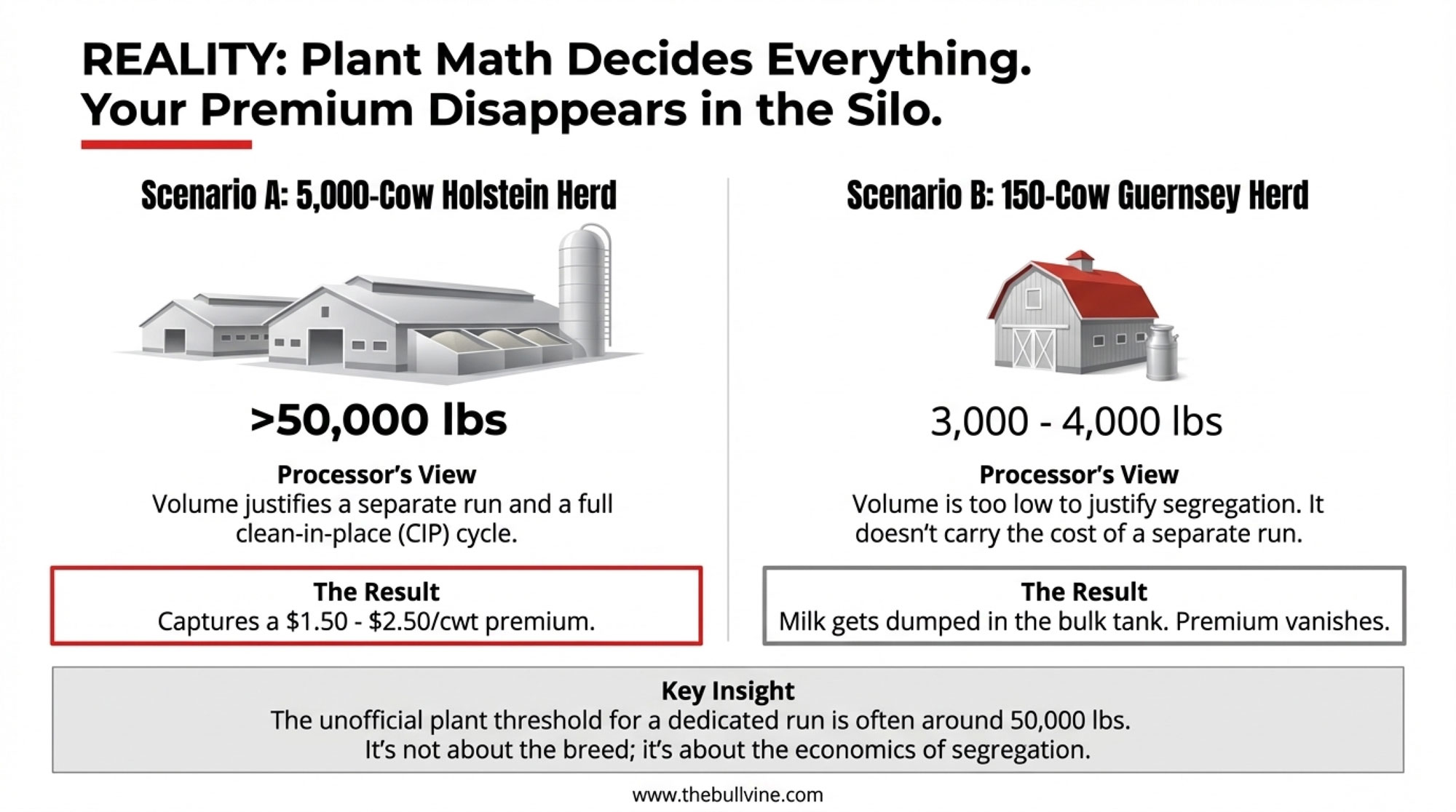

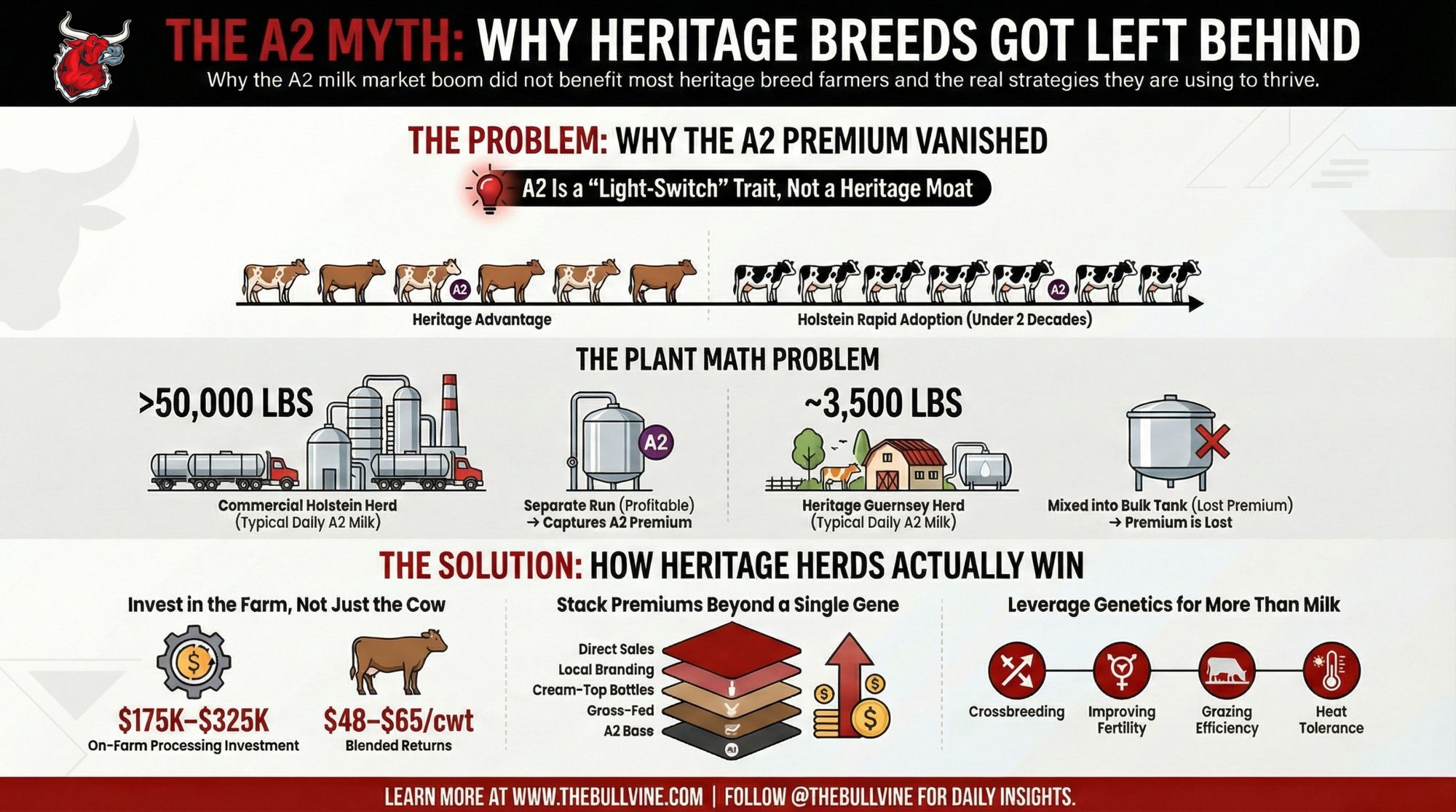

Your Guernseys might be naturally A2—but if you’re not hitting 50,000 lb per run, your premium is probably disappearing in someone else’s silo.

U.S. Guernsey cattle are now officially sitting in the “Watch” category on The Livestock Conservancy’s Conservation Priority List, which is the tier reserved for breeds with fewer than 2,500 annual U.S. registrations and an estimated global population under 10,000 registered animals according to the Conservancy’s parameters. The latest list still places Guernseys in that Watch bracket, which gives you a pretty clear sense of how small the registered population has become compared with where it once was in North America.

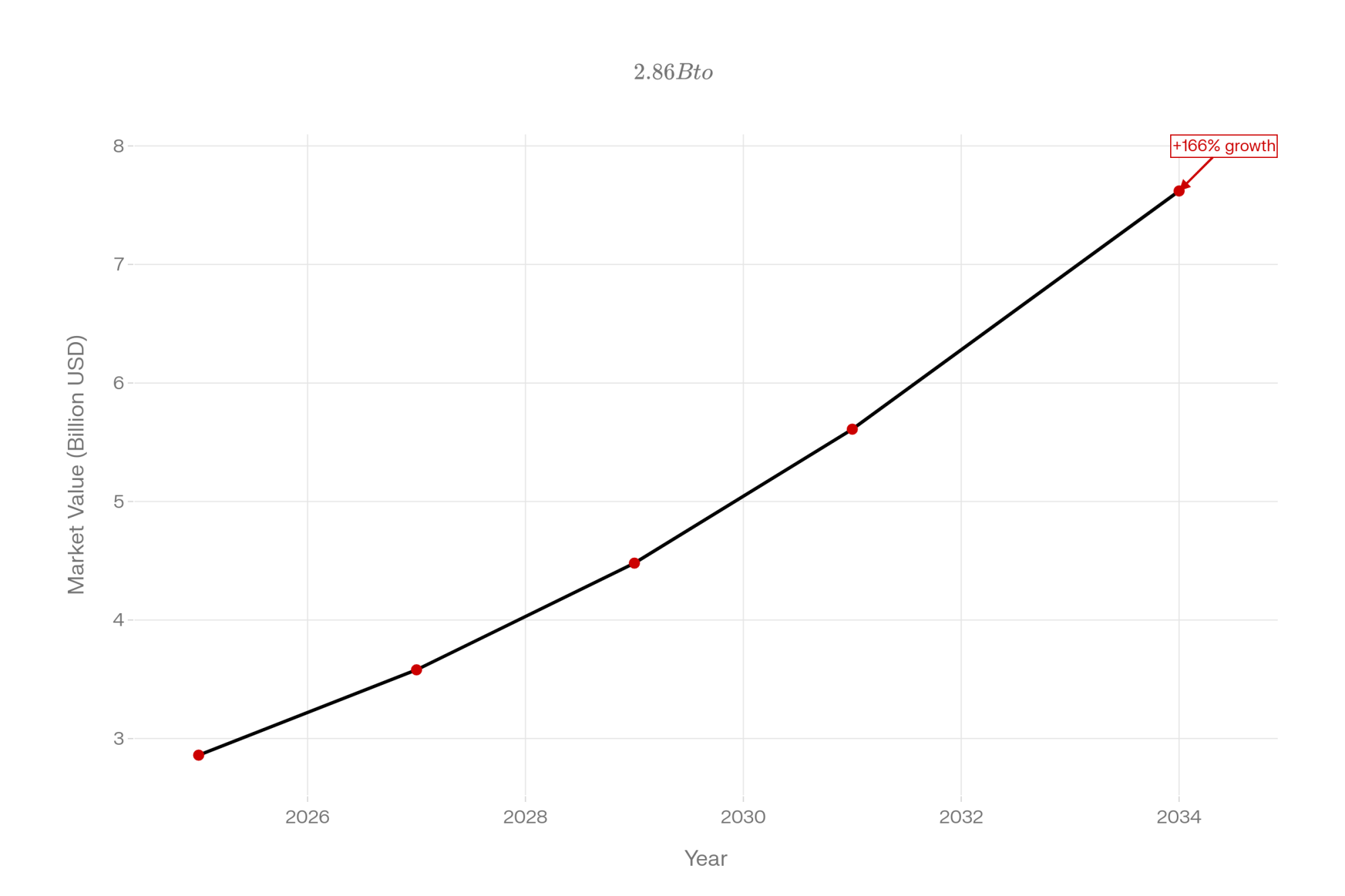

Over roughly the same period, the business around A2 milk has gone from a niche curiosity to serious money. Precedence Research pegs the global A2 milk market at about 2.86 billion U.S. dollars in 2025 and projects it out to around 7.62 billion by 2034 if current demand growth holds, which works out to roughly an 11‑plus percent annual growth rate over that stretch. So you’ve got a rapidly growing premium segment on one hand, and on the other, you’ve got heritage breeds like Guernsey that, based on both breed descriptions and on‑farm A2 testing results, tend to show a very high frequency of the A2 β‑casein variant when samples are sent in.

On paper, you’d think those two things would line up a lot better than they have. As many of us have seen over coffee at meetings or in the bleachers at shows, they mostly haven’t.

What’s interesting here is that once you strip this back to what’s actually in the genes, how plants are built, and where the dollars really move, the answer is pretty straightforward… and a bit uncomfortable.

Looking at the genetics, not the sales pitch

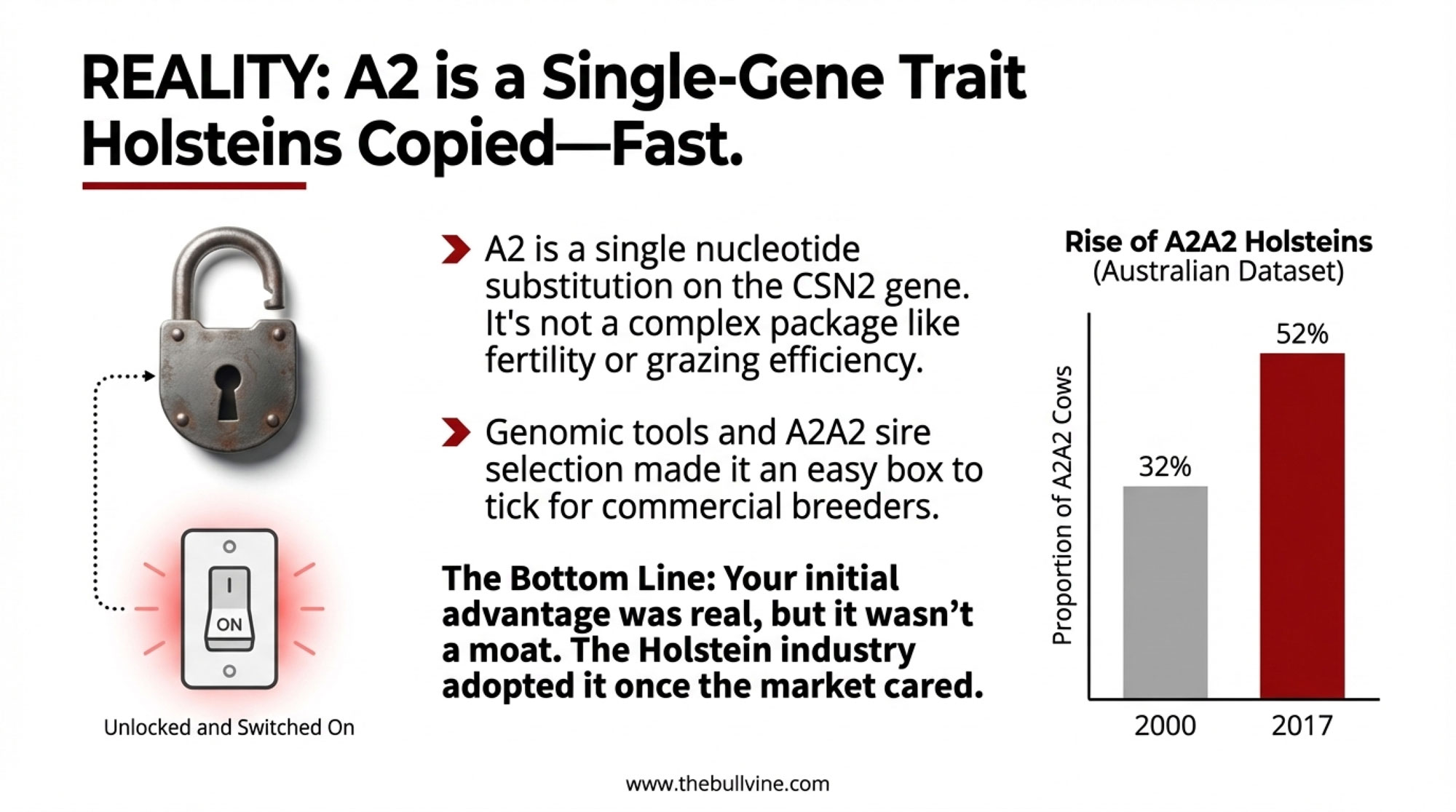

Looking at this trend from the genetics side first, A2 isn’t some magical “heritage package.” It’s one specific change in the β‑casein protein coded by the CSN2 gene—a single nucleotide substitution that flips one amino acid at position 67 from histidine (A1) to proline (A2). Reviews on A2 milk from food science and nutrition researchers keep coming back to the same point: the distinction between A1 and A2 β‑casein is that single amino acid difference, not a wholesale change in the cow or in other milk proteins.

That’s very different from things like butterfat performance, fertility, or how a cow holds up through the transition period in a grazing system, which all involve many genes and years of selection pressure. A2 is more like a light‑switch trait. If you’ve got genomic tools and access to semen catalogues that clearly label A2A2 sires, you can shift the A2 status of a Holstein herd pretty quickly.

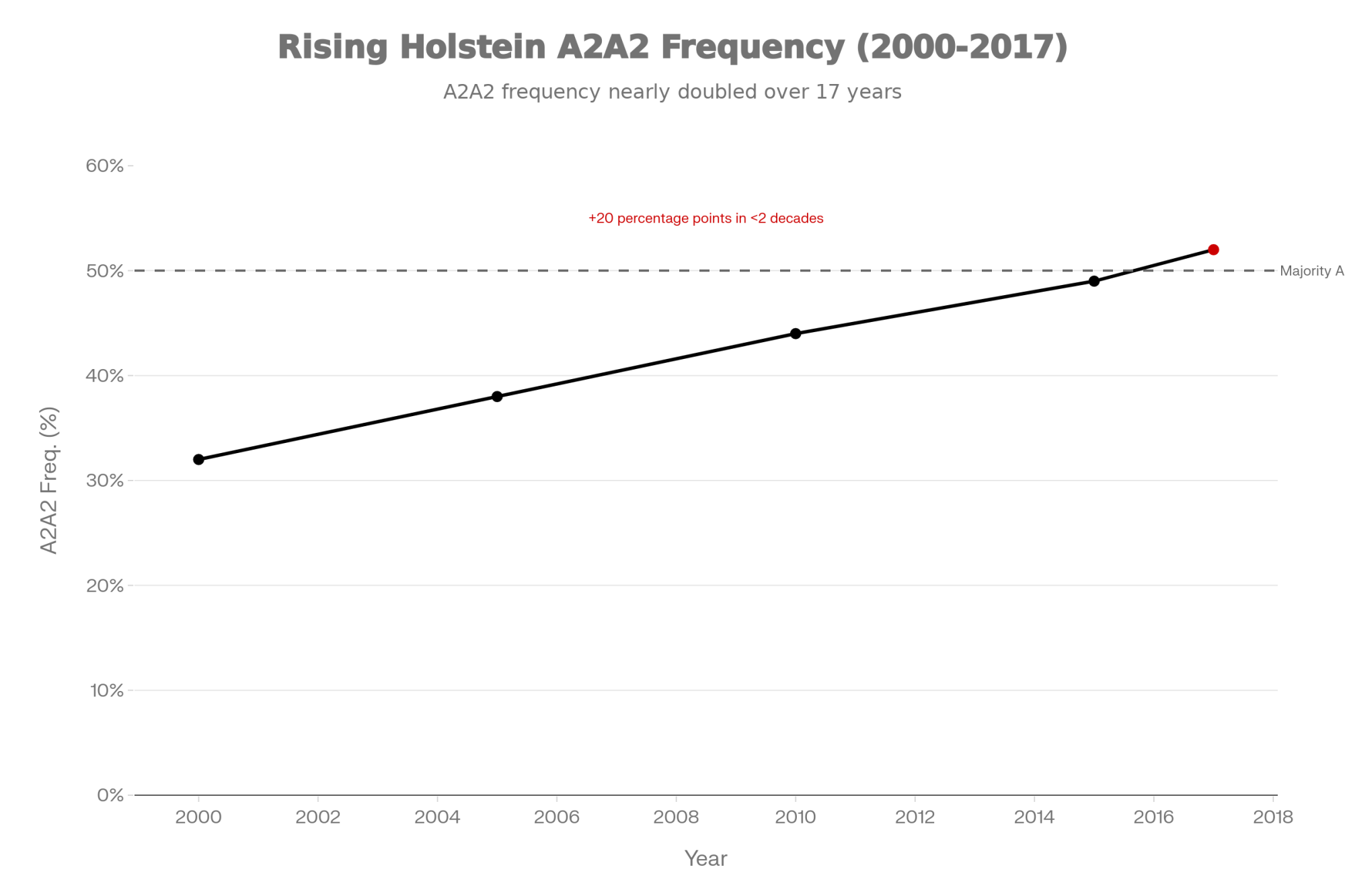

A group led by B.A. Scott in Australia pulled together Holstein genomic data and published it in 2023 in Frontiers in Animal Science. They showed that the proportion of A2A2 Holstein cows in their dataset rose from about 32 percent in 2000 to roughly 52 percent in 2017 as selection for the A2 allele increased in the population. That’s a big shift in less than two decades, driven mainly by AI studs and breeders nudging A2 sires up their lists once the trait started to matter commercially.

Once brands like The a2 Milk Company started talking about A2 in grocery aisles, studs did what they always do: they flagged A2A2 sires clearly in proofs and catalogs and, where feasible, folded A2 into their mating tools and marketing. If a bull was already strong on production, health traits, and type, A2 became one more box that was easy to tick when planning matings.

You can see how fast this can move when you look at operations like Sheldon Creek Dairy in Ontario. Their own story describes how they used Holstein genetics and careful sire selection to transition their herd to produce only A2 β‑casein, then built a bottled milk brand around that. They didn’t need to change breeds to do it.

So if you’ve been told that Guernseys or other heritage breeds had a “baked‑in A2 advantage” that nobody else could catch, the genetics really don’t support that. The initial advantage was real—many Guernsey herds do test very high for A2—but it was easy for Holstein programs to copy once there was a commercial reason to do so.

The plant math that quietly decided everything

Now, genetics is only half the story. The other half is the part that doesn’t show up in glossy brochures: how milk actually moves through a plant, and what it costs to treat a stream as “special.”

Let’s walk through two real‑world scenarios the way you’d probably talk them through around a table with a pencil and a notepad. The numbers themselves will feel familiar if you’ve ever sat down with an extension engineer or a processing consultant.

In Scenario A, imagine a 5,000‑cow Holstein herd. If you decide to test all those cows for A2 using a typical genomic panel that includes β‑casein, you’re probably looking at something in the $45–50 per head range based on current commercial lab pricing in North America. Call it roughly $225,000 to test the whole string.

If around 45 percent of those cows test A2A2—which lines up with where a lot of Holstein herds land once A2 has been on the radar for a while—that’s about 2,250 cows. If those cows are averaging roughly 70 pounds of milk per day, that subset alone is producing around 157,000 pounds of A2 milk per day. Even if a processor only pulls part of that into a dedicated stream, you’re still comfortably over the 50,000‑pound volume that makes a separate A2 run realistic.

Most large plants can justify a separate A2 run at that kind of volume, including a full clean‑in‑place cycle between the A2 product and regular milk. Processors running A2 programs in markets like the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand report premiums of $1.50 to $2.50 per hundredweight over conventional pay prices, depending on contract structure and the products they’re making. Stack that over a month, and you’re talking tens of thousands of dollars in extra revenue, without changing barns, freestall layout, dry lot systems, or core fresh cow management—just sorting cows, managing groups, and scheduling dedicated loads.

Daily production from that herd might be in the 7,500 to 9,000 pound range if cows are giving 50–60 pounds apiece, depending on components, fresh‑cow management, and days in milk. And that’s where the problem starts. In many Guernsey herds that have actually done the testing, a very high proportion of cows do come back A2A2, which matches what breed descriptions and breeders report, even though there isn’t a single global genomic survey that pins down one exact percentage.

Daily production from that herd might be in the 3,000 to 4,000 pound range, depending on butterfat performance, fresh cow management, and days in milk. And that’s where the problem starts. The same plants that are happy to schedule a special A2 run at 50,000 pounds in Scenario A can’t justify a completely separate run for 7–9,000 pounds a day from one small herd. By the time you factor in hauling logistics, testing, and the time and chemicals for a full CIP, that small stream just doesn’t carry its weight in a conventional plant.

Unless you and several neighbours can pool your milk into a unified, A2‑only stream that gets into the tens of thousands of pounds per week, your A2 milk is simply going to disappear into the regular tank. The premium doesn’t vanish because anyone dislikes Guernseys; it vanishes because the plant can’t afford to treat that small volume as a separate product under its current design.

In the Upper Midwest, for example, plant managers will tell you candidly that every new product run means lining up dedicated loads, testing them, possibly tweaking process settings, and then doing a full CIP before switching back. For many plants, a rough threshold where that becomes feasible is somewhere around 50,000 pounds per run, not as a hard rule but as the point where per‑unit costs start to look sensible.

So a lot of heritage herds find themselves at a three‑way fork:

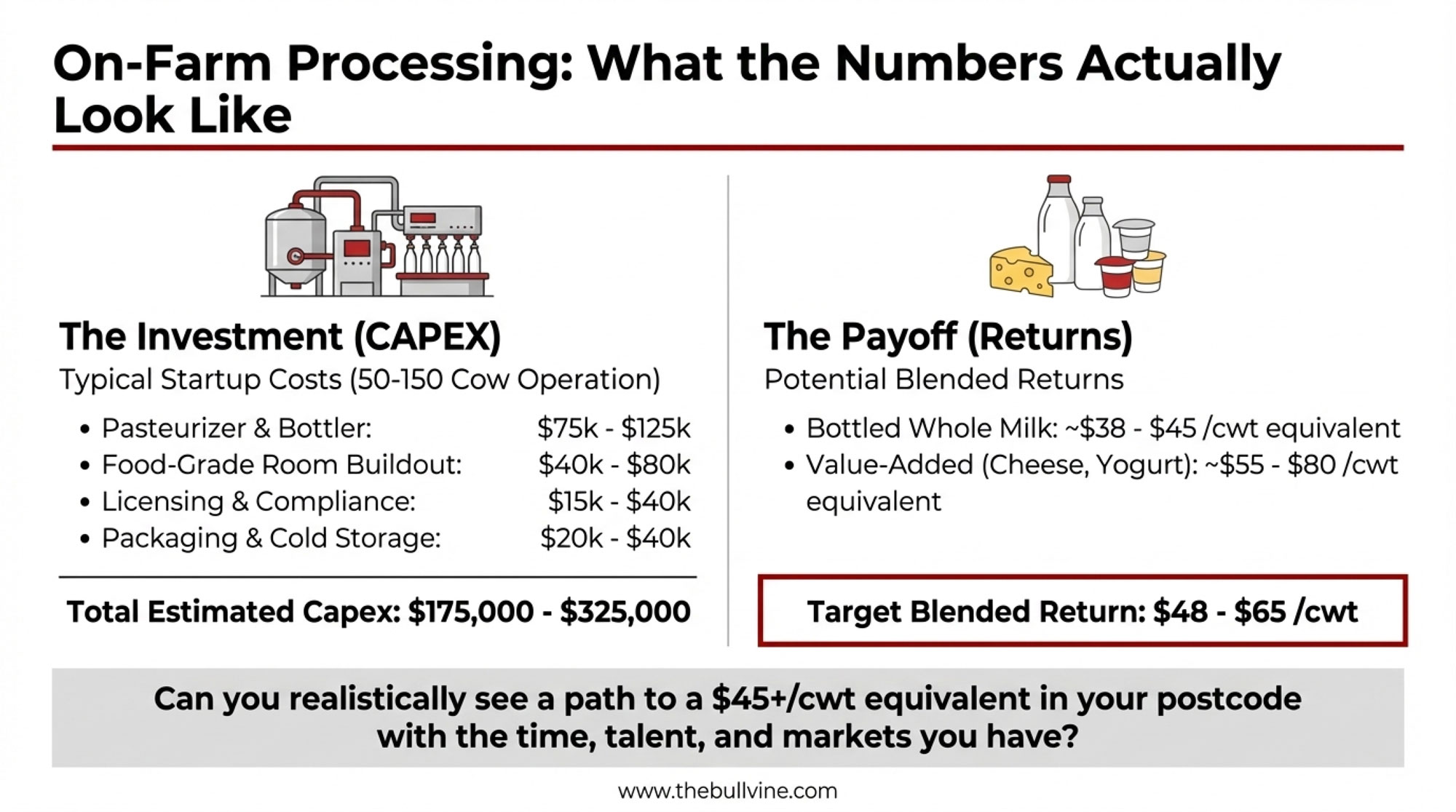

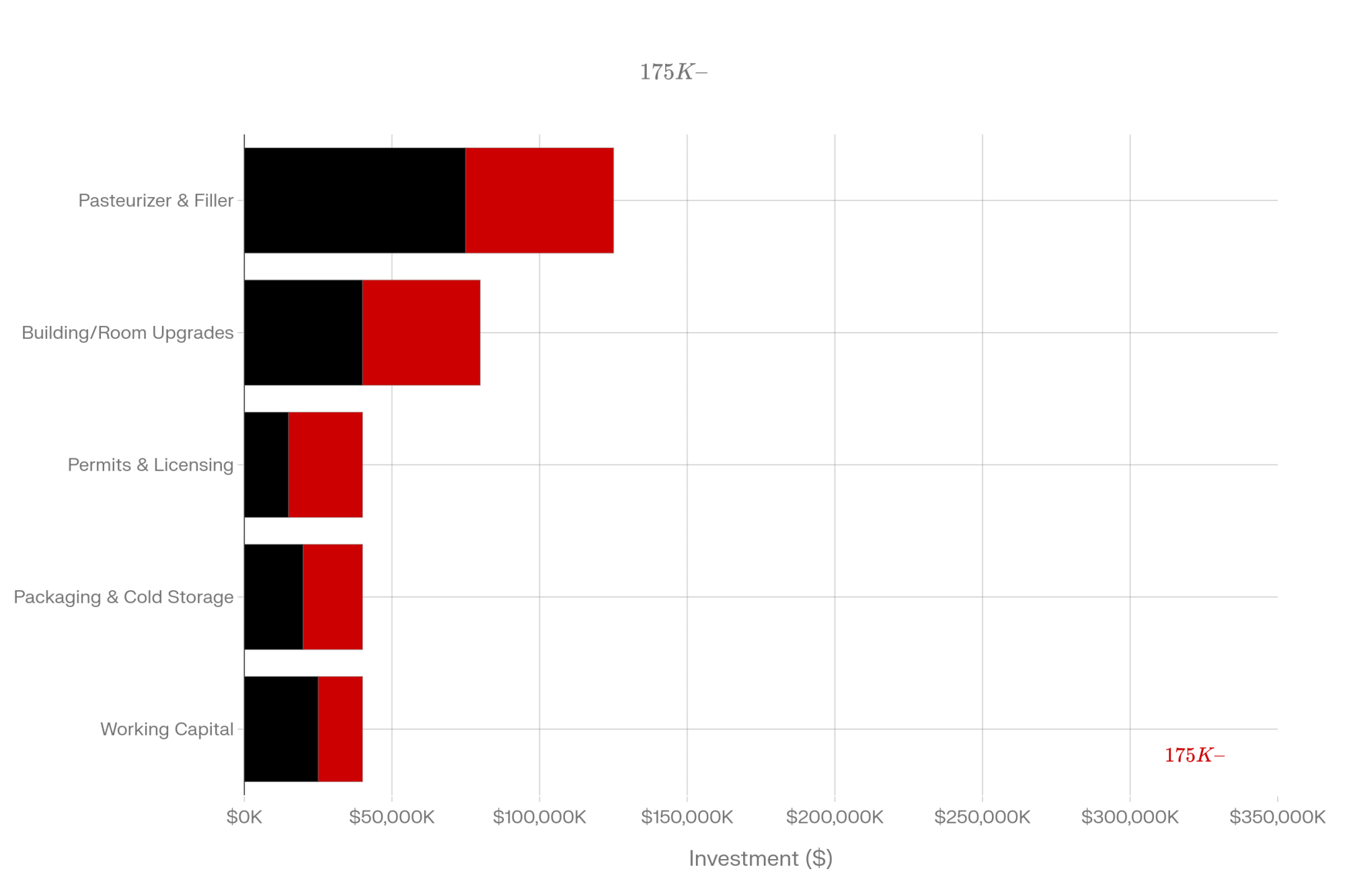

- One path is to invest in some level of on‑farm processing. When you talk to extension specialists and farmstead processors, a modest 50–150 cow setup—pasteurizer, bottling line, food‑grade processing room, cold storage, licensing, and working capital—often lands in the $175,000 to $325,000 range once everything’s on paper.

- Another path is to organize a serious pooled stream with like‑minded neighbours so you can show up at the plant door with enough volume and consistency to justify a separate A2 or heritage run.

- The third path, which many people end up on by default, is to accept that as long as you’re shipping into a conventional pool, A2 alone won’t change your milk cheque much, if at all.

A Vermont producer who priced all this out with advisors summed it up bluntly in a regional article: the A2 premium at the plant is real, he said, but they couldn’t see how to capture it “without becoming a completely different kind of business.” That’s a pretty honest read on the gap between the A2 sales pitch and plant‑level infrastructure.

What on‑farm processing really looks like when you sharpen the pencil

If you’re seriously kicking the tires on processing your own milk—even just part of it—those big ballpark numbers start to look a lot more real once you break them down into line items.

Extension publications and small dairy plant consultants tend to put the major capital costs into a few familiar buckets. A decent-sized batch or HTST pasteurizer, plus a filler and basic controls, might run in the $75,000–$125,000 range, depending on whether you’re buying new or reconditioned equipment. Building out or upgrading a room to meet food‑grade standards—floors, walls, floor drains, CIP‑friendly design, HVAC, and electrical—can easily add another $40,000–$80,000.

Then there’s the regulatory and compliance side. Between design review, permits, inspections, and initial lab work, many farms end up in the $15,000–$40,000 range just to get through licensing. Add in $20,000–$40,000 for packaging and cold storage—bottles, caps, labels, cases, coolers, or a small walk‑in—and whatever you’re comfortable holding as working capital for a few months of payroll and utilities, which might be another $25,000–$40,000.

Put all of that together, and that’s how so many farmstead dairies land in that $175,000–$325,000 startup range for a 50–150 cow operation. It’s a big step, especially when you’re still milking mornings and evenings and trying to keep cows moving cleanly through the transition period.

So what does that investment actually buy you on a per‑hundredweight basis?

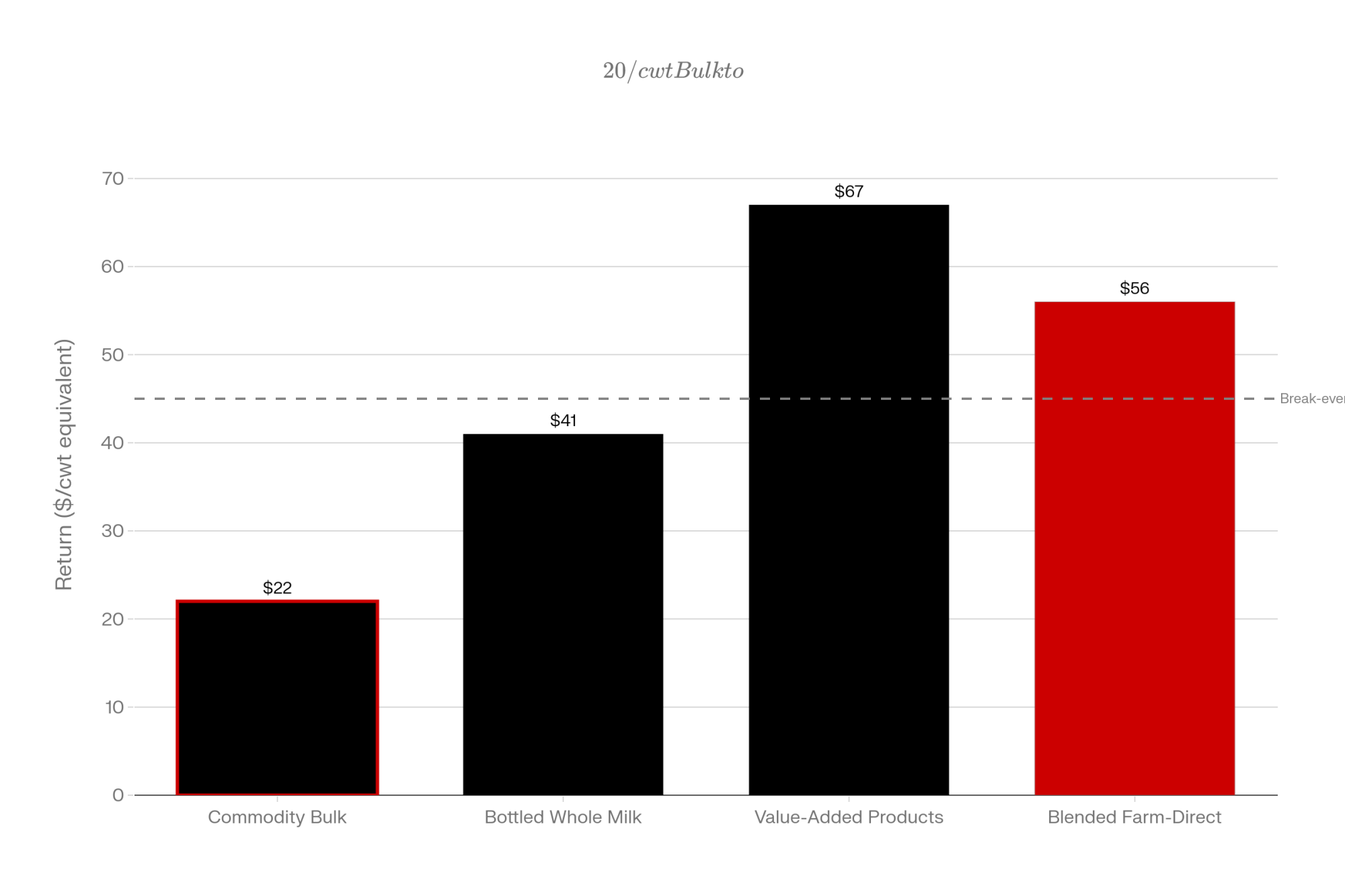

When you talk to direct‑market farms that are selling whole milk under their own label and turning some of the tank into cheese, yogurt, or ice cream, you hear similar patterns in their back‑of‑the‑envelope math. Once they reverse‑engineer their retail sales back to the farm gate, many find that bottled whole milk is effectively returning somewhere in the high‑30s to mid‑40s per hundredweight equivalent. Value‑added products like cheese or yogurt often come out in the mid‑50s to maybe around $80/cwt equivalent in some markets, especially near cities with strong local‑food demand.

Nobody is suggesting that every farm will hit those exact numbers; it depends heavily on your location, customer base, product mix, and ability to manage both the plant and the cows. But when you blend it all together—a portion of the milk as bottled whole, some as chocolate, some as yogurt or cheese—a lot of these operations report blended returns in the roughly $48–$65/cwt equivalent range.

Compare that to a commodity price in the low‑20s per hundredweight in many recent U.S. mailbox averages, and you start to see why some heritage herds are making that jump, even if it means learning to run a pasteurizer in the afternoon instead of heading straight from the parlor to the shop.

The real question for your yard isn’t “Is on‑farm processing a good idea?” It’s “Can I realistically see a path to that blended $45+/cwt equivalent in my own postcode with the time, talent, and markets I have—or can build?”

Who’s actually making heritage genetics pay?

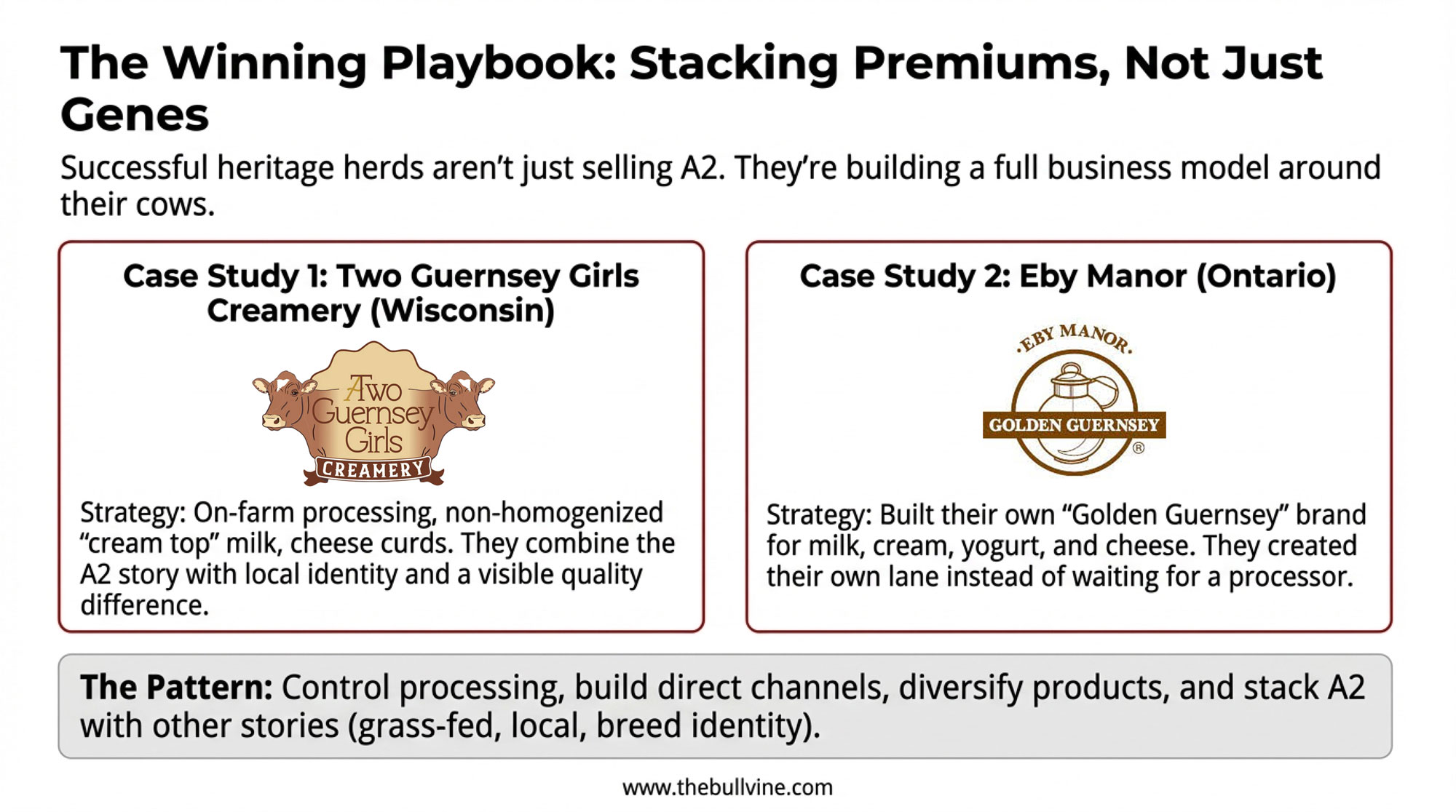

What farmers are finding is that the heritage herds that are growing or at least holding steady aren’t hanging their hats on A2 alone. They’re building full business models around their cows.

Two Guernsey Girls Creamery in Wisconsin is a good example. Owner Tammy Fritsch runs a state‑licensed micro‑dairy near Freedom, milking a small Guernsey herd and processing the milk right there on the farm. The idea didn’t start with spreadsheets; it started with years of showing Guernseys at the Wisconsin State Fair and hearing visitors ask where they could still buy Golden Guernsey milk like they remembered.

Today, that operation tests cows to confirm A2 status, pasteurizes milk on‑farm, and bottles non‑homogenized milk so the cream rises in the bottle—something customers notice right away. They also make Guernsey cheese curds and other products, selling through farm pickup, local stores, and outlets that want something distinct and local. A2 is part of the story, but it sits alongside breed identity, the visible cream line, and a direct relationship between the family and their customers.

In Ontario, Eby Manor near Waterloo has done something similar with its Golden Guernsey label. Their own materials describe their Guernsey milk as naturally rich and A2, and they bottle that into milk, chocolate milk, cream, yogurt, and cheeses under their family brand. They’re working inside a quota system, but the basic approach is similar: don’t wait for a processor to create a Guernsey A2 silo—build your own lane and brand.

When you lay these examples side by side, the pattern is fairly consistent. The heritage herds that are really making it work often share a few traits:

- They’ve taken control of at least some processing and packaging under their own roof.

- They’ve built direct‑to‑consumer channels—farm stores, markets, local grocers, cafés, and delivery.

- They’ve diversified beyond fluid milk into at least one or two value‑added products, often including cheese or yogurt.

- They’re stacking A2 with other premiums like grass‑based feeding, local identity, sometimes organic certification, and the heritage angle itself.

- They’ve built a community of customers who know the farm and the cows by sight.

For heritage herds that are still shipping everything into a single tanker and hoping a processor will someday decide to pay more just because the milk is A2, that’s the real gap.

The consumer confusion that muddies the water

There’s another piece here that’s easy to underestimate when you’re living in the barn: what’s going on in the consumer’s mind.

You probably know this already, but a lot of people use “lactose intolerance” as a catch‑all label for any discomfort they feel after drinking milk, even though true lactose intolerance is about low lactase enzyme levels and not about casein proteins. Reviews that look over the A2 literature point out that many consumers don’t clearly distinguish between issues with lactose and possible differences in how they respond to A1 versus A2 β‑casein.

So someone who’s genuinely lactose intolerant sees A2 milk on the shelf, hears that it’s “easier to digest,” and decides to give it a try. Since A2 milk still contains essentially the same lactose content as regular milk, that person may not feel any better. They walk away thinking, “That was just expensive milk that didn’t help me.”

At the same time, some people do report feeling better on A2 milk in controlled digestion studies, especially in terms of bloating or GI discomfort, but those are often individuals whose issues weren’t driven purely by lactose in the first place. That nuance is tough to convey in three lines on a label or in a 15‑second ad.

For small heritage herds trying to build a local A2 niche, that confusion creates headwinds. The big A2 brands have done a lot to get the term “A2” into consumer vocabulary, which helps. But they haven’t always helped shoppers understand why a local Guernsey A2 milk, sold in glass with a visible cream line and a pasture story, is another step different again.

So what stands out in conversations with farmers here is that A2 can be a door‑opener. It might be the reason someone tries your milk for the first time. But the reasons they keep coming back—flavour, mouthfeel, how they feel after they drink it, the kids’ reactions, what they see when they visit the farm—go way beyond that one gene marker.

What processors are really up against

As many of us have seen, it’s tempting to chalk all this up to processors “not getting it.” But when you actually sit in a plant office and ask how they’d make a heritage A2 run work, the answer often comes down to mechanics: plant design, labour, and scheduling.

In many Midwest plants, managers will tell you that every new product run means lining up dedicated loads, verifying composition, possibly adjusting process settings, and then performing a full CIP before switching back. That’s a lot of labour and downtime for a small stream. For many plants, the rough threshold at which this becomes feasible is around 50,000 pounds per run; below that, the extra cost per unit can erode the premium quickly.

There have been attempts in states like Wisconsin and Vermont to set up specialty pools—grass‑based pools, local pools, sometimes A2 pools. Some of those have made progress; others have run into predictable problems: not enough consistent volume, too much compositional variation, too much scheduling complexity relative to plant capacity. In California’s Central Valley, where a lot of milk moves through very large, highly optimized plants tied to big Holstein herds in freestalls or dry lot systems, there’s even less room to carve out tiny lanes for heritage milk.

So if your business plan is built on a conventional plant paying a stable, meaningful premium just because your milk is both A2 and heritage, at a relatively small volume, you’re basically betting against the way most plants are currently engineered. That doesn’t make processors villains; it just means the system wasn’t built to do what we now wish it could do.

The pasture angle we don’t want to lose sight of

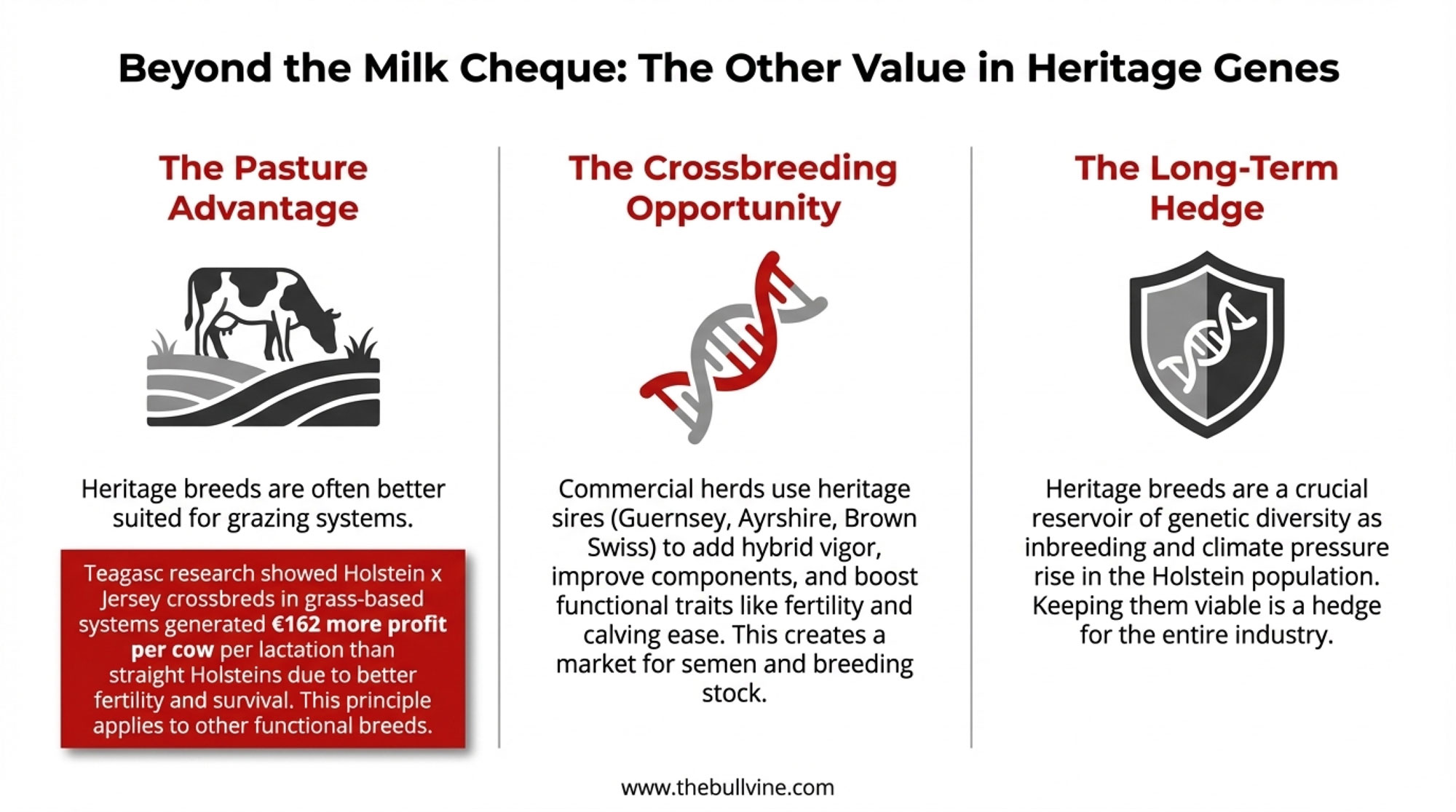

It’s also worth stepping back from the plant for a minute and looking at where these cows actually earn their keep: on the ground.

Teagasc, the Irish agriculture research and advisory organization, has done a lot of work comparing straight Holstein‑Friesian cows with Holstein‑Friesian × Jersey crossbreds in grass‑based, seasonal systems. In several of those multi‑year pasture studies, the crossbreds have come out ahead on profit per cow and per hectare, mainly because of better fertility, survival, and components, even when straight Friesians had an edge on pure volume. An analysis highlighted by Agriland reported that crossbred cows at Teagasc’s Clonakilty research farm were generating around €162 more profit per cow per lactation than straight Holsteins in that grass‑based system.

Those aren’t Guernseys, but they do back up what many graziers in the Northeast and Upper Midwest have already noticed on their own farms: the cow that’s a star on a high‑input TMR in a big freestall isn’t always the cow that makes you the most money when you’re walking to the back paddock in April, dealing with wet springs, and trying to get an efficient bite off grass.

Heritage breeds like Guernsey, Ayrshire, and Brown Swiss, evolved in environments closer to those of grazing systems. The Livestock Conservancy, breed associations, and extension sources describe Guernseys as good grazers that can do well on quality pasture, hardy across a range of climates, and relatively easy to manage. Ayrshires have long been known for strong feet and legs and good performance on rougher ground. Brown Swiss carry a reputation for longevity and for producing milk with protein and casein profiles that work well for cheesemaking, especially in alpine‑style cheeses.

So if you’re in a pasture‑heavy system—think New York’s hill farms, Vermont and Quebec grazing herds, Wisconsin seasonal dairies, or coastal British Columbia—chasing A2 might be less important than asking, “Which genetics give me the best lifetime production and profit per acre on this land base?” A2 can still be part of that picture, but fertility, days in milk, hoof health, and how well a cow converts your grass into fat and protein are often the real levers.

Crossbreeding: where heritage genes quietly move into big herds

There’s also a quieter trend that doesn’t show up in breed registration numbers: heritage genetics getting into commercial herds through deliberate crossbreeding.

Many larger Holstein herds frustrated by fertility, lameness, and short productive lifespans have already considered crossbreeding with Jerseys, Montbéliardes, or Scandinavian Reds, and the literature on crossbred systems consistently shows heterosis benefits for functional traits such as fertility and survival. Adding Guernsey, Ayrshire, or Brown Swiss sires into that mix—especially sires that are A2A2—is another way to bring in hybrid vigor and some of those pasture or functional traits without flipping the whole herd overnight.

Guernsey breeders like Tom Ripley, who has worked extensively with the American Guernsey Association, have shared field reports from producers who use Guernsey sires on Holstein cows and report improvements in calving ease, component levels, and, sometimes, fertility in the resulting crossbreds. These aren’t controlled university trials, and they’re not going to show up in Journal of Dairy Science the same way Teagasc’s work does, but they do line up with the broader crossbreeding literature from New Zealand and Ireland that shows heterosis boosting “functional” traits in many three‑breed systems.

What’s encouraging about that is it opens up revenue beyond the milk cheque for heritage breeders who are paying attention. If you’ve got a Guernsey, Ayrshire, or Brown Swiss family with real performance behind it—good components, sound udders, durable feet and legs—you may have an opportunity to sell semen or breeding stock into commercial herds that want those traits, even if your own milk still goes into a conventional pool.

The bigger genetic picture and why it matters

One more piece that matters more in the long run than in any given month’s milk statement is genetic diversity.

Geneticists working on dairy cattle have been pointing out for years that the effective population size of Holsteins—the number of unrelated founders you’d need to reproduce the existing genetic variation—is relatively small compared with the actual number of Holsteins in barns. That’s what happens when you run intense selection on a fairly narrow group of elite sires for multiple generations. It’s been great for yield and components, but it has nudged inbreeding steadily upward.

Scott’s 2023 analysis of selecting for A2 in the Australian Holstein population went a step further and showed that selecting for the A2 allele alone, without careful management of relationships, could increase both regional and genome‑wide inbreeding, because it narrows the sire pool even more. That’s not a reason to avoid A2 completely, but it’s a reminder that stacking too many selection criteria on top of each other in a single breed can have side effects you don’t fully feel until years down the road.

Heritage breeds like Guernsey, Ayrshire, and Brown Swiss carry trait combinations that aren’t easy to rebuild if we lose them—heat tolerance paired with decent components, strong grazing instincts with solid structure, and cheese‑friendly casein variants, just to name a few. The fact that Guernseys sit in that Watch category, with thresholds of fewer than 2,500 annual U.S. registrations and fewer than 10,000 registered animals globally, is a quiet alarm bell that those options are not endless.

| Breed | Annual U.S. Registrations | Est. Global Population | Conservation Status |

| Holstein | >200,000 | >10 million | Not at risk |

| Jersey | ~40,000 | ~1 million | Not at risk |

| Guernsey | <2,500 | <10,000 | Watch |

| Ayrshire | <1,000 | <5,000 | Threatened |

| Brown Swiss | ~5,000 | ~50,000 | Watch |

| Milking Shorthorn | <500 | <3,000 | Critical |

Source: The Livestock Conservancy Conservation Priority List; breed association estimates

It doesn’t mean every commercial herd needs to go buy a string of Guernseys tomorrow. But it does mean that breed associations, co‑ops, and policy folks should be thinking consciously about whether they want those tools still available when our kids and grandkids are the ones making the breeding decisions.

So, where does this leave you in 2026?

Looking at this trend as a progressive producer, you start to see where the real decision points sit once the dust from the A2 hype settles.

A few things stand out:

- Consumer preferences around A2, local, grass‑based, and heritage products are real in certain markets, especially urban and higher‑income areas, but they’re patchy. Survey‑based work on A2 consumer preferences in Europe and Oceania shows that some shoppers will pay a noticeable premium for A2 milk, while others don’t see enough perceived benefit to justify switching from conventional milk, which mirrors what many of us see in farm stores and markets.

- Heat stress and climate volatility are already costing the dairy sector serious money in lost production and fertility, and those costs are expected to grow rather than shrink. Economic analyses of heat stress in U.S. dairy herds estimate total losses in the billion‑dollar range annually, once you add up milk yield, reproduction, and health impacts. Cows that handle heat and weather swings better are going to become more valuable in most regions.

- Infrastructure support for new models is becoming increasingly flexible. Vermont’s Working Lands Enterprise Initiative, Wisconsin’s Dairy Innovation Hub, and similar programs are investing public funds in on-farm processing, small regional plants, and broader dairy innovation projects. That doesn’t guarantee success, but it does mean there’s some help out there if you want to test a new model rather than go it completely alone.

- Genetic diversification remains an under‑valued hedge. Whether it’s crossbreeding, bringing in some heritage lines, or just broadening your selection goals beyond the next hundred pounds of milk, diversifying your genetics can give you more room to manoeuvre when markets, policies, or weather patterns shift.

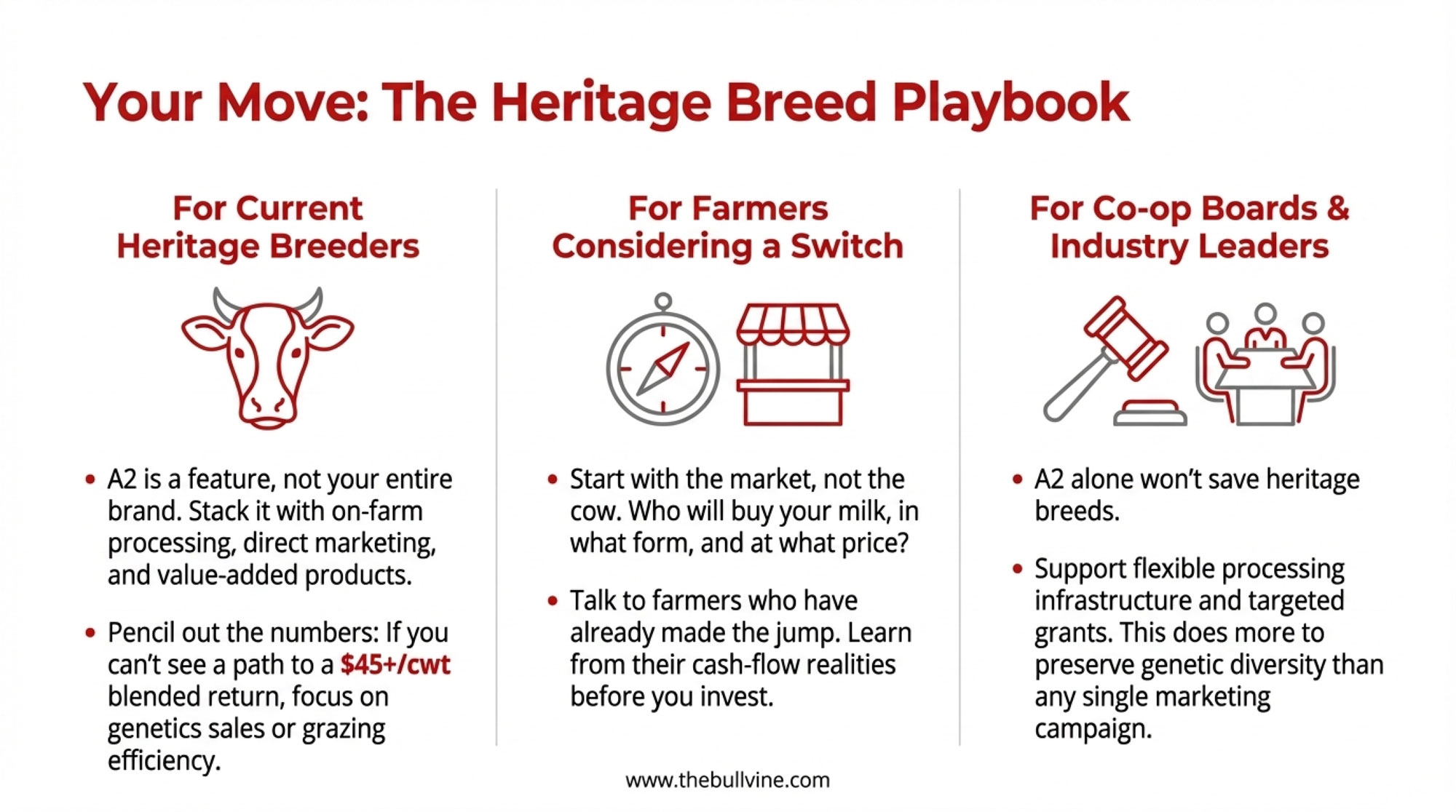

Coffee‑table takeaways, now that the mugs are half empty

If you’re already milking heritage cows, the big takeaway is that A2 is a nice card to have, but it’s not the ace by itself. The herds that are winning with heritage breeds right now are stacking A2 on top of strong butterfat performance, good grazing fit, on‑farm processing, and deep customer relationships. Before you spend a couple of hundred thousand dollars on stainless and concrete, it’s worth asking yourself whether you can realistically see a blended return in that $45+/cwt equivalent range through bottled milk and value‑added products in your area. If you can’t, you may find that your energy is better spent tightening your grazing, strengthening your direct‑to‑consumer channels, or positioning your herd as a source of genetics for crossbreeding and semen sales.

If you’re thinking about moving into heritage breeds, it’s worth starting not with the cow but with the market. Who exactly would buy this milk? In which form? At what price? Is there a realistic path to processing either on‑farm or through a small creamery that’s willing to build a heritage or A2 brand with you? Spending a day or two with people who already made that jump—walking their plant, talking about their transition period, and listening to their cash‑flow stories—is probably one of the best investments you can make before you call a Guernsey breeder. And don’t forget to think about genetic revenue: semen, embryos, and breeding stock can all sit alongside the milk cheque if you build the reputation and the data.

If you’re looking at things more from the 30,000‑foot view—maybe you’re involved in a co‑op board, a breed organization, or a policy group—then the message is that heritage breeds aren’t going to be “saved” by the A2 boom alone. But they still have important roles to play in crossbreeding programs, in pasture‑based systems, and as a reservoir of traits we may need badly in years to come. Supporting more flexible processing infrastructure, targeted grants, and thoughtful breeding work may do more to keep those options alive than any single A2 marketing campaign.

In the end, the A2 boom didn’t so much ignore heritage breeds as flow into the channels that were already built: big Holstein herds, big plants, big distribution. That’s frustrating if you’ve been sitting on a naturally A2 herd for decades. But once you see it clearly, it also frees you up.

Instead of waiting for the system to notice and reward you, you can decide whether you want to build a different kind of business around your cows, or whether you’re better off using their genetics as one tool in a broader, more diversified strategy. It’s more work either way, no doubt about it. But as many of us have seen on farms that have made these choices with clear eyes and solid numbers, that’s also where the real, lasting opportunities tend to live.

Key Takeaways:

- A2 isn’t a heritage lock‑in. It’s a single‑gene trait Holsteins copied fast once the market cared—Guernseys’ natural head start didn’t last.

- Plant math decides who gets the premium. Most processors need ~50,000 lb A2 runs to justify segregation; a 150‑cow Guernsey herd’s 3–4,000 lb/day just disappears into the bulk tank.

- On‑farm processing can pay, but know your numbers. Expect $175K–$325K capex and aim for $45+/cwt blended returns—if you can’t see that path in your market, stainless may not be your move.

- Winning heritage herds stack premiums, not just genes. A2 opens doors, but repeat customers come back for cream‑top bottles, local identity, pasture stories, and real relationships.

- Heritage genetics still matter—for crossbreeding, grazing, and the long game. Functional traits, heat tolerance, and diversity are worth more as inbreeding and climate pressure keep rising.

Executive Summary:

This feature digs into a simple question a lot of producers are asking: if A2 milk is headed toward a $7.6 billion global market, why are Guernseys still on the Watch list instead of cashing in? It shows that A2 is just a single‑gene switch Holsteins adopted quickly, while the real gatekeeper is plant design—big processors need 50,000‑lb A2 runs from 5,000‑cow herds, not 3–4,000 lb/day from 150‑cow heritage barns. You’ll see the hard numbers on on‑farm processing—typical $175,000–$325,000 capex and blended $48–$65/cwt returns—so you can tell if a bottling room pencils out for your postcode or just steals sleep and cashflow. The article profiles Two Guernsey Girls in Wisconsin and Eby Manor in Ontario to show how some herds are actually making heritage genetics pay by stacking A2 with grass‑based stories, cream‑top bottles, and value‑added products. It also walks through where heritage genes fit into crossbreeding, pasture‑based systems, and long‑term genetic diversity, especially as heat stress and inbreeding pressure keep rising. The piece ends with clear, coffee‑table style takeaways that help you decide whether your best move is chasing A2 contracts, investing in stainless, leaning into crossbreeding, or staying bulk and focusing on the cows and markets you already do best.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The 18-Month Protein Window: $11 Billion in New Plants Signals It’s Time to Rethink Your Sire Lineup – Arms you with the “coffee shop math” to calculate your own ROI on genomic testing and component-heavy sires. Breaks down exactly how to align your breeding with the $11 billion processing shift hitting our industry right now.

- What Lactalis’s 270-Farm Cut Really Means for Every Producer – Exposes why commodity milk is effectively dead and how to navigate the 18-month decision window before major processors shut you out. Delivers a hard-nosed roadmap for transitioning into the premium specialty markets that actually pay.

- The $200-Per-Cow Blindspot: What Rising Inbreeding Is Costing You – and What a Decade of Crossbreeding Research Found – Reveals the massive, hidden cost of modern inbreeding and delivers a decade’s worth of data on how strategic crossbreeding is outperforming purebreds. Gain the competitive advantage of high-health, long-lived cows that keep your checkbook healthy.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.