$97,500. That’s what weight-loss drugs are worth to a 500-cow dairy. Here’s how to capture it.

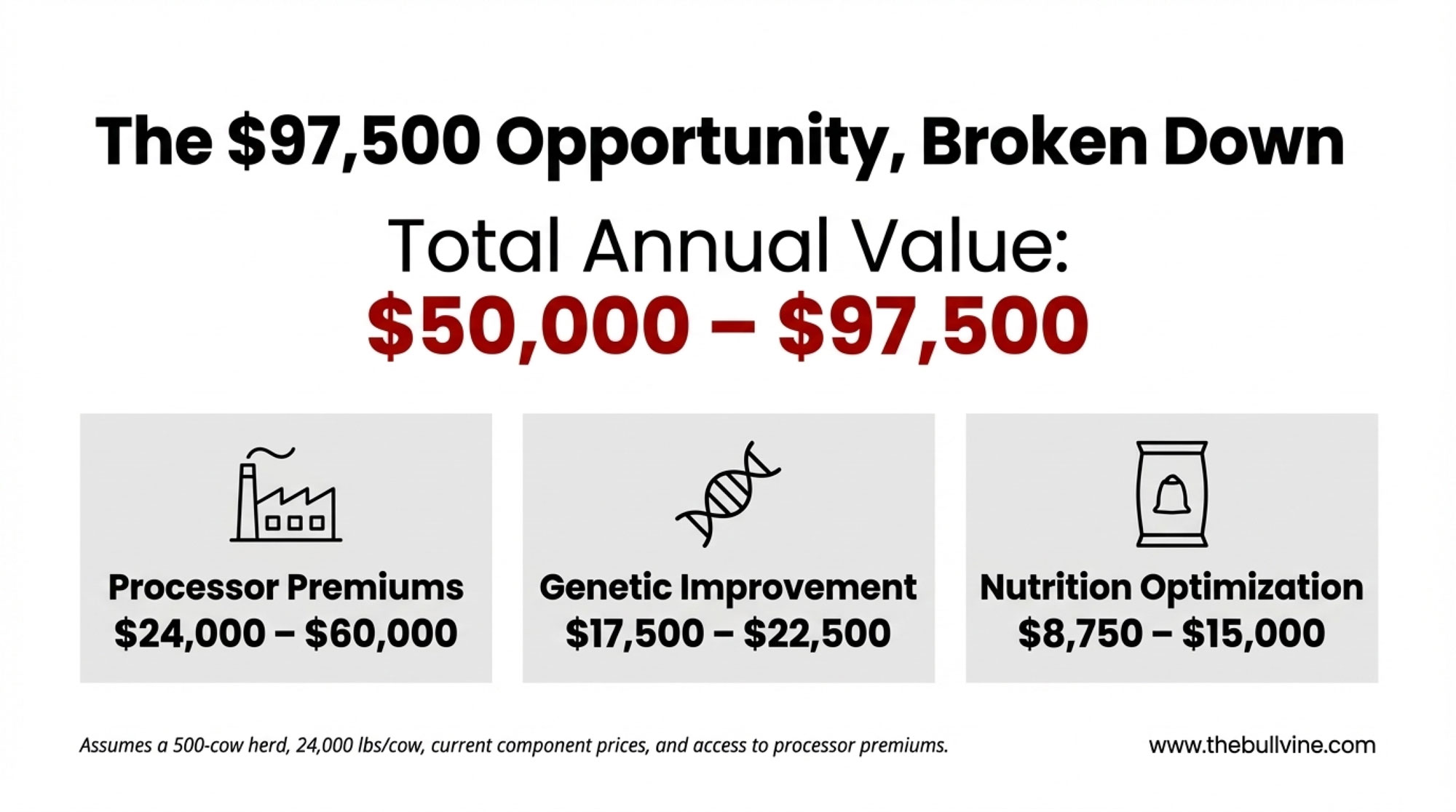

Executive Summary: $97,500 annually. That’s what a 500-cow dairy can capture by responding to the protein shift—a market realignment most producers haven’t traced to its source. GLP-1 weight-loss drugs have reached 41 million Americans who now consume high-protein dairy at triple the normal rate, reshaping what your milk is worth. Protein premiums have hit $5/cwt at cheese facilities, and December’s Federal Order update raised baseline protein to 3.3%—meaning below-average herds now subsidize neighbors who ship higher components. The opportunity stacks three ways: nutrition optimization ($8,750-$15,000), protein-focused genetics ($17,500-$22,500), and processor premiums ($24,000-$60,000). The catch: breeding decisions this spring won’t reach your bulk tank until 2029, rewarding producers who move early. The math is clear, the window is open, and this analysis shows exactly how to capture it.

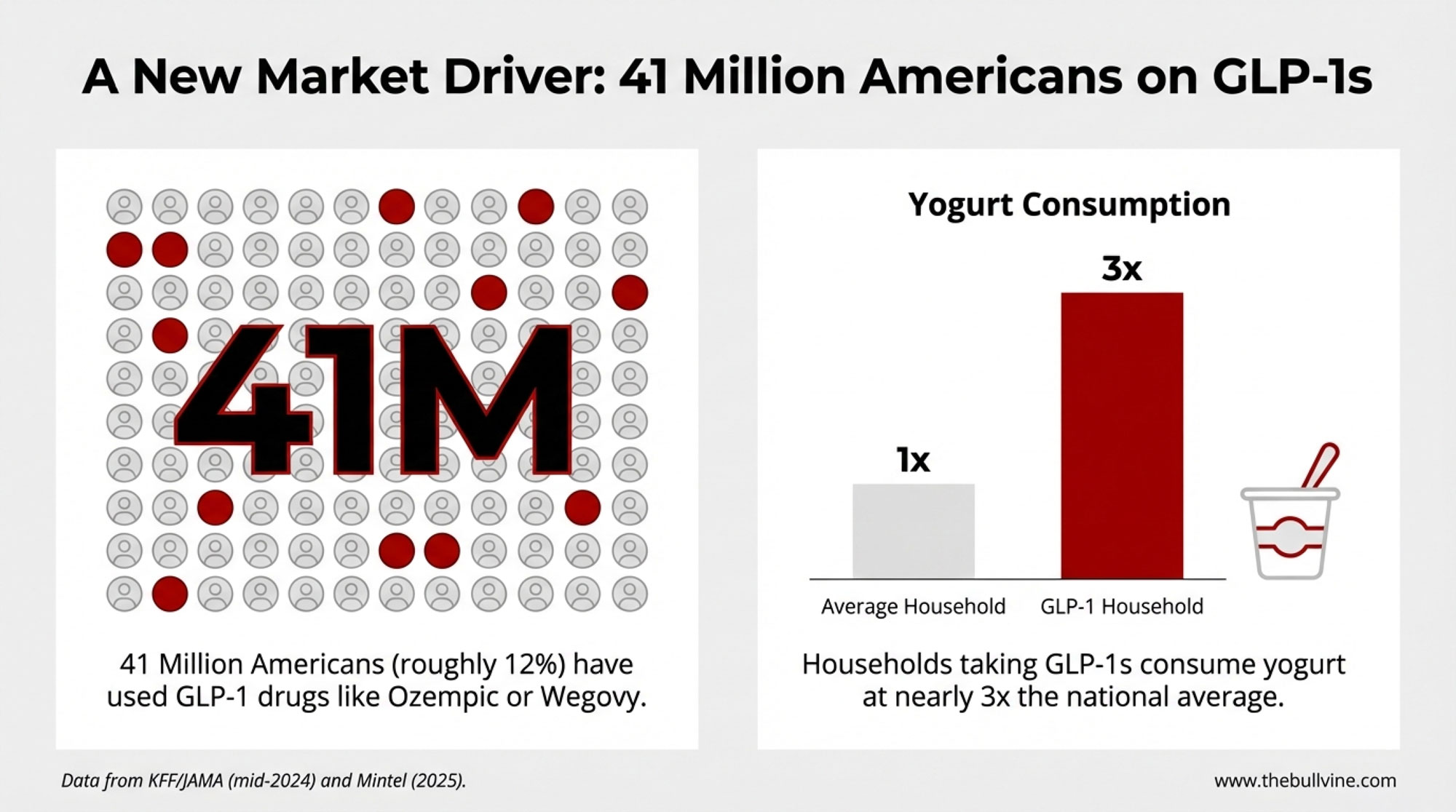

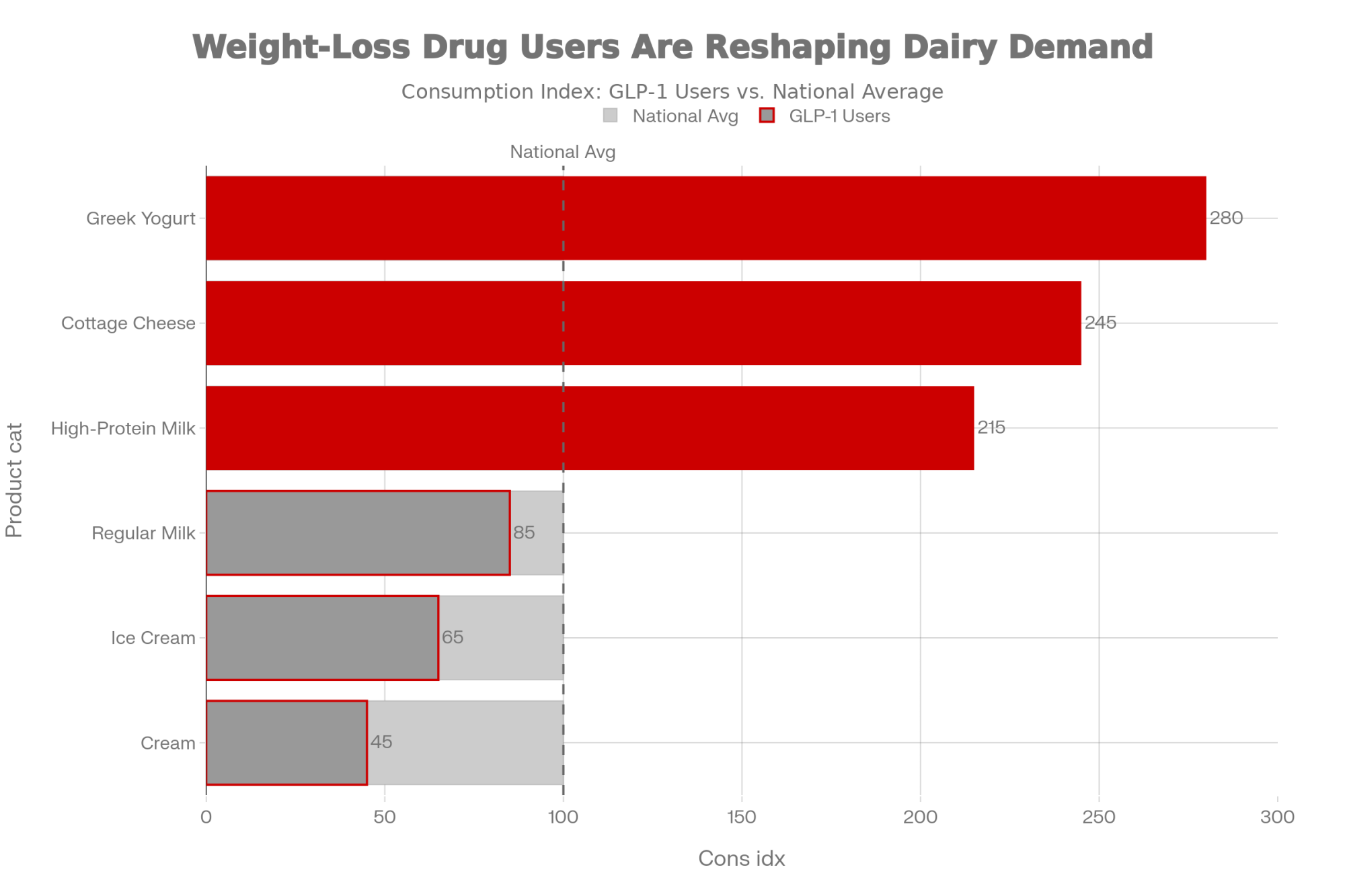

A number worth sitting with: households taking GLP-1 weight-loss medications are consuming yogurt at nearly three times the national average. Not 20% more. Not double. Three times.

That data point comes from Mintel’s 2025 consumer tracking. It tells you something important about where dairy demand is heading—and raises questions worth considering if your breeding program has been focused primarily on butterfat.

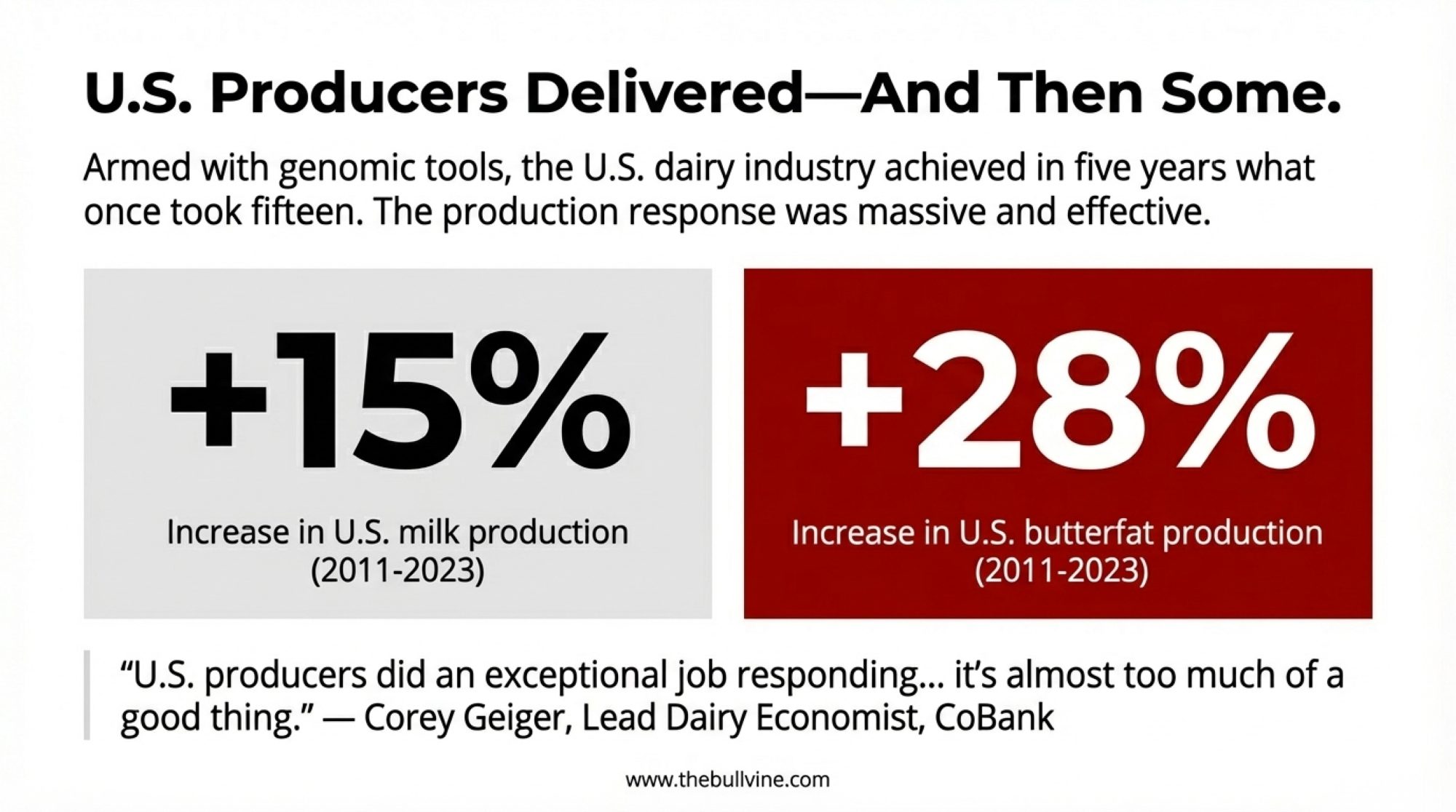

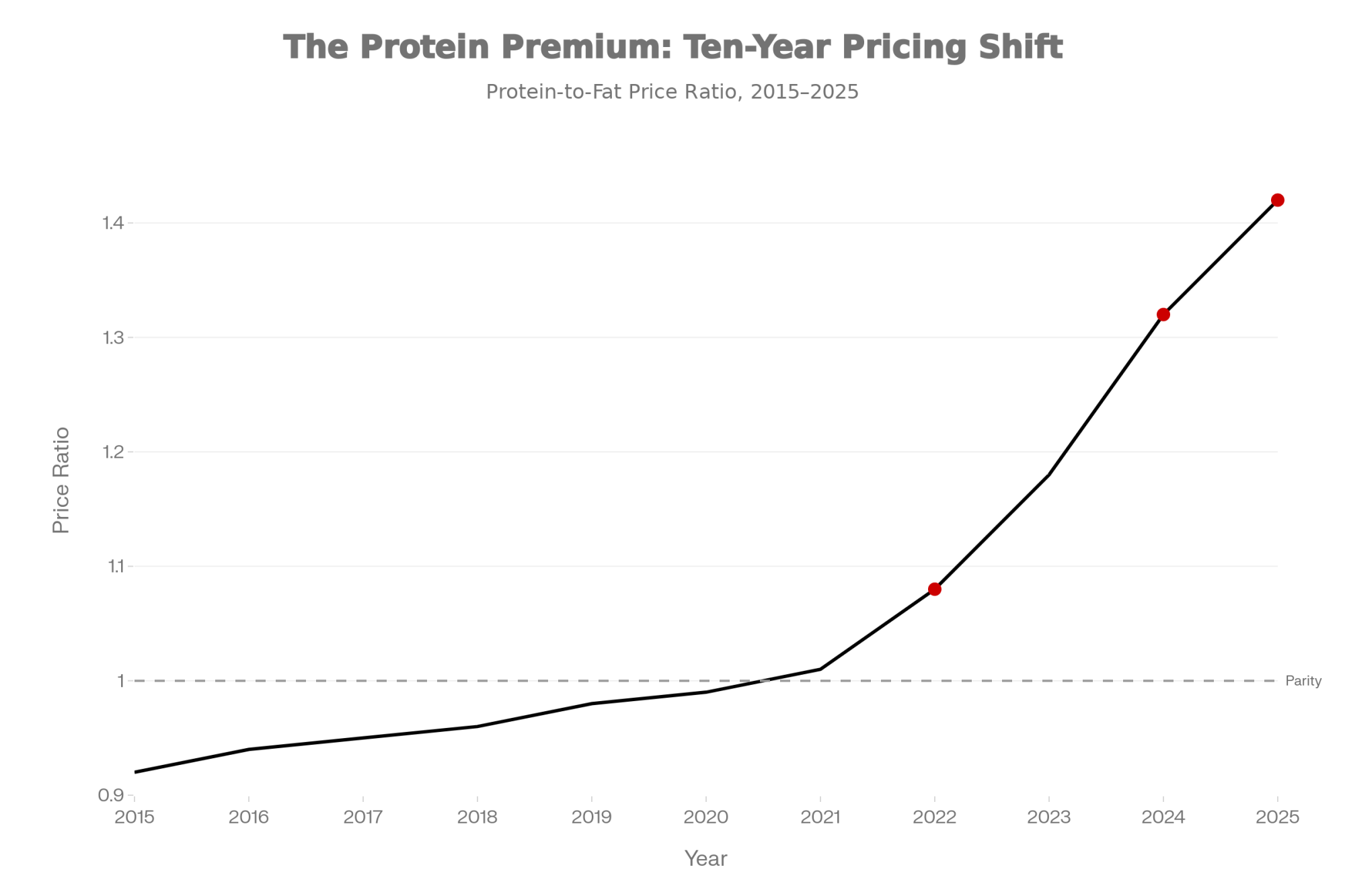

Something meaningful is shifting in how the market values what comes out of your bulk tank. This isn’t a temporary blip or a pricing anomaly. What we’re seeing appears to be a structural change driven by forces that weren’t on most of our radars even five years ago—pharmaceutical trends, aging demographics, and global nutrition demands all converging at once.

This creates opportunities for producers positioned to respond. It also creates challenges for those caught off guard. The difference often comes down to understanding what’s actually driving these changes.

THE QUICK MATH: What’s This Worth?

For a 500-cow herd positioned to capture the protein shift:

| Opportunity | Annual Value |

| Nutrition optimization (amino acid balancing) | $8,750 – $15,000 |

| Genetic improvement (protein-focused selection) | $17,500 – $22,500 |

| Processor premiums (above-baseline protein) | $24,000 – $60,000 |

| Combined Annual Opportunity | $50,000 – $97,500 |

These figures assume: 500 cows, 24,000 lbs/cow annually, current component price relationships, and access to a processor paying protein premiums. Individual results vary based on current herd genetics, ration, and market access.

The Pharmaceutical Connection

When GLP-1 drugs first hit the market, I didn’t give much thought to dairy implications. Weight-loss medications seemed pretty far removed from breeding decisions and component pricing.

That thinking needed updating.

As of late 2025, roughly 12% of Americans—about 41 million people—have used GLP-1 medications like Ozempic, Wegovy, or Mounjaro. That figure comes from a KFF poll reported in JAMA in mid-2024, with subsequent tracking by RAND and others confirming the trend has held. Market projections for these drugs range from $157 billion to $324 billion by 2035, depending on which analyst you ask. This isn’t a niche trend anymore. It’s a mainstream pharmaceutical category reshaping eating behavior at a population level.

What makes this relevant to your operation is how these medications change consumption patterns. GLP-1 drugs work by slowing gastric emptying—patients feel full faster and eat much less. But their protein requirements don’t drop. If anything, clinical guidance suggests they increase.

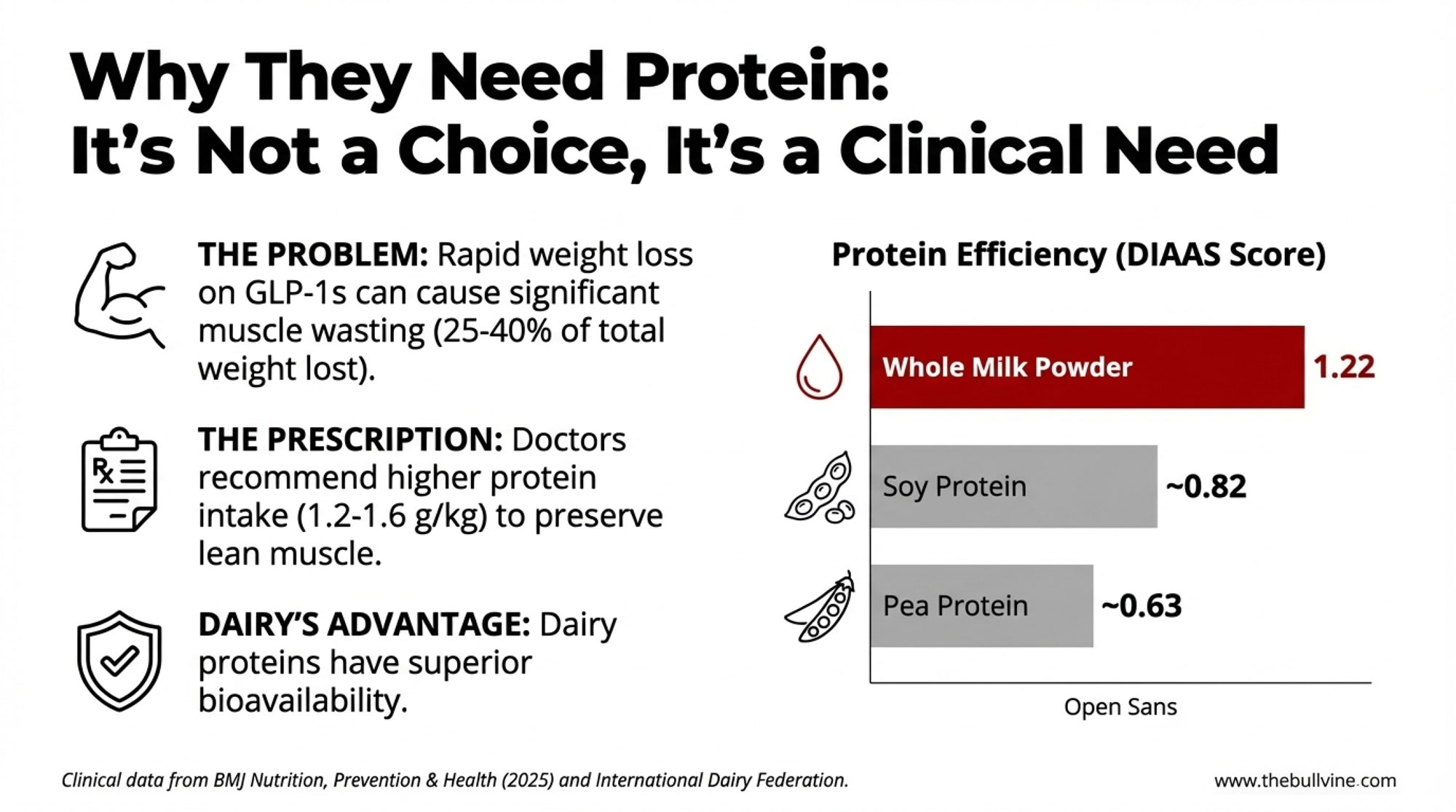

Obesity medicine specialists now recommend GLP-1 users consume 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily—backed by research in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition and clinical practice guidelines from multiple medical organizations. That’s substantially higher than typical recommendations. The reasoning? Rapid weight loss without adequate protein intake leads to significant muscle wasting.

And this is where it gets clinically important: studies published in peer-reviewed journals indicate that between 25% and 40% of weight lost on these medications can come from lean body mass rather than fat. A 2025 analysis in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health quantified this at “about 25%–40%” as a proportion of total weight loss. That’s a real concern for patients and their physicians—and it’s driving specific dietary recommendations.

So you have millions of people who can only eat small portions but genuinely need concentrated protein sources. What foods fit that profile?

High-protein dairy fits it remarkably well.

The consumption data supports this. According to Mintel’s tracking, Greek yogurt and cottage cheese consumption has increased significantly among GLP-1 users, while higher-fat dairy categories have moved in the opposite direction. Reports in June 2025 showed that “plain dairy and protein powders hold steady” while “processed goods are taking the biggest hit.” The exact percentages vary by study, but the directional trend is consistent.

There’s also a bioavailability dimension worth understanding. The DIAAS score—Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score, the FAO-recommended measurement method—indicates how efficiently the body uses different protein sources. According to research by the International Dairy Federation and the Global Dairy Platform, whole milk powder scores around 1.22 on DIAAS, while other dairy proteins consistently score 1.0 or higher. Compare that to soy at roughly 0.75-0.90, depending on processing, and pea protein at 0.62-0.64. For someone eating limited quantities, that efficiency difference matters considerably.

What does this means practically? This isn’t just a preference shift—there’s a physiological basis driving these patients toward nutrient-dense protein sources. Dairy happens to fit that need particularly well.

Reading Your Milk Check Differently

So consumer preferences are shifting. What does that actually mean for component pricing?

The answer depends partly on your market, but broad trends are worth understanding.

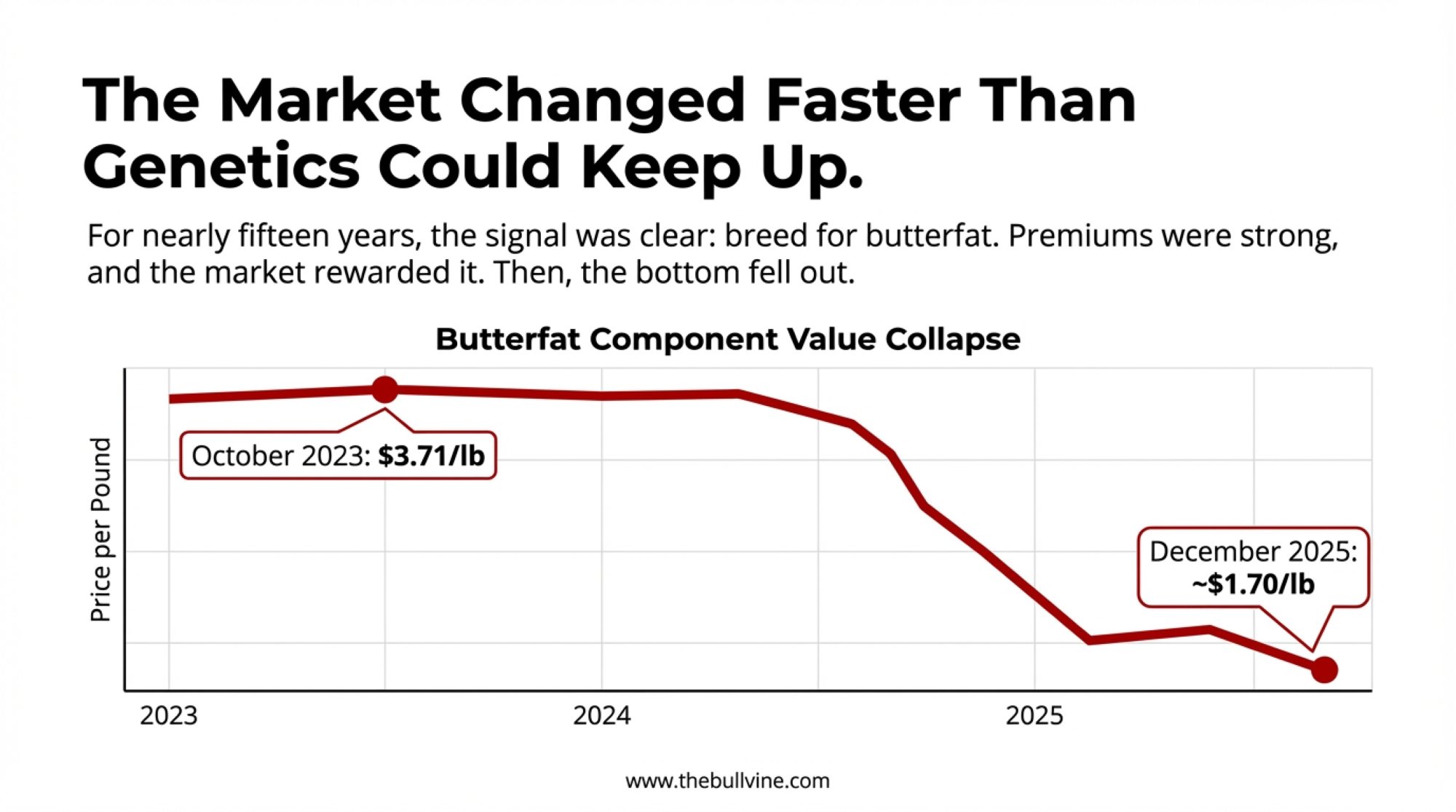

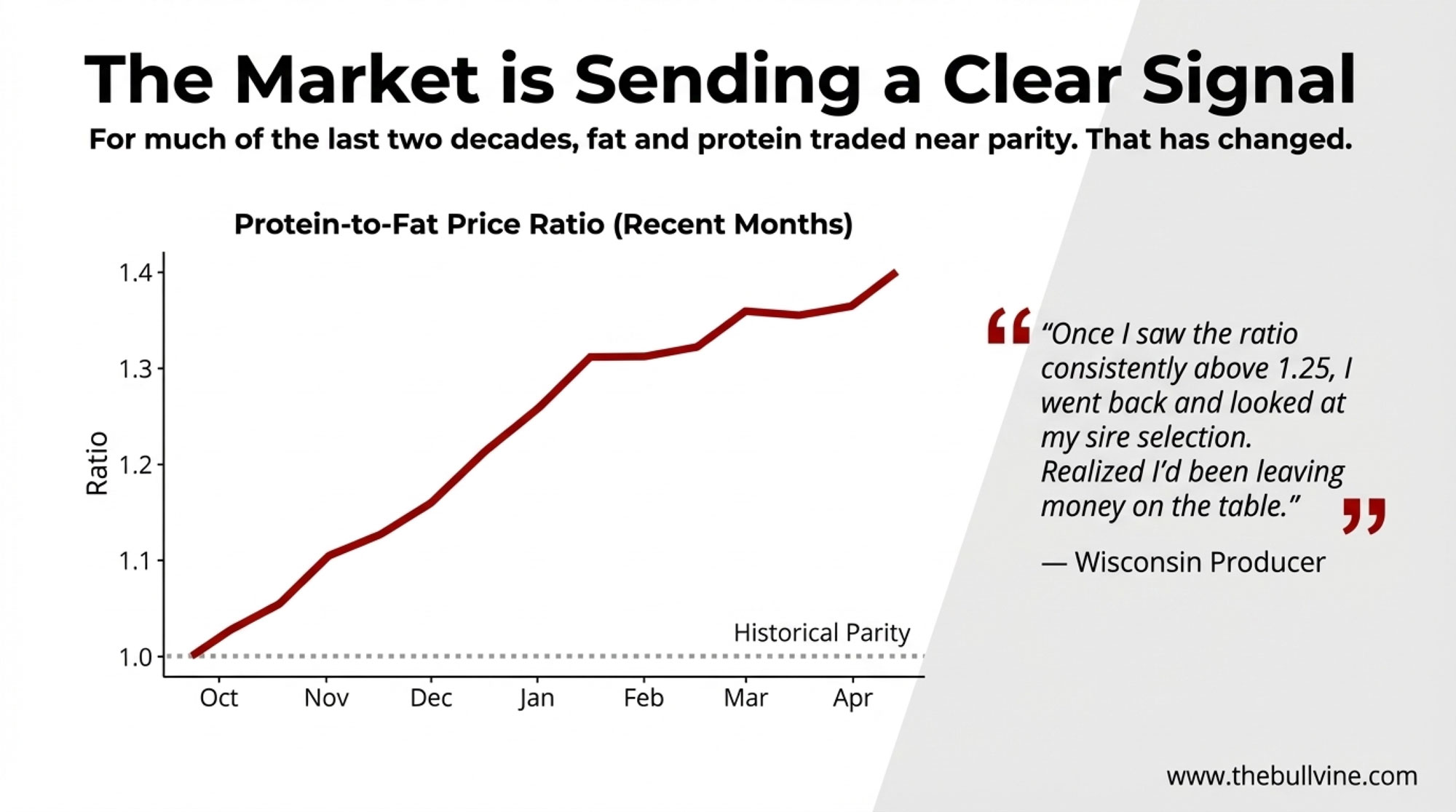

Looking at USDA component price announcements over recent months, protein has traded at a meaningful premium over butterfat. Through late 2025, the protein-to-fat price ratio has been running in the range of 1.3 to 1.4—a notable departure from historical norms. For much of the past two decades, these components traded closer to parity, with fat often commanding a slight premium.

I recently spoke with a Wisconsin producer who’d been closely tracking this shift. “I started paying attention about two years ago,” he told me. “Once I saw the ratio consistently above 1.25, I went back and looked at my sire selection. Realized I’d been leaving money on the table.”

That experience isn’t unusual. Many producers look at their check, review the component breakdowns, and maybe note whether fat or protein prices have changed from last month. But they’re not calculating what the spread actually means for breeding strategy over time.

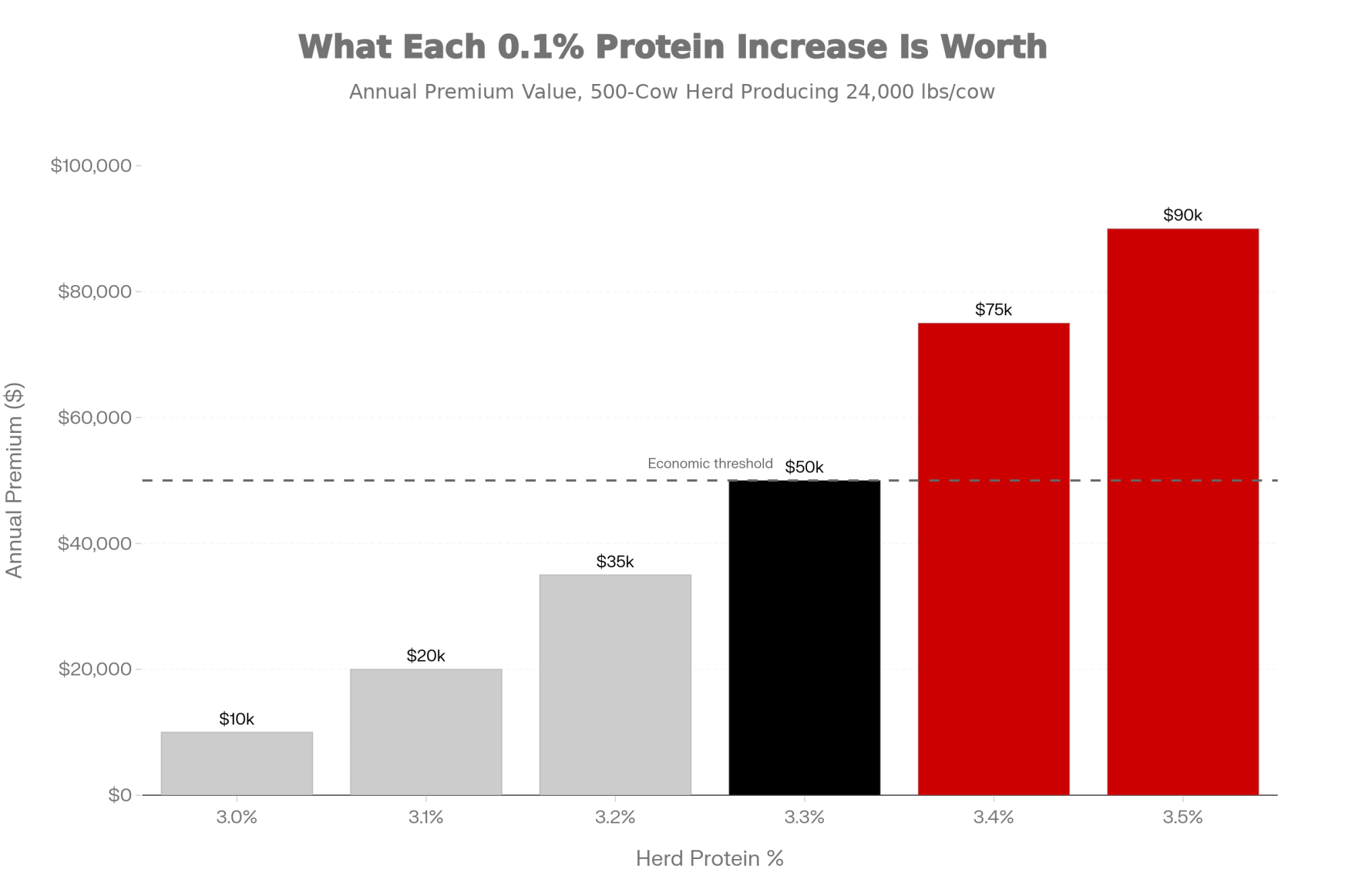

Let me put some illustrative numbers on it, using late 2025 component price relationships as a guide.

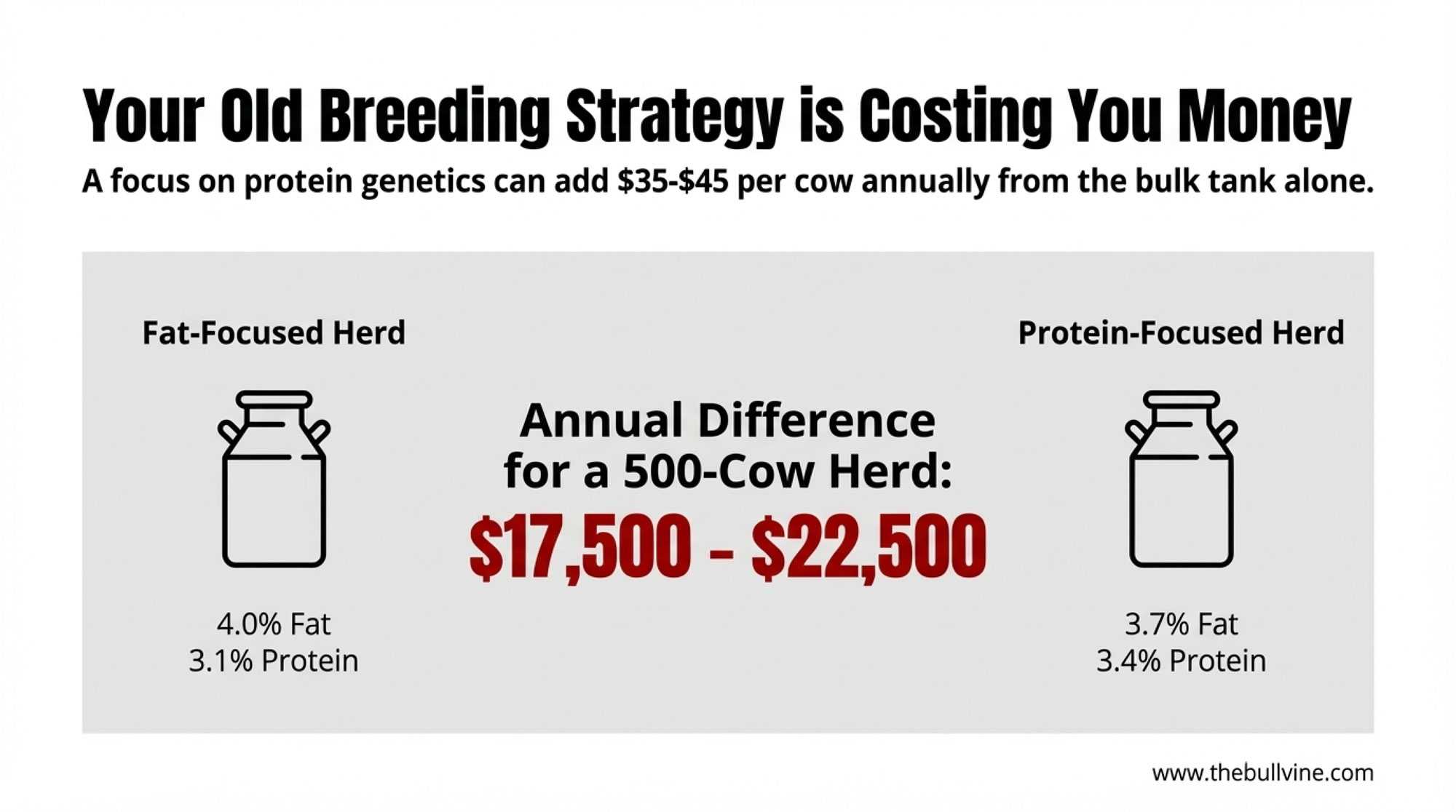

Consider a 500-cow operation producing 24,000 pounds per cow annually. If you compare a fat-focused breeding approach averaging 4.0% fat and 3.1% protein against a protein-focused approach averaging 3.7% fat and 3.4% protein, the difference in total component value can run $35 to $45 per cow annually from the bulk tank alone (these figures shift as component prices move, but the general principle holds when protein maintains its current premium over fat). For that 500-cow herd, you’re looking at roughly $17,500 to $22,500 in annual difference from genetics alone.

That’s before considering processor premiums that cheese and ingredient plants often pay for high-protein milk. Factor those in, and the opportunity can be larger still.

I want to be measured here. I’m not suggesting everyone immediately overhaul their breeding strategy. What I am suggesting is that this ratio deserves more attention than most producers have been giving it.

The Federal Order Update

Another dimension affects how money flows through the pricing system.

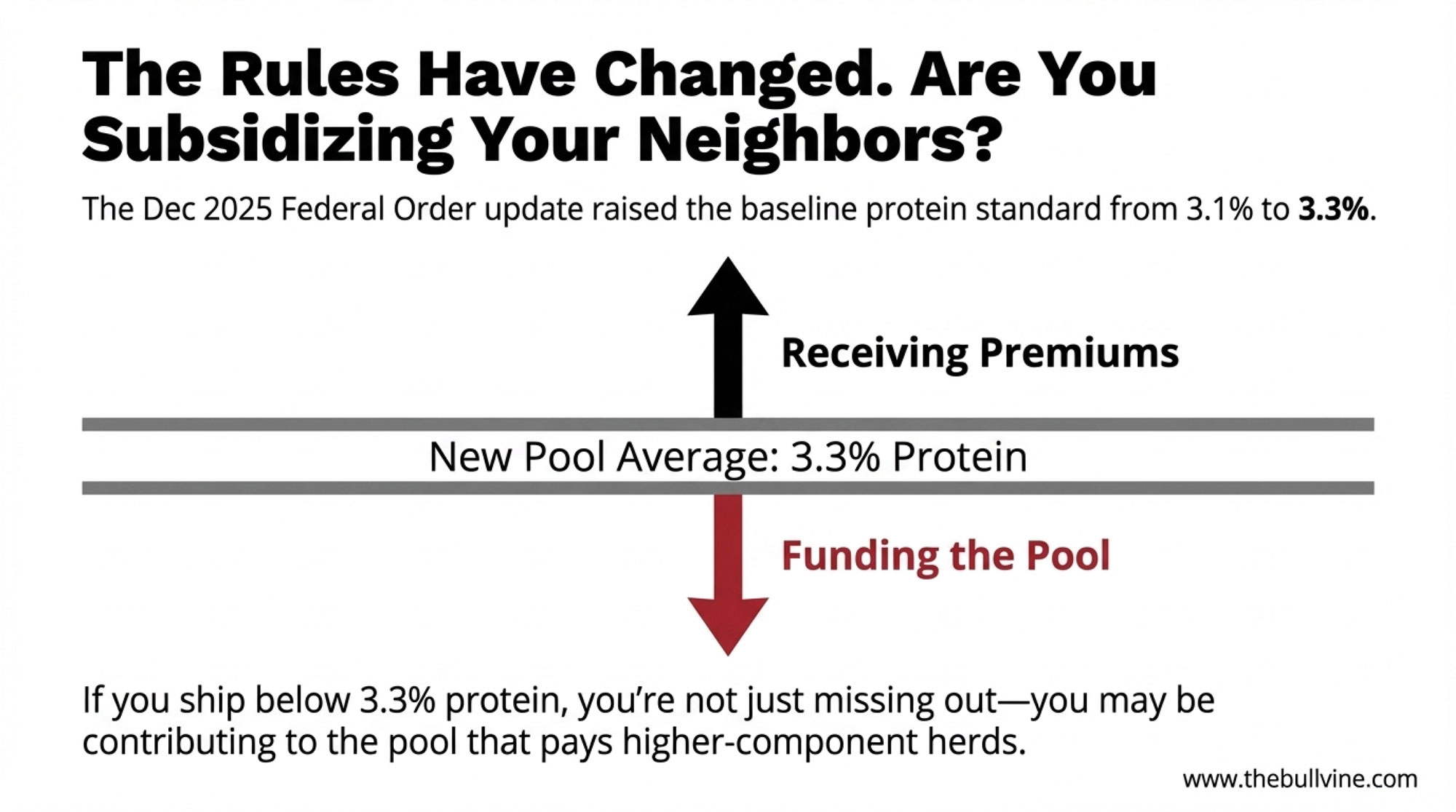

The June 2025 updates to Federal Milk Marketing Order formulas—finalized by USDA in January 2025 after the producer referendum—adjusted baseline composition factors to reflect current herd averages. According to the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service final rule, protein moved from 3.1% to 3.3%, other solids from 5.9% to 6.0%, and nonfat solids from 9.0% to 9.3%. The composition factor updates became effective December 1, 2025.

Why does this matter practically? Processors now assume your milk contains 3.3% protein as the baseline. If you’re consistently shipping 3.0% or 3.1%, you’re not just missing premiums—you may be contributing to the pool that pays premiums to higher-component herds.

I’ve spoken with producers who didn’t fully grasp this dynamic at first. They knew their components were “a little below average” but figured it wasn’t significant. When we worked through their position relative to the pool, they were surprised to see how much value was being transferred out of their operation each month.

The system isn’t unfair—it’s designed to reward quality. But you need to understand where you stand within it.

Genetic Strategies Worth Considering

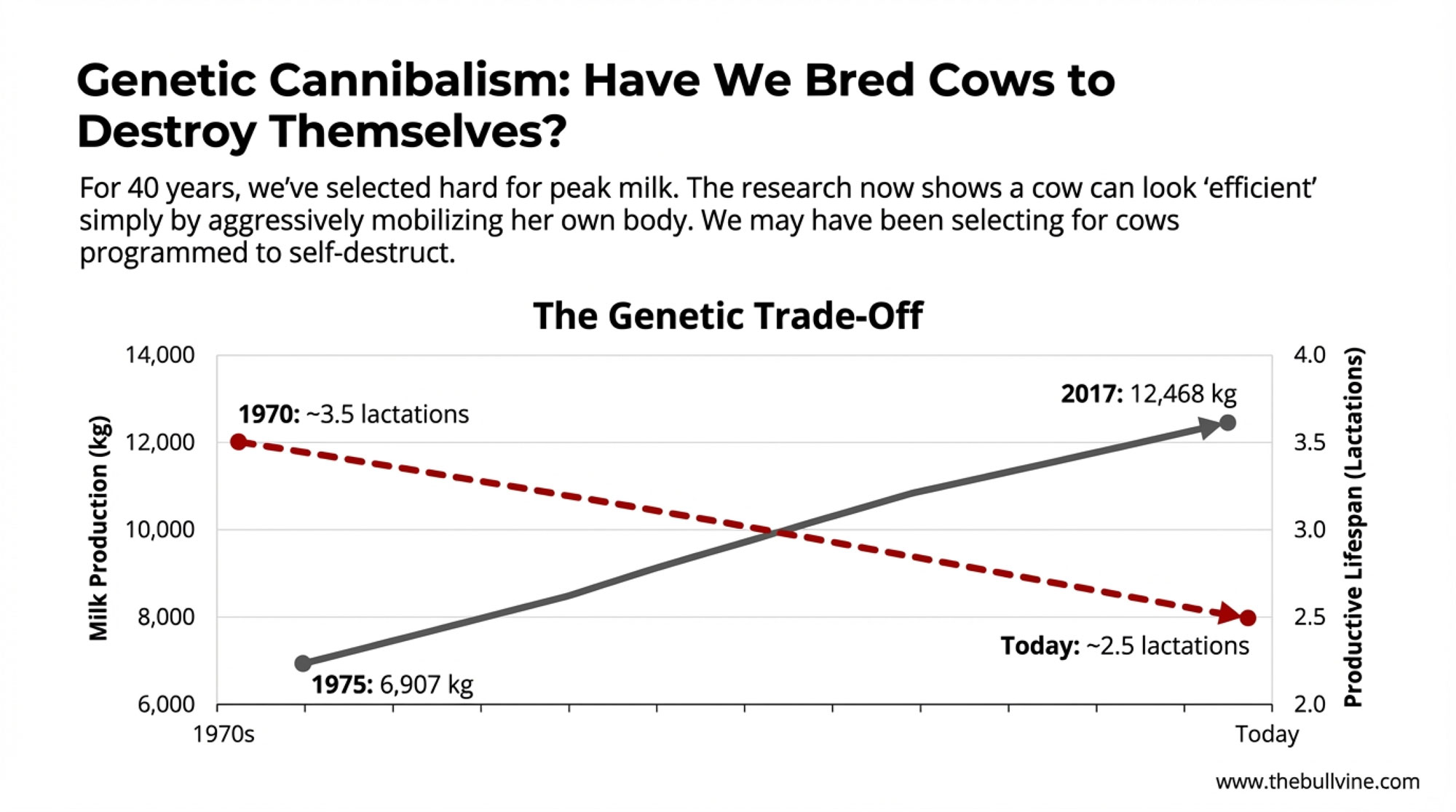

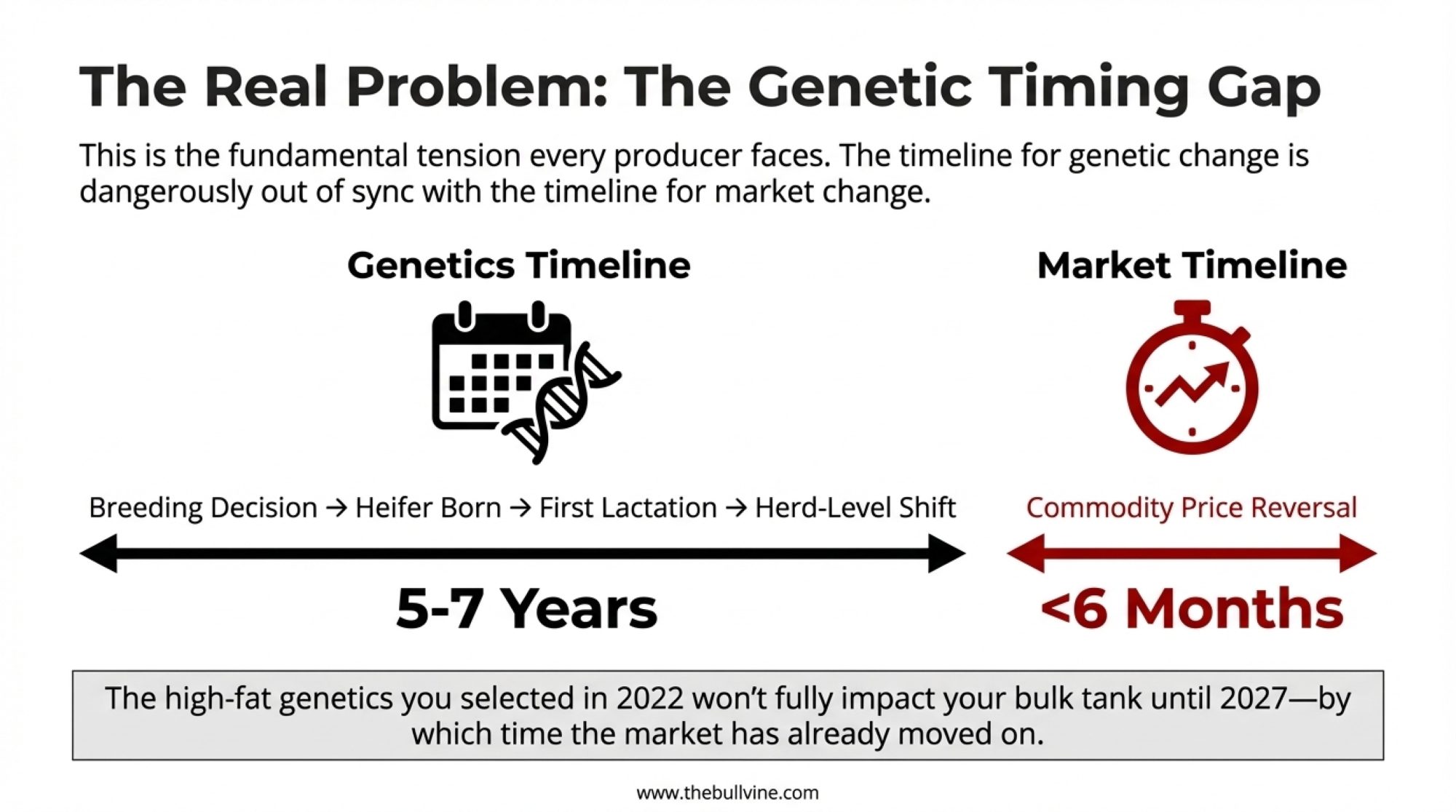

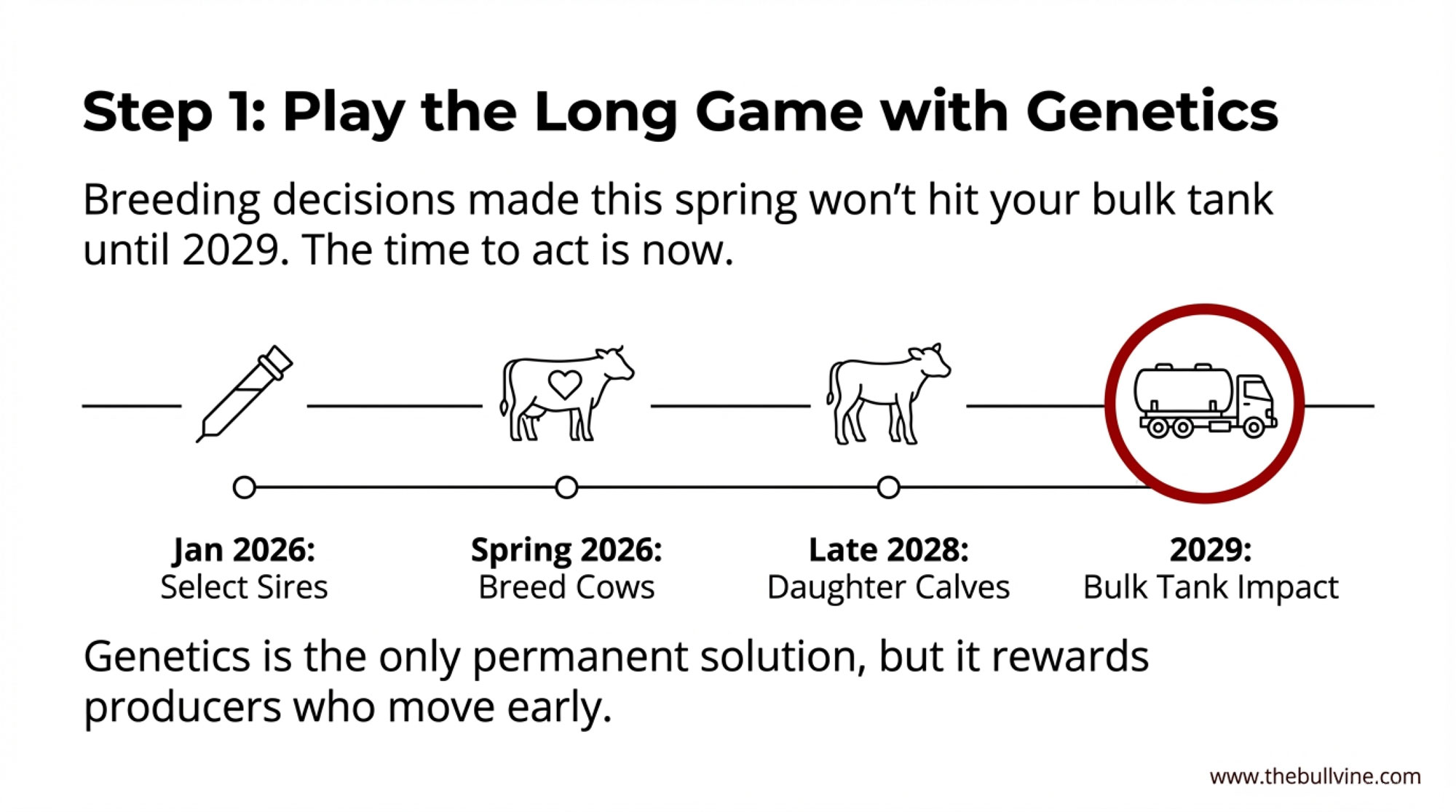

For operations looking to improve protein production, genetic selection offers the most durable path forward. The challenge, as we all know, is that results take time to show up in the bulk tank.

The timeline reality looks something like this:

From Breeding Decision to Bulk Tank Impact

- Select high-protein sires (January 2026) → Semen in tank

- Breed cows (Spring 2026) → Conception

- Gestation (Spring 2026 – Winter 2027) → Calf born

- Heifer development (2027 – 2028) → Growing replacement

- First calving (Late 2028) → Enters milking string

- First full lactation data (2029) → Bulk tank impact measurable

| Phase | Timing | Months from Decision |

|---|---|---|

| Sire Selection | January 2026 | 0 |

| Breeding/Conception | Spring 2026 | 3–6 |

| Gestation | Spring 2026 – Winter 2027 | 12–15 |

| Heifer Development | 2027 – 2028 | 24–30 |

| First Calving | Late 2028 | 33–36 |

| Measurable Bulk Tank Impact | 2029 | 36–48 |

If you breed a cow this spring, her daughter won’t enter the milking string until late 2028 at the earliest. That’s just the biology. So breeding decisions you make in the next few months will shape your herd’s component profile three to five years from now.

| Metric | Fat-Focused Strategy | Protein-Focused Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Avg Fat % | 4.0% | 3.7% |

| Avg Protein % | 3.1% | 3.4% |

| Component Value/Cow/Year | $1,245 | $1,290 |

| Processor Premium/Cow/Year | $0 | $120 |

| Total Annual Herd Revenue (500 cows) | $622,500 | $705,000 |

| Revenue Advantage | — | +$82,500 |

This is why genetics is a long game—but it’s also the only permanent solution. Nutrition can help capture more of your genetic potential today, but it can’t exceed what the genetics allow.

One development that’s accelerating this timeline for some operations: genomic testing. If you’re testing heifers at a few months of age, you can identify your high-protein genetics earlier and make culling decisions before investing in two years of development costs. It doesn’t change the biological timeline, but it does let you be more selective about which animals you’re developing in the first place.

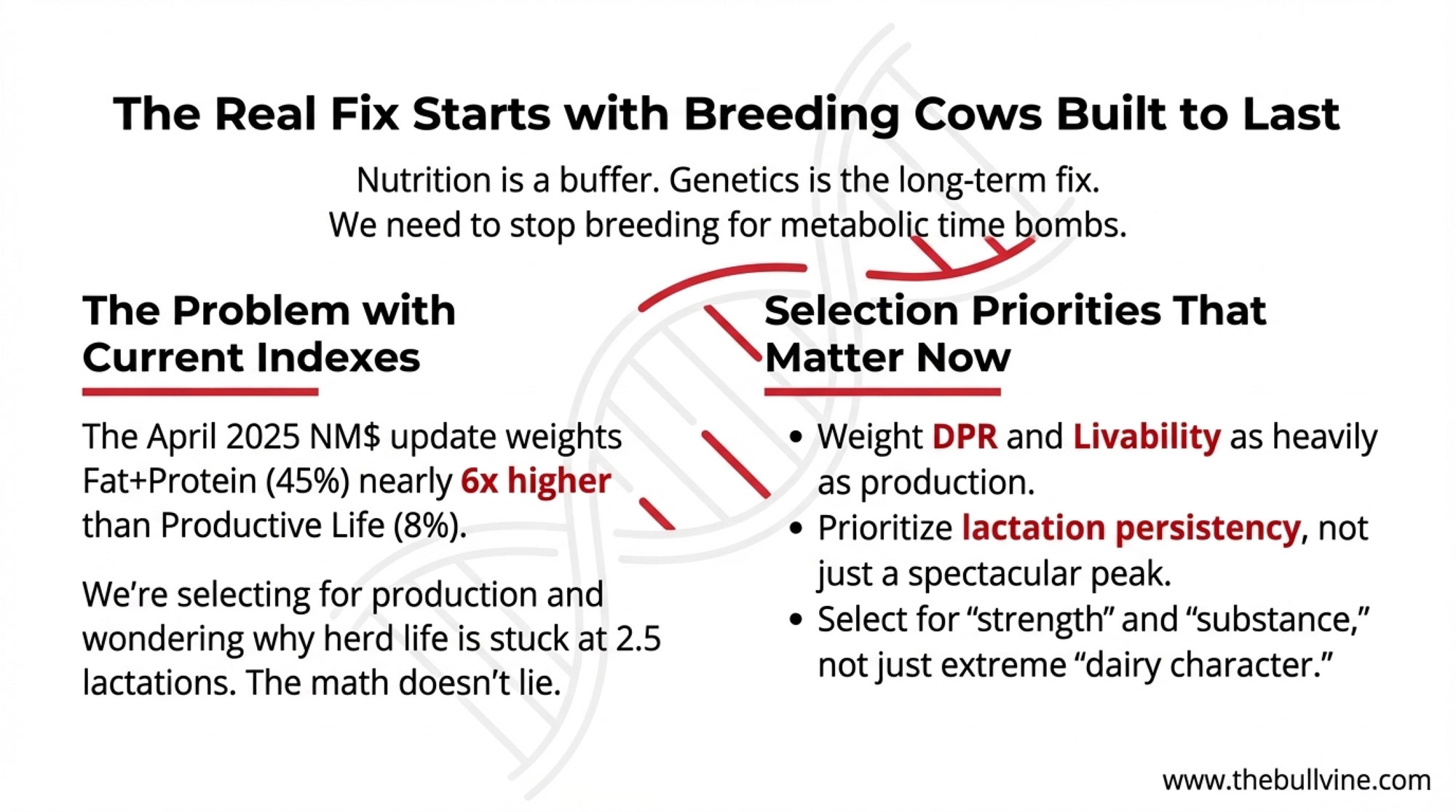

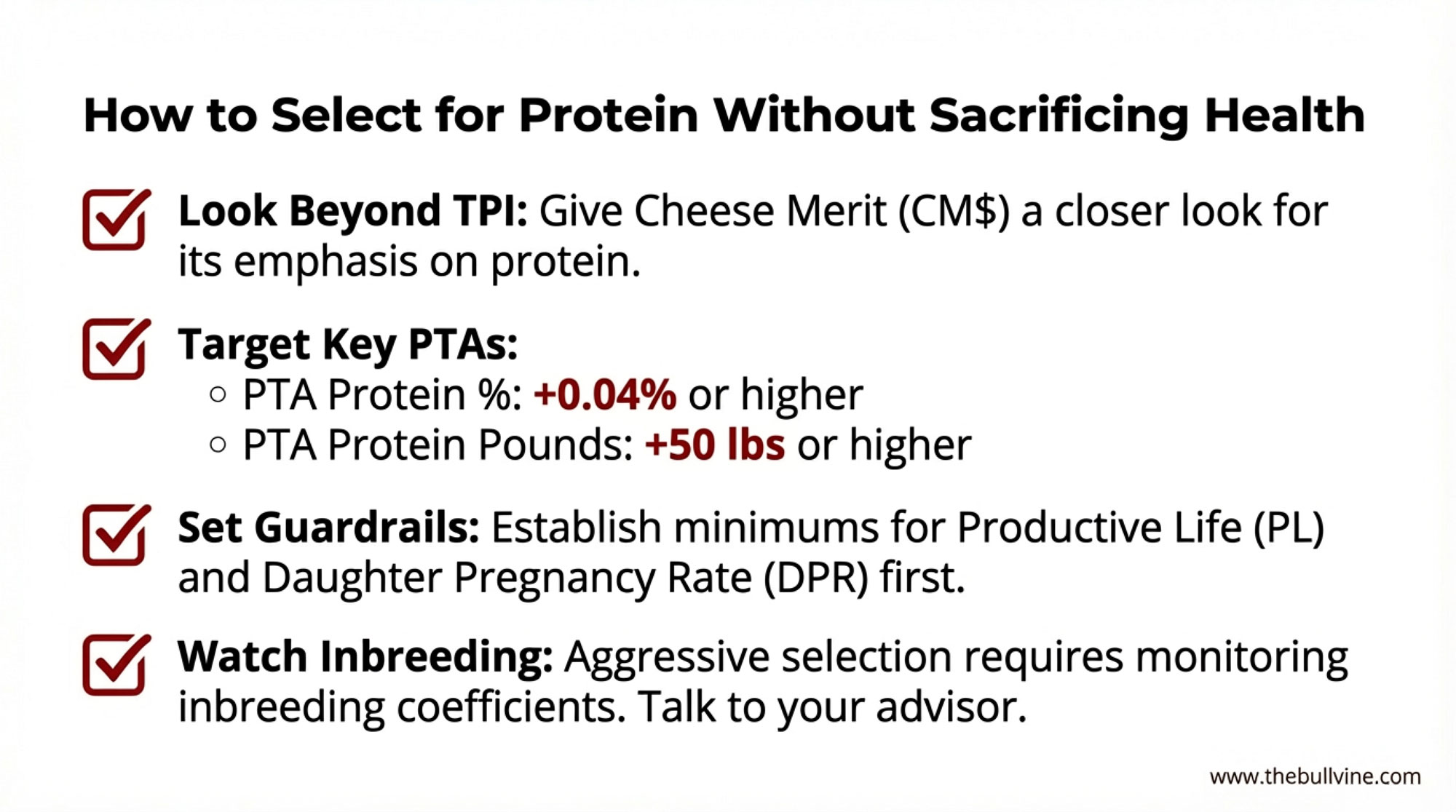

Selection Index Considerations

Most producers default to Total Performance Index (TPI) when evaluating Holstein sires, and it remains useful for balanced selection. But if protein improvement is a specific priority, Cheese Merit (CM$) rankings warrant closer scrutiny.

| Trait Category | Minimum Threshold | Protein-Focused Target | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTA Protein % | +0.03% | +0.04% to +0.06% | Improves concentration—the key to premiums |

| PTA Protein Pounds | +40 lbs | +50 lbs or higher | Ensures volume doesn’t drop as % increases |

| PTA Fat % | No minimum | +0.01% to +0.03% | Hedges against protein premium narrowing |

| Productive Life (PL) | +2.0 | +3.0 or higher | Cows must last long enough to justify investment |

| Daughter Pregnancy Rate (DPR) | +0.5 | +1.0 or higher | Poor fertility destroys genetic progress |

| Somatic Cell Score (SCS) | 2.90 or lower | 2.85 or lower | High SCC kills premiums faster than low protein |

| Inbreeding Coefficient | — | Monitor: keep below 6.25% | Aggressive protein selection can concentrate genes |

| Selection Index | — | Use CM$ or updated NM$ | Better protein weighting than traditional TPI |

CM$ places greater emphasis on protein per pound and protein percentage than TPI does. It was designed for operations shipping to cheese plants, where protein drives vat yield. The updated Net Merit (NM$) formula has also adjusted component weightings in recent years to reflect market realities.

General Thresholds to Consider

When evaluating individual sires for protein improvement, what many nutritionists and AI representatives suggest—keeping in mind these are general guidelines, not hard rules:

- PTA Protein %: Bulls at +0.04% or higher are generally considered strong for protein concentration. Bulls above +0.06% are moving the needle meaningfully.

- PTA Protein Pounds: Targeting +50 lbs or higher helps maintain total protein production while improving percentage.

- Combined approach: The ideal sires show positive values in both categories. Bulls that improve percentage by diluting volume aren’t actually helping you.

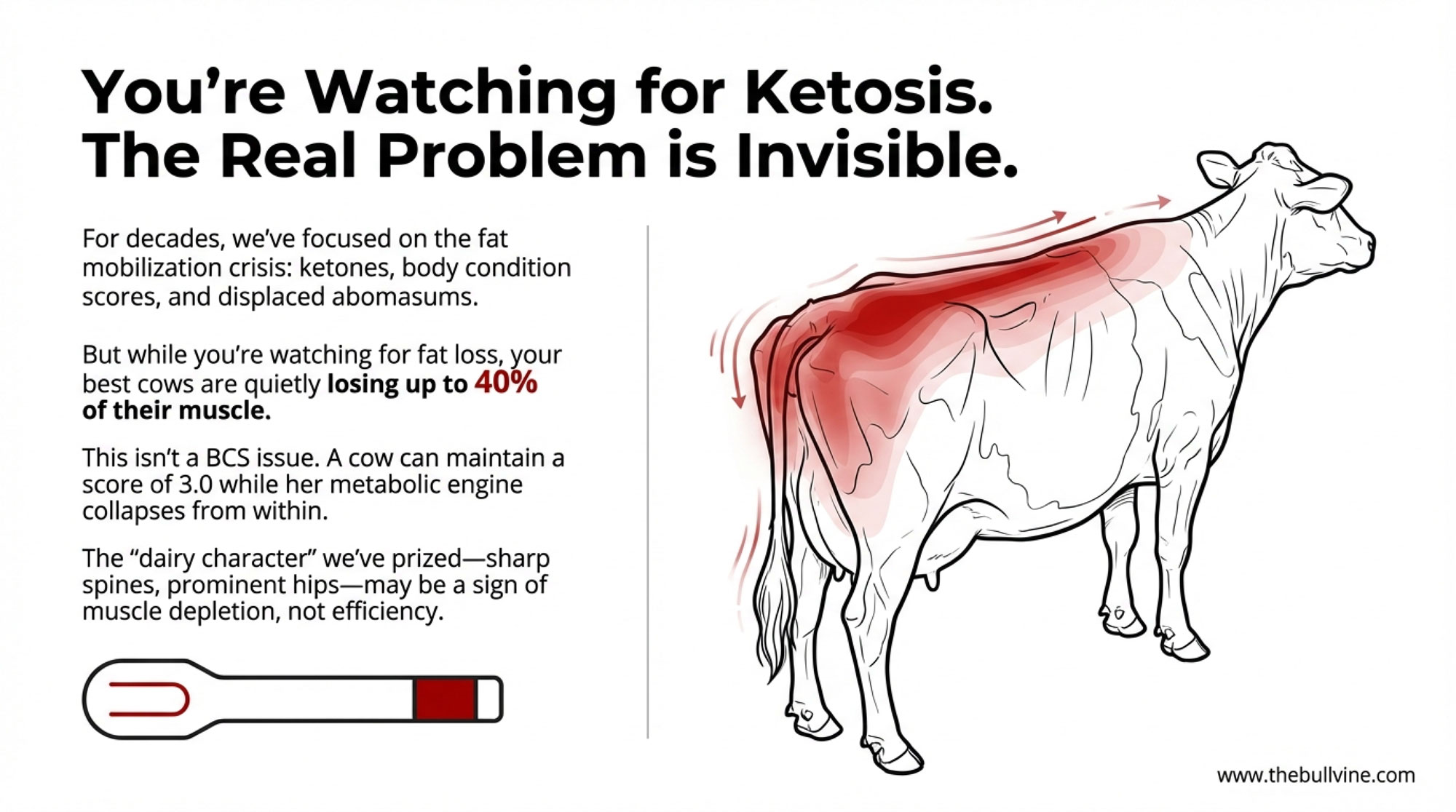

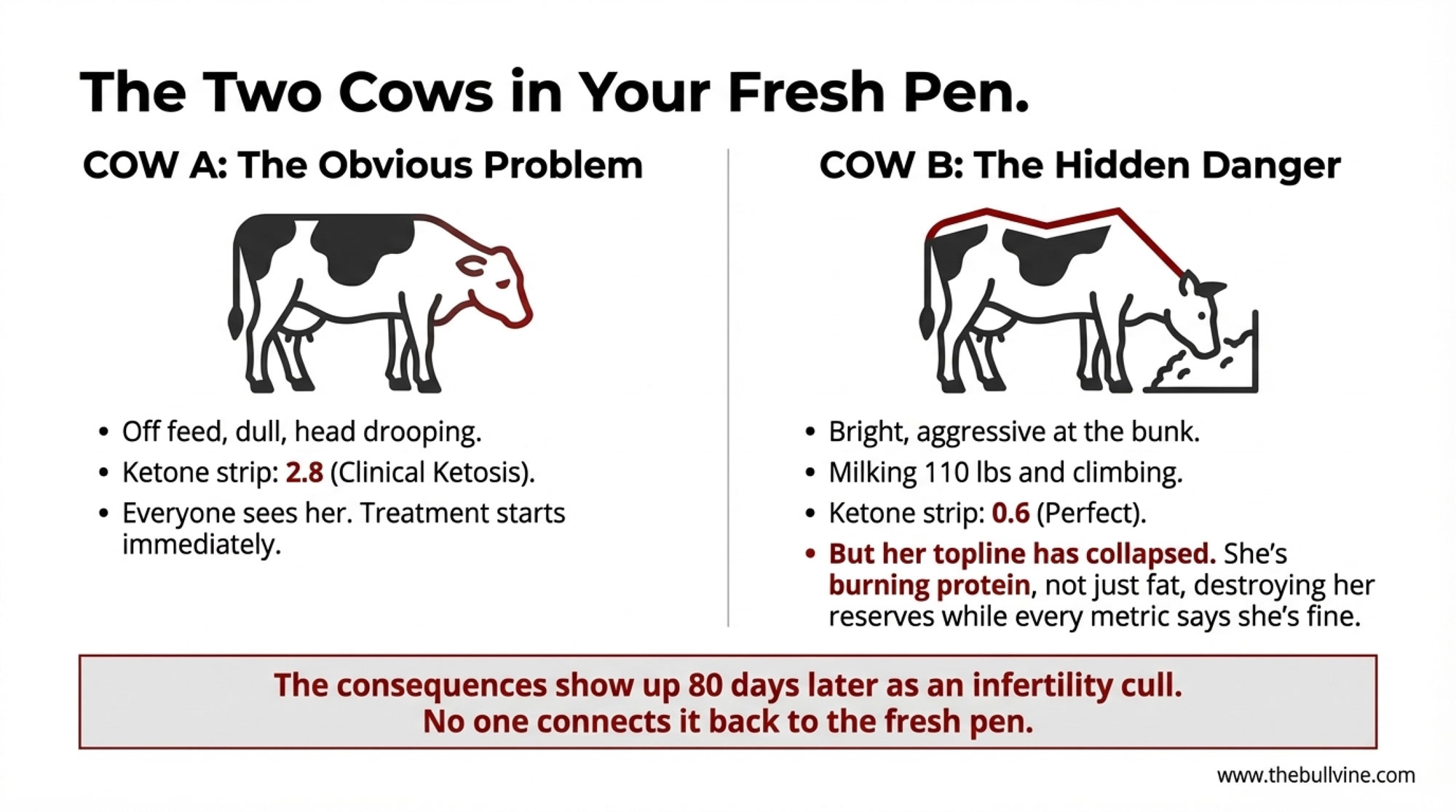

One important caution: don’t chase protein so aggressively that you sacrifice health and fertility traits. A cow that burns out after 1.8 lactations isn’t profitable regardless of her component profile. Setting minimum thresholds for Productive Life and Daughter Pregnancy Rate before optimizing for components makes sense. Talk with your AI rep about what fits your specific situation.

| Intervention Strategy | Low Estimate | High Estimate | Timeline to Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition Optimization (amino acid balancing) | $8,750 | $15,000 | 2–4 weeks |

| Genetic Improvement (protein-focused sires) | $17,500 | $22,500 | 3–5 years |

| Processor Premiums (high-protein milk) | $24,000 | $60,000 | Immediate (if available) |

| TOTAL ANNUAL OPPORTUNITY | $50,250 | $97,500 | Varies by strategy |

A Note on Inbreeding

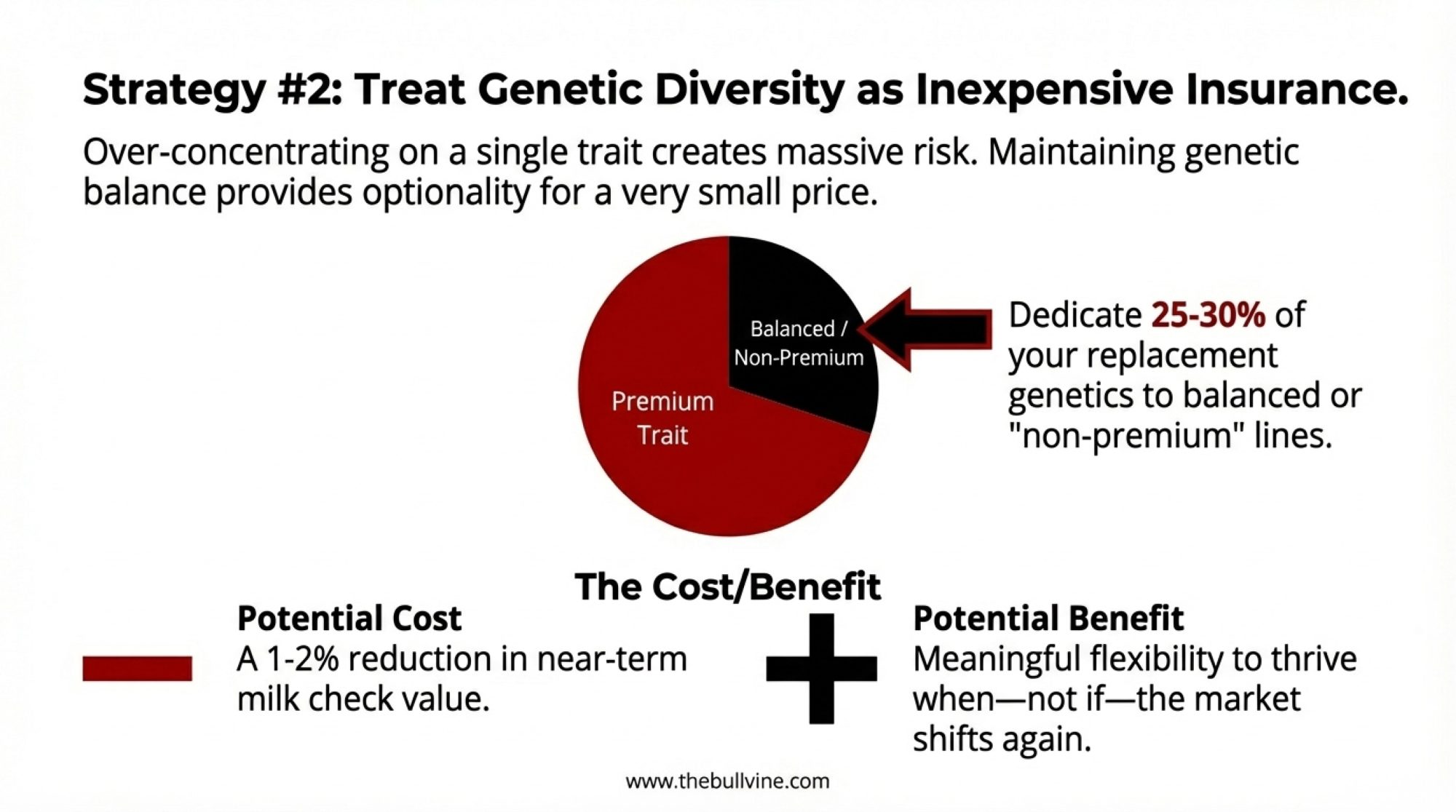

Another consideration doesn’t get discussed enough: selecting heavily for narrow trait clusters can accelerate inbreeding. Pennsylvania State University’s Dr. Chad Dechow, who has extensively studied genetic diversity in Holsteins, notes that intense selection for specific traits can accelerate genetic concentration faster than many producers realize—as he’s put it, “if it works, it’s line breeding; if it doesn’t, it’s inbreeding.” Research published in Frontiers in Animal Science found that selection for homozygosity at specific loci (like A2 protein) significantly increased inbreeding both across the genome and regionally. The takeaway: if you’re selecting aggressively for protein traits, monitor inbreeding coefficients and work with your genetic advisor to maintain adequate diversity in your sire lineup.

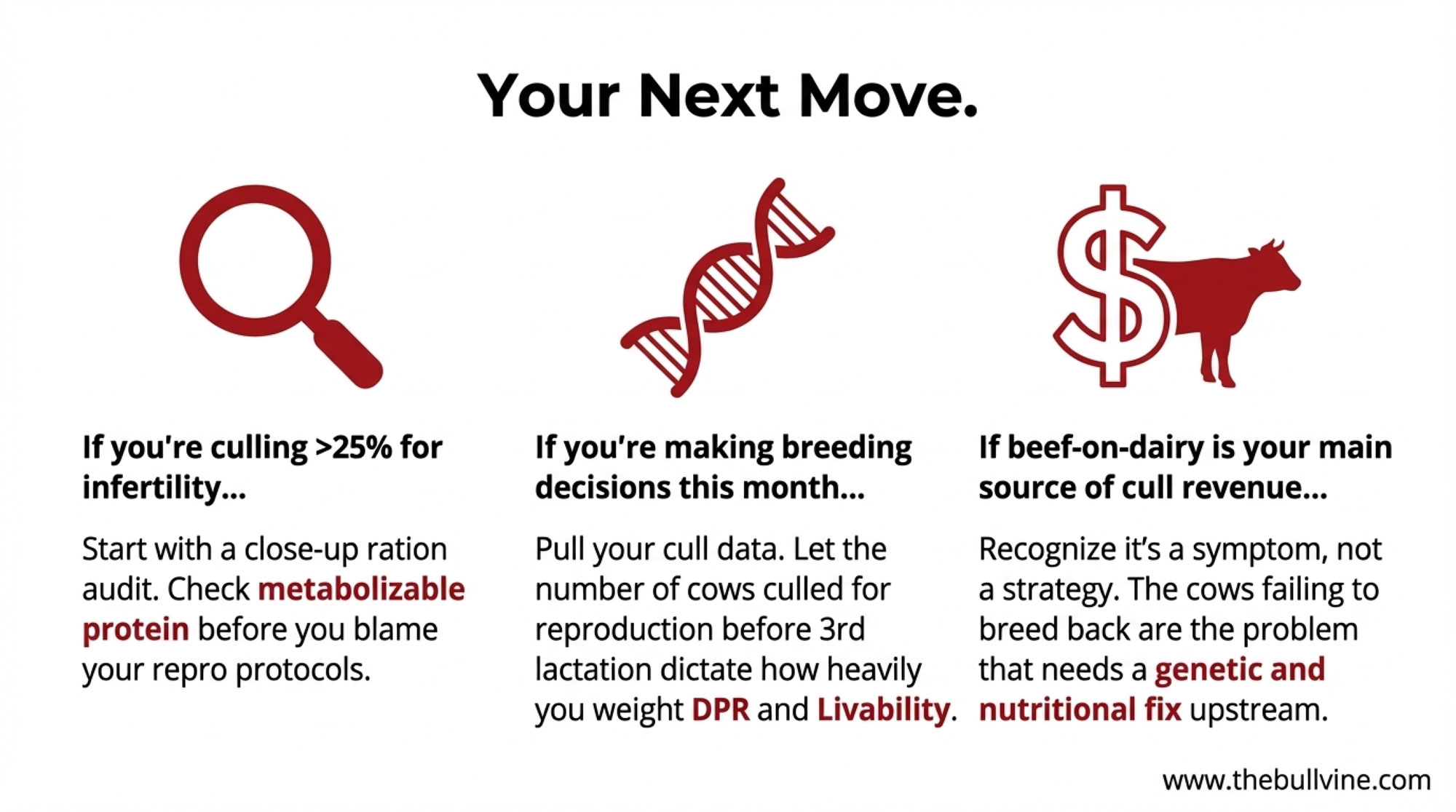

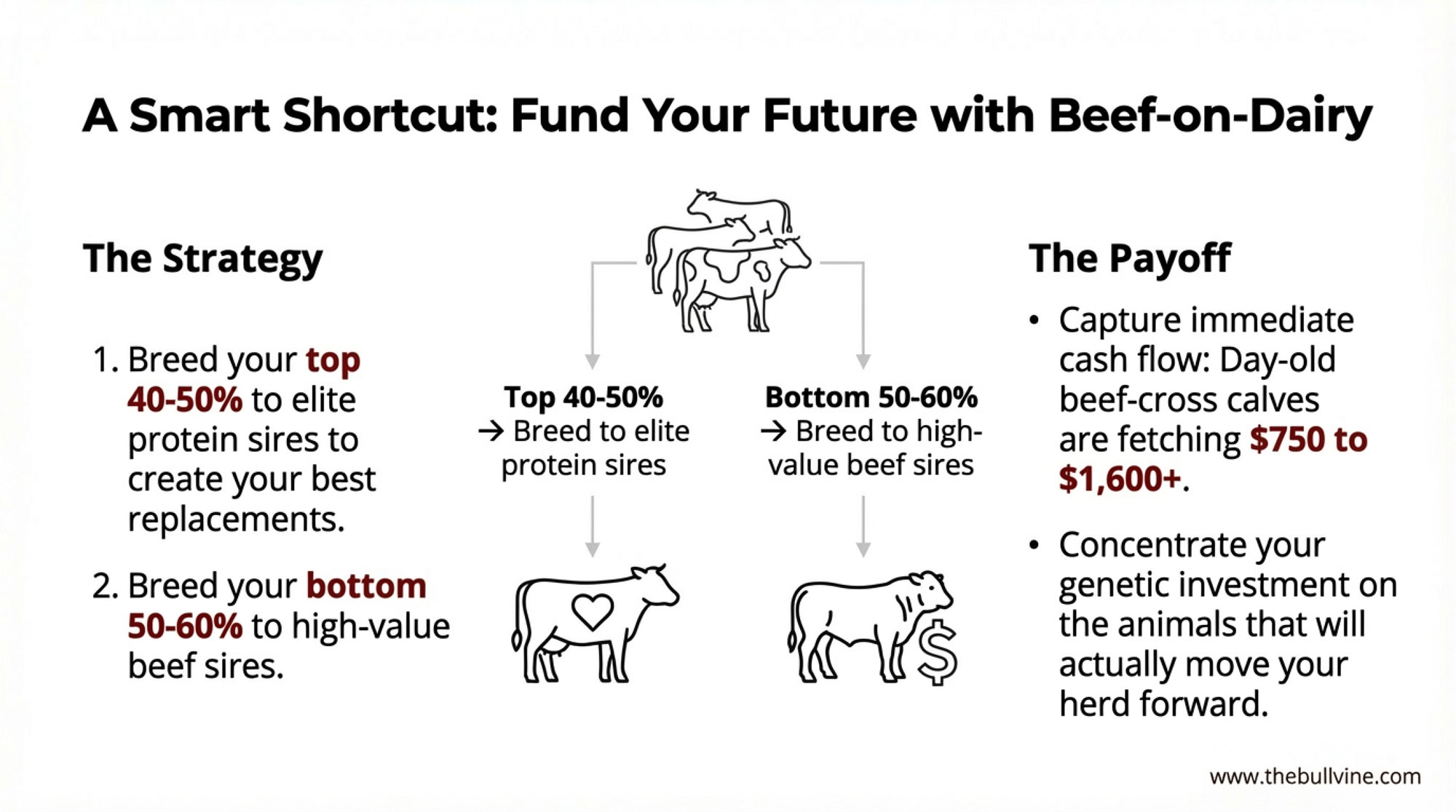

The Beef-on-Dairy Angle

There’s strategic flexibility that comes with the current beef market. Beef-on-dairy calves have been commanding strong prices—industry reports from late 2025 show day-old beef-cross calves going for $750 to over $1,000 in many markets, with well-bred calves sometimes topping $1,600 depending on genetics and condition. Dairy Herd Management reported in August 2025 that Jersey beef-on-dairy calves were fetching $750 to $900 at day of birth, with the market remaining robust through the fall.

Some producers are using this strategically: breed your top 40-50% of the herd to high-protein dairy sires for replacements, and use beef semen on the bottom half. You capture immediate cash flow from beef calves while concentrating genetic improvement on animals that will actually move the herd forward.

A California producer I spoke with recently has been doing exactly this for three years. “It changed my whole approach to replacement decisions,” she said. “I’m more selective about which genetics I’m actually keeping in the herd, and the beef calves are paying their own way.”

It’s not the right approach for every operation, but it’s worth thinking through.

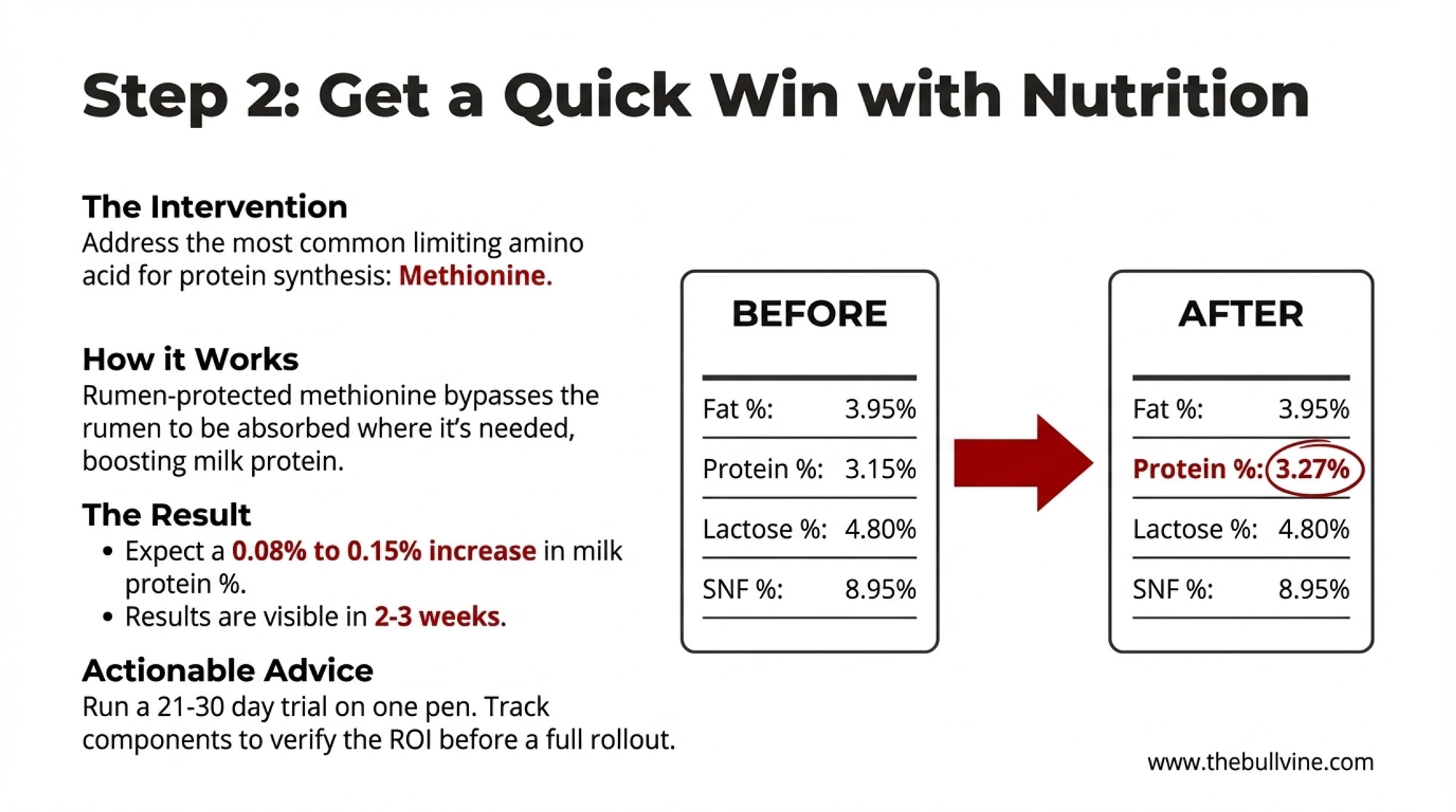

The Nutrition Bridge

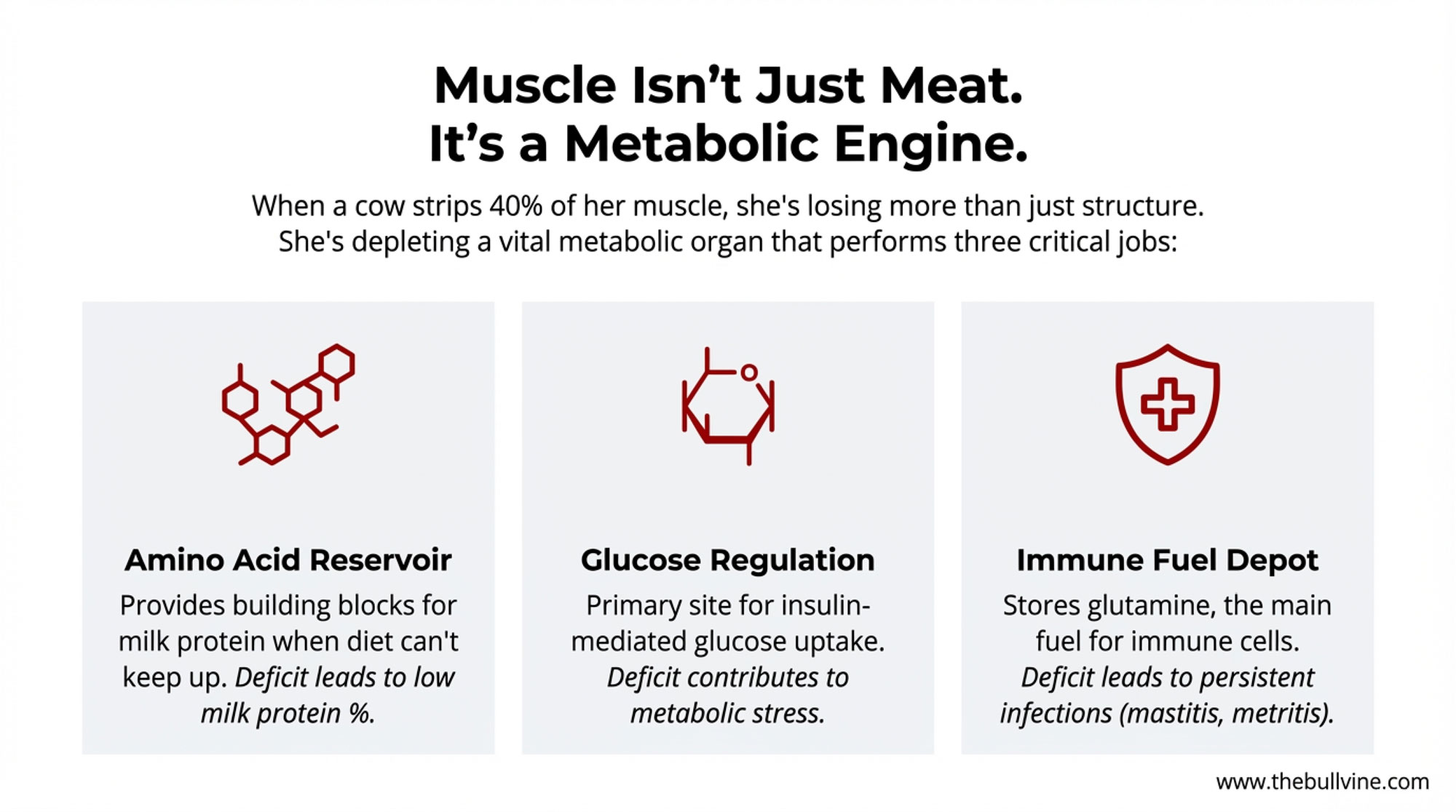

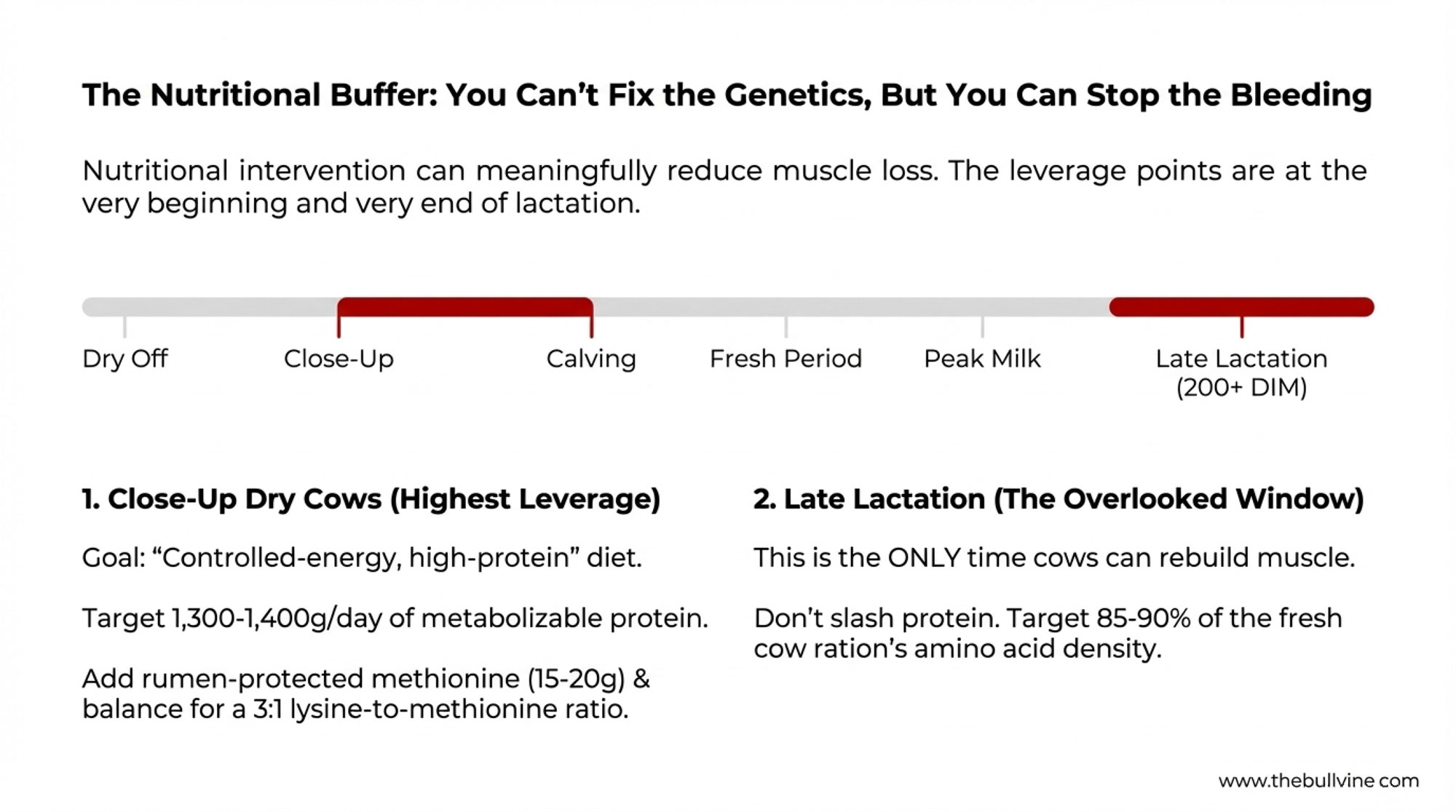

Genetics determine the ceiling for what your cows can produce. Nutrition determines how close you get to that ceiling. And unlike genetics, nutrition interventions can show results within weeks.

The most targeted intervention for protein production involves amino acid supplementation—specifically rumen-protected methionine.

The background: in typical U.S. dairy diets built around corn silage and soybean meal, methionine often becomes the limiting amino acid for milk protein synthesis. You can feed all the crude protein you want, but if the cow runs short on methionine, she can’t efficiently convert it to milk protein. The excess nitrogen gets excreted.

Rumen-protected forms of methionine—coated to survive rumen degradation—allow the amino acid to reach the small intestine, where absorption actually happens.

What the Research Shows

University trials—including work from Cornell, Penn State, and Wisconsin dairy extension programs—have demonstrated that rumen-protected methionine can boost milk protein percentage, often by 0.08% to 0.15% within 2 to 3 weeks of implementation. Results vary by herd and baseline diet, so verifying response on your own operation before committing fully makes sense.

Run a trial with one pen of mid-lactation cows for 21-30 days. Compare their component tests to a control group or their own pre-trial baseline. Work with your nutritionist on the economics—supplement costs, expected response, and whether it pencils at current protein prices. If you’re seeing the expected response, roll it out more broadly. If not, you haven’t invested much to find out.

One thing I’ve noticed, talking with nutritionists across the Midwest and Northeast, is that the response tends to be most consistent in herds that haven’t previously optimized their amino acid balance. If you’ve already been balancing for methionine and lysine, the incremental gain may be smaller. Fresh cows and early-lactation groups often show the most dramatic response, since that’s when protein synthesis is competing most with other metabolic demands during the critical transition period.

For a 500-cow herd seeing a 0.10-0.12% protein increase, that can translate to $8,750 to $15,000 annually in additional component value at current prices—often exceeding the supplement cost by a meaningful margin.

An additional benefit: because you’ve addressed the limiting amino acid, you may be able to reduce total ration crude protein slightly without sacrificing production. That can offset some or all of the supplement cost.

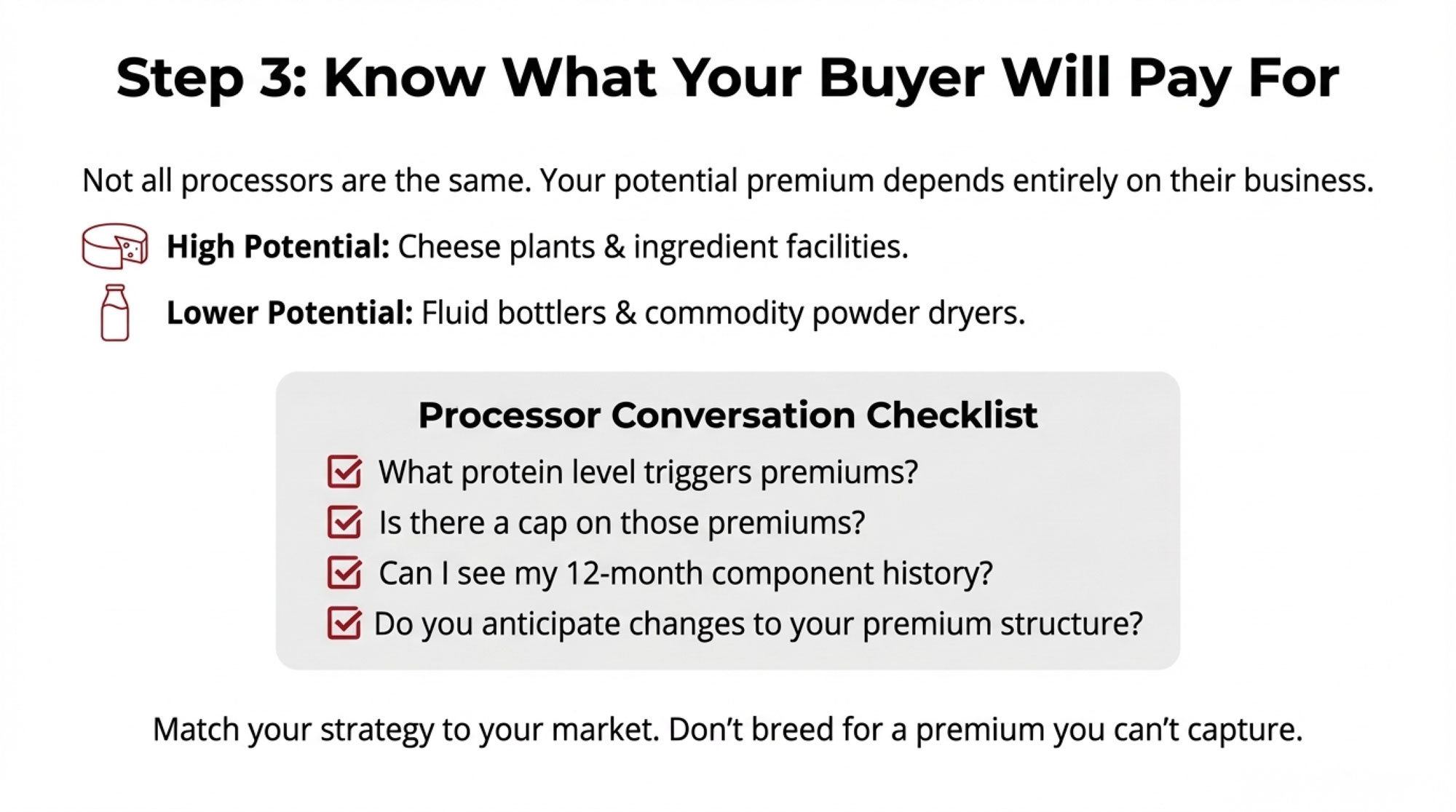

Processor Relationships

This dimension deserves more attention than it typically gets.

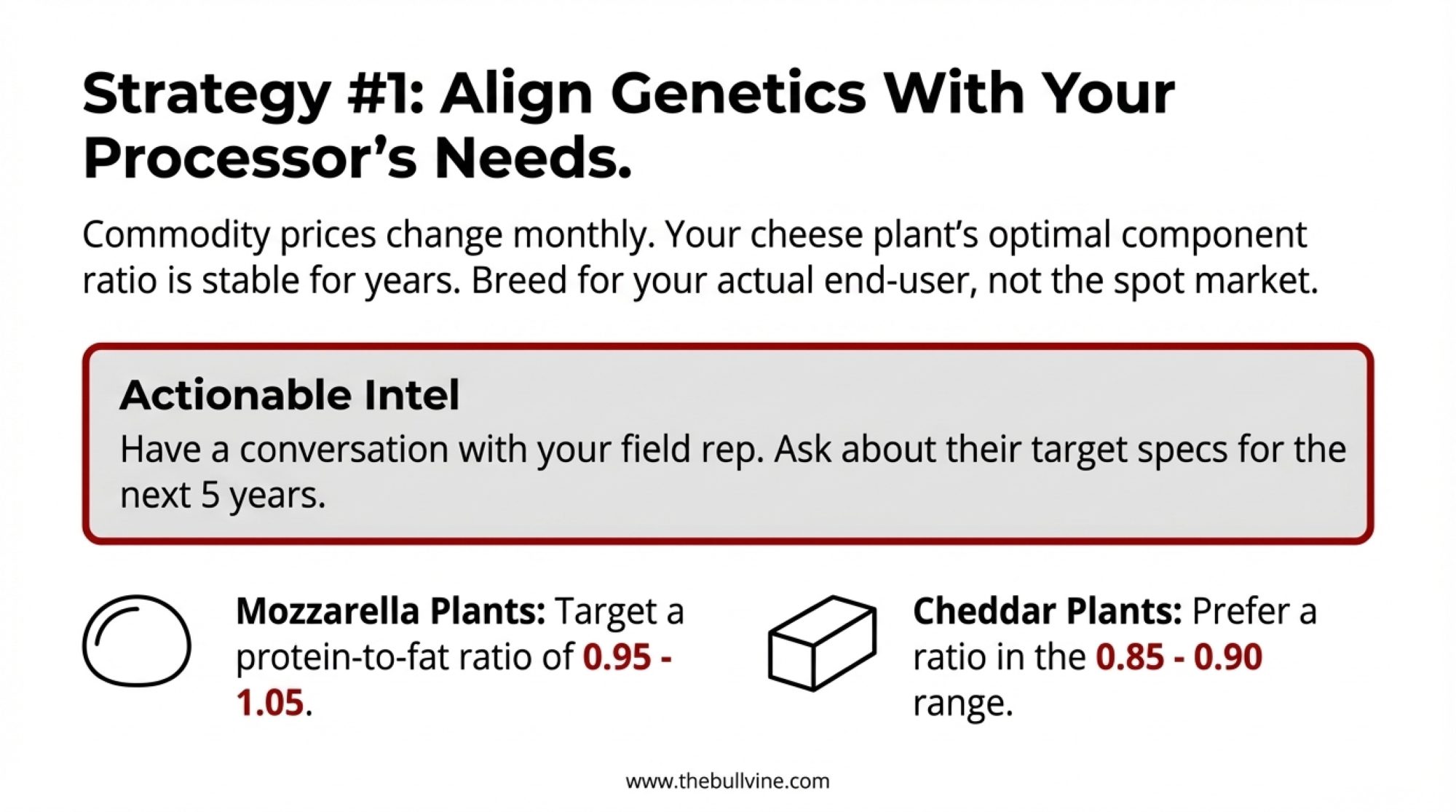

Not all processing facilities are equally equipped to capture the value of high-protein milk. Before making significant changes to your breeding program, it’s essential to understand what your buyer can actually afford.

Cheese plants—particularly the large cooperative facilities across Wisconsin’s cheese belt and specialty operations in California’s Central Valley—are generally the most straightforward. Higher protein concentration means more cheese per gallon processed. A plant can increase output without expanding capacity simply by sourcing higher-protein milk. Clear economic incentive exists to pay for it.

| Processor Type | Protein Threshold | Premium per CWT | Annual Value (500 cows) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity Powder Plant | No premium | $0.00 | $0 |

| Regional Cheese Co-op | 3.3% | $0.50–$0.75 | $60,000–$90,000 |

| Large Cheese Facility (WI) | 3.3% | $1.00–$1.50 | $120,000–$180,000 |

| Specialty Protein Plant | 3.35% | $2.00–$3.00 | $240,000–$360,000 |

| Direct Contract (High-volume) | 3.4% | $3.00–$5.00 | $360,000–$600,000 |

Cheese plant managers I’ve spoken with confirm they’re actively seeking higher-protein milk supplies. One plant manager in central Wisconsin told me their facility has increased protein premiums twice in the past eighteen months, specifically to attract higher-component milk. “We’re competing for that milk now,” he said. “Five years ago, we weren’t having that conversation.”

What Premiums Actually Look Like

Processor premiums vary considerably by region and facility, but here’s what the market data shows: USDA Dairy Market News reports the average protein premium is around $1.25 per hundredweight above baseline. Some producers shipping to cheese-focused cooperatives report premiums in the $0.50 to $0.75/cwt range for modest improvements, while direct contracts with protein-hungry facilities can reach $3.00 to $5.00/cwt for milk consistently testing above 3.35% protein—though these premium contracts typically require volume commitments and consistent quality.

For a 500-cow herd producing 120,000 cwt annually, even a $0.50/cwt premium adds $60,000 to the annual milk check. At $1.00/cwt, that’s $120,000. The math quickly draws producers’ attention.

Ingredient and filtration plants making whey protein concentrates, milk protein isolates, and similar products also value protein highly. Operations in Idaho and across the West are specifically tooled to extract and monetize protein fractions. These facilities serve the growing functional nutrition market, including products for GLP-1 users.

Fluid milk bottlers and commodity powder dryers may have less ability to monetize elevated protein. If a bottler standardizing for the Southeast fluid market is already adjusting milk to regulatory specifications, excess protein beyond those specs doesn’t necessarily yield premium returns.

PROCESSOR CONVERSATION CHECKLIST

Download and bring to your next meeting with your milk buyer:

☐ Premium Structure

- “What protein threshold triggers premium payments?”

- “Is there a cap on protein premiums, or do they scale continuously?”

- “How is the premium calculated—per point above threshold, or tiered brackets?”

☐ Testing & Verification

- “How frequently is my milk tested for components?”

- “Can I access my component test history for the past 12 months?”

☐ Plant Capabilities

- “Does your plant have protein standardization capability?”

- “What’s your target protein level for incoming milk?”

☐ Market Trends

- “Are you seeing increased demand for high-protein products from your customers?”

- “Do you anticipate changes to your premium structure in the next 12-24 months?”

☐ Contract Options

- “Are direct premium contracts available for consistent high-protein suppliers?”

- “What volume and consistency requirements would apply?”

Keep notes from this conversation—the answers should inform your breeding and nutrition decisions.

The answers might influence how aggressively you pursue protein genetics. If your buyer caps premiums at 3.3%, there is less incentive to push for 3.5%. If they’re paying meaningful premiums with no cap because they’re expanding ingredient production, that’s entirely different information.

A Decision Framework

Given this complexity, a framework for thinking through whether an aggressive protein pivot makes sense:

Consider aggressive protein focus if:

- You ship to a cheese plant or ingredient facility

- Your current herd averages below 3.25% protein

- Your buyer explicitly pays protein premiums without caps

- You have flexibility in your replacement strategy

- Your herd health metrics are already solid

Consider a balanced approach if:

- You ship to a fluid bottler or a diversified cooperative

- Your herd already averages 3.3%+ protein

- Your buyer caps protein premiums at a specific threshold

- You’re still working on fertility or longevity genetics

- You operate in a region with limited processor options

Consider maintaining the current strategy if:

- Your processor has no protein premium structure

- Switching buyers isn’t practical for your location

- Your herd has significant health or fertility challenges to address first

- You’re already at or above pool averages for both components

There’s no single right answer here. The key is matching your genetic strategy to your actual market circumstances.

| Your Current Situation | Aggressive Protein Focus | Balanced Approach | Maintain Current Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Processor pays protein premiums? | Yes, uncapped or high cap | Yes, but capped at 3.3–3.4% | No premium structure |

| Current herd protein average | Below 3.25% | 3.25–3.35% | Above 3.35% |

| Milk buyer type | Cheese/protein plant | Diversified co-op | Fluid bottler/powder plant |

| Herd health & fertility status | Already solid (DPR >20%) | Some challenges | Significant problems to fix first |

| Ability to switch processors | Yes, within 50 miles | Limited options | Locked into current contract |

| Replacement strategy flexibility | Can use beef-on-dairy | Raising most replacements | Must raise 100% replacements |

| Risk tolerance | Willing to commit 3+ years | Moderate | Conservative |

| RECOMMENDATION | Go aggressive: aim for 3.4–3.5% protein | Incremental improvement: target 3.3–3.4% | Focus on other profit drivers first |

Regional Considerations

This analysis doesn’t apply uniformly across all operations and regions—something worth acknowledging.

Upper Midwest herds shipping to Wisconsin cheese plants are positioned differently than Southeast operations serving fluid markets. A 3,000-cow operation in the San Joaquin Valley faces different economics than a 100-cow farm in Vermont or a grazing dairy in Missouri.

Those shipping to cheese-focused cooperatives in Wisconsin and Minnesota have generally been tracking protein-to-fat ratios more closely—some for several years—and have adjusted breeding programs accordingly. In conversations with producers in these areas, I’ve repeatedly heard that neighbors who were initially skeptical are now asking about sire selections.

But producers in fluid-heavy markets often take a more measured approach. If your buyer can’t pay for high protein, breeding for a premium you can’t capture doesn’t make economic sense. Watching trends while maintaining flexibility is entirely reasonable.

Both perspectives make sense given their circumstances.

The fundamental trends—GLP-1 adoption, component pricing shifts, global protein demand—are real regardless of location. But how you respond depends on your specific situation: current herd genetics, processor relationship, cash flow position, and risk tolerance.

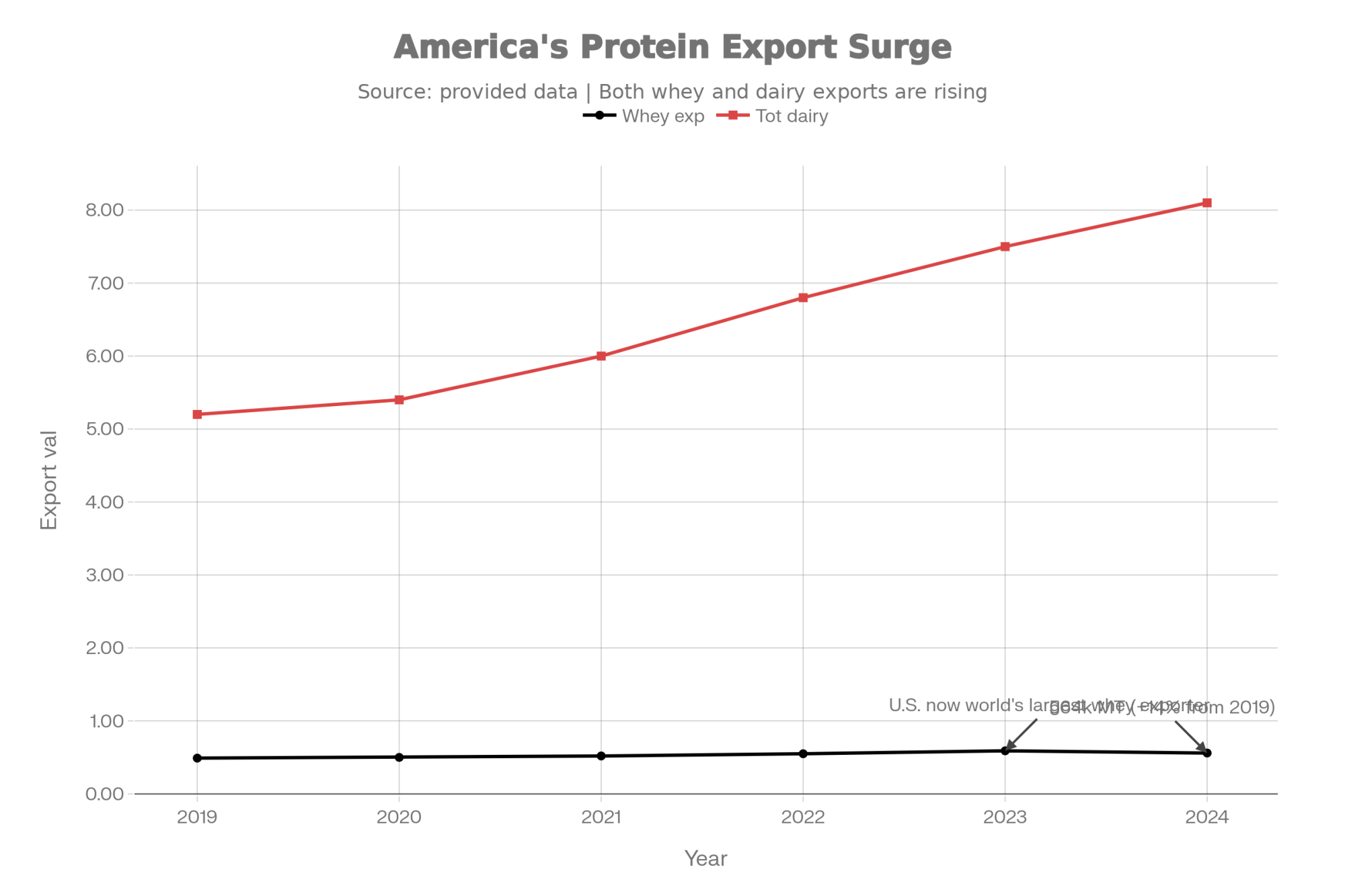

The Global Context: America’s Protein Export Opportunity

What’s happening domestically aligns with broader international patterns—and positions the U.S. dairy industry for a significant strategic shift.

New Zealand’s dairy industry—historically the world’s dominant dairy exporter—has hit production constraints. Environmental regulations capping nitrogen runoff have effectively frozen their national herd. Rather than competing for market share in commodity whole milk powder, they’ve pivoted toward high-value protein products.

According to a 2023 report from DCANZ and Sense Partners, protein products rose from 8.6% to 13.2% of New Zealand’s export mix between 2019 and 2023. DairyNZ reported that protein product exports increased 120% over that period, reaching $3.4 billion. That’s a deliberate strategic shift, not an accident.

Here’s what’s interesting for U.S. producers: we’re no longer just a dairy exporter—we’re increasingly becoming a protein exporter. According to the International Dairy Foods Association, U.S. dairy exports reached $8.2 billion in 2024, the second-highest level ever recorded. That’s a remarkable transformation. As IDFA noted in their February 2025 analysis, “After being a net importer of dairy products a decade ago, the United States now exports $8 billion worth of dairy products to 145 countries.”

The composition of those exports is shifting in telling ways. Brownfield Ag News reported in November 2025 that high-protein whey exports rose nine percent, led by sales to Japan. Farm Progress confirmed in July 2025 that “high-end whey exports continue to grow both in volume and value,” specifically noting that whey protein concentrates and isolates with 80% or more protein are driving the growth. According to the U.S. Dairy Export Council’s reference materials, the United States is now the largest single-country producer and exporter of whey ingredients in the world, with total whey exports reaching 564,000 metric tons in 2023—up 14% from 2019.

The industry is investing, and strong growth prospects have led to $8 billion in new processing plant investments set to increase production over the next two years. By mid-2025, nearly 20 million additional pounds of milk were flowing through new facilities, with much of that capacity focused on cheese—and the whey protein streams that come with it.

This matters for producers because U.S. dairy protein must increasingly meet global specifications. The U.S. Dairy Export Council has been working with the American Dairy Products Institute to develop industry standards for U.S. products and with the International Dairy Federation to develop worldwide technical standards. The National Milk Producers Federation prompted an investigation in 2025—through the U.S. International Trade Commission—into global competitiveness for nonfat milk solids, including milk protein concentrates and isolates.

Why does this matter at the farm level? Asian markets have evolved. China’s domestic milk production has grown, reducing the need for basic powder imports. What they’re purchasing now are specialized high-protein ingredients: lactoferrin for infant formula, protein isolates for clinical nutrition, functional ingredients for the growing urban fitness market.

With New Zealand capacity-constrained and the U.S. investing heavily in protein-processing infrastructure, there’s a genuine opportunity—but only if we’re producing what global buyers want. They’re not paying premium freight costs to import commodity milk. They want protein density that meets international quality standards. The farms supplying that milk are part of an increasingly export-oriented value chain, whether they realize it or not.

Balancing Opportunity and Risk

Any time someone presents a market opportunity, you should ask: “What if the assumptions don’t hold?”

Fair question.

What if the protein premium narrows?

It could happen. Processor capacity might expand. Consumer trends might shift. The protein-to-fat ratio could drift toward historical norms.

My thinking: even if protein premiums moderate, protein is unlikely to become less valuable than fat on a sustained basis. The fundamentals—bioavailability advantages, consumer demand for functional nutrition, processing economics—support continued protein value.

More importantly, breeding for combined solids rather than protein alone provides insurance. Bulls that improve both fat and protein percentages protect against shifts in the ratio. The market has never penalized producers for shipping high total solids. The risk is in low-component production, not in being wrong about which component the market favors most.

What if GLP-1 adoption plateaus?

Possible, but current trajectory suggests otherwise. These medications are being prescribed not just for weight loss but for diabetes management and cardiovascular protection. Insurance coverage is expanding. Pill formulations are entering the market. The user base appears to be institutionalizing rather than peaking.

But even setting GLP-1 aside, other demand drivers—aging populations seeking muscle preservation, fitness culture emphasizing protein intake, Asian markets wanting protein imports—remain intact.

Practical risk management approaches:

- Use Net Merit (NM$) rather than extreme protein indexes for a balanced hedge

- Maintain health and longevity trait minimums regardless of component goals

- Keep some flexibility through beef-on-dairy rather than raising 100% of replacement heifers

- Consider nutrition interventions (reversible) before genetic changes (permanent)

- Monitor inbreeding coefficients when selecting heavily for protein traits

Practical Takeaways

Bringing this together into actionable items:

Understanding Where You Stand

- Calculate the protein-to-fat price ratio from your last few milk checks

- Compare your herd’s protein percentage to the Federal Order pool average (now 3.3%)

- Have an explicit conversation with your milk buyer about protein premiums and thresholds

Evaluating Genetic Options

- Review your current sire lineup for protein trait emphasis

- Consider CM$ or updated NM$ rankings alongside traditional TPI

- Set minimum thresholds for health and fertility traits before optimizing for components

- Look for bulls positive in both protein percentage and protein pounds

- Work with your AI rep on what makes sense for your herd

- If you’re genomic testing heifers, use protein traits in your retention decisions

- Monitor inbreeding levels when concentrating selection on protein traits

Near-Term Nutrition Interventions

- Discuss rumen-protected methionine with your nutritionist

- Consider a 21-30 day pen trial before full implementation

- Track component response carefully to verify ROI on your operation

- Pay particular attention to fresh cow and early lactation response

Timeline Expectations

- Nutrition changes: visible results in 2-4 weeks

- Genetic changes: first daughters milking in 3+ years

- Spring 2026 breeding decisions will shape your 2029 bulk tank

Questions to Keep Asking

- Does my processor have the infrastructure to pay for high-protein milk?

- Am I positioned above or below the pool average for components?

- What’s my risk tolerance for genetic strategy changes?

- Am I tracking the protein-to-fat ratio, or just looking at absolute prices?

The Bottom Line

The dairy industry has navigated plenty of transitions over the decades. What makes this moment noteworthy is the convergence of forces—pharmaceutical, demographic, and economic—pointing in a consistent direction.

I’m not predicting that butterfat will become worthless or that every operation needs to overhaul its breeding program immediately. What I am suggesting is that assumptions many of us have operated under for the past decade deserve fresh examination.

The market is sending signals. Processors are paying premiums for protein that would have seemed unusual five years ago. Consumer demand is shifting in ways that favor nutrient density over volume. Global buyers are seeking protein ingredients, not commodity powder. And American dairy is increasingly positioned as a global protein exporter, not just a domestic commodity producer.

The combined opportunity is real. For a 500-cow herd that optimizes nutrition, adjusts genetic selection, and captures processor premiums—we’re talking $50,000 to $97,500 annually in additional value. That’s not theoretical. It’s math based on current market conditions and achievable improvements.

Producers who take time to understand these dynamics—and thoughtfully evaluate what they mean for their specific operations—are well positioned. Those who assume the old rules still apply may find themselves wondering why neighbors’ milk checks look different.

This isn’t about chasing trends. It’s about recognizing when fundamental market structures are shifting and responding accordingly. For some operations, that response might be modest adjustments. For others, more significant changes might make sense. Either way, understanding what’s actually happening is the essential first step.

That protein-to-fat ratio on your milk check? It’s telling you something.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The $4.78 Spread: Why Protein Premiums Won’t Last Past 2027 – Gain an immediate competitive edge with a targeted 60-day action plan for capturing surging protein premiums. This breakdown delivers the exact math on amino acid balancing and arms you with a high-impact “Must-Do” list for Monday morning.

- Your 0.77 Ratio Is Wrong: The $67,500 Component Fix That Can’t Wait Until 2028 – Reveal the hidden structural flaw in your bulk tank that could be costing you $67,500 annually. This strategic analysis exposes why breeding for butterfat alone is a losing bet and positions your herd for the 2028 processor requirements.

- The GLP-1 Gold Rush: Why Dairy Protein is Pharma’s New Best Friend – Step inside the high-stakes worldwhere pharma meets the milk check. This deep dive into functional nutrition reveals how A2A2 and Kappa-Casein genetics are securing exclusive 15% premiums through new multi-billion dollar weight-loss support contracts.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!