89% tested positive. Only 20% showed signs. By the time you see H5N1, it’s already spreading—and testing alone won’t save you.

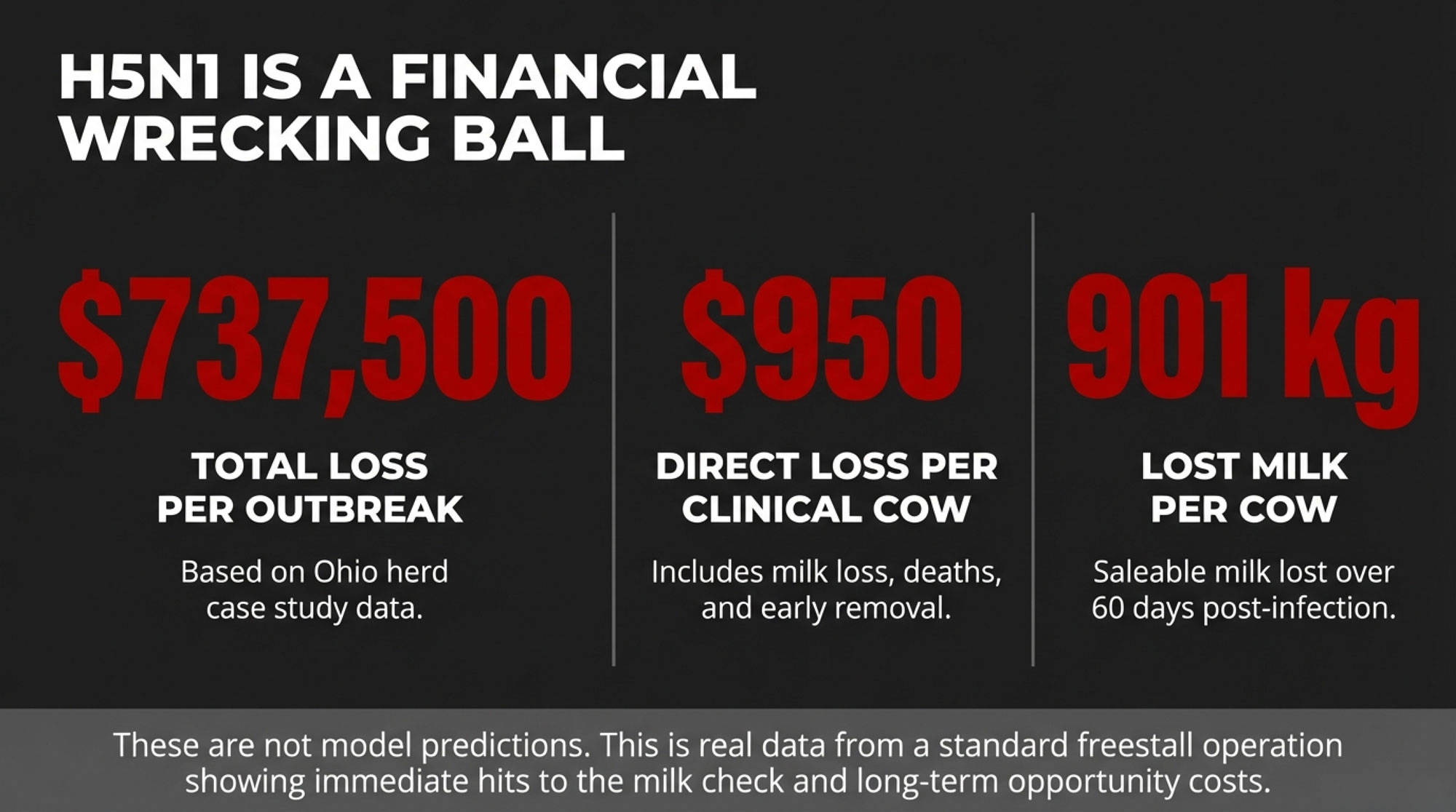

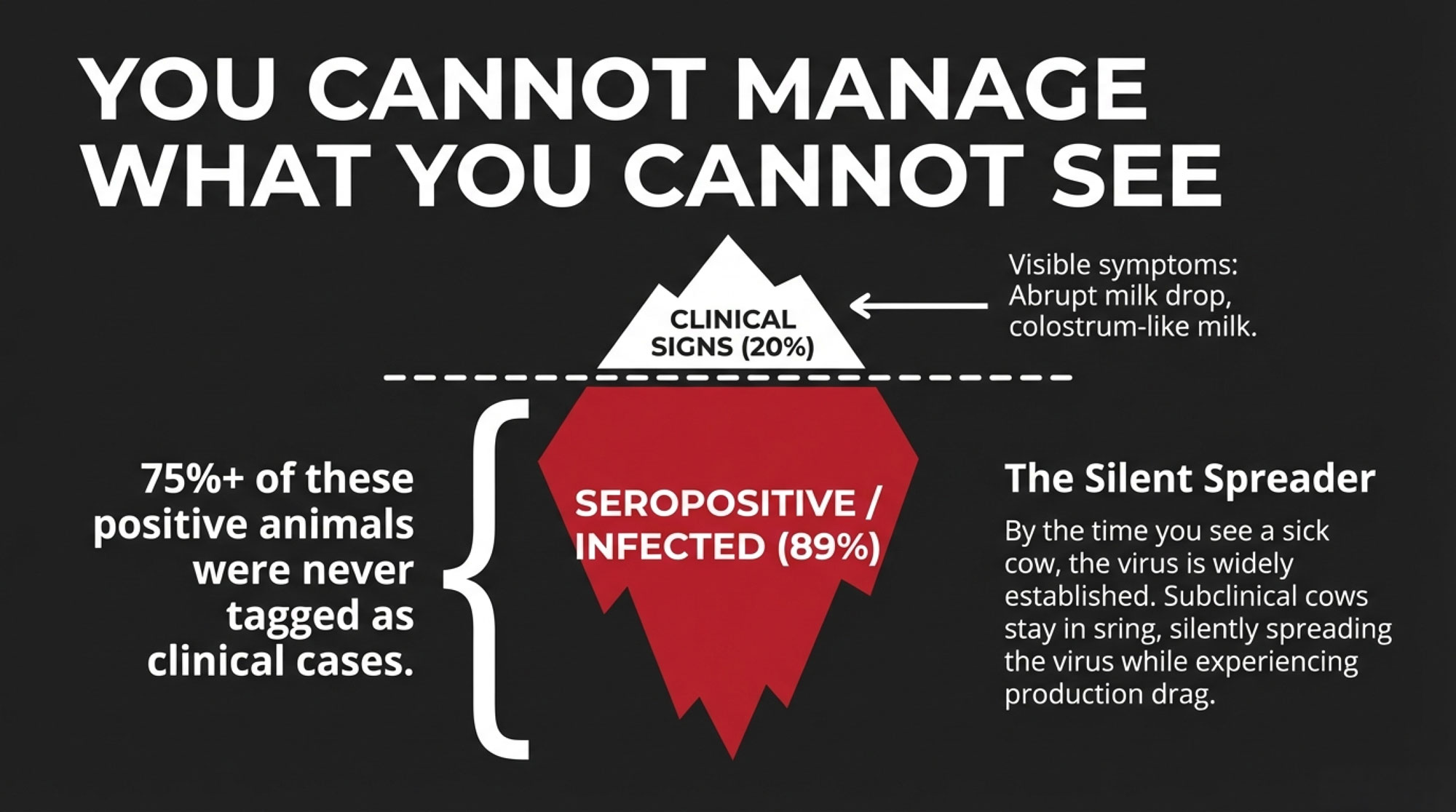

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Over 1,000 U.S. dairy herds have now tested positive for H5N1, and the numbers are brutal: one Ohio operation lost $950 per clinical cow and $737,500 total in a single outbreak. The hidden damage runs deeper—89% of cows tested seropositive while only 20% showed symptoms, meaning the virus spreads silently through milking equipment well before any test catches it. This forces a hard question: should your next biosecurity dollar go toward detection technology or prevention infrastructure? For most mid-size commercial dairies, the evidence is clear—prevention wins. Monitoring helps after H5N1 arrives, but cattle movements bring it in, and tighter gates beat better dashboards for reducing introduction risk. The practical playbook: strengthen sourcing controls, build real quarantine capacity, use bulk tank testing as a smoke detector, and reserve heavy tech investment for large operations or high-value genetics programs where herd size and asset value shift the math.

If you’ve been keeping up to date on the H5N1 situation at all, you’ve probably heard about Wisconsin’s first confirmed dairy case from late 2025. USDA and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection reported that a roughly 500-cow herd in Dodge County turned up positive after a bulk tank sample from the national milk surveillance program flagged highly pathogenic avian influenza.

Here’s what’s interesting about that case. The farm wasn’t seeing a barn full of crashing cows at that moment. State veterinarian Darlene Konkle noted in follow-up briefings that the D1.1 strain found in this herd matched what’s been circulating in Wisconsin waterways via migratory wildfowl—suggesting wildlife contamination around lagoons and feed rather than cattle-to-cattle spread from another dairy.

The lab caught it before anyone on the farm noticed a major production slump or clinical signs in the string.

And that kind of story gets talked about fast at the winter meetings. It leads to the same question I’m hearing from producers in Wisconsin, the High Plains, and the Central Valley: do you put serious money into high-end monitoring and more frequent testing to catch things early, or do you focus first on how cows come onto your place and how they move once they’re there?

What I’ve found, looking across the newest research and real herd experiences, is that the biggest payoff often isn’t where the shiniest technology is pointed.

How H5N1 Actually Behaves in Dairy Cows

Looking at this from the cow’s side first, the biology explains much of what we’re seeing.

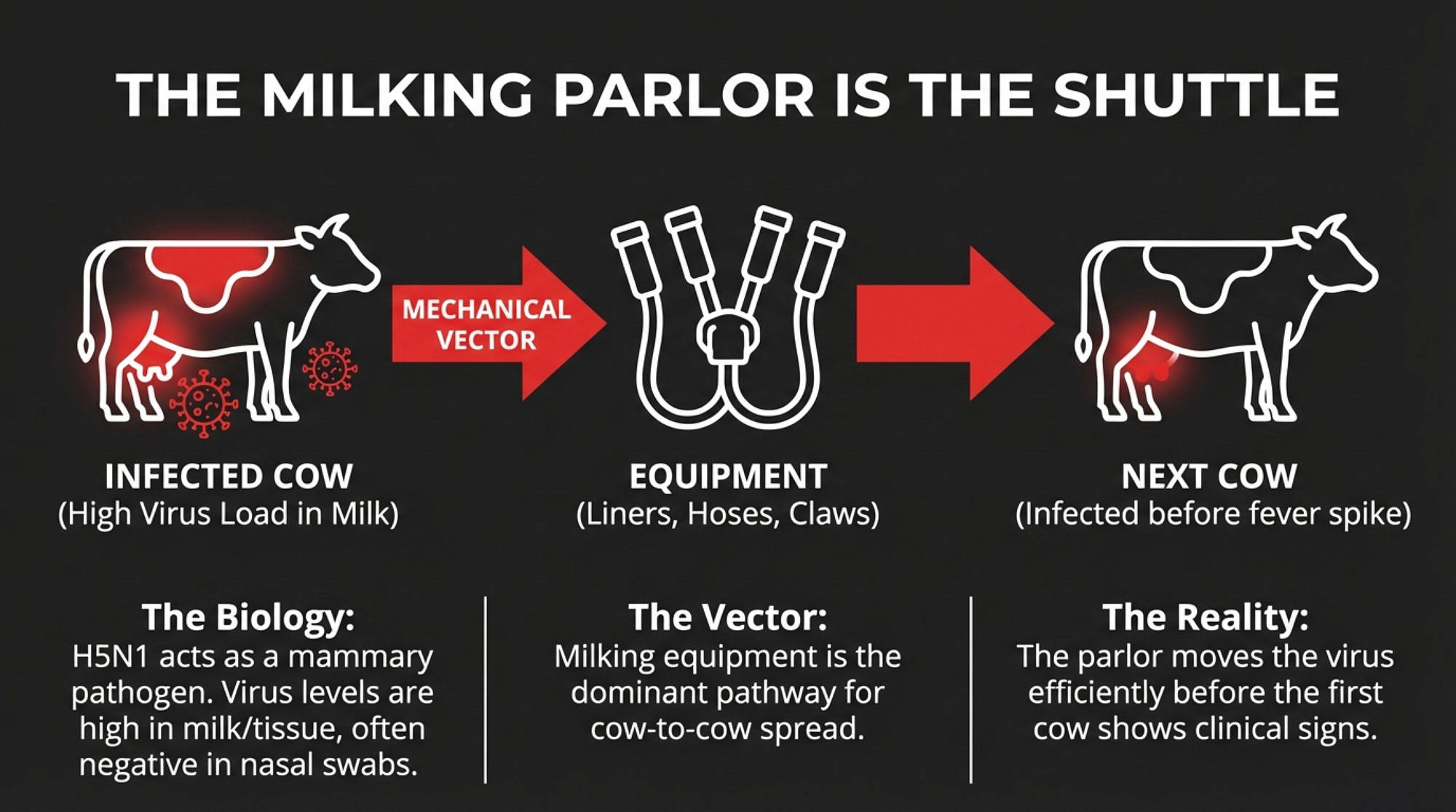

When H5N1 first showed up in U.S. dairy cows in Texas and Kansas in early 2024, pathologists were struck by where the virus was turning up. Research published in Virulence and the Journal of Dairy Science’s “hot topic” papers described very high virus levels in milk and mammary tissue from affected cows, while nasal swabs were often negative or much lower.

USDA’s early epidemiological work reinforced this—they found no evidence of “virus actively replicating within the body of the cow other than the udder.”

In cows, this strain primarily behaves as a mammary pathogen rather than a classic respiratory virus.

Clinically, that’s exactly what many herd vets have been seeing. The Western Canadian Animal Health Network’s dairy summary describes the typical picture as a sudden drop in feed intake and rumination, an abrupt decrease in milk production, thick yellowish milk resembling colostrum in some cows, and more subtle changes in manure with secondary infections sometimes following.

Earlier outbreak reports from Texas and Kansas noted similar signs—off-feed cows, reduced rumination, sudden milk drop—sometimes with respiratory or neurologic symptoms, but with those mastitis-like milk changes front and center.

Here’s what makes that tricky. By the time you see obvious clinical signs, the virus may already be well into your milking string.

Hoard’s Dairyman reported that on infected Michigan dairies, many of these cows had already returned to normal temperatures by the time the drop in rumination or milk was noticed—the fever spike often comes first, then clears within hours.

Once you put that together with a modern freestall or dry lot parlor, the main within-herd transmission route starts to look uncomfortably familiar.

USDA’s investigation and multiple peer-reviewed papers emphasize that milking equipment and procedures—liners, claws, hoses, and other contact points—are the dominant pathways for cow-to-cow spread in affected herds, with respiratory spread playing a secondary role.

In plain terms, once an infected cow is in the string, your parlor can become the shuttle.

Why Testing Alone Won’t Save Your Herd

Now, you might expect all this to show up as a full-on train wreck in your fresh group. In practice, the data show the picture is more mixed—and that’s where many producers are tripped up by the “early detection fixes everything” narrative.

You know how it goes. A vendor comes in, shows you the monitoring dashboard, and suddenly it feels like you can see everything coming. But if your whole H5N1 plan is “we’ll just test more,” you’re betting against how this virus actually behaves in real barns.

A 2024 review in BMC Infectious Diseases on H5N1 in dairy cows notes that clinical morbidity has been estimated at 10–40 percent of lactating cows in some herds, but serologic evidence often reveals far more infections than clinical cases.

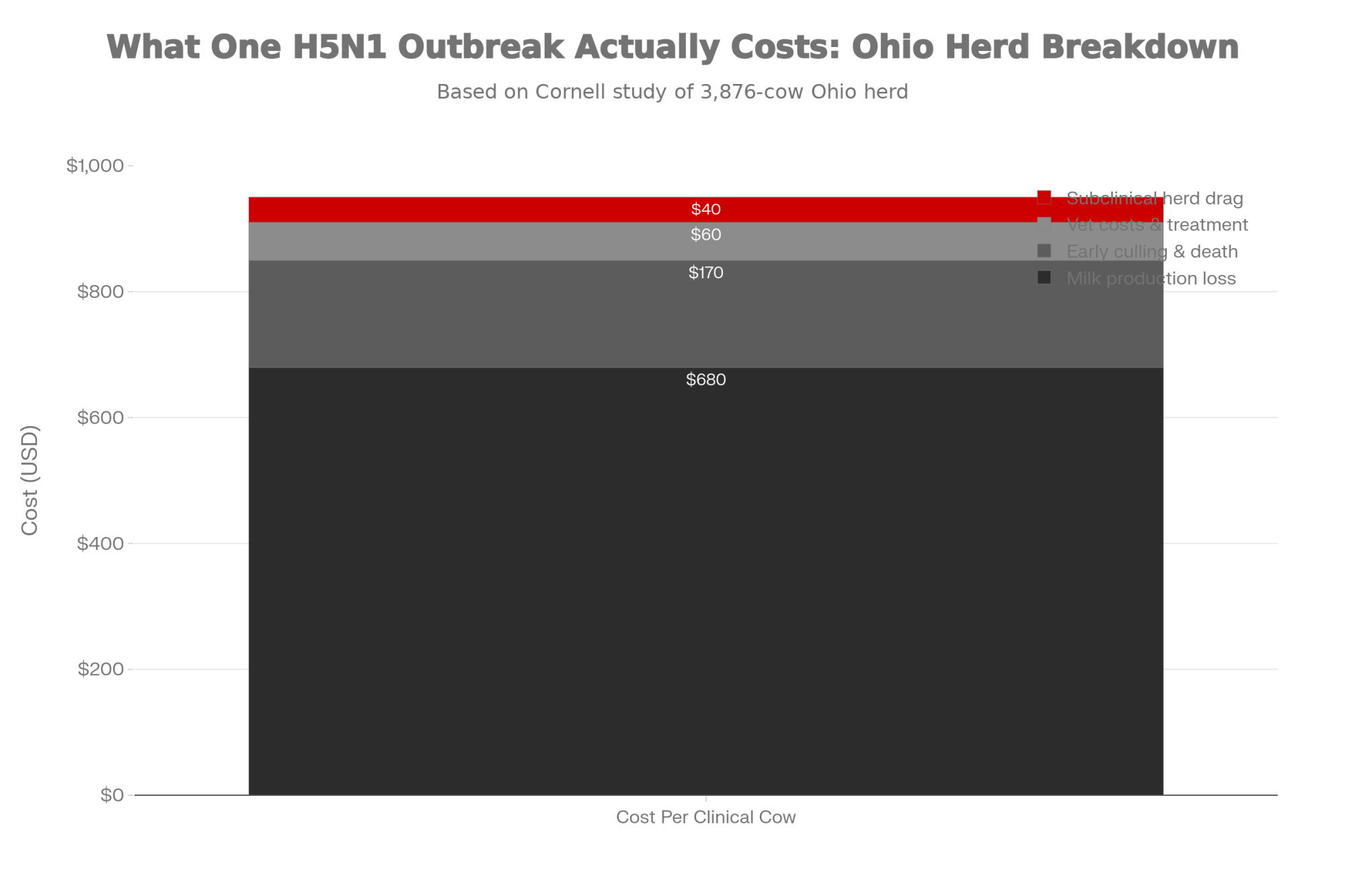

That’s exactly what we saw in the best-documented case so far: a big Ohio freestall herd that Cornell researchers studied in detail.

That Ohio operation milked about 3,876 adult cows in freestalls on a TMR—very typical of many North American herds. During the main outbreak window, 777 cows—about 20 percent of the herd—were classified as clinically affected based on clear signs like abrupt milk drop and abnormal, colostrum-like milk.

When researchers followed those clinical cows for 60 days, they found that each cow produced about 901 kilograms less saleable milk than expected based on her expected curve.

Economists working with that data estimated the direct economic loss at roughly $950 per clinical cow, accounting for milk loss, deaths, and early removals, for total losses of about $737,500 during the period studied. (The full study is publicly available through PMC for anyone who wants to dig into the methodology.)

That’s not a model. That’s a real herd, with numbers that look a lot like what many of us are budgeting against.

Here’s the part that sticks with me. When they tested blood samples from a subset of those cows, about 89 percent were seropositive for H5N1, and more than three-quarters of those seropositive animals had never been tagged as clinical cases.

Those subclinical cows still had smaller but real reductions in production.

The Cornell team cautioned that herd-level averages can mask those losses because low-producing cows are often culled and replaced, making bulk tank trends look better than individual cow records.

If you’re already running tight margins on feed and labor, that kind of hidden drag is exactly the sort of thing that shows up when you reconcile your milk check at year-end.

| Herd Status | Cows Tested Seropositive | Cows Showing Clinical Signs | Hidden Economic Drag |

| What the data shows | 89% | 20% | Subclinical losses in 69% of herd |

| Ohio herd (3,876 cows) | ~3,450 cows infected | 777 cows clinical | 2,673 cows with hidden production loss |

| Your 500-cow herd (projected) | ~445 cows infected | 100 cows clinical | 345 cows quietly costing you money |

| Detection window | Virus present 7–14 days before bulk tank flags it | Clinical signs appear mid-outbreak | Losses already compounding |

The Detection Gap: What “Early” Really Means

Given that picture, it’s no surprise that a lot of energy has gone into early detection. In April 2024, the USDA issued a federal order requiring lactating dairy cows to test negative for influenza A before interstate movement.

During the announcement, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack explained: “The mandatory testing for interstate movement impacts and involves dairy cattle. We’re going to focus on lactating cows initially.”

Since then, USDA has developed a national milk-testing strategy that includes bulk-tank and retail-product sampling. States like Wisconsin have added their own layers—testing requirements for show cows, more routine tank testing—in an effort to see problems earlier.

At the same time, many herds have either adopted or expanded cow-level monitoring platforms that track milk yield, activity, rumination, and sometimes temperature. These systems were already proving their worth in fresh cow management and mastitis detection on large dairies before H5N1 ever showed up.

Now they’re being pitched as an extra set of eyes for catching H5N1-type patterns.

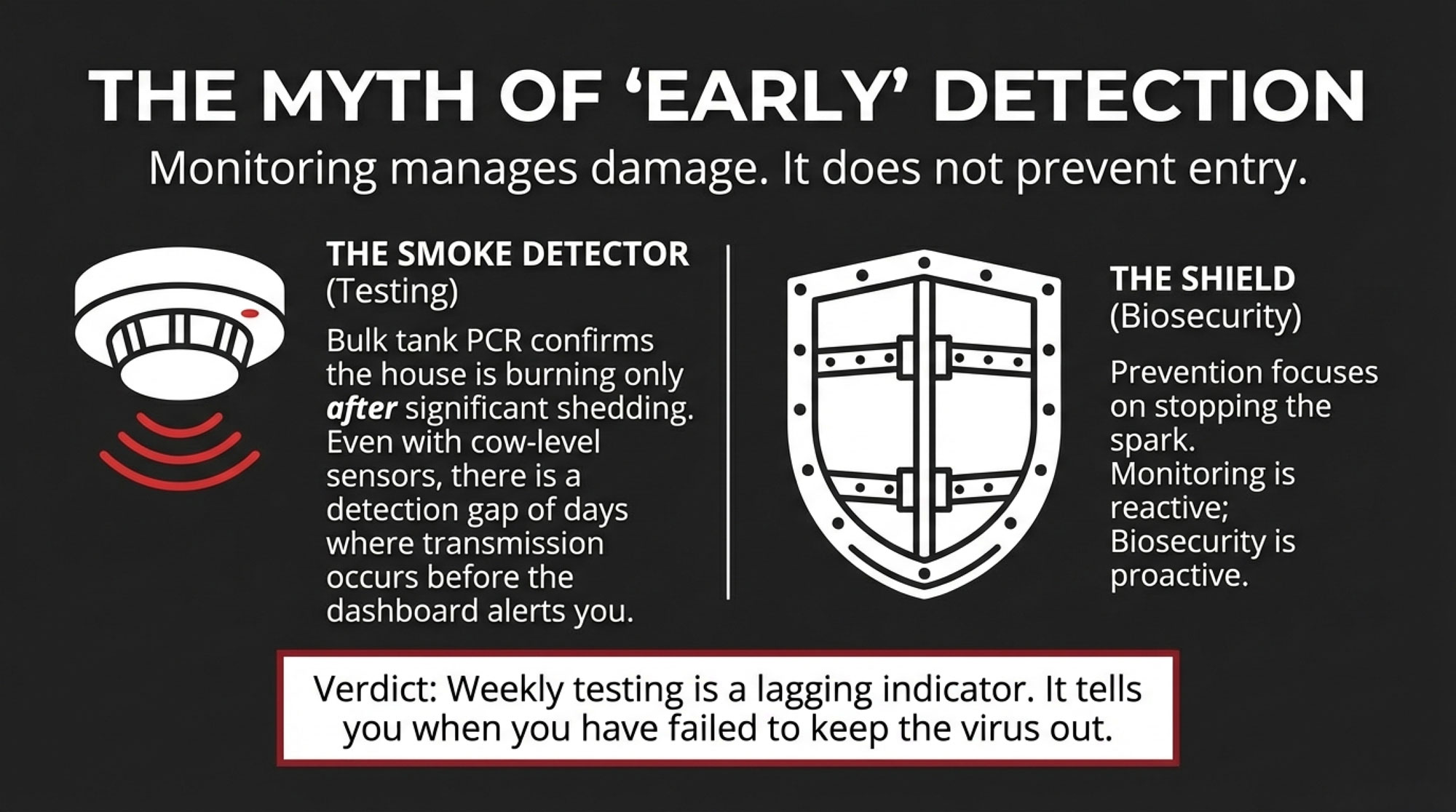

What farmers are finding is that those tools help, but they don’t change the basic rules of how fast this virus moves.

Transmission modeling from 2024 and 2025 suggests that spread within milking strings is relatively efficient once the virus is established—one infected cow tends to lead to at least one additional infection on average, though outbreak dynamics vary considerably depending on how the herd is managed and how quickly producers respond.

Over a couple of weeks in a large freestall or dry lot system, that steady growth can involve a sizable portion of the milking string.

On the detection side, recent work in mBio and JDS Communications, along with the FDA’s own method development, has looked at how bulk tank PCR results relate to within-herd prevalence.

Those studies show that the tank test works best once a substantial fraction of the herd is shedding virus into the milk that ends up in that bulk tank.

When only a small number of cows are infected, particularly in larger herds, the virus signal in the pooled sample can be intermittent—some draws positive, some negative—just based on which cows were milked when.

Weekly bulk tank testing, where many co-ops and labs have landed, is a good smoke detector. It’s very helpful to know when something is burning, but it won’t always catch the very first spark.

Moving to twice-weekly sampling, or tying bulk tank testing into cow-level monitoring that’s already watching for unusual drops in mid-lactation milk or changes in rumination, tends to bring the alarm forward by several days.

On herds that use these systems well, veterinarians report they’ve been able to act roughly one infection cycle earlier than they otherwise would have.

What those systems can’t do is erase the early window. There’s still going to be a period—often days, sometimes more than a week—where H5N1 is present and transmitting in the herd before any bulk tank result or dashboard alert clearly points to it.

That doesn’t make detection a waste of time or money. It just means that when we talk about catching it early… well, we have to be honest about what “early” really looks like for this virus.

Bird Flu Economics: The Real Cost to Your Dairy

So why does that timing nuance matter so much on a working dairy?

The short answer is: because the economics are unforgiving.

I talk to a lot of producers who are trying to figure out where to put their next biosecurity dollar, and honestly, the math is what cuts through all the noise.

The Ohio herd gives us real numbers, not just modeling, for what an outbreak can cost. In that freestall herd, clinical cows lost about 900 kilograms of saleable milk over 60 days, and the total losses were around $950 per clinical cow, for roughly $737,500 in direct costs during the outbreak.

That’s before you factor in the opportunity cost of cows that never reach their genetic potential afterward.

If we use those numbers as a planning tool—not a prediction, but a way to think about risk—for a 500-cow herd in the Midwest or Northeast, the math adds up quickly.

Imagine a big outbreak where 20 percent of cows go clinical: that’s 100 animals. If each one ends up costing about $950 in lost milk and associated impacts, you’re looking at about $95,000 in direct clinical losses.

You’ll also have subclinical losses in the rest of the herd, and likely some fresh cow and repro impacts that aren’t captured in that simple figure.

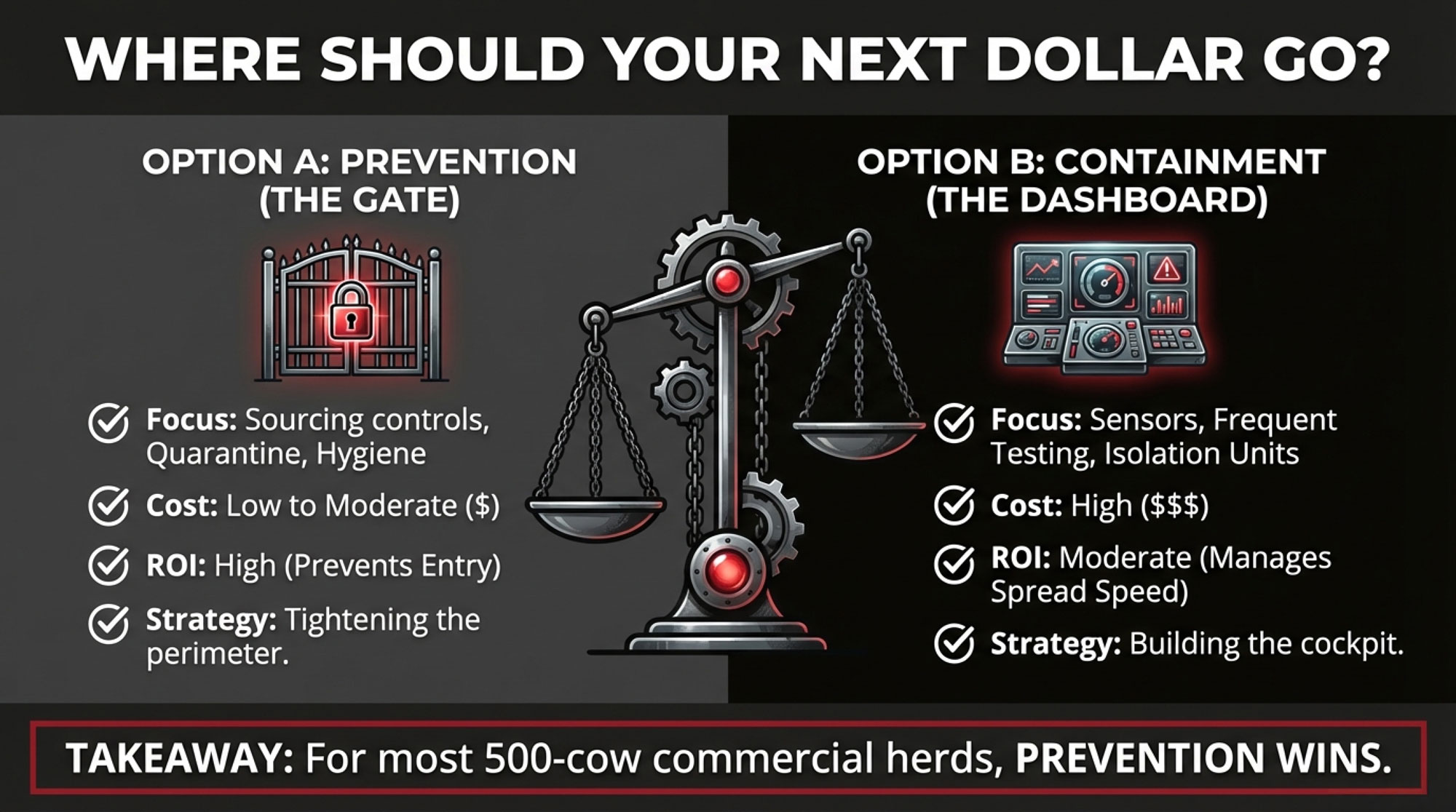

On the investment side, most of the herds I talk with are weighing two big buckets for where the next H5N1 dollar might go.

The Prevention-First Approach

This is the “tighten the gates” option, centered on sourcing and quarantine, plus some practical facility and testing upgrades.

Using current PCR pricing, extension-style building costs, and veterinarian fee schedules, a 500-cow herd can typically:

- Set up a modest but real quarantine area for all incoming and returning cows, with its own fence, water, and tools

- Make small changes in the hospital and isolation space so suspect cows can be handled with less cross-contamination

- Run weekly bulk tank PCR testing as part of routine surveillance

- Stock and consistently use appropriate PPE, disinfectants, and cleaning tools

USDA has offered some support here. APHIS announced up to $1,500 per premises to develop and implement a biosecurity plan, plus $100 for producers who purchase and use an in-line sampler for their milk system.

When you add up a simple quarantine structure, weekly bulk tank testing, additional vet consults, and supplies, the costs vary quite a bit depending on the infrastructure you’re starting with. Some herds are looking at relatively modest investments; others with more to build are looking at figures that push into six figures over several years.

| Approach | Upfront Investment (3-Year Total) | What It Buys You | What It Doesn’t Change | Best Fit |

| Prevention-First | $35,000–$75,000 | Quarantine facility, weekly bulk tank PCR, sourcing controls, PPE, vet protocols | Detection speed once virus is inside | Mid-size herds (300–800 cows), commodity markets |

| Tech-Heavy Detection | $150,000–$350,000+ | Cow-level monitors, expanded isolation, 2–3× weekly testing, dedicated sick-cow milking | Probability virus enters your gate | Large herds (2,000+ cows), high-value genetics |

| Prevention + Smart Tech | $80,000–$150,000 | Quarantine, bulk tank PCR, monitors on fresh/high-value groups only | Full-herd real-time visibility | Growing herds, export-focused dairies |

The Containment-Heavy Tech Approach

This is more of a “build the cockpit” option, where you lean hard into detection and on-farm control:

- Cow-level meters and sensors on most or all lactating cows

- Expanded isolation and hospital capacity, with dedicated milking units and more robust waste-milk handling

- More frequent bulk tank sampling, possibly multiple times per week

- Additional veterinarian time and staff hours to manage a more complex alert and response system

There isn’t a single peer-reviewed price tag for this approach. But when you look at real vendor quotes for herd monitoring systems, construction costs, test fees, and labor, it’s not unusual for a 500-cow herd to be facing substantial investment—potentially several hundred thousand dollars over a multi-year implementation period, depending on herd size and system sophistication.

What Each Approach Actually Buys You

The containment-heavy approach can reduce the number of cows that get infected and the duration of an outbreak once H5N1 is already in the herd.

Modeling and the Ohio case both suggest that earlier action—changing milking order, isolating suspect cows, adjusting fresh cow management—can shave a noticeable number of cases off the top and reduce total losses.

That’s especially compelling in high-value genetic herds or very large operations where each day of delay involves hundreds of cows.

But none of that spending changes the probability that H5N1 ever shows up at your gate to begin with.

That risk is driven mostly by cattle movements, local herd density, wildlife contact, and the level of virus activity in your region.

The prevention-first approach, by contrast, is aimed squarely at those front-end risks. It can’t prevent every wildlife spillover—Wisconsin’s first case is a good reminder of that—but it can significantly reduce the odds that you invite the virus in on a trailer from a high-risk region or from a herd with unknown status.

So, before we even talk brands or product specs, one of the key questions to ask is: are you mostly insuring against H5N1 getting in, or against what it does after it’s inside?

Why Prevention Deserves Your First Dollar

What farmers are finding, as we get more data and more real-world experience, is that prevention has a surprisingly strong case.

A 2024 study published in Virulence and a 2025 comprehensive review both highlight the role of cattle movements in spreading the virus between states.

In particular, some infected herds in Michigan and Idaho had recently received cows from Texas, and genomic analyses linked those movements to local outbreaks.

A broader review of highly pathogenic avian influenza in North America concluded that the 2024 epizootic in dairy cattle and poultry was spread mainly through milking machinery and animal transport, with wild birds seeding some initial introductions.

That’s the backdrop for APHIS’ April 2024 federal order, which requires lactating dairy cattle to test negative for influenza A before crossing state lines and lays out detailed testing, reporting, and quarantine expectations for affected herds.

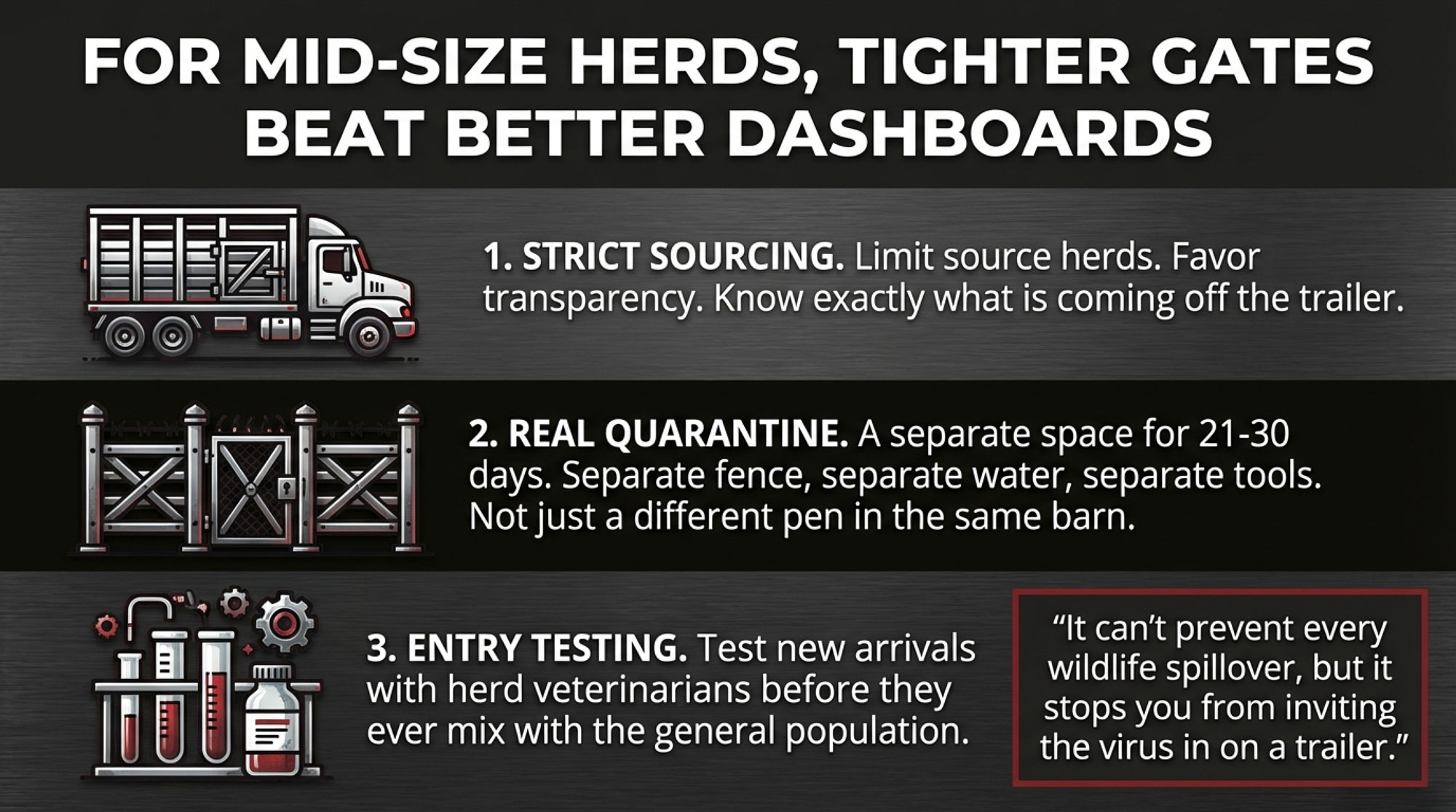

University extension groups have been remarkably consistent in their practical biosecurity advice:

- Limit the number of source herds and favor those with transparent health status and lower H5N1 risk

- Maintain a separate quarantine space for all new and returning animals for 21–30 days, with its own fence, feed, water, and manure-handling tools

- Work with your herd veterinarian to test cows in quarantine at least once early and once near the end of that period, using approved influenza A tests

- Keep good movement and health records so you can track which animals came from where and when problems started

When you look at the cost and hassle of those steps, they’re not small.

But compared to the cost of a major outbreak—or a full tech-heavy build-out—they’re often a very efficient use of the next biosecurity dollar for a 400–800 cow herd.

A 2024 editorial on H5N1 concerns noted that, in the absence of widely available vaccines for dairy cattle, tightening biosecurity around animal movements and focusing on milking hygiene are two of the most effective levers we have to reduce herd-level risk.

So, for many mid-size herds in the Midwest, Northeast, and Eastern US, a prevention-first core—sourcing, quarantine, basic facility upgrades, sensible surveillance—looks like the best place to put the next big dollar.

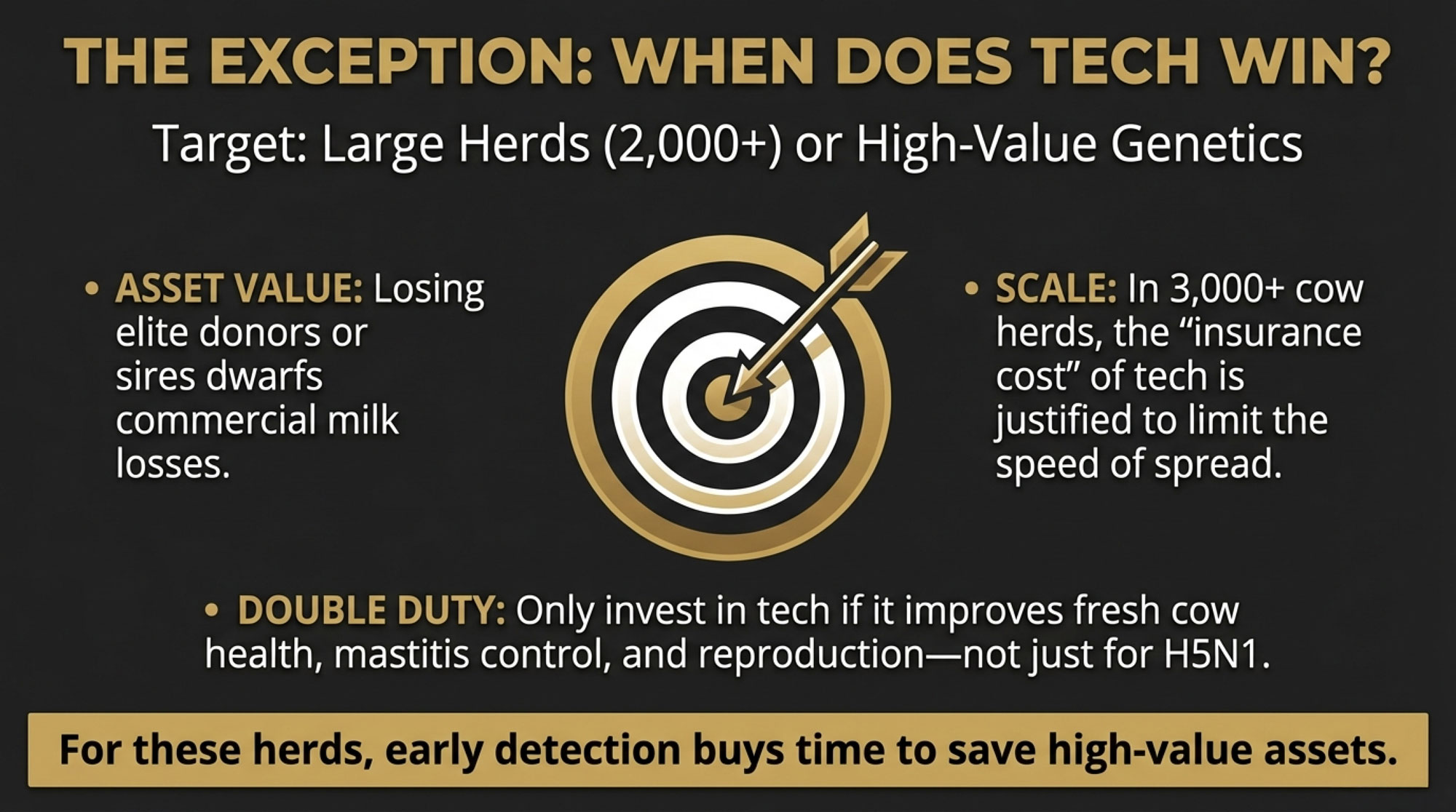

When Detection Technology Earns Its Keep

At the same time, it wouldn’t be accurate to say that detection technology belongs only in brochures.

In large Western herds, where 2,000–3,000 cows per site is common, and operations are often spread across multiple locations, cow-level monitoring has already become part of the management toolkit.

Recent articles have shown how these systems improved fresh cow health, mastitis detection, and reproduction long before H5N1 was on the radar.

A recent feature on what we’re learning about HPAI on dairies noted that using rumination, activity, and milk production data, individual cow effects can be easily observed—and on some large operations, monitoring platforms helped pick up unusual mid-lactation milk drops and activity clusters that prompted earlier investigation and testing.

When you add H5N1, the incremental benefit of those systems grows.

If you can spot a suspicious pattern a few days earlier and rearrange milking order, isolate suspect pens, and tighten parlor hygiene more quickly, the payoff on a 3,000-cow dry lot can be substantial—especially if you’re working with high-value genetics or a tightly contracted supply.

In high-value genetic herds—those selling embryos, bulls, or show cattle—the risk calculus shifts again.

Losing a handful of elite donors or sires in a single outbreak can dwarf the per-cow costs seen in the Ohio commercial herd.

Many of these operations are already at the front of the line in terms of fresh cow management, disease monitoring, and documentation. For them, tuning their existing systems to look for H5N1-type patterns and building a rapid-response protocol around those alerts can be a relatively small additional investment with outsized risk-reduction.

The Export and Processor Angle

There’s also a growing market dimension that many mid-size herds aren’t yet considering.

International buyers are paying close attention to how U.S. dairy manages H5N1 risk, including surveillance, testing programs, and biosecurity.

Dairy Global has reported that European authorities view the likelihood of H5N1 spread through dairy trade as low, but they’re closely watching U.S. controls and transparency.

Joint dairy organization statements in 2024 and 2025 have emphasized the industry’s commitment to biosecurity and surveillance, partly to reassure buyers and consumers.

If you’re shipping high-value cheese into EU or Asian export contracts, or selling to processors with premium-quality programs, enhanced monitoring and documentation may become more than a nice-to-have. They’re part of staying eligible for certain markets.

And finally, in regions where H5N1 has hit multiple herds—parts of Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, and California, for instance—producers are increasingly treating the virus as a recurring management challenge rather than a one-time event.

In that environment, spending more on tools that can shorten and soften each wave becomes easier to justify.

So the practical message isn’t “don’t buy technology.” It’s “build prevention first, then choose technology that pulls double duty” for your herd—supporting fresh cow management, butterfat performance, mastitis control, and H5N1 response—based on your size, genetics, and markets.

Pasteurized vs. Raw: What H5N1 Means for Milk Safety

This is probably the question I get most at producer meetings, and I understand why. It touches on everything from consumer confidence to how you handle waste milk on your own operation.

On the pasteurized side, the evidence to date has been reassuring.

During 2024, the FDA and USDA ran a national commercial milk sampling effort, testing an initial set of 297 retail dairy products—including fluid milk, cream, cottage cheese, and sour cream—from multiple states.

H5N1 viral RNA was detected by PCR in a fraction of those samples, particularly from regions with infected herds, but when PCR-positive samples were tested in eggs and cell culture, no infectious virus was found.

FDA then worked with academic partners to run pilot-scale HTST pasteurization studies using inoculated raw milk. Those experiments showed that standard commercial pasteurization conditions are likely eliminating at least 12 log10 of virus per milliliter—essentially complete inactivation under the tested scenarios.

In a September 2024 letter to the dairy processing industry, the FDA stated plainly: “The FDA and USDA are confident that pasteurization is effective at inactivating H5N1 in raw milk” and that pasteurized dairy products remain safe.

A joint statement from major U.S. dairy organizations in March 2024 made the same point: pasteurization kills pathogens, including influenza viruses such as H5N1.

Raw milk is another story.

Laboratory work published in 2024–2025 showed that H5N1 can remain infectious in refrigerated raw milk for days and that the virus or viral RNA can persist in cheeses made from contaminated raw milk, with only gradual declines during aging.

FDA and public health agencies in the U.S. and Canada have warned that consuming raw or unpasteurized milk from infected herds or regions with active outbreaks may pose a risk and have urged producers and consumers to understand the risks associated with raw milk.

There’s also the animal side to consider.

A U.S. study of H5N1 in dairy cattle and cats in Texas and Kansas documented that cats on affected farms became infected and, in some cases, died after exposure to contaminated environments and likely raw milk. The viruses in those cats were nearly identical to the viruses in cattle on the same farms.

That’s led many veterinarians to recommend rethinking waste milk feeding practices for calves, cats, and dogs, especially during and after outbreaks.

For dairy producers, the practical takeaway looks something like this:

- Pasteurized milk from your herd, once it’s processed adequately through a commercial plant, remains safe based on current retail sampling and pasteurization studies

- On-farm raw milk consumption, and how waste milk is handled, deserve careful consideration in areas with H5N1 activity or after a positive herd test

USDA Assistance: Helpful, But Not a Safety Net

Another question that comes up quickly in these conversations is: if we do get hit, how much can USDA actually help?

In June 2024, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced that USDA would use the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm-raised Fish program—ELAP—to offset some H5N1-related milk production losses.

Under that expansion, eligible dairies with confirmed H5N1 infections can receive payments based on documented declines in milk production for affected cows over a defined window—up to 21 days at zero production and 7 days at 50 percent production—at 90 percent of the average milk price for the state or region.

CIDRAP’s coverage of that announcement noted that ELAP payments can significantly blunt the initial financial hit for clearly documented clinical outbreaks.

At the same time, ELAP is not designed to capture everything.

The program doesn’t fully account for subclinical production losses, longer-term impacts on fresh cow performance and reproduction, or the costs of higher culling and replacement that can ripple out over many months.

There’s also a timing gap; the milk check takes the hit right away, while ELAP payments arrive later.

So ELAP is an important part of the safety net, and it’s smart to understand how to document and apply it if you’re affected. But it’s not a reason to assume you can afford to be casual about prevention.

| H5N1 Outbreak Cost | USDA ELAP Coverage | You Still Pay |

| Milk production loss (clinical cows) | 90% of state avg milk price × up to 21 days at 0% + 7 days at 50% | 10% co-pay + any losses beyond 28-day window |

| Subclinical production losses | Not covered | 100% on you |

| Early culling & death loss | Not covered | 100% on you |

| Veterinary diagnostics & treatment | Not covered | 100% on you |

| Fresh cow performance drag (60+ days post-outbreak) | Not covered | 100% on you |

| Reproduction impacts & delayed breeding | Not covered | 100% on you |

| Labor overtime & management time | Not covered | 100% on you |

A Five-Step Framework for Your Herd

Given everything we’ve seen in the last two seasons—from those early Texas and Kansas herds, to the Ohio numbers, to movement-linked cases in other states, to Wisconsin’s wildlife-linked outbreak and the national milk testing work—what does a workable plan actually look like on farm?

Here’s a framework that’s starting to make sense for a lot of well-run dairies.

1. Lock In The Prevention Basics

Looking at this trend, the herds that are sleeping best at night are the ones that have tightened their basics rather than chasing every new gadget.

- Sourcing and quarantine. Limit your source herds, favor operations and regions with transparent health status and lower known H5N1 activity, and quarantine all incoming and returning animals for 21–30 days in a truly separate space. That means its own fenceline, feed and water, and handling tools.

- Testing new arrivals. With your herd veterinarian, set up a testing protocol for cows in quarantine—typically one influenza A test early on and another before they join the milking herd, using approved laboratory assays.

- Hospital pen and parlor routines. Make sure your sick-cow handling doesn’t undo your good intentions. Simple changes like milking suspect cows last with clearly marked units, cleaning or changing liners between known suspect cows, and adjusting who moves between pens can make a difference.

2. Use Surveillance As A Smoke Detector

What farmers are finding is that surveillance is most useful as an early warning system, not as a guarantee.

- Bulk tank PCR. Work with your processor or local lab to set up a weekly bulk tank PCR schedule for H5N1. In times of higher risk—after bringing in cows from affected states, during peak bird migration, or if a neighbor tests positive—you may choose to bump it to twice-weekly sampling for a while.

- Interpreting results smartly. Treat a negative as “no obvious smoke,” not as proof that zero infection is present. Treat a positive or inconclusive result as a tripwire to move into your response plan.

3. Decide What You’re Really Insuring Against

This is where herd size, genetics, and region really reshape the math.

- Mid-size commercial herds (say 300–800 cows). For many Midwest, Northeast, and Eastern US herds that ship to commodity markets, the primary goal is to reduce the risk of an outbreak and to prevent a rare one from wrecking the year. For these herds, a prevention-first core with sensible surveillance is often where the next dollar works hardest.

- Large herds and genetics programs. For 2,000-cow dry lot systems in the Southwest or herds selling embryos and bulls, the stakes around repeated exposures or losing a few elite animals are much higher. In those cases, investing more in detection tools that also help with fresh cow management, mastitis, repro, and butterfat performance can pay off.

Being honest about what you’re insuring against—one big hit vs. multiple waves, commercial cows vs. elite genetics—helps you avoid buying the wrong insurance.

| Herd Type | Herd Size | Primary Risk | First-Dollar Priority | When to Add Tech | Target Investment (3-Year) |

| Midwest/Northeast commercial | 300–800 cows | Single large outbreak wrecks the year | Quarantine + sourcing + weekly bulk tank PCR | Only if expanding or adding high-value genetics | $35,000–$75,000 |

| Western large commercial | 2,000–5,000 cows | Repeated exposures, extended outbreak duration | Quarantine + bulk tank PCR, THEN cow monitors on fresh groups | Immediately—monitors pay for themselves in early containment | $150,000–$250,000 |

| High-value genetics herd | Any size | Loss of elite donors/sires in single event | Full monitoring + quarantine + 2× weekly testing | From day one | $100,000–$350,000+ |

| Export-focused dairy | 500–1,500 cows | Buyer audits & market access requirements | Quarantine + documentation systems + weekly testing | When buyer contracts require it | $60,000–$120,000 |

4. Layer Technology Where It Does Double Duty

This is where technology really earns its keep.

- Make better use of what you already have. If you’re already running cow-level monitoring, sit down with your data and your vet to figure out what H5N1-type patterns looked like in herds that have gone through it—clusters of sudden mid-lactation milk drops, unusual rumination dips, or patterns tied to a particular pen or fresh cow group. Then bake those patterns into your alert thresholds and standard operating procedures.

- Ask hard questions of new systems. When a vendor is in your kitchen, ask for examples from herds like yours—including herds that have experienced H5N1. Ask, “How many days earlier did this system detect issues compared to bulk tank tests and farm staff?” and “What difference did that make in final case numbers and culling?” Good systems will have case studies; if they don’t, that’s telling.

5. Plan Your “Phone Call Day” Before It Happens

This is something I’ve heard over and over from both vets and producers.

- Define your tripwires. Decide up front what events will trigger a higher-level response: a positive or inconclusive bulk tank result, a sudden cluster of cows with colostrum-like milk, or a confirmed H5N1 herd within your usual trucking radius.

- Pre-plan your responses. For each tripwire, outline the next 24–72 hours: pausing non-essential cattle movement, shifting milking order, increasing PPE in the parlor, pulling individual samples from suspect cows, and calling your herd vet and processor.

- Train your people. Make sure everyone, from the herdsman to the relief milker, knows those steps. The middle of a crisis is a tough time to write and teach a new protocol.

Where Your Next H5N1 Dollar Belongs

By late 2025, USDA surveillance confirmed that over 1,000 U.S. dairy herds across 19 states had been confirmed to have H5N1 infections.

The virus has moved from “that weird thing in Texas” to a background risk we all have to factor into feed decisions, labor planning, fresh cow management, and butterfat targets.

What’s encouraging is that we’re no longer flying blind. We have solid herd-level data from the Ohio case and others, better modeling on how the virus moves through milking strings, clear retail milk safety data, and a defined USDA framework around testing and assistance.

For many 500-cow commercial herds in the Midwest and Northeast US dairy regions, the weight of that evidence points pretty clearly in one direction: the next H5N1 dollar probably belongs in stronger gates, smarter cow flow, and steady surveillance before it goes into more screens in the office.

For larger Western herds, high-value genetics operations, and herds in regions where H5N1 has already become a repeated visitor, adding serious detection technology on top of that prevention foundation can absolutely make sense.

What I’ve consistently seen, talking with producers and veterinarians in different regions, is that the herds that feel best about their choices are the ones that started by tightening the basics, were realistic about their risk, and then chose tools—simple or sophisticated—that made the whole business better: fewer surprises in the fresh group, steadier butterfat performance, fewer mastitis flare-ups, and a clearer plan for the day the lab calls.

The Bottom Line

We still don’t know exactly how long H5N1 will keep pressuring dairy cows, or how the virus might evolve as more data come in. But we do know enough now to make smarter, calmer decisions—and that’s how you keep today’s choices from quietly undermining your herd’s future performance.

In a business built on thin margins, long memories, and a lot of early mornings, that’s a pretty important place to be.

If you do nothing else this month: pick one sourcing change, one quarantine upgrade, and one clear tripwire with your vet—and write them down.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The damage is steep: One Ohio herd lost $950 per clinical cow and $737,500 total—in a single outbreak.

- The spread is invisible: 89% tested positive, only 20% showed symptoms. By the time you see H5N1, it’s already everywhere.

- Prevention beats detection: For most mid-size dairies, tighter gates outperform better dashboards.

- Bulk tank testing is your smoke detector: Cheap and fast—but it only confirms the fire, not prevents it.

- Large herds and elite genetics play by different rules: When exposure is constant, and asset values are high, monitoring tech starts earning its keep.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Biosecurity Changes That Stuck: What Dairy Producers Say Actually Works (And Pays) – Arms you with a field-tested checklist of low-cost biosecurity habits that deliver measurable ROI. It reveals why simple neighbor coordination and traffic management often outperform expensive tech in protecting your milk check from hidden pathogens.

- The Dairy Apocalypse of 2025: Why Your Milk Check Is Disappearing and Who’s Profiting from It – Exposes the “perfect storm” of trade wars and H5N1 market shifts while delivering a survival blueprint for the next five years. It breaks down how to pivot from volume-driven production to aggressive, risk-managed component profit.

- Digital Dairy Detective: How AI-Powered Health Monitoring is Preventing $2,000 Losses Per Cow – Delivers a deep dive into AI systems that identify metabolic crashes five days before clinical signs appear. It provides the technological advantage needed to slash treatment costs by 70% and secure your herd’s genetic future.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!