She wasn’t allowed to milk cows. She now runs a $22B company. How many daughters is your dairy quietly pushing off the lane?

Iowa State research says a big part of the “succession crisis” on family farms isn’t that kids don’t want to farm. It’s who you actually develop for leadership in the first place. If you’re within shouting distance of a transition between now and 2030—thinking about slowing down, selling out, or handing over shares—this is for you.

The payoff is simple: a clearer read on your real successor bench and a practical way to widen it without blowing up the farm or the family.

The 57/8 Split: What the Research Actually Found

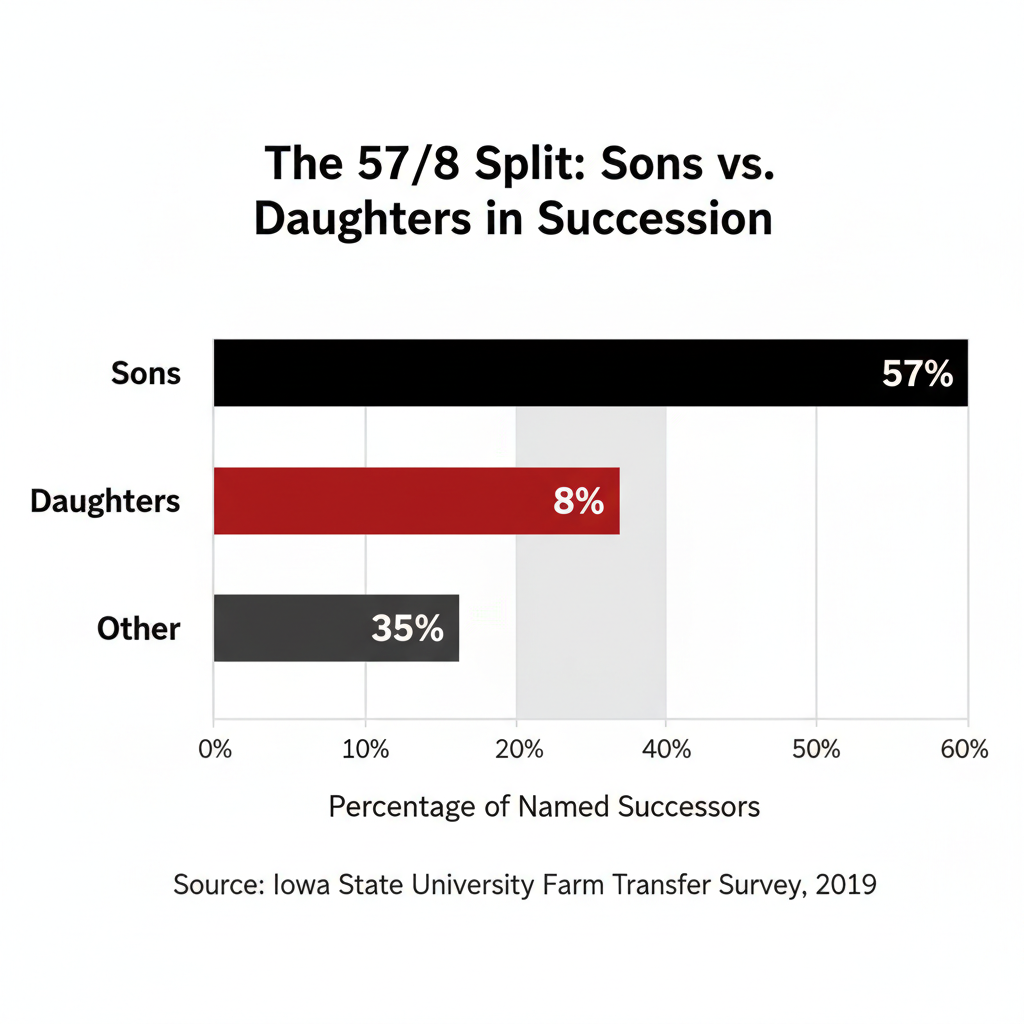

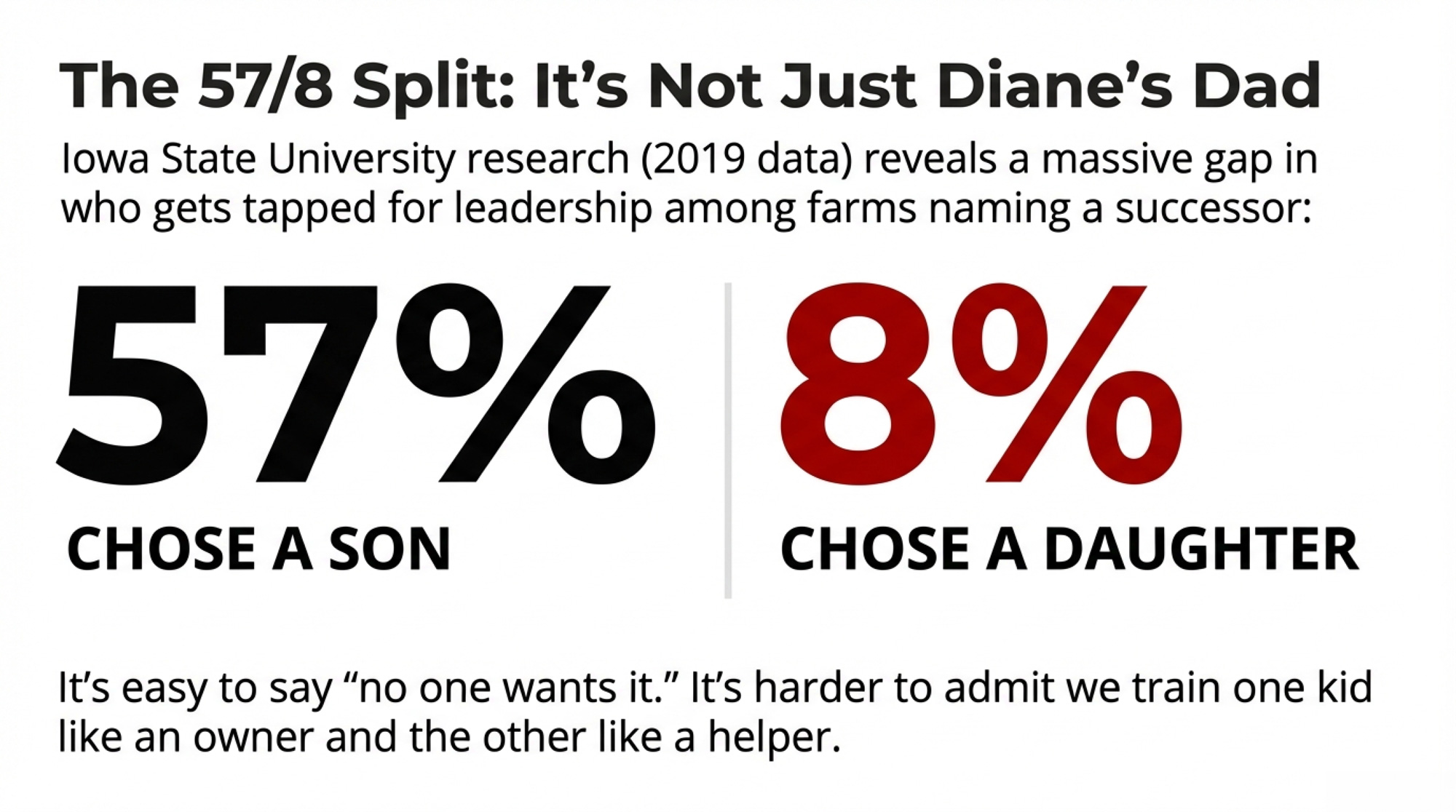

Among Iowa farmers who’ve already named a successor, 57% choose sons, and only 8% choose daughters. That comes straight out of Iowa State University’s “How Gender Affects Successions and Transfers of Iowa Farms,” based on the 2019 Iowa Farm Transfer Survey and published as a CARD working paper in 2022, then as a journal article in 2023.

In Canada, survey work tied to recent Census of Agriculture data suggests that only a small minority of farmers—roughly one in eight in a 2019 Farm Financial Survey analysis—have a completed written succession plan, with about 13% saying they have one in progress. That leaves many producers over 55 running full‑time herds with no formal, written plan for what happens next. Around the kitchen table, that usually gets boiled down to one line: “The kids don’t want it.”

The Iowa work tells a different story. When the researchers dug into the data, they found sons get picked far more often than daughters, even when both have farm experience. This isn’t just about willingness. It’s about who you treat as a serious option.

The Iowa Numbers Sitting at Your Kitchen Table

The Iowa team—Qianyi Liu, Wendong Zhang, Alejandro Plastina, and colleagues—worked with 589 responses to the 2019 Iowa Farm Transfer Survey. Among farms that had already identified a successor:

- 57% chose a son.

- 8% chose a daughter.

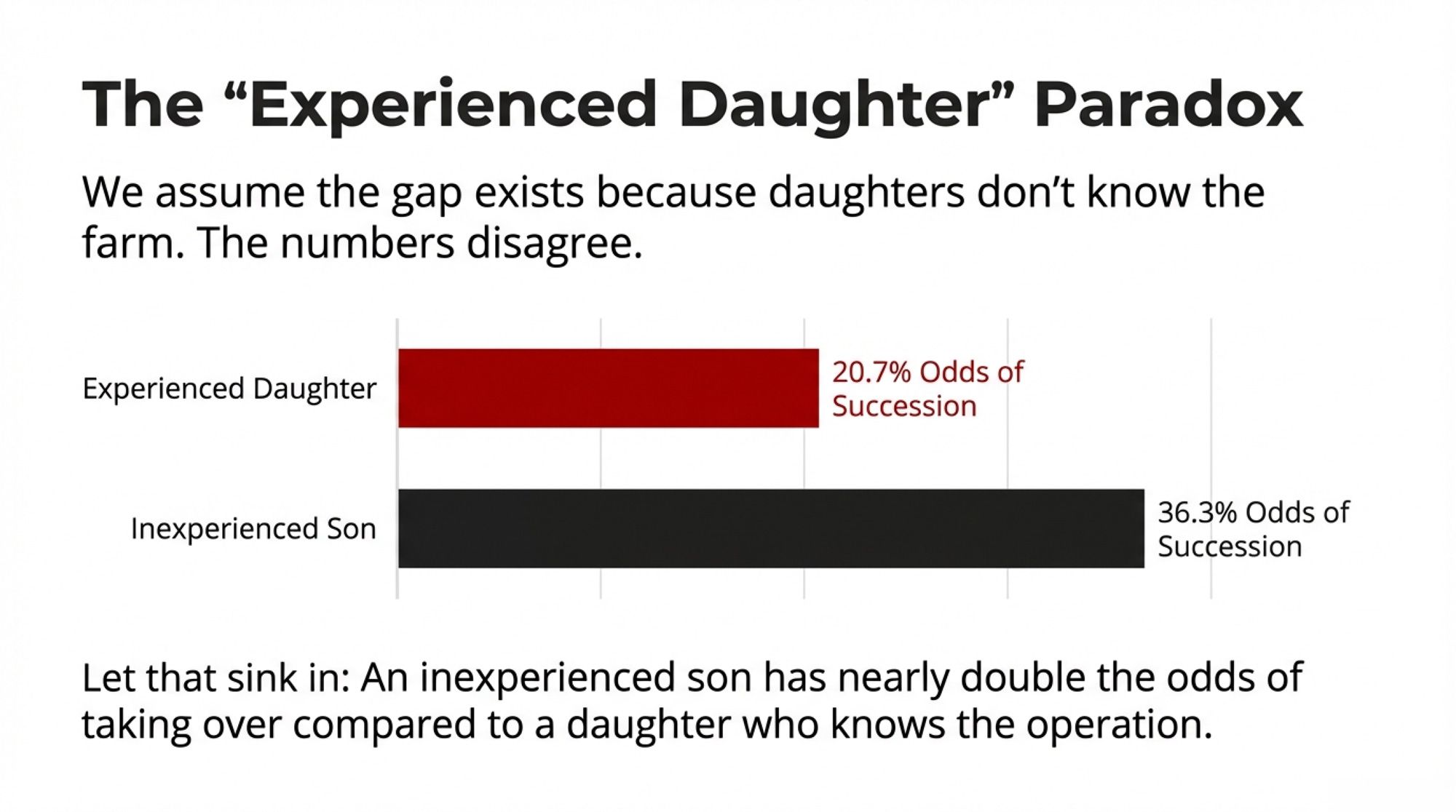

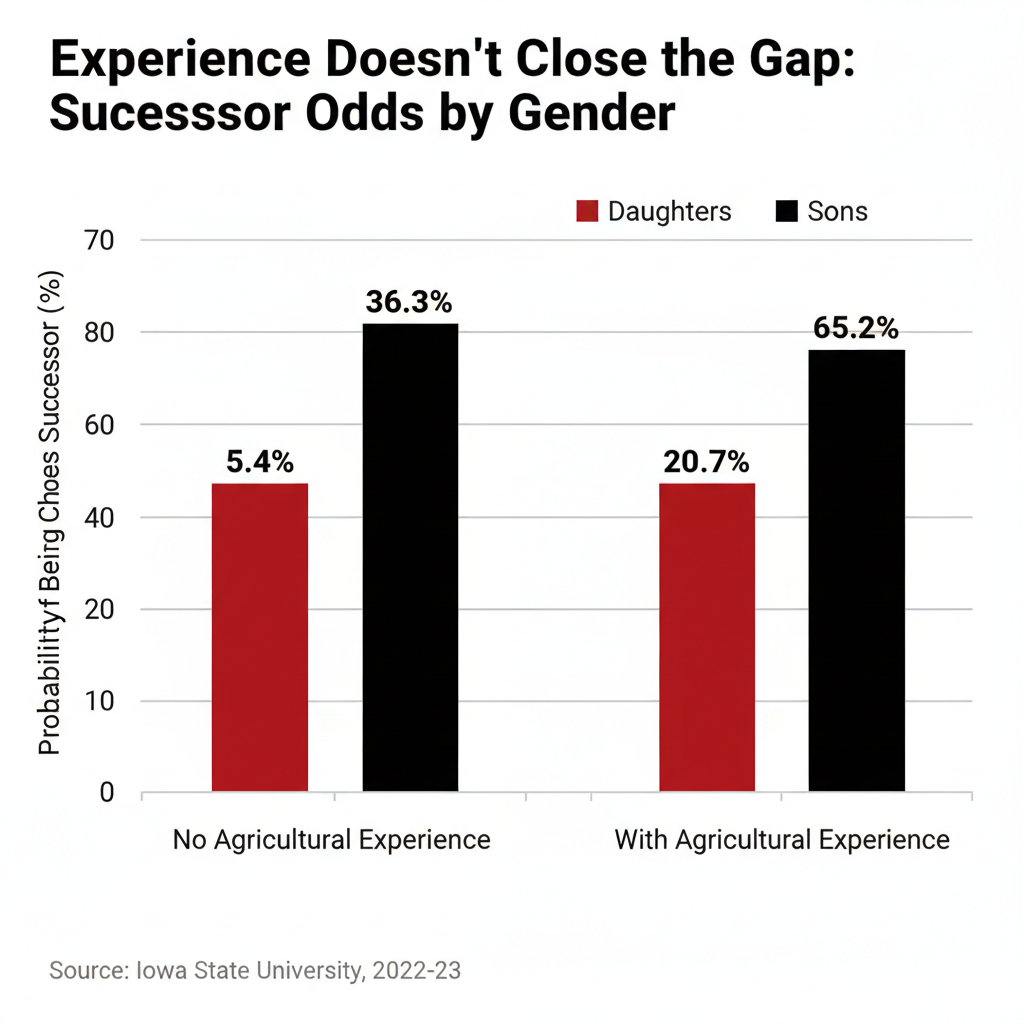

In their models, the gap gets even clearer:

- Daughters without agricultural experience had about a 5.4% chance of being chosen.

- Daughters with agricultural experience jumped to 20.7%.

- Sons without agricultural experience had 36.3% odds.

- Sons with agricultural experience went to 65.2%.

Same parents. Same cows. Same parlor. Almost triple the odds for an inexperienced son compared to an experienced daughter.

The authors don’t dance around why. They point to “cultural norms of gender roles” and differences in farming‑related investments and education for sons versus daughters as major drivers of the gap. Strip the academic language away, and you get this: it’s easy to say “no one wants it.” It’s harder to admit “we trained one kid like an owner and one like a helper.”

From Osseo to ABC Supply: What Dairy Let Walk Away

Diane Hendricks grew up on her parents’ dairy farm near Osseo, Wisconsin—population around 1,800—as one of nine daughters. She’s said many times that the farm gave her the work ethic, cost control, and ownership mindset she later used to build ABC Supply.

Today, ABC Supply is one of the largest roofing and siding distributors in North America. In 2021, the company reported $20.4 billion in revenue and operated more than 900 branches across the United States. Forbes, CNBC, and Guinness now list Hendricks as the richest self‑made woman in America, with a net worth north of $20 billion and 100% ownership of ABC Supply.

Here’s the part that stings if you’ve ever told a daughter to “leave the heavy stuff to your brother.” Hendricks has said her father never allowed her to milk cows or drive tractors. As a ten‑year‑old, watching her parents grind through the work, she made herself a promise:

“I don’t want to be a farmer, and I don’t want to marry a farmer.”

She loved the life. She was never developed to run the business. Dairy taught her the discipline and the numbers, then watched the ROI walk straight out of the lane and into roofing.

How Exclusion Actually Happens on Real Farms

Nobody sits at the table and says, “You’re out because you’re a daughter.” That’s not how it works.

It happens in a thousand small choices over twenty‑plus years:

- Who learns to back the stock trailer at 14.

- Who gets pulled into banker, nutrition, and vet calls.

- Who hears “What are your plans for the farm?” versus “You can do anything.”

Australian farmer Katrina Sasse spent her 2017 Nuffield Scholarship looking at daughters and succession across several countries. Her conclusion was blunt: daughters “aren’t afforded equal opportunity of succession” and are “rarely thought of as future leaders in farming.” The ones who did take over weren’t unicorns. They’d been in the core of the operation early—milking, feeding, driving, troubleshooting—right alongside their brothers.

Hendricks’ story fits that pattern. She talks warmly about growing up with cows, chickens, dogs, and cats. She loved the farm. She just wasn’t allowed to milk or run equipment. She was raised as labour, not leadership.

It doesn’t only cost daughters. It can box sons in, too. When daughters are quietly taken off the board, sons don’t always feel chosen. They feel drafted. That’s a heavy way to step into a multi‑million‑dollar asset with your name on every note.

Most of this isn’t deliberate. It’s what you absorbed from your own parents and neighbours—and then passed on unless you consciously decide to do it differently.

Four Forces Working Against Qualified Daughters

The Iowa work and related research point to four big forces that keep daughters off the “successor” list even when they’re more than capable.

1. The “Better Farm, Better Son” Effect

In the Iowa sample, stronger farms were more likely to go to sons than daughters. When there’s more equity, more land, and better cows, a lot of parents treat sons as the “safe” choice. It’s not really about capability. It’s about perceived risk.

2. The Surname Concern

In outreach around the Iowa research and in succession advising, you hear some parents say they don’t want to be the ones who “gave the farm away from our name.” On paper, that has nothing to do with whether your daughter can manage robots, genetics, staff, and cash flow. In practice, it’s one more quiet mark in the “no” column when she’s 16, and your son is 14. Modern transition plans can include holding companies or LLCs that keep the farm name intact, regardless of the successor’s legal surname.

3. The Sibling Competition Asymmetry

The sibling mix matters.

- In families with only sons, the vast majority chose a son as successor—close to nine out of ten in one Iowa extension summary.

- In families with both sons and daughters, daughters’ odds drop sharply while sons’ odds stay high.

Sons compete against the fact that they’re sons. Daughters compete against brothers. That’s not a level starting line.

4. The Validation Gap

Family business research keeps finding the same thing: when fathers explicitly tell daughters, “you could run this place if you wanted to,” and then hand them real responsibility, a lot of bias disappears. Sons usually don’t need that sentence because the assumption is already baked in. Daughters read the silence loud and clear.

Breaking the Pattern: Where You Actually Start

You’re not going to fix Iowa’s 57/8 split on your own. You can absolutely change what happens in your own kitchen and in your own parlor.

Early Operational Inclusion

In almost every successful daughter‑succession story, she wasn’t “helping.” She was responsible.

| Task Area | Helper Track (Warning Zone) | Owner Track (Successor Zone) |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment | Washes the mixer; told to “leave the tractor to your brother” | Runs skid steer, mixer, robot; troubleshoots breakdowns solo |

| Breeding Decisions | Files genomic reports; enters matings into software | Chooses sires, defends choices to AI rep, owns herd genetic direction |

| Financial Meetings | Not invited; “we’ll fill you in later” | In the room with lender, accountant, nutritionist—treated as a voice |

| Big Purchases | Told the decision after it’s made | Gets 2 quotes, runs ROI, recommends which one and why |

| Responsibility | “Help your brother with…” | Owns calves, transition cows, repro, or parlor performance—held accountable |

| Future Conversations | “You can do anything you want” (translation: leave) | “If you wanted to run this place, what would that look like?” |

On your farm, that might look like:

- Teaching your daughter to run the skid steer, mixer, or robot before she’s out of high school.

- Having her in the room with your lender, nutritionist, and vet, and treating her as a voice, not a spectator.

- Giving her clear responsibility for calves, transition cows, repro, or parlor/robot performance—and holding her accountable for results.

Here’s one that gets overlooked: mating decisions. A lot of daughters end up with the paperwork—registrations, DHI printouts, genomic reports—but not the genetic direction of the herd. That’s a missed opportunity.

Understanding pedigrees, reading genomic proofs, and knowing how to balance Net Merit (NM$) against your herd’s weak spots is exactly the kind of high‑value, strategic work that builds a successor. The 2025 revision of NM$ from USDA‑ARS and CDCB updated economic weights across traits to keep Net Merit focused on lifetime profit, with more emphasis on component‑based pricing, feed efficiency, and fertility while still rewarding cow livability and health. If your daughter can explain why you’re using a particular sire on a particular cow—and defend that choice against your AI rep’s suggestion—she’s doing owner‑level thinking, not helper‑level filing.

Danish farmer Connie Linde is one example from outside North America. When it wasn’t clear she’d have a stake in the home place, she bought her own dairy in her mid‑twenties and later went on to manage a larger, investor‑owned Holstein operation—earning recognition as Denmark’s Young Farmer of the Year along the way. She didn’t get there by endlessly “helping.” She got there by being in charge.

Task‑Based Development Instead of Vague Promises

“Someday this could all be yours” is not a development plan.

If you want real successors—sons or daughters—you’ve got to hand them decisions, not just chores. For example:

- “We’ve got two ventilation quotes with different prices and energy savings. Dig into both and tell me which you’d choose and why.”

- “We’re looking at beef‑on‑dairy contracts. Work out what that does to replacement heifers, cash flow, and risk, and bring me your recommendation.”

If they’re going to steer a multi‑million‑dollar business someday, they need reps making decisions that move a few hundred or a few thousand dollars now. That’s true whether you’re picking sires, signing a milk contract, or deciding how far you lean into robotic milking ROI.

Explicit Succession Conversations with Every Child

If your succession plan is based on assumptions you’ve never checked, you’re flying blind.

Good advisors keep coming back to the same point: talk to each child individually with open‑ended questions. “If the farm being part of your life was genuinely an option, what would you want that to look like?” opens a better door than “Do you want to farm?”

You don’t sell. You don’t defend your past. You listen. If what you hear doesn’t match your current plan, that’s your signal to bring in your accountant, lawyer, or a neutral succession advisor over the next few months while everyone is still talking. If those conversations show real conflict between siblings or between you and your successor, that’s not failure. That’s your early‑warning system.

A simple rule of thumb: if, after those one‑on‑ones, you and your kids are clearly not on the same page about who’s in, who’s out, and on what terms, that’s when you bring in outside help instead of letting it stew.

What This Means for Your Operation

Here’s where all the numbers land back in your lane.

If you’ve got daughters already involved on the farm—even part‑time—you can change their odds by changing the kind of work they do. Moving them from “helping” to “owning” pieces of the operation shifts them from low‑probability successors to realistic options.

If your daughters are off‑farm in other careers, that doesn’t mean the door is closed. But if they’ve never been treated as real candidates, start by owning that. A simple, “We never really offered you a clear path here, and that’s on us,” leads to a very different conversation than, “Do you want to come back?”

If you’re five years or less from wanting out of the day‑to‑day, this isn’t just a fairness question. It’s risk management. A narrow successor pool means:

- Less competition if you need to sell.

- Less flexibility with lenders.

- More pressure on whichever child steps up—or on you, if nobody does.

You’re also trading off legacy decisions. Keeping the surname on the sign at all costs may feel safer today, but it can mean giving up future resilience if the most capable successor is the one who’d change their name on marriage or bring a different surname onto the mailbox.

If you’re already past succession—papers signed, son’s name on the notes—your leverage is in the next generation. Your grandkids are watching who you take seriously. They’re listening when you say, “She could run this place,” or when you never say it at all.

The Iowa numbers aren’t somebody else’s problem. They’re a mirror. You get to decide if your farm’s reflection stays the same or moves.

The Technology Window That’s Open Right Now

For decades, one unspoken reason for keeping daughters on the edge of the operation was the physical grind. Parlors are hard on shoulders and backs. Handling cows isn’t light. Long days on a tractor beat up anybody’s body.

Technology is changing that.

A 2016 Swedish study in Frontiers in Public Health compared dairy farmers’ musculoskeletal problems over 25 years and found farmers using robotic milking systems reported fewer shoulder and lower‑back issues than those in conventional parlors. Robots took over some of the most repetitive, strength‑based jobs.

| Task Category | 1990s Conventional Parlor(Physical Grind) | 2025 Robotic Dairy (Data & Decisions) |

|---|---|---|

| Milking Labor | 4–6 hrs/day in parlor; repetitive unit attachment, heavy lifting, shoulder/back strain | Robot handles milking; operator monitors data, responds to alerts, manages cow flow |

| Herd Health Monitoring | Visual checks; paper records; reactive to obvious illness | Real-time activity, rumination, milk conductivity data; proactive intervention based on algorithms |

| Breeding Management | Manual heat detection (paint, chalk, observation); paper mating records | Automated activity monitors flag heats; genomic-driven mating decisions via software |

| Physical Strength Needed | High—lifting milkers, moving gates, handling 1,400-lb animals in tight spaces | Low—robots do repetitive physical work; focus on troubleshooting sensors, reading reports, managing exceptions |

| Decision Load | Low—follow routine, react to problems | High—interpret data streams, optimize settings, manage cow traffic, balance rations, track KPIs |

| Barrier to Women? | Yes (culturally reinforced as “too hard”) | No (capability = data literacy + cow sense, not upper body strength) |

Dairy Farmers of Canada told the same story from a different angle in a 2024 International Women’s Day profile. Alicia, a Saskatchewan dairy farmer and equal partner in her operation, talked about taking the lead on the technology side—keeping robots running, managing data, and handling herd‑health records—while her husband focuses more on cropping and outside work. Her point was simple: robotics and digital tools have knocked out a lot of the “you’re not strong enough” arguments that used to keep women out of core decision‑making.

The Bullvine’s own coverage of automation shows why that matters. In our look at robotic systems, herds using robots routinely push more milk per full‑time worker than comparable parlor setups when management is dialled in—one clear example of technology turning physical grind into data‑driven management gains. That’s not about biceps. That’s about brains and attention.

If you’ve already invested in robotic milking or other automation, you can make that money work twice. The robot doesn’t care whether it’s a son or daughter reading reports and making calls. It just needs somebody who understands cows, data, and risk.

That’s exactly what you need in a successor.

The 2025–2044 Window: Why This Matters Now

This isn’t just a family‑feelings story. It’s a survival story for the next 20 years.

The 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture shows U.S. farms with milk sales dropped 39% between 2017 and 2022—from 40,336 to 24,470 farms. That’s almost 16,000 dairies gone in five years. Coverage of the 2022 Census has described it as one of the steepest dairy farm declines between Census periods in decades, and there’s nothing in the numbers that suggests consolidation suddenly stops.

At the same time, the Census counted about 1.2 million female producers—around 36% of all producers—a roughly 26% jump over the previous decade. About 33% of female producers and 28% of male producers are classified as “beginning” farmers who’ve been on the land for ten years or less.

Put all that together, and you get a simple picture: fewer dairies, bigger herds, and a producer base that’s getting more female, faster.

Farm Credit Canada has argued that closing revenue gaps for female operators would add billions of dollars to Canadian agriculture’s economic output. Global scenarios from the FAO and World Bank suggest that closing gender gaps in agriculture could unlock very large gains—up to hundreds of billions of dollars in economic output in some models.

On your farm, that shows up as your successor bench. Are you building it from all of your kids—or just from the ones tradition told you to look at?

Key Takeaways

- The 57%/8% split is real and recent. Among Iowa farms that have named a successor, sons are chosen seven times more often than daughters, based on 2019 data published in 2022–23.

- Experience helps daughters, but doesn’t erase the gap. In the Iowa models, agricultural experience lifts a daughter’s chance of being chosen from about 5.4% to 20.7%, but experienced sons still sit at 65.2%.

- You don’t create successors with chores; you create them with decisions. If a daughter never gets to make calls that swing a few hundred or a few thousand dollars, you’re not truly developing her to run the place.

- Robots and genomics have killed most of the “too physical” excuses. Robotic milking and automation reduce physical strain and shift the job toward managing data, people, cows, and breeding decisions—skills that daughters and sons can both own.

- Patterns compound across generations. The Iowa study shows that women who’ve run farms are roughly twice as likely to name daughters as successors (12.4% vs 5.9%). Change your pattern now, and you change your grandkids’ options later.

- Succession risk is business risk. A narrow, male‑only successor pool doesn’t just limit opportunity. It can cost you options with lenders, buyers, and family, especially when things change quickly.

Next Moves This Year

| Timeframe | Action Item | Who’s Involved | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| This Month | Hand your daughter one operational decision worth $500+ (protocol, purchase, contract). Commit to following her call. | You + daughter | Decision made, implemented, results tracked over 30 days |

| This Month | Audit each child’s ownership (not “help”) of specific farm areas. Write it down. | You (solo reflection) | Written list: name, responsibility area, decision authority |

| This Quarter | Bring all children (on-farm + off-farm) into one major financial discussion: robot quote, land rent, milk contract, lender review. | All kids + you (+ spouse if applicable) | Kids ask questions, offer input, see real numbers |

| This Quarter | If expectations misaligned after financial discussion, schedule meeting with accountant or lawyer to map real succession options. | You + advisor + successor candidates | Calendar appointment booked within 60 days |

| Before Year-End | One-on-one conversation with each child: “If the farm were truly an open option, what would you want?” | You + each child individually | You listen more than talk; assumptions challenged |

| Before Year-End | Based on those conversations, update written succession plan and individual development roadmaps for each potential successor. | You + accountant/lawyer | Written plan exists (or is started); kids know you have a plan |

This month

- Hand your daughter one operational decision with at least a few hundred dollars at stake—a protocol choice, a purchase, or a contract—and commit to following her call.

- Take a notepad and write down each child’s name with the specific parts of the operation they truly own today. Not what they “help with.” What they’re responsible for, including any say in breeding and bull selection.

This quarter

- Bring all children—on‑farm and off‑farm—into one major financial discussion: a robot quote, a parlor upgrade, a land rent or milk contract negotiation, or a lender review.

- If those conversations expose big gaps in expectations, schedule time with your accountant or lawyer to map out real options while everyone’s still talking.

Before year‑end

- Have a one‑on‑one conversation with each child about what they’d want if the farm were truly an open option—not a foregone conclusion.

- Based on what you hear, update your written succession plan and your “development list” for each potential successor. If you don’t have a written plan yet, that’s the homework.

The Bottom Line

Diane Hendricks didn’t leave dairy because she couldn’t hack the work. She left because, as a ten‑year‑old girl on a Wisconsin dairy, every signal from the barn said, “This life is not for you.”

She took the work ethic, cost control, and ownership mindset she learned there and used them to build ABC Supply—a company with $20.4 billion in 2021 revenue and more than 900 branches across the U.S.

The question isn’t whether your daughter could run a dairy. Women prove that every day in other industries—and on plenty of farms that opened the door.

The question is what your farm is telling her now, in who you teach, who you trust, and who you call when something really matters. What did she learn from you yesterday? And what do you want her to believe is possible tomorrow?

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Continue the Story

- The Red & White Revolution: Molly Westwood’s Journey Building Panda Holsteins – Walks a similar path of grit, proving that when the home gate is closed, a daughter’s vision can still build a global empire. Molly’s journey from “helper” to visionary breeder echoes the self-made fire of Diane Hendricks.

- Women Shattering Dairy’s Glass Ceiling: Leadership, Innovation, and the Fight for Equality in 2025 – Shaped by the same forces that once sidelined daughters, this piece deepens our understanding of the leadership revolution. It uses fresh data to unmask the hidden history and untapped economic potential of women in our industry.

- Where the Robots Hum and the Cows Stay Calm: The Four Oak Farms Way – Carries forward the story into a future where technology and partnership finally dismantle tradition. Paige and Marcus prove the point that when “lanes” are built on strengths, the farm finds a sustainable rhythm.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!