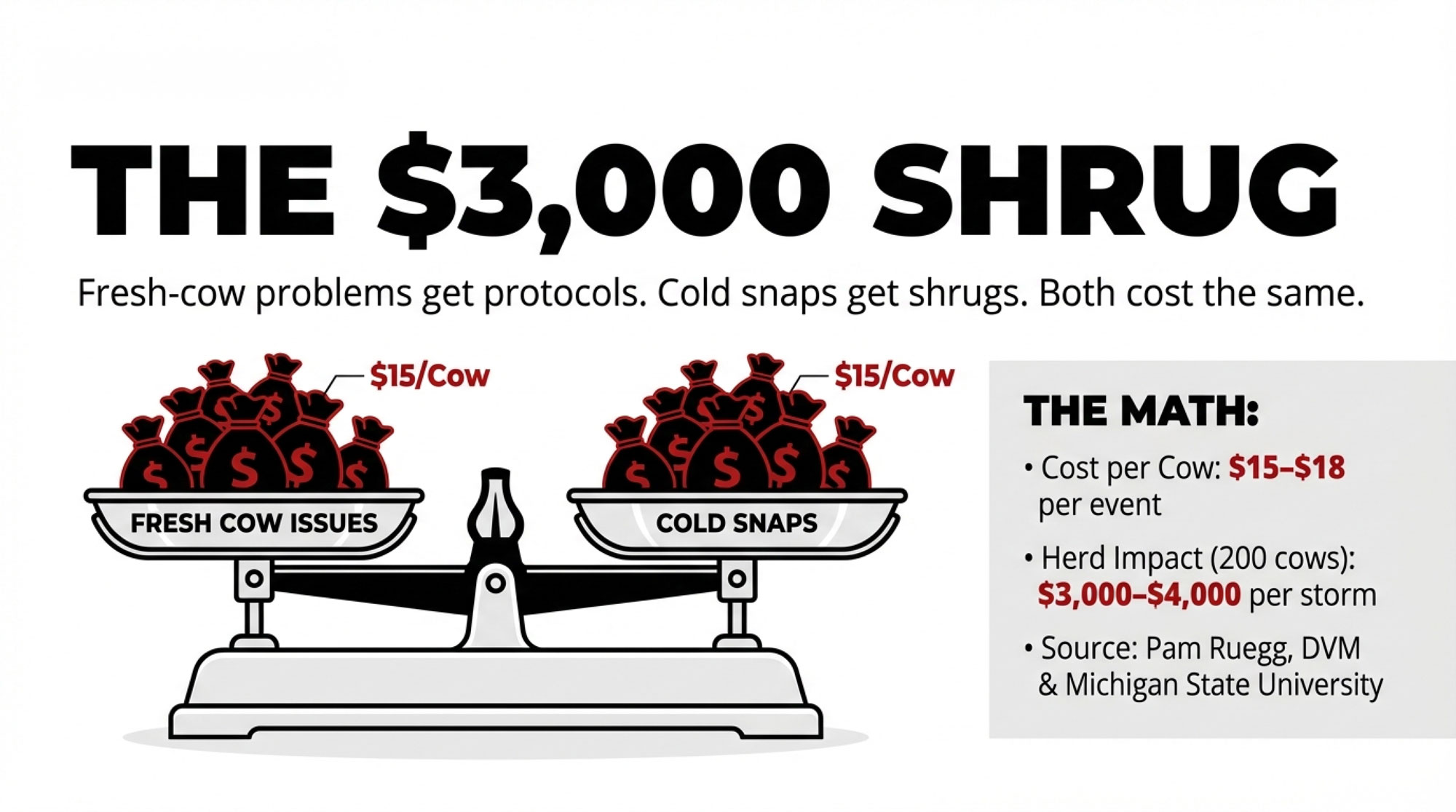

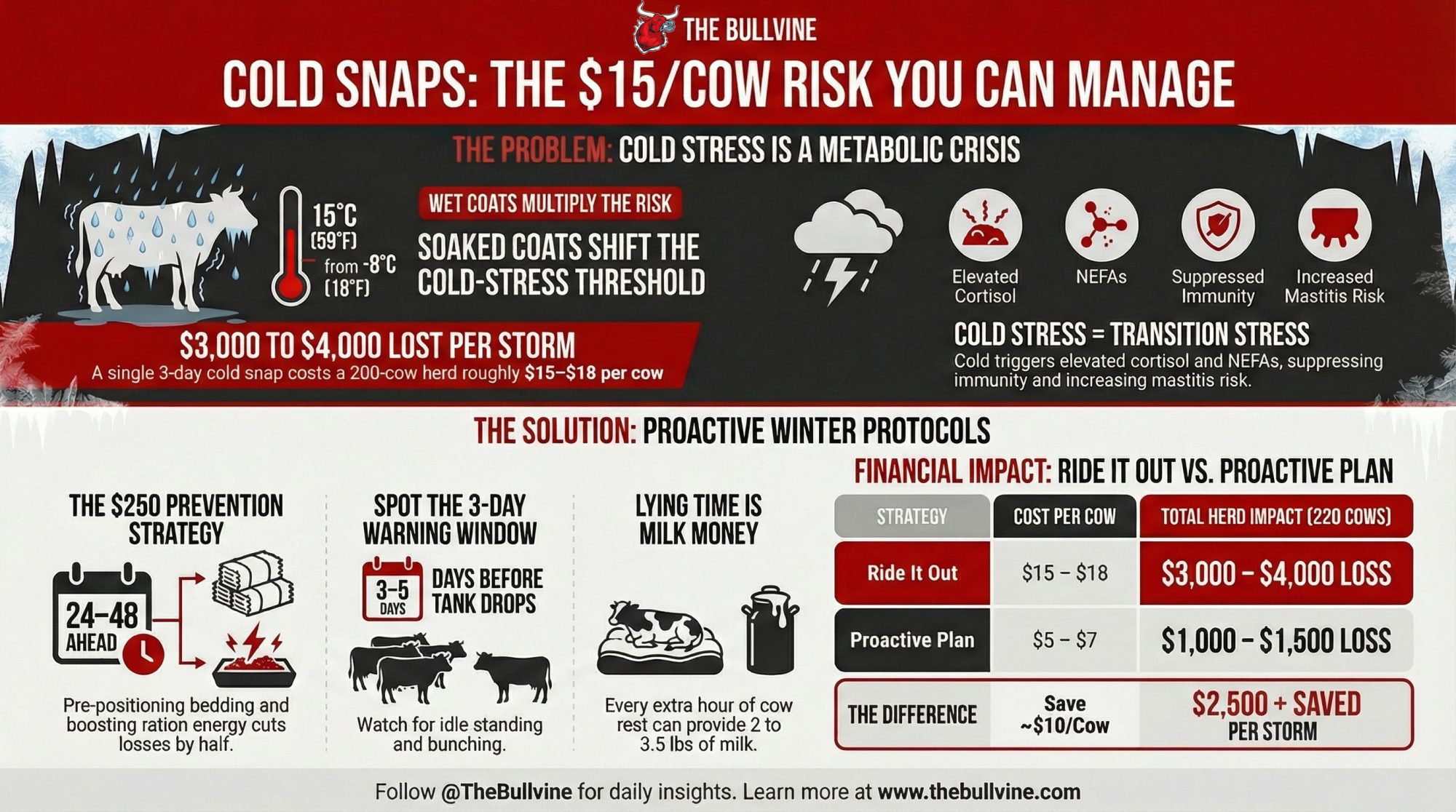

Fresh-cow problems get protocols. Cold snaps get shrugs. Both cost $15/cow. One has a $250 fix that most herds skip.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Most herds have tight protocols for fresh-cow problems but treat cold snaps as weather to ride out—yet both cost roughly the same: $15–$18 per cow per event, or $3,000–$4,000 for a 200-cow herd during a single three-day storm. The connection isn’t coincidental: cold stress triggers the same metabolic cascade as transition challenges—elevated cortisol, spiking NEFAs, and suppressed immunity—which explains why mastitis, lameness, and missed breedings cluster in the weeks after severe cold. What makes this manageable is timing. Cows signal distress 3–5 days before the tank drops through behavioral shifts: increased idle standing, shortened feeding bouts, and bunching in sheltered spots. OMAFRA and Beef Cattle Research Council research confirms that wet coats are the real multiplier, shifting a cow’s cold-stress threshold from -8°C to 15°C and dramatically increasing energy demands. Herds that pre-position $150–$250 in extra bedding and bump ration energy 24–48 hours ahead are cutting losses by more than half, turning a $15/cow storm into a $5–$7 event. The bottom line: cold snaps deserve the same proactive management as calving, and the ROI strongly favors getting ahead of them.

You know how it goes. January turns mean, the wind cuts across the yard, and we slide into that winter routine: check the waterers, push up feed, throw some bedding where it looks worst, and watch for frozen teats or a few cows coughing. It feels like “normal winter chores” when you milk cows where winter actually shows up.

Here’s the thing, though. When you line up newer work from government, universities, and industry with what a lot of good herds are seeing in their own barns, a single cold snap starts to look less like “just winter” and more like a four-figure risk event per herd. The math says these storms can quietly pull three to four thousand dollars out of a 200-cow herd every time they roll through, if you’re not ahead of it. And in a winter where butterfat premiums are making components the profit driver, every pound of lost milk and every tenth of a percent drop in fat hits harder than it would have a decade ago.

Extension specialists are now openly framing winter dairy management as an economic risk because the milk loss, mastitis, lameness, and repro hangover add up fast. The old “they’ll tough it out” mindset still pops up in coffee-shop conversations, but the physiology says something different.

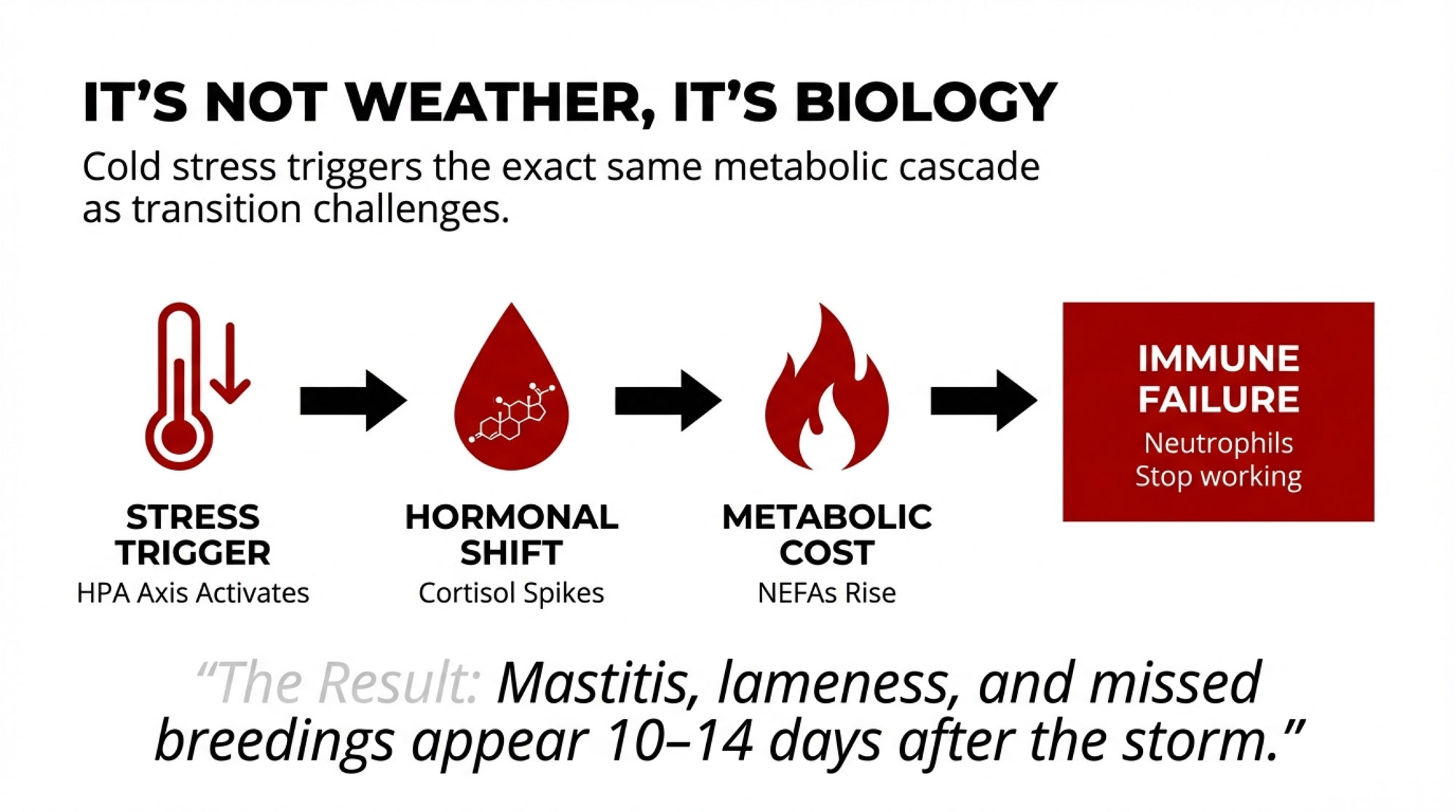

Cold stress isn’t just about the number on the thermometer. Researchers studying cattle in cold environments describe it as a metabolic state within the animal, with shifts in hormones and energy use that look a lot like what we worry about in the transition period. And that’s the part we can manage.

Once you start looking at winter through that lens, a lot of those “mystery January problems” make more sense: the jump in mastitis and pneumonia a week after a brutal cold snap, the dip in lying time right before the tank slides, and the reason two herds under the same winter sky can come out of it with very different results.

Let’s walk through what’s going on, using what the science says and what farms are actually dealing with in Ontario, Wisconsin, the U.S. Northeast, and out in dry lot systems further west.

Dry vs. Wet Coats: Where the Real Math Starts

You probably know this already from winter meetings, but most cold-stress charts start at the same point: the lower critical temperature (LCT). That’s the point where a cow has to start burning extra energy just to keep her core temperature steady.

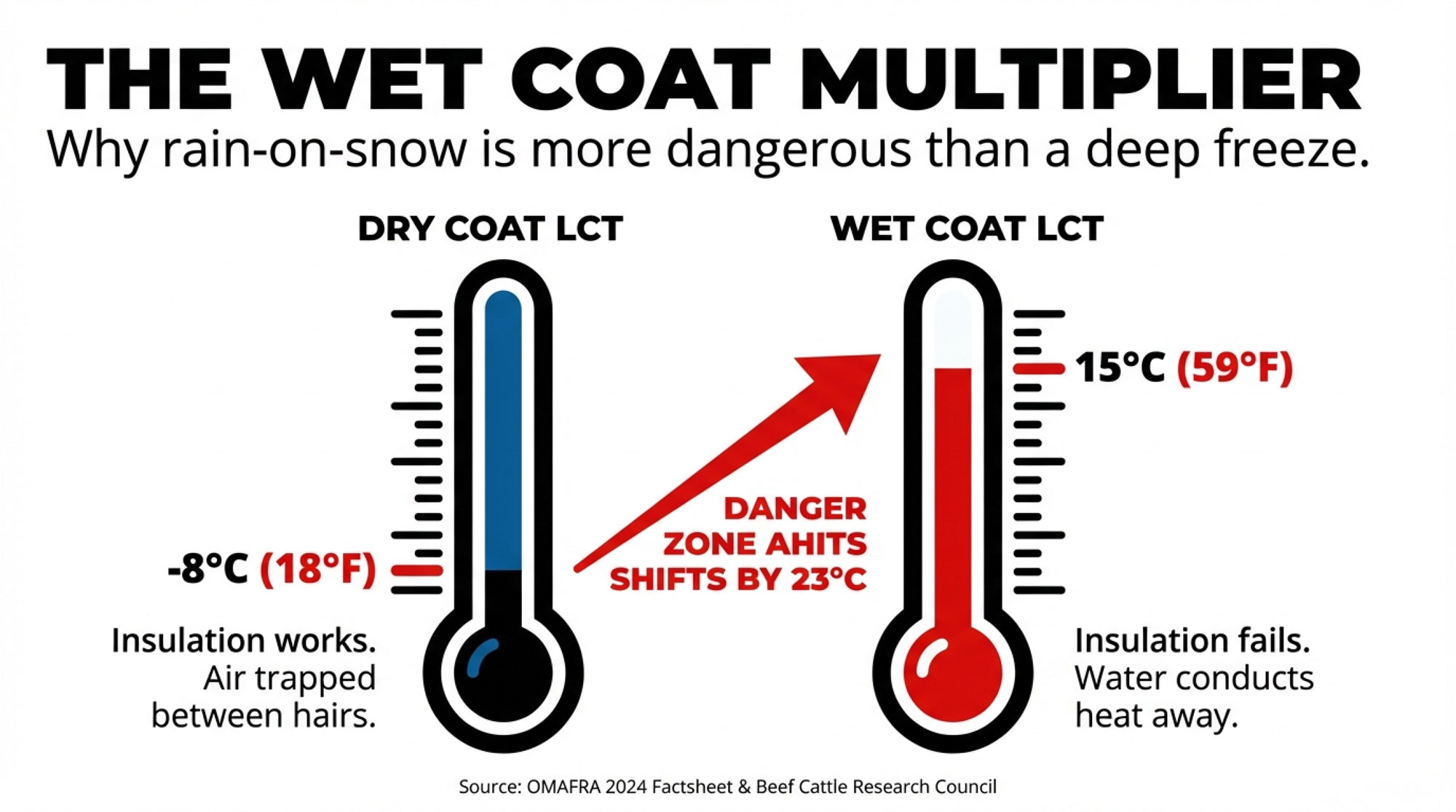

The 2024 “Cold stress in cows” factsheet from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs uses some practical examples based on haircoat. For cattle with a dry, heavy winter coat and decent body condition, they give an example LCT of minus 8 °C (about 18°F) for animals that are dry and sheltered from wind. Alberta’s provincial guidance and the Beef Cattle Research Council’s December 2024 “Winter Management of Beef Cattle” resources use the same basic concept and show that winter-coated cows in good flesh tolerate much lower temperatures than thin or wet animals.

Where cold stress goes from annoying to expensive is when that coat is wet, and the wind comes up.

OMAFRA notes that when a heavy winter coat becomes wet, its insulating value drops sharply, and cold stress is amplified even at temperatures that would otherwise be tolerable. The Beef Cattle Research Council’s tables show that the estimated LCT for cattle with a wet coat jumps to around 15°C—that’s about 59°F. So a cow with a soaked coat can start to feel cold stress at temperatures in the high single digits Celsius, or the 50s Fahrenheit, instead of down near freezing.

Going from dry to wet can effectively shift that cold-stress threshold upward by several tens of degrees Fahrenheit. You don’t need a research paper to relate to that. Anyone who’s worn a soaked parka in a stiff north wind knows how fast the chill goes straight to the bone.

| Coat Condition | Lower Critical Temperature (°C) | Lower Critical Temperature (°F) | Estimated Energy Increase* |

| Dry winter coat, sheltered | -8°C | 18°F | Baseline |

| Dry winter coat, light wind | -3°C | 27°F | +10% energy demand |

| Wet coat, sheltered | 5°C | 41°F | +26% energy demand |

| Wet coat, 20 mph wind | 15°C | 59°F | +60% energy demand |

The physics make sense when you think about it. A dry winter coat traps air between the hairs, and air doesn’t conduct heat very well. Once that haircoat is wet, water replaces the trapped air, and water carries heat away from the body much faster. Add wind, and now cold air is being driven through that wet coat, pulling heat off the cow at a much higher rate. OMAFRA notes that if the animal is wet or dirty, their wind-chill tables actually underestimate the effect.

The Energy Math

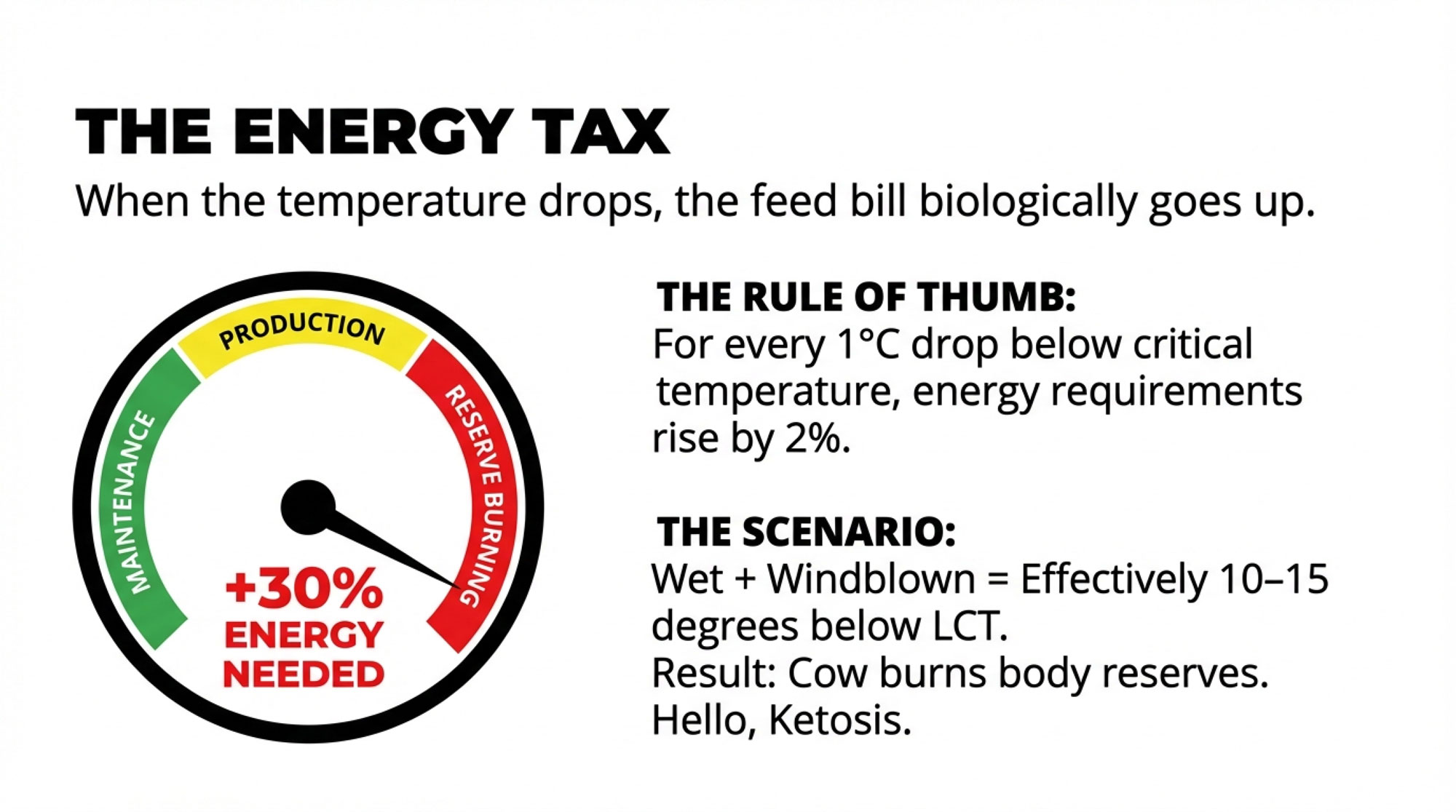

Here’s where the simple rule of thumb comes in. OMAFRA’s factsheet and the Beef Cattle Research Council’s winter-management resources both use the same guideline: for every 1 degree Celsius the effective temperature drops below a cow’s lower critical temperature, her energy requirement increases by about 2%.

Kansas State and Ohio State extension materials express it slightly differently for American audiences—roughly 1% more energy per degree Fahrenheit below LCT—which works out to the same math when you convert.

If you think about a situation where—because of a wet coat and some wind—the effective environment is ten to fifteen degrees Celsius below that cow’s LCT, you’re realistically looking at maintenance energy needs that could be twenty to thirty percent higher than on a calm, dry winter day.

If intake doesn’t keep up, she has to find that energy somewhere. In many cases, that “somewhere” is body reserves, and that’s when we start walking into transition-style problems.

Cold Stress Feels a Lot Like a Transition Problem

What farmers and advisors are finding—and what the research is now backing up—is that cold stress has more in common with transition-period stress than most of us were taught.

A 2023 review in the journal Animals by Kim and colleagues at Chungnam National University pulled together data on how beef cattle respond to cold stress. They showed that when cattle are exposed to low temperatures, you see the classic stress response: the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis kicks in, cortisol rises, heart rate changes, and energy metabolism shifts. Their work showed significant increases in non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) and changes in standing and lying behavior under extreme cold conditions.

Cortisol isn’t “bad” in the short term—it helps the animal cope by freeing up glucose and other substrates, allowing her to generate more heat. The trouble is when that elevated state drags on.

The Physiology in Plain English

Hoard’s Dairyman and several transition-cow reviews have compared cows entering calving with different levels of NEFA and ketone bodies. Cows with higher NEFA and beta-hydroxybutyrate tend to have more metritis, more displaced abomasums, and more early-lactation health issues.

Here’s the barn-level translation: when a cold snap pushes a cow deeper into negative energy balance, she’s not just cold—she’s more vulnerable to mastitis, metritis, and missed heats.

On the immune side, work looking at neutrophils from high-NEFA, low-glucose cows have shown that those cells are less capable of migrating to infection sites, engulfing bacteria, and killing them. Think of it this way: it’s like asking the immune system to do a full day’s work on half a tank of fuel.

Recent reviews of stress and behavior in dairy cattle, including a 2024 paper in Frontiers in Veterinary Science, keep returning to the same triangle: stress hormones, elevated NEFA, and a compromised immune response that manifests as more disease and lost production.

And reproduction? It sits downstream from all of this. Studies examining cows with higher NEFA and BHBA levels in early lactation consistently show more days open and lower conception rates. When winter pushes cows deeper into energy deficits and bumps up mastitis and lameness risk, fertility doesn’t tend to improve.

So when you and I ask, “Are the cows cold?”, the more useful follow-up question is, “Are we quietly adding transition-style stress to cows that are already working hard?”

Lying Time: The Quiet Number That Moves Your Tank

So far, we’ve been talking about internal biology. Let’s step back into the barn and talk about something you can see without a blood test: how many hours a day cows actually spend lying down.

Over the last decade, Cassandra Tucker’s group at UC-Davis and others have put a lot of effort into understanding lying behavior in dairy cows. A summary of her work, shared through Cornell Extension, notes that most lactating cows lie down for 10 to 12 hours per day when conditions are good. Some researchers suggest that 12 to 14 hours may be optimal, and illustrate how herds with very high lying times achieve strong performance and health.

When cows get significantly less rest than that, the wheels start to wobble. Time-budget and welfare studies have linked reduced lying time to higher lameness risk, more udder problems, and lower milk yields.

Many of you have seen the practical side of that: the pen where cows spend more time milling around on the concrete is usually the one where hoof-trimmer day is more interesting, and the tank isn’t as pretty.

| Day | Event Phase | Lying Time (hrs/day) | Milk Yield (kg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

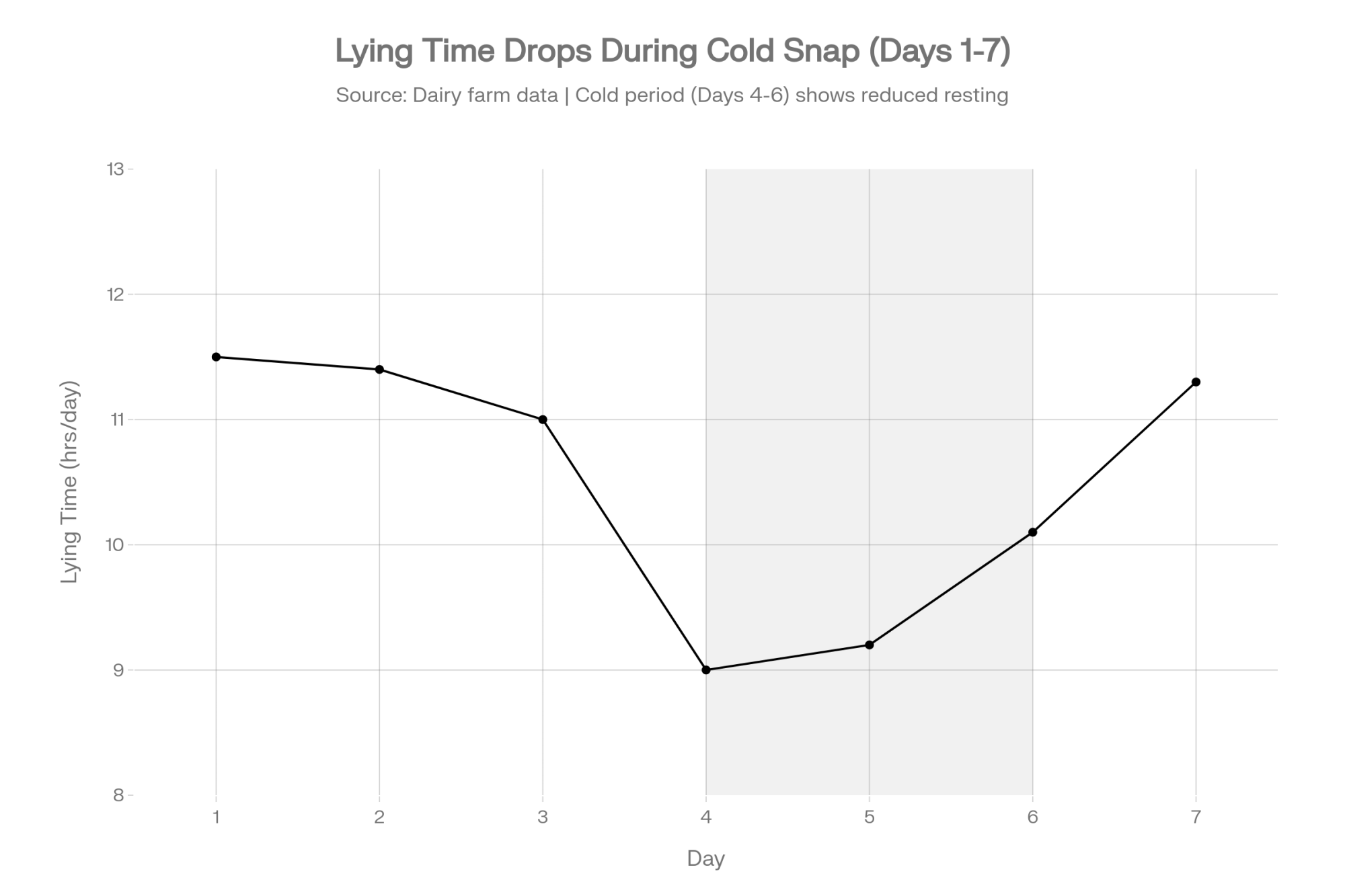

| Day 1 (Mon) | Pre-event baseline | 11.5 | 37.8 |

| Day 2 (Tue) | Pre-event baseline | 11.4 | 37.6 |

| Day 3 (Wed) | Pre-event (behavioral shift begins) | 11.0 | 37.4 |

| Day 4 (Thu) | Cold snap – full stress | 9.0 | 34.8 |

| Day 5 (Fri) | Cold snap – ongoing | 9.2 | 35.2 |

| Day 6 (Sat) | Cold snap – ending | 10.1 | 36.1 |

| Day 7 (Sun) | Post-event recovery | 11.3 | 37.2 |

The Math That Gets Everyone’s Attention

Miner Institute work, echoed in Cornell extension materials, reports that each additional hour of rest per day can be associated with roughly 2 to 3.5 pounds of extra milk per cow per day in freestall herds, depending on the herd and conditions. It’s become a practical rule of thumb across the industry.

If cold or drafty conditions shave two hours off a pen’s lying time, you could reasonably see something like three to seven pounds less milk per cow per day. At current winter milk values in Canadian and northern U.S. component markets, that’s not a rounding error.

And here’s something to keep in mind: for herds paid on components, those three to seven pounds of lost winter milk often come with softer butterfat performance, which hits the milk cheque twice.

Deprivation studies show that cows prevented from lying down exhibit clear signs of stress—restlessness, altered behavior, and, in some trials, short-term drops in milk yield and changes in udder health markers. That lines up with what producers across the Midwest and Ontario have said for years: cows that don’t get their rest just seem more fragile, and udder trouble finds them more easily.

While lying time sometimes gets treated as a soft welfare number, it’s actually a hard performance metric. It connects comfort, milk yield, lameness, udder health, and the smoothness of your transition program.

Behavior as an Early Warning System

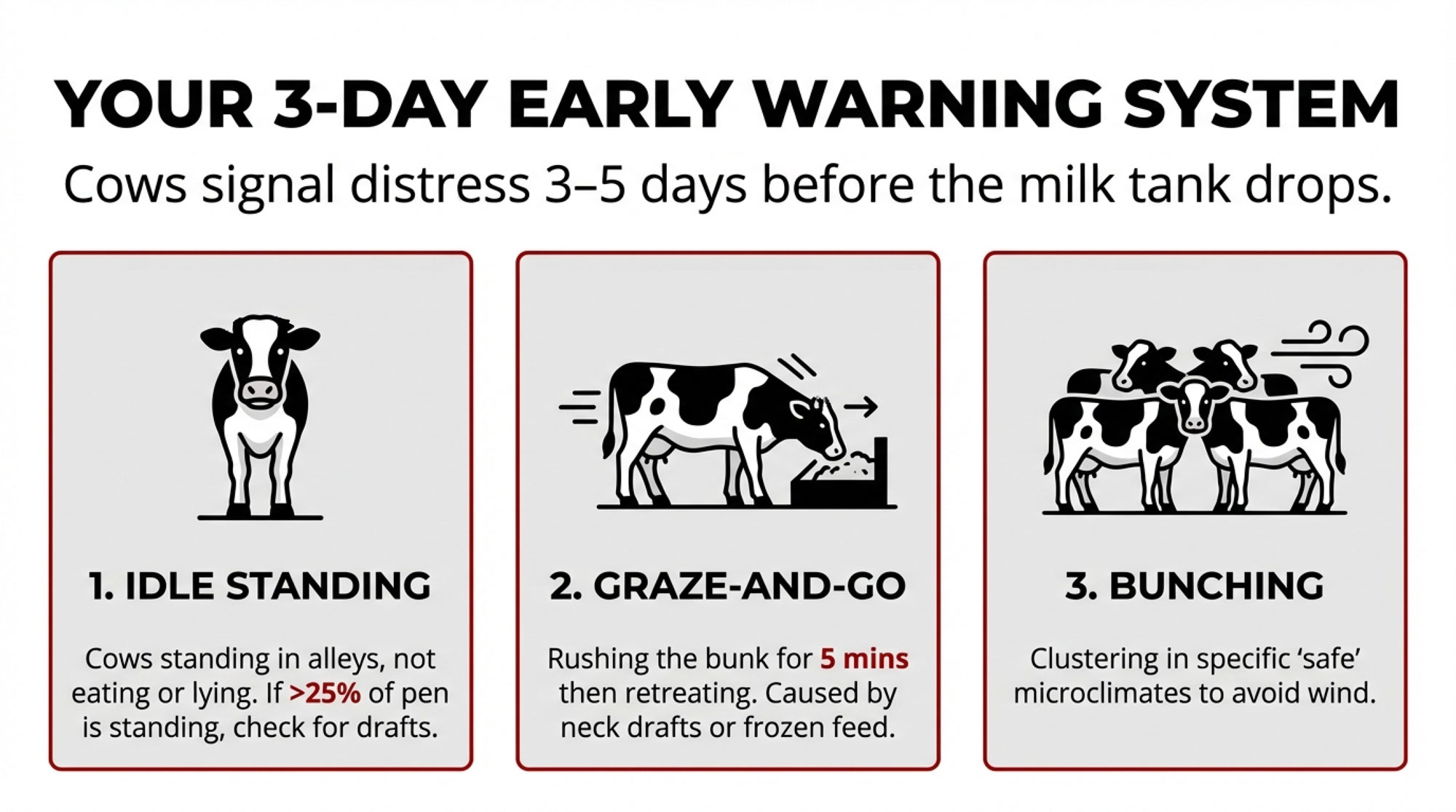

What’s encouraging in all of this is that cows almost always tell us something is off before the milk graph or the mastitis list does. They tell us with behavior.

When you look at the research and then talk to producers in places like Ontario, Wisconsin, upstate New York, or the Prairies, three winter behavior patterns keep showing up as useful early warning signs.

| Timeline | Behavioral Sign | What’s Happening Physiologically | Action to Take | Cost of Inaction |

| Day –5 to –3 Before Cold | Subtle increase in idle standing; cows lingering in feed bunk longer | Early cortisol rise; NEFAs beginning to climb; immune system loosening | Increase ration energy 10–12%; monitor lying time. No visible herd cost yet. | Missed prep window |

| Day –2 to –1 (48 hrs out) | Obvious bunching in preferred spots; shortened “graze-and-go” feed bouts (5–10 min); dry-lot cattle seeking windbreaks | Cortisol elevated; tissue mobilization accelerating; draft/wind sensitivity acute | Order extra bedding NOW; adjust curtains; brief staff on observation protocol | Risk of frozen feed; inadequate bedding |

| Day 0–2 (Cold Snap Active) | Marked reduction in lying time (from 11.5 to 9 hrs); more than 25% of pen standing idle; feed intake visibly reduced | Acute metabolic stress: NEFAs spiking, immune cells compromised, milk production dropping | Increase monitoring to 2×/day; watch for clinical signs (coughing, lameness); ensure water is flowing | Rapid decline in milk; clinical mastitis risk |

| Day 3–5 (Post-Cold, First Week) | Lying time recovering slowly; some cows still bunching; initial clinical cases (lameness, mastitis, pneumonia) appear | Transition-style cascade: High NEFA persisting, neutrophil dysfunction, barrier integrity compromised | Continue elevated ration energy; intensify clinical observation; treat emerging cases aggressively | Cascading health issues; $120–$300/mastitis case |

| Day 6–7 (Recovery Phase) | Lying time returning to baseline; bunching dispersing; most herds stabilizing | Metabolic recovery underway; immune response ramping back up if no secondary infection established | Return ration to baseline gradually; document all cases for winter protocol refinement | Missed learning opportunity |

Too many cows just standing idle. If you walk a freestall pen at a quiet time and see a big chunk of cows just standing in the alleys—no headlocks, not really eating, not at the water—that’s worth paying attention to. Experienced cow-comfort consultants often use a simple rule during barn walks: if roughly a quarter or more of the cows in a pen are just standing around during a quiet period, it’s time to take a harder look at stall comfort and drafts.

In winter, common culprits are cold stall surfaces, thin bedding on mats or mattresses, or a draft across the platform at cow height. Ventilation specialists from groups like Lactanet routinely use smoke tests or handheld airflow meters to show how a small leak in a curtain can turn the outside row into the “avoid” zone for cows.

“Graze-and-go” at the feed bunk. Under decent conditions, feeding-behavior research suggests that cows spend about 3 to 5 hours per day eating, broken into roughly 9 to 14 meals. In winter barns where drafts or freezing feed are a problem, producers often describe a different pattern: cows rush to the bunk, grab a quick bite for maybe five or ten minutes, and then back away—even though there’s plenty of TMR in front of them.

Winter-feeding articles have warned about this: frozen TMR and cold air blowing on cows’ necks at the bunk reduce palatability and discourage a calm, steady meal.

Bunching in the same “safe” spots. If the same group is using the same “preferred” spot at mid-morning, mid-day, and late afternoon, and there’s no obvious feed or water reason, that area is probably offering a nicer microclimate: a little less draft, perhaps a bit warmer, often just drier.

What’s powerful here is that these patterns—more idle standing, shorter feed bouts, consistent bunching—often show up several days before there’s a noticeable change in milk yield, SCC, or disease incidence. That gives you a window—often three to seven days—to fix drafts, deepen bedding, or adjust the ration before the costs show up.

Year One vs. Year Two: A Real-World Comparison

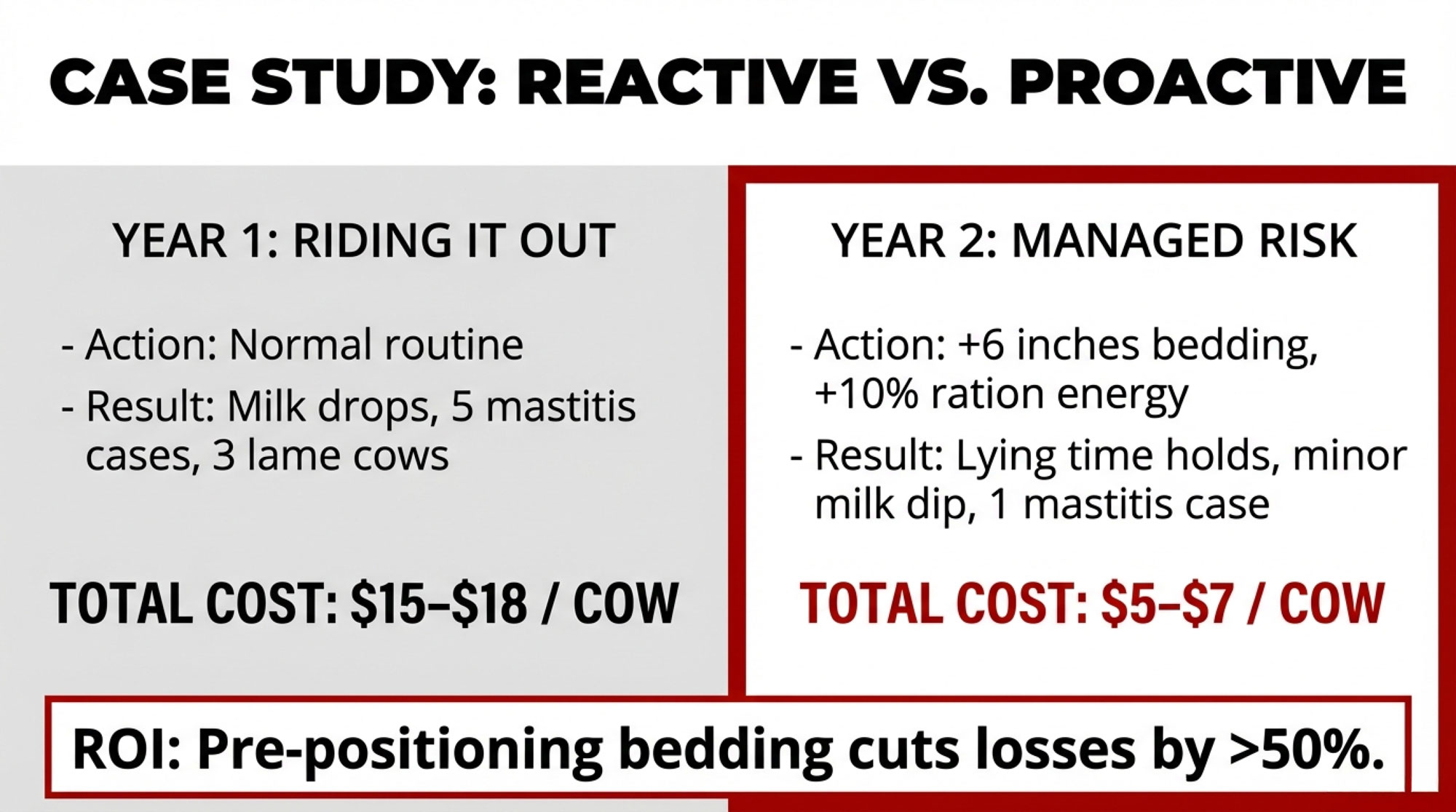

Let’s walk through a realistic scenario. This isn’t a single farm; it’s a composite of what several sand-bedded freestall herds in Ontario and the Upper Midwest have described, and it aligns well with the economic data.

Year One: Riding It Out

A 220-cow Holstein herd in sand-bedded freestalls, shipping around 36–38 kilograms of milk per cow per day with solid butterfat performance. A three-day cold snap hits: daytime highs around minus ten, overnight lows near minus eighteen, winds around twenty miles an hour, and one night of freezing drizzle.

The farm does what many of us would recognize as “being prepared”—waterers checked, modest ration energy bump, extra bedding tossed into obviously wet stalls, curtains at their usual winter setting.

Cows wearing leg-mounted accelerometers show average lying time dropping from about 11.5 hours a day down to roughly nine. More cows than usual stand idle in the alleys. Some TMR sections freeze overnight.

Milk drops by roughly two to three kilograms per cow per day and takes close to a week to climb back to baseline. Five new clinical mastitis cases show up over the next 10 to 14 days, mostly due to environmental organisms. Three new lame cows are identified.

Economic work led by Pam Ruegg, DVM, MPVM, at Michigan State University, along with a 2023 study of 37 Wisconsin dairy farms published in the Journal of Dairy Science, estimates the cost of a clinical mastitis case at about $120 to over $300 per case. Those five cases cost somewhere in the $600–$1,500 neighborhood. Add lameness costs, lost milk, and knock-on effects on fresh cows, and the total impact of that single cold event comes to roughly $3,000 to $4,000.

Divide that by 220 cows, and you’re looking at $15–$18 per cow for one storm.

Quick math for your herd: multiply your cow count by $15 to see what a single bad storm might cost you.

Year Two: Treating It Like a Manageable Risk

The next winter, a similar cold snap is on the way. This time, the farm treats it more like a transition-pen challenge—something you plan for.

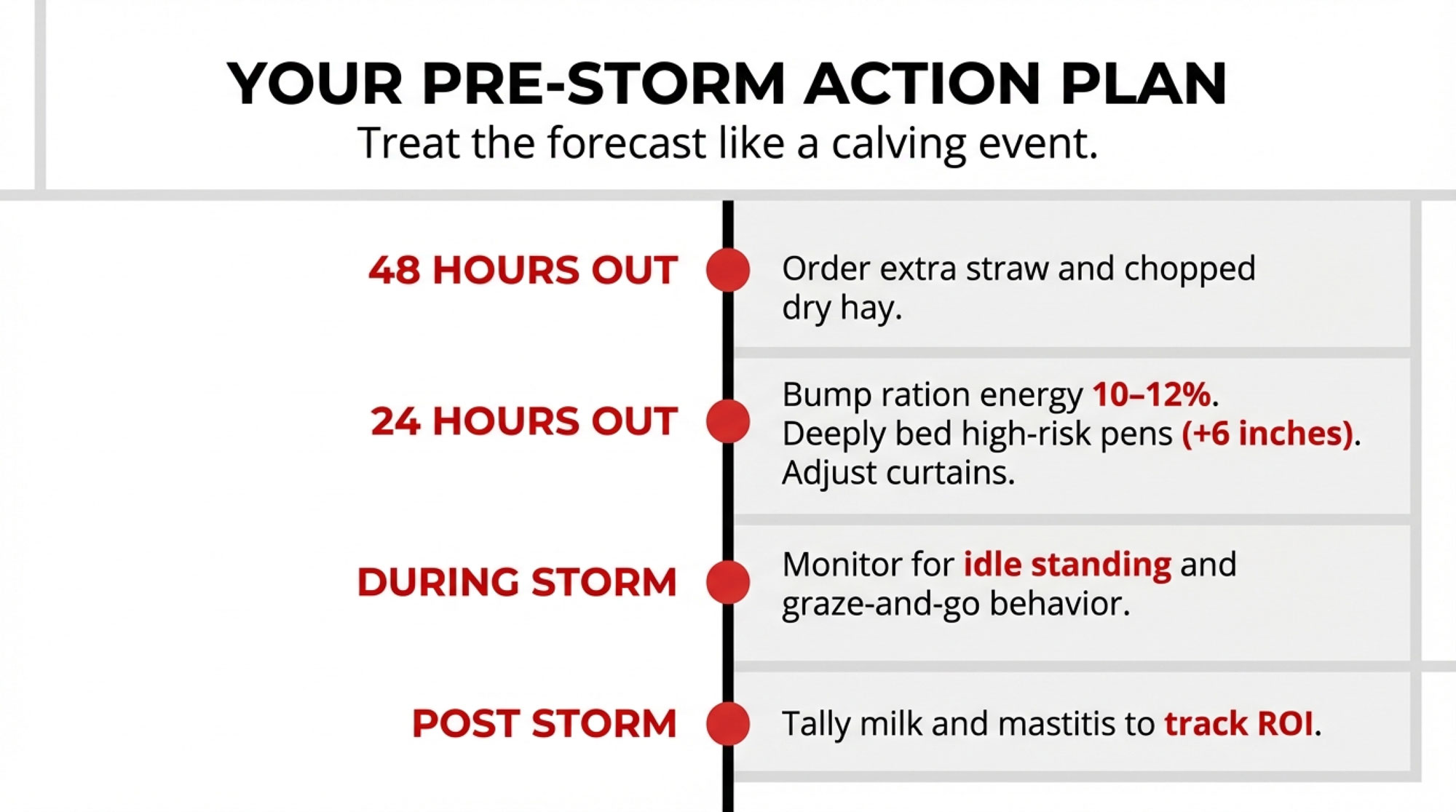

A Midwest nutritionist summed up the mindset shift at a recent winter cow-comfort workshop: “We’ve started thinking about cold snaps the same way we think about calving—get ahead of it, watch the right numbers, and don’t be cheap on bedding.”

Forty-eight hours out, they order extra straw and chopped dry hay. They bump the ration’s energy density by about 10 to 12 percent and start feeding that adjusted ration the day before the cold hits. Staff are briefed to flag immediately any idle standing, short feed bouts, or unusual bunching.

Twenty-four hours out, all stalls in high-risk and fresh-cow pens get an extra six inches of straw and chopped hay—roughly three tons of bedding, about $150–$200. Curtains on the windward side are adjusted down to reduce drafts at cow height.

During the cold snap, lying time bottoms out around 10.5–11 hours instead of dropping to nine. Milk still takes a hit, but it’s smaller and shorter: two to three pounds for a few days, back to baseline within three days. One clinical mastitis case, no obvious lameness spike.

The extra bedding and labor cost around $250. Total impact: closer to $1,000–$1,500.

Spread across 220 cows, that’s $5–$7 per cow instead of $15–$18.

| Cost Component | Year One | Year Two | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedding & Labor | $0.00 | $1.82 | – |

| Milk Loss (kg × milk price) | $6.82 | $2.27 | $4.55 (67% reduction) |

| Mastitis Cases (5 vs. 1) | $6.36 | $1.27 | $5.09 (80% reduction) |

| Lameness Costs (3 cases vs. 0) | $1.82 | $0.00 | $1.82 (100% reduction) |

| Total per Cow | $15.00 | $5.36 | $9.64 (64% reduction) |

It’s not a randomized controlled trial, but the pattern lines up well with mastitis-cost studies, lameness economics, and energy-requirement math. It also mirrors what many producers describe when they compare winters in which they “rode it out” to those in which they went in with a plan.

Different Systems, Different Levers

While the cow’s biology is the same whether she’s in a 300-cow freestall in Ontario or a 2,000-cow dry lot in southern Alberta, the levers you pull look different.

| System Type | Key Winter Levers | Primary Risk Factors |

| Freestall (Ontario, Wisconsin, NY) | Bedding depth, stall surface temperature, cow-level wind protection, ration energy density | Freezing rain, soaking coats, drafts on outside rows, ice in crossovers |

| Compost/Bedded Pack(NY, MN, Quebec) | Pack depth and dryness, drainage, airflow balance | Closing the barn too tight creates a damp pack; wet bedding kills the insulation value |

| Dry Lot/Outwintering(Prairies, Western U.S.) | Windbreaks, dry bedded mounds, feed/water placement, pre-winter body condition | Open exposure, mud, wind without shelter |

| Calf Housing (All regions) | Extra bedding, calf jackets, and higher-energy liquid feeding | Thermoneutral zone 15–25°C (MSU); much higher than adult LCT |

Beef Cattle Research Council fact sheets show clearly that cattle with adequate wind shelter and dry lying areas maintain body condition and performance much better than those on open, muddy, windy ground. Dairy dry cows and heifers sharing those environments follow the same rules.

And for calves—pre-weaned calves under three weeks of age have a thermoneutral zone approximately between 15°C and 25°C (roughly 59 to 77°F), according to resources from South Dakota State, Michigan State, and Canadian calf-care programs. That’s a lot higher than the LCT for adult cows with winter coats. Extra bedding, calf jackets, and higher-energy liquid feeding during cold snaps aren’t pampering—they’re matching the biology.

Why Winter Risk Feels Bigger Now

If it seems like winter is more of a financial and health risk factor than it used to be, you’re not imagining it.

| Category | Year One (Reactive) | Year Two (Proactive) |

|---|---|---|

| Bedding & Labor | $0 | $1.14 |

| Ration Energy Bump | $0 | $0.68 |

| Post-Storm Milk Loss | $6.82 | $2.27 |

| Disease/Lameness | $8.18 | $1.36 |

| Total per Cow | $15.00 | $5.45 |

Kim and colleagues, in their 2023 review, cite IPCC projections, noting that winter extreme weather events are likely to become more frequent in the near future. Climate-trend work looking at Canadian dairy regions has started documenting what many of you have noticed: more variable winters, more frequent swings, more rain-on-snow events.

Think about a scenario that’s becoming more common in Ontario and the Great Lakes: a couple of mild, rainy days in January, then a hard turn to minus fifteen with wind. That’s exactly the wet-coat-to-cold transition where OMAFRA’s LCT math tells us cows can suddenly be far more stressed than the air temperature alone would suggest.

On top of that, genetics, nutrition, and much tighter fresh cow management have pushed production higher. That’s great for the milk cheque, but it means cows are running closer to their metabolic ceiling. The margin for error around extra stress—whether it’s heat stress in summer or cold stress in winter—is smaller than it used to be.

Can the winter plan that “worked fine” for 60-pound herds twenty or thirty years ago really keep 90-pound herds out of trouble today?

In a lot of ways, cold stress feels like where fresh cow problems were a couple of decades ago. Back then, milk fever, retained placenta, and early-lactation mastitis were often shrugged off as “things that happen.” As more research and field data came in, we reframed those issues as largely preventable and closely tied to diet, cow comfort, and transition-period management.

Cold stress is walking down a similar path. The farms still treating January like it’s 1995 are going to keep wondering why their fresh cows struggle every spring.

What You Can Do This Winter

If we were sitting around the farm office, and you wanted a few core ideas to bring back to your team, here’s how I’d boil it down.

The Big Picture

- Cold stress is defined by what happens inside the cow, not just by the thermometer. Haircoat condition, moisture, and wind speed at cow level matter just as much as what the weather app says.

- Wet coats and wind are the big game changers. OMAFRA and BCRC data show that soaking a winter coat can raise the temperature at which cold stress begins from around minus eight degrees Celsius to fifteen degrees Celsius. You’ll almost always get more return by keeping cows dry and cutting drafts at cow height than by trying to “heat” a barn.

- Behavior gives you a head start. Idle standers, short “graze-and-go” feeding bouts, and repeated bunching show up days before milk, SCC, or disease data tell the story.

- Lying time is a powerful indicator. Ten to twelve hours of daily lying time is where high-producing cows do best, and each extra hour of rest can be worth a couple of pounds of milk or more.

- Deep, dry bedding usually pays for itself. Spending roughly a dollar per head before the storm vs losing $10–$15 per head afterward is the kind of math that wins in a tight-margin year.

Your Pre-Storm Checklist

- Set a lying-time and idle-standing threshold for each pen. Know what “normal” looks like so you can spot drift early.

- Build a simple pre-storm bedding and ration protocol. Order extra straw or dry hay 48 hours ahead, bump the ration energy the day before, and make curtain adjustments on a schedule.

- Decide how you’ll watch behavior—sensors, pen walks, or both. Make it somebody’s job to track lying, standing, and bunching patterns and flag changes quickly.

- Have a post-storm huddle to tally milk, mastitis, and lameness. If you don’t track it, you can’t improve it—and you won’t know if your pre-storm investments are paying off.

The Bottom Line

Yes, extra bedding and ration tweaks cost money. But the real winter choice usually isn’t “spend or save.” It’s whether you pay upfront for bedding and energy, or pay later for milk, mastitis, and days open.

Once you start treating cold stress the same way you treat the transition period—something you monitor, anticipate, and actively manage—the “mystery problems” that show up in January and February become a lot less mysterious. They become part of a plan you can actually influence.

And in a business where margins are tight and cows are bred to work hard, turning winter from something that happens to you into a risk you manage isn’t just better for the cows. It’s better for the tank, the treatment log, the breeding board, and the butterfat performance that’s actually paying the bills this winter.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- $15–$18 per cow, every storm—a single three-day cold snap costs a 200-cow herd roughly $3,500, yet most operations still treat winter as weather to endure

- Cold stress hits like a fresh-cow problem—same physiology (spiking cortisol, elevated NEFAs, suppressed immunity), same downstream costs (mastitis, lameness, days open)

- Your cows warn you 3–5 days early—idle standing, shortened meals, and bunching in sheltered spots signal cold stress before the tank does

- Wet coats are the multiplier—a soaked haircoat shifts cold-stress threshold from -8°C to 15°C, which is why rain-before-freeze hits hardest

- $250 in prep beats $3,500 in losses—pre-storm bedding and ration bumps cut per-storm costs by more than half

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Forget Keeping Barns Warm: Why Winter’s Your Most Profitable Season – Arms you with the immediate maintenance hacks and ventilation targets needed to transform your barn from a damp bacteria factory into a high-component profit center. Stop guessing on curtain heights and start protecting your winter milk cheque today.

- Unlocking Cow Comfort: The Hidden Driver of Milk Production in 2025 – Delivers the strategic blueprint for 2025, proving why bedding is your highest-return investment. Break away from old-school crowding mindsets to safeguard your herd’s long-term production ceiling and financial resilience in a tightening market.

- Ditch the Daily Walks: How Precision Monitoring Cuts Labor by 40% While Boosting Transition Success – Reveals how precision monitoring predicts metabolic crashes up to five days before clinical signs appear. Replace the “eyeball test” with data-driven transition protocols to slash labor costs and future-proof your herd’s metabolic performance.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!