Seven dairy farms disappear. Every. Single. Day. If you’re under 500 cows, you have 18 months to choose: Scale, pivot, or exit.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: The dairy industry is experiencing a seismic shift: 7 farms disappear daily as we consolidate from today’s 24,500 operations toward just 8,000-12,000 by 2035, with 400 mega-farms controlling 75% of production. The $11 billion in new processing investment tells the real story—it’s pre-contracted to 5,000+ cow operations, leaving 300-cow dairies facing three brutal choices: invest $3-5 million to scale up, spend $600,000-1.2 million transitioning to premium markets, or exit now for $700,000-1.1 million before equity evaporates. Your cooperative has become your competitor, with DFA controlling 30% of US milk while operating processing plants that profit from keeping your milk prices low. The economics are undeniable: farms with over 1,000 cows achieve 20-25% lower costs, creating an unbridgeable competitive gap for mid-sized operations. Agricultural lenders confirm you have 18 months—credit is tightening, and consolidators’ appetite for acquisitions peaks in 2025-2026. The bottom line is stark: standing still guarantees slow financial death, making no decision the worst decision of all.

You know, I was having a chat with a third-generation Wisconsin dairy farmer last week—runs about 280 cows, really solid butterfat performance, knows his genetics inside and out. He said something that’s been rattling around in my head ever since:

“I feel like I’m playing a game where the rules changed, but nobody sent me the new rulebook.”

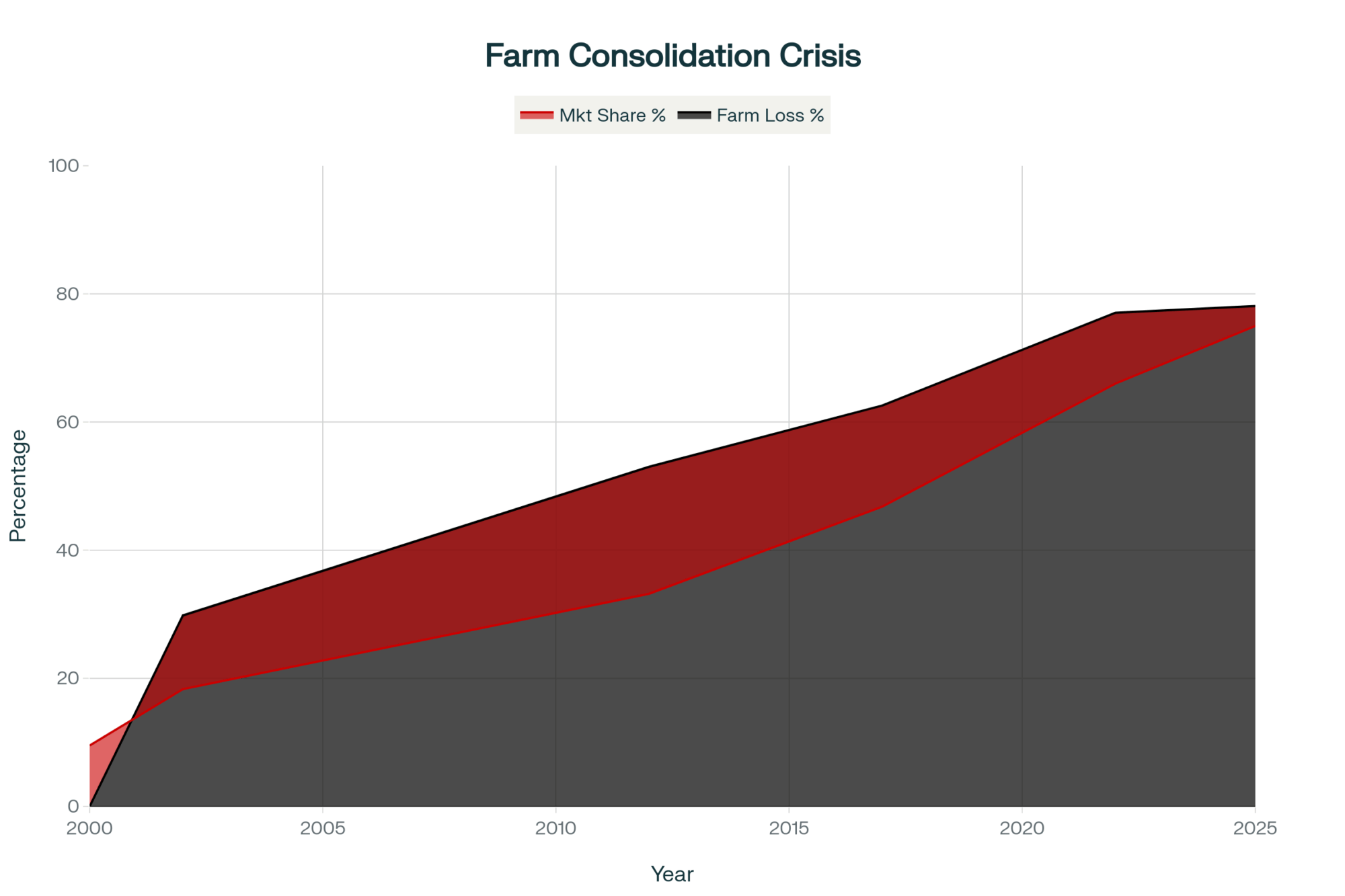

He hit the nail on the head. This isn’t just another rough patch we’re working through; the whole game is structured differently now. What I’ve found in USDA Economic Research Service modeling is that we could see mega-operations producing somewhere between 70 and 75 percent of America’s milk by 2035. We’re talking about going from roughly 24,500 dairy farms today—that January NASS count was eye-opening—down to maybe 8,000 to 12,000 operations in about a decade.

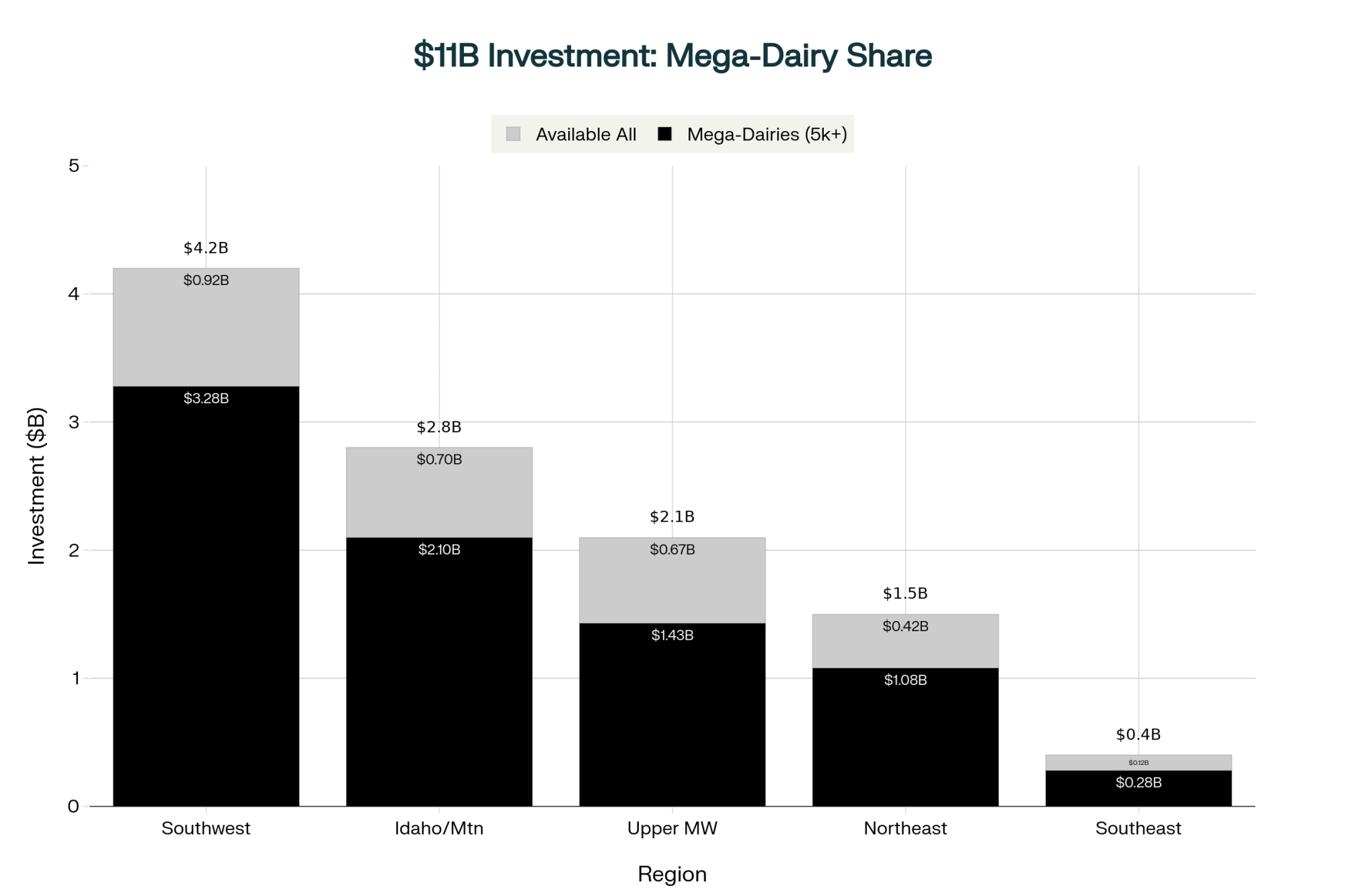

Here’s what’s really striking: the International Dairy Foods Association documented something like $11 billion in processing investments announced between 2024 and 2028. That’s not your typical expansion—that’s the industry rebuilding itself from the ground up.

For those of you managing 300-cow operations—and I talk to so many of you at meetings—understanding what’s happening isn’t about being negative. It’s about seeing clearly where opportunities still exist.

When Your Cooperative Became Something Else

What’s fascinating—and honestly, a bit troubling—is how organizations like Dairy Farmers of America have evolved from their original marketing cooperative model into vertically integrated processors. This completely changes how milk moves from your tank to the market.

Consider this: DFA now controls nearly 30 percent of US milk production according to their annual reports, while operating dozens of processing facilities across North America. Let’s call it what it is: a conflict of interest. When your co-op becomes a processor, their profit margin depends on keeping input costs low. Your milk is the input. Do the math.

I was talking to a producer from upstate New York—does beautiful rotational grazing, really innovative guy—and he put it perfectly:

“After 22 years shipping to the same cooperative, the relationship feels fundamentally different. The negotiating dynamics have shifted in ways that are hard to articulate but impossible to ignore.”

The data backs up what he’s feeling. We’re seeing more and more member milk processed in cooperative-owned facilities, a huge shift from the traditional marketing model. And here’s something that should make everyone pause: federal court records show settlements totaling nearly $200 million since 2013, with the 2016 Northeast case alone hitting $158.6 million. These aren’t just theoretical tensions we’re talking about.

Where That $11 Billion Is Really Going

Everyone’s celebrating this $11 billion in processing investment. But let’s look closer at where that money’s actually flowing. IDFA’s October report details what they’re calling the largest dairy infrastructure investment in American history, and the geographic pattern tells you everything.

Chobani announced back in April that it’s building a $1.2 billion facility in Rome, New York. They’ve got another $450 million expansion going in Twin Falls, Idaho. Leprino Foods continues to expand in Texas, especially around Lubbock. These locations aren’t random—they’re following the consolidation that’s already happening.

What industry analysts from Rabobank and CoBank have been telling us is that processors are increasingly locking up supply agreements with large-scale operations before they even break ground. They don’t publish exact percentages, but the pattern is crystal clear.

A Texas producer with 450 cows shared his experience trying to get into one of these new plants:

“The terms required a 10-year commitment for our entire production at annually-set prices. The minimum volume guarantee was 15 million pounds—more than double what we produce.”

These facilities… they’re not being built for folks like him. They’re designed for operations running 5,000 to 25,000 cows.

But here’s what gives me hope—in Pennsylvania’s Lancaster County, where you’ve still got lots of 100 to 300 cow operations, producers are finding creative solutions. A group of about 31 Amish and Mennonite farmers formed their own micro-cooperative last year, partnering with a local artisan cheese maker.

“We couldn’t compete on volume, but our grass-fed milk and traditional practices commanded premium prices in Philadelphia markets.”

Getting Out with Your Shirt On

NASS quarterly reports show we’re losing approximately 2,700 to 2,800 farms annually. That’s up from maybe 500 to 900 per year back in the early 2000s. Between 2017 and 2022 alone—and these census numbers are sobering—we lost 15,221 operations. Nearly a 38 percent decline in just five years.

The Center for Dairy Profitability at UW-Madison has been digging into these patterns, and its data show that operations with more than 1,000 cows achieve production costs roughly 20 to 25 percent lower than those of 500-cow farms. It’s basic economies of scale—same thing that reshaped retail, same thing that’s hitting us now.

Dr. Mark Stephenson from Wisconsin’s dairy markets program explained it to me this way: reaching competitive scale today requires approximately to 5 million in capital investment. For most mid-sized operations, accessing that capital while managing existing debt… well, you know how that math works out.

Economic modeling suggests we’ll stabilize somewhere between 8,000 and 12,000 operations by 2035. That’s a fundamental restructuring of the American dairy industry.

Three Paths Forward—What’s Actually Working

After talking to dozens of producers this past year, I’ve seen three main strategies emerge for operations in the 200- to 500-cow range. Each has its own opportunities and challenges.

Scaling to Competitive Size

An Idaho producer who expanded from 800 to 3,600 cows over two years shared some hard truths:

“At 800 cows, even with good management, we were losing $200,000 annually at prevailing milk prices. At 3,600, with updated parlor technology and improved feed efficiency, we’re profitable at those same prices. The fixed cost distribution makes all the difference.”

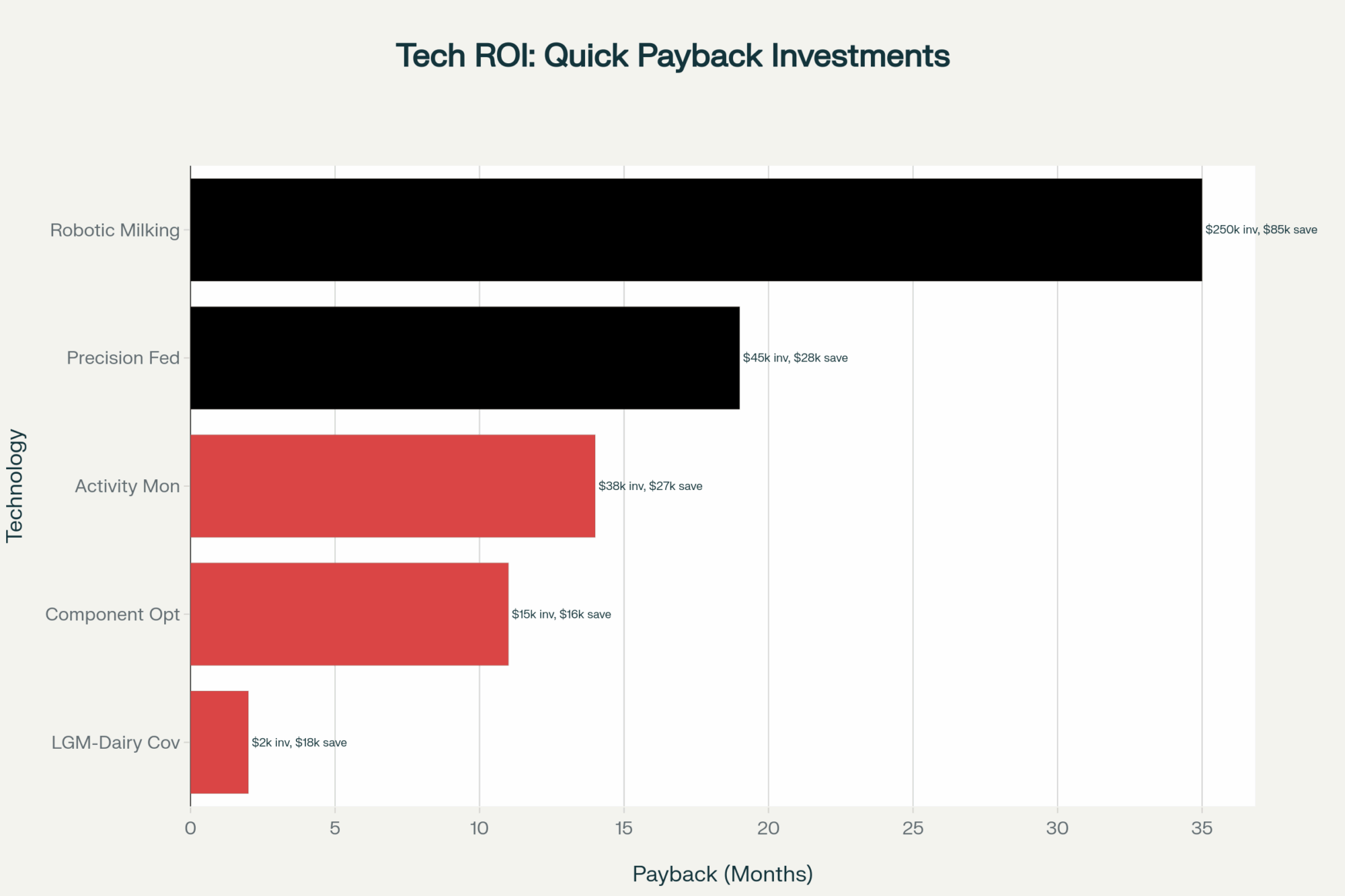

Here’s the reality of scale: You can’t just add cows; you have to add robots and data. USDA farm technology surveys show that robotic milking systems are now on nearly 3 percent of US dairy operations, yet those operations account for over 8 percent of national milk production. It’s mostly these scaling operations where labor efficiency becomes critical.

Based on what lenders are telling us and actual producer experiences, this pathway typically requires:

- $3 to 5 million in capital for facilities, equipment, and genetics

- At least 40 percent equity position for financing approval

- Being close to processing—hauling costs will eat you alive beyond 100 miles

- Committing to 15, maybe 20 years to recoup that investment

The success stories tend to be producers under 55 with strong equity and minimal debt. And timing? Critical. Expansions during favorable price cycles work. During downturns? Different story.

Premium Market Transition

An Alberta producer who transitioned her family’s 320-cow operation to organic five years ago offers another perspective:

“We experienced approximately 30 percent improvement in net farm income despite lower production volumes. The combination of reduced veterinary expenses, premium pricing, and eventually lower input costs created a sustainable model.”

Producers making this transition work report:

- Transition costs of $600,000 to maybe $1.2 million

- You need to be within about 50 miles of a metro market for direct sales

- Need 3 to 5 years of capital reserves during transition

- Marketing becomes just as important as production

“Those first two years nearly broke us. Year three reached break-even. Years four and five delivered the returns that justified the transition.”

A North Carolina producer adds another angle. His 180-cow operation transitioned to A2/A2 genetics and grass-fed production three years ago:

“The Research Triangle market—all those tech workers and university folks—they understand the value proposition. In our local market, we’re getting significantly more per hundredweight than commodity, and our production costs actually decreased once we optimized our grazing rotation.”

Some producers are also exploring renewable energy. A Vermont dairy with 400 cows installed an anaerobic digester system last year. “Between the renewable energy credits and reduced electricity costs, it’s potentially adding substantial value annually to our bottom line,” the owner reports. “It doesn’t solve everything, but it provides a crucial margin in tight years.”

Strategic Exit Planning

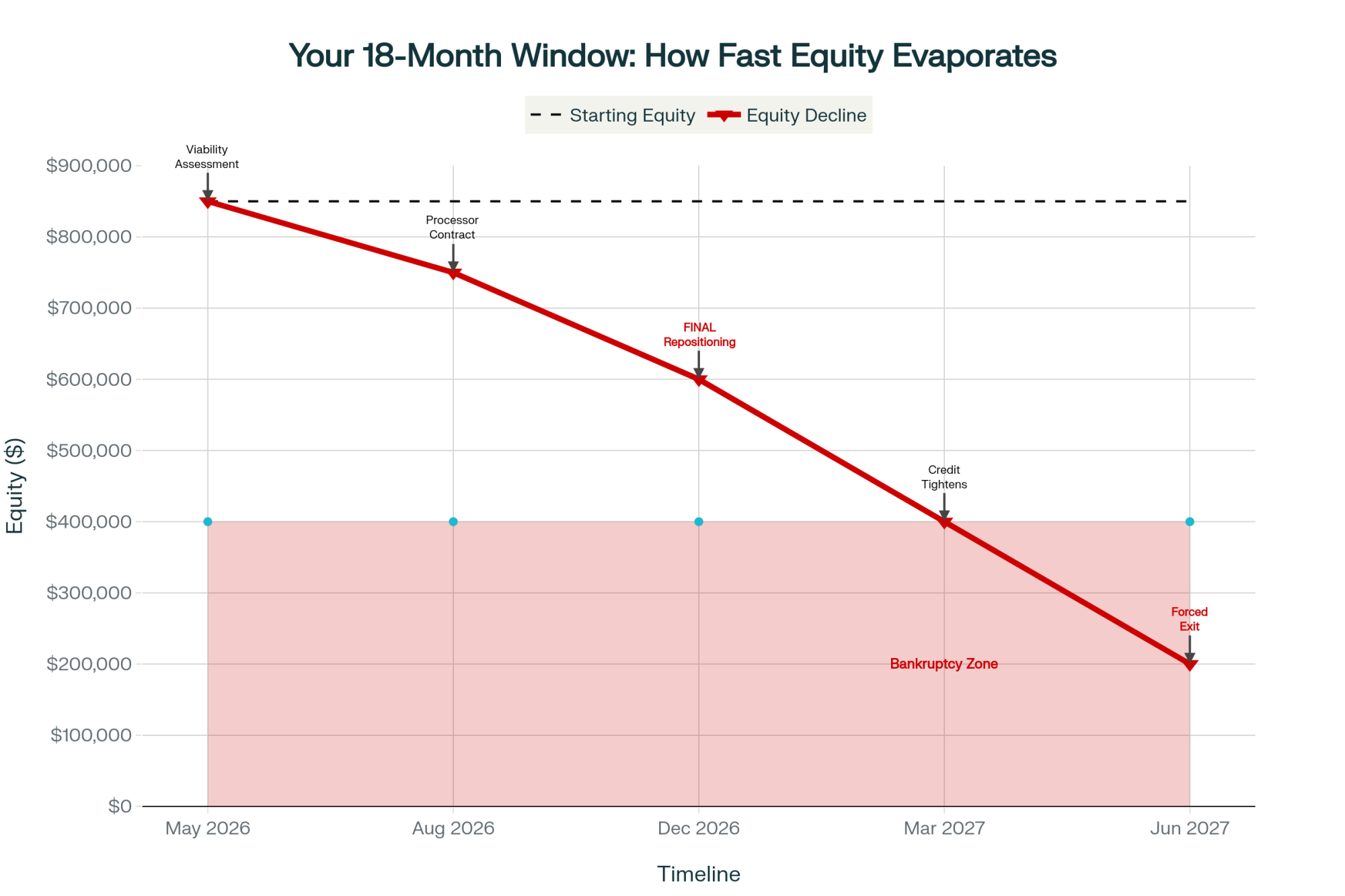

A Wisconsin producer who sold in early 2024 was refreshingly candid:

“With $850,000 in equity, I could have continued operating at marginal profitability for perhaps three more years. Instead, I accepted $720,000 from a consolidator. My neighbor, who waited, went through bankruptcy proceedings and retained maybe $100,000.”

Current market analysis from agricultural real estate specialists suggests:

- Strategic sales to consolidators in 2025-2026: $700,000 to $1.1 million for typical 300-cow operations

- Wait with continued losses: equity could erode to $200,000-400,000 by 2028-2029

- Each year at break-even represents $100,000-200,000 in opportunity cost

| Decision Factor | SCALE UP | PREMIUM PIVOT | STRATEGIC EXIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Investment | $3-5M | $600K-1.2M | $0 |

| Time to Profit | 8-10 years | 3-5 years | Immediate |

| Year 5 Income | +$180K | +$95K | $0 |

| Equity Change | -$1.2M (RED) | -$300K (RED) | +$750K (BLACK) |

| Risk Level | VERY HIGH (RED) | HIGH (RED) | LOW (BLACK) |

| Success Requires | Youth, debt, processing | Metro proximity | Accept reality |

| Best For | <45 yrs, 40%+ equity | Niche positioning | Preserve wealth |

| Regional Viability | Southwest, Idaho only | Northeast, Midwest | All regions |

How Geography Is Reshaping Everything

Based on current investment patterns and USDA projections, American dairy production will concentrate in four primary regions by 2030-2035.

The Southwest—Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona—currently produces 32 to 34 percent of national milk, with projections suggesting a move toward 40 to 45 percent. These are your 5,000 to 15,000 cow dry-lot operations. But here’s the kicker—USGS data shows the Ogallala Aquifer dropping 2 to 3 feet annually. Water’s becoming the limiting factor.

Idaho has transformed remarkably in just one generation, now producing approximately 8 percent of the national milk. Chobani’s investments there… they’re following the consolidation, not driving it.

The Upper Midwest—Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota—that’s an interesting story. Still producing 18 to 20 percent of national milk, down from over 25 percent historically. What you’re seeing is bifurcation—either going mega or going specialty. The middle? That’s where the pressure is.

New York produces about 4 percent of the nation’s milk, yet its processing investment is massive. The capacity appears to exceed local milk supply, which creates interesting supply chain dynamics.

The Southeast faces unique challenges. A Georgia producer managing 400 cows told me:

“We’re seeing farms exit not because of economics alone, but because the next generation won’t tolerate the working conditions. The technology investments needed for heat abatement in our climate add another $500,000 to expansion costs that Northern operations don’t face.”

System Resilience—What Keeps Me Up at Night

The efficiency gains from consolidation are impressive, but when 40 to 45 percent of national milk production concentrates in water-stressed regions, we’re creating single-point vulnerabilities.

Dr. Jennifer Morrison from Cornell’s food systems program put it well: “Efficiency and resilience often exist in tension. We’re building remarkably efficient systems that may prove fragile under stress.”

Recent screwworm detections, shifting climate patterns, labor challenges… USDA APHIS has contingency plans, sure, but concentrated production carries fundamentally different risk profiles than distributed systems.

Collective Action Still Works

Here’s what’s encouraging: in September, approximately 600 Irish dairy farmers successfully pressed Dairygold for written accountability on pricing decisions. The Irish Farmers Journal covered it extensively. They didn’t tear anything down—they just demanded transparency through organized, professional engagement.

Back home, the American Farm Bureau Federation is pushing for modified bloc voting in their 2025 priorities—letting farmers vote individually rather than having cooperatives vote for them. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition mobilized over 130 advocates to engage Congress earlier this year.

Regional organizing is showing promise, too. Vermont producers have formed transparency coalitions to request detailed milk-check breakdowns. California’s Central Valley sees mid-sized dairies exploring collective negotiation.

Pennsylvania offers a particularly instructive example. Approximately 28 dairy farmers started meeting monthly to compare milk check deductions. After finding significant variations within the same cooperative and region, they presented consolidated data to their board and received substantive responses for the first time.

“Individual concerns get dismissed. But 28 farmers with documentation command attention.”

Key Questions for Your Cooperative

Start pressing for transparency with these specific requests:

✓ Request itemized breakdowns of all milk check deductions

✓ Seek written explanations of member versus non-member pricing

✓ Inquire about percentages of cooperative income from member versus non-member business

✓ Request voting records on significant pricing decisions

✓ Understand how board representation aligns with regional membership

What This Means for Different Operation Sizes

For operations with fewer than 250 cows, commodity-market math has become increasingly challenging without exceptional cost management. Premium market transitions offer possibilities if you’re geographically positioned right. Strategic exit planning may preserve more equity than extended marginal operation.

Producers in the 250- to 500-cow range face critical decisions. Scaling to a competitive size requires that $3 to 5 million, which we talked about. The premium market pivots demand, requiring different capital and marketing commitments. Maintaining the status quo typically means gradual equity erosion.

Operations running 500 to 1,000 cows are approaching the minimum viable commodity scale. Strategic partnerships with neighbors, collective arrangements, or, really, locking in processing relationships become essential.

Agricultural lending surveys from late 2024 show credit availability tightening as lenders see these exit rates. If you’re planning expansion, you’re looking at a 12- to 18-month window. M&A advisors specializing in dairy tell me that interest in consolidator acquisitions peaks in 2025-2026.

Addressing What We Don’t Like to Talk About

CDC and NIOSH research shows farmers face a suicide risk approximately 3.5 times higher than the general population. Financial stress is the primary factor, according to the University of Iowa’s agricultural medicine program.

Illinois has expanded mental health support for farmers through their Department of Agriculture wellness initiatives. Other states are developing similar programs. These aren’t just statistics—these are our neighbors, our colleagues, our friends.

A Minnesota farm widow shared something that stays with me:

“Watching three generations of work dissolve feels like personal failure, even when you understand it’s structural economics driving the outcome.”

The Bottom Line

American dairy is experiencing its most significant structural transformation since we mechanized. By 2035, we’ll have mega-operations, specialized premium producers, concentrated processing infrastructure—fundamentally different from the distributed system many of us grew up with.

What’s particularly interesting from a global perspective is how this consolidation positions American dairy internationally. As our production becomes more concentrated and efficient, we’re increasingly competitive in export markets—especially cheese and milk powder bound for Asia and Mexico. This global dimension adds another layer to domestic consolidation pressures.

Understanding these dynamics lets you make informed decisions while options remain. Success stories will emerge from this transition—producers who recognize patterns early and position accordingly. Solutions vary by region, operation size, life stage, and individual circumstances.

After covering this industry for over a decade and talking with hundreds of producers, one thing’s clear: the question isn’t whether to adapt—market forces have made that decision. The question is how to adapt, when to act, and what outcomes to target.

The consolidation reshaping American dairy is real, it’s accelerating, and it’s transformative. But producers who understand these dynamics, assess their positions honestly, and act decisively while maintaining strategic options can still chart successful paths forward.

The clock’s ticking, but opportunity windows remain open. The key is recognizing them and acting with purpose while time allows.

Your next step? This week, schedule time to honestly assess which of these three paths makes sense for your operation. Talk to your lender. Review your equity position. Have the hard conversations with family members. Because in this new game, the worst decision is no decision.

Resources for Industry Support

Mental Health Assistance:

- Farm Aid Hotline: 1-800-FARM-AID

- AgriSafe Network: 1-866-354-3905

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- State-specific farm stress hotlines

Financial and Transition Planning:

- National Young Farmers Coalition: youngfarmers.org

- Farm Financial Standards Council: ffsc.org

- Center for Farm Financial Management: cffm.umn.edu

Industry Advocacy:

- National Farmers Union: nfu.org

- Organization for Competitive Markets: competitivemarkets.com

- Farm Action: farmaction.us

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- The 400-farm future is inevitable: Daily losses of 7 farms are shrinking the industry from 24,500 to 8,000 operations by 2035, with mega-farms claiming 75% of production

- Three paths remain—pick one: Scale to 3,000+ cows ($3-5M), pivot to premium markets ($600K-1.2M), or exit strategically now ($700K-1.1M before it drops to $100K)

- Your co-op became your competitor: Organizations like DFA control 30% of milk AND processing—they profit from low milk prices that destroy you

- Act within 18 months or lose everything: Credit markets are closing, consolidator interest peaks in 2025-2026, and standing still means bleeding equity until bankruptcy

Complete references and supporting documentation are available upon request by contacting the editorial team at editor@thebullvine.com.

Learn More:

- Decide or Decline: 2025 and the Future of Mid-Size Dairies – Provides specific frameworks for the “Scale vs. Optimization” decision, including critical debt ratio benchmarks and management strategies for the 400-600 cow transition zone that directly impact long-term viability.

- The $228,000 Exit Strategy Reshaping Dairy: Inside the 55% Surge in Strategic Bankruptcies – Reveals the counter-intuitive financial reality where Chapter 12 filings may preserve significantly more equity than traditional farm sales, offering a critical alternative for producers evaluating the “Exit” pathway.

- AI and Precision Tech: What’s Actually Changing the Game for Dairy Farms in 2025? – Breaks down specific ROI timelines for precision feeding versus robotics investments, helping producers validate if their “Scale Up” technology spend will deliver returns before credit markets tighten further.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!

Join over 30,000 successful dairy professionals who rely on Bullvine Weekly for their competitive edge. Delivered directly to your inbox each week, our exclusive industry insights help you make smarter decisions while saving precious hours every week. Never miss critical updates on milk production trends, breakthrough technologies, and profit-boosting strategies that top producers are already implementing. Subscribe now to transform your dairy operation’s efficiency and profitability—your future success is just one click away.

Join the Revolution!

Join the Revolution!