When the lowest-cost producer starts hoarding cash, what should you be doing?

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: What farmers are discovering about New Zealand’s record September production—228,839kg of milk solids, up 3.4%—reveals something crucial about the next commodity cycle. Despite Fonterra paying out $16 billion in returns (30% above last year), Reserve Bank data shows their farmers just paid down $1.7 billion in debt over six months rather than expanding. This disconnect between production strength and conservative positioning mirrors patterns from 2014, right before the last major downturn that saw prices crash to NZ$3.90/kgMS for 18 months. China’s Three-Year Action Plan for cheese production, combined with their historical pattern of cutting WMP imports by 240,000 metric tons once domestic capacity matured, suggests the 2027-2030 period could see similar disruption in cheese markets. Smart operators are already adjusting—Federal Reserve data shows U.S. dairy borrowing remains flat despite strong cash flows, while processors with 70% of milk under long-term contracts are reporting better stability than spot-market dependent operations. Here’s what this means for your operation: the window for strengthening balance sheets and securing stable contracts is open now, but it won’t stay that way past 2026.

You know that feeling when something’s just… off? Milk production’s strong, the neighbor’s adding another barn, equipment dealers can’t keep anything in stock. But there’s this nagging sense that these “good times” are different. I think what’s happening in New Zealand right now might help explain why so many of us are feeling cautious.

So here’s what caught my attention: DairyNZ’s latest production statistics show New Zealand just hit their highest September milk collection on record—228,839 kilograms of milk solids. That’s up 3.4% from last year. And Fonterra announced in their FY25 results that total cash returns to shareholders are approaching sixteen billion dollars, which is roughly 30% more than the previous year.

But—and this is the part that makes you think—Global Dairy Trade auction prices have been sliding for three straight months. The October 7th auction settled at $3,921 per tonne. When production’s surging but prices are softening? That tells you something.

Why New Zealand Can’t Actually Choose What They Produce

Here’s what I’ve found most producers outside Oceania don’t really grasp about New Zealand’s system. According to DairyNZ’s seasonal production data, about 84% of their entire national herd calves within a three-month window—August through October. Think about that for a second. Nearly every cow in the country freshening at the same time.

During their spring flush—that’s October through December down there—they’re pushing roughly 60-65% of their entire annual milk volume through processing plants in just three months. Fonterra’s milk collection data shows their plants hit 95% utilization during peak. That’s not efficiency, folks. That’s desperation.

You know what happens then? Industry processing reports show they’re running spray dryers flat out just to keep milk from backing up on farms. According to the Dairy Processing Handbook from Tetra Pak, modern spray dryers typically process 10-15 metric tons per hour, and during New Zealand’s flush, these things run continuously. Day and night.

This is why—and here’s what’s really telling—whole milk powder still represents about 40% of New Zealand’s dairy exports according to USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service analysis. It’s not because they want to make powder. It’s because when that wall of milk hits, you either spray dry it or dump it. There’s no third option.

For those of us running year-round calving systems, this might seem crazy. But it’s actually both their biggest advantage and their Achilles heel, depending on how you look at it.

China’s Playing the Long Game (Again)

What’s happening with China’s import patterns is fascinating—and honestly, a bit concerning. USDA’s Beijing office analyzed China Customs data and found cheese imports are up over 22% while skim milk powder imports jumped 26%. But whole milk powder? Still declining.

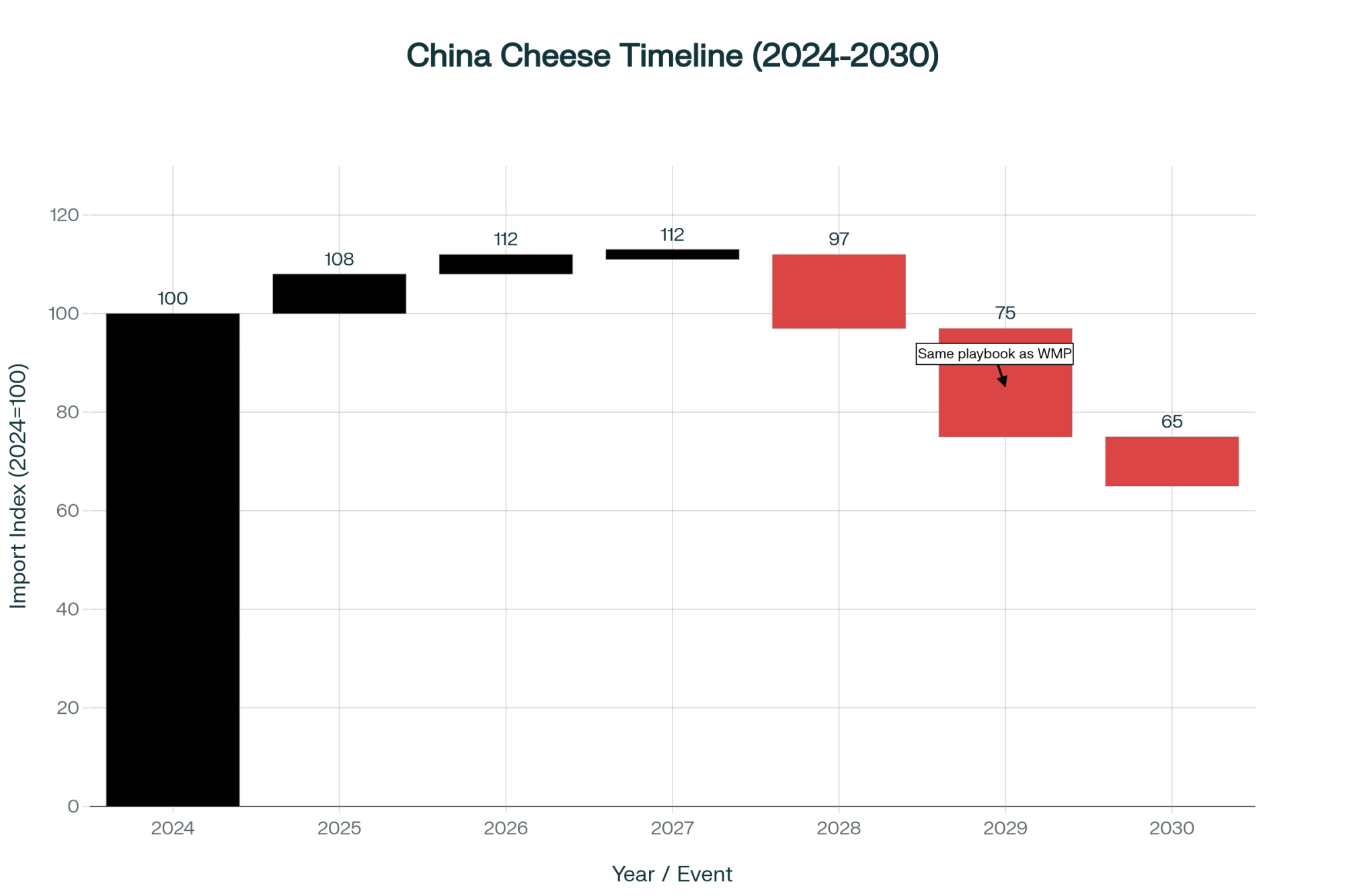

You probably remember what happened with WMP between 2010 and 2018, right? UN Comtrade data shows China kept importing massive volumes while quietly building their own production capacity. Then suddenly—boom—imports dropped from around 670,000 metric tons to 430,000 metric tons. Changed the whole global market.

Now they’re following the same playbook with cheese. China’s Ministry of Agriculture published this Three-Year Action Plan for cheese production development. Their western provinces are already incorporating cheese plants into those massive dairy clusters they’re building. Industry reports indicate China Modern Dairy is producing something like 3,300 tons of raw milk daily now. And get this—their cows are averaging over 13,000 kilograms of production. That’s right up there with good U.S. herds.

Looking at current construction activity tracked by the China Dairy Industry Association, most analysts expect modest import growth through maybe 2026, then watch for new “quality standards” that somehow favor domestic production. By 2027-2030? Well, cheese imports could follow the same path as powder—down 30-40% from peak. Though who knows, right? Economic conditions could speed this up or slow it down. And let’s not forget, precision fermentation and alternative proteins are starting to look more viable every year, though current costs suggest traditional dairy keeps its advantages for commodity uses through at least 2030.

Those “Profitable” Margins Tell a Different Story

DairyNZ’s Economic Survey shows New Zealand producers are looking at breakeven costs around NZ$8.66 per kilogram of milk solids. Fonterra’s announced farmgate price is NZ$10.16. So that’s about a NZ$1.34 spread—in our terms, they’re breaking even around $16.50 per hundredweight compared to the $24.55 it costs to produce milk in California according to CDFA’s May cost study.

Sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? But here’s what I find interesting: Reserve Bank of New Zealand data shows farmers just paid down NZ$1.7 billion in debt in six months through March 2025. That’s not expansion behavior. That’s battening down the hatches.

They remember 2015-16. Fonterra’s historical pricing data shows milk prices crashed to NZ$3.90 per kilogram and stayed there for 18 months. A lot of good operators went under during that stretch.

And now you’ve got climate issues on top of everything else. Federated Farmers officials have been calling recent droughts in Waikato and Taranaki some of the worst in decades. When you’re forced to dry cows off early, or you’re taking 20-30% discounts on spot milk because plants can’t handle your flush volumes… suddenly that cost advantage doesn’t look so solid.

University of Melbourne’s Dairy Futures research projects profitability could drop 10-30% by 2040 without successful climate adaptation. But here’s the catch—every adaptation measure costs money and changes your cost structure. Several Canterbury producers I’ve heard speak at field days who invested in irrigation say the same thing: “It saved our production during the drought, but we’re not a low-cost operation anymore.”

Why Farmers Vote for Cash, Not Strategy

This is where cooperative governance gets really interesting. Industry analysis from Rabobank and others suggests Fonterra needs hundreds of millions in capital investment for specialty protein infrastructure if they want to stay competitive as markets evolve.

But when Fonterra put their Flexible Shareholding structure to a vote in December 2021, you know what happened? Official voting results showed 85.16% approval with over 82% turnout—for a proposal that REDUCED capital requirements from one share per kilogram of milk solids to one share per three kilograms. Farmers overwhelmingly voted for more financial flexibility, not strategic investment.

And honestly? I can’t blame them. If you’re running 500 cows and a 50-cent payout increase means $85,000 in your pocket this year, that’s real money. You can pay down debt, fix that mixer wagon that’s been limping along, help your kid with college. Voting to fund some protein plant that might help in eight years—assuming China doesn’t build their own first—that’s a much tougher sell.

What farmers are finding is that democratic governance, while it protects individual interests, can really limit strategic flexibility. And it’s not just Fonterra—I’ve seen the same tensions in cooperatives here in the States.

Climate’s Changing Everything

You know, the relationship between climate and production systems is getting more complicated every year. New Zealand’s whole model depends on predictable pasture growth synchronized with their seasonal calving. Research published in Agricultural Systems shows those patterns are becoming way less reliable.

Every adaptation has trade-offs. Install irrigation? There goes your low-cost advantage. Switch to split calving? Now you need more stored feed. Build bunker silos for drought reserves? Suddenly you’re looking at cost structures closer to what we have here.

I was talking with a Missouri producer at a grazing conference who’s using New Zealand-style rotational grazing on 650 cows. He made a great point: “Their system works perfectly in their climate. But when spring shows up three weeks late—or sometimes not at all—you understand why we do things differently here.”

Another producer from the Northeast who’s running managed intensive grazing on 400 cows added something interesting: “We took the best parts from New Zealand—the paddock system, focusing on grass quality—but adapted it for our reality. Sometimes that means feeding stored forage for five months instead of two. Our butterfat stays strong at 4.0-4.2%, but we’re definitely not low-cost anymore.”

This suggests to me that climate adaptation is forcing everyone’s costs to converge, which could erode New Zealand’s traditional advantage faster than people realize.

What Smart Operators Are Actually Doing

It’s interesting watching what experienced producers are doing versus what they’re saying. Federal Reserve ag lending data shows dairy borrowing is flat or declining across most mature markets despite strong cash flows. Farm Credit System quarterly reports suggest folks who survived 2015-16 are using this windfall to strengthen balance sheets, not build new facilities.

I know several producers who’ve shifted focus from volume to components. They don’t care if they ship 10% less milk if their butterfat hits 4.2% instead of 3.8%. The math just works better, especially when plants are at capacity.

According to the International Association of Milk Control Agencies, processors with 70% or more of their milk under long-term contracts report much better stability than those chasing spot markets. And something else I’m seeing—producer groups working together to secure whey protein extraction agreements. They’re thinking five years out, not five months.

What’s really telling is how the conversation has shifted. Five years ago, everyone was talking expansion and efficiency. Now? It’s all about flexibility and resilience.

Different Regions, Different Opportunities

Where you’re located really shapes your options. Upper Midwest producers, those new cheese plants—Hilmar’s operations in Texas and Kansas, plus others coming online—are creating massive whey streams according to Dairy Foods reporting. Smart producers are already talking to specialty protein processors about capturing that value.

Irish dairy operations have those same grass advantages as New Zealand but they’re closer to premium markets. Ornua’s annual report shows they hit €3.6 billion in revenues in 2024, proving grass-fed products can command serious premiums, especially here in the U.S. where consumers are willing to pay for that story.

Australian producers have their own advantage—they’re closer to Southeast Asian markets that are growing like crazy. Dairy Australia’s export data shows this proximity really matters for fresh products where New Zealand’s extra shipping time creates opportunities.

Here in the Northeast, as many of you know, being close to major cities provides fresh milk premiums that Western operations can’t touch. I heard a Pennsylvania producer at a recent conference say they’re getting $2.50 premiums for local, grass-fed milk going directly to retailers. That completely changes the economics.

And California? Several large operations are dedicating part of their herds to organic or specialty production for Bay Area markets. As one producer put it, “The premium’s worth it when you’re 150 miles from your customer instead of 7,000.”

Timing Is Everything

Looking at construction permits tracked by the China Dairy Industry Association and their published policy documents, domestic cheese production will probably hit serious scale around 2027-2028. Past cycles show market impacts usually show up 18-24 months after capacity comes online, so we’re looking at 2029-2030 as the potential turning point.

Though honestly? Global economic conditions could speed this up or slow it down. And precision fermentation or alternative proteins could throw a wrench in everything, though current costs suggest traditional dairy keeps its advantages for commodity uses through at least 2030.

If this follows previous patterns, we’ll probably see some softness in 2026 that everyone calls “temporary.” By 2027, it’ll be “challenging conditions.” By 2029-2030? That’s when everyone finally admits there’s structural oversupply.

Producers expanding aggressively right now might find themselves in trouble by decade’s end. But those building cash reserves? They could be in position to buy assets at pretty good discounts. As a Wisconsin ag lender specializing in dairy told me recently, “The farms that survived 2015 and bought their neighbor’s operation in 2017—those are the ones we want to work with today.”

What This Actually Means for Your Farm

Action Item | Investment/Action | Annual Impact (500-cow) | Risk Reduction | Timing Window |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay Down Debt (2:1) | $2 debt reduction per $1 not expanded | $15K-30K interest savings | Resilience 2x vs expansion | NOW (before 2026) |

| Lock 70% Milk Under Contract | Long-term processor agreements | $50K+ volatility reduction | 40% less revenue volatility | NOW (plants at capacity) |

| Optimize Butterfat (4.2% vs 3.8%) | Genetics + feed management | $30K-40K (10% less volume) | Plant capacity independence | Ongoing optimization |

| Secure Grass-Fed Premium | Regional positioning + certification | $125K ($2.50/cwt premium) | Metro market insulation | 2025-2026 (before oversupply) |

| Build 18-24mo Cash Reserves | Reserve fund accumulation | Survival in 18-mo downturn | 90%+ survival (vs 40%) | Immediate (2027-30 risk) |

When the world’s lowest-cost producer is pumping flat out despite softening prices, they’re not celebrating—they’re extracting value while they can. That massive payout Fonterra’s making? To me, that looks more like getting cash to farmers while it’s available, not permanent prosperity.

The practical stuff isn’t complicated, but man, it’s hard to execute when milk checks are good. Agricultural economists at Iowa State have shown that paying down debt gives you about twice the resilience compared to expansion investment when you’re at the top of the cycle. Lock in what you can—supply agreements, input contracts, customer relationships. Stability beats optimization when things get volatile.

Most importantly, focus on what you control. You can’t control Chinese policy or weather patterns. But you can control your debt level, your costs, your flexibility.

The Bottom Line

I recently toured a newer 2,000-cow facility in Wisconsin—beautiful operation with all the bells and whistles. Robotic milkers, genetics that would make anyone jealous, feed efficiency that pushes every boundary. The owner mentioned they’re breaking even around $18-19 per hundredweight, expecting to drive that down with volume.

What struck me was the contrast. New Zealand’s breaking even at $16.50 with minimal infrastructure and grass. Chinese cheese plants coming online will probably achieve competitive costs without shipping milk across oceans. Even Fonterra, with every advantage you could want, can’t pivot fast enough because of how their governance works.

The real question isn’t whether any of us can match New Zealand on cost—probably not, given the fundamental differences. The question is whether we’re positioned to survive when cost advantages matter less because everyone’s dealing with oversupply.

What I’ve learned over the years is that the best time to prepare for a downturn isn’t when prices crash. It’s when production records and big milk checks make everyone think the party will never end.

That disconnect between New Zealand’s record production and falling auction prices? That’s not a contradiction. That’s a signal, if you’re willing to see it.

A California dairyman who’s been through four cycles in 35 years said it best at a recent meeting: “The pattern never changes—just the products and countries involved. Right now feels like 2014, right before things got tough. We’re paying down every dollar of debt we can.”

The industry’s at an interesting crossroads. How we navigate the next few years depends on decisions we’re making right now, while things still feel good. So what makes sense for your operation, given what’s coming?

The clock’s ticking, as it always does in this business. But this time, if we’re paying attention to the right signals, we can see it coming.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Pay down $2 debt for every $1 you’d invest in expansion—Iowa State research shows debt reduction provides twice the resilience during downturns compared to growth investments made at cycle peaks, and with current rates, that could mean $15,000-30,000 annual savings on a typical 500-cow operation

- Lock in 70% of your milk under contracts NOW—processors maintaining this threshold report 40% less revenue volatility than spot-dependent operations, and with Class III-IV spreads widening, that stability could be worth $50,000+ annually

- Focus on butterfat optimization over volume growth—producers achieving 4.2% butterfat versus 3.8% are capturing an extra $0.25/cwt even with plants at capacity, translating to $30,000-40,000 for a 400-cow herd shipping 10% less volume

- Position regionally for 2027-2030—Upper Midwest operations should secure whey protein agreements while new cheese plants create oversupply, Northeast producers can capture $2.50/cwt grass-fed premiums near metro markets, and Western operations need organic/specialty contracts before Chinese cheese capacity hits stride

- Build 18-24 months of cash reserves—the 2015-16 crash lasted 18 months with many good operators going under, but those who survived bought neighboring operations at 40-60% discounts in 2017… and they’re the ones lenders want to work with today

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Is Your Dairy Farm’s Financial Health an Illusion? Here’s How to Tell – This guide provides the tactical framework for stress-testing your balance sheet. It moves beyond cash flow to reveal methods for analyzing working capital and debt-to-asset ratios, ensuring your operation is built for long-term resilience, not just high milk prices.

- Beyond the Jug: How Evolving Consumer Demands are Reshaping Dairy’s Future – While the main article focuses on global commodity risks, this analysis shifts focus to North American consumer trends. It outlines strategies for capturing domestic value-added premiums by aligning your production with growing demand for sustainable and high-component products.

- The Smart Money in Dairy Tech: Which Investments Actually Pay Off? – If you’re pausing expansion, this article demonstrates where to strategically invest capital. It analyzes the real-world ROI of key technologies, showing how automation and precision tools can permanently lower your cost of production and build a more resilient operation.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!