America eats 29 million pounds of cheese today — and the FMMO make allowance ensures your share keeps shrinking.

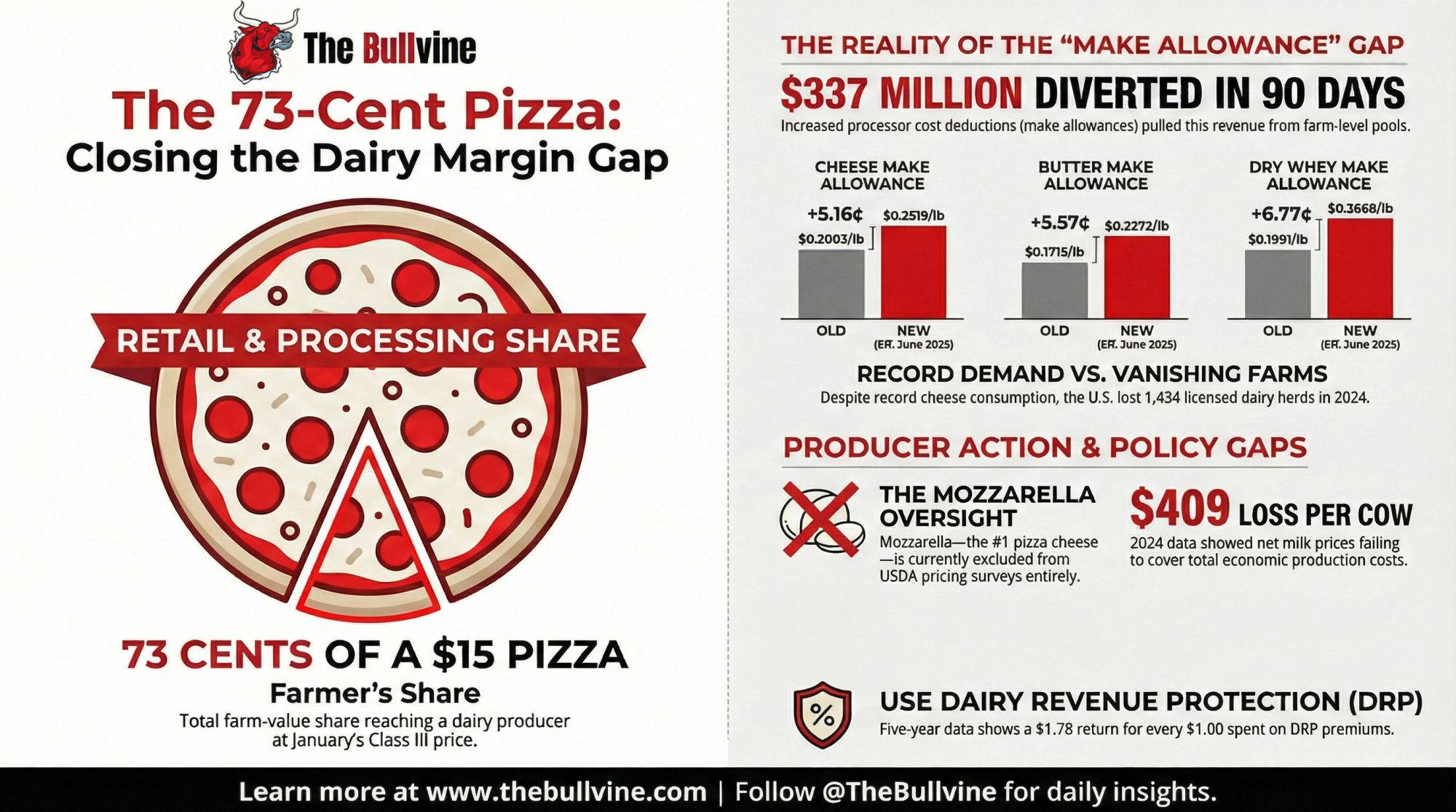

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Americans are tearing into an estimated 29 million pounds of cheese today — six times normal daily volume — and the dairy farmer’s cut of a $15 Super Bowl pizza is 73 cents at January’s Class III price of $14.59/cwt. USDA’s June 2025 make allowance increases widened that gap, diverting an additional 85–93 cents per hundredweight from producer pools to processors and pulling $337 million from farm-level revenue in the first 90 days alone, per the American Farm Bureau Federation’s analysis. The demand story is real; the margin story isn’t. Illinois FBFM data shows dairy operations lost $409 per cow in 2024 on a total economic cost basis — even with per capita cheese consumption hovering near all-time highs. Wisconsin producer Mike Yager calculated the make allowance hit on his 275-cow Mineral Point operation at roughly $55,868 per year in value that now stays with the processor, and says no new premiums have materialized to offset it. If your cash costs are above $17.50/cwt and your order’s blend is anywhere near Class III, your working capital is eroding monthly — and tonight’s pizza binge won’t change that. The lever that matters now: ensuring USDA’s mandatory biennial processor cost surveys — authorized under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed July 4, 2025 — launch on a concrete timeline and include mozzarella, the dominant Super Bowl cheese, which is currently excluded entirely from USDA pricing surveys.”

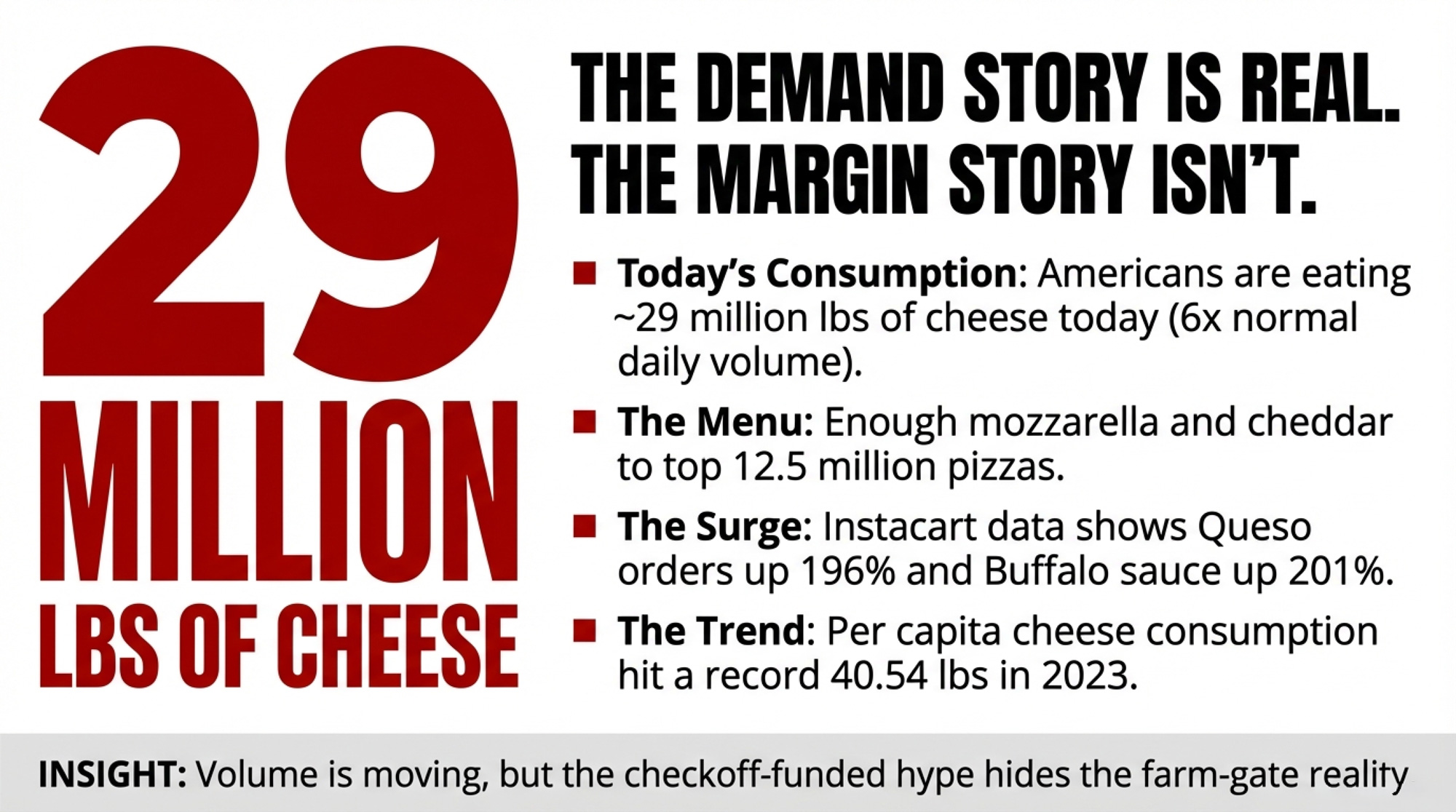

Right about now, Americans are tearing into an estimated 29 million pounds of cheese. That’s the number Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin — the checkoff-funded marketing organization funded by farmers themselves — projects for Super Bowl Sunday, roughly six times what the country consumes on a normal day. Enough mozzarella, cheddar, pepper jack, and queso to top 12.5 million pizzas, fill millions of nacho platters, and anchor every cheese board from Seattle to Miami. Instacart’s 2026 Super Bowl data shows just how dairy-heavy the day has become: queso orders surged 196% and buffalo sauce — the stuff that goes on wings destined for ranch and blue cheese dip — jumped 201% during game week.

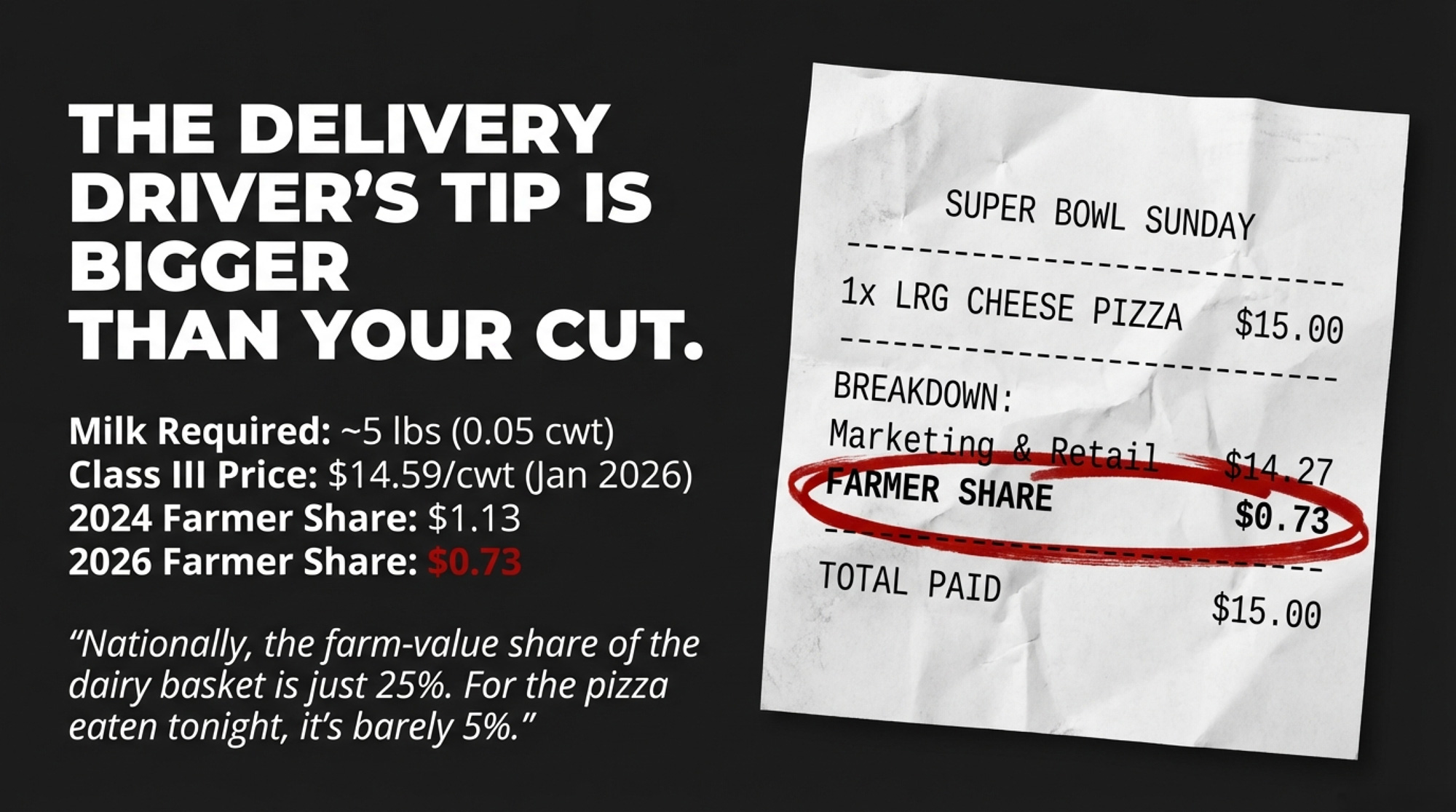

Here’s the kicker: the same farmers who pay into that checkoff fund to promote cheese are getting about $0.73 of farm value on a $15 pizza when January’s Class III sits at $14.59 per hundredweight. If February futures hold near $15.92, that climbs to about 80 cents. Either way, the delivery driver’s tip is almost certainly larger. The FMMO formula is supposed to connect consumer demand with farm-gate value. Super Bowl Sunday is Exhibit A for why it doesn’t.

The Demand Is Real — the Margin Isn’t

That volume translates to real dollars at retail — just not at the farm gate. Wells Fargo’s Agri-Food Institute pegs the average 10-person Super Bowl party spread at about $140 in 2026, up just 1.6% from last year — below the 2.4% food-at-home CPI. Frozen pizza prices actually fell 0.6% year over year. For consumers, dairy-heavy game-day food is a bargain.

Those party-spread prices reflect a deeper pattern. Per capita total cheese consumption hit a record 40.54 pounds in 2023 — the third straight record year, according to USDA ERS data published in late 2024. Then, in 2024, it slipped to the lowest level since 2021, per the ERS’s January 2026 update — the first year-over-year decline since at least 2013. Even at record or near-record consumption, the economics at the farm gate keep tightening.

A note on the 29-million-pound figure: this is a promotional estimate from a checkoff-funded organization, not an independently audited figure. It’s been used for at least the 2024 and 2025 Super Bowls; no 2026-specific update had been published at the time of writing. Treat it as a credible industry estimate, not a USDA-verified statistic.

Following 73 Cents from the Pizza Box to the Bulk Tank

A standard large pizza uses roughly half a pound of mozzarella. Industry yield runs about 10 pounds of milk per pound of cheese. One pizza, therefore, requires approximately 5 pounds of milk — or 0.05 hundredweight.

0.05 cwt × $14.59/cwt (January 2026 Class III, USDA AMS) = $0.73

At 2024’s all-milk price of $22.55 per hundredweight (USDA ERS annual data), that same pizza returned about $1.13 to the farm — still under 8% of the retail price. As of January 2026, Class III levels are barely 5%.

USDA ERS published its 2024 farm-to-retail price spread data in June 2025. Nationally, the farm-value share of the dairy product basket was 25 percent, up from 23 percent in 2023. For cheddar specifically, the farm value was $1.80 per pound against a retail price of $5.66 — a 32 percent farm share. Butter fared better at 57 percent. But cheese — which is what’s disappearing tonight — sits squarely in that one-quarter-to-one-third zone.

The farmer’s share of a $15 Super Bowl pizza: 73 cents. The delivery driver’s tip is almost certainly larger.

| Period | Farm Value ($) | Processor/Retail ($) | Class III ($/cwt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 2026 | 0.73 | 14.27 | 14.59 |

| Feb 2026 Futures | 0.80 | 14.20 | 15.92 |

| 2024 Average | 1.13 | 13.87 | 22.55 |

That’s what happens when the formula pays everyone else first and hands you what’s left.

How the FMMO Make Allowance Sets Your Price Before Game Day

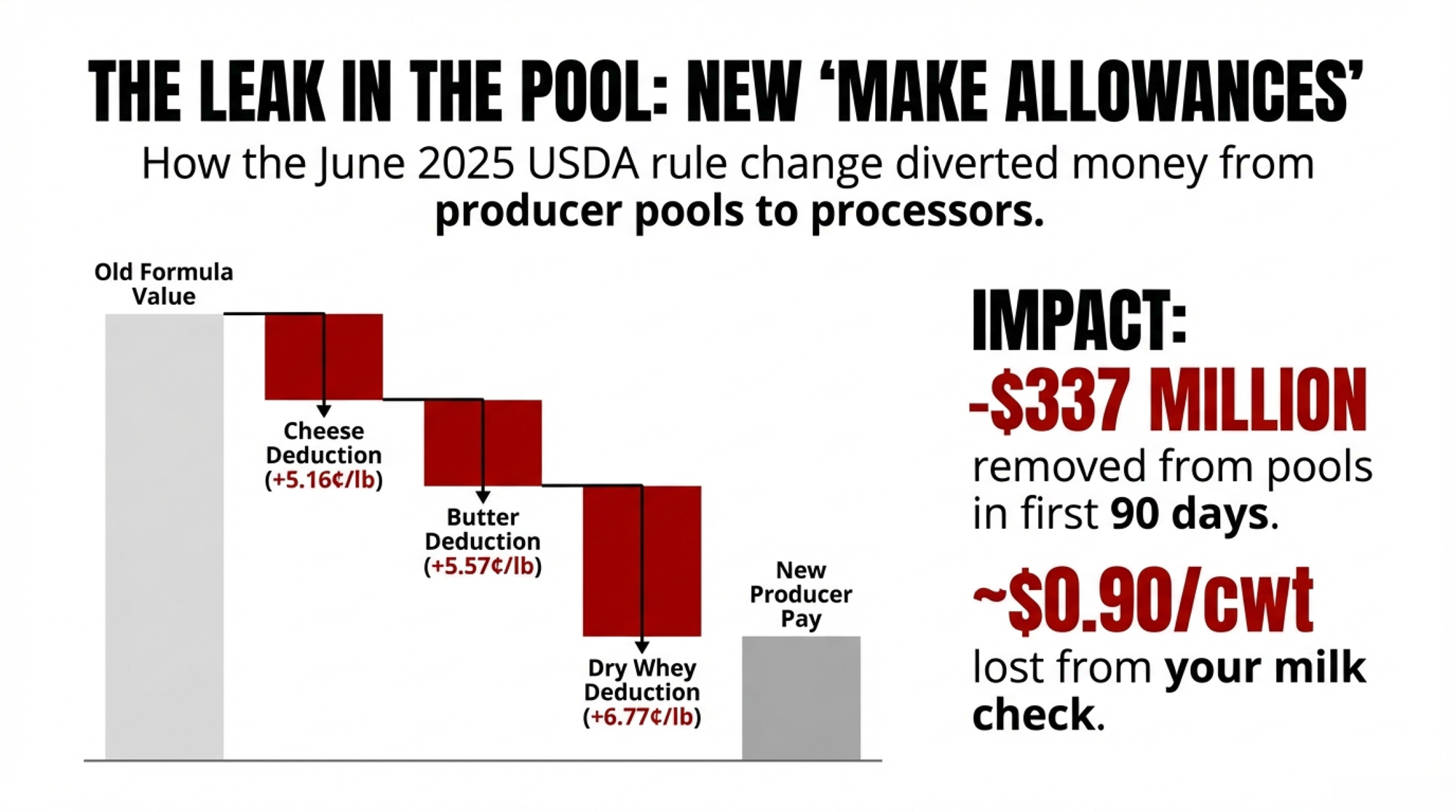

On June 1, 2025, USDA raised the make allowances embedded in all 11 Federal Milk Marketing Orders—the first update since the FMMO system was consolidated in January 2000. These are the processing cost deductions that come off wholesale commodity prices before any value reaches producers.

The American Farm Bureau Federation’s Danny Munch calculated the early damage: class price reductions ranging from 85 to 93 cents per hundredweight, pulling roughly $337 million out of combined producer pool values in just the first 90 days (AFBF Market Intel, September 21, 2025). As Munch told RFD-TV: “Dairy farmers were most concerned about the impact of increased make allowances because they reduce the price farmers receive, and were based on incomplete data during the hearing process”.

| Product | Old Make Allowance ($/lb) | New Make Allowance ($/lb) | Increase (¢/lb) | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheese | $0.2003 | $0.2519 | 5.16¢ | Directly hits Super Bowl cheese |

| Butter | $0.1715 | $0.2272 | 5.57¢ | Record high costs |

| Nonfat Dry Milk | $0.1678 | $0.2393 | 7.15¢ | Highest increase |

| Dry Whey | $0.1991 | $0.2668 | 6.77¢ | Wings & dip tax |

Source: USDA Final Rule on FMMO Amendments, effective June 1, 2025

Take cheese at $1.60 per pound on the CME. Under the old formula, $1.3997 per pound flowed into Class III component values ($1.60 minus $0.2003). Under the new formula, only $1.3481 does ($1.60 minus $0.2519). That extra 5.16 cents per pound never hits the pool—it stays with the processor as cost recovery.

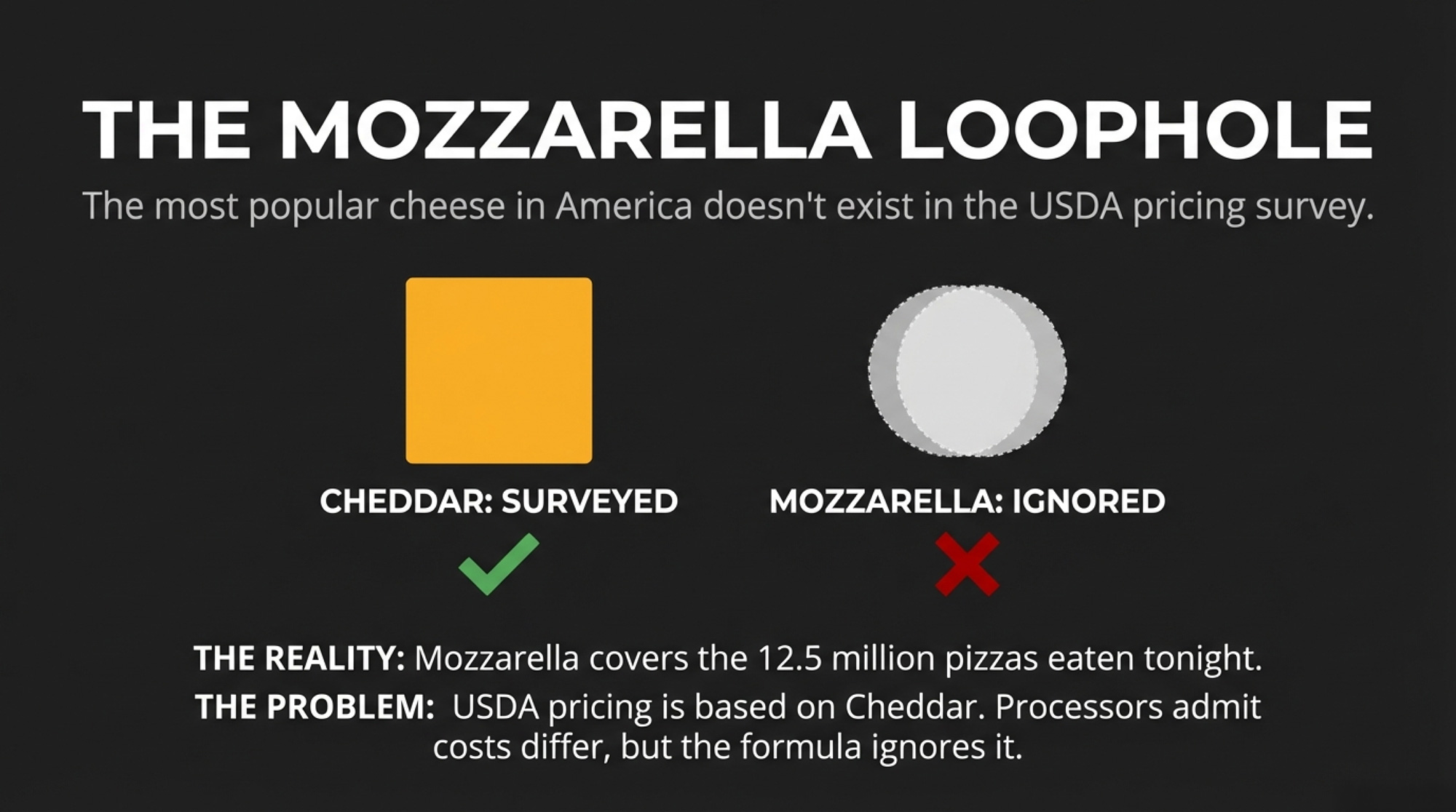

Here’s a detail that should land hard on Super Bowl Sunday: mozzarella — the single most consumed cheese in America, the cheese on every one of those 12.5 million pizzas tonight — is currently excluded from USDA’s pricing surveys and formula pricing entirely. The cheese-making allowance was set using cheddar processing cost data. Processors testified during the FMMO hearing that mozzarella processing costs differ from cheddar, yet the USDA doesn’t track them separately. The dominant game-day cheese is priced off a formula that doesn’t account for how it’s actually made.

Processor costs are genuinely higher than they were in 2000 — energy, labor, and packaging all climbed. But AFBF argues the adjustments “must be grounded in comprehensive, mandatory and independently audited surveys” and warns there is “some likelihood that USDA’s changes will unfairly penalize dairy farmers by overstating processing costs”. The data the USDA used were self-selected and self-reported by processors and were not independently verified.

So when 29 million pounds of cheese disappear tonight, every pound carries that larger deduction. And every hundredweight behind it pays the farmer less than it did a year ago — even if the block price on the CME hasn’t moved.

How Pizza Chains Lock In Their Price While You Ride the Cycle

Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and the major frozen pizza brands don’t buy mozzarella on the spot market in February. They negotiate supply contracts months in advance — typically locking prices or establishing cost-plus formulas that insulate them from short-term CME volatility.

Tonight’s Super Bowl surge was priced into processor order books weeks or months ago. The demand spike is real, but it doesn’t create upward spot-market pressure that would flow back through Class III into your milk check. By the time 29 million pounds of cheese hits the coffee table, the price was already set. And by the time Americans order those 12.5 million pizzas tonight, Yager’s January milk check was already settled.

You’re selling milk into a Class III formula that resets monthly based on USDA commodity surveys. If CME blocks rally in February, you might see a modest lift in your March check. If they don’t, you won’t — regardless of how many pizzas Americans ordered tonight.

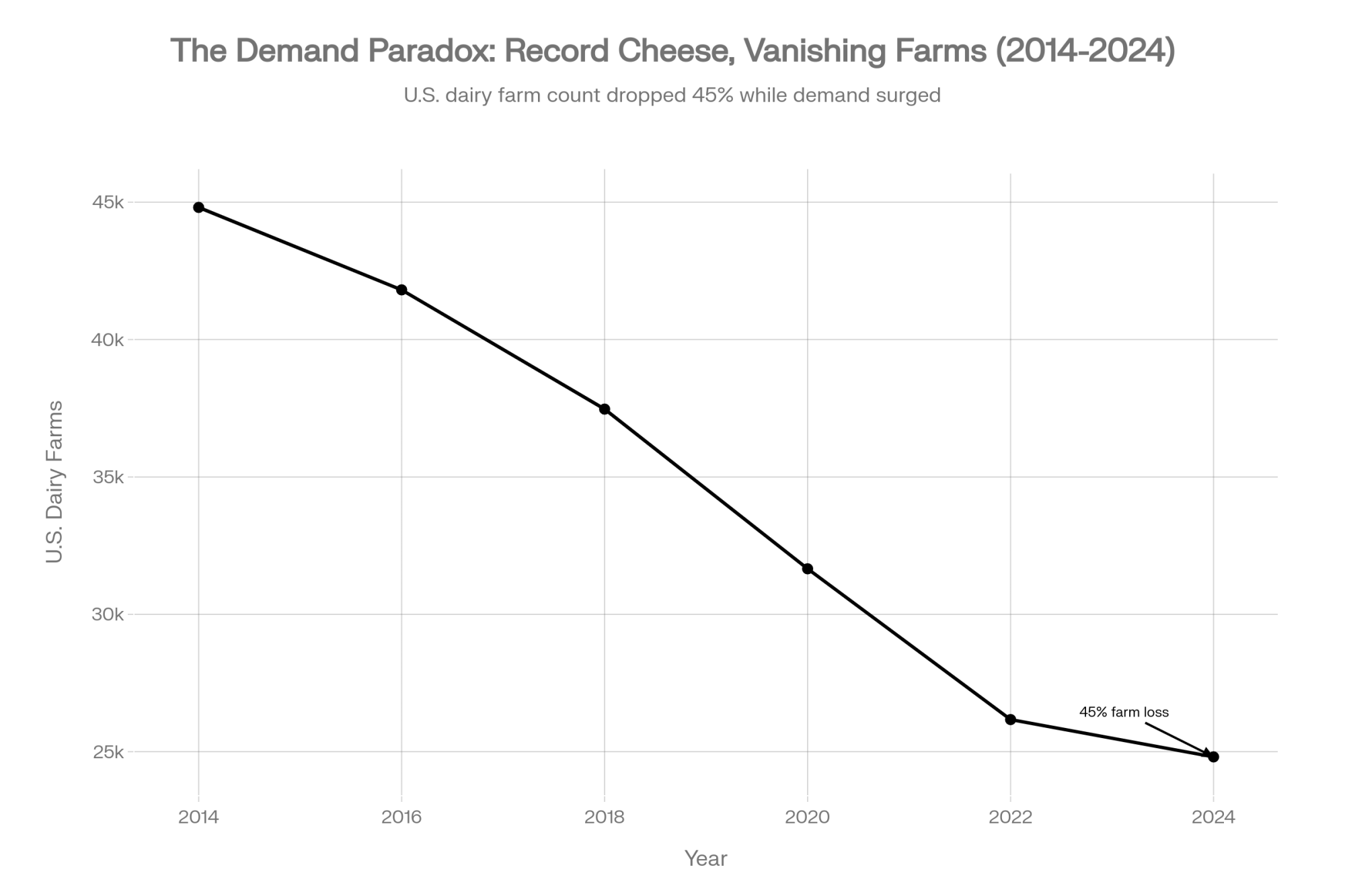

Record Cheese, Vanishing Farms: The Demand Paradox

Americans have never eaten more cheese over a sustained period than they did from 2021 through 2023 — three consecutive record years, peaking at 40.54 pounds per capita in 2023. And yet U.S. dairy farms keep closing at an accelerating rate.

The numbers are stark. USDA NASS data shows the U.S. lost 1,434 licensed dairy herds in 2024 alone — a 5.5% decline in a single year, bringing the national total to 24,811 farms. That’s down from 44,809 just a decade earlier — a 45% loss since 2014. And 86% of the 2024 decline was concentrated in the Midwest and Eastern states: Wisconsin lost 400 herds, Minnesota and New York shed a combined 315, and Pennsylvania dropped another 90.

| Region | Farms Lost (2024) | % of National Loss | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin | 400 | 27.9% | Worst hit |

| Minnesota | 180 | 12.5% | Severe |

| New York | 135 | 9.4% | Severe |

| Pennsylvania | 90 | 6.3% | Major |

| Other Midwest/East | 429 | 29.9% | Critical belt |

| Western States | 200 | 14.0% | Growing regions |

| Total U.S. | 1,434 | 100.0% | 5.5% decline |

The Bullvine reported in October 2025 that 1,420 American dairy farms had exited in the prior year. If that pace continued or accelerated, The Bullvine estimated the 2025 total could approach 2,800 closures — though the actual figure depends on how many operations secured financing versus being forced out. Cornell’s Dr. Andrew Novakovic put it bluntly: “What took ten years then is happening in two or three now” (The Bullvine, November 2025).

Processing capacity, meanwhile, is expanding in the opposite direction. Hilmar Cheese opened a $600 million facility in Dodge City, Kansas, in March 2025, specializing in American-style cheese in 40-pound commercial blocks and employing nearly 250 people. Great Lakes Cheese announced a $185 million expansion in Abilene, Texas, in 2024. These plants are designed to run for decades. And every one of them operates under the wider make allowances that took effect last June.

The View from Two Federal Orders

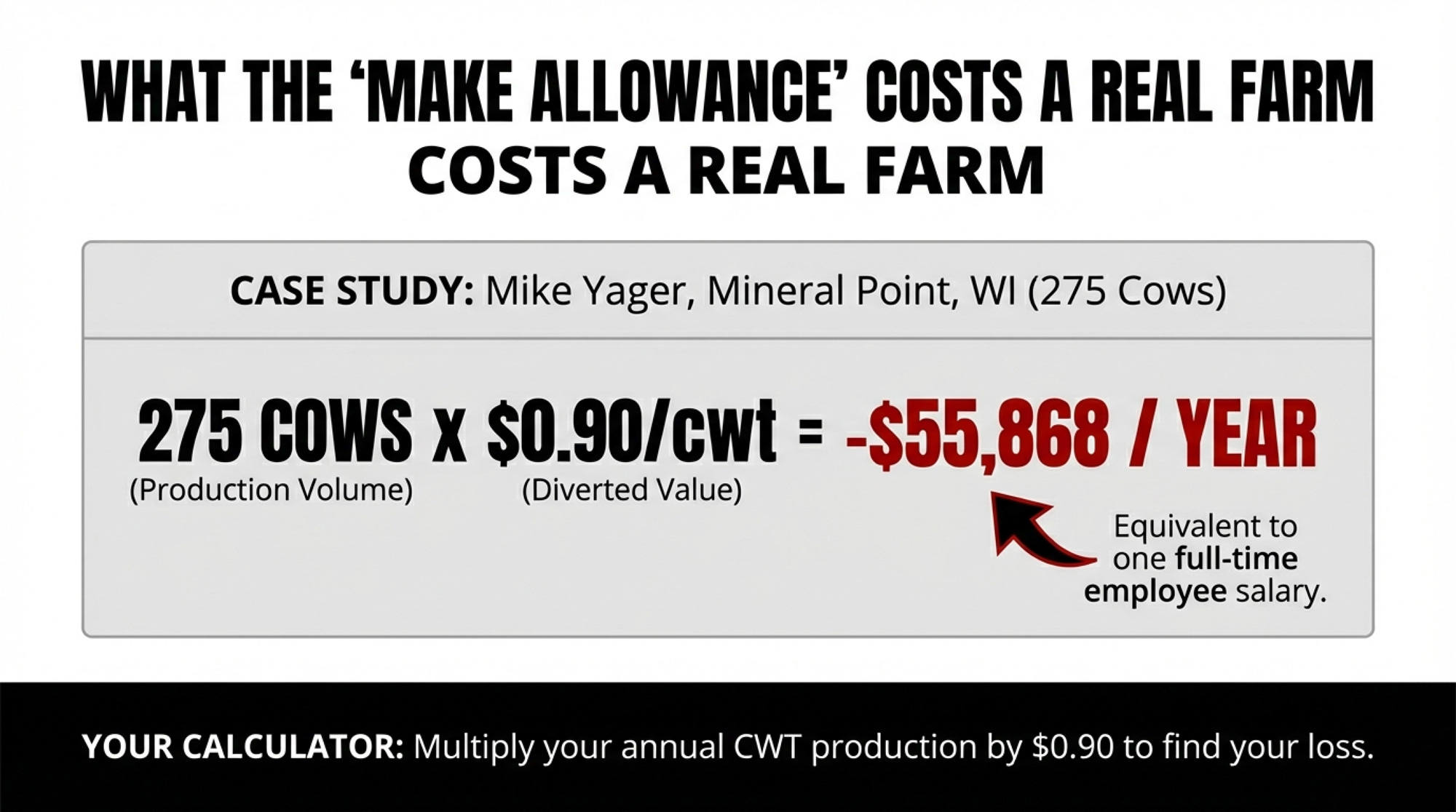

Mike Yager milks 275 Holsteins and grows feed crops near Mineral Point, Wisconsin — squarely in Federal Order 30, the Upper Midwest. When the make allowance increases hit last June, he did his own calculation: that additional 90 cents per hundredweight amounts to roughly $55,868 per year for an average-sized Wisconsin dairy in value that now stays with the processor instead of reaching the bulk tank. To estimate your own hit: multiply your total hundredweight shipped per year by $0.90. A 500-cow herd shipping around 110,000 cwt annually loses roughly $99,000 in pool value.

| Herd Size | Annual Shipment (cwt) | Annual Loss from Make Allowance | Monthly Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mike Yager (275 cows) | 62,076 | $55,868 | $4,656 |

| Average WI (500 cows) | 110,000 | $99,000 | $8,250 |

| Large (1,000 cows) | 220,000 | $198,000 | $16,500 |

| Mega (5,000 cows) | 1,100,000 | $990,000 | $82,500 |

“We as dairy farmers don’t see it on our milk checks. But via the new make allowances, we are losing out on 90 cents per hundredweight additional money that the processors are now receiving.” — Mike Yager, Brownfield Ag News, November 2025

For his operation, that deficit is roughly equivalent to an employee’s salary. And so far, he says, no added premiums have materialized to offset the loss.

The regional numbers vary, but no federal order escaped the hit. In the Northeast, the Milk Dealers and Distributors Industry Association warned during FMMO hearings that reduced minimum prices would be “particularly problematic” amid “widespread and accelerating exit of Northeast dairy farmers” — and could push the milkshed past a point of no return. Calvin Covington estimated Southeast orders will see the largest net benefit from updated Class I differentials — an average $1.42/cwt increase, but only on Class I volume. For Upper Midwest producers like Yager, where the blend skews heavily toward Class III, the make allowance hit lands harder, and the Class I differential cushion is thinner.

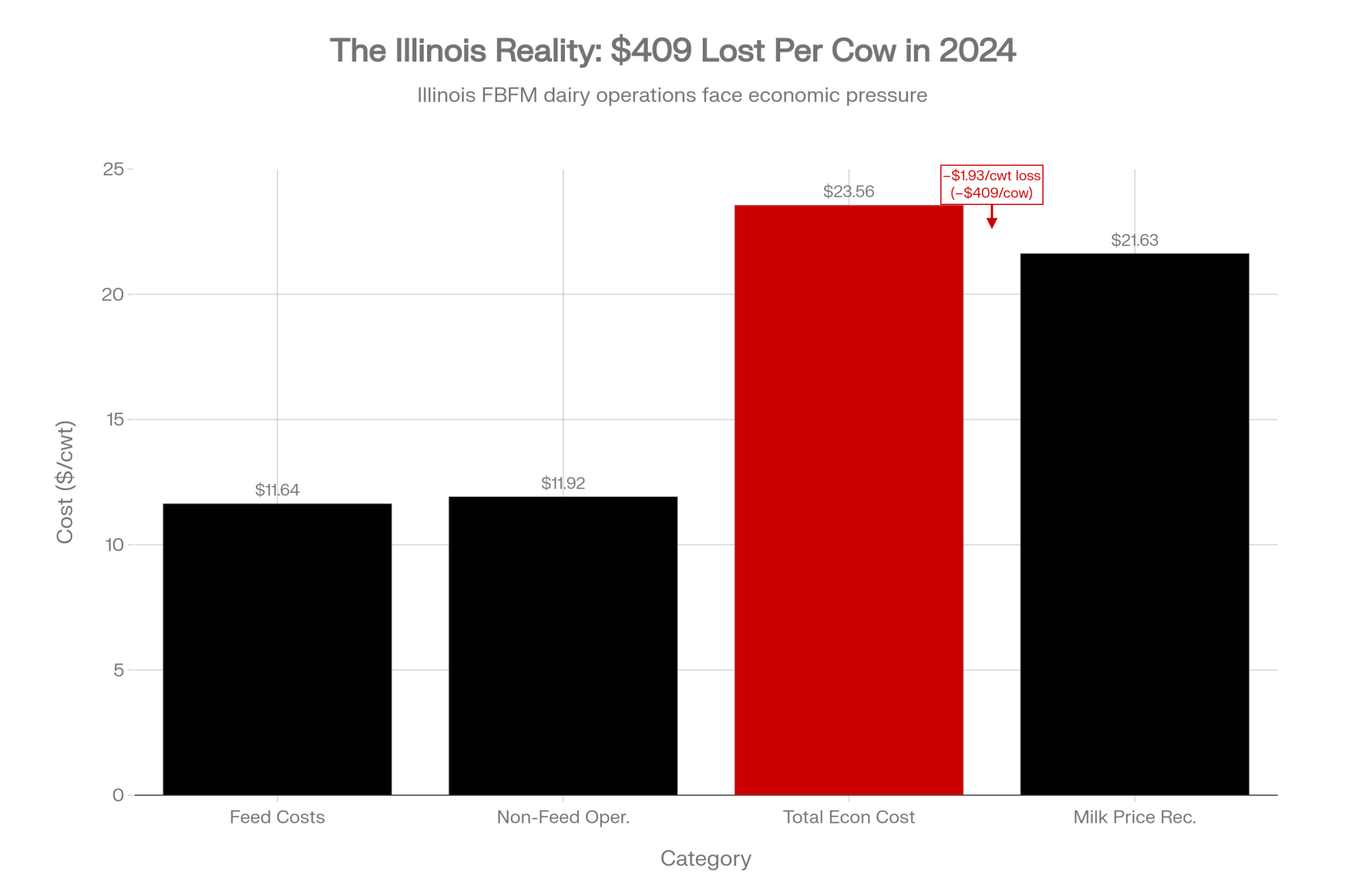

Illinois Farm Business Farm Management data tells the broader story. The 2024 numbers showed an average net milk price of $21.63 per hundredweight against total economic costs of $23.56 — a loss of $1.93/cwt, or negative $409 per cow for the year. Feed costs averaged $11.64/cwt, and nonfeed costs hit a record $11.92/cwt. SDA ERS’s January 2026 Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry Outlook forecasts the 2026 all-milk price at $18.25 per hundredweight, down from $21.15 in 2025 — a decline of nearly $3.00/cwt, or roughly 14% . That’s a wider drop than feed cost savings can absorb.” This is the single most important factual correction in this draft.

If you’re on a component order running 4.0% butterfat and 3.3% protein, there is a premium above the Class III floor — but it’s thinner than you might assume. At January 2026 component prices (butterfat at $1.4525/lb, protein at $2.1768/lb, other solids at $0.4448/lb — per USDA AMS), a hundredweight at those test levels returns roughly $15.53in component value (assuming 5.7% other solids, standard for Holstein herds), about $0.94 above the $14.59 Class III. That’s real money. But the make allowance still comes off the top of every component calculation before those prices are set. High components help. They don’t fix the formula.

What This Means for Your Operation

This isn’t a guilt trip. It’s a math problem — and the math has specific levers you can pull.

- Pull your last 12 months of milk checks and calculate your true net effective price — not the blend, not the gross, but what actually hit your account after deductions, hauling, and co-op assessments. USDA ERS data shows the national dairy farm-value share was 25% of the retail dollar in 2024. If your net is more than $1.50 below the FMMO blend minimum published by your order, you need to understand why.

- Know your breakeven in Class III terms. Illinois FBFM data pegged total economic costs at $23.56/cwt for 2024, with feed and cash operating costs at $17.43/cwt. Your costs vary by region, herd size, and feed situation — but if your cash costs are above $17.50/cwt and January’s $14.59 Class III is anywhere near your order’s blend, your working capital is eroding monthly. That’s the conversation to have with your lender this month, not in May.

- Talk to your crop insurance agent about Dairy Revenue Protection for Q2 and Q3 2026. HighGround Dairy’s five-year analysis found that for every $1.00 spent on DRP premiums, producers received $1.78 in return on average — a net benefit of $0.23/cwt after premiums. Coverage booked three quarters out returned the highest average net benefit at $0.30/cwt, despite higher premiums. With February 2026 advanced cheese prices at $1.4078/lb and butter at $1.4201/lb (USDA AMS, February 4, 2026), markets are signaling continued softness — exactly the environment where DRP has historically paid off. The trade-off is real: DRP premiums are a cash cost that hits quarterly, whether you need the coverage or not, and if milk rallies above coverage levels, you’ve paid for protection you didn’t use. But at current futures, the odds favor the buyer. If you haven’t locked Q3 2026 yet, that window is still open.

- Push USDA to launch mandatory processor cost surveys—and include mozzarella. Congress has already acted: the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed July 4, 2025, mandates biennial cost-of-production surveys covering cheese, butter, and nonfat dry milk processors, with $9 million appropriated for the program. But AFBF’s Danny Munch warns the timeline remains unclear. “They’re going to have to set up a methodology. They’re going to have to have staff and researchers set aside for this,” Munch told Brownfield Ag News at World Dairy Expo. “I don’t expect it to happen anytime soon”. And even when data comes in, there’s no automatic adjustment — a full FMMO hearing would still be required to change make allowances. The gap to push on: the survey covers cheese, butter, and NFDM, but does not explicitly name mozzarella — the single largest-volume cheese in America and the backbone of tonight’s pizza consumption. Push your co-op and trade organization to demand that mozzarella be included in the USDA’s survey methodology before it’s finalized. USDA’s FMMO modernization referendum was approved across all 11 orders in January 2025, with pricing amendments effective June 1, 2025.

- Request one competitive price comparison from an alternative buyer. If you ship to a large co-op, call an independent or a smaller cooperative and ask what they’d pay for your components. Yager’s experience is telling: the fear of being dropped keeps many farmers from asking tough questions about premiums. You don’t have to switch — switching carries real risk, including loss of hauling routes, potential basis penalties during transition, and relationship capital that’s hard to rebuild. But knowing you have options strengthens every negotiation you stay in. And if you’re exploring farmstead cheese or on-farm retail, start with no more than 10–20% of your production; the capital and compliance costs catch more operations than the margins do.

The Three Numbers That Matter Monday Morning

- 73 cents — the farm share of a $15 Super Bowl pizza at January’s Class III. Your actual loss from the make allowance increase scales with production: multiply your annual hundredweight shipped by $0.90. Nationally, the farm-value share of all dairy products at retail was 25% in 2024.

- 29 million pounds of cheese was priced into processor contracts weeks ago. Game-day demand doesn’t create spot-market pressure that flows back to your bulk tank. The consumption is real; the price signal to producers is at best muted.

- Mozzarella — tonight’s dominant cheese — isn’t even in the USDA pricing survey. The make allowance was set on cheddar data. Until the survey includes the cheeses that actually drive demand, the formula will keep underpricing your contribution to the products consumers want most.

Beyond the Final Whistle

Seventy-three cents on a fifteen-dollar pizza. That’s the current system’s answer to record demand. It matters that dairy farmers built what’s on every table in America tonight — and it matters more that the pricing formula doesn’t reflect it.

Yager’s math is blunt: the make allowance increase alone costs an average-sized Wisconsin dairy enough to fund a full-time employee — and so far, no premiums have shown up to replace it. In the Northeast, state industry groups have warned that continued milkshed contraction threatens the infrastructure supporting all small-scale agriculture in rural New England. Novakovic says the consolidation cycle is compressing a decade into two or three years. Whether the system changes fast enough to slow that compression is the open question — and 2,800 farms may not get to wait for the answer.

Pull your numbers this week. If your net effective price is more than $1.50 below the published FMMO blend, call your field rep before March—and then call the people who claim to speak for you and ask one specific question: what are they doing to ensure USDA’s mandatory processor cost surveys include mozzarella and launch before the next make-allowance fight. The gap between what consumers pay and what you receive won’t close on its own.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The $0.90/cwt FMMO Hit: Reset Your Breakeven, DMC Coverage, and Heifer Strategy for 2026 – Gain a survival roadmap for the post-reform environment. This analysis delivers specific calculations to recalibrate your breakeven points and arms you with a tiered DMC and heifer strategy to preserve working capital through the 2026 season.

- 2,800 Farms Will Close in 2025: Here’s Why USDA’s ‘Golden Age’ Isn’t Saving Them – Expose the structural flaws driving record-breaking consolidation. This deep dive reveals why federal safety nets are failing to protect family-sized operations and helps you position your business to weather the industry’s most aggressive contraction cycle.

- Same Milk, Different Payday: How Your Processor’s Product Mix Shapes Your Future – Stop shipping commodity milk and start targeting specific premiums. This breakdown reveals how aligning your herd’s genetic profile with your processor’s specific end-product mix creates a defensive margin advantage that FMMO make allowances simply cannot touch.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!