Your barn ‘smells fine’? At 8 ppm ammonia, you can’t detect it—but your calves’ lungs can. You’re not managing. You’re hoping. And it’s costing you.

Executive Summary: The dairy industry finances $200,000 robots without blinking but ignores $100 interventions that cost 1,200 pounds of milk per heifer over a lifetime. Research from UC Davis, UW-Madison, and Lactanet (2019-2025) shows lung damage begins at 4 ppm ammonia—a level humans can’t detect after regular barn exposure—while colostrum absorption crashes from 95% at hour one to 50% by hour six. One-quarter of colostrum samples fail quality thresholds, and visual assessment is unreliable: thick golden colostrum sometimes tests worse than thin watery batches. The fixes cost almost nothing: a Brix refractometer runs under $100, bedding every 2-3 days cuts diarrhea risk 57%, and tightening colostrum timing requires only protocol discipline. With multiple component pricing placing nearly 90% of milk check value on butterfat and protein, early-life calf health compounds directly into first-lactation revenue. The math is brutal: maternity pen protocols pay back in weeks while that robot takes seven years.

Walk into any progressive dairy operation these days, and you’ll find precision feeding systems calibrated to the gram, genomic testing that predicts lifetime production potential, and automated milking technology that would have seemed like science fiction a generation ago. According to USDA data and industry reports—a single robotic milking unit now runs $150,000-$230,000, and farms are installing them by the thousands. We’ve embraced data-driven decision-making in remarkable ways.

| Investment Decision | Upfront Cost | Annual Debt Service (7 years) | Calf Health Impact | First-Use Payback |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic milking unit | $150,000-$230,000 | $21,000-$33,000/year | None | 7 years |

| Brix refractometer + protocol | <$100 | $0 | Saves 1,200 lbs/heifer × heifers born | Immediate |

But here’s what’s been catching my attention lately. A conversation has been building among veterinarians, extension specialists, and forward-thinking producers over the past few years. The question: What if the biggest opportunity for improvement isn’t in the milking string at all—but in the first 24 hours of a calf’s life?

The emerging data from the University of California, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and on-farm trials across North America reveals something worth considering. The maternity pen—often treated as a simple pass-through area where calves arrive and cows transition—may actually be one of the most underutilized profit centers on many farms. And the interventions that seem to move the needle most don’t require six-figure investments. They require attention, protocol, and a shift in how we think about foundational management.

The Lifetime Value Calculation Worth Revisiting

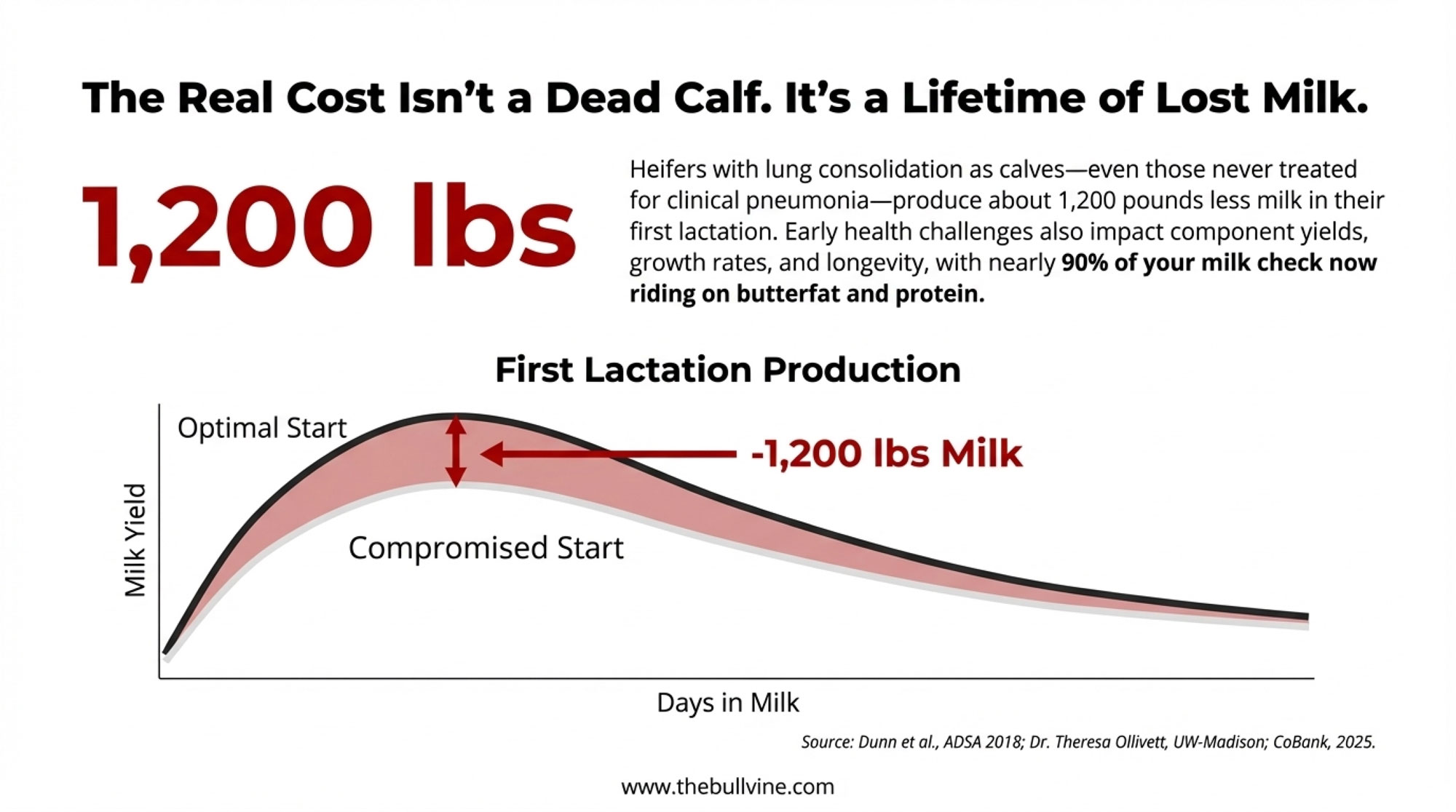

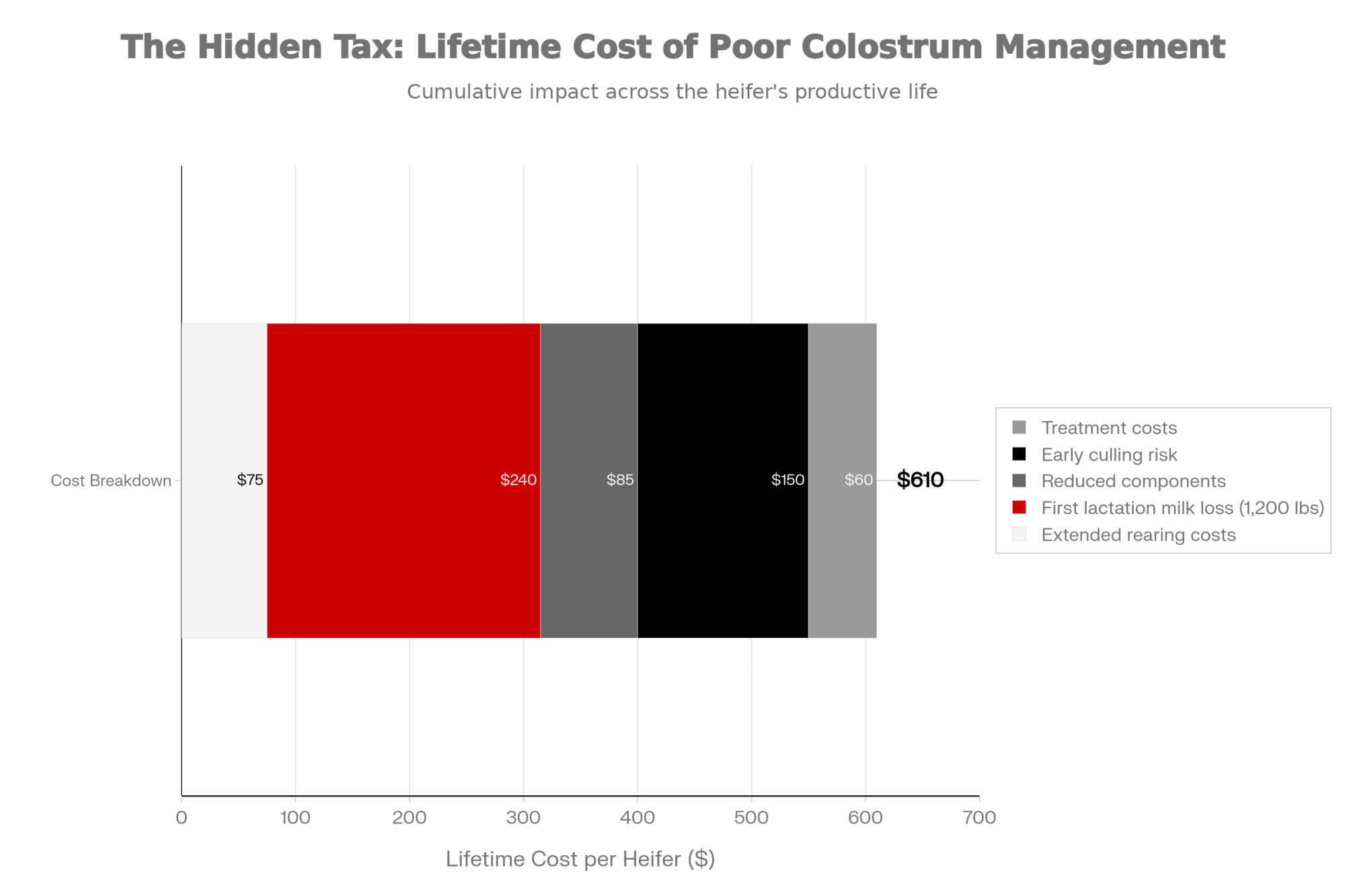

When producers think about calf losses, they typically calculate the immediate cost: the value of a dead calf, maybe $150-200, depending on the market. But that calculation, it turns out, may significantly underestimate what’s really at stake.

Dr. Sheila McGuirk, Professor Emerita at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, has spent decades researching calf health outcomes. Her work, along with research from UC Davis and other land-grant universities, points to a more complete economic picture that extends well beyond immediate mortality.

Consider a thought experiment with two genetically identical heifer calves born on the same farm, same day:

Calf A is born in a maternity pen with adequate but not optimal conditions—bedding changed weekly, moderate ammonia levels that nobody really notices, colostrum delivered within “a few hours” of birth.

Calf B is born in a well-managed environment—fresh bedding, clean air, and colostrum within 90 minutes of hitting the ground.

Both calves survive. Both eventually enter the milking string. But their lifetime trajectories can diverge in ways that compound over the years.

Research published in the Journal of Dairy Science and documented through USDA NAHMS surveys suggests that Calf A faces a series of potential disadvantages:

The growth consideration. Multiple studies show that calves with poor passive transfer or early respiratory disease tend to have lower average daily gain and reach breeding size later, adding weeks to the rearing period and increasing feed and housing costs. Penn State Extension’s 2023 summary of the research found clear links between passive transfer categories and growth outcomes—calves in lower categories simply don’t grow as efficiently.

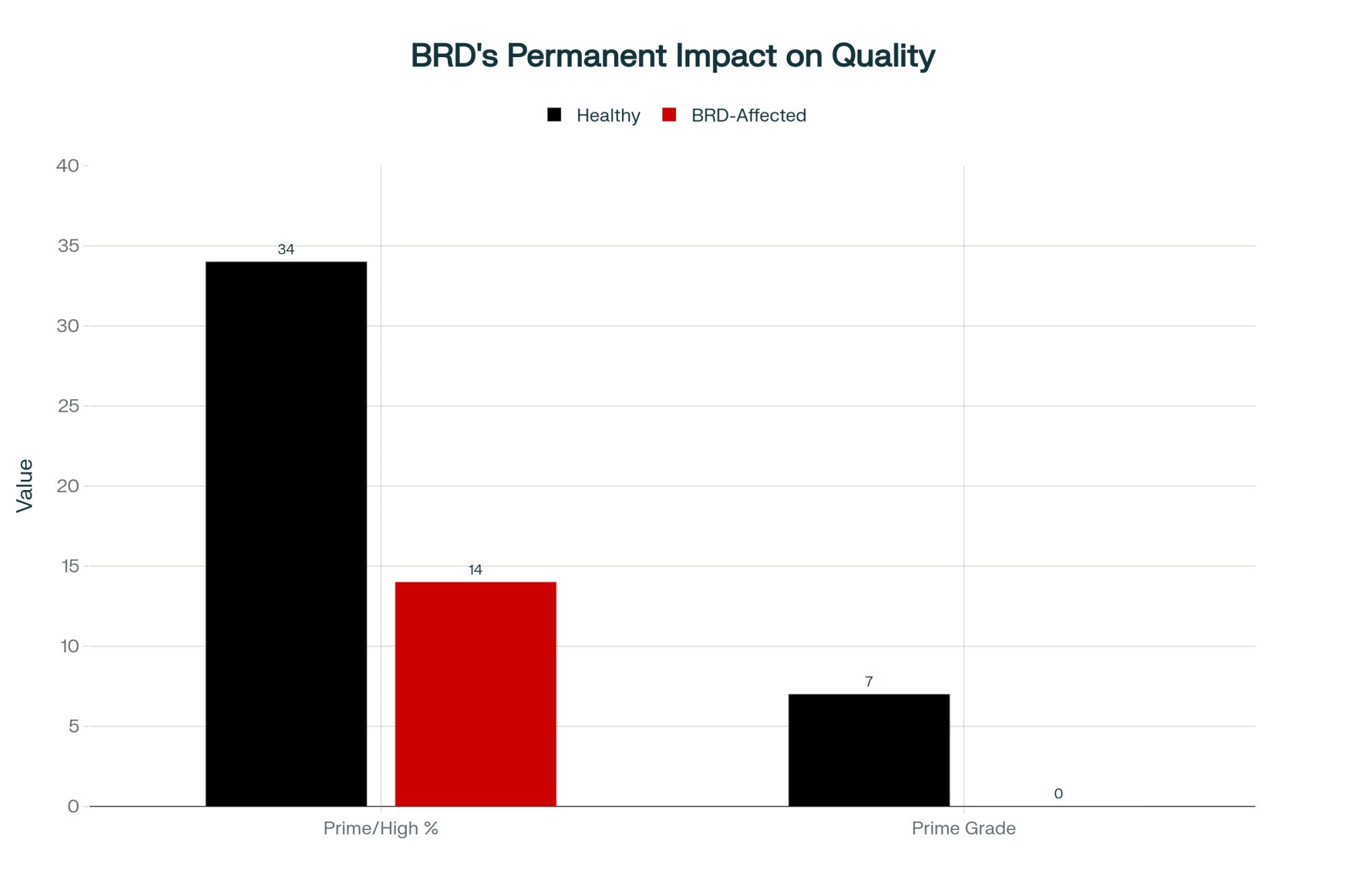

The lung capacity question. This one particularly caught my attention. Research from Dr. Theresa Ollivett at UW-Madison using thoracic ultrasound has documented that calves with lung consolidation—even those never treated for clinical pneumonia—often produce less milk in their first lactation.

The Hidden Milk Loss

A 2018 cohort study by Dunn and colleagues presented at ADSA found that heifers with at least 3 cm of lung consolidation as calves produced about 525 kg (1,150 lbs) less milk in their first 305-day lactation. Dr. Ollivett has noted in extension presentations that any heifer calf with a history of pneumonia tends to produce about 1,200 pounds less milk in her first lactation.

The longevity factor. NAHMS data and follow-up studies indicate that calves experiencing early health challenges have a higher risk of leaving the herd before completing their second lactation. They may be more likely to struggle with metabolic issues at first calving and less likely to breed back efficiently.

The component connection. Here’s something that doesn’t get discussed enough in the calf barn: early-life nutrition and health also affect component production. A 2024 study published in BMC Veterinary Research, tracking 220 heifer calves from eight herds, found that colostrum management and preweaning health measures significantly impacted not only total milk yield but also protein and fat yields in first lactation. Penn State Extension’s review of calf feeding research found that calves fed higher planes of nutrition produced more fat and protein on a daily basis and had higher 3.5% fat-corrected milk in first lactation. With multiple component pricing placing nearly 90% of the milk check value on butterfat and protein, according to CoBank’s 2025 analysis, those early-life investments compound directly into revenue.

When you add these factors together—the extended rearing costs, the potential first-lactation milk loss, the component production impact, the increased culling probability—the lifetime economic impact can reach several hundred dollars per heifer, and in some scenarios more. A 2016 meta-analysis by Raboisson and colleagues, frequently cited by Dr. Sandra Godden at the University of Minnesota, estimated that failure of passive transfer alone costs at least $70 per calf in direct effects.

Worth considering as you evaluate where to focus improvement efforts.

The Bedding Research That’s Getting Attention

Perhaps no finding has generated more discussion among dairy consultants than what’s emerged about bedding management in recent years.

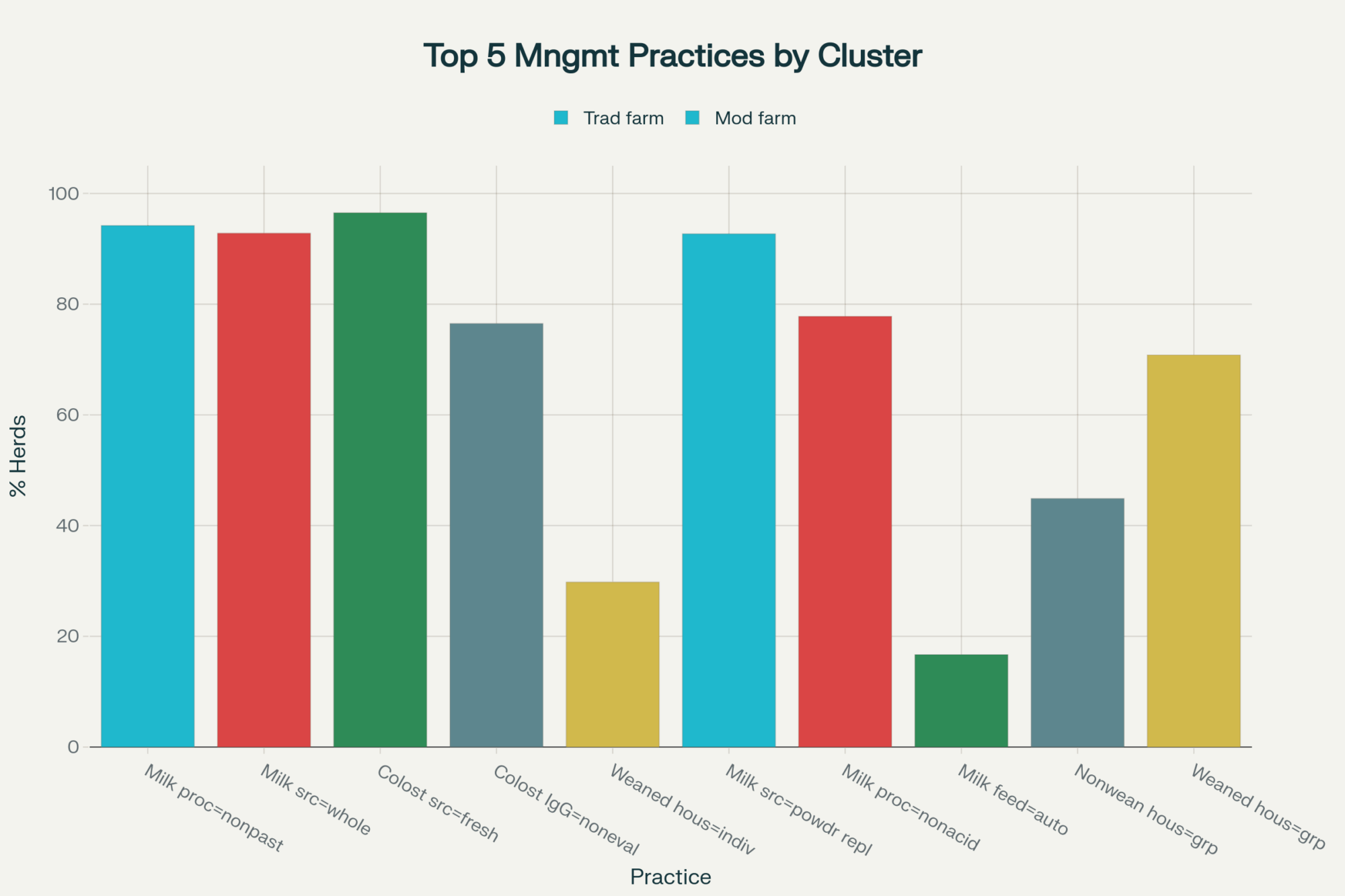

The BRD 10K study, published in the Journal of Dairy Science in 2019 by Dubrovsky and colleagues at UC Davis—including epidemiologist Dr. Sharif Aly—tracked 11,470 calves across six California dairies over a full year. The study examined dozens of management variables to identify which practices correlated with respiratory disease outcomes. What they found reinforced something that’s been gaining traction in calf housing guidance: cleaner, drier environments appear to matter considerably.

The Bedding Frequency Finding

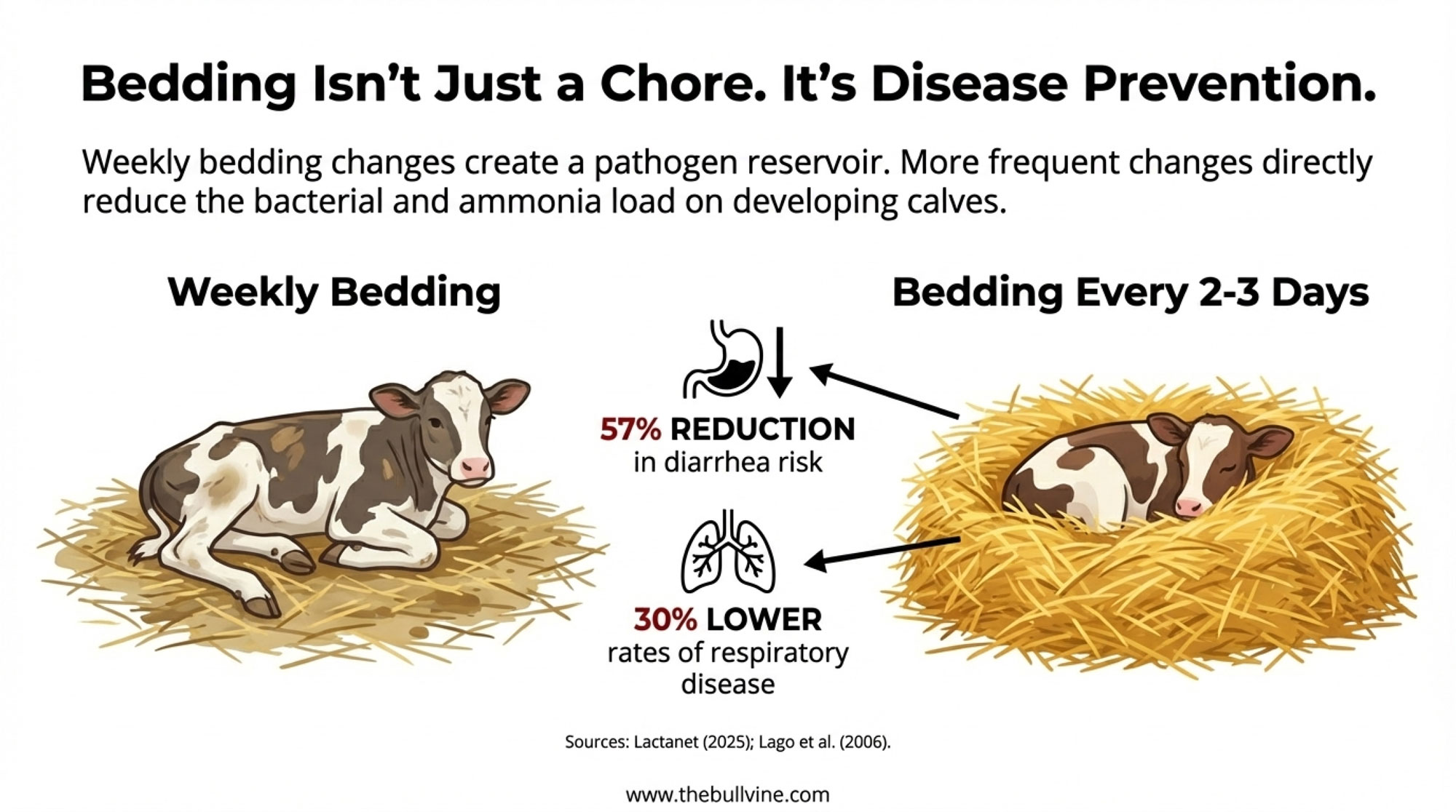

A February 2025 calf housing fact sheet from Lactanet, drawing on research by Medrano-Galarza and colleagues published in Journal of Dairy Science, found that adding fresh bedding every 2 to 3 days, compared with every 7 days or longer, was associated with a 57% reduction in diarrhea risk.

The same Lactanet summary, citing work by Lago and colleagues from 2006, found that calves fully nested in deep straw bedding had 30% lower rates of respiratory disease compared to those with legs visible while lying down.

I recently spoke with a Wisconsin producer who implemented more frequent bedding changes last fall. His observation: the mindset shifted from reactive to preventive. They’re changing bedding before it becomes a problem rather than after noticing one. Within three weeks, he said, respiratory rates in his calf barn had dropped noticeably. Now, that’s one farm’s experience—but it aligns with what the research suggests.

The mechanism makes intuitive sense when you think about it. When bedding sits undisturbed for extended periods, bacterial populations grow in the moist environment. Ammonia accumulates from decomposing organic matter. By the end of a week, the bedding can become a pathogen reservoir—and every breath the calf takes delivers that load to developing lung tissue.

The economics vary by operation, of course. More frequent bedding changes mean more straw and more labor. Those aren’t trivial considerations, especially for operations already stretched thin. But on farms that have carefully tracked outcomes, the returns from reduced treatment costs, improved growth rates, and lower mortality have often exceeded the investment.

I want to be clear: these figures come from specific studies in specific contexts. Operations in the Upper Midwest face conditions different from those in California’s Central Valley or the humid Southeast. Pasture-based systems have their own considerations entirely. The principle seems sound—cleaner environments generally mean healthier calves—but the specific economics will vary based on your starting point, labor costs, and regional factors.

What the “Smell Test” Might Be Missing

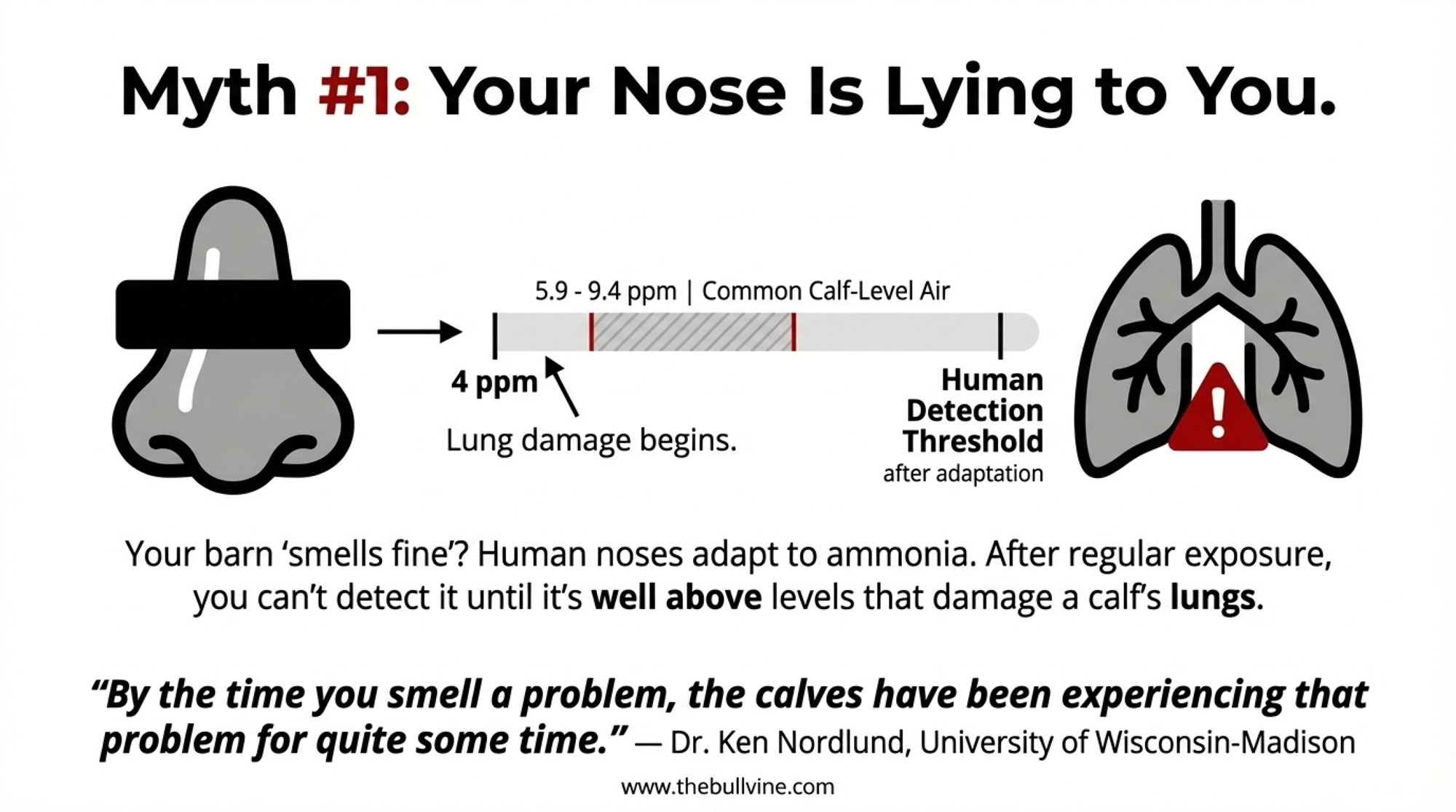

Most dairy producers believe they can assess air quality by smell. If the barn doesn’t reek of ammonia, ventilation must be adequate. It’s a reasonable assumption, and I’ve relied on it myself over the years.

But the biology may tell a different story.

Research from Penn State Extension, corroborated by work at multiple land-grant universities, has documented that humans typically detect ammonia at fairly low concentrations—but here’s the thing: regular exposure creates what researchers call olfactory adaptation. Those of us who work in barns daily often don’t consciously register ammonia until concentrations are well above levels that may affect calves.

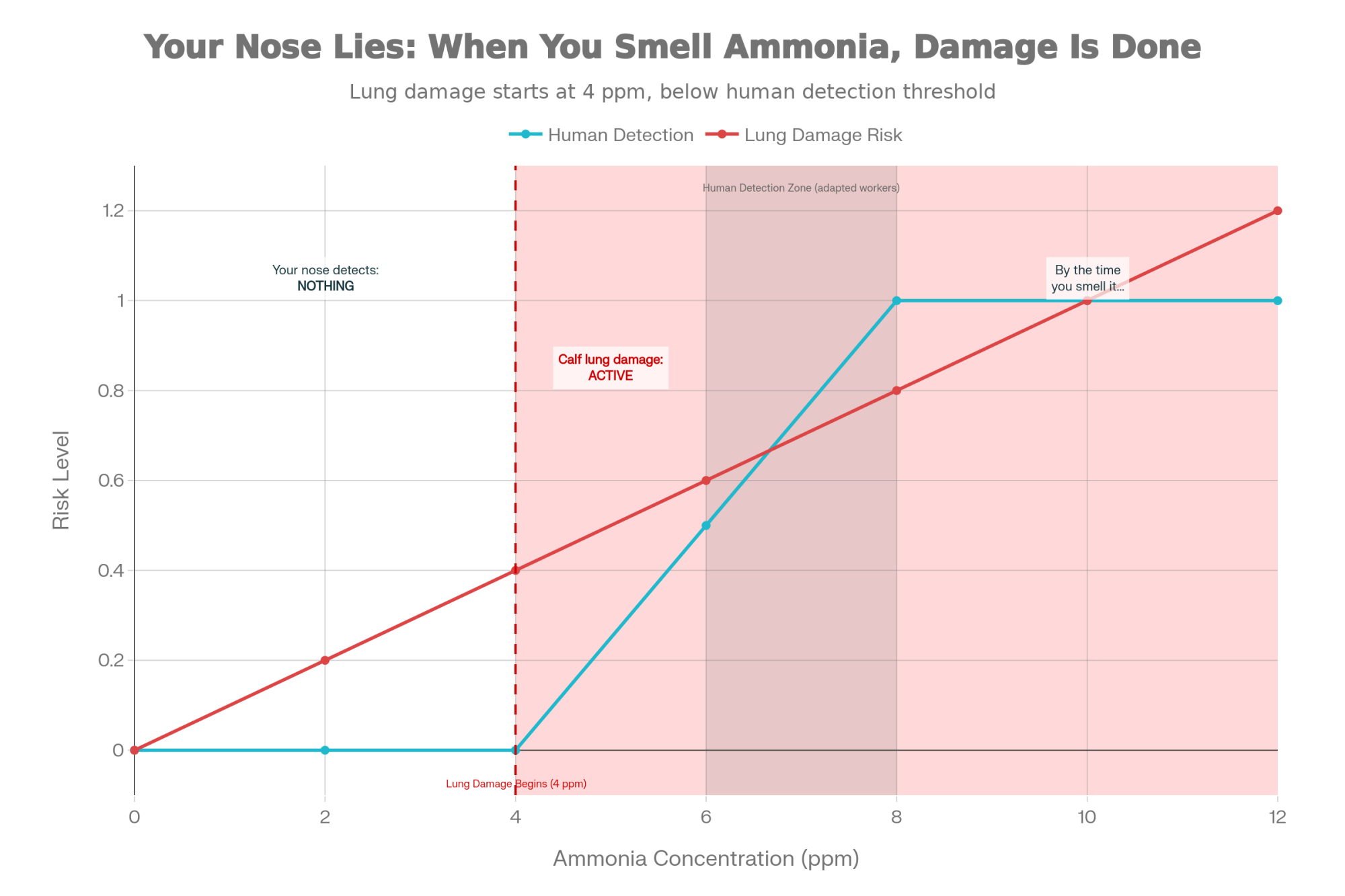

The four ppm Threshold

| Finding | Source |

| Ammonia exposure above four parts per million is significantly associated with lung consolidation (odds ratio 1.73) | Van Leenen et al., 2020, Preventive Veterinary Medicine |

| Four-hour maximum ammonia levels are commonly 5.9-9.4 ppm at calf level | Animals journal, 2024 (Swiss calf housing study) |

| Human nose adapts; calves’ lungs don’t | Multiple land-grant university extension publications |

Dr. Ken Nordlund, who co-authored foundational calf housing recommendations now used through the Dairyland Initiative at UW-Madison, put it plainly:

“By the time you smell a problem, the calves have been experiencing that problem for quite some time.”

— Dr. Ken Nordlund, DVM, University of Wisconsin-Madison

That’s worth thinking about. We walk through and think everything is fine. The calves may be experiencing something different.

Visual Checks That Can Help

What some farmers are discovering is that while human noses adapt, visual and behavioral indicators don’t. Several zero-cost assessments can reveal ventilation concerns before they show up in treatment records:

- The eye check. Fresh cows and young calves with visible tearing, red or watery eyes, are showing mucosal irritation—potentially from ammonia exposure. The eyes don’t adapt the way noses do.

- The bedding moisture test. In winter, if bedding shows heavy condensation or frost at calf nose height in the early morning, moisture may not be adequately exhausted from the barn. That trapped moisture creates favorable conditions for both pathogen growth and ammonia accumulation.

- The breathing observation. This one takes a little practice, but it’s useful. Healthy calves at rest breathe effortlessly from the belly—what veterinarians call diaphragmatic breathing—at 20-30 breaths per minute. If you’re seeing visible flank movement, shoulders working, or labored breathing in resting calves, that’s worth investigating.

- The rafter inspection. Water droplets forming on the underside of the barn roof indicate moisture is condensing rather than being ventilated out.

- The 5-degree rule. According to Cobb et al. (2016), cited in The Dairy Site’s ventilation guidance, when the temperature difference between inside a calf shelter and outside exceeds 5°F, that’s indicative of a ventilation problem—the barn is too closed up.

These assessments take minutes and require no equipment. Just attention and a willingness to look.

The Colostrum Conversation

If there’s one area where the gap between “doing something” and “doing it optimally” is most evident, it’s colostrum management. You probably know most of this already—but the details matter, and I’ve found the research worth revisiting.

Most dairy operations believe they’re handling colostrum adequately because they feed it “within a few hours” of birth. The intention is right. But research from multiple institutions reveals several common gaps that can undermine even well-meaning protocols.

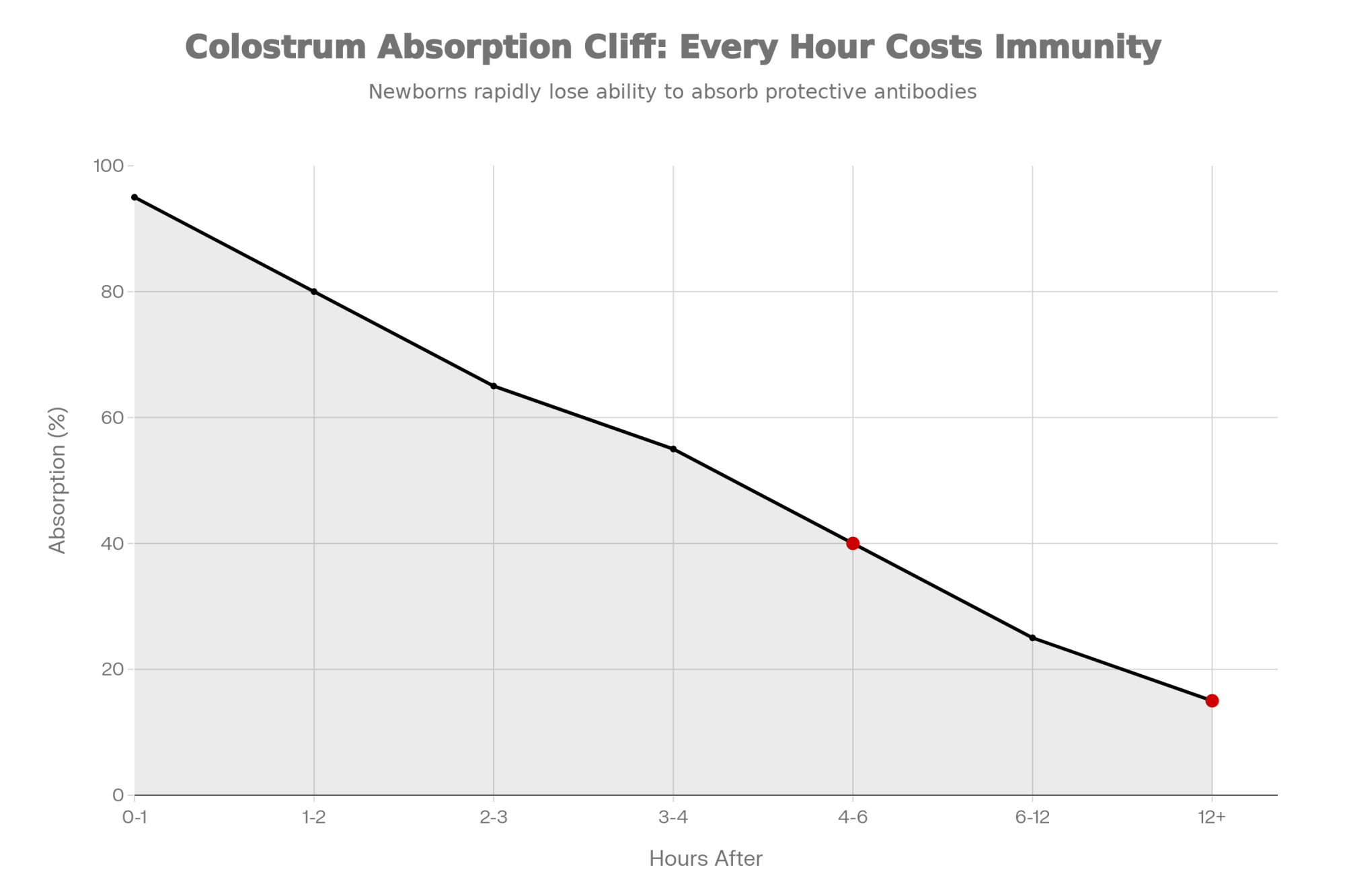

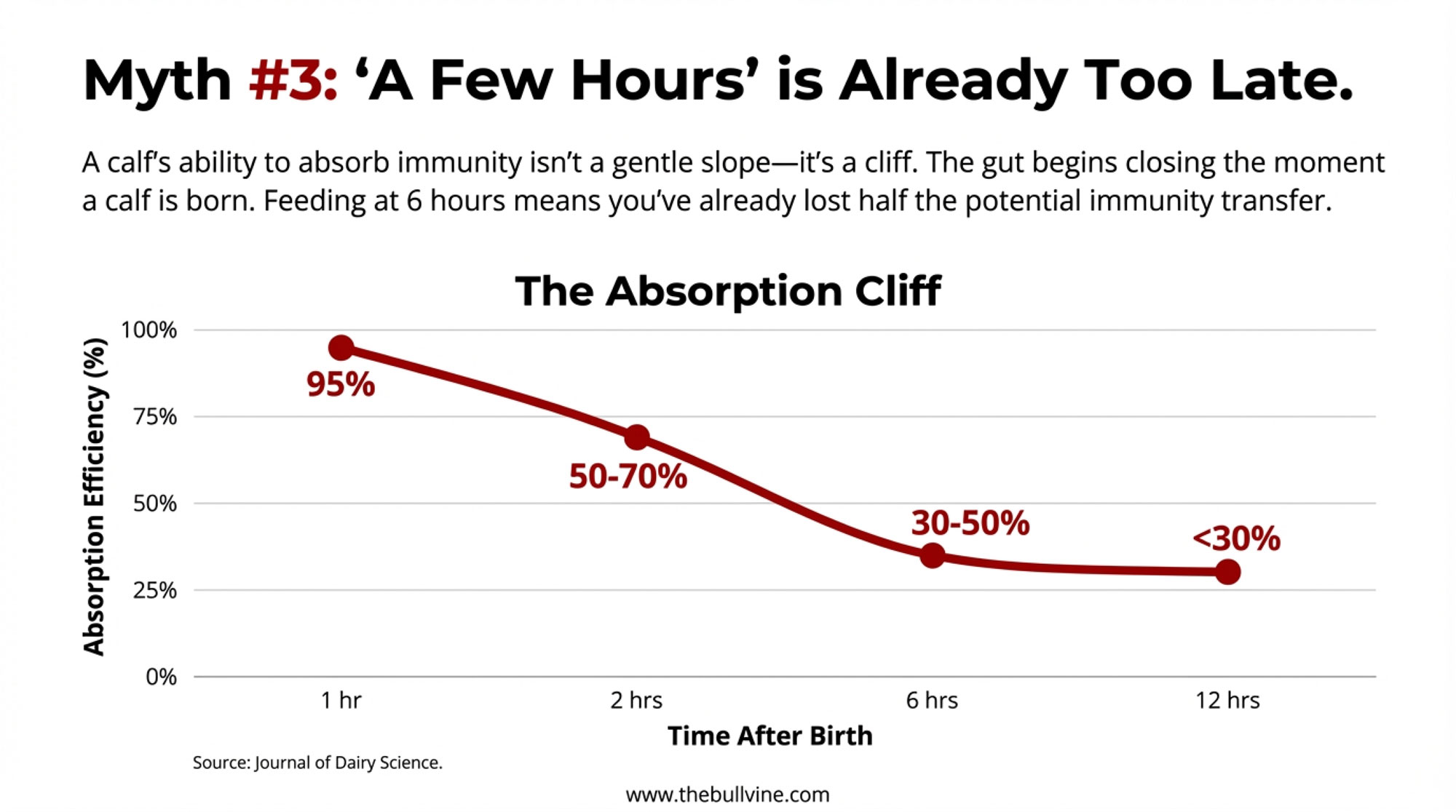

Why Timing Matters More Than We Thought

The calf’s ability to absorb immunoglobulin G from colostrum begins declining immediately after birth. This is intestinal physiology documented extensively in peer-reviewed research. The gut epithelium that allows large antibody molecules to pass into the bloodstream begins closing from the moment the calf is born.

The Absorption Clock

| Time After Birth | Absorption Efficiency |

| Less than 1 hour | 90-100% |

| 1-2 hours | 70-90% |

| 2-6 hours | 50-70% |

| 6-12 hours | 30-50% |

| Beyond 12 hours | Below 30% |

Source: Journal of Dairy Science and multiple university extension summaries

What this means practically: every hour of delay has a cost. A farm that believes it’s feeding “within a few hours” but is actually reaching calves at 5-6 hours has already lost a substantial portion of potential immunity transfer.

Dr. Sandra Godden at the University of Minnesota has published extensively on colostrum management protocols. Her research suggests that “within a few hours” is too vague a target—specific timing protocols that ensure feeding within two hours, and ideally within one hour, tend to produce meaningfully different outcomes.

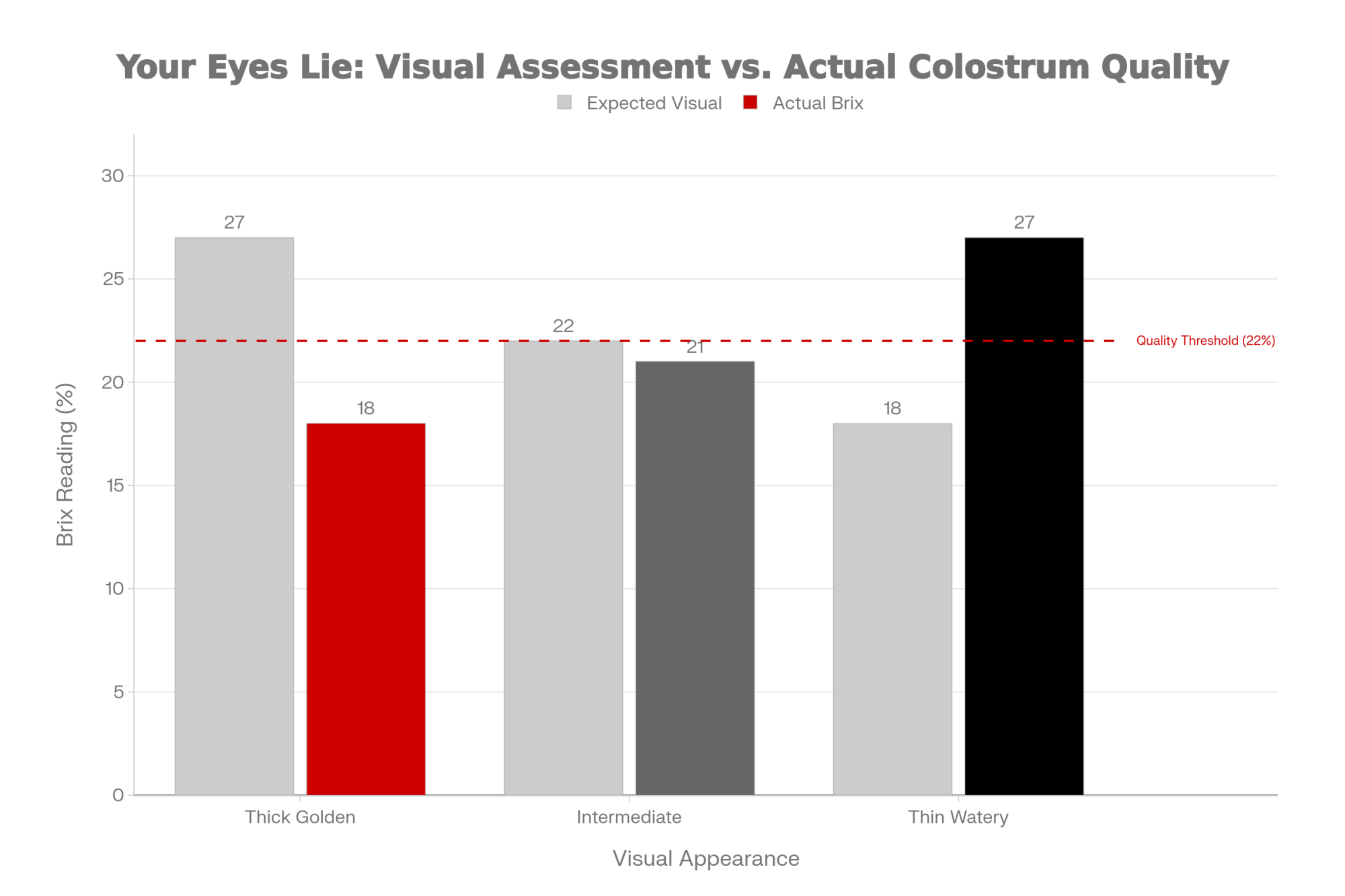

The Visual Assessment Question

One of the more interesting findings I’ve encountered comes from colostrum quality research conducted across multiple U.S. dairy operations.

When researchers asked farmers to visually rank colostrum quality—thick and golden versus thin and watery—and then tested with a Brix refractometer, the results challenged conventional wisdom. As Hanne Skovsgaard Pedersen demonstrated, the first three first-milking colostrum batches harvested the same morning showed surprising results:

- The thick, bright golden yellow batch: Brix reading of 18 (below threshold)

- The intermediate-appearing batch: Brix reading of 21

- The thin, nearly white batch: Brix reading of 27 (excellent quality)

True quality was the direct inverse of perceived quality based on visual assessment alone.

Yet walk through most dairy operations, and you’ll find colostrum assessment still relies primarily on appearance. And here’s the challenge—summaries of NAHMS data and herd-level testing cited in Hoard’s Dairyman suggest that around one-quarter of colostrum samples fall below the commonly used 50 g/L IgG cutoff. That’s approximately 22% on a Brix refractometer, according to the Dairy Calf and Heifer Association Gold Standards. Without testing, farms have limited ways of knowing which batches might be setting calves up for challenges.

| Visual Appearance | What You Think | Actual Brix Reading | Reality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thick, bright golden yellow | “Excellent quality” | 18 | FAILED (below 22% threshold) |

| Intermediate color | “Probably OK” | 21 | Borderline |

| Thin, nearly white | “Poor quality” | 27 | EXCELLENT |

The Affordable Solution

Penn State Extension confirms that a Brix refractometer costs between $100 and several hundred dollars, with many farm-suitable options at the low end of that range. Takes 30 seconds per batch. Compare that to $150,000-$230,000 for a milking robot—and ask yourself which investment has the faster payback.

The Contamination Variable

Even high-quality colostrum can be undermined by bacterial contamination—something that doesn’t always get the attention it deserves.

Research published in the Journal of Dairy Science and reviewed in Canadian Veterinary Journal articles demonstrates that heavy bacterial loads in colostrum can interfere with IgG absorption. The mechanism involves bacterial binding to antibodies, thereby reducing the amount available for uptake. High pathogen exposure may also trigger accelerated gut closure.

The practical result: a calf can receive colostrum with excellent Brix readings and still experience suboptimal passive transfer because contamination compromised absorption.

Sources of contamination include dirty teats at harvest, inadequately cleaned collection equipment, storage in contaminated containers, and direct pathogen shedding from infected mammary glands.

Research on colostrum pasteurization, including work from the University of Minnesota, has found higher serum IgG concentrations and fewer bacterial contaminants in calves receiving pasteurized versus raw colostrum. The heat treatment eliminates pathogens while preserving antibody function.

For operations with persistent passive transfer challenges despite good Brix scores, pasteurization may be worth investigating.

Putting This in Context: When Does This Apply?

I want to address something directly, because useful analysis requires acknowledging that not every farm faces the same situation.

- Operations are already achieving strong outcomes. If your calf mortality is consistently below 3%, your serum total protein testing shows excellent passive transfer rates, and respiratory disease is minimal—your current protocols are working well. The improvements discussed here offer diminishing returns when baseline performance is already strong. Your resources may be better invested elsewhere.

- Pasture-based and seasonal calving systems. The bedding and ventilation research cited here comes primarily from confined housing systems. Operations calving on pasture face different challenges—weather exposure, predation risk, monitoring difficulty—but also different advantages in terms of air quality and pathogen load. The colostrum timing principles apply broadly, but housing-specific recommendations need thoughtful adaptation.

- Small-scale operations. The labor economics of twice-weekly bedding changes look different on a 50-cow dairy than on a 500-cow operation. The principles remain valid, but the implementation needs to align with your operation’s labor availability and management capacity. Sometimes “better” is more achievable than “optimal.”

- Regional and seasonal variation. A barn in Wisconsin during February faces different ventilation dynamics than one in California in July. Humidity, temperature extremes, and baseline pathogen pressure all affect how these recommendations translate to specific operations.

- International considerations. For producers in Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere—regulatory environments, housing norms, and climate conditions vary considerably. The biological principles apply broadly, but specific protocols and cost structures need local adaptation.

“The research provides direction. Local adaptation provides results.”

Regional Protocol Adjustments: What the Research Says

| Region | Primary Challenge | Critical Adjustment | Target Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Midwest (WI, MN, MI) | Winter cold + moisture | Minimum 4 air changes/hour even in winter | <5°F temp difference inside vs outside |

| California / Western | Summer heat + dust | 40-60 air changes/hour in summer | Shade + evaporative cooling |

| Southeast (GA, FL, TX Gulf) | High humidity | Moisture control paramount | Dew point management |

Because ventilation and environment management looks different depending on where you farm, here’s what the research suggests for key regions:

Upper Midwest (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan) — Winter Focus

The challenge in cold-climate barns is balancing fresh air with avoiding drafts. According to Dairy Global and extension guidance:

- Minimum four air changes per hour, even in winter—closing up the barn completely is worse than cold

- Target barn temperature of 40-50°F (4-10°C) in heated facilities; use heat as a ventilation tool to dry air, not primarily for warmth

- Calves are comfortable down to 50°F with adequate nutrition and deep bedding; below that, they start using energy for warmth instead of growth

- Positive pressure ventilation tubes are particularly valuable in winter—a system for a 40×100-foot calf barn costs approximately $1,500-2,000 to install, according to extension estimates

- Watch for the 5°F rule: if the inside temperature exceeds the outside by more than 5 degrees, ventilation is inadequate

California & Western Dry Lot Systems — Summer Focus

Heat stress and dust present different challenges:

- 40-60 air changes per hour are needed in summer conditions

- Shade and water access become critical; evaporative cooling, where feasible

- Dry lot systems have natural ventilation advantages, but require careful attention to dust and bedding moisture management

- Morning and evening feeding may help calves consume adequate nutrition during heat

Southeast (Georgia, Florida, Texas Gulf) — Humidity Focus

High humidity creates unique pathogen pressure:

- Moisture control is paramount—humidity promotes bacterial and fungal growth in bedding

- More frequent bedding changes may be necessary than in drier climates

- Ventilation must address both temperature and humidity; dew point management matters

- According to Dairy Herd Management, keeping dew points lower than external ambient temperature helps prevent condensation

What Getting Started Might Look Like

For farms considering improvements, the question of where to begin can feel daunting. Address bedding, ventilation, and colostrum simultaneously? That approach sometimes leads to implementation challenges—too many changes, unclear attribution of results, and staff feeling overwhelmed.

What seems to work better for many operations is a sequenced approach that builds confidence through visible progress.

| Phase | Action | Timeline | Expected Outcome | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Increase bedding frequency to every 2-3 days | Weeks 1-4 | 57% diarrhea reduction, visible calf health improvement | $4/calf/week |

| Phase 2 | Add Brix testing to every colostrum batch | Weeks 5-6 | Identify failing batches, improve protocol | <$100 one-time |

| Phase 3 | Assess and upgrade ventilation | Months 3-6 | Reduced ammonia, better lung health | $1,500-$2,000 for tube system |

| Payback | Measure first-lactation milk from improved cohort | 24-30 months | +1,200 lbs milk per heifer | Revenue gain |

Consider starting with the bedding protocol.

This isn’t necessarily the highest-impact intervention, but it’s often the most immediately visible. Move to more frequent bedding changes—every 2-3 days rather than weekly. Track two simple metrics: navel scores on a 1-3 scale and respiratory rates on a sample of 10 calves weekly.

Within a few weeks, many operations see measurable improvement. Navel scores drop. Respiratory rates normalize. The barn smells different. Staff notices calves seem healthier.

That visible progress builds confidence that change matters—and creates momentum for the next step.

Then consider adding colostrum testing.

Once bedding improvements show results, adding Brix testing feels like a natural progression. Invest in a refractometer. Test every batch for two weeks.

Many farms discover something uncomfortable: a meaningful percentage of batches fall below quality thresholds. This revelation typically triggers improvements to the protocol organically. Farmers want to address problems they can now see.

Then evaluate ventilation.

With foundational improvements in place, farms are better positioned to assess ventilation investments. Initial improvements—such as fan repositioning and curtain management adjustments—may be relatively modest. More substantial upgrades—such as positive-pressure tube systems and structural modifications—require a greater investment.

The timeline for seeing returns is longer here. But farms that have already experienced benefits from bedding and colostrum work are often more willing to make the investment and allow time for results.

The pattern I’ve observed: farms that sequence improvements tend to sustain them. Farms that attempt comprehensive change all at once sometimes abandon the effort when results are hard to attribute, and staff feels stretched.

The Bottom Line

Let’s be honest here.

Bedding calves every two to three days is a pain. It’s labor-intensive, and straw isn’t getting any cheaper. Testing every batch of colostrum adds another task to an already packed calving routine. And convincing your team that the barn “smells fine” isn’t actually fine? That’s a tough conversation.

| Investment | Typical Cost | Payback Timeline | Impact on Milk Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic milking unit | $150,000-$230,000 | 5-7 years | Long-term efficiency |

| Positive pressure tube system | $1,500-$2,000 | 1-2 seasons | Respiratory health |

| Brix refractometer | Under $100 | First use | 1,200 lbs saved per heifer |

| More frequent bedding | Labor + materials | Weeks to months | 57% diarrhea reduction |

But here’s what I keep coming back to:

If you’re ignoring the 1,200 lbs of milk you’re leaving on the table because you wanted to save an hour of labor on a Tuesday, you aren’t managing a dairy—you’re managing a decline.

We’ll finance a $200,000 robot over seven years without hesitation. We’ll invest in automated feeding because it saves labor. We’ll pay for genomic testing to find the cows with the best production potential.

But then we’ll feed those genetically superior animals compromised colostrum because we didn’t want to spend $100 on a refractometer. We’ll house them in bedding that’s growing bacteria for a week because changing it more often “costs too much.” We’ll let them breathe eight ppm ammonia because we can’t smell it anymore.

The math doesn’t lie. The research is clear. The interventions are cheap compared to almost everything else we invest in.

| Investment | Typical Cost | Payback Timeline |

| Robotic milking unit | $150,000-$230,000 | 5-7 years |

| Positive pressure tube system | $1,500-$2,000 | 1-2 seasons |

| Brix refractometer | Under $100 to several hundred | First use |

| More frequent bedding | Labor + materials | Weeks to months |

The question isn’t whether you can afford to implement better maternity protocols. The question is whether you can afford not to.

Every calf born on your operation is either starting her career with a solid foundation—or starting it with a handicap she’ll carry to the bulk tank for years. The decisions you make in those first 24 hours echo through every lactation that follows.

This isn’t complicated. It’s not sexy. It won’t win you any awards at the equipment dealer’s open house.

But it might be the best return on investment you’ll make all year.

Quick Reference: The Three Thresholds That Matter

| Parameter | Target | Why It Matters |

| Colostrum timing | Within 1 hour of birth | Absorption efficiency drops from 90-100% to below 70% after 2 hours |

| Colostrum quality | Brix ≥22% (50 g/L IgG) | ~25% of samples fail this threshold; visual assessment unreliable |

| Ammonia levels | Below four ppm | Lung damage begins at levels humans can’t detect; your nose lies |

Print this. Post it in the maternity area. Make it non-negotiable.

Key Takeaways:

- $100 beats $200,000: A Brix refractometer (under $100) catches colostrum failures costing 1,200 lbs of milk per heifer. That robot takes seven years to pay back. This pays back on first use.

- Your nose lies: Lung damage starts at 4 ppm ammonia—below human detection after regular barn exposure. By the time you smell it, your calves have been breathing damage for weeks.

- Your eyes lie too: Thick golden colostrum: Brix 18, FAILED. Thin watery batch: Brix 27, EXCELLENT. 25% of samples fail thresholds you cannot see.

- The absorption cliff: Hour 1 = 95%. Hour 6 = 50%. Hour 12 = 30%. Every hour you delay colostrum is immunity that never comes back—and milk that never hits the tank.

- Cheap fixes, lifetime returns: Bedding every 2-3 days cuts diarrhea 57%. Colostrum within one hour costs only protocol discipline. With 90% of your milk check now riding on components, early-life health is first-lactation revenue.

For more information on maternity management protocols and calf health research, consult your herd veterinarian or regional extension dairy specialist. Resources are available through the Dairyland Initiative at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell PRO-DAIRY, UC Davis Dairy Extension, and Lactanet in Canada.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- 17-26x ROI: Why Top Dairies Stopped Saving Calves and Started Preventing Loss – Arms you with a concrete breakdown of the 26x return on prevention investments. It exposes the $1,050 hidden cost of “saving” a sick calf and delivers a prioritized checklist of $50 fixes that stop profit leaks Monday morning.

- 2025 Dairy Year in Review: Ten Forces That Redefined Who’s Positioned to Thrive Through 2028 – Reveals how a structural heifer deficit through 2028 has transformed your maternity pen into a capital goldmine. It breaks down the new math of culling and positions your operation to thrive while others are strangled by record-high replacement costs.

- Cornell Study Proves Less Is More: Why Modern Colostrum Needs Just 2.5 Liters, not 4 – Shatters the “4-liter rule” with 2024 research that actually improves antibody absorption while cutting labor. It delivers a precision feeding blueprint that optimizes gut health and prevents the colic symptoms currently dragging down your growth efficiency.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!