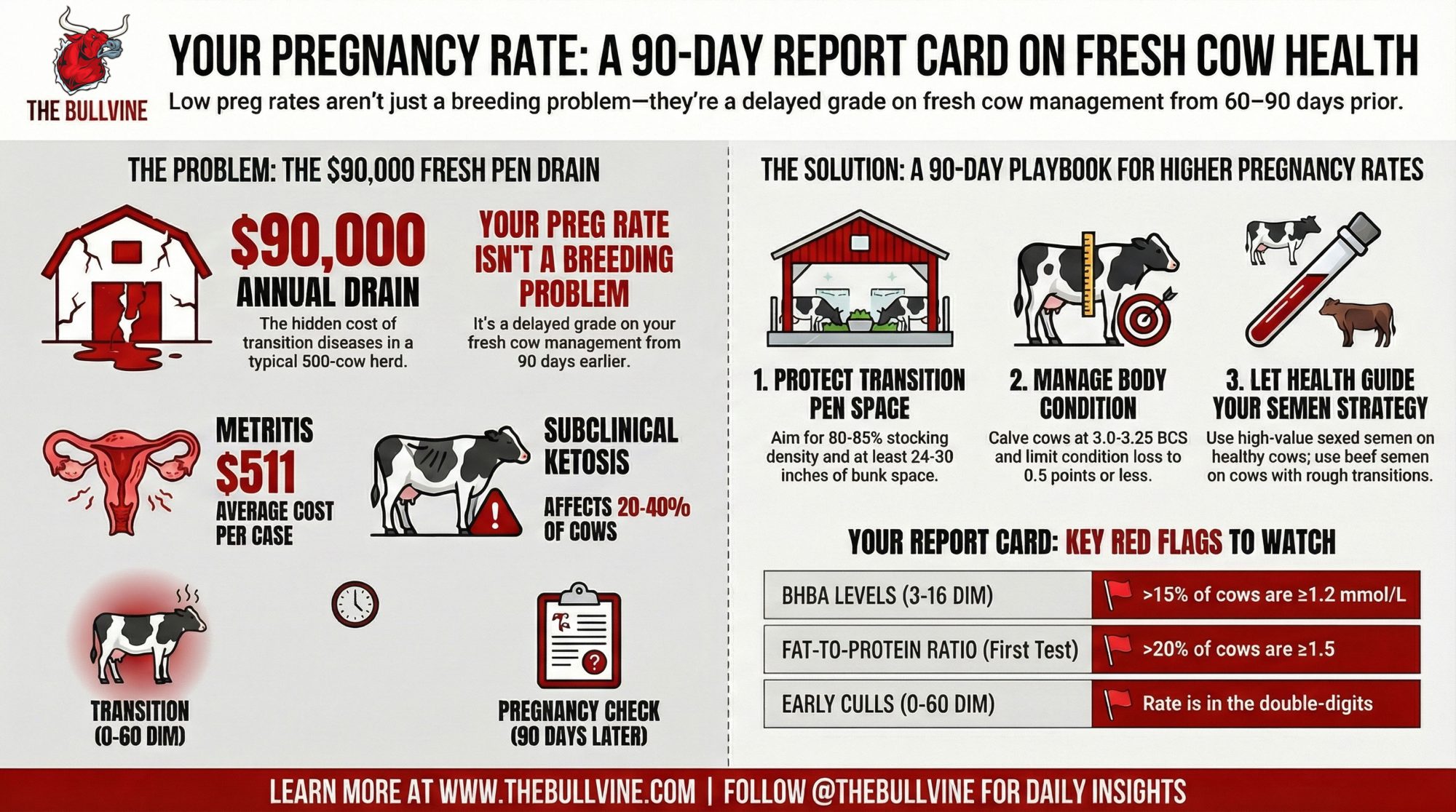

Metritis + SCK can quietly drain US$90,000 from a 500‑cow herd. The fix starts 90 days before you ever thaw a straw.

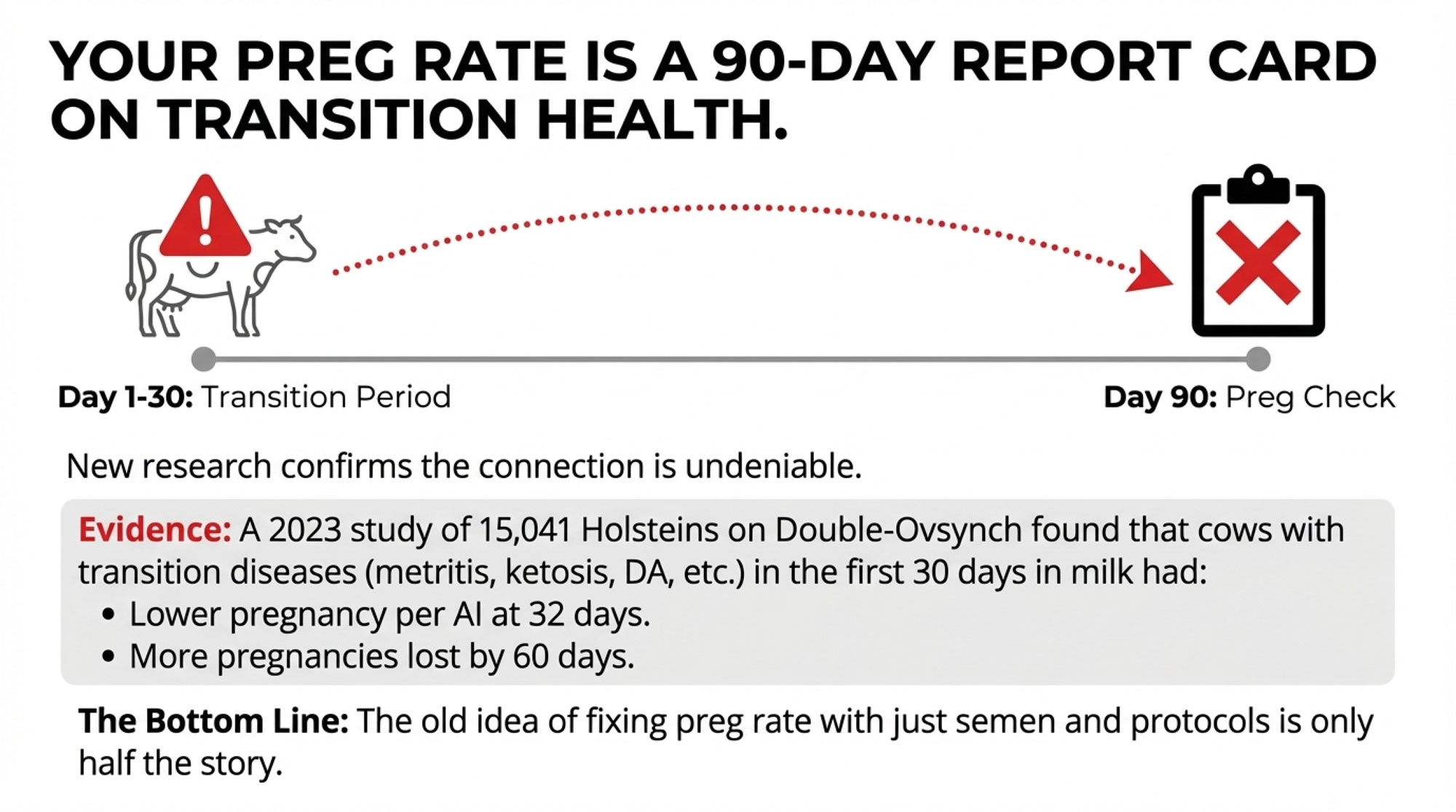

Executive Summary: Most of us still reach for semen, protocols, or the AI tech when pregnancy rate flattens, but what’s interesting is how often the real damage was done 60–90 days earlier in the fresh pen. A 2023 study on 15,041 Holsteins bred on Double‑Ovsynch found that cows with transition diseases in the first 30 DIM had clearly lower pregnancy per AI and more pregnancies lost by 60 days, even under excellent repro management. At the same time, economic work shows metritis averaging about US$511 per case and subclinical ketosis hitting 20–40% of cows in many herds, together easily stripping around US$90,000 a year from a 500‑cow operation once milk loss, disease, extra days open, and early culls are added up. This article treats pregnancy rate as a “90‑day transition report card” and walks through simple tools—NEFA/BHBA thresholds, fat‑to‑protein ratios, peak curves, and early‑lactation culls—that make that connection visible in your own data. From there, it lays out a clear playbook: a BHBA testing routine you can run on Mondays, realistic stocking and bunk space targets, BCS and F:P benchmarks, and a health‑based plan for where to use sexed dairy semen versus beef‑on‑dairy. Whether you’re in a Wisconsin freestall, a Western dry lot system, a Canadian quota barn, or a seasonal grazing herd, the goal is the same—tighten up fresh cow management so the next three preg checks feel a lot less like a guessing game and a lot more like a controlled business decision.

When a herd’s pregnancy rate gets stuck in the low‑to‑mid‑20s, the conversation still usually starts in the breeding pen. You know how it goes: semen choices, heat detection, synchronization tweaks, maybe a quiet question about the AI tech. That’s where the problem shows up in your software, so that’s where everyone looks first.

What’s interesting now is that newer work is making a pretty strong case that your pregnancy rate is really grading your fresh cow management from 60 to 90 days earlier, not just what happened on breeding day. A 2023 study in JDS Communications followed 15,041 Holstein cows in a high‑producing German herd where every first service was done on a Double‑Ovsynch program. Cows that had transition problems—milk fever, retained fetal membranes, metritis, ketosis, left displaced abomasum, or mastitis—in the first 30 days in milk had lower pregnancy per AI at 32 days and, in several of those categories, more pregnancies lost by 60 days than cows that stayed healthy, even though they all followed the same repro protocol.

So the old idea that “I’ll fix my preg rate with better semen and tighter protocols” is really only half the story. The other half is, “What were these cows living through in those first few weeks fresh?”

Looking at This Trend: Biology Keeps Pointing Back 90 Days

Let’s walk through the biology the way we’d talk it through over coffee. Once you see the timing inside the cow, this 90‑day connection stops feeling like a theory and starts looking like common sense.

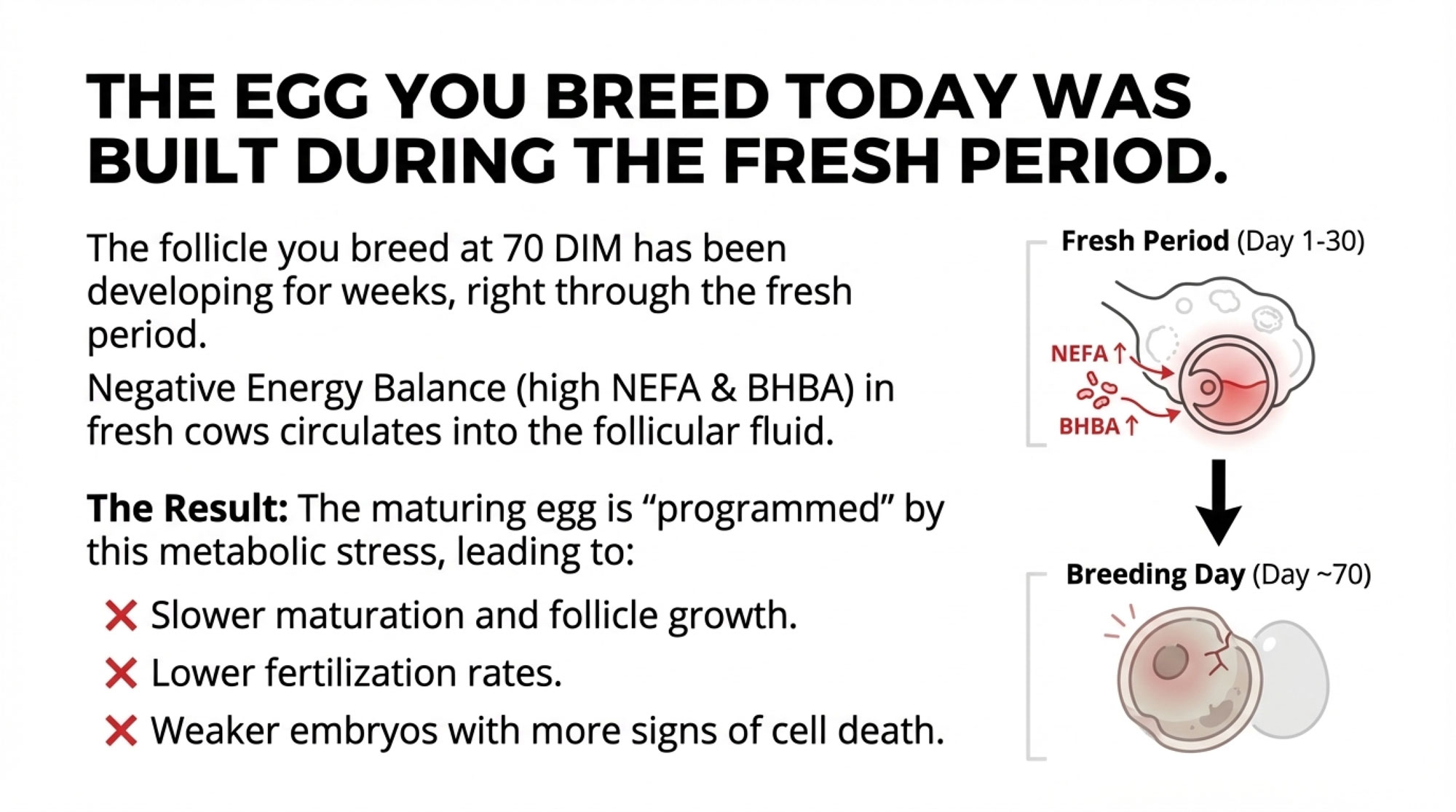

The Egg You Breed Was Built During the Fresh Period

You probably know this already, but we all forget it sometimes: the follicle you breed at 60–80 days in milk didn’t show up last week. It’s been developing for weeks in the ovary. The “high fertility cycle” idea, outlined in a 2020 review, showed that cows that become pregnant around 130 DIM tend to lose less body condition after calving, experience fewer health events, have better fertility at first insemination, and have lower pregnancy loss. That pattern tells us fertility is strongly tied to what happened during the dry period and the early fresh period.

During that stretch, most cows slide into negative energy balance. Milk is ramping up, but dry matter intake hasn’t caught up yet. So the cow pulls more energy from body fat, which pushes non‑esterified fatty acids (NEFA) up in the blood and, if the liver gets overloaded, beta‑hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) as well. Cornell work and follow‑up studies have shown that when too many cows run with high NEFA and BHBA around calving, the herd sees more transition disease and weaker reproductive performance.

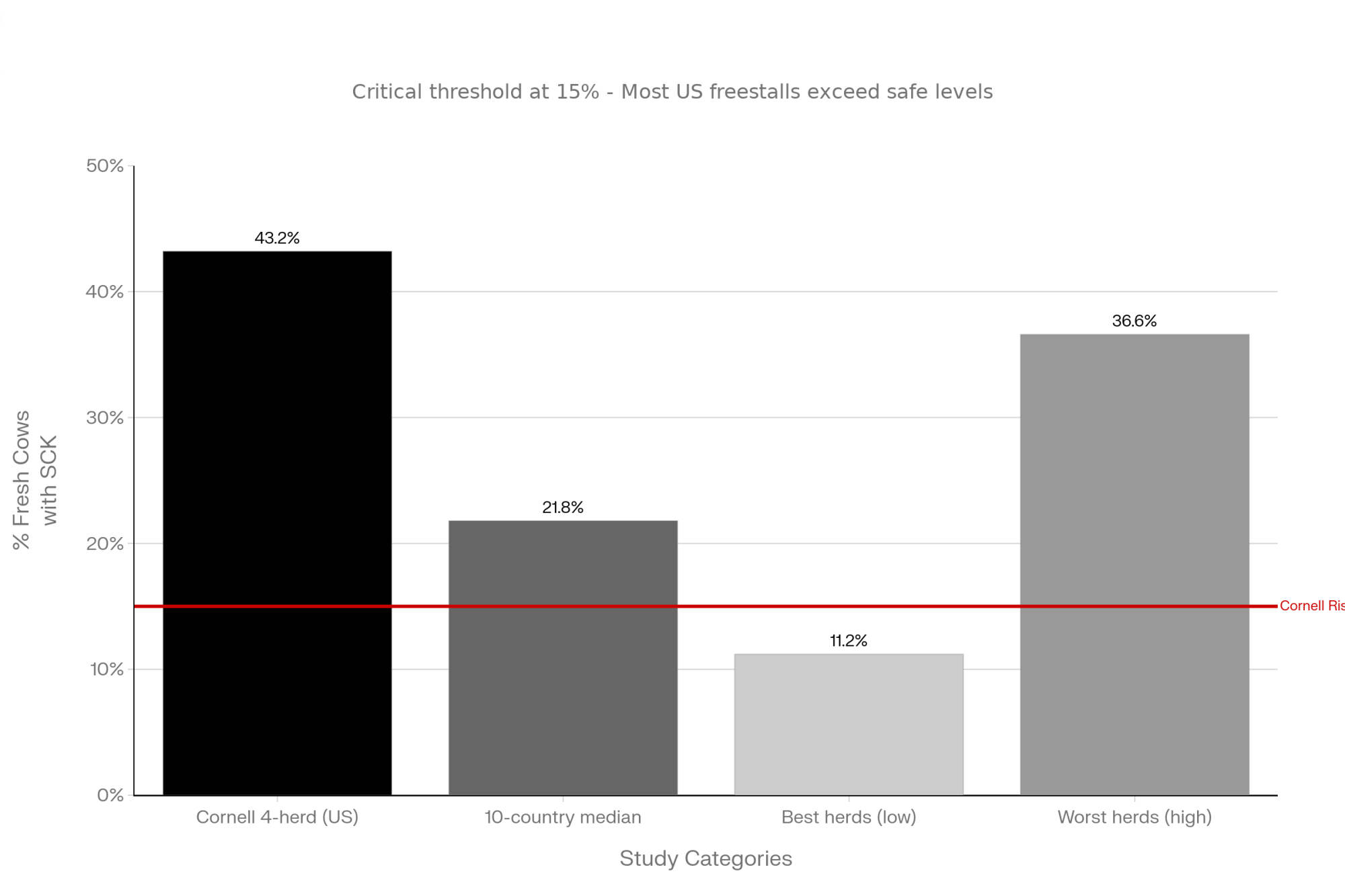

In an epidemiology study many of you will have heard about by now, Jessica McArt, DVM, PhD (Cornell University), and colleagues followed 1,717 cows in four New York and Wisconsin freestall herds. They tested blood BHBA between 3 and 16 days in milk and used 1.2 mmol/L as the cutoff for subclinical ketosis (SCK). In that dataset, 43.2% of cows had at least one BHBA reading at or above 1.2 mmol/L, with risk peaking around day five fresh. A larger study in 10 countries found a median SCK prevalence of 21.8% between 2 and 15 DIM at the same cut point, with herds ranging from 11.2% to 36.6%.

So in many herds, somewhere between one in five and almost half of the fresh cows are running with elevated ketones in that first couple of weeks. That’s a lot of cows quietly working too hard metabolically before we ever talk about breeding.

Now, here’s where it gets uncomfortable biologically. Several studies on negative energy balance and reproduction have shown that elevated NEFA and BHBA don’t just circulate in the blood—they show up in follicular fluid, right where the next oocytes are maturing. Under those conditions, oocytes tend to mature more slowly, fertilization rates are lower, and the embryos that do develop have fewer cells and more signs of stress and cell death in culture. Work examining genetically divergent fertility lines has also shown that cows in deeper negative energy balance after calving can exhibit slower follicle growth and altered ovarian activity compared with cows in better energy status.

In other words, the egg you’re hoping to get pregnant at 70 DIM has already been “programmed” by whatever energy and health storms the cow went through in those first three or four weeks fresh. If she was deep in negative energy balance and battling disease, that egg is starting behind.

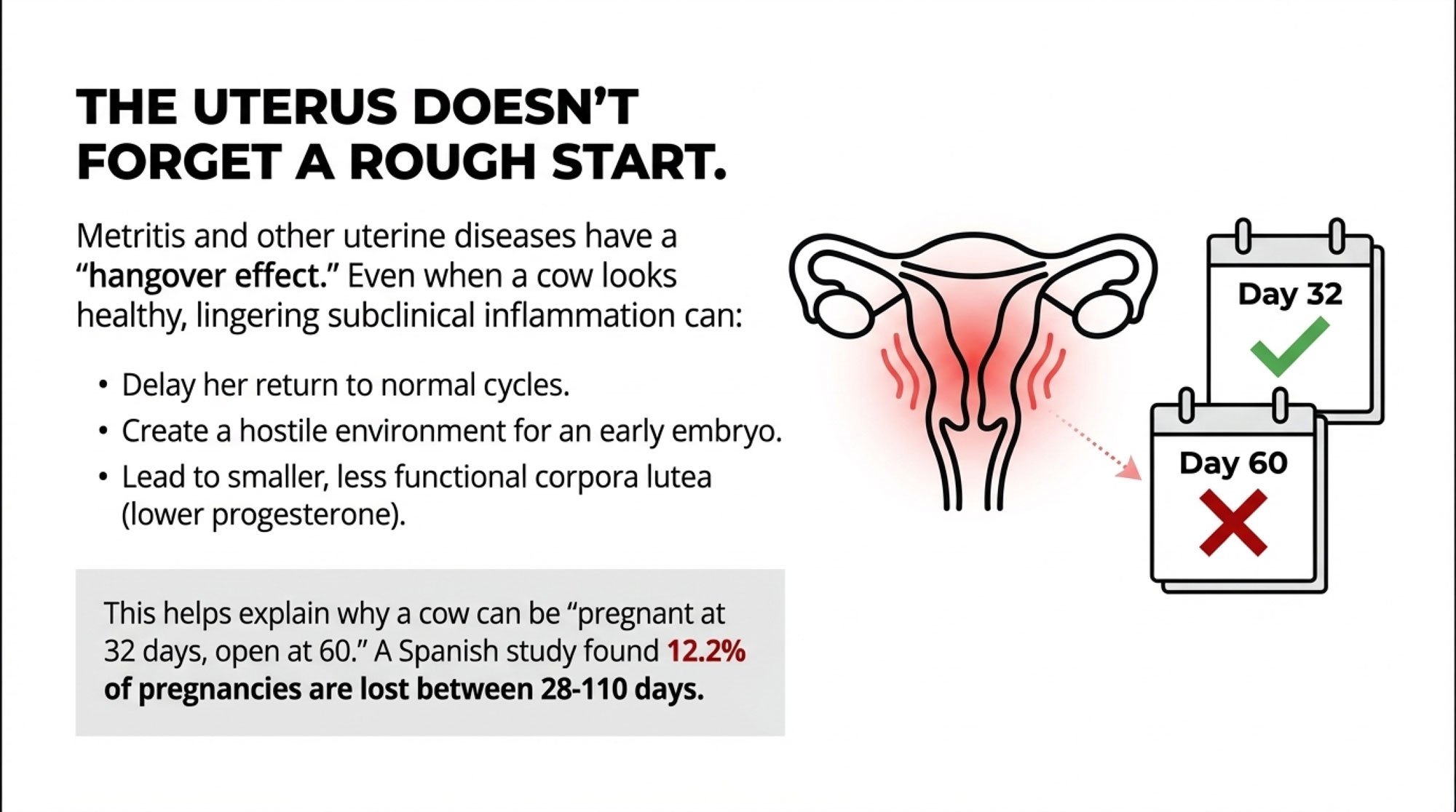

The Uterus Doesn’t Forget a Rough Start

Then there’s the uterus, which is often harder to see from the alley. A metritis cow can look “fixed” pretty quickly: smell is gone, discharge looks cleaner, she’s eating again. It’s easy to mentally tick that box and move on.

But research and field experience say the uterus remembers that rough start longer than we’d like. A Hoard’s Dairyman article that drew on transition cow research described a “hangover effect” of uterine disease—cows that had metritis or retained fetal membranes early on often had slower uterine involution or subclinical inflammation later, even when they looked normal from a distance. That lingering inflammation can delay the return to normal cycles and make it harder for early pregnancies to survive.

The 2023 Double‑Ovsynch study we started with backs up what a lot of vets see in practice. Cows that had transition health events—retained fetal membranes, metritis, mastitis, ketosis, left displaced abomasum—in the first 30 DIM had lower pregnancy per AI and more pregnancies lost between 32 and 60 days, across first‑, second‑, and older‑lactation cows, despite a very standardized repro program.

| Transition Health Status | Pregnancy/AI at 32d | Pregnancy Loss by 60d | Net Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy (no disease) | 42.3% | 8.2% | Baseline |

| Metritis | 36.1% | 11.8% | -6.2% P/AI, +3.6% loss |

| Retained placenta | 37.4% | 10.9% | -4.9% P/AI, +2.7% loss |

| Ketosis (clinical) | 34.8% | 12.4% | -7.5% P/AI, +4.2% loss |

| Displaced abomasum | 31.2% | 14.1% | -11.1% P/AI, +5.9% loss |

| Mastitis (0-30 DIM) | 38.9% | 9.7% | -3.4% P/AI, +1.5% loss |

On top of that, work on postpartum inflammatory conditions has shown that cows dealing with disease during this period can develop smaller or less functional corpora lutea and produce less progesterone, which is not the kind of environment a young embryo wants to live in.

A large retrospective study in intensive Holstein herds in Spain estimated that about 12.2% of pregnancies were lost between 28 and 110 days of gestation. Put that next to the transition‑health and hormone data, and it’s not hard to see how a cow can be “pregnant at 32 days, open at 60,” without anything obvious happening in between.

So, between eggs that were built in a high‑NEFA, high‑BHBA environment and a uterus that may still be recovering from a transition “hangover,” biology keeps pointing back to what happens in those first 30 days fresh.

The Big Dollars: Metritis, SCK, and the Quiet Six‑Figure Drag

The biology matters, but at the end of the month, you’re still staring at a milk cheque, a vet bill, and a loan statement. So let’s put some realistic dollars to these transition issues.

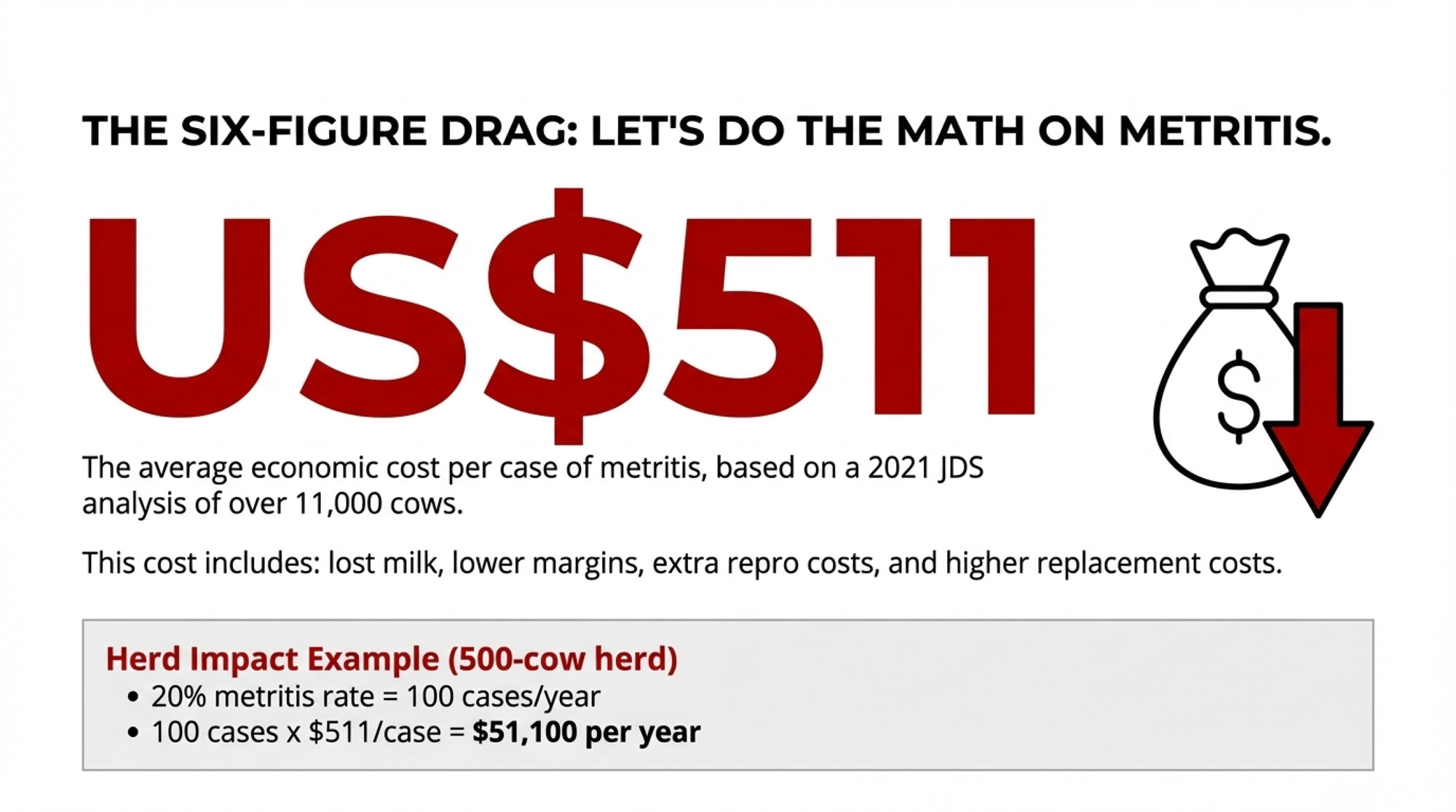

Metritis: A US$511 Per‑Cow Problem

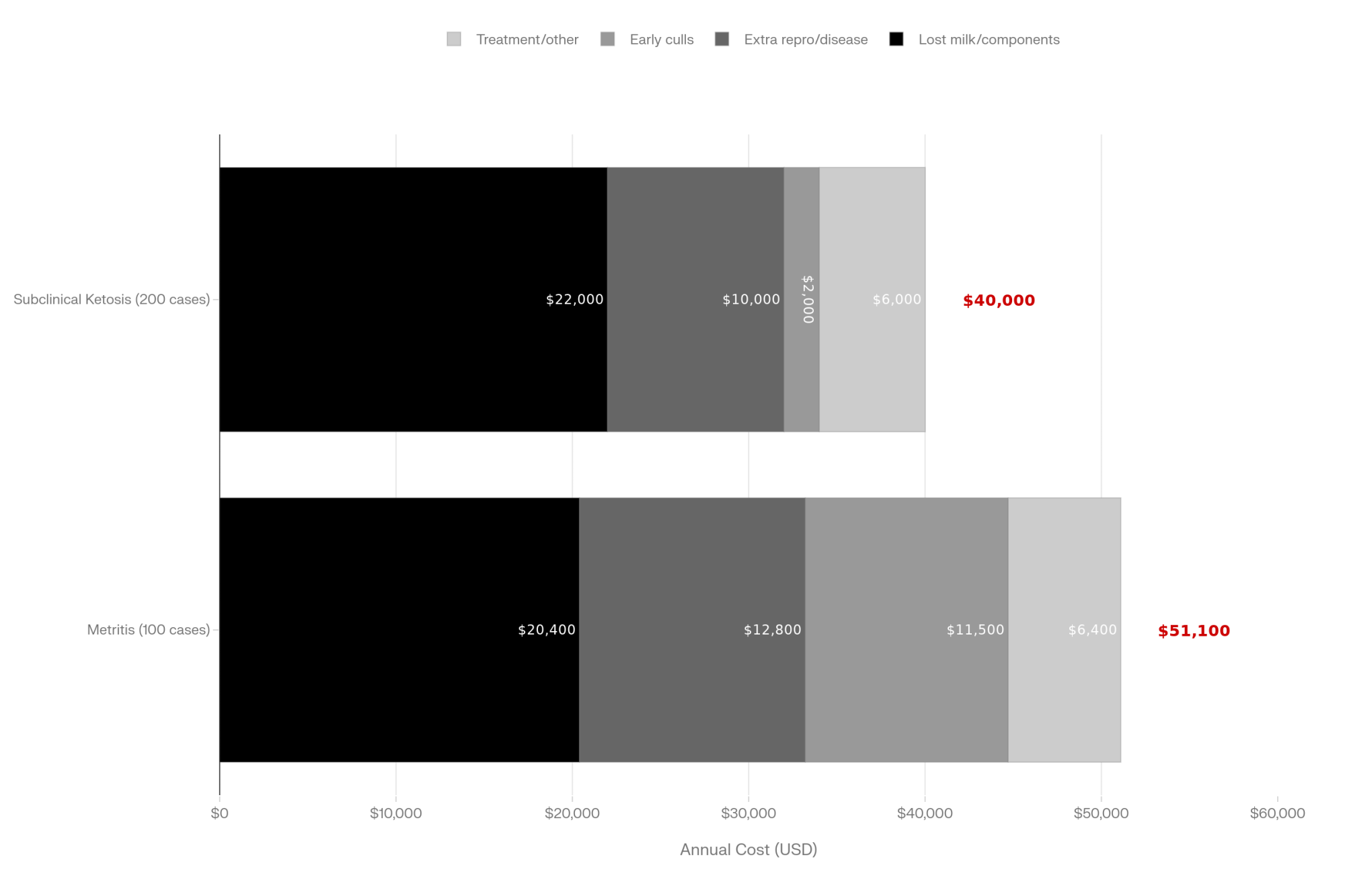

A 2021 paper in the Journal of Dairy Science analyzed 11,733 cows in 16 herds across four U.S. regions and estimated the full economic cost of metritis. Using farm records and simulation, the authors found:

- Mean cost per case: US$511

- Median: US$398

- Simulated mean: US$513, with 95% of scenarios between roughly US$240 and US$884

Those dollars include lost 305‑day milk, lower gross margin per cow, extra reproductive costs, and higher replacement costs because affected cows left the herd sooner. Hoard’s Dairyman, using herd‑level modeling on a large U.S. dairy, landed on metritis costs in the mid‑US$300 range for that specific scenario, which falls within the general range and shows how market conditions and farm structure can tweak the final number.

Now take a 500‑cow herd with a 20% metritis rate among fresh cows—a number that wouldn’t shock many vets in freestall herds. That’s roughly 100 cases of metritis per year. At US$511 per case, you’re into about US$51,000 in metritis‑related costs per year. That’s not just one bad month; that’s a steady leak.

Those costs don’t just sit in the “vet” column, either. A sizable chunk of that US$511 is hidden in longer days open, more services per pregnancy, lower milk, and cows that drift out of the herd earlier than they should.

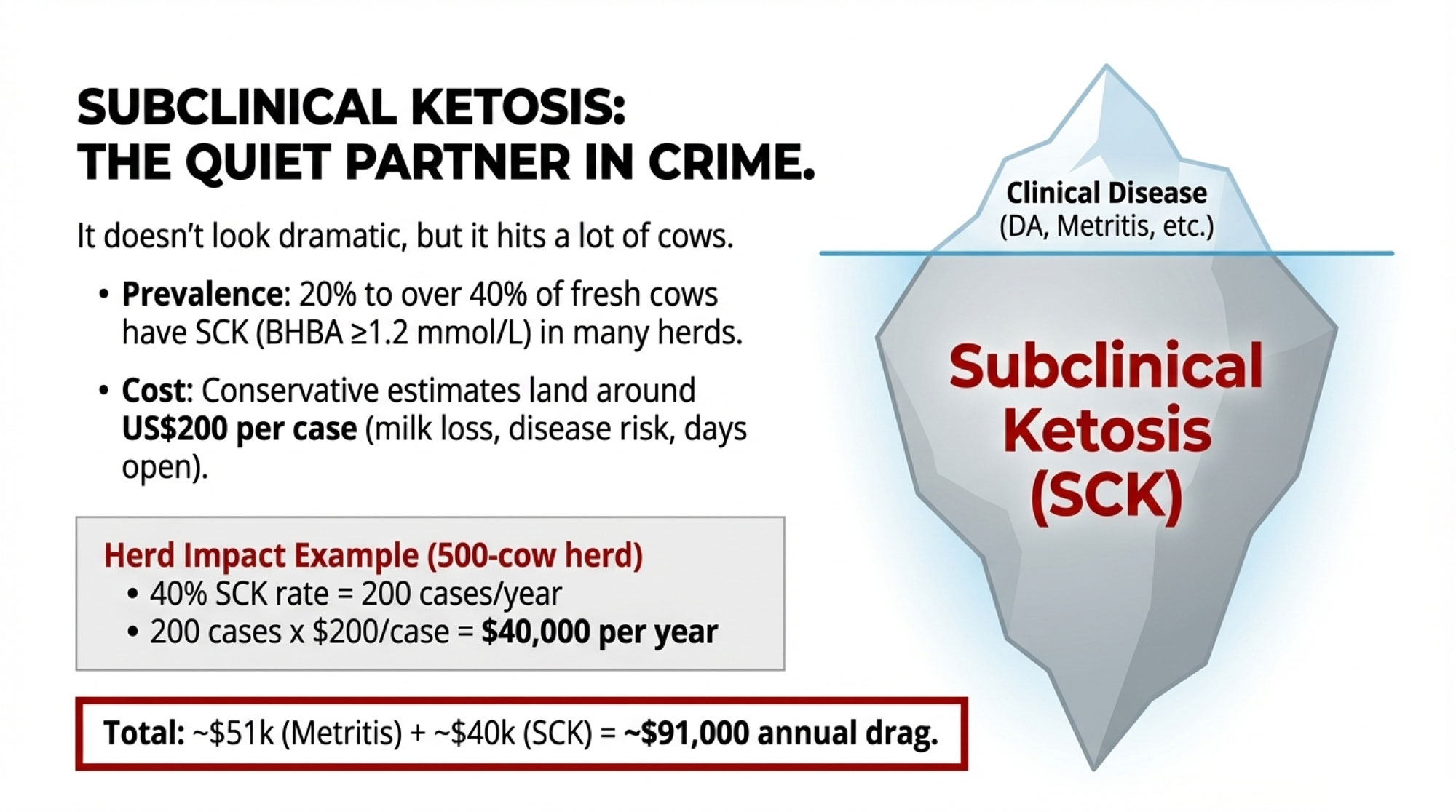

Subclinical Ketosis: Common, Quiet, Costly

Subclinical ketosis doesn’t show up like a twisted stomach or a downer cow, but it quietly hits a lot more animals.

In McArt’s four‑herd study, 43.2% of cows hit SCK—BHBA ≥1.2 mmol/L—at least once between 3 and 16 DIM. In the 10‑country data set, the median herd‑level SCK prevalence was 21.8% between 2 and 15 DIM at the same cut point, with a broad range across herds. Cows with high BHBA were more likely to develop displaced abomasum, clinical ketosis, and metritis, and were more likely to leave the herd earlier.

Economic analyses that bundle milk loss, disease risk, extra days open, and culling generally land in the low‑to‑mid hundreds of dollars per SCK case. The exact number depends on milk prices, feed costs, and replacement values, but it’s not pocket change.

So if around 40% of a 500‑cow herd—about 200 cows—experience SCK in early lactation, even a conservative estimate of US$200 per case means you’re looking at about US$40,000 per year in lost opportunity tied to SCK alone. When you stack that next to the metritis math, it’s easy to see how transition disease can quietly push the total into serious money for a 500‑cow operation.

In Canadian quota systems, there’s another angle. Canadian Dairy Commission figures show that average butterfat tests on Canadian farms have been creeping up—around 4.3% in 2024—helping reduce structural surplus and improve returns per litre. When fresh cows crash, both milk yield and butterfat performance in early lactation tend to suffer. That means quota isn’t being used as efficiently, and you may be under‑delivering butterfat against the quota you paid a lot of money for. Dairy Global has reported that producers in Eastern Canada continue to battle for relatively small amounts of new quota at high butterfat prices per kilogram, reinforcing how valuable every kilogram of component really is. A fresh cow crash is a component crash—and in a quota system, components are your currency.

So these early diseases aren’t just a health story; they’re a transition‑to‑cheque story.

What Farmers Are Finding: NEFA, BHBA, and That Post‑Calving Crash

So how do you tell whether NEB and transition problems are really a big driver on your farm, beyond the feeling that you’re treating too many fresh cows?

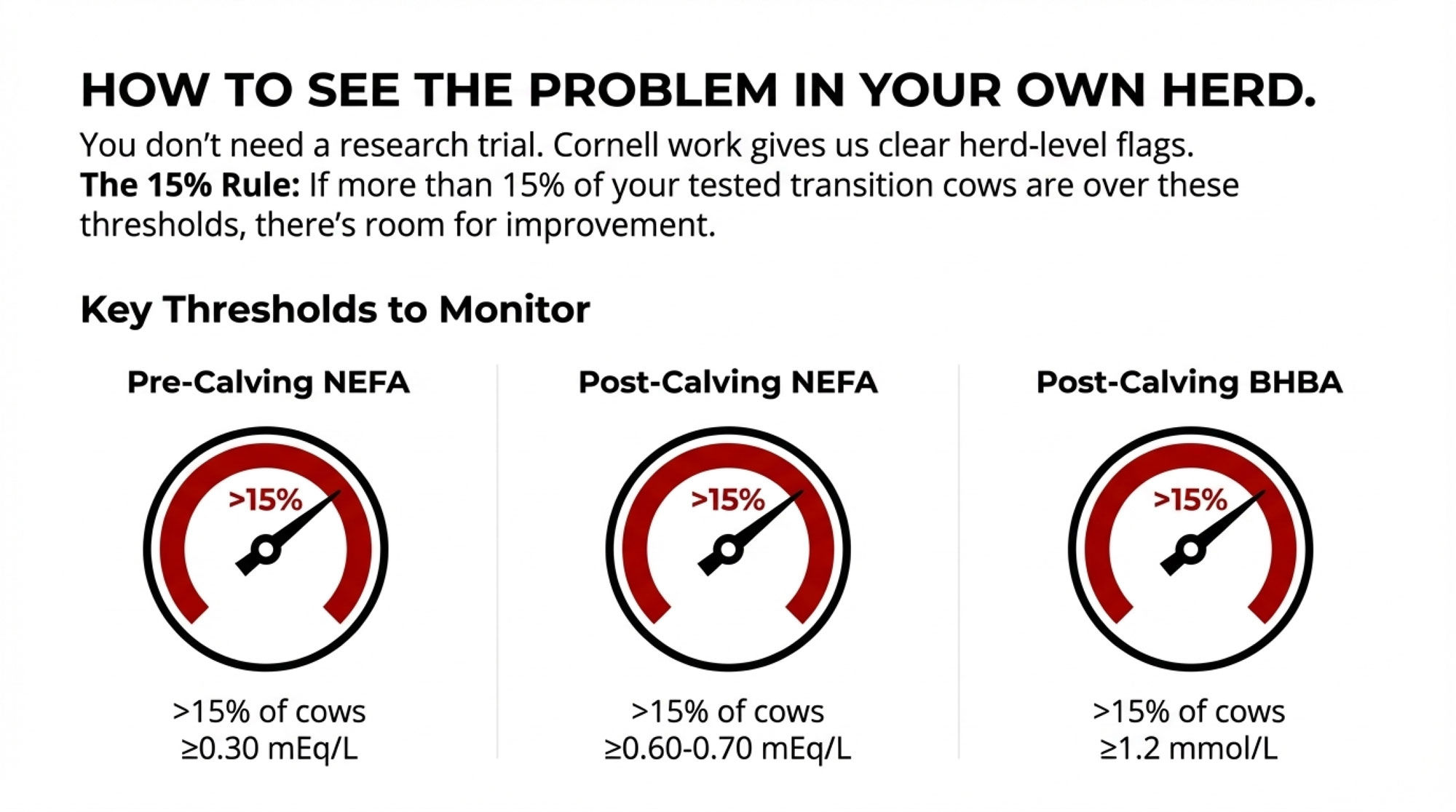

Cornell work has given us some very practical markers. In a series of projects summarized by Tom Overton, PhD (Cornell University), and detailed in work by Ospina and colleagues, three key thresholds emerged when predicting disease and performance:

- Pre‑calving NEFA: When more than about 15% of close‑up cows tested ≥0.30 mEq/L NEFA in the week before calving, the herd saw a higher risk of displaced abomasum, retained placenta, metritis, and poorer reproduction after calving.

- Post‑calving NEFA: When more than about 15% of fresh cows had NEFA ≥0.60–0.70 mEq/L in the first two weeks after calving, early‑lactation disease risks and performance losses increased.

- Post‑calving BHBA: When more than about 15% of cows had BHBA ≥10–12 mg/dL (≈1.0–1.2 mmol/L) in the first couple of weeks, the herd had more DAs, clinical disease, and lower 305‑day mature‑equivalent milk.

Overton and others have translated this into a simple herd‑level rule of thumb: if more than 15% of sampled cows are over those NEFA or BHBA thresholds, there’s likely “room for improvement” in transition energy balance and management.

So, a practical way to use NEFA/BHBA looks like this:

- A few times a year, pull blood on 12–15 close‑up cows and 12–15 fresh cows with your vet.

- See what percentage of each group is over those 0.30 / 0.60–0.70 NEFA levels and ~1.0–1.2 mmol/L BHBA equivalents.

- If that percentage is under about 15%, you’re probably in decent shape. If it’s above 15–20% consistently, it’s a strong signal your transition program is leaving money and pregnancies on the table.

You don’t have to turn your herd into a research trial. A small, well‑chosen sample, taken a few times a year, gives you a pretty honest “weather report” on how tough that transition window really is for your cows.

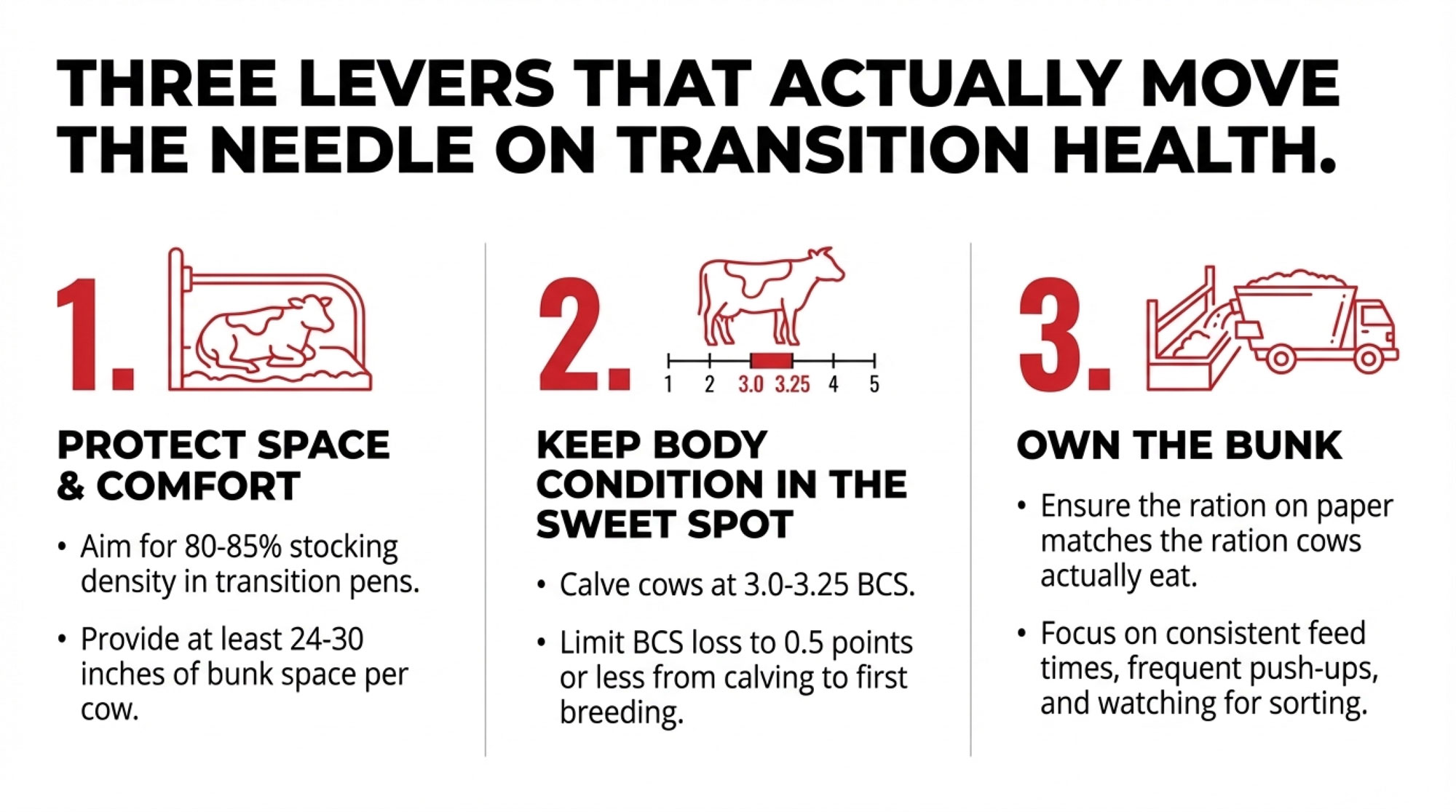

What Farmers Are Doing: Three Management Levers That Actually Move the Needle

So, where are the herds that are doing well on this 90‑day connection, actually putting their time and money? Across extension meetings, Dairyland Initiative resources, and producer discussions, three levers keep coming up.

1. Protecting Space and Comfort in Transition Pens

Looking at this trend across herds, the first word that comes up is space. The University of Wisconsin’s Dairyland Initiative has been very clear: overstocking freestall pens increases competition at the bunk, reduces lying time, keeps cows on concrete longer, and leads to more lameness and lower milk yield. Those effects are especially problematic in close‑up and fresh pens.

Their recommendations—and those of other researchers—generally look like this:

- Aim for about 80–85% stocking density in close‑up and fresh pens, not 100–120%.

- Give at least 24–30 inches of bunk space per cow in these pens to reduce bunk competition.

Penn State Extension has also emphasized that overstocking at the bunk raises risk for SCK, displaced abomasum, and hypocalcemia because lower‑ranking cows end up eating less of the intended ration and at less‑ideal times.

In Wisconsin freestall herds, I’ve noticed that when producers finally protect those transition groups—sometimes at the cost of a tighter late‑lactation pen—fresh cow problems start to ease. Fewer DAs, fewer metritis cases, fewer slow‑starting cows. In Western dry lot systems in California or Idaho, the details change—shade, mud, and feedlane design matter more than stalls—but the principle is the same: if transition cows can’t eat and rest without fighting for it, you’ll pay for it in the breeding pen.

2. Keeping Body Condition in the Sweet Spot

Body condition management isn’t new, but the research has sharpened the targets.

The high fertility cycle paper and postpartum BCS studies suggest that Holsteins do best for health and fertility when they calve around 3.0–3.25 on a 5‑point scale. Cows calving at 3.5 or higher have a higher risk of metabolic problems—SCK, DA, metritis—and more reproductive trouble. On top of that, cows that lose more than about 0.5 BCS points between calving and first breeding tend to have poorer reproductive performance than cows that hold condition or lose only a little.

So a realistic set of targets looks something like:

- Calve the bulk of the herd at 3.0–3.25 BCS.

- Keep BCS loss from calving to first breeding to 0.5 points or less whenever possible.

In a lot of Midwest freestall herds, the big improvements came not from exotic feed additives but from tightening late‑lactation diets, grouping over‑conditioned cows more thoughtfully, and making sure transition rations support steady intakes before and after calving.

In Canadian quota herds, it has a direct butterfat angle as well. When fresh cows calve too heavy and crash in condition, you often see depressed butterfat performance right when you’re trying to maximize component yield against quota, this is critical to improving farm margins in a supply‑managed environment.

3. Making Sure the Ration on Paper Matches the Ration at the Bunk

The third lever is deceptively simple: cows don’t eat the ration in the nutritionist’s software, they eat what’s in front of them.

Penn State and other extension teams keep coming back to a few basics that are easy to slip on when days get long:

- Feed at consistent times so cows know when to expect feed.

- Push up often enough that there’s always feed in reach, especially for timid cows.

- Watch refusals and particle size so you catch sorting before it becomes a habit.

Overstocking the feed bunk makes all three much harder, and that’s a big reason why crowded transition pens and higher SCK/DA/metritis risk so often travel together.

In the herds that really excel at fresh cow management, someone clearly “owns the bunk.” That person is watching how the ration looks in the wagon, how it looks in front of the cows, how cows are eating it, and how much is left—and they’re talking regularly with the feeder and nutritionist about what they see.

What I’ve noticed is that when this bunk piece is tight, you feel it everywhere: smoother fresh cow management, more consistent butterfat performance, fewer surprise DAs, and fewer cows that arrive at first service already behind.

Simple Data Tools That Make the 90‑Day Connection Visible

You don’t need a new monitoring system or a consultant parked at your farm to start connecting transition and reproduction. Three data points most herds already have—or can get easily—can take you a long way: early fat‑to‑protein ratio, peak milk patterns, and early cull rates.

Fat‑to‑Protein Ratio: A Metabolic Weather Report

A 2021 paper revisiting the link between fat‑to‑protein ratio (F:P) and energy balance found that early‑lactation F:P ratios of 1.5 or higher tended to reflect deeper negative energy balance—more body weight loss, higher NEFA, and more metabolic strain. That’s consistent with what a lot of nutritionists already treat as a warning sign.

So, practically:

- If only a small slice of early‑lactation cows have an F:P ≥1.5 on the first test after calving, you’re likely okay.

- If 20% or more of those cows have F:P ≥1.5 on that first test, it’s a good reason to dig into energy balance and SCK risk.

It won’t diagnose the problem for you, but it tells you there’s likely a problem to solve.

Peak Milk Curves: How Fast and How High

In well‑managed Holstein herds on TMR, mature cows often peak around 60–75 DIM, depending on genetics and ration strategy. When transition disease is common, those peaks tend to be lower and show up later in lactation.

Several studies and field analyses have shown that cows with clean transitions tend to have faster‑rising, higher peaks, while cows that battled SCK, metritis, or DA have flatter, delayed peaks and lower overall production. If your software will let you, plotting separate curves for “healthy through 30 DIM” cows and “at least one transition disease” cows can be an eye‑opening exercise in a herd meeting. In many herds, seeing those two curves side‑by‑side does more to justify investing in transition than any lecture.

Early‑Lactation Culls: When Do Cows Leave?

Most herds track the total cull rate. Fewer herds break out 0–60 DIM removals in a way that gets discussed regularly.

Disease‑costing and herd analyses repeatedly show that early culls are among the most expensive, because you’ve carried that cow through a previous lactation and the dry period and then gotten very little milk out of the current one. Herds with strong transition programs often keep early removals in the low single digits as a percentage of calvings, while herds where transition disease is a bigger issue can see early culls drift into double‑digit percentages.

Once you start tagging early culls with clear reasons and comparing them against fresh cow records and BHBA/NEFA test results, a pattern usually emerges: many of those cows never really recovered from the transition period. It’s a tough conversation, but it’s one of the most useful ones you can have.

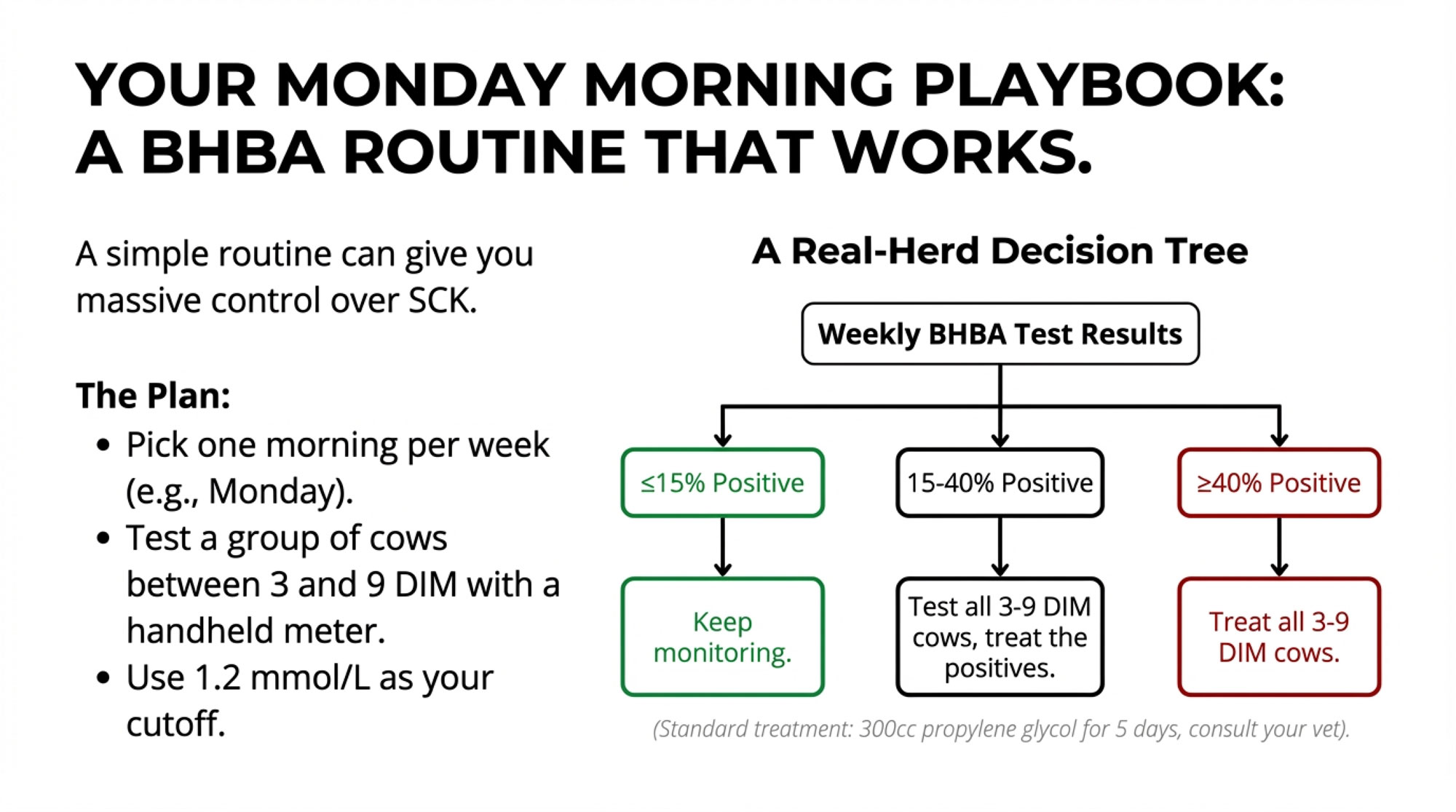

What Farmers Are Doing: A BHBA Routine That Fits Real Herds

Subclinical ketosis is one of those areas where a simple routine can give you a lot of control without turning your farm into a research station.

Building on McArt’s SCK work and field protocols shared by practitioners like Jerry Gaska, DVM (Wisconsin), the routine many herds are adopting looks like this:

- Pick one or two mornings each week.

- On those days, test a group of cows between 3 and 9 DIM using a validated handheld BHBA meter.

- Use 1.2 mmol/L as the cutoff for subclinical ketosis—the same line used in Cornell’s epidemiology work and in many extension programs.

Gaska described a Wisconsin farm where they treat their BHBA results like a herd‑level dashboard:

- If ≤15% of tested cows are at or above 1.2 mmol/L, they just keep monitoring.

- If 15–40% are positive, they test all cows 3–9 DIM and treat the positives.

- If ≥40% are positive, they treat every fresh cow in that DIM range.

Their standard treatment is 300 cc of propylene glycol once daily for 5 days, which is consistent with recommendations from many vets and extension resources. The goal isn’t to drive SCK to zero—it’s to keep the percentage reasonable and to use that weekly number as an early warning system for when transition is slipping.

If you imagine a 500‑cow herd trimming SCK prevalence from 40% down toward 20% over a season or two, using this type of monitoring and better transition management, and you assume each SCK case costs in the low hundreds of dollars, the potential savings add up quickly. And what farmers are finding is that when that BHBA dashboard number improves, DA numbers, metritis cases, and repro results tend to look better a few months later.

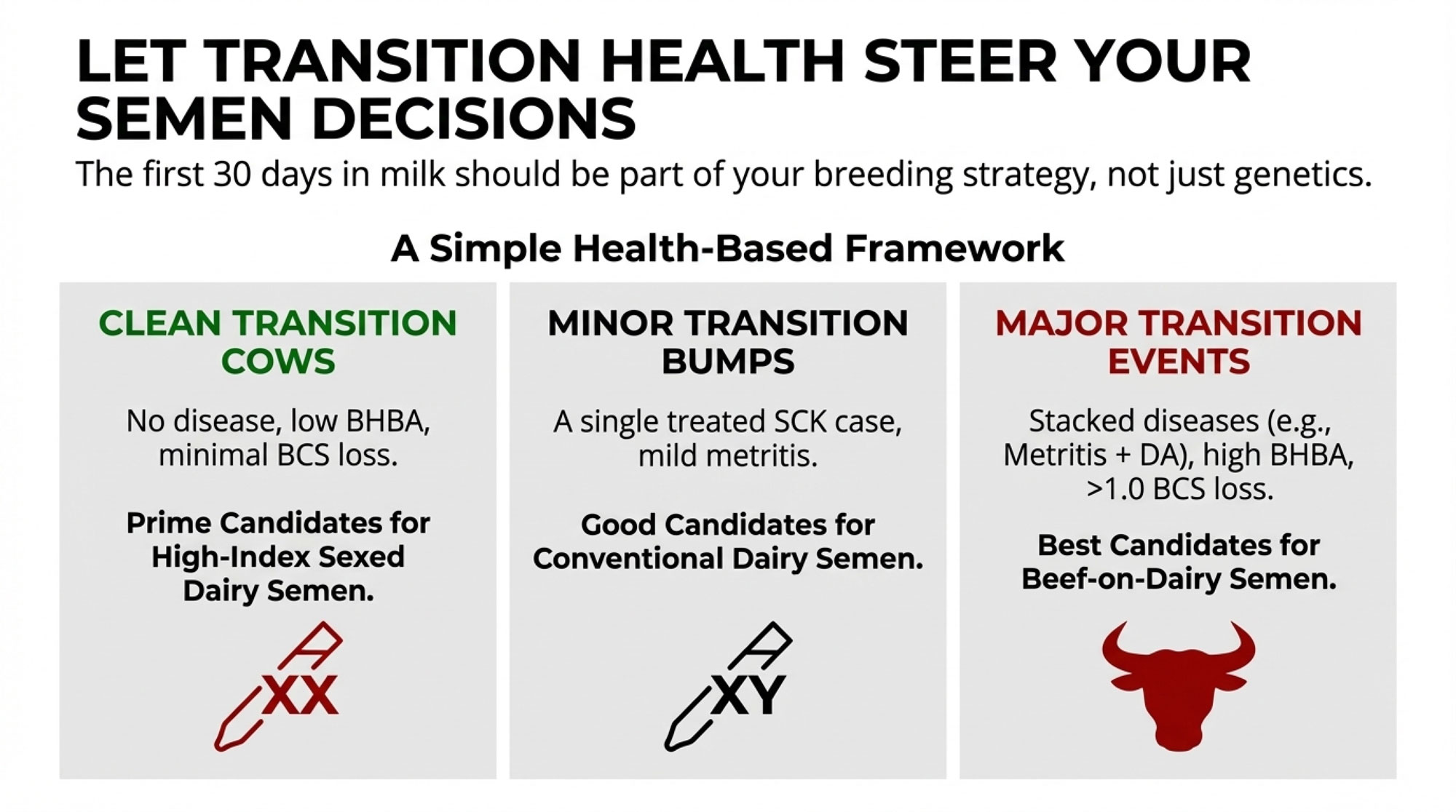

What Farmers Are Finding: Letting Transition Health Steer Semen Use

Now let’s talk about where this transition health story meets some of the hottest decisions on many farms: how to use sexed dairy semen, conventional semen, and beef‑on‑dairy.

Beef‑on‑dairy has moved from “interesting idea” to everyday practice on a lot of operations. Industry reporting and national evaluation data show more herds using sexed dairy semen on a limited top tier and beef semen on lower‑priority cows to capture calf value. At the same time, reproduction leaders like Paul Fricke, PhD (University of Wisconsin–Madison), have been talking about a “reproduction revolution” centered on precision timed‑AI, early pregnancy diagnosis, and targeted use of sexed and beef semen.

What’s encouraging is that more producers are folding transition health into that conversation, not just parity and genetic index.

A Simple Health‑Based Semen Strategy You Can Actually Use

Here’s one way to structure it that fits real herds:

1. Clean Transition Cows

These cows:

- Had no recorded transition disease in the first 30 DIM (no milk fever, metritis, DA, clinical ketosis, retained fetal membranes).

- Stayed below 1.2 mmol/L BHBA on any early‑lactation testing, if you test.

- Lost 0.5 BCS points or less from calving to first breeding.

- Showed a first‑test F:P ratio comfortably under 1.5.

They’re prime candidates for high‑index sexed dairy semen, especially if their genetic merit fits your replacement goals. That’s where you want to invest in future daughters.

2. Minor Transition Bumps

These cows might have:

- A single BHBA reading just over 1.2 mmol/L that responded to propylene glycol.

- A mild metritis case that resolved quickly.

- Slightly more BCS loss than ideal, but nothing dramatic.

They’re often solid cows, just not quite in the “best bets” class. Many herds here lean toward conventional dairy semen, reserving sexed semen for cows that are both genetically strong and biologically set up for success.

3. Major Transition Events

These cows tend to be the ones that:

- Had metritis and a DA or stacked multiple transition diseases.

- Showed consistently high BHBA readings or obvious SCK that lingered.

- Dropped more than a full BCS point between calving and breeding.

A growing number of herds put these cows in the beef‑on‑dairy or “do not breed” category, depending on age, production, and pregnancy status. In Western dry lot systems where beef‑cross calves often have a ready market and good value, managers talk about this as a way to turn a cow with higher reproductive risk into a short‑term calf revenue opportunity instead of betting your future replacements on her.

In Canadian quota herds, where quota additions can be limited and expensive, many producers are using a similar idea: they focus sexed dairy semen on cows that are most likely to be long‑term, high‑component producers under their system, and use beef on cows where the odds of a trouble‑free, high‑butterfat lifetime are lower.

The big shift is that the first 30 days in milk are now part of the semen decision, not just age, production, or genomic index. That’s a very “2020s” way of thinking about reproduction that lines up biology, genetics, and cash flow.

| Transition Health Tier | Health Markers (0-30 DIM) | Semen Strategy | Why This Works | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1: Clean Transition | – No disease events – BHBA <1.2 mmol/L – BCS loss ≤0.5 points – F:P <1.5 | High-index sexed dairy semen | Healthy metabolism during follicle development; strong oocyte quality; optimal uterine environment | High P/AI (40%+); low preg loss; valuable replacement heifers |

| Tier 2: Minor Bumps | – Single mild SCK event (responded to treatment) – Mild metritis (quick resolution) – BCS loss 0.5-0.75 points | Conventional dairy semen | Moderate metabolic challenge; good recovery; acceptable but not optimal fertility | Moderate P/AI (30-38%); acceptable preg loss; solid replacements |

| Tier 3: Major Events | – Metritis + DA – Multiple disease events – Persistent high BHBA – BCS loss >1.0 point | Beef-on-dairy or Do Not Breed | Severe metabolic/uterine damage; compromised oocyte quality; high preg loss risk; poor lifetime potential | Capture calf value; avoid wasting high-value dairy genetics on low-fertility cow |

Nuances That Matter: Heifers, Pregnancy Loss, and Seasonal Herds

There are a few wrinkles worth mentioning, because not every group of cows—or every system—behaves the same.

One nuance that came out of the Cornell NEFA/BHBA work, and was highlighted in Hoard’s Dairyman, is that heifers and older cows don’t always show the same performance patterns at similar NEFA and BHBA levels. In those data, heifers with higher postpartum NEFA (≥0.60 mEq/L) and BHBA (≥9 mg/dL) sometimes produced more milk than heifers with lower levels, while multiparous cows with NEFA ≥0.70 mEq/L and BHBA ≥10 mg/dL produced less and had more disease. That doesn’t mean high ketones are ever “good,” but it does suggest that if time and budget are tight, focusing your most intensive monitoring on older cows may give you more bang for your buck.

On pregnancy loss, the Spanish Holstein work put numbers around something many of us feel: about 12.2% of pregnancies were lost between 28 and 110 days of gestation in intensive systems. Articles in Hoard’s Dairyman and Dairy Global have described pregnancy loss as a major ongoing puzzle in modern dairies, with uterine health and metabolic stress as key suspects. That’s one more reminder that “pregnant at 32 days” isn’t mission accomplished if the transition period was rough.

Seasonal and block‑calving herds—whether in New Zealand, Ireland, or pasture‑based pockets of North America—live and die by this 90‑day connection even more. Research on grazing herds with different fertility breeding values has shown that cows with better transition metabolism and shorter postpartum anestrus intervals are far more likely to conceive in the first 3–6 weeks of mating, which pushes up six‑week in‑calf rates and tightens the calving spread. When transition management has holes, those herds feel it almost immediately in more late‑calvers and a stretched season. When they improve energy balance, BCS management, and fresh cow monitoring, many see their fertility and calving patterns tighten within a couple of seasons.

The biology doesn’t care if you’re on pasture or TMR, quota or open market—the transition pen is still writing a big chunk of the repro story.

Bringing It Home: Benchmarks and Monday‑Morning Moves

If you’re thinking, “This all makes sense, but where do we start without turning the place upside‑down?”, here are some concrete benchmarks and a realistic plan.

Benchmarks to Check Your Own Herd Against

From the work and examples we’ve talked about, here are some practical “sanity check” targets:

- BHBA in early lactation:

If more than 15–20% of sampled cows 3–16 DIM test at or above 1.2 mmol/L, your transition energy balance likely needs work. - NEFA pre‑ and postpartum:

If more than about 15% of close‑up cows have NEFA ≥0.30 mEq/L, or more than 15% of early‑lactation cows have NEFA ≥0.60–0.70 mEq/L postpartum, you’re in a higher‑risk zone for disease and weaker repro. - Body condition:

Calving most Holsteins with BCS 3.0–3.25 and keeping BCS loss from calving to first breeding at ≤0.5 pointssupports better health and fertility. - Fat‑to‑protein ratio:

If roughly 20% or more of early‑lactation cows have an F:P ≥1.5 on their first test after calving, it’s a good sign you should dig into energy balance and SCK. - 0–60 DIM culls:

If early‑lactation culls are creeping into double‑digit percentages of calvings, transition disease is almost certainly playing a major role.

You don’t have to fix every metric at once. The power is in watching them over time and seeing whether changes in your transition program move those numbers in the right direction.

| Metric | Target (Green Zone) | Acceptable (Yellow Zone) | Fix This Now (Red Zone) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHBA Prevalence (3-16 DIM, ≥1.2 mmol/L) | <15% of tested cows | 15-20% of tested cows | >20% of tested cows |

| Postpartum NEFA (0-14 DIM, ≥0.60 mEq/L) | <15% of tested cows | 15-20% of tested cows | >20% of tested cows |

| Calving BCS & Loss | Calve at 3.0-3.25; lose ≤0.5 points to 1st breeding | Calve at 3.25-3.5; lose 0.5-0.75 points | Calve at >3.5 or lose >0.75 points |

| Fat-to-Protein Ratio (1st test postpartum) | <20% of cows with F:P ≥1.5 | 20-30% of cows with F:P ≥1.5 | >30% of cows with F:P ≥1.5 |

| Transition Pen Stocking(close-up & fresh) | 75-85% stocking; 24-30″ bunk/cow | 85-95% stocking; 22-24″ bunk/cow | >95% stocking or <22″ bunk/cow |

| Early Culls (0-60 DIM) | <5% of calvings | 5-8% of calvings | >8% of calvings |

A Realistic Plan for the Next Six Months

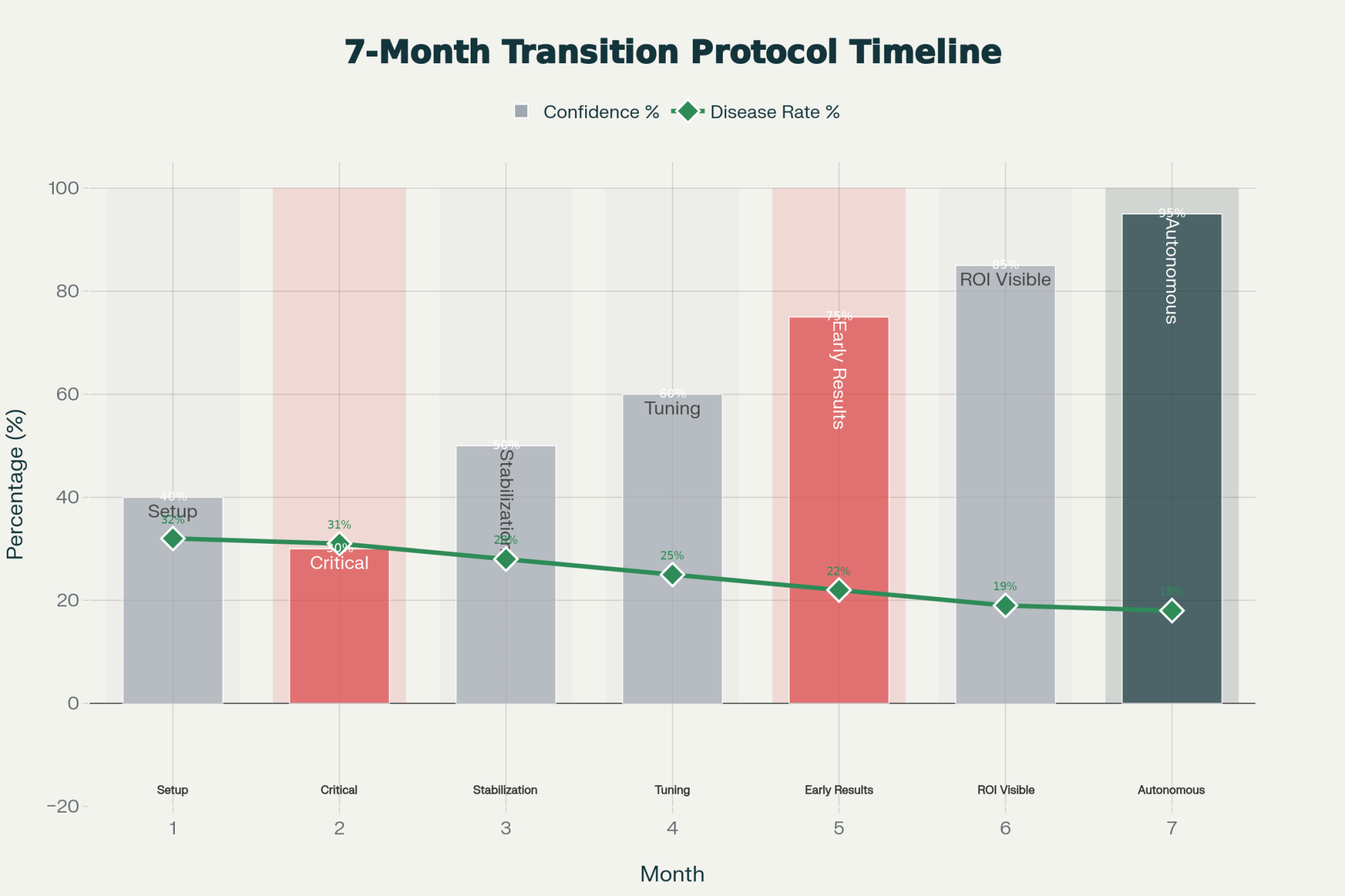

If you want to put this 90‑day lens to work without overwhelming the team, a simple roadmap could look like this:

- Start a BHBA Snapshot.

Once or twice a week, test a small group of cows 3–9 DIM (maybe 6–8 cows in a 100‑cow herd, 10–15 in a 500‑cow herd) using a handheld meter. Track the percentage at or above 1.2 mmol/L, treat positives with a propylene glycol protocol that your vet is comfortable with, and write that weekly percentage where everyone can see it. - Walk Your Transition Pens with a Tape Measure.

Count stalls, count cows, and measure bunk space in your close‑up and fresh pens. If you’re regularly at or above 100% stocking or bunk space is under 24 inches per cow, sit down with your nutritionist and vet to talk through options for regrouping, overflow pens, or small facility tweaks that protect those high‑risk groups. - Bring Transition Health Into the Semen Discussion.

At your next breeding strategy meeting, take along a simple list of fresh cow diseases and BHBA results by cow, plus BCS scores on cows coming up for first service. Sort cows into “clean,” “minor bump,” and “rough transition,” and make deliberate decisions about where sexed dairy semen, conventional semen, and beef‑on‑dairy semen really belong.

The Bottom Line

If there’s one big idea to tuck in your pocket, it’s this: your pregnancy rate isn’t just a breeding‑pen number. It’s a delayed grade on your fresh cow management. The more we treat those first 30 days in milk as the front end of our repro program, not a separate chapter, the more room we give ourselves to improve both the biology and the bottom line.

What’s encouraging is that you don’t need a brand‑new barn or a shiny gadget to get started. Same cows, same buildings, same people—just looked at through a 90‑day lens that connects what happens in the transition pen to what shows up at preg check and, ultimately, on your milk statement.

Key Takeaways:

- Pregnancy rate is really a 90‑day transition report card. Cows with metritis, SCK, or DA in the first 30 DIM have lower pregnancy per AI and more pregnancy loss—even on excellent timed‑AI programs.

- The math adds up fast. Metritis costs about US$511/case; SCK hits 20–40% of fresh cows. Together, they can quietly drain around US$90,000 a year from a 500‑cow herd.

- Simple flags make it visible. BHBA ≥1.2 mmol/L in >15–20% of fresh cows, F:P ≥1.5 in >20% on first test, or 0–60 DIM culls in double digits all signal transition trouble.

- Three levers matter most. Protect stocking (80–85%) and bunk space (24–30″) in transition pens; calve cows at BCS 3.0–3.25 and limit loss to ≤0.5 points; make sure the ration at the bunk matches the ration on paper.

- Use transition health to guide semen decisions. Clean‑transition cows are prime for sexed dairy semen; cows with rough transitions often belong in the beef‑on‑dairy column.

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More

- The 15:1 ROI Protocol: How Anti-Inflammatory Treatment is Cutting Transition Disease in Half – Reveals the tactical anti-inflammatory protocol cutting transition disease in half for just $10 per cow. Gain the specific ROI data needed to transform “firefighting” into high-margin prevention starting this Monday morning.

- Beef-on-Dairy’s $6,215 Secret: Why 72% of Herds Are Playing It Wrong – Exposes why most herds fail at beef-on-dairy economics and arms you with a tiered pregnancy rate strategy for long-term profit. Secure the competitive advantage needed to navigate 2025’s record-high heifer costs.

- AI and Precision Tech: What’s Actually Changing the Game for Dairy Farms in 2025? – Breaks down how AI-powered health monitoring and CattleEye integration deliver 10-20% yield boosts while slashing vet bills. This disruptive insight allows you to automate transition health and eliminate human assessment error.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!