One ICE raid stopped a dairy cold. 35 workers gone. But it also revealed who neighbours really are.

I’ll never forget the first time someone told this story in a room full of dairy people.

It was one of those meetings where the coffee’s lukewarm, the jokes are familiar, and everyone’s half‑listening while thinking about the next milking. Then someone said, “Did you hear about the dairy in New Mexico that lost 35 workers in one morning?”

The whole room went quiet.

Every person at that table started doing their own math. What would that look like here? On our lane? With our crew?

June 4, 2025, started like any other hot, dry morning outside Lovington, New Mexico. The sky was already bright by the time cows lined up in the parlor at Outlook Dairy. Hoses hissed. Units clanked on and off. Spanish and English mixed over the noise in that familiar way you hear on a lot of larger dairies now.

Honestly, if you’d dropped in early that morning, it would’ve sounded a lot like a Tuesday on plenty of farms across North America.

By the end of the day, nothing about it felt ordinary.

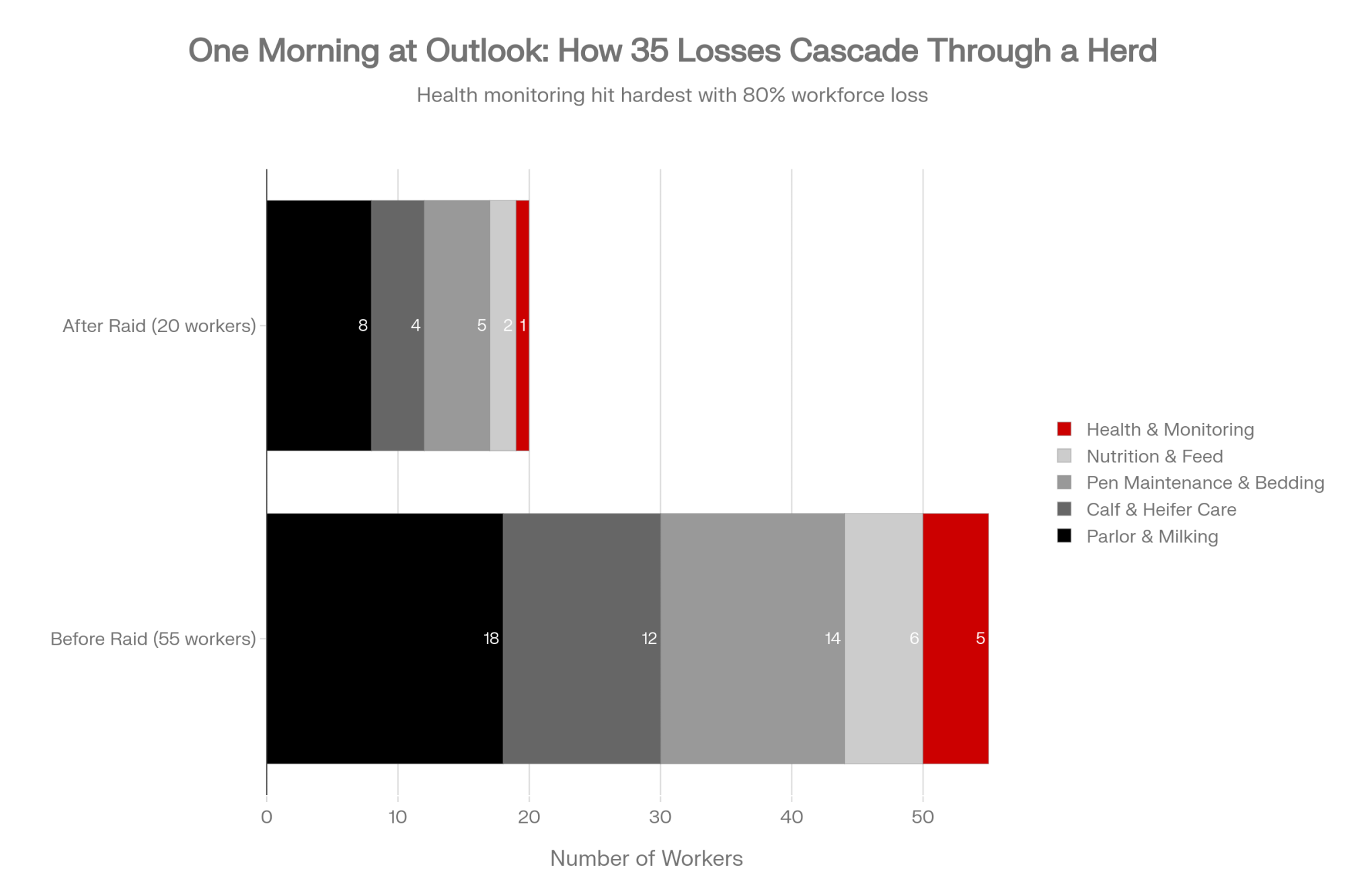

Homeland Security Investigations trucks came down the lane with a search warrant. When they left, 11 workers were in custody. After an employment audit tied to their documents, owner Isaak Bos was told he had to fire 24 more on the spot. In the space of a few hours, Outlook Dairy lost 35 of 55 workers—almost two‑thirds of the people who kept that place running.

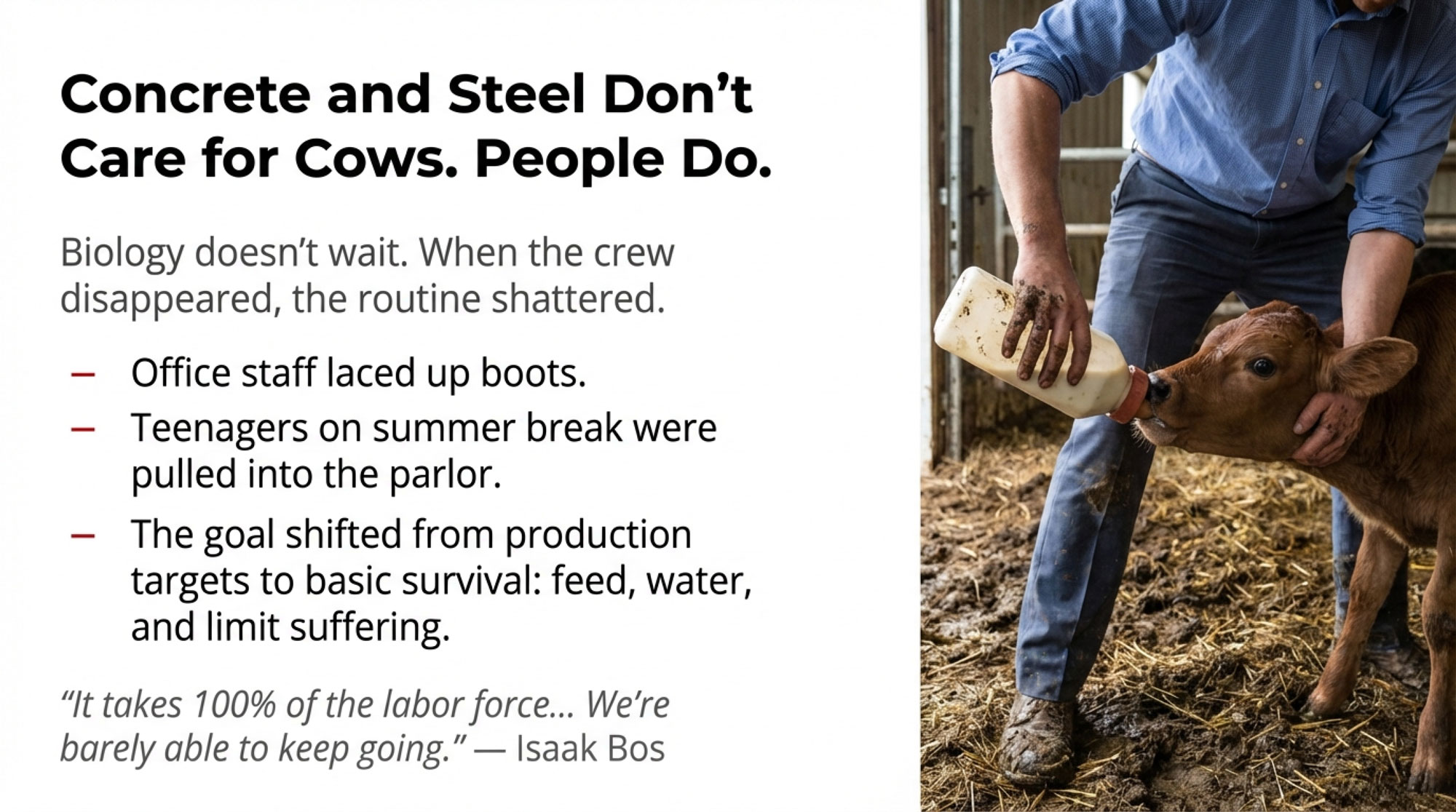

Bos later said milk production had “effectively ceased.” Every remaining person—family, office staff, whoever was available—and even some high school students on summer break were pulled into basic animal care just to keep the cows fed, watered, and milked at all. He put it plainly: “It takes 100% of the labor force, so no day is off right now. It’s detrimental for our cattle. We’re barely able to keep going.”

If you milk cows yourself, you don’t need a graph to understand that. Your stomach does the math for you.

When Everything Stops but the Cows

The thing about a dairy is simple and unforgiving: cows don’t stop just because your labor does.

In Lovington that week, all the routines that make a dairy hum were suddenly missing most of the people who knew them best. The workers who’d been there every day—many of them immigrants who had put down roots in the area—weren’t walking into the parlor, scraping alleys, or checking fresh cows anymore.

Across the U.S., that’s not a side note. It’s the reality of who actually milks the cows. A major industry survey found that foreign‑born workers make up roughly half of all dairy labor, and the farms that rely on them produce nearly 80% of the country’s milk. In barn language: without immigrant labor, most of America’s cows don’t get milked.

That’s true whether you’re pushing cows through a big New Mexico freestall, running a 200‑cow sand‑bedded herd in Wisconsin, or managing a couple of key foreign workers under Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program. It doesn’t take many people to disappear before the whole system starts to wobble.

When an enforcement action hits a dairy, the headlines talk about arrests, charges, and policy. But in the farmhouse, the questions are more basic.

Who’s going to milk tonight?

Who’s going to catch the cow that’s about to crash?

Bos said Outlook went from “operating normally” to crisis mode overnight. People who normally handled phones and paperwork laced up boots and headed to the barn. Teenagers who figured they’d be doing odd jobs suddenly found themselves in the parlor or feeding calves. Production targets weren’t the priority anymore. The new goal was simple: keep the cows alive and limit their suffering until a crew could be rebuilt.

If you’ve ever had flu rip through your family, lost a key employee, or had one bad accident take the legs out from under your schedule, you know a smaller version of that scramble. You stretch days longer than they should be. You pick up one more milking. You cut corners you never wanted to cut because there just aren’t enough hands.

Lovington didn’t invent that feeling. It just pushed it about as far as it can go in a single morning.

The People Behind the Paperwork

From a distance, it’s easy to see “11 arrested, 24 fired” and think in terms of paperwork and status. Up close, those numbers are people.

On that farm, those 35 were workers who had been part of the daily rhythm for years—feeding cows, scraping alleys, watching fresh pens, raising calves. Bos has said all 35 lived locally. Their kids went to the same schools. Their families bought groceries at the same stores. They were neighbours long before a federal truck ever pulled into the yard.

Advocates in the region put it in terms many producers would recognize in their own communities: these aren’t just “workers,” they said. They’re “our neighbors, coworkers and friends,” people who have “contributed to our economy and enriched our culture” in southeastern New Mexico.

After the raid, Bos emphasized that the dairy itself wasn’t charged with wrongdoing. He said the employees had given them false documents and that the operation came without prior warning. Whatever you think about the legal side, you can hear in his words that this wasn’t just about forms to him. It was about people he knew and depended on.

He talked about the “intimidating effect” of the raid and worried that it would scare even more workers away. Any owner who’s spent years building a crew and a culture can feel that in their bones.

Immigrant-rights groups in New Mexico went even further, connecting what happened at Outlook to the broader local economy. They warned that raids like this “threaten the safety and economic well‑being of our communities,” in a region where immigrant workers are “powering industries from dairy farms to oil and gas.” They talked about how every time a worker disappears from a place like Outlook, that absence is felt not just in the barn but in the cash register at the grocery store, in the quiet tables at local restaurants, and in the small shops that count on regular customers from the dairies.

In other dairy regions, people who work closely with farmworkers have been describing the same kind of fear. In Vermont and beyond, organizations that advocate with dairy workers talk about how stepped‑up immigration enforcement has changed everyday life—workers limiting trips to town, skipping church, putting off doctor visits, avoiding school events—because every mile off the farm feels like another chance to end up in a patrol car instead of a pickup.

On paper, that shows up in policy reports and enforcement statistics. On the ground, it looks like people are shrinking their world to the few places that still feel somewhat safe, even as the workload doesn’t let up and the pressure quietly builds.

You don’t have to agree on every policy detail to see how that wears on a crew. And on the people who work alongside them.

What Happens to the Cows When Workers Disappear

Every producer knows this: concrete and steel don’t care for cows. People do.

When most of those people are suddenly gone, the barn feels it long before a reporter ever arrives. In Lovington, reports described remaining family members, non‑farm staff, and local high school students suddenly responsible for nearly everything—feeding, milking, bedding, and keeping an eye on fresh cows—under intense time pressure.

Training someone new in the parlor takes time, even under the best conditions. Getting them comfortable reading cow behavior, spotting a hot quarter, recognizing a twisted stomach before it’s obvious—that takes longer. Doing all of that while you’ve already lost most of your experienced crew and everyone left is exhausted is another thing entirely.

That’s when real risk sneaks in. Not because anyone cares less, but because biology doesn’t wait while people catch up.

Bos said the remaining workers were being “pushed…to the limit.” Most dairy families don’t need that explained. When you’re running on too little sleep, carrying too much worry, and trying to do three jobs at once, little things slip.

A cow that somehow still has a full quarter at the end of milking.

A dull‑eyed calf that should’ve been flagged an hour earlier.

A fresh cow that doesn’t get that second or third look you always meant to give her.

Those aren’t character flaws. They’re the predictable result of stripping away most of the people who knew the herd best and asking the ones who remain to do the impossible.

In Lovington, the raid didn’t just stress a business plan; it shattered it. It stressed a barn full of living animals that had no idea why familiar hands didn’t show up that day. And it stressed the people left behind—owners, spouses, kids, employees—in ways that still don’t fit neatly into any official report but linger in a house and a community long after the headlines move on.

A Town Watching and Worrying

The neighbour’s text came before sunrise for many folks that week: “Did you hear what happened at Outlook?”

At the feed mill, at the co‑op, at the school, people traded pieces of the story they’d heard. Some knew names, some just knew numbers, but everybody understood that losing most of your crew isn’t something you can quietly absorb.

Very quickly, the questions that started in kitchens and pickup trucks found their way into a public meeting in Hobbs. Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham came. So did local officials, church folks, school staff, and people who just needed to look someone in the eye and ask what came next.

In that room, nobody was talking in theories.

People wanted to know what happens to a family when a parent is suddenly detained or fired and there’s no paycheck coming in. They worried about what happens to kids when mom or dad disappears between breakfast and suppertime. They asked what kind of future local agriculture has if dairies can’t keep crews because everyone’s scared of who might show up in the yard.

School staff wondered how to support children who suddenly didn’t know where a parent was—or were afraid to talk about it. Church leaders were hearing from families who now felt too scared to come on Sunday. Small businesses felt the absence of regular customers. In a rural county where agriculture is a backbone, when a dairy loses 35 people in a day, there really isn’t anyone who doesn’t feel some part of the shock.

| Stakeholder | Annual Spending (lost) | Immediate Impact | Long-term Risk |

| School District | ~$120k (tuition, meal programs, supplies) | 8–10 children withdrawn; reduced Title I funding; staff scheduling pressure | Loss of enrollment revenue; fewer teachers retained |

| Churches | ~$45k (tithes, donations, event participation) | Reduced attendance; families too stressed to participate; donation drop | Reduced community support capacity; programming cuts |

| Grocery Stores & Food Retail | ~$280k (weekly family shopping) | “Regular customers vanished overnight” | Delayed inventory restocking; profit margin erosion |

| Gas, Auto, Farm Services | ~$185k (fuel, repairs, feed supplements) | ~25% of typical weekly transactions disappear | Small businesses operate on thin margins; 1-2 months of losses threaten viability |

| Rental Housing | ~$210k (rent income for local landlords) | 20–25 rental units suddenly at risk of non-payment | Risk of foreclosure or property abandonment in already-fragile rural real estate market |

| Health Services & Pharmacy | ~$65k (clinic visits, prescriptions, insurance co-pays) | Delayed care; non-payment of bills; language-barrier service loss | Clinic loses X-ray tech income; pharmacy reduces hours |

| Lovington Municipal Tax Base | ~$75k (property, sales tax from dairy wages) | Immediate pressure on municipal budget | Schools, roads, emergency services underfunded; quality of life declines |

- | TOTAL LOCAL ECONOMIC SHOCK (Direct) | ~$980k/year lost spending power | Cascades through 150+ local businesses | Potential long-term population decline |

Immigrant-rights groups in the area called the raid devastating. They said people were sorrowful, frustrated, and frightened. Those weren’t academic words. They came from organizers who were on the phone with families and workers, trying to make sense of what had happened.

At the same time, the wider dairy industry was circling around the story. Farm media across the country ran pieces on the Lovington raid. The Bullvine called it “a stark preview” of what happens when immigration enforcement collides with the reality of who actually milks America’s cows, noting that removing 64% of a workforce in one morning had effectively brought milk production to a halt. Others described it as an “overnight exodus” and underlined how fragile even large, well‑managed dairies are when labor is shaken that hard.

Put together, the voices from the meeting hall, advocacy groups, media, and the farm itself didn’t produce a neat narrative. They produced something closer to what real life in dairy country looks like.

Complicated. Heavy. And very human.

Not Just One Farm’s Vulnerability

It would be easy to look at Lovington and say, “That’s a New Mexico problem.” But the numbers refuse to keep it that tidy.

| Demographic Group | Number of Workers | % of Workforce | % of U.S. Milk Production |

| Foreign-Born Workers | 180,000 | 51% | 79% |

| U.S.-Born Workers | 170,000 | 49% | 21% |

| Total Dairy Workforce | 350,000 | 100% | 100% |

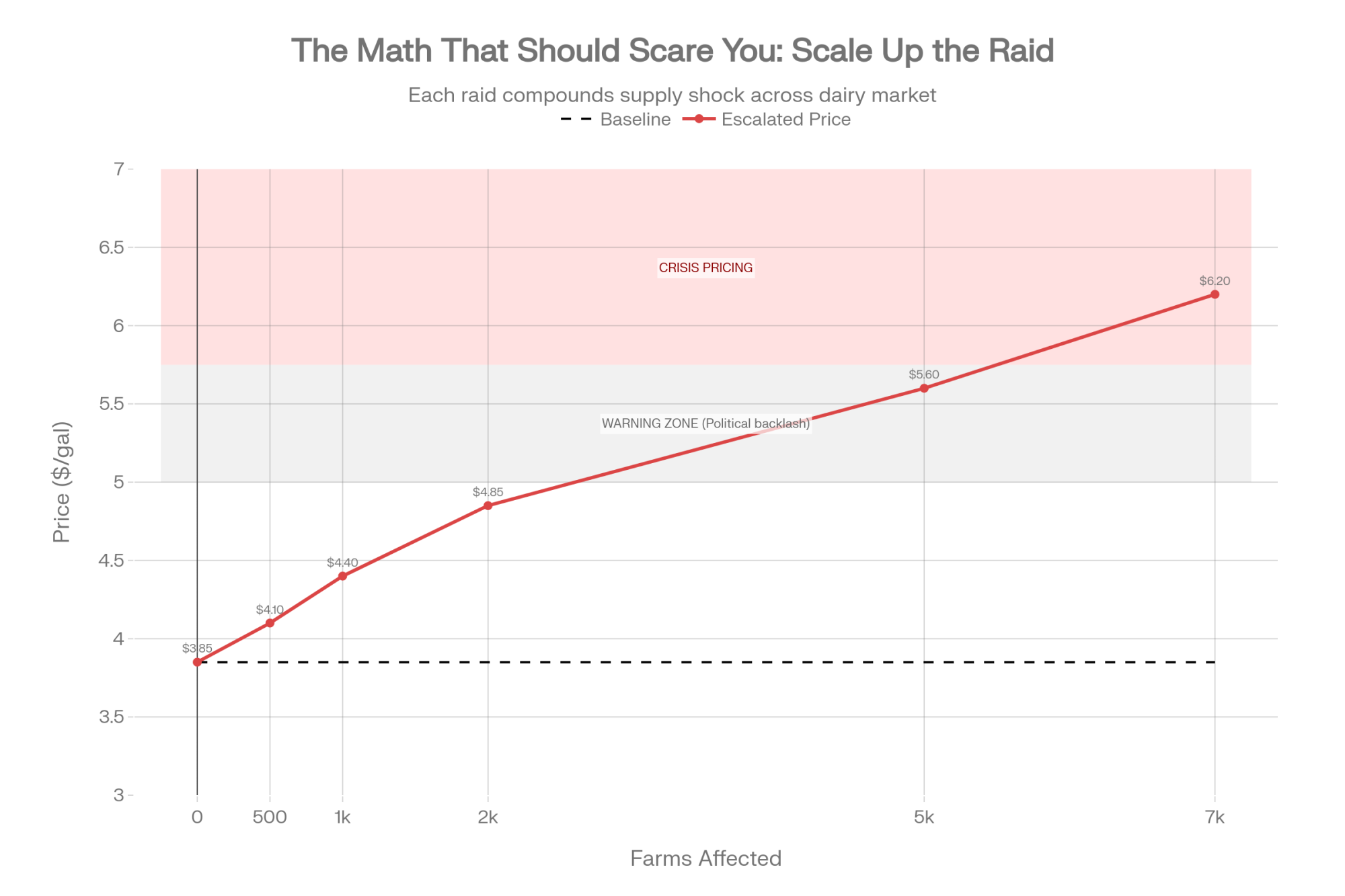

That 2015 national survey on immigrant labor—still the best wide‑angle view we have—estimated that if foreign‑born workers disappeared from U.S. dairies, roughly 7,000 farms would close and milk prices would spike. You don’t have to believe every line of a model to feel the point: the system isn’t built to handle that kind of loss.

In recent years, stepped‑up immigration enforcement hasn’t stayed in one state. Workplace and community raids in different parts of the country, including agriculture and food‑system jobs in states like Oregon and Wisconsin, have fed a constant undercurrent of anxiety in farm country. It’s not just packing plants and warehouses. It’s barns.

In places like Vermont, advocates who work closely with dairy workers have been saying the same thing over and over: fear of being stopped, detained, or deported has pushed many people into deeper isolation. Trips to church, doctor visits, school meetings, even basic shopping—things many of us take for granted—have been cut back or dropped entirely because the risk of being on the road feels too high.

For dairy owners and managers, that climate manifests in different ways. It looks like nights spent looking at the ceiling instead of sleeping, wondering if you’ll have enough hands for the first milking tomorrow. It looks like trying to support workers who are carrying their own fears while you’re also trying to keep the bank at bay and the cows on feed.

It shows up in the lives of farm spouses who balance payroll, kids’ schedules, and the unspoken emotional load of keeping the whole operation from flying apart. It shows up in teenagers who are suddenly taking on more barn work because there isn’t anybody else, watching the adults around them carry stress that’s hard to explain.

Lovington didn’t create that pressure. It just gave everyone a sharper, more public picture of what so many dairy communities have been quietly living with for years.

When Neighbours Became Family

The moment that sticks with a lot of people in stories like this isn’t always the raid itself. It’s what comes after, when the shock wears off, and the sheer amount of work left to do settles on the people who are still standing in the yard.

Standing in the milk house after a day like that, it would be easy to feel alone. The pipeline’s still humming. Cows still need to be fed. The phone won’t stop buzzing. You’re tired enough that the thought of asking for help feels like just one more job.

And then, in a lot of dairy communities, something small but important happens.

A text comes in from down the road: “How bad is it?”

At the feed mill, somebody says, “I heard what happened. Are they okay for help?” A nutritionist or vet decides to swing by sooner than planned. A friend at the co‑op quietly asks if there’s anything the board can do to give a bit of breathing room.

Sometimes it’s as simple as a kid asking their parents if they can go help at the other farm instead of scrolling on their phone that afternoon. On some roads, a teenager showing up to scrape alleys or bed a few pens has been the difference between a barn barely hanging on and a barn where people get to lie down for a couple of hours.

In many dairy communities, when a farm is hit with a fire, a serious illness, a bad accident—or an enforcement action like the one in Lovington—you see familiar patterns:

A neighbour swinging over after their own chores to ask what’s really needed.

A ride into town for someone who doesn’t feel safe driving alone.

A quiet envelope slipped into a hand outside the church because someone heard a family lost their income.

A plate of food left at the back door with the same simple line people have used for generations: “We made too much. Thought you might help us out.”

Most of those acts never see a camera. They don’t end up on Facebook. They don’t make a line in any official report. But for people living through the hardest days of their lives, those moments change how they see their neighbours.

Not as “the guy who runs that place down the road,” but as someone who refused to let them fall alone.

What This Story Asks of the Rest of Us

What moved a lot of people most about Lovington wasn’t just the shock of the raid. It was being forced to look straight at how dependent we’ve all become on workers who carry a lot of risk and not much protection—and at how much we lean on each other, often without saying it out loud.

Sitting at your own kitchen table, you might be thinking, “All right, but what am I supposed to do with this? I’ve got my own headaches.”

That’s fair. Nobody needs one more heavy thing to carry.

Maybe the question isn’t “How do we fix immigration policy?” Maybe it’s smaller and closer to home:

Who do we really depend on here?

Who might depend on us?

On most dairies, there’s at least one person whose cow sense you can’t imagine losing. They might be family. They might be a long‑term employee. They might be the worker who doesn’t speak much in meetings but notices every limp and every change in feed intake. Naming that out loud—and finding ways to show them they matter as a person, not just a set of hands—won’t change federal law. But it might change whether they feel alone when things get hard.

There’s also usually at least one neighbour, advisor, or friend you’d call on your worst day. If you can picture who that is, that relationship is worth investing in now, not someday.

Over supper or during a drive to pick up parts, it might be as simple as saying, “If we ever got hit with something like that New Mexico raid, you’d be one of the first people I’d call. I hope you know that.” And maybe adding, “If anything ever explodes on your place, I hope you’ll call us too.”

Sometimes the bravest thing isn’t staying strong. It’s admitting that if you lost half your crew overnight, you couldn’t do it alone.

Other small things matter more than they look like on a calendar:

Saying yes when the 4‑H leader wants to bring kids through the barn, because those kids might be your next crew—or your next neighbours.

Stopping by a meeting at the co‑op or county when you’re bone‑tired, because being there helps keep agriculture on the agenda.

Checking in on the people who carry the invisible load: the spouse who handles payroll and crisis calls, the teenager who suddenly became the extra hired hand, the worker who hasn’t left the farm in weeks.

And if Lovington has you thinking not just about barns but about the bigger picture, there’s one more step that matters. The same way you’d call a neighbour when the barn is in trouble, you can also let your local representatives know what raids like this look like from your yard. A simple, honest conversation—”Here’s who milks our cows, here’s what happens to our town when those people disappear overnight, and here’s why we need policies that keep both our herds and our communities stable”—isn’t about party lines. It’s about making sure the people writing the rules understand the human and economic reality they’re reaching into.

None of this fixes the whole system. But it does change the way it feels to live in it.

Community & Legacy: What We Build Before the Storm

Lovington is still living with what happened on that June morning. Outlook Dairy has been working to rebuild and get back to something resembling normal. Some legal and immigration cases tied to raids like that can drag on for years. Others end quickly with families separated and people gone before anyone’s ready.

The cameras left a long time ago. The day‑to‑day reality hasn’t.

For dairy people watching from a distance, the story lingers in a different way.

Every time someone mentions losing a chunk of their crew, those numbers in New Mexico—35 out of 55—come back to mind. Every time a producer talks about how much they rely on their immigrant workers, someone remembers Bos’s line: “It’s detrimental for our cattle. We’re barely able to keep going.” Every time a policy discussion treats enforcement like a clean, abstract lever, someone thinks of a parlor that went quiet for all the wrong reasons.

What happened in New Mexico didn’t create the bond between cows, workers, families, and neighbours. It revealed it—and showed how fragile that bond really is when something hits it hard.

The heart of this story isn’t that one farm had a terrible week and made the news. It’s that dairy communities everywhere are quietly being asked the same question Lovington had to face out loud:

When the barn feels empty, and the work looks impossible, will we let each other face it alone?

Most of us can’t choose if or when the next storm hits our lane. It might be enforcement. It might be a barn fire. It might be a health crisis, a brutal price year, or something nobody saw coming.

What we can choose—day in, day out, in a hundred small ways—is what kind of community we’re building long before the sirens ever show up.

The kind where it’s every farm for itself?

Or the kind where, when the worst happens, somebody already has their boots on, their truck running, and their mind made up—not because anyone called a meeting, but because that’s just what neighbours do here.

That decision doesn’t belong to policymakers, reporters, or anyone far away.

It belongs to us.

And if there’s one thing Outlook Dairy’s hardest week made hard to ignore, it’s that the time to make that decision isn’t when the lights are already flashing in the lane.

It’s now.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- One raid. One morning. Everything stopped. An ICE action at Outlook Dairy in New Mexico removed 35 of 55 workers—production halted, and everyone left was pulled into survival mode.

- The math is brutal. Immigrant workers provide 51% of U.S. dairy labor and 79% of the milk. NMPF warns that losing them could close 7,000+ farms and nearly double retail prices.

- Community didn’t ask permission. Neighbors, local teens, churches, and small businesses showed up with hands, rides, and quiet help—no politics, just presence.

- This is your question now: If half your crew vanished tomorrow, who shows up before you call? And whose call would you answer?

- Policy starts at your kitchen table. The people milking your cows have names, kids in local schools, and lives in your community. When you talk to representatives, remember that.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

When an ICE raid hit Outlook Dairy in Lovington, New Mexico, on a June morning in 2025, 35 of 55 workers were suddenly gone, milk production “had effectively ceased,” and everyone left—family, office staff, even local teens—was pulled into basic cow care just to keep the herd going. The article treats those 35 as people, not paperwork, tracing how their disappearance shook the barn and the wider town—schools, churches, grocery aisles, and small businesses that depend on dairy paycheques. It ties that one awful morning to the bigger reality that immigrant workers now provide roughly 51% of U.S. dairy labour and 79% of its milk, with NMPF modelling warning that losing them could close over 7,000 farms and nearly double retail milk prices. Against that backdrop, the heart of the story is the quiet, practical ways neighbours and community leaders show up—extra hands in the parlor, rides into town, support at church and school, and hard conversations in a Hobbs town hall—so one farm isn’t left to carry the crisis alone. It ends back at the kitchen table, asking every producer to name who they’d call if half their crew vanished, who might call them, and what to ask local representatives so the people who actually milk the cows—and the communities built around them—aren’t invisible when the next raid comes.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- Labor Crisis Reality Check: How Immigration Crackdowns Could Increase Milk Prices by 90% and Crash Profits – Traversing from New Mexico to Vermont, this narrative explores other producers who have walked a similar, jagged road. It honors those facing sudden enforcement while wrestling with the same survival math that haunted the Bos family.

- The 51-79 Workforce Bomb: How ICE Raids Became Dairy’s Consolidation Tool – This piece deepens our understanding of the industry forces that turned a quiet morning in Lovington into a national warning. It proves the point that the 51-79 math is the precarious foundation our entire world is built upon.

- Robotic Milking Revolution: Why Modern Dairy Farms Are Choosing Automation in 2025 – Looking toward what happens next, this story follows the next generation as they carry forward family legacies. It examines how automation helps younger farmers walk a path that protects their herds from the instability that stopped Outlook Dairy cold.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!