Think chasing top TPI is pure profit? Your pocketbook might be tanking from inbreeding you can’t see.

A sentiment echoing from industry leaders around the world is that the genetic diversity challenge is about to shift from crucial to absolutely critical. What we’re seeing with inbreeding today is just the tip of the iceberg — this is poised to become a major industry crisis if we don’t get ahead of it now.

You know what keeps coming back to me during all these dairy chats I’ve been having lately? It’s how much time we spend chasing the highest genomic indexes and fancy TPI numbers, but we hardly ever dig into what’s lurking beneath those shiny scores — the risk of losing genetic diversity and quietly bleeding cash without even realizing it.

Just last month, I was up in upstate New York, walking through a solid 2,500-cow operation. The owner was beaming, boasting about his herd’s average TPI, which had hit 2,800. Great numbers, right? But here’s the thing… behind those glittering stats, the genetic base looked dangerously narrow. That’s when our conversation flipped — from celebrating elite genetics to facing the looming threat of a shrinking gene pool.

And honestly? It got uncomfortable real quick.

The Math That Should Keep You Awake at Night

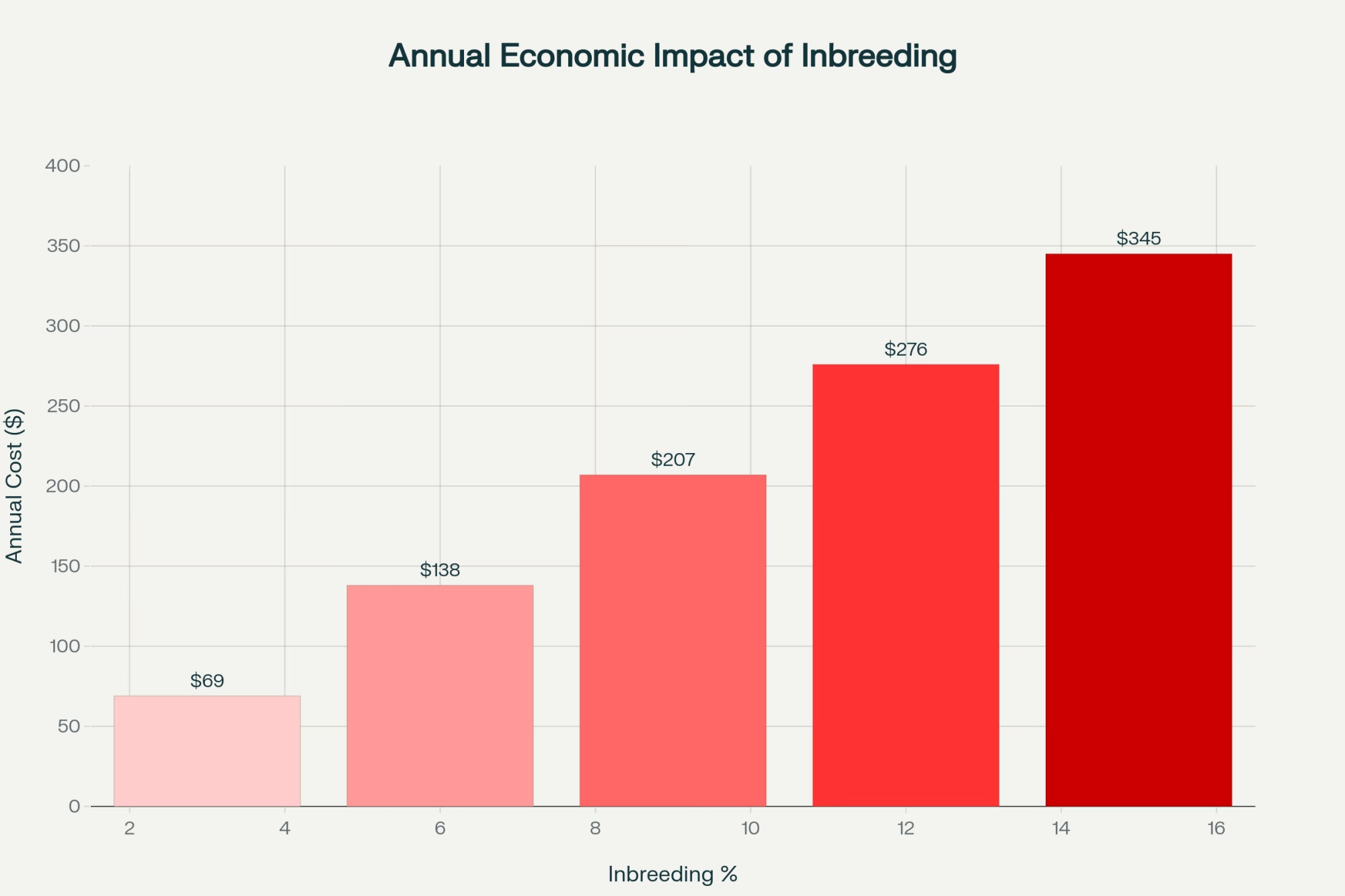

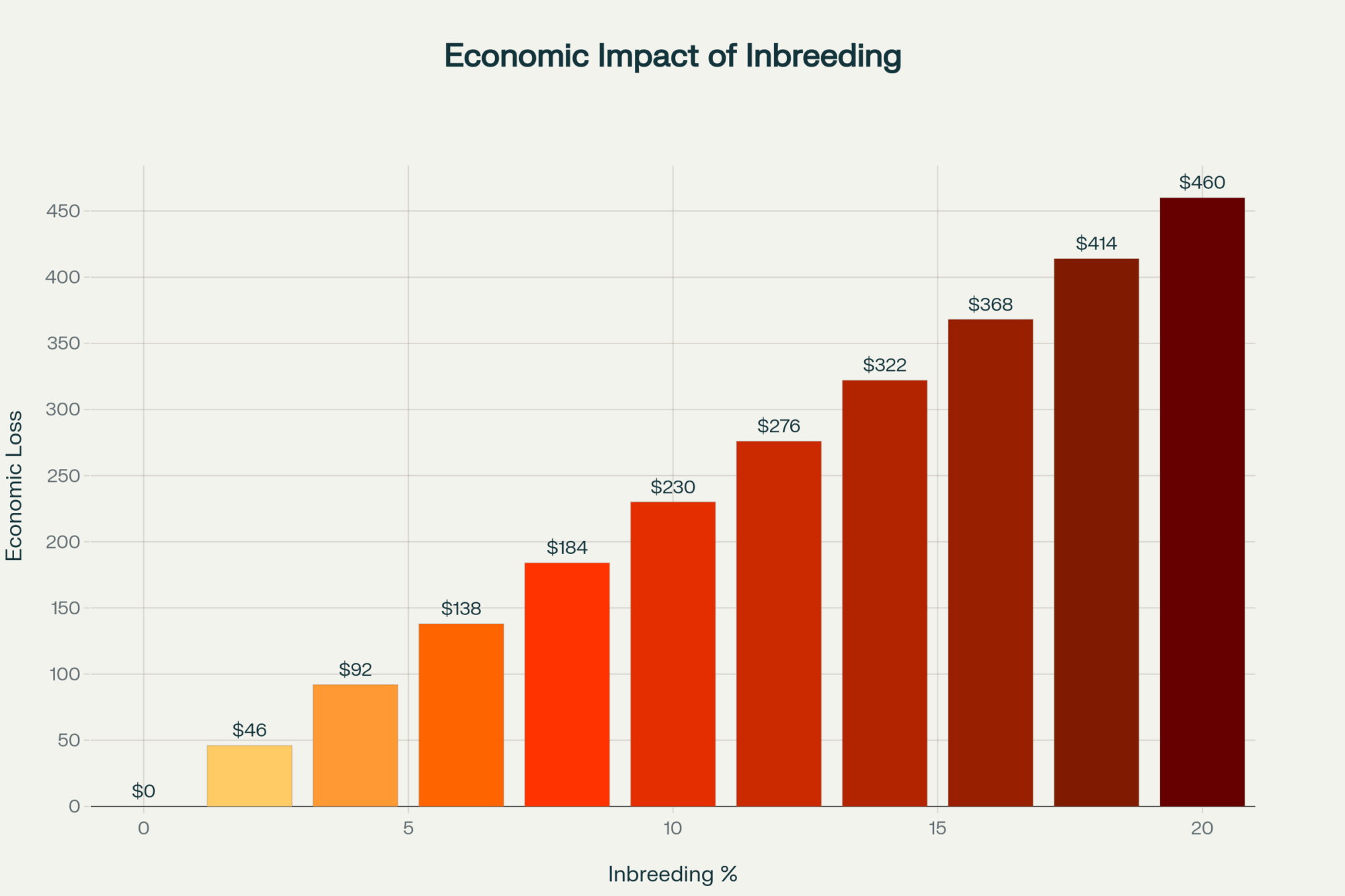

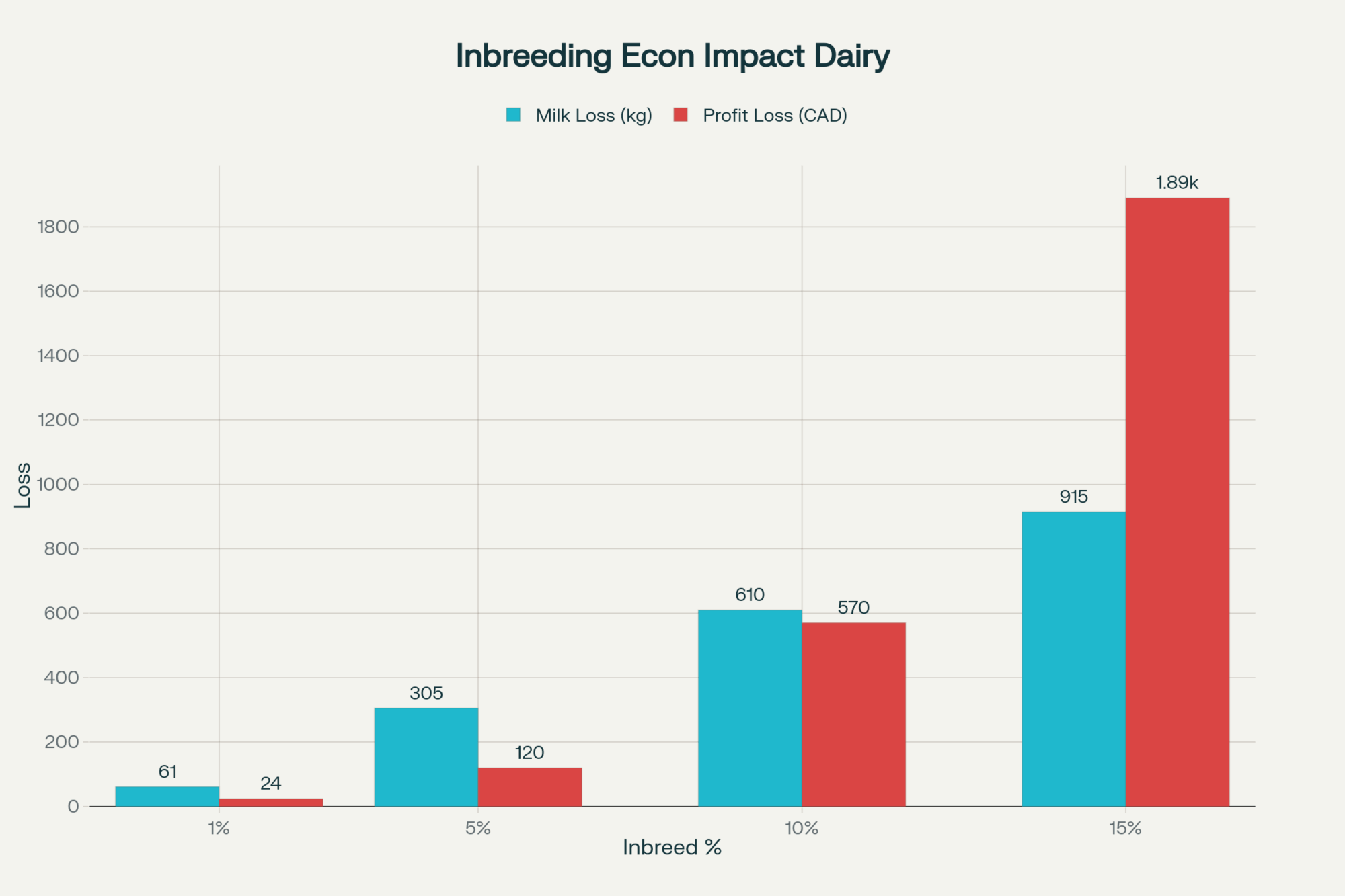

Let’s talk dollars and cents — those losses you actually feel in your wallet. Every 1% uptick in a cow’s inbreeding coefficient can cost you around $22 to $24 in lifetime profit. That’s not some theoretical number buried in research papers; that’s real money walking right out your barn door.

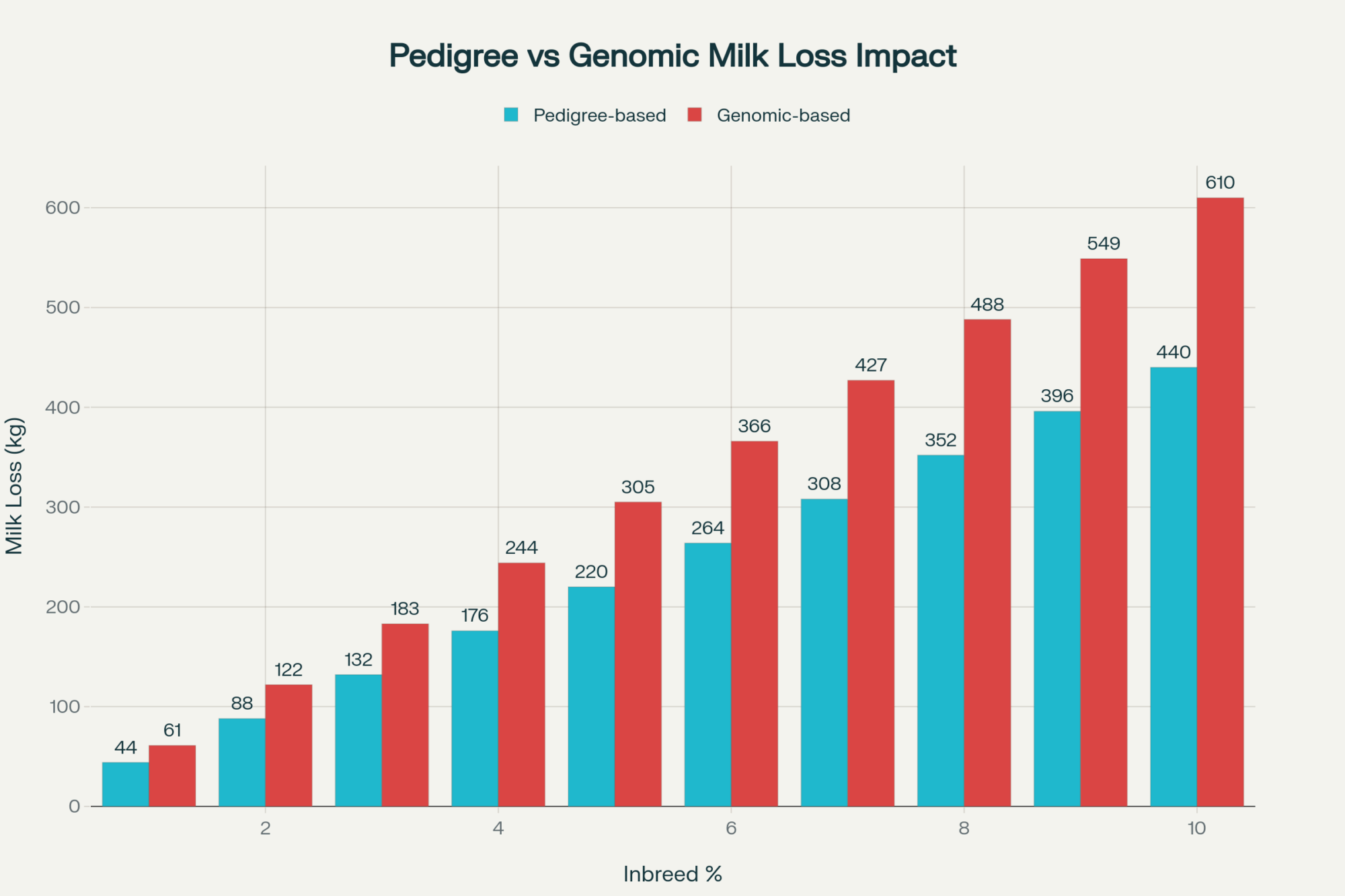

However, here’s the kicker that really makes me sit up: a 2023 Italian study suggested that the real damage might be 40% worse than previous estimates indicated. Put simply, where pedigree-based calculations said you’d lose 44 kg of milk per 1% inbreeding increase, genomic data showed a 61 kg drop. Ouch.

With milk prices hovering near $18.93 a hundredweight and labor costs pushing $18 an hour, those losses aren’t small potatoes. They add up fast, especially when you multiply them across your entire herd.

Have you actually calculated your operation’s inbreeding exposure? Most producers I know haven’t. And I get why — it’s not exactly the sexy topic your AI rep brings up during sire selection meetings.

When “Elite” Becomes the Problem, Nobody Wants to Talk About

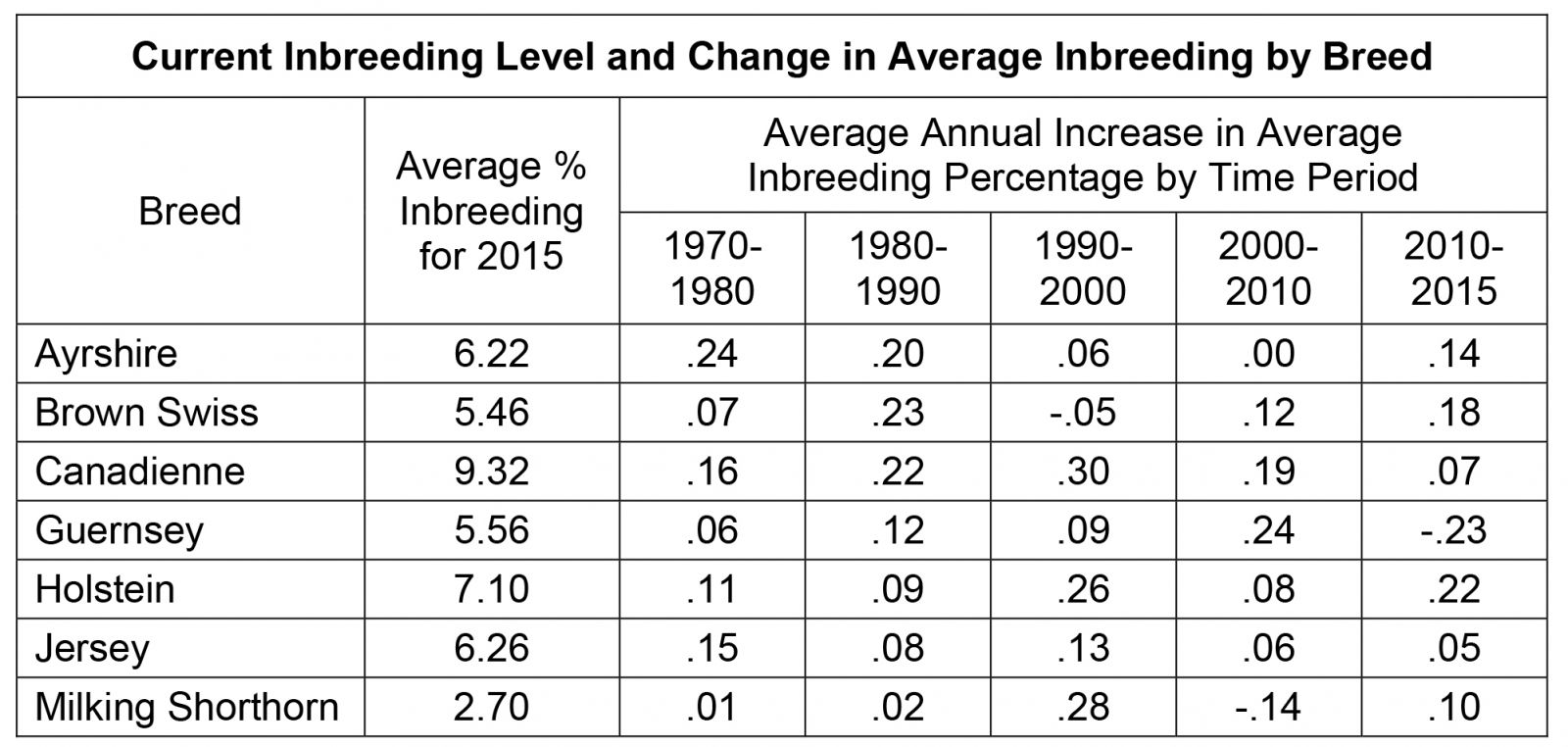

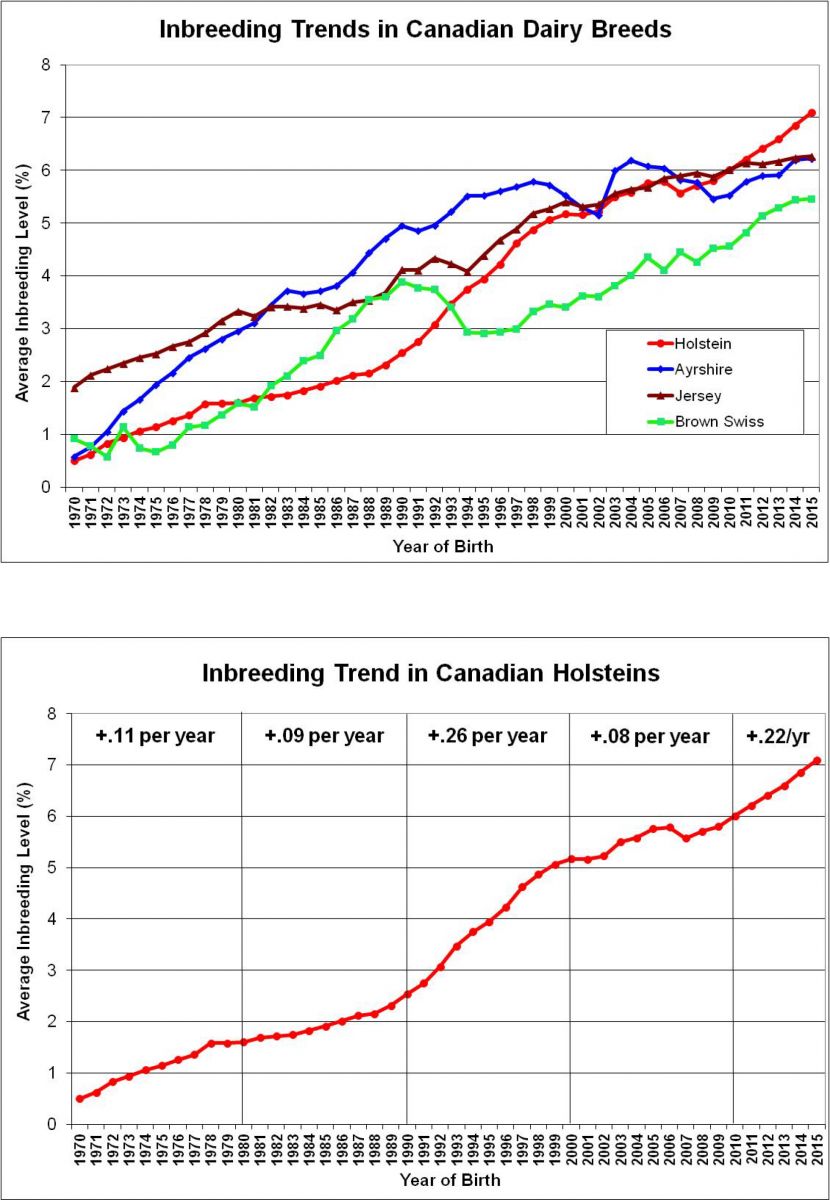

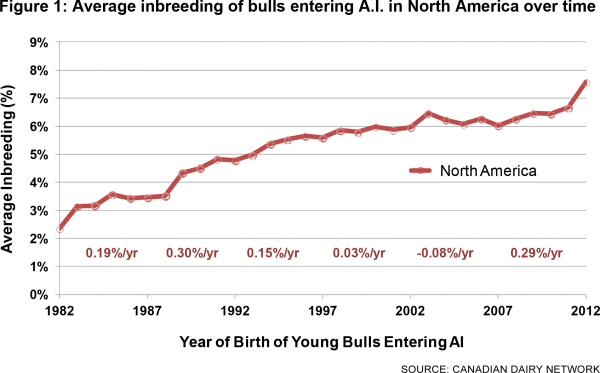

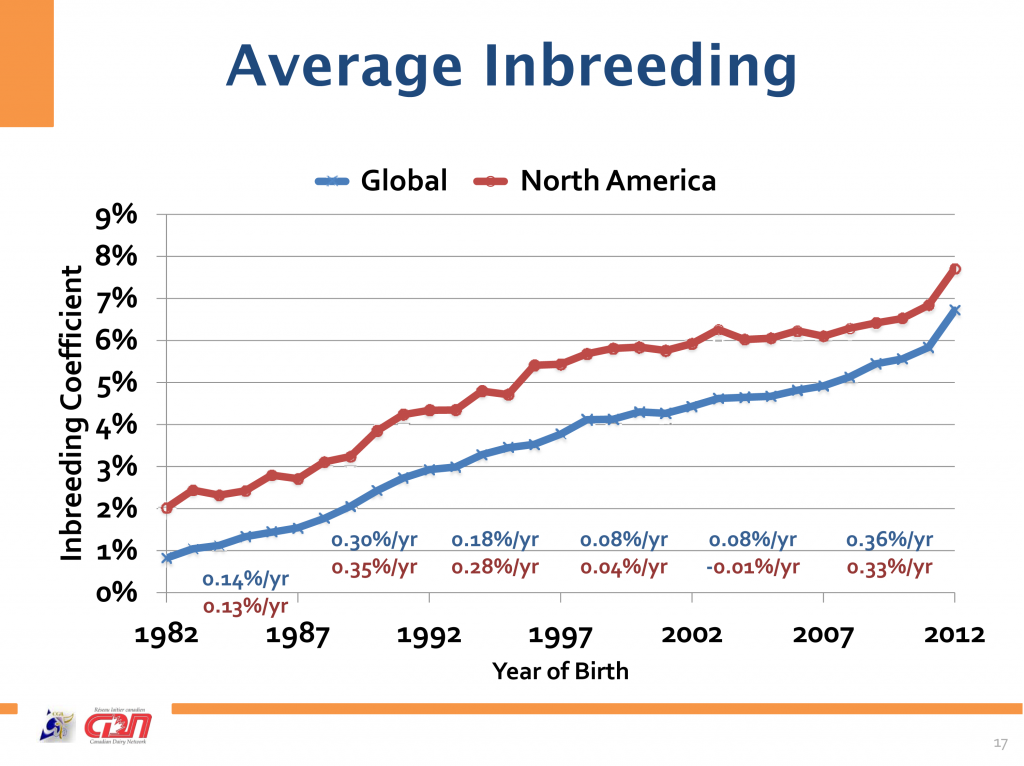

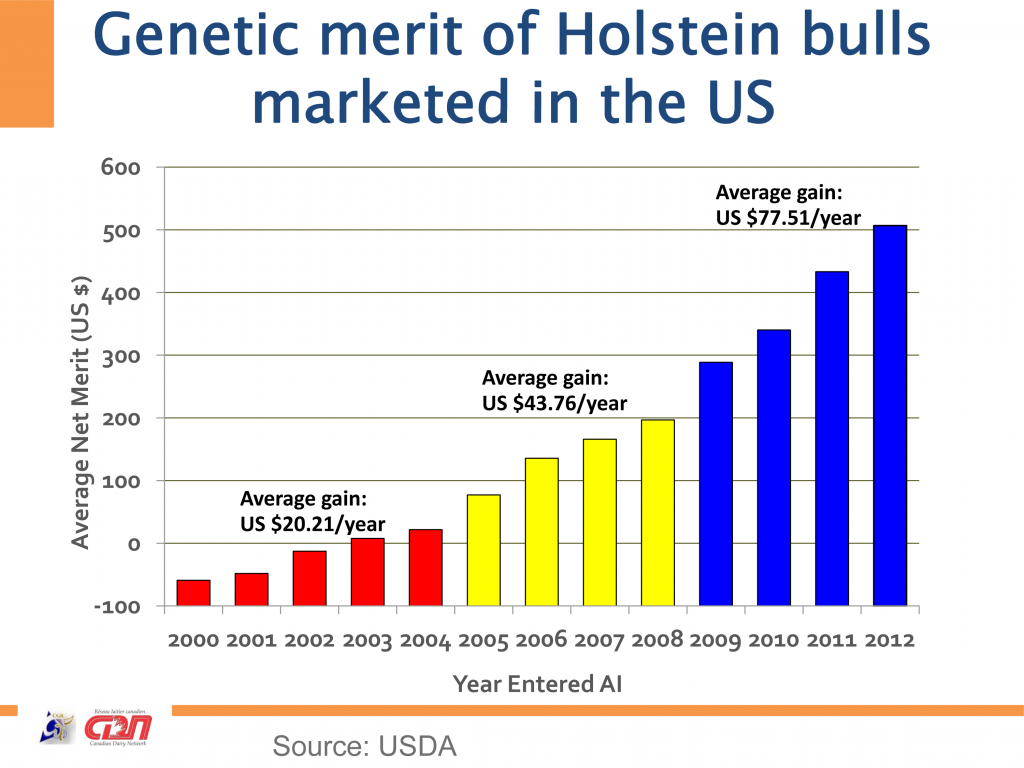

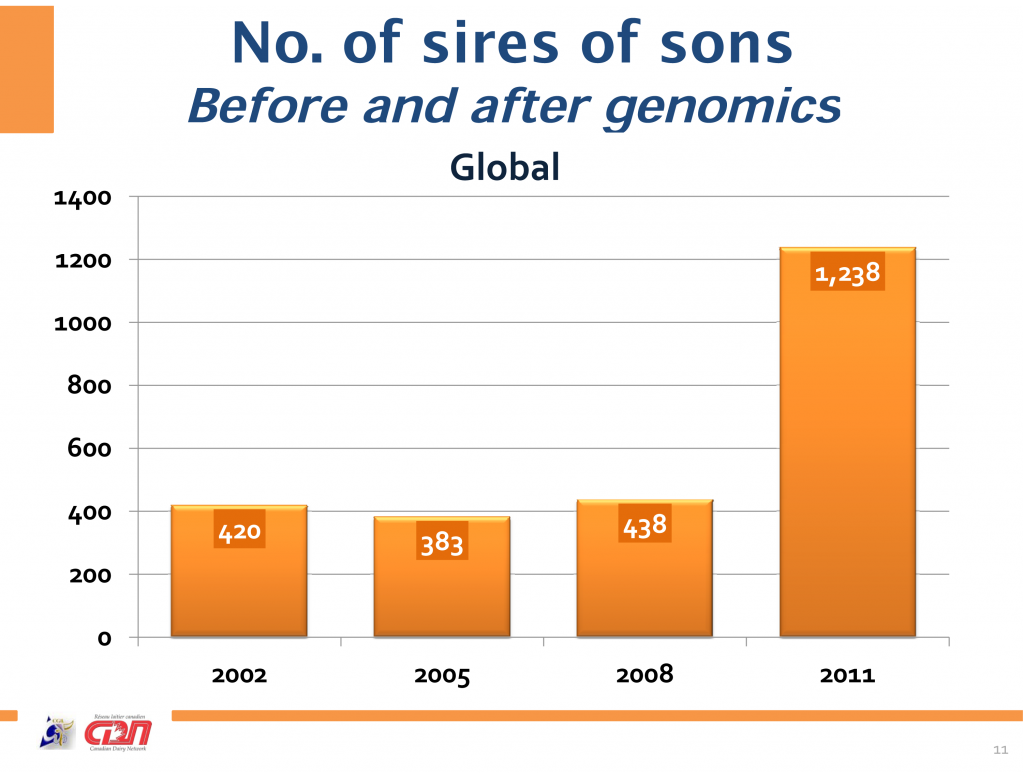

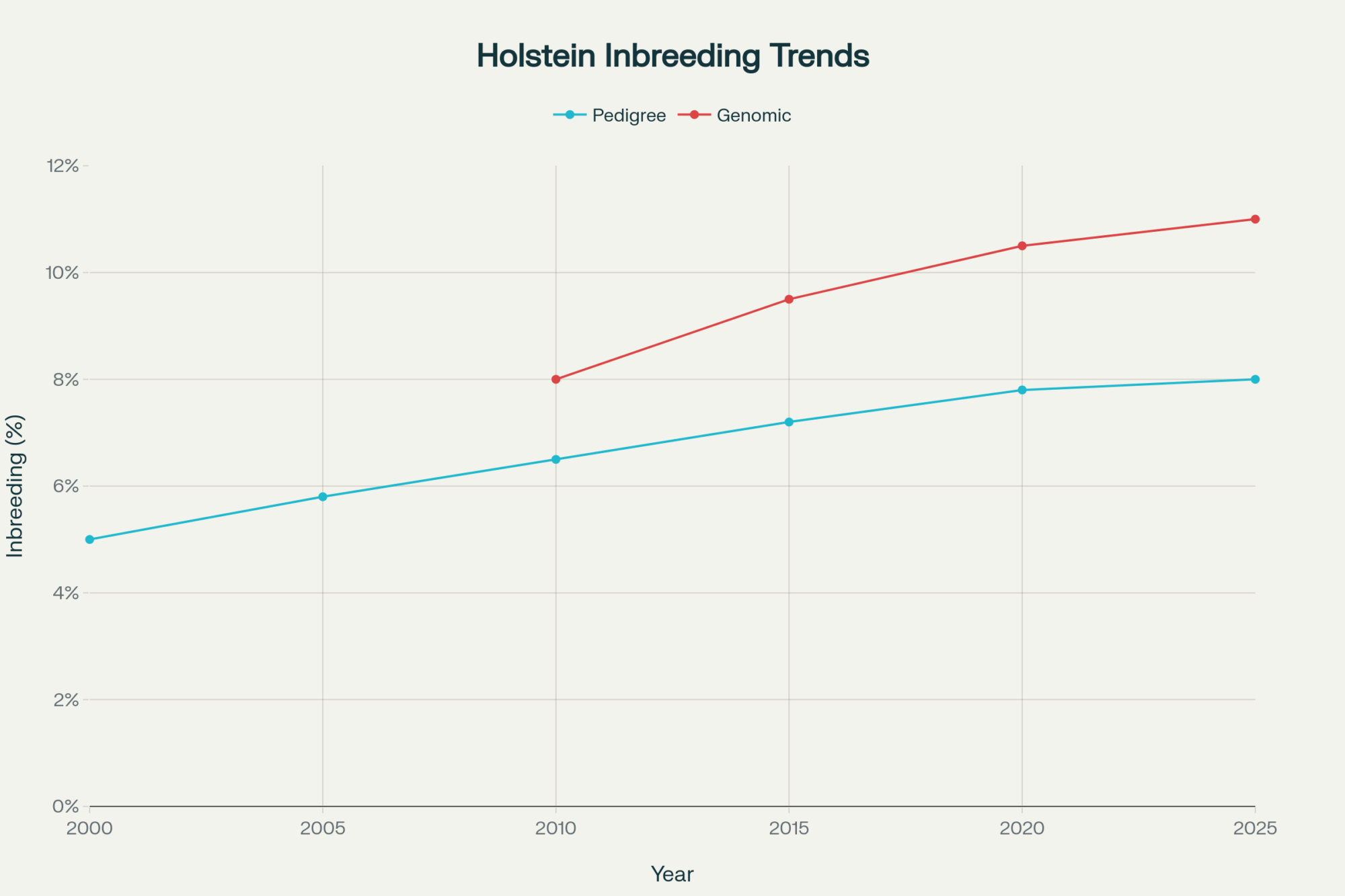

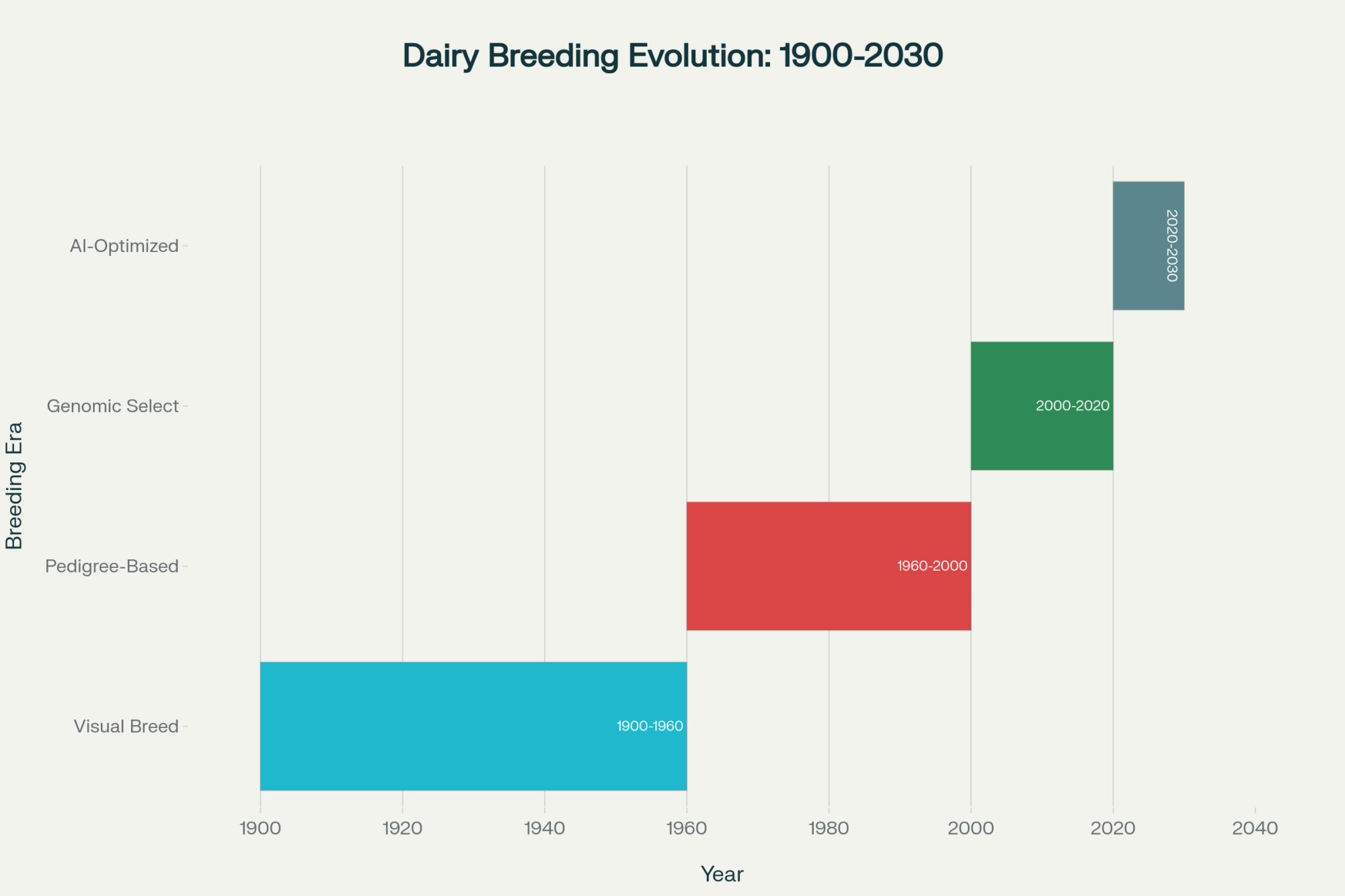

The unspoken consensus among many industry geneticists is that our most powerful tool for genetic advancement has become a double-edged sword. While genomic selection has driven incredible progress, it has also accelerated inbreeding at an unprecedented pace, creating a genetic bottleneck that threatens the health and productivity of our dairy herds.

“Our most powerful tool for genetic advancement has become a double-edged sword.”

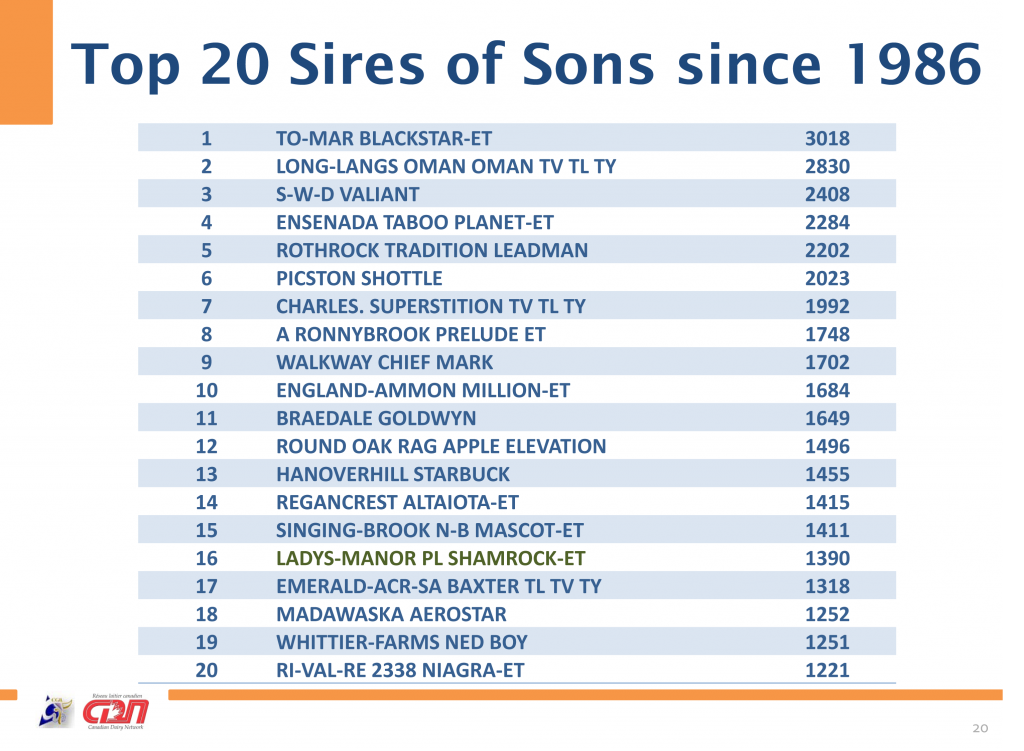

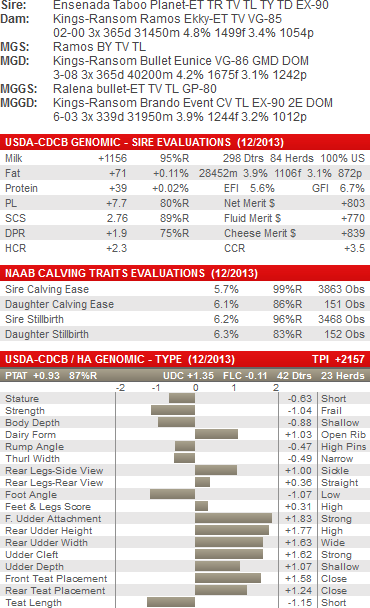

That’s the paradox that’s reshaping everything. The numbers back this up. According to Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding data, genetic concentration in North American AI programs reached concerning levels by 2017, when just a handful of elite sires were responsible for producing the majority of young bulls entering AI programs globally. When you multiply that concentration across millions of breeding decisions… well, you get the picture.

The genetic bottleneck becomes inevitable.

Enter the “Elite Outcross” Revolution

So what’s the fix? This is where things get interesting…

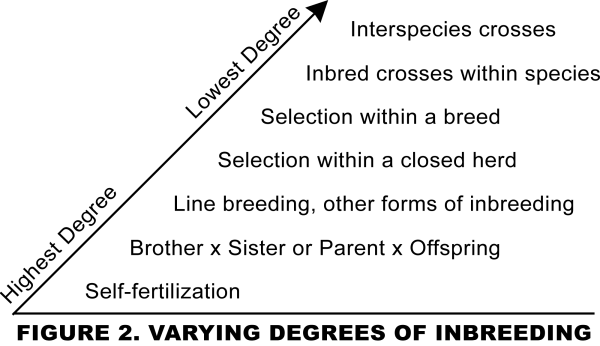

Once, outcrossing had a bad reputation — people feared it would dilute their prized bloodlines. Random mating to genetically distant but inferior animals? Yeah, that would set any breeding program back.

But now? It’s precision science, leveraging genomic data to make calculated, surgical strikes, not wild gambles.

Here’s something that’s caught my attention lately — many industry insiders from companies like Select Sires and ABS are moving away from the term “outcrossing” altogether. They’re talking about “diversity” instead, and their reasoning makes a lot of sense. The real goal isn’t just finding one genetically distant bull — it’s about using many different genetic lines to build true resilience in your herd. A single outcross bull might still be mediocre quality, but when you focus on genetic variety across both sides of the pedigree, you’re building something much stronger.

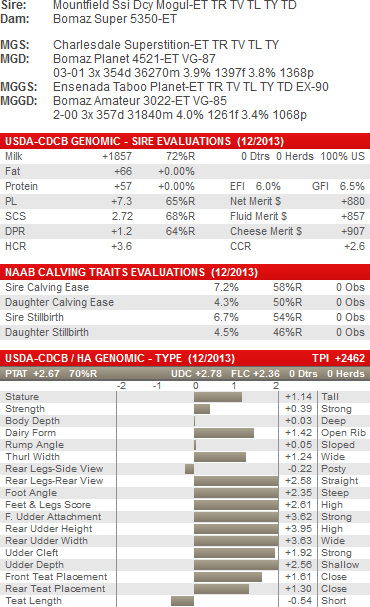

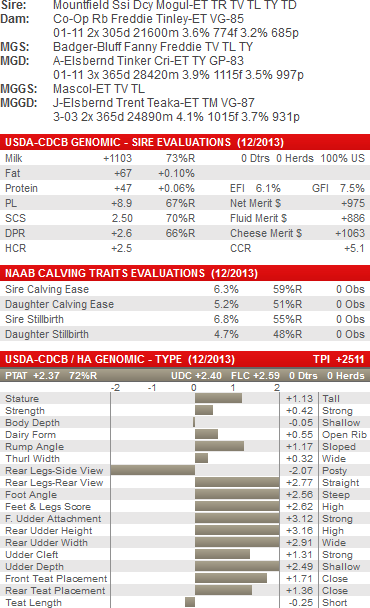

Look at proven examples: CO-OP BOSSIDE MASSEY brought wide appeal, ZANI BOLTON MASCALES introduced European bloodlines to North America, and more recently, stars like 14HO15179 TROOPER and his son 7HO16276 SHEEPSTER proved you can blend unique maternal lines with high merit to create genuine value.

These bulls validate the strategy: outcrossing isn’t gambling when robust genomic data and clear breeding objectives back it.

What’s fascinating is how this shifts the entire conversation. Instead of just asking “What’s his TPI?” the smart money now asks “What’s his relationship to my herd?” and “How does his genetic background complement what I’ve got?”

How the Smart Money Is Playing This Game

AI companies have figured this out, and they’re adapting fast. They’re not just selling semen packages anymore — they’re selling sophisticated genetic risk management.

However, here’s the challenge they’re all facing: German AI professionals have observed that large commercial operations often prioritize top performance indexes over everything else, including diversity of pedigree. The market reality is that many large dairies will select the bull with the highest TPI, regardless of genetic relationships, which doesn’t exactly reward companies for maintaining diverse genetic portfolios.

That’s what makes the Canadian approach so interesting. Semex has deliberately maintained what they call genetically “free” female lines — unique cow families that aren’t heavily related to the mainstream population. This strategy ensures they can always bring something genuinely different to the market when diversity becomes critical. It’s a long-term vision that’s particularly relevant for us here in Ontario, where Semex’s home base provides them with a Canadian perspective on sustainable breeding.

Take ABS Global’s approach. Their Genetic Management System 2.0 utilizes genomic intelligence to guide mating choices, explicitly incorporating genomic inbreeding calculations to manage relationships with greater precision than pedigree-based methods have ever allowed.

Semex hands the keys to farmers through tools like SemexWorks and OptiMate, letting producers define their own economic parameters and build personalized selection indexes. It’s like giving you the GPS instead of just telling you where to go.

Select Sires? They’re mixing high-touch consulting with modern tech, offering programs like StrataGEN that manage inbreeding by rotating distinct, unrelated sire lines every 18 months. Simple but brilliant.

My advice? Don’t take the sales patter at face value. Ask hard questions about true genetic diversity in their outcross catalogs. Who’s really getting you diverse genetics, and who’s just selling shiny promises?

The Future: When AI Meets Genetics

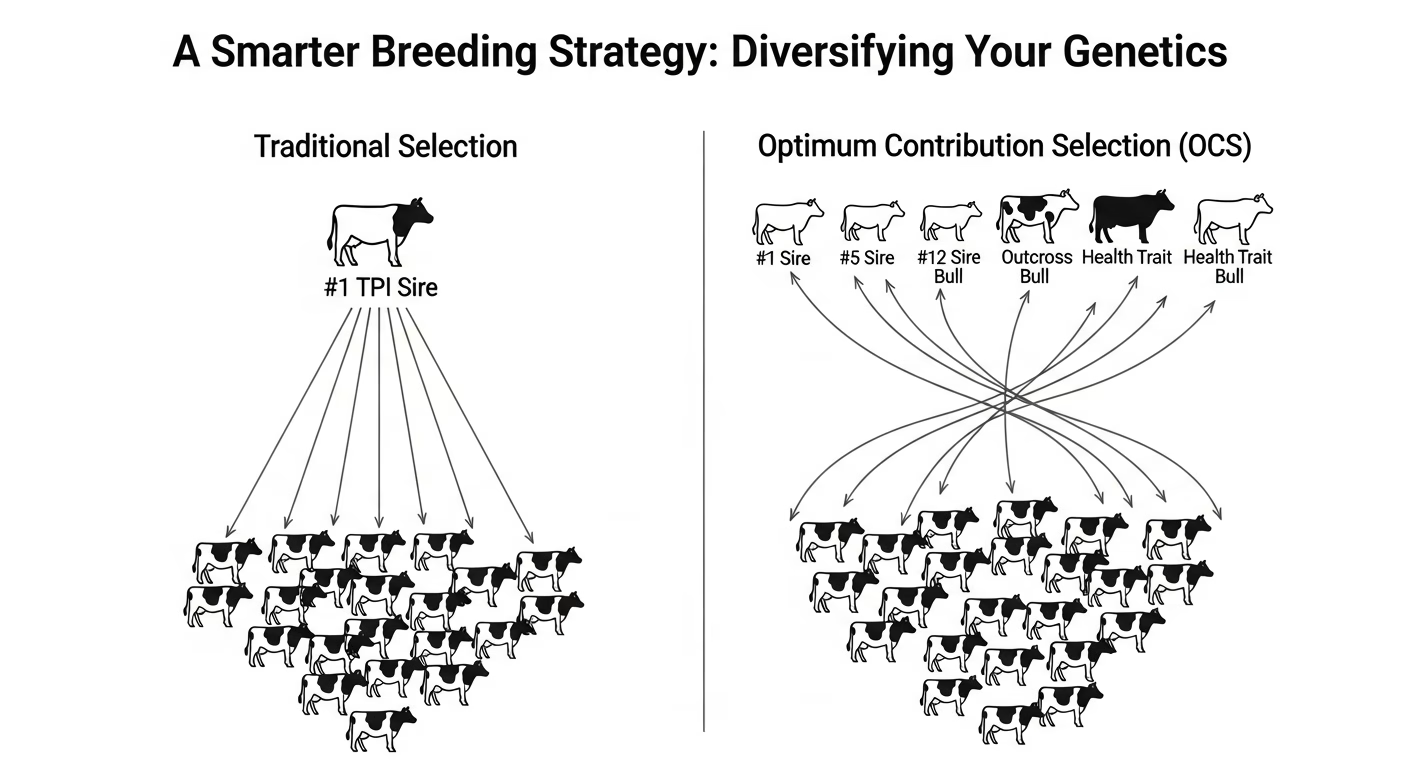

Here’s where it gets really exciting… the future belongs to machine learning, crunching massive genomic databases and optimizing matings through algorithms like Optimal Contribution Selection (OCS).

Think of it as playing chess on a global board, where every move considers not just immediate genetic gain but long-term sustainability. OCS calculates the ideal genetic contribution from each potential parent to maximize progress while simultaneously constraining inbreeding to acceptable levels.

The companies mastering this intersection of artificial intelligence and artificial insemination? They’ll dominate the next chapter. It’s not just about who has the best bulls anymore — it’s about who has the sharpest algorithms.

Your Action Plan (Because Knowledge Without Action Is Just Expensive Education)

First things first: audit your genetic risk exposure. Most producers I work with have zero clear picture of their herds’ inbreeding levels or the relationships among their AI sires. Begin by conducting genomic testing on your breeding females to establish a baseline.

Second, evaluate your AI company’s diversity management capabilities honestly. Companies that utilize genomic inbreeding calculations, offer genuine outcross options, and provide sophisticated mating programs will deliver superior long-term results.

Third, develop a systematic approach to elite outcrossing. Consider this scenario: You have cow families tracing back to the same popular sire line as half of your herd. Instead of using another bull from that same genetic background, identify a high-merit outcross that brings fresh genetics while maintaining or improving economic performance.

That’s not gambling. That’s strategic breeding.

The Global Picture (Because Your Herd Doesn’t Exist in Isolation)

Here’s something that might surprise you: the Holstein breed is now effectively a single global population. Elite genetics flow freely across borders, and North American bloodlines dominate worldwide — sometimes representing over 90% of genetics in certain regions.

Italy is taking this challenge seriously at a policy level. They’ve updated their national genetic index — the PFT — to include a direct mathematical correction based on each bull’s Expected Future Inbreeding. Bulls that increase inbreeding are penalized in their official rankings, while those that bring genetic diversity receive a boost. It’s the first time I’ve seen a country incorporate inbreeding management into its national breeding policy.

Organizations such as the Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding and Interbull work behind the scenes to coordinate international genetic evaluations and ensure data integrity. Their systems help producers understand how genetics will perform under specific conditions while managing global genetic diversity.

Looking Ahead: The Technology Revolution Continues

Gene editing with CRISPR holds incredible promise for precise genetic tweaks — adding polled genetics to elite lines, boosting disease resistance, even modifying milk composition for better cheese yield — all without the linkage drag of traditional breeding.

Think of it as the ultimate “elite outcross.” It’s the surgical introduction of desired genetic diversity without any of the associated baggage.

But regulatory and ethical hurdles remain significant, and public perception will play a huge role in adoption.

The Bottom Line

Ignore genetic risk management at your peril — it quietly drains profits while you’re not looking.

“The most expensive cow isn’t the one that costs the most upfront; it’s the one that silently costs you money for years without you knowing it.”

Start by gauging your herd’s genetic risk, rethink sire selection strategies, and demand transparency from your AI partners. This isn’t just theory — it’s what will separate thriving operations from those scrambling to catch up a decade down the road.

What questions do you have about your herd’s genetic diversity strategy? Because honestly, this conversation is just getting started, and waiting only makes managing the risk more expensive.

Those who act now will be the winners when genetic diversity becomes the industry’s scarcest resource.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Save up to $24 per cow annually by managing inbreeding levels strategically. Start by genomic testing your breeding females to establish baseline inbreeding coefficients (FROH). Context: Essential with 2025’s margin squeeze from high feed and energy costs.

- Recover potentially 61kg of lifetime milk production per cow by reducing genetic bottlenecks. Ask your AI rep specifically about “elite outcross” sires that bring diversity without sacrificing merit. Context: Part of the global shift toward sustainable genetic management happening right now.

- Cut veterinary and replacement costs through better fertility and longevity outcomes. Push for mating strategies using Optimal Contribution Selection (OCS) that balance gain with genetic health. Context: Forward-thinking operations are already seeing results with these AI-driven tools in 2025.

- Future-proof your operation against the genetic squeeze that’s tightening worldwide. Demand transparency from your genetics provider about actual relationships in their bull lineup — don’t just take TPI at face value. Context: Critical as global “holsteinization” continues consolidating the gene pool faster than ever.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

Look, I just dug into some eye-opening research that’s got me pretty fired up. That relentless chase for sky-high genomic indexes? It’s quietly costing you $24 per cow for every 1% jump in inbreeding — and most of us have no clue it’s happening. Here’s the kicker: new Italian data shows we’ve been underestimating milk losses by 40% — we’re talking 61kg drops per percentage point, not the 44kg we thought. With feed costs still brutal and milk prices bouncing around in 2025, this isn’t pocket change anymore. The thing is, this genetic squeeze is happening globally as the same elite bloodlines get used everywhere through AI. But here’s what smart producers are already doing — they’re using genomic testing and something called “elite outcrossing” to keep their herds genetically strong without sacrificing performance. Trust me, you need to get ahead of this before it really bites your bottom line.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Genetic Correlations Upended: Why Sticking with Old Breeding Indices Could Cost Your Dairy $486 Per Cow – And What the Data Really Proves – This strategic analysis dives into the economic impact of the April 2025 genetic base change, revealing how new Net Merit formulas that prioritize fat and feed efficiency offer a massive profit opportunity beyond traditional TPI selection.

- Inbreeding Alert: How Hidden Genetic Forces Are Reshaping Your Dairy Herd’s Future – This article provides tactical steps for managing herd diversity. It explores the practical impact of the 2025 genetic base change on PTAs and delivers actionable strategies for outcross sire selection and using mating programs to improve your herd’s resilience.

- 5 Technologies That Will Make or Break Your Dairy Farm in 2025 – Looking forward, this piece showcases the innovative technologies that complement advanced breeding. It details how smart calf monitoring, automated feeding systems, and whole-life sensors are creating the data-rich environments necessary to maximize the potential of your genetic investments.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!