Spending $2,000 to raise a heifer because she’s got more white? Genomics says that’s a losing bet. Beef-on-dairy says there’s $4+/cwt on the table.

If we were sitting over coffee at a winter meeting in Ontario or Wisconsin, you’d probably hear someone say, “Those white cows just seem to last,” or “I like that kind of pattern; they’re my kind.” A lot of us grew up with that way of thinking. For decades, the way a Holstein looks—her color, pattern, and style—has sat right beside milk records, butterfat levels, and fresh cow management notes when we’ve made breeding decisions, just like breed associations and coat‑color labs still describe for Holsteins today, especially around the red factor and MC1R work coming out of places like the University of Saskatchewan and VHLGenetics.

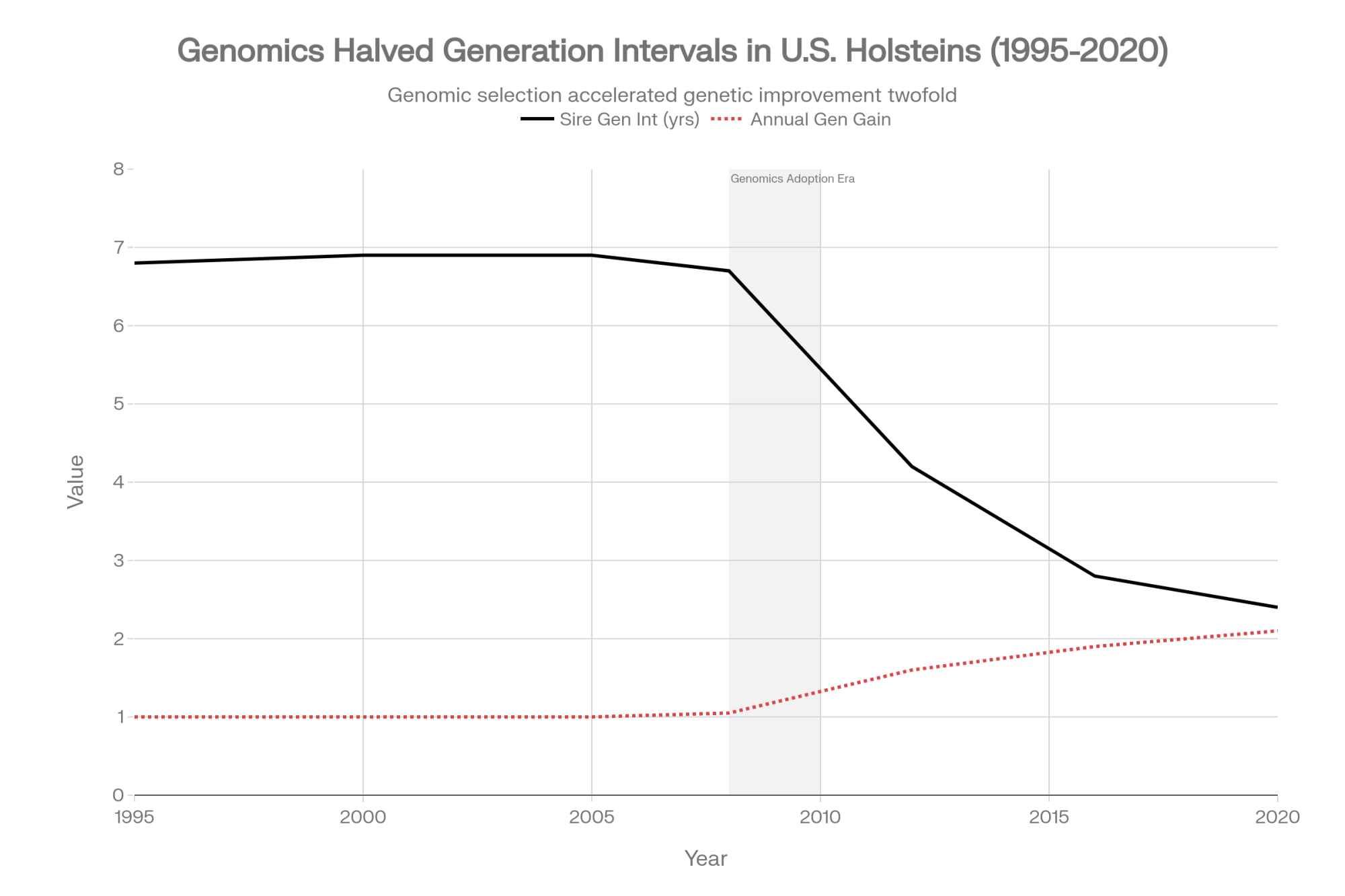

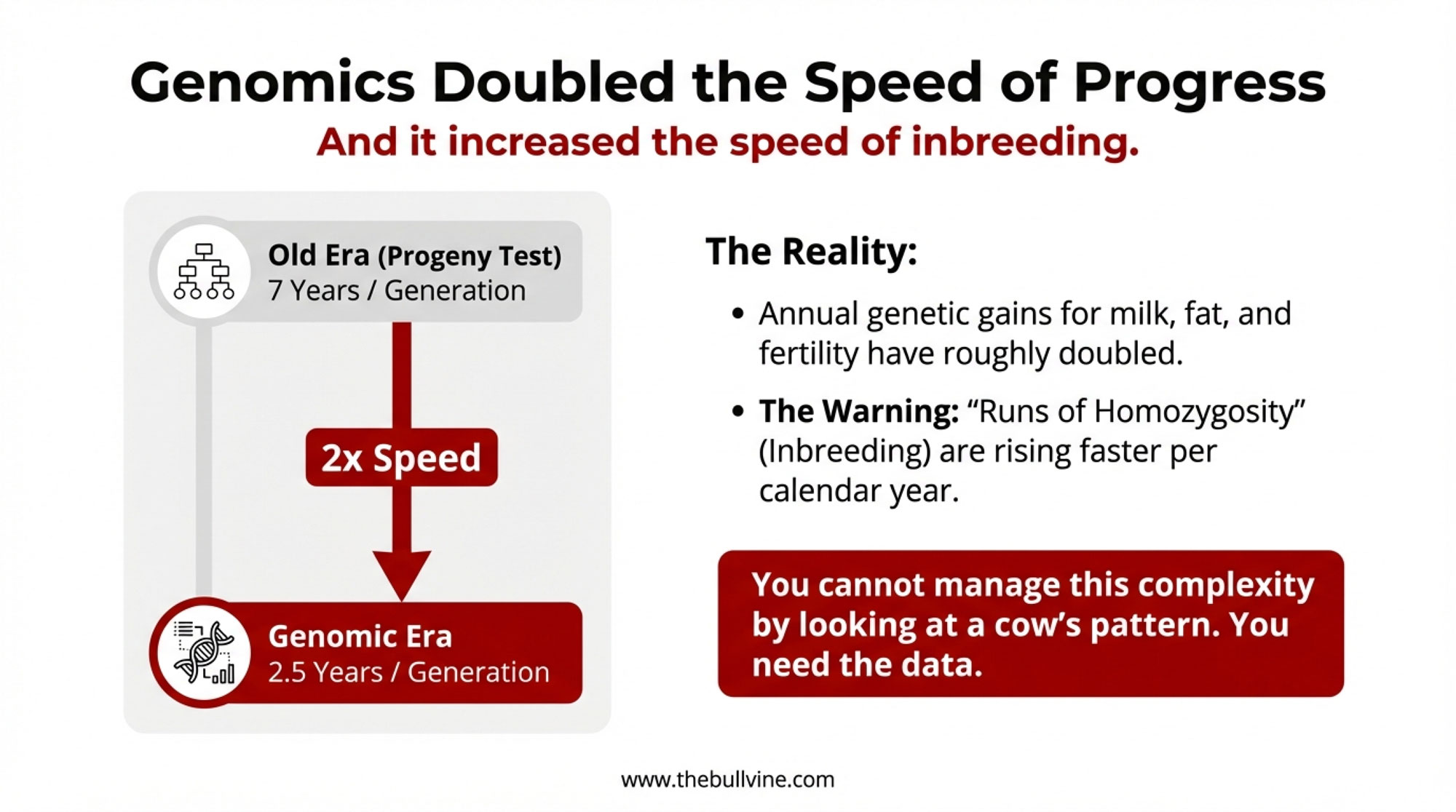

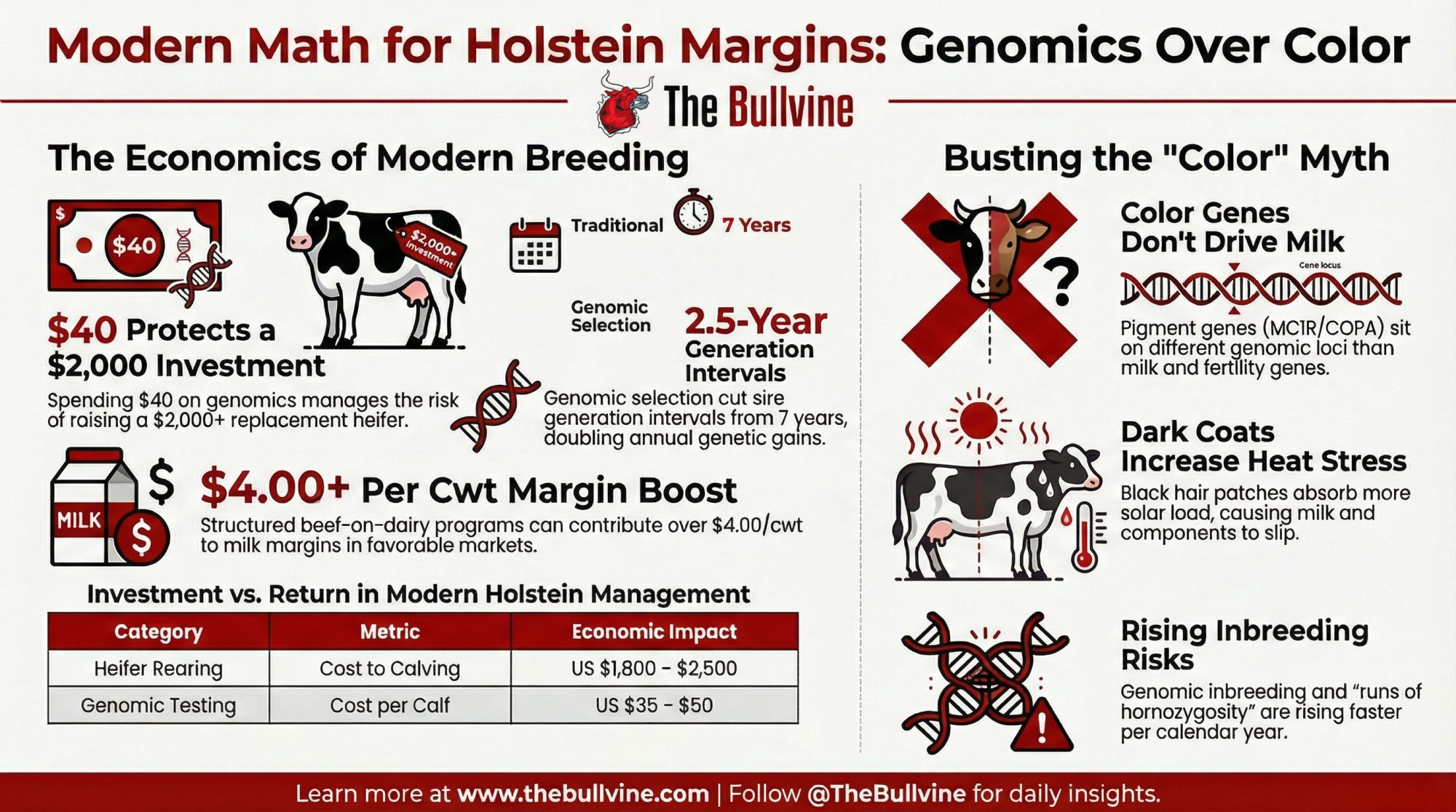

Here’s what’s interesting in 2025. The ground under that old habit has shifted. Genomic evaluations, population‑genetics work on inbreeding, new heat‑stress research, and some pretty eye‑opening 2025 beef‑on‑dairy economics are all pointing in the same direction: your eye still matters a lot, but it’s no longer the sharpest tool for predicting which calves will pay back rearing costs and stay productive through multiple lactations. A big U.S. Holstein study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that once genomic selection came in, the generation interval for sires of young bulls dropped from roughly seven years down to about two and a half, and the annual genetic gains for milk, fat, protein, fertility, and productive life basically doubled compared with the old progeny‑test era.

When you put that next to the economics, the stakes get very real. A Canadian study by CanFax and the Beef Cattle Research Council found that the average cost to raise a replacement heifer was about CA$2,904 in 2023, with a range of CA$1,900 to CA$3,800 across farms. North American dairy budgets generally put that in the US$1,800–2,500 range to get a heifer to calving, once you factor in feed, housing, labor, health, and breeding. At the same time, market analysis from HighGround Dairy in late 2025 estimated that, under strong beef markets and structured beef‑on‑dairy programs, cull cows and beef‑on‑dairy calves together could add more than US$4.00 per hundredweight of milk shipped on some operations, and in another model, they projected beef‑related income above US$4.50 per hundredweight, with several months over US$5.00.

So those breeding calls—who gets sexed Holstein, who gets beef, which heifers you raise—aren’t cosmetic anymore. They’re big‑ticket cash‑flow decisions.

What I’ve found, talking with progressive herds in Ontario, Wisconsin, the northern Plains, and over in parts of Europe, is that the farms making the most consistent progress are letting genomics and economics set the main breeding direction. Then they use their eye to manage cows and fine‑tune individual decisions, not the other way around.

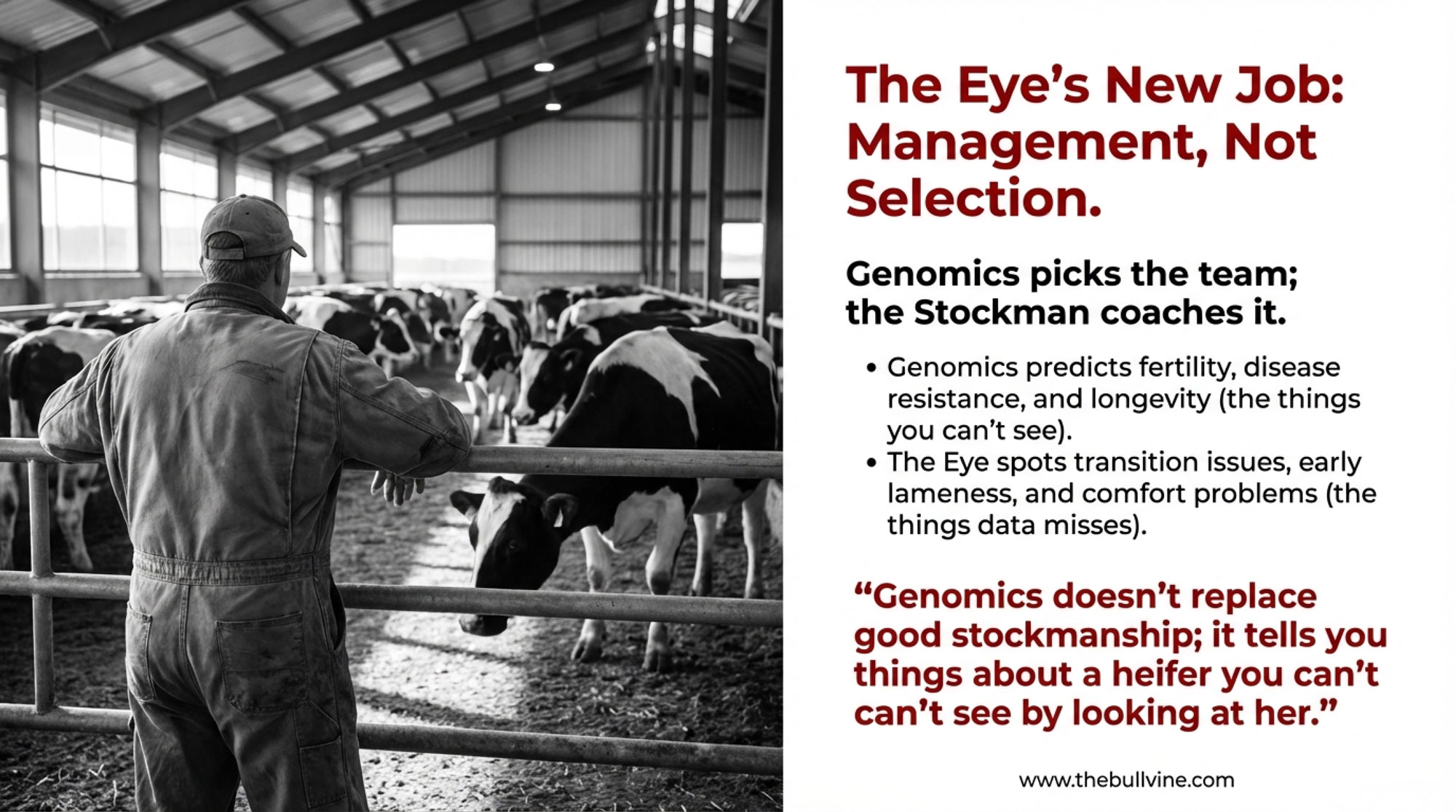

As Kent Weigel, who teaches dairy cattle genetics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and has spent years working with Holstein producers, likes to tell producer groups, genomics doesn’t replace good stockmanship; it just tells you things about a heifer you can’t see by looking at her—things like fertility, disease resistance, and how long she’s likely to stay in the herd. The eye still matters a lot for the day‑to‑day management side.

Looking at This Trend: What Color Really Tells You

Let’s start with the big myth on the coffee‑shop circuit: does coat color actually tell you anything reliable about a Holstein’s genetic merit for milk, fertility, or health?

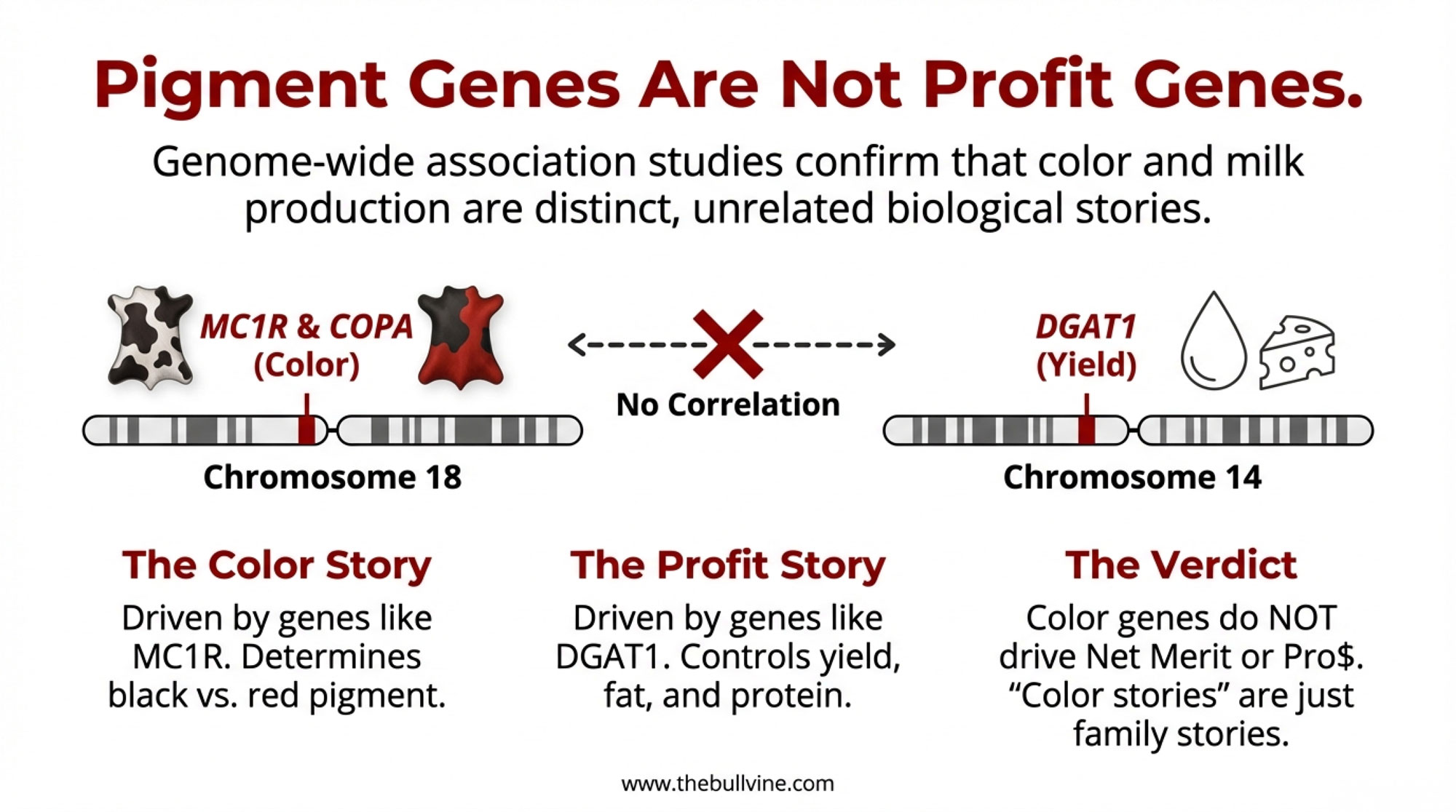

On the black‑versus‑red side, a lot of the story runs through the melanocortin 1 receptor gene—MC1R—on chromosome 18. Geneticists have known for quite a while that MC1R is a central switch between black pigment and red/brown pigment across many species, and Holsteins fit right into that pattern. Holstein‑specific work from Canadian and U.S. labs shows that the main MC1R alleles—often called Dominant Black, Black/Red, wild‑type, and Recessive Red—largely determine whether a Holstein shows up as black‑and‑white or red‑and‑white on the outside.

A really interesting twist came in 2015, when a team publishing in PLOS ONE described a new Dominant Red coat pattern in Holsteins and tied it to a missense mutation in the COPA gene. They showed that this COPA variant acts through the pigment pathway and essentially overrides the usual MC1R signal, turning black areas red. The important point here is that their work was about coat color; they didn’t find evidence that COPA itself was a major driver of milk yield or fertility.

The classic black‑and‑white patch pattern has its own genetic story. Genome‑wide analyses in Holstein‑Friesians have repeatedly identified strong signals around the KIT gene on chromosome 6 and other pigmentation genes, such as MITF, as key players in spotting and patterning. That matches what many of us see in sire families—certain bulls stamp a recognizable pattern on their daughters.

Now, set that beside what we know about the heavy‑hitter milk genes. Large genome‑wide association studies in Holsteins, including recent work from Asia and Europe, continue to confirm major effects for milk yield, fat, and protein near DGAT1 on chromosome 14 and at several other regions. Reviews of milk‑trait genomics and meta‑analyses don’t flag MC1R or COPA as major milk‑yield QTL. They’re busy with DGAT1 and a suite of other production loci scattered around the genome.

So when you map this out, you see two fairly separate stories. One is the pigment story—MC1R, COPA, KIT, MITF. The other is the production story—DGAT1 and dozens of other loci that drive yield, fat, protein, and things like somatic cell score. Color genes just don’t show up as the big drivers of milk or fertility that we see in genomic evaluations.

That doesn’t mean you won’t find a cow family where “the red ones” or “the ones with more white” seem to be your better cows for a while. In a tight family, that absolutely happens. But genetically, what’s going on there is that you’re seeing a family package, not a universal rule. Across the breed, coat color by itself just isn’t a reliable shortcut to Net Merit, Pro$, or the overall profit indexes that matter to the milk cheque.

What Farmers Are Finding: Popular Sires and “Color Stories”

What farmers are finding, especially when you look back over a few decades of AI use, is that our “color stories” are usually really “family stories.”

Most of us can name the bulls that left a big genetic footprint in our barns: Shottle, Goldwyn, Planet, Mogul, Supersire, and now the current crop of genomic sires. Population geneticists call this “popular‑sire” or “founder” effect—when a relatively small number of bulls contribute a large share of the genes in a breed over a short period. A high‑density genomic study in Genetics Selection Evolution examined these selection signatures in Holstein‑Friesians and other breeds and found long stretches of DNA—haplotypes, where variation had been squeezed out by strong selection for milk, components, stature, and udder traits.

When you use a bull like that heavily, his daughters don’t just share his “under the hood” production package; they also share his visible stamp. So for a few generations, a particular pattern or “kind” can feel like it always goes with a particular level of performance. That’s real at the family level. But those haplotype blocks are made up of many linked genes, including both color and production loci. As time goes on and mating gets more diverse again, those blocks break up and recombine.

So inside a family, coat pattern can be a reasonable clue that you’re looking at daughters or granddaughters of a particular bull. At the breed level, the big studies just don’t support simple rules like “more white cows are always better cows.” The family resemblance is real; the population‑wide rule based on color is not.

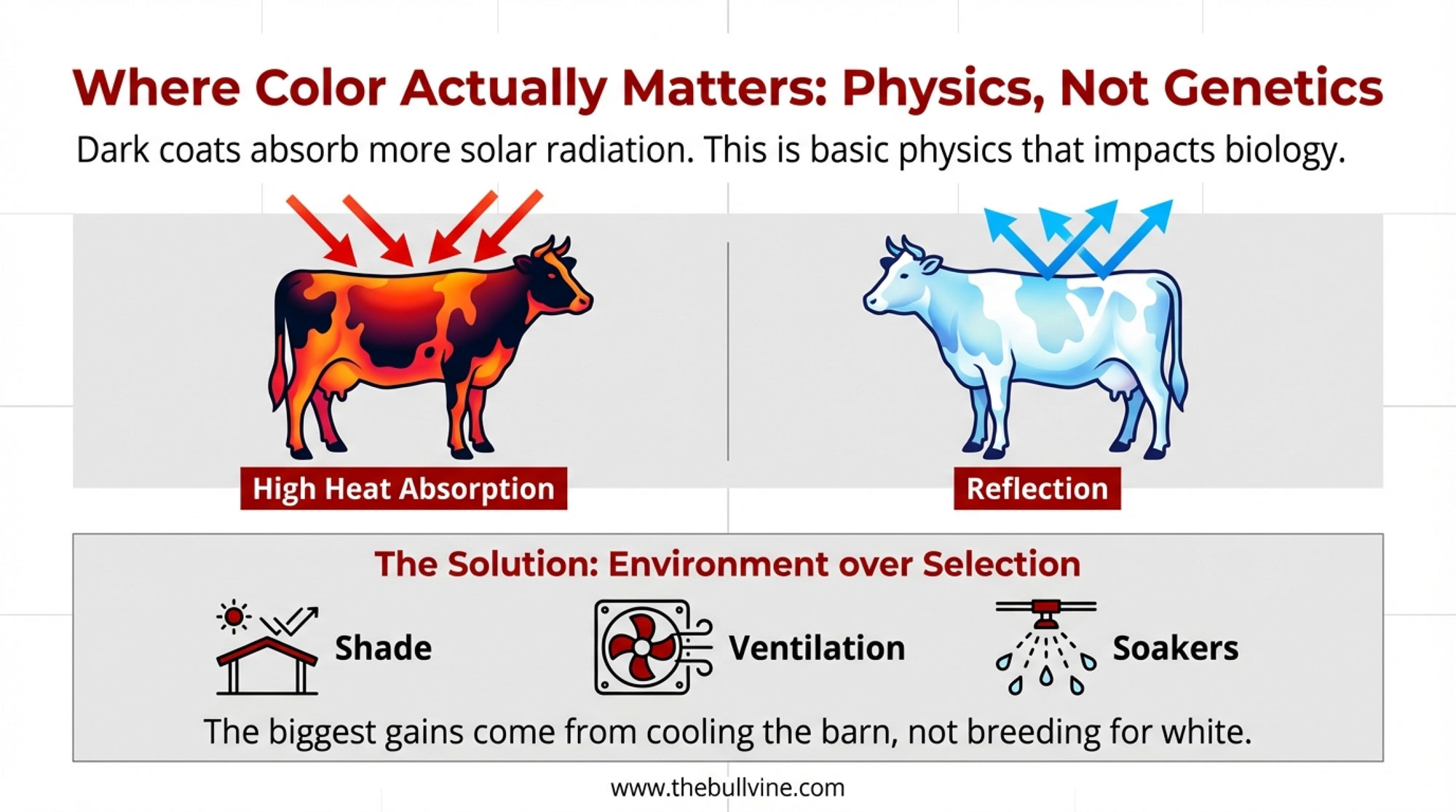

Where Color Really Does Matter: Heat, Sun, and Lost Milk

Now, there is one place where coat color genuinely shows up in performance, and it has nothing to do with type scores or classification sheets. It’s heat.

Dark surfaces absorb more solar radiation than light surfaces; that’s just basic physics. Studies using thermal imaging and surface temperature sensors have shown that black patches of hair on cattle backs can run several degrees hotter than adjacent white patches when animals are in full sun. That extra absorbed heat adds to the load the cow has to get rid of.

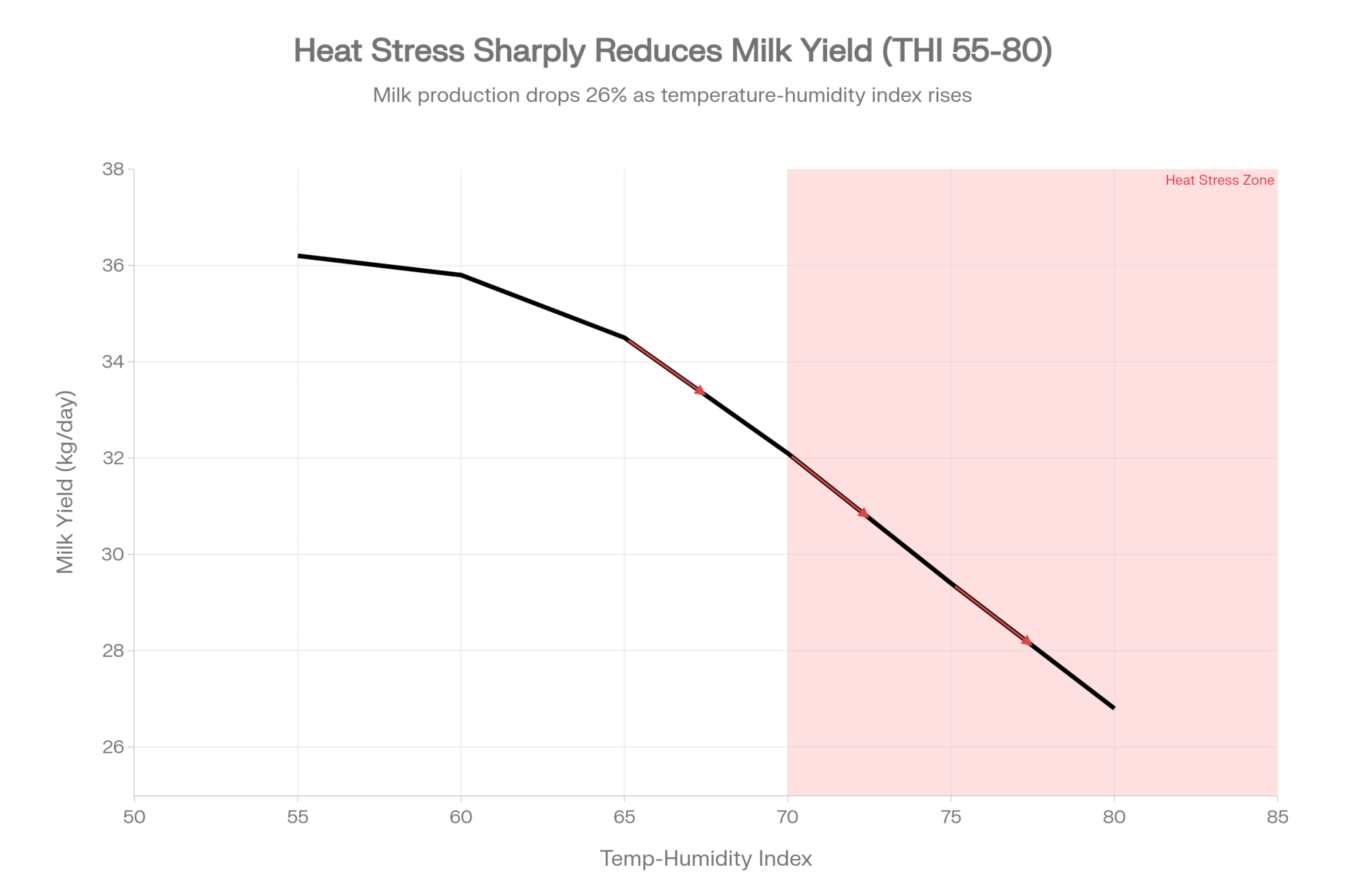

A 2024 paper in the Journal of Dairy Science examined Holstein–Friesian crossbred cows in Tanzania and drew on earlier THI work on Holsteins. As the temperature‑humidity index moved into heat‑stress ranges, the researchers observed that rectal temperature, respiration rate, and panting scores all increased. At the same time, milk yield, milk fat percentage, and solids‑not‑fat percentage dropped. In other words, as cows got hotter, they gave less, and the component tests slipped too.

On pasture‑based systems in New Zealand and Australia, extension folks and researchers have seen the same basic pattern. Under heat stress, cows stand and pant more, graze less, and produce less milk unless they’ve got shade, water, and some form of cooling. Some work suggests that cows with lighter coats or slicker hair hold up a bit better under those conditions, which is why there’s been interest in breeding for heat tolerance in grazing systems.

One pretty eye‑catching example came out of CSIRO. Their team produced Holstein–Friesian calves from embryos edited at a coat‑dilution gene called PMEL. Those calves had lighter coats and, when they were put in the sun, took on less radiative heat than their darker‑coated herdmates. They’re strict research animals, not anything you’ll find on a commercial farm, but it shows how seriously some groups are taking the connection between coat, heat, and performance.

What This Means on Your Farm

Here’s how color and heat pencil out in different setups:

| Your situation | Focus first on |

| Hot, high‑sun region or dry lot with limited shade (Central Valley, CA, parts of Texas/Florida, southern Europe) | Shade structures, fans, sprinklers, and good water access. Don’t count on breeding for more white to solve heat stress. Fix the environment first, because that’s where the biggest gains are. |

| Moderate climate with decent ventilation (Ontario, Wisconsin, Quebec, northern Europe) | Solid ventilation and transition‑period management first. Genomic testing and index‑based selection will move the needle more than fussing over color, though heat‑abating investments still pay on the worst days. |

| Pasture‑based with limited infrastructure (NZ‑style or U.S. grazing herds) | Shade and water access, careful grazing management on hot days, and—if the genetics are available—looking at heat‑tolerant and slick‑hair lines can help, especially as summers get hotter. |

So yes, color does play a role in heat load, especially in hot, bright environments and in dry lot systems. It can absolutely show up as lost milk and tougher breeding if cows are constantly fighting heat stress. But even in those regions, coat color is one part of a bigger heat‑stress and cow‑comfort picture. It’s not a substitute for good ventilation, shade, or water, and it’s not a stand‑alone selection tool for profit.

What Genomics Has Actually Changed for Your Bottom Line

Now let’s talk about genomics, because that’s where the biggest shift has happened in how Holstein genetics translate into dollars.

When genomic evaluations came onto the scene in the U.S. and Canada around 2008–2010, the promise was pretty simple: use DNA information from young animals to predict their genetic merit before they have milking daughters, shorten generation intervals, and speed up genetic progress.

That big U.S. Holstein study in the National Academy Journal really put numbers to it. Once genomics was adopted, the sire‑of‑bull generation interval came down from roughly 6.8–6.9 years to about 2.4 years. Annual genetic gains for milk, fat, and protein almost doubled. For health and fertility traits such as somatic cell score, daughter pregnancy rate, and productive life, gains were three- to four‑fold.

More recent work, including a 2023 paper in the journal G3, has combined fertility traits into a single reproductive index and shown that there’s sufficient genomic signal to select for fertility, not just milk effectively. That lines up with what many of us have seen on real farms: herds that use genomic information well can walk that tightrope of driving production up while also improving fertility and udder health, rather than trading one off against the other.

So genomics gives you a much clearer window into traits your eye just can’t judge in a young heifer. You can’t see the daughter pregnancy rate or expected survival to third lactation by looking across the calf pen, but the DNA markers give you a probability estimate that, while not perfect, is a lot better than guessing.

The Cost Reality

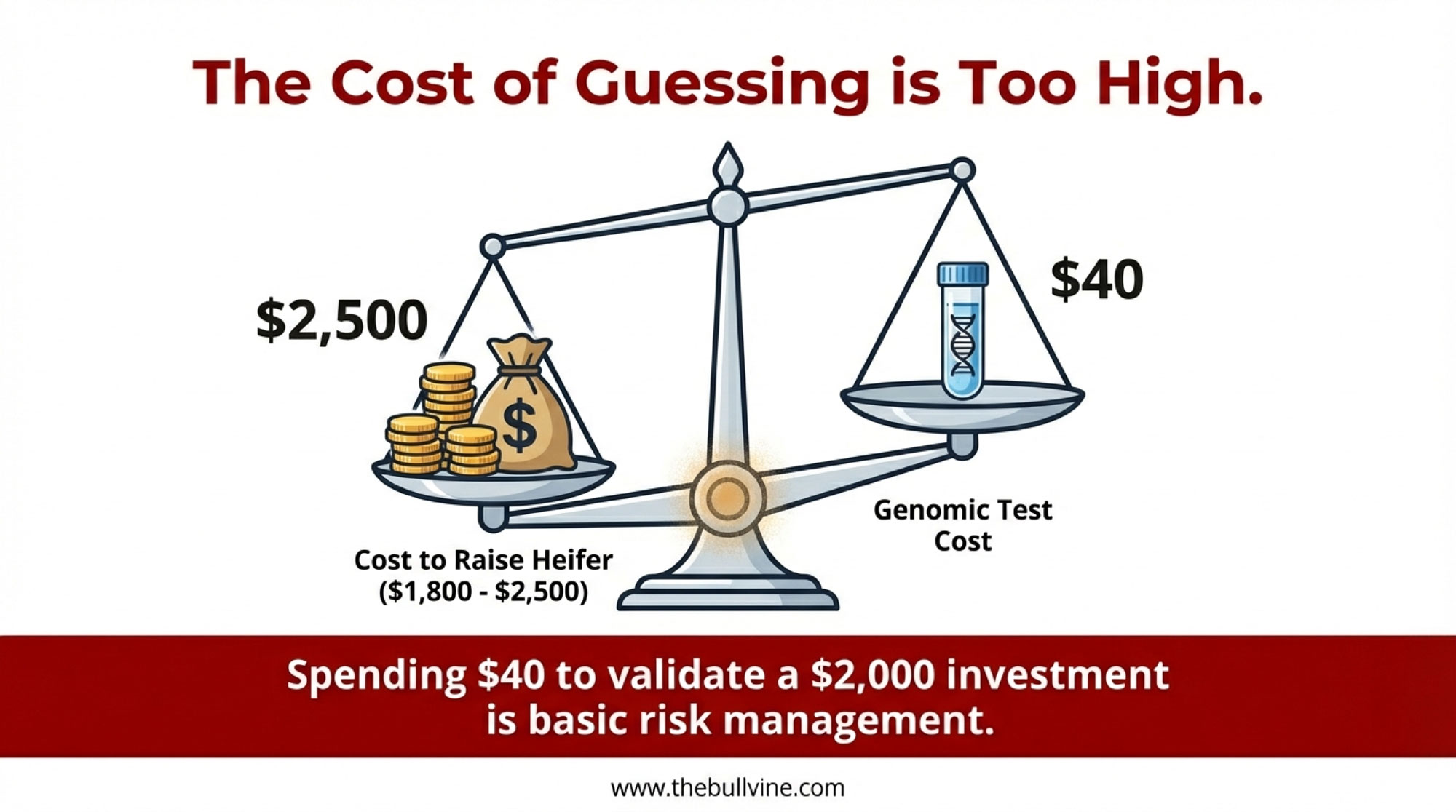

Then there’s the math.

That Canadian heifer‑cost study we talked about pegged the average replacement cost at CA$2,904 per head, with many farms running well over CA$3,000. North American dairy budgets usually land in the US$1,800–2,500 range when you include feed for the entire rearing period, housing, labor, vet bills, and breeding costs.

On the testing side, commercial genomic panels—like CLARIFIDE and similar offerings—typically price out at US$35–50 per heifer in North America, depending on the panel and your volume.

| Cost Component | Typical Range | Strategic Note |

| Feed (to 12–18 months) | $800–$1,200 USD | Largest single expense; improves with forage/commodity costs |

| Housing, bedding, utilities | $300–$500 USD | Per-heifer share of fixed barn and infrastructure |

| Labor (handling, health, records) | $250–$400 USD | Often underestimated; includes AI tech/vet time |

| Veterinary, vaccines, breeding | $200–$350 USD | Reproduction drugs, health treatments, AI straw(s) |

| TOTAL REARING COST (pre-calving) | $1,800–$2,500 USD | Average: ~$2,000 USD or ~$2,900 CAD per head |

| Genomic test (commercial panel) | $35–$50 USD | = 1.75–2.8% of total rearing cost |

| % of Heifers Typically Culled by Index (bottom 20–30%) | $360–$750 USD | Waste eliminated: cost of rearing low-index heifers avoided |

| Payoff: Genomi test cost recovered if you cull just 1–2 poor heifers per year | Break-even: ~$40–75 per year | Risk management, not a luxury |

So when you step back, you’re talking about spending forty dollars to find out whether an animal is worth a two‑thousand‑dollar investment. For a lot of herds, that’s not a luxury; it’s basic risk management.

Looking at Inbreeding: Faster Progress, Tighter Gene Pools

Here’s where the story gets a bit uncomfortable. The same genomic tools that gave us faster gains have also made it very clear that tightening up the gene pool in Holsteins.

A North American Holstein study in BMC Genomics dug into runs of homozygosity—those long stretches of identical DNA on both chromosomes—and tracked them from animals born in 1990 through to 2016. They found that the average number of ROH segments at least 1 megabase long per animal went from around 57 in the 1990 cohort to about 82 in animals born by 2016. In the last five years of that period—right when genomic selection really took off—the yearly increase in these ROH segments was almost double what it had been earlier.

The authors made an important point: on a per‑generation basis, the increase in inbreeding wasn’t dramatic. But because the generation interval was so much shorter, you were stacking generations faster and building inbreeding per calendar year much more quickly.

Italian Holstein data tell a similar story. A 2022 paper in Frontiers in Veterinary Science looked at genetic diversity before and after genomic selection. Pedigree‑based inbreeding was around 7%, but genomic inbreeding, based on ROH, was clearly higher and rising faster, and the effective population size—a measure of how many “independent” genetic contributors you really have—was dropping. Follow‑up work linked higher genomic inbreeding to reduced stayability: more inbred cows simply didn’t stay in the herd as long.

So here’s the irony that’s worth sitting with for a minute. For years, a lot of us chased a very particular “look”—the Goldwyn kind, Shottle daughters, that tall, sharp cow. Then genomics came along, and many herds stopped worrying as much about that look and started chasing the top indexes instead. The data now say that in the process, we’ve pushed a lot harder on the same gene pool, faster, especially through very heavy use of a small number of elite bulls.

You look across your pens today, and the cows may not look as cookie‑cutter as those ‘90s flush families. But under the skin, genetically, they’re more closely related than most of us realize.

What You Can Do About It

The good news is that the same genomic tools that measure inbreeding can help you manage it.

A recent review from Italy on on‑farm genetic management describes how using genomic relationship matrices and “optimal contribution” strategies can balance genetic gain and inbreeding in dairy herds. What that means in practice is this: instead of just looking at pedigree inbreeding, you use the actual genomic relationships between your cows and potential sires to decide who should be the parents of the next crop of replacements.

On a real farm, that often comes down to:

- Using mating programs that incorporate genomic relationship data, not just sire stacks and pedigree inbreeding.

- Being careful about breeding a bull back too heavily to his own daughters and granddaughters.

- Spreading your bull usage across a team of high‑index sires instead of hammering one or two “super sires.”

- Sometimes, being willing to use a slightly lower‑index bull if he’s less related to your cow family and still meets your key trait goals.

It’s worth noting that no one is saying “stop selecting hard.” The point is to keep the inbreeding curve from getting too steep, so you don’t quietly paint yourself into a corner when it comes to health, fertility, or adaptability down the road.

Why the Eye Still Matters—and Where It Fits Now

So with all this talk about genomics and indexes, it’s fair to ask: where does your eye fit now?

In a lot of barns, what I’ve seen is that the role of the eye has shifted from being the primary genetic gatekeeper to being the primary management tool.

You know how this goes. You still need to walk pens and:

- Spot a cow that’s just starting to limp before she’s three‑legged lame.

- Watch body condition as cows move through the transition period to prevent crashes right after calving.

- See how cows actually use stalls, bedding, waterers, robots, and feed lanes in your specific barn layout.

- Catch fresh cows that are “just off” a bit before they show up in the software as a health case.

Genomic indexes and national evaluations can’t do that job. What they can do is take some of the guesswork out of which heifers you invest in and which cows you want daughters from.

At a genetics workshop in Ontario, one Holstein producer described that evolution nicely. He said he used to think his eye was the best tool he had. Now he sees it as his best management tool, while genomic tests tell him which heifers are actually worth raising. A lot of Midwestern and Quebec producers I’ve talked with would say something similar in their own words.

What This Means for Your Holstein Breeding Strategy

So let’s bring this back to your breeding plan, because that’s where all this needs to land.

Picture a 280‑cow Holstein freestall herd in Wisconsin or southwestern Ontario, shipping into a cheese market where butterfat and protein premiums really drive the cheque. Cows are averaging mid‑30s kilos per day with good components, the transition cows get a lot of attention, and the farm already uses some sexed semen and a bit of beef‑on‑dairy.

You could just as easily imagine a 120‑cow tie‑stall in Quebec or a 600‑cow dry lot system in California. The genetics math is the same; you just adjust the heat‑stress and housing parts.

Here’s what a practical, 2025‑ready strategy can look like.

1. Run a One‑Year Genomic Trial

One very low‑risk way to start is a “learn from your own data” trial over 12 months.

- Test every heifer calf for a year. Take hair or tissue samples in the first week or two and send them to your preferred lab—Zoetis, Neogen, Lactanet, or your national provider—and ask for the main economic index your market uses, whether that’s Net Merit, Pro$, or LPI.

- Keep making keep/cull and breeding decisions exactly the way you do now, based on dam performance, cow family, and what you see in the pen.

- At the end of the year, sit down with your vet, nutritionist, or a genetics advisor and compare your actual decisions to the genomic rankings.

In many herds that have tried this, a familiar pattern pops up: there are some heifers you really liked visually that sit only middle‑of‑the‑pack on fertility and longevity indexes, and a few plainer heifers that rank near the top. Seeing that in your own animals tends to carry more weight than any sales pitch.

If your main criterion for keeping a heifer is how much white she has, what the genomic work and the big GWAS studies are saying is that you’re effectively betting a couple of thousand dollars on a trait that doesn’t even show up as a major driver in Net Merit or Pro$. That’s a tough bet to justify once you’ve seen your own data.

2. Let One Economic Index Be Your Compass

To keep it from being overwhelming, most herds do best if they pick one total merit index—Net Merit, Pro$, LPI, or the relevant national index—and let that act as the primary compass.

| Heifer Tier (by Index Rank) | % of Herd | Semen Strategy | Expected Calf Outcome | Economic Note | Action |

| TOP 20–30% (High Index) | 20–30% | Sexed Holstein(maximize daughters) | Female calves; all raised as dairy replacements (or top beef-cross if surplus) | Highest genetic merit; drives herd average; replacements carry forward strong genetics | Prioritize nutrition, health, transition management; track 1st lactation performance |

| MIDDLE 40–50% | 40–50% | Conventional Holstein OR 50% sexed + 50% beef | Holstein bull calves (sold); crossbred calves (beef market); daughters retained if above-average herd | Balances dairy replacement supply with beef revenue; some genetic gain but not peak | Monitor calf sex ratio; align with real replacement needs; consider beef-market strength |

| BOTTOM 15–25% | 15–25% | Beef Semen(Angus, Simmental, etc.) | Crossbred calves premium beef market (black hides command premium); no dairy daughters | Maximizes calf value ($400–600/head vs. $50–100 for dairy bull); eliminates low-merit dairy genetics; often breaks even or profitable on rearing cost | Fast-track to beef channel; NO heifer rearing; recoup heifer costs via calf value |

| PROBLEM COWS (repeat breeders, chronic mastitis, severe structural defects) | 5–10% | Beef Semen | Crossbred calves to beef | Removes undesirable traits from breeding; converts problem cows into profitable calf source | Terminal decision; one more calf, then cull |

Then you:

- Rank all heifers and young cows by that index, high to low.

- Decide on a cutoff—maybe the bottom 10–20% or a certain dollar amount below your herd average—below which you don’t raise heifers as dairy replacements.

- Use that ranking to structure semen use:

- Top tier: sexed Holstein semen on the females you want daughters from.

- Middle tier: conventional Holstein semen.

- Bottom tier and problem cows (chronic mastitis, very poor feet, reproduction issues): beef semen.

This is where the math really shows up. If you’re putting US$35–50 into a genomic test and US$1,800–2,500 into rearing a heifer, using that index ranking to decide who gets a replacement slot and who doesn’t will change your cost per hundredweight over the next few years.

3. Use Mating Programs to Manage Inbreeding

The next step is to ensure your mating program uses genomic data to mitigate inbreeding.

It’s worth asking your AI rep or mating service a couple of direct questions:

- Are you using genomic relationship information, or just pedigree, to calculate inbreeding risk?

- Can you show me the expected genomic inbreeding for each proposed mating?

Given that both the North American and Italian Holstein studies show faster increases in genomic inbreeding and more ROH in the genomic‑selection era, it makes sense to watch this. Some advisors suggest targeting expected genomic inbreeding for replacement heifers in the mid‑single digits, where practical, and only accepting higher values when you’re getting a very significant bump in other traits. The exact target will depend on your herd and sire options, but the principle is to avoid stacking closely related bulls on closely related cows over and over.

In practice, that often looks like still using the elite bulls, but spreading their use across more unrelated cow families, rotating between several high‑index sires instead of just one or two, and sometimes choosing the “second‑highest” bull on a list because he’s less related to your cows, while still very strong on your key traits.

4. Line Up Sexed and Beef Semen With Your Index and Markets

Genomics also helps answer a very practical question: which cows should make your next generation of Holstein replacements, and which should be making calves for the beef market?

Those HighGround Dairy numbers we talked about—over US$4.00 per hundredweight of milk in some scenarios from cull cow and beef‑on‑dairy calf revenue, and earlier projections with several months over US$5.00—show just how big that lever has become on the income side when beef markets are favorable. At the same time, semen‑sales trends and processor programs in North America and Europe show beef‑on‑dairy has become mainstream, especially where packers and branded programs pay up for black‑hided crossbred calves.

A genomics‑aligned plan that a lot of progressive herds are using looks like this:

- Sexed Holstein semen on the top 20–40% of females by your chosen index—the ones you really want daughters from.

- Conventional Holstein semen is on the middle group, where you still want some dairy bull calves and a share of replacements.

- Beef semen on the bottom tier and on cows with traits you don’t want to multiply, such as chronic mastitis, repeat breeders, or severe structural issues.

Combine that with your heifer‑raising cost numbers and your local calf market, and you start to get a very clear picture of where your breeding dollars and semen investments are actually coming back to you.

5. Keep Your Eye in Its Best Role

Through all of this, your eye stays central. It’s just playing a different position on the team.

You know your cows. You know who milks through tough rations, who bounces back after a hard calving in the transition period, and who always seems to find trouble. That day‑to‑day cow sense is the piece no index can replicate.

What genomics does is help you decide which calves deserve the chance to become that kind of cow in the first place. It narrows the group, so you’re not putting full rearing costs into animals that were never likely to reach third or fourth lactation under your system.

Looking Ahead: Diversity, Climate, and the Holstein of 2050

If we zoom out past next year’s milk cheque and think about the Holstein cow of 2040 or 2050, three big forces keep coming up in both research papers and barn‑aisle conversations: genetic diversity, climate, and markets.

On the diversity side, the North American ROH work and the Italian Holstein studies send a pretty consistent message: genomic inbreeding is rising, and effective population size is shrinking in intensively selected Holstein populations. No one credible is predicting a sudden cliff, but there is a very real concern that if we keep pushing hard on a narrow gene pool, we could slowly chip away at the breed’s ability to adapt to new diseases, production systems, or environmental pressures.

On the climate side, more frequent heat waves and higher average summer temperatures are already a reality in parts of the U.S., southern Europe, and elsewhere. That 2024 Journal of Dairy Science review that pulled together heat‑stress studies put numbers on what many of you see in the barn: as THI climbs, cows eat less, energy‑corrected milk drops, and the strain shows up in both milk yield and reproduction. Some of the work digs into the biology—oxidative stress, rumen changes—but the bottom line is simple enough: hot cows don’t use feed efficiently and don’t breed as well.

On the market side, we’re seeing more beef‑on‑dairy programs, more milk cheques driven by components and quality premiums, and more processor attention to consistency and welfare. All of that favors cows that stay in the herd, handle stress, and breed back reliably, not just cows that peak high in first lactation.

What’s encouraging is that we’ve got better tools than ever to work with:

- Genomic inbreeding and relationship data, not just pedigree estimates.

- Mating strategies like optimal contribution that let you balance genetic gain and inbreeding.

- Economic indexes that include fertility, udder health, productive life, and sometimes feed efficiency, alongside milk and butterfat.

- A growing body of heat‑stress research to guide decisions on ventilation, shade, sprinklers, and water management.

- Beef‑on‑dairy programs and pricing signals that can pay you properly for the right kind of crossbred calves.

The challenge is putting those tools together in a way that fits your herd size, your barns, your labor situation, and the markets you’re shipping into.

The Bottom Line

So if we’re back at that kitchen table and you ask, “Alright, what should I actually do with all this?”, here’s how I’d boil it down into concrete moves for the next year or two.

- Run a one‑year genomic test trial on all heifer calves. Don’t change your decisions for that year—just compare what you did to what the index ranking suggests at the end and see where your eye and the DNA agree or disagree.

- Pick one economic index—Net Merit, Pro$, LPI, or your national equivalent—and use it as your main compass to sort females into top, middle, and bottom tiers for semen strategy and replacement decisions.

- Ask your mating program provider to show you genomic inbreeding for planned matings, not just pedigree inbreeding, and work together to avoid pushing replacement heifers into very high genomic inbreeding levels.

- Line up sexed Holstein and beef semen use with both your index ranking and your real replacement needs, keeping today’s heifer‑raising costs and beef‑on‑dairy calf values in mind.

- Take a hard look at your heat‑stress plan before next summer—especially if you’re in hot regions or dry lot systems—and ask whether your shade, fans, sprinklers, and water access match what the research and your own cows are telling you.

The herds that lean into this in the next five years will quietly build cows that last longer and earn more per stall. The ones that keep breeding by color and habit will feel it in higher heifer costs, more inbreeding‑related headaches, and fewer options when weather or markets shift on them.

What this whole development suggests is that the next chapter in Holstein breeding isn’t about arguing whether the eye or the computer is “right.” It’s about putting them in the right jobs and letting them work together.

And if we keep sharing what’s actually working—how herds are using genomic tests, indexes, mating programs, heat‑stress strategies, and beef‑on‑dairy opportunities—then, as a group, we’re in a strong position to keep Holsteins productive, profitable, and adaptable well into 2050.

As for color? It’ll probably always be part of how we talk about Holsteins and the kind of cow we like to look at. It just doesn’t need to be driving the bus anymore.

Key Takeaways:

- Breeding by coat color won’t move your index. Pigment genes like MC1R and COPA are far from the major milk and fertility loci, so selecting heifers based on “more white” doesn’t reliably improve Net Merit or Pro$.

- Genomics doubled genetic gain—and sped up inbreeding. Sire generation intervals dropped from ~7 years to ~2.5 years, nearly doubling annual progress, but genomic inbreeding and runs of homozygosity are climbing faster per calendar year as a result.

- Color matters for heat stress, not genetic merit. In hot climates and dry lots, darker coats absorb more solar load, pushing cows into heat stress sooner and costing milk, components, and fertility when cooling falls short.

- Beef-on-dairy can add $4+/cwt when done right. HighGround Dairy’s 2025 modelling shows well-structured beef programs can add more than US$4.00/cwt to margins in favorable markets—real money that changes breeding math.

- A $40 genomic test protects a $2,000 bet on a heifer. With rearing costs often US$1,800–2,500, using index rankings to decide who gets sexed semen and a replacement slot is risk management, not a luxury. Your eye then shifts to its best role: daily cow management and fresh-cow troubleshooting.

Executive Summary:

Many Holstein herds are still quietly letting coat color and “kind” influence breeding decisions, even though pigment genes like MC1R and COPA sit on different parts of the genome than the big milk and fertility loci that large Holstein GWAS keep identifying. Genomic selection has roughly doubled genetic gain in U.S. Holsteins by cutting sire generation intervals from about 7 years to about 2.5 years, but North American and Italian data also make it clear that genomic inbreeding and runs of homozygosity are rising faster per calendar year as a result. New heat‑stress research backs up what producers in hot regions and dry lot systems see every summer—darker coats absorb more solar load, cows hit heat stress sooner, and milk and components slip—while 2025 modelling from HighGround Dairy shows well‑designed beef‑on‑dairy programs can contribute more than US$4.00 per hundredweight of milk shipped to margins when markets are favorable. With heifer‑raising costs often in the US$1,800–2,500 (or CA$2,000–3,000) range, spending about US$40 on a genomic test to decide which calves actually justify that investment is, in many cases, simple risk management rather than a luxury. This article gives producers a concrete playbook: run a one‑year “test every heifer” trial, use one economic index as the main compass, use genomic mating tools to manage inbreeding, and align sexed Holstein and beef semen use with both index rankings and true replacement needs. The core message is that if you stop breeding by color and start breeding by genomics, heat‑stress realities, and beef‑on‑dairy math, you give your Holstein herd a much better shot at stronger per‑stall margins between now and 2030.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Selective Breeding: The Art and Science of Beef-on-Dairy – Stop guessing at the bunk and start capturing market premiums. This breakdown delivers a field-tested protocol for selecting terminal sires that guarantee the carcass quality beef buyers demand, transforming your bottom-tier cows into high-margin profit centers.

- Navigating the 2025 Dairy Economy: Maximizing Margins in a Volatile Market – Master the shifting financial landscape by aligning your herd expansion goals with current global supply trends. This analysis arms you with the economic foresight to hedge against rising input costs while maximizing your milk-to-beef revenue ratio through 2028.

- Gene Editing and the Dairy Industry: Beyond the Horizon – Break past traditional breeding limits by leveraging CRISPR and slick-gene technology to heat-proof your herd. This deep dive exposes the genetic advancements that will define cow comfort and performance as climate volatility becomes the new normal for global producers.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.