If more than half your milk goes to one plant and you don’t have a 72-hour Plan B, this story is about you.

Executive Summary: An Argentine processor, Lácteos Verónica, collapsed in 2025–26, leaving about 150 dairy families with roughly $60 million in unpaid milk and 3,843 bounced checks, while one small tambo that switched buyers early limited its losses. That story, paired with Dean Foods’ 2018 contract terminations, shows how even strong herds get wrecked when most of their milk goes to a single buyer, and the money stops. The article backs this up with current data on Argentina’s consolidation, rising U.S. Chapter 12 filings, roughly 1,420 U.S. dairy farms lost in 2024, and Wisconsin’s drop to about 5,100 herds, arguing that processor risk—not imports—is the real fault line under 2024–2026 margins. For your farm, it boils processor risk into a four-question audit: how concentrated your milk check is, how many days of true cash runway you have, whether you’d act on early warning signs, and who can take your milk within 72 hours if your current buyer fails. It offers practical markers—like targeting 90 days of operating reserves and keeping any one buyer below 50% of your volume, where the market allows—while being honest that some regions have only one realistic plant. The piece finishes by tying the math back to legacy, contrasting families who waited for “patience” with those who moved while they still had choices, and leaves you with a simple challenge: if your processor stumbled tomorrow, would you be Sedrán—or her neighbors?

In April 2025, an Argentine dairy processor started falling behind on payments to its farmers. By mid-year, the checks weren’t just late—they were bouncing. Within months, Lácteos Verónica owed roughly $60 million to about 150 dairy families across Santa Fe province, according to reports from iProfesional and AgroLatam in January 2026. Whether it’s a dairy processor payment default in South America or a contract termination in the Midwest, the math doesn’t change — if you’re shipping most of your milk to one buyer right now, this is a case study in processor risk that could play out anywhere.

Here’s the question worth sitting with: if your processor stopped paying next month, would you have 90 days of oxygen and a Plan B—or would you be feeding cows for free while waiting on lawyers?

April 2025: When Lácteos Verónica Went Silent

Producer Cecilia Sedrán works 60 hectares and runs a small tambo (dairy farm) near San Genaro, Santa Fe. Her family produces about 1,500 liters of milk a day and had been shipping to Lácteos Verónica since 2011, as she described in interviews with both TN Campo (December 2025) and Bichos de Campo (November 2025). No off-farm income. No government backstop.

“Somos dos familias las que vivimos de esto. Lo que generamos todos los días es lo que reinvertimos. No tenemos otro ingreso.”

(“We’re two families that live off this. What we generate every day is what we reinvest. We have no other income.”) — Cecilia Sedrán to TN Campo, December 2025

In mid-2025, Lácteos Verónica’s checks started bouncing — and didn’t stop. Records from Argentina’s central bank, the BCRA, show exactly 3,843 checks to producers rejected by banks. Trucks still rolled. Milk was still left on the farm. Money didn’t show up.

Sedrán’s family switched processors by July 2025 — months before many of their neighbors acted, according to Bichos de Campo. That move limited their exposure to roughly one month of unpaid milk. Other tambos around San Genaro stayed on the route, hoping things would turn. TN Campo reported in December 2025 that some farms now carry unpaid balances above 100 million pesos — around $100,000 USD at early-2026 parallel-market rates (Argentina maintains official and parallel currency markets; the parallel rate, used here, is the rate most commercial transactions actually reference) — and several have already closed or stand on the brink.

“Lo único que nos dicen es que tengamos paciencia.”

(“The only thing they tell us is to have patience.”) — as reported by TN Campo, December 2025

Dean Foods Did This in 2018 — Without the Bounced Checks

Argentina can feel like a world away from Wisconsin or Pennsylvania. But the underlying risk is the same.

Sedrán’s farm isn’t a hobby. Two families depend on it, as she told TN Campo. When Lácteos Verónica stopped paying, there was no Chapter 12 bankruptcy protection, no Dairy Margin Coverage, no FSA disaster loan to bridge the gap. Just a brutally simple choice: keep feeding cows and hope the processor catches up, or find another buyer before cash and credit run dry.

U.S. producers faced a softer-packaged version of the same thing when Dean Foods — then the largest milk processor in the country — terminated contracts with more than 100 farms across Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, Tennessee, North Carolina, and South Carolina in early 2018. As Jayne Sebright, executive director of Pennsylvania’s Center for Dairy Excellence, told Farm and Dairy at the time, the cancelled suppliers were “excellent family farms” — including “young dairy families that have really invested in their farms.”

They weren’t bad operators. They were good dairies tied to the wrong buyer at the wrong time.

The real difference? U.S. farms at least had a structured legal path and some federal program options. Sedrán’s neighbors had bounced checks and a processor literally telling them to “have patience.”

The Comparison: Why This Matters to You

You might think Argentina’s economy is a special case of chaos. But look at the mechanics of the failure. It’s the same plumbing, just a different leak.

| Risk Factor | Argentina — Lácteos Verónica (2025–26) | United States — Dean Foods (2018) |

| The Warning | 3,843 bounced checks (BCRA data) | Sudden contract termination notices |

| The Fallout | ≈$60 million USD in unpaid milk across ~150 tambos; 3 plants paralyzed (Suardi, Lehmann, Totoras); ~700 workers at risk (per AgroLatam, Jan 2026) | 100+ farms across 8 states forced to find new buyers within ~90 days; multiple plants closed or sold |

| The Safety Net | Ineffective — legal processes exist but take years while inflation erodes value; producers are told to “have patience.” | Chapter 12 bankruptcy protection, Dairy Margin Coverage, FSA disaster loans |

Lácteos Verónica defaulted on payments already owed — milk that had already left the farm. Dean Foods cut ties going forward—devastating, but a different kind of pain. Both left producers scrambling for somewhere to ship milk within days.

The Reality Check: On a 300-cow herd shipping 90 lbs/cow at $18/cwt, a 30-day payment failure is a $145,800 hole in your balance sheet. That isn’t a “bad month” — for many, that’s the end of the road.

| Herd Size | Daily Production | Milk Price | Monthly Production Value | 30-Day Payment Hole |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 cows | 75 lbs/cow | $18.00/cwt | $40,500 | $40,500 |

| 300 cows | 90 lbs/cow | $18.00/cwt | $145,800 | $145,800 |

| 500 cows | 85 lbs/cow | $18.00/cwt | $229,500 | $229,500 |

| 750 cows | 88 lbs/cow | $18.00/cwt | $356,400 | $356,400 |

| 1,000 cows | 90 lbs/cow | $18.00/cwt | $486,000 | $486,000 |

Roberto Perracino, president of Santa Fe’s Meprosafe producer group, told LT9 radio in late December 2025: “El año empezó muy bien, con buenos precios y rentabilidad que permitían pensar en invertir. Pero desde mitad de año todo se desmoronó.” (“The year started very well, with good prices and profitability that allowed you to think about investing. But from mid-year, everything collapsed.”)

He added that while annual inflation ran about 30%, milk prices recovered only 8%, while feed, fuel, and silage costs jumped by 25% to 70%.

You’ve seen that movie. Think 2014 highs sliding into the 2015–16 gut punch, or the optimism of late 2022 crashing into 2023’s margin squeeze. The difference in this Argentine case is the snap: solid margins in Q1, followed by a processor meltdown before year’s end. No slow fade. A cliff.

Argentina’s Processor Crisis Is America’s Preview

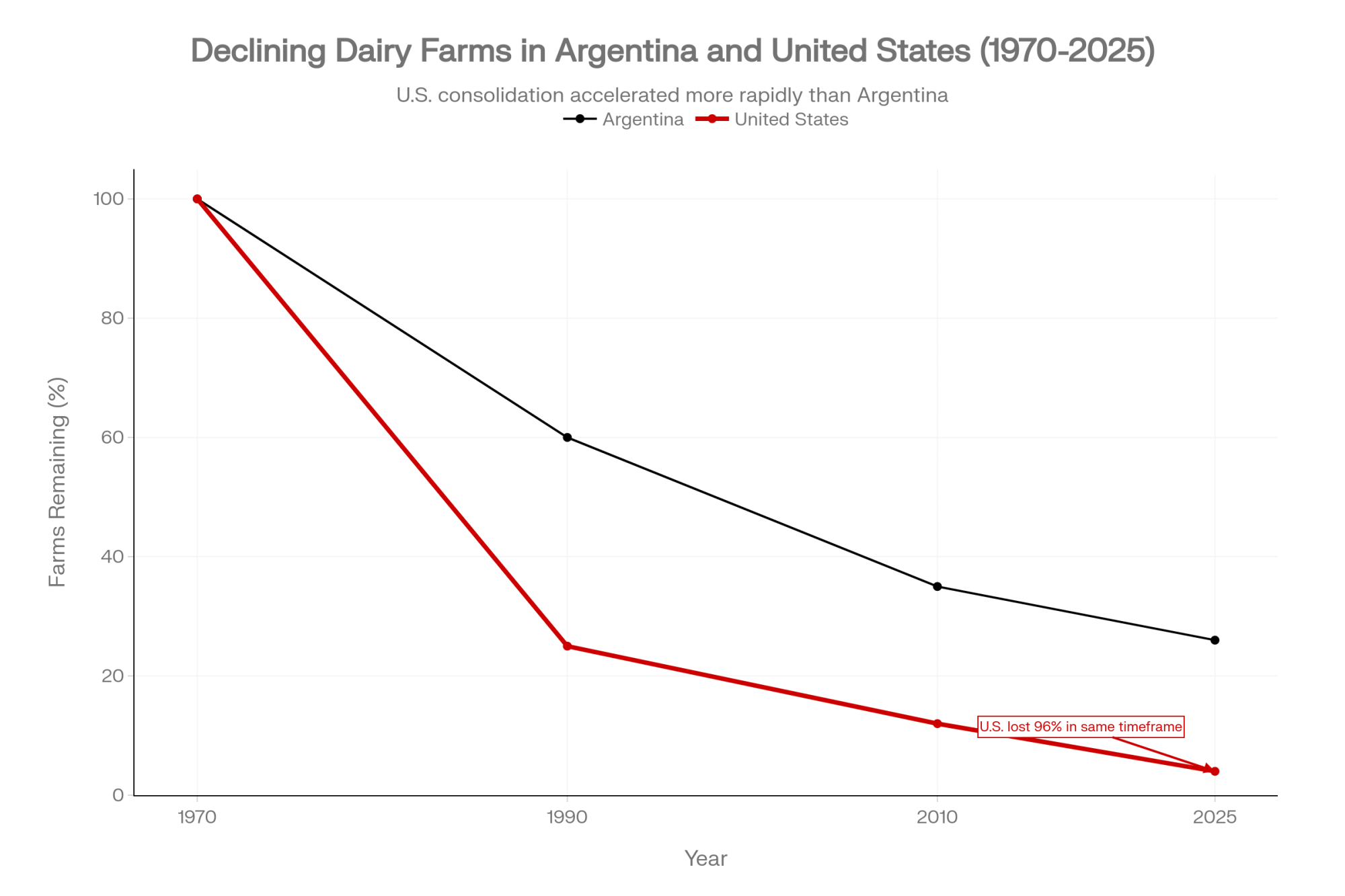

Argentina has already sprinted decades down the consolidation road the U.S. is still running on. Perracino himself put it plainly on LT9: the country went from 35,000 tambos in the 1970s to fewer than 9,000 today.

| Metric | Argentina | United States |

| Peak dairy farms | ~35,000 tambos (1970s, per Meprosafe/Perracino) | 648,000 farms with dairy cows (1970, USDA ERS) |

| Current farms | 9,013 tambos (end of 2025, OCLA/SENASA) | ~24,470 dairy operations (2022 Ag Census) |

| Decline from peak | ~74% | ~96% |

| Avg cows/farm (Argentina) | ~166 cows in 2025, up from ~162 in 2024 | Similar “bigger survivors” pattern |

OCLA data show that just 6.3% of Argentine farms now hold 27.6% of the cows and produce more than a third of the country’s milk. When that much volume is concentrated in a handful of big units, one decision in a boardroom reshapes an entire region’s milk market. And the mid-sized family tambos? They’re negotiating from the weak side of the table every single time.

Wisconsin knows the feeling. The state starts 2026 with about 5,100 licensed dairy herds — 5,115 to be exact, according to USDA NASS data based on Wisconsin DATCP’s Dairy Producer License list as of January 1, 2026. That’s down from more than 15,000 in the early 2000s. The Hartwig family is one example among many. When low prices nearly forced them to sell their Wisconsin herd in 2019, a local banker helped them restructure and survive, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported. Not every family gets that kind of lifeline.

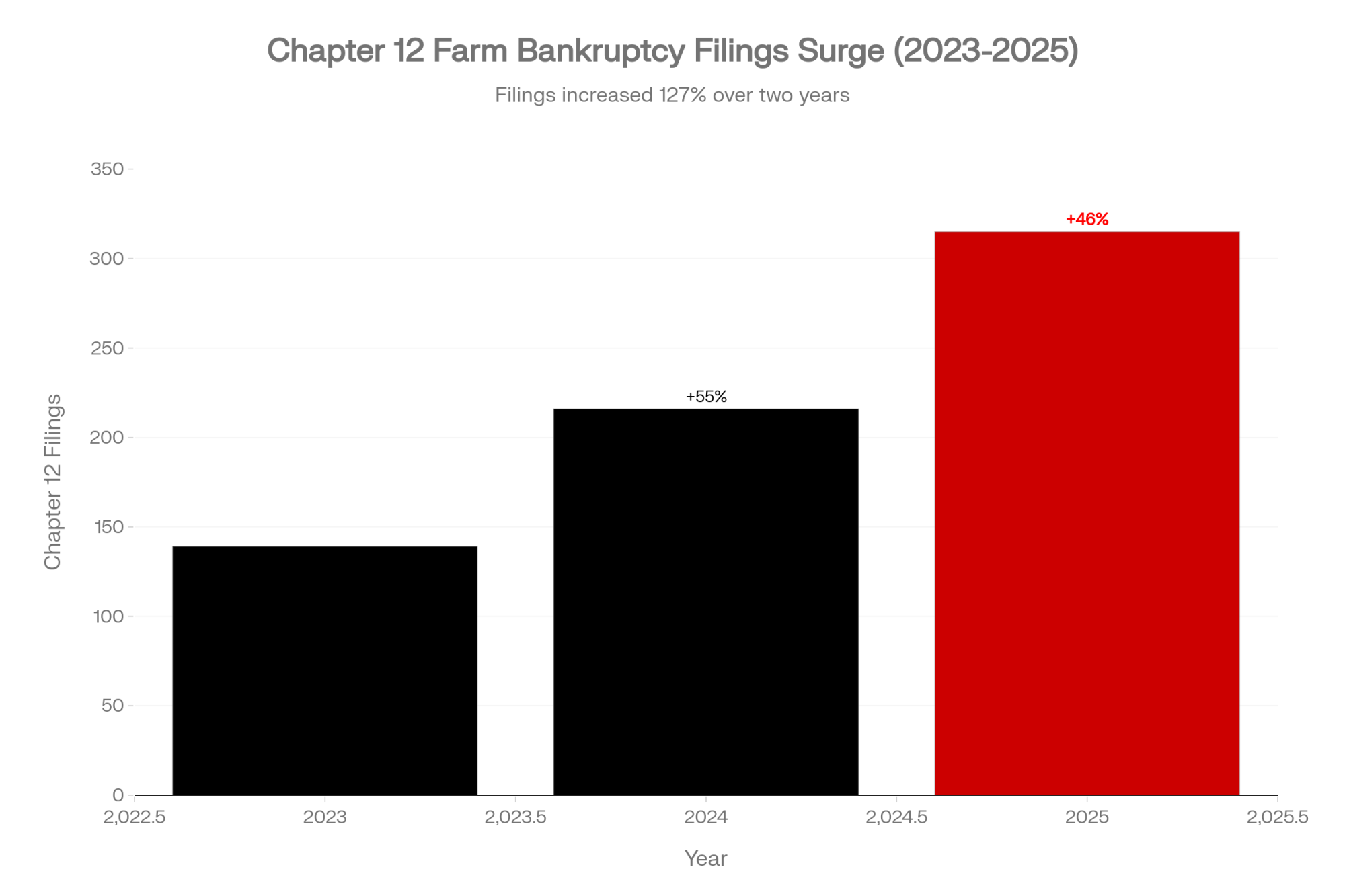

Farm bankruptcy filings have climbed hard across the sector. American Farm Bureau Federation analysis of U.S. district court data shows 216 Chapter 12 farm bankruptcy filings in 2024 — up 55% from 2023. In 2025, that number hit 315, up another 46%. These are all-farm filings, not dairy-specific, but 120 of the 2024 cases were in the 24 major dairy states — and the Midwest dairy belt saw the steepest increases. Meanwhile, USDA data put 2024 dairy farm losses at around 1,420 licensed herds nationally — roughly a 5% drop in a single year.

Same pattern everywhere: mid-sized family dairies getting squeezed between thin farmgate margins and concentrated buyers who have options when you don’t.

Legacy at Risk: When the Tambo Is More Than a Business

Strip this down to dollars, and you miss the deeper loss.

Argentine coverage of the Lácteos Verónica crisis doesn’t just talk about pesos and liters. It talks about legacy. Many Santa Fe tambos have been in the same families since the 1960s and 1970s, often tracing back to Italian and Spanish immigrant settlers. As TN Campo reported in December 2025: “Para muchas familias, el tambo es un legado de generaciones. Hoy, sin ingresos y con deudas en aumento, varios deben abandonar la actividad.” (“For many families, the dairy farm is a generational legacy. Today, without income and with debts mounting, many must abandon the activity.”)

That kind of loss can’t be captured in a spreadsheet. And it plays out the same way in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, or anywhere else a family’s identity is tied to land and livestock.

This Wasn’t an Import Story

You’ll hear folks pin Argentina’s dairy pain on “cheap imports.” The numbers don’t support that.

Argentina is a net dairy exporter. Argentine Agriculture Ministry data show 2025 dairy export value at $1.69 billion — the strongest performance in 12 years — with roughly 27% of total milk production going to export markets. Imports of milk powder and other dairy products remain small relative to what Argentina ships out.

The damage in this story came from inside the chain:

- A major processor overextended and ran out of cash, racking up 3,843 bounced checks and tens of millions in unpaid milk.

- Payments to farmers stopped while plants tried to keep running on fumes.

- Smaller and mid-sized suppliers with no financial buffer absorbed the losses first.

That’s not a trade-war tale. It’s a processor-risk tale. And it’s worth separating the two, because U.S. dairies sit on the exact same fault line: a small number of large processors, thin margins, and no guarantee the company taking your milk today will still be solvent in three years.

Trade agreements like the EU–Mercosur deal and newer U.S.–Argentina frameworks do change long-term competitive dynamics. But in Sedrán’s case, the crisis didn’t start with someone else’s powder. It started with her own buyer’s balance sheet blowing up.

What This Means for Your Operation

This is where the story stops being about Argentina and becomes a planning session for your own farm. Four questions. Write down your honest answers.

| Risk Factor | The Question | High Risk 🚨 | Lower Risk ✓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buyer Concentration | What % of your milk goes to one processor? | > 50% to single buyer | < 50%; multiple outlets |

| Cash Runway | How many days of operating expenses do you have in reserves? | < 30 days liquid cash | ≥ 90 days accessible reserves |

| Early Warning System | Would you act on warning signs—or wait and hope? | “We’ll give them time” | Written response plan; quarterly processor health check |

| 72-Hour Plan B | Who can take your milk within 3 days if your buyer fails? | No answer / “I’d have to call around” | Written list: alt plants, haulers, pricing |

1. How exposed are you to one processor?

Pull your last 90 days of milk checks. If more than 50% of your volume went to a single buyer for that entire stretch, you’re effectively single-sourced.

In some regions, that’s just reality — one major plant within hauling range. But calling it “normal” instead of “high-risk” is exactly how good farms end up in the same spot as Sedrán’s neighbors.

If your number is north of 50%, start thinking about secondary outlets (co-ops, smaller plants, direct-to-consumer channels), contract terms that give you at least some flexibility, and how fast you could actually re-route part of your volume if you needed to. The goal isn’t to blow up a good relationship. It’s to stop pretending concentration doesn’t change the risk math.

2. What’s your cash runway?

Sedrán limited the damage because she had enough cash and credit to stop shipping while she found another buyer. Many of her neighbors didn’t, so they kept feeding cows for free.

Aim for at least 90 days of operating expenses in accessible reserves. On a 500-cow herd, that often means something like $250–$300 per cow in cash or near-cash, depending on your cost structure. Not a magic number — a starting point.

If you’re sitting at 20–30 days right now, don’t beat yourself up. Set a concrete goal to add 5–10 days of cushion each quarter for the next 18–24 months. Slow, boring progress beats “we’re fine” right up until you’re not.

3. Would you see the warning signs — and act?

Sedrán’s neighbors all saw signs: payment dates slipping, checks clearing more slowly, and local media reporting on the company’s financial troubles. Some took action. Others waited, hoping things would turn. You know which group came out ahead.

On your farm, warning signs might include payment schedules being “restructured,” vague responses when you ask about plant capacity, or rumors that your buyer is closing facilities in other states.

Pro-Tip: Watch the “Smoke” If your processor is a private company, ask your lender if they have seen a change in the speed of deposits from that specific entity. Bankers often see the “smoke” (slower clearing times) months before the “fire” (bounced checks).

Once a year, sit down with your lender, accountant, or advisor for a “processor health check.” Pull whatever public data you can — annual reports, credit ratings, news on plant expansions or closures. Ask the blunt question: is this buyer growing, stable, or shrinking? And what would we do if they suddenly “restructured” procurement?

4. What’s your 72-hour Plan B?

If your processor stopped paying tomorrow, who could realistically take your milk in 72 hours? Not six months. Three days.

Write it down: names of alternate plants or co-ops, haulers who could move milk there, rough price expectations in a distressed situation, and how many days you could afford to dump or divert before the bleeding matters.

Put that one-page plan in the same drawer as your emergency vet contacts and power-outage protocol. Make sure at least one other person on the farm knows it exists and where to find it.

Sedrán had enough runway and local options to move quickly. Her neighbors are now pursuing legal claims for their unpaid milk, according to Argentine press reports.

Your Processor Risk Checklist

Print this. Stick it on the office wall. Do the homework before you need to.

- [ ] Identify your exposure: Is more than 50% of your milk going to one buyer? Pull 90 days of milk checks and find out.

- [ ] Calculate your runway: Do you have 90 days of operating expenses in accessible cash or credit? If not, what’s the gap — and what’s your quarterly plan to close it?

- [ ] Monitor the vibe: Are payments slowing down? Is communication getting vague? Schedule an annual “processor health check” with your lender or advisor.

- [ ] Draft your 72-hour Plan B: Who gets the milk if the gate stays locked tomorrow? Write down names, haulers, and timelines. One page. Keep it where someone else can find it.

Key Takeaways

- Processor failure is not abstract: Lácteos Verónica’s collapse left about 150 Argentine dairy families with roughly $60 million in unpaid milk and 3,843 bounced checks, while one family that switched early limited its loss to about a month.

- The same pattern is already on your doorstep, with Dean Foods’ 2018 cuts, rising Chapter 12 filings, roughly 1,420 U.S. dairy farms gone in 2024, and Wisconsin down to about 5,100 herds showing how fast good operations can be stranded when most of their milk goes to one buyer.

- For your farm, processor risk boils down to four questions: how concentrated your milk check is, how many days of true cash runway you have, whether you’ll move on warning signs, and who can take your milk within 72 hours if your current buyer stops paying.

- The practical targets in this piece are simple but hard to ignore: aim for at least 90 days of operating reserves, keep any single buyer under 50% of your volume where markets allow, and put a written 72‑hour Plan B in the same drawer as your emergency vet numbers.

- In the end, the difference between still milking and fighting over unpaid checks wasn’t luck or genetics—it was whether a family treated processor risk as a real threat and acted before hope was their only plan.

The Bottom Line

Cecilia Sedrán didn’t wait to find out how that bet would play out. She moved while she still had choices.

Do you?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Triple Cushion Trap: Why 2025’s Strong Margins Won’t Save You in 2026 – Gain an immediate survival checklist for the 2026 transition. This piece delivers a hard-hitting audit of contract terms and labor efficiency, arming you with specific management shifts needed to bridge the margin gap before financial cushions deflate.

- The 18-Month Window: Why Your Lender Knows Your Dairy’s in Trouble Before You Do – Reveal the invisible timeline lenders use to grade your operation’s viability. This insight exposes how proactive planning preserves 40% more equity than waiting for a crisis, delivering the strategic advantage of choosing your own exit terms.

- Four Farms Exit Daily: The $100K Decision Reshaping Dairy Survival – Arm yourself with unconventional revenue plays like beef-on-dairy and genomic precision that shift annual math by six figures. It breaks down why management effort alone can’t fix structural losses, delivering the innovation roadmap required to stay solvent.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!