What if your transition disease rate isn’t 20%—it’s 35%? That measurement gap costs $42K/year. Worse: your best cows pay the genetic price.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Most dairy operations estimate their transition disease rate at 20%—but farms that actually measure often find it’s closer to 35%. That gap represents roughly $42,000 in annual losses on a 400-cow dairy: lost milk, extra treatments, reproductive delays, and elite cows that never reach their genetic potential. The research points to a clear fix. Work from Guelph, Minnesota, Ohio State, and Wisconsin Extension consistently shows that risk-stratified protocols outperform blanket approaches—intensive care for high-risk mature cows, reduced spending on heifers who don’t need it. The numbers back it up: $500 per disease case, $1,000 for multiple diseases, and subclinical hypocalcemia hitting 73% of mature cows at $150 each. For operations investing in superior genetics, every cow that struggles through transition is a cow whose breeding value may never reach the bulk tank—or produce the next generation of your herd’s best females. The research-backed first step? Stop bolusing first-lactation heifers and redirect those resources where they’ll actually make a difference.

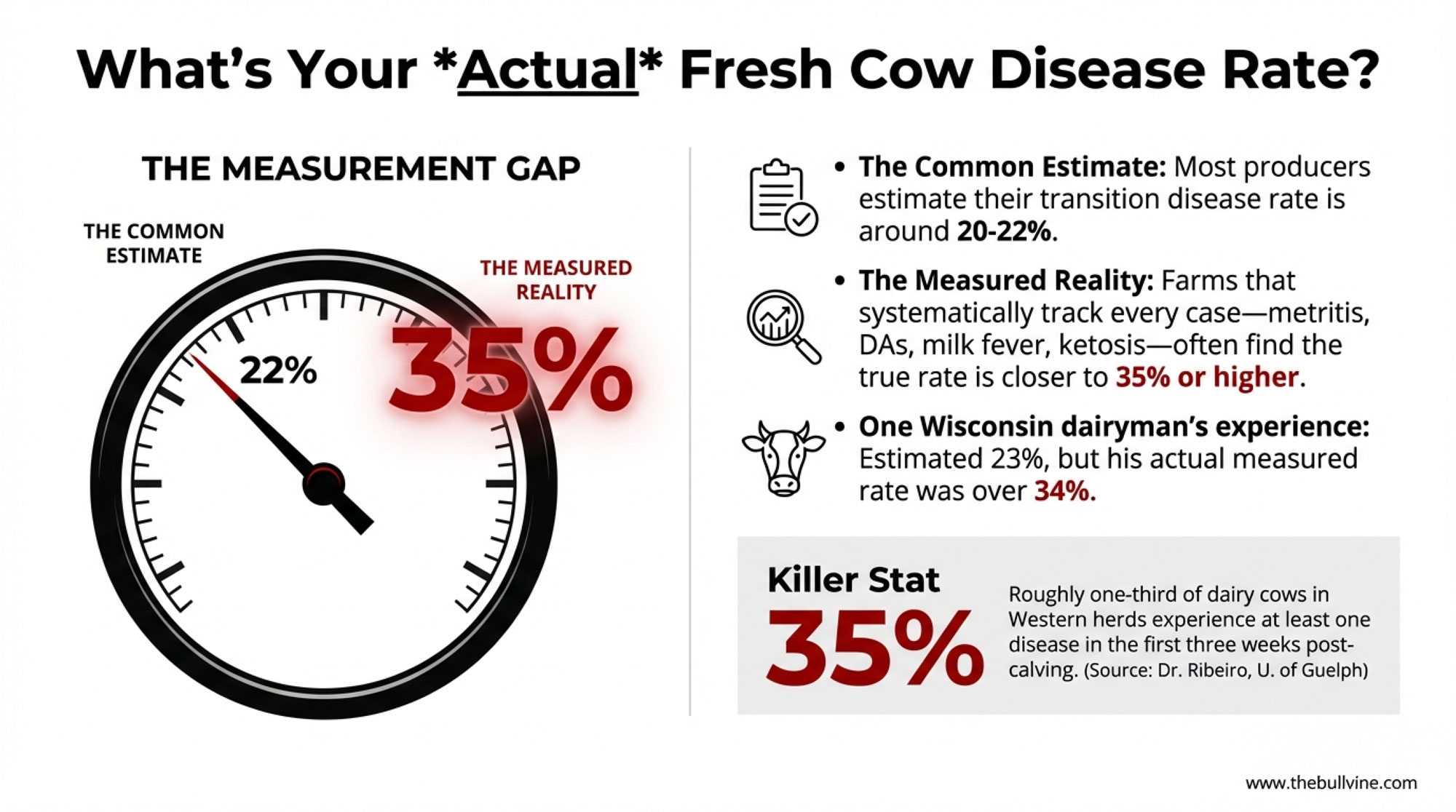

Here’s something that catches a lot of producers off guard. Walk into almost any dairy operation—doesn’t matter if it’s a 200-cow tie-stall in Vermont, a 3,000-cow freestall in California’s Central Valley, or a grazing operation in New Zealand—and ask about fresh cow disease rate. You’ll probably hear something like “Oh, we’re running around 20%, maybe 22%.” Reasonable estimate. Feels about right based on what they’re seeing day to day.

But when farms actually start measuring… well, that’s when things get interesting.

I’ve heard from producers who decided to track every single fresh cow event for 90 days—metritis cases, DAs, milk fever, ketosis treatments, all of it—and discovered their numbers were way off. One Wisconsin dairyman figured he was running about 23%. His actual number? North of 34%. And he’s not alone. When farms start systematically tracking every treatment event, every cow that doesn’t quite hit her stride in early lactation, that 20% estimate often turns out to be closer to 30% or higher.

| Farm Type & Region | Producer’s Estimate | Actual Measured Rate | Disease Rate Gap | Annual Cost Gap (400-cow herd) |

| 200-cow tie-stall, Vermont | 20% | 34% | +14 percentage points | $39,200 |

| 400-cow freestall, Wisconsin | 22% | 35% | +13 percentage points | $36,400 |

| 800-cow freestall, Minnesota | 18% | 31% | +13 percentage points | $72,800 |

| 3,000-cow freestall, California | 21% | 33% | +12 percentage points | $252,000 |

| 600-cow grazing operation, New Zealand | 19% | 29% | +10 percentage points | $42,000 |

Dr. Eduardo de Souza Ribeiro, over at the University of Guelph, puts it pretty directly: cows with a poorer transition produce less milk, take longer to get pregnant, and are more likely to lose a pregnancy or be culled from the herd. That adds up to substantial economic losses. And here’s what’s sobering—his review of the research, published in Dairy Global, found that roughly one-third of dairy cows in Western herds experience at least one disease process in the first three weeks after calving. That’s not outliers. That’s typical across the industry.

So what does that cost? Work by Carvalho and colleagues back in 2019 tried to put a price tag on it, estimating about $500 for a single postpartum disease case and around $1,000 when a cow has multiple problems during that critical window. On a 400-cow dairy, it doesn’t take many extra disease cases to add up to tens of thousands of dollars in lost milk, extra treatments, and reproductive delays—even if the exact number varies by herd and region.

What’s interesting—and honestly, a bit frustrating—is that the research showing how to cut those disease rates significantly has been accumulating for over two decades. The barrier isn’t knowledge. It’s how that knowledge moves (or doesn’t) from research journals to actual farm practice.

“You can have the best genetics in the world, but if your cows can’t get through transition healthy, you’ll never see that potential expressed in the bulk tank or the breeding program.”

The Measurement Gap Nobody Talks About

The foundation of any improvement starts with a surprisingly basic question: What’s your actual disease rate?

You know, most dairies have never systematically answered this. They track individual treatments, sure. They know when a cow develops metritis or throws a DA. But calculating an overall incidence rate—the percentage of cows experiencing any metabolic or reproductive disease in the first 21 days—that’s different. And without that number, you’re essentially flying blind.

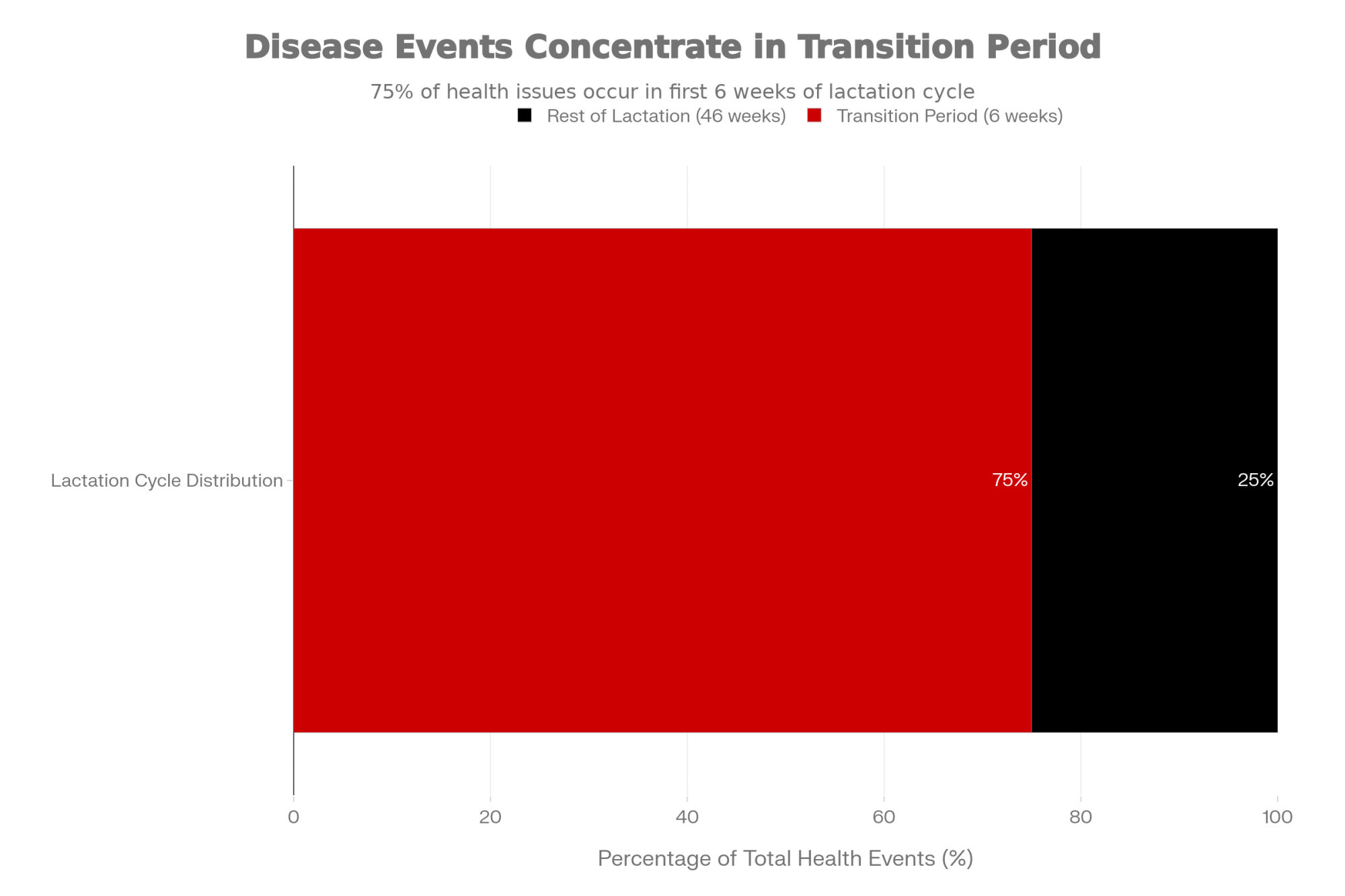

Why does this matter so much? Multiple sources—University of Maryland Extension, Dairy Global, research published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science—all point to the same finding: about 75% of health problems in dairy cows occur during the transition period. That’s the window from roughly two weeks before calving to four weeks after. Three-quarters of your health challenges, concentrated in about six weeks. That’s a massive concentration of risk in a pretty short timeframe, whether you’re running a confinement operation in the Midwest or a pasture-based system in the Southeast.

When farms start systematically tracking, many discover their disease rates are higher than they’d estimated. A 2019 study in the Journal of Dairy Science looked specifically at barriers to successful transition management and found that variation in both farmer attitude and veterinarian involvement significantly affects outcomes. One of the key barriers they identified? Simply not having a clear picture of what’s actually happening. Hard to fix a problem you haven’t quantified.

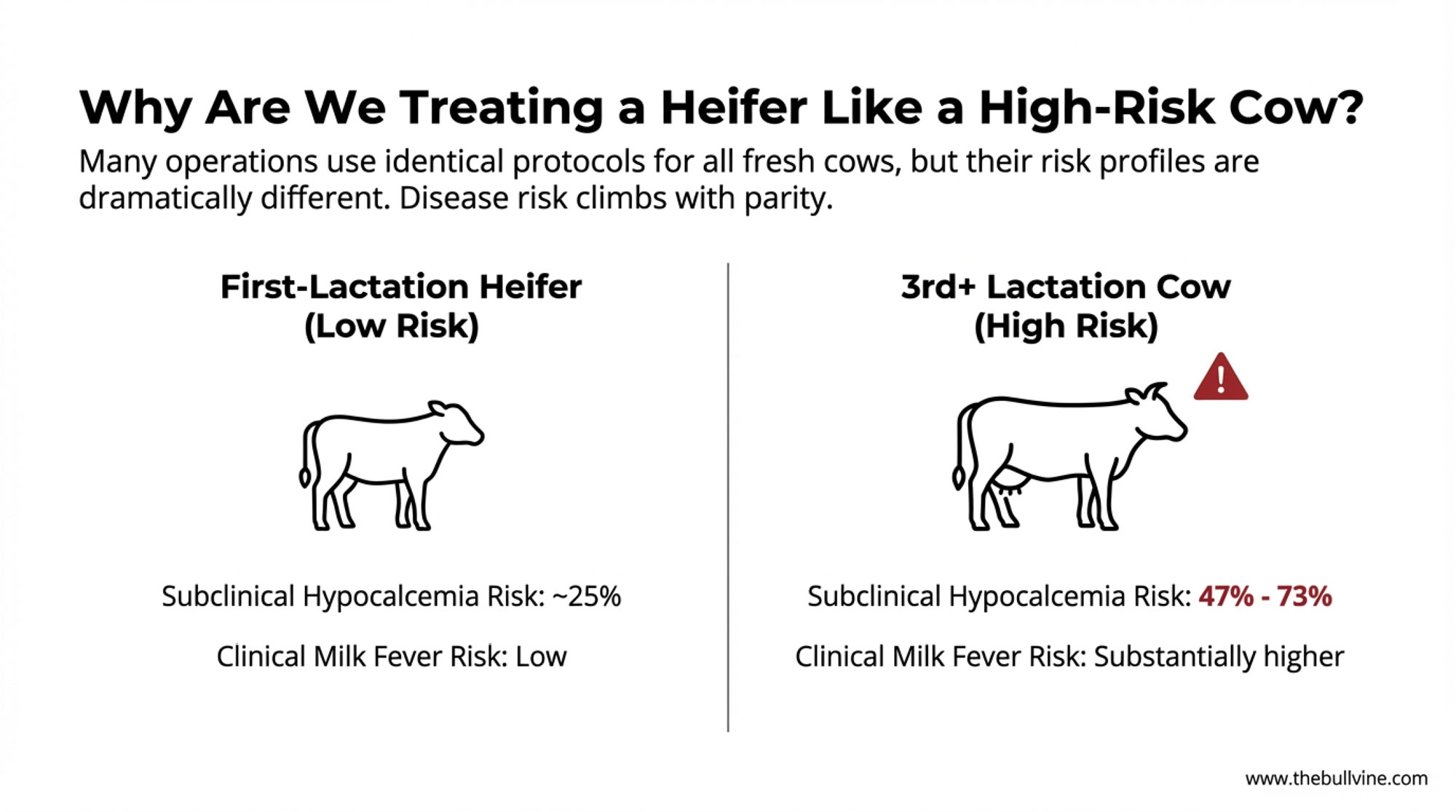

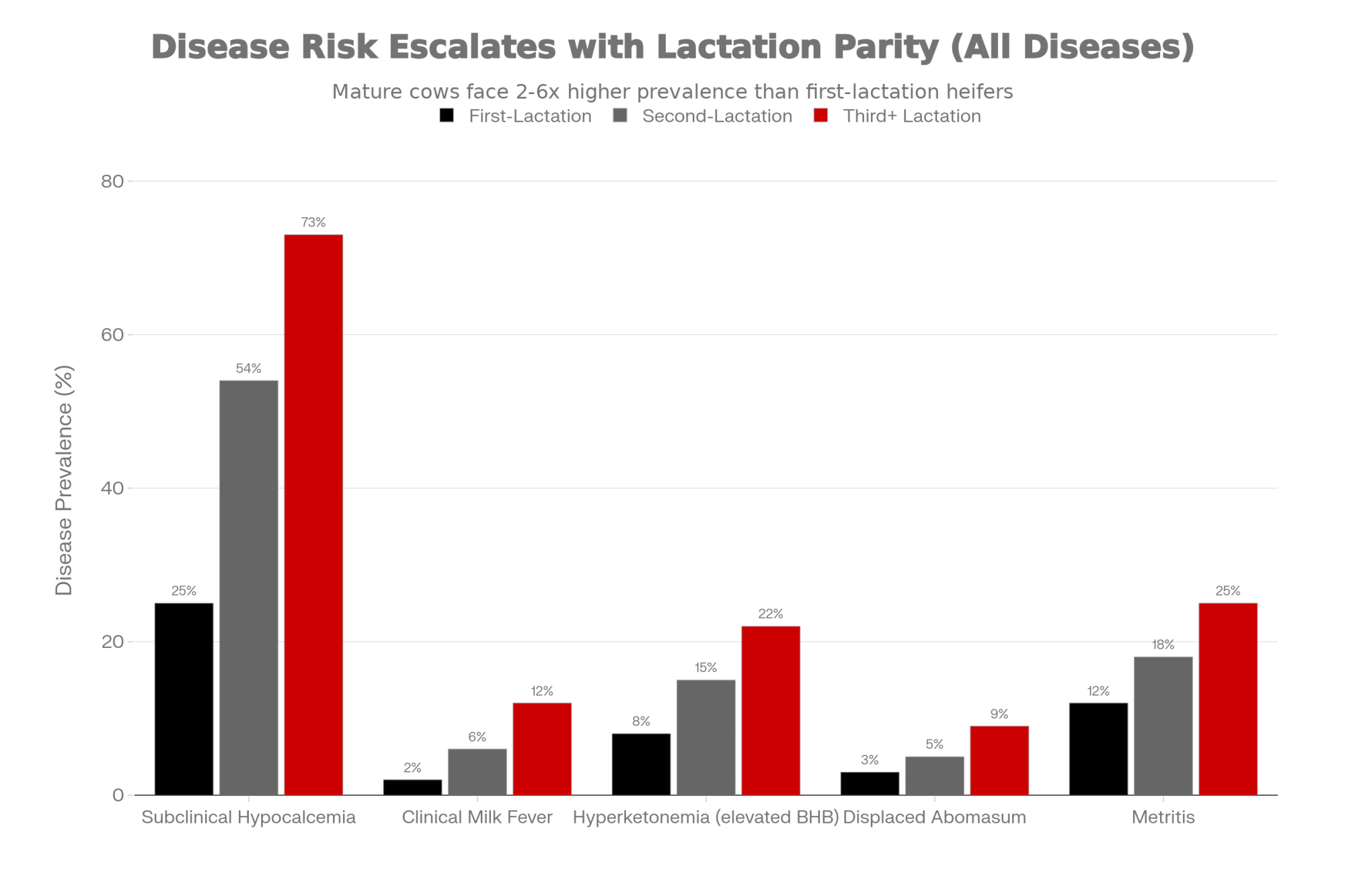

Now, break down the disease by parity, and the picture gets even clearer. This is where it gets really practical for protocol decisions. Field data and NAHMS surveys consistently show that disease risk climbs with parity—first-lactation animals typically have substantially lower rates of metabolic and reproductive disease than third- and fourth-lactation cows. Research showed subclinical hypocalcemia affecting around 47% of second-or-greater lactation cows but only about 25% of first-lactation heifers. Clinical milk fever follows the same pattern—it’s far more common in older cows than in first-lactation animals.

| Disease Type | First-Lactation Heifers | Second-Lactation Cows | Third+ Lactation Cows | Risk Multiplier (3rd+ vs. 1st) |

| Subclinical Hypocalcemia | 25% | 54% | 73% | 2.9× |

| Clinical Milk Fever | 2% | 6% | 12% | 6.0× |

| Hyperketonemia (elevated BHB) | 8% | 15% | 22% | 2.8× |

| Displaced Abomasum | 3% | 5% | 9% | 3.0× |

| Metritis | 12% | 18% | 25% | 2.1× |

| Average Treatment Cost/Cow | $82 | $156 | $247 | 3.0× |

Here’s what that tells us: many operations treat all fresh cows identically—same calcium bolus protocol, same propylene glycol regimen, same monitoring intensity. But different animals have dramatically different risk profiles. And the research is pretty clear that they respond differently to interventions too. So why are we treating a first-calf heifer the same as a fourth-lactation cow? That’s the question worth asking.

What the Research Actually Shows

The scientific literature on transition cow management has reached a level of maturity that’s frankly unusual in agricultural research. We’re not talking about preliminary findings or single studies here. We’re talking about meta-analyses combining decades of data from operations across North America, Europe, and beyond.

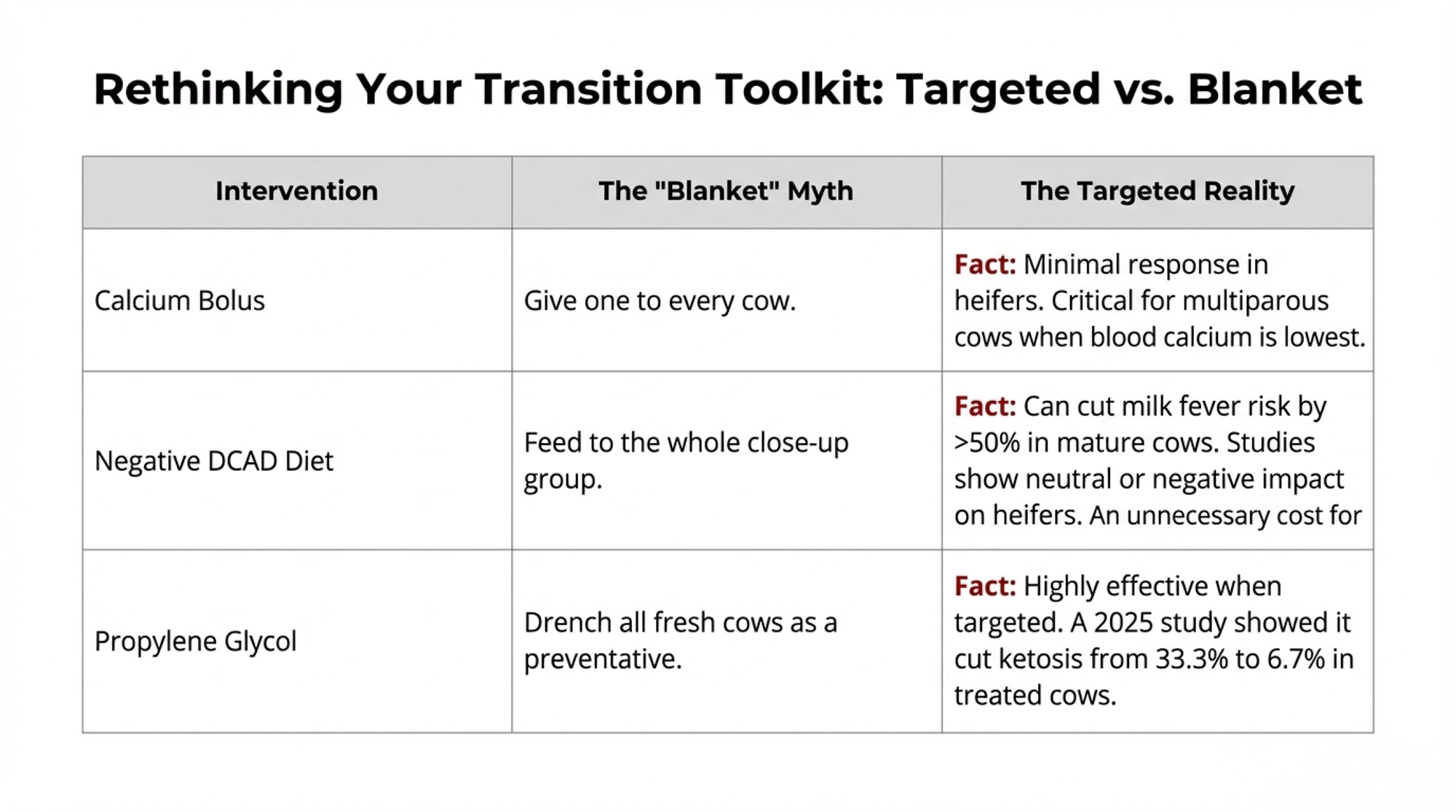

On calcium supplementation: Research consistently shows multiparous cows benefit significantly from calcium support, while first-lactation heifers show minimal response. A 2024 review in the journal Animals noted that dairy cows are at considerable risk for hypocalcemia at the onset of lactation, when daily calcium excretion suddenly increases from about 10 grams to 30 grams per day. Think about that—tripling calcium output almost overnight. But—and this is important—that risk concentrates heavily in mature cows, not heifers.

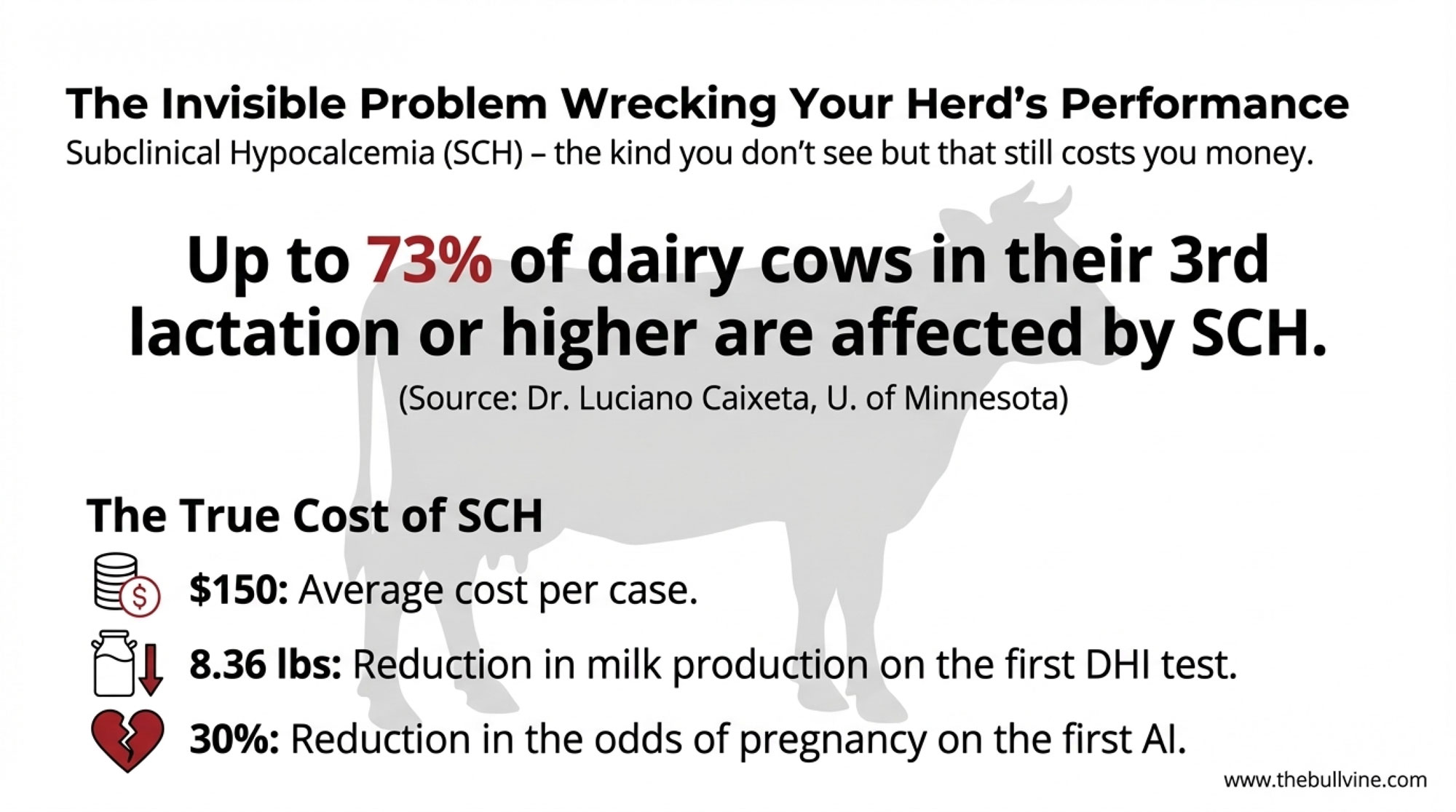

Dr. Luciano Caixeta at the University of Minnesota has noted that subclinical hypocalcemia (the kind you don’t see clinically but still causes problems) has been reported to affect as many as 73% of dairy cows in third or higher lactations, costing an average of about $150 per case. Researchers at the University of Guelph found that herds with a higher incidence of subclinical hypocalcemia experienced an 8.36-pound reduction in milk production on the first test day and a 30% reduction in the odds of pregnancy on the first AI. That’s real money—and real reproductive performance—left on the table.

Dr. Mark van der List, a veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim who’s spoken at numerous industry events on this topic, explains the supplementation approach this way: administering an oral calcium supplement to cows at calving, and again 12 hours later, provides much-needed calcium when blood levels are at their lowest. He also cautions about reading product labels carefully—watch out for products containing calcium carbonate, which is limestone. It’s the cheapest form of calcium, but it’s too slowly absorbed to really make a difference when you need rapid uptake.

On negative DCAD diets: This is one where the research is really solid. University of Wisconsin Extension confirms that feeding a negative DCAD diet during the pre-fresh dry period—that last 21 days before calving—successfully increases blood calcium levels before and immediately after calving. The result is a lower incidence of both clinical and subclinical milk fever.

Meta-analyses and field trials show that properly formulated negative DCAD diets can cut the risk of clinical milk fever by well over half. Some studies report relative risks in the 0.2-0.4 range compared with neutral DCAD diets. That’s substantial protection for your high-risk animals.

But here’s the nuance that matters for your operation—and this is where a lot of folks are spending money they don’t need to spend. The same Wisconsin Extension research notes that while negative DCAD diets can benefit heifers in some ways, studies have shown their impact on productive performance has been either neutral or negative. Heifers have a much lower risk of developing milk fever than multiparous cows, so feeding them a negative DCAD diet is likely unnecessary. That’s a cost you can redirect elsewhere.

On propylene glycol: A 2025 study published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science demonstrated that a targeted propylene glycol protocol effectively decreased ketosis incidence from 33.3% in control cows to 6.7% in treated cows at 14 days postpartum. The research confirms propylene glycol’s efficacy—but notice that word “targeted.” When used appropriately and aimed at cows that actually need it, rather than blanket-treating everyone, the results are strong.

What’s emerging from all this research is a consistent pattern: targeted, risk-stratified protocols generally outperform blanket treatment approaches, both economically and in terms of animal outcomes. Treat the cows that need treatment. Don’t treat the ones that don’t. Seems obvious, but it requires knowing who falls into which category.

Body Condition: The Early Warning System Many Farms Miss

This is where things get really practical—and where, honestly, a lot of farms are leaving money on the table.

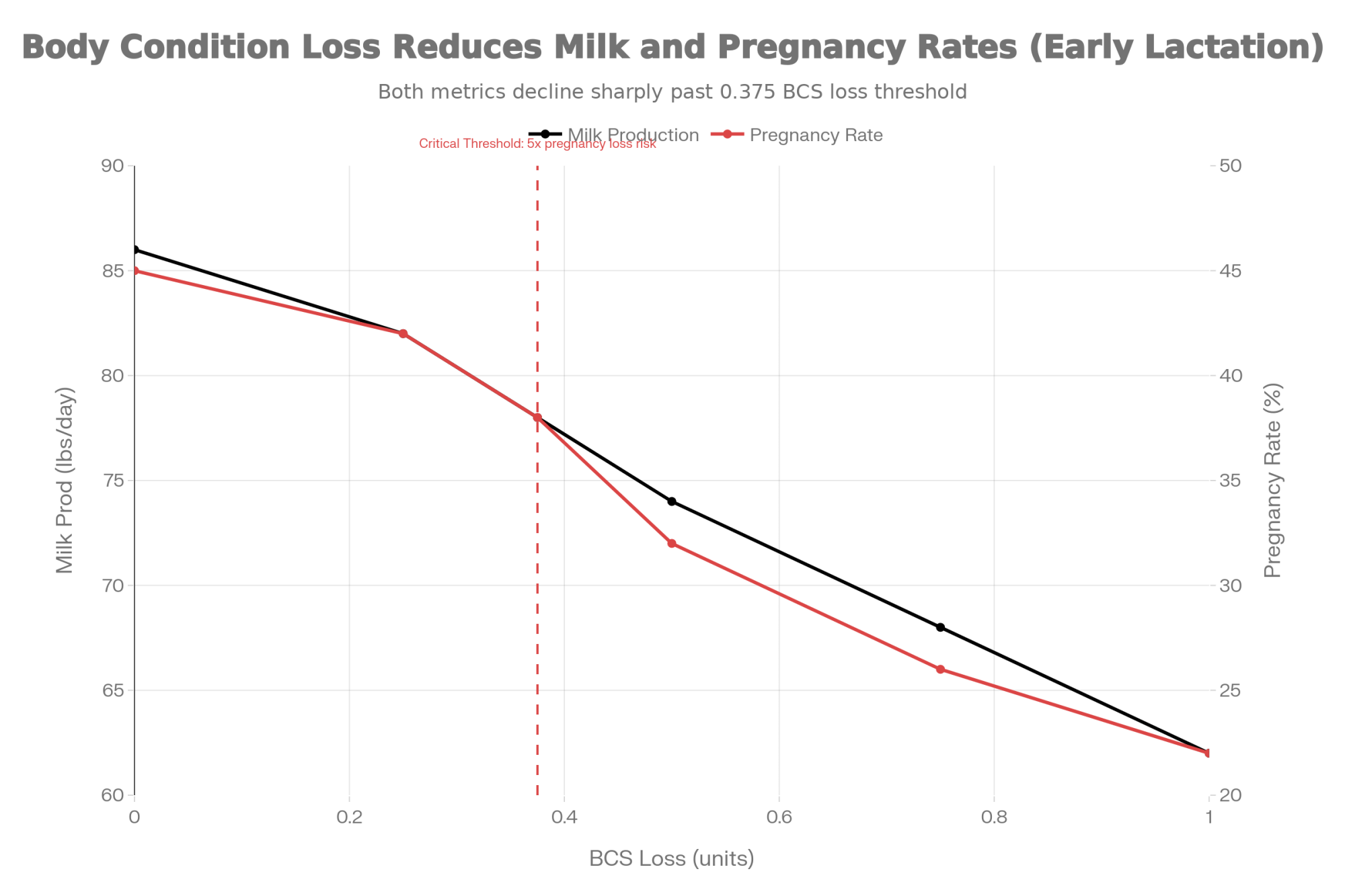

Kirby Krogstad at Ohio State has been doing some fascinating work on the connections between body condition score, hyperketonemia, and downstream health outcomes. His research, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, tracked approximately 900 cows and found some pretty compelling relationships that should inform how we manage transition cows.

Here’s what stood out: cows who lost more than 0.375 BCS in early lactation were nearly five times more likely to lose their pregnancy. Five times. That’s not a subtle effect—that’s a flashing warning sign. And mature cows—third lactation and beyond—testing above 1.2 mmol/L of BHB produced about 11.8 pounds less milk per day than their non-hyperketonemic counterparts. On a 400-cow dairy with even modest prevalence of hyperketonemia in older cows, that adds up fast.

| BCS Loss (units) | Milk Production (lbs/day) | Pregnancy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 86 | 45 |

| 0.25 | 82 | 42 |

| 0.375 | 78 | 38 |

| 0.5 | 74 | 32 |

| 0.75 | 68 | 26 |

| 1.0 | 62 | 22 |

Key Benchmarks (Krogstad, Ohio State): Target ≤10% of 2nd-lactation cows and ≤20% of 3rd+ lactation cows with elevated BHB in week one. Exceeding these thresholds signals protocol problems.

What’s particularly useful is Krogstad’s benchmark recommendations for the first week in milk. He suggests that 10% or less of second-lactation cows should show elevated BHB, and 20% or less of third-plus lactation cows. If your herd exceeds these thresholds, that’s a signal worth paying attention to. It’s a simple metric you can track that tells you whether your transition protocols are working.

Dr. Ribeiro at Guelph recommends that body condition scoring at dry-off should be moderate—3.0 to 3.25 on a 1-to-5 scale—and maintained through calving. The intervention point, importantly, is 100-plus days before calving, not at calving itself. By the time a cow reaches the close-up pen, overconditioned, you’re already playing catch-up. The time to manage body condition is back in late lactation, not when she’s three weeks from freshening.

I’ve heard from California producers who started scoring every cow at 200 DIM and adjusting rations for the overconditioned ones. Several report noticeable drops in fresh cow disease within a couple of lactation cycles. Not because they were doing anything fancy at calving—they were just preventing the problem from developing in the first place. That kind of proactive approach works whether you’re in a dry lot system in the Southwest or a freestall barn in the upper Midwest.

Why This Matters for Your Elite Genetics

Here’s something that doesn’t get talked about enough in the transition cow conversation: the genetic implications.

If you’re investing in elite genetics—whether that’s genomic-tested heifers, embryo transfer calves from proven cow families, or semen from high-ranking sires—transition disease can undermine that entire investment. A cow from an exceptional dam line who struggles through her first lactation due to ketosis or metritis may never express her true genetic potential. Worse, she might get culled before she ever gets a chance to prove herself or contribute daughters to the herd.

Think about it this way: that heifer calf from your best cow family represents years of breeding decisions. She carries genetics for high components, longevity, fertility—whatever traits you’ve been selecting for. But if she hits the fresh pen and immediately battles subclinical hypocalcemia followed by a DA, her first lactation becomes a salvage operation rather than a showcase of her genetic merit.

The research from Guelph on subclinical hypocalcemia showed a 30% reduction in the odds of pregnancy at first AI. For a cow you’re counting on to produce the next generation of your herd’s genetics, that reproductive hit is devastating. You need her pregnant early to get that next heifer calf. You need her healthy to produce enough milk to justify keeping her. Transition disease compromises both.

Dr. Ribeiro’s point about cows with poor transitions being “more likely to get culled from the herd” hits especially hard when you’re talking about animals carrying superior genetics. Every elite cow that leaves the herd early due to transition-related complications represents not just lost milk revenue but lost genetic progress. Her potential replacement heifers never get born. Her genomic contribution to your herd’s improvement disappears.

This is why getting transition management right matters beyond just the immediate economics. It’s about protecting your genetic investment and ensuring your best animals live long enough, and stay healthy enough to reach their potential and pass those genetics forward.

Building Momentum: The First Move That Actually Works

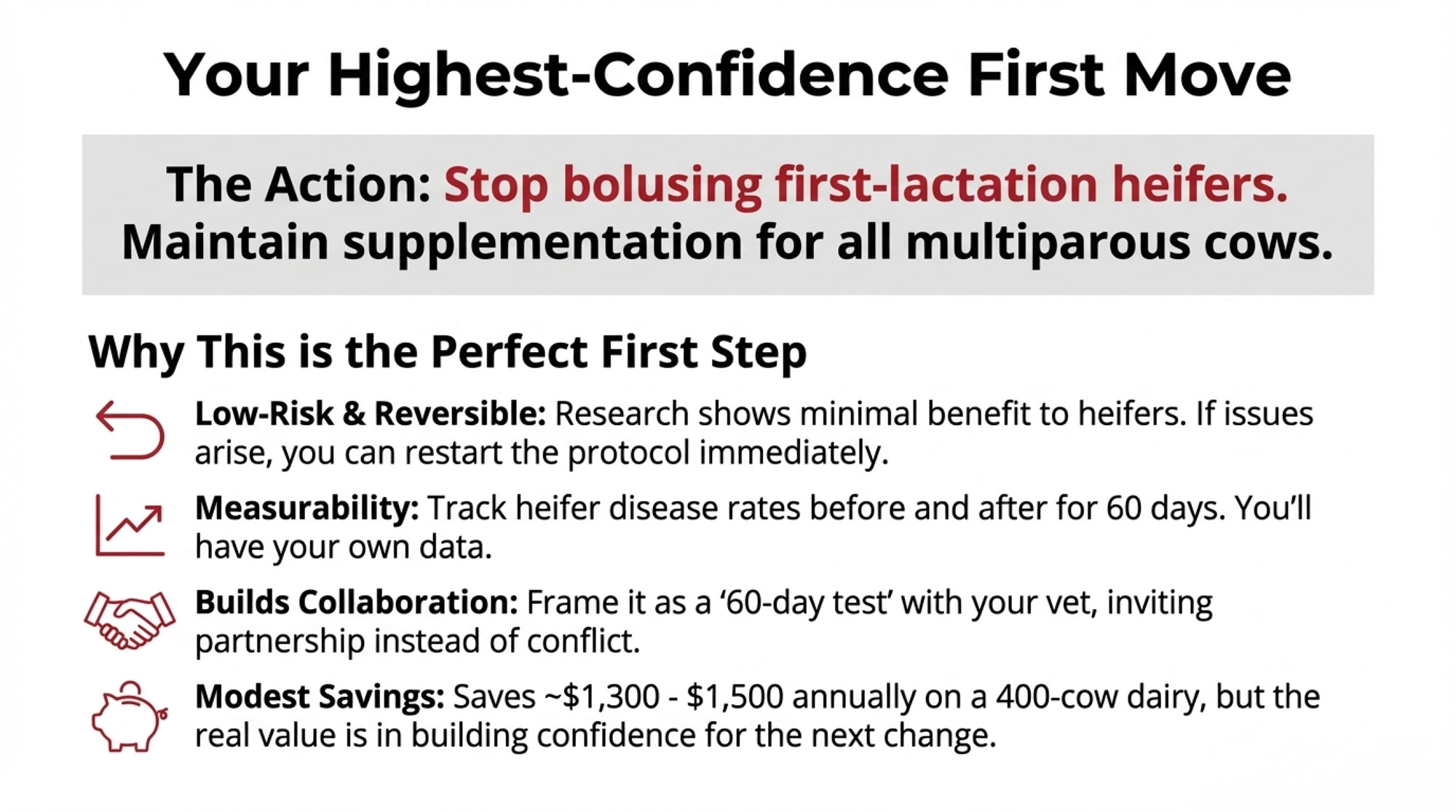

For operations looking to bridge the gap between current practice and what research supports, the question becomes practical: where do you actually start?

The answer, based on both research and what we’re seeing on progressive farms from the Northeast to the Pacific Northwest, might surprise you. Rather than overhauling everything at once (which rarely sticks anyway), the highest-confidence first move is often the simplest: stop bolusing first-lactation heifers while maintaining supplementation for multiparous cows.

The economics here are modest but illustrative. A 400-cow dairy with 33% heifer rotation spends roughly $1,300 to $1,500 annually on heifer calcium boluses. Research suggests this spending produces minimal benefit because heifers face naturally low hypocalcemia risk—remember that Wisconsin Extension finding about neutral or negative performance impacts? You’re spending money for essentially no return.

But more valuable than the direct savings is what this change accomplishes organizationally:

- It’s reversible. If heifer disease somehow increases—unlikely based on research, but possible—you restart the protocol immediately. No permanent commitment required.

- It’s measurable. Track the heifer disease rate before and after. You’ll have concrete evidence of whether it works for your specific operation, your genetics, and your facilities.

- It builds collaborative relationships. Approaching your vet with “Can we try this as a 60-day test?” creates a partnership rather than conflict. You’re not challenging their expertise; you’re inviting them into an experiment.

- It establishes a template. Successfully implementing one evidence-based change creates permission—and confidence—for the next.

Dr. van der List emphasizes this collaborative approach: ask your veterinarian about blood calcium testing, he suggests. They can help you evaluate the results and develop the right supplementation strategies for your herd. That kind of data-driven partnership is exactly what makes protocol changes stick long-term.

The farms achieving the best transition outcomes didn’t get there through revolutionary overnight changes. They built systematic improvement through sequential small wins. One protocol adjustment at a time, measuring as they went.

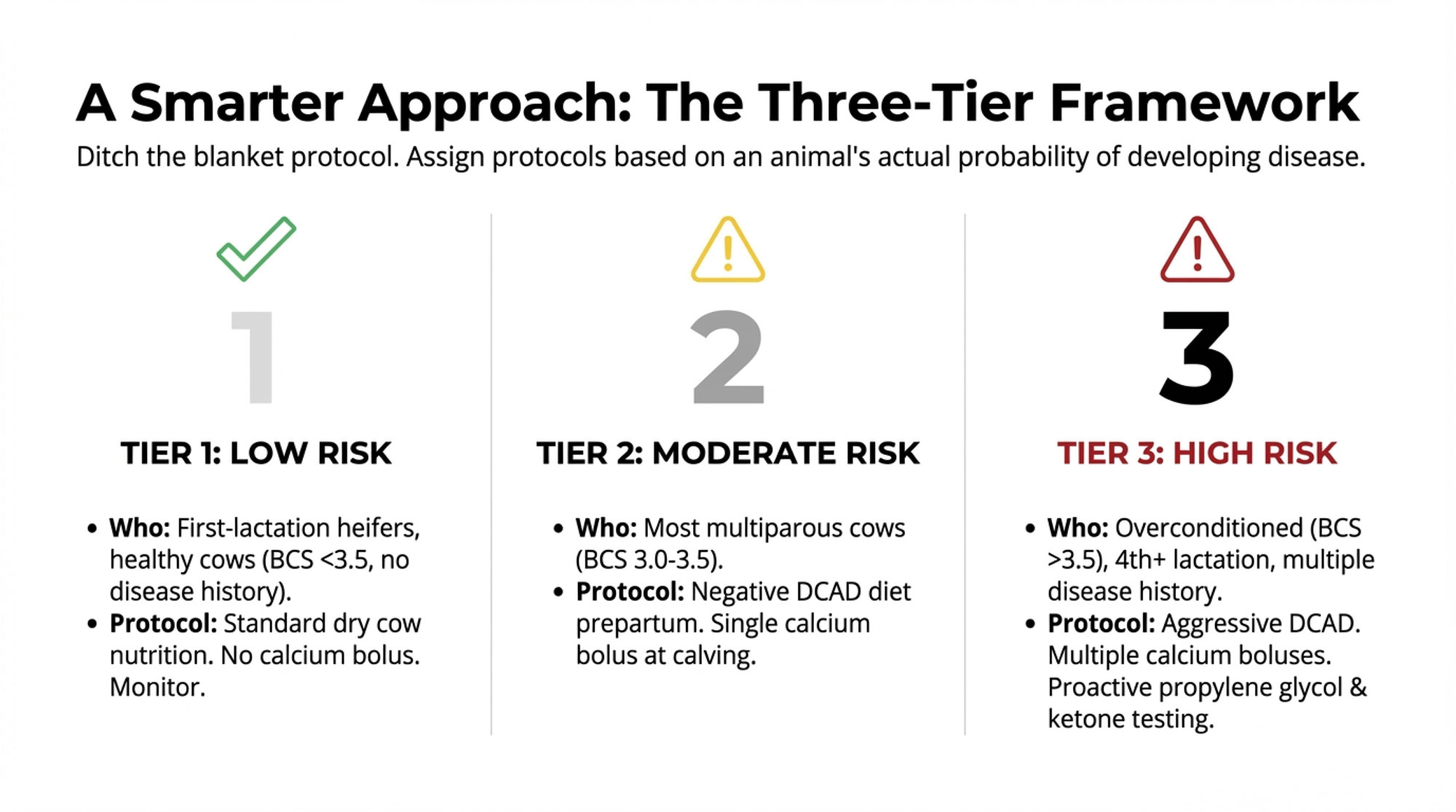

The Three-Tier Framework: How It Works in Practice

Operations that have successfully reduced fresh cow disease often employ some version of risk stratification. The basic principle is straightforward: different animals get different protocols based on their probability of developing disease. Here’s how one common framework breaks down.

Tier 1 (Low Risk): First-lactation heifers and multiparous cows with body condition under 3.5 and no disease history

- Standard dry cow nutrition without DCAD manipulation

- No calcium supplementation at calving

- Propylene glycol only if clinical signs emerge

- Standard monitoring protocols

These are your low-maintenance animals. They don’t need aggressive intervention, and providing it anyway just costs money without improving outcomes.

Tier 2 (Moderate Risk): Multiparous cows with normal body condition (3.0-3.5) or single-episode disease history

- Negative DCAD diet for the final 21 days prepartum

- Single calcium bolus at calving

- Propylene glycol is based on ketone testing, not blanket treatment

- Enhanced daily observation during the fresh period

This is probably your largest group numerically. They need targeted support, based on what we know works.

Tier 3 (High Risk): Overconditioned cows (BCS above 3.5), fourth-plus lactation cows, or those with multiple disease episodes

- Controlled-energy ration beginning at 150 days in milk (because you’re managing body condition early)

- Aggressive DCAD protocol for 21-plus days prepartum

- Multiple calcium boluses (at calving and 12 hours post-calving)

- Propylene glycol protocol from day -7 to +21

- Blood ketone testing days 5-9 postpartum

- Intensive daily monitoring

| Protocol Category | Tier 1: Low Risk (1st-lactation heifers, BCS <3.5) | Tier 2: Moderate Risk (Multiparous, normal BCS) | Tier 3: High Risk (BCS >3.5, 4th+ lactation, disease history) |

| DCAD Diet (Prepartum) | Standard dry cow ration | Negative DCAD for final 21 days | Aggressive negative DCAD for 21+ days |

| Calcium Supplementation | None at calving | Single bolus at calving | Multiple boluses (calving + 12 hrs post) |

| Propylene Glycol | Only if clinical signs emerge | Based on ketone testing, not blanket | Protocol from day -7 to +21 |

| Body Condition Management | Standard monitoring | Monitor at dry-off and calving | Controlled-energy ration starting 150 DIM |

| Monitoring Intensity | Standard fresh cow checks | Enhanced daily observation | Blood ketone testing days 5–9; intensive daily monitoring |

| Estimated Annual Cost/Cow | $18 | $62 | $147 |

| Target Disease Rate | <8% | <15% | <25% (vs. 45%+ without intervention) |

These are your problem children—the cows you know are going to struggle if you don’t get ahead of it. They deserve the intensive protocols because, for them, it actually pays off. And if these happen to be your highest-genetic-merit animals in their fourth or fifth lactation, protecting them through transition protects your breeding program.

The ROI Snapshot: Tier 3 cows receive significantly more intervention, but overall spending frequently decreases because low-risk animals no longer receive unnecessary treatment. You’re reallocating resources, not adding them.

A note on infrastructure: Implementing this kind of stratification does require some basic capabilities. Lactanet’s housing guidelines for dry and transition cows note that well-designed facilities are built with a transition and calving management strategy in mind, addressing factors such as management group sizing, cattle movement, and health needs for different groups.

At minimum, you’ll want the ability to separate close-up cows into at least two groups—or clearly identify high-risk individuals within a mixed group—plus access to DCAD ration formulation through your nutritionist and either cow-side ketone testing or a protocol with your vet for blood work.

Now, I know what some of you are thinking: “We don’t have separate pens for that.” Fair enough. Operations without separate close-up pen capacity can still implement modified stratification by identifying and flagging high-risk individuals for enhanced monitoring and intervention. Some farms use colored leg bands. Others use separate feeding times or headlock sorting. Robotic milking operations sometimes leverage their existing cow identification systems to trigger different supplement protocols. It’s not as clean as separate pens, but it works. The principle matters more than the specific implementation.

A note on seasonality: If you’re running a seasonal calving operation—spring calving in the Upper Midwest, fall calving in parts of the South—you’ll want to think about how heat stress or cold stress might compound transition challenges. The tier assignments don’t change, but your monitoring intensity during environmental stress periods probably should. Summer calvings, in particular, tend to have elevated disease rates even in otherwise healthy cows.

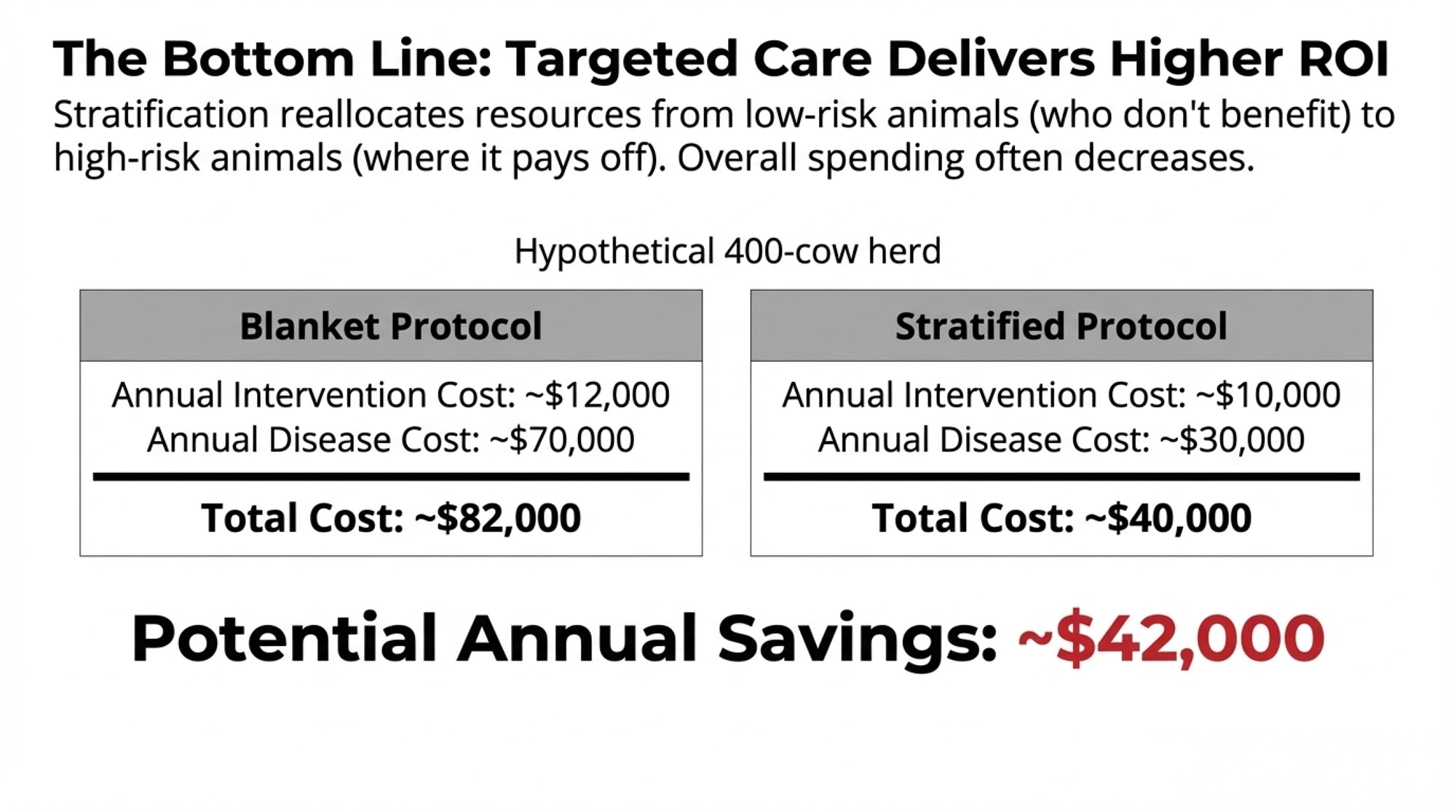

An example scenario for a 400-cow herd might look something like this:

| Approach | Annual Intervention Cost | Disease Events | Disease Cost | Total Cost |

| Blanket Protocol | ~$12,000 | ~140 | ~$70,000 | ~$82,000 |

| Stratified Protocol | ~$10,000 | ~60 | ~$30,000 | ~$40,000 |

| Potential Annual Savings | ~$42,000 |

Your actual numbers will depend on your baseline disease rate, local costs, milk price, and specific herd conditions. But the general principle holds: targeting resources toward high-risk cows while reducing unnecessary interventions in low-risk animals tends to improve both outcomes and economics. It’s not magic—it’s just matching the intervention to the animal that needs it.

Quick Reference: Key Benchmarks

BHB targets (Krogstad, Ohio State, Journal of Dairy Science):

- ≤10% of 2nd-lactation cows with elevated BHB in week 1

- ≤20% of 3rd+ lactation cows with elevated BHB in week 1

Body condition targets (Ribeiro, University of Guelph):

- 3.0-3.25 BCS at dry-off (1-5 scale)

- Maintain through calving; intervene at 200 DIM if needed

Disease cost estimates (Carvalho et al., 2019):

- ~$500 per single disease case

- ~$1,000 for multiple diseases in the same cow

Subclinical hypocalcemia cost (Caixeta, University of Minnesota):

- ~$150 per case

- Affects up to 73% of 3rd+ lactation cows

DCAD timing (University of Wisconsin Extension):

- Final 21 days prepartum for multiparous cows

- Generally unnecessary for first-lactation heifers

When Good Enough Is Good Enough: Knowing Your Optimization Limit

One finding worth noting: operations that substantially reduce their disease rates often shift their optimization focus. Rather than continuing to push on disease reduction, many move toward production and reproduction metrics.

This makes economic sense when you think about it. Some level of transition disease is simply unavoidable—due to genetics, environment, and factors unrelated to nutrition. Retained placenta and certain cases of metritis aren’t fully preventable with nutritional protocols alone. More than 35% of all dairy cows have at least one clinical disease event during the first 90 days in milk, as Dr. Caixeta at Minnesota has noted. Some of that is just the biology we’re working with. You can optimize, but you can’t eliminate.

The research frontier is increasingly focused on inflammation management and precision monitoring technologies. There’s growing evidence that we’ll have more refined best management practices in the coming years—approaches that address dry matter drop, metabolic stress, and inflammation together, because all three are interconnected. Penn State and other extension programs are actively working in this space. It’s worth watching.

The return on investment for moving from high disease rates down to more moderate levels is typically substantial—that’s the $40,000 or more we’ve been discussing. But at some point, the economics of further disease optimization start to diminish relative to improvements in production and reproduction. You’ve reached a point of diminishing returns in disease prevention, and your attention is better directed elsewhere.

What progressive operations tend to optimize once they’ve addressed the big disease issues:

- Early lactation production—targeting 80-plus pounds per day at first DHI test

- Days to conception—pushing below 80 days versus the industry standard of around 100

- Heifer development—getting fresh heifers producing at 90-plus percent of mature cow potential within the first few months

These become your next frontiers once transition health is reasonably controlled.

Why Knowledge Transfer Takes So Long

Perhaps the most thought-provoking aspect of transition cow research is how long it takes proven practices to reach widespread adoption. Negative DCAD feeding was demonstrated to be effective in the late 1980s. More than three decades later, many dairies still don’t use it consistently. Why is that?

That 2019 Journal of Dairy Science study on barriers to successful transition management found something interesting: the lack of a single definition of the transition period emerged as one barrier to improvement. Everyone’s talking about “transition cows,” but not everyone means the same timeframe or the same priorities. And barriers varied significantly across farms, suggesting that a tailored approach is required to achieve meaningful change. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution here—which makes extension work and consulting more challenging.

A 2025 study of Ontario dairy veterinarians published in the Journal of Dairy Science found that trust and communication emerged as critical components of veterinarian-client relationships—and it was acknowledged that these relationships take time to build. The researchers noted that veterinarians observed that proactive producers who implemented preventive strategies achieved better outcomes, whereas others exhibited greater resistance to change, often shaped by multigenerational traditions and economic constraints.

And you know what? None of these dynamics reflect bad intentions. They reflect the practical reality that changing established practices requires more than just evidence—it requires aligned incentives, collaborative relationships, and operational systems that support implementation. A protocol that works great in theory but doesn’t fit your labor situation or facility layout won’t actually be implemented.

What seems to accelerate adoption, based on what we’re seeing across the industry:

- Producers who measure baseline disease rates and calculate their own economics (hard to argue with your own numbers)

- Veterinarians who engage with current literature on transition research

- Nutritionist partnerships focused on outcomes rather than product volume

- Peer networks where successful protocol changes get shared and validated (sometimes the neighbor’s experience is more convincing than any research paper)

The operations achieving the best transition outcomes typically share a common characteristic: they’ve developed collaborative relationships with their advisory team where data-driven protocol adjustments are welcomed rather than resisted. It’s not adversarial—it’s problem-solving together.

Practical Takeaways

Start with measurement. Before changing any protocol, establish your actual disease rate by parity. The exercise takes about 60 days and requires only consistent tracking. Many operations discover rates higher than they’d estimated—and that discovery itself often motivates change.

Consider the parity difference. First-lactation heifers face fundamentally different metabolic challenges than fourth-lactation cows. The research is clear that treating them identically often leaves money on the table. Match your protocols to your animals.

Begin with low-risk changes. Discontinuing calcium supplementation for first-lactation heifers represents one of the lowest-risk, highest-confidence first moves. Frame it as a 60-day test with your veterinarian. Collect data. See what happens.

Collaborate rather than confront. Successful protocol changes typically emerge from partnerships between producers and their advisors. Come with data and questions rather than demands. As the Ontario veterinarian research found, trust and communication are the foundation.

Assess your infrastructure honestly. Stratified protocols work best with separate close-up pen capability, but modified approaches can work with careful individual-cow identification even in mixed groups. Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.

Protect your genetic investment. Your best cows—the ones carrying the genetics you’ve spent years developing—deserve protocols that keep them healthy through transition. A cow that can’t get through the fresh period without complications may never show you what she’s capable of producing or passing on.

Calculate your specific economics. The general principle—that targeted protocols tend to outperform blanket approaches—is well-supported by the research. Your specific numbers will vary, but they’re worth calculating. It’s hard to prioritize what you haven’t quantified.

There’s a real gap between what the research shows and what’s actually happening on many farms—and that gap represents opportunity. The knowledge is there. The economics generally work out. What remains is finding the right starting point for your operation and building from there.

For operations willing to invest the time in systematic measurement and collaborative protocol development, the research suggests meaningful improvement is available—not through revolutionary change, but through thoughtful, evidence-based adjustments applied consistently over time. Small wins, stacked up, become significant results.

The Bullvine brings dairy producers research-backed insights for informed decision-making. For detailed guidance on transition cow protocols, consult with your herd veterinarian and review resources from university extension programs, including University of Wisconsin, Penn State, University of Minnesota, and University of Guelph.

Learn More:

- Mastering the Transition: A Holistic Approach to Dairy Cow Health and Productivity – This comprehensive guide expands on the “Three-Tier” framework by revealing the four pillars of transition success, including team-training strategies that have been proven to reduce fresh cow health issues by 25%.

- The $500 Transition Gap: Why Your Neighbor’s Fresh Cows May Outperform Yours by Next Winter – This analysis investigates the “prevention paradox” and provides deeper economic modeling for targeted protocols. It demonstrates how progressive operations are capturing an additional $200–$500 in net benefit per cow through precision monitoring.

- The $50,000 Question: Why Smart Dairies Follow This 8-Point Protocol Before Any Big Decision – Successful transition management requires high-level decision-making. This article provides a strategic checklist for implementing major operational changes, ensuring your transition improvements deliver the maximum ROI without compromising long-term herd health.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!