A multi-generation Pennsylvania farm, a 15-year policy fight, and a community that kept showing up when it would’ve been easier to stay home

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: When the White House needed dairy farmers to witness the signing of the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act on January 14, 2026, they didn’t just invite the big operations. They invited William Thiele, who milks 40-60 cows with his family on land in Butler County, Pennsylvania, that they’ve farmed since 1868. He got that call because he’d spent 15 years showing up: at Farm Bureau meetings that ran late, policy hearings where the same arguments had to be made again, and pandemic milk distributions where neighbours handed out surplus to families in need. His family’s farm—first in the county to adopt a conservation easement, known locally for Lorraine Thiele’s painted round bale art along the road—has become a quiet example of what grassroots dairy community presence looks like over generations. Whole milk is back in schools, but the honest reality is that milk checks won’t jump overnight, and the harder structural problems in dairy remain unsolved. The deeper message is about the compounding power of showing up—and the question it leaves every reader with: when that call comes to your county, will someone be ready to answer it, and are you helping make sure they’re not doing it alone?

Forty to sixty cows. More than 150 years on the same ground. The Oval Office.

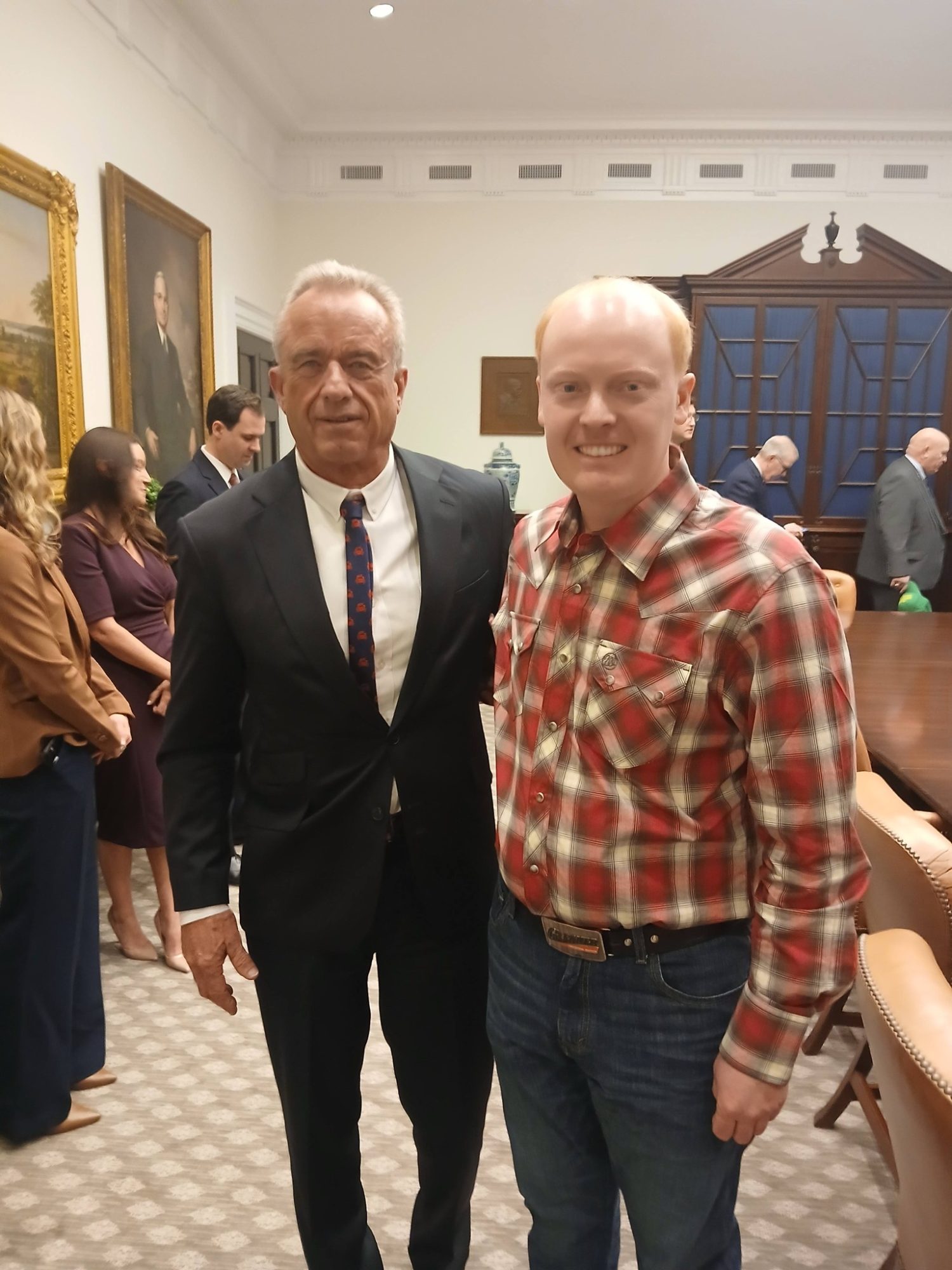

On January 14, 2026, a dairy farmer who milks Holsteins with his family in Butler County, Pennsylvania, stood behind the Resolute Desk as President Trump signed whole milk back into American schools.

William Thiele wasn’t there because his operation is big. He wasn’t there because he has a lobbying budget or a publicist. By all accounts, he was there because, for years—through low milk prices, policy setbacks, and all the reasons people give for why small dairies are supposed to disappear—he and his community kept showing up.

At Farm Bureau meetings that ran past when everyone wanted to be home for evening chores. At policy hearings where the same arguments had to be made again to different faces in the same chairs. At pandemic milk distributions, where families lined up in their cars and volunteers worked until the last gallon was gone. At every unglamorous place where grassroots dairy voices are easy to ignore.

Fifteen years is a long time to keep showing up when nothing seems to change.

But that’s exactly what this community did.

A Farm That’s Still Here After Six Generations

You know the kind of place.

The farmhouse has been added onto more times than anyone can count. The equipment is a mix of generations—some pieces older than the people running them. The cows know the routine better than any written schedule could capture. The lane has ruts that have been there since your grandfather’s time, and somehow that feels right.

Thiele Dairy Farm sits on nearly 300 acres in Jefferson Township, Butler County. The family has been there since 1868—more than 150 years of milking on the same ground, through wars and depressions, milk price crashes, and everything else the world has thrown at dairy.

It’s around a 40 to 60-cow milking operation—roughly 80 head when you count the full herd. Not 400. Not 4,000.

In an industry where small operations face constant pressure to expand or exit, a farm of that size still standing after all these generations is increasingly rare. The fact that this one is still here—and still investing in the future—says something about the people behind it.

The brothers handle most of the daily work. William often serves as the public-facing one, the guy who shows up at meetings and talks to legislators when most farmers would rather be home finishing chores. James handles much of the day-to-day fieldwork and equipment. Their parents, Ed and Lorraine, are still very much in the picture. Ed keeps a close eye on crops and the long-term questions that every multi-generation farm has to wrestle with. Lorraine manages the books and has become unexpectedly well-known for something that has nothing to do with spreadsheets.

More on that in a minute.

The Decision That Shaped Everything After

Back in 1997, when development pressure from Pittsburgh started pushing into Butler County, the Thieles made a choice that still defines the farm.

They enrolled their land in Pennsylvania’s Agricultural Land Preservation Program, permanently protecting it from development. According to state records and a soil health case study by the American Farmland Trust, they were the first farm in Butler County to do it.

Not everyone understood the decision at the time. But the logic was simpler than critics made it sound: if the ground is what you’re handing to the next generation, you’d better make sure it stays ground.

That’s not the kind of thinking that shows up on a balance sheet. But it’s the kind of thinking that keeps farms in families.

Years later, they went further. In 2015, the family transitioned the entire operation to no-till and cover crops. An economic analysis found that the changes reduced machinery costs and increased net farm income per acre. Conservation, it turned out, could also strengthen the bottom line.

Every gallon of milk from those cows goes to Marburger Farm Dairy, a family-owned fluid plant in Evans City that’s been part of western Pennsylvania’s food system since 1938. From there, it ends up in jugs and cartons for schools, stores, and other outlets across the region.

None of this is flashy. But for anyone who’s watched small dairies close one by one—the neighbours who had an auction, the classmates who sold out, the empty barns you pass on the way to town—there’s something worth noticing in an operation that’s still here. Still thinking about the generation that hasn’t arrived yet.

How Years of Showing Up Led to the Oval Office

The phone call that changed everything came on a Monday in early January 2026, while William was at the Pennsylvania Farm Show.

He serves as the Pennsylvania Farm Bureau state board director for District 15, covering Butler, Beaver, Lawrence, and Mercer counties. According to the Butler Eagle and Farm Bureau accounts, that’s what put him on the list when the White House went looking for real dairy farmers to attend the signing of the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act.

The Farm Show is its own kind of community gathering—dairy people from across the state showing cattle, staffing milkshake booths, trading stories in the cattle barns, catching up with folks they only see once a year. That’s where the call found him. After a brief vetting process, he was notified on Tuesday that he’d been selected.

Farm Bureau staff later noted that his years of steady presence—at meetings, hearings, and conversations with legislators—were key to opening that door.

Here’s the part worth sitting with: there was no single dramatic moment that made this happen. No viral video. No one big speech that changed everything. It was the accumulation of ordinary ones. The steady presence at policy discussions, even when progress was slow. The willingness to keep showing up when it would’ve been easier to stay home and finish chores.

If you’ve ever skipped a Farm Bureau meeting because you were too tired, or figured your voice didn’t really matter in the big picture, you’re not alone. Most of us have been there.

But this story suggests that the ones who keep showing up are the ones who end up in the room when the room finally matters.

“Yes, That Butler, Pennsylvania”

The Oval Office—where so much of the nation’s business unfolds—held a small group of farmers that day.

The Resolute Desk sat in the center with a tall glass bottle of milk perched on top. Kids in dress clothes stood nearby—a reminder of who this bill was really about. Cabinet secretaries and senators filled the edges of the room. A small group of dairy farmers—representing operations ranging from a few dozen cows to several thousand—stood behind the President.

William wasn’t the only producer there. Jamie Pagel Witcpalek from Wisconsin represented Pagel’s Ponderosa Dairy and Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperative—an operation milking thousands of cows. Other farmers came from New Mexico, Kansas, Virginia, and elsewhere. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins pointed out that the group represented farms “across the spectrum.”

Big and small. Different regions, different markets, different challenges. But all of them had shown up.

When William introduced himself, he mentioned that he milked cows with his family in Butler County, Pennsylvania.

Then he added something that shifted the energy in the room: “Yes, that Butler, Pennsylvania.”

Everyone understood. Butler had become nationally known after the assassination attempt on Trump during the 2024 campaign. It’s not the story the town wanted to be remembered for, but it’s the one that stuck.

When Rollins mentioned Butler in her remarks, the President responded, “I love Butler.”

For a moment, the distance between a small dairy farm and the most powerful office in the country didn’t seem quite so far.

What He Said When the President Asked

Trump turned to William during the ceremony and invited him to speak.

According to later interviews, William shared remarks about what the day meant for agriculture—not just for dairy farmers, but for kids, schools, and processors too. He called it “perfect legislation” and “a great day for America.”

It’s worth noticing that when given a few seconds of national attention, he talked about the broader impact rather than his own operation. He spoke for the community, not just for himself.

That kind of perspective tends to come from years of being part of something bigger than your own barn.

The 15-Year Fight Behind One Signature

The Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act didn’t appear out of nowhere. Understanding what happened in that Oval Office requires understanding what happened in the 15 years before it.

In 2010, Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. By 2012, USDA regulations effectively removed whole and 2% milk from school cafeterias. Schools could serve only fat-free or low-fat options.

The goal was to reduce saturated fat in children’s diets. The outcome was more complicated.

A lot of kids stopped drinking milk.

USDA and industry data showed significant declines in school milk consumption after the 2012 changes. Representative Glenn “GT” Thompson of Pennsylvania put it bluntly at the 2026 Farm Show: “We’ve lost since 2012 two generations of milk drinkers. The impact on the American dairy farm was devastating.”

Two generations. That’s kids who grew up never learning to like milk—and who aren’t buying it now that they’re adults with their own families.

Thompson had been pushing versions of the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act for over a decade. One version passed the House 330-99 in December 2023 but never moved in the Senate.

Dairy organizations kept the issue alive. Pennsylvania Farm Bureau, Edge Dairy Farmer Cooperative, National Milk Producers Federation, and others continued lobbying, sharing research, and telling stories about kids who liked whole milk but threw away skim.

Year after year. Hearing after hearing. The same arguments, made again, to different faces in the same chairs.

In late 2025, momentum finally shifted. The Senate and House both passed the bill, sending it to the President’s desk.

When Trump signed it on January 14, 2026, it represented the end of a fight that had outlasted multiple administrations and more setbacks than anyone wanted to count.

What This Really Means for Your Milk Check

Here’s the honest part that every producer watching from home deserves to hear.

Whole milk is back in schools. That matters for kids. It matters for the dignity of the product you ship. It matters as a policy win after years of frustration.

But if you’re expecting your February milk check to look dramatically different, you’re likely to be disappointed.

School milk accounts for a limited share of U.S. fluid milk sales. How much any boost shows up in your check depends on where you ship. In high-fluid Federal Orders where Class I makes up most of the pool, a bump could mean modest improvement in the blend price. In manufacturing-heavy regions where cheese and powder dominate, extra school milk will mostly disappear into the blend.

For a small dairy shipping to a regional fluid processor like Marburger, the honest math is: probably pennies, not dollars. At least in the short term.

So let’s be clear about what this law does and doesn’t do.

It doesn’t fix Class III pricing. It doesn’t reverse consolidation. It doesn’t erase debt or solve labour shortages, or make your banker less nervous.

What it does is stop a form of active harm. It removes a rule that was pushing kids away from milk during the years when taste preferences form. It permits schools to serve the product you believe in.

That’s not a win you measure this quarter. It’s a win you measure in who’s still buying milk in 2035.

A Farm That Kept Reaching Out

Even before the White House invitation, Thiele Dairy Farm had developed a reputation for connecting with people beyond the farm gate.

When COVID-19 disrupted supply chains in 2020, Butler County—like dairy communities across the country—organized efforts to get surplus milk to families in need. Local organizations, including the Farm Bureau and area processors, coordinated distributions. The Thieles were among the local farms supporting those community efforts.

Cars lined up on those distribution days. Volunteers worked the line until the coolers were empty. Milk that might have gone down a drain went home with families who needed it.

Then there’s Lorraine’s round bale art.

What started as a creative project—painting hay bales along the road to look like flags, cows, turkeys, and holiday scenes—became an unexpected connection point with the non-farming public. The displays have drawn enough attention that people sometimes drive up the lane thinking they can buy milk directly.

That led the family to use signs and their Facebook page to explain that all their milk is sold through Marburger and can be found at stores where Marburger products are sold. Lorraine has talked about how most people don’t have a clue what dairy farming involves or how it’s done—and how her sons love showing them.

William has leaned into that same instinct through different tools. Using a drone to film planting, chopping, and baling, he’s created videos that show non-farm audiences what the work actually looks like. It’s not polished marketing. It’s just letting people see.

None of this generates direct revenue. But it builds something harder to put a price on: a farm that feels connected to its community rather than isolated from it.

What Other Communities Can Take From This

A few patterns stand out:

- Showing up compounds over time. The Oval Office invitation didn’t come from one dramatic moment. It came from years of Farm Bureau involvement and being present in rooms where small dairies could easily be overlooked. The people who get asked to represent their communities are usually the ones who’ve been quietly showing up all along.

- Community visibility matters. Round bale art and drone videos aren’t going to pay your feed bill. But they can change how neighbours and local officials think about the farms in their area. The farms people know about have an advantage over those that stay invisible.

- Small operations can still have a seat at the table. The signing ceremony included farmers milking thousands of cows, but it also included a multi-generation dairy from Butler County milking around 50 head. If you’ve ever felt like your operation is too small to matter, this is evidence to the contrary.

- Local processors are part of the equation. The Thieles’ relationship with Marburger is part of what keeps their milk connected to schools and communities in western Pennsylvania. Ask your co-op or buyer: “What would it take for whole milk from our area to end up in local schools?”

What You Can Do This Month

If this story has you thinking about your own community, here are a few practical places to start:

- Pick one organization and go to the next meeting. Farm Bureau, dairy promotion committee, co-op advisory board—it doesn’t matter which one. Just pick one and show up. You don’t have to speak. Just be in the room and learn who else is there.

- Ask your processor one direct question. “What would it take for whole milk from our area to end up in local schools?” You may not get the answer you want, but you’ll have started a conversation that might matter down the road.

- Find one way to make your farm visible. Maybe it’s a simple Facebook post about what you’re doing this week. Maybe it’s saying yes the next time a school group asks for a tour. The goal isn’t to go viral. It’s to be known.

- Bring someone younger into a conversation. If there’s a young person in your orbit who’s curious about the industry, invite them to ride along to a meeting. The next generation of dairy advocates has to come from somewhere. It might as well start in your truck.

The Question Worth Asking

Somewhere in your county, there’s probably a farmer who’s been showing up at meetings for years. Someone who volunteers for the thankless jobs. Someone who says yes when the local school needs a field trip destination or the food bank needs milk.

Most of the time, nobody outside the community notices. The work doesn’t make headlines. It just accumulates, quietly, over the years.

Then one day, the phone rings. The White House—or the state ag department, or the processor, or the school board—needs someone who can speak for small dairy. Someone with credibility. Someone who’s been in the conversation long enough to know what they’re talking about.

When that call comes to your community, will someone be ready to answer it?

And here’s the harder question: are you helping make sure they are?

The Thieles didn’t get to the Oval Office alone. They got there because a community kept showing up—at meetings, at distributions, at all the ordinary moments that don’t feel historic until you look back and realize they were building toward something.

That’s the part of this story that belongs to all of us.

The Bottom Line

If this story got you thinking about your own community—about the people who’ve been showing up, or the ways your farm connects with neighbours—we’d like to hear about it.

Who’s the person in your county who keeps showing up when no one’s watching? What’s worked for your farm when it comes to building community connections? What would you want to ask the Thieles if you could sit down with them?

Drop us a line. These are the stories that remind us what dairy is really about.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Small farms still get invited to the table. When the White House needed dairy farmers for the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act signing, they didn’t just call the big operations—they called William Thiele, who milks 40-60 cows with his family on the Butler County, Pennsylvania ground they’ve farmed since 1868.

- Fifteen years of quiet work opened that door. Thiele got the call because he’d spent years in the rooms where small dairy voices are easy to ignore: Farm Bureau meetings that ran late, policy hearings, pandemic milk distributions. No single moment made it happen—just the accumulation of showing up.

- Whole milk is back in schools, but manage your expectations. This is a win for rebuilding long-term demand, not a short-term milk check boost. School milk is a small share of fluid sales—the honest math is pennies, not dollars, at least for now.

- The real question is about your community. Somewhere in your county, someone is doing this quiet, unglamorous work right now. When the call comes for a credible voice to speak for small dairy, will someone be ready—and are you helping make sure they’re not alone?

This article was developed from public reporting, including coverage from the Butler Eagle, Farm and Dairy, American Farmland Trust, and Pennsylvania Farm Bureau records.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- The Hay Bale That Changed Washington: Farmers’ 6-Year Whole Milk Crusade Ends in Unanimous Victory – Nelson Troutman and other grassroots warriors walked a similar path, proving that a painted hay bale and a relentless spirit can move mountains in D.C. This story echoes the Thiele family’s own fifteen-year marathon of quiet, unwavering persistence.

- Whole Milk Is Back in Schools – Pennies on Your Milk Check or Real Class I Impact? – To truly understand the world William was navigating, you must look at the brutal economic math behind the policy. This piece deepens our understanding of the market forces and pricing shifts that shaped this decades-long journey.

- Jodie Nutsford Claims 2025 Holstein UK President’s Medal – Vet, Breeder, and Mentor Wins Industry’s Most Prestigious Young Breeder Honor – Jodie Nutsford carries forward the same passion for advocacy and mentorship that defines the Thiele family’s legacy. Her journey proves the point that the future of dairy is built by those willing to show up and lead.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!