One year after Reed Hostetler’s death at L&R Dairy in Ohio, his community is still proving what farm safety and resilience look like when farmers refuse to let one of their own stand alone.

Executive Summary: Reed Hostetler was 31, co-owner of L&R Dairy in Ohio, and father of three when his tractor tipped into the manure pit on March 5, 2025. He didn’t survive. What his community built in the year since—a barn transformed into a funeral venue, tractors lined up in tribute, months of meals, chores, and quiet financial support that never stopped—is a blueprint every dairy should steal. This article connects Reed’s death to the systemic pit risks that killed six at a Colorado dairy five months later, and to the margin and mental-health pressures squeezing farm families through 2024–2026. It delivers a concrete playbook: phone trees, neighbor check-ins, youth crisis roles, safety protocols that don’t vanish when one person does. The core argument is blunt—community is infrastructure, and the operations that have it recover faster when everything falls apart. Nearly one year later, the only question is whether your road is ready.

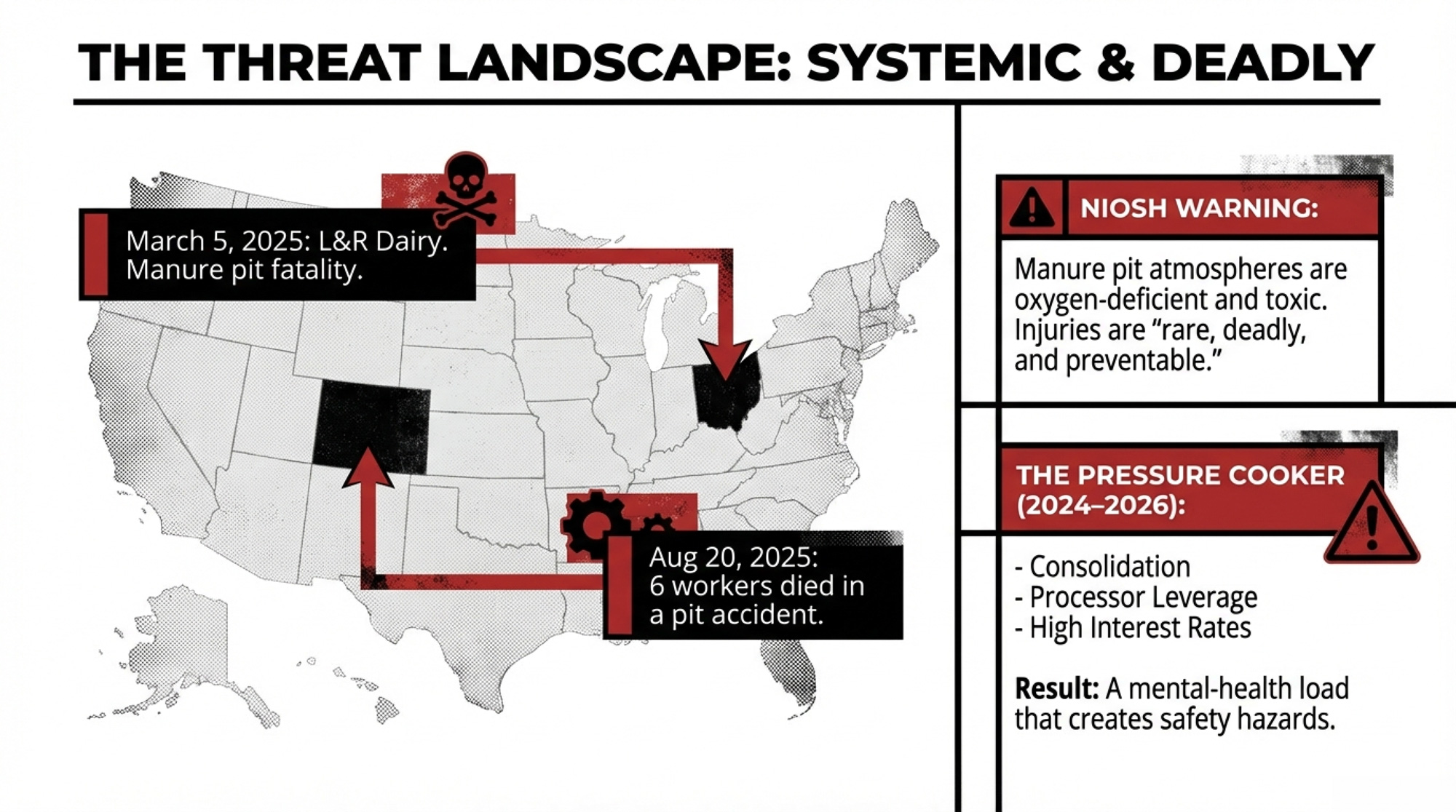

On March 5, 2025, a 31-year-old dairy farmer drowned after his tractor tipped into the manure pit at L&R Dairy in Marshallville, Ohio. Reed Hostetler was a husband, a father of three young kids, and co-owner of the family operation. He was also, by every account, the kind of guy who showed up when his neighbors needed help.

Almost a year later, his community is still showing up for his family. And that’s the part of this story you can actually copy.

You’re not getting a safety manual here. You’re getting something harder to build and more important to have: a real-world playbook for community resilience and dairy farm safety, forged in the worst possible way.

From Barn Wedding to Barn Funeral

Years before the accident, Reed and Abby Hostetler were married in the main barn at L&R Dairy. Same beams. Same alley. Same cows shuffling in the background.

In March 2025, that same barn became the gathering place for family and friends to say goodbye.

Hosting a large crowd in a working dairy barn isn’t just sweeping the alley and stacking a few straw bales. It’s parking logistics, liability questions, shuttle coordination, sound systems, seating, and making sure the space looks like a celebration of a life, not a Tuesday afternoon herd check.

The Hostetlers didn’t have to figure any of that out on their own.

Neighbors and friends showed up days ahead to pressure-wash walls, scrape alleys, and transform the barn into a place where a casket and grieving family could stand with some dignity. Local companies and neighbors brought gravel and equipment to shore up the lane before vehicles started rolling in. Shuttle buses ran from Marshallville Park, so the yard and road didn’t lock up.

While the family was just trying to survive minute by minute, the community quietly handled the logistics that would have broken them.

Reed and Abby’s three kids—Baer (4), Claire (2), and Axe (1) at the time—were too young to remember most of it. But they’ll hear it for the rest of their lives: the barn was full. People came. We weren’t alone.

That’s not sentimental. That’s an asset. You either have it before a crisis—or you don’t.

The Tractor Line That Said What Words Couldn’t

There’s a sound you don’t forget: a line of tractors and semis idling in low gear outside a church or a farm. Not parade noise. Heavier. Slower. You feel it in your chest.

At Grace Church in Wooster, where the reception was held, tractors, semis, trucks, and implements lined the parking lot and road as a silent, steel-and-diesel guard of honor.

Local equipment dealers, co-ops, and farmers coordinated the lineup. Once the first few units were committed, the rest followed. Some of the tractors were polished. Others still carried field mud and manure dust. That mix mattered. It wasn’t a show. It was the working dairy community saying, “He was one of ours.”

As one neighbor put it, it was the hardest funeral they’d ever been to—not just because of who they lost, but because of what they watched happen around the family.

Among friends and neighbors, a simple phrase started making the rounds:

“Lead like Reed.” If something needed doing—hay to chop, kids to watch, cows to milk—people asked, “What would Reed do?” and then they just did it. No committee. No sign-up sheet. Just action.

You don’t get that kind of reputation overnight. You build it one favor, one late-night call, one “yeah, I’ll be there” at a time.

When Our Community Needs Help, Help Comes

Most tragedies follow a pattern: three days of intensity, three weeks of fading attention, and then a long, quiet stretch where the family is expected to “get back to normal” while everything inside them is still upside down.

That’s not how this played out.

Weeks and months after the funeral, people kept showing up: groceries, diapers, dinners; neighbors stepping in for chores unannounced; friends checking in not once but over and over.

Abby has said that seeing people show up changed how she thinks about community—and how she plans to show up the next time someone else needs help. That shift, from “How will we survive this?” to “How do we pay this forward?” is the proof that community isn’t just nice. It’s infrastructure.

The support didn’t stop at the farm gate.

Green Elementary’s PTO organized a “Dine to Donate” night at a local Applebee’s, using a “student day off” incentive to bring in more families and raise money for the family. The dollars helped. The message mattered more: “Your school sees what your family is going through. You’re not invisible.”

A crowdfunding campaign drew donations from people who knew the Hostetlers well and from others who only knew them as “the young dairy family in Ohio.” It turned years of quiet relational equity into real, practical support when the family needed it most.

Someone told Abby that because of the way Reed lived, he’s still taking care of his kids even after his death. In strictly financial terms, that’s true. But the bigger truth is this: he’d invested in people, and when it all went sideways, those people cashed that investment in for his family.

Who Reed Was—and Why It Matters Now

Reed wasn’t just “helping out” on the home farm. He was co-owner of L&R Dairy, part of the next generation taking over and pushing the operation forward.

He’d hiked the entire Appalachian Trail. He’d ridden bulls. He’d done mission work in Thailand. Back home, he was the guy who could fix nearly any piece of machinery on the place and still make time to talk with a neighbor in the yard. Neighbors remember him as the kind of person you’d see under a mixer wagon at 11 p.m. and then at someone else’s place the next morning, making sure their chopper started.

Like most dairy producers, Reed knew manure pits are dangerous spaces. He wasn’t inexperienced or careless around equipment. But as this tragedy shows, sometimes the margin between “busy day” and “life-changing day” is just physics and bad timing.

At home, Reed and Abby were in the same season a lot of you are in right now: three little kids, a 24/7 operation, and a calendar that only worked because somebody gave up sleep. Abby picked up nursing shifts at the hospital and was learning more of the farm side to help cover when family needs shifted.

They were raising calves, raising kids, and—often without noticing—raising the bar on what it means to be part of a community.

The wave of support after the accident didn’t appear out of nowhere. It came from years of small decisions: taking a call instead of letting it go to voicemail, showing up with a skid steer when a neighbor’s barn burned, buying a few extra tickets for a school fundraiser, saying yes when something needed doing.

None of those actions looked like “strategy” at the time. Together, they’re the reason people felt personally responsible for being in that barn and that driveway when everything fell apart.

You can’t fake that after the fact. You either build it before you need it, or you don’t have it.

Why One Ohio Manure-Pit Accident Should Change How Your County Shows Up

It’s tempting to file this under “heartbreaking story from another state” and move on. That’d be a mistake.

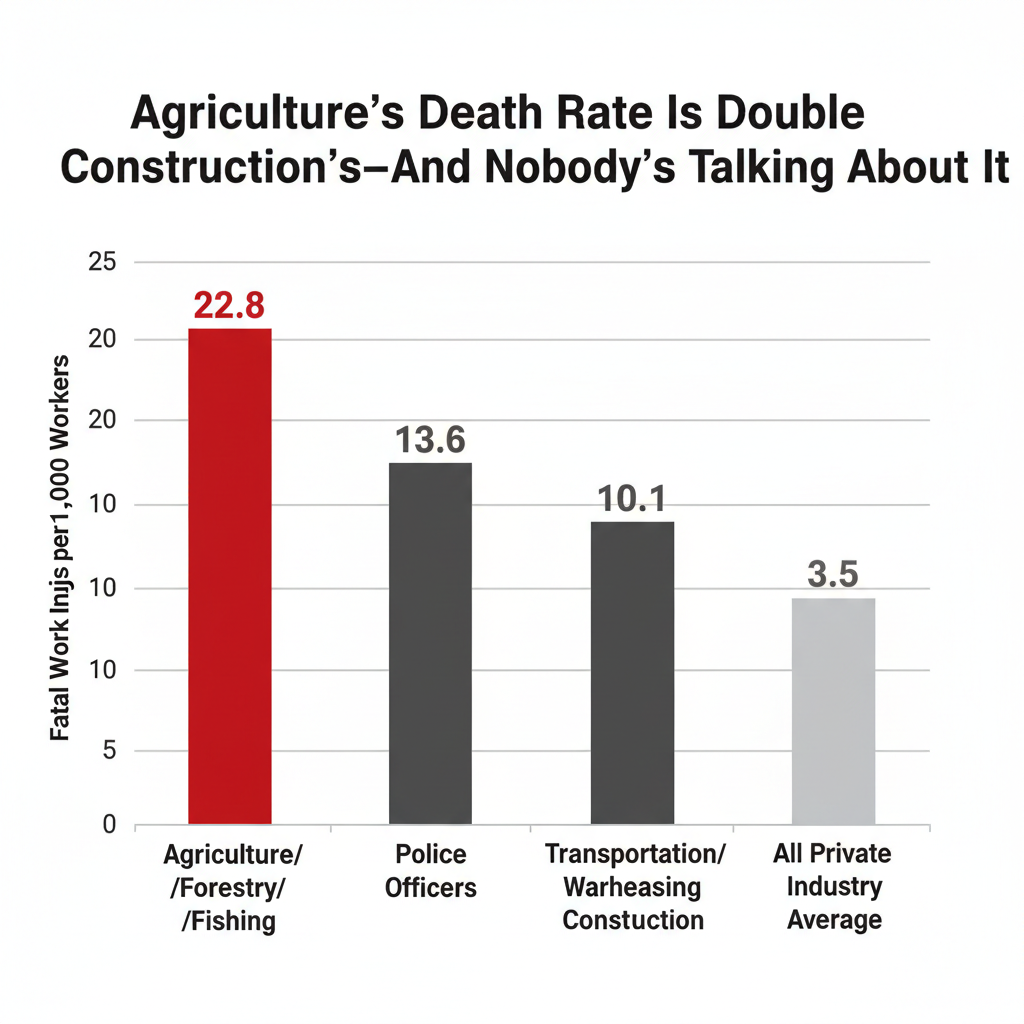

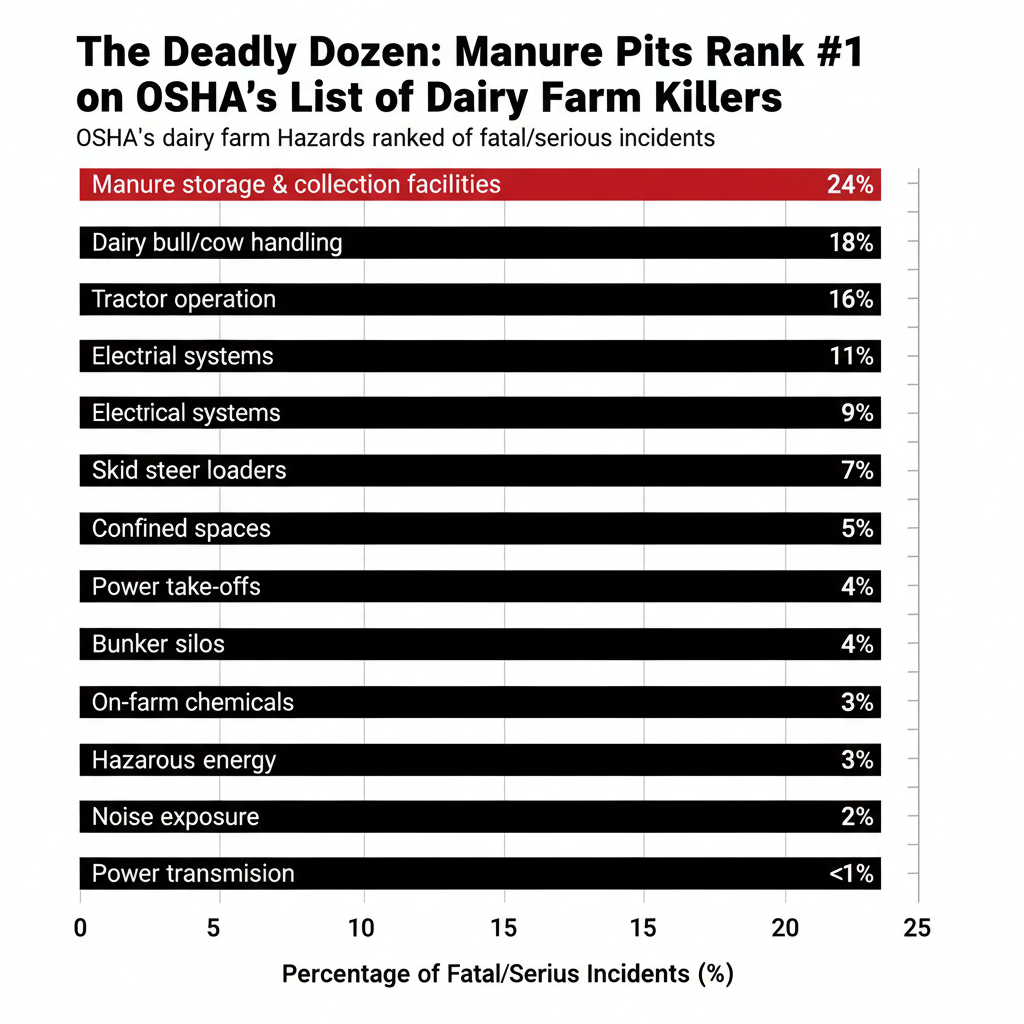

Manure pits have been recognized as a deadly hazard for decades. In a 1993 bulletin titled “Manure Pits Continue to Claim Lives,” NIOSH warned that the oxygen-deficient, toxic atmosphere in manure pits has “claimed many lives” and that hydrogen sulfide, methane, and other gases can overcome workers within seconds when conditions line up the wrong way. A 2012 clinical review published in the Journal of Agromedicine described manure-pit injuries as “rare, deadly, and preventable,” noting that while these incidents don’t happen often compared to other farm injuries, the fatality rate is extremely high once something goes wrong.

And it’s not just Ohio.

On August 20, 2025, six workers—including a 17-year-old—died in a manure-pit accident at Prospect Valley Dairy in Keenesburg, Colorado. Investigators and local reports indicate that a contractor doing routine work likely triggered a hydrogen sulfide release and was overcome almost immediately. Five other workers went in after him in attempts to rescue him. None of them came back out.

When The Bullvine looked back at 2025’s defining dairy stories, Reed’s death in Ohio and the Colorado tragedy both made the list for the same reason: they exposed how thin the margin really is between an ordinary workday and a permanent hole in a family, a workforce, and a local dairy economy. These aren’t freak one-offs. This is systemic risk we’ve tolerated for too long.

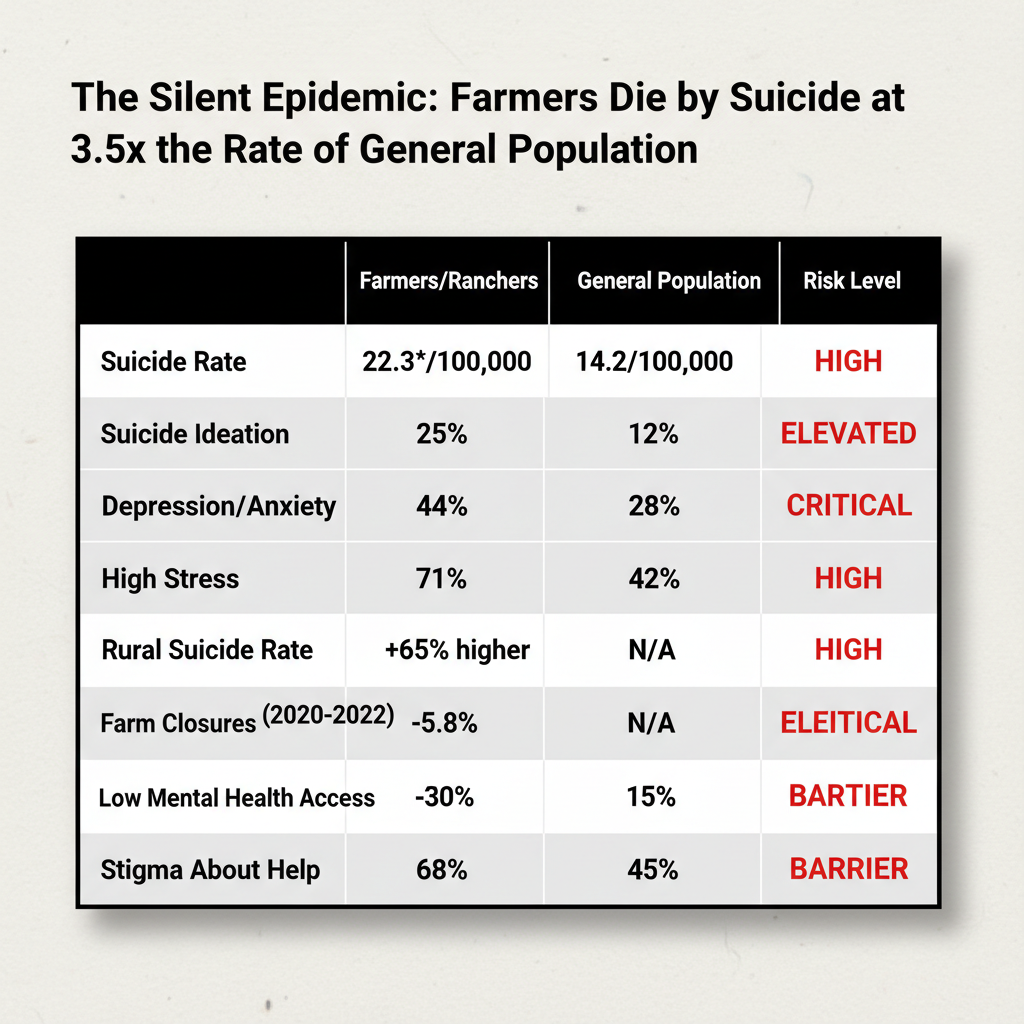

Now layer that on top of 2024–2026 realities—consolidation, processor leverage, stubborn input costs, labor shortages, and interest rates that haven’t dropped the way anyone hoped. You’ve got a mental-health load that doesn’t show up on your milk check but absolutely shows up in your barn and your house.

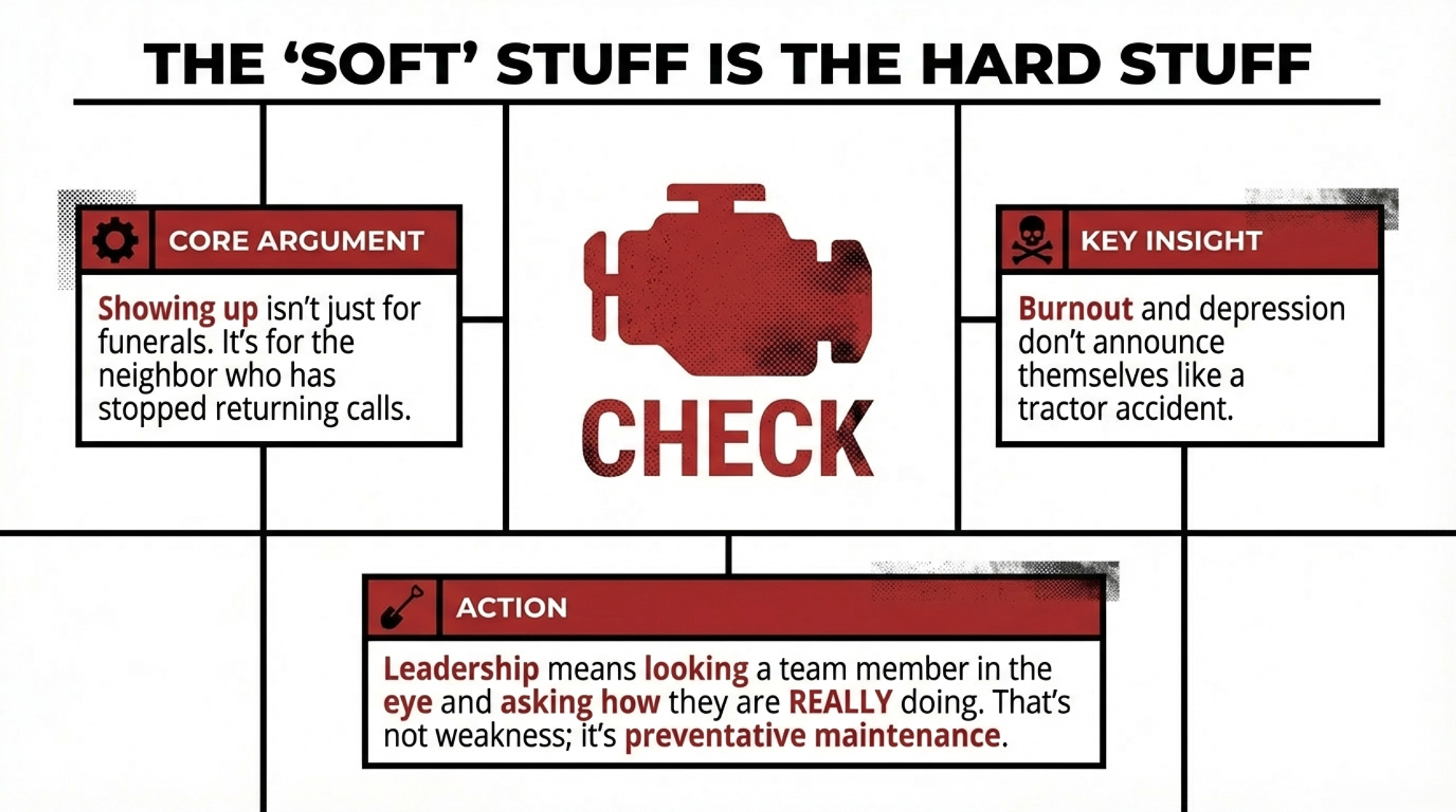

You know people in this business who are running close to the edge—physically, mentally, and financially. “Showing up” can’t just mean after a visible accident. It has to include watching for the quieter stuff: the guy who stops returning calls, the coworker making more mistakes than usual, the family where one bad month of prices seems to hit harder than it should.

Mini-Moments That Show What “Showing Up” Actually Looks Like

Big headlines are built from small, unglamorous decisions. A few details from Wayne County are worth stealing outright.

- The food. Abby jokes that Wayne County people sure know how to cook. For weeks, the kitchen counters stayed full: hot casseroles, snack trays, grab-and-go items for the kids. The food itself wasn’t the point. The point was the message: “You don’t have to think about supper tonight. We’ve got that piece.”

- The quiet chores. One neighbor made a habit of showing up early, doing a full round of chores, and leaving before anyone could say thank you. Calves fed, pens cleaned, gates latched. No Facebook post, no photo, no public pat on the back. Just work done when the farm needed fewer decisions, not more.

- The school connection. Green Elementary’s PTO could’ve checked the “we sent a sympathy card” box and moved on. Instead, they organized the restaurant fundraiser and used a “student day off” incentive to bring in more families. They told the kids, in actions: “Your school sees what your family is going through. You’re not invisible.”

- The tractors. Those machines parked outside the church didn’t fix anything on paper. What they did was silently tell Reed’s kids: “Your dad mattered to a lot of people.” Ten years from now, those kids will remember that wall of iron as clearly as any words they heard.

None of these actions use the word “community.” They don’t have to. They define it.

What This Means for Your Operation

If you strip away the emotions, what Wayne County proved is simple: community is infrastructure. You either invest in it before you need it, or you find out what it costs not to have it when everything goes wrong.

Farm families that aren’t alone recover faster—financially and operationally—because chores, crops, and kid logistics don’t collapse alongside grief. That’s not soft thinking. That’s business continuity.

Here are the hard questions worth asking this month:

- If a tractor rolled or a fire started on your place tomorrow, who are the first three people who would be in your yard without being asked?

- If it happened to a neighbor instead, would anyone automatically assume you were one of those three?

- If you had to line up 20 tractors and trucks as a sign of respect, who would answer that call—and who wouldn’t notice?

- Who on your team or in your circle has been quieter, shorter-tempered, or more withdrawn than usual lately—and when was the last time you looked them in the eye and asked how they’re really doing?

If you can’t rattle off names without thinking too hard, you don’t have a phone tree. You have a hope and a prayer.

And if you sign the checks or make the schedule, you’re the one who can change that.

What You Can Actually Do This Month

If you’re wondering where to start, here’s the short list.

- Build a simple phone tree now. Don’t overcomplicate it. Aim for at least 8–10 key people on your road, in your church, and in your school community. Decide who calls whom in the first 15 minutes if there’s an accident, sudden death, major health crisis, or barn fire. Write it down where people can actually see it—in the milk house, office, or group chat.

- Pick three farms to check on. Not with a text. With a quick call or visit. Ask, “How are you doing—really?” and be ready for the answer to take longer than you planned.

- Involve your youth on purpose. 4-H and FFA clubs can own “comfort” jobs in a crisis: cards, posters, freezer meals, calf chores. Give them clear roles so they grow up knowing how to show up instead of watching from the sidelines.

- Talk about mental health out loud. Put it on the agenda at your discussion group, local dairy association meeting, or men’s breakfast. Share one real story, even if it’s uncomfortable, and be the one who goes first. Make it normal to say, “I’m not okay right now,” before someone breaks. That’s not weakness; it’s maintenance. If you or someone on your team feels overwhelmed, talk to your doctor, a trusted advisor, or a local mental-health provider.

- Practice before the crisis. Help each other with harvest, planting, big herd moves, or barn clean-outs, so you already know how to work together. You’ll spend a few hours now—or you’ll scramble from zero on your worst day.

- Tie safety and support together. As you review protocols around pits, lagoons, and confined spaces—gas monitors, ventilation, entry rules—ask yourself: “Who else knows this? Who would enforce it if I’m not here?” If there’s any task on your farm that only one person can do safely, that’s a red flag. Train at least one backup and write down the protocol. Safety that only lives in your head isn’t safety.

None of this replaces hard safety work around manure pits, lagoons, and confined spaces. You still need lock-out/tag-out, proper equipment, training, and clear protocols.

But when safety systems fail, insurance is slow, milk prices are tight, and official help ends—this is what catches people.

Key Takeaways

- Community doesn’t appear out of thin air in a crisis. It’s built on years of small, quiet favors when nothing is on fire.

- Kids are watching. Who shows up, who kneels down to their level, who keeps coming back after the casseroles are gone—that’s what they’ll remember long after the details fade.

- Leadership on a dairy isn’t just about numbers and banners. It’s about who you are when someone down the road is in trouble.

- “Showing up” includes the quiet stuff. Burnout, withdrawal, depression—these don’t announce themselves the way a tractor accident does. Check on your people before they break.

- Safety that lives only in your head is a liability. If nobody else on your operation knows your protocols or would enforce them without you, that’s a gap you can fix this week.

Lead Like Reed

Underneath all the grief, this is a story about assets—just not the kind your accountant can depreciate.

On the hard-numbers side, you chase efficiency, butterfat, component premiums, and labor stability because the economics of 2024–2026 don’t leave much slack. If you’re not on top of genetics, feed, and contracts, you get run over. We all know that.

On the human side, there’s another question that matters just as much to long-term survival: when—not if—something goes very wrong, is your farm part of a community that knows how to respond?

That’s not a feel-good side issue. It’s about whether your family, your workforce, and your local dairy ecosystem can take a hit without collapsing.

So here’s the challenge, almost a year after Reed’s accident:

Look at your own road. Who would need you if something happened tomorrow?

Look at your own barn. Who would you call first if it was your tractor in the pit, your fire, your heart attack in the parlor, or your brain finally saying “enough” after too many bad months in a row?

Look at your own kids and grandkids. What stories do you want them telling 10 years from now about how your community handled hard things?

Reed didn’t get a vote on what happened on March 5, 2025. His brothers did everything they could in a window that physics, machinery, and toxic gas had already stacked against them. His wife, kids, and parents didn’t choose any of it.

What they did get—and what they’re still getting a year later—is a community that decided they weren’t going to carry it alone. A community that turned a barn into both a wedding hall and a sanctuary of grief. A community that lined up tractors, cooked meals, ran fundraisers, and kept showing up long after the news cycle moved on.

Support Type Wayne County Response Typical Farm Crisis Response

Immediate Response (0-3 days) 20+ neighbors in yard day 1, full chore coverage Family handles alone, maybe 1-2 calls

Funeral/Memorial Logistics Barn transformation, shuttle buses, tractor line, parking coordination Funeral home handles, family figures out details

Food/Meals Weeks of daily hot meals, grab-and-go for kids, coordinated delivery 3 days of casseroles, then silence

Financial Support Crowdfunding, school fundraiser ($5,000+), sustained donations Maybe a GoFundMe, no follow-up

Chore/Labor Coverage Daily unannounced chore coverage for weeks, crop/haying help 1 week if lucky, then “back to normal”

School/Kids Support PTO-organized fundraiser, student engagement, visible recognition Sympathy card, kids expected to cope alone

Long-Term (3+ months) Ongoing check-ins, continued meals, relationship maintenance “How are you holding up?” texts, no action

Phone Tree/Coordination Pre-existing relationships, clear roles, no central organizer needed Confusion, duplicate efforts, gaps in coverage

Mental Health Follow-Up Community members trained to recognize signs, ongoing support “Let us know if you need anything” (passive)

Business Continuity Farm operations maintained, no production loss, equity preserved Operations suffer, milk quality drops, financial losses compound

You can’t control every accident or every market swing. You can control whether anybody in your circle ever has to face one alone.

So the next time you hear about a farm accident, a diagnosis, or a sudden death—whether it’s in your county or three states away—don’t just shake your head and scroll on.

Ask yourself, honestly: “What would ‘lead like Reed’ look like where I live?”

Then do one concrete thing this month to make sure no farmer on your road has to stand alone when their barn—or their mind—goes dark.

| Week | Action Item | Output/Deliverable | Time Required | ✓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Build your phone tree | List of 8-10 names: neighbors, church, school contacts who would respond in first 15 minutes if something went wrong | 2 hours | ☐ |

| Week 2 | Make 3 farm check-ins | Call or visit 3 farms in your area—ask “How are you doing, really?” and be ready for the answer to take longer than you planned | 3 hours | ☐ |

| Week 3 | Assign youth crisis roles | Meet with local 4-H/FFA club—define specific “comfort jobs” (cards, posters, freezer meals, calf chores) youth can own during next community crisis | 1.5 hours | ☐ |

| Week 4 | Put mental health on agenda | Add mental health discussion to your next dairy association meeting, men’s breakfast, or discussion group—share one real story and go first | 1 hour | ☐ |

| BONUS: Practice Before Crisis | Help a neighbor with harvest, planting, big herd move, or barn cleanout so you already know how to work together when everything falls apart | Completed joint work project with neighboring farm | 4-6 hours | ☐ |

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Six Men Died in a Manure Pit This August. Here’s the $450 Fix That Could Have Saved Them – Arms you with a tactical safety audit that bridges the gap between tragedy and prevention. It breaks down the $450 investment in gas detection and strict “no-entry” protocols that eliminate the risk of the deadly “rescue chain” fatality.

- 2025 Dairy Year in Review: Ten Forces That Redefined Who’s Positioned to Thrive Through 2028 – Reveals the structural shifts in replacement heifer math and capital allocation you need to master through 2028. It delivers a roadmap for navigating the “middle-ground” disappearance, ensuring your operation remains on the right side of consolidation pressure.

- Digital Dairy: The Tech Stack That’s Actually Worth Your Investment in 2025 – Exposes the tech-stack hype and highlights the predictive analytics and sensor fusion actually boosting bottom lines in 2026. Gain a competitive advantage by identifying the specific integrations that turn raw barn data into profitable management decisions.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!