Foreign money looks cheap until CFIUS, AFIDA and a 50‑acre cap show up at your kitchen table. Still think it’s the best deal?

Executive Summary: Wisconsin’s AB 218 would slash the state’s foreign‑owned ag land cap from 640 acres to 50, putting a lot of dairy expansion plans that use foreign partners straight into the risk zone. This feature shows how that change, plus CFIUS review fees and AFIDA penalty math, can turn foreign capital from “cheaper money” into slower, more expensive, and higher‑risk money once you count the friction. A 1,400‑cow Wisconsin family dairy serves as the working example to compare domestic and foreign funding using real Seventh District interest rates, CFIUS filing fees, and AFIDA non‑compliance exposure. The article also unpacks how solar, wind, and digester projects can quietly trigger foreign‑ownership rules in the top five dairy states — none of which provide carveouts for energy deals. Arizona’s Fondomonte case drives the point home with wells dropping more than 200 feet, lawsuits, lease cancellations, and a new active management area landing on an operation that was legal when it started. It all builds to one survival test and a practical checklist to help you decide when foreign money is a smart preference for your dairy and when it’s a bet that could take the whole farm down with it.

Picture a typical 1,400‑cow family dairy in southwestern Wisconsin. It’s late 2025, chores are done, and the kitchen table is buried under barn plans, lender letters, and a milk cheque. The family needs about $8.2 million for a new freestall, 400 more acres, and modernized equipment. Farm Credit will stretch to roughly $5.5 million. A European ag fund is offering to fill the $3 million gap as equity.

Looks like the deal that gets the barn built and the next generation anchored. Then their lawyer starts talking about foreign ownership caps, CFIUS, and AFIDA—and suddenly this isn’t a straightforward capital decision anymore. It’s a question about whether foreign investment belongs in your operation’s future, and what happens if regulators rewrite the rules after you’ve already built around the money.

Two Federal Acronyms That Now Sit at Your Kitchen Table

Foreign capital used to mean one thing for most dairies: a bigger cheque or a more flexible partner. In 2025–2026, it also means regulators have a say in who you do business with.

CFIUS — the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States — is the big one. On July 7, 2025, the USDA signed a memorandum of understanding with the Treasury to coordinate on reviews of transactions involving farmland, ag businesses, or ag biotech. That formally pulled agriculture into what used to be a defence‑tech conversation. Once CFIUS accepts a filing, it has 45 days for an initial review. If a full investigation follows, that’s another 45 days, plus 15 days for a presidential decision — and that’s before your state‑level reviews even start.

CFIUS also charges filing fees based on transaction value: for a deal in the $5 million to $50 million range — which covers most dairy expansions involving foreign equity — the fee alone is $7,500, according to the U.S. Treasury’s published fee schedule. And as of 2024, the maximum CFIUS penalty for violations was raised to $5 million per violation, according to a DLA Piper analysis of the 2024 annual report.

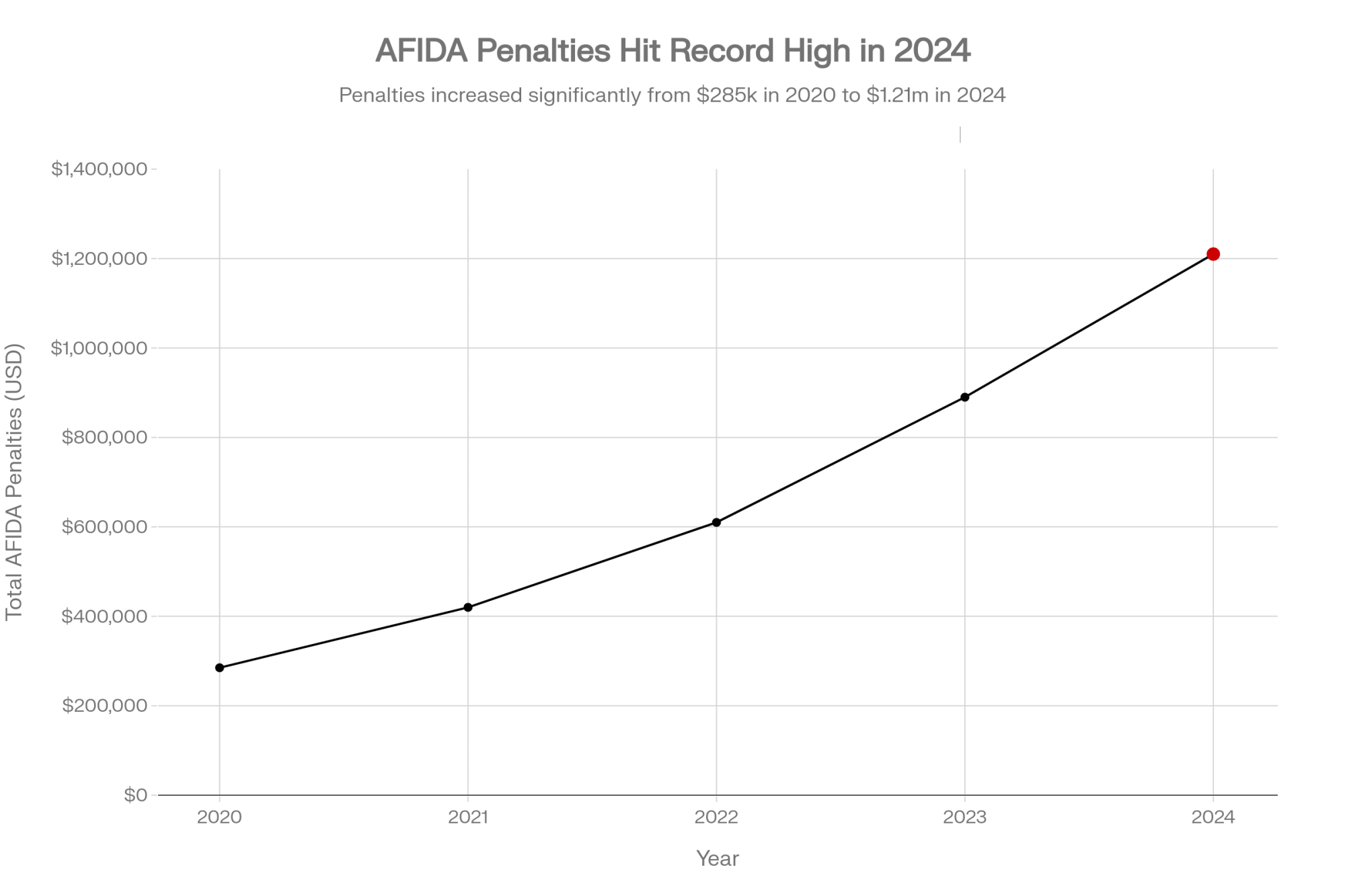

Then there’s AFIDA — the Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act. It’s tracked foreign interests in U.S. ag land since 1978, but USDA is modernizing enforcement with an online portal and tougher penalties. In 2024, AFIDA penalties exceeded $1.2 million — the highest single‑year total on record — predominantly for late filings, according to an American Farm Bureau Federation analysis. The penalty structure isn’t trivial: under federal regulations, late filings carry a fine of 0.1% of the fair market value of the foreign person’s interest per week the violation continues, capped at 25% of FMV. Failure to file or to submit false information can trigger fines of up to 25% outright, per the National Agricultural Law Center.

The scale of foreign ownership keeps climbing. The 2022 AFIDA annual report showed more than 43 million acres in foreign hands, per a January 2024 GAO report. The most recent USDA data pushes that to nearly 45 million acres — about 3.6% of all privately held farmland — with Canadian investors holding the largest share. An AFBF analysis of the 2023 data, reported by Brownfield in June 2025, put the total closer to 46 million acres. Up more than 1.5 million in a single year.

And then there’s a fast‑moving state‑by‑state patchwork on top of it all.

The State‑by‑State Patchwork Is Moving Fast

On top of the federal layer, states are writing their own rules — and they vary wildly. Here’s where the top five dairy‑producing states stand right now:

| State | Current Restriction? | Pending Legislation | Energy Carveout? |

| Wisconsin | Yes — 640‑acre cap under §710.02 (AG upheld, 2014) | AB 218 would reduce the cap to 50 acres, add a 10‑mile military buffer, and ban adversaries. Passed Assembly; pending Senate committee. Session ends ~March 2026. | No |

| California | No — Art. I §20 gives noncitizens equal property rights | SB 1084 passed the legislature 75–0 / 37–0 in 2022, but Gov. Newsom vetoed it Sept. 27, 2022 | No |

| Idaho | Yes — adversary‑nation ban | SB 1149 & HB 356 (April 2025) added AG enforcement, expanded the banned‑country list | No |

| Texas | Yes — S.B. 17 effective Sept. 1, 2025 | Criminal offense for designated‑country nationals acquiring real property | No |

| New York | No — N.Y. Real Prop. Law §10 gives noncitizens equal rights | A3440 (Jan. 2025, Assemblymember Santabarbara) would ban adversary‑nation purchases; referred to Judiciary Committee, no vote yet | No |

Sources: Climate Solutions Law, January 2026; Wisconsin Legislature records; NY Senate; governor’s veto message (CA). According to a Climate Solutions Law analysis, New York has nearly 2,800 dairy farms and approximately 950,000 acres (~5%) of private ag land in foreign hands.

Notice the last column. Not one of these five states carves out renewable energy deals from foreign ownership restrictions. That matters — and we’ll come back to it.

Under Wisconsin Statute §710.02, non‑resident aliens and foreign corporations can’t acquire, own, or hold — directly or indirectly — more than 640 acres of land in the state. That’s been the law for decades, and the Wisconsin Attorney General upheld it in a 2014 advisory opinion. But proposed Assembly Bill 218, introduced in April 2025 by Representative Clint Moses and a bipartisan group of cosponsors, would slash that cap to 50 acres for agricultural land, widen who counts as a foreign person under the law, and cut the sell‑off window from four years to three. Assembly Substitute Amendment 1 added restrictions within ten miles of military bases and a flat ban on adversary‑nation ownership. According to a January 2026 Climate Solutions Law analysis, AB 218 passed the Assembly and is pending in a Senate committee — with the Wisconsin legislative session ending around early March 2026.

Beyond Wisconsin, Idaho, Texas, and Florida — along with Arkansas, Tennessee, Montana, and others — have passed laws restricting or banning adversary‑nation buyers from holding interests in agricultural land. Idaho tightened its rules further in April 2025 with Senate Bill 1149 and House Bill 356, adding enforcement through the Attorney General’s office. Texas’s S.B. 17, effective September 1, 2025, creates a criminal offense for nationals of designated countries acquiring real property. On September 11, 2024, the U.S. House passed Representative Dan Newhouse’s Protecting American Agriculture from Foreign Adversaries Act (H.R. 9456) by a bipartisan vote of 269–149, per congress.gov. As of late 2025, roughly 36 states have enacted some form of restriction on foreign ownership of real property. The list is still growing.

How Foreign Investment Actually Changes Your Expansion Math

Back to that Wisconsin dairy. Once the attorney digs in, the “simple” equity offer gets complicated fast.

Under §710.02, if the fund takes a 25% stake in a single LLC holding both cows and 1,250 acres, regulators could count 312.5 of those acres as foreign‑owned. Today, that passes under the 640‑acre cap. If AB 218 becomes law and drops the limit to 50 acres, the same deal is suddenly offside — a structure that was legal on signing day could violate state law a year later.

The standard workaround: land in one domestic entity owned entirely by the family; cows, equipment, and employees in a separate operating company; foreign investor buys into the operating entity only. That keeps foreign money away from direct land ownership. But it comes with real friction.

| Domestic Lender (e.g., Farm Credit) | Foreign Equity Fund | |

| Typical Rate (mid‑2025, Seventh District) | 7.02% – 7.63% | Often 1–2 points lower (base) |

| CFIUS Filing Fee | N/A | $7,500 (for $5M–$50M transaction value) |

| Closing Timeline | 60 – 90 days | 120 – 180 days (CFIUS + state review) |

| Ongoing Reporting | Standard bank covenants | AFIDA filings, multi‑entity accounting, and potential federal audit |

| Regulatory Risk | Low | High (state law shifts, CFIUS scrutiny) |

| Non‑Compliance Exposure | Standard loan default | AFIDA: up to 25% of FMV; CFIUS: up to $5M per violation |

Domestic rates from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago AgLetter, August 2025 (Seventh District, as of July 1, 2025) — the lowest real estate rates in that region since Q4 2022. CFIUS filing fee per U.S. Treasury fee schedule. The 120–180‑day foreign timeline reflects CFIUS’s statutory 45+45+15‑day review structure plus state processes. AFIDA penalty structure per National Agricultural Law Center (October 2025) and Polsinelli (January 2025). CFIUS penalty ceiling per DLA Piper analysis, August 2025.

On top of these verified costs, ag attorneys who handle foreign‑involved transactions report that total legal and compliance fees — including state‑law opinions, multi‑entity structuring, AFIDA analysis, and CFIUS consultation — run significantly higher than a comparable domestic deal. The Wisconsin State Bar’s October 2025 analysis of §710.02 makes clear that even figuring out who qualifies as a “foreign person” under the statute requires significant legal work. And Bloomberg Law’s October 2025 analysis warns that participants should “expect USDA involvement and prepare for inquiries related to biosecurity measures, agricultural health risks, research affiliations, supply chain vulnerabilities, cybersecurity practices, and land‑use plans.”

| Capital Source | Typical Rate (mid-2025, Seventh District) | CFIUS Filing Fee | Closing Timeline | Ongoing Reporting | Regulatory Risk | Non-Compliance Exposure |

| Domestic Lender (e.g., Farm Credit) | 7.02% – 7.63% | N/A | 60–90 days | Standard bank covenants | Low | Standard loan default |

| Foreign Equity Fund | Often 1–2 points lower (base) | $7,500 | 120–180 days | AFIDA filings, multi-entity accounting, federal audit | High | AFIDA: up to 25% of FMV; CFIUS: up to $5M per violation |

Even if the foreign base rate is lower, how much cheaper is that equity really once you stack the friction on top? For single‑site expansions where foreign terms aren’t dramatically stronger than the best domestic offer, the friction usually tips the math back toward staying local.

| Cost Component | Domestic Term Sheet ($3M, Farm Credit) | Foreign Equity Fund ($3M) |

|---|---|---|

| Base Rate / Expected Return | 7.25% | 5.50% |

| CFIUS Filing Fee | $0 | $7,500 |

| Legal & Structuring (Multi-Entity Setup) | $8,000 – $12,000 | $25,000 – $40,000 |

| Ongoing Compliance (AFIDA, Audit, Reporting) | Minimal (standard covenants) | $5,000 – $8,000/year |

| Timeline to Close (Opportunity Cost) | 60–90 days | 120–180 days |

| Potential AFIDA/CFIUS Exposure (Risk-Adjusted) | None | <span style=”color:#CC0000″>Up to $750,000 (25% of $3M land FMV) + $5M CFIUS penalty risk</span> |

| True First-Year All-In Cost | ~$225,750 | **~$210,000 + $13,000–$48,000 friction = $223,000–$258,000 |

When Your Solar Lease Triggers Foreign Ownership Rules

This isn’t just about barns and freestalls. It runs straight through the new revenue streams many dairies are chasing.

Some dairy operations in the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region see utility‑scale solar ground‑lease offers ranging from roughly $800 to $1,500 per acre per year on 20–35‑year terms, depending on grid access and project scale. That’s income that doesn’t move with the milk price. But look at who’s behind the developer — a lot of “U.S.‑branded” solar and wind companies are ultimately owned by European utilities, Canadian pension funds, or Asian trading houses. A June 2025 Brownfield analysis noted that much of the foreign‑owned farmland in Texas — roughly 5.7 million acres — is already tied to timber and wind rather than traditional agriculture.

In a cap state like Wisconsin, a 25‑year ground lease on 150–200 acres may be treated as an “interest in agricultural land.” In a ban state, a long‑term lease tied to an adversary nation is dead on arrival. And as the table above shows: no energy carveouts in any of the top five dairy states. A January 2025 Polsinelli analysis specifically warned renewable energy developers that AFIDA penalties are now a real cost — failure‑to‑report fines can hit 25% of fair market value.

According to a December 2025 Dairy Business MEA report citing MarketIntelo research, the global dairy farm biogas market was valued at ~US$4.2 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach ~US$10.7 billion by 2033 at a 10.8% CAGR. The opportunity is real. But if foreign money is behind your digester, you need to know whether your state treats that site as an interest in land — and whether you’re close enough to a military base to trigger extra CFIUS scrutiny. Under AB 218’s proposed amendment, Wisconsin would add a ten‑mile buffer zone around military installations.

The Fondomonte Warning Shot

This might feel a world away from your freestall. It’s not.

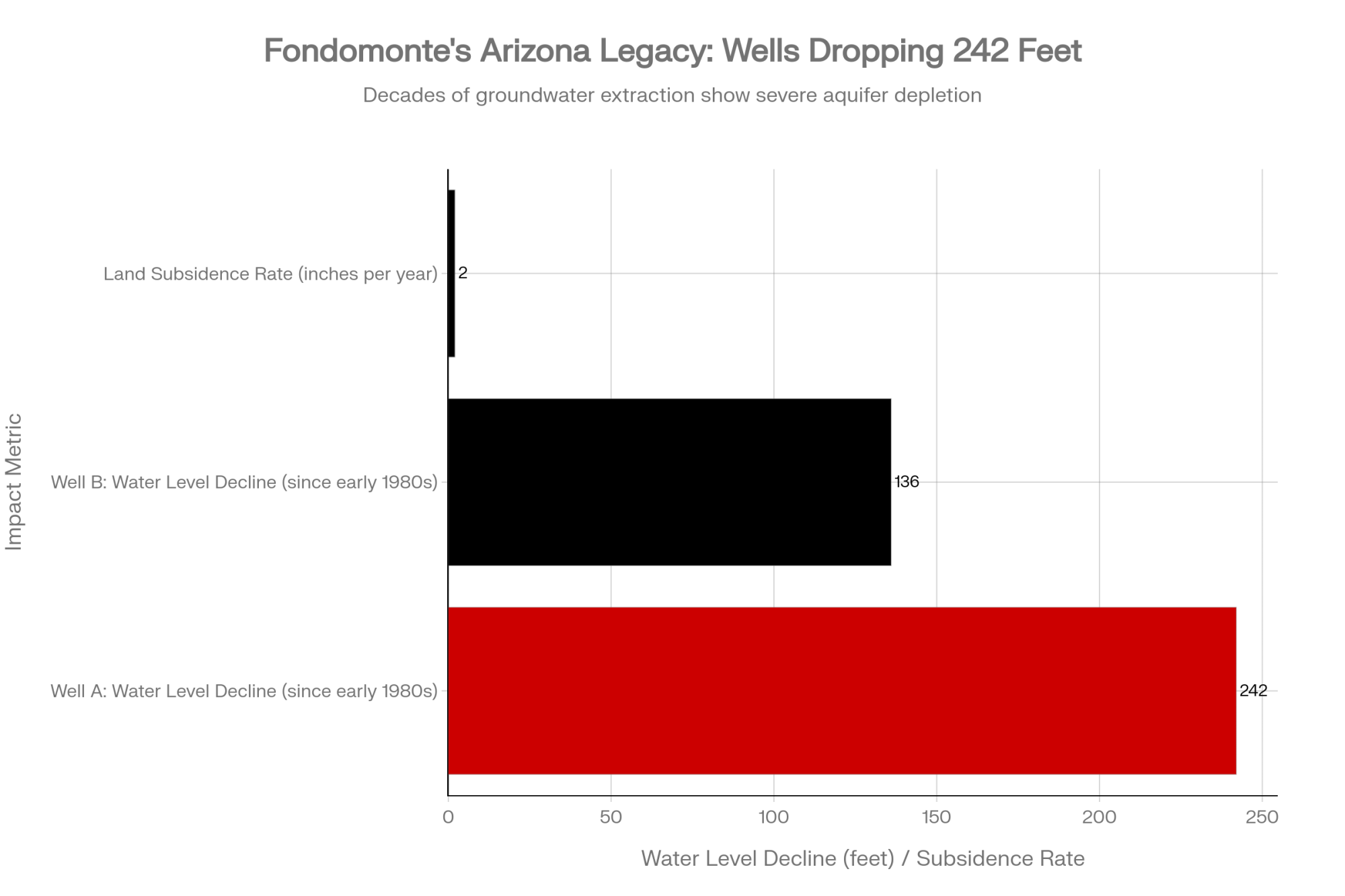

Fondomonte, a subsidiary of Saudi dairy giant Almarai, has been growing alfalfa in Arizona’s Ranegras Plain groundwater basin and shipping it overseas. According to an extensive Los Angeles Times investigation published December 27, 2025, well data tells a stark story: one well’s water level dropped 242 feet since the early 1980s; another declined 136 feet. Arizona’s chief hydrologist, Ryan Mitchell, told residents that current pumping “isn’t sustainable” and land is sinking as much as 2 inches per year in parts of the basin.

Arizona AG Kris Mayes filed a lawsuit alleging Fondomonte uses at least 36 wells and accounts for more than 80% of all pumping in the basin. The state had already terminated Fondomonte’s leases on 3,520 acres of state‑owned farmland after an Arizona Republic investigation revealed below‑market rates — about $83,000 annually for over 6,000 combined acres. Then, on January 9, 2026, Arizona’s Department of Water Resources designated a new active management area in the Ranegras basin — the state’s eighth — prohibiting additional irrigation of farmland. Fondomonte owns 22,873 acres in La Paz County.

Here’s what matters for your dairy: Fondomonte’s structure was legal when it began. A decade later, lease terminations, lawsuits, and a brand‑new AMA designation are reshaping what the company can do on land it owns and leases. A domestic company running the same heavy‑pump, export‑only model would’ve hammered the same aquifer. But most foreign‑ownership bills target who owns the land, not how they use it. That gap matters — and it won’t protect you when the political wind shifts.

The One Question You Can’t Afford to Skip

Before you decide whether your dairy should take foreign money, run every deal through this filter:

If this deal gets blocked, unwound, or challenged eighteen months from now, can my operation survive the fallout?

Don’t answer with your heart. Walk through the ugly versions.

| Scenario | What Happens | Risk Level If No Domestic Backup |

| Deal Blocked Before Closing | CFIUS flags the structure after 6 months, legal fees, steel orders placed. Foreign fund walks. | High Risk — Can you activate a domestic term sheet on 30 days’ notice? |

| Deal Challenged After Closing | Barn is full, cows are milking, state tightens the cap. You’re forced to buy out foreign partner or refinance domestically under pressure. | High Risk — Do you have $3M+ in emergency refinancing capacity? |

| Deal Becomes Political Anchor | Structure is legal, but partner’s home country is all over the news. Co-op board, banker, and neighbors ask uncomfortable questions. | High Risk — Are you prepared to carry reputational and credit risk for 10+ years? |

Deal blocked before closing. You’ve spent six months, paid lawyers, maybe ordered steel. Then CFIUS flags the structure. The fund walks. Do you have a domestic lender with a live term sheet ready to step in?

Deal challenged after closing. The barn is full, the acres are in rotation. Then your state tightens the cap. Can you afford to buy out your foreign partner or refinance domestically on short notice? That’s what’s playing out in Arizona right now.

Deal becomes a political anchor. The structure is legal, but your partner’s home country is all over the news. Your co‑op board asks uncomfortable questions. Your banker quietly re‑assesses risk. Are you ready to carry that for a decade?

When foreign money is a preference — cheaper or more flexible, but not your only lifeline — you can price the regulatory risk and make a clear‑eyed call. When it’s a lifeline, you’re betting the farm on a political horizon nobody can predict.

What This Means for Your Operation

- Nail down whether your deal truly touches land. Operating lines, equipment loans, and barn builds with domestic lenders usually don’t trigger foreign‑ownership rules. The moment a foreign party will own, lease, or hold security over your land — even indirectly — you’re in the regulated zone. Wisconsin’s statute covers direct and indirect interests.

- Map the foreign “nexus” before you fall in love with the terms. Ask bluntly: who ultimately owns this fund, the developer or the lender? Is adversary‑nation capital in the stack? Vague answers are a warning sign, not an invitation to keep talking.

- Know your state’s line in the sand. Use the five‑state table above as a starting point — then have your ag lawyer dig into your specific statutes before committing to any structure. California and New York have no restrictions today, but SB 1084’s unanimous passage (before the veto) and A3440’s introduction tell you where the current is running.

- Price the friction into your cost of capital. Add CFIUS filing fees ($7,500 for most dairy‑scale deals), potential AFIDA exposure (0.1% of FMV per week for late filings), multi‑entity legal structuring, and ongoing compliance costs before declaring foreign capital “cheaper.” Compare that to a current domestic term sheet dated in 2025, not 2021.

- Line up domestic options first—not as a backup. Talk to Farm Credit, your primary bank, and at least one other lender before you go deep with a foreign investor. If a foreign deal falls apart at the last minute, you want to be adjusting an existing domestic proposal rather than starting from scratch.

- Think about succession and exit. A buyer pool that depends on foreign capital is a buyer pool you don’t fully control. Under current Wisconsin law, violators of the 640‑acre cap face forced divestiture within 4 years — AB 218 would cut that to 3 years.

- Treat two‑entity structures as tools, not magic. Separating land and operations can keep some foreign deals alive. But the Wisconsin State Bar’s October 2025 analysis notes that even the “permitted purpose” exceptions under §710.02 require careful structuring. For smaller deals, a cleaner domestic structure at a slightly higher rate is often cheaper and safer.

Key Takeaways

- The real question on foreign investment isn’t “is it legal?” It’s “can my dairy survive if this deal gets taken away after we’ve built around it?”

- Foreign‑linked money now carries verified, concrete friction costs — a $7,500 CFIUS filing fee, AFIDA penalties up to 25% of FMV for non‑compliance, potential CFIUS penalties of up to $5 million per violation, timelines of 120–180 days, and multi‑entity structuring complexity — that must be added to your cost‑of‑capital math before you compare it to domestic options.

- State laws and your partner’s home country matter as much as the rate and terms. California and New York have no restrictions today, but both saw unanimous or near‑unanimous legislative votes to add them — only a governor’s veto and committee timing stand in the way. Idaho, Texas, and Wisconsin already have restrictions with real teeth — and none of the top five dairy states carve out energy deals.

- Domestic capital at 7% in the Seventh District looks expensive until you price in compliance friction and regulatory risk on the foreign side. That gap shrinks fast.

- The Fondomonte case is a live example of what happens when foreign‑linked agricultural deals meet shifting regulatory ground — wells dropping 242 feet, an 80%‑of‑basin pumping allegation, and a brand‑new active management area imposed in January 2026.

- Roughly 36 states now have foreign ownership restrictions on the books, and the list is still growing.

The Bottom Line

Most of these conversations won’t happen in a boardroom. They’ll happen right where this one started — around the kitchen table, after chores, with kids drifting in and out and tomorrow’s milking already on your mind. If foreign money helps you build what your dairy needs without putting that table at risk, it deserves a hard look. If it only works as long as politicians and regulators stand still, you’re better off tightening the plan and betting on capital you can count on when the rules shift again.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- $90K Less Margin, 214K More Cows: Beef‑on‑Dairy, Calf Checks and Your 2026 Survival Playbook – Arms you with a defensive playbook for the $1.80/cwt price drop forecast. This survival guide breaks down how beef-on-dairy income can bridge a $100,000 revenue gap, securing your operation’s cash flow through 2026.

- The $11 Billion Reality Check: Why Dairy Processors Are Banking on Fewer, Bigger Farms – Exposes the $11 billion processor expansion paradox that is quietly squeezing family farms. This strategic reveal delivers the macro-intelligence needed to navigate the “biological ceiling” and reposition your herd for the next decade.

- Revolutionizing Dairy Farming: How AI, Robotics, and Blockchain Are Shaping the Future of Agriculture in 2025 – Delivers a roadmap for weaponizing AI and soil sensors to capture $12,500 in annual carbon credits. This deep dive reveals how transforming manure into bio-CNG can slash diesel costs by 20% and outpace corporate rivals.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!