Your robot’s mastitis alerts aren’t gospel. A $15 strip cup plus selective treatment beat blanket tubes on cost, antibiotics, and cow survival.

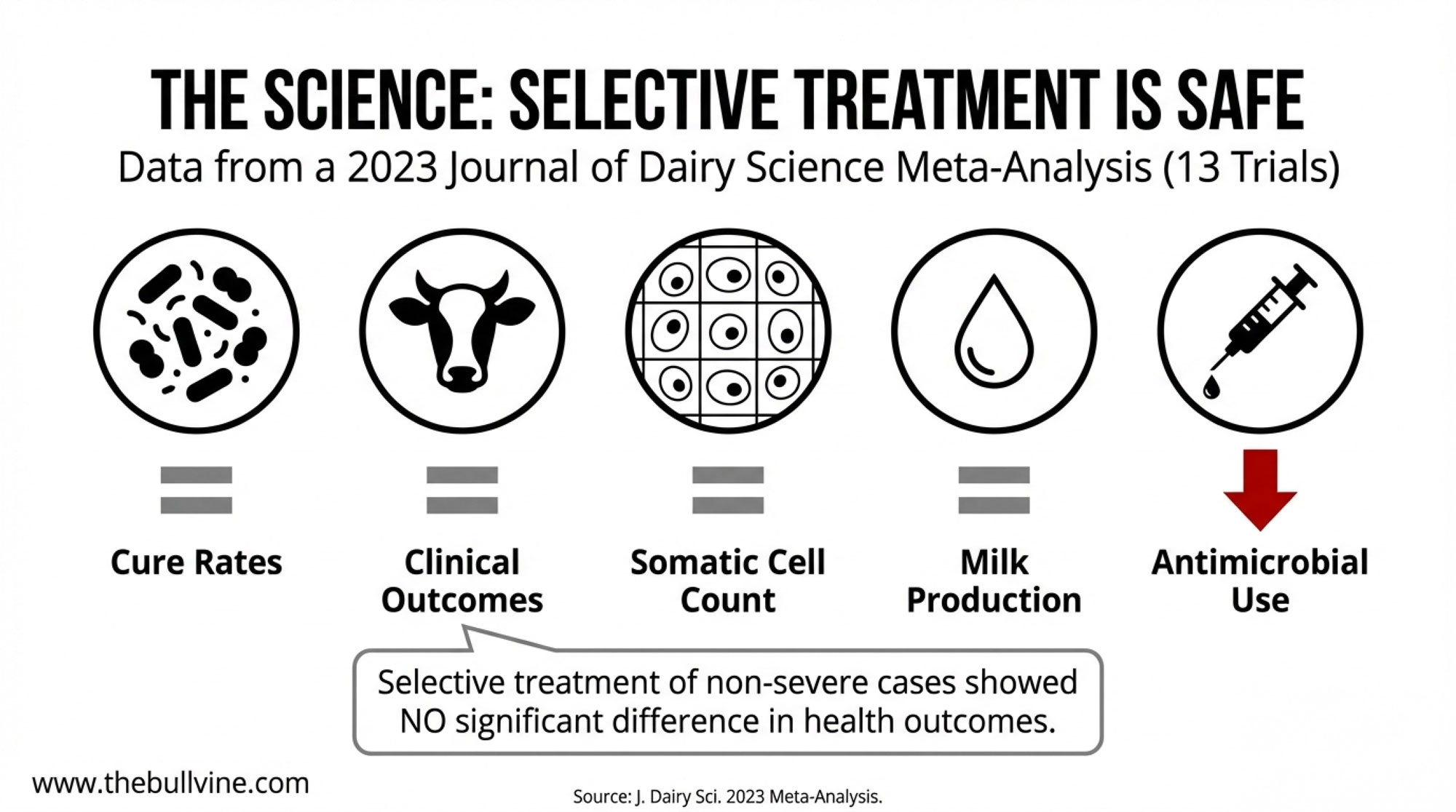

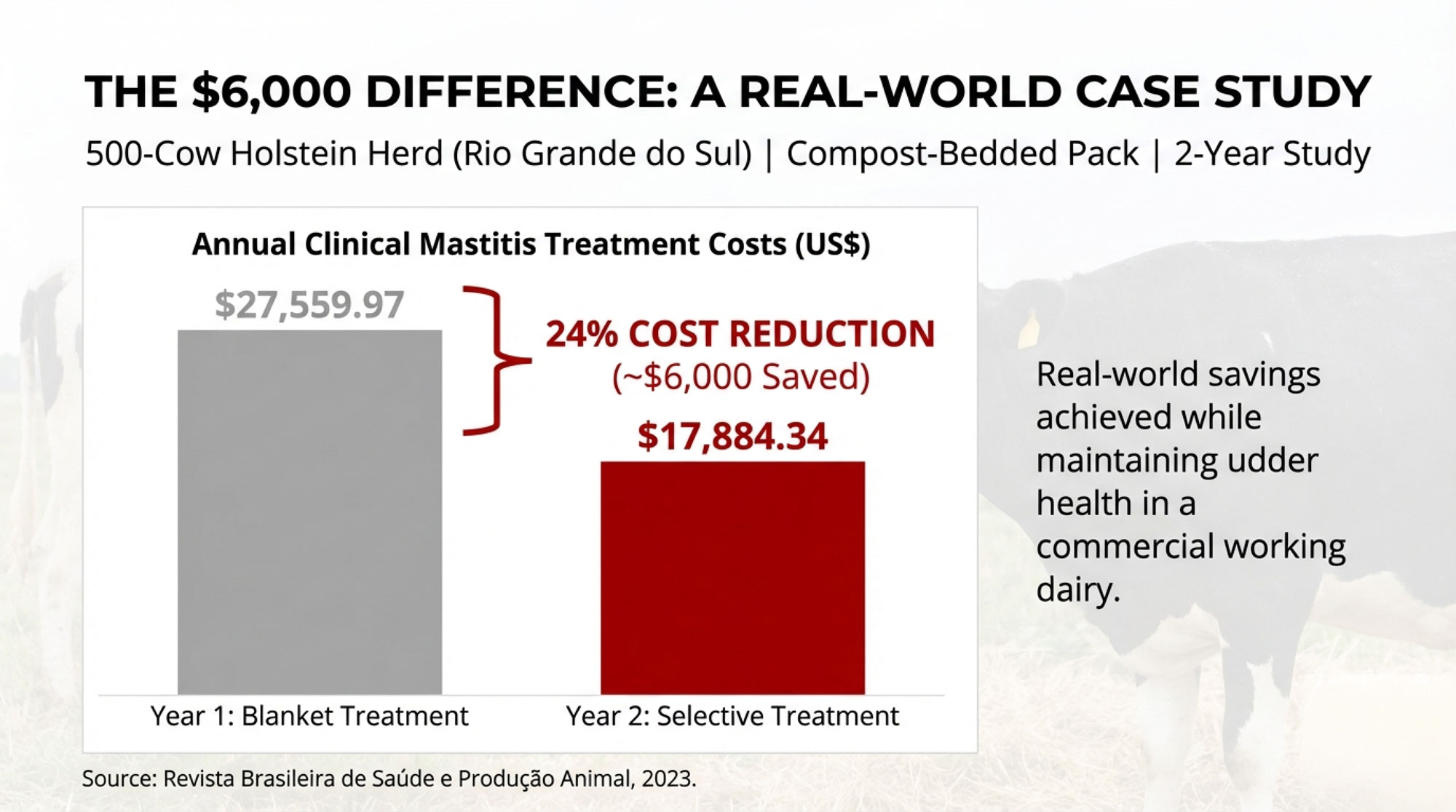

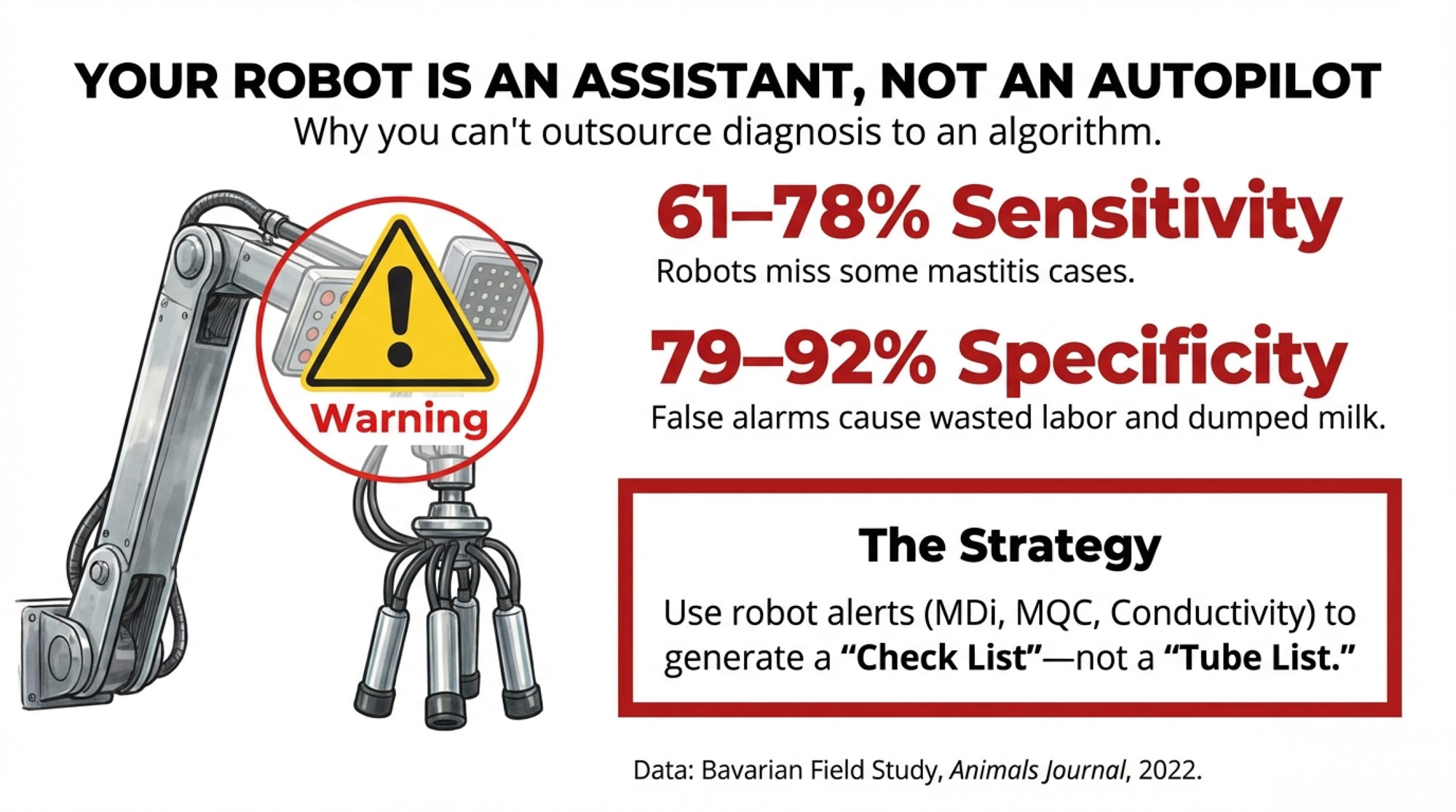

Executive Summary: Most dairies still tube every mastitis cow “just to be safe,” but a 2023 Journal of Dairy Science meta‑analysis of thirteen trials found that selective treatment of non‑severe cases based on bacterial diagnosis can maintain cure, SCC, milk yield, and culling while cutting antimicrobial use. One 500‑cow Holstein herd in southern Brazil, for example, dropped its clinical mastitis treatment costs from US$27,559.97 to US$17,884.34 in a year—a 24% reduction, roughly US$6,000—after switching from blanket treatment to on‑farm culture–guided selective therapy. At the same time, a Bavarian field study showed that robot mastitis alerts have only 61–78% sensitivity and 79–92% specificity, depending on the brand, which means AMS systems are great at generating “cows to check” lists but shouldn’t be deciding which quarters automatically get tubes. This article pulls those threads together into a three‑phase playbook: tighten detection with strip cups, run a six‑ to eight‑week on‑farm culture “learning phase,” then build a vet‑driven selective protocol that fits your pathogen mix and labour reality. The focus is squarely on lowering mastitis costs and antibiotic use while protecting milk, SCC, and butterfat levels in real freestalls, tie‑stalls, and robot barns. The bottom line is that if your SOP still says “treat every case,” you’re probably spending more than you need to on tubes and discarded milk—and this gives you a practical path to test that on your own farm.

| Outcome Measured | Selective Treatment (Diagnosis-Guided) | Blanket Treatment (All Non-Severe Cases Tubed) | Statistically Significant Difference? | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriological Cure Rate | ✓ Maintained | ✓ Maintained | NO | Both protocols achieve cure; diagnosis-guided doesn’t lose ground |

| Clinical Cure Rate | ✓ Maintained (slightly longer time-to-normal: ~0.5 days) | ✓ Maintained | Minor trade-off | One more day to visual recovery is negligible vs. cost savings |

| Bulk Tank SCC | ✓ Maintained / Improved | ✓ Maintained | NO | Selective treatment does NOT compromise herd SCC |

| Milk Yield (kg/day) | ✓ Maintained | ✓ Maintained | NO | No yield penalty; both manage production equally |

| Recurrence Rate | ✓ Maintained | ✓ Maintained | NO | Future mastitis risk is identical between groups |

| Culling Rate | ✓ Maintained | ✓ Maintained | NO | Selective treatment does NOT increase forced culls |

| Antibiotic Use (volume & exposure) | ↓ Significantly Lower | ✓ High | YES – Selective Wins | Fewer cows receive tubes; direct reduction in farm-level antibiotic footprint |

| Treatment Cost (relative) | Base: 100% | Base: 131% | YES – Selective Wins | 24–31% cost savings in real herds (see Visual 2) |

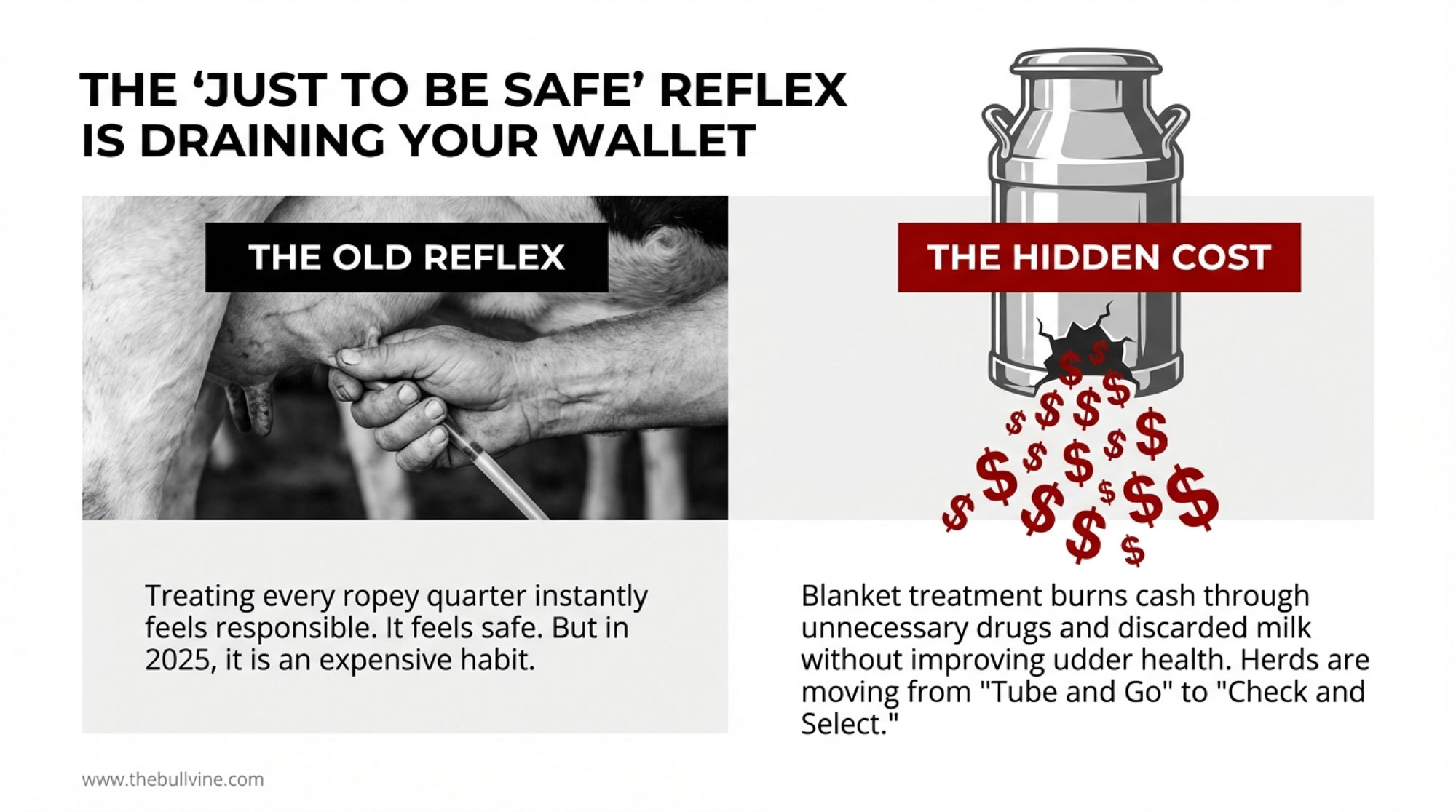

Picture us at a winter dairy meeting, coffee on the table, and someone says, “We treat every ropey quarter the same way—grab a tube and go.” A lot of heads still nod at that. It’s familiar. It feels safe.

Here’s what’s interesting. A 2023 meta‑analysis in the Journal of Dairy Science, led by Dutch and Canadian researchers, including Ellen de Jong, pulled together results from 13 studies that compared selective treatment of non‑severe clinical mastitis to blanket treatment, in which every mild case receives intramammary tubes. The data suggests that when treatment decisions are based on bacterial diagnosis, selective protocols did not worsen bacteriological cure, clinical cure, somatic cell count, milk yield, recurrence, or culling compared with treating every non‑severe case automatically. The only clear trade‑off they picked up was a very small difference—on the order of half a day—in how long it took cows to look clinically normal again.

So that old reflex—tube every non‑severe case “just to be safe”—made sense in a world with less information and less pressure on antimicrobial use. But what this newer work is telling us is that on many farms in 2025, that reflex is quietly draining money in drugs and discarded milk, and it’s not necessarily buying you better udder health.

What I’ve found, walking barns in Ontario, Wisconsin, and across the Northeast, is that the herds making selective treatment work aren’t just university herds or fancy show strings. They’re regular freestalls, tie‑stall barns, and some well‑managed dry lot systems that have tightened up detection, put simple on‑farm culture plates on a bench, and started making more targeted treatment calls. And at the centre of that shift, there’s usually a strip cup that cost about fifteen dollars.

Looking at This Trend: What’s Actually in That Mastitis Quarter?

To make sense of selective treatment, it helps to start with what’s actually going on in the quarter when you see a clinical case.

| Herd Category | Culture-Negative (%) | Gram-Negative (E. coli, Coliforms) (%) | Gram-Positive (Strep, Staph, Lacto) (%) | Sample Size / Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical North American Herds (Meta-analysis range) | 20–40% | 25–35% | 30–50% | 13 trials, meta-analysis |

| Modern European Dairy (mixed systems) | 18–35% | 28–40% | 35–52% | Frontiers Vet Sci, JDS reviews |

| High-SCC Problem Herds | 10–20% | 20–25% | 60–70% | Contagious mastitis-dominant |

| Well-Managed Low-SCC Herds | 25–45% | 30–40% | 25–45% | Environmental mastitis-dominant |

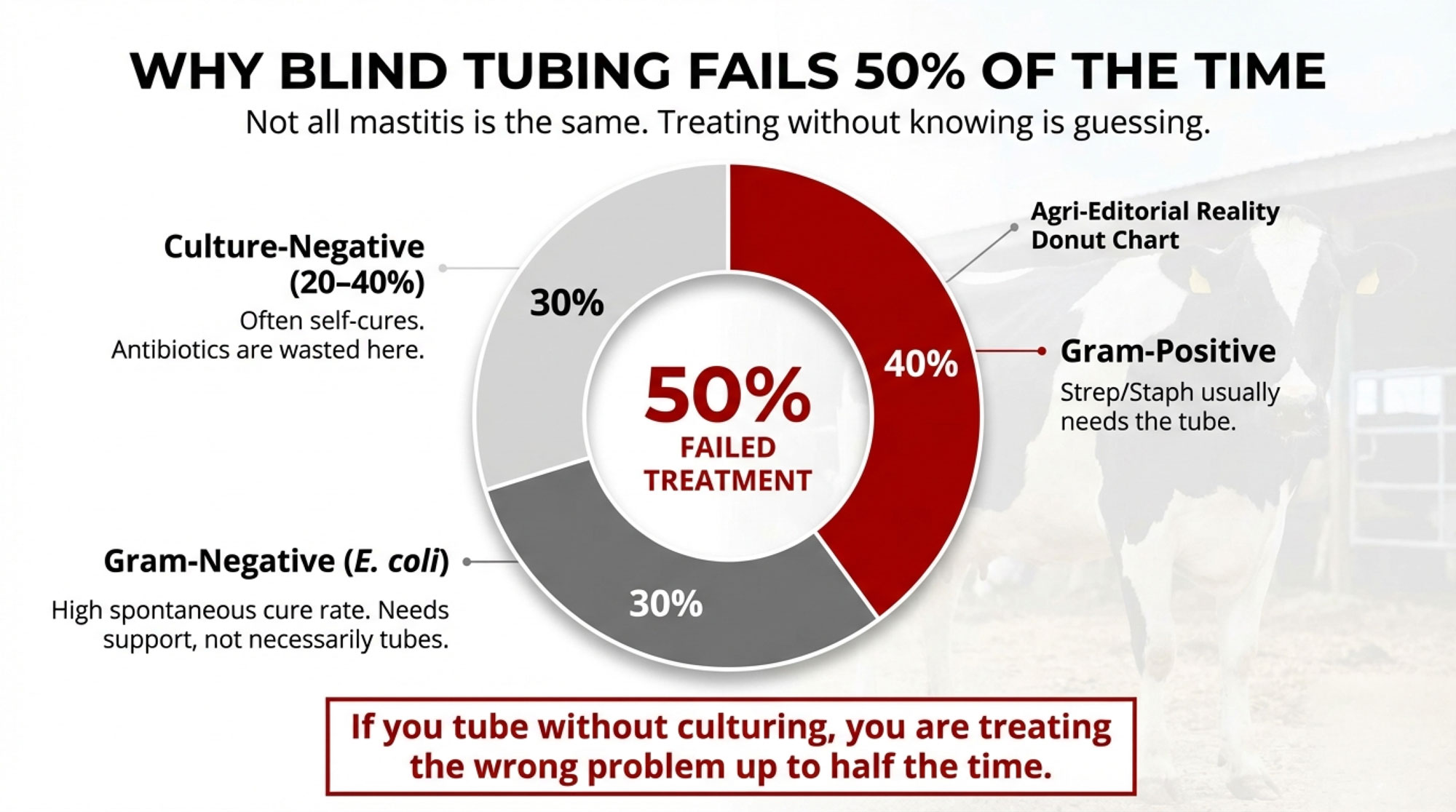

Recent reviews on mastitis in journals like Frontiers in Veterinary Science and Journal of Dairy Science describe how milk from clinical mastitis is usually grouped into three broad categories in research trials and on‑farm diagnostics work:

- Culture‑negative cases, where no growth appears on routine culture media

- Gram‑negative infections, often Escherichia coli and related coliforms

- Gram‑positive infections, like Streptococcus uberis, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and various staphylococci

Across modern datasets from North American and European herds, researchers often report that a substantial share—commonly in the 20 to 40 percent range—of clinical mastitis samples are culture‑negative when they hit the plate. You know how that goes: by the time you see clots or watery milk, and you grab a sample, the cow’s own immune system may already have knocked bacterial numbers down below the detection limit of the culture system.

And here’s where the math starts to matter.

In the non‑severe clinical mastitis trials that fed into that 2023 meta‑analysis, culture‑negative cases were either treated with intramammary antibiotics or left without intramammary therapy, with both groups monitored closely and supported as needed. When researchers pulled those results together, they didn’t see worse bacteriological or clinical cure, SCC, or recurrence in the culture‑negative cows that were managed without intramammary antibiotics, compared with those that received tubes. In plain terms, a lot of those culture‑negative, non‑severe cases were going to get better either way.

For non‑severe gram‑negative cases—especially E. coli—the story is similar in many of the better‑controlled studies. Several trials, including work from Brazil and Europe, show that mild and moderate E. coli mastitis has a relatively high spontaneous cure when cows are otherwise healthy and well monitored. When you look at the numbers in those trials, intramammary tubes don’t always give you a big extra jump in cure compared with careful observation and supportive care, as long as you’re ready to move fast with systemic treatment if a cow spikes a fever, goes off feed, or otherwise starts looking systemically ill.

That’s where good fresh cow management during the transition period and overall environment really start pulling their weight. In herds where cows come into early lactation in good condition, with clean, dry stalls or well‑drained lots and minimal stress, it’s a lot easier for the immune system to do its part in these milder environmental mastitis hits.

Gram‑positive infections are trickier. For years, most of us have felt that these “pay” for a tube, and some work backs that up. Trials are showing that certain gram‑positive pathogens, especially some streptococci and staphylococci, respond better to intramammary antibiotics than to no treatment. At the same time, a 2024 randomized trial in JDS Communications that followed non‑severe gram‑positive mastitis cases identified by on‑farm culture—many of them Lactococcus—found no significant difference in bacteriological cure between several intramammary regimens and no treatment during a 21‑day follow‑up.

So the honest summary is this:

- For non‑severe culture‑negative and many gram‑negative clinical mastitis cases, there’s good evidence that you can withhold intramammary antibiotics and lean on careful monitoring and supportive care without harming overall udder‑health outcomes—provided you still treat severe cows aggressively.

- For non‑severe gram‑positive cases, the evidence is mixed. Some pathogens and situations clearly benefit from targeted intramammary therapy; others, like the Lactococcus‑dominated cases in the 2024 trial, don’t show a big difference in cure either way.

And that’s exactly why just looking at a ropey strip on the floor doesn’t get you very far. As mastitis specialists at places like Minnesota and Penn State keep reminding people, foremilk appearance and udder feel by themselves simply don’t tell you which pathogen group you’re dealing with. If you want a true selective treatment program—not just a dressed‑up version of “treat everything”—you need some sort of diagnostic information, usually from an on‑farm culture plate or a rapid lab test.

A Real‑World Case: A 500‑Cow Herd That Ran the Numbers

Let’s ground this in a real farm.

| Metric | Blanket Treatment Year | Selective Therapy Year | Difference | % Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CM Treatment Cost (USD) | $27,559.97 | $17,884.34 | $9,675.63 | 24.23% |

| Number of CM Cases | 361 | 238 | 123 fewer | 34% case reduction |

| Cost per Case (USD) | $76.35 | $75.17 | $1.18 | 1.5% per-case efficiency |

| Antibiotic Spend Component (est.) | $15,200 | $8,900 | $6,300 | 41% reduction |

| Discarded Milk Cost (est.) | $12,360 | $8,984 | $3,376 | 27% reduction |

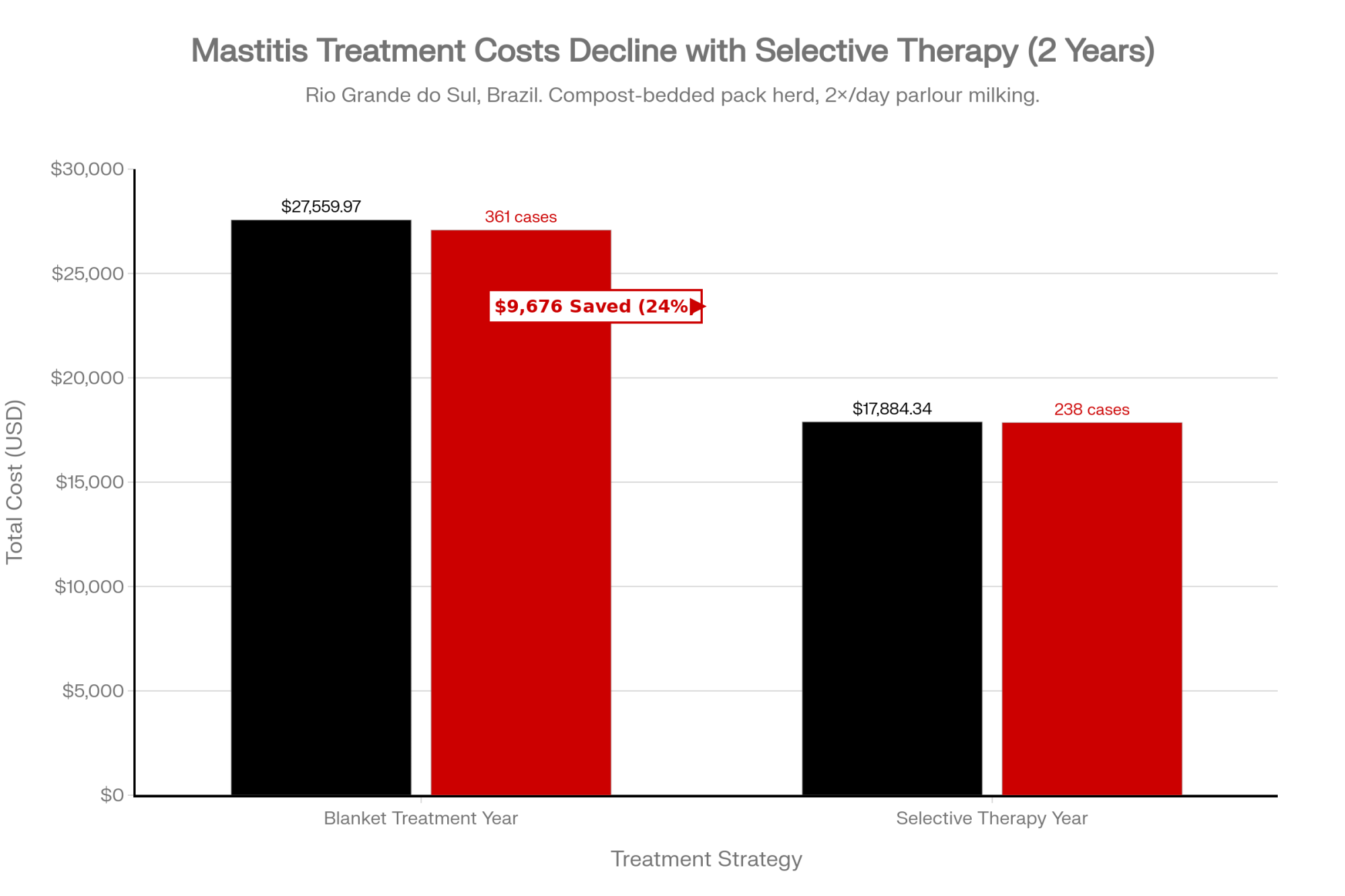

A 2023 Brazilian study in Revista Brasileira de Saúde e Produção Animal followed a commercial Holstein herd of about 500 lactating cows in Rio Grande do Sul as it transitioned from blanket clinical mastitis treatment to selective therapy based on on‑farm pathogen identification. They ran it for two full years: one year before the new protocol and one year after.

During those two years:

- They recorded 599 clinical mastitis cases: 361 in the blanket‑treatment year (period one) and 238 in the first selective‑therapy year (period two).

- They calculated the full cost of treating CM, including antibiotics and discarded milk. Across both years, CM treatment cost the farm US$45,444.31.

- In the blanket year, costs were US$27,559.97.

- In the first year with selective therapy, costs dropped to US$17,884.34.

That’s a 24.23 percent reduction in total CM treatment costs from year one to year two—around US$6,000 saved in that first selective‑therapy year—while also reducing antibiotic use and the volume of milk discarded because of treatment.

It’s worth noting that this wasn’t some disinfected research station. This was a compost‑bedded pack herd, milking twice a day with mechanical parlour equipment, producing roughly 14,000 litres of milk per day at the time of the study. In other words, a big, normal, working dairy.

Now, your milk price and drug costs aren’t going to match that dollar for dollar. But that kind of shift—24% lower CM treatment costs while maintaining udder health—is exactly the kind of “big math” that makes people sit up and ask, “Are we tube‑happy on our farm too?”

You Know This Step Already: Forestripping Still Matters

We can’t talk about selective treatment without talking about detection, because the whole program falls apart if you only find mastitis when the quarter is hard, and the cow is obviously miserable.

National Mastitis Council guidelines, along with extension programs from places like Wisconsin and Minnesota, still place a lot of emphasis on foremilk stripping into a strip cup or onto a dark surface, and on actually looking at that foremilk before you attach the unit. Reviews on on‑farm mastitis diagnostics have pointed out that subtle changes—slightly watery milk, a few fine flakes, a mild shift in colour—often show up before you feel heavy swelling or heat in the udder.

On the ground, in parlours from Ontario to Wisconsin, as many of us have seen, this step can quietly slip. In some operations, it becomes one quick squirt on the floor with barely a glance, and mastitis effectively doesn’t show up on the radar until things are already severe. In others, who’ve decided to do selective treatment or just take udder health seriously, you’ll see strip cups in every milker’s hand and people actually looking at what’s in them.

What’s encouraging is that it doesn’t take a big technology investment to tighten this up. A strip cup is cheap, and retraining people to use it mostly comes down to attention and habit. Once you’re catching more mild cases early, the idea of waiting 18–24 hours to see what grows on a plate in a non‑severe case doesn’t feel as risky as it does when every case you see is already advanced.

Robots and Sensors: Great Assistants, Not Autopilots

A lot of you are milking with robots now, especially in Western Canada, parts of Ontario, the Upper Midwest, and northern Europe. Whether it’s Lely, DeLaval, GEA, or another brand, your automatic milking system is already collecting a ton of data every milking: electrical conductivity, quarter yield, milking interval, flow curves, and in some setups, colour, blood, and somatic cell count.

The natural question is, “If the robot sees all this, do we still need strip cups and culture plates, or can we just let the system decide?”

A 2022 study out of Bavaria, published in the journal Animals, took a close look at that question. Researchers there evaluated four major AMS manufacturers on commercial Bavarian dairy farms and calculated the sensitivity and specificity of each system in detecting clinical mastitis under real‑world conditions.

| AMS Manufacturer | Sensitivity (% of true mastitis detected) | Specificity (% of non-mastitis correctly ruled out) | What This Means in Plain Language | False Positive Rate (approx.) | Field Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lely MQC / MQC-C | ~78% | ~86% | Catches 78 of 100 real mastitis cases; flags ~14% of normal cows as mastitic | ~14% | Colour, EC, temp; somatic cell if MQC-C enabled. Best sensitivity. |

| DeLaval MDi | ~61% | ~89% | Misses ~39 of 100 mastitis cases; very conservative alerting (fewer false alarms, more missed cases). | ~11% | Conductivity + blood detection + interval. Lowest sensitivity; flag for high-risk quarters. |

| GEA DairyMilk M6850 | ~76% | ~79% | Catches 76 of 100; flag rate on false positives is highest among the four (~21%). | ~21% | Permittivity-based SCC categories; no reagents. Good yield of data; more labour on false checks. |

| Lemmer-Fullwood / Other | ~68% | ~92% | Moderate detection; lowest false-positive rate. Conservative alerts, fewer wasted checks. | ~8% | Specialty systems; strong on ruling out false mastitis. Slower to escalate. |

| Theoretical “Perfect” System | 99%+ | 99%+ | Would catch nearly all real cases, rarely flag false alarms. | <1% | Not commercially available; cutting-edge machine learning in development labs. |

They found that:

- The Lely systems in the study showed sensitivity around 78% and specificity around 86%.

- DeLaval systems came in with a sensitivity of around 61% and a specificity of around 89%.

- GEA units had a sensitivity of around 76% and a specificity of around 79%.

- Lemmer‑Fullwood systems showed sensitivity around 68% and specificity around 92%.

The authors described detection performance as “satisfactory,” which is fair. But they also pointed out that none of the systems achieved the 99% specificity needed to eliminate false alarms nearly, and that low specificity can mean more milk unnecessarily discarded and more staff time spent checking cows that ultimately aren’t truly mastitic.

It’s worth knowing what those alerts actually mean.

- Lely’s Milk Quality Control (MQC) system tracks quarter‑level electrical conductivity, colour, and temperature. Farms that bolt on MQC‑C also get real‑time somatic cell count readings, a big step up in monitoring udder health.

- DeLaval’s Mastitis Detection Index (MDi) combines conductivity, blood detection, and milking interval into a single score. Somatic cell counts are handled separately in the DelPro system.

- GEA’s DairyMilk M6850 uses electrical permittivity to give quarter‑level SCC categories without needing reagents, which is attractive for some robot herds that want frequent SCC information.

And in the research world, people are layering machine‑learning approaches on top of SCC data and other signals to improve detection performance beyond these simple thresholds. Those systems have shown they can approach very high sensitivity and specificity when built and trained well, although they’re not yet standard on most commercial farms.

So, if we’re being practical, AMS data is powerful, but it’s not magic. Sensitivity in the 60–70‑something percent range means some mastitis cows are missed. Specificity below the mid‑90s means you’ll get some false positives. That’s fine, as long as you use the system for what it’s good at.

On better managed robot herds I’ve visited—from two‑robot setups in Quebec to larger systems in northern Europe—the farms getting the most out of the technology tend to use the alerts like this:

- The robot generates an “attention list” based on MDi, MQC, conductivity jumps, yield changes, and milking intervals.

- Staff treat that list as “cows to check,” not “cows to tube automatically.” They strip those cows, feel the udder, and decide whether it really looks like clinical mastitis or just a funky day.

- If a quarter truly looks like non‑severe mastitis, they take a clean sample before treating and let their selective protocol, plus the culture result, guide whether they use an intramammary product.

When you treat AMS data as a list generator, not as an autopilot, you get the benefit of the technology without turning it into an expensive random‑number generator for mastitis treatments.

Key Numbers That Are Worth Putting a Pencil To

If you’re like most producers, you probably want to see what this looks like in numbers before you consider changing anything.

A few data points are worth having in your back pocket:

- That 2023 meta‑analysis on non‑severe CM treatment found that, across thirteen studies, selective treatment based on bacterial diagnosis did not worsen bacteriological or clinical cure, SCC, milk yield, recurrence, or culling compared with blanket treatment, aside from a small increase in time to clinical cure.

- In the 500‑cow Brazilian Holstein herd, clinical mastitis treatment costs dropped from US$27,559.97 in the blanket‑treatment year to US$17,884.34 in the first year of on‑farm culture–guided selective therapy—about a 24.23% reduction, roughly US$6,000 in that one year—while CM cases fell from 361 to 238, and overall CM treatment across the two years totalled US$45,444.31.

- The Bavarian AMS study showed sensitivity values in the 61–78% range and specificity from just under 80%to the low 90s, depending on the manufacturer, with the authors warning that lower specificity increases labour and discarded‑milk costs due to false alarms.

Those numbers aren’t your herd, of course. Milk price, mastitis incidence, labour costs, and your payment system will change the exact dollars per cow or per hundredweight. But the pattern across these very different situations is pretty consistent: when you’re able to decide which quarters truly need intramammary treatment, and you stop tubing the ones that don’t, you usually see a meaningful drop in antibiotic use and CM treatment costs without wrecking udder health.

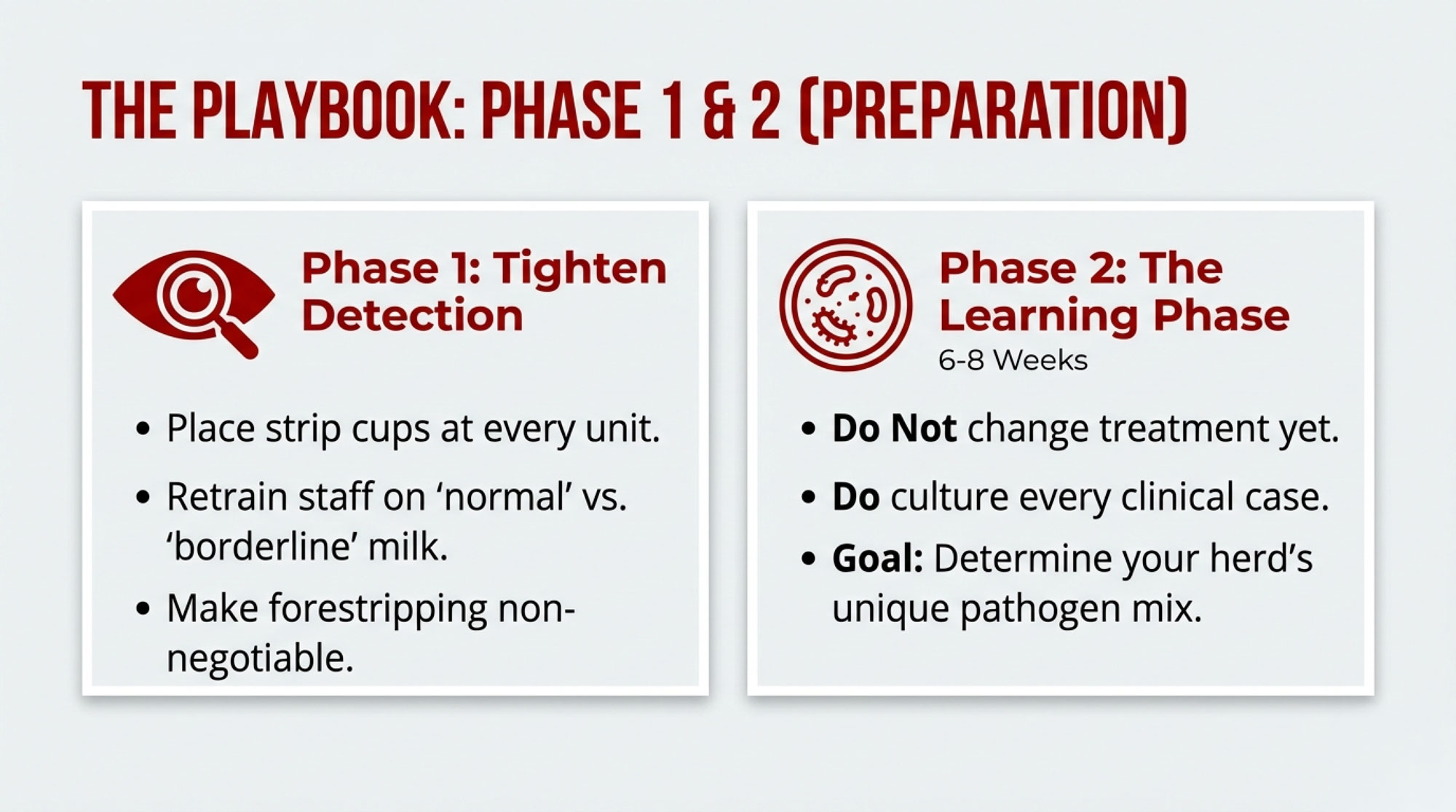

A Simple Three‑Phase Playbook That’s Working on Real Farms

What I’ve found is that the herds that make selective treatment work don’t usually jump straight from “treat everything” to a complicated new protocol overnight. They roll it in over time.

Phase 1: Tighten Up Detection

This is the lowest‑cost, lowest‑risk step, and it pays off whether you ever go fully selective or not.

- Place a strip cup with a dark insert at each milking unit or in each AMS mastitis‑check area.

- Build deliberate foremilk checks back into your milking SOP, not just in your head.

- Use your own herd’s milk—jars of abnormal foremilk, photos, short parlour demos—as training material so everyone sees what “normal,” “borderline,” and “this is mastitis” actually look like in your barn.

In Ontario and Wisconsin operations that do this well, I’ve seen vets and milk quality advisors walk the parlour with staff, looking into strip cups together. You strip some cows, talk through which quarters you’d culture, which you’d treat on sight, and which you’d flag for monitoring. Those conversations often show you that people aren’t always reading the same cow the same way.

Phase 2: Run a 6–8 Week “Learning Phase” With On‑Farm Culture

Once you’re actually catching non‑severe cases early and consistently, the next step is to figure out what bugs you’re dealing with.

For six to eight weeks:

- Pick a validated on‑farm culture system with your vet—something like the Minnesota Easy Culture System or another kit backed by a university.

- Set up a simple incubator and a clean spot for plates, and train one or two key people in aseptic sampling and reading plates using extension resources.

- Culture every clinical mastitis case you reasonably can, but don’t change your treatment protocol yet.

At the end of this “learning phase,” you’ll know:

- What proportion of your CM cases are culture‑negative?

- How many are gram‑negative versus gram‑positive.

- Whether your current habit of tubing every non‑severe case is actually aligned with the kinds of infections that benefit most from intramammary therapy.

In many Midwest and Canadian herds that have done this, people are surprised by how many CM cases are either culture‑negative or mild gram‑negative infections with good spontaneous cure. In other herds, particularly where contagious mastitis is still an issue, they find more gram‑positive problems than they realized. In both cases, the conversation shifts from “studies say” to “this is what our plates are showing.”

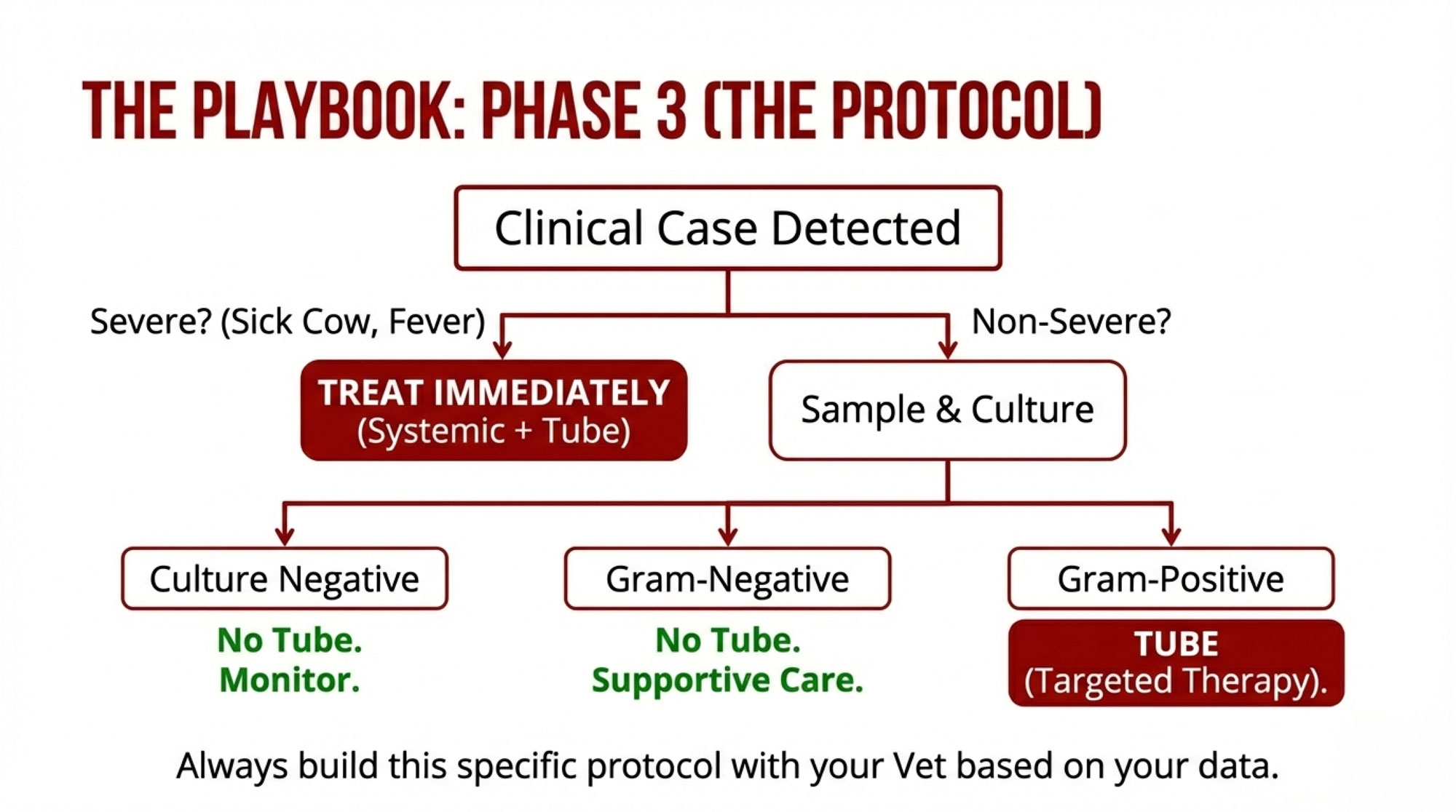

Phase 3: Build a Written Selective CM Protocol With Your Vet

If your culture results and your comfort level say it’s a good idea, then it’s time to sit down with your herd vet and map out a selective treatment protocol that fits your reality.

The protocols that travel well between herds usually look something like this:

- Severe CM cases—cows with fever, depression, or other systemic signs—are always treated aggressively and promptly with appropriate systemic therapy and, when indicated, intramammary products. No waiting for culture there.

- Non‑severe cases—abnormal milk with possibly mild udder changes, but no systemic illness—should be sampled aseptically before any intramammary treatment. Often, they’ll also get an anti‑inflammatory for comfort while you’re waiting for results.

- Culture‑negative non‑severe cases are typically managed without intramammary tubes, with clear monitoring instructions for the next several days.

- Non‑severe gram‑negative cases are often managed with observation and supportive care, with systemic treatment ready to go if the cow deteriorates.

- Gram‑positive cases receive intramammary treatment where evidence and experience suggest there’s a reasonable benefit, with product choice and duration agreed on with your vet.

In Canada, Dairy Farmers of Canada and the Canadian Dairy Network for Antimicrobial Stewardship and Resistance have highlighted this kind of selective, diagnosis‑based CM treatment as one of the key opportunities to reduce antimicrobial use without sacrificing udder health, and it lines up neatly with proAction’s expectations on protocols, veterinary involvement, and responsible drug use. In the U.S. and Europe, major mastitis reviews and one‑health antimicrobial guidelines are making the same point: selective treatment of non‑severe CM is one of the more practical levers farms can pull.

| Phase | Duration | Key Task(s) | Main Deliverable | Cost & Effort | Expected Payoff by End of Phase | Success Signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Tighten Detection | Weeks 1–4 (parallel to normal ops) | – Place strip cup at every unit – Retrain staff on foremilk checks – Use herd’s own milk as training reference – Spot-check compliance weekly | Written SOP for forestripping; trained staff; strip cups in use | ~$50 (strip cups) + 2–3 h management time | Catch 20–30% more non-severe cases early; catch cases beforeudder swelling severe | Foremilk checks are daily habit; staff can name “normal vs. mastitis” by look |

| Phase 2: Learning Phase (On-Farm Culture Pilot) | Weeks 5–12 (8-week pilot) | – Select culture system with vet (e.g., Minnesota Easy Culture) – Set up incubator & clean bench – Train 1–2 key staff on aseptic sampling & plate reading – Culture every CM case (continue normal treatment SOP) – Log & analyze results at weeks 4 and 8 | Culture database of your herd’s pathogen breakdown: % culture-negative, % gram-neg, % gram-pos; cost per case baseline | ~$300–500 (kit, incubator, supplies) + 1–2 h/week staff time (reading plates) | Know your herd’s pathogen mix; baseline CM costs; early confidence in “we can do this” | % culture-negative cases, pathogen ratios, and staff competence confirmed; no major surprises |

| Phase 3: Build & Implement Selective Protocol | Weeks 13–24 (parallel ramp, then full protocol) | – Sit down with vet; review phase 2 culture results – Draft written selective CM protocol (severe vs. non-severe; thresholds for tube vs. observe) – Train staff on new decision tree – Run first 4–6 weeks as “soft launch” (staff practice; vet checks calls) – Adjust protocol based on early feedback; go full by week 20 – Measure outcome (SCC, cases, costs) at weeks 12, 24 | Written, vet-approved selective CM protocol; staff trained & confident; data showing cost drop & SCC maintained | ~$0–200 (any consumables; mostly vet & management time) + 1–2 h/week for first 6 weeks (ramp) | 15–25% reduction in CM treatment costs (based on real herd data) Antibiotic use down 20–30% SCC & cure rates stable or improved | Herd costs drop $5,000–15,000 (scaled to size); staff confidence high; vet sees fewer auto-tube calls |

People and Training: Where It Either Sticks or Slides Back

It’s worth noting—and you’ve probably seen this yourself—that nothing in mastitis management sticks just because it’s written down once.

Reviews of milking routines and mastitis risk keep coming back to the same thing: herds that combine written SOPs, actual staff training, and periodic feedback tend to have better udder health than herds that just have “the way we do it” floating around in people’s heads.

In practice, on farms that make selective CM treatment part of their culture, you see things like:

- An initial team meeting where someone walks through the herd’s CM numbers and costs, shows some culture results, and explains why the protocol is changing.

- Short “toolbox talks” every few weeks in the parlour or robot room, going over a couple of recent CM cases and what was learned.

- Occasional observation of milking and culture work by the herdsperson or manager, followed by specific, friendly feedback.

- A yearly sit‑down with the vet—and sometimes the nutritionist—to review CM incidence, bulk tank SCC, mastitis‑related culls, antibiotic use, and the economics, then adjust the protocol if needed.

In many Wisconsin and Midwest operations, this kind of rhythm already exists for fresh cow checks or repro programs. Selective CM treatment just gets folded into that same cycle of “plan, do, check, adjust.”

When Selective Treatment Makes Sense—and When It Might Need to Wait

Selective CM treatment isn’t the right first move for every herd, and that’s okay.

It tends to work best on farms that:

- Have bulk tank SCC at least under moderate control

- Keep udders reasonably clean and dry in their freestalls or well‑managed dry lots

- Have fairly stable milking routines across shifts

- And have at least one or two people who can reliably handle sampling, culture plates, and record‑keeping

If your bulk tank SCC is high, contagious mastitis problems like uncontrolled Staph aureus are still walking the barn, or staff turnover is so high that basic milking routines aren’t consistent, then your best return in the short term is probably on the fundamentals: stalls, bedding, teat prep, fresh cow management through the transition period, and dealing with chronic high‑cell cows.

If your SCC is on fire, it usually makes more sense to put your energy into the basics first and treat it selectively as a second‑phase project once the house is more in order.

The research base is still growing, too. Most CM-selective treatment trials have been conducted in herds with at least reasonable monitoring and mastitis control. Newer studies are starting to tackle different pathogens and management systems, and we’re seeing some differences, like that 2024 gram‑positive RCT with Lactococcus. That’s why it’s helpful to treat the published data as a strong guide, but still test things against your own herd’s results.

So What’s the Take‑Home in 2025?

If you zoom out and look at this through a 2024–2025 lens—with more talk about antimicrobial stewardship, labour that’s not getting cheaper, and milk cheques that depend more than ever on SCC and butterfat levels—the idea of selective treatment for non‑severe clinical mastitis stops being a theoretical exercise and starts looking like a practical tool.

For a 100‑cow herd shipping on components, pulling even a few fewer high‑SCC cows out of the bulk tank over the year can be the difference between hanging onto a quality premium and watching it slip. For that 500‑cow Brazilian herd, a 24‑percent drop in CM treatment costs was worth about US$6,000 in one year—enough to matter for anyone’s budget.

If you don’t change anything else in your mastitis program this year, four moves are worth your time:

- Put real numbers on your mastitis costs. Work with your vet or advisor to tally up what CM is costing you in drugs, discarded milk, and mastitis‑related culls—per cow and per hundredweight—so you know what your current reflex is actually costing.

- Make strip cups and foremilk checks non‑negotiable again. Get strip cups into everyday use, retrain people as needed, and spot‑check that forestripping and visual checks are happening at every milking, whether you’re in a parlour or running robots.

- Run a six‑ to eight‑week on‑farm culture pilot. Culture every CM case you can without changing your treatment protocol yet, then sit down with your vet to look at what percentage of your cases are culture‑negative, gram‑negative, and gram‑positive.

- Use your own herd’s data to decide on a selective protocol. Don’t just copy the Brazilian farm or a university script. Use your culture results, your cost numbers, and your vet’s judgement to decide if selective treatment of non‑severe CM makes sense for your herd right now—and if it does, write it down and train people on it.

You know as well as I do that doing nothing usually means you keep spending on tubes that don’t always change outcomes, while other herds slowly move those dollars into genetics, better fresh cow programs, improved housing, and lower SCC.

In the end, the question isn’t simply “treat or not treat.” It’s: Which quarters actually pay to treat—and how do you figure that out reliably on your farm?

From that 500‑cow compost‑barn herd in southern Brazil to AMS barns in Europe and North America, the gap between guessing and knowing in mastitis treatment has turned out to be worth a lot more than the price of a strip cup. And quite often, the very first step in closing that gap isn’t new software or a new sensor. It’s a cheap strip cup in a milker’s hand and a small, intentional decision, right in the middle of a busy shift, to pause for a couple of seconds, really look at what’s coming out of each teat, and start letting that information guide where your tubes—and your mastitis dollars—actually go.

Key Takeaways

- The blanket‑treatment reflex is costing you. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 13 trials found that selective treatment of non‑severe mastitis—guided by on‑farm culture—maintained cure, SCC, milk yield, and cow survival while cutting antibiotic use.

- Real‑farm math: 24% lower mastitis costs. One 500‑cow Holstein herd dropped CM treatment spending from US$27,559 to US$17,884 in a single year—about US$6,000 freed up for genetics, transition‑cow programs, or equipment upgrades.

- Your robot’s mastitis alerts aren’t gospel. Field data show that AMS systems achieve only 61–78% sensitivity and 79–92% specificity—great for building a “cows to check” list, but terrible for auto‑tubing decisions.

- Start with a $15 strip cup, not new software. Restore real foremilk checks, run a 6–8 week on‑farm culture pilot, then build a vet‑approved selective protocol matched to your herd’s actual pathogen mix.

- Not every herd is ready today—and that’s okay. If SCC is on fire, contagious mastitis is loose, or staff turnover is constant, lock down the basics first; selective treatment pays best when the foundation is solid.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- 83% of Dairies Overtreat Mastitis – That’s $6,500/Year Walking Out the Door – Gain immediate financial relief by identifying the clinical cases that don’t need expensive tubes. This breakdown delivers the hard math on a 90-day payback system that stops thousands of dollars from walking out your barn door annually.

- The $10 Billion Yogurt Revolution: How Smart Dairy Farmers Are Banking Record Premiums While Others Miss the Biggest Opportunity in Decades – Arms you with the data to capitalize on the manufacturing boom, where sub-200,000 SCC isn’t just a health goal—it’s a prerequisite for $1-2 per cwt premiums. Position your operation as a high-value partner for future contracts.

- The Milking Speed Game-Changer That’s About to Shake Up Your Breeding Program – Reveals how new sensor-based genetic traits are ending the era of subjective milking speed scores. This method leverages objective data to breed a faster, more efficient herd that maintains udder health while slashing total parlor labor.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!