A Peruvian-born professor built a system that predicts mastitis a few days before the cow shows symptoms. So why is a $40-billion industry still running its data infrastructure like it’s 2005?

Dr. Victor Cabrera, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Over 16 years, he’s turned $5.5 million in research funding into tools dairy producers can use the next morning — and an open-source “brain” that’s making the industry’s $40-billion data problem personal.

Five o’clock on a Tuesday morning. A fresh heifer shuffles through the return lane after milking on a pilot dairy in central Wisconsin. She looks fine. Eats fine. Clean filter sock, no heat in the udder, nothing you’d flag on your walk-through.

But a hundred miles of fiber-optic cable away, in a lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison—the kind of place where whiteboards are buried under data pipeline diagrams and the coffee pot never goes cold—a system has already flagged her. It pulled her genomic profile, including her dam’s mastitis history and her own PTA for somatic cell score. It cross-referenced events from her transition period. Then it layered on something no human eye could catch: a subtle shift in milk flow speed and a barely measurable rise in electrical conductivity over her last two milkings.

The prediction: this heifer has a greater than 90% probability of developing clinical mastitis within a few days.

That’s not some research paper sitting in a journal gathering dust. That’s the Dairy Brain—a real system, running on real farm data, built by a guy who grew up in Peru waiting months to get a photocopy of a single research paper.

And honestly? The most surprising part of this story isn’t what the system can do. It’s everything standing in the way of getting it to your farm.

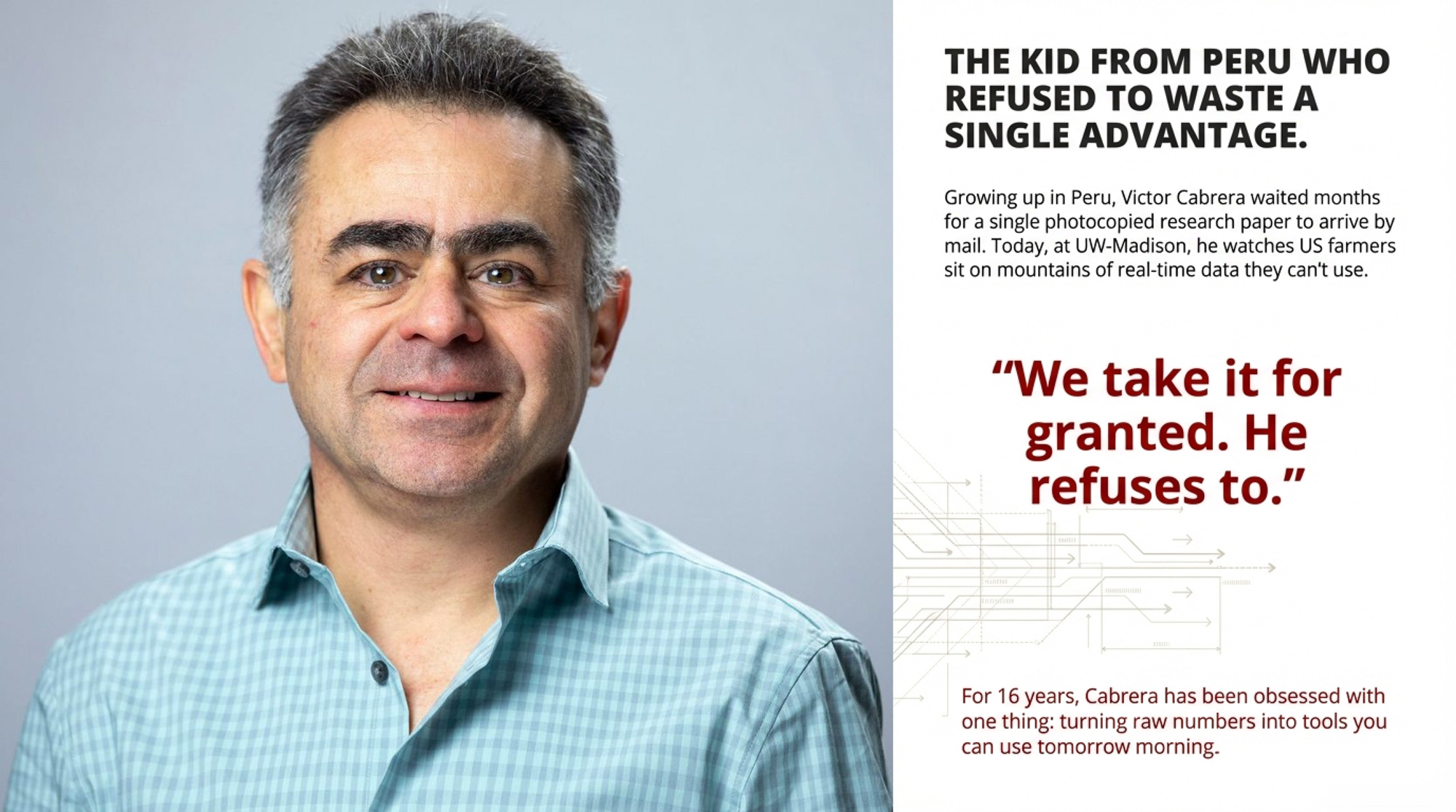

The Kid From Peru Who Wouldn’t Take Anything for Granted

You might not expect this about the man building one of the most sophisticated dairy decision-support platforms in North America: Victor Cabrera didn’t grow up anywhere near a Holstein.

He came to Florida as an international student from Peru—a country where, at the time, access to cutting-edge dairy research meant submitting a formal request and hoping a paper arrived in the mail a few weeks later. Maybe months. The professors whose textbooks he’d studied? Completely unreachable.

Then he arrived in Madison, and those same professors were just… down the hall.

“They were here in the offices, and we could visit with them. They were very approachable,” Cabrera remembers. “We take it for granted nowadays. But I think that’s something—there is still a huge advantage here in the developed world. We feel that, and we appreciate that.”

That appreciation—that refusal to waste a single advantage—shaped everything that came next. Over 16 years at UW–Madison, Cabrera has secured more than $5.5 million in research funding, earned the DeLaval Dairy Extension Award from the American Dairy Science Association, and built a lab that’s produced dozens of practical, producer-facing decision tools. While other researchers might focus on publishing papers and moving on, Cabrera, besides publishing papers, became obsessed with something less glamorous but infinitely more useful: building tools that dairy producers could actually apply the next morning. Not theoretical frameworks. Not academic exercises. Tools.

His lab has produced replacement optimizers, reproductive management calculators, beef-on-dairy breeding simulators, and a nutritional grouping method called OptiGroup that uses optimization algorithms to maximize milk income. Almost all of them, he says, were born from a producer or consultant asking a specific question during a farm visit.

But something kept bugging him. Every single time his team deployed one of these tools on a real dairy, they hit the same wall.

The data was there. It just couldn’t get out.

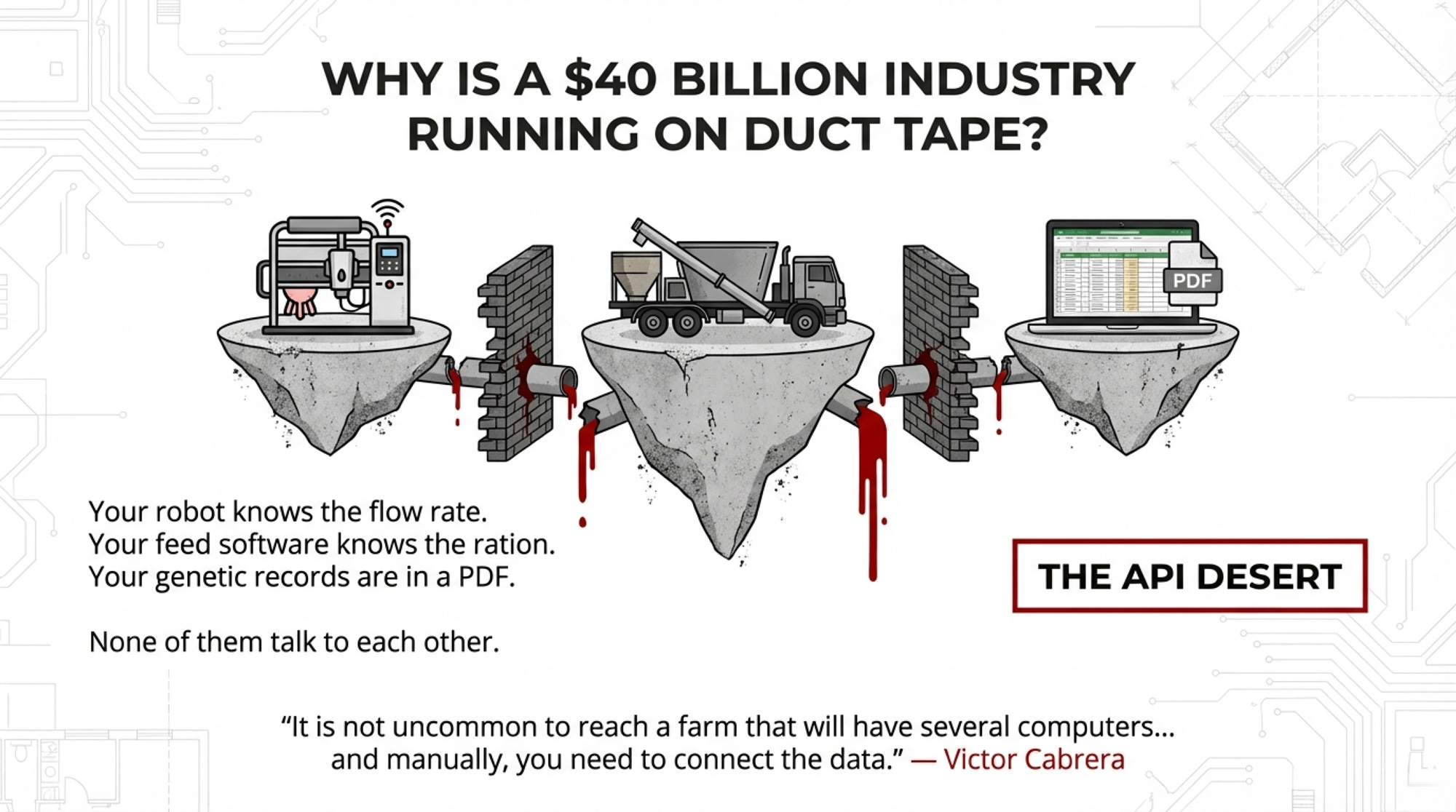

A $40-Billion Industry Running on Spreadsheets and Duct Tape

Walk onto any modern dairy operation in 2026 and count the technology. You’ve got herd management software—maybe Dairy Comp, maybe PCDART, maybe something proprietary from your robot company. There’s feed management software, probably on a different computer. Genetic evaluations come through a third channel. DHI data arrives monthly. If you’re running robots, those systems are generating thousands of data points per cow per day—milk yield, component estimates, conductivity, flow rates, rumination, activity. Maybe you’ve got boluses in fresh cows streaming real-time rumen data.

And almost none of these systems talk to each other, whether you’re running 200 cows in Ontario, 2,000 in Wisconsin, or 8,000 in the Magic Valley—same problem, same fragmentation, same frustration.

“It is not uncommon to reach a farm that will have several computers, each one dedicated to a different software,” Cabrera says. He’s been seeing this for over a decade, and it still gets to him. “In order to have a list of animals for a purpose, you need to print or extract data from one software, from another, and manually—most of the time, manually—you need to connect the data.”

You can transfer money between banks on your phone while standing in the milking parlor. You can share medical records from your doctor to your pharmacy through a secure digital interface in about two seconds. But if you want to cross-reference a cow’s genomic breeding values with her current milk components and her feed efficiency data? Better fire up three programs, export some spreadsheets, and start copying and pasting.

It’s not just inconvenient. It’s costing you money—and preventing decisions that could save you a whole lot more. That frustration is exactly what sparked the Dairy Brain project.

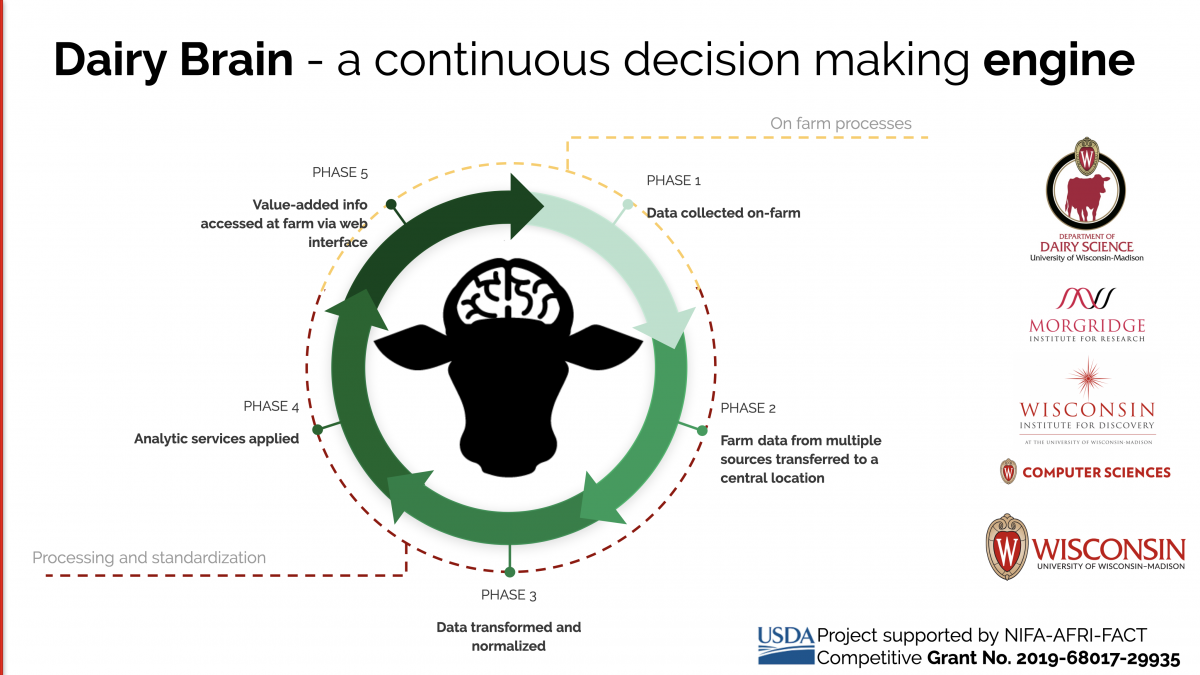

Building the Brain—And Why It Nearly Broke Them

Dairy Brain takes data from every system on a farm and integrates it into a single, real-time ecosystem. Once the data flows together, you layer on artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to generate insights no individual system could produce alone.

“The name means what it says,” Cabrera explains. “It’s providing brain to the dairy based on data-driven decisions.”

On the pilot farms where they’ve gotten it working, producers can see income-over-feed-cost not as a monthly average calculated after the fact, but as a daily, pen-by-pen, cow-by-cow figure. On one Wisconsin dairy, the system caught a subtle change in silage quality and immediately showed the ripple through feed efficiency and margin—days before anyone would’ve noticed in bulk-tank numbers. The farm manager put it: the first time the dashboard flagged something they wouldn’t have caught for another two weeks, it stopped being a research project and started being a tool.

“That has been, I think, the most exciting part of the Dairy Brain,” Cabrera says—and you can hear it in his voice. After years of writing scripts and wrestling with broken data pipelines, watching a producer actually use the system to catch something real? That’s the payoff.

But Cabrera is disarmingly honest about what it took to get there. “We never expected it would be so much time and effort demanding,” he admits. There was a stretch when grant funding gaps coincided with a vendor quietly changing their data export format—and the entire pilot farm pipeline went dark. Weeks of troubleshooting, watching perfectly good farm data sit there going stale, while the team hunted for whatever cell had moved in whatever spreadsheet. Not because the AI failed. Because a single field was shifted in a CSV, and nobody told them.

That kind of fragility points straight to an industry problem that goes way beyond a single university lab.

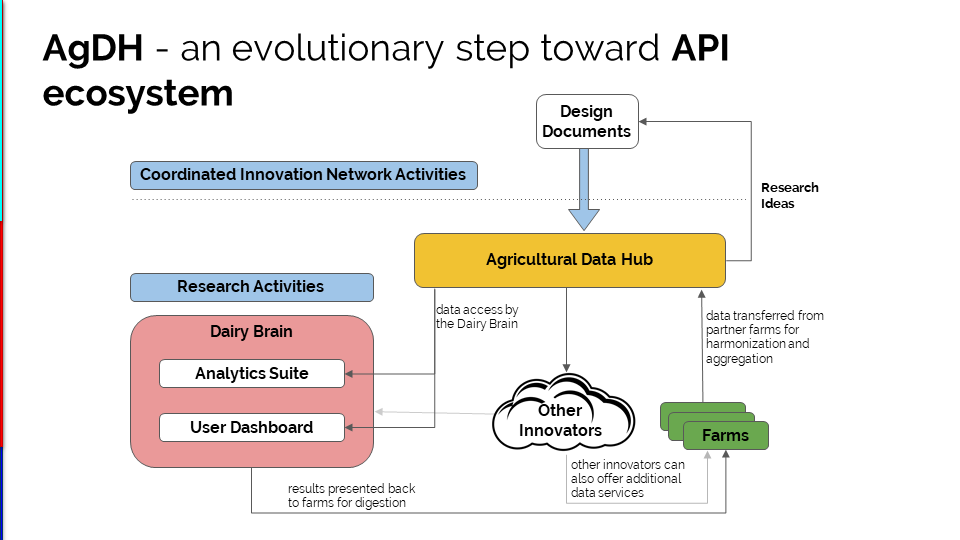

The API Desert—And Why You Should Be Ticked Off About It

In almost every modern industry, data flows between systems through something called an API—an Application Programming Interface. Think of it as the invisible plumbing that lets your banking app talk to your bank, or your health records move between your doctor and your pharmacy. Secure, standardized, reliable. You use APIs 100 times a day without realizing it.

In dairy? Good luck.

“If you go to the dairy industry and you look for APIs, there are not many,” Cabrera says—then gets more direct. “The big majority of companies will not provide an API. The ones who are having some API development are in the development stage.” Even those, he adds, “are not at the level of usability that we would have wanted.”

So Cabrera’s team has had to build custom interfaces from scratch—scraping data from CSV exports, spreadsheets, and, in some cases… PDFs. Yeah. PDFs. One vendor changes a cell location, and the whole pipeline breaks.

And this is where it gets infuriating. This isn’t a technology problem. The technology exists and has for years. The dairy industry is essentially where corporate America was two decades ago, before enough big customers forced companies like Cisco to open their systems. What broke the logjam? Fortune 500 companies told vendors: “Build us an API or we’re leaving.” Eventually, enough said that open integration became a competitive advantage.

The same thing needs to happen in dairy. And Cabrera has identified the leverage point: farmer consent.

“The producer is the consumer of the technology, and they have the say to share the data,” he explains. When a farmer tells their equipment or software vendor, “I want to share my data,” the companies comply. They have to. But—and this is a big but—”they can make it very easy to consume the data, or they can make it extremely difficult.”

Think about that next time you’re evaluating technology. Ask the vendor: Do you have an open API? Can I get my data out in a standard format? Can I integrate with other systems on my farm? If they dodge the question, that tells you where their priorities sit.

Cabrera is also involved with ICAR and IDF working groups developing international data standards, and Europe recently established protocols for farm data sharing—including the EU Data Act, which guarantees farmers’ data portability within 30 days. Standards exist. “ICAR has them. They have a GitHub,” Cabrera notes. “But which companies are actually using them? That’s a different story.”

Open Source, No Commercial Agenda—And Why That Matters

Now, some producers will read all this and think: Great, another university project that sounds amazing in a press release and never makes it to my barn. Fair enough. That skepticism is earned.

But what makes Dairy Brain different is its model. Cabrera’s team is academic—no investors, no proprietary lock-in, no commercial agenda. They’re planning to release the integration scripts as open source, meaning anyone can use, build on, or adapt them. A cooperative, a consultant group, an equipment dealer, even a motivated producer’s tech-savvy kid could take these scripts and deploy them on any farm willing to share its data.

For anyone who’s watched a $15,000 invoice land on their desk to access their own herd records during a system switch, those two words—open source—carry real weight.

“There is a benefit of doing this from that standpoint,” Cabrera says. Commercial platforms will always have their own interests—which is fine —but that means the data-sharing incentives differ.

The trade-off? Academic projects run on grants, and grants come and go. “We have come to a pause in our grant process, and that kind of stops things,” Cabrera admits. Over 16 years, he’s secured more than $5.5 million in research funding —but that’s spread across many projects, and the gaps are real.

What matters is this: if Dairy Brain proves out the concept and the code goes open source, it creates a foundation that commercial developers can build on—without the proprietary walls that fragmented the industry’s data infrastructure in the first place. That’s worth paying attention to. And arguably worth supporting.

Catching Mastitis Before She Knows She’s Sick—The $444-Per-Case Math

Alright, let’s get into the money. Because this is where the Dairy Brain value proposition hits hardest.

Mastitis—clinical and subclinical combined—costs the U.S. dairy industry somewhere between $19.7 billion and $32 billion annually. At the individual cow level, a single clinical case in the first 30 days of lactation runs about $444—that’s production loss, treatment, discarded milk, extra labor, and premature culling rolled into one. Michigan State’s analysis across 37 herds put the more conservative range at $120 to $330 per case in direct out-of-pocket costs, with milk discard accounting for nearly 80% of the expense. And the average herd is running about 25 clinical cases per 100 cows per year.

Do the math on a 1,000-cow dairy. That’s roughly 250 clinical cases annually. Even at the conservative end—say $200 per case—you’re looking at $50,000 a year spent on a problem you didn’t see coming until the cow was already sick.

Now picture standing in your office at midnight. Your robot software is showing one thing. DairyComp is showing another. The genomic reports are in a file somewhere on a third computer. And there’s no way to reconcile any of it without a spreadsheet and an hour you don’t have. Meanwhile, that fresh heifer’s conductivity numbers have been creeping up for two days, and nobody’s connected the dots.

That’s the scenario Dairy Brain eliminates.

What the system does is start building a risk profile before that heifer ever enters the milking string. Using genomic data and health records from the rearing period, it estimates whether a specific animal has a higher probability of developing mastitis compared to her herdmates. Then, once she freshens and starts milking, the real-time data kicks in—milk yield every milking, flow rate, conductivity, transition-period events, all layered on top of the genetic baseline.

“We can have, days before the probability of an animal getting sick, a very good prediction—I’m talking about more than 90% accuracy—that will give us a flag: this animal is going to get sick next week,” Cabrera says.

That accuracy figure comes from integrated data within the Dairy Brain ecosystem across pilot herds; the team has published supporting research across multiple datasets, though results will naturally vary by herd size, data quality, and management system.

And to be clear, the system flags and predicts. It doesn’t make treatment decisions for you. That’s still your call, your vet’s call, your protocol. The AI gives you the heads-up; the human makes the decision. That’s an important distinction, and it’s by design.

Think about what even 80% accuracy means in practice. Instead of treating a clinical case at $200-$444 a pop, you’re flagging a cow for closer monitoring days ahead. Maybe she moves to a hospital pen. Maybe the nutritionist adjusts her ration. Maybe the vet starts a preventive protocol. “We should prevent before the event,” Cabrera argues. “We should not try to cure what has already happened.”

Same shift that’s transforming human medicine—from reactive treatment to predictive prevention. Except on a dairy, the ROI shows up on your milk check within the month.

The Cow at 50 Pounds You Don’t Want to Ship—But Probably Should

Here’s a scenario every dairy farmer will feel in their gut.

You’ve got a cow making 50 pounds. She’s not your star—everyone knows who the stars are. But she’s milking, she’s bred, she’s not really causing problems. The idea of shipping her—taking the net financial hit on salvage minus replacement cost, losing her current production, dealing with the headache of bringing in a new animal—feels wrong. Every instinct says keep her.

And with replacement heifers averaging $3,010 per head nationally as of mid-2025—topping $4,000 in California, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania auction barns—that instinct is screaming even louder right now.

“It’s difficult to convince a farmer that has a cow producing 50 pounds of milk to replace her,” Cabrera acknowledges.

But here’s where data tells a different story. When his replacement optimization models project forward—factoring in the genetic potential of available replacements, the current cow’s production trajectory, her expected health costs, and the opportunity cost of that stall space over the next several lactations—replacement often pencils out. Not today. Not this month. But over the productive life of the next animal in that slot, the net return to the herd is higher.

“You have a space on the farm,” Cabrera explains, “and you need to use that space with the best animal you can in the long term—not today.”

The thing is, we’re all wired to focus on the immediate hit. The visible loss today looms bigger than the invisible gain two years from now. That’s just how we’re wired. Every producer does it. But it’s exactly where data needs to do the heavy lifting—and increasingly, Cabrera’s team is going backward through historical herd data to show what actually happened in herds where replacement decisions were made versus where they weren’t. Not simulations. Outcomes. That’s a much harder argument to walk away from.

The Sustainability Paradox That Should Be on Every Producer’s Talking Points

Picture this: you’re at a county board meeting, or maybe it’s a school tour, or maybe it’s just Thanksgiving dinner with your brother-in-law who reads too much Twitter. Someone looks at you and says, “Aren’t those big dairy farms terrible for the environment?”

You need an answer. And Victor Cabrera’s research just handed you a really good one.

Your highest-producing cows are almost certainly your most sustainable. That’s a fact that makes activists’ heads spin, but that any producer who’s tracked feed efficiency already understands intuitively.

“A higher-producing cow will consume more feed and will produce overall more greenhouse gases, total,” Cabrera confirms. He doesn’t dodge the headline number. “But if we measure that per unit of milk produced, it will be less.”

The science backs this up broadly. Canadian life cycle assessments show that the carbon footprint of producing a litre of milk in Canada is 0.94 kg of CO2-equivalent—well below the global average of 2.5 kg, according to FAO data—and that figure dropped 9% between 2011 and 2021, even as production per cow climbed. Why? The maintenance energy required to keep a cow alive is roughly constant, whether she’s producing 60 or 100 pounds a day. Every additional pound of milk dilutes that overhead across more product.

“Anything we do, whether at the farm level, at the herd level, or at the specific cow level, to improve feed efficiency will be a huge benefit to the environment,” Cabrera says. That includes nutritional grouping, precision feeding, and genetic selection for traits like residual feed intake—which is already a selectable trait—and methane efficiency, which Canada already has, and the U.S. is expected to add soon.

And here’s the kicker that connects everything: your most profitable cow and your most sustainable cow are almost certainly the same animal. Feed efficiency, component yield per unit of dry matter, production per pound of methane emitted—optimize for profit and you’re optimizing for sustainability too.

This circles straight back to Dairy Brain. When all your data systems are actually integrated—genetics, feeding, production, health, and reproduction—identifying which cows sit in that profitability-sustainability sweet spot becomes automatic. Right now, for most operations, that information is spread across five programs, and you’d need a full day with a spreadsheet to assemble it. With integrated data? It’s a dashboard.

And if you want proof that data-driven thinking matters at the herd strategy level—not just the individual cow level—look at what happened when the industry went all-in on beef semen without running the long-term math.

Beef-on-Dairy: The $1,000 Calf That Created a $3,010 Problem

If you want a real-world case study in what happens when an industry chases short-term economics without long-term modeling… well, you’re living in one right now.

Cabrera doesn’t dismiss beef-on-dairy—actually, he’s genuinely enthusiastic about the opportunity. “It’s a great economic alternative,” he says. “And looking at the markets in the future, the opportunity seems here to stay.”

The premiums are real. Beef-cross calves are bringing $680 to $1,160 at auction in Pennsylvania and the Upper Midwest. The U.S. beef cow herd hit a 64-year low in early 2025, and feedlots need calves. This isn’t a fad.

But the industry overdid it. And a lot of producers are now paying the price.

“We looked at the opportunity, and we were having better reproduction performance, and we used too much beef semen,” Cabrera explains. “We entered into the problem—which I think now we are coming out of—which was having not enough replacements.”

The numbers are stark. USDA data from January 2025 put dairy replacement heifer inventories at the lowest level since 1978—a full 18% below 2018 levels. CoBank’s analysis identified roughly 800,000 “missing” heifers across 2025-2026. Replacement prices jumped from $1,140 per head in 2019 to $3,010 by mid-2025, with top animals commanding over $4,000 in high-demand markets.

Let’s make that real for a 200-cow herd running a 35-38% replacement rate. That price shift translates to an extra $126,000 to $144,000 in replacement capital over two years—and that’s if you can find animals to buy.

Think about a producer out in Wisconsin or Central New York—or the Texas Panhandle, or the Boise Valley, doesn’t matter—who went heavy on Angus semen in 2023. Looked great at the time. The beef-cross premiums were strong, repro performance was up, and the math seemed obvious. Now it’s 2026, those calvings have come and gone, and the replacement pen is thin. The heifers that were supposed to fill the gaps? They were born as beef-crosses instead. And buying replacements from outside means $3,000+ per head and no guarantee of genetic quality or health history. That’s the trap Cabrera warned about.

His team has built simulation tools—available on the DairyMGT.info platform—that model this dynamic exactly. Not just optimizing for maximum beef-cross revenue, but balancing that against your replacement pipeline in real time.

The critical insight, and one that a lot of producers miss: you can’t run this analysis once and call it done. “If you do that one-time analysis today, your herd demographics are going to change nine months from now when you’re having the calvings,” Cabrera warns. You need to recalculate continuously—pairing sexed semen on your top genomic animals to secure replacements, then strategically using beef semen on the rest. And you need to monitor that balance until it stabilizes.

The whole beef-on-dairy situation is basically a poster child for Cabrera’s core argument: without integrated data and modeling, you’re flying blind. The producers navigating this well aren’t necessarily smarter—they’re just running the numbers instead of guessing.

Who Actually Owns Your Data? (The $20,000 Question)

The data integration challenges are real. But there’s a softer, messier problem lurking underneath all the technology—and Cabrera says it caught him completely off guard.

“I never thought we would spend so much time and effort thinking and working on that,” he says about data governance. His team has convened a dedicated working group to wrestle with questions that sound simple and turn out to be anything but: Who owns the data generated on your farm? What rights do you have to share it? How do you protect confidentiality when data flows through multiple systems?

These aren’t abstract questions. And the dollars involved aren’t small.

We reported last year on a family near New Hamburg, Ontario, who’d used the same herd management software for eighteen years—building detailed records on 450 cows. The son wanted to switch systems for better functionality. The quote to export their own historical data? Nearly $5,000. Converting it to work in the new system? Another $8,000-$10,000. Training and setup? Add a few thousand more. Total: $15,000-$20,000 to keep using the information their cows generated in their barn.

That’s not an outlier. Ag lenders from TD, RBC, and FCC have all reported that they now specifically assess software dependencies when reviewing succession financing. Data transfer complications delayed several deals in 2025, resulting in average unexpected costs of over $20,000. The EU Data Act now guarantees farmers data portability within 30 days, but North America has nothing comparable.

You provide the genetic samples that power genomic databases—and then pay to get your own evaluations back. Robot systems generate mountains of data inside your barn, on your cows—but accessing that data through anything other than the manufacturer’s own interface ranges from inconvenient to essentially impossible.

Cabrera’s advice? Use the leverage you actually have. “The producer is the consumer of the technology, and they have the say to share the data.” When enough farmers tell their vendors—in writing, not just in conversation—that they want their data in an open, standard format, the industry will move. It happened in corporate tech. It’ll happen in dairy. It just needs enough voices.

| Fragmented Data (Status Quo) | Integrated Data (Dairy Brain) |

| IOFC calculated monthly, herd average only | IOFC visible daily, pen-by-pen, cow-by-cow |

| Mastitis found at clinical signs ($200-$444/case) | Mastitis predicted a few days in advance, 90%+ accuracy |

| Culling decisions based on gut instinct and current production | Replacement optimization modeling long-term herd net return |

| Beef-on-dairy allocation based on a one-time snapshot | Continuous simulation balancing premiums vs. replacement pipeline |

| Sustainability metrics are unmeasured at the individual cow level | Profitability and emissions intensity tracked per animal |

| Silage quality shifts discovered in bulk-tank averages weeks later | Real-time feed efficiency dashboards flag changes within hours |

| Data migration during succession: $15,000-$20,000+ | Open-source scripts, no proprietary lock-in |

What This Means for Your Operation

This isn’t just a profile of a smart researcher doing interesting work. Cabrera’s Dairy Brain project—and the principles behind it—point directly at decisions you’re making right now.

- Grill your tech vendors. Before your next equipment purchase or software renewal, ask three questions in writing: Do you have an open API? Can I export my data in a standard format? Can I integrate with other systems on my farm? If the answer is vague—or if they tell you their system “does everything”—factor that into your buying decision. The vendors who make data sharing easy are investing in your future, not just locking you into theirs.

- Standardize your own data entry—starting tomorrow. Cabrera flagged that even within a single farm, different employees record the same health event with different names—”mastitis,” “mast,” “clinical mast,” “CM”—making later analysis a nightmare. Pick standard terms, write them on a laminated card, and make sure everyone entering records uses them. This one’s free, and it matters more than you’d think.

- Rerun your beef-on-dairy numbers. If you set your breeding strategy in 2024 and haven’t revisited it, your herd demographics have already shifted. The free tools at DairyMGT.info will model your replacement pipeline against your beef-cross revenue. With heifers at $3,000+ per head and USDA projecting continued shortages through 2027, a gap in your replacement pipeline isn’t theoretical—it’s a six-figure problem.

- Know your real profit centers, cow by cow. If you can’t identify your top and bottom 20% by economic value—not just production—you’re leaving money on the table. At $40-50 per genomic test, the ROI on testing everything at birth and making data-driven breeding and culling decisions has never been clearer. It’s the best $40 you’ll spend per animal on your operation.

- Bookmark DairyMGT.info. Cabrera’s lab has built a full suite of decision-support tools—replacement optimizers, beef-on-dairy simulators, feed management calculators—developed directly from producer questions. A subscription model is rolling out in 2026, but Cabrera says anyone with a genuine need should reach out: “I’ll be glad to entertain that.”

The Brain Is Being Built

Victor Cabrera came to Wisconsin from Peru with the kind of hunger that only comes from knowing what it’s like not to have access. He waited months for a research paper. He studied professors he could never meet. And when he finally got to a place where the knowledge, the technology, and the cows were all within arm’s reach, he refused to waste a single bit of it.

That same hunger is what drives Dairy Brain. Not a desire to pile more tech onto what you’ve already got—Lord knows we don’t need that—but an obsession with making the technology you’re already paying for actually earn its keep. Connecting systems that should’ve been connected years ago. Converting the data your cows generate every single milking into decisions that put money in your pocket and keep your operation viable for the next generation.

“Data is a liability until it becomes a decision,” Cabrera says.

The North American dairy industry is sitting on more data than it’s ever had. More sensors, more genomics, more software, more numbers flowing through more systems on more farms than at any point in the last century. And most of it is sitting there doing nothing—trapped in silos, locked behind proprietary walls, or piling up in spreadsheets nobody has time to analyze.

The brain is being built. The question is whether the rest of the industry—the vendors, the breed associations, the tech companies, and yeah, us as producers—will get out of the way and let the data do what it should’ve been doing all along.

Because a heifer in central Wisconsin shouldn’t have to get sick for us to know she was going to get sick.

Executive Summary:

Victor Cabrera’s Dairy Brain project integrates fragmented on-farm data—genetics, milking systems, feed software, DHI records—into a single real-time ecosystem that converts raw numbers into decisions worth real money. His team has demonstrated over 90% accuracy in predicting mastitis days before clinical signs appear, built replacement optimization tools that challenge every gut-instinct culling decision you’ve ever made, and proven that the most profitable cow in your herd is almost certainly your most sustainable one. But the biggest barrier to scaling this? It’s not the AI. It’s the fact that most dairy tech companies still won’t share data through standard interfaces—and the industry is letting them get away with it.

Editor’s Note: This article draws from a direct interview with Dr. Victor Cabrera, University of Wisconsin–Madison, conducted by The Bullvine in early 2026, supplemented by published USDA market data (2024-2025), CoBank’s August 2025 economic analysis, and peer-reviewed research from the Journal of Dairy Science. Mastitis cost estimates are based on reference studies analyzing data from U.S. dairy operations (2015-2024); the $444 figure applies specifically to clinical cases in the first 30 days of lactation and may not reflect all mastitis events or severity levels. The 90%+ prediction accuracy was demonstrated across Dairy Brain pilot herds and will vary by herd size, data quality, and management system. Dairy Brain provides predictive flags and decision support—it does not make autonomous treatment or management decisions. National averages and cost figures may not reflect your specific region, management system, or market conditions. We welcome producer feedback and case studies for future reporting. Contact: editor@thebullvine.com.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- December 1 Deadline: How Cutting 15% of Your Herd Could Add $40,000 to Your Bottom Line – Cabrera’s replacement math meets its match in this narrative of a farm that finally stopped trusting gut instinct. It walks a similar path by proving that culling for profitability, not just volume, is the only way to survive.

- $3,010 Per Heifer. 800,000 Short. Your Beef-on-Dairy Bill Is Due. – Shaped by the same market forces Cabrera warns about, this analysis exposes the 800,000-heifer crunch that turned a short-term beef win into a long-term equity drain. It provides the deep context behind today’s high-stakes breeding decisions.

- Digital Dairy Detective: How AI-Powered Health Monitoring is Preventing $2,000 Losses Per Cow – The predictive power of the Dairy Brain carries forward into this examination of AI systems that watch cows 24/7. It proves the point that waiting for clinical symptoms is a failing strategy in a data-driven world.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

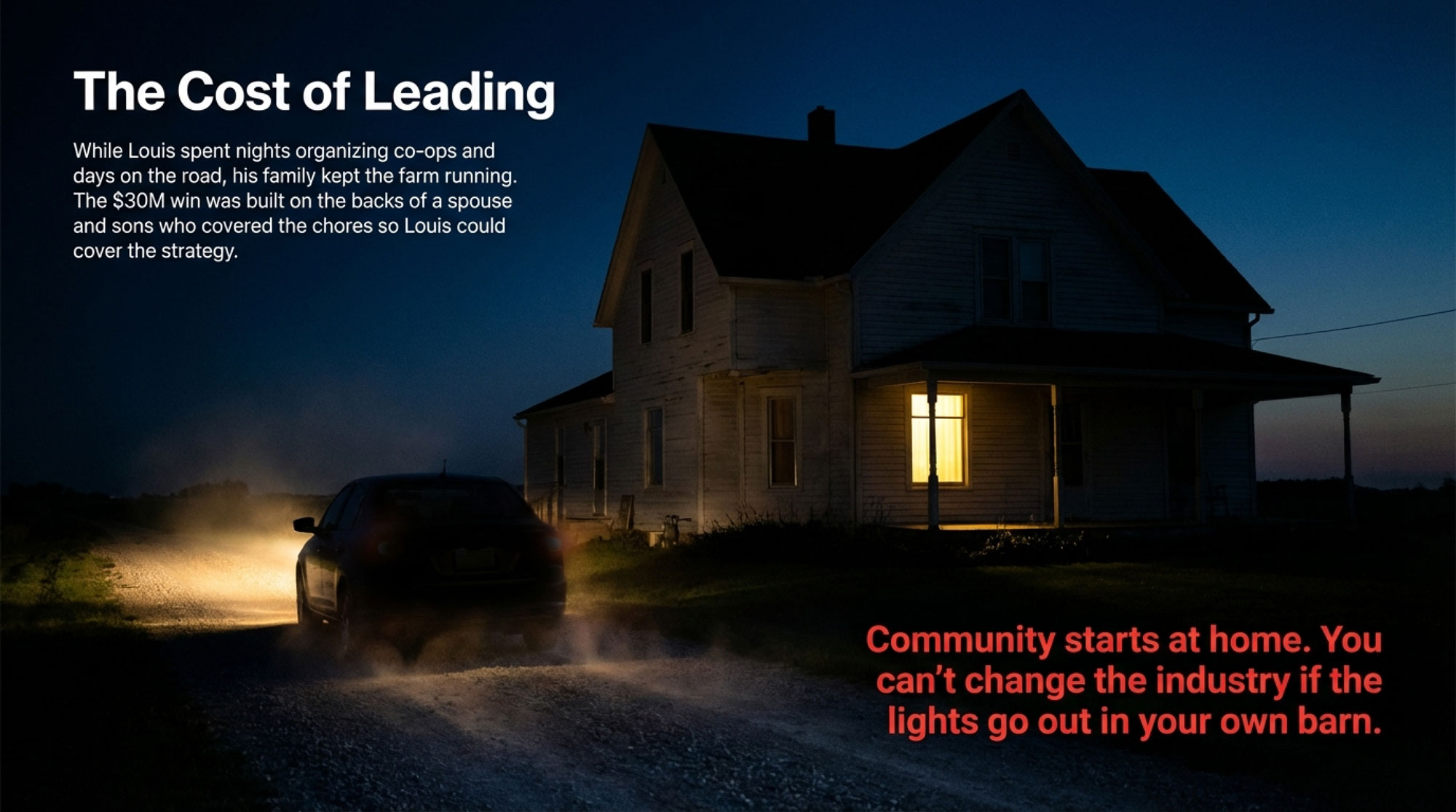

With a firm handshake that reaches your soul and an unwavering commitment to making every interaction count, Bob Hagenow has spent four decades transforming the dairy industry through genuine connections and servant leadership. Growing up on a registered Holstein farm located south of Green Bay, Wisconsin, Bob learned early that success comes from helping others succeed. Whether he’s in the World Dairy Expo show ring, where he’s served as ring steward for 40 years, mentoring young professionals, or solving complex farm challenges, Bob approaches each interaction with the same level of care and attention that has made him one of the industry’s most trusted voices. His philosophy is simple yet profound: “If you don’t have people stepping up, if you don’t have vibrant organizations adding to a community, you don’t have a community.”

With a firm handshake that reaches your soul and an unwavering commitment to making every interaction count, Bob Hagenow has spent four decades transforming the dairy industry through genuine connections and servant leadership. Growing up on a registered Holstein farm located south of Green Bay, Wisconsin, Bob learned early that success comes from helping others succeed. Whether he’s in the World Dairy Expo show ring, where he’s served as ring steward for 40 years, mentoring young professionals, or solving complex farm challenges, Bob approaches each interaction with the same level of care and attention that has made him one of the industry’s most trusted voices. His philosophy is simple yet profound: “If you don’t have people stepping up, if you don’t have vibrant organizations adding to a community, you don’t have a community.”

From her modest origins in Plain City, Ohio, Shirley Kaltenbach started a career that would make her a significant player in the artificial insemination business. As she prepares for retirement, her path shows diligence, commitment, and a relentless love of her industry and the people she works with. A lifelong learner, she has navigated several responsibilities at Select Sires over almost four decades, each adding to her remarkable legacy.

From her modest origins in Plain City, Ohio, Shirley Kaltenbach started a career that would make her a significant player in the artificial insemination business. As she prepares for retirement, her path shows diligence, commitment, and a relentless love of her industry and the people she works with. A lifelong learner, she has navigated several responsibilities at Select Sires over almost four decades, each adding to her remarkable legacy.