90 days to reposition before 2026 hits. The top 25% of dairy operations already moved. This is the playbook they’re using.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Tightening your belt won’t save you this time. The shifts hitting dairy in 2025-2026—production running 4.7% above year-ago levels, replacement heifers at a 47-year low, butterfat collapsed from $3.00 to $1.40/lb, processors leveraging billions in new capacity—aren’t cyclical headwinds that reverse when prices recover. They’re structural changes to how this industry operates. Cornell Pro-Dairy data makes the stakes clear: a $6.35/cwt efficiency gap separates top-quartile from bottom-quartile farms, a difference exceeding $100,000 annually between similar-sized operations. The producers repositioning now—locking in feed costs, enrolling in risk management before January deadlines, recalibrating breeding programs for the beef-on-dairy era—will be the ones thriving in 2028. You have a 90-day window. This is the playbook.

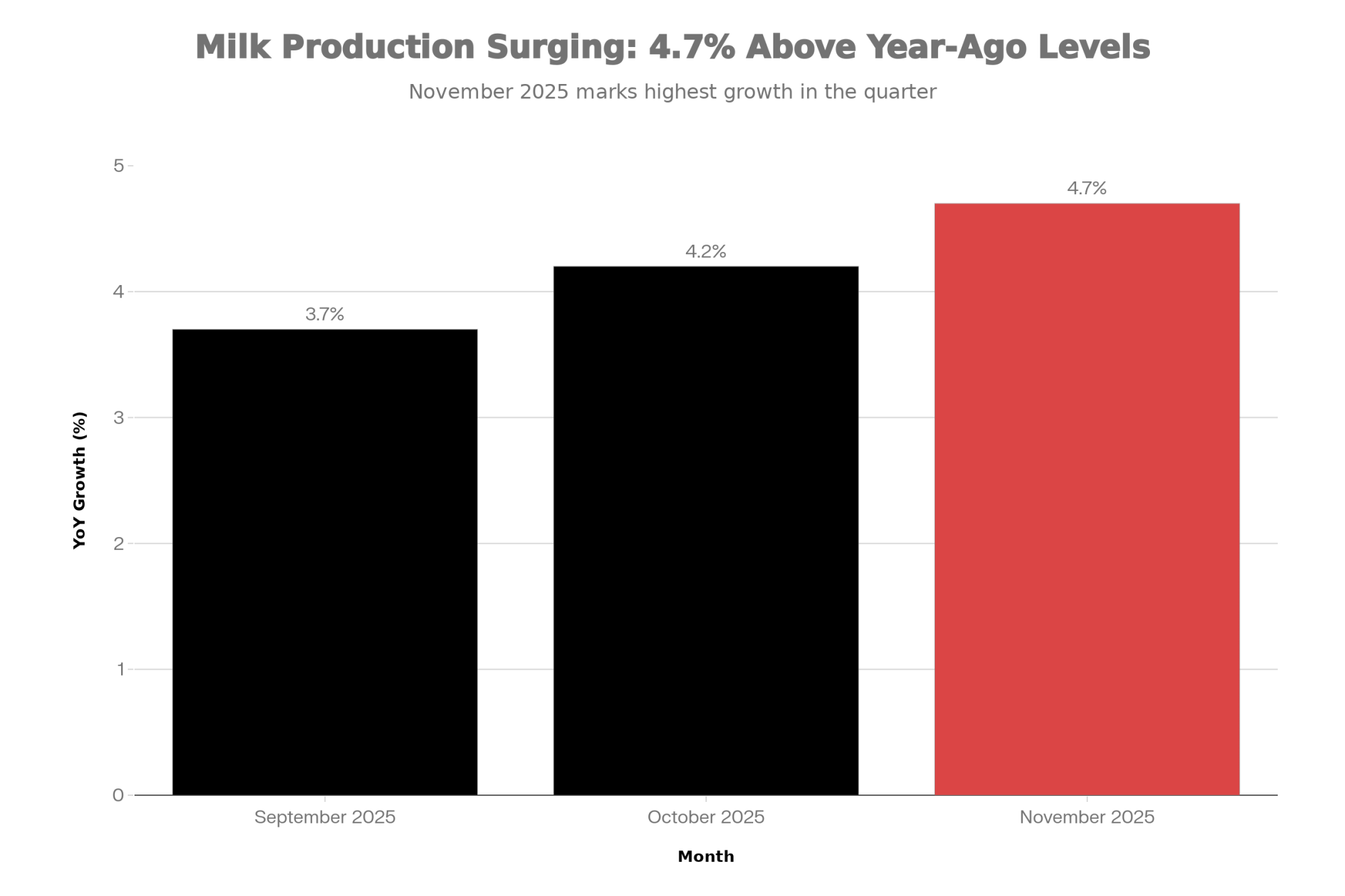

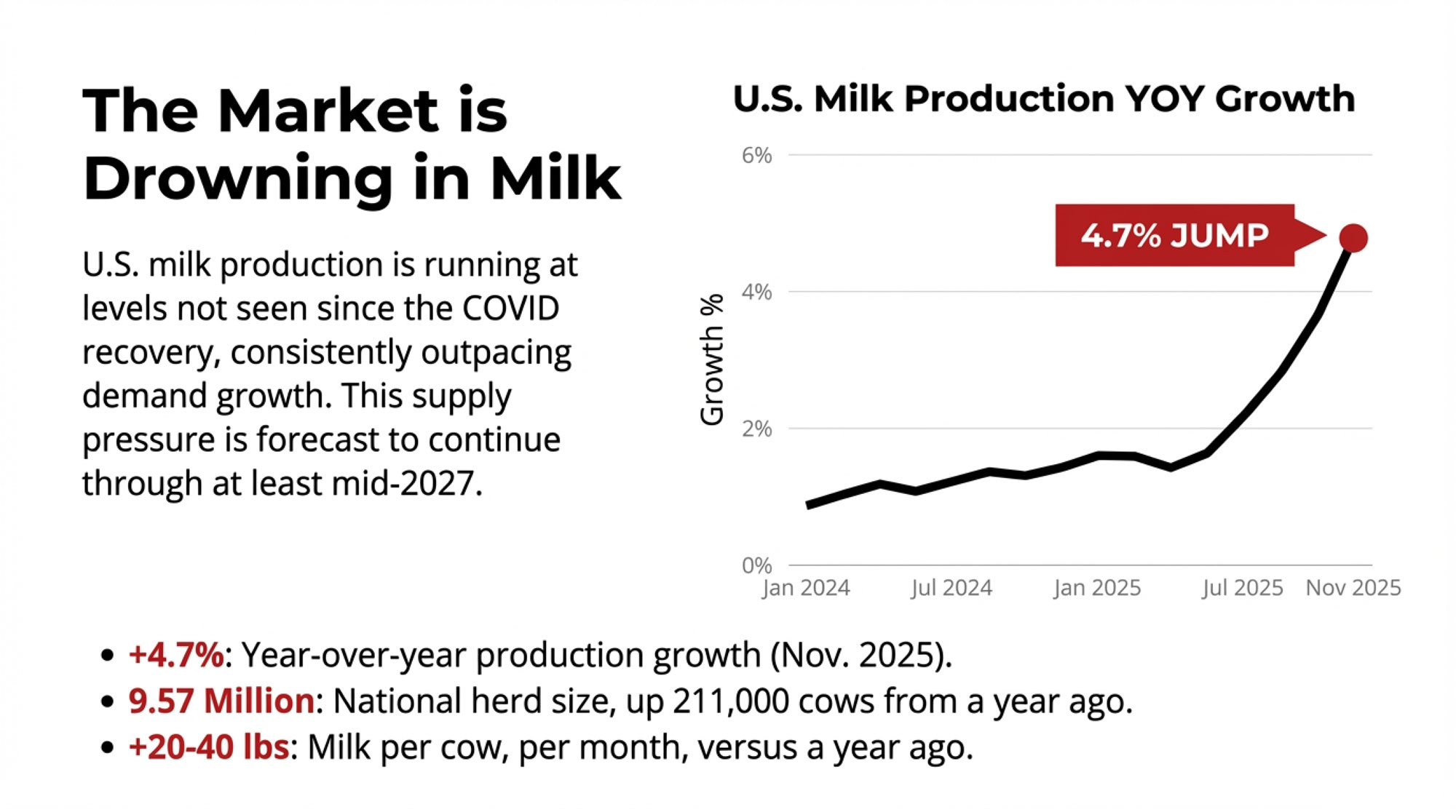

You’ve probably seen the headlines by now. U.S. milk production has been running hot—really hot—through the back half of 2025. We’re talking 3.7 to 4.2 percent above year-ago levels in September and October, and then November came in at 4.7 percent higher than the same month in 2024, according to USDA’s latest milk production reports and Cheese Reporter’s analysis of the data. That’s the kind of year-over-year growth we haven’t seen since the COVID recovery period.

And the industry is still figuring out where all that extra milk should go.

USDA’s November estimates show the national dairy herd has grown to approximately 9.57 million head—up 211,000 cows from a year ago. Per-cow productivity keeps climbing, too. USDA data shows milk per cow running 20 to 40 pounds higher per month than a year earlier across the major dairy states.

When you multiply those gains across millions of cows, you end up with substantial incremental production that needs to find a home.

I’ve been tracking dairy markets for a long time, and this moment feels genuinely different. Not catastrophically so—dairy will remain viable, and there are real opportunities for well-positioned operations—but different enough that the playbook from 2016 or 2020 may need some adjustment in 2026.

Let me walk through what’s actually happening and what it might mean for your operation.

The Production Picture That’s Emerging

The supply situation requires some unpacking because it’s not just about one factor. It’s several forces converging at once.

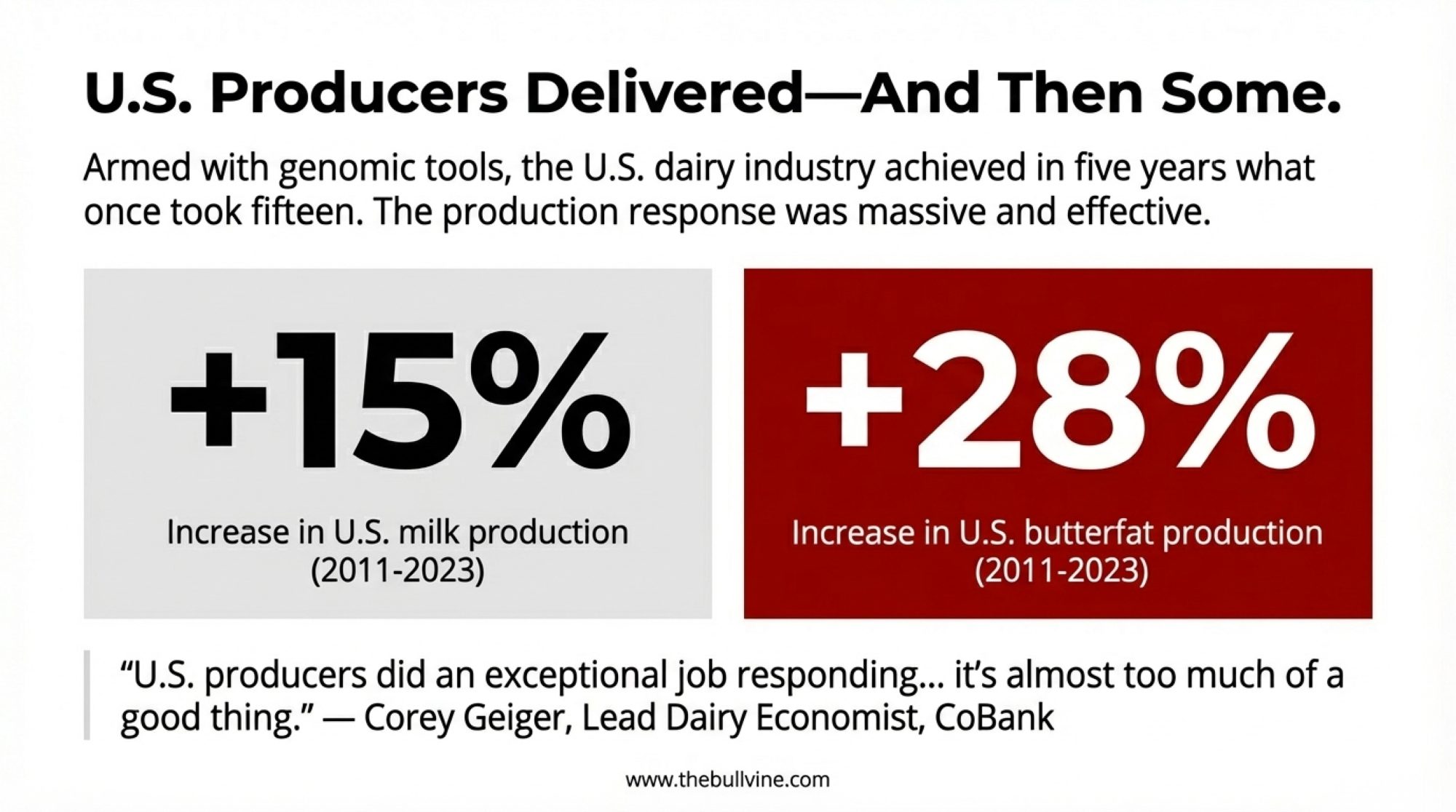

Herd numbers have expanded meaningfully after years of modest growth, and productivity gains keep compounding. Modern genetics and management practices—better transition cow protocols, improved fresh cow management, tighter reproduction programs—keep pushing output higher. That additional 20-40 pounds per cow per month doesn’t sound dramatic until you’re looking at the national numbers.

The regional story has gotten interesting, too. Some areas hit by HPAI and weather challenges in 2024 saw temporary production setbacks, but by late 2025, USDA data show California’s milk output actually rising sharply—up about 6.9 percent year-over-year in October—as both cow numbers and per-cow production recovered.

Meanwhile, expansion in Texas, parts of the Upper Midwest, and states like South Dakota continues to reshape the geography of the U.S. milk supply.

I recently spoke with a producer in the Texas Panhandle who has been farming for 30 years. He noted that five years ago, he could count the large dairies in his county on one hand. Now there are several major operations within a reasonable drive, all competing for the same labor pool and feed resources. That kind of regional shift creates both opportunities and new competitive pressures.

What economists like Dr. Marin Bozic at the University of Minnesota have been tracking is a fundamental geographic redistribution of U.S. milk production. The industry is less concentrated in traditional dairy regions, which has real implications for processor logistics and regional pricing.

For our Canadian readers, the contrast is striking—while U.S. producers navigate oversupply pressure, Canada’s supply management system, with quota prices ranging from CAD $24,000 to over $56,000 per kilogram of butterfat per day, depending on province (according to Agriculture Canada’s 2025 data) and tariffs of 200-300% on imports creates an entirely different market reality. That protection comes with its own trade-offs, but it insulates Canadian producers from the volatility American farmers are facing.

So what does this mean practically? USDA forecasts indicate domestic production will likely continue exceeding consumption growth through at least mid-2027. That suggests continued pressure on milk prices—though as always, unexpected developments could change the trajectory.

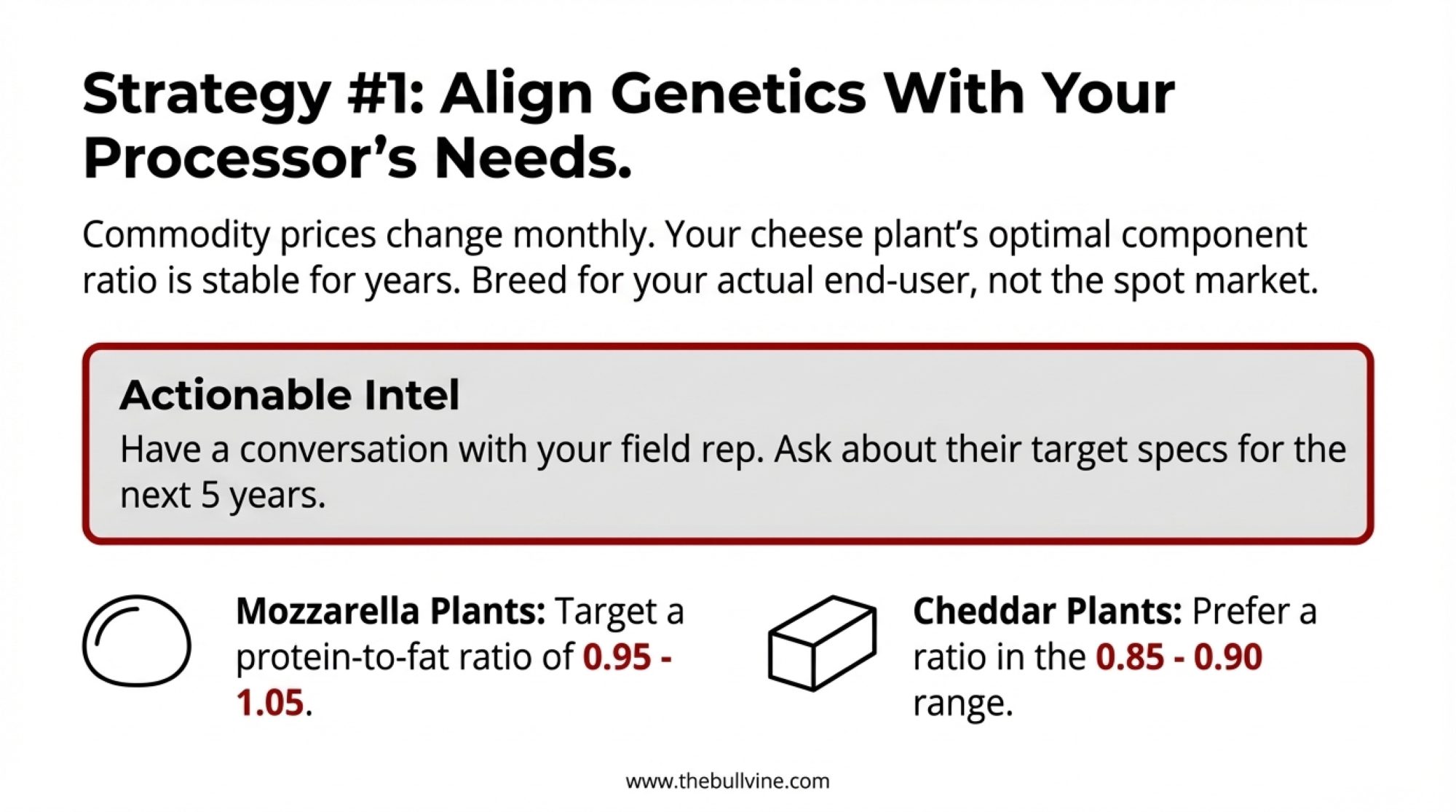

What’s Actually Happening to Component Premiums

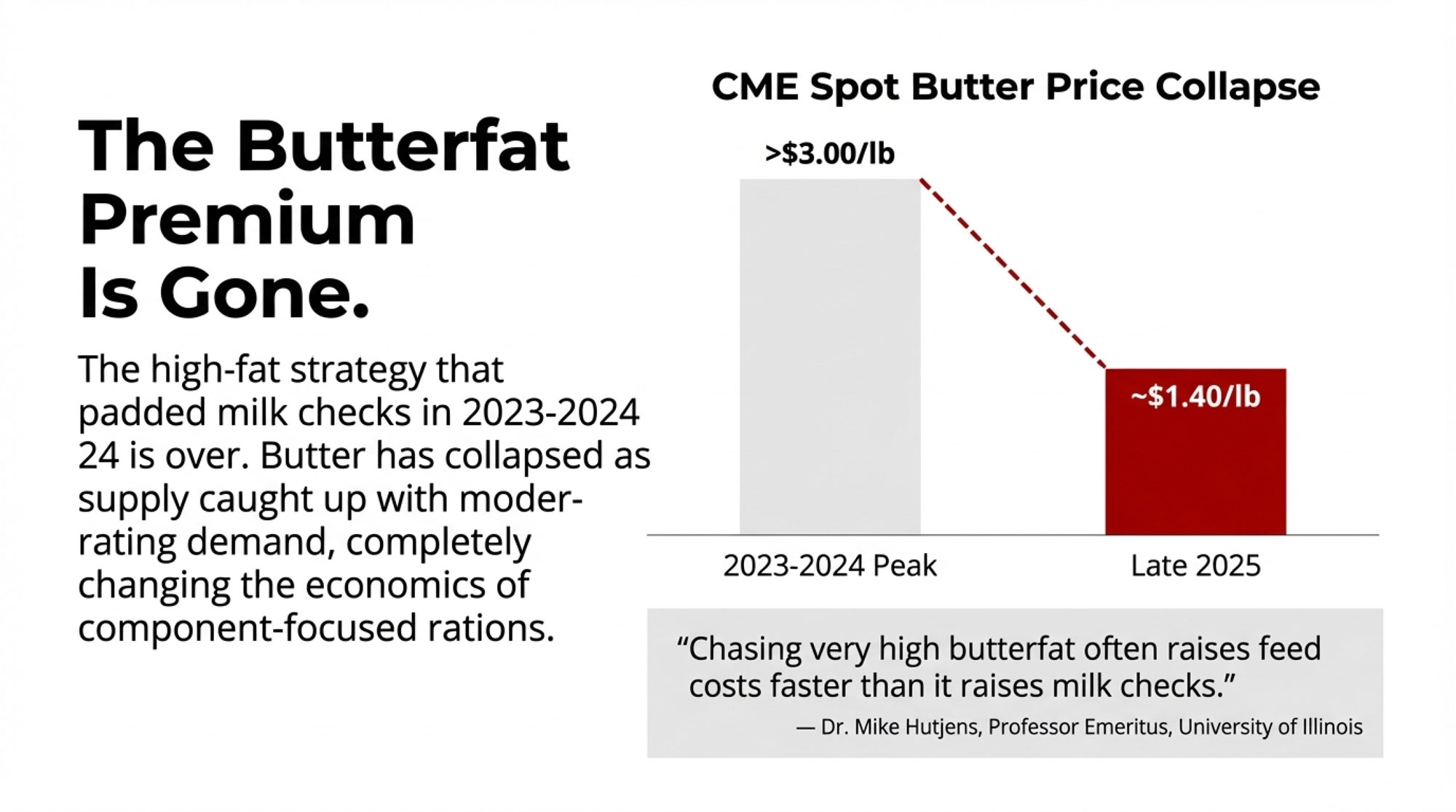

For a lot of operations, component pricing—particularly butterfat premiums—has been a crucial margin driver over the past several years. That dynamic is shifting in ways worth understanding.

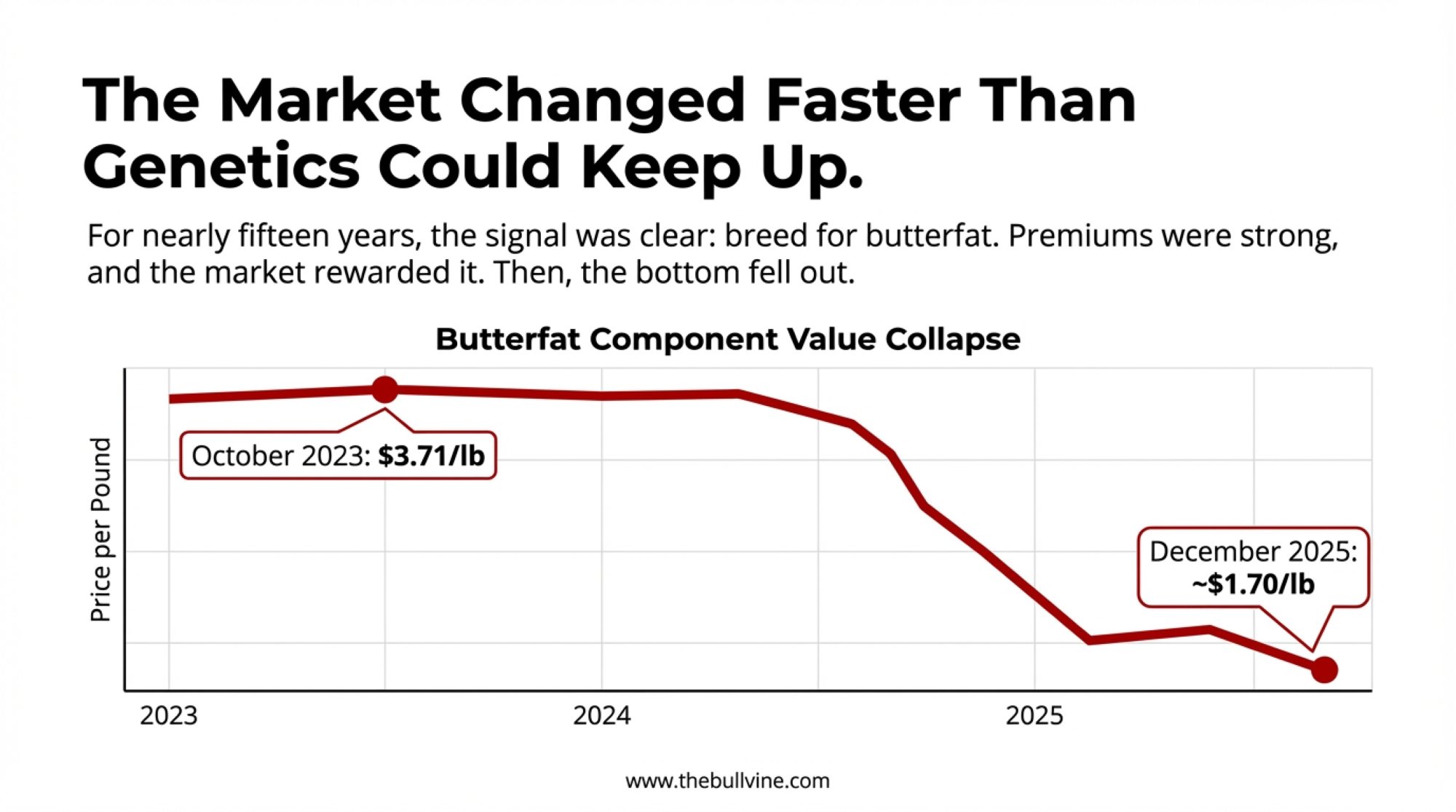

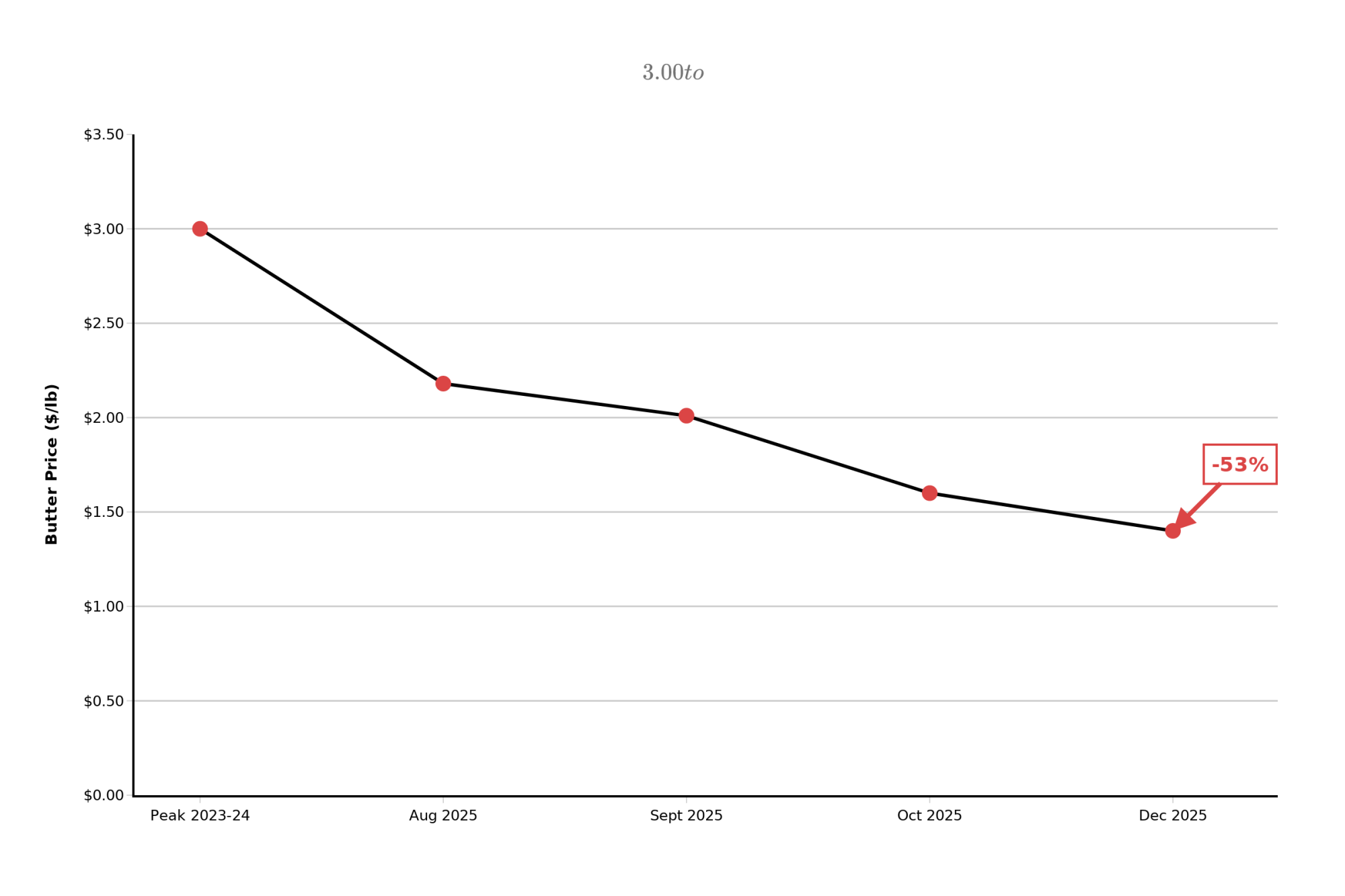

Butterfat values have come down significantly from their recent peaks. CME spot butter prices, which topped $3.00 per pound at various points in 2023-2024, have declined through 2025. By August, prices had dropped to around $2.18 per pound according to market tracking. September brought a new year-to-date low of around $2.01.

And by October, butter had fallen to $1.60 per pound. As of late December, we’re looking at butter trading in the $1.40 range—a meaningful change in butterfat economics that affects the math for many feeding strategies.

What’s driving this? A combination of factors. Farmers responded to high premiums by selecting for higher-fat genetics and adjusting rations—exactly what economic incentives encourage. At the same time, retail demand for butter and full-fat products has moderated somewhat. Supply caught up with demand, and premiums softened accordingly.

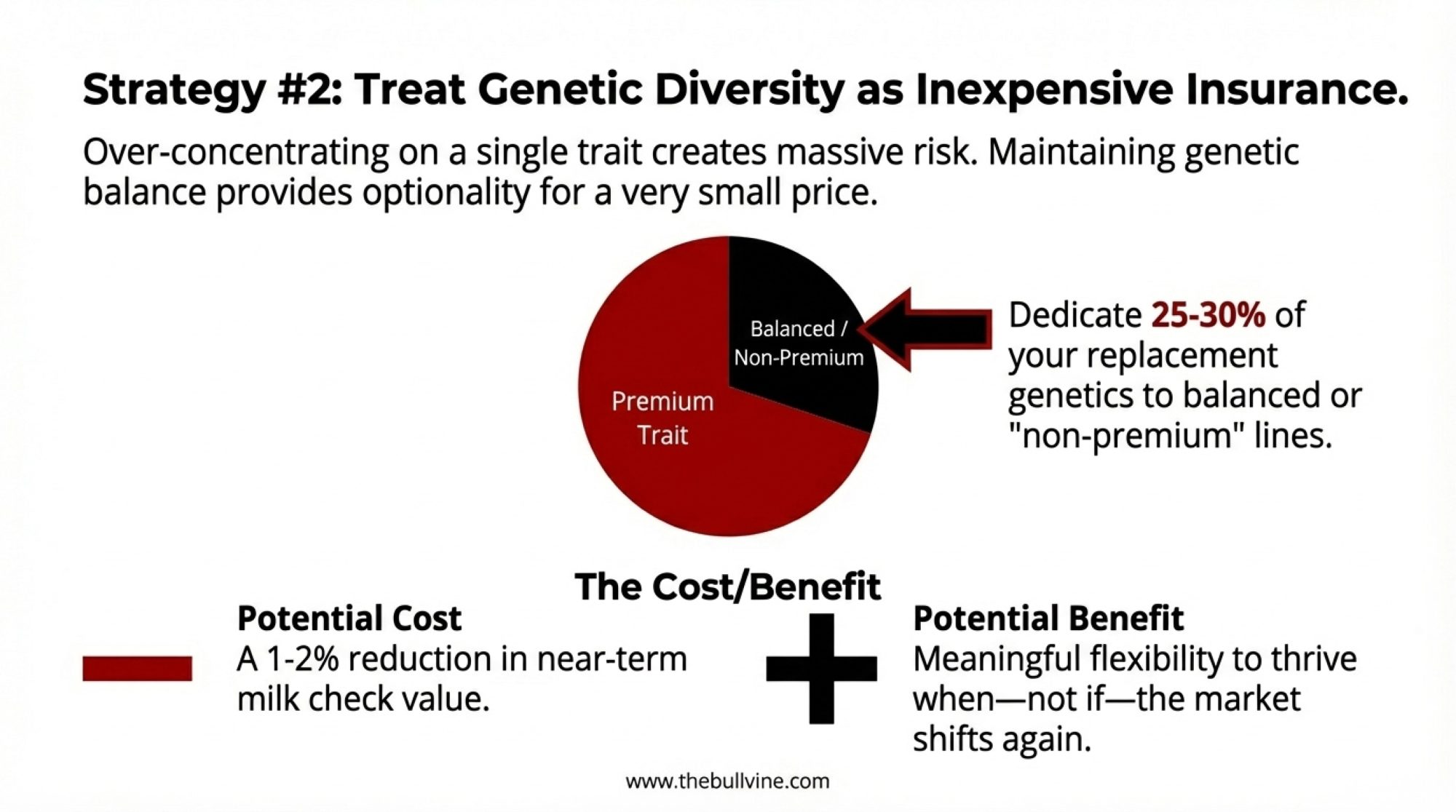

As Dr. Mike Hutjens, Professor Emeritus of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois, has emphasized in his extension work over the years, chasing very high butterfat often raises feed costs faster than it raises milk checks. Many herds find better margins around moderate butterfat—say, 3.8 to 4.0 percent—with solid protein performance, rather than pushing fat above 4.2 percent and paying for the extra inputs.

That guidance feels particularly relevant given where butter is now.

Of course, every operation is different. Farms with cost-effective access to high-fat supplements may still find the economics work. The key is running the numbers for your specific situation rather than assuming what worked in 2023 still pencils out today.

It’s also worth noting that Federal Milk Marketing Order modernization proposals released by USDA in late 2024 are expected to adjust how components are valued over time. How butterfat and protein strategies pay going forward may look quite different than what we’ve seen in the past few years.

The Genetic Revolution That’s Rewriting Replacement Math

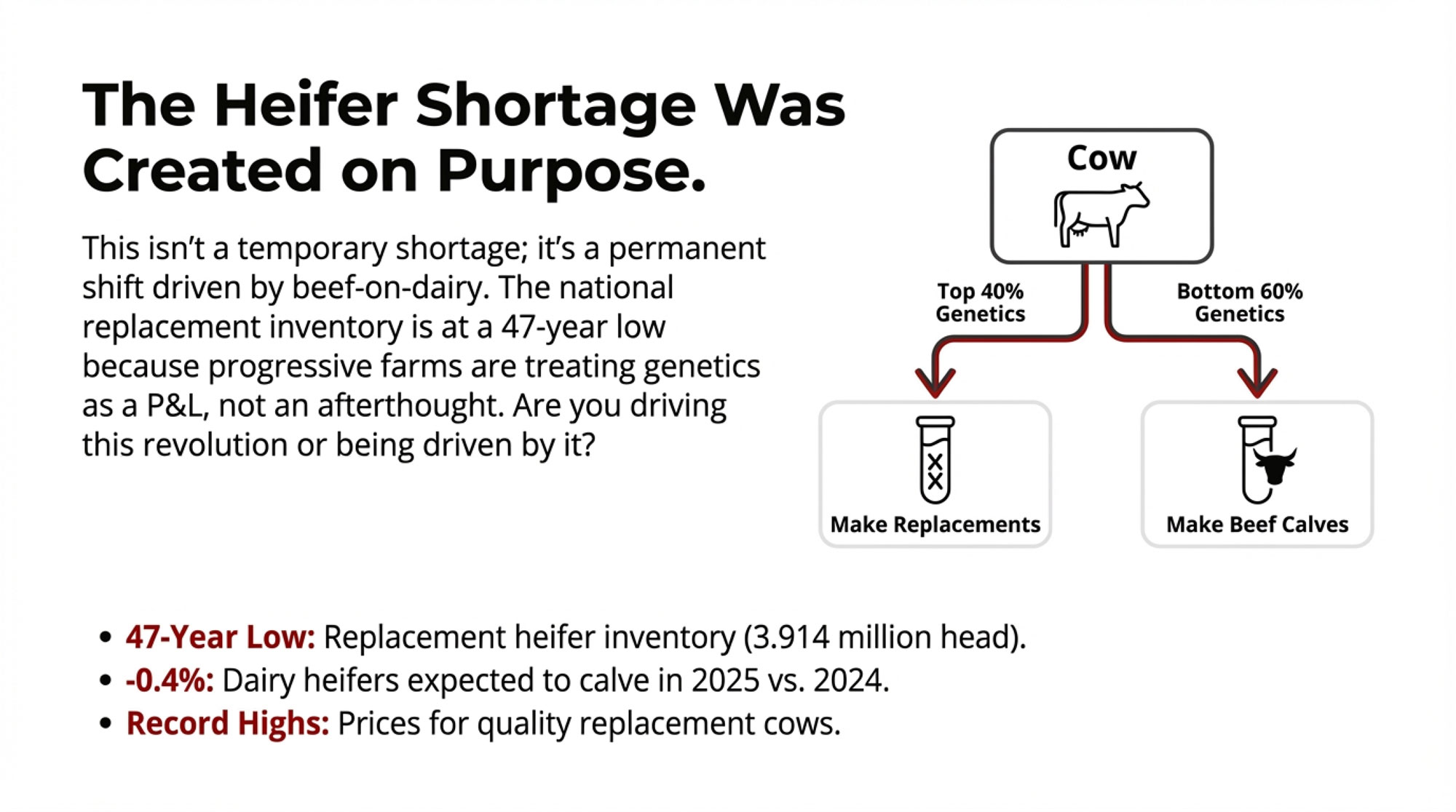

Let’s be direct about something: What’s happening with replacement heifers isn’t just a market trend or a temporary shortage. It’s a genetic revolution that has fundamentally altered how dairy farmers must think about herd replacement—and most operations haven’t yet fully grasped the implications.

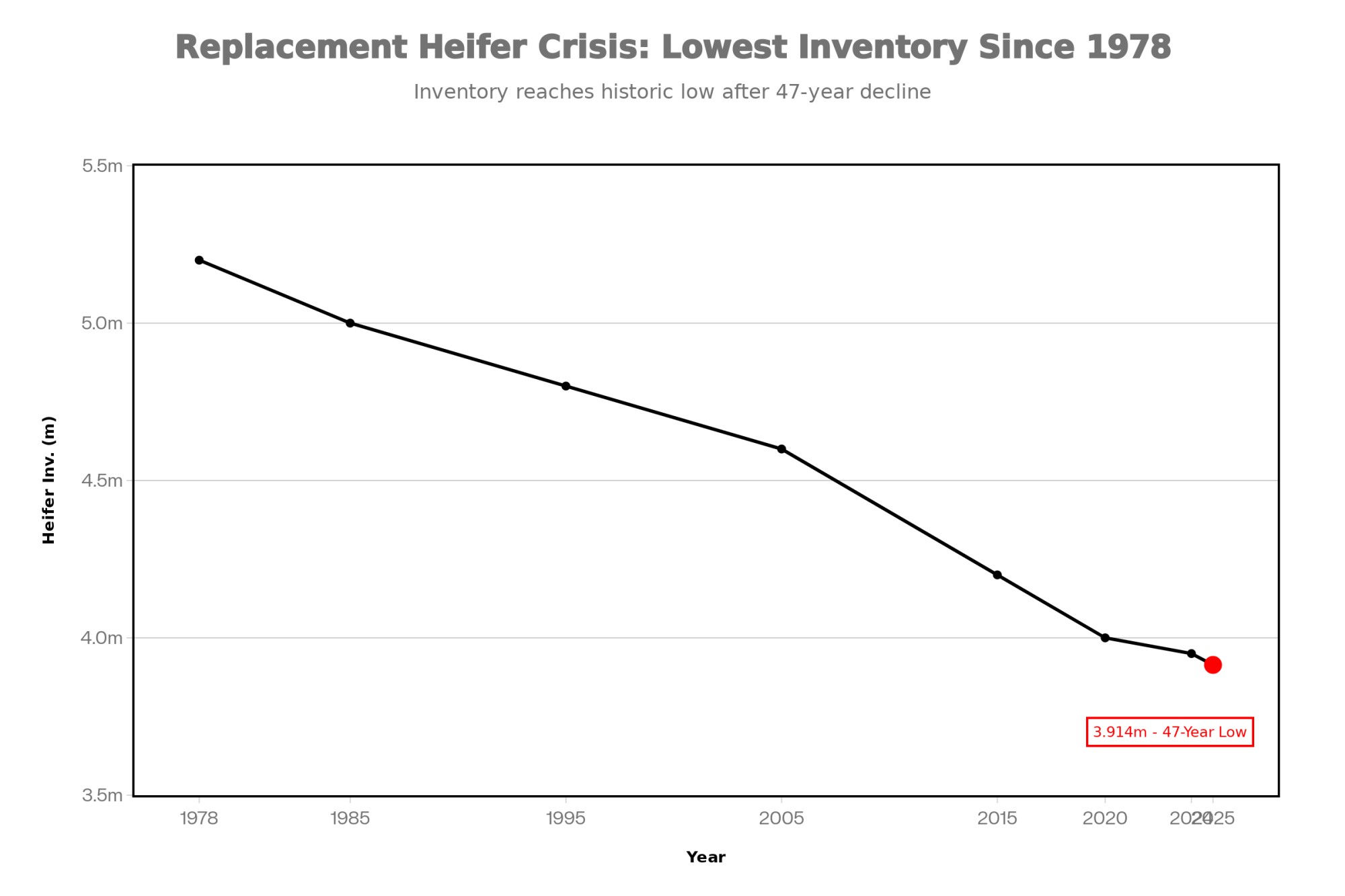

USDA’s January 1, 2025, Cattle Inventory report shows 3.914 million dairy heifers 500 pounds and over. That’s the smallest number since 1978, as Dairy Reporter and multiple other outlets have noted. We’re at a 47-year low for replacement inventory.

The data from USDA and HighGround Dairy shows just 2.5 million dairy heifers expected to calve in 2025—the lowest level since that dataset began in 2001. That’s a drop of 0.4 percent compared to 2024, and industry analysts suggest tight replacement numbers will keep heifer availability constrained for several years.

Here’s what makes this different from previous heifer shortages: this one was deliberately created through breeding decisions.

The beef-on-dairy movement isn’t some accident of market forces—it represents a fundamental shift in how progressive dairy operations view their genetic programs. Every breeding decision is now a strategic choice about whether you’re in the business of making milk, making beef, or both.

The old mental model—breed everything dairy, cull what doesn’t work—is obsolete. The new reality requires treating your replacement pipeline as a distinct enterprise with its own P&L, not an afterthought of your breeding program.

The economic forces driving this shift were compelling. When beef calves were bringing $750 more than they had been two years prior, concentrating dairy genetics on your best animals while capturing beef premiums on the rest made perfect sense. USDA and industry commentary explicitly connect lower replacement inventories to increased use of beef semen on dairy cows.

But here’s what the numbers don’t always show: The farms that executed this strategy well didn’t just chase beef premiums—they simultaneously intensified their genetic selection on the dairy side. They used genomic testing to identify the top 30-40% of females, bred them aggressively with sexed dairy semen, and captured beef value on the rest.

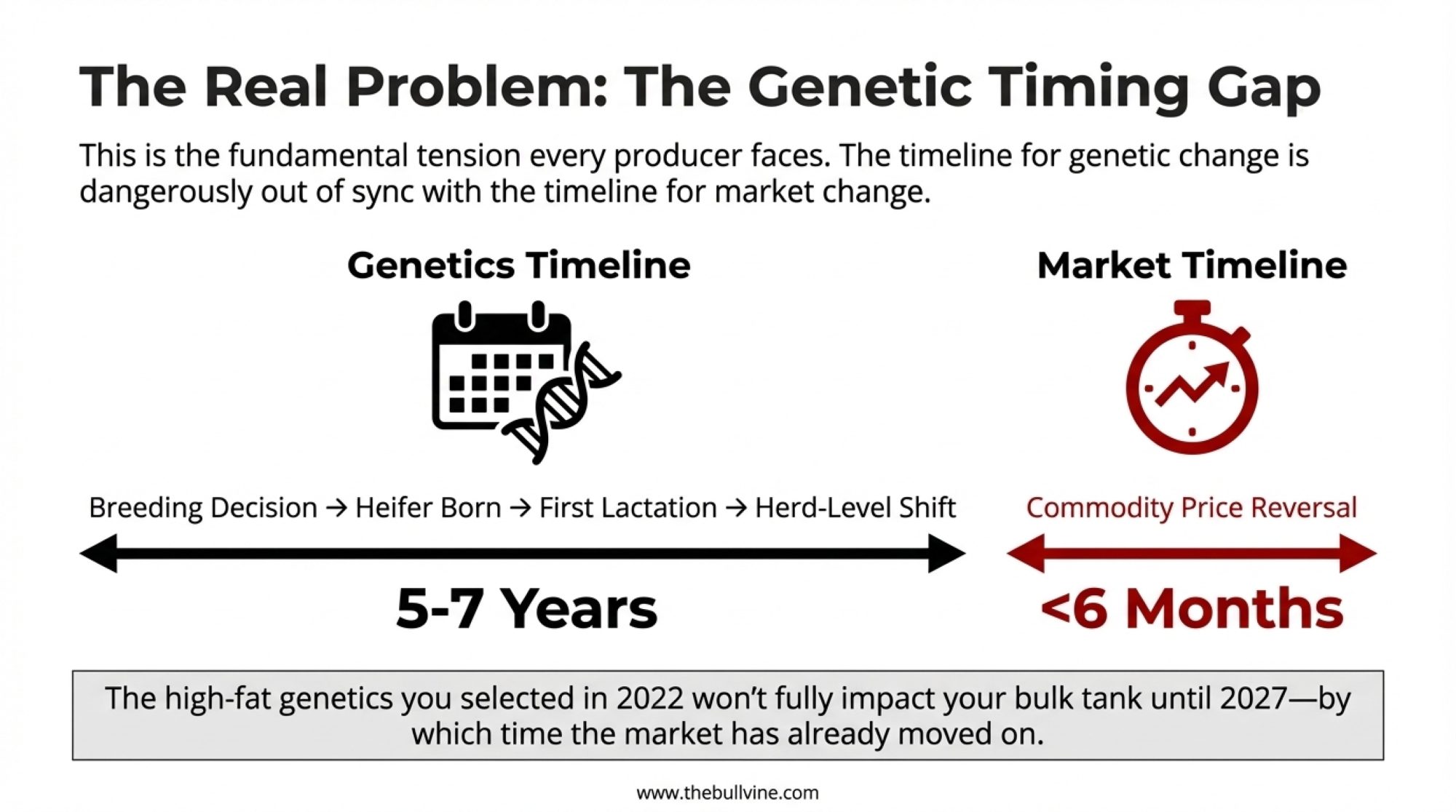

The April 2025 CDCB genetic base change—moving the reference population from cows born in 2015 to cows born in 2020, with updated Net Merit formula weights—gives producers better tools for these decisions. The December 2025 evaluation updates added further refinements to health and type trait data, according to CDCB. Farms making breeding decisions without current genomic information are essentially flying blind in this new environment.

The farms that got caught were the ones who saw beef-on-dairy as a revenue grab rather than a genetic strategy. They reduced dairy breedings without upgrading the genetic intensity of the ones they kept.

Consider a scenario many Midwest operations have navigated: A 600-cow Wisconsin dairy that shifted from 70 percent gender-sorted dairy semen to 40 percent in 2024 might have captured an additional $300,000 in beef calf revenue that year. But that same operation now faces needing 75-100 more replacement heifers than their breeding program will produce—a gap that requires careful planning to address at current prices.

The gain was immediate and visible. The cost is delayed and often larger.

“We got caught up in the beef premium along with everyone else,” one 700-cow operator in central Wisconsin told me. He asked to stay anonymous, which is understandable. “The checks were great in 2024. Now I’m looking at replacement costs that eat into those gains significantly. Looking back, I might have maintained a higher percentage of dairy breedings. But the economics at the time pointed toward beef.”

Recent reports show that U.S. replacement dairy cow prices are reaching record highs in late 2025, with many quality cows and bred heifers trading well above earlier levels of $2,000-$2,200. At those prices, buying your way out of a heifer deficit isn’t just expensive—it may not be possible at scale.

The strategic question every operation needs to answer: What percentage of your herd represents your genetic future, and are you breeding them accordingly?

The good news is that farmers are recalibrating. The National Association of Animal Breeders reports gender-sorted dairy semen sales grew by 1.5 million units in 2024—a 17.9 percent growth rate in just one year—as producers adjust their programs.

The farms that will thrive in this new environment aren’t abandoning beef-on-dairy—they’re getting smarter about it. They’re using genomics to make precise decisions about which animals deserve dairy genetics and which should produce beef calves. They’re treating replacement inventory as a strategic asset, not a byproduct.

This is the genetic revolution in action. The question is whether you’re driving it or being driven by it.

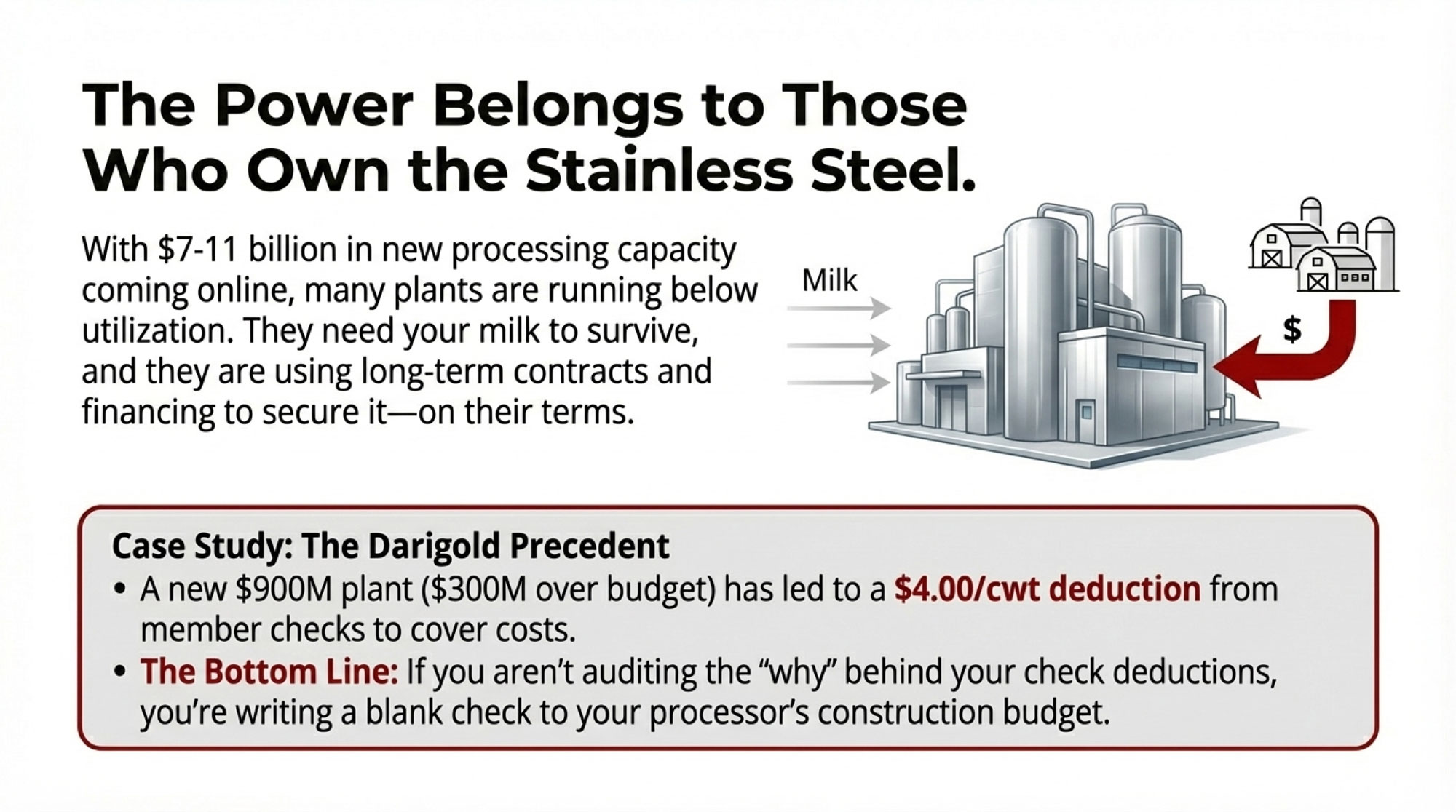

The Power Shift to Those Who Own the Stainless Steel

Let’s talk plainly about something the industry doesn’t always acknowledge directly: The power dynamic between dairy farmers and processors has fundamentally shifted. The leverage now belongs to those who own the stainless steel.

Significant processing capacity has come online over the past several years. Industry reports from Cheese Reporter, CoBank, and others tally multi-billion-dollar investments in new cheese, butter, and specialty dairy plants in the U.S.—with estimates ranging from $7 billion to $11 billion in committed or recent capacity additions, depending on the source and timeframe.

Major projects from Hilmar, Bel Brands, Leprino, and others were predicated on expectations of continued milk supply growth and strong export demand. These processors made massive bets on dairy’s future—and now they need milk to justify those investments.

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable: Analysts and trade publications report that several recently commissioned cheese and powder plants are running below their designed capacity.

That creates enormous pressure for processors carrying major capital investments. And that pressure flows directly to farmers in the form of supply commitments, pricing structures, and partnership terms that increasingly favor the processor’s position.

Run the numbers from their side. A $500 million cheese plant sitting at 70 percent utilization is bleeding money. The incentive to lock up milk supply through multi-year agreements, financing arrangements, and expansion partnerships isn’t altruism—it’s survival.

The Darigold situation in the Pacific Northwest illustrates this dynamic clearly. Local reports indicate their new Pasco, Washington plant has seen its price tag rise from initial estimates of $600 million to over $900 million—approximately $300 million over budget. As a result, the cooperative has implemented a $4 deduction per hundredweight from member milk checks, with $2.50 allocated explicitly to construction costs.

Even in a cooperative structure—where farmers theoretically own the processing—the capital requirements of modern dairy manufacturing mean producers are effectively captive to infrastructure decisions made on their behalf. For a farm shipping 5 million pounds monthly, that $4 deduction represents $200,000 annually coming out of your check. Whether you are in a co-op or independent, if you aren’t auditing the ‘why’ behind your check deductions in 2026, you’re essentially writing a blank check to your processor’s construction budget.

When processors offer financing for heifer purchases, equipment upgrades, or expansion projects in exchange for multi-year milk supply commitments, understand what’s really happening: They’re converting your flexibility into their supply security. That’s not necessarily bad—capital access and price stability have genuine value—but you need to recognize the trade.

Economists like Mark Stephenson, Director of Dairy Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, have observed that processors who invested billions in new capacity now face utilization challenges.

When evaluating these arrangements, consider them with clear eyes:

- Who benefits more from the locked-in supply? In a rising market, fixed pricing hurts you. In a falling market, it helps. But the processor gets supply certainty regardless.

- What are the exit provisions? If your situation changes, what does it cost to get out?

- Are you financing their utilization problem? Expansion commitments that serve processor capacity needs may or may not align with your operation’s optimal scale.

- What’s the opportunity cost of reduced flexibility? Five-year agreements made in 2025 lock you into a world that might look very different by 2028.

None of this means you shouldn’t engage with processors or consider partnership structures. It means you should engage as a businessperson who understands that the party with the capital makes the rules. Get independent financial advice. Model the downside scenarios. Understand what you’re giving up, not just what you’re getting.

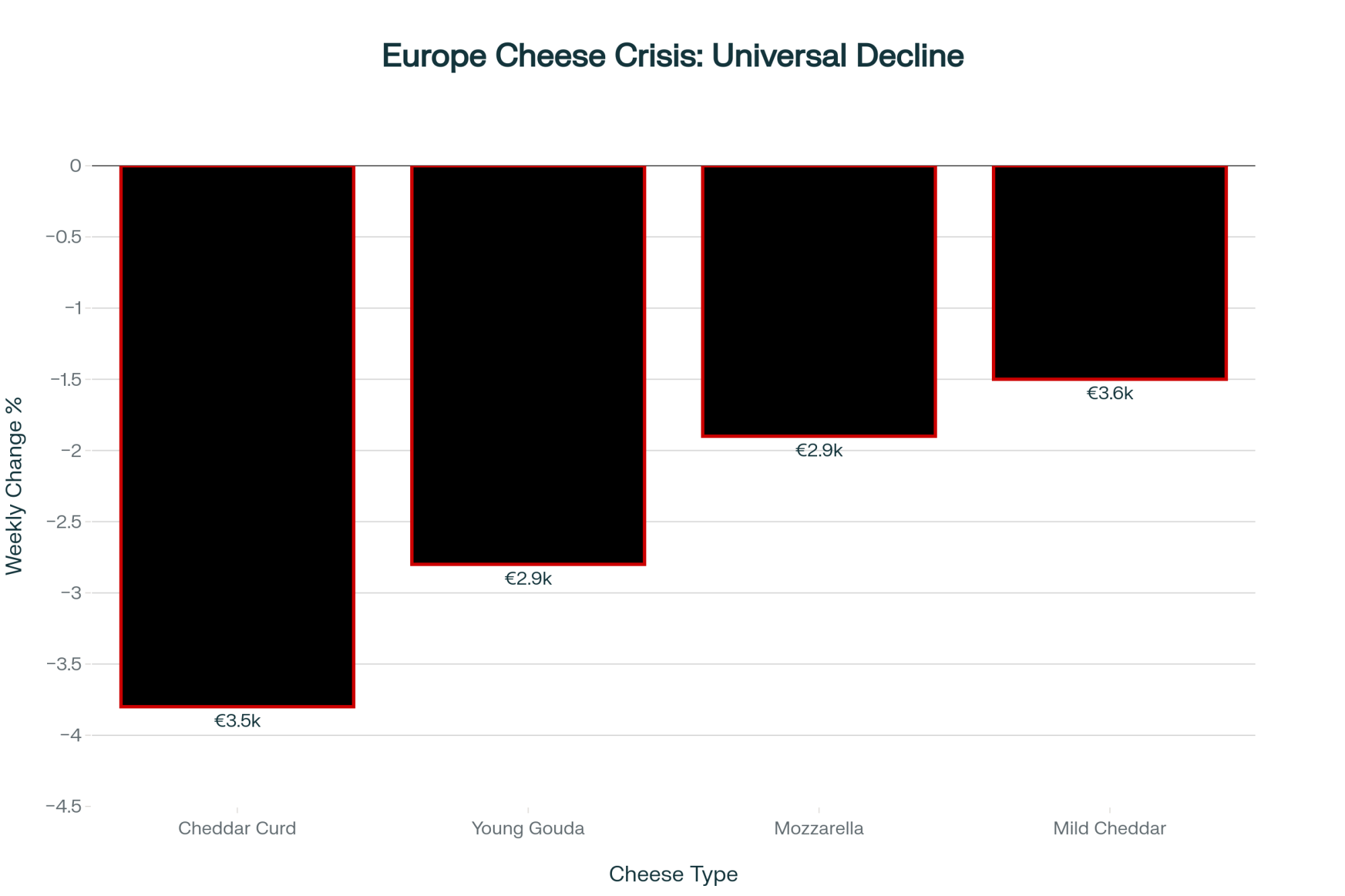

The Export Picture: Opportunity and Uncertainty

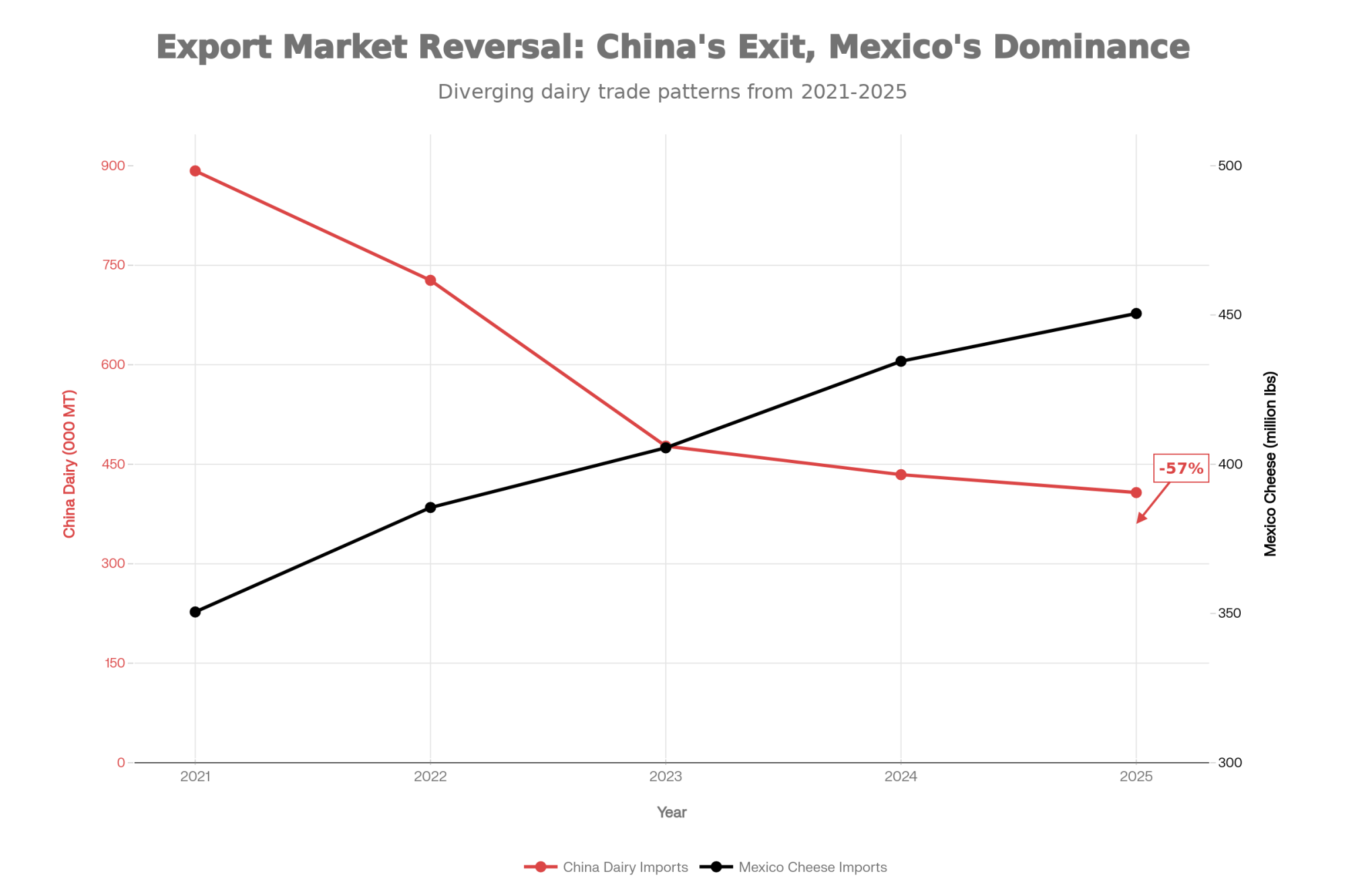

Exports have absorbed substantial U.S. dairy production in recent years, with 2024 reaching $8.2 billion—the second-highest export value ever, according to USDEC and IDFA reporting. Understanding the current export environment helps put domestic market dynamics in context.

Mexico remains the dominant destination—and deserves close attention. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service data and USDEC reporting show Mexico accounts for more than a third of all U.S. cheese export volume—by far the largest single destination. Mexico purchased 37 percent of all U.S. cheese sold to international customers through September 2024, and Cheese Reporter confirms 424 million pounds of cheese were exported to Mexico in 2024.

This concentration creates both opportunity and exposure. Mexican economic conditions—including inflation pressures and remittance flows—directly influence demand. The relationship has been remarkably durable, but it’s worth monitoring.

The China situation represents a more structural shift. USDA and Rabobank analysis show Chinese dairy imports dropping from a peak of nearly 845,000 metric tons in 2021 to about 430,000 metric tons in 2023—a decline of nearly 50 percent in just two years, as Dairy Reporter and Capital Press have documented.

USDA GAIN reports and Rabobank describe China’s strategy to boost domestic raw milk production and reduce import dependence. Chinese dairy imports were down roughly 10-14 percent in early 2024, with forecasts suggesting continued pressure.

The consensus among economists studying global dairy trade is that China deliberately increased self-sufficiency. That suggests planning for Chinese demand to return to 2021 levels may not be realistic—though trade relationships can shift in unexpected ways.

On a more positive note, other markets continue developing. Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Latin America offer growth potential. And USDEC confirms U.S. dairy export volume was up 1.7 percent through the first three quarters of 2025, indicating continued demand despite the China headwinds.

Global competition remains a factor. EU milk production is forecast to decline modestly in 2025, according to European Commission data—about 0.2 percent—as environmental regulations and cost pressures affect European producers. New Zealand, Australia, and South American producers continue competing in key markets.

Building business plans that work at realistic domestic price levels, while remaining positioned to benefit from export opportunities, seems like a prudent approach.

What Could Change This Outlook

Markets regularly surprise us, and it’s worth considering scenarios where conditions might improve faster than current projections suggest.

Weather or disease events could tighten global supply. A significant drought in New Zealand or production challenges in European herds would reduce global competition. U.S. dairy would benefit from being a reliable supplier in that environment.

China’s approach could evolve. Economic pressures, food security priorities, or trade negotiations could reopen Chinese import demand. It’s not the base case, but it’s possible.

Domestic demand could strengthen. Cheese consumption has grown modestly but consistently. A shift in consumer preferences or successful product innovation could accelerate demand. The foodservice recovery post-COVID continues developing.

Trade policy could create openings. New trade agreements or the resolution of existing disputes could improve access to markets that are currently restricted.

I wouldn’t build a business plan assuming these developments, but they’re worth monitoring. They’re also reasons for measured optimism rather than pessimism about dairy’s long-term prospects.

Practical Steps for the Months Ahead

For dairy operators assessing their position, several action areas warrant attention in the near term. These aren’t theoretical—they’re decisions with specific windows. And while the priorities may vary based on your operation’s size and situation, the core principles apply broadly.

Feed Cost Management

With corn prices running around $4.00-4.05 per bushel in late December—down from $4.20-plus earlier in the fall and well below the $5-plus levels of 2023—this represents a genuine opportunity, according to USDA and CME data.

Forward contracting 50-70 percent of the anticipated 2026 grain requirements provides cost certainty regardless of how commodity markets move. For a 600-cow operation, that’s roughly 1,200-1,800 tons of corn equivalent. If prices move higher by spring, you’ve protected yourself.

Smaller operations—say, 100-200 cows—might target the lower end of that range to preserve cash flexibility, while larger commercial dairies with dedicated nutritionists and storage capacity might push toward 70 percent or higher.

I spoke with a nutritionist in the Northeast who mentioned that several of her clients locked in corn in October and are already seeing the benefit as prices have firmed. “It’s not about timing the absolute bottom,” she noted. “It’s about knowing your costs and removing uncertainty.”

The window for favorable pricing exists now, though markets can always move in either direction.

Risk Management Tools

Both the Dairy Revenue Protection and Dairy Margin Coverage programs offer downside protection worth evaluating. Each works differently:

DRP protects revenue and allows customizable coverage levels. Recent quotes in the Upper Midwest have shown producers can often secure Class III price floors in the high-$17 to low-$19 range, with premiums typically running a few dozen cents per hundredweight, depending on coverage level and quarter. These numbers move with the market, so working with your agent on current pricing makes sense.

DMC protects margins—milk price minus feed costs—and offers subsidized rates for smaller operations. As Wisconsin Extension and Ohio State confirm, Tier 1 coverage at $9.50 margin costs just $0.15 per hundredweight for qualifying operations—genuinely affordable protection for smaller producers.

Dr. John Newton, Vice President of Public Policy and Economic Analysis at the American Farm Bureau Federation, has noted that more sophisticated operators are layering both programs. DMC provides base margin protection; DRP covers revenue risk on top of that. The combination requires some investment, but it’s comprehensive.

A note on operation size: DMC’s Tier 1 subsidized rates make it particularly attractive for smaller operations with a production history of under 5 million pounds production history. Larger operations may find DRP more cost-effective on a per-hundredweight basis.

Insurance enrollment deadlines typically fall in mid-to-late January. This is an immediate decision point worth prioritizing.

| Program | What It Protects | Coverage Cost ($/cwt) | Best For | Enrollment Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) | Milk revenue (price × volume) | $0.30 – $0.70 (varies) | Larger operations, revenue focus | Mid-January (quarterly) |

| Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) Tier 1 | Margin (milk price – feed costs) | $0.15 (subsidized) | Small farms (<5M lbs history) | Mid-January (annual) |

| DMC Tier 2 | Margin (milk price – feed costs) | $1.11 – $1.53 | Mid-size operations | Mid-January (annual) |

| No Coverage (Exposed) | Nothing | $0 | High-risk strategy | N/A |

Balance Sheet Assessment

Operations carrying significant debt—particularly debt originated at lower interest rates that’s now repricing—benefit from proactive lender conversations.

The math matters. A $4.5 million debt portfolio repricing from 3.5 to 7.5 percent adds roughly $180,000 in annual interest expense. On a typical-size operation, that extra interest alone can add $1.00-1.50 per hundredweight to your cost of production—money that comes straight off your margin.

Options worth discussing with your lender:

- Amortization extensions that reduce annual payments by stretching repayment

- Refinancing into FSA programs—USDA’s December 2025 announcement confirms current rates at 4.625 percent for direct farm operating loans and 5.75 percent for farm ownership loans

- Covenant modifications that provide flexibility during market transitions

A lender I know in the Upper Midwest told me that producers who come in early with clear projections and a realistic plan typically achieve the best outcomes. “It’s the ones who wait until they’re already stressed who have fewer options,” he observed.

Initiating these conversations proactively, with clear financial projections showing you understand market conditions, typically produces better results than waiting.

Herd Composition Review

Evaluating whether lower-producing animals justify their feed and labor costs becomes more important as margins compress.

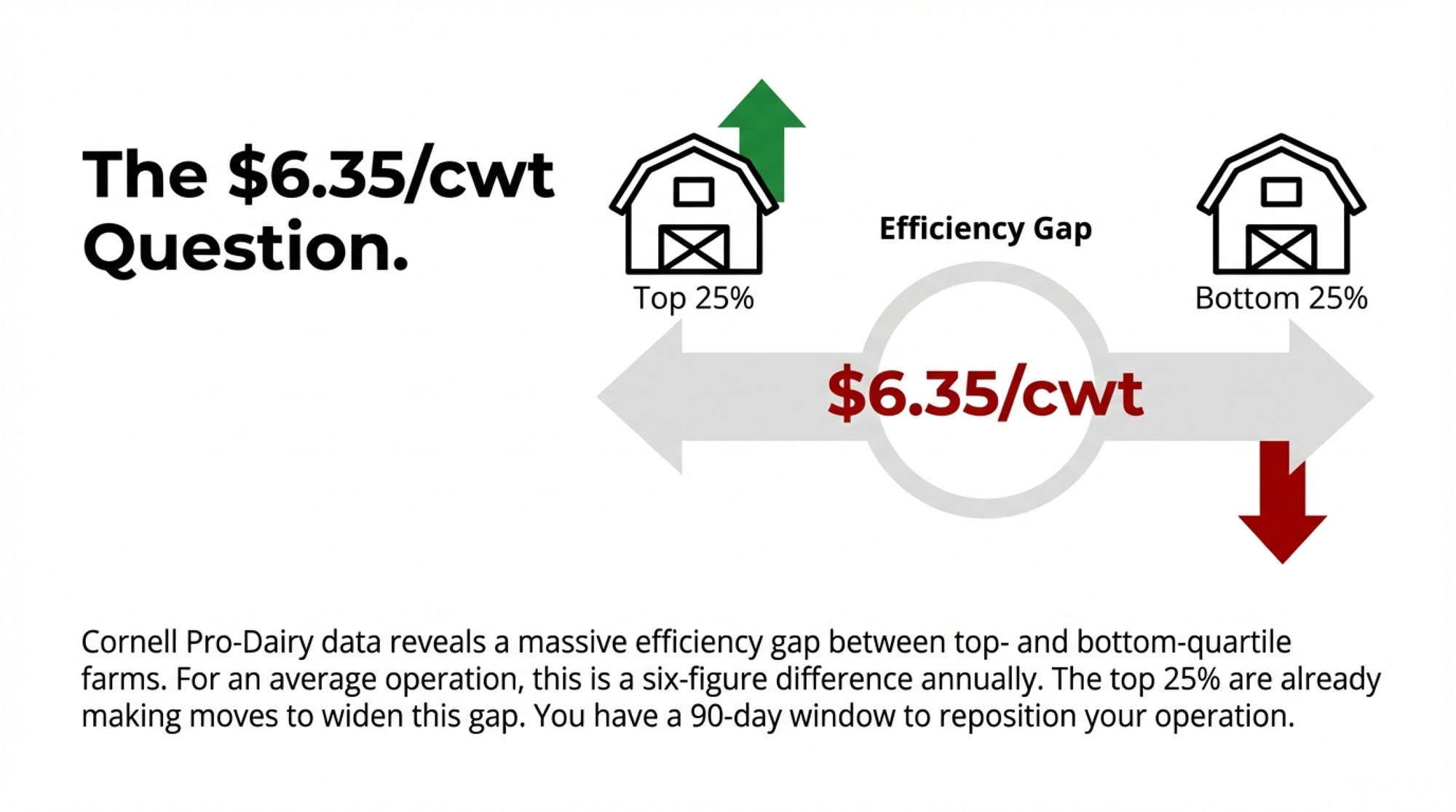

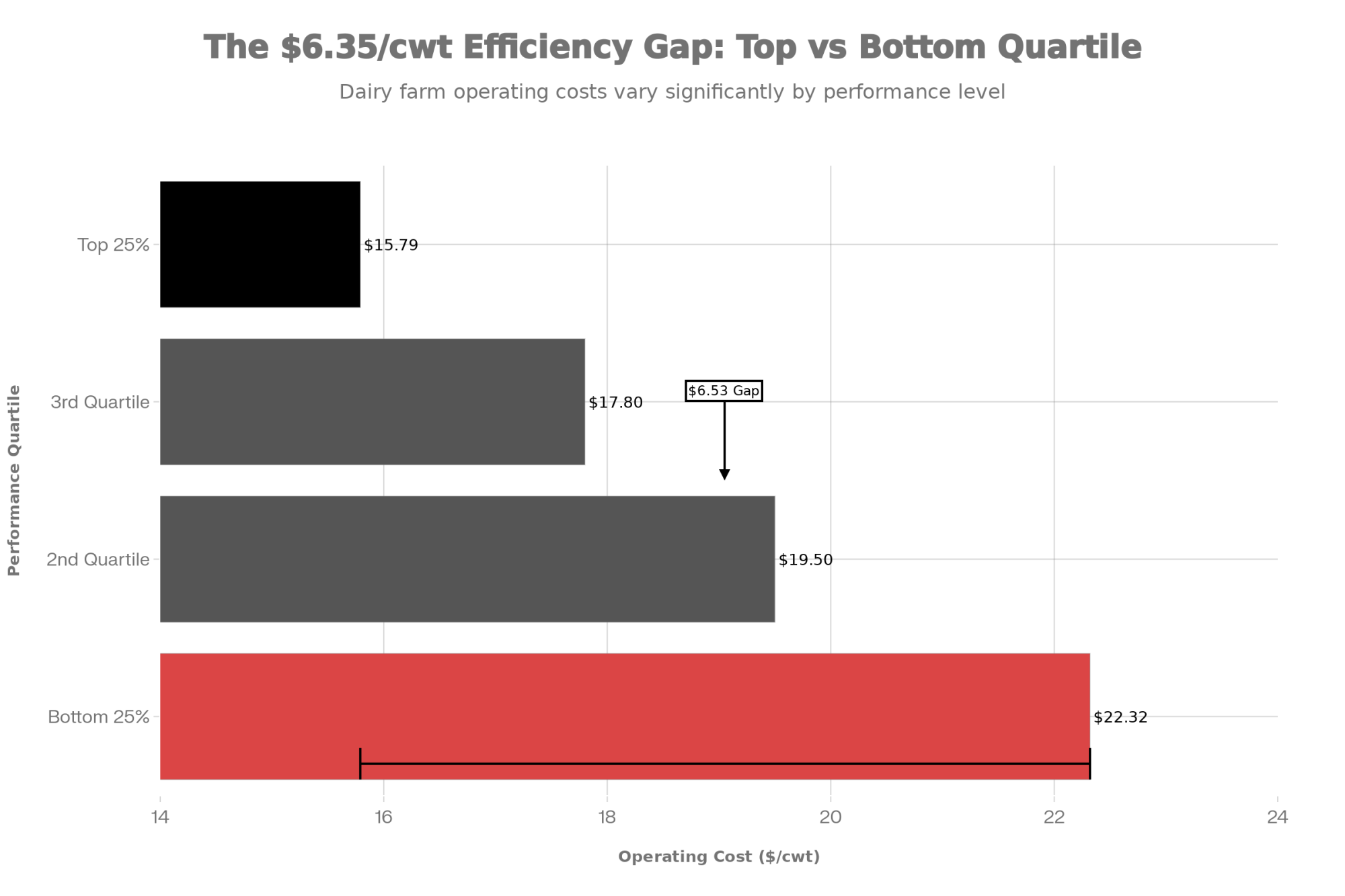

The efficiency gap between top and bottom performers in most herds is larger than many farmers realize. Cornell Pro-Dairy data shows the lowest quartile of farms averaging operating costs of $22.32 per hundredweight, while the highest quartile averages just $15.79—a difference of $6.35 per hundredweight that translates to performance gaps exceeding $100,000 between similarly-sized operations.

The math often favors addressing the bottom 10 percent of producers rather than carrying them through a soft market. For a 600-cow herd, that’s 60 animals consuming feed, requiring labor, and potentially affecting rolling herd average.

This doesn’t necessarily mean culling aggressively—it might mean more intensive management of problem cows, faster culling decisions on chronic cases, or adjusting breeding priorities. The right approach depends on your specific situation.

Regional Considerations

These strategies apply broadly, but regional variations matter.

Operations in Texas and the expanding Southwest face different labor markets and heat stress considerations than Wisconsin or Michigan dairies. California operations navigating recovery from recent challenges have unique constraints. Farms in traditional dairy regions may have more processor options and competitive milk pricing than those in emerging areas.

Working with your local extension specialists and financial advisors to calibrate these recommendations to your specific situation makes sense. Generic advice only goes so far.

The Efficiency Conversation—What It Actually Means

“Get more efficient” has become standard advice. But what does meaningful efficiency improvement actually involve at a practical level?

Milk quality management delivers measurable returns. Operations maintaining somatic cell counts below 200,000 capture quality premiums while avoiding the production losses, treatment costs, and discarded milk associated with elevated SCC.

Extension economists at Cornell, Penn State, and elsewhere estimate that reducing bulk tank SCC from the 400,000 range to under 200,000 can improve returns by several hundred dollars per cow per year, including quality premiums, reduced discarded milk, and lower treatment costs.

I visited a 400-cow operation in Pennsylvania last spring that had invested significantly in parlor upgrades and milking protocols. Their SCC dropped from 280,000 to 140,000 over eighteen months. The owner estimated the combination of premium capture and reduced mastitis treatment was worth about $350 per cow annually. “It wasn’t cheap to get there,” he acknowledged, “but the payback has been solid.”

For operations considering larger capital investments, robotic milking systems are showing compelling economics for the right situations—studies cited by Progressive Dairy and industry analysts show payback periods of 5-7 years when labor savings, production increases, and improved herd health detection are factored together, though ROI varies significantly based on herd size, labor costs, and management intensity.

Feed efficiency metrics matter more than ever. Tracking pounds of milk produced per pound of dry matter intake reveals opportunities many operations overlook.

Research documented in the Journal of Dairy Science and confirmed by Michigan State’s extension work shows each 1 percent improvement in forage NDF digestibility translates to approximately 0.55 pounds additional milk per cow per day and about 0.38 pounds more dry matter intake, according to a summary of the research.

On a 600-cow herd, that 0.55 pounds daily adds up to 330 pounds across the herd, or roughly 120,000 pounds annually. At $16 milk, you’re looking at around $19,000 in additional revenue from a single percentage point improvement in forage quality. That’s why forage testing and harvest timing decisions carry such significant economic weight.

Labor productivity varies widely across operations, too. Farms running 120-140 cows per full-time equivalent generally outperform those at 80-100 cows per FTE on a cost-per-hundredweight basis. This doesn’t mean minimizing staff—it means ensuring labor investments produce proportional output through good systems, appropriate automation, and reduced turnover.

The farms navigating current conditions most successfully tend to excel across multiple efficiency dimensions simultaneously rather than focusing narrowly on any single metric. It’s the combination that creates a durable competitive advantage.

Why ‘Tightening Your Belt’ Won’t Save You This Time

Here’s what I keep coming back to when I look at all of this: The biggest risk for dairy farmers right now isn’t any single market factor. It’s the assumption that this is just another cycle that will correct itself if you tighten your belt and wait it out.

Dairy farmers are extraordinarily resilient. You’ve navigated 2008-2009, 2015-2016, 2020, and everything in between. Every time you cut costs, got more efficient, and made it through to better prices.

That resilience has been your greatest asset. But in this environment, the traditional playbook has limits.

The structural changes we’re seeing—the genetic revolution reshaping replacement dynamics, the power shift toward processors, the permanent loss of Chinese import demand, the capital intensity that favors scale—these aren’t cyclical headwinds that will reverse when milk prices recover. They’re fundamental changes in how the industry operates.

Tightening your belt works when you’re waiting out a temporary downturn. It doesn’t work when the game itself has changed.

The farms that will emerge strongest from 2026-2028 aren’t necessarily the biggest. They’re the ones that recognized early that some operating conditions have shifted permanently and adjusted their approaches accordingly.

That means:

- Building cost structures that work at $16-18 milk, while remaining positioned to benefit if prices improve

- Managing debt proactively rather than assuming refinancing will always be available on favorable terms

- Making breeding decisions that balance near-term revenue with longer-term replacement needs—and treating your genetic program as a strategic asset

- Evaluating processor partnerships with clear eyes about who holds the leverage

- Focusing on profitability at the current size rather than assuming growth solves margin challenges

The Bottom Line

The dairy industry has weathered difficult periods before, and it will navigate this one as well. Domestic and global demand for quality dairy products remains substantial. Well-managed operations will continue finding paths to profitability.

The question is which operations will position themselves to thrive in the industry’s next chapter. And that positioning is happening now, in the decisions being made over the next 90 days.

The farmers who approach this moment with clear-eyed realism—neither panic nor complacency—and take deliberate action to strengthen their operations will look back in 2028 with satisfaction at the choices they made.

That outcome is available to you. That window closes faster than you think.

Key Takeaways

The market reality:

- U.S. milk production running 3.7-4.7 percent above year-ago levels through fall 2025—the strongest growth since the COVID recovery

- National herd at 9.57 million head, up 211,000 from a year ago

- Domestic supply projected to exceed demand growth through at least mid-2027

- China’s import decline—from 845,000 to 430,000 metric tons—represents a structural policy shift

- Mexico accounts for more than a third of U.S. cheese exports

The structural shifts:

- Beef-on-dairy isn’t a trend—it’s a genetic revolution requiring new replacement math

- Power has shifted to processors who control the stainless steel and need milk to justify their investments

- Butterfat premiums have collapsed—butter from over $3.00/lb to around $1.40/lb

- Replacement heifer inventory at 47-year lows (3.914 million head); record prices

Action items for the next 90 days:

- Evaluate forward contracting 50-70 percent of the 2026 feed needs

- Review DRP and DMC options before January enrollment deadlines

- Initiate lender conversations—FSA operating loans at 4.625%

- Reassess breeding strategy: What percentage of your herd represents your genetic future?

- Model breakeven at $16-18 milk and identify improvement areas

The mindset shift:

- “Tightening your belt” is a failing strategy when the game has changed

- Resilience means proactive adaptation, not passive endurance

- Q1 2026 decisions will significantly influence outcomes through 2028

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The Triple Cushion Trap: Why 2025’s Strong Margins Won’t Save You in 2026 – Gain immediate operational clarity through this tactical guide that exposes the temporary “cushions” inflating your current margins and delivers a hard-hitting checklist to right-size your herd before these safety nets vanish in late 2026.

- The $11 Billion Reality Check: Why Dairy Processors Are Banking on Fewer, Bigger Farms – Secure your long-term market position by understanding the structural reset of processing power, where $11 billion in new plant investments are pre-securing 80% of future supply, fundamentally reshaping your regional competitive advantage and market access.

- Bred for $3 Butterfat, Selling at $2.50: Inside the 5-Year Gap That’s Reshaping Genetic Strategy – Master the 2025 Net Merit updates with this deep dive into the “genetic timing trap,” arming you with the precise selection strategies needed to navigate the industry’s massive shift from volume-only to component-centric value.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!