Cheap feed won’t save you. At $19 milk, a 300-cow dairy loses $100K in 2026—even with record corn.

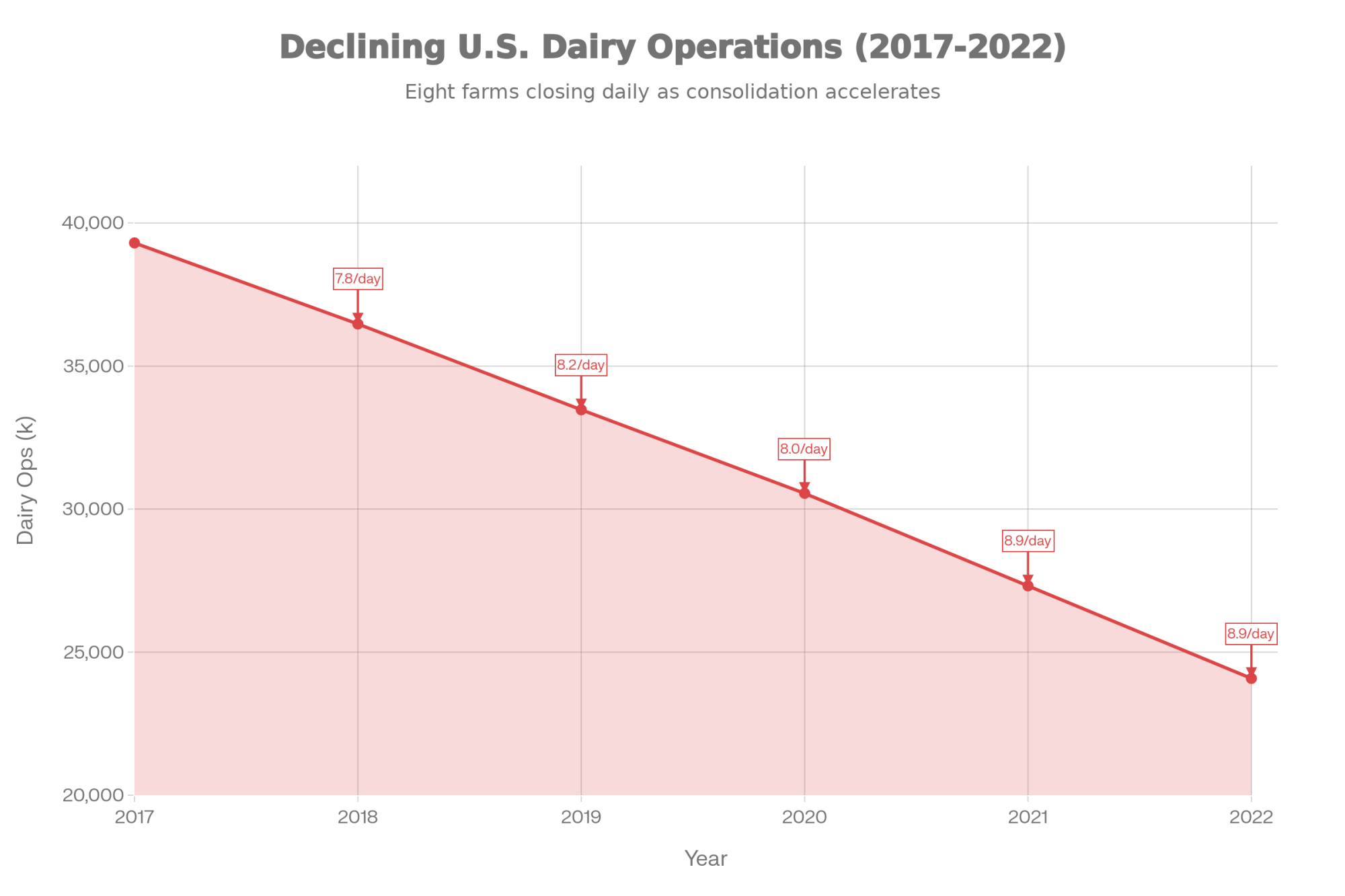

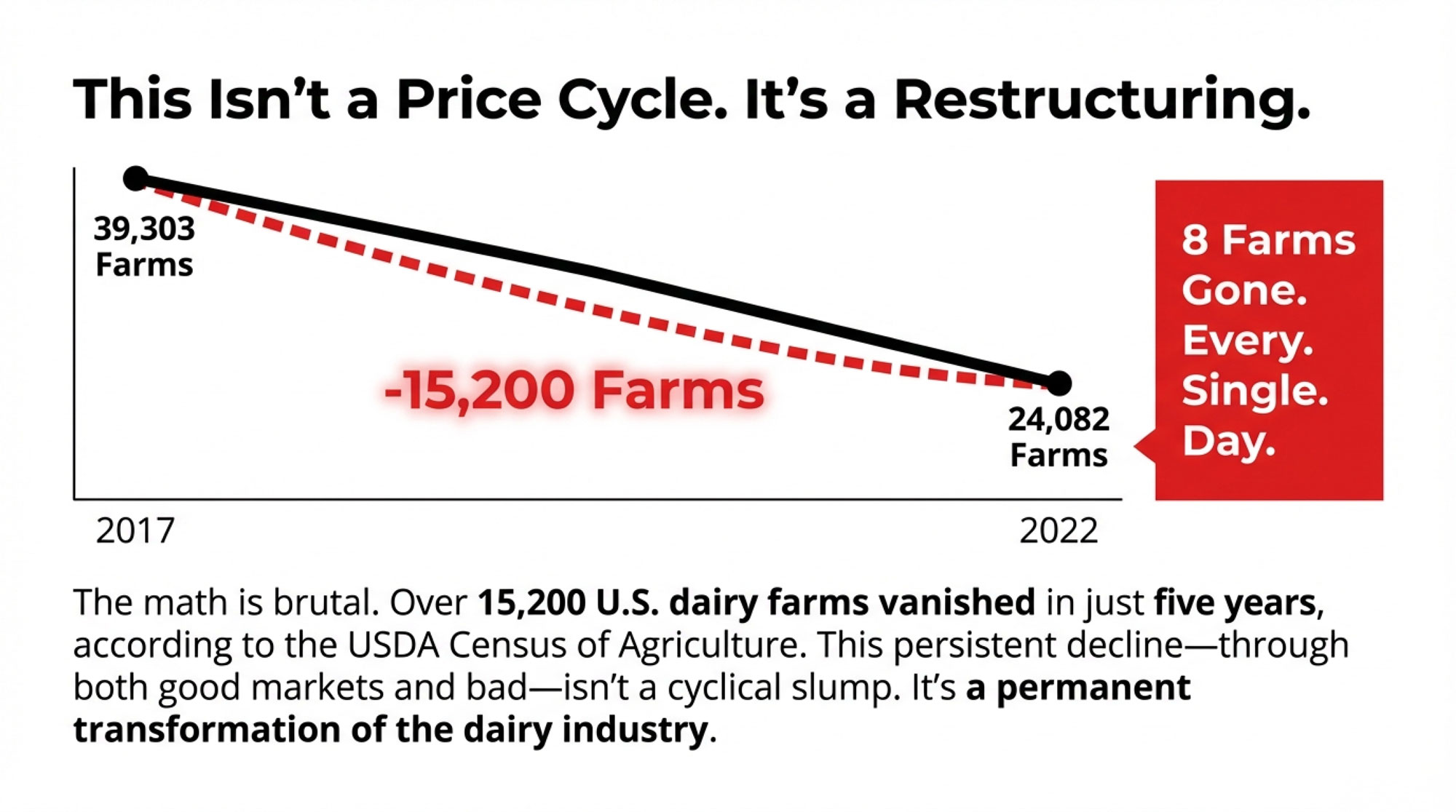

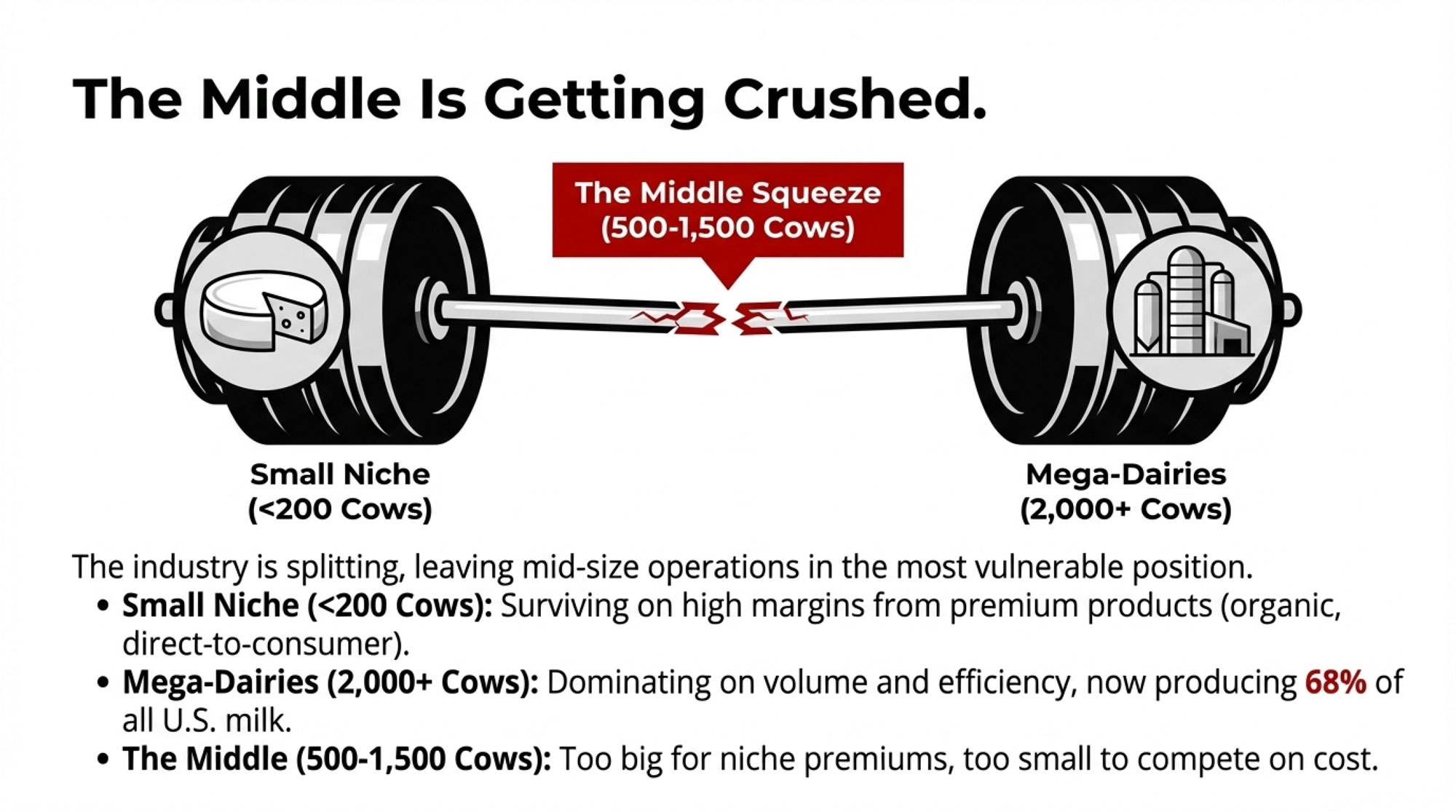

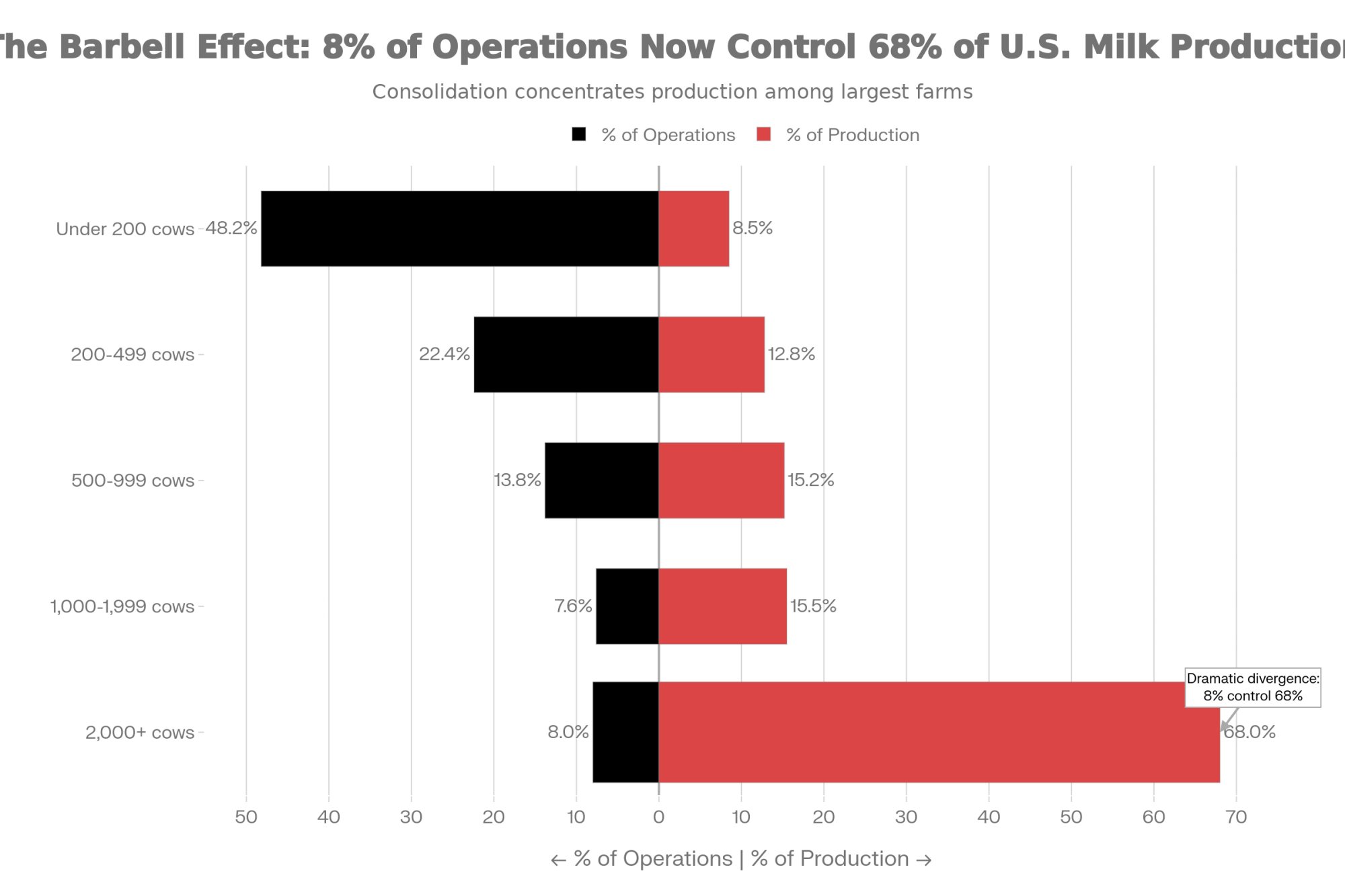

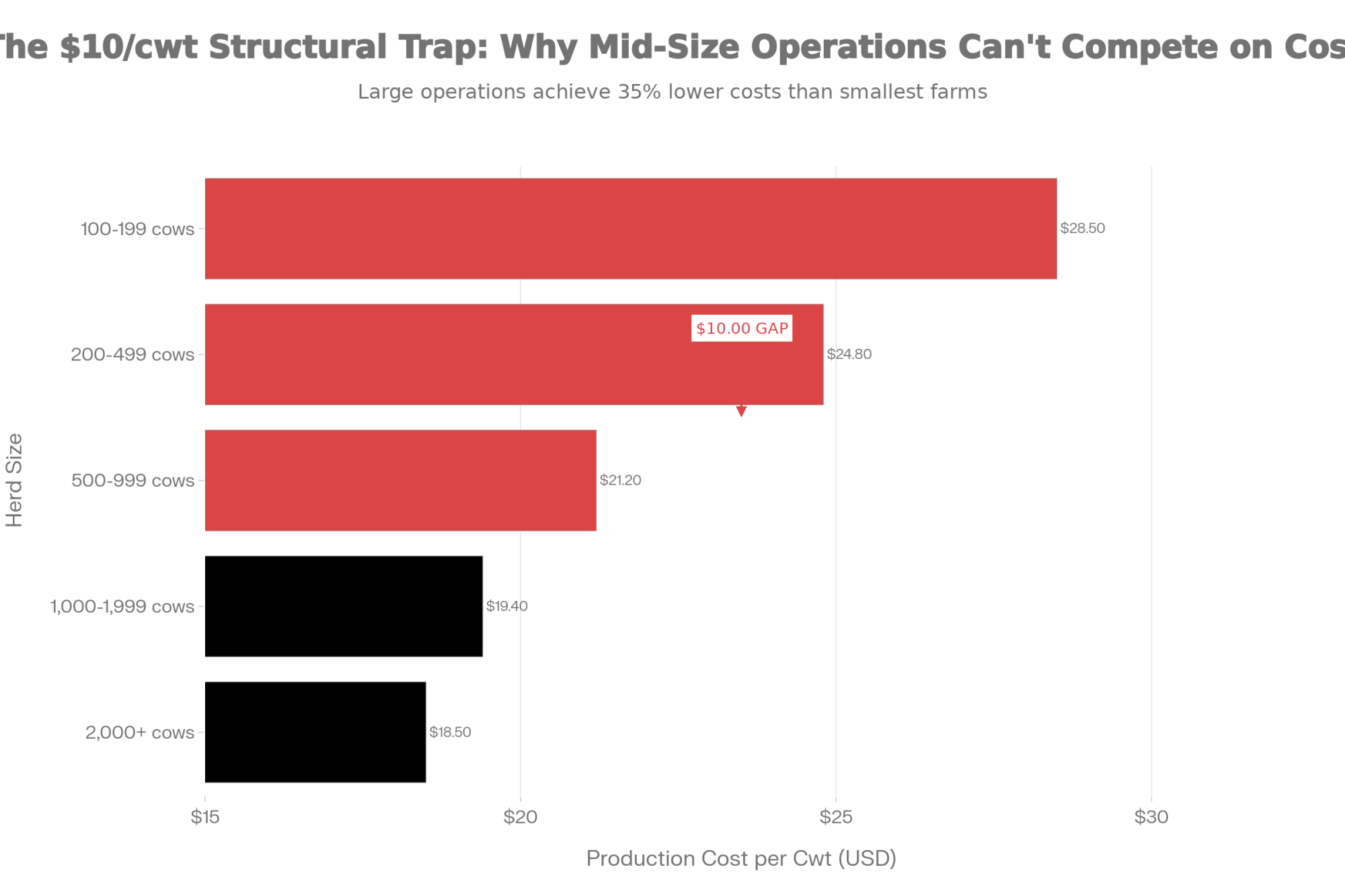

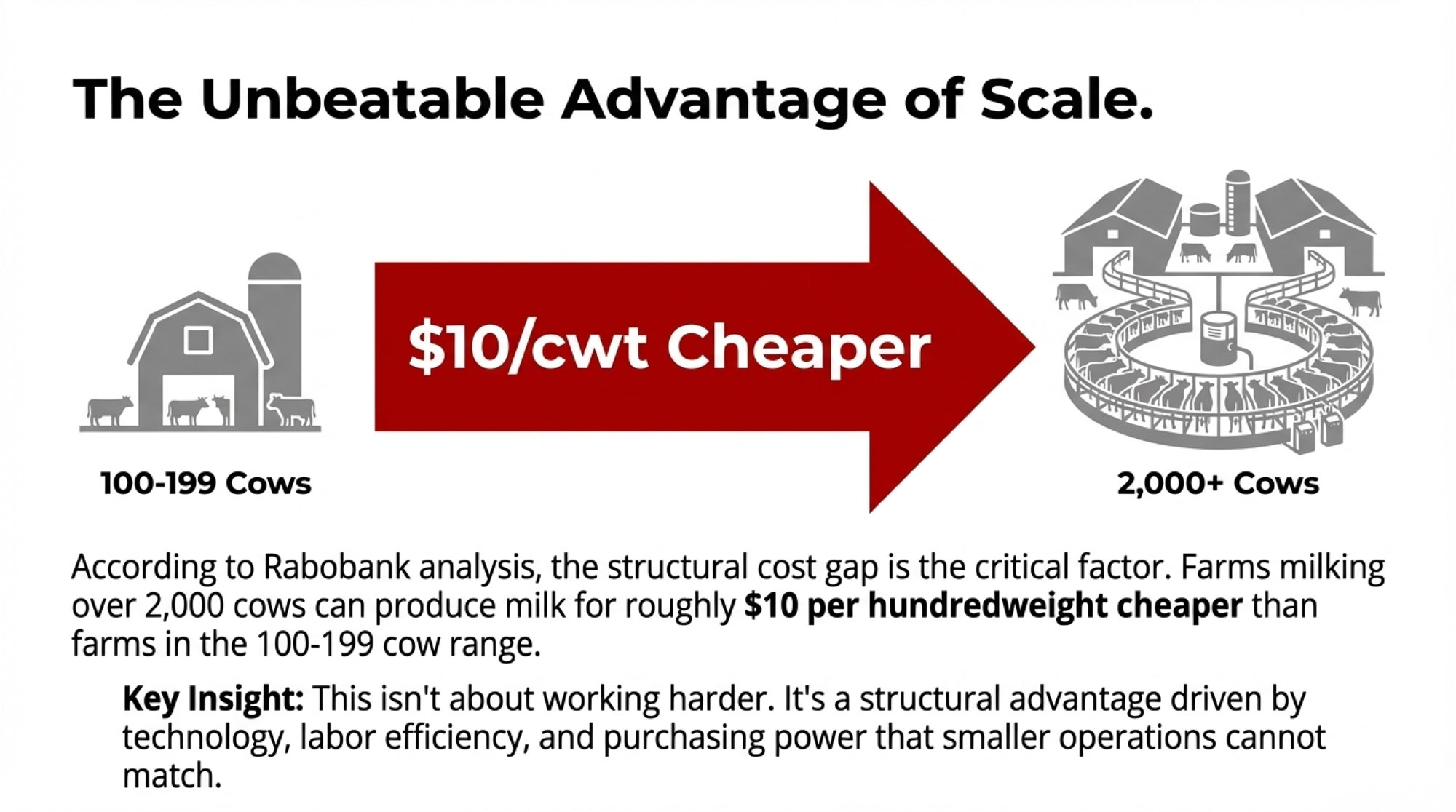

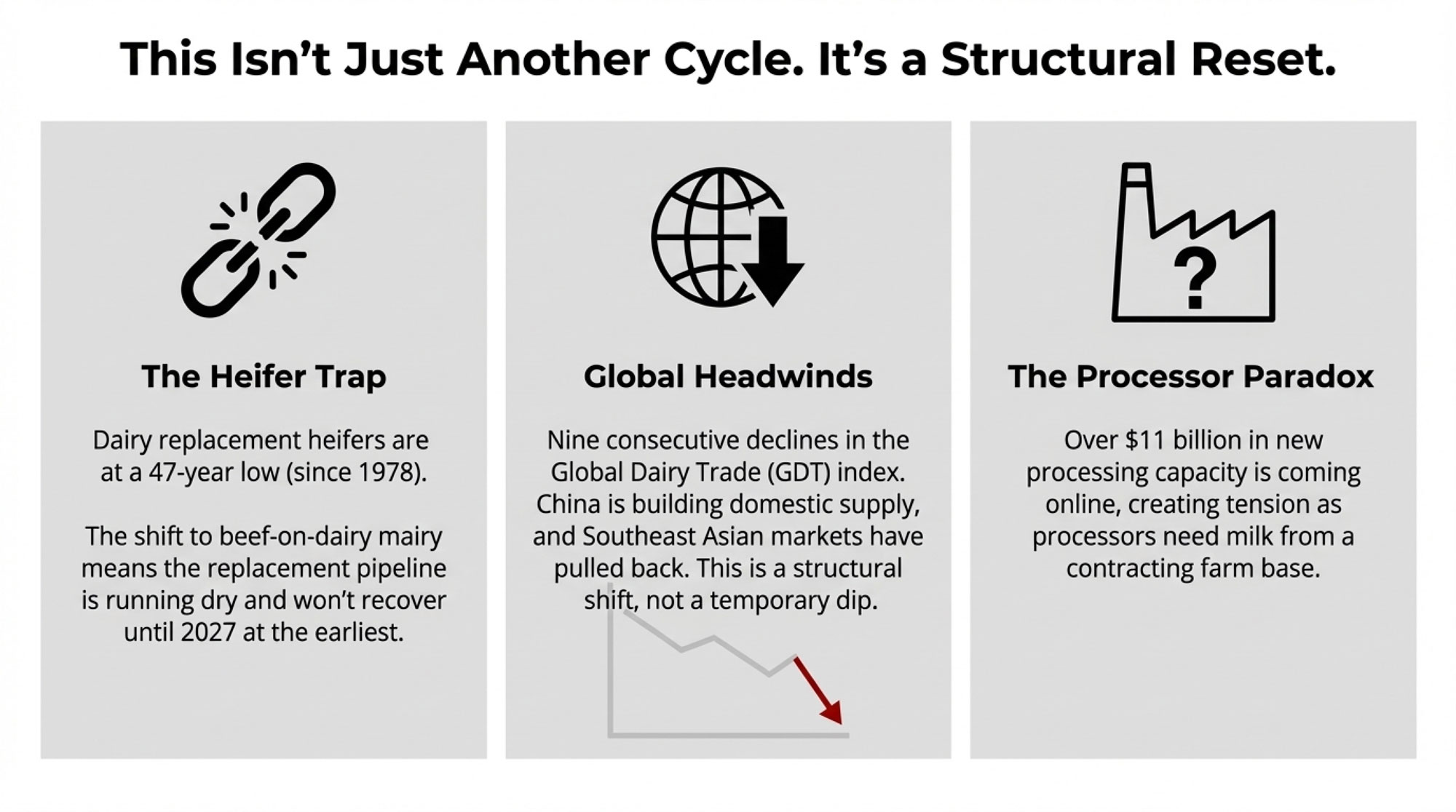

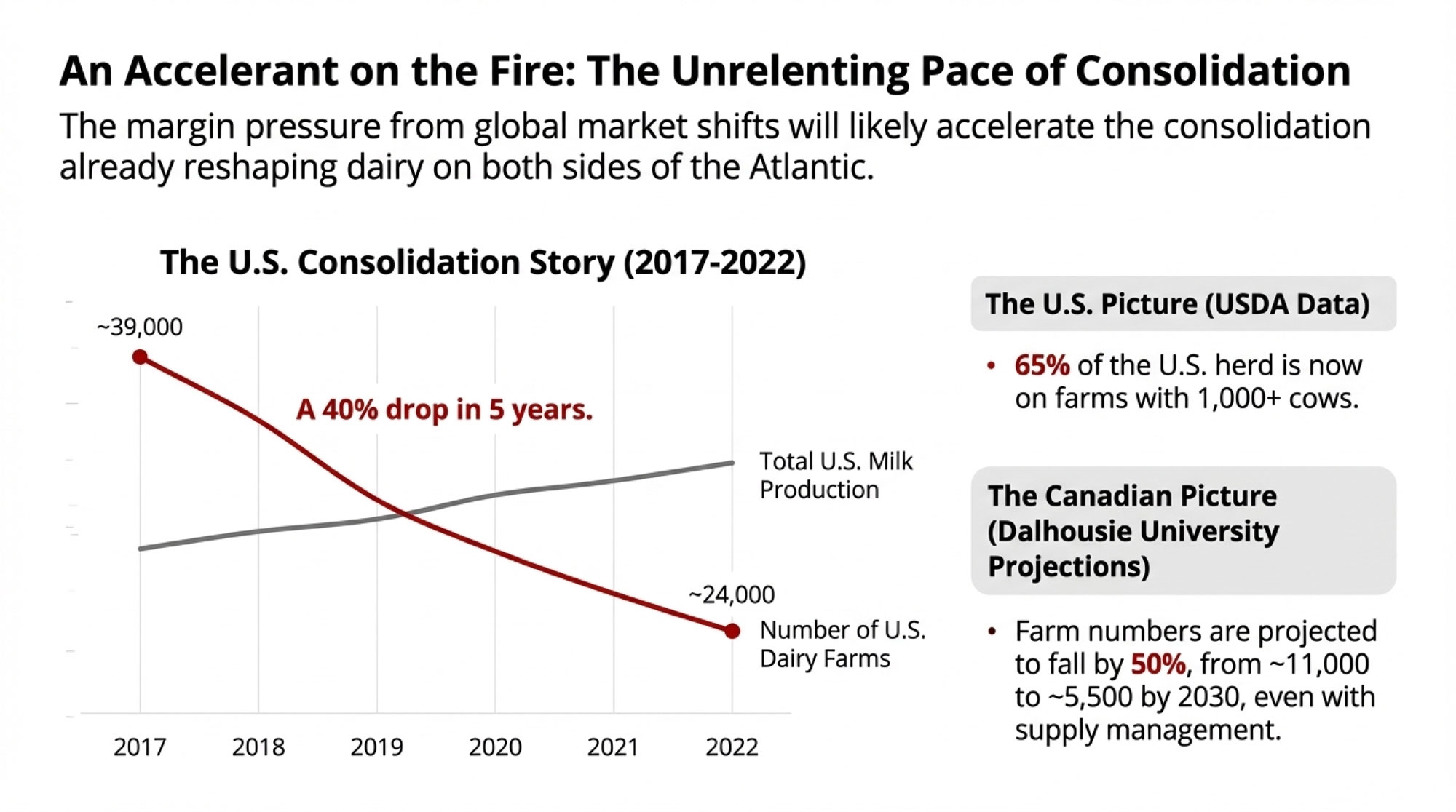

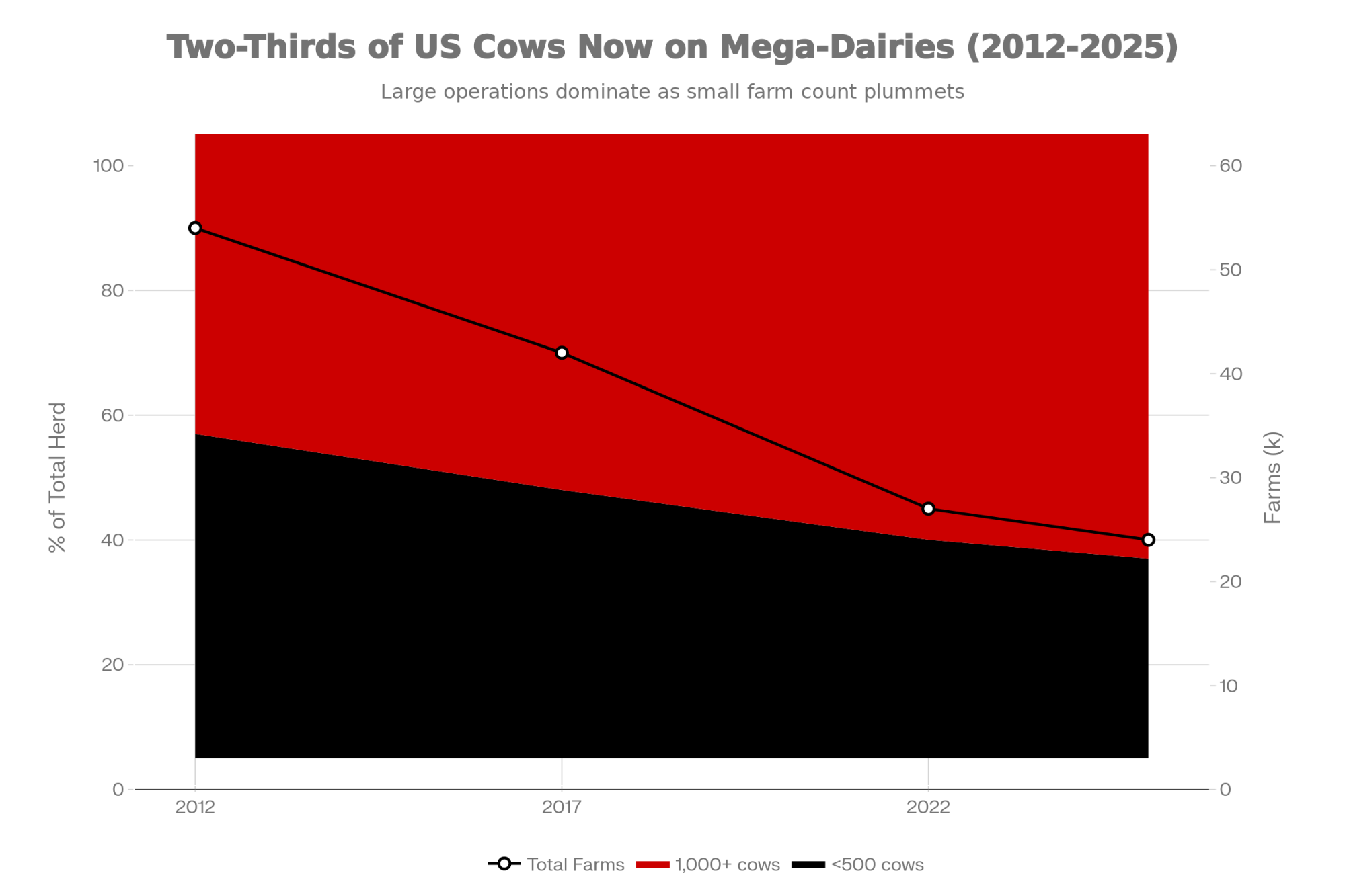

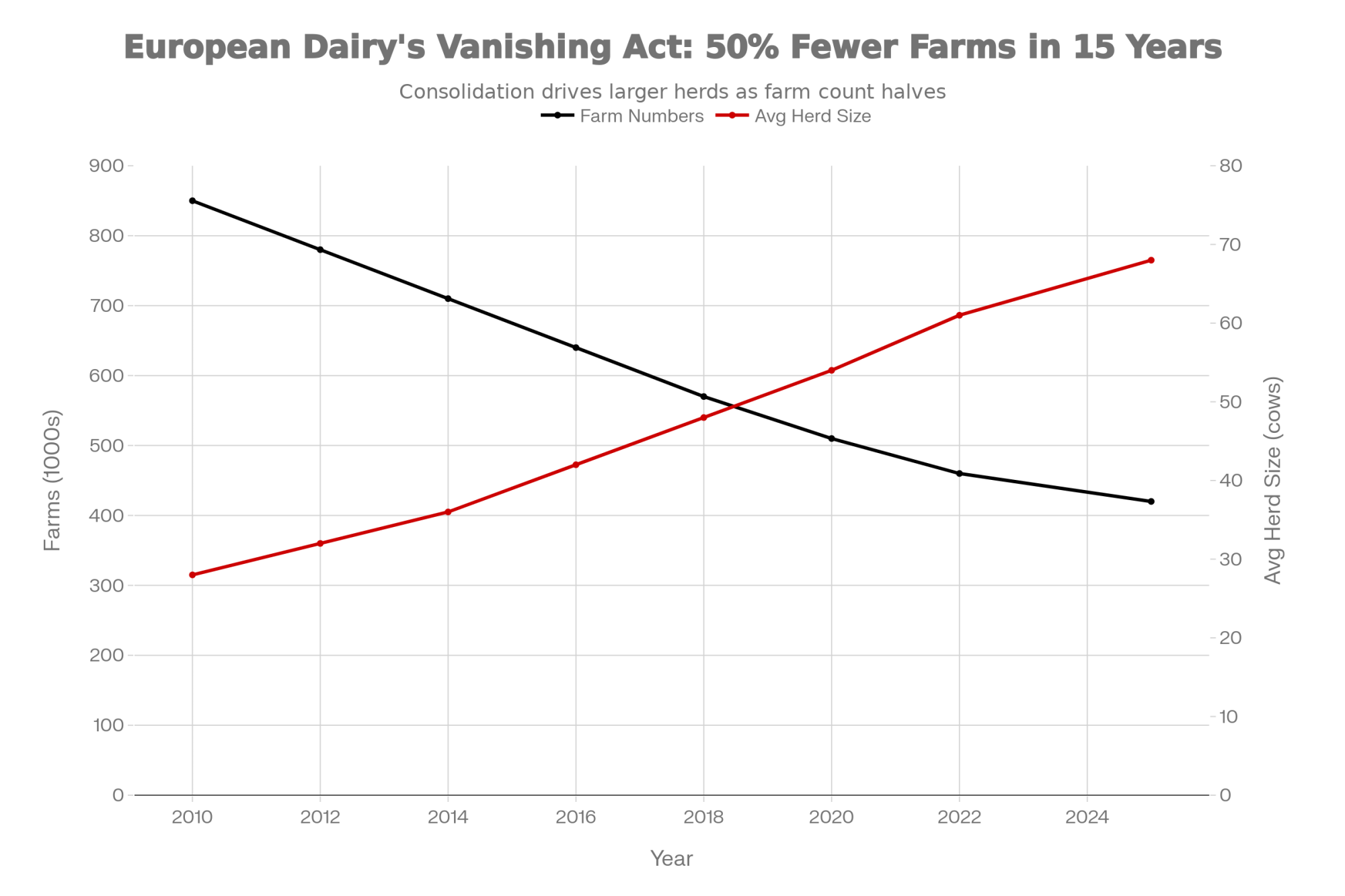

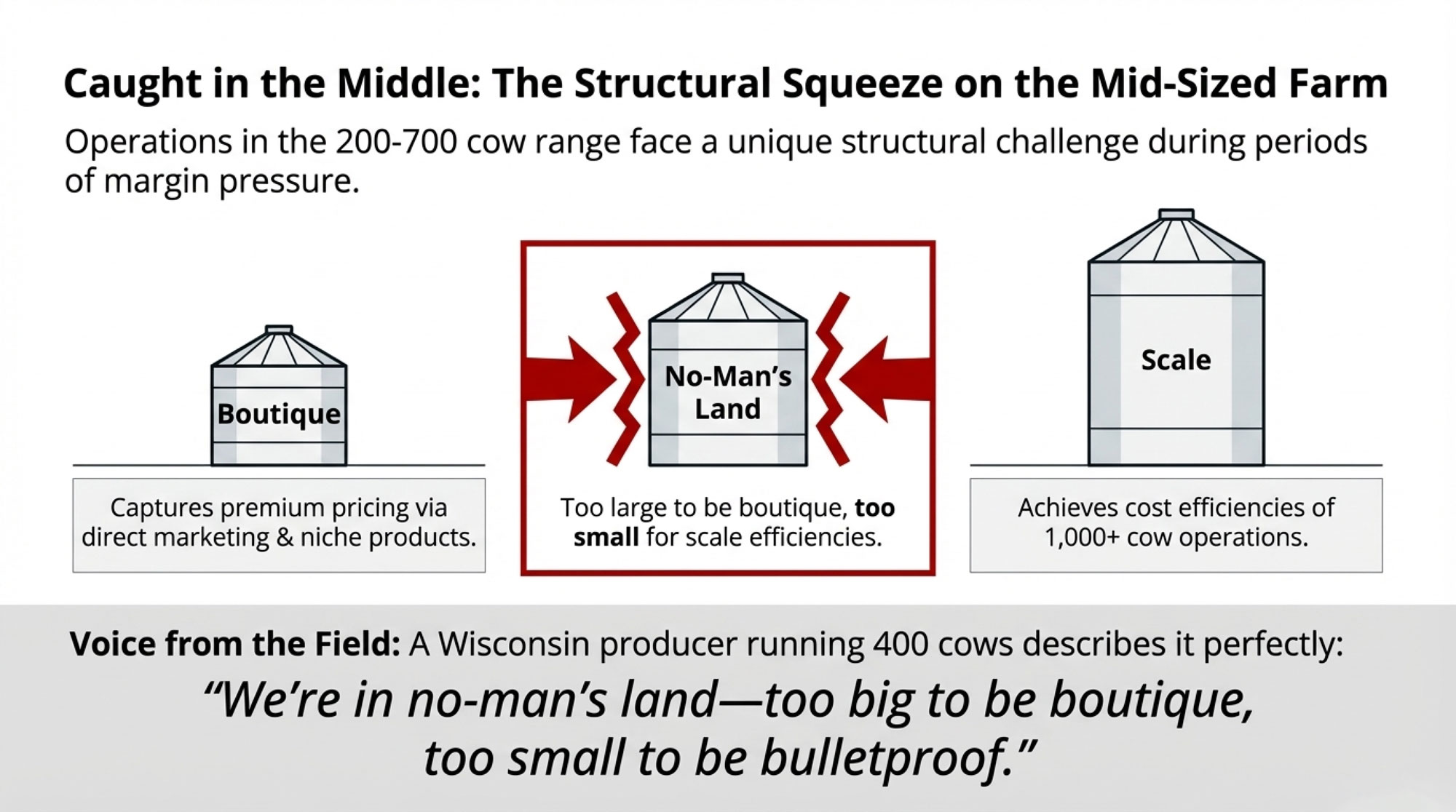

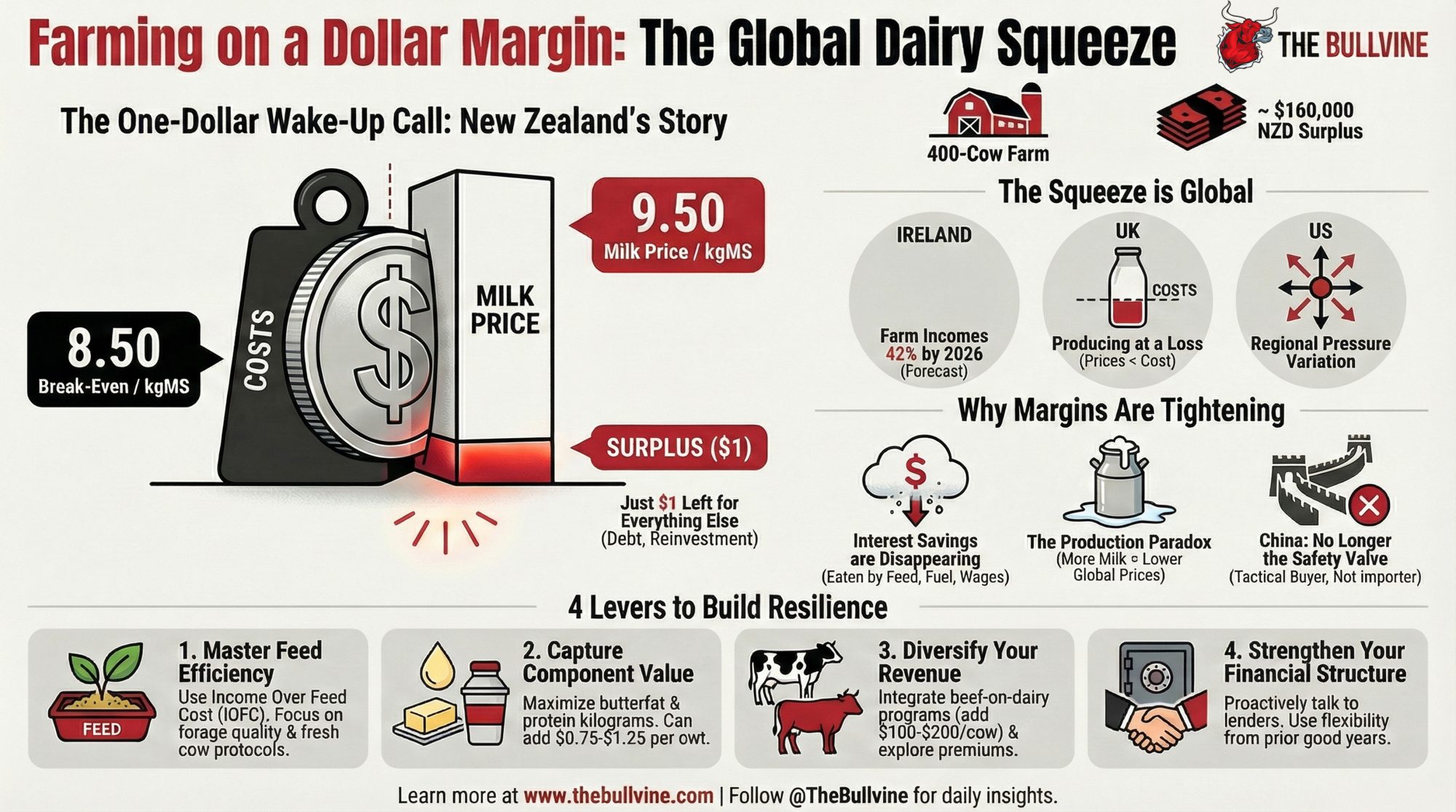

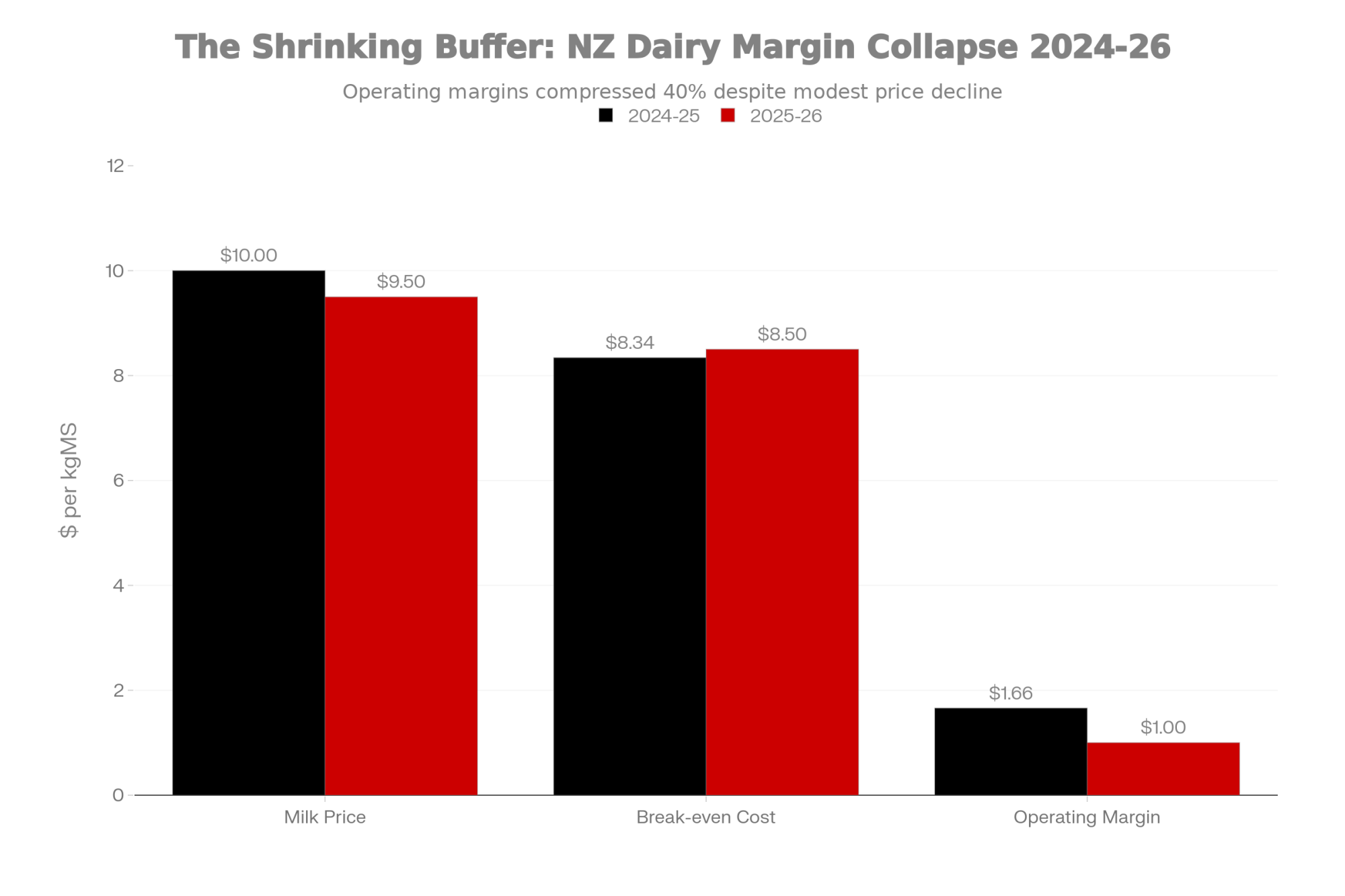

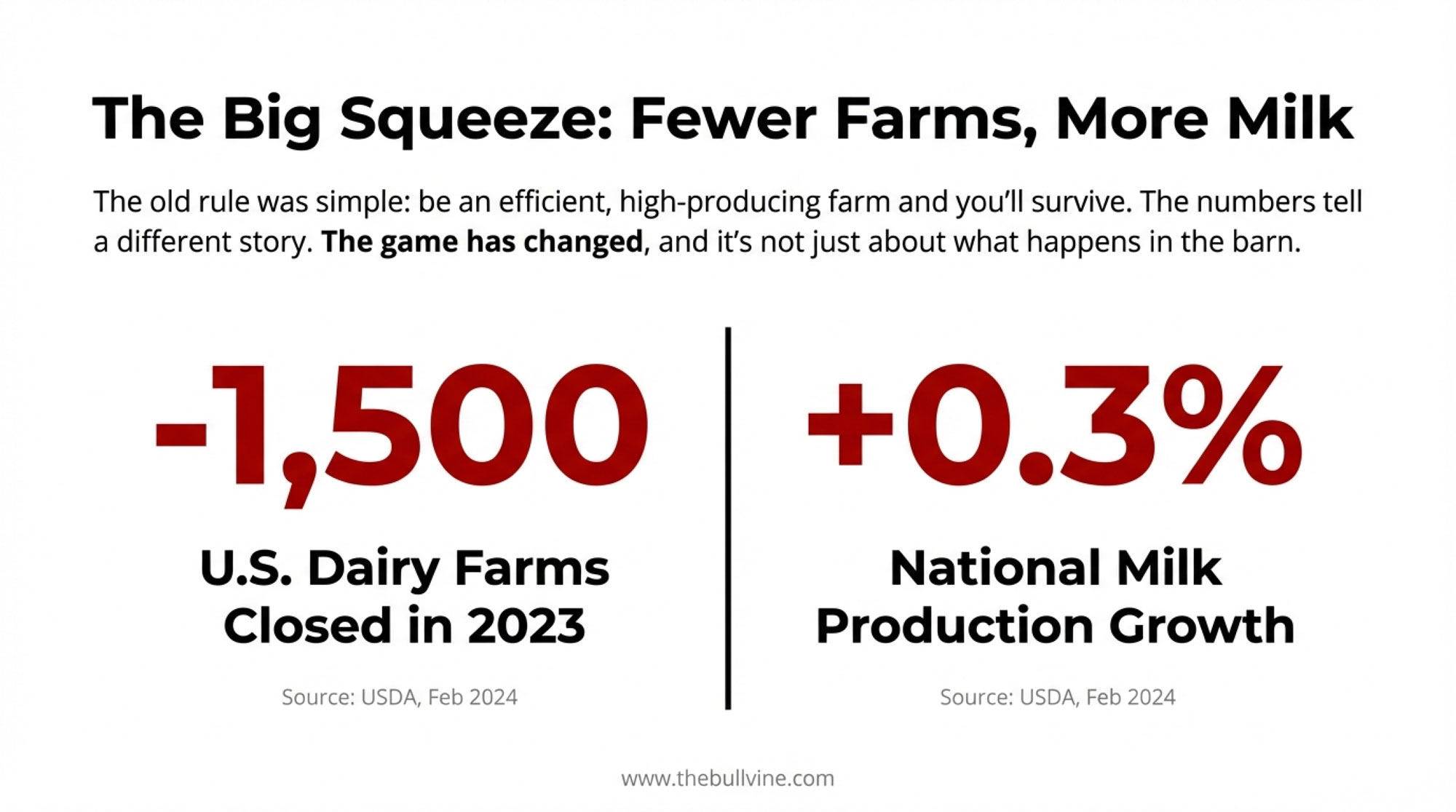

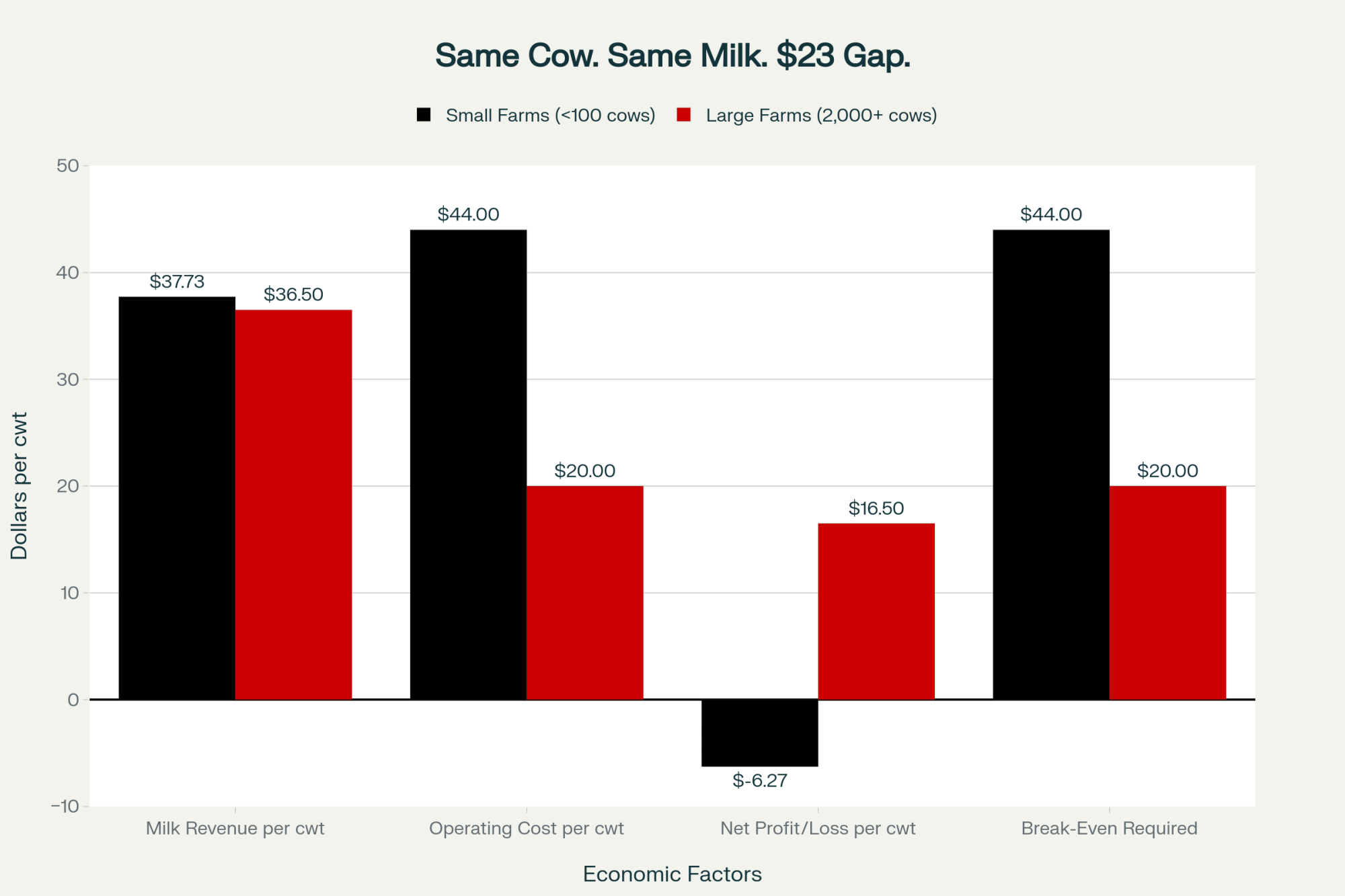

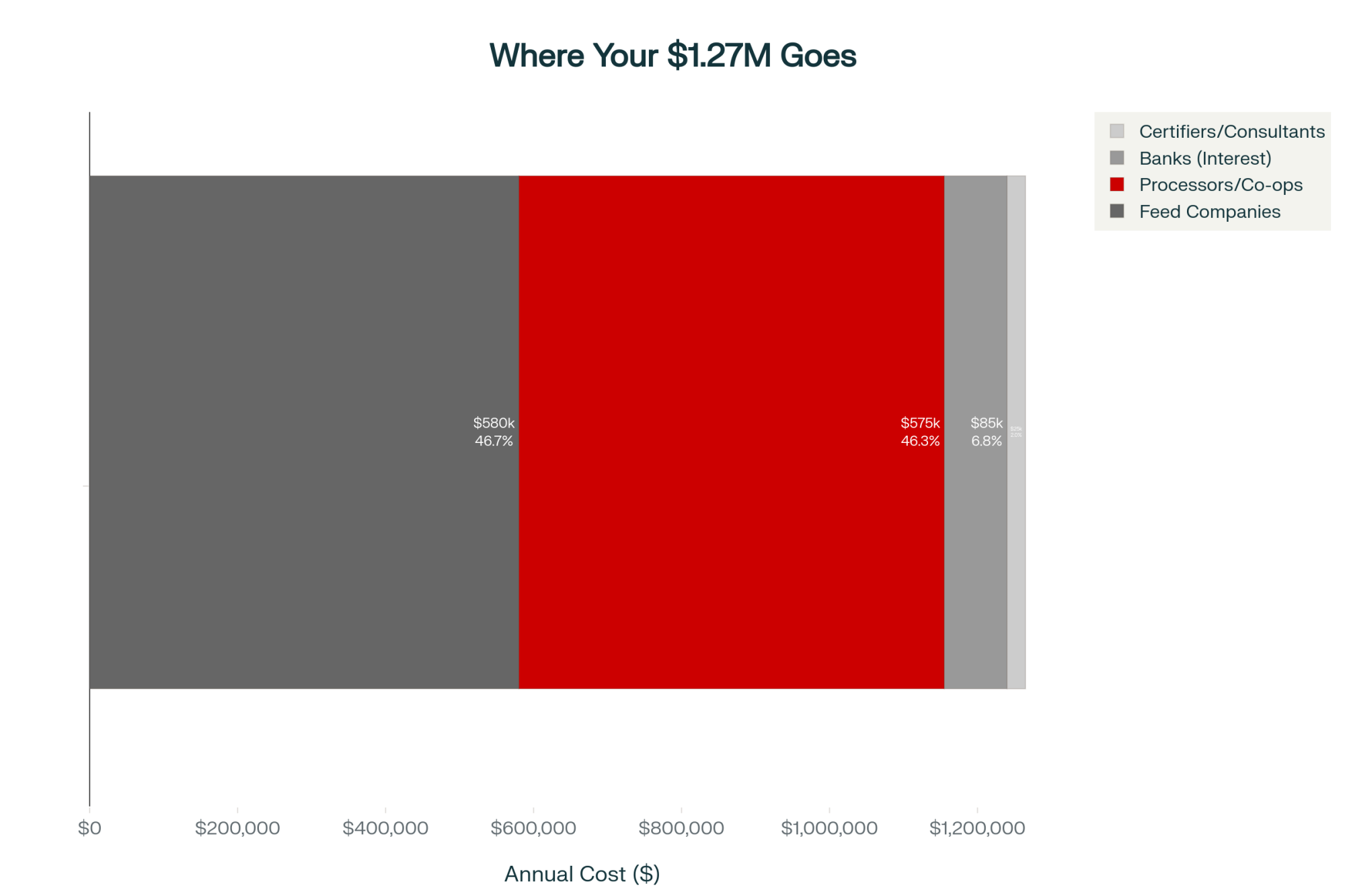

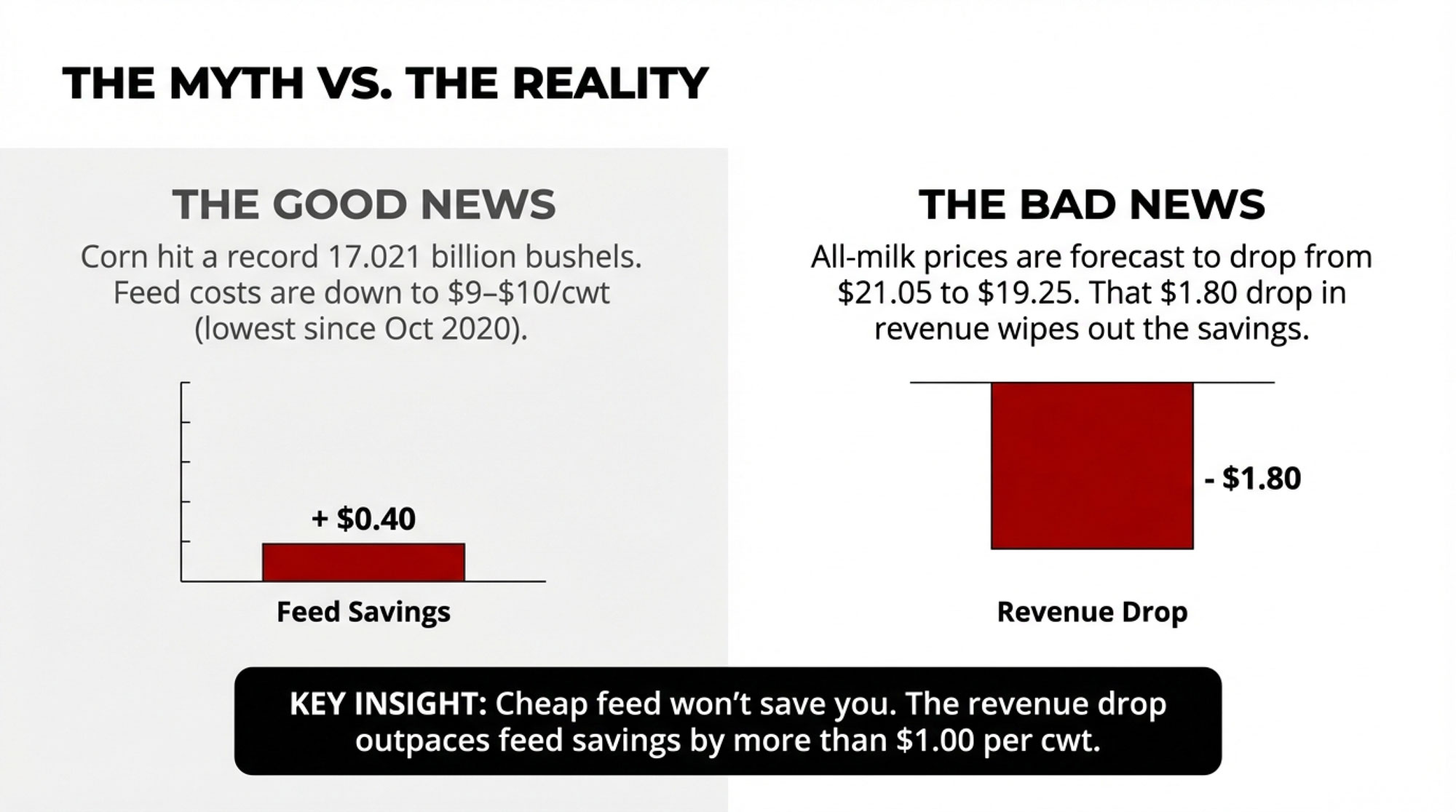

Executive Summary: Cheap feed won’t save you in 2026—and the math proves it. USDA’s January reports confirmed record corn production at 17.021 billion bushels, dropping DMC feed costs to $9–$10/cwt, the lowest since October 2020. But here’s the problem: all-milk prices are forecast to fall from $21.05 to $19.25/cwt, a decline that outpaces feed savings by more than a dollar per hundredweight. For a typical 300-cow dairy, that translates to roughly $90,000–$100,000 less operating margin in 2026 than in 2025. ERS cost data shows the squeeze hits hardest in the middle—herds under 50 cows face $42.70/cwt in total costs, while 2,000+ cow operations run $16–$19/cwt, leaving mid-size dairies caught in between. This is a sorting year: invest in proven efficiency improvements, adjust your business model, or plan an exit while cows and equity are still in good shape.

You’ve probably heard the good news by now: corn is cheap, soybeans are plentiful, and your feed bill should finally give you some breathing room in 2026. And honestly? That part’s true.

But here’s what’s been nagging at me—and what I think deserves a real kitchen-table conversation. When you actually run the numbers, cheaper feed doesn’t automatically mean a better year. For a lot of herds, 2026 could mean tighter margins than 2025, not wider ones. The math surprised me when I first worked through it, and I think it’s worth walking through together.

Let me show you what I mean.

The January Numbers That Changed the Conversation

USDA’s January 2026 reports confirmed what the trade had been whispering about: 2025 U.S. corn production hit a record 17.021 billion bushels on a national yield of 186.5 bushels per acre. Brownfield Ag News and Farm Progress both noted these figures came in above nearly all pre-report estimates, which explains why March corn futures dropped more than 20 cents on release day, sliding into the low $4.20s.

Ending stocks jumped to 2.227 billion bushels, up from 2.029 billion just a month earlier. That’s the most comfortable corn supply we’ve had in years. Soybeans tell a similar story: 4.262 billion bushels at a record 53 bushels per acre, with ending stocks around 350 million bushels.

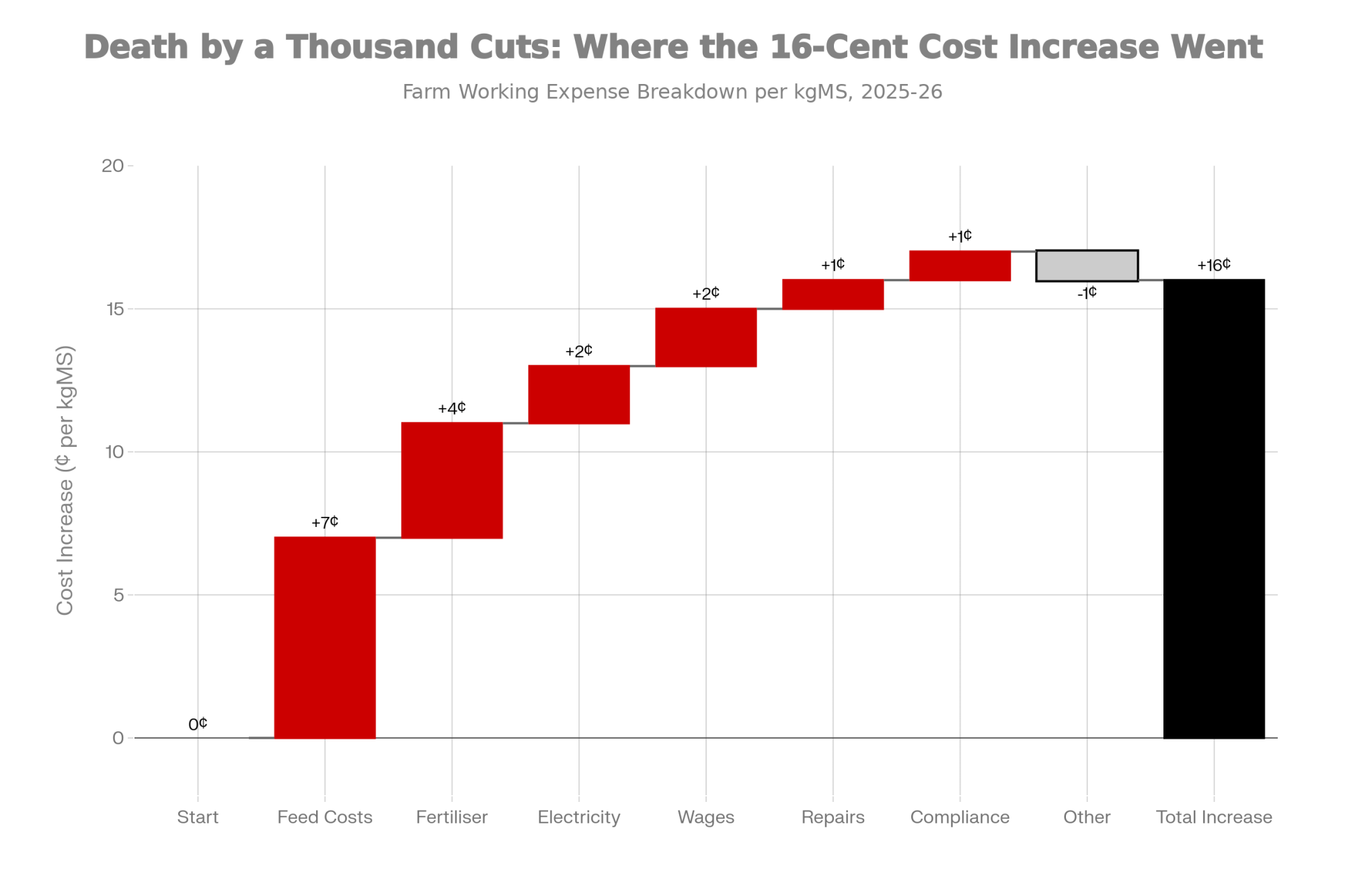

What this means for your feed bunk is straightforward. Dairy Herd reported that DMC feed costs dropped to $9.38 per hundredweight in August 2025—the lowest since October 2020—and DairyReporter’s November analysis showed feed costs expected to stay in that 9–10 dollar band into 2026.

So yes, the feed side genuinely is better. If you’re in a grain-deficit region, this is a different world than the $5-plus corn of recent years.

But here’s where it gets complicated.

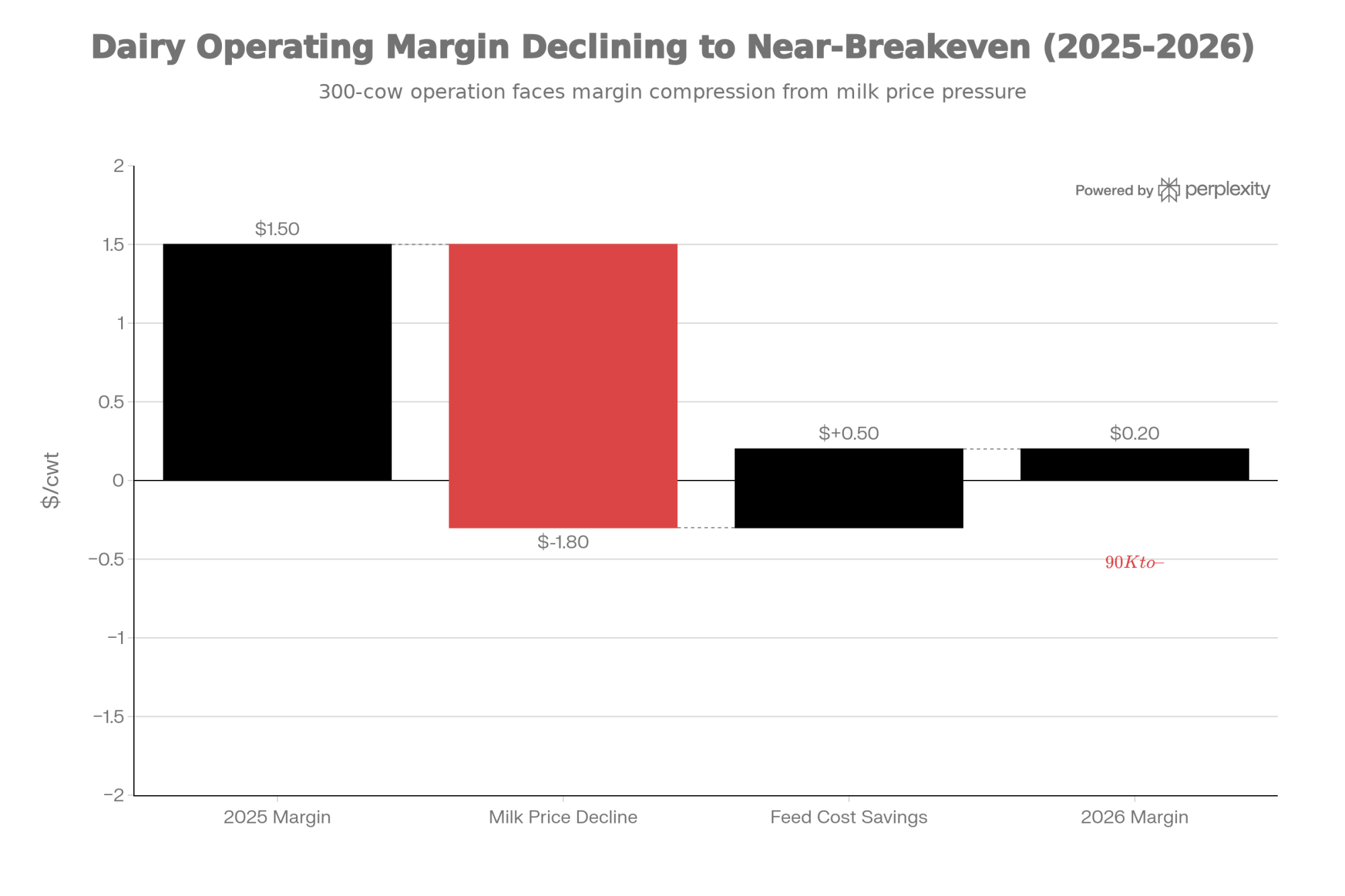

The Milk Price Reality

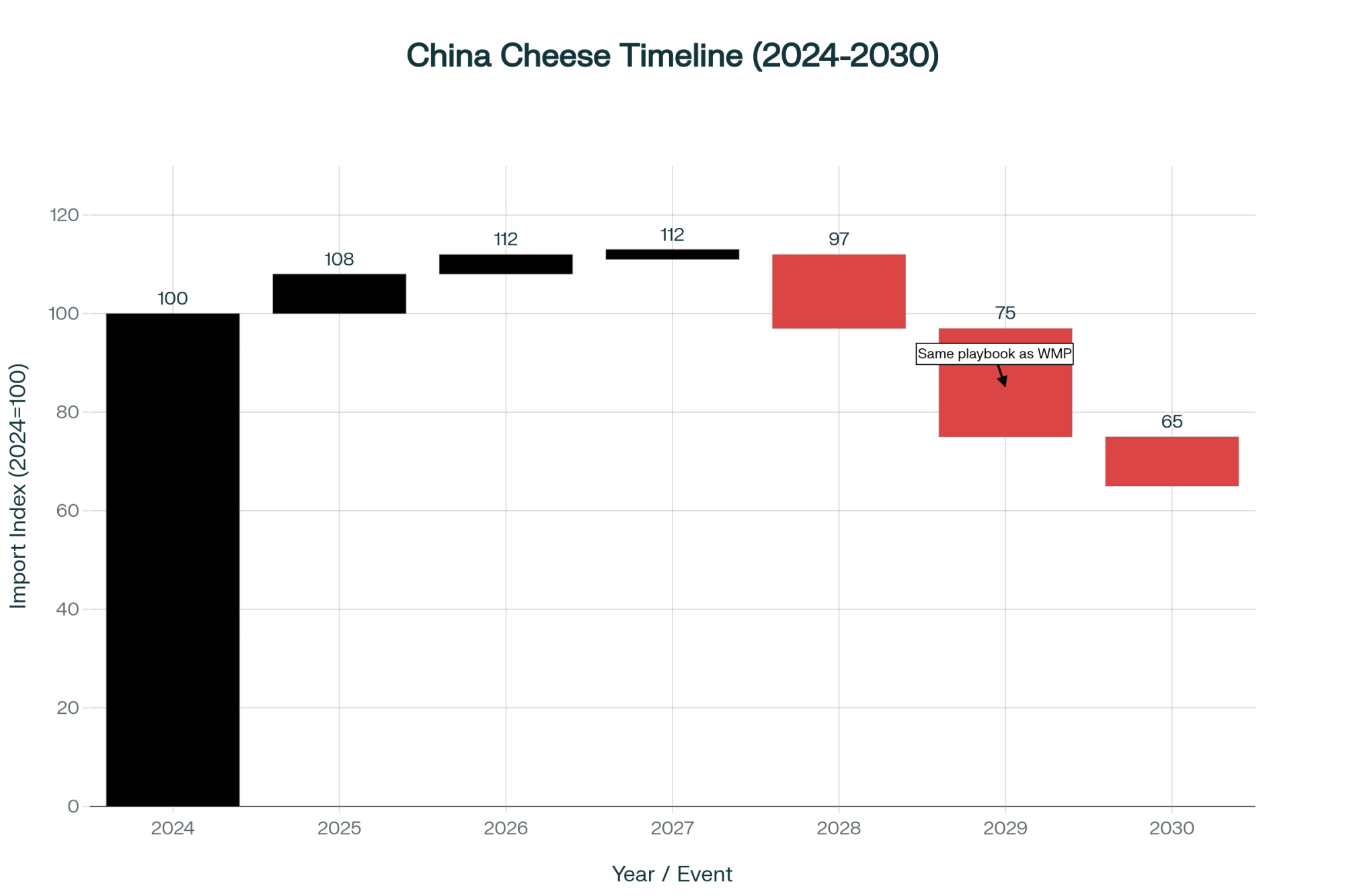

USDA’s current outlook, as reported by DairyReporter and confirmed by Southeast Ag Net, has the U.S. all-milk price averaging about $21.05 per hundredweight in 2025—then dropping to around $19.25 in 2026.

That’s roughly a $1.80 decline in your milk check. And when feed costs only drop by maybe 35–50 cents per hundredweight, the math doesn’t work in your favor.

Analysis published in October 2025 put it bluntly: “Milk Margins Likely to Fall Along with Feed Prices.” CoBank’s dairy analysts commented in early January that dairy markets turned downward in late 2025, and the Class IV futures don’t look encouraging. DairyReporter drew on CoBank’s outlook to note that profit margins for U.S. dairy farmers are expected to tighten in 2026 as rising milk production continues to pressure prices.

This is where herd size and cost structure really start to matter.

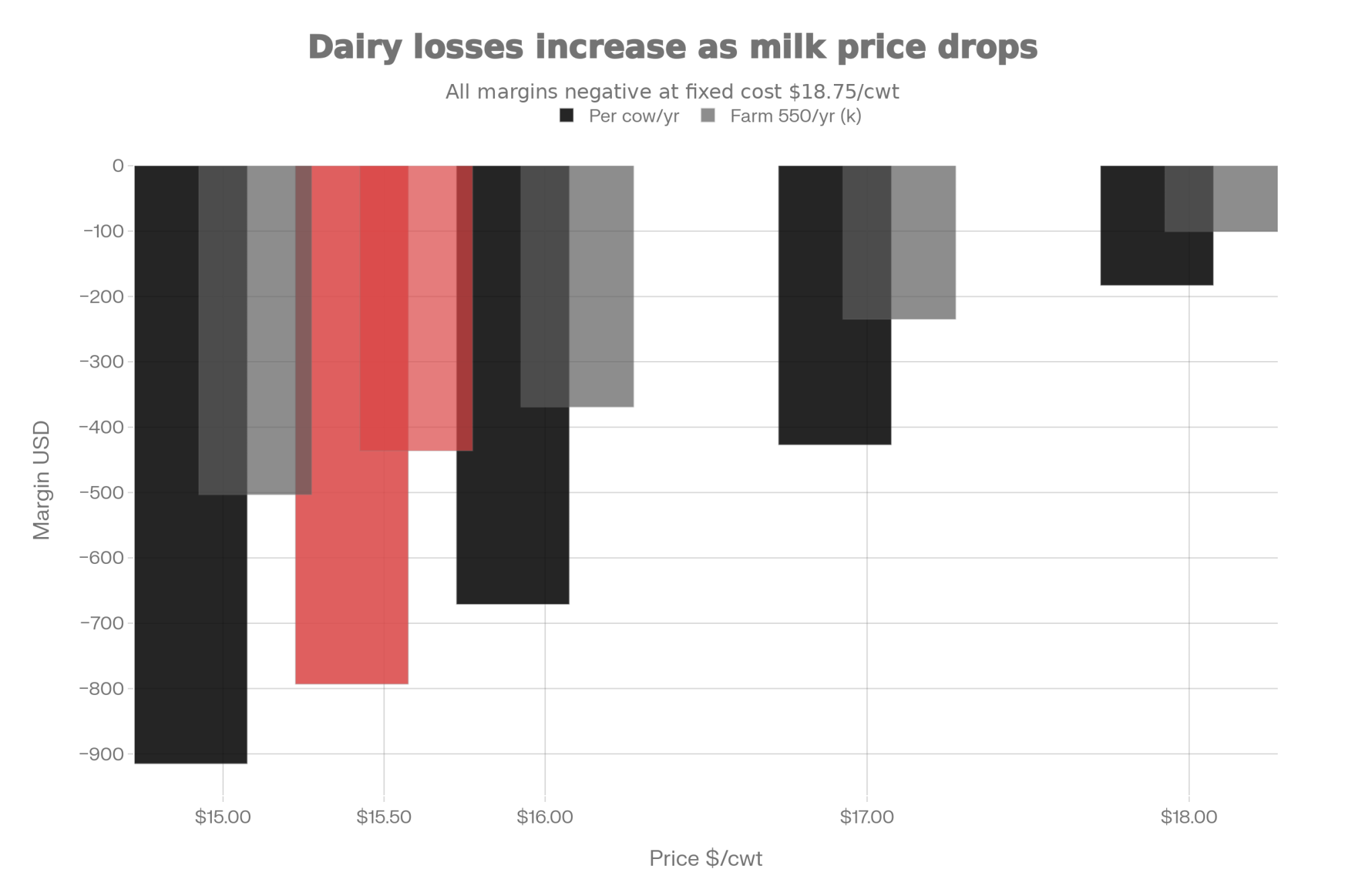

The Cost Curve You Need to See

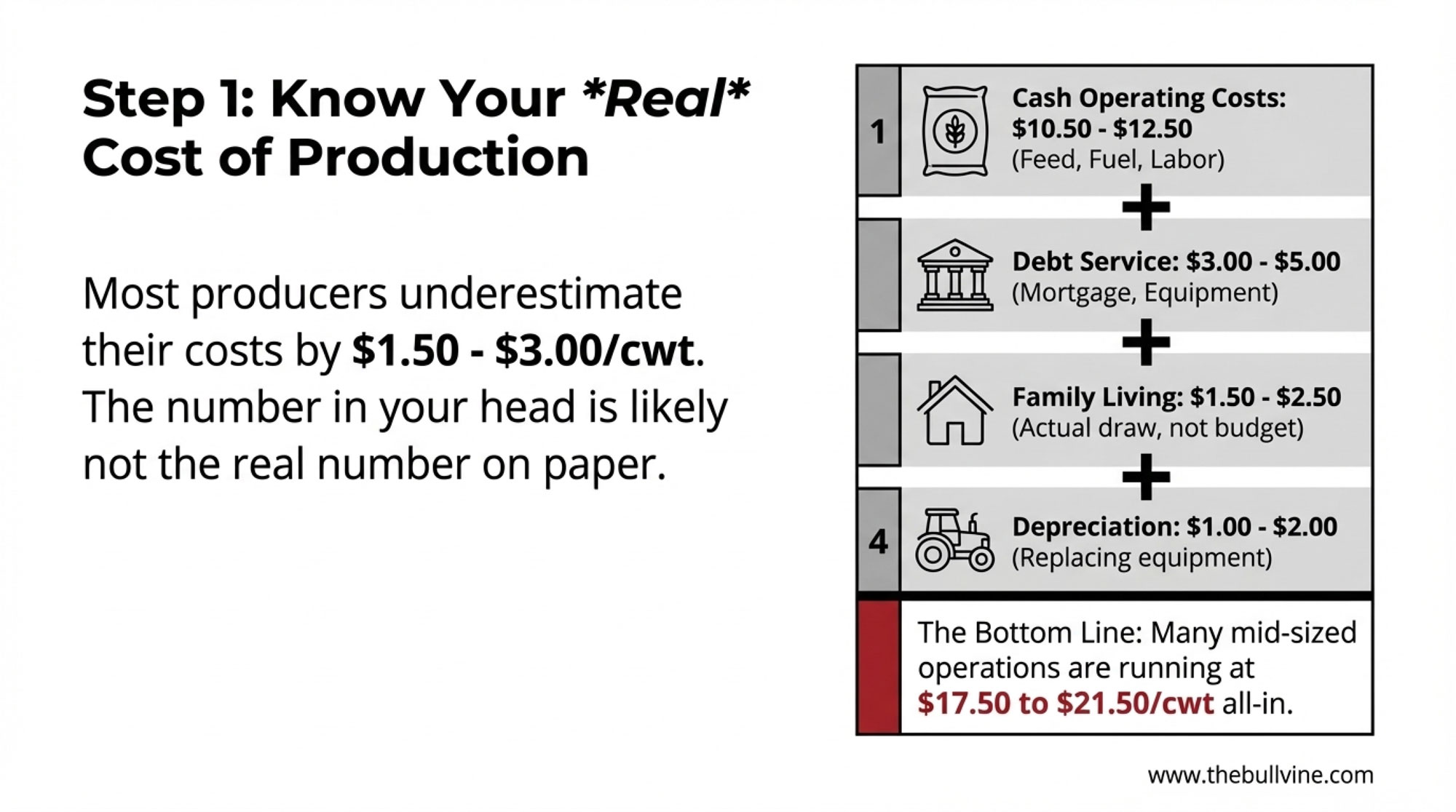

Here’s where the conversation gets real. USDA’s Economic Research Service has been tracking production costs by herd size, and the pattern is stark. Let me lay it out in a way that makes the 2026 implications clear:

| Herd Size | Total Economic Cost ($/cwt) | 2026 Margin at $19.25 Milk | Risk Level |

| <50 cows | $42.70 | –$23.45 (severe deficit) | 🔴 Critical |

| 50–99 cows | $33.54 | –$14.29 (large deficit) | 🔴 Critical |

| 100–499 cows | $19–$21 | $0 to –$1.75 (breakeven/tight) | 🔴 High |

| 500–999 cows | $17–$19 | $0.25–$2.25 (slim) | 🟡 Moderate |

| 2,000+ cows | $16–$19 | $0.25–$3.25 (variable) | 🟡 Moderate |

Sources: ERS 2021 ARMS data; ERS 2016 “Consolidation in U.S. Dairy Farming”; Dairy Global February 2025. Note: Costs vary significantly by management quality within each size class—Hoard’s Dairyman has documented low-cost producers in smaller categories matching high-cost producers in larger categories.

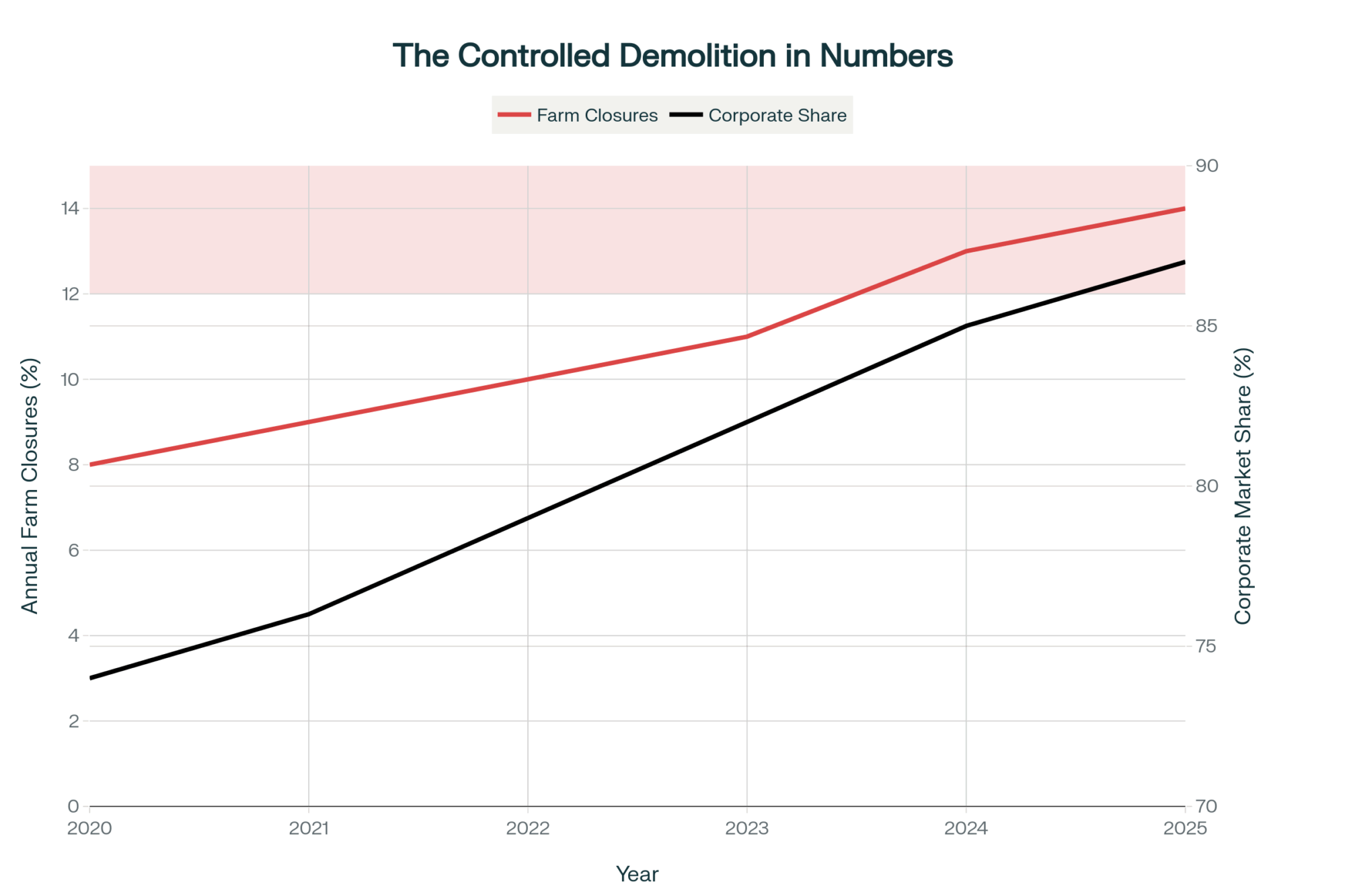

The numbers are sobering. ERS economist Jeffrey Gillespie reported that in 2021, the average total production cost was $42.70 per hundredweight for herds with fewer than 50 cows, versus $19.14 for herds with 2,000 or more. Dairy Herd’s summary of ERS consolidation data showed herds under 50 cows at $33.54 per hundredweight compared to $17.54 for 2,500-cow operations in 2016. Dairy Global’s February 2025 feature showed operating costs of $18.44 for small herds compared to $16.16 for the largest operations.

What’s worth noting here is that there’s huge variation within each size class. Low-cost producers running 100–199 cow herds can have total production costs around $19.76 per hundredweight, which puts them right alongside high-cost producers running 2,000-plus cows at $19.63. Management matters as much as scale.

But that table tells you something important: at $19.25 all-milk, a lot of herds in that 100–499 cow range are looking at breakeven or worse, even with cheap feed. And smaller herds? The math is brutal unless you’re among the best managers in your size class.

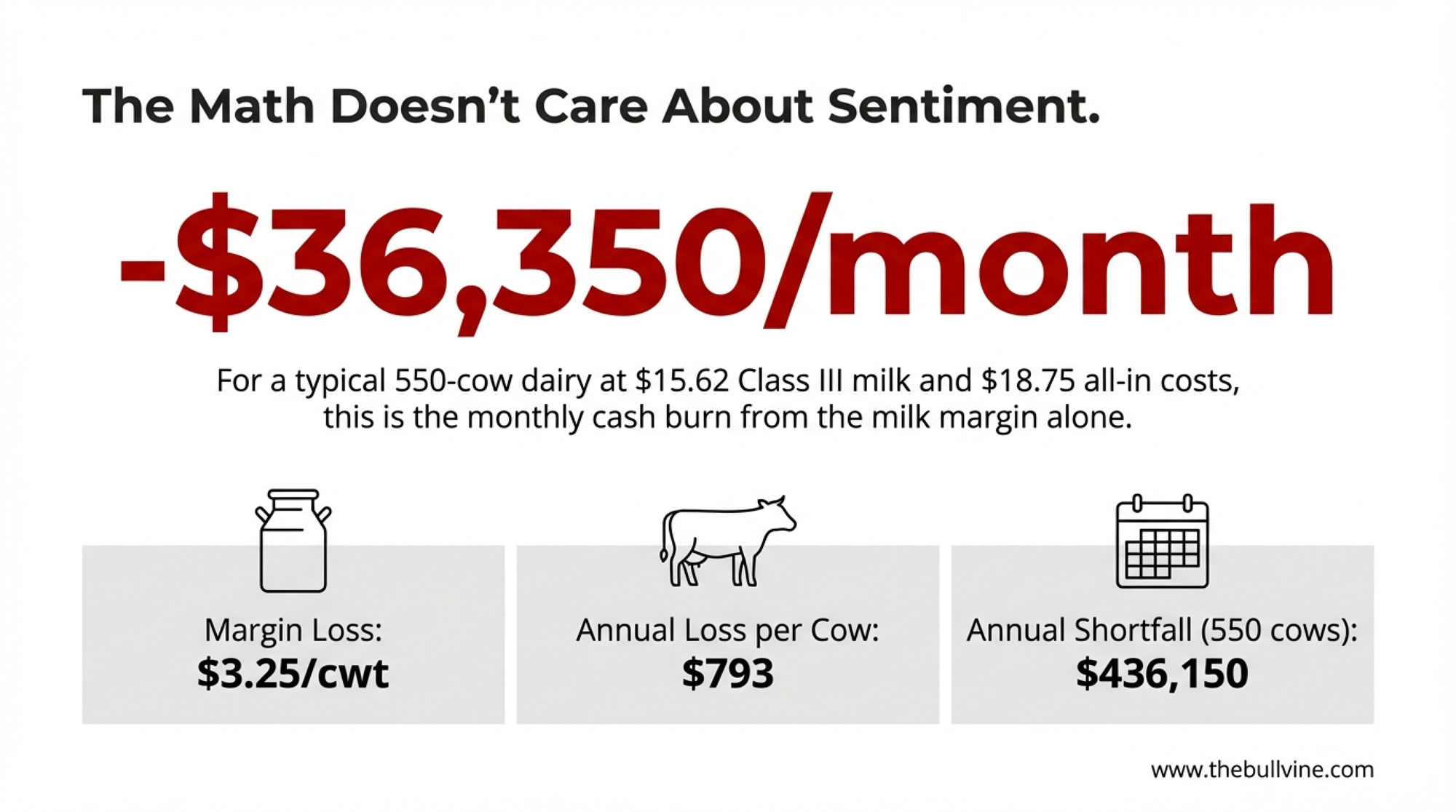

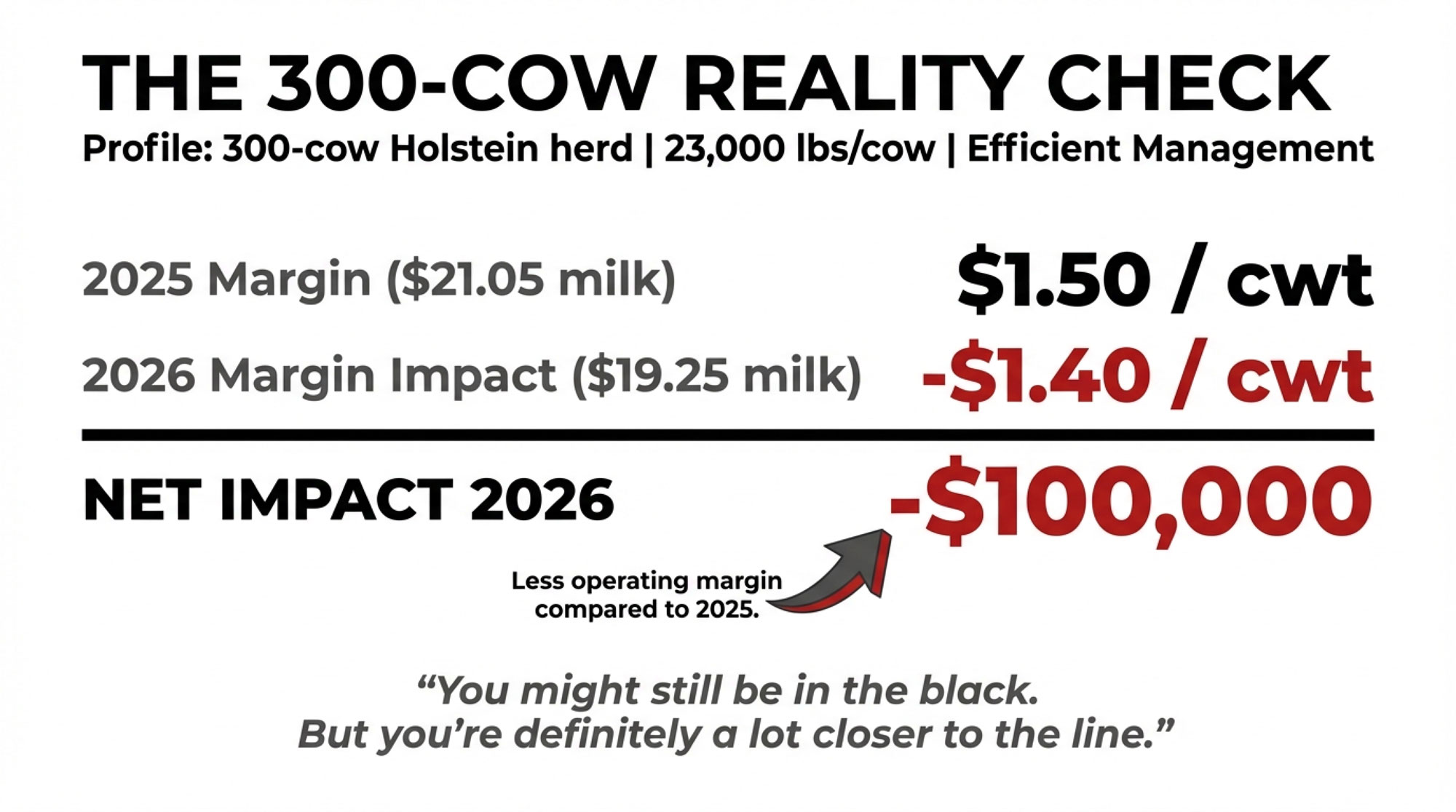

A 300-Cow Reality Check

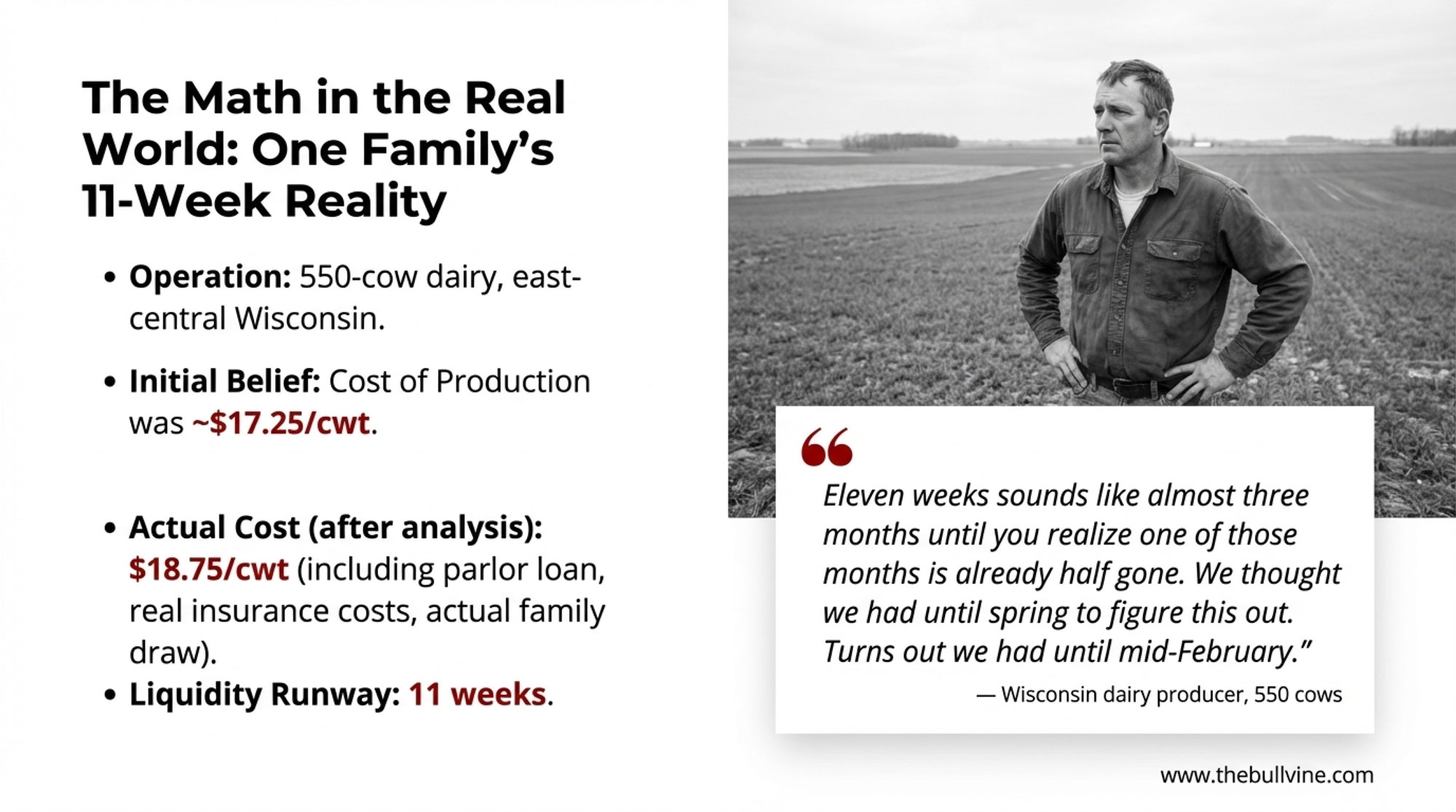

Let’s make this concrete with a scenario that probably feels familiar.

Picture a 300-cow Holstein dairy in Wisconsin, Michigan, or Pennsylvania. Freestall housing, parlor milking, solid fresh cow management, respectable butterfat levels. Annual production around 23,000 pounds per cow—that’s 6.9 million pounds of milk per year, or 69,000 hundredweights.

Based on ERS benchmarks and university cost-of-production data, a well-managed herd in this size range typically runs total economic costs in the upper teens to low twenties per hundredweight—call it $19 to $21 when you include all labor, capital, and overhead.

Now do the math:

- 2025: At $21.05 all-milk, that’s roughly $1–$2/cwt operating margin for well-managed herds

- 2026: At $19.25 all-milk with maybe 40 cents in feed savings, you’re looking at about $1.30–$1.50/cwt lessmargin than 2025

On 69,000 hundredweights, that translates to $90,000 to $100,000 less operating margin in 2026 than in 2025—even with cheaper feed.

You might still be in the black. But you’re definitely a lot closer to the line.

Why USDA’s Big Corn Number Felt Off on the Ground

It’s worth noting that this record corn number felt like a gut punch to many people actually raising the crop.

Interviews with farmers right after the January WASDE. North-central Kansas producer Shale Porter described the report as “kind of a gut punch,” saying the larger-than-expected production and increased ending stocks created a fresh blow to an already fragile marketing environment.

What I’ve noticed over the years is that this disconnect often traces back to structure and technology. The largest crop farms are much more likely to use GPS guidance, yield monitors, and variable-rate fertilization. When USDA aggregates data to calculate a national average yield, that average gets pulled up by highly managed, highly instrumented acres—even in years when smaller or less-equipped farms are just “average” or worse.

On the dairy side, you see a similar pattern in production costs. The national averages don’t always reflect what’s happening on your specific operation.

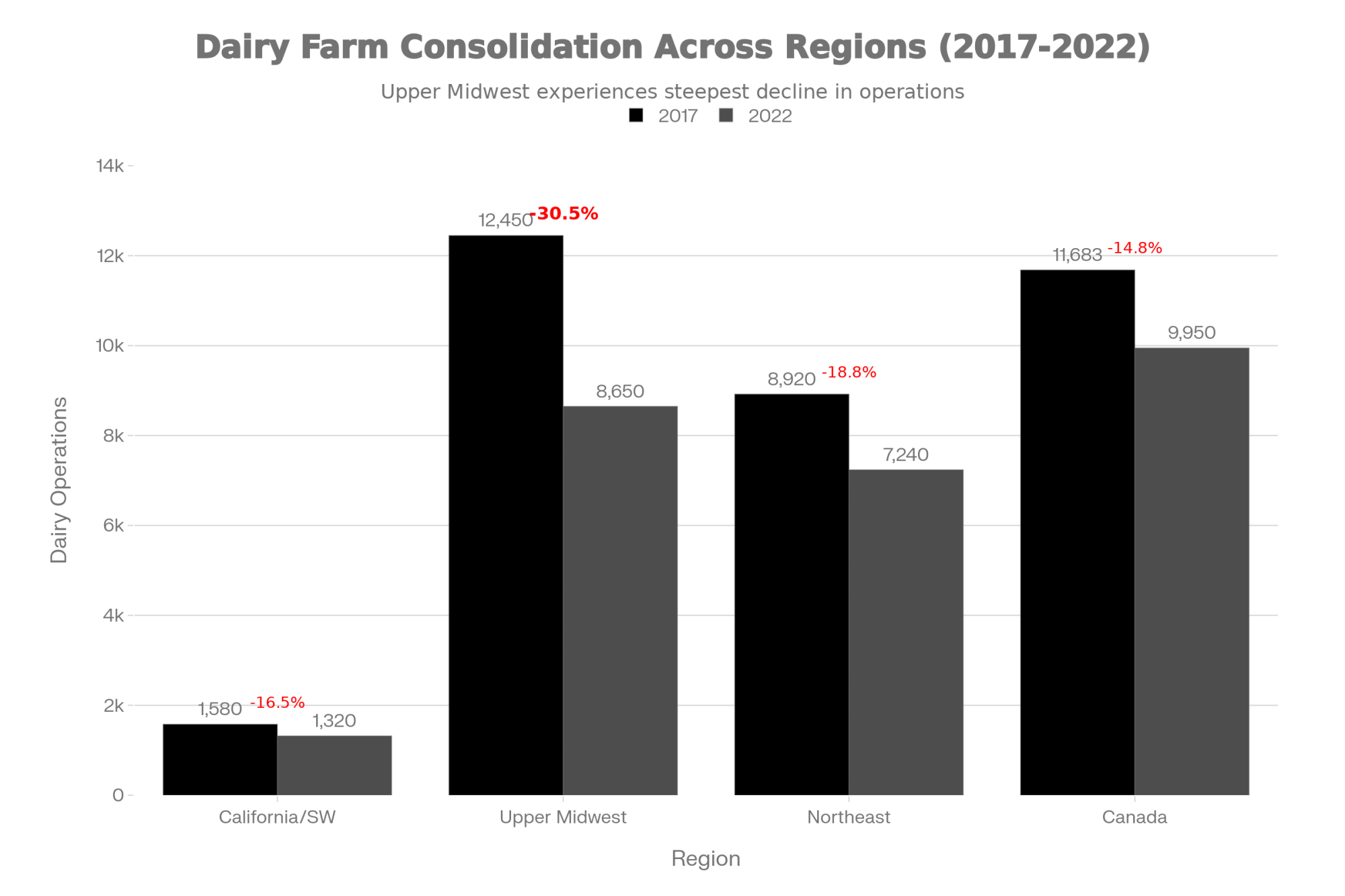

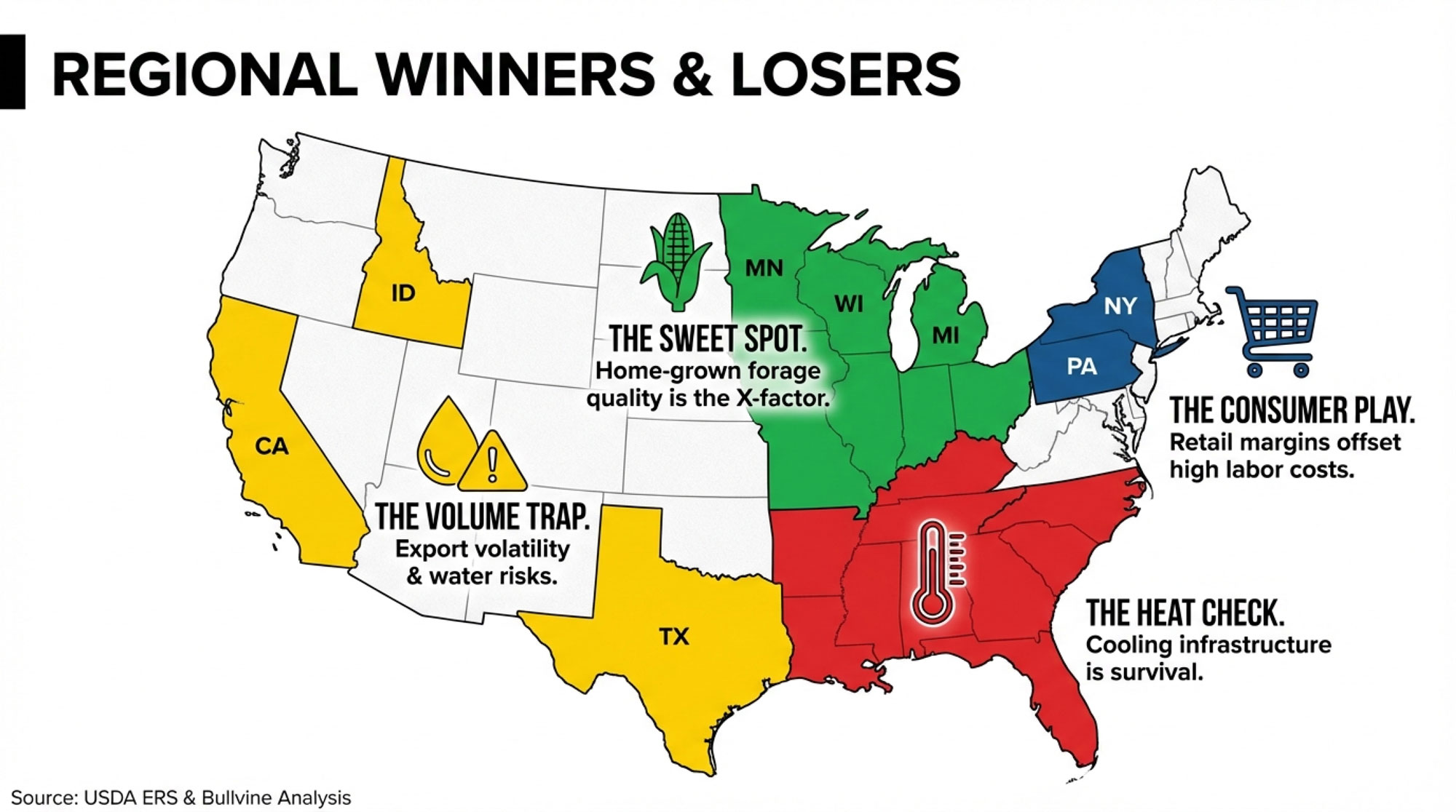

Regional Realities: Same Numbers, Different Stories

The same USDA and ERS numbers play out very differently depending on where your milk truck pulls in. Here’s the quick read on each region:

Upper Midwest (Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota)

- Sweet spot: 200–400 cow herds with strong forage programs

- The X-factor: Home-grown forage quality can make or break competitiveness

- Many operations blend grazing with TMR for cost control without sacrificing precision

- University of Wisconsin data shows well-managed mid-size herds can compete with larger neighbors on cost

Northeast (Pennsylvania, New York, New England)

- Higher land costs and labor, but proximity to dense consumer markets

- Growing success with direct-to-consumer: farmstead cheese, on-farm bottling, farm stores

- Class III/IV prices matter less when retail margins drive revenue

- Penn State and Cornell have documented resilient small/mid-size models

West and Southwest (California, Idaho, Texas, New Mexico)

- Dominated by 1,000–5,000 cow dry lot and large freestall operations

- Lowest per-unit costs, highest milk per cow

- Key vulnerability: Heavy exposure to export markets and Class IV volatility

- Water and environmental scrutiny are intensifying

- CoBank noted butterfat oversupply hitting some processors hard

Southeast

- Heat and humidity are the defining challenge

- Cow cooling isn’t optional—it’s survival infrastructure

- Extension research consistently shows robust cooling improves intake, production, reproduction, and butterfat

- Herds without adequate fans, soakers, and shade see summer production crash

- Heat stress losses can quickly eat up lower feed costs

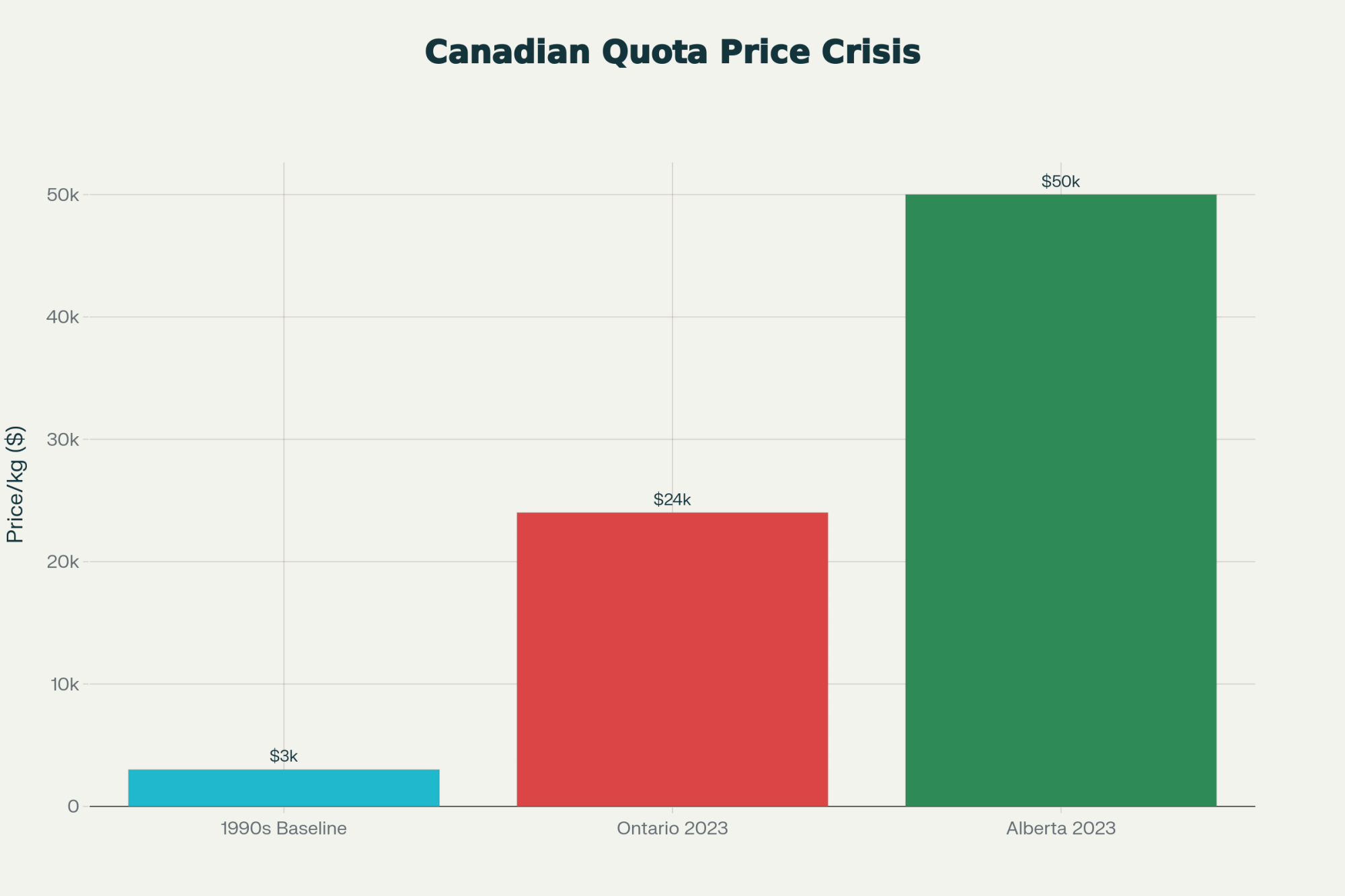

Canada

- Quota changes pricing structure, but not cost fundamentals

- Larger freestall dairies with automation have lower unit costs than smaller tie-stall herds

- Canadian Cattlemen coverage shows technology adoption driving cost differences similar to U.S. patterns

The takeaway: national averages set the stage, but your 2026 story depends on your region, your barn, your debt, and your marketing options.

Where Farms Are Actually Moving the Needle

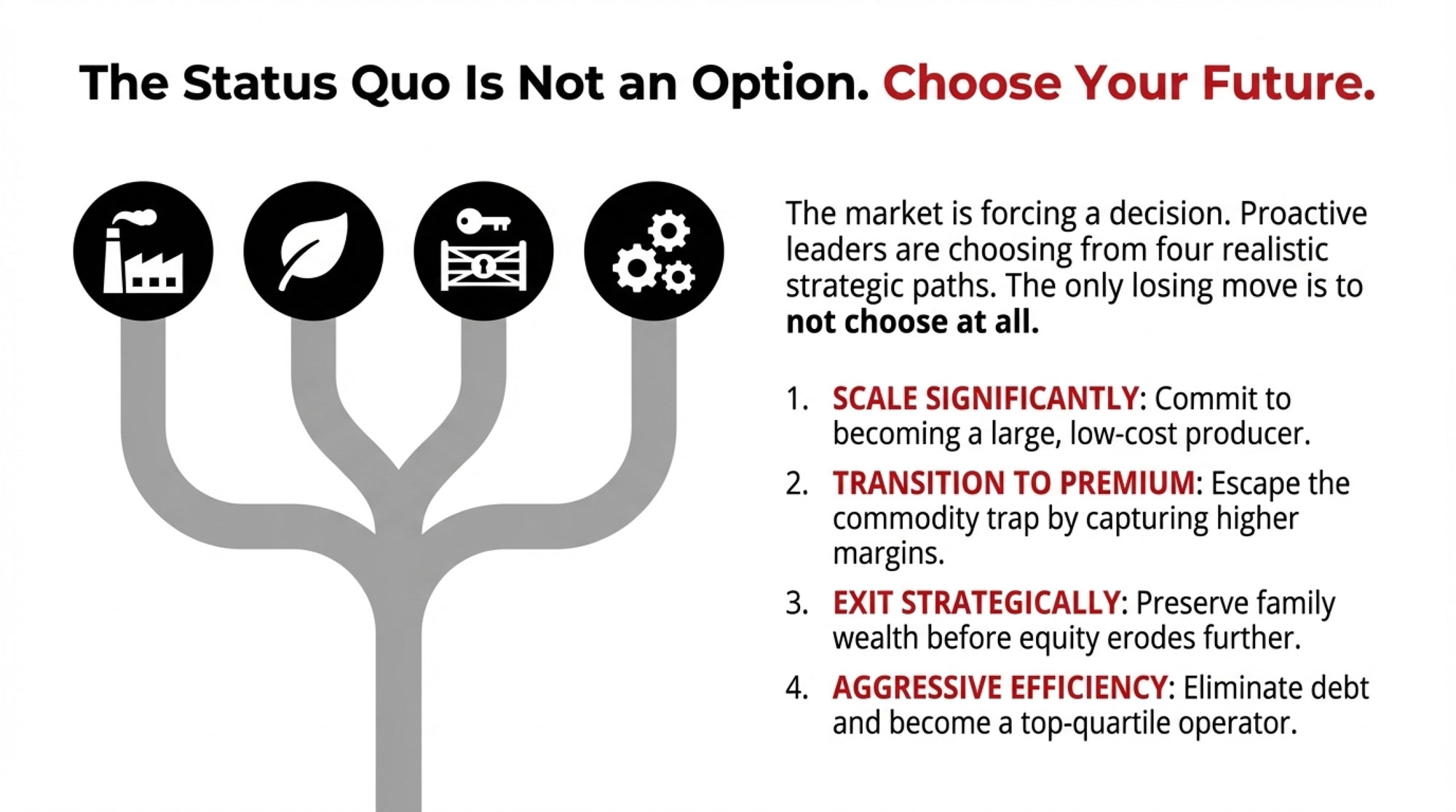

Looking at this trend, farmers are gravitating toward four broad response paths—often combining a couple of them.

1. Tightening the Fundamentals That Still Pay Back Fast

A lot of herds are going back to basics: Where’s the relatively easy money still on the table?

- Feed efficiency: Extension nutritionists discuss feed efficiency benchmarks that vary by lactation stage and measurement method, with top-performing herds consistently outperforming average operations. At 9–10 dollars per feed cost, even modest improvements can be worth meaningful dollars per cow annually. The tools are management, not marble: consistent TMR mixing, solid feed-push habits, minimizing sort.

- Reproduction and transition: University economic modeling regularly puts a significant per-cow annual value on better pregnancy rates and fewer transition disorders—once you count extra milk, fewer days open, fewer culls, and lower treatment costs. Getting days open into the 120s instead of the 150s shows up quickly in milk shipped per stall.

- Mastitis economics: Research consistently shows significant avoidable cost. A 2024 Wageningen University study put typical clinical mastitis costs at $224–$275 per case, while Michigan State work by Dr. Pam Ruegg found costs ranging from about $120 to $330 per cow per case, depending on severity and farm. Hoard’s Dairyman reported similar findings, noting costs of $120 to $350, with an average of around $192. Dropping SCC into the 150–200,000 range protects premiums and usually correlates with steadier production and better butterfat.

What I’ve noticed: lower grain prices give you breathing room to work on these fundamentals without panicking about every extra half-pound of dry matter.

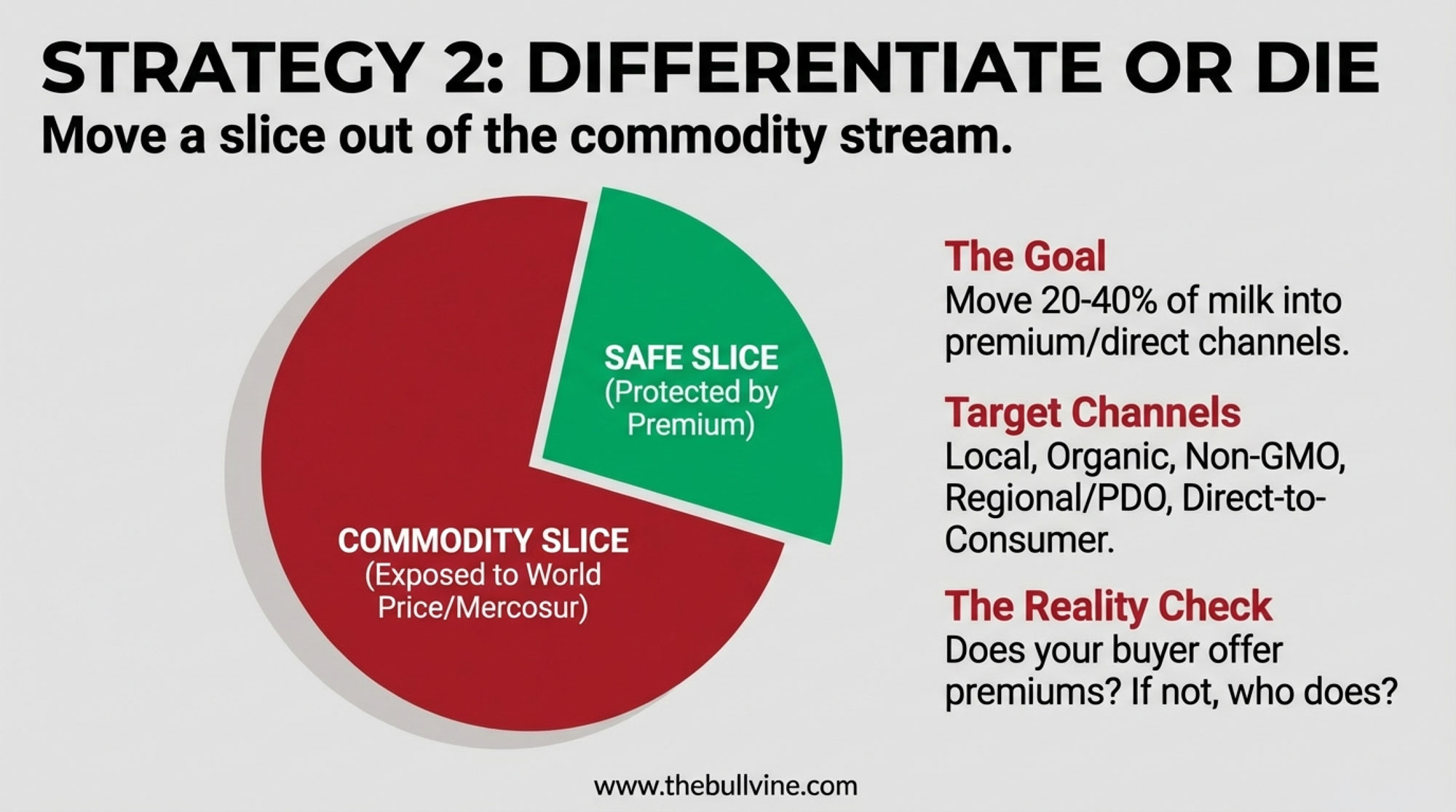

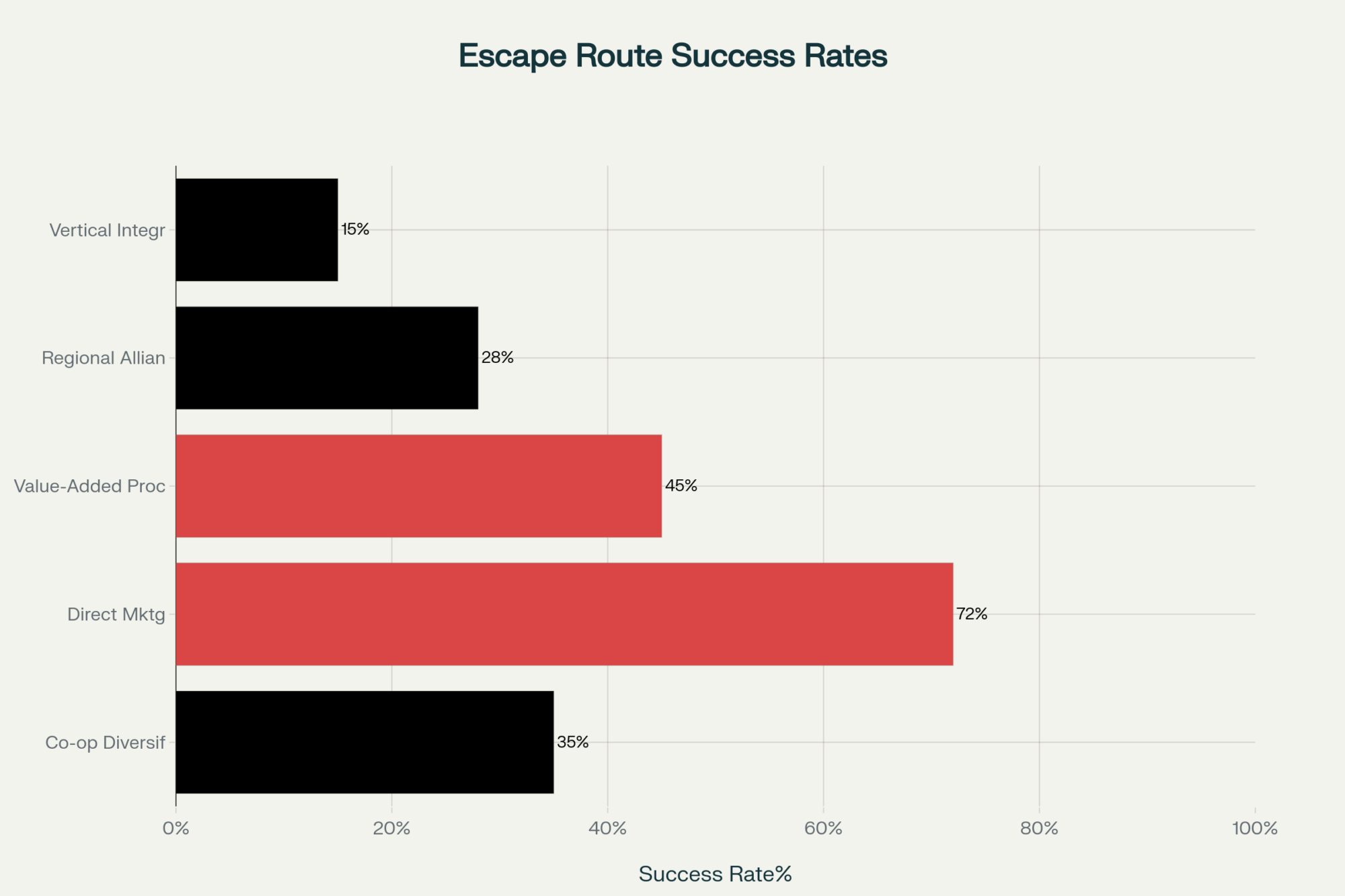

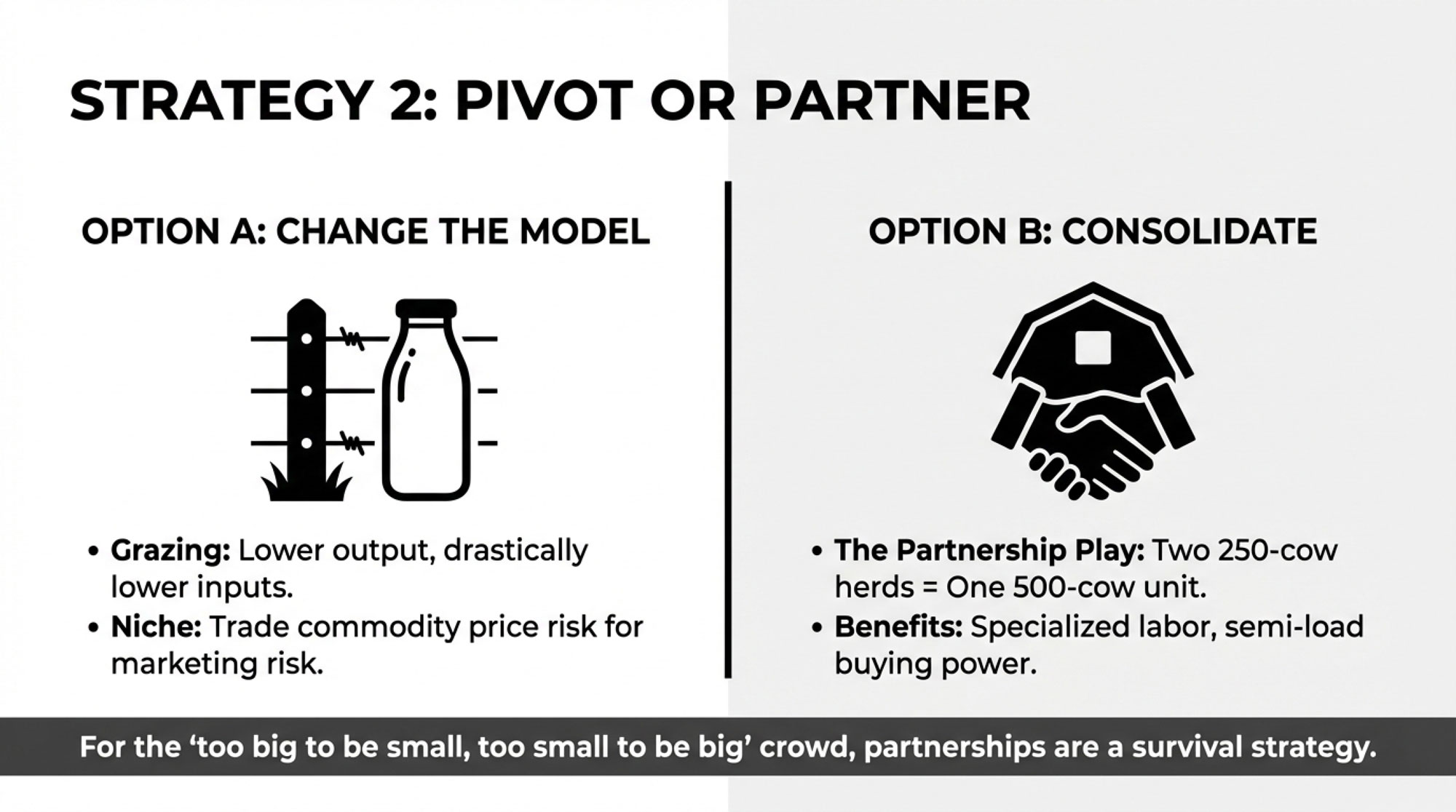

2. Picking a Different Lane: Grazing, Organic, and Specialty

Another group—especially 60–250 cow herds—is asking whether they really want to keep running a pure commodity race.

- Intensive rotational grazing: Cost-of-production work on grass-based dairies shows that well-managed systems can cut total cost per hundredweight by several dollars compared with comparable confinement herds. Milk per cow runs lower (18,000–22,000 pounds), but when debt is manageable and the grain bill is small, net returns can stack up well.

- Organic and premium programs: ERS research shows organic operations have substantially higher production costs—sometimes 50 percent more—but receive much higher farm-gate prices when markets are balanced. Some farms layer on grass-fed, A2A2, or animal-welfare certifications for specific branded programs.

- On-farm processing: University case studies document how small- and mid-size dairies are building resilient businesses on retail margins and consumer loyalty rather than Federal Order checks.

These paths trade commodity risk for marketing and logistics challenges. But for some families, they’re more realistic than trying to quadruple herd size.

3. Teaming Up Instead of Going It Alone

In areas with clusters of mid-size dairies, there’s more serious talk about partnerships.

Dairy Herd’s coverage has highlighted examples of two or three neighboring families forming joint ventures, combining herds, and investing together in more efficient facilities. Think: two 250-cow herds consolidating into one 500-cow freestall with a modern parlor and specialized labor roles.

Common benefits lenders and advisers see:

- Lower labor hours per cow through specialization

- Better delivered feed costs buying in semi loads

- Lower fixed costs per hundredweight across shared infrastructure

Partnerships require trust and clear agreements, but for the “too big to be small, too small to be big” crowd, they’re worth considering.

| Response Strategy | Best For | Key Actions | 2026 Margin Outlook | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INVEST | Well-capitalized, solid-footed herds in viable size range (150–500 cows) | Fresh cow facilities, cooling, precision feed systems, robotic parlor prep | Margin improves 2027+ as efficiency gains compound; 2026 tight but survivable | Debt service if markets weaken further |

| ADJUST | Herds with land, family labor, and willingness to change model (80–250 cows) | Shift to grazing, organic, direct-to-consumer, on-farm processing, dairy partnerships | Higher per-cwt return on lower volume; less commodity-market exposure | Marketing complexity; buyer education required |

| EXIT | Producers within 5–10 years of retirement; tired operators; no clear succession | Plan dispersal while cows/equipment in good condition; family succession or sale-to-neighbor negotiation | Preserve equity; exit on your terms while margins still exist | Emotional; requires discipline not to wait for “better year” |

4. Treating 2026 as a Planning Year

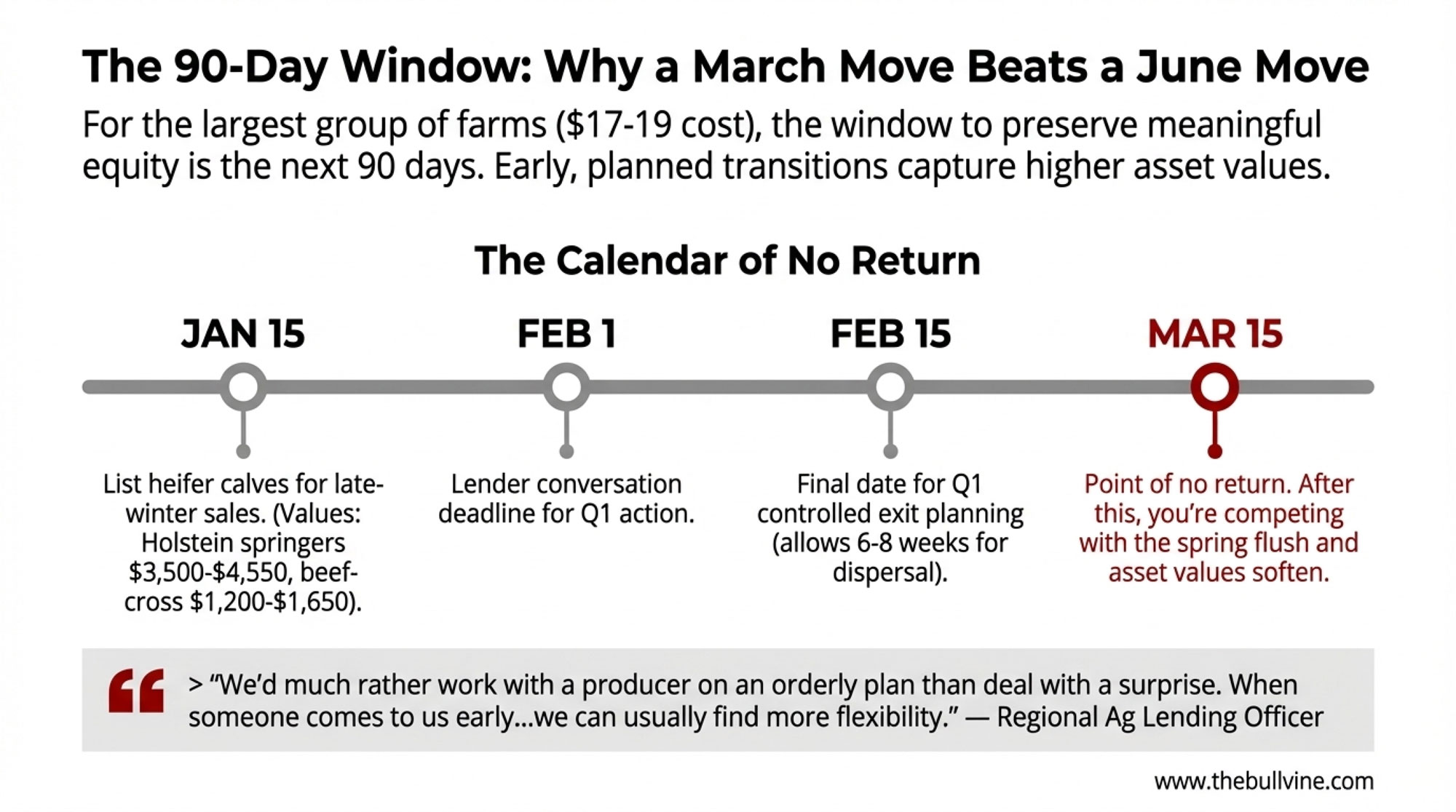

For producers within five to ten years of retirement without a clear successor, this discussion hits differently.

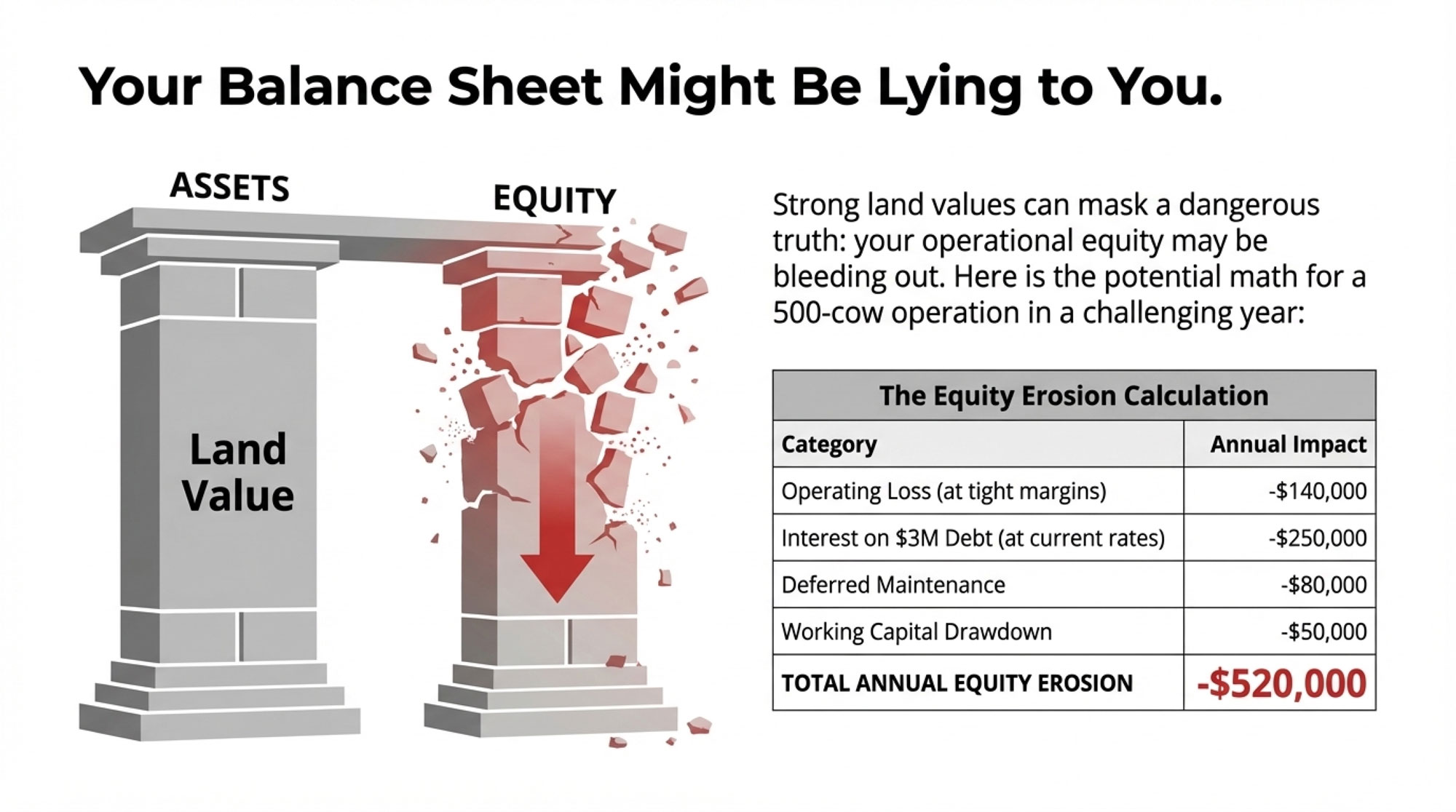

Reports suggest many dairy exits in the next decade will be driven by cost position, age, and family goals more than any single bad year. Advisers stress that planned transitions—family succession, sale to a neighbor, well-timed dispersals—preserve more equity than waiting until tough years force rushed decisions.

Auction data indicate that well-organized dispersal sales, held while cows are in good condition and equipment is maintained, regularly outperform “end-of-the-rope” liquidations.

2026 might be the right year to ask blunt questions: What does cash flow look like at $19 milk and $10 feed for another full cycle? And if you’d rather be out in two to five years, what does exiting on your terms look like while you still have margin?

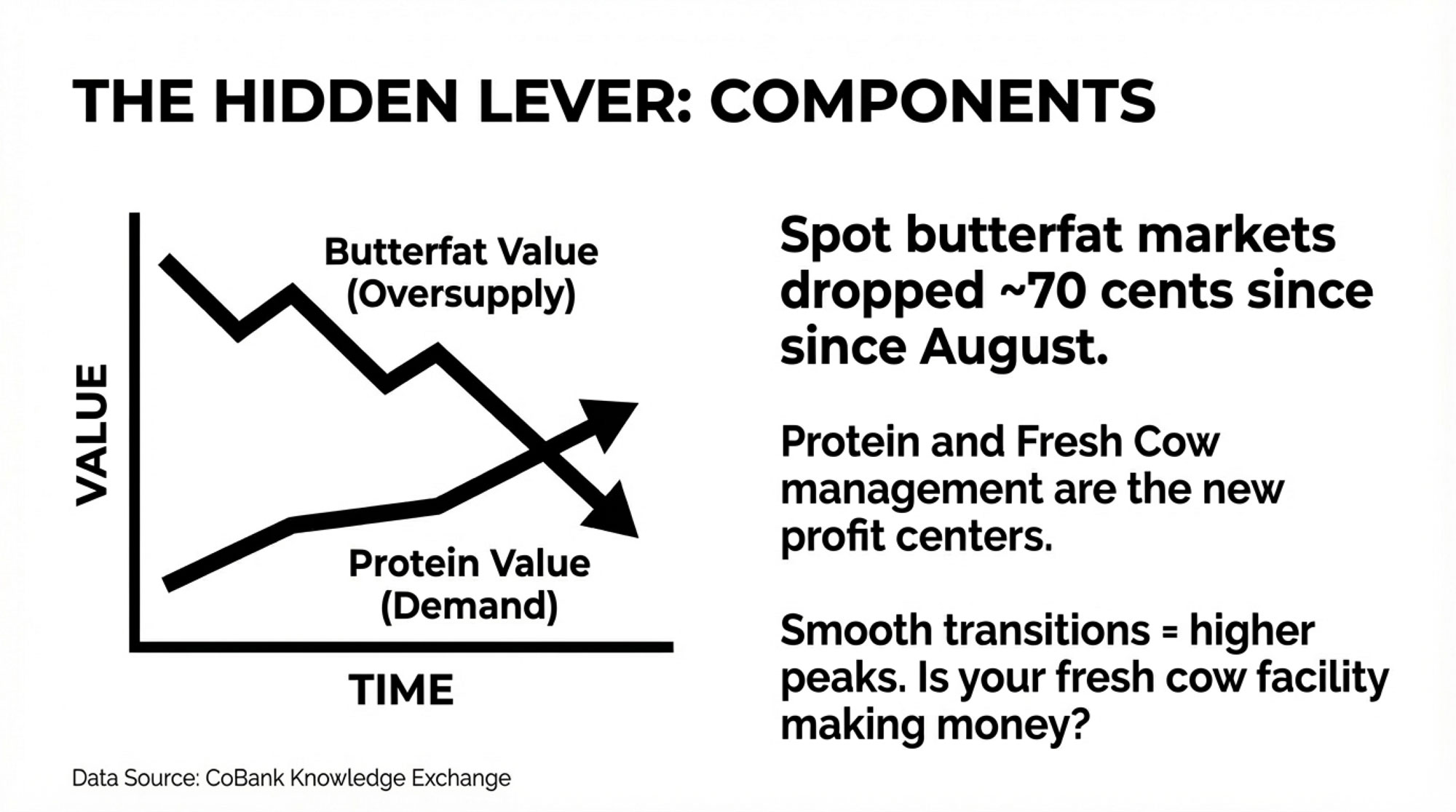

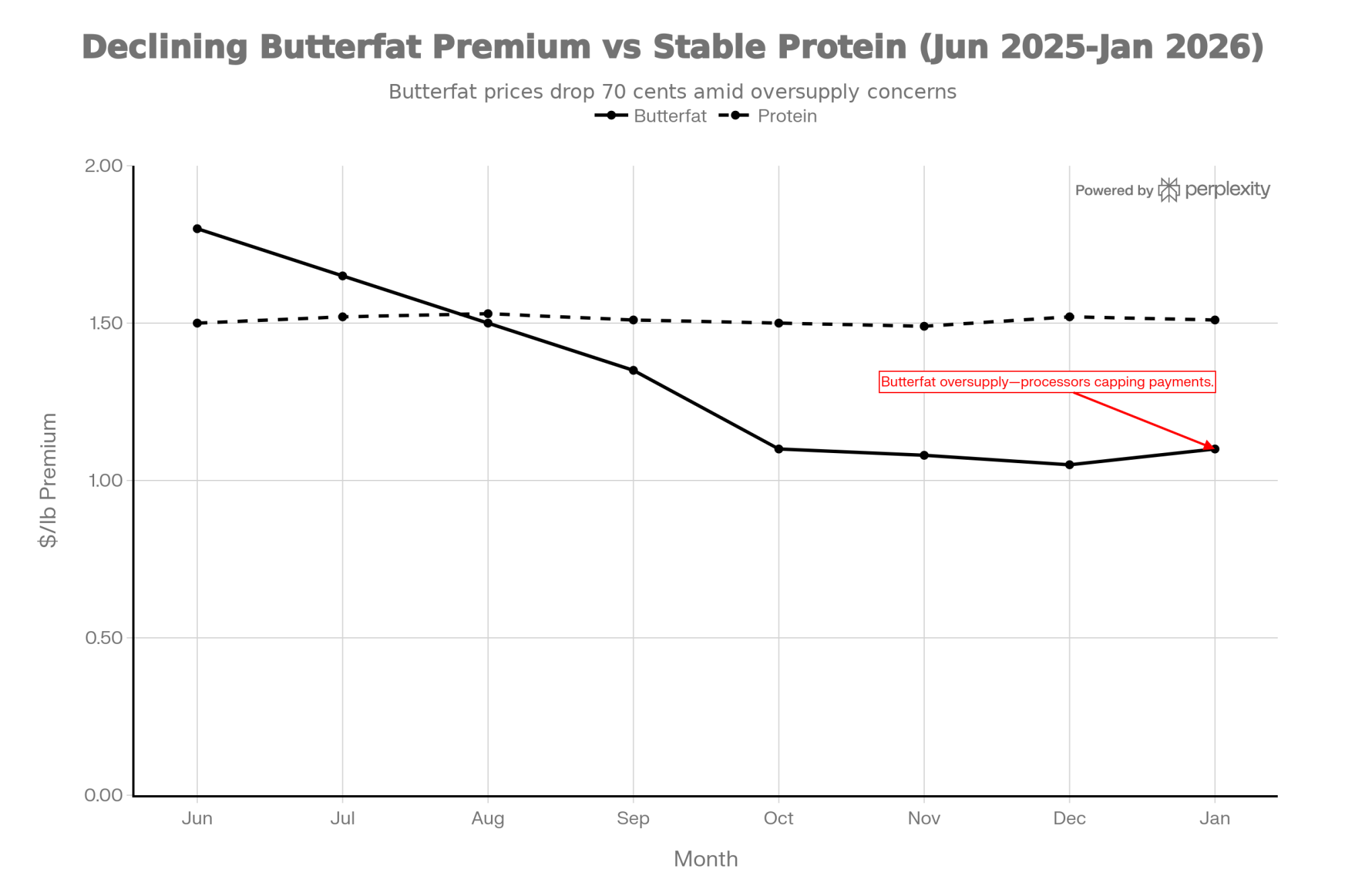

Don’t Lose Sight of Components

With all the feed talk, it’s easy to forget that butterfat and protein still drive a big chunk of your milk check.

Component pricing work shows that butterfat increases can add meaningful revenue—often comparable to or greater than what you’d gain from modest corn price movements on the same volume of milk.

Here’s what’s interesting, though. CoBank’s 2026 outlook noted that butterfat has actually moved to an oversupply situation. Their Knowledge Exchange report from December put it plainly: dairy processors are awash with butterfat, and some have even capped butterfat payment levels on farmgate milk in response. In October, Corey Geiger with CoBank said spot butter markets had dropped almost seventy cents since August 1st due to excess supply.

That underscores why protein may be where the action shifts—and why watching your components still matters even as the market dynamics change.

Fresh cow management sits at the center of component performance. Extension materials consistently show that smooth transitions lead to higher peaks, fewer health problems, better fertility, and stronger components.

The question worth asking: Is there a change in fresh cow management, cow comfort, or milking routine that will pay more in milk and components than you’d ever save squeezing a few more cents from corn?

For a lot of herds, that’s where the biggest upside is hiding.

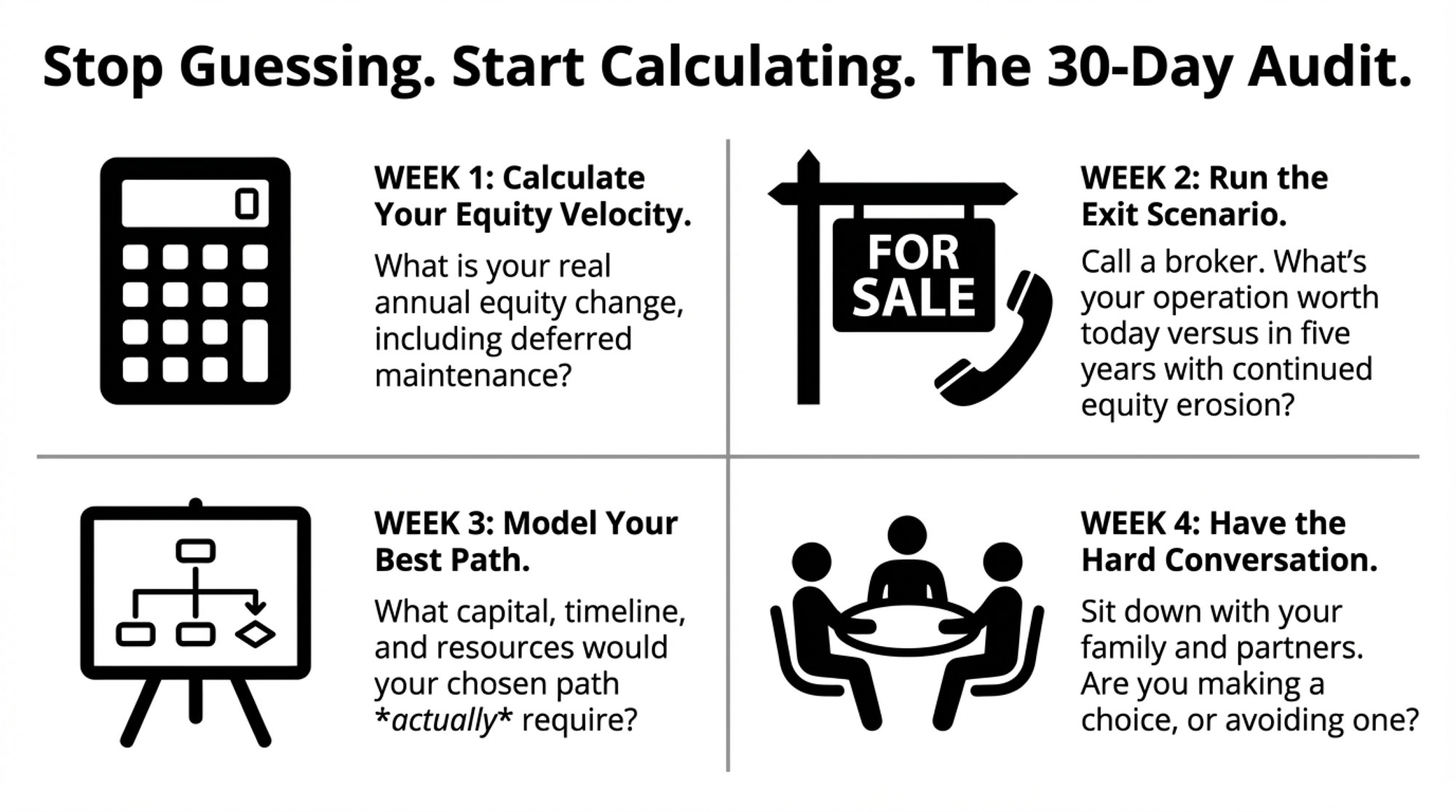

Your 2026 Checklist

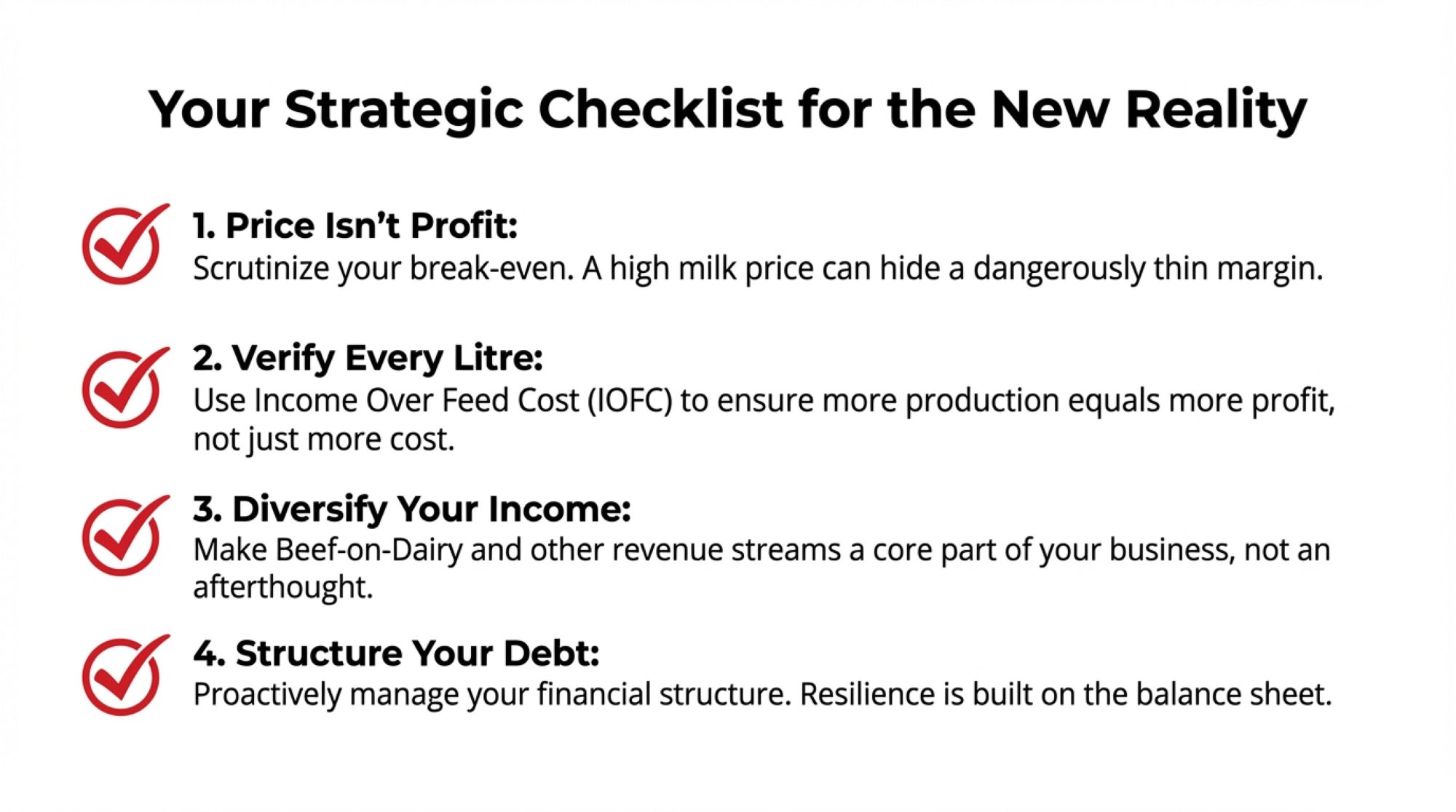

1. Run a realistic 2026 budget.

Use $19.25 all-milk and 9–10 dollar feed costs. Know your actual cost per hundredweight with full labor and overhead. If you’re well north of the upper teens, something has to change.

2. Benchmark where you really stand.

Compare your cost, feed efficiency, reproduction, mastitis rates, and butterfat against ERS benchmarks and regional top-quartile data. Remember what Hoard’s documented: low-cost producers in smaller herds can match the costs of high-cost, large operations. Identify the two or three levers that would move your margin most.

3. Decide: Invest, Adjust, or Exit.

- Invest in proven improvements—fresh cow facilities, cooling, feed systems

- Adjust your model—grazing, organic, processing, partnership

- Plan an exit that protects equity while cows and equipment are still solid

The Bottom Line

2026 doesn’t look like a disaster year, and it doesn’t look like a home-run year. It looks like a sorting year—where clarity and decisions matter most.

Feed is finally in your favor. But milk prices are expected to be below 2025 levels, and most serious margin analyses suggest spreads will tighten for many herds.

The herds that make it through stretches like this aren’t always the biggest. They’re the ones who know their numbers, think beyond the next milk check, and make intentional choices before the market does.

The math this year is universal. What you decide to do with it is personal—written at your own kitchen table, with your own records, and the people you trust sitting there with you.

Key Takeaways

- Cheap feed won’t save you: Record corn pushed DMC feed costs to $9–$10/cwt, but milk prices are dropping faster—net margin tightens, not loosens

- $100K on the line: A typical 300-cow dairy loses roughly $90,000–$100,000 in operating margin in 2026 compared to 2025

- The scale gap is brutal: Small herds face $42.70/cwt total costs vs. $16–$19/cwt for large operations—mid-size dairies are caught in between

- This is a sorting year: Invest in efficiency, adjust your model, or plan your exit—there’s no standing still in 2026

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

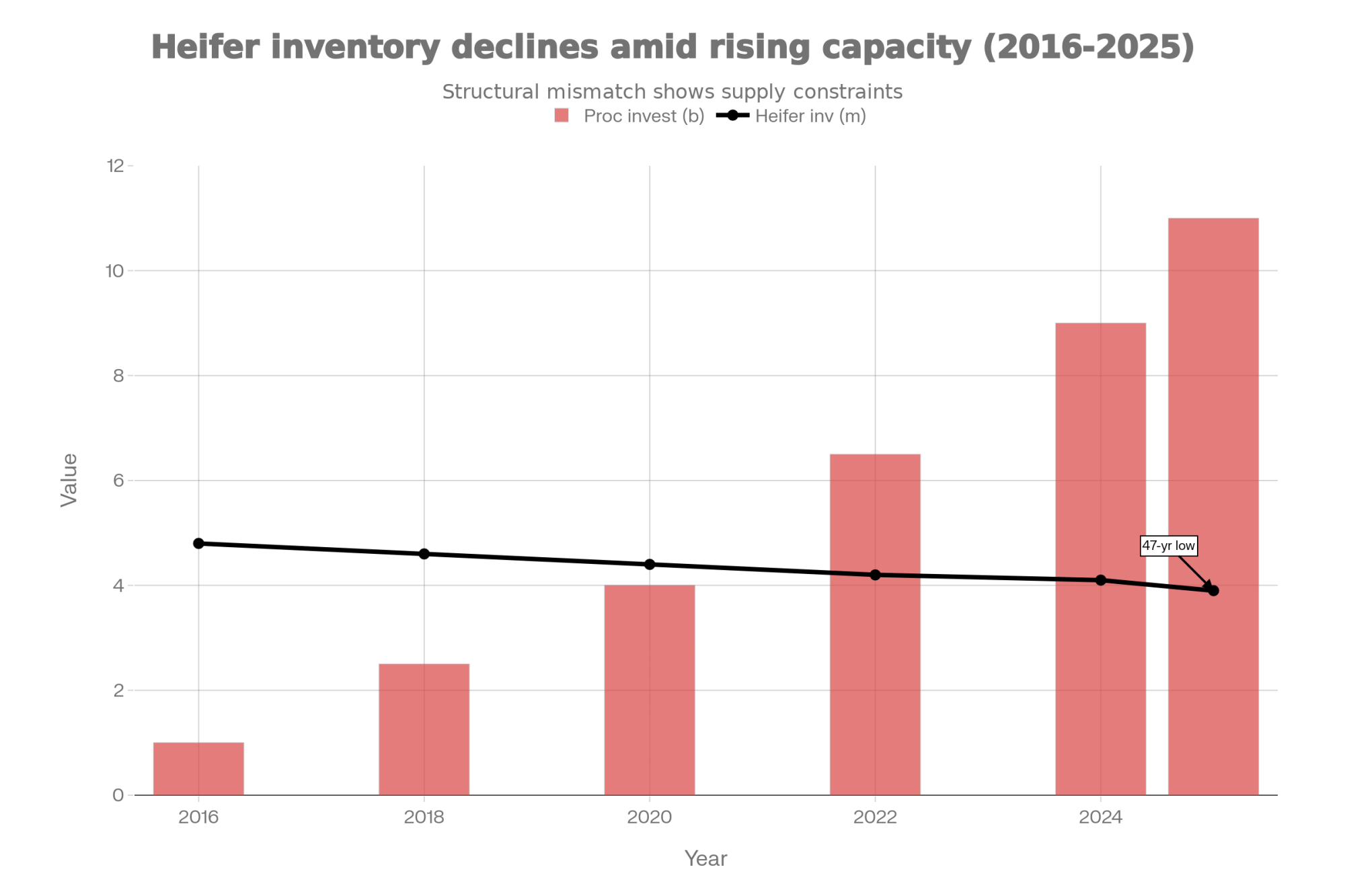

- Squeezed Out? A 12-Month Decision Guide for 300-1,000 Cow Dairies – Reveals the precise ROI calculations for robotic transitions and heifer procurement that define survival for mid-size operations. This guide arms you with a month-by-month tactical roadmap to protect equity while navigating the current 30-month replacement deficit.

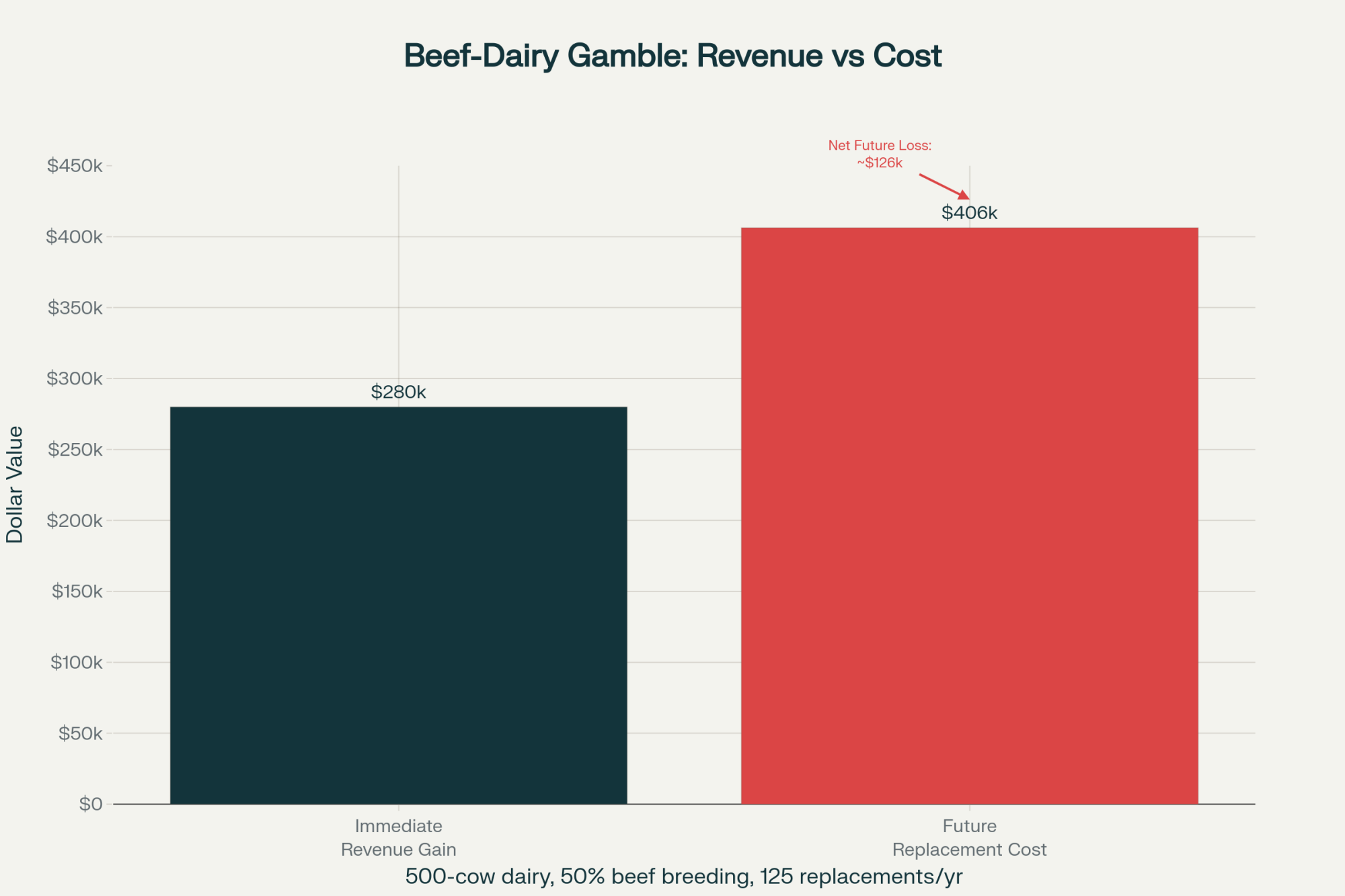

- Why Dairy Markets Can’t Self-Correct Anymore: The Hidden Forces Reshaping the Dairy Industry’s Future – Exposes the seismic shift toward multi-revenue “mega-dairies” where milk is no longer the primary profit driver. This analysis reveals how energy and beef-on-dairy contracts are permanently resetting the industry’s break-even floor through 2027.

- Where Will Tomorrow’s Dairy Herds Come From? U.S. Farmers Navigate Historic Heifer Crisis – Delivers a high-stakes strategy for the “Genomic Guillotine”—using early-life testing to ruthlessly slash heifer rearing costs. It reveals how maverick producers are turning a biological supply crisis into a definitive long-term genetic advantage.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!