If 38.8% turnover feels normal on your farm, you’re not broken. The dairies that are surviving just moved the labor crisis to the kitchen table—and brought neighbours with them.

The neighbour’s text came before sunrise.

“Heard you lost a couple of good guys lately. I’ve got someone you should talk to. Coffee at the diner when you’re done milking?”

It was still dark outside. Steam rolled off the backs of the cows as they shifted in the holding pen. In the milk house, under the hum of the cooling compressor, Mark wiped his hands on his coveralls and stared at his phone.

Milking was only halfway through. His mind was already racing ahead to a feed delivery, a meeting with the banker, and a scraper chain that had started thumping again. He’d lost more good people in a year than in the decade before, and he was out of ideas. It was the labor crunch he’d been trying not to think about showing up in his own milk house.

The message was from his neighbour, Dave. Dave farms on the next road over. He’s ten years older, the kind of guy who’s seen enough tight years and hard decisions to read trouble from a distance. He’d noticed the steady stream of new faces in and out of Mark’s barn.

Mark thumbed out a reply.

“Yeah. I’ll be there.”

Standing in that milk house, still in the middle of the first milking, he felt something he hadn’t let himself feel in a while.

Maybe they didn’t have to figure this out alone.

He wasn’t the only one.

I’ve heard that same moment described at more than one kitchen table these last few years: a pressure point that feels impossible, someone finally saying out loud that they’re in over their head, and then—almost in spite of everything stacked against them—the neighbours start to show up.

What kept these families going wasn’t just the cows.

It was the people around them.

Editor’s Note: The farm stories in this article blend real interviews, conversations, and events from the last few years. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect privacy, and individual scenes and dialogue are composites drawn from multiple farms, not a single family. The situations and community patterns are real, used with permission, and told with care. If you see yourself in Mark, Jennifer, or Jake and Emily, that’s the point—they’re built from the stories we keep hearing at kitchen tables across dairy country, not from just one farm. Every scene and decision in this piece is drawn from real conversations with producers, workers, vets, and advisors. We’ve blended details to protect privacy, not to soften the truth.

The Dairy Labor Crisis by the Numbers

Here’s what’s really going on behind these stories.

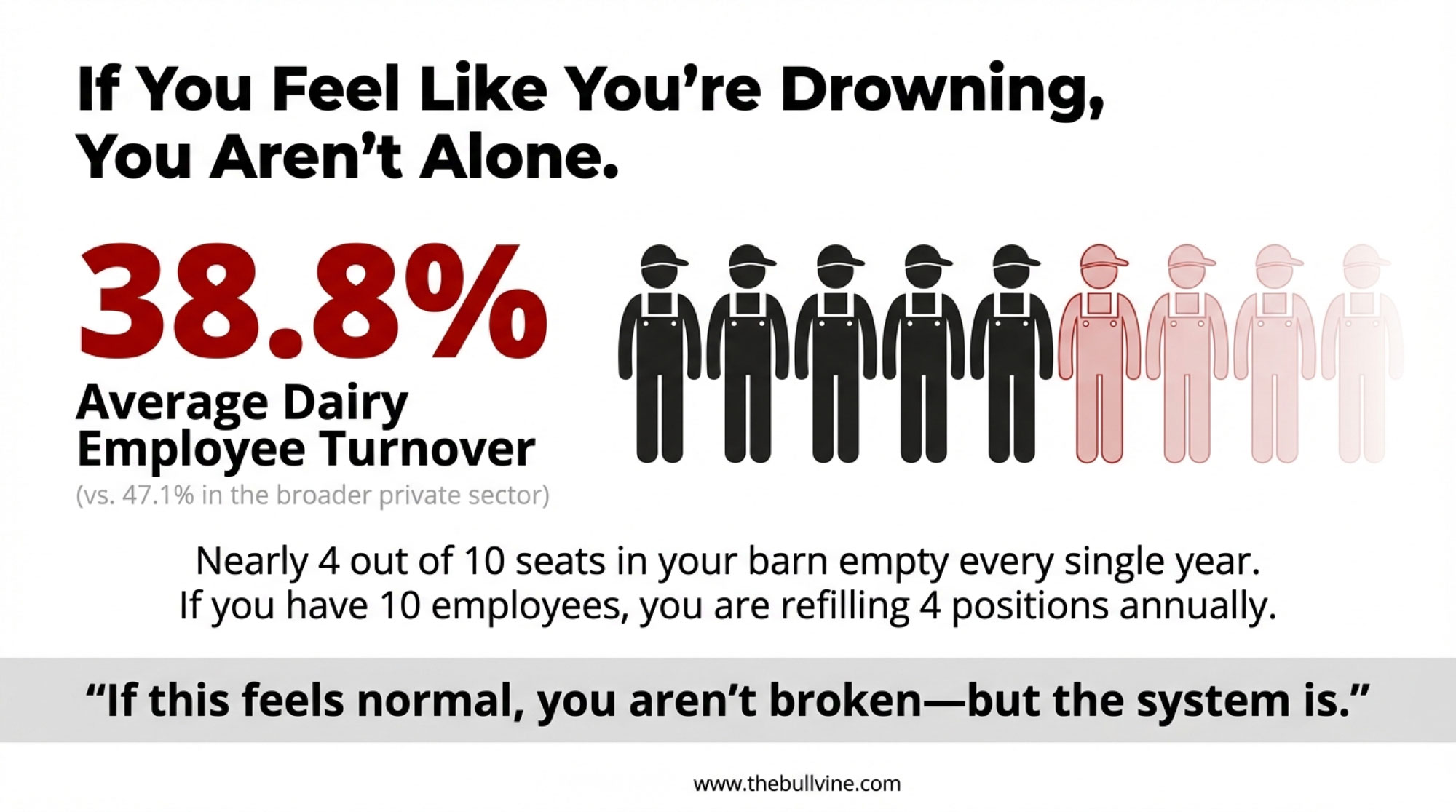

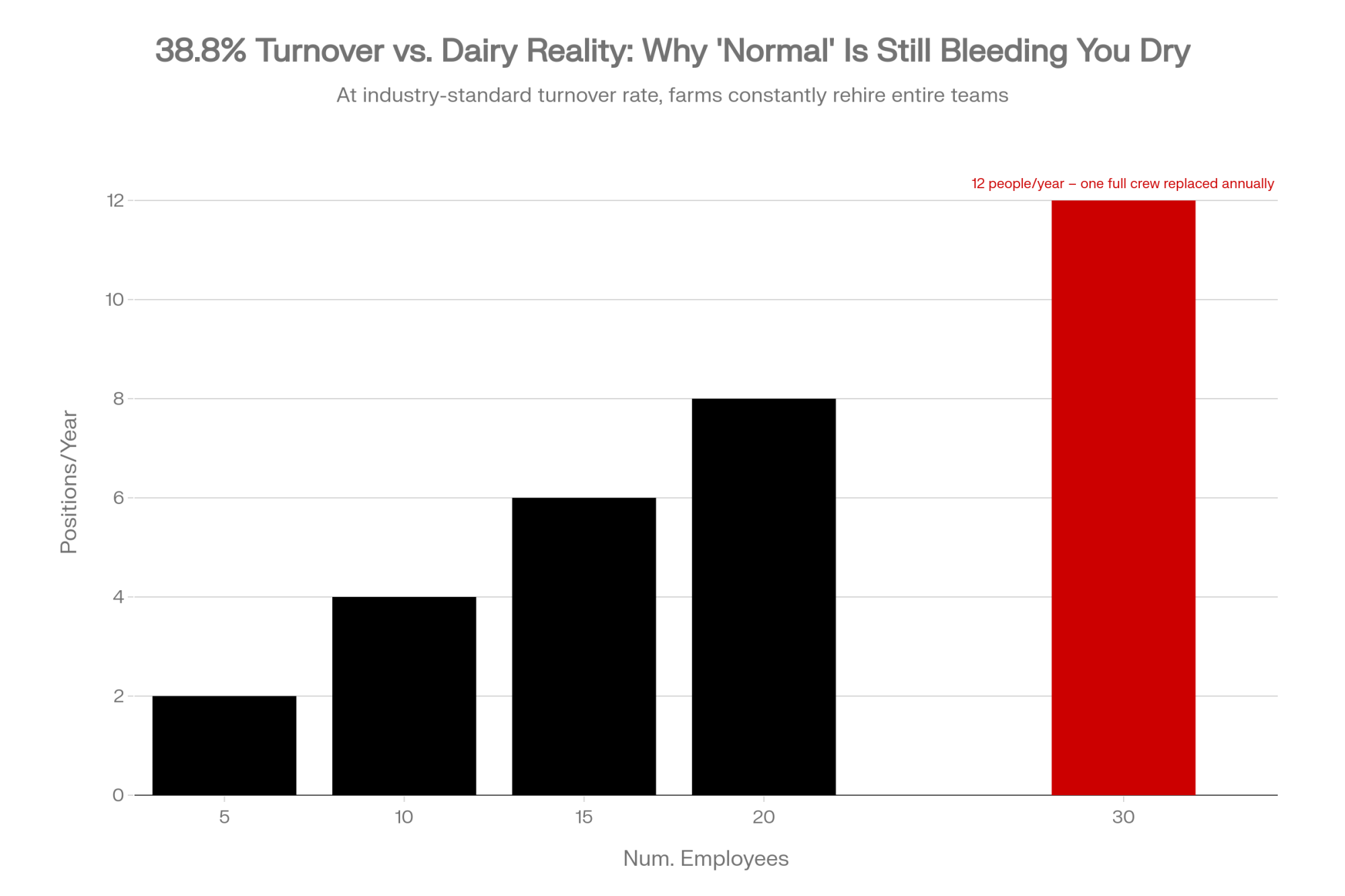

In the FARM Program’s nationwide dairy labor survey, conducted by Texas A&M’s Center for North American Studies and published in 2019, U.S. dairies reported an average employee turnover rate of 38.8 percent, compared with 47.1 percent in the broader private sector. That still means nearly 4 out of 10 positions are turning over every year on the typical dairy. If you’ve got 10 employees, you’re basically refilling almost four seats a year.

Labor is already one of your biggest line items. Michigan State University Extension notes that labor typically accounts for around 14 percent of total cash expenses on dairies, with the exact share varying by herd size and region. When the people you’re investing that money in keep cycling out the door, the quiet bleed on profit and herd performance is worse than most budgets show.

At the same time, the workforce you depend on is structurally fragile. A national survey of dairy farms conducted for the National Milk Producers Federation in 2014 found that immigrant workers accounted for about 51 percent of all dairy labor, and dairies that employed immigrant labor produced roughly 79 percent of the U.S. milk supply. In key dairy states, that reliance runs even higher. If anything shakes that foundation—policy changes, enforcement swings, or fear—it hits your parlor and your bulk tank, not just a headline.

North of the border, the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council’s recent forecasts for 2023–2030 show agriculture facing persistent and growing labor shortages, with dairy among the sectors expected to see higher vacancy rates if nothing changes. Whether you’re shipping to a U.S. cooperative or a Canadian board‑regulated plant, the story is the same: there aren’t enough people lining up to do this work under status‑quo conditions.

So if you feel like you’re constantly training, constantly short, constantly one resignation away from a crisis—you’re not imagining it. You’re sitting right in the middle of the math.

When Neighbours Became Teachers

The diner was half empty by the time Mark walked in. The smell of bacon and coffee hung in the air. Dawn was just starting to pull over the hills.

Dave was already in the corner booth, two mugs on the table.

“I remember he didn’t start with advice,” Mark said. “He just looked at me and asked, ‘How are you sleeping?’ And I laughed, because I thought he was joking. But he wasn’t.”

Mark let out a slow breath.

“I told him the truth. ‘Not great.'”

Over eggs and toast, the conversation drifted from milk prices and weather to the thing they’d both been circling around: people leaving.

“I can’t keep anybody,” Mark admitted. “The ones I really trust, the ones who know fresh cow routines and don’t miss heifer heats, they’re the ones living with the most fear.”

Over the years, he’d watched more than one trusted employee disappear almost overnight. One day, they were putting in a new group of fresh cows, and the next day, their bunk was empty. Families who’d become part of the rhythm of his barn packed up quietly and left, tired of living with the feeling that one traffic stop or one letter in the mail could change everything.

“There wasn’t even a chance to say goodbye,” he said quietly. “Their kids played with my kids. We just…lost them.”

Dave nodded. His eyes went to the window for a second.

“We had that happen here, too,” he said. “You don’t forget it.”

Research across dairy regions confirms what guys like Mark and Dave are living: immigrant and foreign‑born workers are the backbone of modern dairy, and policy uncertainty isn’t an abstract debate—it shows up as fear, turnover, and empty bunks in the bunkhouse.

In the mid‑2020s, when the labor crunch and immigration stalemate seemed to tighten another notch every season, Dave tried one of the legal paths dairy farms can use to give long‑time workers some real footing. It felt like a maze of forms, fees, and deadlines.

“It’s expensive, it’s slow, and the paperwork might as well be written in a different language the first time you see it,” he told Mark. “But it’s one of the only ways we can look somebody in the eye and say, ‘We’re willing to stand beside you.'”

He slid a business card across the table. The name on it was an immigration attorney who’d grown up on a small dairy and knew enough Spanish and farm talk to bridge both worlds.

“She knows cows,” Dave said. “She knows the law. And she’ll tell you what you don’t want to hear, not just what sounds good.”

That night, Mark and his wife spread the first stack of papers out on their kitchen table. They looked at the fees. They thought about the time they’d already poured into training people, about the families who’d already left, about their own kids and the way it shook them every time someone they loved simply vanished from the lane.

They decided to try.

But they also decided they weren’t going to walk that path by themselves.

The next week, they invited a few neighbours over for supper. A handful of couples and a single farmer crowded around the table. The attorney joined on a laptop screen at the end, her face propped between salt and pepper shakers.

They asked every question they could think of.

What if a case gets denied? How long does this really take? What happens if the rules change in the middle? How do we even start talking about this with our workers?

Nobody had a neat, tidy answer for everything. What they did have was a room full of people nodding along.

“By the end of that night, none of us had a clean roadmap,” Mark said. “But we all knew we didn’t want to keep pretending the way things were was okay.”

That kitchen‑table meeting turned into a regular thing. Once a month, after evening chores or on a rainy Sunday, more trucks crowd into the driveway than the yard was ever designed for. People bring casseroles and cookies. Kids drift in and out, grabbing snacks and listening from the stairs.

Around that table, they swap stories.

Someone passes a letter from the government around, the paper soft from being folded and unfolded. Someone else talks about a worker whose case is stuck somewhere in the system and how they’re trying to keep his hopes grounded. The co‑op field rep sits in sometimes, mostly to listen.

“I thought I understood ‘labor issues’ before I sat at that table,” he admitted one night. “I didn’t. Not really.”

He started talking differently at co‑op meetings after that.

“I told them, ‘You think this is a policy issue. Our members are living this at their kitchen tables,” he said. “It changes how you argue for something when you’ve looked those people in the eye.”

Every now and then, an extension educator joins them, too, listening more than talking and jotting notes on what farmers actually need from the next round of workshops.

Over time, farms in that little circle have helped a number of long‑time workers start some kind of legal path forward. Not every case has gone smoothly. There have been delays that felt like gut punches. There have been nights when someone came in ready to give up.

“And then you have three other farmers saying, ‘Yeah, we hit that wall too. Here’s how we got through it—or how we’re still trying,” Mark said. “That’s when it feels less like you versus the system and more like all of us, together, trying to do right by our people.”

One afternoon, long after the paperwork marathon had started, a worker walked into the parlor, holding an envelope as if it were a fragile calf.

Mark took one look and knew what kind it was.

“We just stood there,” he said. “He handed it to me with both hands. He couldn’t say much at first.”

When he found the words, he said something Mark won’t forget: “My daughter can grow up here now.”

Later, someone in the group mentioned that the worker’s child had drawn a picture of the farm at school and told the teacher, “This is where we get to stay now.” That simple comment said more than any thank‑you card ever could.

On rough mornings, when a pump won’t prime, or a heifer finds a new way to wedge herself where she shouldn’t, Mark thinks about that kid.

“I still worry about what might change in town or in the capital,” he said. “But I don’t wake up every day wondering who’s going to be in the parlor anymore. That alone feels different.”

Somewhere in that same valley, another worker’s case is still sitting in a stack of files. The group hasn’t forgotten him. His name comes up at every meeting. Somebody always volunteers to make the next call.

Raising Kids, Cows, and Community in Minnesota

The night everything came to a head for Tom and Sarah, the house was too quiet.

They’d finished evening milking late. Their roughly 200‑plus cows were settled, the parlor was washed, and the pipeline was humming as it cooled. Upstairs, their daughter was sprawled across her bed with textbooks open and earbuds in.

Sarah set a plate of reheated casserole on the table and poured herself a cup of tea, which she never did drink. Tom sat down across from her, shoulders slumped in a way she’d started to see more and more.

“I remember staring at that plate and thinking, ‘If I try to eat this, I’m going to fall asleep right here,'” she said. “I was that tired.”

Over the past months, a string of milkers had come and gone. One left for a job with benefits in town. Another found work with more predictable hours. Others just drifted away. Each time, they scrambled. Each time, they told themselves they’d figure it out.

That night, Sarah finally said what had been rattling around in her head for weeks.

“I don’t even know who’s on the schedule tomorrow,” she told Tom. “I just know I’m bracing for a text at five a.m. that says, ‘Sorry, can’t come.’ And I’m so tired of training people who are already looking for the next thing.”

When they’d asked their daughter not long before if she’d ever think about coming back to the farm after college, she didn’t sugarcoat it. She talked about what she saw: her parents exhausted, a schedule that never let up, and friends working in town who had predictable shifts and benefits.

“She wasn’t trying to hurt us,” Tom said. “She was just telling us what it looked like from where she sat.”

That night at the table, he set his fork down.

“We can’t keep doing this,” he said quietly. “Not to ourselves. Not to them.”

There was a long pause. The clock on the wall ticked louder than usual.

The next day, between vet checks and feeding calves, they started talking seriously about robots.

They’d heard all the stories. Some neighbours swore their automatic milking systems had saved their backs and their marriages. Others grumbled about never‑ending alarms and cows that refused to cooperate. The dealer had glossy brochures full of graphs and smiling families.

Tom and Sarah made a choice that surprised even them. They didn’t start by calling the dealer.

They started by calling their people.

They invited their herd vet, their nutritionist, a neighbour who’d installed robots a couple of years earlier, and their pastor to the farm for a Sunday afternoon.

“It felt a little strange at first,” Sarah admitted. “Like, why is the pastor in the shop talking about robots? But he knew us. He’d seen what the last few years had done to our family. That mattered as much as the numbers.”

They sat on folding chairs in the machine shed with two whiteboards, a pot of coffee, and more nervous energy than any of them wanted to admit. The wind rattled the overhead door. A few calves bawled outside.

They talked about what a bigger loan would really mean for their debt load. They talked about how many hours they could realistically take out of the parlor. They talked about what it would look like for their crew—who might be excited, who might be nervous. They talked about what it would mean for their kids if the farm started to look like something they could actually imagine being part of.

Their vet didn’t sugarcoat it.

“A robot can’t fix a bad ration or a bad attitude,” he told them. “It can change your workload. It might change your stress. But the biggest question is, what do you want your life to look like five years from now?”

Their pastor asked a different question.

“Who are you going to call when something breaks at two in the morning?” he said. “Because it will. And you two can’t be the only answer to that.”

They made a list. The neighbour with robots. The dealer techs. The vet. A couple of younger producers in the area who’d talked about wanting to learn more about AMS. One of their farm‑credit advisors offered to run worst‑case and best‑case cash‑flow scenarios so they weren’t guessing in the dark.

They also did something they hadn’t done before.

They put emergency mental‑health contacts where they could see them—farm stress hotline numbers, their doctor’s office, their pastor’s cell—right on the fridge. Just in case.

The robots did come. The first weeks were rough. Cows balked at the new lanes. Alarms went off for reasons no one could explain. There were nights when Sarah, standing in the glow of a robot screen at three a.m., wondered if they’d made a terrible mistake.

But slowly, the work started to shift.

They sat down with their crew and told them the truth.

“We’re not replacing you,” Tom said. “We’re asking you to work differently.”

They asked who might be interested in learning more about health, breeding, and data.

A quiet milker who’d been with them for a few years raised her hand.

“I don’t want to wash units forever,” she said with a small smile. “Teach me something else.”

They did.

She began working closely with the vet, learning how to read the robot’s reports—conductivity graphs, milk‑flow patterns, visits per cow. A few months in, she noticed that one group’s milking times were creeping up, and the conductivity in a couple of quarters was just a tick higher than normal.

“I thought, ‘Something’s going on in that pen,'” she said. They pulled a few samples and found the beginnings of a mastitis issue they could get ahead of.

The vet shook his head, smiling.

“The robot gave us numbers,” he said. “She gave us insight. That’s the part you can’t buy in a crate.”

| Task | Pre‑Robot Hours | Post‑Robot Hours |

|---|---|---|

| Milking / Parlor Work | 16 | 6 |

| Cow Health & Repro Tasks | 4 | 6 |

| Data & Planning | 1 | 3 |

Upstairs in the farmhouse, something else was shifting. Their daughter, who’d sworn she’d never come back, started wandering into the office when she was home on weekends. At first, she just clicked around the software because it looked like a game. Then she started asking questions about cull rates, reproductive performance, and which cows were actually paying for their stall.

As her daughter dug into the robot data, she also started asking which cows were actually paying for their stall and which matings were producing the kind of trouble‑free cows the robots love.

“For the first time,” she said, “the farm started to look like a place where I could use my brain, not just my back.”

At her university’s dairy club, she found herself helping younger 4‑H members figure out their own families’ robot reports. On show day, she’d be leaning over laptops with twelve‑year‑olds in belts and boots, explaining how to read a graph of milkings per day and why a cow dropping to 1.5 visits needs eyes on her fast.

A few months after that, a neighbour, thinking about robots, called late one night, overwhelmed by costs and alarms he’d heard about.

“Tom sat at the kitchen table and just walked him through the first week,” Sarah said. “We remembered how it felt to sit where he was. It felt good not to let him sit there alone.”

The robots didn’t fix everything. The debt still sat on the balance sheet, heavy as a silo. There were still nights when alarms went off at the worst possible time. There were still hard conversations about who was going to be “on call” over Christmas.

But there were more evenings when the family sat around the table before nine p.m., and more mornings when Tom and Sarah woke up feeling like they hadn’t been run over.

“I won’t pretend it’s all sunshine,” Sarah said. “But we’re not as close to the edge as we were. And the farm looks more like a place our kids might want to come back to, instead of a place they want to run from.”

Down the road, a smaller tie‑stall couple with no real interest in robots at all drove home from one of those barn days and told each other, “We’re not the only ones struggling with labor. That helps.” Their solution looks different—tighter shifts, a shared weekend milker with a neighbour—but they still came away with the same thing.

They’re not alone.

What Fair Wages Really Built in Vermont

The wind cut across the Vermont hillside, blowing fine snow into the ends of the freestall barn. Cows stood in rows, chewing calmly, their breath hanging in the air. In the farmhouse kitchen, a pot of coffee gurgled and the old radiators hissed to life.

Jennifer spread a stack of pay stubs and scribbled notes across the table. Across from her sat two of her employees.

“I want you to understand how we got here,” she told them. “Because this isn’t charity. This is math. And it’s also about what kind of place we want this to be.”

A few years earlier, her roughly 150‑cow organic dairy had started to feel like a revolving door. On paper, the farm looked fine. Good components. Strong butterfat. Pastures that made the milk truck driver smile. But the people side was bleeding.

“I was paying what everyone around here was paying,” she said. “And still, every time I turned around, somebody was leaving.”

She sat down with her accountant and her dad—who’d milked cows on that hill before her—and really looked at the numbers.

The Real Cost of Employee Turnover

Here’s the math Jennifer was staring at, stripped of wishful thinking.

A 2025 Michigan State University Extension analysis estimates turnover costs at 100–150 percent of annual salary for hourly dairy positions, and shows how a $25,000–$30,000 job can generate $37,500–$45,000 in replacement costs when you factor in hiring, training, and lost productivity. On a 20‑employee dairy with 10 percent turnover, that adds up to $75,000–$90,000 per year.

The FARM Workforce Development resources and related industry analysis often use a baseline of about one‑third of annual salary per replacement. With experienced dairy employees commonly earning around $40,000–$42,000 per year, that puts visible replacement costs in the $13,000–$14,000 range before you even count subtle herd impacts.

A number of farm workforce studies and extension resources suggest that $15,000–$25,000 per experienced worker is a realistic minimum once you add up recruiting, training, lower efficiency, and those ripple effects on SCC, reproduction, and cull rates.

To make it a little easier to picture, here’s a simplified breakdown you can lay beside your own numbers:

| Category | Estimated Cost (USD) | What It Includes |

| Recruitment & Hiring | $500–$2,000 | Advertising, interviewing time, background checks, and management hours |

| Training (First 90 Days) | $3,000–$6,000 | Lower efficiency, mentor’s lost time, errors during the learning curve |

| Lost Productivity & Herd Impact | $5,000–$12,000 | Higher SCC, missed heats, protocol slips, extra vet work, milk loss |

| Transition Disruption | $2,000–$5,000 | Coverage gaps, overtime, and burnout risk in the remaining crew |

| Total Per Departure (Conservative) | $10,500–$25,000+ | Varies by farm size and role complexity |

| Scenario | Wage/worker | Turnover | Turnover cost (10‑employee crew) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Status quo – low wage | $38,000 | 40% | $60,000 |

| Slight raise, no benefits | $40,000 | 30% | $45,000 |

| High‑retention wage + basic housing | $45,000 | 15% | $22,500 |

| Jennifer‑style full package | $50,000 | 10% | $15,000 |

That’s the “hidden math” behind a help‑wanted ad that never seems to come down.

Jennifer and her dad realized that on a farm, even with three or four key positions turning over regularly, they were quietly burning through more money than it would cost to make those jobs worth keeping.

It wasn’t a fancy spreadsheet. It was a pen, a legal pad, and a lot of honest math.

Her dad slid his coffee mug to the side, like he was making room for something important.

“If you can’t afford to treat people right,” he said, “you can’t afford to be in business.”

It wasn’t a lecture. It was the plain truth of someone who’d seen what happens when you don’t.

So they did something that felt a little crazy.

They rebuilt their labor plan from the ground up.

They landed on a pay and benefit package that worked out to roughly the mid‑twenties an hour for full‑time work once you factored in housing and basics. They decided to include family housing on the farm, with heat. They added health and dental insurance. They put in paid vacation and sick time. And they set aside money each year per employee household for education, whatever that meant to that family.

Then came the harder part: sitting down with their crew and walking through it.

“We’re not used to bosses opening the books,” one of them said later. “She showed us what the farm could pay, what it cost when people left, what it would mean if we stayed.”

That conversation changed something.

It didn’t magically solve every problem, but it shifted the ground under their feet. Suddenly, this wasn’t just a job that might disappear in six months. It was a place willing to put its money and trust where its words were.

A while later, Jennifer checked in with one of her employees about his son. The boy had been struggling in school; teachers had been sending notes home about focus and math.

“We were worried all the time,” the dad said. “When you don’t know if you’ll have a job next month, it’s hard to think about anything else.”

Jennifer suggested using some of the education support to pay for extra help through the school. At first, he hesitated. He’d never had an employer offer something like that.

They tried it.

Over the following months, the boy’s confidence grew. The grades came up. But what stuck with Jennifer wasn’t one report card moment. It was watching the strain slowly ease from the parents’ faces and hearing them talk about their son’s future with something besides fear.

“I realized I wasn’t just cutting paychecks and hoping people showed up,” she said. “I was part of their family’s story, and they were part of mine.”

That new sense of responsibility started to show up in other places, too.

One summer, a neighbour with a small tie‑stall herd found himself short‑handed with almost no notice. The loss of a key milker came at the worst possible time—middle of the growing season, no backup plan, and real fear about how he’d manage.

Jennifer heard about it from her crew before she saw anything online.

“They came to me and said, ‘We can cover his weekends for a while,'” she said. “They’d already talked it over among themselves. They had a little schedule written out.”

For several weekends, one of her employees pulled into that neighbour’s driveway in the dark, milked his cows, washed his pipeline, and headed back to their own jobs. They refused extra pay.

“We told him, ‘Someday it’ll be somebody else. You’ll be the one showing up in their yard,” one of them said.

In the middle of that neighbour’s fear, when he could barely face walking into that barn alone, his neighbours showed up anyway.

It didn’t fix every problem. It didn’t make the bills go away. But it meant he didn’t have to face that barn alone.

Twice a year, Jennifer opens her kitchen to other farmers. She calls it a “labor open house,” but it feels more like a neighbourhood gathering. There’s chili or soup. Kids run up and down the hallway. Spouses lean on counters with coffee mugs.

She lays out what she pays, what she offers, what it’s costing her, and what she feels like it’s saving her.

The first time she did it, one of the older farmers looked at the numbers and shook his head.

“I can’t pay like that,” he said.

“Maybe not,” Jennifer answered. “But maybe you can do something else. Maybe it’s housing. Maybe it’s one extra day off a month. All I know is, doing nothing is costing us more than we think.”

A little while later, that same farmer teamed up with two neighbours to fix up a worn‑out farmhouse at the end of their road. They turned it into shared housing for families who worked across their farms. The floors creak. The paint is old. But the walls are insulated, the furnace works, and the kids who live there get to stay in the same school all year.

One of the moms who moved in told him, “We’ve never had heat we could count on before. The kids sleep through the night now.”

For those three farms, that farmhouse has become more than just a rental. It’s a promise that they’re planning for people, not just hoping someone will show up.

“It’s not about copying what we do dollar for dollar,” Jennifer said. “It’s about deciding that people are worth planning for, not just hoping for.”

Finding Family in Unexpected Places

On a cold November morning in Wisconsin, the gravel road to Jake and Emily’s farm was lined with bare trees and frost‑covered fence posts. Their couple of hundred cows were already halfway through the morning milking. The skid steer beeped in the yard as someone pushed feed up.

Inside the parlor, an older employee named Pete was rinsing units when a man with a navy stocking cap and a careful smile stepped in.

This was the new hire’s first winter on the farm.

When the call came from a local refugee resettlement agency asking if Jake would consider interviewing someone with livestock experience from halfway around the world, his first reaction had been a knot in his stomach.

“I thought, ‘We’re already behind. I can’t add language barriers and paperwork on top of this,” he said. “But I also thought, ‘We can’t keep doing what we’re doing.'”

Two local high school kids had left for college. A long‑time worker had retired. Ads on the bulletin board at the feed store weren’t getting calls anymore.

So he said yes to a short trial.

On the first morning, there were awkward moments. Communication was harder than anyone expected. At one point, Pete got frustrated trying to explain a change in the feeding routine, and Jake worried the whole thing was about to fall apart.

Then Pete pulled out his phone and opened a translation app. What could have been the end of the trial became the beginning of a solution. They went back and forth like that for a while—half gestures, half phone screen, half shared cow sense. By the end of the week, the two of them had found a rhythm.

“That guy knew more about cattle than half the people I’ve worked with,” Pete said later. “We just had to figure out how to talk to each other.”

Back home, in another country and another climate, the new hire had grown up tending cattle and goats. The cows here were different. The barn was different. The weather could cut you in half. But the animals were still animals.

“I didn’t come here to be saved,” he said. “I came here to work and to build something again. They gave me a chance. I want to make good on it.”

Months later, his wife and kids arrived. They were among the few newcomer families in the little town.

“The first day of school, I walked my daughter in and felt every eye on us,” his wife said. “It was…a lot.”

The principal stepped forward, shook her hand, and said, “We’re glad you’re here.” It wasn’t a speech. It was just one sentence in a crowded hallway, but it mattered.

Emily noticed her hanging back at school pick‑up, hovering near the door. She recognized that careful watching—the way you assess a new situation before committing. One afternoon, she walked over and invited her for coffee.

They sat at Emily’s kitchen table, the same one where so many farm bills had been paid and so many 4‑H posters had dried, and traded stories—with help from a phone app and a lot of gestures. Emily asked if she’d teach her how to make one of her favorite dishes. In return, Emily showed her how she planned meals around milking and chores.

“What started as me trying to help,” Emily said, “turned into me realizing how much I had to learn.”

Out of those visits came the idea for a “cultural night” in the machine shed.

They swept out one bay, set up folding tables, and plugged in slow cookers and coffee pots. The new family brought their food. Emily made chili and apple crisp. Pete brought venison sausage. Somebody else showed up with a pan of bars.

A small crowd of neighbours, a couple of other farmers, a teacher, the mail carrier, and one notoriously private uncle who almost never leaves his own place came that first year.

They didn’t do speeches. There were no name tags. People just ate. Kids ran around the tractors. Someone pulled out a guitar. At one point, the new worker pulled out his phone and showed photos of the cows and fields from home. A few people recognized the look in his eyes when he talked about weather and crop failures. Different country, same worry.

The shift in the neighbourhood didn’t come from one dramatic moment. It came from a hundred small ones. Conversations at the feed mill sounded different. People who’d been quietly skeptical started asking practical questions about how the partnership was working—housing, schedules, school.

“It wasn’t like a switch flipped,” Jake said. “It was more like people kept showing up, and over time, everybody relaxed a little.”

In the months that followed, word spread quietly. A couple of other farms were called the same resettlement agency. One hired someone with small‑ruminant experience to help with calves and yard work. Another found a woman who’d worked at a dairy co‑op overseas and wanted to be back around cows.

Not everything went smoothly. There were miscommunications—about time off, about holidays, about small things that felt big in the moment. Once, a misunderstanding about a schedule change left a pen of calves bedded later than they should’ve been. It took a couple of uncomfortable conversations, more translation‑app back‑and‑forths, and a lot of listening to sort it out.

“But we got there,” Jake said. “We messed up. We apologized. They messed up. They apologized. That’s how families work. That’s how communities work, too.”

Some of those connections stretch beyond the road now. One of the FFA kids who helped set up tables started a group chat with other local farm kids and a few she met at a state conference. They trade photos of calves, swap ideas for farm safety projects, and send “You okay?” messages on the rough weeks.

When you drive past Jake and Emily’s place now, it’s not unusual to see their kids and the newcomer kids racing their bikes down the lane together, or a group of parents—old neighbours and new ones—standing by the yard gate talking about school and silage in the same breath.

A local FFA student who helped set up tables last year tried to put it into words.

“I’ve been to a lot of meetings in that shed,” she said. “I’ve never seen that many different people in here at once, just talking and laughing. It made me want to stick around and see what we build next.”

“What kept us going wasn’t some big plan,” Emily said. “It was small decisions, over and over, to show up for each other.”

Four Models of Community Support: What These Farms Built

Each of the farms in this story found a different path through the labor crisis. None of them had a perfect playbook. But together, they offer a menu of approaches you can adapt.

| Model | Core Strategy | Key Investment | Main Labor Impact | Best Fit For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valley Network – Immigration Circle | Monthly kitchen‑table legal meetings | Shared legal fees + time | Stabilizes long‑term immigrant staff; cuts fear‑driven exits | Farms with core immigrant crews under status pressure |

| Tech + People – Robot Transition | Community‑guided AMS adoption | Capital for robots + support network | Reduces parlor hours; shifts staff into higher‑skill roles | Mid‑size herds facing burnout and succession questions |

| High‑Retention Wages & Housing | Above‑market pay, housing, benefits, open books | Higher wage line, housing, benefit admin | Dramatically lower churn; stronger loyalty and peer support | Solid herds with margin willing to trade cash for stability |

| Refugee Partnership & Cultural Bridge | Work with resettlement programs; invest in integration | Time, patience, school and town relationships | Access to new skilled workers; revitalized rural communities | Areas with shallow local labor but active newcomer programs |

These models aren’t mutually exclusive. A high‑retention wage farm can still partner with a refugee program. A robot barn can still host immigration nights. The point isn’t to copy anyone line‑for‑line. It’s to stop pretending the labor crisis is something you can “manage” with one more ad, one more meeting, or one more guilt trip on your kids.

The Ripple Effect Nobody Put in a Plan

None of these families sat down and wrote a mission statement about community.

Most days, they were just trying to keep their heads above water and get the cows milked on time.

That group in the valley didn’t set out to create an “immigration network.” They just didn’t want to see any more bunks emptied in the middle of the night. The monthly meetings around that kitchen table grew because one farm after another realized it was better to face those letters and forms with a crowd than alone.

The co‑op rep, who had mostly come to listen, found himself talking differently in board meetings.

“I told them, ‘You think this is a policy issue. Our members are living this at their kitchen tables,” he said. “It changes how you argue for something when you’ve looked those people in the eye.”

A few months later, the co‑op quietly added an immigration Q&A and a mental‑health resource slide to its winter producer meeting, not because a consultant told them to, but because members wouldn’t stop bringing it up.

In Minnesota, Tom and Sarah’s robot decision turned into something bigger than their own barn. The neighbour who’d advised them at that first shop meeting invited them to a barn day the next year. They rotated host farms. People walked through robot rooms, talked about fresh cow management and butterfat performance, and stood quietly in corners, admitting they were tired.

“One young couple with a small tie‑stall herd came just to listen,” Sarah said. “They’re not ready for robots. They might never be. But on the drive home, they told us, ‘Just knowing we’re not the only ones struggling with labor made the day worth it.'”

In Vermont, the twice‑yearly labor open houses became a kind of community checkup.

“I thought the first one would be two people,” Jennifer said. “We ended up with farms from across the road and the next valley over around the table. A couple of months later, I started hearing about people changing their schedules, looking for housing, and talking to their kids about what the farm will look like ten years from now. That’s when it hit me—this isn’t just about us.”

One neighbour who’d always sworn he would never commit to a regular day off started guaranteeing his main milker one Sunday a month with his kids.

“He told me, ‘I thought I’d lose production. What I lost was a lot of resentment. He comes in on Monday happier. So do I,” she said.

The shared farmhouse down the road—patched roof, new wiring, coats and backpacks on hooks by the door—became a symbol of that shift. Three farms, who once mostly talked about milk prices at the diner, now sit together sorting out who will pay for which plumbing repair and how to share a worker’s time fairly.

For some much bigger herds a few counties over, the details look different—more formal HR, larger bunkhouses instead of one old farmhouse—but the questions are the same: Who will work here? How will we treat them? And will our kids ever want to carry on this work?

Whether you’re milking 40 cows in a tie‑stall or 2,000 in six rows of freestalls, the math looks different, but the people questions don’t let you off the hook.

Back in Wisconsin, that simple night in the machine shed has turned into an annual event. The second year, the local FFA chapter helped set up tables. The 4‑H dairy club did a little showmanship demonstration for the younger kids. The school principal brought new staff and told Emily, “This is my favorite night of the year now.”

The pastor came too. At the end, he said, quietly, “I didn’t know what I was walking into. What I walked into was community.”

A teenager looked around that second year and said, “I didn’t realize how much our town had changed until I saw everybody in this shed together.”

Some of these connections now cross roads and county lines. A handful of the farmers and families in this story stay in touch through group texts and online producer forums, trading advice about labor, paperwork, and those 2 a.m. robot alarms that never seem to ring at a good time. Once in a while, someone they first met in a comment thread ends up sharing coffee in the stands at a show or sitting beside them at a co‑op meeting, and another piece of this informal network clicks into place.

None of this came from a government program or a glossy industry campaign. It came from kitchen tables and machine sheds, because farmers got tired of waiting for someone else to fix what was breaking them.

Nobody wrote any of that into a strategic plan.

They just made food, opened doors, and let people be people.

The Bottom Line

If you’ve read this far, you don’t need another graph to convince you there’s a dairy labor crisis. You’re living it. You’re fielding texts at 4 a.m. You’re watching good people leave because the system around them is broken. You’re wondering if your kids will ever want to step into your boots.

These farms don’t have all the answers. They’re still wrestling with debt, with time, with rules that don’t quite fit the way dairy actually works. They still have hard days. They still get blindsided by life. Some of them will still have to sell out someday, even with all this support.

But they did something simple and brave.

They started talking.

They let the cracks show. They told the truth about how exhausted and scared they were. And instead of turning inward, they opened their doors—to a neighbour, to an attorney, to a vet, to a pastor, to a resettlement worker, to an employee’s family, to the kid who said she couldn’t see a future on the farm as things stood.

What came out of those conversations wasn’t perfection.

It was a connection.

It was the valley kitchen table crowded with farmers passing around a letter from the government and saying, “You’re not the first. You won’t be the last. Here’s how we handled it.”

It was the Minnesota shop full of whiteboards and coffee and nervous laughter as a family talked about robots and burnout in the same breath, and their pastor asked, “Who are you going to call at two in the morning?”

It was the Vermont parlor where a dad looked at the progress his son was making in school and realized—for once—the farm had made something easier at home instead of harder.

It was the Wisconsin machine shed where a newcomer family and long‑time neighbours ended up swapping recipes, farm stories, and school concerns under the same roof.

Sometimes, even with all the coffee and kitchen tables in the world, a farm still has to sell out. Community matters there too—the neighbours who show up on sale day, the friend who helps polish a résumé, the church ladies who make sure there’s a pan of lasagna in the fridge when the last cow leaves.

Small, Realistic Things You Can Try

So what can you actually do with all this?

Not a list of “10 easy steps to fix labor.” Those don’t exist.

But there are small, realistic things almost any dairy community can try:

- Pick one neighbour and invite them over for supper—or coffee at the diner at an odd hour—and talk honestly about labor. Not just wages. The stress. The fear. The kids. The times you’ve thought, “Maybe we’re done.” Start with, “What’s one part of labor that’s keeping you up at night?”

- Open your kitchen table once with an expert—an attorney, a vet, someone from extension, someone from a resettlement agency—and a couple of neighbours. Put a real letter, contract, or form in the middle of the table and ask, “What are we not seeing clearly about this?”

- Look at what you can offer families, not just workers. Maybe it’s shared housing with a neighbour. Maybe it’s one weekend off a month. Maybe it’s helping an employee’s child get to 4‑H meetings or FFA events because those things take time and gas money that some families don’t have.

- Ask your co‑op or processor, “What are you doing to help us with labor?” and be ready with realistic suggestions—immigration/legal clinics, translation help, training sessions, mental‑health resources at winter meetings. If your co‑op shrugs, that’s still data. It tells you who’s willing to sit at your kitchen table and who isn’t.

- Look around your area for a refugee resettlement group or newcomer program. One phone call—”If you ever have someone with farm or livestock experience who needs a job, give us a call”—can start a whole new chapter.

- Take rural mental health seriously. If Tom and Sarah’s late‑night kitchen table sounds too familiar, write a number on a sticky note and put it on your own fridge. Talk to your doctor, your pastor, your spouse, your neighbour, and say the words, “I’m not okay,” and see who shows up.

- Decide that if you’ve had more than a couple of core employees leave in a year, that’s your signal—not just to grumble—but to call one neighbour and start a different kind of conversation about what needs to change.

- If there’s nobody on your road you feel close to yet, start with someone you met at a meeting or in an online dairy group. Swap phone numbers. Once in a while, send a message that just says, “How’s your week going, really?”

Honestly, if you don’t have time to do all of this, start with the one thing your own turnover math is screaming for—whether that’s a wage rethink, a housing conversation, or one kitchen‑table meeting with the people on your road.

None of that will fix everything.

There will still be long days and short nights. There will still be bills that don’t care how tired you are. There will still be cows calving at the worst possible moment and kids with homework due the same day.

But the work feels different when you know you’re not the only one carrying it.

When a neighbour’s truck shows up in your driveway before daylight.

When a worker walks into the parlor holding an envelope like it’s made of glass and says, “We can stay.”

When a robot alarm goes off, and you’re not the only name on the list.

When the road to your farm fills up—not with headlights for a funeral, but with people coming to learn, to eat, to help, to see each other.

The labor crisis is real. The exhaustion is real. The grief is real.

So is a worn‑out kitchen table, a pot of coffee, and a few neighbours who refuse to walk away.

It won’t fix milk prices or rewrite policy. Nobody in a suit is coming to fix this for you. That’s the bad news.

The good news is, you don’t have to wait for them.

We’ve been waiting a decade for policy solutions that never came. These farmers stopped waiting.

That steady, stubborn decision—shared across fence lines and county lines and sometimes language lines—to keep showing up for each other when the industry shrugs and says, “That’s just how it is,” is already part of the reason some barns are still lit tonight.

- They may not say it out loud, but every time they show up for each other, the message is pretty simple: we’re not done yet.

Key Takeaways:

- 38.8% turnover is bleeding you dry: Replacing one experienced worker costs $15,000–$25,000+ when you add up recruiting, training, lost productivity, and herd hits like SCC spikes and missed heats.

- Four playbooks are actually working: immigration support circles, community-backed robot transitions, high-retention wage/housing models, and refugee partnerships—all built by neighbours, not policy.

- The difference isn’t robots or wages alone—it’s who’s at your table: Farms stabilizing labor brought vets, pastors, attorneys, and neighbours into the conversation and started treating people decisions like breeding decisions.

- You don’t need a 10-step plan—you need one honest conversation: Invite a neighbour for coffee, put a real problem on the table, and ask who else should be in the room.

- Nobody in a suit is coming to fix this: The dairies still lit tonight stopped waiting and started showing up for each other.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Average dairy employee turnover is 38.8% a year, and this story goes inside the barns and kitchen tables of composite families who decided they weren’t going to face that alone. It walks through four real‑world playbooks—an immigration support circle, a community‑driven robot transition, a high‑retention wage and housing model, and a refugee partnership—that turn constant churn into more stable, skilled teams. Along the way, it shows how honest conversations about turnover math, debt, mental health, and kids’ futures reshape labor decisions just as much as any robot or new ration. For you as an owner or manager, the piece connects people decisions directly to profitability, risk, and whether anyone in the next generation actually wants your keys. It finishes with concrete, low‑drama steps—who to invite, what to put on the table, and when your own turnover should be a stop‑sign—not just “be nicer to employees” theory.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- Is Your Dairy Farm a Great Place to Work? – Wrestling with the same management shifts as Jennifer, this story proves that moving from a “hiring boss” to a true leader isn’t just about kindness—it’s the only way to build a farm that survives the current churn.

- The Human Side of Robotic Milking – Much like Tom and Sarah’s kitchen-table epiphany, this piece explores the world where technology and human emotion meet, showing how automation can either bridge the generational gap or create a whole new set of burdens.

- The Modern Dairy Farm: It’s All About People – Carrying forward the spirit of the Wisconsin machine shed, this narrative proves that our industry’s true legacy won’t be found in the bulk tank, but in the stubborn, shared commitment of the people standing beside us.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!