Thinking about adding or expanding on‑farm processing? Read this 75-year doorstep story first. It might change your plan.

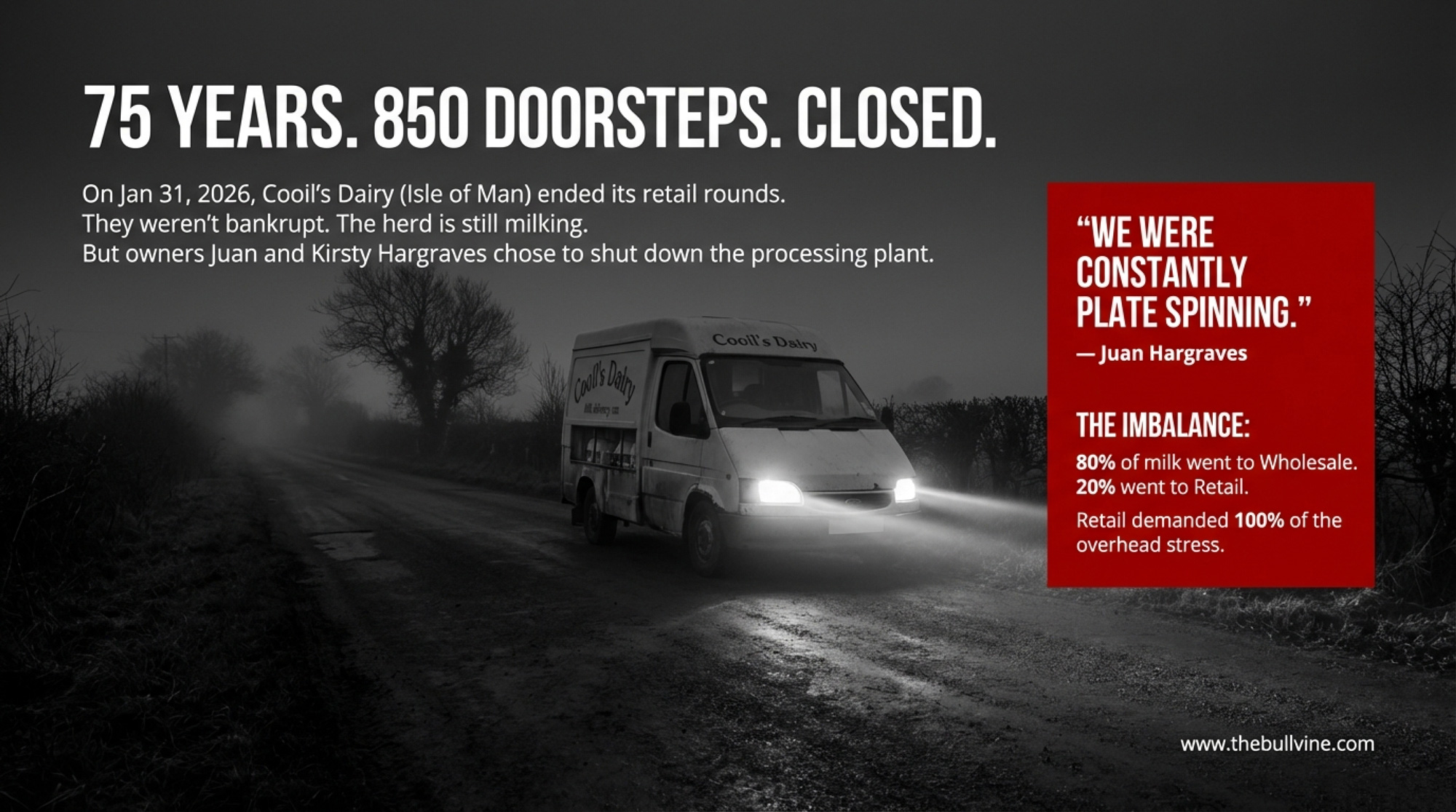

On January 31, 2026, Juan Hargraves finished the last doorstep milk delivery Cooil’s Dairy would ever make — ending an on-farm dairy processing and direct delivery operation his wife Kirsty’s family had run for more than 75 years in the south of the Isle of Man. For some customers, those rounds had been part of life for more than 60 years. Three generations of the same households opening the same door to find the same family’s milk before dawn.

Nobody was angry. Nobody was bankrupt. The herd of 120 to 130 cows is still milked every morning. But the processing plant needed significant investment that the operation couldn’t justify, and Juan and Kirsty made the call while they still had choices—to refocus on farming and family life. “After much discussion and careful consideration,” they wrote, “we are not in a position to make this investment in the current climate”. If you’re running on-farm processing for a retail channel that only handles a minority share of your total output, the number that killed Cooil’s retail operation — their retail‑to‑wholesale ratio — is one you should know cold.

Three Generations, One Route

Leslie Cooil started farming in the Port Erin area around 1942 or 1943, and the doorstep dairy that would define the family business for the next 75 years followed in the early 1950s. “The very start of it would have been Leslie Cooil in about 1942/1943, from what I can get from Ian and Gary Cooil,” Juan told Manx Nostalgia. Ian and Gary — Leslie’s sons — carried on their father’s legacy in the early 1970s, when Ian was about 21 and Gary about 5 years younger. The operation became known locally as Cooil Brothers.

By 2010, Juan had gone from the kid who jumped on the back of the milk truck to a business partner. He first hopped on a Cooil’s truck in 1987, when he was 7, and later went up to the farm to help and worked there until he was 17. In 2004, he took in 120 acres of bare land neighboring the Cooils, running sheep and a few suckler cows while working full‑time on another farm. Buildings went up on that greenfield site in 2007, with more added over time to move the cows to newer facilities and expand the operation. In 2010, entered in to a partnership with the Cooils. In 2014, he bought Ian out upon Ian’s retirement. And in 2020, just six hours after their youngest child was born, Kirsty was signing the papers to buy out Gary’s share of the business — swapping her life as an estate agent for being fully in the dairy with Juan. All of that sits behind the one‑line summary: “Juan and Kirsty took over fully.”

“We’re Cooil’s Dairy Limited. We’ve been Cooil’s Dairy Limited since about 3 years ago now, when my wife, Kirsty, and myself took it over fully,” Juan told Manx Nostalgia in December 2023. “Obviously, our surname is Hargraves, but we’ve kept Cooil as the known trading name”.

By the time they made the decision to close, they were delivering to about 850 houses. Juan is clear: just over 1,000 would have been the peak of COVID, when they took on everyone who wanted deliveries and lived in their area. As customers went back to their usual routines — and as older clients passed away — the number settled back to roughly 850 households.

The team was small and tight. Mark ran two delivery rounds, working pretty much six days a week. Brian handled a third round on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and washed every bottle that came back. Lorna bottled the milk. Kirsty managed the office, the accounts, and all Farm Assurance paperwork — which Juan noted had become “a massive thing to undertake.” Juan covered the farm, the milking, and filled in on delivery routes whenever someone was off. Five people. About 850 households. Every week.

And it wasn’t just milk. Cooil’s delivered fresh Manx milk and cream in recyclable glass bottles, plus eggs, potatoes, homemade cakes, and ice cream.

“We’ve made so many friends over the years, saved lives, moved furniture round and even caught criminals in the act,” Juan wrote in the farewell message. During the blizzard of 1994, the family later recalled, the team delivered by tractor and trailer because the milk had to get through. During COVID‑19, Cooil’s took on a wave of new customers as island residents turned to doorstep delivery — a surge that placed heavy additional demands on processing equipment already built for the existing base.

Two Sites, One Dairy

There’s another piece you don’t see if you only watch the milk truck pull up at the door. The processing plant wasn’t even on the same site as the cows by the time the last round went out.

The herd moved to a new greenfield site in 2015, onto the newer facilities Juan and Kirsty had been building since 2007. The processing stayed at the original Cooil’s site. To bridge the gap, they retro‑fitted a DX bulk tank onto an old grain trailer chassis and hauled milk back for processing five days a week. Every load meant diesel, time, and one more moving part that could go wrong between parlour and pasteurizer.

And the work didn’t stop when the van pulled into the yard. “Every evening we had to make sure we had made any customer changes so that the rounds were ready to go just after 1 a.m., the vans were ok to go and there was enough potatoes etc. to go for the morning,” Juan wrote. Even now, a week later, with the rounds done, they’re still catching up invoices. The reality, he says, “hasn’t fully kicked in” — but they already feel a sense of freedom.

“So it fell to me to cover whatever needed doing,” he admitted. In their house, six children meant Kirsty’s hands were full, especially in the mornings. A young lad was working on the farm, but with limited experience, he couldn’t do it all on his own. Relief staff? They couldn’t afford them — and that’s if you could even find someone willing to milk cows one day, bottle milk the next, and drive rounds in the dark the day after that.

“I’ve seen it a few too many times to care to remember,” Juan wrote, “that I’ve had a milkround to cover and I’ve gone out after tea (evening meal), done half of the round, got home for midnight, up at 5 to milk the cows and then finish the round afterwards, all the while we had customers ringing to say they haven’t had their delivery yet.” His own summary of those years is simple: “I was constantly plate spinning.”

The community felt it. “Thank you, Cooil’s Dairy Ltd for your service over the years in rain, hail, and sun — but usually in the dark,” the Ballasalla Village community page posted. “It’s the end of an era”.

The Collapse of the Middle

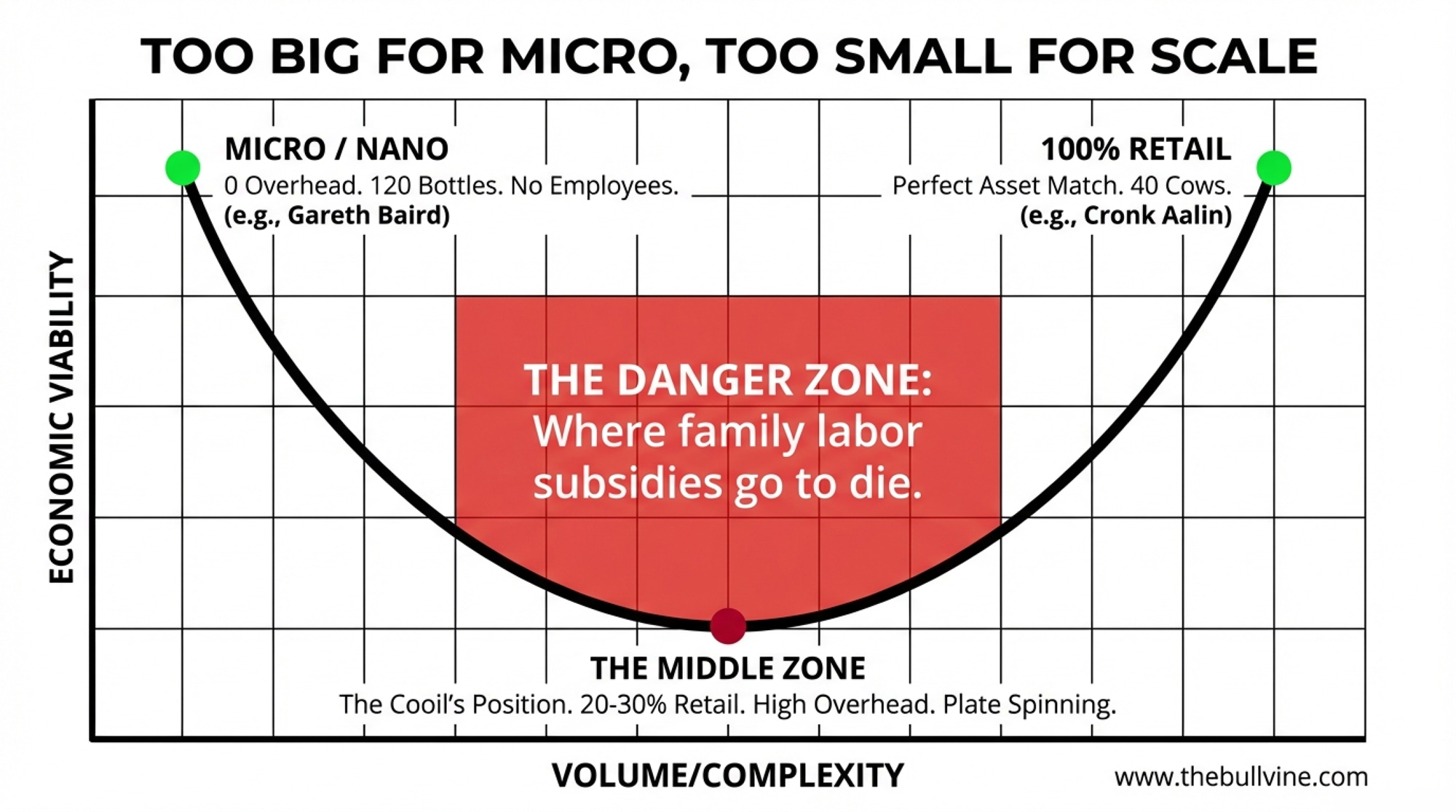

Cooil’s closure fits a pattern that’s been tightening for decades. In the early 1970s, an estimated 99% of UK milk was delivered to doorsteps, according to Andrew Ward’s No Milk Today. By the late 2010s — before the pandemic temporarily reversed the trend — that share had fallen to roughly 3%. But the closures aren’t spread evenly. They concentrate in a specific zone.

At the top end, scale operators grow. McQueens Dairies in Scotland expanded well before COVID, with turnover climbing 30% in the year before their 2019 facility announcement, per BBC Scotland. By early 2021, they’d opened 11 distribution depots across Scotland and northern England and recruited more than 200 new staff in 12 months.

At the bottom end, micro‑operators survive by stripping overhead to nearly zero. Gareth Baird, a young farmer in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, launched his doorstep round in July 2020, targeting 30 bottles on his first night — he delivered 120. No employees. No bottling line. Minimal fixed cost.

The operators disappearing are the ones in between. Family dairies milking 80 to 200 cows, running their own on‑farm processing, employing a small team, and serving a few hundred to a couple thousand retail customers while sending the bulk of their milk to a cooperative. Cooil’s — 120 to 130 cows, five people, 850 houses at the end (just over 1,000 at the COVID peak), 80% of milk to the Creamery — was textbook middle‑zone. And the mechanics that made it unsustainable aren’t unique to the Isle of Man.

Why the Math Stopped Working

If you’re running on‑farm processing, the number that matters most isn’t your customer count. It’s your retail‑to‑wholesale ratio — the share of your total milk output that actually flows through your bottling plant.

At the time of closure, Cooil’s sent approximately 80% of its milk to the Isle of Man Creamery at the cooperative wholesale price, per Manx Radio and 3FM. But that ratio had been worsening. In his Manx Nostalgia interview, Juan described it as “approximately about three quarters” to the Creamery, explaining: “We milk more cows. We’ve got more sort of surplus if you like, and then the rest goes on to the doorstep”. Every cow they added sent more milk to wholesale because the doorstep rounds couldn’t absorb the growth. By the end, only about 20% flowed through the family’s own pasteurizer, bottler, and delivery rounds — and that 20% had to carry the entire fixed cost of processing equipment that costs roughly the same whether it handles a fifth of the herd’s output or all of it (20% utilization means each litre through the bottler carries 5× the fixed cost it would at full capacity).

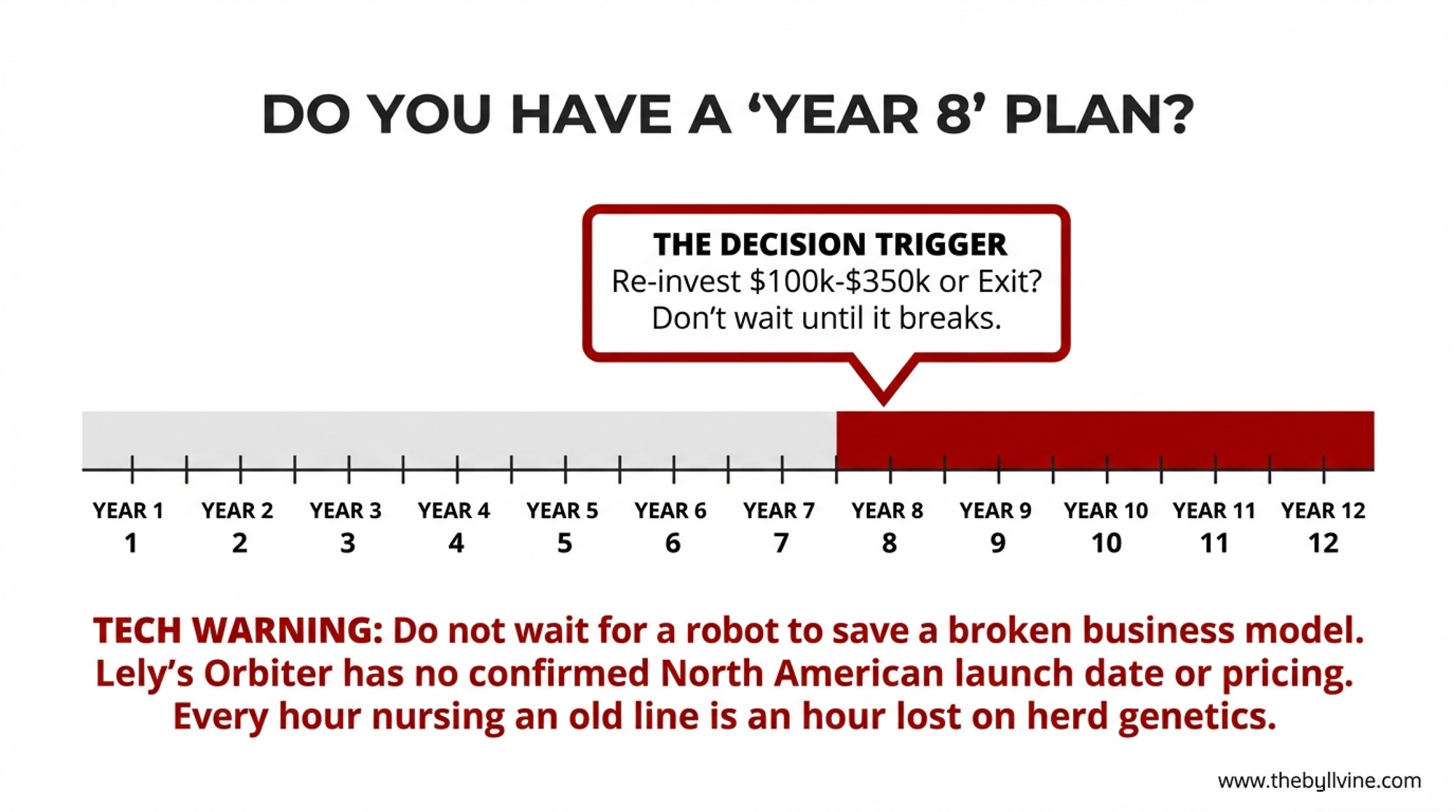

Here’s what that equipment costs to replace. At the micro end, a basic batch pasteurizer starts around $14,000 USD (Tessa Dairy Machinery), while a complete micro‑processing system runs roughly $18,000 USD (MicroDairy Designs). But Cooil’s wasn’t micro — they were making skimmed, semi‑skimmed, and whole milk plus cream for hundreds of doorsteps. The Northeast Dairy Business Innovation Center’s 2024 Processor Modernization grants show real costs at this level: awards ranged from $62,000 to $350,000 per facility for vat pasteurizers, rotary filler‑sealers, and packaging lines.

Take a bottling line with, say, a 12‑year service life and a $150,000 replacement cost. That’s $12,500 set aside every year just to fund its own successor. Spread that across 850–1,000 customers, and it’s roughly $12–$15 per customer per year in depreciation alone — before energy, bottles, labor, fuel, trailer haul‑back, or vehicle maintenance. And every hour Juan spent nursing a bottling line past its service life was an hour not spent on herd genetics, forage quality, or transition cow management — the core drivers of the 80% of the milk that actually paid the bills. That’s opportunity cost, and it compounds quietly.

Cooil’s faced an additional constraint that most mainland operators don’t. The processing plant and the cows were on different sites. Every litre destined for doorstep delivery was pumped into that DX bulk tank on an old grain trailer, hauled back for processing five days a week, then bottled and delivered. That’s haulage, handling, and risk you don’t see on the milk cheque — but you pay for it.

They also operated under a regulated retail price ceiling. The Isle of Man’s Milk Marketing Committee sets retail milk prices by government order. The price per pint rose to 90p in July 2025, the first increase in roughly two and a half years. When your costs are rising, and your price ceiling is externally fixed, the only lever you have is volume. On an island of around 84,000 people, volume has a hard ceiling, too.

QUICK CHECK: Is Your Retail Channel Paying Its Way?

- What would it cost to pay yourself and your partner market rate for every hour you spend on the retail side? That number is your unpaid family labor subsidy. If the retail channel can’t cover it, you’re already eroding — you just can’t see it on the P&L.

- Divide your processing equipment’s total replacement cost by its remaining service life in years. Are you banking that amount annually? If not, you’re consuming the asset without replacing it.

- Call your cooperative and ask one question: “Could you absorb our full supply volume within 90 days?” If yes, your safety net exists. Knowing that changes how you evaluate everything else.

Juan’s answer to those checks is pretty clear in hindsight. “We were understaffed really, and we could not afford to have relief staff,” he wrote, “and that’s if you could find someone who would do a bit of everything.” In the end, it fell to him to cover whatever needed doing. “All these factors led to my heart not being in the job,” he admitted. The bad days — the midnight‑home, 5 a.m. milking, customers ringing because the milk wasn’t there yet — weren’t constant. But they were frequent enough that, by the end, he was “almost begrudging having to do a milkround” while a new building on the farm and six kids at home all needed him too.

“So the end of an era, saying that seems to be the most commonly used phrase,” he wrote. “Yes, it is in its own way, so many people loved our products and are going to miss them.” But the other line that matters is this one: “At the end of the day, it wasn’t a decision that happened overnight, and we have made it for what we feel is right for us going forward as a family.”

Same Island, Two Models, Opposite Outcomes

A useful comparison sits on the same island. Carl Huxham runs Cronk Aalin Farm in Sulby, milking 40 cows but routing 100% of his output through nine delivery rounds using electric vans. Nothing goes to the Creamery. He built the operation from scratch, starting in 2006, buying a second‑hand 16‑point Fullwood parlour and bulk tank for £8,000. Every piece of equipment was sized for the volume it actually serves.

“Being on an island, our input costs are all quite high as everything incurs a shipping cost,” Huxham shared. He sells at the same regulated price ceiling that Cooil’s operated under.

The difference isn’t geography or regulation. It’s ratio. At 100% retail, Huxham’s processing equipment is fully utilized by the revenue it generates. At Cooil’s 80/20 split, theirs couldn’t be. If you’re considering building a farm‑direct operation from scratch, Huxham’s model is the template. If you’re inheriting one that’s already split between retail and wholesale, Cooil’s is the cautionary math.

Four Paths Forward

Across the UK and North America, family dairies navigating the same pressure points are finding distinct paths:

The clean exit to cooperative supply. Cooil’s path: cease retail, route all milk through the cooperative. It eliminates processing and delivery costs entirely, preserves the farm, and can execute within 60 to 90 days. The trade‑off is permanent — you surrender the retail premium and the direct community relationship.

The radical downscale. Baird’s model in Northern Ireland strips out every cost layer that burdened Cooil’s: no paid delivery staff, minimal equipment, a radius one person covers before breakfast. It doesn’t scale. And it depends entirely on one body holding up indefinitely.

The channel swap to vending. Milk vending machines have become one of the fastest‑growing farm‑direct channels in UK dairy. A setup costs roughly £30,000, with margins of 60-80 pence per litre, according to The Bullvine’s July 2025 analysis. The model eliminates delivery cost by bringing the customer to you — but also eliminates the community welfare function.

The community‑supported model. Stroud Micro Dairy in Gloucestershire operates as a cooperative, with customers subscribing to seasonal shares. Over 800 community shareholders own Tablehurst and Plaw Hatch Farms in Sussex. When customers pre‑pay for a season’s milk, you know in January what February looks like. The catch: board meetings, annual reports, and governance paperwork most dairy families didn’t sign up for.

| Path | Entry Cost | Key Trade‑off | Best Fit |

| Clean exit to cooperative | Minimal | Lose retail premium permanently | Retail <30% of output; equipment aging |

| Radical downscale | $5K–$15K | No growth; one person’s stamina | Young farmers; no employees |

| Vending | ~£30K / ~$38K | Lose doorstep relationship | Farms near roads with footfall |

| Community cooperative | Variable | Governance complexity | Peri‑urban; engaged consumer base |

What This Means for Your Operation

This isn’t abstract. Clark Farms Creamery in New York was processing roughly 25% of the farm’s milk — about 3,000 gallons a week — with the remaining 75% still being trucked off. As The Bullvine reported in January, the real premium was roughly $1.15–$2.15 per gallon in extra margin at the cost of 70–90 more hours a week on top of a full dairy workload. Clark shut the creamery down in January 2026 while keeping the cows milking — the same decision Cooil’s made, on the opposite side of the Atlantic.

| Strategic Path | Entry Cost (USD/CAD) | Key Trade-Off | Best Fit |

| Clean Exit to Cooperative | Minimal ($0-$5K transition costs) | Lose retail premium permanently | Retail <30% of output; equipment aging; no succession plan |

| Radical Downscale | $5K-$15K (minimal equipment, no employees) | No growth; limited by one person’s stamina | Young farmers with no family; high energy; willing to work 7 days/week |

| Vending Machine Model | ~$38K CAD / ~£30K GBP | Lose doorstep relationship and community role | Farms near high-traffic roads; peri-urban locations; strong local brand |

| Community Cooperative | Variable ($10K-$50K legal/admin setup) | Governance complexity; board meetings; reporting | Peri-urban locations; engaged customer base willing to invest; strong local food movement |

On Vancouver Island, Mark at Promise Valley Farm took the opposite approach — a small organic Guernsey herd with 100% A2A2 genetics, processing all milk on‑farm through a self‑serve dispensing machine. “Processing our own milk and making value‑added products has to be part of the conversation for future producers,” he shared. But notice: small herd, all milk through the store. Ratio, again.

The advantage you have that Cooil’s didn’t: pricing freedom. No government committee sets your retail price. You can charge what the local market will bear—but only if you use it deliberately. If you’re pricing farm‑store milk just a dollar above the grocery store “to stay competitive,” you may be leaving the margin on the table that would fund your equipment reserves. And here’s the piece that ties to your breeding program: if your herd’s component profile — butterfat, protein — commands premiums through the cooperative, every litre you divert to flat‑rate retail bottles is leaving that premium on the table. If you’re operating under Canadian supply management, the ratio math shifts because your wholesale floor is higher — but the equipment depreciation math doesn’t.

The wholesale safety net itself is under pressure. AHDB warned in January 2026 that farmgate prices are “set to stay under pressure into mid‑2026” as oversupply squeezes values, with the spring flush likely to make the first half of the year particularly difficult. The UK average farmgate price for December 2025 came in at 40.29 pence per litre, down 6.1% from November and 13% below December 2024. Exiting retail into a weakening wholesale market is still a viable move — but the window where wholesale alone feels comfortable is narrower than it was six months ago.

Confirm your cooperative or processor can absorb your full supply before you need them to. Cooil’s transition to the Creamery happened smoothly on February 1 because that relationship was already in place. Your safety net should exist long before the pasteurizer starts making noises it shouldn’t.

The Technology Temptation (Don’t Wait for It)

If you’ve heard about Lely’s Orbiter — an automated on‑farm processor that pasteurizes, homogenizes, and bottles with minimal labor — you might be thinking automation could change this math. As of December 2025, five units were operational in the Netherlands and Belgium, with sales expanding into Germany. The Orbiter page is live on Lely’s North American website. But there’s no announced NA availability date, no published pricing, and no regulatory pathway confirmed. Lely’s own Astronaut A5 Next milking robot won’t reach the US and Canada until “after local validation in 2026”. The Orbiter is further back in the queue. If your bottling line is at year 9 of a 12‑year service life, you can’t afford to wait for technology that may not arrive at a price point that works for your herd. Cooil’s made the call at their convenience. That’s worth more than any piece of equipment.

Key Takeaways

- Track your retail‑to‑wholesale ratio, not just your customer count. When your direct retail channel handles less than 30% of total output, the processing infrastructure is almost certainly overbuilt for the volume. Cooil’s saw that ratio worsen as the herd grew, from about 75% wholesale to 80%. Clark Farms hit the same wall at 75%.

- Count your unpaid family labor as a real cost. Cooil’s ran the entire processing and delivery operation with five people, in addition to the farm work. Add six kids and a second site into that mix, and you can see why Juan described his life as “plate spinning.”

- You need an equipment replacement plan, not just a repair budget. If your retail margin isn’t building a reserve to replace the bottler, the day it fails, the decision happens to you, not with you.

- Surge demand will lie to you. Cooil’s peaked at “just over 1,000” houses during COVID, then settled back to about 850 as people returned to normal. AHDB and Kantar saw similar patterns nationally. Don’t invest based on the peak; invest based on the plateau.

- Genetics and components matter to this decision. Every litre you pull from a high‑component herd and sell at flat retail is a litre that doesn’t earn the cooperative’s butterfat and protein premiums. That’s genetics ROI you’re giving away.

- Year 8 is your red‑flag year. If your processing equipment is past year 8 of a 12‑year life, you should already be working through your options: full retail, clean exit, downscale, vending, or cooperative model. Not when something breaks. Not when Lely announces an Orbiter for your market. Now.

The Bottom Line

Juan and Kirsty Hargraves closed their retail operation while the farm was still healthy, the staff could be thanked by name, and the community had time to say goodbye. “We would like to think that nobody was ever let down,” they wrote. From Leslie Cooil’s first delivery in the early 1950s, through Ian and Gary’s decades behind the wheel, to Juan and Kirsty’s final round on January 31, 2026 — the milk showed up before dawn, to hundreds of doorsteps, every week. That’s not a failure story.

The question for your operation isn’t whether something like this could happen to you. It’s whether you’d recognize the signals at year 8 — not year 12.

If the weight of a decision like this is sitting on you — or on someone you know — the Farm Aid hotline (1‑800‑FARM‑AID) and the Canadian Ag Mental Health Alliance can help. You don’t have to sort it out alone.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The 143-Hour Week at Clark Farms: The Real Math of On-Farm Creamery ROI and Your Time – Reveals the brutal math behind the 143-hour work week. Arms you with a framework to calculate whether your direct-to-consumer processing is actually generating profit or simply consuming your family’s unpaid labor and mental health.

- English Dairy Farms See Earnings Surge in 2024-25 – But Don’t Get Comfortable – Exposes the danger of relying on temporary farmgate surges. This analysis reveals how to leverage current earnings to fortify your operation against the inevitable price slides that catch unprepared producers off-guard in the three-year outlook.

- Milk Vending Machines: Why They Are The Fastest-Growing Farm-Direct Channel – Breaks down the high-margin, low-overhead blueprint for on-farm sales. Discover how vending technology captures a 60-80 pence per litre premium while slashing the delivery and labor costs that eventually sank the traditional doorstep model.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!