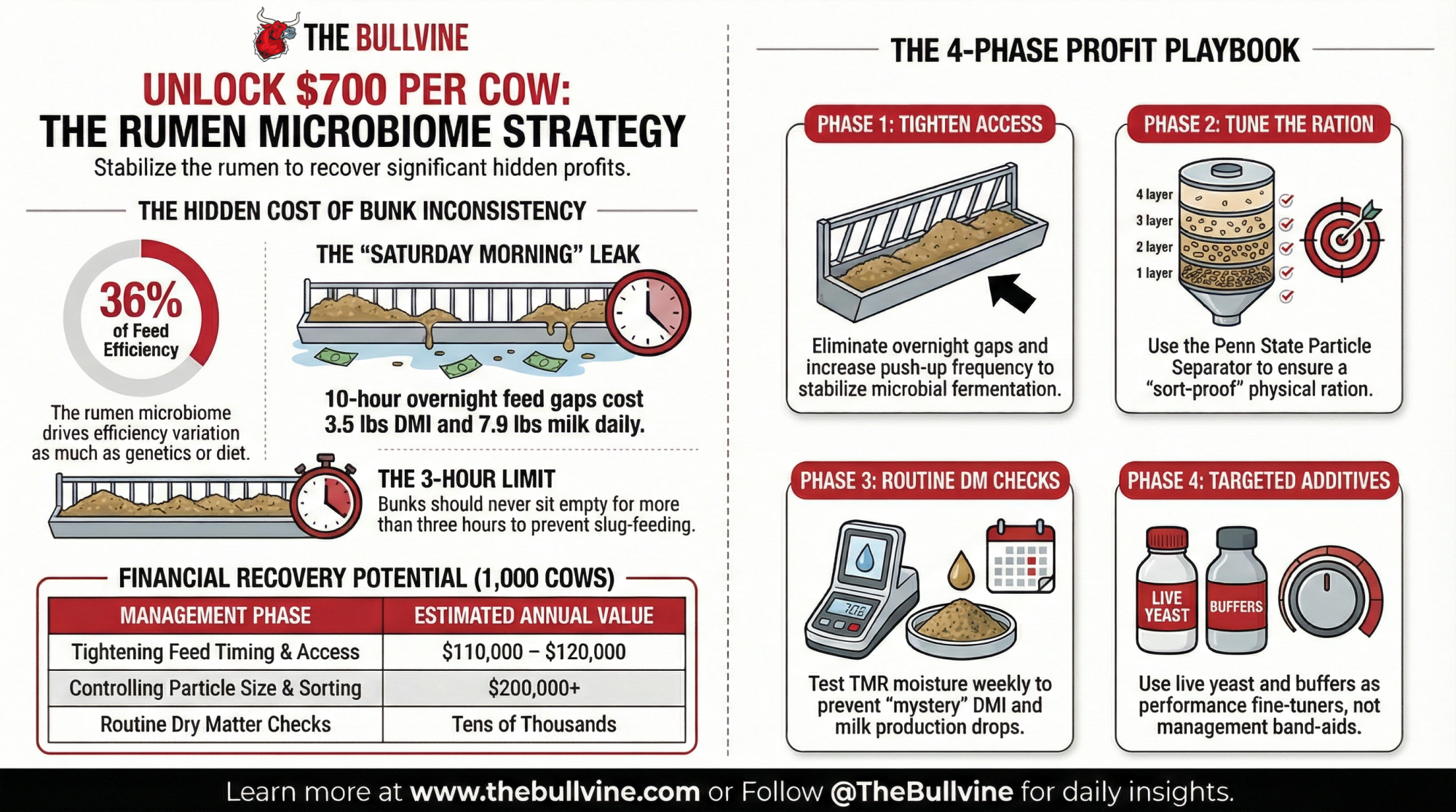

$700/cow is hiding in your bunk. Weekend feed drift, DM swings, and sorting are quietly stealing it. Here’s the four-phase fix.

Sit at enough kitchen tables across dairy country, and you start hearing the same line in different accents.

“We’ve got good cows. The ration looks right on paper. But the milk just isn’t where it should be.”

You know that feeling. The ration balances, butterfat performance ought to be stronger, you’ve invested in genetics and decent forage… and the bulk tank still isn’t telling the story you’d expect.

What’s interesting here is that, in the last few years, some very solid research has started to put a name and a number on part of that gap: the rumen microbiome, and how stable—or unstable—we make it with day‑to‑day management, not just with what we put in the mixer.

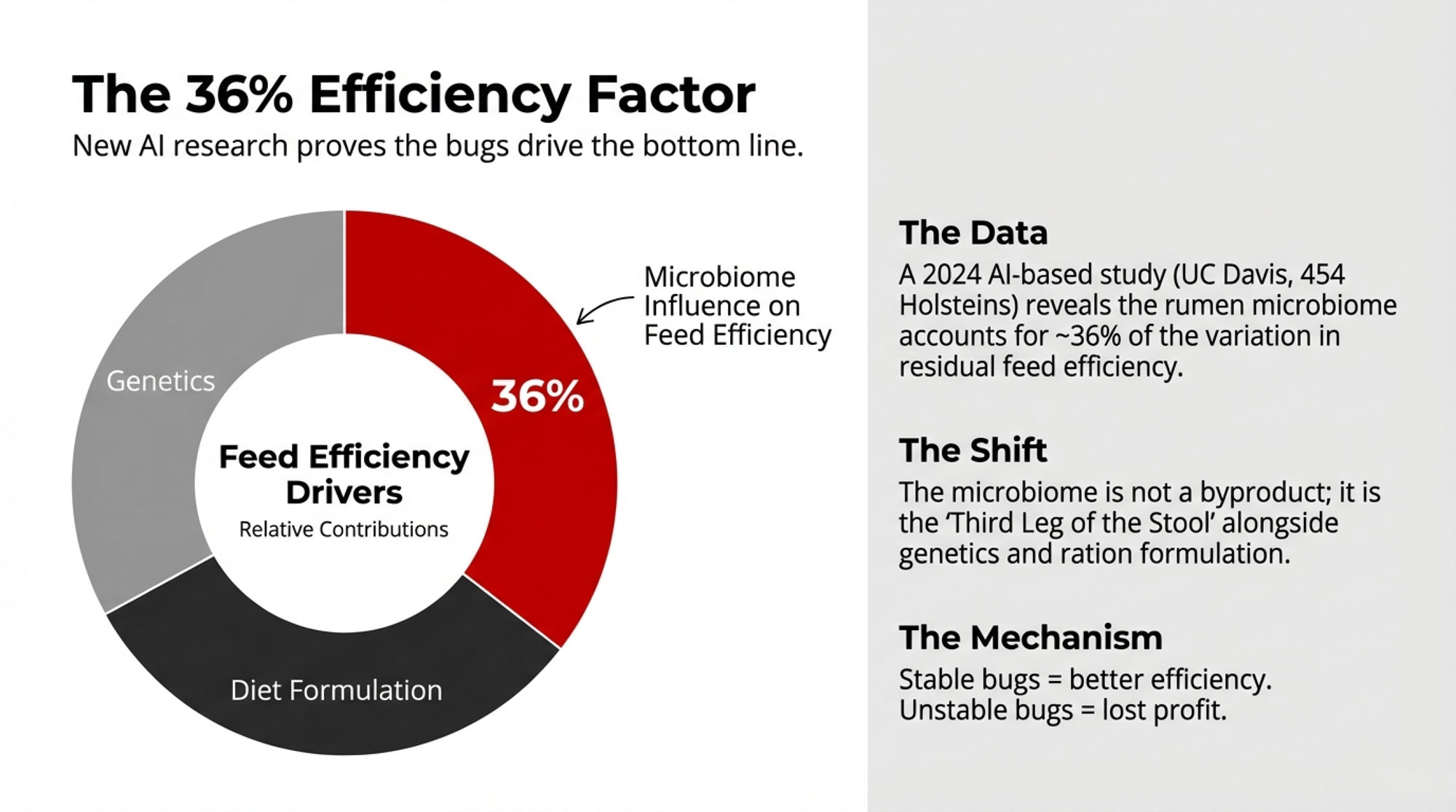

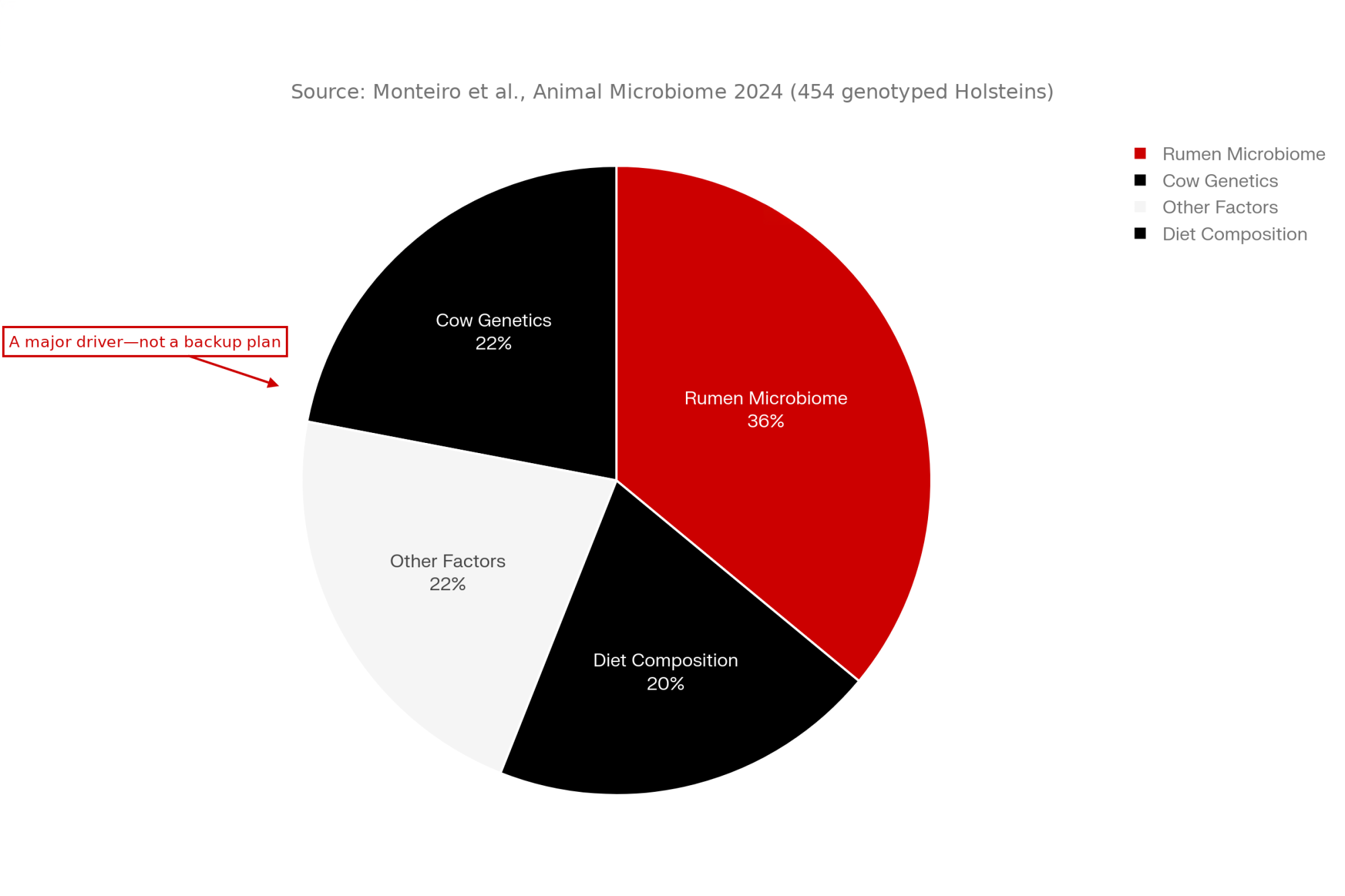

A 2024 paper in Animal Microbiome, led by H.F. Monteiro at the University of California, Davis, used an AI‑based ensemble model on 454 genotyped Holsteins from commercial herds in the U.S. and Canada and found that the rumen microbiome alone accounted for about 36% of the variation in residual feed intake (RFI), even after diet composition and cow traits were accounted for. The authors described the microbiome as a “major driver” of feed efficiency, sitting alongside ration and genetics rather than behind them. That lines up with other work showing that when you follow Holstein cows across a full lactation, the composition of the rumen and lower‑gut microbiomes tracks closely with feed efficiency and production traits, and the prediction of efficient versus inefficient cows improves when microbiome data is added to diet and genetic information.

On top of that, newer host–microbiome projects—such as the 2024 “host genome–microbiome networks” study on mid‑lactation Holsteins—are showing that parts of the core rumen microbiome are heritable and linked to both feed efficiency and methane output. In other words, the cow’s genome and her microbial passengers are working together to shape how she uses feed and what comes out the front of the tank and out the back as gas.

So we’re not throwing out ration formulation or genetics. But the data suggests the microbiome is a third leg of the stool. And, as many of us have seen in the barn, those bugs are very sensitive to how consistent their world is.

Looking at This Trend: What the Bugs Are Quietly Telling Us

What I’ve found, looking at this research alongside what producers are seeing on their own farms, is that microbiome‑first thinking mostly backs up what good cow people have been saying for years. It just gives those instincts a clearer scientific backbone.

You probably know this already, but the rumen community isn’t one thing. Reviews of how the rumen microbiota shifts from the dry period into early lactation show a fairly consistent pattern: bacteria that specialize in rapidly fermentable carbohydrates tend to increase as starch and sugars rise, while classic fibrolytic species such as Fibrobacter and Ruminococcus are more sensitive to drops in rumen pH and rough dietary changes. When the feeding environment is steady—similar ration, predictable feeding and push‑up times, consistent dry matter—those different groups can settle into a balance that supports both butterfat performance and feed efficiency. When we keep changing the rules on them, the fast opportunists win more often, and the slower fiber‑digesters get pushed back.

And as many of us have seen, that can show up as:

- Butterfat levels are bouncing more than the diet changes would suggest

- Fresh cows in the transition period that don’t ramp up on dry matter intake the way we’d expect based on the ration

- More days where rumination, manure consistency, and overall cow behavior feel “off,” even though nothing obvious changed on paper

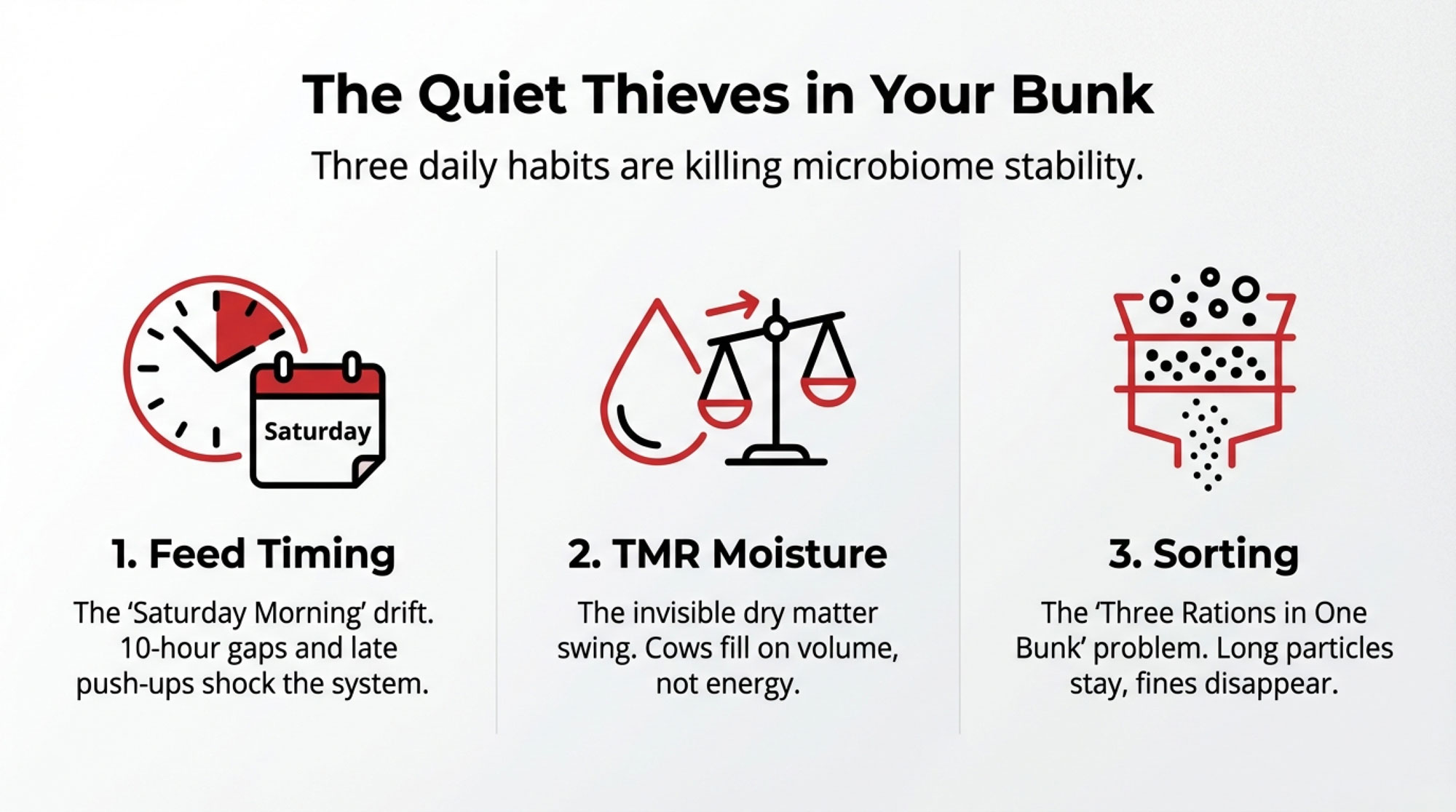

It’s worth noting that when you line up the science with on‑farm experience, three everyday management areas keep coming up as the main microbiome disrupters: feed timing and access, TMR dry matter, and particle size/sorting.

Let’s walk through each one, because that’s where a lot of the opportunity is hiding.

Feed Timing and Access: The “Saturday Morning” Problem

Looking at this trend on real farms, feed timing and access are usually the first places where the microbiome story becomes very concrete.

In many Wisconsin freestall herds—and plenty of Ontario, New York, and Pennsylvania barns too—the weekday schedule on paper looks quite good. Feed at 6 a.m., push up several times in the next few hours, second feeding mid‑afternoon, a couple more push‑ups before night. Then Saturday and Sunday arrive. That 6 a.m. feeding quietly becomes 6:30 or 7:00, the early‑morning routine gets “flexible,” and late‑night push‑ups happen only if there’s time. I’ve noticed that pattern over and over, sitting in farm kitchens from the Midwest to the Northeast.

On larger Western dairies in California or Idaho, the pattern can be different, but the result is similar. You might have multiple feeding crews, and one crew is very tight on timing while another is a bit looser. To the cows—and to their microbes—that still feels like an irregular routine.

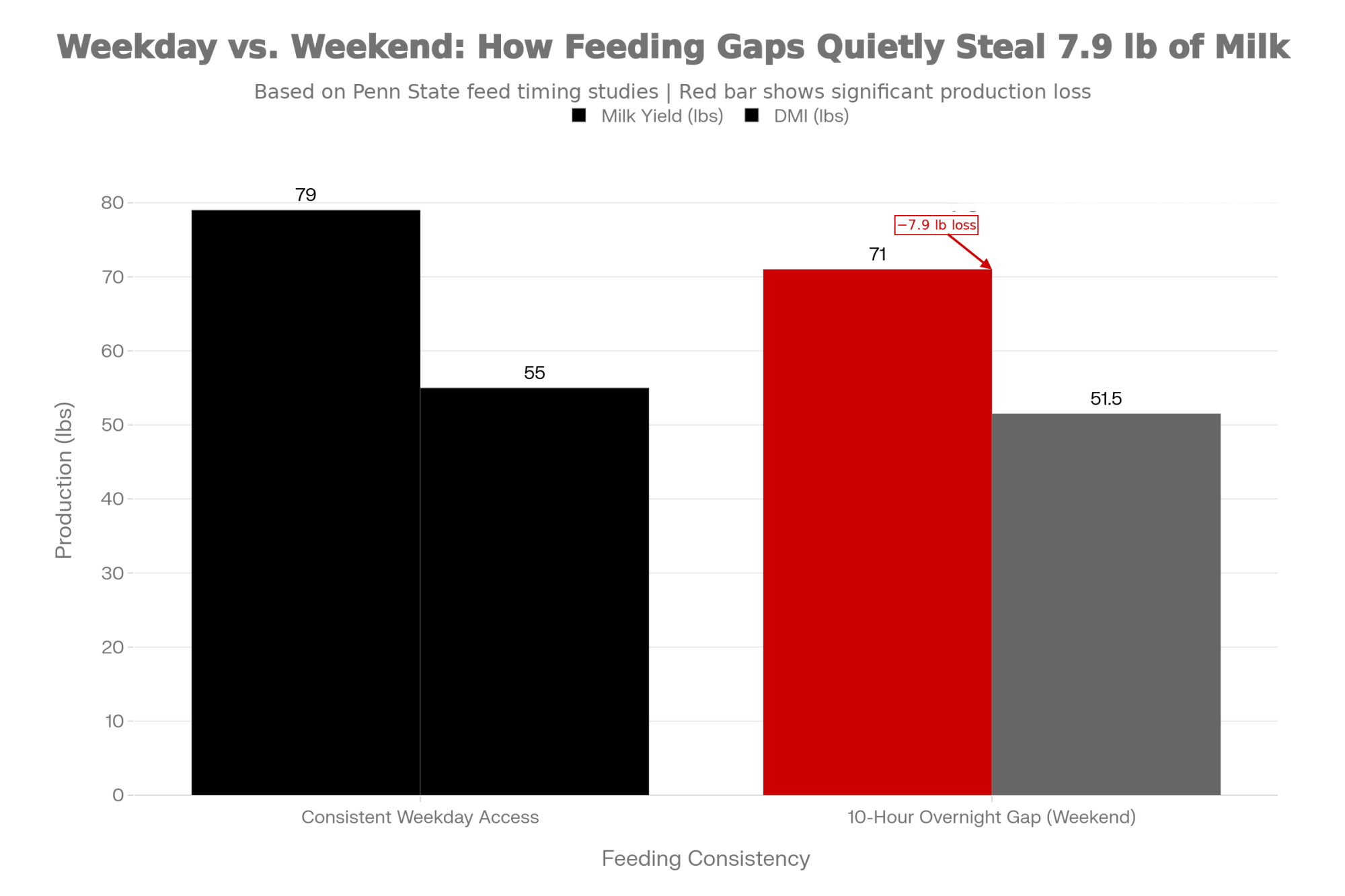

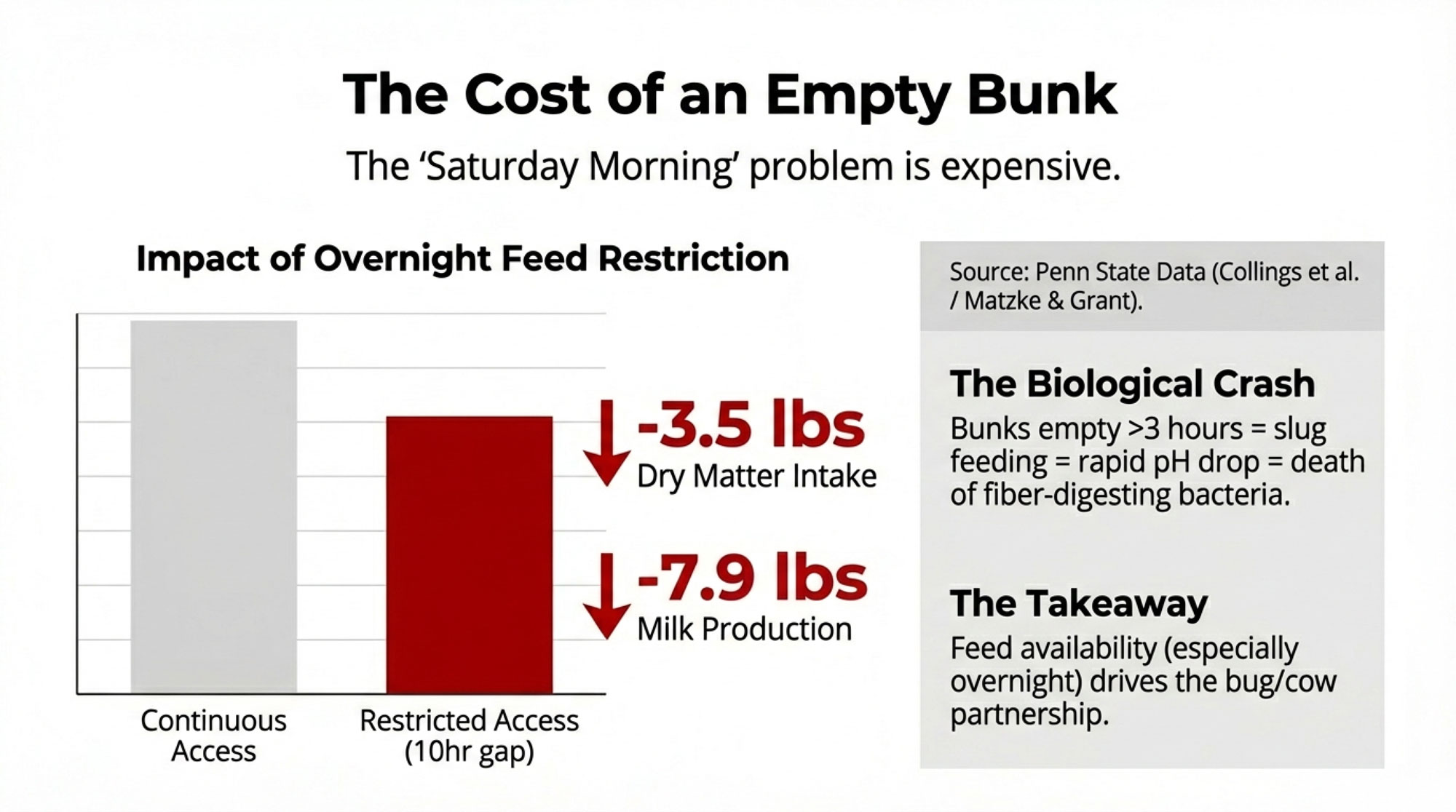

Penn State’s “Benefits of Timely Feed Delivery and Push Ups,” written by extension educator Dr. Virginia Ishler and colleagues, brings together several studies that quantify what many of you have already felt. In their summary of work by Collings et al. and Matzke & Grant, cows that were restricted from feed for about ten hours—typically overnight—ate 3.5 pounds less dry matter per day and produced 7.9 pounds less milk per day than cows that had feed available throughout the night. A Dairy Herd article by Penn State educator Michal Lunak echoes those numbers and adds that herds routinely pushing feed up produced, on average, over eight pounds more milk than herds that didn’t.

When feeding and push‑up practices were adjusted so that feed remained available from midnight to early morning and was pushed up more consistently, dry matter intake and milk yield increased, and cows spent more time both lying and eating. Penn State also highlights that bunk empty time should be kept under about three hours; beyond that, cows’ motivation to eat rises sharply, and they’re more prone to slug‑feeding when feed returns.

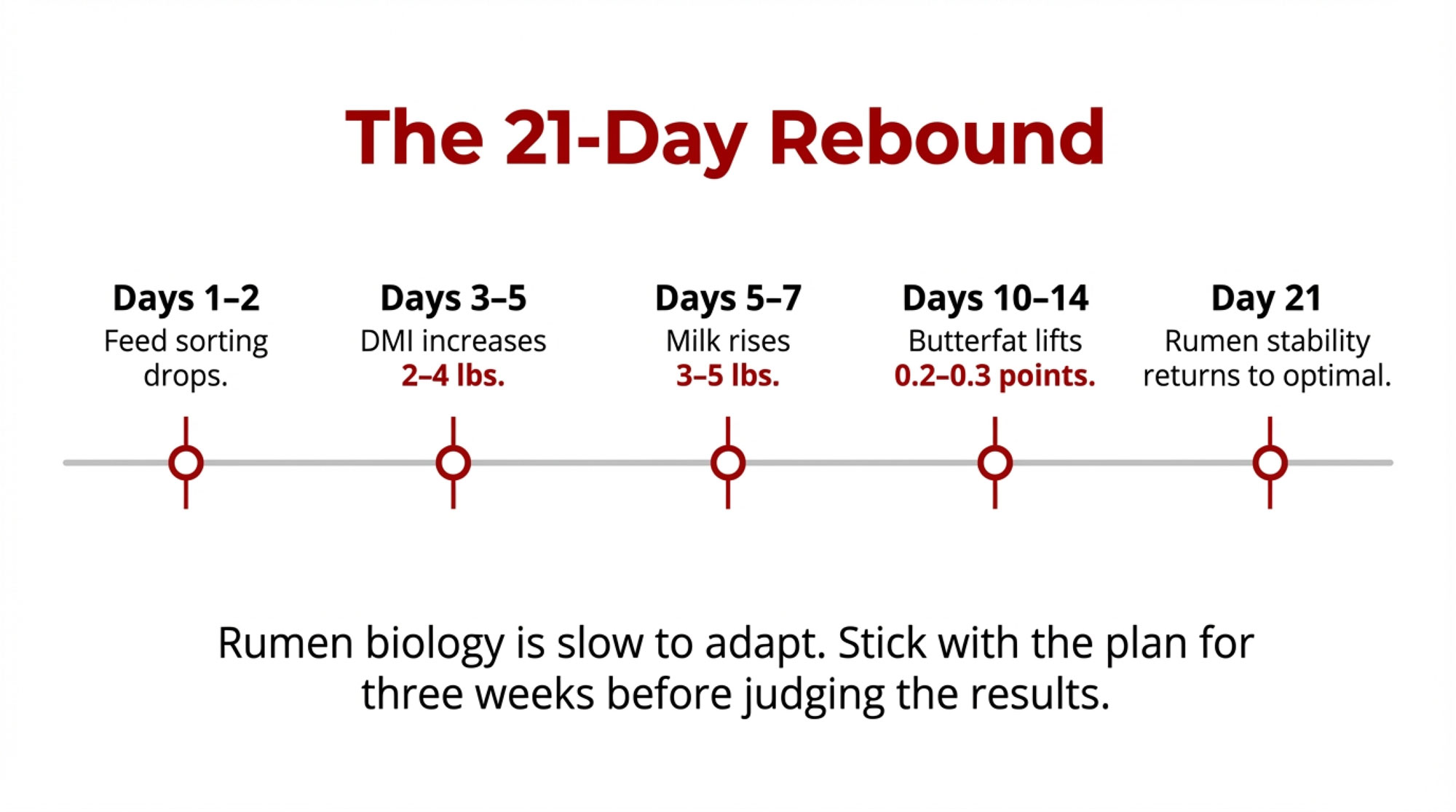

From the microbial side, what’s happening is intuitive once you think about it. When cows go through long stretches with an empty bunk, they’re more likely to slug‑feed when the TMR finally arrives—packing in a big meal quickly. That dumps a heavy load of fermentable carbohydrate into the rumen all at once, causing rumen pH to drop more sharply and the slower fiber‑digesting microbes to get stressed or washed out. In herds that have taken the time to log feed delivery and push‑up times (some have done this with simple charts or camera snapshots), those longer gaps—especially on weekends—often match up with the days when butterfat drops and fat: protein ratios point toward subacute acidosis.

There’s also a broader transition‑cow angle. Work on transition cow nutrition in North American herds has shown that more consistent routines around the dry and fresh periods—fewer abrupt diet changes, grouping, and environmental shocks—are associated with better metabolic profiles and stronger early lactation performance. Feeding schedule is one of the major “time cues” the cow’s system responds to. The microbes, even though they don’t have watches, are reacting to the same pattern.

So one of the first microbiome‑friendly questions to ask is very simple: “How long are my cows actually going without feed they can reach?” Penn State emphasizes that bunks should not be empty for more than about three hours, and that more frequent push‑ups in the first hours after feeding are strongly associated with higher DMI and milk yield. The microbiome is one more good reason to take that seriously.

TMR Dry Matter: The Quiet Thief in the Bunker

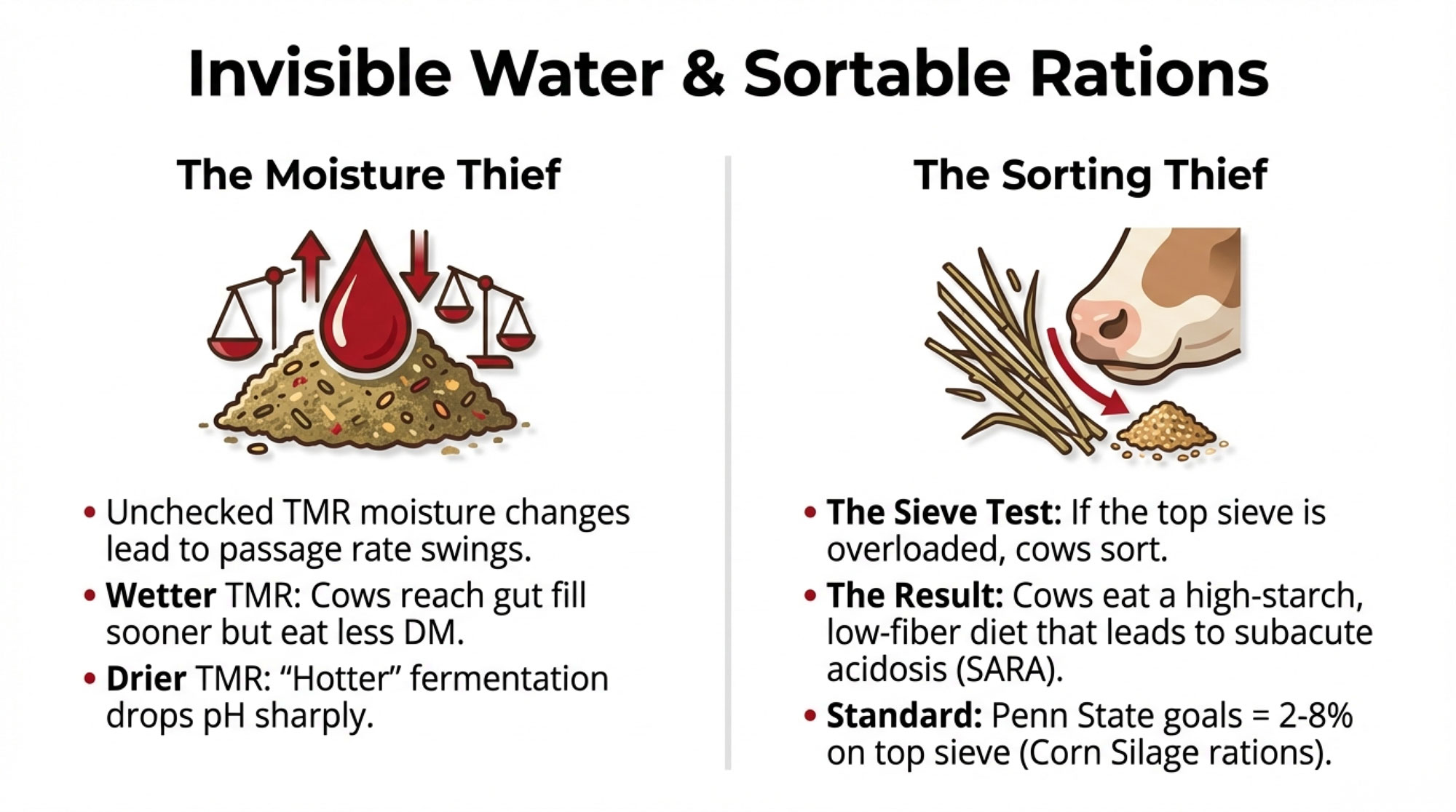

The second lever, TMR dry matter, is one of those things that quietly steals profit when no one’s looking.

Penn State’s “Total Mixed Rations for Dairy Cows,” by Dr. Virginia Ishler and the dairy nutrition team, spells out how changes in TMR dry matter affect what cows actually eat. When a TMR gets wetter but batch weights don’t change, cows fill up on volume but take in fewer kilograms of dry matter than the ration assumes they will. The bulletin shows farms where actual DMI drifts away from predicted intake as TMR moisture changes, and notes that herds that keep actual DMI within about 5% of expected intakes—and pay close attention to TMR accuracy—consistently achieve higher milk and more stable components than herds where DMI and TMR DM are rarely checked.

Industry pieces on TMR moisture, including extension articles and dairy nutrition case reports, have shown that when TMR moisture comes in higher than expected, and no one adjusts, early‑lactation cows can lose several percent of their DMI and a few kilograms of milk per day until someone finally tests dry matter and corrects the ration. Many of you have lived that scenario: “Nothing changed… except we opened a new corner of the bunker or switched bags and didn’t test.”

From the microbiome’s point of view, those moisture swings do two things at once:

- On wetter days, cows reach rumen fill sooner and don’t get the expected dry matter. Passage rate increases, long fiber particles spend less time in the rumen, and fiber‑digesting bacteria have less chance to colonize and break them down.

- On drier days, the same volume of TMR carries more dry matter and more fermentable energy, so the fermentation runs “hotter” and rumen pH can dip more sharply, again putting pressure on the fiber‑digesting community.

What farmers are finding is that you don’t have to nail TMR dry matter at one exact number. But you do want to keep day‑to‑day changes in a reasonable band and adjust batch weights when moisture moves outside that band. Many Midwest and Northeast herds now do at least one or two TMR dry matter checks a week, more often when they start a new section of bunker or change forage sources, and they treat it as part of routine bunk and fresh cow management rather than just troubleshooting.

The evidence suggests that habit alone can prevent many “mystery” weeks in which milk and components slip for reasons nobody can quite explain until someone dusts off the Koster tester.

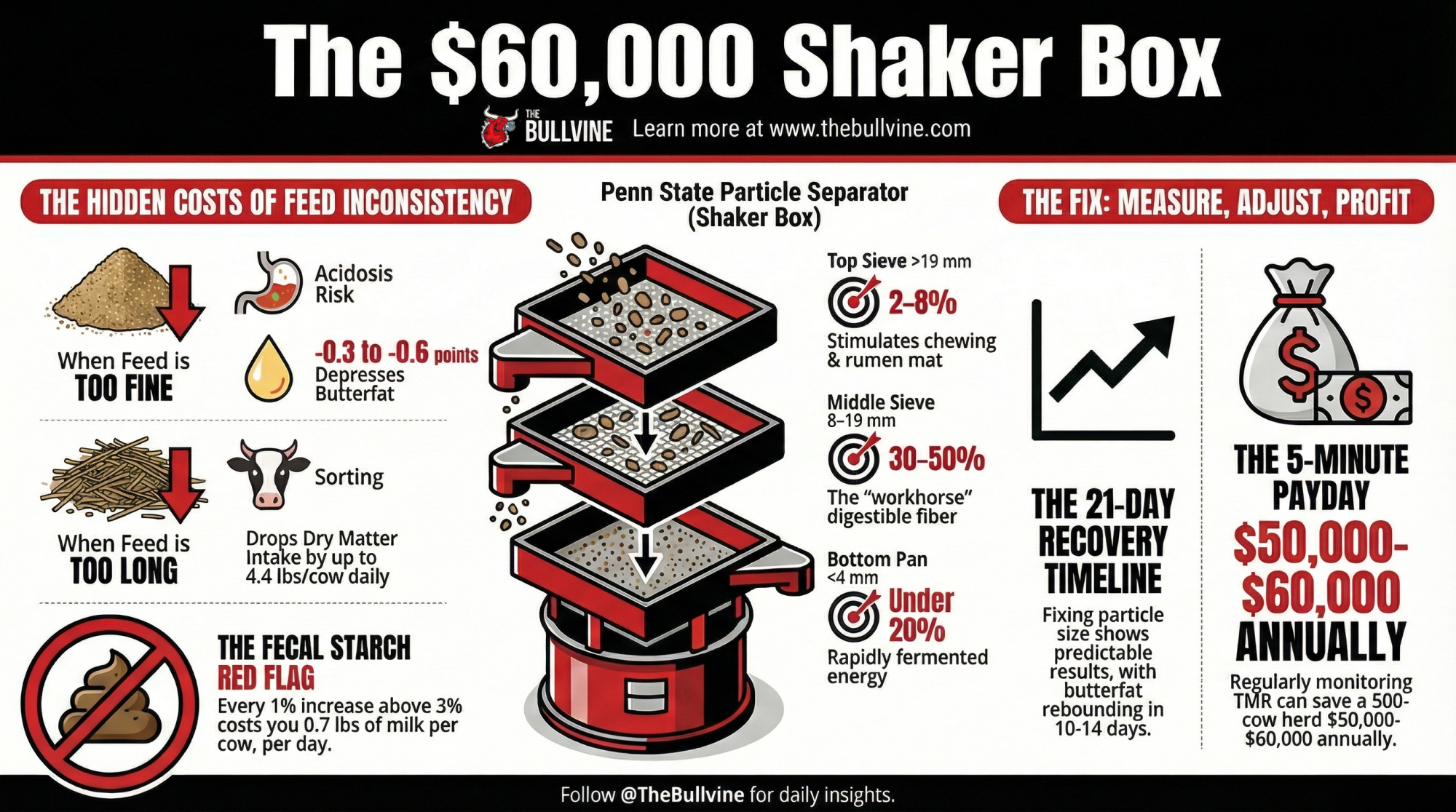

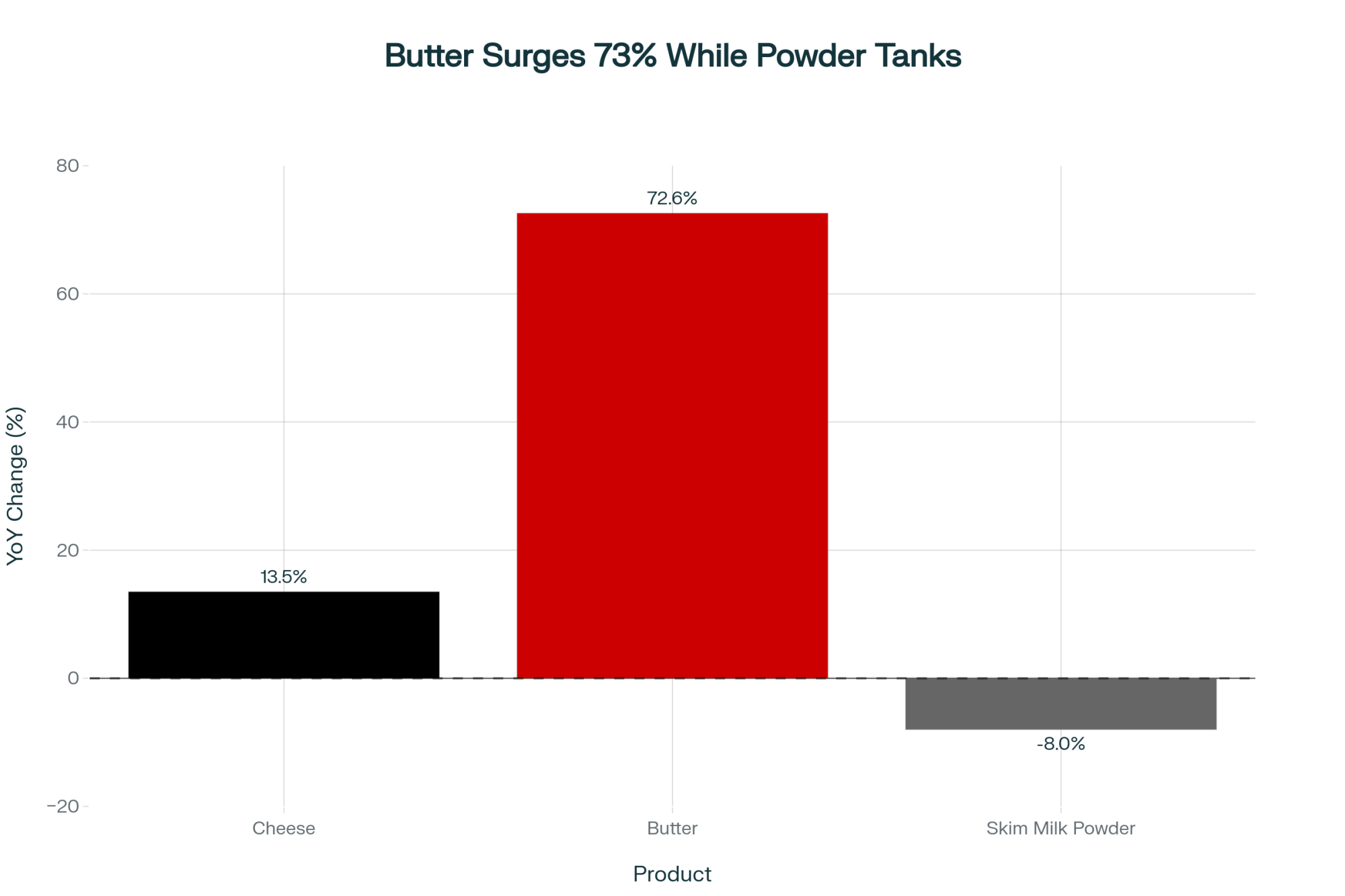

Particle Size and Sorting: Three Rations in One Bunk

The third piece is particle size and sorting—the classic “three rations in one bunk” problem that shows up on farms of all sizes.

After feeding a TMR, it’s common to walk the bunk an hour later and see a line of longer stems pushed out of the way while the finer material has been cleaned up. By early afternoon, cows are picking over what’s left, and what’s left doesn’t look much like the ration the nutritionist balanced. I’ve noticed that on everything from 80‑cow tiestalls to 4,000‑cow freestall barns.

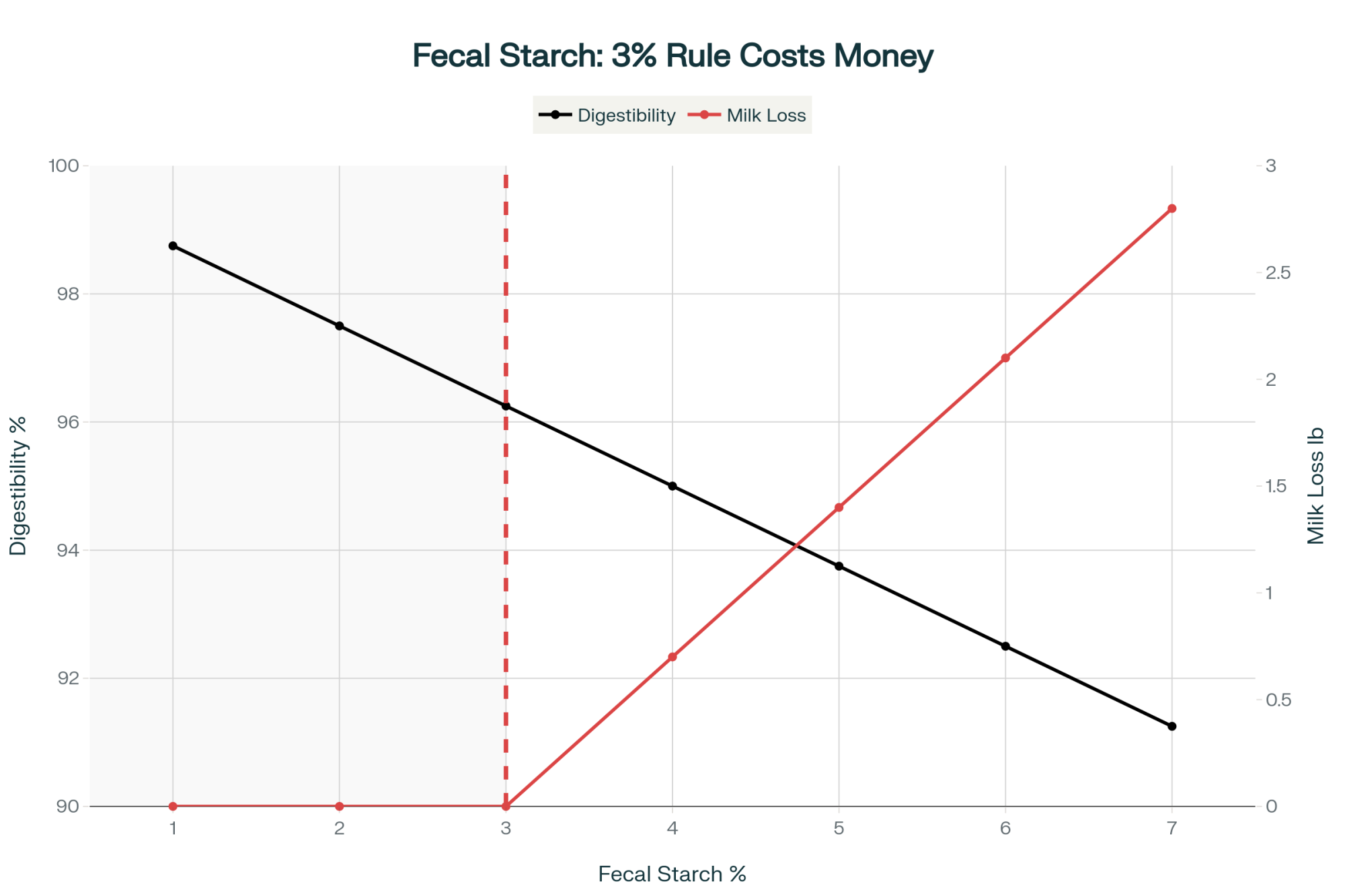

The Penn State Particle Separator (PSPS) has become a standard tool for seeing what’s really happening. For many corn‑silage‑based rations, Penn State guidance suggests that only about 2–8% of the TMR should remain on the top sieve, roughly 30–50% on the next sieve, 10–20% on the 4 mm sieve, and no more than 30–40% in the bottom pan for high‑producing cows. Hoard’s articles on ration particle size have highlighted research showing that diets with overly long particles and high undigested NDF reduced DMI by 5–6 pounds per day, and that finer chopping and better PSPS distributions restored DMI and milk yield.

When a TMR has too much long material on that top sieve, cows can sort around it. They end up eating a diet richer in starch and poorer in effective fiber than intended. Industry articles and extension pieces have repeatedly called out that gap between the “paper ration” and the “eaten ration” as a major driver of inconsistent butterfat performance and subacute rumen acidosis, even when the formulation itself looks sound.

From a microbiome perspective, heavy sorting means you’re constantly pushing the rumen community toward the organisms that thrive on rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, while making life harder for the slower, fiber‑digesting bacteria that underpin fiber utilization and rumen health.

What’s encouraging is that producers in very different environments—freestall barns in Ontario, tiestalls in Quebec, and dry lot systems in hot regions—have all reported improvements after making particle size checks and bunk observations a regular habit. Running the separator weekly for a period, adjusting chop length and mixing time, and watching what’s left at the bunk an hour after feeding are simple, practical tools that align very well with what the bugs seem to be asking for.

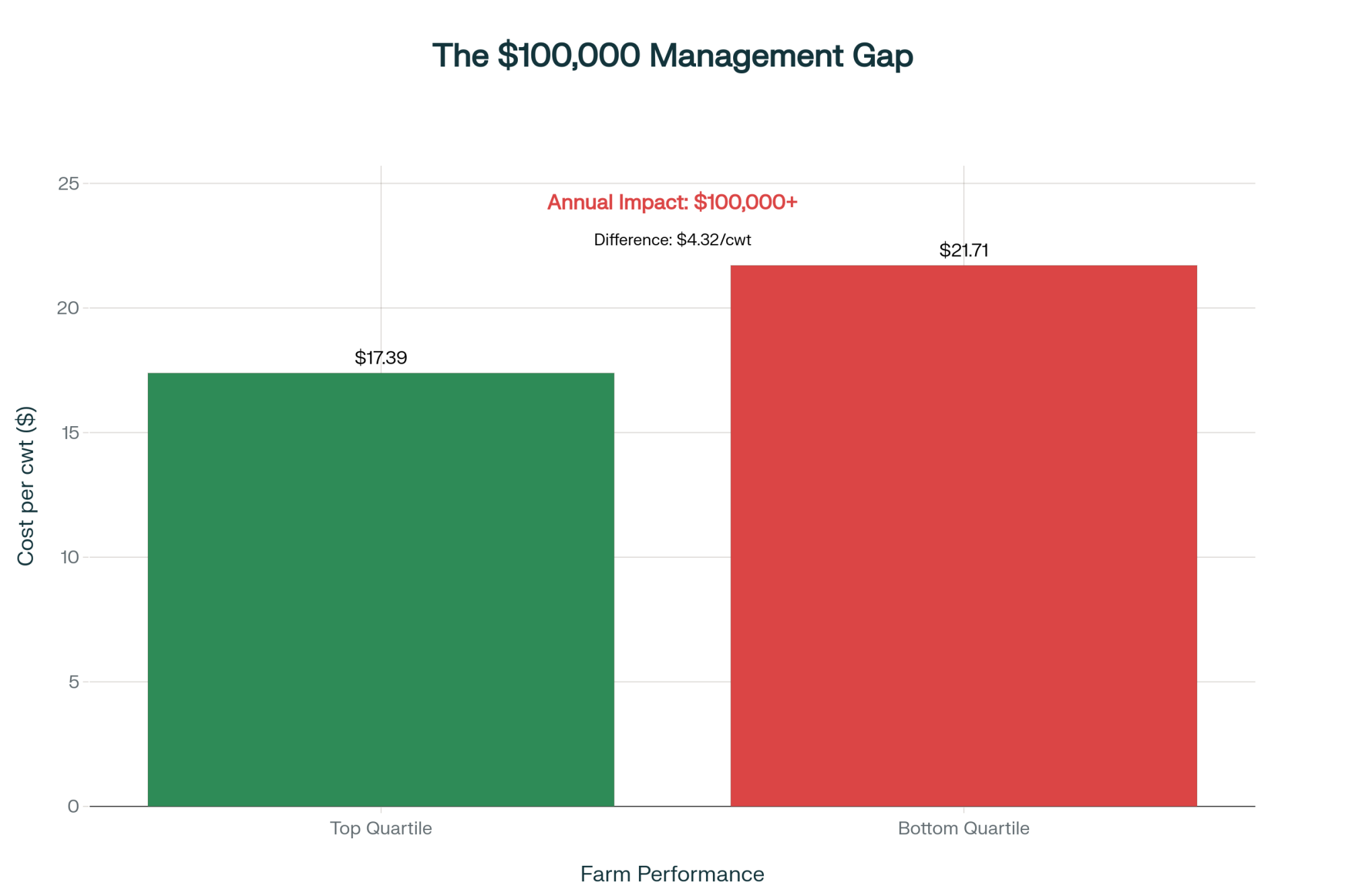

| Management Gap | What Happens | Milk Loss per Cow/Day | Butterfat Impact | Annual Cost per 1,000 Cows |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Hour Overnight Feed Restriction | Cows slug-feed; rumen pH crashes; fiber-digesting microbes washed out | −7.9 lbs | −0.4% (subacute acidosis) | $1,153,600 |

| TMR Dry Matter Drift (+2–3 points) | Cows fill on volume but get fewer kg DM; passage rate increases; fiber digestion drops | −3.5 to −5 lbs | −0.2–0.3% | $510,500–$728,750 |

| Excessive Sorting (Long particles, fine refusal) | Cows select around fiber, eating richer diet; slow fiber-digesters starved out | −5 to −6 lbs | −0.5–0.7% (fat:protein inversion) | $728,750–$876,900 |

| All Three Combined (Common State) | Microbes destabilized; rumen environment chaotic; fresh cows struggle to ramp intake | −14 to −16 lbs | −1.0–1.5% | $2,044,000–$2,332,000 |

What Farmers Are Finding: A Four‑Phase Plan That Fits Real Herds

So with all that on the table, the natural question is: how do you actually use this microbiome‑first lens on your own farm?

What I’ve noticed, talking with producers from Wisconsin, Ontario, the Northeast, and the West, is that the herds getting the most from this approach tend to move through four broad phases. They don’t always call them phases, but the progression shows up again and again, and it lines up nicely with what extension and research folks are seeing.

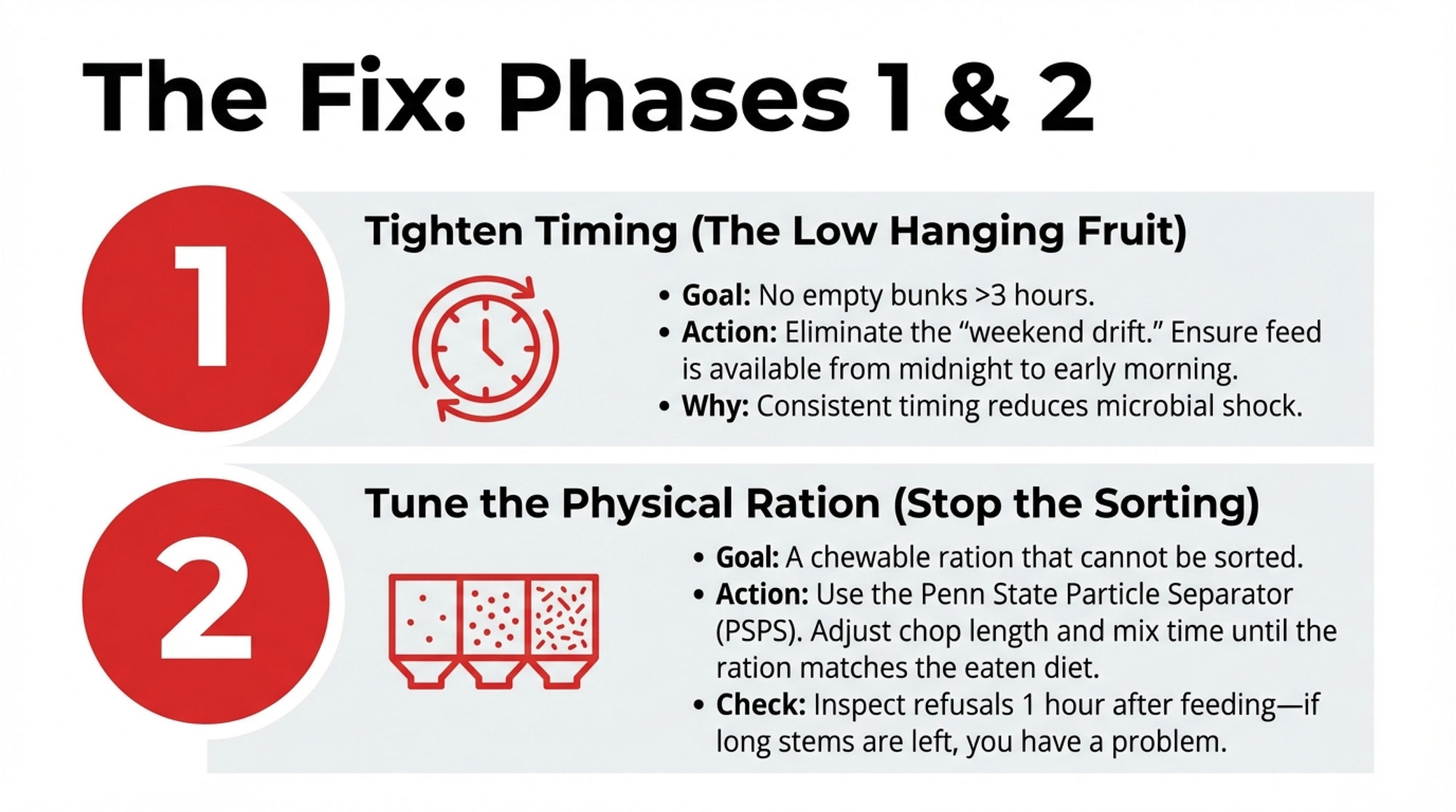

Phase 1: Tighten Timing and Feed Access

Phase 1 is about getting honest about feed access.

A straightforward starting point looks like this:

- For two weeks, write down when feed really hits each group and when it’s last pushed up at night. Don’t rely on memory. Include weekends and holidays.

- Look for recurring long gaps—especially overnight—where cows don’t have feed in front of them or can’t reach it.

- Given your labor and layout, decide what’s realistic in terms of extra push‑ups, an automatic feed pusher, or improved hand‑offs between shifts to shorten those gaps.

Penn State’s work and related industry articles have shown that when cows move from long overnight feed restrictions to continuous access, dry matter intake and milk yield increase in ways that match the 3.5 lb DMI and 7.9 lb milk responses measured when feed is restricted versus available overnight. In a microbiome‑first mindset, you’re reducing the size and frequency of the shocks the microbial community has to deal with each day.

Phase 2: Tune Up the Physical Ration

Once cows can depend on there being feed in front of them most of the time, Phase 2 is about what that feed looks like physically.

On farms where this has really moved the needle, Phase 2 typically includes:

- Running the Penn State Particle Separator on the TMR weekly for a period and working with the nutritionist and forage team to adjust chop length, kernel processing, and mixing until the ration consistently falls into the recommended PSPS distributions for your forage mix.

- Spending time at the bunk 45–60 minutes after feeding, especially in fresh and high pens, to see how much sorting is actually happening and what is left in front of the cows.

- Watching kernel processing scores for corn silage and keeping an eye on haylage or straw length to avoid overloading the top sieve and inviting sorting.

The goal is a ration that’s chewable but not easily sorted. Research and field experience both show that when you hit that sweet spot, you see more consistent chewing, better saliva production, smoother manure, and more stable butterfat performance.

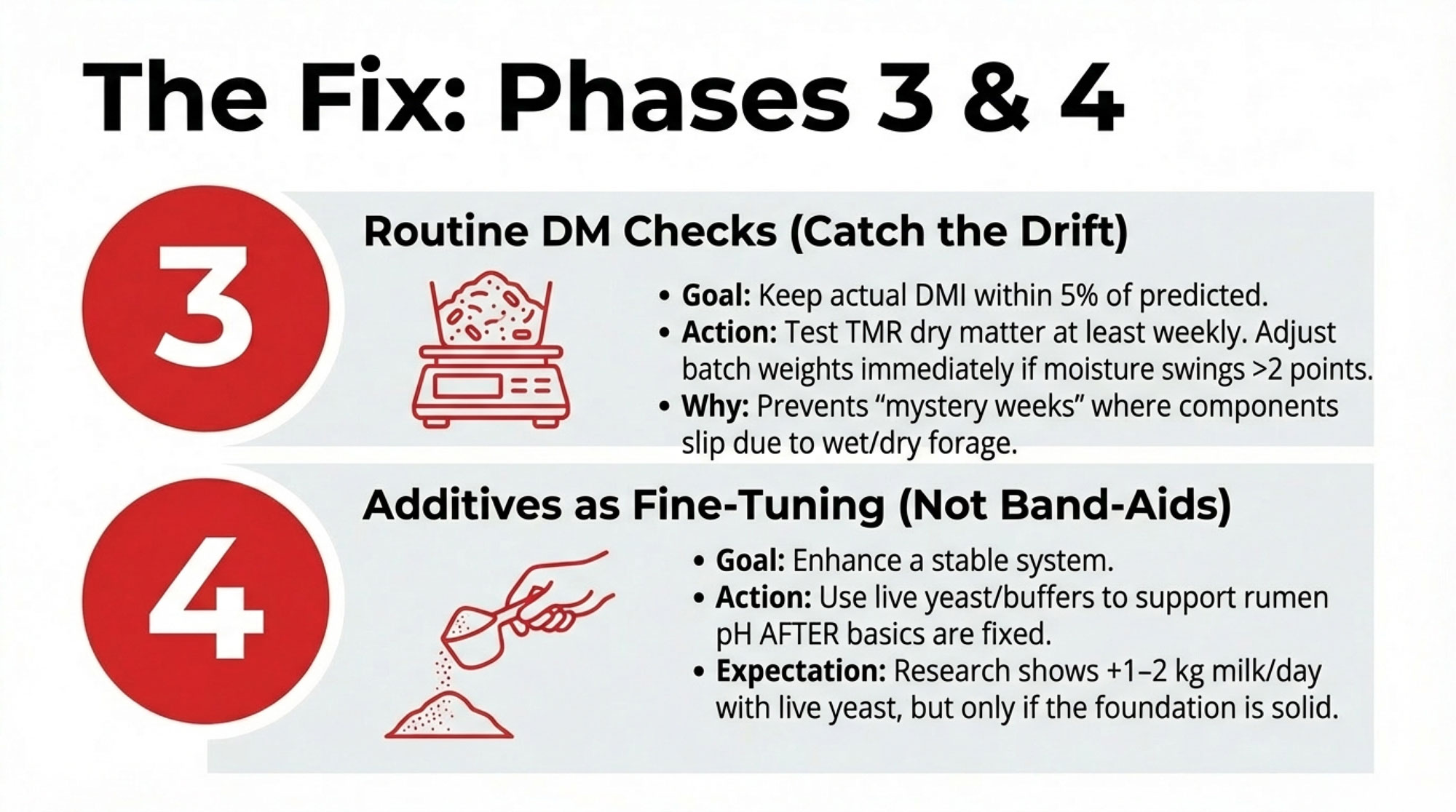

Phase 3: Make Dry Matter Checking Routine

By the time herds get to Phase 3, many notice they’re not seeing as many “mystery” swings in milk and components. Phase 3 is about turning TMR dry matter checks into a standard part of bunk management.

In practical terms, that often means:

- Testing TMR dry matter at set times each week—often early and late in the week.

- Logging those numbers so you and your nutritionist can track when moisture shifts as you move along the bunker or between forage sources.

- Agreeing on a simple trigger—such as a two‑point or greater difference between actual and assumed TMR dry matter—that prompts ration adjustments rather than “wait and see.”

Penn State’s TMR bulletin and related herd‑level analyses suggest that farms with tighter control over TMR dry matter and loading accuracy see higher milk yield and more consistent components than those where dry matter is rarely checked. For the microbiome, this kind of consistency means fewer sudden jumps in fermentable load and a more predictable environment in which to work.

Phase 4: Use Additives to Fine‑Tune, Not Patch

Only after those three pieces feel reasonably solid does it make sense to lean into live yeast, buffers, and other additives.

The research on live Saccharomyces cerevisiae in dairy cows brings several themes together:

- In transition‑cow trials, such as those led by Marinho and colleagues, supplementing live yeast around calving improved postpartum dry matter intake and rumination, led to milder inflammatory and liver stress markers, and increased milk yield compared with unsupplemented cows on the same base ration.

- Reviews and industry summaries that pool results from multiple mid‑lactation trials often report milk yield gains in the range of 1–2 kilograms per day and more stable rumen pH when live yeast is added, particularly in herds with solid basic management.

- Under heat-stress conditions, especially in hot, dry regions, live yeast has been shown to help stabilize rumen pH and support production when combined with effective cooling and feeding strategies.

At the same time, extension and university reviews are clear that additives cannot overcome fundamental problems such as poor forage quality, erratic feeding schedules, or severe overcrowding. In many commercial herds, responses to yeast and buffers are variable, and benefits tend to be largest where the basics are already in decent shape.

In a microbiome‑aware framework, that means treating additives as a way to fine‑tune a system that’s already working reasonably well, rather than as a band‑aid for underlying management issues.

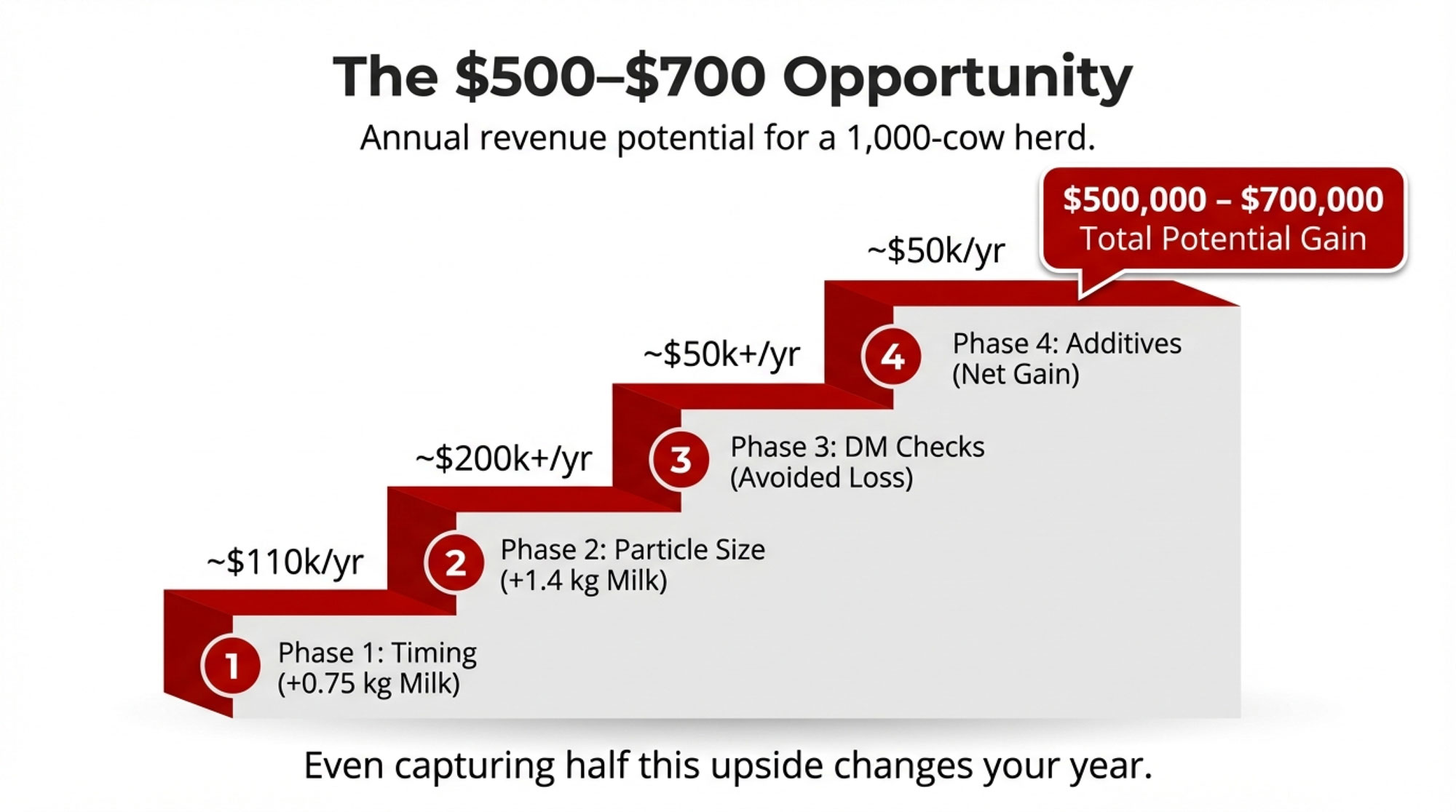

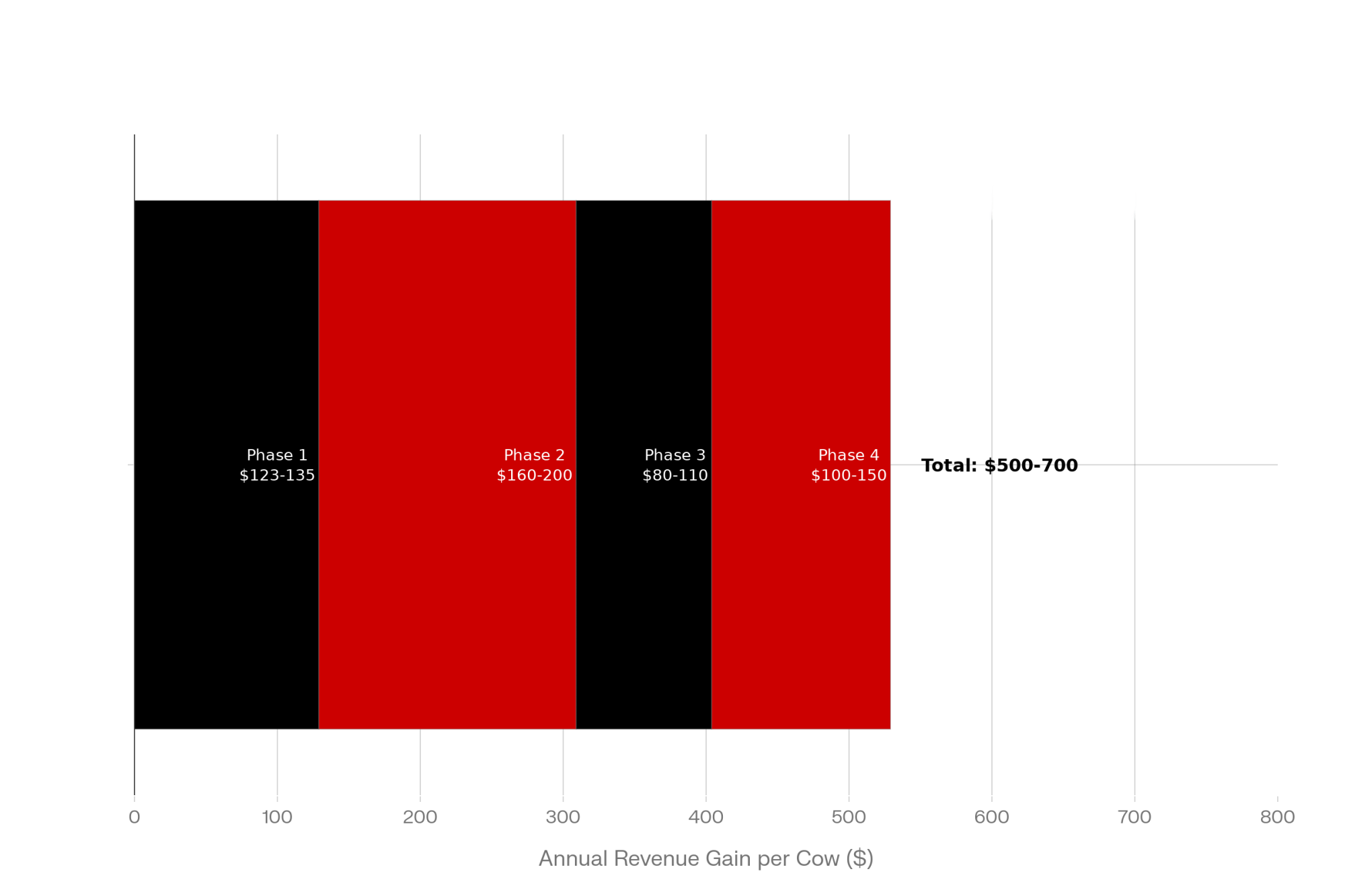

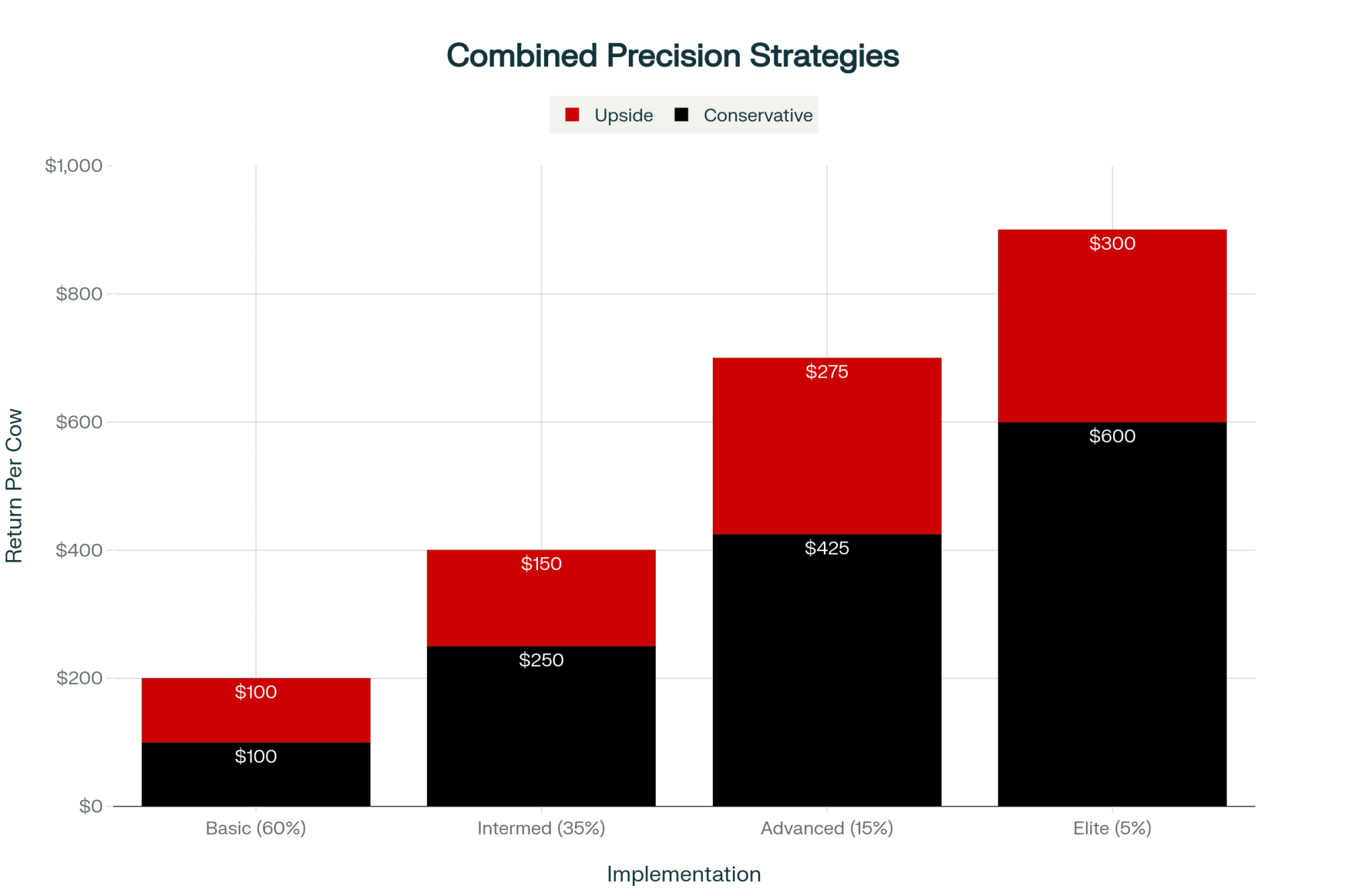

Putting Numbers to the Four Phases: The Economics on a 1,000‑Cow Herd

So why is all this significant? Economics plays a big part in the story.

Imagine a 1,000‑cow freestall herd with:

- Average production is around 38–39 kilograms (about 85 pounds) of milk

- Butterfat at roughly 3.2% and protein just over 3.1%

- Dry matter intake near 25 kilograms (55 pounds) per cow per day

- Milk price is around $0.40 per kilogram, and feed cost is roughly $0.20 per kilogram of dry matter

Those numbers won’t fit every farm, but they’re realistic for many North American herds right now based on recent Hoard’s Dairyman economic analyses and regional milk price reports.

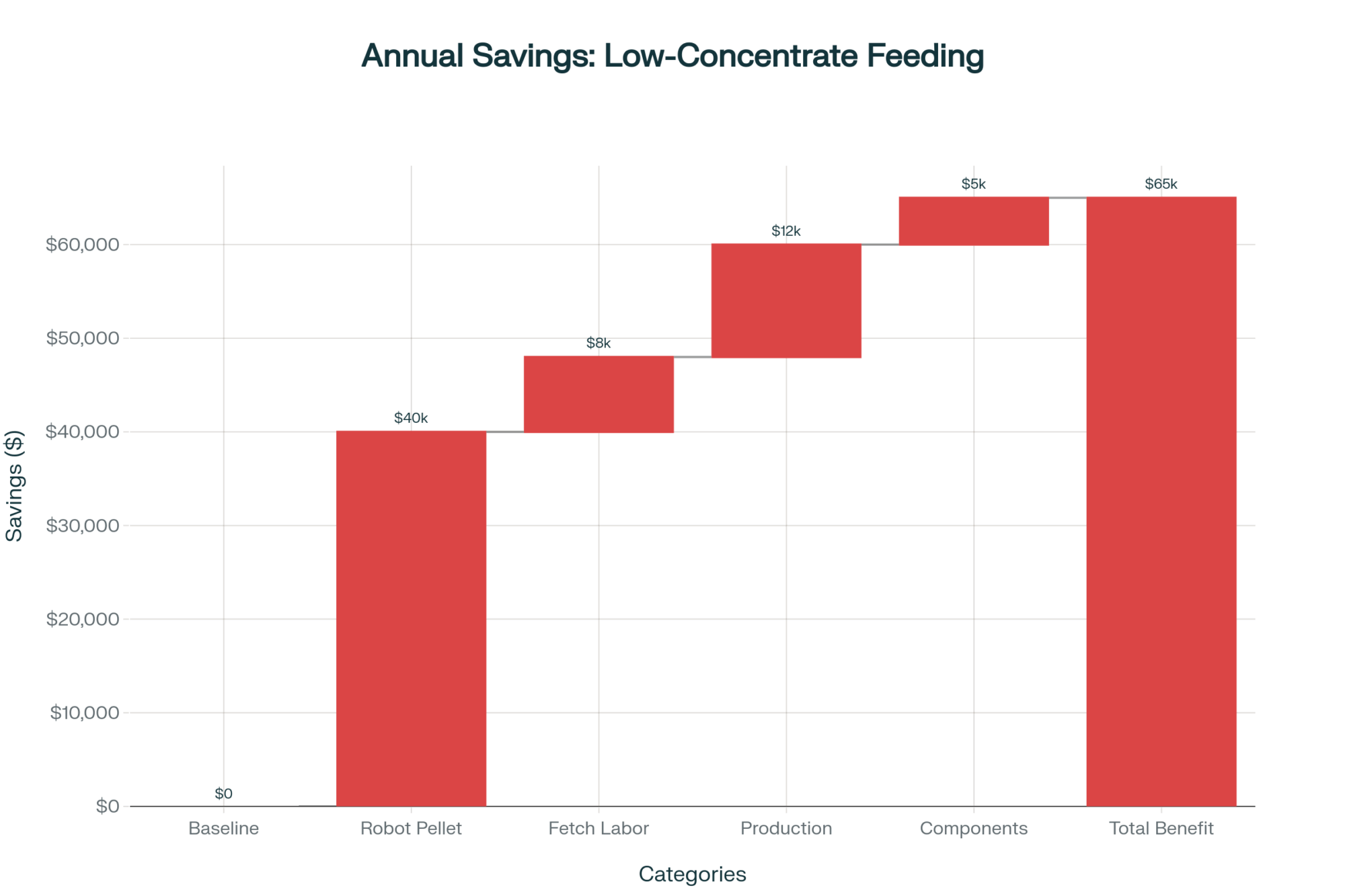

If Phase 1—tightening feeding times and improving access—helps you realistically recover around 0.75–0.8 kilograms of milk per cow per day by eliminating long overnight feed gaps (a conservative figure compared to the 7.9 lb milk response Penn State reports when cows move from restricted to continuous night access), that’s roughly $0.30–0.35 per cow per day. Over a year and 1,000 cows, you’re looking at about $110,000–120,000 in additional milk revenue.

If Phase 2—getting particle size and sorting under control—adds another 1.3–1.4 kilograms of milk per cow per day and nudges butterfat up a bit, that can easily translate into a couple of hundred thousand dollars a year in combined volume and component pay, depending on your milk pricing and how much room there was for improvement. That’s consistent with the kind of DMI and milk yield recoveries seen when rations shift from “too long and sorted” toward better PSPS targets and reduced excessively long particles.

Phase 3—keeping TMR dry matter in line with regular checks and adjustments—might reasonably prevent a 0.5–0.6 kilogram per cow per day loss during those weeks when moisture shifts used to drag DMI and milk down quietly. Extension examples and field data show that even modest, unnoticed drops in DMI from dry matter changes can add up to tens of thousands of dollars per year on larger herds.

Then, in Phase 4, if a well‑designed live yeast program on top of this more stable foundation adds another 0.7–0.8 kilograms of milk per cow per day in the pens you target—figures that fall within the 1–2 kg/day range often reported when live yeast is used in well‑managed herds—then after covering product cost you might realistically net on the order of $50,000 per year.

Put those pieces together, and it’s not hard to model a total improvement on the order of $500,000–700,000 per year for a 1,000‑cow herd. On a per‑cow basis, that’s about $500–700. Early indications from extension economic estimates and field experience suggest that those kinds of gains are achievable in herds with significant room to tighten timing, dry matter control, and sorting—provided they treat this as a stepwise management project rather than a quick fix.

Even if you only capture half of that modeled upside, you’re still talking about a six‑figure swing in annual income on a 1,000‑cow unit. That’s the kind of math that justifies taking a hard look at your feeding routine, DM checks, and PSPS readings.

Of course, if your feeding program is already very tight, your upside may be smaller. And if other bottlenecks like lameness, poor ventilation, water limitations, or chronic fresh cow problems are holding cows back, those will cap how much any microbiome‑focused approach can deliver until they’re addressed.

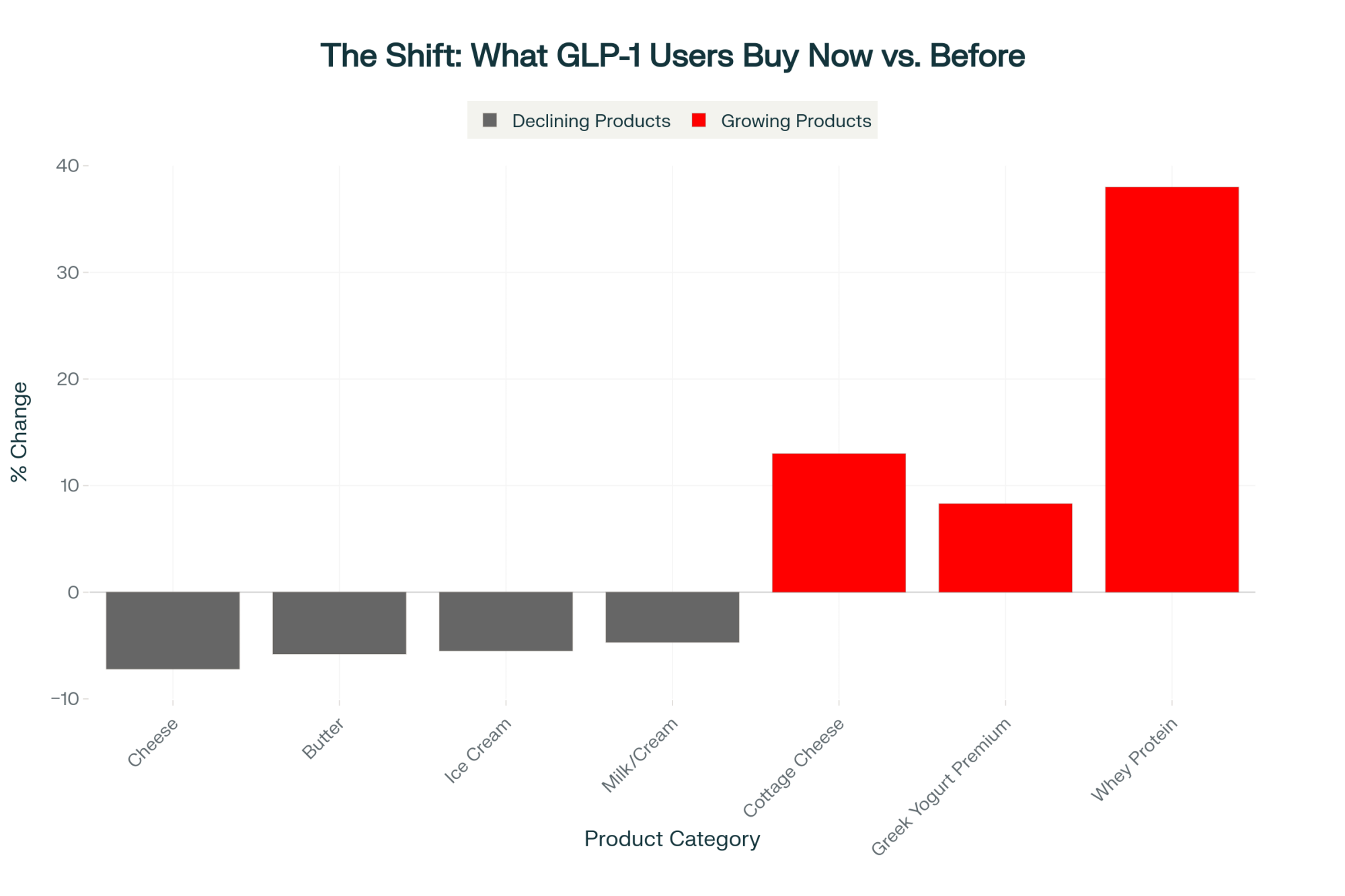

Looking a bit further ahead, this development suggests that herds that get serious about microbiome‑aware management now may also be better positioned for future shifts in breeding goals and processor expectations—especially as more emphasis is placed on feed efficiency and methane in proofs, and as sustainability programs look more closely at emissions and feed conversion.

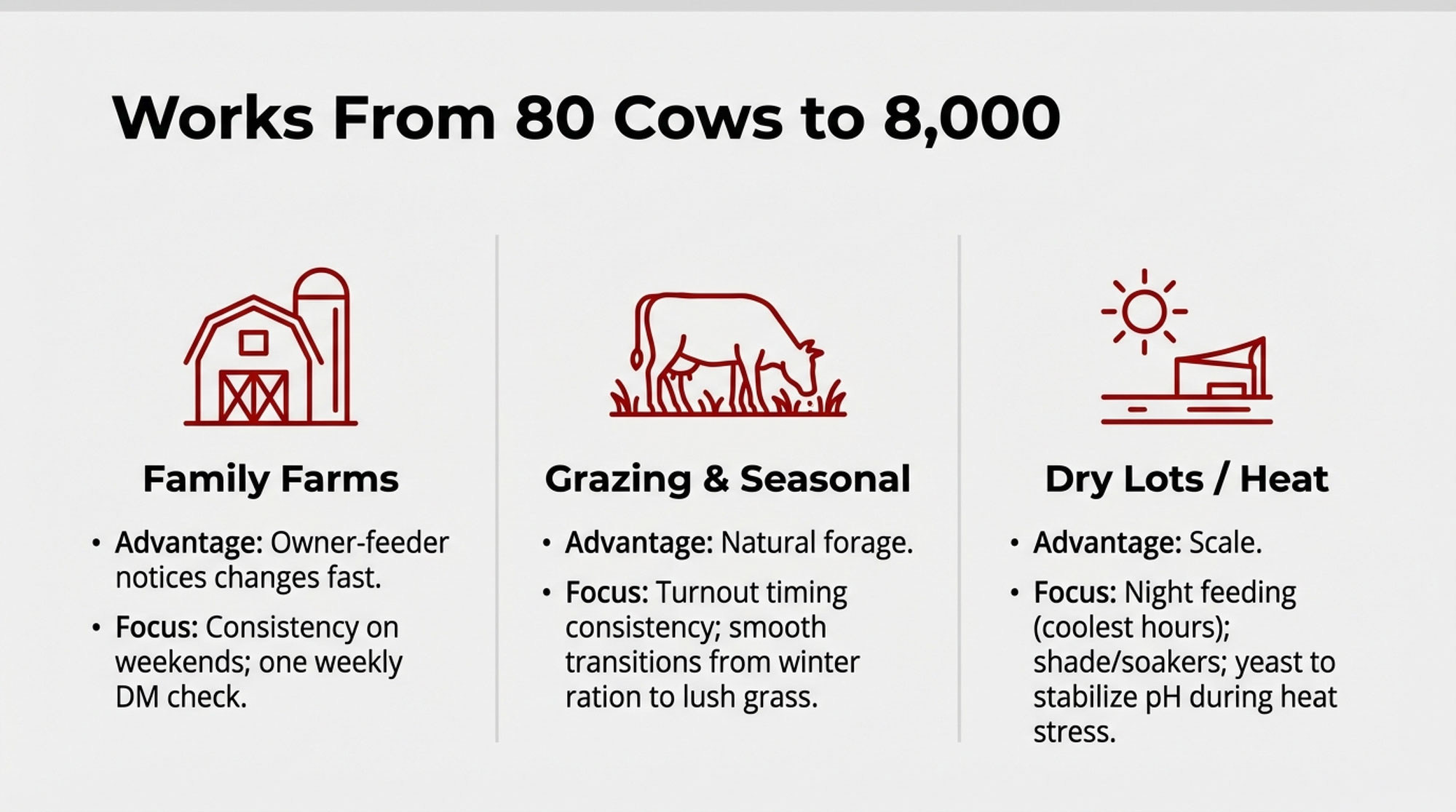

How This Plays Out on Different Types of Farms

It’s also important to note that microbiome‑aware management doesn’t look the same in every system. The principles are the same; the levers change.

Smaller Family Herds

On a 120‑cow tie‑stall in Quebec or a 200‑cow freestall in Wisconsin, the total dollar amount won’t be as large as on a 1,000‑cow dairy, but the per‑cow impact can look very similar. Many of these farms have a key advantage: the people making decisions are the ones feeding cows and walking the alley every day, so they notice subtle changes quickly.

The constraint is usually time. One person may be handling feeding, milking, fresh cow management, and fieldwork. On these operations, the most successful microbiome‑aware changes are often:

- Keeping feed times reasonably consistent every day, including weekends

- Adding a simple weekly TMR or key forage dry matter check, rather than trying to test constantly

- Using the particle separator at least occasionally to see whether sorting might be part of why butterfat performance is more variable than expected

Additives like live yeast or buffers are often targeted at small groups—such as fresh cows during the transition period or high‑risk pens—where the return is easiest to see and monitor.

Grazing and Seasonal Systems

In grazing and seasonal systems—such as many in Atlantic Canada, parts of the Northeast, Ireland, and New Zealand—the basic microbial principles remain the same, but the feeding context differs.

Instead of asking, “When does the TMR arrive?” the questions sound more like:

- “How consistent are turnout times onto fresh pasture?”

- “Are parlor concentrates or supplementary TMR fed at predictable times and rates?”

- “Are we giving fresh cows enough time to adapt when moving from a winter ration to lush spring grass?”

Pasture‑based management guides and research reviews emphasize that consistent grazing rotations, careful pasture dry matter measurement, and smooth transitions between conserved feed and pasture are critical for avoiding digestive upsets and performance drops. In these systems, a microbiome‑aware approach often leads to more deliberate use of fiber sources or buffers alongside high‑sugar grass, and particular attention to fresh cow management so the rumen isn’t shocked by abrupt diet changes.

Hot, Dry Regions and Dry Lot Systems

In hot, dry regions—such as parts of California, Arizona, and Texas—dry lot systems under high temperature‑humidity index conditions add heat stress to the rumen‑stability conversation. Research and field observations show that heat stress depresses intake, alters rumen fermentation (more acid load, lower pH), and can reduce fiber digestibility, making the rumen more fragile.

On those dairies, producers who are thinking in microbiome terms often work on three fronts at once:

- Feeding more of the ration during cooler times of day so cows actually feel like eating

- Making sure shade, fans, and soakers are set up and managed so cows can stay comfortable enough to use the feed that’s in front of them

- Using live yeast and buffers strategically, once cooling and feeding basics are in place, to help stabilize rumen pH and fermentation under heat stress

Industry sources have reported that, under those conditions, live yeast can provide a positive return when it’s part of a broader heat‑stress management package, not a stand‑alone solution.

| Farm Type | Herd Size | Key Implementation Focus | Primary Labor Barrier | Realistic Annual Gain per Cow | Total Herd Annual Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tie-Stall Family | 120–200 cows | Consistent daily feeding times; weekly DM test; occasional PSPS | Single operator doing feeding + milking + fieldwork; weekends are tight | $250–350 per cow | $30,000–$70,000 |

| Smaller Freestall | 300–500 cows | 2–3 week DM checks; PSPS quarterly; better push-up routine with existing crew | Hand-offs between shifts; weekend consistency | $350–450 per cow | $105,000–$225,000 |

| Mid-Size Freestall | 800–1,200 cows | Full four-phase playbook; weekly DM; PSPS monthly; automatic feed pusher ROI positive | Crew discipline on timing; shift management | $450–550 per cow | $360,000–$660,000 |

| Dry Lot & Hot Climate | 2,000–8,000 cows | Phase 1 (timing) + heat-stress additives; cooler-hour feeding; aggressive yeast use | Cooling infrastructure consistency; feed crew schedule discipline | $300–400 per cow (capped by heat stress) | $600,000–$3,200,000 |

| Grazing/Seasonal | 80–300 cows (milk + calf) | Pasture turnout timing consistency; transition management (winter→spring); forage DM variability | Seasonal labor shifts; pasture readiness unpredictability | $180–280 per cow | $14,400–$84,000 |

Where Microbiome‑First Efforts Can Go Off Track

As promising as this way of thinking is, it’s not a magic wand. There are a few common ways it can go sideways.

One is partial implementation. If a herd tightens up feeding times but leaves a very sortable ration unchanged, cows may simply eat more of the fast‑fermenting portion of the diet more consistently. In the short term, that can actually increase the risk of rumen acidosis rather than reduce it, which aligns with PSPS‑based research and field reports showing that excessively long particles encourage sorting.

Another is overestimating labor capacity. On many family farms, it’s simply not realistic to add frequent night push‑ups and multiple TMR dry matter tests per week. Extension advisers often recommend starting with one or two high‑impact changes—like a weekly DM check and better weekend feeding consistency—that everyone believes can be sustained.

A third is expecting additives to solve structural issues. In herds where forage quality is poor, dry cow and fresh cow housing are limiting, or stocking density is excessive, yeast and buffers might help at the margins, but they won’t turn the situation around on their own. Reviews of direct‑fed microbials and buffers emphasize that these tools complement, but cannot replace, sound ration formulation, forage management, and cow comfort.

So while the microbiome lens is very useful, it’s healthiest to treat it as a way to prioritize and sharpen management decisions, not as a replacement for the fundamentals.

A Practical Starting Checklist

If we were wrapping this up over coffee in your farm office, here’s the simple checklist I’d leave on the table:

- Log what really happens. For two weeks, write down actual feed delivery and push‑up times by group, including weekends and holidays. Let those numbers—not memory—show where the biggest gaps are.

- Watch the bunk after feeding. Stand at the bunk 45–60 minutes after a TMR delivery. What are cows doing? What’s left on the bunk? If you can borrow or buy a particle separator, run both fresh TMR and refusals at least once to see how much the ration changes between wagon and cow.

- Add one dry matter check to your week. Pick a day each week to test TMR dry matter and compare it to the value in your ration program. Talk with your nutritionist about adjusting when the difference becomes large enough to matter for DMI.

- Use pen‑level data as an early warning. Look at fat: protein ratios, rumination indices (if you have monitors), and manure scores by group. Treat changes there as early hints that the rumen—and the bugs—may not be as stable as you’d like.

- Put additives in their proper place. Once timing, TMR structure, and dry matter are under reasonable control, then sit down with your nutritionist to design a focused, time‑limited trial with yeast or buffers in specific pens, rather than making a blanket change and hoping for the best.

The Bottom Line

At the end of the day, we’re not just feeding cows. We’re managing microbial ecosystems that live inside those cows and turn this season’s feed bill into next month’s milk cheque.

What’s encouraging is that many of the things those microbes seem to like—steady routines, consistent dry matter, well‑structured rations, thoughtful fresh cow management—line up closely with what good producers have been working toward for a long time. The microbiome‑first perspective doesn’t throw any of that out. It simply connects the “why” and the “how much” in a way that helps you decide where your next management tweak should be, whether you’re milking 80 cows in a tie stall or 8,000 cows in a dry lot system.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The rumen microbiome drives 36% of feed efficiency—manage it or lose it. A 2024 AI study on 454 Holsteins found microbiome composition rivals genetics and diet in determining which cows convert feed to milk efficiently.

- Three bunk-management gaps are quietly draining your tank. Weekend feed-time drift, unnoticed TMR dry matter shifts, and sortable rations cost pounds of DMI and milk every single day—often without any obvious ration change.

- A 10-hour feed gap costs 3.5 lb DMI and 7.9 lb milk per cow per day. Penn State data shows that fixing overnight access alone can recover much of that loss. Bunks should never sit empty for more than three hours.

- Additives can’t fix bad timing or a sortable ration. Follow the four-phase playbook: tighten feed delivery and push-ups first, tune particle size with the PSPS, make weekly DM checks routine, then use live yeast to fine-tune—not to patch.

- The math: $500–700 per cow per year. Stack those four phases on a 1,000-cow herd, and you’re looking at $500,000–700,000 in recoverable margin. Even capturing half changes your year.

Executive Summary:

If your ration looks right but the bulk tank keeps coming up short, this article explains why the missing piece may be your cows’ rumen microbiome—and how you manage the bunk around it. It starts with new AI‑based research showing the rumen microbiome accounts for roughly 36% of residual feed intake variation in Holsteins, then ties that directly to three daily levers you control: feed timing and access, TMR dry matter, and particle size/sorting. Using Penn State data, it quantifies how 10‑hour overnight feed gaps, unnoticed TMR moisture shifts, and highly sortable rations can quietly cost 3.5 lb of DMI and 7–8 lb of milk per cow per day—even in herds that think they’re “feeding well.” From there, it lays out a four‑phase, microbiome‑aware playbook: tighten feeding schedules and push‑ups, get the physical ration right with the PSPS, make routine DM checks part of bunk management, then use live yeast and buffers as fine‑tuning tools instead of expensive band‑aids. A realistic 1,000‑cow example shows how stacking those phases can unlock about $500–700 per cow per year—$500,000–700,000 across the herd—if you’re starting from the “common” level of drift in timing, DM, and sorting. Finally, the article shows how this approach scales from 80‑cow tiestalls to 8,000‑cow dry lot systems, with a simple checklist you can use to pick your first one or two changes and start turning microbiome theory into extra dollars on your milk cheque.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- Your Feed Room’s Hidden $58400 Leak – And How Smart Dairy Farms Are Plugging It – Exposes the invisible “shrink” that drains $58,400 from average herds every year. This guide arms you with precision-tracking methods to eliminate loading errors, ensuring the expensive ration you paid for actually reaches the rumen instead of the floor.

- The Cheap Feed Trap: Why the Wall of Milk Won’t Break and How to Protect Your Margins – Multi-year highs in milk-to-feed ratios are creating a dangerous “cheap feed trap” for North American producers. This analysis delivers a strategy for long-term positioning, helping you protect margins by looking beyond simple ration spreads to total business cost.

- The $30,000 Question: Is Feed Efficiency Measurement Finally Worth It? (New Research Says Yes) – Break away from traditional scales with this guide to metabolic-efficiency sensors. It reveals how GreenFeed technology identifies elite, efficient cows that conventional data misses, turning feed conversion into a measurable genetic advantage for your breeding program.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

An effective nutrition consultant will investigate and analyze all the issues impacting your cows and thus impacting your success. The Bullvine went to Dr. Scott Bascom to get some insight on the value of working with a nutrition consultant. Dr. Bascom is the Director of Technical Services at

An effective nutrition consultant will investigate and analyze all the issues impacting your cows and thus impacting your success. The Bullvine went to Dr. Scott Bascom to get some insight on the value of working with a nutrition consultant. Dr. Bascom is the Director of Technical Services at  From the Bunker to the Bank!

From the Bunker to the Bank! Beyond the Basics to Practical and Personal

Beyond the Basics to Practical and Personal