Think an “outsider” can’t build a serious dairy? An Oscar‑winner with Golden Guernseys proved otherwise — right up until the war took her help away.

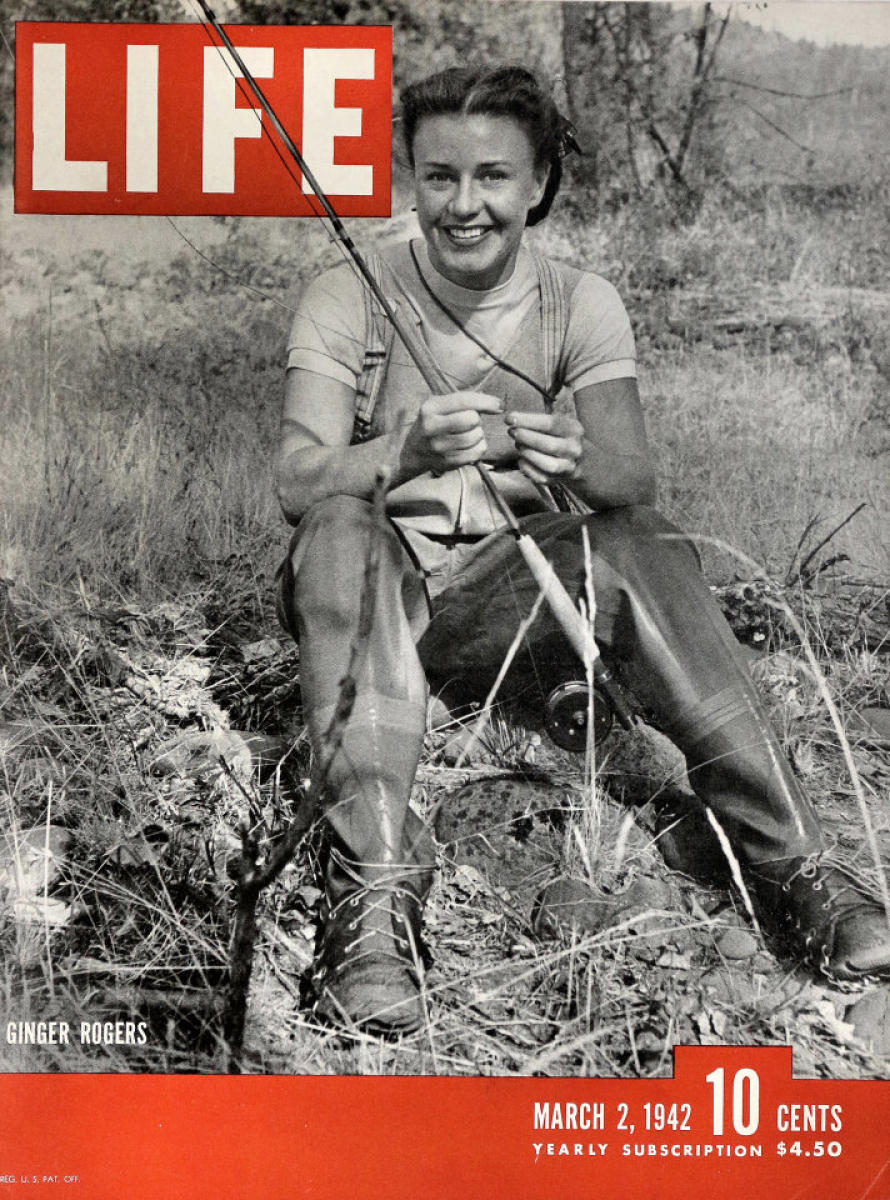

On March 2, 1942, LIFE Magazine hit newsstands with Ginger Rogers on the cover. Not in a sequined gown. Not mid-pirouette with Fred Astaire. She was in fishing gear — rod in hand, somewhere on the banks of her own river in southern Oregon.

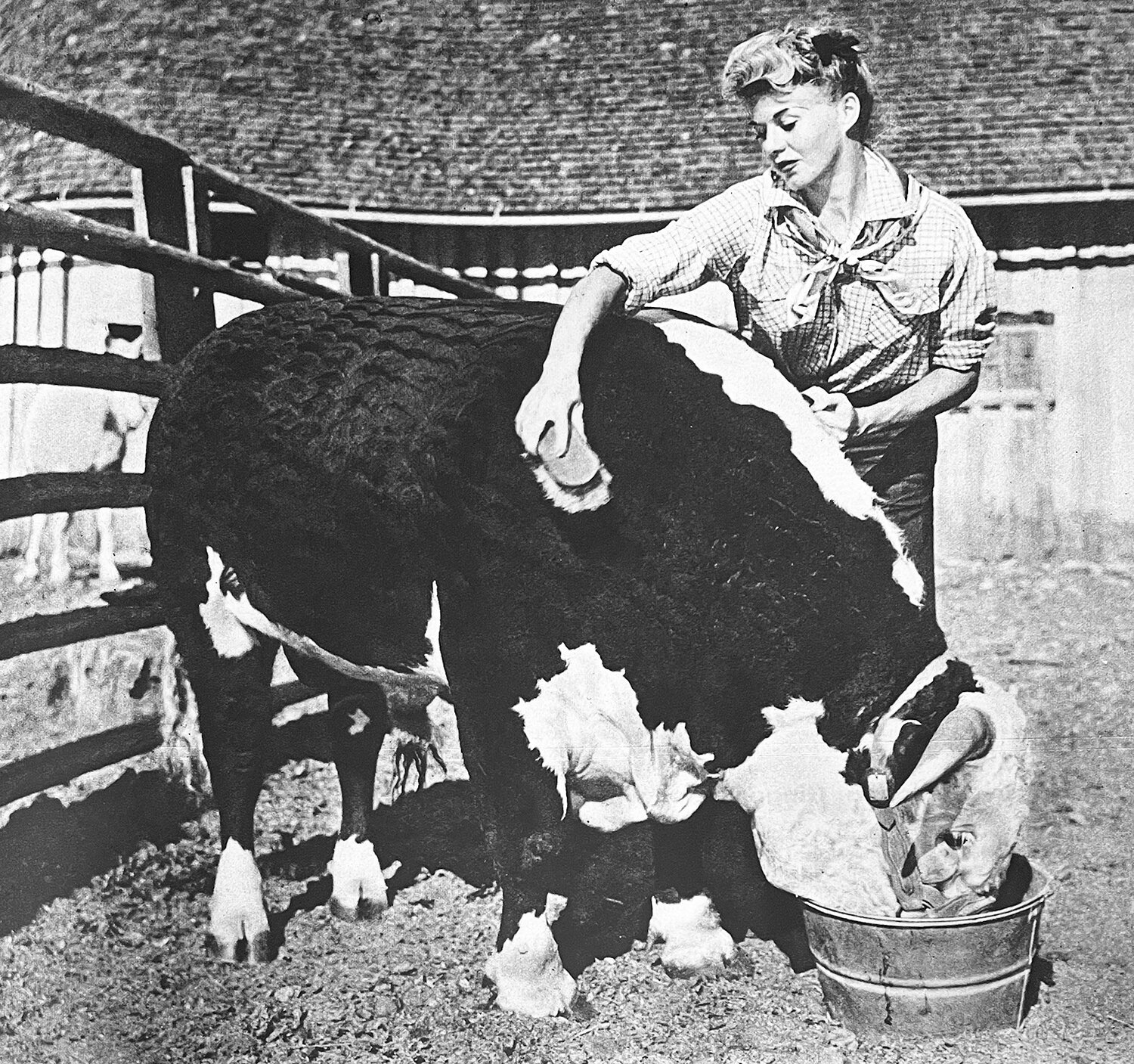

Inside the magazine, the photographs told a deeper story. One showed Rogers on the roof of her ranch house, surveying more than 1,000 acres of the Rogue River Valley — the LIFE caption noted it took her 15 hours to drive here from Hollywood, but she went there often “for a taste of honest country life.” In another, she was feeding wildflowers to one of her 22 cows. And in a third, she leaned against a fence rail with her mother, Lela, and their farm manager, watching the cattle at dinnertime — with a Jersey and a Guernsey looking straight at the camera.

This wasn’t a photo op. By the spring of 1942, Virginia Katherine McMath — the girl from Independence, Missouri, who’d tap-danced her way to an Academy Award — had sunk serious money into Guernsey dairy cattle, purebred Angus beef, and a milking parlor built to standards that meant business. Barely a year off her Oscar win for Kitty Foyleat the 13th Academy Awards on February 27, 1941 — she’d beaten Katharine Hepburn, no less — and still only 30 years old, she was RKO Studios’ hottest commodity.

And she was pouring it all into a dairy.

The Ranch That Wasn’t a Playground

The purchase happened in 1941, the same year as that Oscar. Rogers and her mother bought what would become Rogers’ Rogue River Ranch — locally known as the “4R” — near the hamlet of Eagle Point, about 17 miles north of Medford. Two parcels combined: 470 acres on the east side of the Rogue River, 380 on the west. Eight hundred fifty acres to start.

By 1942, additional purchases pushed the holding past 1,050 acres, with more than 2.5 miles of river frontage on both banks.

Now, the thing about Lela Rogers — she wasn’t some Hollywood stage mother content to ride her daughter’s fame. She’d been a newspaper reporter, a screenwriter, a Marine Corps publicist during World War I. The kind of woman who ran a household like a business long before there was a ranch to manage. When the Medford Mail Tribune came calling, Lela didn’t gush about views or country air. She gave them numbers.

“We will have possibly 50 dairy cows and as many blooded cattle as the ranch will accommodate,” she told the paper. The plan: purebred Angus east of the river, an ultra-modern dairy on the west side, and full stocking within two years.

Two women. A thousand acres. A river between the beef and the milk.

And every skeptic in Jackson County watching to see how fast the movie star would get bored.

The Joke About Bees

The skepticism came fast. When Dr. W. H. Lytle of the Oregon State Department of Agriculture needed to remind celebrity landowners about brand registration, he passed the word through fellow actor Eugene Pallette — a character actor who actually did ranch in eastern Oregon — and cracked that Rogers’ livestock would “probably consist of nothing but bees.”

If you’ve ever been the outsider at a breed association meeting — the one without three generations of family history in the barn — you know exactly the weight behind a joke like that. In rural Oregon in the early 1940s, the idea of a tap-dancing Academy Award winner running a real cattle operation ranked somewhere between unlikely and laughable.

Lela answered in writing. Her daughter had already purchased Golden Guernsey cattle. The brand was decided: “4R.” The letter was firm, factual, and entirely devoid of Hollywood charm.

Then Ginger shut the conversation down herself. When a reporter asked if she really expected the ranch to pay, she didn’t finesse it:

“You’re joking, aren’t you? Why, darn it, I am making it pay. That ranch is no hobby with me. I have enough hobbies. It’s my insurance, and when I’m through in films, I’m going up there to live. I spend all the time I can there now.”

That word — insurance — tells you everything. She’d watched Hollywood careers flame out overnight. She’d seen what happened to stars when the box office turned cold. And somewhere in the back of her mind, the daughter of a woman who’d already reinvented herself half a dozen times decided that land and livestock were the only assets a studio couldn’t take back.

Why Golden Guernseys?

Here’s the breed question, and it’s the one most people skip right over in the “movie star buys a farm” version of this story.

Rogers didn’t fill her parlor with Holsteins. She could have. Holsteins were already the volume leaders by the early 1940s — the safe choice, the breed any co-op fieldman would’ve recommended without thinking twice. Instead, she went looking for Guernseys. And this was back when you could still find them everywhere, before the black-and-white tide swept the breed landscape clean.

The nucleus of her herd traces to breeders in Skagit County, Washington; local Shady Cove historians point to the Tillamook dairy country of northern Oregon. She may have bought from both — a woman stocking a thousand-acre ranch from scratch doesn’t always stop at one sale barn. What we know for certain: by 1942, she had applied for membership in the American Guernsey Cattle Club, formally tying the “4R” brand into the registered breed community.

That wasn’t a casual move. Joining the breed association meant committing to registration, to recordkeeping, to the long game of documented genetics.

What nobody standing in those Rogue River pastures could have known — what Rogers herself couldn’t possibly have predicted — was that the very traits pulling her toward Guernseys in 1942 would, eight decades later, become the foundation of a multibillion-dollar premium milk market. The rich golden color, caused by high beta-carotene that passes directly into the milk. The butterfat that routinely runs above 4.5%, with protein over 3.4%. And a trait nobody had a name for yet: the breed’s extraordinary proportion of A2 beta-casein protein — a genetic characteristic that would eventually reshape how consumers choose their milk.

She picked the golden milk breed before “golden milk” was a marketing phrase. She chose the A2 cow before A2 was a line item on a genomic test.

Twelve Cows, 150 Gallons, and a War

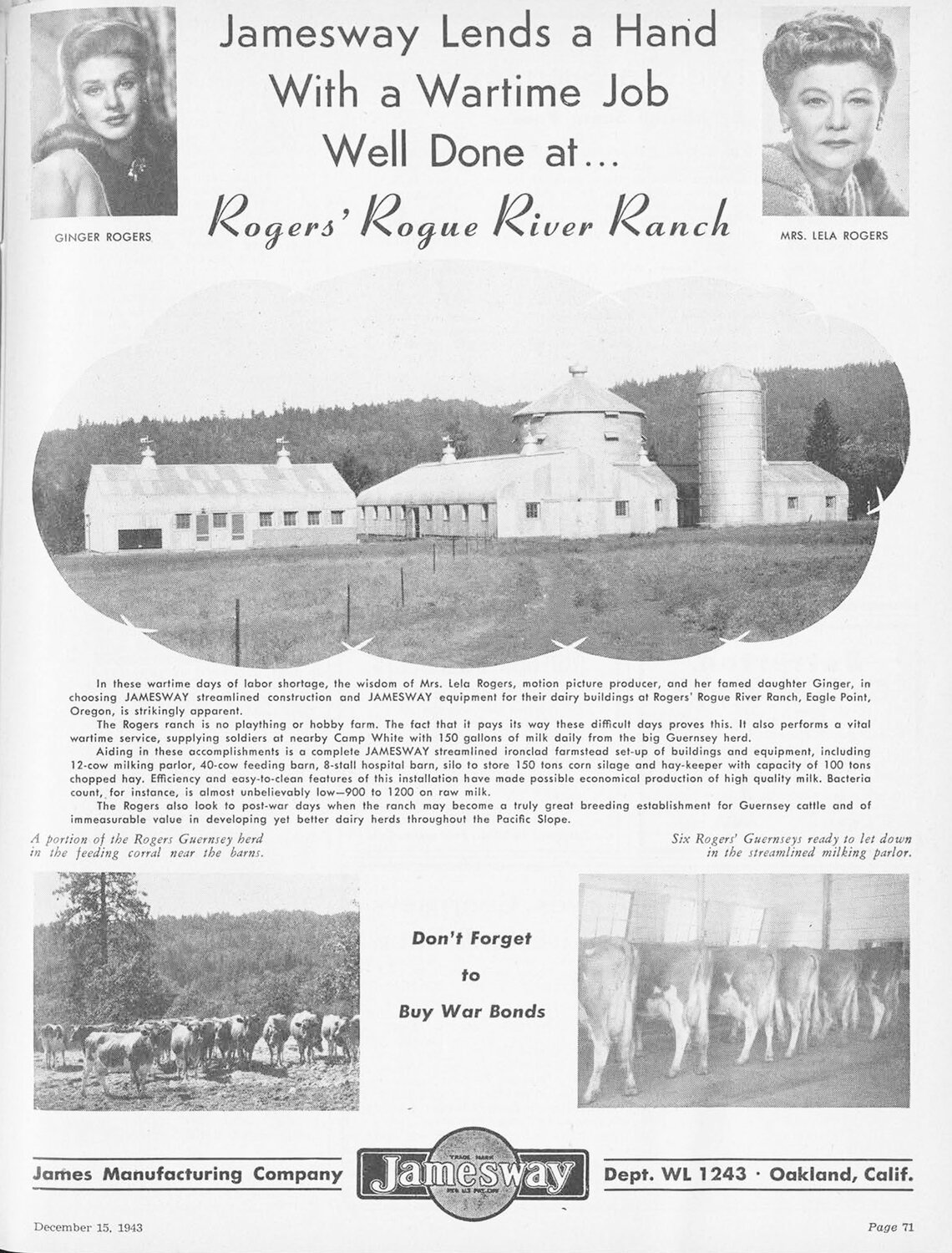

A 12-cow milking parlor with electric milkers — no hand milking, no romance about it. A 40-cow feeding barn adjacent to the parlor. An eight-stall hospital barn — and that’s the detail worth pausing on. She built dedicated space for fresh cows and sick cows, the kind of investment that says somebody on this ranch understood cow care isn’t optional. The woman who fed wildflowers to her cattle also built them a hospital. A 150-ton corn silage silo. A hay-keeper rated for about 100 tons of haylage.

The LIFE photographs show approximately 22 cows in early 1942, with the herd growing to 32 Guernseys at peak capacity. At least one Jersey appears in the LIFE photos alongside the Guernseys — so the dairy may not have been exclusively one breed, though Guernseys clearly dominated and carried the brand identity.

Between filming Roxie Hart — which premiered at the Craterian Theater in Medford in April 1942, the same stage she’d first danced on as a 14-year-old vaudeville performer on April 21, 1926 — Rogers commuted those 15 hours from Hollywood to work the ranch. After gas rationing kicked in later that year, that drive became even harder to justify. She kept making it. She admitted she kept the chores light: no plowing, no hoeing. The electric milkers and the hired crew handled the heavy fieldwork.

And then, in January 1942, the U.S. Army started building a city nine miles from her front gate.

Camp White rose from the Agate Desert in six months flat. A $27 million construction project — more than 1,300 buildings thrown up around the clock, designed to house and train tens of thousands of soldiers. By that August, the 91st “Fir Tree” Division reactivated at a camp that hadn’t existed eight months earlier. At its peak, more than 40,000 soldiers were stationed there, with a training pipeline that would process well over 100,000 during the war years.

Think about that for a second. A military installation the size of a small city, materializing overnight in the Rogue Valley. And a small city needs milk. A lot of it.

The 4R dairy stepped into that gap. Rogers’ Guernseys shipped approximately 150 gallons per day to Camp White, helping supply more than 2,000 soldiers. Run the math: 150 gallons is roughly 1,300 pounds of milk daily. Spread across 32 cows, you’re looking at about 40 pounds per cow per day — solid, honest Guernsey production for the 1940s, right in line with what the breed could deliver under competent management.

The milk had to be clean. Military contracts meant rigorous bacteria-count standards, and the parlor’s infrastructure — electric milkers, dedicated hospital barn, proper feeding facilities — suddenly makes even more sense as equipment designed for consistency and sanitation, not show.

For one brief, brilliant window, the 4R dairy had the best possible setup for a small Guernsey operation: a captive institutional customer with an enormous appetite, a product that stood apart — golden, rich, high in components — and a brand that no other farm in Jackson County could match.

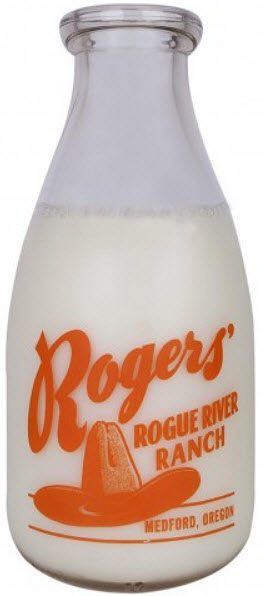

Those embossed Duraglas quart bottles told the whole story. On the glass: “Golden Guernsey (Trade Mark), America’s Table Milk.”

When the War Took the Help Away

Here’s where the story hits the fencepost.

The same war that gave Rogers Camp White as a customer gutted her labor supply. Young men who might have run hay crews, cleaned the parlor, and managed irrigation were shipping out to the Pacific or building Liberty ships in Portland. Rural Oregon was emptying out, and a ranch that needed hands to function was competing for workers against a war economy that paid better and wrapped itself in patriotism besides.

Rogers sold animals from the herd. She entered a profit-sharing arrangement with a partner to keep the operation running. Every dairy farmer who’s ever had to let a hired man go because the margins couldn’t carry the payroll knows exactly what those decisions feel like. These aren’t hobby-farm problems. These are the desperate, 2 a.m. math problems of someone fighting to hold a real business together.

And then — around 1943, barely two years after those first Guernseys arrived — the dairy herd was sold.

Let that land for a moment.

The woman who’d stood in front of reporters and declared “darn it, I am making it pay” watched her Golden Guernseys leave the property. The parlor went quiet. The bulk tank went dry. The “4R” brand stayed on the Angus, but the dairy — the thing she’d joined the American Guernsey Cattle Club for, the thing she’d built a hospital barn and a silage silo for — was done.

She never said publicly how that felt. But remember what she’d told writer Jack Holland: the ranch was her “biggest thrill,” her “secret desire.” She’d confessed she never told anyone about wanting it — “Perhaps because I didn’t want to listen to a lot of idle talk and advice as to why I would be foolish to buy a ranch.”

Selling those Guernseys must have tasted like proving every skeptic right. Even though the real enemy wasn’t bad judgment. It was a world war.

Holding On

A lesser person walks away. Rogers held the land.

The Angus stayed. The river kept running. She fished steelhead on drift boats with Glen Wooldridge — the pioneer whitewater guide who later said she was one of the best guests he ever took on the Rogue. She took camping trips without leaving her own property. A thousand acres was enough wilderness to get lost in, if getting lost was what you needed. She climbed her own silo — a photograph that still circulates on the internet eight decades later, showing an Academy Award winner in work clothes scaling a concrete tower like she owned the place. reddit

Because she did.

In 1948, three years after the war ended, she started restocking the ranch with cattle, aiming for another run at the vision she and Lela had sketched in 1941.

But the dairy world she re-entered was shifting underneath her. Artificial insemination was gaining traction. Holstein dominance was accelerating. The breed landscape that had been a patchwork of Guernseys, Jerseys, Ayrshires, and Brown Swiss was beginning its long consolidation into the black-and-white monoculture that would define the next half-century. Decades later, a woman from Tillamook County who’d raised a Guernsey 4-H calf named Java Jive in 1962 would look around her community and mourn: “Those were the days when Jerseys and Guernseys were everywhere. Now, Tillamook is a black and white landscape of Holsteins.”

Rogers’ Guernseys had already become part of that disappearing world.

By 1959, a portion of the ranch went up for sale — the first crack in the thousand-acre footprint. She held the rest for three more decades, finally selling the remaining parcels in 1990. She kept a home in the area — a resident of nearby Shady Cove, according to local records. On November 21, 1993, just over a year before her death, the 82-year-old Rogers stood on the stage of the Craterian Theater, the same house where she’d danced as a teenager in 1926 and premiered Roxie Hart in April 1942, and urged the crowd to help save the aging building. She re-introduced what she called her favorite film and helped raise more than $100,000 for the theater’s restoration.

For half a century, the communities along the Upper Rogue knew her not as the woman who danced backwards in high heels, but as the neighbor who ran a ranch as a business, fished the river like she meant it, and never treated southern Oregon like a set that could be struck after the cameras stopped rolling.

On April 25, 1995, Ginger Rogers died at her home in Rancho Mirage, California. She was 83. She was cremated and interred at Oakwood Memorial Park in Chatsworth — next to Lela.

Mother and daughter, together at the end. The way they’d been together at that fence rail, watching cattle come in at dinnertime on the Rogue.

After her death, more than 3,000 locals signed a petition to rename the Craterian Theater in her honor. The Medford City Council agreed. It became the Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater — and the stage carries her name to this day.

The Milk Bottle That Outlasted the Parlor

You can still hold one of Ginger Rogers’ milk bottles in your hands.

The Owens-Rogers Museum in Independence, Missouri — the town where she was born — has sold original 4R Dairy Duraglas quart bottles, donated by Rogers’ longtime secretary, Roberta Olden. Turn one over and you’ll find the words that mattered: “Golden Guernsey (Trade Mark), America’s Table Milk.”

That phrase — embossed in glass, surviving decades after the cows that filled those bottles were sold, after the parlor that processed their milk went silent, after the woman who built it all was laid to rest — carries more weight now than it did in 1942.

Because the bet Ginger Rogers placed on Golden Guernsey milk has turned out to be exactly right.

The Breed She Saw Before Anyone Else

Of all tested Guernseys in the American Guernsey Association database, over 80% carry the A2A2 genotype for beta-casein — and every Guernsey sire currently in AI service tests 100% A2A2. That’s not an accident. Decades of selection by breeders who understood that what makes Guernsey milk different is what makes it valuable produced a breed now sitting at the front of a consumer revolution.

The global A2 milk market — driven by buyers seeking milk they believe is easier to digest — is projected to grow from roughly $3 billion to over $7 billion by 2034. Guernseys, with their naturally dominant A2 genetics, own the inside lane.

Layer on butterfat above 4.5%, protein over 3.4%, and that unmistakable golden color — the same color that made Rogers’ bottles look different from every other quart in Jackson County in 1942 — and you’ve got a breed that seems purpose-built for the premium, direct-to-consumer, story-driven dairy model attracting a new generation of farmers.

Farms like Promise Valley Farm & Creamery on Vancouver Island are the living proof. Mark and Caroline Nagtegaal — both first-generation dairy farmers — tried conventional Holsteins first. Struggled financially. Dispersed the herd in 2015 and sold their quota. But they still had the dream. They connected with Leon Zweegman at Rozelyn Farm in Lynden, Washington, a passionate Guernsey breeder who sold them their foundation animals. Today, their 14-cow registered Guernsey herd is 100% A2A2 and certified organic — the only certified organic Guernsey herd in Canada. They process on-farm into yogurt, whole milk in branded glass bottles from a self-serve dispenser, and feta in traditional whey brine.

In Idaho, Paul Herndon at Pleasant Meadow Creamery runs a similar operation: all registered Guernseys, every animal A2A2, raw milk sold direct to consumers who drive to the farm specifically because they want what Guernseys produce.

Rogers didn’t have yogurt cups or self-serve dispensers or Instagram. But she made the same fundamental move these operations are built on: pick a breed that produces something visibly, measurably different. Find a customer who values that difference. Build the infrastructure to deliver it every single day.

What Ginger Rogers Left the Dairy Industry

She didn’t leave a prefix in the herdbook. The 4R Guernseys, dispersed around 1943, are too far back and too few in number to trace forward into modern pedigrees or sire catalogs. Her genetic footprint in the breed is, honestly, invisible.

But the legacy that matters here isn’t written in bloodlines. It’s written in conviction.

Rogers proved — in 1941, when the notion was laughable — that someone from entirely outside the industry could enter dairy farming with serious intent, build a real operation, join the breed community, and produce milk that met the standards of a wartime military contract. She didn’t succeed permanently. The dairy lasted barely two years before economics and labor broke it. But she tried with everything she had. And when the herd was gone, she held the land for five more decades because she believed in what it represented.

Every time a career-changer walks into a Guernsey breeder’s barn and says “I want to build something different,” they’re walking a path she helped beat through the skepticism. Every time a 14-cow Guernsey dairy stamps “A2A2” and “Golden Guernsey” on a glass bottle and sells it for three times the conventional price, they’re reaching for the same thing an Oscar-winning actress and her mother reached for on the banks of the Rogue River, 85 years ago.

Her Place in Dairy History

The bottles are still out there. Heavy Duraglas quart glass, embossed with the 4R logo and the words that told the whole story.

The woman who filled them is gone. The cows are gone. The parlor is gone. The ranch itself has been carved into pieces and sold to strangers. But the bet she placed — that golden milk from a breed most people overlooked could be worth more than a studio contract — has never looked smarter.

Somewhere in southern Oregon, the Rogue River still runs past the ground where an actress decided her real life wasn’t on a soundstage. It was in a barn, at dawn, with Golden Guernseys breathing steam into the morning air.

For a woman who spent her whole career proving she could do anything Fred Astaire did — backwards, and in high heels — this might have been the role she was proudest of.

Key Takeaways

- Ginger Rogers didn’t play “hobby farm.” She poured Oscar money into 1,000 Rogue River acres, a 12-cow Guernsey parlor, and real, working-dairy infrastructure.

- At its peak, her 4R Guernseys shipped about 150 gallons a day of Golden Guernsey milk to Camp White, helping fuel over 2,000 WWII soldiers on the Agate Desert.

- The same war that created that market stripped her labor and forced a painful herd dispersal after just a few years — yet she held the land for roughly 50.

- Today’s A2A2 Guernsey micro-dairies — from Promise Valley in Canada to Pleasant Meadow in Idaho — are finally monetizing the golden milk and components she chose.

- For modern producers, her legacy isn’t in pedigrees but in mindset: premium milk, clear breed identity, and the guts to build a serious dairy as an “outsider” can still pay.

Continue the Story

- After 75 Years and 850 Doorsteps, One Number Forced Cooil’s Dairy to Choose – How Close Are You? – Built in the same 1942 era Rogers was navigating, Leslie Cooil’s start parallels the 4R vision of service and direct-to-consumer sustainability. It is a powerful look at the grueling long-game commitment Rogers was forced to leave behind.

- Why the A2 Boom Bypassed Heritage Breeds – And What’s Actually Working – This deep-dive into breed politics and market shifts explains the industry forces Rogers saw coming. It provides the essential context for understanding why her bet on Golden Guernseys was genetically sound but economically ahead of its time.

- Waterloo dairy farm producing milk that’s easier to digest – Tracing the line from Rogers’ “Golden Guernsey” quart bottles to the modern success of operations like Eby Manor, this profile proves her foundation held. It shows how today’s breeders finally monetized the “insurance” she first identified on the Rogue.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!