Military helicopters dropping vaccines. Farmers in riot gear standoffs with police. A disease that jumped 300 kilometers in weeks despite aggressive containment. France’s lumpy skin disease crisis is writing the playbook for foreign animal disease preparedness in real time—and the rest of us get to learn before it’s our turn.

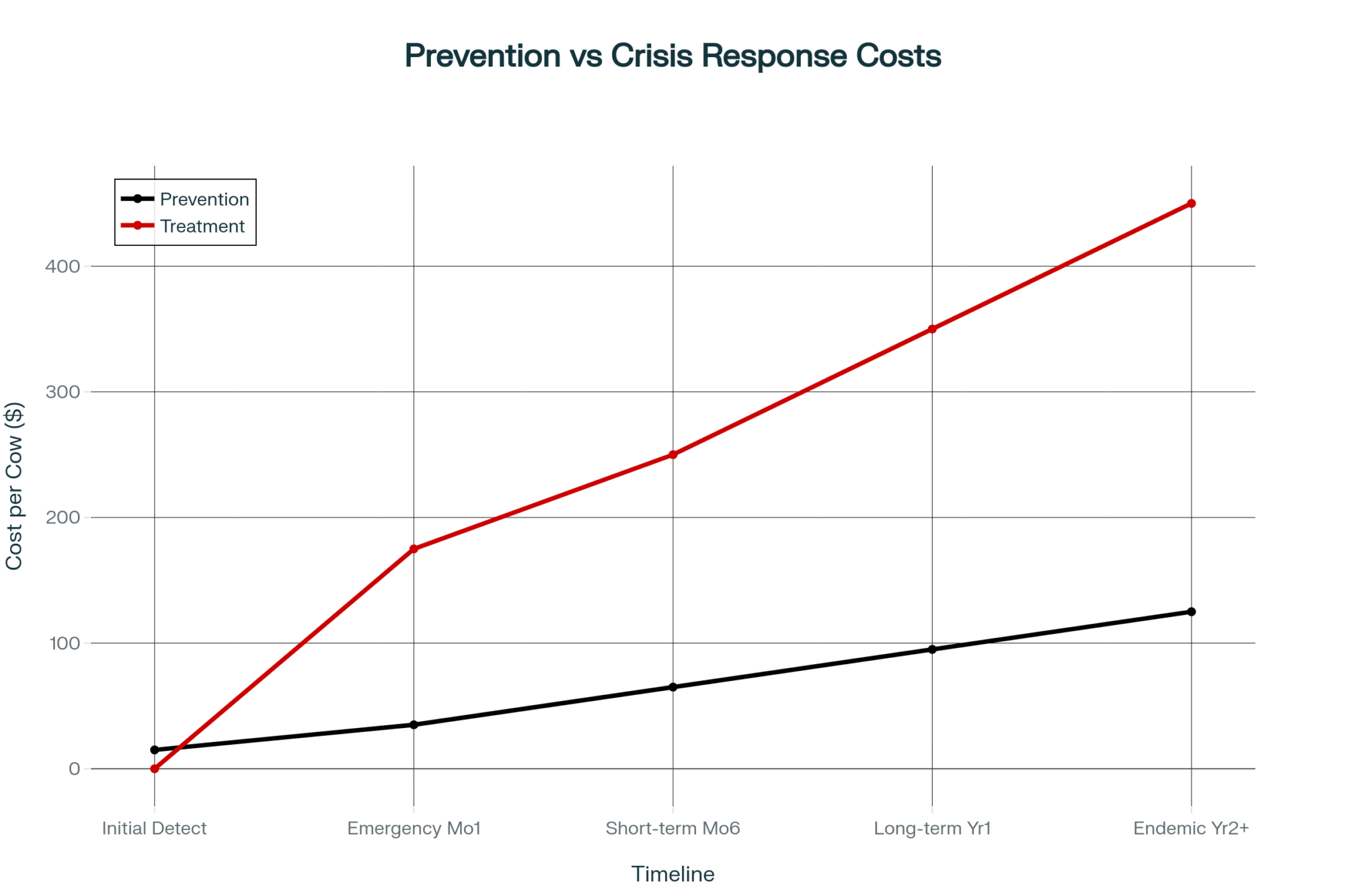

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Six months after France confirmed its first case, lumpy skin disease has exploded to 113 outbreaks and 3,300 cattle culled—with military helicopters deploying vaccines and riot police confronting farmers who’ve blockaded roads rather than surrender herds to mandatory slaughter. This disease has never reached North America, but France’s crisis is exposing failures that matter everywhere: veterinary surge capacity that couldn’t scale, cold chain logistics that collapsed under pressure, and a culling-first policy that shattered the farmer trust essential for disease surveillance. When reporting sick cattle means losing everything, producers stop reporting—and containment becomes impossible. EFSA research shows that vaccination outperforms culling even when vaccines aren’t perfect, yet France chose aggressive depopulation anyway. The economic precedent is sobering: India lost $2.44 billion to endemic LSD in two years; Canada spent 22 years rebuilding export markets after BSE. For North American producers—especially those with genetics programs dependent on trade—the window to establish biosecurity protocols, quarantine procedures, and veterinary relationships is now, while there’s still time to prepare rather than improvise.

You know, there are moments when agricultural policy stops being abstract and becomes deeply, painfully human. December 12, 2025, was one of those moments.

Police in riot gear faced off against hundreds of farmers who had barricaded a small farm in France’s Ariège region with chopped trees, hay bales, and sheer desperation. Tear gas filled the evening air. The standoff wasn’t about wages or trade policy—it was about cattle marked for slaughter in the name of disease control.

What made the scene even more gut-wrenching? The farm belonged to two brothers. One had agreed to the government’s culling order. The other refused. That division within a single family tells you something about the impossible choices this disease is forcing on people across the French countryside.

And for those of us watching from North America, Australia, or anywhere else still free of lumpy skin disease, France’s unfolding crisis offers something genuinely valuable: time to learn before the same pressures arrive at our gates.

QUICK REFERENCE: Know the Threat Landscape

| Lumpy Skin Disease | H5N1 (Avian Influenza) | Bluetongue (BTV-3) | |

| Primary Vector | Biting insects (stable flies, midges, mosquitoes) | Direct contact, aerosol, contaminated equipment | Culicoides biting midges |

| Species Affected | Cattle, buffalo | Dairy cattle, poultry, wild birds | Cattle, sheep, goats, deer |

| Current Spread | France: 113 outbreaks (Dec 2025) | US: ~1,790 herds/18 states (Dec 2025) | Netherlands, Belgium, France, UK, Germany |

| Incubation Period | 4-14 days (up to 28 days) | 2-5 days (in cattle) | 5-20 days |

| Milk Production Impact | Significant (18%+ drop in affected animals) | Severe: ~73% drop at peak; ~2,000 lbs cumulative loss/cow over 60 days | ~2 lbs/cow/day for 9-10 weeks |

| Human Health Risk | None | Yes (rare but serious) | None |

| Vaccine Available | Yes (live attenuated) | Limited | Yes (serotype-specific) |

Sources: WOAH, EFSA, USDA APHIS, CDC, Hoard’s Dairyman, Frontiers in Veterinary Science

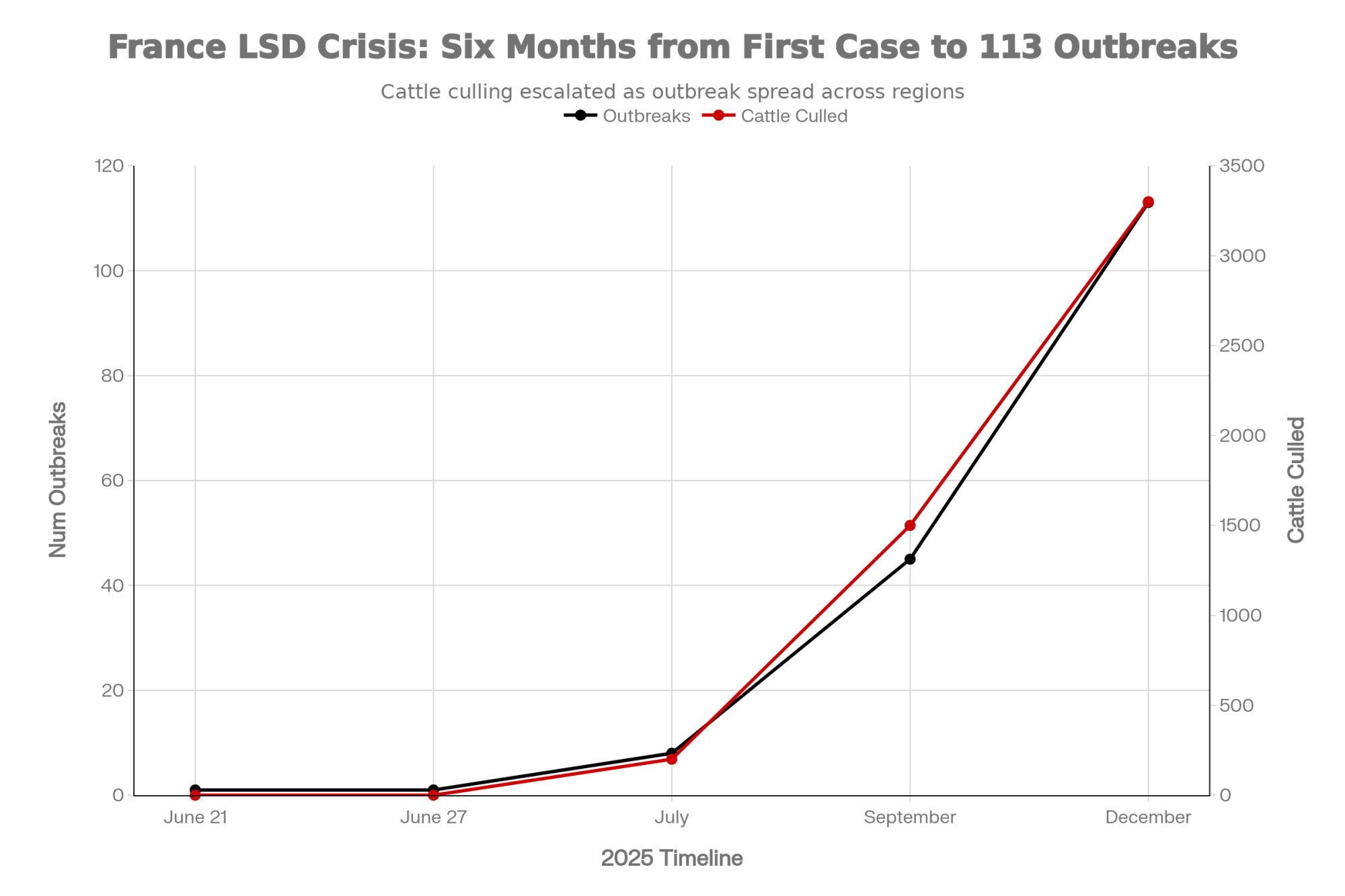

How a Single Case Became 113 Outbreaks in Six Months

Here’s where the timeline gets troubling.

LSD first appeared in Western Europe when Italy confirmed a case in Sardinia on June 21, 2025—the European Commission’s Animal Disease Information System flagged it almost immediately. Six days later, France confirmed its first positive case on a dairy operation near Chambéry in the Alpine department of Savoie, as Dairy Global reported at the time.

French authorities moved fast, I’ll give them that. Vaccination campaigns launched by mid-July. Protection zones extending 50 kilometers went up around affected areas. The response looked impressive on paper:

- Over 220,000 cattle vaccinated within two months, according to Reuters

- Mandatory movement restrictions across affected regions

- Military logistics deployed by December, including transport aircraft and army medical personnel

And yet by mid-December, Reuters was reporting 113 confirmed outbreaks with approximately 3,300 cattle culled. The disease had spread from two eastern departments to span regions across the country—including southwestern areas near the Spanish border, more than 300 kilometers from where it started.

The disease jumped containment lines that should have held. What happened? The answer isn’t any single failure. It’s a cascade of interconnected problems that overwhelmed even a well-resourced system.

CLINICAL SIGNS: What LSD Looks Like in Your Herd

Early Warning Signs (First 1-2 Days):

- High fever exceeding 40.5°C (105°F), sometimes reaching 41°C (106°F)

- Watery discharge from the eyes and nose

- Enlarged superficial lymph nodes (subscapular, prefemoral—easily palpable)

- Decreased milk production in lactating cows

- Depression and loss of appetite

Characteristic Signs (Days 7-14 Post-Infection, can extend to 21 days):

- Firm, raised skin nodules 2-5 cm in diameter

- Nodules appear on the head, neck, limbs, udder, genitalia, and perineum

- Nodules involve skin, subcutaneous tissue, and sometimes underlying muscle

- Nasal discharge becomes thicker (mucopurulent)

- Excessive salivation

- Limb swelling and brisket edema

In Calves:

- More severe clinical presentation than adults

- Higher mortality risk, especially in calves under 3 months

- Generalized weakness and diarrhea

Report any suspected cases immediately to your state/provincial veterinarian

Sources: WOAH, Merck Veterinary Manual, Animal Health Australia

The Infrastructure Gap Nobody Talks About

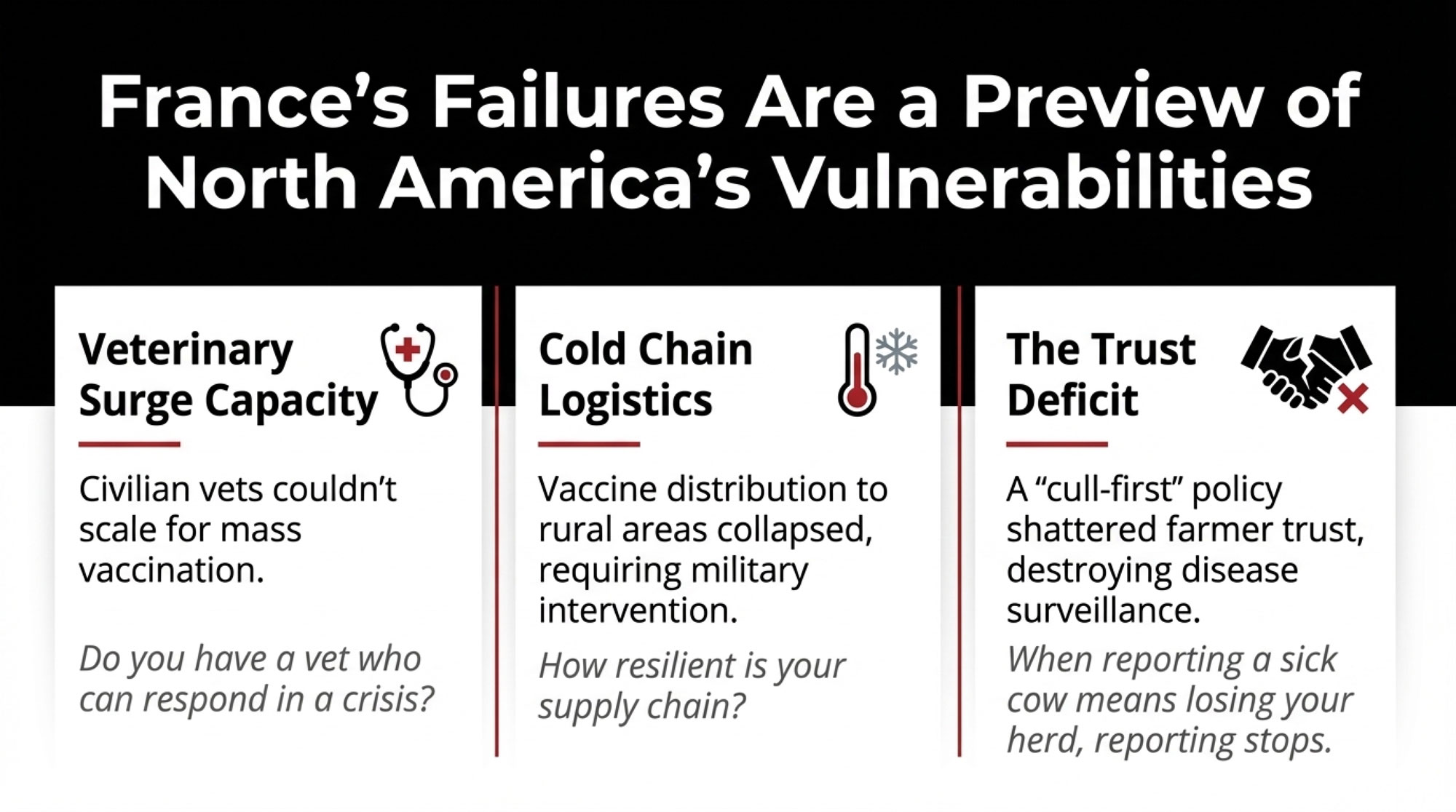

One of the most important lessons coming out of France—and this applies to all of us—involves the difference between having resources on paper and actually deploying them under pressure.

France has world-class veterinary infrastructure. The ANSES laboratory network ranks among Europe’s best. The animal health surveillance system is sophisticated and well-funded. What France lacked, and what most countries lack, is surge capacity.

Vaccine supply became the first bottleneck. France had to access the European stockpile after the first case appeared rather than drawing on pre-positioned reserves. That created delays—days in some areas, weeks in others.

The veterinary workforce was the second constraint. If you’re already struggling to get your herd vet out for a routine visit, imagine what happens when your whole region needs emergency vaccinations. Dairy Global reported in 2023 that of Germany’s roughly 22,000 practicing veterinarians, only about 3,500 still work with agricultural livestock. France faces similar ratios. When mass vaccination required hundreds of additional personnel, the civilian system simply couldn’t scale.

Cold chain logistics emerged as the third challenge. Distributing temperature-sensitive live attenuated vaccines to remote rural areas proved harder than planned. By December, Reuters confirmed the French government had brought in military transport aircraft specifically because civilian logistics couldn’t keep pace.

What’s interesting here is that none of these constraints were invisible beforehand. Agricultural ministries across Europe have documented veterinary workforce shortages for years. But there’s often a significant gap between recognizing a structural problem and having a solution ready when a crisis hits.

The practical takeaway for those of us elsewhere? Even countries with excellent veterinary services face significant delays when novel diseases appear. Operations with established biosecurity protocols and regular veterinary relationships will respond faster than those depending entirely on government systems.

HOW LSD SPREADS: Understanding Transmission

Primary Route: Biting Insects (Mechanical Vectors)

Unlike many viral diseases, LSD spreads mainly through biting insects that carry virus particles on their mouthparts—not through the air or direct animal contact.

INFECTED ANIMAL → BITING INSECT FEEDS → INSECT MOVES → HEALTHY ANIMAL INFECTED

- Virus present in skin nodules and blood

- Virus retained on mouthparts for 6-10 days

- Virus deposited into the skin during the next blood meal

- Infection is established in a new host

Known Vectors:

- Stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) — Primary mechanical vector

- Mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti, Culex species) — Can retain virus 6-10 days

- Biting midges (Culicoides species) — Field evidence of involvement

Why This Matters for Biosecurity:

- Vector control (fly management, standing water elimination) directly reduces transmission risk

- Disease can spread without animal-to-animal contact

- Infected insects can travel significant distances, especially with the wind

- Peak transmission occurs during warm, wet conditions when vector populations surge

Minor Transmission Routes:

- Direct contact with infected animals (considered inefficient)

- Contaminated equipment or fomites (limited evidence)

- Semen from infected bulls (documented but uncommon)

Sources: WOAH, PMC research (Paslaru et al. 2022), EFSA

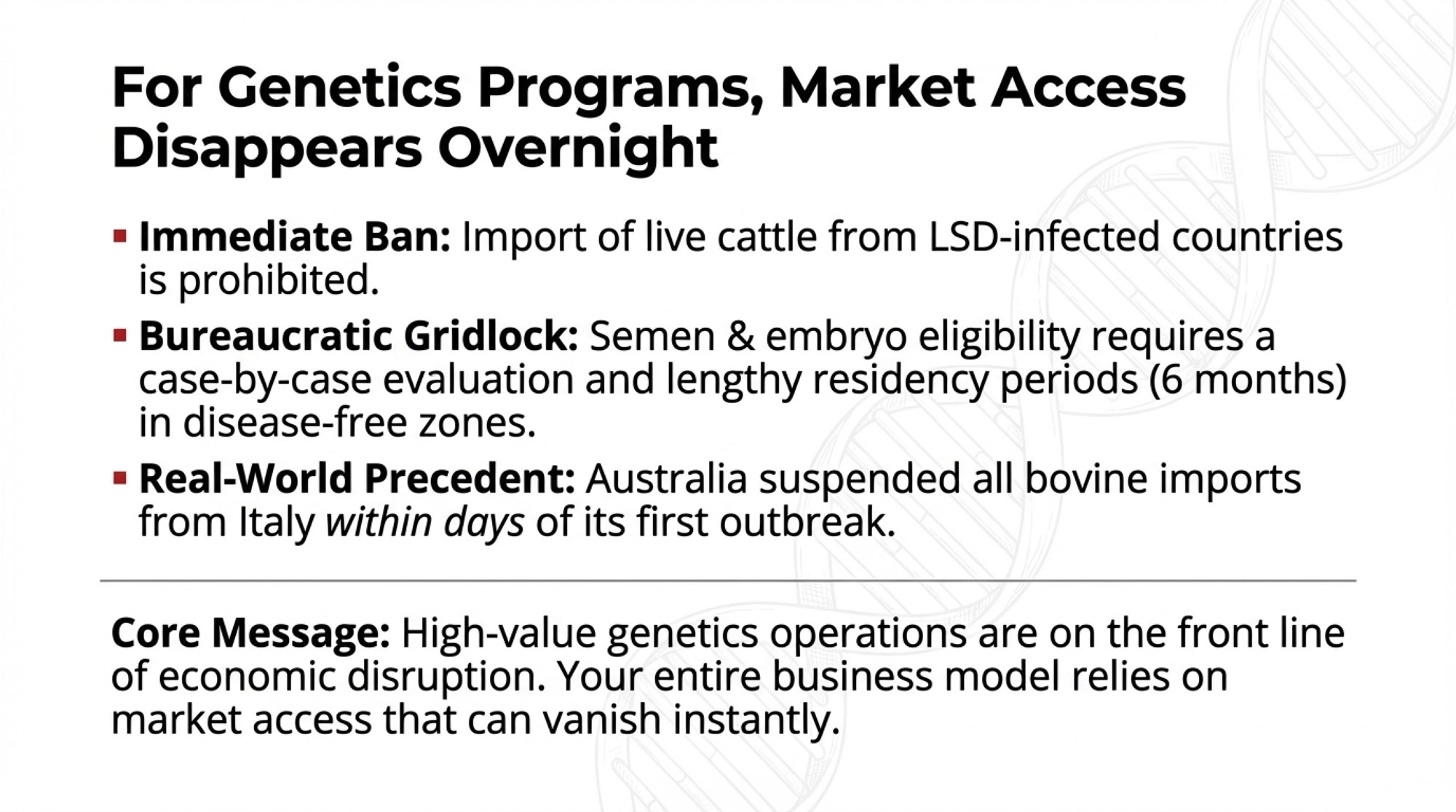

What This Means for Your Genetics Program

For operations with significant genetics investments—AI programs, embryo transfer work, show herds, or A2A2 breeding programs—LSD introduces complications that go well beyond direct animal health.

Here’s the reality: The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has confirmed that importation of live cattle or water buffalo from LSD-infected countries is prohibited outright. Semen and embryos collected more than 60 days prior to an outbreak may be eligible, but only following case-by-case evaluation. That’s not “business as usual”—that’s bureaucratic uncertainty at exactly the wrong moment.

The international standards are even more restrictive. WOAH’s Terrestrial Code requires donor animals to have been resident for six months in an LSD-free country or zone before embryo collection can begin. For semen, PCR testing on blood samples is mandatory at commencement, conclusion, and at least every 28 days during collection.

What does this mean practically? If LSD ever reaches North America, operations with high-value genetics face immediate complications: AI studs would need to implement enhanced testing protocols, export markets would close pending disease-free certification, and movement restrictions could strand valuable animals in the wrong locations. Premium genetics programs—particularly those reliant on international trade—face heightened exposure to these disruptions.

Australia’s response to Italy’s outbreak offers a preview. Within days, the Australian Department of Agriculture removed Italy from its LSD-free country list and suspended imports of bovine fluids and tissues, as Dairy Global reported. That’s how fast market access disappears.

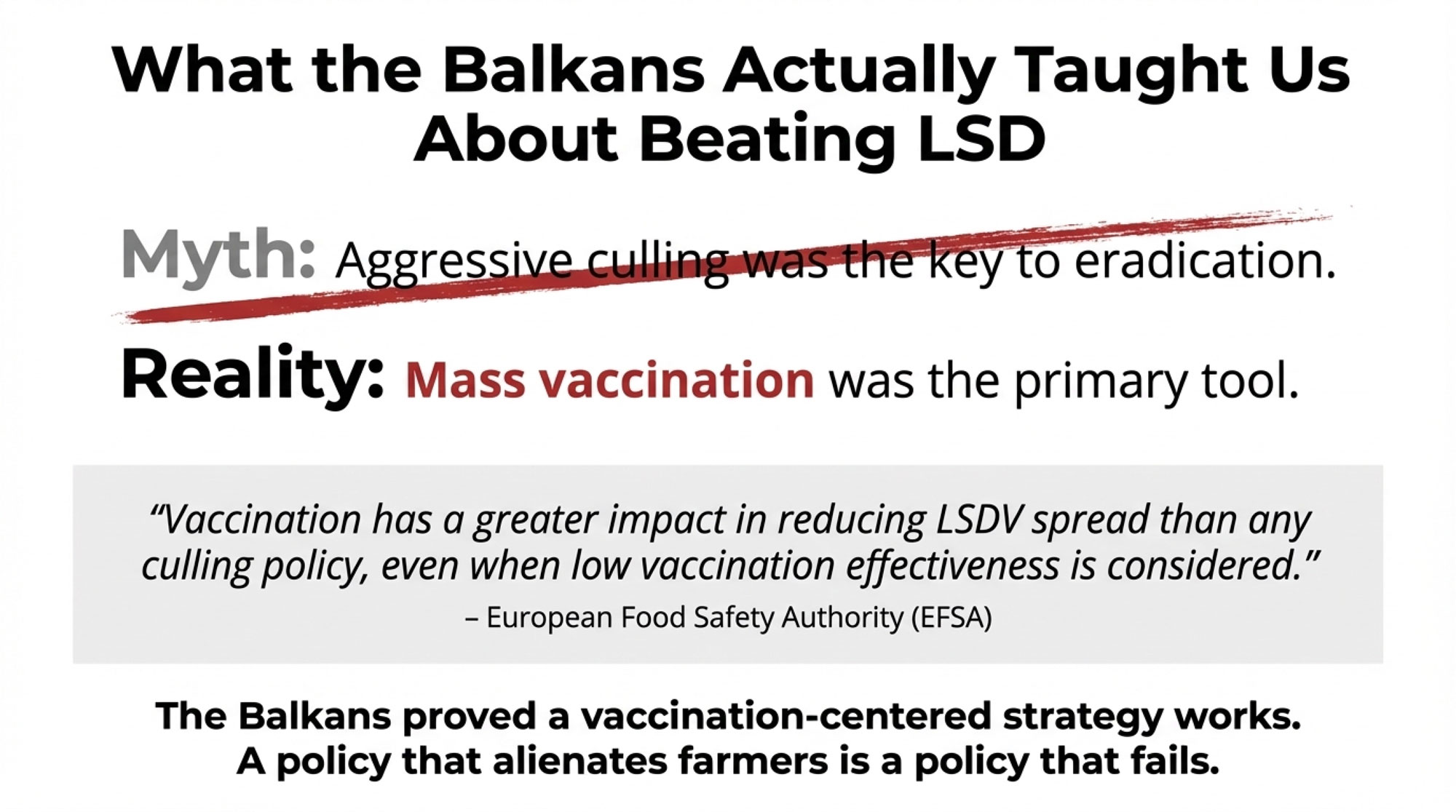

What the Balkans Actually Did (It’s Not What You’ve Heard)

French officials have pointed to southeastern Europe’s successful LSD eradication from 2015-2018 as justification for aggressive culling. But looking closer at what Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia actually did reveals a more nuanced story—and honestly, it’s one that should inform how we think about disease response.

When LSD spread across the Balkans beginning in 2015, affected nations achieved eradication within about three years. That success is often attributed primarily to stamping-out policies. The evidence, though, tells a different story.

Mass vaccination was the primary tool, not culling.

According to the WOAH Regional Representation for Europe, Bulgaria became the first country in the region to achieve 100% cattle vaccination coverage—by July 15, 2016. By 2017-2018, regional vaccination coverage exceeded 70% across all affected countries, with EFSA reporting over 2.5 million animals vaccinated annually to maintain that level of protection.

And here’s the key finding from the European Food Safety Authority’s 2016 analysis: “Vaccination has a greater impact in reducing LSDV spread than any culling policy, even when low vaccination effectiveness is considered.”

That’s significant. The modeling showed vaccination mattered more than culling even when the vaccines didn’t work perfectly. Greece—often cited as the culling success story—actually implemented vaccination as its primary strategy, while selectively using targeted depopulation.

Now, this doesn’t mean France’s current approach is wrong. Every outbreak involves different circumstances, trade considerations, and policy factors that aren’t always visible from the outside. But the Balkan experience does demonstrate that vaccination-centered strategies work against LSD when implemented at scale and sustained over time.

When Farmer Trust Breaks Down, Surveillance Dies

This might be the most important lesson from France, and it doesn’t show up in epidemiological models. It’s about psychology as much as biology.

By December 2025, the relationship between French farmers and authorities had deteriorated badly:

- Farmers in southwestern France organized highway blockades with over 60 tractors

- Some producers physically prevented vaccination teams from accessing properties

- Reports emerged of farmers declining to report suspected cases

- By mid-afternoon on December 19, Le Monde reported the Interior Ministry counted 93 protest actions nationwide involving nearly 4,000 people and 900 tractors

The economic pressure driving this isn’t hard to understand. French agricultural unions have documented that many farmers were already facing severe financial strain before LSD appeared. When total herd depopulation becomes the standard response to a positive test, farmers face an impossible choice: report disease and lose everything, or stay silent and hope.

It’s worth recalling what the FAO advised during the Balkan response back in 2017, as quoted by Dairy Global: “Stamping out—the proactive culling of all animals on an infected farm—should be used as a last resort because stamping out can have a drastic impact on farmers’ livelihoods, particularly those of smallholders.”

What makes this dynamic so dangerous for disease control is that effective surveillance depends entirely on voluntary reporting. The moment farmers believe that calling a veterinarian will lead to the loss of their entire operation, the information flow stops. Cases go unreported. Disease spreads invisibly. And containment becomes exponentially harder.

Here’s the trade-off France is learning—painfully: Vaccination protects herds but may delay disease-free certification. Aggressive culling accelerates certification but destroys farmer trust and surveillance cooperation. And the second trade-off may be worse.

The Endemic Scenario: What’s Really at Stake

In France’s substantial dairy sector, an important question is being discussed in industry circles: What happens if eradication fails?

Countries where LSD has become endemic offer sobering guidance.

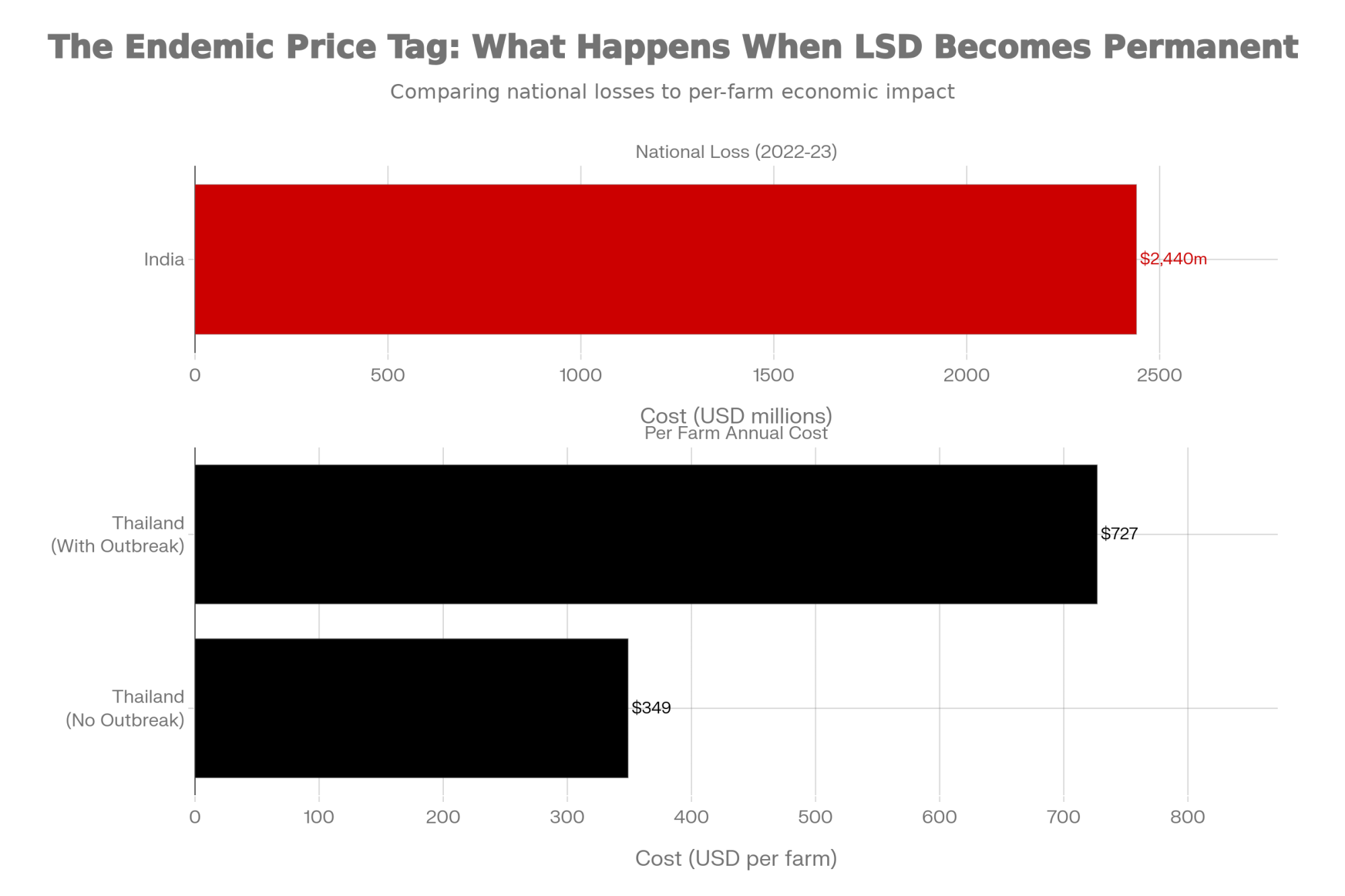

India’s experience since 2019 illustrates the potential scale. A March 2025 study in Frontiers in Veterinary Science used stochastic modeling to estimate economic losses from LSD at approximately $2.44 billion over 2022-2023, with Rajasthan alone experiencing annual losses of around $314 million.

Thailand’s ongoing management since 2021 shows the persistent costs of endemic disease. Research published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science this past January found per-farm financial impacts ranging from $349 on farms that avoided outbreaks—covering vaccination and prevention costs—to $727 on farms that experienced active infections, including treatment and production losses. And those costs continue indefinitely.

For France specifically, endemic status would likely mean:

- Loss of disease-free certification affecting cattle export markets

- Restrictions on the genetics trade, including semen and embryo shipments

- Ongoing vaccination expenses across the national herd

- Competitive disadvantage relative to disease-free neighbors

Now, some argue that endemic management is economically preferable to aggressive eradication—that the costs of culling and farmer resistance outweigh the costs of living with the disease. There’s a case there for countries where LSD is already widespread. But for North American producers? We still have a disease-free status. And when BSE hit Canada in 2003, it took nine years to regain access to beef exports to South Korea and Peru, and a full 22 years before Australia reopened to Canadian beef in July 2025, according to CFIA. That certification represents real value that’s easy to take for granted until it’s gone.

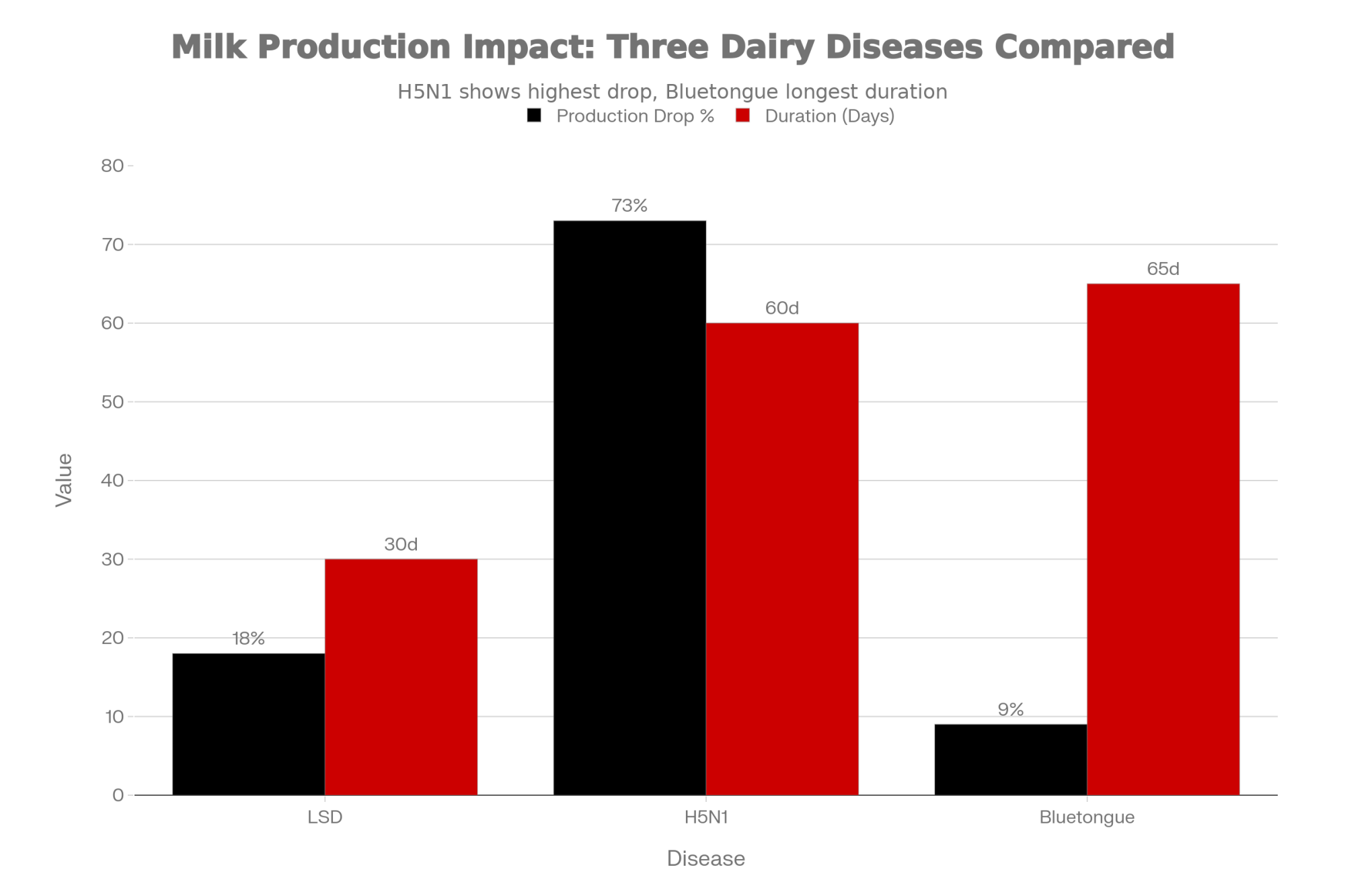

Dairy Cattle Disease 2025: LSD in Context

France’s LSD crisis isn’t occurring in isolation—it’s part of a broader pattern of emerging disease pressures reshaping risk calculations for livestock producers worldwide. Understanding this context helps explain why France’s response capacity was already stretched thin when LSD arrived.

H5N1 in US dairy cattle emerged in March 2024, and by December 2025, CIDRAP reported cases in approximately 1,790 herds across 18 states. What’s striking is the production impact—peer-reviewed research in Frontiers in Veterinary Science found that affected cows experienced approximately a 73% decline in milk production at peak infection, with cumulative losses averaging around 2,000 pounds per cow over 60 days.

Bluetongue BTV-3 re-emerged in the Netherlands in September 2023 and spread to Belgium, France, the UK, and Germany. Infected cattle experience roughly 2 pounds of lost production per cow per day for 9 to 10 weeks.

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease affected over 4,500 French farms by summer 2024—creating overlapping response demands before LSD even appeared.

But here’s what makes LSD different: Unlike H5N1 (which poses human health concerns driving rapid government response) or bluetongue (which European producers have managed through multiple outbreaks), LSD is genuinely novel to Western Europe. There’s no institutional memory, no existing vaccination infrastructure, no producer experience recognizing early signs. France is writing the playbook in real time.

| Disease | Milk Drop % | Duration | Loss per Cow | Human Risk | Current Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumpy Skin Disease | 18% | Variable | Significant | None | 113 farms (FR) |

| H5N1 Avian Flu | 73% ⚠️ | 60 days | ~2,000 lbs ⚠️ | Yes | 1,790 herds (US) |

| Bluetongue BTV-3 | 8-10% | 9-10 weeks | ~140-200 lbs | None | Multiple EU |

What Prepared Producers Are Doing Right Now

Against this backdrop, forward-thinking operations are taking practical steps—not out of panic, but out of recognition that preparation before a crisis beats improvisation during one.

Biosecurity fundamentals that actually matter:

- Written quarantine protocols. New animals are isolated for a minimum of 21 days before joining the main herd, with dedicated equipment and documented testing requirements. Having this written and posted matters when you’re making decisions at 3 a.m. during a crisis. You know how it goes—everyone assumes someone else wrote it down.

- Controlled access management. Single farm entrance, where feasible; visitor logs; foot baths at barn entries; and defined biosecure zones. A producer in Wisconsin’s dairy corridor mentioned that making biosecurity part of the morning routine—the same crew member checks gates and foot baths before first milking every day—made consistency almost automatic.

- Vector control. Given LSD’s insect-borne transmission, fly management is particularly important. Eliminating standing water, maintaining manure management, and using appropriate insecticides during peak vector season all reduce transmission risk.

- Established veterinary relationships. Farms with trusted, ongoing relationships with their veterinarians respond more quickly when concerns arise. Your herd vet should know your operation well enough to spot when something seems unusual.

- Insurance review. Here’s something worth checking: most standard livestock mortality policies don’t explicitly cover losses from foreign animal diseases like LSD. Specialized policies may include provisions for border closure and disease-related depopulation, but coverage varies significantly. Worth a conversation with your agent before you need to file a claim.

- Neighbor communication networks. Informal information sharing between nearby operations often identifies emerging concerns faster than official channels. A quick text from down the road beats a government bulletin by weeks.

THIS WEEK ACTION CHECKLIST

☐ Download biosecurity assessment checklist (CFIA: inspection.canada.ca or FARM Program: nationaldairyfarm.com)

☐ Walk your perimeter—identify fence gaps, uncontrolled access points

☐ Write a one-page quarantine protocol: duration, location, equipment, testing, end criteria

☐ Review fly control program—identify standing water sources and elimination opportunities

☐ Create a laminated vet contact card: herd vet, state/provincial vet, your GPS coordinates

☐ Call your insurance agent—ask specifically about foreign animal disease coverage

☐ Have an informal conversation with 1-2 neighboring operations about recent herd health observations

Estimated time: 4-5 hours spread across the week

Estimated cost: $350-500 (foot bath supplies, signage, veterinary consultation)

| Action | Time | Cost | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Download biosecurity assessment checklist | 30 min | $0 | CRITICAL ⚠️ |

| Walk farm perimeter – identify gaps | 45 min | $0 | High |

| Write one-page quarantine protocol | 1 hour | $0 | CRITICAL ⚠️ |

| Review fly control & standing water | 1 hour | $200-300 | High |

| Create laminated vet contact card | 30 min | $50 | CRITICAL ⚠️ |

| Call insurance re: FAD coverage | 45 min | $0 | Medium |

| Talk with neighboring operations | 30 min | $0 | Medium |

| TOTALS | 4.5-5 hours | $250-350 | 3 Critical + 4 High/Med |

For Canadian Producers Specifically

Canada’s proximity to the evolving US H5N1 situation makes foreign animal disease preparedness particularly relevant right now. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency offers comprehensive biosecurity planning resources at inspection.canada.ca, including province-specific guidance and self-assessment tools.

One thing worth noting: provincial veterinary contacts and disease reporting protocols differ by region. Ontario requires immediate reporting of serious animal health risks—within 18 hours—through OMAFRA’s Agricultural Information Contact Centre at 1-877-424-1300, while western provinces have different reporting structures and timelines. Having your specific provincial contacts documented before you need them eliminates uncertainty when timing matters.

As of December 2025, CFIA has implemented proactive import measures following Europe’s LSD outbreaks, including restrictions on live cattle, certain dairy products, and germplasm from affected countries. The agency’s stated priority: “Preventing the introduction of LSD into Canada is critical because the disease can spread quickly and significantly impact cattle production and trade.”

What I’ve noticed talking with producers across different provinces: the operations that feel most confident about their preparedness aren’t necessarily the largest or most technologically sophisticated. They’re the ones where someone took time to work through the “what if” scenarios before circumstances made that planning urgent.

The Insight That Ties Everything Together

Looking at France’s crisis—the surveillance challenges, the economic pressure, the farmer frustration, the infrastructure gaps—one pattern emerges that underlies everything else:

The operations that survive aren’t the ones that improvise best. They’re the ones who decided their protocols, triggers, and response plans before the crisis arrived.

France improvised. The government moved from one approach to another as circumstances evolved. Farmers found themselves caught between compliance and survival. Veterinarians ended up in impossible positions. When nobody has pre-committed frameworks, confusion fills the gap. And confusion is lethal to disease control.

The farms that will navigate the next decade successfully won’t necessarily be the most optimized or the most efficient in normal times. They’ll be the ones with biosecurity protocols already documented, veterinary relationships already established, neighbor networks already communicating, and financial reserves already set aside.

That’s not paranoia. That’s pattern recognition from what’s actually happening—right now—in France, Thailand, India, and increasingly across the global dairy sector.

Key Takeaways

On what France teaches:

- Surge capacity matters more than baseline infrastructure

- Biosecurity protocols are most valuable when they exist before they’re needed

- Financial reserves matter enormously in a world of recurring disease pressures

On disease response dynamics:

- Vaccination-centered strategies have demonstrated effectiveness against LSD at scale

- Farmer trust is essential infrastructure—systems that undermine trust undermine themselves

- The gap between “response started” and “disease controlled” can stretch for months

On taking action this week:

- Complete a biosecurity assessment using available checklists

- Establish written quarantine protocols and post them where they’ll be followed

- Decide your operational tripwires while your head is clear

The Bottom Line

France is still fighting. Whether eradication remains achievable or France must adapt to endemic management will become clearer in the coming months.

But for those of us elsewhere, France has already provided the lesson that matters most: the time to prepare is before disease arrives, before trust collapses, before you’re making existential decisions at 3 a.m. with no playbook.

The producers who act on that lesson—who spend a few hours this week on biosecurity, who document their protocols, who build their networks—will be the ones still standing when the next challenge arrives.

And in this era of expanding disease pressures, the next wave is always coming.

For biosecurity planning resources, Canadian producers can access CFIA’s farm assessment tools at inspection.canada.ca. US producers can find guidance through the FARM Program at nationaldairyfarm.com and through state extension services. We’ll continue following France’s LSD situation and its implications for global dairy operations.

Learn More

- The Biosecurity Myth: Journal of Dairy Science Reveals Why Enhanced Protocols Failed Against H5N1 – Exposes the fatal flaws in standard defense plans and arms you with a high-ROI prevention framework. Gain immediate operational clarity with non-negotiable protocols and verified cost-impact data that protect your $950-per-cow revenue risk.

- The Day LSD Crossed the Channel: Why This Changes Everything for Dairy Producers – Breaks down the 10:1 ROI of proactive vaccination and delivers the strategic leverage needed to outpace outbreaks. Position your operation for the next three years by auditing vector management systems that slash potential six-month recovery timelines.

- Genetic Game-Changer: How 115 Genes Could Save Dairy Farmers Millions in TB Losses – Reveals the groundbreaking DNA roadmap for breeding naturally resistant herds. Secure a long-term competitive advantage by implementing precision genomic selection that slashes future testing costs by $120 per heifer and eliminates the need for reactive culling.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!