Half a million lost calves. Thirty billion dollars in milk. One bull at the center of both: Walkway Chief Mark.

Walk into any Holstein barn in North America tonight. Pick out the best-uddered cow in the string — the one whose fore attachment makes you stop mid-stride, the one pushing components that keep surprising you. Trace her pedigree back far enough, and you’ll almost certainly land on the same bull.

A bull who was never supposed to be sampled. A bull who got his shot because his brother died.

His name was Walkway Chief Mark. He accounts for roughly seven percent of every Holstein genome on this continent. And his story is the strangest, most consequential accident in the history of dairy cattle breeding.

A Farmer’s Eye and a Dead Brother

Foster Walk farmed outside Neoga, Illinois — a speck of a town in Cumberland County where the land flattens out and the horizon stretches until it gives up. This was the late 1970s. Corn ran under two bucks a bushel, Elevation daughters were the standard everyone measured type against, and most breeding decisions happened on gut instinct and a phone call to your AI rep. Genomic testing? That was science fiction nobody had dreamed up yet.

Foster had what the old cattlemen call “the eye.” While big-name breeders flew to national sales and bid top dollar on headline animals, Foster worked the margins. He’d buy groups of heifers at 21 cents a pound — bargain-bin stock by any standard — and somehow spot genetic potential hiding under less-than-perfect frames. Diamonds in the rough. That was his phrase, and he had an infuriating tendency to be right about it.

Walkway Farm wasn’t some fly-by-night operation, either. Foster had been advertising registered Holsteins in Holstein World as far back as 1958 — two full decades before his most famous calf hit the ground. When a cow in his herd hit a production milestone, the Journal Gazette and Times-Courier out of Mattoon ran it: Walkway Janice Prince, 20,511 pounds of milk and 876 pounds of butterfat in 365 days. This was a working dairy with the Walkway prefix on real cattle making real milk, not just a pedigree footnote.

A young sire analyst named Charlie Will had grown up in the same neighborhood. He’d graduated from the University of Illinois in 1974 and tried to get hired at Select Sires. They turned him down. He took a sales territory in Wisconsin that nobody else wanted, worked it until a sire analyst position finally opened in 1978, and got his shot — the same year Chief Mark was born.

Charlie had his eye on Foster’s operation, but not for the calf who’d change everything. He wanted Monroe — Chief Mark’s older brother. The contract was signed and the collection schedule set. Monroe was the plan.

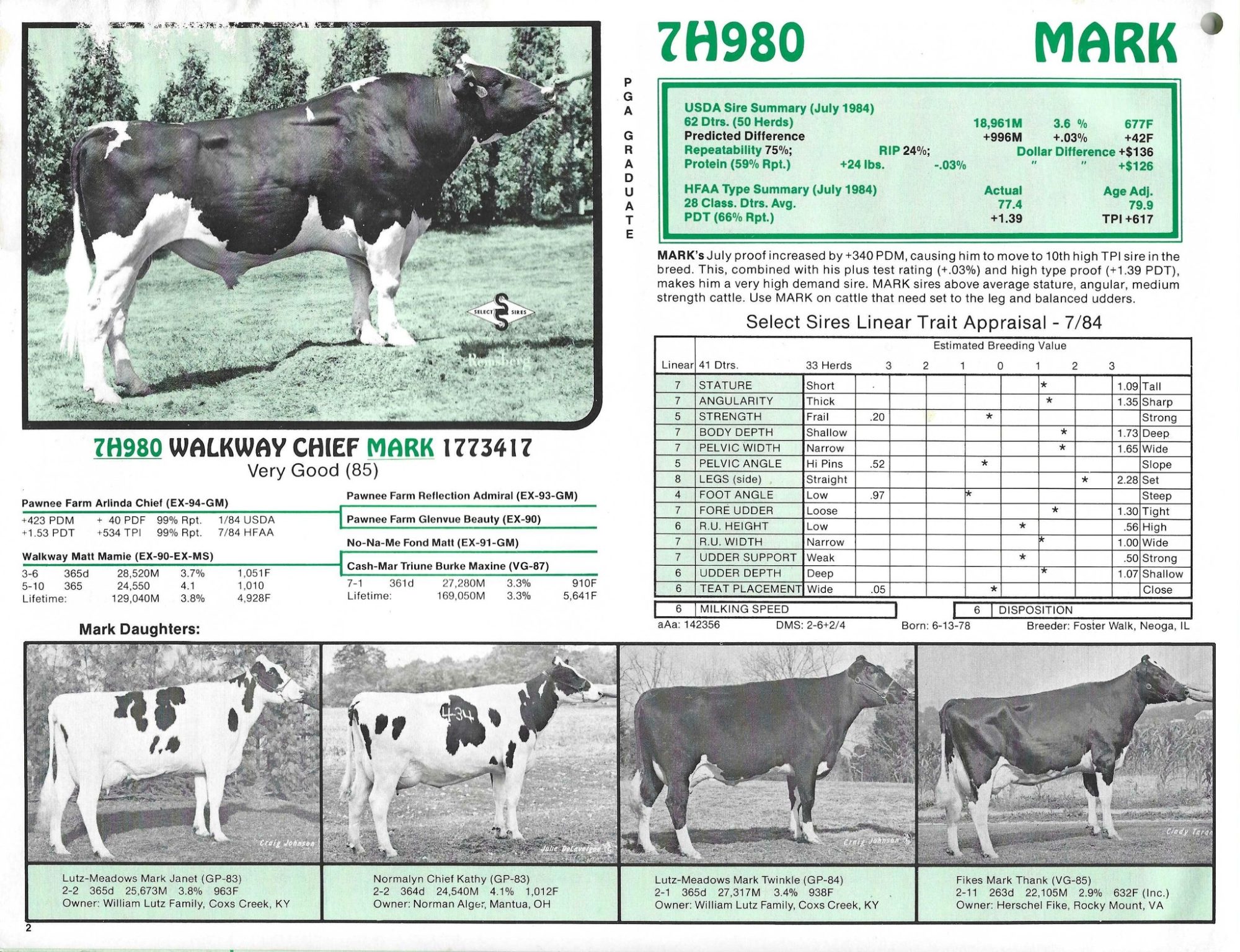

Then Monroe died during test services.

One phone call. Charlie Will — the analyst who’d been rejected himself — decided to gamble on the younger full brother. Born June 13, 1978, registration HOUSA000001773417, a Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief son out of a EX-90 No-Na-Me Fond Matt daughter named Walkway Matt Mamie (EX-90 GMD DOM). Mark was the first bull Charlie ever bought for Select Sires. (Read more: Charlie Will’s Comeback: How One Rejection Letter Created Holstein History)

A rejected analyst picking a replacement bull from a neighbor’s farm as his very first acquisition. You can’t make this stuff up.

Whether Foster or Charlie imagined what that calf would become, the record doesn’t say. But that replacement bull would go on to sire 57,654 daughters and reshape the genetic architecture of an entire breed.

The Contradiction

When Chief Mark’s first daughter proofs came back through Select Sires — coded 7HO980 in every AI catalog in the country — the reaction wasn’t celebration. It was bewilderment.

You have to understand how breeding evaluation worked in the early 1980s. There were no genomic predictions. No SNP chips. You bred daughters, waited years, measured them against their contemporaries, and published the deviations. Everything was relative — how much better or worse did this bull’s daughters perform compared to the current cow population?

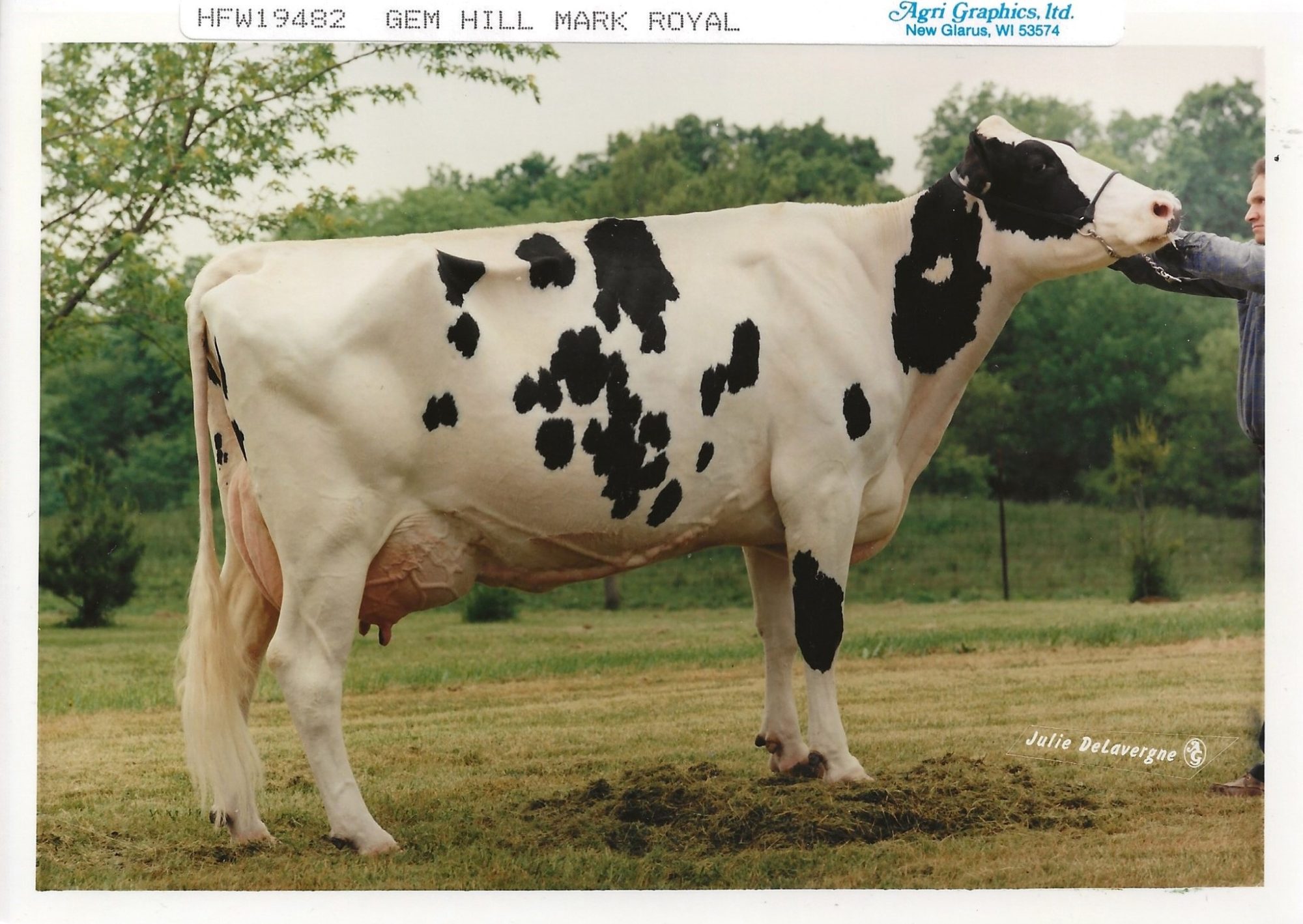

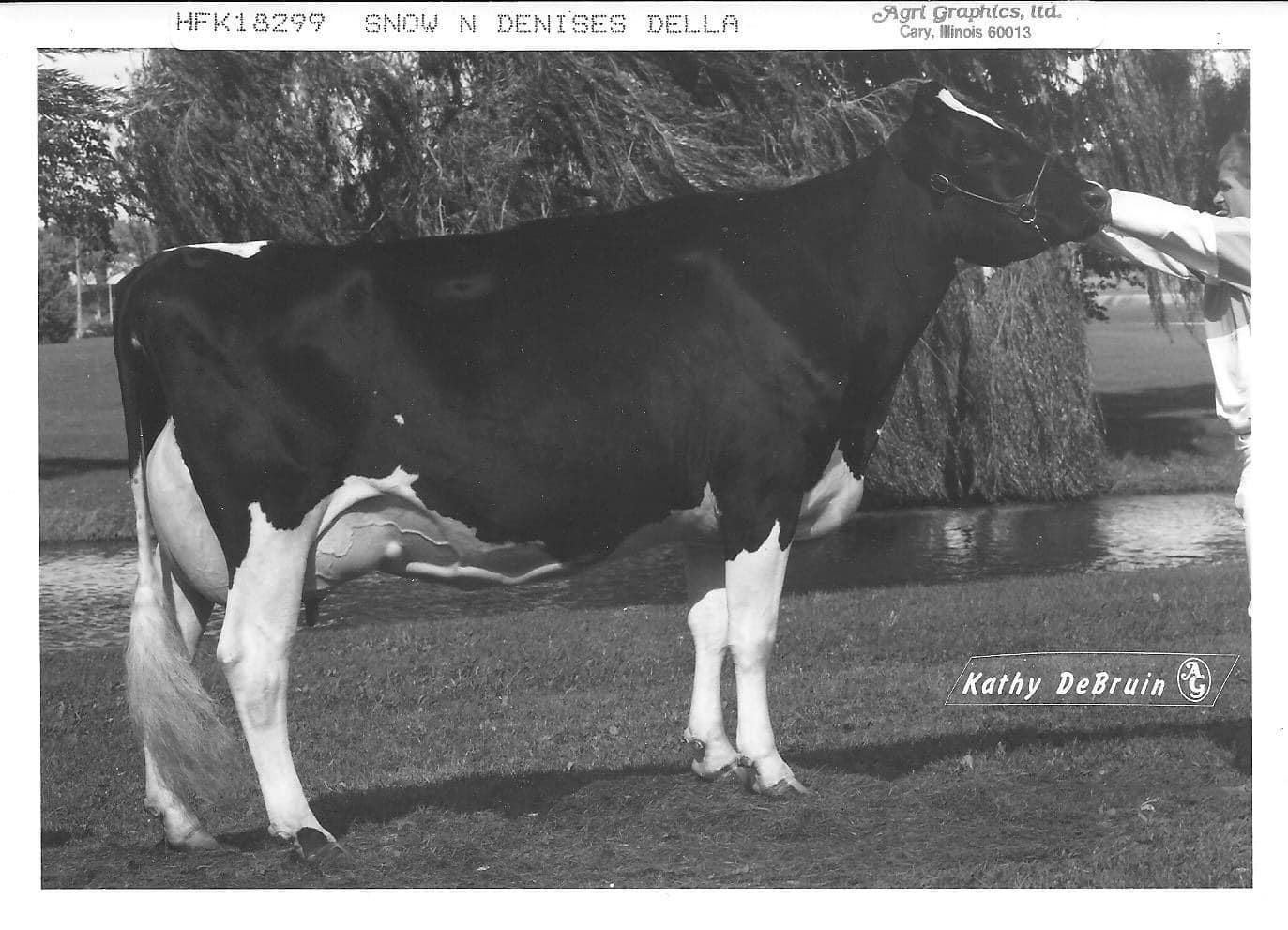

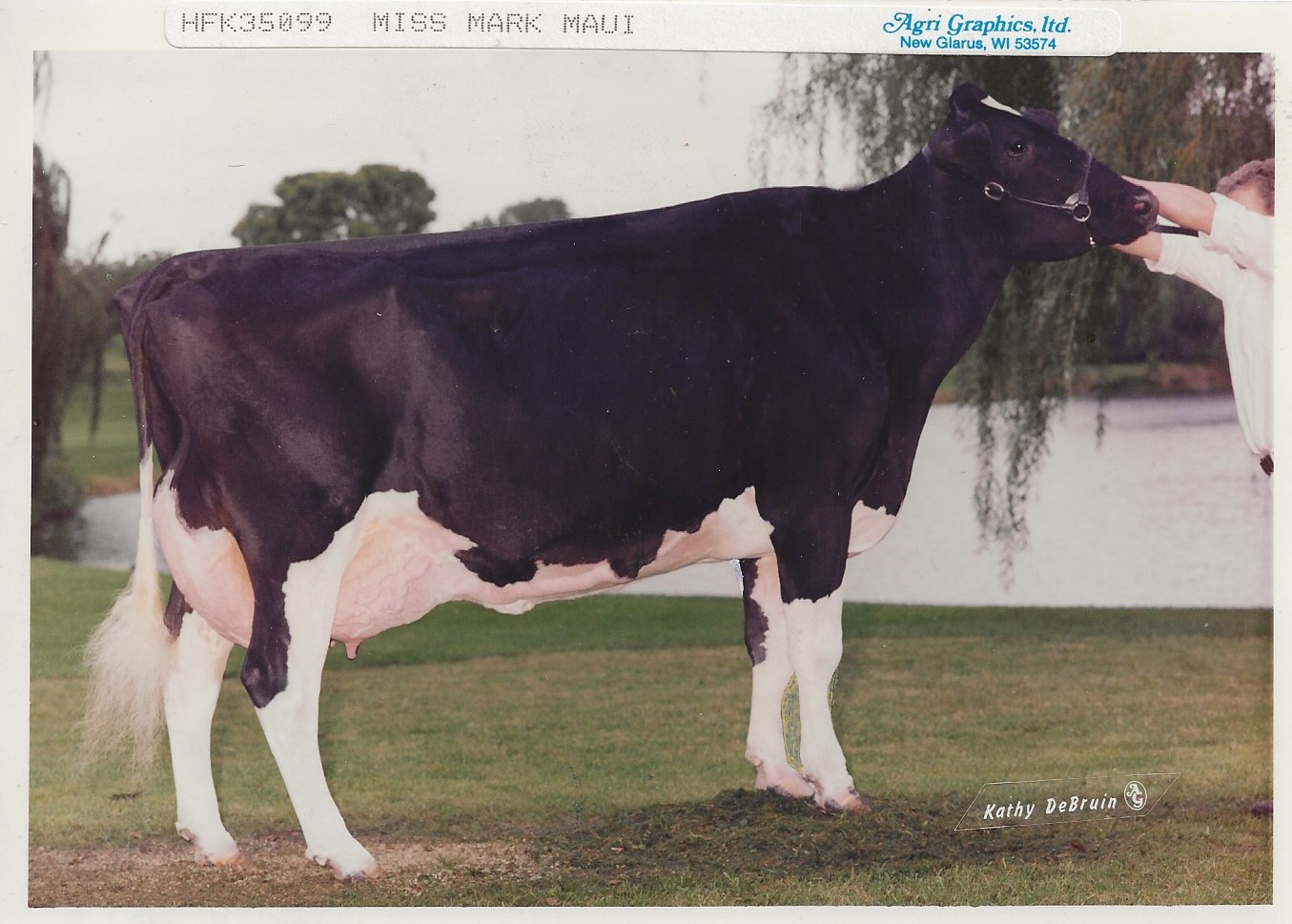

Relative to the Holstein cows of that era, Chief Mark’s udder transmitting ability was a leap forward, unlike anything the breed had seen at that scale. Fore attachments, rear attachments, teat placement, udder depth — all trending dramatically above what anyone else in the lineup was producing. Breeders who saw his early daughters in person talk about them with a specific kind of reverence: large, sharply attached mammary systems with long, clean necks into the body wall, deep angular ribbing, dairy character you could spot from across the yard. One breeder on a Holstein forum captured it perfectly: “When they come into the show, you love them”.

Then he finished the thought: “however when they turned side way, you see the legs and high pins”.

There it was. The paradox.

Because when you flipped to the structural data, even on a relative basis, the numbers were devastating. Shallow heels. Weak pasterns. The structural curse traced back through his maternal line, through No-Na-Me Fond Matt, like a family inheritance nobody could outrun.

Measured against the cows of his era, the greatest udder improver of his generation was also one of the worst structural sires alive. The same genetics that built those magnificent mammary systems wrecked the feet beneath them.

And breeders had a decision to make.

The Deal with Fine Print

They took it. By the thousands.

Ask anyone who milked Chief Mark daughters in the ’90s, and they’ll tell you the same thing: best udders in the barn, worst feet in the barn. Some guys swore by him. Some guys swore at him. Most did both.

Smart breeders figured out the workaround. As one veteran put it, “you would have to protect the mating”—use Chief Mark on cow families with strong feet and legs, and let the udder magic do its work. The strategy wasn’t perfect, but it worked often enough to justify the gamble. When it worked, the daughters were jaw-dropping.

By the mid-1990s, the NAAB database would eventually show 57,654 production-tested daughters carrying his genetics across American herds. Most AI studs don’t produce that many daughters from their entire lineup in a decade. Chief Mark did it from a single catalog entry.

But genetics always collects its debts.

On larger operations that used him heavily without careful mating management, the structural toll was brutal. By the third lactation, the feet caught up. Trimming schedules accelerated. Digital dermatitis became a constant battle. You’d walk through a pen of Chief Mark daughters, making 90-pound peaks — udders attached like textbook illustrations, production numbers rewriting the farm’s economics — and half of them were sore-footed.

You don’t want to ship a cow making that kind of milk. But you can’t keep a cow that can’t stand up.

The Hidden Killer Nobody Knew About

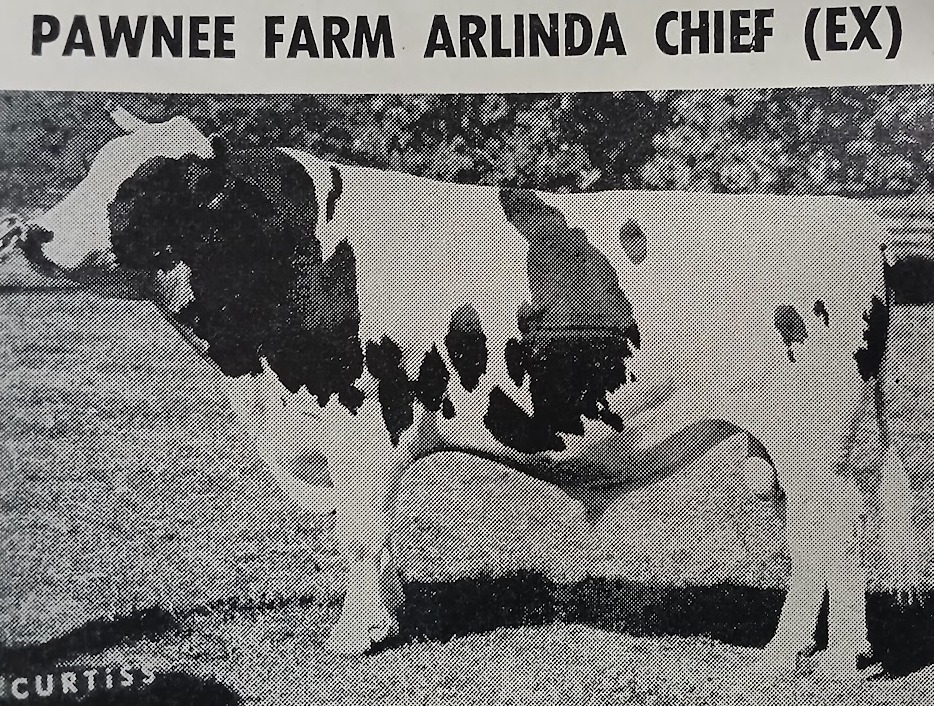

The scope of Chief Mark’s influence becomes truly staggering when you trace it back to his father.

Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief was born in 1962 and produced 16,000 daughters, 500,000 granddaughters, and more than 2 million great-granddaughters. His chromosomes account for almost 14 percent of the genome in the current U.S. Holstein population. Chief Mark, as one of Chief’s most prolific sons, carried and amplified that genetic footprint through a massive daughter population of his own.

What nobody knew — for three decades — was that Chief had given his descendants something besides production and udder quality.

In 2011, USDA researchers identified a problematic haplotype on chromosome 5 in Holstein cows that was associated with lower fertility and embryo loss. They traced it back to Chief. They contacted Harris Lewin, a geneticist who had sequenced both Chief and Chief Mark at the University of Illinois in 2009, and asked whether his team could identify a candidate mutation.

Lewin and co-author Heather Adams found it in less than 24 hours.

“It was a Eureka moment!” Lewin said.

The mutation sat in a gene called APAF1 — a “nonsense” mutation that shortens an amino acid chain critical for protein-to-protein interactions. One copy makes a calf a carrier. Two copies — one from each parent — kill the embryo. Among more than 246,000 Holsteins tested, researchers found zero animals carrying APAF1 from both parents. Every double-copy pregnancy ended before the calf drew a breath.

The numbers were staggering. Over 30 years, the APAF1 mutation caused an estimated 500,000 spontaneous abortions worldwide — more than 100,000 in the United States alone. A single midterm abortion costs a dairy about $800. Total estimated loss: approximately $420 million.

Think about that for a second. For decades, every time a farmer milking Chief descendants saw an unexplained pregnancy loss, they shrugged, logged it as bad luck, and moved on — that was APAF1. One bull’s hidden genetic tax, collected silently across thousands of operations for a generation.

But the math cuts both directions. Chief’s beneficial genetic contributions — the production, the udders, the overall improvement — are estimated at roughly $30 billion in increased milk production over the same period. Thirty billion against $420 million. The value outpaced the cost seventy-to-one.

And now breeders can test for APAF1 and avoid mating two carriers while keeping everything that made the lineage great. The curse has been identified and neutralized. The gifts remain.

Both Sides of the Pedigree

When analysts traced the pedigrees of the breed’s top 10 GTPI females they kept running into the same name. Mark. Forty-two times across those ten pedigrees, with Starbuck the only other bull in the same league at thirty-five. And here’s the telling detail: thirty-three of those Mark appearances were as sire of a female in the lineage, while nine were as sire of the male. He dominated both sides of the pedigree.

Only a handful of bulls in Holstein history have earned what The Bullvine’s own analysis calls the distinction of “sons and daughters both extraordinary”. Chief Mark was one of them.

And the most consequential genetic river flowing from Chief Mark ran through a son named Mark CJ Gilbrook Grand.

The Goldwyn Connection

Grand’s name doesn’t ring bells with most modern breeders. But it should. Because Grand sired Shoremar James. And Shoremar James sired Braedale Goldwyn.

In Goldwyn’s lineage were three crosses to Walkway Chief Mark: Shoremar James and Braedale Gypsy Grand were both by Mark CJ Gillbrook Grand, a Chief Mark son; while Gypsy’s maternal granddam was Sunnylodge Chief Vick (VG 2*), a Chief Mark daughter”.

Three crosses. Three separate paths through one pedigree, all converging on a backup bull from Neoga, Illinois.

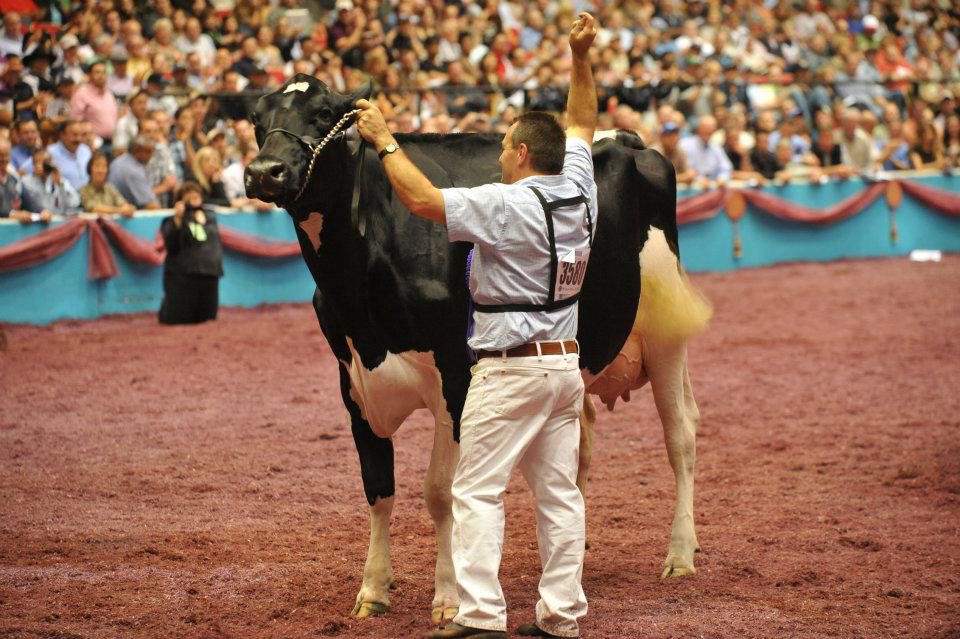

Goldwyn — bred by Braedale Holsteins at Cumberland, Ontario — became arguably the most decorated show sire in modern Holstein history. Premier Sire at the World Dairy Expo ten times. His daughters, RF Goldwyn Hailey (EX-97) and Eastside Lewisdale Gold Missy (EX-95) became the most famous show cows of their generation. By October 2018, he’d produced 3,415 Excellent daughters in Canada alone, according to Holstein Canada. Goldwyn died in 2008, just eight years old, but his genetics kept sweeping classes at Madison and the Royal for another decade and beyond.

Woven through all of it — three times in every Goldwyn pedigree — was Walkway Chief Mark.

The Supersire Empire

Chief Mark’s genetics didn’t just flow through the show ring.

Through maternal pedigree lines — including Jeanlu Louange Chief Mark (VG-87), a Chief Mark daughter deep in the maternal line — his influence reached Seagull-Bay Supersire, a Robust son bred by the Andersen family in American Falls, Idaho, and owned by Select Sires.

Supersire debuted as the breed’s No. 1 GTPI sire in April 2015 and reigned as the breed leader for four consecutive genetic evaluations. He’d scored 2530 gTPI as a genomic young sire back in December 2012; six years and 33,087 daughters later, his proven TPI came in at 2518. Holstein International called it “right in the DNA bull’s eye” and named him a “milk transmitter par excellence” — the world’s 55th millionaire sire and Select Sires’ eleventh bull to sell one million units of semen.

“The beautiful thing about SUPERSIRE daughters is they outproduce the herd while doing it in a healthy fashion,” said Rick VerBeek, Holstein sire analyst at Select Sires. “SUPERSIRE should be regarded as one of the all-time great profit generators of his generation!”

In 2019, more than 60 percent of bulls on the Select Sires active lineup carried Supersire in their pedigree. Sixty percent of an entire AI organization’s catalog, tracing back through a genetic chain that started with a second-choice bull and a phone call about a dead brother.

Supersire passed away in late 2021. His legacy was already secure. But buried in that pedigree — quiet, easy to miss, generations back on the maternal side — was the ghost of Walkway Chief Mark, still shaping the breed he’d accidentally been invited to improve.

Twenty-Five Times

And then came Lambda.

In 2024, an analysis that made even seasoned geneticists pause. They’d been tracing the pedigree of Farnear Delta-Lambda — one of the most influential contemporary sires in the global breed, the bull behind Siemers Paris 27856 EX-91, Global Cow of the Year in 2023, and her high-ranking son Parfect.

When they finished mapping Lambda’s ancestry, they found Walkway Chief Mark appeared twenty-five times. Twenty-five separate lines of descent converging in a single pedigree, all flowing back to a replacement bull born on a modest Illinois farm in June of 1978.

Holstein International called it “the righteous revenge of Walkway Chief Mark.” Together with Lambda mania, they wrote, “we can also talk about Mark mania”.

Forty-seven years after a dead brother opened the door, the backup plan’s roar is louder than ever.

The Ghost at 4 AM

Chief Mark’s story doesn’t come with a tidy ending. There’s no dispersal sale to narrate, no final show-ring walk, no sunset-lit portrait. His semen was collected, stored, and distributed across the globe, and his physical life passed quietly while his genetic life was only beginning its exponential expansion. The NAAB database lists him as “Inactive” — a status that says everything about bureaucracy and nothing about legacy.

Whether Foster Walk lived to see the full scope of what his backup bull built, the record doesn’t tell us. But his eye for diamonds in the rough — that eye is now validated in 57,654 daughters, seven percent of a continental genome, and 25 appearances in the pedigree of one of the breed’s most influential modern sires.

What the record also tells us: three crosses in the pedigree of the most decorated show sire in modern Holstein history. A Chief Mark daughter deep in the maternal line of a millionaire sire who reshaped global dairy genetics. A hidden lethal mutation — half a million dead calves — was identified and neutralized because someone had the foresight to sequence his DNA back in 2009. And a reputation as an udder improver that, decades and multiple base changes later, still echoes in the mammary quality of his descendants’ descendants’ descendants.

He arrived as a replacement. He became irreplaceable.

Every breeding decision echoes forward through time. Most of those echoes fade within a generation or two — diluted, selected against, bred out. Chief Mark’s didn’t fade. It amplified. Seven percent of a continental genome, a frequency so deep it has become the baseline hum of the breed itself. The backup plan from Neoga, Illinois, built an empire nobody saw coming.

Next time you’re walking your barn before dawn — flashlight cutting through the steam rising off a hundred backs, bulk tank humming in the parlor, a fresh cow somewhere letting down for the first time — look at the udders. Look at the attachments. Look at the dairy character carved into the ribs and flanks of your best animals. You’re looking at Foster Walk’s diamond in the rough, still paying dividends nearly five decades and fifty-seven thousand daughters later. Still proving what every breeder who ever took a chance on an unlikely animal already knows in their bones: in this business, the ones who change everything aren’t always the ones you planned on.

Key Takeaways:

- Walkway Chief Mark started as the backup bull from Foster Walk’s Neoga, Illinois herd, sampled only after his brother Monroe died — but his genes now account for about 7% of every Holstein on the continent.

- He gave breeders one of the biggest trade‑offs in Holstein history: daughters with era‑setting udders and some of the weakest relative feet and legs, forcing anyone who used him to “protect the mating” or live with the consequences.

- Together with his sire Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief, he helped define modern Holstein genetics on both sides of the ledger — huge gains in type and production, and the APAF1 lethal mutation later linked to roughly 500,000 spontaneous abortions worldwide before it was identified and managed.

- His blood now threads through three confirmed crosses in Braedale Goldwyn’s pedigree, deep in the maternal line of Seagull‑Bay Supersire, and an astonishing 25 times in Farnear Delta‑Lambda’s ancestry, tying one small Illinois farm to many of today’s most influential sires.

- The piece leaves readers in a pre‑dawn barn with a simple realization: when you study the best udders in your herd today, you’re almost certainly looking at the long shadow of a once‑overlooked bull from Neoga.

Executive Summary:

Walkway Chief Mark was never meant to be a legend; he was the backup bull from Foster Walk’s Neoga, Illinois herd, sampled only because his brother Monroe died — yet his DNA now sits in roughly seven percent of every Holstein you milk. His proof told a story every breeder understands: daughters with era-changing udders riding on some of the weakest relative feet and legs in the book, forcing people to “protect the mating” if they wanted the magic without the wreckage below the hocks. The article walks through that reality in the barn, then zooms out to show how Chief Mark and his sire Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief helped build the modern Holstein genome — for better (udder quality, production, show-ring type) and for worse, through the APAF1 mutation tied to an estimated 500,000 spontaneous abortions before scientists pinned it down in 2011. From there, it follows his blood into names everyone knows today: three confirmed crosses in Braedale Goldwyn’s pedigree, deep maternal influence in Seagull-Bay Supersire, and an almost unbelievable 25 Chief Mark appearances in Farnear Delta-Lambda’s ancestry. Along the way, Foster Walk steps out of the shadows as a real dairyman — a guy whose Walkway cows showed up in Holstein World ads and local production records long before anyone dreamed of genomic percentiles. It all ends back in a quiet 4 a.m. barn, inviting readers to study the best udders in their own string and realize that, whether they planned it or not, they’re still working with a once-forgotten bull from Neoga whose influence just won’t let go.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- Charlie Will: A Career Spent at the Top of the Chart – Experience the era through the eyes of the man who risked his early reputation on a neighbor’s backup bull, proving that the breed’s greatest genetic leaps often come from analysts with the guts to trust their eye.

- Pawnee Farm Arlinda Chief – Genetic Giant – Step back into the world that birthed an empire and explore the massive shadow cast by Mark’s sire, a bull who fundamentally rewrote the Holstein blueprint and set the stage for a global genomic revolution.

- Durham vs. Goldwyn: A Clash of Two Titans – Trace the lineage from Foster Walk’s quiet Illinois farm to the bright lights of Madison, where Mark’s genetic influence finally found its ultimate expression in a show-ring rivalry that defined a whole generation of breeders.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!