At 50°F, your calf is already cold-stressed—burning feed for heat, not growth. That’s 1,000+ kg of milk you’ll never see. Warm water. Deep straw. Simple fixes, big payoff.

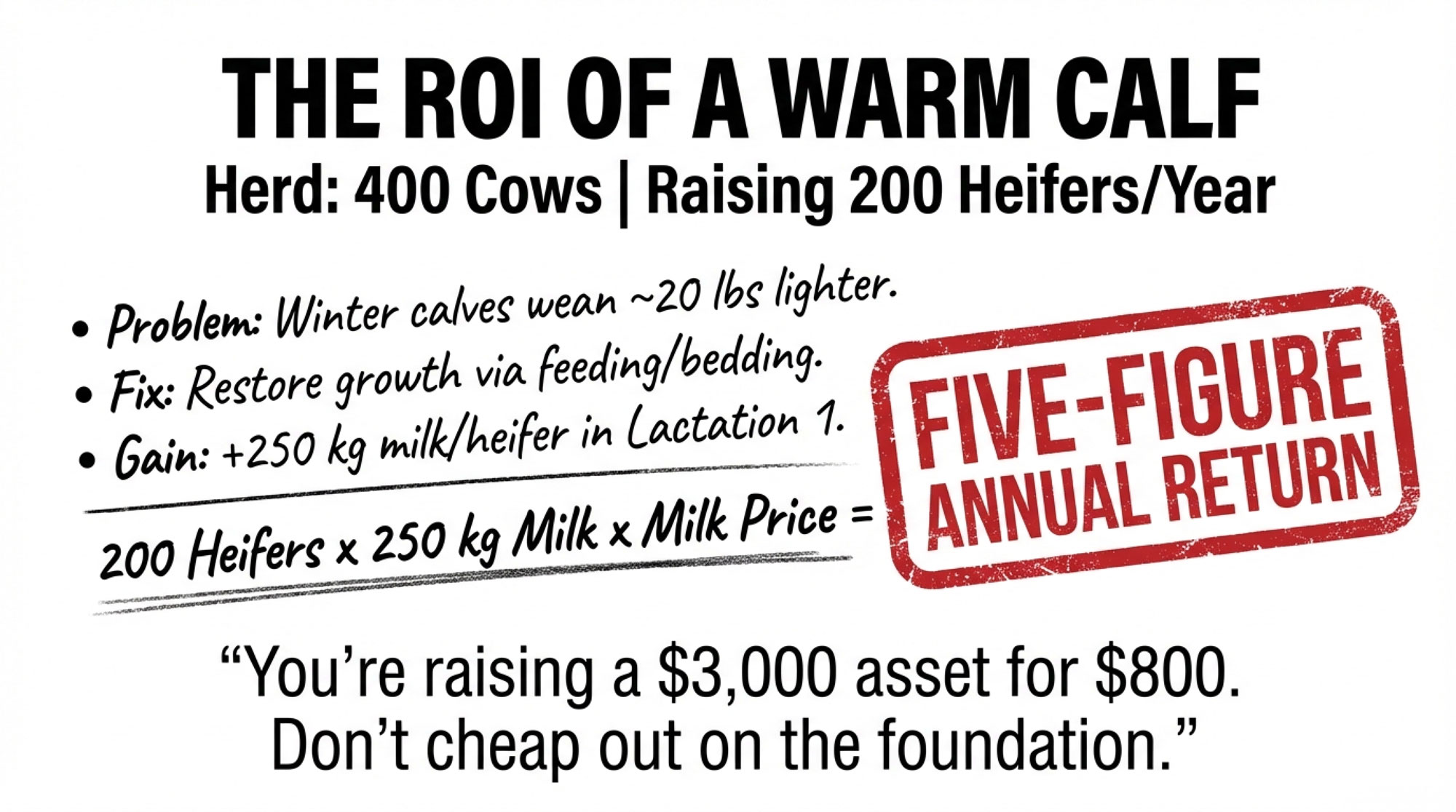

Executive Summary: Your winter calves might look healthy, but at about 10°C (50°F), they’re already cold‑stressed and burning feed for heat instead of growth. That’s a big deal, because Cornell research and a large meta‑analysis show every extra kilogram per day of preweaning gain can add roughly 850–1,550 kg of milk in first lactation, and a 2024 study links each extra kilogram of weaning weight to about 25.5 kg more milk plus extra fat and protein. Slow‑gaining winter calves are quietly locking in lower lifetime milk and butterfat cheques, even if they never break with scours or pneumonia. The good news is the levers are simple: bump milk replacer roughly 2% for every degree below 5°C, feed 4 L of warm, high‑Brix colostrum within two hours, bed to a true nesting score of 3 with deep dry straw, and offer warm water so the rumen isn’t fighting ice‑cold buckets. Herds that make those changes—and put one person clearly in charge of calves—see higher preweaning gains, heavier weaning weights, and fewer pulls in the fresh‑cow group a few years later.[page:aphis.usda.gov] For a 400‑cow operation raising 200 heifers a year, even a conservative 200–300 kg increase in first‑lactation milk per heifer adds up to a solid five‑figure annual return and more freedom in how aggressively you cull and where you use sexed or beef‑on‑dairy semen.

Picture this. It’s a January morning, wind cutting across the yard, and you’re walking past a row of hutches. Fifteen calves under three weeks old, all standing, all drinking, no scours, no coughing. It’s pretty natural to think, “They’re fine.”

Last winter, a 400‑cow herd I was in southern Ontario thought the same thing—until they finally weighed calves and realized their December–February heifers were weaning almost 20 lb lighter than their summer calves, despite “clean and bright” calves in the line. When we overlaid Cornell data, LifeStart results, and a 2024 colostrum and health study, it became obvious: those “fine” winter calves were quietly giving up hundreds of kilos of first‑lactation milk and a chunk of butterfat cheque three years down the road.

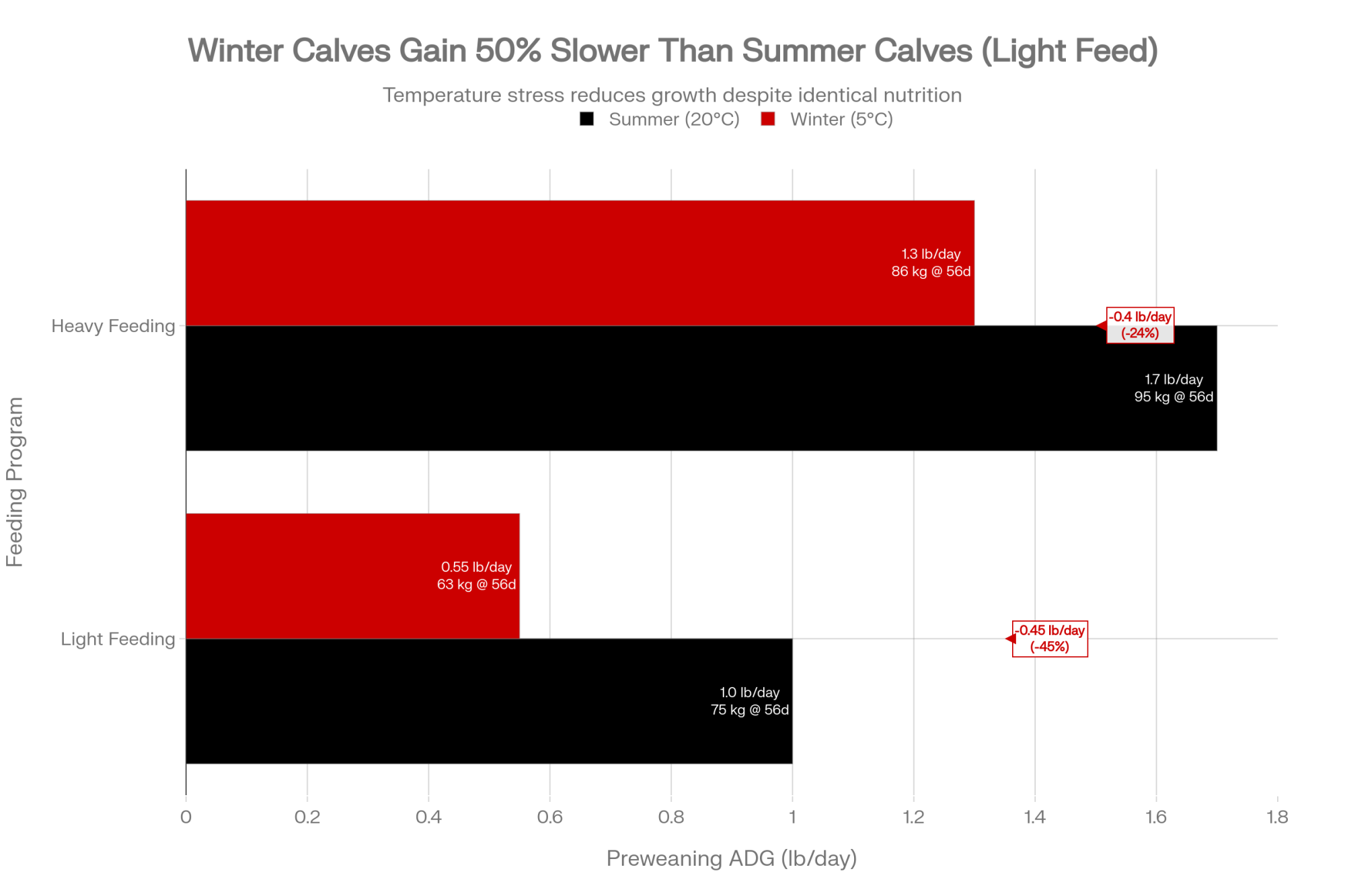

| Scenario | Season / Condition | ADG (lb/day) | Weaning Weight at 56 Days (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light feeding, warm (20°C) | Summer | 1.0 | 75 |

| Light feeding, cold (5°C) | Winter, underheated housing | 0.55 | 63 |

| Heavy feeding, warm (20°C) | Summer | 1.7 | 95 |

| Heavy feeding, cold (5°C) | Winter, well-bedded hutch | 1.3 | 86 |

Here’s what’s really going on—and what you can actually change before the snow melts.

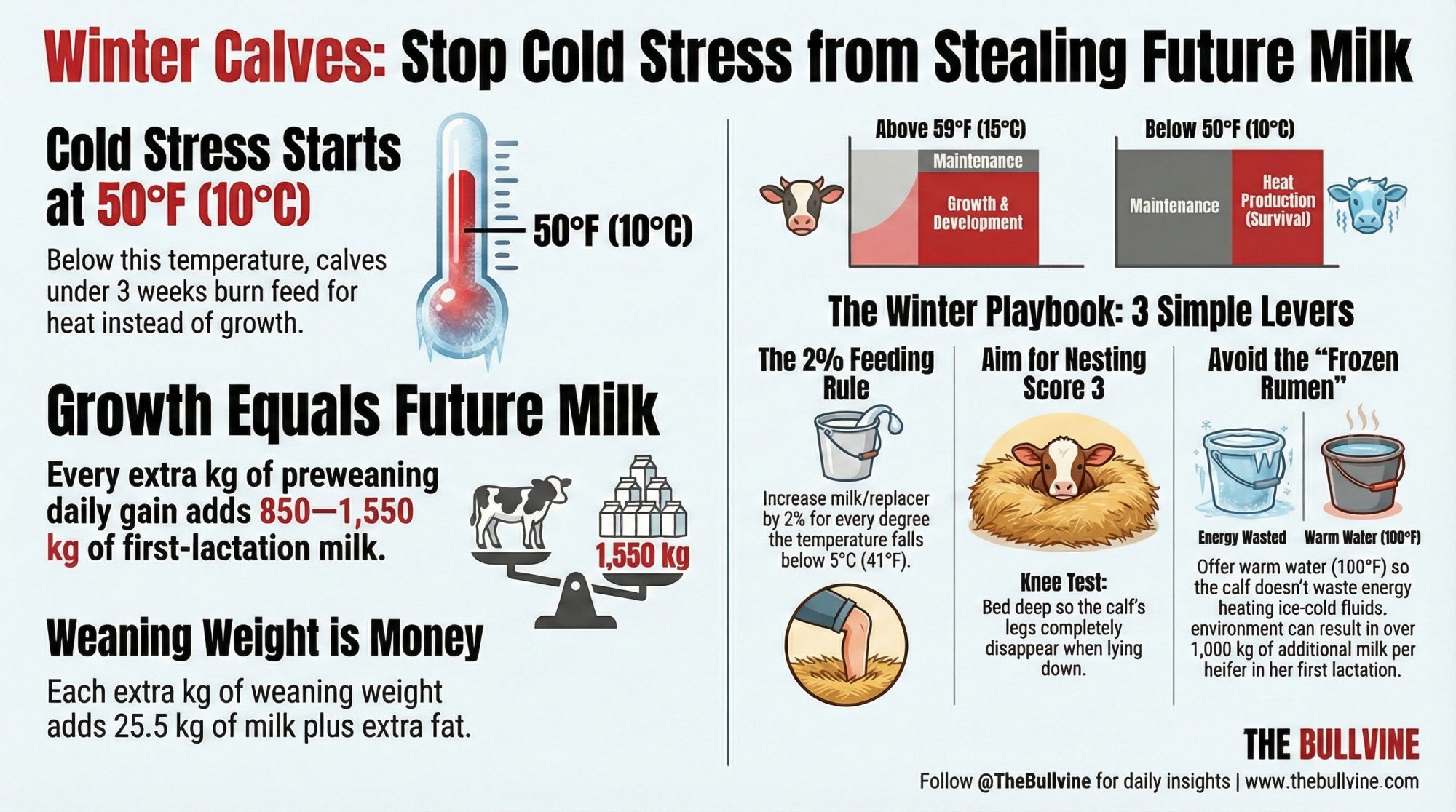

When “Cold” Starts for a Calf (Hint: It’s Warmer Than You Think)

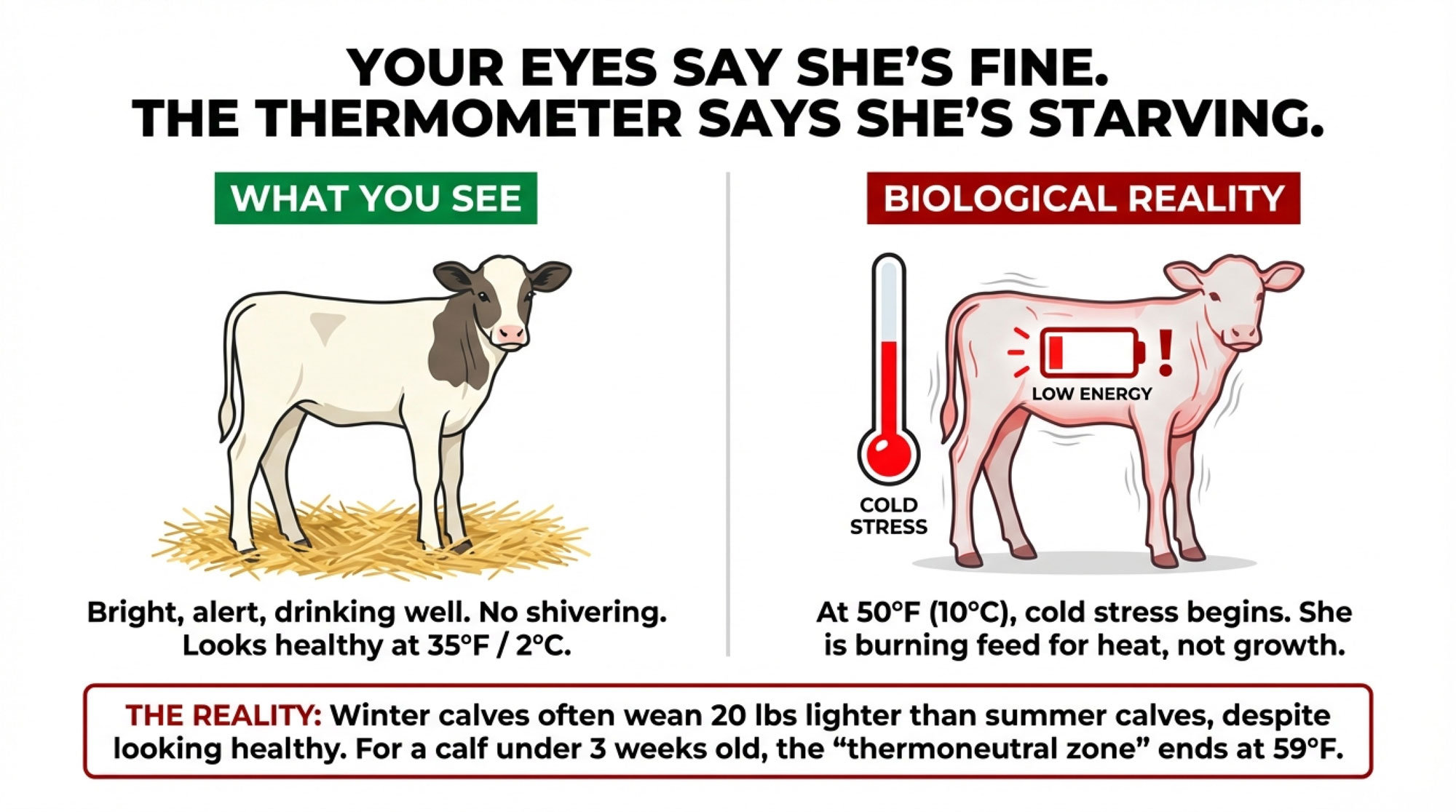

For calves under about three weeks of age, work from the Miner Institute and University of Wisconsin puts the thermoneutral zone—the range where they don’t have to spend extra energy to stay warm—at roughly 15–25°C, or 59–77°F. Below that range, every degree drop means more energy burned on heat and less on growth.

CalfCare Canada’s cold weather feeding guide takes a practical run at this. It recommends increasing milk or milk replacer once temperatures fall below about 10°C (50°F) for calves under three weeks old, and below about 0°C (32°F) for older preweaned calves in unheated housing. That’s their way of telling you: once you’re into typical winter temperatures, a young calf is out of her comfort zone and into “maintenance overload.”

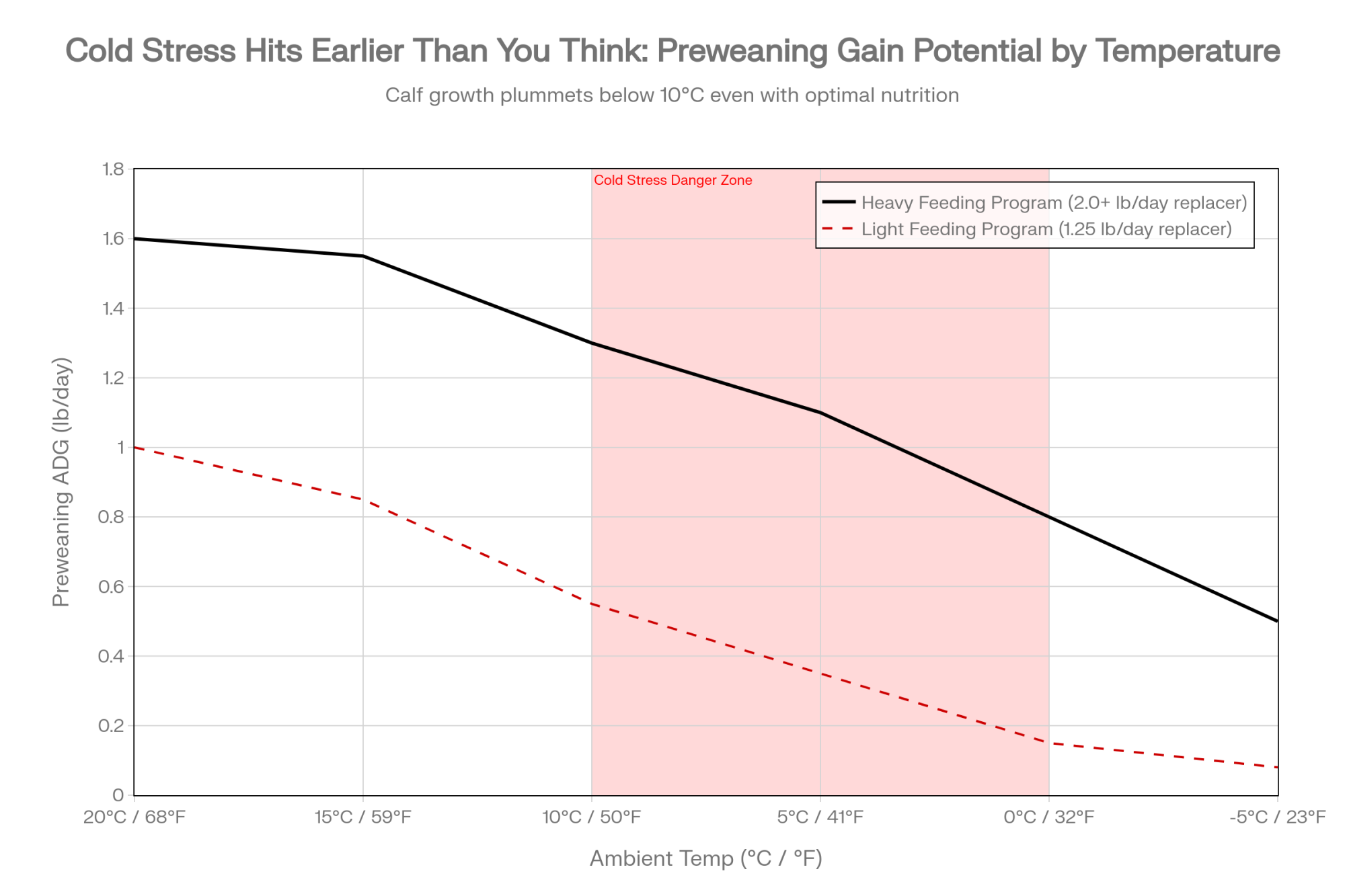

| Temp (°C) | Temp (°F) | Heavy Program ADG (lb/day) | Light Program ADG (lb/day) | Est. First Lac. Milk Diff (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 68 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0 |

| 15 | 59 | 1.55 | 0.85 | -400 |

| 10 | 50 | 1.3 | 0.55 | -900 |

| 5 | 41 | 1.1 | 0.35 | -1,300 |

| 0 | 32 | 0.8 | 0.15 | -1,650 |

| -5 | 23 | 0.5 | 0.08 | -2,000 |

In plain language, when the air is in the upper‑40s or low‑50s°F, a 10‑day‑old calf is already giving up some growth just to stay warm.[page:aphis.usda.gov] She may look bright, drink well, and never spike a temp, but she’s quietly spending nutrients on heat instead of frame, organs, and early mammary development.

Using NRC models, you can see how this plays out in example scenarios: a 45‑kg (100‑lb) calf on a light feeding program in cold conditions might only gain around 0.4 lb per day, while a similar calf on a higher‑energy program in better housing can push past 1.6 lb per day. As the thermometer drops, the gap between “alive” and “growing to full potential” gets wider.

So when your yard thermometer says 35°F, and you’re telling yourself, “It’s cold but manageable,” your 10‑day‑old heifer is already playing nutritional catch‑up.

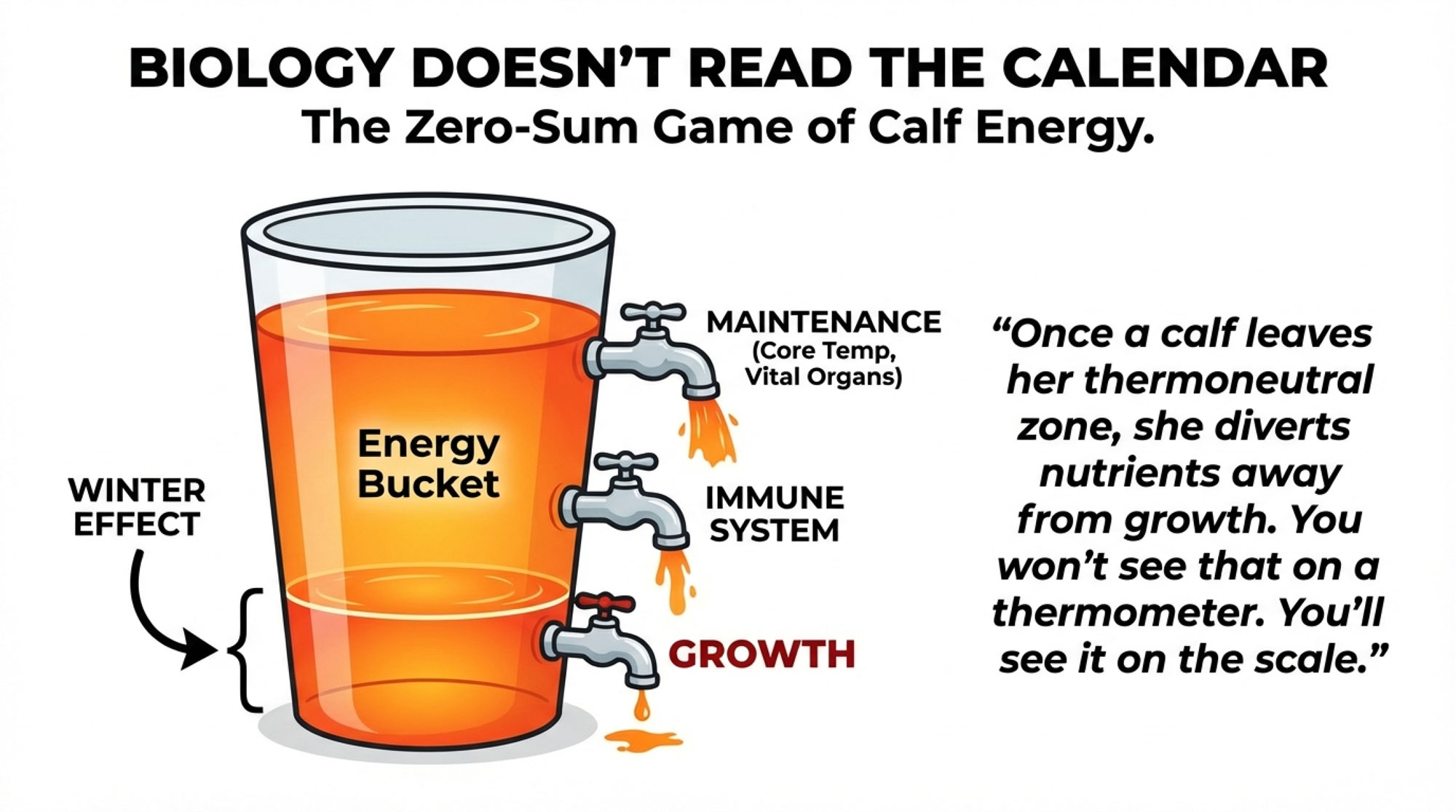

How a Calf Spends Energy When She’s Cold

Once you think about how a calf spends energy, the winter pattern starts to make sense.

Her priorities are brutally simple:

- Keep core temperature and vital organs functioning

- Run basic metabolism—heart, lungs, brain, kidneys

- Support the immune system

- Use whatever is left for growth and early mammary development

Reviews on calf thermal stress and welfare make it very clear: once a calf leaves her thermoneutral zone, she diverts nutrients away from growth and immune function toward heat dissipation and basic life support. You won’t see that on a thermometer. You’ll see it on the scale.

USDA’s Dairy 2014 Calf Component Summary found that average preweaning gains in Holstein heifers ranged from about 1.5 to 1.7 lb per day, depending on whether calves were fed milk replacer, whole milk, or a combination. Calves on combination diets topped the list.[page:aphis.usda.gov] Many heifer programs now treat roughly 1.6–1.8 lb per day as a realistic “top‑end” target for well‑managed Holsteins.

When you overlay that with NRC winter models, you see what’s happening on a lot of farms: summer calves may flirt with those 1.6–1.8 lb gains, while winter calves—on the same program, in colder air—slide down toward the bottom of the 1.5–1.7 average, or worse, without anyone really noticing. Two calves can stand in a row of hutches on a frosty morning, both look bright and drink well, but if one is gaining 1.7 lb a day and the other is stuck under 0.6 lb, you’re essentially raising two very different first‑lactation cows.

If you haven’t actually weighed winter calves lately, odds are they’re growing slower than you think.

Why Scours at Two Weeks and Pneumonia at Four Weeks Feel Inevitable

You know this story already. Most of us have lived it.

- Scours hits hardest in the first two to three weeks.

- Pneumonia peaks somewhere between three and eight weeks.

USDA Dairy 2014 data and multiple veterinary reviews line right up with that experience: diarrhea is most common in the first three weeks of life, while respiratory disease is more common later in the preweaning period, often affecting around a quarter of calves in some herds.

Layer that onto the cold‑stress and colostrum picture.

In the first day or two, the calf is riding on passive immunity. If she doesn’t get enough IgG, if it’s fed late, or if bacterial load is high, she starts life with fewer antibodies and more bugs than you’d like. Now put that calf in a 10°C (50°F) or colder environment where she’s burning extra energy just to hold core temperature. That’s hitting the immune system from both sides.

By 7–21 days, the pathogen pressure in your calf area—rotavirus, coronavirus, cryptosporidium—is often high, especially in winter when bedding and cleaning get stretched. Calves with weak passive transfer and tight energy budgets are the first to tip into clinical scours. Then, from three to eight weeks, viruses and bacteria behind bovine respiratory disease (BRD) take center stage. Calves that had poor colostrum or early diarrhea are at higher risk of BRD later.

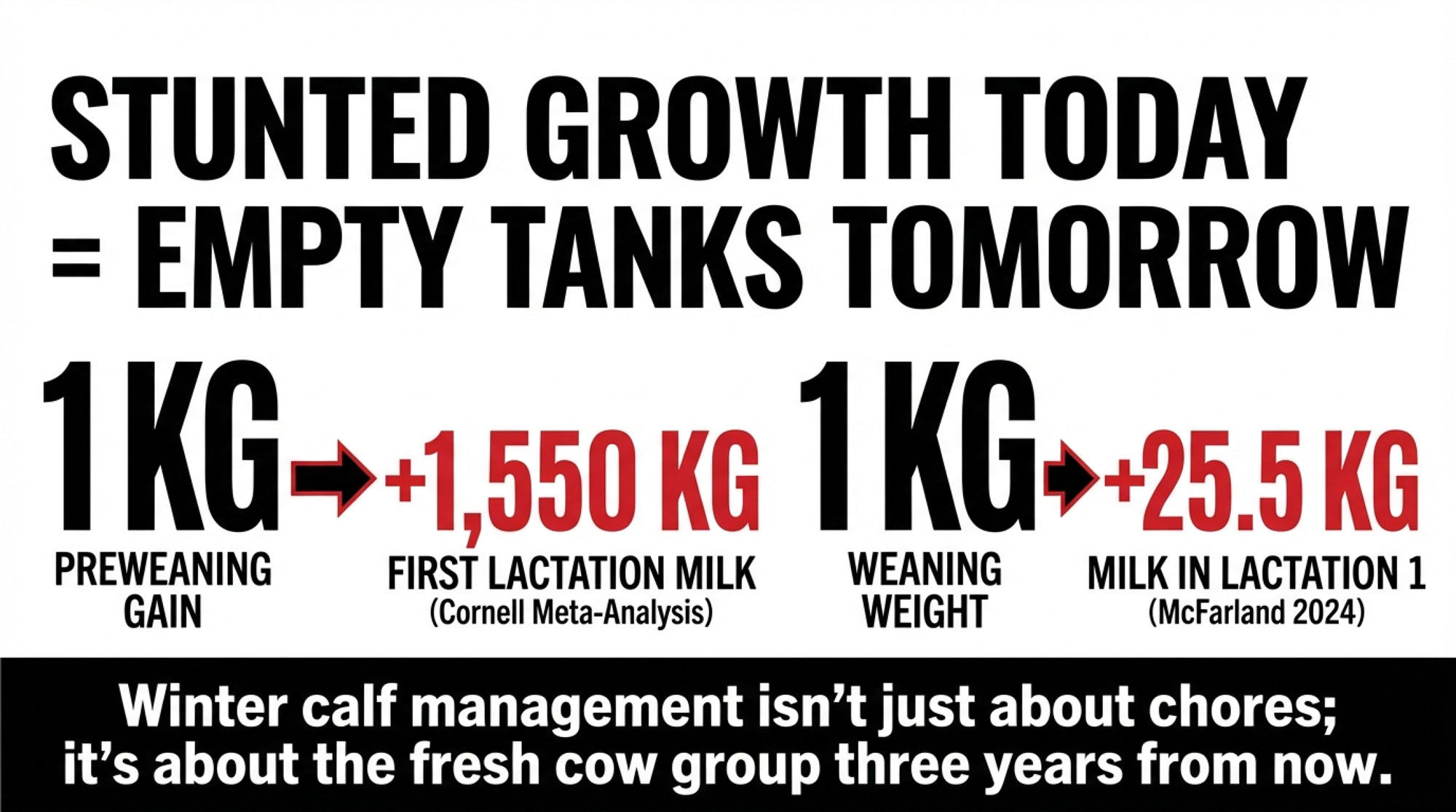

A 2024 Journal of Animal Science paper by Emily McFarland and colleagues connected those dots all the way to the bulk tank. They found that calves with stronger colostrum programs and fewer preweaning disease events weaned heavier and then produced more milk, fat, and protein in the first three lactations. In that dataset, every extra kilogram of weaning weight was associated with 25.5 kg more milk, 0.82 kg more protein, and 1.01 kg more fat in the first lactation.

This is where it stops being a “baby calf” conversation. It’s not just about whether she survives scours or pneumonia. It’s about how much health baggage she drags into your fresh cow group three years from now.

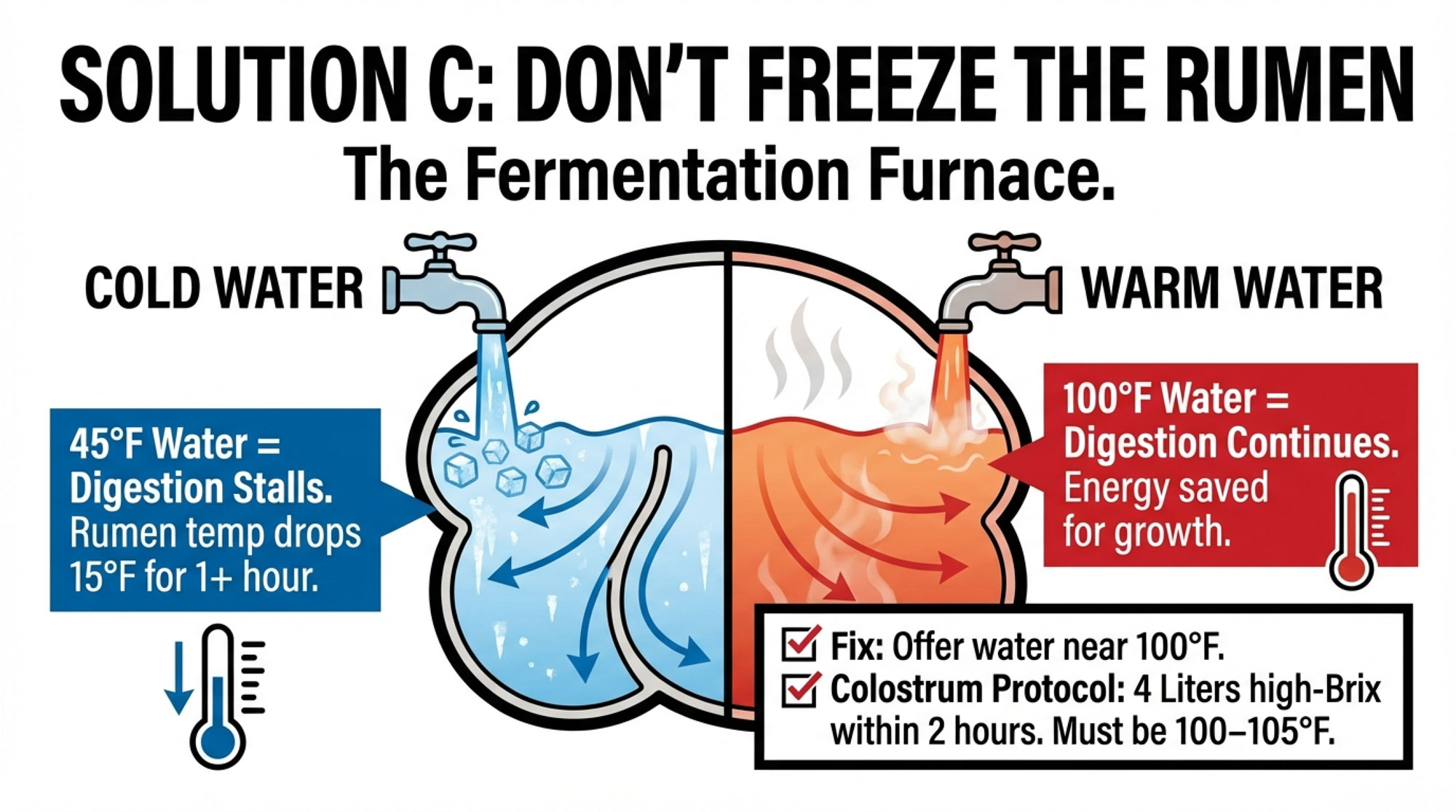

The Frozen Rumen: Why Cold Water Is a Growth Killer

Before we dive into feeding rules, let’s hit one of the most underrated winter levers: water temperature.

Back in the 1960s, researchers measured rumen temperature in calves after they drank water at different temperatures. Sarah Morrison, PhD, at the Miner Institute, summarized that work: when calves drank water between about 46 and 81°F, rumen temperature dropped for roughly 1 to 2 hours and by as much as 15°F at the coldest temperatures. When they drank water at around 99°F, the rumen temperature changed minimally and only for a short time.

Newer work from the University of Wisconsin extension tells the same story: when calves drink very cold water—around 45°F—the rumen temperature drops noticeably and takes about an hour to recover. Warmer water, in roughly the 60–100°F range, still cools the rumen briefly, but the drop is smaller, and recovery is faster.

Why should you care? Because the rumen is where starter fermentation kicks off, and that fermentation generates metabolic heat that helps calves handle cold and grow. When you chill the rumen with ice‑cold water, you essentially shut down the fermentation furnace for a while and force the calf to burn extra energy just to warm everything back up.

Calves prefer warm water, and offering water near 100°F means they don’t have to spend as much energy heating it in the rumen. Very cold water not only drains energy from warming the fluid, but also lowers rumen temperature enough to reduce rumen efficiency and metabolic heat production.

So on a morning when the bucket is half ice, and you’re thinking, “At least they’ve got water,” ask yourself if you’d drink it. If the answer is no, that calf isn’t thrilled either—and if she does drink, she’s paying for it with growth.

Preweaning Growth and Lifetime Milk: The Big Math

Now to the part that should make every replacement‑minded breeder sit up.

At Cornell, Fernando Soberon and Mike Van Amburgh followed calves from birth through first lactation. In one analysis, each additional kilogram per day of preweaning average daily gain (ADG) in the Cornell research herd was associated with about 850 kg more milk in first lactation. In a commercial herd they looked at, the response was about 1,113 kg per kilogram of preweaning ADG.

Then they zoomed out. A 2013 meta‑analysis looking across 13 different calf studies found an even stronger relationship: roughly 1,550 kg of additional first‑lactation milk for each extra kilogram per day of preweaning ADG. That’s not a small bump. That’s a whole lactation’s worth of difference in some systems.

LifeStart’s industry work points the same way. In the Kempenshof LifeStart trial, calves on an elevated preweaning feeding program gained about 150–155 g per day more than conventionally fed calves and produced roughly 400 litres more fat‑corrected milk in first lactation. A broader LifeStart review notes that elevated nutrition levels in several trials increased preweaning ADG by 70–355 g/day, with consistent improvements in lifetime performance, including milk yield and survival.

A 2016 meta‑analysis on preweaning nutrition and later performance concluded that calves offered higher nutrient intake before weaning had significantly higher milk yield and better survival later in life. More recent work in 2023 on immune and metabolic development in intensively fed heifers shows that the benefits of better early nutrition carry through in immune competence and metabolic markers.

Add McFarland’s 2024 data to the pile: every 1 kg increase in weaning weight was associated with 25.5 kg more milk, 0.82 kg more protein, and 1.01 kg more fat in first lactation, with positive effects across later lactations as well. In component‑driven markets, those extra kilos of fat and protein are exactly what keep the banker calmer and the cull list shorter.

| Preweaning Gain Improvement | Extra Weaning Weight (kg) | First-Lactation Milk Increase (kg) — Conservative Estimate (Cornell) | First-Lactation Milk Increase (kg) — Meta-Analysis High-End (13 studies) | Estimated Revenue Impact @ 35¢/kg Milk & Extra Fat (CAD/heifer) |

| +0.1 lb/day (+45 g/day) | +2.5 | +106 | +155 | +$52–$65/heifer |

| +0.2 lb/day (+91 g/day) | +5 | +213 | +310 | +$104–$130/heifer |

| +0.3 lb/day (+136 g/day) | +7.5 | +319 | +465 | +$156–$195/heifer |

| +0.4 lb/day (+182 g/day) | +10 | +425 | +620 | +$208–$260/heifer |

| +0.5 lb/day (+227 g/day) | +12.5 | +532 | +775 | +$260–$325/heifer |

Now, not every herd will see 1,500 kg of extra milk per kilogram of ADG or 400 L per calf. Genetics, disease load, housing, and how consistently you run your program all matter. Pasture‑based and organic systems with more variable post‑weaning nutrition may see a smaller response. But across Cornell, LifeStart, the meta‑analyses, and field data, the direction is iron‑clad: better preweaning growth goes with more milk and stronger butterfat performance later on.

Those first eight weeks aren’t just “calf chores.” They’re one of the most valuable phases in your entire herd strategy.

Colostrum: The First Non‑Negotiable

Look at herds that consistently do well with winter calves, and you’ll almost always see the same thing: colostrum protocols that you could write on the wall and everyone knows by heart.

The science‑backed targets are remarkably consistent:

- At least 150–200 grams of IgG in the first feeding.

- For Holsteins, that typically means 4 litres of good‑quality colostrum with a Brix score of around 22 percent or higher.

- First feeding within 2 hours of birth, followed by a second feeding of colostrum or transition milk within roughly 12 hours.

- Clean collection, rapid cooling or feeding, and increasingly, heat‑treating colostrum at about 60°C for 60 minutes to cut bacterial load while preserving IgG.

In winter, colostrum temperature matters even more. Feeding it at or near body temperature—roughly 38–40°C (100–105°F)—means the calf isn’t spending scarce energy warming up cold colostrum and improves gut motility and antibody absorption.

| Colostrum Program & Serum TP Outcome | Serum TP (g/dL) | Passive Transfer Quality | Preweaning Scours & Pneumonia Rate (%) | First-Lactation Milk Impact vs. Poor Transfer (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor: Late feeding, low Brix, cold colostrum | <5.0 | Failure | 35–40 | –200 to –400 |

| Fair: On-time (6–12 hr), adequate Brix, lukewarm | 5.0–5.5 | Partial | 20–25 | –75 to –150 |

| Good: Within 2 hr, high Brix (22%), warm (4L) | 5.5–6.5 | Adequate | 10–12 | +50 to +100 |

| Excellent: 4L high Brix within 2 hr, heat-treated, warm | >6.5 | Excellent | 5–7 | +200 to +300 |

When farms actually implement those steps and check serum total protein in calf samples, they see many more animals land in the “excellent passive transfer” category. Down the road, that shows up as fewer preweaning disease events and better growth. That pattern has been documented in North American and European studies that follow the same colostrum benchmarks.

And it doesn’t care what kind of parlor you milk in. Tie‑stall dairies in the Northeast, 1,000‑cow freestalls in the Midwest, pasture‑based systems bringing calves into pens straight off pasture—if you hit volume, quality, timing, cleanliness, and temperature, you stack the deck in your favor.

If your scours cases spike in January compared to July, it’s not just “weather.” That’s your sign to look hard at both colostrum and cold stress.

For extra depth on the first feeding, pair this article with Bullvine’s past colostrum management features when you publish it.

Bedding, Nesting, and the “Would You Kneel Here?” Test

Once colostrum and nutrition are in a decent place, the next big winter lever is the stuff under the calf.

The Dairyland Initiative and the Dairy Calf and Heifer Association lean on a simple nesting score system:

- Score 1: calf lying down with all legs clearly visible.

- Score 2: some legs are partially covered but still visible.

- Score 3: legs disappear in the bedding; calf is deeply nested.

Dairyland’s fieldwork shows that calves consistently housed at a nesting score of 3 in cold weather have lower respiratory disease rates than those on thinner or wetter bedding. You don’t need to memorize the exact odds ratios; what matters is the direction: deep, dry straw is about as cheap a pneumonia‑prevention tool as you’ll ever buy.

Canadian veal and calf housing resources say the same thing in their own way: use enough long straw over a dry base so calves can nest, and their legs disappear when lying down. That keeps them insulated from cold ground and shielded from low‑level drafts.

Here’s a no‑excuses test you can use in any system: the knee test. Step into the hutch or pen, kneel where the calf lies, and stay there 20–30 seconds. If your knees get cold and wet, the bedding isn’t doing its job. Farms that adopt the nesting score and knee test tend to move from “We bed on a schedule” to “We bed to a standard”—the standard being, “Can this calf actually nest?”

| Nesting Score | Mild Winter (5–10°C) | Cold Winter (–5 to 5°C) | Very Cold (≤–15°C) | Average BRD Cases per 100 Calves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 1 (legs visible) | 12% | 24% | 38% | 24.7 |

| Score 2 (partial cover) | 8% | 16% | 28% | 17.3 |

| Score 3 (deeply nested) | 5% | 8% | 12% | 8.3 |

Now add wind. In exposed sites—prairie hutches, hilltops, western dry lots—wind at calf level can turn a 35°F day into something that acts like the low‑20s°F in terms of heat loss. Ventilation guides from Lactanet and U.S. extension stress the same simple rules: block drafts at calf level, let fresh air in overhead. Turning hutches so their backs face prevailing winds, lining bales, or adding snow fencing can all cut effective wind chill.

We’ve seen farms in Ontario, New York, and the Dakotas cut winter BRD cases significantly just by getting serious about nesting score 3 bedding, knee tests, and basic wind control. No magic products, just physics and straw.

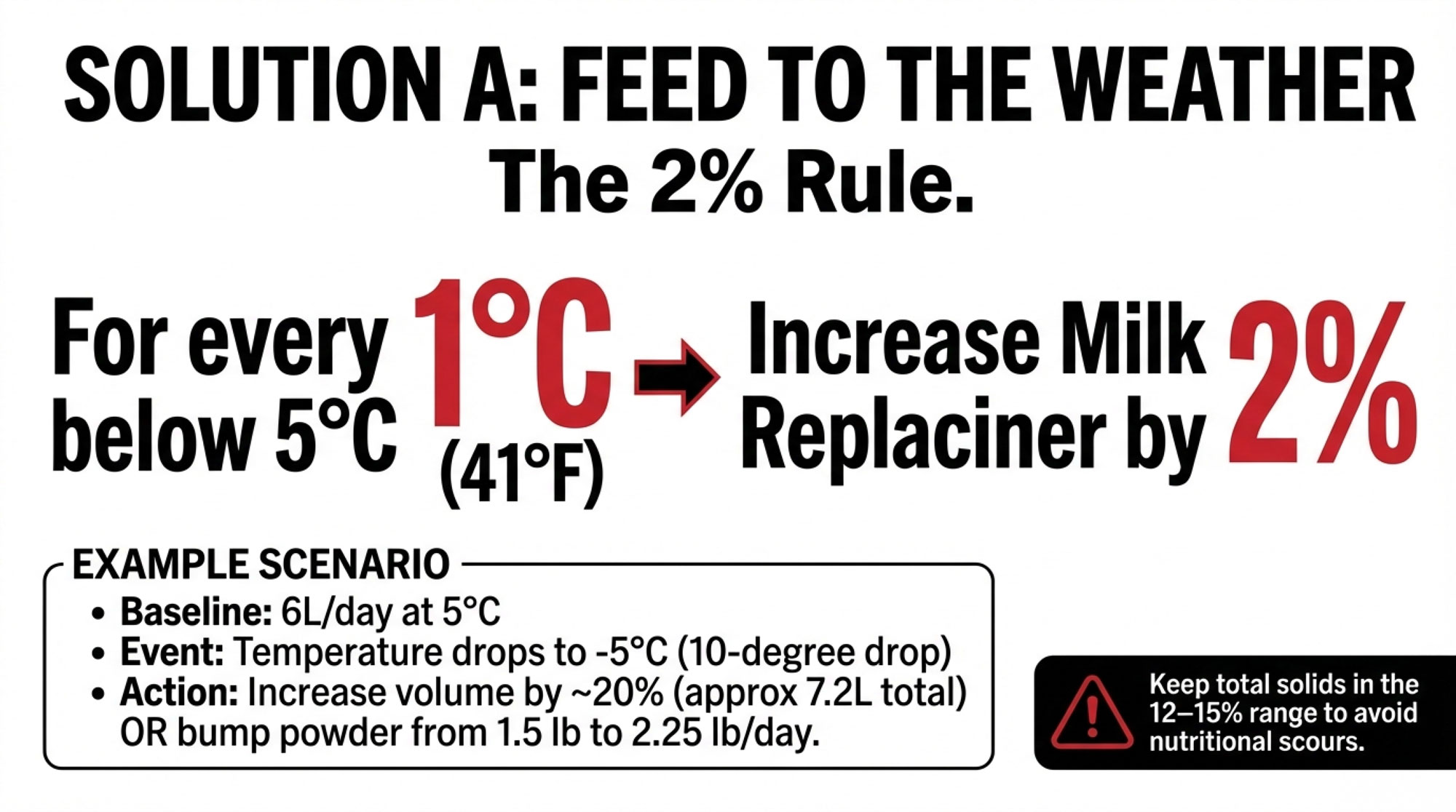

Winter Calf Feeding: The 2% Rule and Beyond

This is where the rubber meets the road: if maintenance needs go up when it’s cold, how much more should you actually feed?

CalfCare Canada gives a simple starting point: for young calves in unheated housing, increase milk replacer by about 2 percent for every degree the temperature falls below 5°C (41°F).

So if your baseline is 6 litres per day at 5°C and the average temperature drops to –5°C (a 10°C drop), that rule points to roughly a 20 percent increase—about 7.2 litres per day—as a starting point. You then fine‑tune that with your nutritionist based on your calves’ growth and manure.

Hoard’s Dairyman’s NRC‑based examples show why this matters. At around 20°C (68°F), a standard feeding program might support about 1.0–1.1 lb of daily gain. Take the same program down to 0°C (32°F), and the potential gain drops sharply. At –18°C (0°F), some lightly fed calves may barely gain at all, because nearly all of the energy they consume is going to maintenance. That lines up with northern extension messaging: maintenance requirements increase as temperatures drop, especially for the youngest calves.

In real herds, that 2% rule gets translated into moves like:

- Bumping young calves from 4 litres per day of whole milk in mild weather to 6 litres per day in winter.

- Increasing milk replacer from roughly 1.25–1.5 lb per day up toward 2.0–2.25 lb per day when temperatures stay below freezing, keeping total solids in the 12–15 percent range to avoid nutritional scours.

- Adding a third feeding in very cold stretches so total energy goes up without dumping huge meals into cold calves.

Research on higher planes of preweaning nutrition and automatic feeders shows that, when managed well, higher milk allowances improve growth and are associated with higher first‑lactation milk yield. Reviews on early‑life feeding also show better immune and metabolic markers in calves that receive more nutrients before weaning.

The catch is how you get out the other end. Studies on weaning timing and milk allowance show that calves on higher planes of nutrition can get hammered by abrupt weaning, especially in groups. That’s why so many advisers now push step‑down weaning, particularly on autofeeders: reduce milk gradually while calves increase starter, instead of dropping them off a cliff.

Even with that wrinkle, the core truth doesn’t change: if winter calves are on the same liquid program as summer calves, you’re choosing lower lifetime milk for those winter heifers. Biology doesn’t read the calendar.

Why Some Herds Sail Through Winter and Others Just “Get By”

Talk to vets, extension folks, and calf specialists, and you see a pattern.

Dairy 2014 and follow‑up work on preweaned heifer management found herds with higher ADG and lower mortality often had a few things in common: written colostrum and feeding protocols, clearly assigned calf‑care staff, regular training, and at least basic data tracking—serum total protein, birth and weaning weights, and disease recording. Case examples from North America and Europe show that herds with very low preweaning mortality often run tight, monitored calf programs.

On the people side, research on stockperson attitudes and training has shown that better-supported calf caregivers tend to have fewer issues with growth and respiratory disease. That’s not “soft” stuff; that’s part of your health and performance program.

Honestly, one of the biggest turning points I see on farms in New York, Wisconsin, and Ontario is when calf care stops being “whoever has time after milking” and becomes somebody’s job. When one or two people truly own the calf program and are empowered to say, “We need more straw here,” or “These weaning weights aren’t cutting it,” numbers usually shift faster than any bag of powder can manage.

Different Systems, Same Calf Biology

Now, let’s be clear: there isn’t one “correct” way to house calves.

Some of you are running:

- Individual hutches on gravel or concrete pads in Ontario or the Prairies

- Group pens with autofeeders in insulated barns in Wisconsin or Minnesota

- Super‑hutches in the Northeast

- Small pack or tie‑stall setups for the youngest calves on family farms

- Dry lot systems with shade and windbreaks in California and other western states

The good news is the calf doesn’t rewrite her biology based on where she sleeps. Her thermoneutral zone, immune development, and growth response to nutrition are the same whether she’s drinking from a bottle in a single hutch or a teat bar on a robot feeder.

In group pens with autofeeders, the winter conversation usually centers on:

- Setting higher maximum milk allowances for the youngest calves during cold periods.

- Watching software closely so shy calves aren’t getting left behind.

- Managing drafts and humidity so calves aren’t breathing cold, damp air all day.

In naturally ventilated barns in Quebec, New York, and the Midwest, producers talk about:

- How they set curtains and inlets

- Airspeed at calf level

- Whether bedding depth really delivers a nesting score of 3 in January, not just in photos.

In western dry lot systems, the focus shifts to:

- Windbreaks (trees, solid fences, stacked bales)

- Raised, well‑drained mounds or pads

- Feeding plans based on night‑time lows, not just daytime highs.

Extension educators and consultants working across these systems frequently report the same pattern: herds that step up winter milk allowances, bedding, and colostrum protocols see fewer pneumonia treatments and more consistent weaning weights within a couple of seasons. Eastern Canadian tie‑stall herds that commit to deep straw and warm water report steadier winter performance and fewer scours calls.

If you’re in a pasture‑based or organic system where milk allowance is capped, your big winter levers are colostrum quality, dry deep bedding, and blocking wind at calf level. You might not be able to change everything, but you can still move the needle with those three.

Every system has winter levers. The question isn’t whether you’re in hutches or pens; it’s whether you’re actually pulling the levers your system gives you.

A Coffee‑Table Example: Turning Research into a Herd-Level Decision

Let’s sketch this like we would on a napkin over coffee.

You’ve got a 400‑cow Holstein herd in a northern climate—southern Ontario, northern New York, or Wisconsin. You’re raising about 200 heifer calves a year. A big chunk are born from December through March in outdoor hutches.

Right now, your winter program might be:

- About 1.5 lb per day of a 20‑20 milk replacer, fed twice a day

- Four to six inches of straw over a lime base in each hutch

- Colostrum is usually fed within a few hours of birth, of decent quality, but not always warmed to body temperature

- No regular weighing; “looks good” is the main metric

One winter, you finally weigh. You heart‑girth a batch at birth and at weaning and realize:

- Winter calves: ~0.55 lb/day gain

- Summer calves: ~0.9 lb/day gain

Over a 56‑day preweaning period, that’s roughly a 20‑lb gap in weaning weight.

Now think back to the numbers we just walked through:

- Cornell: 850–1,113 kg more first‑lactation milk per 1 kg/day extra preweaning ADG in individual herds.

- Cornell meta‑analysis: ~1,550 kg per 1 kg/day ADG across 13 data sets.

- Kempenshof: 150 g/day extra ADG → ~400 L more FCM.

- McFarland 2024: 1 kg extra weaning weight → 25.5 kg more milk plus extra fat and protein.

If you take a conservative slice of that—say your herd only ever captures 200–300 kg extra milk in first lactation per heifer for an improvement in preweaning growth—that’s still meaningful. At typical component‑adjusted values, those extra kilos per heifer show up as a noticeable bump in revenue. Multiply that across 200 heifers, and you’re easily into a five‑figure herd‑level impact.

That’s the “$3,000 calf you’re raising for $800” concept: you’re putting in a modest preweaning investment, and that calf is capable of paying you back over and over again—but only if you feed and house her like you actually believe she’ll make it to second lactation.

Now flip the napkin and sketch a modest winter upgrade, grounded in the research and extension work we’ve talked about:

- Move toward ~2.0 lb/day of milk replacer in winter for young calves, keeping solids in the 12–15% range.

- Add a third feeding for the youngest calves during the worst cold snaps.

- Bed to a true nesting score of 3 and check with the knee test regularly.

- Treat 4 L of warm, high‑Brix colostrum within 2 hours, plus warm water, as non‑negotiables in winter.

Cold‑weather feeding suggestions from CalfCare and university extension say that such a program adds the equivalent of a few dozen dollars per calf to preweaning costs, depending on your replacer and straw prices. You won’t know your exact number until you cost it out, but even if you only capture a fraction of the milk response those Cornell, LifeStart, and McFarland datasets suggest is possible, it doesn’t take long before the spreadsheet leans in your favor.

On top of the math, extension educators and consultants often report smoother fresh‑cow transitions, fewer pulls, and more flexibility in culling and replacements once early‑life growth and health improve. That’s hard to put into a single number, but you feel it when you’re not standing in the fresh pen every morning, wondering which calving‑pen mistake is about to bite you next.

For some progressive herds, better winter calf performance has also opened the door to more strategic use of sexed semen and beef‑on‑dairy matings: raise only the top‑tier replacements you truly need and use beef sires on lower‑merit animals to boost calf value. That takes winter calves out of the “cost center” bucket and puts them squarely in your genetics and marketing strategy.

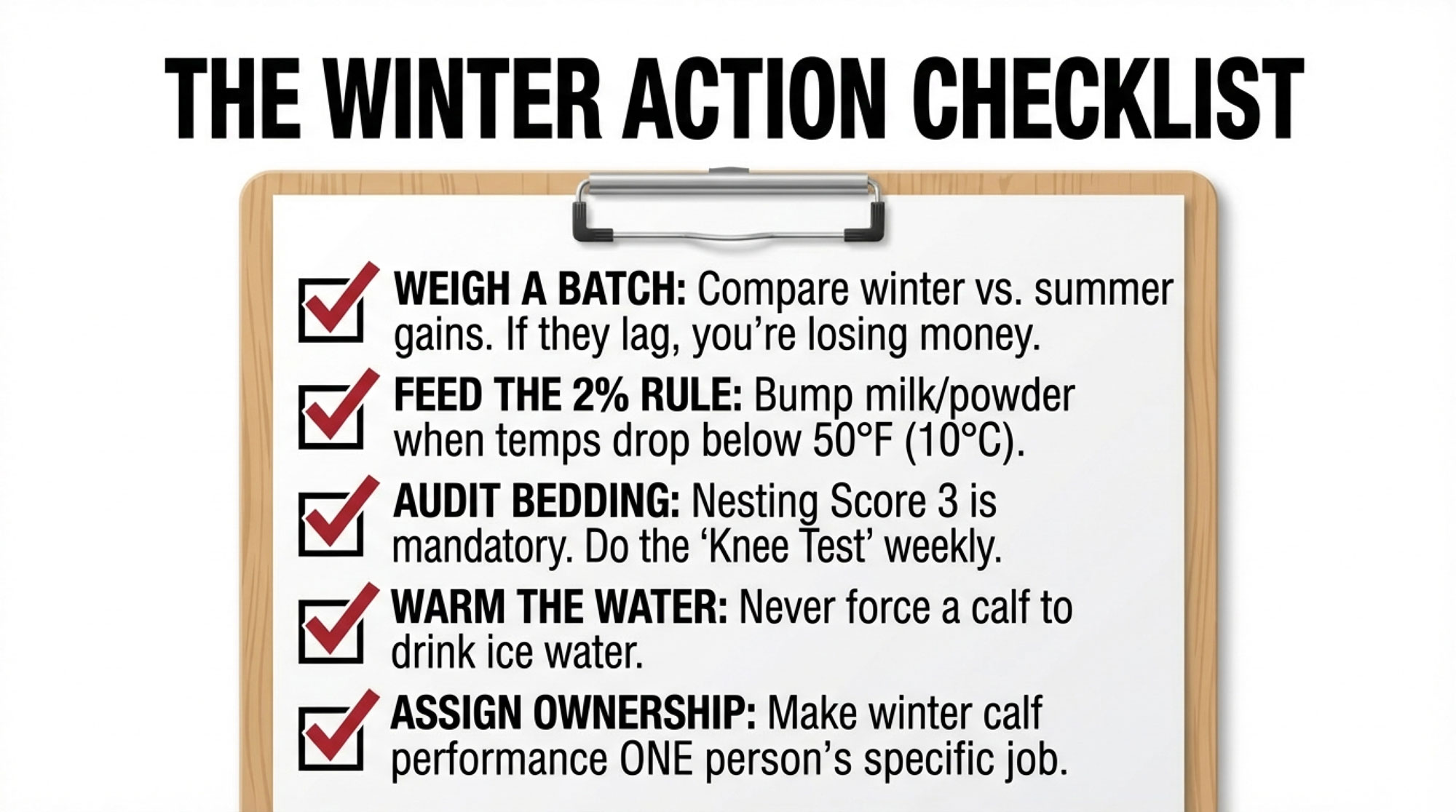

What This Means for Your Operation

Here’s a checklist you can literally tape to the calf‑barn wall. It’s not theory; it’s a simple way to see where your winter levers really are.

1. Measure at least a few calves

- Weigh or heart‑girth a batch of winter calves at birth and again at weaning.

- Compare their gains to that 1.6–1.8 lb/day “top‑end” target many heifer programs use for Holsteins.

- If winter calves are lagging summer calves by more than a couple of tenths of a pound, you’ve just found cheap milk in your own system.

2. Feed to the weather, not the calendar

- Once temps are in the low‑50s°F or below, young calves are already dipping below their thermoneutral zone.

- Use the CalfCare rule of thumb—about 2% more milk replacer for every 1°C drop below 5°C (41°F)—as a starting point, then adjust with your nutritionist.

- Remember NRC’s message: if you don’t feed more when it’s cold, you’ve told that calf growth is optional.

3. Protect from cold, wet, and wind

- Aim for a nesting score of 3: if you can see calves’ legs when they lie down, you’re not there yet.

- Use the knee test weekly. If your knees are cold and wet after 20–30 seconds, the calf is losing energy through the floor.

- Walk the site with your hood down on a windy day and feel what the calves feel; then use windbreaks, bale lines, or hutch orientation to take the edge off.

4. Make colostrum and water non‑negotiables

- Feed 4 litres of clean, high‑Brix colostrum within 2 hours of birth, followed by a second big feeding within about 12 hours.

- Keep colostrum close to body temperature; cold colostrum in a cold calf is a double hit.

- In freezing weather, dump ice‑cold water and replace it with warm water multiple times a day; it’s one of the cheapest ways to support rumen development and starter intake.

5. Put someone clearly in charge of calves

- Make calf care somebody’s job, not everybody’s chore.[page:aphis.usda.gov]

- Give that person the authority to say, “No, this isn’t enough straw,” or “We’re changing this feeding rate.”

- Check in regularly with data—weights, serum total protein, health records—, so you’re not just going by gut feel.

Turn that list into a laminated sheet in the calf barn, and suddenly, winter calf care stops being “whatever we’ve always done” and starts being a program.

| Cost / Benefit Category | Current Winter Program (200 heifers/yr) | Proposed Winter Upgrade | Incremental Cost or Gain |

| PREWEANING INPUTS | |||

| Milk replacer (1.5 → 2.0 lb/day × 56 days) | $14,000 | $18,500 | +$4,500 |

| Deep straw & bedding materials (nesting score 3) | $2,000 | $3,200 | +$1,200 |

| Warm water setup & labour (daily in winter) | $500 | $1,800 | +$1,300 |

| Total Preweaning Cost Increase | $16,500 | $23,500 | +$7,000/yr |

| FIRST-LACTATION PAYBACK (Years 1–3) | |||

| Preweaning ADG improvement | 0.55 lb/day | 0.70 lb/day | +0.15 lb/day |

| Weaning weight increase per calf (kg) | ~63 | ~72 | +9 kg |

| Est. first-lactation milk per heifer | baseline | +250 kg | — |

| Revenue per heifer @ 35¢/kg milk + fat/protein | — | +$87.50 | — |

| Total Revenue from 200 Heifers (Years 1–3) | — | — | +$17,500 |

| NET HERD-LEVEL PAYBACK (3 years) | — | — | +$10,500 |

Three Changes to Make This Winter

If you only have the bandwidth to tackle a few things before spring, these are the heavy hitters.

- Feed to the actual temperature.

As soon as ambient temperatures fall below 5°C (41°F), start increasing milk or milk replacer by roughly 2% for every 1°C drop, and work with your nutritionist to keep total solids in the safe 12–15% range and avoid nutritional scours. - Use straw and windbreaks as cheap health insurance.

Commit to a real nesting score of 3 (legs buried in straw), check with the knee test, and fix drafts at calf level with windbreaks or better hutch orientation. It’s low‑tech, high‑impact BRD prevention. - Stop letting cold water and cool colostrum steal growth.

Make 4 L of warm, high‑quality colostrum within 2 hours and warm drinking water in winter is non‑negotiable; ice‑cold water and lukewarm colostrum silently siphon energy away from growth and into basic heating.

The Bottom Line

When you connect the dots—from Cornell’s 1,550‑kg‑per‑kg ADG meta‑analysis, to LifeStart’s 400‑L gains, to McFarland’s 2024 component numbers—it’s pretty tough to keep thinking of winter calves as just a “cost center” off to the side.

Those first eight weeks, especially in winter, are the front end of your fresh‑cow group three years from now. Early growth and health don’t just shift calf‑barn stats; they show up in first‑lactation milk, butterfat performance, fertility, and longevity across multiple lactations.

Not every farm is going to rebuild calf facilities or double feeding rates overnight. There are always trade‑offs—milk price versus replacer cost, straw versus labour, replacement targets versus beef‑on‑dairy opportunities.[page:aphis.usda.gov] But most of the big levers we’ve talked about—feeding to the weather, bedding to a nesting score of 3, blocking wind, warming colostrum and water, and giving someone ownership of the calf program—are already in your hands.

In a tight‑margin world, standing still on winter calves is really just a slow decision to grow a slightly weaker fresh‑cow herd three years from now. If you only change a couple of things this winter:

- Weigh 10 winter calves from birth to weaning

- Bump feeding rates on the next cold snap and see what the scale says

- Walk the calf line with the knee test this weekend

- Make sure that the first colostrum is big, clean, warm, and on time

Farms that commit even that much often say the calf barn feels different by the end of the season—and a few years later, the fresh‑cow pen starts to look different too.

So maybe the question for this winter isn’t “Are my calves fine?” It’s “Knowing what we now know about cold stress and lifetime milk, what one or two changes are we actually willing to test—in our system, with our cows—to move winter calves from just surviving to truly growing, and then let the bulk tank tell us whether it was worth it?”

And while you’re at it, I’d genuinely like to hear from you: What’s the coldest temperature your calves have truly thrived in, and what winter bedding or water hacks have made the biggest difference on your farm?

Key Takeaways

- Cold stress starts at 50°F—not freezing. At about 10°C (50°F), your young calves are already burning feed for heat instead of growth, even when they look perfectly fine.

- Preweaning growth shows up in your bulk tank for years. Cornell and meta-analysis data show each extra kg/day of preweaning ADG can add 850–1,550 kg of first-lactation milk. A 2024 study found that every extra kg of weaning weight adds ~25.5 kg more milk plus extra fat and protein.

- The winter playbook fits on a napkin. Bump milk replacer ~2% for every degree below 5°C. Feed 4 L of warm, high-Brix colostrum within 2 hours. Bed to nesting score 3. Replace ice-cold water with warm water.

- Fix the calf barn now, see it in your fresh-cow pen later. Fewer scours and pneumonia cases, heavier weaning weights, and smoother fresh-cow transitions—starting about three years from now.

- A five-figure payback is within reach. For a 400-cow herd raising 200 heifers/year, even a conservative 200–300 kg increase in first-lactation milk per heifer delivers meaningful annual ROI and more flexibility in culling and breeding.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- $3,010 Heifers, 30% Labor Jumps: The Mid-Size Dairy Survival Crisis – Grasp the raw math behind the $3,010 replacement crisis. This breakdown arms you with 2025 labor and interest benchmarks, revealing exactly why internal heifer raising now offers a massive cost advantage over buying into a depleted market.

- Beef-on-Dairy’s $3,000 Trap: 800,000 Missing Heifers and Who Pays the Bill – Expose the 800,000-heifer shortage redrawing the dairy survival map. This strategy guide delivers the “guard rails” for pregnancy rates and breeding ratios to ensure you aren’t quietly scheduling a catastrophic inventory gap for late 2027.

- Tech Reality Check: The Farm Technologies That Delivered ROI in 2024 (And Those That Failed) – Pinpoint the automation tools that actually paid back in 2024. This reality check strips away the hype, revealing how smart calf sensors slash mortality by 40% with a seven-month ROI that secures your future herd.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!