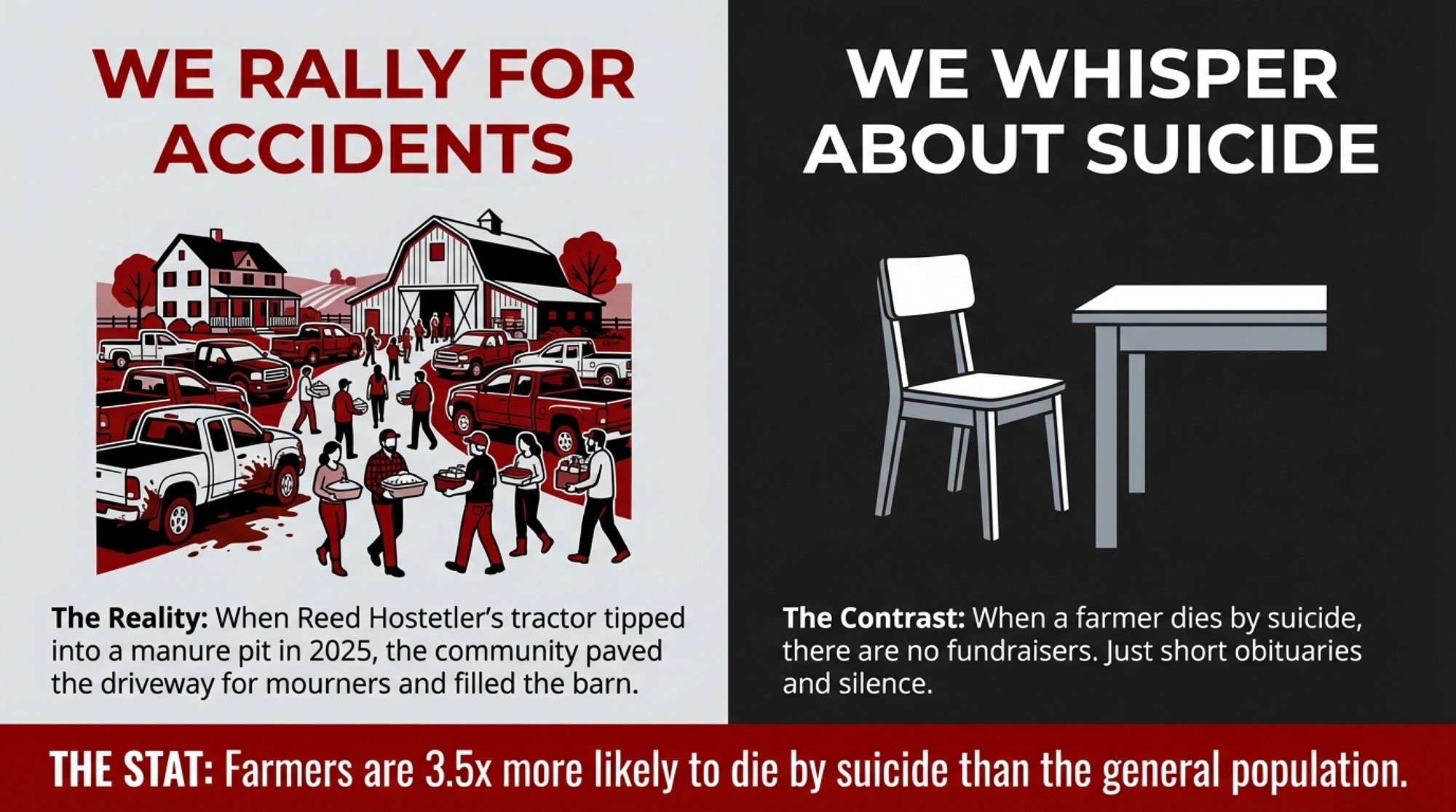

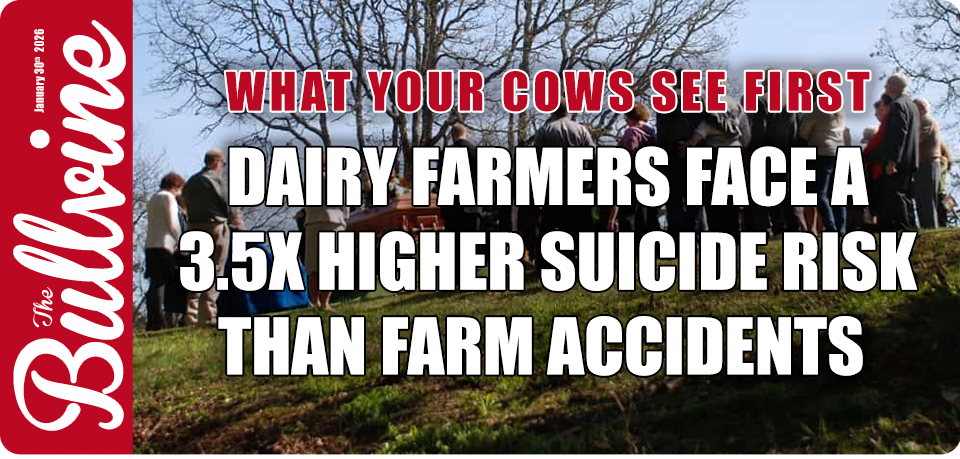

Funerals for farm accidents draw a crowd. Suicides get whispers. Yet dairy farmers are far more likely to die by suicide than in an accident.

Reed Hostetler never planned to be a headline.

On March 5, 2025, the 31‑year‑old Ohio dairyman climbed onto a tractor to agitate a manure pit on his family’s farm near Marshallville, Ohio. The tractor tipped. Reed went in. His brothers jumped in after him, but the pit won. The community did what farm communities do: they fixed up the long gravel driveway so mourners wouldn’t sink in the mud, filled the barn for the funeral, and stood shoulder to shoulder for a young dad who was known for being careful around that pit.

What almost nobody talked about that week were the other dairy farmers who died the way this industry quietly loses far too many colleagues: not in a lagoon, but by their own hand. No fundraisers. No, “we lost one of our own.” Just short obituaries, a cause of death that gets whispered if it’s mentioned at all, and another empty chair at a kitchen table.

| Cause of Death | Rate per 100,000 Farmers | Diagnosed Mental Illness on Record | Community Response | Mental Health System Visibility |

| Farm Accidents | 12.4 | Not applicable | Funeral draws crowd; fundraisers; “we lost one of our own” | High — accident reports, OSHA data, safety training |

| Suicide (Farming-Related) | 43.2 | 36.1% (vs 46.1% non-farm rural) | Whispers; short obituary; cause often omitted | Low — 60% never used mental health services in final 6 weeks |

| General Population Suicide | 12.3 | ~46% diagnosed | Varies widely | Moderate — clinical records, hotline data |

| All Occupations Combined | 16.9 (occupational suicide) | Not farming-specific | Varies | Moderate |

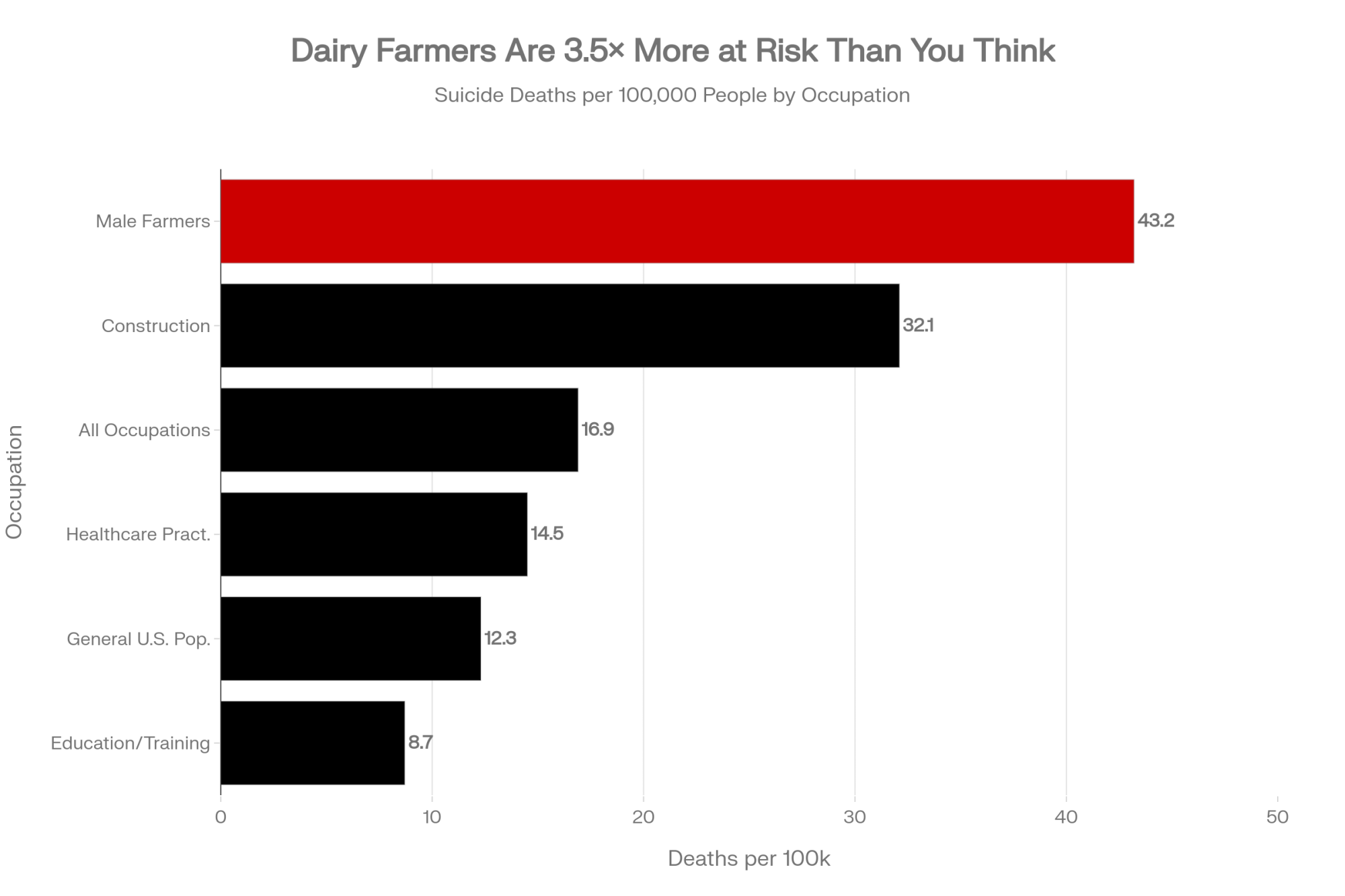

Here’s what’s really going on: according to the National Rural Health Association, available information indicates that the suicide rate among farmers is about 3.5 times higher than in the general population. Occupational data show male farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural managers at about 43.2 deaths per 100,000, compared with much lower averages for all workers. That’s not a rounding error. That’s a different world.

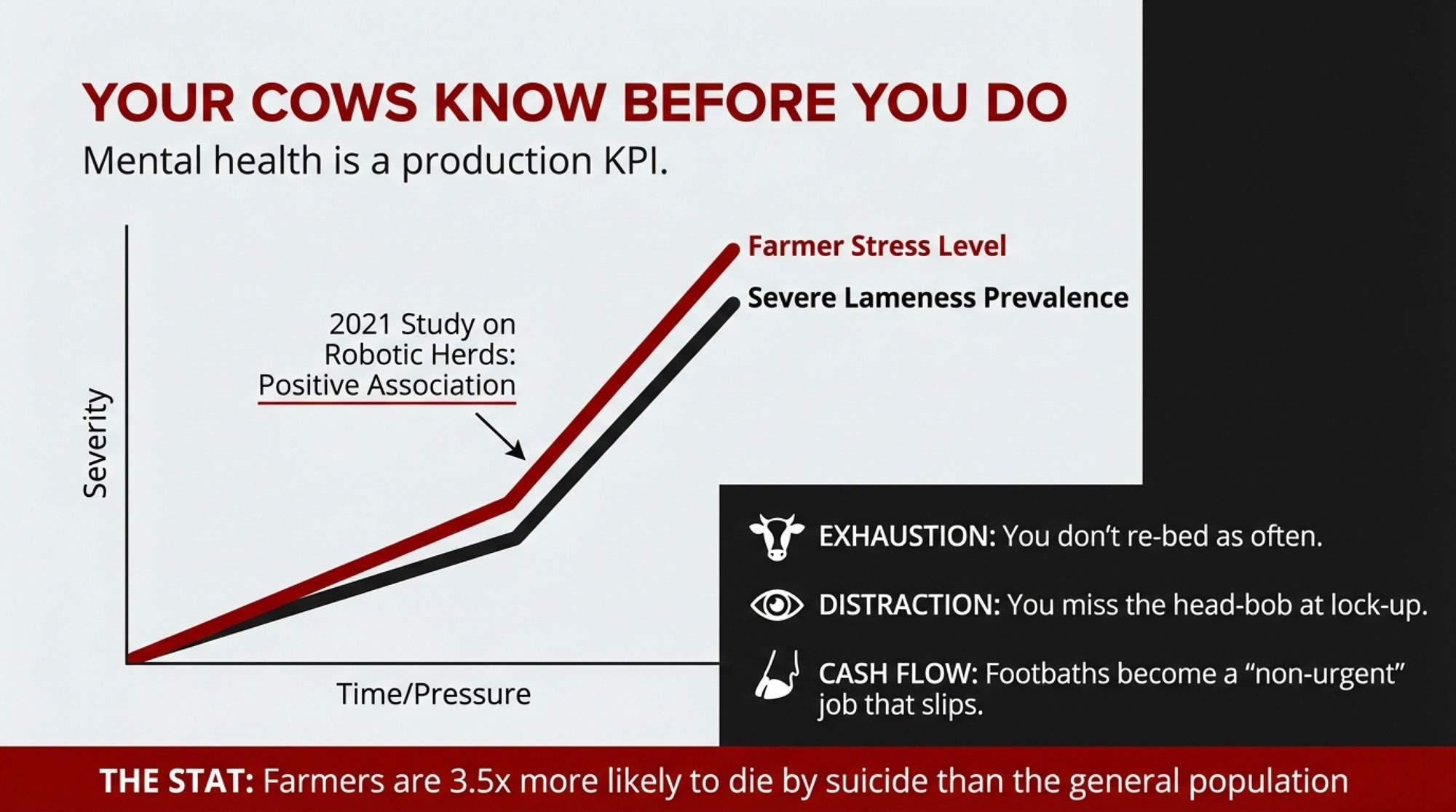

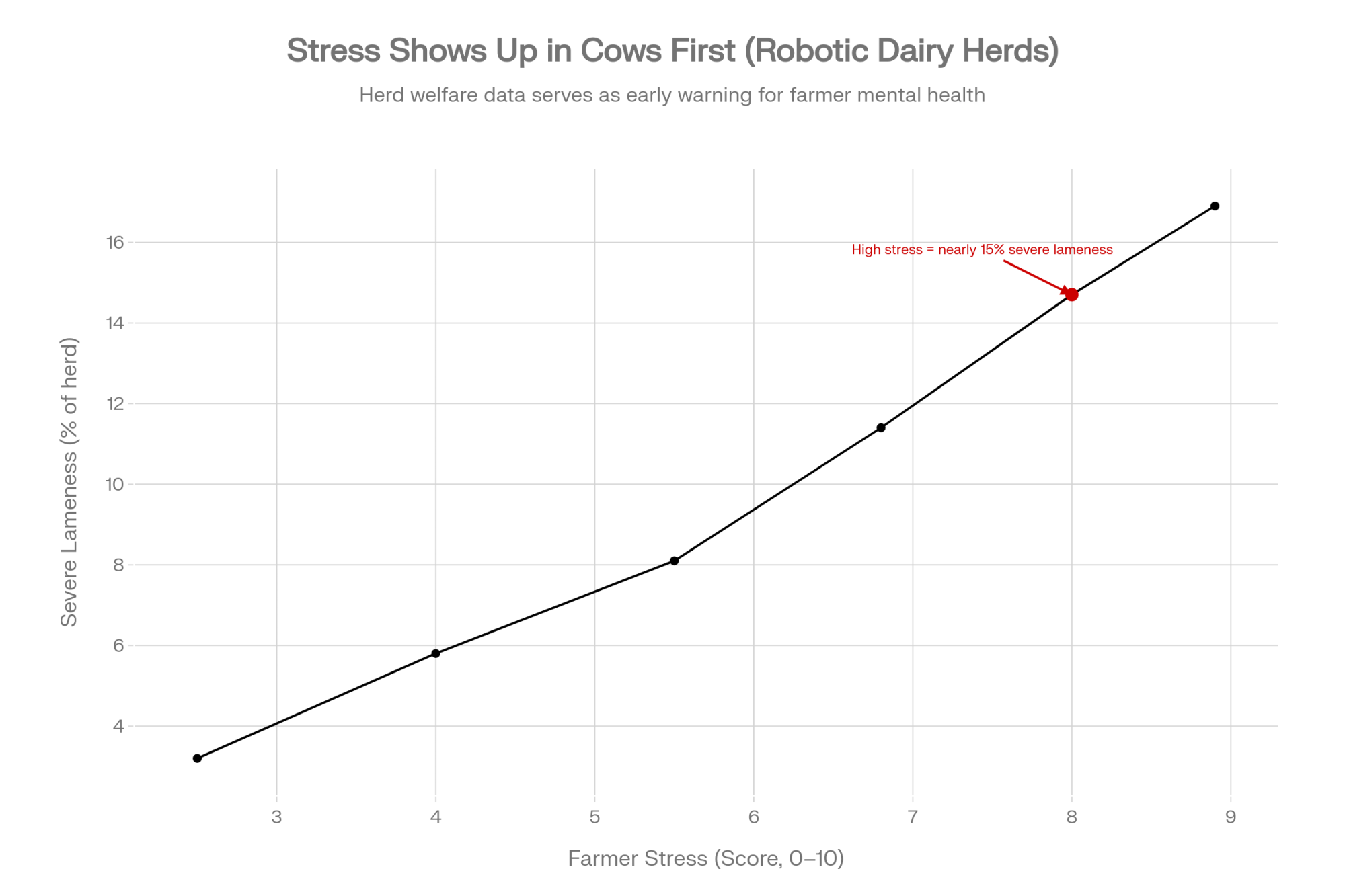

And here’s the part that should make you sit up a bit straighter: a 2021 study on robotic‑milking herds found that farmer stress was positively associated with severe lameness prevalence — the more stressed you are, the more severely lame cows you’re likely to have standing in your alleys. When your head is underwater, your cows will often show it before you’ll ever admit it.

This isn’t soft “awareness” content. This is survival work for your family, your genetics program, and your long‑term herd strategy.

Farmer Suicide by the Numbers: How Bad Is It, Really?

Let’s park the emotion for half a minute and look at the scoreboard.

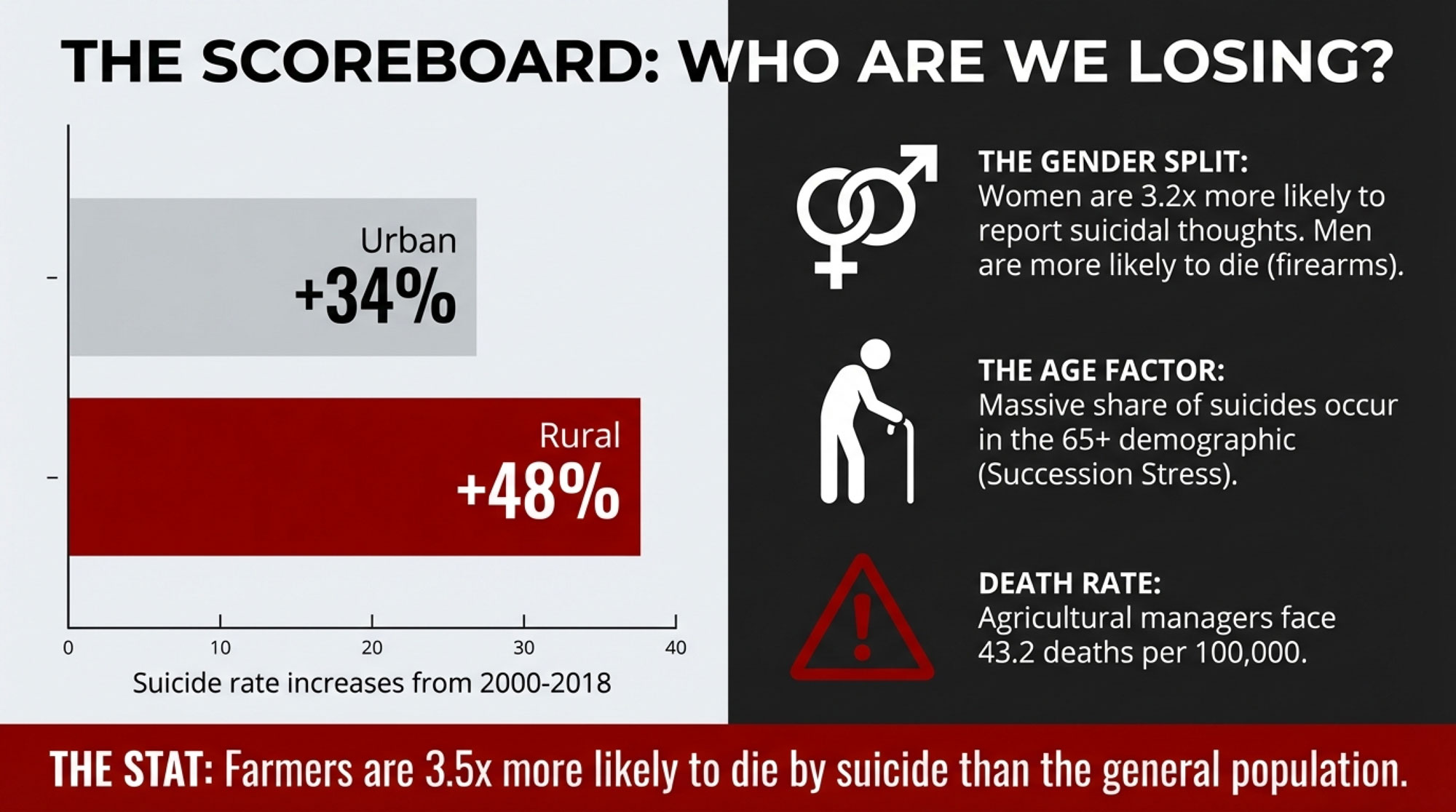

From 2000 to 2018, suicide rates rose 48% in rural areas versus 34% in urban areas in the United States. Rural populations, plain and simple, are dying by suicide more often than urban ones, and the curve is steeper out where you and your neighbors live.

Inside that rural picture, farmers stand out.

The National Rural Health Association and multiple rural‑health groups say the same thing: farmers’ suicide rate is about 3.5 times higher than that of the broader population. In 2017, male farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural managers had a suicide rate of 43.2 per 100,000, markedly higher than the rate for all occupations combined. International reviews back that up: one 2021 synthesis found agricultural workers consistently over‑represented in suicide data, with relative risks often between 1.5 and 2.5 times that of the general population, and in some sub‑groups pushing up toward 3–5×.

Now look at how farmers show up — or don’t show up — in the mental‑health system.

An Australian “life chart” analysis comparing farming‑related suicides to other rural suicides found that people whose deaths were tied to farming were less likely to have a diagnosed mental illness on record (36.1% vs 46.1% for non‑farm rural suicides; odds ratio 0.66). They were also less likely to have used mental‑health services in the six weeks before death (39.8% vs 50.0%; odds ratio 0.66). In other words, the people who die are often the ones who were never in the system.

A British farmer‑mental‑health study reported that, compared with the general population, farmers had lower measured psychiatric morbidity but a higher proportion who felt that life was not worth living. They don’t say, “I have major depressive disorder.” They say, “I’m done,” or, “Maybe they’d be better off without me.”

Gender twists the knife further. A 2022 study of farmers found that female farmers were about 3.28 times more likely to report suicidal ideation than male farmers. Women think about it more. Men die more. That lines up with broader suicide patterns and tells you that your wife, daughter, or sister may be carrying more unspoken weight than you realize.

Age and method matter too:

- A large share of farming‑related suicides occurs among people aged 65 and older — in some datasets, the proportion in that top age bracket approaches half of all cases.

- Firearms are the dominant method in farming suicides, with higher odds of firearm use compared to non‑farming rural suicides.

And there’s one more pressure that doesn’t show up on a milk cheque but sits on a lot of 65‑year‑old shoulders: succession.

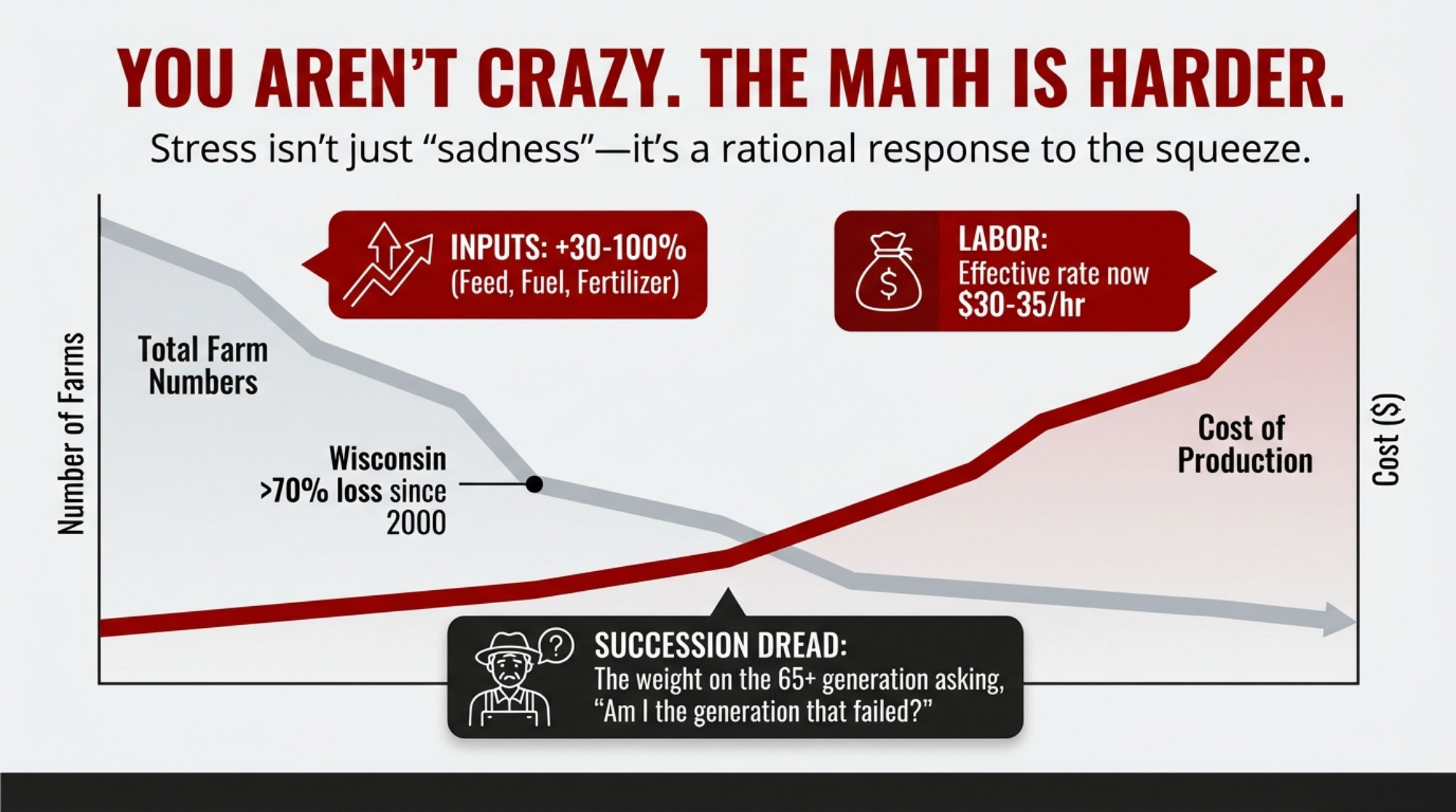

Recent research with farmers and agricultural advisors has found that having no clear succession plan, or feeling unsure whether the next generation even wants the farm, is a major source of anxiety, depression, and stress for older producers. Advisors talk about older farmers wrestling with “identity confusion, guilt, and a lost sense of purpose” when they don’t know how or to whom the business will transition. Qualitative work reports that farmers feel ashamed to be “the generation that failed” if the operation ends with them, or see themselves as a burden if they can’t hand over a viable unit. In at least one U.S. farm‑family survey, a large majority of respondents said that fear of losing the farm took a significant toll on their mental health.

If you’re looking at 65 with no clear plan for who comes next, that stress doesn’t clock out when you shut the lights off in the barn. It follows you into bed.

Why Farmers Don’t Show Up in the System

If you’ve ever said, “We don’t really have that around here, I don’t know any farmers with mental‑health issues,” you’ve actually proved the point.

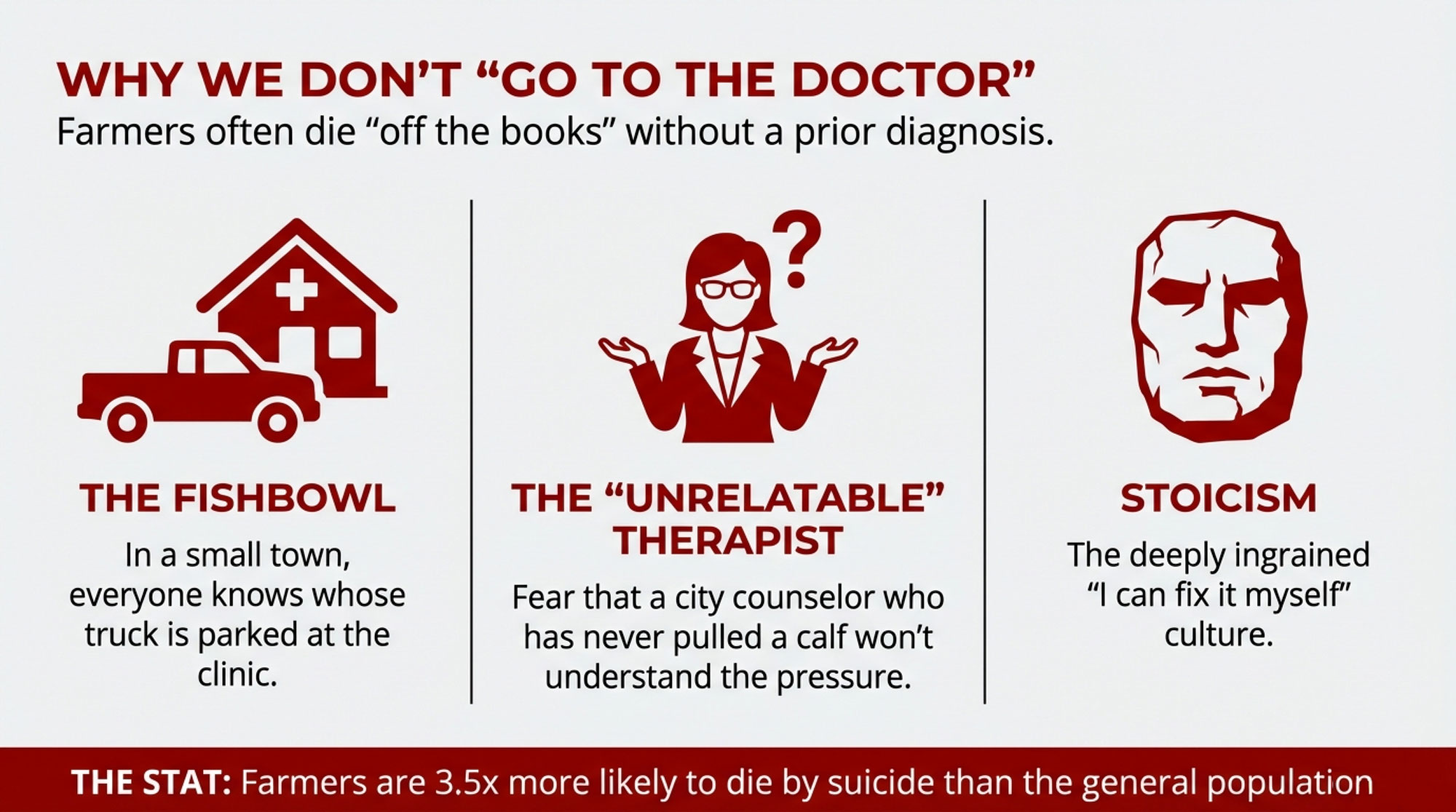

Across Canadian, U.S., and European work on farmer mental health, the same barriers keep coming up:

- Stigma and reputation. In a national Canadian survey, roughly 40% of farmers said they’d feel uneasy seeking professional help because of what others might think. Walking into a counseling office can feel worse than walking into the bank.

- Small‑town fishbowl. In many rural communities, everyone knows whose truck is parked where. Farmers worry that neighbors, lenders, or processors will see them at a clinic and start their own stories.

- “They’ll never understand farming.” Qualitative studies across the UK, Canada, and Australia show producers deeply skeptical that a counselor who’s never pulled a calf or watched a barnful of cows load on a truck can really understand what they’re carrying.

- Access deserts. Many rural counties have zero psychiatrists and very few psychologists. Reports from both sides of the border flag long waits, patchy broadband, and gaps in cost or insurance as major barriers.

- Identity and culture. Farmers often define themselves as tough, independent, and the person others lean on when things go bad. That identity makes it hard to say, “I can’t manage this on my own.”

| Program | Region | What You Get | How to Access | Key Detail |

| Farmer Wellness Initiative (FWI) | Ontario, Canada | Free, confidential counseling from farm-literate professionals | 24/7 phone: 1-866-267-6255; phone, video, or in-person | English, French, Spanish; no referral needed |

| Farm Family Wellness Alliance | U.S. (national) | Anonymous online peer support moderated 24/7 by clinicians | Togetherall platform; free for farm families age 16+ | Backed by AFBF, Farm Credit, Land O’Lakes, NFU |

| AgWellness Vouchers | Utah, U.S. | Up to $2,000/person for therapy, virtual counseling, hospital services | Through Utah State Extension | ~250 people served/year; ~$263k in care covered |

| Manitoba Farmer Wellness Program | Manitoba, Canada | Free counseling from professionals with farm experience | Direct MFWP contact | Renewed 2026; $300k over 2 years; led by “Recovering Farmer” |

| Crisis Lines | U.S./Canada | Immediate crisis intervention, suicide prevention, resource connection | U.S.: 988 / Canada: 1-866-FARMS01 | Available 24/7; confidential |

Put that together, and the diagnostic paradox suddenly makes sense. The pain is real. It just doesn’t get written down.

That British work summed it up: farmers reported lower psychiatric morbidity but a higher proportion endorsing that life was not worth living. They don’t show up in charts as “major depression, severe.” They show up in eulogies as “we had no idea.”

If you treated mastitis this way — never culturing, never logging cases, never calling the vet — you’d be “a herd with no mastitis problem” right up until you shipped half the string.

That’s exactly what’s happening with mental health.

When Your Cows Know Before You Do

Here’s where this stops being a generic suicide story and gets uncomfortably dairy‑specific.

A 2021 study on farms using robotic milking systems scored about 30 cows per farm for lameness and under‑conditioning, then matched that to farmer mental‑health surveys. The researchers found that farmer stress was positively associated with the prevalence of severely lame cows — more stress, more severe lameness. Stress levels were higher among female farmers, among those feeding manually rather than using an automated system, and among those working alone. Anxiety and depression were also higher on farms with higher severe lameness and lower milk protein.

At the same time, welfare and economics work keeps reminding us what you already see in the alley: lameness is one of the most painful and economically damaging conditions a dairy cow can have, hammering intake, milk, fertility, and longevity. You pay for it in lost production, extra trims, treatments, and culls.

We like to talk about lameness as a stall‑design problem, a footbath problem, or a genetics problem. It is. But this research forces an awkward add‑on: lameness can also be a mental‑health KPI.

Think about how stress behaves in your barn:

- When you’re exhausted and running on caffeine and adrenaline, you don’t re‑bed quite as often.

- When your head is spinning over milk cheques and lender calls, you don’t notice the slight head‑bob at lock‑up.

- When you’re short on cash and long on worry, hoof‑bath schedules and trim lists are the first “non‑urgent” jobs that slip.

None of that makes you a bad farmer. It makes you human.

But it does mean this: if your severe lameness rate is up, cow comfort is down, and at the same time your own sleep, patience, and appetite are going the wrong way, that’s not just a cow problem. That’s your herd screaming that you are in trouble.

You already treat SCC, repro, and cull rate as red‑flag metrics. The tough truth is that some of your welfare data may be telling you your own brain is breaking down before you ever say it out loud.

Ignoring that isn’t just bad welfare. It’s bad business.

The Economic Squeeze Behind the Crisis

This isn’t just, “Farming has always been tough.” The current squeeze has its own shape.

Take Wisconsin. Between around 2000 and 2024, dairy farm numbers fell from the mid‑teens in thousands to roughly 5,222 farms, a loss of over 70% according to state data and media analysis. That’s not normal churn. That’s ripping the middle out of America’s Dairyland.

| Year | Wisconsin Dairy Farms | Avg. Herd Size (cows) | Milk Price ($/cwt, approx.) | Key Economic Event |

| 2000 | ~15,500 | ~70 | $12.50 | Baseline: smaller herds, moderate prices |

| 2008 | ~13,000 | ~95 | $18.20 (peak) → $11.30 (crash) | Financial crisis; many 100–200 cow herds exit |

| 2015 | ~9,500 | ~140 | $16.50 → $14.00 | Trade volatility; “get big or get out” accelerates |

| 2020 | ~7,000 | ~175 | $18.00 → $13.00 (COVID crash) | Pandemic; supply-chain chaos; labor costs spike |

| 2024 | ~5,222 | ~210 | $16.50–$17.50 (volatile) | 70% farm loss from 2000; bankruptcies +50% YoY in some regions |

In a Wisconsin Watch story, dairyman Jerry Volenec spelled out what “get big or get out” actually meant on his farm. He started with about 70 cows after college and eventually built up to roughly 300, milking three times a day, farming more land and cattle than he ever thought he would, with fewer people than he had at 70. He said he was never financially comfortable and only broke even through “great personal sacrifice”.

“The happiness and joy has been sucked out of me,” he said. “I don’t want to be this guy”.

Now add the 2020s economics:

- Bankruptcies. Court data and farm‑finance commentary show that in the mid‑2020s, Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies turned sharply higher, with some regions and periods seeing year‑over‑year increases on the order of 50% or more.

- Price and policy shocks. Trade disputes and tariff swings with Mexico, Canada, China, and the EU have repeatedly moved milk prices by something in the range of $0.65–$1.75 per cwt, based on past tariff episodes and mailbox/Class III price analyses. When your margin is a buck a hundredweight on a good month, those aren’t background blips.

- Input cost squeeze. From roughly 2021 through 2024, feed, fuel, and labor costs climbed hard in many regions, with some cost‑of‑production work showing 30–100% increases in key line items while milk prices rose more modestly. That spread is where your equity bleeds out.

- Labor reality. Once you add housing, transportation, visa fees, and compliance, several 2024–2025 cost breakdowns suggest that the true effective hourly cost for H‑2A or similar dairy labor can range from $30–35/hour across many operations. That’s a long way from the “cheap labor” story some still tell.

- Processor leverage and formulas. Changes to the Class I mover, make allowances, depooling rules, and processor‑specific base/excess programs over the last several years have shifted a lot of pricing power off the farm. Farm‑credit and industry analyses show significant value migrating from producers to processors through these mechanisms.

Iowa farmer and advocate Matt Russell described it this way: the farm economy is always a roller coaster, “and right now we’re in one of those down cycles… the economics right now are really driving a lot of stress”.

You can sprint in that environment for a while. You can’t sprint that way forever.

On some farms, the first cracks show up in skipped maintenance and delayed upgrades. On others, it’s in marriages and kids who want nothing to do with taking over. For too many, it ends in a funeral.

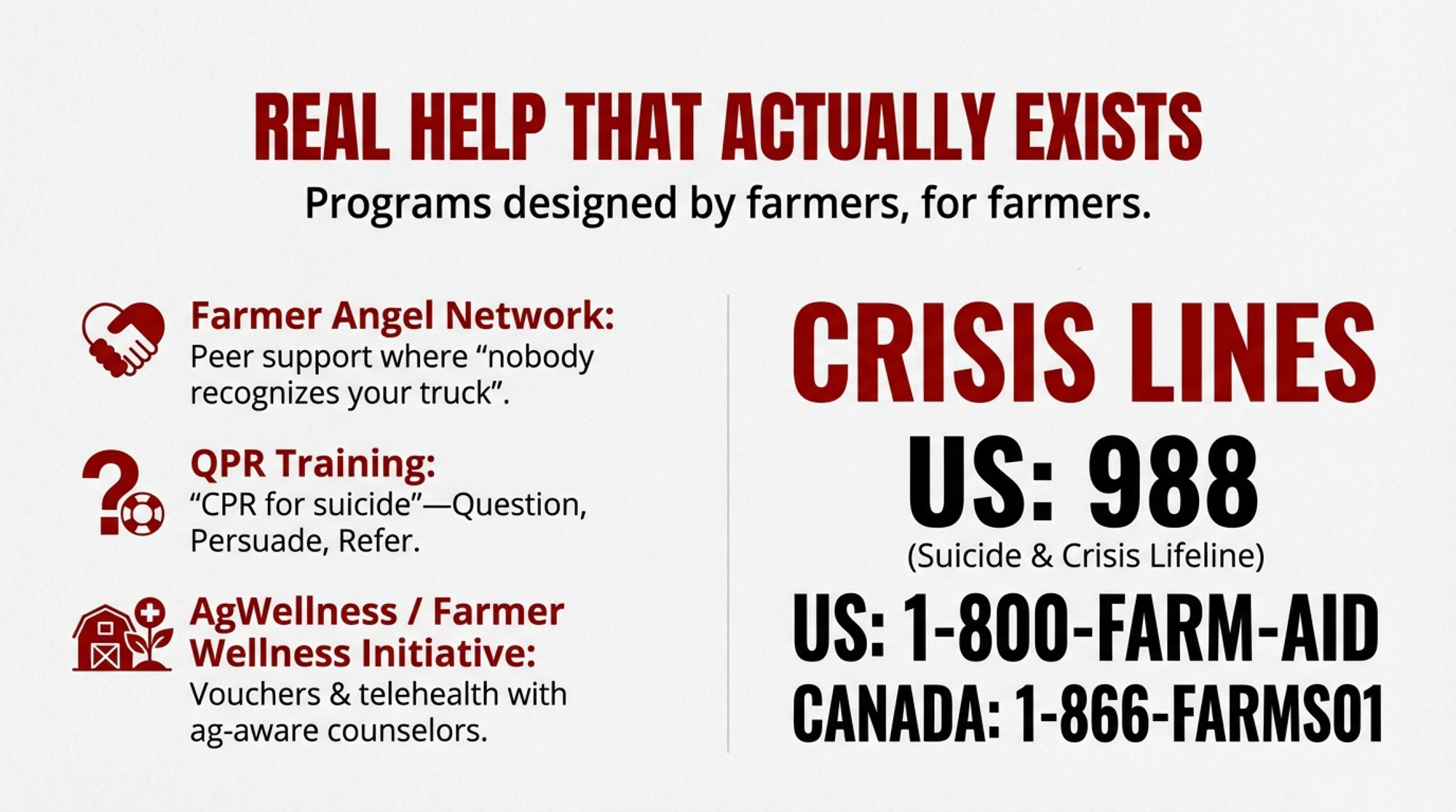

The New Toolkit: Telehealth, Vouchers, and Real Help

Here’s the part that doesn’t get enough airtime: the mental‑health world has finally started moving toward farmers. It’s still uneven. But there are real tools now that didn’t exist a decade ago.

Farmer‑Focused Mental Health Programs at a Glance

| Program | Region | What You Get | How to Access | Key Detail |

| Farmer Wellness Initiative (FWI) | Ontario, Canada | Free, confidential counselling from licensed professionals familiar with farm life | 24/7 phone: 1‑866‑267‑6255; phone, video, or in‑person sessions | English, French, Spanish; no referral needed |

| Farm Family Wellness Alliance | U.S. (national) | Anonymous online peer support moderated 24/7 by clinicians; self‑assessment tools; pathways to care | Togetherall platform; free for farm family members age 16+ | Backed by AFBF, Farm Credit, Land O’Lakes, NFU, and others |

| AgWellness Vouchers | Utah, U.S. | Up to $2,000/person toward behavioral‑health care — therapy, virtual counseling, and some hospital services | Through Utah State University Extension | In one recent year, ~250 people served, 1,600+ sessions funded, about $263k in care covered |

| Manitoba Farmer Wellness Program (MFWP) | Manitoba, Canada | Free counselling from professionals with farm literacy; flex scheduling around milking and fieldwork | Direct contact with MFWP | Renewed in 2026 with $300k over two years; led by “Recovering Farmer” Gerry Friesen |

None of these programs will fix milk prices or rebuild equity. But they can help make sure you’re still here to fight another day.

Other Key Hotlines and Crisis Lines

| Line | Number | Who It Serves |

| Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (U.S.) | 988 | Anyone in the U.S. |

| National Farmer Crisis Line (Canada) | 1‑866‑327‑6701 (1‑866‑FARMS01) | Canadian farmers and farm families |

| Farm Aid Hotline (U.S.) | 1‑800‑327‑6243 (1‑800‑FARM‑AID) | U.S. farmers needing financial, legal, or emotional support |

Post these where you post rations. Office wall. Parlor whiteboard. Shop fridge.

Peer Support: The Help Farmers Actually Use

Every serious review of farmer suicide prevention lands in the same place: farmers are far more likely to open up to other farmers and trusted rural professionals than to strangers in town.

Wisconsin – Randy Roecker and the Farmer Angel Network

You probably know a Randy in your own area, even if the name is different.

Wisconsin dairyman Randy Roecker built a modern free‑stall barn and parlor just before the 2008 crash. At one point, he estimates his family was losing about $30,000 a month. He stopped shaving, stopped eating, and hardly slept. Over time, he went through multiple doctors and therapists, more than 20 medications, a series of electroconvulsive treatments, and a week‑long inpatient psychiatric stay.

He’s talked about picturing his kids at his graveside and realizing he couldn’t do that to them.

Randy’s still here.

Today, he helps lead the Farmer Angel Network in rural Wisconsin:

- They hold peer‑support gatherings in a local church.

- Farmers drive two or three hours to attend because they feel safer opening up in a different county where nobody recognizes their truck.

- Roecker and others have taken QPR and similar trainings and now teach milk haulers, nutritionists, and other service providers how to spot warning signs and respond.

“So many times, I just needed someone to not ask, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ and just listen,” he said in an interview. That’s not therapy jargon. That’s a farmer describing what actually helped.

Canada – Sentinels and Do More Ag

In Quebec, a Sentinel Program has trained hundreds of “Sentinels” — farmers, vets, agronomists, feed reps — to recognize distress and connect producers to help. They’re not counselors. They’re trusted neighbors with a bit of extra training.

Nationally, the Do More Agriculture Foundation has become a focal point for farm‑mental‑health work in Canada. They sponsor campaigns, webinars, and on‑farm events under messages like “Talk it out, don’t tough it out,” and support projects like the “Deep Rooted” documentary series. In that series, Saskatchewan rancher Kole Normanrecounts being “definitely very suicidal” but worried that reaching out would look weak — and then discovering that actually getting help was harder than it should’ve been.

Australia – Help That Shows Up at the Farm

Australian suicide‑prevention work with male farmers shows a consistent pattern: these men prefer informal, familiar settings — on farm, at field days, at the rural accountant’s office — over clinics. Programs that send peer workers or rural financial counselors out to properties, quietly, without fanfare, have been especially effective at getting men to talk.

If you sit on a co‑op board or in a processor’s C‑suite, the takeaway is simple: if your mental‑health “strategy” is a poster and a hotline, you’re missing where the trust lives. Put real dollars behind peer networks, Sentinels, and on‑farm support, or admit you’re just ticking a CSR box.

Your Vets, Feed Reps, and Lenders Are First Responders

Every week, people walk onto your yard who might spot trouble before your family does.

- Your veterinarian sees if herd checks get pushed back, if fresh‑cow protocols slip, or if you suddenly go quiet where you used to be engaged.

- Your feed rep or nutritionist sees when you stretch inventory too far, skip needed ration changes, or stare at the bunk like your mind’s a million miles away.

- Your ag lender or Farm Credit advisor hears it when you start sounding numb, evasive, or resigned instead of frustrated but engaged.

You already trust these people with treatment plans, feed rations, and loan structures. The next logical step is to make them informal “mental‑health first responders” for the farms they serve.

Mental Health First Aid & “In the Know”

Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) has versions tailored for rural and agricultural settings. It teaches people to:

- Recognize signs of depression, anxiety, substance use, and crisis.

- Start a conversation without making things worse.

- Assess suicide risk and connect someone to appropriate care.

“In the Know”, developed at the University of Guelph, is a mental‑health literacy program built specifically for farmers and those who work with them. Evaluations show it improves knowledge and confidence for recognizing and responding to mental‑health problems in rural and farm contexts.

Extension and ag‑safety programs in the U.S. and Canada now run MHFA, In the Know, and similar courses for vets, feed reps, agronomists, and producer leaders.

QPR – Question, Persuade, Refer for Farmers

QPR — Question, Persuade, Refer — is CPR’s cousin for suicide risk. In agriculture‑focused trainings run by groups like AgriSafe and Texas AgrAbility, often 60–90 minutes long, participants learn to:

- Ask directly about suicidal thoughts.

- Persuade someone to accept help.

- Refer them to appropriate resources and stay involved.

A Kentucky QPR evaluation found that after training, participants were significantly more willing to intervene, with men showing the largest improvement despite starting lower than women. In a demographic where most suicide deaths are male, that matters.

If you’re a vet, feed rep, agronomist, or lender, here’s the blunt version:

- Put one MHFA, In the Know, or QPR‑style training on your calendar this year.

- Save crisis and local program numbers in your phone and your truck.

- On every farm visit, ask at least one question about how the person is doing, not just how the herd is doing.

You don’t have to fix anyone. You just have to notice—and not walk away.

How to Talk to a Farmer Under Stress

This is where most of us freeze. You see the neighbor who used to argue milk price now staring through the parlor wall. You see the spouse who’s suddenly snapping at kids and kicking tools. You feel the tension. And then you talk about corn silage and go back to your own chaos.

Farm‑focused guidance from Michigan State University Extension and AgrAbility gives some simple ways to start.

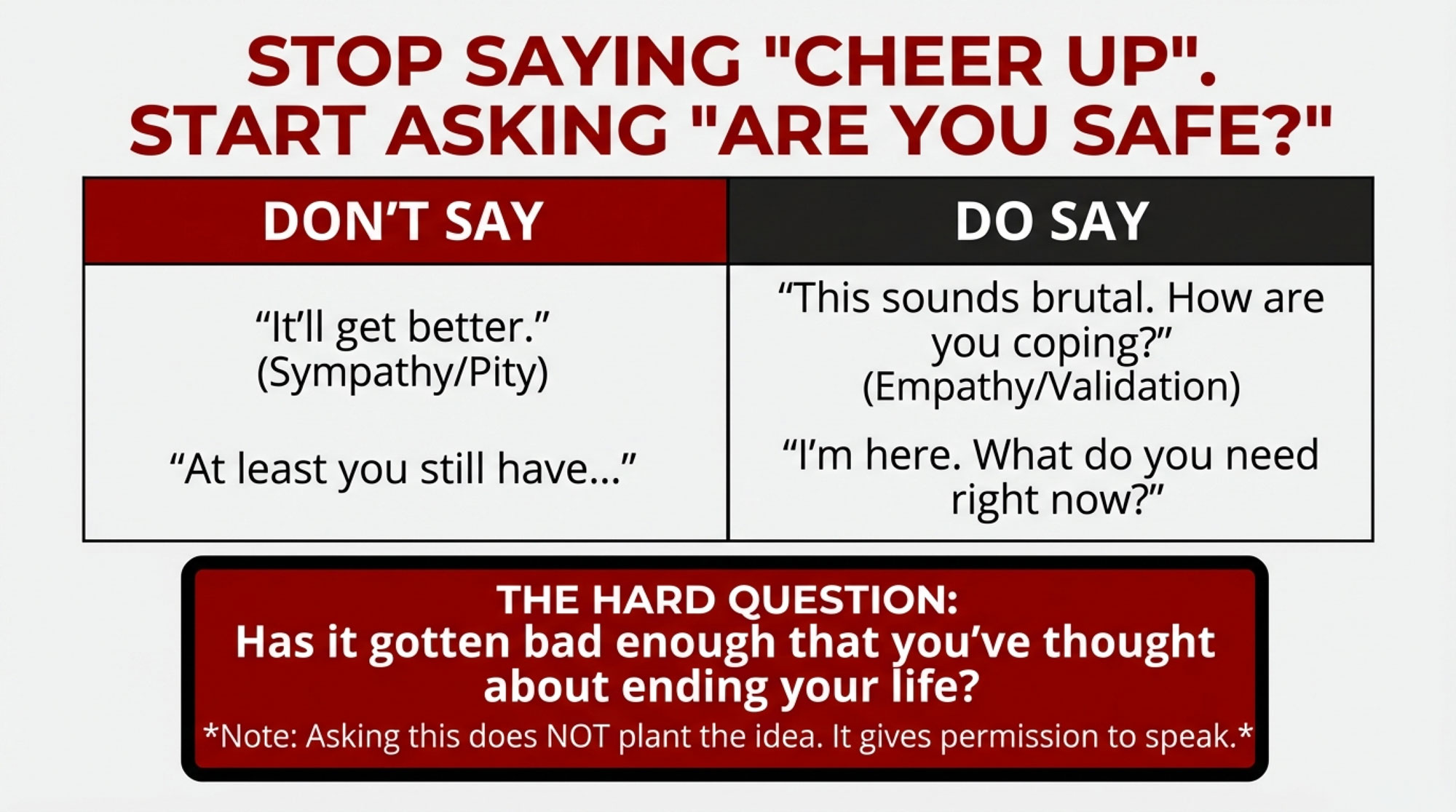

What to Say Instead of “Cheer Up”

Try openers like:

- “I hear you saying you’re running flat‑out, and it still feels like you’re falling behind. How are you coping with all this?”

- “This sounds like a lot to carry. What’s been the hardest part lately?”

- “It sounds like this year’s been brutal. I care about you. What would actually help right now?”

Then be quiet. Let the silence sit. You don’t have to fill it in the first thirty seconds.

Sympathy vs Empathy

Sympathy often sounds like:

“I’m so sorry, it’s devastating that you have to sell the farm.”

It might be true, but it can land like pity.

Empathy sounds more like:

“Being in this spot is brutal. I know a couple of farms who had to make similar calls. If it helps, I can connect you with one of them — or we can just sit here and talk through what happens next.”

One says, “Poor you.” The other says, “You’re not crazy, and you’re not alone.”

The Question Everyone’s Afraid to Ask

Every serious suicide‑prevention training says the same thing: if you’re worried someone might harm themself, ask directly.

- “Has it gotten bad enough that you’ve thought about ending your life?”

You will not “put the idea in their head.” If they’re considering it, the thought is already there. Asking gives them a chance to say it out loud.

If the answer is yes — or even “sometimes” — your job is clear:

- Stay with them. Don’t leave them alone “to think.”

- Help them call 988 (U.S.), 1‑866‑FARMS01 (Canada), or your local crisis line.

- If you’re on the farm, calmly help get them away from guns, high places, and chemicals until professional help is engaged.

Then follow up: a text in two days, a coffee next week. Most survivors don’t point to one dramatic movie‑style rescue. They talk about a string of small check‑ins that convinced them they mattered.

What This Means for Your Operation

Enough big‑picture talk. Here’s what this actually means on your farm — and in your role — this year.

If You’re an Owner or Herd Manager

Here’s what you can do this week:

- Post the numbers where you post rations. Put these in the office, parlor, shop, and staff room:

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (U.S.).

- National Farmer Crisis Line (Canada): 1‑866‑FARMS01 (1‑866‑327‑6701).

- Farm Aid Hotline (U.S.): 1‑800‑FARM‑AID (1‑800‑327‑6243).

- Farmer Wellness Initiative (Ontario): 1‑866‑267‑6255.

- Any provincial, state, or regional farm‑mental‑health lines you have locally.

- Make one call if you’re at a 7/10 or higher most days. If most mornings you wake up feeling like you’re already behind, consider that a 7 or higher. Pick one of the numbers or a program like FWI, MFWP, or AgWellness and book a session. You’re not signing a lifetime contract. You’re testing for one hour.

- Look at your herd data as a mirror. Pull 12 months of lameness, SCC, and fresh‑cow problem rates. If severe lameness is creeping up, more fresh cows look rough, and more little details are getting missed — all while your sleep and patience are sliding — treat that as a combined red flag. It’s a herd‑health and farmer‑health issue.

Here’s what you can do this year:

- Train at least one person on your farm. Get yourself, your spouse, or a key employee through QPR, MHFA, or In the Know. Make mental‑health first aid as normal as CPR or chemical‑safety training.

- Plan for your headspace like you plan for feed—and legacy. When you sit down with your nutritionist, banker, and genetics rep to map out the year, add the human and legacy column: what’s your realistic work capacity, when you can actually be off farm, and what your honest plan is for succession. Even a rough transition sketch can take some of the “it all ends with me” weight off your back.

If You’re a Vet, Feed Rep, Agronomist, or Lender

You already know which clients worry you. Here’s how to move from worried to useful:

- Get trained once. Put one MHFA, In the Know, or QPR‑style training on your calendar this year. Treat it as core professional development, not charity.

- Carry resources like any other handout. Keep a one‑pager with crisis lines and local farm‑focused programs in your truck and on your phone. Hand it over the same way you’d hand out a new ration sheet or loan summary.

- Ask one real question per visit. On every farm call, ask some version of, “How are you holding up with all this?” Then listen long enough to hear the answer behind the answer.

If You’re a Co‑op, Processor, or Ag Organization

You put “farmer‑focused” on your website. Here’s where that gets tested.

- Fund real counselling capacity. Partner with a group like Do More Ag, a provincial wellness program, or a local university to underwrite at least one counselor or mental‑health navigator dedicated to farm families in your region.

- Train your field staff as standard. Make QPR, MHFA, or similar training mandatory for field reps, member‑relations staff, and account managers. If they can talk about components and premiums, they can learn to ask, “Are you OK?”

- Stop writing around suicide when families are willing to name it. When a family chooses to be open about losing someone to suicide, support them. Don’t bury it in euphemisms. The shame isn’t on the farmer who died. It’s on a culture and system that let them die in silence.

Every time you lose a farmer, you lose not just milk. You lose decades of genetics, management experience, and community leadership—and you send a chill through every other supplier watching.

The Bottom Line

You already know what happens if you ignore numbers. Ignore pregnancy rate, and you don’t magically get more calves. Ignore components, and you don’t stumble into a butterfat premium. Ignore lameness, and you don’t suddenly wake up with a sound herd.

Suicide risk is the same. There are patterns. Some tools work. There are programs already funded and waiting for you or your neighbor to pick up the phone.

You wouldn’t leave a cow in obvious pain because you were embarrassed to call the vet again.

You’re allowed to care that much about yourself.

And if that quiet thought has ever crossed your mind — that your family, your farm, or this industry would somehow be better off without you — hear this as plainly as I can say it: they wouldn’t.

Call. Text. Talk. Post the numbers. Train your people. And the next time someone in your circle looks like the joy has been sucked out of them, have the guts to ask the hard question — and then stay for the answer.

Honestly, that might be the most profitable decision you make all year.

Key Takeaways

- Farmers face about a 3.5× higher suicide rate than the general population, with especially elevated risk among older men and in farm‑linked occupations.

- Farming‑related suicides are less likely to have a diagnosis or recent mental‑health contact on record, which means traditional systems are missing many of the people most at risk.

- Herd‑welfare data — especially severe lameness on robotic herds — can act as an early‑warning sign of farmer stress, not just a management KPI.

- Succession planning, or the lack of it, is a major mental‑health stressor for older farmers, tied to identity, legacy, and fears of “failing” the previous generation.

- Concrete tools exist now: region‑specific counselling programs (FWI, MFWP, AgWellness), anonymous online communities (Farm Family Wellness Alliance), peer‑support networks (Farmer Angel Network, Sentinels, Do More Ag), and trainings (MHFA, In the Know, QPR).

- You can start this week: post crisis numbers, make one call if your stress is at a 7/10 or higher, look at your lameness and fresh‑cow data as a mirror, and get at least one person on your farm or in your business trained in mental‑health first aid.

Executive Summary:

Dairy farmers today face a suicide risk roughly 3.5 times higher than the general population, yet the industry still rallies louder for visible farm accidents than for the suicides happening in the same communities. Using the 2025 death of Ohio dairyman Reed Hostetler as a starting point, the article contrasts public grief over a manure‑pit tragedy with the quiet, often hidden losses to suicide on other farms. It pulls in recent data showing that many farmers who die by suicide never appear in the mental‑health system and that higher farmer stress is linked to higher rates of severe lameness in robotic‑milking herds, meaning your cows may flag a problem before you do. The piece puts those numbers in context with the current squeeze: consolidation, policy and price shocks, rising input and labor costs, and succession uncertainty, all of which weigh heavily on older producers. From there, it outlines a concrete toolkit of farmer‑specific supports — provincial counselling programs, U.S. telehealth and vouchers, peer‑support networks, and trainings like QPR and Mental Health First Aid — and shows how vets, feed reps, and lenders can act as first responders. It closes with a clear playbook for you: watch lameness and fresh‑cow data as a mirror, post and use crisis numbers, get at least one person on your farm trained in mental‑health first aid, and choose to ask the hard questions when someone around you starts to slip.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- Vermont Drought Forces Dairy Farms Into Costly Survival Mode – Walks a similar path of high-stakes survival as producers wrestle with environmental blows that mirror the internal pressure of a financial crisis, proving the point that resilience has its limits when the hits keep coming.

- 2025’s $21 Milk Reality: The 18-Month Window to Transform Your Dairy Before Consolidation Decides for You – Deepens the understanding of the brutal market forces and consolidation trends mentioned in Reed’s story, showing exactly how the modern economic squeeze forces the gut-wrenching decisions that weigh on every kitchen table.

- 5 Quiet Ways Dairy Neighbours Keep Farmers Going in the Winter Stress Storm – Carries forward the mission of the Farmer Angel Network by detailing the specific, small-scale peer interventions that bridge the gap between “we had no idea” and actually saving a life in the barn.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!