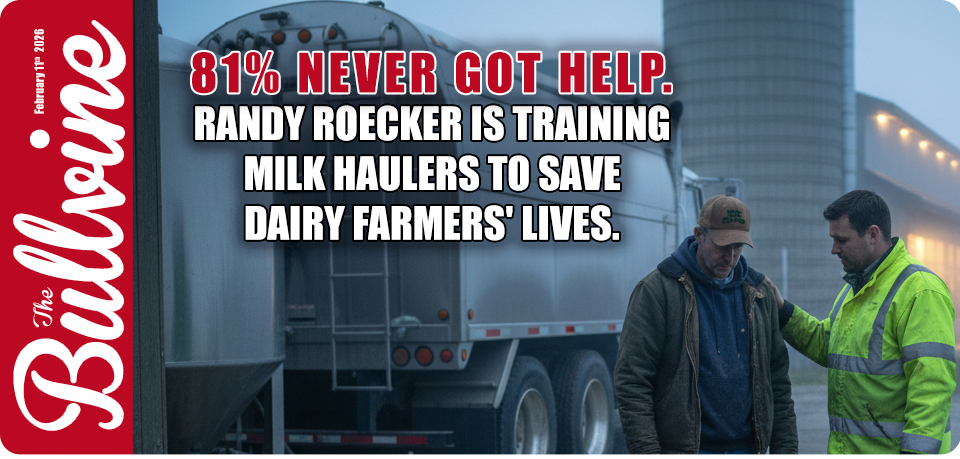

Most suicide training starts in a classroom. Randy Roecker started his in the driveway — with milk haulers, vets, and nutritionists who already know every bump in your lane.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses suicide, depression, and financial distress in farming. If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or call the Wisconsin Farmer Wellness Helpline at 1-888-901-2558. Suicide data cited here draws from the CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System (Bjornestad et al., American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2022), the National Rural Health Association, and peer-reviewed research in Animal Welfare (King et al., 2021). Individual experiences vary widely, and this article is informational—not medical advice.

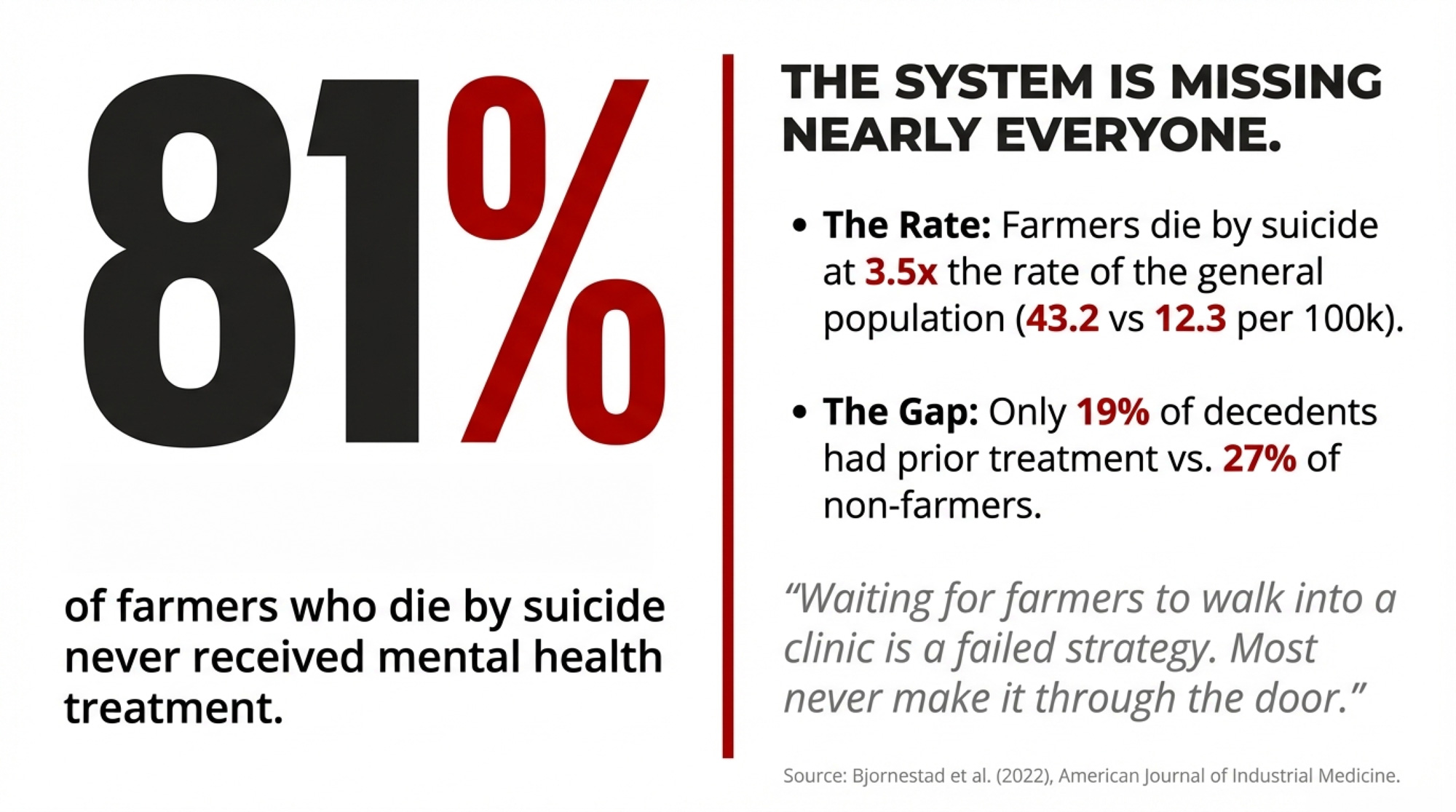

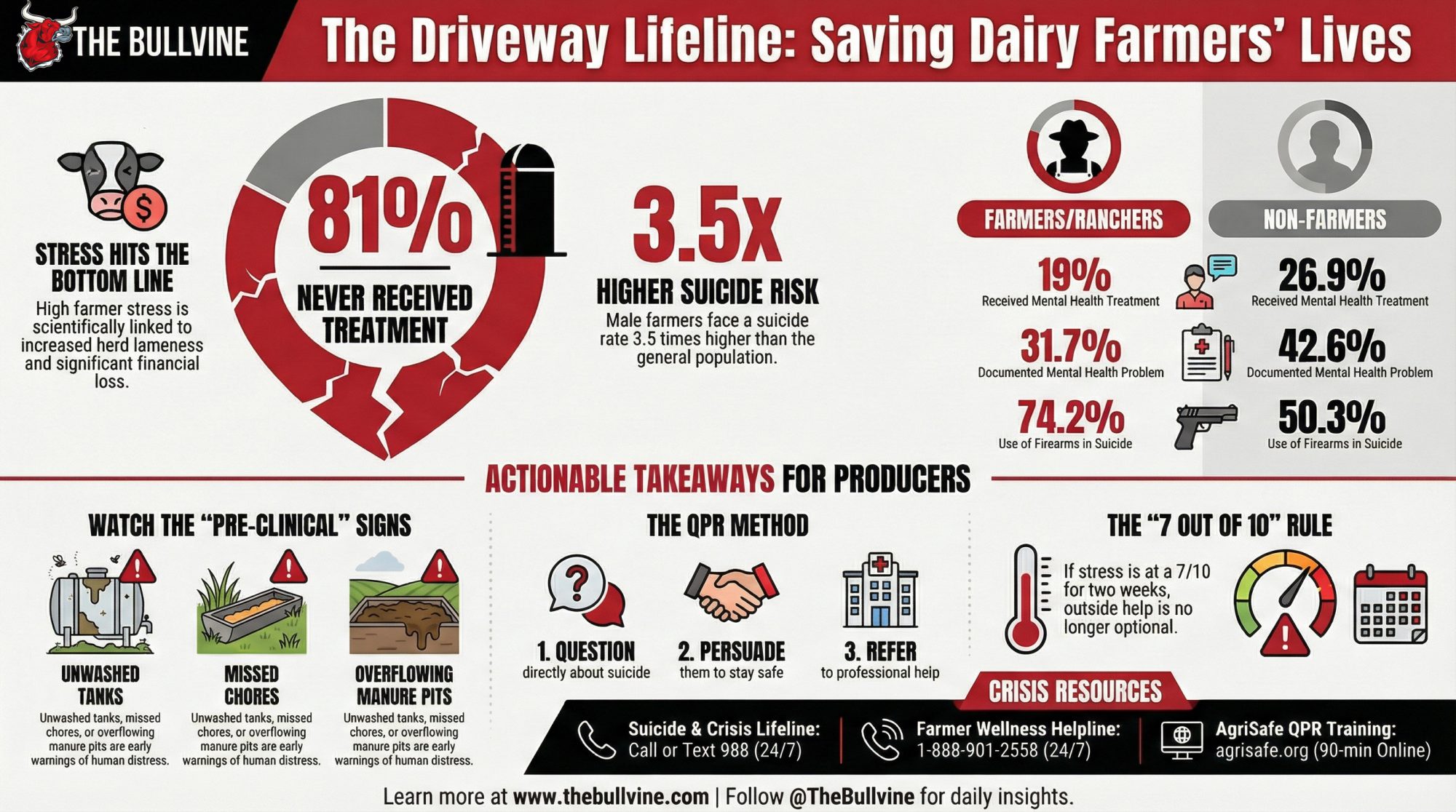

Here’s a number that should change how you think about farmer suicide prevention and dairy farmer mental health: 81% of farmers who die by suicide had never received any mental health treatment. That comes from Bjornestad et al., published in the American Journal of Industrial Medicine in 2022, analyzing 1,935 farmer and rancher decedents from CDC NVDRS data spanning 2003–2018. Not most. Not many. Eighty-one percent. The formal system isn’t missing a few. It’s missing nearly all of them.

Randy Roecker, a third-generation dairy farmer from Loganville, Wisconsin, fought depression for seven years — treatment after treatment, and none of it was enough. What finally made a difference wasn’t another appointment. It was a neighbor’s suicide, a breakdown in a church parking lot, and a question that sounds almost too simple: what if the real first responders to a farm crisis are the people already pulling into the driveway?

That question became the Farmer Angel Network. The model it built — peer fellowship, QPR gatekeeper training for milk haulers and vets, and community events that lead with celebration rather than pathology — is now being replicated across Wisconsin. It’s drawn coverage from NBC Nightly News, a platform on NMPF’s Dairy Defined podcast, and meetings with a U.S. senator. Here’s why it works, what the research actually says, and what you can do about it regardless of where you farm.

| Metric | Farmers (%) | Non-Farmers (%) |

| Never received mental health treatment | 81.0% ↑ | 73.1% |

| Received mental health treatment | 19.0% | 26.9% |

| Had documented mental health problem | 31.7% | 42.6% |

| Treatment gap (percentage points) | −7.9 ↓ | — |

From $3 Million in Leverage to $30,000 a Month in Losses

Roecker’s identity was rooted in 700 acres his grandfather established near Loganville in the 1930s. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin Farm and Industry Short Course, he came home with a plan to modernize. In 2006, he committed to a major expansion at Roecker’s Rolling Acres: a new free-stall barn and milking parlor with capacity for 300 cows, carrying roughly $3 million in new debt. Milk prices were near $18.00/cwt. The math worked — until it didn’t.

By 2009, the 2008 financial crisis had sent prices below $9.00/cwt in some markets. For a farm leveraged at $3 million, there was zero margin left. By late 2008, the family was hemorrhaging an estimated $30,000 every month. At an American Farm Bureau Federation convention workshop, Roecker put it plainly: “I was afraid of being the one to lose my grandfather’s farm, the one to lose this legacy for the children and for the future.”

The financial pressure triggered a depression that would consume seven years. Roecker has described the spiral publicly — the kind that’s invisible to everyone except the cows and the person staring at the parlor wall at 4 a.m. He spent those years in treatment for depression. The treatment kept him alive. But not a single provider in that pipeline spoke the language of a dairy operation, understood why he couldn’t “take time off,” or involved anyone who actually set foot on his farm.

A Neighbor’s Death, a Parking Lot, and 50 People in a Church

On October 8, 2018, Leon Statz — a 57-year-old neighbor and fellow dairy farmer — died by suicide, leaving behind his wife Brenda Statz and their family. Statz had battled depression for more than 20 years. He’d sought help over those two decades — but the system hadn’t given him or his family the tools to manage his worst episodes at home.

Roecker couldn’t attend the funeral. It hit too close to his own history. But shortly after, standing in the parking lot of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Loganville, he broke down in front of friends: “You guys just don’t know what it’s like dealing with this.”

That moment led to the first community meeting inside the church. About 50 people showed up. “A lot of tears shed,” Roecker has said. Nobody had a nonprofit charter. Nobody had a five-year plan. They just decided the silence was going to stop.

The 3.5× Risk and Why Farmer Suicide Prevention Can’t Start in a Clinic

The data behind that decision is staggering—and still underappreciated by most of the industry.

CDC occupational suicide data, widely cited by the National Rural Health Association, places the rate among male farmers, ranchers, and agricultural managers at approximately 43.2 per 100,000 — compared to roughly 12.3 for the general population. That’s 3.5 times the rate. A separate Wisconsin-specific analysis of 2017–2018 death certificates (Ringgenberg et al., 2021, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health) identified 44 farm-related suicides in just two years, at 14.3 per 100,000, and not a single one of those cases had been captured by existing agricultural injury surveillance systems.

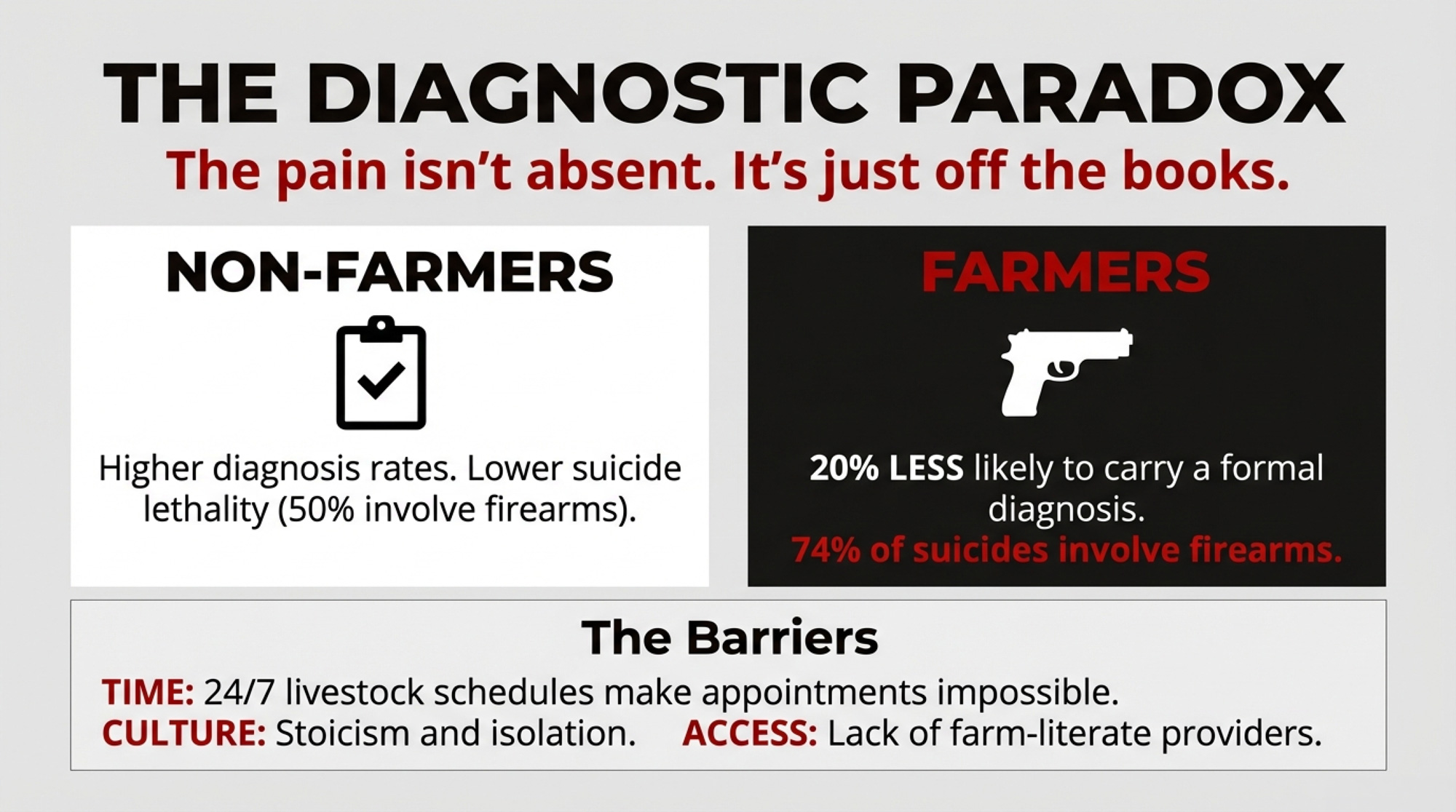

But the most alarming finding isn’t the rate itself. It’s the diagnostic paradox. Bjornestad et al. (2022), analyzing CDC NVDRS data from 2003–2018, found that among 1,935 farmer and rancher suicide decedents:

- Only 19% had received mental health treatment (vs. 26.9% of nonfarmers)

- Just 31.7% had any documented mental health problem (vs. 42.6%)

- Farmers were 20% less likely to carry a diagnosed mental illness than nonfarmers (adjusted odds ratio: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9)

- 74.2% involved firearms, compared to 50.3% of nonfarm suicides — a lethality gap that makes early intervention especially critical

| Suicide Method | Farmers (%) | Non-Farmers (%) |

| Firearms | 74.2% ↑ | 50.3% |

| Other methods | 25.8% | 49.7% |

| Lethality gap (percentage points) | +23.9 ↑ | — |

The pain isn’t absent. It’s off the books. Agrarian toughing-it-out culture, geographic isolation, 24/7 livestock schedules, and a critical shortage of farm-literate providers all mean that when a farmer reaches the breaking point, there’s typically no trail in the healthcare system. And with firearms present on nearly every operation, there’s often no second attempt. That’s the specific gap Roecker set out to fill.

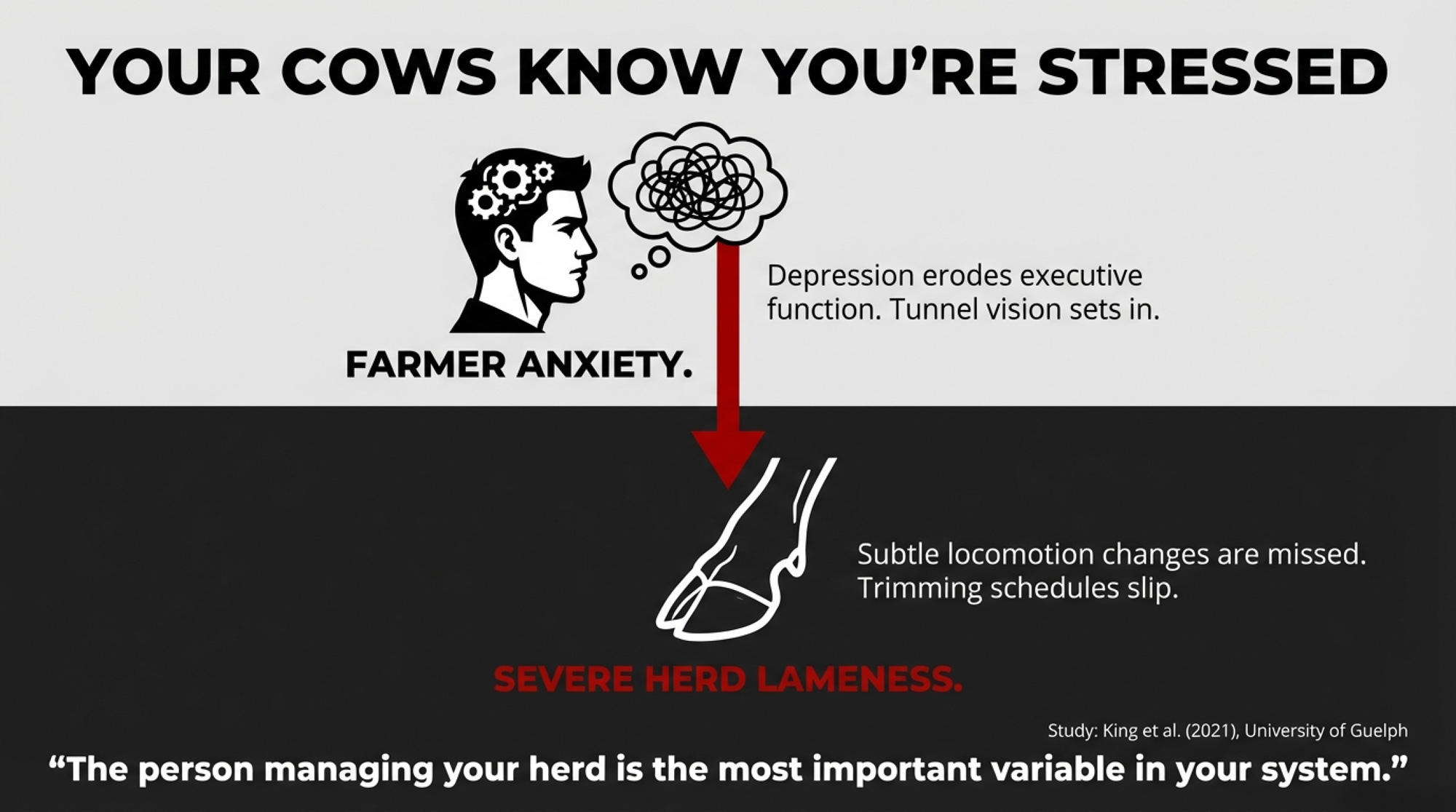

Why Your Herd Data Might Be the First Warning Sign

If you’re a vet or nutritionist, here’s where this stops being a “soft” story and becomes an operational one.

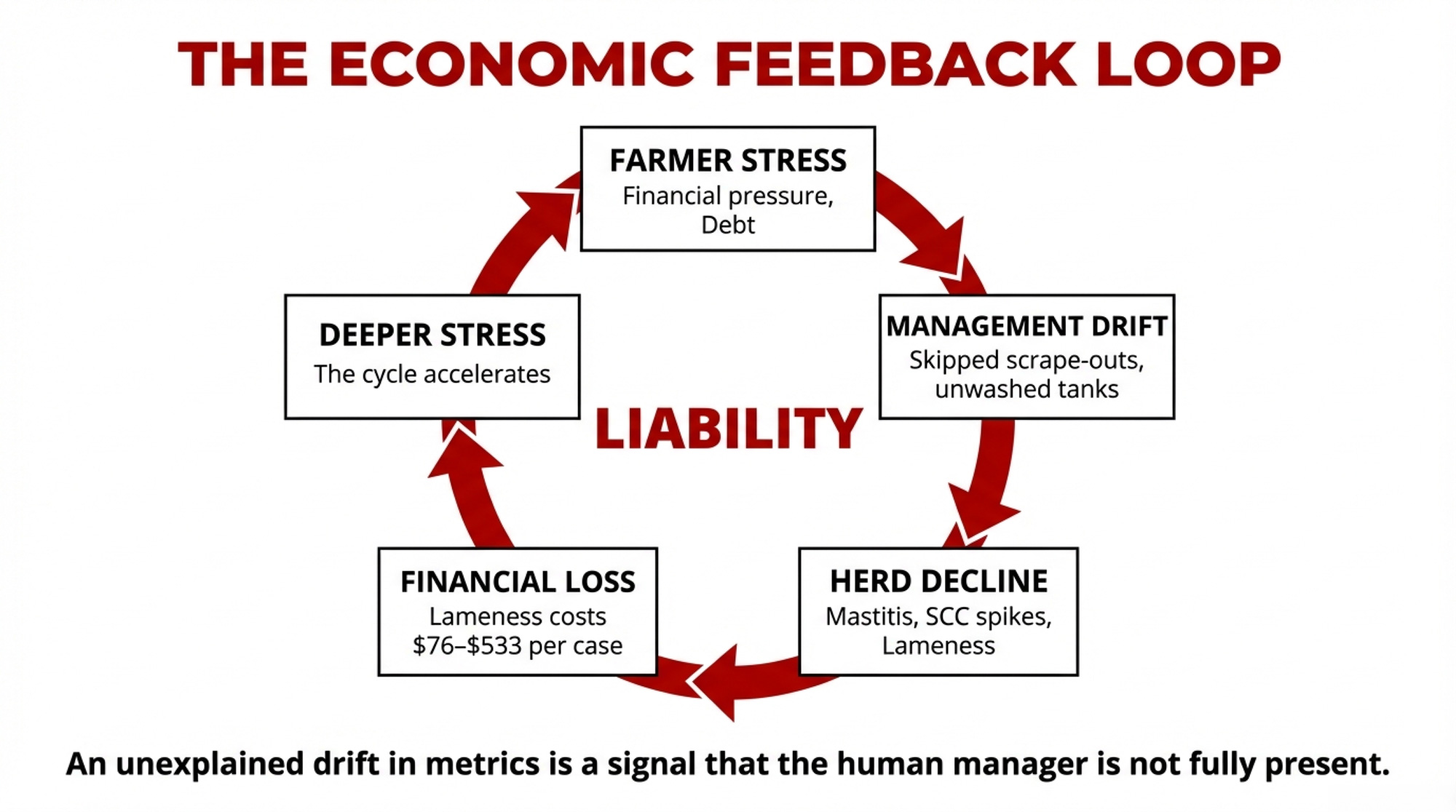

Milk haulers and field reps are often the first to see the “pre-clinical” signs of a crisis. They see the farm at 3 a.m. when the lights are off, but the farmer’s truck is still in the driveway. They see the unwashed tank, the skipped scrape-out, or the overflowing manure pit days or weeks before a vet is ever called for a sick cow.

A 2021 University of Guelph study (King et al., Animal Welfare, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 25–38) surveyed 28 Ontario dairy farms using robotic milking systems and found a statistically significant association between farmer anxiety and depression scores and the prevalence of severe lameness in their herds. First published study to draw a direct line between dairy farmer mental health and measurable cow health outcomes. The research focused on robotic herds in Ontario — this association hasn’t been replicated in conventional operations or outside Canada, though the behavioral mechanism (stress reducing the management attention cows normally get) is unlikely to respect borders.

Lameness runs $76 to $533 per case, depending on severity, lost production, reduced fertility, and culling costs. The mechanism is behavioral: severe depression erodes the executive function you need to catch subtle locomotion changes, stay on top of trimming schedules, and maintain fresh-cow protocols. Tunnel vision sets in. And a feedback loop takes hold that any experienced herd manager will recognize:

Farmer stress → Management drift → Increased lameness and mastitis → Financial loss → Deeper farmer stress

Rumination sensors and milk meters can flag performance drops days before clinical signs become visible — some sensor validation studies have documented alerts three to five days ahead of diagnosis, though the window varies by condition and system. On some farms, an unexplained drift in herd metrics isn’t just a cow problem. It’s a signal that the human manager is no longer fully present.

From Church Basement to National Model

The Farmer Angel Network didn’t begin as a 501(c)(3). It began as neighbors showing up — and as co-founders Randy Roecker and Brenda Statz turning their own grief into a reason to keep other farm families here.

What happened in those early rooms was different from anything a clinical setting could offer. No patient-provider hierarchy. No intake forms. Everyone there had calved at 2 a.m. and understood what it feels like to fail three generations at once. Nobody had to explain why they couldn’t “just take a vacation.”

Dorothy Harms, FAN’s chairperson, has been blunt about the lesson in framing that made everything else possible. “An early lesson learned in hosting gatherings was the focus needed to be on celebrating farming and appreciation for the hard work of farmers by providing an inviting space for farm families to gather,” she wrote in a Wisconsin Farm Bureau feature. Mental health resources were tucked inside those events — in goodie bags, on back-table flyers, through speakers who happened to be QPR-trained — not stamped on the front door.

The result: drive-in movie nights drawing dozens of farm families. Soup-and-sandwich lunches. County fair booths. A room that someone running at a 7-out-of-10 stress level could walk into without admitting anything to anyone. Roecker has noted that some farmers drive two or three hours to attend events because they feel safer in a county where nobody recognizes their truck.

FAN formalized with a board that spans farmers, healthcare workers, vets, Extension educators, and church members. Core activities include peer fellowship gatherings, QPR gatekeeper training for on-farm service providers, direct financial assistance for farmers in acute distress, and partnerships with the Wisconsin Farm Center for counseling vouchers and financial consultants. Culver’s Thank You Farmers Project has backed FAN as one of its named beneficiary organizations. Roecker, who also serves on the Foremost Farms board, has carried the model to the NMPF’s Dairy Defined podcast, NBC Nightly News, and meetings with U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin.

After Brian Webster, a 58-year-old farmer from the Ellsworth area of Pierce County, died by suicide on August 3, 2023, his daughter Jennifer and wife Kim founded a sister chapter in Western Wisconsin — using memorial funds to bring FAN’s peer model to their community. The Washington Post profiled the Webster family’s effort in December 2023. That chapter now hosts its own annual memorial picnic, QPR trainings, and community events.

QPR: What 90 Minutes of Training Sounds Like at 6 a.m.

QPR — Question, Persuade, Refer — is what FAN teaches to people who are already in the driveway. AgriSafe Network offers a 1.5-hour online QPR course tailored to agricultural communities, available at no cost through some state- and grant-funded programs, and offering continuing education credits. As of mid-2022, over 1,700 agricultural community gatekeepers had completed AgriSafe’s QPR program, with 57 certified trainers active across multiple states. Those numbers have almost certainly grown since.

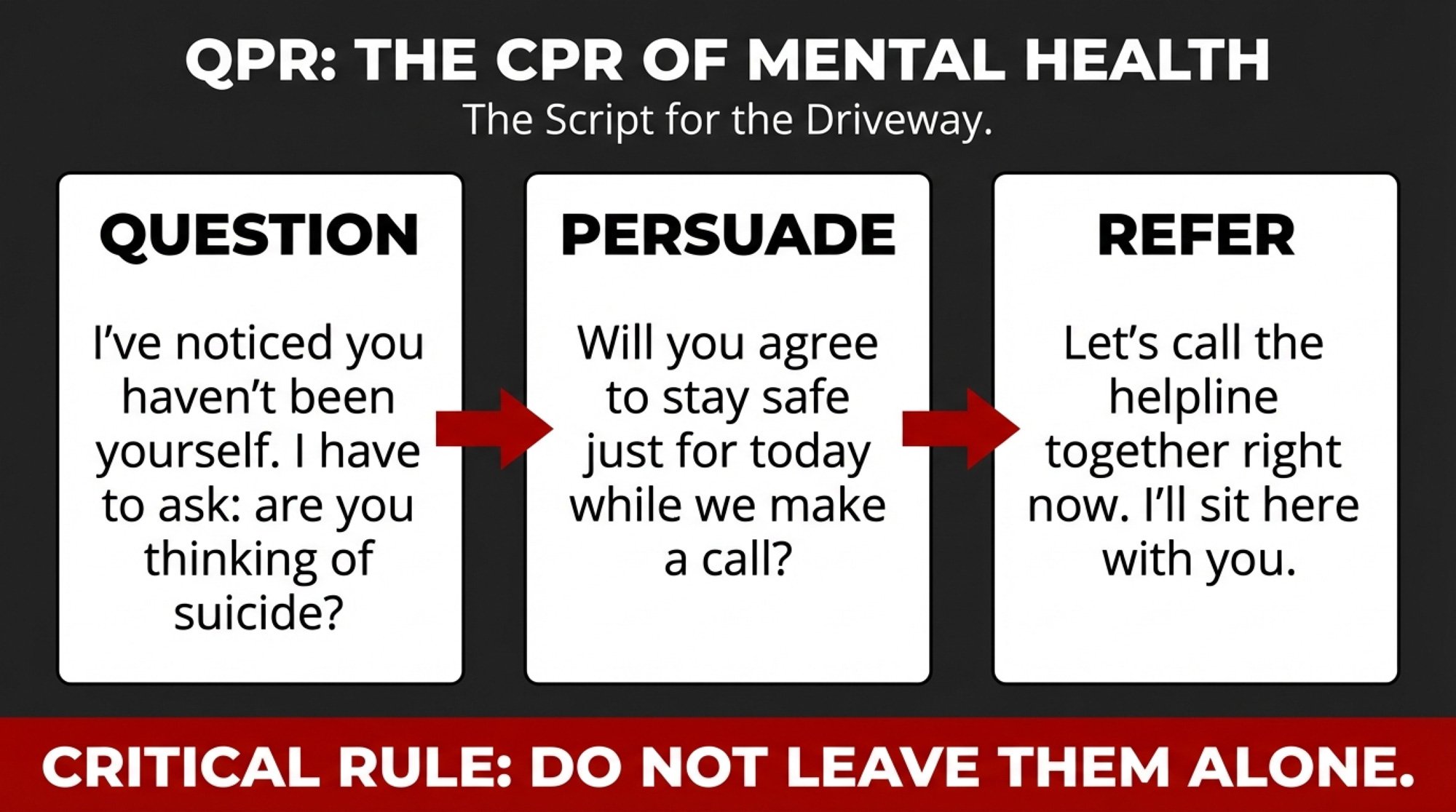

Here’s what each step actually sounds like on a working dairy:

Question — Ground it in something you’ve observed, then go direct. “I’ve noticed the bunk’s not pushed up, you haven’t been yourself the last few pickups. I have to ask you straight: are you thinking about suicide?” You use the word. A systematic review by Dazzi et al. (2014, Psychological Medicine) covering 13 studies found no evidence that asking about suicide increases suicidal ideation, and some evidence that it actually reduces distress.

Persuade — You’re not arguing anyone out of their feelings. You’re securing two things: a time-bound commitment to stay safe today, and agreement to accept help right now. “Can you agree you won’t do anything to hurt yourself today while we get someone on the phone?”

Refer — Don’t hand over a number and drive away. Stay and make the call together. “Let’s call the Farmer Wellness Helpline right now from my truck. I’ll sit here with you.” The FAN playbook is explicit: do not leave someone in immediate danger alone. Offer to drive them to an appointment or help them make the first call.

Biggest mistake in the Persuade step? Trying to talk the farmer out of their pain — “Think about your kids,” “You’ve got too much to live for” — instead of focusing on the one achievable ask: stay safe today, accept one phone call right now.

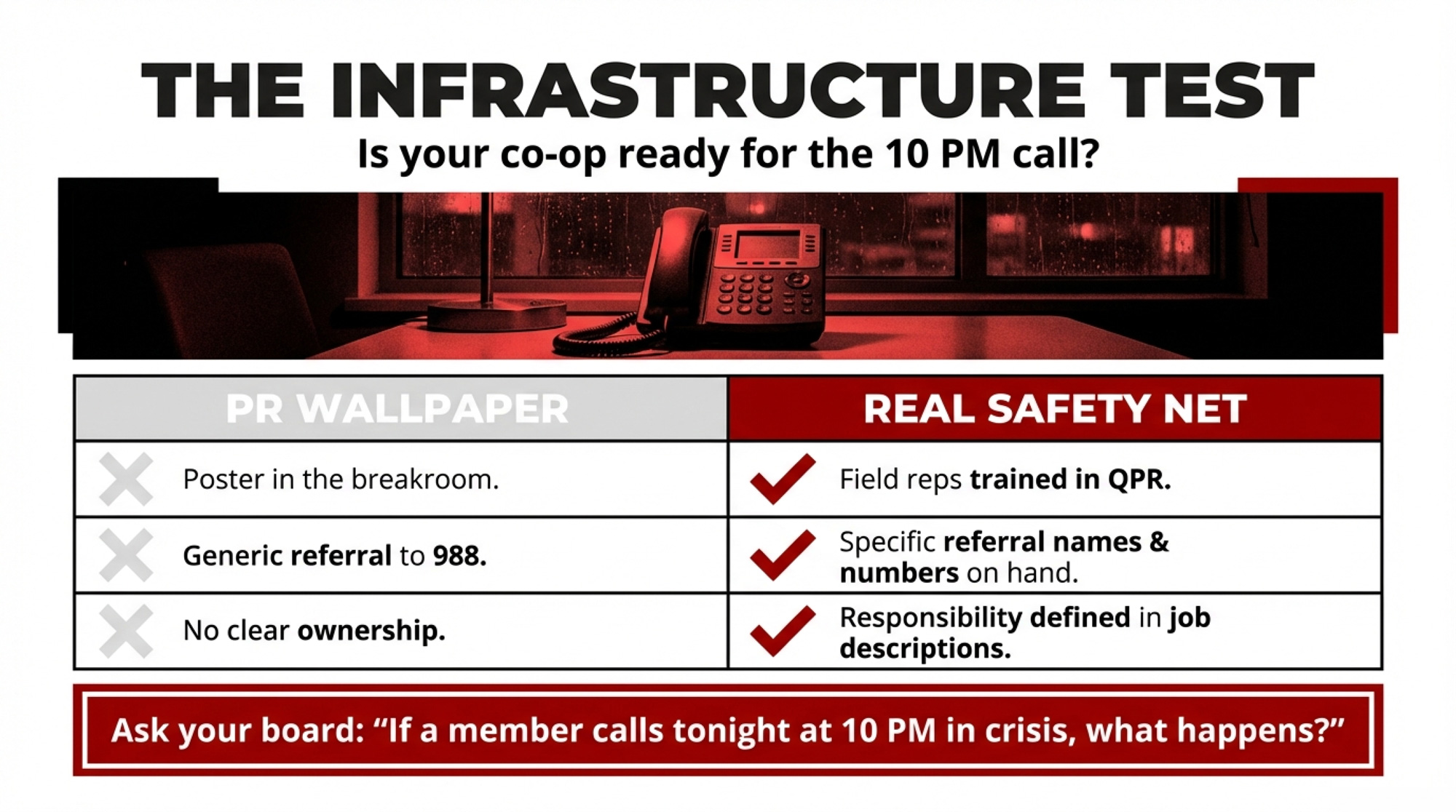

What Real Infrastructure Looks Like vs. the PR Version

Co-ops and industry organizations have ramped up mental health messaging over the last few years. Some of it is genuine infrastructure. Some of it is wallpaper.

Real infrastructure means someone with operational authority owns farmer wellness as part of their job description and budget. Field reps are QPR-trained. There’s a referral pathway to farm-literate counselors. When a member calls in distress at 10 p.m., the person who answers knows what to do—and has permission to do it.

Performance means the hotline number’s printed on the milk check, there’s a conference panel once a year, and nobody can tell you who’s on point if a producer actually calls. Awareness without a pathway is an acknowledgment. It’s not a solution.

Here’s one litmus test: ask your co-op or processor, “If a member called this organization in obvious crisis tonight, what would happen?” If the answer involves specific names, specific training, and specific next steps, that’s infrastructure. If the answer is “we’d tell them to call 988,” you’ve found the gap.

What This Means for Your Operation

- If your stress has been at a 7 out of 10 or higher for two consecutive weeks, that’s the threshold the Farmer Angel Network identifies as the point where outside help isn’t optional — it’s overdue.

- If you’re a vet, nutritionist, or herd consultant watching unexplained drifts in lameness, SCC, or fresh-cow performance — paired with a farmer who seems checked out — you may be looking at one problem with two faces. The Guelph data says the connection between farmer stress and cow lameness is real and measurable (King et al., 2021).

- If you manage field staff at a co-op or processing company, audit whether your people are trained to respond to a farmer in crisis or just trained to hand out a phone number. AgriSafe’s QPR course takes 90 minutes. Over 1,700 ag gatekeepers have completed it. There’s no good reason your haulers and field reps shouldn’t be among them.

- If you sit on a co-op board, ask the infrastructure question at your next meeting: What happens when a member calls us in crisis at 10 p.m.? Don’t accept a vague answer. Make someone own it.

- If your region has nothing like FAN, the minimum viable first step isn’t a nonprofit filing—it’s three phone calls. One farmer you trust, one service provider who sees a lot of farms, one room booked for an hour. Call it a “farmer appreciation coffee.” Give the meeting one job: figure out who in your county already has pieces of the puzzle, agree on one next step, and don’t leave without a date on the calendar.

- If you’ve already lost the farm, Roecker’s story says something the industry rarely says out loud: your life has value and purpose on the other side of that loss. The worst-case scenario is survivable.

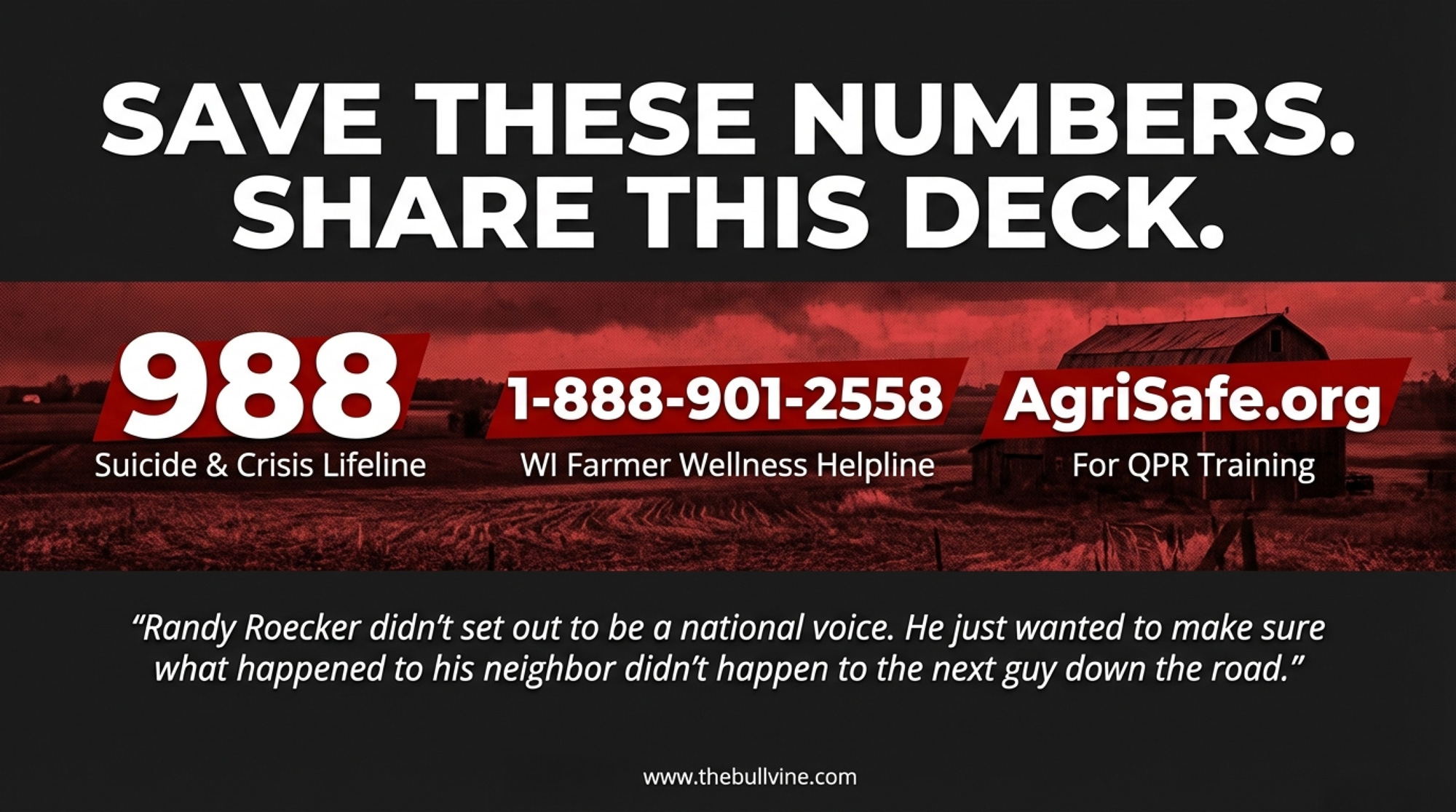

Crisis Resources — Post These Where Your People Can See Them

| Resource | Contact | Availability |

| 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline | Call or text 988 | 24/7 |

| Crisis Text Line | Text HOME to 741741 | 24/7 |

| Wisconsin Farmer Wellness Helpline | 1-888-901-2558 | 24/7, free, confidential |

| Wisconsin Farm Center (DATCP) | 1-800-942-2474 | Business hours + crisis referral |

| Farm Aid Hotline | 1-800-FARM-AID | Mon–Fri, 9am–9pm ET |

| AgriSafe QPR Training | agrisafe.org | 1.5-hour online course |

| Farmer Angel Network | farmerangelnetwork.com | Events, resources, referrals |

The Bottom Line

The person managing your herd is the most important variable in your system. Not the genetics. Not the ration. Not the robot. When that person is drowning — and 81% of the time, nobody in the formal system even knows — everything downstream drifts. Lameness. SCC. Death loss. The cows notice before anyone else does.

Wisconsin went from roughly 15,500 dairy farms in 2000 to 5,222 in 2024. As The Bullvine’s Dairy Curve projection maps out, the industry may be heading toward 15,000 U.S. herds by 2035 and under 10,000 by 2050 if current pressures hold. Every one of those exits is a person, and the system Roecker built exists because nobody was catching them on the way out.

Randy Roecker didn’t set out to become a national voice on farmer mental health. He set out to make sure what happened to Leon Statz wouldn’t happen to the next guy down the road. And he’s still showing up — for the farmer who’s terrified, exhausted, and convinced nobody gets it. That might be the most credible voice there is.

Three phone calls. One room. One next step. The blueprint exists, and the training is available. Who in your county is going to make them?

Key Takeaways

- The gap is real: Dairy farmers are dying by suicide at roughly 3.5× the general rate, and in about 81% of those cases, the farmer never had any mental health treatment at all.

- The driveway beats the clinic: Farmer Angel Network proves you reach more producers when you start with potlucks, fairs, and church basements, then tuck the mental health tools inside.

- Train the people who see you: When milk haulers, vets, nutritionists, and field staff know QPR, they can spot trouble in your yard long before any doctor gets a call.

- Your herd will tell on you: Studies tying farmer stress to higher severe lameness make it clear that ignoring your own mental health eventually shows up in cow health and in your bottom line.

- You can move first: Set your own “7 out of 10 for two weeks” stress line, post 988, and your state farm helpline where everyone on the farm can see them, and push your co-op to have a real plan for the 10 p.m. crisis call — not just a number on the milk check.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Learn More

- Dairy Farmers Face a 3.5x Higher Suicide Risk Than Farm Accidents – What Your Cows See First – Arms you with an immediate action plan to identify hidden red flags in your herd data and deploy on-farm safety nets that actually catch people before they reach the breaking point.

- The Bullvine Dairy Curve: 15,000 U.S. Farms by 2035 and Under 10,000 by 2050 – Who’s Still Milking? – Exposes the brutal structural shift known as “The Dairy Curve,” forcing a hard look at your 2050 survival model and the psychological endurance required to stay in the game.

- Beyond Entertainment: How “Green and Gold” Is Reshaping Agricultural Advocacy – Reveals how unconventional advocacy and media disruption are finally dismantling the cultural silence in rural communities, unlocking millions in new funding for grassroots support networks like the Farmer Angel Network.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!