2,000-cow dairies are learning something from robots that has nothing to do with labor: cows can’t make milk while standing in line.

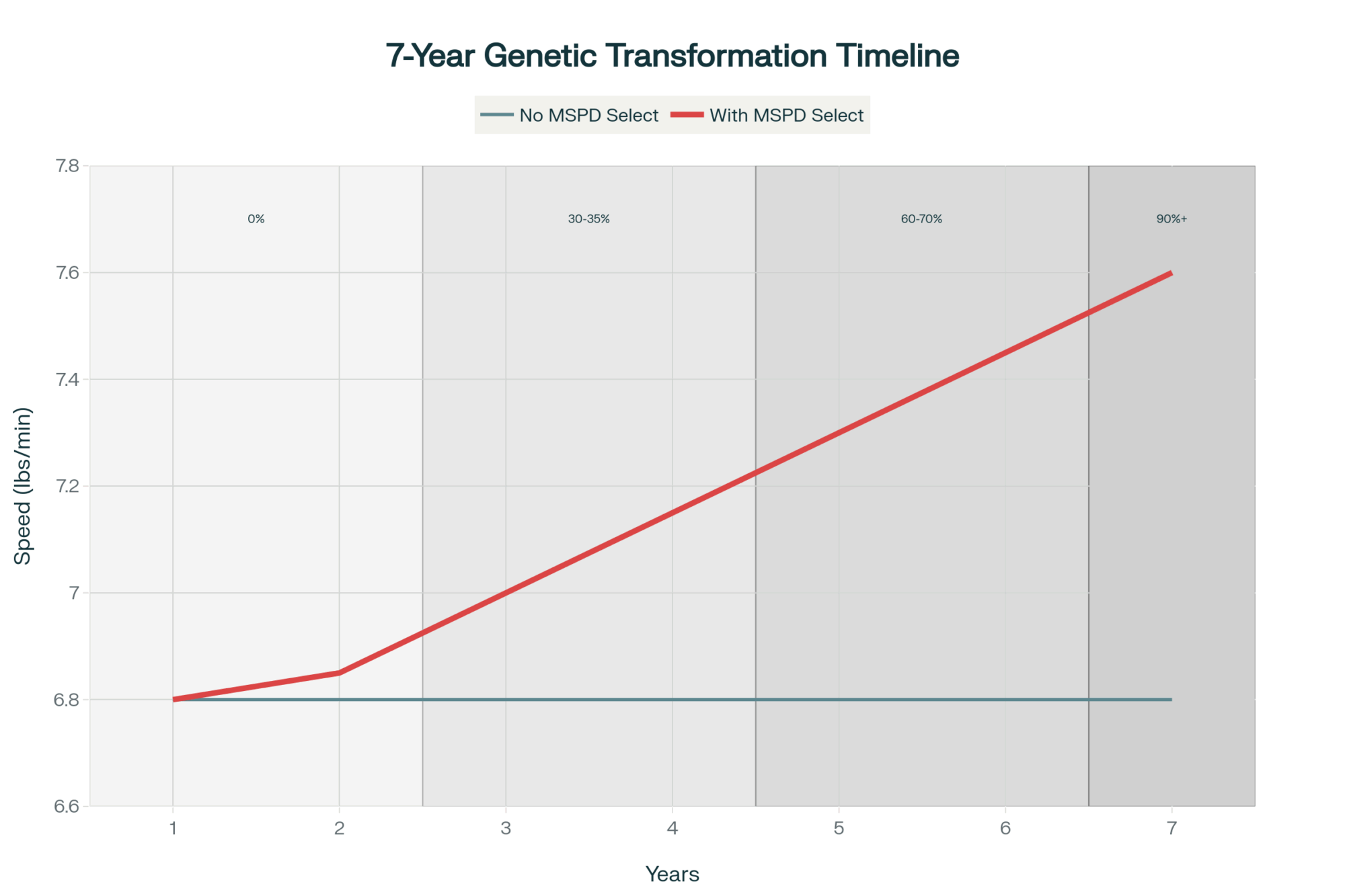

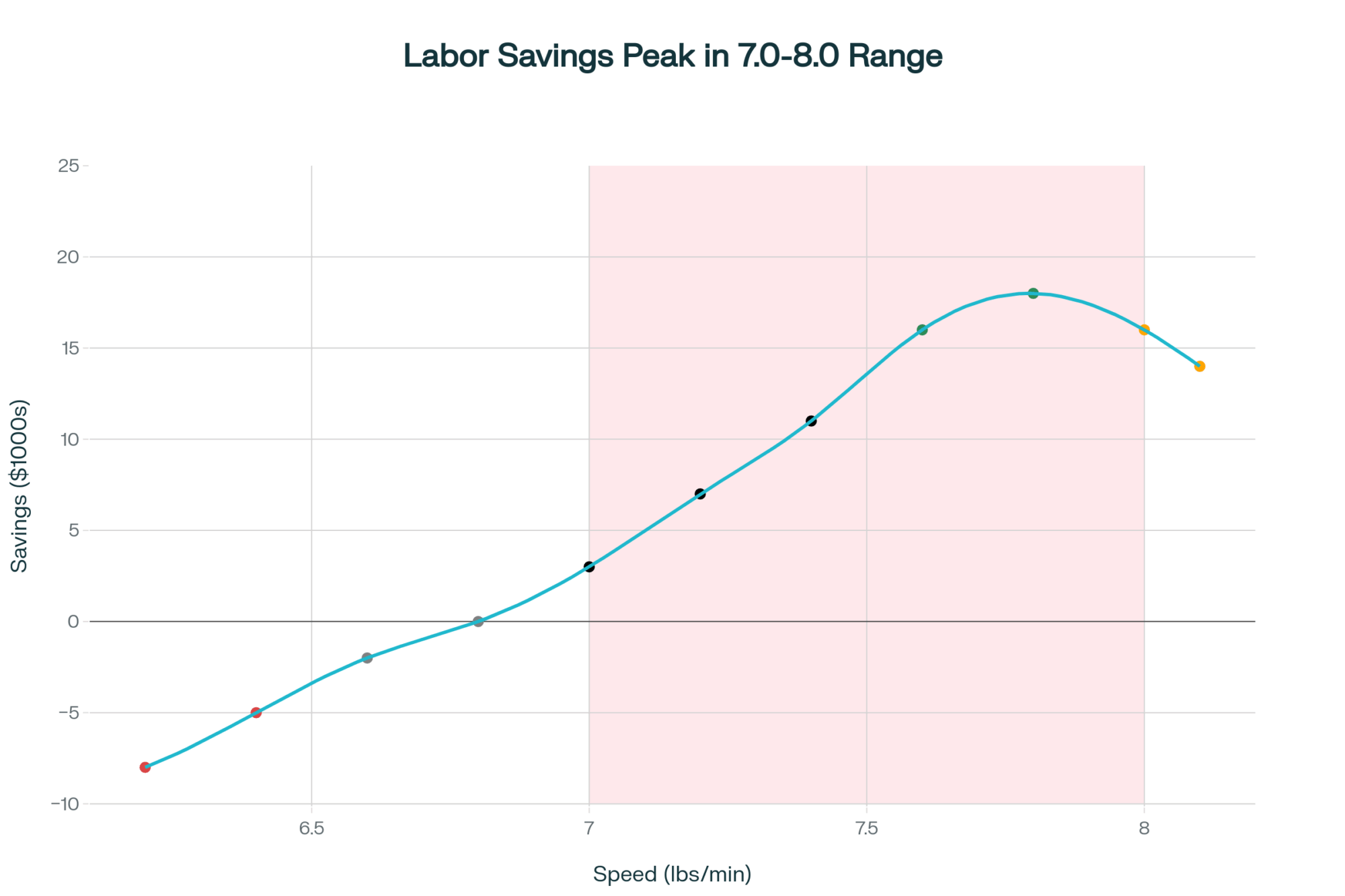

Executive Summary: Large dairies have measured success in cows per hour for decades. Operations that thrive with robots have flipped that metric—they manage by cow time instead. The biology is clear: high producers need 12–14 hours of lying time daily, and every hour lost to walking or waiting costs 1.5–3.5 pounds of milk. On many 3x parlors, that’s 3–5 hours of hidden loss every day. Robot herds that nail the fundamentals—55–60 cows per unit, proper heifer training, solid hoof health—report 3–8% higher milk per cow after stabilization. But the economics demand honesty: real payback runs 5–7 years, not the 3.8–5 years in vendor models. Recent research adds a key insight: milking speed is 42% heritable, but willingness to visit the robot is almost entirely management-driven. For 2,000-cow operators, the question isn’t robots vs. parlors—it’s whether you’re ready to build around cow biology, not just throughput.

You know the drill. On a lot of big dairies, the proud number is still the same: “We run 450–500 cows an hour through this parlor.” And to be fair, that’s impressive steel and scheduling. But here’s what’s interesting—as more large herds adopt automatic milking systems, a different story is emerging. Cows per hour and true cow productivity? They’re not always pointing in the same direction.

What farmers are finding is that robots aren’t just a different way to get cows milked. They’re shining a light on hidden time losses, showing how much genetic potential may still be sitting on the table, and prompting a more honest look at labor risk and management discipline.

And here’s the thing—the biggest differences between successful and struggling AMS herds rarely come down to the brand of robot. They come down to cow time, barn design, and how well you run the people side of the business.

Looking at This Trend Through Cow Time, Not Steel

If you strip everything back, a dairy cow still lives on a 1,440‑minute clock every day. Extension specialists keep coming back to the same basic targets you’ve probably heard at meetings.

High‑producing Holsteins and Jerseys should be getting at least 10–12 hours of lying time, with 12–14 hours often cited as the ideal target for top performance and hoof health. The research on this is fairly consistent—according to time-budget studies summarized by multiple land-grant universities, each hour of lying time you lose can cost you roughly 1.5–3.5 pounds of milk per cow per day, depending on stage of lactation and environmental conditions.

Time away from stalls—walking, standing in headlocks, sitting in a holding pen—comes straight out of that lying and ruminating budget.

On many large 3x parlors, especially those with long alleys or dry lot systems feeding into a central milk center, total time away from stalls can run 3–5 hours per day when you add up walk time, holding, and actual milking. When you layer on 4–6 hours of feeding and watering, plus social and transition time, you can see how quickly you approach that 12‑hour rest target.

I was talking with a nutritionist recently who works across several large California operations. The way she put it was simple: “Most producers don’t realize how much milk they’re leaving on the table until they actually track where their cows spend their hours.”

And the data backs that up. Studies that track both lying time and milk yield tell a consistent story—cows losing just 2 hours of rest per day commonly give 3–7 pounds less milk, and first‑lactation animals tend to be even more sensitive to this.

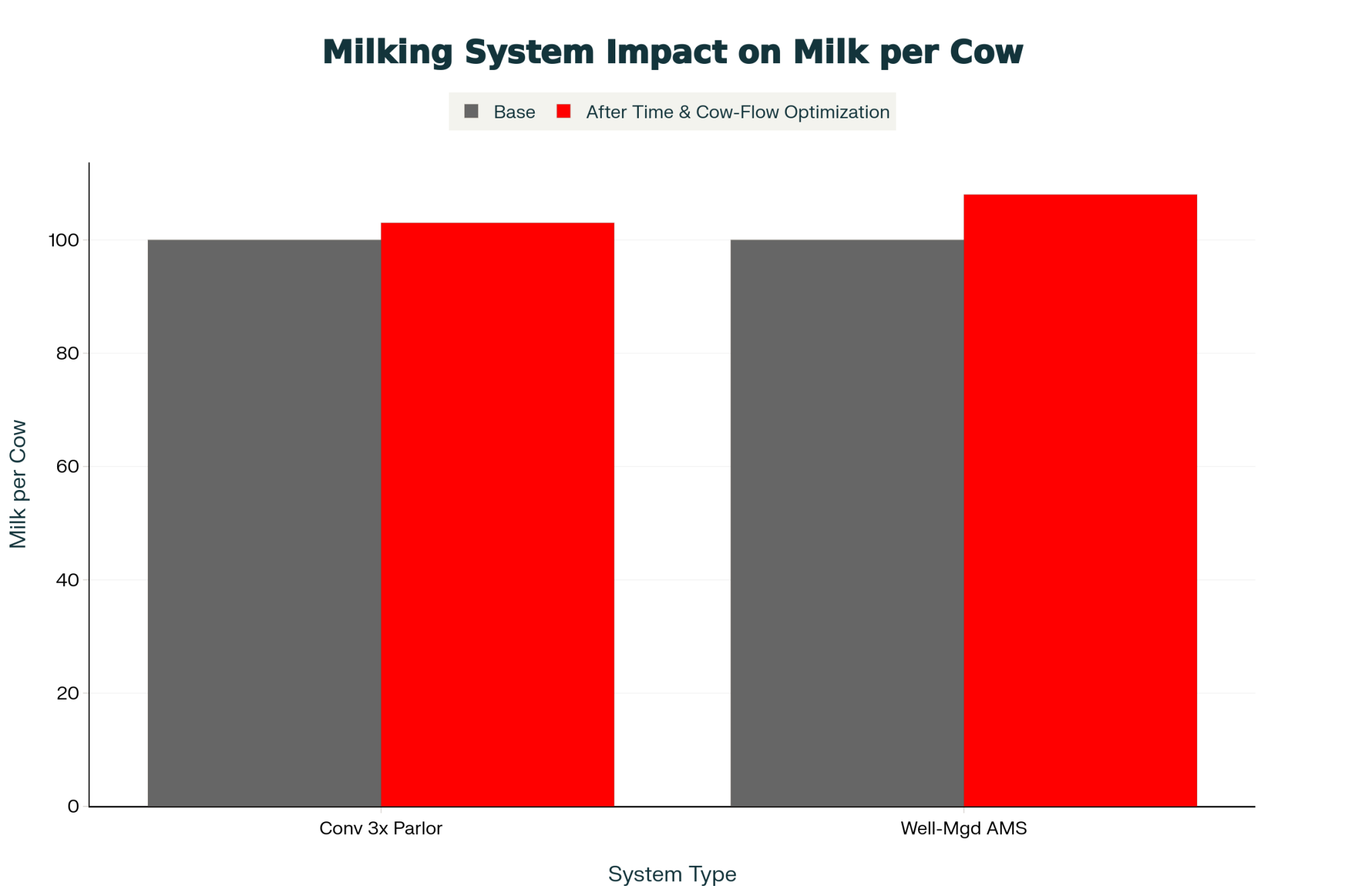

What’s particularly noteworthy is that when herds later install robots, whether on part of the herd or across the board, many report 3–8% higher milk per cow once the system stabilizes, even when they end up milking fewer total cows. The common thread? Cows reclaim time for lying and ruminating instead of standing in concrete alleys.

Now, that doesn’t mean every robot install boosts milk. But it does highlight just how significant those quiet time‑budget losses can be.

The Bimodal Milk Curve Challenge

There’s another factor in high‑throughput parlors that only shows up when you examine milk‑flow curves. And it does not get talked about enough.

Biologically, most cows need about 90–120 seconds between effective teat stimulation and full oxytocin release for a complete milk letdown. But in fast parlors—and many of us have walked through them—it’s common to strip, dip, wipe, and attach in 30–60 seconds, especially when crews are working to hit those cows‑per‑hour targets.

On‑farm flow meters and research trials have documented what happens in these situations.

You get a quick spike as cisternal milk is removed. Then there’s a flat or low‑flow phase while the cow is still waiting hormonally for full letdown. Finally, a second rise once oxytocin finally peaks.

That “start–stop–start” pattern is what we call a bimodal curve. And here’s what the field studies suggest—when you don’t allow enough time for effective letdown, cows can noticeably reduce daily milk harvest, especially high‑yielding, early‑lactation animals who have the most to give.

What I’ve observed in some very fast parlors is that the graphs look great for turns per hour, but not nearly as strong when judged by milk per milking minute.

Robots don’t automatically solve this, but the software makes it easier to respect biology. AMS units can apply consistent stimulation—often with brushes or controlled vacuum—and then wait the full lag period before expecting peak flow. When you look at their flow curves, you generally see a single, smooth peak rather than the “double hump,” suggesting a more complete harvest.

What Farmers Are Finding About Genetics and Milking Frequency

Genetic progress has outpaced a lot of our old assumptions. And this is something worth sitting with for a moment.

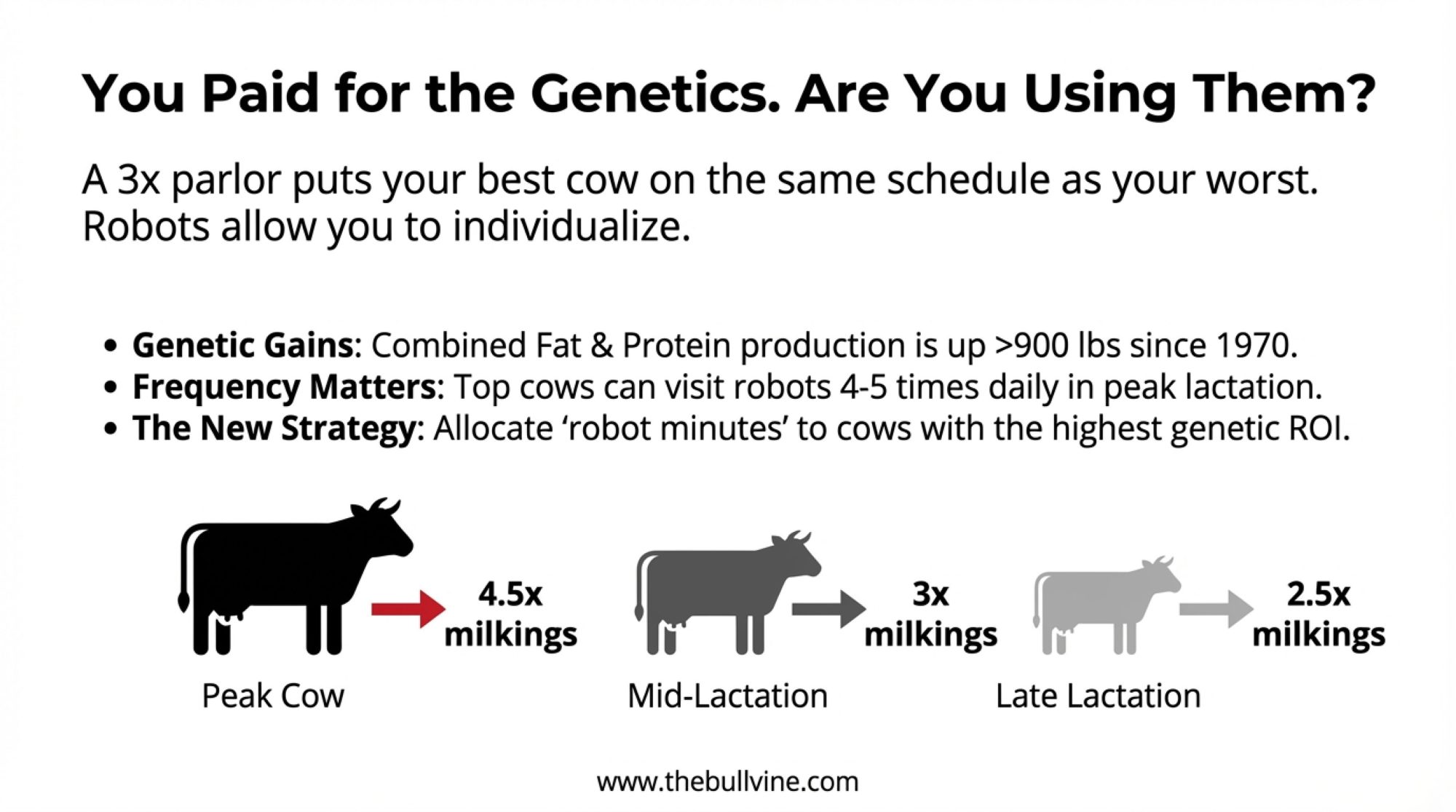

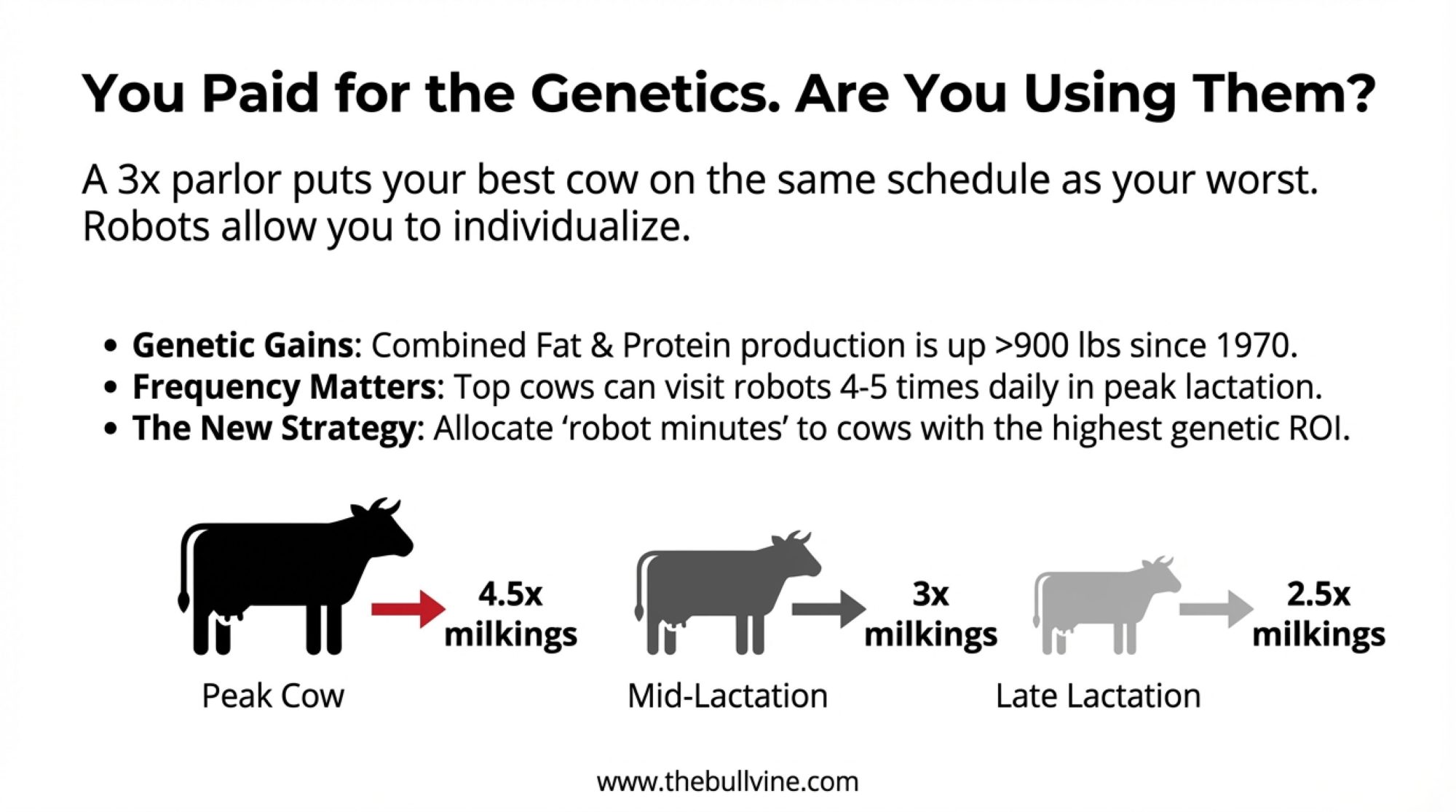

Between 1970 and 2020, combined fat and protein production in U.S. Holstein populations increased by more than 900 pounds per cow, with national evaluations crediting about 60–65% of that gain to genetics when you separate out management and environment. Jerseys have shown similar patterns for component yield and feed‑efficiency traits.

The challenge is that realizing that genetic potential depends heavily on milking frequency and cow comfort.

Controlled studies and on‑farm trials provide some useful guideposts. Moving from 2x to 3x milking often increases yield by 8–15% in controlled settings, particularly during early and peak lactation.

Short periods of 4x milking in early lactation can create persistent yield benefits across the whole lactation—because of how additional milkings affect mammary cell activity. And cows differ genetically in their response to higher frequency. Some families show much larger gains than others.

In a conventional 3x parlor, your top and bottom cows are on the same schedule. A high‑genetic‑merit cow that could profitably be milked 4 or 5 times a day stands in line with a late‑lactation cow you’re trying to dry off clean. Both take the same parlor time, even though the return on that time is very different.

What robots change, when managed well, is the flexibility to match milking frequency to each cow’s potential.

In free‑flow AMS barns, peak cows often visit robots 3.5–4.5 times per day, while late‑lactation or lower‑producing cows may be permitted 2–2.5 milkings. Permissions can be adjusted cow by cow based on days in milk, udder health, and butterfat performance.

One illustration worth noting is Countyline LLC in California’s Central Valley—one of the largest robotic Jersey projects in North America, with 32 robots designed for roughly 2,000+ Jerseys, transitioning from a conventional double‑32 parlor. Public profiles indicate strong per‑cow production for first‑ and second‑lactation animals, with the high components you’d expect from intensively managed Jersey herds.

What this development suggests is that, in a robotic setup, “robot minutes” become a resource you allocate to the cows with the best genetic and economic returns, rather than treating all cows equally in terms of time.

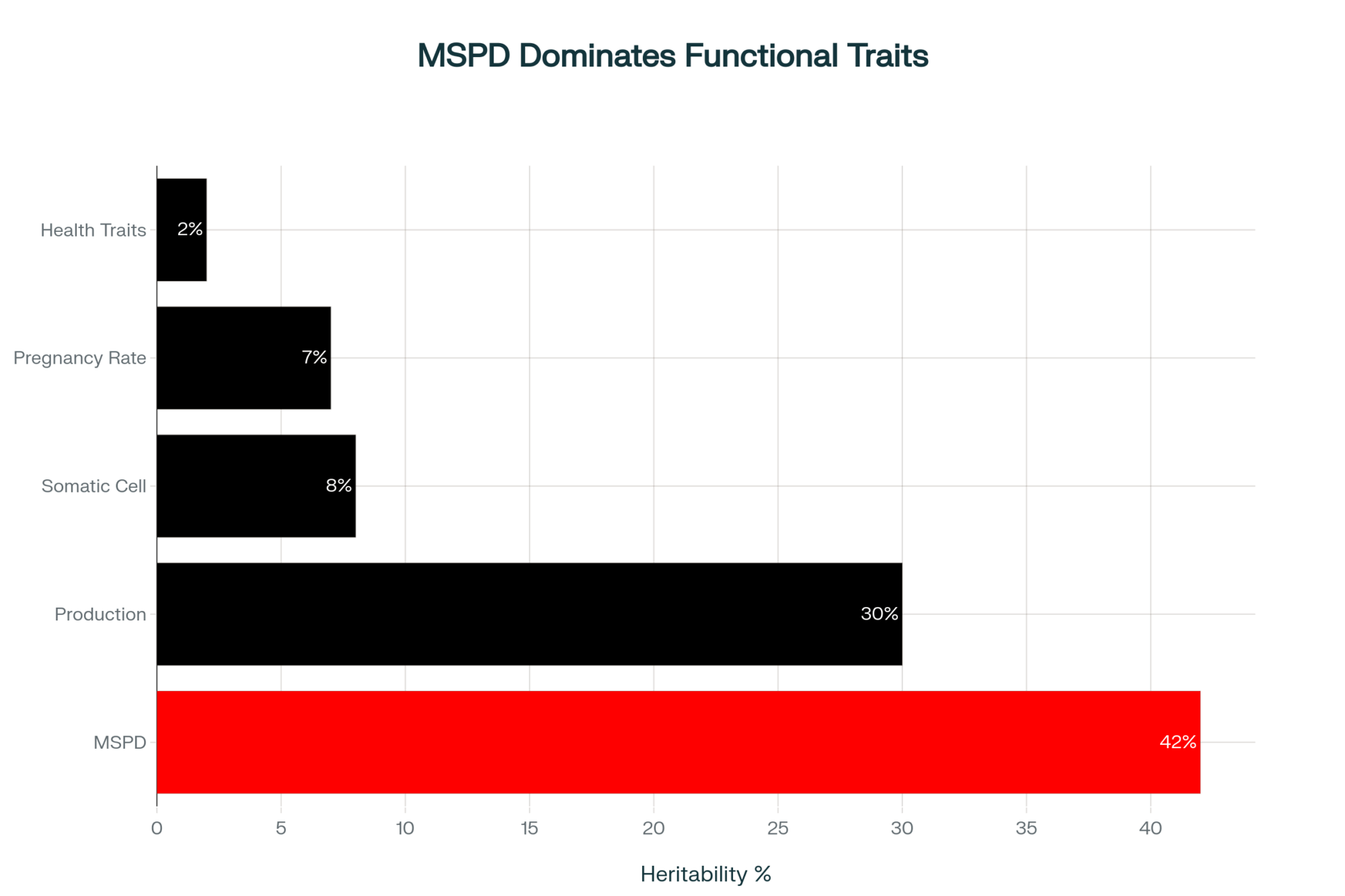

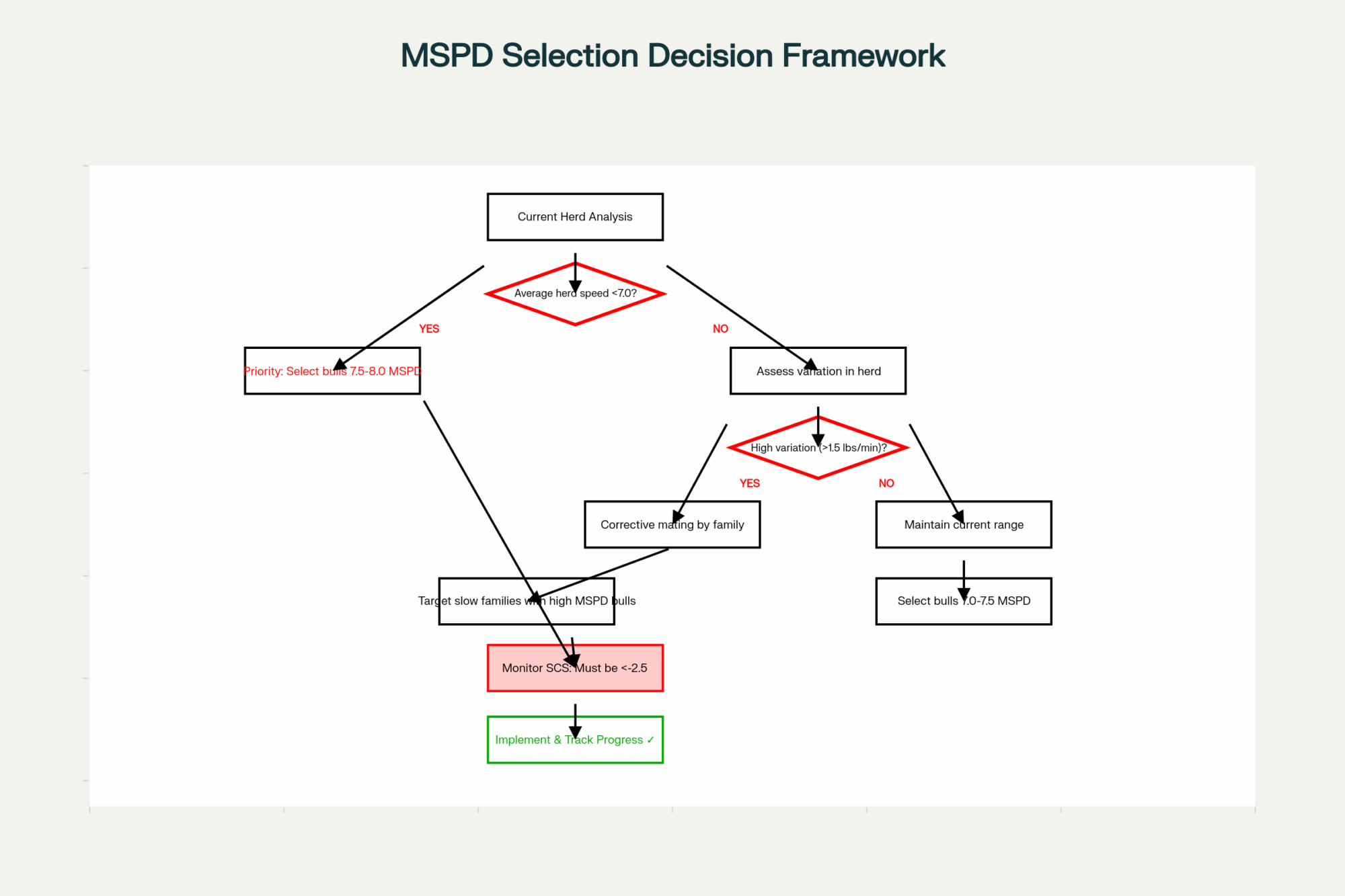

Here’s something else worth noting on the genetics front—and it’s one of those details that doesn’t get enough attention. According to research published in the Journal of Dairy Science in 2023, milking speed traits show remarkably high heritability. Average milk flow rate runs 0.43–0.52, and maximum flow rate hits 0.47–0.58 in the AMS data. The new CDCB Milking Speed evaluation released in August 2025 estimates heritability at 42% based on conventional parlor data, making it the highest heritability of any of the 50 traits they publish. The reason both parlor and AMS data point in the same direction is straightforward: how fast a cow lets down milk is fundamentally biological, not system-dependent.

By contrast, behavioral traits like robot visit frequency and milking interval show much lower heritability—around 0.08–0.10, according to a July 2025 Journal of Dairy Science study—indicating they are more management-driven than genetics-driven.

The practical takeaway? You can select fairly quickly for cows that milk efficiently, but willingness to visit the robot voluntarily depends more on training, facility design, and hoof health than on pedigree.

What Robots Really Change Economically

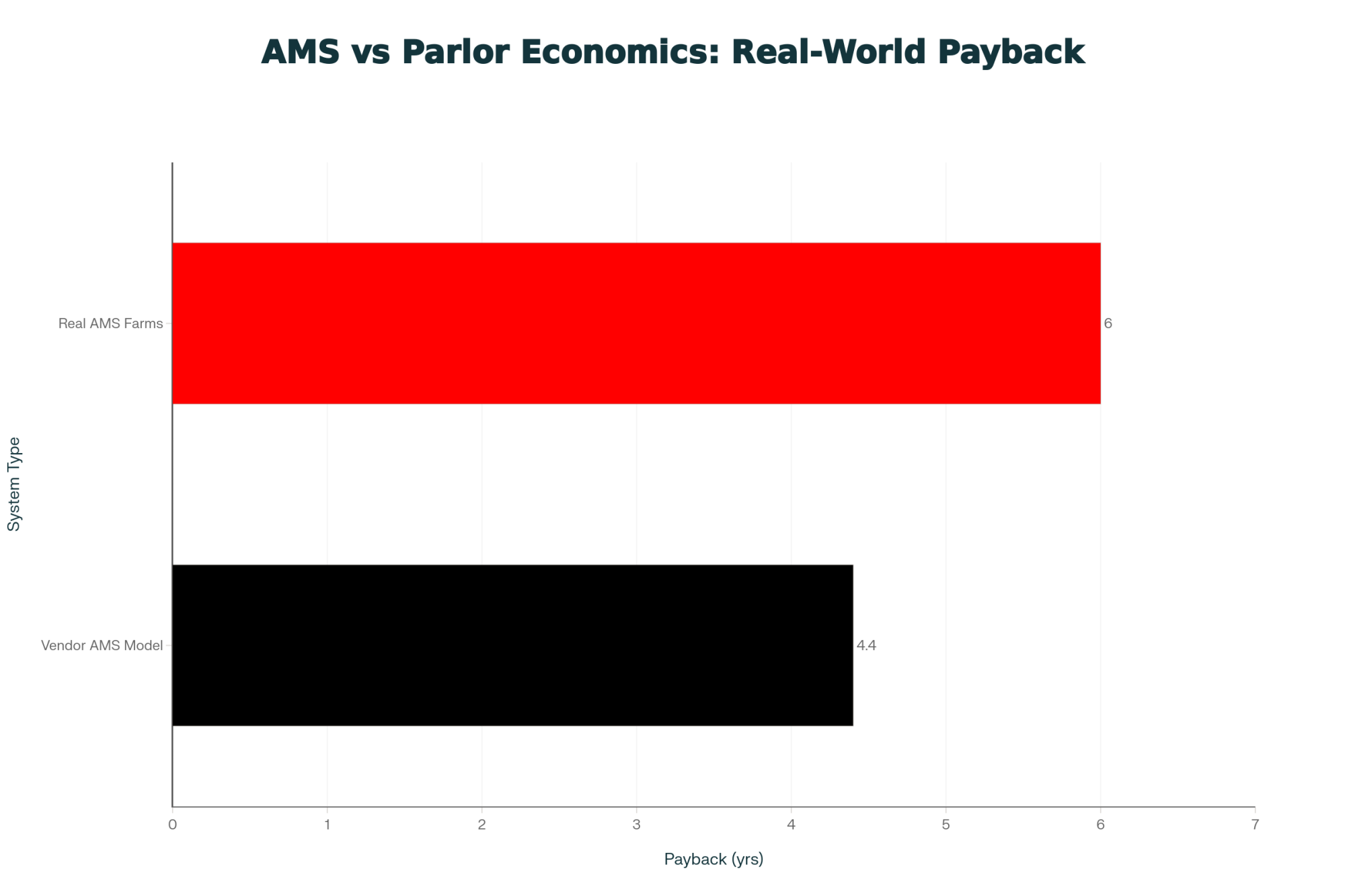

When a 2,000‑cow operator looks at a capital plan and sees a multi‑million‑dollar robot build versus a more modest investment in a rotary or expanded parallel, payback is naturally front and center. It’s also where vendor projections and independent analyses sometimes diverge.

University extension economists in the U.S. and Canada have built a range of AMS vs parlor budgets. According to economic analyses from Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Canadian extension programs, under good design and strong management, payback for robots often falls in the 3.8–5-year range, driven mostly by labor savings and modest production gains.

But on real farms? Those same teams report that it’s more common to see 5–7 years, especially when you include a realistic transition period.

Looking at those models and field reports side by side, three economic factors consistently emerge:

Labor savings. Studies and case farms typically show milking‑related labor dropping 25–30%, with pounds of milk shipped per full‑time equivalent often rising from around 1.5 million to about 2.2 million pounds per worker per year in AMS herds.

Milk per cow. Once cows and people get through the adjustment period, many robot herds in reviews and surveys report 3–8% higher milk per cow, driven by smoother time budgets, more consistent routines, and higher milking frequency for the top animals.

Overhead considerations. Depreciation, maintenance contracts, electricity, and consumables are higher per cow in a robotic setup than in a parlor, which offsets part of the labor savings.

A multi‑country review comparing AMS and conventional herds over five years found that average profitability was often similar when you adjusted for milk price, scale, and stocking rate. In other words, robots didn’t automatically outperform parlors—the farms that did well in each system tended to be the ones with tight management and good facilities.

So why is this significant? Because it suggests the decision isn’t purely economic for many operators.

In a 2023 peer-reviewed survey of large U.S. farms using seven or more robots, producers identified their top reasons for adopting AMS as chronic difficulty finding and keeping qualified parlor employees, concerns about future wage and regulatory changes, desire for more consistent milking procedures and teat prep, and interest in shifting employees into roles focused on fresh cow management, herd health, and reproduction.

This aligns with what economists are now saying—that robots function as a labor‑risk management tool as much as a production tool. It also explains why some herds are comfortable with a 7–10 year real payback if the alternative is an increasingly uncertain labor situation.

At the same time, extension guidance is clear that in regions where labor remains relatively available and affordable, and where regulatory conditions are different, a well‑designed rotary or parallel parlor may still be the most economical choice—especially for herds that are already efficient on cows‑per‑hour and milk quality.

I’ve seen herds in the Upper Midwest and Southwest with strong local workforces choose a new rotary and perform very well, precisely because their challenge wasn’t labor risk but something like cow flow, parlor age, or heat‑stress management.

A Snapshot from the Pacific Northwest

To make this more concrete, let’s look at one example from the Pacific Northwest that’s been profiled in industry publications.

A Washington State dairy milking around 1,100 cows installed roughly 20 robots in a retrofit scenario, driven largely by labor shortages and a desire for more manageable schedules for both owners and employees.

According to reports from Dairy Herd Management and follow‑up coverage on robotic cow flow, they initially struggled with cow traffic and fetch rates—especially among first‑lactation heifers—and saw milk per cow dip during the first months.

Over time, they made three significant adjustments. They reworked the pen design to create clearer, free‑flow traffic patterns. They invested more heavily in heifer training and hoof health before calving. And they reduced cows per robot into the mid‑50s, even though that meant fewer total cows in milk.

Two to three years in, they reported that milk per cow had recovered and surpassed pre‑robot levels, milking labor had dropped significantly, and owner lifestyle was more sustainable—though maintenance costs were higher than initially expected.

This “dip‑and‑recover” pattern appears fairly typical on well‑managed AMS transitions. A challenging learning year, followed by a more stable, data‑driven routine. It’s something worth keeping in mind if you’re considering the switch.

Understanding Fetch Cows and Building “Robot‑Ready” Herds

Once the new system is running, many managers quickly realize that a significant part of their day is determined by one number: how many cows walk themselves to the robot.

A fetch cow is a cow that doesn’t visit the AMS within the target interval and has to be brought by staff. Extension guidelines and AMS consultants commonly set a goal of no more than 5% of the herd on the fetch list on a given day—roughly three cows per robot—to preserve labor savings and minimize cow stress.

In herds that are struggling with the transition? It’s not unusual to see fetch rates of 15–25%, which can turn “automatic milking” into a time‑consuming cow‑management challenge.

And here’s what’s interesting—fetch cows aren’t random. Several consistent factors show up in both the research and on real farms.

The 4 Primary Causes of Fetching

1. Personality and Temperament Research in Europe and South America has used standardized behavioral tests to classify cow personalities. Cows that are bolder and moderately active tend to adapt faster to robots and end up on fetch lists less often. Very fearful or highly reactive cows typically need more support during the transition.

2. Heifer Training (or Lack Thereof) Studies on “phantom robot” training—where heifers are exposed to the robot area and its sounds before calving—show lower fetching during the first weeks of lactation and better early milk letdown compared with untrained heifers. Many AMS advisors now treat heifer training as a required piece of fresh cow management, not an optional extra.

3. Lameness Lame cows are far less inclined to walk to a robot voluntarily. Reviews from industry publications and North American extension programs connect higher lameness prevalence to higher fetch rates and lower milk per cow. Lame cows in AMS herds are often roughly twice as likely to show up on fetch lists as sound cows.

4. Stocking Density and Barn Design Pushing 70–80 cows per robot to “maximize utilization” tends to mean longer robot queues, more competition, and more timid or subordinate cows giving up on voluntary visits. According to facility guidelines from Wisconsin extension and Lactanet, 55–60 cows per robot is a realistic upper limit for high‑producing herds. Some of the most successful operations intentionally stay a bit lower in fresh or high‑yield pens.

Genetics is part of the picture, too. Analyses of AMS data in North American Holsteins have estimated moderate heritability—0.10–0.15—for traits such as number of successful robot visits and milking interval, with higher heritability for milking speed and teat/udder traits that affect attachment.

This means over time we can genuinely select for “robot‑ready” cows—those that move well, milk quickly, and have udders suited to the technology.

In herds that make robots work well, a common pattern emerges. They run 50–60 cows per robot, especially in fresh and high groups. They emphasize sand‑bedded freestalls, regular hoof trimming, and alley cleanliness before and during the transition. They build structured heifer training into their fresh cow management program. And they make timely culling decisions on chronic fetch cows, regardless of pedigree.

Why Some Large Herds Struggle—or Step Back

It’s worth acknowledging that not every large herd that installs robots ends up satisfied with the decision. In Europe and New Zealand, there are documented cases of farms decommissioning robots and returning to parlors after several difficult years, usually due to a combination of design challenges, unrealistic expectations, and management strain.

Looking at the available data and field experience, a few patterns keep recurring.

Retrofitting Robots into Parlor‑Designed Barns

You probably know this one. The 2023 peer-reviewed survey of large U.S. AMS herds—those with seven robots or more—found that about one‑third of producers said they would change barn design decisions if they could do it again, especially around robot placement and traffic lanes.

Retrofitting robots into barns built around straight‑through parlor flow often creates narrow alleys and “pinch points” near robot rooms, robots positioned in corners rather than integrated into main cow paths, and pen layouts that require cows to move against group flow to reach the milking area.

These issues then manifest as higher fetch rates, reduced lying time, and more variable production—problems that are very difficult to address once the concrete is poured.

Overstocking Robots

On paper, putting 75 cows on a robot instead of 55 looks like an efficient way to spread capital cost. But from the cow’s perspective, it often means longer queues in front of the robot, dominant cows monopolizing access, and timid, lame, or fresh heifers being pushed out and becoming chronic fetch cows.

AMS facility guidelines from Lactanet and university extension programs consistently recommend designing for 55–60 cows per robot for high‑producing Holstein or Jersey herds, with flexibility to run lighter stocking in certain pens when conditions warrant.

Underestimating the Learning Curve

Several studies following farms through AMS transitions report that it typically takes 6–12 months for milk yield, robot utilization, and daily routines to stabilize.

During that period, herds may see a temporary dip in production, elevated somatic cell counts while prep and attachment protocols are refined, and more labor devoted to training cows and staff than initial budgets anticipated.

Case studies and reviews suggest that operations expecting immediate labor relief and a smooth transition tend to experience the most frustration, while those who plan for a “learning year” are more likely to report satisfaction by year two or three.

Data Engagement and Management Approach

The same hardware can produce very different results depending on how it’s managed.

Performance reviews highlight that successful herds check robot and cow data daily—milkings per cow, refusals, failed attachments, activity, conductivity, lying time—and use those numbers to adjust grouping, feeding, and hoof care.

Less successful herds often log in less frequently, focus primarily on bulk tank output, and treat robot alerts as nuisances rather than diagnostic information.

What I’ve observed is that the large herds thriving with robots were typically already comfortable managing by data—tracking fresh‑cow performance, pen‑level butterfat, reproductive metrics, and time budgets—before they ever contacted a robot dealer. Robots don’t compensate for management gaps. They tend to amplify whatever approach is already in place.

Different Regions, Different Right Answers

It’s worth remembering that not every region is facing the same set of pressures.

In parts of the U.S. and Canada where labor is tight, wages are rising, and regulatory requirements are expanding, robots can be a way to convert unpredictable labor costs into more predictable capital and maintenance expenses, even if the margin over feed is similar. In those situations, producers often tell me they value stability as much as financial returns.

In other regions—where there’s still a reliable, reasonably priced local workforce and where dry lot systems and centralized parlors align well with climate and land base—a new rotary or expanded parallel, paired with strong management, can absolutely remain the right choice.

I’ve seen herds in the Upper Midwest, Southwest, and Latin America achieve excellent milk, health, and labor metrics with conventional parlors because they were designed around cow flow and time budgets just as thoughtfully as any robot barn. One Wisconsin operation I visited last year had just installed a new 60‑stall rotary, and they’re hitting numbers that would make any robot farm proud—because they obsessed over time budgets, stall comfort, and consistent protocols.

Seasonal considerations matter too. In hot summers, for example, extra time in holding pens or long walks from dry lots can push cows past their heat‑stress threshold more quickly, whether they’re going to a parlor or a robot. That’s one more reason why time budgets and cow comfort form the foundation, regardless of which milking system you choose.

The broader trend is that the margin for loose time management and inconsistent protocols is narrowing on both sides of the technology discussion. Whether you choose a rotary or robots, cows still need adequate lying time, clean stalls, smooth, fresh cow management, and consistent routines.

Key Considerations for 2,000‑Cow Operators

So, if you’re operating in that 2,000‑cow range and genuinely evaluating your options, what should you take from all this?

Start by measuring time, not by shopping for equipment. Before committing to any major investment, spend several months tracking time away from stalls, lying time, and lock‑up duration in your current system. That exercise alone will reveal how much opportunity—or hidden cost—exists in your current operation.

Recognize that genetics need the right schedule to deliver. Today’s Holstein and Jersey genetics can produce impressive milk and components, but only when milking frequency, comfort, and fresh-cow management align with their capabilities.

Frame robots as a risk‑management decision, not purely an efficiency calculation. Economic models suggest a 3.8–5 year payback is achievable under favorable conditions, but many real farms land closer to 5–7 years, and some take longer. Whether that timeline makes sense depends significantly on your labor outlook and long‑term operational plans.

Take fetch cows, lameness, and heifer training seriously. These three factors will largely determine how “automatic” your automatic milking actually feels. If you’re not prepared to invest in hoof health, stall comfort, and structured training before the robots arrive, your payback will likely be slower regardless of which system you choose.

Be honest about your management approach. If your team already operates from data—milk weights, butterfat performance, reproductive metrics, time budgets—you’re better positioned to succeed with AMS. If decisions are made primarily by intuition, the first investment might need to be in people and processes rather than technology.

Accept that there isn’t a single “right” answer. In some regions and operational contexts, a new rotary with excellent cow flow may be the most sensible long‑term investment. In others, robots will be the best path forward, given labor-market realities unlikely to reverse.

The Bottom Line

What’s interesting about this moment in the industry is that robots are prompting all of us—whether we ever purchase one or not—to think more carefully about how cows spend their time, how we develop and retain our people, and how we build systems capable of performing well over the next 10–15 years.

If this discussion helps you ask better questions, whether you ultimately install a new rotary, a row of robots, or neither, then it’s served its purpose.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Track cow time, not cows per hour: High producers need 12–14 hours of lying time daily. Every hour lost costs 1.5–3.5 lbs of milk—and on many 3x parlors, cows lose 3–5 hours to walking and waiting.

- Robots recover time, and time recovers milk: Well-managed AMS herds report 3–8% higher production per cow by giving back the hours that parlor routines take away.

- Use honest economics: Real payback runs 5–7 years, not the 3.8–5 in vendor models. Budget for a 6–12 month learning curve before expecting stable results.

- Nail the fundamentals before install: 55–60 cows per robot maximum, structured heifer training, and excellent hoof health aren’t optional—they separate success from struggle.

- Select for speed, train for visits: Milking speed is 42% heritable—breed for it. Willingness to visit the robot is almost entirely management-driven—design and train for it.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Essential Tips for Successful Robotic Milking with Fresh Cows: Maximize Milk Production – Provides specific strategies for fresh cow management, including the critical 80-90% stocking rate rule and bunk space requirements that prevent early lactation failures in robotic herds.

- The Robot Truth: 86% Satisfaction, 28% Profitability – Who’s Really Winning? – Delivers a stark economic reality check, revealing the “Scale Trap” that threatens herds in the 60-120 cow range and why satisfaction doesn’t always correlate with net profit.

- The Milking Speed Game-Changer That’s About to Shake Up Your Breeding Program – Explains how to leverage the new 42% heritability data for milking speed, offering actionable bull screening thresholds to breed a herd that matches your facility’s throughput goals.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

Every week, thousands of producers, breeders, and industry insiders open Bullvine Weekly for genetics insights, market shifts, and profit strategies they won’t find anywhere else. One email. Five minutes. Smarter decisions all week.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.

The Sunday Read Dairy Professionals Don’t Skip.