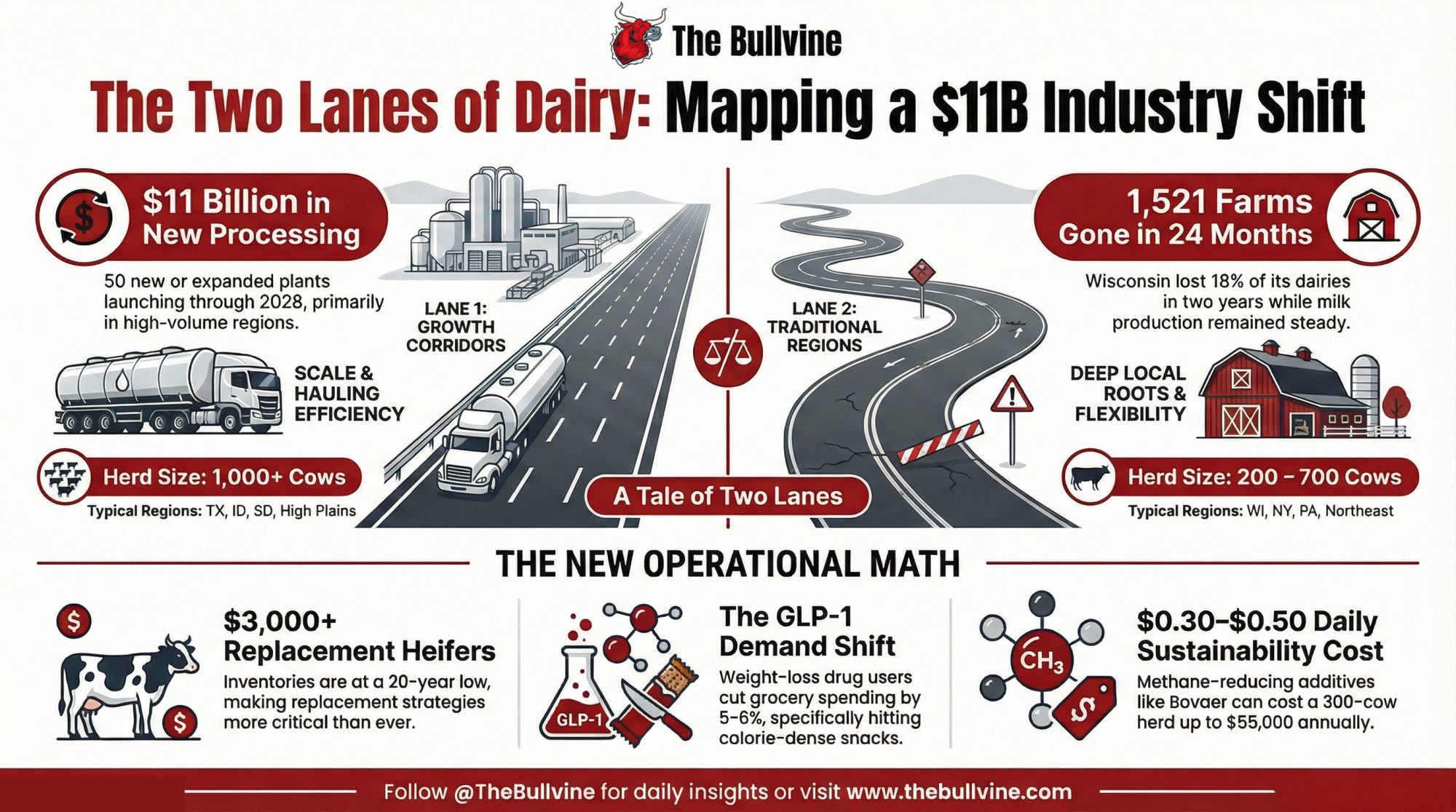

Dairy just sorted itself into two lanes. $10B in new plants is flowing to one. The other lost 1,521 farms while milk output held steady. Where does a 300-cow herd fit? Let’s map it.

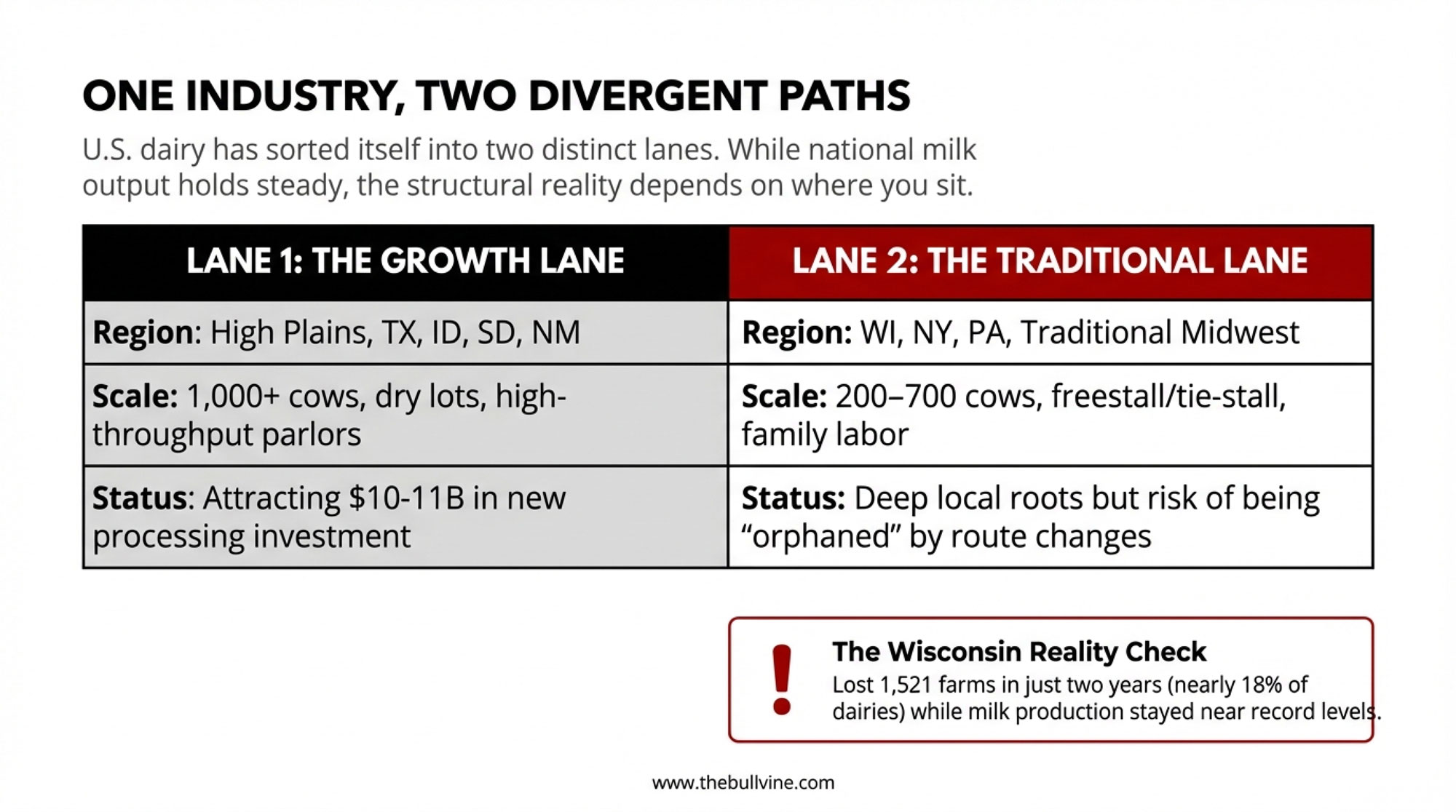

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: U.S. dairy has sorted into two lanes—and most 300-cow herds didn’t pick theirs. Lane 1 (large operations in Texas, Idaho, the High Plains) is pulling $10-11 billion in new processing investment, per CoBank and IDFA data. Lane 2 (mid-sized family dairies in Wisconsin, New York, the traditional Midwest) watched 1,521 farms disappear in two years while milk output held steady. The pressure is structural, not cyclical: heifer inventories at a 20-year low, bred replacements topping $3,000, GLP-1 drugs shifting grocery spending, and sustainability mandates like Bovaer adding $0.30-0.50/cow/day. Here’s the playbook—stress-test your margins against hard scenarios, map your processing exposure, calibrate beef-on-dairy carefully, vet sustainability contracts like any major deal, and have the family conversation about whether staying, growing, or a well-timed exit is your version of winning. The math is uncomfortable. But it’s yours to run.

If you sit around enough kitchen tables in Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania, or Minnesota, you start to hear a very different conversation than the one you get on the conference stage.

On stage, the slides say U.S. dairy is strong, national milk volumes are holding, and there’s a massive wave of new stainless going into places like South Dakota and the Texas Panhandle. And you know what? Those slides aren’t wrong.

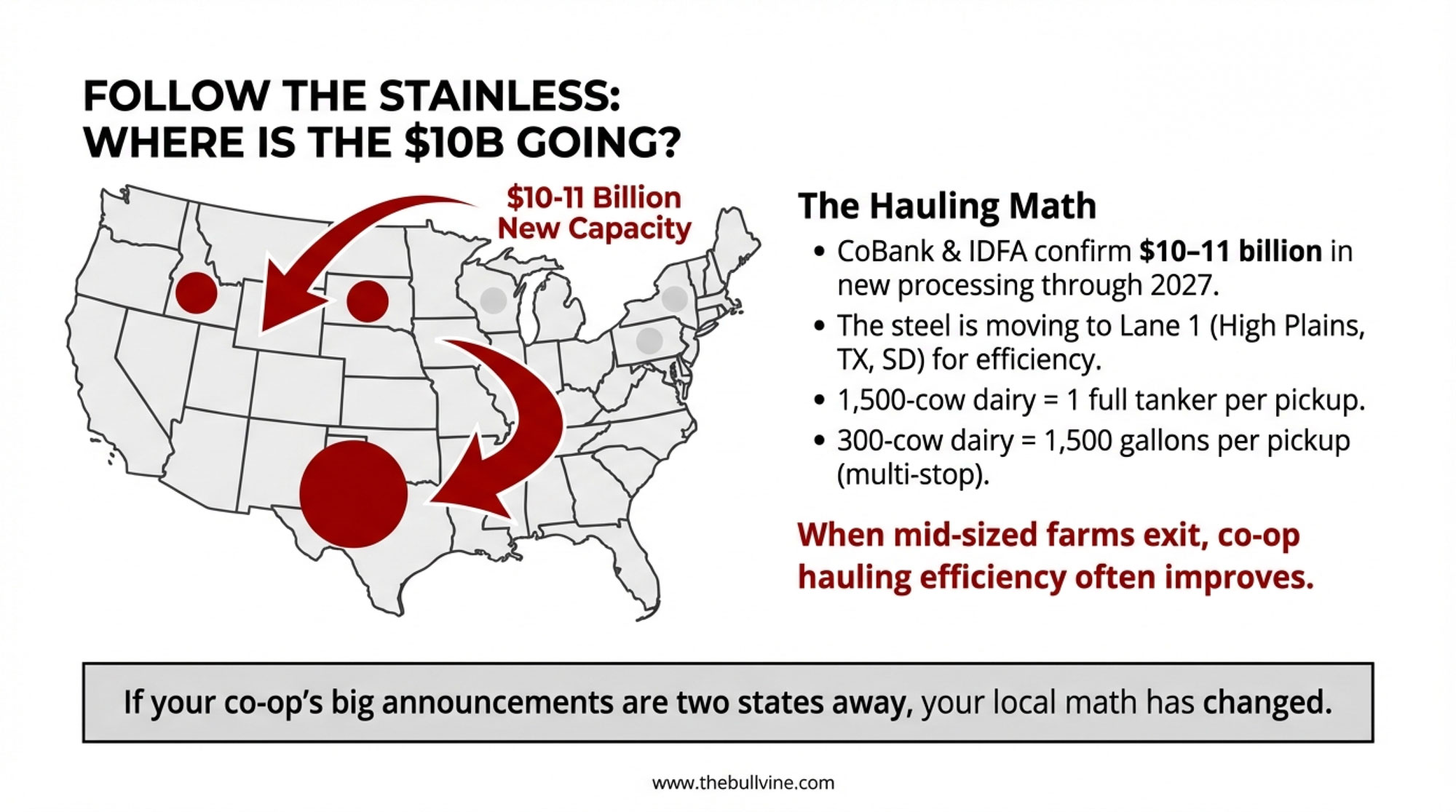

CoBank’s dairy economists peg new U.S. dairy processing investment at about $10 billion expected to come online through 2027, much of it in large cheese, powder, and beverage plants anchored in high‑volume regions. The International Dairy Foods Association announced in October 2025 that processors are investing more than $11 billion in 50 new or expanded plants across 19 states between 2025 and early 2028.

| Region | 2025 ($B) | 2026 ($B) | 2027 ($B) | Total ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texas Panhandle / High Plains | 3.5 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 10.5 |

| Idaho / Western Growth | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 3.6 |

| Wisconsin / Northeast / Traditional | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 |

But over coffee, the conversation sounds more like this:

“Given everything that’s changed—markets, plants, even what people eat now—does it really make sense for us to keep milking 250 or 400 cows? Or are we better off stepping out while we still have something solid to pass on?”

You can’t answer that honestly without stepping back and looking at how the whole system has shifted. So let’s walk through the big pieces together, then bring it right back to a farm that probably looks a lot like yours.

Five Big Forces Hitting Mid‑Sized Dairies Right Now

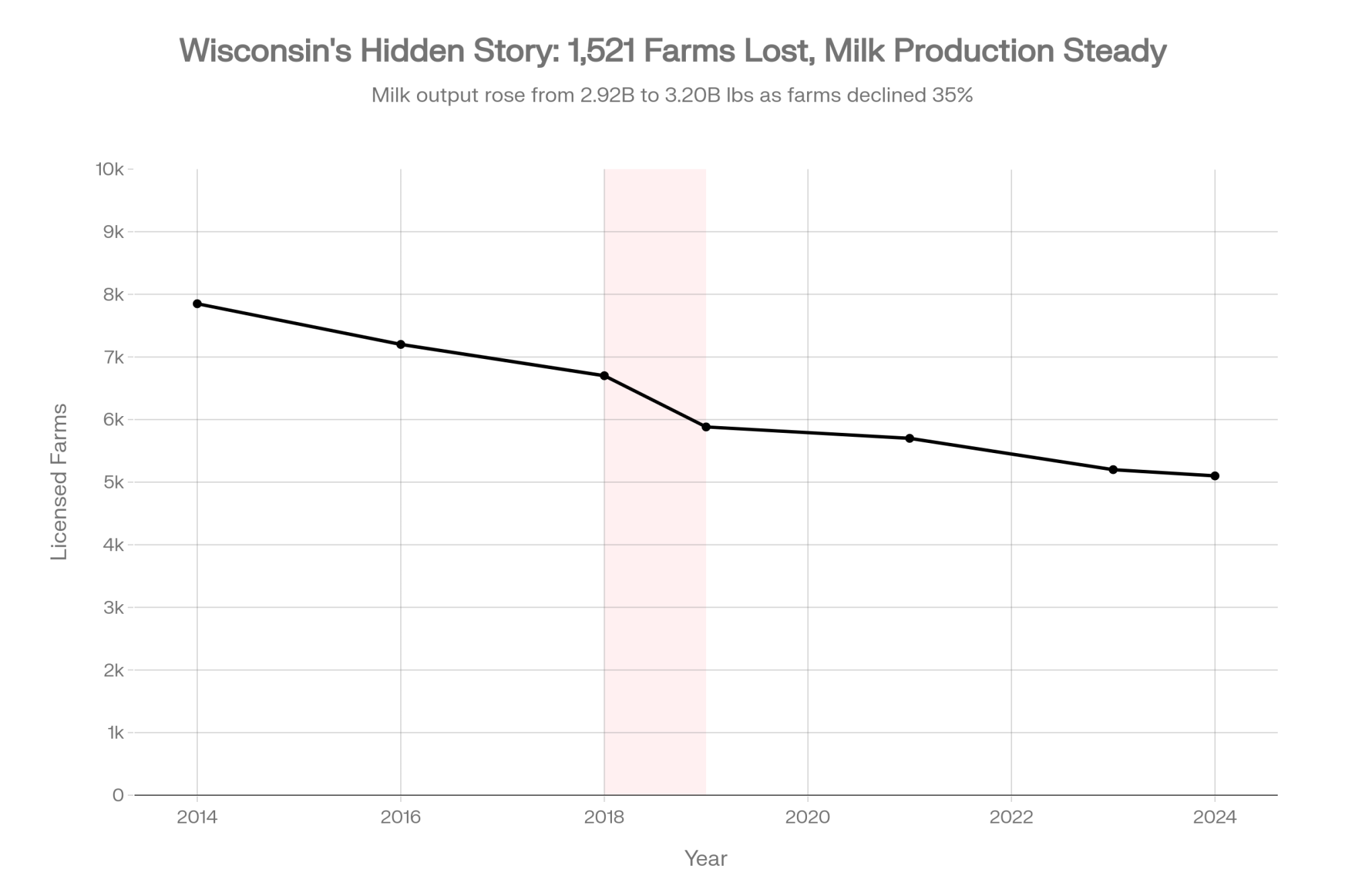

| Year | Farms | Milk Production (B lbs/yr) |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 7,850 | 2.92 |

| 2016 | 7,200 | 3.04 |

| 2018 | 6,700 | 3.11 |

| 2019 | 5,882 | 3.15 |

| 2021 | 5,700 | 3.18 |

| 2023 | 5,200 | 3.22 |

| 2024 | 5,100 | 3.20 |

Here’s the quick snapshot before we dig in:

- Processing geography is shifting. That $10–11 billion in new capacity? It’s heavily concentrated in growth regions—the High Plains, Texas Panhandle, parts of the West and Upper Midwest—where large herds and cheap land can feed big plants efficiently.

- Farm numbers are dropping fast, even when milk holds. In Wisconsin alone 818 licensed dairy farms disappeared in 2019—over 10% of the state’s dairies in a single year. Farm Progress adds that 703 farms shut down in 2018, bringing the two‑year total to 1,521 farms gone—nearly 18% of Wisconsin’s dairies—while milk production stayed near record levels.

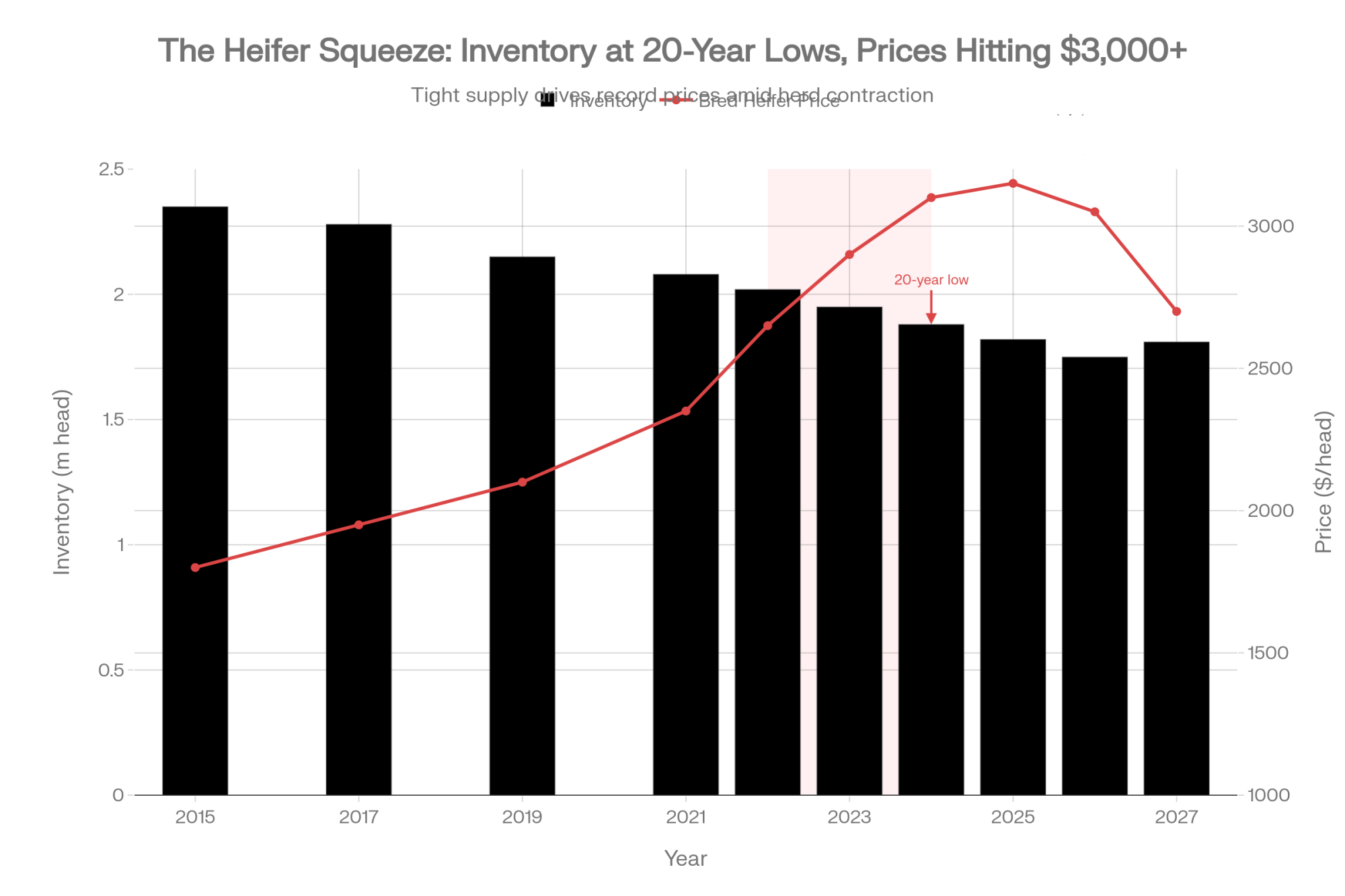

- Replacement heifers are tight and expensive. U.S. replacement heifer inventories have fallen to about a 20‑year low. CoBank’s modeling projects an additional 800,000‑head decline over the next two years before a rebound in 2027. And bred heifer prices? They’ve climbed well above $3,000 per head in many markets.

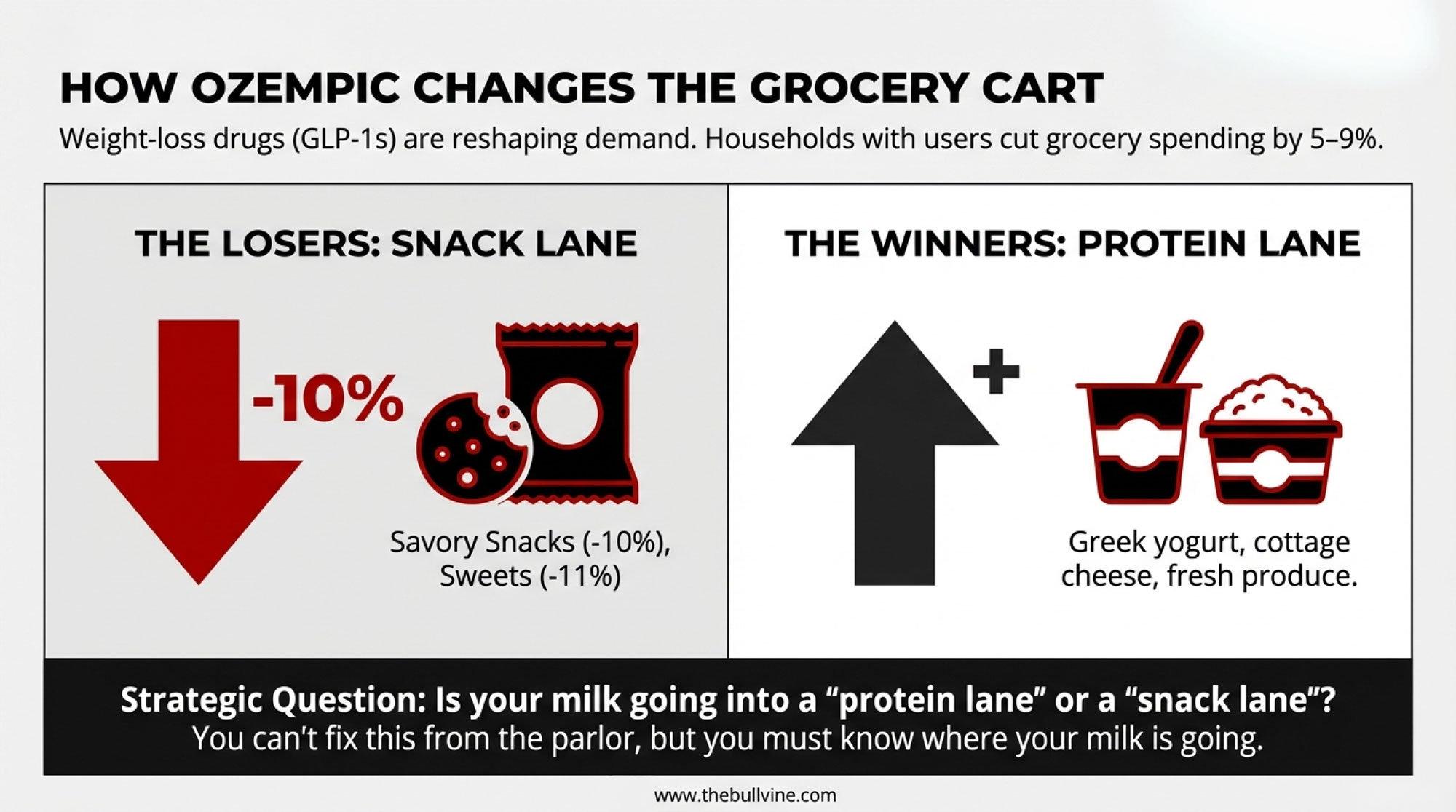

- GLP‑1 weight‑loss drugs are changing grocery carts. A Cornell University–Numerator study found that households with a GLP‑1 user cut grocery spending by about 5–6% within six months, with higher‑income households cutting nearly 9%. The biggest reductions hit calorie‑dense, processed items—spending on savory snacks, baked goods, and cookies dropped between 6.7% and 11.1%.

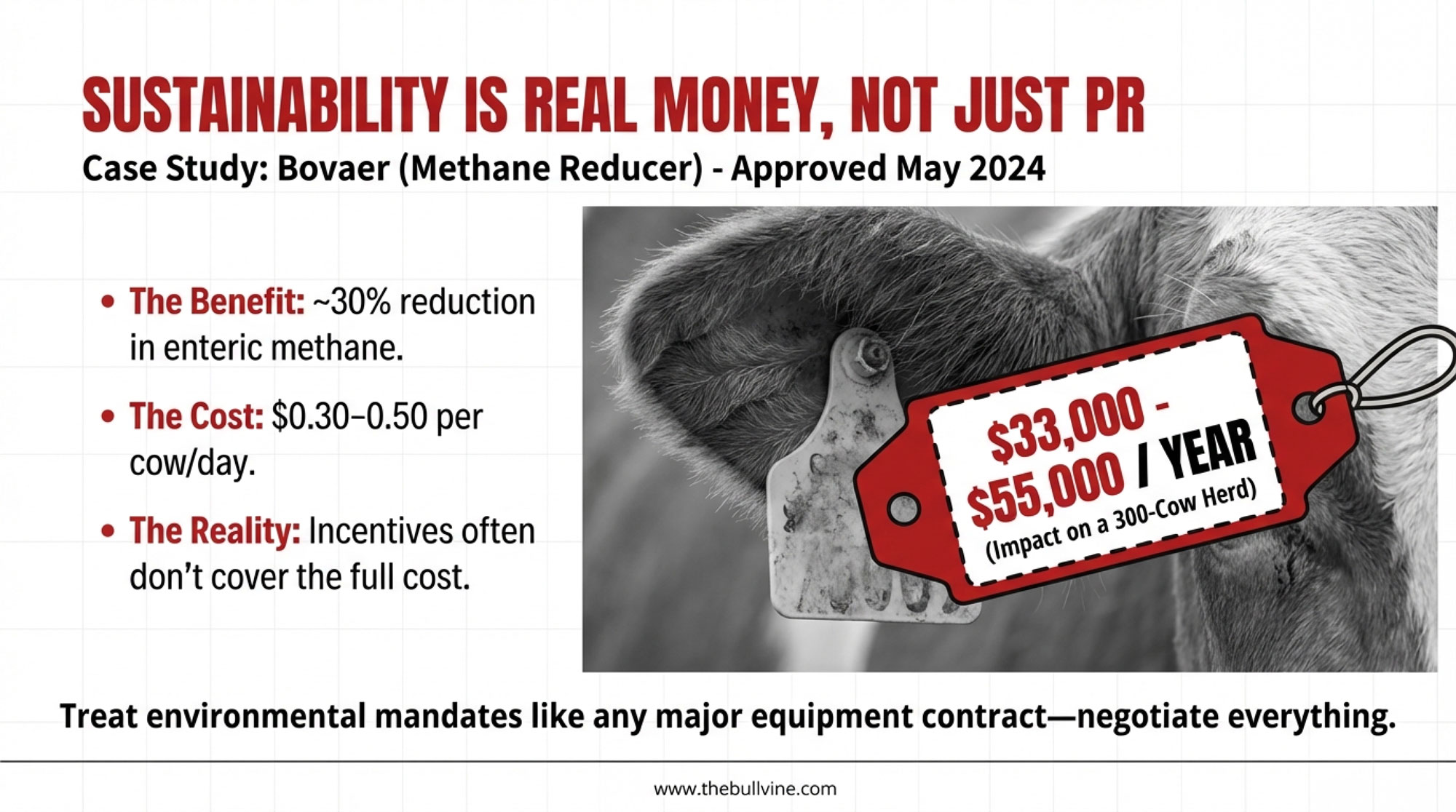

- Sustainability is real money now. The FDA approved Elanco’s methane‑reducing feed additive Bovaer for U.S. dairy cattle in May 2024. Studies show it can cut enteric methane emissions by about 30%—roughly 1.2 metric tons of CO₂‑equivalent per cow per year. But it’s not free. Independent technical reviews and industry coverage suggest early commercial costs tend to fall in the $0.30–0.50 per cow per day range, depending on region and feeding system.

Those are the big gears turning while you’re focused on butterfat levels, fresh cow management through the transition period, and whether that next heifer pen will be full.

Two Lanes, One Industry: Where Does Your Herd Really Fit?

You’ve probably noticed this yourself: U.S. dairy has quietly split into two main “lanes,” even though nobody formally labeled them that way.

| Lane | Typical Regions | Herd Size | Housing & Systems | Key Upside | Key Risk |

| Lane 1 | Texas Panhandle, eastern New Mexico, Idaho’s Magic Valley, eastern South Dakota | 1,000+ cows | Dry lot systems, high‑throughput parlors | Scale, hauling efficiency, tight and fit with the new capacity | Dependence on large‑plant contracts |

| Lane 2 | Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, broader Northeast/Upper Midwest | 200–700 cows | Freestall or tie‑stall, family plus small hired teams | Deep local roots, flexible management | Risk of being “orphaned” by route changes |

Lane 1: Big herds in growth corridors

In one lane, you’ve got the big outfits—often 1,000 cows and up—in places like the Texas Panhandle, eastern New Mexico, Idaho’s Magic Valley, and eastern South Dakota. They run dry lot systems or hybrid housing, big parlors, and high daily ship volumes.

CoBank and IDFA data show that much of that $10–11 billion in new processing capacity is landing in exactly these regions. From the processor’s point of view, that makes sense. Fewer farms, bigger loads, more predictable butterfat and protein flows for specific product specs and export programs.

Lane 2: Mid‑sized family barns in traditional regions

In the other lane are the herds many of us grew up around: 200–700 cows, freestall or tie‑stall barns, double‑8 or double‑12 parlors, family labour plus a handful of employees.

Take Wisconsin as the clearest example. Using National Ag Statistics Service data, reported that the state lost 818 licensed dairy farms in 2019—over 10% in a single year. The decline was the largest in state history.

In addition, 703 farms shut down in 2018, bringing the two‑year total to 1,521 farms—nearly 18% of Wisconsin’s dairies—while milk production stayed near record levels as larger herds added cows and pushed components.

So at the state level, the narrative is “Wisconsin dairy is holding its own.” At the township level, it’s more like, “We’ve lost a third of the trucks that used to go past this mailbox.”

If you’re milking 300 cows in Marathon County or 450 in northern New York, you’re in that second lane whether you chose it or not. And the system treats you differently than it treats a 3,000‑cow dry lot in the Panhandle.

What Co‑ops and Plants Are Really Optimizing For

You probably already sense this from watching milk routes in your area, but it’s worth laying out the math plainly.

When Associated Milk Producers Inc. announced in late 2019 that it would discontinue production at its Arlington, Iowa, nonfat dry milk plant and its Rochester, Minnesota, cheese plant, AMPI pointed straight at lower regional milk production and the long‑term loss of dairy farms as key reasons.

Their statement noted that Minnesota had lost 40% of its dairy farms since 2008, and Iowa has lost 50% during that same period.

Here’s the part that stings but tracks with every hauling study:

- A 300‑cow freestall might add 1,500–2,000 gallons per pickup.

- A 1,500‑cow dairy can fill a tanker—or more—from one driveway.

When several mid‑sized farms exit, and their volume consolidates onto larger herds, a co‑op’s per‑unit hauling cost and plant efficiency can actually improve, even as rural communities feel hollowed out.

Here’s the blunt reality: if your co‑op’s last three big announcements were about plants two states away, they’re telling you something about where they see their future milk coming from. It’s frustrating, but it’s not random.

GLP‑1 Weight‑Loss Drugs: The New Demand Wildcard

Now let’s step off the farm for a minute. GLP‑1 medications—Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, and similar—started as diabetes drugs, but their use for weight loss has exploded.

Industry tracking suggests approximately 15 million U.S. adults were using GLP‑1 medications by 2023, and clinical reviews show these drugs can cut daily calorie intake by around 20%.

Cornell University and Numerator linked shoppers’ survey‑reported GLP‑1 use to their actual grocery purchases. The study found that households with a GLP‑1 user cut grocery spending by about 5–6% within 6 months of starting the medication, roughly $ 400 per year on average, and by 9% for higher‑income households.

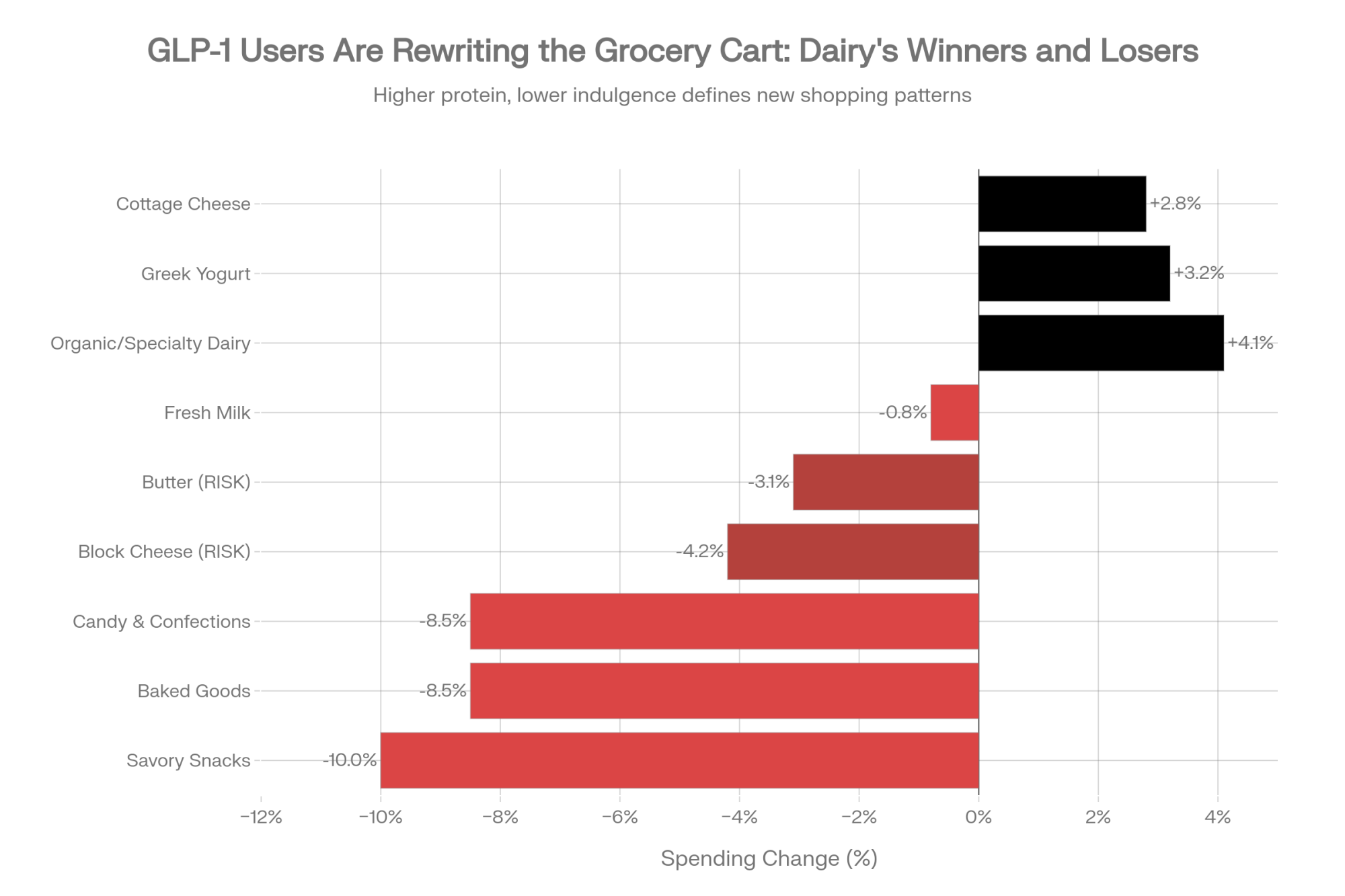

The biggest cuts landed on calorie‑dense, processed categories. Spending on savory snacks fell by about 10%, while categories like baked goods and cookies saw reductions of 6.7% to 11.1%.

| Category | Average Household Spending Change | % Change | Milk Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savory Snacks (chips, crackers, popcorn) | −$24 to −$32 | −10.0% | High—processed milk/whey used |

| Baked Goods (cookies, cakes, pastries) | −$18 to −$26 | −6.7% to −11.1% | High—butter, milk powder, butterfat |

| Candy & Confections | −$12 to −$18 | −8.5% | Moderate—dairy ingredients |

| Block Cheese (cheddar, American, processed) | −$8 to −$14 | −4.2% | HIGH RISK—commodity pressure |

| Butter (salted, unsalted) | −$6 to −$10 | −3.1% | HIGH RISK—indulgence category |

| Greek Yogurt (high-protein) | +$4 to +$8 | +3.2% | WINNER—protein focus aligns |

| Cottage Cheese (high-protein) | +$3 to +$5 | +2.8% | WINNER—protein focus aligns |

| Fresh Milk (milk, cream, fresh dairy) | −$2 to +$1 | −0.8% to +0.5% | Neutral to slight decline |

| Organic/Specialty Dairy | +$6 to +$10 | +4.1% | WINNER—premium positioning |

Meanwhile, yogurt and fresh produce saw modest increases.

What does this mean for your milk? If most of your production ends up in commodity cheese blocks and butter, GLP‑1 makes those categories a little more crowded. If it’s heading into high‑protein dairy—Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, protein drinks—you’re closer to where the growth is.

You can’t fix GLP‑1 from the parlor. But you can understand where your milk is going and whether that’s a “protein‑forward” lane or an indulgence lane.

When Plants Move, the Local Math Changes

You don’t need a consultant to tell you that when a local plant closes or changes hands, everything around it feels it. We’ve already talked about AMPI’s closures and the logic behind them.

Economic impact work for USDA and state ag departments has consistently shown that every dairy cow supports multiple off‑farm jobs—feed, vet, fuel, trucking, processing, retail. When processing capacity leaves a region, that ripple shrinks.

Meanwhile, the fresh steel is going into places that CoBank and IDFA keep pointing to: South Dakota, Texas, New Mexico, Idaho, parts of Kansas, and the Upper Midwest, where milk production is rising and component‑rich milk can efficiently fill new plants.

Cows follow plants, and plants follow cows—it’s a feedback loop.

For a 300‑cow family dairy in Marathon County or northern Pennsylvania, the processing map now matters almost as much as your soil map. If your buyer is putting new capital into your region, that’s one kind of future. If most of their big announcements are two or three states away, that’s another.

Sustainability and Bovaer: Real Emission Cuts, Real Costs

Let’s talk sustainability, because it’s showing up in almost every processor and retailer playbook now.

Bovaer is one of the most talked‑about tools on the enteric methane side. In May 2024, the FDA completed its review and approved Bovaer for use in U.S. dairy cows.

Elanco’s data shows that feeding one tablespoon per lactating dairy cow per day can reduce methane emissions by about 30%—roughly 1.2 metric tons of CO₂‑equivalent per cow per year.

On cost, the picture is still evolving. Independent technical reviews, including Dellait’s analysis and industry coverage, suggest early commercial costs tend to fall in the $0.30–0.50 per cow per day range, depending on region and feeding system.

On a 300‑cow herd, that works out to roughly $33,000–$55,000 per year before any incentives.

Some co‑ops and processors are offering payments tied to documented methane reductions, and a few early pilots show those can offset part of the cost—especially for larger herds or brand‑aligned programs. But in many cases, the net benefit to a 250–600‑cow herd is still very case‑by‑case.

What’s encouraging is that not all sustainability steps look like pure cost. Extension work on energy efficiency, manure storage, and nutrient management shows that improving fans and pumps, optimizing manure handling, and tightening nutrient management plans can lower energy bills, reduce purchased fertilizer, and sometimes improve milk quality at the same time.

The big takeaway? Treat sustainability offers like any other major business contract: get the full cost per cow and per hundredweight, understand how incentives are calculated and how long they last, and talk to producers already in the program before you sign.

Beef‑on‑Dairy: Great Tool, Dangerous Autopilot

Most of you have already seen the beef‑on‑dairy story firsthand. A decade ago, Holstein bull calves in many Midwest barns weren’t worth the time it took to haul them. Today? That’s changed.

In 2024–2025, newborn beef‑on‑dairy cross calves have often sold in the $600–$900 range in the Midwest and Western markets, with some lots hitting or exceeding $1,000 when beef supplies are especially tight.

Compared to the $50–$150 Holstein bull calves many of us remember, that’s a different world entirely.

Here’s the catch. As more producers bred a high share of cows to beef, replacement heifer inventories dropped.

CoBank’s 2025 report concludes that U.S. replacement heifer numbers have already fallen to a 20‑year low and could shrink by another 800,000 head across the next two years before recovering in 2027.

| Year | Heifer Inventory (M head) | Bred Heifer Price ($/head) |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2.35 | $1,800 |

| 2017 | 2.28 | $1,950 |

| 2019 | 2.15 | $2,100 |

| 2021 | 2.08 | $2,350 |

| 2022 | 2.02 | $2,650 |

| 2023 | 1.95 | $2,900 |

| 2024 | 1.88 | $3,100 |

| 2025E | 1.82 | $3,150 |

| 2026E | 1.75 | $3,050 |

| 2027E | 1.81 | $2,700 |

During the same period, bred heifer prices have spiked “well above $3,000 per head” and in some cases significantly more.

So if a 320‑cow herd runs several years of aggressive beef‑on‑dairy use without a disciplined replacement plan, it can easily end up short on heifers and forced to buy back in at a painful price.

What farmers are finding is that beef‑on‑dairy works best as a controlled tool:

- Set your replacement target. Use your actual cull rate, age at first calving, and herd size to calculate how many heifers you truly need each year. Many herds land near 30–36 replacements per 100 cows per year, depending on goals and longevity.

- Use sexed dairy semen and genomics where they pay. Focus dairy semen on your top‑end cows and heifers—animals that will move butterfat performance, protein yield, and health traits in the right direction for your market.

- Then layer beef‑on‑dairy on the rest. Once you’ve covered replacements, you can confidently use beef semen on the remainder to capture calf premiums without jeopardizing your future herd.

It’s like balancing protein and energy in a ration. Pushing beef semen to the max without watching replacement numbers might feel good in the short term, but the payback can hurt.

Canada’s Supply Management: Different Rules, Different Outcomes

Whenever the conversation gets tough in U.S. barns, someone inevitably says, “Canada doesn’t seem to be going through this the same way. What are they doing differently?”

Statistics Canada census data shows that Canadian dairy farm numbers have declined while average herd sizes have grown—a pattern similar to the U.S., but from a different starting point and under different rules.

Western Canada tends toward larger freestall herds while Québec maintains many smaller, tie‑stall family dairies.

Canadian dairy operates under supply management: production quotas, farmgate prices set by cost‑of‑production formulas, and import controls that cap foreign dairy entering the market. That framework has helped maintain relatively stable farmgate milk prices and a higher proportion of mid‑sized family dairies than in the U.S.

Could the U.S. copy that model? Realistically, not quickly. The U.S. sector is far larger, heavily involved in export markets, and bound by trade agreements that assume relatively open dairy trade.

The point here isn’t that one country is “right” and the other “wrong.” It’s that the rules you play under matter a lot. Canadian mid‑sized herds operate in a structure designed to support them. U.S. mid‑sized herds operate in a structure that rewards volume, efficiency, and export competitiveness.

The Human Load: When the System Sits on People

Under all these numbers are people—families, hired teams, neighbors.

In 2023 that farmers may face a suicide rate roughly 3.5 times higher than the general U.S. population, citing CDC‑linked occupational mortality data.

The National Rural Health Association and Senator Chuck Schumer’s office have both cited similar figures based on CDC research. Rural Minds, a nonprofit focused on rural mental health, notes that suicide rates in rural areas climbed significantly faster than in metro areas over the past two decades.

You see that in real life when a neighbor sells out under pressure or when a family member quietly struggles.

What’s encouraging is that more support is becoming available. Rural Minds maintains directories of confidential mental‑health and stress resources for farm families, and the Farm Aid hotline (1‑800‑FARM‑AID) connects farmers to local financial, legal, and crisis support.

Many states now have dedicated farm stress lines and behavioral‑health programs through their departments of agriculture and extension systems.

Reaching out for that kind of help is not a sign you “can’t handle it.” It’s part of taking care of yourself and the business in an industry where the pressures are structurally high.

Back at the 320‑Cow Freestall: What Do You Actually Do With This?

Let’s bring this down to the barn level.

Picture a fairly typical operation in central Wisconsin or upstate New York: about 320 cows in a freestall barn, a double‑8 or double‑12 parlor, corn silage and alfalfa on a few hundred acres, butterfat performance around 3.9–4.2% with solid protein test, shipping to a co‑op that’s already changed plant destinations once or twice in the past decade, and one or two younger family members quietly wrestling with whether to come home full‑time.

Here are five practical steps that kind of herd—and many like it—can take using the “uncomfortable math” instead of being blindsided by it.

1. Run a real stress test, not just a hope test

Sit down with your lender or advisor and run a few realistic stress scenarios:

- Milk price in the mid‑teens for 12–18 months.

- Beef‑on‑dairy calf prices are dropping 30–50% from current highs.

- A methane‑reduction requirement adding $0.30–0.50 per cow per day without guaranteed long‑term premiums.

On 320 cows, that additive alone could run $35,000–$58,000 per year. If you’ve been selling 80–100 beef‑cross calves at $800 and the market falls back toward $500–600, you could be looking at $16,000–$24,000 less revenue from calves.

When you spread those costs and revenue hits over your annual milk shipped, it can easily move your effective margin by $0.50–$1.00 per cwt, depending on production.

| Scenario | Milk Price | Beef Calf Price | Bovaer Adoption | Replacement Heifer Shortage | Annual Margin Impact | Margin/cwt vs. Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Normal) | $18.50 | $800 | None | None | $52,000 | +$0.80 |

| Scenario 1: Mild Stress | $17.00 (−$1.50) | $700 (−$1,100) | Optional | None | $38,500 | +$0.59 (−$0.21) |

| Scenario 2: Moderate Stress | $16.00 (−$2.50) | $550 (−$22,500) | Mandated ($0.40/day) | 5 heifers forced to buy @ $3,100 | $19,200 | +$0.30 (−$0.50) |

| Scenario 3: Hard Stress | $15.00 (−$3.50) | $450 (−$31,500) | Mandated ($0.50/day) | 10 heifers forced to buy @ $3,100 | −$8,900 | −$0.14 (−$0.94) |

| Scenario 4: Structural Crisis | $14.50 (−$4.00) | $400 (−$36,000) | Mandated ($0.50/day) | 15 heifers forced to buy @ $3,100 | −$61,500 | −$0.95 (−$1.75) |

Some families will find they’re more resilient than they feared. Others may realize that one hard cycle like that would dramatically change their options.

2. Map your marketing and processing exposure

Just like you map soil types and yield history, sketch out your marketing picture:

- How many serious buyers exist within a practical hauling radius for your size?

- Which plants have closed, reduced capacity, or changed ownership within that radius over the past 10–15 years?

- Where are your co‑op’s and main buyer’s latest big processing investments—locally, or in other states?

If you’re located near multiple growing plants, you’ve got a different risk profile than if you’re in a region with flat or shrinking capacity.

3. Calibrate beef‑on‑dairy as a tool, not autopilot

The starting point is knowing your true replacement needs. Work with your records, your cull rate, and extension benchmarks to set a realistic target.

Use sexed dairy semen and genomic testing where they actually pay—on the top tier of cows and heifers that will move your components and herd health the right way. Once those replacement slots are safely covered, assign beef semen to the rest.

Over‑raising heifers ties up capital, but under‑producing replacements pushes you into a high‑priced replacement market like the one we’re in now.

4. Approach sustainability projects like any other major contract

When someone pitches you a sustainability project—Bovaer, a digester, a low‑carbon milk program—try to approach it like you would a custom harvesting contract or a parlor upgrade.

Questions to put on paper:

- What’s the total cost per cow and per hundredweight, including product, equipment, extra labour, data collection, and verification?

- How exactly are incentives or premiums calculated, and how long are they guaranteed?

- Can you talk one‑on‑one with two or three producers already in the program to hear what works and what surprised them?

5. Make space for the family conversation about “what’s next.”

Most multi‑generation 250–600‑cow farms will eventually have to sit down and talk about who really wants to be on the farm in 5, 10, or 15 years, what level of debt and volatility everyone is willing to live with, and what “winning” means: staying roughly the same size, expanding, diversifying, or planning an orderly exit.

Many farm families are discovering that having a neutral third party—a mediator, succession planner, or extension specialist—at the table helps those conversations stay constructive. fb

I’ve heard from families in Wisconsin and New York who decided that selling a 280‑cow herd while land values were strong and equity was intact was their version of success. They’d run the numbers, talked with their kids, and realized they could leave with their health and their equity—and, for them, that felt like winning.

That won’t be the right path for everybody. Some will grow, some will pivot, some will partner, some will exit.

Your Next Three Moves

The math in this piece isn’t meant to scare you into any particular decision. It’s meant to show you the landscape clearly so you can choose your path with your eyes open.

If you take nothing else from this:

- Run the uncomfortable stress test and write down the results. Not in your head—on paper or in a spreadsheet, with real numbers.

- Decide whether you’re playing in Lane 1 or Lane 2—and whether that matches your long‑term goal. If there’s a mismatch, that’s the conversation to have next.

- Make a timeline for a real family conversation, with outside help lined up if you need it. Succession planning isn’t about giving up. It’s about choosing your terms.

Doing nothing is also a decision—it just hands the timing and terms to markets, processors, and lenders.

The uncomfortable math is a planning tool, not a verdict. The decision about whether to stay, grow, partner, or step away while you’re still on your feet—that still belongs to you, your family, your cows, and your land.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Two lanes, diverging fast: Lane 1 (1,000+ cow herds) is pulling $10-11B in new plants. Lane 2 (mid-sized dairies in WI, NY, PA) lost 1,521 farms in two years while milk output held steady.

- Heifer trap is set: 20-year-low inventory. 800,000 more head gone by 2027. Bred replacements topping $3,000. Beef-on-dairy without a replacement plan backfires hard.

- GLP-1 is sorting winners: Users cut grocery spending 5-6%—snacks down 10%, sweets down 11%. Greek yogurt and cottage cheese are gaining popularity. Know where your milk lands.

- Sustainability has a price tag: Bovaer cuts methane 30% but costs $0.30-0.50/cow/day ($33K-55K/year for 300 cows). Incentives rarely cover it. Negotiate like it’s a major contract.

- This is structural, not cyclical: Stress-test your margins. Map your processing exposure. Decide if staying, growing, or exiting on your terms is the win.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The 2026 Breeding Playbook: Using Calf-Health Genomics and Beef-on-Dairy to Unlock $50,000 in Your Herd– Deliver an immediate $2.50/cwt revenue boost by implementing a disciplined, rule-based breeding hierarchy. This tactical guide arms you with the specific genomic thresholds needed to capture peak beef-on-dairy premiums without starving your own replacement pipeline.

- The $11 Billion Reality Check: Why Dairy Processors Are Banking on Fewer, Bigger Farms – Expose the hidden processor contracts that have already locked in 80% of future milk supply. You’ll gain the strategic clarity to navigate the permanent structural shift toward high-volume corridors before the December 2026 repositioning window slams shut.

- 5 Technologies That Will Make or Break Your Dairy Farm in 2025 – Slash your fresh cow treatment costs by 40% and reclaim your sleep with AI-powered sensors that catch health crises a week early. This breakdown reveals the specific ROI of autonomous systems that turn your herd into a self-monitoring profit engine.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.