One farm ET that barely penciled out. Four decades later, the bull from that flush shapes 60% of Select’s lineup — and your herd’s inbreeding curve.

One pregnancy.

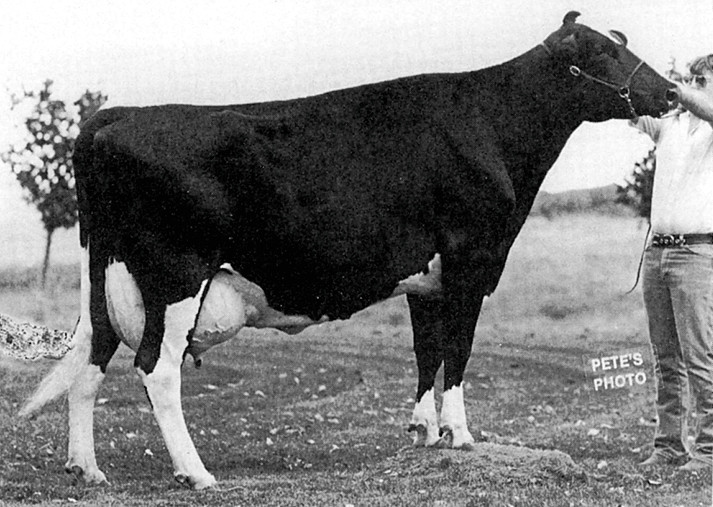

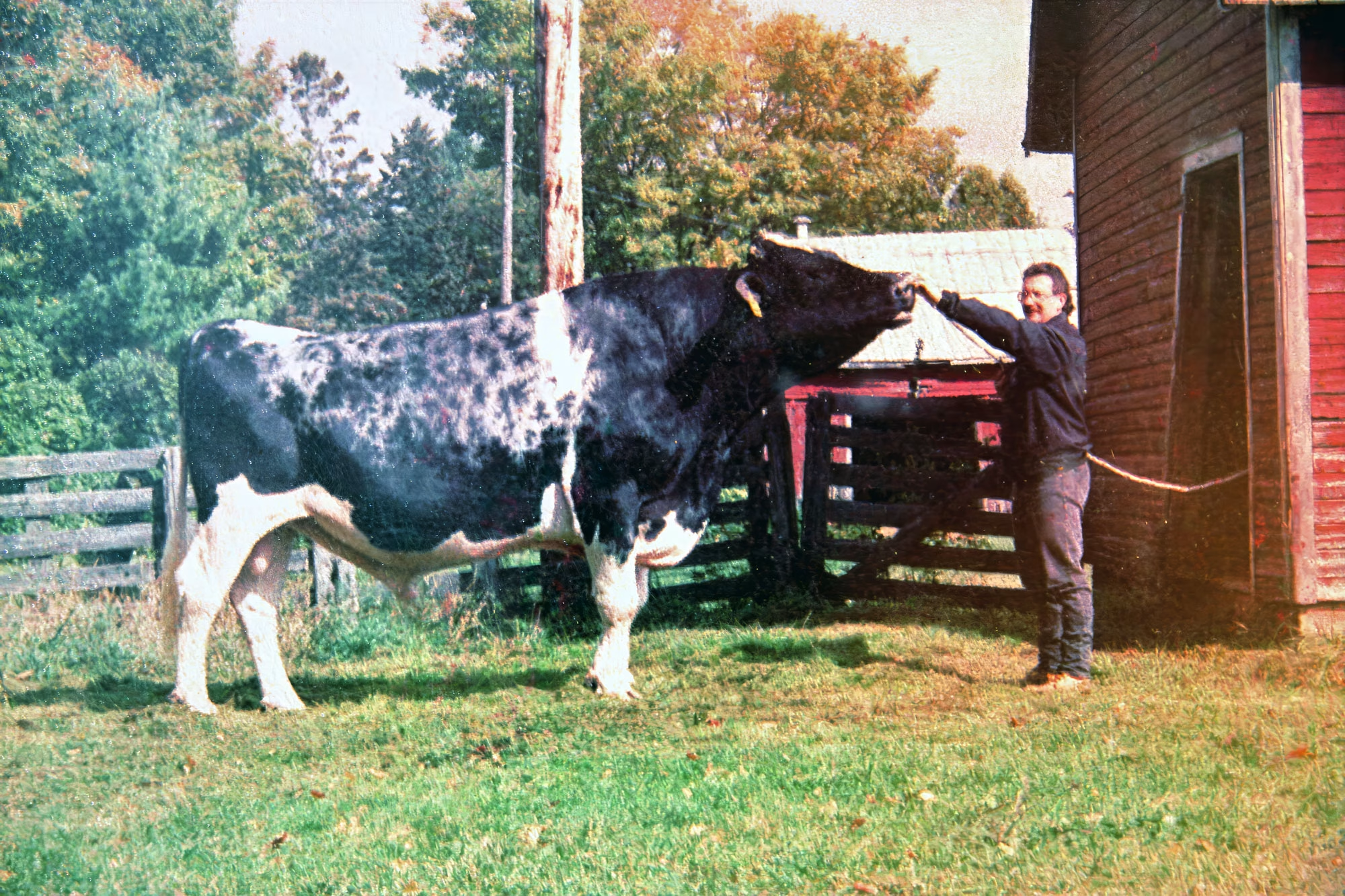

That’s what Randy Tompkins got from his first embryo transfer attempt in 1981. He flushed To-Mar Wayne Hay — a solid, unglamorous second-lactation cow producing 25,110 pounds, sired by Cal-Clark Board Chairman — and the vet packed up with a single viable embryo for the whole effort. Anyone who’s sweated through an ET flush knows what that arithmetic feels like: you’re standing in the barn doing the math before the vet’s boots are off, stacking the cost against what a bull calf might bring, wondering if you just torched money you didn’t have to spare.

For a working dairy in Marengo, Iowa — registered cattle alongside commercials, always watching corn prices, every decision measured against the milk check — that kind of return was a gut-punch.

That single embryo became a coal-black bull calf born May 17, 1983, and nothing about him said history. The Tompkins family named him To-Mar Blackstar, went back to milking, and didn’t think much more about it.

For about nine years.

The Cow Nobody Wrote Up

What keeps pulling me back to the Blackstar story is where it started. Not with a legendary dam, not with a calculated million-dollar mating — it started with a cow named Hanna.

Royal-Cedar Oak Hanna was Wayne Hay’s dam, and she was the kind of cow that experienced dairymen notice, but nobody puts on a cover. Tight udder. Sturdy frame. Deep through the heart girth in a way that told you she’d been converting feed into milk for years without drama, without a vet call, without anyone having to worry about her. She wasn’t winning banners. She was paying bills — quietly, reliably, lactation after lactation.

You know this cow. You’ve probably got three of her in your barn right now, and if you’re honest, she’s the one keeping your operation solvent while the flashy ones eat up your time and your treatment budget.

Wayne Hay inherited that durability. The Tompkins operation wasn’t Hanover Hill — this wasn’t a high-profile genetics program with deep pockets and a marketing department. This was an Iowa dairy where every decision had to pencil out, or it didn’t happen, and when Randy decided to try ET for the first time, flushing Wayne Hay to Board Chairman and coming away with exactly one pregnancy… that was real money on a real gamble that hadn’t paid off yet.

Why Did the Holstein Breed Need Blackstar in 1985?

To understand why this particular bull landed like a bomb, you need to remember what the Holstein breeding world looked like in the mid-1980s — because the show ring and the milk parlor had drifted dangerously far apart.

Bell daughters were flooding barns with milk nobody had seen before — +1,704 pounds predicted difference, over 30% of the cows on the Holstein Locator List by mid-decade — but they were falling apart structurally by second lactation. Small frames, weak substance, udders that couldn’t sustain the metabolic load they were built to carry. The Bullvine’s own analysis calls Bell “the worst best bull in Holstein history,” and that’s not hyperbole: producers who’d built their programs around Bell production were watching replacement rates climb, and herd life drop, and the smarter ones were getting nervous.

Meanwhile, up in Canada, Starbuck was emerging as the type answer — 70% of his daughters scored Good Plus or better, 200,000 daughters by the mid-’80s, and he’d collect 27 Premier Sire titles between ’86 and ’95. Beautiful cattle, showring dominance. But the production gap was real, and Starbuck was a type bull in an era when the milk check still decided who survived. (Read more: Hanoverhill Starbuck’s DNA Dynasty: The Holstein Legend Bridging 20th-Century Breeding to Genomic Futures)

The breeders paying attention — and by the late ’80s, that was a growing number — knew the breed needed something else entirely. A bull that could improve conformation without sacrificing components; type married to production in the same proof sheet. Everyone wanted it, and nobody could find it.

The bull that delivered it was sitting in a barn in central Iowa, bred by a family that wasn’t trying to solve the industry’s identity crisis. They were trying to make a good cow a little better.

The Mystery of 7H1897

Blackstar’s first proof dropped in January 1989, and the numbers were unlike anything the industry had seen from one animal: +58 pounds fat, +63 pounds protein, and a +3.16 PTAT.

A PTAT above 3.0 from a bull who was also positive on components — in 1989, that combination was unicorn territory. You picked type bulls, or you picked production bulls, and that was the deal everyone had accepted. Getting both at this level from a first-time ET calf out of a cow nobody outside Iowa County had heard of wasn’t supposed to happen.

But the moment that really captures how Blackstar emerged isn’t about the proof sheet. It’s about Ron Long.

Long was at Select Sires, working through classification data from herds across the country — the way you tracked genetic quality before genomics made everything instant. He kept flagging one sire code, herd after herd, state after state, because daughters of this particular bull were classifying well above expectations, and the pattern was unmistakable. But the bull wasn’t on anybody’s radar.

“I do not know which bull is 7H1897,” Long told his colleagues, “but his daughters are actually classifying extremely well.”

7H1897 was Blackstar. Before the industry knew his name, before a single marketing dollar was spent, before anyone at Select Sires had built a campaign around him, his daughters were already proving him on concrete — in real barns, on real DHIA sheets, from the Midwest to the Southeast. The data was finding him, not the other way around.

How Blackstar Topped the TPI List in 1992

Then the phone started ringing.

Blackstar had just topped the TPI list at 1,256 points — at that point was the highest total performance index any Holstein sire had ever achieved — and in a pre-internet world where you secured semen by picking up the telephone and hoping the AI stud had inventory, that number set off something close to a stampede. At Select Sires, the switchboard was overwhelmed: international calls stacking up, wire transfers from Germany, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, breeders on three continents competing for straws selling at hundreds of dollars each in 1992 money, when proven semen from a solid bull ran a fraction of that.

Jeff Ziegler, Select’s breeding manager, would later put the constraint in perspective: “From Blackstar, no more than 500,000 doses were sold, since our semen collection methods back then were very different.”

Half a million doses from one bull in an era when collection technology produced far fewer straws per session than modern methods allow. No bull before him had generated that kind of sustained, global demand.

The morning that the first proof sheet must have arrived at the Marengo farm — a Select Sires envelope, a page of numbers that looked like any other mailing — it’s hard to imagine Randy Tompkins understood he was holding the breeding industry’s next decade in his hands. By all accounts, he wasn’t a man who sought the spotlight. He’d bred one bull, and the bull was doing the rest. But by the summer of ’92, with international calls coming in before dawn and wire transfers landing from three continents, the distance between that single-embryo gamble in 1981 and what it had become must have felt impossible to bridge.

What His Daughters Proved on Concrete

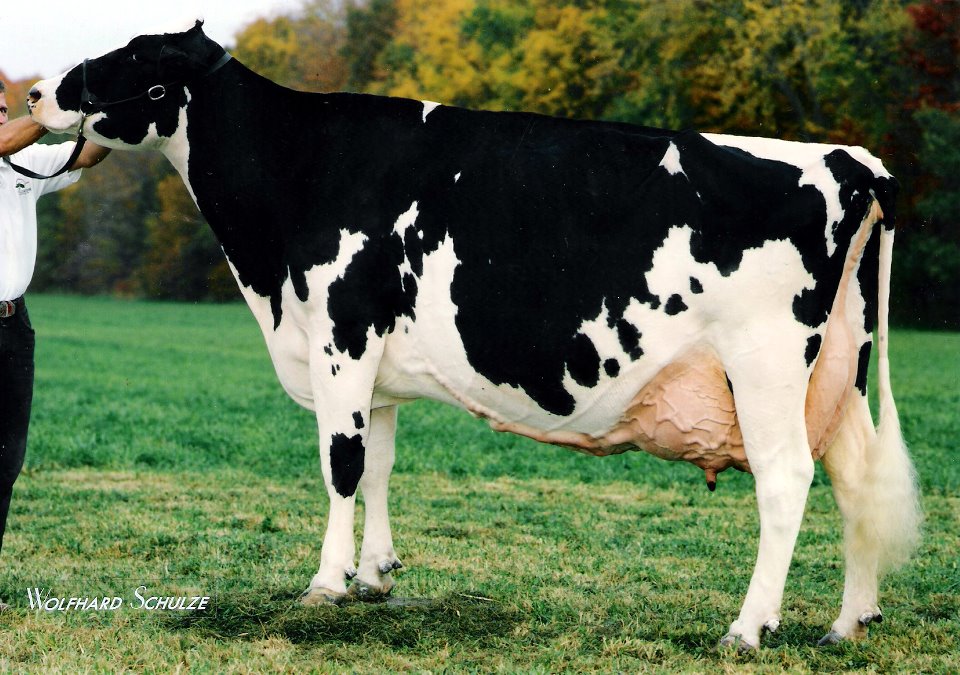

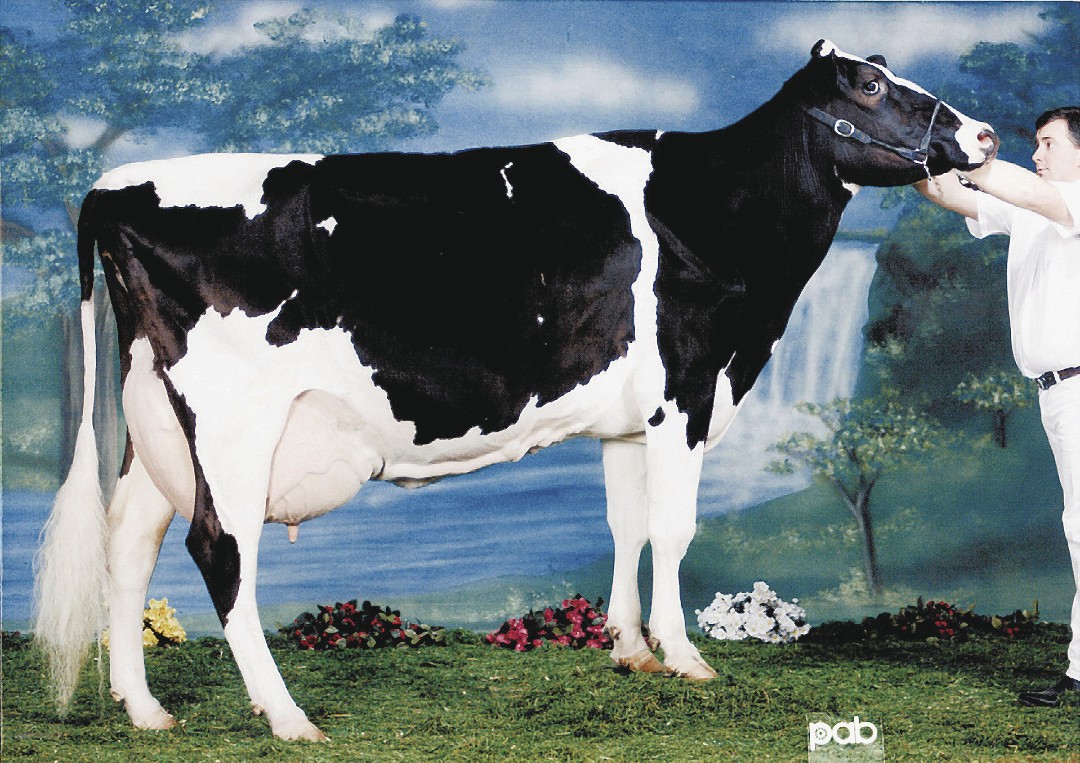

You could spot a Blackstar daughter from across the free-stall alley, and not because she was flashy — it was the opposite. She looked right. Depth through the heart that meant genuine capacity, not the narrow, weedy frame, the show ring had been rewarding for a decade. Spring of rib that told you she could handle a heavy TMR load without burning through body condition in sixty days. And the udders — tight fore attachment, strong medial, teat placement that meant your milking crew wasn’t fighting her twice a day, and this was back when udder quality actually differentiated sires, before everyone’s proof sheet started looking the same.

The real proof, though, was in the bulk tank.

LA-Foster Blackstar Lucy 607, down in North Carolina, became world production champion in 1998: 75,275 pounds of milk with 1,738 pounds of fat and 2,164 pounds of protein in a single 365-day lactation. The Foster family described her the way any dairyman would understand: “She’s either at the feed bunk or at the water trough. She eats and eats and produces that milk!” Over 200 pounds a day, sustained for an entire year, without breaking down — and when corn’s at seven dollars, and your margins are measured in pennies per hundredweight, that kind of metabolic engine separates the operations making the payment from the ones having a difficult conversation with their lender.

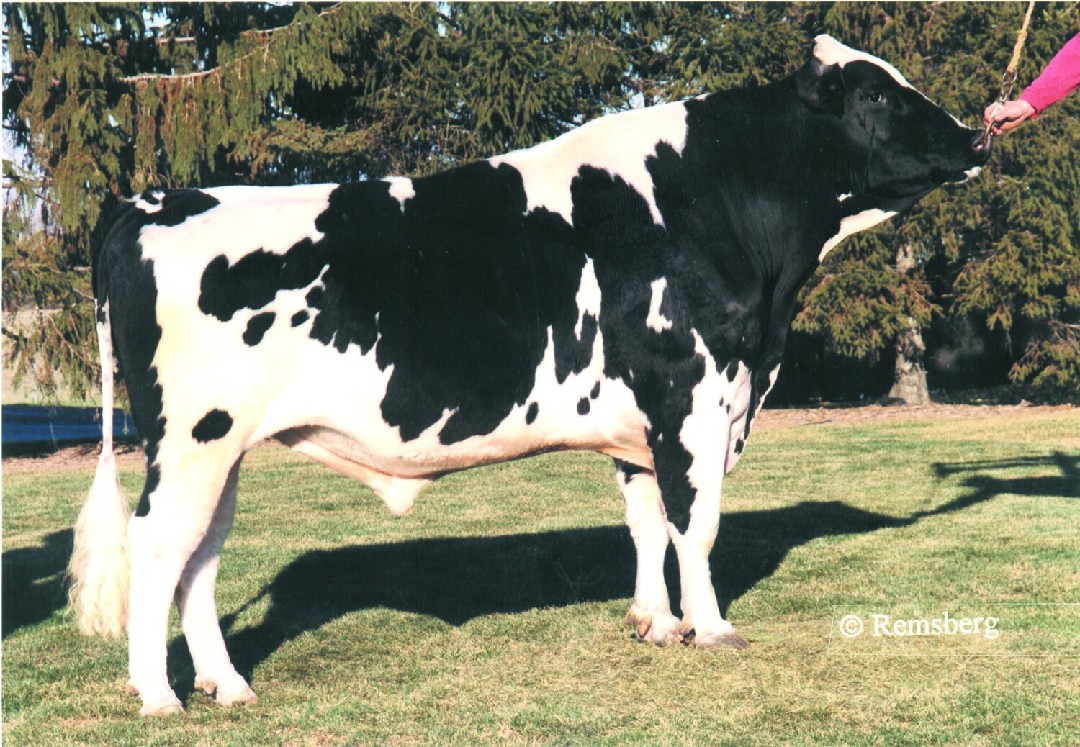

Then there was Stookey Elm Park Blackrose — classified EX-96-USA 3E GMD DOM, one of the highest classification scores ever assigned to a Holstein female. Bred by Jack Stookey and purchased by Mark Rueth and the Schaufs from Indianhead Holsteins as a hiefer, they developed her into something genuinely rare: All-American Junior Two-Year-Old in 1992, All-American Junior Three-Year-Old in 1993, and then Grand Champion at the 1995 Royal Winter Fair, joining that exclusive club of American-bred cows to win Canada’s most prestigious show. At 5 years old, she posted 42,229 pounds of milk, with 1,940 pounds of fat and 1,433 pounds of protein, and her lifetime production reached 149,881 pounds over 1,609 days in milk. She wasn’t just a producer and a show cow — she became a foundation brood cow whose AI sons carried the Blackstar blueprint into herds across the continent, and whose descendants were still winning banners as recently as the 2016 Hokkaido Winter Fair in Japan. (Read more: When Financial Disaster Breeds Genetic Gold: The Blackrose Story That Changed Everything)

Lucy and Blackrose weren’t outliers — and that’s what mattered most to producers milking Blackstar daughters day after day. As a group, his daughters consistently showed above-average productivity and lower somatic cell counts, peaking in their fourth and fifth lactations rather than flaming out as two-year-olds. The kind of cow your milking crew mentions at year’s end because she never once showed up on the treatment list, the kind that lets you amortize rearing costs over six or seven years instead of two.

That profile — the one every sustainability conversation in this industry eventually circles back to — came from a cow named Hanna.

2,500 Sons and the Mistake Nobody Stopped

The AI industry sampled nearly 2,500 of Blackstar’s sons globally, representing roughly half the world’s total sampling capacity in any given year, poured into the offspring of a single sire. The results were spectacular, and the consequences were severe, but nobody hit the brakes.

MJR Blackstar Emory was the crown jewel — 50% of his sons achieved proven sire status, against an industry norm of about 10%. Among them, Fustead Emory Blitz became a super-millionaire at over 1.52 million doses sold, a record at Select Sires that still stands. Blitz sired Velvet-View KJ Socrates, and Socrates gave us Roylane Socra Robust — who died young, before anyone fully grasped what they had — and from Robust came Seagull-Bay Supersire, a massive milk transmitter whose son JoSuper carried that Blackstar blueprint into yet another generation of elite matings. If that lineage sounds familiar, it should — Walkway Chief Mark, the backup bull behind 7% of every Holstein cow alive today, sits in these same pedigree networks.

Through Etazon Lord Lily, a millionaire son in his own right, Blackstar genetics reached Vision-Gen Ozzie and eventually influenced Ransom-Rail Facebook Paris. Up in Quebec, the Comestar program took Blackstar’s impact in a different direction entirely: three daughters out of Comestar Laurie Sheik produced six AI sons, including Comestar Lee, Outside, and Lheros — all millionaire sires distributed worldwide through Semex. One cow family, one mating sire, and a genetic footprint that reshaped Canadian breeding for a decade.

And then there’s the line that ties the whole modern breed together. Through Dixie-Lee Bstar Betsie — dam of Carol Prelude Mtoto, the Italian specialist whose improbable origin story we profiled last year — and then through Mtoto’s son Picston Shottle, Blackstar’s fingerprint reaches into virtually every elite Holstein pedigree walking the planet today. If you’ve used Shottle genetics in the last fifteen years, and you have, you’ve been using Blackstar genetics whether you knew it or not.

This global saturation wasn’t just a numbers game; it was a masterclass in pedigree dominance that reached into every major breeding powerhouse. While the Comestar family was cementing the line in Canada, the influence was echoing through the Netherlands and Italy via the Dutch-born Blackstar Betsy. A daughter of the foundation cow Prices Chiefs Bess, Betsy’s ET journey across the Atlantic eventually produced Carol Prelude Mtoto, the sire of Picston Shottle—widely considered one of the top ten most influential bulls in history. Meanwhile, the lineage was branching through “super-millionaire” Fustead Emory Blitz to Roylane Socra Robust, and eventually to Siemers Lambda, ensuring that whether a breeder was looking for high-type show winners or high-profit commercial producers, they were inevitably tapping back into the same Marengo, Iowa, source.

Jeff Ziegler estimates that more than 60% of Select Sires’ current bull lineup carries Blackstar in its pedigree.

Sixty percent. From one ET pregnancy on a farm cow in Iowa.

Now, somewhere in the late ’90s, a breeder whose promising young sire got buried under the Blackstar avalanche — sampled too late, overlooked because the sure thing was already proven and available — must have said exactly what plenty of us are thinking now. But nobody was listening. When you look at the four bulls who reshaped the entire breed, Blackstar’s concentration story fits a pattern the industry has repeated — and may be repeating.

15.8% of Every Holstein Alive

USDA Animal Genomics and Improvement Laboratory data, estimated with a 1960 base year, puts the cost of that concentration in numbers nobody can argue with: Blackstar has a 15.8% relationship to the current your herd, higher than Elevation at 15.2%, higher than Chief at 14.8%, higher than any individual sire in the breed’s documented history. A 1999 Journal of Dairy Science study by P.M. VanRaden found that Blackstar’s expected inbreeding of future progeny — the metric that captures how deeply a single animal is embedded in the breed — was 7.9%, the highest of any Holstein sire evaluated.

And the breed’s effective population size — the measure geneticists use for how much diversity actually exists, regardless of raw numbers? Multiple peer-reviewed studies using both pedigree and genomic methods have estimated it at somewhere between 40 and 70 animals for major Holstein populations, with a consistent downward trend accelerating since genomic selection began. For context, conservation biologists flag vertebrate species with an effective population size below 50 as at risk of inbreeding depression under IUCN guidelines. We’re talking about the most numerous dairy breed on earth, and its genetic base has collapsed to the equivalent of a small village.

We did this to ourselves.

AI companies would never again sample as many sons from one bull as they did from Blackstar — not because his genetics fell short, but because the wholesale use of his offspring meant other potentially great bulls never got their chance. Good genetics pushed to the margins, diversity sacrificed because the sure thing was right there, proven, in demand, and profitable to sell.

The rate of inbreeding per generation has increased since genomic selection was introduced — a 2022 Frontiers in Veterinary Science study of Italian Holsteins found an annual inbreeding rate at +0.27% by pedigree and +0.44% by genomic measures, corresponding to roughly +1.4% to +2.2% per generation. Better tools, faster concentration, different instrument, same mistake. We learned the lesson with Bell in the ’80s: the risk of concentration, lethal recessives, structural compromise. Then we learned it again with Blackstar in the ’90s. And the genomic era is running the same experiment a third time, at higher speed, with more data and less excuse for not knowing better.

The Lesson from Marengo

Blackstar was classified EX-93-GM — as good a specimen as he was a genetic force. During his long career at Select Sires, his semen was nearly continuously sold out, the demand outlasting trend after trend as the industry moved through the ’90s and into the 2000s.

The traits he stamped on the breed — components, functional type, udder quality, productive life — remain at the center of every modern selection index. Automated milking systems reward the kind of teat placement and udder depth his daughters were known for; feed efficiency research validates the metabolic capacity his genetics delivered. When processors push harder on environmental metrics, and they will, the ability to produce more from less across more lactations is exactly what survival looks like. Every time you walk through a robotic barn and see a cow whose udder sits perfectly for the machine, whose body condition holds through peak, whose SCC stays low without intervention — you’re looking at traits Blackstar helped build into the breed.

But the lesson of To-Mar Blackstar isn’t just “breed for function over fashion.” That part’s been obvious for thirty years. The deeper lesson — the one this industry learned through him and appears determined to learn a third time through genomics — is about what happens when you find something extraordinary and use it on everything.

Randy Tompkins flushed one cow and got one calf. He was trying to make a good bull from a good cow on a working dairy where every decision had to pencil out. The industry took that bull and built a genetic monopoly — 2,500 sons sampled, half a million doses sold, pedigrees saturated across six continents — and four decades later, the narrowed genetic base he helped create is one of the breed’s most pressing long-term vulnerabilities.

One pregnancy. One bull. A breed forever changed and permanently narrowed.

What Blackstar’s Legacy Means for Your 2026 Matings

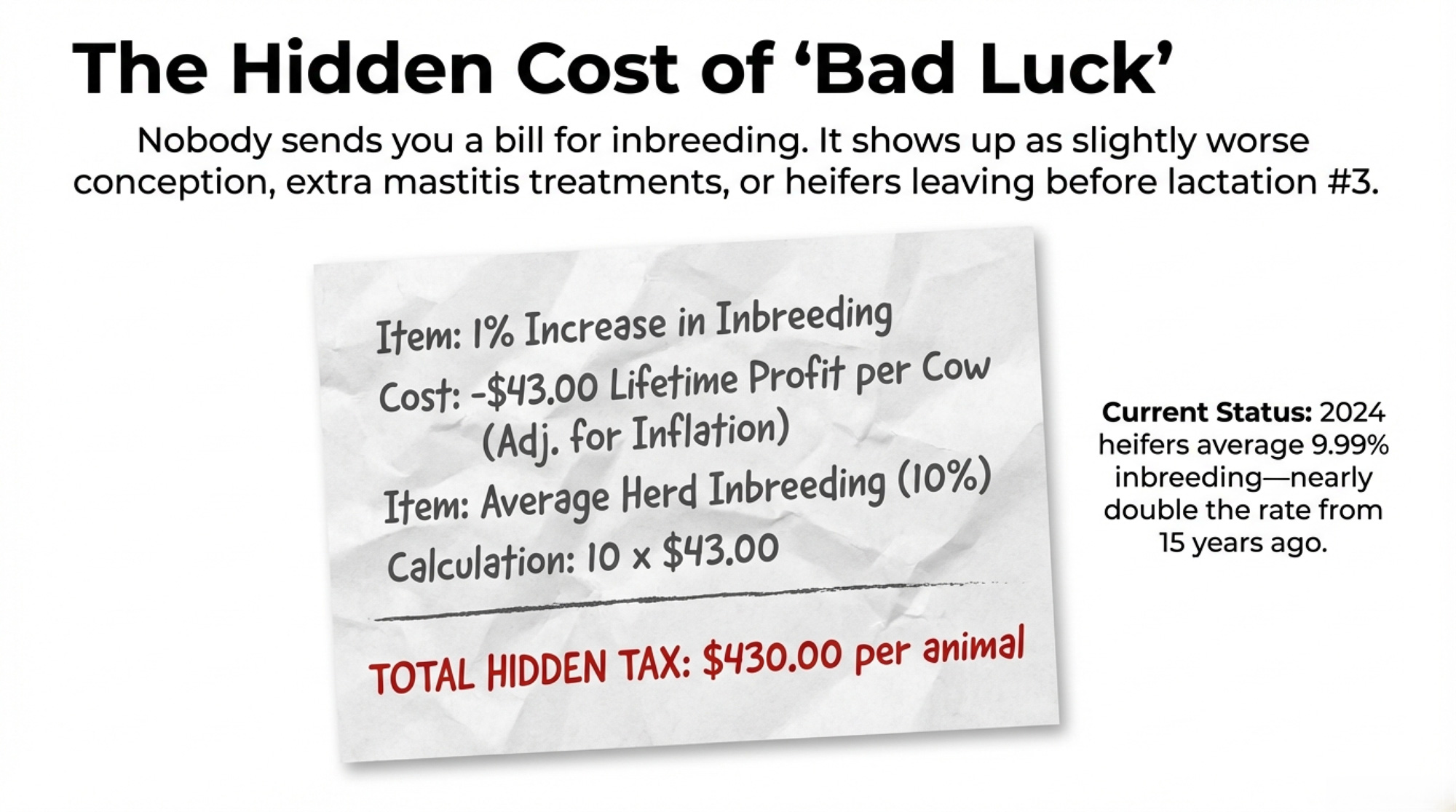

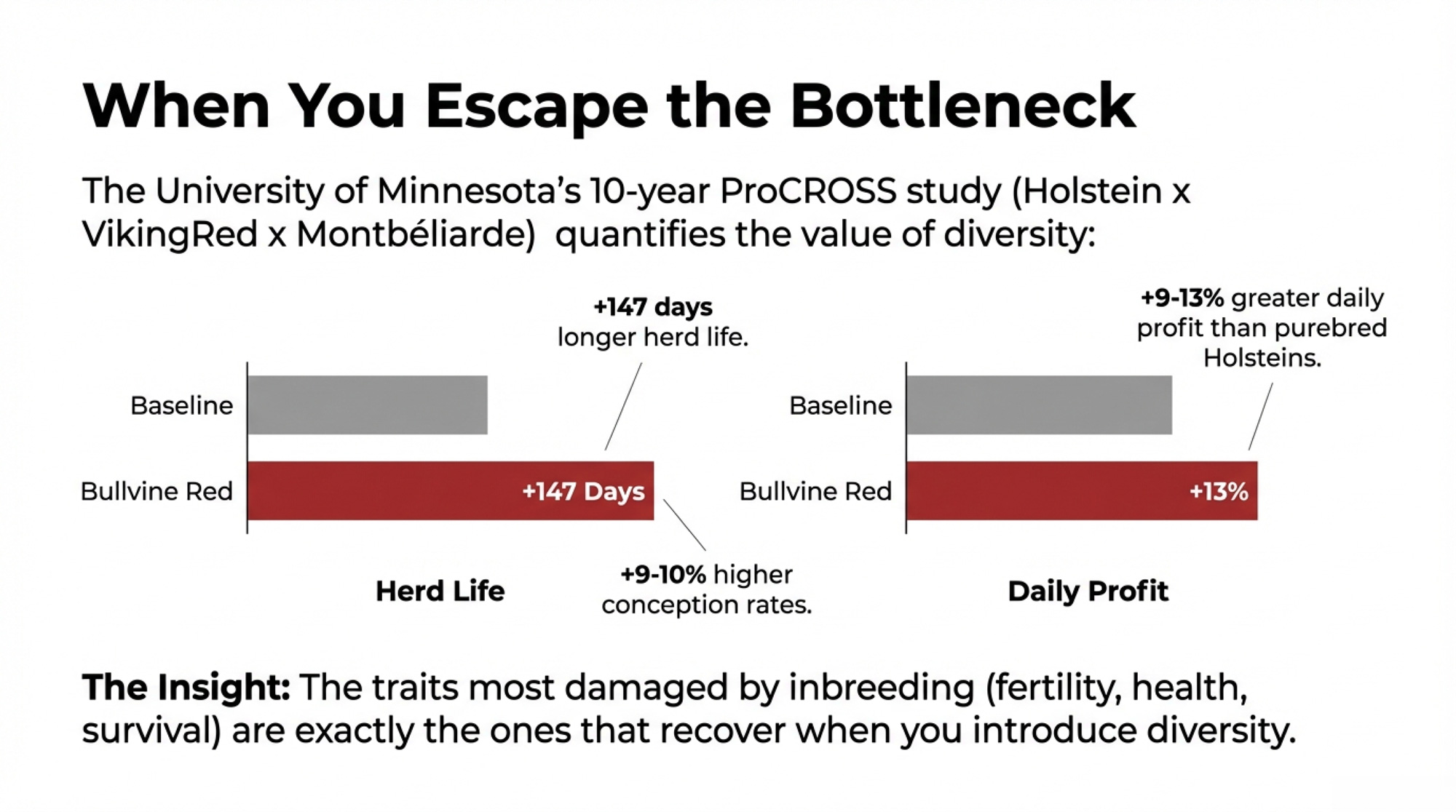

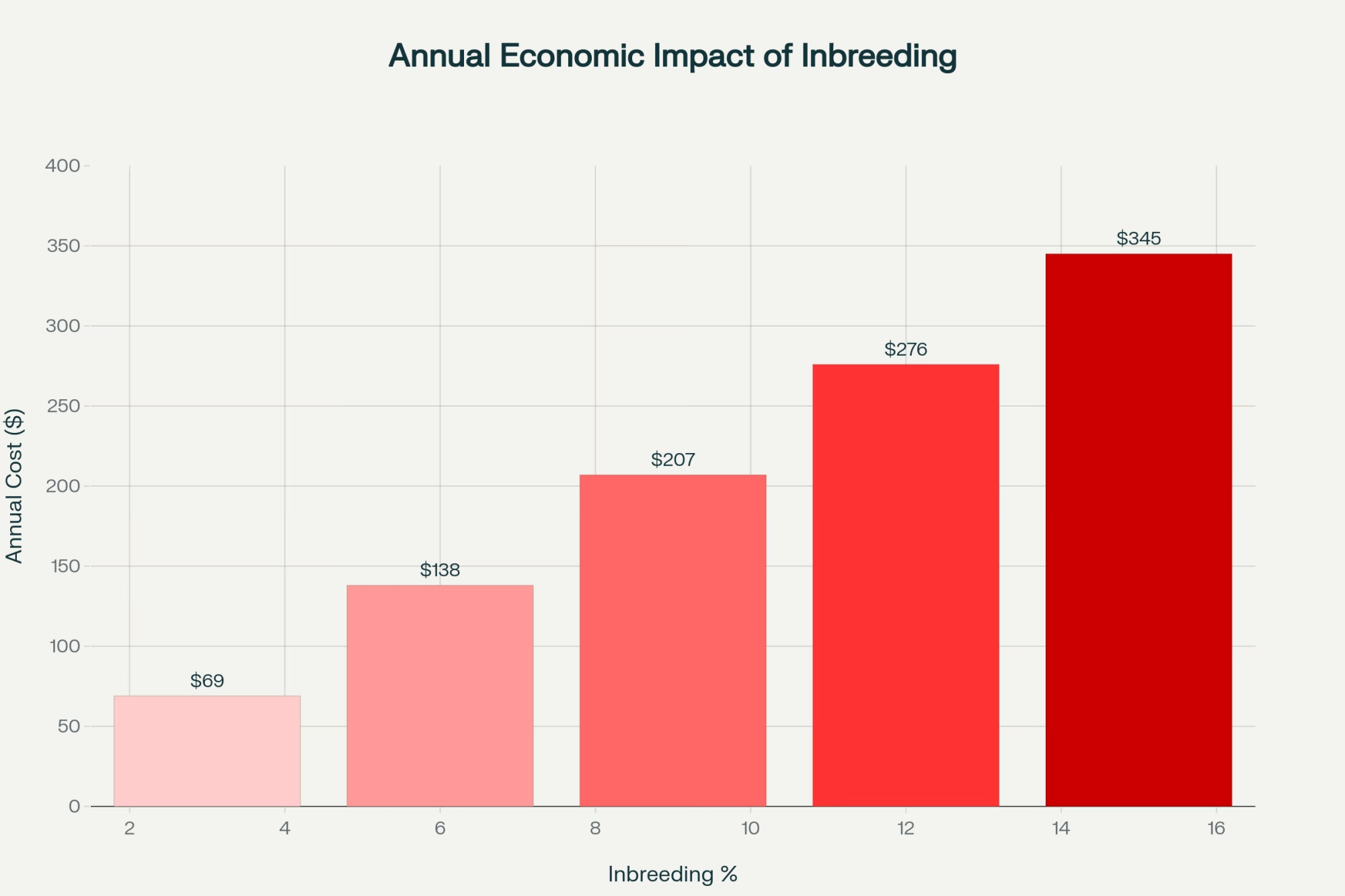

The math on inbreeding depression isn’t abstract anymore. Research estimates the cost at approximately $22–$24 per cow per lifetime for every 1% increase in pedigree inbreeding, in 1999 dollars. Canadian Holstein data show 2024-born heifers averaging 9.99% genomic inbreeding, roughly triple that of 2014. At those levels, you’re looking at $200–$400 per cow in hidden lifetime losses: extra breedings, transition problems, productive cows culled too soon — costs that don’t appear on any single report but show up everywhere in your bottom line.

Here’s what you can do about it:

- This month: Pull your herd’s average inbreeding coefficient from your genetic management software, breed association records, or CDCB query. Identify what percentage of your pedigree traces through Blackstar, Chief, and Bell lineages. If your average exceeds 8%, you’re already paying for it.

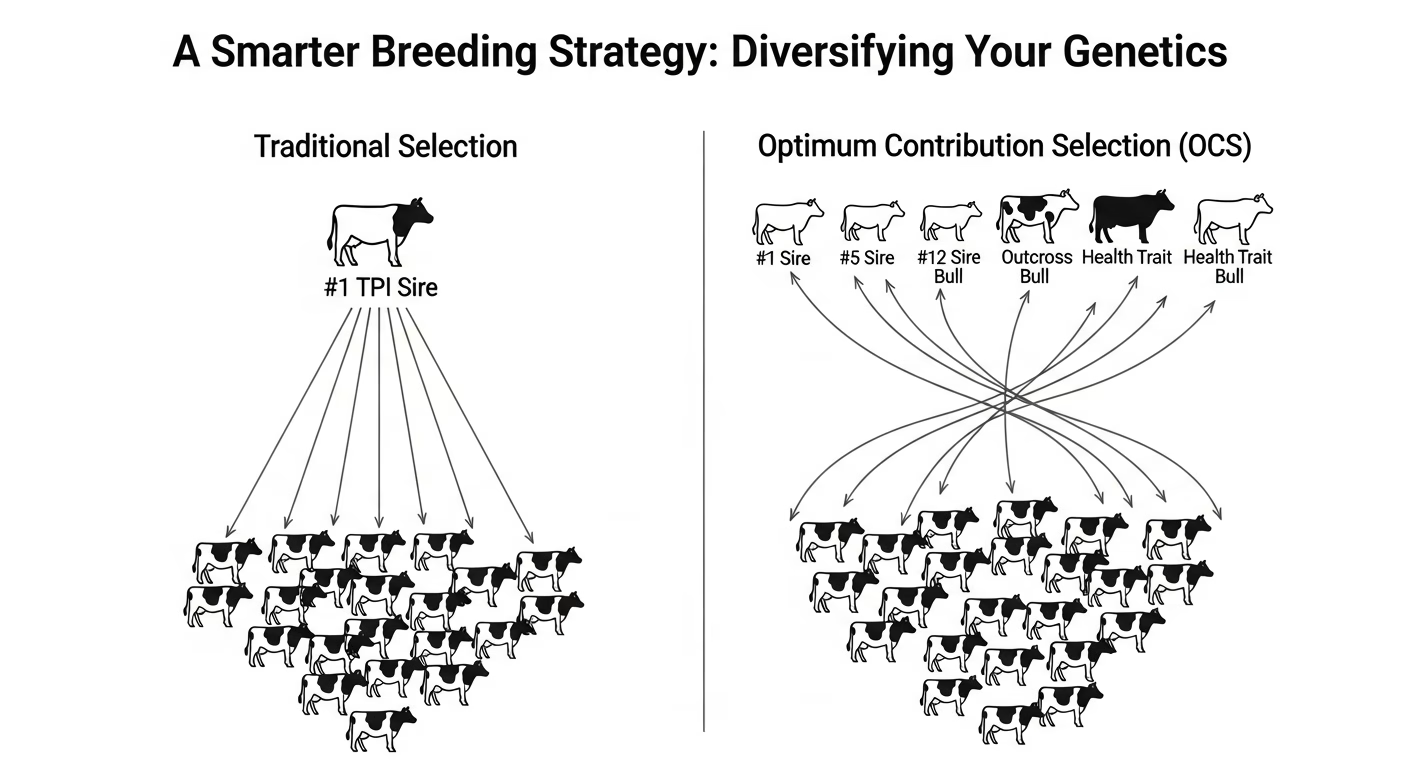

- Before the April proof run: Build a sire portfolio using a minimum of 8–10 unrelated sires. No single bull should appear on more than 12–15% of your matings. Prioritize outcross lines on your bottom-third genomic females — that’s where concentration costs compound fastest.

- Over the next year: Genomically test every replacement heifer and run mating programs that cap individual-sire inbreeding contribution. Track your herd’s F-coefficient quarterly rather than annually. Treat genetic diversity like feed inventory — monitor it before it runs out, not after.

Key Takeaways:

- One ET calf on a commercial Iowa dairy became one of the most influential Holstein sires in history, with the USDA estimating that To-Mar Blackstar now has a 15.8% relationship to the US Holstein population.

- His daughters combined high components, strong udders, and longer productive life, which drove roughly 500,000 doses sold and ~2,500 sons sampled worldwide, but also funneled a huge share of the breed’s genetics through a single sire line.

- VanRaden’s 1999 work flagged Blackstar as the Holstein bull with the highest expected inbreeding of future progeny (7.9%), and more recent Italian Holstein data show that inbreeding is still climbing by about +0.27% to +0.44% per year in the genomic era.

- Virginia Tech research pegs each 1% of inbreeding at $22–$24 in lost lifetime net income per cow (1999 dollars; roughly $43–$47 adjusted to 2026). At 2024-born Canadian heifer inbreeding levels of ~10%, that’s $430–$470 per cow in hidden lifetime drag.

- For a working dairy, the punchline is simple: Blackstar genetics helped build the kind of cows you like to milk, but the article shows how to measure the inbreeding bill you’re paying and lays out a 30/90/365-day plan to diversify sires and protect profit.

The Bottom Line

The tension hasn’t changed since 1992: the best genetics concentrate the fastest, and managing that concentration is the cost of using them responsibly.

The next proof run is scheduled for April. Before you pick up the semen catalog, pull that inbreeding report and trace how much of it flows through a single bull from a farm where the family was trying to make the numbers work. Because somewhere in that catalog right now — ranking 300-something on TPI, priced at a premium nobody wants to pay, getting skipped for cheaper bulls with flashier numbers — is the next Blackstar. The next bull whose daughters show up every morning, breed back without complaint, and quietly outlast everything around them.

History says the cheap bulls with the big numbers don’t last.

Your move.

Continue the Story

- Walkway Chief Mark: The Backup Bull Behind Seven Percent of Every Holstein Cow – Walk through the parallel history of another unheralded farm bull from the 1980s whose accidental rise at Select Sires mirrored Blackstar’s journey, creating a massive genetic footprint that still dictates how we breed today.

- Round Oak Rag Apple Elevation: The Bull of the Century – Explore the industry-shaping era of the “Bull of the Century,” whose balanced blueprint for production and type created the very world Blackstar was bred to improve, anchoring the pedigrees that define our modern breed.

- From Depression-Era Auction to Global Dominance: The Picston Shottle Legacy – Follow Blackstar’s lasting fingerprint into the story of the next global superstar, tracing how those essential Iowa traits for udder quality and longevity paved the way for Shottle to dominate the genomic era.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.