I’ve been known to be random. Quite random in fact. Anyone who reads the Bullvine will find that sometimes there will be articles that seem to come out of nowhere. This is because my mind seems wander all over the place sometimes and then all of sudden I get an idea and a thought for a new article or topic of discussion comes out of the blue. The other day I was looking through my Facebook news stream and saw a picture of a turkey wrapped in bacon, which I shared of course because, in my unbiased opinion, there is nothing better than turkey and bacon together. Nevertheless this is not a naturally occurring combination. And, while delicious, it is definitely selectively controlled. This spurred the thought about the need to be random in sire sampling and how our young sire programs have gone from being random to totally controlled.

The Evolution of Genetic Evaluations

Prior to the introduction of Genomics, a young sire who was selectively sampled, say regionally, would have never been touched as breeders would have limited confidence in this sire’s ability to transmit when used in other herd environments. That is because in order to get an accurate genetic evaluation of a young sire you needed to have young bulls sampled in many different herd environments where their daughters’ performance could be compared with contemporaries under a range of different circumstances. This is the very foundation that our “Animal Model” is built on.

Over the years the way we look at sires has changed drastically. First we looked at how their daughters’ average performance compared to other sires, with no regard for herd mate performance. A method I see some old school breeders still using today. In the 1970’s came the Modified Contemporary Comparison (MCC), which started to incorporate the performance of herd mates into evaluating sires. This system was further improved to incorporate more information from relatives and resulted in the introduction of the full (cow and bull) Animal Model in 1989.

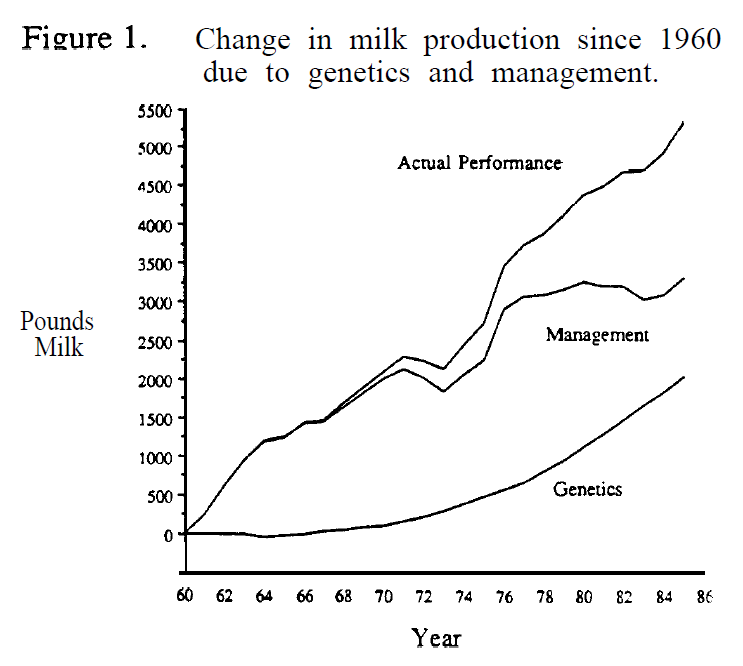

It is interesting to see that if you look at the rate of genetic gain prior to 1974 (prior to the introduction of the MCC), you see that the rate has greatly increased since.

The five key factors that are considered in the animal model are:

- The cow’s management group

- The cow’s genetic merit

- The cow’s permanent environment

- The common environment of paternal-half sisters

- Other unexplained random environment

Where the problem lies is with that fifth factor” other unexplained random environment.” Typically, that is meant to refer to the differences that still exist among cows’ records that haven’t been explained by other factors in the model. In the past this was temporary as it does not affect a cow’s transmitting ability, as in the case of decline in milk yield due to mastitis flare-up. The problem is this still assumed that everything thing was being done on a random basis with no herd and no selective sampling.

The Genomic Era – Not Random

The simplest way for the Animal Model to account for all things that cannot be explained is as a random event. When spread over a large enough sample size, those random events will average out and we will be left with the true genetic merit of those animals we are evaluating. That all worked just fine, prior to the introduction of genomics, when young sires where randomly sampled over many different herd environments, and a wide variety of dams with different degrees of genetic merit. But with the introduction of genomics, no longer are young sires being sampled on just average cows. They are now being selectively used on some of the highest genetic merit cattle in the world. This is totally kicking that random principle out the window.

Young sires are no longer randomly sampled. In today’s genomic age, a lot of the systems and controls are gone. Yes, many of the sires are still offered to all breeders (well at least they say they are), but these high-ranking young sires are sold at a much higher price, and marketed much heavier. In addition often the first release semen is only used on contract matings on extremely high index, carefully selected mates. This results in anything but random sampling and in reality is almost the perfect method for receiving an inflated proof. It isn’t just because of the actual mates they are being used on but also because of the care the resulting calves will receive.

Sure you can say that the Animal Model is supposed to account for this. See bullet number 2 in factors considered by the animal model. But is it doing so accurately? Of even more concern is the bias resulting from the preferential treatment that offspring of the highest genomics sires receive (Read more: Preferential Treatment – The Bull Proof Killer). It’s only natural for these animals to receive this preferential treatment. The problem is that the Animal Model does not account for it.

This is not a new problem. It’s just being amplified. In the past this happened very frequently. Just look at second country proofs of some elite daughter proven sires, Shottle, Planet, Man-O-Man, preferential treatment and selective use had these sire skyrocket to the top of the lists, only to settle back down once more random sampling occurred. This is something we have already seen with Observer, His initial proof had him #1 in the US for TPI then once more daughters were added he settled to a respectable #8 among 99% reliable sires (Read more: Genomics at Work – August 2013).

One way this was dealt with in the past was to increase the minimum level of reliability for foreign bulls to receive domestic proofs. In general this strategy was sufficient in the pre-genomic era, but even the centers that produce the genetic evaluations, such as CDN, are no longer finding this works in the current animal model.

The Bullvine Bottom Line

At the Bullvine we would love to say we know the solution. The challenge is we don’t. Furthermore, I am not sure even those responsible for solving this problem have a clear grip on how to handle this. Sure we could up the requirement for sires to receive their first proof, but is that really going to solve the problem? What I do know is that time is of the essence. Within the next 12 months many of the sires that heavily promoted and selectively used post the introduction of genomics will be receiving progeny proofs in 2014. If we don’t find a solution to this problem soon, we are all going to look as manufactured as bacon wrapped turkeys.

Not sure what all this hype about genomics is all about?

Want to learn what it is and what it means to your breeding program?