When Sarah Chase returned from college to her family farm in Pine Plains, she wasn’t expecting to take after her parents and become a dairy farmer.

“My dad had made it clear that dairy farming, especially for small farms like ours, is kind of impossible,” she said. “He had done his best to pinch pennies, but he never expected anyone to come back here.”

Chase realized that she wanted to pursue a more holistic approach to organic dairy farming by focusing on fully pasturing her herd of more than 90 cows and only producing 100 percent grass-fed organic milk.

“The idea was to be grazing so I could spend less money on grain. To do everything in a certain kind of way to improve overall health of the soil and increase yields over time and have less and less of a dependence on imported seeds,” Chase said.

Grass-fed farming is linked to the practice of regenerative agriculture. The practice emphasizes creating a healthier environment by building topsoil and reducing erosion. Animals naturally moving through pasture and grazing on a variety of native plants encourages grasslands to rebuild.

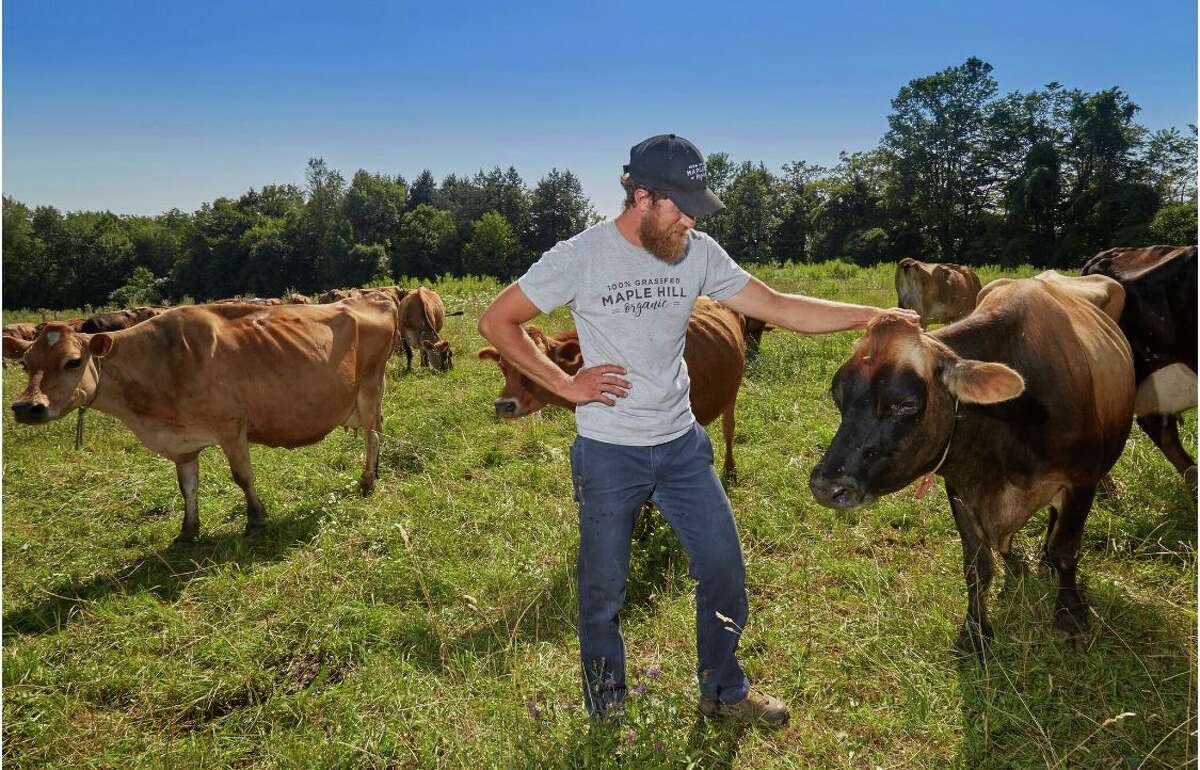

Maple Hill Creamery

New York is the fourth largest milk producer in the country and the largest producer of yogurt, cottage cheese, and sour cream. Yet, as the industry continues to consolidate around profit margins and consumers explore milk alternatives, small farms are either pushed out or forced to sacrifice quality for quantity. Between 2009 and 2019, the state lost around 1,500 dairy farmers, according to data from the state’s Department of Agriculture and Markets.

Grass-fed dairy farming in New York State (NYS) is still just a small drop in the overall bucket of about 4,000 dairy farms across the state, but it is providing small farmers a specialized niche that caters to consumers who want a connection to local farmers and communities while offering the health benefits of fully-pastured cows. Yet, the market for products that claim ethical agricultural practices like organic dairy (or dairy alternatives like nut and oat milks) has become crowded, challenging grass-fed dairies to gain a foothold with consumers.

Chase has run Chaseholm Farm for nine years and has slowly bred a herd that efficiently produces grass-fed milk. She sells her milk through some local wholesalers and to her brother who owns and operates Chaseholm Farm Creamery (a separate business even though they often work together). A lot of Chaseholm milk is made into yogurt which is the “moneymaker” at the on-site farm store, Chase said.

Chase farms 550 acres and leases another 300 acres of land to harvest enough hay to feed the herd in colder months when the cows can’t go out on the land.

Chaseholm Farm

The cost of production is high in grass-fed dairy farming because each cow needs multiple acres to graze on, and farmers need to move their herds through different pastures to allow the grasses to regrow. Conventional dairy operations have hundreds if not thousands of cows, so this would require doubling or tripling its typical acreage, making it cost-prohibitive.

Instead, these larger, conventional dairies rely on keeping cows in pens where the animals are fed grain and corn. This maximizes the size of the herd, allows the cows to produce more milk in a shorter period, and requires significantly less land. But this conventional approach emphasizing milk volume runs counter to a cow’s natural diet and often shortens a traditional dairy cow’s lifespan.

The leader of the grass-fed herd

“When you feed a cow what it was supposed to be fed, they are going to produce what their bodies were intended to produce, not anything more,” said Carl Gerlach, CEO of Maple Hill Creamery. “And that is considerably less than what it is if they are fed corn or grain.”

Farmers wanting to label their milk as USDA organic (as opposed to conventional milk) have their own challenges, including offering pasture to graze, new feeding regimes, and buying (or growing) organic feed grain. Buying organic grain is expensive and growing feed crops requires labor, equipment, and time devoted to tilling and harvesting feed. Adapting a herd to graze on fields requires time for the animals to adapt to a more natural diet, but in the end, reduces costs to farmers.

Chaseholm Farm

Maple Hill Creamery is one of the leaders in the grass-fed dairy movement. The company was founded in late 2009 on one farm in Little Falls and has grown into the largest grass-fed dairy in the country. It buys pastured milk from around 180 partner farms in New York state, and its products are found nationwide.

The company believes that grass-fed is driving the organic dairy segment and will only continue to grow as people learn more about it, Gerlach said. “Consumers know about it, they like it, they try it again, they pay more for it because of all of the work that goes into producing a super high-quality product.”

Going grass-fed to stay in farming

Further west in Worcester in Otsego County, Tom McGrath sees grass-fed organic dairy farming as a way to save the small family farm. He has spent the last 10 years adapting his herd to be 100 percent grass-fed and recently built a processing plant to focus on a regional brand called Family Farmstead that offers grass-fed milk that is not homogenized or high temperature pasteurized.

McGrath is vat pasteurizing at 145 degrees which retains more natural enzymes and good bacteria. The downside is that the shelf-life is 20 days as opposed to the multiple months that ultra-pasteurized milk can stay shelf-stable, he said.

Along with the milk being “nearly raw” in terms of processing, Family Farmstead also markets its products as containing the A2 protein which some studies show is easier to digest than conventional milk.

“A lot of people call or email me saying ‘I haven’t been able to drink milk in 10 years without having side effects and I’m drinking your milk no problem,’” he said.

So far production is still relatively small at around 1600 gallons of milk a week. Besides his own milk, McGrath buys from two other farms and another will be coming on in the fall. The idea is to bring more young farmers into the network and both learn from each other as well as increase consumer awareness of the benefits of grass-fed dairy and support local farms.

“People want to support small family farms,” he said. “I don’t think you have to chase that big, big model to survive.”

The economics of grass-fed dairy farming in the Hudson Valley

Andrew Novakovic, agricultural economist at Cornell University, is still unsure if adopting this particular agricultural practice will be rewarded in the marketplace to offset the increased cost of production.

Places like Kentucky, Ireland, or New Zealand are better suited for grass-fed dairy models because grass grows there year-round, or at least 10 months of the year, Novakovic said. “That doesn’t really describe the lower Hudson Valley all that successfully.”

Family Farmstead

The advantage that the lower Hudson Valley — and New York state as a whole — does have is the New York City market, where expensive products that claim to be better for the animals, the environment, and offer nutritional benefits are successful. A basic economic perspective says New York City offers a lot on the demand side of the equation even if the supply side is not ideal, Novakovic said.

Data that Chicago-based research company SPINS supplied to Maple Hill calculated that grass-fed milk is up 26.1 percent in sales in the last year — more than any other segment of milk.

Environmental benefits of grass-fed dairies

A report by Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) illuminated why the grass-fed dairy market has grown in recent years. One key finding was that consumers prefer foods that provide animal health and environmental benefits. And pasturing cows turns out to be uniquely helpful to the Hudson Valley’s terrain.

Maple Hill Creamery

The rolling hills of the Hudson Valley are more prone to erosion, runoff, and leaching of nutrients from the soil, so a grass-fed model can help maintain the ecology of the landscape, said Kristan Foster Reed, assistant professor of dairy cattle nutrition at Cornell University.

Plowing fields can destroy the organic matter in the soil, leaving it exposed to runoff. And pasturing animals minimizes the inputs farmers have on the land.

“If the cows themselves are the ones fertilizing and maintaining the fertility … of those fields, there’s the environmental benefit of maintaining perennial grasses, on smaller, often hillier, less productive fields,” said Foster Reed.

The fully pastured model could also help slow global warming.

Soil that is completely covered in native plants and grasses reduces the mechanisms of climate change by sequestering more carbon in the ground, said A. Fay Benson, one of the collaborators on the SARE program and a member of the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Cortland County.

Says Benson: “A grass-covered pasture is probably one of the healthiest conditions for soil to be in.”

Source: timesunion.com