Why does your CEO make $5.9M selling what you built while you struggle with $3.67 diesel?

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Here’s what we discovered: Fonterra’s about to sell their consumer business for $4.2 billion—the same division showing 103% profit growth—and farmers are celebrating a one-time $320,000 payout that’ll leave them underwater in 13 years. CEO Miles Hurrell’s compensation jumped 29% to $5.9 million NZ last year (that’s what, 100 dairy farms’ worth of profit?), following the exact playbook Dean Foods used before bankruptcy when their CEO banked $66 million. The data tells a different story than cooperative newsletters: DFA’s paid out over $330 million in price-fixing settlements since 2011, McKinsey’s drawing roadmaps for multinational takeovers using your cooperative dues, and Tom Vilsack’s making nearly a million bucks bouncing between USDA and Dairy Management Inc. October 30th, ten thousand Fonterra farmers vote on whether to keep control or cash out… and based on everything we’ve seen, they’ll take the money. Your cooperative could be next—hell, if you’re in any major co-op, somebody’s already running spreadsheets on what your assets are worth to Nestlé or Saputo.

So I’m standing in line for coffee at a cattle show – you know how those lines get, everybody needs their caffeine fix—and this guy who grew up in New Zealand starts telling me about his family’s Fonterra payout. Three hundred and twenty thousand dollars. He’s practically glowing.

I almost spit out my coffee.

Look, I get it. Last spring, when corn prices were fluctuating and diesel hit $3.67 a gallon… $320,000 sounds like salvation. That’s a down payment on a new robotic milking system. That’s two decent John Deeres if you know a guy who knows a guy. But here’s the thing—and I had to walk this poor bastard through it right there by the show ring—they’re selling their consumer business to Lactalis for $4.2 billion. And nobody’s doing the real math.

Can you believe that? Four point two billion. With a B.

The Math Nobody Wants You Running

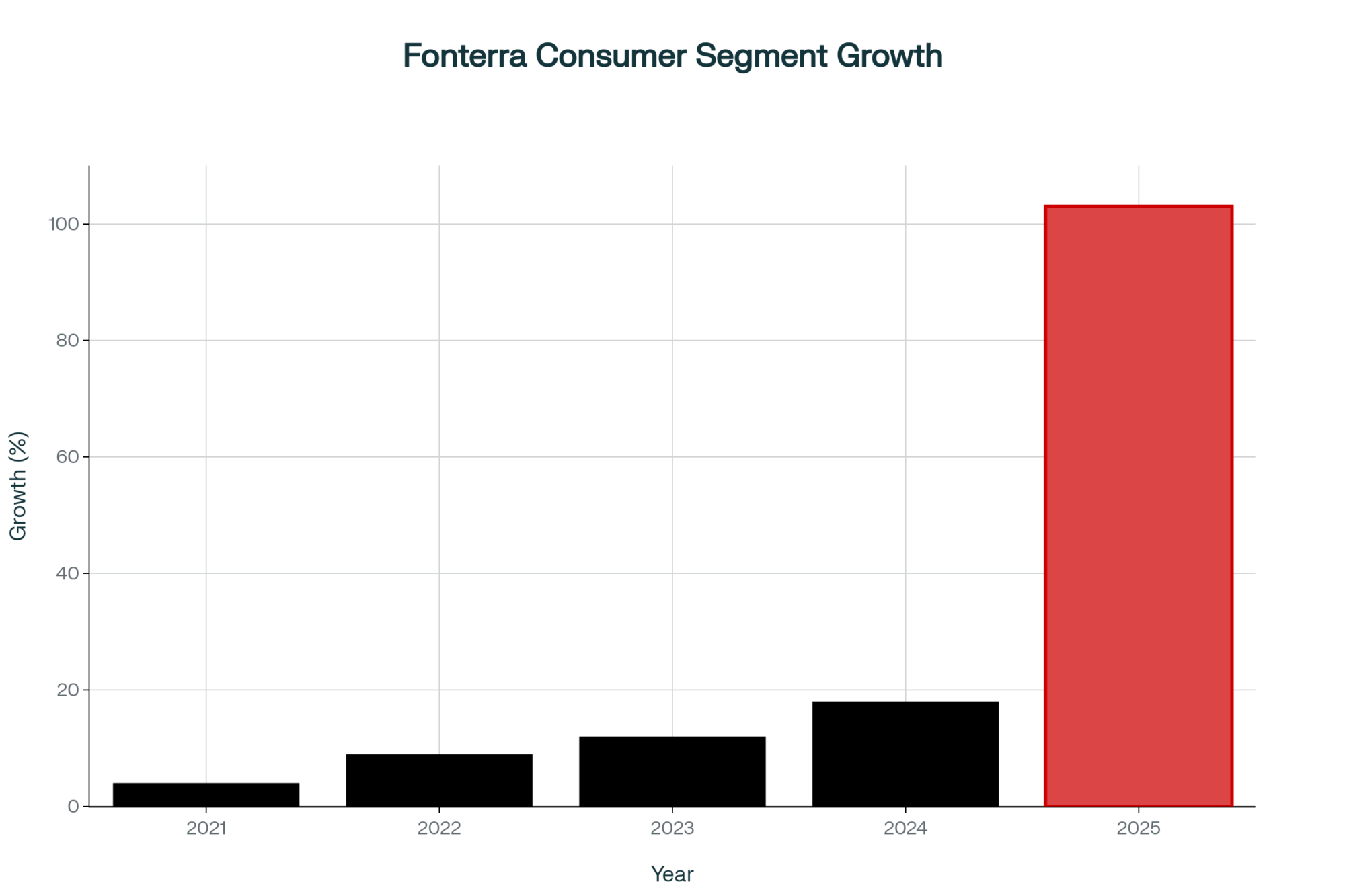

I was up until 2 AM last night going through Fonterra’s actual financials—not the glossy newsletter they send to farmers, but the real SEC-type filings—and I almost fell out of my chair. Their consumer segment? The one they’re selling? It showed 103% profit growth in the third quarter. Operating profit jumped to $319 million New Zealand dollars, up $71 million from the previous year.

Let me say that again. One hundred and three percent growth. And they’re selling it.

You know what’s revealing? Just yesterday—literally yesterday morning—the Otago Daily Times ran a piece stating that Fonterra’s return on capital is 10.9%. That’s the whole company, mind you. They won’t tell you what the consumer segment alone makes—I wonder why—but come on, that’s a bit of a stretch. If something’s growing at 103%, it ain’t the weak link.

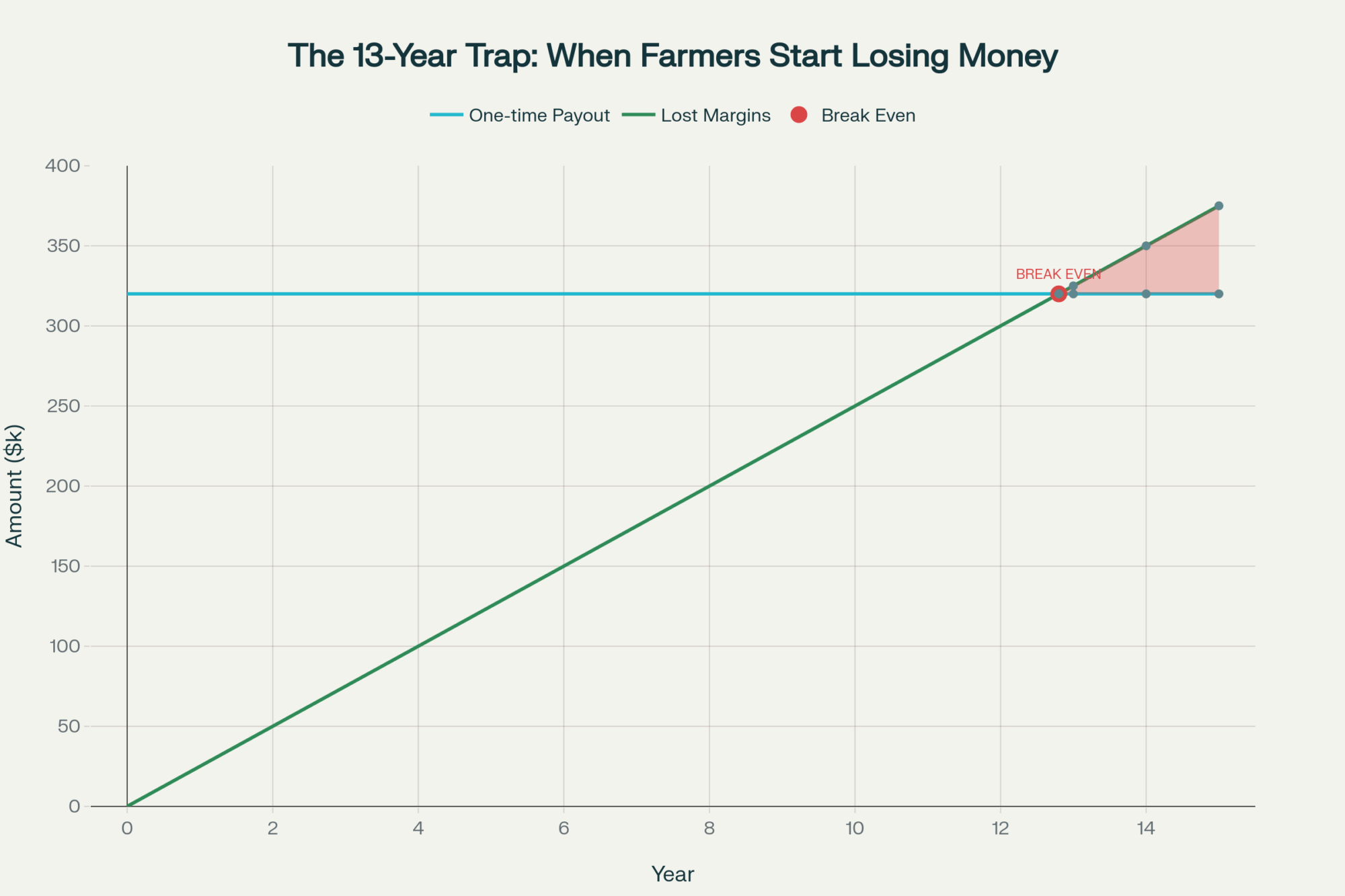

The thing about these numbers that really gets me… I ran some calculations on a napkin at the hotel bar. If you’re giving up even 25 grand a year in future margins—and honestly, with premium dairy products exploding like they are, that’s probably conservative as hell—you’re underwater by… what, year thirteen? Perhaps sooner if inflation continues at its current pace. By the time your kids take over? They’re down a couple of hundred thousand, easy. Maybe more.

But that’s not even the part that concerns me most…

When Your CEO Makes More Than a Whole Dairy

You sitting down? Good. Because Miles Hurrell—Fonterra’s CEO—pulled in 5.9 million New Zealand dollars last year. Simply Wall Street experienced a breakdown in November, which is equivalent to approximately $ 3.5 million U.S. dollars. And get this—it was a 29% jump from the year before.

Twenty-nine percent! A Vermont dairy producer who follows executive compensation told me, “When’s the last time your milk check went up 29%?” Never, that’s when.

His base salary alone is 2.46 million NZ. The rest? “Performance bonuses.” And what was the big performance? Oh, just selling off the fastest-growing part of the business to the French. Makes you wonder about the incentive structure.

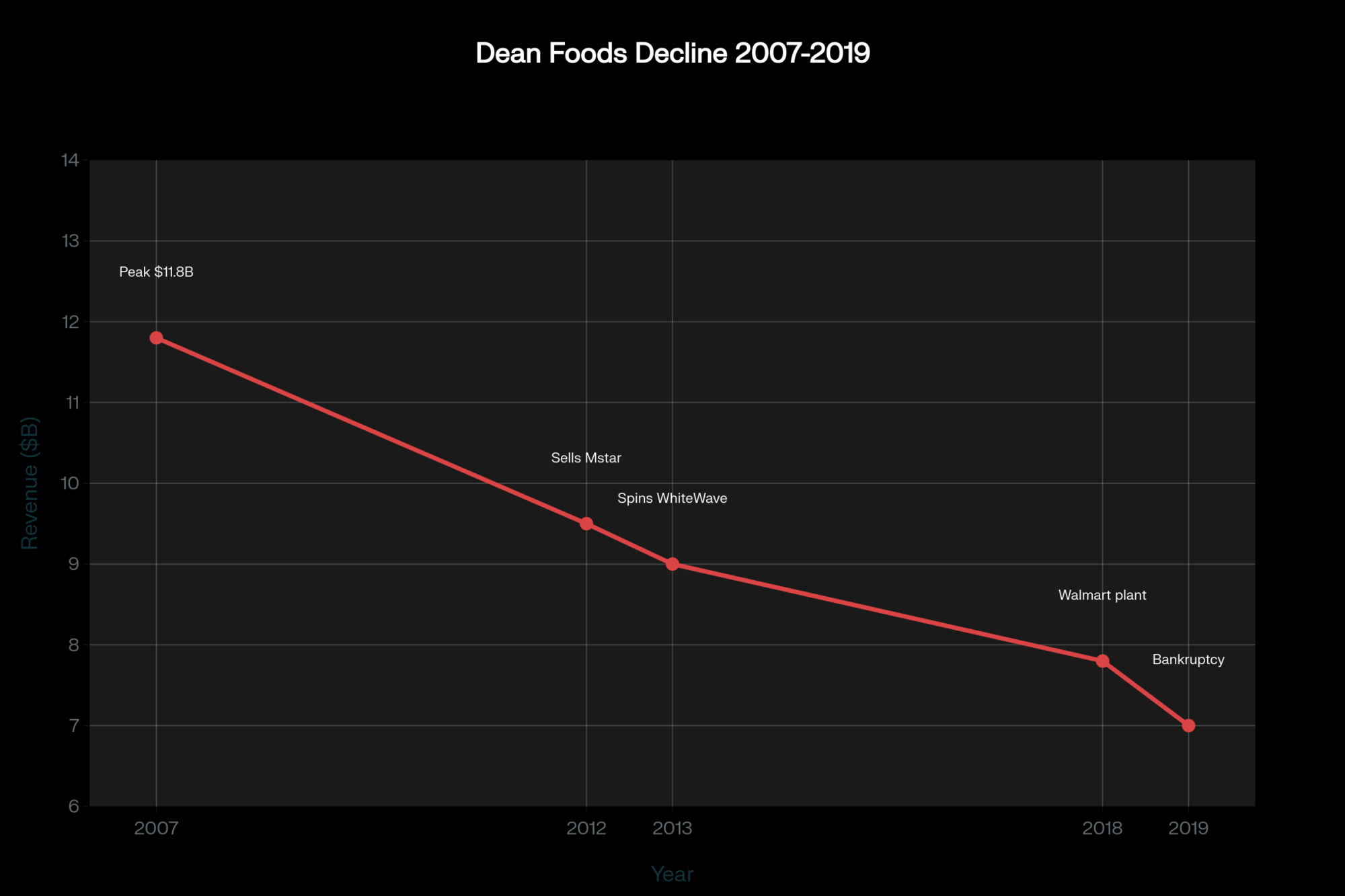

What strikes me about this whole executive comp thing… you remember Dean Foods? I was actually at a conference in Dallas when The Milkweed broke that story about their CEO compensation. Gregg Engles—this was back in 2007—earned $ 66 million. Sixty-six! They had to borrow money to pay his 39.6 million stock bonus. Borrowed it! Meanwhile, farmers were getting what, $12 milk?

Then they burn through CEOs like my neighbor goes through hired help, and by 2019, boom, bankruptcy. But the executives? They’d already cashed out.

I spoke with an Irish dairy farmer at the hotel—runs 300 cows outside Cork—and he’s telling me Kerry Group’s doing the exact same dance. Executive pay is through the roof, strategic consultants are everywhere, and next thing you know, they’re “repositioning assets.” It’s as if they all attended the same school of corporate restructuring.

The Consultants Getting Rich Off Your Dues

Oh, and here’s what’s particularly troubling—Herbert Smith Freehills, some fancy law firm, they’re bragging in their press releases about advising Fonterra. Russell McVeagh’s handling the New Zealand side. You know what these firms typically charge?

A former M&A lawyer I know—used to work for one of these big firms before switching to agricultural law—tells me, for a deal this size? One to two percent is standard. So that’s what, $40 to $80 million? For pushing paper? And that’s just the lawyers!

This trend makes me wonder… McKinsey put out this report in 2019—”A Winning Growth Formula for Dairy” or some such BS—and while they don’t come right out and say “sell everything to multinationals,” they’re basically drawing you a map. All this talk about “consumer analytics” and “supply chain agility”…

You know who’s paying McKinsey? Your cooperative. Through your dues. They’re literally using your money to figure out how to restructure your own industry.

I find it ironic—we’re essentially funding our own displacement.

The Pattern Repeats: Other Cooperatives Face Similar Pressures

Now, Fonterra’s not alone in this. The pattern of executive enrichment while farmers struggle is playing out across cooperatives globally. Take DFA in the States—they just settled another price-fixing lawsuit in July this year. Thirty-four point four million dollars. DFA’s paying $24.5 million, while Select’s kicking in almost $10. Reuters had it, The Bullvine covered it… hell, everyone except the cooperatives’ own newsletters covered it.

A Texas dairy producer who runs about 800 head near Amarillo pointed out to me, “Isn’t this the third time?”

Yeah, it is. They paid out 140 million back in 2011. I remember because that’s the year I bought my first new pickup in a decade and thought I was doing good. Then, in 2013, Farm and Dairy reported another settlement—$ 158.6 million at the time. Now this one.

Add it up. That’s over 330 million dollars in settlements. And these cooperatives—whether it’s Fonterra selling assets or DFA settling lawsuits—they still operate with antitrust immunity! The Capper-Volstead Act, enacted in 1922—when my great-grandfather was milking 12 cows by hand—it’s supposed to protect farmer cooperatives in the United States. Instead it’s protecting… well, I’m not sure what it’s protecting anymore. Sure as hell ain’t farmers.

The connection here is clear: whether through asset sales, like Fonterra’s, or price manipulation, like DFA’s, cooperative executives are getting rich while farmers get the short end of the stick.

Your Government at Work (For Someone Else)

The thing about government oversight that really concerns me? The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission announced they would not oppose” the Fonterra-Lactalis deal. Would not oppose. Like they’re doing us all a favor.

And Tom Vilsack in the States? After his first run as USDA Secretary, you know where he went? Dairy Management Inc. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel—God bless ’em—dug into it. He earned $999,421 per year. Basically a million bucks to… what? Promote cheese? Then he comes back to USDA, and farmers are supposed to trust him with their future?

A senior USDA official I spoke with at a meeting in Madison last month—someone who’s been with the department for years—when I asked him straight up about Vilsack’s ability to be neutral after making a million a year from the industry, just shrugged. “That’s how Washington works,” he said.

Well, maybe that’s the problem…

Some Guys Are Fighting Back (And Winning)

But here’s the thing—and this is why I haven’t completely given up—some farmers are figuring this out.

There’s this Dutch farmer I met at a conference in Europe last year… who has a place called Dobbelhoeve. Only 120 cows, but he installed one of those Lely Orbiter systems. Processes his own milk right on the farm. According to Lely’s case studies, he’s getting 1.69 euros for a bottle—less than a liter—in local stores. That’s like two bucks U.S. for basically a quart of milk!

Now, I called around about the Orbiter… nobody wants to give you a straight price (which tells you something right there), but industry sources who’ve looked into it say you’re looking at a minimum of six figures. But here’s the thing—if you’re keeping all those processing margins instead of letting Lactalis have them…

And closer to home? Beef-on-dairy is printing money right now. I was at a sale barn in Wisconsin last week—a little place outside Shawano—and Holstein bull calves were going for 400 to 600 bucks. The beef crosses? Thousand minimum. Saw one little Angus-cross bull, 116 pounds, go for $1,450.

Fourteen hundred and fifty dollars! For a day-old calf!

A Missouri dairy farmer I know—runs about 300 head down near Springfield—he switched his whole program to beef semen two years ago. Figures he’s making an extra two, two and a half bucks per hundredweight just on calf value. On 300 cows, milking year-round? Do the math.

What strikes me here… Pennsylvania’s keeping their over-order premium at a dollar per hundredweight for Class I—Cheese Reporter confirmed it in December. It’s not huge money, but it’s something. Several Pennsylvania producers selling raw milk with all the proper permits tell me they’re receiving premium prices, although they’re understandably reluctant to share exact numbers. Smart, if you ask me—why advertise what you’re making when the big boys might come after your market?

How to See the Screwing Coming

I’ve been watching this long enough… there’s always signs. Always.

First thing? Executive pay starts jumping. Not cost-of-living increases—I mean 20-30 percent bumps. Like Hurrell’s 29% increase. When you see that in your cooperative’s annual report (and yes, you should be reading that boring thing), start asking questions. Start asking loud questions.

Then come the consultants. McKinsey shows up, or Deloitte, or some “strategic advisory group” nobody’s heard of. The moment that shows up in board minutes? You’ve got maybe 18 months before they announce something that’ll make you want to punch a wall.

The thing about these new board members… “Independent directors” with Wall Street backgrounds. Not farmers, not even agricultural professionals. Finance types who say things like “optimizing the portfolio” and “right-sizing the enterprise.” When you hear that language at your annual meeting… they’re already picking out buyers.

I attended a DFA meeting two years ago—before the latest settlement—and they kept saying “strategic repositioning.” I leaned over to the guy next to me and said, “That’s corporate speak for trouble.” He didn’t laugh. Neither did I.

What the Hell Can We Actually Do?

Alright, so… I know this all sounds concerning. Like we’re facing insurmountable challenges. But we’re not. Not if we get smart about it.

First—and I cannot stress this enough—you have rights as a member-owner. You can request to see the actual books, contracts, and board minutes. Not the newsletter version. The real stuff. Most guys don’t even know they can ask.

I assisted a group of farmers in Minnesota with this project last year. We hired a lawyer—costing us about $10,000 split 20 ways—but the information we uncovered was worth every penny.

What really matters here is that you need to build a coalition. About 25% of members is the magic number where boards start sweating. That’s when they can’t just ignore you anymore. Start with your neighbors, the guys at the feed store, your milk hauler—he talks to everybody.

And start looking at options now. Even if you’re not ready to jump ship. Can you direct-market some milk? Producers are operating legally, holding all the necessary permits, and earning good premiums. Not everyone can swing it, but… options give you power.

I’m not saying it’s easy. Hell, nothing about dairy’s easy anymore. But rolling over and taking it? That’s not an option either.

This Is Different

Look, I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I covered the 2009 crash when guys were literally dumping milk. I was there in 2014 when everyone thought $24 milk would last forever and borrowed accordingly. This… this is different.

This isn’t markets. It’s not the weather, feed costs, or even those futures traders in Chicago. This is systematic. It’s coordinated. It’s our own leadership selling us out for consulting fees and executive bonuses.

Fonterra farmers receive their $ 320,000 and think they’ve won. But Hurrell’s making 5.9 million just in salary—that’s before whatever else is buried in the fine print. Your cooperative could be next. Hell, if you’re in any major co-op, somebody’s probably already got a PowerPoint about how much your assets are worth to Nestlé or Saputo.

The vote’s on October 30th for Fonterra. Ten thousand farmers will decide if they want to take the money now or keep control of their future. Based on everything I’ve seen? They’ll take the money. They always do. Because when you’re looking at these feed prices and diesel over three-fifty and that broken TMR mixer… 320 thousand looks like salvation.

Even when it’s really just selling your grandkids down the river.

I’m not sure… maybe I’m wrong. Perhaps these McKinsey consultants, with their algorithms, really do know better than farmers who’ve been doing this for five generations. Maybe Lactalis will be wonderful overlords who’ll always pay us fair prices.

And maybe I’ll win the lottery tomorrow. The odds are about the same.

You know what really gets me? I’ve watched too many young farmers—kids who grew up showing cattle, who know their EPDs better than most veterinarians, who have all the passion and knowledge to carry this industry forward—they’re looking at their future and seeing nothing but contract production for multinationals. These are the ones who should be taking over, building on what their parents and grandparents created. Instead, they’re watching it get sold off piece by piece.

That concerns me more than anything. We’re not just selling out ourselves. We’re selling out an entire generation that hasn’t even had their chance yet.

Better fight now while we still can. Because once it’s gone—once those assets transfer, once that control shifts—it’s gone forever. And that 320 thousand? In 20 years, it won’t even cover the lawyer fees to try and get it back.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- The $25K annual loss nobody’s calculating: If you give up processing margins for a one-time payout, you’re down $200,000+ by year 20—and that’s using conservative estimates on premium dairy growth that’s exploding globally right now

- Watch for these three warning signs: Executive comp jumping 20-30% (like Hurrell’s 29%), McKinsey or Deloitte showing up for “strategic reviews,” and new board members with Wall Street backgrounds who’ve never touched a teat cup

- Beef-on-dairy’s printing $350-500 more per calf while you’re distracted by cooperative drama—Wisconsin sales showing Holstein bulls at $400-600 versus beef crosses hitting $1,450 for day-old calves

- You’ve got member-owner rights you’re not using: Demand the real books and board minutes (not newsletters), build a 25% member coalition to force accountability, and start exploring direct-marketing options before your leverage disappears

- The pattern’s global and accelerating: Whether it’s Fonterra in New Zealand, DFA in the States, or Kerry Group in Ireland, executives are getting rich restructuring farmer assets—and they’re using the same playbook every time

The Bullvine spent three months digging through financial filings, court documents, and talking to farmers who’ve lived through these transitions. Every number here comes from public records or verified sources. This is the story your cooperative leadership hopes you’re too busy to figure out.