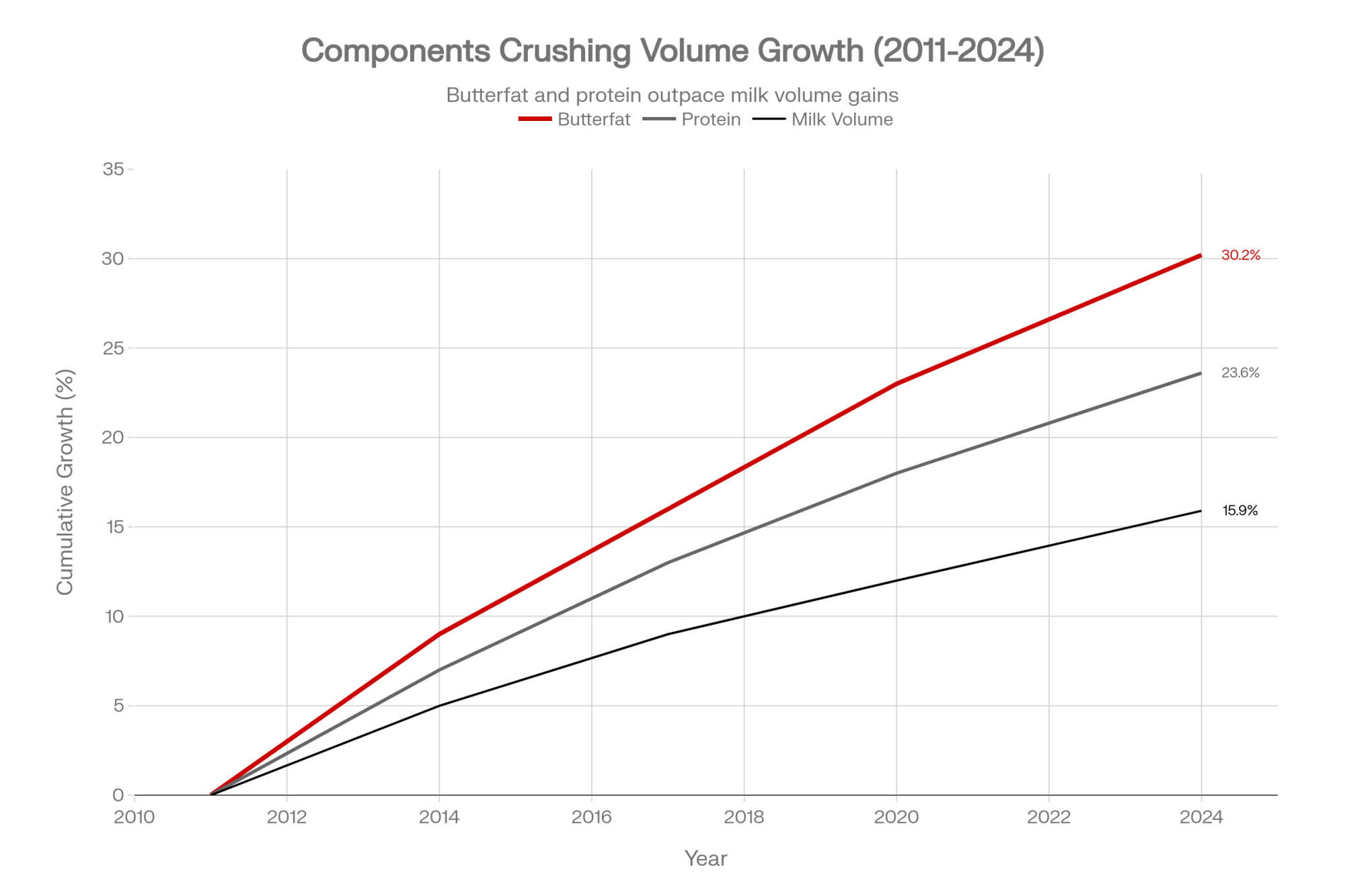

The evidence points toward structural separation. CoBank’s lead dairy economist Corey Geiger laid out the financial logic in a March 2025 Knowledge Exchange report: “there’s a clear financial incentive for producers given that multiple component pricing programs place nearly 90% of the milk check value on butterfat and protein.” And the genetic pipeline is delivering. Butterfat in US Holsteins hit a record 4.23% in 2024, and protein reached 3.29% — both per USDA/NASS data. Between 2011 and 2024, butterfat production surged 30.2% and protein by 23.6%, both outpacing the 15.9% growth in fluid milk volume (CoBank, March 2025). For a broader context on where this is heading, see the 2025 genetic evaluation updates.

“Selecting animals for highly heritable traits and having a market incentive to do so has formed a strong foundation for dairy producers to develop their herds to produce more butterfat and protein,” Geiger wrote. “Genetics should continue to gain momentum in the coming years.”

In the UK, 112,507 cows were genomically tested in 2024 — a 19% jump over the prior year. The adoption curve is accelerating. Marco Winters, head of animal genetics at AHDB, put it bluntly: “Improving genetics is probably the cheapest and most sustainable way of making long-term improvements to any herd, and when you’re using a genetic index which has been developed specifically to increase profitability, this feeds straight through to a farm’s bottom line.”

In Australia, DataGene’s ImProving Herds project — which tracked 27 Genetic Focus Farms and 7 Herd Test Focus Farms — found that every single case study farm adopting data-informed genetic decisions reported improved business performance, even during a severe milk price crash and drought (DataGene, 2023 final report). Six of seven Herd Test Focus Farms continued testing permanently. Once the feedback loop started working, going back felt reckless.

Here’s what makes genetics different from every other efficiency tool on your dairy. Feed systems, robotic milkers, and activity monitors — they all require ongoing capital and operating expense. Genetic gains are baked into the biology. They compound without additional spend. In a margin squeeze, the operation running genetically superior cows carries a fundamentally lower breakeven. Not because they manage better. Because their cows are biologically cheaper to run.

What This Means for Your Operation

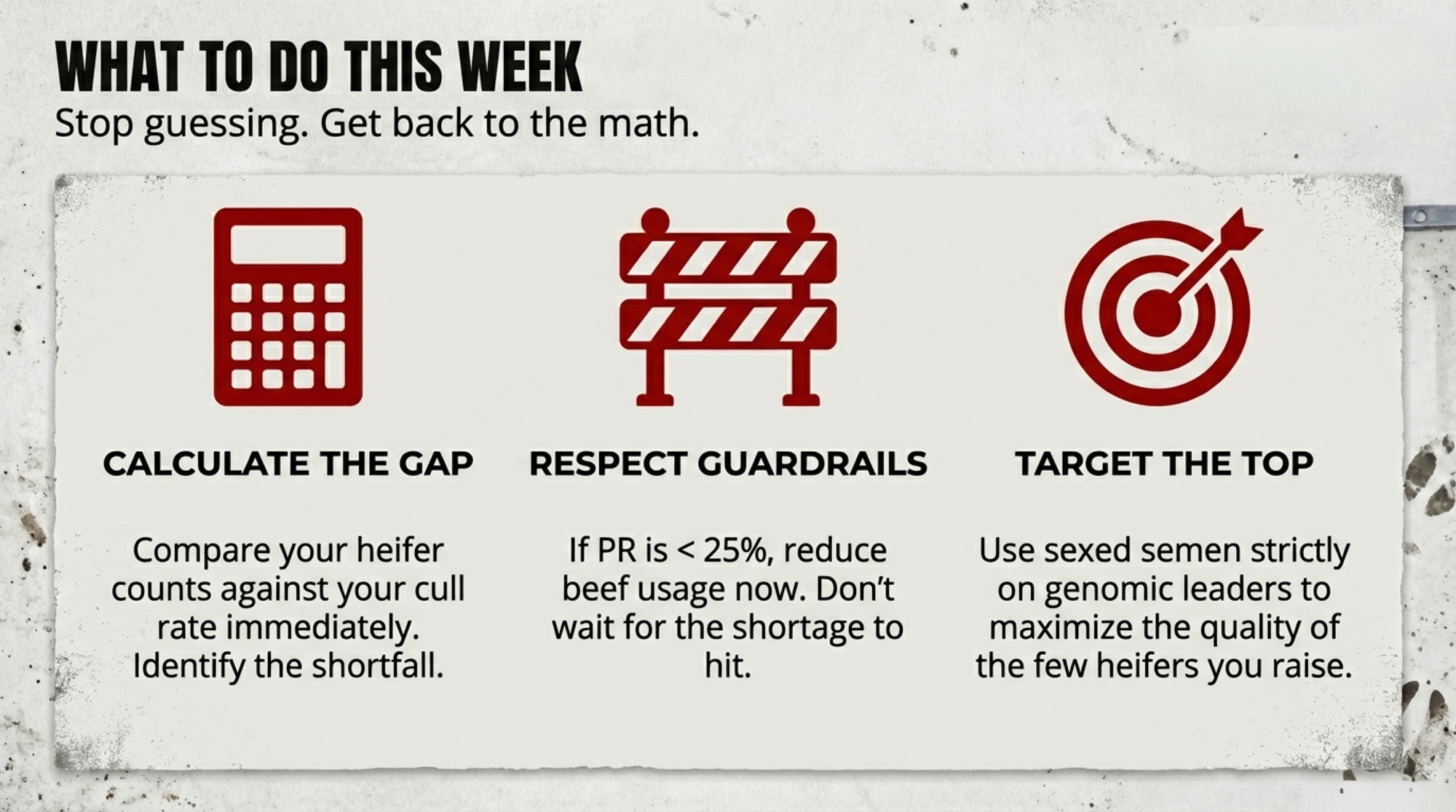

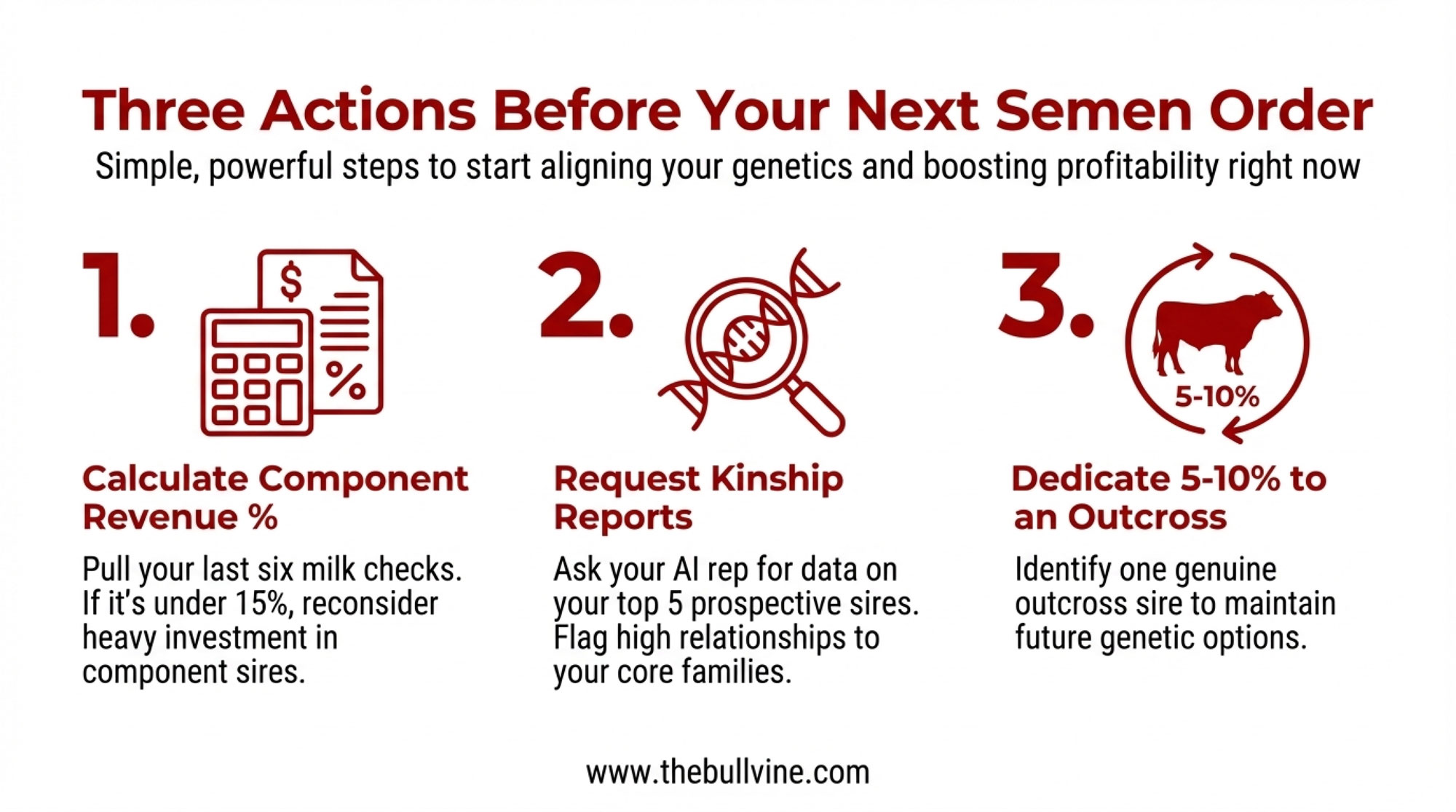

- Before your next semen order, build the one-page scorecard. Thirty minutes, five questions, taped to the wall. Every sire candidate is scored against your herd’s actual needs—not catalog rankings or rep recommendations.

- This month, genomic test your next 20 breeding-age heifers. Use the results to split your replacement pipeline: dairy sires on top-tier females, beef sires on the rest. Test them all — not just the ones you think are best.

- At your next rep conversation, hand them the scorecard and ask them to fill four roster positions—not just recommend their current favorites. Which bull addresses your top cull reason? What’s the Expected Future Inbreeding for each sire mated to your herd? Do they have outcross options from distinct sire lines?

- Every proof round (April, August, December), revisit your roster. December 2025 reshuffled the rankings significantly. A lineup built in January may need adjusting by August.

- If your herd averages over 1,600 lbs body weight, the NM$ maintenance cost recalibration means your feed costs per unit of production are likely higher than your old genetic plan accounted for. With BWC now carrying −11% emphasis in NM$, selecting for lower body weight composite and positive Feed Saved isn’t optional anymore.

- If you market breeding stock or show cattle, recognize that NM$ reflects commercial priorities. Weighting type traits more heavily is a legitimate strategic choice — just make it with full awareness of the trade-off in commercial efficiency.

Questions to Ask Your Genetics Rep This Week

Print this. Bring it up in your next conversation about your semen order.

- Can you show me trait profiles — not just index rankings — for every bull in my current lineup?

- Which of my current sires directly addresses my top cull reason?

- What is the Expected Future Inbreeding for each bull when mated to my herd?

- Do you have outcross options from distinct sire lines and maternal grandsires?

- How does my current lineup score on Feed Saved and body weight composite under the 2025 NM$ revision?

The Longest Game You Play

Tonight’s Super Bowl ends in four quarters. Your sire decisions don’t resolve for a decade.

Vander Woude has been at this for over a decade now. He wouldn’t still be testing 6,000 cows if he didn’t believe it paid for itself. “It’s really hard to quantify how it pays for itself,” he shared. “But I have a much better herd of cows.” Dave Erf, his Zoetis geneticist, was more specific: “I’ve never seen such a good reproduction performing herd… I think genetics helped them get there.”

Know your cows. Know your numbers. Match the bull to the need. That’s the whole shift in one sentence—and the data shows most of the industry still isn’t doing it.

Your semen tank is right there. The scorecard takes half an hour. And every daughter that walks into your parlor two years from now will be the commercial that plays on repeat, for better or worse, for the rest of the decade.

Key Takeaways

- Your sire choices now move $869 per cow in lifetime profit, based on a nine‑year Zoetis study of 12,952 Holsteins on 11 US dairies — that’s $173,800 a generation on 200 cows.

- The 2025 NM$ changes pay you more for Feed Saved and longevity and hit you for excess cow size (−11% BWC), so chasing big, showy cows is now a direct hit to commercial profitability.

- You can upgrade from “favorite bulls” to a real breeding game plan by running a four‑slot sire roster: franchise profit bull, high‑component hammer, durability/fertility fixer, and an outcross to keep inbreeding in check.

- A one‑page scorecard (NM$ floor, EFI cap, top three cull reasons, facility needs) plus genomic testing on your next 20 heifers is enough to start sorting dairy vs. beef matings with confidence.

- If you’re getting paid on butterfat and protein, genetics is no longer a “nice extra” — it’s one of the few levers that can permanently pull your breakeven down while feed and labor keep marching up.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

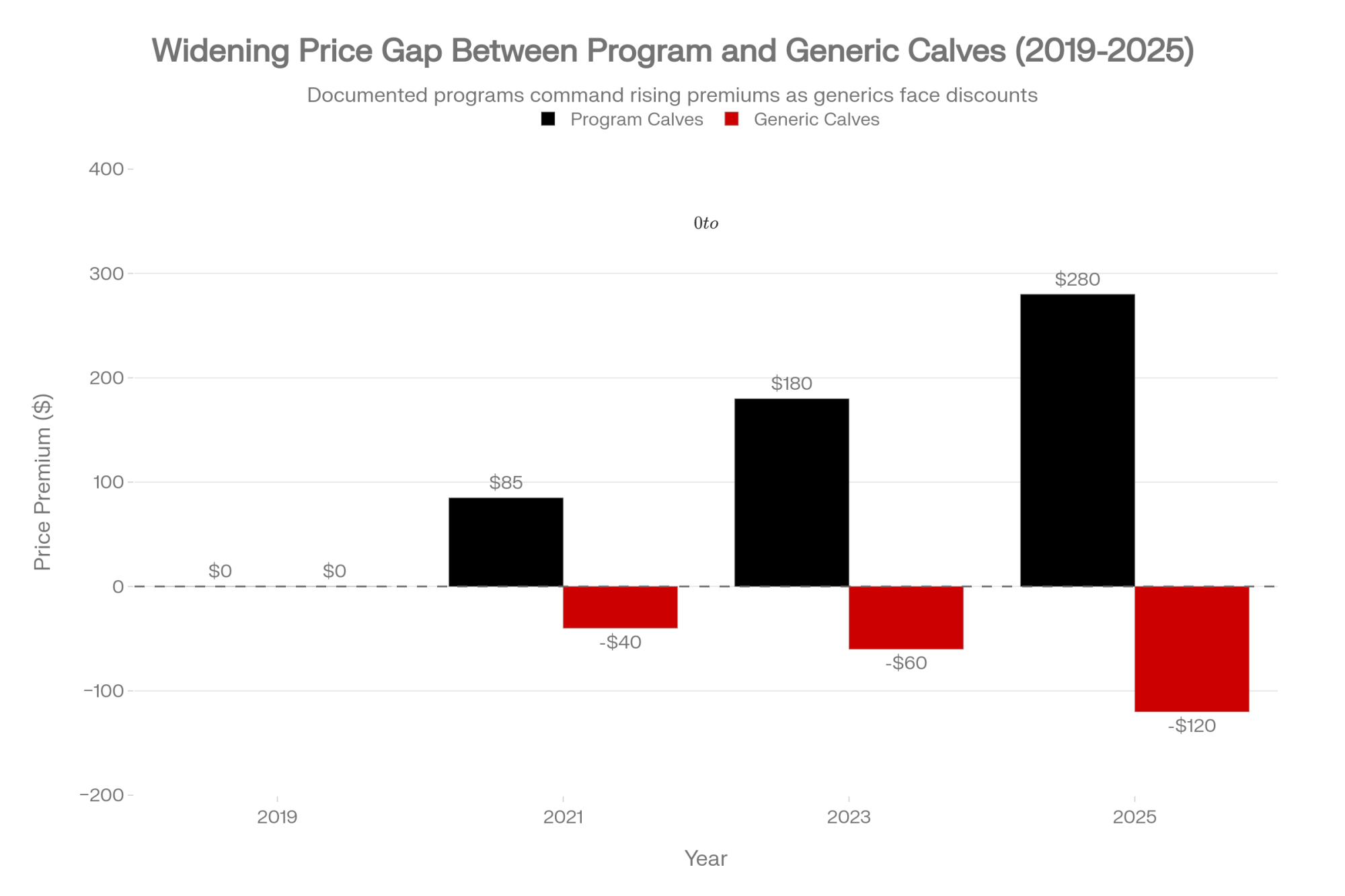

- The $1750 Calf: Is Your 2026 Breeding Plan Leaving $800 a Head on the Table? – Arms you with a 90-day blueprint to capitalize on the $1,750 beef-on-dairy market without hollowing out your future herd. This guide delivers the specific math you need to convert surplus pregnancies into immediate, high-margin revenue.

- Bred for $3 Butterfat, Selling at $2.50: Inside the 5-Year Gap That’s Reshaping Genetic Strategy – Exposes the “ironic index trap” of breeding for yesterday’s premiums while positioning your operation for 2030. You’ll gain a methodical approach to hedging against market volatility throughout the multi-year genetic expression cycle.

- The Next Frontier: What’s Really Coming for Dairy Cattle Breeding (2025-2030) – Breaks down the 2025–2030 roadmap of AI-driven selection and microbiome markers that promise 70% labor reductions. This vision of the future delivers a massive early-adopter advantage for producers ready to move beyond traditional production metrics.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!