What farmers are discovering about the gap between processing expansion and workforce reality—and the practical lessons emerging from projects like Darigold’s Pasco plant

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The U.S. dairy industry is pouring $11 billion into processing plants it can’t staff—and farmers are paying for this disconnect through devastating milk check deductions. Darigold’s Pasco facility exemplifies the crisis: costs exploded from $600 million to over $900 million, forcing 300 member farms to cover the overrun at $4 per hundredweight, slashing their income by 20-25%. This infrastructure boom collides with an existential workforce crisis where immigrant workers, who produce 79% of America’s milk, face deportation while dairy remains locked out of legal visa programs that other agricultural sectors freely use. Farmers had no vote on these massive expansions, yet cooperative governance ensures they absorb all losses while contractors pocket overrun profits and board members face zero consequences. Some producers are finding lifelines through direct-to-consumer sales (commanding 400-600% premiums), smaller regional cooperatives, and strategic production management, but these are individual escapes from a systemic failure. Without fundamental reforms in cooperative governance and immigration policy, the industry will complete these factories just in time to discover there’s nobody left to run them—or milk the cows.

You know that feeling when you watch a neighbor build a massive new freestall barn, and you can’t help but wonder—who exactly is going to milk all those cows?

That’s not just a neighborhood curiosity anymore. It is the $11 billion question hanging over the entire dairy industry. Except we aren’t talking about barns; we’re talking about processing plants. And the answer is costing you $4.00 per hundredweight.

[IMAGE TAG: Wide shot of massive dairy processing plant under construction with empty parking lots]

So here’s what’s happening. When Darigold opened its new Pasco, Washington processing facility this past June, they had every reason to celebrate. The 500,000-square-foot facility can handle 8 million pounds of milk daily—that’s enough capacity to churn out 280 million pounds of powdered milk and 175 million pounds of butter annually. The technology really is impressive—state-of-the-art dryers, low-emission burners, the whole nine yards.

But here’s where it gets complicated, and you probably know where I’m going with this. That shiny new plant ended up costing over $900 million, even though the original budget was $600 million. That’s a 50% overrun, and if you’re shipping to Darigold, you already know who’s paying for it—their 300 member farms are covering it through that $4 per hundredweight deduction from milk checks.

I’ve been talking with producers who say it accounts for 20-25% of their payments. Think about that for a minute. You’re already juggling feed costs that won’t quit, trying to find workers who’ll actually show up, dealing with market swings that’d make your head spin, and suddenly a quarter of your milk check disappears to cover someone else’s construction overrun.

“A quarter of your milk check disappears to cover someone else’s construction overrun while you struggle with feed costs, labor shortages, and market volatility.”

What’s interesting is that Pasco isn’t some weird outlier. The International Dairy Foods Association released their October report showing we’re looking at over $11 billion in new processing capacity coming online between now and 2028. We’re talking over 50 major projects here—it’s the largest infrastructure expansion I’ve seen in… well, honestly, ever.

And yet—and this is the kicker—this massive bet on processing capacity is running headfirst into a reality that anyone who’s tried to hire a milker recently knows all too well. We simply can’t find enough workers to operate the facilities we’ve already got, let alone staff new ones.

Quick Facts: The $11 Billion Reality Check

- Total Infrastructure Investment: $11+ billion (2025-2028)

- Major Projects: 50+ processing facilities announced or under construction

- Darigold Overrun: $300 million (50% over budget)

- Farmer Impact: $4/cwt deduction = 20-25% payment reduction

- Farms Closing in 2025: 2,800 operations

- Workforce Reality: 51% immigrant workers producing 79% of the U.S. milk

Understanding the Infrastructure Surge

Let me walk you through what’s actually being built out there, because the scale really is something else.

Chobani broke ground on a $1.2 billion facility in Rome, New York, back in April. Governor Hochul’s office is promising 1,000+ jobs and the capacity to process 12 million pounds of milk daily. Now, I’ve driven through that region recently—beautiful country, no doubt about it. But here’s what’s nagging at me: New York lost more than half its dairy farms between 2009 and 2022. The Census of Agriculture data doesn’t lie. So where exactly is all that milk going to come from?

Then you’ve got Hilmar Cheese Company’s operation in Dodge City, Kansas. It’s a $600+ million plant that started running this past March. They designed it to process 8 million pounds of milk daily, supposedly creating 250 jobs. But here’s what’s interesting—and this is November, mind you—they’re still scrambling to fill critical positions. Maintenance mechanics, facilitators, and milk receivers for night shifts. These aren’t entry-level gigs where you can train someone up in a week. These are technical roles that require people who know what they’re doing.

Fairlife—you know, the Coca-Cola folks—they’re building a $650 million ultra-filtration facility in Webster, New York. It’s part of what the state’s calling a $2.8 billion surge in dairy processing investments. Largest state investment in the nation, they say.

Michael Dykes, over at the International Dairy Foods Association, he’s confident about all this expansion. In their October industry report, he said: “Don’t fret for one moment—dairy farmers hear the market calling for milk. Milk will come.”

I appreciate the optimism, I really do. And on paper, it makes sense. Global dairy demand is growing, especially in Southeast Asia. Export opportunities are expanding. Processing innovation is creating new product categories we couldn’t have imagined ten years ago.

What could go wrong, right?

Well, let me tell you what’s already going wrong.

The Labor Reality Check

[IMAGE TAG: Split screen showing empty milking parlor positions vs. ICE raid at dairy farm]

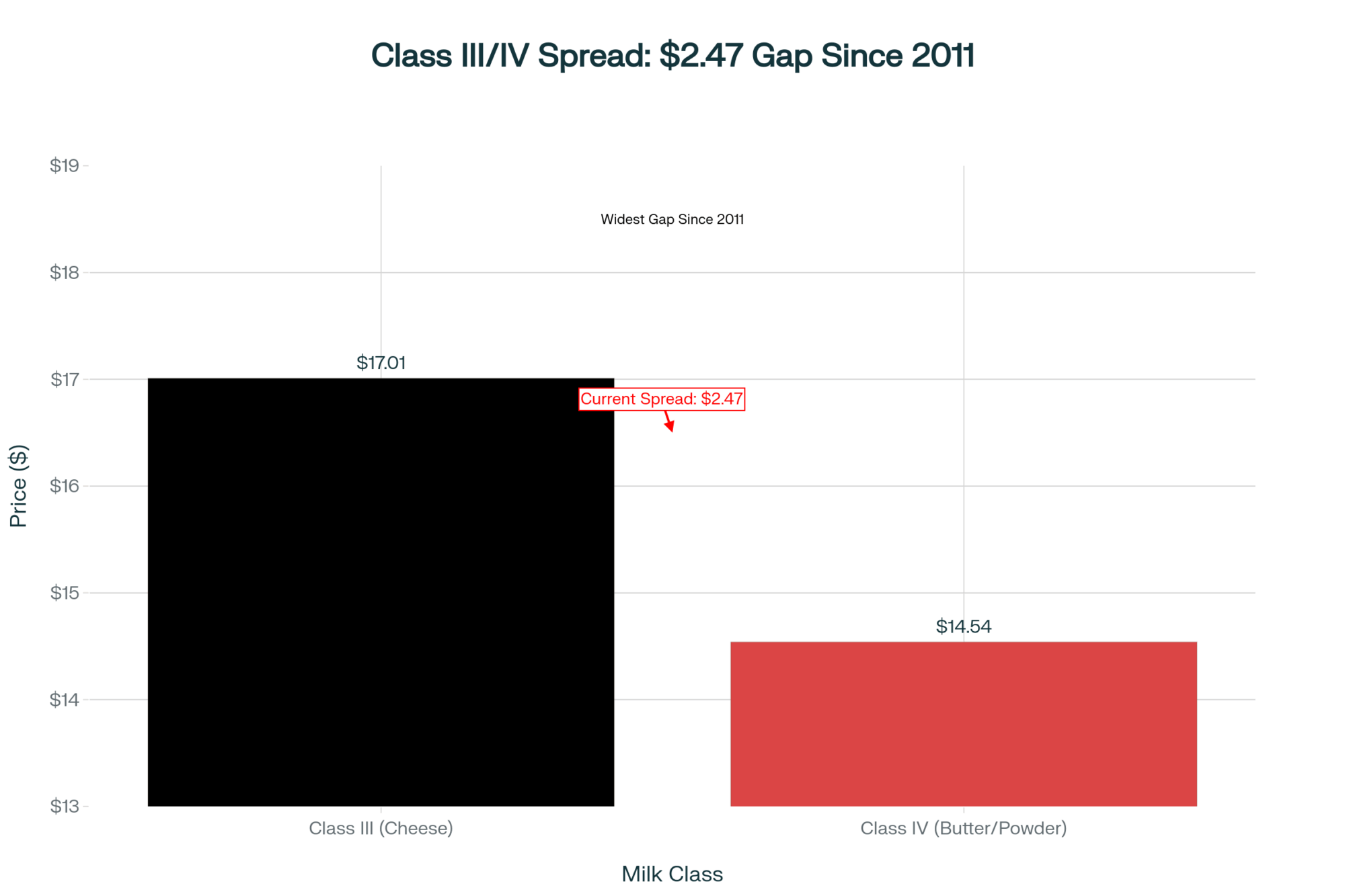

Here’s the number that should keep every processor awake at night—and probably keeps many of you awake too. Texas A&M did a study in 2023, and the National Milk Producers Federation confirmed it: 51% of the dairy workforce consists of immigrant workers who produce 79% of America’s milk supply. I’ve cross-checked these numbers with multiple sources. If anything, they might be conservative.

Meanwhile—and this is where it gets frustrating—the H-2A temporary agricultural worker program has grown from about 48,000 certified positions back in 2005 to nearly 380,000 in fiscal 2024. Department of Labor tracks all this. But dairy? We’re completely locked out. Why? Because their regulations say work has to be “seasonal or temporary.”

Last I checked, cows need milking 365 days a year. They don’t take vacations.

“51% of the dairy workforce consists of immigrant workers who produce 79% of America’s milk. Yet dairy is locked out of H-2A visas because cows don’t take vacations.”

What really gets me is that sheep herding operations—sheep herding!—have H-2A access, even though that’s year-round work too. It’s right there in the H-2A Herder Final Rule if you want to look it up. Jaime Castaneda, who handles policy for the National Milk Producers Federation, he’s been beating this drum for years. As he told me, “We have written to the Department of Labor a number of different times and actually even pointed to the fact that the sheep herding industry has access to H-2A, and it’s a very similar industry to dairy.”

But nothing changes.

And it’s not just dairy facing this squeeze. The Associated Builders and Contractors released its 2025 workforce report: the construction industry needs 439,000 additional workers this year just to meet demand. This labor shortage is exactly what’s driving delays and cost overruns on these dairy processing projects. Darigold learned that the hard way.

Workforce Crisis by the Numbers

Let me give you the regional breakdown, because it varies depending on where you’re farming:

- Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin School for Workers did a survey in 2023. Found that 70% of dairy workers are undocumented. Seven out of ten.

- South Dakota: The Bureau of Labor Statistics shows unemployment under 2%. You literally cannot find local workers.

- Looking ahead, USDA’s Economic Research Service forecasts 5,000 unfilled dairy jobs by 2030.

- Worst-case scenario: Cornell’s research suggests that if we saw full deportation, milk prices could rise by 90% and we’d lose 2.1 million cows from the national herd.

Lessons from the Darigold Experience

So let me dig into what actually happened with Darigold, because if you’re in a co-op—and most of us are—there are some important lessons here.

What Went Wrong

Back in September 2024, Darigold sent out an update to members trying to explain the delays and cost overruns. I’ve reviewed their communications and spoken with affected producers. Here’s what really happened.

First off, supply chain disruptions hit way harder than anyone expected. And I’m not talking about generic delays here. The specialized dairy processing equipment—most of it comes from Europe—faced 12-18 month lead times instead of the usual 6-9 months. When you’re building something this complex, one delayed component throws everything off. It’s like dominoes.

Second, building regulations changed mid-construction. The Port of Pasco confirmed this in their regulatory filings. These weren’t just minor tweaks either. We’re talking structural changes that required completely new engineering calculations, new permits, and the works.

Third—and this is what really killed them—labor shortages in construction trades meant paying absolutely premium rates for skilled workers. You need specialized stainless steel welders who can work to food-grade standards? You can’t just grab someone off the street. Local construction sources tell me these folks were commanding $45-50 per hour plus benefits. And honestly? They were worth it because you couldn’t get the job done without them.

The plant was originally supposed to open in early 2024. It didn’t actually start operations until mid-2025. By September 2024, Stan Ryan, Darigold’s CEO, had to admit to the Tri-City Herald that it was only 60% complete, with costs already over $900 million.

How Farmers Are Paying the Price

This is where it gets personal for a lot of us. To cover the overrun, Darigold implemented what they’re calling a “temporary” deduction structure. I’ve seen the letters they sent to members. The language is… well, it’s stark.

Jason Vander Kooy runs Harmony Dairy near Mount Vernon, Washington—about 1,400 cows with his brother Eric. What he told Capital Press in May really stuck with me:

“There are a lot of guys who don’t want to quit farming, but can’t keep farming if this continues. The problem is we don’t have any other options. We just can’t leave the plant half constructed and walk away.”

Dan DeRuyter’s operation in Yakima County? They lost almost $5 million over 2 years due to these deductions. Five million. He told Capital Press, “It’s awful. I can’t go on much longer. I don’t think producers will be able to stay in business.”

“Dan DeRuyter’s dairy lost almost $5 million over two years from deductions to cover Darigold’s construction overruns. ‘I don’t think producers will be able to stay in business.'”

What strikes me about these stories—and maybe you’re feeling this too—is that these aren’t struggling operations. These are successful, multi-generational farms that suddenly find themselves cash-flow negative because of decisions they had no real say in making.

John DeJong’s family has been shipping to Darigold for 75 years. Seventy-five years! He put it pretty bluntly: “The deduction has eliminated investment. We’re more in survival mode. This is not a sustainable position—to dip into producers’ pockets.”

The Governance Question

Now, this is where things get interesting—and maybe a little uncomfortable—from a cooperative governance perspective.

Darigold said in their June announcement that “farmer-owners approved the Pasco project in 2021.” But when you dig into what that actually means… well, it’s not what most folks would consider democratic approval.

Based on how cooperative governance typically works—and on the extensive research by agricultural law experts at the University of Wisconsin—the approval probably came through board representatives rather than a direct member vote. Think about it. When was the last time your co-op asked you to vote on specific project budgets? On contractor selections? On who bears the risk if things go sideways?

Cornell’s cooperative research program has documented this pattern. Major capital investments often proceed based on board decisions, with members learning about cost overruns only when the deductions appear on milk checks.

I should mention that when I reached out, Darigold declined to provide specific details about their member approval process. They cited confidentiality of internal governance procedures. Make of that what you will.

The Immigration Policy Disconnect

You can’t talk about dairy labor without addressing the elephant in the barn—immigration policy. And boy, is this getting complicated.

Farmers Caught in Political Contradictions

I’ve spent a lot of time talking with farmers about this lately, and the cognitive dissonance is real.

Take Greg Moes. He manages a four-generation dairy operation near Goodwin, South Dakota, with 40 workers—half of them foreign-born. There was this CNN interview back in December that’s been making the rounds. Moes said: “We will not have food… grocery store shelves could be emptied within two days if the labor force disappears.”

Then there’s John Rosenow, who runs Roseholm-Wolfe Dairy up in Buffalo County, Wisconsin. Eighteen workers, half foreign-born. He told PBS Wisconsin this past October: “I’m out of business. And it wouldn’t take long.”

“We’re voting against our own workforce. I’m not making a political statement here, just observing the contradiction that’s tearing rural communities apart.”

What’s fascinating—and frankly, a bit troubling—is how many of these same farmers vote for politicians promising strict immigration enforcement. It’s like we’re voting against our own workforce. I’m not making a political statement here, just observing the contradiction that’s tearing rural communities apart.

Real-World Impact of Enforcement

And this isn’t theoretical anymore.

This past June, Homeland Security Investigations raided Isaak Bos’s dairy in Lovington, New Mexico. Multiple news outlets covered it. The operation lost 35 out of 55 workers in a single day. Milk production basically stopped. Bos had to scramble—brought in family members, high school students on summer break, anybody who could help keep the livestock alive.

Nicole Elliott’s Drumgoon Dairy in South Dakota went through an I-9 audit. The Argus Leader reported she went from over 50 employees down to just 16. As she told reporters, “We’ve effectively turned off the tap, yet we have not made any efforts to establish a solution for acquiring employees in the dairy sector.”

What I’ve noticed—and maybe you’ve seen this too—is that after these raids, remaining workers often self-deport out of fear. It creates this cascade effect that ripples through entire dairy regions. One raid, and suddenly everybody’s looking over their shoulder.

Understanding the Financial Flow

[IMAGE TAG: Infographic showing money flow – $300M overrun split between contractors, designers, vendors vs farmers]

When we talk about a $300 million cost overrun, it’s worth understanding where that money actually goes—and who absorbs the losses. This isn’t abstract accounting. It’s real money from real farms.

Who Profits from Overruns

So I’ve been looking into this based on construction industry analysis and Engineering News-Record’s contractor rankings.

Construction contractors like Miron Construction—they had $1.74 billion in revenue in 2024, according to ENR’s Top 400 list—typically operate under cost-plus contracts. Their fees increase in proportion to project costs. When projects run over? Their percentage-based fees go up, too. It’s built into the system.

Design firms like E.A. Bonelli & Associates, who designed Darigold’s facility, typically charge 6-12% of total construction costs. That’s standard according to the American Institute of Architects. So a $300 million overrun? That can mean millions more in design fees. Not a bad day at the office.

Equipment vendors benefit from supply chain premiums and change orders. When specialized European equipment is scarce—and it has been—vendors can command premium prices. I’ve seen quotes for processing equipment jump 30-40% during the pandemic supply crunch. Supply and demand, right?

Public entities, such as the Port of Pasco, invested $25+ million in infrastructure to support the project, according to port commission records. They get the economic development win, the ribbon-cutting photo ops, regardless of whether farmers can afford the milk check deductions.

The Processor’s Perspective

Now, to be fair, I did reach out to several processor representatives to get their side of the story. Darigold declined specific comment, but an IDFA spokesperson—speaking on background—made some points worth considering:

“Processors are caught between rising global demand and workforce constraints just like farmers. These investments are made with 20-30 year horizons. Yes, there are challenges today, but we believe in the long-term future of American dairy. The alternative—not investing in capacity—means losing market share to international competitors.”

That’s a reasonable position. It really is. Even if it doesn’t help farmers paying today’s deductions for tomorrow’s theoretical benefits.

Who Bears the Cost

But at the end of the day, it comes down to this: the financial burden falls squarely on cooperative members. The 300 Darigold farms absorbed every penny of that overrun through milk check deductions. They had no direct vote on contractor selection. No control over budget management. No recourse when costs exploded.

“300 Darigold farms absorbed every penny of a $300 million overrun. No vote on contractors. No control over budgets. No recourse when costs exploded.”

Practical Paths Forward for Farmers

Given all these structural challenges, what realistic options do we actually have? I’ve been tracking several strategies that producers are using to create some alternatives.

1. Diversification Beyond Cooperatives

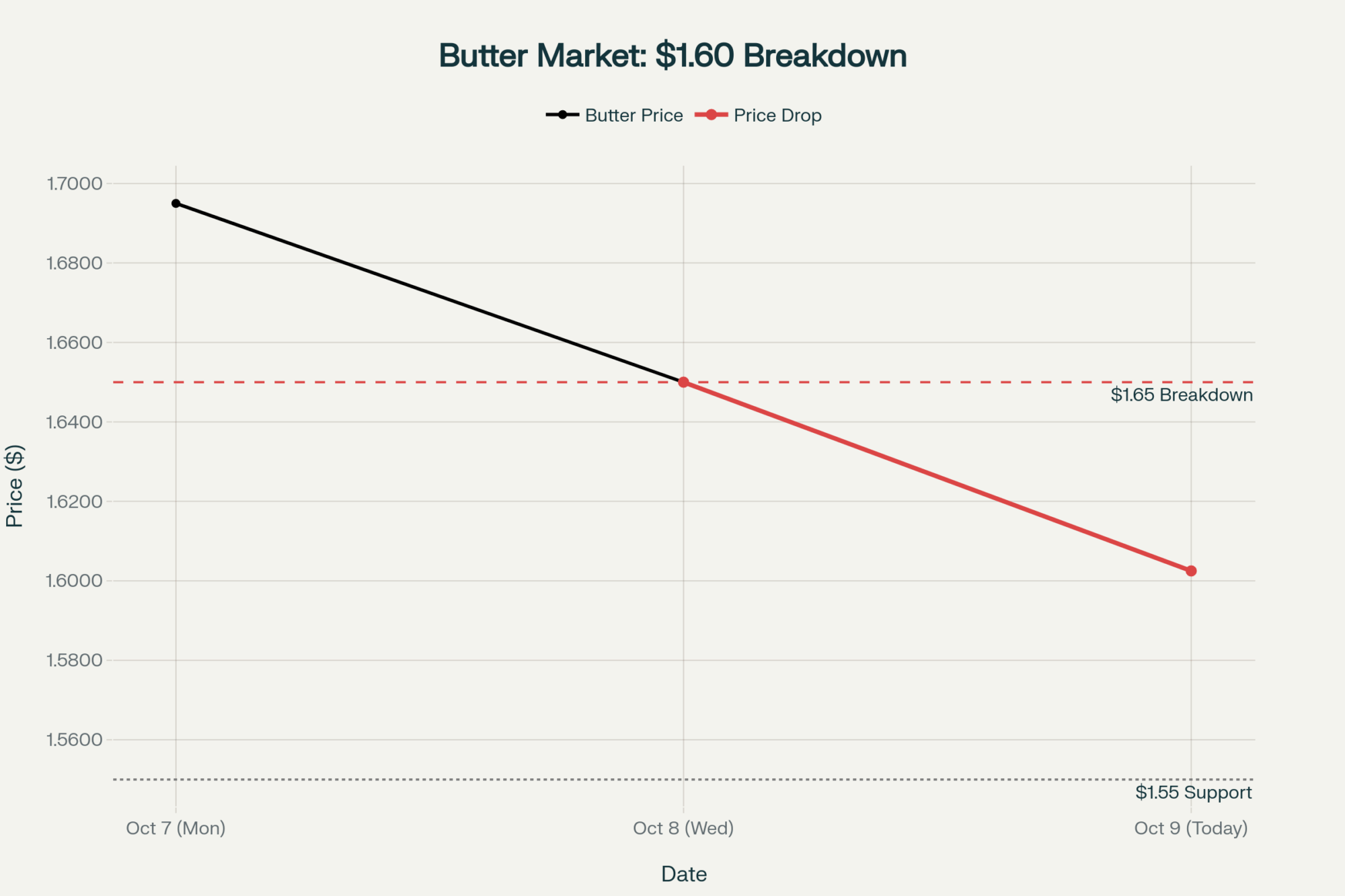

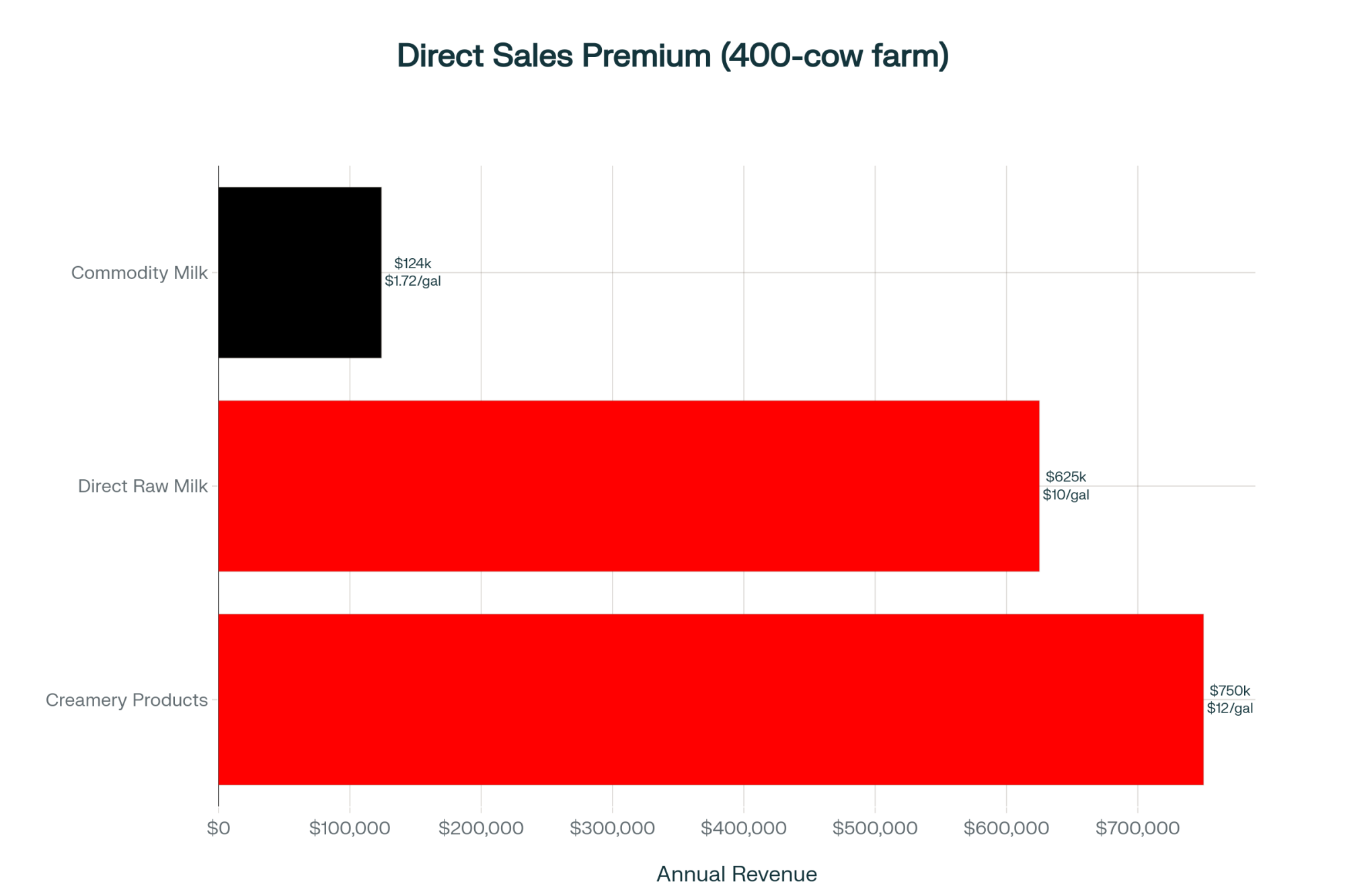

Direct-to-consumer sales are providing some farmers with genuine pricing power. The Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund tracks this—28 states now allow raw milk sales in some form. Farmers I’ve talked with are getting $8-12 per gallon. That’s a 400-600% premium over conventional farmgate prices.

Cost Comparison Reality Check: Let me break down the numbers:

- Conventional milk price: $18-20/cwt (works out to roughly $1.55-1.72/gallon)

- Direct raw milk sales: $8-12/gallon

- Investment needed: $50,000-150,000 for on-farm processing setup

- Payback period: Generally 18-36 months if you shift 20% of production to direct sales

Even moving 20% of your production to direct sales can fundamentally change your negotiating position. You’re no longer completely dependent on that co-op milk check.

Dan Stauffer, a California dairy farmer I know, started an on-farm creamery specifically because—as she put it—”the $4.00 deduct combined with all the other standard deductions has made it impossible for us to cash flow.” She didn’t wait for reform. She built an alternative.

One important note, though: regulations vary significantly by state. What works in Pennsylvania won’t necessarily fly in Wisconsin. Always check with your state department of agriculture before making any moves.

2. Regional Cooperative Alternatives

Some farmers are successfully exploring smaller, regional cooperatives with more transparent governance. Research from the University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives shows these smaller co-ops often feature:

- Direct member voting on major investments (imagine that!)

- Transparent pricing tied to actual costs

- Limited or no speculative facility construction

- Focus on value-added products rather than commodity volume

The challenge? Leaving a major cooperative often involves exit fees, equity complications. But here’s what I’m seeing—when groups of farmers coordinate their intentions (legally, of course), cooperatives sometimes become more flexible on governance reforms. Funny how that works.

3. Advocacy for Practical Reforms

Rather than waiting for comprehensive federal legislation—which, let’s be honest, probably isn’t coming anytime soon—farmers are pursuing achievable state-level reforms.

In Wisconsin, a group of farmers filed formal complaints with the state Department of Agriculture regarding violations of cooperative governance. Outcomes are still pending, but it’s gotten attention.

Similarly, farmers in New York are working with their state attorney general’s office on transparency requirements for agricultural cooperatives. These aren’t radical demands. Just basic stuff like seeing the actual construction contracts before being asked to pay for overruns.

4. Strategic Production Management

This one’s delicate, but some farmers are discovering they can influence cooperative behavior through coordinated (but legal) production decisions. If enough members strategically manage production volumes, it creates leverage for governance reforms.

I’m not talking about illegal collusion here. Just individual business decisions that happen to align. When cooperatives see milk volumes dropping, board meetings suddenly become much more interesting.

Key Industry Trends to Watch

Based on conversations I’ve had with industry analysts and extension economists, here’s what I’m tracking:

Processing capacity utilization: Multiple sources suggest plants will operate at 65-75% capacity through 2026 due to milk supply constraints from labor shortages. That’s going to create margin pressure throughout the system. No way around it.

Consolidation acceleration: USDA data shows 2,800 farms closed in 2025. And that’s not the peak—it’s the baseline. Mid-size operations (500-1,500 cows) are facing the greatest pressure. I’m particularly worried about dairies in that sweet spot—too big to go niche but too small to achieve mega-dairy economies of scale.

Immigration policy evolution: Watch for potential executive orders creating temporary pathways for dairy workers. Congressional solutions remain blocked, but I’m hearing administrative workarounds are being discussed at USDA. Sources familiar with the discussions say something might be coming, but I’ll believe it when I see it.

Cooperative governance pressure: The Darigold situation has awakened member interest in governance reform across multiple cooperatives. I’m hearing rumblings from DFA and Land O’ Lakes members about demanding more transparency. About time, if you ask me.

Alternative marketing growth: Direct sales, regional brands, on-farm processing—all continuing to expand. The economics are compelling. Capturing even a portion of that processor-to-retail margin changes everything.

Practical Takeaways for Dairy Farmers

After researching this issue and talking with dozens of farmers, here’s my best advice:

1. Understand your cooperative’s governance structure. Get copies of the bylaws. Read them. Actually read them. Request documentation of how major capital decisions are made. Know your rights—you might have more than you think.

2. Evaluate diversification options. Run the numbers on direct sales or value-added processing. Even if you don’t pull the trigger, knowing your alternatives strengthens your position.

3. Document workforce challenges. Keep detailed records of recruitment efforts, wage offers, and position vacancies. This data matters for policy advocacy and might be required for future visa programs.

4. Build regional alliances. There’s strength in numbers. Coordinated action among neighboring farms—whether for governance reform, marketing alternatives, or workforce solutions—multiplies individual leverage.

5. Monitor capacity developments. Understanding regional processing capacity and utilization rates helps inform production and marketing decisions. If your processor is running at 60% capacity, that affects your negotiating position.

6. Prepare for workforce disruption. Develop contingency plans now. Cross-train employees, investigate automation options where feasible, and build relationships with temporary labor providers. Hope for the best, plan for the worst.

The Road Ahead

Looking at this $11 billion infrastructure investment, I see both dairy’s ambition and its fundamental challenge. We’re building world-class processing capacity while the workforce foundation—both on farms and in plants—is crumbling beneath us.

The Darigold experience isn’t just a cautionary tale. It’s a preview of what happens when expansion proceeds without addressing underlying structural issues. Farmers pay the price while contractors, consultants, and executives move on to the next project.

What’s become clear to me is that the disconnect between processing infrastructure and workforce reality isn’t just a temporary mismatch. It’s a structural crisis that requires fundamental reforms in how cooperatives govern themselves, how immigration policy treats agricultural workers, and how the industry plans for the future.

For dairy farmers navigating this environment, waiting for top-down solutions while writing checks for bottom-up failures isn’t sustainable. The operations that survive and thrive will be those that recognize the current system’s limitations and actively build alternatives—whether through direct marketing, governance reform, or strategic cooperation with like-minded producers.

The infrastructure bet has been placed. The steel is welded, and the dryers are installed. Now we need to ensure farmers aren’t the only ones covering the spread when the dice don’t roll our way.

Because at the end of the day, all those shiny new plants don’t mean a damn thing if there’s nobody left to milk the cows—or if the farmers have gone broke paying for the factory’s cost overruns.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Check your cooperative governance NOW: If your board can approve $50M+ projects without direct member vote, you’re one announcement away from a $4/cwt deduction. Demand to see construction contracts, board votes, and risk allocation before the next expansion—farmers discovering they have legal recourse for unapproved overruns.

- Build your escape route before you need it: Direct-to-consumer sales command $8-12/gallon (vs. $1.72 conventional) with $50-150K setup costs and 18-36 month payback. Moving just 20% of production creates leverage and covers deduction losses—28 states allow it, but check regulations first.

- Document everything related to the workforce crisis: keep detailed records of every recruitment attempt, wage offers ($45-50/hr for skilled positions), and unfilled positions. You’ll need this evidence when immigration reform finally comes or when explaining why you can’t meet production contracts after raids.

- Power comes from numbers, not hoping: Cooperative boards ignore individual complaints but panic when 10+ farms coordinate action. Whether demanding governance reforms, exploring alternative cooperatives, or strategic production management—allied farmers are getting results while solo operators just get bills.

Learn More:

- Why This Dairy Market Correction Feels Different – and What It Means for Our Farms – This article provides direct, actionable strategies for surviving the extended 24-month market downturn. Discover how to leverage direct-to-consumer sales for 40-60% premiums and identify alternative revenue streams like carbon credits that stabilize your operation.

- Your Milk Check Just Got $337M Lighter – And Your Co-op Helped Plan It – Go deeper into the crisis of cooperative governance. This piece reveals how regulatory changes (like FMMO make allowance hikes) are systematically slashing your milk price by 85-90¢/cwt, and outlines strategies for producer alliances and reform.

- ICE Raids Resume: Why Dairy’s $48 Billion Labor Crisis Exposes Our Innovation Failure – Stop depending on fragile immigration policy. Learn the financial case for automation, including how robotic milking systems achieve 18-24 month payback and eliminate up to 70% of routine labor, building operational independence.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!