Your tank is full because of Bell. Your calves die because of Bell. Welcome to the dairy’s devil’s bargain.

Picture this: It’s a crisp September morning in 1971, and John Carlin is driving across Oklahoma with a cattle trailer he’d just picked up, heading to help a friend at an auction. The future Kansas governor isn’t planning to buy anything—he’s just there to read pedigrees as a favor to Bob Braswell, who’s dispersing his B&W herd.

But when that first heifer steps into the ring… something clicks.

“I liked her for many reasons,” Carlin would say later, though he couldn’t have known he was looking at the dam of the most controversial Holstein bull in modern history.

That heifer was B&W Heilo Creamelle. Her son would be Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell—and honestly? He’d end up tearing our industry right down the middle, and we’re still dealing with the consequences today.

Here’s what gets me about Bell’s story… it’s still playing out in every genomic evaluation we look at. Every time you see those sky-high milk numbers paired with concerning type scores, you’re having the exact same conversation dairy producers had forty years ago. The technology’s better, the data’s more precise, but that fundamental question hasn’t changed: What do we really value in a dairy cow?

When Production Went Nuclear

From what I’m seeing on farms—and I’ve been visiting operations from Wisconsin to California for the past thirty years—Bell’s daughters were like nothing producers had experienced before. We’re talking about cows that made milk meters spin like slot machines, hitting a jackpot.

Those early 1980s… man, I remember walking into freestall barns across the Midwest and seeing something that just didn’t compute. These smaller-framed cows would come into the parlor with an incredible intensity, as if they understood their job at a cellular level. They’d attach cleanly, stand quietly, and just flood the system with milk.

The thing is, though… walk those same barns with the classic breeders—the folks building their reputations on show-ring champions—and you’d get a completely different reaction. They’d pause at the Bell daughters, squint a little, then shake their heads. “Small, weak, narrow,” they’d mutter, and they weren’t wrong.

One breeder nailed it perfectly: Bell was like “a drunken guest at a house party”—undeniably powerful, but lacking the refinement you’d want representing your operation at the county fair.

Both sides were absolutely right. And that’s what made Bell so fascinating… and so dangerous.

I was talking to a nutritionist last month who made an interesting observation about what we’re seeing in modern herds. “The Holstein’s appetite for production isn’t just about genetics,” he said. “It’s about metabolic programming that goes back generations. Bell didn’t just change what cows could produce; he changed how they thought about producing.”

That intensity? That relentless drive to convert feed into milk? You can trace it straight back to Bell’s genetic signature, still humming through our herds nearly fifty years later.

Kansas Politics Meets Dairy Genetics

What strikes me about Bell’s origin is how perfectly it captures the way breakthrough genetics often emerge—not from grand master plans, but from good stockmanship meeting opportunity at exactly the right moment. Kind of like how the best breeding decisions happen when you’re not overthinking them.

John Carlin was living a double life that would be impossible today. Picture this: 4 AM milkings on his 800-acre operation, then rushing to the state capitol for afternoon legislative sessions as he climbed toward the governor’s mansion. His partner Lawrence Mayer handled the day-to-day stuff (“I took care of the cattle,” Mayer once said with typical understatement), but Carlin made the breeding calls.

And that September day in Oklahoma… here’s where it gets interesting. Carlin figured out exactly why Braswell started his dispersal with Creamelle. If you’re selling your herd and you lead with one animal, that’s the one you believe has the most potential. Classic stockman’s intuition—something you can’t teach in ag school.

The fact that Carlin had just picked up a cattle trailer on his way to the sale? Pure luck. But recognizing genetic potential when you see it? That’s a skill developed over years of watching cows move through parlors, studying udder attachments, and understanding what makes a cow work in commercial conditions.

I’ve often wondered what would’ve happened if Carlin had stayed home that day. Would someone else have spotted Creamelle’s potential? Would Bell have ever existed? Sometimes the biggest changes in our industry hang on the smallest decisions—like whether to help a friend read pedigrees on a September morning.

The AI Gamble That Almost Didn’t Happen

When John Hecker from Select Sires visited Carlin Farms in spring 1973, he almost walked away empty-handed. Think about what the AI industry was like then—no genomic tests, no DNA profiles, no reliability percentages. Just visual appraisal, production records, and pedigree knowledge built up over decades.

Hecker looked at Creamelle—who’d classified 84 points as a two-year-old (decent, not spectacular)—and wasn’t impressed. Her family tree showed unclassified dams with modest production. In today’s world, we’d have genomic data showing exactly what she carried for everything from milk yield to haplotype carriers. Back then? You had to trust your eye and your gut.

What saved the day was outcross breeding. Commercial producers were drowning in Chief and Elevation descendants, and here was genuine diversity—Burkgov Inka DeKol through her sire, plus some rare Dauntless-Dunloggin genetics further back. The industry was hungry for something different, something that could break through the genetic bottleneck that was starting to worry thoughtful breeders.

The deal Hecker struck shows how much faith—and financial risk—went into sire development back then. Select Sires would mate Creamelle to Penn State Ivanhoe Star and, if the calf were a bull, buy it if it reclassified at 85 points or better. She made it. Barely.

That “outcross” marketing angle? Brilliant, even if slightly misleading. Bell and Elevation were actually “kissing cousins” through Osborndale Ivanhoe—something that would raise red flags with today’s genetic diversity protocols. But the maternal side offered genuine diversity that commercial producers desperately needed.

It’s worth noting that, buried deep in Bell’s maternal pedigree, was an extraordinary genetic treasure that nobody fully appreciated at the time. His twelfth dam was May Walker Ollie Homestead—the first cow in the United States to produce 1,500 pounds of butter and the first to mother three All-American offspring. This deep, powerful maternal ancestry provided a production foundation that would re-emerge with explosive force generations later.

The Production Revolution Nobody Saw Coming

When Bell’s first daughters hit milking parlors across America, something unprecedented happened. We’re not just talking about higher production—we’re talking about a fundamental shift in what Holstein genetics could deliver under real farm conditions.

Picture walking into a modern freestall barn in central Wisconsin, circa 1982. The Bell daughters are unmistakable—smaller framed than their herdmates, but with this incredible… intensity. They’d come into the parlor with purpose, attach cleanly, and just flood the system with milk.

These cows were producing extreme milk, fat, and protein yields that showed up immediately in monthly milk checks. But here’s what made Bell different from other high-production bulls: his daughters actually worked in commercial settings. Good feet and legs that held up on concrete. Well-attached udders with proper teat placement that made milking efficient. Calving ease that meant fewer middle-of-the-night vet calls.

Select Sires knew exactly how to market this combination: “for the discriminating dairymen looking for economical, highly productive dairy cattle”. Translation? These cows will make you money without breaking your back—a message that resonated powerfully with producers dealing with tight margins and labor shortages.

By the mid-1980s, Bell was siring over 30% of the cows on the Holstein Locator List. His Predicted Difference for milk was +1,704 pounds based on over 32,000 daughters across 8,221 herds. Those numbers put him among the most elite production sires of his era.

But those same daughters… they carried problems that wouldn’t become fully apparent until years later.

When the Numbers Tell a Darker Story

Here’s where Bell’s story gets complicated—and frankly, a little scary when you think about modern AI practices and genetic concentration.

The structural issues were obvious from the start. Picture this: you’re walking through a herd where 40% of the cows trace back to Bell. What you’d see is cow after cow that looked… diminished. Small frames, weak substance, udders that just didn’t have the capacity for the kind of longevity that builds sustainable herds.

His daughters were described as “small, weak, and narrow”. The classic breeders weren’t being picky—they were seeing real deficiencies that would impact herd sustainability. These cows might flood the bulk tank for a few lactations, but they wouldn’t be around long enough to build a genetic foundation on.

The health concerns were subtler but equally serious. Higher somatic cell scores were associated with more mastitis treatments. A below-average productive life meant more frequent—and expensive—replacements. What initially appeared to be fertility issues in the field (though his modern genetic evaluation actually shows a positive Daughter Pregnancy Rate of +2.8—interesting how initial impressions can stick even when the data tells a different story).

But the real nightmare was still hidden in his DNA.

The Genetic Time Bomb

What’s happening across the industry today—all our genetic testing, carrier screening, and mandatory disclosure requirements—traces back to Bell and the crisis he inadvertently created.

Picture getting that phone call in 1999. Danish researchers had just discovered this lethal genetic disorder called Complex Vertebral Malformation in Holstein calves. When they traced its origins, every single case led back to one source: Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell. He was also carrying Bovine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency, another lethal recessive.

The emotional and economic impact was devastating. Lost pregnancies, culled cows, dead calves. I remember talking to a veterinarian in Iowa who’d seen his first CVM case in the late ’90s. “It was heartbreaking,” he told me. “Here’s this producer who’d been using Bell genetics for fifteen years, building his whole program around that production, and suddenly he’s losing calves to something he’d never heard of.”

Imagine that conversation in the farm kitchen. Your favorite cow—maybe a Bell daughter or granddaughter who’d been flooding your bulk tank for years—just lost her calf. Not to a difficult birth, not to environmental factors, but to a genetic defect that’s been lurking in your herd’s bloodlines for decades.

By the time we understood what was happening, 31% of elite Danish sires and 32.5% of Japanese sires were CVM carriers. Bell hadn’t created these mutations—he’d inherited them from his sire and grandsire—but his massive popularity had spread them globally.

This is what happens when one bull gets too popular, too fast. The AI industry learned a costly lesson about genetic concentration that still influences every breeding decision we make today.

Real Farm Stories: Living with the Consequences

The reality of the Bell daughters comes through in conversations I’ve had with producers who milked them during their heyday. The experience was… let’s call it educational.

One producer in central Wisconsin told me about his herd composition in the late 1980s—about 40% Bell daughters. “Those cows could milk like nothing we’d ever seen,” he said, his voice mixing pride with something closer to regret. “I’d never seen butterfat numbers like that on our operation. But they were small, and when the market got tough in ’89, they were the first ones to go. The production was incredible, but the longevity just wasn’t there.”

I’ve heard similar stories from operations across the Midwest. The Bell daughters would give you these fantastic first and second lactations—milk production that made you feel like you’d figured out the secret to dairy farming. Then you’d watch them struggle to maintain condition in their third lactation, their small frames just not built for the metabolic demands of sustained high production.

That productive life issue was real. Modern data shows that Bell daughters had an average of 2.2 years less productive life than their contemporaries. For a commercial operation, that’s the difference between profitable cows and replacement headaches.

But here’s the interesting part—and this is where Bell’s story gets really nuanced. Producers who used him strategically, mating him only to their tallest, strongest cows, often got exceptional results. The legendary Emprise Bell Elton came from exactly this approach—Bell bred to a tall, powerful Glendell daughter. Sometimes the genetic magic happened when you provided the right maternal foundation.

What strikes me about these stories is how they capture an essential tension in our industry: the constant struggle between short-term profit and long-term sustainability. Bell daughters could deliver immediate cash flow, but they also forced producers to confront the hidden costs of genetic shortcuts.

The Corrective Breeding Breakthrough

What’s really interesting here is how the smartest breeders figured out how to turn Bell’s flaws into advantages. They didn’t abandon Bell genetics—they learned to use them surgically, almost like a precision tool.

The classic example? The Bell x Chief Mark cross.

Think about it: Chief Mark sired spectacular udders but struggled with feet and legs. Bell’s single greatest strength was transmitting correct feet and legs. Match a Bell daughter to Chief Mark, and you got the best of both worlds—assuming you could manage the other genetic variables.

Snow-N Denises Dellia became the poster child for this strategy. Picture the excitement when this mating worked: her dam was a Bell daughter, her sire was Chief Mark, and she combined elite type with the Bell family’s relentless will to milk. This wasn’t just lucky—this was sophisticated corrective breeding that showed the industry how to turn genetic weaknesses into strengths.

The success stories kept coming: Hartline Titanic, Carol Prelude Mtoto, all built on that Chief Mark-Bell foundation. What had seemed like an impossible choice—production or structure—suddenly became achievable through strategic mating.

This approach resonates today as we evaluate genomic bulls. The question isn’t whether a bull has weaknesses—they all do. The question is whether you can use those strengths strategically while protecting against the flaws. Bell taught us that even imperfect genetics can contribute to genetic progress when used with wisdom and restraint.

The Line Breeding Success Nobody Expected

Here’s where it gets really complicated, though. Bell actually line-bred better than almost any bull with serious structural flaws had a right to. Makes you wonder about the deeper genetic mechanisms at work.

The secret was distance and selection pressure. The further back Bell appeared in a pedigree, the more generations of selection had occurred to preserve his production ability while weeding out his structural problems. Breeders in Holland and the U.S. began deliberately line-breeding on Bell, creating bulls like Etazon Celsius, Regancrest Elton Durham, and Mara-Thon BW Marshall.

Marshall’s particularly fascinating—he was approved for AI service in 2007 and 2008, more than thirty years after Bell’s birth. That’s the mark of genetics with genuine staying power, genes that could survive multiple generations of selection and still contribute something valuable.

This pattern teaches us something important about genetic evaluation: sometimes the most valuable genetics come wrapped in imperfect packages. The breeders who succeeded with Bell weren’t the ones who used him indiscriminately—they were the ones who understood his profile well enough to concentrate his strengths while selecting against his weaknesses.

What Bell Teaches Modern Breeders

Walk into any dairy operation today, and you’ll find Bell’s influence. Recent pedigree analysis shows his genetic presence remains significant in modern Holstein populations—a staggering persistence for a bull born in 1974.

But here’s what’s really relevant for today’s breeding decisions: Bell’s story perfectly illustrates both the power and the danger of our genetic selection tools.

In Bell’s era, a bull with his production power would have been used regardless of his structural flaws. We didn’t have the testing capabilities to identify BLAD and CVM carriers beforehand. We couldn’t predict daughter longevity with today’s accuracy. Breeding decisions were made with limited information and huge risks.

Today’s genomic tools would have revealed Bell’s genetic defects decades before widespread use. Modern evaluations provide reliable predictions for traits such as productive life and somatic cell score. We can identify carrier status for dozens of genetic disorders before a bull ever enters AI service.

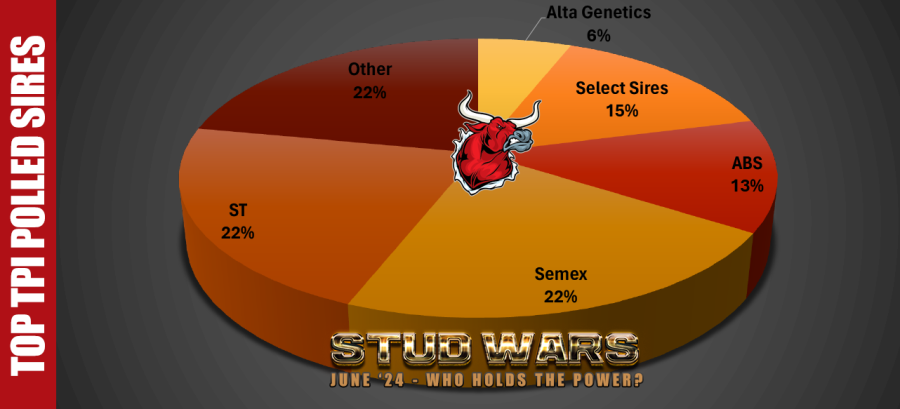

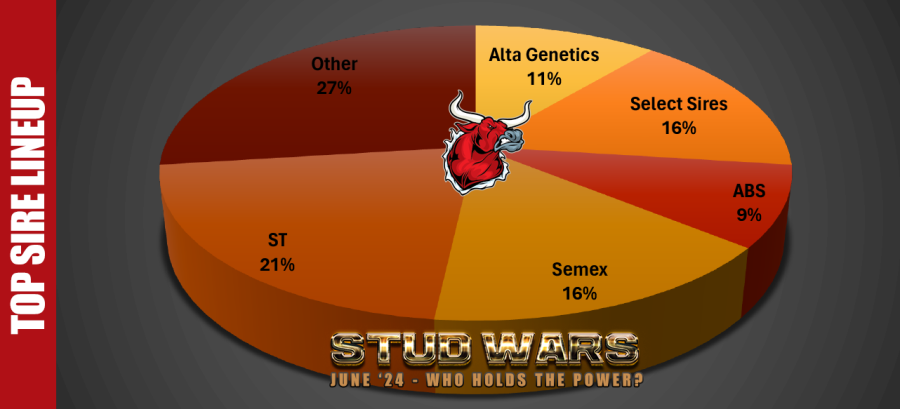

But—and this is crucial—we’re still making the same fundamental trade-offs. Look at any current genomic ranking, and you’ll find bulls with exceptional production but concerning type scores. The tools are better, but the decisions are just as complex.

Here’s what I tell producers when they’re evaluating bulls: Bell’s story isn’t ancient history—it’s a roadmap for understanding genetic risk. Every time you see a bull with extreme production but structural concerns, you’re looking at a potential Bell scenario. The question isn’t whether to use him, but how to use him strategically.

Current genomic selection practices have their own version of the Bell dilemma. We’re selecting for production traits with unprecedented accuracy, but are we creating new genetic bottlenecks? Are we trading today’s problems for tomorrow’s crises?

Take a bull like Ladys-Manor Park. Exceptional genomics for production and health, but not exactly what you’d call a structural powerhouse. Sound familiar? The same decisions we made with Bell—use him strategically on the right cows, manage his weaknesses, capture his strengths—apply to every bull evaluation we make today.

The Enduring Will to Milk

What can’t be disputed—even by Bell’s harshest critics—is his singular contribution to Holstein production capacity. He “injected the breed with a tremendous will to milk”, and that drive continues to flow through modern dairy herds in ways that would probably surprise him.

Visit operations across the Midwest, Northeast, or California, and you’ll see it in action. That relentless, efficient conversion of feed to milk that characterizes today’s Holstein cow? It owes much to the genetic foundation Bell established. Walk through a modern freestall barn during peak lactation, and you’re witnessing the culmination of decades of selection for metabolic efficiency that started with bulls like Bell.

The economic realities of modern dairying—thin margins, volatile feed costs, labor shortages, and environmental regulations—make Bell’s production genetics more relevant than ever. His daughters might have been small and structurally challenged, but they understood their job: convert feed to milk as efficiently as possible.

I was talking to a nutritionist last month who made an interesting observation about what we’re seeing in modern herds. “The Holstein’s appetite for production isn’t just about genetics,” he said. “It’s about metabolic programming that goes back generations. Bell didn’t just change what cows could produce; he changed how they thought about producing.”

This metabolic intensity—this cellular understanding of the cow’s primary function—is part of Bell’s enduring legacy. Every time we see a fresh cow attack her TMR with purpose, every time we watch a high-producing cow maintain her body condition through peak lactation, we’re seeing echoes of Bell’s genetic contribution.

The Lessons That Still Matter

Here’s what Bell’s story really teaches us about our industry: genetic progress is never simple, never perfect, and never without unintended consequences.

He forced us to confront uncomfortable questions about breeding priorities that we’re still wrestling with today. Do we breed for short-term profitability or long-term sustainability? How much structural compromise is acceptable for production gains? When does genetic concentration become dangerous?

The answers vary by operation, by market conditions, and by management philosophy. But the questions remain constant, and they’re more pressing now than ever.

Bell’s legacy isn’t just about one controversial bull—it’s about the ongoing challenge of making breeding decisions with incomplete information and competing priorities. Every genomic evaluation we study, every mating decision we make, every genetic trend we follow connects back to the fundamental tension Bell embodied.

Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if we’d had today’s genetic testing when Bell entered AI service. Would we have used him differently? Would we have avoided the CVM and BLAD crisis? Would the industry have progressed faster… or slower?

The thing is, though, we can’t rewrite history. But we can learn from it.

What strikes me most about Bell’s story is how it reveals the inherent tension in our industry between innovation and tradition, between risk and reward, between the pull of profit and the push of principle. Every generation of dairy farmers faces this same dilemma in different forms.

We’re seeing it again with genomic selection. We have incredible tools for identifying production potential, but are we adequately accounting for the complexity of genetic interactions? Are we preserving enough genetic diversity? Are we learning from Bell’s lessons about the dangers of genetic concentration?

The reality is that breeding decisions will always involve trade-offs. The key is making those trade-offs consciously, with full awareness of the risks and benefits, and with strategies for managing the consequences.

Bell taught us that genetic power comes with genetic responsibility. That convenience and profit can’t be our only considerations. That diversity matters as much as elite performance. That the decisions we make today will echo through generations of cattle—and farmers—we’ll never meet.

The Ghost in Every Tank

And in those quiet moments between milkings, when we watch the steady rhythm of modern Holsteins moving through our parlors, we’re witnessing the complicated legacy of a Kansas-born bull who refused to be simple, refused to be perfect, but somehow managed to be transformational.

That tension between greatness and compromise? It’s still there in every breeding decision we make. Every time we look at a genomic evaluation. Every time we balance production against longevity, efficiency against sustainability, profit against principle.

Bell just made it impossible to ignore.

His ghost is still in the machine—in the genetic algorithms that drive modern selection, in the milk flowing through our bulk tanks, in the conversations we have about what really matters in a dairy cow. He’s there in every difficult breeding decision, every genetic trade-off, every moment when we have to choose between competing priorities.

The bull who split our industry in half also taught us something invaluable: that genetic progress requires both courage and wisdom, both innovation and restraint, both the willingness to take risks and the humility to learn from our mistakes.

In the end, maybe that’s Bell’s greatest legacy—not just the milk he put in our tanks, but the questions he forced us to ask, the lessons he taught us about the complexity of genetic improvement, and the reminder that every breeding decision has consequences that ripple through generations.

Every time we use a high-production bull with structural concerns, we’re walking in Bell’s footsteps. Every time we implement carrier testing, we’re applying lessons learned from his genetic legacy. Every time we balance short-term gains against long-term sustainability, we’re grappling with the same fundamental questions he forced our industry to confront.

The ghost in the machine isn’t just Bell’s genetics—it’s the enduring challenge of making breeding decisions that serve both our immediate needs and our industry’s future. He didn’t solve that challenge. But he made sure we could never ignore it.

Key Takeaways

- Bell’s bargain: +1,704 lbs milk came with CVM and BLAD—proving maximum production demands maximum caution

- The 2-lactation trap: Bell daughters peaked early, died young—replacements cost more than the milk was worth

- Corrective breeding genius: Matching Bell daughters to Chief Mark created legends—flawed genetics + smart strategy = gold

- Today’s blind spot: We learned nothing—genomic concentration is creating Bell 2.0 right now

Executive Summary:

Bell made dairymen rich, then made them pay—his daughters’ record production came packaged with early death and lethal genetics that still kill calves today. From a chance $1,500 purchase in 1971 to global genetic disaster by 1999, Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell’s story reads like a Greek tragedy: the bull who revolutionized Holstein production (+1,704 lbs milk) while secretly spreading CVM and BLAD to 31% of elite sires worldwide. Commercial producers worshipped him; traditional breeders saw disaster coming, calling Bell’s influence “a drunken guest at a house party.” The industry learned to harness his flaws through strategic breeding—Bell daughters crossed with Chief Mark created legends—proving that even poisoned genetics could produce gold with the right management. Five decades later, Bell’s ghost haunts every genomic evaluation, his legacy a permanent warning: today’s genetic miracle is tomorrow’s industry crisis.

Learn More:

- Stop Sacrificing Pregnancies for Convenience: The $144,000 Annual Cost of Choosing CoSynch Over Biology– While the main article focuses on genetic selection, this guide provides the tactical knowledge to ensure those genetics result in pregnancies. It reveals how to implement research-backed synchronization protocols to boost conception rates, directly impacting your breeding program’s ROI.

- Global Dairy Market Trends 2025: European Decline, US Expansion Reshaping Industry Landscape – This strategic analysis provides the global economic context for today’s breeding decisions. It explains the market forces driving the relentless push for production efficiency that began with bulls like Bell, helping producers align their long-term genetic strategy with future industry demand.

- From $200 Holstein Bulls to $1400 Beef Crosses: Your 3-Week Implementation Guide – This article presents an innovative solution to the genetic questions raised by Bell’s legacy. It demonstrates how to leverage modern technologies like sexed semen and beef-on-dairy crosses to maximize revenue from the lower-genetic-merit portion of your herd.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

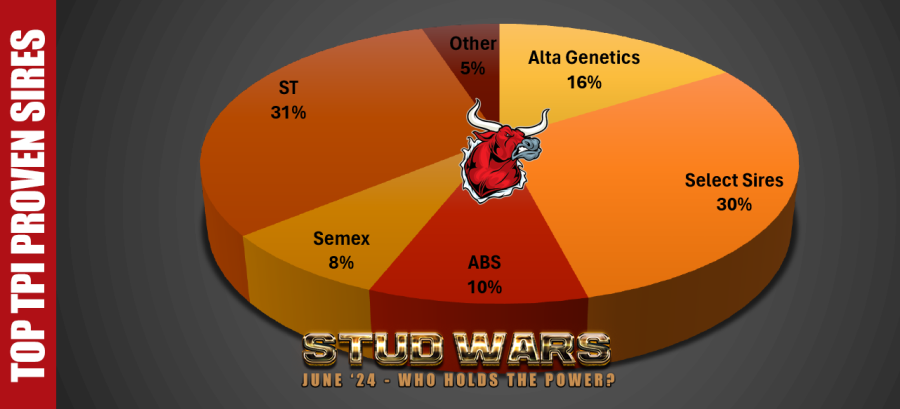

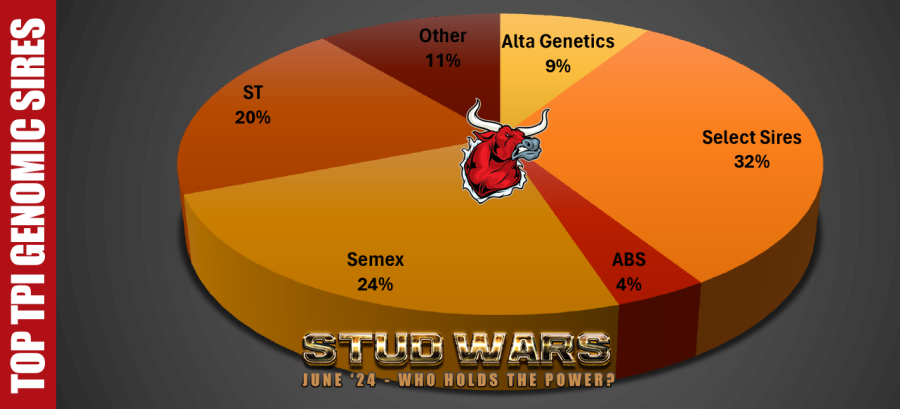

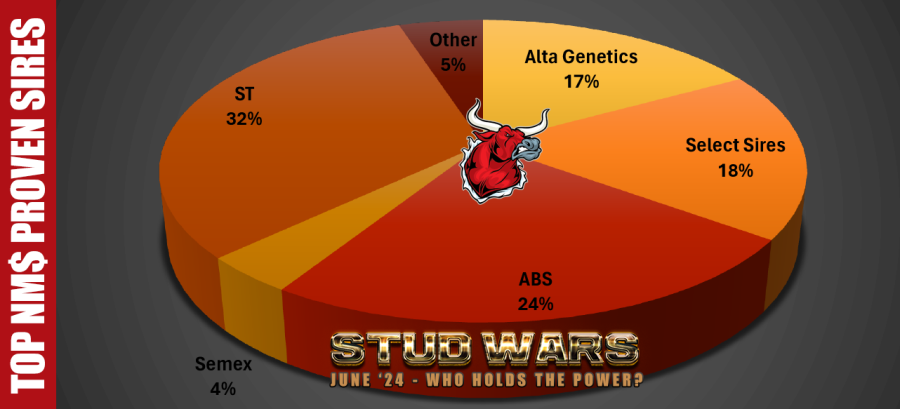

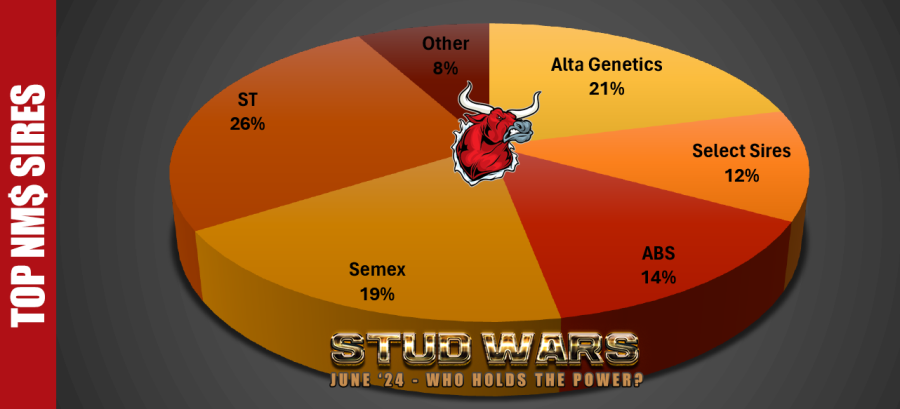

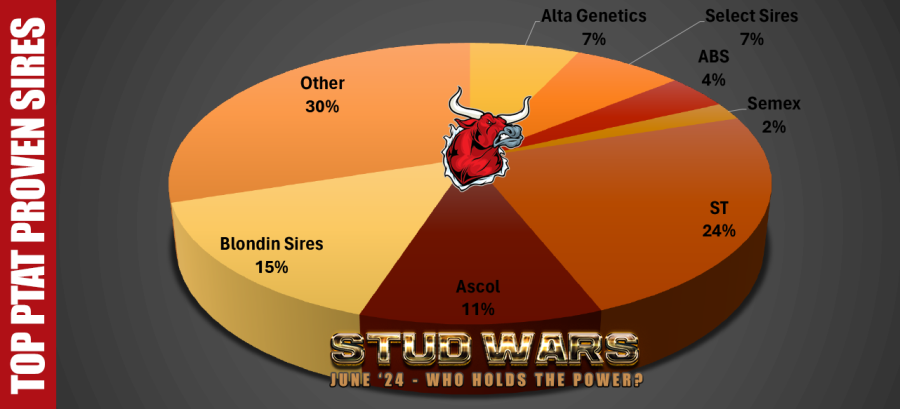

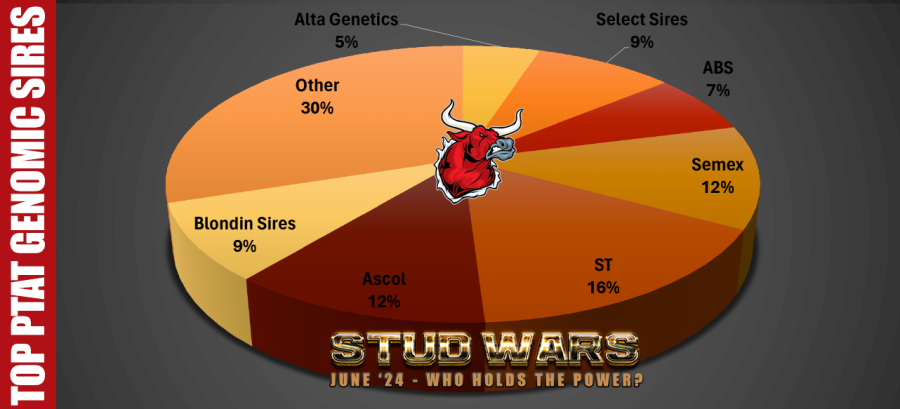

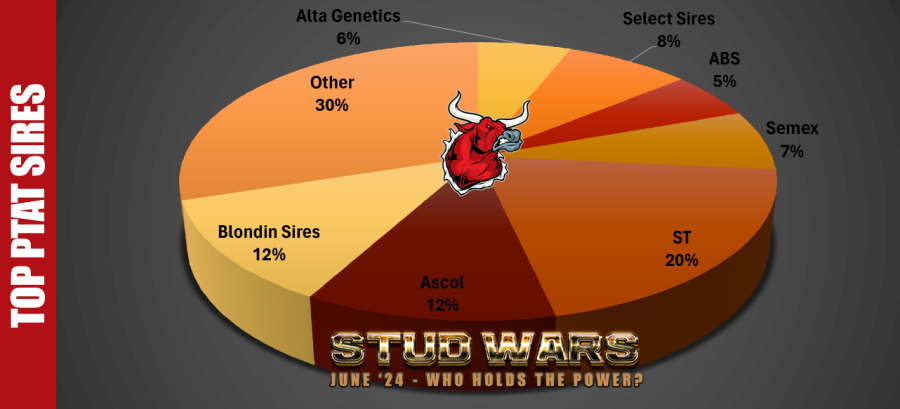

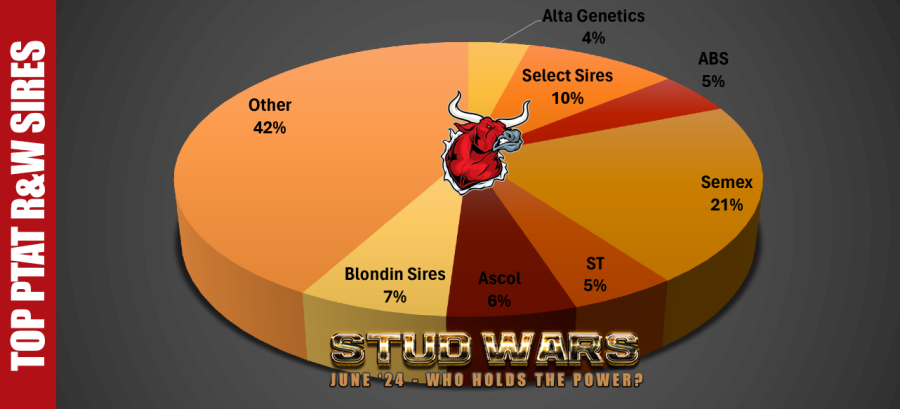

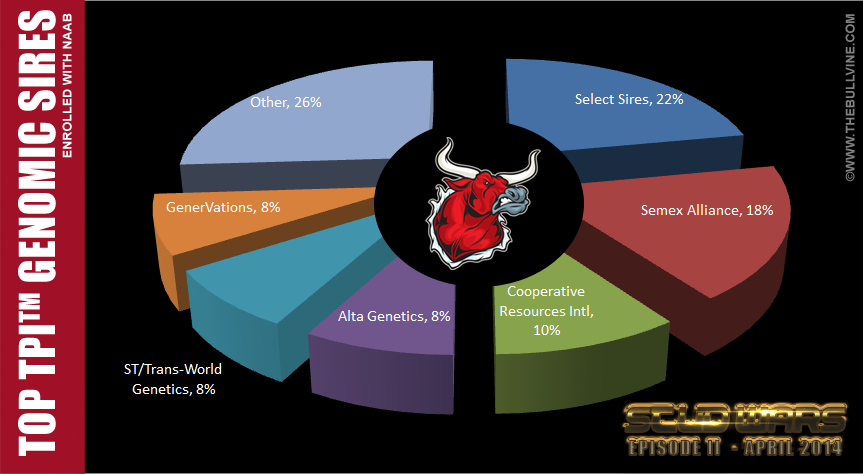

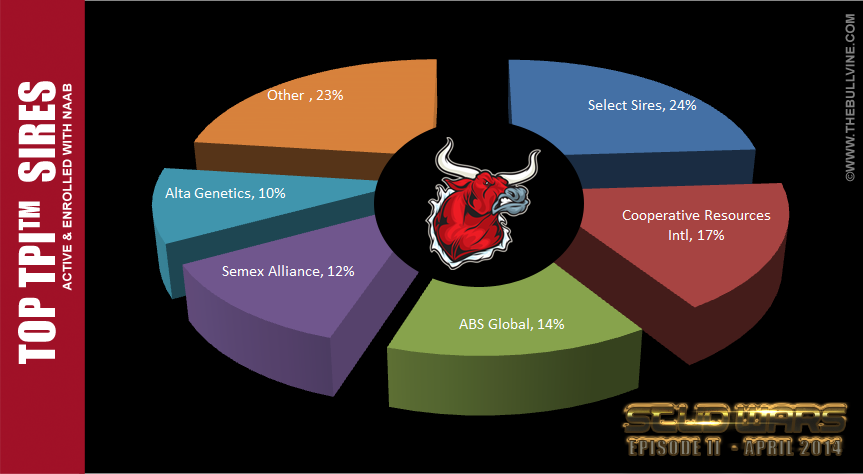

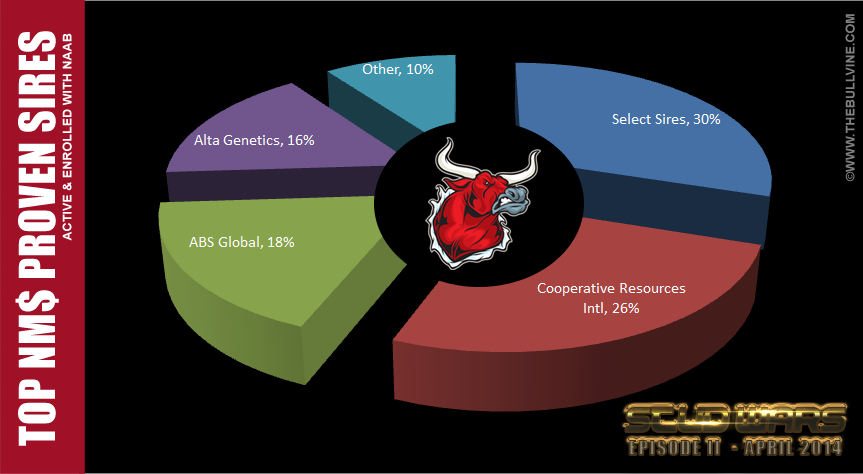

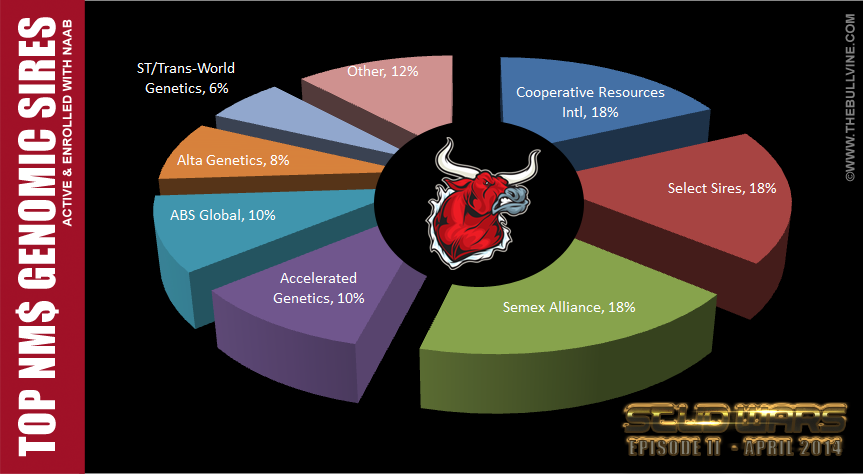

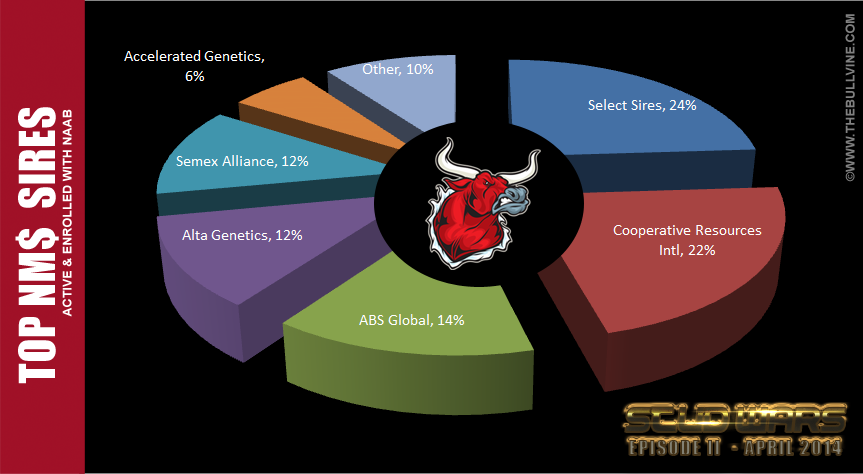

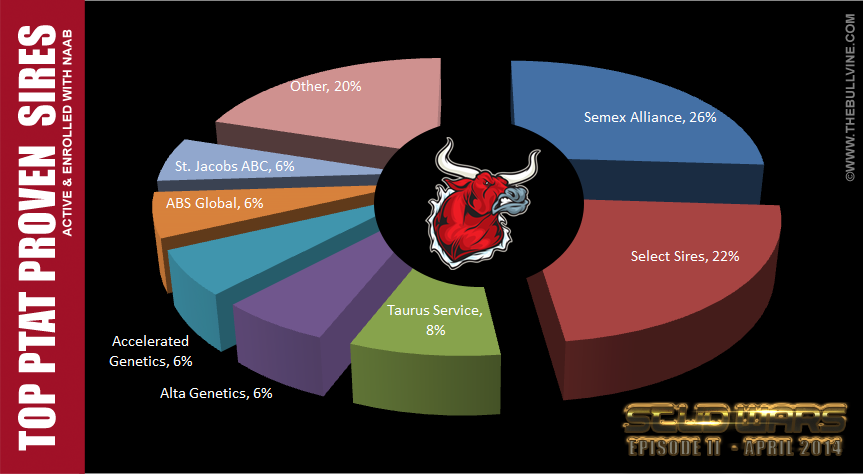

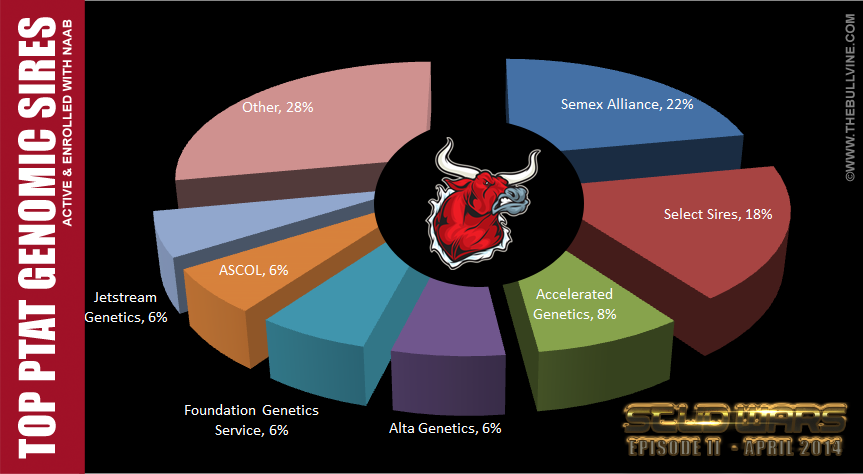

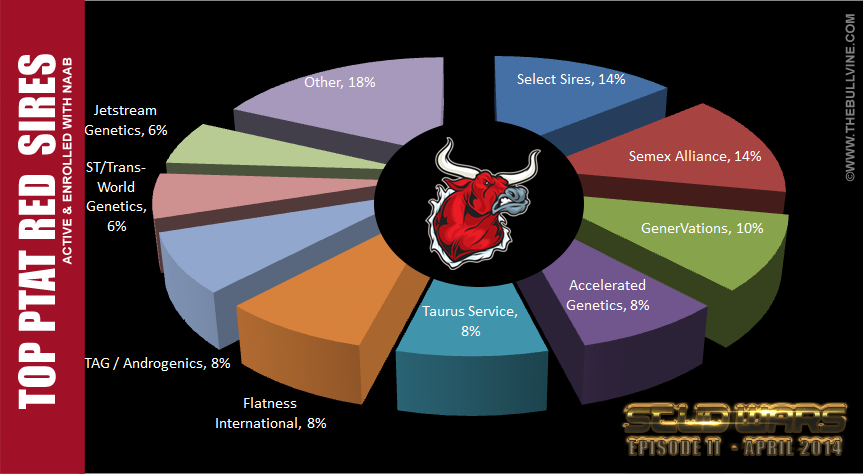

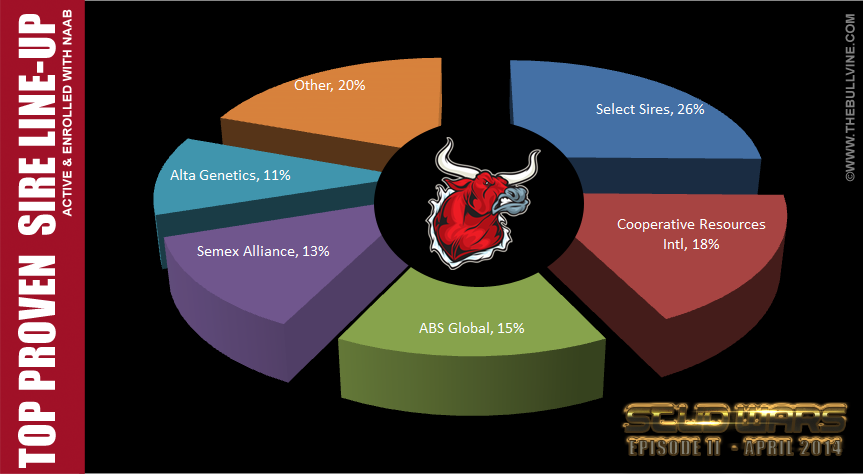

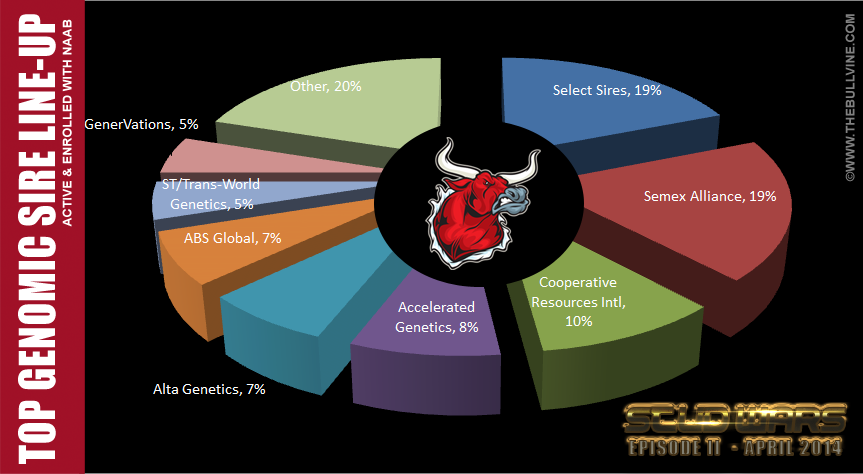

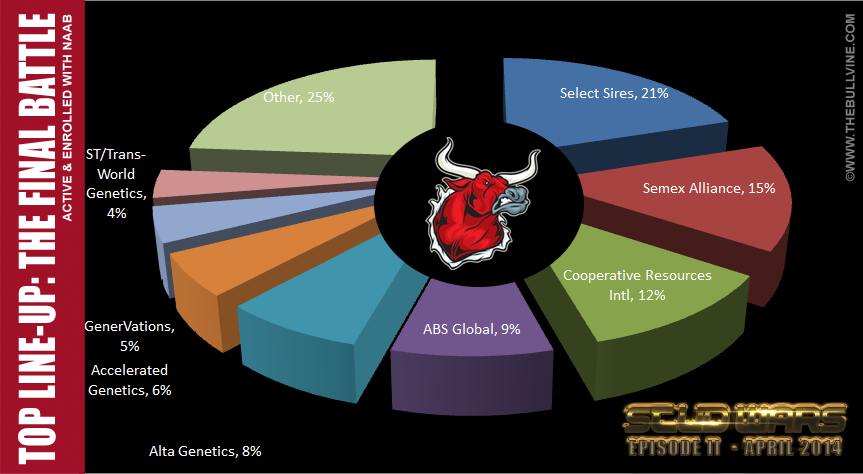

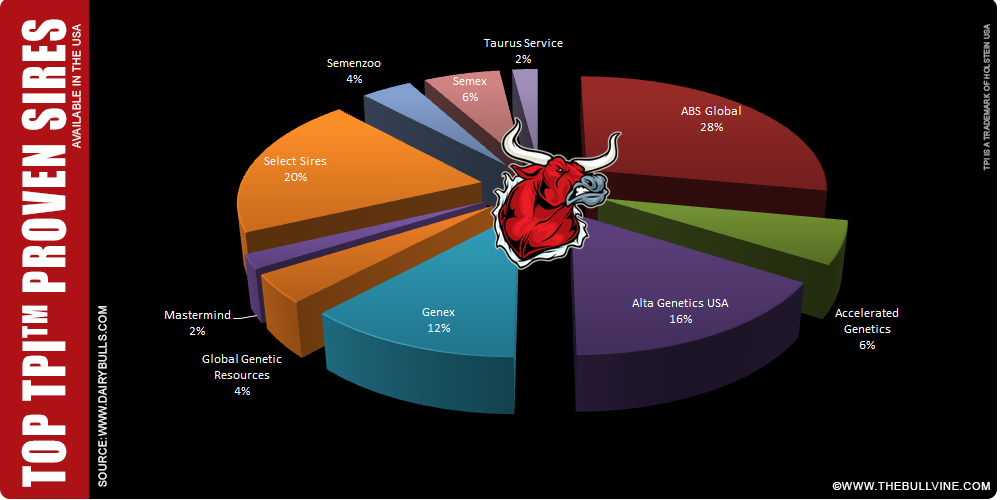

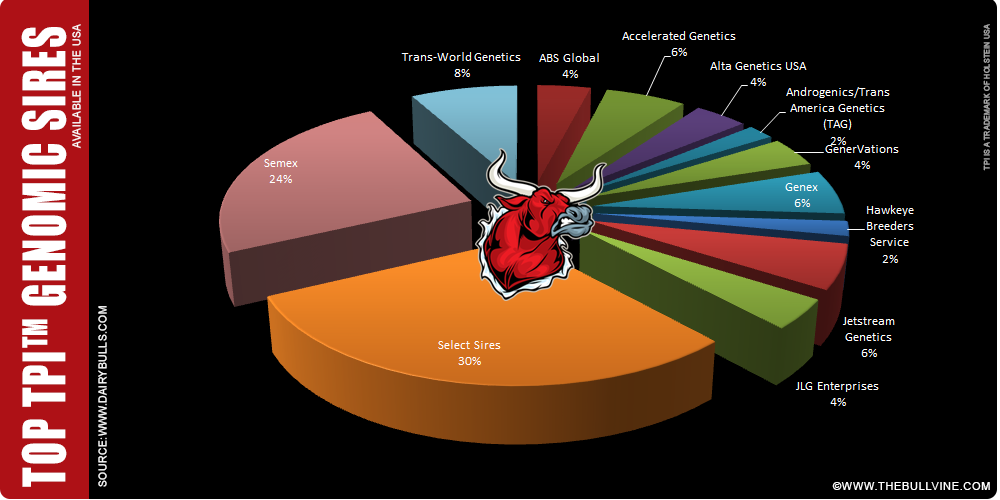

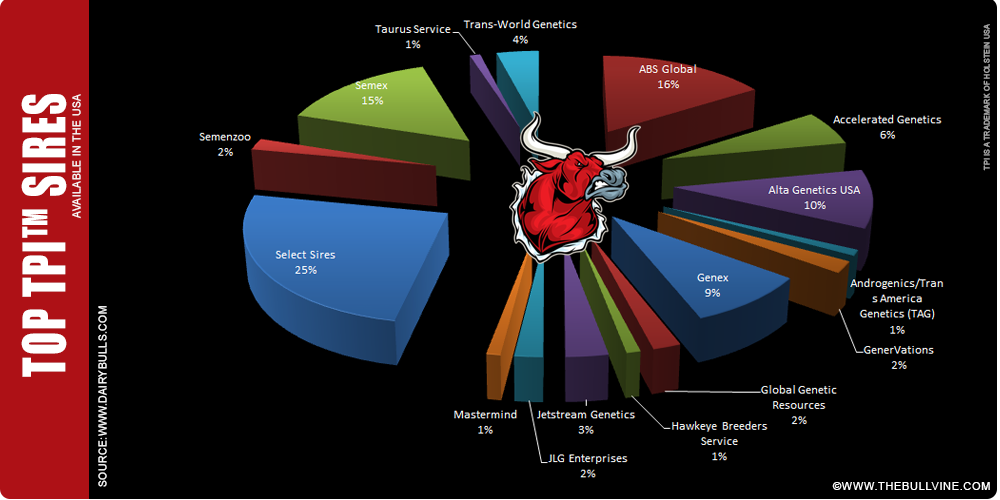

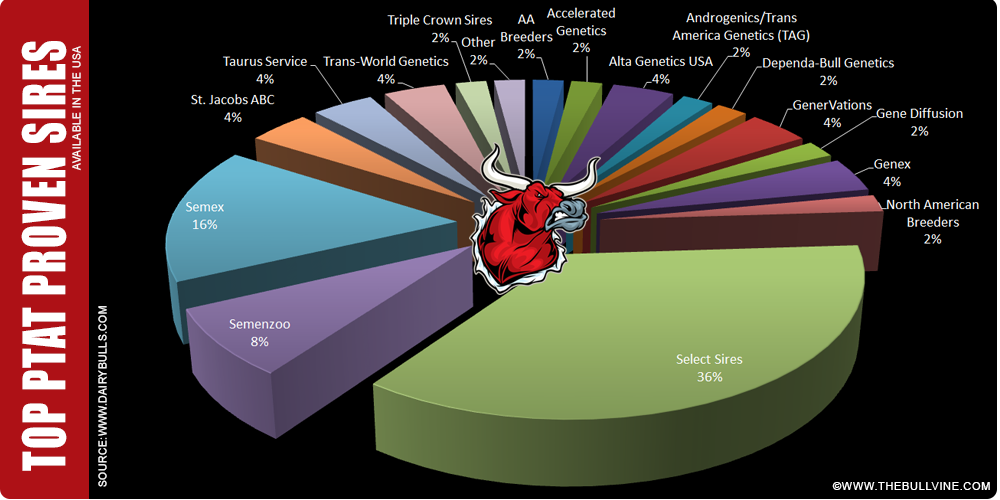

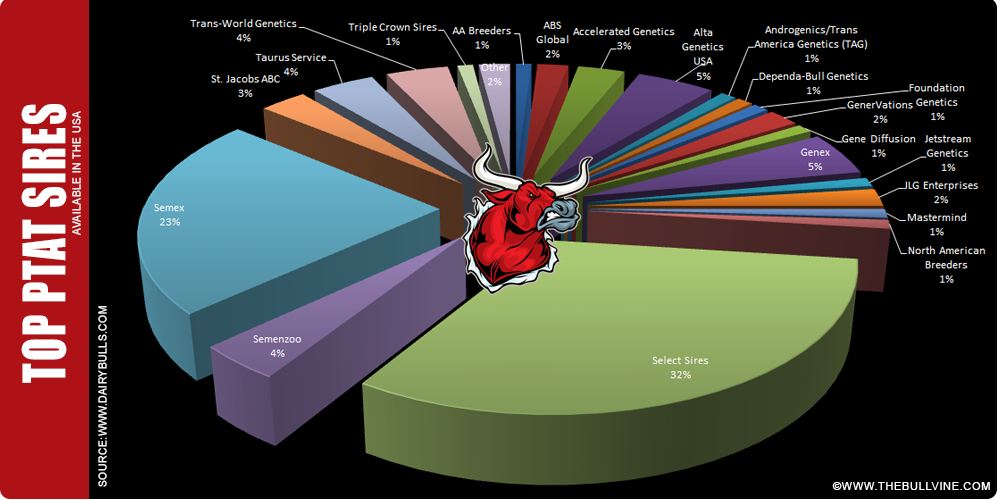

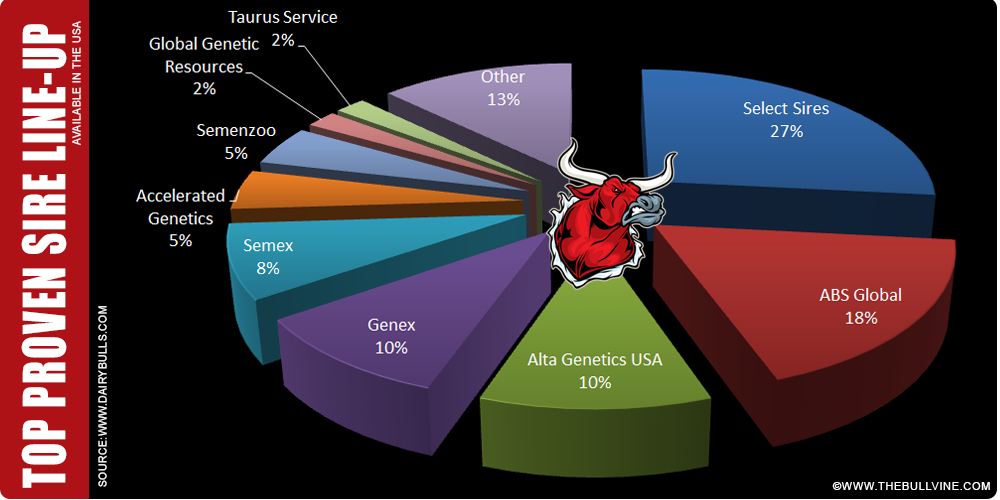

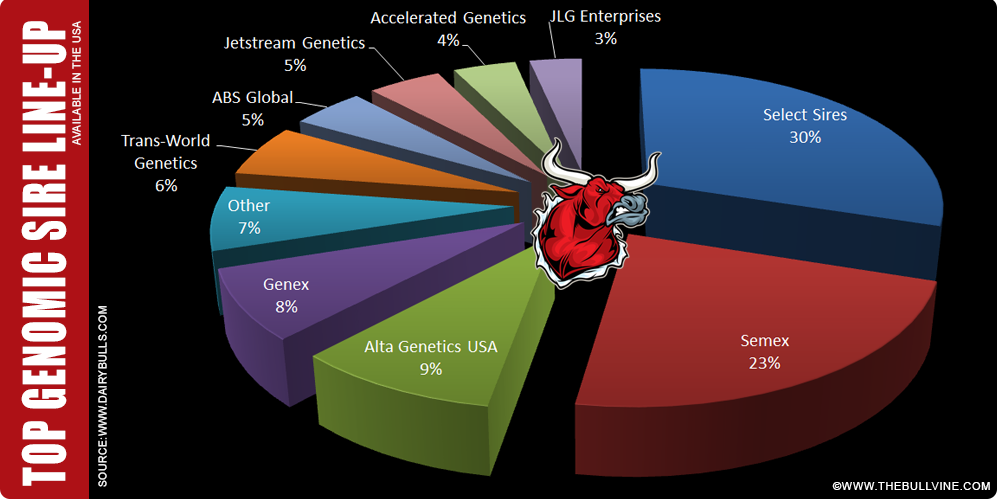

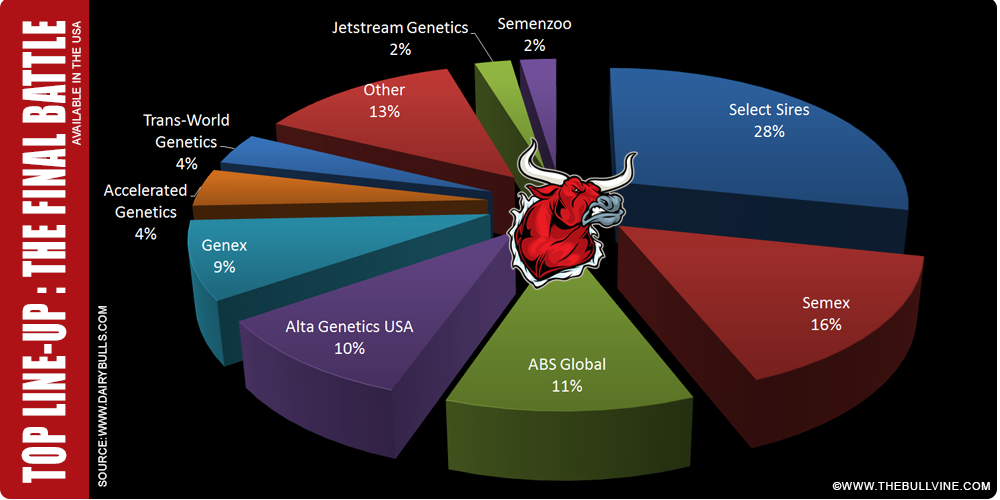

In today’s business world, if you don’t have a better product, you had better do a great job of marketing your product. For years, Semex has been able to market and sell based on the ‘Canadian Kind’. However, genomic evaluations has pretty much all but removed any customer loyalty and regional advantages that may have existed for AI companies in the past. Breeding programs have been adjusted by most major AI companies so they can deliver product that will satisfy breeders individual breeding strategies. AI companies, the world over, have had to redefine their business model over the past few years and rebranding has had to be addressed. Recent print ads and website changes would suggest that without the top of the list product to sell Semex has started to rebrand itself.

In today’s business world, if you don’t have a better product, you had better do a great job of marketing your product. For years, Semex has been able to market and sell based on the ‘Canadian Kind’. However, genomic evaluations has pretty much all but removed any customer loyalty and regional advantages that may have existed for AI companies in the past. Breeding programs have been adjusted by most major AI companies so they can deliver product that will satisfy breeders individual breeding strategies. AI companies, the world over, have had to redefine their business model over the past few years and rebranding has had to be addressed. Recent print ads and website changes would suggest that without the top of the list product to sell Semex has started to rebrand itself.