A margarine cup on a farm kid’s tray in Iowa County helped spark Wisconsin’s school butter bill—and proved what grassroots dairy advocacy can still do.

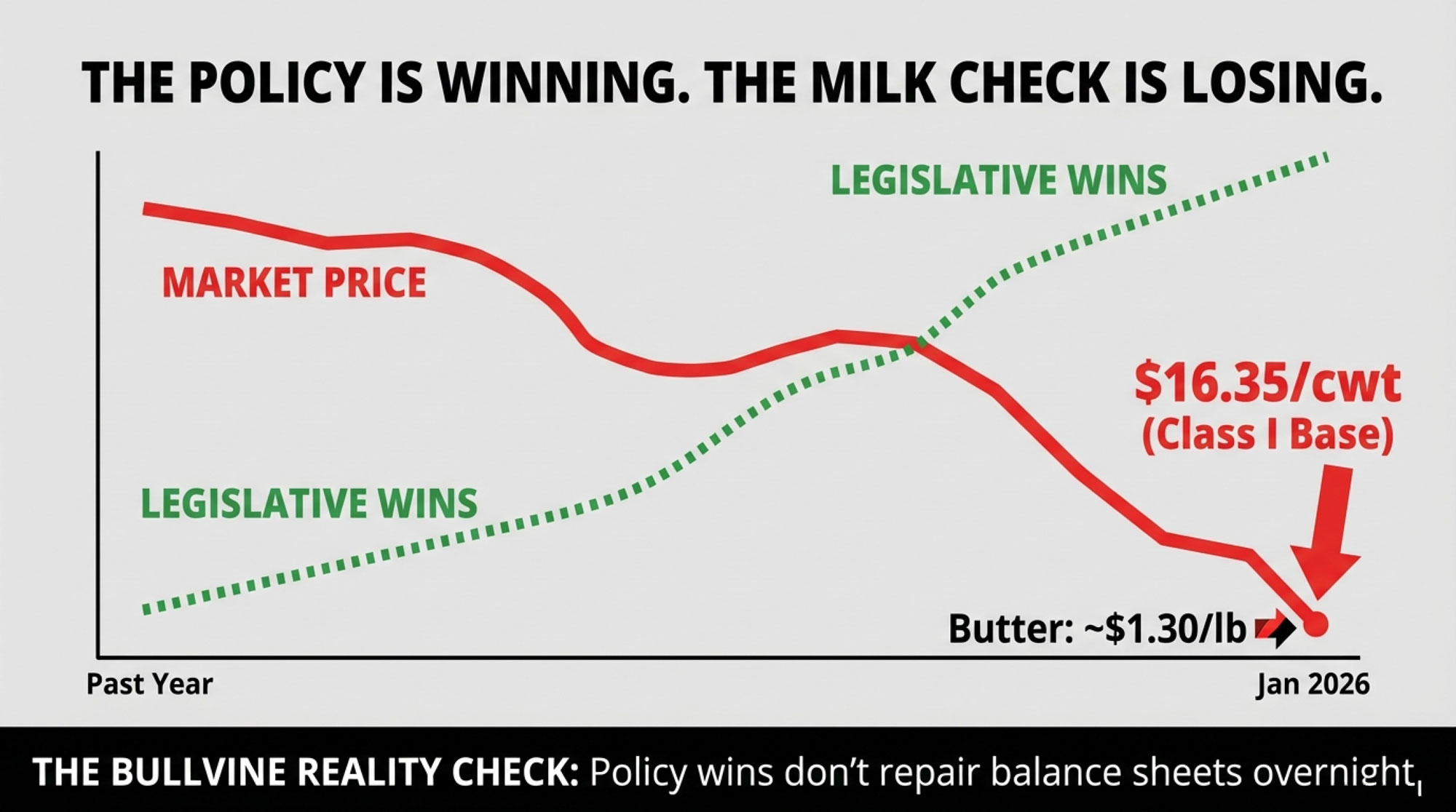

Executive Summary: A Wisconsin farm kid came home from school with a margarine cup instead of butter, and when that story hit a local Farm Bureau meeting, dairy neighbors and legislators turned it into a bipartisan “Butter in Our Schools” bill. Senator Howard Marklein and Representative Todd Novak, both raised on farms, responded to calls from family farmers by drafting Wisconsin Senate Bill 645, which would bar schools from using margarine in place of butter except for students with specific dietary needs. Their effort landed just as President Donald Trump signed the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act, allowing schools nationwide to offer whole and 2% milk again, excluding milk fat from saturated‑fat limits, and—via USDA’s SP 01‑2026 memo—giving districts immediate authority to adjust their National School Lunch menus. Even so, a Class I base price around $16.35/cwt and butter in the $1.30–$1.37/lb range show that markets remain tough, and policy wins alone won’t repair farm balance sheets. This feature uses that Iowa County story to show how a single kitchen‑table frustration, when channeled through Farm Bureau, associations, and responsive lawmakers, can still move dairy policy—and why producers who care about school milk and butter choices should see local advocacy as a practical lever, not a feel‑good extra.

The story starts the way so many do in dairy country—with a kid, a school lunch tray, and something that just didn’t sit right.

Somewhere in Iowa County, Wisconsin, a young boy came home from school one afternoon in the fall of 2025 and told his mother something that stuck with her. There’s no more butter, he said. They’re giving us margarine now.

For most families, it might have been a footnote. A shrug. But for this family dairy farm—shipping milk every day, building their lives around what their cows produce—it landed differently. In America’s Dairyland, their own child was being handed a foil‑topped cup of something made from vegetable oil instead of the real thing.

The family didn’t make a scene. They didn’t call the newspaper. But they did bring those margarine packets to the next Iowa County Farm Bureau meeting. And when they set them on the table and told their story, something shifted in that room.

“They’re dairy farmers, and it really irritated them,” State Senator Howard Marklein later told reporters. “This is America’s Dairyland, and so I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect that our schools will serve something that comes from our dairy cows.”

That September meeting in a community hall somewhere in southwestern Wisconsin became the spark for something much bigger than one family’s frustration. It became a reminder of what happens when dairy people decide they’ve had enough of being quietly written out of the story—and when their neighbors, associations, and lawmakers actually listen.

When a Room Full of Neighbors Said “Enough”

Nobody recorded what happened in that Farm Bureau meeting. There’s no transcript, no viral video. Just the memory of farmers gathered after chores, talking about the usual things—milk prices, weather, the impact of new Federal Milk Marketing Order changes coming in June—when one family spoke up about something smaller and somehow bigger at the same time.

The margarine packets sat on the table like evidence.

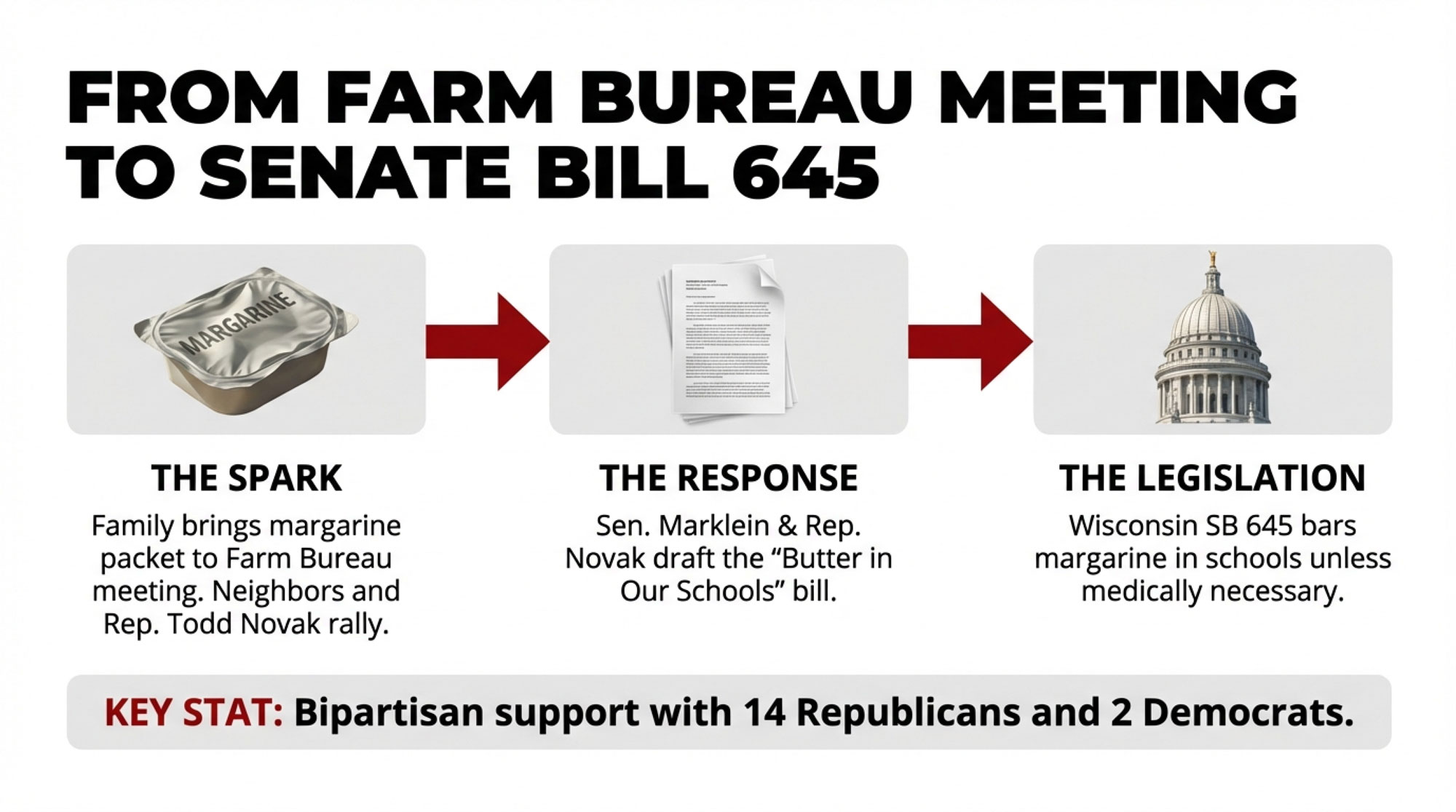

The concern resonated. According to Representative Todd Novak, the bill that followed was “a response to calls from family farmers who voiced strong opposition” to margarine replacing butter in at least one local school—this wasn’t just one family’s frustration. Others in the room had heard similar stories from their own schools, their own kids.

Novak, whose district includes some of the most agriculture‑dependent townships in the state, heard about it soon after. He’d grown up milking cows himself. When the story reached him, he didn’t file it away as a minor complaint. It hit differently, he said, because most schools in his area still serve butter, which made this one school’s quiet switch feel less like a budget decision and more like an erasure.

“After attending a local Farm Bureau meeting, I was shocked to hear a local school was no longer serving butter with lunches, but instead an artificial alternative with a long list of ingredients,” he said.

Within weeks, Novak and Senator Marklein—both raised on farms, both still deeply connected to the dairy communities they represent—had drafted a bill. By mid‑November 2025, Wisconsin Senate Bill 645 was introduced, with bipartisan support: fourteen Republicans and two Democrats backing a measure that would require schools to serve real butter, not margarine, unless a student’s dietary needs required otherwise.

The family who brought those packets to the meeting? They’ve stayed mostly out of the spotlight. Their names haven’t appeared in the news coverage. But their frustration—and their willingness to say something instead of just stewing at the kitchen table—set something in motion that’s still moving today.

“This Is the Type of Bill I Love”

There’s a certain kind of bill that doesn’t come from lobbyists or think tanks. It comes from someone’s kitchen, someone’s school, someone’s kid coming home with the wrong thing on their tray.

For Novak, that’s exactly what makes this one matter.

“I grew up milking cows,” he told reporters. “This is kind of the type of bill I love doing because it’s constituent‑oriented.”

Wisconsin already has laws restricting the use of margarine in certain settings. Restaurants can’t substitute it for butter unless they’re explicitly asked, and prisons serve the real thing. But schools had slipped through the cracks, quietly swapping to cheaper alternatives as budgets tightened and nobody was watching too closely.

Chad Zuleger, who advocates for dairy farmers through the Dairy Business Association, has been pushing for the bill since he first heard the story. The image stuck with him: a young boy walking through the door after school, confused and a little upset, telling his mom that butter was gone.

“A young boy came home and told his mother that there’s no more butter and they’re giving us margarine,” Zuleger recounted. “People are looking at cheaper alternatives, and everybody is looking to save a buck.”

But for Zuleger and the families he works with, this isn’t just about saving money. It’s about what message gets sent to farm kids when their own schools quietly stop serving what their parents produce.

“I think with the new dietary guidelines and the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act being signed, we’re going to have a resurgence in dairy,” he said. “We want to make sure butter is part of that.”

Whole Milk Comes Home—and Butter Wants to Follow

The timing of Wisconsin’s butter push couldn’t be more fitting.

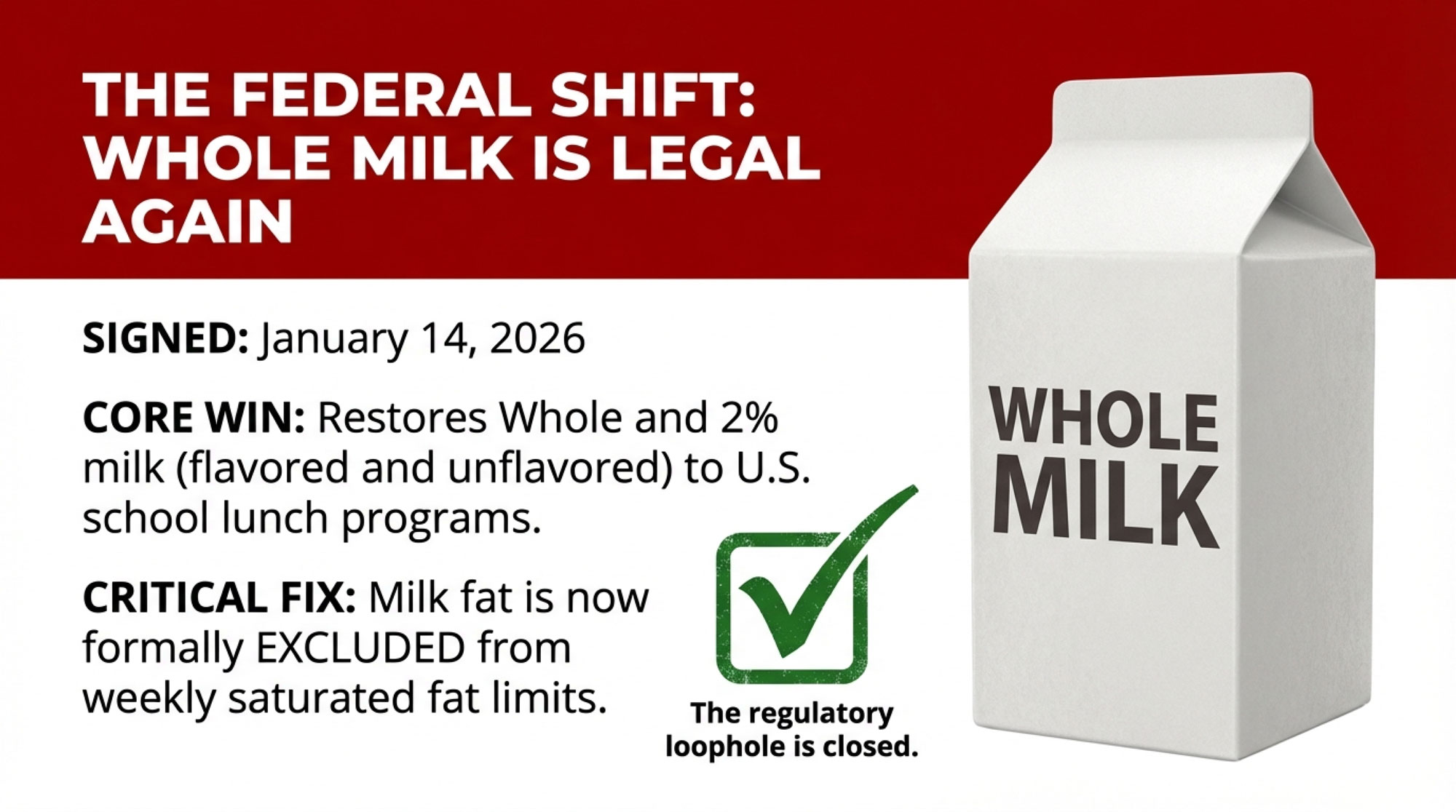

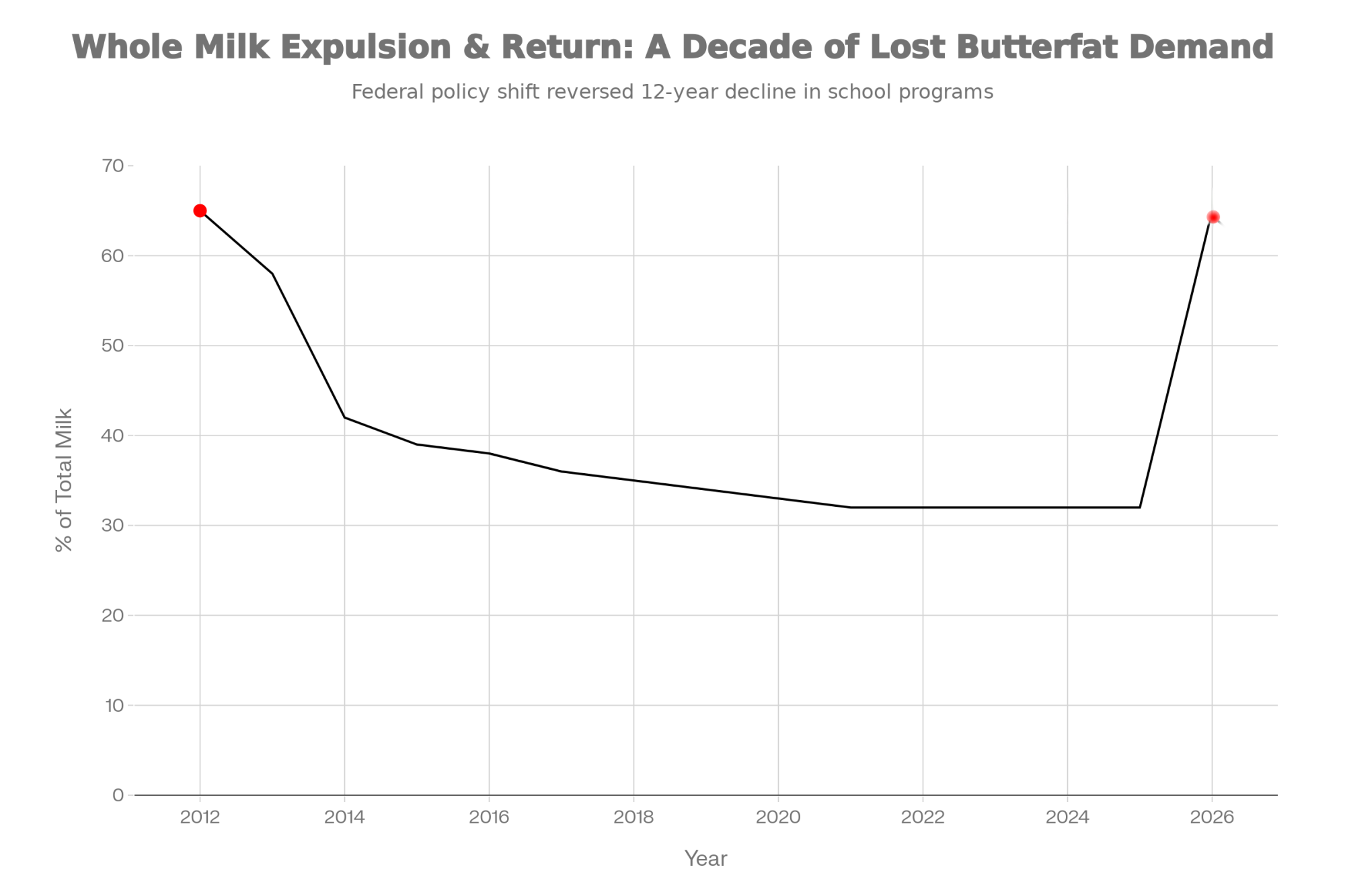

On January 14, 2026, President Donald Trump signed the bipartisan Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act into law, restoring whole and 2% milk options in U.S. schools for the first time in more than a decade. For dairy families who’d watched school milk consumption plummet after whole and reduced‑fat milk were pushed out of cafeterias, it felt like a long‑overdue correction.

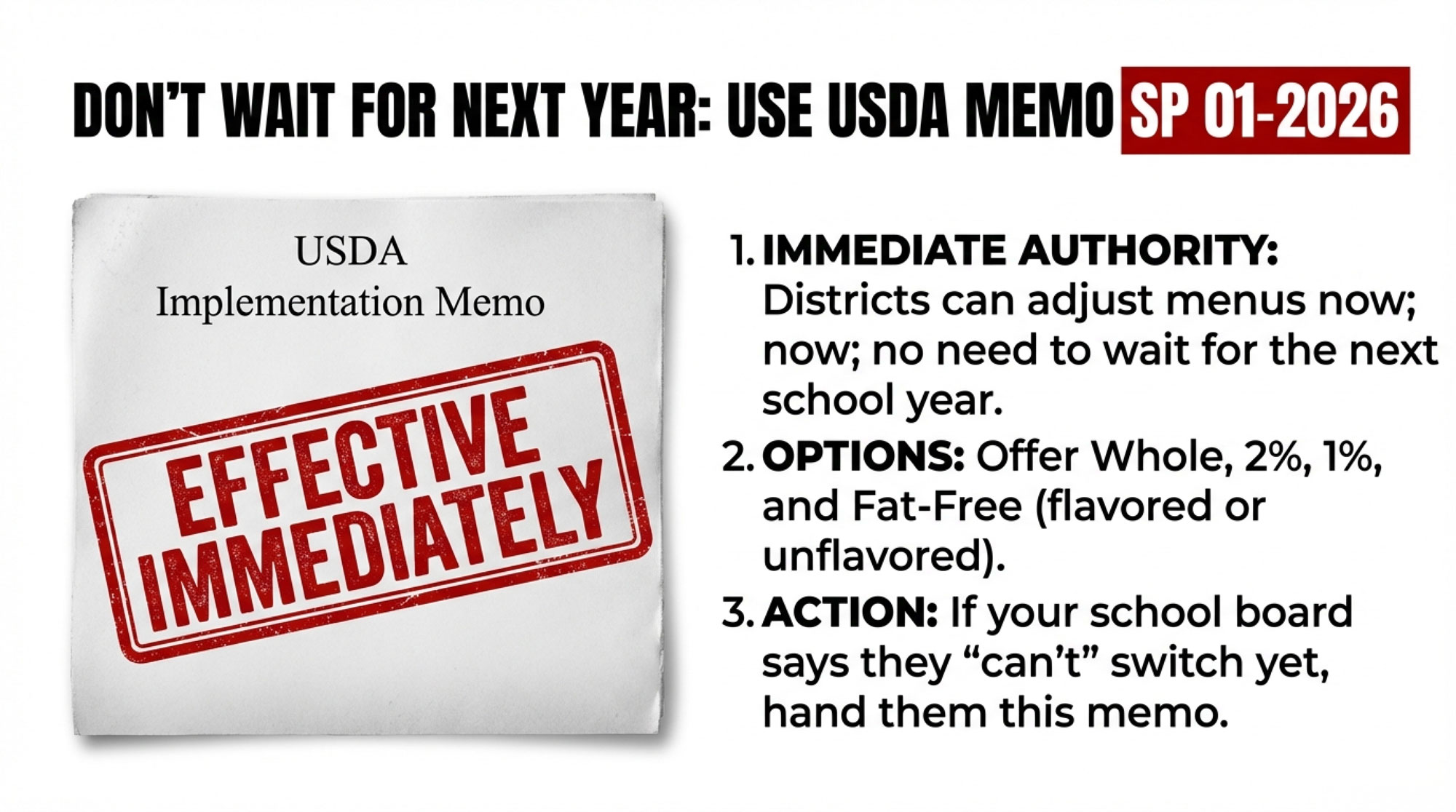

USDA followed the same day with an implementation memo, SP 01‑2026, telling school districts they could immediately expand their milk offerings within the National School Lunch Program. In simple terms, here’s what changed for schools:

- Schools can now offer whole, reduced‑fat (2%), low‑fat (1%), and fat‑free milk at lunch, including lactose‑free options, in both flavored and unflavored forms.

- Milk fat in fluid milk is excluded from the weekly saturated fat limit, making it easier for nutrition directors to offer whole and 2% milk without failing federal nutrition audits.

- Schools may also offer nondairy beverages that are nutritionally equivalent to milk as substitutes, with simplified rules for parents to request them.

The new 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, released just a week earlier, had already endorsed full‑fat dairy as part of a healthy diet—a major shift from years of low‑fat messaging that had shaped school meal rules since 2012.

| School Year | Whole | 2% | 1% | Fat-Free | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–09 | 850M | 900M | 180M | 70M | 2,000M | Pre-mandate baseline |

| 2009–10 | 820M | 920M | 190M | 90M | 2,020M | |

| 2010–11 | 795M | 945M | 210M | 120M | 2,070M | Trend shift begins |

| 2011–12 | 700M | 900M | 350M | 200M | 2,150M | Final year before mandate |

| 2012–13 | 180M | 520M | 800M | 450M | 1,950M | Low-fat mandate → cliff |

| 2013–14 | 160M | 480M | 850M | 510M | 2,000M | |

| 2014–15 | 140M | 420M | 900M | 540M | 2,000M | |

| 2018–19 | 100M | 350M | 950M | 600M | 2,000M | Stabilized at new low |

| 2020–21 | 80M | 280M | 920M | 720M | 2,000M | COVID impact |

| 2023–24 | 95M | 310M | 940M | 655M | 2,000M | Pre-reversal |

| 2025–26 | 540M | 650M | 400M | 410M | 2,000M | Projected post-Whole Milk Act |

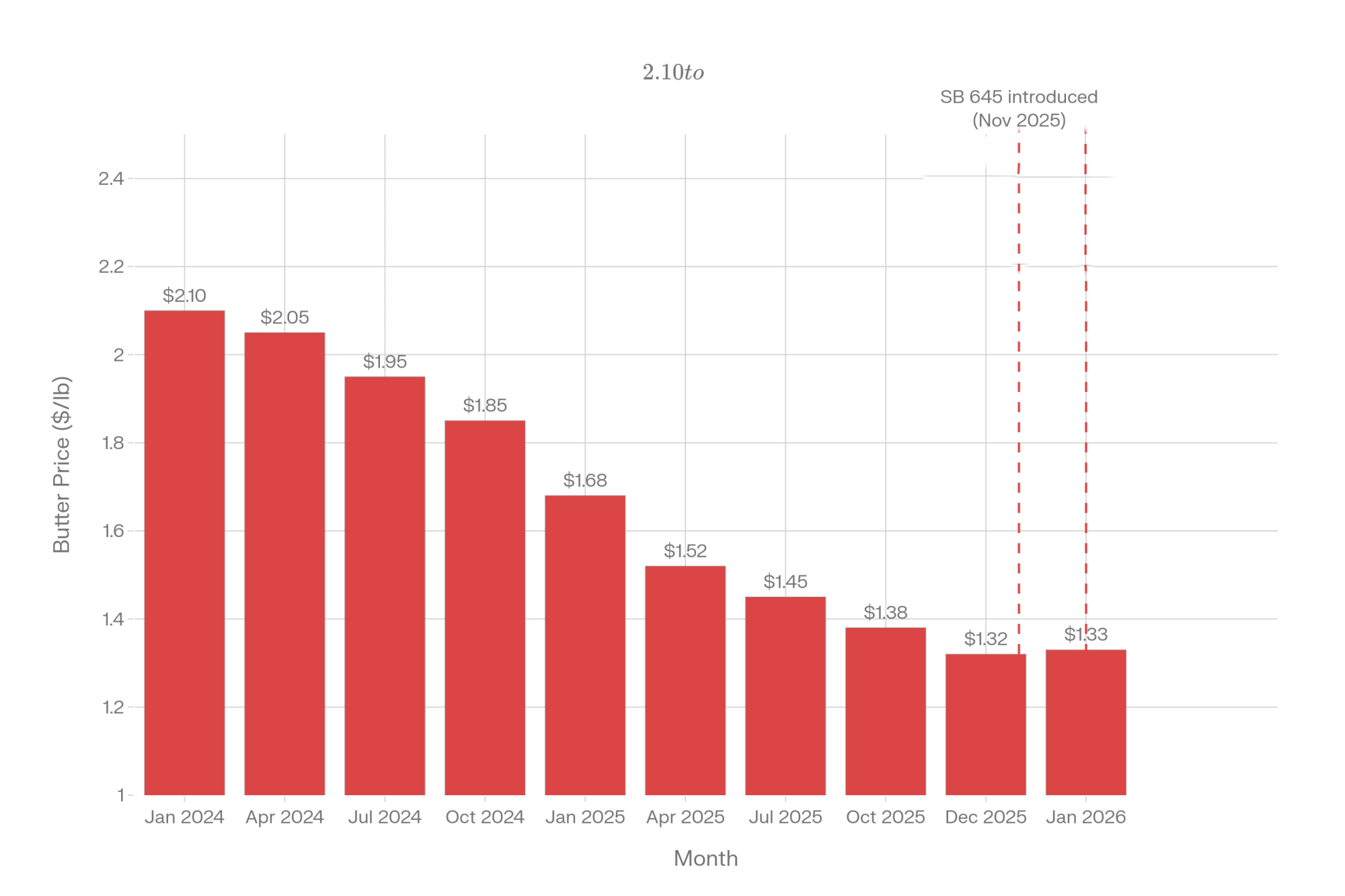

For the farmers who pushed for the return of whole milk, the win was real. Industry groups estimate the law could add meaningful butterfat demand to the Class I pool over time, especially in high‑fluid markets where kids actually drink their milk when they like the options. But the celebration came with a sober reminder: the January 2026 Class I base price sat around $16.35 per hundredweight—the lowest in nearly five years—and butter was trading around $1.30 to $1.37 a pound, more than a third lower than the year before.

| Year | Whole + 2% Milk (%) | Policy Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 65% | Pre-low-fat mandate |

| 2014 | 42% | 3 years post-mandate |

| 2016 | 38% | Continued decline |

| 2018 | 35% | Plateau begins |

| 2020 | 33% | COVID disruption |

| 2024 | 32% | Pre-Trump/SP 01-2026 |

| 2026 | 65% (projected) | Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act signed Jan 14 |

The policy was finally catching up to what dairy families had been saying for years. The milk check? Not so much.

That’s part of what makes Wisconsin’s butter bill feel like more than just a quirky state law. It’s a signal that dairy communities aren’t waiting for Washington to fix everything. They’re pushing on the levers they can reach—school boards, state legislatures, local Farm Bureau chapters—because those levers are closer to home and sometimes move faster.

| Month | Butter ($/lb) | Class I ($/cwt) | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 2024 | $2.10 | $18.50 | Year ago baseline |

| Apr 2024 | $2.05 | $18.10 | |

| Jul 2024 | $1.95 | $17.80 | Summer softness |

| Oct 2024 | $1.85 | $17.20 | Fall decline |

| Jan 2025 | $1.68 | $16.80 | School year trends |

| Apr 2025 | $1.52 | $16.50 | |

| Jul 2025 | $1.45 | $16.20 | |

| Oct 2025 | $1.38 | $16.35 | SB 645 introduced (Nov) |

| Dec 2025 | $1.32 | $16.35 | Trump signs Whole Milk Act (Jan 14) |

| Jan 2026 | $1.30–$1.37 | $16.35 | Policy win, prices flat |

Senator Marklein put it simply: “I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect that our schools will serve something that comes from our dairy cows.”

What One Family’s Frustration Taught a Community

The family who started all this didn’t set out to make headlines. They just wanted someone to listen.

And here’s what still strikes you about this story: they found listeners. Not just one sympathetic neighbor, but a whole room of them. Not just a friendly ear at the co‑op, but an association that carried their concern to the capitol. Not just a vague promise to “look into it,” but an actual bill with bipartisan support, moving through committee as this goes to press.

That doesn’t always happen. Anyone who’s tried to push back against institutional inertia knows how often small frustrations get swallowed up by bigger problems, filed away, forgotten. But in Iowa County, something different happened. A community decided that a margarine cup was worth fighting over—not because it was the biggest issue on their plate, but because it symbolized something that mattered.

Their kids were being taught, in small, quiet ways, that what their families produced wasn’t good enough for their school cafeteria.

And the community said: “Not here. Not in Wisconsin.”

The Quiet Work That Makes It Possible

Stories like this don’t happen without a web of relationships that most people never see.

There’s the Farm Bureau chapter that holds monthly meetings even when turnout is thin, and the agenda feels routine. There’s the association staffer who picks up the phone when a frustrated farmer calls and doesn’t dismiss the concern as too small. There’s the lawmaker who still remembers what it felt like to haul milk before school and hasn’t forgotten where he comes from.

There are also the neighbors who show up when someone speaks up, the ones who’ve been shipping milk alongside you for years, standing next to you at the show ring, answering the phone at odd hours when something goes wrong in the barn. The kind of people who don’t let a moment pass without adding their voice when it counts.

None of that is automatic. It’s built over years—over church potlucks and auction barns, over 4‑H meetings and FFA banquets, over the slow accumulation of trust that comes from showing up when it matters.

Wisconsin’s butter bill is still in committee. There’s no guarantee it will pass. The family who brought those margarine packets to the meeting may never see their names in print, and that’s probably fine with them. What they wanted wasn’t fame. They just wanted their community to care about the same things they cared about.

And for a little while, in a community hall in southwestern Wisconsin, they found out it did.

What This Means for the Rest of Us

| Policy Lever | Decision-Maker | Dairy Family Influence | Timeline to Impact |

| School meal standards (butter vs. margarine, milk fat %) | Local school board + nutrition director | High | 1–3 months (direct constituent pressure; immediate board access) |

| State dairy labeling & sourcing mandates (e.g., “real butter” bills) | State legislature + agriculture committee | High | 1–2 years (Farm Bureau chapters + lawmaker relationships; visible constituency) |

| Federal school lunch nutrition rules (USDA SP memos, dietary guidelines) | USDA + HHS nutrition committees | Low | 3–5+ years (national coalition required; individual farm voice diluted) |

| Fluid milk marketing order pricing (Class I minimums, pooling rules) | USDA Federal Milk Marketing Orders | Medium | 2–4 years (requires dairy cooperative + large-producer bloc; marginal farmer limited influence) |

| State/local co-op milk procurement & contracts | Co-op board + processor supply chain | Medium–High | 6–18 months (direct access to local leadership; implementation variable) |

| Farm-to-school direct-market programs (branded farm milk in local schools) | School district + individual farm negotiations | High | 3–12 months (local relationships; direct farm-to-school partnerships most agile) |

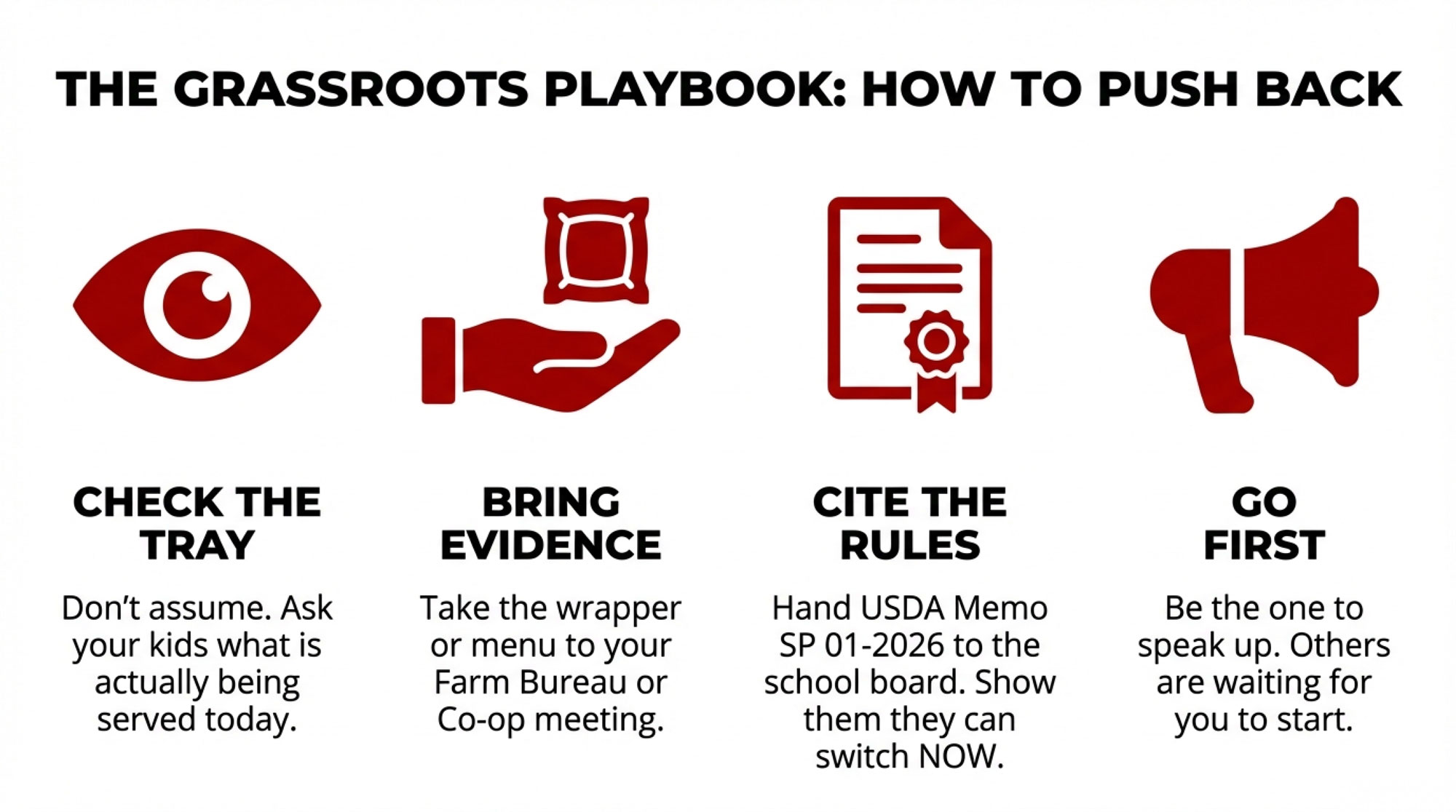

You don’t have to live in Iowa County to recognize something familiar in this story.

Most dairy communities have their own version of the margarine cup—some small moment when it became clear that the wider world had quietly moved on from something that still mattered deeply at home. Maybe it was the day flavored milk disappeared from the cooler. Maybe it was a budget meeting where ag programs got cut. Maybe it was a school board decision that nobody thought to fight until it was already done.

The question isn’t whether those moments will come. They will. The question is what happens next.

Do you stew at the kitchen table and let it go? Or do you bring it to the next meeting, set it on the table, and see who else feels the same way?

Here’s what one Wisconsin family learned: sometimes, people are just waiting for someone to go first.

If you’ve been thinking about speaking up at your local Farm Bureau, your co‑op meeting, your school board—this might be the nudge you needed. You don’t have to have all the answers. You don’t have to be a polished speaker. You just have to be willing to say, “This bothers me, and I think it should bother us.”

And then you have to trust that the community you’ve been building, year after year, might just show up when it counts.

Small Cups, Big Questions

A margarine packet is a small thing. It fits in a child’s hand, gets torn open in seconds, and ends up in the trash before the lunch bell rings.

But what it represents isn’t small at all.

It’s about whether dairy families feel like their own state—their own schools, their own kids’ cafeterias—still believes in what they produce. It’s about whether the slow erosion of dairy’s place in American food culture can be pushed back, one policy at a time, one school board at a time, one Farm Bureau meeting at a time.

It’s about whether communities still have the power to say, “Not here.”

Wisconsin’s butter bill may pass or stall. The Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act is just beginning to be implemented, and nobody knows yet how many districts will actually change. The markets are tough, the margins are thin, and there are plenty of reasons to feel like the world has moved on from the kind of farming that built places like Iowa County.

But here’s what this story keeps coming back to: a family showed up to a meeting with a handful of margarine packets and a story about their kid. And instead of being ignored, they were heard. Instead of being told it was too small to matter, they watched their neighbors and their lawmakers say, “This matters to us too.”

That’s not nothing. In a time when it’s easy to feel like nobody’s listening, it might be everything.

The butter isn’t back in Wisconsin schools yet. But the conversation is. And sometimes, that’s how change starts—not with a grand announcement, but with a parent, a packet, and a room full of neighbors who heard something in that story that sounded like their own.

Key Takeaways

- One margarine cup sparked a bill: A Wisconsin farm kid came home with margarine instead of butter—and after that story hit a local Farm Bureau meeting, Senator Marklein and Rep. Novak introduced SB 645, a bipartisan bill requiring schools to serve real butter.

- Whole milk returns to schools: President Trump signed the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act on January 14, 2026, restoring whole and 2% milk in school lunch programs and exempting milk fat from weekly saturated‑fat limits.

- USDA greenlights immediate action: SP 01‑2026 gives districts authority to expand milk options right away—but local school boards and supplier contracts will determine how fast anything changes on the tray.

- Policy wins, prices don’t: Class I base near $16.35/cwt and butter around $1.30–$1.37/lb are the lowest in years—good policy alone won’t fix a tough milk check.

- Local advocacy still works: Farm Bureau chapters, dairy associations, co‑ops, and school boards remain the places where dairy families can actually shape what kids eat and drink—and this story proves it.

Senate Bill 645 is currently in committee in the Wisconsin State Legislature. The Bullvine will continue to follow its progress. If your community has a story like this—about showing up, speaking out, and finding out that your neighbors were waiting for someone to go first—we’d like to hear it.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Whole Milk Returns to Schools After $4.3B Loss – But Only Mega-Dairies Can Capture the Win – Gain an immediate edge on school milk contracts with this 90-day action plan. It delivers the exact questions for your co-op and reveals the administrative thresholds you must hit before the January RFP window slams shut.

- The $200K Dairy Margin Trap: What Cheap Feed Won’t Tell You About 2026 – Exposes the $200,000 margin trap hiding behind cheap feed in 2026. This analysis arms you with a strategic checklist—from beef-on-dairy to component audits—to protect your operation against the forecast $1.80 drop in the all-milk price.

- Revolutionizing Dairy Farming: How AI, Robotics, and Blockchain Are Shaping the Future of Agriculture in 2025 – Reveals how AI and blockchain are transforming standard commodity milk into a high-value “billboard of trust.” It breaks down the methods for capturing 15% price premiums through transparency, giving you a distinct advantage in a crowded market.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!