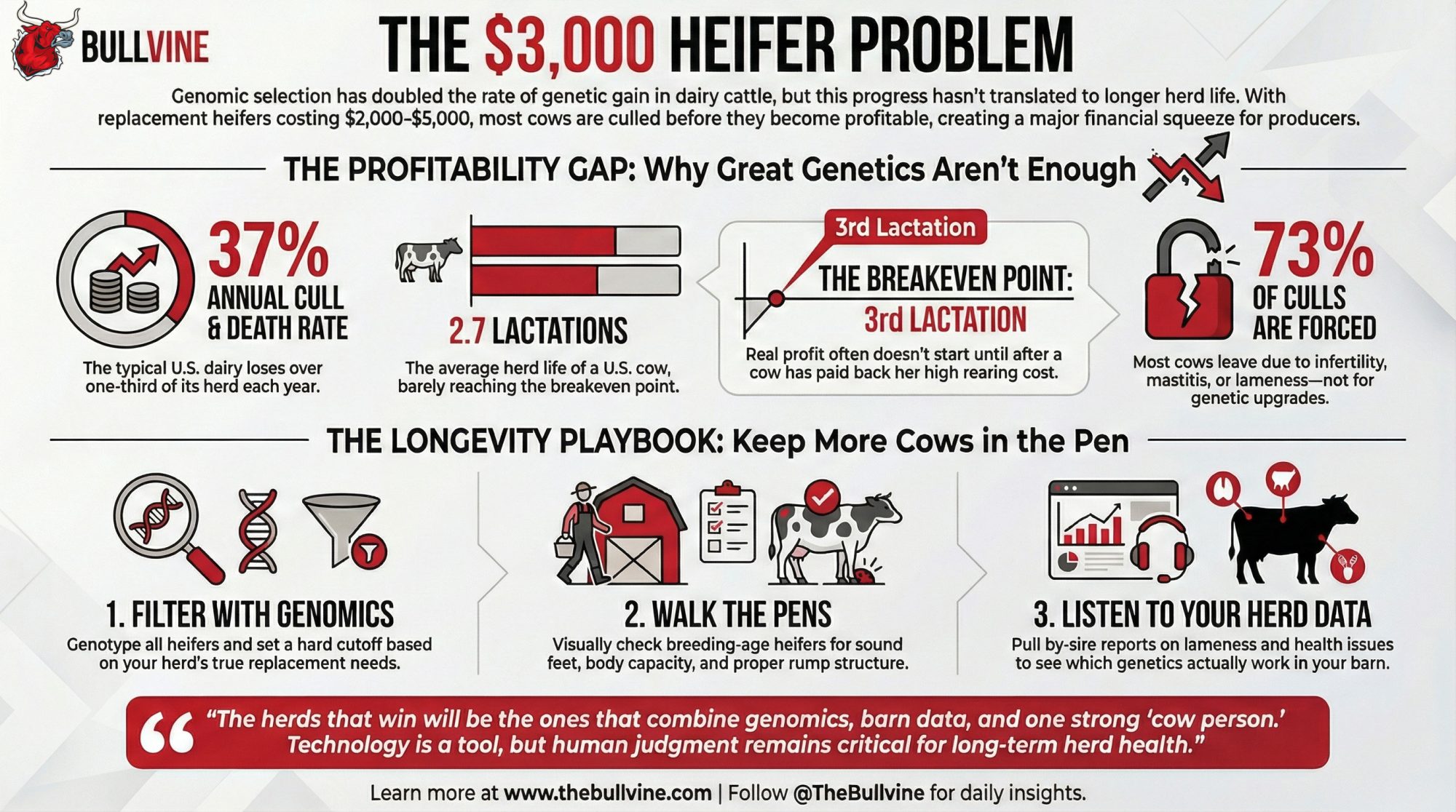

Did genomics really deliver what you think it did—or is that extra $238,000 in profit still stuck in your semen tank?

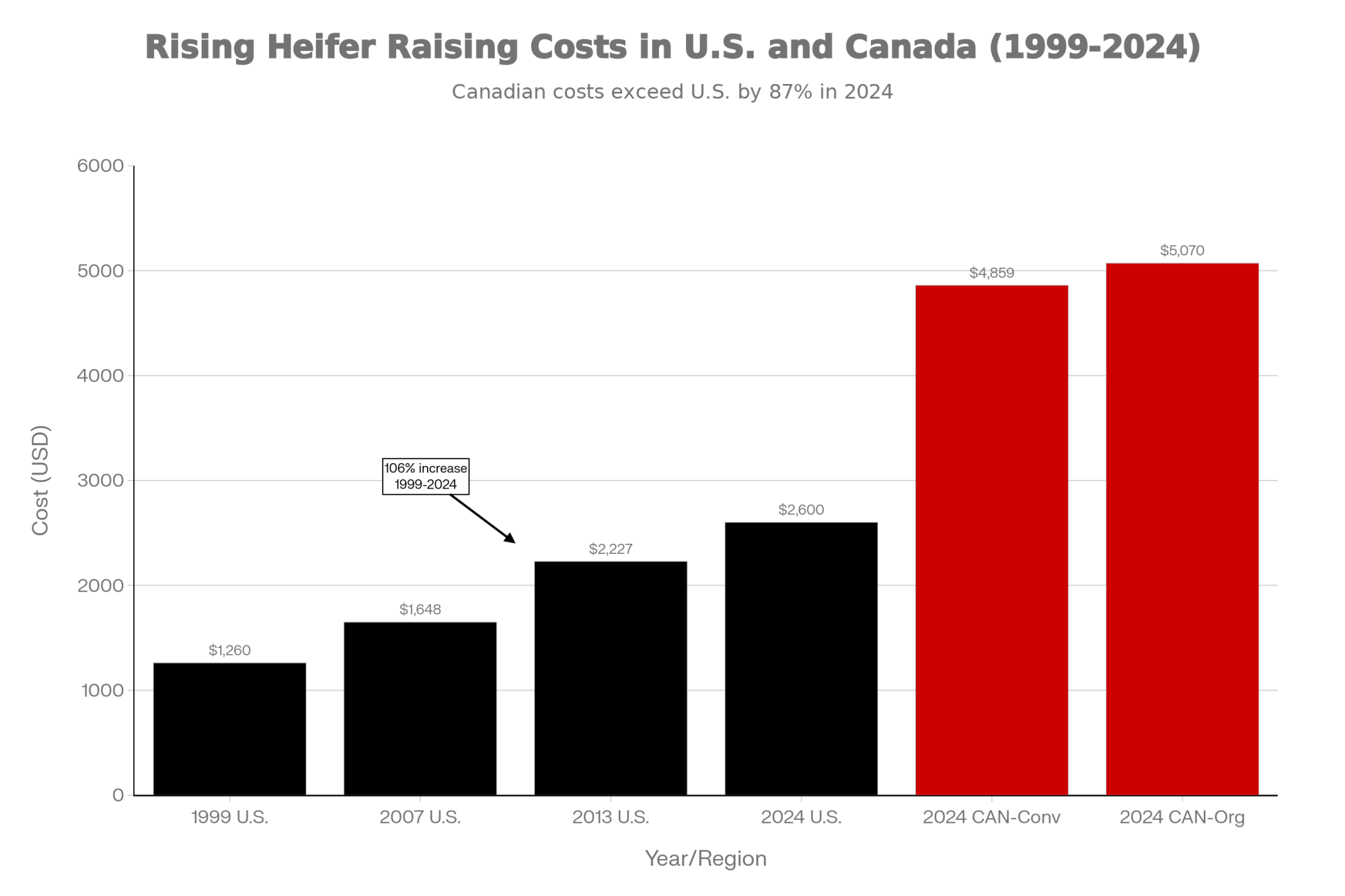

Let’s sit with a big number for a minute: a couple thousand dollars more lifetime profit per cow. That’s the kind of difference Lactanet uses in its Pro$ examples when it compares daughters of today’s high‑Pro$ sires to daughters of a decade older, lower‑ranking bulls, because Pro$ is built to reflect expected lifetime profit per cow based on real Canadian revenue and cost data up to six years of age or disposal.

If you spread that kind of genetic advantage across a few hundred cows over several breeding seasons, you’re quickly into tens of thousands of dollars in extra lifetime profit per year, the result of breeding decisions—assuming your fresh cow management, herd reproduction, and culling strategy actually lets those genetics show up in the tank.

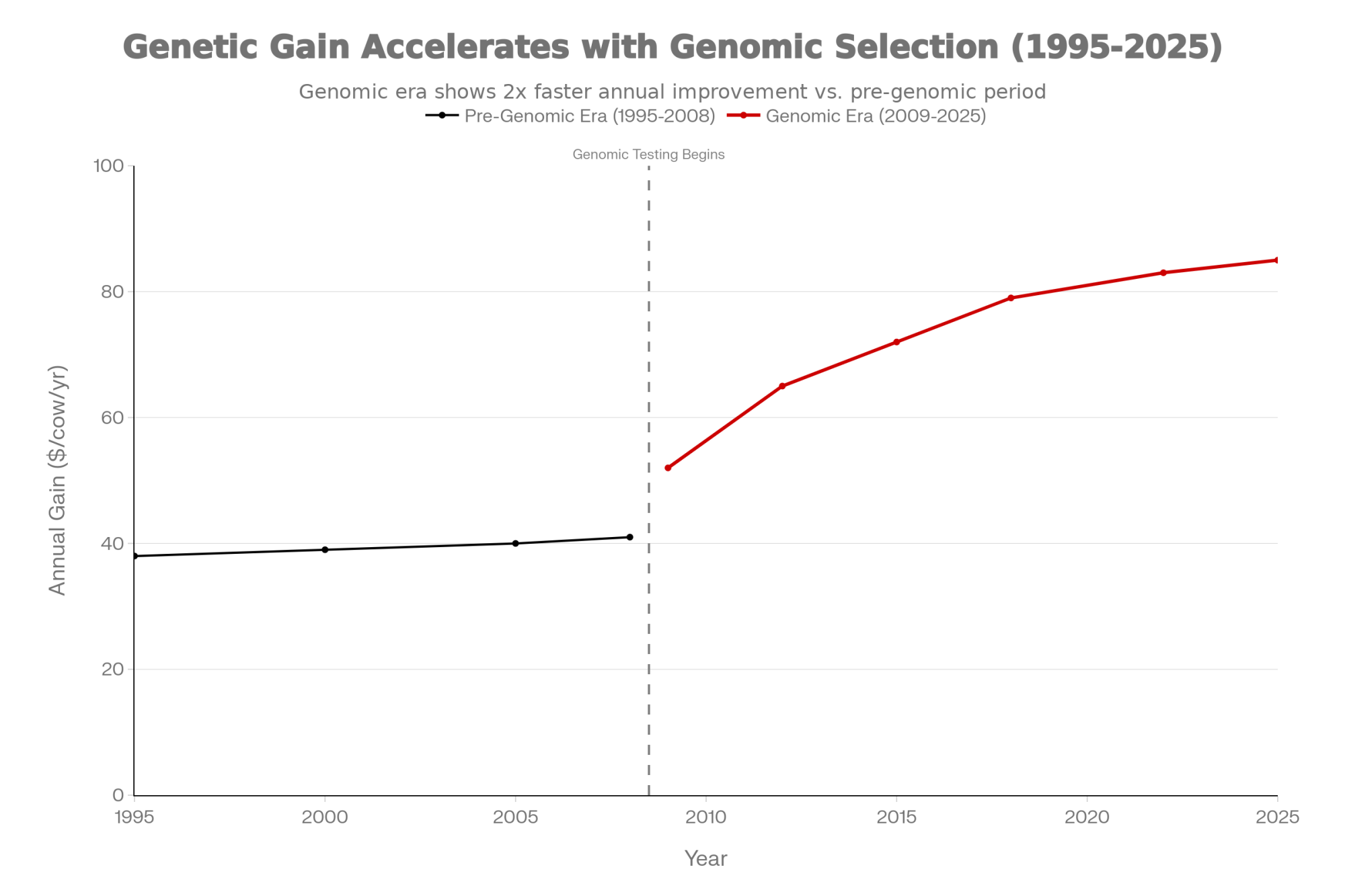

That’s not hype. That’s the math behind Pro$, and it aligns with what genomic selection has achieved globally, where genetic progress in milk, fat, protein, health, and longevity has accelerated by 50–100% compared with the pre‑genomic era.

What’s interesting, though, is that when you start peeling back the layers on how we got here, you see both huge wins and some red flashing lights—especially around diversity, fertility, and hidden genetic risks.

That’s what this conversation is really about.

When Banners Steered the Breeding Bus

If you look back 15–20 years, you can probably still picture the late‑2000s bull lists. In Canada, Holstein Canada sire‑usage data from that era show a relatively tight group of sires—Goldwyn, Buckeye, Dolman, and their close relatives—accounting for a significant share of registrations.

In 2008, just three bulls (Dolman, Goldwyn, Buckeye) accounted for about 12% of all registered Holstein females in Canada, and the top five sires together made up roughly 15.7% of registrations. That kind of concentration perfectly reflected the breeding philosophy of the time: moderate yield, “true type” conformation, and pedigrees that lit up both classifier sheets and show‑ring banners, but not always the enterprise balance sheet.

On many commercial freestall and tie‑stall farms, those cows were often the ones that:

- Struggled harder through the transition period

- Needed more care of their feet and legs

- Didn’t routinely make it to that profitable fourth or fifth lactation

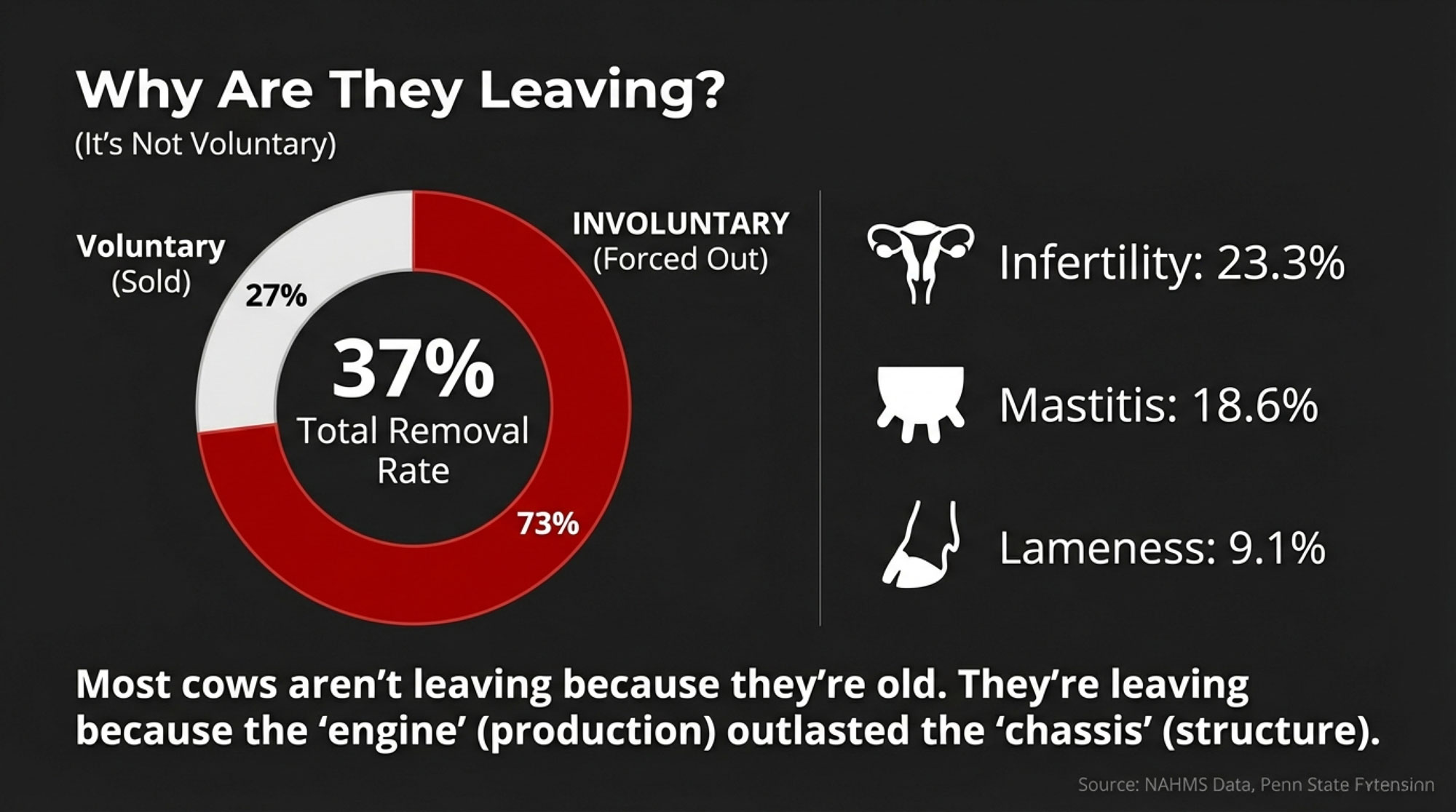

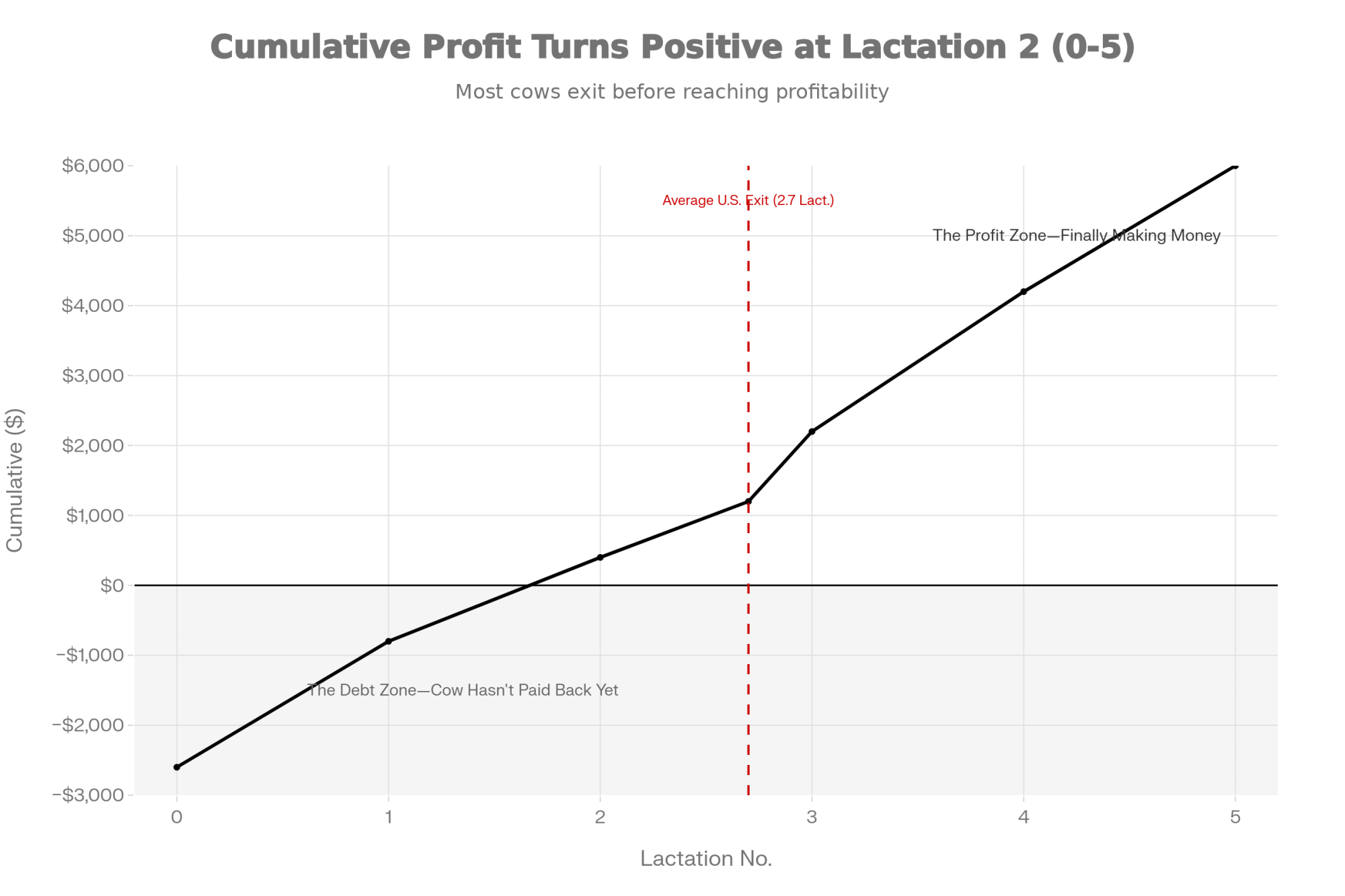

That isn’t just coffee‑shop talk. Work from the University of Guelph and Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada has consistently shown that lifetime profitability is closely tied to lifetime milk revenue, length of productive life, days dry, age at first calving, and reproductive-related interventions. Cows that leave early, spend more time open, racking up vet bills, and simply don’t deliver their potential lifetime profit—even if they look great and milk well in first lactation.

Producers like Don Bennink at North Florida Holsteins have been lightning rods on this topic for years. He’s been very blunt that high production, strong health traits, and feed efficiency are the bywords for breeding profitable cows—not show ribbons—and that genomics has “increased our progress at a rate we could never have dreamed of previously,” creating a huge profitability gap between herds that use genomic information and those that don’t.

So even before we talk about SNP chips and genomic proofs, there was already a clear split between what wins banners and what pays bills in freestalls, robots, parlors, and dry‑lot systems.

From Pedigree and Type to Profit and Function

The Canadian Holstein breeding landscape has gone through one of the most profound shifts in its history since about 2008. Over 16 years, selection has moved from pedigree‑driven, visually focused decisions to a much more complete “facts‑first” approach that prioritizes profitability, health, and functionality based on accurate animal and herd data.

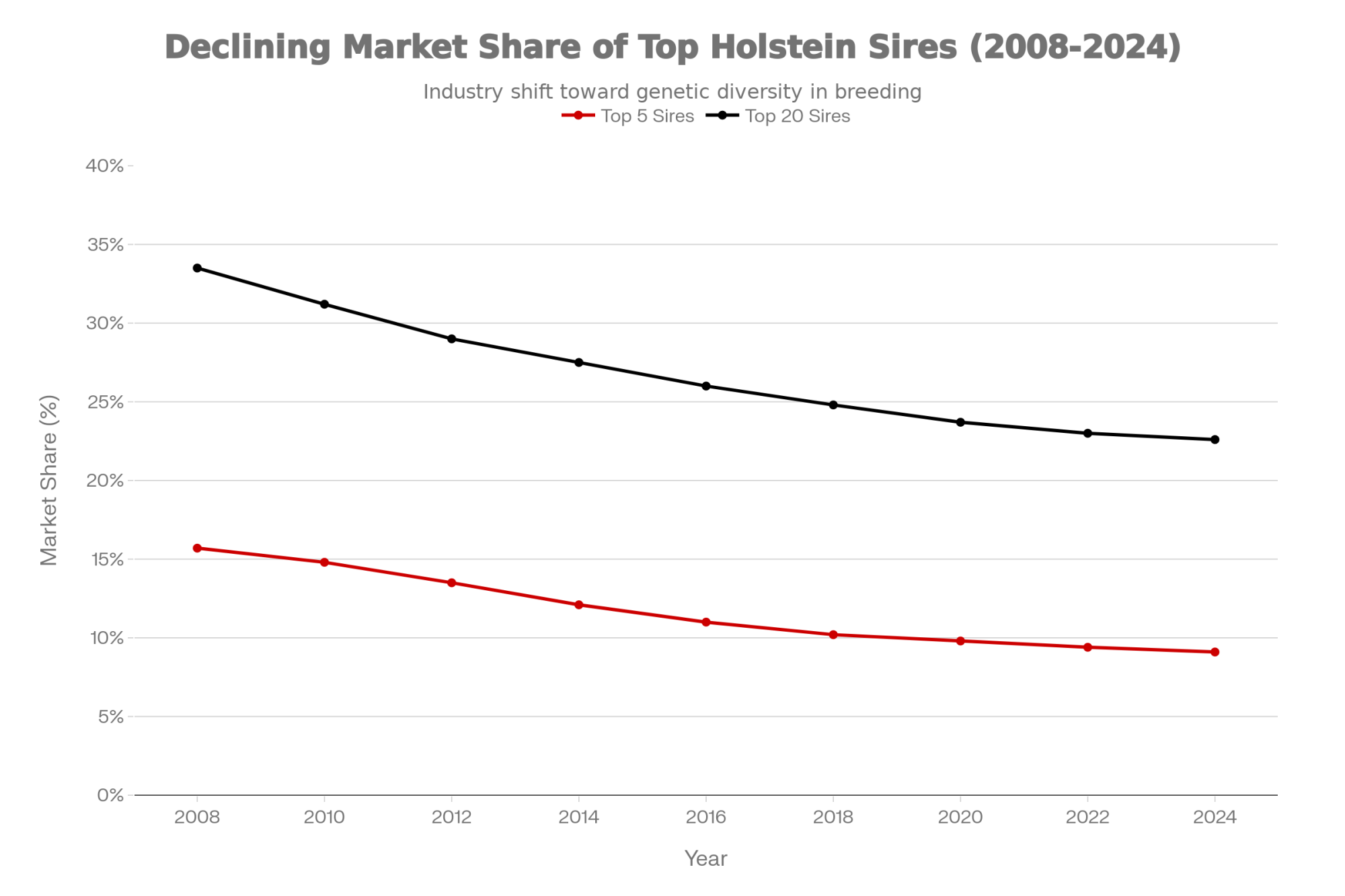

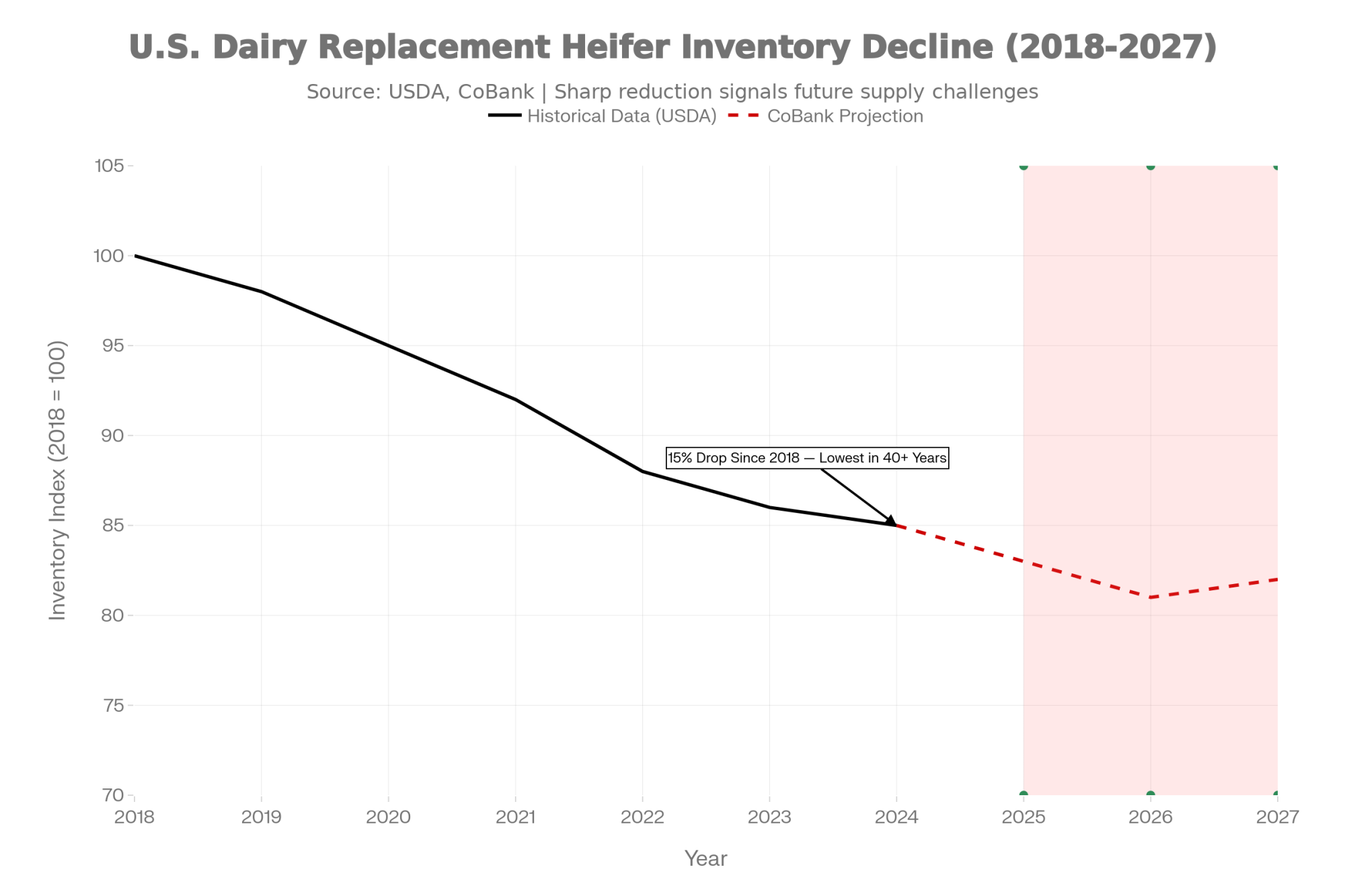

You can see this change clearly in which sires actually sired the most daughters in Canada. In 2008, the most‑used 20 sires accounted for about 33.5% of all registered females, and the average “top‑sire” had over 4,300 daughters. By 2024, that share dropped to around 22.6%, and the average daughters per top sire fell to roughly 2,984. At the same time, the top five sires in 2024 (Pursuit, Alcove, Lambda, Fuel, Zoar) represented only about 9.1% of registrations—down from that 15.7% level in 2008.

Overview of Top Sires of Canadian Holstein Female Registrations

| Category | 2008 | 2012 | 2016 | 2020 | 2024 |

| Total Female Registrations | 257,040 | 272,264 | 273,785 | 297,192 | 263,149 |

| Five Sires with Most Daughters | Dolman | Windbrook | Impression | Lautrust | Pursuit |

| Goldwyn | Fever | Superpower | Impression | Alcove | |

| Buckeye | Steady | Jett Air | Alcove | Lambda | |

| Frosty | Lauthority | Dempsey | Bardo | Fuel | |

| Sept Storm | Jordan | Uno | Unix | Zoar | |

| Percent of Registrations | |||||

| – Top Five Sires | 15.70% | 14.80% | 7.30% | 7.50% | 9.10% |

| – Top Ten Sires | 23.70% | 22.20% | 13.50% | 12.60% | 14.90% |

| – Top Twenty Sires | 33.50% | 30.10% | 22.20% | 20.20% | 22.60% |

| – Top Thirty Sires | 39.90% | 34.70% | 28.10% | 25.90% | 28.70% |

| Top Twenty Sires – avg # Daus | 4,309 | 4,093 | 3,035 | 3,001 | 2,984 |

| Highest Ranking Genomic Sire | 30th | 27th | 8th | 6th | 5th |

| No. Genomic Sires in Top Ten | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Percent of Sires – A2A2 | 20% | 25% | 35% | 50% | 60% |

That’s not a “bull of the month” world anymore. That’s breeders intentionally spreading genetic risk, targeting specific trait profiles, and using more bulls per herd for shorter periods, while still driving genetic gain.

The underlying philosophy has evolved from two narrow extremes—high‑conformation or high‑milk two‑lactation cows that were often culled early—to a more complete target: four‑plus‑lactation, healthy, fertile, self‑sufficient, high‑solids cows that can survive modern housing, automation, and economic pressure.

What Genomics Actually Changed

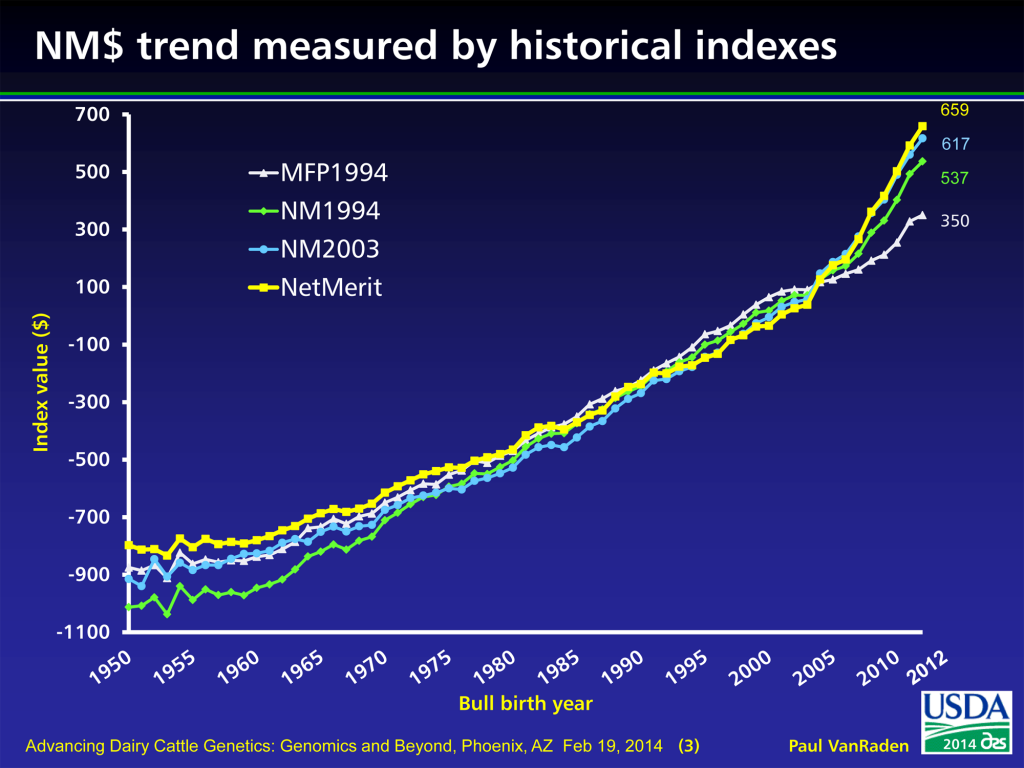

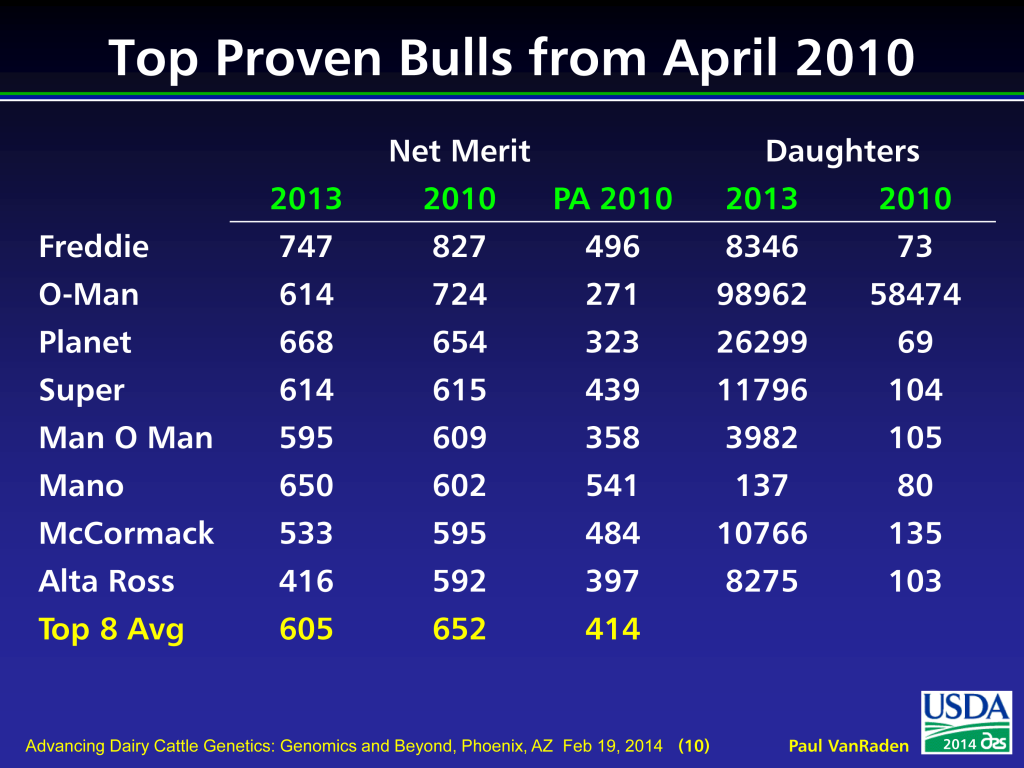

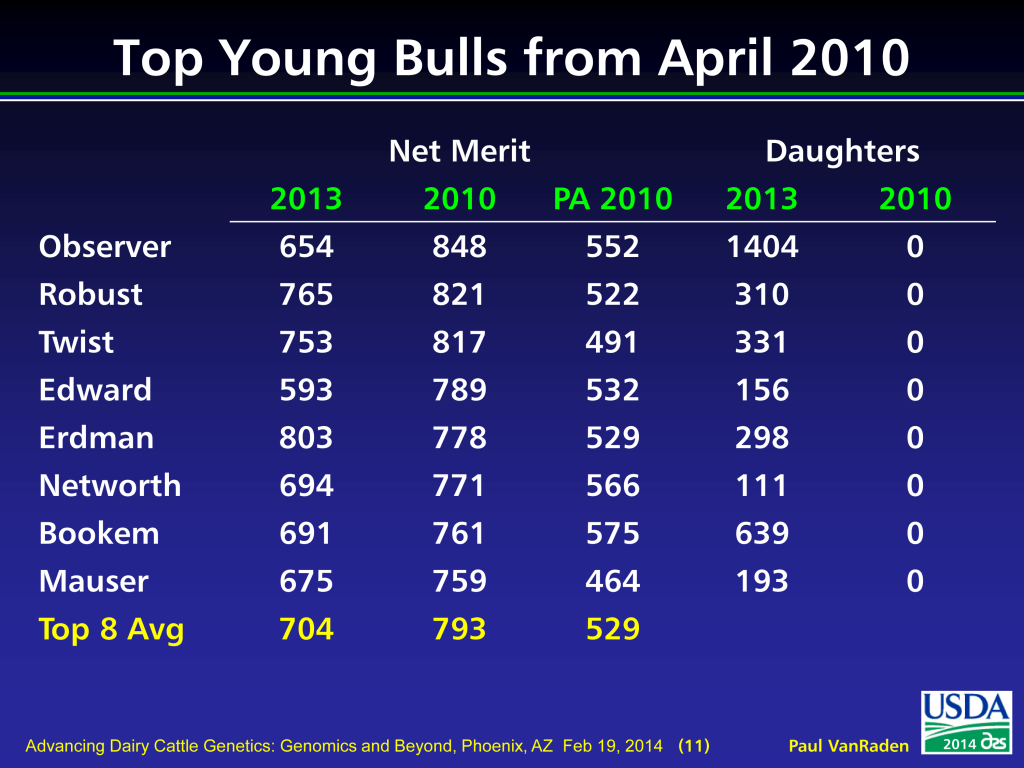

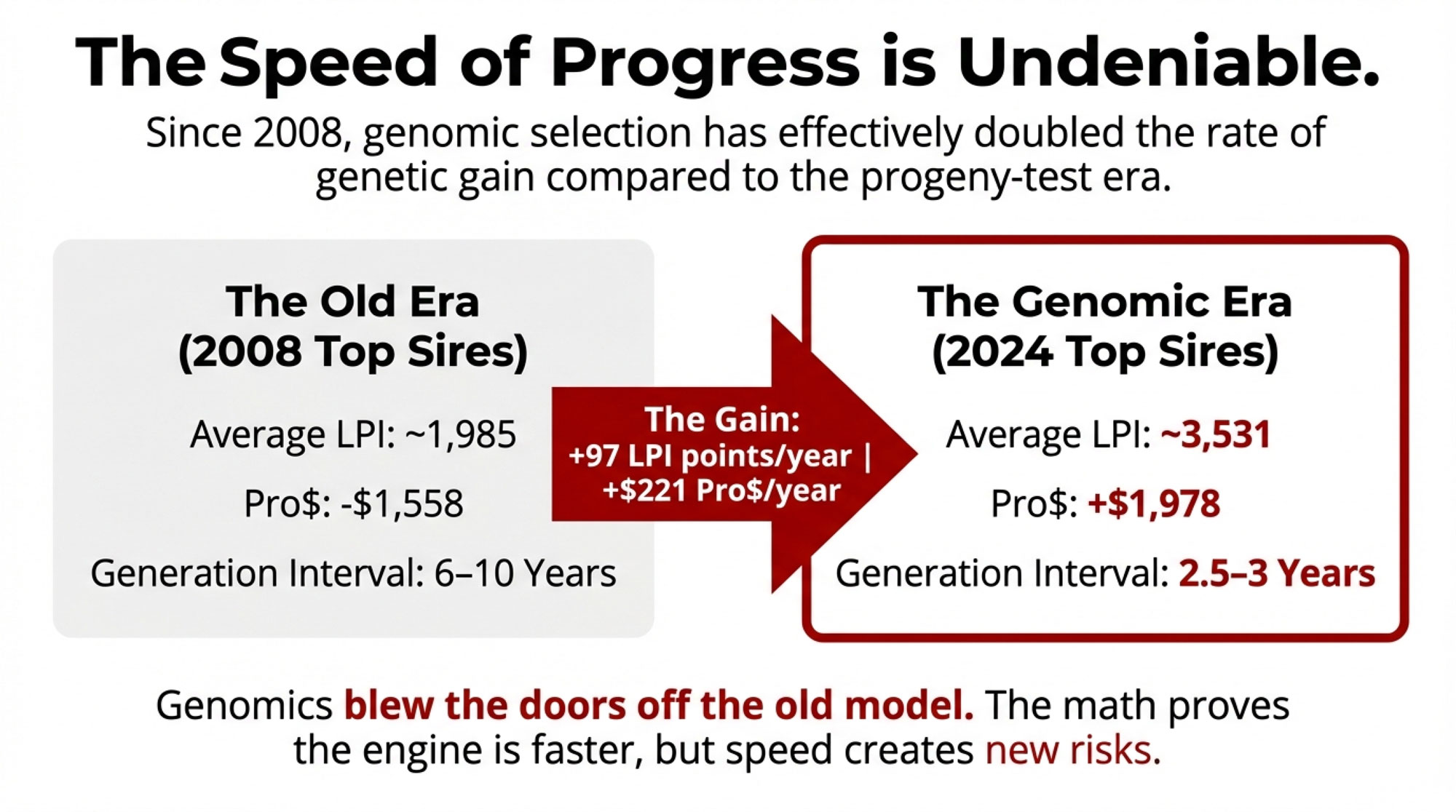

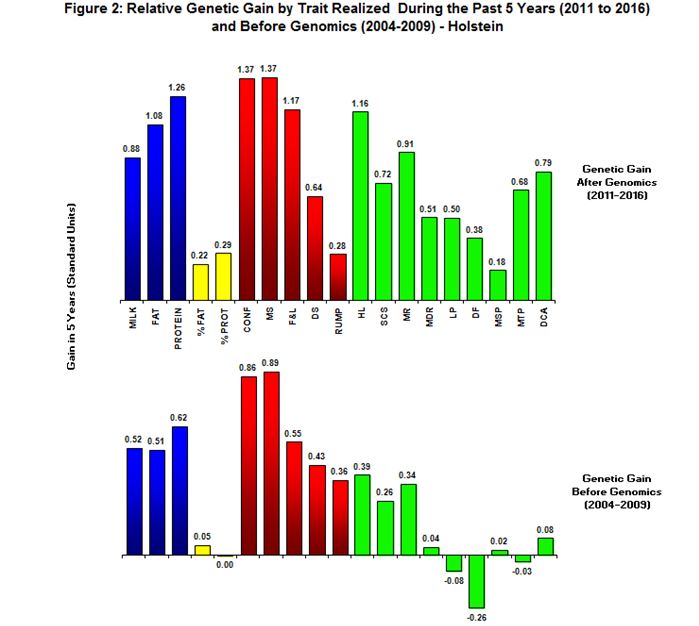

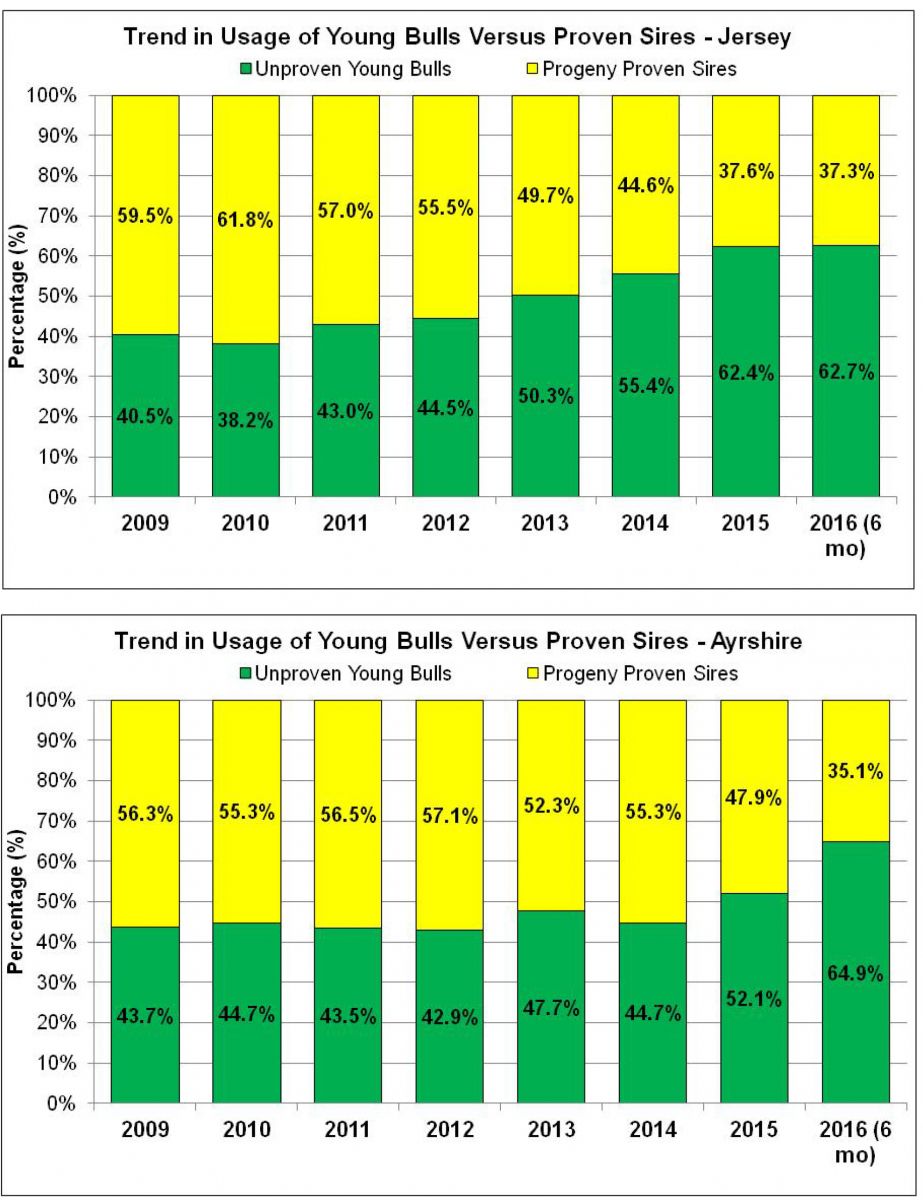

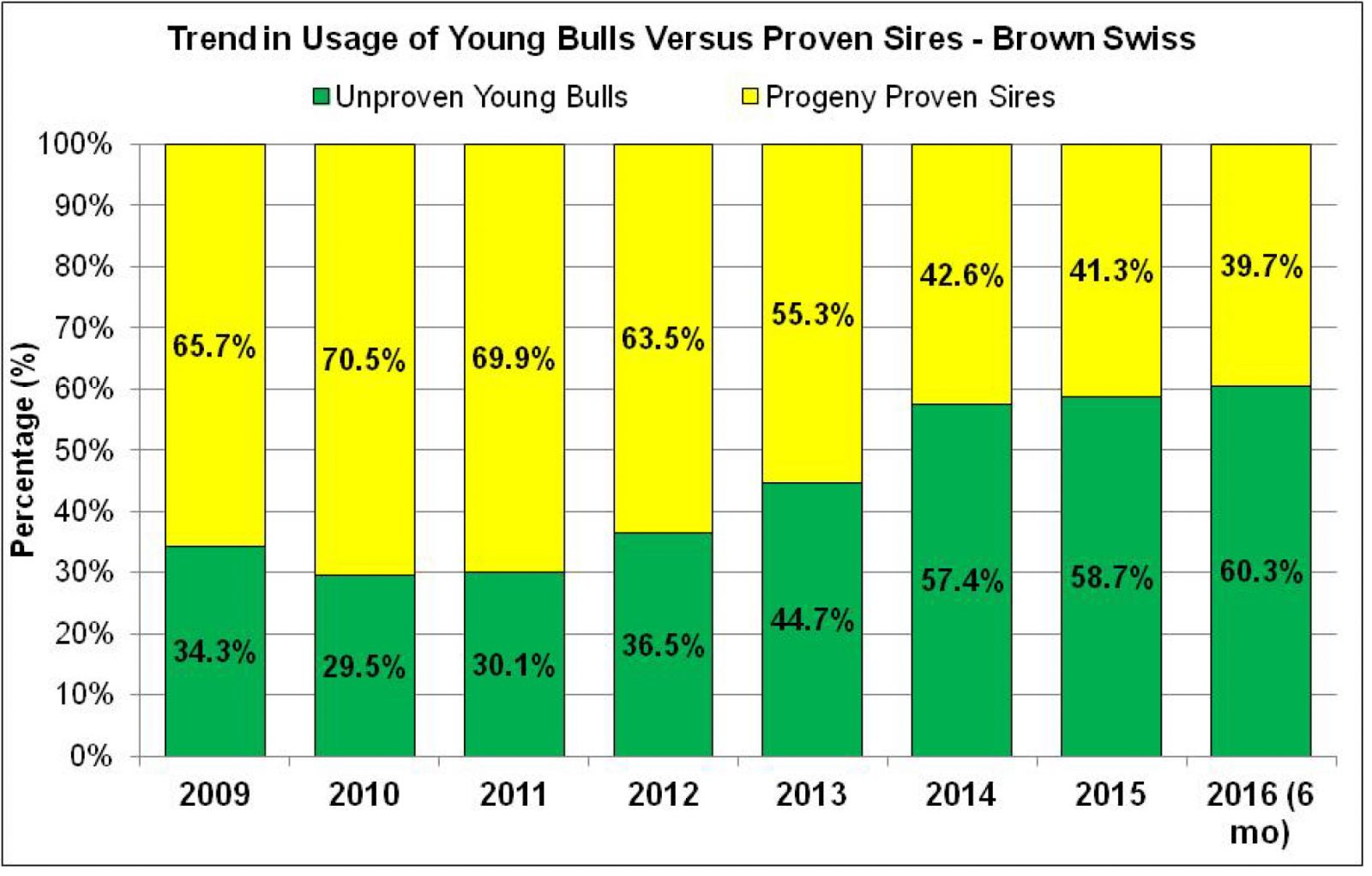

When genomic evaluations hit around 2008–2009, they blew the doors off the old progeny‑testing model. Researchers like Adriana García‑Ruiz and Paul VanRaden, working with US national Holstein data at USDA‑AGIL, showed that once genomics was adopted, sire‑of‑sons generation intervals were effectively cut in half, dropping from roughly 6–10 years down to around 2.5–3 years. Canadian data tracked the same pattern.

That shorter generation interval, combined with higher selection intensity and more accurate young‑animal evaluations, is exactly why genetic gains picked up speed. Analyses of Holstein breeding programs published in the Journal of Dairy Science and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences report:

- 50–100% higher rates of genetic gain for milk, fat, and protein in the genomic era

- 3–4x higher genetic progress in some health and productive‑life traits between 2008 and 2014

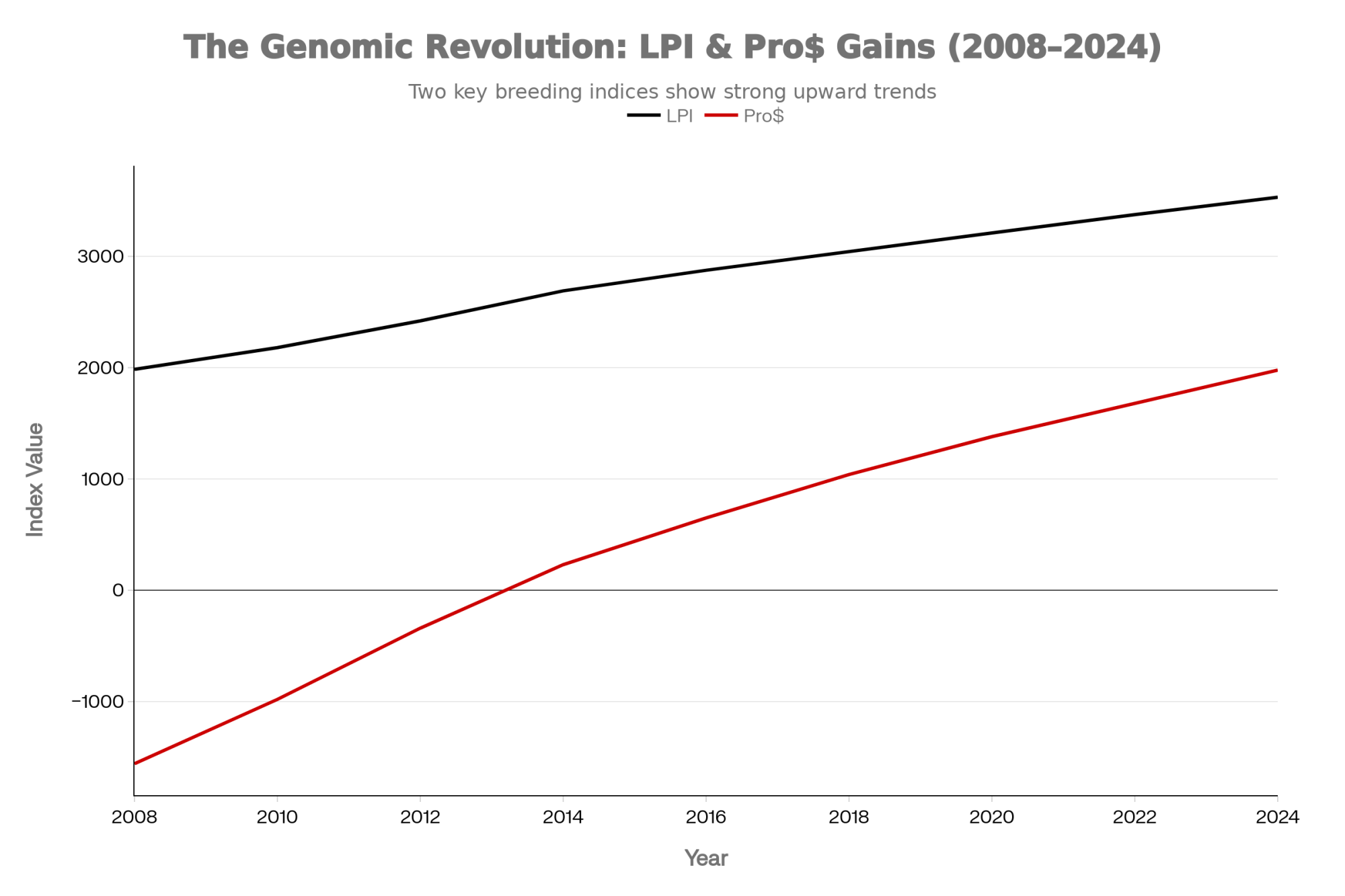

| Metric | 2008 (Progeny-Testing Era) | 2024 (Genomic Era) |

| Average LPI (Top 20 Sires) | 1,985 | 3,531 |

| Average Pro$ (Top 20 Sires) | -$1,558 | +$1,978 |

| Milk Proof (kg) | -578 | +860 |

| Fat Proof (kg) | -33 (-0.10%) | +85 (+0.31%) |

| Protein Proof (kg) | -27 (-0.07%) | +50 (+0.15%) |

| Top 5 Sires’ Market Share | 15.7% | 9.1% |

| Daughters per Top Sire | 4,300 | 2,984 |

| Top 20 Sires’ Market Share | 33.5% | 22.6% |

| Inbreeding (Top Sires’ Daughters) | ~9.5% | 11.5% |

Canada’s own data comparing bull April 2025 indexes on the 20 most‑used sires, 2008 vs 2024, makes this very real:

- The average LPI of those bulls climbed from about 1,985 in 2008 to around 3,531 in 2024—roughly +97 LPI points per year.

- Pro$ swung from about –$1,558 in 2008 to about +$1,978 in 2024—roughly +$221 per year in predicted daughter lifetime profit.

- Average proofs for those sires went from roughly –578 kg milk, –33 kg fat (–0.10%F), and –27 kg protein (–0.07%P) in 2008 to about +860 kg milk, +85 kg fat (+0.31%F), and +50 kg protein (+0.15%P) by 2024.

That works out to about +90 kg of milk, +7.4 kg of fat, and +4.8 kg of protein in genetic improvement per year in the bulls that Canadian Holstein breeders actually used the most.

| Year | LPI | Pro$ |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 1,985 | -$1,558 |

| 2010 | 2,180 | -$980 |

| 2012 | 2,420 | -$340 |

| 2014 | 2,690 | +$230 |

| 2016 | 2,875 | +$650 |

| 2018 | 3,045 | +$1,040 |

| 2020 | 3,210 | +$1,380 |

| 2022 | 3,375 | +$1,680 |

| 2024 | 3,531 | +$1,978 |

Put simply: genomics, combined with LPI and Pro$, did exactly what it was supposed to do in Canada—faster genetic gain for production and overall profit.

Indexes for Twenty Sires with the Most Registered Daughters

| Year | LPI | Pro$ | Milk | Fat / %F | Protein / %P | CONF | Mammary | Feet & Legs | D Strength | Rump |

| 2008 | 1985 | -1558 | -578 | -33 / -.10% | -27 / -.07% | -6 | -6 | -4 | 1 | 0 |

| 2012 | 2378 | -728 | -415 | -14 / .01% | -17 / -.02% | 1 | -1 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| 2016 | 2680 | 173 | 130 | 6 / .00% | 2 / -.05% | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2020 | 3054 | 1016 | 555 | 45 / .21% | 25 / .04% | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 2024 | 3531 | 1978 | 860 | 85 / .31% | 50 / .15% | 8 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 5 |

| Change/Year | 97 | 221 | 90 | 7.4 | 4.8 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 0.31 |

*Lactanet Indexes Published in April 2025

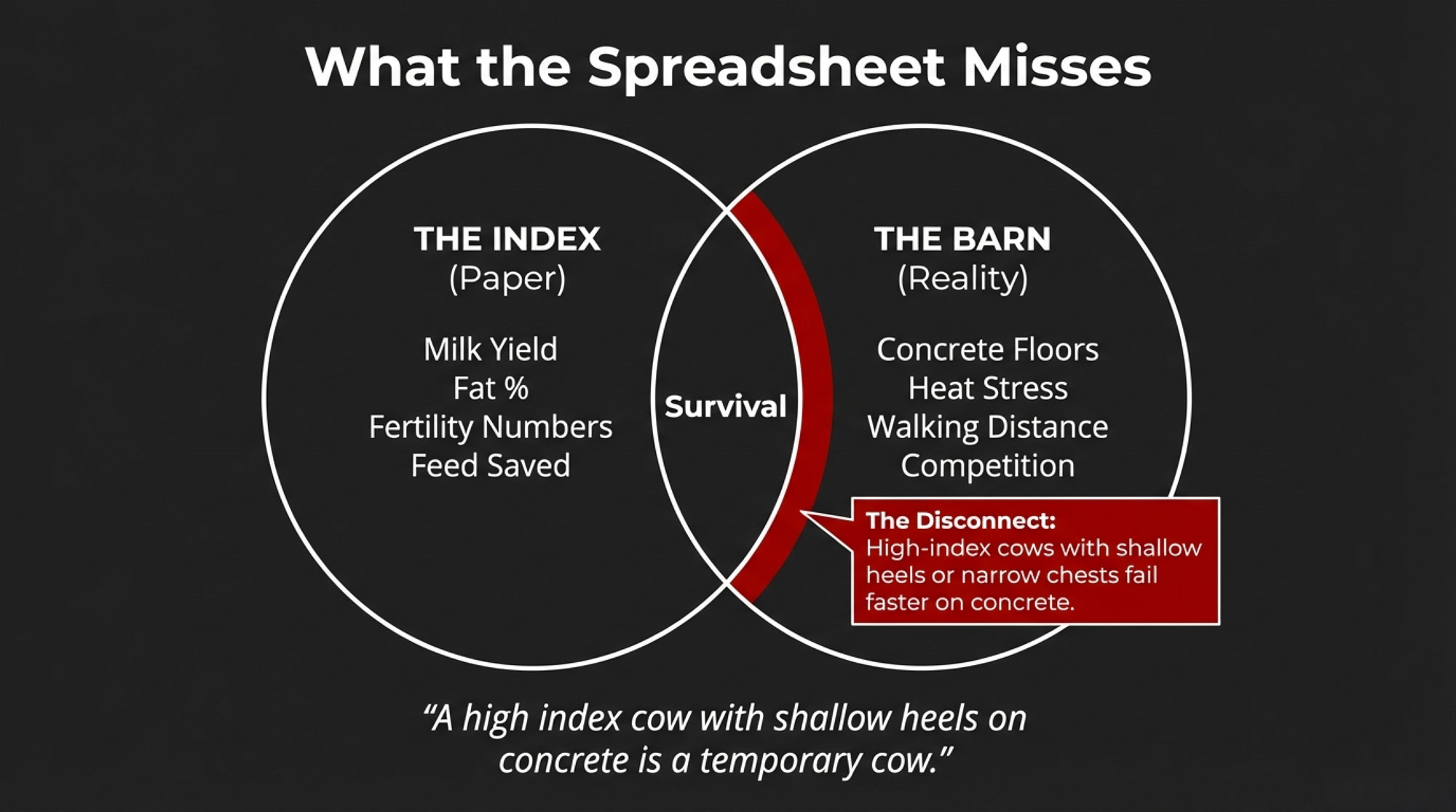

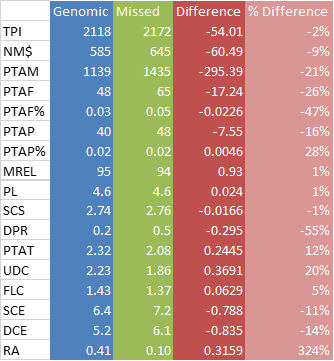

Where biology pushes back is on which traits move fastest. Higher‑heritability traits like milk, fat, and protein, as well as major type traits, make faster genetic progress than lower‑heritability traits like fertility, health, and productive life. Genomics improves accuracy across the board, but when semen catalogs and marketing materials still lead with production and type, it’s easy for those traits to keep outrunning fertility and health on the genetic trend lines.

That’s how we end up with a proof landscape that shows: extreme strength in production and conformation, modest but improving gains in fertility and health, and some nagging functional issues that still frustrate producers.

The Diversity Question: Are We Painting Ourselves Into a Corner?

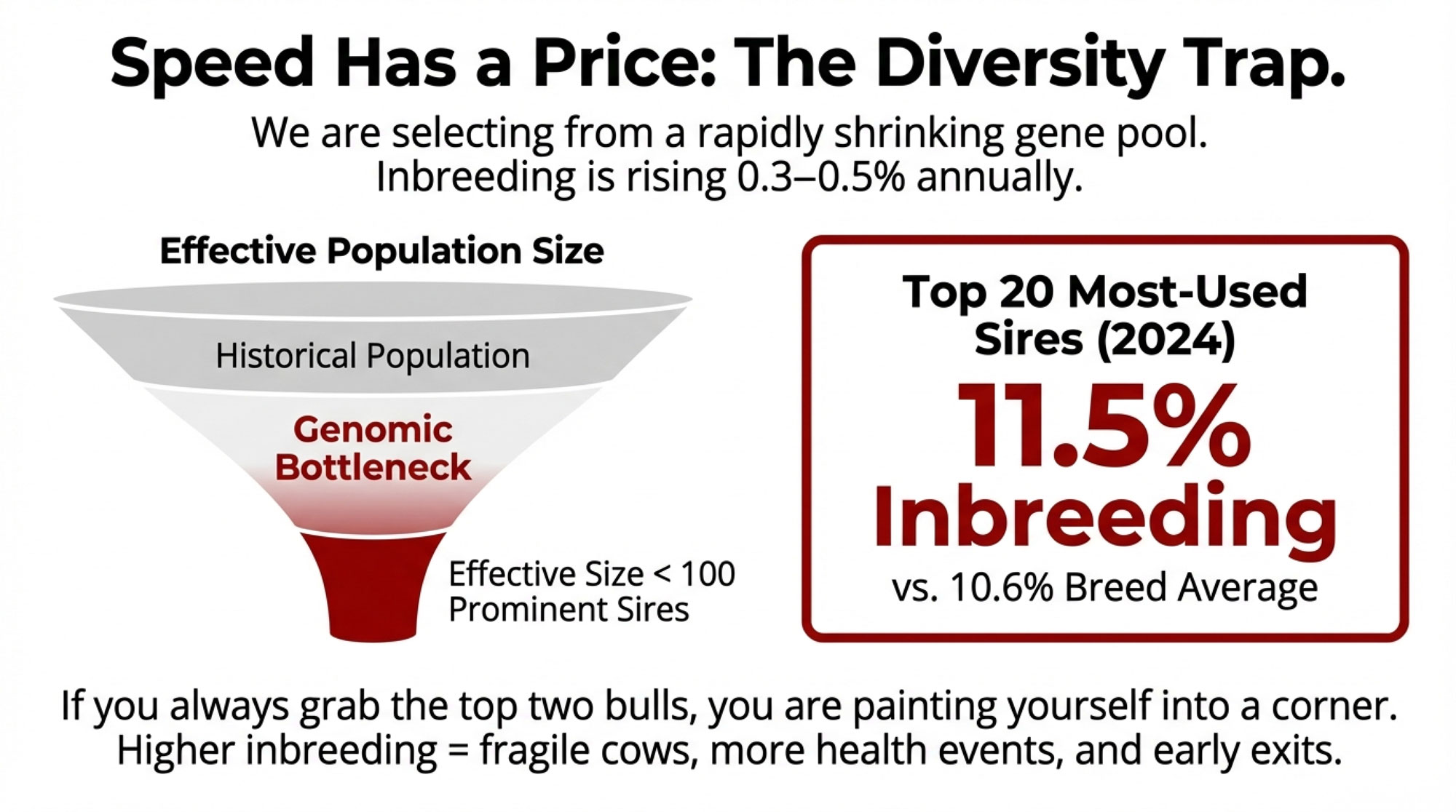

One major concern that doesn’t appear directly on a proof sheet is genetic diversity.

Geneticists talk about effective population size—the number of prominent sires contributing progeny, especially genomic sires entering AI programs and daughters being used as bull dams. Dutch and Italian Holstein genomic studies have examined this closely. In one well‑cited Dutch‑Flemish analysis, effective population size in AI bulls born between 1986 and 2015 ranged from about 50 to 115 prominent sires at different periods, with lower values during times of intense selection. Italian and Nordic Holstein work using both pedigree and SNP data has reported similar patterns—effective population sizes are often below 100, with prominent sires trending downward in the genomic era.

International guidelines from the FAO and genetic diversity experts generally suggest that an effective population size of 100 or more prominent sires is acceptable. Values below about 50 for prominent sires raise concerns about inbreeding depression and lost adaptability.

At the same time, genomic and pedigree analyses across multiple countries have shown that inbreeding is rising faster each year in the genomic era—often increasing by 0.3–0.5 percentage points annually. At current generation intervals, that can mean 1.5–2.5% per generation. Pedigree studies summarized by Chad Dechow at Penn State and reported in Hoard’s Dairyman have also highlighted how a disproportionate share of modern Holstein ancestry traces back to just a handful of bulls (Chief, Elevation, Ivanhoe), underlining how concentrated the global gene pool has become.

In the Canadian context, that broader story plays out in very practical ways. The 20 most‑used sires in 2024 have daughters with an average inbreeding coefficient of about 11.5%—above a Holstein breed average already considered uncomfortably high at around 10.6%. That means the bulls delivering the most genetic progress on paper are also nudging herds further into undesirable inbreeding territory.

Practically, if you always grab the top two or three bulls on the list:

- You’ll quickly improve your herd’s genetic level.

- While you’ll also make your heifers more closely related to each other, especially if those bulls also share cow families.

On farm, that’s when inbreeding starts to show up in ways you feel: more fertility trouble, more health events, and cows that don’t seem as robust as the previous generation—even while milk solids and type keep improving.

Hidden Passengers: Haplotype and Recessive Stories

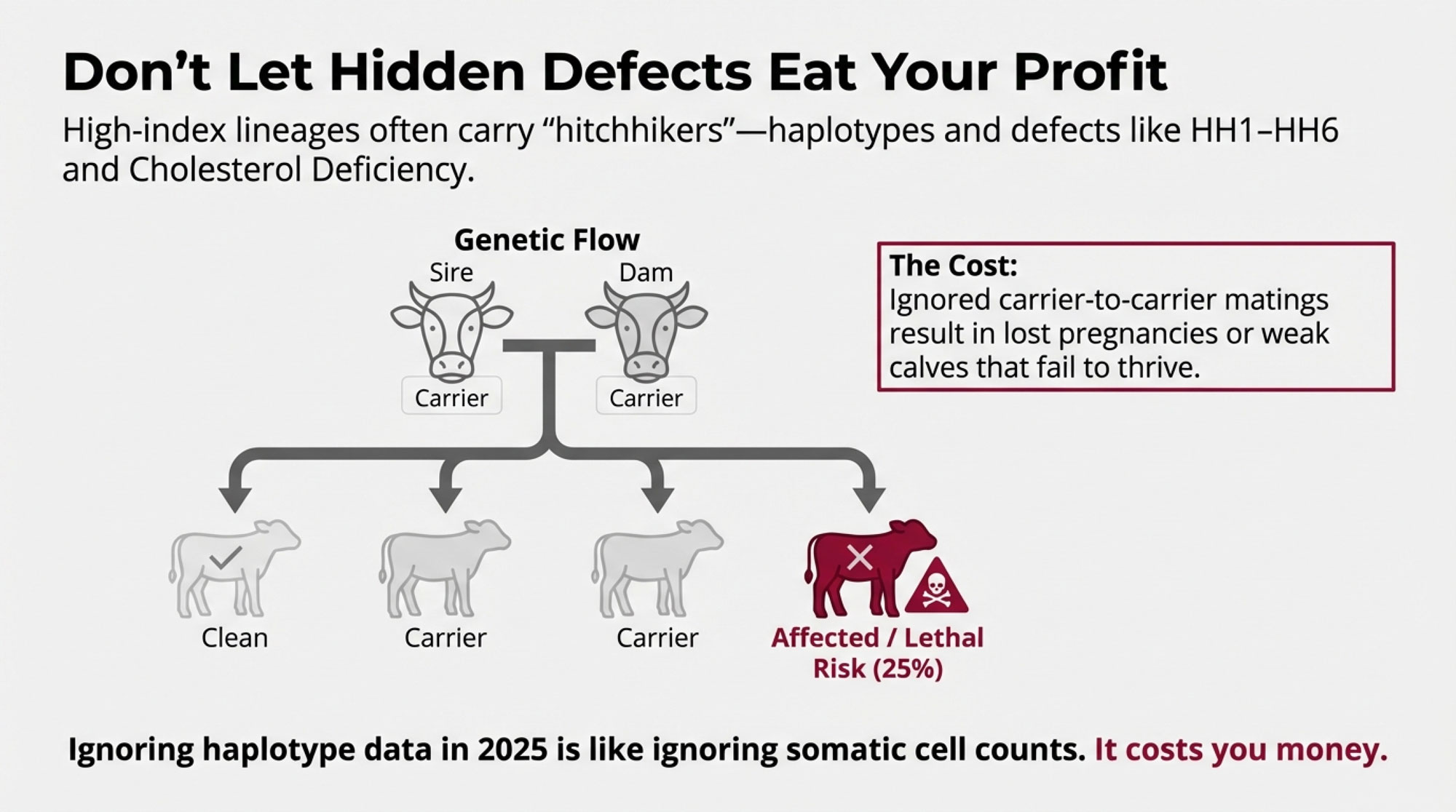

Another layer that genomics exposed is fertility haplotypes and single‑gene defects.

Over the past decade, collaborations between the USDA’s Animal Genomics and Improvement Lab, European institutes, and AI organizations have identified several Holstein haplotypes—HH1, HH2, HH3, HH4, HH5, HH6—and defects like cholesterol deficiency (CD/HCD) that are tied to embryonic loss or weak calves.

The pattern is pretty straightforward:

- These haplotypes are stretches of DNA where homozygous calves (same version from sire and dam) often die early in gestation or are born weak and fail to thrive.

- Carrier frequencies in many national populations sit in the low single digits but can reach 5–10% for some haplotypes in certain birth years and cow families.

The cholesterol deficiency story is a good cautionary tale. CD traces back to lines including Maughlin Storm and involves a mutation affecting fat metabolism; affected calves often die within weeks due to diarrhea and failure to thrive, while carriers look normal and can be high‑index animals.

The good news:

- Major AI studs routinely test their bulls for these defects, and they, their breeds, and genetic evaluation centers publish the carrier status of animals.

- Mating programs can automatically avoid carrier × carrier matings once herd and sire statuses are known.

If you don’t use those tools, the math can quietly bite you. Even a few percent of pregnancies lost to lethal combinations in a 400–500 cow herd can mean thousands of dollars in dead calves, extra breedings, and longer calving intervals each year—losses that are largely avoidable with the data breeders already have access to.

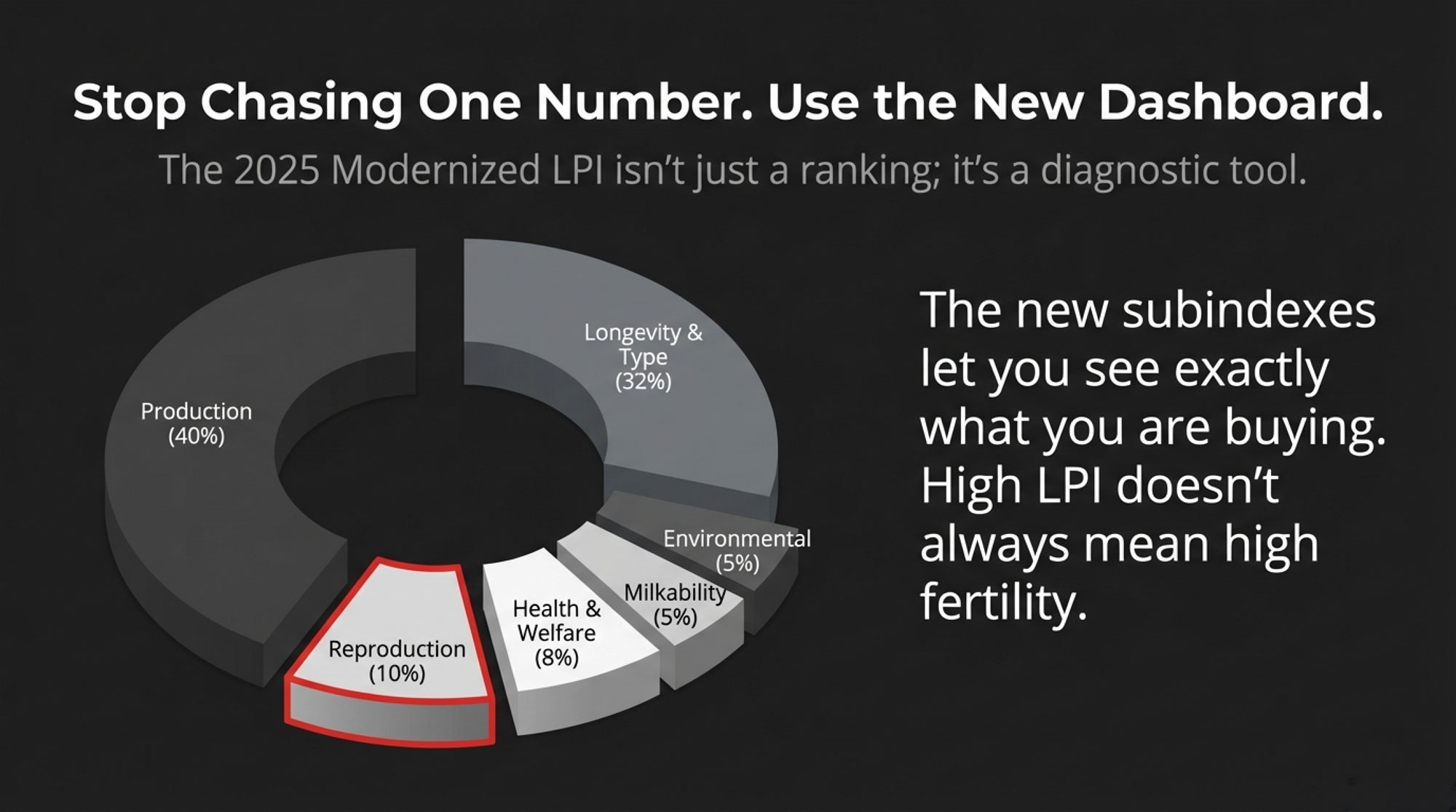

The 2025 Modernized LPI: A Better Dashboard

All of this—faster genetic gain, tighter diversity, more trait data, and new environmental pressure—is why genetic evaluation systems are updating how they calculate and present information.

In Canada, Lactanet launched a modernized Lifetime Performance Index (LPI) framework in April 2025. The old three‑group structure (Production, Durability, Health & Fertility) was replaced with six subindexes for Holsteins and five subindexes for the other breeds:

- Production Index (PI)

- Longevity & Type Index (LTI)

- Health & Welfare Index (HWI)

- Reproduction Index (RI)

- Milkability Index (MI)

- Environmental Impact Index (EII)

For Holsteins, these subindexes carry specific weightings in the new LPI formula: about 40% on Production, 32% on Longevity & Type, 8% on Health & Welfare, 10% on Reproduction, 5% on Milkability, and 5% on Environmental Impact. As well, Lactanet has an online routine where breeders can rank bulls by assigning their own weightings for the subindexes.

Two important comfort points from Lactanet:

- The correlation between the current and modernized LPI is expected to be around 0.98, so the bulls you like don’t suddenly become “bad”—their strengths and weaknesses just become more visible.

- Splitting Health & Fertility into Health & Welfare and Reproduction, plus the creation of a separate Milkability subindex, allows new traits such as calving ability, daughter calving ability, milking speed, temperament, and environmental traits (such as feed and methane‑related efficiencies) to be properly handled in the indexing.

For a lot of producers, the practical value is this: you can now see at a glance where a bull stands not only on overall LPI or Pro$, but on:

- Reproduction

- Health & Welfare

- Environmental footprint

On separate scales, without having to decode 20 individual trait proofs.

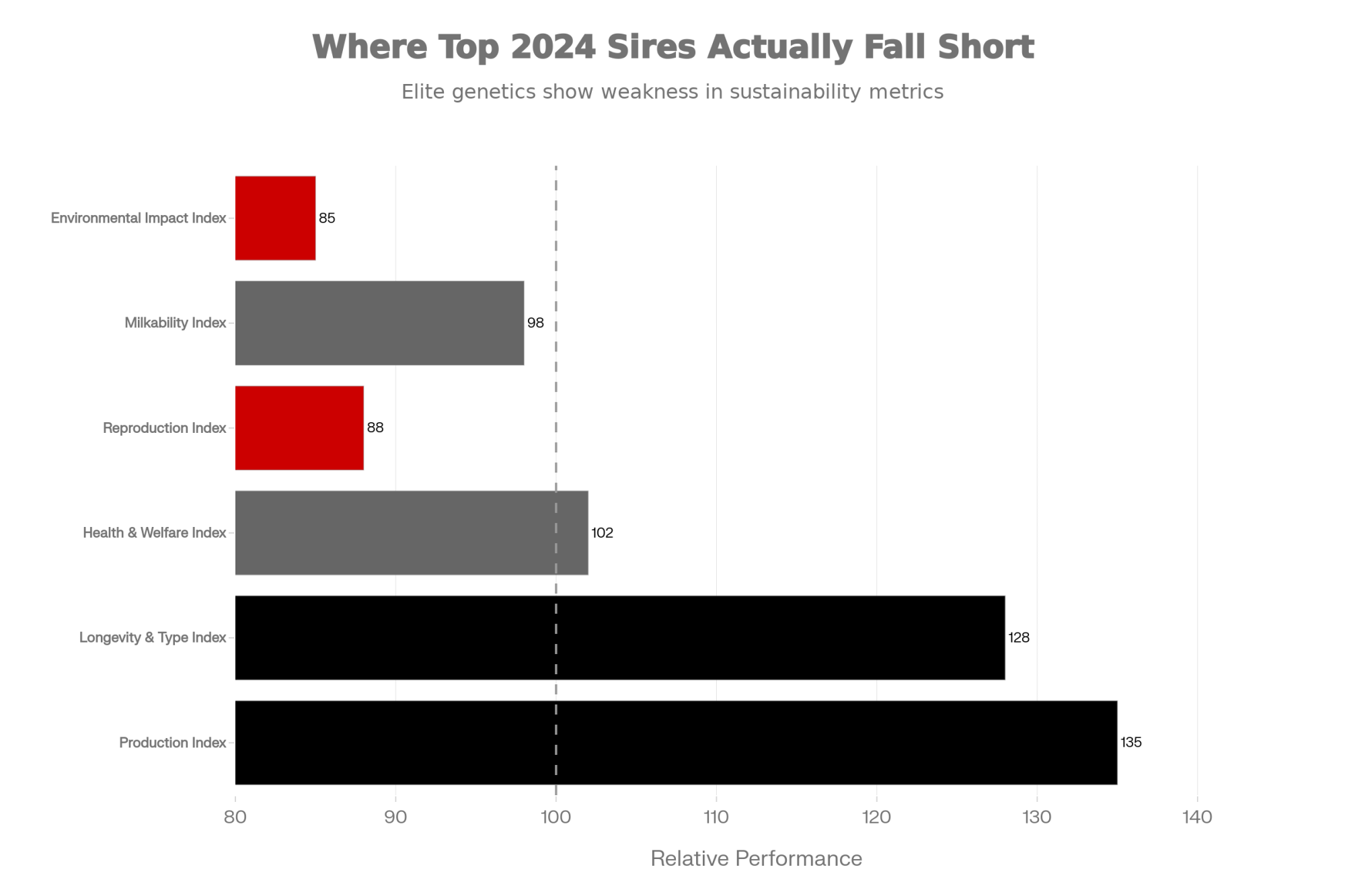

What the Top 2024 Sires Miss—and What That Means for 2026 Matings

Here’s where the Canadian sire usage data really tells a story.

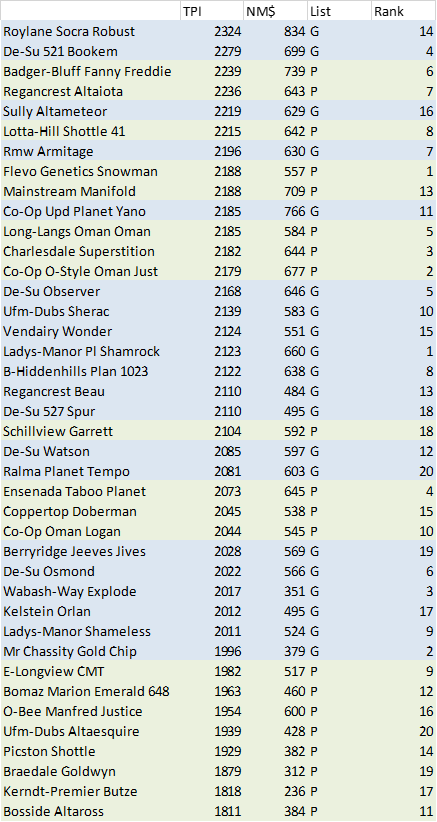

April ’25 Indexes for Twenty 2024 Sires with Most Registered Daughters

| Category | Avg Index | Index%RK | Range in %RK | % Sires Below AVG |

| Lifetime Performance Index (LPI) | 3531 | 98%RK | 81 – 99 %RK | 0% |

| Production Subindex (PI) | 659 | 93%RK | 70 – 99 %RK | 0% |

| Longevity & Type Subindex (LTI) | 678 | 98%RK | 57 – 99 %RK | 0% |

| Health & Welfare Subindex (HWI) | 500 | 50%RK | 02 – 93 %RK | 60% |

| Reproduction Subindex (RI) | 450 | 29%RK | 01 – 65 %RK | 75% |

| Milkability Subindex (MI) | 516 | 52%RK | 10 – 92 %RK | 45% |

| Environmental Impact Subindex (EII) | 475 | 40%RK | 02 – 96 %RK | 75% |

When you line up the 20 sires with the most registered daughters in 2024 and score them on the new subindexes, you get a clear pattern:

- They’re elite for LPI, Pro$, the Production, and the combined Longevity & Type subindexes.

- They’re roughly breed average for Health & Welfare and Milkability subindexes.

- They’re significantly below the breed average for Reproduction and Environmental Impact subindexes.

- Their daughters are running about 11.5% inbreeding vs a breed average of 10.6%.

In plain language:

- We’ve done an excellent job selecting bulls that lead the pack in production, type, and overall profit indexes.

- We’ve been less aggressive on fertility, cow survival under stress, and environmental footprint.

- The bulls that did the most “work” in Canadian herds in 2024 also nudged inbreeding higher.

That sets up the key question for 2026: What are you going to do when you breed those daughters?

If you continue stacking similar high‑production, below‑average‑fertility, high‑relationship sires on top of them, you’ll keep moving LPI and Pro$ up—but you may also:

- Push inbreeding higher.

- Put more strain on reproduction and transition‑cow programs.

- Lag on traits processors and regulators are starting to reward, like feed efficiency and methane‑related performance.

The alternative is to stay aggressive on genetic gain where it matters most for your herd, while using the new LPI subindexes and genomic tools to protect functional traits and diversity.

It’s worth noting that many AI companies are now actively promoting outcross or lower‑relationship bulls and subindex “balanced” sires to help address future genetic needs. Those options are on the semen delivery truck—it just comes down to whether we actually use them.

What Progressive Herds Are Doing Differently

Across Canadian Lactanet‑profiled herds, US herds highlighted in Hoard’s and Dairy Herd, and European setups facing tight environmental rules, the most progressive operations tend to do four things with their breeding programs.

1. They Don’t Stop at the Top Line Index

Most of us have, at some point, just circled the top two or three bulls on our preferred total merit index list—LPI, Pro$, Net Merit, etc.—and then called it a breeding plan. It’s quick—and to be fair, it used to work “well enough.”

The herds that are pulling ahead now ask:

- What are my top three herd problems right now—reproduction, mastitis, lameness, culling age, transition disease?

- How do those problems line up with the Reproduction, Health & Welfare, Longevity & Type, and Milkability subindexes?

Then they pick bulls that are high enough on LPI/Pro$/Net Merit and are very strong where their herd is weakest.

Examples:

- A Western Canadian quota herd shipping into a butterfat‑heavy market may load more weight on fat %, reproductive efficiency, and Environmental Impact (feed efficiency, methane efficiency), because contract and policy pressures are moving in that direction.

- A robot barn in Ontario may rank bulls first on Milkability (speed, temperament, udder/teat traits compatible with robots), then on LPI/Pro$, because slow‑milkers drag down box throughput.

The point is: the overall index gets you in the right ballpark; the subindexes and trait profiles decide whether you actually fix the problems that cost you money.

2. They Set Clear Inbreeding and Relationship Limits

Modern mating programs—whether through AI company software or integrated herd tools—let you set an expected inbreeding ceiling per mating.

A common approach:

- Target: keeping individual matings under about 8% expected inbreeding (roughly “cousin‑level” or less).

- Cap: avoid using any one sire providing more than 5–10% of replacements in a given year, so you don’t wake up in five years and realize half the herd traces back to only two bulls.

Genomic relationship data give much sharper views of how closely related bulls actually are, so herds and advisors are using it to:

- Avoid stacking very closely related sires on the same cow families.

- Balance high‑index sires across different lines to keep the gene pool wider.

This isn’t about avoiding genomics—it’s about using genomics to capture speed without painting yourself into a corner.

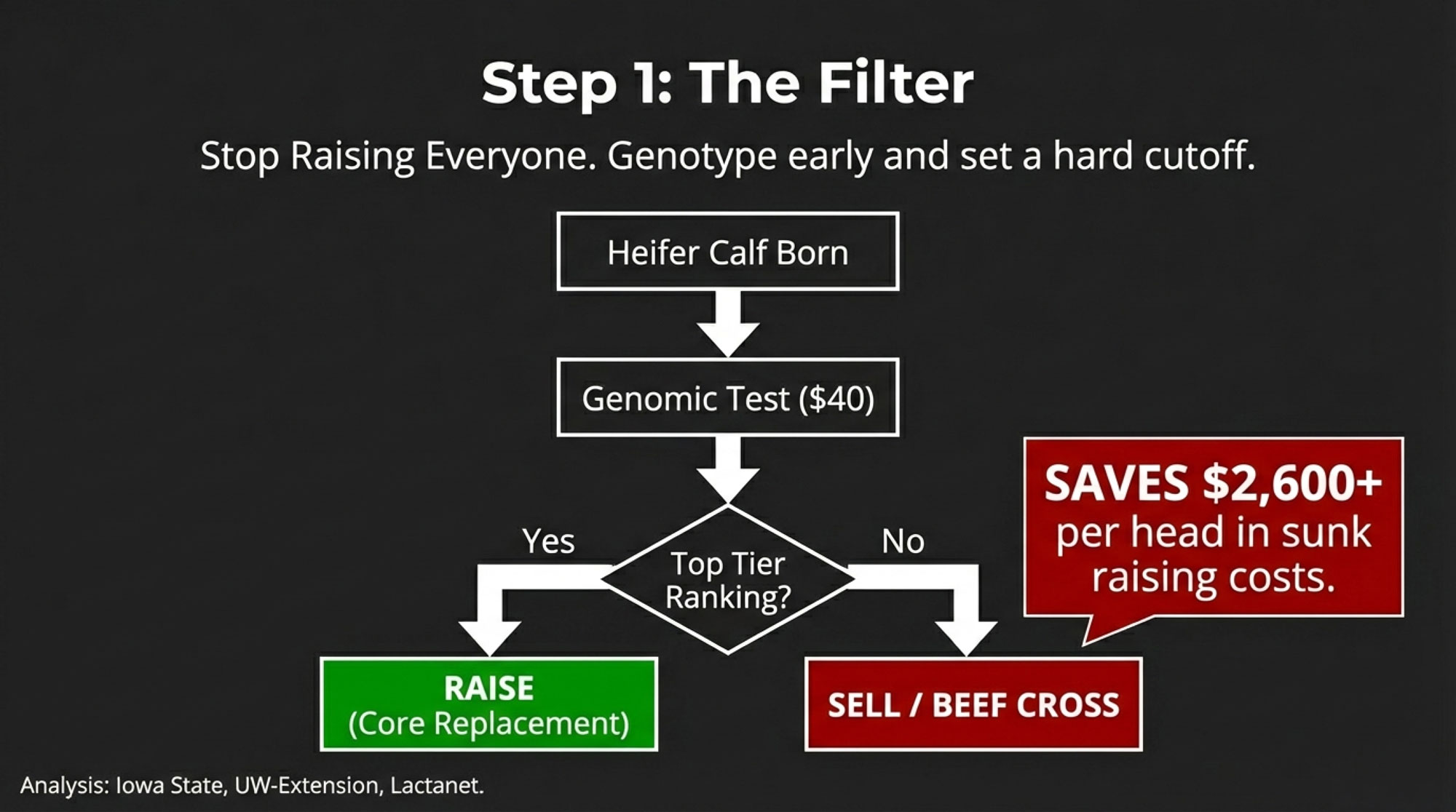

3. They Treat Haplotypes and Recessives as Standard Inputs

In 2026, ignoring fertility haplotype and genetic defect data is a bit like ignoring somatic cell counts. You can do it, but it will cost you.

The practical rule of thumb:

- Carrier sires are okay if they bring needed strengths.

- Carrier × carrier matings are not made.

On the farm, that means:

- Genomically test all replacement heifers.

- Make sure genomic testing and AI reports clearly identify carrier cows and bulls for known Holstein defects (HH1–HH6, CD/HCD, and others tracked by your provider).

- Turn on “block carrier × carrier” in mating programs.

- Review your herd’s carrier percentages; if a high proportion of heifers carry a given defect, re‑balance the sire lineup to avoid stacking that issue deeper.

Preventing even a handful of lost pregnancies or weak calves per year more than pays for the time it takes to configure those filters.

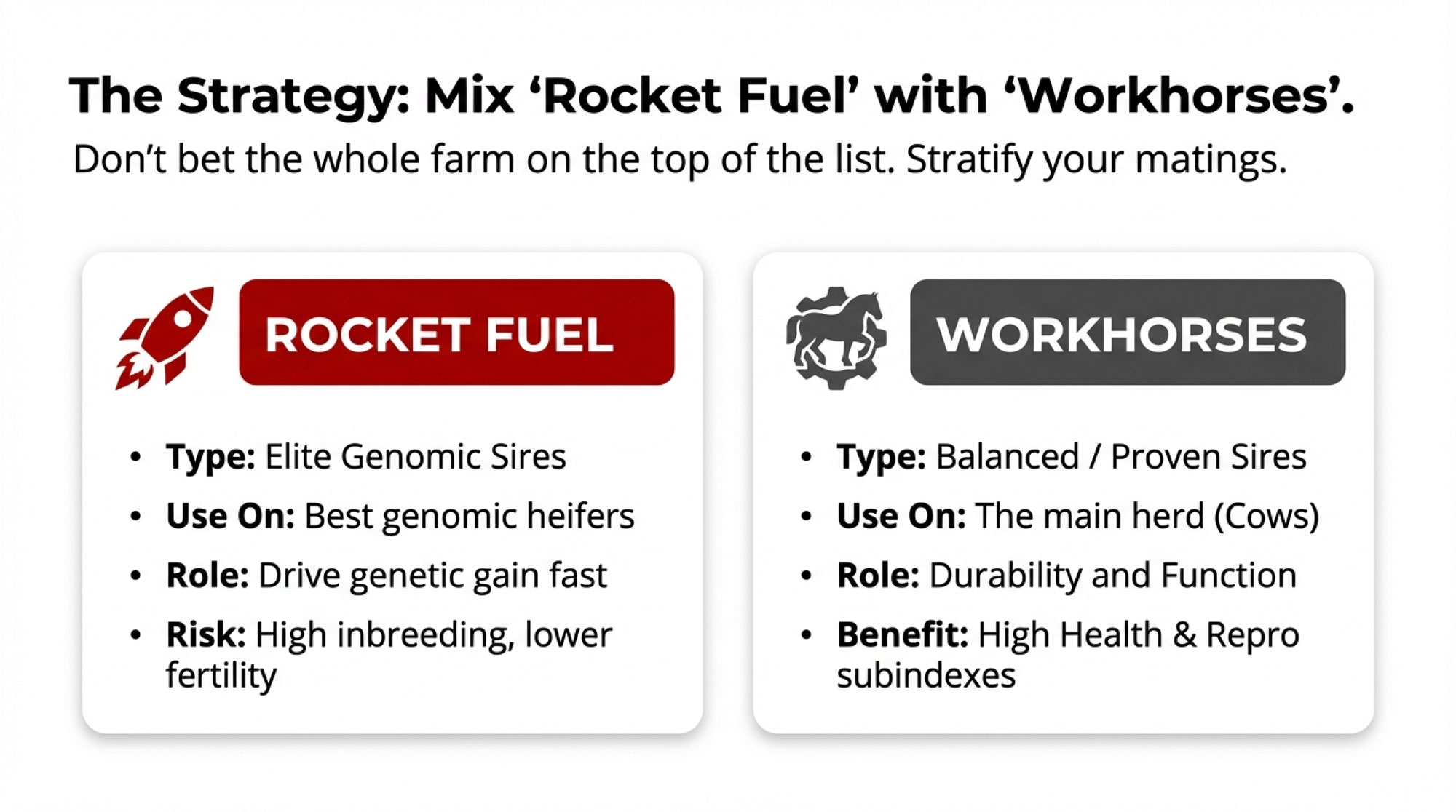

4. They Mix “Rocket Fuel” and “Workhorse” Genetics on Purpose

A pattern that shows up in data‑driven herds is deliberate stratification of matings.

For example:

- Use a select group of very high‑index “rocket fuel” sires (top LPI/Pro$/Net Merit) on the very best genomic heifers and cow families to keep the top of the herd pushing forward fast.

- Use a broader group of balanced “workhorse” sires—above average for Reproduction and Health & Welfare, solid for Longevity & Type—on the rest of the herd, especially family lines that have given you trouble on fertility or health.

That way, you:

- Capture the upside of genomics where it pays the most.

- Build a herd that isn’t full of fragile “one‑and‑done” cows that leave before third lactation.

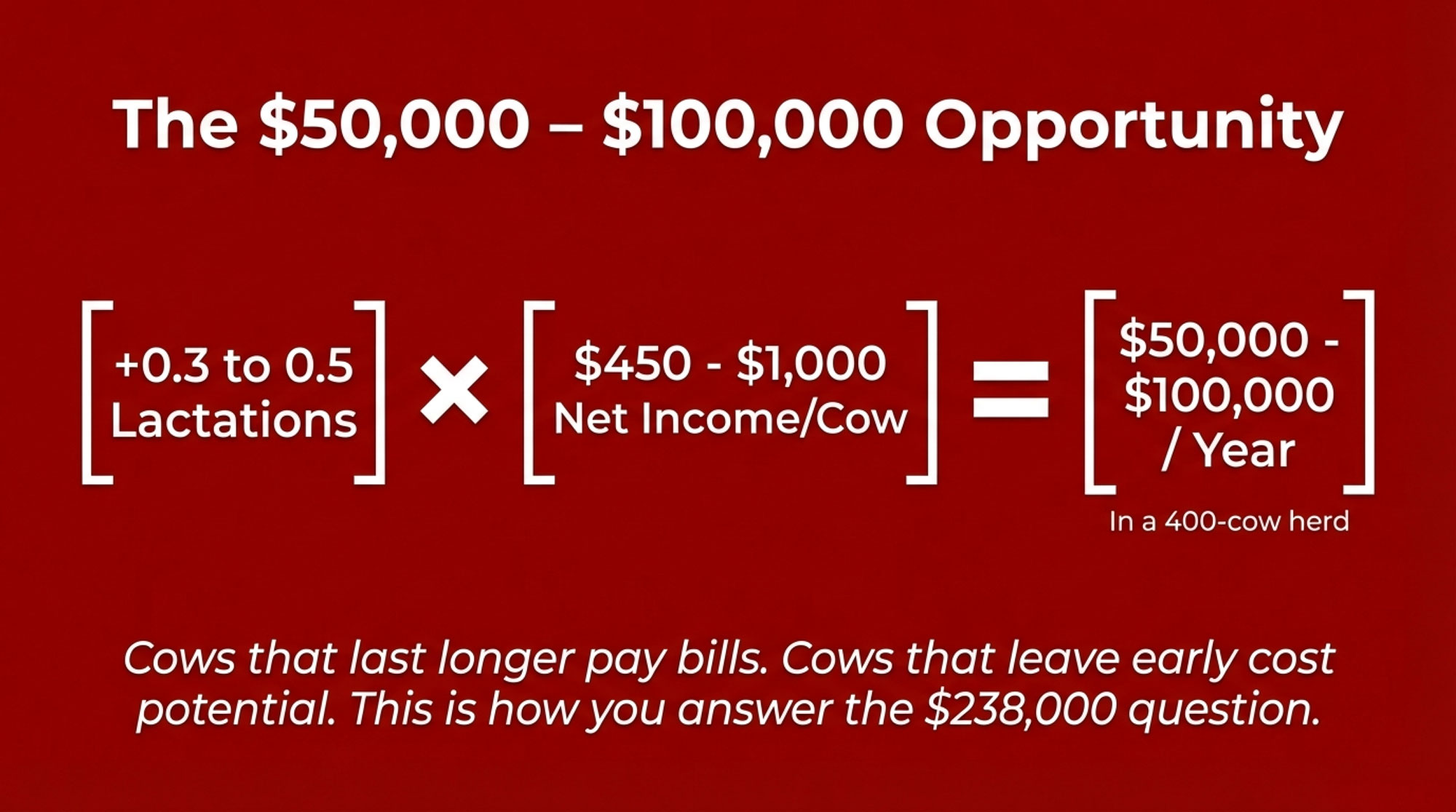

A Quick Ontario Illustration

Imagine a 400‑cow Holstein herd.

The numbers say:

- Too many cows are leaving before their fourth lactation.

- Reproduction is “okay” but not great.

- The current sire used list is heavy on very high LPI/Pro$ bulls that are below breed average for Reproduction Index and only average for Health & Welfare, with some matings up around 12–14% expected inbreeding.

A revised 3–4 year strategy might look like this:

- Keep one or two of those elite genomic or proven sires for your best genomic heifers and highest‑index cows.

- Add three to four “workhorse” genomic or proven less inbred bulls that are at or above breed average for Reproduction Index and Health & Welfare Index, and still have solid LPI/Pro$ numbers, even if they’re 200–300 points lower than the “rocket fuel” bulls.

- Set an inbreeding ceiling goal of around 8% in the mating program.

- Turn on avoidance for key haplotypes and genetic defects.

Over the next few years, you’re likely to see:

- Modest improvement in pregnancy rate and fewer days open.

- More cows are making it into fourth and fifth lactation without a parade of health or welfare events.

- Slightly slower LPI/Pro$ progress on paper, but higher actual milk shipped per cow over a lifetime, because more cows stick around long enough to exceed paying back their rearing cost and reach peak productivity.

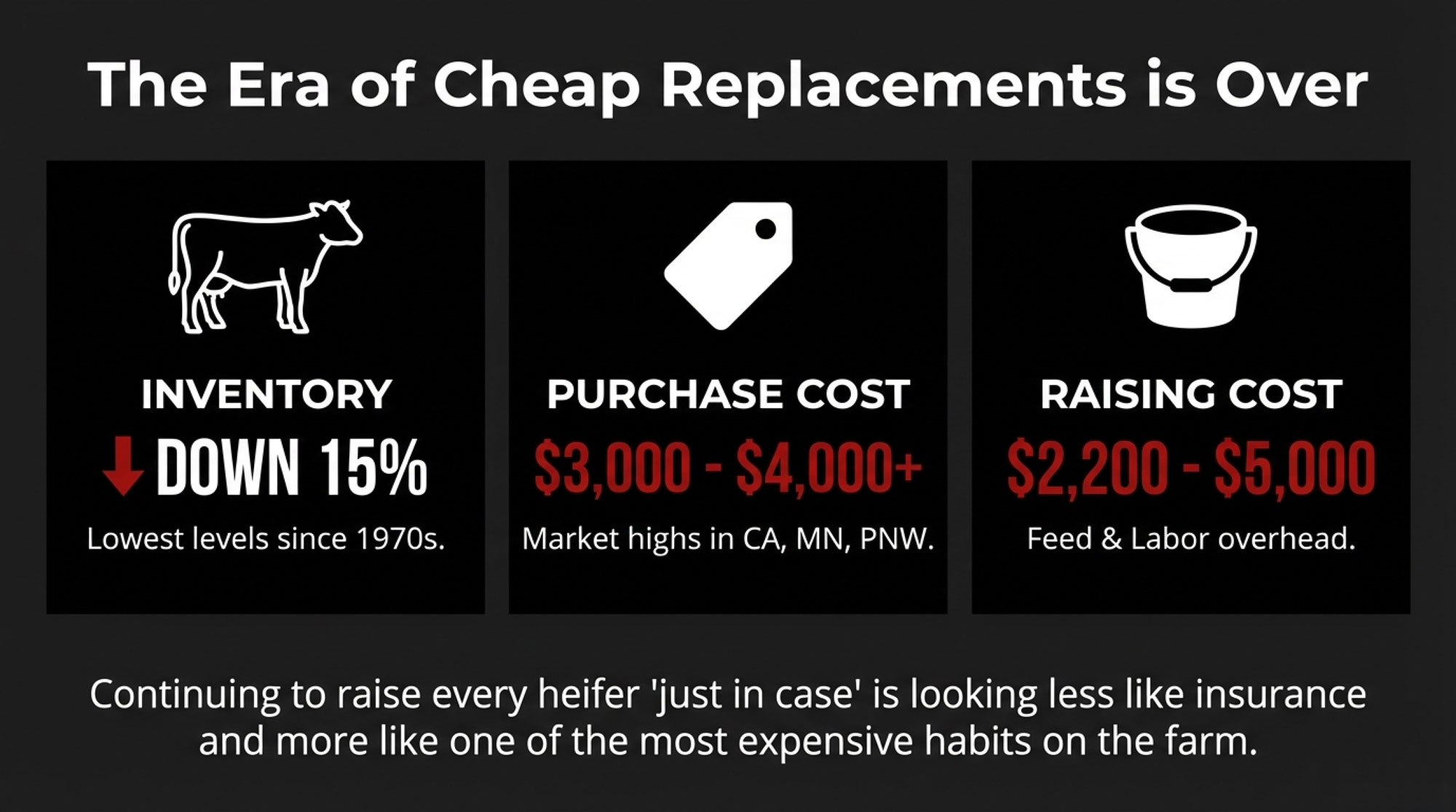

Here’s the rough math on that last point. If shifting your sire mix means an average cow stays an extra 0.3–0.5 lactations, and each additional lactation is worth roughly $1,500–$2,000 in net margin after feed and overhead, you’re looking at $450–$1,000 extra net income per cow over her lifetime. In a 400‑cow herd turning over 30–35% of cows per year, that trade‑off can easily be worth $50,000–$100,000+ per year on the income side—money that more than offsets a slightly slower climb on paper index.

| Metric | “Rocket Fuel Only” Strategy | Balanced “Rocket + Workhorse” Strategy | Difference |

| Avg LPI/Pro$ Annual Gain | +110 LPI / +240PRO$ | +85 LPI / +190PRO$ | -25 LPI / -50PRO$ |

| Avg Productive Life (Lactations) | 2.8 | 3.3 | +0.5 lactations |

| % Cows Reaching 4th Lactation | 32% | 48% | +16 percentage points |

| Avg Inbreeding (%) | 12.8% | 9.2% | -3.6 percentage points |

| Pregnancy Rate (21-day) | 18.5% | 22.0% | +3.5 points |

| Extra Net Income per Cow (Lifetime) | Baseline | +$650–$900 | +$650–$900 |

| 400-Cow Herd (Annual Impact) | Baseline | +$65,000–$90,000/year | +$65,000–$90,000/year |

| 3–5 Year Cumulative ROI | Baseline | $195,000–$450,000 | $195,000–$450,000 |

That trade‑off—slightly less “flash” for more “cows that work longer and require less individual care”—is where the real money often sits.

Three Questions to Ask Your AI Rep This Spring

If you’re not sure where to start, these questions cut through the catalog noise fast:

- “Which bulls in your lineup are above breed average for both Reproduction and Health & Welfare subindexes, and still strong on LPI/Pro$?”

This forces the conversation beyond the very top LPI or Net Merit names. - “Can you run a report showing my herd’s average expected inbreeding and carrier status for major Holstein haplotypes and genetic defects?”

This gives you a baseline for both diversity and hidden risk. - “If I wanted to balance my sire lineup between a few elite ‘rocket fuel’ bulls and more ‘workhorse’ functional sires, what would that look like for my herd?”

This turns a product pitch into a strategy discussion tailored to your data.

A Straightforward Pre‑Order Checklist

Before your next semen order or breeding push, a simple checklist ties all of this together:

- Pull the last 2 years of herd data.

- Look at culling reasons and ages; how many cows leave before fourth lactation?

- Check key KPIs: pregnancy rate, days open, mastitis/health events, SCC trends.

- Review your current sire lineup by subindex.

- For each bull, jot down Production, Longevity & Type, Reproduction, Health & Welfare, Milkability, and Environmental Impact scores under the new LPI structure.

- Flag bulls that are strong for Production but clearly below breed average for Reproduction or Health & Welfare.

- Decide on an inbreeding ceiling and diversity plan.

- Work with your advisor to set a mating target (e.g., an expected inbreeding level below 8%).

- Consider setting limits on how much any single bull can contribute to replacements over the next 1–2 years.

- Make sure haplotype and recessive filters are turned on.

- Confirm your mating software blocks carrier × carrier matings for known Holstein haplotypes and genetic defects.

- Ask for a herd‑level carrier summary so you know your starting point.

- Balance your sire list.

- Keep a select group of elite “rocket fuel” sires for the very top females.

- Add at least one or two “workhorse” sires that are clearly strong for Reproduction and Health & Welfare to shore up your everyday cows.

If you remember nothing else, remember those three pillars: protect functional traits, manage diversity, and balance elite and workhorse genetics. Together, they do more for long‑term profitability than chasing any single proof list.

So, Did Genomics Deliver? The $238,000 Answer

If we’re honest, the answer is “yes—and.”

Yes, genomics delivered faster progress and more precise selection. Studies from the US, Canada, and Europe are very clear: genetic gains in production, health, fertility, and longevity traits are higher now than in the old progeny‑testing era.

And at the same time, genomics amplified both the strengths and the weak spots in our breeding goals:

- We pushed production and type forward fast.

- We made positive strides in some health and fertility traits, but they still lag behind production in terms of genetic gain rate.

- We leaned hard on a relatively small set of sire and cow families, tightening the gene pool and increasing inbreeding.

- We uncovered haplotypes and genetic defects hitchhiking on high‑index lineages, reminding us that progress always comes with complexity.

The good news is that the tools to manage those trade‑offs—modernized LPI, Pro$, genomic testing, mating software, and herd analytics—are better than ever.

The Bottom Line

Here’s the critical point: without genomics, there is no measurable ROI on genetic improvement. In the pre‑genomic era, you couldn’t reliably capture this kind of return because you couldn’t accurately identify high‑profit genetics early enough or fast enough. Today you can—and the math works out. A 400‑cow herd making smarter breeding decisions with genomic tools can realistically capture $50,000–$100,000+ per year in additional lifetime profit from cows that stay longer, breed back faster, and require less intervention. Over a typical planning horizon of three to five years, that’s the $238,000 question answered: genomics delivered the tools; your breeding decisions determine whether you actually capture that ROI.

Most of us aren’t in this to win a banner once and sell the herd. The goal is herds we actually like milking: cows that calve in with ease, handle transition without a parade of treatments, breed back on a reasonable schedule, stay sound on their feet, and survive long enough to make heifer raising pencil out positively.

The bulls you choose this year will still have daughters freshening in your barn in 2032. The closer those daughters are to the cows you actually want in your parlor—on reproduction records, on health reports, and on your balance sheet—the more of genomics’ promise you’ll actually capture.

Genomics gave us the speed. Now the job is making sure we’re steering it in the right direction for our own future dairy enterprise.

Key Takeaways

- Genomics delivered: Genetic gains for milk, fat, protein, health, and longevity have roughly doubled since 2008—faster than progeny testing ever achieved.

- But there’s a catch: Intense selection on a small elite group has pushed inbreeding past 11% and narrowed the gene pool, quietly eroding fertility and robustness.

- New tools help you see the trade-offs: Lactanet’s six LPI subindexes show exactly where a bull stands on Reproduction, Health & Welfare, Milkability, and Environmental Impact—not just total merit.

- Progressive herds are steering, not chasing: They mix “rocket fuel” and “workhorse” sires, cap inbreeding under 8%, and block carrier × carrier matings for haplotypes and defects.

- The payoff is real: A 400-cow herd using these strategies can capture $50,000–$100,000+ per year in extra lifetime profit—that’s the $238,000 answer over 3–5 years.

Executive Summary:

Genomic selection has roughly doubled the rate of genetic gain for milk, fat, and protein, while also improving health and longevity traits compared with the old progeny‑testing era. Canadian data on the 20 most‑used Holstein sires show LPI and Pro$ values rising so fast since 2008 that daughters now generate several thousand dollars more lifetime profit per cow, adding up to $50,000–$100,000 or more per year in a well‑run 400‑cow herd. The flip side is that heavy reliance on a small group of elite families has increased inbreeding and reduced effective population size, which can chip away at fertility, health, and robustness if it’s ignored. Lactanet’s modernized LPI, with subindexes for Reproduction, Health & Welfare, Milkability, and Environmental Impact, gives breeders the dashboard they need to see those trade‑offs instead of just chasing one total merit number. Leading herds are using genomics to cap inbreeding, avoid carrier‑to‑carrier matings for haplotypes and defects, and deliberately mix a few high‑index “rocket fuel” sires with more balanced “workhorse” bulls that protect functional traits. In that context, the “$238,000 question” has a clear answer: genomics really can deliver that level of return over a few years, but only for farms that actively steer their breeding programs rather than letting the proof list do the driving.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Missing Piece in Genomic Selection: Why the Best Herds Still Walk the Pens – Stop the profit drain of early exits by identifying why cows leave before paying back their $2,600 rearing costs. This breakdown arms you with a tactical checklist to filter genomics through “cow sense” and secure more third-plus lactations.

- 2025 Dairy Year in Review: Ten Forces That Redefined Who’s Positioned to Thrive Through 2028 – Exposes the ten structural forces—from beef-on-dairy premiums to a shrinking replacement pipeline—shaping the next three years. It delivers the strategy to treat breeding as capital allocation, positioning your operation to thrive through the most volatile heifer market in 20 years.

- The Methane Efficiency Breakthrough: How Smart Breeding Cuts Emissions 30% While Boosting Your Bottom Line – Reveals how to turn the “Environmental Impact” index into a 30% efficiency win by redirecting wasted energy back into your milk check. This deep dive into methane genetics delivers a permanent competitive advantage that temporary feed additives simply cannot match.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

For decades dairy production systems have faced the challenge of attaining adequate fertility levels. Insufficient reproductive performance will result on reductions on the proportion of cows at their peak production period, increments in insemination costs, and delayed genetic progress. Moreover, impaired fertility is one of the most frequent reasons for culling and increased days open are associated with a greater risk of death or culling in the subsequent lactation.

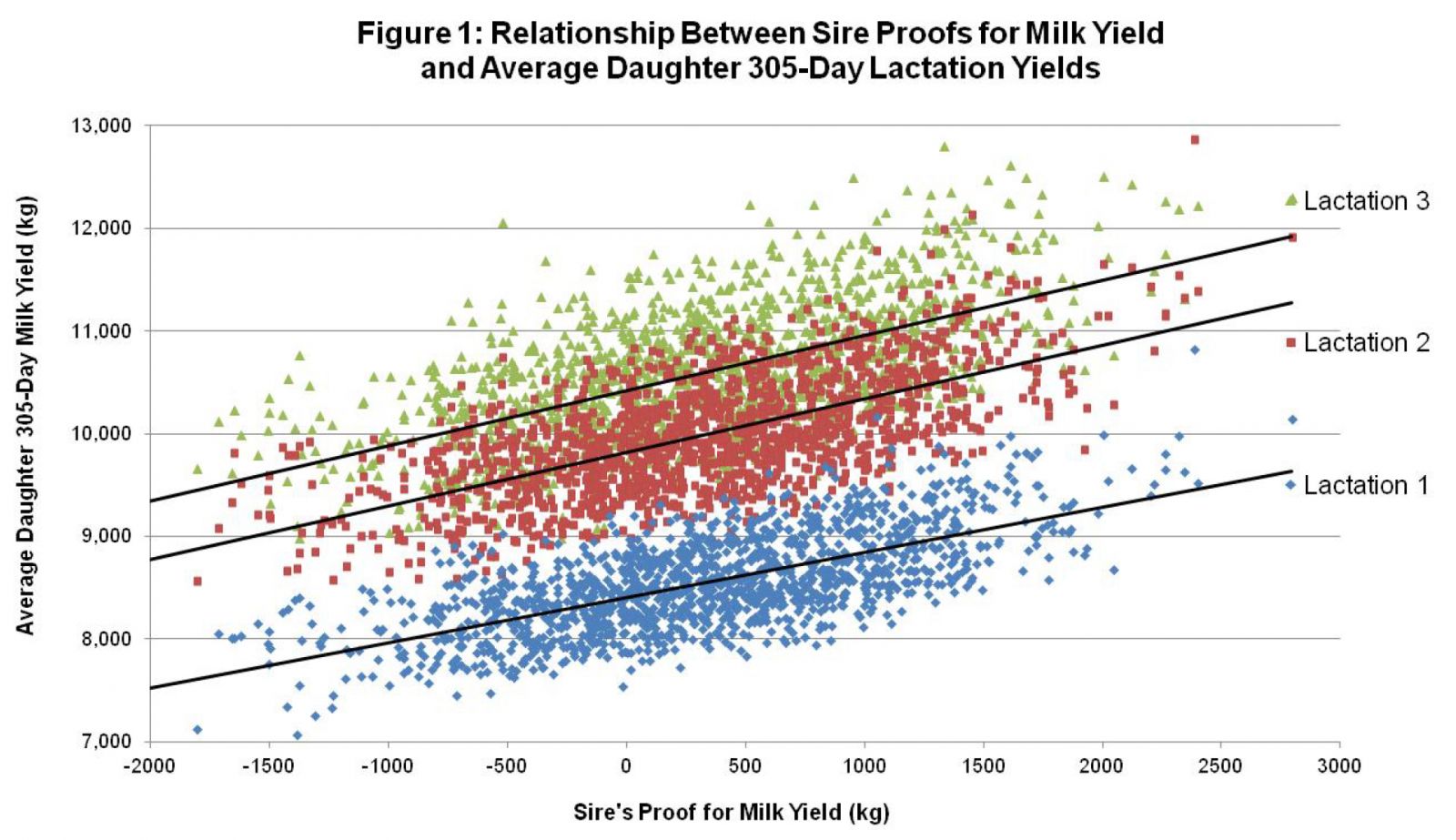

For decades dairy production systems have faced the challenge of attaining adequate fertility levels. Insufficient reproductive performance will result on reductions on the proportion of cows at their peak production period, increments in insemination costs, and delayed genetic progress. Moreover, impaired fertility is one of the most frequent reasons for culling and increased days open are associated with a greater risk of death or culling in the subsequent lactation. Dramatic changes have occurred in dairy sire selection practices in recent years. These changes have been facilitated by the sequencing of the bovine genome, which led to the discovery of thousands of DNA markers, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs. The development of predicted breeding values based on marker data alone (Meuwissen et al., 2001), coupled with a reduction in the cost of genotyping, has allowed for accurate genomic selection of dairy sires by AI centers. As described by Hayes et al. (2009) genomic selection refers to selection decisions based on genomic breeding values (GEBV). Before continuing the discussion on genomic selection, however, it is important to understand traditional progeny testing. Historically, progeny testing was key to genetic improvement of dairy cattle (Sattler, 2013), via identification of the best bulls for widespread use and as sires of bulls for the next generation.

Dramatic changes have occurred in dairy sire selection practices in recent years. These changes have been facilitated by the sequencing of the bovine genome, which led to the discovery of thousands of DNA markers, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs. The development of predicted breeding values based on marker data alone (Meuwissen et al., 2001), coupled with a reduction in the cost of genotyping, has allowed for accurate genomic selection of dairy sires by AI centers. As described by Hayes et al. (2009) genomic selection refers to selection decisions based on genomic breeding values (GEBV). Before continuing the discussion on genomic selection, however, it is important to understand traditional progeny testing. Historically, progeny testing was key to genetic improvement of dairy cattle (Sattler, 2013), via identification of the best bulls for widespread use and as sires of bulls for the next generation.

In the coming weeks, Irish dairy farmers will be sitting down to select sires to breed the next generation of cows on their farms.

In the coming weeks, Irish dairy farmers will be sitting down to select sires to breed the next generation of cows on their farms.

.jpg)

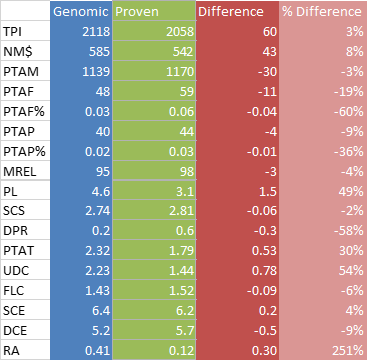

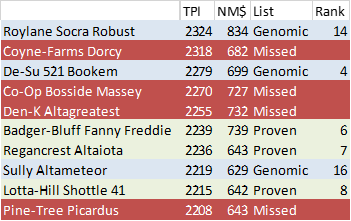

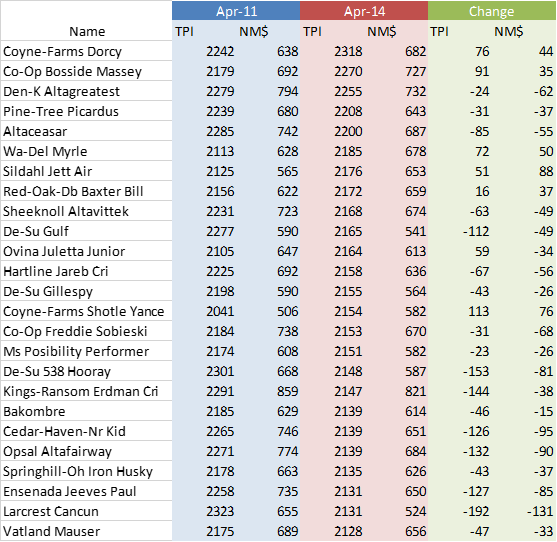

We’re well into the genomic era. If you’re like most producers, you’re now comfortable incorporating genomic-proven bulls as part of your balanced breeding program.

We’re well into the genomic era. If you’re like most producers, you’re now comfortable incorporating genomic-proven bulls as part of your balanced breeding program.

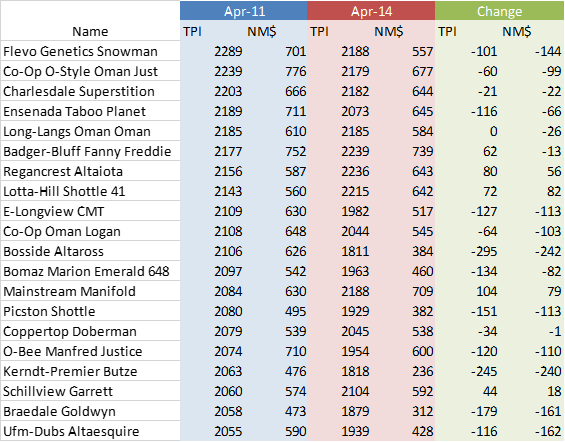

Graph 3. Histogram of difference in TPI from genomic release in 2013 to April 2017 daughter proof

Graph 3. Histogram of difference in TPI from genomic release in 2013 to April 2017 daughter proof Graph 4. Histogram of difference in NM$ from genomic release in 2013 to April 2017 daughter proof

Graph 4. Histogram of difference in NM$ from genomic release in 2013 to April 2017 daughter proof.JPG)

A University of Wisconsin research professor is nearly finished with a study on genomic selection for feed efficiency in dairy cows.

A University of Wisconsin research professor is nearly finished with a study on genomic selection for feed efficiency in dairy cows. Scotland may be best known for bagpipes, but it’s the data derived from Scottish dairy cows that is music to the ears of genomic researchers.

Scotland may be best known for bagpipes, but it’s the data derived from Scottish dairy cows that is music to the ears of genomic researchers. In light of some recent election results, “giving the people what they want” isn’t always the way to go. When those people are the beneficiaries of research efforts, however, it’s not a bad idea.

In light of some recent election results, “giving the people what they want” isn’t always the way to go. When those people are the beneficiaries of research efforts, however, it’s not a bad idea..jpg)

Advances in genomic testing create new opportunities for commercial dairy producers to have more control over their herds’ profit potential. With an abundance of available replacement heifers, producers have the ability to replace less profitable cows with genetically superior heifers, shortening the generation interval and accelerating the genetic progress.

Advances in genomic testing create new opportunities for commercial dairy producers to have more control over their herds’ profit potential. With an abundance of available replacement heifers, producers have the ability to replace less profitable cows with genetically superior heifers, shortening the generation interval and accelerating the genetic progress.![Neogen-logo[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Neogen-logo1.gif) For genomic selection, researchers look for markers or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A SNP is a place in a chromosome where the DNA sequence can differ among individuals. SNPs are most useful when they occur close to a gene that contributes to an important trait. Most traits are controlled by many genes, making this a very complex process. Significant progress was made when a genotyping computer chip was developed that could identify more than 50,000 SNPs (50K test) on the genome.

For genomic selection, researchers look for markers or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). A SNP is a place in a chromosome where the DNA sequence can differ among individuals. SNPs are most useful when they occur close to a gene that contributes to an important trait. Most traits are controlled by many genes, making this a very complex process. Significant progress was made when a genotyping computer chip was developed that could identify more than 50,000 SNPs (50K test) on the genome. Seven years into it, genomics has become nearly as common of a term as AI. We’re now used to the genetic technology and feel confident using genomic-proven bulls as part of a balanced breeding program.

Seven years into it, genomics has become nearly as common of a term as AI. We’re now used to the genetic technology and feel confident using genomic-proven bulls as part of a balanced breeding program.

Dr. Weigel grew up in Iowa on the family farm (Weigeline Holsteins) and graduated from Iowa State University with a Degree in Dairy Science. He received both his M.S. and PhD from Virginia Tech, with his dissertation focusing on the prediction of genetic merit for lifetime profitability in Holsteins. Before joining the R&D group of Zoetis (formerly Pfizer Animal Health) in 1995, Dr. Weigel served as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Guelph working on the implementation of Multiple Across Country Evaluations (MACE) for conformation traits of Holstein sires. Dr. Weigel’s current role with Zoetis is in Outcomes Research and he remains active as a breeder of Registered Holsteins.

Dr. Weigel grew up in Iowa on the family farm (Weigeline Holsteins) and graduated from Iowa State University with a Degree in Dairy Science. He received both his M.S. and PhD from Virginia Tech, with his dissertation focusing on the prediction of genetic merit for lifetime profitability in Holsteins. Before joining the R&D group of Zoetis (formerly Pfizer Animal Health) in 1995, Dr. Weigel served as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Guelph working on the implementation of Multiple Across Country Evaluations (MACE) for conformation traits of Holstein sires. Dr. Weigel’s current role with Zoetis is in Outcomes Research and he remains active as a breeder of Registered Holsteins.![zoetis[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/zoetis1.jpg)

Lindsey Worden has worked as Holstein Association USA’s Executive Director of Holstein Genetic Services since October 2013. In her role, she oversees staff responsible for maintaining the Association’s genomic and genetic testing programs and software programs such as Red Book Plus/MultiMate, as well as other performance programs such as classification and production records products, providing guidance and direction for various Association initiatives. Worden was HAUSA’s project manager for the development of the Enlight™ genetic management tool, which was developed in collaboration with Zoetis, and now oversees the team responsible for supporting the product. Prior to her current responsibilities, she served as Holstein Association USA’s communications manager for more than 6 years. Worden is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she studied dairy science and life science communications and was an active member of the Association of Women in Agriculture, Badger Dairy Club and the dairy judging team. She has had a lifetime of involvement in the dairy industry and Registered Holsteins growing up on her family’s dairy operations in New York and New Mexico, and in her free time still enjoys helping out on her family’s Central New York dairy and working with her cattle. Worden works out of the Holstein Association USA headquarters in scenic Brattleboro, Vermont.

Lindsey Worden has worked as Holstein Association USA’s Executive Director of Holstein Genetic Services since October 2013. In her role, she oversees staff responsible for maintaining the Association’s genomic and genetic testing programs and software programs such as Red Book Plus/MultiMate, as well as other performance programs such as classification and production records products, providing guidance and direction for various Association initiatives. Worden was HAUSA’s project manager for the development of the Enlight™ genetic management tool, which was developed in collaboration with Zoetis, and now oversees the team responsible for supporting the product. Prior to her current responsibilities, she served as Holstein Association USA’s communications manager for more than 6 years. Worden is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she studied dairy science and life science communications and was an active member of the Association of Women in Agriculture, Badger Dairy Club and the dairy judging team. She has had a lifetime of involvement in the dairy industry and Registered Holsteins growing up on her family’s dairy operations in New York and New Mexico, and in her free time still enjoys helping out on her family’s Central New York dairy and working with her cattle. Worden works out of the Holstein Association USA headquarters in scenic Brattleboro, Vermont. Cheryl Marti is the U.S. Marketing Manager for Dairy Genetics and Reproductive Products for Zoetis. She received her B.S. from the University of Minnesota in Animal Sciences, her M.S. in Dairy Science (Genetics emphasis) at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, and her MBA from UW-Whitewater. Cheryl worked in the AI industry at ABS Global for over 11 years in many different capacities, including management, marketing, training and technical support of the Genetic Management System (a genetic mate assignment program), and also worked in the Sire Acquisition and Research areas. She joined Pfizer Animal Health, now Zoetis, in 2005, first as a Fresh Cow Reproduction Manager in the Great Lakes states and later as a Dairy Production Specialist in WI where she often worked with large dairies on genomics, reproduction, records analysis, and transition cows until mid-2014 when she moved into her current role. Her experiences include working with herds of all sizes across the U.S. and over a dozen countries on 6 continents. Cheryl’s passion for the dairy industry and genetics began at her family’s Registered Holstein farm in Sleepy Eye, MN, where she owns some cattle, and her sister and brother-in-law own and operate their family farm of 700 acres and a 160-cow dairy called “Olmar Farms.

Cheryl Marti is the U.S. Marketing Manager for Dairy Genetics and Reproductive Products for Zoetis. She received her B.S. from the University of Minnesota in Animal Sciences, her M.S. in Dairy Science (Genetics emphasis) at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, and her MBA from UW-Whitewater. Cheryl worked in the AI industry at ABS Global for over 11 years in many different capacities, including management, marketing, training and technical support of the Genetic Management System (a genetic mate assignment program), and also worked in the Sire Acquisition and Research areas. She joined Pfizer Animal Health, now Zoetis, in 2005, first as a Fresh Cow Reproduction Manager in the Great Lakes states and later as a Dairy Production Specialist in WI where she often worked with large dairies on genomics, reproduction, records analysis, and transition cows until mid-2014 when she moved into her current role. Her experiences include working with herds of all sizes across the U.S. and over a dozen countries on 6 continents. Cheryl’s passion for the dairy industry and genetics began at her family’s Registered Holstein farm in Sleepy Eye, MN, where she owns some cattle, and her sister and brother-in-law own and operate their family farm of 700 acres and a 160-cow dairy called “Olmar Farms.

![lucky_20679[2]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/lucky_206792-210x300.jpg) In the 1920’s and 30’s cigarette companies not only denied the health risks of smoking, they actually promoted them as a good thing, by putting up testimonials and stats about doctors who smoked. During the 1920s, Lucky Strike was the dominant cigarette brand. This brand, made by American Tobacco Company, was the first to use the image of a physician in its advertisements. “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating,” its ads proclaimed. Of course many years later we are well aware of the health risks (480,000 people die prematurely each year in the US, due to smoking or being exposed to smoke). It’s flashbacks to this false advertising experience that dairy breeders are referencing when they distrust the use of genomics in dairy cattle breeding. They feel that it’s just the AI companies “forcing” genomics down their throats, in the same way that the tobacco companies “forced” smoking down the throats of millions, by using the weight of doctors’ credibility.

In the 1920’s and 30’s cigarette companies not only denied the health risks of smoking, they actually promoted them as a good thing, by putting up testimonials and stats about doctors who smoked. During the 1920s, Lucky Strike was the dominant cigarette brand. This brand, made by American Tobacco Company, was the first to use the image of a physician in its advertisements. “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating,” its ads proclaimed. Of course many years later we are well aware of the health risks (480,000 people die prematurely each year in the US, due to smoking or being exposed to smoke). It’s flashbacks to this false advertising experience that dairy breeders are referencing when they distrust the use of genomics in dairy cattle breeding. They feel that it’s just the AI companies “forcing” genomics down their throats, in the same way that the tobacco companies “forced” smoking down the throats of millions, by using the weight of doctors’ credibility.![camels_doctors_whiteshirt[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/camels_doctors_whiteshirt1-234x300.jpg) For a long time, physicians were the authority on health. Patients trusted their doctor’s education and expertise and, for the most part, followed their advice. When health concerns about cigarettes began to receive public attention in the 1930s, tobacco companies took preemptive action. They capitalised on people’s trust of physicians, to quell concerns about the dangers of smoking. Thus was born the use of doctors in cigarette advertisements. Executives at tobacco companies knew they had to take action to suppress the public’s fears about tobacco products.

For a long time, physicians were the authority on health. Patients trusted their doctor’s education and expertise and, for the most part, followed their advice. When health concerns about cigarettes began to receive public attention in the 1930s, tobacco companies took preemptive action. They capitalised on people’s trust of physicians, to quell concerns about the dangers of smoking. Thus was born the use of doctors in cigarette advertisements. Executives at tobacco companies knew they had to take action to suppress the public’s fears about tobacco products.![MW-AK965_cigare_20110621090115_MG[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/MW-AK965_cigare_20110621090115_MG1.jpg)

April Fools. There are just those breeders who will never accept Genomics as a tool in their breeding toolbox. For those of you who have or are still need convincing on why to use genomics in your breeding strategy we offer the following articles:

April Fools. There are just those breeders who will never accept Genomics as a tool in their breeding toolbox. For those of you who have or are still need convincing on why to use genomics in your breeding strategy we offer the following articles:

The dairy industry needs to “wake up” to the dangers of using genomic bulls on maiden heifers, according to a breeding specialist.

The dairy industry needs to “wake up” to the dangers of using genomic bulls on maiden heifers, according to a breeding specialist.![330px-Diffusion_of_ideas.svg[1]](https://www.thebullvine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/330px-Diffusion_of_ideas.svg1_.png) The reason for this has nothing to do with the merits of genomic sires versus proven sires. Rather it has to do with the historical patterns of adoption of new technologies. The theory behind this is called the Diffusion of Innovations. According to this theory, consumers differ in their readiness and willingness to adopt new technology. There are the innovators (2.5 percent of the population), the early adopters (13.5 percent), the early majority (34 percent), the late majority (34 percent), and the laggards (16 percent), who are also the people who still don’t have cell phones or who are not on Facebook.

The reason for this has nothing to do with the merits of genomic sires versus proven sires. Rather it has to do with the historical patterns of adoption of new technologies. The theory behind this is called the Diffusion of Innovations. According to this theory, consumers differ in their readiness and willingness to adopt new technology. There are the innovators (2.5 percent of the population), the early adopters (13.5 percent), the early majority (34 percent), the late majority (34 percent), and the laggards (16 percent), who are also the people who still don’t have cell phones or who are not on Facebook.

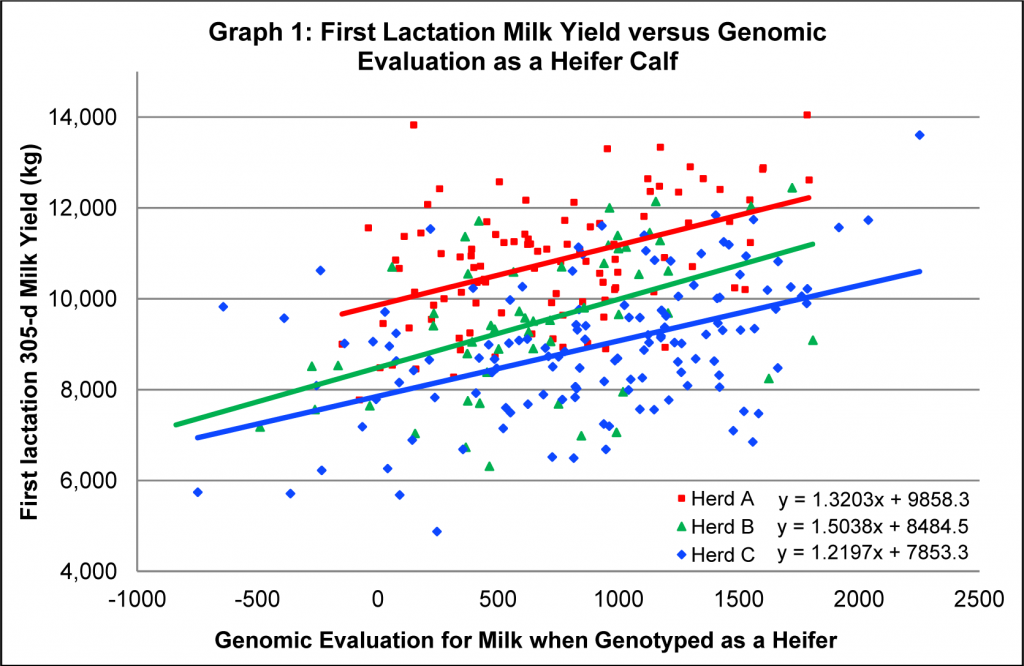

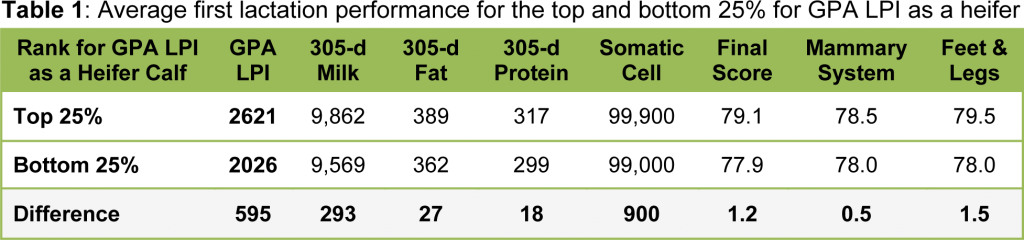

Over the past few years, we’ve seen many examples of the benefits of genomics on the sire side. Quantifying the advantages of genomic selection on the female side has been slower, primarily due to the cautious adoption of the technology at the herd level. Of the registered Holstein heifers born in Canada in 2013, less than 5% were genotyped. On the other hand, CDN projections show that uptake could increase to surpass the 18% mark by year 2020.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen many examples of the benefits of genomics on the sire side. Quantifying the advantages of genomic selection on the female side has been slower, primarily due to the cautious adoption of the technology at the herd level. Of the registered Holstein heifers born in Canada in 2013, less than 5% were genotyped. On the other hand, CDN projections show that uptake could increase to surpass the 18% mark by year 2020.

The dairy industry has greatly evolved over the years with necessity-driven innovation. In order to be efficient in feeding a growing world, it has to.

The dairy industry has greatly evolved over the years with necessity-driven innovation. In order to be efficient in feeding a growing world, it has to.